User login

Exophytic Papule on the Chin of a Child

Exophytic Papule on the Chin of a Child

THE DIAGNOSIS: Rhabdomyomatous Mesenchymal Hamartoma

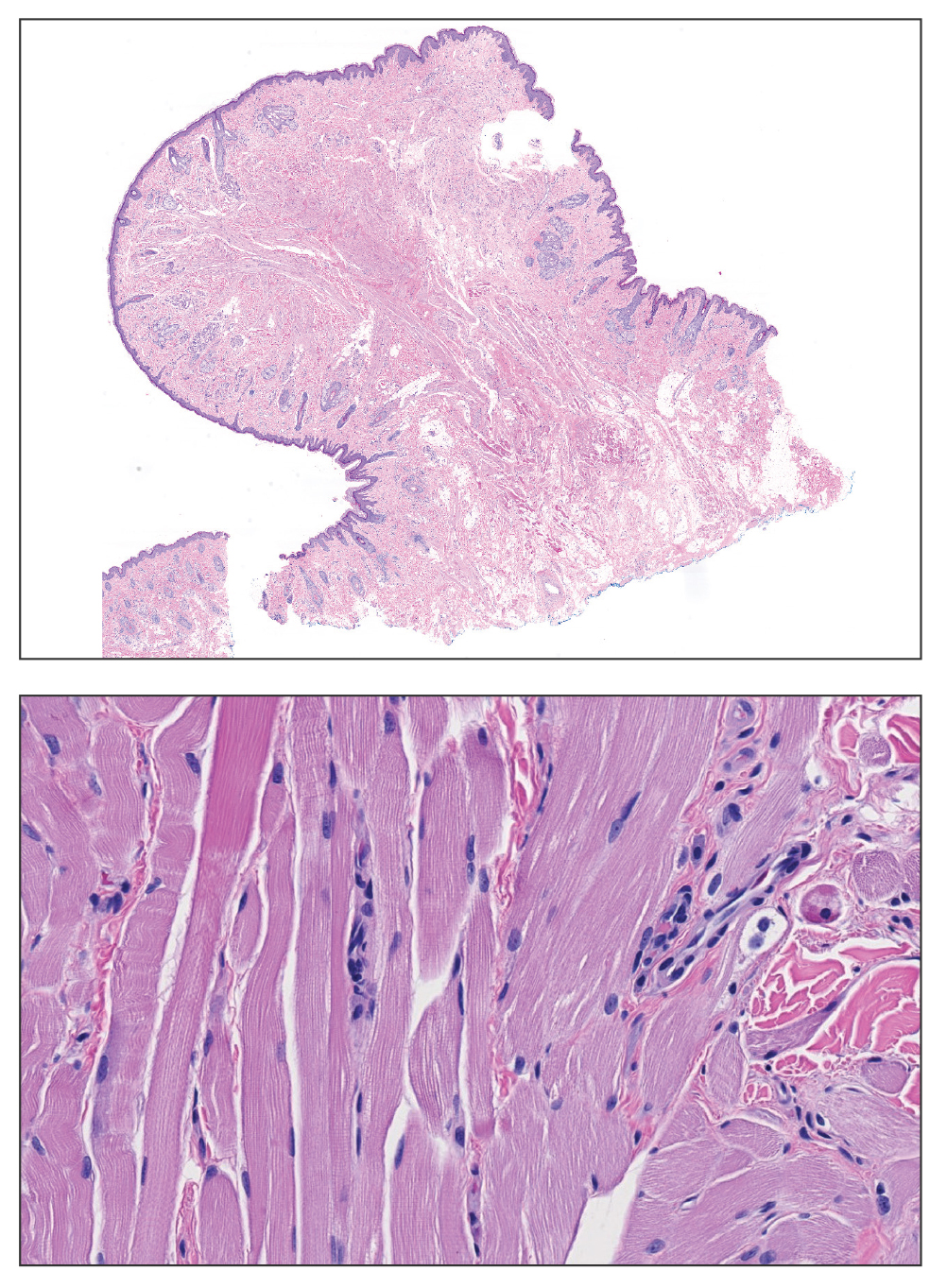

Histopathologic examination of the excised tissue revealed haphazardly arranged bundles of mature striated muscle within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue admixed with adipose tissue, adnexal structures, blood vessels, and nerves. The presence of the lesion since birth, midline clinical presentation, and histologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma (RMH).

Also referred to as striated muscle hamartoma, RMH is a rare benign lesion thought to have embryonic origin due to its midline presentation.1 The etiology of RMH is unknown but is hypothesized to be due to abnormal migration or growth of embryonic mesenchymal tissue. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma typically manifests in infancy or early childhood as a solitary midline papule on the head or neck, although there have been rare reports of development in adulthood.2-4 Lesions often are polypoid or exophytic but may manifest as smooth papules or subcutaneous nodules.2 Although benign, RMH may be associated with other congenital abnormalities and conditions, such as Delleman syndrome, which is caused by a sporadic genetic abnormality and results in defects of the eye, central nervous system, and skin.5 Treatment for RMH is not needed, but surgical excision for cosmetic purposes can be performed with low risk for recurrence. Histologically, RMH demonstrates a normal epidermis overlying disorganized bundles of skeletal muscle accompanied by varying amounts of other mature dermal and subcutaneous tissues including nerves, blood vessels, adipose tissue, and other adnexal structures.2,6 Myoglobin and desmin are positive within the skeletal muscle bundles.7

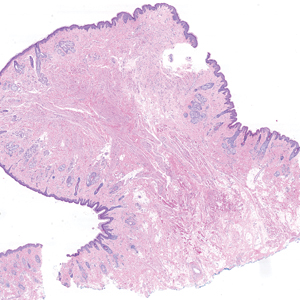

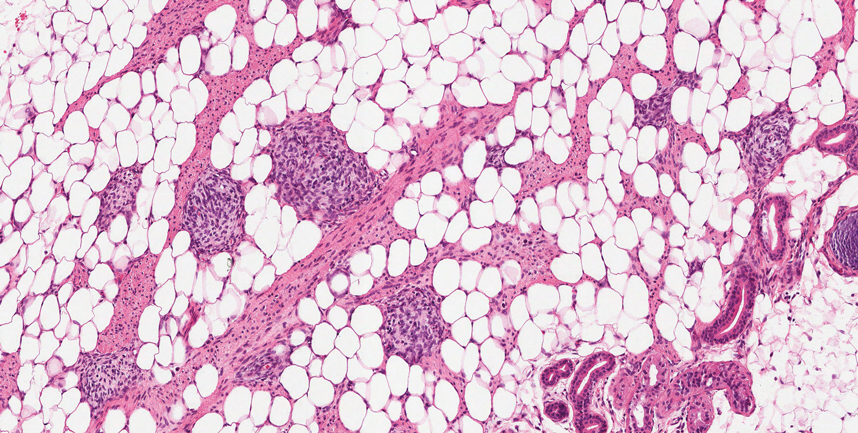

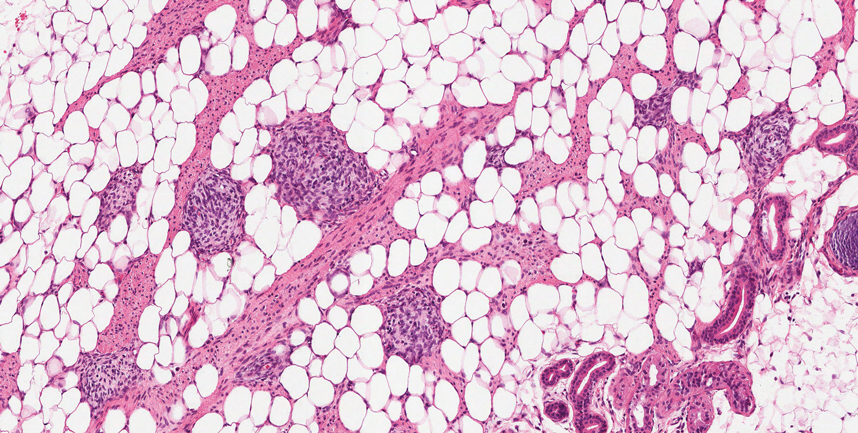

Fibrous hamartoma of infancy (FHI) often manifests as a movable, ill-defined nodule within the subcutaneous tissue. While also occurring in young children—typically within the first 2 years of life—FHI primarily is found on the upper arms, back, and axillae, in contrast to FHI.8 The classic histopathologic presentation of FHI consists of a triphasic morphology consisting of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells and dense fibroblastic/myofibroblastic tissue with mature adipose tissue woven throughout in islands (Figure 1).9 Skeletal muscle is not a component of this tumor.

