User login

FDA approves hyaluronic acid filler for lip augmentation, perioral rhytids

, the manufacturer has announced.

Approval was supported by results of a phase 3 clinical trial in which a lower amount of Restylane Kysse was needed to see an improvement in lip fullness (1.82 mL) vs. a comparator (2.24 mL), according to the press release issued by Galderma. After 1 year, 78% of those who received the Restylane product were satisfied, and it was also shown to be safe and well tolerated, the release said.

In the statement, the company said that it is “working to determine the appropriate launch timing and availability” of this new product.

[email protected]

, the manufacturer has announced.

Approval was supported by results of a phase 3 clinical trial in which a lower amount of Restylane Kysse was needed to see an improvement in lip fullness (1.82 mL) vs. a comparator (2.24 mL), according to the press release issued by Galderma. After 1 year, 78% of those who received the Restylane product were satisfied, and it was also shown to be safe and well tolerated, the release said.

In the statement, the company said that it is “working to determine the appropriate launch timing and availability” of this new product.

[email protected]

, the manufacturer has announced.

Approval was supported by results of a phase 3 clinical trial in which a lower amount of Restylane Kysse was needed to see an improvement in lip fullness (1.82 mL) vs. a comparator (2.24 mL), according to the press release issued by Galderma. After 1 year, 78% of those who received the Restylane product were satisfied, and it was also shown to be safe and well tolerated, the release said.

In the statement, the company said that it is “working to determine the appropriate launch timing and availability” of this new product.

[email protected]

The resurgence of Plaquenil (hydroxychloroquine)

Two of the most unusual dermatologic drugs have resurged as possible first-line therapy for rescue treatment of hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2, despite extremely limited clinical data supporting their efficacy, optimal dose, treatment duration, and potential adverse effects.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine were introduced as treatment and prophylaxis of malaria and approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1949 and 1955, respectively. They belong to a class of drugs called 4-aminoquinolones and have a flat aromatic core and a basic side chain. The basic property of these drugs contribute to their ability to accumulate in lysosomes. They have a large volume of distribution in the blood and a half-life of 40-60 days. Important interactions include use with tamoxifen, proton pump inhibitors, and with smoking. Although both drugs cross the placenta, they don’t have any notable effects on the fetus.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine enter the cell and accumulate in the lysosomes along a pH gradient. Within the lysosome, they increase the pH, thereby stabilizing lysosomes and inhibiting eosinophil and neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytic activity. They also inhibit complement-mediated hemolysis, reduce acute phase reactants, and prevent MHC class II–mediated auto antigen presentation. Additionally, they decrease cell-mediated immunity by decreasing the production of interleukin-1 and plasma cell synthesis. Hydroxychloroquine can also accumulate in endosomes and inhibit toll-like receptor signaling, thereby reducing the production of proinflammatory cytokines.

One of the ways SARS-CoV-2 enters cells is by up-regulating and binding to ACE2. Chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine reduce glycosylation of ACE2 and thus inhibit viral entry. Additionally, by increasing the endosomal pH, they potentially inactivate enzymes that viruses require for replication. Their lifesaving benefits, however, are thought to involve blocking the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 and suppressing the cytokine storm thought to induce acute respiratory distress syndrome. Interestingly, chloroquine has also been shown to allow zinc ions into the cell, and zinc is a potent inhibitor of coronavirus RNA polymerase.

Side effects of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine include GI upset, retinal toxicity with long-term use, hypoglycemia, cardiomyopathy, QT prolongation, ventricular arrhythmias, and renal and liver toxicity. Adverse effects have been observed with long-term daily doses of more than 3.5 mg/kg of chloroquine or more than 6.5 mg/kg of hydroxychloroquine. Cutaneous effects include pruritus, morbilliform rashes (in an estimated 10% of those treated) and psoriasis flares, and blue-black hyperpigmentation (in about 25%) of the shins, face, oral palate, and nails.

Initial In February 2020, the first clinical results of 100 patients treated with chloroquine were reported in a news briefing by the Chinese government. On March 20, the first clinical trial was published offering guidelines for the treatment of COVID-19 using hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin combination therapy – albeit with many limitations and reported biases in the study. Despite the poorly designed studies and inconclusive evidence, on March 28, the FDA issued an Emergency Use Authorization that allows providers to request a supply of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for hospitalized patients with COVID-19 who are unable to join a clinical trial.

On April 2, the first clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in adults hospitalized with COVID-19 began at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. The ORCHID trial (Outcomes Related to COVID-19 Treated With Hydroxychloroquine Among In-patients With Symptomatic Disease), funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. This blinded, placebo-controlled study is evaluating hydroxychloroquine treatment of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in hopes of treating the severe complications of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Participants are randomly assigned to receive 400 mg hydroxychloroquine twice daily as a loading dose and then 200 mg twice daily thereafter on days 2-5. As of this writing, this study is currently underway and outcomes are expected in the upcoming weeks.

There is now a shortage of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in patients who have severe dermatologic and rheumatologic diseases, which include some who been in remission for years because of these medications and are in grave danger of recurrence. During this crisis, we desperately need well-controlled, randomized studies to test the efficacy and prolonged safety profile of these drugs in COVID-19 patients, as well as appropriate funding to source these medications for hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients in need.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. They had no relevant disclosures. Write to them at [email protected].

Sources

Liu J et al. Cell Discov. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0156-0.

Vincent MJ et al. Virol J. 2005 Aug 22;2:69.

Gautret P et al. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 Mar 20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949.

Devaux CA et al. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 Mar 12:105938. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105938.

Aronson J et al. COVID-19 trials registered up to 8 March 2020 – an analysis of 382 studies. 2020. Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. https://www.cebm.net/oxford-covid-19/covid-19-registered-trials-and-analysis/

Savarino A et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003 Nov;3(11):722-7.

Yazdany J, Kim AHJ. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 31. doi: 10.7326/M20-1334.

Xue J et al. PLoS One. 2014 Oct 1;9(10):e109180.

te Velthuis AJ et al. PLoS Pathog. 2010 Nov 4;6(11):e1001176.

Two of the most unusual dermatologic drugs have resurged as possible first-line therapy for rescue treatment of hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2, despite extremely limited clinical data supporting their efficacy, optimal dose, treatment duration, and potential adverse effects.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine were introduced as treatment and prophylaxis of malaria and approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1949 and 1955, respectively. They belong to a class of drugs called 4-aminoquinolones and have a flat aromatic core and a basic side chain. The basic property of these drugs contribute to their ability to accumulate in lysosomes. They have a large volume of distribution in the blood and a half-life of 40-60 days. Important interactions include use with tamoxifen, proton pump inhibitors, and with smoking. Although both drugs cross the placenta, they don’t have any notable effects on the fetus.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine enter the cell and accumulate in the lysosomes along a pH gradient. Within the lysosome, they increase the pH, thereby stabilizing lysosomes and inhibiting eosinophil and neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytic activity. They also inhibit complement-mediated hemolysis, reduce acute phase reactants, and prevent MHC class II–mediated auto antigen presentation. Additionally, they decrease cell-mediated immunity by decreasing the production of interleukin-1 and plasma cell synthesis. Hydroxychloroquine can also accumulate in endosomes and inhibit toll-like receptor signaling, thereby reducing the production of proinflammatory cytokines.

One of the ways SARS-CoV-2 enters cells is by up-regulating and binding to ACE2. Chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine reduce glycosylation of ACE2 and thus inhibit viral entry. Additionally, by increasing the endosomal pH, they potentially inactivate enzymes that viruses require for replication. Their lifesaving benefits, however, are thought to involve blocking the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 and suppressing the cytokine storm thought to induce acute respiratory distress syndrome. Interestingly, chloroquine has also been shown to allow zinc ions into the cell, and zinc is a potent inhibitor of coronavirus RNA polymerase.

Side effects of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine include GI upset, retinal toxicity with long-term use, hypoglycemia, cardiomyopathy, QT prolongation, ventricular arrhythmias, and renal and liver toxicity. Adverse effects have been observed with long-term daily doses of more than 3.5 mg/kg of chloroquine or more than 6.5 mg/kg of hydroxychloroquine. Cutaneous effects include pruritus, morbilliform rashes (in an estimated 10% of those treated) and psoriasis flares, and blue-black hyperpigmentation (in about 25%) of the shins, face, oral palate, and nails.

Initial In February 2020, the first clinical results of 100 patients treated with chloroquine were reported in a news briefing by the Chinese government. On March 20, the first clinical trial was published offering guidelines for the treatment of COVID-19 using hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin combination therapy – albeit with many limitations and reported biases in the study. Despite the poorly designed studies and inconclusive evidence, on March 28, the FDA issued an Emergency Use Authorization that allows providers to request a supply of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for hospitalized patients with COVID-19 who are unable to join a clinical trial.

On April 2, the first clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in adults hospitalized with COVID-19 began at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. The ORCHID trial (Outcomes Related to COVID-19 Treated With Hydroxychloroquine Among In-patients With Symptomatic Disease), funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. This blinded, placebo-controlled study is evaluating hydroxychloroquine treatment of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in hopes of treating the severe complications of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Participants are randomly assigned to receive 400 mg hydroxychloroquine twice daily as a loading dose and then 200 mg twice daily thereafter on days 2-5. As of this writing, this study is currently underway and outcomes are expected in the upcoming weeks.

There is now a shortage of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in patients who have severe dermatologic and rheumatologic diseases, which include some who been in remission for years because of these medications and are in grave danger of recurrence. During this crisis, we desperately need well-controlled, randomized studies to test the efficacy and prolonged safety profile of these drugs in COVID-19 patients, as well as appropriate funding to source these medications for hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients in need.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. They had no relevant disclosures. Write to them at [email protected].

Sources

Liu J et al. Cell Discov. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0156-0.

