User login

Acral Erythema, Edema, and Scaly Plaques in a Patient With Polyneuropathy

Acral Erythema, Edema, and Scaly Plaques in a Patient With Polyneuropathy

THE DIAGNOSIS: Borderline-Borderline Leprosy With Type 1 Lepra Reaction

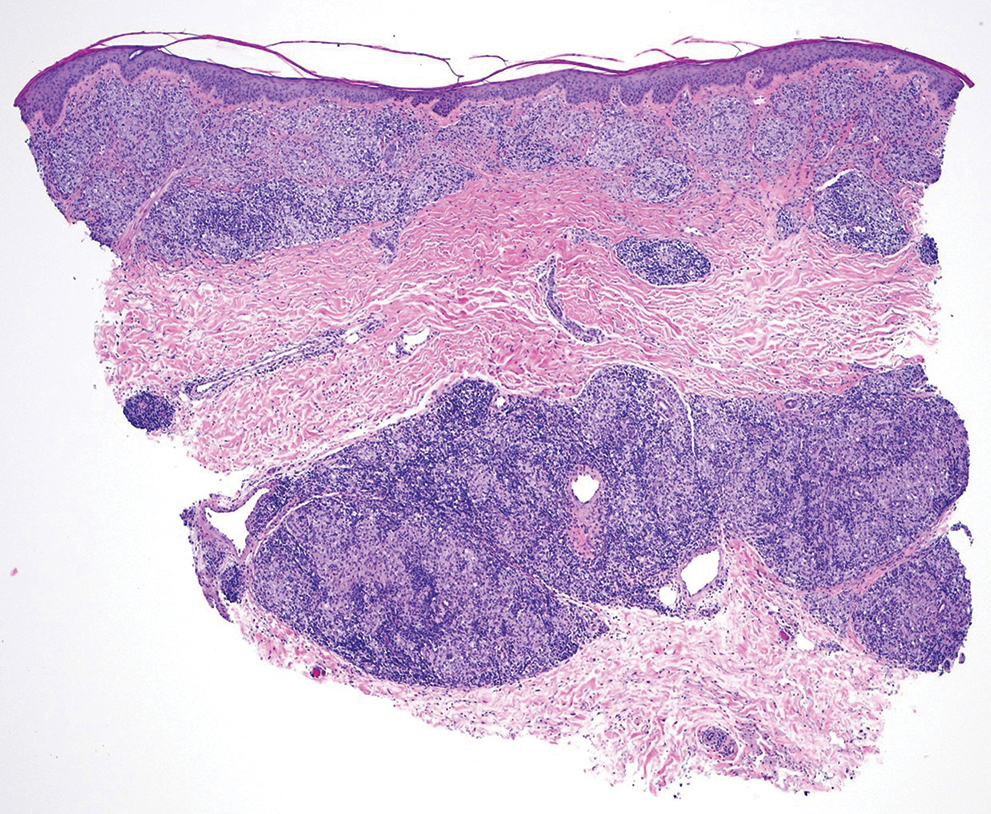

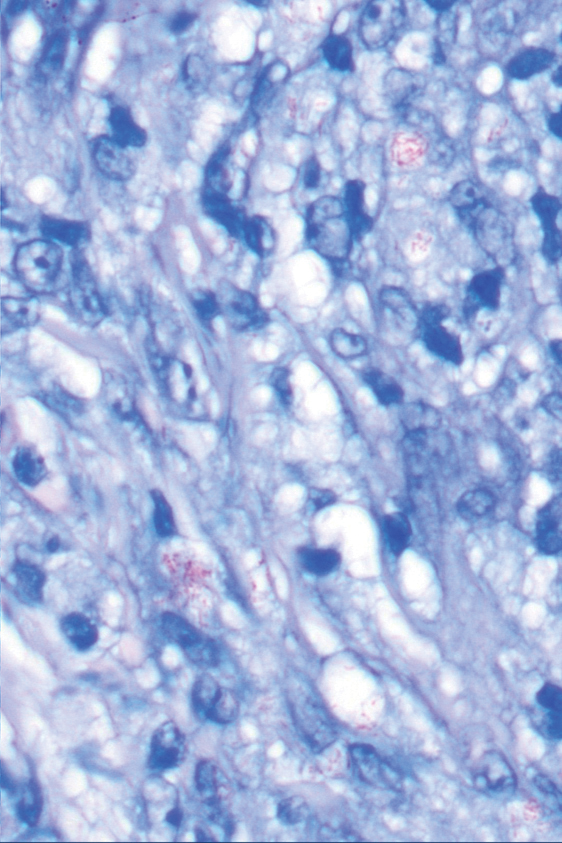

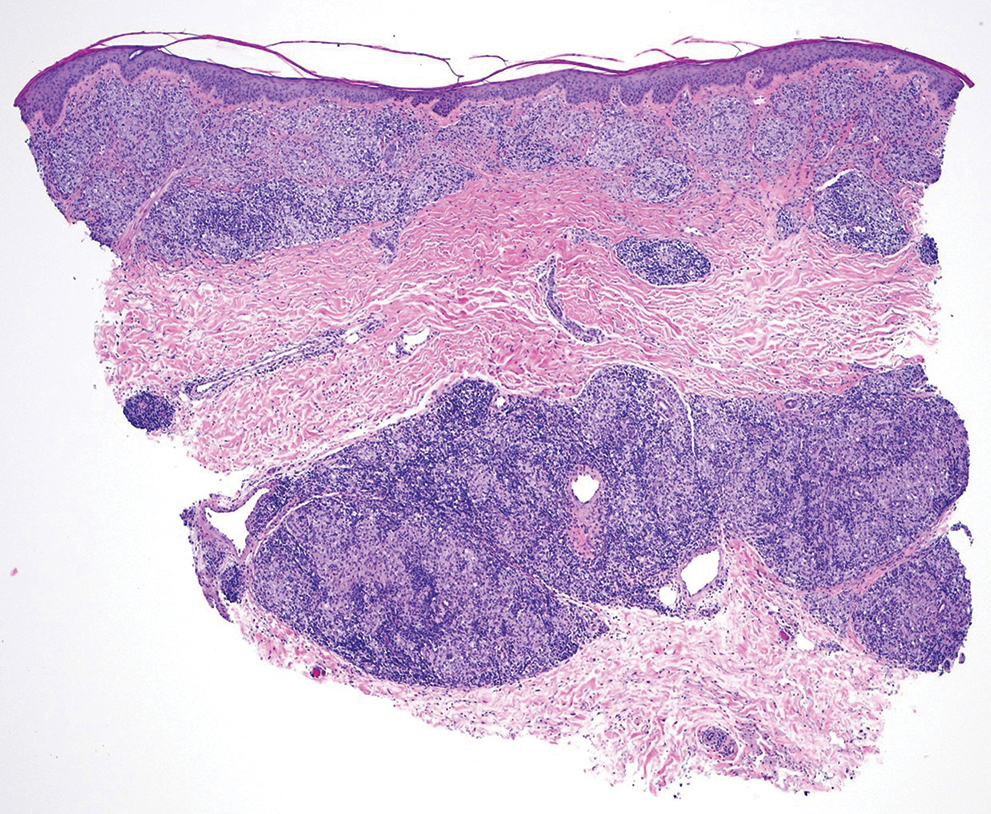

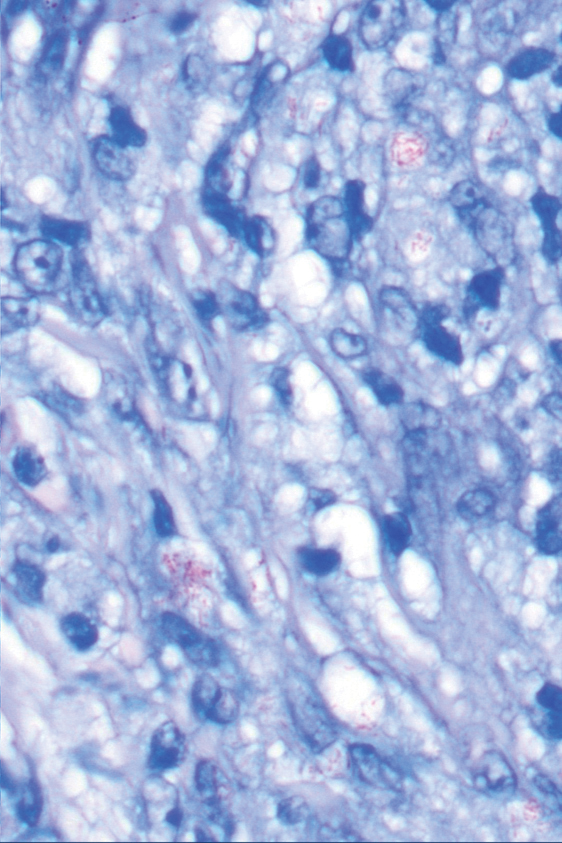

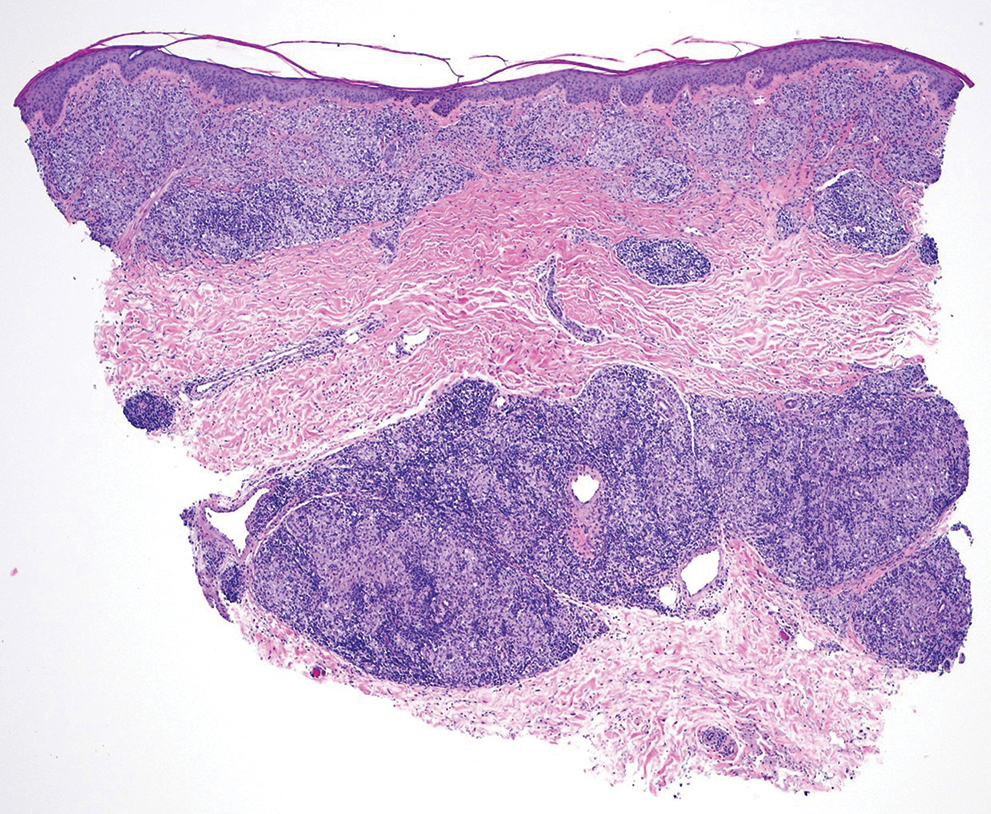

Punch biopsies from plaques on the right elbow and right shin revealed diffuse granulomatous dermatitis (Figure 1) with a narrow Grenz zone in the superficial dermis. The upper dermis contained a dense bandlike infiltrate of histiocytes with abundant foamy-gray cytoplasm and a moderate admixture of lymphocytes. The mid and deep dermis contained a nodular, perivascular, periadnexal, and perineural infiltrate of histiocytes and a dense admixture of lymphocytes. Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains were negative for microorganisms. Fite stain was positive for numerous organisms in histiocytes and small dermal nerves (Figure 2). These findings and the clinical examination confirmed a diagnosis of borderline-borderline leprosy with type 1 lepra reaction. The patient was started on dapsone 100 mg, rifampin 600 mg, and clofazimine 100 mg once daily and experienced clinical improvement within 6 months.

The World Health Organization reported more than 200,000 new leprosy cases globally in 2019, with most occurring in India, Brazil, and Indonesia.1 About 150 to 250 new cases are detected in the United States annually.1 The Ridley-Jopling classification of leprosy divides the condition into 5 categories: tuberculoid, borderline tuberculoid, borderline-borderline (BB), borderline lepromatous, and lepromatous. At one end of the spectrum, tuberculoid leprosy—a predominant Th1 immune response mediated by CD4 lymphocytes, interleukin (IL) 2, and interferon gamma2—is characterized by sharply demarcated erythematous and hypopigmented plaques with raised borders and an annular appearance.2,3 Lesions typically have atrophic and hypopigmented centers that often appear in an asymmetric distribution on the arms and legs.2,3 Histologic features include dermal tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells—some located directly beneath the epidermis and others around deep vessels and nerves3—multinucleated Langerhans giant cells, thickened peripheral nerves with intraneural lymphocytic infiltrates, and granulomas with central necrosis. Fite-Faraco staining exhibits few bacteria.2

