User login

Growing plaque on foot

An 82-year-old African American woman with a history of pancreatic cancer came into the clinic for evaluation of a growing, asymptomatic lesion on her right dorsal foot. She first noticed the lesion a year ago, when it was pinpoint size. It was now a 2.5 cm × 1 cm hyperpigmented plaque.

The lesion was dark brown and black and had irregular borders. It also had a central hyperkeratotic area (FIGURE 1). There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. We performed an incisional biopsy.

FIGURE 1

Growing lesion with irregular borders

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Pigmented Bowen’s disease

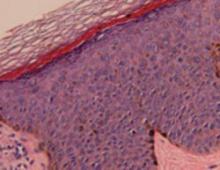

Histopathological evaluation of the lesion revealed hyperkeratosis, large atypical keratinocytes, increased mitotic figures, and an intact basement membrane (FIGURE 2), leading us to diagnose pigmented Bowen’s disease.

Bowen’s disease, an intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (carcinoma in situ), is a common type of nonmelanoma skin cancer. However, the form our patient had—pigmented Bowen’s disease—is a rare form of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in situ (2% of cases).1 The pigmented form of Bowen’s disease is more common in individuals with darker skin tones, while the nonpigmented is more common in fair-skinned individuals.

Bowen’s disease typically presents as a slow-growing, sharply demarcated, scaly erythematous plaque ranging in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. Crusting, fissuring, hyperkeratosis, and pigmentation, as seen in our case, are also associated findings.2 Bowen’s disease often presents as a solitary lesion, with most cases (approximately 75%) associated with sun damage.3

The most common sites for Bowen’s disease include the head, neck, and hands. Rarely, the nail bed, oral mucosa, or anogenital region may be affected.

The mean age of diagnosis occurs in the sixth decade4 and there is an equal incidence in men and women. Bowen’s disease in men usually occurs on the scalp and ears, while in women, the lower legs are the most common site.5 Three to eight percent of Bowen’s disease cases progress to invasive carcinoma if left untreated.6

FIGURE 2

Histopathology of pigmented Bowen’s disease

A disease that’s linked to the sun—but also, HPV

The development of Bowen’s disease has been linked to sunlight exposure, human papilloma virus (HPV), and chronic arsenic intoxication.7

Sunlight exposure. Cumulative ultraviolet sunlight exposure is one of the most important etiologic factors. There is a doubling in the incidence of SCC for every 8- to 10-degree decrease in latitude.8

HPV. Human papillomavirus is common in patients who have SCCs in their genital areas.9 There is a poor correlation between nonanogenital Bowen’s disease and HPV infection. However, HPV types 2, 16, 18, 34, and 35 are occasionally identified in these lesions.10

Patients with penile Bowen’s disease (referred to as erythroplasia of Queyrat) are typically uncircumcised men with red, velvety plaques on the glans penis. Occasional itching and bleeding may be associated symptoms.

Arsenic intoxication. Chronic arsenic poisoning from drinking water is a documented cause of cancers occurring in the lung, bladder, kidney, liver, and skin. The US Geological Survey found the highest arsenic contamination levels of ground-water in the West, Midwest, and North-east United States.11

Unlike non-arsenical Bowen’s disease, arsenic-induced Bowen’s disease (As-BD) can occur on non-sun-exposed skin. As-BD typically appears 10 years after initial arsenic exposure, with pulmonary carcinoma appearing 30 years after exposure. As a result, it’s advisable to screen all patients with As-BD for cancer of the lung and bladder.12

Is it Bowen’s, or something more serious?

The differential diagnosis of this lesion includes superficial spreading melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma, atypical melanocytic nevus, and seborrheic keratosis. These different skin conditions may be difficult to distinguish on clinical examination and ultimately may require a biopsy.

Although pigmented Bowen’s disease can occur in anyone, Caucasian patients (as noted earlier) tend to have the more typical nonpigmented, erythematous scaly plaques in sun-exposed sites (FIGURE 3). Darker pigmented individuals are more likely to present with pigmented cutaneous lesions, which may mimic malignant melanoma,13 as was the case with our patient.

