User login

Recurrent Nodule on the First Toe

Recurrent Nodule on the First Toe

THE DIAGNOSIS: Hidradenocarcinoma

Both the original and recurrent lesions were interpreted as a chondroid syringoma, a benign adnexal tumor; however, the third biopsy of the lesion revealed a low-grade adnexal neoplasm with irregular nests of variably sized epithelial cells demonstrating mild nuclear atypia and low mitotic activity. Given the multiple recurrences, accelerated growth, and more aggressive histologic findings, the patient was referred to our clinic for surgical management.

We elected to perform modified Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) with permanent tissue sections to enable the application of immunohistochemical stains to fully characterize the tumor. Histopathology showed a poorly circumscribed infiltrative dermal neoplasm composed of basaloid cells with a solid and cystic growth pattern in a background of hyalinized, fibrotic stroma (Figure, A and B). There were focal clear cell and squamous features as well as focal ductal differentiation (Figure, C and D). No obvious papillary structures were noted. The tumor cells were positive for D2-40, and staining for CD31 failed to reveal lymphovascular invasion. Based on the infiltrative features in conjunction with the findings from the prior biopsies, a diagnosis of hidradenocarcinoma (HAC) was made. Deep and peripheral margins were cleared after 2 stages of MMS.

Initially described in 1954, HAC is an exceedingly rare adnexal tumor of apocrine and eccrine derivation.1 Historically, nomenclature for this entity has varied in the literature, including synonyms such as malignant nodular hidradenoma, malignant acrospiroma, solid-cystic adenocarcinoma, and malignant clear cell myoepithelioma.2,3 Approximately 6% of all malignant eccrine tumors worldwide are HACs, which account for only 1 in 13,000 dermatopathology specimens.1 These tumors may transform from clear cell hidradenomas (their benign counterparts) but more commonly arise de novo. Compared to benign hidradenomas, HACs are poorly circumscribed with infiltrative growth patterns on histopathology and may exhibit nuclear pleomorphism, prominent mitotic activity, necrosis, and perineural or vascular invasion.2

Clinically, HAC manifests as a 1- to 5-cm, solitary, firm, intradermal pink or violaceous nodule with possible ulceration.2,4 The nodule often is asymptomatic but may be tender, as in our patient. There seems to be no clear anatomic site of predilection, with approximately 42% of HACs localized to the head and neck and the remainder occurring on the trunk, arms, and legs.3,5-7 Females and males are affected equally, and lesions tend to arise in the seventh decade of life.7

Reports in the literature suggest that HAC is a very aggressive tumor with a generally poor prognosis.1 Several studies have found that up to half of tumors locally recur despite aggressive surgical management, and metastasis occurs in 20% to 60% of patients.3,8 However, a large study of US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data investigating the clinicopathologic characteristics of 289 patients with HAC revealed a more favorable prognosis.7 Mean overall survival and cancer-specific survival were greater than 13 years, and 10-year overall survival and cancer-specific survival rates were 60.2% and 90.5%, respectively.

Traditionally used to treat keratinocyte carcinomas, including basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, complete margin assessment with MMS is increasingly being utilized in the management of other cutaneous malignancies, including adnexal tumors.8 Due to its rarity, there remains no standard optimal treatment approach for HAC. One small retrospective study of 10 patients with HAC treated with MMS demonstrated favorable outcomes with no cases of recurrence, metastasis, or diseaserelated mortality in a mean 7-year follow-up period.9

Whole-body positron emission tomography/computed tomography performed in our patient approximately 1 month after MMS revealed mildly hypermetabolic left inguinal lymph nodes, which were thought to be reactive, and a question of small hypermetabolic foci in the liver. Follow-up computed tomography of the abdomen subsequently was performed and was negative for hepatic metastases. The patient will be monitored closely for local recurrence; however, the clearance of the tumor with MMS, which allowed complete margin assessment, is encouraging and supports MMS as superior to traditional surgical excision in the treatment of HAC. At his most recent examination 17 months after Mohs surgery, the patient remained tumor free.

Aggressive digital papillary adenocarcinoma (ADPA) is a rare malignant tumor originating in the sweat glands that can occur on the first toe but most commonly arises on the fingers. While both HAC and ADPA can manifest with an infiltrative growth pattern and cytologic atypia, ADPA classically reveals a well-circumscribed multinodular tumor in the dermis comprised of solid and cystic proliferation as well as papillary projections. In addition, ADPA has been described as having back-to-back glandular and ductal structures.10 Giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath is a benign fibrohistiocytic tumor that also typically manifests on the fingers but rarely can occur on the foot, including the first toe.11,12 This tumor is more common in women and most frequently affects individuals aged 30 to 50 years.12 Microscopically, giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath is characterized by a proliferation of osteoclastlike giant cells, epithelioid histiocytelike cells, mononuclear cells, and xanthomatous cells among collagenous bands.11

Osteosarcoma is an uncommon tumor of osteoidproducing cells that usually arises in the metaphysis of long bones and manifests as a tender subcutaneous mass. It has a bimodal age distribution, peaking in adolescents and adults older than 65 years.13 While very rare, osteosarcoma has been reported to occur in the bones of the feet, including the phalanges.14 Given the recurrent nature of our patient’s tumor, metastasis should always be considered; however, in his case, full-body imaging was negative for additional malignancy.

- Gauerke S, Driscoll JJ. Hidradenocarcinomas: a brief review and future directions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:781-785. doi:10.5858/134.5.781

- Ahn CS, Sangüeza OP. Malignant sweat gland tumors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:53-71. doi:10.1016/J.HOC.2018.09.002

- Ohta M, Hiramoto M, Fujii M, et al. Nodular hidradenocarcinoma on the scalp of a young woman: case report and review of literature. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1265-1268. doi:10.1111/J.1524-4725.2004.30390.X

- Souvatzidis P, Sbano P, Mandato F, et al. Malignant nodular hidradenoma of the skin: report of seven cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:549-554. doi:10.1111/J.1468-3083.2007.02504.X

- Yavel R, Hinshaw M, Rao V, et al. Hidradenomas and a hidradenocarcinoma of the scalp managed using Mohs micrographic surgery and a multidisciplinary approach: case reports and review of the literature. Dermatolog Surg. 2009;35:273-281. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34424.x

- Kazakov DV, Ivan D, Kutzner H, et al. Cutaneous hidradenocarcinoma: a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, and molecular biologic study of 14 cases, including Her2/neu gene expression/ amplification, TP53 gene mutation analysis, and t(11;19) translocation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:236-247. doi:10.1097/DAD.0B013E3181984F10

- Gao T, Pan S, Li M, et al. Prognostic analysis of hidradenocarcinoma: a SEER-based observational study. Ann Med. 2022;54:454-463. doi:10 .1080/07853890.2022.2032313

- Tolkachjov SN. Adnexal carcinomas treated with Mohs micrographic surgery: a comprehensive review. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1199-1207. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001167

- Tolkachjov SN, Hocker TL, Hochwalt PC, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of hidradenocarcinoma: the mayo clinic experience from 1993 to 2013. Dermatolog Surg. 2015;41:226-231. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000242

- Weingertner N, Gressel A, Battistella M, et al. Aggressive digital papillary adenocarcinoma: a clinicopathological study of 19 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:549-558.e1. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2017.02.028

- Paral KM, Petronic-Rosic V. Acral manifestations of soft tissue tumors. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:85-98. doi:10.1016/J.CLINDER MATOL.2016.09.012

- Kondo RN, Crespigio J, Pavezzi PD, et al. Giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath in the left hallux. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:704-705. doi:10.1590/ABD1806-4841.20165769

- Ottaviani G, Jaffe N. The epidemiology of osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat Res. 2009;152:3-13. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0284-9_1

- Anninga JK, Picci P, Fiocco M, et al. Osteosarcoma of the hands and feet: a distinct clinico-pathological subgroup. Virchows Arch. 2013;462:109- 120. doi:10.1007/S00428-012-1339-3

THE DIAGNOSIS: Hidradenocarcinoma

Both the original and recurrent lesions were interpreted as a chondroid syringoma, a benign adnexal tumor; however, the third biopsy of the lesion revealed a low-grade adnexal neoplasm with irregular nests of variably sized epithelial cells demonstrating mild nuclear atypia and low mitotic activity. Given the multiple recurrences, accelerated growth, and more aggressive histologic findings, the patient was referred to our clinic for surgical management.

We elected to perform modified Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) with permanent tissue sections to enable the application of immunohistochemical stains to fully characterize the tumor. Histopathology showed a poorly circumscribed infiltrative dermal neoplasm composed of basaloid cells with a solid and cystic growth pattern in a background of hyalinized, fibrotic stroma (Figure, A and B). There were focal clear cell and squamous features as well as focal ductal differentiation (Figure, C and D). No obvious papillary structures were noted. The tumor cells were positive for D2-40, and staining for CD31 failed to reveal lymphovascular invasion. Based on the infiltrative features in conjunction with the findings from the prior biopsies, a diagnosis of hidradenocarcinoma (HAC) was made. Deep and peripheral margins were cleared after 2 stages of MMS.

Initially described in 1954, HAC is an exceedingly rare adnexal tumor of apocrine and eccrine derivation.1 Historically, nomenclature for this entity has varied in the literature, including synonyms such as malignant nodular hidradenoma, malignant acrospiroma, solid-cystic adenocarcinoma, and malignant clear cell myoepithelioma.2,3 Approximately 6% of all malignant eccrine tumors worldwide are HACs, which account for only 1 in 13,000 dermatopathology specimens.1 These tumors may transform from clear cell hidradenomas (their benign counterparts) but more commonly arise de novo. Compared to benign hidradenomas, HACs are poorly circumscribed with infiltrative growth patterns on histopathology and may exhibit nuclear pleomorphism, prominent mitotic activity, necrosis, and perineural or vascular invasion.2

Clinically, HAC manifests as a 1- to 5-cm, solitary, firm, intradermal pink or violaceous nodule with possible ulceration.2,4 The nodule often is asymptomatic but may be tender, as in our patient. There seems to be no clear anatomic site of predilection, with approximately 42% of HACs localized to the head and neck and the remainder occurring on the trunk, arms, and legs.3,5-7 Females and males are affected equally, and lesions tend to arise in the seventh decade of life.7

Reports in the literature suggest that HAC is a very aggressive tumor with a generally poor prognosis.1 Several studies have found that up to half of tumors locally recur despite aggressive surgical management, and metastasis occurs in 20% to 60% of patients.3,8 However, a large study of US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data investigating the clinicopathologic characteristics of 289 patients with HAC revealed a more favorable prognosis.7 Mean overall survival and cancer-specific survival were greater than 13 years, and 10-year overall survival and cancer-specific survival rates were 60.2% and 90.5%, respectively.

