User login

Racial Limitations of Fitzpatrick Skin Type

Fitzpatrick skin type (FST) is the most commonly used classification system in dermatologic practice. It was developed by Thomas B. Fitzpatrick, MD, PhD, in 1975 to assess the propensity of the skin to burn during phototherapy.1 Fitzpatrick skin type also can be used to assess the clinical benefits and efficacy of cosmetic procedures, including laser hair removal, chemical peel and dermabrasion, tattoo removal, spray tanning, and laser resurfacing for acne scarring.2 The original FST classifications included skin types I through IV; skin types V and VI were later added to include individuals of Asian, Indian, and African origin.1 As a result, FST often is used by providers as a means of describing constitutive skin color and ethnicity.3

How did FST transition from describing the propensity of the skin to burn from UV light exposure to categorizing skin color, thereby becoming a proxy for race? It most likely occurred because there has not been another widely adopted classification system for describing skin color that can be applied to all skin types. Even when the FST classification scale is used as intended, there are inconsistencies with its accuracy; for example, self-reported FSTs have correlated poorly with sunburn risk as well as physician-reported FSTs.4,5 Although physician-reported FSTs have been demonstrated to correlate with race, race does not consistently correlate with objective measures of pigmentation or self-reported FSTs.5 For example, Japanese women often self-identify as FST type II, but Asian skin generally is considered to be nonwhite.1 Fitzpatrick himself acknowledged that race and ethnicity are cultural and political terms with no scientific basis.6 Fitzpatrick skin type also has been demonstrated to correlate poorly with constitutive skin color and minimal erythema dose values.7

We conducted an anonymous survey of dermatologists and dermatology trainees to evaluate how providers use FST in their clinical practice as well as how it is used to describe race and ethnicity.

Methods

The survey was distributed electronically to dermatologists and dermatology trainees from March 13 to March 28, 2019, using the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserv, as well as in person at the annual Skin of Color Society meeting in Washington, DC, on February 28, 2019. The 8-item survey included questions about physician demographics (ie, primary practice setting, board certification, and geographic location); whether the respondent identified as an individual with skin of color; and how the respondent utilized FST in clinical notes (ie, describing race/ethnicity, skin cancer risk, and constitutive [baseline] skin color; determining initial phototherapy dosage and suitability for laser treatments, and likelihood of skin burning). A t test was used to determine whether dermatologists who identified as having skin of color utilized FST differently.

Results

A total of 141 surveys were returned, and 140 respondents were included in the final analysis. Given the methods used to distribute the survey, a response rate could not be calculated. The respondents included more board-certified dermatologists (70%) than dermatology trainees (30%). Ninety-three percent of respondents indicated an academic institution as their primary practice location. Notably, 26% of respondents self-identified as having skin of color.

Forty-one percent of all respondents agreed that FST should be included in their clinical documentation. In response to the question “In what scenarios would you refer to FST in a clinical note?” 31% said they used FST to describe patients’ race or ethnicity, 47% used it to describe patients’ constitutive skin color, and 22% utilized it in both scenarios. Respondents who did not identify as having skin of color were more likely to use FST to describe constitutive skin color, though this finding was not statistically significant (P=.063). Anecdotally, providers also included FST in clinical notes on postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, melasma, and treatment with cryotherapy.

Comment

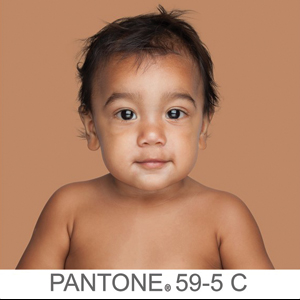

The US Census Bureau has estimated that half of the US population will be of non-European descent by 2050.8 As racial and ethnic distinctions continue to be blurred, attempts to include all nonwhite skin types under the umbrella term skin of color becomes increasingly problematic. The true number of skin colors is unknown but likely is infinite, as Brazilian artist Angélica Dass has demonstrated with her photographic project “Humanae” (Figure). Given this shift in demographics and the limitations of the FST, alternative methods of describing skin color must be developed.

© Angélica Dass | Humanae Work in Progress (Courtesy of the artist).

The results of our survey suggest that approximately one-third to half of academic dermatologists/dermatology trainees use FST to describe race/ethnicity and/or constitutive skin color. This misuse of FST may occur more frequently among physicians who do not identify as having skin of color. Additionally, misuse of FST in academic settings may be problematic and confusing for medical students who may learn to use this common dermatologic tool outside of its original intent.