FIGURE 3

Nonpigmented Bowen’s disease

Surgical excision is extremely effective

Bowen’s disease can be treated with cryotherapy; curettage and electrodesiccation; surgical excision, including Mohs micrographic surgery; laser surgery; photodynamic therapy; radiation therapy; topical 5-fluorouracil; and topical imiquimod. Invasive or higher risk lesions require surgical excision or Mohs surgery. Surgical excision of SCCs is extremely effective, with 5-year cure rates of 92%.14

A delay in treatment for our patient

Our patient was scheduled to undergo surgical excision with graft repair of the site. However, she was receiving chemotherapy for mucinous adenocarcinoma of the pancreas and declined excision due to concerns about possible infection.

She later underwent curettage and electrodesiccation, followed by topical imiquimod therapy for 10 weeks. She remains free of any Bowen’s disease recurrences 2 years after her diagnosis.

Correspondence

Claudia Hernandez, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Illinois at Chicago, 808 S Wood St, MC 624, Chicago, IL 60612-7300.

1. Ragi G, Turner MS, Klein LE, Stoll HL. Pigmented Bowen’s disease and review of 420 Bowen’s disease lesions. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:756-759.

2. Rinker MH, Fenske NA, Scalf LA, Glass LF. Histologic variants of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Can Control. 2001;8:354-363.

3. Lee MM, Wick MM. Bowen’s disease. CA Cancer J Clin. 1990;40:237-242.

4. Kossard S, Rosen R. Cutaneous Bowen’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:406-410.

5. VanderSpek LAL, Pond GR, Wells W, Tsang RW. Radiation therapy for Bowen’s disease of the skin. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:505-510.

6. Leibovitch I, Huilgol SC, Selva D, Richards S, Paver R. Cutaneous squamous carcinoma in situ (Bowen’s disease: treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:997-1002.

7. Stante M, De Giorgi V, Massi D, Chiarugi A, Carli P. Pigmented Bowen’s disease mimicking cutaneous melanoma: clinical and dermoscopic aspects. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:541-544.

8. Rundel RD. Promotional effects of ultraviolet radiation on human basal and squamous cell carcinoma. Photochem Photobiol. 1983;38:569-575.

9. Crum CP, Ikenberg H, Richart RM, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 and early cervical neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:880-883.

10. Amagi N, Feldman B, Lobel S, Williams C. Irregularly pigmented hyperkeratotic plaque on the thumb. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1045-1048.

11. United States Geologic Survey. Arsenic in Ground-water Resources of the United States. Available at: http://water.usgs.gov/nawqa/trace/pubs/fs-063-00/fs-063-00.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2008.

12. Yu HS, Liao WT, Chai CY. Arsenic carcinogenesis in the skin. J Biomed Sci. 2006;13:657-66.

13. Krishnan R, Lewis A, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Pigmented Bowen’s disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ): a mimic of malignant melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:673-674.

14. Miller SJ, Moresi JM. Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Mosby; 2003:1677-1696.

An 82-year-old African American woman with a history of pancreatic cancer came into the clinic for evaluation of a growing, asymptomatic lesion on her right dorsal foot. She first noticed the lesion a year ago, when it was pinpoint size. It was now a 2.5 cm × 1 cm hyperpigmented plaque.

The lesion was dark brown and black and had irregular borders. It also had a central hyperkeratotic area (FIGURE 1). There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. We performed an incisional biopsy.

FIGURE 1

Growing lesion with irregular borders

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Pigmented Bowen’s disease

Histopathological evaluation of the lesion revealed hyperkeratosis, large atypical keratinocytes, increased mitotic figures, and an intact basement membrane (FIGURE 2), leading us to diagnose pigmented Bowen’s disease.

Bowen’s disease, an intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (carcinoma in situ), is a common type of nonmelanoma skin cancer. However, the form our patient had—pigmented Bowen’s disease—is a rare form of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in situ (2% of cases).1 The pigmented form of Bowen’s disease is more common in individuals with darker skin tones, while the nonpigmented is more common in fair-skinned individuals.

