User login

Itching and rash in a boy and his grandmother

A boy came to the office with a rash and progressively severe itching for approximately 2 months (FIGURE 1). Examination showed an excoriated generalized papular eruption, including some urticarial-type papules and chronic eczematoid changes near the waist, axillae, hands, and wrists.

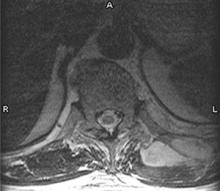

His grandmother, with whom he spends most weekends and a lot of time after school, also has had a rash and progressive itch for approximately 3 weeks. One feature of the dermopathy observed clinically, first located by hand lens examination and then confirmed by dermoscopy, is depicted in FIGURE 2.

FIGURE 1

Excoriated eruptions

FIGURE 2

Dermoscopic photograph of the dermatosis

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Scabies

The boy and his grandmother both have scabies, an infectious disease—in fact, the first human disease proven to be caused by a specific agent.1Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis, or scabies, is a mite in the arachnid class.2 In some states and localities, scabies cases or scabies outbreaks are reportable to the public health department.

The cardinal symptom of scabies is pruritus. The itch, especially with initial scabietic infestation, may be gradual in onset.3 Physical examination findings can vary from subtle and nonspecific to overwhelming and distinctive. Scabies can also mimic other dermopathies, complicating diagnosis. Undiagnosed and untreated, scabies can last a protracted period.

The dermopathy may be characterized by urticarial-type papules, vesicles, eczematoid change, excoriation, and bacterial superinfection, especially in children. Nodules may be present, particularly on the penis and scrotum. These may last for months after the infestation has cleared.3 The most commonly involved areas include fingers and finger webs, wrist folds, elbows, knees, the lower abdomen, armpits, thighs, male genitals, nipples, breasts, buttocks, and shoulder blades.3,4 In young children, scabies may be found anywhere, including palms, soles, face and scalp.

Affliction of multiple family members and finding dermatitis in these distinctive locations is helpful in diagnosis. Finding the mites’ burrows is considered pathognomonic because other burrowing diseases (eg, cutaneous larva migrans) are easily distinguished clinically.4 Extensive excoriation is a clinical clue to look for burrows.3

Transmission usually skin-to-skin

Scabies is generally transmitted by prolonged skin-to-skin contact, such as occurs in families or during sexual contact. It is possible to acquire scabies infestation via contaminated items of clothing or bed linens, but this is not regarded as a significant route of transmission.3 Transmission by casual contact, such as a handshake or hug, is unlikely.

Infestation with the S scabiei mite, referred to as scabies in man, is termed “mange” in other mammals known to host the mite (dogs, cats, rabbits, cattle, pigs, and horses). Mites from one host species generally do not establish themselves on another species, and thus are referred to as varieties, variants, or forms. Humans develop a transient dermopathy from infestation by animal scabies, but such infestations are mild and disappear spontaneously unless the person is in frequent contact with the infested animal.3,4

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of scabies—a great masquerader—is extensive, and includes atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, impetigo, insect bites, vasculitis, neurodermatitis, folliculitis, prurigo nodularis, psoriasis (crusted scabies), and a host of other dermopathies.3,4

Confirming the diagnosis

Finding the causative mite, its ova (eggs), or scybala (feces), confirms the diagnosis, although failure to find these does not rule out scabies. Papules or burrows that have not been excoriated are best for obtaining preparations for microscopic examination.3 Burrows may be found with nakedeye inspection, although use of a hand-held magnifier and good illumination make finding burrows easier.

Dermoscopy

Dermoscopy, performed with an otoscope-like, illuminated magnifier designed for skin assessment, provides reliable confirmation of S- or Z-shaped burrows. During dermoscopy, carefully examining the distal end of the burrows in the skin may reveal the “triangular black dot” of the scabies mite (FIGURE 2, top right)—the head of the mite.5 The body of the mite—light in color and oval—is not visible even with the most careful dermoscopic examination. The “black dot” of the mite may be visible with careful inspection with a hand lens. In the appropriate clinical setting, dermoscopic identification of an unequivocal burrow with the dark “triangle sign” at one end is diagnostic for scabies. When a digital photograph obtained through the dermatoscope is magnified, the distal end of the burrow (FIGURE 3) reveals the triangular head parts of the mite and the body within the burrow. This body is not evident with dermoscopy alone; the additional magnification via photography allows its visualization.

FIGURE 3

Magnification

Scabies mount

In instances where the physician is going to make an institution-wide recommendation with major ramifications, it is wise to positively identify the mite. A scabies mount performed at the location of the triangular dot will readily provide a mite for identification. Scabies mounts are prepared via a very superficial shave technique without anesthesia. The skin flakes are transferred to a slide and a drop of mineral oil is added. Alternatively, a drop of mineral oil can be placed on the skin and a superficial sample obtained.

Note that this technique differs from that of potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation for fungal identification. The scabies mount technique is more like a superficial shave biopsy (with the knife blade parallel to the skin) than a KOH preparation (blade dragged along the skin surface more perpendicular to the skin).Microscopic examination of each slide reveals a mite (FIGURES 4 AND 5).

In our patient, 3 burrows were identified with a hand lens and confirmed by dermoscopy. In 2 burrows, the triangular dots were transferred to slides by doing a very superficial shave (without anesthesia) of the stratum corneum with a number 15 blade and handle. The material was placed on a slide, a drop of mineral oil added, and the slide examined microscopically (FIGURES 4 AND 5). These dermoscopically guided preparations each yielded a mite and little other debris.

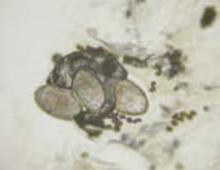

FIGURE 4

Scabies mite

FIGURE 5

Mite, ova, and feces

Ink test

The “ink test” is another adjunct to help identify burrows. A nontoxic, watersoluble felt-tip marker is rubbed over an area suspected of having burrows. After waiting a few moments for the ink to sink into the disrupted stratum corneum overlying burrows, the ink is washed off, leaving an ink-demarcated burrow to examine.4 This can be performed as an adjunct to dermoscopy.5

The course of scabies

The mite’s life cycle

There are 4 stages in the mite’s life cycle: egg, larva, nymph, and adult. Female mites deposit 2 to 3 eggs per day as they create their burrows. The eggs are oval, 0.1 to 0.15 mm in length, and hatch in 3 to 8 days. The resultant larvae migrate to the skin surface and burrow into the intact stratum corneum to construct almost invisible, short burrows called molting pouches.

The larvae progress through 2 nymphal stages before a final molt to the adult stage. Larvae and nymphs live in molting pouches or in hair follicles. They appear similar to adults except for smaller size and, during the larval stage, 3 pair of legs. Adult female mites are 0.3 to 0.4 mm long and about 0.25 to 0.35 mm wide, about twice the size of males. Mating occurs when a male penetrates the molting pouch of the adult female. Impregnated females then extend their molting pouches to form the characteristic serpentine burrows, laying eggs in the process. The total period to progress from egg to the gravid female stage takes 10 to 14 days. The impregnated females spend the remaining 2 months of their lives in burrows.3,4

The mites live in and on the stratum corneum, burrowing into but never below the stratum corneum. The burrows appear as raised, serpentine lines varying from a few millimeters up to several centimeters long. Transmission occurs by the transfer of ova-bearing females.3,4

Cause of the rash and itch

The mites do not “bite.” Instead, the hallmark of scabies, when found, are the burrows created by the mites. However, it is common to see a papular urticarial type response as an allergic reaction to antigens associated with the mite itself, its scybala, and eggs. In fact, after acquiring scabies for the first time, itch does not appear for 2 to 6 weeks (average, 3 to 4 weeks) because the host needs to be sensitized to these antigens.4

It is not until the immunologic reactivity or sensitization develops that the host becomes symptomatic and aware of a problem. This requirement for sensitization explains the often gradual onset of itch. The incubation period is important in transmission to other individuals during the asymptomatic phase.3 However, a previously sensitized host may experience itch within hours to days after reinfestation.4

Epidemiology of scabies

Scabies infestations occur in all geographic areas and climates, and affects people of all ages and socioeconomic strata.7 For unexplained reasons, those with African ancestry rarely acquire scabies.7

