User login

Painful and swollen hands

A 67-year-old woman came to the office with pain in her hands. She had just arrived from Panama to live with her son. She has had this pain for decades: she refers to it as artritisin Spanish but does not know what type of arthritis. Aspirin had helped in the past, but lately she had not been getting enough relief from it. Her hands feel stiff in the morning for at least 1 hour, which interferes with cooking and sewing.

Her hands showed signs of joint swelling and deformities (Figure 1). Her swollen joints felt warm. She also had knee pain.

FIGURE 1

Painful,swollen hands

What type of arthritis does she have?

Are any diagnostic tests necessary?

What are the best treatments available?

That same day, another patient was seen with painful hands (Figure 2). What type of arthritis does she have, and how does it differ from the condition of the patient in Figure 1 ?

FIGURE 2

Another patient with hand pain

The obvious ulnar deviation of her fingers and the swelling of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints (Figure 1) are strongly indicative of rheumatoid arthritis. The patient in Figure 2 has swelling and deformities in her proximal inter-phalangeal (PIP) and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints, indicating that she most likely has osteoarthritis. The swelling of the PIP joints is called Bouchard’s nodes; the swelling of the DIP joints is called Heberden’s nodes.

Differential diagnosis: types of arthritis

The first decision point in diagnosing chronic (>6 weeks) polyarticular joint pain is distinguishing between inflammatory and noninflammatory arthritis. Key features of inflammatory arthritis are stiffness in the morning or after inactivity, and visible joint swelling. The differential diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis includes rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, seronegative spondyloarthropathies, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

After the age of 50, maturity-onset seronegative synovitis syndrome and crystal-induced synovitis should also be considered.1 Although osteoarthritis is considered noninflammatory, inflammation of the joint tissue occurs occasionally due to the joint’s degenerative loss of cartilage and bony overgrowth.

It is critical to identify rheumatoid arthritis early, as prompt intervention can delay disease progression, and reduce the substantial morbidity and mortality of rheumatoid arthritis.2 A diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis requires 4 of the following: morning stiffness; arthritis in 3 or more joints; arthritis in the wrist, MCP joints, or PIP joints; symmetric arthritis; rheumatoid nodules; positive rheumatoid factor; radiographic changes.1 This patient has the morning stiffness, arthritis in more than 3 joints, symmetric arthritis, and rheumatoid nodules on her feet (Figure 3).

The most common noninflammatory arthritis is osteoarthritis, which affects 21 million Americans.2 The weight-bearing joints are usually affected, and damage may occur because of trauma or repetitive impact. When the hands are involved, the DIP and PIP joints are more likely to be involved than the MCP joints.

FIGURE 3

Rheumatoid nodules on feet

Diagnostic tests can differentiate between causes

Laboratory tests can help differentiate between conditions causing inflammatory arthritis. Rheumatoid factor is positive in 70% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and the antinuclear antibody is invariably positive for patients with SLE. Maturity-onset seronegative synovitis has negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody tests with marked elevation in erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Polyarticular gout may have increased serum uric acid, and is best diagnosed by demonstrating crystals in the joint fluid.

Laboratory tests are not helpful in diagnosing psoriatic arthritis, seronegative spondylo-arthropathies, and osteoarthritis with inflammation.1 Radiographic studies may show joint erosions in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis for more than a year, and typical osteophytes and joint-space narrowing in osteoarthritis.1

Radiographs are not necessary for the diagnosis of this patient but may help management, especially if hand surgery is going to be considered. In this case, the radiographs showed joint erosions and unequivocal juxta-auricular osteopenia.

Management: decrease pain, optimize mobility

The management of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis is different. However, in all types of arthritis the goals of therapy are to decrease pain, optimize mobility, and maximize quality of life. In rheumatoid arthritis, another goal is to slow the progression of the disease with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

Osteoarthritis. First-line therapy for osteo arthritis includes exercise, weight loss (if indicated), and acetaminophen in scheduled doses up to 1000 mg 4 times a day. A recent Cochrane Review concluded that acetaminophen is clearly superior to placebo, but slightly less efficacious than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pain relief in osteoarthritis (level of evidence [LOE]: 1a). Acetaminophen and NSAIDs were equivalent in improving function. This evidence supports the use of acetaminophen first, reserving NSAIDs for those who do not respond.3 Adding NSAIDs may improve pain relief, but carries an increased risk of gastrointestinal ulcerations or bleeding.

A cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor may be preferred to NSAIDs for patients at high risk for gastrointestinal complications. Other treatments include topical analgesics, glucosamine, and chondroitin. Large clinical trials for glucosamine and chondroitin are ongoing.

