User login

Red pruritic area on forehead

|

|

We diagnosed a fungal infection. The annular pattern on the face (FIGURE 1) was suggestive of a dermatophyte infection. The differential diagnosis included granuloma annulare and psoriasis.

We looked at the patient’s feet, groin, and under the breasts for additional clues. This patient had what appeared to be fungal infections in all of these areas. The patient had severe tinea pedis in a moccasin distribution and tinea cruris (FIGURE 2). We performed a scraping for fungus from the groin infection and added a fungal stain with potassium hydroxide to the slide. Branching hyphae were seen under the microscope. The patient was treated with an oral antifungal agent (terbinafine, 250 mg daily) for 1 month. Her fungal infection cleared from all sites.

This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Cutaneous fungal infections: overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:539-544.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

|

|

We diagnosed a fungal infection. The annular pattern on the face (FIGURE 1) was suggestive of a dermatophyte infection. The differential diagnosis included granuloma annulare and psoriasis.

We looked at the patient’s feet, groin, and under the breasts for additional clues. This patient had what appeared to be fungal infections in all of these areas. The patient had severe tinea pedis in a moccasin distribution and tinea cruris (FIGURE 2). We performed a scraping for fungus from the groin infection and added a fungal stain with potassium hydroxide to the slide. Branching hyphae were seen under the microscope. The patient was treated with an oral antifungal agent (terbinafine, 250 mg daily) for 1 month. Her fungal infection cleared from all sites.

This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Cutaneous fungal infections: overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:539-544.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

|

|

We diagnosed a fungal infection. The annular pattern on the face (FIGURE 1) was suggestive of a dermatophyte infection. The differential diagnosis included granuloma annulare and psoriasis.

We looked at the patient’s feet, groin, and under the breasts for additional clues. This patient had what appeared to be fungal infections in all of these areas. The patient had severe tinea pedis in a moccasin distribution and tinea cruris (FIGURE 2). We performed a scraping for fungus from the groin infection and added a fungal stain with potassium hydroxide to the slide. Branching hyphae were seen under the microscope. The patient was treated with an oral antifungal agent (terbinafine, 250 mg daily) for 1 month. Her fungal infection cleared from all sites.

This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Cutaneous fungal infections: overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:539-544.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Worsening low back pain

A 44-year-old African American man went to his primary care provider complaining of 5/10 dull lower back pain, which he attributed to a recent fall. He reported no radiation of the pain, lower extremity weakness or numbness, or any bowel/ bladder incontinence. Further review of systems and past medical history was unremarkable. He was initially treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and physical therapy. Approximately 2 months later he returned with similar persistent lower back pain complaints; an opiate was added to his pain control regimen. The following week he went to the emergency department (ED), where he reported worsening pain.

In the ED, he was afebrile with normal vital signs. He had a benign musculoskeletal and abdominal exam, and his neurological exam was without any focal deficits. Blood tests revealed a hemoglobin level of 9.8 g/dL with a hematocrit of 27.9%, serum blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio of 143/11.0 mg/dL, potassium of 6.5 mmol/L, calcium of 11.8 mg/dL, and phosphorus of 8.5 mg/dL. Urine protein was elevated at 88 mg/dL.

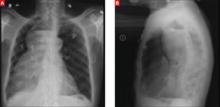

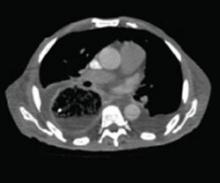

A stat CT of the patient’s abdomen and pelvis revealed no signs of obstructive uropathy to explain his acute renal failure. A sagittal CT reconstruction in bone windows of the initial ED radiological workup was revealing (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1

Sagittal CT reconstruction of thoracolumbar spine

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Dx: Multiple myeloma

The sagittal CT reconstruction in bone windows of the thoracolumbar spine (FIGURE 1) revealed multiple lucent foci throughout the osseous structures, with an anterior compression deformity of the L2 vertebral body. A subsequent skeletal survey showed a diffuse salt and pepper pattern affecting most of the osseous structures, with additional lytic lesions in the calvarium and extremities.

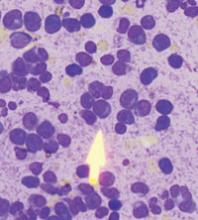

Following inpatient admission, the patient underwent a bone marrow biopsy that showed 90% marrow plasma cells (FIGURE 2). Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and immunofixation electrophoresis revealed an elevated monoclonal protein of 7.52 g/dL IgG kappa, prompting us to diagnose multiple myeloma.

FIGURE 2

Bone marrow smear reveals 90% marrow plasma cells

Patients are typically much older

Multiple myeloma is a malignant proliferation of plasma cells derived from a single clone and accounts for 13% of all hematologic malignancies in Caucasians and 33% in African Americans. As with most hematopoeitic malignancies, the incidence of multiple myeloma increases with age, with the median age at diagnosis estimated at 69 years. In addition, 47% of multiple myeloma patients are >70 years of age, and 75% are >60.1

Clinical findings in multiple myeloma vary from asymptomatic patients whose disease is discovered incidentally to patients presenting with life-threatening symptoms. In a recent study of more than 1000 newly diagnosed patients, the most common presenting symptoms were bone pain (58%), fatigue (32%), and weight loss (24%).2 Tumor cells, tumor products (ie, monoclonal immunoglobulin protein), and host response to both elements account for other focal and systemic symptoms, including bone fracture, anemia, renal failure, vascular manifestations of hyperviscosity, hypercalcemia, and increased susceptibility to infection.

This presentation, in conjunction with radiological evidence of lytic bone lesions, increased total serum protein concentration, and a monoclonal protein in the urine or serum, constitutes the hallmark findings of multiple myeloma.

Working group keys in on 3 criteria

The International Myeloma Working Group has agreed on 3 simplified criteria for diagnosis of symptomatic multiple myeloma.3 These include the presence of (1) clonal bone marrow plasma cells or plasmacytoma, (2) an M-protein in serum of unspecified concentration, and (3) tissue- or organ-related impairment, such as renal insufficiency or anemia.

Our patient easily met all 3. His bone marrow biopsy displayed 90% plasma cell cellularity. Additionally, his SPEP exhibited markedly increased IgG immunoglobulin, and immunofixation data suggested IgG type kappa monoclonal gammopathy. These findings, in combination with our patient’s blood chemistry abnormalities, marked proteinuria, and imaging findings, confirmed the diagnosis of multiple myeloma.

Rule out MGUS

The differential diagnosis for multiple myeloma includes monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). The characteristic findings of MGUS include:

- absence of symptoms,

- M-protein component (either IgG, IgA, or IgM) <3 g/dL,

- <10% plasma cells in the marrow,

- absence of lytic lesions, and

- no signs of anemia, hypercalcemia, or renal insufficiency.

Essentially, MGUS is a milder form of myeloma with a more indolent course. However, MGUS does carry a 1% annual risk of progression to frank myeloma. An additional concern for patients with multiple myeloma is progression to plasma cell leukemia (PCL). The prognosis for PCL is poor, and the diagnosis is made when the absolute plasma cell count exceeds 2000/mcL. The rate of occurrence of PCL as a progression of multiple myeloma is 1% to 4%.4

In addition to MGUS, the differential diagnosis for multiple myeloma includes tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and metastatic disease.

A 2-pronged Tx approach

There has been a paradigm shift in the treatment of multiple myeloma in the past decade, and while it appears to be incurable with current approaches, considerable progress has been made.5 Median survival prior to 1997 was nearly 2.5 years; it is now nearly 4 years for patients diagnosed in the last decade.5

Treatment of multiple myeloma generally consists of systemic chemotherapy to control progression and supportive care to prevent serious complications. The standard treatment has traditionally consisted of intermittent pulses of an alkylating agent and prednisone administered for 4 to 7 days every 4 to 6 weeks.