It is most common in those who have close physical contact with others and, therefore, disproportionately affects children, mothers of young children, sexually active young adults, nursing home populations, and those in crowded living situations. Scabies is commonplace in developing countries. It is possible to acquire scabies after sleeping in unsanitary bedding. The scabies mite does not carry other diseases.7

Crusted scabies

Crusted scabies, a rare form of scabies also known as Norwegian scabies, is an aggressive infestation that usually occurs in immunodeficient, debilitated, or malnourished persons. Crusted scabies, because of the huge mite burden, is associated with greater transmissibility than scabies.7 Interestingly, because of impaired allergic response or indifference to itch, some of these patients may exhibit little pruritus.7

Treatment of scabies

Perhaps the most difficult job in treatment of scabies is treating asymptomatic contacts. Physicians may be reluctant to prescribe, and contacts themselves may be reluctant to take, appropriate treatment. These individuals often spread the infection for 4 to 6 weeks before they develop sensitization and clinical symptoms. Thus, it is essential that these asymptomatic contacts be treated or a cycle of reinfestation will be created.3 All sexual contacts, close personal contacts, and household contacts from within the preceding month should be examined and treated.8

Permethrin cream. The recommended treatment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is permethrin cream (5%) applied to all areas of the body from the neck down and thoroughly washed off after 8 to 14 hours. This recommendation includes careful application under fingernails, between toes, and on palms and soles. Infants may need the face and scalp treated in addition. Treatment of the face beyond infancy frequently results in a contact irritant dermatitis. Permethrin is effective and safe but costs more than lindane.8

Lindane. The CDC guidelines offer 2 alternatives to permethrin. One alternative, lindane 1% cream or lotion, can be applied in a thin layer to all areas of the body from the neck down and thoroughly washed off after 8 hours.

Lindane should not be used immediately after a bath or shower, and should not be used by persons who have extensive dermatitis, pregnant or lactating women, or children aged less than 2 years. Lindane resistance has been reported, including in the United States. Seizures have occurred when lindane was applied after a bath or used by patients who had extensive dermatitis. Aplastic anemia following lindane use also has been reported. Infants, young children, and pregnant or lactating women should not be treated with lindane; they can be treated with permethrin.8

Applying topical treatments. Topical scabicides should be applied to all skin from neck down, including intertriginous areas and the gluteal fold. The medication needs to be reapplied to hands if the hands are washed after application. It is advisable to cut fingernails short before applying scabicides and to ensure that scabicide is applied under fingernails. A toothpick can be used if necessary to assist in application under nails. In infants and small children, medication should be applied to face and scalp, avoiding the periorbital area.6

Other treatments. Ivermectin, the third treatment recommended by the CDC, can be administered as a single dose of 200 mcg/kg orally, and repeated in 2 weeks. Ivermectin is not recommended for pregnant or lactating patients. The safety of ivermectin in children who weigh less than 15 kg has not been determined.8

Some specialists recommend retreatment after 1 to 2 weeks for patients who are still symptomatic. Patients who do not respond to the recommended treatment should be retreated with an alternative regimen.8

Patients who have uncomplicated scabies and also are infected with HIV should receive the same treatment regimens as those who are HIV-negative.8 For patients with crusted scabies, the optimal regimen is unknown because no controlled therapeutic trials have been conducted. Expert opinion suggests augmented and combined regimens should be used for this aggressive infestation. Lindane should be avoided because of risks of neurotoxicity with heavy applications.8 Control of scabies epidemics (eg, in nursing homes, hospitals, residential facilities) require treatment of the entire population at risk.

Ancillary measures

Scabies mites may survive for a few days after leaving human skin. Thus, frequent bed linen changes minimize transmission via bedding. Hot-water laundry in temperatures of 120°F (49°s mites in 10 minutes and is sufficient to disinfect all bedding, clothing, and washable items.3

Other methods of disinfection include placing items in a dryer on the hot cycle for 10 to 30 minutes, pressing them with a warm iron, dry-cleaning, or placing in a sealed plastic bag for 7 to 14 days. Carpets or upholstery should be vacuumed through the heavy traffic areas. Fumigation of living areas and furniture with insecticide is unnecessary.6-8 Pets do not need to be treated.6 Children may return to school and childcare immediately following initial treatment.6

Follow-up of scabies patient

The boy’s mother is allowed to view the mites through the microscope, fostering her accepting the diagnosis and enhancing the chance for compliance with treatment, which involves treating the entire family.

Patients should be informed that the rash and pruritus of scabies may persist for 4 weeks after treatment because scabietic antigenic material remains until natural epidermal sloughing and turnover occurs.3 When symptoms or signs persist, evaluation should ensue for faulty application of topical scabicides and for treatment failure.7

Acknowledgments

The author (GNF) wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Peggy Elston and Heather Martinez, without whose assistance photographs like these would never happen; and Lisa Nichols, without whose acquisitive skills it never would have occurred to me to mite-hunt with a dermatoscope.

CORRESPONDENCE

Gary N. Fox, MD, Defiance Clinic, 1400 East Second Street, Defiance, OH 43512. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Binder WD. Scabies. eMedicine [online database]. Available at: www.emedicine.com/emerg/topic517.htm. Accessed on July 6, 2006.

2. Arachnid. Wikipedia [online encyclopedia]. Available at: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arachnid. Accessed on July 6, 2006.

3. Scabies. DPDx—CDC Parasitology Diagnostic Website. Available at: www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Scabies.htm. Accessed on July 6, 2006.

4. Arya V, Molinaro MJ, Majewski SS, Schwartz RA. Pediatric scabies. Cutis 2003;71:193-196.

5. Vazquez-Lopez F, Kreusch JF, Marghoob AA. Other uses of dermoscopy. In: Marghoob AA, Braun RP, Kopf AW, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2005:301,305-306.

6. FAQs—scabies. Texas Department of Health Services, Infectious Disease Control Unit website. Available at: www.dshs.state.tx.us/idcu/disease/scabies/faqs/. Accessed on July 6, 2006.

7. Infestations and bites [chapter 15]. In: Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. New York: Mosby; 2004:497-503.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2002. MMWR Recomm Rep 2002;51(RR-6):68-69.

A boy came to the office with a rash and progressively severe itching for approximately 2 months (FIGURE 1). Examination showed an excoriated generalized papular eruption, including some urticarial-type papules and chronic eczematoid changes near the waist, axillae, hands, and wrists.

His grandmother, with whom he spends most weekends and a lot of time after school, also has had a rash and progressive itch for approximately 3 weeks. One feature of the dermopathy observed clinically, first located by hand lens examination and then confirmed by dermoscopy, is depicted in FIGURE 2.

FIGURE 1

Excoriated eruptions

FIGURE 2

Dermoscopic photograph of the dermatosis

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Scabies

The boy and his grandmother both have scabies, an infectious disease—in fact, the first human disease proven to be caused by a specific agent.1Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis, or scabies, is a mite in the arachnid class.2 In some states and localities, scabies cases or scabies outbreaks are reportable to the public health department.

The cardinal symptom of scabies is pruritus. The itch, especially with initial scabietic infestation, may be gradual in onset.3 Physical examination findings can vary from subtle and nonspecific to overwhelming and distinctive. Scabies can also mimic other dermopathies, complicating diagnosis. Undiagnosed and untreated, scabies can last a protracted period.

The dermopathy may be characterized by urticarial-type papules, vesicles, eczematoid change, excoriation, and bacterial superinfection, especially in children. Nodules may be present, particularly on the penis and scrotum. These may last for months after the infestation has cleared.3 The most commonly involved areas include fingers and finger webs, wrist folds, elbows, knees, the lower abdomen, armpits, thighs, male genitals, nipples, breasts, buttocks, and shoulder blades.3,4 In young children, scabies may be found anywhere, including palms, soles, face and scalp.

Affliction of multiple family members and finding dermatitis in these distinctive locations is helpful in diagnosis. Finding the mites’ burrows is considered pathognomonic because other burrowing diseases (eg, cutaneous larva migrans) are easily distinguished clinically.4 Extensive excoriation is a clinical clue to look for burrows.3

Transmission usually skin-to-skin

Scabies is generally transmitted by prolonged skin-to-skin contact, such as occurs in families or during sexual contact. It is possible to acquire scabies infestation via contaminated items of clothing or bed linens, but this is not regarded as a significant route of transmission.3 Transmission by casual contact, such as a handshake or hug, is unlikely.

