User login

Oozing puncture wound on foot

A 49-year-old, unkempt-looking Indian man came into our emergency department in Singapore complaining of increasing right foot swelling and worsening pain that he’d had for a month after having stepped on a fish bone while walking on the beach. Our patient pulled the bone out himself and did not seek immediate medical attention.

Our patient said that he had occasional fever with chills and rigors. His medical history was unremarkable, and there was no history of previous injury or surgery to the right foot. He worked as an “oiler” refueling ships, and said that he did not drink alcohol or smoke.

He was dehydrated, and there were no other sources of infection or sores on his body. Our patient was febrile (38.3°C [100.9°F]), his blood pressure was 112/74 mm Hg, and he was tachycardic at 117 beats per minute.

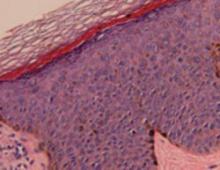

His right foot was boggy, swollen, and tender with significant crepitus. Brownish discharge was oozing from the sole of his foot (FIGURE 1). There were large infected subcutaneous bullae on the dorsum of his foot (FIGURE 2). We could feel a popliteal pulse in both legs, but could not feel a right dorsalis pedis pulse.

What is your diagnosis?

FIGURE 1

Swollen, dusky foot

FIGURE 2

Dark bullae

Diagnosis: Necrotizing fasciitis

Necrotizing fasciitis infections are characterized by fulminant destruction of tissue, systemic signs of toxicity, and high rates of mortality. The incidence of necrotizing fasciitis in adults is 0.40 cases per 100,000 population, while the incidence in children is 0.08 cases per 100,000 population. Mortality rates as high as 73% have been reported.1 Early clinical suspicion, early surgical intervention (surgical debridement), and systemic antibiotics are of the utmost importance.

Necrotizing fasciitis is caused by gram positive, gram negative, and/or anaerobic bacteria. Local tissue hypoxia from trauma, surgery, or a medically compromised state creates an ideal opportunistic environment for bacterial proliferation.

Necrotizing fasciitis can be broadly classified into 2 main types:

Type 1 necrotizing fasciitis is a polymicrobial infection caused by facultative bacteria along with anaerobes. Polymicrobial infections with anaerobes are common (up to 74%) in infected puncture wounds in patients with diabetes.2

Type 2 necrotizing fasciitis is caused by group A streptococci alone, but sometimes in association with Staphylococcus aureus. Vibrio vulnificus infection has also been reported in fish bone piercing injuries leading to necrotizing fasciitis.3

Typical early signs and symptoms include severe pain, rapidly progressing erythema, dusky or purplish skin discoloration, and systemic signs of septic toxicity such as fever, tachycardia, a generalized unwell feeling, and even hypotension. (A lack of classic tissue inflammatory signs may mask an ongoing necrotizing fasciitis beneath the skin.) The involved region may become numb due to the necrosis of the innervating nerve fibers. Discharge or crepitus may also be noted.

Late clinical signs of necrotizing fasciitis include cellulitis, skin discoloration, discharge of “dishwater” fluid, blistering, and hemorrhagic bullae. Findings of crepitus and soft tissue air on plain radiographs are seen in 37% and 57% of patients, respectively.4 Our patient’s X-ray findings revealed extensive gas pockets within soft tissue and osteomyelitis changes of the 5th metatarsal head.

The differential diagnosis for necrotizing fasciitis includes:

- pyogenic soft tissue cellulitis

- clostridial cellulitis (which may also present with soft tissue crepitus)

- nonclostridial anaerobic cellulitis

- acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis

- acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy

- erythema induratum (nodular vasculitis).

Diagnosis is often made on clinical evaluation

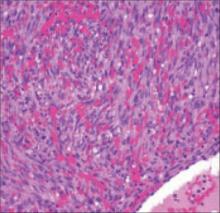

The definitive diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis is made by histological examination of the debrided specimen or deep skin tissue biopsy. Fascial necrosis with thrombosed blood vessels and a dense infiltrate of inflammatory cells is seen on histological evaluation.

However, diagnosis is often reached on clinical evaluation. Rapidly deteriorating local signs and symptoms together with systemic toxicity should prompt a working diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis.

Laboratory tests (white blood cell count, blood urea nitrogen level, sodium levels, creatinine levels, erythrocyte sedimentation rates, C-reactive protein levels) and radiographic evaluation (X-rays, computed tomography [CT], and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) are useful adjuncts in reaching the diagnosis.

Prompt treatment is the name of the game

Antibiotic therapy is guided by gram stain and bacterial culture results. (When the clinical suspicion of necrotizing fasciitis is reached, empirical antibiotics should be started right away.) Broad-spectrum antibiotics covering gram positive, gram negative, and anaerobic bacteria should be used. The patient’s age, weight, and liver and renal function should also be considered before starting antibiotics.

Choices of antibiotics include penicillin for gram positive cover and an aminoglycoside or third-generation cephalosporin for gram negative counteraction. Metronidazole (Flagyl) may be considered for anaerobic superimposed infections. Adjunctive clindamycin is also recommended—especially in group A streptococcal infections—because it suppresses toxin production, inhibits M-protein synthesis, and facilitates phagocytosis.5 In addition, hyperbaric oxygen therapy and intravenous immunoglobulin are increasingly being utilized in the management of necrotizing fasciitis.6 Their efficacy has yet to be conclusively established.

Surgical debridement. The importance of prompt and thorough surgical debridement cannot be stressed enough. Large soft-tissue defects created by surgery can be treated with vacuum-assisted closure dressings, local or free soft-tissue flaps, and/or skin grafts. In extreme cases, limb amputation may be necessary.

Aggressive steps were needed for our patient

In the emergency department, we treated our patient with intravenous cloxacillin, gentamicin, and metronidazole. He later underwent surgical debridement and had pus drained from deep abscesses in his foot. Intraoperative findings indicated that there was necrotic tissue involving 80% of the dorsum of the foot and the necrosis extended proximally to the ankle and distally to the toes.

Wound cultures grew group B Streptococcus (Peptostreptococcus species) and Bacteroides. He was treated with intravenous amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (IV Augmentin, available in Singapore) and oral metronidazole. An endocrinologist evaluated him and determined that he had diabetes. He was started on insulin.

Postoperatively, our patient remained septic. Five days later, he underwent a below-the-knee amputation; the surgeons noted that his foot was gangrenous.

Our patient stayed in the hospital for 7 more days and was discharged about 2 weeks after his arrival at the ER.

Correspondence

Ramesh Subramaniam, MBBS, National University Hospital, 5 Lower Kent Ridge Road, Singapore 119074

1. Trent JT, Kirsner RS. Necrotizing fasciitis. Wounds. 2002;14:284-292.

2. Lavery LA, Harkless LB, Felder-Johnson K, et al. Bacterial pathogens in infected puncture wounds in adults with diabetes. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1994;33:91-97.

3. Oliver JD. Wound infections caused by Vibrio vulnificus and other marine bacteria. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:383-391.

4. Elliott DC, Kufera JA, Myers RA. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. Risk factors for mortality and strategies for management. Ann Surg. 1996;224:672-683.

5. Stevens DL. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: spectrum of disease, pathogenesis and new concepts in treatment. Emerg Infect Dis. 1995;1:69.

6. Young MH, Aronoff DM, Engleberg NC. Necrotizing fasciitis: pathogenesis and treatment. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2005;3:279-294.

A 49-year-old, unkempt-looking Indian man came into our emergency department in Singapore complaining of increasing right foot swelling and worsening pain that he’d had for a month after having stepped on a fish bone while walking on the beach. Our patient pulled the bone out himself and did not seek immediate medical attention.

Our patient said that he had occasional fever with chills and rigors. His medical history was unremarkable, and there was no history of previous injury or surgery to the right foot. He worked as an “oiler” refueling ships, and said that he did not drink alcohol or smoke.

He was dehydrated, and there were no other sources of infection or sores on his body. Our patient was febrile (38.3°C [100.9°F]), his blood pressure was 112/74 mm Hg, and he was tachycardic at 117 beats per minute.

His right foot was boggy, swollen, and tender with significant crepitus. Brownish discharge was oozing from the sole of his foot (FIGURE 1). There were large infected subcutaneous bullae on the dorsum of his foot (FIGURE 2). We could feel a popliteal pulse in both legs, but could not feel a right dorsalis pedis pulse.

What is your diagnosis?

