User login

Vascular Nodule on the Upper Chest

Vascular Nodule on the Upper Chest

THE DIAGNOSIS: Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma

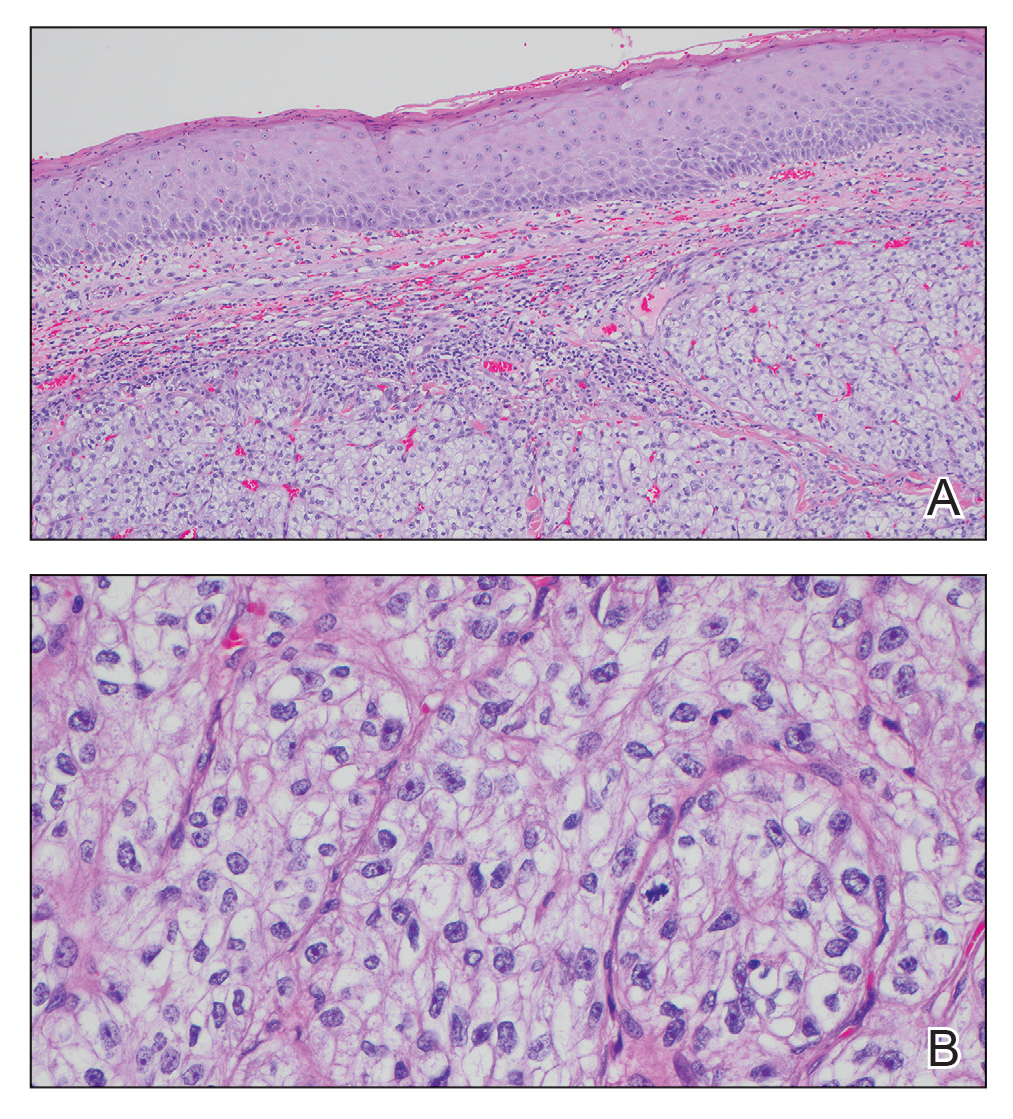

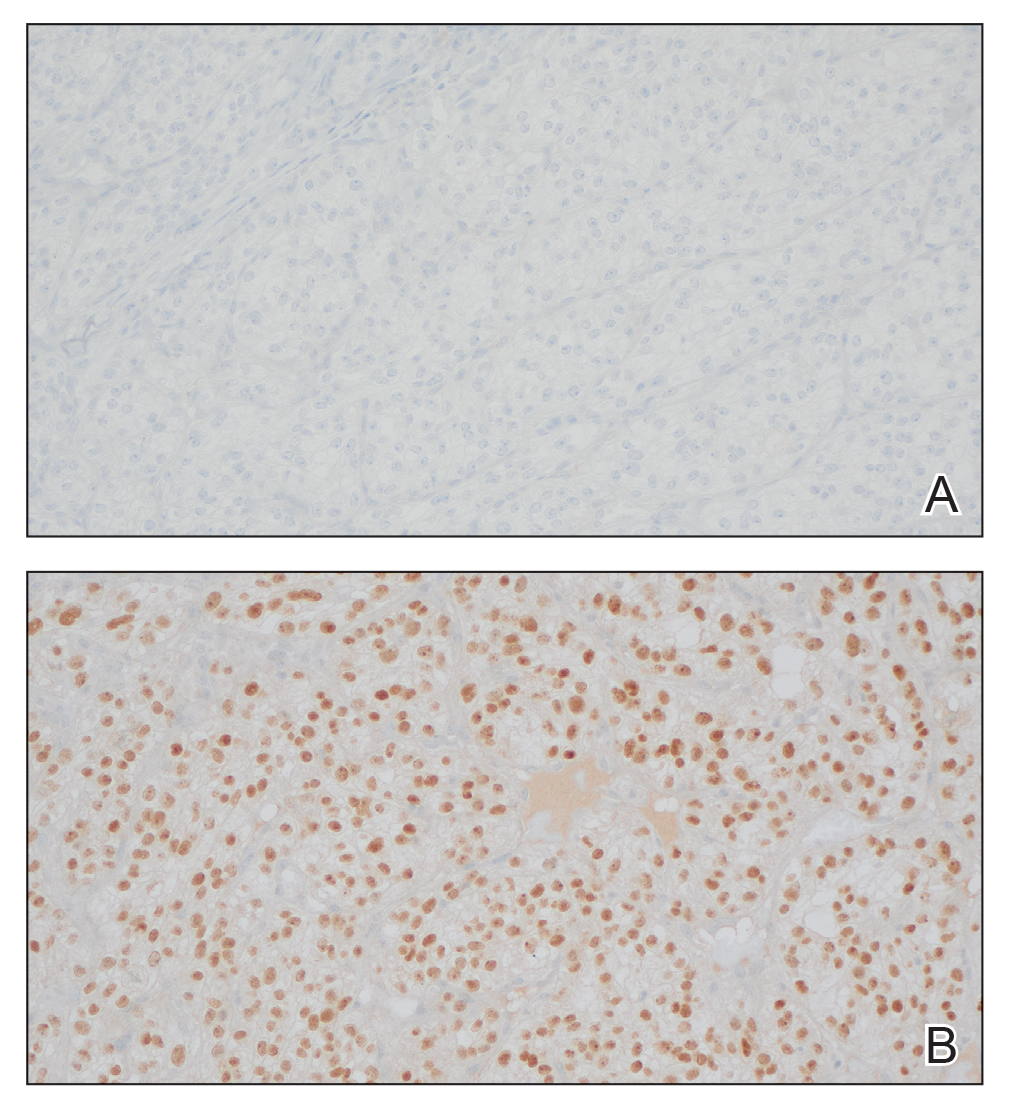

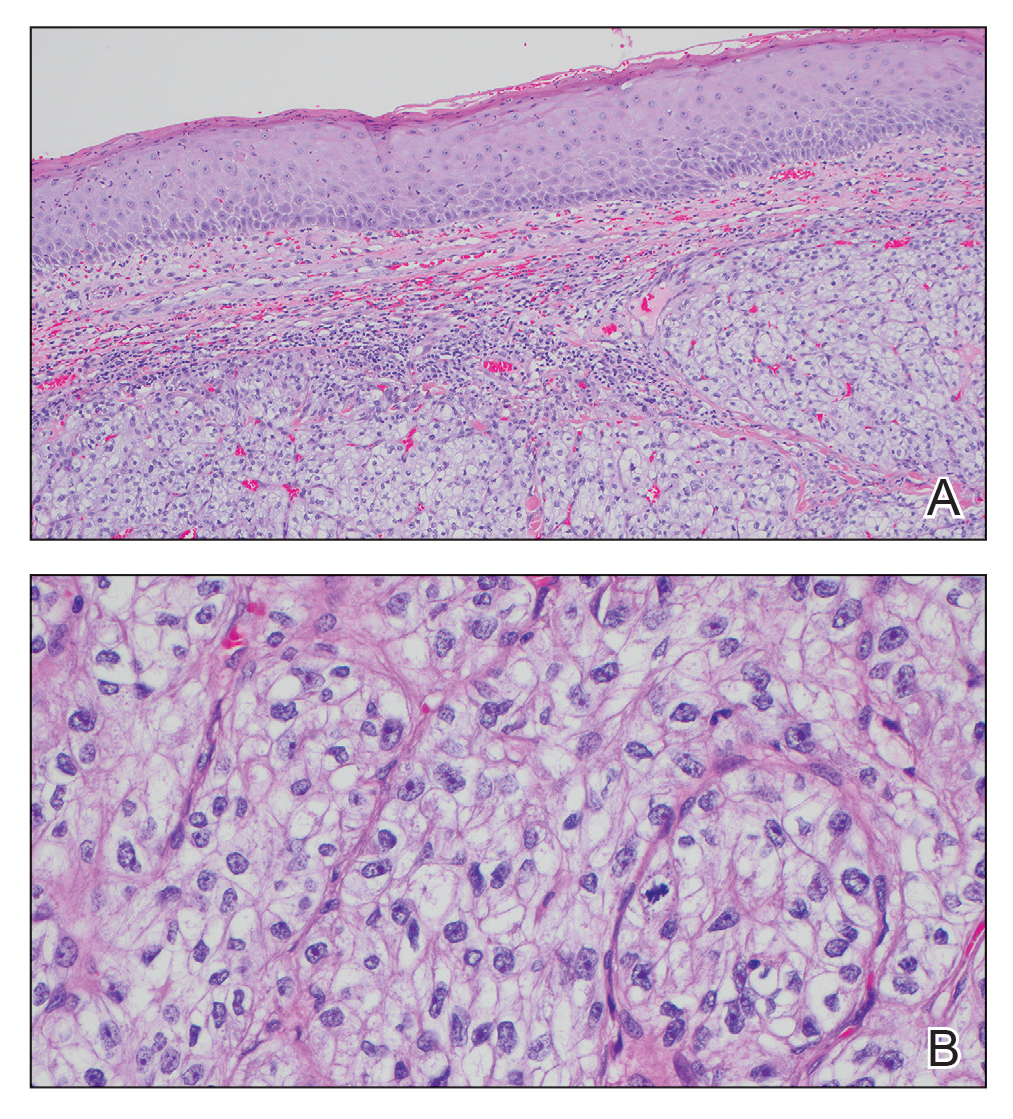

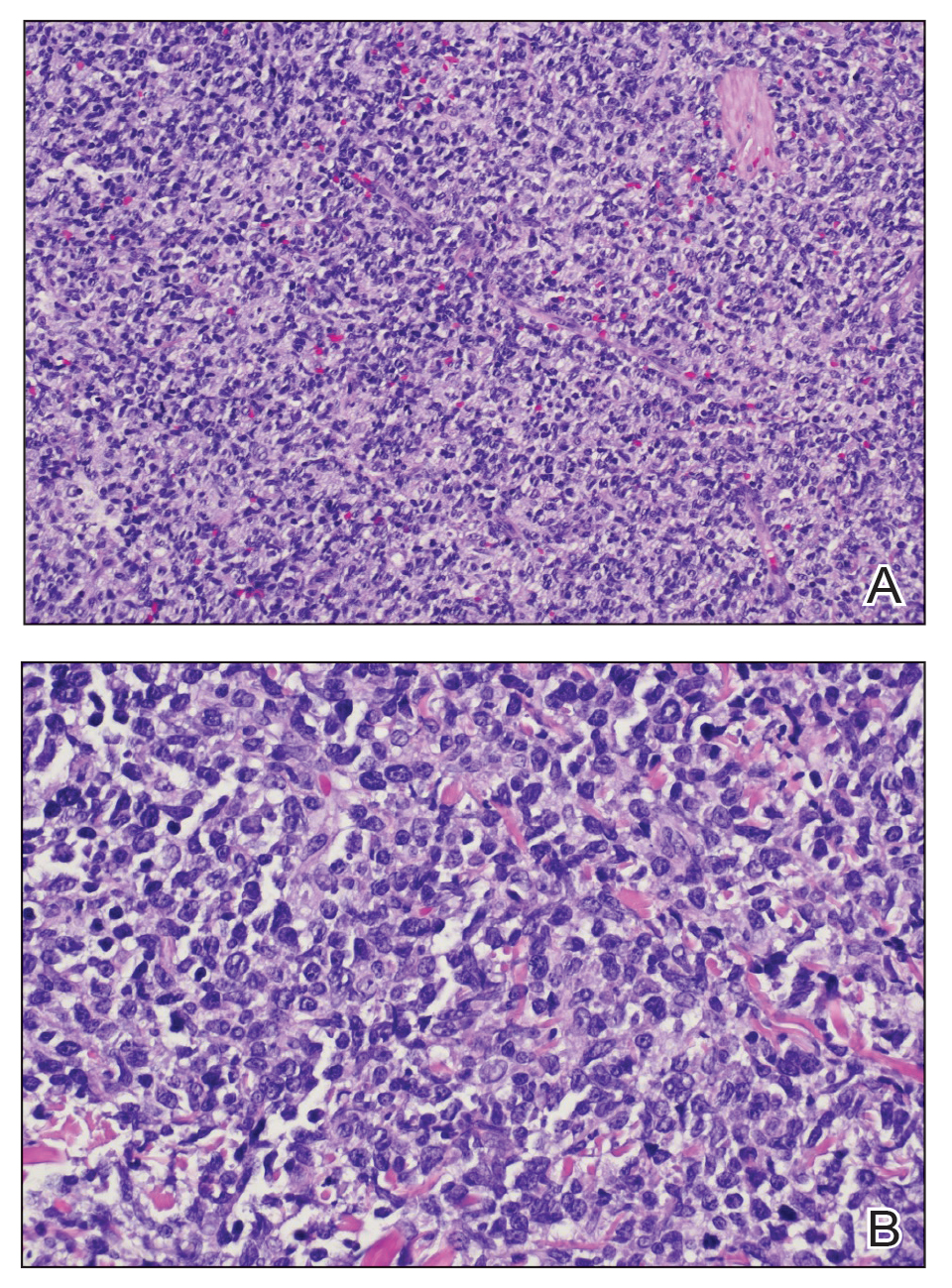

The shave biopsy revealed large cells with prominent nucleoli, clear cytoplasm, and thin cell borders in a nestlike arrangement (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical examination was negative for cytokeratin 5/6 and positive for PAX8 (Figure 2), which finalized the diagnosis of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Later, our patient had a core biopsy-proven metastasis to the C6 spinous process, with concern for additional metastasis to the liver and lungs on positron emission tomography. Our patient’s treatment plan included pembrolizumab and axitinib to manage further cutaneous metastasis and radiation therapy for the C6 spinous process metastasis.

Renal cell carcinoma denotes cancer originating from the renal epithelium and is the most common kidney tumor in adults.1 Renal cell carcinoma accounts for more than 90% of kidney malignancies in the United States and has 3 main subtypes: clear cell RCC, papillary RCC, and chromophobe RCC.2 About 25% of cases metastasize, commonly to the lungs, liver, bones, lymph nodes, contralateral kidney, and adrenal glands.3

Cutaneous metastasis of RCC is rare, with an incidence of approximately 3.3%.4 Notably, 80% to 90% of patients with metastatic skin lesions had a prior diagnosis of RCC.2 Skin metastases associated with RCC predominantly are found on the face and scalp, appearing as nodular, swiftly expanding, circular, or oval-shaped growths. The robust vascular element of these lesions can lead to confusion with regard to the proper diagnosis, as they often resemble hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomas, or Kaposi sarcomas.4