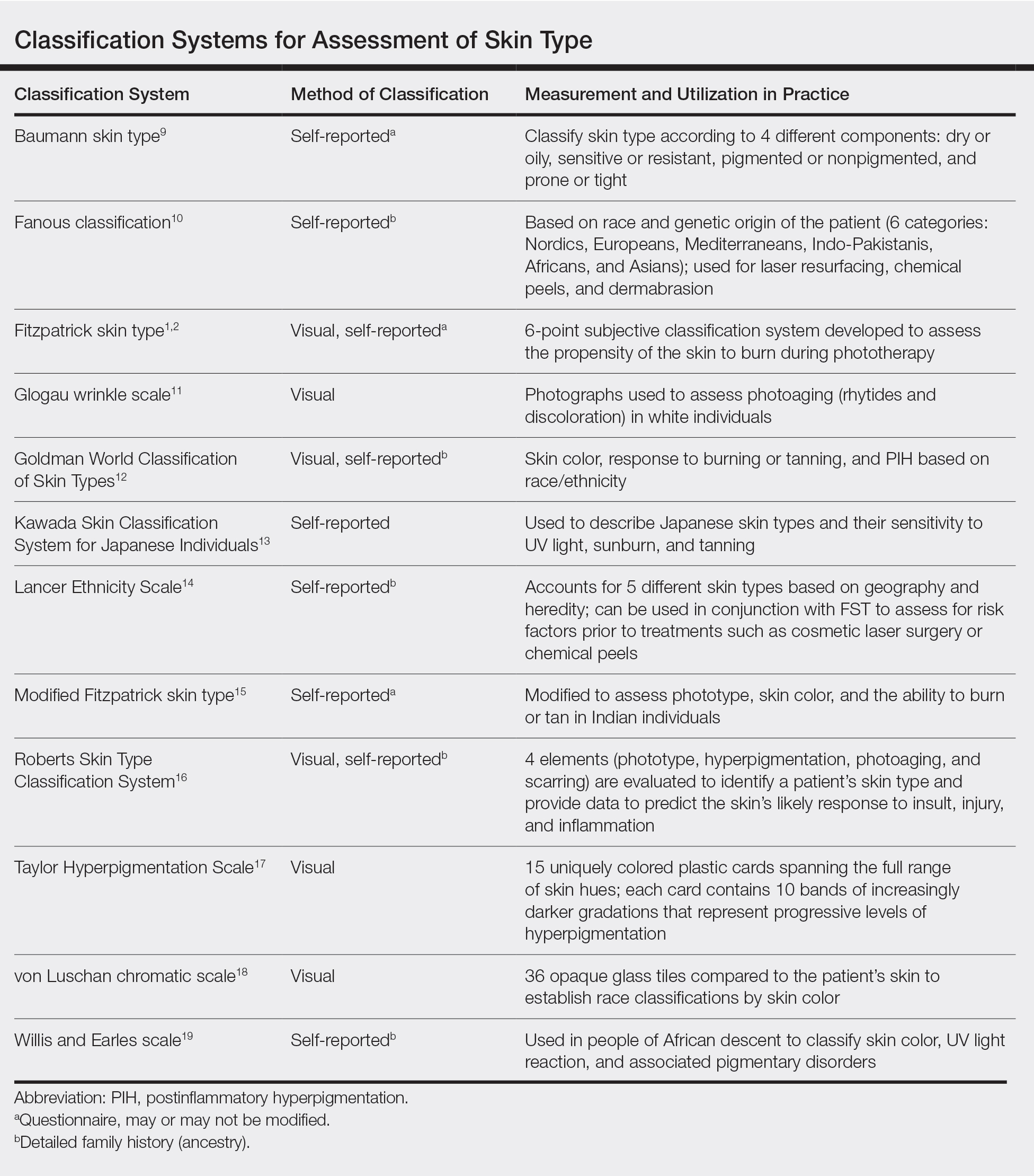

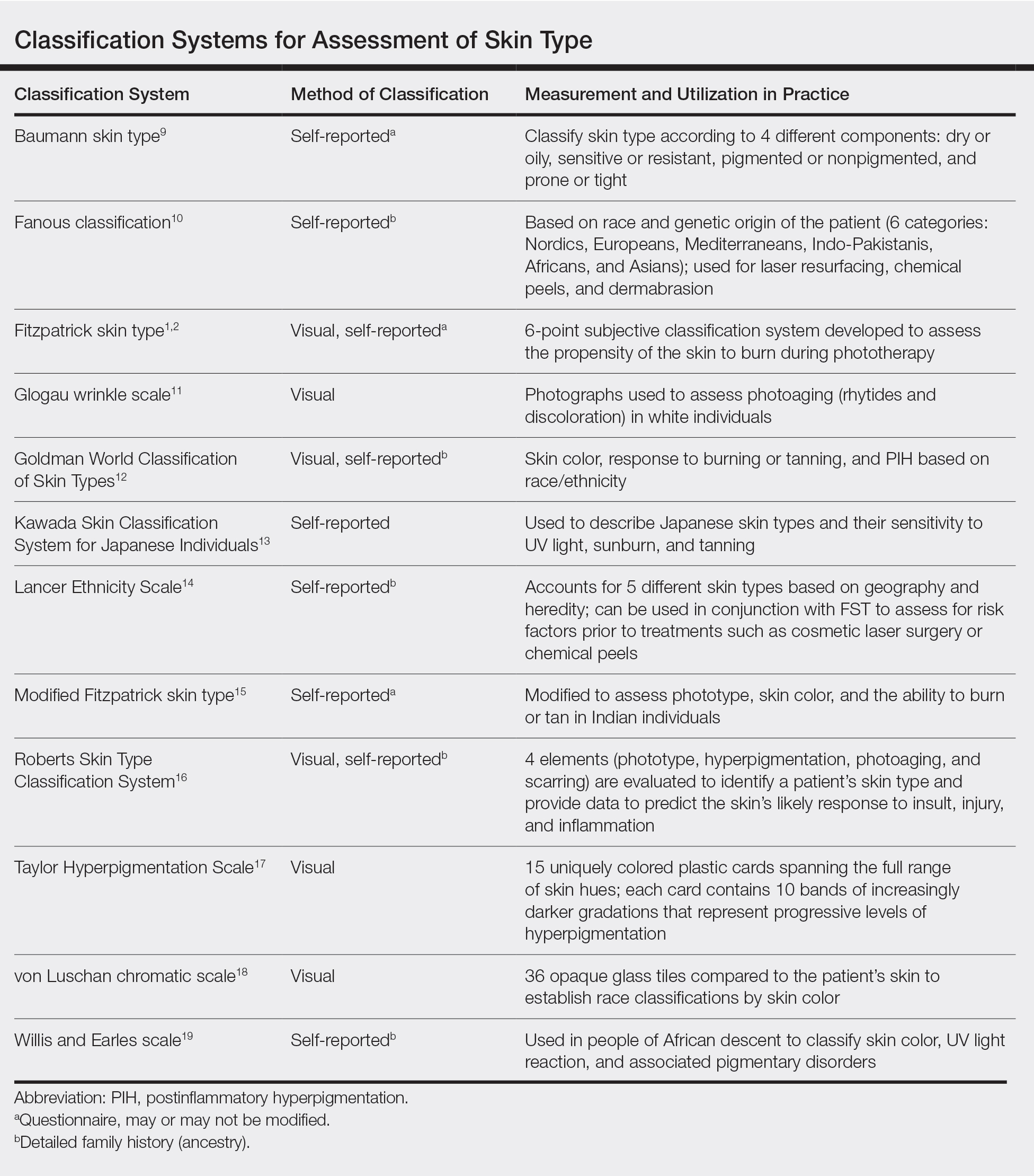

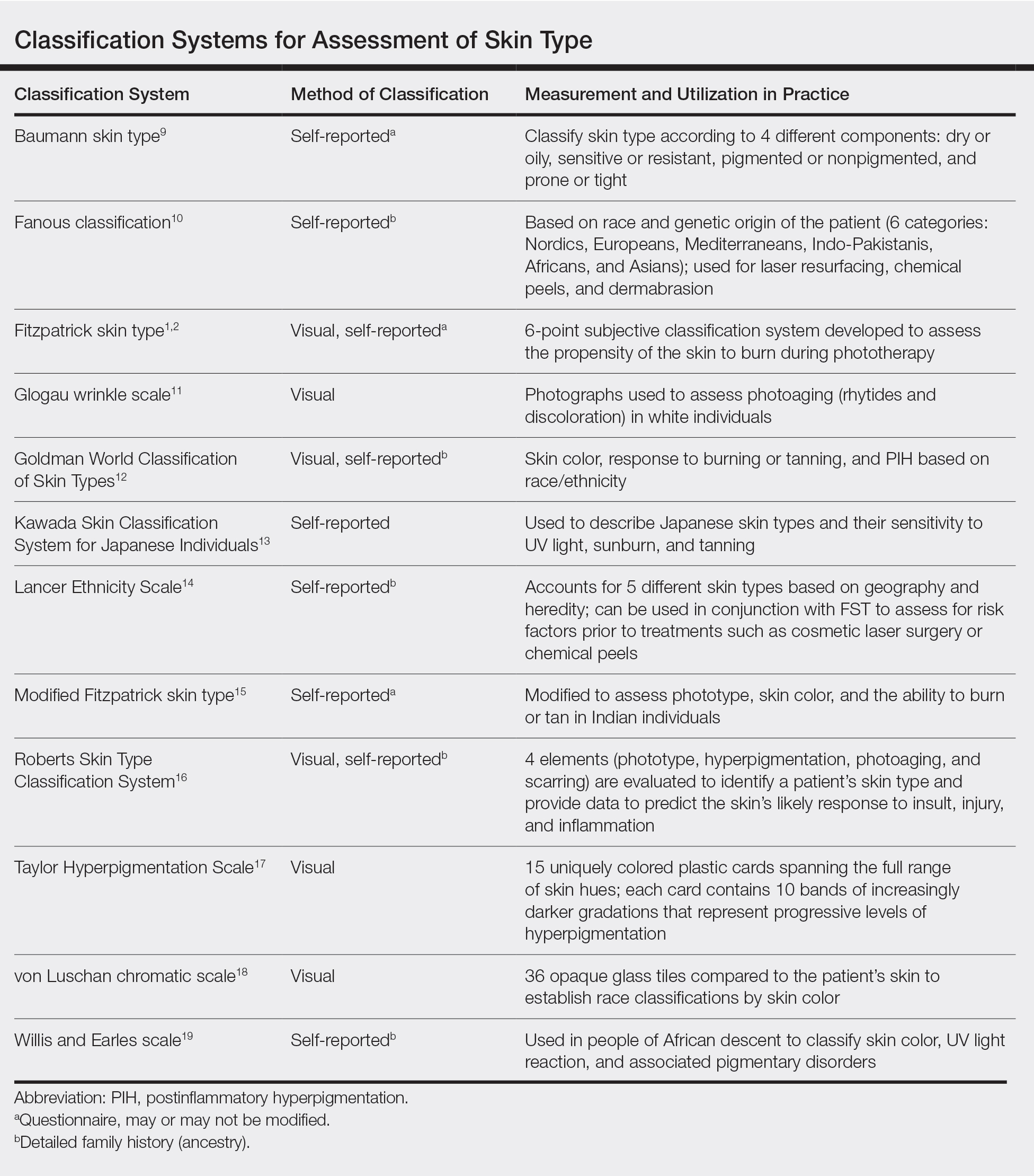

We acknowledge that the conundrum of how to classify individuals with nonwhite skin or skin of color is not simply answered. Several alternative skin classification models have been proposed to improve the sensitivity and specificity of identifying patients with skin of color (Table). Refining FST classification is one approach. Employing terms such as skin irritation, tenderness, itching, or skin becoming darker from sun exposure rather than painful burn or tanning may result in better identification.1,4 A study conducted in India modified the FST questionnaire to acknowledge cultural behaviors.15 Because lighter skin is culturally valued in this population, patient experience with purposeful sun exposure was limited; thus, the questionnaire was modified to remove questions on the use of tanning booths and/or creams as well as sun exposure and instead included more objective questions regarding dark brown eye color, black and dark brown hair color, and dark brown skin color.15 Other studies have suggested that patient-reported photosensitivity assessed via a questionnaire is a valid measure for assessing FST but is associated with an overestimation of skin color, known as “the dark shift.”20

Sharma et al15 utilized reflectance spectrophotometry as an objective measure of melanin and skin erythema. The melanin index consistently showed a positive correlation with FSTs as opposed to the erythema index, which correlated poorly.15 Although reflectance spectrometry accurately identifies skin color in patients with nonwhite skin,21,22 it is an impractical and cost-prohibitive tool for daily practice. A more practical tool for the clinical setting would be a visual color scale with skin hues spanning FST types I to VI, including bands of increasingly darker gradations that would be particularly useful in assessing skin of color. Once such tool is the Taylor Hyperpigmentation Scale.17 Although currently not widely available, this tool could be further refined with additional skin hues.

Conclusion

Other investigators have criticized the various limitations of FST, including physician vs patient assessment, interview vs questionnaire, and phrasing of questions on skin type.23 Our findings suggest that medical providers should be cognizant of conflating race and ethnicity with FST. Two authors of this report (O.R.W. and J.E.D.) are medical students with skin of color and frequently have observed the addition of FST to the medical records of patients who were not receiving phototherapy as a proxy for race. We believe that more culturally appropriate and clinically relevant methods for describing skin of color need to be developed and, in the interim, the original intent of FST should be emphasized and incorporated in medical school and resident education.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Adewole Adamson, MD (Austin, Texas), for discussion and feedback.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Sachdeva S. Fitzpatrick skin typing: applications in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:93-96.

- Everett JS, Budescu M, Sommers MS. Making sense of skin color in clinical care. Clin Nurs Res. 2012;21:495-516.

- Eilers S, Bach DQ, Gaber R, et al. Accuracy of self-report in assessingFitzpatrick skin phototypes I through VI. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1289-1294.