Rheumatoid arthritis. In rheumatoid arthritis, the recommendation from the American College of Rheumatology is for early, aggressive intervention with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, often within a few months of the onset of the disease.4 Unfortunately, the patient in Figure 1 has had rheumatoid arthritis for decades. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis also benefit from exercise and physical therapy.

Other treatments include low-dose corticosteroids and NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors. COX-2 inhibitors have similar efficacy to NSAIDs, with a lower risk of gastrointestinal complications (LOE: 1a).5,6 COX-2 inhibitors should be considered in place of NSAIDs for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, as these patients are almost twice as likely to suffer from serious gastrointestinal complications as the general population.2 COX-2 inhibitors, however, are much more expensive than NSAIDs, which limits their use.

Patient’s outcome

The patient was started on an anti-inflammatory medication and referred to a rheumatologist for consideration of a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Michael Fischbach, MD, in the Rheumatology Department of the University of Texas Health Science Center for his contribution to this article.

Correspondence

Richard P. Usatine, Editor, Photo Rounds, University of Texas HealthSciences Center at San Antonio, Dept of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd CurlDrive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Klinkhoff A. Rheumatology: 5. Diagnosis and management of inflammatory polyarthritis. CMAJ 2000;162:1833-1838

2. Kuritzky L, Weaver A. Advances in rheumatology: coxibs and beyond. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003;25(2 Suppl):S6-S20.

3. Towheed TE, Judd MJ, Hochberg MC, Wells G. Acetaminophen for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(2):CD004257-

4. Guidelines for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis from the American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis Guidelines. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:328-346.

5. Garner S, Fidan D, Frankish R, et al. Rofecoxib for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(3):CD003685.-

6. Garner S, Fidan D, Frankish R, et al. Celecoxib for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(4):CD003831.

A 67-year-old woman came to the office with pain in her hands. She had just arrived from Panama to live with her son. She has had this pain for decades: she refers to it as artritisin Spanish but does not know what type of arthritis. Aspirin had helped in the past, but lately she had not been getting enough relief from it. Her hands feel stiff in the morning for at least 1 hour, which interferes with cooking and sewing.

Her hands showed signs of joint swelling and deformities (Figure 1). Her swollen joints felt warm. She also had knee pain.

FIGURE 1

Painful,swollen hands

What type of arthritis does she have?

Are any diagnostic tests necessary?

What are the best treatments available?

That same day, another patient was seen with painful hands (Figure 2). What type of arthritis does she have, and how does it differ from the condition of the patient in Figure 1 ?

FIGURE 2

Another patient with hand pain

The obvious ulnar deviation of her fingers and the swelling of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints (Figure 1) are strongly indicative of rheumatoid arthritis. The patient in Figure 2 has swelling and deformities in her proximal inter-phalangeal (PIP) and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints, indicating that she most likely has osteoarthritis. The swelling of the PIP joints is called Bouchard’s nodes; the swelling of the DIP joints is called Heberden’s nodes.

Differential diagnosis: types of arthritis

The first decision point in diagnosing chronic (>6 weeks) polyarticular joint pain is distinguishing between inflammatory and noninflammatory arthritis. Key features of inflammatory arthritis are stiffness in the morning or after inactivity, and visible joint swelling. The differential diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis includes rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, seronegative spondyloarthropathies, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

After the age of 50, maturity-onset seronegative synovitis syndrome and crystal-induced synovitis should also be considered.1 Although osteoarthritis is considered noninflammatory, inflammation of the joint tissue occurs occasionally due to the joint’s degenerative loss of cartilage and bony overgrowth.

It is critical to identify rheumatoid arthritis early, as prompt intervention can delay disease progression, and reduce the substantial morbidity and mortality of rheumatoid arthritis.2 A diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis requires 4 of the following: morning stiffness; arthritis in 3 or more joints; arthritis in the wrist, MCP joints, or PIP joints; symmetric arthritis; rheumatoid nodules; positive rheumatoid factor; radiographic changes.1 This patient has the morning stiffness, arthritis in more than 3 joints, symmetric arthritis, and rheumatoid nodules on her feet (Figure 3).

The most common noninflammatory arthritis is osteoarthritis, which affects 21 million Americans.2 The weight-bearing joints are usually affected, and damage may occur because of trauma or repetitive impact. When the hands are involved, the DIP and PIP joints are more likely to be involved than the MCP joints.

FIGURE 3

Rheumatoid nodules on feet

Diagnostic tests can differentiate between causes

Laboratory tests can help differentiate between conditions causing inflammatory arthritis. Rheumatoid factor is positive in 70% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and the antinuclear antibody is invariably positive for patients with SLE. Maturity-onset seronegative synovitis has negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody tests with marked elevation in erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Polyarticular gout may have increased serum uric acid, and is best diagnosed by demonstrating crystals in the joint fluid.