Many cutaneous metastases linked to RCC exhibit a histomorphologic pattern consistent with clear cell adenocarcinoma.2 The malignant cells are large and possess transparent cytoplasm, round to oval nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. The cells can form glandular, acinar, or papillary arrangements; extravasated red blood cells frequently are found within the surrounding fibrovascular tissue.5 The presence of cytoplasmic glycogen can be revealed through periodic acid–Schiff staining. Other immunohistochemical markers commonly used to identify skin metastasis of RCC include epithelioid membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and CD-10.1

Various mechanisms are involved in the cutaneous metastases of RCC. The most common pathway involves infiltration of the skin directly overlying the malignant renal mass; additional potential mechanisms include the introduction of abnormal cells into the skin during surgical or diagnostic interventions and their dissemination through the lymphatic system or bloodstream.1 Among urogenital malignancies other than RCC, skin metastases predominantly manifest in the abdominal region.2 Conversely, the head and neck region are more frequently impacted in RCC. The vascular composition of these tumors plays a role in facilitating the extension of cancer cells through the bloodstream, fostering the emergence of distant metastases.6

The development of cutaneous metastasis in RCC is associated with a poor prognosis, as most patients die within 6 months of detection.3 Treatment options thus are limited and palliative. Although local excision is an alternative treatment for localized cutaneous metastasis, it often provides little benefit in the presence of extensive metastasis; radiotherapy also has been shown to have a limited effect on primary RCC, though its devascularization of the lesion may be effective in metastatic cases.5 Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab and ipilimumab have improved progression-free survival in patients with metastatic RCC, though uncertainty remains regarding their efficacy in attenuating cutaneous metastasis.5,6