Complications requiring supportive therapy include infections (eg, in the urinary tract), pneumonia, hypercalcemia, and renal failure. Of note, hypercalcemia and renal failure may be alleviated with adequate hydration. If necessary, more aggressive management with dialysis may be initiated.

Other considerations include the administration of allopurinol during chemotherapy, which may help control hyperuricemia from tumor lysis. Transfusions may be required for anemic patients, and plasmapheresis may be indicated to treat hyperviscosity syndrome.

Our patient improves

In the hospital our patient began 4 days on dexamethasone, a 7-day regimen of plasmapheresis, and dialysis. He was also started on a proteasome inhibitor (bortezomib), a newer antineoplastic agent approved for the treatment of multiple myeloma.6 The patient responded well and was discharged home with hematology-oncology follow-up, where he remains clinically improved after treatment with a combination of bortezomib and dexamethasone.

CORRESPONDENCE

Vincent Timpone, MD, Department of Radiology, David Grant United States Air Force Medical Center, Travis Air Force Base, CA 94535; [email protected]

1. Zulian GB, Babare R, Zagonel V. Multiple myeloma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1998;27:165-167.

2. Kyle RA, Gertz MA. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:21-33.

3. International Myeloma Working Group. Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:749-757.

4. Blade J, Kyle RA. Nonsecretory myeloma, immunoglobulin D myeloma, and plasma cell leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1999;13:1259-1272.

5. Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood. 2008;111:2516-2520.

6. Jagannath S, Durie BG, Wolf J, et al. Bortezomib therapy alone and in combination with dexamethasone for previously untreated symptomatic multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:776-783.

A 44-year-old African American man went to his primary care provider complaining of 5/10 dull lower back pain, which he attributed to a recent fall. He reported no radiation of the pain, lower extremity weakness or numbness, or any bowel/ bladder incontinence. Further review of systems and past medical history was unremarkable. He was initially treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and physical therapy. Approximately 2 months later he returned with similar persistent lower back pain complaints; an opiate was added to his pain control regimen. The following week he went to the emergency department (ED), where he reported worsening pain.

In the ED, he was afebrile with normal vital signs. He had a benign musculoskeletal and abdominal exam, and his neurological exam was without any focal deficits. Blood tests revealed a hemoglobin level of 9.8 g/dL with a hematocrit of 27.9%, serum blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio of 143/11.0 mg/dL, potassium of 6.5 mmol/L, calcium of 11.8 mg/dL, and phosphorus of 8.5 mg/dL. Urine protein was elevated at 88 mg/dL.

A stat CT of the patient’s abdomen and pelvis revealed no signs of obstructive uropathy to explain his acute renal failure. A sagittal CT reconstruction in bone windows of the initial ED radiological workup was revealing (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1

Sagittal CT reconstruction of thoracolumbar spine

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Dx: Multiple myeloma

The sagittal CT reconstruction in bone windows of the thoracolumbar spine (FIGURE 1) revealed multiple lucent foci throughout the osseous structures, with an anterior compression deformity of the L2 vertebral body. A subsequent skeletal survey showed a diffuse salt and pepper pattern affecting most of the osseous structures, with additional lytic lesions in the calvarium and extremities.

Following inpatient admission, the patient underwent a bone marrow biopsy that showed 90% marrow plasma cells (FIGURE 2). Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and immunofixation electrophoresis revealed an elevated monoclonal protein of 7.52 g/dL IgG kappa, prompting us to diagnose multiple myeloma.

FIGURE 2

Bone marrow smear reveals 90% marrow plasma cells

Patients are typically much older

Multiple myeloma is a malignant proliferation of plasma cells derived from a single clone and accounts for 13% of all hematologic malignancies in Caucasians and 33% in African Americans. As with most hematopoeitic malignancies, the incidence of multiple myeloma increases with age, with the median age at diagnosis estimated at 69 years. In addition, 47% of multiple myeloma patients are >70 years of age, and 75% are >60.1

Clinical findings in multiple myeloma vary from asymptomatic patients whose disease is discovered incidentally to patients presenting with life-threatening symptoms. In a recent study of more than 1000 newly diagnosed patients, the most common presenting symptoms were bone pain (58%), fatigue (32%), and weight loss (24%).2 Tumor cells, tumor products (ie, monoclonal immunoglobulin protein), and host response to both elements account for other focal and systemic symptoms, including bone fracture, anemia, renal failure, vascular manifestations of hyperviscosity, hypercalcemia, and increased susceptibility to infection.

This presentation, in conjunction with radiological evidence of lytic bone lesions, increased total serum protein concentration, and a monoclonal protein in the urine or serum, constitutes the hallmark findings of multiple myeloma.

Working group keys in on 3 criteria

The International Myeloma Working Group has agreed on 3 simplified criteria for diagnosis of symptomatic multiple myeloma.3 These include the presence of (1) clonal bone marrow plasma cells or plasmacytoma, (2) an M-protein in serum of unspecified concentration, and (3) tissue- or organ-related impairment, such as renal insufficiency or anemia.

Our patient easily met all 3. His bone marrow biopsy displayed 90% plasma cell cellularity. Additionally, his SPEP exhibited markedly increased IgG immunoglobulin, and immunofixation data suggested IgG type kappa monoclonal gammopathy. These findings, in combination with our patient’s blood chemistry abnormalities, marked proteinuria, and imaging findings, confirmed the diagnosis of multiple myeloma.

Rule out MGUS

The differential diagnosis for multiple myeloma includes monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). The characteristic findings of MGUS include:

- absence of symptoms,

- M-protein component (either IgG, IgA, or IgM) <3 g/dL,

- <10% plasma cells in the marrow,

- absence of lytic lesions, and

- no signs of anemia, hypercalcemia, or renal insufficiency.

Essentially, MGUS is a milder form of myeloma with a more indolent course. However, MGUS does carry a 1% annual risk of progression to frank myeloma. An additional concern for patients with multiple myeloma is progression to plasma cell leukemia (PCL). The prognosis for PCL is poor, and the diagnosis is made when the absolute plasma cell count exceeds 2000/mcL. The rate of occurrence of PCL as a progression of multiple myeloma is 1% to 4%.4

In addition to MGUS, the differential diagnosis for multiple myeloma includes tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and metastatic disease.

A 2-pronged Tx approach

There has been a paradigm shift in the treatment of multiple myeloma in the past decade, and while it appears to be incurable with current approaches, considerable progress has been made.5 Median survival prior to 1997 was nearly 2.5 years; it is now nearly 4 years for patients diagnosed in the last decade.5

Treatment of multiple myeloma generally consists of systemic chemotherapy to control progression and supportive care to prevent serious complications. The standard treatment has traditionally consisted of intermittent pulses of an alkylating agent and prednisone administered for 4 to 7 days every 4 to 6 weeks.

Complications requiring supportive therapy include infections (eg, in the urinary tract), pneumonia, hypercalcemia, and renal failure. Of note, hypercalcemia and renal failure may be alleviated with adequate hydration. If necessary, more aggressive management with dialysis may be initiated.

Other considerations include the administration of allopurinol during chemotherapy, which may help control hyperuricemia from tumor lysis. Transfusions may be required for anemic patients, and plasmapheresis may be indicated to treat hyperviscosity syndrome.

Our patient improves

In the hospital our patient began 4 days on dexamethasone, a 7-day regimen of plasmapheresis, and dialysis. He was also started on a proteasome inhibitor (bortezomib), a newer antineoplastic agent approved for the treatment of multiple myeloma.6 The patient responded well and was discharged home with hematology-oncology follow-up, where he remains clinically improved after treatment with a combination of bortezomib and dexamethasone.

CORRESPONDENCE

Vincent Timpone, MD, Department of Radiology, David Grant United States Air Force Medical Center, Travis Air Force Base, CA 94535; [email protected]

A 44-year-old African American man went to his primary care provider complaining of 5/10 dull lower back pain, which he attributed to a recent fall. He reported no radiation of the pain, lower extremity weakness or numbness, or any bowel/ bladder incontinence. Further review of systems and past medical history was unremarkable. He was initially treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and physical therapy. Approximately 2 months later he returned with similar persistent lower back pain complaints; an opiate was added to his pain control regimen. The following week he went to the emergency department (ED), where he reported worsening pain.