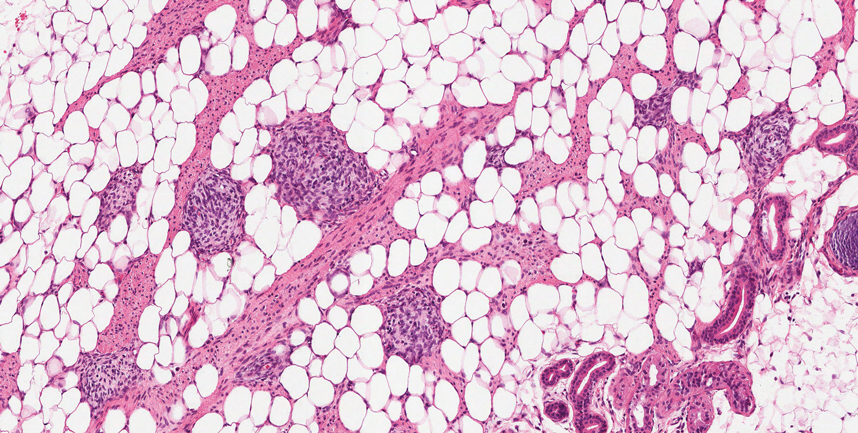

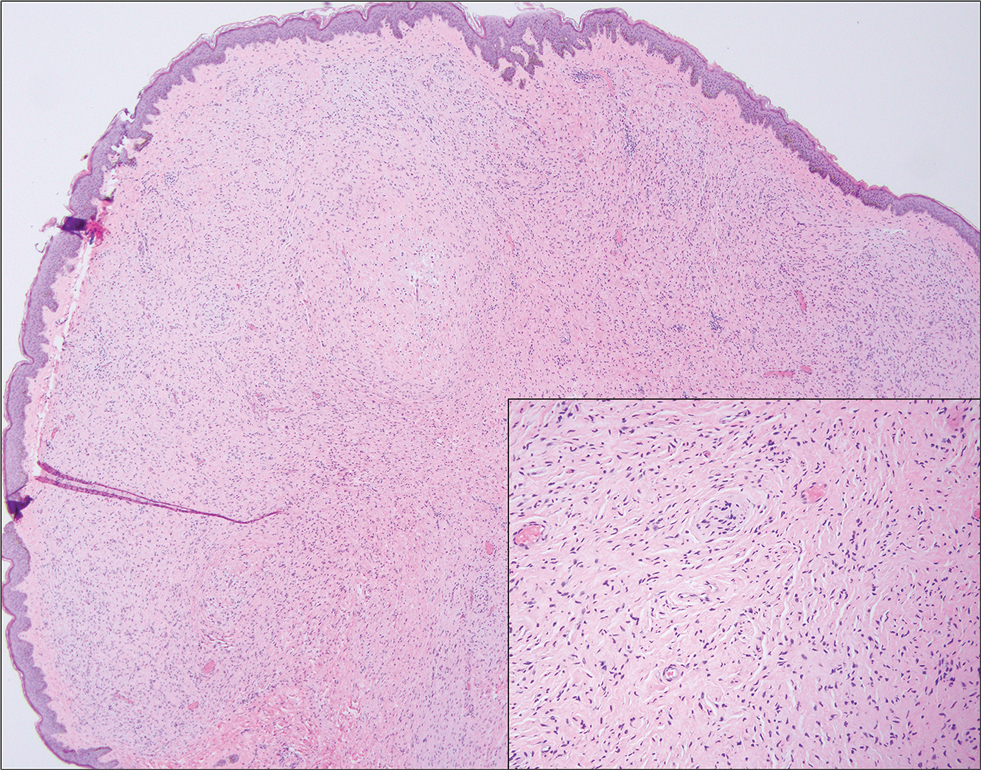

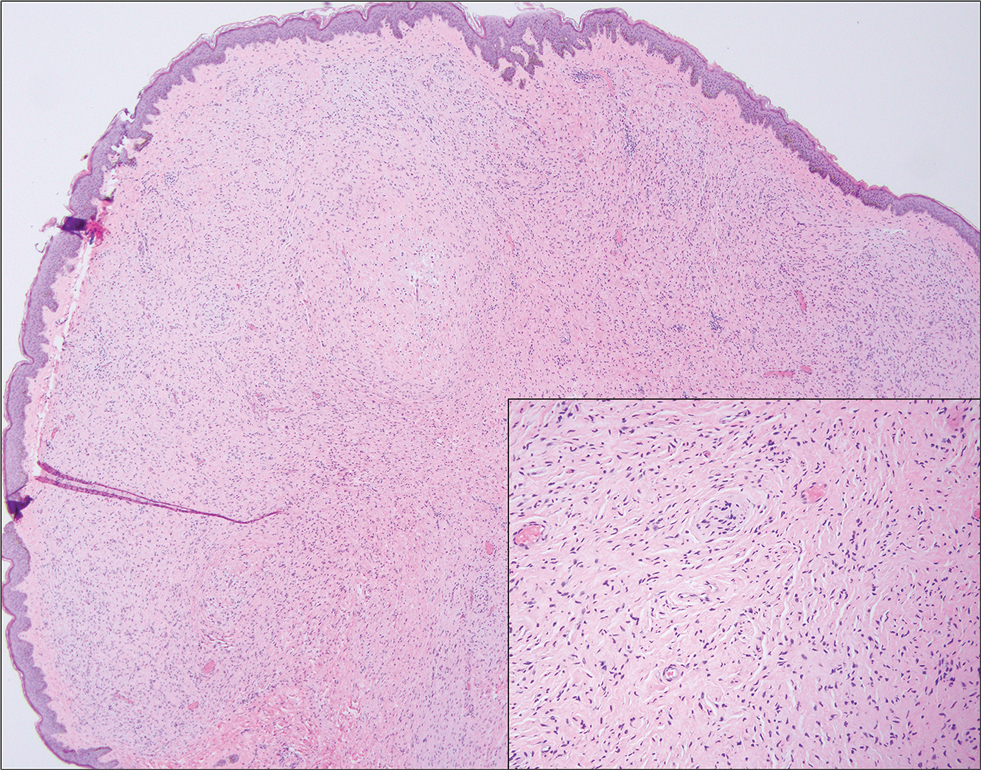

Neurofibromas also may manifest clinically as papules or nodules and arise from the peripheral nerve sheath. There are 3 major subtypes of neurofibromas—localized, diffuse, and plexiform—with the last being strongly associated with neurofibromatosis type 1.10 The plexiform type has a rare risk for malignant transformation. The typical histopathologic finding of a localized cutaneous neurofibroma is a dermal proliferation of spindle cells with wavy nuclei within a variably myxoid stroma (Figure 2).11 Interspersed mast cells also can be seen. A plexiform neurofibroma typically involves multiple nerve fascicles and comprises multinodular or tortuous bundles of cytologically bland spindle cells. Compared to RMH, skeletal muscle is not a component of this tumor.

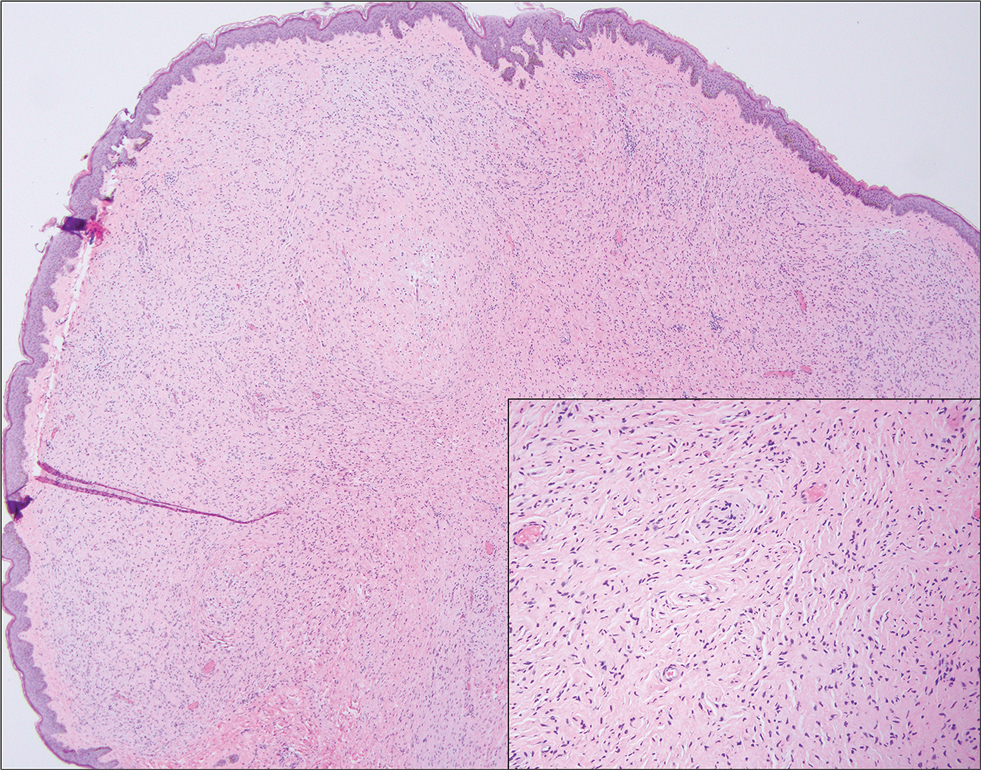

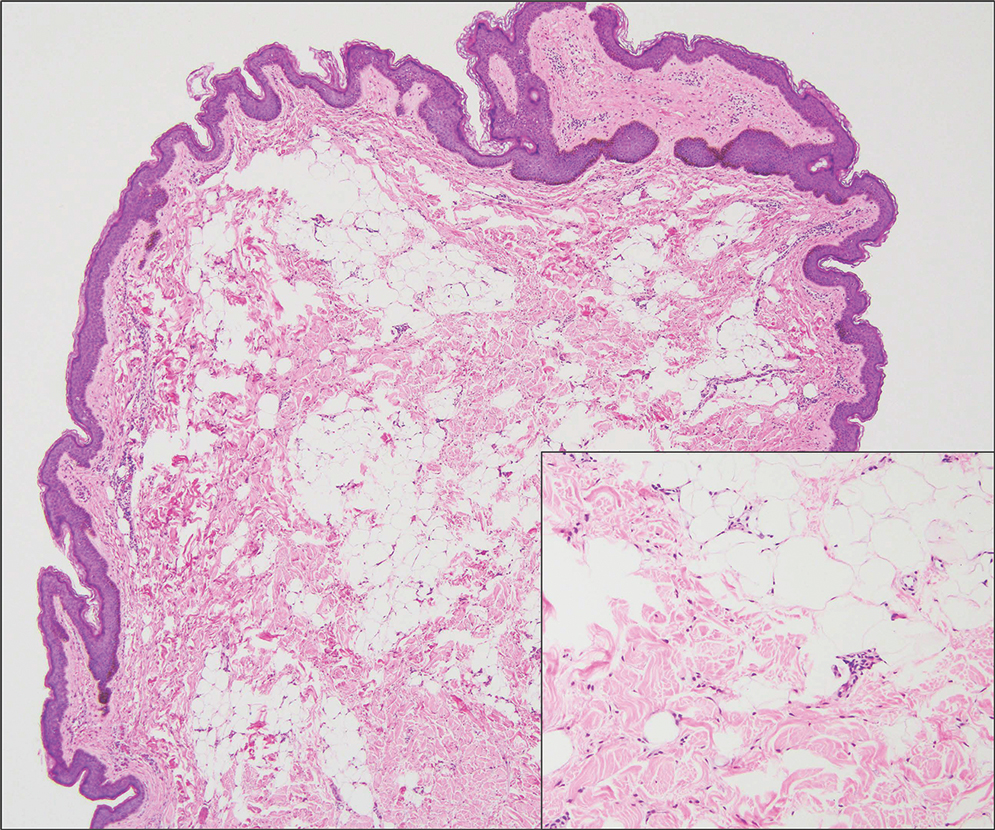

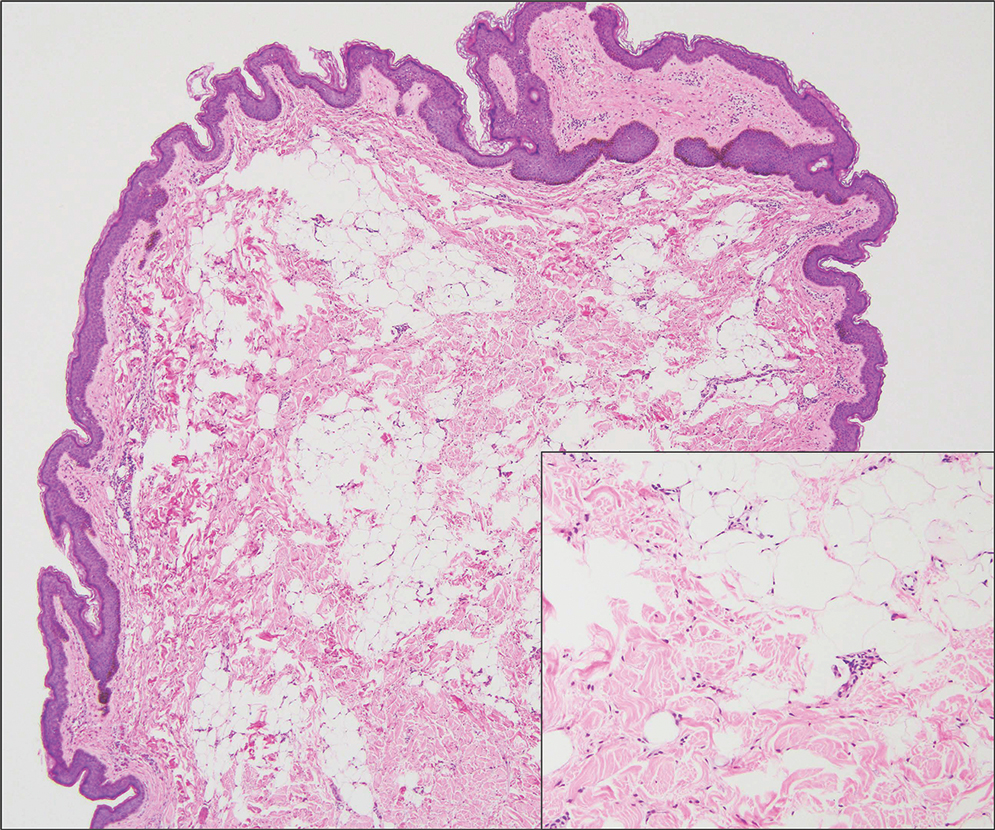

Nevus lipomatosus superficialis is a benign hamartoma that can manifest as a pedunculated or exophytic papule. The lesions may be solitary or multiple and, unlike RMH, are most common on the buttocks, upper thighs, and trunk.12 The histopathologic features of nevus lipomatosus superficialis include clusters of mature adipose tissue in the superficial dermis admixed with collagen fibers and variably increased vasculature (Figure 3).13 Nevus lipomatosus superficialis does not contain skeletal muscle within the tumor in comparison to RMH.