FIGURE 1

Swollen, dusky foot

FIGURE 2

Dark bullae

Diagnosis: Necrotizing fasciitis

Necrotizing fasciitis infections are characterized by fulminant destruction of tissue, systemic signs of toxicity, and high rates of mortality. The incidence of necrotizing fasciitis in adults is 0.40 cases per 100,000 population, while the incidence in children is 0.08 cases per 100,000 population. Mortality rates as high as 73% have been reported.1 Early clinical suspicion, early surgical intervention (surgical debridement), and systemic antibiotics are of the utmost importance.

Necrotizing fasciitis is caused by gram positive, gram negative, and/or anaerobic bacteria. Local tissue hypoxia from trauma, surgery, or a medically compromised state creates an ideal opportunistic environment for bacterial proliferation.

Necrotizing fasciitis can be broadly classified into 2 main types:

Type 1 necrotizing fasciitis is a polymicrobial infection caused by facultative bacteria along with anaerobes. Polymicrobial infections with anaerobes are common (up to 74%) in infected puncture wounds in patients with diabetes.2

Type 2 necrotizing fasciitis is caused by group A streptococci alone, but sometimes in association with Staphylococcus aureus. Vibrio vulnificus infection has also been reported in fish bone piercing injuries leading to necrotizing fasciitis.3

Typical early signs and symptoms include severe pain, rapidly progressing erythema, dusky or purplish skin discoloration, and systemic signs of septic toxicity such as fever, tachycardia, a generalized unwell feeling, and even hypotension. (A lack of classic tissue inflammatory signs may mask an ongoing necrotizing fasciitis beneath the skin.) The involved region may become numb due to the necrosis of the innervating nerve fibers. Discharge or crepitus may also be noted.

Late clinical signs of necrotizing fasciitis include cellulitis, skin discoloration, discharge of “dishwater” fluid, blistering, and hemorrhagic bullae. Findings of crepitus and soft tissue air on plain radiographs are seen in 37% and 57% of patients, respectively.4 Our patient’s X-ray findings revealed extensive gas pockets within soft tissue and osteomyelitis changes of the 5th metatarsal head.

The differential diagnosis for necrotizing fasciitis includes:

- pyogenic soft tissue cellulitis

- clostridial cellulitis (which may also present with soft tissue crepitus)

- nonclostridial anaerobic cellulitis

- acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis

- acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy

- erythema induratum (nodular vasculitis).

Diagnosis is often made on clinical evaluation

The definitive diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis is made by histological examination of the debrided specimen or deep skin tissue biopsy. Fascial necrosis with thrombosed blood vessels and a dense infiltrate of inflammatory cells is seen on histological evaluation.

However, diagnosis is often reached on clinical evaluation. Rapidly deteriorating local signs and symptoms together with systemic toxicity should prompt a working diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis.

Laboratory tests (white blood cell count, blood urea nitrogen level, sodium levels, creatinine levels, erythrocyte sedimentation rates, C-reactive protein levels) and radiographic evaluation (X-rays, computed tomography [CT], and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) are useful adjuncts in reaching the diagnosis.

Prompt treatment is the name of the game

Antibiotic therapy is guided by gram stain and bacterial culture results. (When the clinical suspicion of necrotizing fasciitis is reached, empirical antibiotics should be started right away.) Broad-spectrum antibiotics covering gram positive, gram negative, and anaerobic bacteria should be used. The patient’s age, weight, and liver and renal function should also be considered before starting antibiotics.

Choices of antibiotics include penicillin for gram positive cover and an aminoglycoside or third-generation cephalosporin for gram negative counteraction. Metronidazole (Flagyl) may be considered for anaerobic superimposed infections. Adjunctive clindamycin is also recommended—especially in group A streptococcal infections—because it suppresses toxin production, inhibits M-protein synthesis, and facilitates phagocytosis.5 In addition, hyperbaric oxygen therapy and intravenous immunoglobulin are increasingly being utilized in the management of necrotizing fasciitis.6 Their efficacy has yet to be conclusively established.

Surgical debridement. The importance of prompt and thorough surgical debridement cannot be stressed enough. Large soft-tissue defects created by surgery can be treated with vacuum-assisted closure dressings, local or free soft-tissue flaps, and/or skin grafts. In extreme cases, limb amputation may be necessary.

Aggressive steps were needed for our patient

In the emergency department, we treated our patient with intravenous cloxacillin, gentamicin, and metronidazole. He later underwent surgical debridement and had pus drained from deep abscesses in his foot. Intraoperative findings indicated that there was necrotic tissue involving 80% of the dorsum of the foot and the necrosis extended proximally to the ankle and distally to the toes.

Wound cultures grew group B Streptococcus (Peptostreptococcus species) and Bacteroides. He was treated with intravenous amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (IV Augmentin, available in Singapore) and oral metronidazole. An endocrinologist evaluated him and determined that he had diabetes. He was started on insulin.

Postoperatively, our patient remained septic. Five days later, he underwent a below-the-knee amputation; the surgeons noted that his foot was gangrenous.

Our patient stayed in the hospital for 7 more days and was discharged about 2 weeks after his arrival at the ER.

Correspondence

Ramesh Subramaniam, MBBS, National University Hospital, 5 Lower Kent Ridge Road, Singapore 119074

A 49-year-old, unkempt-looking Indian man came into our emergency department in Singapore complaining of increasing right foot swelling and worsening pain that he’d had for a month after having stepped on a fish bone while walking on the beach. Our patient pulled the bone out himself and did not seek immediate medical attention.

Our patient said that he had occasional fever with chills and rigors. His medical history was unremarkable, and there was no history of previous injury or surgery to the right foot. He worked as an “oiler” refueling ships, and said that he did not drink alcohol or smoke.

He was dehydrated, and there were no other sources of infection or sores on his body. Our patient was febrile (38.3°C [100.9°F]), his blood pressure was 112/74 mm Hg, and he was tachycardic at 117 beats per minute.

His right foot was boggy, swollen, and tender with significant crepitus. Brownish discharge was oozing from the sole of his foot (FIGURE 1). There were large infected subcutaneous bullae on the dorsum of his foot (FIGURE 2). We could feel a popliteal pulse in both legs, but could not feel a right dorsalis pedis pulse.

What is your diagnosis?

FIGURE 1

Swollen, dusky foot

FIGURE 2

Dark bullae

Diagnosis: Necrotizing fasciitis

Necrotizing fasciitis infections are characterized by fulminant destruction of tissue, systemic signs of toxicity, and high rates of mortality. The incidence of necrotizing fasciitis in adults is 0.40 cases per 100,000 population, while the incidence in children is 0.08 cases per 100,000 population. Mortality rates as high as 73% have been reported.1 Early clinical suspicion, early surgical intervention (surgical debridement), and systemic antibiotics are of the utmost importance.

Necrotizing fasciitis is caused by gram positive, gram negative, and/or anaerobic bacteria. Local tissue hypoxia from trauma, surgery, or a medically compromised state creates an ideal opportunistic environment for bacterial proliferation.

Necrotizing fasciitis can be broadly classified into 2 main types:

Type 1 necrotizing fasciitis is a polymicrobial infection caused by facultative bacteria along with anaerobes. Polymicrobial infections with anaerobes are common (up to 74%) in infected puncture wounds in patients with diabetes.2

Type 2 necrotizing fasciitis is caused by group A streptococci alone, but sometimes in association with Staphylococcus aureus. Vibrio vulnificus infection has also been reported in fish bone piercing injuries leading to necrotizing fasciitis.3

Typical early signs and symptoms include severe pain, rapidly progressing erythema, dusky or purplish skin discoloration, and systemic signs of septic toxicity such as fever, tachycardia, a generalized unwell feeling, and even hypotension. (A lack of classic tissue inflammatory signs may mask an ongoing necrotizing fasciitis beneath the skin.) The involved region may become numb due to the necrosis of the innervating nerve fibers. Discharge or crepitus may also be noted.

Late clinical signs of necrotizing fasciitis include cellulitis, skin discoloration, discharge of “dishwater” fluid, blistering, and hemorrhagic bullae. Findings of crepitus and soft tissue air on plain radiographs are seen in 37% and 57% of patients, respectively.4 Our patient’s X-ray findings revealed extensive gas pockets within soft tissue and osteomyelitis changes of the 5th metatarsal head.

The differential diagnosis for necrotizing fasciitis includes:

- pyogenic soft tissue cellulitis

- clostridial cellulitis (which may also present with soft tissue crepitus)

- nonclostridial anaerobic cellulitis

- acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis

- acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy

- erythema induratum (nodular vasculitis).

