User login

Tender Nodule on the Umbilicus

Tender Nodule on the Umbilicus

THE DIAGNOSIS: Villar Nodule

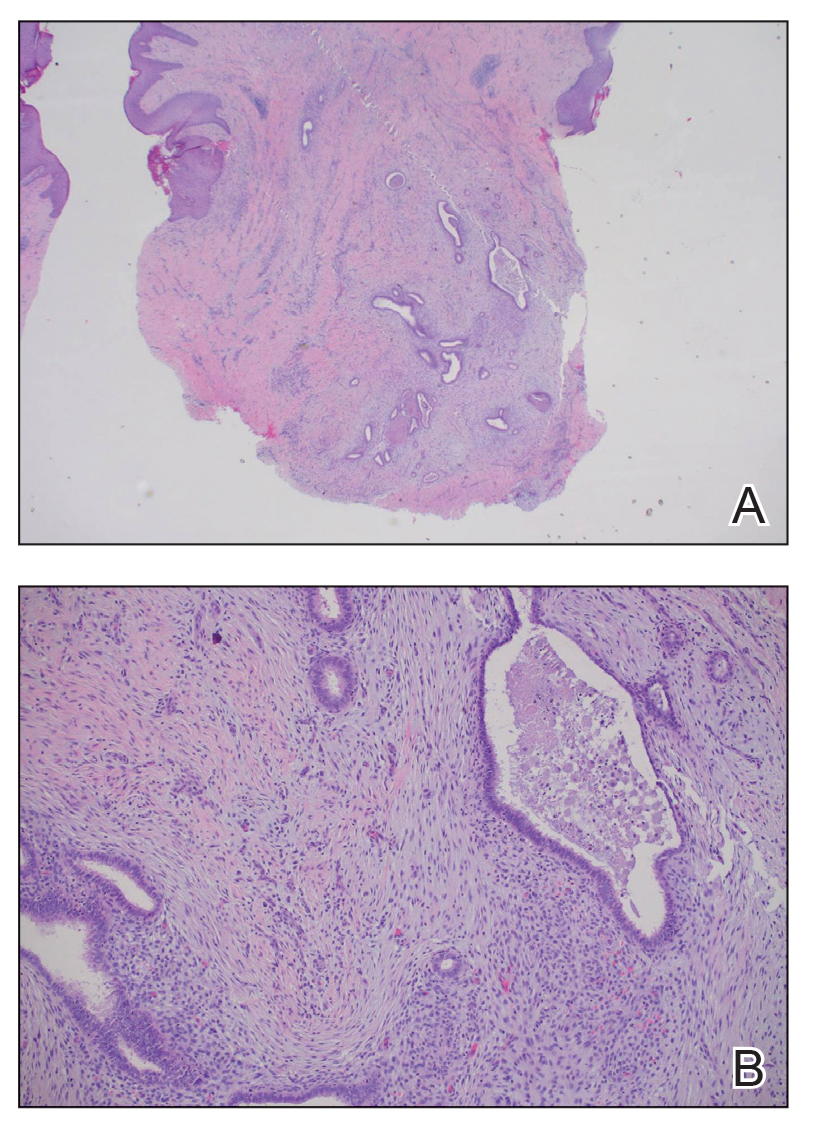

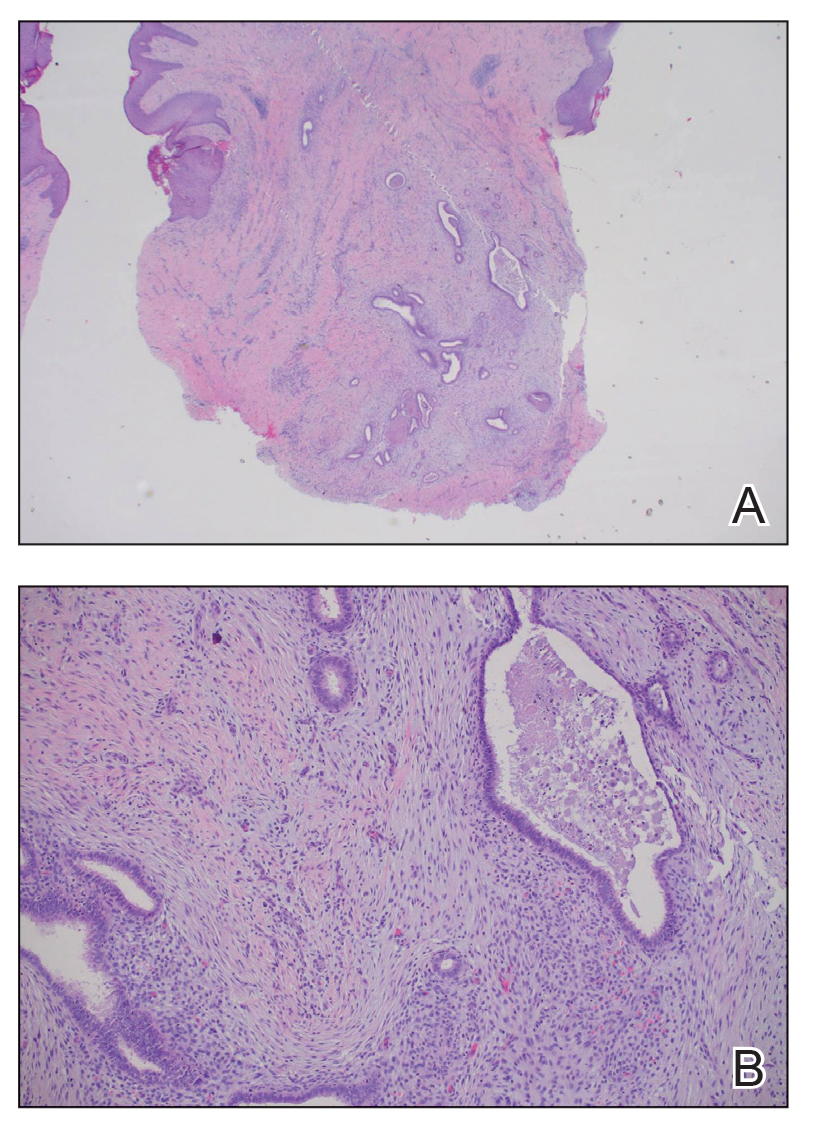

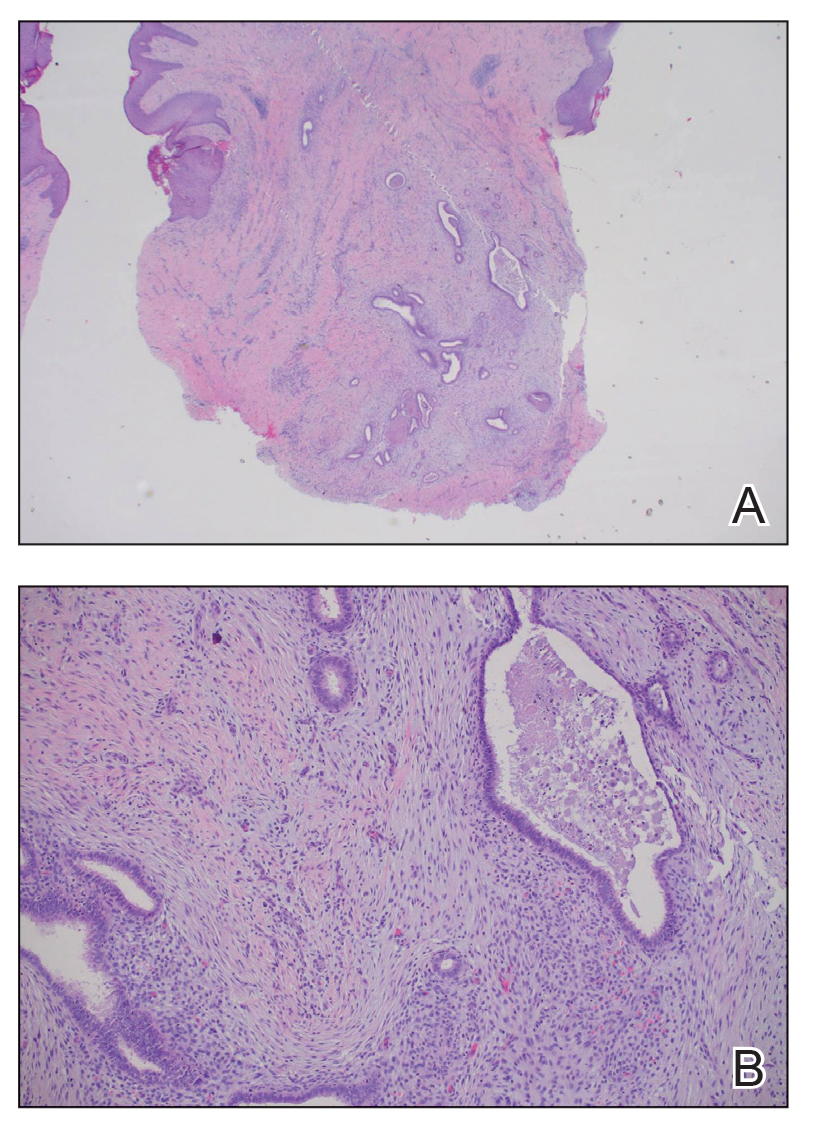

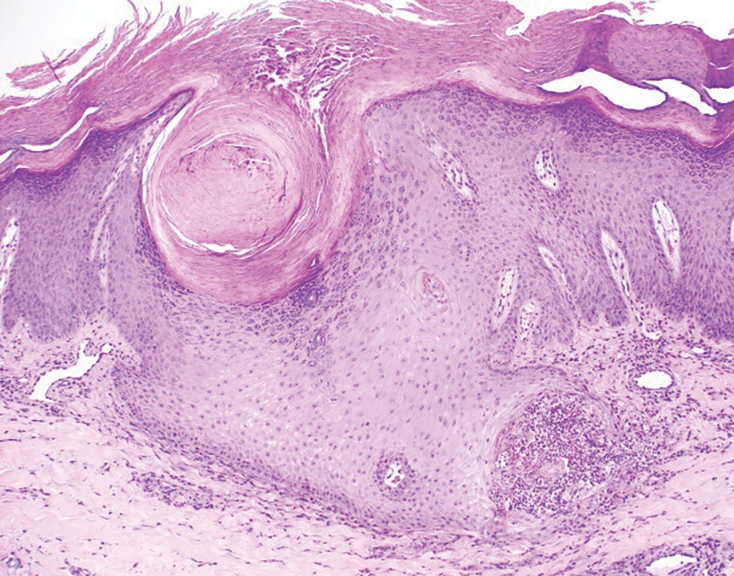

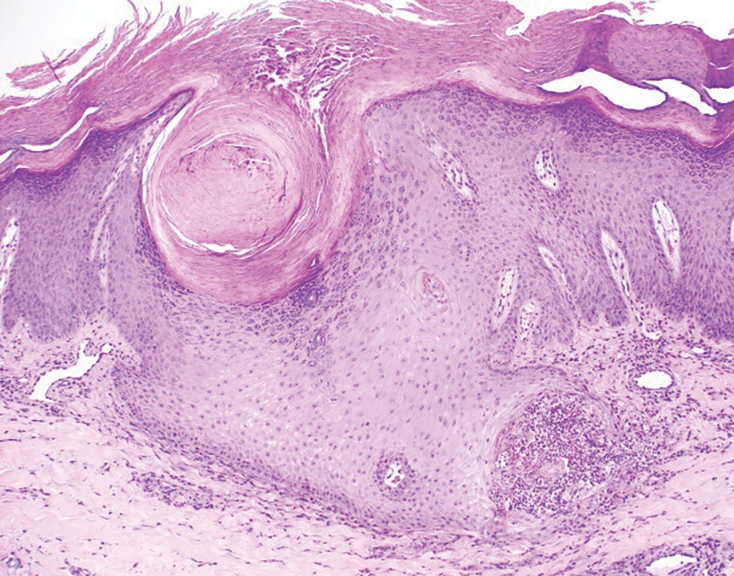

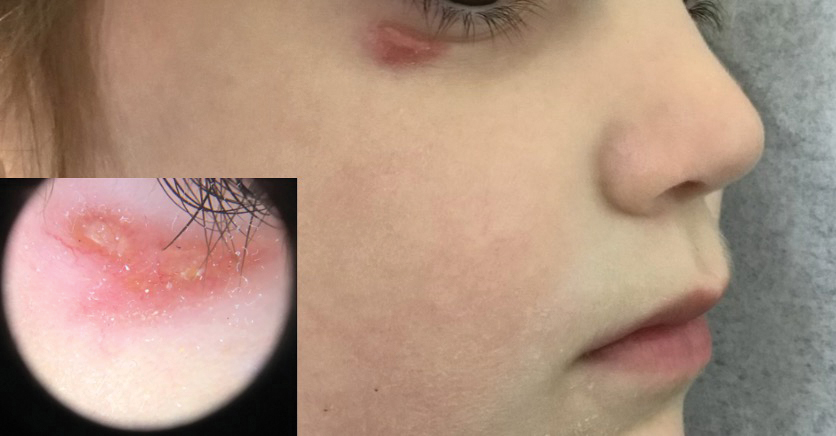

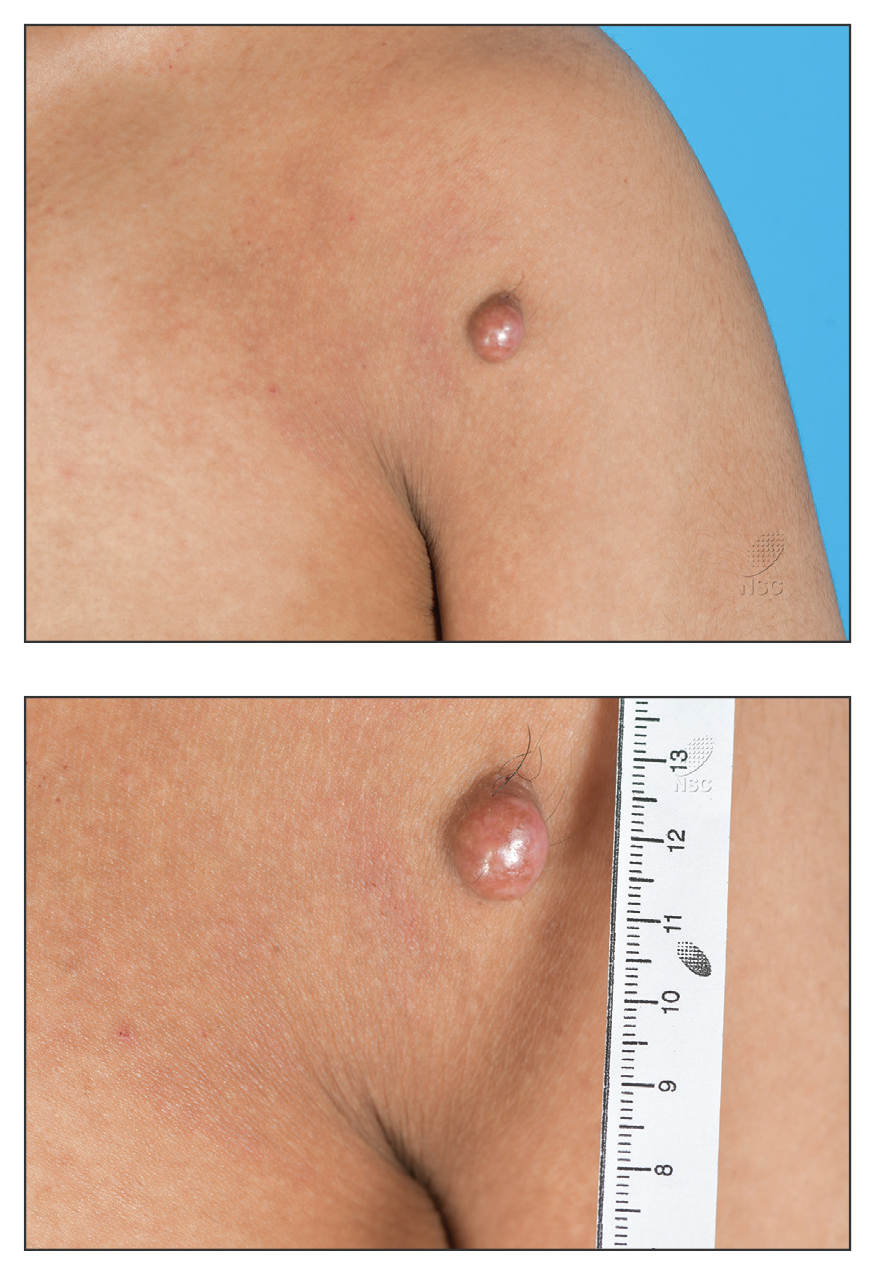

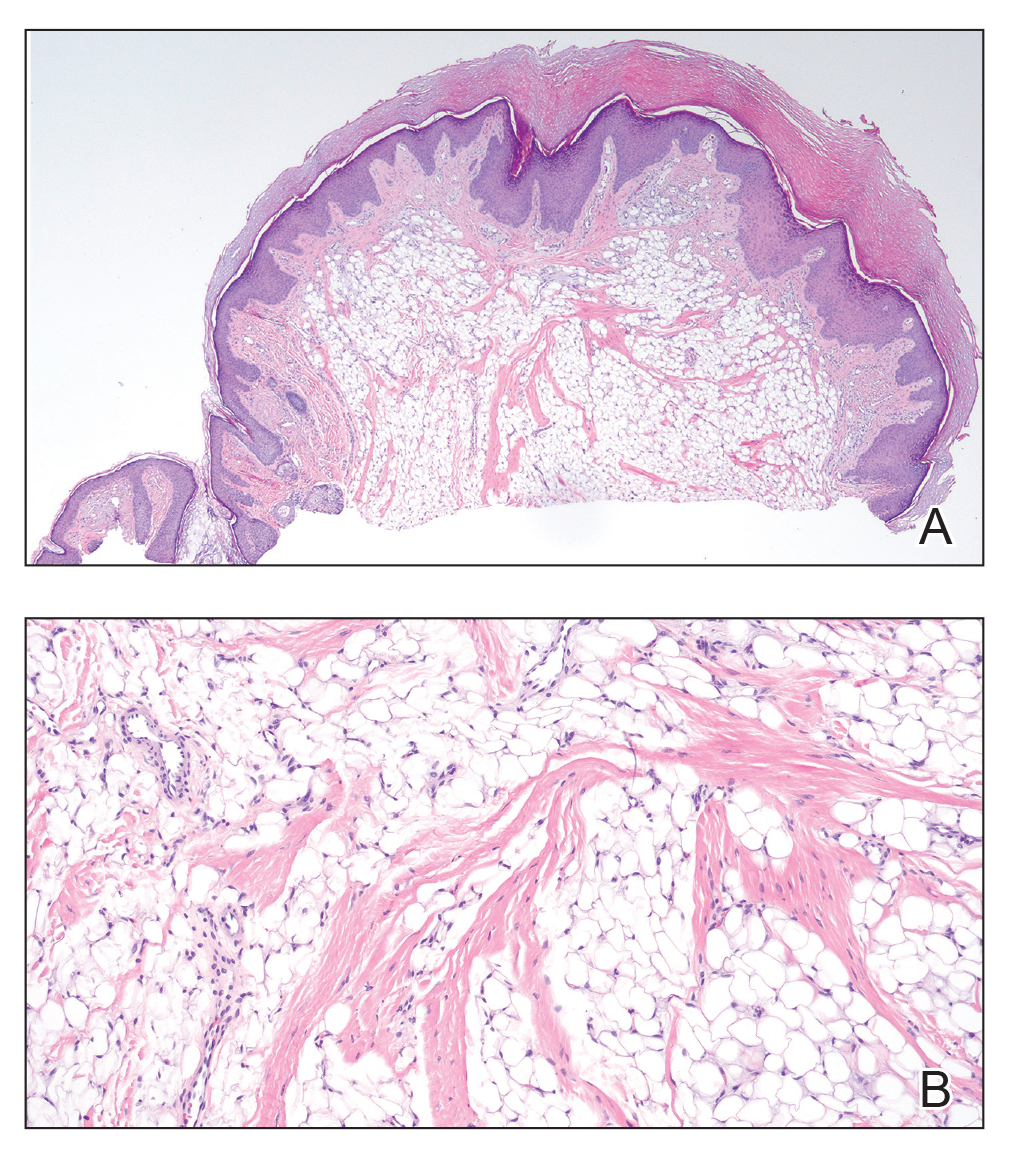

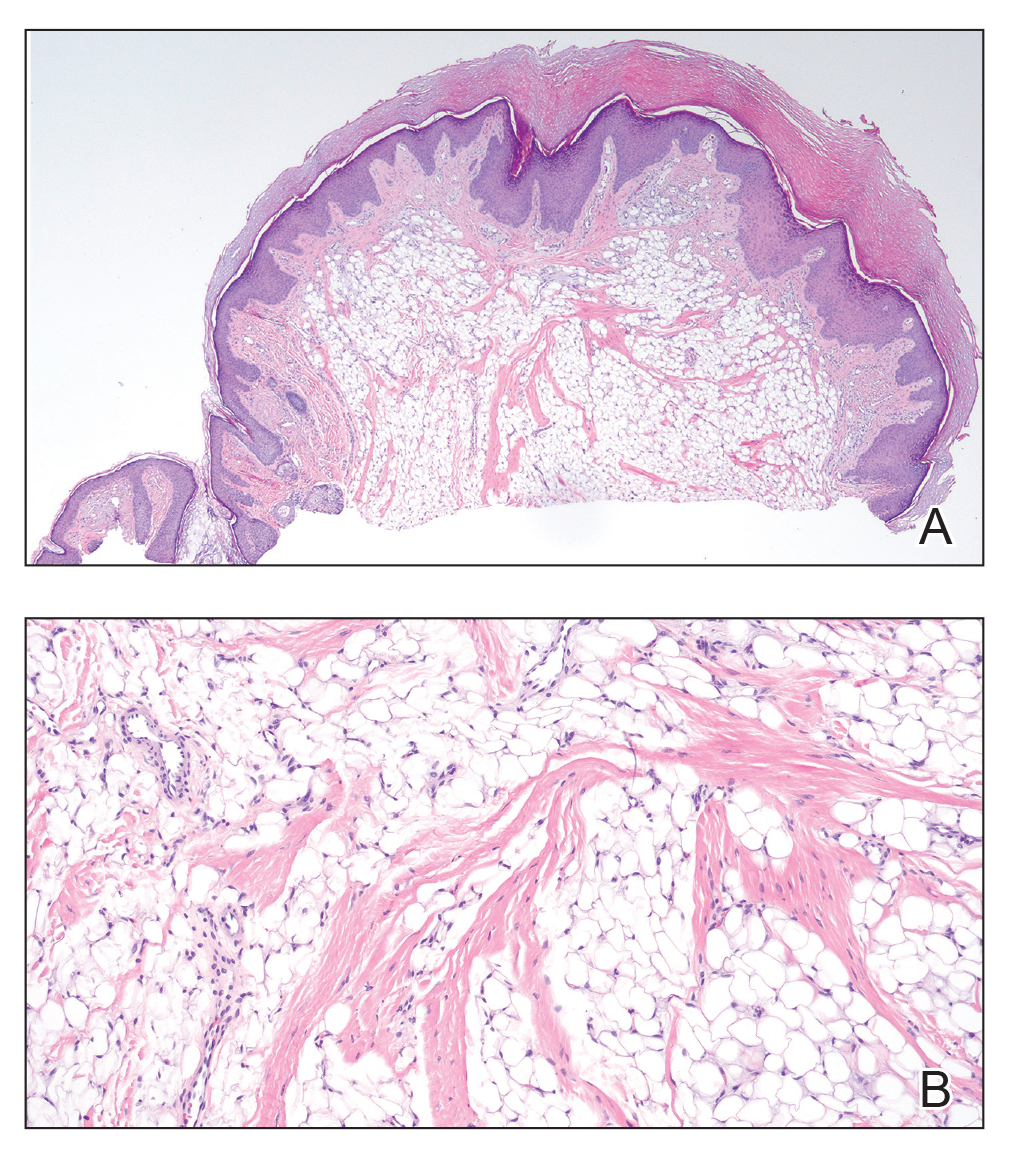

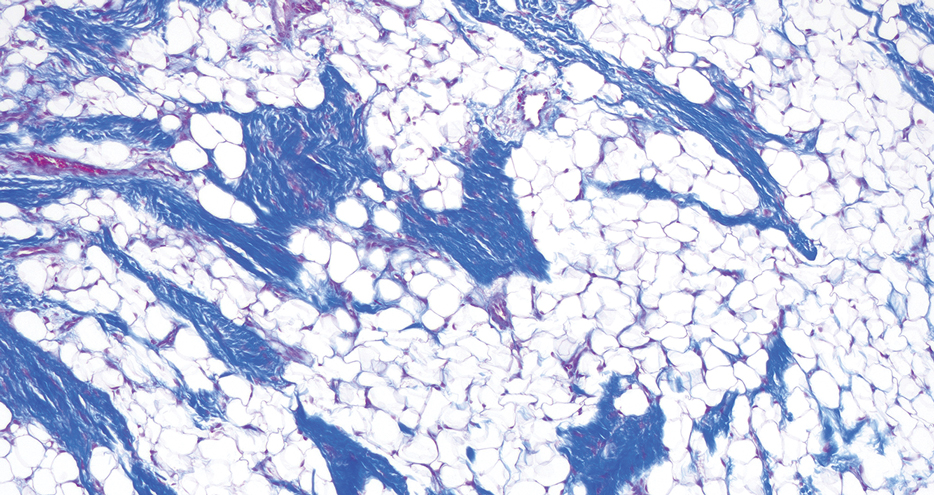

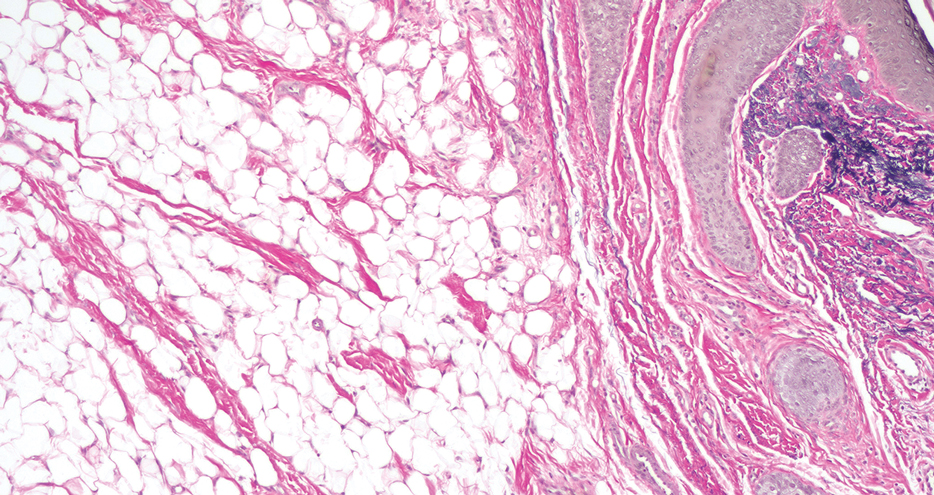

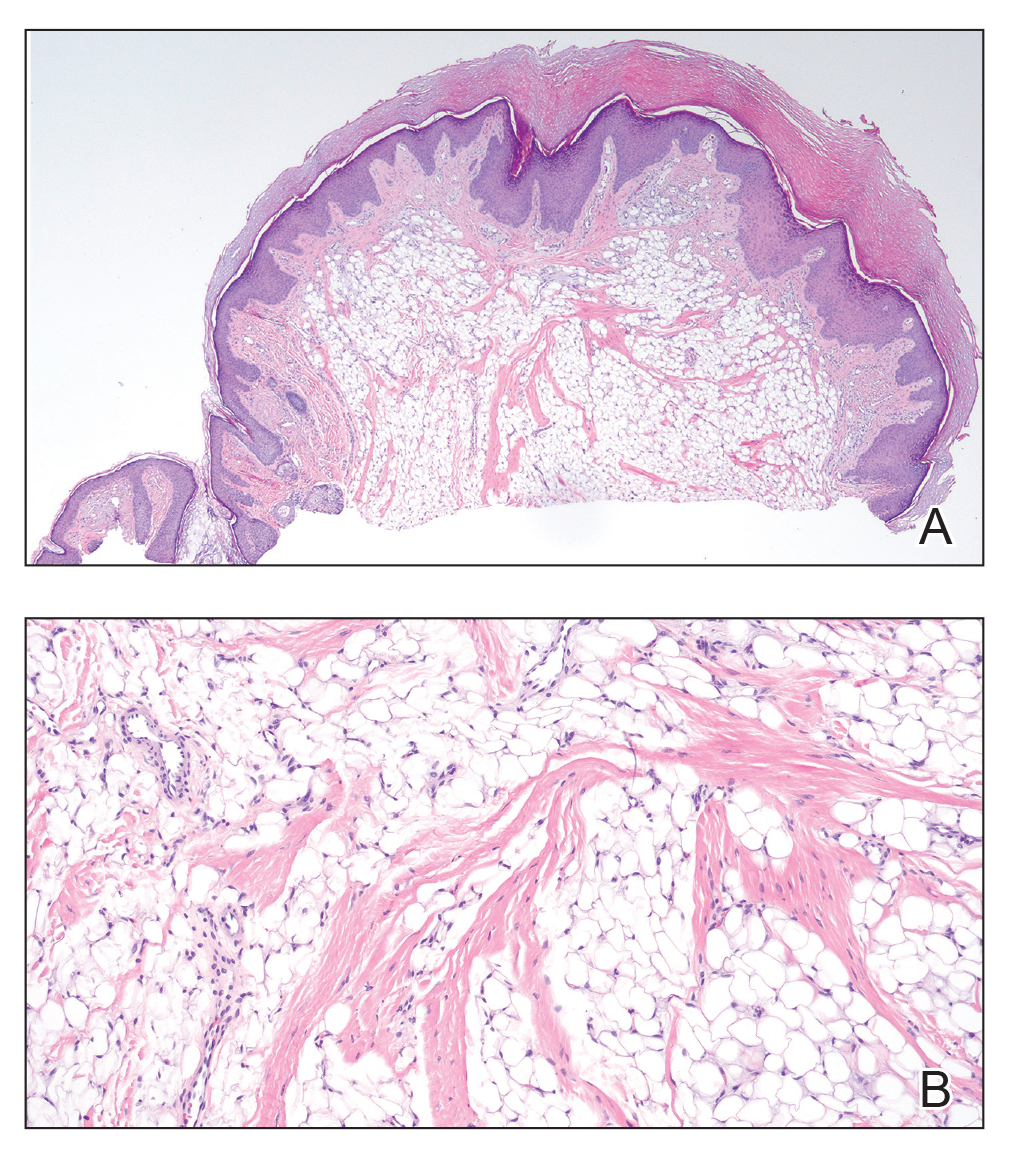

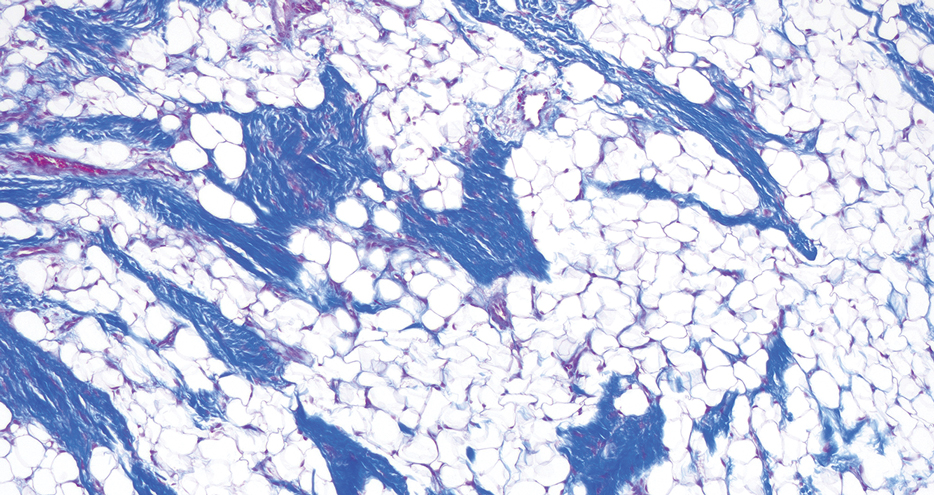

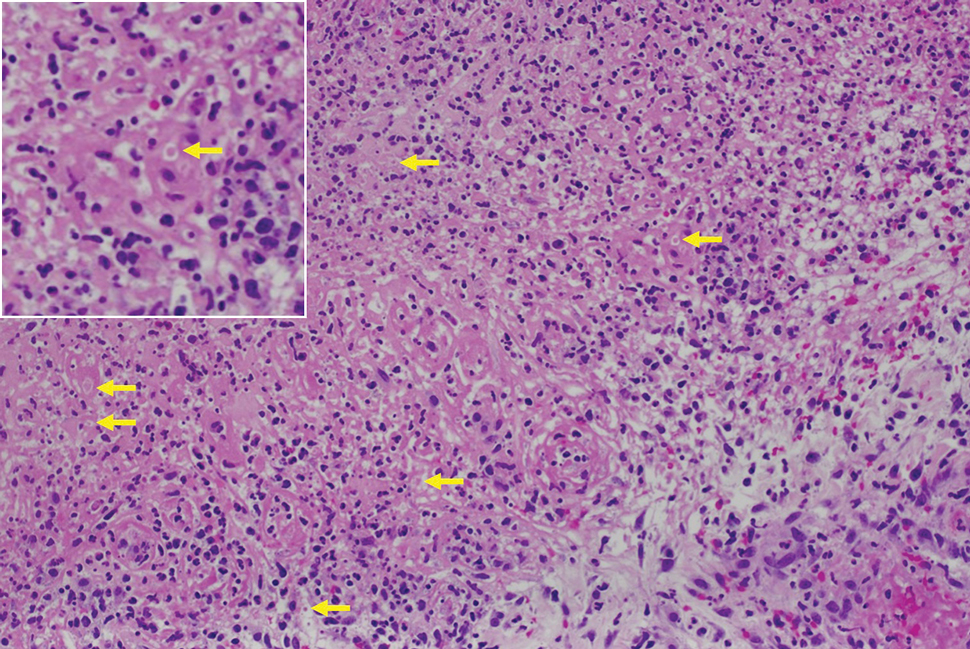

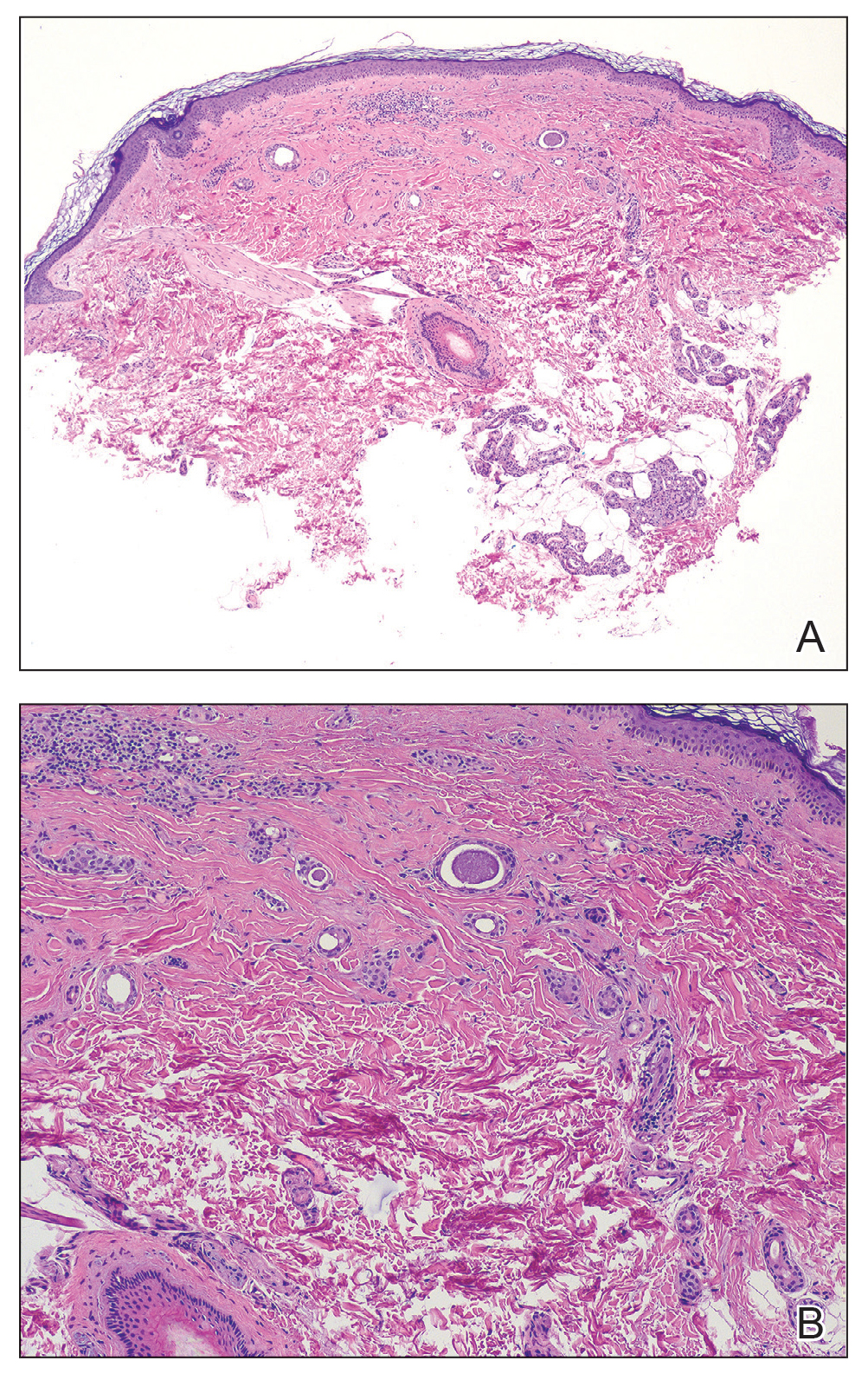

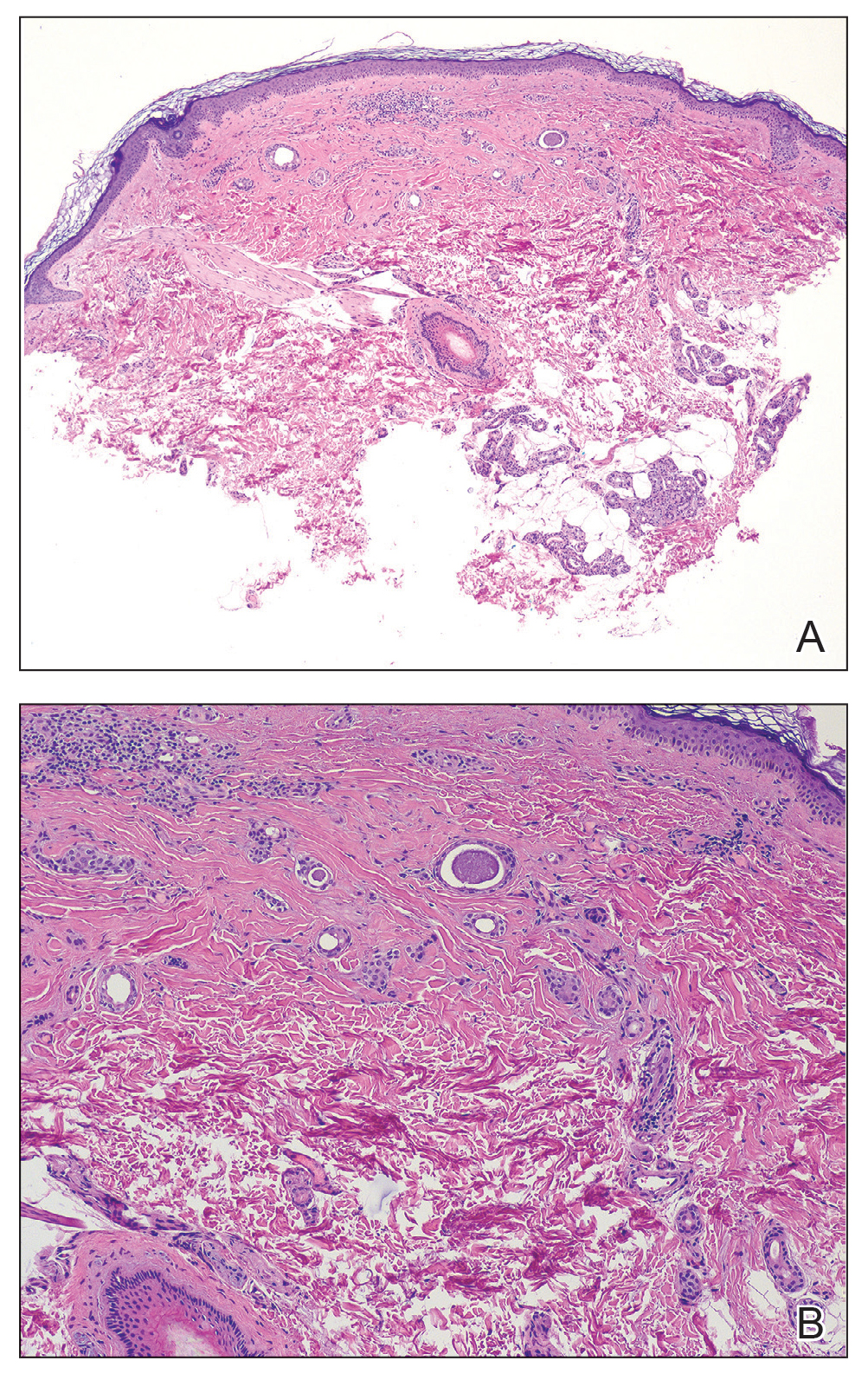

The biopsy revealed features consistent with cutaneous endometriosis in the setting of a painful, tender, multilobulated nodule with a cyclical bleeding pattern (Figure 1). The bleeding pattern of the nodule during menses and lack of surgical history supported the diagnosis of primary cutaneous endometriosis in our patient. She was diagnosed with endometriosis by gynecology, and her primary care physician started her on an oral contraceptive based on this diagnosis. She also was referred to gynecology and plastic surgery for a joint surgical consultation to remove the nodule. She initially decided to do a trial of the oral contraceptive but subsequently underwent umbilical endometrioma excision with neo-umbilicus creation with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis should be considered in young females who present with tender umbilical nodules. Endometriosis refers to the presence of an endometriumlike epithelium outside the endometrium and myometrium.1 The condition affects 10% to 15% of reproductive-aged (ie, 18-49 years) women in the United States and typically involves tissues within the pelvis, such as the ovaries, pouch of Douglas, or pelvic ligaments.2 Cutaneous endometriosis is the growth of endometrial tissue in the skin and is rare, accounting for less than 5.5% of cases of extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide, affecting primarily the umbilicus, abdominal wall, and vulva.3,4