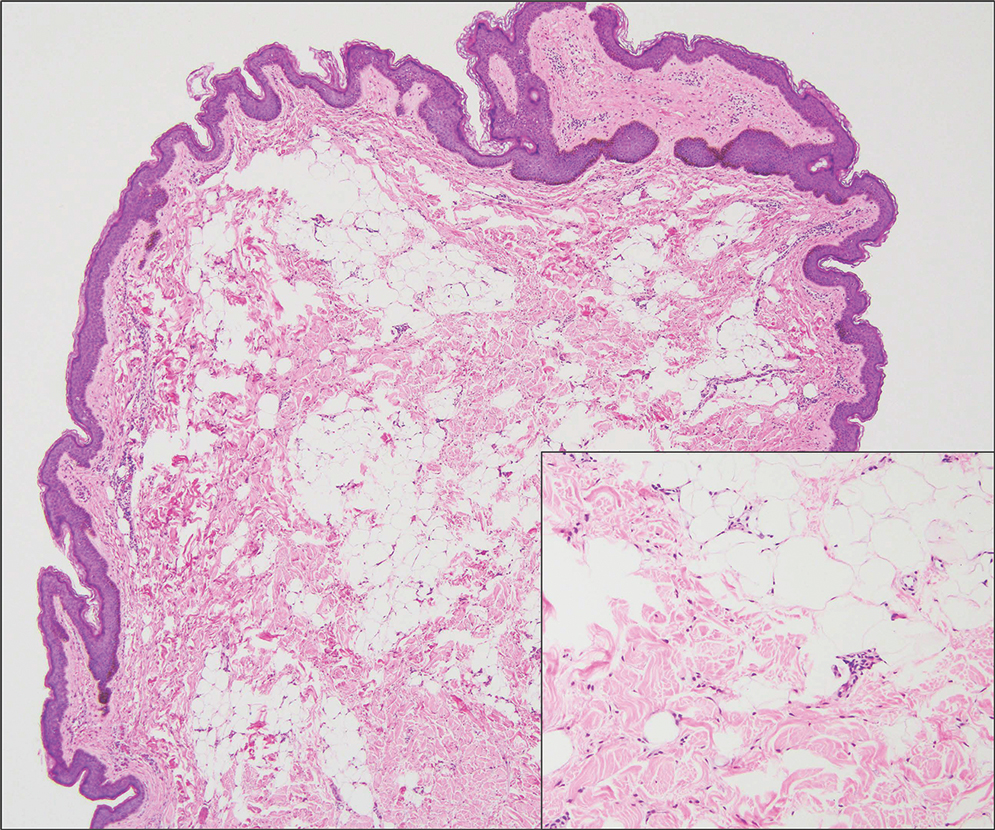

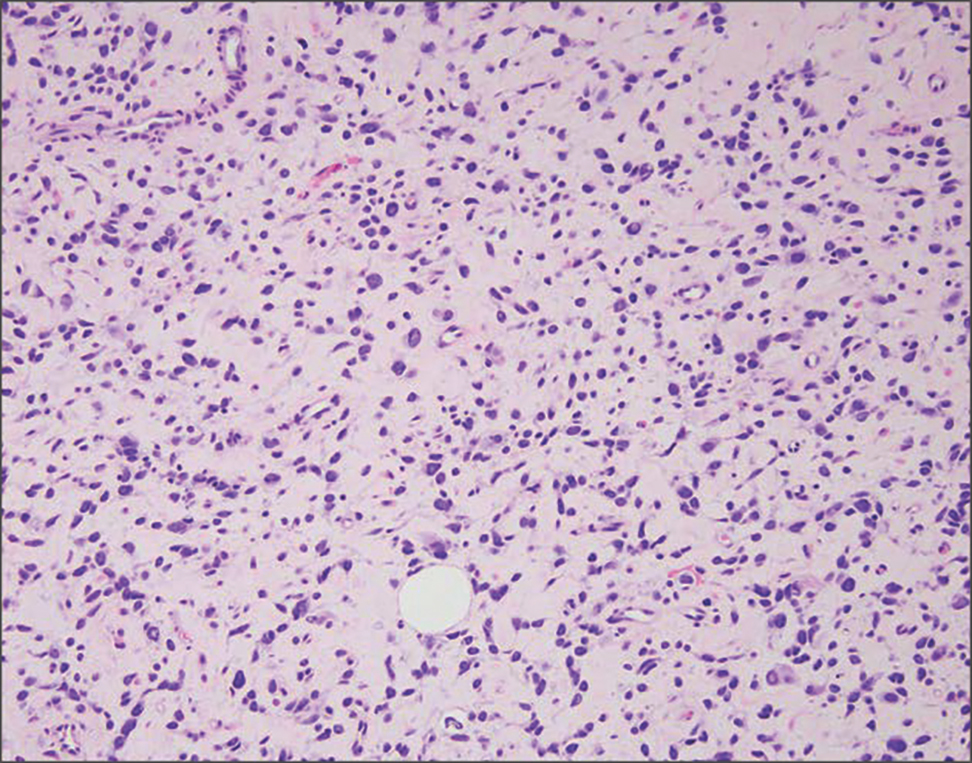

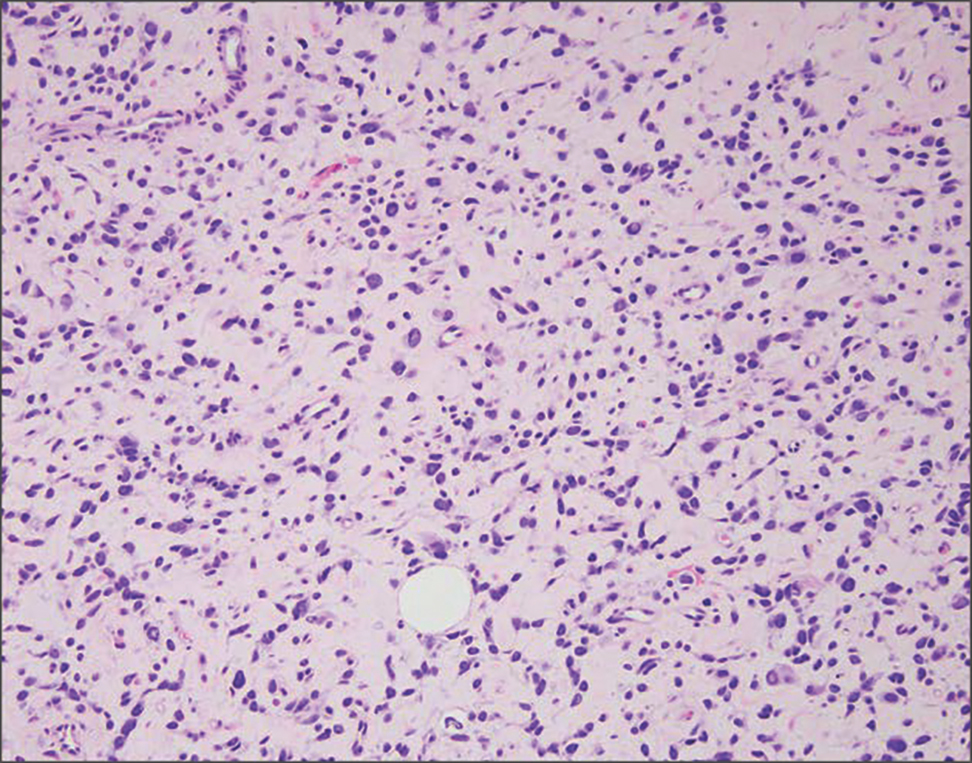

It is important to distinguish rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) from RMH, as it is associated with increased mortality and morbidity. Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common soft-tissue sarcoma in children and is derived from mesenchyme with variable degrees of skeletal muscle differentiation.14 Due to its mesenchymal origin, these tumors can manifest in a variety of places but most commonly on the head and neck and in the genital region.15 The most common subtype is embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Histologically, embryonal RMS shows a moderately cellular tumor composed of sheets of spindle-shaped or round cells with scant or eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 4). The absence of genetic translocation in the paired box-forkhead box protein 01 (PAX-FOXO1) gene helps distinguish it from solid alveolar RMS, the second most common and more aggressive subtype.12 Positive immunohistochemical staining for desmin, myoblast determination protein 1 (MyoD1), and myogenin supports myogenic differentiation.14

- Bernal-Mañas CM, Isaac-Montero MA, Vargas-Uribe MC, et al. Hamartoma mesenquimal rabdomiomatoso [rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2013;78:260-262. doi:10.1016/j.anpedi.2012.08.005

- Al Amri R, De Stefano DV, Wang Q, et al. Morphologic spectrum of rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartomas (striated muscle hamartomas) in pediatric dermatopathology. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022;44:170-173. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000002062

- Carboni A, Fomin D. A rare adult presentation of a congenital tumor discovered incidentally after trauma. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;31:121-123. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.10.024

- Chang CP, Chen GS. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma: a plaque-type variant in an adult. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005; 21(4):185-188. doi:10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70299-2

- Bahmani M, Naseri R, Iraniparast A, et al. Oculocerebrocutaneous syndrome (Delleman syndrome): a case with a novel presentation of orbital involvement. Case Rep Pediatr. 2021;2021:5524131. doi:10.1155/2021/5524131

- Kim H, Chung JH, Sung HM, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma presenting as a midline mass on a chin. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017;18:292-295. doi:10.7181/acfs.2017.18.4.292.

- Lin CP, Nguyen JM, Aboutalebi S, et al. Incidental rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;34:161-162. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1801087

- Ji Y, Hu P, Zhang C, et al. Fibrous hamartoma of infancy: radiologic features and literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20:356. doi:10.1186/s12891-019-2743-5

- Yu G, Wang Y, Wang G, et al. Fibrous hamartoma of infancy: a clinical pathological analysis of seventeen cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:3374-3377.

- Ferner RE, O’Doherty MJ. Neurofibroma and schwannoma. Curr Opin Neurol. 2002;15:679-684. doi:10.1097/01.wco.0000044763.39452.aa

- Miettinen MM, Antonescu CR, Fletcher CDM, et al. Histopathologic evaluation of atypical neurofibromatous tumors and their transformation into malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in patients with neurofibromatosis 1-a consensus overview. Hum Pathol. 2017;67:1-10. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2017.05.010

- Kim RH, Stevenson ML, Hale CS, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt2cb3c5t3.

- Singh P, Anandani GM. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis, an unusual case report. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11:4045-4047. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2352_21

- Shern JF, Yohe ME, Khan J. Pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma. Crit Rev Oncog. 2015;20:227-243. doi:10.1615/critrevoncog.2015013800

- Rogers TN, Dasgupta R. Management of rhabdomyosarcoma in pediatric patients. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2021;30:339-353. doi:10.1016/j.soc.2020.11.003

- Machado I, Mayordomo-Aranda E, Giner F, et al. The role of immunohistochemistry in rhabdomyosarcoma diagnosis using tissue microarray technology and a xenograft model. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2015;34:271-281. doi:10.3109/15513815.2015.1042604

THE DIAGNOSIS: Rhabdomyomatous Mesenchymal Hamartoma

Histopathologic examination of the excised tissue revealed haphazardly arranged bundles of mature striated muscle within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue admixed with adipose tissue, adnexal structures, blood vessels, and nerves. The presence of the lesion since birth, midline clinical presentation, and histologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma (RMH).

Also referred to as striated muscle hamartoma, RMH is a rare benign lesion thought to have embryonic origin due to its midline presentation.1 The etiology of RMH is unknown but is hypothesized to be due to abnormal migration or growth of embryonic mesenchymal tissue. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma typically manifests in infancy or early childhood as a solitary midline papule on the head or neck, although there have been rare reports of development in adulthood.2-4 Lesions often are polypoid or exophytic but may manifest as smooth papules or subcutaneous nodules.2 Although benign, RMH may be associated with other congenital abnormalities and conditions, such as Delleman syndrome, which is caused by a sporadic genetic abnormality and results in defects of the eye, central nervous system, and skin.5 Treatment for RMH is not needed, but surgical excision for cosmetic purposes can be performed with low risk for recurrence. Histologically, RMH demonstrates a normal epidermis overlying disorganized bundles of skeletal muscle accompanied by varying amounts of other mature dermal and subcutaneous tissues including nerves, blood vessels, adipose tissue, and other adnexal structures.2,6 Myoglobin and desmin are positive within the skeletal muscle bundles.7

Fibrous hamartoma of infancy (FHI) often manifests as a movable, ill-defined nodule within the subcutaneous tissue. While also occurring in young children—typically within the first 2 years of life—FHI primarily is found on the upper arms, back, and axillae, in contrast to FHI.8 The classic histopathologic presentation of FHI consists of a triphasic morphology consisting of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells and dense fibroblastic/myofibroblastic tissue with mature adipose tissue woven throughout in islands (Figure 1).9 Skeletal muscle is not a component of this tumor.

