User login

Skin rash and muscle weakness

A 48-year-old Hispanic woman came to the clinic as a new patient—her chief complaint was a rash that appeared on her face 3 months before and had recently spread to her chest and hands (FIGURES 1-3). It itched occasionally and seemed to worsen after exposure to the sun.

She also said that for the last month she had been feeling very weak—she had difficulty rising from a seated position and walking up the stairs to her apartment. She also felt as if her arms were heavy, making it difficult for her to brush and dry her hair in the morning.

The patient was otherwise healthy with no known medical conditions, and she was not taking any medications. Her family history was noncontributory.

A musculoskeletal examination showed the following:

Upper extremities:

- 4/5 strength shoulder abduction, internal and external rotation

- 5/5 strength biceps, triceps, wrist extension/flexion, grip

- 2+ biceps and triceps deep tendon reflexes bilaterally

Lower extremities:

- 4/5 strength hip flexors, quadriceps, hamstrings

- 5/5 dorsiflexion/plantar flexion

- 2+ patellar and ankle deep tendon reflexes bilaterally.

FIGURE 1

Facial rash and swelling

FIGURE 2

Rash spreading to chest

FIGURE 3

Plaques on knuckles

What is your diagnosis?

What diagnostic tests would you order for confirmation?

Diagnosis: Dermatomyositis

Dermatomyositis is a systemic disease classified as a type of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Dermatomyositis is a rare disease but one that may present initially to the family physician. It affects people at any age but is more commonly seen among children or adults aged >40 years.

Dermatomyositis involves the skin as well as skeletal muscle. Its cause is unknown; however, among those aged >50 years, malignancy may be an underlying cause. Cancers most commonly associated with dermatomyositis include those of the breast, ovary, lung, and gastrointestinal tract.

Skin manifestations may precede, follow, or present simultaneously with muscle involvement. Patients often complain of having difficulty ascending stairs, rising from a seated position, and performing overhead activities such as combing their hair. Patients may or may not have muscle tenderness and atrophy. Patients can have cutaneous involvement for more than a year before developing muscle weakness.1

The dermatologic signs of dermatomyositis to watch for:

- Periorbital heliotrope erythema, usually associated with edema (FIGURE 1).

- Gottron’s papules—smooth, purple to red papules located over the knuckles, on the sides of the fingers, and sometimes on the elbows and knees. For adults, it is not uncommon to have plaques over the knuckles as opposed to the classic Gottron’s papules (FIGURE 3). In juvenile-onset dermatomyositis, distinct papules are much more evident upon presentation (FIGURE 4). Note that systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can present with a rash on the dorsum of the hands, but the rash spares the skin over the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints and affects the skin between the joints (FIGURE 5).

- Violaceous papular dermatitis with scale—may occur in localized areas, such as elbows and knees, or be diffusely distributed, starting off as a patchy erythema that coalesces and becomes slightly raised with scale. It tends to be confined to sun-exposed areas and worsens after sun exposure (FIGURE 2).

- Periungual erythema and telangiectasia—“moth-eaten” cuticles, a characteristic seen in other connective tissue diseases (FIGURE 6).1

FIGURE 4

Papules on knuckles

FIGURE 5

Sparing interphalangeal joints

FIGURE 6

Cuticles with erythema

Differential diagnosis

Seborrheic dermatitis—white or yellow, greasy scales on an erythematous base with distribution on scalp, nasolabial folds and chest.

Atopic dermatitis—chronic history of pruritic papules or plaques with scale localized to flexural areas or may be generalized; lichenification may be seen.

Contact dermatitis—papules and vesicles that correspond to contact with allergen.

Polymorphous light eruption—clusters of erythematous, pruritic papules or vesicles occurring most frequently on the neck, anterior chest, arms, and forearms following sun exposure; most common among women in their twenties.

Lichen planus—pruritic, purple, polygonal papules (4 Ps) that may involve hair, nails, and mucous membranes in addition to the skin; more common among women, with onset between 30 to 60 years of age; may last months to years.

Psoriasis—well-demarcated papules and plaques on an erythematous base with thick, silvery scale; characteristically found on elbows, knees, scalp, nails, and genitalia.

Steroid myopathy—A side effect of systemic steroids, usually seen 4 to 6 weeks after beginning of treatment.

Dermatomyositis-like reaction—onset of similar skin findings with initiation of the following medications and improvement with discontinuation: penicillamine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and carbamazepine.

Overlap syndrome—The term “overlap” denotes that certain signs are seen in both dermatomyositis and other connective tissue diseases such as scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus erythematosus. Scleroderma and dermatomyositis are the most commonly associated conditions and have been termed sclerodermatomyositis or mixed connective disease. In mixed connective tissue disease, features of SLE, scleroderma, and polymyositis are evident such as malar rash, alopecia, Raynaud’s phenomenon, waxy-appearing skin, and proximal muscle weakness.1,2

Diagnostic tests: Muscle enzymes, EMG, biopsy

The diagnosis of dermatomyositis is confirmed by 3 laboratory tests: elevated muscle enzyme levels, electromyography, and muscle biopsy. A punch biopsy is helpful in differentiating dermatomyositis from other papulosquamous diseases such as lichen planus and psoriasis, but be careful as the histology of dermatomyositis is indistinguishable from cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

During the acute active phase, the following serum muscle enzymes may be elevated: creatine kinase (CK), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alanine aminotransferase (ALT or SGPT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST or SGOT), and aldolase. CK is elevated among 65% of patients and is most specific for muscle disease.3 Only one of the aforementioned enzymes may be elevated, so it is necessary to measure them all.

Measuring antibodies such as antinuclear antibody (ANA), Jo-1, SSA (Ro), SSB (La) supports the diagnosis if positive but dermatomyositis cannot be diagnosed solely on positive titers. It is not necessary to obtain an electromyograph or muscle biopsy for a patient with the characteristic skin findings and evidence of elevated muscle enzymes, as the diagnosis of dermatomyositis can be made with confidence. For a patient in whom the presentation is not as straightforward, it may be useful to obtain the electromyograph and muscle biopsy.

Management: Corticosteroids, watch for malignancy

Oral corticosteroids are the treatment of choice (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B).1,4 Prednisone 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg body weight per day has been recommended until muscle enzyme levels trend toward normal limits, at which time you can taper the dose. Steroid myopathy is a potential side effect of this treatment regimen; it may occur 4 to 6 weeks after therapy starts.

Several steroid-sparing agents such as methotrexate and cyclosporine are being prescribed by clinicians for dermomyositis but with little published evidence to support effectiveness. Methotrexate is an option for those who do not respond to prednisone or are in need of a steroid-sparing agent secondary to side effects (SOR: C).2,3 A suggested regimen starts with 7.5 to 10 mg/wk, then increases the dose to 2.5 mg/wk until reaching a total dose of 25 mg/wk. The dose of prednisone should be decreased as the methotrexate dose increases. Azathioprine is another option to consider along with methotrexate, but choosing one agent over another or a combination of 2 agents remains empirical. With any of the immunosuppressants or immunomodulatory agents, it is important to look at their side-effect profiles and monitor the patient accordingly.

After initiating treatment, look for evidence of malignancy among those patients older than 50 years so as not to miss an underlying cancer as the cause for their dermatomyositis. For women without any risk factors, a complete annual physical exam—including pelvic, breast, and rectal exam—is sufficient.2 It is not necessary to order expensive radiological studies blindly searching for malignancy, especially more than 2 years after the diagnosis is made. The greatest risk of malignancy occurs during the first year after diagnosis with a six-fold increase.1 The risk drops during the second year and a patient’s risk for malignancy is comparable to the normal population in the years following. A mammogram and colonoscopy might be indicated after considering the patient’s age and family history.

The patient’s treatment and outcome

The patient was started on 60 mg of oral prednisone, taken in a single daily dose. She also began physical therapy twice a week in order to prevent muscle atrophy and maximize function. She took the prednisone for 1 month, at which time her creatine kinase level was trending towards normal. We then began slowly tapering the prednisone over the next 6 months.