Traditionally used to treat keratinocyte carcinomas, including basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, complete margin assessment with MMS is increasingly being utilized in the management of other cutaneous malignancies, including adnexal tumors.8 Due to its rarity, there remains no standard optimal treatment approach for HAC. One small retrospective study of 10 patients with HAC treated with MMS demonstrated favorable outcomes with no cases of recurrence, metastasis, or diseaserelated mortality in a mean 7-year follow-up period.9

Whole-body positron emission tomography/computed tomography performed in our patient approximately 1 month after MMS revealed mildly hypermetabolic left inguinal lymph nodes, which were thought to be reactive, and a question of small hypermetabolic foci in the liver. Follow-up computed tomography of the abdomen subsequently was performed and was negative for hepatic metastases. The patient will be monitored closely for local recurrence; however, the clearance of the tumor with MMS, which allowed complete margin assessment, is encouraging and supports MMS as superior to traditional surgical excision in the treatment of HAC. At his most recent examination 17 months after Mohs surgery, the patient remained tumor free.

Aggressive digital papillary adenocarcinoma (ADPA) is a rare malignant tumor originating in the sweat glands that can occur on the first toe but most commonly arises on the fingers. While both HAC and ADPA can manifest with an infiltrative growth pattern and cytologic atypia, ADPA classically reveals a well-circumscribed multinodular tumor in the dermis comprised of solid and cystic proliferation as well as papillary projections. In addition, ADPA has been described as having back-to-back glandular and ductal structures.10 Giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath is a benign fibrohistiocytic tumor that also typically manifests on the fingers but rarely can occur on the foot, including the first toe.11,12 This tumor is more common in women and most frequently affects individuals aged 30 to 50 years.12 Microscopically, giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath is characterized by a proliferation of osteoclastlike giant cells, epithelioid histiocytelike cells, mononuclear cells, and xanthomatous cells among collagenous bands.11

Osteosarcoma is an uncommon tumor of osteoidproducing cells that usually arises in the metaphysis of long bones and manifests as a tender subcutaneous mass. It has a bimodal age distribution, peaking in adolescents and adults older than 65 years.13 While very rare, osteosarcoma has been reported to occur in the bones of the feet, including the phalanges.14 Given the recurrent nature of our patient’s tumor, metastasis should always be considered; however, in his case, full-body imaging was negative for additional malignancy.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Hidradenocarcinoma

Both the original and recurrent lesions were interpreted as a chondroid syringoma, a benign adnexal tumor; however, the third biopsy of the lesion revealed a low-grade adnexal neoplasm with irregular nests of variably sized epithelial cells demonstrating mild nuclear atypia and low mitotic activity. Given the multiple recurrences, accelerated growth, and more aggressive histologic findings, the patient was referred to our clinic for surgical management.

We elected to perform modified Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) with permanent tissue sections to enable the application of immunohistochemical stains to fully characterize the tumor. Histopathology showed a poorly circumscribed infiltrative dermal neoplasm composed of basaloid cells with a solid and cystic growth pattern in a background of hyalinized, fibrotic stroma (Figure, A and B). There were focal clear cell and squamous features as well as focal ductal differentiation (Figure, C and D). No obvious papillary structures were noted. The tumor cells were positive for D2-40, and staining for CD31 failed to reveal lymphovascular invasion. Based on the infiltrative features in conjunction with the findings from the prior biopsies, a diagnosis of hidradenocarcinoma (HAC) was made. Deep and peripheral margins were cleared after 2 stages of MMS.

Initially described in 1954, HAC is an exceedingly rare adnexal tumor of apocrine and eccrine derivation.1 Historically, nomenclature for this entity has varied in the literature, including synonyms such as malignant nodular hidradenoma, malignant acrospiroma, solid-cystic adenocarcinoma, and malignant clear cell myoepithelioma.2,3 Approximately 6% of all malignant eccrine tumors worldwide are HACs, which account for only 1 in 13,000 dermatopathology specimens.1 These tumors may transform from clear cell hidradenomas (their benign counterparts) but more commonly arise de novo. Compared to benign hidradenomas, HACs are poorly circumscribed with infiltrative growth patterns on histopathology and may exhibit nuclear pleomorphism, prominent mitotic activity, necrosis, and perineural or vascular invasion.2

Clinically, HAC manifests as a 1- to 5-cm, solitary, firm, intradermal pink or violaceous nodule with possible ulceration.2,4 The nodule often is asymptomatic but may be tender, as in our patient. There seems to be no clear anatomic site of predilection, with approximately 42% of HACs localized to the head and neck and the remainder occurring on the trunk, arms, and legs.3,5-7 Females and males are affected equally, and lesions tend to arise in the seventh decade of life.7

Reports in the literature suggest that HAC is a very aggressive tumor with a generally poor prognosis.1 Several studies have found that up to half of tumors locally recur despite aggressive surgical management, and metastasis occurs in 20% to 60% of patients.3,8 However, a large study of US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data investigating the clinicopathologic characteristics of 289 patients with HAC revealed a more favorable prognosis.7 Mean overall survival and cancer-specific survival were greater than 13 years, and 10-year overall survival and cancer-specific survival rates were 60.2% and 90.5%, respectively.

Traditionally used to treat keratinocyte carcinomas, including basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, complete margin assessment with MMS is increasingly being utilized in the management of other cutaneous malignancies, including adnexal tumors.8 Due to its rarity, there remains no standard optimal treatment approach for HAC. One small retrospective study of 10 patients with HAC treated with MMS demonstrated favorable outcomes with no cases of recurrence, metastasis, or diseaserelated mortality in a mean 7-year follow-up period.9

Whole-body positron emission tomography/computed tomography performed in our patient approximately 1 month after MMS revealed mildly hypermetabolic left inguinal lymph nodes, which were thought to be reactive, and a question of small hypermetabolic foci in the liver. Follow-up computed tomography of the abdomen subsequently was performed and was negative for hepatic metastases. The patient will be monitored closely for local recurrence; however, the clearance of the tumor with MMS, which allowed complete margin assessment, is encouraging and supports MMS as superior to traditional surgical excision in the treatment of HAC. At his most recent examination 17 months after Mohs surgery, the patient remained tumor free.

Aggressive digital papillary adenocarcinoma (ADPA) is a rare malignant tumor originating in the sweat glands that can occur on the first toe but most commonly arises on the fingers. While both HAC and ADPA can manifest with an infiltrative growth pattern and cytologic atypia, ADPA classically reveals a well-circumscribed multinodular tumor in the dermis comprised of solid and cystic proliferation as well as papillary projections. In addition, ADPA has been described as having back-to-back glandular and ductal structures.10 Giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath is a benign fibrohistiocytic tumor that also typically manifests on the fingers but rarely can occur on the foot, including the first toe.11,12 This tumor is more common in women and most frequently affects individuals aged 30 to 50 years.12 Microscopically, giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath is characterized by a proliferation of osteoclastlike giant cells, epithelioid histiocytelike cells, mononuclear cells, and xanthomatous cells among collagenous bands.11

Osteosarcoma is an uncommon tumor of osteoidproducing cells that usually arises in the metaphysis of long bones and manifests as a tender subcutaneous mass. It has a bimodal age distribution, peaking in adolescents and adults older than 65 years.13 While very rare, osteosarcoma has been reported to occur in the bones of the feet, including the phalanges.14 Given the recurrent nature of our patient’s tumor, metastasis should always be considered; however, in his case, full-body imaging was negative for additional malignancy.

- Gauerke S, Driscoll JJ. Hidradenocarcinomas: a brief review and future directions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:781-785. doi:10.5858/134.5.781

- Ahn CS, Sangüeza OP. Malignant sweat gland tumors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:53-71. doi:10.1016/J.HOC.2018.09.002

- Ohta M, Hiramoto M, Fujii M, et al. Nodular hidradenocarcinoma on the scalp of a young woman: case report and review of literature. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1265-1268. doi:10.1111/J.1524-4725.2004.30390.X

- Souvatzidis P, Sbano P, Mandato F, et al. Malignant nodular hidradenoma of the skin: report of seven cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:549-554. doi:10.1111/J.1468-3083.2007.02504.X

- Yavel R, Hinshaw M, Rao V, et al. Hidradenomas and a hidradenocarcinoma of the scalp managed using Mohs micrographic surgery and a multidisciplinary approach: case reports and review of the literature. Dermatolog Surg. 2009;35:273-281. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34424.x

- Kazakov DV, Ivan D, Kutzner H, et al. Cutaneous hidradenocarcinoma: a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, and molecular biologic study of 14 cases, including Her2/neu gene expression/ amplification, TP53 gene mutation analysis, and t(11;19) translocation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:236-247. doi:10.1097/DAD.0B013E3181984F10

- Gao T, Pan S, Li M, et al. Prognostic analysis of hidradenocarcinoma: a SEER-based observational study. Ann Med. 2022;54:454-463. doi:10 .1080/07853890.2022.2032313

- Tolkachjov SN. Adnexal carcinomas treated with Mohs micrographic surgery: a comprehensive review. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1199-1207. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001167

- Tolkachjov SN, Hocker TL, Hochwalt PC, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of hidradenocarcinoma: the mayo clinic experience from 1993 to 2013. Dermatolog Surg. 2015;41:226-231. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000242

- Weingertner N, Gressel A, Battistella M, et al. Aggressive digital papillary adenocarcinoma: a clinicopathological study of 19 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:549-558.e1. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2017.02.028

- Paral KM, Petronic-Rosic V. Acral manifestations of soft tissue tumors. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:85-98. doi:10.1016/J.CLINDER MATOL.2016.09.012

- Kondo RN, Crespigio J, Pavezzi PD, et al. Giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath in the left hallux. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:704-705. doi:10.1590/ABD1806-4841.20165769