- He SY, McCulloch CE, Boscardin WJ, et al. Self-reported pigmentary phenotypes and race are significant but incomplete predictors of Fitzpatrick skin phototype in an ethnically diverse population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:731-737.

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869-871.

- Leenutaphong V. Relationship between skin color and cutaneous response to ultraviolet radiation in Thai. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1996;11:198-203.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2015.

- Baumann L. Understanding and treating various skin types: the Baumann Skin Type Indicator. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:359-373.

- Fanous N. A new patient classification for laser resurfacing and peels: predicting responses, risks, and results. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2002;26:99-104.

- Glogau RG. Chemical peeling and aging skin. J Geriatric Dermatol. 1994;2:30-35.

- Goldman M. Universal classification of skin type. In: Shiffman M, Mirrafati S, Lam S, et al, eds. Simplified Facial Rejuvenation. Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2008:47-50.

- Kawada A. UVB-induced erythema, delayed tanning, and UVA-induced immediate tanning in Japanese skin. Photodermatol. 1986;3:327-333.

- Lancer HA. Lancer Ethnicity Scale (LES). Lasers Surg Med. 1998;22:9.

- Sharma VK, Gupta V, Jangid BL, et al. Modification of the Fitzpatrick system of skin phototype classification for the Indian population, and its correlation with narrowband diffuse reflectance spectrophotometry. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:274-280.

- Roberts WE. The Roberts Skin Type Classification System. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:452-456.

- Taylor SC, Arsonnaud S, Czernielewski J. The Taylor hyperpigmentation scale: a new visual assessment tool for the evaluation of skin color and pigmentation. Cutis. 2005;76:270-274.

- Treesirichod A, Chansakulporn S, Wattanapan P. Correlation between skin color evaluation by skin color scale chart and narrowband reflectance spectrophotometer. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:339-342.

- Willis I, Earles RM. A new classification system relevant to people of African descent. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2005;18:209-216.

- Reeder AI, Hammond VA, Gray AR. Questionnaire items to assess skin color and erythemal sensitivity: reliability, validity, and “the dark shift.” Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1167-1173.

- Dwyer T, Muller HK, Blizzard L, et al. The use of spectrophotometry to estimate melanin density in Caucasians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:203-206.

- Pershing LK, Tirumala VP, Nelson JL, et al. Reflectance spectrophotometer: the dermatologists’ sphygmomanometer for skin phototyping? J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1633-1640.

- Trakatelli M, Bylaite-Bucinskiene M, Correia O, et al. Clinical assessment of skin phototypes: watch your words! Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:615-619.

Fitzpatrick skin type (FST) is the most commonly used classification system in dermatologic practice. It was developed by Thomas B. Fitzpatrick, MD, PhD, in 1975 to assess the propensity of the skin to burn during phototherapy.1 Fitzpatrick skin type also can be used to assess the clinical benefits and efficacy of cosmetic procedures, including laser hair removal, chemical peel and dermabrasion, tattoo removal, spray tanning, and laser resurfacing for acne scarring.2 The original FST classifications included skin types I through IV; skin types V and VI were later added to include individuals of Asian, Indian, and African origin.1 As a result, FST often is used by providers as a means of describing constitutive skin color and ethnicity.3

How did FST transition from describing the propensity of the skin to burn from UV light exposure to categorizing skin color, thereby becoming a proxy for race? It most likely occurred because there has not been another widely adopted classification system for describing skin color that can be applied to all skin types. Even when the FST classification scale is used as intended, there are inconsistencies with its accuracy; for example, self-reported FSTs have correlated poorly with sunburn risk as well as physician-reported FSTs.4,5 Although physician-reported FSTs have been demonstrated to correlate with race, race does not consistently correlate with objective measures of pigmentation or self-reported FSTs.5 For example, Japanese women often self-identify as FST type II, but Asian skin generally is considered to be nonwhite.1 Fitzpatrick himself acknowledged that race and ethnicity are cultural and political terms with no scientific basis.6 Fitzpatrick skin type also has been demonstrated to correlate poorly with constitutive skin color and minimal erythema dose values.7

We conducted an anonymous survey of dermatologists and dermatology trainees to evaluate how providers use FST in their clinical practice as well as how it is used to describe race and ethnicity.

Methods

The survey was distributed electronically to dermatologists and dermatology trainees from March 13 to March 28, 2019, using the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserv, as well as in person at the annual Skin of Color Society meeting in Washington, DC, on February 28, 2019. The 8-item survey included questions about physician demographics (ie, primary practice setting, board certification, and geographic location); whether the respondent identified as an individual with skin of color; and how the respondent utilized FST in clinical notes (ie, describing race/ethnicity, skin cancer risk, and constitutive [baseline] skin color; determining initial phototherapy dosage and suitability for laser treatments, and likelihood of skin burning). A t test was used to determine whether dermatologists who identified as having skin of color utilized FST differently.

Results

A total of 141 surveys were returned, and 140 respondents were included in the final analysis. Given the methods used to distribute the survey, a response rate could not be calculated. The respondents included more board-certified dermatologists (70%) than dermatology trainees (30%). Ninety-three percent of respondents indicated an academic institution as their primary practice location. Notably, 26% of respondents self-identified as having skin of color.

Forty-one percent of all respondents agreed that FST should be included in their clinical documentation. In response to the question “In what scenarios would you refer to FST in a clinical note?” 31% said they used FST to describe patients’ race or ethnicity, 47% used it to describe patients’ constitutive skin color, and 22% utilized it in both scenarios. Respondents who did not identify as having skin of color were more likely to use FST to describe constitutive skin color, though this finding was not statistically significant (P=.063). Anecdotally, providers also included FST in clinical notes on postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, melasma, and treatment with cryotherapy.

Comment

The US Census Bureau has estimated that half of the US population will be of non-European descent by 2050.8 As racial and ethnic distinctions continue to be blurred, attempts to include all nonwhite skin types under the umbrella term skin of color becomes increasingly problematic. The true number of skin colors is unknown but likely is infinite, as Brazilian artist Angélica Dass has demonstrated with her photographic project “Humanae” (Figure). Given this shift in demographics and the limitations of the FST, alternative methods of describing skin color must be developed.

© Angélica Dass | Humanae Work in Progress (Courtesy of the artist).

The results of our survey suggest that approximately one-third to half of academic dermatologists/dermatology trainees use FST to describe race/ethnicity and/or constitutive skin color. This misuse of FST may occur more frequently among physicians who do not identify as having skin of color. Additionally, misuse of FST in academic settings may be problematic and confusing for medical students who may learn to use this common dermatologic tool outside of its original intent.

We acknowledge that the conundrum of how to classify individuals with nonwhite skin or skin of color is not simply answered. Several alternative skin classification models have been proposed to improve the sensitivity and specificity of identifying patients with skin of color (Table). Refining FST classification is one approach. Employing terms such as skin irritation, tenderness, itching, or skin becoming darker from sun exposure rather than painful burn or tanning may result in better identification.1,4 A study conducted in India modified the FST questionnaire to acknowledge cultural behaviors.15 Because lighter skin is culturally valued in this population, patient experience with purposeful sun exposure was limited; thus, the questionnaire was modified to remove questions on the use of tanning booths and/or creams as well as sun exposure and instead included more objective questions regarding dark brown eye color, black and dark brown hair color, and dark brown skin color.15 Other studies have suggested that patient-reported photosensitivity assessed via a questionnaire is a valid measure for assessing FST but is associated with an overestimation of skin color, known as “the dark shift.”20

Sharma et al15 utilized reflectance spectrophotometry as an objective measure of melanin and skin erythema. The melanin index consistently showed a positive correlation with FSTs as opposed to the erythema index, which correlated poorly.15 Although reflectance spectrometry accurately identifies skin color in patients with nonwhite skin,21,22 it is an impractical and cost-prohibitive tool for daily practice. A more practical tool for the clinical setting would be a visual color scale with skin hues spanning FST types I to VI, including bands of increasingly darker gradations that would be particularly useful in assessing skin of color. Once such tool is the Taylor Hyperpigmentation Scale.17 Although currently not widely available, this tool could be further refined with additional skin hues.

Conclusion

Other investigators have criticized the various limitations of FST, including physician vs patient assessment, interview vs questionnaire, and phrasing of questions on skin type.23 Our findings suggest that medical providers should be cognizant of conflating race and ethnicity with FST. Two authors of this report (O.R.W. and J.E.D.) are medical students with skin of color and frequently have observed the addition of FST to the medical records of patients who were not receiving phototherapy as a proxy for race. We believe that more culturally appropriate and clinically relevant methods for describing skin of color need to be developed and, in the interim, the original intent of FST should be emphasized and incorporated in medical school and resident education.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Adewole Adamson, MD (Austin, Texas), for discussion and feedback.