She reported improvement in her strength 3 months after starting the systemic steroids. Little improvement was seen in the patient’s skin while on systemic steroids, but after prescribing 0.1% triamcinolone ointment, recommending a broad-spectrum sunscreen, and limiting sun exposure, the patient reported less erythema and edema.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Department of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004.

2. Dalakas MC, Hohlfeld R. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet 2003;362:971-982.

3. Woff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

4. Choy EHS, Hoogendijk JE, Lecky B, Winer JB. Immunosuppressant and immunomodulatory treatment for dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;Issue 3:CD003643.

A 48-year-old Hispanic woman came to the clinic as a new patient—her chief complaint was a rash that appeared on her face 3 months before and had recently spread to her chest and hands (FIGURES 1-3). It itched occasionally and seemed to worsen after exposure to the sun.

She also said that for the last month she had been feeling very weak—she had difficulty rising from a seated position and walking up the stairs to her apartment. She also felt as if her arms were heavy, making it difficult for her to brush and dry her hair in the morning.

The patient was otherwise healthy with no known medical conditions, and she was not taking any medications. Her family history was noncontributory.

A musculoskeletal examination showed the following:

Upper extremities:

- 4/5 strength shoulder abduction, internal and external rotation

- 5/5 strength biceps, triceps, wrist extension/flexion, grip

- 2+ biceps and triceps deep tendon reflexes bilaterally

Lower extremities:

- 4/5 strength hip flexors, quadriceps, hamstrings

- 5/5 dorsiflexion/plantar flexion

- 2+ patellar and ankle deep tendon reflexes bilaterally.

FIGURE 1

Facial rash and swelling

FIGURE 2

Rash spreading to chest

FIGURE 3

Plaques on knuckles

What is your diagnosis?

What diagnostic tests would you order for confirmation?

Diagnosis: Dermatomyositis

Dermatomyositis is a systemic disease classified as a type of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Dermatomyositis is a rare disease but one that may present initially to the family physician. It affects people at any age but is more commonly seen among children or adults aged >40 years.

Dermatomyositis involves the skin as well as skeletal muscle. Its cause is unknown; however, among those aged >50 years, malignancy may be an underlying cause. Cancers most commonly associated with dermatomyositis include those of the breast, ovary, lung, and gastrointestinal tract.

Skin manifestations may precede, follow, or present simultaneously with muscle involvement. Patients often complain of having difficulty ascending stairs, rising from a seated position, and performing overhead activities such as combing their hair. Patients may or may not have muscle tenderness and atrophy. Patients can have cutaneous involvement for more than a year before developing muscle weakness.1

The dermatologic signs of dermatomyositis to watch for:

- Periorbital heliotrope erythema, usually associated with edema (FIGURE 1).

- Gottron’s papules—smooth, purple to red papules located over the knuckles, on the sides of the fingers, and sometimes on the elbows and knees. For adults, it is not uncommon to have plaques over the knuckles as opposed to the classic Gottron’s papules (FIGURE 3). In juvenile-onset dermatomyositis, distinct papules are much more evident upon presentation (FIGURE 4). Note that systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can present with a rash on the dorsum of the hands, but the rash spares the skin over the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints and affects the skin between the joints (FIGURE 5).

- Violaceous papular dermatitis with scale—may occur in localized areas, such as elbows and knees, or be diffusely distributed, starting off as a patchy erythema that coalesces and becomes slightly raised with scale. It tends to be confined to sun-exposed areas and worsens after sun exposure (FIGURE 2).

- Periungual erythema and telangiectasia—“moth-eaten” cuticles, a characteristic seen in other connective tissue diseases (FIGURE 6).1

FIGURE 4

Papules on knuckles

FIGURE 5

Sparing interphalangeal joints

FIGURE 6

Cuticles with erythema

Differential diagnosis

Seborrheic dermatitis—white or yellow, greasy scales on an erythematous base with distribution on scalp, nasolabial folds and chest.

Atopic dermatitis—chronic history of pruritic papules or plaques with scale localized to flexural areas or may be generalized; lichenification may be seen.

Contact dermatitis—papules and vesicles that correspond to contact with allergen.

Polymorphous light eruption—clusters of erythematous, pruritic papules or vesicles occurring most frequently on the neck, anterior chest, arms, and forearms following sun exposure; most common among women in their twenties.

Lichen planus—pruritic, purple, polygonal papules (4 Ps) that may involve hair, nails, and mucous membranes in addition to the skin; more common among women, with onset between 30 to 60 years of age; may last months to years.

Psoriasis—well-demarcated papules and plaques on an erythematous base with thick, silvery scale; characteristically found on elbows, knees, scalp, nails, and genitalia.

Steroid myopathy—A side effect of systemic steroids, usually seen 4 to 6 weeks after beginning of treatment.

Dermatomyositis-like reaction—onset of similar skin findings with initiation of the following medications and improvement with discontinuation: penicillamine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and carbamazepine.

Overlap syndrome—The term “overlap” denotes that certain signs are seen in both dermatomyositis and other connective tissue diseases such as scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus erythematosus. Scleroderma and dermatomyositis are the most commonly associated conditions and have been termed sclerodermatomyositis or mixed connective disease. In mixed connective tissue disease, features of SLE, scleroderma, and polymyositis are evident such as malar rash, alopecia, Raynaud’s phenomenon, waxy-appearing skin, and proximal muscle weakness.1,2

Diagnostic tests: Muscle enzymes, EMG, biopsy

The diagnosis of dermatomyositis is confirmed by 3 laboratory tests: elevated muscle enzyme levels, electromyography, and muscle biopsy. A punch biopsy is helpful in differentiating dermatomyositis from other papulosquamous diseases such as lichen planus and psoriasis, but be careful as the histology of dermatomyositis is indistinguishable from cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

During the acute active phase, the following serum muscle enzymes may be elevated: creatine kinase (CK), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alanine aminotransferase (ALT or SGPT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST or SGOT), and aldolase. CK is elevated among 65% of patients and is most specific for muscle disease.3 Only one of the aforementioned enzymes may be elevated, so it is necessary to measure them all.

Measuring antibodies such as antinuclear antibody (ANA), Jo-1, SSA (Ro), SSB (La) supports the diagnosis if positive but dermatomyositis cannot be diagnosed solely on positive titers. It is not necessary to obtain an electromyograph or muscle biopsy for a patient with the characteristic skin findings and evidence of elevated muscle enzymes, as the diagnosis of dermatomyositis can be made with confidence. For a patient in whom the presentation is not as straightforward, it may be useful to obtain the electromyograph and muscle biopsy.

Management: Corticosteroids, watch for malignancy

Oral corticosteroids are the treatment of choice (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B).1,4 Prednisone 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg body weight per day has been recommended until muscle enzyme levels trend toward normal limits, at which time you can taper the dose. Steroid myopathy is a potential side effect of this treatment regimen; it may occur 4 to 6 weeks after therapy starts.

Several steroid-sparing agents such as methotrexate and cyclosporine are being prescribed by clinicians for dermomyositis but with little published evidence to support effectiveness. Methotrexate is an option for those who do not respond to prednisone or are in need of a steroid-sparing agent secondary to side effects (SOR: C).2,3 A suggested regimen starts with 7.5 to 10 mg/wk, then increases the dose to 2.5 mg/wk until reaching a total dose of 25 mg/wk. The dose of prednisone should be decreased as the methotrexate dose increases. Azathioprine is another option to consider along with methotrexate, but choosing one agent over another or a combination of 2 agents remains empirical. With any of the immunosuppressants or immunomodulatory agents, it is important to look at their side-effect profiles and monitor the patient accordingly.

After initiating treatment, look for evidence of malignancy among those patients older than 50 years so as not to miss an underlying cancer as the cause for their dermatomyositis. For women without any risk factors, a complete annual physical exam—including pelvic, breast, and rectal exam—is sufficient.2 It is not necessary to order expensive radiological studies blindly searching for malignancy, especially more than 2 years after the diagnosis is made. The greatest risk of malignancy occurs during the first year after diagnosis with a six-fold increase.1 The risk drops during the second year and a patient’s risk for malignancy is comparable to the normal population in the years following. A mammogram and colonoscopy might be indicated after considering the patient’s age and family history.