Infestation with the S scabiei mite, referred to as scabies in man, is termed “mange” in other mammals known to host the mite (dogs, cats, rabbits, cattle, pigs, and horses). Mites from one host species generally do not establish themselves on another species, and thus are referred to as varieties, variants, or forms. Humans develop a transient dermopathy from infestation by animal scabies, but such infestations are mild and disappear spontaneously unless the person is in frequent contact with the infested animal.3,4

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of scabies—a great masquerader—is extensive, and includes atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, impetigo, insect bites, vasculitis, neurodermatitis, folliculitis, prurigo nodularis, psoriasis (crusted scabies), and a host of other dermopathies.3,4

Confirming the diagnosis

Finding the causative mite, its ova (eggs), or scybala (feces), confirms the diagnosis, although failure to find these does not rule out scabies. Papules or burrows that have not been excoriated are best for obtaining preparations for microscopic examination.3 Burrows may be found with nakedeye inspection, although use of a hand-held magnifier and good illumination make finding burrows easier.

Dermoscopy

Dermoscopy, performed with an otoscope-like, illuminated magnifier designed for skin assessment, provides reliable confirmation of S- or Z-shaped burrows. During dermoscopy, carefully examining the distal end of the burrows in the skin may reveal the “triangular black dot” of the scabies mite (FIGURE 2, top right)—the head of the mite.5 The body of the mite—light in color and oval—is not visible even with the most careful dermoscopic examination. The “black dot” of the mite may be visible with careful inspection with a hand lens. In the appropriate clinical setting, dermoscopic identification of an unequivocal burrow with the dark “triangle sign” at one end is diagnostic for scabies. When a digital photograph obtained through the dermatoscope is magnified, the distal end of the burrow (FIGURE 3) reveals the triangular head parts of the mite and the body within the burrow. This body is not evident with dermoscopy alone; the additional magnification via photography allows its visualization.

FIGURE 3

Magnification

Scabies mount

In instances where the physician is going to make an institution-wide recommendation with major ramifications, it is wise to positively identify the mite. A scabies mount performed at the location of the triangular dot will readily provide a mite for identification. Scabies mounts are prepared via a very superficial shave technique without anesthesia. The skin flakes are transferred to a slide and a drop of mineral oil is added. Alternatively, a drop of mineral oil can be placed on the skin and a superficial sample obtained.

Note that this technique differs from that of potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation for fungal identification. The scabies mount technique is more like a superficial shave biopsy (with the knife blade parallel to the skin) than a KOH preparation (blade dragged along the skin surface more perpendicular to the skin).Microscopic examination of each slide reveals a mite (FIGURES 4 AND 5).

In our patient, 3 burrows were identified with a hand lens and confirmed by dermoscopy. In 2 burrows, the triangular dots were transferred to slides by doing a very superficial shave (without anesthesia) of the stratum corneum with a number 15 blade and handle. The material was placed on a slide, a drop of mineral oil added, and the slide examined microscopically (FIGURES 4 AND 5). These dermoscopically guided preparations each yielded a mite and little other debris.

FIGURE 4

Scabies mite

FIGURE 5

Mite, ova, and feces

Ink test

The “ink test” is another adjunct to help identify burrows. A nontoxic, watersoluble felt-tip marker is rubbed over an area suspected of having burrows. After waiting a few moments for the ink to sink into the disrupted stratum corneum overlying burrows, the ink is washed off, leaving an ink-demarcated burrow to examine.4 This can be performed as an adjunct to dermoscopy.5

The course of scabies

The mite’s life cycle

There are 4 stages in the mite’s life cycle: egg, larva, nymph, and adult. Female mites deposit 2 to 3 eggs per day as they create their burrows. The eggs are oval, 0.1 to 0.15 mm in length, and hatch in 3 to 8 days. The resultant larvae migrate to the skin surface and burrow into the intact stratum corneum to construct almost invisible, short burrows called molting pouches.

The larvae progress through 2 nymphal stages before a final molt to the adult stage. Larvae and nymphs live in molting pouches or in hair follicles. They appear similar to adults except for smaller size and, during the larval stage, 3 pair of legs. Adult female mites are 0.3 to 0.4 mm long and about 0.25 to 0.35 mm wide, about twice the size of males. Mating occurs when a male penetrates the molting pouch of the adult female. Impregnated females then extend their molting pouches to form the characteristic serpentine burrows, laying eggs in the process. The total period to progress from egg to the gravid female stage takes 10 to 14 days. The impregnated females spend the remaining 2 months of their lives in burrows.3,4

The mites live in and on the stratum corneum, burrowing into but never below the stratum corneum. The burrows appear as raised, serpentine lines varying from a few millimeters up to several centimeters long. Transmission occurs by the transfer of ova-bearing females.3,4

Cause of the rash and itch

The mites do not “bite.” Instead, the hallmark of scabies, when found, are the burrows created by the mites. However, it is common to see a papular urticarial type response as an allergic reaction to antigens associated with the mite itself, its scybala, and eggs. In fact, after acquiring scabies for the first time, itch does not appear for 2 to 6 weeks (average, 3 to 4 weeks) because the host needs to be sensitized to these antigens.4

It is not until the immunologic reactivity or sensitization develops that the host becomes symptomatic and aware of a problem. This requirement for sensitization explains the often gradual onset of itch. The incubation period is important in transmission to other individuals during the asymptomatic phase.3 However, a previously sensitized host may experience itch within hours to days after reinfestation.4

Epidemiology of scabies

Scabies infestations occur in all geographic areas and climates, and affects people of all ages and socioeconomic strata.7 For unexplained reasons, those with African ancestry rarely acquire scabies.7

It is most common in those who have close physical contact with others and, therefore, disproportionately affects children, mothers of young children, sexually active young adults, nursing home populations, and those in crowded living situations. Scabies is commonplace in developing countries. It is possible to acquire scabies after sleeping in unsanitary bedding. The scabies mite does not carry other diseases.7

Crusted scabies

Crusted scabies, a rare form of scabies also known as Norwegian scabies, is an aggressive infestation that usually occurs in immunodeficient, debilitated, or malnourished persons. Crusted scabies, because of the huge mite burden, is associated with greater transmissibility than scabies.7 Interestingly, because of impaired allergic response or indifference to itch, some of these patients may exhibit little pruritus.7

Treatment of scabies

Perhaps the most difficult job in treatment of scabies is treating asymptomatic contacts. Physicians may be reluctant to prescribe, and contacts themselves may be reluctant to take, appropriate treatment. These individuals often spread the infection for 4 to 6 weeks before they develop sensitization and clinical symptoms. Thus, it is essential that these asymptomatic contacts be treated or a cycle of reinfestation will be created.3 All sexual contacts, close personal contacts, and household contacts from within the preceding month should be examined and treated.8

Permethrin cream. The recommended treatment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is permethrin cream (5%) applied to all areas of the body from the neck down and thoroughly washed off after 8 to 14 hours. This recommendation includes careful application under fingernails, between toes, and on palms and soles. Infants may need the face and scalp treated in addition. Treatment of the face beyond infancy frequently results in a contact irritant dermatitis. Permethrin is effective and safe but costs more than lindane.8

Lindane. The CDC guidelines offer 2 alternatives to permethrin. One alternative, lindane 1% cream or lotion, can be applied in a thin layer to all areas of the body from the neck down and thoroughly washed off after 8 hours.

Lindane should not be used immediately after a bath or shower, and should not be used by persons who have extensive dermatitis, pregnant or lactating women, or children aged less than 2 years. Lindane resistance has been reported, including in the United States. Seizures have occurred when lindane was applied after a bath or used by patients who had extensive dermatitis. Aplastic anemia following lindane use also has been reported. Infants, young children, and pregnant or lactating women should not be treated with lindane; they can be treated with permethrin.8

Applying topical treatments. Topical scabicides should be applied to all skin from neck down, including intertriginous areas and the gluteal fold. The medication needs to be reapplied to hands if the hands are washed after application. It is advisable to cut fingernails short before applying scabicides and to ensure that scabicide is applied under fingernails. A toothpick can be used if necessary to assist in application under nails. In infants and small children, medication should be applied to face and scalp, avoiding the periorbital area.6

Other treatments. Ivermectin, the third treatment recommended by the CDC, can be administered as a single dose of 200 mcg/kg orally, and repeated in 2 weeks. Ivermectin is not recommended for pregnant or lactating patients. The safety of ivermectin in children who weigh less than 15 kg has not been determined.8

Some specialists recommend retreatment after 1 to 2 weeks for patients who are still symptomatic. Patients who do not respond to the recommended treatment should be retreated with an alternative regimen.8

Patients who have uncomplicated scabies and also are infected with HIV should receive the same treatment regimens as those who are HIV-negative.8 For patients with crusted scabies, the optimal regimen is unknown because no controlled therapeutic trials have been conducted. Expert opinion suggests augmented and combined regimens should be used for this aggressive infestation. Lindane should be avoided because of risks of neurotoxicity with heavy applications.8 Control of scabies epidemics (eg, in nursing homes, hospitals, residential facilities) require treatment of the entire population at risk.

