User login

Nonhealing Ulcer on the Lower Lip

Nonhealing Ulcer on the Lower Lip

THE DIAGNOSIS: Syphilis

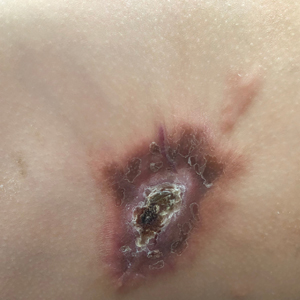

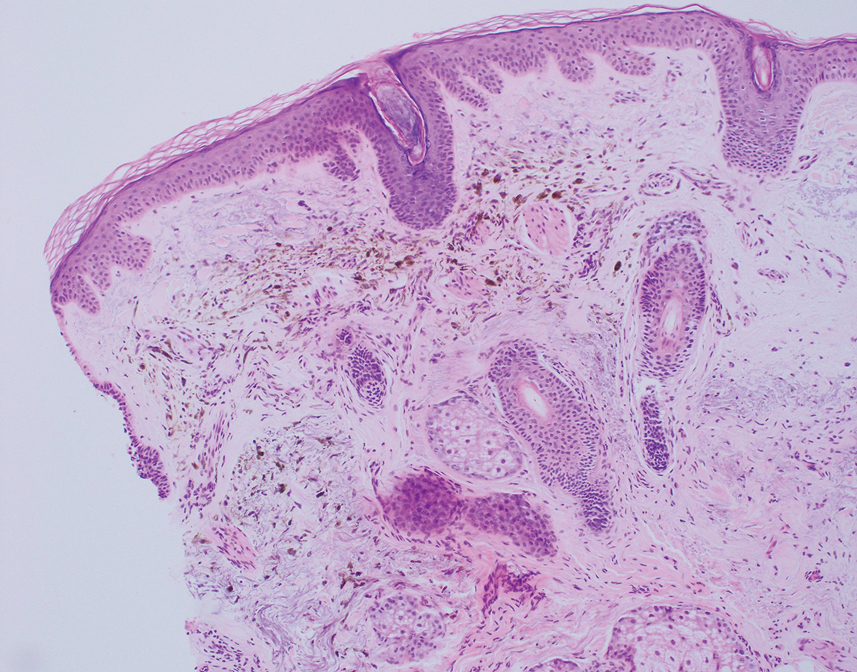

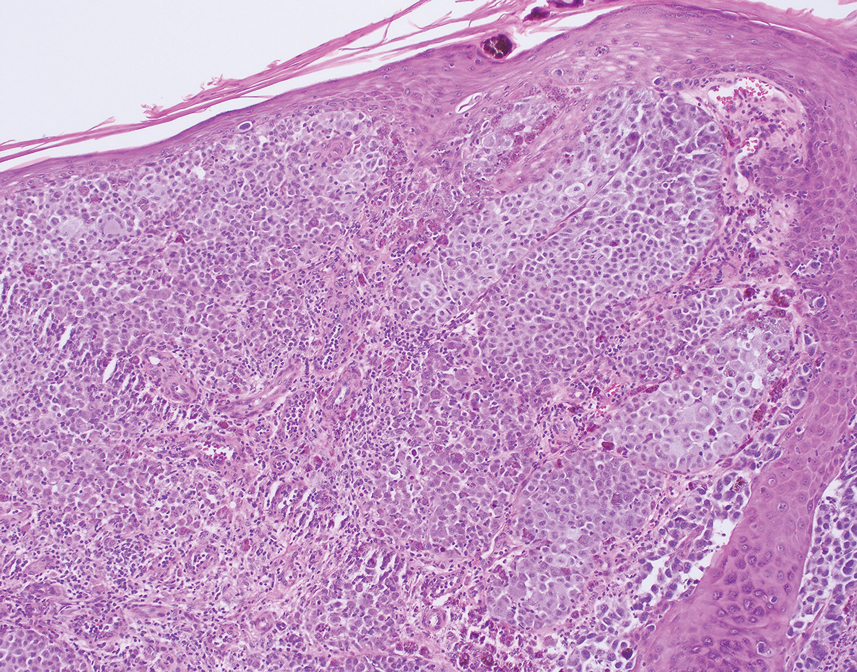

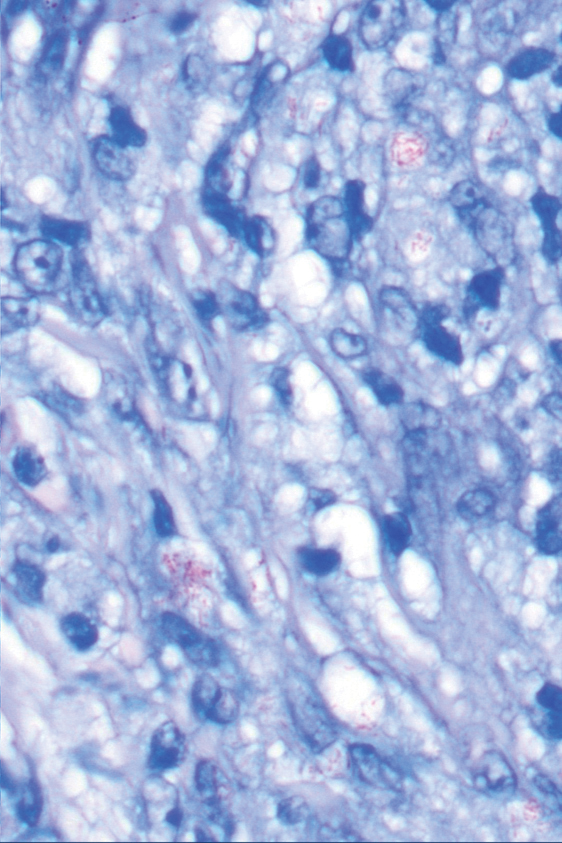

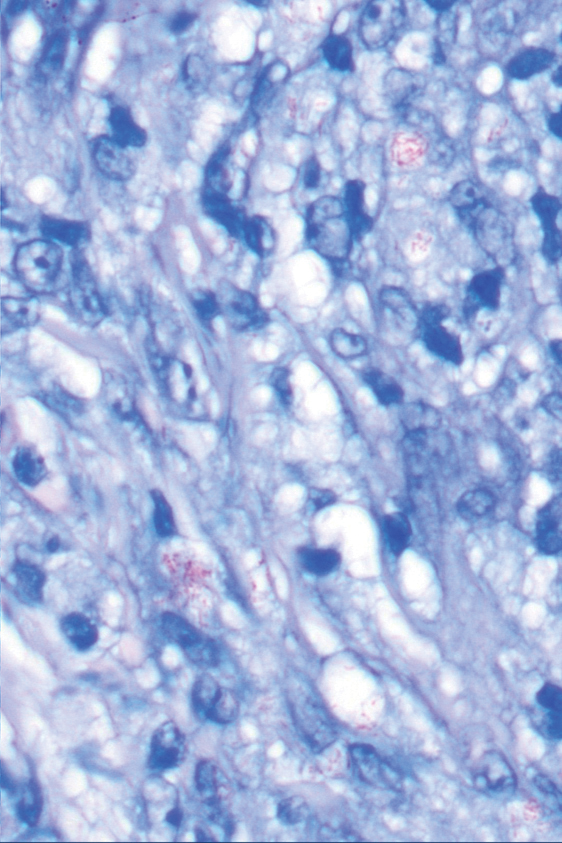

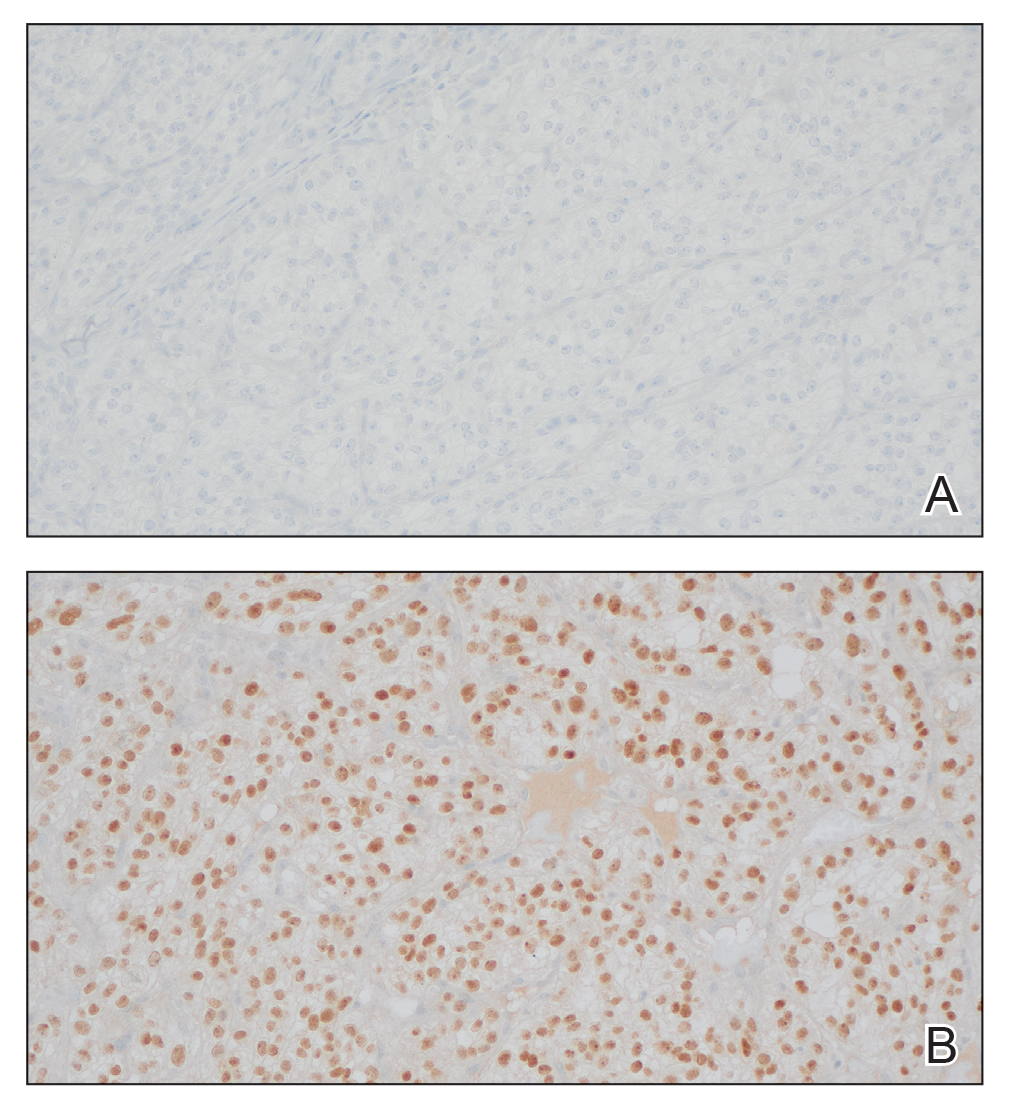

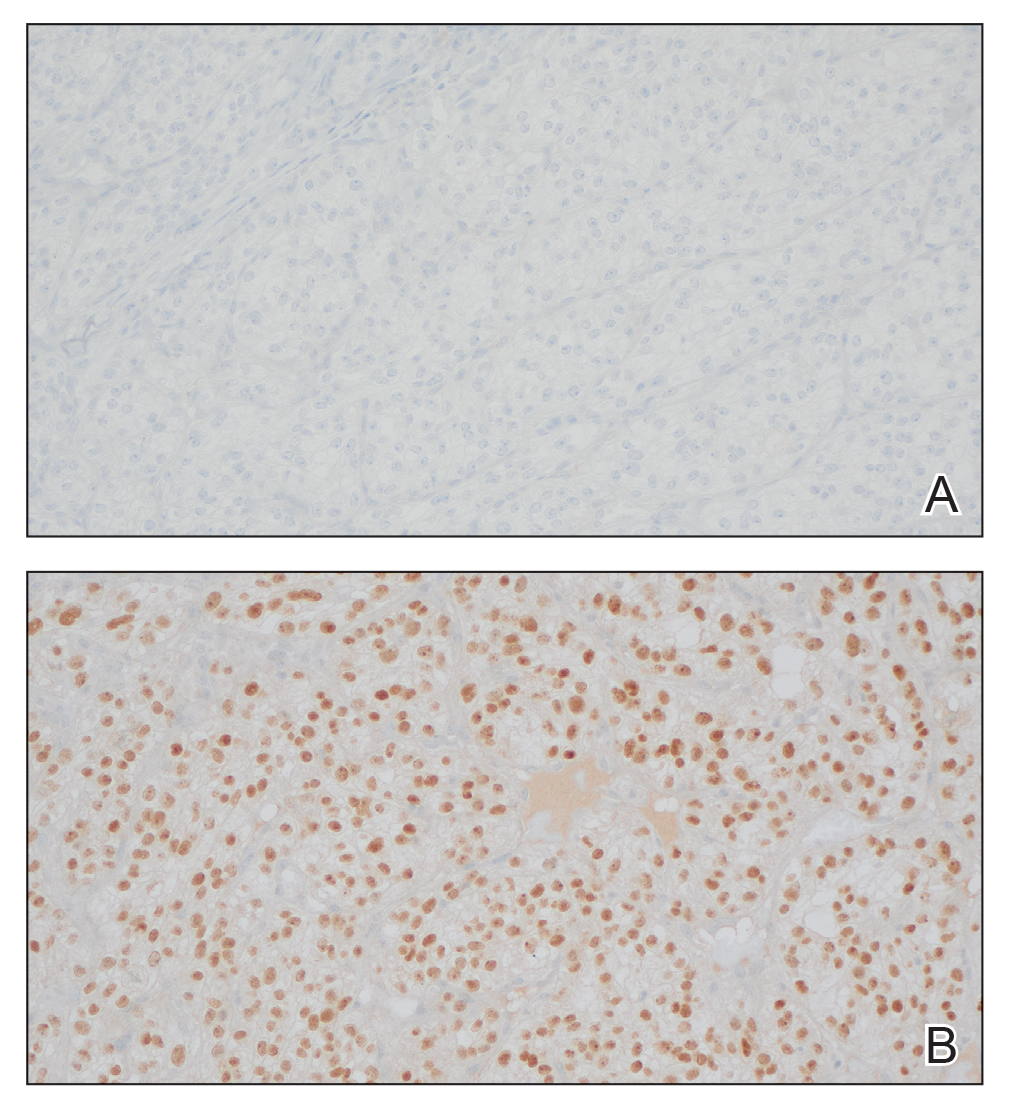

The differential diagnosis of oral lesions can be complex; in our patient, we considered conditions such as pyogenic granuloma, herpes simplex virus, and syphilis, despite the presence of pain. Immunohistochemical staining for spirochete antigens was positive, and serologic confirmation through a positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test confirmed the diagnosis of primary syphilis. The patient was promptly referred back to the primary care physician for treatment with intramuscular penicillin, leading to resolution of the lesion. At 3 months’ follow-up in our clinic, the lesion was fully resolved.

A primary syphilitic chancre is the initial lesion caused by Treponema pallidum, typically manifesting as a painless ulcer at the infection site, usually in the genital area; however, chancres also may manifest in other locations (eg, the anus or oral cavity) due to direct contact with infectious lesions on another individual. Our case represents an atypical presentation of an oral syphilitic chancre.

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection with various clinical manifestations. It is crucial to consider syphilis in the differential diagnosis of ulcerative lesions even when pain is present, especially in high-risk individuals such as those who engage in unprotected sex.1,2 Oral syphilitic chancres have been documented in the medical literature for more than a century, underscoring the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for diagnosis and a low threshold for obtaining an RPR test to facilitate early detection and treatment.2,3 Notably, the prevalence of syphilis is higher in men who have sex with men, particularly among those who engage in unprotected oral and anal sex. Increased screening and early treatment are essential to control the spread of disease within all populations. Doxycycline postexposure prophylaxis (doxyPEP) is used as a preventive measure for syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea.4 This regimen consists of 200 mg of doxycycline taken within 24 hours but no later than 72 hours after unprotected anal, vaginal, or oral sex.

Our case highlights the importance of considering the differential diagnosis of oral ulcers, particularly in high-risk populations such as men who have sex with men. Prompt diagnosis, effective treatment, and preventive strategies such as doxyPEP are essential for controlling syphilis. Comprehensive patient education and regular follow-up appointments are critical components of successful management.

The United States has experienced a considerable rise in primary and congenital syphilis cases, with an 80% increase between 2018 and 2022.6 Serologic testing is the primary method for diagnosing, staging, and managing syphilis. Sexually active patients with suspected syphilis or unexplained symptoms should undergo testing. Prompt diagnosis and treatment can prevent systemic complications, including ocular involvement and permanent blindness.

Syphilis is transmitted through direct contact with a syphilitic ulcer or saliva or blood from an infected individual. Oral syphilitic ulcers can develop on the lips, tongue, oral mucosa, and tonsils. Chancres can range from a few millimeters to several centimeters, with an incubation period of 10 to 90 days (average, 21 days). The chancre lasts 3 to 6 weeks and heals spontaneously. Without treatment, primary syphilis can progress to secondary syphilis, characterized by a papulosquamous eruption and mucosal involvement, and potentially tertiary syphilis, which can affect the central nervous system, heart, bones, and skin.7

Immunocompromised patients, especially those diagnosed with HIV, face increased risks including altered clinical presentations (eg, multiple or deep chancres), delayed healing, overlapping stages of disease, and increased severity of organ involvement. All sexually active individuals should be screened for syphilis every 3 to 6 months, particularly those with unexplained oral ulcers.

Serologic testing is fundamental for syphilis diagnosis and management. Nontreponemal tests such as RPR and treponemal tests such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test provide comprehensive diagnostic information. Early diagnosis and empiric treatment are crucial in suspected cases. Ocular screening is recommended for suspected or confirmed syphilis cases.7

Management of syphilis includes treating all sexual partners and providing thorough patient education on the disease. Monitoring for the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction—an acute febrile reaction following penicillin therapy—is important, especially in pregnant patients.5 Serologic evaluation at 6 and 12 months posttreatment is recommended, with more frequent evaluations if follow-up is uncertain, particularly for those with inconsistent access to health care or in whom reinfection is suspected. Guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advocate for intramuscular penicillin G benzathine as the preferred treatment, with specific dosing for adults and children.7 Due to the ongoing bicillin shortage, alternatives such as extencilline have temporarily been allowed for use in the United States.8

The rising incidence of syphilis in the United States underscores the critical need for enhanced public health initiatives focusing on education, screening, and early intervention. Comprehensive sexual education that includes information about syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections, proper use of prophylactic measures such as condoms, and the benefits of doxyPEP can considerably reduce transmission rates. Health care providers should routinely discuss these preventive measures with their patients, especially those in high-risk groups.