The patient’s treatment and outcome

The patient was started on 60 mg of oral prednisone, taken in a single daily dose. She also began physical therapy twice a week in order to prevent muscle atrophy and maximize function. She took the prednisone for 1 month, at which time her creatine kinase level was trending towards normal. We then began slowly tapering the prednisone over the next 6 months.

She reported improvement in her strength 3 months after starting the systemic steroids. Little improvement was seen in the patient’s skin while on systemic steroids, but after prescribing 0.1% triamcinolone ointment, recommending a broad-spectrum sunscreen, and limiting sun exposure, the patient reported less erythema and edema.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Department of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected]

A 48-year-old Hispanic woman came to the clinic as a new patient—her chief complaint was a rash that appeared on her face 3 months before and had recently spread to her chest and hands (FIGURES 1-3). It itched occasionally and seemed to worsen after exposure to the sun.

She also said that for the last month she had been feeling very weak—she had difficulty rising from a seated position and walking up the stairs to her apartment. She also felt as if her arms were heavy, making it difficult for her to brush and dry her hair in the morning.

The patient was otherwise healthy with no known medical conditions, and she was not taking any medications. Her family history was noncontributory.

A musculoskeletal examination showed the following:

Upper extremities:

- 4/5 strength shoulder abduction, internal and external rotation

- 5/5 strength biceps, triceps, wrist extension/flexion, grip

- 2+ biceps and triceps deep tendon reflexes bilaterally

Lower extremities:

- 4/5 strength hip flexors, quadriceps, hamstrings

- 5/5 dorsiflexion/plantar flexion

- 2+ patellar and ankle deep tendon reflexes bilaterally.

FIGURE 1

Facial rash and swelling

FIGURE 2

Rash spreading to chest

FIGURE 3

Plaques on knuckles

What is your diagnosis?

What diagnostic tests would you order for confirmation?

Diagnosis: Dermatomyositis

Dermatomyositis is a systemic disease classified as a type of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Dermatomyositis is a rare disease but one that may present initially to the family physician. It affects people at any age but is more commonly seen among children or adults aged >40 years.

Dermatomyositis involves the skin as well as skeletal muscle. Its cause is unknown; however, among those aged >50 years, malignancy may be an underlying cause. Cancers most commonly associated with dermatomyositis include those of the breast, ovary, lung, and gastrointestinal tract.

Skin manifestations may precede, follow, or present simultaneously with muscle involvement. Patients often complain of having difficulty ascending stairs, rising from a seated position, and performing overhead activities such as combing their hair. Patients may or may not have muscle tenderness and atrophy. Patients can have cutaneous involvement for more than a year before developing muscle weakness.1

The dermatologic signs of dermatomyositis to watch for:

- Periorbital heliotrope erythema, usually associated with edema (FIGURE 1).

- Gottron’s papules—smooth, purple to red papules located over the knuckles, on the sides of the fingers, and sometimes on the elbows and knees. For adults, it is not uncommon to have plaques over the knuckles as opposed to the classic Gottron’s papules (FIGURE 3). In juvenile-onset dermatomyositis, distinct papules are much more evident upon presentation (FIGURE 4). Note that systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can present with a rash on the dorsum of the hands, but the rash spares the skin over the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints and affects the skin between the joints (FIGURE 5).

- Violaceous papular dermatitis with scale—may occur in localized areas, such as elbows and knees, or be diffusely distributed, starting off as a patchy erythema that coalesces and becomes slightly raised with scale. It tends to be confined to sun-exposed areas and worsens after sun exposure (FIGURE 2).

- Periungual erythema and telangiectasia—“moth-eaten” cuticles, a characteristic seen in other connective tissue diseases (FIGURE 6).1

FIGURE 4

Papules on knuckles

FIGURE 5

Sparing interphalangeal joints

FIGURE 6

Cuticles with erythema

Differential diagnosis

Seborrheic dermatitis—white or yellow, greasy scales on an erythematous base with distribution on scalp, nasolabial folds and chest.

Atopic dermatitis—chronic history of pruritic papules or plaques with scale localized to flexural areas or may be generalized; lichenification may be seen.

Contact dermatitis—papules and vesicles that correspond to contact with allergen.

Polymorphous light eruption—clusters of erythematous, pruritic papules or vesicles occurring most frequently on the neck, anterior chest, arms, and forearms following sun exposure; most common among women in their twenties.

Lichen planus—pruritic, purple, polygonal papules (4 Ps) that may involve hair, nails, and mucous membranes in addition to the skin; more common among women, with onset between 30 to 60 years of age; may last months to years.

Psoriasis—well-demarcated papules and plaques on an erythematous base with thick, silvery scale; characteristically found on elbows, knees, scalp, nails, and genitalia.

Steroid myopathy—A side effect of systemic steroids, usually seen 4 to 6 weeks after beginning of treatment.

Dermatomyositis-like reaction—onset of similar skin findings with initiation of the following medications and improvement with discontinuation: penicillamine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and carbamazepine.

Overlap syndrome—The term “overlap” denotes that certain signs are seen in both dermatomyositis and other connective tissue diseases such as scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus erythematosus. Scleroderma and dermatomyositis are the most commonly associated conditions and have been termed sclerodermatomyositis or mixed connective disease. In mixed connective tissue disease, features of SLE, scleroderma, and polymyositis are evident such as malar rash, alopecia, Raynaud’s phenomenon, waxy-appearing skin, and proximal muscle weakness.1,2

Diagnostic tests: Muscle enzymes, EMG, biopsy

The diagnosis of dermatomyositis is confirmed by 3 laboratory tests: elevated muscle enzyme levels, electromyography, and muscle biopsy. A punch biopsy is helpful in differentiating dermatomyositis from other papulosquamous diseases such as lichen planus and psoriasis, but be careful as the histology of dermatomyositis is indistinguishable from cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

During the acute active phase, the following serum muscle enzymes may be elevated: creatine kinase (CK), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alanine aminotransferase (ALT or SGPT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST or SGOT), and aldolase. CK is elevated among 65% of patients and is most specific for muscle disease.3 Only one of the aforementioned enzymes may be elevated, so it is necessary to measure them all.

Measuring antibodies such as antinuclear antibody (ANA), Jo-1, SSA (Ro), SSB (La) supports the diagnosis if positive but dermatomyositis cannot be diagnosed solely on positive titers. It is not necessary to obtain an electromyograph or muscle biopsy for a patient with the characteristic skin findings and evidence of elevated muscle enzymes, as the diagnosis of dermatomyositis can be made with confidence. For a patient in whom the presentation is not as straightforward, it may be useful to obtain the electromyograph and muscle biopsy.

Management: Corticosteroids, watch for malignancy

Oral corticosteroids are the treatment of choice (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B).1,4 Prednisone 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg body weight per day has been recommended until muscle enzyme levels trend toward normal limits, at which time you can taper the dose. Steroid myopathy is a potential side effect of this treatment regimen; it may occur 4 to 6 weeks after therapy starts.

Several steroid-sparing agents such as methotrexate and cyclosporine are being prescribed by clinicians for dermomyositis but with little published evidence to support effectiveness. Methotrexate is an option for those who do not respond to prednisone or are in need of a steroid-sparing agent secondary to side effects (SOR: C).2,3 A suggested regimen starts with 7.5 to 10 mg/wk, then increases the dose to 2.5 mg/wk until reaching a total dose of 25 mg/wk. The dose of prednisone should be decreased as the methotrexate dose increases. Azathioprine is another option to consider along with methotrexate, but choosing one agent over another or a combination of 2 agents remains empirical. With any of the immunosuppressants or immunomodulatory agents, it is important to look at their side-effect profiles and monitor the patient accordingly.

After initiating treatment, look for evidence of malignancy among those patients older than 50 years so as not to miss an underlying cancer as the cause for their dermatomyositis. For women without any risk factors, a complete annual physical exam—including pelvic, breast, and rectal exam—is sufficient.2 It is not necessary to order expensive radiological studies blindly searching for malignancy, especially more than 2 years after the diagnosis is made. The greatest risk of malignancy occurs during the first year after diagnosis with a six-fold increase.1 The risk drops during the second year and a patient’s risk for malignancy is comparable to the normal population in the years following. A mammogram and colonoscopy might be indicated after considering the patient’s age and family history.