In the ED, he was afebrile with normal vital signs. He had a benign musculoskeletal and abdominal exam, and his neurological exam was without any focal deficits. Blood tests revealed a hemoglobin level of 9.8 g/dL with a hematocrit of 27.9%, serum blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio of 143/11.0 mg/dL, potassium of 6.5 mmol/L, calcium of 11.8 mg/dL, and phosphorus of 8.5 mg/dL. Urine protein was elevated at 88 mg/dL.

A stat CT of the patient’s abdomen and pelvis revealed no signs of obstructive uropathy to explain his acute renal failure. A sagittal CT reconstruction in bone windows of the initial ED radiological workup was revealing (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1

Sagittal CT reconstruction of thoracolumbar spine

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Dx: Multiple myeloma

The sagittal CT reconstruction in bone windows of the thoracolumbar spine (FIGURE 1) revealed multiple lucent foci throughout the osseous structures, with an anterior compression deformity of the L2 vertebral body. A subsequent skeletal survey showed a diffuse salt and pepper pattern affecting most of the osseous structures, with additional lytic lesions in the calvarium and extremities.

Following inpatient admission, the patient underwent a bone marrow biopsy that showed 90% marrow plasma cells (FIGURE 2). Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and immunofixation electrophoresis revealed an elevated monoclonal protein of 7.52 g/dL IgG kappa, prompting us to diagnose multiple myeloma.

FIGURE 2

Bone marrow smear reveals 90% marrow plasma cells

Patients are typically much older

Multiple myeloma is a malignant proliferation of plasma cells derived from a single clone and accounts for 13% of all hematologic malignancies in Caucasians and 33% in African Americans. As with most hematopoeitic malignancies, the incidence of multiple myeloma increases with age, with the median age at diagnosis estimated at 69 years. In addition, 47% of multiple myeloma patients are >70 years of age, and 75% are >60.1

Clinical findings in multiple myeloma vary from asymptomatic patients whose disease is discovered incidentally to patients presenting with life-threatening symptoms. In a recent study of more than 1000 newly diagnosed patients, the most common presenting symptoms were bone pain (58%), fatigue (32%), and weight loss (24%).2 Tumor cells, tumor products (ie, monoclonal immunoglobulin protein), and host response to both elements account for other focal and systemic symptoms, including bone fracture, anemia, renal failure, vascular manifestations of hyperviscosity, hypercalcemia, and increased susceptibility to infection.

This presentation, in conjunction with radiological evidence of lytic bone lesions, increased total serum protein concentration, and a monoclonal protein in the urine or serum, constitutes the hallmark findings of multiple myeloma.

Working group keys in on 3 criteria

The International Myeloma Working Group has agreed on 3 simplified criteria for diagnosis of symptomatic multiple myeloma.3 These include the presence of (1) clonal bone marrow plasma cells or plasmacytoma, (2) an M-protein in serum of unspecified concentration, and (3) tissue- or organ-related impairment, such as renal insufficiency or anemia.

Our patient easily met all 3. His bone marrow biopsy displayed 90% plasma cell cellularity. Additionally, his SPEP exhibited markedly increased IgG immunoglobulin, and immunofixation data suggested IgG type kappa monoclonal gammopathy. These findings, in combination with our patient’s blood chemistry abnormalities, marked proteinuria, and imaging findings, confirmed the diagnosis of multiple myeloma.

Rule out MGUS

The differential diagnosis for multiple myeloma includes monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). The characteristic findings of MGUS include:

- absence of symptoms,

- M-protein component (either IgG, IgA, or IgM) <3 g/dL,

- <10% plasma cells in the marrow,

- absence of lytic lesions, and

- no signs of anemia, hypercalcemia, or renal insufficiency.

Essentially, MGUS is a milder form of myeloma with a more indolent course. However, MGUS does carry a 1% annual risk of progression to frank myeloma. An additional concern for patients with multiple myeloma is progression to plasma cell leukemia (PCL). The prognosis for PCL is poor, and the diagnosis is made when the absolute plasma cell count exceeds 2000/mcL. The rate of occurrence of PCL as a progression of multiple myeloma is 1% to 4%.4

In addition to MGUS, the differential diagnosis for multiple myeloma includes tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and metastatic disease.

A 2-pronged Tx approach

There has been a paradigm shift in the treatment of multiple myeloma in the past decade, and while it appears to be incurable with current approaches, considerable progress has been made.5 Median survival prior to 1997 was nearly 2.5 years; it is now nearly 4 years for patients diagnosed in the last decade.5

Treatment of multiple myeloma generally consists of systemic chemotherapy to control progression and supportive care to prevent serious complications. The standard treatment has traditionally consisted of intermittent pulses of an alkylating agent and prednisone administered for 4 to 7 days every 4 to 6 weeks.

Complications requiring supportive therapy include infections (eg, in the urinary tract), pneumonia, hypercalcemia, and renal failure. Of note, hypercalcemia and renal failure may be alleviated with adequate hydration. If necessary, more aggressive management with dialysis may be initiated.

Other considerations include the administration of allopurinol during chemotherapy, which may help control hyperuricemia from tumor lysis. Transfusions may be required for anemic patients, and plasmapheresis may be indicated to treat hyperviscosity syndrome.

Our patient improves

In the hospital our patient began 4 days on dexamethasone, a 7-day regimen of plasmapheresis, and dialysis. He was also started on a proteasome inhibitor (bortezomib), a newer antineoplastic agent approved for the treatment of multiple myeloma.6 The patient responded well and was discharged home with hematology-oncology follow-up, where he remains clinically improved after treatment with a combination of bortezomib and dexamethasone.

CORRESPONDENCE

Vincent Timpone, MD, Department of Radiology, David Grant United States Air Force Medical Center, Travis Air Force Base, CA 94535; [email protected]

1. Zulian GB, Babare R, Zagonel V. Multiple myeloma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1998;27:165-167.

2. Kyle RA, Gertz MA. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:21-33.

3. International Myeloma Working Group. Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:749-757.

4. Blade J, Kyle RA. Nonsecretory myeloma, immunoglobulin D myeloma, and plasma cell leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1999;13:1259-1272.

5. Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood. 2008;111:2516-2520.

6. Jagannath S, Durie BG, Wolf J, et al. Bortezomib therapy alone and in combination with dexamethasone for previously untreated symptomatic multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:776-783.

1. Zulian GB, Babare R, Zagonel V. Multiple myeloma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1998;27:165-167.

2. Kyle RA, Gertz MA. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:21-33.

3. International Myeloma Working Group. Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:749-757.

4. Blade J, Kyle RA. Nonsecretory myeloma, immunoglobulin D myeloma, and plasma cell leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1999;13:1259-1272.

5. Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood. 2008;111:2516-2520.

6. Jagannath S, Durie BG, Wolf J, et al. Bortezomib therapy alone and in combination with dexamethasone for previously untreated symptomatic multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:776-783.

Flat lesions on thigh

This patient was diagnosed with flat warts, based on their typical appearance and location. The differential diagnosis included lichen planus and seborrheic keratoses. Lichen planus is bilateral and the most common sites are the ankles, wrists, and back. Seborrheic keratoses are typically found in clusters on the face and trunk, so this would have been an unusual location for a cluster of these lesions.

Flat warts may be treated with salicylates, 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, cryotherapy, or tretinoin. The clinician discussed the treatment choices with the patient, and she chose to have initial cryotherapy followed by topical, over-the-counter salicylic acid.

This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Flat warts. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:527-529.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

This patient was diagnosed with flat warts, based on their typical appearance and location. The differential diagnosis included lichen planus and seborrheic keratoses. Lichen planus is bilateral and the most common sites are the ankles, wrists, and back. Seborrheic keratoses are typically found in clusters on the face and trunk, so this would have been an unusual location for a cluster of these lesions.