Laboratory tests are not helpful in diagnosing psoriatic arthritis, seronegative spondylo-arthropathies, and osteoarthritis with inflammation.1 Radiographic studies may show joint erosions in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis for more than a year, and typical osteophytes and joint-space narrowing in osteoarthritis.1

Radiographs are not necessary for the diagnosis of this patient but may help management, especially if hand surgery is going to be considered. In this case, the radiographs showed joint erosions and unequivocal juxta-auricular osteopenia.

Management: decrease pain, optimize mobility

The management of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis is different. However, in all types of arthritis the goals of therapy are to decrease pain, optimize mobility, and maximize quality of life. In rheumatoid arthritis, another goal is to slow the progression of the disease with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

Osteoarthritis. First-line therapy for osteo arthritis includes exercise, weight loss (if indicated), and acetaminophen in scheduled doses up to 1000 mg 4 times a day. A recent Cochrane Review concluded that acetaminophen is clearly superior to placebo, but slightly less efficacious than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pain relief in osteoarthritis (level of evidence [LOE]: 1a). Acetaminophen and NSAIDs were equivalent in improving function. This evidence supports the use of acetaminophen first, reserving NSAIDs for those who do not respond.3 Adding NSAIDs may improve pain relief, but carries an increased risk of gastrointestinal ulcerations or bleeding.

A cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor may be preferred to NSAIDs for patients at high risk for gastrointestinal complications. Other treatments include topical analgesics, glucosamine, and chondroitin. Large clinical trials for glucosamine and chondroitin are ongoing.

Rheumatoid arthritis. In rheumatoid arthritis, the recommendation from the American College of Rheumatology is for early, aggressive intervention with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, often within a few months of the onset of the disease.4 Unfortunately, the patient in Figure 1 has had rheumatoid arthritis for decades. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis also benefit from exercise and physical therapy.

Other treatments include low-dose corticosteroids and NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors. COX-2 inhibitors have similar efficacy to NSAIDs, with a lower risk of gastrointestinal complications (LOE: 1a).5,6 COX-2 inhibitors should be considered in place of NSAIDs for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, as these patients are almost twice as likely to suffer from serious gastrointestinal complications as the general population.2 COX-2 inhibitors, however, are much more expensive than NSAIDs, which limits their use.

Patient’s outcome

The patient was started on an anti-inflammatory medication and referred to a rheumatologist for consideration of a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Michael Fischbach, MD, in the Rheumatology Department of the University of Texas Health Science Center for his contribution to this article.

Correspondence

Richard P. Usatine, Editor, Photo Rounds, University of Texas HealthSciences Center at San Antonio, Dept of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd CurlDrive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected]

A 67-year-old woman came to the office with pain in her hands. She had just arrived from Panama to live with her son. She has had this pain for decades: she refers to it as artritisin Spanish but does not know what type of arthritis. Aspirin had helped in the past, but lately she had not been getting enough relief from it. Her hands feel stiff in the morning for at least 1 hour, which interferes with cooking and sewing.

Her hands showed signs of joint swelling and deformities (Figure 1). Her swollen joints felt warm. She also had knee pain.

FIGURE 1

Painful,swollen hands

What type of arthritis does she have?

Are any diagnostic tests necessary?

What are the best treatments available?

That same day, another patient was seen with painful hands (Figure 2). What type of arthritis does she have, and how does it differ from the condition of the patient in Figure 1 ?

FIGURE 2

Another patient with hand pain

The obvious ulnar deviation of her fingers and the swelling of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints (Figure 1) are strongly indicative of rheumatoid arthritis. The patient in Figure 2 has swelling and deformities in her proximal inter-phalangeal (PIP) and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints, indicating that she most likely has osteoarthritis. The swelling of the PIP joints is called Bouchard’s nodes; the swelling of the DIP joints is called Heberden’s nodes.

Differential diagnosis: types of arthritis

The first decision point in diagnosing chronic (>6 weeks) polyarticular joint pain is distinguishing between inflammatory and noninflammatory arthritis. Key features of inflammatory arthritis are stiffness in the morning or after inactivity, and visible joint swelling. The differential diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis includes rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, seronegative spondyloarthropathies, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

After the age of 50, maturity-onset seronegative synovitis syndrome and crystal-induced synovitis should also be considered.1 Although osteoarthritis is considered noninflammatory, inflammation of the joint tissue occurs occasionally due to the joint’s degenerative loss of cartilage and bony overgrowth.

It is critical to identify rheumatoid arthritis early, as prompt intervention can delay disease progression, and reduce the substantial morbidity and mortality of rheumatoid arthritis.2 A diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis requires 4 of the following: morning stiffness; arthritis in 3 or more joints; arthritis in the wrist, MCP joints, or PIP joints; symmetric arthritis; rheumatoid nodules; positive rheumatoid factor; radiographic changes.1 This patient has the morning stiffness, arthritis in more than 3 joints, symmetric arthritis, and rheumatoid nodules on her feet (Figure 3).