Our case highlights the importance of considering syphilis in the differential diagnosis of oral ulcers, particularly in high-risk populations. Timely diagnosis, effective treatment, and preventive measures such as doxyPEP are essential for managing and controlling syphilis. The rising incidence of syphilis in the United States warrants increased screening, patient education, and public health interventions to address this notable health challenge. The syphilis crisis calls for coordinated efforts from health care providers, public health officials, and community leaders to curb the spread of this infection and protect public health.

- Mayer KH, Traeger M, Marcus JL. Doxycycline postexposure prophylaxis and sexually transmitted infections. JAMA. 2023;330:1381-1382. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.16416

- Cossman JP, Fournier JB. Frequency of syphilis diagnoses by dermatologists. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:718-719. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2017.0460

- Porterfield C, Brodell D, Dolohanty L, et al. Primary syphilis presenting as a chronic lip ulcer. Cureus. 2020;12:E7086. doi:10.7759 /cureus.7086

- Schamberg JF. An epidemic of chancres of the lip from kissing. JAMA. 1911;LVII:783-784. doi:10.1001/jama.1911.04260090005002

- Farmer TW. Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in early syphilis. JAMA. 1948;138:480–485. doi:10.1001/jama.1948.02900070012003

- Winney A. Why is syphilis spiking in the U.S.? Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Published March 13, 2024. Accessed April 30, 2025. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/why-is-syphilis-spiking-in-the-us

- Koundanya VV, Tripathy K. Syphilis ocular manifestations. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Updated August 25, 2023. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558957/

- CDC. FDA announcement on availability of extencilline. National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and Tuberculosis Prevention. Published July 19, 2024. Accessed April 30, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/director-letters/extencilline-during-bicillin-l-a-shortage.html

THE DIAGNOSIS: Syphilis

The differential diagnosis of oral lesions can be complex; in our patient, we considered conditions such as pyogenic granuloma, herpes simplex virus, and syphilis, despite the presence of pain. Immunohistochemical staining for spirochete antigens was positive, and serologic confirmation through a positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test confirmed the diagnosis of primary syphilis. The patient was promptly referred back to the primary care physician for treatment with intramuscular penicillin, leading to resolution of the lesion. At 3 months’ follow-up in our clinic, the lesion was fully resolved.

A primary syphilitic chancre is the initial lesion caused by Treponema pallidum, typically manifesting as a painless ulcer at the infection site, usually in the genital area; however, chancres also may manifest in other locations (eg, the anus or oral cavity) due to direct contact with infectious lesions on another individual. Our case represents an atypical presentation of an oral syphilitic chancre.

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection with various clinical manifestations. It is crucial to consider syphilis in the differential diagnosis of ulcerative lesions even when pain is present, especially in high-risk individuals such as those who engage in unprotected sex.1,2 Oral syphilitic chancres have been documented in the medical literature for more than a century, underscoring the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for diagnosis and a low threshold for obtaining an RPR test to facilitate early detection and treatment.2,3 Notably, the prevalence of syphilis is higher in men who have sex with men, particularly among those who engage in unprotected oral and anal sex. Increased screening and early treatment are essential to control the spread of disease within all populations. Doxycycline postexposure prophylaxis (doxyPEP) is used as a preventive measure for syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea.4 This regimen consists of 200 mg of doxycycline taken within 24 hours but no later than 72 hours after unprotected anal, vaginal, or oral sex.

Our case highlights the importance of considering the differential diagnosis of oral ulcers, particularly in high-risk populations such as men who have sex with men. Prompt diagnosis, effective treatment, and preventive strategies such as doxyPEP are essential for controlling syphilis. Comprehensive patient education and regular follow-up appointments are critical components of successful management.

The United States has experienced a considerable rise in primary and congenital syphilis cases, with an 80% increase between 2018 and 2022.6 Serologic testing is the primary method for diagnosing, staging, and managing syphilis. Sexually active patients with suspected syphilis or unexplained symptoms should undergo testing. Prompt diagnosis and treatment can prevent systemic complications, including ocular involvement and permanent blindness.

Syphilis is transmitted through direct contact with a syphilitic ulcer or saliva or blood from an infected individual. Oral syphilitic ulcers can develop on the lips, tongue, oral mucosa, and tonsils. Chancres can range from a few millimeters to several centimeters, with an incubation period of 10 to 90 days (average, 21 days). The chancre lasts 3 to 6 weeks and heals spontaneously. Without treatment, primary syphilis can progress to secondary syphilis, characterized by a papulosquamous eruption and mucosal involvement, and potentially tertiary syphilis, which can affect the central nervous system, heart, bones, and skin.7

Immunocompromised patients, especially those diagnosed with HIV, face increased risks including altered clinical presentations (eg, multiple or deep chancres), delayed healing, overlapping stages of disease, and increased severity of organ involvement. All sexually active individuals should be screened for syphilis every 3 to 6 months, particularly those with unexplained oral ulcers.

Serologic testing is fundamental for syphilis diagnosis and management. Nontreponemal tests such as RPR and treponemal tests such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test provide comprehensive diagnostic information. Early diagnosis and empiric treatment are crucial in suspected cases. Ocular screening is recommended for suspected or confirmed syphilis cases.7

Management of syphilis includes treating all sexual partners and providing thorough patient education on the disease. Monitoring for the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction—an acute febrile reaction following penicillin therapy—is important, especially in pregnant patients.5 Serologic evaluation at 6 and 12 months posttreatment is recommended, with more frequent evaluations if follow-up is uncertain, particularly for those with inconsistent access to health care or in whom reinfection is suspected. Guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advocate for intramuscular penicillin G benzathine as the preferred treatment, with specific dosing for adults and children.7 Due to the ongoing bicillin shortage, alternatives such as extencilline have temporarily been allowed for use in the United States.8

The rising incidence of syphilis in the United States underscores the critical need for enhanced public health initiatives focusing on education, screening, and early intervention. Comprehensive sexual education that includes information about syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections, proper use of prophylactic measures such as condoms, and the benefits of doxyPEP can considerably reduce transmission rates. Health care providers should routinely discuss these preventive measures with their patients, especially those in high-risk groups.

Our case highlights the importance of considering syphilis in the differential diagnosis of oral ulcers, particularly in high-risk populations. Timely diagnosis, effective treatment, and preventive measures such as doxyPEP are essential for managing and controlling syphilis. The rising incidence of syphilis in the United States warrants increased screening, patient education, and public health interventions to address this notable health challenge. The syphilis crisis calls for coordinated efforts from health care providers, public health officials, and community leaders to curb the spread of this infection and protect public health.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Syphilis

The differential diagnosis of oral lesions can be complex; in our patient, we considered conditions such as pyogenic granuloma, herpes simplex virus, and syphilis, despite the presence of pain. Immunohistochemical staining for spirochete antigens was positive, and serologic confirmation through a positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test confirmed the diagnosis of primary syphilis. The patient was promptly referred back to the primary care physician for treatment with intramuscular penicillin, leading to resolution of the lesion. At 3 months’ follow-up in our clinic, the lesion was fully resolved.

A primary syphilitic chancre is the initial lesion caused by Treponema pallidum, typically manifesting as a painless ulcer at the infection site, usually in the genital area; however, chancres also may manifest in other locations (eg, the anus or oral cavity) due to direct contact with infectious lesions on another individual. Our case represents an atypical presentation of an oral syphilitic chancre.

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection with various clinical manifestations. It is crucial to consider syphilis in the differential diagnosis of ulcerative lesions even when pain is present, especially in high-risk individuals such as those who engage in unprotected sex.1,2 Oral syphilitic chancres have been documented in the medical literature for more than a century, underscoring the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for diagnosis and a low threshold for obtaining an RPR test to facilitate early detection and treatment.2,3 Notably, the prevalence of syphilis is higher in men who have sex with men, particularly among those who engage in unprotected oral and anal sex. Increased screening and early treatment are essential to control the spread of disease within all populations. Doxycycline postexposure prophylaxis (doxyPEP) is used as a preventive measure for syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea.4 This regimen consists of 200 mg of doxycycline taken within 24 hours but no later than 72 hours after unprotected anal, vaginal, or oral sex.

Our case highlights the importance of considering the differential diagnosis of oral ulcers, particularly in high-risk populations such as men who have sex with men. Prompt diagnosis, effective treatment, and preventive strategies such as doxyPEP are essential for controlling syphilis. Comprehensive patient education and regular follow-up appointments are critical components of successful management.

The United States has experienced a considerable rise in primary and congenital syphilis cases, with an 80% increase between 2018 and 2022.6 Serologic testing is the primary method for diagnosing, staging, and managing syphilis. Sexually active patients with suspected syphilis or unexplained symptoms should undergo testing. Prompt diagnosis and treatment can prevent systemic complications, including ocular involvement and permanent blindness.

Syphilis is transmitted through direct contact with a syphilitic ulcer or saliva or blood from an infected individual. Oral syphilitic ulcers can develop on the lips, tongue, oral mucosa, and tonsils. Chancres can range from a few millimeters to several centimeters, with an incubation period of 10 to 90 days (average, 21 days). The chancre lasts 3 to 6 weeks and heals spontaneously. Without treatment, primary syphilis can progress to secondary syphilis, characterized by a papulosquamous eruption and mucosal involvement, and potentially tertiary syphilis, which can affect the central nervous system, heart, bones, and skin.7

Immunocompromised patients, especially those diagnosed with HIV, face increased risks including altered clinical presentations (eg, multiple or deep chancres), delayed healing, overlapping stages of disease, and increased severity of organ involvement. All sexually active individuals should be screened for syphilis every 3 to 6 months, particularly those with unexplained oral ulcers.

Serologic testing is fundamental for syphilis diagnosis and management. Nontreponemal tests such as RPR and treponemal tests such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test provide comprehensive diagnostic information. Early diagnosis and empiric treatment are crucial in suspected cases. Ocular screening is recommended for suspected or confirmed syphilis cases.7

Management of syphilis includes treating all sexual partners and providing thorough patient education on the disease. Monitoring for the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction—an acute febrile reaction following penicillin therapy—is important, especially in pregnant patients.5 Serologic evaluation at 6 and 12 months posttreatment is recommended, with more frequent evaluations if follow-up is uncertain, particularly for those with inconsistent access to health care or in whom reinfection is suspected. Guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advocate for intramuscular penicillin G benzathine as the preferred treatment, with specific dosing for adults and children.7 Due to the ongoing bicillin shortage, alternatives such as extencilline have temporarily been allowed for use in the United States.8

The rising incidence of syphilis in the United States underscores the critical need for enhanced public health initiatives focusing on education, screening, and early intervention. Comprehensive sexual education that includes information about syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections, proper use of prophylactic measures such as condoms, and the benefits of doxyPEP can considerably reduce transmission rates. Health care providers should routinely discuss these preventive measures with their patients, especially those in high-risk groups.

Our case highlights the importance of considering syphilis in the differential diagnosis of oral ulcers, particularly in high-risk populations. Timely diagnosis, effective treatment, and preventive measures such as doxyPEP are essential for managing and controlling syphilis. The rising incidence of syphilis in the United States warrants increased screening, patient education, and public health interventions to address this notable health challenge. The syphilis crisis calls for coordinated efforts from health care providers, public health officials, and community leaders to curb the spread of this infection and protect public health.

- Mayer KH, Traeger M, Marcus JL. Doxycycline postexposure prophylaxis and sexually transmitted infections. JAMA. 2023;330:1381-1382. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.16416

- Cossman JP, Fournier JB. Frequency of syphilis diagnoses by dermatologists. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:718-719. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2017.0460

- Porterfield C, Brodell D, Dolohanty L, et al. Primary syphilis presenting as a chronic lip ulcer. Cureus. 2020;12:E7086. doi:10.7759 /cureus.7086

- Schamberg JF. An epidemic of chancres of the lip from kissing. JAMA. 1911;LVII:783-784. doi:10.1001/jama.1911.04260090005002

- Farmer TW. Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in early syphilis. JAMA. 1948;138:480–485. doi:10.1001/jama.1948.02900070012003

- Winney A. Why is syphilis spiking in the U.S.? Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Published March 13, 2024. Accessed April 30, 2025. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/why-is-syphilis-spiking-in-the-us

- Koundanya VV, Tripathy K. Syphilis ocular manifestations. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Updated August 25, 2023. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558957/

- CDC. FDA announcement on availability of extencilline. National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and Tuberculosis Prevention. Published July 19, 2024. Accessed April 30, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/director-letters/extencilline-during-bicillin-l-a-shortage.html

- Mayer KH, Traeger M, Marcus JL. Doxycycline postexposure prophylaxis and sexually transmitted infections. JAMA. 2023;330:1381-1382. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.16416

- Cossman JP, Fournier JB. Frequency of syphilis diagnoses by dermatologists. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:718-719. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2017.0460

- Porterfield C, Brodell D, Dolohanty L, et al. Primary syphilis presenting as a chronic lip ulcer. Cureus. 2020;12:E7086. doi:10.7759 /cureus.7086

- Schamberg JF. An epidemic of chancres of the lip from kissing. JAMA. 1911;LVII:783-784. doi:10.1001/jama.1911.04260090005002

- Farmer TW. Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in early syphilis. JAMA. 1948;138:480–485. doi:10.1001/jama.1948.02900070012003

- Winney A. Why is syphilis spiking in the U.S.? Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Published March 13, 2024. Accessed April 30, 2025. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/why-is-syphilis-spiking-in-the-us

- Koundanya VV, Tripathy K. Syphilis ocular manifestations. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Updated August 25, 2023. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558957/

- CDC. FDA announcement on availability of extencilline. National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and Tuberculosis Prevention. Published July 19, 2024. Accessed April 30, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/director-letters/extencilline-during-bicillin-l-a-shortage.html

Nonhealing Ulcer on the Lower Lip

Nonhealing Ulcer on the Lower Lip

A 54-year-old HIV-negative man with a history of having sex with men presented to his primary care physician with an ulcer on the lower lip of 3 weeks’ duration. The patient reported that the lesion had appeared as a typical cold sore with pain in the area. A 9-day course of oral valacyclovir prescribed by the primary care physician provided no relief or improvement. A 2-mm punch biopsy was performed.