Flat warts may be treated with salicylates, 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, cryotherapy, or tretinoin. The clinician discussed the treatment choices with the patient, and she chose to have initial cryotherapy followed by topical, over-the-counter salicylic acid.

This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Flat warts. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:527-529.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

This patient was diagnosed with flat warts, based on their typical appearance and location. The differential diagnosis included lichen planus and seborrheic keratoses. Lichen planus is bilateral and the most common sites are the ankles, wrists, and back. Seborrheic keratoses are typically found in clusters on the face and trunk, so this would have been an unusual location for a cluster of these lesions.

Flat warts may be treated with salicylates, 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, cryotherapy, or tretinoin. The clinician discussed the treatment choices with the patient, and she chose to have initial cryotherapy followed by topical, over-the-counter salicylic acid.

This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Flat warts. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:527-529.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Rash on back

This patient had impetigo. The honey crusted erythematous lesions are typical for this superficial bacterial skin infection. Impetigo is caused by Staphylococcus aureus and/or group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS). The differential diagnosis for this case included herpes simplex, tinea corporis, and superinfected atopic dermatitis.

There is good evidence that topical mupirocin is equally or more effective than oral treatment for people with limited impetigo. Mupirocin also covers methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Extensive impetigo should be treated for at least 7 days with antibiotics that cover group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus and S aureus.

We treated our patient with oral cephalexin 35 mg/kg/day and the impetigo was resolved at a 2-week follow-up visit. The culture grew out S aureus sensitive to cephalosporins.

This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Impetigo. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:461-465.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

This patient had impetigo. The honey crusted erythematous lesions are typical for this superficial bacterial skin infection. Impetigo is caused by Staphylococcus aureus and/or group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS). The differential diagnosis for this case included herpes simplex, tinea corporis, and superinfected atopic dermatitis.

There is good evidence that topical mupirocin is equally or more effective than oral treatment for people with limited impetigo. Mupirocin also covers methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Extensive impetigo should be treated for at least 7 days with antibiotics that cover group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus and S aureus.

We treated our patient with oral cephalexin 35 mg/kg/day and the impetigo was resolved at a 2-week follow-up visit. The culture grew out S aureus sensitive to cephalosporins.

This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Impetigo. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:461-465.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

This patient had impetigo. The honey crusted erythematous lesions are typical for this superficial bacterial skin infection. Impetigo is caused by Staphylococcus aureus and/or group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS). The differential diagnosis for this case included herpes simplex, tinea corporis, and superinfected atopic dermatitis.

There is good evidence that topical mupirocin is equally or more effective than oral treatment for people with limited impetigo. Mupirocin also covers methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Extensive impetigo should be treated for at least 7 days with antibiotics that cover group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus and S aureus.

We treated our patient with oral cephalexin 35 mg/kg/day and the impetigo was resolved at a 2-week follow-up visit. The culture grew out S aureus sensitive to cephalosporins.

This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Impetigo. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:461-465.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Painful sore on finger

The diagnosis

The patient had herpetic whitlow—a herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection of the finger. Other conditions that could look like this include paronychia (infection of the nail fold) from a bacterial infection, or a felon, which is a bacterial infection of the pulp of the distal finger.

Herpetic whitlow used to be a common infection among dental hygienists. Now the use of gloves and universal precautions has made this less likely. Our patient had no idea where she picked up this infection, but was eager to receive treatment.

The physician pierced the pustule with a #11 blade and cultures were sent for bacteria and HSV. The patient was started on acyclovir since her physician felt HSV was the most likely cause of the infection. She had pain relief within a day and the lesion was fully clear in 2 weeks.

This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Herpes simplex. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:513-517.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The diagnosis

The patient had herpetic whitlow—a herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection of the finger. Other conditions that could look like this include paronychia (infection of the nail fold) from a bacterial infection, or a felon, which is a bacterial infection of the pulp of the distal finger.

Herpetic whitlow used to be a common infection among dental hygienists. Now the use of gloves and universal precautions has made this less likely. Our patient had no idea where she picked up this infection, but was eager to receive treatment.

The physician pierced the pustule with a #11 blade and cultures were sent for bacteria and HSV. The patient was started on acyclovir since her physician felt HSV was the most likely cause of the infection. She had pain relief within a day and the lesion was fully clear in 2 weeks.

This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Herpes simplex. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:513-517.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The diagnosis

The patient had herpetic whitlow—a herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection of the finger. Other conditions that could look like this include paronychia (infection of the nail fold) from a bacterial infection, or a felon, which is a bacterial infection of the pulp of the distal finger.

Herpetic whitlow used to be a common infection among dental hygienists. Now the use of gloves and universal precautions has made this less likely. Our patient had no idea where she picked up this infection, but was eager to receive treatment.

The physician pierced the pustule with a #11 blade and cultures were sent for bacteria and HSV. The patient was started on acyclovir since her physician felt HSV was the most likely cause of the infection. She had pain relief within a day and the lesion was fully clear in 2 weeks.

This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Herpes simplex. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:513-517.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

A newborn with peeling skin

Our patient, a Hispanic baby boy, was born at 37 weeks’ gestation after induction of labor. He was delivered vaginally without complication. The newborn’s Apgar scores were 8 and 9, and he weighed 2.24 kg.

The child was born with cracked and peeling skin on his face, chest, hands, and feet. The skin on his face and chest had a taut, cellophane-like appearance. He had fine stubble on his scalp and no eyebrows or eyelashes (FIGURE 1A AND 1B).

The mother’s medical history and serology were unremarkable. Her prior obstetric history included a female infant who had died at 3 months of age of pneumonia, a skin infection, and dehydration. The mother indicated that the deceased child had “fish scale disease.”

FIGURE 1

Cracked skin, absence of eyebrows and eyelashes

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Congenital ichthyosis

Our patient had the congenital form of ichthyosis—a disorder that is sometimes referred to as fish scale disease. Congenital ichthyosis is a phenotypic expression of several different genotypes, and presents with varying degrees of severity. It is fairly common, occurring in 1 in 250 to 300 people.1,2 An extremely rare acquired form of ichthyosis may appear in adults, usually as a result of systemic disease or a medication reaction.

The diagnosis of congenital ichthyosis is made based on skin findings. Skin biopsy and genetic testing are typically not necessary for diagnosis.

Congenital ichthyosis is suspected in newborns who are either collodion babies (as was our patient) or who have harlequin ichthyosis.3

Collodion babies appear to be encased in a cellophane-like membrane at birth. The surface of the skin of the collodion baby usually appears taut and shiny. An absence of eyebrows, eyelashes, and scalp hair is common in these newborns; scarring alopecia can occur.4

The skin undergoes a variable degree of cracking and fissuring. Affected newborns may demonstrate ectropion (everted eyelids), eclabium (mouth held open by taut skin), and contracture of the fingers and joints.4,5 Degree of skin involvement at birth does not necessarily correlate with later disease severity.6

The collodion baby usually has a transglutaminase 1 gene mutation, which can cause either lamellar ichthyosis or congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma.7 (Absence of transglutaminase causes failed cross-linking of the proteins in the keratinocyte cellular envelope.)

Harlequin ichthyosis is a severe and usually lethal form of congenital ichthyosis, caused by a mutation in the ABCA12 gene. The product of this gene acts as a lipid transporter in epidermal keratinocytes. It is crucial for the correct formation of intercellular lipid layers in the stratum corneum, and its absence causes defective lipid transport and a loss of the skin lipid barrier.8

Affected infants have thick, armorlike plates of skin with deep moist fissures, along with severe ectropion and eclabium.4,5 Scaling and fissuring occur on the scalp, but hair is usually present.5

Differential diagnosis includes scalded skin syndrome

The differential for an infant with peeling skin includes staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, physiologic desquamation, and infantile seborrheic dermatitis.