The patient’s treatment and outcome

The patient was started on 60 mg of oral prednisone, taken in a single daily dose. She also began physical therapy twice a week in order to prevent muscle atrophy and maximize function. She took the prednisone for 1 month, at which time her creatine kinase level was trending towards normal. We then began slowly tapering the prednisone over the next 6 months.

She reported improvement in her strength 3 months after starting the systemic steroids. Little improvement was seen in the patient’s skin while on systemic steroids, but after prescribing 0.1% triamcinolone ointment, recommending a broad-spectrum sunscreen, and limiting sun exposure, the patient reported less erythema and edema.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Department of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004.

2. Dalakas MC, Hohlfeld R. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet 2003;362:971-982.

3. Woff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

4. Choy EHS, Hoogendijk JE, Lecky B, Winer JB. Immunosuppressant and immunomodulatory treatment for dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;Issue 3:CD003643.

1. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004.

2. Dalakas MC, Hohlfeld R. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet 2003;362:971-982.

3. Woff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

4. Choy EHS, Hoogendijk JE, Lecky B, Winer JB. Immunosuppressant and immunomodulatory treatment for dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;Issue 3:CD003643.

Red facial rash with “granitos”

A 56-year-old Hispanic woman came to the office distraught about the red rash on her face. The rash has been on her cheeks and nose for 5 years, but over the past 2 weeks she has developed red, mildly pruritic, and very tender papules that she calls granitos (the Spanish term for pimples). Foods do not make the rash better or worse, but it gets redder with sun exposure. She had not tried any lotions or sought medical attention until now, when she noticed that the papules were increasing in number but not size.

A few years ago she first noticed small blood vessels becoming more prominent, especially on her cheeks. The lesions have not bled or ulcerated. Her health has been generally good within the past year, with no recent infections. Review of systems indicated no changes in vision, upper respiratory illness, or systemic conditions. She is being treated for type 2 diabetes and hypertension. She does not have a family history of the same rash. FIGURES 1 AND 2 show erythema and telangiectasias distributed symmetrically on both cheeks and nose. A cluster of smooth papules were seen under the nose. No scales were noted.

FIGURE 1

Facial rash

FIGURE 2

Close-up

What is the diagnosis?

How would you treat this condition?

Diagnosis: Rosacea

The patient has rosacea. Rosacea is a common inflammatory skin condition characterized by erythema, edema, papules, pustules, or telangiectasias, most notably found on the concave portions of the cheeks, forehead, chin, and nose.1 Its peak incidence is between the ages of 30 and 50 years.

Because of the marked flushing due to inflammation and capillary hyperreactivity and dilation, the rash has brought a certain degree of social embarrassment for some patients. Moreover, some equate rosacea with excessive alcohol consumption, but this is simply not true.

Although rosacea is a chronic disorder, it does alternate between periods of flare-up and remission. Flares may be triggered by stress, sun exposure, heat, hot drinks and spicy foods, alcohol, exercise, wind, and hot baths. In 50% of all rosacea patients, there are some ocular symptoms, ranging from mild dryness and grittiness to blepharitis, conjunctivitis, and even keratitis.2

Differential diagnosis

Although the differential diagnosis of rosacea is wide—acne, folliculitis, sarcoid, seborrheic dermatitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]—there are unique characteristics that can help distinguish these from rosacea.

For example, the age of onset for rosacea tends to be 30 to 50 years, much later than the onset for acne vulgaris. Similarly, in acne vulgaris comedones are often present, but they are absent in rosacea.

Seborrheic dermatitis tends to produce scales while rosacea does not. Moreover, while both seborrheic dermatitis and rosacea can affect the central facial area, papules and telangiectasias are absent in the former while present with the latter.

SLE can be scarring, does not produce papules or pustules, and it spares the nasolabial folds and nose. Whereas rosacea has a more central face distribution, folliculitis typically presents with pustules visibly surrounding hair follicles and has associated tenderness to palpation and sometimes severe pruritus.

Causes and pathophysiology of rosacea

Although the cause of rosacea is unknown, its mechanism is understood to be nonspecific inflammation followed by dilation around follicles and hyperreactive capillaries. Oftentimes these dilated capillaries present as telangiectasias, which collectively exacerbate the red flushing. As the disorder progresses, diffuse hypertrophy of the connective tissue and sebaceous glands ensues.

Rosacea is more common in women than men (FIGURE 3). Men are typically more prone to the extreme forms of hyperplasia, which causes rhinophymatous rosacea (FIGURE 4)—eg,W C Fields’s nose.

Alcohol may accentuate erythema, but does not cause the disease. Sun exposure may precipitate an acute rosacea flare, but flare-ups can happen without sun exposure.

A significant increase in the hair follicle mite Demadex folliculorum is sometimes found in rosacea. It is theorized that these mites play a role because they incite an inflammatory or allergic reaction by mechanical blockage of follicles.

FIGURE 3

Papulopustular rosacea

FIGURE 4

Rhinophymatous rosacea

Stages of rosacea

There are 4 stages or subtypes of rosacea.

- Subtype 1: Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. This stage is characterized by frequent mild to severe blushing with trace persistent central facial erythema in an individual.

- Subtype 2: Papulopustular rosacea (seen in FIGURES 1 , 2, AND 3). This is a highly vascular stage that involves longer periods of flushing than the first stage—often lasting from days to weeks. Minute telangiectasias and papules start to form by this stage, and some patients begin having very mild ocular complaints such as ocular grittiness or conjunctivitis.

Subtype 3: Phymatous rosacea. The third stage is also called the rhinophymatous stage. It is characterized by deepening shades of erythema and more papules and pustules. In the chronic forms of rosacea, hyperplasia of the sebaceous glands occurs, which forms a thickened confluent plaque of erythema at the tip of the nose known as rhinophyma. This hyperplasia can cause significant disfigurement to the forehead, eyelids, chin, and nose. The nasal disfiguration is seen more commonly in men than women (FIGURE 4).

Subtype 4: Ocular rosacea.The final or fourth stage is an advanced variation of rosacea that is characterized by impressive, severe flushing with persistent telangiectasias, papules, and pustules. At this point, more severe forms of conjunctivitis and blepharitis are more fullblown. The patient may complain of watery eyes, a foreign body sensation, burning, dryness, vision changes, and lid or periocular erythema.3

Diagnosis and treatment

Diagnostic tests

The diagnosis of rosacea is a clinical one. There is no confirmatory laboratory test. Biopsy is warranted only to rule out alternative diagnoses, since histopathological findings are not diagnostic. Scrapings may reveal Demadex folliculorum infection.1

Treatment: Target the inflammation It is important to reassure patients about the benign nature of the disorder as well as explain that its cause is unknown. It may be useful to direct patients to information, such as web sites like those of the National Rosacea Society (www.rosacea.org). Advise patients to keep a daily diary to identify precipitating factors. These can include hot and humid weather, alcohol, hot beverages, spicy foods, and large hot meals. Suggest daily application of sunscreen, which protects against UVA and UVB rays.

Depending on the severity of the skin rosacea, the first-line treatment is an oral antibiotic (tetracycline or erythromycin) and/or topical metronidazole (0.75%–1.0%) twice daily. These antibiotics target the inflammation because rosacea is not a true infection. There is concern in the medical literature about how long-term use of antibiotics can promote drug resistance. Wolf et al4 proposed that once a patient’s lesions have improved after treatment with full-dose antibiotics, the clinician can consider switching to a lower dose and adding a topical agent such as metronidazole for maintenance.4 Studies have shown that 1.0% and 0.75% cream are equally effective.

TABLERosacea treatments

| TREATMENT | DELIVERY | ODDS RATIO* (MEDICATION VS PLACEBO) |

|---|---|---|

| Azelaic acid | Topical | 2.45 |

| Metronidazole | Topical | 5.96 |

| Tetracycline | Oral | 6.06 |

| * Larger number indicates a more effective response to treatment. | ||

Another useful therapy is topical azelaic acid. While the evidence for scabicides in rosacea is limited, some clinicians use these medications for rosacea that is refractory to antibiotics. This is based on the idea that the Demadex mite is a causative agent in rosacea. If a patient has severe papulopustular disease refractory to antibiotics and topical treatments, the physician can start an oral isotretinoin regimen at a low dose of 0.1 to 0.5 mg/kg. Pulse-dye laser and electrosurgery can be used to treat the telangiectasias associated with rosacea.