Vincent MJ et al. Virol J. 2005 Aug 22;2:69.

Gautret P et al. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 Mar 20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949.

Devaux CA et al. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 Mar 12:105938. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105938.

Aronson J et al. COVID-19 trials registered up to 8 March 2020 – an analysis of 382 studies. 2020. Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. https://www.cebm.net/oxford-covid-19/covid-19-registered-trials-and-analysis/

Savarino A et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003 Nov;3(11):722-7.

Yazdany J, Kim AHJ. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 31. doi: 10.7326/M20-1334.

Xue J et al. PLoS One. 2014 Oct 1;9(10):e109180.

te Velthuis AJ et al. PLoS Pathog. 2010 Nov 4;6(11):e1001176.

Two of the most unusual dermatologic drugs have resurged as possible first-line therapy for rescue treatment of hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2, despite extremely limited clinical data supporting their efficacy, optimal dose, treatment duration, and potential adverse effects.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine were introduced as treatment and prophylaxis of malaria and approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1949 and 1955, respectively. They belong to a class of drugs called 4-aminoquinolones and have a flat aromatic core and a basic side chain. The basic property of these drugs contribute to their ability to accumulate in lysosomes. They have a large volume of distribution in the blood and a half-life of 40-60 days. Important interactions include use with tamoxifen, proton pump inhibitors, and with smoking. Although both drugs cross the placenta, they don’t have any notable effects on the fetus.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine enter the cell and accumulate in the lysosomes along a pH gradient. Within the lysosome, they increase the pH, thereby stabilizing lysosomes and inhibiting eosinophil and neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytic activity. They also inhibit complement-mediated hemolysis, reduce acute phase reactants, and prevent MHC class II–mediated auto antigen presentation. Additionally, they decrease cell-mediated immunity by decreasing the production of interleukin-1 and plasma cell synthesis. Hydroxychloroquine can also accumulate in endosomes and inhibit toll-like receptor signaling, thereby reducing the production of proinflammatory cytokines.

One of the ways SARS-CoV-2 enters cells is by up-regulating and binding to ACE2. Chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine reduce glycosylation of ACE2 and thus inhibit viral entry. Additionally, by increasing the endosomal pH, they potentially inactivate enzymes that viruses require for replication. Their lifesaving benefits, however, are thought to involve blocking the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 and suppressing the cytokine storm thought to induce acute respiratory distress syndrome. Interestingly, chloroquine has also been shown to allow zinc ions into the cell, and zinc is a potent inhibitor of coronavirus RNA polymerase.

Side effects of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine include GI upset, retinal toxicity with long-term use, hypoglycemia, cardiomyopathy, QT prolongation, ventricular arrhythmias, and renal and liver toxicity. Adverse effects have been observed with long-term daily doses of more than 3.5 mg/kg of chloroquine or more than 6.5 mg/kg of hydroxychloroquine. Cutaneous effects include pruritus, morbilliform rashes (in an estimated 10% of those treated) and psoriasis flares, and blue-black hyperpigmentation (in about 25%) of the shins, face, oral palate, and nails.

Initial In February 2020, the first clinical results of 100 patients treated with chloroquine were reported in a news briefing by the Chinese government. On March 20, the first clinical trial was published offering guidelines for the treatment of COVID-19 using hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin combination therapy – albeit with many limitations and reported biases in the study. Despite the poorly designed studies and inconclusive evidence, on March 28, the FDA issued an Emergency Use Authorization that allows providers to request a supply of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for hospitalized patients with COVID-19 who are unable to join a clinical trial.

On April 2, the first clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in adults hospitalized with COVID-19 began at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. The ORCHID trial (Outcomes Related to COVID-19 Treated With Hydroxychloroquine Among In-patients With Symptomatic Disease), funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. This blinded, placebo-controlled study is evaluating hydroxychloroquine treatment of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in hopes of treating the severe complications of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Participants are randomly assigned to receive 400 mg hydroxychloroquine twice daily as a loading dose and then 200 mg twice daily thereafter on days 2-5. As of this writing, this study is currently underway and outcomes are expected in the upcoming weeks.

There is now a shortage of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in patients who have severe dermatologic and rheumatologic diseases, which include some who been in remission for years because of these medications and are in grave danger of recurrence. During this crisis, we desperately need well-controlled, randomized studies to test the efficacy and prolonged safety profile of these drugs in COVID-19 patients, as well as appropriate funding to source these medications for hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients in need.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. They had no relevant disclosures. Write to them at [email protected].

Sources

Liu J et al. Cell Discov. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0156-0.

Vincent MJ et al. Virol J. 2005 Aug 22;2:69.

Gautret P et al. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 Mar 20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949.

Devaux CA et al. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 Mar 12:105938. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105938.

Aronson J et al. COVID-19 trials registered up to 8 March 2020 – an analysis of 382 studies. 2020. Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. https://www.cebm.net/oxford-covid-19/covid-19-registered-trials-and-analysis/

Savarino A et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003 Nov;3(11):722-7.

Yazdany J, Kim AHJ. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 31. doi: 10.7326/M20-1334.

Xue J et al. PLoS One. 2014 Oct 1;9(10):e109180.

te Velthuis AJ et al. PLoS Pathog. 2010 Nov 4;6(11):e1001176.

Mother of pearl: The power of pearl powder

Because of its dense protein and mineral composition, it has been used to treat several skin and bone disorders, as well as palpitations, insomnia, and epilepsy.3,4 The pearl-farming industry itself was established in Japan and has existed for more than a century; today, pearls are cultured globally and continue to receive attention for conferring health benefits.5

Calcium carbonate is the primary component of mollusk shells (roughly 95%), with the remainder an organic matrix including proteins, glycoproteins, and polysaccharides.6 Pearl powder is known to have exhibited antiaging, antioxidant, antiradiative, and tonic activities; in recent years, it has been incorporated into health foods for such properties and used in the clinical setting to treat ulcers (aphthous, gastric, and duodenal).4,7 Consisting of multiple active proteins, pearl powder is thought to be conducive to skin cell growth and effective for wound repair.4 This column focuses on recent research into the dermatologic potential of the powder derived from mother of pearl.

Wound healing

A decade ago, Jian-Ping et al. showed in mice that the water-soluble matrix of pearl powder (Hyriopsis cumingii) could significantly induce oral fibroblast proliferation and collagen accumulation, suppress matrix metalloproteinase-2 activity, and significantly foster TIMP-1 synthesis. The investigators concluded that the wound healing facilitated by pearl powder derives, in part, from its capacity to promote fibroblast mitosis, collagen deposition, and production of TIMP-1.8

Two years later, Lee et al. evaluated the effects of water-soluble nacre (mother of pearl) on second-degree burn wound healing in porcine skin as a proxy for human skin. They found that its application quickly led to burn-induced granulation areas filling with collagen, with normal skin appearance restored to wounded dermis and epidermis. Angiogenesis was also promoted by water-soluble nacre as was wound recovery in areas with apoptotic and necrotic cellular damage. Murine fibroblast NIH3T3 cells treated with water-soluble nacre also demonstrated augmented proliferation and collagen production. The researchers cited the restoration of angiogenesis and fibroblast activity as the primary benefits of water-soluble nacre, suggesting its potential as a wound therapy, preferable to powdered nacre due to better biocompatibility with less discomfort.9

The next year, Li et al. found that mother of pearl extract promoted cell migration of fibroblasts in cell culture, demonstrating its potential as a wound healing model.7In 2019, Chen et al. studied the effects of pearl powders of varying particle sizes to treat wounds in vitro and in vivo. They found that micro- and nanosized pearl powders augmented proliferation and migration of skin cells and shortened wound closure time. All powders also improved the biomechanical strength of healed skin, enhanced collagen formation and deposition, and expanded cutaneous angiogenesis, with nanoscale pearl powder displaying greatest efficiency.4

Skin tone and atopic dermatitis

In 2000, Lopez et al. implanted powdered nacre (mother of pearl derived from Pinctada maxima), which can promote and regulate bone-forming cells, into rat dermis to evaluate its effects on skin fibroblasts. They noted that the implant yielded well-vascularized tissue and improved extracellular matrix production, synthesis of substances involved in cellular adhesion and communication, and tissue regeneration (such as collagen types I and III). The investigators concluded that the powdered nacre contributed to the conditions necessary for improved skin tone and proper physiologic functioning of the skin.10

Rousseau et al. extracted lipids from the nacre of the oyster P. margaritifera to test on artificially dehydrated skin explants with the intention of developing new treatments for atopic dermatitis. The researchers determined that the lipids spurred a reconstitution of the intercellular material of the stratum corneum, concluding that new products to treat atopic dermatitis might be based on the signaling activity of nacre lipids.11

Antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory activity

A 2015 study by Yang et al. showed that a room-temperature superextraction system to yield the main active constituents of pearl was successful in enhancing their anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic activity in human keratinocyte cells (HaCaT) exposed to low-dose UVB. The investigators combined pearl extract and poly (gamma-glutamic acid) hydrogels and observed reductions in inflammation and apoptosis of HaCaT cells. They concluded that a marketed pearl extract may be able to suppress radiation dermatitis present in keratinocytes.12

Two years later, Latire et al. used human dermal fibroblasts in primary culture to assess the potential biological activities of the matrix macromolecular components extracted from the shells of two edible mollusks (the blue mussel Mytilus edulis and the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas). The investigators found that both extracts influenced metabolic functions of the cells and reduced type I collagen levels, with an associated rise in matrix metalloproteinase-1 activity. Given their findings implying the effectiveness of the extracts in facilitating the catabolic pathway of human dermal fibroblasts, the authors suggest that these shell matrices present the potential for use in treating fibrosis, especially for scleroderma.6