- Kanwal R. Metastasis in renal cell carcinoma: biology and treatment. Adv Cancer Biol Metastasis. 2023;7:100094. doi:10.1016 /j.adcanc.2023.100094

- Ferhatoglu MF, Senol K, Filiz AI. Skin metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cureus. 2018;10:E3614. doi:10.7759/cureus.3614

- Bianchi M, Sun M, Jeldres C, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in renal cell carcinoma: a population-based analysis. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:973-980. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdr362

- Lorenzo-Rios D, Cruzval-O’Reilly E, Rabelo-Cartagena J. Facial cutaneous metastasis in renal cell carcinoma. Cureus. 2020;12:E12093. doi:10.7759/cureus.12093

- Iliescu CA, Beiu C, Racovit·a¢ A, et al. Atypical presentation of rapidly progressive cutaneous metastases of clear cell renal carcinoma: a case report. Medicina. 2024;60:1797. doi:10.3390/medicina60111797

- Joyce MJ. Management of skeletal metastases in renal cell carcinoma patients. In: Bukowski RM, Novick AC, eds. Clinical Management of Renal Tumors. Springer; 2008: 421-459.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma

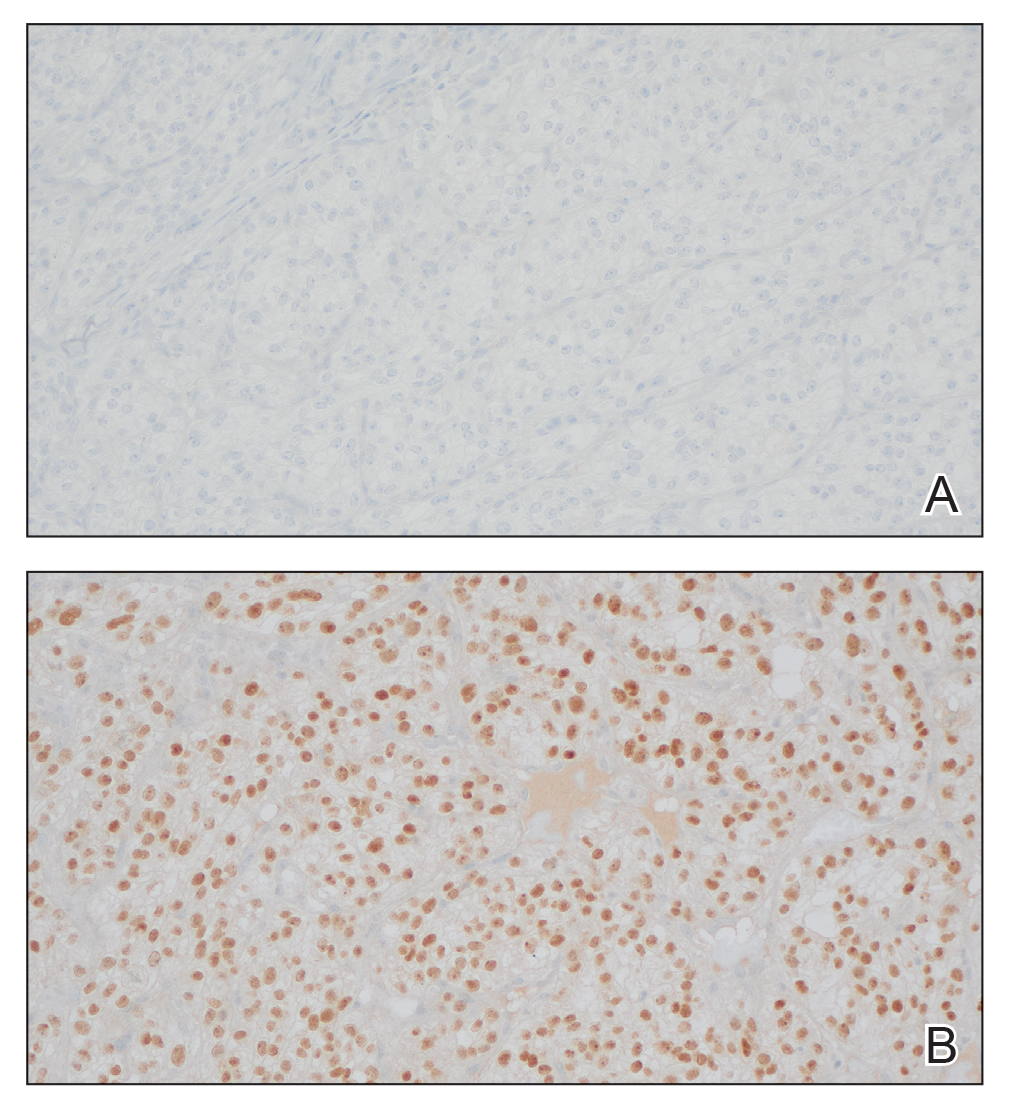

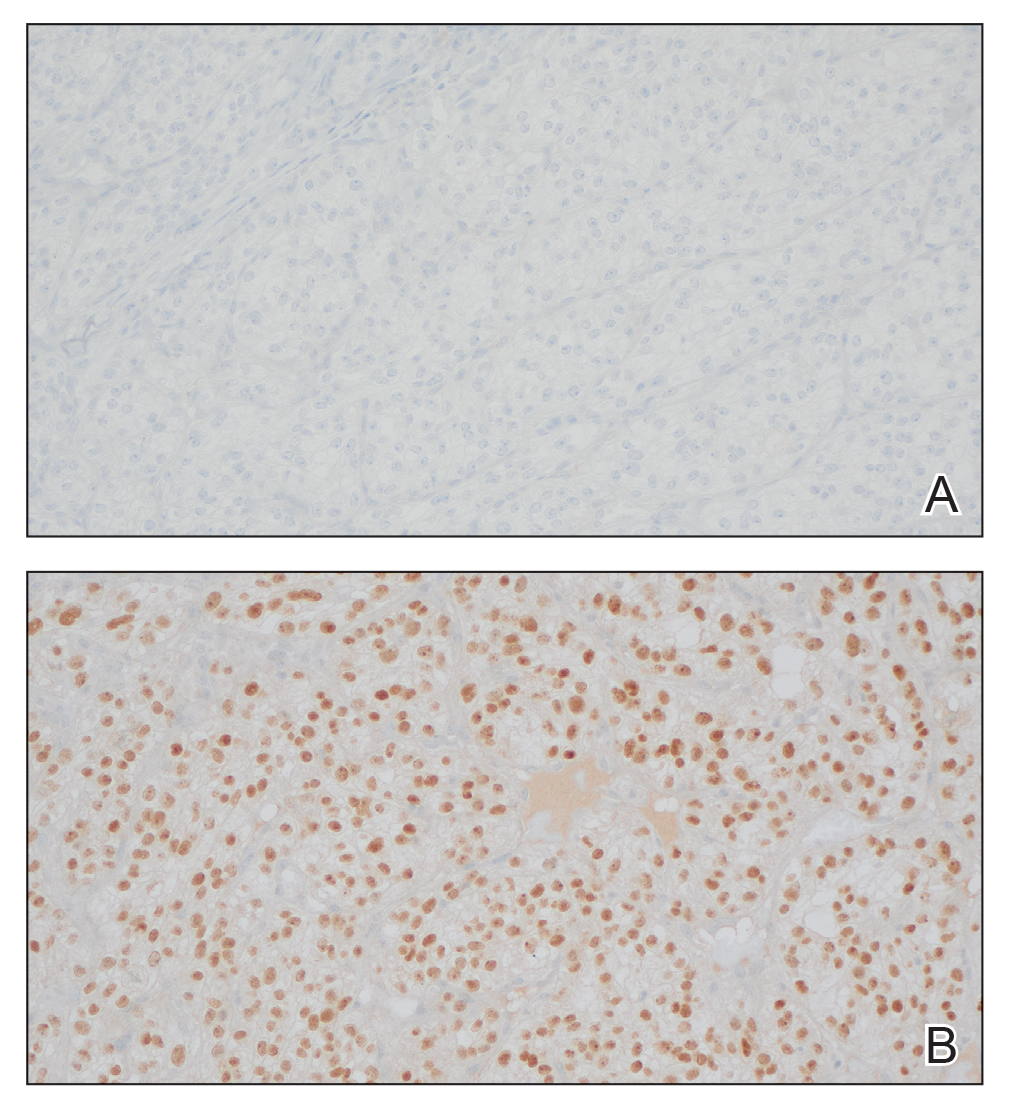

The shave biopsy revealed large cells with prominent nucleoli, clear cytoplasm, and thin cell borders in a nestlike arrangement (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical examination was negative for cytokeratin 5/6 and positive for PAX8 (Figure 2), which finalized the diagnosis of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Later, our patient had a core biopsy-proven metastasis to the C6 spinous process, with concern for additional metastasis to the liver and lungs on positron emission tomography. Our patient’s treatment plan included pembrolizumab and axitinib to manage further cutaneous metastasis and radiation therapy for the C6 spinous process metastasis.