The 2 main types of cutaneous endometriosis are primary (spontaneous) and secondary. Primary lesions develop in patients without prior surgical history, and secondary lesions occur within previous surgical incision sites, often scars from cesarean delivery.5 Less than 30% of cases of cutaneous endometriosis are primary disease.6 Primary cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus, known as Villar nodule, was first described in 1886.3,7 Up to 40% of patients with extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide presented with Villar nodules in a systematic literature review.6 The prevalence of these nodules is unknown, but the incidence is less than 1% of cases of extragenital endometriosis.4

There are 2 leading theories of primary cutaneous endometriosis pathogenesis. The first is the transportation theory, in which endometrial cells are transported outside the uterus via the lymphatic system.8 The second is the metaplasia theory, which proposed that endometrial cells develop in the coelomic mesothelium in the presence of high estrogen levels.8,9

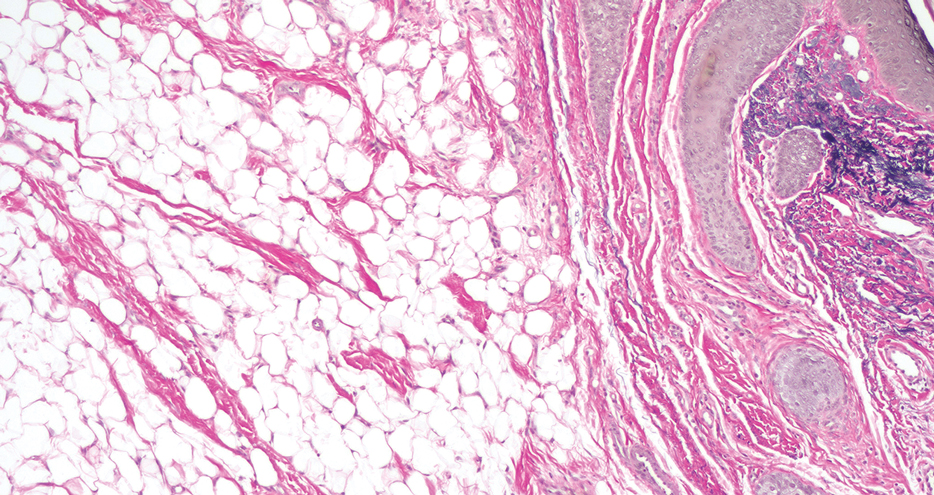

Secondary cutaneous endometriosis, also known as scar endometriosis, is suspected to be caused by an iatrogenic implantation of endometrial cells at the scar of a prior surgical site.9 Although our patient had an existing umbilicus scar from a piercing, it was improbable for that to have been the nidus, as the keloid scar was superficial and did not have contact with the abdominal cavity for iatrogenic implantation. Clinical diagnosis for secondary cutaneous endometriosis often is made based on a triad of features: a nonmalignant abdominal mass, recurring pain and bleeding of the lesion with menses, and prior history of abdominal surgery.9,10 On clinical examination, these features typically manifest as a palpable subcutaneous