Neurofibromas also may manifest clinically as papules or nodules and arise from the peripheral nerve sheath. There are 3 major subtypes of neurofibromas—localized, diffuse, and plexiform—with the last being strongly associated with neurofibromatosis type 1.10 The plexiform type has a rare risk for malignant transformation. The typical histopathologic finding of a localized cutaneous neurofibroma is a dermal proliferation of spindle cells with wavy nuclei within a variably myxoid stroma (Figure 2).11 Interspersed mast cells also can be seen. A plexiform neurofibroma typically involves multiple nerve fascicles and comprises multinodular or tortuous bundles of cytologically bland spindle cells. Compared to RMH, skeletal muscle is not a component of this tumor.

Nevus lipomatosus superficialis is a benign hamartoma that can manifest as a pedunculated or exophytic papule. The lesions may be solitary or multiple and, unlike RMH, are most common on the buttocks, upper thighs, and trunk.12 The histopathologic features of nevus lipomatosus superficialis include clusters of mature adipose tissue in the superficial dermis admixed with collagen fibers and variably increased vasculature (Figure 3).13 Nevus lipomatosus superficialis does not contain skeletal muscle within the tumor in comparison to RMH.

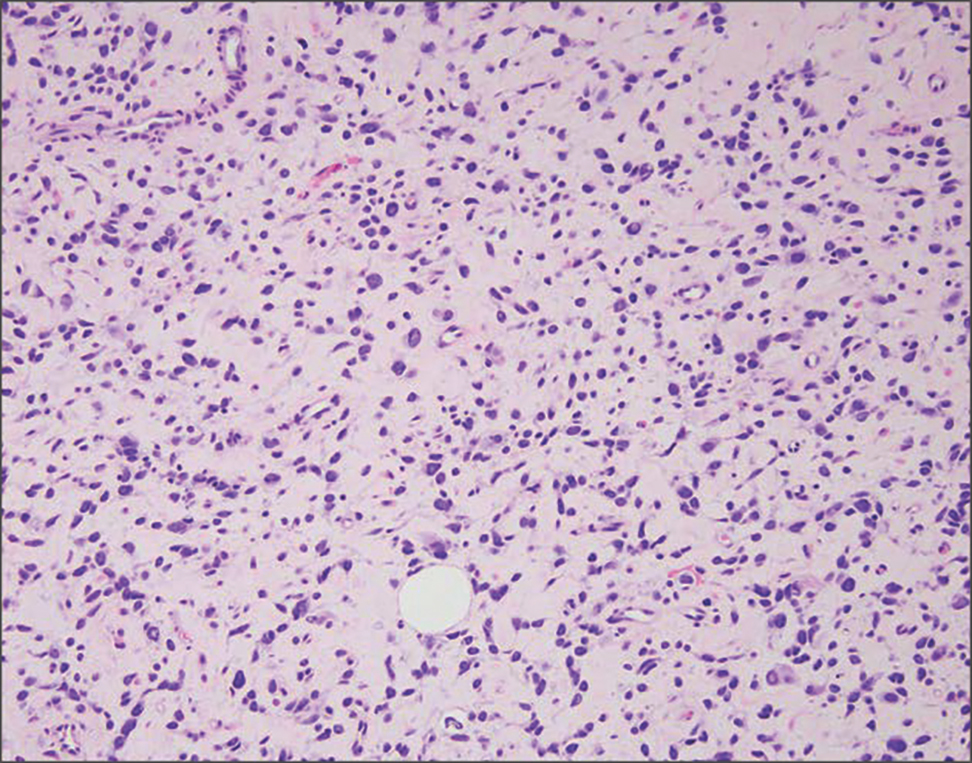

It is important to distinguish rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) from RMH, as it is associated with increased mortality and morbidity. Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common soft-tissue sarcoma in children and is derived from mesenchyme with variable degrees of skeletal muscle differentiation.14 Due to its mesenchymal origin, these tumors can manifest in a variety of places but most commonly on the head and neck and in the genital region.15 The most common subtype is embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Histologically, embryonal RMS shows a moderately cellular tumor composed of sheets of spindle-shaped or round cells with scant or eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 4). The absence of genetic translocation in the paired box-forkhead box protein 01 (PAX-FOXO1) gene helps distinguish it from solid alveolar RMS, the second most common and more aggressive subtype.12 Positive immunohistochemical staining for desmin, myoblast determination protein 1 (MyoD1), and myogenin supports myogenic differentiation.14

THE DIAGNOSIS: Rhabdomyomatous Mesenchymal Hamartoma

Histopathologic examination of the excised tissue revealed haphazardly arranged bundles of mature striated muscle within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue admixed with adipose tissue, adnexal structures, blood vessels, and nerves. The presence of the lesion since birth, midline clinical presentation, and histologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma (RMH).

Also referred to as striated muscle hamartoma, RMH is a rare benign lesion thought to have embryonic origin due to its midline presentation.1 The etiology of RMH is unknown but is hypothesized to be due to abnormal migration or growth of embryonic mesenchymal tissue. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma typically manifests in infancy or early childhood as a solitary midline papule on the head or neck, although there have been rare reports of development in adulthood.2-4 Lesions often are polypoid or exophytic but may manifest as smooth papules or subcutaneous nodules.2 Although benign, RMH may be associated with other congenital abnormalities and conditions, such as Delleman syndrome, which is caused by a sporadic genetic abnormality and results in defects of the eye, central nervous system, and skin.5 Treatment for RMH is not needed, but surgical excision for cosmetic purposes can be performed with low risk for recurrence. Histologically, RMH demonstrates a normal epidermis overlying disorganized bundles of skeletal muscle accompanied by varying amounts of other mature dermal and subcutaneous tissues including nerves, blood vessels, adipose tissue, and other adnexal structures.2,6 Myoglobin and desmin are positive within the skeletal muscle bundles.7

Fibrous hamartoma of infancy (FHI) often manifests as a movable, ill-defined nodule within the subcutaneous tissue. While also occurring in young children—typically within the first 2 years of life—FHI primarily is found on the upper arms, back, and axillae, in contrast to FHI.8 The classic histopathologic presentation of FHI consists of a triphasic morphology consisting of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells and dense fibroblastic/myofibroblastic tissue with mature adipose tissue woven throughout in islands (Figure 1).9 Skeletal muscle is not a component of this tumor.

Neurofibromas also may manifest clinically as papules or nodules and arise from the peripheral nerve sheath. There are 3 major subtypes of neurofibromas—localized, diffuse, and plexiform—with the last being strongly associated with neurofibromatosis type 1.10 The plexiform type has a rare risk for malignant transformation. The typical histopathologic finding of a localized cutaneous neurofibroma is a dermal proliferation of spindle cells with wavy nuclei within a variably myxoid stroma (Figure 2).11 Interspersed mast cells also can be seen. A plexiform neurofibroma typically involves multiple nerve fascicles and comprises multinodular or tortuous bundles of cytologically bland spindle cells. Compared to RMH, skeletal muscle is not a component of this tumor.

Nevus lipomatosus superficialis is a benign hamartoma that can manifest as a pedunculated or exophytic papule. The lesions may be solitary or multiple and, unlike RMH, are most common on the buttocks, upper thighs, and trunk.12 The histopathologic features of nevus lipomatosus superficialis include clusters of mature adipose tissue in the superficial dermis admixed with collagen fibers and variably increased vasculature (Figure 3).13 Nevus lipomatosus superficialis does not contain skeletal muscle within the tumor in comparison to RMH.

It is important to distinguish rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) from RMH, as it is associated with increased mortality and morbidity. Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common soft-tissue sarcoma in children and is derived from mesenchyme with variable degrees of skeletal muscle differentiation.14 Due to its mesenchymal origin, these tumors can manifest in a variety of places but most commonly on the head and neck and in the genital region.15 The most common subtype is embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Histologically, embryonal RMS shows a moderately cellular tumor composed of sheets of spindle-shaped or round cells with scant or eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 4). The absence of genetic translocation in the paired box-forkhead box protein 01 (PAX-FOXO1) gene helps distinguish it from solid alveolar RMS, the second most common and more aggressive subtype.12 Positive immunohistochemical staining for desmin, myoblast determination protein 1 (MyoD1), and myogenin supports myogenic differentiation.14

- Bernal-Mañas CM, Isaac-Montero MA, Vargas-Uribe MC, et al. Hamartoma mesenquimal rabdomiomatoso [rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2013;78:260-262. doi:10.1016/j.anpedi.2012.08.005

- Al Amri R, De Stefano DV, Wang Q, et al. Morphologic spectrum of rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartomas (striated muscle hamartomas) in pediatric dermatopathology. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022;44:170-173. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000002062

- Carboni A, Fomin D. A rare adult presentation of a congenital tumor discovered incidentally after trauma. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;31:121-123. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.10.024

- Chang CP, Chen GS. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma: a plaque-type variant in an adult. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005; 21(4):185-188. doi:10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70299-2

- Bahmani M, Naseri R, Iraniparast A, et al. Oculocerebrocutaneous syndrome (Delleman syndrome): a case with a novel presentation of orbital involvement. Case Rep Pediatr. 2021;2021:5524131. doi:10.1155/2021/5524131

- Kim H, Chung JH, Sung HM, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma presenting as a midline mass on a chin. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017;18:292-295. doi:10.7181/acfs.2017.18.4.292.

- Lin CP, Nguyen JM, Aboutalebi S, et al. Incidental rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;34:161-162. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1801087

- Ji Y, Hu P, Zhang C, et al. Fibrous hamartoma of infancy: radiologic features and literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20:356. doi:10.1186/s12891-019-2743-5

- Yu G, Wang Y, Wang G, et al. Fibrous hamartoma of infancy: a clinical pathological analysis of seventeen cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:3374-3377.

- Ferner RE, O’Doherty MJ. Neurofibroma and schwannoma. Curr Opin Neurol. 2002;15:679-684. doi:10.1097/01.wco.0000044763.39452.aa

- Miettinen MM, Antonescu CR, Fletcher CDM, et al. Histopathologic evaluation of atypical neurofibromatous tumors and their transformation into malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in patients with neurofibromatosis 1-a consensus overview. Hum Pathol. 2017;67:1-10. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2017.05.010

- Kim RH, Stevenson ML, Hale CS, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt2cb3c5t3.

- Singh P, Anandani GM. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis, an unusual case report. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11:4045-4047. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2352_21

- Shern JF, Yohe ME, Khan J. Pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma. Crit Rev Oncog. 2015;20:227-243. doi:10.1615/critrevoncog.2015013800

- Rogers TN, Dasgupta R. Management of rhabdomyosarcoma in pediatric patients. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2021;30:339-353. doi:10.1016/j.soc.2020.11.003

- Machado I, Mayordomo-Aranda E, Giner F, et al. The role of immunohistochemistry in rhabdomyosarcoma diagnosis using tissue microarray technology and a xenograft model. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2015;34:271-281. doi:10.3109/15513815.2015.1042604

- Bernal-Mañas CM, Isaac-Montero MA, Vargas-Uribe MC, et al. Hamartoma mesenquimal rabdomiomatoso [rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2013;78:260-262. doi:10.1016/j.anpedi.2012.08.005

- Al Amri R, De Stefano DV, Wang Q, et al. Morphologic spectrum of rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartomas (striated muscle hamartomas) in pediatric dermatopathology. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022;44:170-173. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000002062

- Carboni A, Fomin D. A rare adult presentation of a congenital tumor discovered incidentally after trauma. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;31:121-123. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.10.024

- Chang CP, Chen GS. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma: a plaque-type variant in an adult. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005; 21(4):185-188. doi:10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70299-2

- Bahmani M, Naseri R, Iraniparast A, et al. Oculocerebrocutaneous syndrome (Delleman syndrome): a case with a novel presentation of orbital involvement. Case Rep Pediatr. 2021;2021:5524131. doi:10.1155/2021/5524131

- Kim H, Chung JH, Sung HM, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma presenting as a midline mass on a chin. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017;18:292-295. doi:10.7181/acfs.2017.18.4.292.