Fitzpatrick skin type (FST) is the most commonly used classification system in dermatologic practice. It was developed by Thomas B. Fitzpatrick, MD, PhD, in 1975 to assess the propensity of the skin to burn during phototherapy.1 Fitzpatrick skin type also can be used to assess the clinical benefits and efficacy of cosmetic procedures, including laser hair removal, chemical peel and dermabrasion, tattoo removal, spray tanning, and laser resurfacing for acne scarring.2 The original FST classifications included skin types I through IV; skin types V and VI were later added to include individuals of Asian, Indian, and African origin.1 As a result, FST often is used by providers as a means of describing constitutive skin color and ethnicity.3

How did FST transition from describing the propensity of the skin to burn from UV light exposure to categorizing skin color, thereby becoming a proxy for race? It most likely occurred because there has not been another widely adopted classification system for describing skin color that can be applied to all skin types. Even when the FST classification scale is used as intended, there are inconsistencies with its accuracy; for example, self-reported FSTs have correlated poorly with sunburn risk as well as physician-reported FSTs.4,5 Although physician-reported FSTs have been demonstrated to correlate with race, race does not consistently correlate with objective measures of pigmentation or self-reported FSTs.5 For example, Japanese women often self-identify as FST type II, but Asian skin generally is considered to be nonwhite.1 Fitzpatrick himself acknowledged that race and ethnicity are cultural and political terms with no scientific basis.6 Fitzpatrick skin type also has been demonstrated to correlate poorly with constitutive skin color and minimal erythema dose values.7

We conducted an anonymous survey of dermatologists and dermatology trainees to evaluate how providers use FST in their clinical practice as well as how it is used to describe race and ethnicity.

Methods

The survey was distributed electronically to dermatologists and dermatology trainees from March 13 to March 28, 2019, using the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserv, as well as in person at the annual Skin of Color Society meeting in Washington, DC, on February 28, 2019. The 8-item survey included questions about physician demographics (ie, primary practice setting, board certification, and geographic location); whether the respondent identified as an individual with skin of color; and how the respondent utilized FST in clinical notes (ie, describing race/ethnicity, skin cancer risk, and constitutive [baseline] skin color; determining initial phototherapy dosage and suitability for laser treatments, and likelihood of skin burning). A t test was used to determine whether dermatologists who identified as having skin of color utilized FST differently.

Results

A total of 141 surveys were returned, and 140 respondents were included in the final analysis. Given the methods used to distribute the survey, a response rate could not be calculated. The respondents included more board-certified dermatologists (70%) than dermatology trainees (30%). Ninety-three percent of respondents indicated an academic institution as their primary practice location. Notably, 26% of respondents self-identified as having skin of color.

Forty-one percent of all respondents agreed that FST should be included in their clinical documentation. In response to the question “In what scenarios would you refer to FST in a clinical note?” 31% said they used FST to describe patients’ race or ethnicity, 47% used it to describe patients’ constitutive skin color, and 22% utilized it in both scenarios. Respondents who did not identify as having skin of color were more likely to use FST to describe constitutive skin color, though this finding was not statistically significant (P=.063). Anecdotally, providers also included FST in clinical notes on postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, melasma, and treatment with cryotherapy.

Comment

The US Census Bureau has estimated that half of the US population will be of non-European descent by 2050.8 As racial and ethnic distinctions continue to be blurred, attempts to include all nonwhite skin types under the umbrella term skin of color becomes increasingly problematic. The true number of skin colors is unknown but likely is infinite, as Brazilian artist Angélica Dass has demonstrated with her photographic project “Humanae” (Figure). Given this shift in demographics and the limitations of the FST, alternative methods of describing skin color must be developed.

© Angélica Dass | Humanae Work in Progress (Courtesy of the artist).

The results of our survey suggest that approximately one-third to half of academic dermatologists/dermatology trainees use FST to describe race/ethnicity and/or constitutive skin color. This misuse of FST may occur more frequently among physicians who do not identify as having skin of color. Additionally, misuse of FST in academic settings may be problematic and confusing for medical students who may learn to use this common dermatologic tool outside of its original intent.

We acknowledge that the conundrum of how to classify individuals with nonwhite skin or skin of color is not simply answered. Several alternative skin classification models have been proposed to improve the sensitivity and specificity of identifying patients with skin of color (Table). Refining FST classification is one approach. Employing terms such as skin irritation, tenderness, itching, or skin becoming darker from sun exposure rather than painful burn or tanning may result in better identification.1,4 A study conducted in India modified the FST questionnaire to acknowledge cultural behaviors.15 Because lighter skin is culturally valued in this population, patient experience with purposeful sun exposure was limited; thus, the questionnaire was modified to remove questions on the use of tanning booths and/or creams as well as sun exposure and instead included more objective questions regarding dark brown eye color, black and dark brown hair color, and dark brown skin color.15 Other studies have suggested that patient-reported photosensitivity assessed via a questionnaire is a valid measure for assessing FST but is associated with an overestimation of skin color, known as “the dark shift.”20

Sharma et al15 utilized reflectance spectrophotometry as an objective measure of melanin and skin erythema. The melanin index consistently showed a positive correlation with FSTs as opposed to the erythema index, which correlated poorly.15 Although reflectance spectrometry accurately identifies skin color in patients with nonwhite skin,21,22 it is an impractical and cost-prohibitive tool for daily practice. A more practical tool for the clinical setting would be a visual color scale with skin hues spanning FST types I to VI, including bands of increasingly darker gradations that would be particularly useful in assessing skin of color. Once such tool is the Taylor Hyperpigmentation Scale.17 Although currently not widely available, this tool could be further refined with additional skin hues.

Conclusion

Other investigators have criticized the various limitations of FST, including physician vs patient assessment, interview vs questionnaire, and phrasing of questions on skin type.23 Our findings suggest that medical providers should be cognizant of conflating race and ethnicity with FST. Two authors of this report (O.R.W. and J.E.D.) are medical students with skin of color and frequently have observed the addition of FST to the medical records of patients who were not receiving phototherapy as a proxy for race. We believe that more culturally appropriate and clinically relevant methods for describing skin of color need to be developed and, in the interim, the original intent of FST should be emphasized and incorporated in medical school and resident education.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Adewole Adamson, MD (Austin, Texas), for discussion and feedback.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Sachdeva S. Fitzpatrick skin typing: applications in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:93-96.

- Everett JS, Budescu M, Sommers MS. Making sense of skin color in clinical care. Clin Nurs Res. 2012;21:495-516.

- Eilers S, Bach DQ, Gaber R, et al. Accuracy of self-report in assessingFitzpatrick skin phototypes I through VI. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1289-1294.

- He SY, McCulloch CE, Boscardin WJ, et al. Self-reported pigmentary phenotypes and race are significant but incomplete predictors of Fitzpatrick skin phototype in an ethnically diverse population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:731-737.

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869-871.

- Leenutaphong V. Relationship between skin color and cutaneous response to ultraviolet radiation in Thai. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1996;11:198-203.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2015.

- Baumann L. Understanding and treating various skin types: the Baumann Skin Type Indicator. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:359-373.

- Fanous N. A new patient classification for laser resurfacing and peels: predicting responses, risks, and results. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2002;26:99-104.

- Glogau RG. Chemical peeling and aging skin. J Geriatric Dermatol. 1994;2:30-35.

- Goldman M. Universal classification of skin type. In: Shiffman M, Mirrafati S, Lam S, et al, eds. Simplified Facial Rejuvenation. Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2008:47-50.

- Kawada A. UVB-induced erythema, delayed tanning, and UVA-induced immediate tanning in Japanese skin. Photodermatol. 1986;3:327-333.

- Lancer HA. Lancer Ethnicity Scale (LES). Lasers Surg Med. 1998;22:9.

- Sharma VK, Gupta V, Jangid BL, et al. Modification of the Fitzpatrick system of skin phototype classification for the Indian population, and its correlation with narrowband diffuse reflectance spectrophotometry. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:274-280.

- Roberts WE. The Roberts Skin Type Classification System. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:452-456.

- Taylor SC, Arsonnaud S, Czernielewski J. The Taylor hyperpigmentation scale: a new visual assessment tool for the evaluation of skin color and pigmentation. Cutis. 2005;76:270-274.

- Treesirichod A, Chansakulporn S, Wattanapan P. Correlation between skin color evaluation by skin color scale chart and narrowband reflectance spectrophotometer. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:339-342.

- Willis I, Earles RM. A new classification system relevant to people of African descent. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2005;18:209-216.

- Reeder AI, Hammond VA, Gray AR. Questionnaire items to assess skin color and erythemal sensitivity: reliability, validity, and “the dark shift.” Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1167-1173.

- Dwyer T, Muller HK, Blizzard L, et al. The use of spectrophotometry to estimate melanin density in Caucasians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:203-206.

- Pershing LK, Tirumala VP, Nelson JL, et al. Reflectance spectrophotometer: the dermatologists’ sphygmomanometer for skin phototyping? J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1633-1640.

- Trakatelli M, Bylaite-Bucinskiene M, Correia O, et al. Clinical assessment of skin phototypes: watch your words! Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:615-619.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Sachdeva S. Fitzpatrick skin typing: applications in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:93-96.

- Everett JS, Budescu M, Sommers MS. Making sense of skin color in clinical care. Clin Nurs Res. 2012;21:495-516.

- Eilers S, Bach DQ, Gaber R, et al. Accuracy of self-report in assessingFitzpatrick skin phototypes I through VI. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1289-1294.

- He SY, McCulloch CE, Boscardin WJ, et al. Self-reported pigmentary phenotypes and race are significant but incomplete predictors of Fitzpatrick skin phototype in an ethnically diverse population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:731-737.

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869-871.