mass that is black, blue, brown, or red. Often, the lesions enlarge and bleed during the menstrual cycle, causing pain, tenderness, or pruritus.3 Dermoscopic features of secondary cutaneous endometriosis are erythematous umbilical nodules with a homogeneous vascular pattern that appears red with a brownish hue (Figure 2).9,11 Dermoscopic features may vary with the hormone cycle; for example, the follicular phase (correlating with day 7 of menses) demonstrates polypoid projections, erythematous violaceous color, dark-brown spots, and active bleeding of the lesion.12 Clinical and dermoscopic examination are useful tools in this diagnosis.

Imaging such as ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging may be useful in identifying abdominal endometriomas.8,13,14 Pelvic involvement of endometriosis was found in approximately 15% of patients in a case series,4 with concurrent primary umbilical endometriosis. Imaging studies may assist evaluation for fistula formation, presence of malignancies, and the extent of endometriosis within the abdominal cavity.

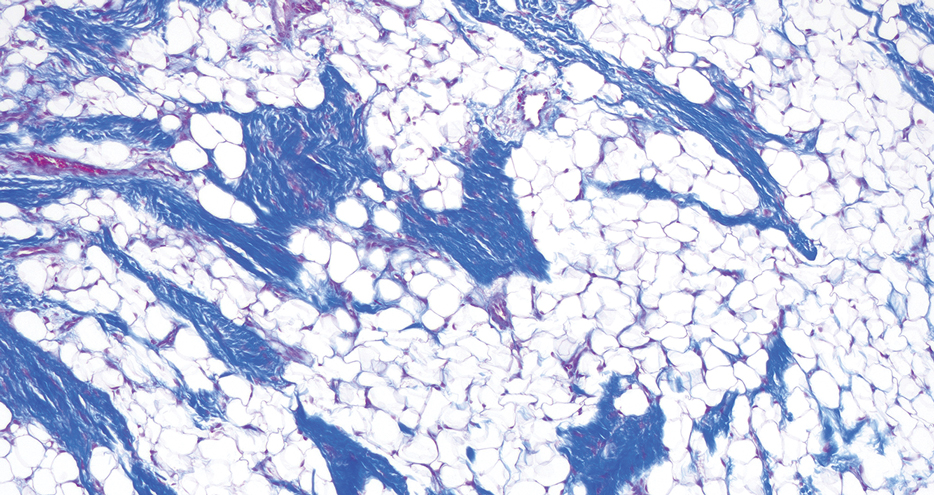

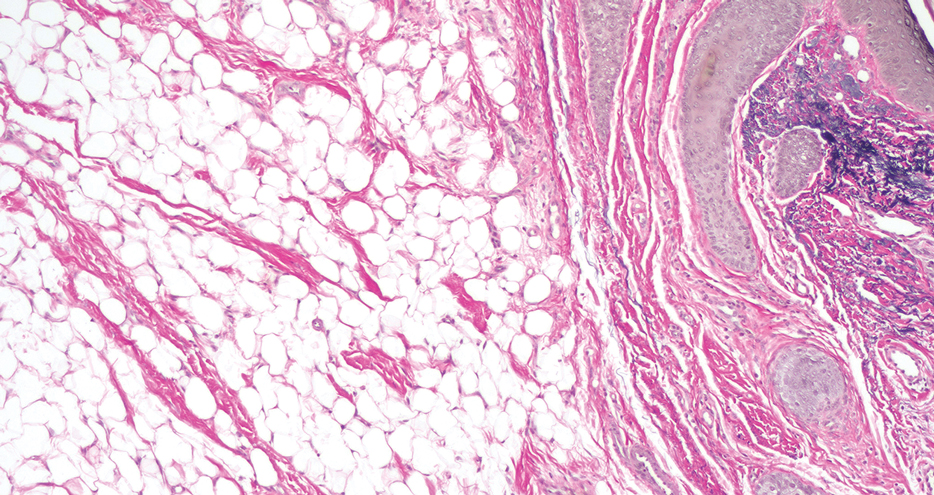

Histopathology is key to confirming cutaneous endometriosis and shows multiple bland-appearing glands of varying sizes with loose, concentric, edematous, or fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 1).3 Red blood cells sometimes are found with hemosiderin within the stroma. Immunohistochemical staining with estrogen receptors may aid in identifying the endometriumlike epithelial cells.13

Standard treatment involves surgical excision with 1-cm margins and umbilical preservation, which results in a recurrence rate of less than 10%.4,10 Medical therapy, such as aromatase inhibitors, progestogens, antiprogestogens, combined oral contraceptives, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or antagonists may help manage pain or reduce the size of the nodule.4,15 Simple observation also is a potential course for patients who decline treatment options.