- Lin CP, Nguyen JM, Aboutalebi S, et al. Incidental rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;34:161-162. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1801087

- Ji Y, Hu P, Zhang C, et al. Fibrous hamartoma of infancy: radiologic features and literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20:356. doi:10.1186/s12891-019-2743-5

- Yu G, Wang Y, Wang G, et al. Fibrous hamartoma of infancy: a clinical pathological analysis of seventeen cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:3374-3377.

- Ferner RE, O’Doherty MJ. Neurofibroma and schwannoma. Curr Opin Neurol. 2002;15:679-684. doi:10.1097/01.wco.0000044763.39452.aa

- Miettinen MM, Antonescu CR, Fletcher CDM, et al. Histopathologic evaluation of atypical neurofibromatous tumors and their transformation into malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in patients with neurofibromatosis 1-a consensus overview. Hum Pathol. 2017;67:1-10. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2017.05.010

- Kim RH, Stevenson ML, Hale CS, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt2cb3c5t3.

- Singh P, Anandani GM. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis, an unusual case report. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11:4045-4047. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2352_21

- Shern JF, Yohe ME, Khan J. Pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma. Crit Rev Oncog. 2015;20:227-243. doi:10.1615/critrevoncog.2015013800

- Rogers TN, Dasgupta R. Management of rhabdomyosarcoma in pediatric patients. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2021;30:339-353. doi:10.1016/j.soc.2020.11.003

- Machado I, Mayordomo-Aranda E, Giner F, et al. The role of immunohistochemistry in rhabdomyosarcoma diagnosis using tissue microarray technology and a xenograft model. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2015;34:271-281. doi:10.3109/15513815.2015.1042604

Exophytic Papule on the Chin of a Child

Exophytic Papule on the Chin of a Child

A 3-year-old boy presented to the dermatology department for evaluation of an asymptomatic papule on the chin that had been present since birth. His medical history was otherwise unremarkable. Physical examination revealed a 4×2-mm, flesh-colored, exophytic papule on the midline chin. An excisional biopsy was performed.

Large Bullae on the Legs in a Hospitalized Patient Following a Gunshot Wound

Large Bullae on the Legs in a Hospitalized Patient Following a Gunshot Wound

THE DIAGNOSIS: Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Biopsy results showed an intraepidermal blister with a floor composed of maturing epidermis. The roof of the blister was composed of necrotic keratinocytes with overlying orthokeratosis, and the cavity was filled with a moderate amount of fibrin and dead cells with neutrophils. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) using specific antihuman IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, and fibrin was negative. Aerobic, anaerobic, and fungal cultures also were negative. With these histopathologic findings, medication exposure, and timing of bullae onset, our patient was diagnosed with bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis (BHD) secondary to enoxaparin administration. Enoxaparin was continued due to increased risk for coagulopathy, and there was complete resolution of the bullae after 5 weeks with no residual symptoms.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a rare eruption that can occur after administration of heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin, with enoxaparin being the most commonly implicated drug.1 The lesions typically are seen in elderly men in the seventh decade of life and appear within a median of 7 days after drug exposure. The time course for the postexposure eruption can vary from 2 to 21 days, with reports of skin lesions appearing up to 4 months after exposure.1,2 hemorrhagic bullae (Figure) typically on the arms and legs, though lesions also can develop on the trunk. The lesions can occur in distant areas from the injection site, suggesting BHD may be a systemic reaction, although the etiology is poorly understood.1

Another heparin reaction that can manifest similarly to BHD is heparin-induced skin necrosis.3 Patients with this condition also may have associated heparin-induced thrombocytopenia upon laboratory investigation and have a more aggressive clinical course than BHD. Biopsy can help differentiate BHD and early heparin-induced skin necrosis if the clinical manifestation is unclear. Histopathologically, BHD typically has intraepidermal bullae filled with blood, whereas heparin-induced skin necrosis has dermal thrombi.1,4 Treatment of both conditions differs in whether to discontinue anticoagulants: heparin-induced skin necrosis requires discontinuation of the medication, while BHD does not.2,3

In patients with BHD, the lesions are self-resolving, and treatment is supportive, although whether enoxaparin is discontinued varies among physicians.2 Lesions typically resolve within 2 weeks of onset, although it is unclear whether continuing anticoagulants delays resolution.1 Discontinuing anticoagulants in certain patients can be life-threatening due to complex comorbidities (eg, risk for venous thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism from prolonged hospitalization or severe trauma) and is not necessary for the resolution of BHD.

In addition to BHD and heparin-induced skin necrosis, our differential diagnosis included bullous pemphigoid, coma blisters, and Vibrio vulnificus infection. Although bullous pemphigoid can manifest with tense bullae that are pauci-inflammatory on histology, DIF would show linear IgG and C3 deposition at the dermal-epidermal junction. In our patient, DIF was negative and favored another etiology for the lesions. Coma blisters can occur in areas of sustained pressure and typically develop in patients with a prolonged hospitalization or those who are sedentary for long periods of time. The distribution of bullae on our patient’s bilateral pretibial shins made this diagnosis unlikely. Vibrio vulnificus infection can manifest as hemorrhagic bullae, though typically after a break in the skin exposed to brackish water. Vibrio vulnificus infection can be life-threatening, resulting in septicemia and increased mortality, and a thorough patient history is important for diagnosis.5

- Russo A, Curtis S, Balbuena-Merle R, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an under-recognized side effect of full dose lowmolecular weight heparin: a case report and review of the literature. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2018;7:15. doi:10.1186/s40164-018-0108-7

- Dhattarwal N, Gurjar R. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: a rare cutaneous reaction of heparin. J Postgrad Med. 2023;69:97-98. doi:10.4103/jpgm.jpgm_282_22

- Maldonado Cid P, Alonso de Celada RM, Noguera Morel L, et al. Cutaneous adverse events associated with heparin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:707-711. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04395.x

- Handschin AE, Trentz O, Kock HJ, et al. Low molecular weight heparininduced skin necrosis-a systematic review. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2005;390:249-254. doi:10.1007/s00423-004-0522-7

- Jones MK, Oliver JD. Vibrio vulnificus: disease and pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1723-1733. doi:10.1128/IAI.01046-08

THE DIAGNOSIS: Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Biopsy results showed an intraepidermal blister with a floor composed of maturing epidermis. The roof of the blister was composed of necrotic keratinocytes with overlying orthokeratosis, and the cavity was filled with a moderate amount of fibrin and dead cells with neutrophils. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) using specific antihuman IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, and fibrin was negative. Aerobic, anaerobic, and fungal cultures also were negative. With these histopathologic findings, medication exposure, and timing of bullae onset, our patient was diagnosed with bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis (BHD) secondary to enoxaparin administration. Enoxaparin was continued due to increased risk for coagulopathy, and there was complete resolution of the bullae after 5 weeks with no residual symptoms.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a rare eruption that can occur after administration of heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin, with enoxaparin being the most commonly implicated drug.1 The lesions typically are seen in elderly men in the seventh decade of life and appear within a median of 7 days after drug exposure. The time course for the postexposure eruption can vary from 2 to 21 days, with reports of skin lesions appearing up to 4 months after exposure.1,2 hemorrhagic bullae (Figure) typically on the arms and legs, though lesions also can develop on the trunk. The lesions can occur in distant areas from the injection site, suggesting BHD may be a systemic reaction, although the etiology is poorly understood.1

Another heparin reaction that can manifest similarly to BHD is heparin-induced skin necrosis.3 Patients with this condition also may have associated heparin-induced thrombocytopenia upon laboratory investigation and have a more aggressive clinical course than BHD. Biopsy can help differentiate BHD and early heparin-induced skin necrosis if the clinical manifestation is unclear. Histopathologically, BHD typically has intraepidermal bullae filled with blood, whereas heparin-induced skin necrosis has dermal thrombi.1,4 Treatment of both conditions differs in whether to discontinue anticoagulants: heparin-induced skin necrosis requires discontinuation of the medication, while BHD does not.2,3

In patients with BHD, the lesions are self-resolving, and treatment is supportive, although whether enoxaparin is discontinued varies among physicians.2 Lesions typically resolve within 2 weeks of onset, although it is unclear whether continuing anticoagulants delays resolution.1 Discontinuing anticoagulants in certain patients can be life-threatening due to complex comorbidities (eg, risk for venous thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism from prolonged hospitalization or severe trauma) and is not necessary for the resolution of BHD.

In addition to BHD and heparin-induced skin necrosis, our differential diagnosis included bullous pemphigoid, coma blisters, and Vibrio vulnificus infection. Although bullous pemphigoid can manifest with tense bullae that are pauci-inflammatory on histology, DIF would show linear IgG and C3 deposition at the dermal-epidermal junction. In our patient, DIF was negative and favored another etiology for the lesions. Coma blisters can occur in areas of sustained pressure and typically develop in patients with a prolonged hospitalization or those who are sedentary for long periods of time. The distribution of bullae on our patient’s bilateral pretibial shins made this diagnosis unlikely. Vibrio vulnificus infection can manifest as hemorrhagic bullae, though typically after a break in the skin exposed to brackish water. Vibrio vulnificus infection can be life-threatening, resulting in septicemia and increased mortality, and a thorough patient history is important for diagnosis.5

THE DIAGNOSIS: Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Biopsy results showed an intraepidermal blister with a floor composed of maturing epidermis. The roof of the blister was composed of necrotic keratinocytes with overlying orthokeratosis, and the cavity was filled with a moderate amount of fibrin and dead cells with neutrophils. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) using specific antihuman IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, and fibrin was negative. Aerobic, anaerobic, and fungal cultures also were negative. With these histopathologic findings, medication exposure, and timing of bullae onset, our patient was diagnosed with bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis (BHD) secondary to enoxaparin administration. Enoxaparin was continued due to increased risk for coagulopathy, and there was complete resolution of the bullae after 5 weeks with no residual symptoms.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a rare eruption that can occur after administration of heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin, with enoxaparin being the most commonly implicated drug.1 The lesions typically are seen in elderly men in the seventh decade of life and appear within a median of 7 days after drug exposure. The time course for the postexposure eruption can vary from 2 to 21 days, with reports of skin lesions appearing up to 4 months after exposure.1,2 hemorrhagic bullae (Figure) typically on the arms and legs, though lesions also can develop on the trunk. The lesions can occur in distant areas from the injection site, suggesting BHD may be a systemic reaction, although the etiology is poorly understood.1

Another heparin reaction that can manifest similarly to BHD is heparin-induced skin necrosis.3 Patients with this condition also may have associated heparin-induced thrombocytopenia upon laboratory investigation and have a more aggressive clinical course than BHD. Biopsy can help differentiate BHD and early heparin-induced skin necrosis if the clinical manifestation is unclear. Histopathologically, BHD typically has intraepidermal bullae filled with blood, whereas heparin-induced skin necrosis has dermal thrombi.1,4 Treatment of both conditions differs in whether to discontinue anticoagulants: heparin-induced skin necrosis requires discontinuation of the medication, while BHD does not.2,3

In patients with BHD, the lesions are self-resolving, and treatment is supportive, although whether enoxaparin is discontinued varies among physicians.2 Lesions typically resolve within 2 weeks of onset, although it is unclear whether continuing anticoagulants delays resolution.1 Discontinuing anticoagulants in certain patients can be life-threatening due to complex comorbidities (eg, risk for venous thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism from prolonged hospitalization or severe trauma) and is not necessary for the resolution of BHD.

