User login

Rupturing bullae not responding to antibiotics

A 33-year-old African American woman came to the office with a 2-week history of skin lesions and itching. The lesions started with a single blister on her left elbow; numerous other blisters subsequently appeared on her forearm and hands. One week before this visit, she had been given a presumptive diagnosis of bullous impetigo and was treated with cephalexin.

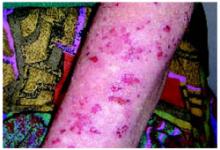

Despite the antibiotics, other lesions soon appeared in the nuchal and breast folds, axillae, and scalp areas. Several had ruptured, producing purulent, malodorous material. She had no known allergies, no medical problems aside from obesity, and no significant family history or recent travels. She denied any illicit drug use and had not been on any medications.

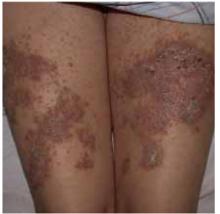

On physical exam, 1 large bulla was seen on the fourth digit of her left hand (Figure 1). The patient was obese, and inspection of the skin folds of her abdomen showed multiple suppurative lesions and erosions where previous bullae were found (Figure 2). No oral or gingival erosions were seen. Labs showed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 10.5 x109L], hemoglobin of 11.0 g/dL, and hemoglobin A1cof 5.5; liver function tests were normal. Gram stain showed no WBC and had rare Gram-positive bacilli. Potassium hydroxide prep of a skin lesion scraping showed no fungal elements. A herpes culture was performed along with a punch biopsy.

FIGURE 1

Bulla on the index finger

FIGURE 2

Multiple bullae on the trunk

What is the diagnosis?

Differential diagnosis

Many diseases manifest with bullae/vesicles. Workup should begin with a complete history and physical exam. A skin biopsy may be needed to make a definitive diagnosis.

Herpes zoster typically manifests with clustered pruritic vesicular lesions on a red base that follow a dermatomal distribution. Pemphigus vulgaris appears with flaccid blisters, erosions, and tend to have oral mucosal lesions. A positive Nikolsky’s sign is characteristic of pemphigus vulgaris. Bullous impetigo appears with scattered lesions of erythema and macules, progressing to thin roofed bullae and subsequently to “honey-crusted” lesions. In toxic epidermal necrolysis, the bullae are widespread and lead to sloughing of the skin. Pyoderma gangrenosum has ulcer formation preceded by pustules that typically expand rapidly to approximately 20 cm. These ulcers have necrotic bluish edges.

Diagnostic test results

The patient’s herpes culture was negative. Fortunately, the punch biopsy was sent for direct immunofluorescence. Direct immunofluorescence showed positive staining with immunoglobulin (Ig) G in the intercellular regions of the epidermis and no staining with IgA, IgM, C3, or fibrinogen. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections showed suprabasal blistering containing neutrophils and a few eosinophils. These results are consistent with pemphigus vulgaris.

Diagnosis: pemphigus vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is blistering disease involving the skin and mucous membranes, with severe morbidity and occasional mortality. Prior to the development of effective treatment, the disease was 75% fatal within 5 years.1

Its prevalence is equal among men and women, with a rate of occurrence of 0.5/100,000 people per year. The average age of onset is in the fifth and sixth decades of life, but there is wide variation in age. It has multiple causes and risk factors (Table).

The clinical manifestation of pemphigus typically features mucocutaneous blisters followed by erosions. Often they appear first in mucous membranes and may not appear cutaneously until several months later.2 The skin lesions are painful flaccid blisters that may appear anywhere. A characteristic finding of pemphigus vulgaris is the Nikolsky sign, in which lateral stress applied to perilesional skin causes an expansion of the blistering.

There are 2 major subtypes of pemphigus. Pemphigus vulgaris has blisters extending to the deep epidermis, and pemphigus foliaceus has more superficial involvement of the epidermis. Pemphigus can also be seen in paraneoplastics syndromes.

In pemphigus, the epidermal cells lose normal cell contacts and form a blister. Electron microscopy shows desmosomal abnormalities at desmosomal junctions. It is these junctions that guarantee the integrity of the epithelium. Direct immunofluorescence shows IgG deposition in intercellular spaces.

TABLECauses and risk factors for pemphigus vulgaris

| Penicillamine |

| Captopril |

| Rifampin |

| Phenol-based drugs |

| Amide-based drugs |

| Foods: garlic, leek, onion |

| Pregnancy |

| Pesticide exposure |

| Herpes virus infection |

| Cytomegalovirus infection |

| Epstein-Barr virus infectyion |

| Adapted from: Benner et al 2003.4 |

Treatment: Steroids and adjuvant drugs

Inducing remission is the main goal of therapy for pemphigus vulgaris. Epidemiological studies have shown up to a 75% remission rate 10 years after initial diagnosis.3 Corticosteroids are the preferred therapy for the management of pemphigus vulgaris (based on expert opinion). Also, adjuvant drugs such as azathioprine and cyclophosphamide are commonly used in combination with corticosteroids, with the aim of increasing efficacy and of having a steroid-sparing action (level of evidence: 5, expert opinion).

A tailored dosing schedule of steroids has been advocated according to the severity of the disease. Mild disease can be treated with an initial prednisone dose of 40 to 60 mg/d; in severe cases, 60 to 100 mg/d. Other agents that have been used to treat pemphigus vulgaris are intramuscular gold, dapsone, and intravenous immunoglobulin.

Patient outcome

The patient was treated with oral prednisone starting at 60 mg/d and her skin began to clear. A full course of oral prednisone was continued and tapered over 1 month. Currently, she remains in remission off all medications.

Conclusion

Pemphigus vulgaris is a potentially life-threatening condition that must be recognized and treated promptly. With a lack of large-scale controlled studies, the diagnosis and management of pemphigus vulgaris has based on expert opinion.3 Complications such as superimposed infection of the lesions, cellulitis, and sepsis can occur. Its association with underlying neoplasm, thymomas, myasthenia gravis, and other autoimmune disorders warrants consideration for additional workup when indicated.

Correspondence

John Sauret, MD, Department of Family Medicine, State University of New York at Buffalo, 150 Family Medical Modular Complex, Buffalo, NY 14214-3013. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Sami N, Ahmed AR. Dual diagnosis of pemphigus and pemphigoid. Retrospective review of 30 cases in the literature. Dermatol 2001;202:293-301.

2. Ahmed AR, Graham J. Pemphigus: current concepts. Ann Intern Med 1980;92:396-405.

3. Harman KE, Albert S, Black MM. Guidelines for the management of pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:926-937.

4. Benner S, Mashiah J, Tamir E, Goldberg I, Wohl Y. PEMPHIGUS: an acronym for a disease with multiple etiologies. Skinmed 2003;2:163-167.

A 33-year-old African American woman came to the office with a 2-week history of skin lesions and itching. The lesions started with a single blister on her left elbow; numerous other blisters subsequently appeared on her forearm and hands. One week before this visit, she had been given a presumptive diagnosis of bullous impetigo and was treated with cephalexin.

Despite the antibiotics, other lesions soon appeared in the nuchal and breast folds, axillae, and scalp areas. Several had ruptured, producing purulent, malodorous material. She had no known allergies, no medical problems aside from obesity, and no significant family history or recent travels. She denied any illicit drug use and had not been on any medications.

On physical exam, 1 large bulla was seen on the fourth digit of her left hand (Figure 1). The patient was obese, and inspection of the skin folds of her abdomen showed multiple suppurative lesions and erosions where previous bullae were found (Figure 2). No oral or gingival erosions were seen. Labs showed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 10.5 x109L], hemoglobin of 11.0 g/dL, and hemoglobin A1cof 5.5; liver function tests were normal. Gram stain showed no WBC and had rare Gram-positive bacilli. Potassium hydroxide prep of a skin lesion scraping showed no fungal elements. A herpes culture was performed along with a punch biopsy.

FIGURE 1

Bulla on the index finger

FIGURE 2

Multiple bullae on the trunk

What is the diagnosis?

Differential diagnosis

Many diseases manifest with bullae/vesicles. Workup should begin with a complete history and physical exam. A skin biopsy may be needed to make a definitive diagnosis.

Herpes zoster typically manifests with clustered pruritic vesicular lesions on a red base that follow a dermatomal distribution. Pemphigus vulgaris appears with flaccid blisters, erosions, and tend to have oral mucosal lesions. A positive Nikolsky’s sign is characteristic of pemphigus vulgaris. Bullous impetigo appears with scattered lesions of erythema and macules, progressing to thin roofed bullae and subsequently to “honey-crusted” lesions. In toxic epidermal necrolysis, the bullae are widespread and lead to sloughing of the skin. Pyoderma gangrenosum has ulcer formation preceded by pustules that typically expand rapidly to approximately 20 cm. These ulcers have necrotic bluish edges.