Differential diagnoses include lobular capillary hemangioma, also known as pyogenic granuloma; Sister Mary Joseph nodule; umbilical hernia; and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Lobular capillary hemangiomas commonly are acquired benign vascular proliferations of the skin that are friable and tend to ulcerate.16 These lesions typically grow rapidly and often are located on the face, lips, mucosae, and fingers. Histopathologic examination may show an exophytic lesion with lobules of proliferating capillaries within an edematous matrix, superficial ulceration, and an epithelial collarette.17 Treatment includes surgical excision, cauterization, laser treatments, sclerotherapy, injectable medications, and topical medications, but recurrence is possible with any of these interventions.18

Cutaneous metastasis of an internal solid organ cancer, commonly known as a Sister Mary Joseph nodule, typically manifests as an erythematous, irregularly shaped nodule that may protrude from the umbilicus.14 Gastrointestinal symptoms such as change in bowel habits or obstructive symptoms in the setting of a progressive malignancy are common.14 Clinical features include a firm fixed lesion, oozing, and ulceration.19 On dermoscopy, polymorphous vascular patterns, milky red structureless areas, and white lines typically are present.11 Although dermoscopic features may differentiate this entity from cutaneous endometriosis, tissue sampling and histologic examination are crucial diagnostic tools to identify malignant vs benign lesions.

An umbilical hernia is a protrusion of omentum, bowel, or other intra-abdominal organs in an abdominal wall defect. Clinical presentation includes a soft protrusion that may be reduced on palpation if nonstrangulated.20 Treatment includes watchful waiting or surgical repair. The reducibility and presence of an abdominal wall defect may point to this diagnosis. Imaging also may aid in the diagnosis if the history and physical examination are unclear.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-developing, low- to intermediate-grade, soft-tissue sarcoma that occurs in less than 0.1% of all cancers in the United States.21 Lesions often manifest as small, firm, slow-growing, painless, flesh-colored dermal plaques; subcutaneous thickening; or atrophic nonprotuberant lesions typically involving the trunk.21 Histopathologically, they are composed of uniform spindle-cell proliferation growing in a storiform pattern and subcutaneous fat trapping that has strong and diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.21,22 Pathologic examination typically distinguishes this diagnosis from cutaneous endometriosis. Treatment includes tumor resection that may or may not involve radiotherapy and targeted therapy, as recurrence and metastases are possible.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis is a rare but important diagnosis for dermatologists to consider when evaluating umbilical nodules. Clinical features may include bleeding masses during menses in females of reproductive age. Dermoscopic examination aids in workup, and histopathologic testing can confirm the diagnosis and rule out malignancies. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice with a low rate of recurrence.

- International Working Group of AAGL, ESGE, ESHRE and WES; Tomassetti C, Johnson NP, et al. An international terminology for endometriosis, 2021. Hum Reprod Open. 2021;2021:hoab029. doi:10.1093/hropen/hoab029

- Batista M, Alves F, Cardoso J, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: a differential diagnosis of umbilical nodule. Acta Med Port. 2020; 33:282-284. doi:10.20344/amp.10966

- Brown ME, Osswald S, Biediger T. Cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus (Villar’s nodule). Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:214-215. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.01.001

- Bindra V, Sampurna S, Kade S, et al. Primary umbilical endometriosis - case series and review of clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;94:107134. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.107134

- Loh SH, Lew BL, Sim WY. Primary cutaneous endometriosis of umbilicus. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:621-625. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.621

- Victory R, Diamond MP, Johns DA. Villar’s nodule: a case report and systematic literature review of endometriosis externa of the umbilicus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:23-32. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2006.07.01

- Van den Nouland D, Kaur M. Primary umbilical endometriosis: a case report. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2017;9:115-119.

- Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:194. doi:10.1186/1746-1596-8-194

- Huang QF, Jiang B, Yang X, et al. Primary versus secondary cutaneous endometriosis: literature review and case study. Heliyon. 2023;9:E20094. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20094

- Gonzalez RH, Singh MS, Hamza SA. Cutaneous endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:E932493. doi:10.12659/AJCR.932493

- Buljan M, Arzberger E, Šitum M, et al. The use of dermoscopy in differentiating Sister Mary Joseph nodule and cutaneous endometriosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:E233-E235. doi:10.1111/ajd.12980

- Costa IM, Gomes CM, Morais OO, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: dermoscopic findings related to phases of the female hormonal cycle. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E130-E132. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2012.05854.x

- Mohaghegh F, Hatami P, Rajabi P, et al. Coexistence of cutaneous endometriosis and ovarian endometrioma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16:256. doi:10.1186/s13256-022-03483-8

- Raffi L, Suresh R, McCalmont TH, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:384-386. doi:10.1016 /j.ijwd.2019.06.025

- Saunders PTK, Horne AW. Endometriosis: etiology, pathobiology, and therapeutic prospects. Cell. 2021;184:2807-2824. doi:10.1016 /j.cell.2021.04.041

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology a Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. St. Louis, Mo. Elsevier; 2016.

- Patrice SJ, Wiss K, Mulliken JB. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma): a clinicopathologic study of 178 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:267-276. doi:10.1111/j.15251470.1991.tb00931.x

- Kaleeny JD, Janis JE. Pyogenic granuloma diagnosis and management: a practical review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12:E6160. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000006160

- Ha DL, Yang MY, Shin JO, et al. Benign umbilical tumors resembling Sister Mary Joseph nodule. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2021;15:1179554921995022. doi:10.1177/1179554921995022

- Lawrence PF, Smeds M, Jessica Beth O’connell. Essentials of General Surgery and Surgical Specialties. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2019.

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752. doi:10.3390/jcm9061752

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

THE DIAGNOSIS: Villar Nodule

The biopsy revealed features consistent with cutaneous endometriosis in the setting of a painful, tender, multilobulated nodule with a cyclical bleeding pattern (Figure 1). The bleeding pattern of the nodule during menses and lack of surgical history supported the diagnosis of primary cutaneous endometriosis in our patient. She was diagnosed with endometriosis by gynecology, and her primary care physician started her on an oral contraceptive based on this diagnosis. She also was referred to gynecology and plastic surgery for a joint surgical consultation to remove the nodule. She initially decided to do a trial of the oral contraceptive but subsequently underwent umbilical endometrioma excision with neo-umbilicus creation with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis should be considered in young females who present with tender umbilical nodules. Endometriosis refers to the presence of an endometriumlike epithelium outside the endometrium and myometrium.1 The condition affects 10% to 15% of reproductive-aged (ie, 18-49 years) women in the United States and typically involves tissues within the pelvis, such as the ovaries, pouch of Douglas, or pelvic ligaments.2 Cutaneous endometriosis is the growth of endometrial tissue in the skin and is rare, accounting for less than 5.5% of cases of extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide, affecting primarily the umbilicus, abdominal wall, and vulva.3,4

The 2 main types of cutaneous endometriosis are primary (spontaneous) and secondary. Primary lesions develop in patients without prior surgical history, and secondary lesions occur within previous surgical incision sites, often scars from cesarean delivery.5 Less than 30% of cases of cutaneous endometriosis are primary disease.6 Primary cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus, known as Villar nodule, was first described in 1886.3,7 Up to 40% of patients with extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide presented with Villar nodules in a systematic literature review.6 The prevalence of these nodules is unknown, but the incidence is less than 1% of cases of extragenital endometriosis.4

There are 2 leading theories of primary cutaneous endometriosis pathogenesis. The first is the transportation theory, in which endometrial cells are transported outside the uterus via the lymphatic system.8 The second is the metaplasia theory, which proposed that endometrial cells develop in the coelomic mesothelium in the presence of high estrogen levels.8,9

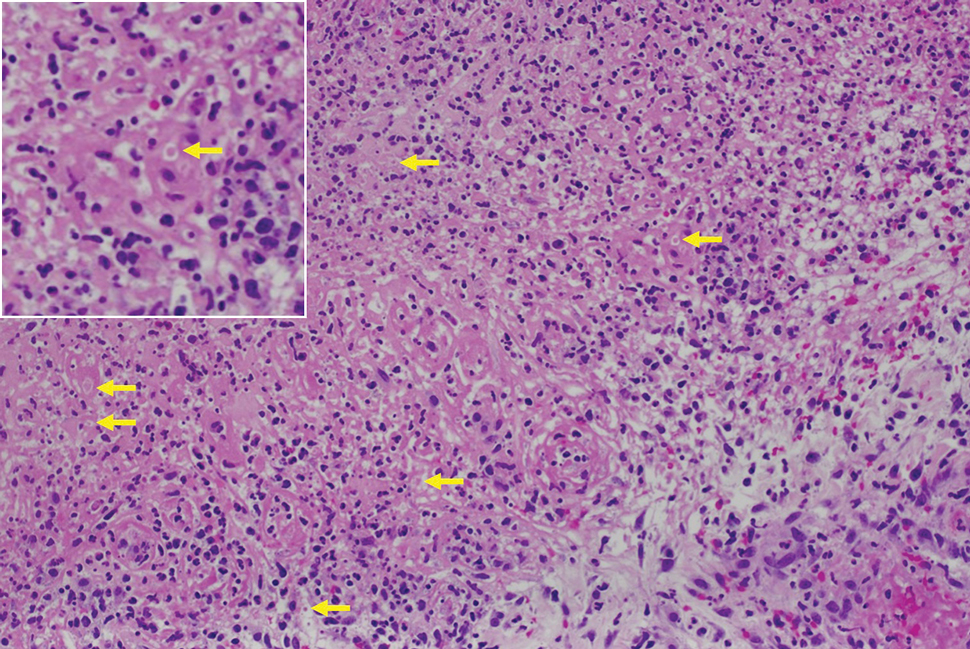

Secondary cutaneous endometriosis, also known as scar endometriosis, is suspected to be caused by an iatrogenic implantation of endometrial cells at the scar of a prior surgical site.9 Although our patient had an existing umbilicus scar from a piercing, it was improbable for that to have been the nidus, as the keloid scar was superficial and did not have contact with the abdominal cavity for iatrogenic implantation. Clinical diagnosis for secondary cutaneous endometriosis often is made based on a triad of features: a nonmalignant abdominal mass, recurring pain and bleeding of the lesion with menses, and prior history of abdominal surgery.9,10 On clinical examination, these features typically manifest as a palpable subcutaneous mass that is black, blue, brown, or red. Often, the lesions enlarge and bleed during the menstrual cycle, causing pain, tenderness, or pruritus.3 Dermoscopic features of secondary cutaneous endometriosis are erythematous umbilical nodules with a homogeneous vascular pattern that appears red with a brownish hue (Figure 2).9,11 Dermoscopic features may vary with the hormone cycle; for example, the follicular phase (correlating with day 7 of menses) demonstrates polypoid projections, erythematous violaceous color, dark-brown spots, and active bleeding of the lesion.12 Clinical and dermoscopic examination are useful tools in this diagnosis.

Imaging such as ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging may be useful in identifying abdominal endometriomas.8,13,14 Pelvic involvement of endometriosis was found in approximately 15% of patients in a case series,4 with concurrent primary umbilical endometriosis. Imaging studies may assist evaluation for fistula formation, presence of malignancies, and the extent of endometriosis within the abdominal cavity.

Histopathology is key to confirming cutaneous endometriosis and shows multiple bland-appearing glands of varying sizes with loose, concentric, edematous, or fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 1).3 Red blood cells sometimes are found with hemosiderin within the stroma. Immunohistochemical staining with estrogen receptors may aid in identifying the endometriumlike epithelial cells.13

Standard treatment involves surgical excision with 1-cm margins and umbilical preservation, which results in a recurrence rate of less than 10%.4,10 Medical therapy, such as aromatase inhibitors, progestogens, antiprogestogens, combined oral contraceptives, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or antagonists may help manage pain or reduce the size of the nodule.4,15 Simple observation also is a potential course for patients who decline treatment options.

Differential diagnoses include lobular capillary hemangioma, also known as pyogenic granuloma; Sister Mary Joseph nodule; umbilical hernia; and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Lobular capillary hemangiomas commonly are acquired benign vascular proliferations of the skin that are friable and tend to ulcerate.16 These lesions typically grow rapidly and often are located on the face, lips, mucosae, and fingers. Histopathologic examination may show an exophytic lesion with lobules of proliferating capillaries within an edematous matrix, superficial ulceration, and an epithelial collarette.17 Treatment includes surgical excision, cauterization, laser treatments, sclerotherapy, injectable medications, and topical medications, but recurrence is possible with any of these interventions.18

Cutaneous metastasis of an internal solid organ cancer, commonly known as a Sister Mary Joseph nodule, typically manifests as an erythematous, irregularly shaped nodule that may protrude from the umbilicus.14 Gastrointestinal symptoms such as change in bowel habits or obstructive symptoms in the setting of a progressive malignancy are common.14 Clinical features include a firm fixed lesion, oozing, and ulceration.19 On dermoscopy, polymorphous vascular patterns, milky red structureless areas, and white lines typically are present.11 Although dermoscopic features may differentiate this entity from cutaneous endometriosis, tissue sampling and histologic examination are crucial diagnostic tools to identify malignant vs benign lesions.