Renal cell carcinoma denotes cancer originating from the renal epithelium and is the most common kidney tumor in adults.1 Renal cell carcinoma accounts for more than 90% of kidney malignancies in the United States and has 3 main subtypes: clear cell RCC, papillary RCC, and chromophobe RCC.2 About 25% of cases metastasize, commonly to the lungs, liver, bones, lymph nodes, contralateral kidney, and adrenal glands.3

Cutaneous metastasis of RCC is rare, with an incidence of approximately 3.3%.4 Notably, 80% to 90% of patients with metastatic skin lesions had a prior diagnosis of RCC.2 Skin metastases associated with RCC predominantly are found on the face and scalp, appearing as nodular, swiftly expanding, circular, or oval-shaped growths. The robust vascular element of these lesions can lead to confusion with regard to the proper diagnosis, as they often resemble hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomas, or Kaposi sarcomas.4

Many cutaneous metastases linked to RCC exhibit a histomorphologic pattern consistent with clear cell adenocarcinoma.2 The malignant cells are large and possess transparent cytoplasm, round to oval nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. The cells can form glandular, acinar, or papillary arrangements; extravasated red blood cells frequently are found within the surrounding fibrovascular tissue.5 The presence of cytoplasmic glycogen can be revealed through periodic acid–Schiff staining. Other immunohistochemical markers commonly used to identify skin metastasis of RCC include epithelioid membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and CD-10.1

Various mechanisms are involved in the cutaneous metastases of RCC. The most common pathway involves infiltration of the skin directly overlying the malignant renal mass; additional potential mechanisms include the introduction of abnormal cells into the skin during surgical or diagnostic interventions and their dissemination through the lymphatic system or bloodstream.1 Among urogenital malignancies other than RCC, skin metastases predominantly manifest in the abdominal region.2 Conversely, the head and neck region are more frequently impacted in RCC. The vascular composition of these tumors plays a role in facilitating the extension of cancer cells through the bloodstream, fostering the emergence of distant metastases.6

The development of cutaneous metastasis in RCC is associated with a poor prognosis, as most patients die within 6 months of detection.3 Treatment options thus are limited and palliative. Although local excision is an alternative treatment for localized cutaneous metastasis, it often provides little benefit in the presence of extensive metastasis; radiotherapy also has been shown to have a limited effect on primary RCC, though its devascularization of the lesion may be effective in metastatic cases.5 Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab and ipilimumab have improved progression-free survival in patients with metastatic RCC, though uncertainty remains regarding their efficacy in attenuating cutaneous metastasis.5,6

THE DIAGNOSIS: Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma

The shave biopsy revealed large cells with prominent nucleoli, clear cytoplasm, and thin cell borders in a nestlike arrangement (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical examination was negative for cytokeratin 5/6 and positive for PAX8 (Figure 2), which finalized the diagnosis of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Later, our patient had a core biopsy-proven metastasis to the C6 spinous process, with concern for additional metastasis to the liver and lungs on positron emission tomography. Our patient’s treatment plan included pembrolizumab and axitinib to manage further cutaneous metastasis and radiation therapy for the C6 spinous process metastasis.

Renal cell carcinoma denotes cancer originating from the renal epithelium and is the most common kidney tumor in adults.1 Renal cell carcinoma accounts for more than 90% of kidney malignancies in the United States and has 3 main subtypes: clear cell RCC, papillary RCC, and chromophobe RCC.2 About 25% of cases metastasize, commonly to the lungs, liver, bones, lymph nodes, contralateral kidney, and adrenal glands.3

Cutaneous metastasis of RCC is rare, with an incidence of approximately 3.3%.4 Notably, 80% to 90% of patients with metastatic skin lesions had a prior diagnosis of RCC.2 Skin metastases associated with RCC predominantly are found on the face and scalp, appearing as nodular, swiftly expanding, circular, or oval-shaped growths. The robust vascular element of these lesions can lead to confusion with regard to the proper diagnosis, as they often resemble hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomas, or Kaposi sarcomas.4

Many cutaneous metastases linked to RCC exhibit a histomorphologic pattern consistent with clear cell adenocarcinoma.2 The malignant cells are large and possess transparent cytoplasm, round to oval nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. The cells can form glandular, acinar, or papillary arrangements; extravasated red blood cells frequently are found within the surrounding fibrovascular tissue.5 The presence of cytoplasmic glycogen can be revealed through periodic acid–Schiff staining. Other immunohistochemical markers commonly used to identify skin metastasis of RCC include epithelioid membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and CD-10.1

Various mechanisms are involved in the cutaneous metastases of RCC. The most common pathway involves infiltration of the skin directly overlying the malignant renal mass; additional potential mechanisms include the introduction of abnormal cells into the skin during surgical or diagnostic interventions and their dissemination through the lymphatic system or bloodstream.1 Among urogenital malignancies other than RCC, skin metastases predominantly manifest in the abdominal region.2 Conversely, the head and neck region are more frequently impacted in RCC. The vascular composition of these tumors plays a role in facilitating the extension of cancer cells through the bloodstream, fostering the emergence of distant metastases.6

The development of cutaneous metastasis in RCC is associated with a poor prognosis, as most patients die within 6 months of detection.3 Treatment options thus are limited and palliative. Although local excision is an alternative treatment for localized cutaneous metastasis, it often provides little benefit in the presence of extensive metastasis; radiotherapy also has been shown to have a limited effect on primary RCC, though its devascularization of the lesion may be effective in metastatic cases.5 Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab and ipilimumab have improved progression-free survival in patients with metastatic RCC, though uncertainty remains regarding their efficacy in attenuating cutaneous metastasis.5,6

- Kanwal R. Metastasis in renal cell carcinoma: biology and treatment. Adv Cancer Biol Metastasis. 2023;7:100094. doi:10.1016 /j.adcanc.2023.100094

- Ferhatoglu MF, Senol K, Filiz AI. Skin metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cureus. 2018;10:E3614. doi:10.7759/cureus.3614

- Bianchi M, Sun M, Jeldres C, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in renal cell carcinoma: a population-based analysis. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:973-980. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdr362

- Lorenzo-Rios D, Cruzval-O’Reilly E, Rabelo-Cartagena J. Facial cutaneous metastasis in renal cell carcinoma. Cureus. 2020;12:E12093. doi:10.7759/cureus.12093

- Iliescu CA, Beiu C, Racovit·a¢ A, et al. Atypical presentation of rapidly progressive cutaneous metastases of clear cell renal carcinoma: a case report. Medicina. 2024;60:1797. doi:10.3390/medicina60111797

- Joyce MJ. Management of skeletal metastases in renal cell carcinoma patients. In: Bukowski RM, Novick AC, eds. Clinical Management of Renal Tumors. Springer; 2008: 421-459.

- Kanwal R. Metastasis in renal cell carcinoma: biology and treatment. Adv Cancer Biol Metastasis. 2023;7:100094. doi:10.1016 /j.adcanc.2023.100094

- Ferhatoglu MF, Senol K, Filiz AI. Skin metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cureus. 2018;10:E3614. doi:10.7759/cureus.3614

- Bianchi M, Sun M, Jeldres C, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in renal cell carcinoma: a population-based analysis. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:973-980. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdr362

- Lorenzo-Rios D, Cruzval-O’Reilly E, Rabelo-Cartagena J. Facial cutaneous metastasis in renal cell carcinoma. Cureus. 2020;12:E12093. doi:10.7759/cureus.12093

- Iliescu CA, Beiu C, Racovit·a¢ A, et al. Atypical presentation of rapidly progressive cutaneous metastases of clear cell renal carcinoma: a case report. Medicina. 2024;60:1797. doi:10.3390/medicina60111797

- Joyce MJ. Management of skeletal metastases in renal cell carcinoma patients. In: Bukowski RM, Novick AC, eds. Clinical Management of Renal Tumors. Springer; 2008: 421-459.