Lepromatous leprosy occurs in individuals with impaired T-cell immunity, leading to multiple red-brown nodular infiltrates in the skin and mucous membranes.2,3 Lesions typically are symmetric and favor the face and auricle of the ear.2,3 Histologically, there are bluish-gray foamy macrophages that form diffuse or nodular infiltrates with few lymphocytes,2 with a Grenz zone between the epidermis and dermis. Nerves may show lamination of the perineurium resembling an onion skin.2,3 Immunohistochemistry shows predominant CD8-positive infiltrates with a Th2 response and positive IL-4 and IL-10. Fite-Faraco stain shows numerous mycobacteria arranged in clusters and in histiocytes.2

Tuberculoid leprosy is treated with dapsone 100 mg and rifampin 600 mg once daily for 6 months,4 and lepromatous leprosy is treated with dapsone 100 mg, rifampin 600 mg, and clofazimine 50 mg once daily for 12 months.4 The prognosis for both is good with treatment; erythema and induration of skin lesions may improve within a few months, but residual nerve damage is common, especially in those with advanced disease prior to treatment.2 For direct contacts, a single dose of rifampin may be given.4

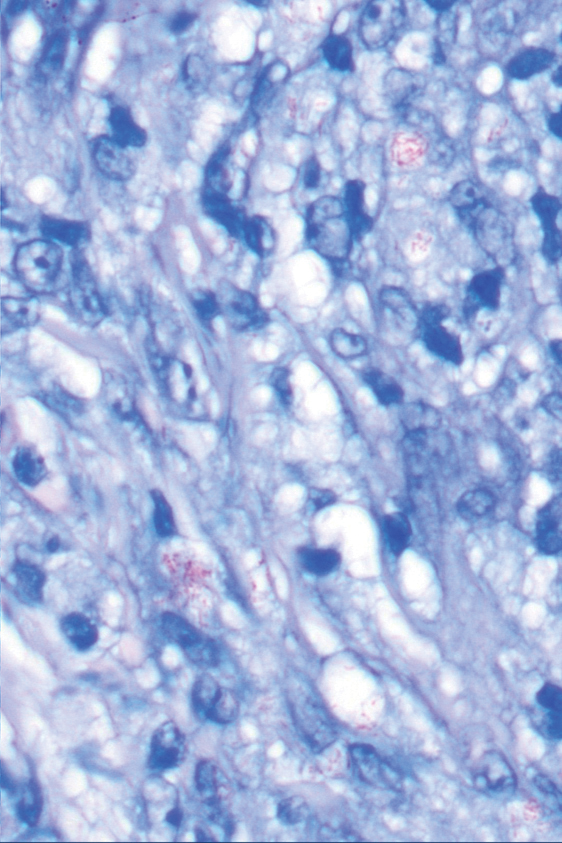

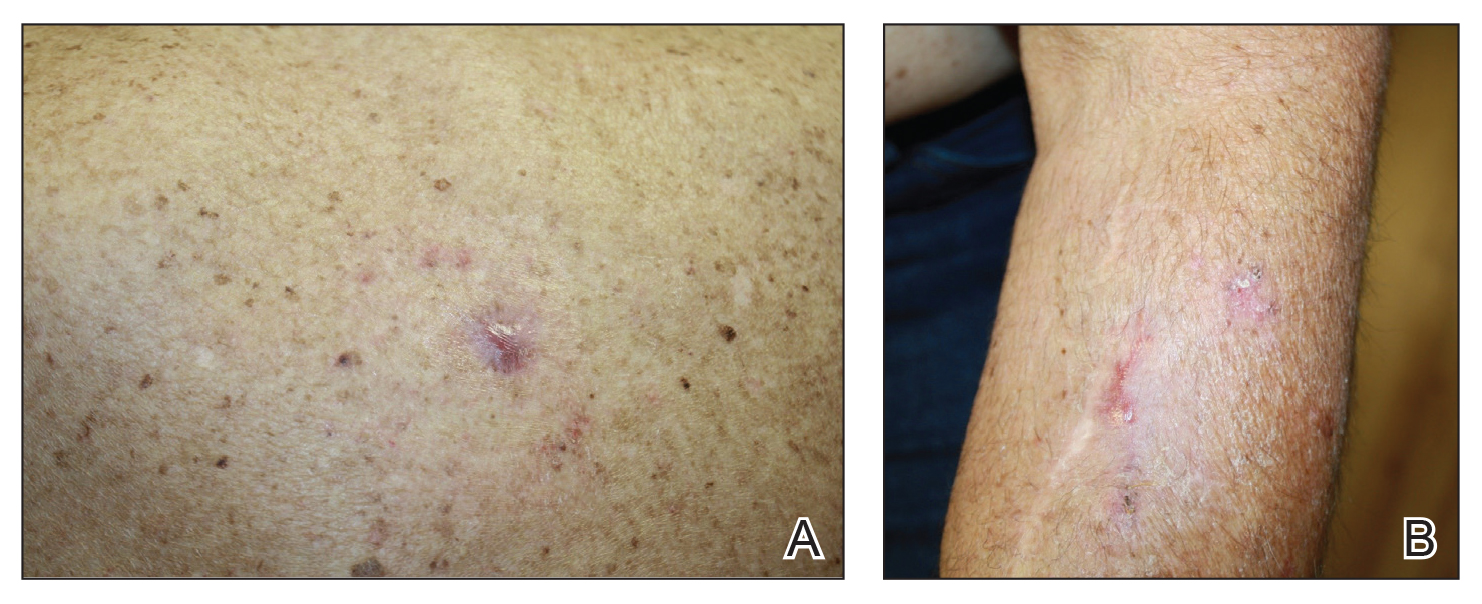

Borderline-borderline leprosy manifests with numerous asymmetric annular plaques, as seen in our patient (Figure 3). Histology findings can be variable and often overlap with other forms of leprosy. There can be epithelioid granulomas and only a few acid-fast bacilli (AFB) or diffuse histiocytic aggregates with foamy histiocytes containing large numbers of AFB.3 Nerve involvement is variable but can be severe in the setting of type 1 lepra reaction, which was present in our patient. Type 1 lepra reaction—a type IV cell-mediated allergic hypersensitivity reaction to Mycobacterium leprae antigens—manifests clinically with hyperesthesia, erythema, edema, and subsequent scaling.2 It occurs in up to 30% of patients with borderline leprosy, usually within 12 months of treatment initiation.2 Our patient had considerable edema and erythema of the hands and feet (Figure 4) along with extensive polyneuropathy prior to starting therapy.