A systematic review by Van Zuuren et al5 examined the efficacy of metronidazole, tetracycline, and azelaic acid in treating rosacea. Twenty-nine randomized controlled trials were found. Pooled data from 2 of the trials involving 174 participants indicated that, according to the participants, topical metronidazole was more effective than placebo (odds ratio [OR]=5.96; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.95–12.06).

There was a definite improvement in the azelaic acid group; the rates of treatment success were approximately 70 to 80% versus 50% to 55% (OR=2.45; 95% CI, 1.82–3.28). Data pooled from 3 studies of oral tetracycline vs placebo involving 152 participants showed that, according to physicians, tetracycline was more effective than placebo (OR=6.06; 95% CI, 2.96–12.42).

Maintenance therapy

Because relapse occurs within weeks in about 25% of patients after the cessation of systemic therapy, topical therapy is usually used in an effort to maintain remission.6 The required duration of maintenance therapy is unknown, but a period of 6 months is generally advised. After this time, some patients report that they can keep their skin free of papulopustular lesions with topical therapy applied on alternate days or twice weekly, whereas others require repeated courses of systemic medication. After a few years, the disease may disappear spontaneously.

Patient management

Our patient was counseled about her rosacea and given the web site address for the National Rosacea Organization. She was advised to avoid sun exposure as much as possible and to use sunscreen and a hat to protect her face. She was prescribed tetracycline 500 mg and topical metronidazole to be used twice daily. Follow-up was set for 1 month. At that time, patient will be offered the option of electrocoagulation of her most prominent telangiectasias.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Department of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Wolf K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

2. Randleman J, Loft E. Ocular rosacea. eMedicine website. Available at: www.emedicine.com/oph/topic115.htm. Accessed on August 2, 2005.

3. National Rosacea Organization Website. Available at rosacea.org/grading/gradingsystem.pdf. Accessed on August 2, 2005.

4. Wolf J, Parkerson R. Preventing antibiotic resistance in the treatment of rosacea. Fam Pract Recertification 2005;27:50-55.

5. Van Zuuren E, Graber M, Hollis S, Chaudhry M, Gupta A, Gover M. Interventions for rosacea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(3):CD003262.-

6. Powell F. Rosacea. N Engl J Med 2005;352:793-803.

A 56-year-old Hispanic woman came to the office distraught about the red rash on her face. The rash has been on her cheeks and nose for 5 years, but over the past 2 weeks she has developed red, mildly pruritic, and very tender papules that she calls granitos (the Spanish term for pimples). Foods do not make the rash better or worse, but it gets redder with sun exposure. She had not tried any lotions or sought medical attention until now, when she noticed that the papules were increasing in number but not size.

A few years ago she first noticed small blood vessels becoming more prominent, especially on her cheeks. The lesions have not bled or ulcerated. Her health has been generally good within the past year, with no recent infections. Review of systems indicated no changes in vision, upper respiratory illness, or systemic conditions. She is being treated for type 2 diabetes and hypertension. She does not have a family history of the same rash. FIGURES 1 AND 2 show erythema and telangiectasias distributed symmetrically on both cheeks and nose. A cluster of smooth papules were seen under the nose. No scales were noted.

FIGURE 1

Facial rash

FIGURE 2

Close-up

What is the diagnosis?

How would you treat this condition?

Diagnosis: Rosacea

The patient has rosacea. Rosacea is a common inflammatory skin condition characterized by erythema, edema, papules, pustules, or telangiectasias, most notably found on the concave portions of the cheeks, forehead, chin, and nose.1 Its peak incidence is between the ages of 30 and 50 years.

Because of the marked flushing due to inflammation and capillary hyperreactivity and dilation, the rash has brought a certain degree of social embarrassment for some patients. Moreover, some equate rosacea with excessive alcohol consumption, but this is simply not true.

Although rosacea is a chronic disorder, it does alternate between periods of flare-up and remission. Flares may be triggered by stress, sun exposure, heat, hot drinks and spicy foods, alcohol, exercise, wind, and hot baths. In 50% of all rosacea patients, there are some ocular symptoms, ranging from mild dryness and grittiness to blepharitis, conjunctivitis, and even keratitis.2

Differential diagnosis

Although the differential diagnosis of rosacea is wide—acne, folliculitis, sarcoid, seborrheic dermatitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]—there are unique characteristics that can help distinguish these from rosacea.

For example, the age of onset for rosacea tends to be 30 to 50 years, much later than the onset for acne vulgaris. Similarly, in acne vulgaris comedones are often present, but they are absent in rosacea.

Seborrheic dermatitis tends to produce scales while rosacea does not. Moreover, while both seborrheic dermatitis and rosacea can affect the central facial area, papules and telangiectasias are absent in the former while present with the latter.

SLE can be scarring, does not produce papules or pustules, and it spares the nasolabial folds and nose. Whereas rosacea has a more central face distribution, folliculitis typically presents with pustules visibly surrounding hair follicles and has associated tenderness to palpation and sometimes severe pruritus.

Causes and pathophysiology of rosacea

Although the cause of rosacea is unknown, its mechanism is understood to be nonspecific inflammation followed by dilation around follicles and hyperreactive capillaries. Oftentimes these dilated capillaries present as telangiectasias, which collectively exacerbate the red flushing. As the disorder progresses, diffuse hypertrophy of the connective tissue and sebaceous glands ensues.

Rosacea is more common in women than men (FIGURE 3). Men are typically more prone to the extreme forms of hyperplasia, which causes rhinophymatous rosacea (FIGURE 4)—eg,W C Fields’s nose.

Alcohol may accentuate erythema, but does not cause the disease. Sun exposure may precipitate an acute rosacea flare, but flare-ups can happen without sun exposure.

A significant increase in the hair follicle mite Demadex folliculorum is sometimes found in rosacea. It is theorized that these mites play a role because they incite an inflammatory or allergic reaction by mechanical blockage of follicles.

FIGURE 3

Papulopustular rosacea

FIGURE 4

Rhinophymatous rosacea

Stages of rosacea

There are 4 stages or subtypes of rosacea.

- Subtype 1: Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. This stage is characterized by frequent mild to severe blushing with trace persistent central facial erythema in an individual.

- Subtype 2: Papulopustular rosacea (seen in FIGURES 1 , 2, AND 3). This is a highly vascular stage that involves longer periods of flushing than the first stage—often lasting from days to weeks. Minute telangiectasias and papules start to form by this stage, and some patients begin having very mild ocular complaints such as ocular grittiness or conjunctivitis.

Subtype 3: Phymatous rosacea. The third stage is also called the rhinophymatous stage. It is characterized by deepening shades of erythema and more papules and pustules. In the chronic forms of rosacea, hyperplasia of the sebaceous glands occurs, which forms a thickened confluent plaque of erythema at the tip of the nose known as rhinophyma. This hyperplasia can cause significant disfigurement to the forehead, eyelids, chin, and nose. The nasal disfiguration is seen more commonly in men than women (FIGURE 4).

Subtype 4: Ocular rosacea.The final or fourth stage is an advanced variation of rosacea that is characterized by impressive, severe flushing with persistent telangiectasias, papules, and pustules. At this point, more severe forms of conjunctivitis and blepharitis are more fullblown. The patient may complain of watery eyes, a foreign body sensation, burning, dryness, vision changes, and lid or periocular erythema.3

Diagnosis and treatment

Diagnostic tests

The diagnosis of rosacea is a clinical one. There is no confirmatory laboratory test. Biopsy is warranted only to rule out alternative diagnoses, since histopathological findings are not diagnostic. Scrapings may reveal Demadex folliculorum infection.1

Treatment: Target the inflammation It is important to reassure patients about the benign nature of the disorder as well as explain that its cause is unknown. It may be useful to direct patients to information, such as web sites like those of the National Rosacea Society (www.rosacea.org). Advise patients to keep a daily diary to identify precipitating factors. These can include hot and humid weather, alcohol, hot beverages, spicy foods, and large hot meals. Suggest daily application of sunscreen, which protects against UVA and UVB rays.