In addition to BHD and heparin-induced skin necrosis, our differential diagnosis included bullous pemphigoid, coma blisters, and Vibrio vulnificus infection. Although bullous pemphigoid can manifest with tense bullae that are pauci-inflammatory on histology, DIF would show linear IgG and C3 deposition at the dermal-epidermal junction. In our patient, DIF was negative and favored another etiology for the lesions. Coma blisters can occur in areas of sustained pressure and typically develop in patients with a prolonged hospitalization or those who are sedentary for long periods of time. The distribution of bullae on our patient’s bilateral pretibial shins made this diagnosis unlikely. Vibrio vulnificus infection can manifest as hemorrhagic bullae, though typically after a break in the skin exposed to brackish water. Vibrio vulnificus infection can be life-threatening, resulting in septicemia and increased mortality, and a thorough patient history is important for diagnosis.5

- Russo A, Curtis S, Balbuena-Merle R, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an under-recognized side effect of full dose lowmolecular weight heparin: a case report and review of the literature. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2018;7:15. doi:10.1186/s40164-018-0108-7

- Dhattarwal N, Gurjar R. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: a rare cutaneous reaction of heparin. J Postgrad Med. 2023;69:97-98. doi:10.4103/jpgm.jpgm_282_22

- Maldonado Cid P, Alonso de Celada RM, Noguera Morel L, et al. Cutaneous adverse events associated with heparin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:707-711. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04395.x

- Handschin AE, Trentz O, Kock HJ, et al. Low molecular weight heparininduced skin necrosis-a systematic review. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2005;390:249-254. doi:10.1007/s00423-004-0522-7

- Jones MK, Oliver JD. Vibrio vulnificus: disease and pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1723-1733. doi:10.1128/IAI.01046-08

- Russo A, Curtis S, Balbuena-Merle R, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an under-recognized side effect of full dose lowmolecular weight heparin: a case report and review of the literature. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2018;7:15. doi:10.1186/s40164-018-0108-7

- Dhattarwal N, Gurjar R. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: a rare cutaneous reaction of heparin. J Postgrad Med. 2023;69:97-98. doi:10.4103/jpgm.jpgm_282_22

- Maldonado Cid P, Alonso de Celada RM, Noguera Morel L, et al. Cutaneous adverse events associated with heparin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:707-711. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04395.x

- Handschin AE, Trentz O, Kock HJ, et al. Low molecular weight heparininduced skin necrosis-a systematic review. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2005;390:249-254. doi:10.1007/s00423-004-0522-7

- Jones MK, Oliver JD. Vibrio vulnificus: disease and pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1723-1733. doi:10.1128/IAI.01046-08

Large Bullae on the Legs in a Hospitalized Patient Following a Gunshot Wound

Large Bullae on the Legs in a Hospitalized Patient Following a Gunshot Wound

A 19-year-old man developed fluid-filled blisters on both legs within 1 month of a prolonged hospitalization following a gunshot wound that resulted in complete paralysis of the legs. His medical history was otherwise unremarkable. Medications started during hospitalization included moxifloxacin, levetiracetam, and prophylactic subcutaneous enoxaparin. Physical examination by dermatology revealed tense blood-filled bullae measuring several centimeters with well-demarcated, pink to red, irregularly shaped patches on both legs. A biopsy of a blister was taken.

What’s Eating You? Triatoma and Arilus cristatus Bugs

Classification

Triatomine bugs (Triatoma) and the wheel bug (Arilus cristatus) are part of the family Reduviidae (order Hemiptera, a name that describes the sucking proboscis on the front of the insect’s head).1,2 Both arthropods are found in multiple countries and are especially common in warmer areas, including in the United States, where they can be seen from Texas to California.3,4 Because blood-feeding triatomines need a blood meal to survive while laying eggs and then throughout their 5 developmental nymph stages to undergo molting, they feed on mammals, such as opossums, raccoons, pack rats, and armadillos, whereas wheel bugs mainly prey on soft-bodied insects.1,4-6

Triatoma bugs seek cutaneous blood vessels using thermosensors in their antennae to locate blood flow under the skin for feeding. After inserting the proboscis, they release nitric oxide and an anticoagulant that allows for continuous blood flow while feeding.7 It has been reported that triatomine bugs are not able to bite through clothing, instead seeking exposed skin, particularly near mucous membranes, such as the hands, arms, feet, head, and trunk. The name kissing bug for triatomines was coined because bites near the mouth are common.6 The bite typically is painless and occurs mainly at night when the insect is most active. After obtaining a blood meal, triatomine bugs seek shelter and hide in mud and daub structures, cracks, crevices, and furniture.1,8

Unlike Triatoma species, A cristatus does not require a blood meal for development and survival, leading it to prey on soft-bodied insects. Piercing prey with the proboscis, wheel bugs inject a toxin to digest the contents and suck the digested contents through this apparatus.4 Because the wheel bug does not require a blood meal, it typically bites a human only for defense if it feels threatened. Unlike the painless bite of a triatomine bug, the bite of A cristatus is extremely painful; it has been described as the worst arthropod bite—worse than a hornet’s sting. The pain from the bite is caused by the toxin being injected into the skin; possible retention of the proboscis makes the pain worse.4,9 In addition, when A cristatus is disturbed, it exudes pungent material from a pair of bright orange subrectal glands while stridulating to repulse predators.9

Although Triatoma species and A cristatus have separate roles in nature and vastly different impacts on health, they often are mistaken for the same arthropod when seen in nature. Features that members of Reduviidae share include large bodies (relative to their overall length); long thin legs; a narrow head; wings; and a long sucking proboscis on the front of the head.10

Characteristics that differentiate Triatoma and A cristatus species include size, color, and distinctive markings. Most triatomine bugs are 12- to 36-mm long; are dark brown or black; and have what are called tiger-stripe orange markings on the peripheral two-thirds of the body (Figure 1).11 In contrast, wheel bugs commonly are bigger—measuring longer than 1.25 inches—and gray, with a cogwheel-like structure on the thorax (Figure 2).10

Dermatologic Presentation and Clinical Symptoms

The area of involved skin on patients presenting with Triatoma or A cristatus bites may resemble other insect bites. Many bites from Triatoma bugs and A cristatus initially present as an erythematous, raised, pruritic papule with a central punctum that is visible because of the involvement of the proboscis. However, other presentations of bites from both arthropods have been reported4,6,7: grouped vesicles on an erythematous base; indurated, giant, urticarial-type wheels measuring 10 to 15 mm in diameter; and hemorrhagic bullous nodules (Figure 3). Associated lymphangitis or lymphadenitis is typical of the latter 2 variations.6 These variations in presentation can be mistaken for other causes of similarly presenting lesions, such as shingles or spider bites, leading to delayed or missed diagnosis.

Patients may present with a single bite or multiple bites due to the feeding pattern of Triatoma bugs; if the host moves or disrupts its feeding, the arthropod takes multiple bites to finish feeding.8 In comparison, 4 common variations of wheel bug bites have been reported: (1) a painful bite without complications; (2) a cutaneous horn and papilloma at the site of toxin injection; (3) a necrotic ulcer around the central punctum caused by injected toxin; and (4) an abscess under the central punctum due to secondary infection.4

Anaphylaxis—Although the bites of Triatoma and A cristatus present differently, both can cause anaphylaxis. Triatoma is implicated more often than A cristatus as the cause of anaphylaxis.12 In fact, Triatoma bites are among the more common causes of anaphylaxis from bug bites, with multiple cases of these reactions reported in the literature.12,13

Symptoms of Triatoma anaphylaxis include acute-onset urticarial rash, flushing, dyspnea, wheezing, nausea, vomiting, and localized edema.2 The cause of anaphylaxis is proteins in Triatoma saliva, including 20-kDa procalin, which incites the systemic reaction. Other potential causes of anaphylaxis include serine protease, which has similarities to salivary protein and desmoglein in humans.11

The degree of reaction to a bite depends on the patient's sensitization to antigenic proteins in each insect’s saliva.4,6 Patients who have a bite from a triatomine bug are at risk for subsequent bites, as household infestation is likely due to the pliability of the insect, allowing it to hide in small spaces unnoticed.8 In the case of a bite from Triatoma or A cristatus, sensitization may lead to severe and worsening reactions with subsequent bites, which ultimately can result in life-threatening anaphylaxis.1,6

Treatment and Prevention

Treatment of Triatoma and A cristatus bites depends on the severity of the patient’s reaction to the bite. A local reaction to a bite from either insect can be treated supportively with local corticosteroids and antihistamines.3 If the patient is sensitized to proteins associated with a bite, standard anaphylaxis treatment such as epinephrine and intravenous antihistamines may be indicated.14 Secondary infection can be treated with antibiotics; a formed abscess might need to be drained or debrided.15

There’s No Place Like Home—Because Triatoma bugs have a pliable exoskeleton and can squeeze into small spaces, they commonly infest dwellings where they find multiple attractants: light, heat, carbon dioxide, and lactic acid.8 The more household occupants (including pets), the higher the levels of carbon dioxide and lactic acid, thus the greater the attraction. Infestation of a home can lead to the spread of diseases harbored by Triatoma, including Chagas disease, which is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi.5

Preventive measures can be taken to reduce the risk and extent of home infestation by Triatoma bugs, including insecticides, a solid foundation, window screens, air conditioning, sealing of cracks and crevices, outdoor light management, and removal of clutter throughout the house.8 Because Triatoma bugs cannot bite through clothing, protective clothing and bug repellent on exposed skin can be employed. Another degree of protection is offered by pest management, especially control of rodents by removing food, water, and nests in areas where triatomine bugs feed off of that population.8,14

Unlike triatomine bugs, wheel bugs tend not to invade houses; therefore, these preventive measures are unnecessary. If a wheel bug is identified, do not engage the arthropod due to the defensive nature of its attack.4,9 Such deliberate avoidance should ensure protection from the wheel bug’s painful bite.

Medical Complications

Although triatomine bugs and wheel bugs are in the same taxonomic family, subsequent infection is unique to Triatoma bugs because they need a blood meal to survive. Because Triatoma bugs feed on mammals, they present an increased opportunity for transmitting the causative agents of infection from hosts on which they have fed.12 The principal parasite transmitted by triatomines is T cruzi, which causes Chagas disease and lives in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of the insect.5 When a triatomine bug seeks out a mucosal surface to bite, including the mouth, it defecates and urinates during or shortly after feeding, leading to contamination of the initial wound or mucosal surfaces. In addition, Triatoma bugs are vectors for transmission of Serratia marcescans, Bartonella henselae, and Mycobacterium leprae.16

Chagas Disease—This infection has 3 stages: acute, intermediate, and chronic.5 The acute stage can present with symptoms of conjunctivitis, fever, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and anemia. The intermediate stage typically is asymptomatic. The chronic stage usually involves the heart and GI tract and causes cardiac aneurysms, cardiomegaly, megacolon, and megaesophagus. Initial symptoms can be a localized nodule (chagoma) at the inoculation site, fever, fatigue, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly.2 Unilateral palpebral edema with associated lymphadenopathy (Romaña sign) also can be seen—not to be confused with bilateral swelling in an acute reaction to an insect bite. Romaña sign is pathognomonic of T cruzi infection; bilateral palpebral swelling is typical of an allergic reaction.12

Identification of a triatomine bite is the first step in diagnosing Chagas disease, which can be life-threatening. Among chronic carriers of Chagas disease, 30% develop GI and cardiac symptoms, of which 20% to 30% develop cardiomyopathy, with serious symptoms that present 10 to 20 years after the asymptomatic intermediate phase.2

Chagas disease is endemic to Central and South America but is also seen in North America; 28,000 new cases are reported annually in South America and North America combined. Human migration from endemic areas and from rural to urban areas has promoted the spread of Chagas disease.2 However, patients in the United States have a relatively low risk for Chagas disease, largely because of the quality of housing construction and use of insecticides.

Treatment options for Chagas disease include nifurtimox and benznidazole. Without treatment, the host immune response typically controls acute replication of the parasite but will lead to a chronic state, ultimately involving the heart and GI tract.5

- Vetter R. Kissing bugs (Triatoma) and the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2001;7:6.

- Zemore ZM, Wills BK. Kissing bug bite. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearlsPublishing; 2023.

- Edwards L, Lynch PJ. Anaphylactic reaction to kissing bug bites. Ariz Med. 1984;41:159-161.