Diagnostic test results

The patient’s herpes culture was negative. Fortunately, the punch biopsy was sent for direct immunofluorescence. Direct immunofluorescence showed positive staining with immunoglobulin (Ig) G in the intercellular regions of the epidermis and no staining with IgA, IgM, C3, or fibrinogen. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections showed suprabasal blistering containing neutrophils and a few eosinophils. These results are consistent with pemphigus vulgaris.

Diagnosis: pemphigus vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is blistering disease involving the skin and mucous membranes, with severe morbidity and occasional mortality. Prior to the development of effective treatment, the disease was 75% fatal within 5 years.1

Its prevalence is equal among men and women, with a rate of occurrence of 0.5/100,000 people per year. The average age of onset is in the fifth and sixth decades of life, but there is wide variation in age. It has multiple causes and risk factors (Table).

The clinical manifestation of pemphigus typically features mucocutaneous blisters followed by erosions. Often they appear first in mucous membranes and may not appear cutaneously until several months later.2 The skin lesions are painful flaccid blisters that may appear anywhere. A characteristic finding of pemphigus vulgaris is the Nikolsky sign, in which lateral stress applied to perilesional skin causes an expansion of the blistering.

There are 2 major subtypes of pemphigus. Pemphigus vulgaris has blisters extending to the deep epidermis, and pemphigus foliaceus has more superficial involvement of the epidermis. Pemphigus can also be seen in paraneoplastics syndromes.

In pemphigus, the epidermal cells lose normal cell contacts and form a blister. Electron microscopy shows desmosomal abnormalities at desmosomal junctions. It is these junctions that guarantee the integrity of the epithelium. Direct immunofluorescence shows IgG deposition in intercellular spaces.

TABLECauses and risk factors for pemphigus vulgaris

| Penicillamine |

| Captopril |

| Rifampin |

| Phenol-based drugs |

| Amide-based drugs |

| Foods: garlic, leek, onion |

| Pregnancy |

| Pesticide exposure |

| Herpes virus infection |

| Cytomegalovirus infection |

| Epstein-Barr virus infectyion |

| Adapted from: Benner et al 2003.4 |

Treatment: Steroids and adjuvant drugs

Inducing remission is the main goal of therapy for pemphigus vulgaris. Epidemiological studies have shown up to a 75% remission rate 10 years after initial diagnosis.3 Corticosteroids are the preferred therapy for the management of pemphigus vulgaris (based on expert opinion). Also, adjuvant drugs such as azathioprine and cyclophosphamide are commonly used in combination with corticosteroids, with the aim of increasing efficacy and of having a steroid-sparing action (level of evidence: 5, expert opinion).

A tailored dosing schedule of steroids has been advocated according to the severity of the disease. Mild disease can be treated with an initial prednisone dose of 40 to 60 mg/d; in severe cases, 60 to 100 mg/d. Other agents that have been used to treat pemphigus vulgaris are intramuscular gold, dapsone, and intravenous immunoglobulin.

Patient outcome

The patient was treated with oral prednisone starting at 60 mg/d and her skin began to clear. A full course of oral prednisone was continued and tapered over 1 month. Currently, she remains in remission off all medications.

Conclusion

Pemphigus vulgaris is a potentially life-threatening condition that must be recognized and treated promptly. With a lack of large-scale controlled studies, the diagnosis and management of pemphigus vulgaris has based on expert opinion.3 Complications such as superimposed infection of the lesions, cellulitis, and sepsis can occur. Its association with underlying neoplasm, thymomas, myasthenia gravis, and other autoimmune disorders warrants consideration for additional workup when indicated.

Correspondence

John Sauret, MD, Department of Family Medicine, State University of New York at Buffalo, 150 Family Medical Modular Complex, Buffalo, NY 14214-3013. E-mail: [email protected].

A 33-year-old African American woman came to the office with a 2-week history of skin lesions and itching. The lesions started with a single blister on her left elbow; numerous other blisters subsequently appeared on her forearm and hands. One week before this visit, she had been given a presumptive diagnosis of bullous impetigo and was treated with cephalexin.

Despite the antibiotics, other lesions soon appeared in the nuchal and breast folds, axillae, and scalp areas. Several had ruptured, producing purulent, malodorous material. She had no known allergies, no medical problems aside from obesity, and no significant family history or recent travels. She denied any illicit drug use and had not been on any medications.

On physical exam, 1 large bulla was seen on the fourth digit of her left hand (Figure 1). The patient was obese, and inspection of the skin folds of her abdomen showed multiple suppurative lesions and erosions where previous bullae were found (Figure 2). No oral or gingival erosions were seen. Labs showed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 10.5 x109L], hemoglobin of 11.0 g/dL, and hemoglobin A1cof 5.5; liver function tests were normal. Gram stain showed no WBC and had rare Gram-positive bacilli. Potassium hydroxide prep of a skin lesion scraping showed no fungal elements. A herpes culture was performed along with a punch biopsy.

FIGURE 1

Bulla on the index finger

FIGURE 2

Multiple bullae on the trunk

What is the diagnosis?

Differential diagnosis

Many diseases manifest with bullae/vesicles. Workup should begin with a complete history and physical exam. A skin biopsy may be needed to make a definitive diagnosis.

Herpes zoster typically manifests with clustered pruritic vesicular lesions on a red base that follow a dermatomal distribution. Pemphigus vulgaris appears with flaccid blisters, erosions, and tend to have oral mucosal lesions. A positive Nikolsky’s sign is characteristic of pemphigus vulgaris. Bullous impetigo appears with scattered lesions of erythema and macules, progressing to thin roofed bullae and subsequently to “honey-crusted” lesions. In toxic epidermal necrolysis, the bullae are widespread and lead to sloughing of the skin. Pyoderma gangrenosum has ulcer formation preceded by pustules that typically expand rapidly to approximately 20 cm. These ulcers have necrotic bluish edges.

Diagnostic test results

The patient’s herpes culture was negative. Fortunately, the punch biopsy was sent for direct immunofluorescence. Direct immunofluorescence showed positive staining with immunoglobulin (Ig) G in the intercellular regions of the epidermis and no staining with IgA, IgM, C3, or fibrinogen. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections showed suprabasal blistering containing neutrophils and a few eosinophils. These results are consistent with pemphigus vulgaris.

Diagnosis: pemphigus vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is blistering disease involving the skin and mucous membranes, with severe morbidity and occasional mortality. Prior to the development of effective treatment, the disease was 75% fatal within 5 years.1

Its prevalence is equal among men and women, with a rate of occurrence of 0.5/100,000 people per year. The average age of onset is in the fifth and sixth decades of life, but there is wide variation in age. It has multiple causes and risk factors (Table).

The clinical manifestation of pemphigus typically features mucocutaneous blisters followed by erosions. Often they appear first in mucous membranes and may not appear cutaneously until several months later.2 The skin lesions are painful flaccid blisters that may appear anywhere. A characteristic finding of pemphigus vulgaris is the Nikolsky sign, in which lateral stress applied to perilesional skin causes an expansion of the blistering.

There are 2 major subtypes of pemphigus. Pemphigus vulgaris has blisters extending to the deep epidermis, and pemphigus foliaceus has more superficial involvement of the epidermis. Pemphigus can also be seen in paraneoplastics syndromes.

In pemphigus, the epidermal cells lose normal cell contacts and form a blister. Electron microscopy shows desmosomal abnormalities at desmosomal junctions. It is these junctions that guarantee the integrity of the epithelium. Direct immunofluorescence shows IgG deposition in intercellular spaces.

TABLECauses and risk factors for pemphigus vulgaris

| Penicillamine |

| Captopril |

| Rifampin |

| Phenol-based drugs |

| Amide-based drugs |

| Foods: garlic, leek, onion |

| Pregnancy |

| Pesticide exposure |

| Herpes virus infection |

| Cytomegalovirus infection |

| Epstein-Barr virus infectyion |

| Adapted from: Benner et al 2003.4 |

Treatment: Steroids and adjuvant drugs

Inducing remission is the main goal of therapy for pemphigus vulgaris. Epidemiological studies have shown up to a 75% remission rate 10 years after initial diagnosis.3 Corticosteroids are the preferred therapy for the management of pemphigus vulgaris (based on expert opinion). Also, adjuvant drugs such as azathioprine and cyclophosphamide are commonly used in combination with corticosteroids, with the aim of increasing efficacy and of having a steroid-sparing action (level of evidence: 5, expert opinion).