Depending on the severity of the skin rosacea, the first-line treatment is an oral antibiotic (tetracycline or erythromycin) and/or topical metronidazole (0.75%–1.0%) twice daily. These antibiotics target the inflammation because rosacea is not a true infection. There is concern in the medical literature about how long-term use of antibiotics can promote drug resistance. Wolf et al4 proposed that once a patient’s lesions have improved after treatment with full-dose antibiotics, the clinician can consider switching to a lower dose and adding a topical agent such as metronidazole for maintenance.4 Studies have shown that 1.0% and 0.75% cream are equally effective.

TABLERosacea treatments

| TREATMENT | DELIVERY | ODDS RATIO* (MEDICATION VS PLACEBO) |

|---|---|---|

| Azelaic acid | Topical | 2.45 |

| Metronidazole | Topical | 5.96 |

| Tetracycline | Oral | 6.06 |

| * Larger number indicates a more effective response to treatment. | ||

Another useful therapy is topical azelaic acid. While the evidence for scabicides in rosacea is limited, some clinicians use these medications for rosacea that is refractory to antibiotics. This is based on the idea that the Demadex mite is a causative agent in rosacea. If a patient has severe papulopustular disease refractory to antibiotics and topical treatments, the physician can start an oral isotretinoin regimen at a low dose of 0.1 to 0.5 mg/kg. Pulse-dye laser and electrosurgery can be used to treat the telangiectasias associated with rosacea.

A systematic review by Van Zuuren et al5 examined the efficacy of metronidazole, tetracycline, and azelaic acid in treating rosacea. Twenty-nine randomized controlled trials were found. Pooled data from 2 of the trials involving 174 participants indicated that, according to the participants, topical metronidazole was more effective than placebo (odds ratio [OR]=5.96; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.95–12.06).

There was a definite improvement in the azelaic acid group; the rates of treatment success were approximately 70 to 80% versus 50% to 55% (OR=2.45; 95% CI, 1.82–3.28). Data pooled from 3 studies of oral tetracycline vs placebo involving 152 participants showed that, according to physicians, tetracycline was more effective than placebo (OR=6.06; 95% CI, 2.96–12.42).

Maintenance therapy

Because relapse occurs within weeks in about 25% of patients after the cessation of systemic therapy, topical therapy is usually used in an effort to maintain remission.6 The required duration of maintenance therapy is unknown, but a period of 6 months is generally advised. After this time, some patients report that they can keep their skin free of papulopustular lesions with topical therapy applied on alternate days or twice weekly, whereas others require repeated courses of systemic medication. After a few years, the disease may disappear spontaneously.

Patient management

Our patient was counseled about her rosacea and given the web site address for the National Rosacea Organization. She was advised to avoid sun exposure as much as possible and to use sunscreen and a hat to protect her face. She was prescribed tetracycline 500 mg and topical metronidazole to be used twice daily. Follow-up was set for 1 month. At that time, patient will be offered the option of electrocoagulation of her most prominent telangiectasias.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Department of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected]

A 56-year-old Hispanic woman came to the office distraught about the red rash on her face. The rash has been on her cheeks and nose for 5 years, but over the past 2 weeks she has developed red, mildly pruritic, and very tender papules that she calls granitos (the Spanish term for pimples). Foods do not make the rash better or worse, but it gets redder with sun exposure. She had not tried any lotions or sought medical attention until now, when she noticed that the papules were increasing in number but not size.

A few years ago she first noticed small blood vessels becoming more prominent, especially on her cheeks. The lesions have not bled or ulcerated. Her health has been generally good within the past year, with no recent infections. Review of systems indicated no changes in vision, upper respiratory illness, or systemic conditions. She is being treated for type 2 diabetes and hypertension. She does not have a family history of the same rash. FIGURES 1 AND 2 show erythema and telangiectasias distributed symmetrically on both cheeks and nose. A cluster of smooth papules were seen under the nose. No scales were noted.

FIGURE 1

Facial rash

FIGURE 2

Close-up

What is the diagnosis?

How would you treat this condition?

Diagnosis: Rosacea

The patient has rosacea. Rosacea is a common inflammatory skin condition characterized by erythema, edema, papules, pustules, or telangiectasias, most notably found on the concave portions of the cheeks, forehead, chin, and nose.1 Its peak incidence is between the ages of 30 and 50 years.

Because of the marked flushing due to inflammation and capillary hyperreactivity and dilation, the rash has brought a certain degree of social embarrassment for some patients. Moreover, some equate rosacea with excessive alcohol consumption, but this is simply not true.

Although rosacea is a chronic disorder, it does alternate between periods of flare-up and remission. Flares may be triggered by stress, sun exposure, heat, hot drinks and spicy foods, alcohol, exercise, wind, and hot baths. In 50% of all rosacea patients, there are some ocular symptoms, ranging from mild dryness and grittiness to blepharitis, conjunctivitis, and even keratitis.2

Differential diagnosis

Although the differential diagnosis of rosacea is wide—acne, folliculitis, sarcoid, seborrheic dermatitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]—there are unique characteristics that can help distinguish these from rosacea.

For example, the age of onset for rosacea tends to be 30 to 50 years, much later than the onset for acne vulgaris. Similarly, in acne vulgaris comedones are often present, but they are absent in rosacea.

Seborrheic dermatitis tends to produce scales while rosacea does not. Moreover, while both seborrheic dermatitis and rosacea can affect the central facial area, papules and telangiectasias are absent in the former while present with the latter.

SLE can be scarring, does not produce papules or pustules, and it spares the nasolabial folds and nose. Whereas rosacea has a more central face distribution, folliculitis typically presents with pustules visibly surrounding hair follicles and has associated tenderness to palpation and sometimes severe pruritus.

Causes and pathophysiology of rosacea

Although the cause of rosacea is unknown, its mechanism is understood to be nonspecific inflammation followed by dilation around follicles and hyperreactive capillaries. Oftentimes these dilated capillaries present as telangiectasias, which collectively exacerbate the red flushing. As the disorder progresses, diffuse hypertrophy of the connective tissue and sebaceous glands ensues.

Rosacea is more common in women than men (FIGURE 3). Men are typically more prone to the extreme forms of hyperplasia, which causes rhinophymatous rosacea (FIGURE 4)—eg,W C Fields’s nose.

Alcohol may accentuate erythema, but does not cause the disease. Sun exposure may precipitate an acute rosacea flare, but flare-ups can happen without sun exposure.

A significant increase in the hair follicle mite Demadex folliculorum is sometimes found in rosacea. It is theorized that these mites play a role because they incite an inflammatory or allergic reaction by mechanical blockage of follicles.

FIGURE 3

Papulopustular rosacea

FIGURE 4

Rhinophymatous rosacea

Stages of rosacea

There are 4 stages or subtypes of rosacea.

- Subtype 1: Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. This stage is characterized by frequent mild to severe blushing with trace persistent central facial erythema in an individual.

- Subtype 2: Papulopustular rosacea (seen in FIGURES 1 , 2, AND 3). This is a highly vascular stage that involves longer periods of flushing than the first stage—often lasting from days to weeks. Minute telangiectasias and papules start to form by this stage, and some patients begin having very mild ocular complaints such as ocular grittiness or conjunctivitis.

Subtype 3: Phymatous rosacea. The third stage is also called the rhinophymatous stage. It is characterized by deepening shades of erythema and more papules and pustules. In the chronic forms of rosacea, hyperplasia of the sebaceous glands occurs, which forms a thickened confluent plaque of erythema at the tip of the nose known as rhinophyma. This hyperplasia can cause significant disfigurement to the forehead, eyelids, chin, and nose. The nasal disfiguration is seen more commonly in men than women (FIGURE 4).