Ancillary measures

Scabies mites may survive for a few days after leaving human skin. Thus, frequent bed linen changes minimize transmission via bedding. Hot-water laundry in temperatures of 120°F (49°s mites in 10 minutes and is sufficient to disinfect all bedding, clothing, and washable items.3

Other methods of disinfection include placing items in a dryer on the hot cycle for 10 to 30 minutes, pressing them with a warm iron, dry-cleaning, or placing in a sealed plastic bag for 7 to 14 days. Carpets or upholstery should be vacuumed through the heavy traffic areas. Fumigation of living areas and furniture with insecticide is unnecessary.6-8 Pets do not need to be treated.6 Children may return to school and childcare immediately following initial treatment.6

Follow-up of scabies patient

The boy’s mother is allowed to view the mites through the microscope, fostering her accepting the diagnosis and enhancing the chance for compliance with treatment, which involves treating the entire family.

Patients should be informed that the rash and pruritus of scabies may persist for 4 weeks after treatment because scabietic antigenic material remains until natural epidermal sloughing and turnover occurs.3 When symptoms or signs persist, evaluation should ensue for faulty application of topical scabicides and for treatment failure.7

Acknowledgments

The author (GNF) wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Peggy Elston and Heather Martinez, without whose assistance photographs like these would never happen; and Lisa Nichols, without whose acquisitive skills it never would have occurred to me to mite-hunt with a dermatoscope.

CORRESPONDENCE

Gary N. Fox, MD, Defiance Clinic, 1400 East Second Street, Defiance, OH 43512. E-mail: [email protected]

A boy came to the office with a rash and progressively severe itching for approximately 2 months (FIGURE 1). Examination showed an excoriated generalized papular eruption, including some urticarial-type papules and chronic eczematoid changes near the waist, axillae, hands, and wrists.

His grandmother, with whom he spends most weekends and a lot of time after school, also has had a rash and progressive itch for approximately 3 weeks. One feature of the dermopathy observed clinically, first located by hand lens examination and then confirmed by dermoscopy, is depicted in FIGURE 2.

FIGURE 1

Excoriated eruptions

FIGURE 2

Dermoscopic photograph of the dermatosis

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Scabies

The boy and his grandmother both have scabies, an infectious disease—in fact, the first human disease proven to be caused by a specific agent.1Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis, or scabies, is a mite in the arachnid class.2 In some states and localities, scabies cases or scabies outbreaks are reportable to the public health department.

The cardinal symptom of scabies is pruritus. The itch, especially with initial scabietic infestation, may be gradual in onset.3 Physical examination findings can vary from subtle and nonspecific to overwhelming and distinctive. Scabies can also mimic other dermopathies, complicating diagnosis. Undiagnosed and untreated, scabies can last a protracted period.

The dermopathy may be characterized by urticarial-type papules, vesicles, eczematoid change, excoriation, and bacterial superinfection, especially in children. Nodules may be present, particularly on the penis and scrotum. These may last for months after the infestation has cleared.3 The most commonly involved areas include fingers and finger webs, wrist folds, elbows, knees, the lower abdomen, armpits, thighs, male genitals, nipples, breasts, buttocks, and shoulder blades.3,4 In young children, scabies may be found anywhere, including palms, soles, face and scalp.

Affliction of multiple family members and finding dermatitis in these distinctive locations is helpful in diagnosis. Finding the mites’ burrows is considered pathognomonic because other burrowing diseases (eg, cutaneous larva migrans) are easily distinguished clinically.4 Extensive excoriation is a clinical clue to look for burrows.3

Transmission usually skin-to-skin

Scabies is generally transmitted by prolonged skin-to-skin contact, such as occurs in families or during sexual contact. It is possible to acquire scabies infestation via contaminated items of clothing or bed linens, but this is not regarded as a significant route of transmission.3 Transmission by casual contact, such as a handshake or hug, is unlikely.

Infestation with the S scabiei mite, referred to as scabies in man, is termed “mange” in other mammals known to host the mite (dogs, cats, rabbits, cattle, pigs, and horses). Mites from one host species generally do not establish themselves on another species, and thus are referred to as varieties, variants, or forms. Humans develop a transient dermopathy from infestation by animal scabies, but such infestations are mild and disappear spontaneously unless the person is in frequent contact with the infested animal.3,4

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of scabies—a great masquerader—is extensive, and includes atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, impetigo, insect bites, vasculitis, neurodermatitis, folliculitis, prurigo nodularis, psoriasis (crusted scabies), and a host of other dermopathies.3,4

Confirming the diagnosis

Finding the causative mite, its ova (eggs), or scybala (feces), confirms the diagnosis, although failure to find these does not rule out scabies. Papules or burrows that have not been excoriated are best for obtaining preparations for microscopic examination.3 Burrows may be found with nakedeye inspection, although use of a hand-held magnifier and good illumination make finding burrows easier.

Dermoscopy

Dermoscopy, performed with an otoscope-like, illuminated magnifier designed for skin assessment, provides reliable confirmation of S- or Z-shaped burrows. During dermoscopy, carefully examining the distal end of the burrows in the skin may reveal the “triangular black dot” of the scabies mite (FIGURE 2, top right)—the head of the mite.5 The body of the mite—light in color and oval—is not visible even with the most careful dermoscopic examination. The “black dot” of the mite may be visible with careful inspection with a hand lens. In the appropriate clinical setting, dermoscopic identification of an unequivocal burrow with the dark “triangle sign” at one end is diagnostic for scabies. When a digital photograph obtained through the dermatoscope is magnified, the distal end of the burrow (FIGURE 3) reveals the triangular head parts of the mite and the body within the burrow. This body is not evident with dermoscopy alone; the additional magnification via photography allows its visualization.

FIGURE 3

Magnification

Scabies mount

In instances where the physician is going to make an institution-wide recommendation with major ramifications, it is wise to positively identify the mite. A scabies mount performed at the location of the triangular dot will readily provide a mite for identification. Scabies mounts are prepared via a very superficial shave technique without anesthesia. The skin flakes are transferred to a slide and a drop of mineral oil is added. Alternatively, a drop of mineral oil can be placed on the skin and a superficial sample obtained.

Note that this technique differs from that of potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation for fungal identification. The scabies mount technique is more like a superficial shave biopsy (with the knife blade parallel to the skin) than a KOH preparation (blade dragged along the skin surface more perpendicular to the skin).Microscopic examination of each slide reveals a mite (FIGURES 4 AND 5).

In our patient, 3 burrows were identified with a hand lens and confirmed by dermoscopy. In 2 burrows, the triangular dots were transferred to slides by doing a very superficial shave (without anesthesia) of the stratum corneum with a number 15 blade and handle. The material was placed on a slide, a drop of mineral oil added, and the slide examined microscopically (FIGURES 4 AND 5). These dermoscopically guided preparations each yielded a mite and little other debris.

FIGURE 4

Scabies mite

FIGURE 5

Mite, ova, and feces

Ink test

The “ink test” is another adjunct to help identify burrows. A nontoxic, watersoluble felt-tip marker is rubbed over an area suspected of having burrows. After waiting a few moments for the ink to sink into the disrupted stratum corneum overlying burrows, the ink is washed off, leaving an ink-demarcated burrow to examine.4 This can be performed as an adjunct to dermoscopy.5

The course of scabies

The mite’s life cycle

There are 4 stages in the mite’s life cycle: egg, larva, nymph, and adult. Female mites deposit 2 to 3 eggs per day as they create their burrows. The eggs are oval, 0.1 to 0.15 mm in length, and hatch in 3 to 8 days. The resultant larvae migrate to the skin surface and burrow into the intact stratum corneum to construct almost invisible, short burrows called molting pouches.