An umbilical hernia is a protrusion of omentum, bowel, or other intra-abdominal organs in an abdominal wall defect. Clinical presentation includes a soft protrusion that may be reduced on palpation if nonstrangulated.20 Treatment includes watchful waiting or surgical repair. The reducibility and presence of an abdominal wall defect may point to this diagnosis. Imaging also may aid in the diagnosis if the history and physical examination are unclear.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-developing, low- to intermediate-grade, soft-tissue sarcoma that occurs in less than 0.1% of all cancers in the United States.21 Lesions often manifest as small, firm, slow-growing, painless, flesh-colored dermal plaques; subcutaneous thickening; or atrophic nonprotuberant lesions typically involving the trunk.21 Histopathologically, they are composed of uniform spindle-cell proliferation growing in a storiform pattern and subcutaneous fat trapping that has strong and diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.21,22 Pathologic examination typically distinguishes this diagnosis from cutaneous endometriosis. Treatment includes tumor resection that may or may not involve radiotherapy and targeted therapy, as recurrence and metastases are possible.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis is a rare but important diagnosis for dermatologists to consider when evaluating umbilical nodules. Clinical features may include bleeding masses during menses in females of reproductive age. Dermoscopic examination aids in workup, and histopathologic testing can confirm the diagnosis and rule out malignancies. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice with a low rate of recurrence.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Villar Nodule

The biopsy revealed features consistent with cutaneous endometriosis in the setting of a painful, tender, multilobulated nodule with a cyclical bleeding pattern (Figure 1). The bleeding pattern of the nodule during menses and lack of surgical history supported the diagnosis of primary cutaneous endometriosis in our patient. She was diagnosed with endometriosis by gynecology, and her primary care physician started her on an oral contraceptive based on this diagnosis. She also was referred to gynecology and plastic surgery for a joint surgical consultation to remove the nodule. She initially decided to do a trial of the oral contraceptive but subsequently underwent umbilical endometrioma excision with neo-umbilicus creation with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis should be considered in young females who present with tender umbilical nodules. Endometriosis refers to the presence of an endometriumlike epithelium outside the endometrium and myometrium.1 The condition affects 10% to 15% of reproductive-aged (ie, 18-49 years) women in the United States and typically involves tissues within the pelvis, such as the ovaries, pouch of Douglas, or pelvic ligaments.2 Cutaneous endometriosis is the growth of endometrial tissue in the skin and is rare, accounting for less than 5.5% of cases of extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide, affecting primarily the umbilicus, abdominal wall, and vulva.3,4

The 2 main types of cutaneous endometriosis are primary (spontaneous) and secondary. Primary lesions develop in patients without prior surgical history, and secondary lesions occur within previous surgical incision sites, often scars from cesarean delivery.5 Less than 30% of cases of cutaneous endometriosis are primary disease.6 Primary cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus, known as Villar nodule, was first described in 1886.3,7 Up to 40% of patients with extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide presented with Villar nodules in a systematic literature review.6 The prevalence of these nodules is unknown, but the incidence is less than 1% of cases of extragenital endometriosis.4

There are 2 leading theories of primary cutaneous endometriosis pathogenesis. The first is the transportation theory, in which endometrial cells are transported outside the uterus via the lymphatic system.8 The second is the metaplasia theory, which proposed that endometrial cells develop in the coelomic mesothelium in the presence of high estrogen levels.8,9

Secondary cutaneous endometriosis, also known as scar endometriosis, is suspected to be caused by an iatrogenic implantation of endometrial cells at the scar of a prior surgical site.9 Although our patient had an existing umbilicus scar from a piercing, it was improbable for that to have been the nidus, as the keloid scar was superficial and did not have contact with the abdominal cavity for iatrogenic implantation. Clinical diagnosis for secondary cutaneous endometriosis often is made based on a triad of features: a nonmalignant abdominal mass, recurring pain and bleeding of the lesion with menses, and prior history of abdominal surgery.9,10 On clinical examination, these features typically manifest as a palpable subcutaneous mass that is black, blue, brown, or red. Often, the lesions enlarge and bleed during the menstrual cycle, causing pain, tenderness, or pruritus.3 Dermoscopic features of secondary cutaneous endometriosis are erythematous umbilical nodules with a homogeneous vascular pattern that appears red with a brownish hue (Figure 2).9,11 Dermoscopic features may vary with the hormone cycle; for example, the follicular phase (correlating with day 7 of menses) demonstrates polypoid projections, erythematous violaceous color, dark-brown spots, and active bleeding of the lesion.12 Clinical and dermoscopic examination are useful tools in this diagnosis.

Imaging such as ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging may be useful in identifying abdominal endometriomas.8,13,14 Pelvic involvement of endometriosis was found in approximately 15% of patients in a case series,4 with concurrent primary umbilical endometriosis. Imaging studies may assist evaluation for fistula formation, presence of malignancies, and the extent of endometriosis within the abdominal cavity.

Histopathology is key to confirming cutaneous endometriosis and shows multiple bland-appearing glands of varying sizes with loose, concentric, edematous, or fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 1).3 Red blood cells sometimes are found with hemosiderin within the stroma. Immunohistochemical staining with estrogen receptors may aid in identifying the endometriumlike epithelial cells.13

Standard treatment involves surgical excision with 1-cm margins and umbilical preservation, which results in a recurrence rate of less than 10%.4,10 Medical therapy, such as aromatase inhibitors, progestogens, antiprogestogens, combined oral contraceptives, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or antagonists may help manage pain or reduce the size of the nodule.4,15 Simple observation also is a potential course for patients who decline treatment options.

Differential diagnoses include lobular capillary hemangioma, also known as pyogenic granuloma; Sister Mary Joseph nodule; umbilical hernia; and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Lobular capillary hemangiomas commonly are acquired benign vascular proliferations of the skin that are friable and tend to ulcerate.16 These lesions typically grow rapidly and often are located on the face, lips, mucosae, and fingers. Histopathologic examination may show an exophytic lesion with lobules of proliferating capillaries within an edematous matrix, superficial ulceration, and an epithelial collarette.17 Treatment includes surgical excision, cauterization, laser treatments, sclerotherapy, injectable medications, and topical medications, but recurrence is possible with any of these interventions.18

Cutaneous metastasis of an internal solid organ cancer, commonly known as a Sister Mary Joseph nodule, typically manifests as an erythematous, irregularly shaped nodule that may protrude from the umbilicus.14 Gastrointestinal symptoms such as change in bowel habits or obstructive symptoms in the setting of a progressive malignancy are common.14 Clinical features include a firm fixed lesion, oozing, and ulceration.19 On dermoscopy, polymorphous vascular patterns, milky red structureless areas, and white lines typically are present.11 Although dermoscopic features may differentiate this entity from cutaneous endometriosis, tissue sampling and histologic examination are crucial diagnostic tools to identify malignant vs benign lesions.

An umbilical hernia is a protrusion of omentum, bowel, or other intra-abdominal organs in an abdominal wall defect. Clinical presentation includes a soft protrusion that may be reduced on palpation if nonstrangulated.20 Treatment includes watchful waiting or surgical repair. The reducibility and presence of an abdominal wall defect may point to this diagnosis. Imaging also may aid in the diagnosis if the history and physical examination are unclear.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-developing, low- to intermediate-grade, soft-tissue sarcoma that occurs in less than 0.1% of all cancers in the United States.21 Lesions often manifest as small, firm, slow-growing, painless, flesh-colored dermal plaques; subcutaneous thickening; or atrophic nonprotuberant lesions typically involving the trunk.21 Histopathologically, they are composed of uniform spindle-cell proliferation growing in a storiform pattern and subcutaneous fat trapping that has strong and diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.21,22 Pathologic examination typically distinguishes this diagnosis from cutaneous endometriosis. Treatment includes tumor resection that may or may not involve radiotherapy and targeted therapy, as recurrence and metastases are possible.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis is a rare but important diagnosis for dermatologists to consider when evaluating umbilical nodules. Clinical features may include bleeding masses during menses in females of reproductive age. Dermoscopic examination aids in workup, and histopathologic testing can confirm the diagnosis and rule out malignancies. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice with a low rate of recurrence.

- International Working Group of AAGL, ESGE, ESHRE and WES; Tomassetti C, Johnson NP, et al. An international terminology for endometriosis, 2021. Hum Reprod Open. 2021;2021:hoab029. doi:10.1093/hropen/hoab029

- Batista M, Alves F, Cardoso J, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: a differential diagnosis of umbilical nodule. Acta Med Port. 2020; 33:282-284. doi:10.20344/amp.10966

- Brown ME, Osswald S, Biediger T. Cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus (Villar’s nodule). Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:214-215. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.01.001

- Bindra V, Sampurna S, Kade S, et al. Primary umbilical endometriosis - case series and review of clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;94:107134. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.107134

- Loh SH, Lew BL, Sim WY. Primary cutaneous endometriosis of umbilicus. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:621-625. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.621

- Victory R, Diamond MP, Johns DA. Villar’s nodule: a case report and systematic literature review of endometriosis externa of the umbilicus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:23-32. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2006.07.01

- Van den Nouland D, Kaur M. Primary umbilical endometriosis: a case report. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2017;9:115-119.

- Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:194. doi:10.1186/1746-1596-8-194

- Huang QF, Jiang B, Yang X, et al. Primary versus secondary cutaneous endometriosis: literature review and case study. Heliyon. 2023;9:E20094. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20094

- Gonzalez RH, Singh MS, Hamza SA. Cutaneous endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:E932493. doi:10.12659/AJCR.932493

- Buljan M, Arzberger E, Šitum M, et al. The use of dermoscopy in differentiating Sister Mary Joseph nodule and cutaneous endometriosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:E233-E235. doi:10.1111/ajd.12980

- Costa IM, Gomes CM, Morais OO, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: dermoscopic findings related to phases of the female hormonal cycle. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E130-E132. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2012.05854.x

- Mohaghegh F, Hatami P, Rajabi P, et al. Coexistence of cutaneous endometriosis and ovarian endometrioma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16:256. doi:10.1186/s13256-022-03483-8

- Raffi L, Suresh R, McCalmont TH, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:384-386. doi:10.1016 /j.ijwd.2019.06.025

- Saunders PTK, Horne AW. Endometriosis: etiology, pathobiology, and therapeutic prospects. Cell. 2021;184:2807-2824. doi:10.1016 /j.cell.2021.04.041

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology a Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. St. Louis, Mo. Elsevier; 2016.

- Patrice SJ, Wiss K, Mulliken JB. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma): a clinicopathologic study of 178 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:267-276. doi:10.1111/j.15251470.1991.tb00931.x

- Kaleeny JD, Janis JE. Pyogenic granuloma diagnosis and management: a practical review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12:E6160. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000006160

- Ha DL, Yang MY, Shin JO, et al. Benign umbilical tumors resembling Sister Mary Joseph nodule. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2021;15:1179554921995022. doi:10.1177/1179554921995022

- Lawrence PF, Smeds M, Jessica Beth O’connell. Essentials of General Surgery and Surgical Specialties. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2019.

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752. doi:10.3390/jcm9061752

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

- International Working Group of AAGL, ESGE, ESHRE and WES; Tomassetti C, Johnson NP, et al. An international terminology for endometriosis, 2021. Hum Reprod Open. 2021;2021:hoab029. doi:10.1093/hropen/hoab029

- Batista M, Alves F, Cardoso J, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: a differential diagnosis of umbilical nodule. Acta Med Port. 2020; 33:282-284. doi:10.20344/amp.10966

- Brown ME, Osswald S, Biediger T. Cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus (Villar’s nodule). Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:214-215. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.01.001

- Bindra V, Sampurna S, Kade S, et al. Primary umbilical endometriosis - case series and review of clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;94:107134. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.107134

- Loh SH, Lew BL, Sim WY. Primary cutaneous endometriosis of umbilicus. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:621-625. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.621

- Victory R, Diamond MP, Johns DA. Villar’s nodule: a case report and systematic literature review of endometriosis externa of the umbilicus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:23-32. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2006.07.01

- Van den Nouland D, Kaur M. Primary umbilical endometriosis: a case report. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2017;9:115-119.

- Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:194. doi:10.1186/1746-1596-8-194

- Huang QF, Jiang B, Yang X, et al. Primary versus secondary cutaneous endometriosis: literature review and case study. Heliyon. 2023;9:E20094. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20094

- Gonzalez RH, Singh MS, Hamza SA. Cutaneous endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:E932493. doi:10.12659/AJCR.932493

- Buljan M, Arzberger E, Šitum M, et al. The use of dermoscopy in differentiating Sister Mary Joseph nodule and cutaneous endometriosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:E233-E235. doi:10.1111/ajd.12980

- Costa IM, Gomes CM, Morais OO, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: dermoscopic findings related to phases of the female hormonal cycle. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E130-E132. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2012.05854.x

- Mohaghegh F, Hatami P, Rajabi P, et al. Coexistence of cutaneous endometriosis and ovarian endometrioma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16:256. doi:10.1186/s13256-022-03483-8

- Raffi L, Suresh R, McCalmont TH, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:384-386. doi:10.1016 /j.ijwd.2019.06.025

- Saunders PTK, Horne AW. Endometriosis: etiology, pathobiology, and therapeutic prospects. Cell. 2021;184:2807-2824. doi:10.1016 /j.cell.2021.04.041

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology a Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. St. Louis, Mo. Elsevier; 2016.

- Patrice SJ, Wiss K, Mulliken JB. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma): a clinicopathologic study of 178 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:267-276. doi:10.1111/j.15251470.1991.tb00931.x

- Kaleeny JD, Janis JE. Pyogenic granuloma diagnosis and management: a practical review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12:E6160. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000006160

- Ha DL, Yang MY, Shin JO, et al. Benign umbilical tumors resembling Sister Mary Joseph nodule. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2021;15:1179554921995022. doi:10.1177/1179554921995022

- Lawrence PF, Smeds M, Jessica Beth O’connell. Essentials of General Surgery and Surgical Specialties. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2019.

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752. doi:10.3390/jcm9061752

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

Tender Nodule on the Umbilicus

Tender Nodule on the Umbilicus

A 25-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology clinic by her primary care provider for evaluation of a tender nodule on the inferior umbilicus of 2 years' duration at the site of a preexisting keloid scar. The patient reported that the lesion caused occasional pain and tenderness. A few weeks prior to the current presentation, a dark-red bloody discharge developed at the superior aspect of the lesion that subsequently crusted over. The patient denied any use of oral contraceptives or history of abdominal surgery.

The original keloid scar had been treated successfully by an outside physician with intralesional steroid injections, and the patient was interested in a similar procedure for the current nodule. She also had a history of a hyperpigmented hypertrophic scar on the superior periumbilical area from a previous piercing that had resolved several years prior to presentation.

Physical examination of the lesion revealed a 1.2-cm, soft, tender, violaceous nodule with scant yellow crust along the superior surface of the umbilicus. There was no palpable abdominal wall defect, and the nodule was not reducible into the abdominal cavity. An interval history revealed bleeding of the lesion during the patient's menstrual cycle with persistent pain and tenderness. A punch biopsy was performed.