Antioxidant and antiaging activity

Shao et al. demonstrated 10 years ago that pearl powder provides a moisturizing effect on the skin, with ultramicro pearl powder delivering a more robust moisturizing result than water-soluble pearl powder. These two types of pearl powder, along with another one tested (ultranano pearl powder), also significantly diminished the activation of tyrosinase and free radicals. Water-soluble pearl powder did not perform as well as the other two formulations in free radical scavenging. The investigators suggested that their results support the use of pearl powder to combat aging and enhance beauty, and could be used in the clinical setting.13

In 2017, Yang et al. reported on the in vitro antihemolytic and antioxidant activity of pearl powder in shielding human erythrocytes against 2,2’-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride–induced oxidative damage to membrane proteins/lipids. The researchers contend that the strong antioxidant qualities of pearl powder could be applied to prevent or protect against various diseases resulting from free radical damage.2

Human trials: Antioxidant, antiaging, skin appearance

Chiu et al. studied the antioxidant activity of various pearl powder extracts in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 2018. They also investigated the life span–prolonging effects of the powders using wild-type Caenorhabditis elegans. Twenty healthy middle-aged subjects were separated into two groups (experimental and placebo), with 3 g of pearl powder administered in capsules to the former and 3 g of placebo to the latter over 8 weeks. Blood samples taken at the beginning and every 2 weeks during the trial and in the 10th week revealed maximum antioxidant activity of the pearl powder and prolongation of C. elegans lifespan by 18.87%. Subjects using pearl powder demonstrated significant increases in total antioxidant capacity, thiols, glutathione, and enzymic antioxidant activity, along with notably inhibited lipid peroxidation products. The investigators concluded that pearl powder extract acted as a potent antioxidant and its use may be warranted to treat degenerative conditions related to aging.3

A recent study of the perception of blue light on Korean women’s faces using blue pearl pigment revealed that the pigment does indeed elicit the perception of the blue-light effect, notably transparency and gloss, which is particularly valued in Korea.14

Conclusion

The use of mother of pearl and pearl powder in traditional Chinese medicine and as a cosmetic and food additive has a rich and lengthy history. Contemporary research clearly suggests interesting avenues for further investigation and some promising results. Much more research is necessary, though, to delineate the potential roles of pearl powder in the skin care arsenal.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems. Write to her at [email protected]

References

1. Zhang J et al. J Sep Sci. 2015 May;38(9):1552-60.

2. Yang HL et al. J Food Drug Anal. 2017 Oct;25(4):898-907.

3. Chiu HF et al. J Food Drug Anal. 2018 Jan;26(1):309-17.

4. Chen X et al. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2019 Jun;45(6):1009-16.

5. Nagai K. Zoolog Sci. 2013 Oct;30(10):783-93.

6. Latire T et al. Cytotechnology. 2017 Oct;69(5):815-29.

7. Li YC et al. Pharm Biol. 2013 Mar;51(3):289-97.

8. Jian-Ping D et al. Pharm Biol. 2010 Feb;48(2):122-7.

9. Lee K et al. Mol Biol Rep. 2012 Mar;39(3):3211-8.

10. Lopez E et al. Tissue Cell. 2000 Feb;32(1):95-101.

11. Rousseau M et al. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2006 Sep;145(1):1-9.

12. Yang YL et al. Biomed Mater Eng. 2015;26 Suppl 1:S139-45.

13. Shao DZ et al. J Cosmet Sci. 2010 Mar-Apr;61(2):133-45.

14. Lee M et al. Skin Res Technol. 2020 Jan;26(1):76-80.

Because of its dense protein and mineral composition, it has been used to treat several skin and bone disorders, as well as palpitations, insomnia, and epilepsy.3,4 The pearl-farming industry itself was established in Japan and has existed for more than a century; today, pearls are cultured globally and continue to receive attention for conferring health benefits.5

Calcium carbonate is the primary component of mollusk shells (roughly 95%), with the remainder an organic matrix including proteins, glycoproteins, and polysaccharides.6 Pearl powder is known to have exhibited antiaging, antioxidant, antiradiative, and tonic activities; in recent years, it has been incorporated into health foods for such properties and used in the clinical setting to treat ulcers (aphthous, gastric, and duodenal).4,7 Consisting of multiple active proteins, pearl powder is thought to be conducive to skin cell growth and effective for wound repair.4 This column focuses on recent research into the dermatologic potential of the powder derived from mother of pearl.

Wound healing

A decade ago, Jian-Ping et al. showed in mice that the water-soluble matrix of pearl powder (Hyriopsis cumingii) could significantly induce oral fibroblast proliferation and collagen accumulation, suppress matrix metalloproteinase-2 activity, and significantly foster TIMP-1 synthesis. The investigators concluded that the wound healing facilitated by pearl powder derives, in part, from its capacity to promote fibroblast mitosis, collagen deposition, and production of TIMP-1.8

Two years later, Lee et al. evaluated the effects of water-soluble nacre (mother of pearl) on second-degree burn wound healing in porcine skin as a proxy for human skin. They found that its application quickly led to burn-induced granulation areas filling with collagen, with normal skin appearance restored to wounded dermis and epidermis. Angiogenesis was also promoted by water-soluble nacre as was wound recovery in areas with apoptotic and necrotic cellular damage. Murine fibroblast NIH3T3 cells treated with water-soluble nacre also demonstrated augmented proliferation and collagen production. The researchers cited the restoration of angiogenesis and fibroblast activity as the primary benefits of water-soluble nacre, suggesting its potential as a wound therapy, preferable to powdered nacre due to better biocompatibility with less discomfort.9

The next year, Li et al. found that mother of pearl extract promoted cell migration of fibroblasts in cell culture, demonstrating its potential as a wound healing model.7In 2019, Chen et al. studied the effects of pearl powders of varying particle sizes to treat wounds in vitro and in vivo. They found that micro- and nanosized pearl powders augmented proliferation and migration of skin cells and shortened wound closure time. All powders also improved the biomechanical strength of healed skin, enhanced collagen formation and deposition, and expanded cutaneous angiogenesis, with nanoscale pearl powder displaying greatest efficiency.4

Skin tone and atopic dermatitis

In 2000, Lopez et al. implanted powdered nacre (mother of pearl derived from Pinctada maxima), which can promote and regulate bone-forming cells, into rat dermis to evaluate its effects on skin fibroblasts. They noted that the implant yielded well-vascularized tissue and improved extracellular matrix production, synthesis of substances involved in cellular adhesion and communication, and tissue regeneration (such as collagen types I and III). The investigators concluded that the powdered nacre contributed to the conditions necessary for improved skin tone and proper physiologic functioning of the skin.10

Rousseau et al. extracted lipids from the nacre of the oyster P. margaritifera to test on artificially dehydrated skin explants with the intention of developing new treatments for atopic dermatitis. The researchers determined that the lipids spurred a reconstitution of the intercellular material of the stratum corneum, concluding that new products to treat atopic dermatitis might be based on the signaling activity of nacre lipids.11

Antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory activity

A 2015 study by Yang et al. showed that a room-temperature superextraction system to yield the main active constituents of pearl was successful in enhancing their anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic activity in human keratinocyte cells (HaCaT) exposed to low-dose UVB. The investigators combined pearl extract and poly (gamma-glutamic acid) hydrogels and observed reductions in inflammation and apoptosis of HaCaT cells. They concluded that a marketed pearl extract may be able to suppress radiation dermatitis present in keratinocytes.12

Two years later, Latire et al. used human dermal fibroblasts in primary culture to assess the potential biological activities of the matrix macromolecular components extracted from the shells of two edible mollusks (the blue mussel Mytilus edulis and the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas). The investigators found that both extracts influenced metabolic functions of the cells and reduced type I collagen levels, with an associated rise in matrix metalloproteinase-1 activity. Given their findings implying the effectiveness of the extracts in facilitating the catabolic pathway of human dermal fibroblasts, the authors suggest that these shell matrices present the potential for use in treating fibrosis, especially for scleroderma.6

Antioxidant and antiaging activity

Shao et al. demonstrated 10 years ago that pearl powder provides a moisturizing effect on the skin, with ultramicro pearl powder delivering a more robust moisturizing result than water-soluble pearl powder. These two types of pearl powder, along with another one tested (ultranano pearl powder), also significantly diminished the activation of tyrosinase and free radicals. Water-soluble pearl powder did not perform as well as the other two formulations in free radical scavenging. The investigators suggested that their results support the use of pearl powder to combat aging and enhance beauty, and could be used in the clinical setting.13

In 2017, Yang et al. reported on the in vitro antihemolytic and antioxidant activity of pearl powder in shielding human erythrocytes against 2,2’-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride–induced oxidative damage to membrane proteins/lipids. The researchers contend that the strong antioxidant qualities of pearl powder could be applied to prevent or protect against various diseases resulting from free radical damage.2

Human trials: Antioxidant, antiaging, skin appearance

Chiu et al. studied the antioxidant activity of various pearl powder extracts in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 2018. They also investigated the life span–prolonging effects of the powders using wild-type Caenorhabditis elegans. Twenty healthy middle-aged subjects were separated into two groups (experimental and placebo), with 3 g of pearl powder administered in capsules to the former and 3 g of placebo to the latter over 8 weeks. Blood samples taken at the beginning and every 2 weeks during the trial and in the 10th week revealed maximum antioxidant activity of the pearl powder and prolongation of C. elegans lifespan by 18.87%. Subjects using pearl powder demonstrated significant increases in total antioxidant capacity, thiols, glutathione, and enzymic antioxidant activity, along with notably inhibited lipid peroxidation products. The investigators concluded that pearl powder extract acted as a potent antioxidant and its use may be warranted to treat degenerative conditions related to aging.3

A recent study of the perception of blue light on Korean women’s faces using blue pearl pigment revealed that the pigment does indeed elicit the perception of the blue-light effect, notably transparency and gloss, which is particularly valued in Korea.14