Large Bullae on the Legs in a Hospitalized Patient Following a Gunshot Wound

Large Bullae on the Legs in a Hospitalized Patient Following a Gunshot Wound

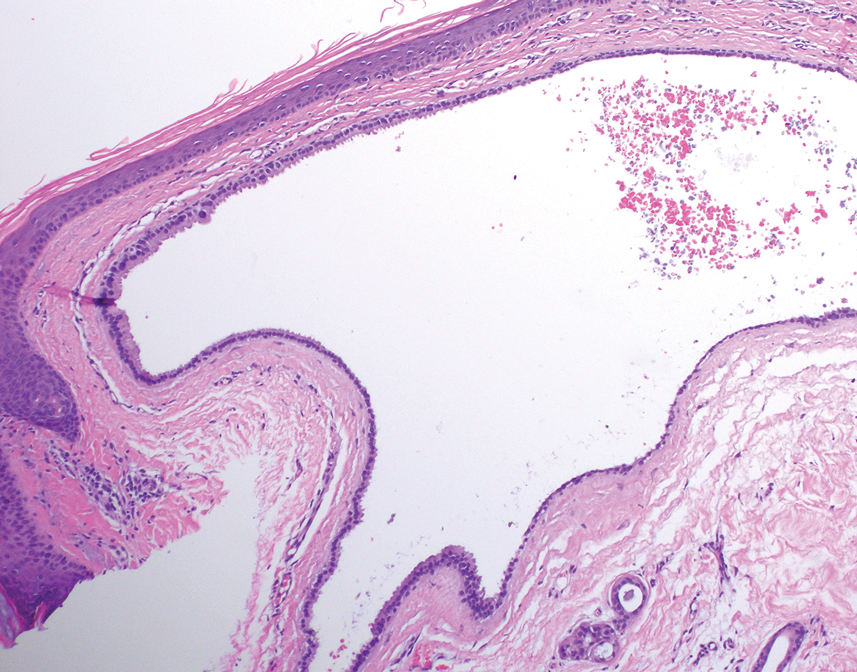

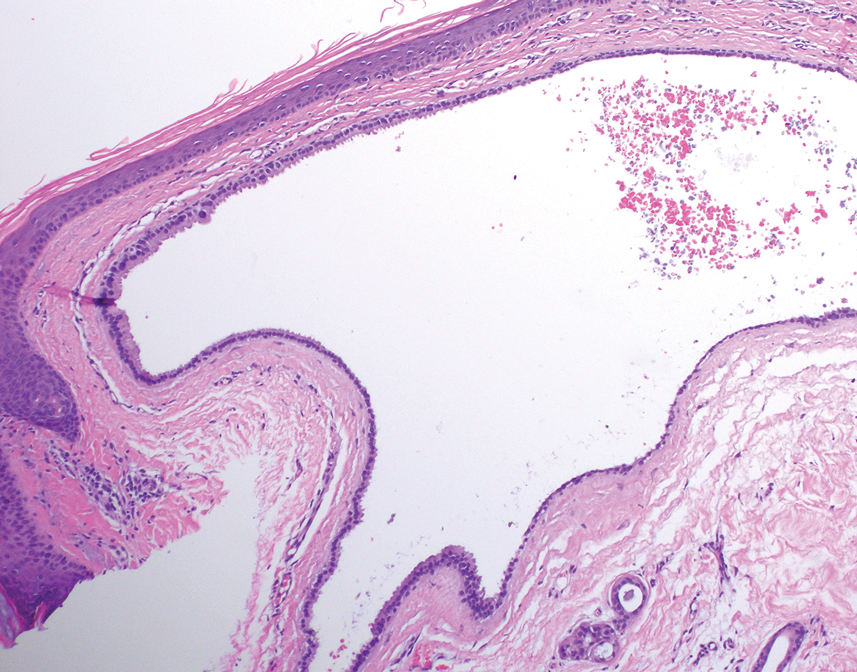

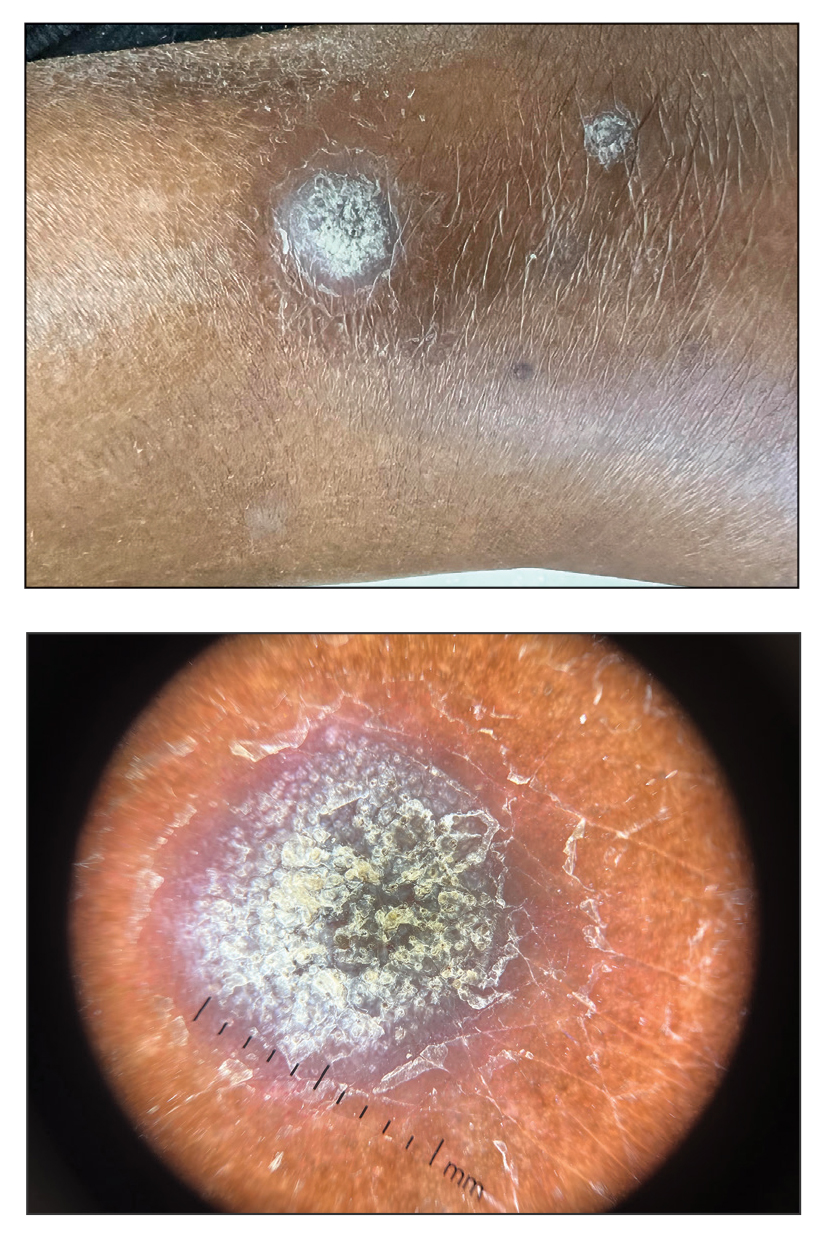

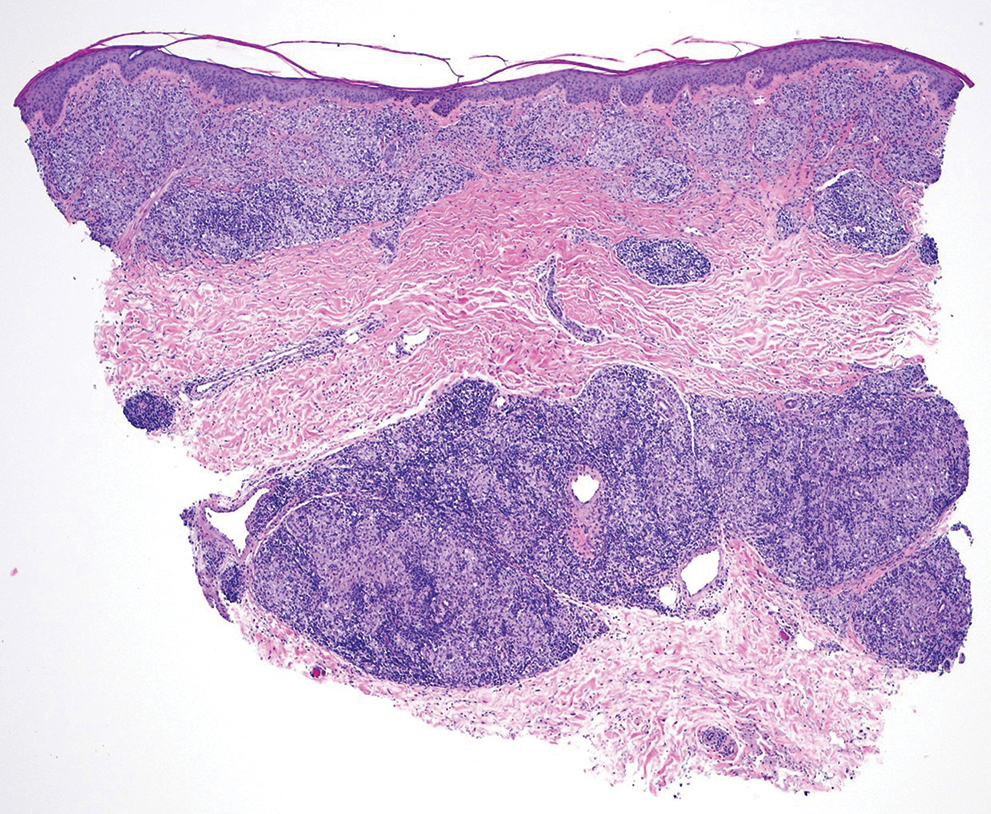

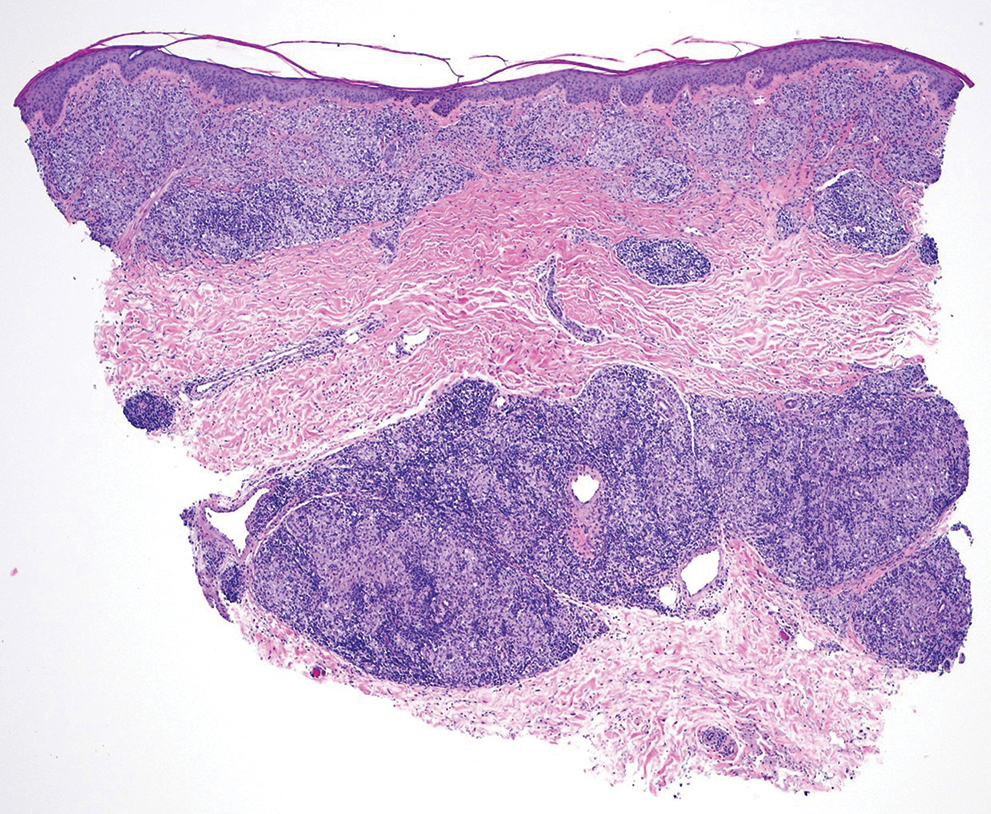

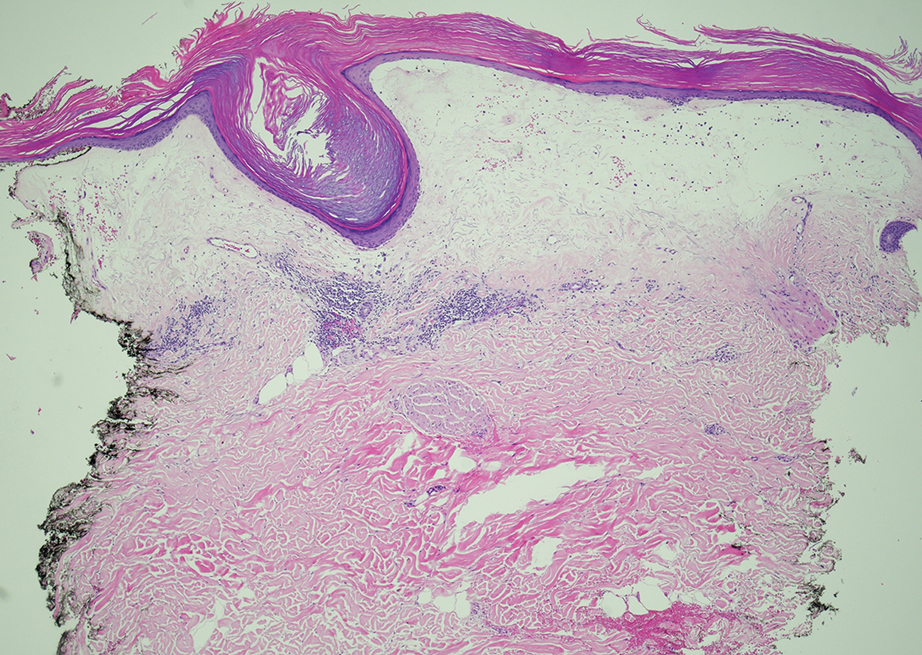

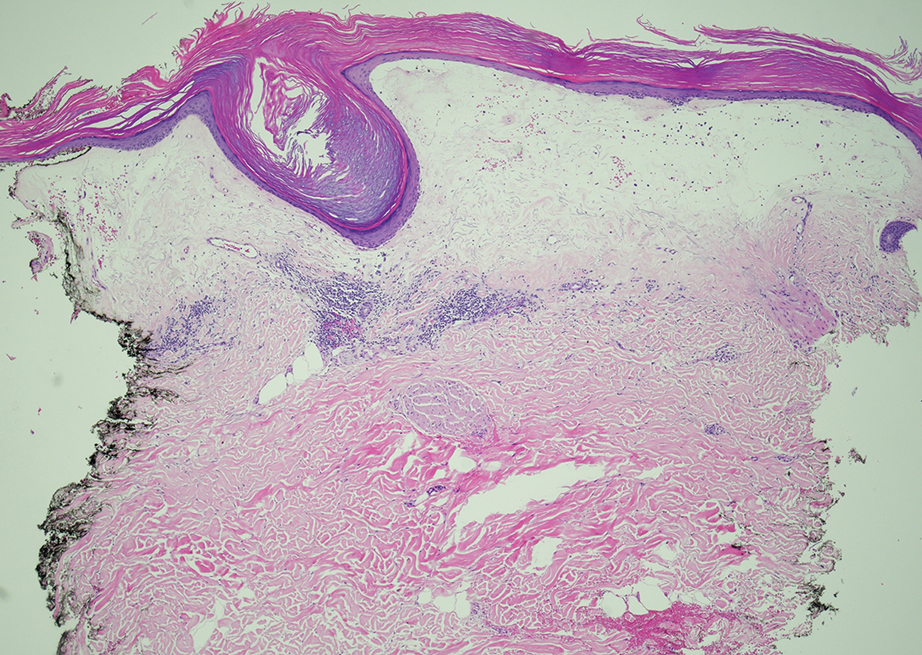

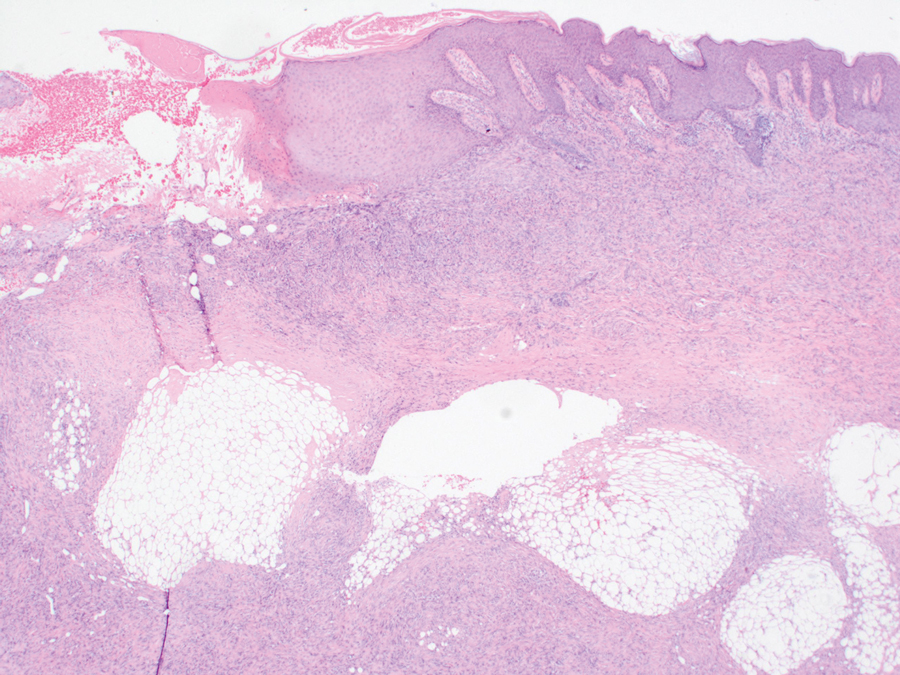

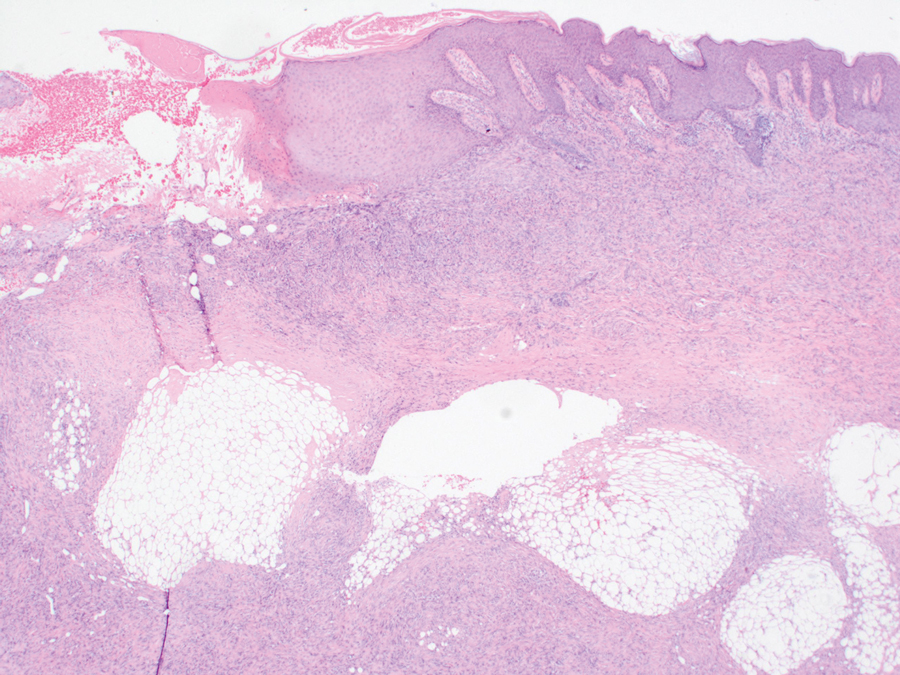

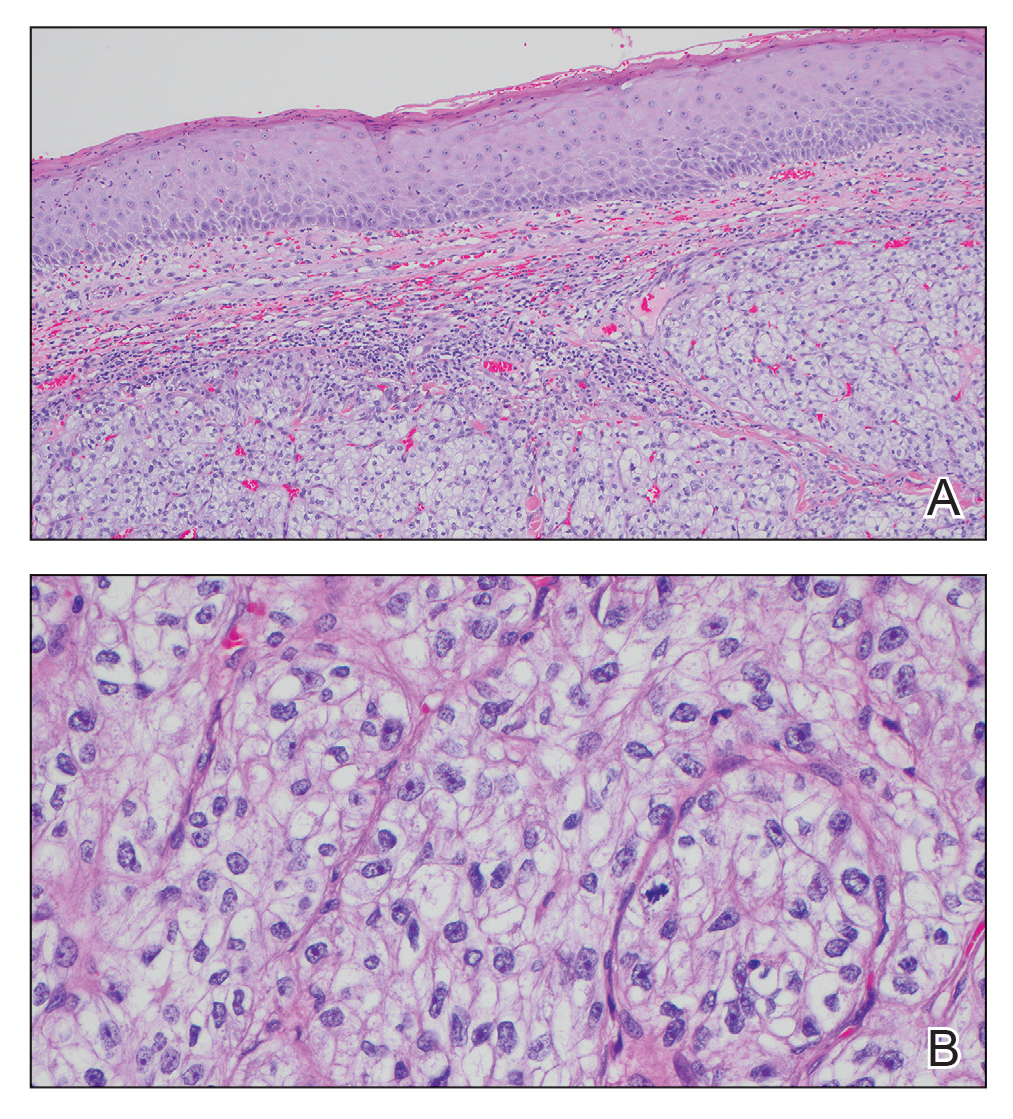

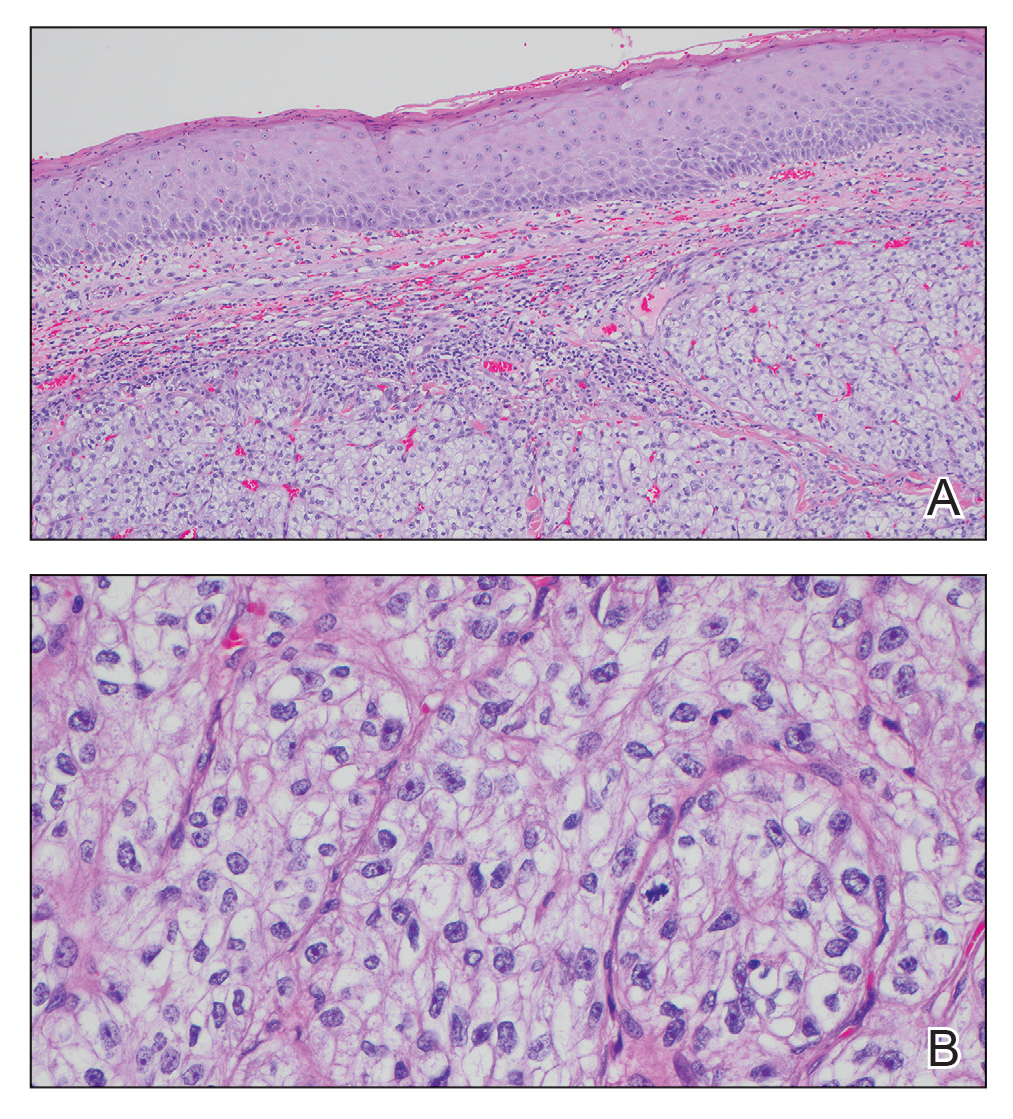

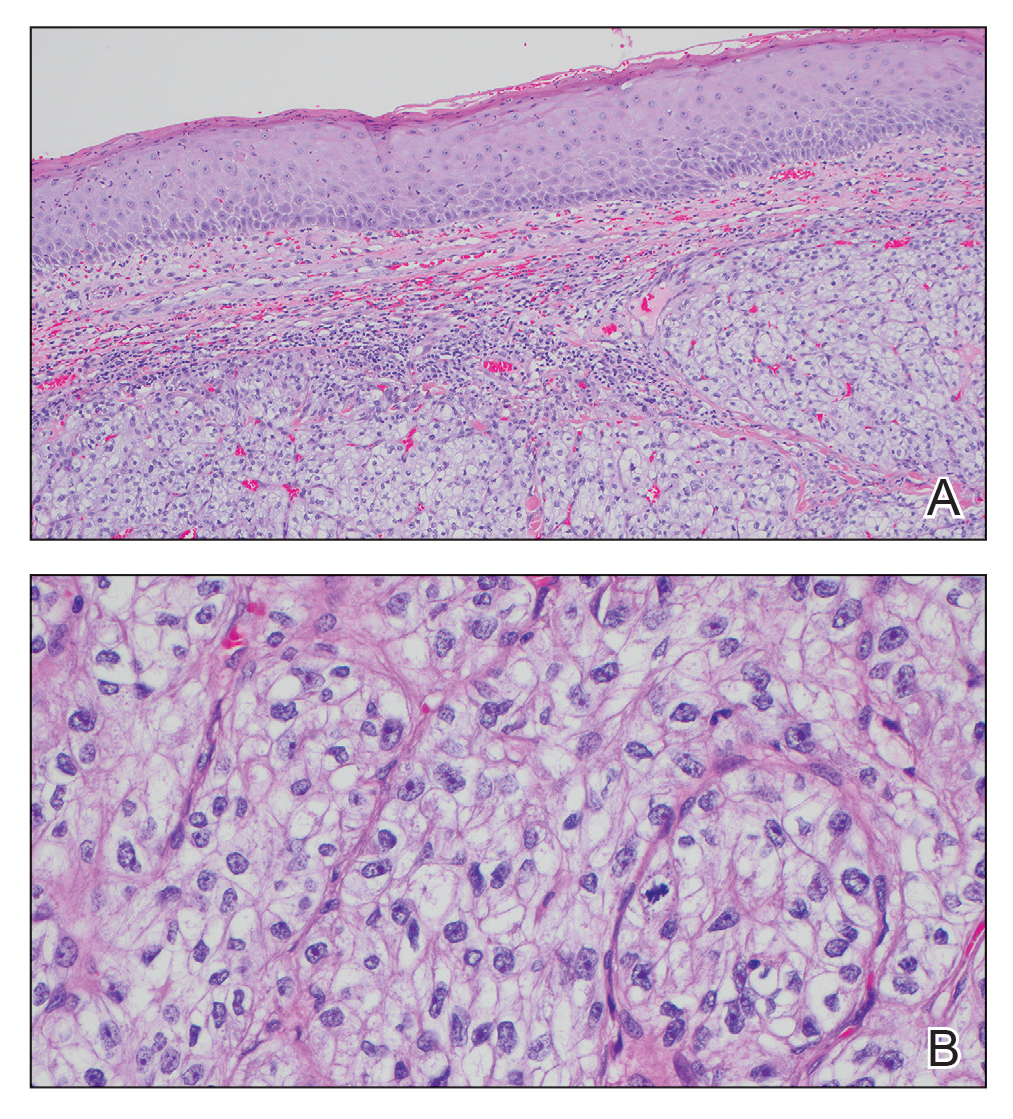

THE DIAGNOSIS: Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Biopsy results showed an intraepidermal blister with a floor composed of maturing epidermis. The roof of the blister was composed of necrotic keratinocytes with overlying orthokeratosis, and the cavity was filled with a moderate amount of fibrin and dead cells with neutrophils. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) using specific antihuman IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, and fibrin was negative. Aerobic, anaerobic, and fungal cultures also were negative. With these histopathologic findings, medication exposure, and timing of bullae onset, our patient was diagnosed with bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis (BHD) secondary to enoxaparin administration. Enoxaparin was continued due to increased risk for coagulopathy, and there was complete resolution of the bullae after 5 weeks with no residual symptoms.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a rare eruption that can occur after administration of heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin, with enoxaparin being the most commonly implicated drug.1 The lesions typically are seen in elderly men in the seventh decade of life and appear within a median of 7 days after drug exposure. The time course for the postexposure eruption can vary from 2 to 21 days, with reports of skin lesions appearing up to 4 months after exposure.1,2 hemorrhagic bullae (Figure) typically on the arms and legs, though lesions also can develop on the trunk. The lesions can occur in distant areas from the injection site, suggesting BHD may be a systemic reaction, although the etiology is poorly understood.1

Another heparin reaction that can manifest similarly to BHD is heparin-induced skin necrosis.3 Patients with this condition also may have associated heparin-induced thrombocytopenia upon laboratory investigation and have a more aggressive clinical course than BHD. Biopsy can help differentiate BHD and early heparin-induced skin necrosis if the clinical manifestation is unclear. Histopathologically, BHD typically has intraepidermal bullae filled with blood, whereas heparin-induced skin necrosis has dermal thrombi.1,4 Treatment of both conditions differs in whether to discontinue anticoagulants: heparin-induced skin necrosis requires discontinuation of the medication, while BHD does not.2,3

In patients with BHD, the lesions are self-resolving, and treatment is supportive, although whether enoxaparin is discontinued varies among physicians.2 Lesions typically resolve within 2 weeks of onset, although it is unclear whether continuing anticoagulants delays resolution.1 Discontinuing anticoagulants in certain patients can be life-threatening due to complex comorbidities (eg, risk for venous thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism from prolonged hospitalization or severe trauma) and is not necessary for the resolution of BHD.

In addition to BHD and heparin-induced skin necrosis, our differential diagnosis included bullous pemphigoid, coma blisters, and Vibrio vulnificus infection. Although bullous pemphigoid can manifest with tense bullae that are pauci-inflammatory on histology, DIF would show linear IgG and C3 deposition at the dermal-epidermal junction. In our patient, DIF was negative and favored another etiology for the lesions. Coma blisters can occur in areas of sustained pressure and typically develop in patients with a prolonged hospitalization or those who are sedentary for long periods of time. The distribution of bullae on our patient’s bilateral pretibial shins made this diagnosis unlikely. Vibrio vulnificus infection can manifest as hemorrhagic bullae, though typically after a break in the skin exposed to brackish water. Vibrio vulnificus infection can be life-threatening, resulting in septicemia and increased mortality, and a thorough patient history is important for diagnosis.5

- Russo A, Curtis S, Balbuena-Merle R, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an under-recognized side effect of full dose lowmolecular weight heparin: a case report and review of the literature. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2018;7:15. doi:10.1186/s40164-018-0108-7

- Dhattarwal N, Gurjar R. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: a rare cutaneous reaction of heparin. J Postgrad Med. 2023;69:97-98. doi:10.4103/jpgm.jpgm_282_22

- Maldonado Cid P, Alonso de Celada RM, Noguera Morel L, et al. Cutaneous adverse events associated with heparin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:707-711. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04395.x

- Handschin AE, Trentz O, Kock HJ, et al. Low molecular weight heparininduced skin necrosis-a systematic review. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2005;390:249-254. doi:10.1007/s00423-004-0522-7

- Jones MK, Oliver JD. Vibrio vulnificus: disease and pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1723-1733. doi:10.1128/IAI.01046-08

THE DIAGNOSIS: Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

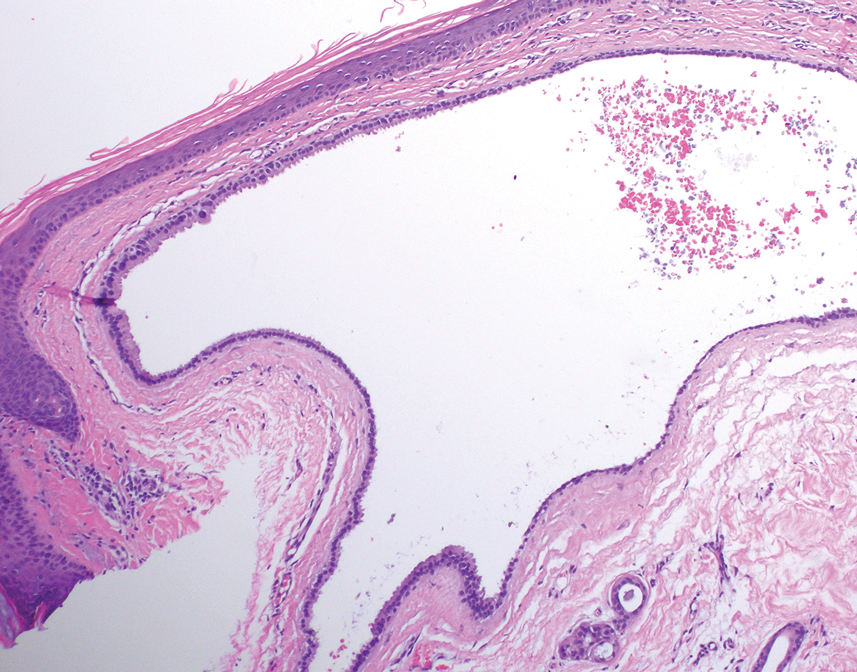