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a blistering skin disease induced by exfoliative toxins of Staphylococcus aureus. Toxins enter the skin, most often from the circulation, and disrupt intercellular linkages in the epidermis.9 Patients have generalized erythema, fever, and skin tenderness followed by the formation of large bullae, which rupture with slight pressure (Nikolsky sign). Rupture of these bullae results in extensive areas of denuded skin. These lesions do not scar because epidermal disruption occurs superficially.10 There is no hair loss.

Diagnosis is primarily clinical, but is supported by bacterial culture results. Sepsis can be a comorbid condition.

Physiologic desquamation is a common benign condition of full-term and post-date neonatal skin. Fine, diffuse scaling and peeling typically begin on the second day of life and last a few days. There is no hair loss or shiny membrane formation.11

Infantile seborrheic dermatitis, or “cradle cap,” is a common condition characterized by erythema and greasy white-to-yellowish scales on the scalp, forehead, eyebrows, cheeks, paranasal and nasolabial folds, retroauricular area, chest, and axillae.12 This condition usually develops in the first 3 to 4 weeks of life, but immunocompromised neonates often have generalized scaling and desquamation at birth.13 While hair loss is not caused by the primary process, aggressive scale removal during treatment can cause secondary hair loss. The etiology is unknown, but some evidence points to an abnormal host response to the yeast Malassezia.12

Management focuses on fluids and emollients

Management of congenital ichthyosis involves adequate pulmonary support, as the scaling and/or plate formation may cause a restrictive ventilatory defect; the use of humidified incubators; fluid and electrolyte replacement; emollients and wet compresses to maintain skin moisture and prevent further scaling or tautness of the membrane; ophthalmologic consultation to manage ectropion; and the treatment of infection.4,5 Oral retinoids are used in select cases.14

The prognosis varies with disease severity, but complications include infection, temperature instability, and dehydration secondary to skin barrier dysfunction. Most collodion babies survive to adulthood while few, if any, babies affected with harlequin ichthyosis survive the neonatal period. Ongoing research in corrective gene transfer provides hope for future therapy.15

Our patient required a humidified incubator

Following a consult with our hospital neonatologist, we closely monitored our patient’s volume status and electrolytes, placed him in a humidified incubator, and ensured that he was treated with emollient creams. Our patient was also treated for neonatal jaundice.

We obtained a consultation with a genetics counselor, who agreed with our diagnosis and ordered appropriate genetic testing. The patient has since been lost to follow-up.

Correspondence

T. Aaron Zeller, MD, 155 Academy Avenue, Greenwood, SC 29646; [email protected]

1. Schwartz RA. Ichthyosis vulgaris, hereditary and acquired. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1112753-overview. Accessed May 2, 2009.

2. Foundation for Ichthyosis & Related Skin Types FIRST). About ichthyosis. Available at: http://www.scalyskin.org/column.cfm?ColumnID=13. Accessed May 8, 2009.

3. Bale SJ, Richard G. Autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis. Gene Reviews. December 11, 2008. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=gene&part=li-ar. Accessed April 29, 2009.

4. Shwayder T, Akland T. Neonatal skin barrier: structure, function, and disorders. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18:87-103.

5. Akiyama M. Severe congenital ichthyosis of the neonate. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:722-728.

6. Moss C. Genetic skin disorders. Semin Neonatol. 2000;5:311-320.

7. Parmentier L, Blanchet-Bardon C, Nguyen S, et al. Autosomal recessive lamellar ichthyosis: identification of a new mutation in transglutaminase 1 and evidence for genetic heterogeneity. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1391-1395.

8. Akiyama M. Pathomechanisms of harlequin ichthyosis and ABCA transporters in human diseases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:914-918.

9. Ladhani S, Evans RW. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1998;78:85-88.

10. Farrell AM. Staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. Lancet. 1999;354:880-881.

11. Wallach D. Diagnosis of common, benign neonatal dermatoses. Clin Dermatol. 2003;21:264-268.

12. Elish D, Silverberg NB. Infantile seborrheic dermatitis. Cutis. 2006;77:297-300.

13. Kim HJ, Lim YS, Choi HY, et al. Generalized seborrheic dermatitis in an immunodeficient newborn. Cutis. 2001;67:52-54.

14. Lacour M, Mehta-Nikhar B, Atherton DJ, et al. An appraisal of acitretin therapy in children with inherited disorders of keratinization. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:1023-1029.

15. Akiyama M, Sugiyama-Nakagirl Y, Sakai K. Mutations in lipid transporter ABCA12 in harlequin ichthyosis and functional recovery by corrective gene transfer. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1777-1784.

Our patient, a Hispanic baby boy, was born at 37 weeks’ gestation after induction of labor. He was delivered vaginally without complication. The newborn’s Apgar scores were 8 and 9, and he weighed 2.24 kg.

The child was born with cracked and peeling skin on his face, chest, hands, and feet. The skin on his face and chest had a taut, cellophane-like appearance. He had fine stubble on his scalp and no eyebrows or eyelashes (FIGURE 1A AND 1B).

The mother’s medical history and serology were unremarkable. Her prior obstetric history included a female infant who had died at 3 months of age of pneumonia, a skin infection, and dehydration. The mother indicated that the deceased child had “fish scale disease.”

FIGURE 1

Cracked skin, absence of eyebrows and eyelashes

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Congenital ichthyosis

Our patient had the congenital form of ichthyosis—a disorder that is sometimes referred to as fish scale disease. Congenital ichthyosis is a phenotypic expression of several different genotypes, and presents with varying degrees of severity. It is fairly common, occurring in 1 in 250 to 300 people.1,2 An extremely rare acquired form of ichthyosis may appear in adults, usually as a result of systemic disease or a medication reaction.

The diagnosis of congenital ichthyosis is made based on skin findings. Skin biopsy and genetic testing are typically not necessary for diagnosis.

Congenital ichthyosis is suspected in newborns who are either collodion babies (as was our patient) or who have harlequin ichthyosis.3

Collodion babies appear to be encased in a cellophane-like membrane at birth. The surface of the skin of the collodion baby usually appears taut and shiny. An absence of eyebrows, eyelashes, and scalp hair is common in these newborns; scarring alopecia can occur.4

The skin undergoes a variable degree of cracking and fissuring. Affected newborns may demonstrate ectropion (everted eyelids), eclabium (mouth held open by taut skin), and contracture of the fingers and joints.4,5 Degree of skin involvement at birth does not necessarily correlate with later disease severity.6

The collodion baby usually has a transglutaminase 1 gene mutation, which can cause either lamellar ichthyosis or congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma.7 (Absence of transglutaminase causes failed cross-linking of the proteins in the keratinocyte cellular envelope.)

Harlequin ichthyosis is a severe and usually lethal form of congenital ichthyosis, caused by a mutation in the ABCA12 gene. The product of this gene acts as a lipid transporter in epidermal keratinocytes. It is crucial for the correct formation of intercellular lipid layers in the stratum corneum, and its absence causes defective lipid transport and a loss of the skin lipid barrier.8

Affected infants have thick, armorlike plates of skin with deep moist fissures, along with severe ectropion and eclabium.4,5 Scaling and fissuring occur on the scalp, but hair is usually present.5

Differential diagnosis includes scalded skin syndrome

The differential for an infant with peeling skin includes staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, physiologic desquamation, and infantile seborrheic dermatitis.

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a blistering skin disease induced by exfoliative toxins of Staphylococcus aureus. Toxins enter the skin, most often from the circulation, and disrupt intercellular linkages in the epidermis.9 Patients have generalized erythema, fever, and skin tenderness followed by the formation of large bullae, which rupture with slight pressure (Nikolsky sign). Rupture of these bullae results in extensive areas of denuded skin. These lesions do not scar because epidermal disruption occurs superficially.10 There is no hair loss.