- Ottaviani G, Jaffe N. The epidemiology of osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat Res. 2009;152:3-13. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0284-9_1

- Anninga JK, Picci P, Fiocco M, et al. Osteosarcoma of the hands and feet: a distinct clinico-pathological subgroup. Virchows Arch. 2013;462:109- 120. doi:10.1007/S00428-012-1339-3

- Gauerke S, Driscoll JJ. Hidradenocarcinomas: a brief review and future directions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:781-785. doi:10.5858/134.5.781

- Ahn CS, Sangüeza OP. Malignant sweat gland tumors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:53-71. doi:10.1016/J.HOC.2018.09.002

- Ohta M, Hiramoto M, Fujii M, et al. Nodular hidradenocarcinoma on the scalp of a young woman: case report and review of literature. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1265-1268. doi:10.1111/J.1524-4725.2004.30390.X

- Souvatzidis P, Sbano P, Mandato F, et al. Malignant nodular hidradenoma of the skin: report of seven cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:549-554. doi:10.1111/J.1468-3083.2007.02504.X

- Yavel R, Hinshaw M, Rao V, et al. Hidradenomas and a hidradenocarcinoma of the scalp managed using Mohs micrographic surgery and a multidisciplinary approach: case reports and review of the literature. Dermatolog Surg. 2009;35:273-281. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34424.x

- Kazakov DV, Ivan D, Kutzner H, et al. Cutaneous hidradenocarcinoma: a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, and molecular biologic study of 14 cases, including Her2/neu gene expression/ amplification, TP53 gene mutation analysis, and t(11;19) translocation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:236-247. doi:10.1097/DAD.0B013E3181984F10

- Gao T, Pan S, Li M, et al. Prognostic analysis of hidradenocarcinoma: a SEER-based observational study. Ann Med. 2022;54:454-463. doi:10 .1080/07853890.2022.2032313

- Tolkachjov SN. Adnexal carcinomas treated with Mohs micrographic surgery: a comprehensive review. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1199-1207. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001167

- Tolkachjov SN, Hocker TL, Hochwalt PC, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of hidradenocarcinoma: the mayo clinic experience from 1993 to 2013. Dermatolog Surg. 2015;41:226-231. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000242

- Weingertner N, Gressel A, Battistella M, et al. Aggressive digital papillary adenocarcinoma: a clinicopathological study of 19 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:549-558.e1. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2017.02.028

- Paral KM, Petronic-Rosic V. Acral manifestations of soft tissue tumors. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:85-98. doi:10.1016/J.CLINDER MATOL.2016.09.012

- Kondo RN, Crespigio J, Pavezzi PD, et al. Giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath in the left hallux. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:704-705. doi:10.1590/ABD1806-4841.20165769

- Ottaviani G, Jaffe N. The epidemiology of osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat Res. 2009;152:3-13. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0284-9_1

- Anninga JK, Picci P, Fiocco M, et al. Osteosarcoma of the hands and feet: a distinct clinico-pathological subgroup. Virchows Arch. 2013;462:109- 120. doi:10.1007/S00428-012-1339-3

Recurrent Nodule on the First Toe

Recurrent Nodule on the First Toe

A 56-year-old man was referred to the dermatology clinic for treatment of a recurrent nodule on the left first toe. The lesion first appeared 12 years prior and was resected by an outside dermatologist, who diagnosed the lesion as benign based on biopsy results. Approximately 10 years later, the lesion began to grow back with a similar appearance to the original nodule; it again was diagnosed as benign based on another biopsy and excised by the outside dermatologist. Two years later, the patient had a second recurrence of the lesion, which was excised by his dermatologist. The biopsy report at that time identified the lesion as a low-grade adnexal neoplasm. The patient had a rapid recurrence of the tumor after 6 months and was referred to our clinic for Mohs micrographic surgery. Physical examination revealed a tender, 2.5×1.8-cm, firm, exophytic, subcutaneous nodule on the left first toe with no associated lymphadenopathy.

Differences in Underrepresented in Medicine Applicant Backgrounds and Outcomes in the 2020-2021 Dermatology Residency Match

Dermatology is one of the least diverse medical specialties with only 3% of dermatologists being Black and 4% Latinx.1 Leading dermatology organizations have called for specialty-wide efforts to improve diversity, with a particular focus on the resident selection process.2,3 Medical students who are underrepresented in medicine (UIM)(ie, those who identify as Black, Latinx, Native American, or Pacific Islander) face many potential barriers in applying to dermatology programs, including financial limitations, lack of support and mentorship, and less exposure to the specialty.1,2,4 The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges in the residency application process with limitations on clinical, research, and volunteer experiences; decreased opportunities for in-person mentorship and away rotations; and a shift to virtual recruitment. Although there has been increased emphasis on recruiting diverse candidates to dermatology, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated existing barriers for UIM applicants.

We surveyed dermatology residency program directors (PDs) and applicants to evaluate how UIM students approach and fare in the dermatology residency application process as well as the effects of COVID-19 on the most recent application cycle. Herein, we report the results of our surveys with a focus on racial differences in the application process.

Methods

We administered 2 anonymous online surveys—one to 115 PDs through the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) email listserve and another to applicants who participated in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle through the Dermatology Interest Group Association (DIGA) listserve. The surveys were distributed from March 29 through May 23, 2021. There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants on the DIGA listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (approval #UP-21-00118).

Participants were not required to answer every survey question; response rates varied by question. Survey responses with less than 10% completion were excluded from analysis. Data were collected, analyzed, and stored using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. The test of equal or given proportions in R studio was used to determine statistically significant differences between variables (P<.05 indicated statistical significance).

Results

The PD survey received 79 complete responses (83.5% complete responses, 73.8% response rate) and the applicant survey received 232 complete responses (83.6% complete responses).