Biopsy results showed an intraepidermal blister with a floor composed of maturing epidermis. The roof of the blister was composed of necrotic keratinocytes with overlying orthokeratosis, and the cavity was filled with a moderate amount of fibrin and dead cells with neutrophils. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) using specific antihuman IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, and fibrin was negative. Aerobic, anaerobic, and fungal cultures also were negative. With these histopathologic findings, medication exposure, and timing of bullae onset, our patient was diagnosed with bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis (BHD) secondary to enoxaparin administration. Enoxaparin was continued due to increased risk for coagulopathy, and there was complete resolution of the bullae after 5 weeks with no residual symptoms.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a rare eruption that can occur after administration of heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin, with enoxaparin being the most commonly implicated drug.1 The lesions typically are seen in elderly men in the seventh decade of life and appear within a median of 7 days after drug exposure. The time course for the postexposure eruption can vary from 2 to 21 days, with reports of skin lesions appearing up to 4 months after exposure.1,2 hemorrhagic bullae (Figure) typically on the arms and legs, though lesions also can develop on the trunk. The lesions can occur in distant areas from the injection site, suggesting BHD may be a systemic reaction, although the etiology is poorly understood.1

Another heparin reaction that can manifest similarly to BHD is heparin-induced skin necrosis.3 Patients with this condition also may have associated heparin-induced thrombocytopenia upon laboratory investigation and have a more aggressive clinical course than BHD. Biopsy can help differentiate BHD and early heparin-induced skin necrosis if the clinical manifestation is unclear. Histopathologically, BHD typically has intraepidermal bullae filled with blood, whereas heparin-induced skin necrosis has dermal thrombi.1,4 Treatment of both conditions differs in whether to discontinue anticoagulants: heparin-induced skin necrosis requires discontinuation of the medication, while BHD does not.2,3

In patients with BHD, the lesions are self-resolving, and treatment is supportive, although whether enoxaparin is discontinued varies among physicians.2 Lesions typically resolve within 2 weeks of onset, although it is unclear whether continuing anticoagulants delays resolution.1 Discontinuing anticoagulants in certain patients can be life-threatening due to complex comorbidities (eg, risk for venous thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism from prolonged hospitalization or severe trauma) and is not necessary for the resolution of BHD.

In addition to BHD and heparin-induced skin necrosis, our differential diagnosis included bullous pemphigoid, coma blisters, and Vibrio vulnificus infection. Although bullous pemphigoid can manifest with tense bullae that are pauci-inflammatory on histology, DIF would show linear IgG and C3 deposition at the dermal-epidermal junction. In our patient, DIF was negative and favored another etiology for the lesions. Coma blisters can occur in areas of sustained pressure and typically develop in patients with a prolonged hospitalization or those who are sedentary for long periods of time. The distribution of bullae on our patient’s bilateral pretibial shins made this diagnosis unlikely. Vibrio vulnificus infection can manifest as hemorrhagic bullae, though typically after a break in the skin exposed to brackish water. Vibrio vulnificus infection can be life-threatening, resulting in septicemia and increased mortality, and a thorough patient history is important for diagnosis.5

THE DIAGNOSIS: Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Biopsy results showed an intraepidermal blister with a floor composed of maturing epidermis. The roof of the blister was composed of necrotic keratinocytes with overlying orthokeratosis, and the cavity was filled with a moderate amount of fibrin and dead cells with neutrophils. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) using specific antihuman IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, and fibrin was negative. Aerobic, anaerobic, and fungal cultures also were negative. With these histopathologic findings, medication exposure, and timing of bullae onset, our patient was diagnosed with bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis (BHD) secondary to enoxaparin administration. Enoxaparin was continued due to increased risk for coagulopathy, and there was complete resolution of the bullae after 5 weeks with no residual symptoms.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a rare eruption that can occur after administration of heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin, with enoxaparin being the most commonly implicated drug.1 The lesions typically are seen in elderly men in the seventh decade of life and appear within a median of 7 days after drug exposure. The time course for the postexposure eruption can vary from 2 to 21 days, with reports of skin lesions appearing up to 4 months after exposure.1,2 hemorrhagic bullae (Figure) typically on the arms and legs, though lesions also can develop on the trunk. The lesions can occur in distant areas from the injection site, suggesting BHD may be a systemic reaction, although the etiology is poorly understood.1

Another heparin reaction that can manifest similarly to BHD is heparin-induced skin necrosis.3 Patients with this condition also may have associated heparin-induced thrombocytopenia upon laboratory investigation and have a more aggressive clinical course than BHD. Biopsy can help differentiate BHD and early heparin-induced skin necrosis if the clinical manifestation is unclear. Histopathologically, BHD typically has intraepidermal bullae filled with blood, whereas heparin-induced skin necrosis has dermal thrombi.1,4 Treatment of both conditions differs in whether to discontinue anticoagulants: heparin-induced skin necrosis requires discontinuation of the medication, while BHD does not.2,3

In patients with BHD, the lesions are self-resolving, and treatment is supportive, although whether enoxaparin is discontinued varies among physicians.2 Lesions typically resolve within 2 weeks of onset, although it is unclear whether continuing anticoagulants delays resolution.1 Discontinuing anticoagulants in certain patients can be life-threatening due to complex comorbidities (eg, risk for venous thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism from prolonged hospitalization or severe trauma) and is not necessary for the resolution of BHD.