Diagnosis is primarily clinical, but is supported by bacterial culture results. Sepsis can be a comorbid condition.

Physiologic desquamation is a common benign condition of full-term and post-date neonatal skin. Fine, diffuse scaling and peeling typically begin on the second day of life and last a few days. There is no hair loss or shiny membrane formation.11

Infantile seborrheic dermatitis, or “cradle cap,” is a common condition characterized by erythema and greasy white-to-yellowish scales on the scalp, forehead, eyebrows, cheeks, paranasal and nasolabial folds, retroauricular area, chest, and axillae.12 This condition usually develops in the first 3 to 4 weeks of life, but immunocompromised neonates often have generalized scaling and desquamation at birth.13 While hair loss is not caused by the primary process, aggressive scale removal during treatment can cause secondary hair loss. The etiology is unknown, but some evidence points to an abnormal host response to the yeast Malassezia.12

Management focuses on fluids and emollients

Management of congenital ichthyosis involves adequate pulmonary support, as the scaling and/or plate formation may cause a restrictive ventilatory defect; the use of humidified incubators; fluid and electrolyte replacement; emollients and wet compresses to maintain skin moisture and prevent further scaling or tautness of the membrane; ophthalmologic consultation to manage ectropion; and the treatment of infection.4,5 Oral retinoids are used in select cases.14

The prognosis varies with disease severity, but complications include infection, temperature instability, and dehydration secondary to skin barrier dysfunction. Most collodion babies survive to adulthood while few, if any, babies affected with harlequin ichthyosis survive the neonatal period. Ongoing research in corrective gene transfer provides hope for future therapy.15

Our patient required a humidified incubator

Following a consult with our hospital neonatologist, we closely monitored our patient’s volume status and electrolytes, placed him in a humidified incubator, and ensured that he was treated with emollient creams. Our patient was also treated for neonatal jaundice.

We obtained a consultation with a genetics counselor, who agreed with our diagnosis and ordered appropriate genetic testing. The patient has since been lost to follow-up.

Correspondence

T. Aaron Zeller, MD, 155 Academy Avenue, Greenwood, SC 29646; [email protected]

Our patient, a Hispanic baby boy, was born at 37 weeks’ gestation after induction of labor. He was delivered vaginally without complication. The newborn’s Apgar scores were 8 and 9, and he weighed 2.24 kg.

The child was born with cracked and peeling skin on his face, chest, hands, and feet. The skin on his face and chest had a taut, cellophane-like appearance. He had fine stubble on his scalp and no eyebrows or eyelashes (FIGURE 1A AND 1B).

The mother’s medical history and serology were unremarkable. Her prior obstetric history included a female infant who had died at 3 months of age of pneumonia, a skin infection, and dehydration. The mother indicated that the deceased child had “fish scale disease.”

FIGURE 1

Cracked skin, absence of eyebrows and eyelashes

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Congenital ichthyosis

Our patient had the congenital form of ichthyosis—a disorder that is sometimes referred to as fish scale disease. Congenital ichthyosis is a phenotypic expression of several different genotypes, and presents with varying degrees of severity. It is fairly common, occurring in 1 in 250 to 300 people.1,2 An extremely rare acquired form of ichthyosis may appear in adults, usually as a result of systemic disease or a medication reaction.

The diagnosis of congenital ichthyosis is made based on skin findings. Skin biopsy and genetic testing are typically not necessary for diagnosis.

Congenital ichthyosis is suspected in newborns who are either collodion babies (as was our patient) or who have harlequin ichthyosis.3

Collodion babies appear to be encased in a cellophane-like membrane at birth. The surface of the skin of the collodion baby usually appears taut and shiny. An absence of eyebrows, eyelashes, and scalp hair is common in these newborns; scarring alopecia can occur.4

The skin undergoes a variable degree of cracking and fissuring. Affected newborns may demonstrate ectropion (everted eyelids), eclabium (mouth held open by taut skin), and contracture of the fingers and joints.4,5 Degree of skin involvement at birth does not necessarily correlate with later disease severity.6

The collodion baby usually has a transglutaminase 1 gene mutation, which can cause either lamellar ichthyosis or congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma.7 (Absence of transglutaminase causes failed cross-linking of the proteins in the keratinocyte cellular envelope.)

Harlequin ichthyosis is a severe and usually lethal form of congenital ichthyosis, caused by a mutation in the ABCA12 gene. The product of this gene acts as a lipid transporter in epidermal keratinocytes. It is crucial for the correct formation of intercellular lipid layers in the stratum corneum, and its absence causes defective lipid transport and a loss of the skin lipid barrier.8

Affected infants have thick, armorlike plates of skin with deep moist fissures, along with severe ectropion and eclabium.4,5 Scaling and fissuring occur on the scalp, but hair is usually present.5

Differential diagnosis includes scalded skin syndrome

The differential for an infant with peeling skin includes staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, physiologic desquamation, and infantile seborrheic dermatitis.

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a blistering skin disease induced by exfoliative toxins of Staphylococcus aureus. Toxins enter the skin, most often from the circulation, and disrupt intercellular linkages in the epidermis.9 Patients have generalized erythema, fever, and skin tenderness followed by the formation of large bullae, which rupture with slight pressure (Nikolsky sign). Rupture of these bullae results in extensive areas of denuded skin. These lesions do not scar because epidermal disruption occurs superficially.10 There is no hair loss.

Diagnosis is primarily clinical, but is supported by bacterial culture results. Sepsis can be a comorbid condition.

Physiologic desquamation is a common benign condition of full-term and post-date neonatal skin. Fine, diffuse scaling and peeling typically begin on the second day of life and last a few days. There is no hair loss or shiny membrane formation.11

Infantile seborrheic dermatitis, or “cradle cap,” is a common condition characterized by erythema and greasy white-to-yellowish scales on the scalp, forehead, eyebrows, cheeks, paranasal and nasolabial folds, retroauricular area, chest, and axillae.12 This condition usually develops in the first 3 to 4 weeks of life, but immunocompromised neonates often have generalized scaling and desquamation at birth.13 While hair loss is not caused by the primary process, aggressive scale removal during treatment can cause secondary hair loss. The etiology is unknown, but some evidence points to an abnormal host response to the yeast Malassezia.12

Management focuses on fluids and emollients

Management of congenital ichthyosis involves adequate pulmonary support, as the scaling and/or plate formation may cause a restrictive ventilatory defect; the use of humidified incubators; fluid and electrolyte replacement; emollients and wet compresses to maintain skin moisture and prevent further scaling or tautness of the membrane; ophthalmologic consultation to manage ectropion; and the treatment of infection.4,5 Oral retinoids are used in select cases.14

The prognosis varies with disease severity, but complications include infection, temperature instability, and dehydration secondary to skin barrier dysfunction. Most collodion babies survive to adulthood while few, if any, babies affected with harlequin ichthyosis survive the neonatal period. Ongoing research in corrective gene transfer provides hope for future therapy.15

Our patient required a humidified incubator

Following a consult with our hospital neonatologist, we closely monitored our patient’s volume status and electrolytes, placed him in a humidified incubator, and ensured that he was treated with emollient creams. Our patient was also treated for neonatal jaundice.

We obtained a consultation with a genetics counselor, who agreed with our diagnosis and ordered appropriate genetic testing. The patient has since been lost to follow-up.

Correspondence

T. Aaron Zeller, MD, 155 Academy Avenue, Greenwood, SC 29646; [email protected]

1. Schwartz RA. Ichthyosis vulgaris, hereditary and acquired. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1112753-overview. Accessed May 2, 2009.

2. Foundation for Ichthyosis & Related Skin Types FIRST). About ichthyosis. Available at: http://www.scalyskin.org/column.cfm?ColumnID=13. Accessed May 8, 2009.

3. Bale SJ, Richard G. Autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis. Gene Reviews. December 11, 2008. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=gene&part=li-ar. Accessed April 29, 2009.