Bowen’s disease typically presents as a slow-growing, sharply demarcated, scaly erythematous plaque ranging in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. Crusting, fissuring, hyperkeratosis, and pigmentation, as seen in our case, are also associated findings.2 Bowen’s disease often presents as a solitary lesion, with most cases (approximately 75%) associated with sun damage.3

The most common sites for Bowen’s disease include the head, neck, and hands. Rarely, the nail bed, oral mucosa, or anogenital region may be affected.

The mean age of diagnosis occurs in the sixth decade4 and there is an equal incidence in men and women. Bowen’s disease in men usually occurs on the scalp and ears, while in women, the lower legs are the most common site.5 Three to eight percent of Bowen’s disease cases progress to invasive carcinoma if left untreated.6

FIGURE 2

Histopathology of pigmented Bowen’s disease

A disease that’s linked to the sun—but also, HPV

The development of Bowen’s disease has been linked to sunlight exposure, human papilloma virus (HPV), and chronic arsenic intoxication.7

Sunlight exposure. Cumulative ultraviolet sunlight exposure is one of the most important etiologic factors. There is a doubling in the incidence of SCC for every 8- to 10-degree decrease in latitude.8

HPV. Human papillomavirus is common in patients who have SCCs in their genital areas.9 There is a poor correlation between nonanogenital Bowen’s disease and HPV infection. However, HPV types 2, 16, 18, 34, and 35 are occasionally identified in these lesions.10

Patients with penile Bowen’s disease (referred to as erythroplasia of Queyrat) are typically uncircumcised men with red, velvety plaques on the glans penis. Occasional itching and bleeding may be associated symptoms.

Arsenic intoxication. Chronic arsenic poisoning from drinking water is a documented cause of cancers occurring in the lung, bladder, kidney, liver, and skin. The US Geological Survey found the highest arsenic contamination levels of ground-water in the West, Midwest, and North-east United States.11

Unlike non-arsenical Bowen’s disease, arsenic-induced Bowen’s disease (As-BD) can occur on non-sun-exposed skin. As-BD typically appears 10 years after initial arsenic exposure, with pulmonary carcinoma appearing 30 years after exposure. As a result, it’s advisable to screen all patients with As-BD for cancer of the lung and bladder.12

Is it Bowen’s, or something more serious?

The differential diagnosis of this lesion includes superficial spreading melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma, atypical melanocytic nevus, and seborrheic keratosis. These different skin conditions may be difficult to distinguish on clinical examination and ultimately may require a biopsy.

Although pigmented Bowen’s disease can occur in anyone, Caucasian patients (as noted earlier) tend to have the more typical nonpigmented, erythematous scaly plaques in sun-exposed sites (FIGURE 3). Darker pigmented individuals are more likely to present with pigmented cutaneous lesions, which may mimic malignant melanoma,13 as was the case with our patient.

FIGURE 3

Nonpigmented Bowen’s disease

Surgical excision is extremely effective

Bowen’s disease can be treated with cryotherapy; curettage and electrodesiccation; surgical excision, including Mohs micrographic surgery; laser surgery; photodynamic therapy; radiation therapy; topical 5-fluorouracil; and topical imiquimod. Invasive or higher risk lesions require surgical excision or Mohs surgery. Surgical excision of SCCs is extremely effective, with 5-year cure rates of 92%.14

A delay in treatment for our patient

Our patient was scheduled to undergo surgical excision with graft repair of the site. However, she was receiving chemotherapy for mucinous adenocarcinoma of the pancreas and declined excision due to concerns about possible infection.

She later underwent curettage and electrodesiccation, followed by topical imiquimod therapy for 10 weeks. She remains free of any Bowen’s disease recurrences 2 years after her diagnosis.

Correspondence

Claudia Hernandez, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Illinois at Chicago, 808 S Wood St, MC 624, Chicago, IL 60612-7300.

An 82-year-old African American woman with a history of pancreatic cancer came into the clinic for evaluation of a growing, asymptomatic lesion on her right dorsal foot. She first noticed the lesion a year ago, when it was pinpoint size. It was now a 2.5 cm × 1 cm hyperpigmented plaque.

The lesion was dark brown and black and had irregular borders. It also had a central hyperkeratotic area (FIGURE 1). There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. We performed an incisional biopsy.