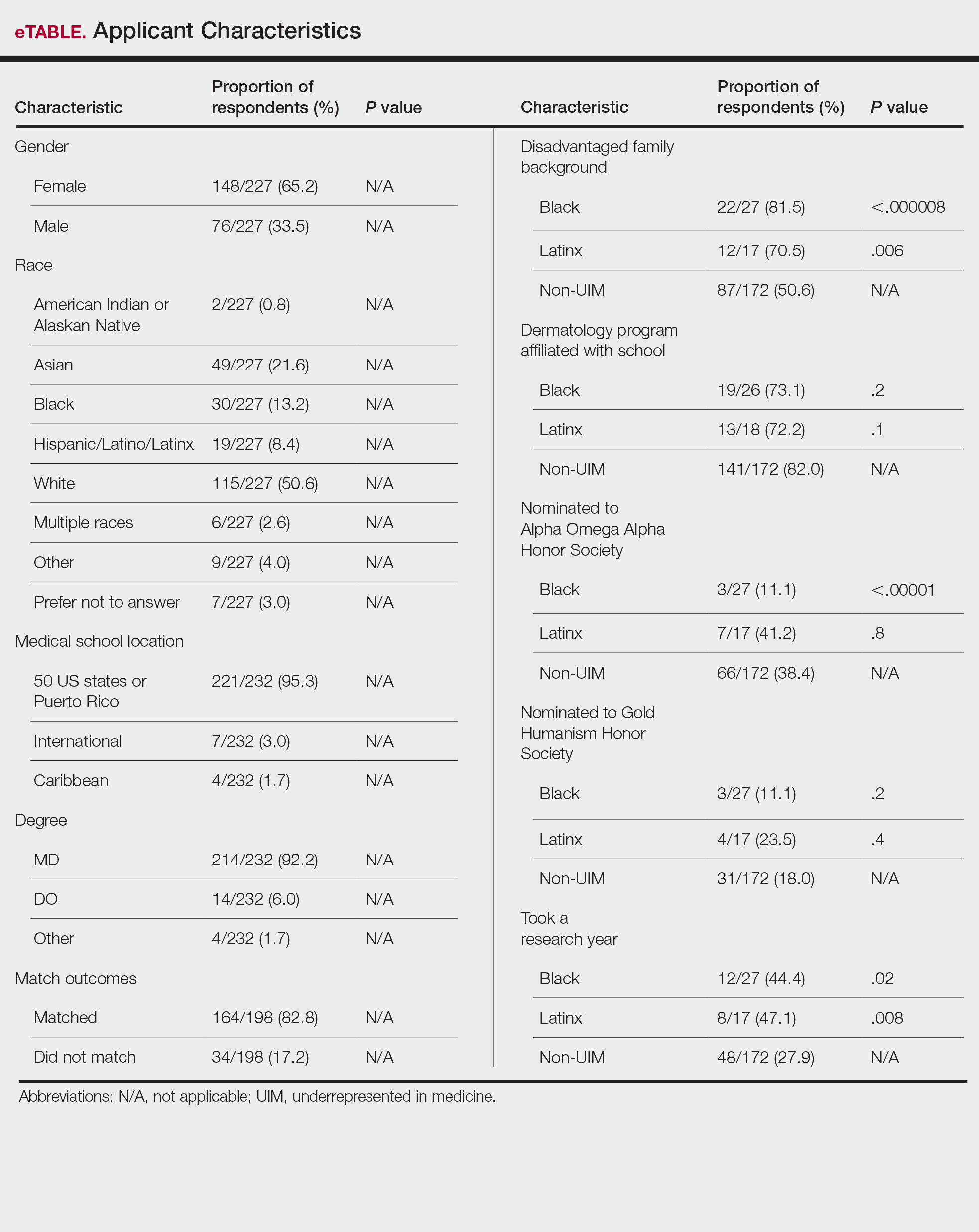

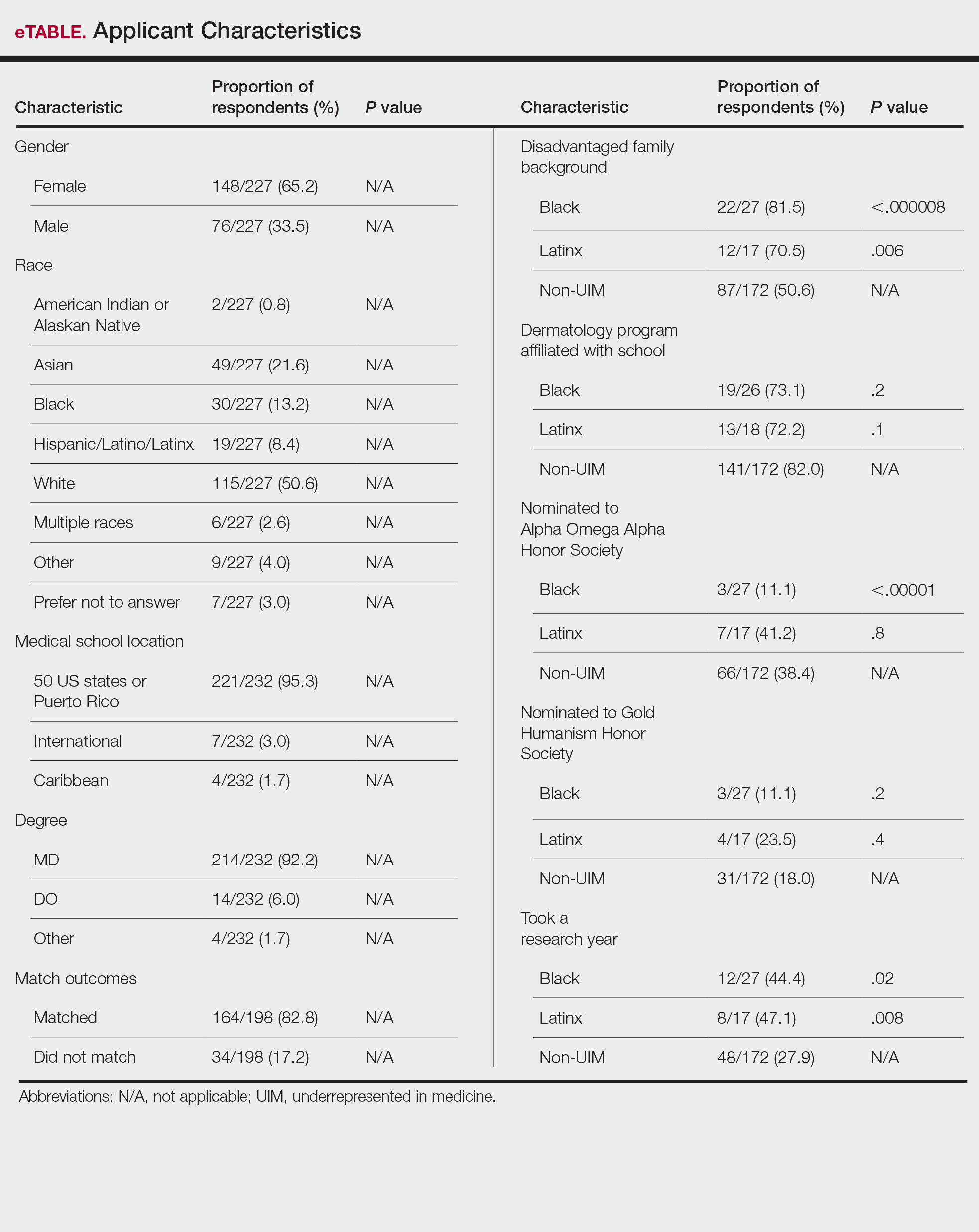

Applicant Characteristics—Applicant characteristics are provided in the eTable; 13.2% and 8.4% of participants were Black and Latinx (including those who identify as Hispanic/Latino), respectively. Only 0.8% of respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native and were excluded from the analysis due to the limited sample size. Those who identified as White, Asian, multiple races, or other and those who preferred not to answer were considered non-UIM participants.

Differences in family background were observed in our cohort, with UIM candidates more likely to have experienced disadvantages, defined as being the first in their family to attend college/graduate school, growing up in a rural area, being a first-generation immigrant, or qualifying as low income. Underrepresented in medicine applicants also were less likely to have a dermatology program at their medical school (both Black and Latinx) and to have been elected to honor societies such as Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society (Black only).

Underrepresented in medicine applicants were more likely to complete a research gap year (eTable). Most applicants who took research years did so to improve their chances of matching, regardless of their race/ethnicity. For those who did not complete a research year, Black applicants (46.7%) were more likely to base that decision on financial limitations compared to non-UIMs (18.6%, P<.0001). Interestingly, in the PD survey, only 4.5% of respondents considered completion of a research year extremely or very important when compiling rank lists.