The most common noninflammatory arthritis is osteoarthritis, which affects 21 million Americans.2 The weight-bearing joints are usually affected, and damage may occur because of trauma or repetitive impact. When the hands are involved, the DIP and PIP joints are more likely to be involved than the MCP joints.

FIGURE 3

Rheumatoid nodules on feet

Diagnostic tests can differentiate between causes

Laboratory tests can help differentiate between conditions causing inflammatory arthritis. Rheumatoid factor is positive in 70% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and the antinuclear antibody is invariably positive for patients with SLE. Maturity-onset seronegative synovitis has negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody tests with marked elevation in erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Polyarticular gout may have increased serum uric acid, and is best diagnosed by demonstrating crystals in the joint fluid.

Laboratory tests are not helpful in diagnosing psoriatic arthritis, seronegative spondylo-arthropathies, and osteoarthritis with inflammation.1 Radiographic studies may show joint erosions in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis for more than a year, and typical osteophytes and joint-space narrowing in osteoarthritis.1

Radiographs are not necessary for the diagnosis of this patient but may help management, especially if hand surgery is going to be considered. In this case, the radiographs showed joint erosions and unequivocal juxta-auricular osteopenia.

Management: decrease pain, optimize mobility

The management of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis is different. However, in all types of arthritis the goals of therapy are to decrease pain, optimize mobility, and maximize quality of life. In rheumatoid arthritis, another goal is to slow the progression of the disease with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

Osteoarthritis. First-line therapy for osteo arthritis includes exercise, weight loss (if indicated), and acetaminophen in scheduled doses up to 1000 mg 4 times a day. A recent Cochrane Review concluded that acetaminophen is clearly superior to placebo, but slightly less efficacious than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pain relief in osteoarthritis (level of evidence [LOE]: 1a). Acetaminophen and NSAIDs were equivalent in improving function. This evidence supports the use of acetaminophen first, reserving NSAIDs for those who do not respond.3 Adding NSAIDs may improve pain relief, but carries an increased risk of gastrointestinal ulcerations or bleeding.

A cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor may be preferred to NSAIDs for patients at high risk for gastrointestinal complications. Other treatments include topical analgesics, glucosamine, and chondroitin. Large clinical trials for glucosamine and chondroitin are ongoing.

Rheumatoid arthritis. In rheumatoid arthritis, the recommendation from the American College of Rheumatology is for early, aggressive intervention with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, often within a few months of the onset of the disease.4 Unfortunately, the patient in Figure 1 has had rheumatoid arthritis for decades. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis also benefit from exercise and physical therapy.

Other treatments include low-dose corticosteroids and NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors. COX-2 inhibitors have similar efficacy to NSAIDs, with a lower risk of gastrointestinal complications (LOE: 1a).5,6 COX-2 inhibitors should be considered in place of NSAIDs for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, as these patients are almost twice as likely to suffer from serious gastrointestinal complications as the general population.2 COX-2 inhibitors, however, are much more expensive than NSAIDs, which limits their use.

Patient’s outcome

The patient was started on an anti-inflammatory medication and referred to a rheumatologist for consideration of a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Michael Fischbach, MD, in the Rheumatology Department of the University of Texas Health Science Center for his contribution to this article.

Correspondence

Richard P. Usatine, Editor, Photo Rounds, University of Texas HealthSciences Center at San Antonio, Dept of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd CurlDrive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Klinkhoff A. Rheumatology: 5. Diagnosis and management of inflammatory polyarthritis. CMAJ 2000;162:1833-1838

2. Kuritzky L, Weaver A. Advances in rheumatology: coxibs and beyond. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003;25(2 Suppl):S6-S20.

3. Towheed TE, Judd MJ, Hochberg MC, Wells G. Acetaminophen for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(2):CD004257-

4. Guidelines for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis from the American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis Guidelines. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:328-346.

5. Garner S, Fidan D, Frankish R, et al. Rofecoxib for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(3):CD003685.-

6. Garner S, Fidan D, Frankish R, et al. Celecoxib for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(4):CD003831.

1. Klinkhoff A. Rheumatology: 5. Diagnosis and management of inflammatory polyarthritis. CMAJ 2000;162:1833-1838

2. Kuritzky L, Weaver A. Advances in rheumatology: coxibs and beyond. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003;25(2 Suppl):S6-S20.

3. Towheed TE, Judd MJ, Hochberg MC, Wells G. Acetaminophen for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(2):CD004257-

4. Guidelines for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis from the American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis Guidelines. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:328-346.