- Leenutaphong V. Relationship between skin color and cutaneous response to ultraviolet radiation in Thai. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1996;11:198-203.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2015.

- Baumann L. Understanding and treating various skin types: the Baumann Skin Type Indicator. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:359-373.

- Fanous N. A new patient classification for laser resurfacing and peels: predicting responses, risks, and results. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2002;26:99-104.

- Glogau RG. Chemical peeling and aging skin. J Geriatric Dermatol. 1994;2:30-35.

- Goldman M. Universal classification of skin type. In: Shiffman M, Mirrafati S, Lam S, et al, eds. Simplified Facial Rejuvenation. Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2008:47-50.

- Kawada A. UVB-induced erythema, delayed tanning, and UVA-induced immediate tanning in Japanese skin. Photodermatol. 1986;3:327-333.

- Lancer HA. Lancer Ethnicity Scale (LES). Lasers Surg Med. 1998;22:9.

- Sharma VK, Gupta V, Jangid BL, et al. Modification of the Fitzpatrick system of skin phototype classification for the Indian population, and its correlation with narrowband diffuse reflectance spectrophotometry. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:274-280.

- Roberts WE. The Roberts Skin Type Classification System. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:452-456.

- Taylor SC, Arsonnaud S, Czernielewski J. The Taylor hyperpigmentation scale: a new visual assessment tool for the evaluation of skin color and pigmentation. Cutis. 2005;76:270-274.

- Treesirichod A, Chansakulporn S, Wattanapan P. Correlation between skin color evaluation by skin color scale chart and narrowband reflectance spectrophotometer. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:339-342.

- Willis I, Earles RM. A new classification system relevant to people of African descent. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2005;18:209-216.

- Reeder AI, Hammond VA, Gray AR. Questionnaire items to assess skin color and erythemal sensitivity: reliability, validity, and “the dark shift.” Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1167-1173.

- Dwyer T, Muller HK, Blizzard L, et al. The use of spectrophotometry to estimate melanin density in Caucasians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:203-206.

- Pershing LK, Tirumala VP, Nelson JL, et al. Reflectance spectrophotometer: the dermatologists’ sphygmomanometer for skin phototyping? J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1633-1640.

- Trakatelli M, Bylaite-Bucinskiene M, Correia O, et al. Clinical assessment of skin phototypes: watch your words! Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:615-619.

Practice Points

- Medical providers should be cognizant of conflating race and ethnicity with Fitzpatrick skin type (FST).

- Misuse of FST may occur more frequently among physicians who do not identify as having skin of color.

- Although alternative skin type classification systems have been proposed, more clinically relevant methods for describing skin of color need to be developed.

Social media may negatively influence acne treatment

A small survey suggests many patients consult social media for advice on acne treatment and follow recommendations that don’t align with clinical guidelines.

Of the 130 patients surveyed, 45% consulted social media for advice on acne treatment, and 52% of those patients followed recommendations that don’t correspond to American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines. Most patients reported no improvement (40%) or minimal improvement (53%) in their acne after following advice from social media.

“These results suggest that dermatologists should inquire about social media acne treatment advice and directly address misinformation,” wrote Ahmed Yousaf, of West Virginia University, Morgantown, W.Va., and colleagues. Their report is in Pediatric Dermatology.

They conducted the survey of 130 patients treated for acne at West Virginia University. Most patients were female (60%), and a majority were adolescents (54%) or adults (44%). About half of the patients (51%) said their acne was moderate, 38% said it was severe, and 11% said it was mild.

Most patients said they consulted a medical professional for their first acne treatment (58%). However, 16% of patients said they first went to social media for advice, 26% said they consulted family or friends, and 10% took “other” steps as their first approach to acne treatment.

In all, 45% of patients consulted social media for acne treatment advice at some point. This includes 54% of women, 31% of men, 41% of adolescents, and 51% of adults. Social media consultation was more common among patients with severe acne (54%) than among those with mild (36%) or moderate (39%) acne.

The most common social media platforms used were YouTube and Instagram (58% each), followed by Pinterest (31%), Facebook (19%), Twitter (9%), Snapchat (7%), and Tumblr (3%). (Patients could select more than one social media platform.)

Roughly half (52%) of patients who consulted social media followed advice that does not align with AAD guidelines, 31% made changes that are recommended by the AAD, and 17% did not provide information on recommendations they followed.

The social media advice patients followed included using over-the-counter products (81%), making dietary changes (40%), using self-made products (19%), taking supplements (16%), and making changes in exercise routines (7%). (Patients could select more than one treatment approach.)

Among the patients who followed social media advice, 40% said they saw no change in their acne, and 53% reported minimal improvement.

“Only 7% of social media users reported significant improvement in their acne,” Mr. Yousaf and colleagues wrote. “This may be due to less accurate content found on social media compared to other health care sources.”

The authors acknowledged that the patients surveyed were recruited from a dermatology clinic. Therefore, these results “likely underestimate the percentage of patients who improve from social media acne treatment advice and do not consult a medical professional.”

Mr. Yousaf and colleagues did not disclose any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Yousaf A et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020 Jan 15. doi: 10.1111/pde.14091.

A small survey suggests many patients consult social media for advice on acne treatment and follow recommendations that don’t align with clinical guidelines.

Of the 130 patients surveyed, 45% consulted social media for advice on acne treatment, and 52% of those patients followed recommendations that don’t correspond to American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines. Most patients reported no improvement (40%) or minimal improvement (53%) in their acne after following advice from social media.

“These results suggest that dermatologists should inquire about social media acne treatment advice and directly address misinformation,” wrote Ahmed Yousaf, of West Virginia University, Morgantown, W.Va., and colleagues. Their report is in Pediatric Dermatology.

They conducted the survey of 130 patients treated for acne at West Virginia University. Most patients were female (60%), and a majority were adolescents (54%) or adults (44%). About half of the patients (51%) said their acne was moderate, 38% said it was severe, and 11% said it was mild.

Most patients said they consulted a medical professional for their first acne treatment (58%). However, 16% of patients said they first went to social media for advice, 26% said they consulted family or friends, and 10% took “other” steps as their first approach to acne treatment.

In all, 45% of patients consulted social media for acne treatment advice at some point. This includes 54% of women, 31% of men, 41% of adolescents, and 51% of adults. Social media consultation was more common among patients with severe acne (54%) than among those with mild (36%) or moderate (39%) acne.

The most common social media platforms used were YouTube and Instagram (58% each), followed by Pinterest (31%), Facebook (19%), Twitter (9%), Snapchat (7%), and Tumblr (3%). (Patients could select more than one social media platform.)

Roughly half (52%) of patients who consulted social media followed advice that does not align with AAD guidelines, 31% made changes that are recommended by the AAD, and 17% did not provide information on recommendations they followed.

The social media advice patients followed included using over-the-counter products (81%), making dietary changes (40%), using self-made products (19%), taking supplements (16%), and making changes in exercise routines (7%). (Patients could select more than one treatment approach.)

Among the patients who followed social media advice, 40% said they saw no change in their acne, and 53% reported minimal improvement.

“Only 7% of social media users reported significant improvement in their acne,” Mr. Yousaf and colleagues wrote. “This may be due to less accurate content found on social media compared to other health care sources.”

The authors acknowledged that the patients surveyed were recruited from a dermatology clinic. Therefore, these results “likely underestimate the percentage of patients who improve from social media acne treatment advice and do not consult a medical professional.”

Mr. Yousaf and colleagues did not disclose any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Yousaf A et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020 Jan 15. doi: 10.1111/pde.14091.

A small survey suggests many patients consult social media for advice on acne treatment and follow recommendations that don’t align with clinical guidelines.

Of the 130 patients surveyed, 45% consulted social media for advice on acne treatment, and 52% of those patients followed recommendations that don’t correspond to American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines. Most patients reported no improvement (40%) or minimal improvement (53%) in their acne after following advice from social media.

“These results suggest that dermatologists should inquire about social media acne treatment advice and directly address misinformation,” wrote Ahmed Yousaf, of West Virginia University, Morgantown, W.Va., and colleagues. Their report is in Pediatric Dermatology.

They conducted the survey of 130 patients treated for acne at West Virginia University. Most patients were female (60%), and a majority were adolescents (54%) or adults (44%). About half of the patients (51%) said their acne was moderate, 38% said it was severe, and 11% said it was mild.

Most patients said they consulted a medical professional for their first acne treatment (58%). However, 16% of patients said they first went to social media for advice, 26% said they consulted family or friends, and 10% took “other” steps as their first approach to acne treatment.

In all, 45% of patients consulted social media for acne treatment advice at some point. This includes 54% of women, 31% of men, 41% of adolescents, and 51% of adults. Social media consultation was more common among patients with severe acne (54%) than among those with mild (36%) or moderate (39%) acne.

The most common social media platforms used were YouTube and Instagram (58% each), followed by Pinterest (31%), Facebook (19%), Twitter (9%), Snapchat (7%), and Tumblr (3%). (Patients could select more than one social media platform.)

Roughly half (52%) of patients who consulted social media followed advice that does not align with AAD guidelines, 31% made changes that are recommended by the AAD, and 17% did not provide information on recommendations they followed.