Diagnosis is often made on clinical evaluation

The definitive diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis is made by histological examination of the debrided specimen or deep skin tissue biopsy. Fascial necrosis with thrombosed blood vessels and a dense infiltrate of inflammatory cells is seen on histological evaluation.

However, diagnosis is often reached on clinical evaluation. Rapidly deteriorating local signs and symptoms together with systemic toxicity should prompt a working diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis.

Laboratory tests (white blood cell count, blood urea nitrogen level, sodium levels, creatinine levels, erythrocyte sedimentation rates, C-reactive protein levels) and radiographic evaluation (X-rays, computed tomography [CT], and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) are useful adjuncts in reaching the diagnosis.

Prompt treatment is the name of the game

Antibiotic therapy is guided by gram stain and bacterial culture results. (When the clinical suspicion of necrotizing fasciitis is reached, empirical antibiotics should be started right away.) Broad-spectrum antibiotics covering gram positive, gram negative, and anaerobic bacteria should be used. The patient’s age, weight, and liver and renal function should also be considered before starting antibiotics.

Choices of antibiotics include penicillin for gram positive cover and an aminoglycoside or third-generation cephalosporin for gram negative counteraction. Metronidazole (Flagyl) may be considered for anaerobic superimposed infections. Adjunctive clindamycin is also recommended—especially in group A streptococcal infections—because it suppresses toxin production, inhibits M-protein synthesis, and facilitates phagocytosis.5 In addition, hyperbaric oxygen therapy and intravenous immunoglobulin are increasingly being utilized in the management of necrotizing fasciitis.6 Their efficacy has yet to be conclusively established.

Surgical debridement. The importance of prompt and thorough surgical debridement cannot be stressed enough. Large soft-tissue defects created by surgery can be treated with vacuum-assisted closure dressings, local or free soft-tissue flaps, and/or skin grafts. In extreme cases, limb amputation may be necessary.

Aggressive steps were needed for our patient

In the emergency department, we treated our patient with intravenous cloxacillin, gentamicin, and metronidazole. He later underwent surgical debridement and had pus drained from deep abscesses in his foot. Intraoperative findings indicated that there was necrotic tissue involving 80% of the dorsum of the foot and the necrosis extended proximally to the ankle and distally to the toes.

Wound cultures grew group B Streptococcus (Peptostreptococcus species) and Bacteroides. He was treated with intravenous amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (IV Augmentin, available in Singapore) and oral metronidazole. An endocrinologist evaluated him and determined that he had diabetes. He was started on insulin.

Postoperatively, our patient remained septic. Five days later, he underwent a below-the-knee amputation; the surgeons noted that his foot was gangrenous.

Our patient stayed in the hospital for 7 more days and was discharged about 2 weeks after his arrival at the ER.

Correspondence

Ramesh Subramaniam, MBBS, National University Hospital, 5 Lower Kent Ridge Road, Singapore 119074

1. Trent JT, Kirsner RS. Necrotizing fasciitis. Wounds. 2002;14:284-292.

2. Lavery LA, Harkless LB, Felder-Johnson K, et al. Bacterial pathogens in infected puncture wounds in adults with diabetes. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1994;33:91-97.

3. Oliver JD. Wound infections caused by Vibrio vulnificus and other marine bacteria. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:383-391.

4. Elliott DC, Kufera JA, Myers RA. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. Risk factors for mortality and strategies for management. Ann Surg. 1996;224:672-683.

5. Stevens DL. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: spectrum of disease, pathogenesis and new concepts in treatment. Emerg Infect Dis. 1995;1:69.

6. Young MH, Aronoff DM, Engleberg NC. Necrotizing fasciitis: pathogenesis and treatment. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2005;3:279-294.

1. Trent JT, Kirsner RS. Necrotizing fasciitis. Wounds. 2002;14:284-292.

2. Lavery LA, Harkless LB, Felder-Johnson K, et al. Bacterial pathogens in infected puncture wounds in adults with diabetes. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1994;33:91-97.

3. Oliver JD. Wound infections caused by Vibrio vulnificus and other marine bacteria. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:383-391.

4. Elliott DC, Kufera JA, Myers RA. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. Risk factors for mortality and strategies for management. Ann Surg. 1996;224:672-683.

5. Stevens DL. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: spectrum of disease, pathogenesis and new concepts in treatment. Emerg Infect Dis. 1995;1:69.

6. Young MH, Aronoff DM, Engleberg NC. Necrotizing fasciitis: pathogenesis and treatment. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2005;3:279-294.

Bilateral thumbnail deformity

During my recent deployment to Afghanistan, a 31-year-old man came into our aid station with a bilateral thumbnail deformity that he’d had for several weeks. He was concerned about a thumbnail infection and wanted to discuss antifungal treatment. His history was unremarkable, and he said he had no nail fold infections or other skin conditions. He was taking doxycycline for malaria prophylaxis. He also mentioned that he had recently started working as a military intelligence officer, putting in 18-hour days.

His exam revealed sharp, closely spaced horizontal grooves on both of his thumbnails (FIGURE). His nails had no hyperkeratotic debris or pitting. His nail folds appeared hypopigmented with scaling, but they were nontender to palpation. His other fingernails were normal in appearance. The remainder of the skin exam was unremarkable.

FIGURE

Horizontal grooves on both thumbnails

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Habit-tic deformity

Habit-tic deformity is a common nail condition caused by a conscious or unconscious rubbing or picking of the proximal nail folds. Horizontal grooves are formed proximally due to nail matrix damage and subsequently move distally with fingernail growth. The dominant thumbnail is most often affected by frequent rubbing with the ipsilateral index fingernail, although all nails can be involved.

This deformity is more common during periods of stress—which my patient was experiencing in his new role as an intelligence officer—and is believed to result from a compulsive or impulse control disorder.

Differential diagnosis includes onychomycosis

The differential diagnosis of external nail deformation includes median nail dystrophy, chronic proximal nail fold inflammation, onychomycosis, psoriasis, Beau’s lines, and habit-tic-like dystrophy.

Median nail dystrophy. This nail deformity has a distinctive longitudinal split in the center of the nail plate with several cracks projecting laterally, resembling a fir tree. The etiology of this disorder is unknown, although some have suggested that habit-tic deformity and median nail dystrophy are different manifestations of the same disorder.1

Chronic proximal nail fold inflammation. Chronic paronychia is an inflammation of the proximal nail fold, and is one of 2 forms of inflammation included in the differential. It is characterized by tenderness and swelling around the proximal and lateral nail folds, most often due to contact irritant exposure. The cuticle separates from the nail plate, which creates a space for infection. The nail plate surface subsequently becomes brown and develops ripples that can mimic the habit-tic deformity. Chronic eczematous inflammation is the second form of inflammation in the differential and can produce results that are similar to chronic paronychia. Both forms of proximal nail fold inflammation tend to resemble rounded waves, as opposed to the narrow, closely spaced grooves seen in habit-tic deformity.

Onychomycosis. Habit-tic deformity is often confused with onychomycosis, though the 2 can be easily distinguished upon close inspection. Unlike habit-tic deformity, onychomycosis classically has nail thickening and hyperkeratotic debris. Diagnosis can be solidified by a potassium hydroxide examination and culture.

Psoriasis. Psoriatic nail lesions can occur in the absence of classic skin findings. Nail pitting is the hallmark nail finding in psoriasis. Other findings such as onycholysis (separation of the nail from the nail bed), nail fragmentation and crumbling, and splinter hemorrhages can distinguish psoriatic nails from habit-tic deformity.

Beau’s lines. This disorder is characterized by horizontal depressions in most or all of the nails. These depressions occur at the proximal portion of the nail weeks after trauma, medication use, or illness interrupts nail formation. Chemotherapeutic agents, systemic illnesses such as syphilis, myocarditis, peripheral vascular disease, and uncontrolled diabetes, as well as illnesses associated with high fevers, such as scarlet fever, hand-foot-mouth disease, and pneumonia, have all been linked to Beau’s lines.2

The lines (usually one per nail) eventually move distally to the nail’s free edge. The nail on either side of the depression is normal in appearance.

Habit-tic-like dystrophy. Nail deformities that closely resemble habit-tic deformity on exam have been reported in patients who explicitly deny trauma. One report in the literature indicates that 2 patients who denied trauma—one with systemic lupus erythematous and another with no significant past medical history—responded to treatment with a multivitamin rich in biotin, vitamins B6, C, and E, and riboflavin.3 Another report describes habit-tic-like deformity that occurred in patients who were taking aromatic retinoids. The disorder resolved when the patients stopped taking the medication.1

Low-tech approach to treatment

The simplest approach to cosmetic improvement is to have the patient tape the proximal portion of the affected nails during the day when he or she picks at and rubs them. The tape acts as a barrier to the repetitive trauma and also serves as a reminder to the patient. The patient can expect improvement in several weeks if the tape is applied consistently. In addition, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may play a role in treatment, because habit-tic deformity is believed to be a compulsive disorder.4

My patient tried the taping method for 2 months and had moderate improvement of his nail deformity. He was not, however, completely satisfied with the results, so we discussed vitamin supplementation as an additional therapy. His tour ended shortly thereafter, and he was lost to follow-up.