The larvae progress through 2 nymphal stages before a final molt to the adult stage. Larvae and nymphs live in molting pouches or in hair follicles. They appear similar to adults except for smaller size and, during the larval stage, 3 pair of legs. Adult female mites are 0.3 to 0.4 mm long and about 0.25 to 0.35 mm wide, about twice the size of males. Mating occurs when a male penetrates the molting pouch of the adult female. Impregnated females then extend their molting pouches to form the characteristic serpentine burrows, laying eggs in the process. The total period to progress from egg to the gravid female stage takes 10 to 14 days. The impregnated females spend the remaining 2 months of their lives in burrows.3,4

The mites live in and on the stratum corneum, burrowing into but never below the stratum corneum. The burrows appear as raised, serpentine lines varying from a few millimeters up to several centimeters long. Transmission occurs by the transfer of ova-bearing females.3,4

Cause of the rash and itch

The mites do not “bite.” Instead, the hallmark of scabies, when found, are the burrows created by the mites. However, it is common to see a papular urticarial type response as an allergic reaction to antigens associated with the mite itself, its scybala, and eggs. In fact, after acquiring scabies for the first time, itch does not appear for 2 to 6 weeks (average, 3 to 4 weeks) because the host needs to be sensitized to these antigens.4

It is not until the immunologic reactivity or sensitization develops that the host becomes symptomatic and aware of a problem. This requirement for sensitization explains the often gradual onset of itch. The incubation period is important in transmission to other individuals during the asymptomatic phase.3 However, a previously sensitized host may experience itch within hours to days after reinfestation.4

Epidemiology of scabies

Scabies infestations occur in all geographic areas and climates, and affects people of all ages and socioeconomic strata.7 For unexplained reasons, those with African ancestry rarely acquire scabies.7

It is most common in those who have close physical contact with others and, therefore, disproportionately affects children, mothers of young children, sexually active young adults, nursing home populations, and those in crowded living situations. Scabies is commonplace in developing countries. It is possible to acquire scabies after sleeping in unsanitary bedding. The scabies mite does not carry other diseases.7

Crusted scabies

Crusted scabies, a rare form of scabies also known as Norwegian scabies, is an aggressive infestation that usually occurs in immunodeficient, debilitated, or malnourished persons. Crusted scabies, because of the huge mite burden, is associated with greater transmissibility than scabies.7 Interestingly, because of impaired allergic response or indifference to itch, some of these patients may exhibit little pruritus.7

Treatment of scabies

Perhaps the most difficult job in treatment of scabies is treating asymptomatic contacts. Physicians may be reluctant to prescribe, and contacts themselves may be reluctant to take, appropriate treatment. These individuals often spread the infection for 4 to 6 weeks before they develop sensitization and clinical symptoms. Thus, it is essential that these asymptomatic contacts be treated or a cycle of reinfestation will be created.3 All sexual contacts, close personal contacts, and household contacts from within the preceding month should be examined and treated.8

Permethrin cream. The recommended treatment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is permethrin cream (5%) applied to all areas of the body from the neck down and thoroughly washed off after 8 to 14 hours. This recommendation includes careful application under fingernails, between toes, and on palms and soles. Infants may need the face and scalp treated in addition. Treatment of the face beyond infancy frequently results in a contact irritant dermatitis. Permethrin is effective and safe but costs more than lindane.8

Lindane. The CDC guidelines offer 2 alternatives to permethrin. One alternative, lindane 1% cream or lotion, can be applied in a thin layer to all areas of the body from the neck down and thoroughly washed off after 8 hours.

Lindane should not be used immediately after a bath or shower, and should not be used by persons who have extensive dermatitis, pregnant or lactating women, or children aged less than 2 years. Lindane resistance has been reported, including in the United States. Seizures have occurred when lindane was applied after a bath or used by patients who had extensive dermatitis. Aplastic anemia following lindane use also has been reported. Infants, young children, and pregnant or lactating women should not be treated with lindane; they can be treated with permethrin.8

Applying topical treatments. Topical scabicides should be applied to all skin from neck down, including intertriginous areas and the gluteal fold. The medication needs to be reapplied to hands if the hands are washed after application. It is advisable to cut fingernails short before applying scabicides and to ensure that scabicide is applied under fingernails. A toothpick can be used if necessary to assist in application under nails. In infants and small children, medication should be applied to face and scalp, avoiding the periorbital area.6

Other treatments. Ivermectin, the third treatment recommended by the CDC, can be administered as a single dose of 200 mcg/kg orally, and repeated in 2 weeks. Ivermectin is not recommended for pregnant or lactating patients. The safety of ivermectin in children who weigh less than 15 kg has not been determined.8

Some specialists recommend retreatment after 1 to 2 weeks for patients who are still symptomatic. Patients who do not respond to the recommended treatment should be retreated with an alternative regimen.8

Patients who have uncomplicated scabies and also are infected with HIV should receive the same treatment regimens as those who are HIV-negative.8 For patients with crusted scabies, the optimal regimen is unknown because no controlled therapeutic trials have been conducted. Expert opinion suggests augmented and combined regimens should be used for this aggressive infestation. Lindane should be avoided because of risks of neurotoxicity with heavy applications.8 Control of scabies epidemics (eg, in nursing homes, hospitals, residential facilities) require treatment of the entire population at risk.

Ancillary measures

Scabies mites may survive for a few days after leaving human skin. Thus, frequent bed linen changes minimize transmission via bedding. Hot-water laundry in temperatures of 120°F (49°s mites in 10 minutes and is sufficient to disinfect all bedding, clothing, and washable items.3

Other methods of disinfection include placing items in a dryer on the hot cycle for 10 to 30 minutes, pressing them with a warm iron, dry-cleaning, or placing in a sealed plastic bag for 7 to 14 days. Carpets or upholstery should be vacuumed through the heavy traffic areas. Fumigation of living areas and furniture with insecticide is unnecessary.6-8 Pets do not need to be treated.6 Children may return to school and childcare immediately following initial treatment.6

Follow-up of scabies patient

The boy’s mother is allowed to view the mites through the microscope, fostering her accepting the diagnosis and enhancing the chance for compliance with treatment, which involves treating the entire family.

Patients should be informed that the rash and pruritus of scabies may persist for 4 weeks after treatment because scabietic antigenic material remains until natural epidermal sloughing and turnover occurs.3 When symptoms or signs persist, evaluation should ensue for faulty application of topical scabicides and for treatment failure.7

Acknowledgments

The author (GNF) wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Peggy Elston and Heather Martinez, without whose assistance photographs like these would never happen; and Lisa Nichols, without whose acquisitive skills it never would have occurred to me to mite-hunt with a dermatoscope.

CORRESPONDENCE

Gary N. Fox, MD, Defiance Clinic, 1400 East Second Street, Defiance, OH 43512. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Binder WD. Scabies. eMedicine [online database]. Available at: www.emedicine.com/emerg/topic517.htm. Accessed on July 6, 2006.

2. Arachnid. Wikipedia [online encyclopedia]. Available at: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arachnid. Accessed on July 6, 2006.

3. Scabies. DPDx—CDC Parasitology Diagnostic Website. Available at: www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Scabies.htm. Accessed on July 6, 2006.

4. Arya V, Molinaro MJ, Majewski SS, Schwartz RA. Pediatric scabies. Cutis 2003;71:193-196.

5. Vazquez-Lopez F, Kreusch JF, Marghoob AA. Other uses of dermoscopy. In: Marghoob AA, Braun RP, Kopf AW, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2005:301,305-306.

6. FAQs—scabies. Texas Department of Health Services, Infectious Disease Control Unit website. Available at: www.dshs.state.tx.us/idcu/disease/scabies/faqs/. Accessed on July 6, 2006.

7. Infestations and bites [chapter 15]. In: Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. New York: Mosby; 2004:497-503.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2002. MMWR Recomm Rep 2002;51(RR-6):68-69.

1. Binder WD. Scabies. eMedicine [online database]. Available at: www.emedicine.com/emerg/topic517.htm. Accessed on July 6, 2006.