The social media advice patients followed included using over-the-counter products (81%), making dietary changes (40%), using self-made products (19%), taking supplements (16%), and making changes in exercise routines (7%). (Patients could select more than one treatment approach.)

Among the patients who followed social media advice, 40% said they saw no change in their acne, and 53% reported minimal improvement.

“Only 7% of social media users reported significant improvement in their acne,” Mr. Yousaf and colleagues wrote. “This may be due to less accurate content found on social media compared to other health care sources.”

The authors acknowledged that the patients surveyed were recruited from a dermatology clinic. Therefore, these results “likely underestimate the percentage of patients who improve from social media acne treatment advice and do not consult a medical professional.”

Mr. Yousaf and colleagues did not disclose any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Yousaf A et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020 Jan 15. doi: 10.1111/pde.14091.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Lasers expunge mucosal tattoos

, researchers reported.

Mucocutaneous tattoos are relatively rare, and lasers have been used for their removal, but cases and results have not been well documented, wrote Hao Feng, MD, then of the Laser & Skin Surgery Center of New York, and the department of dermatology, New York University, and coauthors.

In a report published in Lasers in Surgery and Medicine, the clinicians noted significant improvement with no scarring or dyspigmentation at 1 month after the last treatment session in two patients, with mucosal tattoos that had not been previously treated.

In one case, a healthy 19-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type II presented for removal of a 6‐month‐old, black tattoo on the mucosal surface of her lower lip. She received six treatment sessions at months 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, and 12 with a QS 694‐nm ruby laser at settings of 6-mm spot size, 20-nanosecond pulse duration, and 3.0-3.5 J/cm2.

In a second case, a 30‐year‐old man with Fitzpatrick skin type IV presented for removal of a 10‐year‐old black tattoo on his left buccal mucosa. He received one treatment with 755-nm alexandrite picosecond lasers at settings of 2.5-mm spot size, 500-picosecond pulse duration, and 3.36 J/cm2.

Both patients experienced local mild discomfort, erythema, and edema after treatment.

“Older tattoos respond better and quicker on the skin to laser treatments, and it is likely the reason why the buccal mucosa tattoo (10 years) resolved with a single treatment whereas the lower lip tattoo (6 months) required six treatments,” the authors noted.

Mucosal tattoos, they added, “tend to respond better, faster, and with less unwanted side effects than tattoos on the skin. This may relate to the fact that mucosal skin is thinner, non-keratinized, well‐vascularized, and contains less melanin content.”

As to which laser is the best choice for removing mucosal tattoos, the authors noted that it is unclear, but while they said they have been using picosecond lasers for tattoo removals, QS lasers “remain excellent treatment modalities,” they wrote.

“Given the excellent clinical response combined with lack of scarring and dyspigmentation in our highly satisfied patients, it is the authors’ opinion that laser treatment should be considered as the first‐line treatment in removing unwanted cosmetic mucosal tattoos. This can be accomplished with various wavelengths in the picosecond and nanosecond domains,” they concluded.

Dr. Feng, who is now director of laser surgery and cosmetic dermatology at the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, disclosed serving as a consultant and medical monitor for Cytrellis Biosystems. Another author disclosed serving on the advisory boards for Cytrellis, Syneron Candela, and Cynosure; owning stocks or having stock options with Cytrellis; and investing in Syneron Candela, Cynosure, and Cytrellis. The remaining two authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Feng H et al. Lasers Surg Med. 2019 Dec 30. doi: 10.1002/lsm.23207.

, researchers reported.

Mucocutaneous tattoos are relatively rare, and lasers have been used for their removal, but cases and results have not been well documented, wrote Hao Feng, MD, then of the Laser & Skin Surgery Center of New York, and the department of dermatology, New York University, and coauthors.

In a report published in Lasers in Surgery and Medicine, the clinicians noted significant improvement with no scarring or dyspigmentation at 1 month after the last treatment session in two patients, with mucosal tattoos that had not been previously treated.

In one case, a healthy 19-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type II presented for removal of a 6‐month‐old, black tattoo on the mucosal surface of her lower lip. She received six treatment sessions at months 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, and 12 with a QS 694‐nm ruby laser at settings of 6-mm spot size, 20-nanosecond pulse duration, and 3.0-3.5 J/cm2.

In a second case, a 30‐year‐old man with Fitzpatrick skin type IV presented for removal of a 10‐year‐old black tattoo on his left buccal mucosa. He received one treatment with 755-nm alexandrite picosecond lasers at settings of 2.5-mm spot size, 500-picosecond pulse duration, and 3.36 J/cm2.

Both patients experienced local mild discomfort, erythema, and edema after treatment.

“Older tattoos respond better and quicker on the skin to laser treatments, and it is likely the reason why the buccal mucosa tattoo (10 years) resolved with a single treatment whereas the lower lip tattoo (6 months) required six treatments,” the authors noted.

Mucosal tattoos, they added, “tend to respond better, faster, and with less unwanted side effects than tattoos on the skin. This may relate to the fact that mucosal skin is thinner, non-keratinized, well‐vascularized, and contains less melanin content.”

As to which laser is the best choice for removing mucosal tattoos, the authors noted that it is unclear, but while they said they have been using picosecond lasers for tattoo removals, QS lasers “remain excellent treatment modalities,” they wrote.

“Given the excellent clinical response combined with lack of scarring and dyspigmentation in our highly satisfied patients, it is the authors’ opinion that laser treatment should be considered as the first‐line treatment in removing unwanted cosmetic mucosal tattoos. This can be accomplished with various wavelengths in the picosecond and nanosecond domains,” they concluded.

Dr. Feng, who is now director of laser surgery and cosmetic dermatology at the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, disclosed serving as a consultant and medical monitor for Cytrellis Biosystems. Another author disclosed serving on the advisory boards for Cytrellis, Syneron Candela, and Cynosure; owning stocks or having stock options with Cytrellis; and investing in Syneron Candela, Cynosure, and Cytrellis. The remaining two authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Feng H et al. Lasers Surg Med. 2019 Dec 30. doi: 10.1002/lsm.23207.

, researchers reported.

Mucocutaneous tattoos are relatively rare, and lasers have been used for their removal, but cases and results have not been well documented, wrote Hao Feng, MD, then of the Laser & Skin Surgery Center of New York, and the department of dermatology, New York University, and coauthors.

In a report published in Lasers in Surgery and Medicine, the clinicians noted significant improvement with no scarring or dyspigmentation at 1 month after the last treatment session in two patients, with mucosal tattoos that had not been previously treated.

In one case, a healthy 19-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type II presented for removal of a 6‐month‐old, black tattoo on the mucosal surface of her lower lip. She received six treatment sessions at months 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, and 12 with a QS 694‐nm ruby laser at settings of 6-mm spot size, 20-nanosecond pulse duration, and 3.0-3.5 J/cm2.

In a second case, a 30‐year‐old man with Fitzpatrick skin type IV presented for removal of a 10‐year‐old black tattoo on his left buccal mucosa. He received one treatment with 755-nm alexandrite picosecond lasers at settings of 2.5-mm spot size, 500-picosecond pulse duration, and 3.36 J/cm2.

Both patients experienced local mild discomfort, erythema, and edema after treatment.

“Older tattoos respond better and quicker on the skin to laser treatments, and it is likely the reason why the buccal mucosa tattoo (10 years) resolved with a single treatment whereas the lower lip tattoo (6 months) required six treatments,” the authors noted.

Mucosal tattoos, they added, “tend to respond better, faster, and with less unwanted side effects than tattoos on the skin. This may relate to the fact that mucosal skin is thinner, non-keratinized, well‐vascularized, and contains less melanin content.”

As to which laser is the best choice for removing mucosal tattoos, the authors noted that it is unclear, but while they said they have been using picosecond lasers for tattoo removals, QS lasers “remain excellent treatment modalities,” they wrote.

“Given the excellent clinical response combined with lack of scarring and dyspigmentation in our highly satisfied patients, it is the authors’ opinion that laser treatment should be considered as the first‐line treatment in removing unwanted cosmetic mucosal tattoos. This can be accomplished with various wavelengths in the picosecond and nanosecond domains,” they concluded.

Dr. Feng, who is now director of laser surgery and cosmetic dermatology at the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, disclosed serving as a consultant and medical monitor for Cytrellis Biosystems. Another author disclosed serving on the advisory boards for Cytrellis, Syneron Candela, and Cynosure; owning stocks or having stock options with Cytrellis; and investing in Syneron Candela, Cynosure, and Cytrellis. The remaining two authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Feng H et al. Lasers Surg Med. 2019 Dec 30. doi: 10.1002/lsm.23207.

FROM LASERS IN SURGERY AND MEDICINE

CD1a and cosmetic-related contact dermatitis

As industries develop more chemical extraction techniques for synthetic or purified botanical ingredients to include in cosmetic and personal care products, the incidence of contact dermatitis is rising. Contact dermatitis (irritant or allergic) is the most common occupational skin disease, with current lifetime incidence exceeding 50%. For allergic contact dermatitis, type IV hypersensitivity (or delayed-type hypersensitivity) is thought to be the immunologic mediated pathway in which a T cell–mediated response occurs approximately 72 hours after exposure to the contact allergen. Diagnosis currently is predominately made clinically, after identifying the potential allergen or via patch testing. Treatment typically involves topical steroids or anti-inflammatories should a rash occur, and avoidance of the identified allergen.