Disclosure

The author reported no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the author and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of Defense.

Correspondence

Edwin A. Farnell IV, MD, Urgent Care Clinic, Moncrief Army Community Hospital, 4500 Stuart Street, Fort Jackson, SC 29207-5720; [email protected]

1. Griego RD, Orengo IF, Scher RK. Median nail dystrophy and habit tic deformity: are they different forms of the same disorder? Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:799-800.

2. Habif TB. Nail diseases. In: Clinical Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby–Elsevier; 2004:869-884.

3. Gloster H. Habit-tic-like and median nail-like dystrophies treated with multivitamins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:543-544.

4. Vittorio C, Phillips K. Treatment of habit-tic deformity with fluoxetine. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1203-1204.

During my recent deployment to Afghanistan, a 31-year-old man came into our aid station with a bilateral thumbnail deformity that he’d had for several weeks. He was concerned about a thumbnail infection and wanted to discuss antifungal treatment. His history was unremarkable, and he said he had no nail fold infections or other skin conditions. He was taking doxycycline for malaria prophylaxis. He also mentioned that he had recently started working as a military intelligence officer, putting in 18-hour days.

His exam revealed sharp, closely spaced horizontal grooves on both of his thumbnails (FIGURE). His nails had no hyperkeratotic debris or pitting. His nail folds appeared hypopigmented with scaling, but they were nontender to palpation. His other fingernails were normal in appearance. The remainder of the skin exam was unremarkable.

FIGURE

Horizontal grooves on both thumbnails

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Habit-tic deformity

Habit-tic deformity is a common nail condition caused by a conscious or unconscious rubbing or picking of the proximal nail folds. Horizontal grooves are formed proximally due to nail matrix damage and subsequently move distally with fingernail growth. The dominant thumbnail is most often affected by frequent rubbing with the ipsilateral index fingernail, although all nails can be involved.

This deformity is more common during periods of stress—which my patient was experiencing in his new role as an intelligence officer—and is believed to result from a compulsive or impulse control disorder.

Differential diagnosis includes onychomycosis

The differential diagnosis of external nail deformation includes median nail dystrophy, chronic proximal nail fold inflammation, onychomycosis, psoriasis, Beau’s lines, and habit-tic-like dystrophy.

Median nail dystrophy. This nail deformity has a distinctive longitudinal split in the center of the nail plate with several cracks projecting laterally, resembling a fir tree. The etiology of this disorder is unknown, although some have suggested that habit-tic deformity and median nail dystrophy are different manifestations of the same disorder.1

Chronic proximal nail fold inflammation. Chronic paronychia is an inflammation of the proximal nail fold, and is one of 2 forms of inflammation included in the differential. It is characterized by tenderness and swelling around the proximal and lateral nail folds, most often due to contact irritant exposure. The cuticle separates from the nail plate, which creates a space for infection. The nail plate surface subsequently becomes brown and develops ripples that can mimic the habit-tic deformity. Chronic eczematous inflammation is the second form of inflammation in the differential and can produce results that are similar to chronic paronychia. Both forms of proximal nail fold inflammation tend to resemble rounded waves, as opposed to the narrow, closely spaced grooves seen in habit-tic deformity.

Onychomycosis. Habit-tic deformity is often confused with onychomycosis, though the 2 can be easily distinguished upon close inspection. Unlike habit-tic deformity, onychomycosis classically has nail thickening and hyperkeratotic debris. Diagnosis can be solidified by a potassium hydroxide examination and culture.

Psoriasis. Psoriatic nail lesions can occur in the absence of classic skin findings. Nail pitting is the hallmark nail finding in psoriasis. Other findings such as onycholysis (separation of the nail from the nail bed), nail fragmentation and crumbling, and splinter hemorrhages can distinguish psoriatic nails from habit-tic deformity.

Beau’s lines. This disorder is characterized by horizontal depressions in most or all of the nails. These depressions occur at the proximal portion of the nail weeks after trauma, medication use, or illness interrupts nail formation. Chemotherapeutic agents, systemic illnesses such as syphilis, myocarditis, peripheral vascular disease, and uncontrolled diabetes, as well as illnesses associated with high fevers, such as scarlet fever, hand-foot-mouth disease, and pneumonia, have all been linked to Beau’s lines.2

The lines (usually one per nail) eventually move distally to the nail’s free edge. The nail on either side of the depression is normal in appearance.

Habit-tic-like dystrophy. Nail deformities that closely resemble habit-tic deformity on exam have been reported in patients who explicitly deny trauma. One report in the literature indicates that 2 patients who denied trauma—one with systemic lupus erythematous and another with no significant past medical history—responded to treatment with a multivitamin rich in biotin, vitamins B6, C, and E, and riboflavin.3 Another report describes habit-tic-like deformity that occurred in patients who were taking aromatic retinoids. The disorder resolved when the patients stopped taking the medication.1

Low-tech approach to treatment

The simplest approach to cosmetic improvement is to have the patient tape the proximal portion of the affected nails during the day when he or she picks at and rubs them. The tape acts as a barrier to the repetitive trauma and also serves as a reminder to the patient. The patient can expect improvement in several weeks if the tape is applied consistently. In addition, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may play a role in treatment, because habit-tic deformity is believed to be a compulsive disorder.4

My patient tried the taping method for 2 months and had moderate improvement of his nail deformity. He was not, however, completely satisfied with the results, so we discussed vitamin supplementation as an additional therapy. His tour ended shortly thereafter, and he was lost to follow-up.

Disclosure

The author reported no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the author and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of Defense.

Correspondence

Edwin A. Farnell IV, MD, Urgent Care Clinic, Moncrief Army Community Hospital, 4500 Stuart Street, Fort Jackson, SC 29207-5720; [email protected]

During my recent deployment to Afghanistan, a 31-year-old man came into our aid station with a bilateral thumbnail deformity that he’d had for several weeks. He was concerned about a thumbnail infection and wanted to discuss antifungal treatment. His history was unremarkable, and he said he had no nail fold infections or other skin conditions. He was taking doxycycline for malaria prophylaxis. He also mentioned that he had recently started working as a military intelligence officer, putting in 18-hour days.

His exam revealed sharp, closely spaced horizontal grooves on both of his thumbnails (FIGURE). His nails had no hyperkeratotic debris or pitting. His nail folds appeared hypopigmented with scaling, but they were nontender to palpation. His other fingernails were normal in appearance. The remainder of the skin exam was unremarkable.

FIGURE

Horizontal grooves on both thumbnails

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Habit-tic deformity

Habit-tic deformity is a common nail condition caused by a conscious or unconscious rubbing or picking of the proximal nail folds. Horizontal grooves are formed proximally due to nail matrix damage and subsequently move distally with fingernail growth. The dominant thumbnail is most often affected by frequent rubbing with the ipsilateral index fingernail, although all nails can be involved.

This deformity is more common during periods of stress—which my patient was experiencing in his new role as an intelligence officer—and is believed to result from a compulsive or impulse control disorder.

Differential diagnosis includes onychomycosis

The differential diagnosis of external nail deformation includes median nail dystrophy, chronic proximal nail fold inflammation, onychomycosis, psoriasis, Beau’s lines, and habit-tic-like dystrophy.

Median nail dystrophy. This nail deformity has a distinctive longitudinal split in the center of the nail plate with several cracks projecting laterally, resembling a fir tree. The etiology of this disorder is unknown, although some have suggested that habit-tic deformity and median nail dystrophy are different manifestations of the same disorder.1

Chronic proximal nail fold inflammation. Chronic paronychia is an inflammation of the proximal nail fold, and is one of 2 forms of inflammation included in the differential. It is characterized by tenderness and swelling around the proximal and lateral nail folds, most often due to contact irritant exposure. The cuticle separates from the nail plate, which creates a space for infection. The nail plate surface subsequently becomes brown and develops ripples that can mimic the habit-tic deformity. Chronic eczematous inflammation is the second form of inflammation in the differential and can produce results that are similar to chronic paronychia. Both forms of proximal nail fold inflammation tend to resemble rounded waves, as opposed to the narrow, closely spaced grooves seen in habit-tic deformity.

