User login

Cyclically Bleeding Umbilical Papules

Cyclically Bleeding Umbilical Papules

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Endometriosis

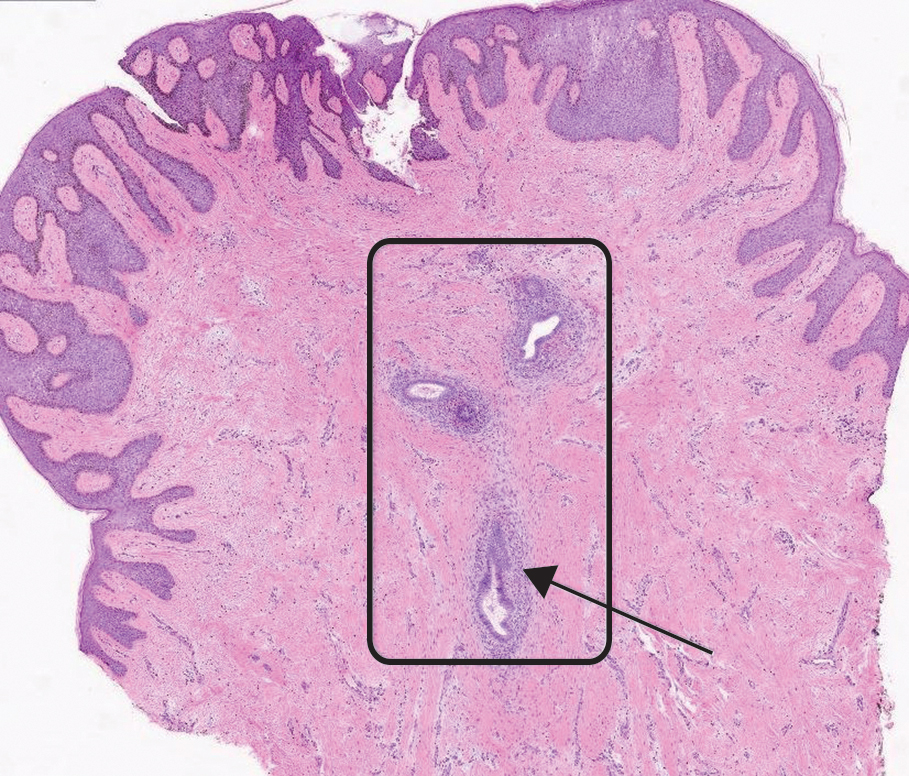

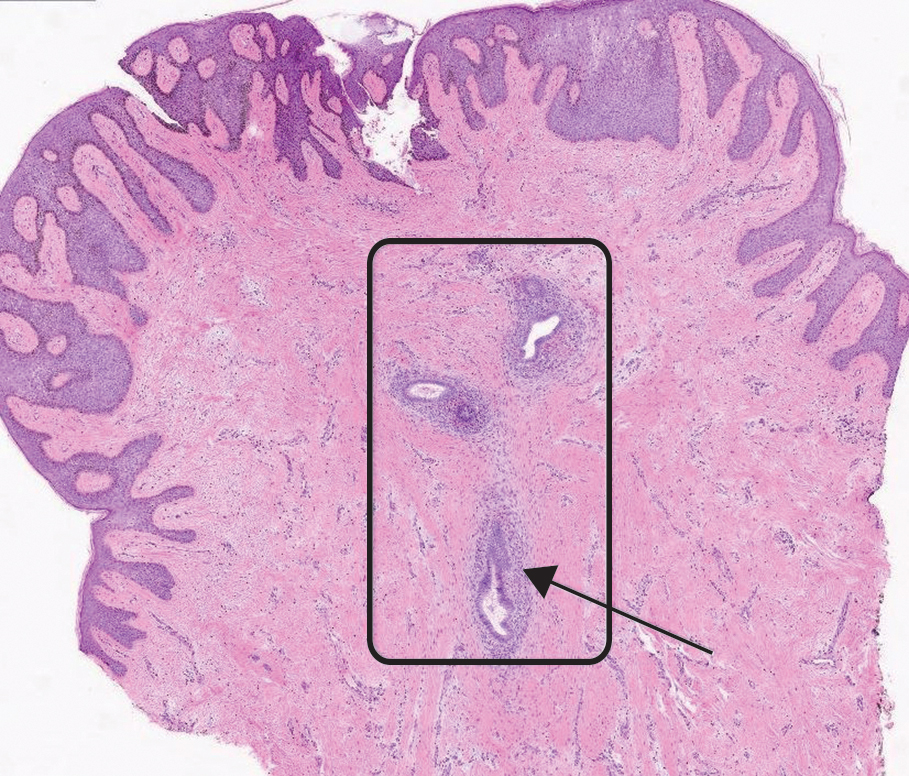

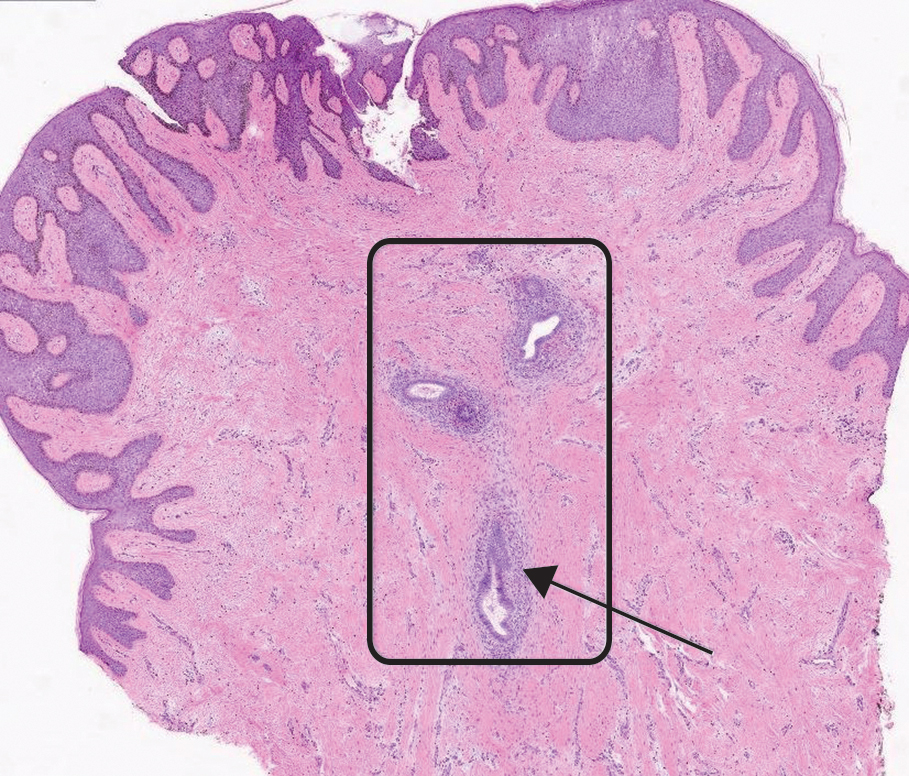

On histopathology, a biopsy specimen of an umbilical papule showed a dermal lymphohistiocyticrich infiltrate, hemorrhage, and ectopic endometrial glands consistent with cutaneous endometriosis (CE)(Figure). Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare condition that typically affects females of reproductive potential and is characterized by endometrial glands and stroma within the dermis and hypodermis. Cutaneous endometriosis is classified as primary or secondary. There is no surgical history of the abdomen or pelvis in primary CE. In contrast, a history of abdominopelvic surgery is the defining characteristic of secondary CE, which is more common than primary CE and typically manifests as painful red, brown, or purple papules along preexisting surgical scars of the umbilicus, lower abdomen, or pelvic region.1 Our patient may have developed secondary CE related to the laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed 10 years prior. Surgical excision is considered the definitive treatment for CE, and hormonal therapy with danazol or leuprolide may help ameliorate symptoms.1 Our patient deferred any hormonal or surgical interventions to undergo fertility treatments for pregnancy.