A tailored dosing schedule of steroids has been advocated according to the severity of the disease. Mild disease can be treated with an initial prednisone dose of 40 to 60 mg/d; in severe cases, 60 to 100 mg/d. Other agents that have been used to treat pemphigus vulgaris are intramuscular gold, dapsone, and intravenous immunoglobulin.

Patient outcome

The patient was treated with oral prednisone starting at 60 mg/d and her skin began to clear. A full course of oral prednisone was continued and tapered over 1 month. Currently, she remains in remission off all medications.

Conclusion

Pemphigus vulgaris is a potentially life-threatening condition that must be recognized and treated promptly. With a lack of large-scale controlled studies, the diagnosis and management of pemphigus vulgaris has based on expert opinion.3 Complications such as superimposed infection of the lesions, cellulitis, and sepsis can occur. Its association with underlying neoplasm, thymomas, myasthenia gravis, and other autoimmune disorders warrants consideration for additional workup when indicated.

Correspondence

John Sauret, MD, Department of Family Medicine, State University of New York at Buffalo, 150 Family Medical Modular Complex, Buffalo, NY 14214-3013. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Sami N, Ahmed AR. Dual diagnosis of pemphigus and pemphigoid. Retrospective review of 30 cases in the literature. Dermatol 2001;202:293-301.

2. Ahmed AR, Graham J. Pemphigus: current concepts. Ann Intern Med 1980;92:396-405.

3. Harman KE, Albert S, Black MM. Guidelines for the management of pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:926-937.

4. Benner S, Mashiah J, Tamir E, Goldberg I, Wohl Y. PEMPHIGUS: an acronym for a disease with multiple etiologies. Skinmed 2003;2:163-167.

1. Sami N, Ahmed AR. Dual diagnosis of pemphigus and pemphigoid. Retrospective review of 30 cases in the literature. Dermatol 2001;202:293-301.

2. Ahmed AR, Graham J. Pemphigus: current concepts. Ann Intern Med 1980;92:396-405.

3. Harman KE, Albert S, Black MM. Guidelines for the management of pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:926-937.

4. Benner S, Mashiah J, Tamir E, Goldberg I, Wohl Y. PEMPHIGUS: an acronym for a disease with multiple etiologies. Skinmed 2003;2:163-167.

Pearly penile lesions

A 22-year-old man came into the office concerned he may have warts on his penis. He believed the warts appeared about 3 months ago. He was single and did not have a sexual partner. He had been dating a woman for 1 year until he graduated from college 4 months ago. His sexual history was serial monogamy with 5 lifetime female sexual partners.

After some hesitation, he noted he slept with a woman one night following a graduation party. He admitted that they were both drunk and that he did not use a condom. He asked if this was how the condition could have developed.

He denied any history of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the result of an HIV test was negative when he donated blood last year. He did not have urethral discharge or burning on urination. The patient had no other symptoms and no chronic illnesses. He generally had a healthy lifestyle, without drug and tobacco use. He said he used to drink at college parties, but rarely had a drink since starting work full-time.

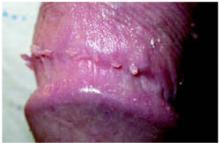

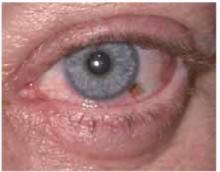

On physical exam, the patient had no fever or lymphadenopathy. A genital exam (Figure 1) with the foreskin retracted revealed skin-colored papules on the shaft of the penis that were somewhat verrucous. The papules seemed to make a ring around the shaft just proximal to the corona of the glans. Closer inspection showed smaller pearly papules surrounding the glans on the corona (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1

Large verrucuous papules

FIGURE 2

Detail of the smaller papules

Are The Larger Verrucous Papules Really Warts?

What Are The Smaller Papules And do they need treatment?

Diagnosis: Condyloma Acuminata

The larger verrucous papules are genital warts, also known as condyloma acuminata. These are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV) and are sexually transmitted. The patient most likely acquired these from his last unprotected sexual encounter, but he may have been infected earlier and the warts just became visible in the last 3 months. The differential diagnosis includes condyloma lata, the flat warts of secondary syphilis, but these are much less common.

The small pearly papules on the corona are not warts but a variation of the normal male anatomy, called pearly penile papules. The reason to recognize these papules is to reassure worried men that they are normal and to avoid performing any invasive treatments to remove them.

Laboratory Examination

All patients with any sexually transmitted disease should be tested for syphilis and HIV regardless of other risk factors.1 In this case, testing for syphilis with either a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or VDRL will also be helpful to rule out condyloma lata.

These genital warts do not need to be biopsied to make the diagnosis. No data support the use of type-specific HPV nucleic acid tests in the routine diagnosis or management of visible genital warts.1

Treatment: Removal With Medication Or Surgery

The primary goal of treating visible genital warts is the removal of symptomatic warts.1 Treatment can induce wart-free periods. Available therapies for genital warts may reduce, but probably do not eradicate, infectivity.1 No evidence suggests any available treatment is superior to another, and no single treatment is ideal for all patients or all warts. The natural history of genital warts is benign, and the types of HPV that usually cause external genital warts (HPV 6 and 11) are not associated with cancer.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2002 treatment guidelines1 for STDs recommend the following options. Cost data are given in the Table.

TABLE

Self-administered medications for HPV

| Medication | Method | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Podofilox 0.5% solution or gel (podophyllotoxin) | Apply twice daily for 3 days, then off 4 days. May repeat cycle total of 4 times | Gel 0.5%, one 3.5-g tube:$164 Solution 0.5% one 3.5-g tube:$121* |

| Imiquimod 5% cream | Apply nightly 3 times per week. | 12 packets:$159* (enough for 4 weeks of therapy if 1 packet is used per application;using a packet for more than 1 day is possible) |

| Wash off after 6 to 10 hours. | ||

| May use up to 16 weeks. | ||

| * Prices from ePocrates,accessed on October 3,2004. | ||

Patient-applied treatments

- Podofilox 0.5% solution or gel. Patients should apply podofilox solution with a cotton swab, or podofilox gel with a finger, to visible genital warts twice a day for 3 days, followed by 4 days of no therapy. This cycle may be repeated, as necessary, for up to 4 cycles. The health care provider may apply the initial treatment to demonstrate the proper application technique and identify which warts should be treated.

- Imiquimod 5% cream. Patients should apply imiquimod cream once daily at bedtime, 3 times a week for up to 16 weeks. The treatment area should be washed with soap and water 6 to 10 hours after the application.

Provider-administered treatments

- Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen or cryoprobe. Repeat applications every 1 to 2 weeks.

- Podophyllin resin 10% to 25% in a compound tincture of benzoin. A small amount should be applied to each wart and allowed to air-dry. The treatment can be repeated weekly, if necessary. To avoid the possibility of complications associated with systemic absorption and toxicity, some specialists recommend that application be limited to ≤0.5 mL of podophyllin or an area of <10 cm2 of warts per session. Some specialists suggest the preparation should be thoroughly washed off 1 to 4 hours after application to reduce local irritation. The safety of podophyllin during pregnancy has not been established.

- Trichloroacetic acid (TCA): a small amount should be applied only to warts and allowed to dry, at which time a white “frosting” develops (Figure 3). This treatment can be repeated weekly, if necessary.

- Surgical removal either by tangential scissor excision, tangential shave excision, curettage, or electrosurgery.

FIGURE 3

Treatment of genital warts

Keratinized vs nonkeratinized warts

In choosing the type of therapy for a patient, it is helpful to note that the soft, nonkeratinized warts respond well to the various forms of podophyllin and trichloroacetic acid. The more keratinized lesions, however, respond better to physical ablative methods such as cryotherapy, excision, or electrocautery. Imiquimod appears to work well for both types of lesions but is more effective for the nonkeratinized warts.

The softer, nonkeratinized warts are found more often on softer mucosa around the anus, under the foreskin, and around the female introitus. The firmer, more keratinized warts are found more often on more keratinized skin such as on the shaft of the penis.

Most options yield inadequate results

The reason for so many treatment options is in part due to the therapeutic inadequacy of any one of them. Cure rates are far less than optimal, and relapse rates are disappointing. While we have reasonable treatment guidelines from the CDC, studies on many of the treatment options are limited. There are few head-to-head studies of one method vs another.