5. Garner S, Fidan D, Frankish R, et al. Rofecoxib for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(3):CD003685.-

6. Garner S, Fidan D, Frankish R, et al. Celecoxib for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(4):CD003831.

Red eyes with a brown spot

A 32-year-old woman came to the rescue mission clinic with her 2 sons because she had red eyes and a runny nose. Her sons both had symptoms highly suggestive of viral upper respiratory infection. They lived in a homeless shelter.

The patient stated she did not use contact lenses or have any eye trauma, itching, photophobia, loss or change of vision, eye pain, eye discharge, or previous episodes of pinkeye. She had no other medical problems or history of allergies.

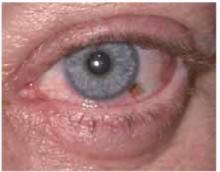

On physical exam, her vital signs were normal. She had conjunctival injection, without purulent discharge or limbal blush (Figures 1 and 2). Eyelids were mildly erythematous with no cobble-stoning. Pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light. The anterior chamber by flashlight exam from the side did not show a narrow angle. Visual acuity was normal by Snellen exam. She had clear nasal discharge and bilateral preauricular lymphadenopathy.

In addition, she had a brown macule under the left iris on the conjunctiva. The patient said this had been present since childhood and it had not changed.

FIGURE 1

Red eyes

FIGURE 2

Brown macule

What is the differential iagnosis?

What about the brown macule?

Are any diagnostic tests Necessary for either condition?

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a red eye includes:

- Conjunctivitis

- Uveitis

- Acute glaucoma

- Corneal disease or foreign body trauma

- Scleritis and episcleritis.1

For this patient, conjunctivitis is the most likely diagnosis. The absence of eye pain or loss of vision makes uveitis, acute glaucoma, or corneal disease (including foreign-body trauma) less likely. The round shape of the pupil and the absence of the limbal blush also make uveitis less likely. The pattern of injection does not match the wedge-shaped inflammation of episcleritis or the depth of scleritis.

Diagnosis: viral conjunctivitis

This patient has viral conjunctivitis. Conjunctivitis can be infectious, allergic, chemical/irritative, or autoimmune in origin. The most common infectious agents are viral—specifically, the adenoviruses. Other infectious agents include bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae), chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus.

Both infectious and allergic conjunctivitis are common. In this patient, the presence of nasal discharge, preauricular lymphadenopathy, and the lack of pruritus make viral infection more likely than allergic. Conjunctivitis that is bilateral without purulent discharge is more likely to be viral than bacterial.

What about the brown macule?

This patient also had a brown macule on her conjunctiva. The differential diagnosis of pigmented areas on the conjunctiva includes nevus, racial melanosis, primary acquired melanosis, secondary pigmentary deposition, and ocular melanoma.2 These conditions (besides ocular melanoma) are benign.

Although ocular melanoma is the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults, and the second most likely location for primary melanoma after the skin, it is still exceedingly rare. In the Causasian population, it has an average annual incidence of 6 cases per million, with approximately 1200 cases diagnosed each year. Ocular melanoma occurs in the uvea much more commonly than in the conjunctiva, at a ratio of 35:1. Conjunctival melanomas have a propensity for regional spread to the lymph nodes analogous to cutaneous disease, with 10-year survival rates of more than 80%.3

In this case, the patient had this dark spot since childhood and had noted no growth or change. It was consistent with a conjunctival nevus and did not need biopsy.

Diagnostic tests: only for cases that do not respond

When viral conjunctivitis is suspected, no laboratory tests are routinely recommended. Bacterial and viral cultures may be helpful to establish the diagnosis in cases that do not resolve or when patients have recurrent episodes. Infections that do not respond to empiric treatment should be cultured for the suspected organisms (bacteria, chlamydia, or herpes simplex). When chlamydial conjunctivitis is suspected, the diagnosis should be confirmed by means of an immunodiagnostic test (direct fluorescent antibody [DFA]) or culture (level of evidence [LOE]=1a).4

A fluorescein exam is helpful in cases with a question of corneal involvement from foreign-body trauma, herpes simplex, or epidemic kerato-conjunctivitis. Herpes simplex infections have a dendritic pattern of ulceration, and epidemic keratoconjunctivitis infections cause multiple small areas of increased fluorescein uptake.

Management: conjunctivitis usually self-limiting

Typical viral conjunctivitis caused by the adenoviruses or other common viruses (not herpes) does not require medication. Warm compresses may be recommended to reduce discomfort. Infectious conjunctivitis caused by bacteria are also usually self-limiting; however, a recent meta-analysis indicates that treatment with antibiotics can shorten the clinical duration (LOE=1a).5

Appropriate medications for bacterial conjunctivitis include 0.3% tobramycin or gentamycin, 10% sodium sulfacetamide, or erythromycin ophthalmic ointment. If herpetic keratoconjuntivitis is suspected, prompt ophthalmologic referral is indicated.1

Patient’s treatment and outcome

This patient was managed with reassurance and symptomatic treatment of her viral respiratory illness. Her red eyes and upper respiratory infection both resolved spontaneously within 1 week.