Lucio phenomenon is a rare leprosy reaction found in patients with untreated lepromatous leprosy characterized by erythematous to violaceous macules that lead to ulceronecrotic lesions.5 Histologically, there are many AFB in the vascular endothelium, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and ischemic epidermal necrosis.5 Our patient did not have ulcerative or necrotic lesions.

The classic skin lesions of psoriasis vulgaris can be described as well-demarcated pink plaques with white or silvery scales that usually are distributed symmetrically and often are found on extensor surfaces.6 Rapidly progressive lesions can be annular with normal skin in the center, mimicking the lesions seen in tuberculoid leprosy. Clinically, both psoriasis and tuberculoid forms of leprosy are sharply demarcated; however, psoriatic lesions often have micaceous overlying scale that is not present in leprosy. Characteristic histologic findings of psoriasis are hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis with dilated blood vessels and a lymphocytic infiltrate, predominantly into the dermis.7 Psoriatic arthritis has a variable clinical course but tends to emerge 5 to 12 years after initial skin manifestation.8 Classic clinical symptoms include swelling, tenderness, stiffness, and pain in joints and surrounding tissues.8 Other than edema, our patient did not exhibit signs of psoriatic arthritis.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by noncaseating epithelioid granulomas affecting various organs, with cutaneous manifestations present in approximately 30% of all cases. Cutaneous manifestations can be variable, including maculopapular lesions, plaques, and nodules.9 Differentiating between cutaneous sarcoidosis and tuberculoid leprosy can be challenging, as both are granulomatous processes; however, histology of sarcoidosis demonstrates noncaseating granulomas in the dermis and/or subcutaneous tissues without AFB9 compared to granulomas with necrotic centers in tuberculoid leprosy.

Cutaneous tuberculosis has variable morphologies. One subtype, lupus vulgaris, can manifest with violaceous, scaly, eroded plaques that could be confused for leprosy. Lupus vulgaris usually results from hematogenous or lymphatic seeding in individuals with high or moderate immunity to M tuberculosis.10

Histologically, the dermis has tuberculoid granulomas containing multinucleated giant cells,10 which can mimic those seen in BB leprosy. Tuberculin skin test results often are positive10; while this test was not performed in our patient, chest radiography was unremarkable, making this diagnosis less likely.

Mycobacterium leprae infections should be considered in a patient with a worsening rash and progressive polyneuropathy. Clinical diagnosis can be challenging due to similarities with other diseases; however, histopathologic findings can help differentiate M leprae from other conditions. This infection is treatable, and early detection can minimize long-term patient morbidity.

- CDC. Hansen’s disease (leprosy). Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/leprosy/about/index.html

- Fischer M. Leprosy—an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:801-827.

- Maymone MBC, Laughter M, Venkatesh S, et al. Leprosy: clinical aspects and diagnostic techniques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020; 83:1-14.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of leprosy. October 6, 2018. Accessed April 2, 2025. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789290226383

- Frade MAC, Coltro PS, Filho FB, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: a systematic literature review of definition, clinical features, histopathogenesis and management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2022;88:464-477.

- Kimmel GW, Lebwohl M. Psoriasis: overview and diagnosis. In: Evidence-Based Psoriasis. Springer International Publishing; 2018:1-16.

- Griffiths CE, Barker JN. Pathogenesis and clinical features of psoriasis. Lancet. 2007;370:263-271.

- Menter A. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis overview. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(8 suppl):S216-S224.

- Wu JH, Imadojemu S, Caplan AS. The evolving landscape of cutaneous sarcoidosis: pathogenic insight, clinical challenges, and new frontiers in therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:499-514.

- Hill MK, Sanders CV. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5:1-6.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Borderline-Borderline Leprosy With Type 1 Lepra Reaction

Punch biopsies from plaques on the right elbow and right shin revealed diffuse granulomatous dermatitis (Figure 1) with a narrow Grenz zone in the superficial dermis. The upper dermis contained a dense bandlike infiltrate of histiocytes with abundant foamy-gray cytoplasm and a moderate admixture of lymphocytes. The mid and deep dermis contained a nodular, perivascular, periadnexal, and perineural infiltrate of histiocytes and a dense admixture of lymphocytes. Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains were negative for microorganisms. Fite stain was positive for numerous organisms in histiocytes and small dermal nerves (Figure 2). These findings and the clinical examination confirmed a diagnosis of borderline-borderline leprosy with type 1 lepra reaction. The patient was started on dapsone 100 mg, rifampin 600 mg, and clofazimine 100 mg once daily and experienced clinical improvement within 6 months.

The World Health Organization reported more than 200,000 new leprosy cases globally in 2019, with most occurring in India, Brazil, and Indonesia.1 About 150 to 250 new cases are detected in the United States annually.1 The Ridley-Jopling classification of leprosy divides the condition into 5 categories: tuberculoid, borderline tuberculoid, borderline-borderline (BB), borderline lepromatous, and lepromatous. At one end of the spectrum, tuberculoid leprosy—a predominant Th1 immune response mediated by CD4 lymphocytes, interleukin (IL) 2, and interferon gamma2—is characterized by sharply demarcated erythematous and hypopigmented plaques with raised borders and an annular appearance.2,3 Lesions typically have atrophic and hypopigmented centers that often appear in an asymmetric distribution on the arms and legs.2,3 Histologic features include dermal tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells—some located directly beneath the epidermis and others around deep vessels and nerves3—multinucleated Langerhans giant cells, thickened peripheral nerves with intraneural lymphocytic infiltrates, and granulomas with central necrosis. Fite-Faraco staining exhibits few bacteria.2

Lepromatous leprosy occurs in individuals with impaired T-cell immunity, leading to multiple red-brown nodular infiltrates in the skin and mucous membranes.2,3 Lesions typically are symmetric and favor the face and auricle of the ear.2,3 Histologically, there are bluish-gray foamy macrophages that form diffuse or nodular infiltrates with few lymphocytes,2 with a Grenz zone between the epidermis and dermis. Nerves may show lamination of the perineurium resembling an onion skin.2,3 Immunohistochemistry shows predominant CD8-positive infiltrates with a Th2 response and positive IL-4 and IL-10. Fite-Faraco stain shows numerous mycobacteria arranged in clusters and in histiocytes.2

Tuberculoid leprosy is treated with dapsone 100 mg and rifampin 600 mg once daily for 6 months,4 and lepromatous leprosy is treated with dapsone 100 mg, rifampin 600 mg, and clofazimine 50 mg once daily for 12 months.4 The prognosis for both is good with treatment; erythema and induration of skin lesions may improve within a few months, but residual nerve damage is common, especially in those with advanced disease prior to treatment.2 For direct contacts, a single dose of rifampin may be given.4

Borderline-borderline leprosy manifests with numerous asymmetric annular plaques, as seen in our patient (Figure 3). Histology findings can be variable and often overlap with other forms of leprosy. There can be epithelioid granulomas and only a few acid-fast bacilli (AFB) or diffuse histiocytic aggregates with foamy histiocytes containing large numbers of AFB.3 Nerve involvement is variable but can be severe in the setting of type 1 lepra reaction, which was present in our patient. Type 1 lepra reaction—a type IV cell-mediated allergic hypersensitivity reaction to Mycobacterium leprae antigens—manifests clinically with hyperesthesia, erythema, edema, and subsequent scaling.2 It occurs in up to 30% of patients with borderline leprosy, usually within 12 months of treatment initiation.2 Our patient had considerable edema and erythema of the hands and feet (Figure 4) along with extensive polyneuropathy prior to starting therapy.

Lucio phenomenon is a rare leprosy reaction found in patients with untreated lepromatous leprosy characterized by erythematous to violaceous macules that lead to ulceronecrotic lesions.5 Histologically, there are many AFB in the vascular endothelium, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and ischemic epidermal necrosis.5 Our patient did not have ulcerative or necrotic lesions.

The classic skin lesions of psoriasis vulgaris can be described as well-demarcated pink plaques with white or silvery scales that usually are distributed symmetrically and often are found on extensor surfaces.6 Rapidly progressive lesions can be annular with normal skin in the center, mimicking the lesions seen in tuberculoid leprosy. Clinically, both psoriasis and tuberculoid forms of leprosy are sharply demarcated; however, psoriatic lesions often have micaceous overlying scale that is not present in leprosy. Characteristic histologic findings of psoriasis are hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis with dilated blood vessels and a lymphocytic infiltrate, predominantly into the dermis.7 Psoriatic arthritis has a variable clinical course but tends to emerge 5 to 12 years after initial skin manifestation.8 Classic clinical symptoms include swelling, tenderness, stiffness, and pain in joints and surrounding tissues.8 Other than edema, our patient did not exhibit signs of psoriatic arthritis.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by noncaseating epithelioid granulomas affecting various organs, with cutaneous manifestations present in approximately 30% of all cases. Cutaneous manifestations can be variable, including maculopapular lesions, plaques, and nodules.9 Differentiating between cutaneous sarcoidosis and tuberculoid leprosy can be challenging, as both are granulomatous processes; however, histology of sarcoidosis demonstrates noncaseating granulomas in the dermis and/or subcutaneous tissues without AFB9 compared to granulomas with necrotic centers in tuberculoid leprosy.