Onychomycosis. Habit-tic deformity is often confused with onychomycosis, though the 2 can be easily distinguished upon close inspection. Unlike habit-tic deformity, onychomycosis classically has nail thickening and hyperkeratotic debris. Diagnosis can be solidified by a potassium hydroxide examination and culture.

Psoriasis. Psoriatic nail lesions can occur in the absence of classic skin findings. Nail pitting is the hallmark nail finding in psoriasis. Other findings such as onycholysis (separation of the nail from the nail bed), nail fragmentation and crumbling, and splinter hemorrhages can distinguish psoriatic nails from habit-tic deformity.

Beau’s lines. This disorder is characterized by horizontal depressions in most or all of the nails. These depressions occur at the proximal portion of the nail weeks after trauma, medication use, or illness interrupts nail formation. Chemotherapeutic agents, systemic illnesses such as syphilis, myocarditis, peripheral vascular disease, and uncontrolled diabetes, as well as illnesses associated with high fevers, such as scarlet fever, hand-foot-mouth disease, and pneumonia, have all been linked to Beau’s lines.2

The lines (usually one per nail) eventually move distally to the nail’s free edge. The nail on either side of the depression is normal in appearance.

Habit-tic-like dystrophy. Nail deformities that closely resemble habit-tic deformity on exam have been reported in patients who explicitly deny trauma. One report in the literature indicates that 2 patients who denied trauma—one with systemic lupus erythematous and another with no significant past medical history—responded to treatment with a multivitamin rich in biotin, vitamins B6, C, and E, and riboflavin.3 Another report describes habit-tic-like deformity that occurred in patients who were taking aromatic retinoids. The disorder resolved when the patients stopped taking the medication.1

Low-tech approach to treatment

The simplest approach to cosmetic improvement is to have the patient tape the proximal portion of the affected nails during the day when he or she picks at and rubs them. The tape acts as a barrier to the repetitive trauma and also serves as a reminder to the patient. The patient can expect improvement in several weeks if the tape is applied consistently. In addition, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may play a role in treatment, because habit-tic deformity is believed to be a compulsive disorder.4

My patient tried the taping method for 2 months and had moderate improvement of his nail deformity. He was not, however, completely satisfied with the results, so we discussed vitamin supplementation as an additional therapy. His tour ended shortly thereafter, and he was lost to follow-up.

Disclosure

The author reported no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the author and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of Defense.

Correspondence

Edwin A. Farnell IV, MD, Urgent Care Clinic, Moncrief Army Community Hospital, 4500 Stuart Street, Fort Jackson, SC 29207-5720; [email protected]

1. Griego RD, Orengo IF, Scher RK. Median nail dystrophy and habit tic deformity: are they different forms of the same disorder? Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:799-800.

2. Habif TB. Nail diseases. In: Clinical Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby–Elsevier; 2004:869-884.

3. Gloster H. Habit-tic-like and median nail-like dystrophies treated with multivitamins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:543-544.

4. Vittorio C, Phillips K. Treatment of habit-tic deformity with fluoxetine. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1203-1204.

1. Griego RD, Orengo IF, Scher RK. Median nail dystrophy and habit tic deformity: are they different forms of the same disorder? Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:799-800.

2. Habif TB. Nail diseases. In: Clinical Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby–Elsevier; 2004:869-884.

3. Gloster H. Habit-tic-like and median nail-like dystrophies treated with multivitamins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:543-544.

4. Vittorio C, Phillips K. Treatment of habit-tic deformity with fluoxetine. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1203-1204.

Tumor with central crusting

A 63-year-old man came into our dermatologic surgery clinic with a growth on his left cheek just anterior to his sideburn (FIGURE). Our patient indicated that the lesion, which appeared 6 weeks earlier, started as a small, hard papule with a central depression and rapidly grew to reach its current size and shape.

The patient’s face was sun damaged, and he had a prominent 2.1×1.8 cm well-circumscribed, skin-colored tumor on his cheek. The tumor had a central depression covered by a crust that appeared to conceal a deep keratinous plug. The tumor also had a volcano-like shape and was firm in texture, but tender to palpation and pressure. No lymphadenopathy was present.

The patient had a history of extensive sun exposure, and he’d had previous nonmelanoma skin cancers treated with various medical and surgical techniques. The rest of his history and exam were within normal limits. We performed a biopsy to confirm our clinical diagnosis.

FIGURE

Rapidly growing skin-colored tumor

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Solitary keratoacanthoma

Our patient had a solitary keratoacanthoma, a unique epidermal tumor that’s characterized by rapid, abundant growth and spontaneous resolution. This tumor goes by many names—molluscum sebaceum, molluscum pseudocarcinomatosum, cutaneous sebaceous neoplasm, and self-healing squamous epithelioma—but keratoacanthoma is the preferred term.1,2

There are several types of keratoacanthoma, but solitary keratoacanthoma remains the most common. It is typically found in light-skinned people in hair-bearing, sun-exposed areas. Peak incidence occurs between the ages of 50 and 69, although the tumors have been reported in patients of all ages. Both sexes are about equally affected, although there is a slight predilection for males. Keratoacanthomas mainly develop on the face (lower lip, cheek, nose, and eyelid), neck, and hands.

The tumors are often considered benign, but they become aggressive in 20% of cases—showing signs of perineural, perivascular, and intravascular invasion and metastases to regional lymph nodes. As a result, some clinicians consider keratoacanthoma to be a pseudomalignancy with self-regressing potential, while others view it as a pseudo-benign tumor progressing into an invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).1,2

The exact etiology of keratoacanthoma is unknown. However, several precipitating factors have been implicated. Primary among them is exposure to ultraviolet light. Other etiological factors include:3-6

- chemical carcinogens (tar, pitch, mineral oil, and cigarette smoking)

- trauma (body peel, carbon dioxide laser resurfacing, megavoltage radiation therapy, and cryosurgery)

- immunosuppression

- surgical scar

- human papilloma virus (HPV).

A tumor with 3 stages

Keratoacanthoma undergoes a proliferative, mature, and involution stage.

In the proliferative stage, there is a rapid increase in tumor size; the tumor can get as big as 10 to 25 mm in diameter in 6 to 8 weeks.1,7

In the mature stage, the tumor stops growing and maintains a typical volcano-like form with a central keratin-filled crater.

In the involution stage, up to 50% of keratoacanthomas undergo spontaneous resolution with expulsion of the keratin plug and resorption of the tumoral mass. The process lasts 4 to 6 weeks, on average, but may take up to 1 year. What’s left behind is a residual atrophic and hypopigmented scar.8

Some lesions persist for a year or more, although the entire process from start to spontaneous resolution usually takes about 4 to 9 months.2,7,8

Is it an SCC or keratoacanthoma?

Histology is the gold standard in diagnosing a keratoacanthoma. A deep biopsy specimen that preferably includes part or full subcutaneous fat with excision of the entire lesion should allow for good histologic interpretation and diagnosis. Keratoacanthoma presents as a downgrowth of well-differentiated squamous epithelium. However, even with a well-performed biopsy, the diagnosis of keratoacanthoma remains challenging due to the lack of sufficient sensitive or specific histological features that can distinguish between keratoacanthomas and SCCs.

As a rule, a normal surface epithelium surrounding the keratin plug with sharp demarcation between tumor and stroma favors keratoacanthoma, whereas ulceration, numerous mitoses, and marked pleomorphism/anaplasia favor SCC. Because of the lack of a universal diagnostic criterion, several experts recommend that all keratoacanthomas be considered potential SCCs and thus treated as such.1,2

When in doubt, cut it out

Although the natural course of a keratoacanthoma is spontaneous regression, the lack of reliable criteria to differentiate it from an SCC with confidence renders therapeutic intervention the safest approach. Solitary keratoacanthomas respond well to surgical excision and may require aggressive procedures if they become too large or invade other structures. Since Mohs’ micrographic surgery is tissue sparing, consider it the treatment of choice if the keratoacanthoma is located in a sensitive area, such as the face.

Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen, electrodessication and curettage, radiation therapy, and CO2 laser surgery have all been used in small solitary keratoacanthomas with good success.9,10 Other treatment options include intralesional and/or topical treatment using several compounds, such as 5-fluorouracil, corticosteroids, bleomycin, imiquimod, interferon alpha 2b, and methotrexate.7,9-13

Keratoacanthoma patients are often UV light sensitive, so they must avoid excessive sun exposure and use sunscreen with high SPF at all times to prevent recurrence and minimize scarring.