Subtype 4: Ocular rosacea.The final or fourth stage is an advanced variation of rosacea that is characterized by impressive, severe flushing with persistent telangiectasias, papules, and pustules. At this point, more severe forms of conjunctivitis and blepharitis are more fullblown. The patient may complain of watery eyes, a foreign body sensation, burning, dryness, vision changes, and lid or periocular erythema.3

Diagnosis and treatment

Diagnostic tests

The diagnosis of rosacea is a clinical one. There is no confirmatory laboratory test. Biopsy is warranted only to rule out alternative diagnoses, since histopathological findings are not diagnostic. Scrapings may reveal Demadex folliculorum infection.1

Treatment: Target the inflammation It is important to reassure patients about the benign nature of the disorder as well as explain that its cause is unknown. It may be useful to direct patients to information, such as web sites like those of the National Rosacea Society (www.rosacea.org). Advise patients to keep a daily diary to identify precipitating factors. These can include hot and humid weather, alcohol, hot beverages, spicy foods, and large hot meals. Suggest daily application of sunscreen, which protects against UVA and UVB rays.

Depending on the severity of the skin rosacea, the first-line treatment is an oral antibiotic (tetracycline or erythromycin) and/or topical metronidazole (0.75%–1.0%) twice daily. These antibiotics target the inflammation because rosacea is not a true infection. There is concern in the medical literature about how long-term use of antibiotics can promote drug resistance. Wolf et al4 proposed that once a patient’s lesions have improved after treatment with full-dose antibiotics, the clinician can consider switching to a lower dose and adding a topical agent such as metronidazole for maintenance.4 Studies have shown that 1.0% and 0.75% cream are equally effective.

TABLERosacea treatments

| TREATMENT | DELIVERY | ODDS RATIO* (MEDICATION VS PLACEBO) |

|---|---|---|

| Azelaic acid | Topical | 2.45 |

| Metronidazole | Topical | 5.96 |

| Tetracycline | Oral | 6.06 |

| * Larger number indicates a more effective response to treatment. | ||

Another useful therapy is topical azelaic acid. While the evidence for scabicides in rosacea is limited, some clinicians use these medications for rosacea that is refractory to antibiotics. This is based on the idea that the Demadex mite is a causative agent in rosacea. If a patient has severe papulopustular disease refractory to antibiotics and topical treatments, the physician can start an oral isotretinoin regimen at a low dose of 0.1 to 0.5 mg/kg. Pulse-dye laser and electrosurgery can be used to treat the telangiectasias associated with rosacea.

A systematic review by Van Zuuren et al5 examined the efficacy of metronidazole, tetracycline, and azelaic acid in treating rosacea. Twenty-nine randomized controlled trials were found. Pooled data from 2 of the trials involving 174 participants indicated that, according to the participants, topical metronidazole was more effective than placebo (odds ratio [OR]=5.96; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.95–12.06).

There was a definite improvement in the azelaic acid group; the rates of treatment success were approximately 70 to 80% versus 50% to 55% (OR=2.45; 95% CI, 1.82–3.28). Data pooled from 3 studies of oral tetracycline vs placebo involving 152 participants showed that, according to physicians, tetracycline was more effective than placebo (OR=6.06; 95% CI, 2.96–12.42).

Maintenance therapy

Because relapse occurs within weeks in about 25% of patients after the cessation of systemic therapy, topical therapy is usually used in an effort to maintain remission.6 The required duration of maintenance therapy is unknown, but a period of 6 months is generally advised. After this time, some patients report that they can keep their skin free of papulopustular lesions with topical therapy applied on alternate days or twice weekly, whereas others require repeated courses of systemic medication. After a few years, the disease may disappear spontaneously.

Patient management

Our patient was counseled about her rosacea and given the web site address for the National Rosacea Organization. She was advised to avoid sun exposure as much as possible and to use sunscreen and a hat to protect her face. She was prescribed tetracycline 500 mg and topical metronidazole to be used twice daily. Follow-up was set for 1 month. At that time, patient will be offered the option of electrocoagulation of her most prominent telangiectasias.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Department of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Wolf K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

2. Randleman J, Loft E. Ocular rosacea. eMedicine website. Available at: www.emedicine.com/oph/topic115.htm. Accessed on August 2, 2005.

3. National Rosacea Organization Website. Available at rosacea.org/grading/gradingsystem.pdf. Accessed on August 2, 2005.

4. Wolf J, Parkerson R. Preventing antibiotic resistance in the treatment of rosacea. Fam Pract Recertification 2005;27:50-55.

5. Van Zuuren E, Graber M, Hollis S, Chaudhry M, Gupta A, Gover M. Interventions for rosacea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(3):CD003262.-

6. Powell F. Rosacea. N Engl J Med 2005;352:793-803.

1. Wolf K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

2. Randleman J, Loft E. Ocular rosacea. eMedicine website. Available at: www.emedicine.com/oph/topic115.htm. Accessed on August 2, 2005.

3. National Rosacea Organization Website. Available at rosacea.org/grading/gradingsystem.pdf. Accessed on August 2, 2005.

4. Wolf J, Parkerson R. Preventing antibiotic resistance in the treatment of rosacea. Fam Pract Recertification 2005;27:50-55.

5. Van Zuuren E, Graber M, Hollis S, Chaudhry M, Gupta A, Gover M. Interventions for rosacea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(3):CD003262.-

6. Powell F. Rosacea. N Engl J Med 2005;352:793-803.

Abdominal pain in a pregnant woman

A 24-year-old woman, pregnant with a fetus at 22 weeks gestational age, came to the OB triage area with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. She described a sharp pain that began the night before, starting at the umbilicus and radiating toward her right side; she rated it 7 out of 10.

The patient said there had been no contractions, vaginal bleeding or fluid leaking, or dysuria. She reported having GERD at times. She experienced chills the day before, but no fever. She had similar pain 1 month before that resolved spontaneously, and for which a cause was never determined. She had nothing significant in her medical history; family history was noncontributory.

On examination, she was afebrile, normotensive, and in no apparent distress. Her heart and lungs were normal. Her abdomen was soft and gravid with a fundal height of 22 cm. Bowel sounds were present in all 4 quadrants. Fetal heart tones were normal, and there was no indication of contractions. Her abdomen was diffusely tender, with significant tenderness to deep palpation in the right upper quadrant at first. There was no rebound or guarding. The psoas sign was negative. The obturator sign was positive, with increased pain 4 out of 10 in the right lower quadrant. There were no abdominal masses. Digital rectal examination revealed no rectal masses, and a guaiac stool test result was negative. A few hours later, the tenderness seemed to move toward the right lower quadrant (FIGURES 1 AND 2).

What is the most likely diagnosis?

How do the ultrasound images help you make the diagnosis?

FIGURE 1

Ultrasound of RLQ

FIGURE 2

A second ultrasound of RLQ

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of abdominal pain in a gravid patient includes placental abruption, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, appendicitis, intussusception, pyelonephritis, round ligament syndrome, hydronephrosis, ovarian torsion, uterine fibroid degeneration, ovarian cysts or tumors, intra-abdominal and rectus muscle abscesses, and Crohn’s disease with diffuse peritoneal inflammation. Given the location of the pain and the lack of vaginal bleeding, the most likely diagnoses are cholecystitis and appendicitis.

Making the diagnosis

We performed several laboratory analyses, including a complete blood count, chemistry panel (including electrolytes and liver function studies), amylase, lipase, and a urinalysis. The test results were all normal. She had a white blood cell count of 15,000/μL, which can be normal in pregnancy. The initial evaluating physician had obtained a right upper quadrant ultrasound, which showed no gallstones or bilateral hydronephrosis; unfortunately, no attempt was made to visualize the right lower quadrant or appendix at that time.

In light of the physical exam findings and the absence of gallstones, the patient was admitted to rule out appendicitis. The surgery team at the university hospital was consulted. They requested a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen with and without contrast. To avoid the risk of radiation to the fetus, the family medicine team spoke with Radiology to obtain another ultrasound.

The ultrasound showed an enlarged and inflamed appendix with a transverse diameter of 13 mm (normal is <6 mm) (FIGURES 3 AND 4).1 A graded compression technique was used to assess the appendix. This involves using pressure of the ultrasound probe starting above the area of tenderness and working toward the tender area while scanning for the appendix. This showed obvious peristalsis in the cecum and no movement within the appendix, indicating obstruction or inflammation.