Cutaneous tuberculosis has variable morphologies. One subtype, lupus vulgaris, can manifest with violaceous, scaly, eroded plaques that could be confused for leprosy. Lupus vulgaris usually results from hematogenous or lymphatic seeding in individuals with high or moderate immunity to M tuberculosis.10

Histologically, the dermis has tuberculoid granulomas containing multinucleated giant cells,10 which can mimic those seen in BB leprosy. Tuberculin skin test results often are positive10; while this test was not performed in our patient, chest radiography was unremarkable, making this diagnosis less likely.

Mycobacterium leprae infections should be considered in a patient with a worsening rash and progressive polyneuropathy. Clinical diagnosis can be challenging due to similarities with other diseases; however, histopathologic findings can help differentiate M leprae from other conditions. This infection is treatable, and early detection can minimize long-term patient morbidity.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Borderline-Borderline Leprosy With Type 1 Lepra Reaction

Punch biopsies from plaques on the right elbow and right shin revealed diffuse granulomatous dermatitis (Figure 1) with a narrow Grenz zone in the superficial dermis. The upper dermis contained a dense bandlike infiltrate of histiocytes with abundant foamy-gray cytoplasm and a moderate admixture of lymphocytes. The mid and deep dermis contained a nodular, perivascular, periadnexal, and perineural infiltrate of histiocytes and a dense admixture of lymphocytes. Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains were negative for microorganisms. Fite stain was positive for numerous organisms in histiocytes and small dermal nerves (Figure 2). These findings and the clinical examination confirmed a diagnosis of borderline-borderline leprosy with type 1 lepra reaction. The patient was started on dapsone 100 mg, rifampin 600 mg, and clofazimine 100 mg once daily and experienced clinical improvement within 6 months.

The World Health Organization reported more than 200,000 new leprosy cases globally in 2019, with most occurring in India, Brazil, and Indonesia.1 About 150 to 250 new cases are detected in the United States annually.1 The Ridley-Jopling classification of leprosy divides the condition into 5 categories: tuberculoid, borderline tuberculoid, borderline-borderline (BB), borderline lepromatous, and lepromatous. At one end of the spectrum, tuberculoid leprosy—a predominant Th1 immune response mediated by CD4 lymphocytes, interleukin (IL) 2, and interferon gamma2—is characterized by sharply demarcated erythematous and hypopigmented plaques with raised borders and an annular appearance.2,3 Lesions typically have atrophic and hypopigmented centers that often appear in an asymmetric distribution on the arms and legs.2,3 Histologic features include dermal tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells—some located directly beneath the epidermis and others around deep vessels and nerves3—multinucleated Langerhans giant cells, thickened peripheral nerves with intraneural lymphocytic infiltrates, and granulomas with central necrosis. Fite-Faraco staining exhibits few bacteria.2

Lepromatous leprosy occurs in individuals with impaired T-cell immunity, leading to multiple red-brown nodular infiltrates in the skin and mucous membranes.2,3 Lesions typically are symmetric and favor the face and auricle of the ear.2,3 Histologically, there are bluish-gray foamy macrophages that form diffuse or nodular infiltrates with few lymphocytes,2 with a Grenz zone between the epidermis and dermis. Nerves may show lamination of the perineurium resembling an onion skin.2,3 Immunohistochemistry shows predominant CD8-positive infiltrates with a Th2 response and positive IL-4 and IL-10. Fite-Faraco stain shows numerous mycobacteria arranged in clusters and in histiocytes.2

Tuberculoid leprosy is treated with dapsone 100 mg and rifampin 600 mg once daily for 6 months,4 and lepromatous leprosy is treated with dapsone 100 mg, rifampin 600 mg, and clofazimine 50 mg once daily for 12 months.4 The prognosis for both is good with treatment; erythema and induration of skin lesions may improve within a few months, but residual nerve damage is common, especially in those with advanced disease prior to treatment.2 For direct contacts, a single dose of rifampin may be given.4

Borderline-borderline leprosy manifests with numerous asymmetric annular plaques, as seen in our patient (Figure 3). Histology findings can be variable and often overlap with other forms of leprosy. There can be epithelioid granulomas and only a few acid-fast bacilli (AFB) or diffuse histiocytic aggregates with foamy histiocytes containing large numbers of AFB.3 Nerve involvement is variable but can be severe in the setting of type 1 lepra reaction, which was present in our patient. Type 1 lepra reaction—a type IV cell-mediated allergic hypersensitivity reaction to Mycobacterium leprae antigens—manifests clinically with hyperesthesia, erythema, edema, and subsequent scaling.2 It occurs in up to 30% of patients with borderline leprosy, usually within 12 months of treatment initiation.2 Our patient had considerable edema and erythema of the hands and feet (Figure 4) along with extensive polyneuropathy prior to starting therapy.

Lucio phenomenon is a rare leprosy reaction found in patients with untreated lepromatous leprosy characterized by erythematous to violaceous macules that lead to ulceronecrotic lesions.5 Histologically, there are many AFB in the vascular endothelium, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and ischemic epidermal necrosis.5 Our patient did not have ulcerative or necrotic lesions.

The classic skin lesions of psoriasis vulgaris can be described as well-demarcated pink plaques with white or silvery scales that usually are distributed symmetrically and often are found on extensor surfaces.6 Rapidly progressive lesions can be annular with normal skin in the center, mimicking the lesions seen in tuberculoid leprosy. Clinically, both psoriasis and tuberculoid forms of leprosy are sharply demarcated; however, psoriatic lesions often have micaceous overlying scale that is not present in leprosy. Characteristic histologic findings of psoriasis are hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis with dilated blood vessels and a lymphocytic infiltrate, predominantly into the dermis.7 Psoriatic arthritis has a variable clinical course but tends to emerge 5 to 12 years after initial skin manifestation.8 Classic clinical symptoms include swelling, tenderness, stiffness, and pain in joints and surrounding tissues.8 Other than edema, our patient did not exhibit signs of psoriatic arthritis.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by noncaseating epithelioid granulomas affecting various organs, with cutaneous manifestations present in approximately 30% of all cases. Cutaneous manifestations can be variable, including maculopapular lesions, plaques, and nodules.9 Differentiating between cutaneous sarcoidosis and tuberculoid leprosy can be challenging, as both are granulomatous processes; however, histology of sarcoidosis demonstrates noncaseating granulomas in the dermis and/or subcutaneous tissues without AFB9 compared to granulomas with necrotic centers in tuberculoid leprosy.

Cutaneous tuberculosis has variable morphologies. One subtype, lupus vulgaris, can manifest with violaceous, scaly, eroded plaques that could be confused for leprosy. Lupus vulgaris usually results from hematogenous or lymphatic seeding in individuals with high or moderate immunity to M tuberculosis.10

Histologically, the dermis has tuberculoid granulomas containing multinucleated giant cells,10 which can mimic those seen in BB leprosy. Tuberculin skin test results often are positive10; while this test was not performed in our patient, chest radiography was unremarkable, making this diagnosis less likely.

Mycobacterium leprae infections should be considered in a patient with a worsening rash and progressive polyneuropathy. Clinical diagnosis can be challenging due to similarities with other diseases; however, histopathologic findings can help differentiate M leprae from other conditions. This infection is treatable, and early detection can minimize long-term patient morbidity.

- CDC. Hansen’s disease (leprosy). Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/leprosy/about/index.html

- Fischer M. Leprosy—an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:801-827.

- Maymone MBC, Laughter M, Venkatesh S, et al. Leprosy: clinical aspects and diagnostic techniques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020; 83:1-14.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of leprosy. October 6, 2018. Accessed April 2, 2025. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789290226383

- Frade MAC, Coltro PS, Filho FB, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: a systematic literature review of definition, clinical features, histopathogenesis and management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2022;88:464-477.

- Kimmel GW, Lebwohl M. Psoriasis: overview and diagnosis. In: Evidence-Based Psoriasis. Springer International Publishing; 2018:1-16.

- Griffiths CE, Barker JN. Pathogenesis and clinical features of psoriasis. Lancet. 2007;370:263-271.

- Menter A. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis overview. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(8 suppl):S216-S224.

- Wu JH, Imadojemu S, Caplan AS. The evolving landscape of cutaneous sarcoidosis: pathogenic insight, clinical challenges, and new frontiers in therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:499-514.

- Hill MK, Sanders CV. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5:1-6.

- CDC. Hansen’s disease (leprosy). Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/leprosy/about/index.html

- Fischer M. Leprosy—an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:801-827.

- Maymone MBC, Laughter M, Venkatesh S, et al. Leprosy: clinical aspects and diagnostic techniques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020; 83:1-14.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of leprosy. October 6, 2018. Accessed April 2, 2025. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789290226383

- Frade MAC, Coltro PS, Filho FB, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: a systematic literature review of definition, clinical features, histopathogenesis and management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2022;88:464-477.

- Kimmel GW, Lebwohl M. Psoriasis: overview and diagnosis. In: Evidence-Based Psoriasis. Springer International Publishing; 2018:1-16.

- Griffiths CE, Barker JN. Pathogenesis and clinical features of psoriasis. Lancet. 2007;370:263-271.

- Menter A. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis overview. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(8 suppl):S216-S224.

- Wu JH, Imadojemu S, Caplan AS. The evolving landscape of cutaneous sarcoidosis: pathogenic insight, clinical challenges, and new frontiers in therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:499-514.

- Hill MK, Sanders CV. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5:1-6.