2. Arachnid. Wikipedia [online encyclopedia]. Available at: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arachnid. Accessed on July 6, 2006.

3. Scabies. DPDx—CDC Parasitology Diagnostic Website. Available at: www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Scabies.htm. Accessed on July 6, 2006.

4. Arya V, Molinaro MJ, Majewski SS, Schwartz RA. Pediatric scabies. Cutis 2003;71:193-196.

5. Vazquez-Lopez F, Kreusch JF, Marghoob AA. Other uses of dermoscopy. In: Marghoob AA, Braun RP, Kopf AW, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2005:301,305-306.

6. FAQs—scabies. Texas Department of Health Services, Infectious Disease Control Unit website. Available at: www.dshs.state.tx.us/idcu/disease/scabies/faqs/. Accessed on July 6, 2006.

7. Infestations and bites [chapter 15]. In: Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. New York: Mosby; 2004:497-503.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2002. MMWR Recomm Rep 2002;51(RR-6):68-69.

A 47-year-old man with eruptions on his trunk

A 47-year-old white male came to the hospital emergency department complaining of chest pain. At admission, it was noted that the patient had numerous lesions on his buttocks, abdomen, back, and all extremities (FIGURES 1 AND 2). These lesions had been there for approximately 5 months—they developed after he discontinued his cholesterol medication due to lapsed insurance coverage. He had a similar eruption when he went off cholesterol medication on another occasion.

The patient’s medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and hyperlipidemia. He has had multiple heart catheterizations with stent placement, most recently 2 years ago. His mother also had diabetes mellitus, and she died at age 58 from a myocardial infarction.

On examination, his lesions were painless and nonpruritic. He had numerous yellow papules on his buttocks, abdomen, back, and upper and lower extremities. He had no lesions on his face. The rest of the physical exam showed no abnormal results.

FIGURE 1

Nodular lesions on back

The patient had yellow nodular lesions covering his entire trunk and all 4 extremities.

FIGURE 2

Close-up

What is your diagnosis?

What laboratory tests should be done to help make the diagnosis?

DIAGNOSIS: Eruptive xanthomas

This patient has eruptive xanthomas secondary to hypertriglyceridemia. His type IV hyperlipidemia has been worsened by long-standing, poorly controlled type 2 diabetes.

Xanthomas are lipid deposits in the skin and tendons that occur secondarily to a lipid abnormality. These lipid deposits are yellow and frequently firm.1 Although certain types of xanthomas are characteristic of particular lipid abnormalities, none is totally specific because the same form of xanthomas occurs in many different diseases.2

Xanthomas occur in various metabolic disorders and can also be associated with neoplasms. They may be associated with familial or acquired disorders resulting in hyperlipidemia or may be present with no underlying disorder.3

Types of xanthomas. Xanthomas are classified into 5 types based on clinical appearance. Tuberous and tendinous xanthomas both occur on the extensors of fingers and Achilles tendon. They appear as yellow nodules. Plane xanthomas are associated with biliary disease and appear as linear yellow lesions. Xanthelasmas appear as yellow plaques on the eyelids. Eruptive xanthomas are yellow papules that appear and disappear according to variations in lipid levels, especially triglycerides.3 As in this case, eruptive xanthomas usually appear over the buttocks, shoulders, back, and extensor surfaces of the extremities.4

Laboratory tests helpful in making the diagnosis

The patient’s tests on hospital admission showed normal cardiac enzymes and a normal electrocardiogram (ECG). His electrolytes were within normal limits except for a pseudohyponatremia of 133 mEq/dL due to an elevated glucose of 549 mg/dL.

A lipid profile the following morning revealed a triglyceride level of 1976 mg/dL, a total cholesterol level of 323 mg/dL, and a high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level of 24 mg/dL. The low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol could not be calculated due to the high triglyceride level.

Differential diagnosis

Neurofibromas may have an appearance similar to eruptive xanthomas, but would usually be less numerous and less symptomatic. Prurigo nodularis would be another condition to be considered; however, this patient did not have any excoriations. Primary milia can also appear as keratinfilled cysts; however, these are much smaller and usually located on the face.

TREATMENT: Control the lipids and triglycerides

Patients may be prescribed HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) and fibric acid derivatives for control of lipid and triglyceride abnormalities. Further, counseling should involve diet modification, exercise, smoking cessation, and stringent control of diabetes.5 As a general rule, high doses of statins should not be given to patients who are taking fibrates.6 The combination of a statin and fibric acid derivative is not without risks: it may increase the risk of myopathy and rhabdomyolysis.

We started this patient on fenofibrate (Tricor) along with rosuvastatin (Crestor). When given in combination with any statin medication, fenofibrate resulted in fewer reports of rhabdomyolysis and myopathy than the older fibrate gemfibrozil (Lopid). It is believed that fenofibrate undergoes a different pathway of glucuronidation than gemfibrozil. Most statins undergo glucuronidation in the same family of enzymes as gemfibrozil, which could cause competition in converting the statin to a form that undergoes liver metabolism. Thus, metabolism of the statin is decreased and adverse effects such as rhabdomyolysis and myopathy occurs.7

Outcome

The patient started on rosuvastatin 10 mg once a day and fenofibrate 145 mg once a day. The patient’s xanthomas improved dramatically within a month (FIGURES 3 AND 4). His cholesterol, on the therapy described above, improved dramatically. His triglycerides decreased to 363 mg/dL. His total cholesterol was now 138 mg/dL, with an HDL of 34 mg/dL and an LDL of 31 mg/dL.

FIGURE 3

After treatment

FIGURE 4

Close-up

The patient reported no adverse effects from the medications. It was recommended that he continue on his present therapy indefinitely with the proper laboratory follow-up. We have not increased his dose of either medication, since his admission and no side effects have been encountered. We will continue to monitor his liver function tests and adjust the dose of his medications as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jay Shubrook, DO, Parks Hall, Ohio University College of Medicine, Athens, OH 45701.

1. Damjanov I, Linder J. Diseases of the skin and connective tissues. In: Anderson’s Pathology. 10th ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby, 1996:2454-2455.

2. Habif T. Xanthomas and dyslipoproteinemia. In: Clinical Dermatology. 4th ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby, 2004:902-904.

3. Kumar V, Abbas A, Fausto N. Diseases of organ systems. In: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier Saunders, 2005:1248.

4. Freedberg I, Eisen A, Wolff K, et al. Xanthomatoses and lipoprotein disorders. In: Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1999:1804-1809.

5. Braunwald E, Fauci A, Kasper D, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J. Disorders of lipoprotein metabolism. In: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 15th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001:2245-2256.

6. Knopp RH. Drug treatment of lipid disorders. N Engl J Med 1999;341:498-511.

7. Corsini A, Bellosta S, Davidson MH. Pharmacokinetic interactions between statins and fibrates. Am J Cardiol 2005;96(9A):44K–49K; 34K-35K. Epub 2005 Oct 21.

A 47-year-old white male came to the hospital emergency department complaining of chest pain. At admission, it was noted that the patient had numerous lesions on his buttocks, abdomen, back, and all extremities (FIGURES 1 AND 2). These lesions had been there for approximately 5 months—they developed after he discontinued his cholesterol medication due to lapsed insurance coverage. He had a similar eruption when he went off cholesterol medication on another occasion.

The patient’s medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and hyperlipidemia. He has had multiple heart catheterizations with stent placement, most recently 2 years ago. His mother also had diabetes mellitus, and she died at age 58 from a myocardial infarction.

On examination, his lesions were painless and nonpruritic. He had numerous yellow papules on his buttocks, abdomen, back, and upper and lower extremities. He had no lesions on his face. The rest of the physical exam showed no abnormal results.

FIGURE 1

Nodular lesions on back

The patient had yellow nodular lesions covering his entire trunk and all 4 extremities.

FIGURE 2

Close-up

What is your diagnosis?

What laboratory tests should be done to help make the diagnosis?

DIAGNOSIS: Eruptive xanthomas

This patient has eruptive xanthomas secondary to hypertriglyceridemia. His type IV hyperlipidemia has been worsened by long-standing, poorly controlled type 2 diabetes.