One double-blind, randomized, multicenter, vehicle-controlled study2 demonstrated that 0.5% podofilox gel was significantly better than vehicle gel for successfully eliminating and reducing the number and size of anogenital warts. In the intention-to-treat population, 37% treated with podofilox gel had complete clearing of the treated areas, compared with 2% who had clearing of warts with the vehicle gel after 4 weeks (P<.001; number needed to treat=3) (level of evidence [LOE]: 1b).

The best systematic review of genital wart treatment was published in 2004 in the International Journal of STD & AIDS.3 Imiquimod has proven effective in many studies, including 3 randomized controlled trials in which clearance rates were 37% to 52% after 8 to 16 weeks of treatment (LOE=1a).3 One study using imiquimod found that clearance rates were twofold higher for women than for men (72% and 33%, respectively).4 This is probably because genital warts in females are less keratinized than warts on the usual site in males, the penile shaft. Similarly, clearance rates with imiquimod seem to be higher in uncircumcised men (62%) than circumcised men (33%), probably related to the degree of keratinization.3

Recurrence rates for sole therapy with imiquimod (9%–19%) are substantially lower than for most other genital wart treatments, including podophyllotoxin.3 Imiquimod may even be effective in reducing wart recurrence rates when used as an adjunct to surgical treatment.3

The Patient’s Treatment: Cryotherapy, Imiquimod Cream

The treatment options were discussed with the patient. The patient decided to have cryotherapy performed in the office and was given a prescription for imiquimod cream to be used on any remaining warts. The normal pearly penile papules on the corona were left alone and the patient tolerated the cryotherapy to the real warts with an acceptable level of temporary discomfort.

- Imiquimod • Aldara

- Podofilox • Condylox

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep 2002;51(RR-6):1-78.Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/. (Note: The CDC 2002 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines are available for download and use on a Palm handheld computer at the following website: www.cdcnpin.org/scripts/std/pda.asp.)

2. Tyring S, Edwards L, Cherry LK, et al. Safety and efficacy of 0.5% podofilox gel in the treatment of anogenital warts. Arch Dermatol 1998;134:33-38.

3. Maw R. Critical appraisal of commonly used treatment for genital warts. Int J STD AIDS 2004;15:357-364.

4. Sauder DN, Skinner RB, Fox TL, Owens ML. Topical imiquimod 5% cream as an effective treatment for external genital and perianal warts in different patient populations. Sex Transm Dis 2003;Feb;30(2):124-8.

A 22-year-old man came into the office concerned he may have warts on his penis. He believed the warts appeared about 3 months ago. He was single and did not have a sexual partner. He had been dating a woman for 1 year until he graduated from college 4 months ago. His sexual history was serial monogamy with 5 lifetime female sexual partners.

After some hesitation, he noted he slept with a woman one night following a graduation party. He admitted that they were both drunk and that he did not use a condom. He asked if this was how the condition could have developed.

He denied any history of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the result of an HIV test was negative when he donated blood last year. He did not have urethral discharge or burning on urination. The patient had no other symptoms and no chronic illnesses. He generally had a healthy lifestyle, without drug and tobacco use. He said he used to drink at college parties, but rarely had a drink since starting work full-time.

On physical exam, the patient had no fever or lymphadenopathy. A genital exam (Figure 1) with the foreskin retracted revealed skin-colored papules on the shaft of the penis that were somewhat verrucous. The papules seemed to make a ring around the shaft just proximal to the corona of the glans. Closer inspection showed smaller pearly papules surrounding the glans on the corona (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1

Large verrucuous papules

FIGURE 2

Detail of the smaller papules

Are The Larger Verrucous Papules Really Warts?

What Are The Smaller Papules And do they need treatment?

Diagnosis: Condyloma Acuminata

The larger verrucous papules are genital warts, also known as condyloma acuminata. These are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV) and are sexually transmitted. The patient most likely acquired these from his last unprotected sexual encounter, but he may have been infected earlier and the warts just became visible in the last 3 months. The differential diagnosis includes condyloma lata, the flat warts of secondary syphilis, but these are much less common.

The small pearly papules on the corona are not warts but a variation of the normal male anatomy, called pearly penile papules. The reason to recognize these papules is to reassure worried men that they are normal and to avoid performing any invasive treatments to remove them.

Laboratory Examination

All patients with any sexually transmitted disease should be tested for syphilis and HIV regardless of other risk factors.1 In this case, testing for syphilis with either a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or VDRL will also be helpful to rule out condyloma lata.

These genital warts do not need to be biopsied to make the diagnosis. No data support the use of type-specific HPV nucleic acid tests in the routine diagnosis or management of visible genital warts.1

Treatment: Removal With Medication Or Surgery

The primary goal of treating visible genital warts is the removal of symptomatic warts.1 Treatment can induce wart-free periods. Available therapies for genital warts may reduce, but probably do not eradicate, infectivity.1 No evidence suggests any available treatment is superior to another, and no single treatment is ideal for all patients or all warts. The natural history of genital warts is benign, and the types of HPV that usually cause external genital warts (HPV 6 and 11) are not associated with cancer.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2002 treatment guidelines1 for STDs recommend the following options. Cost data are given in the Table.

TABLE

Self-administered medications for HPV

| Medication | Method | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Podofilox 0.5% solution or gel (podophyllotoxin) | Apply twice daily for 3 days, then off 4 days. May repeat cycle total of 4 times | Gel 0.5%, one 3.5-g tube:$164 Solution 0.5% one 3.5-g tube:$121* |

| Imiquimod 5% cream | Apply nightly 3 times per week. | 12 packets:$159* (enough for 4 weeks of therapy if 1 packet is used per application;using a packet for more than 1 day is possible) |

| Wash off after 6 to 10 hours. | ||

| May use up to 16 weeks. | ||

| * Prices from ePocrates,accessed on October 3,2004. | ||

Patient-applied treatments

- Podofilox 0.5% solution or gel. Patients should apply podofilox solution with a cotton swab, or podofilox gel with a finger, to visible genital warts twice a day for 3 days, followed by 4 days of no therapy. This cycle may be repeated, as necessary, for up to 4 cycles. The health care provider may apply the initial treatment to demonstrate the proper application technique and identify which warts should be treated.

- Imiquimod 5% cream. Patients should apply imiquimod cream once daily at bedtime, 3 times a week for up to 16 weeks. The treatment area should be washed with soap and water 6 to 10 hours after the application.

Provider-administered treatments

- Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen or cryoprobe. Repeat applications every 1 to 2 weeks.

- Podophyllin resin 10% to 25% in a compound tincture of benzoin. A small amount should be applied to each wart and allowed to air-dry. The treatment can be repeated weekly, if necessary. To avoid the possibility of complications associated with systemic absorption and toxicity, some specialists recommend that application be limited to ≤0.5 mL of podophyllin or an area of <10 cm2 of warts per session. Some specialists suggest the preparation should be thoroughly washed off 1 to 4 hours after application to reduce local irritation. The safety of podophyllin during pregnancy has not been established.

- Trichloroacetic acid (TCA): a small amount should be applied only to warts and allowed to dry, at which time a white “frosting” develops (Figure 3). This treatment can be repeated weekly, if necessary.

- Surgical removal either by tangential scissor excision, tangential shave excision, curettage, or electrosurgery.

FIGURE 3

Treatment of genital warts

Keratinized vs nonkeratinized warts

In choosing the type of therapy for a patient, it is helpful to note that the soft, nonkeratinized warts respond well to the various forms of podophyllin and trichloroacetic acid. The more keratinized lesions, however, respond better to physical ablative methods such as cryotherapy, excision, or electrocautery. Imiquimod appears to work well for both types of lesions but is more effective for the nonkeratinized warts.

The softer, nonkeratinized warts are found more often on softer mucosa around the anus, under the foreskin, and around the female introitus. The firmer, more keratinized warts are found more often on more keratinized skin such as on the shaft of the penis.

Most options yield inadequate results

The reason for so many treatment options is in part due to the therapeutic inadequacy of any one of them. Cure rates are far less than optimal, and relapse rates are disappointing. While we have reasonable treatment guidelines from the CDC, studies on many of the treatment options are limited. There are few head-to-head studies of one method vs another.

One double-blind, randomized, multicenter, vehicle-controlled study2 demonstrated that 0.5% podofilox gel was significantly better than vehicle gel for successfully eliminating and reducing the number and size of anogenital warts. In the intention-to-treat population, 37% treated with podofilox gel had complete clearing of the treated areas, compared with 2% who had clearing of warts with the vehicle gel after 4 weeks (P<.001; number needed to treat=3) (level of evidence [LOE]: 1b).