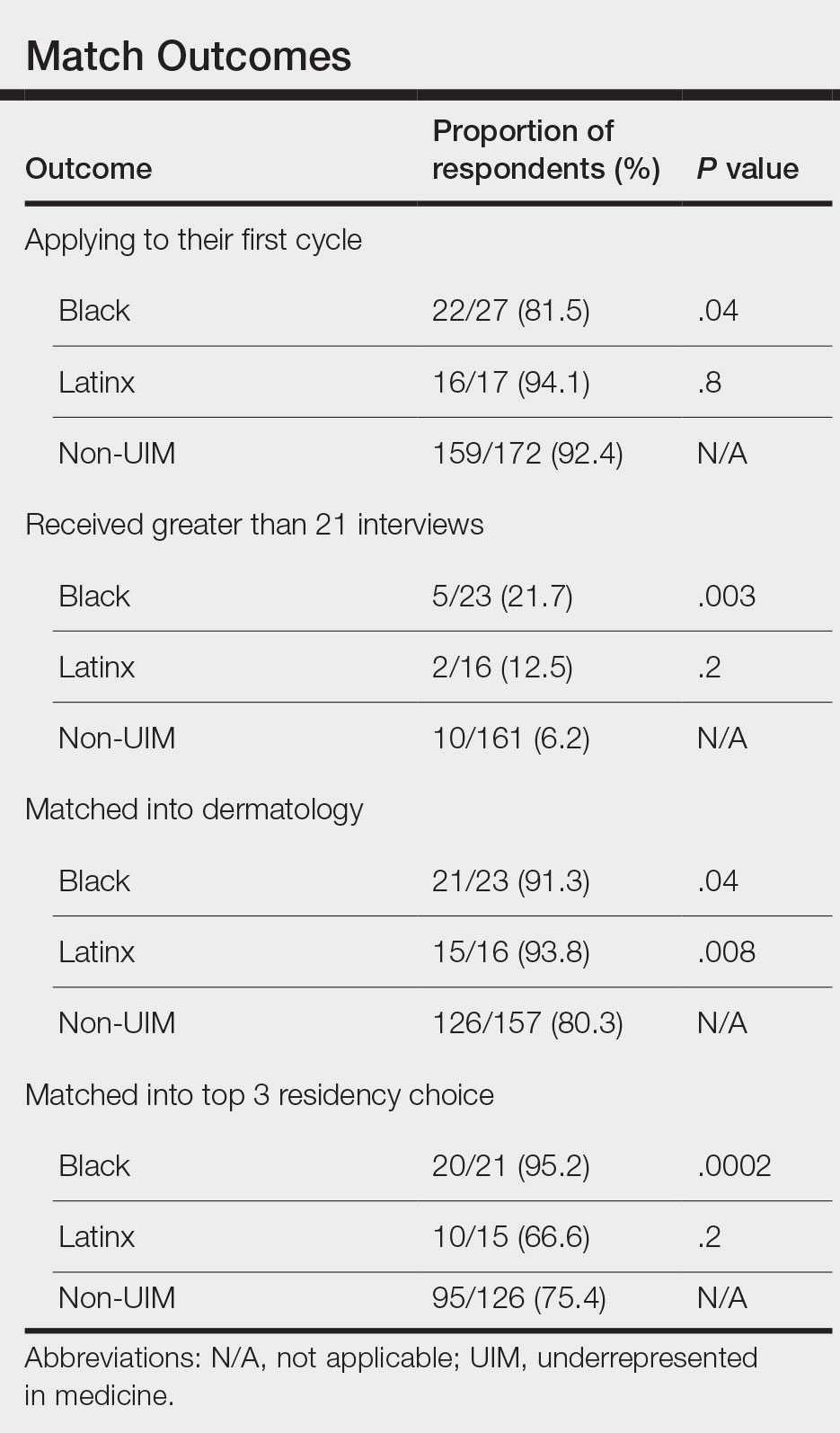

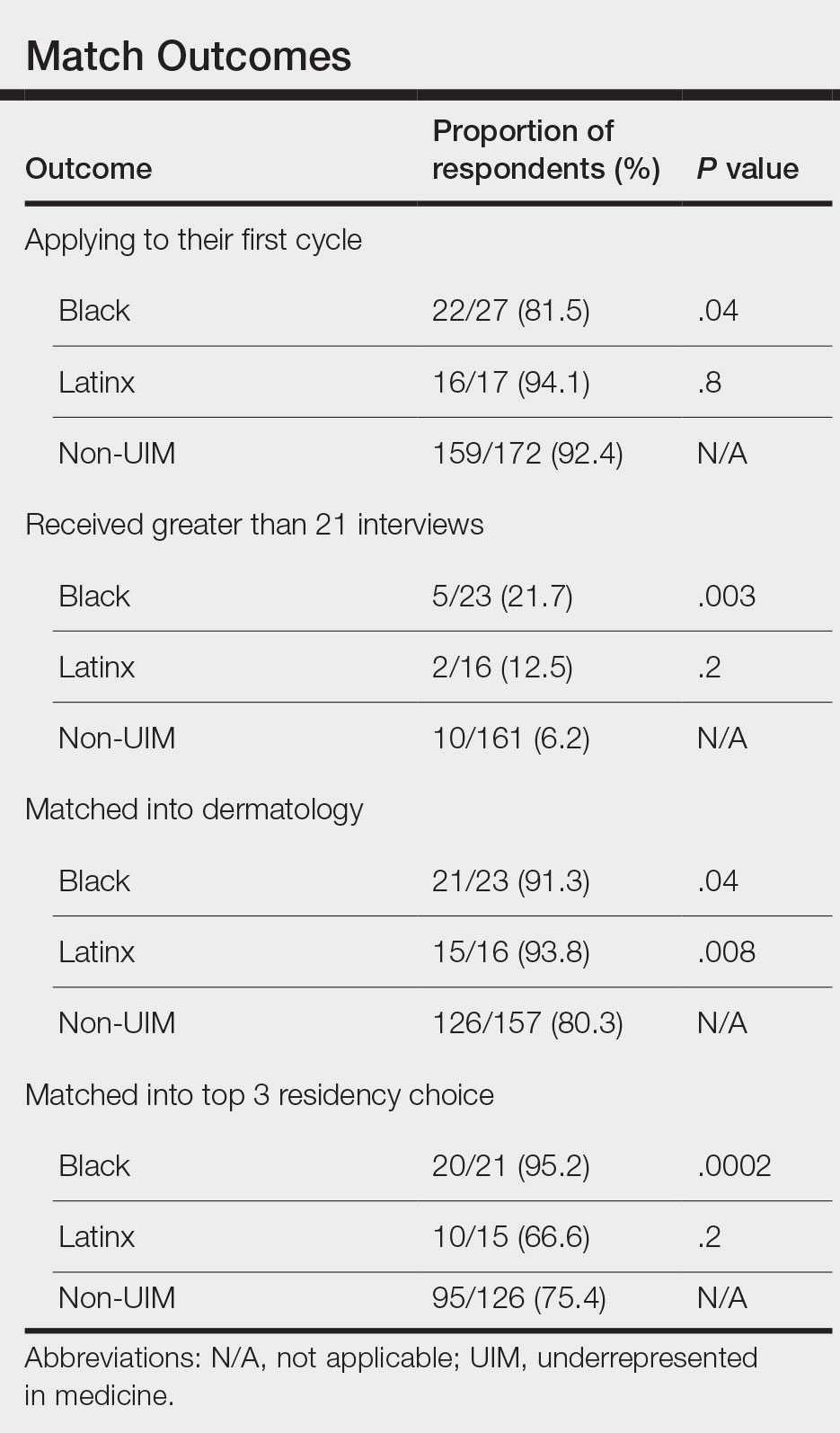

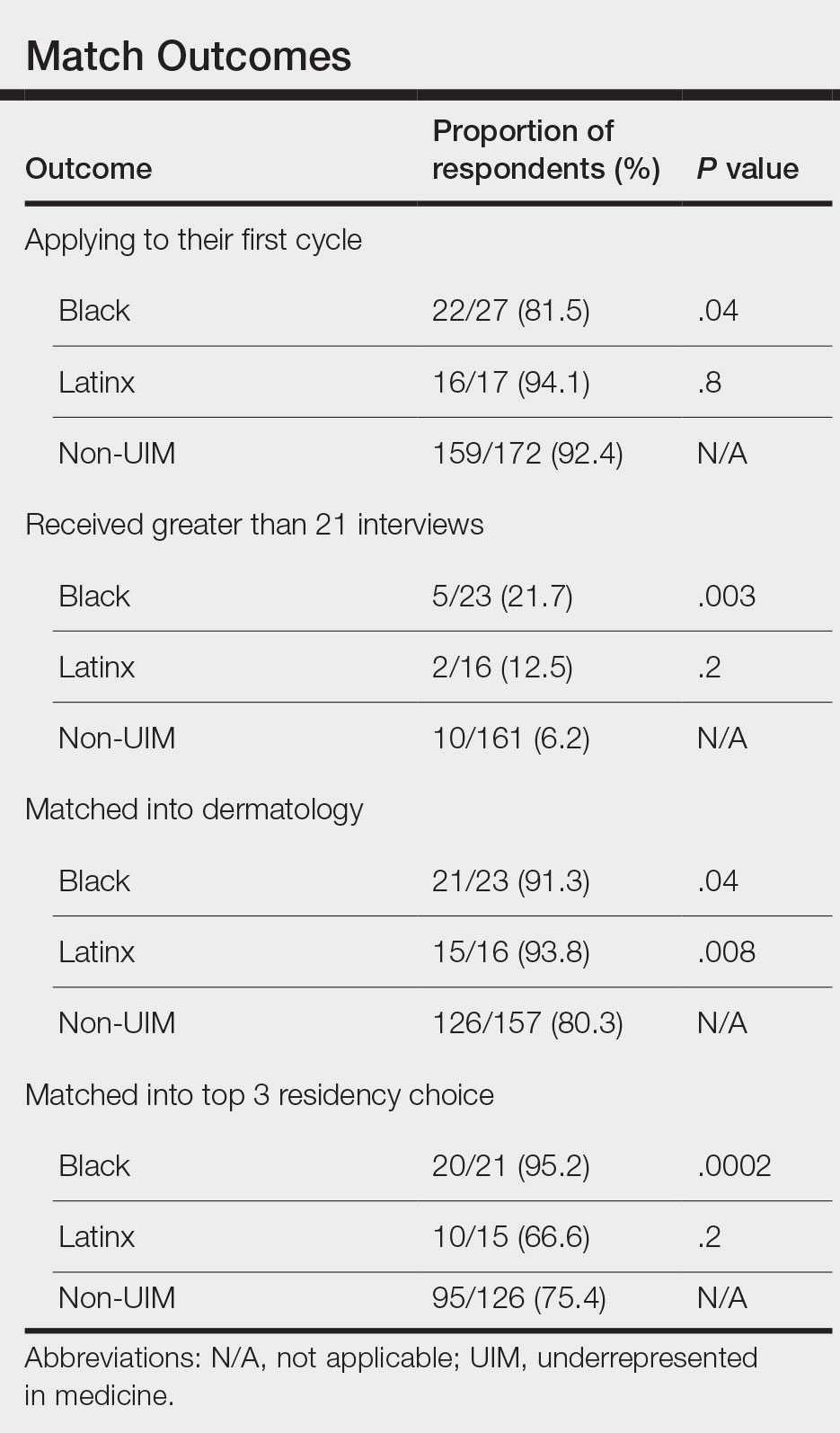

Application Process and Match Outcomes—The Table highlights differences in how UIM applicants approached the application process. Black but not Latinx applicants were less likely to be first-time applicants to dermatology compared to non-UIM applicants. Black applicants (8.3%) were significantly less likely to apply to more than 100 programs compared to non-UIM applicants (29.5%, P=.0002). Underrepresented in medicine applicants received greater numbers of interviews despite applying to fewer programs overall.