Acral Erythema, Edema, and Scaly Plaques in a Patient With Polyneuropathy

Acral Erythema, Edema, and Scaly Plaques in a Patient With Polyneuropathy

A 67-year-old man presented to his primary care physician with scaly plaques on the extensor surfaces along with distal neuropathy that had been slowly worsening over the past 6 months. The patient was prescribed triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily for presumed atopic dermatitis. Three months later, his symptoms rapidly worsened and he developed edema of the hands and feet. He was seen by neurology, and electromyography revealed severe distal sensorimotor neuropathy, prompting hospital admission for further evaluation of a potential rapidly progressive autoimmune disease. Laboratory workup and imaging were ordered, and the patient began an intravenous course of methylprednisolone. Minimal improvement in his symptoms was noted after 1 day, at which time dermatology was consulted.

Physical examination by dermatology revealed well-defined plaques with annular scale on extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, and edema on the hands and feet as well as distal sensorimotor neuropathy. The patient reported associated unspecified weight loss but denied any chest pain, shortness of breath, fevers, chills, cough, night sweats, exposure to chemicals, or recent travel. He reported that he had immigrated from India 37 years prior; his last visit to India was 6 years ago. He currently was taking famotidine for gastrointestinal reflux disease and losartan for hypertension. There was no personal or family history of autoimmune diseases. A complete workup for hematologic, thyroid, liver, and renal function was unremarkable. Initial autoimmune workup was negative for antinuclear antibodies and rheumatoid factor. Serum protein electrophoresis was normal. Results of testing for HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C were negative. Chest radiography was unremarkable. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level were elevated.

Clinical Pearl: Topical Timolol for Refractory Hypergranulation

Practice Gap

Hypergranulation is a frequent complication of dermatologic surgery, especially when surgical defects are left to heal by secondary intention (eg, after electrodesiccation and curettage). Although management of postoperative hypergranulation with routine wound care, superpotent topical corticosteroids, and/or topical silver nitrate often is effective, refractory cases pose a difficult challenge given the paucity of treatment options. Effective management of these cases is important because hypergranulation can delay wound healing, cause patient discomfort, and lead to poor wound cosmesis.

The Technique

If refractory hypergranulation fails to respond to treatment with routine wound care and topical silver nitrate, we prescribe twice-daily application of timolol maleate ophthalmic gel forming solution 0.5% for up to 14 days or until complete resolution of the hypergranulation is achieved. We counsel patients to continue routine wound care with daily dressing changes in conjunction with topical timolol application.