Conclusion

The use of mother of pearl and pearl powder in traditional Chinese medicine and as a cosmetic and food additive has a rich and lengthy history. Contemporary research clearly suggests interesting avenues for further investigation and some promising results. Much more research is necessary, though, to delineate the potential roles of pearl powder in the skin care arsenal.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems. Write to her at [email protected]

References

1. Zhang J et al. J Sep Sci. 2015 May;38(9):1552-60.

2. Yang HL et al. J Food Drug Anal. 2017 Oct;25(4):898-907.

3. Chiu HF et al. J Food Drug Anal. 2018 Jan;26(1):309-17.

4. Chen X et al. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2019 Jun;45(6):1009-16.

5. Nagai K. Zoolog Sci. 2013 Oct;30(10):783-93.

6. Latire T et al. Cytotechnology. 2017 Oct;69(5):815-29.

7. Li YC et al. Pharm Biol. 2013 Mar;51(3):289-97.

8. Jian-Ping D et al. Pharm Biol. 2010 Feb;48(2):122-7.

9. Lee K et al. Mol Biol Rep. 2012 Mar;39(3):3211-8.

10. Lopez E et al. Tissue Cell. 2000 Feb;32(1):95-101.

11. Rousseau M et al. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2006 Sep;145(1):1-9.

12. Yang YL et al. Biomed Mater Eng. 2015;26 Suppl 1:S139-45.

13. Shao DZ et al. J Cosmet Sci. 2010 Mar-Apr;61(2):133-45.

14. Lee M et al. Skin Res Technol. 2020 Jan;26(1):76-80.

Because of its dense protein and mineral composition, it has been used to treat several skin and bone disorders, as well as palpitations, insomnia, and epilepsy.3,4 The pearl-farming industry itself was established in Japan and has existed for more than a century; today, pearls are cultured globally and continue to receive attention for conferring health benefits.5

Calcium carbonate is the primary component of mollusk shells (roughly 95%), with the remainder an organic matrix including proteins, glycoproteins, and polysaccharides.6 Pearl powder is known to have exhibited antiaging, antioxidant, antiradiative, and tonic activities; in recent years, it has been incorporated into health foods for such properties and used in the clinical setting to treat ulcers (aphthous, gastric, and duodenal).4,7 Consisting of multiple active proteins, pearl powder is thought to be conducive to skin cell growth and effective for wound repair.4 This column focuses on recent research into the dermatologic potential of the powder derived from mother of pearl.

Wound healing

A decade ago, Jian-Ping et al. showed in mice that the water-soluble matrix of pearl powder (Hyriopsis cumingii) could significantly induce oral fibroblast proliferation and collagen accumulation, suppress matrix metalloproteinase-2 activity, and significantly foster TIMP-1 synthesis. The investigators concluded that the wound healing facilitated by pearl powder derives, in part, from its capacity to promote fibroblast mitosis, collagen deposition, and production of TIMP-1.8

Two years later, Lee et al. evaluated the effects of water-soluble nacre (mother of pearl) on second-degree burn wound healing in porcine skin as a proxy for human skin. They found that its application quickly led to burn-induced granulation areas filling with collagen, with normal skin appearance restored to wounded dermis and epidermis. Angiogenesis was also promoted by water-soluble nacre as was wound recovery in areas with apoptotic and necrotic cellular damage. Murine fibroblast NIH3T3 cells treated with water-soluble nacre also demonstrated augmented proliferation and collagen production. The researchers cited the restoration of angiogenesis and fibroblast activity as the primary benefits of water-soluble nacre, suggesting its potential as a wound therapy, preferable to powdered nacre due to better biocompatibility with less discomfort.9

The next year, Li et al. found that mother of pearl extract promoted cell migration of fibroblasts in cell culture, demonstrating its potential as a wound healing model.7In 2019, Chen et al. studied the effects of pearl powders of varying particle sizes to treat wounds in vitro and in vivo. They found that micro- and nanosized pearl powders augmented proliferation and migration of skin cells and shortened wound closure time. All powders also improved the biomechanical strength of healed skin, enhanced collagen formation and deposition, and expanded cutaneous angiogenesis, with nanoscale pearl powder displaying greatest efficiency.4

Skin tone and atopic dermatitis

In 2000, Lopez et al. implanted powdered nacre (mother of pearl derived from Pinctada maxima), which can promote and regulate bone-forming cells, into rat dermis to evaluate its effects on skin fibroblasts. They noted that the implant yielded well-vascularized tissue and improved extracellular matrix production, synthesis of substances involved in cellular adhesion and communication, and tissue regeneration (such as collagen types I and III). The investigators concluded that the powdered nacre contributed to the conditions necessary for improved skin tone and proper physiologic functioning of the skin.10

Rousseau et al. extracted lipids from the nacre of the oyster P. margaritifera to test on artificially dehydrated skin explants with the intention of developing new treatments for atopic dermatitis. The researchers determined that the lipids spurred a reconstitution of the intercellular material of the stratum corneum, concluding that new products to treat atopic dermatitis might be based on the signaling activity of nacre lipids.11

Antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory activity

A 2015 study by Yang et al. showed that a room-temperature superextraction system to yield the main active constituents of pearl was successful in enhancing their anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic activity in human keratinocyte cells (HaCaT) exposed to low-dose UVB. The investigators combined pearl extract and poly (gamma-glutamic acid) hydrogels and observed reductions in inflammation and apoptosis of HaCaT cells. They concluded that a marketed pearl extract may be able to suppress radiation dermatitis present in keratinocytes.12

Two years later, Latire et al. used human dermal fibroblasts in primary culture to assess the potential biological activities of the matrix macromolecular components extracted from the shells of two edible mollusks (the blue mussel Mytilus edulis and the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas). The investigators found that both extracts influenced metabolic functions of the cells and reduced type I collagen levels, with an associated rise in matrix metalloproteinase-1 activity. Given their findings implying the effectiveness of the extracts in facilitating the catabolic pathway of human dermal fibroblasts, the authors suggest that these shell matrices present the potential for use in treating fibrosis, especially for scleroderma.6

Antioxidant and antiaging activity

Shao et al. demonstrated 10 years ago that pearl powder provides a moisturizing effect on the skin, with ultramicro pearl powder delivering a more robust moisturizing result than water-soluble pearl powder. These two types of pearl powder, along with another one tested (ultranano pearl powder), also significantly diminished the activation of tyrosinase and free radicals. Water-soluble pearl powder did not perform as well as the other two formulations in free radical scavenging. The investigators suggested that their results support the use of pearl powder to combat aging and enhance beauty, and could be used in the clinical setting.13

In 2017, Yang et al. reported on the in vitro antihemolytic and antioxidant activity of pearl powder in shielding human erythrocytes against 2,2’-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride–induced oxidative damage to membrane proteins/lipids. The researchers contend that the strong antioxidant qualities of pearl powder could be applied to prevent or protect against various diseases resulting from free radical damage.2

Human trials: Antioxidant, antiaging, skin appearance

Chiu et al. studied the antioxidant activity of various pearl powder extracts in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 2018. They also investigated the life span–prolonging effects of the powders using wild-type Caenorhabditis elegans. Twenty healthy middle-aged subjects were separated into two groups (experimental and placebo), with 3 g of pearl powder administered in capsules to the former and 3 g of placebo to the latter over 8 weeks. Blood samples taken at the beginning and every 2 weeks during the trial and in the 10th week revealed maximum antioxidant activity of the pearl powder and prolongation of C. elegans lifespan by 18.87%. Subjects using pearl powder demonstrated significant increases in total antioxidant capacity, thiols, glutathione, and enzymic antioxidant activity, along with notably inhibited lipid peroxidation products. The investigators concluded that pearl powder extract acted as a potent antioxidant and its use may be warranted to treat degenerative conditions related to aging.3

A recent study of the perception of blue light on Korean women’s faces using blue pearl pigment revealed that the pigment does indeed elicit the perception of the blue-light effect, notably transparency and gloss, which is particularly valued in Korea.14

Conclusion

The use of mother of pearl and pearl powder in traditional Chinese medicine and as a cosmetic and food additive has a rich and lengthy history. Contemporary research clearly suggests interesting avenues for further investigation and some promising results. Much more research is necessary, though, to delineate the potential roles of pearl powder in the skin care arsenal.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems. Write to her at [email protected]

References

1. Zhang J et al. J Sep Sci. 2015 May;38(9):1552-60.

2. Yang HL et al. J Food Drug Anal. 2017 Oct;25(4):898-907.

3. Chiu HF et al. J Food Drug Anal. 2018 Jan;26(1):309-17.

4. Chen X et al. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2019 Jun;45(6):1009-16.

5. Nagai K. Zoolog Sci. 2013 Oct;30(10):783-93.

6. Latire T et al. Cytotechnology. 2017 Oct;69(5):815-29.

7. Li YC et al. Pharm Biol. 2013 Mar;51(3):289-97.

8. Jian-Ping D et al. Pharm Biol. 2010 Feb;48(2):122-7.

9. Lee K et al. Mol Biol Rep. 2012 Mar;39(3):3211-8.

10. Lopez E et al. Tissue Cell. 2000 Feb;32(1):95-101.

11. Rousseau M et al. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2006 Sep;145(1):1-9.

12. Yang YL et al. Biomed Mater Eng. 2015;26 Suppl 1:S139-45.

13. Shao DZ et al. J Cosmet Sci. 2010 Mar-Apr;61(2):133-45.

14. Lee M et al. Skin Res Technol. 2020 Jan;26(1):76-80.

Hand washing and hand sanitizer on the skin and COVID-19 infection risk

As we deal with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, hand washing and the use of hand sanitizers have been key for infection prevention. With drier, colder weather in many of the communities initially affected by COVID-19, skin was already prone to dryness and a skin barrier compromised, and hand eczema was more prevalent because of these factors alone. This article explores the while maintaining the maximum possible degree of infection prevention.