Vascular Nodule on the Upper Chest

Vascular Nodule on the Upper Chest

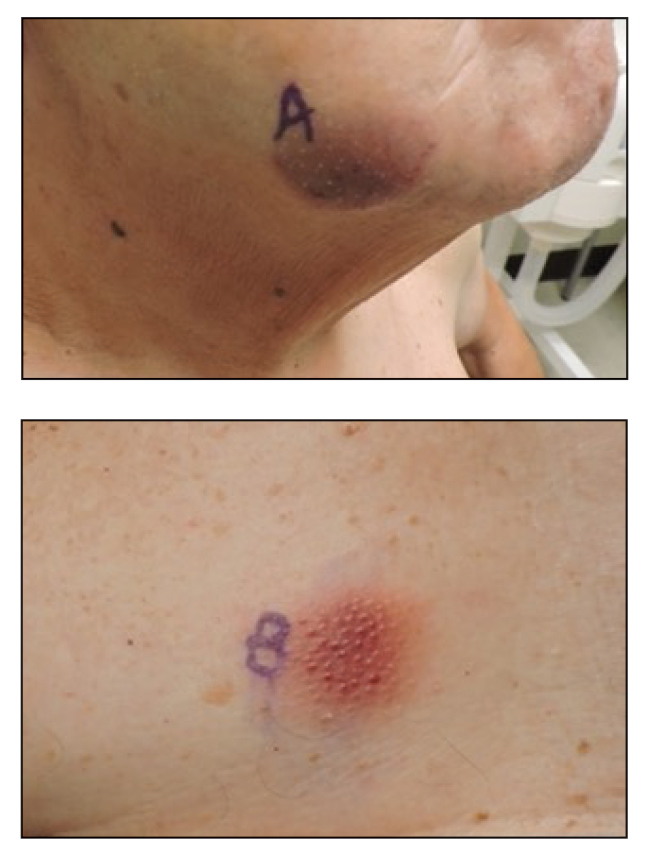

A 45-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a bleeding nodule on the upper chest of 2 months’ duration. He had a history of a low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the left parotid gland that was diagnosed 14 years prior and was treated via parotidectomy with 1 positive lymph node removed. Two months prior to the current presentation, the patient presented to the emergency department with unintentional weight loss and fatigue and subsequently was diagnosed with clear cell renal cell carcinoma that was treated via radical nephrectomy.

At the current presentation, the patient denied any recent fatigue, fever, weight loss, shortness of breath, or abdominal pain but reported neck stiffness. Physical examination revealed a solitary, smooth, vascular, 1.5×1.5 cm nodule on the left upper chest with no overlying skin changes. The remainder of the skin examination was unremarkable. A shave biopsy of the nodule was performed.