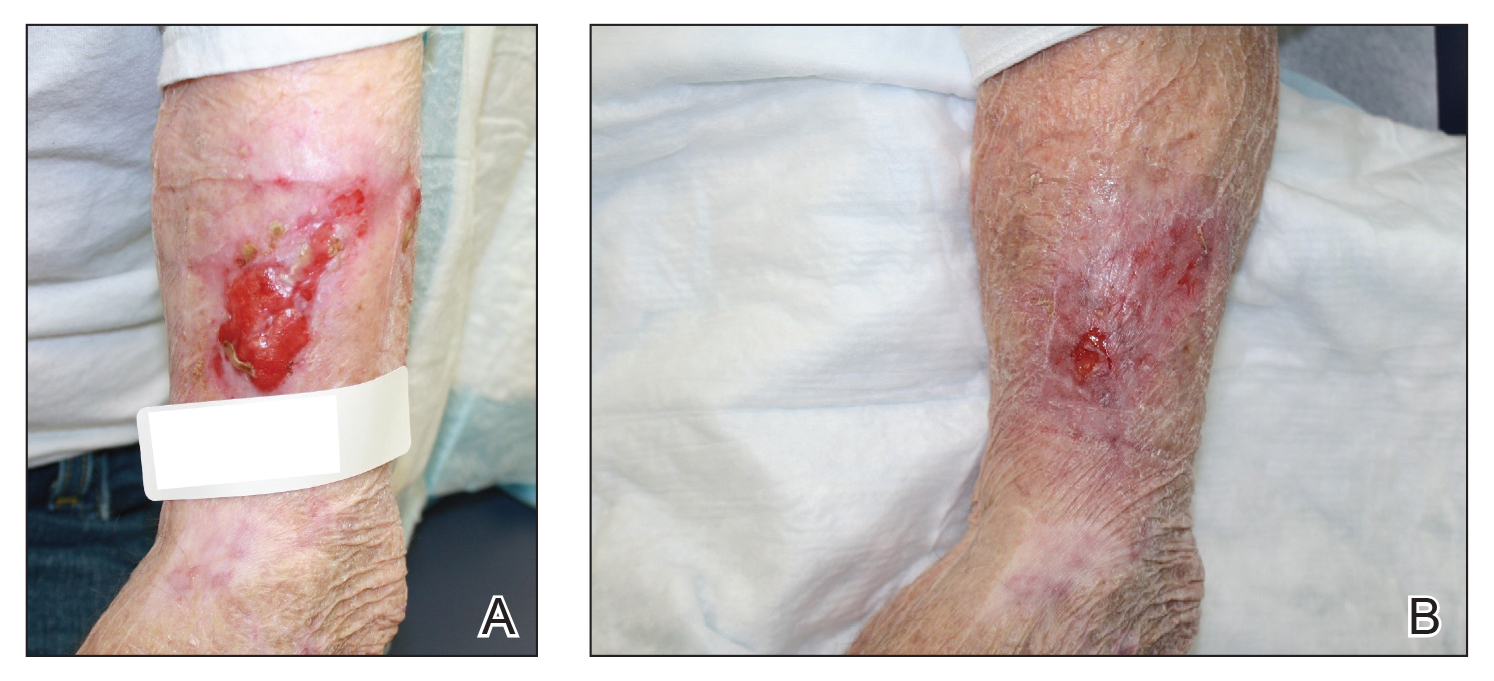

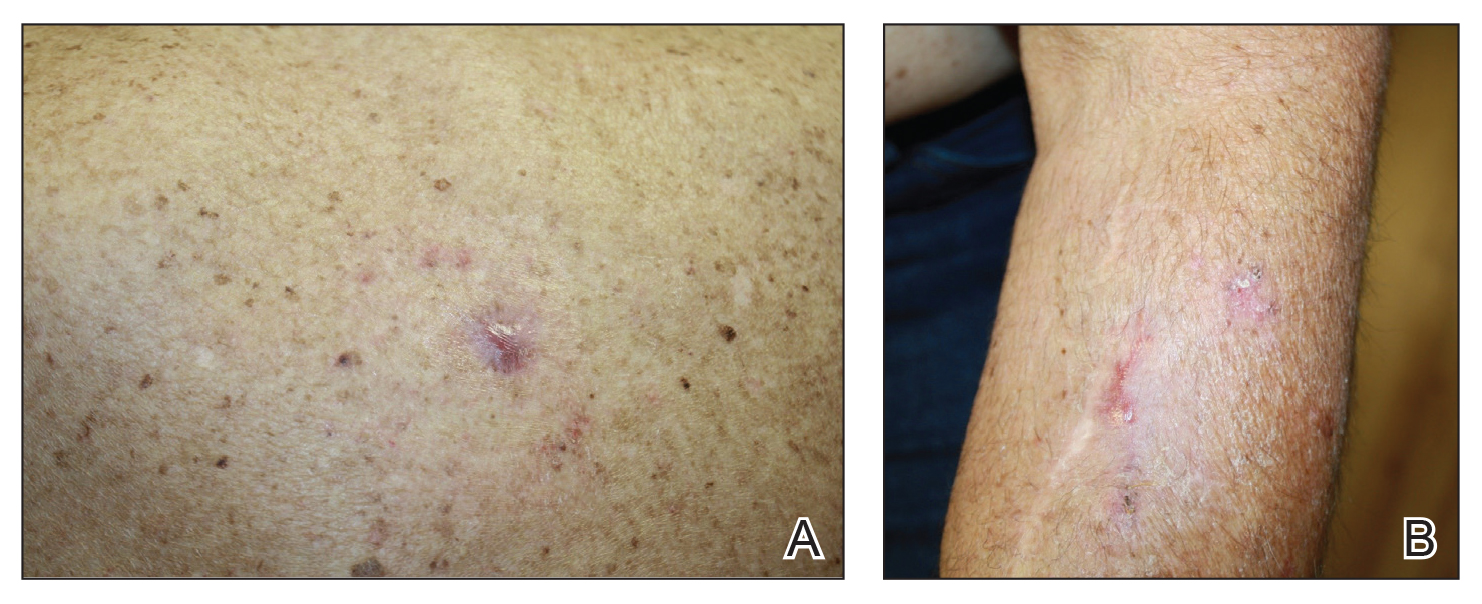

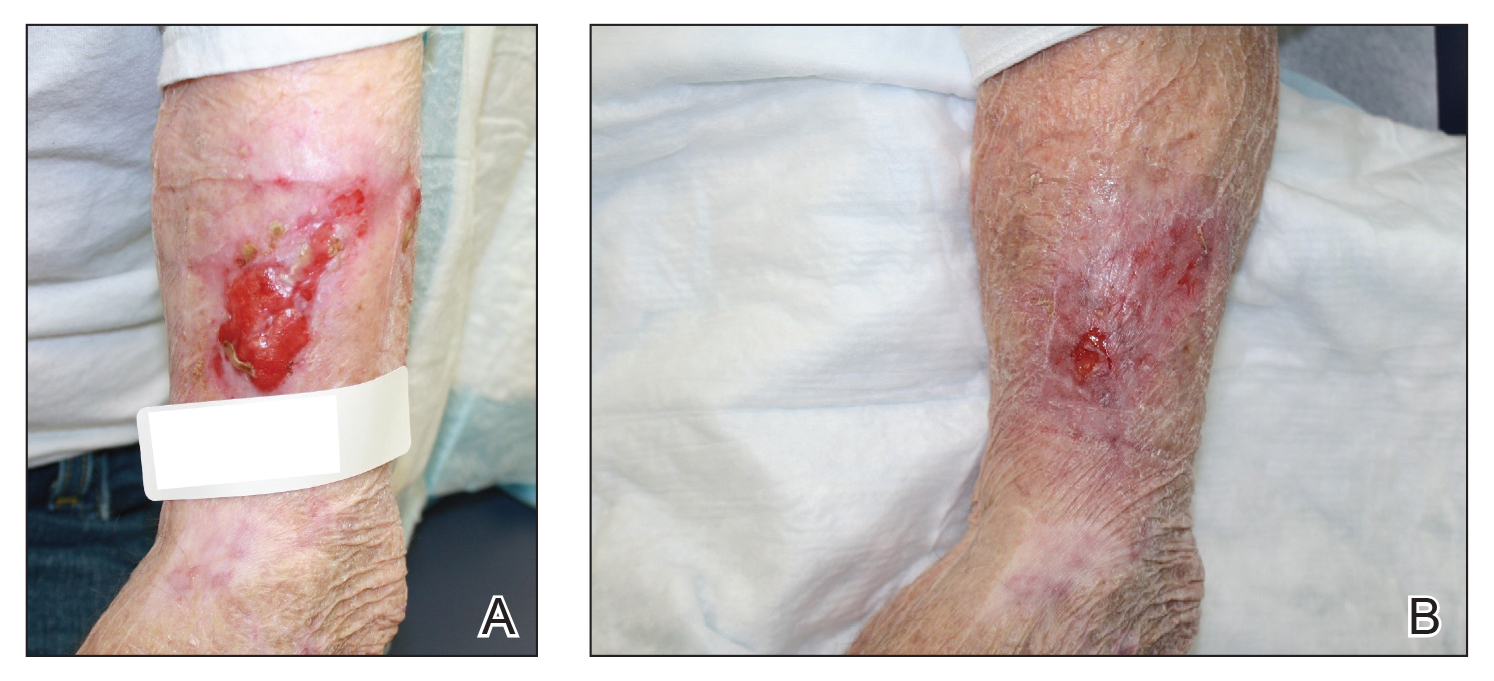

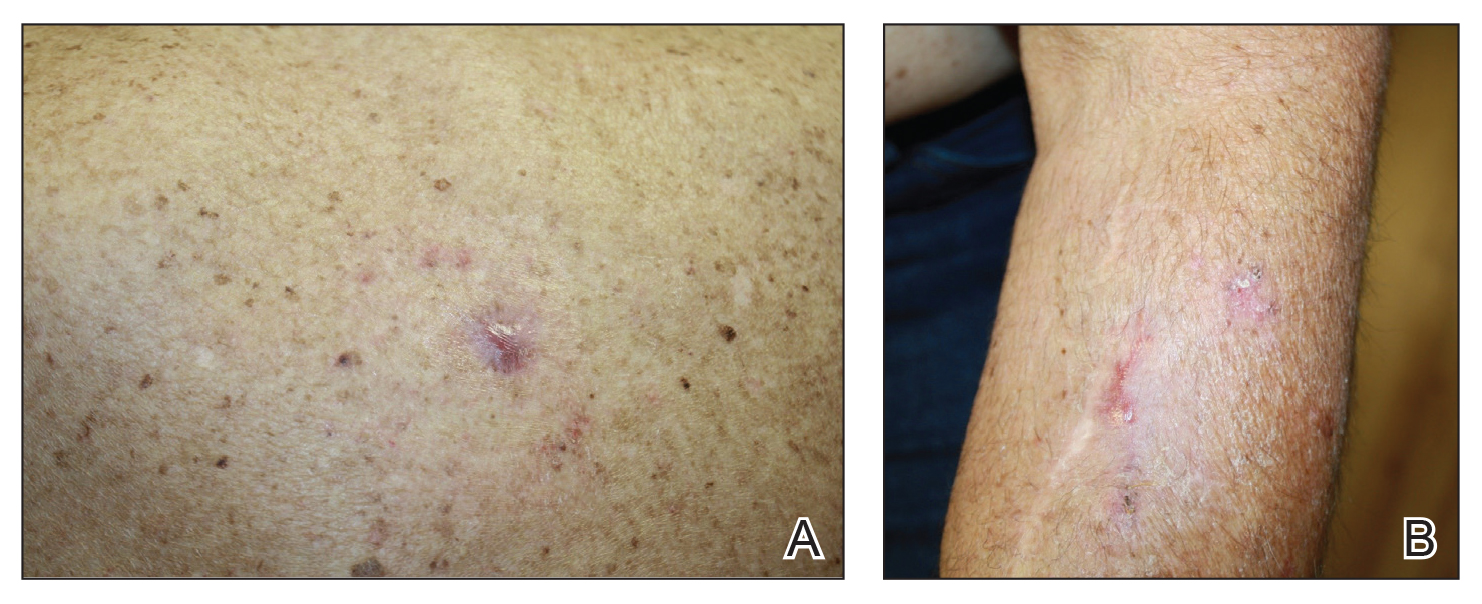

We initiated treatment with topical timolol in a patient who developed hypergranulation at 2 separate electrodesiccation and curettage sites that was refractory to 6 weeks of routine wound care with white petrolatum under nonadherent sterile gauze dressings and 2 subsequent topical silver nitrate applications (Figure 1). After 2 weeks of treatment with topical timolol, resolution of the hypergranulation and re-epithelialization of the surgical sites was observed (Figure 2). Another patient presented with hypergranulation that developed following a traumatic injury on the left upper arm and had been treated unsuccessfully for several months at a wound care clinic with daily nonadherent sterile gauze dressings and both topical and oral antibiotics (Figure 3A). After treatment for 9 days with topical timolol, resolution of the hypergranulation and re-epithelialization of the surgical sites was observed (Figure 3B).

Practice Implications

Beta-blockers are increasingly being used for management of chronic nonhealing wounds since the 1990s when oral administration of propranolol initially was reported to be an effective adjuvant therapy for managing severe burns.1 Since then, topical beta-blockers have been reported to be effective for management of ulcerated hemangiomas, venous stasis ulcers, chronic diabetic ulcers, and chronic nonhealing surgical wounds; however, there are no known reports of using topical beta-blockers for management of hypergranulation.2-5 We found timolol ophthalmic gel to be an excellent second-line therapy for management of postoperative hypergranulation if prior treatment with routine wound care and superpotent topical corticosteroids has failed. To date, we have found no reported adverse effects from the use of topical timolol for this indication that have required discontinuation of the medication. Use of this simple and safe intervention can be effective as a solution to a common postoperative condition.

- Herndon DN, Hart DW, Wolf SE, et al. Reversal of catabolism by beta-blockade after severe burns. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1223-1229.

- Pope E, Chakkittakandiyil A. Topical timolol gel for infantile hemangiomas: a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:564-565.

- Braun L, Lamel S, Richmond N, et al. Topical timolol for recalcitrant wounds. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1400-1402.

- Thomas B, Kurien J, Jose T, et al. Topical timolol promotes healing of chronic leg ulcer. J Vasc Surg. 2017;5:844-850.

- Tang J, Dosal J, Kirsner RS. Topical timolol for a refractory wound. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:135-138.

Practice Gap

Hypergranulation is a frequent complication of dermatologic surgery, especially when surgical defects are left to heal by secondary intention (eg, after electrodesiccation and curettage). Although management of postoperative hypergranulation with routine wound care, superpotent topical corticosteroids, and/or topical silver nitrate often is effective, refractory cases pose a difficult challenge given the paucity of treatment options. Effective management of these cases is important because hypergranulation can delay wound healing, cause patient discomfort, and lead to poor wound cosmesis.

The Technique

If refractory hypergranulation fails to respond to treatment with routine wound care and topical silver nitrate, we prescribe twice-daily application of timolol maleate ophthalmic gel forming solution 0.5% for up to 14 days or until complete resolution of the hypergranulation is achieved. We counsel patients to continue routine wound care with daily dressing changes in conjunction with topical timolol application.

We initiated treatment with topical timolol in a patient who developed hypergranulation at 2 separate electrodesiccation and curettage sites that was refractory to 6 weeks of routine wound care with white petrolatum under nonadherent sterile gauze dressings and 2 subsequent topical silver nitrate applications (Figure 1). After 2 weeks of treatment with topical timolol, resolution of the hypergranulation and re-epithelialization of the surgical sites was observed (Figure 2). Another patient presented with hypergranulation that developed following a traumatic injury on the left upper arm and had been treated unsuccessfully for several months at a wound care clinic with daily nonadherent sterile gauze dressings and both topical and oral antibiotics (Figure 3A). After treatment for 9 days with topical timolol, resolution of the hypergranulation and re-epithelialization of the surgical sites was observed (Figure 3B).

Practice Implications

Beta-blockers are increasingly being used for management of chronic nonhealing wounds since the 1990s when oral administration of propranolol initially was reported to be an effective adjuvant therapy for managing severe burns.1 Since then, topical beta-blockers have been reported to be effective for management of ulcerated hemangiomas, venous stasis ulcers, chronic diabetic ulcers, and chronic nonhealing surgical wounds; however, there are no known reports of using topical beta-blockers for management of hypergranulation.2-5 We found timolol ophthalmic gel to be an excellent second-line therapy for management of postoperative hypergranulation if prior treatment with routine wound care and superpotent topical corticosteroids has failed. To date, we have found no reported adverse effects from the use of topical timolol for this indication that have required discontinuation of the medication. Use of this simple and safe intervention can be effective as a solution to a common postoperative condition.

Practice Gap

Hypergranulation is a frequent complication of dermatologic surgery, especially when surgical defects are left to heal by secondary intention (eg, after electrodesiccation and curettage). Although management of postoperative hypergranulation with routine wound care, superpotent topical corticosteroids, and/or topical silver nitrate often is effective, refractory cases pose a difficult challenge given the paucity of treatment options. Effective management of these cases is important because hypergranulation can delay wound healing, cause patient discomfort, and lead to poor wound cosmesis.