4. Shwayder T, Akland T. Neonatal skin barrier: structure, function, and disorders. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18:87-103.

5. Akiyama M. Severe congenital ichthyosis of the neonate. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:722-728.

6. Moss C. Genetic skin disorders. Semin Neonatol. 2000;5:311-320.

7. Parmentier L, Blanchet-Bardon C, Nguyen S, et al. Autosomal recessive lamellar ichthyosis: identification of a new mutation in transglutaminase 1 and evidence for genetic heterogeneity. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1391-1395.

8. Akiyama M. Pathomechanisms of harlequin ichthyosis and ABCA transporters in human diseases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:914-918.

9. Ladhani S, Evans RW. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1998;78:85-88.

10. Farrell AM. Staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. Lancet. 1999;354:880-881.

11. Wallach D. Diagnosis of common, benign neonatal dermatoses. Clin Dermatol. 2003;21:264-268.

12. Elish D, Silverberg NB. Infantile seborrheic dermatitis. Cutis. 2006;77:297-300.

13. Kim HJ, Lim YS, Choi HY, et al. Generalized seborrheic dermatitis in an immunodeficient newborn. Cutis. 2001;67:52-54.

14. Lacour M, Mehta-Nikhar B, Atherton DJ, et al. An appraisal of acitretin therapy in children with inherited disorders of keratinization. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:1023-1029.

15. Akiyama M, Sugiyama-Nakagirl Y, Sakai K. Mutations in lipid transporter ABCA12 in harlequin ichthyosis and functional recovery by corrective gene transfer. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1777-1784.

1. Schwartz RA. Ichthyosis vulgaris, hereditary and acquired. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1112753-overview. Accessed May 2, 2009.

2. Foundation for Ichthyosis & Related Skin Types FIRST). About ichthyosis. Available at: http://www.scalyskin.org/column.cfm?ColumnID=13. Accessed May 8, 2009.

3. Bale SJ, Richard G. Autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis. Gene Reviews. December 11, 2008. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=gene&part=li-ar. Accessed April 29, 2009.

4. Shwayder T, Akland T. Neonatal skin barrier: structure, function, and disorders. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18:87-103.

5. Akiyama M. Severe congenital ichthyosis of the neonate. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:722-728.

6. Moss C. Genetic skin disorders. Semin Neonatol. 2000;5:311-320.

7. Parmentier L, Blanchet-Bardon C, Nguyen S, et al. Autosomal recessive lamellar ichthyosis: identification of a new mutation in transglutaminase 1 and evidence for genetic heterogeneity. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1391-1395.

8. Akiyama M. Pathomechanisms of harlequin ichthyosis and ABCA transporters in human diseases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:914-918.

9. Ladhani S, Evans RW. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1998;78:85-88.

10. Farrell AM. Staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. Lancet. 1999;354:880-881.

11. Wallach D. Diagnosis of common, benign neonatal dermatoses. Clin Dermatol. 2003;21:264-268.

12. Elish D, Silverberg NB. Infantile seborrheic dermatitis. Cutis. 2006;77:297-300.

13. Kim HJ, Lim YS, Choi HY, et al. Generalized seborrheic dermatitis in an immunodeficient newborn. Cutis. 2001;67:52-54.

14. Lacour M, Mehta-Nikhar B, Atherton DJ, et al. An appraisal of acitretin therapy in children with inherited disorders of keratinization. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:1023-1029.

15. Akiyama M, Sugiyama-Nakagirl Y, Sakai K. Mutations in lipid transporter ABCA12 in harlequin ichthyosis and functional recovery by corrective gene transfer. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1777-1784.

Photo Rounds Friday

PHOTO ROUNDS FRIDAY

| Click to see full size image |

The diagnosis

This patient had a typical case of infantile acropustulosis, which is often misdiagnosed as scabies. This intensely pruritic, vesiculopustular disease of young children is rare, and typically begins in the second or third months of life, though it can begin when the patient is 10 months old. It occurs slightly more often in darker skinned patients and in boys, can be recurrent, and typically remits when the child is 6 to 36 months of age.

It’s unclear what causes acropustulosis, though some speculate that it is a persistent reaction to scabies (“postscabies syndrome”). Oral antihistamines may be helpful in controlling pruritus. Pramoxine (lotion or cream) may be used topically to control itching as it works by a different mechanism than antihistamine. Corticosteroids (topical and oral) are generally not effective.

We reassured the mother that the condition is not dangerous and would go away on its own. We told her to return with her son if the pustular eruption significantly worsened.

This case was adapted from: Shedd A, Usatine R. Pustular diseases of childhood. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009: 432-434.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

* http://www.mhprofessional.com/product.php?isbn=0071474641

PHOTO ROUNDS FRIDAY

| Click to see full size image |

The diagnosis

This patient had a typical case of infantile acropustulosis, which is often misdiagnosed as scabies. This intensely pruritic, vesiculopustular disease of young children is rare, and typically begins in the second or third months of life, though it can begin when the patient is 10 months old. It occurs slightly more often in darker skinned patients and in boys, can be recurrent, and typically remits when the child is 6 to 36 months of age.

It’s unclear what causes acropustulosis, though some speculate that it is a persistent reaction to scabies (“postscabies syndrome”). Oral antihistamines may be helpful in controlling pruritus. Pramoxine (lotion or cream) may be used topically to control itching as it works by a different mechanism than antihistamine. Corticosteroids (topical and oral) are generally not effective.

We reassured the mother that the condition is not dangerous and would go away on its own. We told her to return with her son if the pustular eruption significantly worsened.

This case was adapted from: Shedd A, Usatine R. Pustular diseases of childhood. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009: 432-434.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

* http://www.mhprofessional.com/product.php?isbn=0071474641

PHOTO ROUNDS FRIDAY

| Click to see full size image |

The diagnosis

This patient had a typical case of infantile acropustulosis, which is often misdiagnosed as scabies. This intensely pruritic, vesiculopustular disease of young children is rare, and typically begins in the second or third months of life, though it can begin when the patient is 10 months old. It occurs slightly more often in darker skinned patients and in boys, can be recurrent, and typically remits when the child is 6 to 36 months of age.

It’s unclear what causes acropustulosis, though some speculate that it is a persistent reaction to scabies (“postscabies syndrome”). Oral antihistamines may be helpful in controlling pruritus. Pramoxine (lotion or cream) may be used topically to control itching as it works by a different mechanism than antihistamine. Corticosteroids (topical and oral) are generally not effective.

We reassured the mother that the condition is not dangerous and would go away on its own. We told her to return with her son if the pustular eruption significantly worsened.

This case was adapted from: Shedd A, Usatine R. Pustular diseases of childhood. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009: 432-434.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

* http://www.mhprofessional.com/product.php?isbn=0071474641

Hyperpigmented papules and plaques on chest

A 20-year-old black man came into our medical center with a mildly pruritic scaly rash affecting his neck and upper body for 2 weeks. Physical exam revealed well-demarcated, hyperpigmented hyperkeratotic papules coalescing to form large plaques on his central chest, back, and shoulders. He had a reticulated pattern on his shoulders and arms (FIGURE 1). His face, intertriginous skin, genitals, mucous membranes, and lower extremities were spared. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable.

Woods lamp and potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation were negative. Labs, including fasting blood glucose and thyroid function test, were normal. Our patient denied any recent travel, fever, night sweats, or weight loss. He noted only that he used the weight benches at the gym. His medical and family histories were unremarkable, and he was not taking any medications or supplements.

FIGURE 1

Plaques on chest, reticulated pattern on arms

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Dx: Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud (CRP) is a rare skin disorder characterized by benign blue-gray or brown hyperpigmented hyperkeratotic papules and plaques. The lesions initially occur on the trunk or central chest as 1- to 2-mm warty papules that become confluent to form plaques, spreading to the neck, abdomen, and upper extremities. Peripherally, the lesions are distributed in a reticular pattern. Although less common, CRP may be isolated to one part of the body, including the face and genitals; the mucous membranes are swpared.