As her nevus had not changed in many years, she was instructed to continue to watch the nevus and report any changes to a physician for evaluation. If the lesion changed in the future, she should be referred to an ophthalmologist.

- Erythromycin (ophthalmic) • Ilotycin

- Gentamycin (ophthalmic) • Garamycin, Genoptic Liquifilm, Genoptic SOP, Gentacidin, Gentafair, Gentak, Ocu-Mycin, Spectro-Genta

- Sulfacetamide (ophthalmic) • AK-Sulf, Bleph-10, Cetamide, Isopto Cetamide, Ocusulf-10, Sodium Sulamyd, Sulf-10

- Tobramycin (ophthalmic) • AKTob, Tobrex

Correspondence

Richard P. Usatine, Editor, Photo Rounds, University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, Dept of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Ricketson CW. Conjunctivitis in 5-minute clinical consult. Dambro, MR (ed). InfoRetriever [electronic database]. Charlottesville, Va: InfoPOEMs, Inc; 2004.

2. Shields CL, Shields JA. Tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea. Surv Ophthalmol 2004;49:3-24.

3. Hurst EA, Harbour JW, Cornelius LA. Ocular melanoma: a review and the relationship to cutaneous melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:1067-1073.

4. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Preferred Practice Patterns. Conjunctivitis. Available at: www.aao.org/aao/education/library/ppp/index.cfm. Accessed on February 3, 2004.

5. Sheikh A, Hurwitz B, Cave J. Antibiotics versus placebo for acute bacterial conjunctivitis (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 2003.

A 32-year-old woman came to the rescue mission clinic with her 2 sons because she had red eyes and a runny nose. Her sons both had symptoms highly suggestive of viral upper respiratory infection. They lived in a homeless shelter.

The patient stated she did not use contact lenses or have any eye trauma, itching, photophobia, loss or change of vision, eye pain, eye discharge, or previous episodes of pinkeye. She had no other medical problems or history of allergies.

On physical exam, her vital signs were normal. She had conjunctival injection, without purulent discharge or limbal blush (Figures 1 and 2). Eyelids were mildly erythematous with no cobble-stoning. Pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light. The anterior chamber by flashlight exam from the side did not show a narrow angle. Visual acuity was normal by Snellen exam. She had clear nasal discharge and bilateral preauricular lymphadenopathy.

In addition, she had a brown macule under the left iris on the conjunctiva. The patient said this had been present since childhood and it had not changed.

FIGURE 1

Red eyes

FIGURE 2

Brown macule

What is the differential iagnosis?

What about the brown macule?

Are any diagnostic tests Necessary for either condition?

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a red eye includes:

- Conjunctivitis

- Uveitis

- Acute glaucoma

- Corneal disease or foreign body trauma

- Scleritis and episcleritis.1

For this patient, conjunctivitis is the most likely diagnosis. The absence of eye pain or loss of vision makes uveitis, acute glaucoma, or corneal disease (including foreign-body trauma) less likely. The round shape of the pupil and the absence of the limbal blush also make uveitis less likely. The pattern of injection does not match the wedge-shaped inflammation of episcleritis or the depth of scleritis.

Diagnosis: viral conjunctivitis

This patient has viral conjunctivitis. Conjunctivitis can be infectious, allergic, chemical/irritative, or autoimmune in origin. The most common infectious agents are viral—specifically, the adenoviruses. Other infectious agents include bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae), chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus.

Both infectious and allergic conjunctivitis are common. In this patient, the presence of nasal discharge, preauricular lymphadenopathy, and the lack of pruritus make viral infection more likely than allergic. Conjunctivitis that is bilateral without purulent discharge is more likely to be viral than bacterial.

What about the brown macule?

This patient also had a brown macule on her conjunctiva. The differential diagnosis of pigmented areas on the conjunctiva includes nevus, racial melanosis, primary acquired melanosis, secondary pigmentary deposition, and ocular melanoma.2 These conditions (besides ocular melanoma) are benign.

Although ocular melanoma is the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults, and the second most likely location for primary melanoma after the skin, it is still exceedingly rare. In the Causasian population, it has an average annual incidence of 6 cases per million, with approximately 1200 cases diagnosed each year. Ocular melanoma occurs in the uvea much more commonly than in the conjunctiva, at a ratio of 35:1. Conjunctival melanomas have a propensity for regional spread to the lymph nodes analogous to cutaneous disease, with 10-year survival rates of more than 80%.3

In this case, the patient had this dark spot since childhood and had noted no growth or change. It was consistent with a conjunctival nevus and did not need biopsy.