The Technique

If refractory hypergranulation fails to respond to treatment with routine wound care and topical silver nitrate, we prescribe twice-daily application of timolol maleate ophthalmic gel forming solution 0.5% for up to 14 days or until complete resolution of the hypergranulation is achieved. We counsel patients to continue routine wound care with daily dressing changes in conjunction with topical timolol application.

We initiated treatment with topical timolol in a patient who developed hypergranulation at 2 separate electrodesiccation and curettage sites that was refractory to 6 weeks of routine wound care with white petrolatum under nonadherent sterile gauze dressings and 2 subsequent topical silver nitrate applications (Figure 1). After 2 weeks of treatment with topical timolol, resolution of the hypergranulation and re-epithelialization of the surgical sites was observed (Figure 2). Another patient presented with hypergranulation that developed following a traumatic injury on the left upper arm and had been treated unsuccessfully for several months at a wound care clinic with daily nonadherent sterile gauze dressings and both topical and oral antibiotics (Figure 3A). After treatment for 9 days with topical timolol, resolution of the hypergranulation and re-epithelialization of the surgical sites was observed (Figure 3B).

Practice Implications

Beta-blockers are increasingly being used for management of chronic nonhealing wounds since the 1990s when oral administration of propranolol initially was reported to be an effective adjuvant therapy for managing severe burns.1 Since then, topical beta-blockers have been reported to be effective for management of ulcerated hemangiomas, venous stasis ulcers, chronic diabetic ulcers, and chronic nonhealing surgical wounds; however, there are no known reports of using topical beta-blockers for management of hypergranulation.2-5 We found timolol ophthalmic gel to be an excellent second-line therapy for management of postoperative hypergranulation if prior treatment with routine wound care and superpotent topical corticosteroids has failed. To date, we have found no reported adverse effects from the use of topical timolol for this indication that have required discontinuation of the medication. Use of this simple and safe intervention can be effective as a solution to a common postoperative condition.

- Herndon DN, Hart DW, Wolf SE, et al. Reversal of catabolism by beta-blockade after severe burns. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1223-1229.

- Pope E, Chakkittakandiyil A. Topical timolol gel for infantile hemangiomas: a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:564-565.

- Braun L, Lamel S, Richmond N, et al. Topical timolol for recalcitrant wounds. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1400-1402.

- Thomas B, Kurien J, Jose T, et al. Topical timolol promotes healing of chronic leg ulcer. J Vasc Surg. 2017;5:844-850.

- Tang J, Dosal J, Kirsner RS. Topical timolol for a refractory wound. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:135-138.

- Herndon DN, Hart DW, Wolf SE, et al. Reversal of catabolism by beta-blockade after severe burns. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1223-1229.

- Pope E, Chakkittakandiyil A. Topical timolol gel for infantile hemangiomas: a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:564-565.

- Braun L, Lamel S, Richmond N, et al. Topical timolol for recalcitrant wounds. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1400-1402.

- Thomas B, Kurien J, Jose T, et al. Topical timolol promotes healing of chronic leg ulcer. J Vasc Surg. 2017;5:844-850.

- Tang J, Dosal J, Kirsner RS. Topical timolol for a refractory wound. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:135-138.

Solitary Nodule on the Proximal Nail Fold

The Diagnosis: Superficial Acral Fibromyxoma

A shave biopsy revealed an uninvolved grenz zone and mildly cellular spindle cell dermal proliferation in a collagenous and myxoid background (Figure 1). Spindle cells were seen in a myxoid background among dense coarse collagen (Figure 2A). Spindle cells also were seen in a myxoid background with mast cells and capillary network (Figure 2B). Histopathologic examination of the biopsy specimen revealed spindle cells that were diffusely positive for CD34 (Figure 3); focally positive for epithelial membrane antigen; and negative for melanocytic markers, smooth muscle markers, and cytokeratin. A diagnosis of superficial acral fibromyxoma (SAFM) was made based on clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical findings.

Superficial acral fibromyxomas, also known as digital fibromyxomas, are soft, slow-growing tumors that have a predilection for subungual or periungual regions of the hands and feet. Superficial acral fibromyxomas most frequently occur on the hallux and rarely occur on the ankle or leg. They can present as nodular, dome-shaped, polyploid, or verrucous masses. They can be soft to firm, gelatinous or solid, off-white to gray-white and can have fasciculate cut surfaces. Superficial acral fibromyxomas can be either painful or painless and present with a deformed nail in 9% of cases. Superficial acral fibromyxoma is a superficial lesion with frequent infiltration of the dermal collagen and subcutaneous tissue and may even erode or infiltrate into the underlying bone in rare cases.1-4 Although SAFMs are rare tumors, documented cases of SAFM have been reported at an increasing rate since the first published report by Fetsch et al2 in 2001.

Patients often delay seeking medical treatment and present with a solitary mass that has been slowly growing for months to years. In a study of 124 patients, Hollmann et al1 found that symptoms exist for a mean of 35 months and present with a small mass with a mean tumor size of 1.7 cm before biopsy or excision. Although the age range is broad, SAFM mostly affects middle-aged adults (median age, 49 years).1 Hollmann et al1 also reported a male predominance (1.3:1 ratio), and preexisting local trauma is reported in 25% of cases.2-4

The differential for SAFM should include dermatofibroma, keloid, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, acquired digital fibrokeratoma, infantile digital fibromatosis, neurolemmoma, sclerosing perineurioma, superficial angiomyxoma, low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, and acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma.1-4

Superficial acral fibromyxomas are composed of CD34+ spindle or stellate-shaped cells that are embedded in a myxoid and/or dense hyalinized collagenous stroma in a random or loosely fascicular growth pattern. The spindle or stellate-shaped cells in SAFMs also have been found to be focally positive for epithelial membrane antigen and CD99. Lesions have accentuated microvasculature and increased mast cells.5-8

Conservative management is reasonable, but patients presenting with persistent pain and/or local deformity should be definitively treated with complete excision and follow-up. Hollmann et al1 found that 24% of tumors recurred locally upon incomplete excision after a mean interval of 27 months. All recurrent tumors had positive margins at excision or initial biopsy.1 To date, no reports of tumors metastasizing have been documented.1-4

- Hollmann TJ, Bovée JV, Fletcher CD. Digital fibromyxoma (superficial acral fibromyxoma): a detailed characterization of 124 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:789-798.

- Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 37 cases of a distinctive soft tissue tumor with a predilection for the fingers and toes. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:704-714.

- Al-Daraji WI, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathological analysis of 32 tumors including 4 in the heel. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1020-1026.

- Ashby-Richardson H, Rogers GS, Stadecker MJ. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: an overview. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:1064-1066.

- Quaba O, Evans A, Al-Nafussi AA, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:561-564.

- Oteo-Alvaro A, Meizoso T, Scarpellini A, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the toe, with erosion of the distal phalanx: a clinical report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:271-274.

- Meyerle J, Keller RA, Krivda SJ. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the index finger. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:134-136.

- Kazakov DV, Mentzel T, Buro G, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: report of two cases. Dermatology. 2002;205:285-288.

The Diagnosis: Superficial Acral Fibromyxoma

A shave biopsy revealed an uninvolved grenz zone and mildly cellular spindle cell dermal proliferation in a collagenous and myxoid background (Figure 1). Spindle cells were seen in a myxoid background among dense coarse collagen (Figure 2A). Spindle cells also were seen in a myxoid background with mast cells and capillary network (Figure 2B). Histopathologic examination of the biopsy specimen revealed spindle cells that were diffusely positive for CD34 (Figure 3); focally positive for epithelial membrane antigen; and negative for melanocytic markers, smooth muscle markers, and cytokeratin. A diagnosis of superficial acral fibromyxoma (SAFM) was made based on clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical findings.

Superficial acral fibromyxomas, also known as digital fibromyxomas, are soft, slow-growing tumors that have a predilection for subungual or periungual regions of the hands and feet. Superficial acral fibromyxomas most frequently occur on the hallux and rarely occur on the ankle or leg. They can present as nodular, dome-shaped, polyploid, or verrucous masses. They can be soft to firm, gelatinous or solid, off-white to gray-white and can have fasciculate cut surfaces. Superficial acral fibromyxomas can be either painful or painless and present with a deformed nail in 9% of cases. Superficial acral fibromyxoma is a superficial lesion with frequent infiltration of the dermal collagen and subcutaneous tissue and may even erode or infiltrate into the underlying bone in rare cases.1-4 Although SAFMs are rare tumors, documented cases of SAFM have been reported at an increasing rate since the first published report by Fetsch et al2 in 2001.