The best systematic review of genital wart treatment was published in 2004 in the International Journal of STD & AIDS.3 Imiquimod has proven effective in many studies, including 3 randomized controlled trials in which clearance rates were 37% to 52% after 8 to 16 weeks of treatment (LOE=1a).3 One study using imiquimod found that clearance rates were twofold higher for women than for men (72% and 33%, respectively).4 This is probably because genital warts in females are less keratinized than warts on the usual site in males, the penile shaft. Similarly, clearance rates with imiquimod seem to be higher in uncircumcised men (62%) than circumcised men (33%), probably related to the degree of keratinization.3

Recurrence rates for sole therapy with imiquimod (9%–19%) are substantially lower than for most other genital wart treatments, including podophyllotoxin.3 Imiquimod may even be effective in reducing wart recurrence rates when used as an adjunct to surgical treatment.3

The Patient’s Treatment: Cryotherapy, Imiquimod Cream

The treatment options were discussed with the patient. The patient decided to have cryotherapy performed in the office and was given a prescription for imiquimod cream to be used on any remaining warts. The normal pearly penile papules on the corona were left alone and the patient tolerated the cryotherapy to the real warts with an acceptable level of temporary discomfort.

- Imiquimod • Aldara

- Podofilox • Condylox

A 22-year-old man came into the office concerned he may have warts on his penis. He believed the warts appeared about 3 months ago. He was single and did not have a sexual partner. He had been dating a woman for 1 year until he graduated from college 4 months ago. His sexual history was serial monogamy with 5 lifetime female sexual partners.

After some hesitation, he noted he slept with a woman one night following a graduation party. He admitted that they were both drunk and that he did not use a condom. He asked if this was how the condition could have developed.

He denied any history of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the result of an HIV test was negative when he donated blood last year. He did not have urethral discharge or burning on urination. The patient had no other symptoms and no chronic illnesses. He generally had a healthy lifestyle, without drug and tobacco use. He said he used to drink at college parties, but rarely had a drink since starting work full-time.

On physical exam, the patient had no fever or lymphadenopathy. A genital exam (Figure 1) with the foreskin retracted revealed skin-colored papules on the shaft of the penis that were somewhat verrucous. The papules seemed to make a ring around the shaft just proximal to the corona of the glans. Closer inspection showed smaller pearly papules surrounding the glans on the corona (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1

Large verrucuous papules

FIGURE 2

Detail of the smaller papules

Are The Larger Verrucous Papules Really Warts?

What Are The Smaller Papules And do they need treatment?

Diagnosis: Condyloma Acuminata

The larger verrucous papules are genital warts, also known as condyloma acuminata. These are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV) and are sexually transmitted. The patient most likely acquired these from his last unprotected sexual encounter, but he may have been infected earlier and the warts just became visible in the last 3 months. The differential diagnosis includes condyloma lata, the flat warts of secondary syphilis, but these are much less common.

The small pearly papules on the corona are not warts but a variation of the normal male anatomy, called pearly penile papules. The reason to recognize these papules is to reassure worried men that they are normal and to avoid performing any invasive treatments to remove them.

Laboratory Examination

All patients with any sexually transmitted disease should be tested for syphilis and HIV regardless of other risk factors.1 In this case, testing for syphilis with either a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or VDRL will also be helpful to rule out condyloma lata.

These genital warts do not need to be biopsied to make the diagnosis. No data support the use of type-specific HPV nucleic acid tests in the routine diagnosis or management of visible genital warts.1

Treatment: Removal With Medication Or Surgery

The primary goal of treating visible genital warts is the removal of symptomatic warts.1 Treatment can induce wart-free periods. Available therapies for genital warts may reduce, but probably do not eradicate, infectivity.1 No evidence suggests any available treatment is superior to another, and no single treatment is ideal for all patients or all warts. The natural history of genital warts is benign, and the types of HPV that usually cause external genital warts (HPV 6 and 11) are not associated with cancer.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2002 treatment guidelines1 for STDs recommend the following options. Cost data are given in the Table.

TABLE

Self-administered medications for HPV

| Medication | Method | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Podofilox 0.5% solution or gel (podophyllotoxin) | Apply twice daily for 3 days, then off 4 days. May repeat cycle total of 4 times | Gel 0.5%, one 3.5-g tube:$164 Solution 0.5% one 3.5-g tube:$121* |

| Imiquimod 5% cream | Apply nightly 3 times per week. | 12 packets:$159* (enough for 4 weeks of therapy if 1 packet is used per application;using a packet for more than 1 day is possible) |

| Wash off after 6 to 10 hours. | ||

| May use up to 16 weeks. | ||

| * Prices from ePocrates,accessed on October 3,2004. | ||

Patient-applied treatments

- Podofilox 0.5% solution or gel. Patients should apply podofilox solution with a cotton swab, or podofilox gel with a finger, to visible genital warts twice a day for 3 days, followed by 4 days of no therapy. This cycle may be repeated, as necessary, for up to 4 cycles. The health care provider may apply the initial treatment to demonstrate the proper application technique and identify which warts should be treated.

- Imiquimod 5% cream. Patients should apply imiquimod cream once daily at bedtime, 3 times a week for up to 16 weeks. The treatment area should be washed with soap and water 6 to 10 hours after the application.

Provider-administered treatments

- Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen or cryoprobe. Repeat applications every 1 to 2 weeks.

- Podophyllin resin 10% to 25% in a compound tincture of benzoin. A small amount should be applied to each wart and allowed to air-dry. The treatment can be repeated weekly, if necessary. To avoid the possibility of complications associated with systemic absorption and toxicity, some specialists recommend that application be limited to ≤0.5 mL of podophyllin or an area of <10 cm2 of warts per session. Some specialists suggest the preparation should be thoroughly washed off 1 to 4 hours after application to reduce local irritation. The safety of podophyllin during pregnancy has not been established.

- Trichloroacetic acid (TCA): a small amount should be applied only to warts and allowed to dry, at which time a white “frosting” develops (Figure 3). This treatment can be repeated weekly, if necessary.

- Surgical removal either by tangential scissor excision, tangential shave excision, curettage, or electrosurgery.

FIGURE 3

Treatment of genital warts

Keratinized vs nonkeratinized warts

In choosing the type of therapy for a patient, it is helpful to note that the soft, nonkeratinized warts respond well to the various forms of podophyllin and trichloroacetic acid. The more keratinized lesions, however, respond better to physical ablative methods such as cryotherapy, excision, or electrocautery. Imiquimod appears to work well for both types of lesions but is more effective for the nonkeratinized warts.

The softer, nonkeratinized warts are found more often on softer mucosa around the anus, under the foreskin, and around the female introitus. The firmer, more keratinized warts are found more often on more keratinized skin such as on the shaft of the penis.

Most options yield inadequate results

The reason for so many treatment options is in part due to the therapeutic inadequacy of any one of them. Cure rates are far less than optimal, and relapse rates are disappointing. While we have reasonable treatment guidelines from the CDC, studies on many of the treatment options are limited. There are few head-to-head studies of one method vs another.

One double-blind, randomized, multicenter, vehicle-controlled study2 demonstrated that 0.5% podofilox gel was significantly better than vehicle gel for successfully eliminating and reducing the number and size of anogenital warts. In the intention-to-treat population, 37% treated with podofilox gel had complete clearing of the treated areas, compared with 2% who had clearing of warts with the vehicle gel after 4 weeks (P<.001; number needed to treat=3) (level of evidence [LOE]: 1b).

The best systematic review of genital wart treatment was published in 2004 in the International Journal of STD & AIDS.3 Imiquimod has proven effective in many studies, including 3 randomized controlled trials in which clearance rates were 37% to 52% after 8 to 16 weeks of treatment (LOE=1a).3 One study using imiquimod found that clearance rates were twofold higher for women than for men (72% and 33%, respectively).4 This is probably because genital warts in females are less keratinized than warts on the usual site in males, the penile shaft. Similarly, clearance rates with imiquimod seem to be higher in uncircumcised men (62%) than circumcised men (33%), probably related to the degree of keratinization.3

Recurrence rates for sole therapy with imiquimod (9%–19%) are substantially lower than for most other genital wart treatments, including podophyllotoxin.3 Imiquimod may even be effective in reducing wart recurrence rates when used as an adjunct to surgical treatment.3

The Patient’s Treatment: Cryotherapy, Imiquimod Cream

The treatment options were discussed with the patient. The patient decided to have cryotherapy performed in the office and was given a prescription for imiquimod cream to be used on any remaining warts. The normal pearly penile papules on the corona were left alone and the patient tolerated the cryotherapy to the real warts with an acceptable level of temporary discomfort.