With many viruses, including coronavirus, the virus is a self-assembled nanoparticle in which the most vulnerable structure is the outer lipid bilayer. Soaps dissolve the lipid membrane and the virus breaks apart, inactivating it; they are also alkaline surfactants that pick up particles – including dirt, bacteria, and viruses – which are removed from the surface of the skin when the soaps are rinsed off. In the process of washing, the alkalinity of the soap (pH approximately 9-10), compared with the normal outer skin pH of approximately 5.5 or lower, also can affect the skin barrier as well as the resident skin microflora. In a study by Lambers et al., it was found that an acid skin pH (4-4.5) keeps the resident bacterial flora attached to the skin, whereas an alkaline pH (8-9) promotes the dispersal from the skin in assessments of the volar forearm.

With regard to the effectiveness of hand washing against viruses, the length of time spent hand washing has been shown to have an impact on influenza-like illness. In a recent study of 2,082 participants by Bin Abdulrahman et al., those who spent only 5-10 seconds hand washing with soap and hand rubbing were at a higher risk of more frequent influenza-like illness (odds ratio, 1.37; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.75), compared with those who washed their hands for 15 seconds or longer. Moreover, hand washing with soap and rubbing after shaking hands was found to be an independent protective factor against frequent influenza-like illness (adjusted OR, 0.59; 95% confidence interval, 0.37-0.94). Previous studies on the impact of hand washing on bacterial and parasitic illnesses also found similar results: Hand washing for 15-20 seconds or longer reduces infection.

Alcohol, long known as a disinfectant, has been recommended for disinfecting the hands since the late 1800s. Most alcohol-based hand antiseptics contain isopropanol, ethanol, N-propanol, or a combination of two of these products. The antimicrobial activity of alcohols can be attributed to their ability to denature and coagulate proteins, thereby lysing microorganisms’ cells, and disrupting their cellular metabolism. Alcohol solutions containing 60%-95% alcohol are the most effective. Notably, very high concentrations of alcohol are less potent because less water is found in higher concentrations of alcohol and proteins are not denatured easily in the absence of water. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers also often contain humectants, such as glycerin and/or aloe vera, to help prevent skin dryness and replace water content that is stripped by the use of alcohol on the skin surface.

Other topical disinfectants can also be used to inactivate coronaviruses from surfaces, including the skin. A recently published analysis of 22 studies found that human coronaviruses – such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus, or endemic human coronaviruses (HCoV) – can persist on inanimate surfaces such as metal, glass, or plastic for up to 9 days (COVID-19 was found in a study to persist on metal for up to 2-3 days), but can be efficiently inactivated by surface disinfection procedures with 62%-71% ethanol, 0.5% hydrogen peroxide, or 0.1% sodium hypochlorite within 1 minute. Other biocidal agents, such as 0.05%-0.2% benzalkonium chloride or 0.02% chlorhexidine digluconate, are less effective.

In the case of SARS, treatment of SARS-CoV with povidone-iodine products for 2 minutes reduced virus infectivity to below the detectable level, equivalent to the effect of ethanol, in one study. Formalin fixation of the infected cells and heating the virus to 56° C, as used in routine tissue processing, were found to inactivate several coronaviruses as well. Based on this information, ethanol-based hand sanitizers, typically containing ethanol content of 60% or higher, can be used to inactivate coronaviruses on the skin, including COVID-19.

In patients with influenza-virus infections, whether pathogens were in wet or dried mucus played a role in whether hand washing or rubbing with hand sanitizer was more effective. In a study that examined the effects of hand washing versus antiseptic hand rubbing with an ethanol-based hand disinfectant on inactivation of influenza A virus adhered to the hands, the investigators showed that the effectiveness of the ethanol-based disinfectant against influenza A virus in mucus was reduced, compared with influenza A virus in saline. Influenza A in mucus remained active, despite 120 seconds of hand rubbing with hand sanitizer; however, influenza A in saline was completely inactivated within 30 seconds. Interestingly, rubbing hands with an ethanol-based disinfectant inactivated influenza A virus in mucus within 30 seconds with mucus that had dried completely because the hydrogel characteristics had been eliminated. Hand washing rapidly inactivated influenza A virus whether in mucus form, saline, or dried mucous.

It is important to note that in COVID-19 infections, a productive cough or rhinorrhea are not as common compared with dry cough. Regardless, the findings of the study described above should be considered if mucous symptoms develop during a COVID-19 infection when determining infection control. Luckily, with COVID-19, both hand washing and use of an ethanol-based hand sanitizer are seemingly effective in inactivating the virus or removing it from the skin surface.

After frequent hand washing, we all can experience dryness and potentially cracked skin as well. With hand sanitizer, the alcohol content can also cause burning of skin, especially compromised skin.

Vanilloid receptor-1 (VR1), a heat-gated ion channel, is responsible for the burning sensation caused by capsaicin. Ethanol lowers the amount of heat needed to turn on VR1 nocioceptive pain receptors by almost ten degrees, resulting in a potential burning sensation when applied.

Nails are affected as well with frequent hand washing and/or application of hand sanitizer and can become cracked or brittle. Contact dermatitis, both irritant and allergic, can occur with increased use of disinfectants, particularly household cleaners without proper barrier protection.

We’ve previously mentioned the effect of hand washing disrupting the resident skin microflora. Maintaining the skin microflora and barrier is an important component of skin health for preventing both dermatitis and infection. Hand washing or use of hand sanitizer is of paramount importance and effective in infection control for COVID-19. To maintain skin health and the skin barrier, applying lotion or cream after hand washing is recommended. It is recommended to avoid scrubbing hands while washing, since this causes breaks in the skin. Using water that is too hot is not recommended as it can inflame the skin further and disrupt the skin barrier.

Wearing gloves, if possible, is recommended when using household disinfectant products to further decrease skin irritation, barrier disruption, and risk of contact dermatitis. I have found hand emollients that contain ceramides or ingredients higher in omega 6 fatty acids, such as borage seed oil or other oils high in linoleic acid content, to be helpful. In addition to improving the skin barrier, emollients and perhaps those with topical pre- or probiotics, may help restore the skin microflora, potentially improving infection control further. Application of hand moisturizer each time after hand washing to maintain better infection control and barrier protection was also recommended by the recent consensus statement of Chinese experts on protection of skin and mucous membrane barrier for health care workers fighting against COVID-19.

We and our patients have remarked how it seems like our hands have aged 20-50 years in the previous 2 weeks. No one is complaining, everyone understands that protecting themselves and others against a potentially lethal virus is paramount. Maintaining skin health is of secondary concern, but maintaining healthy skin may also protect the skin barrier, another important component of potential infection control.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. They had no relevant disclosures. Write to them at [email protected].

Resources

Lambers H et al. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2006 Oct;28(5):359-70.

Bin Abdulrahman AK et al. BMC Public Health. 2019 Oct 22;19(1):1324. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-77.

Kariwa H et al. Dermatology. 2006;212 Suppl 1:119-23.

HIrose R et al. mSphere. 2019 Sep 18;4(5). pii: e00474-19. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00474-19.

Trevisani M et al. Nat Neurosci. 2002 Jun;5(6):546-51.

Yan Y et al. Dermatol Ther. 2020 Mar 13:e13310. doi: 10.1111/dth.13310.

As we deal with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, hand washing and the use of hand sanitizers have been key for infection prevention. With drier, colder weather in many of the communities initially affected by COVID-19, skin was already prone to dryness and a skin barrier compromised, and hand eczema was more prevalent because of these factors alone. This article explores the while maintaining the maximum possible degree of infection prevention.

With many viruses, including coronavirus, the virus is a self-assembled nanoparticle in which the most vulnerable structure is the outer lipid bilayer. Soaps dissolve the lipid membrane and the virus breaks apart, inactivating it; they are also alkaline surfactants that pick up particles – including dirt, bacteria, and viruses – which are removed from the surface of the skin when the soaps are rinsed off. In the process of washing, the alkalinity of the soap (pH approximately 9-10), compared with the normal outer skin pH of approximately 5.5 or lower, also can affect the skin barrier as well as the resident skin microflora. In a study by Lambers et al., it was found that an acid skin pH (4-4.5) keeps the resident bacterial flora attached to the skin, whereas an alkaline pH (8-9) promotes the dispersal from the skin in assessments of the volar forearm.

With regard to the effectiveness of hand washing against viruses, the length of time spent hand washing has been shown to have an impact on influenza-like illness. In a recent study of 2,082 participants by Bin Abdulrahman et al., those who spent only 5-10 seconds hand washing with soap and hand rubbing were at a higher risk of more frequent influenza-like illness (odds ratio, 1.37; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.75), compared with those who washed their hands for 15 seconds or longer. Moreover, hand washing with soap and rubbing after shaking hands was found to be an independent protective factor against frequent influenza-like illness (adjusted OR, 0.59; 95% confidence interval, 0.37-0.94). Previous studies on the impact of hand washing on bacterial and parasitic illnesses also found similar results: Hand washing for 15-20 seconds or longer reduces infection.

Alcohol, long known as a disinfectant, has been recommended for disinfecting the hands since the late 1800s. Most alcohol-based hand antiseptics contain isopropanol, ethanol, N-propanol, or a combination of two of these products. The antimicrobial activity of alcohols can be attributed to their ability to denature and coagulate proteins, thereby lysing microorganisms’ cells, and disrupting their cellular metabolism. Alcohol solutions containing 60%-95% alcohol are the most effective. Notably, very high concentrations of alcohol are less potent because less water is found in higher concentrations of alcohol and proteins are not denatured easily in the absence of water. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers also often contain humectants, such as glycerin and/or aloe vera, to help prevent skin dryness and replace water content that is stripped by the use of alcohol on the skin surface.