Patients often delay seeking medical treatment and present with a solitary mass that has been slowly growing for months to years. In a study of 124 patients, Hollmann et al1 found that symptoms exist for a mean of 35 months and present with a small mass with a mean tumor size of 1.7 cm before biopsy or excision. Although the age range is broad, SAFM mostly affects middle-aged adults (median age, 49 years).1 Hollmann et al1 also reported a male predominance (1.3:1 ratio), and preexisting local trauma is reported in 25% of cases.2-4

The differential for SAFM should include dermatofibroma, keloid, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, acquired digital fibrokeratoma, infantile digital fibromatosis, neurolemmoma, sclerosing perineurioma, superficial angiomyxoma, low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, and acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma.1-4

Superficial acral fibromyxomas are composed of CD34+ spindle or stellate-shaped cells that are embedded in a myxoid and/or dense hyalinized collagenous stroma in a random or loosely fascicular growth pattern. The spindle or stellate-shaped cells in SAFMs also have been found to be focally positive for epithelial membrane antigen and CD99. Lesions have accentuated microvasculature and increased mast cells.5-8

Conservative management is reasonable, but patients presenting with persistent pain and/or local deformity should be definitively treated with complete excision and follow-up. Hollmann et al1 found that 24% of tumors recurred locally upon incomplete excision after a mean interval of 27 months. All recurrent tumors had positive margins at excision or initial biopsy.1 To date, no reports of tumors metastasizing have been documented.1-4

The Diagnosis: Superficial Acral Fibromyxoma

A shave biopsy revealed an uninvolved grenz zone and mildly cellular spindle cell dermal proliferation in a collagenous and myxoid background (Figure 1). Spindle cells were seen in a myxoid background among dense coarse collagen (Figure 2A). Spindle cells also were seen in a myxoid background with mast cells and capillary network (Figure 2B). Histopathologic examination of the biopsy specimen revealed spindle cells that were diffusely positive for CD34 (Figure 3); focally positive for epithelial membrane antigen; and negative for melanocytic markers, smooth muscle markers, and cytokeratin. A diagnosis of superficial acral fibromyxoma (SAFM) was made based on clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical findings.

Superficial acral fibromyxomas, also known as digital fibromyxomas, are soft, slow-growing tumors that have a predilection for subungual or periungual regions of the hands and feet. Superficial acral fibromyxomas most frequently occur on the hallux and rarely occur on the ankle or leg. They can present as nodular, dome-shaped, polyploid, or verrucous masses. They can be soft to firm, gelatinous or solid, off-white to gray-white and can have fasciculate cut surfaces. Superficial acral fibromyxomas can be either painful or painless and present with a deformed nail in 9% of cases. Superficial acral fibromyxoma is a superficial lesion with frequent infiltration of the dermal collagen and subcutaneous tissue and may even erode or infiltrate into the underlying bone in rare cases.1-4 Although SAFMs are rare tumors, documented cases of SAFM have been reported at an increasing rate since the first published report by Fetsch et al2 in 2001.

Patients often delay seeking medical treatment and present with a solitary mass that has been slowly growing for months to years. In a study of 124 patients, Hollmann et al1 found that symptoms exist for a mean of 35 months and present with a small mass with a mean tumor size of 1.7 cm before biopsy or excision. Although the age range is broad, SAFM mostly affects middle-aged adults (median age, 49 years).1 Hollmann et al1 also reported a male predominance (1.3:1 ratio), and preexisting local trauma is reported in 25% of cases.2-4

The differential for SAFM should include dermatofibroma, keloid, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, acquired digital fibrokeratoma, infantile digital fibromatosis, neurolemmoma, sclerosing perineurioma, superficial angiomyxoma, low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, and acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma.1-4

Superficial acral fibromyxomas are composed of CD34+ spindle or stellate-shaped cells that are embedded in a myxoid and/or dense hyalinized collagenous stroma in a random or loosely fascicular growth pattern. The spindle or stellate-shaped cells in SAFMs also have been found to be focally positive for epithelial membrane antigen and CD99. Lesions have accentuated microvasculature and increased mast cells.5-8

Conservative management is reasonable, but patients presenting with persistent pain and/or local deformity should be definitively treated with complete excision and follow-up. Hollmann et al1 found that 24% of tumors recurred locally upon incomplete excision after a mean interval of 27 months. All recurrent tumors had positive margins at excision or initial biopsy.1 To date, no reports of tumors metastasizing have been documented.1-4

- Hollmann TJ, Bovée JV, Fletcher CD. Digital fibromyxoma (superficial acral fibromyxoma): a detailed characterization of 124 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:789-798.

- Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 37 cases of a distinctive soft tissue tumor with a predilection for the fingers and toes. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:704-714.

- Al-Daraji WI, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathological analysis of 32 tumors including 4 in the heel. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1020-1026.

- Ashby-Richardson H, Rogers GS, Stadecker MJ. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: an overview. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:1064-1066.

- Quaba O, Evans A, Al-Nafussi AA, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:561-564.

- Oteo-Alvaro A, Meizoso T, Scarpellini A, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the toe, with erosion of the distal phalanx: a clinical report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:271-274.

- Meyerle J, Keller RA, Krivda SJ. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the index finger. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:134-136.

- Kazakov DV, Mentzel T, Buro G, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: report of two cases. Dermatology. 2002;205:285-288.

- Hollmann TJ, Bovée JV, Fletcher CD. Digital fibromyxoma (superficial acral fibromyxoma): a detailed characterization of 124 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:789-798.

- Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 37 cases of a distinctive soft tissue tumor with a predilection for the fingers and toes. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:704-714.

- Al-Daraji WI, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathological analysis of 32 tumors including 4 in the heel. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1020-1026.

- Ashby-Richardson H, Rogers GS, Stadecker MJ. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: an overview. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:1064-1066.

- Quaba O, Evans A, Al-Nafussi AA, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:561-564.

- Oteo-Alvaro A, Meizoso T, Scarpellini A, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the toe, with erosion of the distal phalanx: a clinical report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:271-274.

- Meyerle J, Keller RA, Krivda SJ. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the index finger. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:134-136.

- Kazakov DV, Mentzel T, Buro G, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: report of two cases. Dermatology. 2002;205:285-288.

A 62-year-old man presented for evaluation of a slowly growing, nonpainful nodule on the first proximal toenail fold of the right foot of 6 years' duration. He reported that the nail plate of the affected toe was thickened and malaligned. He denied a history of trauma. Physical examination revealed a 2.0×1.6-cm, flesh-colored, nontender, well-defined, rubbery nodule with prominent overlying tortuous telangiectases on the medial aspect of the first proximal toenail fold of the right foot. The associated nail plate was yellow, thickened, and angled laterally into the second toe. Radiograph of the right hallux identified a soft tissue density contiguous with the dorsal aspect of the distal portion of the phalanx. There was no evidence of bony involvement. A shave saucerization biopsy specimen was obtained and sent for hematoxylin and eosin and immunohistochemical staining. The spindle cells were diffusely positive for CD34.

Clinical Pearl: A Simple and Effective Technique for Improving Surgical Closures for the Early-Learning Resident

Practice Gap

For first-year dermatology residents, dermatologic surgeries can present many challenges. Although approximation of wound edges following excision may be intuitive for the experienced surgeon, an early trainee may need some guidance. Infusion of anesthetics can distort the normal skin field or it may be difficult for the patient to remain in the same position for the required period of time; for example, an elderly patient who requires an excision on the posterior aspect of the neck may be unable to assume the same position for the full duration of the procedure. We offer a simple and effective technique for early-learning dermatology residents to improve surgical closures.

The Technique

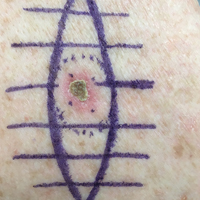

We propose drawing straight lines using a sterile marking pen perpendicular to the fusiform plane laid out for any simple, intermediate, or complex linear closure (Figure 1). These lines can then be used as scaffolding for the surgical closure (Figure 2). We recommend drawing the lines at the time of initial planning when the site of excision is in the normal anatomic position.

Practice Implications

By creating a sketch with perpendicular lines, approximation of skin edges and surgical closures may become easier for the learning resident. Patients also can rest more comfortably during the procedure, and the overall cosmesis, healing, and outcome of the procedure may improve. The addition of a sterile marking pen to the surgical tray may aide in highlighting faded pen markings for easier visualization after cleansing of the surgical site.

Practice Gap

For first-year dermatology residents, dermatologic surgeries can present many challenges. Although approximation of wound edges following excision may be intuitive for the experienced surgeon, an early trainee may need some guidance. Infusion of anesthetics can distort the normal skin field or it may be difficult for the patient to remain in the same position for the required period of time; for example, an elderly patient who requires an excision on the posterior aspect of the neck may be unable to assume the same position for the full duration of the procedure. We offer a simple and effective technique for early-learning dermatology residents to improve surgical closures.

The Technique

We propose drawing straight lines using a sterile marking pen perpendicular to the fusiform plane laid out for any simple, intermediate, or complex linear closure (Figure 1). These lines can then be used as scaffolding for the surgical closure (Figure 2). We recommend drawing the lines at the time of initial planning when the site of excision is in the normal anatomic position.

Practice Implications

By creating a sketch with perpendicular lines, approximation of skin edges and surgical closures may become easier for the learning resident. Patients also can rest more comfortably during the procedure, and the overall cosmesis, healing, and outcome of the procedure may improve. The addition of a sterile marking pen to the surgical tray may aide in highlighting faded pen markings for easier visualization after cleansing of the surgical site.

Practice Gap

For first-year dermatology residents, dermatologic surgeries can present many challenges. Although approximation of wound edges following excision may be intuitive for the experienced surgeon, an early trainee may need some guidance. Infusion of anesthetics can distort the normal skin field or it may be difficult for the patient to remain in the same position for the required period of time; for example, an elderly patient who requires an excision on the posterior aspect of the neck may be unable to assume the same position for the full duration of the procedure. We offer a simple and effective technique for early-learning dermatology residents to improve surgical closures.

The Technique

We propose drawing straight lines using a sterile marking pen perpendicular to the fusiform plane laid out for any simple, intermediate, or complex linear closure (Figure 1). These lines can then be used as scaffolding for the surgical closure (Figure 2). We recommend drawing the lines at the time of initial planning when the site of excision is in the normal anatomic position.

Practice Implications

By creating a sketch with perpendicular lines, approximation of skin edges and surgical closures may become easier for the learning resident. Patients also can rest more comfortably during the procedure, and the overall cosmesis, healing, and outcome of the procedure may improve. The addition of a sterile marking pen to the surgical tray may aide in highlighting faded pen markings for easier visualization after cleansing of the surgical site.