We opted for Mohs’ surgery for our patient

Given the cosmetically sensitive location of our patient’s keratoacanthoma, the size of it, and the patient’s history of skin cancers, we decided to use Mohs’ micrographic surgery for the management of this tumor, with good clinical outcome. There were no new lesions or recurrence on follow-up visit 6 months later.

Correspondence

Amor Khachemoune, MD, CWS, Assistant Professor, Ronald O. Perelman Department of Dermatology, New York University School of Medicine, 530 First Avenue, Suite 7R, New York, NY 10016; [email protected].

1. Beham A, Regauer S, Soyer HP, Beham-Schmid C. Keratoacanthoma: a clinically distinct variant of well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Ad Anat Pathol. 1998;5:269-280.

2. Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma: a clinico-pathologic enigma. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(2 Pt 2):326-333; discussion 333.

3. Miot HA, Miot LD, da Costa AL, Matsuo CY, Stolf HO, Marques ME. Association between solitary keratoacanthoma and cigarette smoking: a case-control study. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12(2):2.-

4. Pattee SF, Silvis NG. Keratoacanthoma developing in sites of previous trauma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(2 suppl):S35-S38.

5. Goldberg LH, Silapunt S, Beyrau KK, Peterson SR, Friedman PM, Alam M. Keratoacanthoma as a postoperative complication of skin cancer excision. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:753-758.

6. Stockfleth E, Meinke B, Arndt R, Christophers E, Meyer T. Identification of DNA sequences of both genital and cutaneous HPV types in a small number of keratoacanthomas of nonimmunosuppressed patients. Dermatology. 1999;198:122-125.

7. Oh CK, Son HS, Lee JB, Jang HS, Kwon KS. Intralesional interferon alfa-2b treatment of keratoacanthomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(5 suppl):S177-S180.

8. Griffiths RW. Keratoacanthoma observed. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57:485-501.

9. Caccialanza M, Sopelana N. Radiation therapy of keratoacanthomas: results in 55 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;16:475-477.

10. Gray RJ, Meland NB. Topical 5-fluorouracil as primary therapy for keratoacanthoma. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;44:82-85.

11. Sanders S, Busam KJ, Halpern AC, Nehal KS. Intralesional corticosteroid treatment of multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas: case report and review of a controversial therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:954-958.

12. Di Lernia V, Ricci C, Albertini G. Spontaneous regression of keratoacanthoma can be promoted by topical treatment with imiquimod cream. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:626-629.

13. Cohen PR, Schulze KE, Teller CF, Nelson BR. Intralesional methotrexate for keratoacanthoma of the nose. Skinmed. 2005;4:393-395.

A 63-year-old man came into our dermatologic surgery clinic with a growth on his left cheek just anterior to his sideburn (FIGURE). Our patient indicated that the lesion, which appeared 6 weeks earlier, started as a small, hard papule with a central depression and rapidly grew to reach its current size and shape.

The patient’s face was sun damaged, and he had a prominent 2.1×1.8 cm well-circumscribed, skin-colored tumor on his cheek. The tumor had a central depression covered by a crust that appeared to conceal a deep keratinous plug. The tumor also had a volcano-like shape and was firm in texture, but tender to palpation and pressure. No lymphadenopathy was present.

The patient had a history of extensive sun exposure, and he’d had previous nonmelanoma skin cancers treated with various medical and surgical techniques. The rest of his history and exam were within normal limits. We performed a biopsy to confirm our clinical diagnosis.

FIGURE

Rapidly growing skin-colored tumor

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Solitary keratoacanthoma

Our patient had a solitary keratoacanthoma, a unique epidermal tumor that’s characterized by rapid, abundant growth and spontaneous resolution. This tumor goes by many names—molluscum sebaceum, molluscum pseudocarcinomatosum, cutaneous sebaceous neoplasm, and self-healing squamous epithelioma—but keratoacanthoma is the preferred term.1,2

There are several types of keratoacanthoma, but solitary keratoacanthoma remains the most common. It is typically found in light-skinned people in hair-bearing, sun-exposed areas. Peak incidence occurs between the ages of 50 and 69, although the tumors have been reported in patients of all ages. Both sexes are about equally affected, although there is a slight predilection for males. Keratoacanthomas mainly develop on the face (lower lip, cheek, nose, and eyelid), neck, and hands.

The tumors are often considered benign, but they become aggressive in 20% of cases—showing signs of perineural, perivascular, and intravascular invasion and metastases to regional lymph nodes. As a result, some clinicians consider keratoacanthoma to be a pseudomalignancy with self-regressing potential, while others view it as a pseudo-benign tumor progressing into an invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).1,2

The exact etiology of keratoacanthoma is unknown. However, several precipitating factors have been implicated. Primary among them is exposure to ultraviolet light. Other etiological factors include:3-6

- chemical carcinogens (tar, pitch, mineral oil, and cigarette smoking)

- trauma (body peel, carbon dioxide laser resurfacing, megavoltage radiation therapy, and cryosurgery)

- immunosuppression

- surgical scar

- human papilloma virus (HPV).

A tumor with 3 stages

Keratoacanthoma undergoes a proliferative, mature, and involution stage.

In the proliferative stage, there is a rapid increase in tumor size; the tumor can get as big as 10 to 25 mm in diameter in 6 to 8 weeks.1,7

In the mature stage, the tumor stops growing and maintains a typical volcano-like form with a central keratin-filled crater.

In the involution stage, up to 50% of keratoacanthomas undergo spontaneous resolution with expulsion of the keratin plug and resorption of the tumoral mass. The process lasts 4 to 6 weeks, on average, but may take up to 1 year. What’s left behind is a residual atrophic and hypopigmented scar.8

Some lesions persist for a year or more, although the entire process from start to spontaneous resolution usually takes about 4 to 9 months.2,7,8

Is it an SCC or keratoacanthoma?

Histology is the gold standard in diagnosing a keratoacanthoma. A deep biopsy specimen that preferably includes part or full subcutaneous fat with excision of the entire lesion should allow for good histologic interpretation and diagnosis. Keratoacanthoma presents as a downgrowth of well-differentiated squamous epithelium. However, even with a well-performed biopsy, the diagnosis of keratoacanthoma remains challenging due to the lack of sufficient sensitive or specific histological features that can distinguish between keratoacanthomas and SCCs.

As a rule, a normal surface epithelium surrounding the keratin plug with sharp demarcation between tumor and stroma favors keratoacanthoma, whereas ulceration, numerous mitoses, and marked pleomorphism/anaplasia favor SCC. Because of the lack of a universal diagnostic criterion, several experts recommend that all keratoacanthomas be considered potential SCCs and thus treated as such.1,2

When in doubt, cut it out

Although the natural course of a keratoacanthoma is spontaneous regression, the lack of reliable criteria to differentiate it from an SCC with confidence renders therapeutic intervention the safest approach. Solitary keratoacanthomas respond well to surgical excision and may require aggressive procedures if they become too large or invade other structures. Since Mohs’ micrographic surgery is tissue sparing, consider it the treatment of choice if the keratoacanthoma is located in a sensitive area, such as the face.

Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen, electrodessication and curettage, radiation therapy, and CO2 laser surgery have all been used in small solitary keratoacanthomas with good success.9,10 Other treatment options include intralesional and/or topical treatment using several compounds, such as 5-fluorouracil, corticosteroids, bleomycin, imiquimod, interferon alpha 2b, and methotrexate.7,9-13

Keratoacanthoma patients are often UV light sensitive, so they must avoid excessive sun exposure and use sunscreen with high SPF at all times to prevent recurrence and minimize scarring.

We opted for Mohs’ surgery for our patient

Given the cosmetically sensitive location of our patient’s keratoacanthoma, the size of it, and the patient’s history of skin cancers, we decided to use Mohs’ micrographic surgery for the management of this tumor, with good clinical outcome. There were no new lesions or recurrence on follow-up visit 6 months later.

Correspondence

Amor Khachemoune, MD, CWS, Assistant Professor, Ronald O. Perelman Department of Dermatology, New York University School of Medicine, 530 First Avenue, Suite 7R, New York, NY 10016; [email protected].

A 63-year-old man came into our dermatologic surgery clinic with a growth on his left cheek just anterior to his sideburn (FIGURE). Our patient indicated that the lesion, which appeared 6 weeks earlier, started as a small, hard papule with a central depression and rapidly grew to reach its current size and shape.