Skin Lesions on the Face and Chest

The Diagnosis: Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm

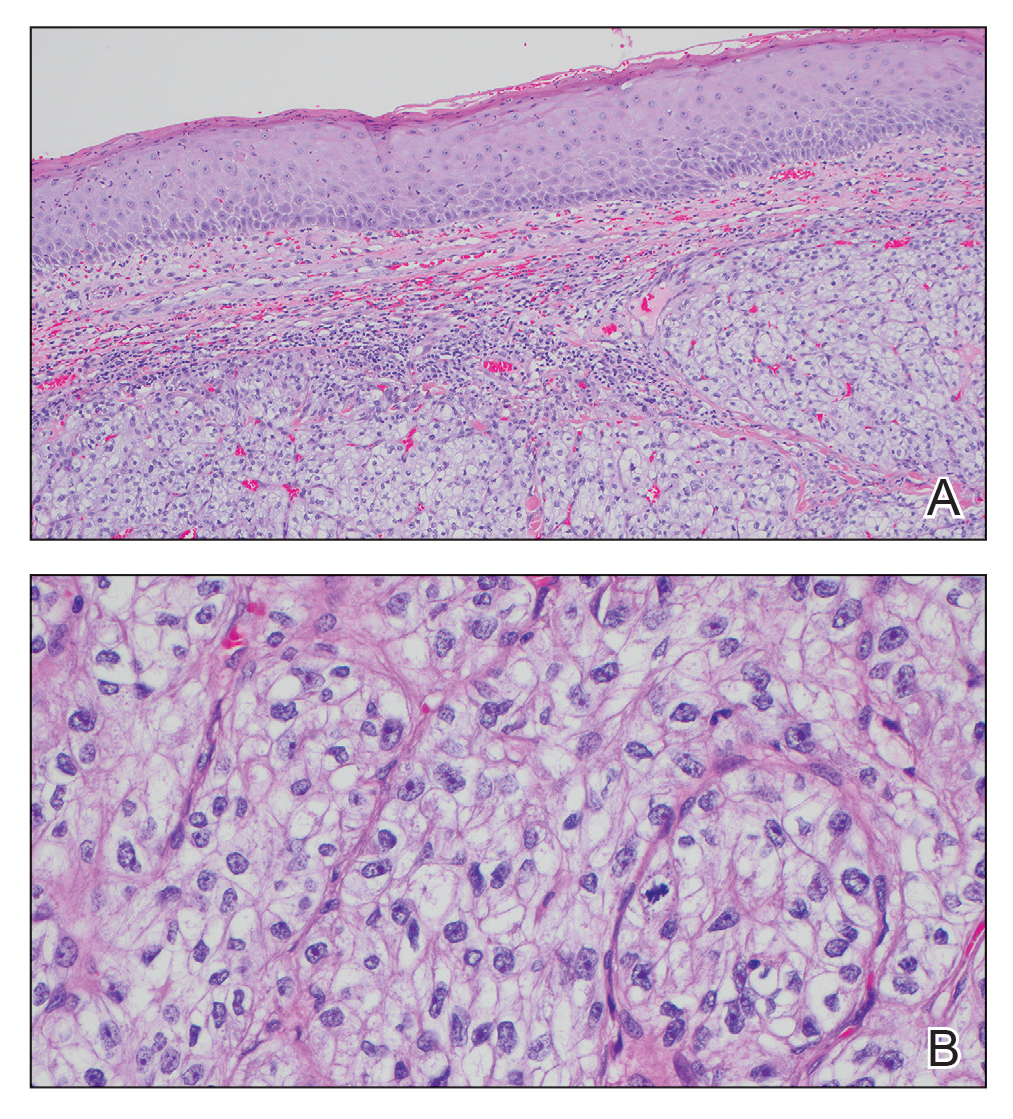

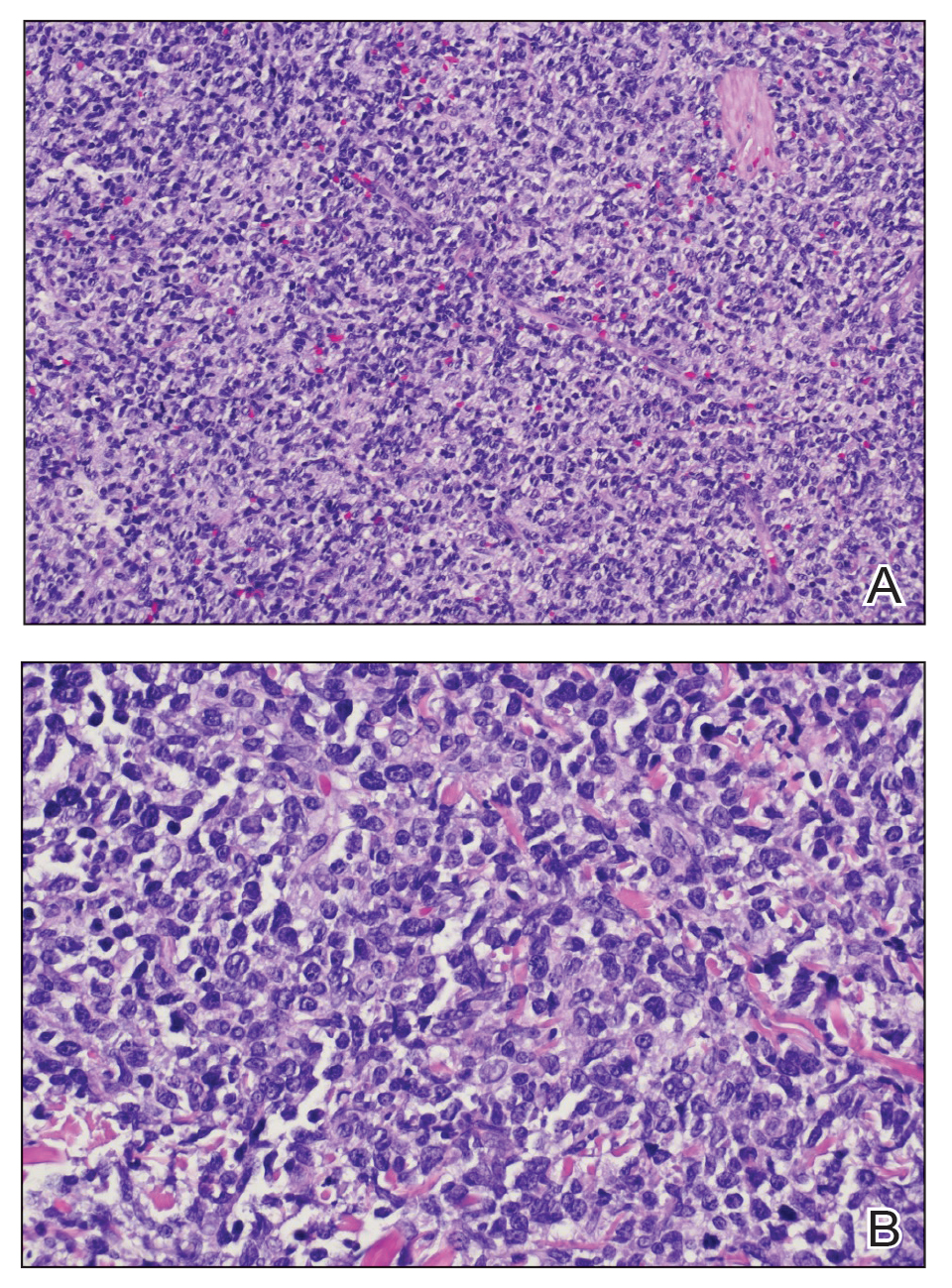

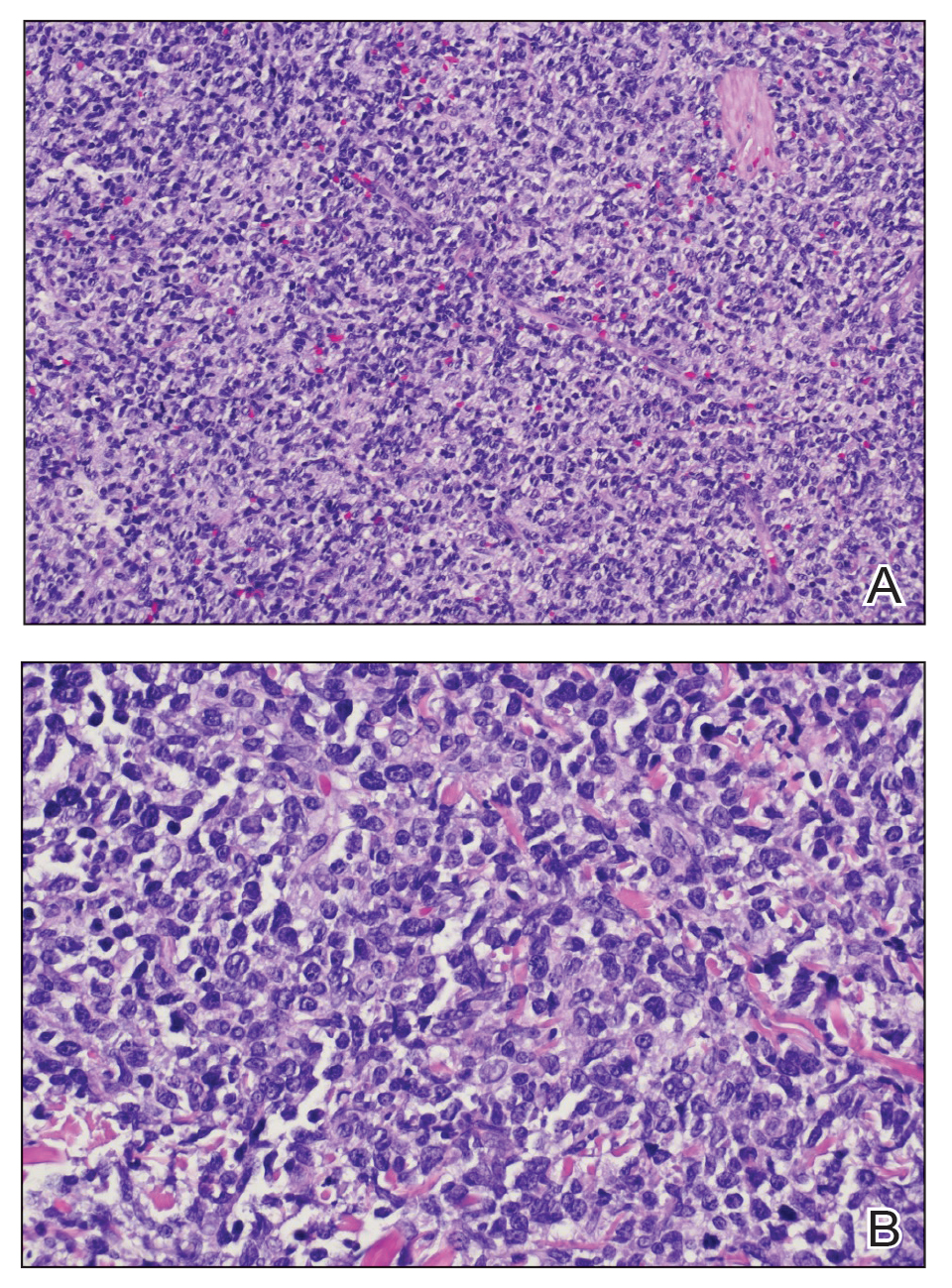

Cutaneous plasmacytoma initially was suspected because of the patient’s history of monoclonal gammopathy as well as angiosarcoma due to the purpuric vascular appearance of the lesions. However, histopathology revealed a pleomorphic cellular dermal infiltrate characterized by atypical cells with mediumlarge nuclei, fine chromatin, and small nucleoli; the cells also had little cytoplasm (Figure). The infiltrate did not involve the epidermis but extended into the subcutaneous tissue. Immunohistochemistry revealed that the cells were positive for CD45, CD43, CD4, CD7, CD56, CD123, CD33, T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1, and CD68. The cells were negative for CD2, CD3, CD5, CD8, T-cell intracellular antigen 1, CD13, CD15, CD19, CD20, CD21, CD23, cyclin D1, Bcl-2, Bcl-6, CD10, PAX5, MUM1, lysozyme, myeloperoxidase, perforin, granzyme B, CD57, CD34, CD117, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, activin receptorlike kinase 1 βF1, Epstein-Barr virus– encoded small RNA, CD30, CD163, and pancytokeratin. Thus, the clinical and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN), a rare and aggressive hematologic malignancy.

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm affects males older than 60 years.1 It is characterized by the clonal proliferation of precursor plasmacytoid dendritic cells—otherwise known as professional type I interferonproducing cells or plasmacytoid monocytes—of myeloid origin. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells have been renamed on several occasions, reflecting uncertainties of their histogenesis. The diagnosis of BPDCN requires a biopsy showing the morphology of plasmacytoid dendritic blast cells and immunophenotypic criteria established by either immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry.2,3 Tumor cells morphologically show an immature blastic appearance, and the diagnosis rests upon the demonstration of CD4 and CD56, together with markers more restricted to plasmacytoid dendritic cells (eg, BDCA-2, CD123, T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1, CD2AP, BCL11A) and negativity for lymphoid and myeloid lineage–associated antigens.1,4

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasms account for less than 1% of all hematopoietic neoplasms. Cutaneous lesions occur in 64% of patients with the disease and often are the reason patients seek medical care.5 Clinical findings include numerous erythematous and violaceous papules, nodules, and plaques that resemble purpura or vasculitis. Cutaneous lesions can vary in size from a few millimeters to 10 cm and vary in color. Moreover, patients often present with bruiselike patches, disseminated lesions, or mucosal lesions.1 Extracutaneous involvement includes lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and cytopenia caused by bone marrow infiltration, which may be present at diagnosis or during disease progression. Bone marrow involvement often is present with thrombocytopenia, anemia, and neutropenia. One-third of patients with BPDCN have central nervous system involvement and no disease relapse.6 Other affected sites include the liver, lungs, tonsils, soft tissues, and eyes. Patients with BPDCN may present with a history of myeloid neoplasms, such as acute/chronic myeloid leukemia, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, or myelodysplastic syndrome.4 Our case highlights the importance of skin biopsy for making the correct diagnosis, as BPDCN manifests with cutaneous lesions that are nonspecific for neoplastic or nonneoplastic etiologies.

Given the aggressive nature of BPDCN, along with its potential for acute leukemic transformation, treatment has been challenging due to both poor response rates and lack of consensus and treatment strategies. Historically, patients who have received high-dose acute leukemia–based chemotherapy followed by an allogeneic stem cell transplant during the first remission appeared to have the best outcomes.7 Conventional treatments have included surgical excision with radiation and various leukemia-based chemotherapy regimens, with hyper- CVAD (fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone-methotrexate, and cytarabine) being the most commonly used regimen.7,8 Venetoclax, a B-cell lymphoma 2 protein inhibitor, has shown promise when used in combination with hyper-CVAD. For older patients who may not tolerate aggressive chemotherapy, hypomethylating agents are preferred for their tolerability. Although tagraxofusp, a CD123-directed cytotoxin, has been utilized, Sapienza et al9 demonstrated an association with capillary leak syndrome.