Diffuse Pruritic Keratotic Papules

Diffuse Pruritic Keratotic Papules

THE DIAGNOSIS: Reactive Perforating Collagenosis

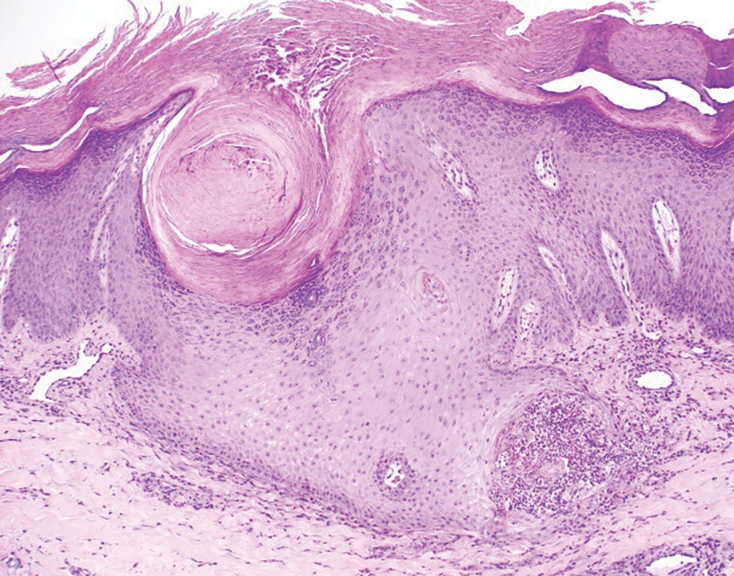

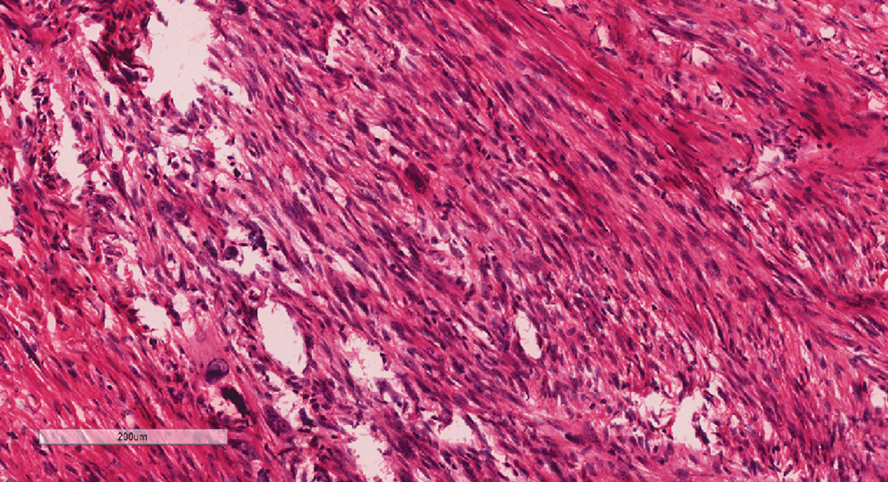

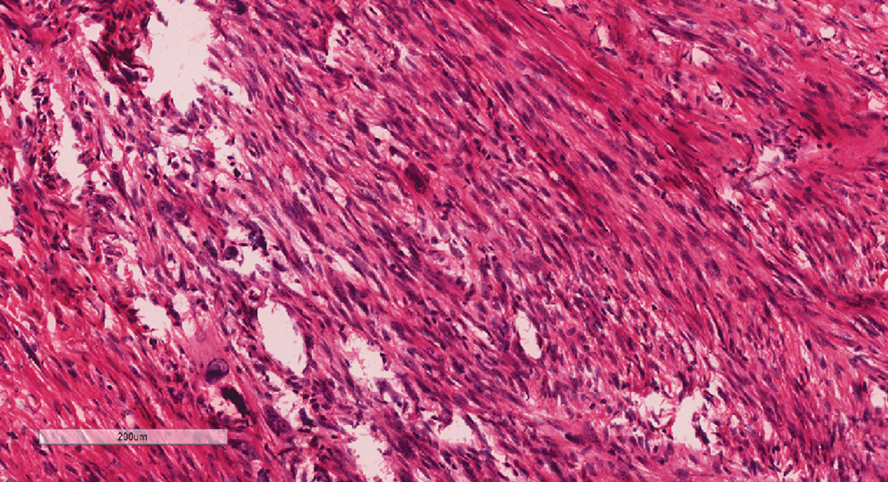

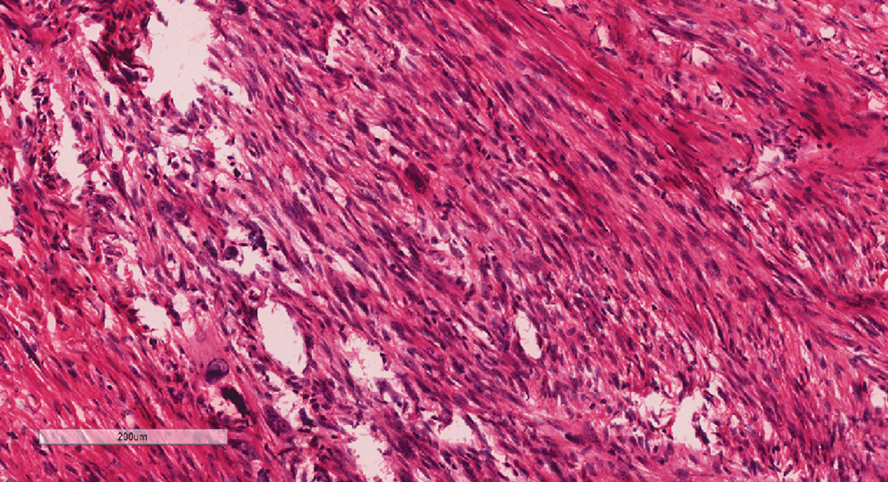

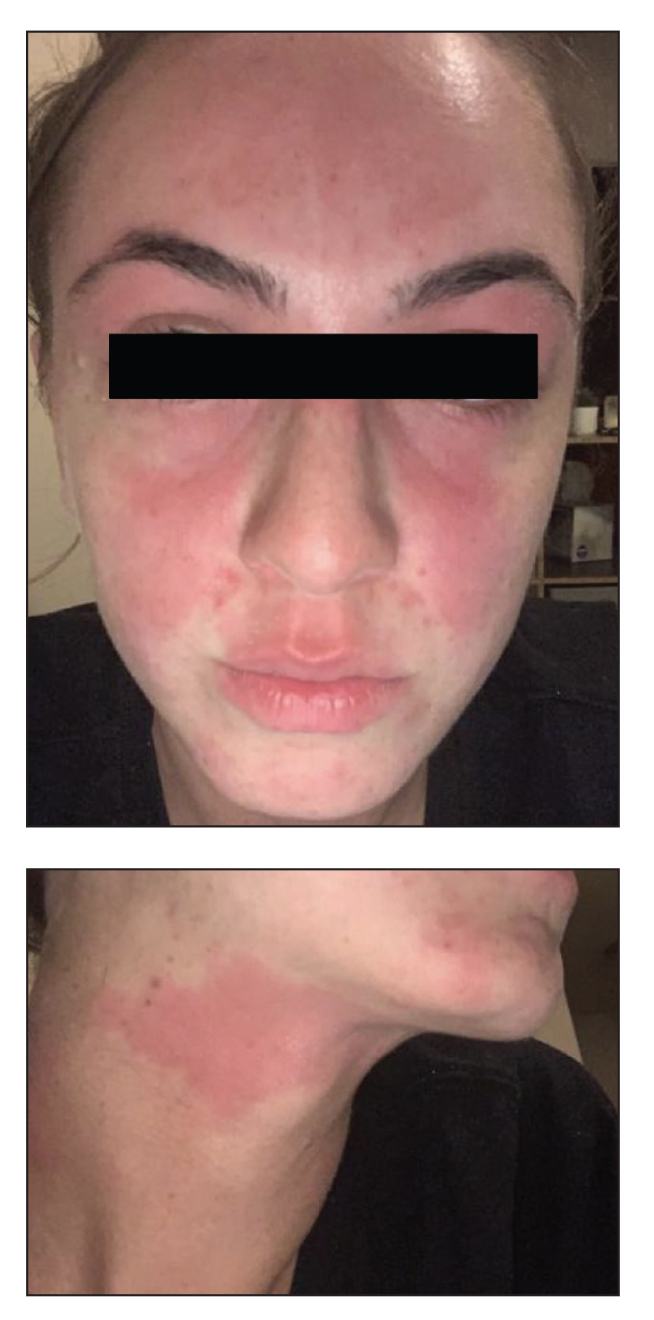

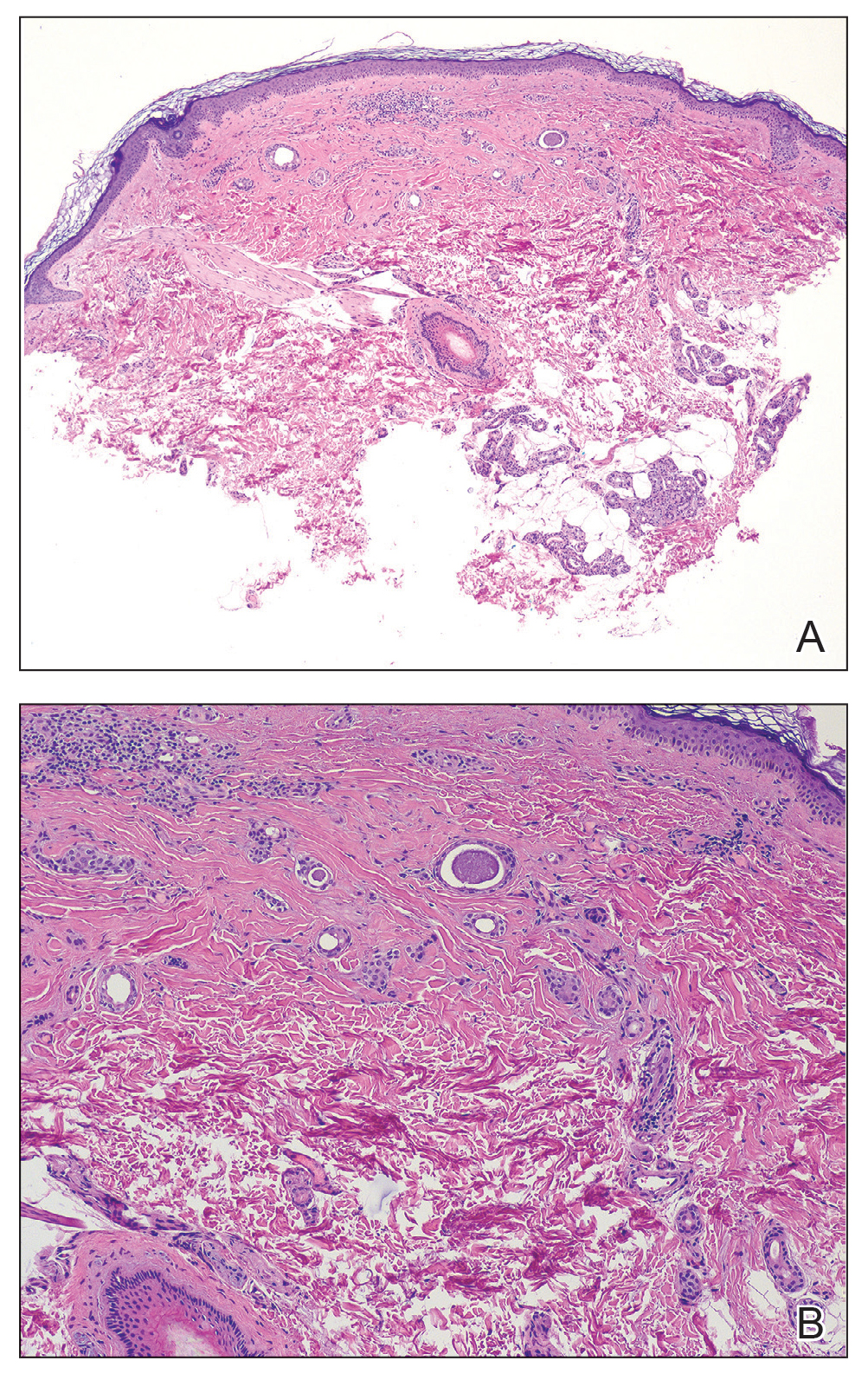

Histopathology revealed invagination of the epidermis with hyperkeratosis; prominent epidermal hyperplasia; and a central basophilic plug of keratin, collagen, and inflammatory debris. Transepidermal elimination of bright eosinophilic altered collagen fibers was seen (Figure). The findings were consistent with a diagnosis of reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC).

Reactive perforating collagenosis, a subtype of perforating dermatosis, is a rare skin condition in which altered collagen is eliminated through the epidermis.1 There are 2 forms of RPC: the inherited form, which is very rare and manifests in childhood, and the acquired form, which manifests in adulthood and is associated with systemic diseases, most notably diabetes and/or chronic renal failure, both of which our patient had been diagnosed with.1,2 The clinical presentation of RPC includes erythematous papules or nodules that evolve into umbilicated 4- to 10-mm craterlike ulcerations with a central keratotic plug. The lesions favor a linear distribution along the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, trunk, and gluteal area. Involvement of the head, neck, and scalp has been reported less commonly, which makes our case particularly unique.3 Histopathologically, RPC is characterized by a cup-shaped depression of the epidermis with an overlying keratin plug containing inflammatory cells, keratinous debris, and collagen fibers. Vertically oriented collagen fibers are seen extruded through the epidermis.4,5

While the pathogenesis of RPC remains unknown, it is believed that superficial trauma due to chronic scratching results in transepithelial elimination of collagen. Due to the association of acquired RPC (ARPC) with diabetes, it also has been proposed that scratching can cause microtrauma and necrosis of the dermal structures, potentially due to diabetic microangiopathy.3 Additionally, RPC is associated with overexpression of transforming growth factor beta 3 in lesional skin, suggesting that transforming growth factor beta 3 is involved with tissue repair and extracellular remodeling in this condition.6

Treatment of ARPC should include the management of underlying disease. While no definitive treatment has been reported to date, topical corticosteroids, retinoids, keratolytics, emollients, antihistamines, narrow-band UVB phototherapy, and psoralen plus UVA phototherapy have been used with varying degrees of improvement. Typically, the lesions self-resolve within 6 to 8 weeks; however, they often recur and usually leave scarring with or without hyperpigmentation.2,7-10

Acquired RPC can be misdiagnosed initially, as it mimics several other conditions and commonly is associated with systemic diseases. While biopsy is necessary for diagnosis, if it cannot be performed or the results are indeterminate, dermoscopy can serve as a helpful diagnostic tool. The most common dermoscopic patterns seen in RPC include a yellow-brown structureless area in the center of the lesion with a peripheral surface crust and surrounding white rim—thought to represent epidermal invagination or keratinous debris. Additionally, inflammation with visible vessels both centrally and peripherally is represented by an outer pink circle on dermoscopy.5,11

The differential diagnoses for RPC include perforating folliculitis (PF), elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS), prurigo nodularis, and keratoacanthomas. The primary perforating dermatoses (PF, EPS, and RPC) are similarly characterized by elimination of altered dermal material through the epidermis. As these conditions manifest with similar features on clinical examination, differentiation is made by the type of epidermal damage and the features of elimination material, making histopathologic examination paramount for definitive diagnosis.

Perforating folliculitis manifests as erythematous, follicular papules with a small central keratotic core or a central hair. Histopathologically, PF reveals a widely dilated follicle containing keratin, necrotic debris, and degenerated inflammatory cells. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa manifests clinically as hyperkeratotic papules in serpiginous patterns rather than the linear pattern commonly seen with ARPC. Histopathologically, EPS reveals thickened elastic fibers, rather than collagen fibers as seen in ARPC, extruded through the epidermis. Prurigo nodularis manifests clinically as dome-shaped papules with possible excoriation and crusting. Histopathologic examination reveals epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis; however, the characteristic features of transepithelial elimination of collagen and invaginations of epidermis differentiate ARPC from prurigo nodularis.12,13 Keratoacanthomas manifest clinically as an eruption of small, round, pink papules that rapidly grow and evolve into 1- to 2-cm dome-shaped nodules with central keratinaceous plugs, mimicking a crateriform appearance. Histopathologic examination reveals a circumscribed proliferation of well-differentiated keratinocytes. Multilobular exophytic or endophytic cystlike invaginations of the epidermis also are noted. The expulsion of collagen from the epidermis is more consistent with ARPC.14

- Cohen RW, Auerbach R. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):287-289. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(89)80059-3

- Bejjanki H, Siroy AE, Koratala A. Reactive perforating collagenosis in end-stage renal disease: not all that itches is uremic pruritis! Am J Med. 2019;132:E658-E660. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.015

- Gontijo JRV, Júnior FF, Pereira LB, et al. Trauma-induced acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:392-393. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.06.022

- Ambalathinkal JJ, Phiske MM, Someshwar SJ. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis, a rare entity at uncommon site. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2022;65:895-897. doi:10.4103/ijpm.ijpm_333_21

- Ormerod E, Atwan A, Intzedy L, et al. Dermoscopy features of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: a case series. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2018;8:303-305. doi:10.5826/dpc.0804a11

- Fei C, Wang Y, Gong Y, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: a report of a typical case. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:E4305. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000004305

- Bartling SJ, Naff JL, Canevari MM, et al. Pruritic rash in an elderly patient with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. AACE Clin Case Rep. 2018;5:E146-E149. doi:10.4158/ACCR-2018-0388

- Kollipara H, Satya RS, Rao GR, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: case series. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2023;14:72-76. doi:10.4103/idoj.idoj_373_22

- Wang C, Liu YH, Wang YX, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133:2119-2120. doi:10.1097 /cm9.0000000000000906

- Harbaoui S, Litaiem N. Acquired perforating dermatosis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 13, 2023. Accessed August 13, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539715/

- Elmas ÖF, Kilitci A, Uyar B. Dermoscopic patterns of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11:E2020085. doi:10.5826/dpc.1101a85

- Patterson JW. The perforating disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:561-581. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80259-5

- Huang AH, Williams KA, Kwatra SG. Prurigo nodularis: epidemiology and clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1559-1565. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.183

- Zito PM, Scharf R. Keratoacanthoma. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed August 13, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499931/

THE DIAGNOSIS: Reactive Perforating Collagenosis

Histopathology revealed invagination of the epidermis with hyperkeratosis; prominent epidermal hyperplasia; and a central basophilic plug of keratin, collagen, and inflammatory debris. Transepidermal elimination of bright eosinophilic altered collagen fibers was seen (Figure). The findings were consistent with a diagnosis of reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC).

Reactive perforating collagenosis, a subtype of perforating dermatosis, is a rare skin condition in which altered collagen is eliminated through the epidermis.1 There are 2 forms of RPC: the inherited form, which is very rare and manifests in childhood, and the acquired form, which manifests in adulthood and is associated with systemic diseases, most notably diabetes and/or chronic renal failure, both of which our patient had been diagnosed with.1,2 The clinical presentation of RPC includes erythematous papules or nodules that evolve into umbilicated 4- to 10-mm craterlike ulcerations with a central keratotic plug. The lesions favor a linear distribution along the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, trunk, and gluteal area. Involvement of the head, neck, and scalp has been reported less commonly, which makes our case particularly unique.3 Histopathologically, RPC is characterized by a cup-shaped depression of the epidermis with an overlying keratin plug containing inflammatory cells, keratinous debris, and collagen fibers. Vertically oriented collagen fibers are seen extruded through the epidermis.4,5

While the pathogenesis of RPC remains unknown, it is believed that superficial trauma due to chronic scratching results in transepithelial elimination of collagen. Due to the association of acquired RPC (ARPC) with diabetes, it also has been proposed that scratching can cause microtrauma and necrosis of the dermal structures, potentially due to diabetic microangiopathy.3 Additionally, RPC is associated with overexpression of transforming growth factor beta 3 in lesional skin, suggesting that transforming growth factor beta 3 is involved with tissue repair and extracellular remodeling in this condition.6

Treatment of ARPC should include the management of underlying disease. While no definitive treatment has been reported to date, topical corticosteroids, retinoids, keratolytics, emollients, antihistamines, narrow-band UVB phototherapy, and psoralen plus UVA phototherapy have been used with varying degrees of improvement. Typically, the lesions self-resolve within 6 to 8 weeks; however, they often recur and usually leave scarring with or without hyperpigmentation.2,7-10

Acquired RPC can be misdiagnosed initially, as it mimics several other conditions and commonly is associated with systemic diseases. While biopsy is necessary for diagnosis, if it cannot be performed or the results are indeterminate, dermoscopy can serve as a helpful diagnostic tool. The most common dermoscopic patterns seen in RPC include a yellow-brown structureless area in the center of the lesion with a peripheral surface crust and surrounding white rim—thought to represent epidermal invagination or keratinous debris. Additionally, inflammation with visible vessels both centrally and peripherally is represented by an outer pink circle on dermoscopy.5,11

The differential diagnoses for RPC include perforating folliculitis (PF), elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS), prurigo nodularis, and keratoacanthomas. The primary perforating dermatoses (PF, EPS, and RPC) are similarly characterized by elimination of altered dermal material through the epidermis. As these conditions manifest with similar features on clinical examination, differentiation is made by the type of epidermal damage and the features of elimination material, making histopathologic examination paramount for definitive diagnosis.