- Imiquimod • Aldara

- Podofilox • Condylox

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep 2002;51(RR-6):1-78.Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/. (Note: The CDC 2002 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines are available for download and use on a Palm handheld computer at the following website: www.cdcnpin.org/scripts/std/pda.asp.)

2. Tyring S, Edwards L, Cherry LK, et al. Safety and efficacy of 0.5% podofilox gel in the treatment of anogenital warts. Arch Dermatol 1998;134:33-38.

3. Maw R. Critical appraisal of commonly used treatment for genital warts. Int J STD AIDS 2004;15:357-364.

4. Sauder DN, Skinner RB, Fox TL, Owens ML. Topical imiquimod 5% cream as an effective treatment for external genital and perianal warts in different patient populations. Sex Transm Dis 2003;Feb;30(2):124-8.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep 2002;51(RR-6):1-78.Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/. (Note: The CDC 2002 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines are available for download and use on a Palm handheld computer at the following website: www.cdcnpin.org/scripts/std/pda.asp.)

2. Tyring S, Edwards L, Cherry LK, et al. Safety and efficacy of 0.5% podofilox gel in the treatment of anogenital warts. Arch Dermatol 1998;134:33-38.

3. Maw R. Critical appraisal of commonly used treatment for genital warts. Int J STD AIDS 2004;15:357-364.

4. Sauder DN, Skinner RB, Fox TL, Owens ML. Topical imiquimod 5% cream as an effective treatment for external genital and perianal warts in different patient populations. Sex Transm Dis 2003;Feb;30(2):124-8.

Facial lesion that came “out of nowhere”

A 33-year-old woman had a facial lesion (Figures 1 and 2) that seemed to “come out of nowhere,” but it was months before she sought medical attention. She was certain that the duration was months, not years, but could not date the exact onset.

The lesion was asymptomatic except for its prominence and aesthetics. The patient had tried cutting the lesion off several times, but it regrew each time. She was married, mono-gamous by history, not pregnant, had no major underlying medical conditions, and had no personal or family history of skin malignancy. The remainder of the skin examination was normal.

FIGURE 1

Facial lesion with sudden onset

FIGURE 2

Detail of the lesion

What is your diagnosis?

What would be your management plan?

Diagnosis: Cutaneous horn

Cutaneous horn,also referred to as cornu cutaneum, is a clinical (morphologic) diagnosis, not a precise pathologic diagnosis. It describes an asymptomatic, projectile, conical, dense, hyperkeratotic lesion that resembles the horn of an animal.

Cutaneous horns can arise from a variety of primary underlying pathologic processes, including benign, premalignant, and malignant lesions. Thus, the important issue when confronted with a cutaneous horn is determining the causative pathologic process. Therefore, for treatment, most authors stress surgical excision with attention to removing the base of the specimen for histopathologic examination.1-4

Cutaneous horns may vary considerably in size and shape. Most are a few millimeters in length, but there are reports of some measuring up to 6 cm in length. They may be perpendicular or inclined in relation to the underlying skin. They usually occur singly and may grow slowly over decades.2,4

Cutaneous horns are more common in older and white individuals, although they have been reported in children and African Americans.5The higher prevalence in older and light-skinned individuals is secondary to the fact that many cutaneous horns are caused by cumulative sun damage over many years, leading to actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of the underlying causes of cutaneous horns is extensive. Some causes are listed in the Table ; common ones include actinic keratoses (25%–35% of patients with cutaneous horns), verruca vulgaris (15%–25%), and cutaneous malignancies (15%–40%).1

Features that have been reported to increase the chance of an underlying malignancy include older age, male sex, lesion geometry (either alarge base or a large height-to-base ratio), and presence on a sun-exposed location (face, pinnae, dorsal hands and forearms, scalp). More than 70% of cutaneous horns with underlying premalignant or malignant lesions are found on these sun-exposed areas.3,6 Additionally, cutaneous horns on these locations are twice as likely to harbor underlying premalignant or malignant lesions.6 Of patients with malignancies underlying their cutaneous horns, up to one third have a history of skin malignancy.7

TABLE

Some causes of cutaneous horn

| Benign–noninfectious |

| Angiokeratoma |

| Angioma |

| Dermatofibroma |

| Epidermal inclusion cyst (“sebaceous cyst”) |

| Linear verrucous epidermal nevus |

| Fibroma |

| Lichen simplex chronicus (“neurodermatitis”) |

| Lichenoid keratosis |

| Prurigo nodularis |

| Pyogenic granuloma |

| Sebaceous adenoma |

| Seborrheic keratosis |

| Trichilemma |

| Benign–infectious |

| Condyloma acuminata (genital warts) |

| Molluscum contagiosum |

| Verruca vulgaris (common wart) |

| Premalignant/malignant |

| Actinic keratosis |

| Basal cell carcinoma |

| Bowen’s disease |

| Epidermoid carcinoma |

| Kaposi’s sarcoma |

| Keratoacanthoma |

| Malignant melanoma |

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Sources: Gould and Brodell 1999,1Akan et al 2001,6 Khaitan 1999.9 |

Treatment options

Cryosurgery

Some textbooks list cryosurgical therapy as an option.8 If there were a clearly benign pre-existing underlying dermopathy, such as verruca vulgaris or molluscum contagiosum, cryosurgery might be considered. However, cryosurgery is destructive; it does not preserve a specimen for pathologic examination. Because cutaneous horns have a 15% to 40% chance of underlying malignancy,1,4 it is difficult to recommend cryosurgical destruction without an initial biopsy-proven diagnosis.

Punch biopsy

In this patient, a 3-mm excisional punch biopsy was performed using a punch-to-ellipse technique. The skin is stretched parallel to the skin lines as the punch biopsy is performed. As the skin relaxes after removal of the punch instrument, an elliptical defect remains, enhancing cosmesis of the repair. Especially for a convex facial surface (which heals less well cosmetically than concave facial surfaces), this technique was believed to offer the potential for a better long-term cosmetic result.

In this case, a shave biopsy would have been a good option for both diagnosis and treatment. If the pathology from a punch biopsy or shave biopsy turned out to demonstrate an underlying skin cancer, then a fusiform excision would be needed to provide adequate surgical margins for the definitive treatment.

Results of histologic exam

With this patient, histologic examination revealed that the underlying condition was verruca vulgaris, or the common wart. Several months after removal of the cutaneous horn, the patient could not locate the surgical site, a cosmetically acceptable result to her and her physician ( Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

After successful treatment

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the unfailing cooperation and expert assistance of the St. Vincent Mercy Medical Center library staff.

Correspondence

Gary N. Fox, MD, 2200 Jefferson Avenue, Toledo, OH 43624. E- mail: [email protected].

1. Gould JW, Brodell RT. Giant cutaneous horn associated with verruca vulgaris. Cutis. 1999;64:111-112.

2. Kastanioudakis I, Skevas A, Assimakopoulos D, Daneilidis B. Cutaneous horn of the auricle. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118:735.-

3. Korkut T, Tan NB, Oztan Y. Giant cutaneous horn: a patient report. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;39:654-655.

4. Stavroulaki P, Mal RK. Squamous cell carcinoma presenting as a cutaneous horn. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2000;27:277-279.

5. Souza LN, Martins CR, de Paula AM. Cutaneous horn occurring on the lip of a child. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2003;13:365-367.

6. Akan M, Yildirim S, Avci G, Akoz T. Xeroderma pigmento sum with a giant cutaneous horn. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;46:665-666.

7. Spira J, Rabinovitz H. Cutaneous horn present for two months. Dermatol Online J. 2000;6:11.-

8. Benignkin tumors (Chapter 20)Cutaneous horn. In: Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2004;706.:

9. Khaitan BK, Sood A, Singh MK. Lichen simplex chronicus with a cutaneous horn. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:243.-

10. Agarwalla A, Agrawal CS, Thakur A, et al. Cutaneous horn on condyloma acuminatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:159.

A 33-year-old woman had a facial lesion (Figures 1 and 2) that seemed to “come out of nowhere,” but it was months before she sought medical attention. She was certain that the duration was months, not years, but could not date the exact onset.