Leukemia cutis is characterized by infiltration of the skin by malignant leukocytes, often associated with a prior diagnosis of systemic leukemia or myelodysplasia. Extramedullary accumulation of leukemic cells typically is referred to as myeloid sarcoma, while leukemia cutis serves as a general term for specific skin involvement.10 In rare instances, cutaneous lesions may manifest as the initial sign of systemic disease.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas comprise a diverse group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that manifest as malignant monoclonal T-lymphocyte infiltration in the skin. Mycosis fungoides, Sézary syndrome, and primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphomas are among the key subtypes. Histologically, differentiating these conditions from benign inflammatory disorders can be challenging due to subtle features such as haloed lymphocytes, epidermotropism, and Pautrier microabscesses seen in mycosis fungoides.11

Multiple myeloma involves monoclonal plasma cell proliferation, primarily affecting bone and bone marrow. Extramedullary plasmacytomas can occur outside these sites through hematogenous spread or adjacent infiltration, while metastatic plasmacytomas result from metastasis. Cutaneous plasmacytomas may arise from hematogenous dissemination or infiltration from neighboring structures.12

Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, manifests as aggressive mid-facial necrotizing lesions with extranodal involvement, notably in the nasal/paranasal area. These lesions can cause local destruction of cartilage, bone, and soft tissues and may progress through stages or arise de novo. Diagnostic challenges arise from the historical variety of terms used to describe extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, including midline lethal granuloma and lymphomatoid granulomatosis.13

- Cheng W, Yu TT, Tang AP, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: progress in cell origin, molecular biology, diagnostic criteria and therapeutic approaches. Curr Med Sci. 2021;41:405-419. doi:10.1007/s11596-021-2393-3

- Chang HJ, Lee MD, Yi HG, et al. A case of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm initially mimicking cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Cancer Res Treat. 2010;42:239-243. doi:10.4143/crt.2010.42.4.239

- Garnache-Ottou F, Vidal C, Biichlé S, et al. How should we diagnose and treat blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm patients? Blood Adv. 2019;3:4238-4251. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000647

- Sweet K. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. Curr Opin Hematol. 2020;27:103-107. doi:10.1097/moh.0000000000000569

- Julia F, Petrella T, Beylot-Barry M, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: clinical features in 90 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:579-586. doi:10.1111/bjd.12412

- Molina Castro D, Perilla Suárez O, Cuervo-Sierra J, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm with central nervous system involvement: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14:e23888. doi:10.7759 /cureus.23888

- Grushchak S, Joy C, Gray A, et al. Novel treatment of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:E9452.

- Lim MS, Lemmert K, Enjeti A. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN): a rare entity. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2015214093. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-214093

- Sapienza MR, Pileri A, Derenzini E, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: state of the art and prospects. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:595. doi:10.3390/cancers11050595

- Wang CX, Pusic I, Anadkat MJ. Association of leukemia cutis with survival in acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:826. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0052

- Ralfkiaer U, Hagedorn PH, Bangsgaard N, et al. Diagnostic micro RNA profiling in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). Blood. 2011;118: 5891-5900. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-06-358382

- Tsang DS, Le LW, Kukreti V. Treatment and outcomes for primary cutaneous extramedullary plasmacytoma: a case series. Curr Oncol. 2016;23:630-646. doi:10.3747/co.23.3288

- Lee J, Kim W, Park Y, et al. Nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma: clinical features and treatment outcome. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1226-1230. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602502

The Diagnosis: Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm

Cutaneous plasmacytoma initially was suspected because of the patient’s history of monoclonal gammopathy as well as angiosarcoma due to the purpuric vascular appearance of the lesions. However, histopathology revealed a pleomorphic cellular dermal infiltrate characterized by atypical cells with mediumlarge nuclei, fine chromatin, and small nucleoli; the cells also had little cytoplasm (Figure). The infiltrate did not involve the epidermis but extended into the subcutaneous tissue. Immunohistochemistry revealed that the cells were positive for CD45, CD43, CD4, CD7, CD56, CD123, CD33, T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1, and CD68. The cells were negative for CD2, CD3, CD5, CD8, T-cell intracellular antigen 1, CD13, CD15, CD19, CD20, CD21, CD23, cyclin D1, Bcl-2, Bcl-6, CD10, PAX5, MUM1, lysozyme, myeloperoxidase, perforin, granzyme B, CD57, CD34, CD117, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, activin receptorlike kinase 1 βF1, Epstein-Barr virus– encoded small RNA, CD30, CD163, and pancytokeratin. Thus, the clinical and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN), a rare and aggressive hematologic malignancy.

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm affects males older than 60 years.1 It is characterized by the clonal proliferation of precursor plasmacytoid dendritic cells—otherwise known as professional type I interferonproducing cells or plasmacytoid monocytes—of myeloid origin. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells have been renamed on several occasions, reflecting uncertainties of their histogenesis. The diagnosis of BPDCN requires a biopsy showing the morphology of plasmacytoid dendritic blast cells and immunophenotypic criteria established by either immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry.2,3 Tumor cells morphologically show an immature blastic appearance, and the diagnosis rests upon the demonstration of CD4 and CD56, together with markers more restricted to plasmacytoid dendritic cells (eg, BDCA-2, CD123, T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1, CD2AP, BCL11A) and negativity for lymphoid and myeloid lineage–associated antigens.1,4

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasms account for less than 1% of all hematopoietic neoplasms. Cutaneous lesions occur in 64% of patients with the disease and often are the reason patients seek medical care.5 Clinical findings include numerous erythematous and violaceous papules, nodules, and plaques that resemble purpura or vasculitis. Cutaneous lesions can vary in size from a few millimeters to 10 cm and vary in color. Moreover, patients often present with bruiselike patches, disseminated lesions, or mucosal lesions.1 Extracutaneous involvement includes lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and cytopenia caused by bone marrow infiltration, which may be present at diagnosis or during disease progression. Bone marrow involvement often is present with thrombocytopenia, anemia, and neutropenia. One-third of patients with BPDCN have central nervous system involvement and no disease relapse.6 Other affected sites include the liver, lungs, tonsils, soft tissues, and eyes. Patients with BPDCN may present with a history of myeloid neoplasms, such as acute/chronic myeloid leukemia, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, or myelodysplastic syndrome.4 Our case highlights the importance of skin biopsy for making the correct diagnosis, as BPDCN manifests with cutaneous lesions that are nonspecific for neoplastic or nonneoplastic etiologies.

Given the aggressive nature of BPDCN, along with its potential for acute leukemic transformation, treatment has been challenging due to both poor response rates and lack of consensus and treatment strategies. Historically, patients who have received high-dose acute leukemia–based chemotherapy followed by an allogeneic stem cell transplant during the first remission appeared to have the best outcomes.7 Conventional treatments have included surgical excision with radiation and various leukemia-based chemotherapy regimens, with hyper- CVAD (fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone-methotrexate, and cytarabine) being the most commonly used regimen.7,8 Venetoclax, a B-cell lymphoma 2 protein inhibitor, has shown promise when used in combination with hyper-CVAD. For older patients who may not tolerate aggressive chemotherapy, hypomethylating agents are preferred for their tolerability. Although tagraxofusp, a CD123-directed cytotoxin, has been utilized, Sapienza et al9 demonstrated an association with capillary leak syndrome.

Leukemia cutis is characterized by infiltration of the skin by malignant leukocytes, often associated with a prior diagnosis of systemic leukemia or myelodysplasia. Extramedullary accumulation of leukemic cells typically is referred to as myeloid sarcoma, while leukemia cutis serves as a general term for specific skin involvement.10 In rare instances, cutaneous lesions may manifest as the initial sign of systemic disease.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas comprise a diverse group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that manifest as malignant monoclonal T-lymphocyte infiltration in the skin. Mycosis fungoides, Sézary syndrome, and primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphomas are among the key subtypes. Histologically, differentiating these conditions from benign inflammatory disorders can be challenging due to subtle features such as haloed lymphocytes, epidermotropism, and Pautrier microabscesses seen in mycosis fungoides.11

Multiple myeloma involves monoclonal plasma cell proliferation, primarily affecting bone and bone marrow. Extramedullary plasmacytomas can occur outside these sites through hematogenous spread or adjacent infiltration, while metastatic plasmacytomas result from metastasis. Cutaneous plasmacytomas may arise from hematogenous dissemination or infiltration from neighboring structures.12

Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, manifests as aggressive mid-facial necrotizing lesions with extranodal involvement, notably in the nasal/paranasal area. These lesions can cause local destruction of cartilage, bone, and soft tissues and may progress through stages or arise de novo. Diagnostic challenges arise from the historical variety of terms used to describe extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, including midline lethal granuloma and lymphomatoid granulomatosis.13

The Diagnosis: Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm

Cutaneous plasmacytoma initially was suspected because of the patient’s history of monoclonal gammopathy as well as angiosarcoma due to the purpuric vascular appearance of the lesions. However, histopathology revealed a pleomorphic cellular dermal infiltrate characterized by atypical cells with mediumlarge nuclei, fine chromatin, and small nucleoli; the cells also had little cytoplasm (Figure). The infiltrate did not involve the epidermis but extended into the subcutaneous tissue. Immunohistochemistry revealed that the cells were positive for CD45, CD43, CD4, CD7, CD56, CD123, CD33, T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1, and CD68. The cells were negative for CD2, CD3, CD5, CD8, T-cell intracellular antigen 1, CD13, CD15, CD19, CD20, CD21, CD23, cyclin D1, Bcl-2, Bcl-6, CD10, PAX5, MUM1, lysozyme, myeloperoxidase, perforin, granzyme B, CD57, CD34, CD117, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, activin receptorlike kinase 1 βF1, Epstein-Barr virus– encoded small RNA, CD30, CD163, and pancytokeratin. Thus, the clinical and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN), a rare and aggressive hematologic malignancy.