The patient’s face was sun damaged, and he had a prominent 2.1×1.8 cm well-circumscribed, skin-colored tumor on his cheek. The tumor had a central depression covered by a crust that appeared to conceal a deep keratinous plug. The tumor also had a volcano-like shape and was firm in texture, but tender to palpation and pressure. No lymphadenopathy was present.

The patient had a history of extensive sun exposure, and he’d had previous nonmelanoma skin cancers treated with various medical and surgical techniques. The rest of his history and exam were within normal limits. We performed a biopsy to confirm our clinical diagnosis.

FIGURE

Rapidly growing skin-colored tumor

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Solitary keratoacanthoma

Our patient had a solitary keratoacanthoma, a unique epidermal tumor that’s characterized by rapid, abundant growth and spontaneous resolution. This tumor goes by many names—molluscum sebaceum, molluscum pseudocarcinomatosum, cutaneous sebaceous neoplasm, and self-healing squamous epithelioma—but keratoacanthoma is the preferred term.1,2

There are several types of keratoacanthoma, but solitary keratoacanthoma remains the most common. It is typically found in light-skinned people in hair-bearing, sun-exposed areas. Peak incidence occurs between the ages of 50 and 69, although the tumors have been reported in patients of all ages. Both sexes are about equally affected, although there is a slight predilection for males. Keratoacanthomas mainly develop on the face (lower lip, cheek, nose, and eyelid), neck, and hands.

The tumors are often considered benign, but they become aggressive in 20% of cases—showing signs of perineural, perivascular, and intravascular invasion and metastases to regional lymph nodes. As a result, some clinicians consider keratoacanthoma to be a pseudomalignancy with self-regressing potential, while others view it as a pseudo-benign tumor progressing into an invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).1,2

The exact etiology of keratoacanthoma is unknown. However, several precipitating factors have been implicated. Primary among them is exposure to ultraviolet light. Other etiological factors include:3-6

- chemical carcinogens (tar, pitch, mineral oil, and cigarette smoking)

- trauma (body peel, carbon dioxide laser resurfacing, megavoltage radiation therapy, and cryosurgery)

- immunosuppression

- surgical scar

- human papilloma virus (HPV).

A tumor with 3 stages

Keratoacanthoma undergoes a proliferative, mature, and involution stage.

In the proliferative stage, there is a rapid increase in tumor size; the tumor can get as big as 10 to 25 mm in diameter in 6 to 8 weeks.1,7

In the mature stage, the tumor stops growing and maintains a typical volcano-like form with a central keratin-filled crater.

In the involution stage, up to 50% of keratoacanthomas undergo spontaneous resolution with expulsion of the keratin plug and resorption of the tumoral mass. The process lasts 4 to 6 weeks, on average, but may take up to 1 year. What’s left behind is a residual atrophic and hypopigmented scar.8

Some lesions persist for a year or more, although the entire process from start to spontaneous resolution usually takes about 4 to 9 months.2,7,8

Is it an SCC or keratoacanthoma?

Histology is the gold standard in diagnosing a keratoacanthoma. A deep biopsy specimen that preferably includes part or full subcutaneous fat with excision of the entire lesion should allow for good histologic interpretation and diagnosis. Keratoacanthoma presents as a downgrowth of well-differentiated squamous epithelium. However, even with a well-performed biopsy, the diagnosis of keratoacanthoma remains challenging due to the lack of sufficient sensitive or specific histological features that can distinguish between keratoacanthomas and SCCs.

As a rule, a normal surface epithelium surrounding the keratin plug with sharp demarcation between tumor and stroma favors keratoacanthoma, whereas ulceration, numerous mitoses, and marked pleomorphism/anaplasia favor SCC. Because of the lack of a universal diagnostic criterion, several experts recommend that all keratoacanthomas be considered potential SCCs and thus treated as such.1,2

When in doubt, cut it out

Although the natural course of a keratoacanthoma is spontaneous regression, the lack of reliable criteria to differentiate it from an SCC with confidence renders therapeutic intervention the safest approach. Solitary keratoacanthomas respond well to surgical excision and may require aggressive procedures if they become too large or invade other structures. Since Mohs’ micrographic surgery is tissue sparing, consider it the treatment of choice if the keratoacanthoma is located in a sensitive area, such as the face.

Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen, electrodessication and curettage, radiation therapy, and CO2 laser surgery have all been used in small solitary keratoacanthomas with good success.9,10 Other treatment options include intralesional and/or topical treatment using several compounds, such as 5-fluorouracil, corticosteroids, bleomycin, imiquimod, interferon alpha 2b, and methotrexate.7,9-13

Keratoacanthoma patients are often UV light sensitive, so they must avoid excessive sun exposure and use sunscreen with high SPF at all times to prevent recurrence and minimize scarring.

We opted for Mohs’ surgery for our patient

Given the cosmetically sensitive location of our patient’s keratoacanthoma, the size of it, and the patient’s history of skin cancers, we decided to use Mohs’ micrographic surgery for the management of this tumor, with good clinical outcome. There were no new lesions or recurrence on follow-up visit 6 months later.

Correspondence

Amor Khachemoune, MD, CWS, Assistant Professor, Ronald O. Perelman Department of Dermatology, New York University School of Medicine, 530 First Avenue, Suite 7R, New York, NY 10016; [email protected].

1. Beham A, Regauer S, Soyer HP, Beham-Schmid C. Keratoacanthoma: a clinically distinct variant of well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Ad Anat Pathol. 1998;5:269-280.

2. Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma: a clinico-pathologic enigma. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(2 Pt 2):326-333; discussion 333.

3. Miot HA, Miot LD, da Costa AL, Matsuo CY, Stolf HO, Marques ME. Association between solitary keratoacanthoma and cigarette smoking: a case-control study. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12(2):2.-

4. Pattee SF, Silvis NG. Keratoacanthoma developing in sites of previous trauma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(2 suppl):S35-S38.

5. Goldberg LH, Silapunt S, Beyrau KK, Peterson SR, Friedman PM, Alam M. Keratoacanthoma as a postoperative complication of skin cancer excision. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:753-758.

6. Stockfleth E, Meinke B, Arndt R, Christophers E, Meyer T. Identification of DNA sequences of both genital and cutaneous HPV types in a small number of keratoacanthomas of nonimmunosuppressed patients. Dermatology. 1999;198:122-125.

7. Oh CK, Son HS, Lee JB, Jang HS, Kwon KS. Intralesional interferon alfa-2b treatment of keratoacanthomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(5 suppl):S177-S180.

8. Griffiths RW. Keratoacanthoma observed. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57:485-501.

9. Caccialanza M, Sopelana N. Radiation therapy of keratoacanthomas: results in 55 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;16:475-477.

10. Gray RJ, Meland NB. Topical 5-fluorouracil as primary therapy for keratoacanthoma. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;44:82-85.

11. Sanders S, Busam KJ, Halpern AC, Nehal KS. Intralesional corticosteroid treatment of multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas: case report and review of a controversial therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:954-958.

12. Di Lernia V, Ricci C, Albertini G. Spontaneous regression of keratoacanthoma can be promoted by topical treatment with imiquimod cream. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:626-629.

13. Cohen PR, Schulze KE, Teller CF, Nelson BR. Intralesional methotrexate for keratoacanthoma of the nose. Skinmed. 2005;4:393-395.

1. Beham A, Regauer S, Soyer HP, Beham-Schmid C. Keratoacanthoma: a clinically distinct variant of well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Ad Anat Pathol. 1998;5:269-280.

2. Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma: a clinico-pathologic enigma. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(2 Pt 2):326-333; discussion 333.

3. Miot HA, Miot LD, da Costa AL, Matsuo CY, Stolf HO, Marques ME. Association between solitary keratoacanthoma and cigarette smoking: a case-control study. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12(2):2.-

4. Pattee SF, Silvis NG. Keratoacanthoma developing in sites of previous trauma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(2 suppl):S35-S38.

5. Goldberg LH, Silapunt S, Beyrau KK, Peterson SR, Friedman PM, Alam M. Keratoacanthoma as a postoperative complication of skin cancer excision. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:753-758.

6. Stockfleth E, Meinke B, Arndt R, Christophers E, Meyer T. Identification of DNA sequences of both genital and cutaneous HPV types in a small number of keratoacanthomas of nonimmunosuppressed patients. Dermatology. 1999;198:122-125.

7. Oh CK, Son HS, Lee JB, Jang HS, Kwon KS. Intralesional interferon alfa-2b treatment of keratoacanthomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(5 suppl):S177-S180.

8. Griffiths RW. Keratoacanthoma observed. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57:485-501.

9. Caccialanza M, Sopelana N. Radiation therapy of keratoacanthomas: results in 55 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;16:475-477.