In delayed-type hypersensitivity, most T-cell receptors recognize a peptide antigen bound to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) I or MHC II proteins, which stimulates a subsequent inflammatory immune response. However, in a recently published study, the authors wrote that “most known contact allergens are nonpeptidic small molecules, cations, or metals that are typically delivered to skin as drugs, oils, cosmetics, skin creams, or fragrances.” The chemical nature and structure of contact allergens “does not match the chemical structures of most antigens commonly recognized within the TCR-peptide-MHC axis,” they added. Thus, the mechanism by which nonpeptide molecules found in cosmetics cause a T cell–mediated hypersensitivity is poorly understood.

In that study, investigators from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston; Columbia University, New York; and Monash University, Melbourne, looked at whether a protein found in immune cells – CD1a – could be involved in these allergic reactions. In a press release describing the results, cosenior author D. Branch Moody, MD, a principal investigator and physician in Brigham and Women’s division of rheumatology, inflammation, and immunity, noted that they “questioned the prevailing paradigm that T cell–mediated allergic reaction is only triggered when T cells respond to proteins or peptide antigens,” and found “a mechanism through which fragrance can initiate a T-cell response through a protein called CD1a.”

In their study, CD1a was identified as the and personal care products. Specifically, balsam of Peru (a tree oil commonly found in cosmetics and toothpaste), benzyl benzoate, benzyl cinnamate, and farnesol (often present in “fragrance”) after positive patch tests were found to elicit a CD1a-mediated immune response. Their findings suggest that, for these hydrophobic contact allergens, in forming CD1a-farnesol (or other) complexes, displacement of self-lipids normally bound to CD1a occurs, exposing T cell–stimulatory surface regions of CD1a that are normally hidden, thereby eliciting T cell–mediated hypersensitivity reactions.

The authors note that having a better understanding of how these ingredients elicit an immune response on a molecular level can help us potentially identify other molecules that can potentially block this response in humans, thereby treating or potentially mitigating allergic skin disease from these ingredients.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Resource

Nicolai S et al. Sci Immunol. 2020 Jan 3. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aax5430.

As industries develop more chemical extraction techniques for synthetic or purified botanical ingredients to include in cosmetic and personal care products, the incidence of contact dermatitis is rising. Contact dermatitis (irritant or allergic) is the most common occupational skin disease, with current lifetime incidence exceeding 50%. For allergic contact dermatitis, type IV hypersensitivity (or delayed-type hypersensitivity) is thought to be the immunologic mediated pathway in which a T cell–mediated response occurs approximately 72 hours after exposure to the contact allergen. Diagnosis currently is predominately made clinically, after identifying the potential allergen or via patch testing. Treatment typically involves topical steroids or anti-inflammatories should a rash occur, and avoidance of the identified allergen.

In delayed-type hypersensitivity, most T-cell receptors recognize a peptide antigen bound to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) I or MHC II proteins, which stimulates a subsequent inflammatory immune response. However, in a recently published study, the authors wrote that “most known contact allergens are nonpeptidic small molecules, cations, or metals that are typically delivered to skin as drugs, oils, cosmetics, skin creams, or fragrances.” The chemical nature and structure of contact allergens “does not match the chemical structures of most antigens commonly recognized within the TCR-peptide-MHC axis,” they added. Thus, the mechanism by which nonpeptide molecules found in cosmetics cause a T cell–mediated hypersensitivity is poorly understood.

In that study, investigators from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston; Columbia University, New York; and Monash University, Melbourne, looked at whether a protein found in immune cells – CD1a – could be involved in these allergic reactions. In a press release describing the results, cosenior author D. Branch Moody, MD, a principal investigator and physician in Brigham and Women’s division of rheumatology, inflammation, and immunity, noted that they “questioned the prevailing paradigm that T cell–mediated allergic reaction is only triggered when T cells respond to proteins or peptide antigens,” and found “a mechanism through which fragrance can initiate a T-cell response through a protein called CD1a.”

In their study, CD1a was identified as the and personal care products. Specifically, balsam of Peru (a tree oil commonly found in cosmetics and toothpaste), benzyl benzoate, benzyl cinnamate, and farnesol (often present in “fragrance”) after positive patch tests were found to elicit a CD1a-mediated immune response. Their findings suggest that, for these hydrophobic contact allergens, in forming CD1a-farnesol (or other) complexes, displacement of self-lipids normally bound to CD1a occurs, exposing T cell–stimulatory surface regions of CD1a that are normally hidden, thereby eliciting T cell–mediated hypersensitivity reactions.

The authors note that having a better understanding of how these ingredients elicit an immune response on a molecular level can help us potentially identify other molecules that can potentially block this response in humans, thereby treating or potentially mitigating allergic skin disease from these ingredients.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Resource

Nicolai S et al. Sci Immunol. 2020 Jan 3. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aax5430.

As industries develop more chemical extraction techniques for synthetic or purified botanical ingredients to include in cosmetic and personal care products, the incidence of contact dermatitis is rising. Contact dermatitis (irritant or allergic) is the most common occupational skin disease, with current lifetime incidence exceeding 50%. For allergic contact dermatitis, type IV hypersensitivity (or delayed-type hypersensitivity) is thought to be the immunologic mediated pathway in which a T cell–mediated response occurs approximately 72 hours after exposure to the contact allergen. Diagnosis currently is predominately made clinically, after identifying the potential allergen or via patch testing. Treatment typically involves topical steroids or anti-inflammatories should a rash occur, and avoidance of the identified allergen.

In delayed-type hypersensitivity, most T-cell receptors recognize a peptide antigen bound to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) I or MHC II proteins, which stimulates a subsequent inflammatory immune response. However, in a recently published study, the authors wrote that “most known contact allergens are nonpeptidic small molecules, cations, or metals that are typically delivered to skin as drugs, oils, cosmetics, skin creams, or fragrances.” The chemical nature and structure of contact allergens “does not match the chemical structures of most antigens commonly recognized within the TCR-peptide-MHC axis,” they added. Thus, the mechanism by which nonpeptide molecules found in cosmetics cause a T cell–mediated hypersensitivity is poorly understood.

In that study, investigators from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston; Columbia University, New York; and Monash University, Melbourne, looked at whether a protein found in immune cells – CD1a – could be involved in these allergic reactions. In a press release describing the results, cosenior author D. Branch Moody, MD, a principal investigator and physician in Brigham and Women’s division of rheumatology, inflammation, and immunity, noted that they “questioned the prevailing paradigm that T cell–mediated allergic reaction is only triggered when T cells respond to proteins or peptide antigens,” and found “a mechanism through which fragrance can initiate a T-cell response through a protein called CD1a.”

In their study, CD1a was identified as the and personal care products. Specifically, balsam of Peru (a tree oil commonly found in cosmetics and toothpaste), benzyl benzoate, benzyl cinnamate, and farnesol (often present in “fragrance”) after positive patch tests were found to elicit a CD1a-mediated immune response. Their findings suggest that, for these hydrophobic contact allergens, in forming CD1a-farnesol (or other) complexes, displacement of self-lipids normally bound to CD1a occurs, exposing T cell–stimulatory surface regions of CD1a that are normally hidden, thereby eliciting T cell–mediated hypersensitivity reactions.

The authors note that having a better understanding of how these ingredients elicit an immune response on a molecular level can help us potentially identify other molecules that can potentially block this response in humans, thereby treating or potentially mitigating allergic skin disease from these ingredients.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Resource

Nicolai S et al. Sci Immunol. 2020 Jan 3. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aax5430.

Pyrrolidone carboxylic acid may be a key cutaneous biomarker

Pyrrolidone carboxylic acid (PCA), the primary constituent of the natural moisturizing factor (NMF),1 including its derivatives – such as simple2 and novel3 esters as well as sugar complexes4 – is the subject of great interest and research regarding its capacity to moisturize the stratum corneum via topical application.