Perforating folliculitis manifests as erythematous, follicular papules with a small central keratotic core or a central hair. Histopathologically, PF reveals a widely dilated follicle containing keratin, necrotic debris, and degenerated inflammatory cells. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa manifests clinically as hyperkeratotic papules in serpiginous patterns rather than the linear pattern commonly seen with ARPC. Histopathologically, EPS reveals thickened elastic fibers, rather than collagen fibers as seen in ARPC, extruded through the epidermis. Prurigo nodularis manifests clinically as dome-shaped papules with possible excoriation and crusting. Histopathologic examination reveals epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis; however, the characteristic features of transepithelial elimination of collagen and invaginations of epidermis differentiate ARPC from prurigo nodularis.12,13 Keratoacanthomas manifest clinically as an eruption of small, round, pink papules that rapidly grow and evolve into 1- to 2-cm dome-shaped nodules with central keratinaceous plugs, mimicking a crateriform appearance. Histopathologic examination reveals a circumscribed proliferation of well-differentiated keratinocytes. Multilobular exophytic or endophytic cystlike invaginations of the epidermis also are noted. The expulsion of collagen from the epidermis is more consistent with ARPC.14

THE DIAGNOSIS: Reactive Perforating Collagenosis

Histopathology revealed invagination of the epidermis with hyperkeratosis; prominent epidermal hyperplasia; and a central basophilic plug of keratin, collagen, and inflammatory debris. Transepidermal elimination of bright eosinophilic altered collagen fibers was seen (Figure). The findings were consistent with a diagnosis of reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC).

Reactive perforating collagenosis, a subtype of perforating dermatosis, is a rare skin condition in which altered collagen is eliminated through the epidermis.1 There are 2 forms of RPC: the inherited form, which is very rare and manifests in childhood, and the acquired form, which manifests in adulthood and is associated with systemic diseases, most notably diabetes and/or chronic renal failure, both of which our patient had been diagnosed with.1,2 The clinical presentation of RPC includes erythematous papules or nodules that evolve into umbilicated 4- to 10-mm craterlike ulcerations with a central keratotic plug. The lesions favor a linear distribution along the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, trunk, and gluteal area. Involvement of the head, neck, and scalp has been reported less commonly, which makes our case particularly unique.3 Histopathologically, RPC is characterized by a cup-shaped depression of the epidermis with an overlying keratin plug containing inflammatory cells, keratinous debris, and collagen fibers. Vertically oriented collagen fibers are seen extruded through the epidermis.4,5

While the pathogenesis of RPC remains unknown, it is believed that superficial trauma due to chronic scratching results in transepithelial elimination of collagen. Due to the association of acquired RPC (ARPC) with diabetes, it also has been proposed that scratching can cause microtrauma and necrosis of the dermal structures, potentially due to diabetic microangiopathy.3 Additionally, RPC is associated with overexpression of transforming growth factor beta 3 in lesional skin, suggesting that transforming growth factor beta 3 is involved with tissue repair and extracellular remodeling in this condition.6

Treatment of ARPC should include the management of underlying disease. While no definitive treatment has been reported to date, topical corticosteroids, retinoids, keratolytics, emollients, antihistamines, narrow-band UVB phototherapy, and psoralen plus UVA phototherapy have been used with varying degrees of improvement. Typically, the lesions self-resolve within 6 to 8 weeks; however, they often recur and usually leave scarring with or without hyperpigmentation.2,7-10

Acquired RPC can be misdiagnosed initially, as it mimics several other conditions and commonly is associated with systemic diseases. While biopsy is necessary for diagnosis, if it cannot be performed or the results are indeterminate, dermoscopy can serve as a helpful diagnostic tool. The most common dermoscopic patterns seen in RPC include a yellow-brown structureless area in the center of the lesion with a peripheral surface crust and surrounding white rim—thought to represent epidermal invagination or keratinous debris. Additionally, inflammation with visible vessels both centrally and peripherally is represented by an outer pink circle on dermoscopy.5,11

The differential diagnoses for RPC include perforating folliculitis (PF), elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS), prurigo nodularis, and keratoacanthomas. The primary perforating dermatoses (PF, EPS, and RPC) are similarly characterized by elimination of altered dermal material through the epidermis. As these conditions manifest with similar features on clinical examination, differentiation is made by the type of epidermal damage and the features of elimination material, making histopathologic examination paramount for definitive diagnosis.

Perforating folliculitis manifests as erythematous, follicular papules with a small central keratotic core or a central hair. Histopathologically, PF reveals a widely dilated follicle containing keratin, necrotic debris, and degenerated inflammatory cells. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa manifests clinically as hyperkeratotic papules in serpiginous patterns rather than the linear pattern commonly seen with ARPC. Histopathologically, EPS reveals thickened elastic fibers, rather than collagen fibers as seen in ARPC, extruded through the epidermis. Prurigo nodularis manifests clinically as dome-shaped papules with possible excoriation and crusting. Histopathologic examination reveals epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis; however, the characteristic features of transepithelial elimination of collagen and invaginations of epidermis differentiate ARPC from prurigo nodularis.12,13 Keratoacanthomas manifest clinically as an eruption of small, round, pink papules that rapidly grow and evolve into 1- to 2-cm dome-shaped nodules with central keratinaceous plugs, mimicking a crateriform appearance. Histopathologic examination reveals a circumscribed proliferation of well-differentiated keratinocytes. Multilobular exophytic or endophytic cystlike invaginations of the epidermis also are noted. The expulsion of collagen from the epidermis is more consistent with ARPC.14

- Cohen RW, Auerbach R. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):287-289. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(89)80059-3

- Bejjanki H, Siroy AE, Koratala A. Reactive perforating collagenosis in end-stage renal disease: not all that itches is uremic pruritis! Am J Med. 2019;132:E658-E660. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.015

- Gontijo JRV, Júnior FF, Pereira LB, et al. Trauma-induced acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:392-393. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.06.022

- Ambalathinkal JJ, Phiske MM, Someshwar SJ. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis, a rare entity at uncommon site. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2022;65:895-897. doi:10.4103/ijpm.ijpm_333_21

- Ormerod E, Atwan A, Intzedy L, et al. Dermoscopy features of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: a case series. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2018;8:303-305. doi:10.5826/dpc.0804a11

- Fei C, Wang Y, Gong Y, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: a report of a typical case. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:E4305. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000004305

- Bartling SJ, Naff JL, Canevari MM, et al. Pruritic rash in an elderly patient with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. AACE Clin Case Rep. 2018;5:E146-E149. doi:10.4158/ACCR-2018-0388

- Kollipara H, Satya RS, Rao GR, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: case series. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2023;14:72-76. doi:10.4103/idoj.idoj_373_22

- Wang C, Liu YH, Wang YX, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133:2119-2120. doi:10.1097 /cm9.0000000000000906

- Harbaoui S, Litaiem N. Acquired perforating dermatosis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 13, 2023. Accessed August 13, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539715/

- Elmas ÖF, Kilitci A, Uyar B. Dermoscopic patterns of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11:E2020085. doi:10.5826/dpc.1101a85

- Patterson JW. The perforating disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:561-581. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80259-5

- Huang AH, Williams KA, Kwatra SG. Prurigo nodularis: epidemiology and clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1559-1565. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.183

- Zito PM, Scharf R. Keratoacanthoma. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed August 13, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499931/

- Cohen RW, Auerbach R. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):287-289. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(89)80059-3

- Bejjanki H, Siroy AE, Koratala A. Reactive perforating collagenosis in end-stage renal disease: not all that itches is uremic pruritis! Am J Med. 2019;132:E658-E660. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.015

- Gontijo JRV, Júnior FF, Pereira LB, et al. Trauma-induced acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:392-393. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.06.022

- Ambalathinkal JJ, Phiske MM, Someshwar SJ. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis, a rare entity at uncommon site. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2022;65:895-897. doi:10.4103/ijpm.ijpm_333_21

- Ormerod E, Atwan A, Intzedy L, et al. Dermoscopy features of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: a case series. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2018;8:303-305. doi:10.5826/dpc.0804a11

- Fei C, Wang Y, Gong Y, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: a report of a typical case. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:E4305. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000004305

- Bartling SJ, Naff JL, Canevari MM, et al. Pruritic rash in an elderly patient with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. AACE Clin Case Rep. 2018;5:E146-E149. doi:10.4158/ACCR-2018-0388

- Kollipara H, Satya RS, Rao GR, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: case series. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2023;14:72-76. doi:10.4103/idoj.idoj_373_22

- Wang C, Liu YH, Wang YX, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133:2119-2120. doi:10.1097 /cm9.0000000000000906

- Harbaoui S, Litaiem N. Acquired perforating dermatosis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 13, 2023. Accessed August 13, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539715/

- Elmas ÖF, Kilitci A, Uyar B. Dermoscopic patterns of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11:E2020085. doi:10.5826/dpc.1101a85

- Patterson JW. The perforating disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:561-581. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80259-5

- Huang AH, Williams KA, Kwatra SG. Prurigo nodularis: epidemiology and clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1559-1565. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.183

- Zito PM, Scharf R. Keratoacanthoma. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed August 13, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499931/

Diffuse Pruritic Keratotic Papules

Diffuse Pruritic Keratotic Papules

A 65-year-old woman presented to dermatology with an intensely pruritic rash on the arms, legs, neck, and face of several months’ duration. The patient reported scratching the lesions but denied any recent trauma to the affected areas. She previously had been evaluated by her primary care provider, who prescribed cephalexin with no improvement. Her medical history was remarkable for chronic renal failure on dialysis, diabetes, hypertension, and congestive heart failure. Physical examination of the skin revealed hard white cutaneous nodules distributed on the proximal posterior upper arms, bilateral proximal pretibial regions, right elbow, and left knee. Two shave biopsies from the right elbow and left knee were obtained for histopathology.

Painful Edematous Labial Erosions

Painful Edematous Labial Erosions

THE DIAGNOSIS: Kaposi Varicelliform Eruption

Genital erosions tested positive for herpes simplex virus (HSV) 2 via PCR, confirming a Kaposi varicelliform eruption (KVE) in a patient with mycosis fungoides. The medical team began antiviral therapy with intravenous (IV) acyclovir; however, susceptibility testing during the hospital admission confirmed acyclovir resistance, requiring a transition to cidofovir cream 1% and IV foscarnet.1 Subsequent concerns by the care team about chemical burns, dysuria, and renal impairment led to discontinuation of both the cidofovir and foscarnet, considerably narrowing the treatment options.1 The patient’s condition was complicated by polymicrobial bacteremia. Additionally, worsening acidosis and acute kidney injury required initiation of continuous renal replacement therapy.1 Considering these conditions, the patient was enrolled in a promising clinical trial for pritelivir, a novel antiviral medication; however, due to the development of oliguria and the progression of renal failure, this course of treatment had to be discontinued. Faced with potential viral encephalitis, the infectious disease team concluded that, despite previous adverse reactions, resumption of IV foscarnet treatment would present more benefits than risks, given the patient’s critical situation.1

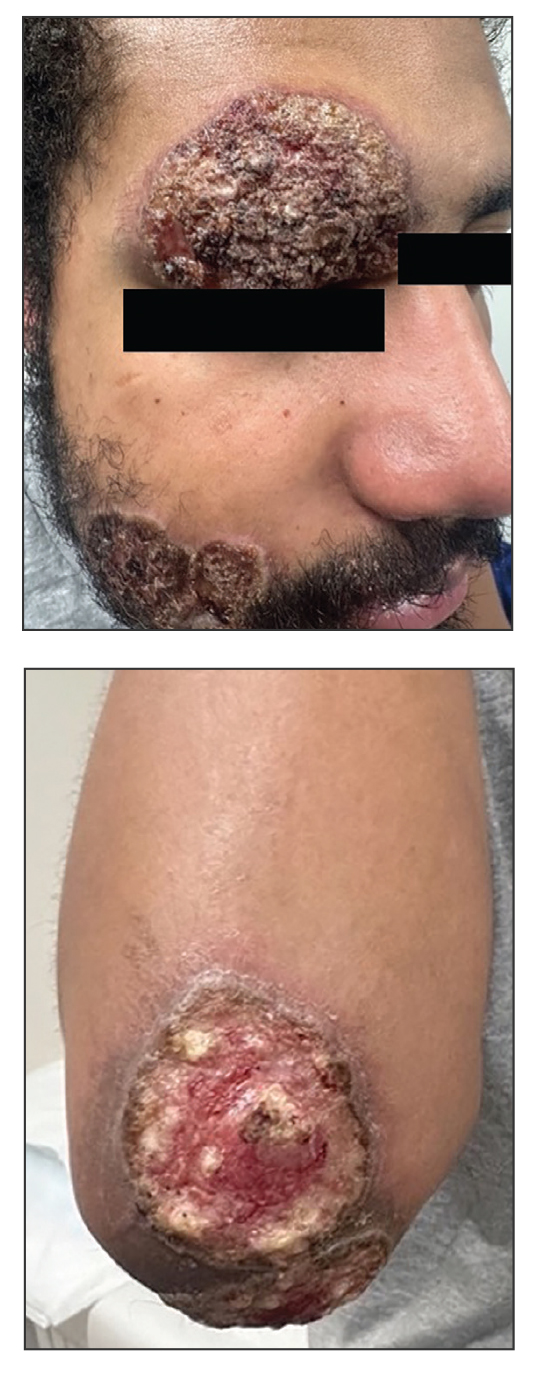

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is a slowly progressive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma of CD4+ cells that primarily affects the skin. Clinically, it often is characterized by pruritic scaly patches or plaques with sharply demarcated borders, the enduring nature of which consistently poses a therapeutic challenge due to their noted resistance to preliminary lines of treatment. Presently, potential cures are limited to allogeneic stem cell transplantation and unilesional radiotherapy for advanced MF; however, no treatment has been found to notably improve survival rates.1 Mycosis fungoides can result in various complications including diffuse spread of a skin infection caused by HSV, known as KVE.1 Kaposi varicelliform eruption usually manifests clinically with painful skin vesicles that often are accompanied by systemic signs such as fever and malaise. The vesicles rapidly progress into pustules or erosions, predominantly affecting regions such as the head, neck, groin, and upper torso (Figure 1).2 Kaposi varicelliform eruption is considered a dermatologic emergency due to its potential to precipitate serious complications such as life-threatening secondary bacterial infection, HSV viremia, and multiorgan involvement; it also carries the risk of instigating ocular complications, such as keratitis, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, uveitis, and potential vision loss.2

Kaposi varicelliform eruption usually is diagnosed through clinical examination supported by polymerase chain reaction, viral culture, histopathology, HSV serology, and Tzanck smear.2 The differential diagnosis includes varicella, atypical varicella, herpes genitalis, herpes zoster, allergic or irritant contact dermatitis, or MF, which may result in painful skin ulcers.2-4 If an HSV superinfection is suspected, a polymerase chain reaction test ideally should be conducted within the first 72 hours of symptom onset.2 Herpes simplex virus infection may be reinforced by histologic features such as intraepidermal blistering, acantholysis, keratinocyte ballooning degeneration, and multinuclear giant cells with intranuclear inclusions. Given its severe nature, immediate empiric antiviral treatment for KVE is essential, even while awaiting confirmatory tests. The recommended treatment protocol involves acyclovir (400 mg orally 3 times daily or 10 mg/kg IV) or valacyclovir (500 mg orally twice daily), continued until KVE resolves.2