In addition to BHD and heparin-induced skin necrosis, our differential diagnosis included bullous pemphigoid, coma blisters, and Vibrio vulnificus infection. Although bullous pemphigoid can manifest with tense bullae that are pauci-inflammatory on histology, DIF would show linear IgG and C3 deposition at the dermal-epidermal junction. In our patient, DIF was negative and favored another etiology for the lesions. Coma blisters can occur in areas of sustained pressure and typically develop in patients with a prolonged hospitalization or those who are sedentary for long periods of time. The distribution of bullae on our patient’s bilateral pretibial shins made this diagnosis unlikely. Vibrio vulnificus infection can manifest as hemorrhagic bullae, though typically after a break in the skin exposed to brackish water. Vibrio vulnificus infection can be life-threatening, resulting in septicemia and increased mortality, and a thorough patient history is important for diagnosis.5

- Russo A, Curtis S, Balbuena-Merle R, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an under-recognized side effect of full dose lowmolecular weight heparin: a case report and review of the literature. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2018;7:15. doi:10.1186/s40164-018-0108-7

- Dhattarwal N, Gurjar R. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: a rare cutaneous reaction of heparin. J Postgrad Med. 2023;69:97-98. doi:10.4103/jpgm.jpgm_282_22

- Maldonado Cid P, Alonso de Celada RM, Noguera Morel L, et al. Cutaneous adverse events associated with heparin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:707-711. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04395.x

- Handschin AE, Trentz O, Kock HJ, et al. Low molecular weight heparininduced skin necrosis-a systematic review. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2005;390:249-254. doi:10.1007/s00423-004-0522-7

- Jones MK, Oliver JD. Vibrio vulnificus: disease and pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1723-1733. doi:10.1128/IAI.01046-08

- Russo A, Curtis S, Balbuena-Merle R, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an under-recognized side effect of full dose lowmolecular weight heparin: a case report and review of the literature. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2018;7:15. doi:10.1186/s40164-018-0108-7

- Dhattarwal N, Gurjar R. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: a rare cutaneous reaction of heparin. J Postgrad Med. 2023;69:97-98. doi:10.4103/jpgm.jpgm_282_22

- Maldonado Cid P, Alonso de Celada RM, Noguera Morel L, et al. Cutaneous adverse events associated with heparin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:707-711. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04395.x

- Handschin AE, Trentz O, Kock HJ, et al. Low molecular weight heparininduced skin necrosis-a systematic review. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2005;390:249-254. doi:10.1007/s00423-004-0522-7

- Jones MK, Oliver JD. Vibrio vulnificus: disease and pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1723-1733. doi:10.1128/IAI.01046-08

Large Bullae on the Legs in a Hospitalized Patient Following a Gunshot Wound

Large Bullae on the Legs in a Hospitalized Patient Following a Gunshot Wound

A 19-year-old man developed fluid-filled blisters on both legs within 1 month of a prolonged hospitalization following a gunshot wound that resulted in complete paralysis of the legs. His medical history was otherwise unremarkable. Medications started during hospitalization included moxifloxacin, levetiracetam, and prophylactic subcutaneous enoxaparin. Physical examination by dermatology revealed tense blood-filled bullae measuring several centimeters with well-demarcated, pink to red, irregularly shaped patches on both legs. A biopsy of a blister was taken.

Pigmented Cystic Masses on the Scalp

THE DIAGNOSIS: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

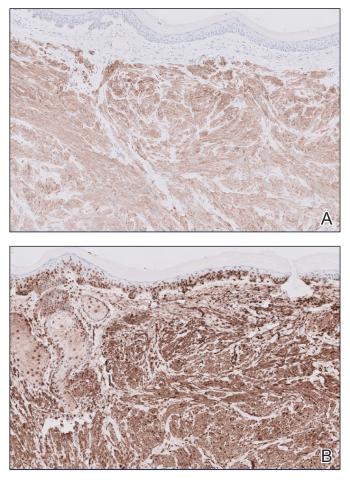

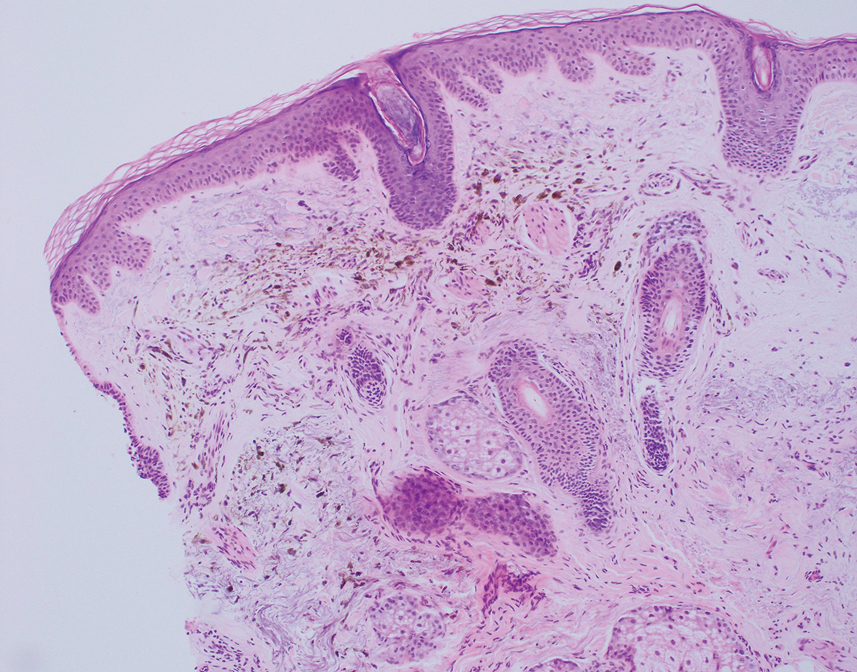

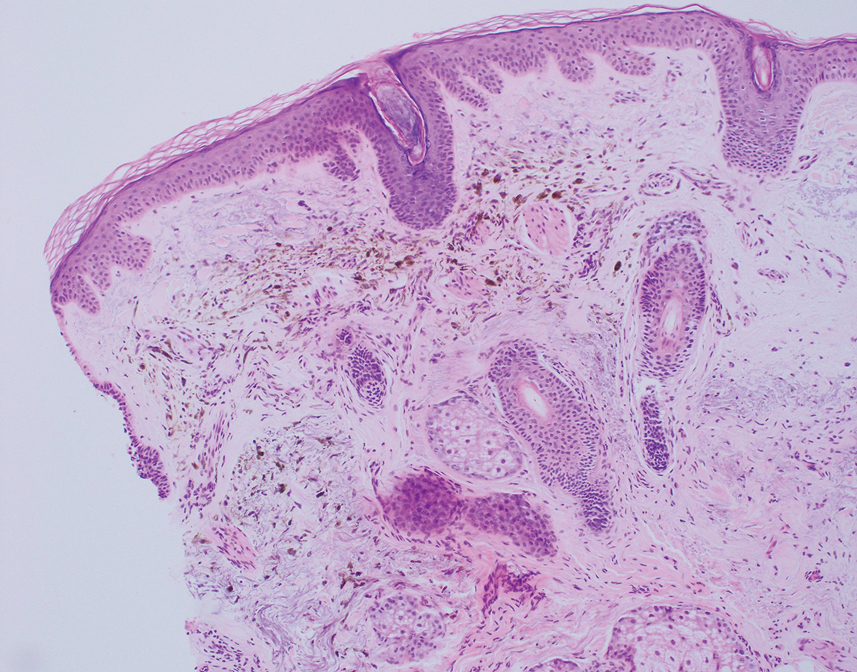

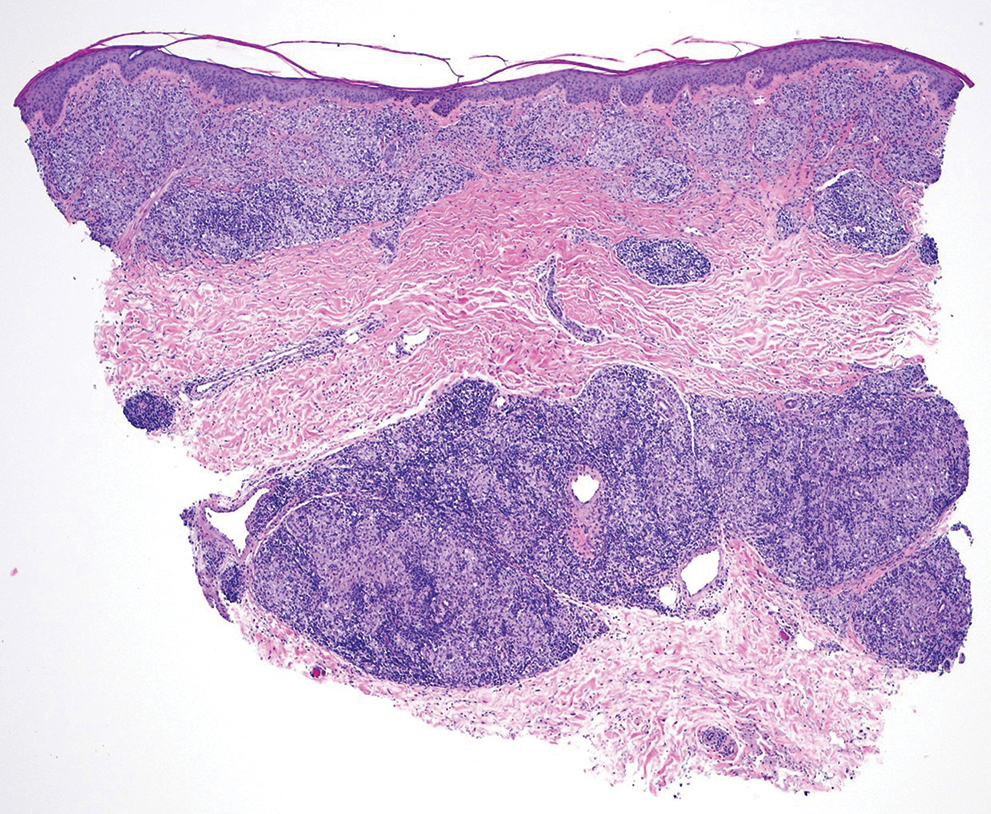

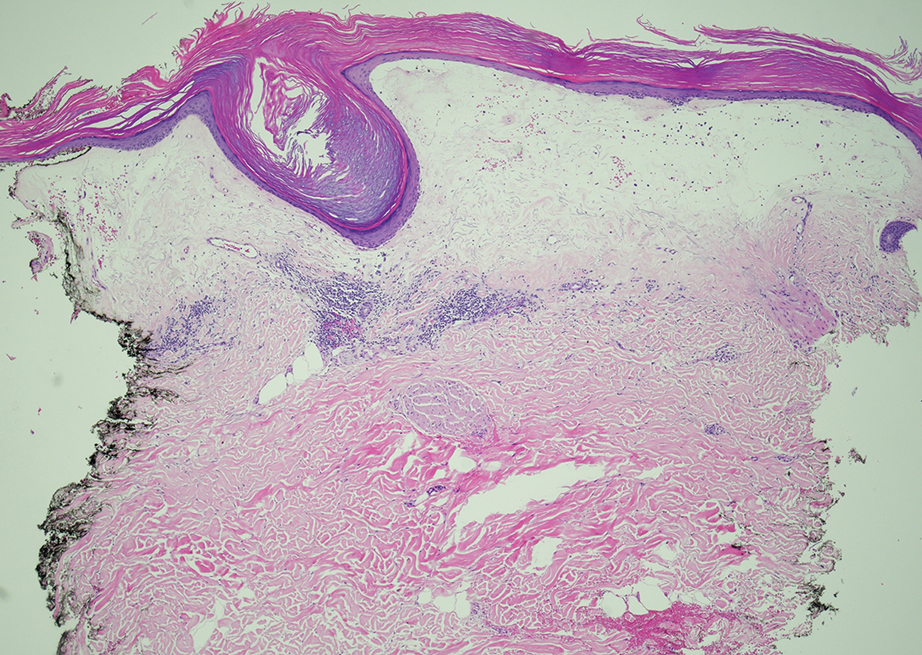

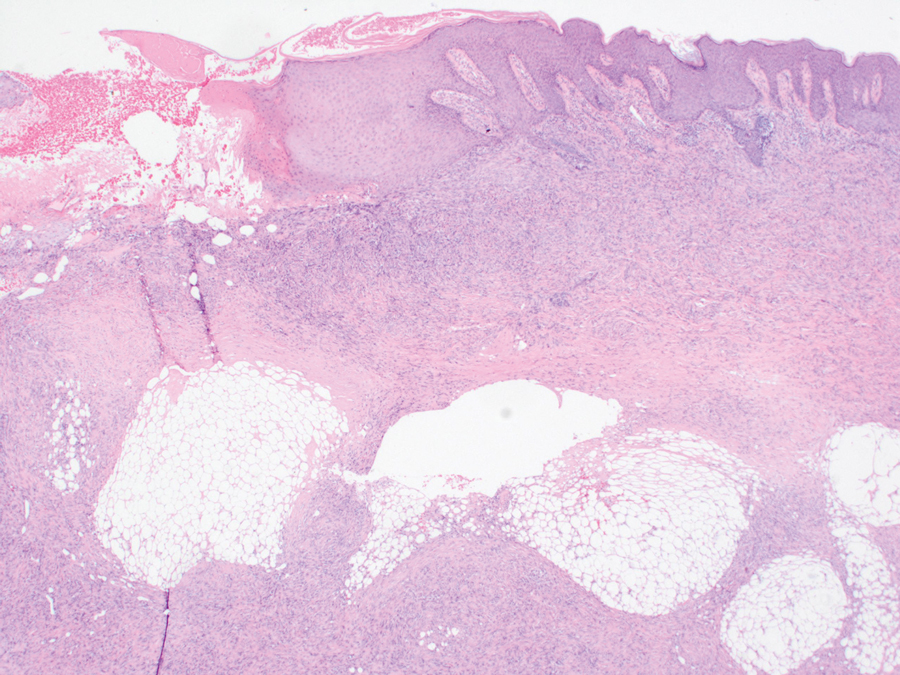

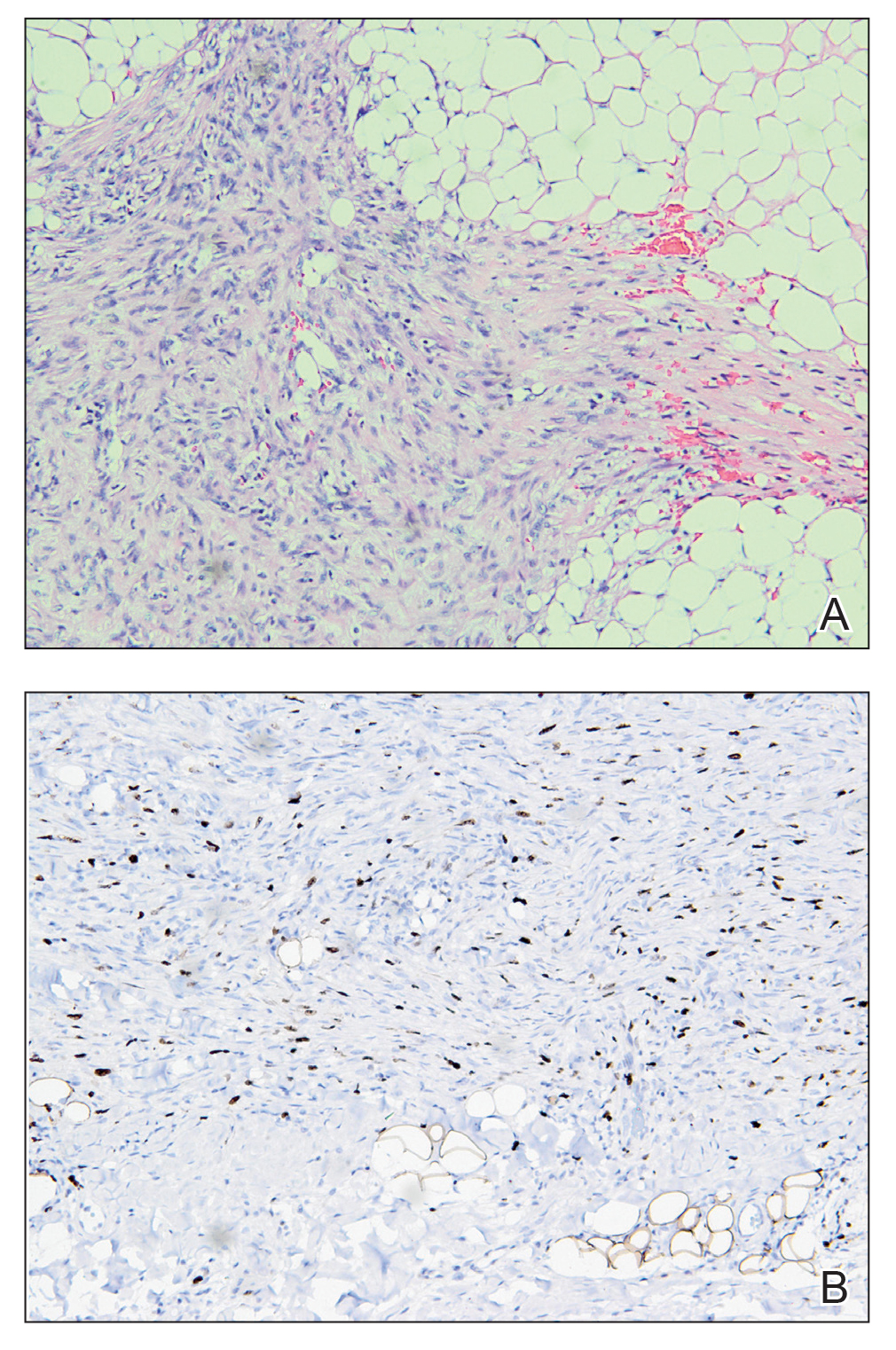

Histology for all 3 lesions demonstrated similar cystic structures lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells, with the outermost layer composed of flattened myoepithelial cells and the inner layer composed of cells with apocrine features (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystoma was made. The patient underwent successful surgical excision shortly thereafter without recurrence at follow-up 1 year later.