FIGURE 1

Growing lesion with irregular borders

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Pigmented Bowen’s disease

Histopathological evaluation of the lesion revealed hyperkeratosis, large atypical keratinocytes, increased mitotic figures, and an intact basement membrane (FIGURE 2), leading us to diagnose pigmented Bowen’s disease.

Bowen’s disease, an intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (carcinoma in situ), is a common type of nonmelanoma skin cancer. However, the form our patient had—pigmented Bowen’s disease—is a rare form of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in situ (2% of cases).1 The pigmented form of Bowen’s disease is more common in individuals with darker skin tones, while the nonpigmented is more common in fair-skinned individuals.

Bowen’s disease typically presents as a slow-growing, sharply demarcated, scaly erythematous plaque ranging in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. Crusting, fissuring, hyperkeratosis, and pigmentation, as seen in our case, are also associated findings.2 Bowen’s disease often presents as a solitary lesion, with most cases (approximately 75%) associated with sun damage.3

The most common sites for Bowen’s disease include the head, neck, and hands. Rarely, the nail bed, oral mucosa, or anogenital region may be affected.

The mean age of diagnosis occurs in the sixth decade4 and there is an equal incidence in men and women. Bowen’s disease in men usually occurs on the scalp and ears, while in women, the lower legs are the most common site.5 Three to eight percent of Bowen’s disease cases progress to invasive carcinoma if left untreated.6

FIGURE 2

Histopathology of pigmented Bowen’s disease

A disease that’s linked to the sun—but also, HPV

The development of Bowen’s disease has been linked to sunlight exposure, human papilloma virus (HPV), and chronic arsenic intoxication.7

Sunlight exposure. Cumulative ultraviolet sunlight exposure is one of the most important etiologic factors. There is a doubling in the incidence of SCC for every 8- to 10-degree decrease in latitude.8

HPV. Human papillomavirus is common in patients who have SCCs in their genital areas.9 There is a poor correlation between nonanogenital Bowen’s disease and HPV infection. However, HPV types 2, 16, 18, 34, and 35 are occasionally identified in these lesions.10

Patients with penile Bowen’s disease (referred to as erythroplasia of Queyrat) are typically uncircumcised men with red, velvety plaques on the glans penis. Occasional itching and bleeding may be associated symptoms.

Arsenic intoxication. Chronic arsenic poisoning from drinking water is a documented cause of cancers occurring in the lung, bladder, kidney, liver, and skin. The US Geological Survey found the highest arsenic contamination levels of ground-water in the West, Midwest, and North-east United States.11

Unlike non-arsenical Bowen’s disease, arsenic-induced Bowen’s disease (As-BD) can occur on non-sun-exposed skin. As-BD typically appears 10 years after initial arsenic exposure, with pulmonary carcinoma appearing 30 years after exposure. As a result, it’s advisable to screen all patients with As-BD for cancer of the lung and bladder.12

Is it Bowen’s, or something more serious?

The differential diagnosis of this lesion includes superficial spreading melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma, atypical melanocytic nevus, and seborrheic keratosis. These different skin conditions may be difficult to distinguish on clinical examination and ultimately may require a biopsy.

Although pigmented Bowen’s disease can occur in anyone, Caucasian patients (as noted earlier) tend to have the more typical nonpigmented, erythematous scaly plaques in sun-exposed sites (FIGURE 3). Darker pigmented individuals are more likely to present with pigmented cutaneous lesions, which may mimic malignant melanoma,13 as was the case with our patient.

FIGURE 3

Nonpigmented Bowen’s disease

Surgical excision is extremely effective

Bowen’s disease can be treated with cryotherapy; curettage and electrodesiccation; surgical excision, including Mohs micrographic surgery; laser surgery; photodynamic therapy; radiation therapy; topical 5-fluorouracil; and topical imiquimod. Invasive or higher risk lesions require surgical excision or Mohs surgery. Surgical excision of SCCs is extremely effective, with 5-year cure rates of 92%.14

A delay in treatment for our patient

Our patient was scheduled to undergo surgical excision with graft repair of the site. However, she was receiving chemotherapy for mucinous adenocarcinoma of the pancreas and declined excision due to concerns about possible infection.