Diagnostic tests: only for cases that do not respond

When viral conjunctivitis is suspected, no laboratory tests are routinely recommended. Bacterial and viral cultures may be helpful to establish the diagnosis in cases that do not resolve or when patients have recurrent episodes. Infections that do not respond to empiric treatment should be cultured for the suspected organisms (bacteria, chlamydia, or herpes simplex). When chlamydial conjunctivitis is suspected, the diagnosis should be confirmed by means of an immunodiagnostic test (direct fluorescent antibody [DFA]) or culture (level of evidence [LOE]=1a).4

A fluorescein exam is helpful in cases with a question of corneal involvement from foreign-body trauma, herpes simplex, or epidemic kerato-conjunctivitis. Herpes simplex infections have a dendritic pattern of ulceration, and epidemic keratoconjunctivitis infections cause multiple small areas of increased fluorescein uptake.

Management: conjunctivitis usually self-limiting

Typical viral conjunctivitis caused by the adenoviruses or other common viruses (not herpes) does not require medication. Warm compresses may be recommended to reduce discomfort. Infectious conjunctivitis caused by bacteria are also usually self-limiting; however, a recent meta-analysis indicates that treatment with antibiotics can shorten the clinical duration (LOE=1a).5

Appropriate medications for bacterial conjunctivitis include 0.3% tobramycin or gentamycin, 10% sodium sulfacetamide, or erythromycin ophthalmic ointment. If herpetic keratoconjuntivitis is suspected, prompt ophthalmologic referral is indicated.1

Patient’s treatment and outcome

This patient was managed with reassurance and symptomatic treatment of her viral respiratory illness. Her red eyes and upper respiratory infection both resolved spontaneously within 1 week.

As her nevus had not changed in many years, she was instructed to continue to watch the nevus and report any changes to a physician for evaluation. If the lesion changed in the future, she should be referred to an ophthalmologist.

- Erythromycin (ophthalmic) • Ilotycin

- Gentamycin (ophthalmic) • Garamycin, Genoptic Liquifilm, Genoptic SOP, Gentacidin, Gentafair, Gentak, Ocu-Mycin, Spectro-Genta

- Sulfacetamide (ophthalmic) • AK-Sulf, Bleph-10, Cetamide, Isopto Cetamide, Ocusulf-10, Sodium Sulamyd, Sulf-10

- Tobramycin (ophthalmic) • AKTob, Tobrex

Correspondence

Richard P. Usatine, Editor, Photo Rounds, University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, Dept of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected].

A 32-year-old woman came to the rescue mission clinic with her 2 sons because she had red eyes and a runny nose. Her sons both had symptoms highly suggestive of viral upper respiratory infection. They lived in a homeless shelter.

The patient stated she did not use contact lenses or have any eye trauma, itching, photophobia, loss or change of vision, eye pain, eye discharge, or previous episodes of pinkeye. She had no other medical problems or history of allergies.

On physical exam, her vital signs were normal. She had conjunctival injection, without purulent discharge or limbal blush (Figures 1 and 2). Eyelids were mildly erythematous with no cobble-stoning. Pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light. The anterior chamber by flashlight exam from the side did not show a narrow angle. Visual acuity was normal by Snellen exam. She had clear nasal discharge and bilateral preauricular lymphadenopathy.

In addition, she had a brown macule under the left iris on the conjunctiva. The patient said this had been present since childhood and it had not changed.

FIGURE 1

Red eyes

FIGURE 2

Brown macule

What is the differential iagnosis?

What about the brown macule?

Are any diagnostic tests Necessary for either condition?

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a red eye includes:

- Conjunctivitis

- Uveitis

- Acute glaucoma

- Corneal disease or foreign body trauma

- Scleritis and episcleritis.1

For this patient, conjunctivitis is the most likely diagnosis. The absence of eye pain or loss of vision makes uveitis, acute glaucoma, or corneal disease (including foreign-body trauma) less likely. The round shape of the pupil and the absence of the limbal blush also make uveitis less likely. The pattern of injection does not match the wedge-shaped inflammation of episcleritis or the depth of scleritis.

Diagnosis: viral conjunctivitis

This patient has viral conjunctivitis. Conjunctivitis can be infectious, allergic, chemical/irritative, or autoimmune in origin. The most common infectious agents are viral—specifically, the adenoviruses. Other infectious agents include bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae), chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus.

Both infectious and allergic conjunctivitis are common. In this patient, the presence of nasal discharge, preauricular lymphadenopathy, and the lack of pruritus make viral infection more likely than allergic. Conjunctivitis that is bilateral without purulent discharge is more likely to be viral than bacterial.

What about the brown macule?