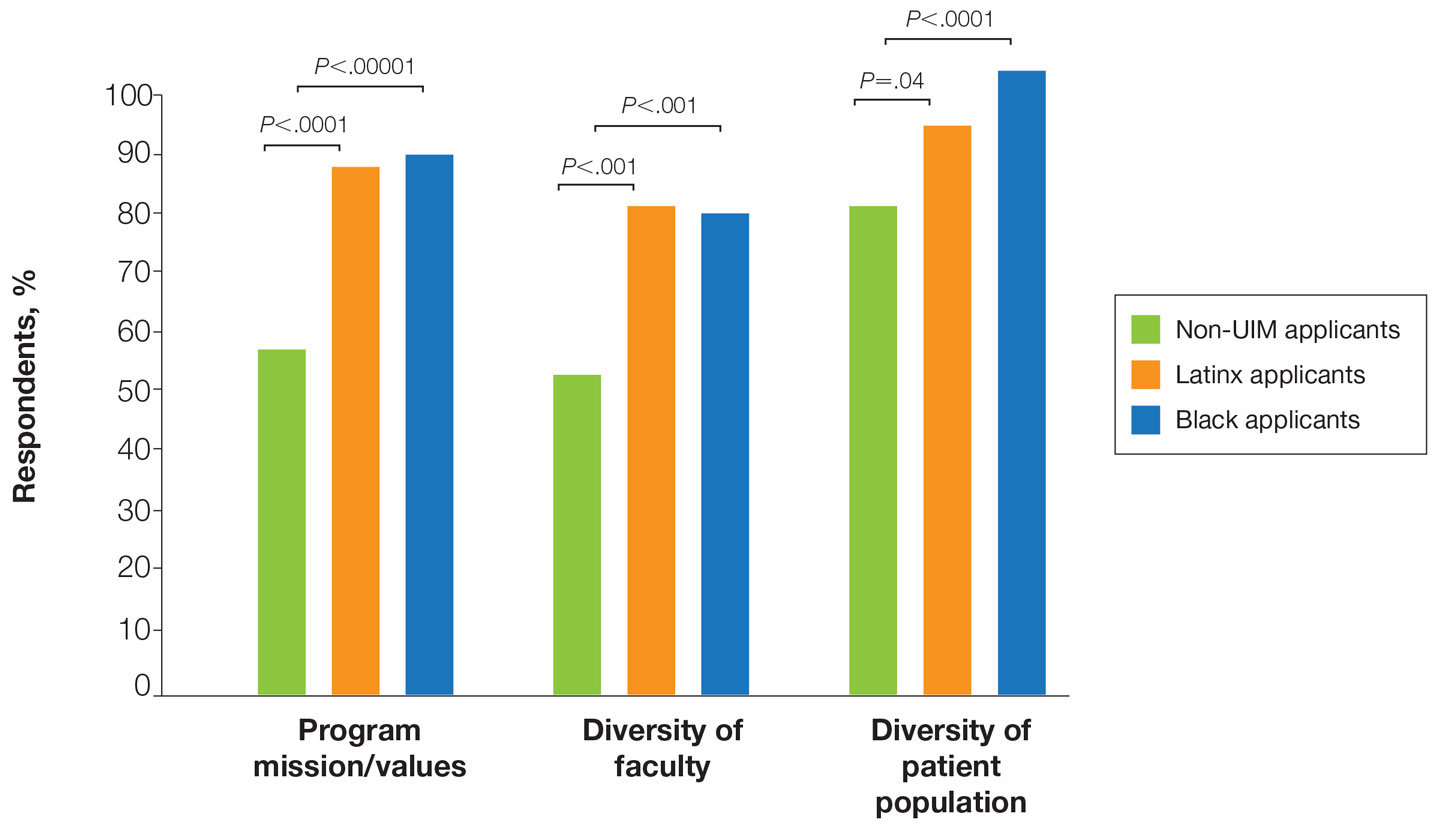

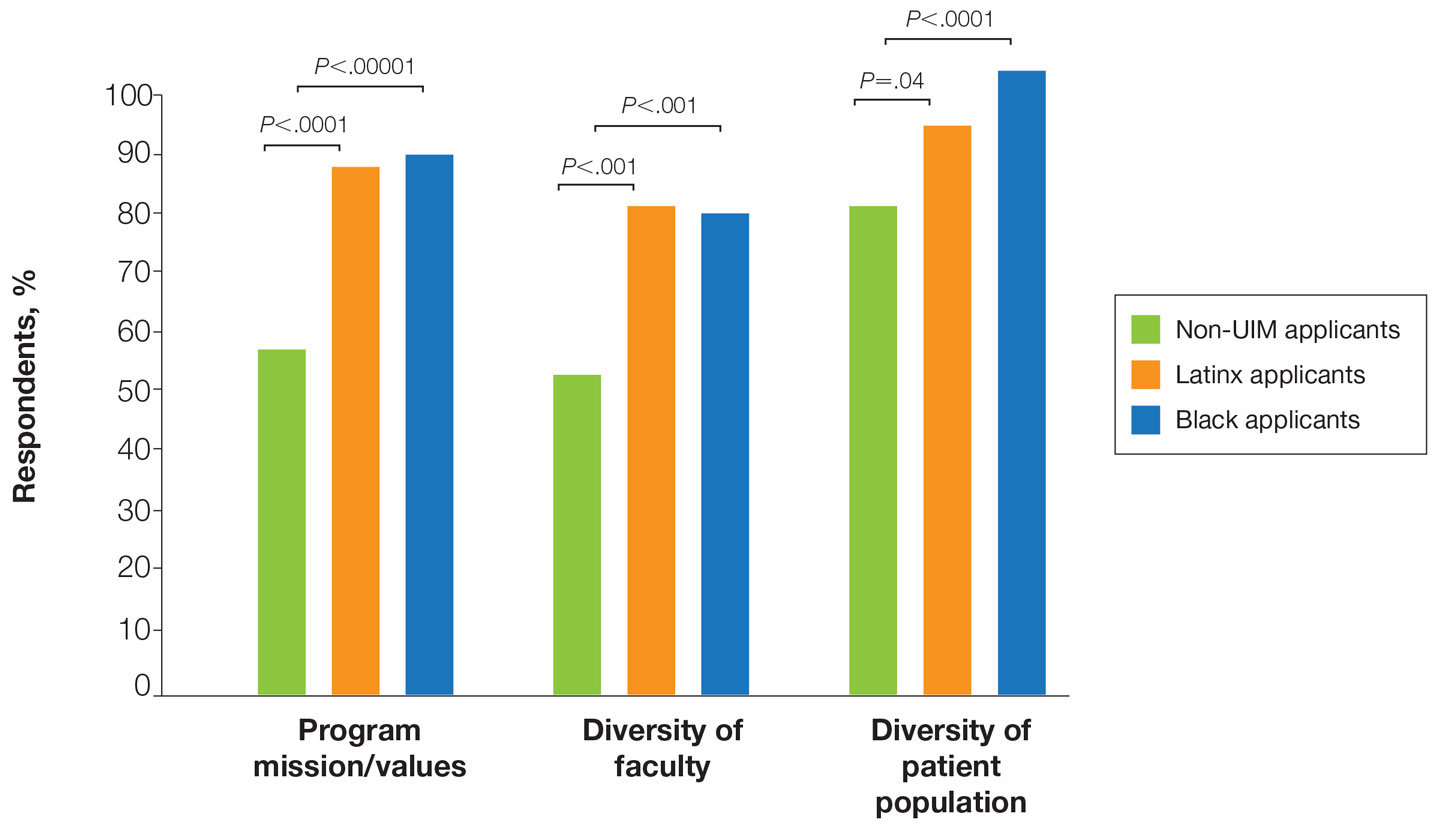

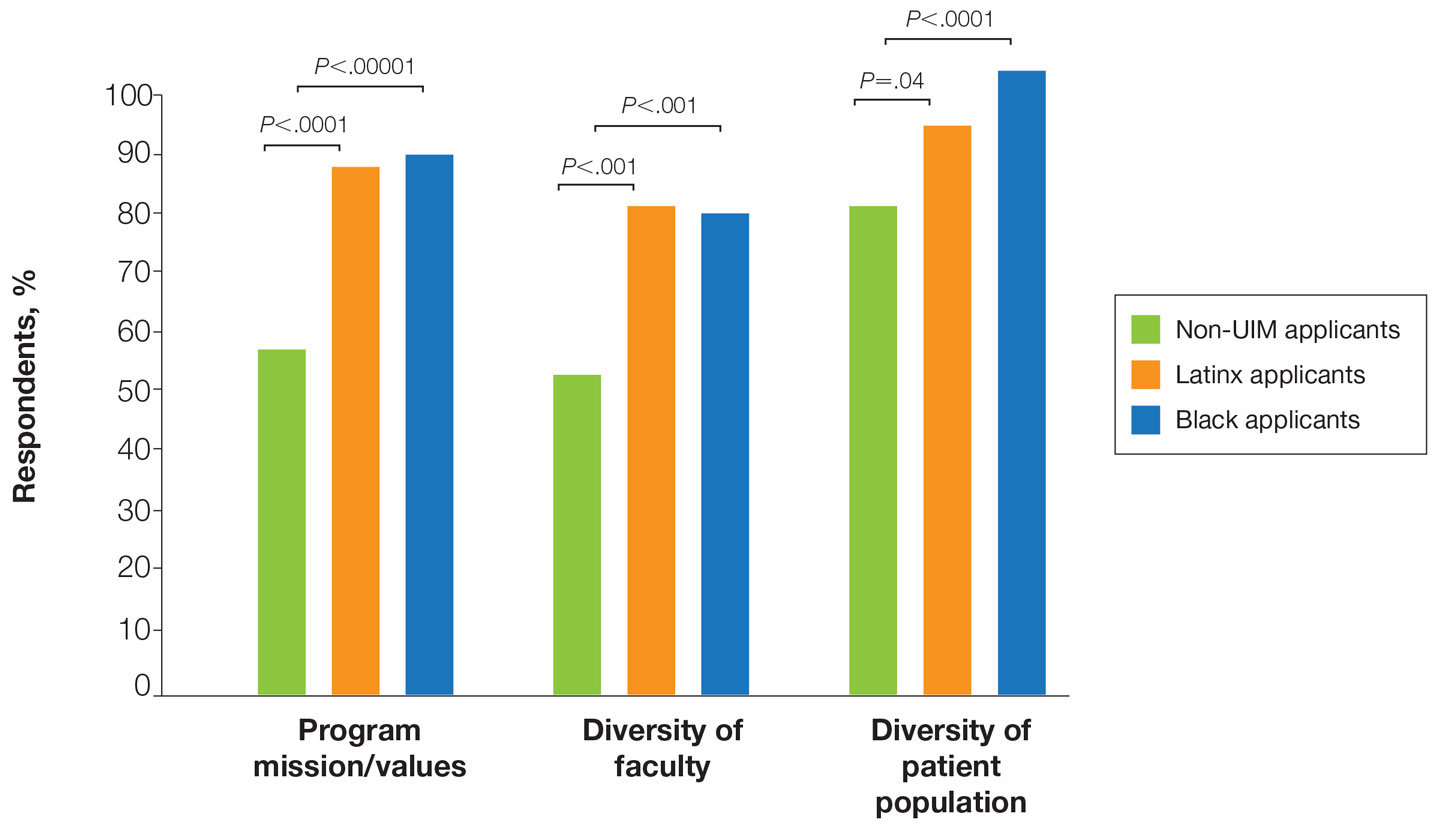

There also were differences in how UIM candidates approached their rank lists, with Black and Latinx applicants prioritizing diversity of patient populations and program faculty as well as program missions and values (Figure).

In our cohort, UIM candidates were more likely than non-UIM to match, and Black applicants were most likely to match at one of their top 3 choices (Table). In the PD survey, 77.6% of PDs considered contribution to diversity an important factor when compiling their rank lists.

Comment

Applicant Background—Dermatology is a competitive specialty with a challenging application process2 that has been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study elucidated how the 2020-2021 application cycle affected UIM dermatology applicants. Prior studies have found that UIM medical students were more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; financial constraints pose a major barrier for UIM and low-income students interested in dermatology.4-6 We found this to be true in our cohort, as Black and Latinx applicants were significantly more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds (P<.000008 and P=.006, respectively). Additionally, we found that Black applicants were more likely than any other group to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not taking a research gap year.

Although most applicants who completed a research year did so to increase their chances of matching, a higher percentage of UIMs took research years compared to non-UIM applicants. This finding could indicate greater anxiety about matching among UIM applicants vs their non-UIM counterparts. Black students have faced discrimination in clinical grading,7 have perceived racial discrimination in residency interviews,8,9 and have shown to be less likely to be elected to medical school honor societies.10 We found that UIM applicants were more likely to pursue a research year compared to other applicants,11 possibly because they felt additional pressure to enhance their applications or because UIM candidates were less likely to have a home dermatology program. Expansion of mentorship programs, visiting student electives, and grants for UIMs may alleviate the need for these candidates to complete a research year and reduce disparities in the application process.

Factors Influencing Rank Lists for Applicants—In our cohort, UIMs were significantly more likely to rank diversity of patients (P<.0001 for Black applicants and P=.04 for Latinx applicants) and faculty (P<.001 for Black applicants and P<.001 for Latinx applicants) as important factors in choosing a residency program. Historically, dermatology has been disproportionately White in its physician workforce and patient population.1,12 Students with lower incomes or who identify as minorities cite the lack of diversity in dermatology as a considerable barrier to pursuing a career in the specialty.4,5 Service learning, pipeline programs aimed at early exposure to dermatology, and increased access to care for diverse patient populations are important measures to improve diversity in the dermatology workforce.13-15 Residency programs should consider how to incorporate these aspects into didactic and clinical curricula to better recruit diverse candidates to the field.

Equity in the Application Process—We found that Black applicants were more likely than non-UIM applicants to be reapplicants to dermatology; however, Black applicants in our study also were more likely to receive more interview invites, match into dermatology, and match into one of their top 3 programs. These findings are interesting, particularly given concerns about equity in the application process. It is possible that Black applicants who overcome barriers to applying to dermatology ultimately are more successful applicants. Recently, there has been an increased focus in the field on diversifying dermatology, which was further intensified last year.2,3 Indicative of this shift, our PD survey showed that most programs reported that applicants’ contributions to diversity were important factors in the application process. Additionally, an emphasis by PDs on a holistic review of applications coupled with direct advocacy for increased representation may have contributed to the increased match rates for UIM applicants reported in our survey.