Cyclical bleeding and pain that coincides with menstruation is consistent with CE; however, cyclical symptoms are not always present, which can lead to delayed or incorrect diagnosis. Biopsy and histopathologic analysis are required for definitive diagnosis and are critical for distinguishing CE from other conditions. The differential diagnosis in our patient included pyogenic granuloma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, keloid, and cutaneous metastasis of a primary malignancy. Vascular lesions such as pyogenic granuloma can manifest with bleeding but have a characteristic histopathologic lobular capillary arrangement that was not present in our patient.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, slow-growing, malignant soft-tissue sarcoma that most commonly manifests on the trunk, arms, and legs.2 It is characterized by a slow-growing, indurated plaque that often is present for years and may suddenly progress into a smooth, red-brown, multinodular mass. Histopathology typically shows spindle cells infiltrating the dermis and subcutaneous tissue in storiform or whorled pattern with variations based on the tumor stage, as well as diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.2

Keloids are dense, raised, hyperpigmented, fibrous nodules—sometimes with accompanying telangiectasias—that typically grow secondary to trauma and project past the boundaries of the initial trauma site.1 Keloids are more commonly seen in individuals with darker skin types and tend to grow larger in this population. Histopathology reveals thickened hyalinized collagen bundles, which were not seen in our patient.1

Metastatic skin lesions of the umbilicus are rare but can arise from internal malignancies including cancers of the lung, colon, and breast.3 We considered Sister Mary Joseph nodule, which is caused most commonly by metastasis of a primary gastrointestinal cancer and signifies poor prognosis. The histopathology of metastatic lesions would reveal the presence of atypical cells with cancer-specific markers. Histopathology along with the patient’s personal and family history, a comprehensive review of symptoms, and cancer screening may help with reaching the correct diagnosis.

The average duration between abdominopelvic surgery and onset of secondary CE symptoms is 3.7 to 5.3 years.4 Our patient presented 10 years post surgery and after cessation of oral contraception, which may suggest a potential role of hormonal contraception in delayed CE onset. Diagnosis of CE can be challenging due to atypical signs or symptoms, delayed onset, and lack of awareness among health care professionals. Patients with delayed diagnosis may endure multiple procedures, prolonged physical pain, and emotional distress. Furthermore, 30% to 50% of females with endometriosis experience infertility. Delayed diagnosis of CE compounded with associated age-related increase in oocyte atresia could potentially worsen fecundity as patients age.5 It is important to consider CE in the differential diagnosis of females of reproductive age who present with cyclical bleeding and abdominal or umbilical nodules.

- James WD, Elston D, Treat JR, et al. Andrews Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2019. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://search.worldcat.org/title/1084979207

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752.

- Komurcugil I, Arslan Z, Bal ZI, et al. Cutaneous metastases different clinical presentations: case series and review of the literature. Dermatol Reports. 2022;15:9553.

- Marras S, Pluchino N, Petignat P, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: an 11-year retrospective observational cohort study. Published online September 16, 2019. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, et al. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:784-796.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Endometriosis

On histopathology, a biopsy specimen of an umbilical papule showed a dermal lymphohistiocyticrich infiltrate, hemorrhage, and ectopic endometrial glands consistent with cutaneous endometriosis (CE)(Figure). Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare condition that typically affects females of reproductive potential and is characterized by endometrial glands and stroma within the dermis and hypodermis. Cutaneous endometriosis is classified as primary or secondary. There is no surgical history of the abdomen or pelvis in primary CE. In contrast, a history of abdominopelvic surgery is the defining characteristic of secondary CE, which is more common than primary CE and typically manifests as painful red, brown, or purple papules along preexisting surgical scars of the umbilicus, lower abdomen, or pelvic region.1 Our patient may have developed secondary CE related to the laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed 10 years prior. Surgical excision is considered the definitive treatment for CE, and hormonal therapy with danazol or leuprolide may help ameliorate symptoms.1 Our patient deferred any hormonal or surgical interventions to undergo fertility treatments for pregnancy.