This patient also had a brown macule on her conjunctiva. The differential diagnosis of pigmented areas on the conjunctiva includes nevus, racial melanosis, primary acquired melanosis, secondary pigmentary deposition, and ocular melanoma.2 These conditions (besides ocular melanoma) are benign.

Although ocular melanoma is the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults, and the second most likely location for primary melanoma after the skin, it is still exceedingly rare. In the Causasian population, it has an average annual incidence of 6 cases per million, with approximately 1200 cases diagnosed each year. Ocular melanoma occurs in the uvea much more commonly than in the conjunctiva, at a ratio of 35:1. Conjunctival melanomas have a propensity for regional spread to the lymph nodes analogous to cutaneous disease, with 10-year survival rates of more than 80%.3

In this case, the patient had this dark spot since childhood and had noted no growth or change. It was consistent with a conjunctival nevus and did not need biopsy.

Diagnostic tests: only for cases that do not respond

When viral conjunctivitis is suspected, no laboratory tests are routinely recommended. Bacterial and viral cultures may be helpful to establish the diagnosis in cases that do not resolve or when patients have recurrent episodes. Infections that do not respond to empiric treatment should be cultured for the suspected organisms (bacteria, chlamydia, or herpes simplex). When chlamydial conjunctivitis is suspected, the diagnosis should be confirmed by means of an immunodiagnostic test (direct fluorescent antibody [DFA]) or culture (level of evidence [LOE]=1a).4

A fluorescein exam is helpful in cases with a question of corneal involvement from foreign-body trauma, herpes simplex, or epidemic kerato-conjunctivitis. Herpes simplex infections have a dendritic pattern of ulceration, and epidemic keratoconjunctivitis infections cause multiple small areas of increased fluorescein uptake.

Management: conjunctivitis usually self-limiting

Typical viral conjunctivitis caused by the adenoviruses or other common viruses (not herpes) does not require medication. Warm compresses may be recommended to reduce discomfort. Infectious conjunctivitis caused by bacteria are also usually self-limiting; however, a recent meta-analysis indicates that treatment with antibiotics can shorten the clinical duration (LOE=1a).5

Appropriate medications for bacterial conjunctivitis include 0.3% tobramycin or gentamycin, 10% sodium sulfacetamide, or erythromycin ophthalmic ointment. If herpetic keratoconjuntivitis is suspected, prompt ophthalmologic referral is indicated.1

Patient’s treatment and outcome

This patient was managed with reassurance and symptomatic treatment of her viral respiratory illness. Her red eyes and upper respiratory infection both resolved spontaneously within 1 week.

As her nevus had not changed in many years, she was instructed to continue to watch the nevus and report any changes to a physician for evaluation. If the lesion changed in the future, she should be referred to an ophthalmologist.

- Erythromycin (ophthalmic) • Ilotycin

- Gentamycin (ophthalmic) • Garamycin, Genoptic Liquifilm, Genoptic SOP, Gentacidin, Gentafair, Gentak, Ocu-Mycin, Spectro-Genta

- Sulfacetamide (ophthalmic) • AK-Sulf, Bleph-10, Cetamide, Isopto Cetamide, Ocusulf-10, Sodium Sulamyd, Sulf-10

- Tobramycin (ophthalmic) • AKTob, Tobrex

Correspondence

Richard P. Usatine, Editor, Photo Rounds, University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, Dept of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Ricketson CW. Conjunctivitis in 5-minute clinical consult. Dambro, MR (ed). InfoRetriever [electronic database]. Charlottesville, Va: InfoPOEMs, Inc; 2004.

2. Shields CL, Shields JA. Tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea. Surv Ophthalmol 2004;49:3-24.

3. Hurst EA, Harbour JW, Cornelius LA. Ocular melanoma: a review and the relationship to cutaneous melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:1067-1073.

4. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Preferred Practice Patterns. Conjunctivitis. Available at: www.aao.org/aao/education/library/ppp/index.cfm. Accessed on February 3, 2004.

5. Sheikh A, Hurwitz B, Cave J. Antibiotics versus placebo for acute bacterial conjunctivitis (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 2003.

1. Ricketson CW. Conjunctivitis in 5-minute clinical consult. Dambro, MR (ed). InfoRetriever [electronic database]. Charlottesville, Va: InfoPOEMs, Inc; 2004.

2. Shields CL, Shields JA. Tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea. Surv Ophthalmol 2004;49:3-24.

3. Hurst EA, Harbour JW, Cornelius LA. Ocular melanoma: a review and the relationship to cutaneous melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:1067-1073.

4. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Preferred Practice Patterns. Conjunctivitis. Available at: www.aao.org/aao/education/library/ppp/index.cfm. Accessed on February 3, 2004.

5. Sheikh A, Hurwitz B, Cave J. Antibiotics versus placebo for acute bacterial conjunctivitis (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 2003.