Latinx Applicants—Our study showed differences in how Latinx candidates fared in the application process; although Latinx applicants were more likely than their non-Latinx counterparts to match into dermatology, they were less likely than non-Latinx applicants to match into one of their top 3 programs. Given that Latinx encompasses ethnicity, not race, there may be a difference in how intentional focus on and advocacy for increasing diversity in dermatology affected different UIM applicant groups. Both race and ethnicity are social constructs rather than scientific categorizations; thus, it is difficult in survey studies such as ours to capture the intersectionality present across and between groups. Lastly, it is possible that the respondents to our applicant survey are not representative of the full cohort of UIM applicants.

Study Limitations—A major limitation of our study was that we did not have a method of reaching all dermatology applicants. Although our study shows promising results suggestive of increased diversity in the last application cycle, release of the National Resident Matching Program results from 2020-2021 with racially stratified data will be imperative to assess equity in the match process for all specialties and to confirm the generalizability of our results.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4683

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Diversity In Dermatology: Diversity Committee Approved Plan 2021-2023. Published January 26, 2021. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://assets.ctfassets.net/1ny4yoiyrqia/xQgnCE6ji5skUlcZQHS2b/65f0a9072811e11afcc33d043e02cd4d/DEI_Plan.pdf

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatologyresidency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Patel PM, et al. Considerations for dermatology residency applicants underrepresented in medicine amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E247.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.141

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Grbic D, Jones DJ, Case ST. The role of socioeconomic status in medical school admissions: validation of a socioeconomic indicator for use in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2015;90:953-960. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Ellis J, Otugo O, Landry A, et al. Interviewed while Black [published online November 11, 2020]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2401-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2023999

- Anthony Douglas II, Hendrix J. Black medical student considerations in the era of virtual interviews. Ann Surg. 2021;274:232-233. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004946

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Runge M, Renati S, Helfrich Y. 16146 dermatology residency applicants: how many pursue a dedicated research year or dual-degree, and do their stats differ [published online December 1, 2020]? J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.304

- Stern RS. Dermatologists and office-based care of dermatologic disease in the 21st century. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:126-130. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09108.x

- Oyesanya T, Grossberg AL, Okoye GA. Increasing minority representation in the dermatology department: the Johns Hopkins experience. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1133-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2018

- Humphrey VS, James AJ. The importance of service learning in dermatology residency: an actionable approach to improve resident education and skin health equity. Cutis. 2021;107:120-122. doi:10.12788/cutis.0199

Dermatology is one of the least diverse medical specialties with only 3% of dermatologists being Black and 4% Latinx.1 Leading dermatology organizations have called for specialty-wide efforts to improve diversity, with a particular focus on the resident selection process.2,3 Medical students who are underrepresented in medicine (UIM)(ie, those who identify as Black, Latinx, Native American, or Pacific Islander) face many potential barriers in applying to dermatology programs, including financial limitations, lack of support and mentorship, and less exposure to the specialty.1,2,4 The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges in the residency application process with limitations on clinical, research, and volunteer experiences; decreased opportunities for in-person mentorship and away rotations; and a shift to virtual recruitment. Although there has been increased emphasis on recruiting diverse candidates to dermatology, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated existing barriers for UIM applicants.

We surveyed dermatology residency program directors (PDs) and applicants to evaluate how UIM students approach and fare in the dermatology residency application process as well as the effects of COVID-19 on the most recent application cycle. Herein, we report the results of our surveys with a focus on racial differences in the application process.

Methods

We administered 2 anonymous online surveys—one to 115 PDs through the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) email listserve and another to applicants who participated in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle through the Dermatology Interest Group Association (DIGA) listserve. The surveys were distributed from March 29 through May 23, 2021. There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants on the DIGA listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (approval #UP-21-00118).

Participants were not required to answer every survey question; response rates varied by question. Survey responses with less than 10% completion were excluded from analysis. Data were collected, analyzed, and stored using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. The test of equal or given proportions in R studio was used to determine statistically significant differences between variables (P<.05 indicated statistical significance).

Results

The PD survey received 79 complete responses (83.5% complete responses, 73.8% response rate) and the applicant survey received 232 complete responses (83.6% complete responses).

Applicant Characteristics—Applicant characteristics are provided in the eTable; 13.2% and 8.4% of participants were Black and Latinx (including those who identify as Hispanic/Latino), respectively. Only 0.8% of respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native and were excluded from the analysis due to the limited sample size. Those who identified as White, Asian, multiple races, or other and those who preferred not to answer were considered non-UIM participants.

Differences in family background were observed in our cohort, with UIM candidates more likely to have experienced disadvantages, defined as being the first in their family to attend college/graduate school, growing up in a rural area, being a first-generation immigrant, or qualifying as low income. Underrepresented in medicine applicants also were less likely to have a dermatology program at their medical school (both Black and Latinx) and to have been elected to honor societies such as Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society (Black only).

Underrepresented in medicine applicants were more likely to complete a research gap year (eTable). Most applicants who took research years did so to improve their chances of matching, regardless of their race/ethnicity. For those who did not complete a research year, Black applicants (46.7%) were more likely to base that decision on financial limitations compared to non-UIMs (18.6%, P<.0001). Interestingly, in the PD survey, only 4.5% of respondents considered completion of a research year extremely or very important when compiling rank lists.

Application Process and Match Outcomes—The Table highlights differences in how UIM applicants approached the application process. Black but not Latinx applicants were less likely to be first-time applicants to dermatology compared to non-UIM applicants. Black applicants (8.3%) were significantly less likely to apply to more than 100 programs compared to non-UIM applicants (29.5%, P=.0002). Underrepresented in medicine applicants received greater numbers of interviews despite applying to fewer programs overall.

There also were differences in how UIM candidates approached their rank lists, with Black and Latinx applicants prioritizing diversity of patient populations and program faculty as well as program missions and values (Figure).

In our cohort, UIM candidates were more likely than non-UIM to match, and Black applicants were most likely to match at one of their top 3 choices (Table). In the PD survey, 77.6% of PDs considered contribution to diversity an important factor when compiling their rank lists.

Comment

Applicant Background—Dermatology is a competitive specialty with a challenging application process2 that has been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study elucidated how the 2020-2021 application cycle affected UIM dermatology applicants. Prior studies have found that UIM medical students were more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; financial constraints pose a major barrier for UIM and low-income students interested in dermatology.4-6 We found this to be true in our cohort, as Black and Latinx applicants were significantly more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds (P<.000008 and P=.006, respectively). Additionally, we found that Black applicants were more likely than any other group to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not taking a research gap year.

Although most applicants who completed a research year did so to increase their chances of matching, a higher percentage of UIMs took research years compared to non-UIM applicants. This finding could indicate greater anxiety about matching among UIM applicants vs their non-UIM counterparts. Black students have faced discrimination in clinical grading,7 have perceived racial discrimination in residency interviews,8,9 and have shown to be less likely to be elected to medical school honor societies.10 We found that UIM applicants were more likely to pursue a research year compared to other applicants,11 possibly because they felt additional pressure to enhance their applications or because UIM candidates were less likely to have a home dermatology program. Expansion of mentorship programs, visiting student electives, and grants for UIMs may alleviate the need for these candidates to complete a research year and reduce disparities in the application process.

Factors Influencing Rank Lists for Applicants—In our cohort, UIMs were significantly more likely to rank diversity of patients (P<.0001 for Black applicants and P=.04 for Latinx applicants) and faculty (P<.001 for Black applicants and P<.001 for Latinx applicants) as important factors in choosing a residency program. Historically, dermatology has been disproportionately White in its physician workforce and patient population.1,12 Students with lower incomes or who identify as minorities cite the lack of diversity in dermatology as a considerable barrier to pursuing a career in the specialty.4,5 Service learning, pipeline programs aimed at early exposure to dermatology, and increased access to care for diverse patient populations are important measures to improve diversity in the dermatology workforce.13-15 Residency programs should consider how to incorporate these aspects into didactic and clinical curricula to better recruit diverse candidates to the field.

Equity in the Application Process—We found that Black applicants were more likely than non-UIM applicants to be reapplicants to dermatology; however, Black applicants in our study also were more likely to receive more interview invites, match into dermatology, and match into one of their top 3 programs. These findings are interesting, particularly given concerns about equity in the application process. It is possible that Black applicants who overcome barriers to applying to dermatology ultimately are more successful applicants. Recently, there has been an increased focus in the field on diversifying dermatology, which was further intensified last year.2,3 Indicative of this shift, our PD survey showed that most programs reported that applicants’ contributions to diversity were important factors in the application process. Additionally, an emphasis by PDs on a holistic review of applications coupled with direct advocacy for increased representation may have contributed to the increased match rates for UIM applicants reported in our survey.

Latinx Applicants—Our study showed differences in how Latinx candidates fared in the application process; although Latinx applicants were more likely than their non-Latinx counterparts to match into dermatology, they were less likely than non-Latinx applicants to match into one of their top 3 programs. Given that Latinx encompasses ethnicity, not race, there may be a difference in how intentional focus on and advocacy for increasing diversity in dermatology affected different UIM applicant groups. Both race and ethnicity are social constructs rather than scientific categorizations; thus, it is difficult in survey studies such as ours to capture the intersectionality present across and between groups. Lastly, it is possible that the respondents to our applicant survey are not representative of the full cohort of UIM applicants.

Study Limitations—A major limitation of our study was that we did not have a method of reaching all dermatology applicants. Although our study shows promising results suggestive of increased diversity in the last application cycle, release of the National Resident Matching Program results from 2020-2021 with racially stratified data will be imperative to assess equity in the match process for all specialties and to confirm the generalizability of our results.

Dermatology is one of the least diverse medical specialties with only 3% of dermatologists being Black and 4% Latinx.1 Leading dermatology organizations have called for specialty-wide efforts to improve diversity, with a particular focus on the resident selection process.2,3 Medical students who are underrepresented in medicine (UIM)(ie, those who identify as Black, Latinx, Native American, or Pacific Islander) face many potential barriers in applying to dermatology programs, including financial limitations, lack of support and mentorship, and less exposure to the specialty.1,2,4 The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges in the residency application process with limitations on clinical, research, and volunteer experiences; decreased opportunities for in-person mentorship and away rotations; and a shift to virtual recruitment. Although there has been increased emphasis on recruiting diverse candidates to dermatology, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated existing barriers for UIM applicants.