She later underwent curettage and electrodesiccation, followed by topical imiquimod therapy for 10 weeks. She remains free of any Bowen’s disease recurrences 2 years after her diagnosis.

Correspondence

Claudia Hernandez, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Illinois at Chicago, 808 S Wood St, MC 624, Chicago, IL 60612-7300.

1. Ragi G, Turner MS, Klein LE, Stoll HL. Pigmented Bowen’s disease and review of 420 Bowen’s disease lesions. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:756-759.

2. Rinker MH, Fenske NA, Scalf LA, Glass LF. Histologic variants of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Can Control. 2001;8:354-363.

3. Lee MM, Wick MM. Bowen’s disease. CA Cancer J Clin. 1990;40:237-242.

4. Kossard S, Rosen R. Cutaneous Bowen’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:406-410.

5. VanderSpek LAL, Pond GR, Wells W, Tsang RW. Radiation therapy for Bowen’s disease of the skin. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:505-510.

6. Leibovitch I, Huilgol SC, Selva D, Richards S, Paver R. Cutaneous squamous carcinoma in situ (Bowen’s disease: treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:997-1002.

7. Stante M, De Giorgi V, Massi D, Chiarugi A, Carli P. Pigmented Bowen’s disease mimicking cutaneous melanoma: clinical and dermoscopic aspects. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:541-544.

8. Rundel RD. Promotional effects of ultraviolet radiation on human basal and squamous cell carcinoma. Photochem Photobiol. 1983;38:569-575.

9. Crum CP, Ikenberg H, Richart RM, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 and early cervical neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:880-883.

10. Amagi N, Feldman B, Lobel S, Williams C. Irregularly pigmented hyperkeratotic plaque on the thumb. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1045-1048.

11. United States Geologic Survey. Arsenic in Ground-water Resources of the United States. Available at: http://water.usgs.gov/nawqa/trace/pubs/fs-063-00/fs-063-00.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2008.

12. Yu HS, Liao WT, Chai CY. Arsenic carcinogenesis in the skin. J Biomed Sci. 2006;13:657-66.

13. Krishnan R, Lewis A, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Pigmented Bowen’s disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ): a mimic of malignant melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:673-674.

14. Miller SJ, Moresi JM. Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Mosby; 2003:1677-1696.

1. Ragi G, Turner MS, Klein LE, Stoll HL. Pigmented Bowen’s disease and review of 420 Bowen’s disease lesions. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:756-759.

2. Rinker MH, Fenske NA, Scalf LA, Glass LF. Histologic variants of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Can Control. 2001;8:354-363.

3. Lee MM, Wick MM. Bowen’s disease. CA Cancer J Clin. 1990;40:237-242.

4. Kossard S, Rosen R. Cutaneous Bowen’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:406-410.

5. VanderSpek LAL, Pond GR, Wells W, Tsang RW. Radiation therapy for Bowen’s disease of the skin. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:505-510.

6. Leibovitch I, Huilgol SC, Selva D, Richards S, Paver R. Cutaneous squamous carcinoma in situ (Bowen’s disease: treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:997-1002.

7. Stante M, De Giorgi V, Massi D, Chiarugi A, Carli P. Pigmented Bowen’s disease mimicking cutaneous melanoma: clinical and dermoscopic aspects. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:541-544.

8. Rundel RD. Promotional effects of ultraviolet radiation on human basal and squamous cell carcinoma. Photochem Photobiol. 1983;38:569-575.

9. Crum CP, Ikenberg H, Richart RM, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 and early cervical neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:880-883.

10. Amagi N, Feldman B, Lobel S, Williams C. Irregularly pigmented hyperkeratotic plaque on the thumb. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1045-1048.

11. United States Geologic Survey. Arsenic in Ground-water Resources of the United States. Available at: http://water.usgs.gov/nawqa/trace/pubs/fs-063-00/fs-063-00.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2008.

12. Yu HS, Liao WT, Chai CY. Arsenic carcinogenesis in the skin. J Biomed Sci. 2006;13:657-66.

13. Krishnan R, Lewis A, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Pigmented Bowen’s disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ): a mimic of malignant melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:673-674.

14. Miller SJ, Moresi JM. Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Mosby; 2003:1677-1696.