Cyclical bleeding and pain that coincides with menstruation is consistent with CE; however, cyclical symptoms are not always present, which can lead to delayed or incorrect diagnosis. Biopsy and histopathologic analysis are required for definitive diagnosis and are critical for distinguishing CE from other conditions. The differential diagnosis in our patient included pyogenic granuloma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, keloid, and cutaneous metastasis of a primary malignancy. Vascular lesions such as pyogenic granuloma can manifest with bleeding but have a characteristic histopathologic lobular capillary arrangement that was not present in our patient.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, slow-growing, malignant soft-tissue sarcoma that most commonly manifests on the trunk, arms, and legs.2 It is characterized by a slow-growing, indurated plaque that often is present for years and may suddenly progress into a smooth, red-brown, multinodular mass. Histopathology typically shows spindle cells infiltrating the dermis and subcutaneous tissue in storiform or whorled pattern with variations based on the tumor stage, as well as diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.2

Keloids are dense, raised, hyperpigmented, fibrous nodules—sometimes with accompanying telangiectasias—that typically grow secondary to trauma and project past the boundaries of the initial trauma site.1 Keloids are more commonly seen in individuals with darker skin types and tend to grow larger in this population. Histopathology reveals thickened hyalinized collagen bundles, which were not seen in our patient.1

Metastatic skin lesions of the umbilicus are rare but can arise from internal malignancies including cancers of the lung, colon, and breast.3 We considered Sister Mary Joseph nodule, which is caused most commonly by metastasis of a primary gastrointestinal cancer and signifies poor prognosis. The histopathology of metastatic lesions would reveal the presence of atypical cells with cancer-specific markers. Histopathology along with the patient’s personal and family history, a comprehensive review of symptoms, and cancer screening may help with reaching the correct diagnosis.

The average duration between abdominopelvic surgery and onset of secondary CE symptoms is 3.7 to 5.3 years.4 Our patient presented 10 years post surgery and after cessation of oral contraception, which may suggest a potential role of hormonal contraception in delayed CE onset. Diagnosis of CE can be challenging due to atypical signs or symptoms, delayed onset, and lack of awareness among health care professionals. Patients with delayed diagnosis may endure multiple procedures, prolonged physical pain, and emotional distress. Furthermore, 30% to 50% of females with endometriosis experience infertility. Delayed diagnosis of CE compounded with associated age-related increase in oocyte atresia could potentially worsen fecundity as patients age.5 It is important to consider CE in the differential diagnosis of females of reproductive age who present with cyclical bleeding and abdominal or umbilical nodules.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Endometriosis

On histopathology, a biopsy specimen of an umbilical papule showed a dermal lymphohistiocyticrich infiltrate, hemorrhage, and ectopic endometrial glands consistent with cutaneous endometriosis (CE)(Figure). Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare condition that typically affects females of reproductive potential and is characterized by endometrial glands and stroma within the dermis and hypodermis. Cutaneous endometriosis is classified as primary or secondary. There is no surgical history of the abdomen or pelvis in primary CE. In contrast, a history of abdominopelvic surgery is the defining characteristic of secondary CE, which is more common than primary CE and typically manifests as painful red, brown, or purple papules along preexisting surgical scars of the umbilicus, lower abdomen, or pelvic region.1 Our patient may have developed secondary CE related to the laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed 10 years prior. Surgical excision is considered the definitive treatment for CE, and hormonal therapy with danazol or leuprolide may help ameliorate symptoms.1 Our patient deferred any hormonal or surgical interventions to undergo fertility treatments for pregnancy.