The lesion was asymptomatic except for its prominence and aesthetics. The patient had tried cutting the lesion off several times, but it regrew each time. She was married, mono-gamous by history, not pregnant, had no major underlying medical conditions, and had no personal or family history of skin malignancy. The remainder of the skin examination was normal.

FIGURE 1

Facial lesion with sudden onset

FIGURE 2

Detail of the lesion

What is your diagnosis?

What would be your management plan?

Diagnosis: Cutaneous horn

Cutaneous horn,also referred to as cornu cutaneum, is a clinical (morphologic) diagnosis, not a precise pathologic diagnosis. It describes an asymptomatic, projectile, conical, dense, hyperkeratotic lesion that resembles the horn of an animal.

Cutaneous horns can arise from a variety of primary underlying pathologic processes, including benign, premalignant, and malignant lesions. Thus, the important issue when confronted with a cutaneous horn is determining the causative pathologic process. Therefore, for treatment, most authors stress surgical excision with attention to removing the base of the specimen for histopathologic examination.1-4

Cutaneous horns may vary considerably in size and shape. Most are a few millimeters in length, but there are reports of some measuring up to 6 cm in length. They may be perpendicular or inclined in relation to the underlying skin. They usually occur singly and may grow slowly over decades.2,4

Cutaneous horns are more common in older and white individuals, although they have been reported in children and African Americans.5The higher prevalence in older and light-skinned individuals is secondary to the fact that many cutaneous horns are caused by cumulative sun damage over many years, leading to actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of the underlying causes of cutaneous horns is extensive. Some causes are listed in the Table ; common ones include actinic keratoses (25%–35% of patients with cutaneous horns), verruca vulgaris (15%–25%), and cutaneous malignancies (15%–40%).1

Features that have been reported to increase the chance of an underlying malignancy include older age, male sex, lesion geometry (either alarge base or a large height-to-base ratio), and presence on a sun-exposed location (face, pinnae, dorsal hands and forearms, scalp). More than 70% of cutaneous horns with underlying premalignant or malignant lesions are found on these sun-exposed areas.3,6 Additionally, cutaneous horns on these locations are twice as likely to harbor underlying premalignant or malignant lesions.6 Of patients with malignancies underlying their cutaneous horns, up to one third have a history of skin malignancy.7

TABLE

Some causes of cutaneous horn

| Benign–noninfectious |

| Angiokeratoma |

| Angioma |

| Dermatofibroma |

| Epidermal inclusion cyst (“sebaceous cyst”) |

| Linear verrucous epidermal nevus |

| Fibroma |

| Lichen simplex chronicus (“neurodermatitis”) |

| Lichenoid keratosis |

| Prurigo nodularis |

| Pyogenic granuloma |

| Sebaceous adenoma |

| Seborrheic keratosis |

| Trichilemma |

| Benign–infectious |

| Condyloma acuminata (genital warts) |

| Molluscum contagiosum |

| Verruca vulgaris (common wart) |

| Premalignant/malignant |

| Actinic keratosis |

| Basal cell carcinoma |

| Bowen’s disease |

| Epidermoid carcinoma |

| Kaposi’s sarcoma |

| Keratoacanthoma |

| Malignant melanoma |

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Sources: Gould and Brodell 1999,1Akan et al 2001,6 Khaitan 1999.9 |

Treatment options

Cryosurgery

Some textbooks list cryosurgical therapy as an option.8 If there were a clearly benign pre-existing underlying dermopathy, such as verruca vulgaris or molluscum contagiosum, cryosurgery might be considered. However, cryosurgery is destructive; it does not preserve a specimen for pathologic examination. Because cutaneous horns have a 15% to 40% chance of underlying malignancy,1,4 it is difficult to recommend cryosurgical destruction without an initial biopsy-proven diagnosis.

Punch biopsy

In this patient, a 3-mm excisional punch biopsy was performed using a punch-to-ellipse technique. The skin is stretched parallel to the skin lines as the punch biopsy is performed. As the skin relaxes after removal of the punch instrument, an elliptical defect remains, enhancing cosmesis of the repair. Especially for a convex facial surface (which heals less well cosmetically than concave facial surfaces), this technique was believed to offer the potential for a better long-term cosmetic result.

In this case, a shave biopsy would have been a good option for both diagnosis and treatment. If the pathology from a punch biopsy or shave biopsy turned out to demonstrate an underlying skin cancer, then a fusiform excision would be needed to provide adequate surgical margins for the definitive treatment.

Results of histologic exam

With this patient, histologic examination revealed that the underlying condition was verruca vulgaris, or the common wart. Several months after removal of the cutaneous horn, the patient could not locate the surgical site, a cosmetically acceptable result to her and her physician ( Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

After successful treatment

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the unfailing cooperation and expert assistance of the St. Vincent Mercy Medical Center library staff.

Correspondence

Gary N. Fox, MD, 2200 Jefferson Avenue, Toledo, OH 43624. E- mail: [email protected].

A 33-year-old woman had a facial lesion (Figures 1 and 2) that seemed to “come out of nowhere,” but it was months before she sought medical attention. She was certain that the duration was months, not years, but could not date the exact onset.

The lesion was asymptomatic except for its prominence and aesthetics. The patient had tried cutting the lesion off several times, but it regrew each time. She was married, mono-gamous by history, not pregnant, had no major underlying medical conditions, and had no personal or family history of skin malignancy. The remainder of the skin examination was normal.

FIGURE 1

Facial lesion with sudden onset

FIGURE 2

Detail of the lesion

What is your diagnosis?

What would be your management plan?

Diagnosis: Cutaneous horn

Cutaneous horn,also referred to as cornu cutaneum, is a clinical (morphologic) diagnosis, not a precise pathologic diagnosis. It describes an asymptomatic, projectile, conical, dense, hyperkeratotic lesion that resembles the horn of an animal.

Cutaneous horns can arise from a variety of primary underlying pathologic processes, including benign, premalignant, and malignant lesions. Thus, the important issue when confronted with a cutaneous horn is determining the causative pathologic process. Therefore, for treatment, most authors stress surgical excision with attention to removing the base of the specimen for histopathologic examination.1-4

Cutaneous horns may vary considerably in size and shape. Most are a few millimeters in length, but there are reports of some measuring up to 6 cm in length. They may be perpendicular or inclined in relation to the underlying skin. They usually occur singly and may grow slowly over decades.2,4

Cutaneous horns are more common in older and white individuals, although they have been reported in children and African Americans.5The higher prevalence in older and light-skinned individuals is secondary to the fact that many cutaneous horns are caused by cumulative sun damage over many years, leading to actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of the underlying causes of cutaneous horns is extensive. Some causes are listed in the Table ; common ones include actinic keratoses (25%–35% of patients with cutaneous horns), verruca vulgaris (15%–25%), and cutaneous malignancies (15%–40%).1

Features that have been reported to increase the chance of an underlying malignancy include older age, male sex, lesion geometry (either alarge base or a large height-to-base ratio), and presence on a sun-exposed location (face, pinnae, dorsal hands and forearms, scalp). More than 70% of cutaneous horns with underlying premalignant or malignant lesions are found on these sun-exposed areas.3,6 Additionally, cutaneous horns on these locations are twice as likely to harbor underlying premalignant or malignant lesions.6 Of patients with malignancies underlying their cutaneous horns, up to one third have a history of skin malignancy.7

TABLE

Some causes of cutaneous horn

| Benign–noninfectious |

| Angiokeratoma |

| Angioma |

| Dermatofibroma |

| Epidermal inclusion cyst (“sebaceous cyst”) |

| Linear verrucous epidermal nevus |

| Fibroma |

| Lichen simplex chronicus (“neurodermatitis”) |

| Lichenoid keratosis |

| Prurigo nodularis |

| Pyogenic granuloma |

| Sebaceous adenoma |

| Seborrheic keratosis |

| Trichilemma |

| Benign–infectious |

| Condyloma acuminata (genital warts) |

| Molluscum contagiosum |

| Verruca vulgaris (common wart) |

| Premalignant/malignant |

| Actinic keratosis |

| Basal cell carcinoma |

| Bowen’s disease |

| Epidermoid carcinoma |

| Kaposi’s sarcoma |

| Keratoacanthoma |

| Malignant melanoma |

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Sources: Gould and Brodell 1999,1Akan et al 2001,6 Khaitan 1999.9 |

Treatment options

Cryosurgery

Some textbooks list cryosurgical therapy as an option.8 If there were a clearly benign pre-existing underlying dermopathy, such as verruca vulgaris or molluscum contagiosum, cryosurgery might be considered. However, cryosurgery is destructive; it does not preserve a specimen for pathologic examination. Because cutaneous horns have a 15% to 40% chance of underlying malignancy,1,4 it is difficult to recommend cryosurgical destruction without an initial biopsy-proven diagnosis.