Creams and lotions containing the sodium salt of PCA are widely reported to aid in hydrating the skin and ameliorating dry flaky skin conditions.5,6 In addition, the zinc salt of L-pyrrolidone carboxylate is a longtime cosmetic ingredient due to antimicrobial and astringent qualities. This column briefly addresses the role of PCA in skin health.7

Dry skin

In a comprehensive literature review from 1981, Clar and Fourtanier reported conclusive evidence that PCA acts as a hydrating agent and that all the cosmetic formulations with a minimum of 2% PCA and PCA salt that they tested in their own 8-year study enhanced dry skin in short- and long-term conditions given suitable vehicles (no aqueous solutions).6

In a 2014 clinical study of 64 healthy white women with either normal or cosmetic dry skin, Feng et al. noted that tape stripped samples of stratum corneum revealed significantly lower ratios of free amino acids to protein and PCA to protein. This was associated with decreased hydration levels compared with normal skin. The investigators concluded that lower NMF levels across the depth of the stratum corneum and reduced cohesivity characterize cosmetic dry skin and that these clinical endpoints merit attention in evaluating the usefulness of treatments for dry skin.8

In 2016, Wei et al. reported on their assessment of the barrier function, hydration, and dryness of the lower leg skin of 25 female patients during the winter and then in the subsequent summer. They found that PCA levels were significantly greater during the summer, as were keratins. Hydration was also higher during the summer, while transepidermal water loss and visual dryness grades were substantially lower.9

Atopic dermatitis

A 2014 clinical study by Brandt et al. in patients with skin prone to developing atopic dermatitis (AD) revealed that a body wash composed of the filaggrin metabolites arginine and PCA was well tolerated and diminished pruritus. Patients reported liking the product and suggested that it improved their quality of life.10

Later that year, Jung et al. characterized the relationship of PCA levels, and other factors, with the clinical severity of AD. Specifically, in a study of 73 subjects (21 with mild AD, 21 with moderate to severe AD, 13 with X-linked ichthyosis as a negative control for filaggrin gene mutation, and 18 healthy controls), the investigators assessed transepidermal water loss, stratum corneum hydration, and skin surface pH. They found that PCA levels and caspase-14 were lower in inflammatory lesions compared with nonlesional skin in subjects with AD. These levels also were associated with clinical AD severity as measured by eczema area and severity index scores as well as skin barrier function.11

PCA as a biomarker

In 2009, Kezic et al. determined that the use of tape stripping to cull PCA in the stratum corneum was effective in revealing that PCA concentration in the outermost skin layer is a viable biomarker of filaggrin genotype.12

Raj et al. conducted an interesting study in 2016 in which they set out to describe the various markers for total NMF levels and link them to the activities of plasmin and corneocyte maturation in the photoexposed cheek and photoprotected postauricular regions of healthy white, black African, and albino African women in South Africa. PCA levels were highest among the albino African group, followed by black African and then white participants. The investigators also found that bleomycin hydrolase was linked to PCA synthesis, as suggested by higher bleomycin levels in albino African participants. In this group, corneocyte maturation was also observed to be impeded.13

The next year, the same team studied stratum corneum physiology and biochemistry of the cheeks in 48 white women with sensitive skin. The goal was to ascertain the connections between bleomycin hydrolase and calpain-1, PCA levels, corneocyte maturation, and transglutaminase and plasmin activities. Capsaicin sensitivity was observed in 52% of subjects, with PCA levels and bleomycin hydrolase activity found to be lower in the capsaicin-sensitive panel and correlated in subjects not sensitive to capsaicin. The researchers concluded that reduced levels of PCA, bleomycin hydrolase, and transglutaminase combined with a larger volume of immature corneocytes suggest comparatively poor stratum corneum maturation in individuals with sensitive skin.14

Other uses

In 2012, Takino et al. used cultured normal human dermal fibroblasts to show that zinc l-pyrrolidone carboxylate blocked UVA induction of activator protein-1, diminished matrix metalloproteinase-1 synthesis, and spurred type I collagen production. The researchers suggested that such results suggest the potential of zinc PCA for further investigation as an agent to combat photoaging.7

Conclusion

. Recent research suggests that it may serve as an important biomarker of filaggrin, NMF levels, and skin hydration. In addition, new data point to its usefulness as a gauge for ADs. More investigations are necessary to ascertain the feasibility of adjusting PCA levels through topical administration and what effects topically applied PCA may have on various skin parameters.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks, “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002) and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), as well as a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Björklund S et al. Soft Matter. 2014 Jul 7;10(25):4535-46.

2. Hall KJ, Hill JC. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1986;37(6):397-407.

3. Tezuka T et al. Dermatology. 1994;188(1):21-4.

4. Kwoya Hakko Kogyo Co. Pyrrolidone carboxylic acid esters containing composition used to prevent loss of moisture from the skin. Patent JA 48 82 046 (1982).

5. Org Santerre. l-pyrrolidone carboxylic acid-sugar compounds as rehydrating ingredients in cosmetics. Patent Fr 2 277 823 (1977).

6. Clar EJ, Fourtanier A. Int J Cosmet Sci. 1981 Jun;3(3):101-13.

7. Takino Y et al. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2012 Feb;34(1):23-8.

8. Feng L et al. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2014 Jun;36(3):231-8.

9. Wei KS et al. J Cosmet Sci. 2016 May-Jun;67(3):185-203.

10. Brandt S et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014 Sep;13(9):1108-11.

11. Jung M et al. J Dermatol Sci. 2014 Dec;76(3):231-9.

12. Kezic S et al. Br J Dermatol. 2009 Nov;161(5):1098-104.

13. Raj N et al. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016 Dec;38(6):567-75.

14. Raj N et al. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2017 Feb;39(1):2-10.

Pyrrolidone carboxylic acid (PCA), the primary constituent of the natural moisturizing factor (NMF),1 including its derivatives – such as simple2 and novel3 esters as well as sugar complexes4 – is the subject of great interest and research regarding its capacity to moisturize the stratum corneum via topical application.

Creams and lotions containing the sodium salt of PCA are widely reported to aid in hydrating the skin and ameliorating dry flaky skin conditions.5,6 In addition, the zinc salt of L-pyrrolidone carboxylate is a longtime cosmetic ingredient due to antimicrobial and astringent qualities. This column briefly addresses the role of PCA in skin health.7

Dry skin

In a comprehensive literature review from 1981, Clar and Fourtanier reported conclusive evidence that PCA acts as a hydrating agent and that all the cosmetic formulations with a minimum of 2% PCA and PCA salt that they tested in their own 8-year study enhanced dry skin in short- and long-term conditions given suitable vehicles (no aqueous solutions).6

In a 2014 clinical study of 64 healthy white women with either normal or cosmetic dry skin, Feng et al. noted that tape stripped samples of stratum corneum revealed significantly lower ratios of free amino acids to protein and PCA to protein. This was associated with decreased hydration levels compared with normal skin. The investigators concluded that lower NMF levels across the depth of the stratum corneum and reduced cohesivity characterize cosmetic dry skin and that these clinical endpoints merit attention in evaluating the usefulness of treatments for dry skin.8

In 2016, Wei et al. reported on their assessment of the barrier function, hydration, and dryness of the lower leg skin of 25 female patients during the winter and then in the subsequent summer. They found that PCA levels were significantly greater during the summer, as were keratins. Hydration was also higher during the summer, while transepidermal water loss and visual dryness grades were substantially lower.9

Atopic dermatitis

A 2014 clinical study by Brandt et al. in patients with skin prone to developing atopic dermatitis (AD) revealed that a body wash composed of the filaggrin metabolites arginine and PCA was well tolerated and diminished pruritus. Patients reported liking the product and suggested that it improved their quality of life.10

Later that year, Jung et al. characterized the relationship of PCA levels, and other factors, with the clinical severity of AD. Specifically, in a study of 73 subjects (21 with mild AD, 21 with moderate to severe AD, 13 with X-linked ichthyosis as a negative control for filaggrin gene mutation, and 18 healthy controls), the investigators assessed transepidermal water loss, stratum corneum hydration, and skin surface pH. They found that PCA levels and caspase-14 were lower in inflammatory lesions compared with nonlesional skin in subjects with AD. These levels also were associated with clinical AD severity as measured by eczema area and severity index scores as well as skin barrier function.11

PCA as a biomarker

In 2009, Kezic et al. determined that the use of tape stripping to cull PCA in the stratum corneum was effective in revealing that PCA concentration in the outermost skin layer is a viable biomarker of filaggrin genotype.12

Raj et al. conducted an interesting study in 2016 in which they set out to describe the various markers for total NMF levels and link them to the activities of plasmin and corneocyte maturation in the photoexposed cheek and photoprotected postauricular regions of healthy white, black African, and albino African women in South Africa. PCA levels were highest among the albino African group, followed by black African and then white participants. The investigators also found that bleomycin hydrolase was linked to PCA synthesis, as suggested by higher bleomycin levels in albino African participants. In this group, corneocyte maturation was also observed to be impeded.13

The next year, the same team studied stratum corneum physiology and biochemistry of the cheeks in 48 white women with sensitive skin. The goal was to ascertain the connections between bleomycin hydrolase and calpain-1, PCA levels, corneocyte maturation, and transglutaminase and plasmin activities. Capsaicin sensitivity was observed in 52% of subjects, with PCA levels and bleomycin hydrolase activity found to be lower in the capsaicin-sensitive panel and correlated in subjects not sensitive to capsaicin. The researchers concluded that reduced levels of PCA, bleomycin hydrolase, and transglutaminase combined with a larger volume of immature corneocytes suggest comparatively poor stratum corneum maturation in individuals with sensitive skin.14

Other uses

In 2012, Takino et al. used cultured normal human dermal fibroblasts to show that zinc l-pyrrolidone carboxylate blocked UVA induction of activator protein-1, diminished matrix metalloproteinase-1 synthesis, and spurred type I collagen production. The researchers suggested that such results suggest the potential of zinc PCA for further investigation as an agent to combat photoaging.7

Conclusion

. Recent research suggests that it may serve as an important biomarker of filaggrin, NMF levels, and skin hydration. In addition, new data point to its usefulness as a gauge for ADs. More investigations are necessary to ascertain the feasibility of adjusting PCA levels through topical administration and what effects topically applied PCA may have on various skin parameters.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks, “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002) and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), as well as a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Björklund S et al. Soft Matter. 2014 Jul 7;10(25):4535-46.

2. Hall KJ, Hill JC. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1986;37(6):397-407.

3. Tezuka T et al. Dermatology. 1994;188(1):21-4.