We surveyed dermatology residency program directors (PDs) and applicants to evaluate how UIM students approach and fare in the dermatology residency application process as well as the effects of COVID-19 on the most recent application cycle. Herein, we report the results of our surveys with a focus on racial differences in the application process.

Methods

We administered 2 anonymous online surveys—one to 115 PDs through the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) email listserve and another to applicants who participated in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle through the Dermatology Interest Group Association (DIGA) listserve. The surveys were distributed from March 29 through May 23, 2021. There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants on the DIGA listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (approval #UP-21-00118).

Participants were not required to answer every survey question; response rates varied by question. Survey responses with less than 10% completion were excluded from analysis. Data were collected, analyzed, and stored using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. The test of equal or given proportions in R studio was used to determine statistically significant differences between variables (P<.05 indicated statistical significance).

Results

The PD survey received 79 complete responses (83.5% complete responses, 73.8% response rate) and the applicant survey received 232 complete responses (83.6% complete responses).

Applicant Characteristics—Applicant characteristics are provided in the eTable; 13.2% and 8.4% of participants were Black and Latinx (including those who identify as Hispanic/Latino), respectively. Only 0.8% of respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native and were excluded from the analysis due to the limited sample size. Those who identified as White, Asian, multiple races, or other and those who preferred not to answer were considered non-UIM participants.

Differences in family background were observed in our cohort, with UIM candidates more likely to have experienced disadvantages, defined as being the first in their family to attend college/graduate school, growing up in a rural area, being a first-generation immigrant, or qualifying as low income. Underrepresented in medicine applicants also were less likely to have a dermatology program at their medical school (both Black and Latinx) and to have been elected to honor societies such as Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society (Black only).

Underrepresented in medicine applicants were more likely to complete a research gap year (eTable). Most applicants who took research years did so to improve their chances of matching, regardless of their race/ethnicity. For those who did not complete a research year, Black applicants (46.7%) were more likely to base that decision on financial limitations compared to non-UIMs (18.6%, P<.0001). Interestingly, in the PD survey, only 4.5% of respondents considered completion of a research year extremely or very important when compiling rank lists.

Application Process and Match Outcomes—The Table highlights differences in how UIM applicants approached the application process. Black but not Latinx applicants were less likely to be first-time applicants to dermatology compared to non-UIM applicants. Black applicants (8.3%) were significantly less likely to apply to more than 100 programs compared to non-UIM applicants (29.5%, P=.0002). Underrepresented in medicine applicants received greater numbers of interviews despite applying to fewer programs overall.

There also were differences in how UIM candidates approached their rank lists, with Black and Latinx applicants prioritizing diversity of patient populations and program faculty as well as program missions and values (Figure).

In our cohort, UIM candidates were more likely than non-UIM to match, and Black applicants were most likely to match at one of their top 3 choices (Table). In the PD survey, 77.6% of PDs considered contribution to diversity an important factor when compiling their rank lists.

Comment

Applicant Background—Dermatology is a competitive specialty with a challenging application process2 that has been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study elucidated how the 2020-2021 application cycle affected UIM dermatology applicants. Prior studies have found that UIM medical students were more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; financial constraints pose a major barrier for UIM and low-income students interested in dermatology.4-6 We found this to be true in our cohort, as Black and Latinx applicants were significantly more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds (P<.000008 and P=.006, respectively). Additionally, we found that Black applicants were more likely than any other group to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not taking a research gap year.

Although most applicants who completed a research year did so to increase their chances of matching, a higher percentage of UIMs took research years compared to non-UIM applicants. This finding could indicate greater anxiety about matching among UIM applicants vs their non-UIM counterparts. Black students have faced discrimination in clinical grading,7 have perceived racial discrimination in residency interviews,8,9 and have shown to be less likely to be elected to medical school honor societies.10 We found that UIM applicants were more likely to pursue a research year compared to other applicants,11 possibly because they felt additional pressure to enhance their applications or because UIM candidates were less likely to have a home dermatology program. Expansion of mentorship programs, visiting student electives, and grants for UIMs may alleviate the need for these candidates to complete a research year and reduce disparities in the application process.

Factors Influencing Rank Lists for Applicants—In our cohort, UIMs were significantly more likely to rank diversity of patients (P<.0001 for Black applicants and P=.04 for Latinx applicants) and faculty (P<.001 for Black applicants and P<.001 for Latinx applicants) as important factors in choosing a residency program. Historically, dermatology has been disproportionately White in its physician workforce and patient population.1,12 Students with lower incomes or who identify as minorities cite the lack of diversity in dermatology as a considerable barrier to pursuing a career in the specialty.4,5 Service learning, pipeline programs aimed at early exposure to dermatology, and increased access to care for diverse patient populations are important measures to improve diversity in the dermatology workforce.13-15 Residency programs should consider how to incorporate these aspects into didactic and clinical curricula to better recruit diverse candidates to the field.

Equity in the Application Process—We found that Black applicants were more likely than non-UIM applicants to be reapplicants to dermatology; however, Black applicants in our study also were more likely to receive more interview invites, match into dermatology, and match into one of their top 3 programs. These findings are interesting, particularly given concerns about equity in the application process. It is possible that Black applicants who overcome barriers to applying to dermatology ultimately are more successful applicants. Recently, there has been an increased focus in the field on diversifying dermatology, which was further intensified last year.2,3 Indicative of this shift, our PD survey showed that most programs reported that applicants’ contributions to diversity were important factors in the application process. Additionally, an emphasis by PDs on a holistic review of applications coupled with direct advocacy for increased representation may have contributed to the increased match rates for UIM applicants reported in our survey.

Latinx Applicants—Our study showed differences in how Latinx candidates fared in the application process; although Latinx applicants were more likely than their non-Latinx counterparts to match into dermatology, they were less likely than non-Latinx applicants to match into one of their top 3 programs. Given that Latinx encompasses ethnicity, not race, there may be a difference in how intentional focus on and advocacy for increasing diversity in dermatology affected different UIM applicant groups. Both race and ethnicity are social constructs rather than scientific categorizations; thus, it is difficult in survey studies such as ours to capture the intersectionality present across and between groups. Lastly, it is possible that the respondents to our applicant survey are not representative of the full cohort of UIM applicants.

Study Limitations—A major limitation of our study was that we did not have a method of reaching all dermatology applicants. Although our study shows promising results suggestive of increased diversity in the last application cycle, release of the National Resident Matching Program results from 2020-2021 with racially stratified data will be imperative to assess equity in the match process for all specialties and to confirm the generalizability of our results.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4683

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Diversity In Dermatology: Diversity Committee Approved Plan 2021-2023. Published January 26, 2021. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://assets.ctfassets.net/1ny4yoiyrqia/xQgnCE6ji5skUlcZQHS2b/65f0a9072811e11afcc33d043e02cd4d/DEI_Plan.pdf

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatologyresidency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Patel PM, et al. Considerations for dermatology residency applicants underrepresented in medicine amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E247.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.141

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Grbic D, Jones DJ, Case ST. The role of socioeconomic status in medical school admissions: validation of a socioeconomic indicator for use in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2015;90:953-960. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Ellis J, Otugo O, Landry A, et al. Interviewed while Black [published online November 11, 2020]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2401-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2023999

- Anthony Douglas II, Hendrix J. Black medical student considerations in the era of virtual interviews. Ann Surg. 2021;274:232-233. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004946

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Runge M, Renati S, Helfrich Y. 16146 dermatology residency applicants: how many pursue a dedicated research year or dual-degree, and do their stats differ [published online December 1, 2020]? J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.304

- Stern RS. Dermatologists and office-based care of dermatologic disease in the 21st century. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:126-130. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09108.x

- Oyesanya T, Grossberg AL, Okoye GA. Increasing minority representation in the dermatology department: the Johns Hopkins experience. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1133-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2018

- Humphrey VS, James AJ. The importance of service learning in dermatology residency: an actionable approach to improve resident education and skin health equity. Cutis. 2021;107:120-122. doi:10.12788/cutis.0199

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4683

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Diversity In Dermatology: Diversity Committee Approved Plan 2021-2023. Published January 26, 2021. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://assets.ctfassets.net/1ny4yoiyrqia/xQgnCE6ji5skUlcZQHS2b/65f0a9072811e11afcc33d043e02cd4d/DEI_Plan.pdf

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatologyresidency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Patel PM, et al. Considerations for dermatology residency applicants underrepresented in medicine amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E247.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.141

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Grbic D, Jones DJ, Case ST. The role of socioeconomic status in medical school admissions: validation of a socioeconomic indicator for use in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2015;90:953-960. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Ellis J, Otugo O, Landry A, et al. Interviewed while Black [published online November 11, 2020]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2401-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2023999

- Anthony Douglas II, Hendrix J. Black medical student considerations in the era of virtual interviews. Ann Surg. 2021;274:232-233. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004946

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Runge M, Renati S, Helfrich Y. 16146 dermatology residency applicants: how many pursue a dedicated research year or dual-degree, and do their stats differ [published online December 1, 2020]? J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.304

- Stern RS. Dermatologists and office-based care of dermatologic disease in the 21st century. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:126-130. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09108.x

- Oyesanya T, Grossberg AL, Okoye GA. Increasing minority representation in the dermatology department: the Johns Hopkins experience. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1133-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2018

- Humphrey VS, James AJ. The importance of service learning in dermatology residency: an actionable approach to improve resident education and skin health equity. Cutis. 2021;107:120-122. doi:10.12788/cutis.0199

Practice Points

- Underrepresented in medicine (UIM) dermatology residency applicants (Black and Latinx) are more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds and to have financial concerns about the residency application process.

- When choosing a dermatology residency program, diversity of patients and faculty are more important to UIM dermatology residency applicants than to their non-UIM counterparts.

- Increased awareness of and focus on a holistic review process by dermatology residency programs may contribute to higher rates of matching among Black applicants in our study.