Other topical disinfectants can also be used to inactivate coronaviruses from surfaces, including the skin. A recently published analysis of 22 studies found that human coronaviruses – such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus, or endemic human coronaviruses (HCoV) – can persist on inanimate surfaces such as metal, glass, or plastic for up to 9 days (COVID-19 was found in a study to persist on metal for up to 2-3 days), but can be efficiently inactivated by surface disinfection procedures with 62%-71% ethanol, 0.5% hydrogen peroxide, or 0.1% sodium hypochlorite within 1 minute. Other biocidal agents, such as 0.05%-0.2% benzalkonium chloride or 0.02% chlorhexidine digluconate, are less effective.

In the case of SARS, treatment of SARS-CoV with povidone-iodine products for 2 minutes reduced virus infectivity to below the detectable level, equivalent to the effect of ethanol, in one study. Formalin fixation of the infected cells and heating the virus to 56° C, as used in routine tissue processing, were found to inactivate several coronaviruses as well. Based on this information, ethanol-based hand sanitizers, typically containing ethanol content of 60% or higher, can be used to inactivate coronaviruses on the skin, including COVID-19.

In patients with influenza-virus infections, whether pathogens were in wet or dried mucus played a role in whether hand washing or rubbing with hand sanitizer was more effective. In a study that examined the effects of hand washing versus antiseptic hand rubbing with an ethanol-based hand disinfectant on inactivation of influenza A virus adhered to the hands, the investigators showed that the effectiveness of the ethanol-based disinfectant against influenza A virus in mucus was reduced, compared with influenza A virus in saline. Influenza A in mucus remained active, despite 120 seconds of hand rubbing with hand sanitizer; however, influenza A in saline was completely inactivated within 30 seconds. Interestingly, rubbing hands with an ethanol-based disinfectant inactivated influenza A virus in mucus within 30 seconds with mucus that had dried completely because the hydrogel characteristics had been eliminated. Hand washing rapidly inactivated influenza A virus whether in mucus form, saline, or dried mucous.

It is important to note that in COVID-19 infections, a productive cough or rhinorrhea are not as common compared with dry cough. Regardless, the findings of the study described above should be considered if mucous symptoms develop during a COVID-19 infection when determining infection control. Luckily, with COVID-19, both hand washing and use of an ethanol-based hand sanitizer are seemingly effective in inactivating the virus or removing it from the skin surface.

After frequent hand washing, we all can experience dryness and potentially cracked skin as well. With hand sanitizer, the alcohol content can also cause burning of skin, especially compromised skin.

Vanilloid receptor-1 (VR1), a heat-gated ion channel, is responsible for the burning sensation caused by capsaicin. Ethanol lowers the amount of heat needed to turn on VR1 nocioceptive pain receptors by almost ten degrees, resulting in a potential burning sensation when applied.

Nails are affected as well with frequent hand washing and/or application of hand sanitizer and can become cracked or brittle. Contact dermatitis, both irritant and allergic, can occur with increased use of disinfectants, particularly household cleaners without proper barrier protection.

We’ve previously mentioned the effect of hand washing disrupting the resident skin microflora. Maintaining the skin microflora and barrier is an important component of skin health for preventing both dermatitis and infection. Hand washing or use of hand sanitizer is of paramount importance and effective in infection control for COVID-19. To maintain skin health and the skin barrier, applying lotion or cream after hand washing is recommended. It is recommended to avoid scrubbing hands while washing, since this causes breaks in the skin. Using water that is too hot is not recommended as it can inflame the skin further and disrupt the skin barrier.

Wearing gloves, if possible, is recommended when using household disinfectant products to further decrease skin irritation, barrier disruption, and risk of contact dermatitis. I have found hand emollients that contain ceramides or ingredients higher in omega 6 fatty acids, such as borage seed oil or other oils high in linoleic acid content, to be helpful. In addition to improving the skin barrier, emollients and perhaps those with topical pre- or probiotics, may help restore the skin microflora, potentially improving infection control further. Application of hand moisturizer each time after hand washing to maintain better infection control and barrier protection was also recommended by the recent consensus statement of Chinese experts on protection of skin and mucous membrane barrier for health care workers fighting against COVID-19.

We and our patients have remarked how it seems like our hands have aged 20-50 years in the previous 2 weeks. No one is complaining, everyone understands that protecting themselves and others against a potentially lethal virus is paramount. Maintaining skin health is of secondary concern, but maintaining healthy skin may also protect the skin barrier, another important component of potential infection control.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. They had no relevant disclosures. Write to them at [email protected].

Resources

Lambers H et al. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2006 Oct;28(5):359-70.

Bin Abdulrahman AK et al. BMC Public Health. 2019 Oct 22;19(1):1324. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-77.

Kariwa H et al. Dermatology. 2006;212 Suppl 1:119-23.

HIrose R et al. mSphere. 2019 Sep 18;4(5). pii: e00474-19. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00474-19.

Trevisani M et al. Nat Neurosci. 2002 Jun;5(6):546-51.

Yan Y et al. Dermatol Ther. 2020 Mar 13:e13310. doi: 10.1111/dth.13310.

As we deal with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, hand washing and the use of hand sanitizers have been key for infection prevention. With drier, colder weather in many of the communities initially affected by COVID-19, skin was already prone to dryness and a skin barrier compromised, and hand eczema was more prevalent because of these factors alone. This article explores the while maintaining the maximum possible degree of infection prevention.

With many viruses, including coronavirus, the virus is a self-assembled nanoparticle in which the most vulnerable structure is the outer lipid bilayer. Soaps dissolve the lipid membrane and the virus breaks apart, inactivating it; they are also alkaline surfactants that pick up particles – including dirt, bacteria, and viruses – which are removed from the surface of the skin when the soaps are rinsed off. In the process of washing, the alkalinity of the soap (pH approximately 9-10), compared with the normal outer skin pH of approximately 5.5 or lower, also can affect the skin barrier as well as the resident skin microflora. In a study by Lambers et al., it was found that an acid skin pH (4-4.5) keeps the resident bacterial flora attached to the skin, whereas an alkaline pH (8-9) promotes the dispersal from the skin in assessments of the volar forearm.

With regard to the effectiveness of hand washing against viruses, the length of time spent hand washing has been shown to have an impact on influenza-like illness. In a recent study of 2,082 participants by Bin Abdulrahman et al., those who spent only 5-10 seconds hand washing with soap and hand rubbing were at a higher risk of more frequent influenza-like illness (odds ratio, 1.37; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.75), compared with those who washed their hands for 15 seconds or longer. Moreover, hand washing with soap and rubbing after shaking hands was found to be an independent protective factor against frequent influenza-like illness (adjusted OR, 0.59; 95% confidence interval, 0.37-0.94). Previous studies on the impact of hand washing on bacterial and parasitic illnesses also found similar results: Hand washing for 15-20 seconds or longer reduces infection.

Alcohol, long known as a disinfectant, has been recommended for disinfecting the hands since the late 1800s. Most alcohol-based hand antiseptics contain isopropanol, ethanol, N-propanol, or a combination of two of these products. The antimicrobial activity of alcohols can be attributed to their ability to denature and coagulate proteins, thereby lysing microorganisms’ cells, and disrupting their cellular metabolism. Alcohol solutions containing 60%-95% alcohol are the most effective. Notably, very high concentrations of alcohol are less potent because less water is found in higher concentrations of alcohol and proteins are not denatured easily in the absence of water. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers also often contain humectants, such as glycerin and/or aloe vera, to help prevent skin dryness and replace water content that is stripped by the use of alcohol on the skin surface.

Other topical disinfectants can also be used to inactivate coronaviruses from surfaces, including the skin. A recently published analysis of 22 studies found that human coronaviruses – such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus, or endemic human coronaviruses (HCoV) – can persist on inanimate surfaces such as metal, glass, or plastic for up to 9 days (COVID-19 was found in a study to persist on metal for up to 2-3 days), but can be efficiently inactivated by surface disinfection procedures with 62%-71% ethanol, 0.5% hydrogen peroxide, or 0.1% sodium hypochlorite within 1 minute. Other biocidal agents, such as 0.05%-0.2% benzalkonium chloride or 0.02% chlorhexidine digluconate, are less effective.

In the case of SARS, treatment of SARS-CoV with povidone-iodine products for 2 minutes reduced virus infectivity to below the detectable level, equivalent to the effect of ethanol, in one study. Formalin fixation of the infected cells and heating the virus to 56° C, as used in routine tissue processing, were found to inactivate several coronaviruses as well. Based on this information, ethanol-based hand sanitizers, typically containing ethanol content of 60% or higher, can be used to inactivate coronaviruses on the skin, including COVID-19.

In patients with influenza-virus infections, whether pathogens were in wet or dried mucus played a role in whether hand washing or rubbing with hand sanitizer was more effective. In a study that examined the effects of hand washing versus antiseptic hand rubbing with an ethanol-based hand disinfectant on inactivation of influenza A virus adhered to the hands, the investigators showed that the effectiveness of the ethanol-based disinfectant against influenza A virus in mucus was reduced, compared with influenza A virus in saline. Influenza A in mucus remained active, despite 120 seconds of hand rubbing with hand sanitizer; however, influenza A in saline was completely inactivated within 30 seconds. Interestingly, rubbing hands with an ethanol-based disinfectant inactivated influenza A virus in mucus within 30 seconds with mucus that had dried completely because the hydrogel characteristics had been eliminated. Hand washing rapidly inactivated influenza A virus whether in mucus form, saline, or dried mucous.

It is important to note that in COVID-19 infections, a productive cough or rhinorrhea are not as common compared with dry cough. Regardless, the findings of the study described above should be considered if mucous symptoms develop during a COVID-19 infection when determining infection control. Luckily, with COVID-19, both hand washing and use of an ethanol-based hand sanitizer are seemingly effective in inactivating the virus or removing it from the skin surface.

After frequent hand washing, we all can experience dryness and potentially cracked skin as well. With hand sanitizer, the alcohol content can also cause burning of skin, especially compromised skin.