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm affects males older than 60 years.1 It is characterized by the clonal proliferation of precursor plasmacytoid dendritic cells—otherwise known as professional type I interferonproducing cells or plasmacytoid monocytes—of myeloid origin. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells have been renamed on several occasions, reflecting uncertainties of their histogenesis. The diagnosis of BPDCN requires a biopsy showing the morphology of plasmacytoid dendritic blast cells and immunophenotypic criteria established by either immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry.2,3 Tumor cells morphologically show an immature blastic appearance, and the diagnosis rests upon the demonstration of CD4 and CD56, together with markers more restricted to plasmacytoid dendritic cells (eg, BDCA-2, CD123, T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1, CD2AP, BCL11A) and negativity for lymphoid and myeloid lineage–associated antigens.1,4

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasms account for less than 1% of all hematopoietic neoplasms. Cutaneous lesions occur in 64% of patients with the disease and often are the reason patients seek medical care.5 Clinical findings include numerous erythematous and violaceous papules, nodules, and plaques that resemble purpura or vasculitis. Cutaneous lesions can vary in size from a few millimeters to 10 cm and vary in color. Moreover, patients often present with bruiselike patches, disseminated lesions, or mucosal lesions.1 Extracutaneous involvement includes lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and cytopenia caused by bone marrow infiltration, which may be present at diagnosis or during disease progression. Bone marrow involvement often is present with thrombocytopenia, anemia, and neutropenia. One-third of patients with BPDCN have central nervous system involvement and no disease relapse.6 Other affected sites include the liver, lungs, tonsils, soft tissues, and eyes. Patients with BPDCN may present with a history of myeloid neoplasms, such as acute/chronic myeloid leukemia, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, or myelodysplastic syndrome.4 Our case highlights the importance of skin biopsy for making the correct diagnosis, as BPDCN manifests with cutaneous lesions that are nonspecific for neoplastic or nonneoplastic etiologies.

Given the aggressive nature of BPDCN, along with its potential for acute leukemic transformation, treatment has been challenging due to both poor response rates and lack of consensus and treatment strategies. Historically, patients who have received high-dose acute leukemia–based chemotherapy followed by an allogeneic stem cell transplant during the first remission appeared to have the best outcomes.7 Conventional treatments have included surgical excision with radiation and various leukemia-based chemotherapy regimens, with hyper- CVAD (fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone-methotrexate, and cytarabine) being the most commonly used regimen.7,8 Venetoclax, a B-cell lymphoma 2 protein inhibitor, has shown promise when used in combination with hyper-CVAD. For older patients who may not tolerate aggressive chemotherapy, hypomethylating agents are preferred for their tolerability. Although tagraxofusp, a CD123-directed cytotoxin, has been utilized, Sapienza et al9 demonstrated an association with capillary leak syndrome.

Leukemia cutis is characterized by infiltration of the skin by malignant leukocytes, often associated with a prior diagnosis of systemic leukemia or myelodysplasia. Extramedullary accumulation of leukemic cells typically is referred to as myeloid sarcoma, while leukemia cutis serves as a general term for specific skin involvement.10 In rare instances, cutaneous lesions may manifest as the initial sign of systemic disease.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas comprise a diverse group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that manifest as malignant monoclonal T-lymphocyte infiltration in the skin. Mycosis fungoides, Sézary syndrome, and primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphomas are among the key subtypes. Histologically, differentiating these conditions from benign inflammatory disorders can be challenging due to subtle features such as haloed lymphocytes, epidermotropism, and Pautrier microabscesses seen in mycosis fungoides.11

Multiple myeloma involves monoclonal plasma cell proliferation, primarily affecting bone and bone marrow. Extramedullary plasmacytomas can occur outside these sites through hematogenous spread or adjacent infiltration, while metastatic plasmacytomas result from metastasis. Cutaneous plasmacytomas may arise from hematogenous dissemination or infiltration from neighboring structures.12

Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, manifests as aggressive mid-facial necrotizing lesions with extranodal involvement, notably in the nasal/paranasal area. These lesions can cause local destruction of cartilage, bone, and soft tissues and may progress through stages or arise de novo. Diagnostic challenges arise from the historical variety of terms used to describe extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, including midline lethal granuloma and lymphomatoid granulomatosis.13

- Cheng W, Yu TT, Tang AP, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: progress in cell origin, molecular biology, diagnostic criteria and therapeutic approaches. Curr Med Sci. 2021;41:405-419. doi:10.1007/s11596-021-2393-3

- Chang HJ, Lee MD, Yi HG, et al. A case of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm initially mimicking cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Cancer Res Treat. 2010;42:239-243. doi:10.4143/crt.2010.42.4.239

- Garnache-Ottou F, Vidal C, Biichlé S, et al. How should we diagnose and treat blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm patients? Blood Adv. 2019;3:4238-4251. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000647

- Sweet K. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. Curr Opin Hematol. 2020;27:103-107. doi:10.1097/moh.0000000000000569

- Julia F, Petrella T, Beylot-Barry M, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: clinical features in 90 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:579-586. doi:10.1111/bjd.12412

- Molina Castro D, Perilla Suárez O, Cuervo-Sierra J, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm with central nervous system involvement: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14:e23888. doi:10.7759 /cureus.23888

- Grushchak S, Joy C, Gray A, et al. Novel treatment of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:E9452.

- Lim MS, Lemmert K, Enjeti A. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN): a rare entity. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2015214093. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-214093

- Sapienza MR, Pileri A, Derenzini E, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: state of the art and prospects. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:595. doi:10.3390/cancers11050595

- Wang CX, Pusic I, Anadkat MJ. Association of leukemia cutis with survival in acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:826. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0052

- Ralfkiaer U, Hagedorn PH, Bangsgaard N, et al. Diagnostic micro RNA profiling in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). Blood. 2011;118: 5891-5900. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-06-358382

- Tsang DS, Le LW, Kukreti V. Treatment and outcomes for primary cutaneous extramedullary plasmacytoma: a case series. Curr Oncol. 2016;23:630-646. doi:10.3747/co.23.3288

- Lee J, Kim W, Park Y, et al. Nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma: clinical features and treatment outcome. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1226-1230. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602502

- Cheng W, Yu TT, Tang AP, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: progress in cell origin, molecular biology, diagnostic criteria and therapeutic approaches. Curr Med Sci. 2021;41:405-419. doi:10.1007/s11596-021-2393-3

- Chang HJ, Lee MD, Yi HG, et al. A case of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm initially mimicking cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Cancer Res Treat. 2010;42:239-243. doi:10.4143/crt.2010.42.4.239

- Garnache-Ottou F, Vidal C, Biichlé S, et al. How should we diagnose and treat blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm patients? Blood Adv. 2019;3:4238-4251. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000647

- Sweet K. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. Curr Opin Hematol. 2020;27:103-107. doi:10.1097/moh.0000000000000569

- Julia F, Petrella T, Beylot-Barry M, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: clinical features in 90 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:579-586. doi:10.1111/bjd.12412

- Molina Castro D, Perilla Suárez O, Cuervo-Sierra J, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm with central nervous system involvement: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14:e23888. doi:10.7759 /cureus.23888

- Grushchak S, Joy C, Gray A, et al. Novel treatment of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:E9452.

- Lim MS, Lemmert K, Enjeti A. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN): a rare entity. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2015214093. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-214093

- Sapienza MR, Pileri A, Derenzini E, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: state of the art and prospects. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:595. doi:10.3390/cancers11050595

- Wang CX, Pusic I, Anadkat MJ. Association of leukemia cutis with survival in acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:826. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0052

- Ralfkiaer U, Hagedorn PH, Bangsgaard N, et al. Diagnostic micro RNA profiling in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). Blood. 2011;118: 5891-5900. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-06-358382

- Tsang DS, Le LW, Kukreti V. Treatment and outcomes for primary cutaneous extramedullary plasmacytoma: a case series. Curr Oncol. 2016;23:630-646. doi:10.3747/co.23.3288

- Lee J, Kim W, Park Y, et al. Nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma: clinical features and treatment outcome. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1226-1230. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602502

A 79-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with multiple skin lesions of 4 months’ duration. The patient had a history of monoclonal gammopathy and reported no changes in medication, travel, or trauma. He reported tenderness only when trying to comb hair over the left occipital nodule. He denied fevers, night sweats, weight loss, or poor appetite. Physical examination revealed 4 concerning skin lesions: a 3×3-cm violaceous nodule with underlying ecchymosis on the right medial jaw (top), a 3×2.5-cm violaceous nodule on the posterior occiput, a pink plaque with 1-mm vascular papules on the right mid-chest (bottom), and a 4×2.5-cm oval pink patch on the left side of the lower back. Punch biopsies were performed on the right medial jaw nodule and right mid-chest plaque.