Xanthomas are lipid deposits in the skin and tendons that occur secondarily to a lipid abnormality. These lipid deposits are yellow and frequently firm.1 Although certain types of xanthomas are characteristic of particular lipid abnormalities, none is totally specific because the same form of xanthomas occurs in many different diseases.2

Xanthomas occur in various metabolic disorders and can also be associated with neoplasms. They may be associated with familial or acquired disorders resulting in hyperlipidemia or may be present with no underlying disorder.3

Types of xanthomas. Xanthomas are classified into 5 types based on clinical appearance. Tuberous and tendinous xanthomas both occur on the extensors of fingers and Achilles tendon. They appear as yellow nodules. Plane xanthomas are associated with biliary disease and appear as linear yellow lesions. Xanthelasmas appear as yellow plaques on the eyelids. Eruptive xanthomas are yellow papules that appear and disappear according to variations in lipid levels, especially triglycerides.3 As in this case, eruptive xanthomas usually appear over the buttocks, shoulders, back, and extensor surfaces of the extremities.4

Laboratory tests helpful in making the diagnosis

The patient’s tests on hospital admission showed normal cardiac enzymes and a normal electrocardiogram (ECG). His electrolytes were within normal limits except for a pseudohyponatremia of 133 mEq/dL due to an elevated glucose of 549 mg/dL.

A lipid profile the following morning revealed a triglyceride level of 1976 mg/dL, a total cholesterol level of 323 mg/dL, and a high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level of 24 mg/dL. The low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol could not be calculated due to the high triglyceride level.

Differential diagnosis

Neurofibromas may have an appearance similar to eruptive xanthomas, but would usually be less numerous and less symptomatic. Prurigo nodularis would be another condition to be considered; however, this patient did not have any excoriations. Primary milia can also appear as keratinfilled cysts; however, these are much smaller and usually located on the face.

TREATMENT: Control the lipids and triglycerides

Patients may be prescribed HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) and fibric acid derivatives for control of lipid and triglyceride abnormalities. Further, counseling should involve diet modification, exercise, smoking cessation, and stringent control of diabetes.5 As a general rule, high doses of statins should not be given to patients who are taking fibrates.6 The combination of a statin and fibric acid derivative is not without risks: it may increase the risk of myopathy and rhabdomyolysis.

We started this patient on fenofibrate (Tricor) along with rosuvastatin (Crestor). When given in combination with any statin medication, fenofibrate resulted in fewer reports of rhabdomyolysis and myopathy than the older fibrate gemfibrozil (Lopid). It is believed that fenofibrate undergoes a different pathway of glucuronidation than gemfibrozil. Most statins undergo glucuronidation in the same family of enzymes as gemfibrozil, which could cause competition in converting the statin to a form that undergoes liver metabolism. Thus, metabolism of the statin is decreased and adverse effects such as rhabdomyolysis and myopathy occurs.7

Outcome

The patient started on rosuvastatin 10 mg once a day and fenofibrate 145 mg once a day. The patient’s xanthomas improved dramatically within a month (FIGURES 3 AND 4). His cholesterol, on the therapy described above, improved dramatically. His triglycerides decreased to 363 mg/dL. His total cholesterol was now 138 mg/dL, with an HDL of 34 mg/dL and an LDL of 31 mg/dL.

FIGURE 3

After treatment

FIGURE 4

Close-up

The patient reported no adverse effects from the medications. It was recommended that he continue on his present therapy indefinitely with the proper laboratory follow-up. We have not increased his dose of either medication, since his admission and no side effects have been encountered. We will continue to monitor his liver function tests and adjust the dose of his medications as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jay Shubrook, DO, Parks Hall, Ohio University College of Medicine, Athens, OH 45701.

A 47-year-old white male came to the hospital emergency department complaining of chest pain. At admission, it was noted that the patient had numerous lesions on his buttocks, abdomen, back, and all extremities (FIGURES 1 AND 2). These lesions had been there for approximately 5 months—they developed after he discontinued his cholesterol medication due to lapsed insurance coverage. He had a similar eruption when he went off cholesterol medication on another occasion.

The patient’s medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and hyperlipidemia. He has had multiple heart catheterizations with stent placement, most recently 2 years ago. His mother also had diabetes mellitus, and she died at age 58 from a myocardial infarction.

On examination, his lesions were painless and nonpruritic. He had numerous yellow papules on his buttocks, abdomen, back, and upper and lower extremities. He had no lesions on his face. The rest of the physical exam showed no abnormal results.

FIGURE 1

Nodular lesions on back

The patient had yellow nodular lesions covering his entire trunk and all 4 extremities.

FIGURE 2

Close-up

What is your diagnosis?

What laboratory tests should be done to help make the diagnosis?

DIAGNOSIS: Eruptive xanthomas

This patient has eruptive xanthomas secondary to hypertriglyceridemia. His type IV hyperlipidemia has been worsened by long-standing, poorly controlled type 2 diabetes.

Xanthomas are lipid deposits in the skin and tendons that occur secondarily to a lipid abnormality. These lipid deposits are yellow and frequently firm.1 Although certain types of xanthomas are characteristic of particular lipid abnormalities, none is totally specific because the same form of xanthomas occurs in many different diseases.2

Xanthomas occur in various metabolic disorders and can also be associated with neoplasms. They may be associated with familial or acquired disorders resulting in hyperlipidemia or may be present with no underlying disorder.3

Types of xanthomas. Xanthomas are classified into 5 types based on clinical appearance. Tuberous and tendinous xanthomas both occur on the extensors of fingers and Achilles tendon. They appear as yellow nodules. Plane xanthomas are associated with biliary disease and appear as linear yellow lesions. Xanthelasmas appear as yellow plaques on the eyelids. Eruptive xanthomas are yellow papules that appear and disappear according to variations in lipid levels, especially triglycerides.3 As in this case, eruptive xanthomas usually appear over the buttocks, shoulders, back, and extensor surfaces of the extremities.4

Laboratory tests helpful in making the diagnosis

The patient’s tests on hospital admission showed normal cardiac enzymes and a normal electrocardiogram (ECG). His electrolytes were within normal limits except for a pseudohyponatremia of 133 mEq/dL due to an elevated glucose of 549 mg/dL.

A lipid profile the following morning revealed a triglyceride level of 1976 mg/dL, a total cholesterol level of 323 mg/dL, and a high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level of 24 mg/dL. The low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol could not be calculated due to the high triglyceride level.

Differential diagnosis

Neurofibromas may have an appearance similar to eruptive xanthomas, but would usually be less numerous and less symptomatic. Prurigo nodularis would be another condition to be considered; however, this patient did not have any excoriations. Primary milia can also appear as keratinfilled cysts; however, these are much smaller and usually located on the face.

TREATMENT: Control the lipids and triglycerides

Patients may be prescribed HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) and fibric acid derivatives for control of lipid and triglyceride abnormalities. Further, counseling should involve diet modification, exercise, smoking cessation, and stringent control of diabetes.5 As a general rule, high doses of statins should not be given to patients who are taking fibrates.6 The combination of a statin and fibric acid derivative is not without risks: it may increase the risk of myopathy and rhabdomyolysis.

We started this patient on fenofibrate (Tricor) along with rosuvastatin (Crestor). When given in combination with any statin medication, fenofibrate resulted in fewer reports of rhabdomyolysis and myopathy than the older fibrate gemfibrozil (Lopid). It is believed that fenofibrate undergoes a different pathway of glucuronidation than gemfibrozil. Most statins undergo glucuronidation in the same family of enzymes as gemfibrozil, which could cause competition in converting the statin to a form that undergoes liver metabolism. Thus, metabolism of the statin is decreased and adverse effects such as rhabdomyolysis and myopathy occurs.7

Outcome

The patient started on rosuvastatin 10 mg once a day and fenofibrate 145 mg once a day. The patient’s xanthomas improved dramatically within a month (FIGURES 3 AND 4). His cholesterol, on the therapy described above, improved dramatically. His triglycerides decreased to 363 mg/dL. His total cholesterol was now 138 mg/dL, with an HDL of 34 mg/dL and an LDL of 31 mg/dL.

FIGURE 3

After treatment

FIGURE 4

Close-up

The patient reported no adverse effects from the medications. It was recommended that he continue on his present therapy indefinitely with the proper laboratory follow-up. We have not increased his dose of either medication, since his admission and no side effects have been encountered. We will continue to monitor his liver function tests and adjust the dose of his medications as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jay Shubrook, DO, Parks Hall, Ohio University College of Medicine, Athens, OH 45701.