Apocrine hidrocystomas are rare benign cystic lesions that are considered to be adenomatous proliferations of apocrine glands. They typically manifest as solitary asymptomatic lesions measuring 3 to 15 mm.1 They tend to appear on the face, usually in the periorbital region, but also have been described on the neck, scalp, trunk, arms, and legs.2-4 Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas can be a marker of 2 rare inherited disorders: Gorlin-Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome.5 Apocrine hidrocystomas may be flesh colored or may have a blue, black, or brown appearance due to the Tyndall effect, in which light with shorter wavelengths is scattered by the contents of the lesions.2 Histologically, apocrine hidrocystomas are cysts lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells. The inner layer is composed of cells with apocrine features, and the outer layer is composed of flattened myoepithelial cells. Due to their range of colors and predilection for sun-exposed surfaces, apocrine hidrocystomas may be mistaken for various malignant neoplasms, including melanoma.6,7

The differential diagnosis for our patient included agminated blue nevi, melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and seborrheic keratosis. A blue nevus is a dermal melanocytic lesion that manifests as a well-demarcated, blue to blue-black papule that typically appears on the face, scalp, arms, legs, lower back, and buttocks. Although there are several histologic subtypes, the common blue nevus usually manifests as a solitary lesion measuring less than 1 cm, often developing during childhood to young adulthood.8 Histologically, common blue nevi are characterized by a dermal proliferation of deeply pigmented bipolar spindled melanocytes embedded in thickened collagen bundles, often with scattered epithelioid melanophages, and no conspicuous mitotic activity (Figure 2).9 There are other types of blue nevi, including cellular blue nevi, which tend to be larger and manifest commonly on the buttocks and sacrococcygeal region in early adulthood.9 Histologically, cellular blue nevi contain oval to spindled melanocytes with scattered melanophages forming a well-demarcated nodule typically in the reticular dermis. There may be bulbous extension into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Occasional mitoses may be seen.9,10 Melanoma can arise from common or cellular blue nevi, though it more frequently occurs with cellular blue nevi. Other subtypes of blue nevi have been described, including the sclerosing, plaque-type, combined, hypomelanotic/amelanotic, and pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma.11 However, they typically have features of the common blue nevus or cellular blue nevus, such as oval/spindle cell morphology, some degree of melanin, and biphasic architecture, but are classified according to their dominant histologic characteristics.

Given the location of our patient’s lesions on the scalp and his extensive history of sun exposure, malignancy was high in the differential. Multiple synchronous primary melanomas including nodular melanoma, blue nevus–like metastatic melanoma, and metastatic melanoma were considered. The leg and the scalp have the highest reported incidence of cutaneous metastases of melanoma, with many cases presenting as dermal or subcutaneous nodules and eruptive blue nevus–like papules, similar to our patient’s clinical presentation.12,13 Nodular melanoma (NM) is one of 4 major types of melanoma, accounting for approximately 15% to 30% of cases in the United States.14 Nodular melanoma typically manifests as a smooth, raised, symmetric, well-circumscribed lesion with variable pigmentation, from very dark to amelanotic. Histologically, NM is defined as a dermal mass, either in isolation or with an epidermal component, not to exceed 3 rete ridges beyond the dermal component.15 Tumor cells have a high cell density with pleomorphism, usually with atypical epithelioid cells with vesicular nuclei and irregular cytoplasm, and occasionally spindle cells (Figure 2).16 Mitoses and necrosis are frequent. Scalp location independently is responsible for worse survival, both overall and melanoma specific.17 Nodular melanoma tends to have greater Breslow thickness at diagnosis than other melanoma subtypes and often carries a worse prognosis.

Malignant melanomas that develop from or in conjunction with or bear histologic resemblance to blue nevi are termed blue nevus–like melanoma or blue nevus–associated melanoma. These malignancies are exceedingly rare, accounting for only 0.3% of melanomas in one Turkey-based multicenter study.18 The histologic criteria for diagnosing blue nevus–like melanoma are poorly defined, and terminology of these lesions has led to some debate in naming conventions.19 Nevertheless, unlike blue nevus, blue nevus–like melanoma demonstrates histologic features of malignancy, including pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, mitotic activity, vascular invasion, and potential necrosis.10 The lack of an inflammatory infiltrate, surrounding fibrosis, junctional activity, and pre-existing nevus can help distinguish cutaneous melanoma metastases from primary nodular melanoma. Immunohistochemical stains such as S100, Melan-A/MART1, or SOX-10 can help confirm melanocytic lineage.12

Pigmented BCC is a clinical and histologic variant of BCC characterized by increased melanin pigmentation due to melanocytes admixed with tumor cells. Dermoscopically, the pigment can have a maple leaf–like appearance with spoke-wheel areas, in-focus dots, and concentric structures at the dermoepidermal junction, which is more characteristic of superficial and infiltrating BCC.20 In nodular BCC, the pigment occurs as blue-gray ovoid nests and globules in deeper layers of the dermis.20

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) can vary widely in clinical appearance, with pigmentation ranging from flesh colored to yellow to brown to black. Melanoacanthomas are acanthotic SKs that are highly pigmented due to intermixed epidermal melanocytes and subepidermal melanophages.21 Dermoscopy can help distinguish cutaneous malignancies from SKs, which often demonstrate fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and milialike cysts. Biopsy sometimes is required to assess for malignancy, as was the case in our patient. The classic histologic features of SKs include acanthosis, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis.22

This case highlights the need to consider apocrine hidrocystoma, along with malignancy, in the differential diagnosis of pigmented cystic masses of the face and scalp. Because apocrine hidrocystomas are benign, they do not need to be treated but often are surgically excised for cosmesis or complete histopathologic examination. Destruction via electrodessication, carbon dioxide ablation, trichloroacetic acid chemical ablation, botulinum toxin injection, and anticholinergic creams sometimes is used, especially for cosmetic treatment of multiple small lesions.5 Our patient was treated with surgical excision with no evidence of recurrence on follow-up 1 year later.

- Ioannidis DG, Drivas EI, Papadakis CE, et al. Hidrocystoma of the external auditory canal: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:79. doi:10.1186/1757- 1626-2-79

- Nguyen HP, Barker HS, Bloomquist L, et al. Giant pigmented apocrine hidrocystoma of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26. doi:10.5070/D3268049895

- Mendoza-Cembranos MD, Haro R, Requena L, et al. Digital apocrine hidrocystoma: the exception confirms the rule. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:79. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001044

- May C, Chang O, Compton N. A giant apocrine hidrocystoma of the trunk. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23. doi:10.5070/D3239036497

- Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Hidrocystomas—a brief review. Medscape Gen Med. 2006;8:57.

- Kruse ALD, Zwahlen R, Bredell MG, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma of the cheek. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:594-596. doi:10.1097 /SCS.0b013e3181d08c77

- Zaballos P, Bañuls J, Medina C, et al. Dermoscopy of apocrine hidrocystomas: a morphological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:378-381. doi:10.1111/jdv.12044

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405. doi:10.1002 /1097-0142(196803)21:3<393::aid-cncr2820210309>3.0.co;2-k

- Murali R, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Blue nevi and related lesions: a review highlighting atypical and newly described variants, distinguishing features and diagnostic pitfalls. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:365. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181bb6b53

- Borgenvik TL, Karlsvik TM, Ray S, et al. Blue nevus-like and blue nevusassociated melanoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:345-349. doi:10.1111/ans.13946

- de la Fouchardiere A. Blue naevi and the blue tumour spectrum. Pathology. 2023;55:187-195. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.12.342

- Lowe L. Metastatic melanoma and rare melanoma variants: a review. Pathology (Phila). 2023;55:236-244. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.11.006

- Plaza JA, Torres-Cabala C, Evans H, et al. Cutaneous metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic study of 192 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:129-136. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181b34a19

- Shaikh WR, Xiong M, Weinstock MA. The contribution of nodular subtype to melanoma mortality in the United States, 1978 to 2007. Archives of Dermatology. 2012;148:30-36. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.264

- Clark WH, From L, Bernardino EA, et al. The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res. 1969;29:705-727.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321. doi:10.23736/S2784-8671.21.06958-3

- Ozao-Choy J, Nelson DW, Hiles J, et al. The prognostic importance of scalp location in primary head and neck melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:337-343. doi:10.1002/jso.24679

- Gamsizkan M, Yilmaz I, Buyukbabani N, et al. A retrospective multicenter evaluation of cutaneous melanomas in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2014;15:10451-10456. doi:10.7314 /apjcp.2014.15.23.10451

- Mones JM, Ackerman AB. “Atypical” blue nevus, “malignant” blue nevus, and “metastasizing” blue nevus: a critique in historical perspective of three concepts flawed fatally. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:407-430. doi:10.1097/00000372-200410000-00012

- Tanese K. Diagnosis and management of basal cell carcinoma Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:13. doi:10.1007/s11864 -019-0610-0

- Barthelmann S, Butsch F, Lang BM, et al. Seborrheic keratosis. JDDG J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023;21:265-277. doi:10.1111/ddg.14984

- Taylor S. Advancing the understanding of seborrheic keratosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:419-424.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

Histology for all 3 lesions demonstrated similar cystic structures lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells, with the outermost layer composed of flattened myoepithelial cells and the inner layer composed of cells with apocrine features (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystoma was made. The patient underwent successful surgical excision shortly thereafter without recurrence at follow-up 1 year later.

Apocrine hidrocystomas are rare benign cystic lesions that are considered to be adenomatous proliferations of apocrine glands. They typically manifest as solitary asymptomatic lesions measuring 3 to 15 mm.1 They tend to appear on the face, usually in the periorbital region, but also have been described on the neck, scalp, trunk, arms, and legs.2-4 Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas can be a marker of 2 rare inherited disorders: Gorlin-Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome.5 Apocrine hidrocystomas may be flesh colored or may have a blue, black, or brown appearance due to the Tyndall effect, in which light with shorter wavelengths is scattered by the contents of the lesions.2 Histologically, apocrine hidrocystomas are cysts lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells. The inner layer is composed of cells with apocrine features, and the outer layer is composed of flattened myoepithelial cells. Due to their range of colors and predilection for sun-exposed surfaces, apocrine hidrocystomas may be mistaken for various malignant neoplasms, including melanoma.6,7

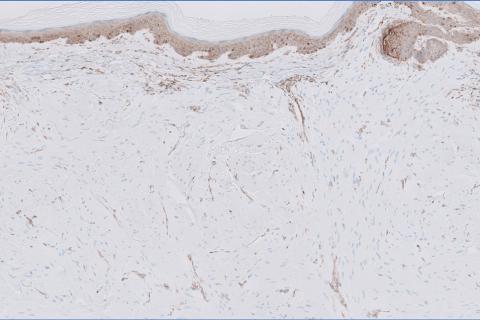

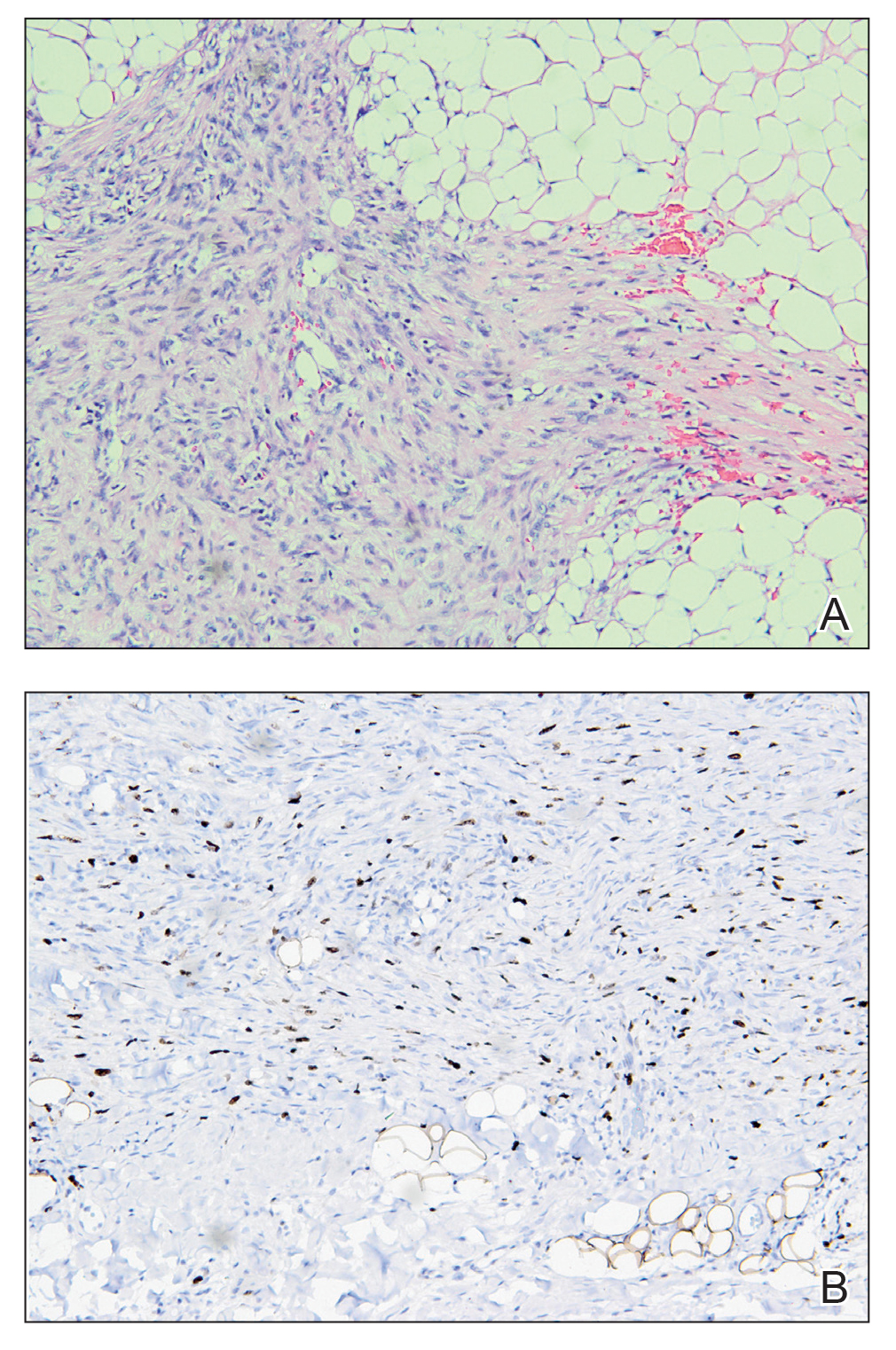

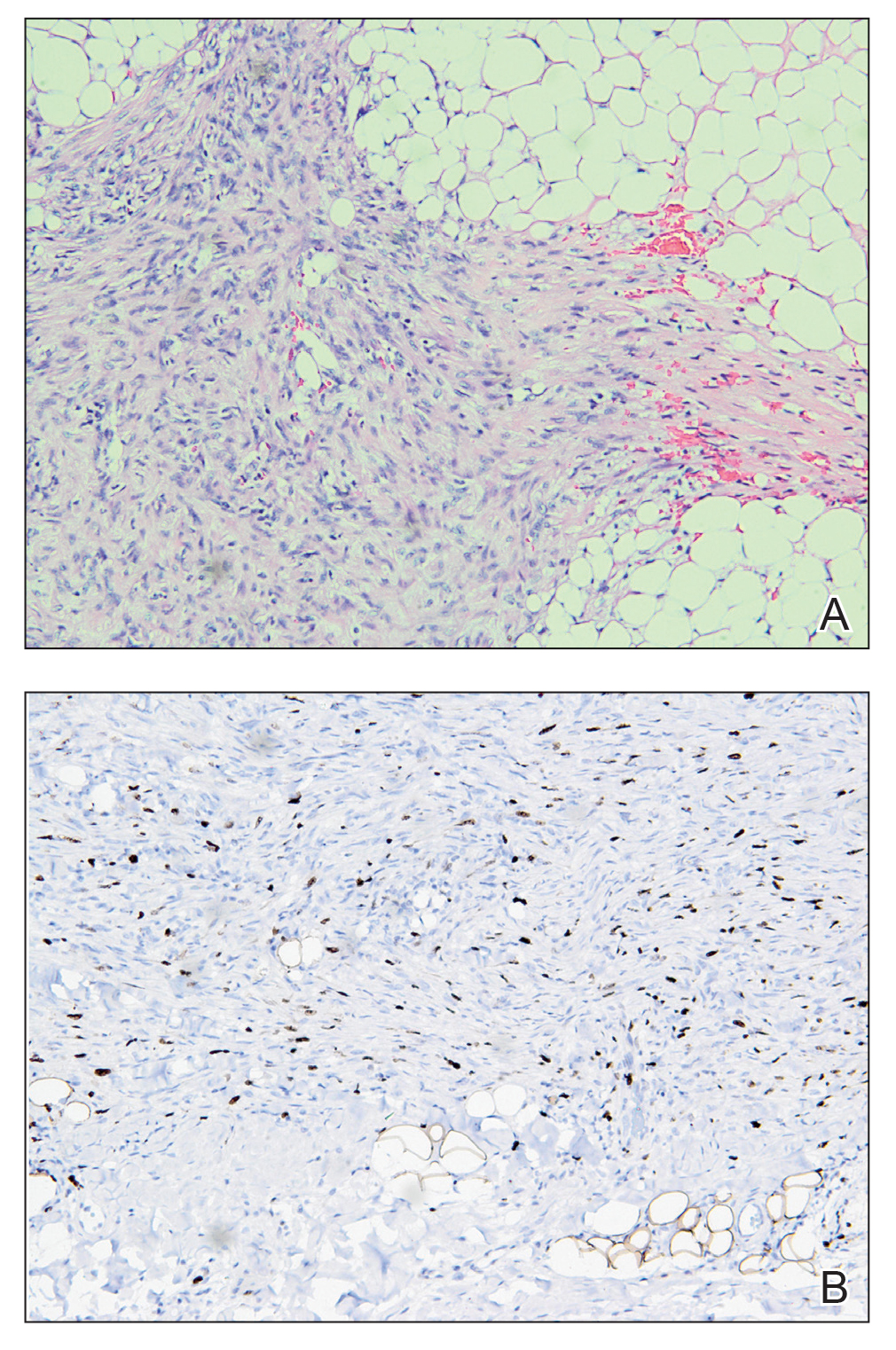

The differential diagnosis for our patient included agminated blue nevi, melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and seborrheic keratosis. A blue nevus is a dermal melanocytic lesion that manifests as a well-demarcated, blue to blue-black papule that typically appears on the face, scalp, arms, legs, lower back, and buttocks. Although there are several histologic subtypes, the common blue nevus usually manifests as a solitary lesion measuring less than 1 cm, often developing during childhood to young adulthood.8 Histologically, common blue nevi are characterized by a dermal proliferation of deeply pigmented bipolar spindled melanocytes embedded in thickened collagen bundles, often with scattered epithelioid melanophages, and no conspicuous mitotic activity (Figure 2).9 There are other types of blue nevi, including cellular blue nevi, which tend to be larger and manifest commonly on the buttocks and sacrococcygeal region in early adulthood.9 Histologically, cellular blue nevi contain oval to spindled melanocytes with scattered melanophages forming a well-demarcated nodule typically in the reticular dermis. There may be bulbous extension into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Occasional mitoses may be seen.9,10 Melanoma can arise from common or cellular blue nevi, though it more frequently occurs with cellular blue nevi. Other subtypes of blue nevi have been described, including the sclerosing, plaque-type, combined, hypomelanotic/amelanotic, and pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma.11 However, they typically have features of the common blue nevus or cellular blue nevus, such as oval/spindle cell morphology, some degree of melanin, and biphasic architecture, but are classified according to their dominant histologic characteristics.