FIGURE 3

Appendix: Longitudinal view

FIGURE 4

Appendix: Transverse view

Patient management and outcome

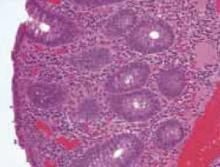

An open appendectomy was performed. The appendix was inflamed and enlarged as suspected. The histology showed neutrophilic infiltration of mucosa, muscle, and serosa (FIGURE 5). Postoperatively, the patient recovered in Labor and Delivery to monitor for possible preterm labor. She did not develop any signs or symptoms of preterm labor, and was transferred to a regular antepartum floor after being observed for 6 hours.

She did well during her hospitalization, and was sent home on post-op day 2. Her abdominal pain had resolved, and she had very little post-op tenderness.

FIGURE 5

Histology

Discussion: Appendicitis in pregnancy

Acute appendicitis is the most common condition requiring surgery during pregnancy.2 Suspected appendicitis accounts for nearly two thirds of all nonobstetric exploratory laparotomies performed during pregnancy; most cases occur in the second and third trimesters.

The incidence of appendicitis is 0.4 to 1.4 per 1000 pregnancies.2 Although the incidence of appendicitis in not increased during pregnancy, rupture of the appendix occurs 2 to 3 times more frequently in pregnancy secondary to delays in diagnosis and operation. Maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity rates are greatly increased when appendicitis is complicated by peritonitis.

A difficult diagnosis

Diagnosis is difficult because many symptoms are considered to be normal during pregnancy. Many times, pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen may be attributed to round ligament pain or urinary tract infection. After the first trimester, the appendix is gradually displaced above McBurney’s point, with horizontal rotation of its base. This upward displacement occurs until the eighth month of gestation, when more than 90% of appendices lie above the iliac crest, and 80% rotate upward and toward the right subcostal area.2,3

The most consistent clinical symptom encountered in pregnant women with appendicitis is vague right-sided abdominal pain.2 Depending on the gestation, muscle guarding and rebound tenderness may or may not be present. Nausea, vomiting, and anorexia are usually present as in the nonpregnant patient. Twenty five percent of pregnant patients with appendicitis are afebrile, as our patient was.2,4

The leukocytosis of pregnancy makes it difficult to determine if there is an infection. Not all pregnant patients with appendicitis will have a white blood cell count greater than 16,000/μL, but approximately 75% of them will have a left shift in the differential.2 A urinalysis may reveal pyuria and hematuria and can mislead the physician to explain the symptoms as pyelonephritis.2

Treatment: Appendectomy, antibiotics if needed

Treatment of nonperforated acute appendicitis in pregnancy is appendectomy. In the first trimester, a laparoscopic appendectomy may be performed.2 Intravenous antibiotics are indicated with perforation, peritonitis or abscess formation.2,5

Tocolysis is unnecessary in uncomplicated appendicitis, but may be indicated if the patient goes into labor after surgery. In the late third trimester, with perforation or peritonitis, a cesarean section is indicated.

Evaluation is imperative

Fetal loss may occur in association with preterm labor and delivery or with generalized peritonitis and sepsis, and occurs only rarely in uncomplicated appendicitis. Fetal loss appears to be more closely associated with severity of appendicitis than with surgical intervention.2,5,6

Imaging test characteristics: Is sonography enough?

Thus, it is imperative that any pregnant patient that comes in to the hospital or clinic with abdominal pain be evaluated for appendicitis. Ultrasound was a valuable diagnostic tool in this case and saved both the patient and developing fetus the radiation exposure of a CT scan. Ultrasound has a high specificity for diagnosing appendicitis if the appendix is visualized with abnormal findings. However, the sensitivity is not as high as CT, and failure to visualize the appendix adequately would have required a decision between appendectomy on clinical grounds only or going through with the CT scan.

The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for ultrasonography and CT scans in the diagnosis of appendicitis are given in the TABLE (level of evidence [LOE]=1a).7

In a prospective study of patients with clinical signs and symptoms of acute appendicitis using a graded compression technique of ultrasonography, sonographic testing was as accurate as the focused unenhanced single-detector helical CT. The primary sonographic criterion for diagnosing acute appendicitis was an incompressible appendix with a transverse outer diameter of 6 mm or larger, as seen in this patient. The sensitivity of CT and sonography was 76% and 79%, respectively; the specificity was 83% and 78%; the accuracy was 78% and 78%; the positive predictive value was 90% and 87%; and the negative predictive value was 64% and 65% (LOE=2a).8

In conclusion, it is reasonable to use graded compression ultrasonography in a pregnant woman with suspected appendicitis. If the suspicion for appendicitis is high, a negative result may still need further evaluation with a CT or ultimately lead to abdominal surgery despite negative imaging studies.

TABLEUltrasound and CT in the diagnosis of appendicitis

| TEST | SN | SP | LR+ | LR– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound | 0.86 (0.83–0.88) | 0.81 (0.78–0.84) | 5.8 (3.5–9.5) | .019 (0.13–0.27) |

| CT | 0.94 (0.91–0.95) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | 13.3 (9.9–17.9) | 0.09 (0.07–0.12) |

| Sn, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR–, negative likelihood ratio; CT, computed tomography. | ||||

| Source: Teresawa et al, Ann Intern Med 2004.7 | ||||

Corresponding Author

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Department of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Hansen GC, Toot PJ, Lynch CO. Subtle ultrasound signs of appendicitis in pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med 1993;3:223-224.

2. Tamir IL, Bongard FS, Klein SR. Acute appendicitis in the pregnant patient. Am J Surg 1990;160:571-576.

3. Hodjati H, Kazerooni T. Location of the appendix in the gravid patient: a re-evaluation of the established concept. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2003;81:245-247.

4. Morad JDO, Elliott JP, Lisboa L. Appendicitis in pregnancy:new information that contradicts long held clinical beliefs. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;182:1027-1029.

5. Andersen B, Nielsen TF. Appendicitis in pregnancy: diagnosis, management and complications. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1999;78:758-762.

6. Thurnau GR, Hales KA. Appendicitis in pregnancy. Female Patient 1992;17:81.

7. Terasawa T, Blackmore CC, Bent S, Kohlwes RJ. Systematic review: computed tomography and ultrasonography to detect acute appendicitis in adults and adolescents. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:537-546.

8. Poortman P, Lohle PN, Schoemaker CM, et al. Comparison of CT and sonography in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis: a blinded prospective study. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;181:1355-1359.

A 24-year-old woman, pregnant with a fetus at 22 weeks gestational age, came to the OB triage area with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. She described a sharp pain that began the night before, starting at the umbilicus and radiating toward her right side; she rated it 7 out of 10.

The patient said there had been no contractions, vaginal bleeding or fluid leaking, or dysuria. She reported having GERD at times. She experienced chills the day before, but no fever. She had similar pain 1 month before that resolved spontaneously, and for which a cause was never determined. She had nothing significant in her medical history; family history was noncontributory.

On examination, she was afebrile, normotensive, and in no apparent distress. Her heart and lungs were normal. Her abdomen was soft and gravid with a fundal height of 22 cm. Bowel sounds were present in all 4 quadrants. Fetal heart tones were normal, and there was no indication of contractions. Her abdomen was diffusely tender, with significant tenderness to deep palpation in the right upper quadrant at first. There was no rebound or guarding. The psoas sign was negative. The obturator sign was positive, with increased pain 4 out of 10 in the right lower quadrant. There were no abdominal masses. Digital rectal examination revealed no rectal masses, and a guaiac stool test result was negative. A few hours later, the tenderness seemed to move toward the right lower quadrant (FIGURES 1 AND 2).

What is the most likely diagnosis?

How do the ultrasound images help you make the diagnosis?

FIGURE 1

Ultrasound of RLQ

FIGURE 2

A second ultrasound of RLQ

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of abdominal pain in a gravid patient includes placental abruption, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, appendicitis, intussusception, pyelonephritis, round ligament syndrome, hydronephrosis, ovarian torsion, uterine fibroid degeneration, ovarian cysts or tumors, intra-abdominal and rectus muscle abscesses, and Crohn’s disease with diffuse peritoneal inflammation. Given the location of the pain and the lack of vaginal bleeding, the most likely diagnoses are cholecystitis and appendicitis.

Making the diagnosis