Cyclical bleeding and pain that coincides with menstruation is consistent with CE; however, cyclical symptoms are not always present, which can lead to delayed or incorrect diagnosis. Biopsy and histopathologic analysis are required for definitive diagnosis and are critical for distinguishing CE from other conditions. The differential diagnosis in our patient included pyogenic granuloma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, keloid, and cutaneous metastasis of a primary malignancy. Vascular lesions such as pyogenic granuloma can manifest with bleeding but have a characteristic histopathologic lobular capillary arrangement that was not present in our patient.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, slow-growing, malignant soft-tissue sarcoma that most commonly manifests on the trunk, arms, and legs.2 It is characterized by a slow-growing, indurated plaque that often is present for years and may suddenly progress into a smooth, red-brown, multinodular mass. Histopathology typically shows spindle cells infiltrating the dermis and subcutaneous tissue in storiform or whorled pattern with variations based on the tumor stage, as well as diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.2

Keloids are dense, raised, hyperpigmented, fibrous nodules—sometimes with accompanying telangiectasias—that typically grow secondary to trauma and project past the boundaries of the initial trauma site.1 Keloids are more commonly seen in individuals with darker skin types and tend to grow larger in this population. Histopathology reveals thickened hyalinized collagen bundles, which were not seen in our patient.1

Metastatic skin lesions of the umbilicus are rare but can arise from internal malignancies including cancers of the lung, colon, and breast.3 We considered Sister Mary Joseph nodule, which is caused most commonly by metastasis of a primary gastrointestinal cancer and signifies poor prognosis. The histopathology of metastatic lesions would reveal the presence of atypical cells with cancer-specific markers. Histopathology along with the patient’s personal and family history, a comprehensive review of symptoms, and cancer screening may help with reaching the correct diagnosis.

The average duration between abdominopelvic surgery and onset of secondary CE symptoms is 3.7 to 5.3 years.4 Our patient presented 10 years post surgery and after cessation of oral contraception, which may suggest a potential role of hormonal contraception in delayed CE onset. Diagnosis of CE can be challenging due to atypical signs or symptoms, delayed onset, and lack of awareness among health care professionals. Patients with delayed diagnosis may endure multiple procedures, prolonged physical pain, and emotional distress. Furthermore, 30% to 50% of females with endometriosis experience infertility. Delayed diagnosis of CE compounded with associated age-related increase in oocyte atresia could potentially worsen fecundity as patients age.5 It is important to consider CE in the differential diagnosis of females of reproductive age who present with cyclical bleeding and abdominal or umbilical nodules.

- James WD, Elston D, Treat JR, et al. Andrews Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2019. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://search.worldcat.org/title/1084979207

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752.

- Komurcugil I, Arslan Z, Bal ZI, et al. Cutaneous metastases different clinical presentations: case series and review of the literature. Dermatol Reports. 2022;15:9553.

- Marras S, Pluchino N, Petignat P, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: an 11-year retrospective observational cohort study. Published online September 16, 2019. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, et al. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:784-796.

- James WD, Elston D, Treat JR, et al. Andrews Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2019. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://search.worldcat.org/title/1084979207

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752.

- Komurcugil I, Arslan Z, Bal ZI, et al. Cutaneous metastases different clinical presentations: case series and review of the literature. Dermatol Reports. 2022;15:9553.

- Marras S, Pluchino N, Petignat P, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: an 11-year retrospective observational cohort study. Published online September 16, 2019. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, et al. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:784-796.

Cyclically Bleeding Umbilical Papules

Cyclically Bleeding Umbilical Papules

A 38-year-old nulligravid female with menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea presented with cyclical umbilical bleeding of 1 year’s duration. Shortly before the onset of symptoms, the patient had discontinued oral contraceptive therapy with the intent to become pregnant. She had an uncomplicated laparoscopic cholecystectomy 10 years prior, but her medical history was otherwise unremarkable. At the current presentation, physical examination revealed multilobular brown papules with serosanguineous crusting in the umbilicus.