Given the location of our patient’s lesions on the scalp and his extensive history of sun exposure, malignancy was high in the differential. Multiple synchronous primary melanomas including nodular melanoma, blue nevus–like metastatic melanoma, and metastatic melanoma were considered. The leg and the scalp have the highest reported incidence of cutaneous metastases of melanoma, with many cases presenting as dermal or subcutaneous nodules and eruptive blue nevus–like papules, similar to our patient’s clinical presentation.12,13 Nodular melanoma (NM) is one of 4 major types of melanoma, accounting for approximately 15% to 30% of cases in the United States.14 Nodular melanoma typically manifests as a smooth, raised, symmetric, well-circumscribed lesion with variable pigmentation, from very dark to amelanotic. Histologically, NM is defined as a dermal mass, either in isolation or with an epidermal component, not to exceed 3 rete ridges beyond the dermal component.15 Tumor cells have a high cell density with pleomorphism, usually with atypical epithelioid cells with vesicular nuclei and irregular cytoplasm, and occasionally spindle cells (Figure 2).16 Mitoses and necrosis are frequent. Scalp location independently is responsible for worse survival, both overall and melanoma specific.17 Nodular melanoma tends to have greater Breslow thickness at diagnosis than other melanoma subtypes and often carries a worse prognosis.

Malignant melanomas that develop from or in conjunction with or bear histologic resemblance to blue nevi are termed blue nevus–like melanoma or blue nevus–associated melanoma. These malignancies are exceedingly rare, accounting for only 0.3% of melanomas in one Turkey-based multicenter study.18 The histologic criteria for diagnosing blue nevus–like melanoma are poorly defined, and terminology of these lesions has led to some debate in naming conventions.19 Nevertheless, unlike blue nevus, blue nevus–like melanoma demonstrates histologic features of malignancy, including pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, mitotic activity, vascular invasion, and potential necrosis.10 The lack of an inflammatory infiltrate, surrounding fibrosis, junctional activity, and pre-existing nevus can help distinguish cutaneous melanoma metastases from primary nodular melanoma. Immunohistochemical stains such as S100, Melan-A/MART1, or SOX-10 can help confirm melanocytic lineage.12

Pigmented BCC is a clinical and histologic variant of BCC characterized by increased melanin pigmentation due to melanocytes admixed with tumor cells. Dermoscopically, the pigment can have a maple leaf–like appearance with spoke-wheel areas, in-focus dots, and concentric structures at the dermoepidermal junction, which is more characteristic of superficial and infiltrating BCC.20 In nodular BCC, the pigment occurs as blue-gray ovoid nests and globules in deeper layers of the dermis.20

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) can vary widely in clinical appearance, with pigmentation ranging from flesh colored to yellow to brown to black. Melanoacanthomas are acanthotic SKs that are highly pigmented due to intermixed epidermal melanocytes and subepidermal melanophages.21 Dermoscopy can help distinguish cutaneous malignancies from SKs, which often demonstrate fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and milialike cysts. Biopsy sometimes is required to assess for malignancy, as was the case in our patient. The classic histologic features of SKs include acanthosis, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis.22

This case highlights the need to consider apocrine hidrocystoma, along with malignancy, in the differential diagnosis of pigmented cystic masses of the face and scalp. Because apocrine hidrocystomas are benign, they do not need to be treated but often are surgically excised for cosmesis or complete histopathologic examination. Destruction via electrodessication, carbon dioxide ablation, trichloroacetic acid chemical ablation, botulinum toxin injection, and anticholinergic creams sometimes is used, especially for cosmetic treatment of multiple small lesions.5 Our patient was treated with surgical excision with no evidence of recurrence on follow-up 1 year later.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

Histology for all 3 lesions demonstrated similar cystic structures lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells, with the outermost layer composed of flattened myoepithelial cells and the inner layer composed of cells with apocrine features (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystoma was made. The patient underwent successful surgical excision shortly thereafter without recurrence at follow-up 1 year later.

Apocrine hidrocystomas are rare benign cystic lesions that are considered to be adenomatous proliferations of apocrine glands. They typically manifest as solitary asymptomatic lesions measuring 3 to 15 mm.1 They tend to appear on the face, usually in the periorbital region, but also have been described on the neck, scalp, trunk, arms, and legs.2-4 Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas can be a marker of 2 rare inherited disorders: Gorlin-Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome.5 Apocrine hidrocystomas may be flesh colored or may have a blue, black, or brown appearance due to the Tyndall effect, in which light with shorter wavelengths is scattered by the contents of the lesions.2 Histologically, apocrine hidrocystomas are cysts lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells. The inner layer is composed of cells with apocrine features, and the outer layer is composed of flattened myoepithelial cells. Due to their range of colors and predilection for sun-exposed surfaces, apocrine hidrocystomas may be mistaken for various malignant neoplasms, including melanoma.6,7

The differential diagnosis for our patient included agminated blue nevi, melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and seborrheic keratosis. A blue nevus is a dermal melanocytic lesion that manifests as a well-demarcated, blue to blue-black papule that typically appears on the face, scalp, arms, legs, lower back, and buttocks. Although there are several histologic subtypes, the common blue nevus usually manifests as a solitary lesion measuring less than 1 cm, often developing during childhood to young adulthood.8 Histologically, common blue nevi are characterized by a dermal proliferation of deeply pigmented bipolar spindled melanocytes embedded in thickened collagen bundles, often with scattered epithelioid melanophages, and no conspicuous mitotic activity (Figure 2).9 There are other types of blue nevi, including cellular blue nevi, which tend to be larger and manifest commonly on the buttocks and sacrococcygeal region in early adulthood.9 Histologically, cellular blue nevi contain oval to spindled melanocytes with scattered melanophages forming a well-demarcated nodule typically in the reticular dermis. There may be bulbous extension into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Occasional mitoses may be seen.9,10 Melanoma can arise from common or cellular blue nevi, though it more frequently occurs with cellular blue nevi. Other subtypes of blue nevi have been described, including the sclerosing, plaque-type, combined, hypomelanotic/amelanotic, and pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma.11 However, they typically have features of the common blue nevus or cellular blue nevus, such as oval/spindle cell morphology, some degree of melanin, and biphasic architecture, but are classified according to their dominant histologic characteristics.

Given the location of our patient’s lesions on the scalp and his extensive history of sun exposure, malignancy was high in the differential. Multiple synchronous primary melanomas including nodular melanoma, blue nevus–like metastatic melanoma, and metastatic melanoma were considered. The leg and the scalp have the highest reported incidence of cutaneous metastases of melanoma, with many cases presenting as dermal or subcutaneous nodules and eruptive blue nevus–like papules, similar to our patient’s clinical presentation.12,13 Nodular melanoma (NM) is one of 4 major types of melanoma, accounting for approximately 15% to 30% of cases in the United States.14 Nodular melanoma typically manifests as a smooth, raised, symmetric, well-circumscribed lesion with variable pigmentation, from very dark to amelanotic. Histologically, NM is defined as a dermal mass, either in isolation or with an epidermal component, not to exceed 3 rete ridges beyond the dermal component.15 Tumor cells have a high cell density with pleomorphism, usually with atypical epithelioid cells with vesicular nuclei and irregular cytoplasm, and occasionally spindle cells (Figure 2).16 Mitoses and necrosis are frequent. Scalp location independently is responsible for worse survival, both overall and melanoma specific.17 Nodular melanoma tends to have greater Breslow thickness at diagnosis than other melanoma subtypes and often carries a worse prognosis.

Malignant melanomas that develop from or in conjunction with or bear histologic resemblance to blue nevi are termed blue nevus–like melanoma or blue nevus–associated melanoma. These malignancies are exceedingly rare, accounting for only 0.3% of melanomas in one Turkey-based multicenter study.18 The histologic criteria for diagnosing blue nevus–like melanoma are poorly defined, and terminology of these lesions has led to some debate in naming conventions.19 Nevertheless, unlike blue nevus, blue nevus–like melanoma demonstrates histologic features of malignancy, including pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, mitotic activity, vascular invasion, and potential necrosis.10 The lack of an inflammatory infiltrate, surrounding fibrosis, junctional activity, and pre-existing nevus can help distinguish cutaneous melanoma metastases from primary nodular melanoma. Immunohistochemical stains such as S100, Melan-A/MART1, or SOX-10 can help confirm melanocytic lineage.12

Pigmented BCC is a clinical and histologic variant of BCC characterized by increased melanin pigmentation due to melanocytes admixed with tumor cells. Dermoscopically, the pigment can have a maple leaf–like appearance with spoke-wheel areas, in-focus dots, and concentric structures at the dermoepidermal junction, which is more characteristic of superficial and infiltrating BCC.20 In nodular BCC, the pigment occurs as blue-gray ovoid nests and globules in deeper layers of the dermis.20

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) can vary widely in clinical appearance, with pigmentation ranging from flesh colored to yellow to brown to black. Melanoacanthomas are acanthotic SKs that are highly pigmented due to intermixed epidermal melanocytes and subepidermal melanophages.21 Dermoscopy can help distinguish cutaneous malignancies from SKs, which often demonstrate fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and milialike cysts. Biopsy sometimes is required to assess for malignancy, as was the case in our patient. The classic histologic features of SKs include acanthosis, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis.22

This case highlights the need to consider apocrine hidrocystoma, along with malignancy, in the differential diagnosis of pigmented cystic masses of the face and scalp. Because apocrine hidrocystomas are benign, they do not need to be treated but often are surgically excised for cosmesis or complete histopathologic examination. Destruction via electrodessication, carbon dioxide ablation, trichloroacetic acid chemical ablation, botulinum toxin injection, and anticholinergic creams sometimes is used, especially for cosmetic treatment of multiple small lesions.5 Our patient was treated with surgical excision with no evidence of recurrence on follow-up 1 year later.

- Ioannidis DG, Drivas EI, Papadakis CE, et al. Hidrocystoma of the external auditory canal: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:79. doi:10.1186/1757- 1626-2-79

- Nguyen HP, Barker HS, Bloomquist L, et al. Giant pigmented apocrine hidrocystoma of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26. doi:10.5070/D3268049895

- Mendoza-Cembranos MD, Haro R, Requena L, et al. Digital apocrine hidrocystoma: the exception confirms the rule. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:79. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001044

- May C, Chang O, Compton N. A giant apocrine hidrocystoma of the trunk. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23. doi:10.5070/D3239036497

- Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Hidrocystomas—a brief review. Medscape Gen Med. 2006;8:57.

- Kruse ALD, Zwahlen R, Bredell MG, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma of the cheek. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:594-596. doi:10.1097 /SCS.0b013e3181d08c77

- Zaballos P, Bañuls J, Medina C, et al. Dermoscopy of apocrine hidrocystomas: a morphological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:378-381. doi:10.1111/jdv.12044

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405. doi:10.1002 /1097-0142(196803)21:3<393::aid-cncr2820210309>3.0.co;2-k

- Murali R, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Blue nevi and related lesions: a review highlighting atypical and newly described variants, distinguishing features and diagnostic pitfalls. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:365. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181bb6b53

- Borgenvik TL, Karlsvik TM, Ray S, et al. Blue nevus-like and blue nevusassociated melanoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:345-349. doi:10.1111/ans.13946

- de la Fouchardiere A. Blue naevi and the blue tumour spectrum. Pathology. 2023;55:187-195. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.12.342

- Lowe L. Metastatic melanoma and rare melanoma variants: a review. Pathology (Phila). 2023;55:236-244. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.11.006

- Plaza JA, Torres-Cabala C, Evans H, et al. Cutaneous metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic study of 192 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:129-136. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181b34a19

- Shaikh WR, Xiong M, Weinstock MA. The contribution of nodular subtype to melanoma mortality in the United States, 1978 to 2007. Archives of Dermatology. 2012;148:30-36. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.264

- Clark WH, From L, Bernardino EA, et al. The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res. 1969;29:705-727.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321. doi:10.23736/S2784-8671.21.06958-3

- Ozao-Choy J, Nelson DW, Hiles J, et al. The prognostic importance of scalp location in primary head and neck melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:337-343. doi:10.1002/jso.24679

- Gamsizkan M, Yilmaz I, Buyukbabani N, et al. A retrospective multicenter evaluation of cutaneous melanomas in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2014;15:10451-10456. doi:10.7314 /apjcp.2014.15.23.10451

- Mones JM, Ackerman AB. “Atypical” blue nevus, “malignant” blue nevus, and “metastasizing” blue nevus: a critique in historical perspective of three concepts flawed fatally. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:407-430. doi:10.1097/00000372-200410000-00012

- Tanese K. Diagnosis and management of basal cell carcinoma Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:13. doi:10.1007/s11864 -019-0610-0

- Barthelmann S, Butsch F, Lang BM, et al. Seborrheic keratosis. JDDG J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023;21:265-277. doi:10.1111/ddg.14984

- Taylor S. Advancing the understanding of seborrheic keratosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:419-424.

- Ioannidis DG, Drivas EI, Papadakis CE, et al. Hidrocystoma of the external auditory canal: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:79. doi:10.1186/1757- 1626-2-79

- Nguyen HP, Barker HS, Bloomquist L, et al. Giant pigmented apocrine hidrocystoma of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26. doi:10.5070/D3268049895

- Mendoza-Cembranos MD, Haro R, Requena L, et al. Digital apocrine hidrocystoma: the exception confirms the rule. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:79. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001044

- May C, Chang O, Compton N. A giant apocrine hidrocystoma of the trunk. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23. doi:10.5070/D3239036497

- Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Hidrocystomas—a brief review. Medscape Gen Med. 2006;8:57.

- Kruse ALD, Zwahlen R, Bredell MG, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma of the cheek. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:594-596. doi:10.1097 /SCS.0b013e3181d08c77

- Zaballos P, Bañuls J, Medina C, et al. Dermoscopy of apocrine hidrocystomas: a morphological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:378-381. doi:10.1111/jdv.12044

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405. doi:10.1002 /1097-0142(196803)21:3<393::aid-cncr2820210309>3.0.co;2-k

- Murali R, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Blue nevi and related lesions: a review highlighting atypical and newly described variants, distinguishing features and diagnostic pitfalls. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:365. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181bb6b53

- Borgenvik TL, Karlsvik TM, Ray S, et al. Blue nevus-like and blue nevusassociated melanoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:345-349. doi:10.1111/ans.13946

- de la Fouchardiere A. Blue naevi and the blue tumour spectrum. Pathology. 2023;55:187-195. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.12.342

- Lowe L. Metastatic melanoma and rare melanoma variants: a review. Pathology (Phila). 2023;55:236-244. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.11.006

- Plaza JA, Torres-Cabala C, Evans H, et al. Cutaneous metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic study of 192 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:129-136. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181b34a19

- Shaikh WR, Xiong M, Weinstock MA. The contribution of nodular subtype to melanoma mortality in the United States, 1978 to 2007. Archives of Dermatology. 2012;148:30-36. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.264

- Clark WH, From L, Bernardino EA, et al. The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res. 1969;29:705-727.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321. doi:10.23736/S2784-8671.21.06958-3

- Ozao-Choy J, Nelson DW, Hiles J, et al. The prognostic importance of scalp location in primary head and neck melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:337-343. doi:10.1002/jso.24679

- Gamsizkan M, Yilmaz I, Buyukbabani N, et al. A retrospective multicenter evaluation of cutaneous melanomas in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2014;15:10451-10456. doi:10.7314 /apjcp.2014.15.23.10451

- Mones JM, Ackerman AB. “Atypical” blue nevus, “malignant” blue nevus, and “metastasizing” blue nevus: a critique in historical perspective of three concepts flawed fatally. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:407-430. doi:10.1097/00000372-200410000-00012

- Tanese K. Diagnosis and management of basal cell carcinoma Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:13. doi:10.1007/s11864 -019-0610-0

- Barthelmann S, Butsch F, Lang BM, et al. Seborrheic keratosis. JDDG J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023;21:265-277. doi:10.1111/ddg.14984

- Taylor S. Advancing the understanding of seborrheic keratosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:419-424.

A 67-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with 3 asymptomatic pigmented papules on the scalp. The patient reported that he was unaware of the lesions until they were pointed out weeks earlier by his primary care physician during a routine visit. He then was referred to dermatology for follow-up. Physical examination at the current presentation revealed clustered firm, smooth, well-circumscribed, pigmented papules on the scalp measuring 5 to 8 mm. The patient reported no personal or family history of skin cancer but stated that he spent a lot of time outdoors and had a history of 6 blistering sunburns in his life. A punch biopsy of each lesion was performed.