- Smith FD, Miller NG, Carnazzo SJ, et al. Insect bite by Arilus cristatus, a North American reduviid. AMA Arch Derm. 1958;77:324-330. doi:10.1001/archderm.1958.01560030070011

- Nguyen T, Waseem M. Chagas disease. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Shields TL, Walsh EN. Kissing bug bite. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74:14-21. doi:10.1001/archderm.1956.01550070016004

- Beatty NL, Klotz SA. The midnight bite! a kissing bug nightmare. Am J Med. 2018;131:E43-E44. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.10.013

- Klotz SA, Smith SL, Schmidt JO. Kissing bug intrusions into homes in the Southwest United States. Insects. 2021;12:654. doi:10.3390/insects12070654

- Aldrich JR, Chauhan KR, Zhang A, et al. Exocrine secretions of wheel bugs (Heteroptera: Reduviidae: Arilus spp.): clarification and chemistry. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2013;68:522-526.

- Boggs J. They’re wheel bugs, NOT kissing bugs. Buckeye Yard and Garden onLine [Internet]. September 17, 2020. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://bygl.osu.edu/node/1688

- Weber RW. Allergen of the month—assassin bug. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115:A9.

- Klotz JH, Dorn PL, Logan JL, et al. “Kissing bugs”: potential disease vectors and cause of anaphylaxis. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:1629-1634. doi:10.1086/652769

- Anderson C, Belnap C. The kiss of death: a rare case of anaphylaxis to the bite of the “red margined kissing bug”. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2015;74(9 suppl 2):33-35.

- Moffitt JE, Venarske D, Goddard J, et al. Allergic reactions to Triatoma bites. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:122-128. doi:10.1016/s1081-1206(10)62165-5

- Burnett JW, Calton GJ, Morgan RJ. Triatoma: the “kissing bug”. Cutis. 1987;39:399.

- Vieira CB, Praça YR, Bentes K, et al. Triatomines: Trypanosomatids, bacteria, and viruses potential vectors? Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:405. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2018.00405

Classification

Triatomine bugs (Triatoma) and the wheel bug (Arilus cristatus) are part of the family Reduviidae (order Hemiptera, a name that describes the sucking proboscis on the front of the insect’s head).1,2 Both arthropods are found in multiple countries and are especially common in warmer areas, including in the United States, where they can be seen from Texas to California.3,4 Because blood-feeding triatomines need a blood meal to survive while laying eggs and then throughout their 5 developmental nymph stages to undergo molting, they feed on mammals, such as opossums, raccoons, pack rats, and armadillos, whereas wheel bugs mainly prey on soft-bodied insects.1,4-6

Triatoma bugs seek cutaneous blood vessels using thermosensors in their antennae to locate blood flow under the skin for feeding. After inserting the proboscis, they release nitric oxide and an anticoagulant that allows for continuous blood flow while feeding.7 It has been reported that triatomine bugs are not able to bite through clothing, instead seeking exposed skin, particularly near mucous membranes, such as the hands, arms, feet, head, and trunk. The name kissing bug for triatomines was coined because bites near the mouth are common.6 The bite typically is painless and occurs mainly at night when the insect is most active. After obtaining a blood meal, triatomine bugs seek shelter and hide in mud and daub structures, cracks, crevices, and furniture.1,8

Unlike Triatoma species, A cristatus does not require a blood meal for development and survival, leading it to prey on soft-bodied insects. Piercing prey with the proboscis, wheel bugs inject a toxin to digest the contents and suck the digested contents through this apparatus.4 Because the wheel bug does not require a blood meal, it typically bites a human only for defense if it feels threatened. Unlike the painless bite of a triatomine bug, the bite of A cristatus is extremely painful; it has been described as the worst arthropod bite—worse than a hornet’s sting. The pain from the bite is caused by the toxin being injected into the skin; possible retention of the proboscis makes the pain worse.4,9 In addition, when A cristatus is disturbed, it exudes pungent material from a pair of bright orange subrectal glands while stridulating to repulse predators.9

Although Triatoma species and A cristatus have separate roles in nature and vastly different impacts on health, they often are mistaken for the same arthropod when seen in nature. Features that members of Reduviidae share include large bodies (relative to their overall length); long thin legs; a narrow head; wings; and a long sucking proboscis on the front of the head.10

Characteristics that differentiate Triatoma and A cristatus species include size, color, and distinctive markings. Most triatomine bugs are 12- to 36-mm long; are dark brown or black; and have what are called tiger-stripe orange markings on the peripheral two-thirds of the body (Figure 1).11 In contrast, wheel bugs commonly are bigger—measuring longer than 1.25 inches—and gray, with a cogwheel-like structure on the thorax (Figure 2).10

Dermatologic Presentation and Clinical Symptoms

The area of involved skin on patients presenting with Triatoma or A cristatus bites may resemble other insect bites. Many bites from Triatoma bugs and A cristatus initially present as an erythematous, raised, pruritic papule with a central punctum that is visible because of the involvement of the proboscis. However, other presentations of bites from both arthropods have been reported4,6,7: grouped vesicles on an erythematous base; indurated, giant, urticarial-type wheels measuring 10 to 15 mm in diameter; and hemorrhagic bullous nodules (Figure 3). Associated lymphangitis or lymphadenitis is typical of the latter 2 variations.6 These variations in presentation can be mistaken for other causes of similarly presenting lesions, such as shingles or spider bites, leading to delayed or missed diagnosis.

Patients may present with a single bite or multiple bites due to the feeding pattern of Triatoma bugs; if the host moves or disrupts its feeding, the arthropod takes multiple bites to finish feeding.8 In comparison, 4 common variations of wheel bug bites have been reported: (1) a painful bite without complications; (2) a cutaneous horn and papilloma at the site of toxin injection; (3) a necrotic ulcer around the central punctum caused by injected toxin; and (4) an abscess under the central punctum due to secondary infection.4

Anaphylaxis—Although the bites of Triatoma and A cristatus present differently, both can cause anaphylaxis. Triatoma is implicated more often than A cristatus as the cause of anaphylaxis.12 In fact, Triatoma bites are among the more common causes of anaphylaxis from bug bites, with multiple cases of these reactions reported in the literature.12,13

Symptoms of Triatoma anaphylaxis include acute-onset urticarial rash, flushing, dyspnea, wheezing, nausea, vomiting, and localized edema.2 The cause of anaphylaxis is proteins in Triatoma saliva, including 20-kDa procalin, which incites the systemic reaction. Other potential causes of anaphylaxis include serine protease, which has similarities to salivary protein and desmoglein in humans.11

The degree of reaction to a bite depends on the patient's sensitization to antigenic proteins in each insect’s saliva.4,6 Patients who have a bite from a triatomine bug are at risk for subsequent bites, as household infestation is likely due to the pliability of the insect, allowing it to hide in small spaces unnoticed.8 In the case of a bite from Triatoma or A cristatus, sensitization may lead to severe and worsening reactions with subsequent bites, which ultimately can result in life-threatening anaphylaxis.1,6

Treatment and Prevention

Treatment of Triatoma and A cristatus bites depends on the severity of the patient’s reaction to the bite. A local reaction to a bite from either insect can be treated supportively with local corticosteroids and antihistamines.3 If the patient is sensitized to proteins associated with a bite, standard anaphylaxis treatment such as epinephrine and intravenous antihistamines may be indicated.14 Secondary infection can be treated with antibiotics; a formed abscess might need to be drained or debrided.15

There’s No Place Like Home—Because Triatoma bugs have a pliable exoskeleton and can squeeze into small spaces, they commonly infest dwellings where they find multiple attractants: light, heat, carbon dioxide, and lactic acid.8 The more household occupants (including pets), the higher the levels of carbon dioxide and lactic acid, thus the greater the attraction. Infestation of a home can lead to the spread of diseases harbored by Triatoma, including Chagas disease, which is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi.5

Preventive measures can be taken to reduce the risk and extent of home infestation by Triatoma bugs, including insecticides, a solid foundation, window screens, air conditioning, sealing of cracks and crevices, outdoor light management, and removal of clutter throughout the house.8 Because Triatoma bugs cannot bite through clothing, protective clothing and bug repellent on exposed skin can be employed. Another degree of protection is offered by pest management, especially control of rodents by removing food, water, and nests in areas where triatomine bugs feed off of that population.8,14

Unlike triatomine bugs, wheel bugs tend not to invade houses; therefore, these preventive measures are unnecessary. If a wheel bug is identified, do not engage the arthropod due to the defensive nature of its attack.4,9 Such deliberate avoidance should ensure protection from the wheel bug’s painful bite.

Medical Complications

Although triatomine bugs and wheel bugs are in the same taxonomic family, subsequent infection is unique to Triatoma bugs because they need a blood meal to survive. Because Triatoma bugs feed on mammals, they present an increased opportunity for transmitting the causative agents of infection from hosts on which they have fed.12 The principal parasite transmitted by triatomines is T cruzi, which causes Chagas disease and lives in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of the insect.5 When a triatomine bug seeks out a mucosal surface to bite, including the mouth, it defecates and urinates during or shortly after feeding, leading to contamination of the initial wound or mucosal surfaces. In addition, Triatoma bugs are vectors for transmission of Serratia marcescans, Bartonella henselae, and Mycobacterium leprae.16

Chagas Disease—This infection has 3 stages: acute, intermediate, and chronic.5 The acute stage can present with symptoms of conjunctivitis, fever, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and anemia. The intermediate stage typically is asymptomatic. The chronic stage usually involves the heart and GI tract and causes cardiac aneurysms, cardiomegaly, megacolon, and megaesophagus. Initial symptoms can be a localized nodule (chagoma) at the inoculation site, fever, fatigue, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly.2 Unilateral palpebral edema with associated lymphadenopathy (Romaña sign) also can be seen—not to be confused with bilateral swelling in an acute reaction to an insect bite. Romaña sign is pathognomonic of T cruzi infection; bilateral palpebral swelling is typical of an allergic reaction.12

Identification of a triatomine bite is the first step in diagnosing Chagas disease, which can be life-threatening. Among chronic carriers of Chagas disease, 30% develop GI and cardiac symptoms, of which 20% to 30% develop cardiomyopathy, with serious symptoms that present 10 to 20 years after the asymptomatic intermediate phase.2

Chagas disease is endemic to Central and South America but is also seen in North America; 28,000 new cases are reported annually in South America and North America combined. Human migration from endemic areas and from rural to urban areas has promoted the spread of Chagas disease.2 However, patients in the United States have a relatively low risk for Chagas disease, largely because of the quality of housing construction and use of insecticides.

Treatment options for Chagas disease include nifurtimox and benznidazole. Without treatment, the host immune response typically controls acute replication of the parasite but will lead to a chronic state, ultimately involving the heart and GI tract.5

Classification

Triatomine bugs (Triatoma) and the wheel bug (Arilus cristatus) are part of the family Reduviidae (order Hemiptera, a name that describes the sucking proboscis on the front of the insect’s head).1,2 Both arthropods are found in multiple countries and are especially common in warmer areas, including in the United States, where they can be seen from Texas to California.3,4 Because blood-feeding triatomines need a blood meal to survive while laying eggs and then throughout their 5 developmental nymph stages to undergo molting, they feed on mammals, such as opossums, raccoons, pack rats, and armadillos, whereas wheel bugs mainly prey on soft-bodied insects.1,4-6

Triatoma bugs seek cutaneous blood vessels using thermosensors in their antennae to locate blood flow under the skin for feeding. After inserting the proboscis, they release nitric oxide and an anticoagulant that allows for continuous blood flow while feeding.7 It has been reported that triatomine bugs are not able to bite through clothing, instead seeking exposed skin, particularly near mucous membranes, such as the hands, arms, feet, head, and trunk. The name kissing bug for triatomines was coined because bites near the mouth are common.6 The bite typically is painless and occurs mainly at night when the insect is most active. After obtaining a blood meal, triatomine bugs seek shelter and hide in mud and daub structures, cracks, crevices, and furniture.1,8

Unlike Triatoma species, A cristatus does not require a blood meal for development and survival, leading it to prey on soft-bodied insects. Piercing prey with the proboscis, wheel bugs inject a toxin to digest the contents and suck the digested contents through this apparatus.4 Because the wheel bug does not require a blood meal, it typically bites a human only for defense if it feels threatened. Unlike the painless bite of a triatomine bug, the bite of A cristatus is extremely painful; it has been described as the worst arthropod bite—worse than a hornet’s sting. The pain from the bite is caused by the toxin being injected into the skin; possible retention of the proboscis makes the pain worse.4,9 In addition, when A cristatus is disturbed, it exudes pungent material from a pair of bright orange subrectal glands while stridulating to repulse predators.9

Although Triatoma species and A cristatus have separate roles in nature and vastly different impacts on health, they often are mistaken for the same arthropod when seen in nature. Features that members of Reduviidae share include large bodies (relative to their overall length); long thin legs; a narrow head; wings; and a long sucking proboscis on the front of the head.10

Characteristics that differentiate Triatoma and A cristatus species include size, color, and distinctive markings. Most triatomine bugs are 12- to 36-mm long; are dark brown or black; and have what are called tiger-stripe orange markings on the peripheral two-thirds of the body (Figure 1).11 In contrast, wheel bugs commonly are bigger—measuring longer than 1.25 inches—and gray, with a cogwheel-like structure on the thorax (Figure 2).10

Dermatologic Presentation and Clinical Symptoms

The area of involved skin on patients presenting with Triatoma or A cristatus bites may resemble other insect bites. Many bites from Triatoma bugs and A cristatus initially present as an erythematous, raised, pruritic papule with a central punctum that is visible because of the involvement of the proboscis. However, other presentations of bites from both arthropods have been reported4,6,7: grouped vesicles on an erythematous base; indurated, giant, urticarial-type wheels measuring 10 to 15 mm in diameter; and hemorrhagic bullous nodules (Figure 3). Associated lymphangitis or lymphadenitis is typical of the latter 2 variations.6 These variations in presentation can be mistaken for other causes of similarly presenting lesions, such as shingles or spider bites, leading to delayed or missed diagnosis.