Punch biopsy

In this patient, a 3-mm excisional punch biopsy was performed using a punch-to-ellipse technique. The skin is stretched parallel to the skin lines as the punch biopsy is performed. As the skin relaxes after removal of the punch instrument, an elliptical defect remains, enhancing cosmesis of the repair. Especially for a convex facial surface (which heals less well cosmetically than concave facial surfaces), this technique was believed to offer the potential for a better long-term cosmetic result.

In this case, a shave biopsy would have been a good option for both diagnosis and treatment. If the pathology from a punch biopsy or shave biopsy turned out to demonstrate an underlying skin cancer, then a fusiform excision would be needed to provide adequate surgical margins for the definitive treatment.

Results of histologic exam

With this patient, histologic examination revealed that the underlying condition was verruca vulgaris, or the common wart. Several months after removal of the cutaneous horn, the patient could not locate the surgical site, a cosmetically acceptable result to her and her physician ( Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

After successful treatment

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the unfailing cooperation and expert assistance of the St. Vincent Mercy Medical Center library staff.

Correspondence

Gary N. Fox, MD, 2200 Jefferson Avenue, Toledo, OH 43624. E- mail: [email protected].

1. Gould JW, Brodell RT. Giant cutaneous horn associated with verruca vulgaris. Cutis. 1999;64:111-112.

2. Kastanioudakis I, Skevas A, Assimakopoulos D, Daneilidis B. Cutaneous horn of the auricle. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118:735.-

3. Korkut T, Tan NB, Oztan Y. Giant cutaneous horn: a patient report. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;39:654-655.

4. Stavroulaki P, Mal RK. Squamous cell carcinoma presenting as a cutaneous horn. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2000;27:277-279.

5. Souza LN, Martins CR, de Paula AM. Cutaneous horn occurring on the lip of a child. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2003;13:365-367.

6. Akan M, Yildirim S, Avci G, Akoz T. Xeroderma pigmento sum with a giant cutaneous horn. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;46:665-666.

7. Spira J, Rabinovitz H. Cutaneous horn present for two months. Dermatol Online J. 2000;6:11.-

8. Benignkin tumors (Chapter 20)Cutaneous horn. In: Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2004;706.:

9. Khaitan BK, Sood A, Singh MK. Lichen simplex chronicus with a cutaneous horn. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:243.-

10. Agarwalla A, Agrawal CS, Thakur A, et al. Cutaneous horn on condyloma acuminatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:159.

1. Gould JW, Brodell RT. Giant cutaneous horn associated with verruca vulgaris. Cutis. 1999;64:111-112.

2. Kastanioudakis I, Skevas A, Assimakopoulos D, Daneilidis B. Cutaneous horn of the auricle. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118:735.-

3. Korkut T, Tan NB, Oztan Y. Giant cutaneous horn: a patient report. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;39:654-655.

4. Stavroulaki P, Mal RK. Squamous cell carcinoma presenting as a cutaneous horn. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2000;27:277-279.

5. Souza LN, Martins CR, de Paula AM. Cutaneous horn occurring on the lip of a child. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2003;13:365-367.

6. Akan M, Yildirim S, Avci G, Akoz T. Xeroderma pigmento sum with a giant cutaneous horn. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;46:665-666.

7. Spira J, Rabinovitz H. Cutaneous horn present for two months. Dermatol Online J. 2000;6:11.-

8. Benignkin tumors (Chapter 20)Cutaneous horn. In: Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2004;706.:

9. Khaitan BK, Sood A, Singh MK. Lichen simplex chronicus with a cutaneous horn. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:243.-

10. Agarwalla A, Agrawal CS, Thakur A, et al. Cutaneous horn on condyloma acuminatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:159.

Excoriations and ulcers on the arms and legs

A 55-year-old woman came to the clinic complaining of severe itching on her arms and legs. Although she itched throughout the day, it became intolerable at night, disrupting her sleep. She would sometimes scratch her arms and legs until exhaustion but could find no relief. Being outside in warm and sunny weather aggravated the problem. She had used moisturizers, emollients, and topical corticosteroids, but they only alleviated the itching temporarily. The itching began 10 months earlier, just after she finalized the divorce from her husband of 20 years.

Examination of the skin revealed numerous excoriations with ulcerations and xerosis on the arms and left leg (Figure 1 and 2). The excoriations were located extensively from the dorsum of her left foot to above the knee and bilaterally from the wrist to above the elbow. They also showed signs of infection. The patient admitted they were self-inflicted. The patient’s right leg had been amputated 5 years before after a car accident, and she wore a prosthetic leg. Examination of other areas showed nothing remarkable.

The patient readily admitted to a great deal of psychological distress. She described feeling depressed since her divorce. She has had difficulty securing a full-time job and has high anxiety about being able to pay her rent and bills.

FIGURE 1

Excoriations on the arms…

FIGURE 2

…and the left leg

WHAT IS THE DIAGNOSIS?

WHAT IS THE TREATMENT STRATEGY?

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS: PSYCHODERMATOLOGIC DISORDER

The patient’s history and physical examination points to a psychodermatologic disorder. Psycho-dermatologic disorders are conditions involving an interaction between the mind and skin and are classified as:3

- Psychophysiologic disorders:skin disorders worsened by emotional stress

- Primary psychiatric disorders:usually caused by psychological conditions with self-induced skin damage

- Secondary psychiatric disorders: psychological problems developed as a consequence of a disfiguring skin disorder, which negatively effects self-esteem and body image.3

This patient’s excoriations and ulcers are due to self-mutilation. The differential diagnosis includes psychogenic parasitosis, factitial dermatitis, and neurotic excoriations. These 3 skin conditions are primary psychiatric symptoms, and proper diagnosis revolves around being able to assess the dermatologic features and associated psychological disorder.2

Psychogenic parasitosis

Also known as delusional parasitosis, psychogenic parasitosis is a psychodermatologic disorder in which patients believe they are infested with parasites. Patients with this disorder report seeing or feeling parasites on their skin, and they damage their skin in an attempt to remove them. Patients create excoriations and ulcers on easily reached areas, usually the ears, eyes, nose, and extremities. They often present with what is termed the “matchbox sign,” in which they bring containers filled with “small bits of excoriated skin, dried blood, debris, or insect parts as proof of infestation.”2

Women over the age of 50 years are more often affected with psychogenic parasitosis, and the disorder is associated with anxiety, depression, and hypochondriasis.

Factitial dermatitis

Factitial dermatitis, also known as dermatitis artefacta, is a psychodermatologic disorder in which patients damage their skin but deny their self-involvement. This disorder encompasses a wide range of lesions, including blisters, cuts, ulcers, and burns. Patients often are unable to describe how the lesions evolved. Lesions exhibit bizarre patterns not characteristic of any disease.

Young adults and adolescents are more commonly affected, and it is 4 times more common among women than men. Psychological disorders involved with factitial dermatitis include personality disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder.2

Neurotic excoriations

Neurotic excoriations, sometimes referred to as neurodermatitis, are a result of a psychodermatologic disorder in which patients inflict excoriations and ulcers on their skin and admit to their involvement.3 The condition is characterized by excoriations similar in size and shape that are localized on areas easily reached by the patient, such as the arms, legs, and upper back.

The lesions may present in various stages, varying from dugout ulcers to ulcers covered with crusts and surrounded by erythema to areas receding into depressed scars. These lesions are a result of repetitive scratching and digging by the patient, usually without an underlying physical pathology but sometimes initiated by pruritus.1,2

Studies show the condition primarily affects women, with a mean onset between the ages of 30 to 45 years.1 Common psychiatric problems associated with neurotic excoriations include significant social stress, depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Diagnosis: Neurotic excoriations due to depression and stress

The patient’s history and physical examination suggests a diagnosis of neurotic excoriations due to the characteristics of the excoriations and ulcers on her arms and leg, her admission of their self-inflicted nature, and the associated depression and psychosocial stress.

Laboratory tests

Although there are no available laboratory tests to confirm a positive finding of neurotic excoriations, tests could be performed to disprove any systemic causes of pruritus and the resulting dermatological damage.5 These tests include complete blood count with differential, chemistry profile, determination of thyroid-stimulating hormone levels, fasting plasma glucose level, and skin biopsies.1,