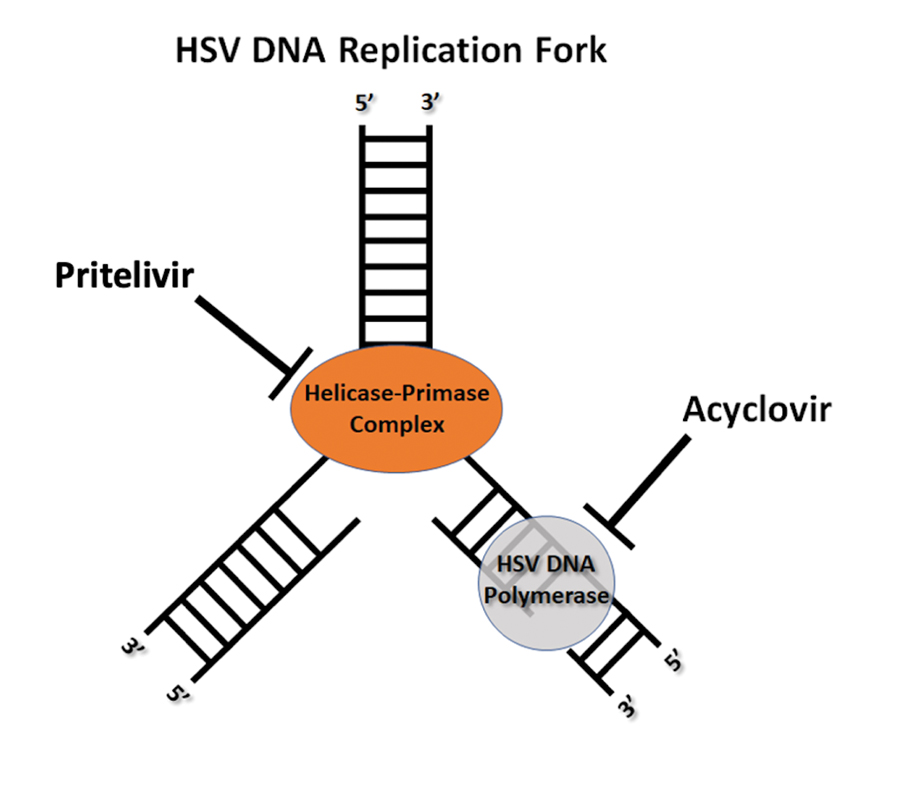

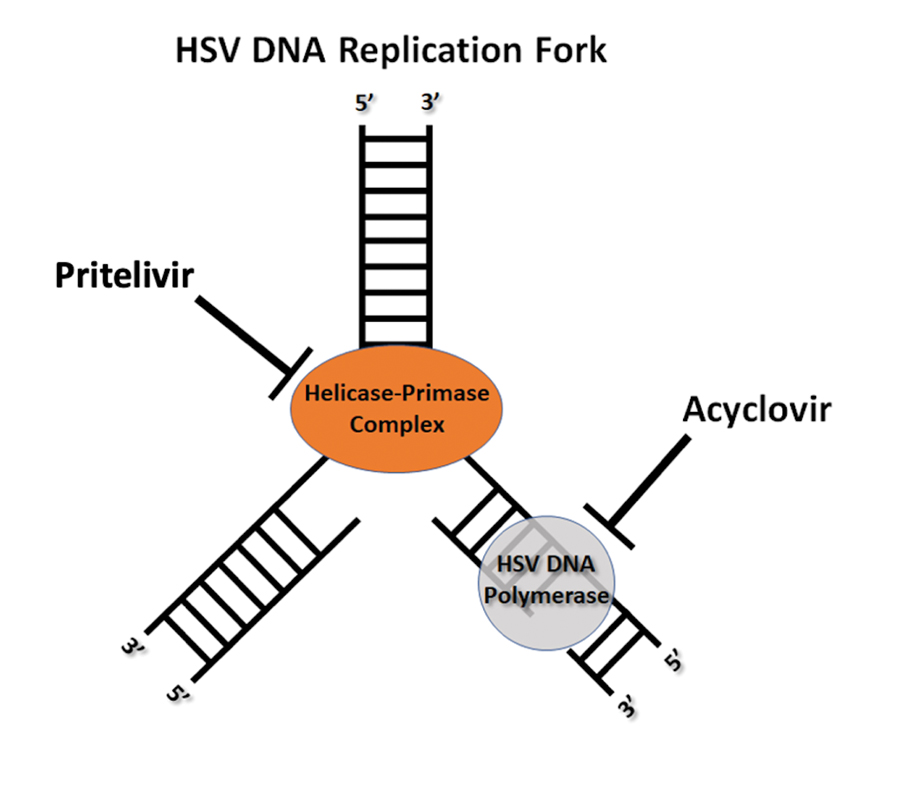

Herpes genitalis caused by HSV-2 is estimated to affect approximately 45 million adults in the United States.2 First-line treatment for HSV-2 includes acyclovir and its derivatives, which are viral nucleoside analogs that inhibit viral DNA polymerases.5,6 However, over the past 2 decades, increasing HSV resistance to acyclovir and its derivatives has been noted among immunocompromised patients.5,6 Second-line agents, such as IV foscarnet and cidofovir, require close laboratory monitoring for nephrotoxicity and are contraindicated in those with renal insufficiency, thus limiting their use.5 To combat acyclovir resistance, novel antivirals such as pritelivir are being developed. Pritelivir targets the HSV helicase-primase complex and has been shown to outperform acyclovir in in-vitro animal models.7 Due to its unique mechanism of action (Figure 2), pritelivir is effective against acyclovir-resistant HSV strains, and clinical trials suggest its serum half-life may allow for daily dosing. A phase 2 study showed pritelivir reduced viral shedding days, sped up genital lesion healing in adults infected with HSV-2, and exhibited a good safety profile.7 Our patient participated in ongoing open-label trials of pritelivir that aimed to assess its efficacy and safety in immunocompromised patients. Given the limited alternative treatments for acyclovir-resistant HSV-2, clinicians need to stay updated on antiviral agents under development.

- García-Díaz N, Piris MÁ, Ortiz-Romero PL, et al. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: an integrative review of the pathophysiology, molecular drivers, and targeted therapy. Cancers. 2021;13:1931. doi:10.3390/cancers13081931

- Baaniya B, Agrawal S. Kaposi varicelliform eruption in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2020;2020:6695342. doi:10.1155/2020/6695342

- Shin D, Lee MS, Kim DY, et al. Increased large unstained cells value in varicella patients: a valuable parameter to aid rapid diagnosis of varicella infection. J Dermatol. 2015;42:795-799. doi:10.1111

- Joshi A, Sah SP, Agrawal S. Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption or atypical chickenpox in a normal individual. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:126-127.

- Groves MJ. Genital herpes: a review. Am Fam Physician. 2016; 93:928-934.

- Fleming DT, Leone P, Esposito D, et al. Herpes virus type 2 infection and genital symptoms in primary care patients. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:416-421. doi:10.1097/01.olq.0000200578.86276.0b

- Poole CL, James SH. Antiviral therapies for herpesviruses: current agents and new directions. Clin Ther. 2018;40:1282-1298. doi:10.1016 /j.clinthera.2018.07.006.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Kaposi Varicelliform Eruption

Genital erosions tested positive for herpes simplex virus (HSV) 2 via PCR, confirming a Kaposi varicelliform eruption (KVE) in a patient with mycosis fungoides. The medical team began antiviral therapy with intravenous (IV) acyclovir; however, susceptibility testing during the hospital admission confirmed acyclovir resistance, requiring a transition to cidofovir cream 1% and IV foscarnet.1 Subsequent concerns by the care team about chemical burns, dysuria, and renal impairment led to discontinuation of both the cidofovir and foscarnet, considerably narrowing the treatment options.1 The patient’s condition was complicated by polymicrobial bacteremia. Additionally, worsening acidosis and acute kidney injury required initiation of continuous renal replacement therapy.1 Considering these conditions, the patient was enrolled in a promising clinical trial for pritelivir, a novel antiviral medication; however, due to the development of oliguria and the progression of renal failure, this course of treatment had to be discontinued. Faced with potential viral encephalitis, the infectious disease team concluded that, despite previous adverse reactions, resumption of IV foscarnet treatment would present more benefits than risks, given the patient’s critical situation.1

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is a slowly progressive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma of CD4+ cells that primarily affects the skin. Clinically, it often is characterized by pruritic scaly patches or plaques with sharply demarcated borders, the enduring nature of which consistently poses a therapeutic challenge due to their noted resistance to preliminary lines of treatment. Presently, potential cures are limited to allogeneic stem cell transplantation and unilesional radiotherapy for advanced MF; however, no treatment has been found to notably improve survival rates.1 Mycosis fungoides can result in various complications including diffuse spread of a skin infection caused by HSV, known as KVE.1 Kaposi varicelliform eruption usually manifests clinically with painful skin vesicles that often are accompanied by systemic signs such as fever and malaise. The vesicles rapidly progress into pustules or erosions, predominantly affecting regions such as the head, neck, groin, and upper torso (Figure 1).2 Kaposi varicelliform eruption is considered a dermatologic emergency due to its potential to precipitate serious complications such as life-threatening secondary bacterial infection, HSV viremia, and multiorgan involvement; it also carries the risk of instigating ocular complications, such as keratitis, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, uveitis, and potential vision loss.2

Kaposi varicelliform eruption usually is diagnosed through clinical examination supported by polymerase chain reaction, viral culture, histopathology, HSV serology, and Tzanck smear.2 The differential diagnosis includes varicella, atypical varicella, herpes genitalis, herpes zoster, allergic or irritant contact dermatitis, or MF, which may result in painful skin ulcers.2-4 If an HSV superinfection is suspected, a polymerase chain reaction test ideally should be conducted within the first 72 hours of symptom onset.2 Herpes simplex virus infection may be reinforced by histologic features such as intraepidermal blistering, acantholysis, keratinocyte ballooning degeneration, and multinuclear giant cells with intranuclear inclusions. Given its severe nature, immediate empiric antiviral treatment for KVE is essential, even while awaiting confirmatory tests. The recommended treatment protocol involves acyclovir (400 mg orally 3 times daily or 10 mg/kg IV) or valacyclovir (500 mg orally twice daily), continued until KVE resolves.2

Herpes genitalis caused by HSV-2 is estimated to affect approximately 45 million adults in the United States.2 First-line treatment for HSV-2 includes acyclovir and its derivatives, which are viral nucleoside analogs that inhibit viral DNA polymerases.5,6 However, over the past 2 decades, increasing HSV resistance to acyclovir and its derivatives has been noted among immunocompromised patients.5,6 Second-line agents, such as IV foscarnet and cidofovir, require close laboratory monitoring for nephrotoxicity and are contraindicated in those with renal insufficiency, thus limiting their use.5 To combat acyclovir resistance, novel antivirals such as pritelivir are being developed. Pritelivir targets the HSV helicase-primase complex and has been shown to outperform acyclovir in in-vitro animal models.7 Due to its unique mechanism of action (Figure 2), pritelivir is effective against acyclovir-resistant HSV strains, and clinical trials suggest its serum half-life may allow for daily dosing. A phase 2 study showed pritelivir reduced viral shedding days, sped up genital lesion healing in adults infected with HSV-2, and exhibited a good safety profile.7 Our patient participated in ongoing open-label trials of pritelivir that aimed to assess its efficacy and safety in immunocompromised patients. Given the limited alternative treatments for acyclovir-resistant HSV-2, clinicians need to stay updated on antiviral agents under development.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Kaposi Varicelliform Eruption

Genital erosions tested positive for herpes simplex virus (HSV) 2 via PCR, confirming a Kaposi varicelliform eruption (KVE) in a patient with mycosis fungoides. The medical team began antiviral therapy with intravenous (IV) acyclovir; however, susceptibility testing during the hospital admission confirmed acyclovir resistance, requiring a transition to cidofovir cream 1% and IV foscarnet.1 Subsequent concerns by the care team about chemical burns, dysuria, and renal impairment led to discontinuation of both the cidofovir and foscarnet, considerably narrowing the treatment options.1 The patient’s condition was complicated by polymicrobial bacteremia. Additionally, worsening acidosis and acute kidney injury required initiation of continuous renal replacement therapy.1 Considering these conditions, the patient was enrolled in a promising clinical trial for pritelivir, a novel antiviral medication; however, due to the development of oliguria and the progression of renal failure, this course of treatment had to be discontinued. Faced with potential viral encephalitis, the infectious disease team concluded that, despite previous adverse reactions, resumption of IV foscarnet treatment would present more benefits than risks, given the patient’s critical situation.1

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is a slowly progressive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma of CD4+ cells that primarily affects the skin. Clinically, it often is characterized by pruritic scaly patches or plaques with sharply demarcated borders, the enduring nature of which consistently poses a therapeutic challenge due to their noted resistance to preliminary lines of treatment. Presently, potential cures are limited to allogeneic stem cell transplantation and unilesional radiotherapy for advanced MF; however, no treatment has been found to notably improve survival rates.1 Mycosis fungoides can result in various complications including diffuse spread of a skin infection caused by HSV, known as KVE.1 Kaposi varicelliform eruption usually manifests clinically with painful skin vesicles that often are accompanied by systemic signs such as fever and malaise. The vesicles rapidly progress into pustules or erosions, predominantly affecting regions such as the head, neck, groin, and upper torso (Figure 1).2 Kaposi varicelliform eruption is considered a dermatologic emergency due to its potential to precipitate serious complications such as life-threatening secondary bacterial infection, HSV viremia, and multiorgan involvement; it also carries the risk of instigating ocular complications, such as keratitis, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, uveitis, and potential vision loss.2

Kaposi varicelliform eruption usually is diagnosed through clinical examination supported by polymerase chain reaction, viral culture, histopathology, HSV serology, and Tzanck smear.2 The differential diagnosis includes varicella, atypical varicella, herpes genitalis, herpes zoster, allergic or irritant contact dermatitis, or MF, which may result in painful skin ulcers.2-4 If an HSV superinfection is suspected, a polymerase chain reaction test ideally should be conducted within the first 72 hours of symptom onset.2 Herpes simplex virus infection may be reinforced by histologic features such as intraepidermal blistering, acantholysis, keratinocyte ballooning degeneration, and multinuclear giant cells with intranuclear inclusions. Given its severe nature, immediate empiric antiviral treatment for KVE is essential, even while awaiting confirmatory tests. The recommended treatment protocol involves acyclovir (400 mg orally 3 times daily or 10 mg/kg IV) or valacyclovir (500 mg orally twice daily), continued until KVE resolves.2

Herpes genitalis caused by HSV-2 is estimated to affect approximately 45 million adults in the United States.2 First-line treatment for HSV-2 includes acyclovir and its derivatives, which are viral nucleoside analogs that inhibit viral DNA polymerases.5,6 However, over the past 2 decades, increasing HSV resistance to acyclovir and its derivatives has been noted among immunocompromised patients.5,6 Second-line agents, such as IV foscarnet and cidofovir, require close laboratory monitoring for nephrotoxicity and are contraindicated in those with renal insufficiency, thus limiting their use.5 To combat acyclovir resistance, novel antivirals such as pritelivir are being developed. Pritelivir targets the HSV helicase-primase complex and has been shown to outperform acyclovir in in-vitro animal models.7 Due to its unique mechanism of action (Figure 2), pritelivir is effective against acyclovir-resistant HSV strains, and clinical trials suggest its serum half-life may allow for daily dosing. A phase 2 study showed pritelivir reduced viral shedding days, sped up genital lesion healing in adults infected with HSV-2, and exhibited a good safety profile.7 Our patient participated in ongoing open-label trials of pritelivir that aimed to assess its efficacy and safety in immunocompromised patients. Given the limited alternative treatments for acyclovir-resistant HSV-2, clinicians need to stay updated on antiviral agents under development.

- García-Díaz N, Piris MÁ, Ortiz-Romero PL, et al. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: an integrative review of the pathophysiology, molecular drivers, and targeted therapy. Cancers. 2021;13:1931. doi:10.3390/cancers13081931

- Baaniya B, Agrawal S. Kaposi varicelliform eruption in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2020;2020:6695342. doi:10.1155/2020/6695342

- Shin D, Lee MS, Kim DY, et al. Increased large unstained cells value in varicella patients: a valuable parameter to aid rapid diagnosis of varicella infection. J Dermatol. 2015;42:795-799. doi:10.1111

- Joshi A, Sah SP, Agrawal S. Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption or atypical chickenpox in a normal individual. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:126-127.