1. Damjanov I, Linder J. Diseases of the skin and connective tissues. In: Anderson’s Pathology. 10th ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby, 1996:2454-2455.

2. Habif T. Xanthomas and dyslipoproteinemia. In: Clinical Dermatology. 4th ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby, 2004:902-904.

3. Kumar V, Abbas A, Fausto N. Diseases of organ systems. In: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier Saunders, 2005:1248.

4. Freedberg I, Eisen A, Wolff K, et al. Xanthomatoses and lipoprotein disorders. In: Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1999:1804-1809.

5. Braunwald E, Fauci A, Kasper D, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J. Disorders of lipoprotein metabolism. In: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 15th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001:2245-2256.

6. Knopp RH. Drug treatment of lipid disorders. N Engl J Med 1999;341:498-511.

7. Corsini A, Bellosta S, Davidson MH. Pharmacokinetic interactions between statins and fibrates. Am J Cardiol 2005;96(9A):44K–49K; 34K-35K. Epub 2005 Oct 21.

1. Damjanov I, Linder J. Diseases of the skin and connective tissues. In: Anderson’s Pathology. 10th ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby, 1996:2454-2455.

2. Habif T. Xanthomas and dyslipoproteinemia. In: Clinical Dermatology. 4th ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby, 2004:902-904.

3. Kumar V, Abbas A, Fausto N. Diseases of organ systems. In: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier Saunders, 2005:1248.

4. Freedberg I, Eisen A, Wolff K, et al. Xanthomatoses and lipoprotein disorders. In: Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1999:1804-1809.

5. Braunwald E, Fauci A, Kasper D, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J. Disorders of lipoprotein metabolism. In: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 15th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001:2245-2256.

6. Knopp RH. Drug treatment of lipid disorders. N Engl J Med 1999;341:498-511.

7. Corsini A, Bellosta S, Davidson MH. Pharmacokinetic interactions between statins and fibrates. Am J Cardiol 2005;96(9A):44K–49K; 34K-35K. Epub 2005 Oct 21.

Dark brown scaly plaques on face and ears

A 27-year-old woman, otherwise healthy, presented for evaluation of a mildly pruritic eruption of plaques on her face and ears. The eruption started as a few small, scaly red papules on her cheeks and nose about 3 months earlier. The papules slowly expanded to form well-demarcated, rounded, dark brown plaques covered with superficial scale. Similar lesions appeared on the concha of both ears. The older lesions started to regress after 2 months. Complete regression was followed by residual scarring and hyperpigmentation.

Physical examination revealed multiple well-defined, erythematous, hyperpigmented, round plaques covered with adherent scale affecting her nose, cheeks, and the concha of both ears (FIGURE 1). The mucosae and the rest of her skin and adnexa were unaffected. She had no personal or family history of similar skin findings or autoimmune disorders. She also had no history of any drug intake prior to the eruption. Her routine blood tests and urinalysis results were unremarkable, and the serological analysis for antinuclear antibodies had negative results.

A punch biopsy was taken from one of the lesions for histopathology. The epidermal histopathological findings were remarkable for hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, pigment incontinence, and vacuolization of the basal cell layer. There was a predominantly lymphocytic infiltrate of the subepidermal and perivascular dermal areas.

FIGURE 1

Facial plaques

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Discoid lupus erythematosus

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is an autoimmune inflammatory disorder of the skin that often leads to scarring and alopecia. It may be localized to sun-exposed areas such as the face, ears, and scalp but occasionally is much more extensive, involving the trunk and extremities. Most patients are otherwise healthy, and DLE may be the only clinical finding.

Although its prevalence is not known, DLE is not uncommon. It affects females twice as often as males, and patients fall between the ages of 25 to 45 years, with no racial predilection. While about 15% to 20% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) manifest DLE lesions, only about 5% to 10% of patients with DLE go on to develop SLE.1

Like SLE, DLE is believed to be an autoimmune disorder. Unlike SLE, however, DLE patients do not have similar serologic abnormalities. Skin trauma and ultraviolet light exposure have been reported to induce or exacerbate the lesions of DLE. Sex hormones may also play a role: exacerbation may occur during pregnancy, during menstrual or premenstrual periods, or while taking oral contraceptives. Drugs such as procainamide, hydralazine, isoniazid, diphenylhydantoin, methyldopa, penicillamine, guanides, and lithium may also precipitate DLE lesions.2

DLE usually begins as dull red macules with adherent scales on sun-exposed areas. If the overlying scales are removed, an undersurface of horny plugs is revealed. These plugs fill the follicles and resemble carpet tacks or a cat’s tongue (langue au chat). The macules slowly expand to form large plaques.

Usually only a mild pruritus and tenderness is seen with DLE lesions. As the lesions progress, the scale may thicken and pigmentary changes become evident. The lesions heal with atrophy, scarring, telangiectasias, and changes in pigmentation. Morphological appearance of older lesions may vary from erythematous plaques to hyperkeratotic, dark gray plaques with centrally depressed scars.3 Scalp involvement in DLE results in more sclerotic and depressed scars with subsequent scarring alopecia.4

Differential diagnosis is wide. The differential diagnosis of DLE is extensive and includes actinic keratosis, dermatomyositis, granuloma annulare, granuloma faciale, keratoacanthoma, lichen planus, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, rosacea, sarcoidosis, squamous cell carcinoma, syphilis, and nongenital warts.

Histopathology

Histopathological findings include hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, follicular plugging, telangiectasias, and atrophy of the epidermis. Liquefaction or hydropic degeneration of the basal layer leads to pigmentary incontinence. A perivascular and perifollicular mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate is present in the superficial and deep dermis.5,6

Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates immunoglobulins and complement deposits at the dermoepidermal junction.5 This test was not recommended for this patient, as the diagnosis of DLE had already been confirmed on clinical and histopathologic grounds.

Workup: Exam, biopsy

In addition to a routine history and physical examination, the workup for DLE should include a complete blood count, antinuclear antibody levels, anti-Ro, anti-La, hepatic and renal function tests, and urinalysis. Consider a diagnosis of SLE by using the American College of Rheumatology criteria. A biopsy for histopathology of a fresh lesion or a biopsy for immunofluorescence of an old lesion can confirm the diagnosis.

Therapeutic options are varied

Effective early therapies for DLE are available, but patients who do not respond appropriately may end up with deep scars, alopecia, and pigmentary changes that are considerably disfiguring, especially for dark-skinned people. Therefore, the goal of treatment is not only to improve the appearance of the skin by minimizing the scarring and preventing further lesions, but also to prevent future complications.

Avoiding sunlight. The primary therapeutic approach is to educate patients regarding exposure to sunlight. Sun-protective measures include the use of high-SPF sunscreen lotions and protective clothing, such as baseball caps without vent holes and wide-brimmed hats.7

Medication options. Current treatment options for DLE include antimalarial agents such as chloroquine, topical and intralesional glucocorticoids, and thalidomide. The use of potent topical steroids may prevent significant scarring and deformity, especially of the face. Common side effects include steroid withdrawal syndrome, perioral dermatitis, steroid acne, and rosacea. All of these side effects can be treated and result in less long-term deformity than untreated DLE (FIGURE 2).

Systemic agents. Widespread disease may require you use systemic agents, such as antimalarials. Chloroquine has long been considered the gold standard in the treatment of DLE.8 Due to the frequency of ocular side effects with chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine is by far the most widely used agent. Hydroxychloroquine at a dose of 6.5 mg/kg/d for 3 months may lead to resolution of lesions for many patients.7 In resistant cases, higher dosages (eg, 400 mg/d) or combinations (eg, hydroxychloroquine 200 mg/d plus quinacrine 50 to 100 mg/d) may be required for months or even years. An ophthalmological evaluation is advisable before starting antimalarial treatment, and you should repeat it at 4- to 6-month intervals during treatment.9 Systemic corticosteroids may be needed to obtain timely initial control, especially for widespread and disfiguring lesions.

When this therapy is inadequate, other treatments for DLE include azathioprine, retinoids, and dapsone. Recent reports confirm the efficacy of thalidomide for cutaneous lupus erythematosus in dosages ranging from 50 to 200 mg/d.10 Twice-daily application of tacrolimus 0.01% has also been shown to be effective in a few clinical trials.11