Patients may present with a single bite or multiple bites due to the feeding pattern of Triatoma bugs; if the host moves or disrupts its feeding, the arthropod takes multiple bites to finish feeding.8 In comparison, 4 common variations of wheel bug bites have been reported: (1) a painful bite without complications; (2) a cutaneous horn and papilloma at the site of toxin injection; (3) a necrotic ulcer around the central punctum caused by injected toxin; and (4) an abscess under the central punctum due to secondary infection.4

Anaphylaxis—Although the bites of Triatoma and A cristatus present differently, both can cause anaphylaxis. Triatoma is implicated more often than A cristatus as the cause of anaphylaxis.12 In fact, Triatoma bites are among the more common causes of anaphylaxis from bug bites, with multiple cases of these reactions reported in the literature.12,13

Symptoms of Triatoma anaphylaxis include acute-onset urticarial rash, flushing, dyspnea, wheezing, nausea, vomiting, and localized edema.2 The cause of anaphylaxis is proteins in Triatoma saliva, including 20-kDa procalin, which incites the systemic reaction. Other potential causes of anaphylaxis include serine protease, which has similarities to salivary protein and desmoglein in humans.11

The degree of reaction to a bite depends on the patient's sensitization to antigenic proteins in each insect’s saliva.4,6 Patients who have a bite from a triatomine bug are at risk for subsequent bites, as household infestation is likely due to the pliability of the insect, allowing it to hide in small spaces unnoticed.8 In the case of a bite from Triatoma or A cristatus, sensitization may lead to severe and worsening reactions with subsequent bites, which ultimately can result in life-threatening anaphylaxis.1,6

Treatment and Prevention

Treatment of Triatoma and A cristatus bites depends on the severity of the patient’s reaction to the bite. A local reaction to a bite from either insect can be treated supportively with local corticosteroids and antihistamines.3 If the patient is sensitized to proteins associated with a bite, standard anaphylaxis treatment such as epinephrine and intravenous antihistamines may be indicated.14 Secondary infection can be treated with antibiotics; a formed abscess might need to be drained or debrided.15

There’s No Place Like Home—Because Triatoma bugs have a pliable exoskeleton and can squeeze into small spaces, they commonly infest dwellings where they find multiple attractants: light, heat, carbon dioxide, and lactic acid.8 The more household occupants (including pets), the higher the levels of carbon dioxide and lactic acid, thus the greater the attraction. Infestation of a home can lead to the spread of diseases harbored by Triatoma, including Chagas disease, which is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi.5

Preventive measures can be taken to reduce the risk and extent of home infestation by Triatoma bugs, including insecticides, a solid foundation, window screens, air conditioning, sealing of cracks and crevices, outdoor light management, and removal of clutter throughout the house.8 Because Triatoma bugs cannot bite through clothing, protective clothing and bug repellent on exposed skin can be employed. Another degree of protection is offered by pest management, especially control of rodents by removing food, water, and nests in areas where triatomine bugs feed off of that population.8,14

Unlike triatomine bugs, wheel bugs tend not to invade houses; therefore, these preventive measures are unnecessary. If a wheel bug is identified, do not engage the arthropod due to the defensive nature of its attack.4,9 Such deliberate avoidance should ensure protection from the wheel bug’s painful bite.

Medical Complications

Although triatomine bugs and wheel bugs are in the same taxonomic family, subsequent infection is unique to Triatoma bugs because they need a blood meal to survive. Because Triatoma bugs feed on mammals, they present an increased opportunity for transmitting the causative agents of infection from hosts on which they have fed.12 The principal parasite transmitted by triatomines is T cruzi, which causes Chagas disease and lives in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of the insect.5 When a triatomine bug seeks out a mucosal surface to bite, including the mouth, it defecates and urinates during or shortly after feeding, leading to contamination of the initial wound or mucosal surfaces. In addition, Triatoma bugs are vectors for transmission of Serratia marcescans, Bartonella henselae, and Mycobacterium leprae.16

Chagas Disease—This infection has 3 stages: acute, intermediate, and chronic.5 The acute stage can present with symptoms of conjunctivitis, fever, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and anemia. The intermediate stage typically is asymptomatic. The chronic stage usually involves the heart and GI tract and causes cardiac aneurysms, cardiomegaly, megacolon, and megaesophagus. Initial symptoms can be a localized nodule (chagoma) at the inoculation site, fever, fatigue, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly.2 Unilateral palpebral edema with associated lymphadenopathy (Romaña sign) also can be seen—not to be confused with bilateral swelling in an acute reaction to an insect bite. Romaña sign is pathognomonic of T cruzi infection; bilateral palpebral swelling is typical of an allergic reaction.12

Identification of a triatomine bite is the first step in diagnosing Chagas disease, which can be life-threatening. Among chronic carriers of Chagas disease, 30% develop GI and cardiac symptoms, of which 20% to 30% develop cardiomyopathy, with serious symptoms that present 10 to 20 years after the asymptomatic intermediate phase.2

Chagas disease is endemic to Central and South America but is also seen in North America; 28,000 new cases are reported annually in South America and North America combined. Human migration from endemic areas and from rural to urban areas has promoted the spread of Chagas disease.2 However, patients in the United States have a relatively low risk for Chagas disease, largely because of the quality of housing construction and use of insecticides.

Treatment options for Chagas disease include nifurtimox and benznidazole. Without treatment, the host immune response typically controls acute replication of the parasite but will lead to a chronic state, ultimately involving the heart and GI tract.5

- Vetter R. Kissing bugs (Triatoma) and the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2001;7:6.

- Zemore ZM, Wills BK. Kissing bug bite. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearlsPublishing; 2023.

- Edwards L, Lynch PJ. Anaphylactic reaction to kissing bug bites. Ariz Med. 1984;41:159-161.

- Smith FD, Miller NG, Carnazzo SJ, et al. Insect bite by Arilus cristatus, a North American reduviid. AMA Arch Derm. 1958;77:324-330. doi:10.1001/archderm.1958.01560030070011

- Nguyen T, Waseem M. Chagas disease. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Shields TL, Walsh EN. Kissing bug bite. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74:14-21. doi:10.1001/archderm.1956.01550070016004

- Beatty NL, Klotz SA. The midnight bite! a kissing bug nightmare. Am J Med. 2018;131:E43-E44. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.10.013

- Klotz SA, Smith SL, Schmidt JO. Kissing bug intrusions into homes in the Southwest United States. Insects. 2021;12:654. doi:10.3390/insects12070654

- Aldrich JR, Chauhan KR, Zhang A, et al. Exocrine secretions of wheel bugs (Heteroptera: Reduviidae: Arilus spp.): clarification and chemistry. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2013;68:522-526.

- Boggs J. They’re wheel bugs, NOT kissing bugs. Buckeye Yard and Garden onLine [Internet]. September 17, 2020. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://bygl.osu.edu/node/1688

- Weber RW. Allergen of the month—assassin bug. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115:A9.

- Klotz JH, Dorn PL, Logan JL, et al. “Kissing bugs”: potential disease vectors and cause of anaphylaxis. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:1629-1634. doi:10.1086/652769

- Anderson C, Belnap C. The kiss of death: a rare case of anaphylaxis to the bite of the “red margined kissing bug”. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2015;74(9 suppl 2):33-35.

- Moffitt JE, Venarske D, Goddard J, et al. Allergic reactions to Triatoma bites. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:122-128. doi:10.1016/s1081-1206(10)62165-5

- Burnett JW, Calton GJ, Morgan RJ. Triatoma: the “kissing bug”. Cutis. 1987;39:399.

- Vieira CB, Praça YR, Bentes K, et al. Triatomines: Trypanosomatids, bacteria, and viruses potential vectors? Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:405. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2018.00405

- Vetter R. Kissing bugs (Triatoma) and the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2001;7:6.

- Zemore ZM, Wills BK. Kissing bug bite. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearlsPublishing; 2023.

- Edwards L, Lynch PJ. Anaphylactic reaction to kissing bug bites. Ariz Med. 1984;41:159-161.

- Smith FD, Miller NG, Carnazzo SJ, et al. Insect bite by Arilus cristatus, a North American reduviid. AMA Arch Derm. 1958;77:324-330. doi:10.1001/archderm.1958.01560030070011

- Nguyen T, Waseem M. Chagas disease. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Shields TL, Walsh EN. Kissing bug bite. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74:14-21. doi:10.1001/archderm.1956.01550070016004

- Beatty NL, Klotz SA. The midnight bite! a kissing bug nightmare. Am J Med. 2018;131:E43-E44. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.10.013

- Klotz SA, Smith SL, Schmidt JO. Kissing bug intrusions into homes in the Southwest United States. Insects. 2021;12:654. doi:10.3390/insects12070654

- Aldrich JR, Chauhan KR, Zhang A, et al. Exocrine secretions of wheel bugs (Heteroptera: Reduviidae: Arilus spp.): clarification and chemistry. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2013;68:522-526.

- Boggs J. They’re wheel bugs, NOT kissing bugs. Buckeye Yard and Garden onLine [Internet]. September 17, 2020. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://bygl.osu.edu/node/1688

- Weber RW. Allergen of the month—assassin bug. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115:A9.

- Klotz JH, Dorn PL, Logan JL, et al. “Kissing bugs”: potential disease vectors and cause of anaphylaxis. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:1629-1634. doi:10.1086/652769

- Anderson C, Belnap C. The kiss of death: a rare case of anaphylaxis to the bite of the “red margined kissing bug”. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2015;74(9 suppl 2):33-35.

- Moffitt JE, Venarske D, Goddard J, et al. Allergic reactions to Triatoma bites. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:122-128. doi:10.1016/s1081-1206(10)62165-5

- Burnett JW, Calton GJ, Morgan RJ. Triatoma: the “kissing bug”. Cutis. 1987;39:399.

- Vieira CB, Praça YR, Bentes K, et al. Triatomines: Trypanosomatids, bacteria, and viruses potential vectors? Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:405. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2018.00405

Practice Points

- Triatomine bugs (Triatoma) and the wheel bug (Arilus cristatus) are found throughout North America with a concentration in southern regions.

- Bites of triatomine bugs can cause anaphylaxis; prevention of bites to diminish household infestation is important because sensitization can result in increased severity of anaphylaxis upon subsequent exposure.

- Chagas disease—caused by transmission of the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi—can be a complication of a Triatoma bite in endemic areas; treatments include nifurtimox and benznidazole.

- Left undiagnosed and untreated, Chagas disease can have long-lasting implications for cardiac and gastrointestinal pathology.