With the exception of Japan, where a male predominance is seen, young women are more commonly affected.1 Patients are typically asymptomatic, or complain of mild pruritus and cosmetic concerns.

A disorder of keratinocyte maturation and differentiation?

The cause of CRP is unknown. Several theories have been entertained: an underlying endocrine disorder, a rare form of cutaneous amyloidosis, reaction to bacteria or fungus on the skin, and a keratinization abnormality.1 Most patients with CRP do not have an underlying endocrine disorder or any evidence of amyloidosis, making these theories less likely. KOH preparation for fungal elements is typically negative and patients do not respond to antifungal therapy.

A bacterial cause has been implicated because CRP responds to antibiotics, but many have argued that antibiotics are acting as an anti-inflammatory agent rather than an antibacterial medication.1 Others have suggested antibiotics may be acting to decrease epidermal proliferation by blocking protein and DNA synthesis and reducing keratinocyte production of cytokines.2

Overall, the most accepted theory is that it is a disorder of keratinocyte maturation and differentiation.1,3 Histological analysis, electron microscopy (EM), and immunohistochemical studies support this theory. Hyperkeratosis can be seen on histological examination. On EM, the stratum granulosum contains more lamellar granules and a larger transition cell layer, and immunochemical analysis reveals an increased expression of genetic markers associated with keratinization.1

The etiology of this keratinization abnormality is poorly understood.

CRP has been reported in several family members, prompting suggestions by some of a possible genetic component.4 Others have proposed staphylococcal enterotoxin B may promote certain immune factors causing abnormal keratinization.2

Is it CRP or tinea versicolor?

The differential for CRP includes:

- tinea or pityriasis versicolor

- tinea corporis

- seborrheic dermatitis

- keratosis follicularis (Darier disease)

- acanthosis nigricans

- macular amyloidosis.

Of all of these, however, CRP is most likely to be confused with tinea versicolor, as both are associated with hyper- or hypopigmented papules and plaques on the chest and back, as well as mild pruritus. In CRP, however, a Woods lamp and KOH will be negative, while with tinea versicolor, KOH will be positive and the Woods lamp may reveal yellow-green fluorescence.

If a patient’s KOH is negative and/ or the patient does not respond to treatment for tinea versicolor (which includes topical or oral antifungals), a trial of oral antibiotics for CRP may be reasonable. Response to an oral antibiotic, such as minocycline, will help to confirm the diagnosis. Although most patients with CRP do not have an endocrine disorder, it’s a good idea to keep this reported association in mind, and perform further testing, as needed.

Oral minocycline is the treatment of choice

The preferred treatment for CRP is oral minocycline (100 mg orally twice a day for 6 weeks).1,2 Oral azithromycin, erythromycin, clarithromycin, tetracycline, cefdinir,3 roxithromycin,5 doxycycline,2 and amoxicillin6 have also been used. Isotretinoin is an effective alternative to oral antibiotics, but clinicians often avoid it because of the adverse side effect profile.

With oral antibiotic therapy, the patient may completely clear and stay clear, or go on to have multiple recurrences or exacerbations. Topical retinoids have also been used with some success,4 but most reported cases have been successfully treated with oral antibiotics.1

Our patient required Tx for several months

We initially treated our patient with doxycycline (100 mg orally twice a day) for 1 month. The lesions cleared after 2 weeks and then recurred during week 4 of treatment. We discontinued the doxycycline, and started the patient on minocycline. The primary lesions resolved after 5 weeks of minocycline, though we noted residual post-inflammatory hyper-pigmentation (FIGURE 2). Our patient continued the medication for an additional 8 weeks. He was lost to follow-up.

FIGURE 2

Weeks later, hyperpigmentation remains

Correspondence

Kendall Lane, MD, LCDR, MC, United States Navy, Navy Medical Center San Diego, 34520 Bob Wilson Drive, Suite 300, San Diego, CA 92134

1. Schwartz R. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. Available at: http://www.emedicine.com/derm/topic82.htm. Accessed March 25, 2009.

2. Greenblatt D, Cintra M, Teixiera F, et al. Hyperpigmented plaques on a young man. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:896-898.

3. Scheinfeld N. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a review of the literature. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:305-313.

4. Schwartzberg JB, Schwartzberg HA. Response of confluent and reticulate papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud to topical tretinoin. Cutis. 2000;66:291-293.

5. Ito S, Hatamochi A, Yamazaki S. A case of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis that successfully responded to roxithromycin. J Dermatol. 2006;33:71-72.

6. Davis RF, Harman KE. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis successfully treated with amoxicillin. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:583-584.

A 20-year-old black man came into our medical center with a mildly pruritic scaly rash affecting his neck and upper body for 2 weeks. Physical exam revealed well-demarcated, hyperpigmented hyperkeratotic papules coalescing to form large plaques on his central chest, back, and shoulders. He had a reticulated pattern on his shoulders and arms (FIGURE 1). His face, intertriginous skin, genitals, mucous membranes, and lower extremities were spared. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable.

Woods lamp and potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation were negative. Labs, including fasting blood glucose and thyroid function test, were normal. Our patient denied any recent travel, fever, night sweats, or weight loss. He noted only that he used the weight benches at the gym. His medical and family histories were unremarkable, and he was not taking any medications or supplements.

FIGURE 1

Plaques on chest, reticulated pattern on arms

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Dx: Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud (CRP) is a rare skin disorder characterized by benign blue-gray or brown hyperpigmented hyperkeratotic papules and plaques. The lesions initially occur on the trunk or central chest as 1- to 2-mm warty papules that become confluent to form plaques, spreading to the neck, abdomen, and upper extremities. Peripherally, the lesions are distributed in a reticular pattern. Although less common, CRP may be isolated to one part of the body, including the face and genitals; the mucous membranes are swpared.

With the exception of Japan, where a male predominance is seen, young women are more commonly affected.1 Patients are typically asymptomatic, or complain of mild pruritus and cosmetic concerns.

A disorder of keratinocyte maturation and differentiation?

The cause of CRP is unknown. Several theories have been entertained: an underlying endocrine disorder, a rare form of cutaneous amyloidosis, reaction to bacteria or fungus on the skin, and a keratinization abnormality.1 Most patients with CRP do not have an underlying endocrine disorder or any evidence of amyloidosis, making these theories less likely. KOH preparation for fungal elements is typically negative and patients do not respond to antifungal therapy.

A bacterial cause has been implicated because CRP responds to antibiotics, but many have argued that antibiotics are acting as an anti-inflammatory agent rather than an antibacterial medication.1 Others have suggested antibiotics may be acting to decrease epidermal proliferation by blocking protein and DNA synthesis and reducing keratinocyte production of cytokines.2

Overall, the most accepted theory is that it is a disorder of keratinocyte maturation and differentiation.1,3 Histological analysis, electron microscopy (EM), and immunohistochemical studies support this theory. Hyperkeratosis can be seen on histological examination. On EM, the stratum granulosum contains more lamellar granules and a larger transition cell layer, and immunochemical analysis reveals an increased expression of genetic markers associated with keratinization.1

The etiology of this keratinization abnormality is poorly understood.

CRP has been reported in several family members, prompting suggestions by some of a possible genetic component.4 Others have proposed staphylococcal enterotoxin B may promote certain immune factors causing abnormal keratinization.2

Is it CRP or tinea versicolor?

The differential for CRP includes:

- tinea or pityriasis versicolor

- tinea corporis

- seborrheic dermatitis

- keratosis follicularis (Darier disease)

- acanthosis nigricans

- macular amyloidosis.

Of all of these, however, CRP is most likely to be confused with tinea versicolor, as both are associated with hyper- or hypopigmented papules and plaques on the chest and back, as well as mild pruritus. In CRP, however, a Woods lamp and KOH will be negative, while with tinea versicolor, KOH will be positive and the Woods lamp may reveal yellow-green fluorescence.