Papulonodules on the Ankle in a Patient with Lung Cancer

Papulonodules on the Ankle in a Patient with Lung Cancer

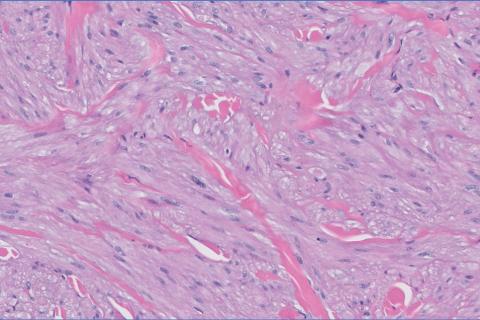

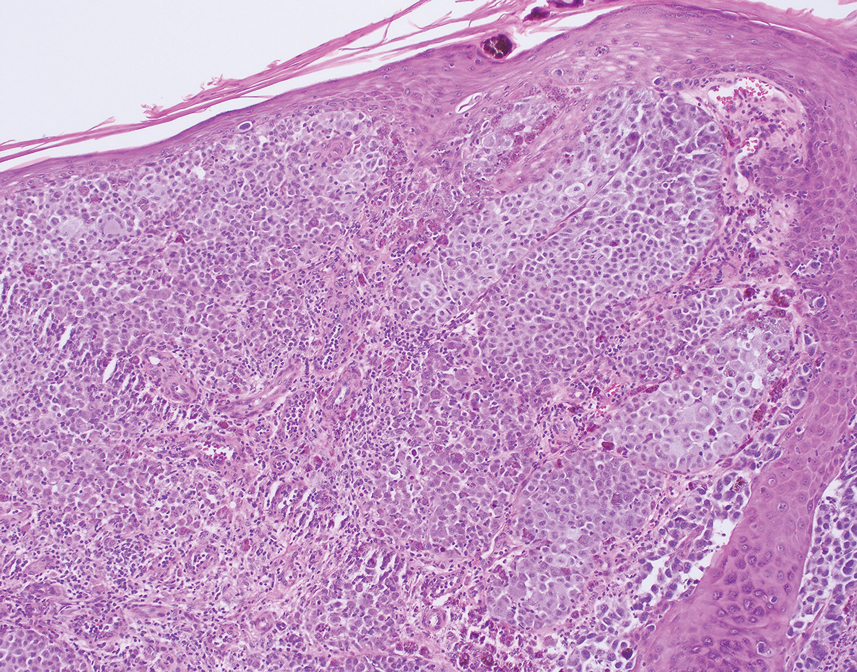

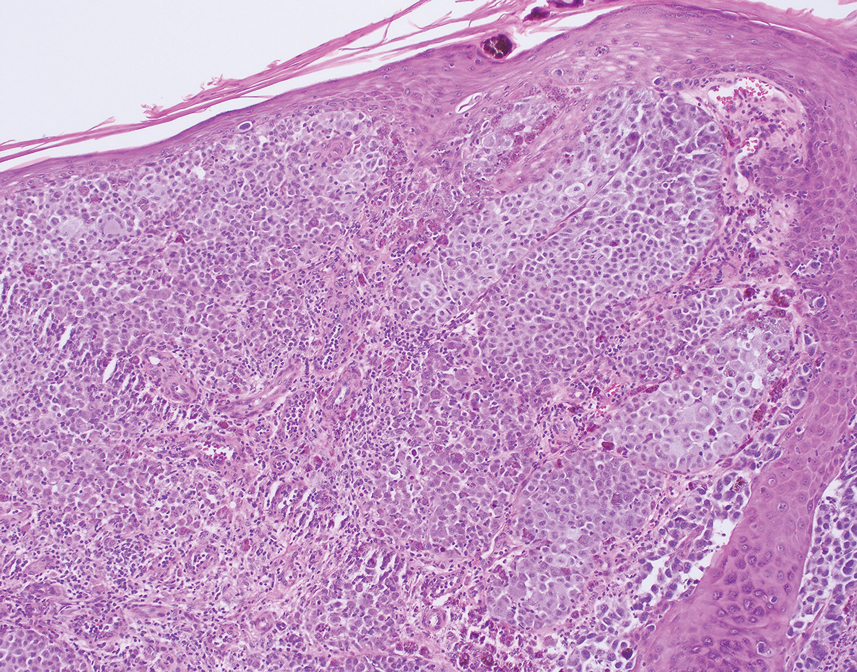

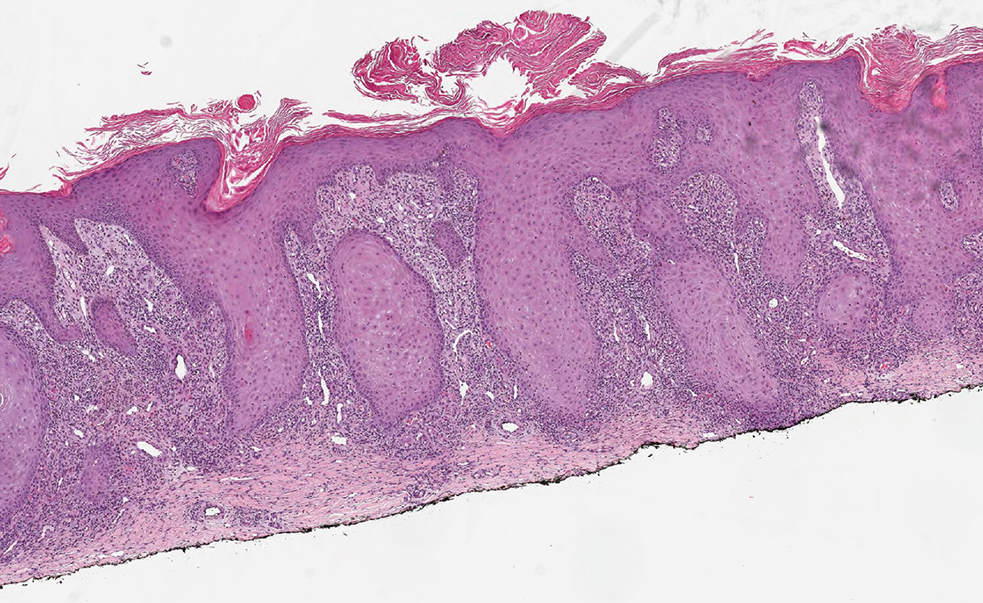

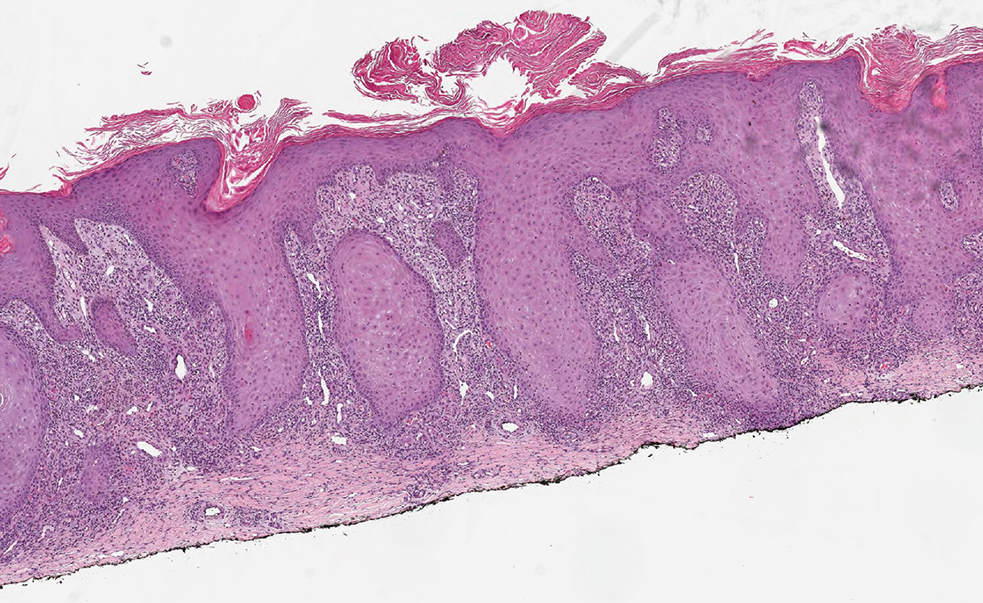

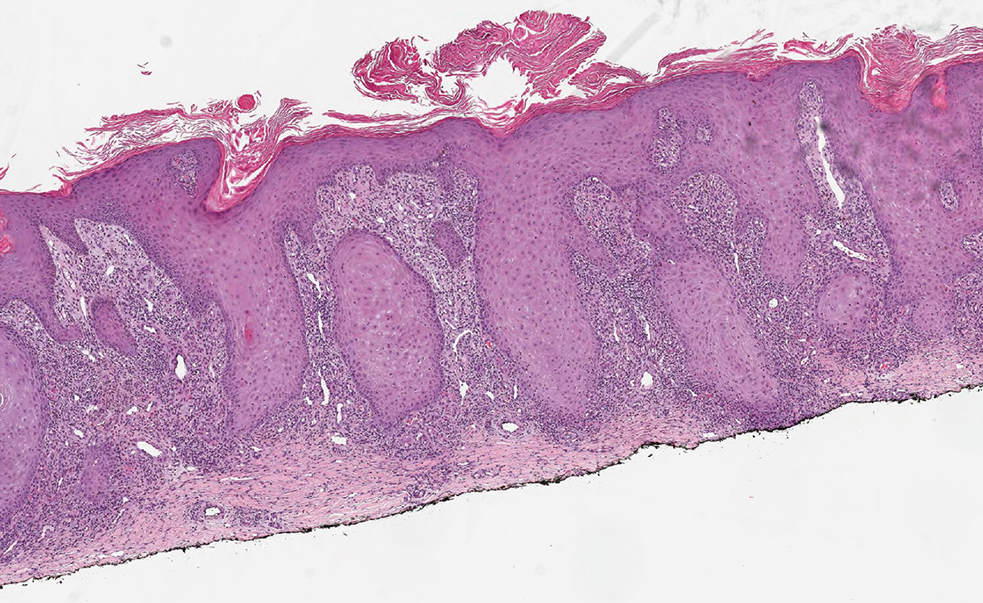

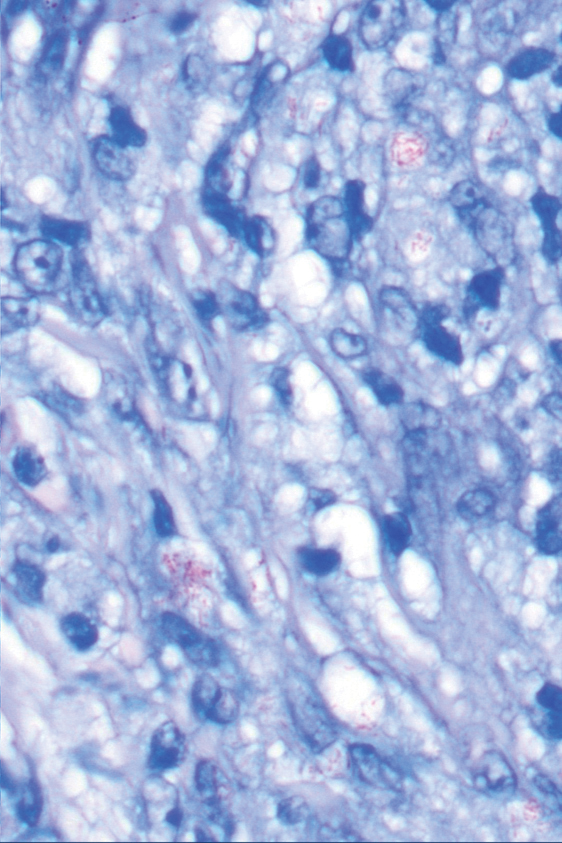

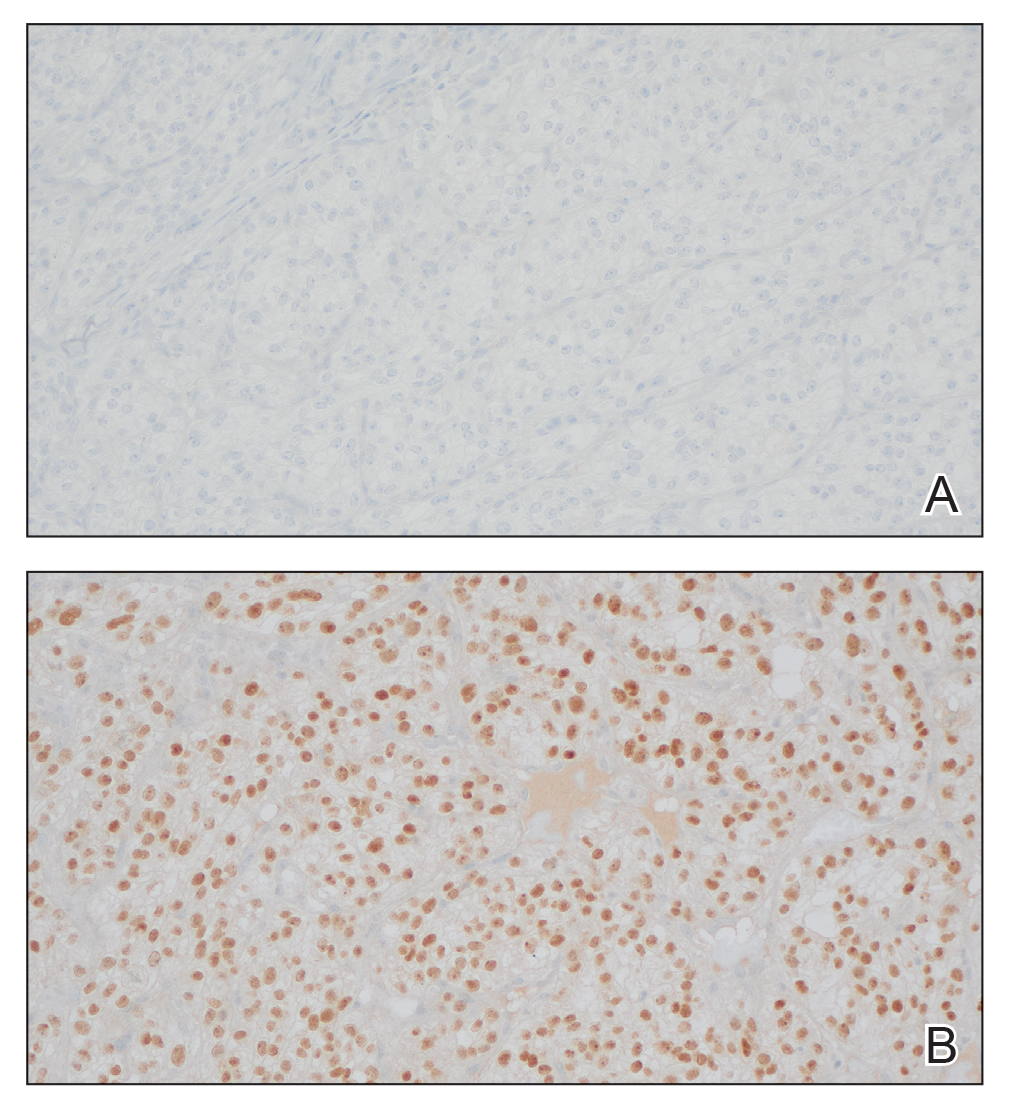

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pembrolizumab-Induced Eruptive Squamous Proliferation

Histopathology showed a broad squamous proliferation with acanthosis of the epidermis. Large glassy keratinocytes were seen with scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure), and a dense lichenoid band of inflammation was present subjacent to the proliferation. Notably, no hypergranulosis, remarkable keratinocyte atypia, or increased mitotic figures were seen. Based on the patient’s medical history and biopsy results, a diagnosis of pembrolizumab-induced eruptive squamous proliferation was made. The diagnosis was supported by a growing body of evidence of this type of reaction in patients taking programmed death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors.1,2 Conservative treatment with clobetasol ointment 0.05% was initiated with complete resolution of the lesions at the 2-month follow-up appointment. Other common treatments include topical steroids, injected corticosteroids, or cryosurgery to locally control the inflammation and atypical proliferation of cells.3

Pembrolizumab is a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody targeting the PD-1 receptor that has been utilized for its antitumor activity against various cancers, including unresectable and metastatic melanoma, head and neck cancers, and non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).1,4,5 While this drug has extended the lives of many patients with cancer, there are adverse reactions associated with PD-1 inhibitors (eg, pembrolizumab, nivolumab). Skin toxicity to PD-1 inhibitors is the one of most common immune-mediated reactions worldwide, occurring in approximately 30% of patients.6,7 Reactions can occur while a patient is taking the inciting drug and can continue up to 2 months after treatment discontinuation.8 Skin reactions associated with PD-1 inhibitors vary from lichenoid reactions and vitiligolike patches to psoriasis or eczema flares and are organized into 4 categories: inflammatory, immunobullous, alteration of keratinocytes, and alteration of melanocytes.9 Our patient demonstrated alteration of keratinocytes, which is characterized by overlapping features of hypertrophic lichen planus and early keratoacanthoma.

The differential diagnoses for pembrolizumab-induced eruptive squamous proliferation include squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), psoriasis, hypertrophic lichen planus, and cutaneous metastasis of NSCLC. Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus also is a well-documented reaction to use of immune-checkpoint inhibitors.10 Direct immunofluorescence could have helped differentiate hypertrophic lupus erythematosus from an eruptive squamous proliferation in our patient; however, due to her response to treatment, no additional workup was done.

Squamous cell carcinoma, which is the most common type of skin cancer in Black patients in the United States,11 has been shown to manifest after a PD-1 inhibitor is taken.12 Although it typically has a more chronic persistent course, the clinical appearance of SCC can be similar to the findings seen in our patient. Histologically, SCC may demonstrate necrosis, but the atypical proliferations will invade the dermis—a feature not seen in our patient’s histopathology.13

Lichen planus (LP) is an eruptive immune reaction of violaceous polygonal papules and plaques commonly seen on the ankles14 that has been shown to be an adverse effect of pembrolizumab.15 There are several subtypes of LP including hypertrophic versions, which can appear clinically similar to the findings seen in our patient. On dermoscopy, the classic finding of white lines, known as Wickham striae, is seen in all subtypes and can help diagnose this pathologic process. Under the microscope, LP can manifest with hyperkeratosis without parakeratosis, irregular thickening of the stratum granulosum, sawtooth rete ridges, and destruction of the basal layer.14

Psoriasis also has been shown to be exacerbated by anti–PD-1 therapy, although the majority of patients diagnosed with PD-1–induced psoriasis have a personal or family history of the disease.6 Clinically, psoriasis can have a hyperpigmented or violaceous appearance in patients with skin of color.16 The histopathology of psoriasis typically reveals confluent parakeratosis, neutrophils in the stratum corneum, regular acanthosis, thinning of the suprapapillary plates, and vessels in the dermal papillae.17

Although cutaneous metastasis of NSCLC may appear clinically similar to the current case, it is one of the rarer organ sites of metastasis for lung cancer.18 In our patient, biopsy quickly ruled out this diagnosis. If it had been a site of metastasis, histopathology would have shown a dermal-based proliferation of dysplastic cells without epidermal connection.19

It is important for dermatologists to recognize eruptive squamous proliferations associated with pembrolizumab, as they often respond to conservative treatment and typically do not require dose reduction or discontinuation of the inciting drug.

- Freshwater T, Kondic A, Ahamadi M, et al. Evaluation of dosing strategy for pembrolizumab for oncology indications. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:43. doi:10.1186/s40425-017-0242-5

- Preti BTB, Pencz A, Cowger JJM, et al. Skin deep: a fascinating case report of immunotherapy-triggered, treatment-refractory autoimmune lichen planus and keratoacanthoma. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14: 1189-1193. doi:10.1159/000518313

- Fradet M, Sibaud V, Tournier E, et al. Multiple keratoacanthoma-like lesions in a patient treated with pembrolizumab. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:1301-1302. doi:10.2340/00015555-3301