Vanilloid receptor-1 (VR1), a heat-gated ion channel, is responsible for the burning sensation caused by capsaicin. Ethanol lowers the amount of heat needed to turn on VR1 nocioceptive pain receptors by almost ten degrees, resulting in a potential burning sensation when applied.

Nails are affected as well with frequent hand washing and/or application of hand sanitizer and can become cracked or brittle. Contact dermatitis, both irritant and allergic, can occur with increased use of disinfectants, particularly household cleaners without proper barrier protection.

We’ve previously mentioned the effect of hand washing disrupting the resident skin microflora. Maintaining the skin microflora and barrier is an important component of skin health for preventing both dermatitis and infection. Hand washing or use of hand sanitizer is of paramount importance and effective in infection control for COVID-19. To maintain skin health and the skin barrier, applying lotion or cream after hand washing is recommended. It is recommended to avoid scrubbing hands while washing, since this causes breaks in the skin. Using water that is too hot is not recommended as it can inflame the skin further and disrupt the skin barrier.

Wearing gloves, if possible, is recommended when using household disinfectant products to further decrease skin irritation, barrier disruption, and risk of contact dermatitis. I have found hand emollients that contain ceramides or ingredients higher in omega 6 fatty acids, such as borage seed oil or other oils high in linoleic acid content, to be helpful. In addition to improving the skin barrier, emollients and perhaps those with topical pre- or probiotics, may help restore the skin microflora, potentially improving infection control further. Application of hand moisturizer each time after hand washing to maintain better infection control and barrier protection was also recommended by the recent consensus statement of Chinese experts on protection of skin and mucous membrane barrier for health care workers fighting against COVID-19.

We and our patients have remarked how it seems like our hands have aged 20-50 years in the previous 2 weeks. No one is complaining, everyone understands that protecting themselves and others against a potentially lethal virus is paramount. Maintaining skin health is of secondary concern, but maintaining healthy skin may also protect the skin barrier, another important component of potential infection control.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. They had no relevant disclosures. Write to them at [email protected].

Resources

Lambers H et al. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2006 Oct;28(5):359-70.

Bin Abdulrahman AK et al. BMC Public Health. 2019 Oct 22;19(1):1324. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-77.

Kariwa H et al. Dermatology. 2006;212 Suppl 1:119-23.

HIrose R et al. mSphere. 2019 Sep 18;4(5). pii: e00474-19. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00474-19.

Trevisani M et al. Nat Neurosci. 2002 Jun;5(6):546-51.

Yan Y et al. Dermatol Ther. 2020 Mar 13:e13310. doi: 10.1111/dth.13310.

Rapid Development of Perifolliculitis Following Mesotherapy

To the Editor:

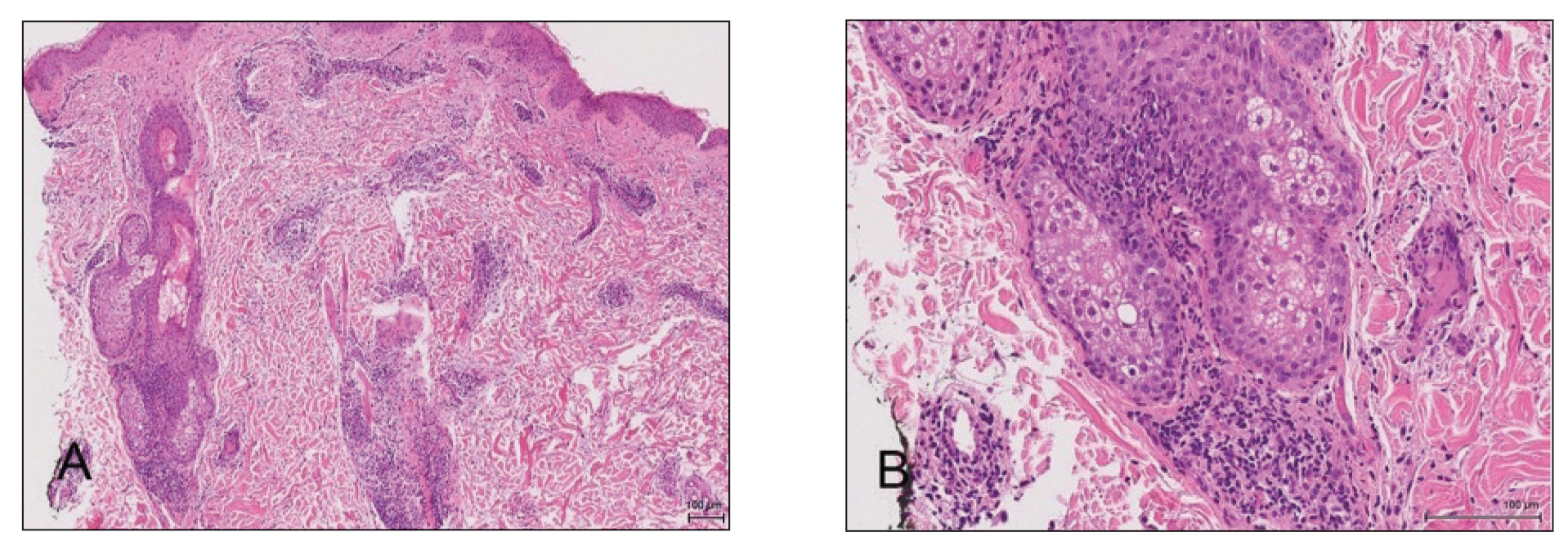

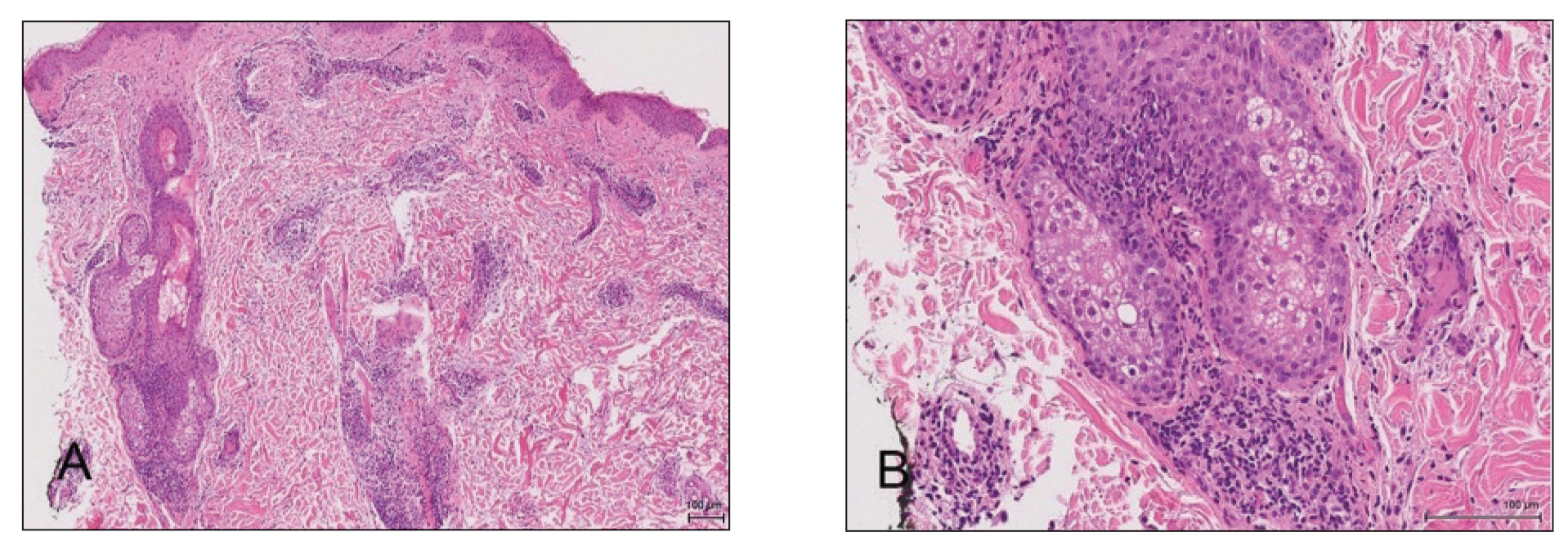

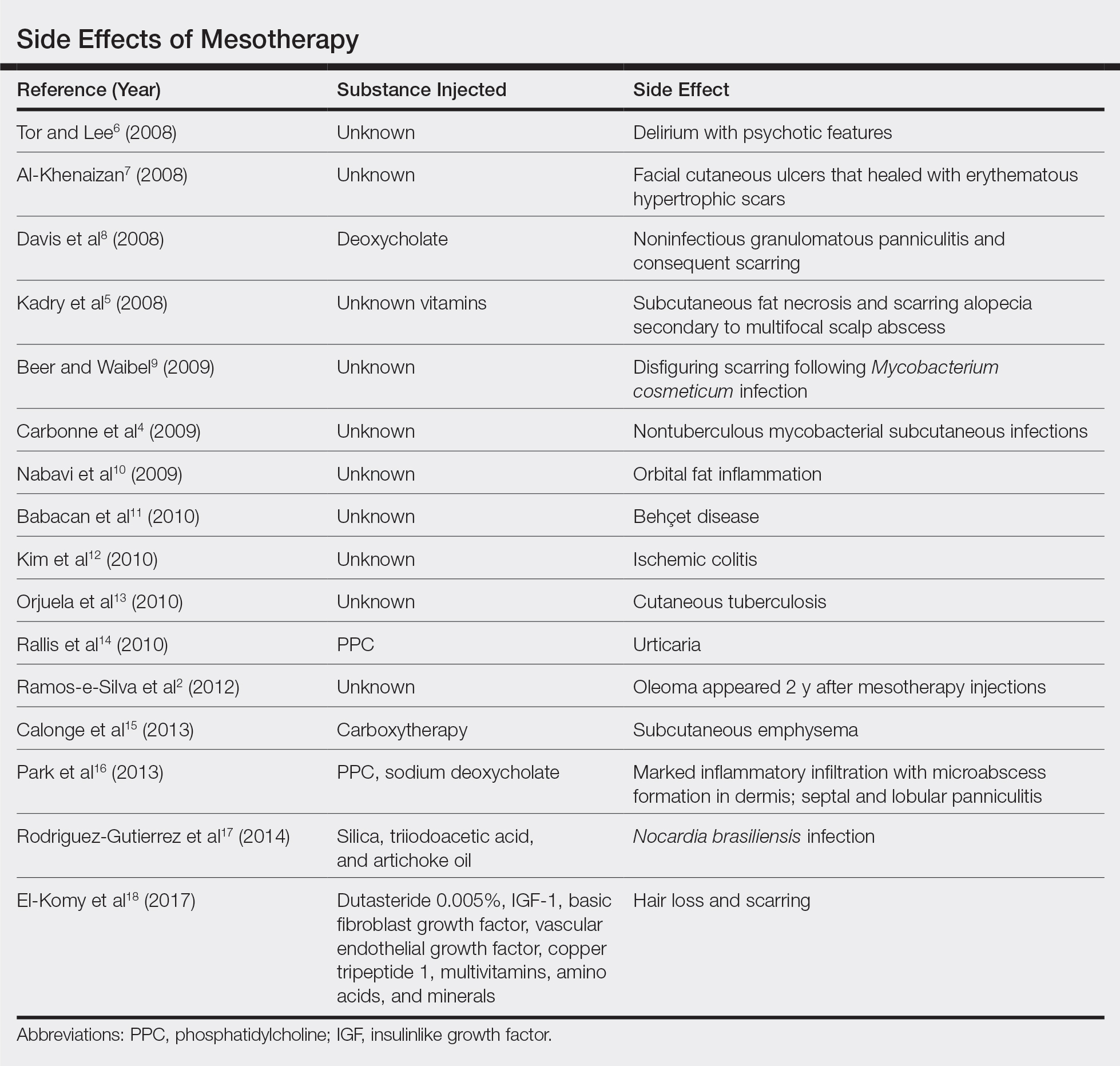

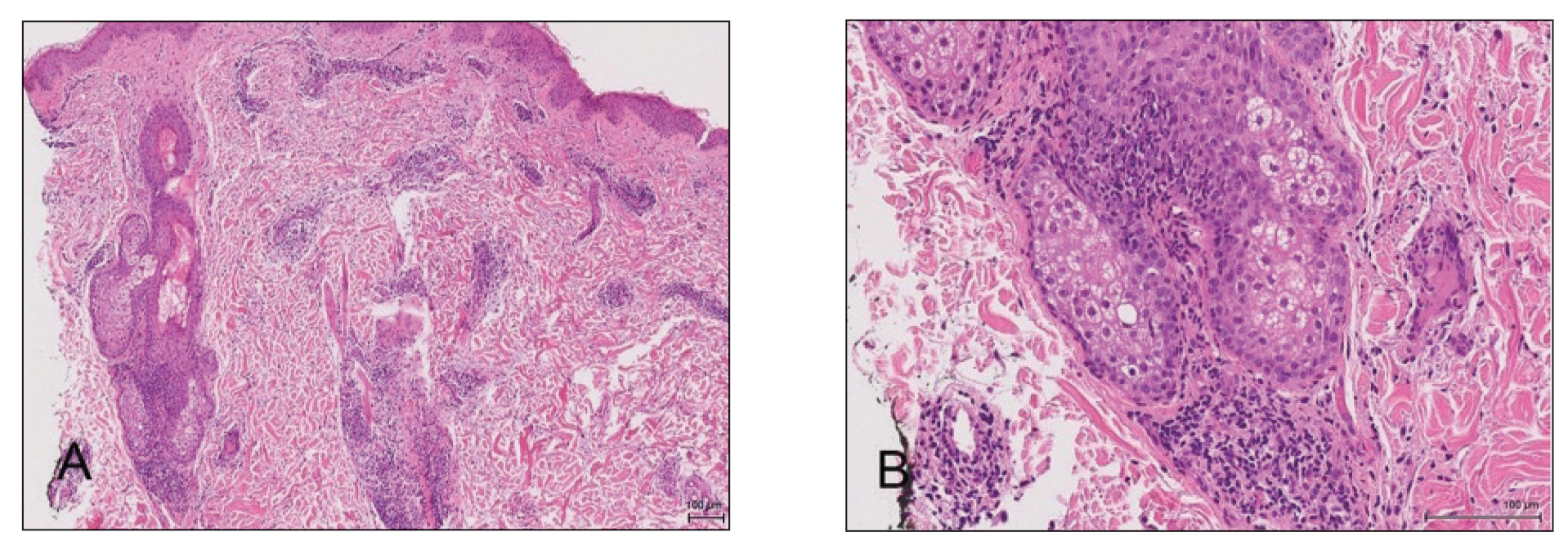

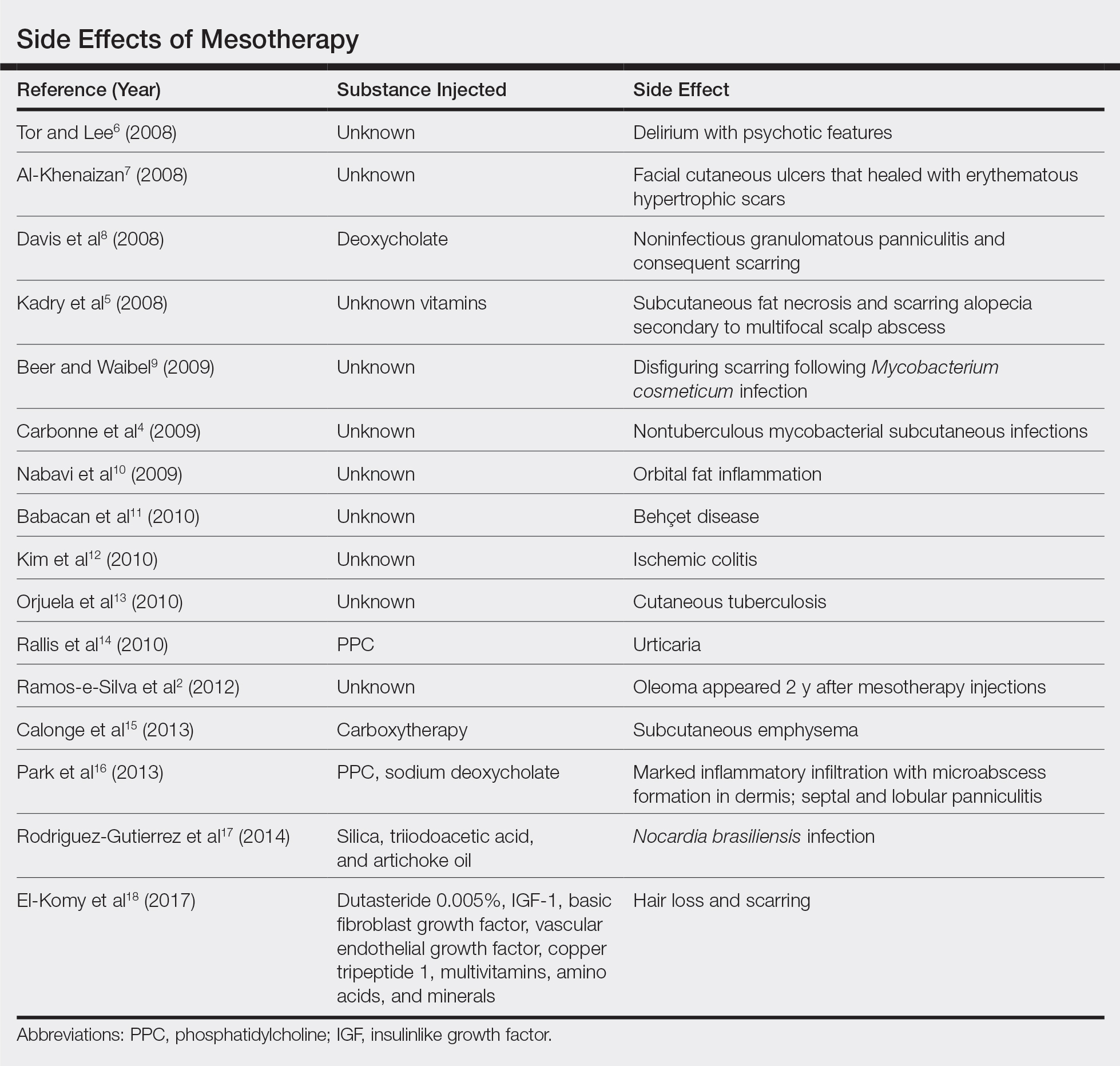

Mesotherapy, also known as intradermotherapy, is a cosmetic procedure in which multiple intradermal or subcutaneous injections of homeopathic substances, vitamins, chemicals, and plant extracts are administered.1 First conceived in Europe, mesotherapy is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration but is gaining popularity in the United States as an alternative cosmetic procedure for various purposes, including lipolysis, body contouring, stretch marks, acne scars, actinic damage, and skin rejuvenation.1,2 We report a case of a healthy woman who developed perifolliculitis, transaminitis, and neutropenia 2 weeks after mesotherapy administration to the face, neck, and chest. We also review other potential side effects of this procedure.

A 36-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department with a worsening pruritic and painful rash on the face, chest, and neck of 2 weeks’ duration. The rash had developed 3 days after the patient received mesotherapy with an unknown substance for cosmetic rejuvenation; the rash was localized only to the injection sites. She did not note any fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, arthralgia, or upper respiratory tract symptoms. She further denied starting any new medications, herbal products, or topical therapies apart from the procedure she had received 2 weeks prior.