10. Gray RJ, Meland NB. Topical 5-fluorouracil as primary therapy for keratoacanthoma. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;44:82-85.

11. Sanders S, Busam KJ, Halpern AC, Nehal KS. Intralesional corticosteroid treatment of multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas: case report and review of a controversial therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:954-958.

12. Di Lernia V, Ricci C, Albertini G. Spontaneous regression of keratoacanthoma can be promoted by topical treatment with imiquimod cream. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:626-629.

13. Cohen PR, Schulze KE, Teller CF, Nelson BR. Intralesional methotrexate for keratoacanthoma of the nose. Skinmed. 2005;4:393-395.

Growing plaque on foot

An 82-year-old African American woman with a history of pancreatic cancer came into the clinic for evaluation of a growing, asymptomatic lesion on her right dorsal foot. She first noticed the lesion a year ago, when it was pinpoint size. It was now a 2.5 cm × 1 cm hyperpigmented plaque.

The lesion was dark brown and black and had irregular borders. It also had a central hyperkeratotic area (FIGURE 1). There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. We performed an incisional biopsy.

FIGURE 1

Growing lesion with irregular borders

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Pigmented Bowen’s disease

Histopathological evaluation of the lesion revealed hyperkeratosis, large atypical keratinocytes, increased mitotic figures, and an intact basement membrane (FIGURE 2), leading us to diagnose pigmented Bowen’s disease.

Bowen’s disease, an intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (carcinoma in situ), is a common type of nonmelanoma skin cancer. However, the form our patient had—pigmented Bowen’s disease—is a rare form of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in situ (2% of cases).1 The pigmented form of Bowen’s disease is more common in individuals with darker skin tones, while the nonpigmented is more common in fair-skinned individuals.

Bowen’s disease typically presents as a slow-growing, sharply demarcated, scaly erythematous plaque ranging in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. Crusting, fissuring, hyperkeratosis, and pigmentation, as seen in our case, are also associated findings.2 Bowen’s disease often presents as a solitary lesion, with most cases (approximately 75%) associated with sun damage.3

The most common sites for Bowen’s disease include the head, neck, and hands. Rarely, the nail bed, oral mucosa, or anogenital region may be affected.

The mean age of diagnosis occurs in the sixth decade4 and there is an equal incidence in men and women. Bowen’s disease in men usually occurs on the scalp and ears, while in women, the lower legs are the most common site.5 Three to eight percent of Bowen’s disease cases progress to invasive carcinoma if left untreated.6

FIGURE 2

Histopathology of pigmented Bowen’s disease

A disease that’s linked to the sun—but also, HPV

The development of Bowen’s disease has been linked to sunlight exposure, human papilloma virus (HPV), and chronic arsenic intoxication.7

Sunlight exposure. Cumulative ultraviolet sunlight exposure is one of the most important etiologic factors. There is a doubling in the incidence of SCC for every 8- to 10-degree decrease in latitude.8

HPV. Human papillomavirus is common in patients who have SCCs in their genital areas.9 There is a poor correlation between nonanogenital Bowen’s disease and HPV infection. However, HPV types 2, 16, 18, 34, and 35 are occasionally identified in these lesions.10

Patients with penile Bowen’s disease (referred to as erythroplasia of Queyrat) are typically uncircumcised men with red, velvety plaques on the glans penis. Occasional itching and bleeding may be associated symptoms.

Arsenic intoxication. Chronic arsenic poisoning from drinking water is a documented cause of cancers occurring in the lung, bladder, kidney, liver, and skin. The US Geological Survey found the highest arsenic contamination levels of ground-water in the West, Midwest, and North-east United States.11

Unlike non-arsenical Bowen’s disease, arsenic-induced Bowen’s disease (As-BD) can occur on non-sun-exposed skin. As-BD typically appears 10 years after initial arsenic exposure, with pulmonary carcinoma appearing 30 years after exposure. As a result, it’s advisable to screen all patients with As-BD for cancer of the lung and bladder.12

Is it Bowen’s, or something more serious?

The differential diagnosis of this lesion includes superficial spreading melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma, atypical melanocytic nevus, and seborrheic keratosis. These different skin conditions may be difficult to distinguish on clinical examination and ultimately may require a biopsy.

Although pigmented Bowen’s disease can occur in anyone, Caucasian patients (as noted earlier) tend to have the more typical nonpigmented, erythematous scaly plaques in sun-exposed sites (FIGURE 3). Darker pigmented individuals are more likely to present with pigmented cutaneous lesions, which may mimic malignant melanoma,13 as was the case with our patient.

FIGURE 3

Nonpigmented Bowen’s disease

Surgical excision is extremely effective

Bowen’s disease can be treated with cryotherapy; curettage and electrodesiccation; surgical excision, including Mohs micrographic surgery; laser surgery; photodynamic therapy; radiation therapy; topical 5-fluorouracil; and topical imiquimod. Invasive or higher risk lesions require surgical excision or Mohs surgery. Surgical excision of SCCs is extremely effective, with 5-year cure rates of 92%.14

A delay in treatment for our patient

Our patient was scheduled to undergo surgical excision with graft repair of the site. However, she was receiving chemotherapy for mucinous adenocarcinoma of the pancreas and declined excision due to concerns about possible infection.

She later underwent curettage and electrodesiccation, followed by topical imiquimod therapy for 10 weeks. She remains free of any Bowen’s disease recurrences 2 years after her diagnosis.

Correspondence

Claudia Hernandez, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Illinois at Chicago, 808 S Wood St, MC 624, Chicago, IL 60612-7300.

1. Ragi G, Turner MS, Klein LE, Stoll HL. Pigmented Bowen’s disease and review of 420 Bowen’s disease lesions. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:756-759.

2. Rinker MH, Fenske NA, Scalf LA, Glass LF. Histologic variants of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Can Control. 2001;8:354-363.

3. Lee MM, Wick MM. Bowen’s disease. CA Cancer J Clin. 1990;40:237-242.

4. Kossard S, Rosen R. Cutaneous Bowen’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:406-410.

5. VanderSpek LAL, Pond GR, Wells W, Tsang RW. Radiation therapy for Bowen’s disease of the skin. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:505-510.

6. Leibovitch I, Huilgol SC, Selva D, Richards S, Paver R. Cutaneous squamous carcinoma in situ (Bowen’s disease: treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:997-1002.

7. Stante M, De Giorgi V, Massi D, Chiarugi A, Carli P. Pigmented Bowen’s disease mimicking cutaneous melanoma: clinical and dermoscopic aspects. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:541-544.

8. Rundel RD. Promotional effects of ultraviolet radiation on human basal and squamous cell carcinoma. Photochem Photobiol. 1983;38:569-575.

9. Crum CP, Ikenberg H, Richart RM, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 and early cervical neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:880-883.

10. Amagi N, Feldman B, Lobel S, Williams C. Irregularly pigmented hyperkeratotic plaque on the thumb. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1045-1048.

11. United States Geologic Survey. Arsenic in Ground-water Resources of the United States. Available at: http://water.usgs.gov/nawqa/trace/pubs/fs-063-00/fs-063-00.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2008.

12. Yu HS, Liao WT, Chai CY. Arsenic carcinogenesis in the skin. J Biomed Sci. 2006;13:657-66.

13. Krishnan R, Lewis A, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Pigmented Bowen’s disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ): a mimic of malignant melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:673-674.

14. Miller SJ, Moresi JM. Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Mosby; 2003:1677-1696.

An 82-year-old African American woman with a history of pancreatic cancer came into the clinic for evaluation of a growing, asymptomatic lesion on her right dorsal foot. She first noticed the lesion a year ago, when it was pinpoint size. It was now a 2.5 cm × 1 cm hyperpigmented plaque.

The lesion was dark brown and black and had irregular borders. It also had a central hyperkeratotic area (FIGURE 1). There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. We performed an incisional biopsy.

FIGURE 1

Growing lesion with irregular borders

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Pigmented Bowen’s disease

Histopathological evaluation of the lesion revealed hyperkeratosis, large atypical keratinocytes, increased mitotic figures, and an intact basement membrane (FIGURE 2), leading us to diagnose pigmented Bowen’s disease.

Bowen’s disease, an intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (carcinoma in situ), is a common type of nonmelanoma skin cancer. However, the form our patient had—pigmented Bowen’s disease—is a rare form of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in situ (2% of cases).1 The pigmented form of Bowen’s disease is more common in individuals with darker skin tones, while the nonpigmented is more common in fair-skinned individuals.