User login

Pigmented Cystic Masses on the Scalp

THE DIAGNOSIS: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

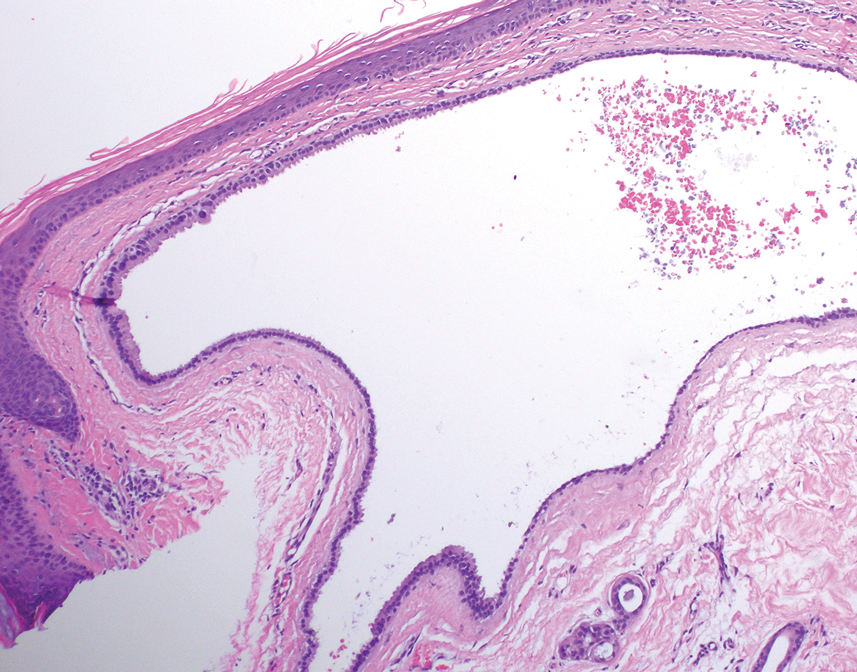

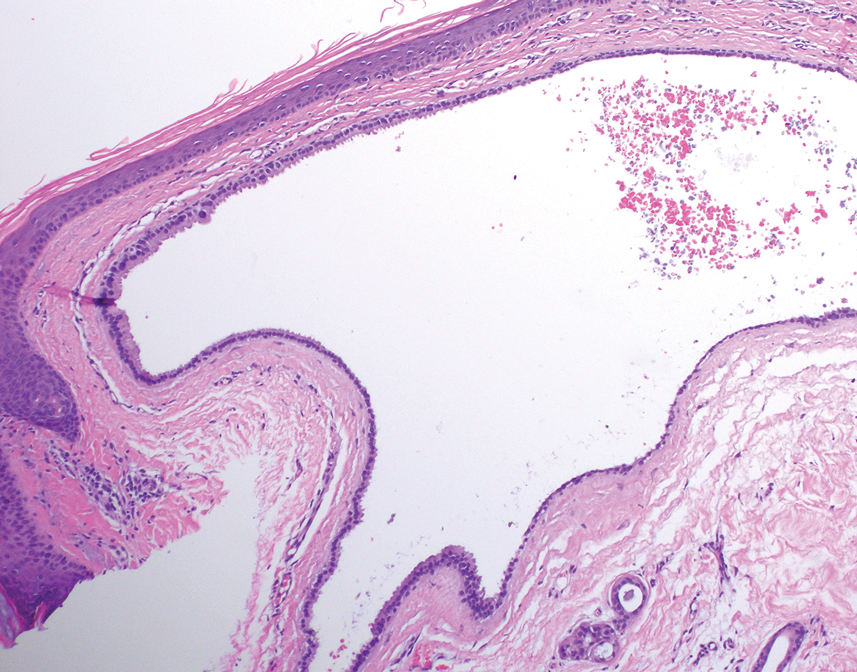

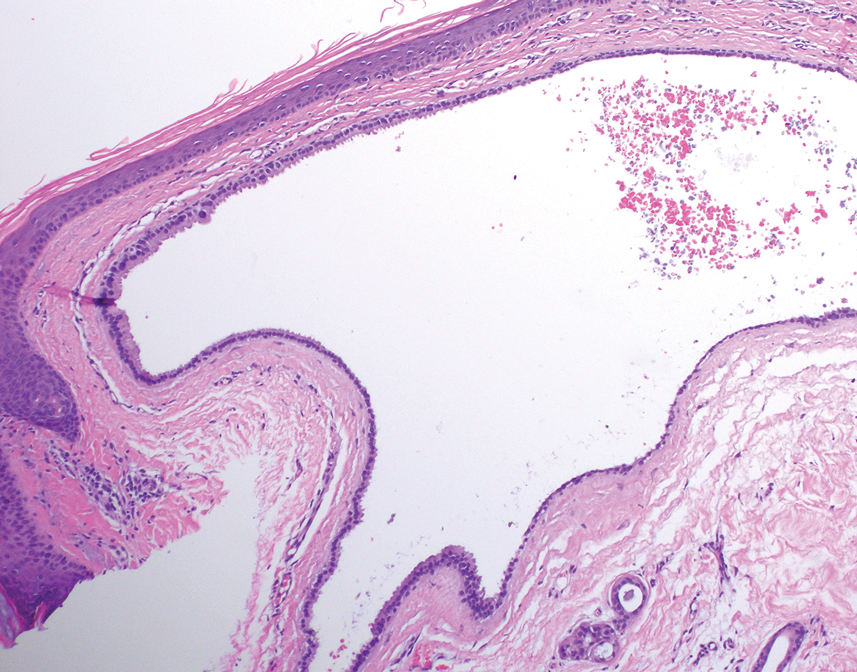

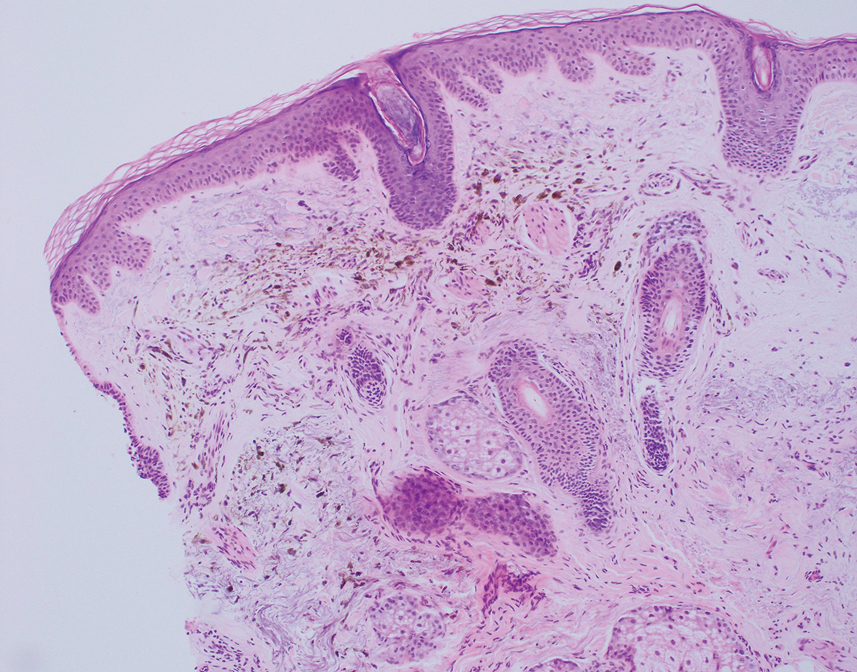

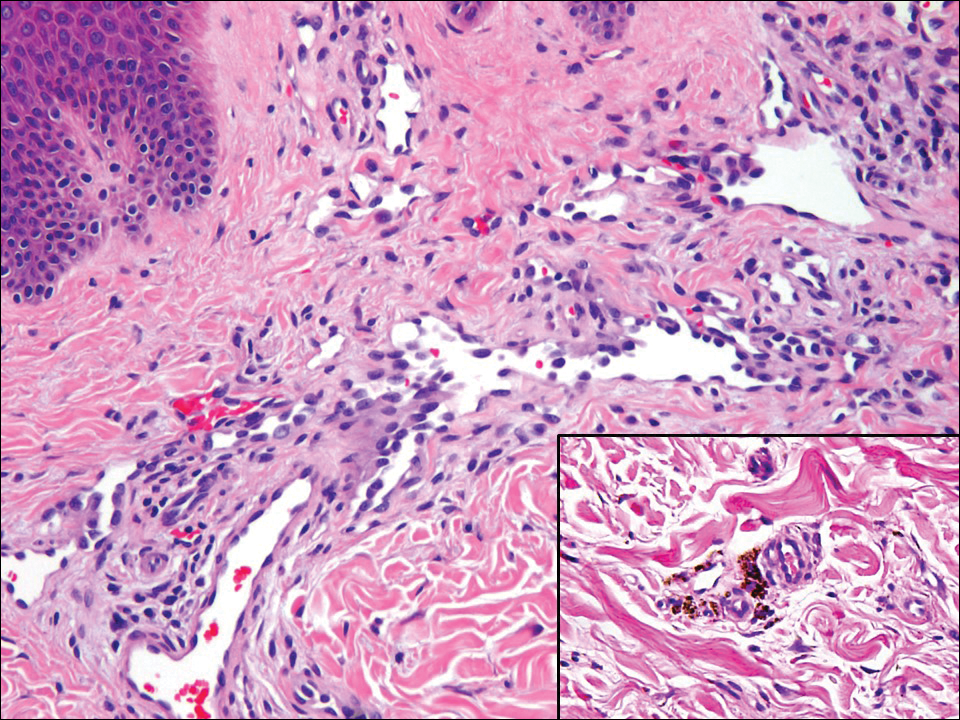

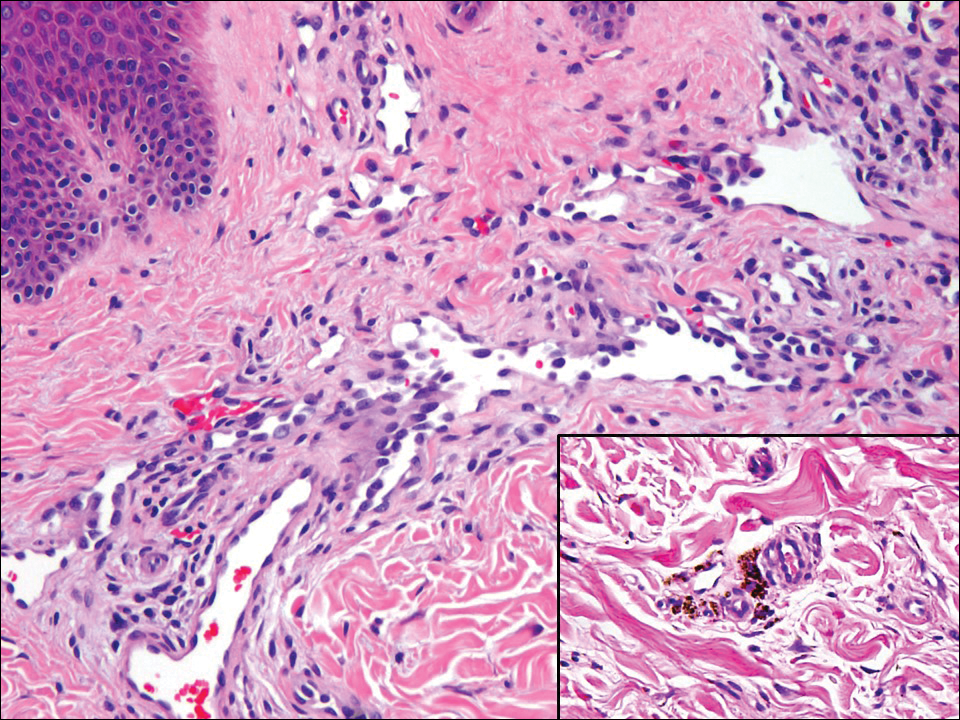

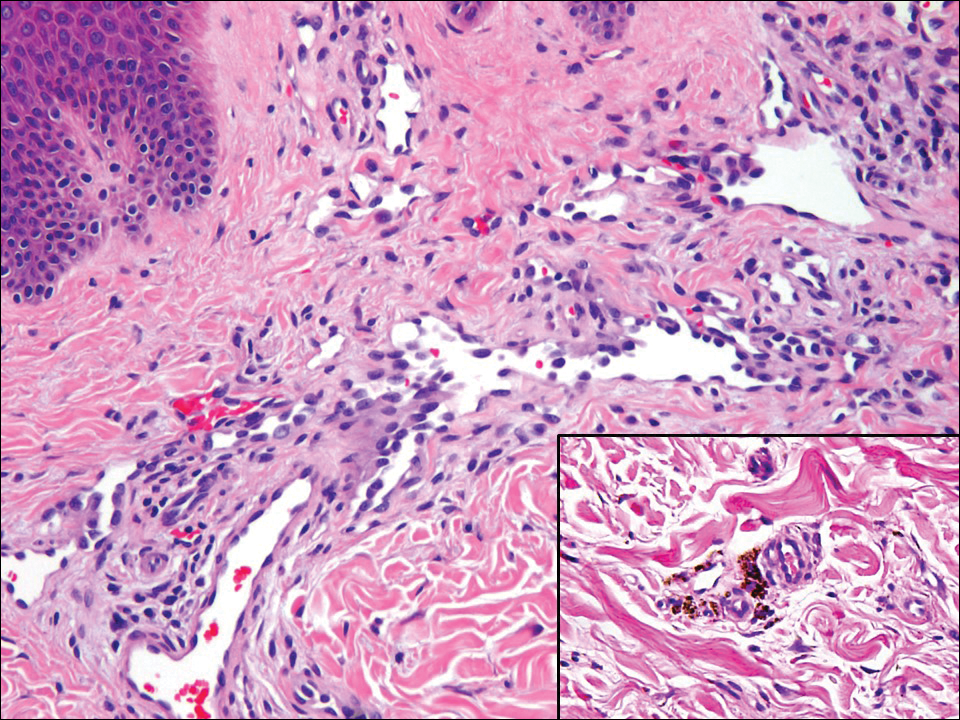

Histology for all 3 lesions demonstrated similar cystic structures lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells, with the outermost layer composed of flattened myoepithelial cells and the inner layer composed of cells with apocrine features (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystoma was made. The patient underwent successful surgical excision shortly thereafter without recurrence at follow-up 1 year later.

Apocrine hidrocystomas are rare benign cystic lesions that are considered to be adenomatous proliferations of apocrine glands. They typically manifest as solitary asymptomatic lesions measuring 3 to 15 mm.1 They tend to appear on the face, usually in the periorbital region, but also have been described on the neck, scalp, trunk, arms, and legs.2-4 Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas can be a marker of 2 rare inherited disorders: Gorlin-Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome.5 Apocrine hidrocystomas may be flesh colored or may have a blue, black, or brown appearance due to the Tyndall effect, in which light with shorter wavelengths is scattered by the contents of the lesions.2 Histologically, apocrine hidrocystomas are cysts lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells. The inner layer is composed of cells with apocrine features, and the outer layer is composed of flattened myoepithelial cells. Due to their range of colors and predilection for sun-exposed surfaces, apocrine hidrocystomas may be mistaken for various malignant neoplasms, including melanoma.6,7

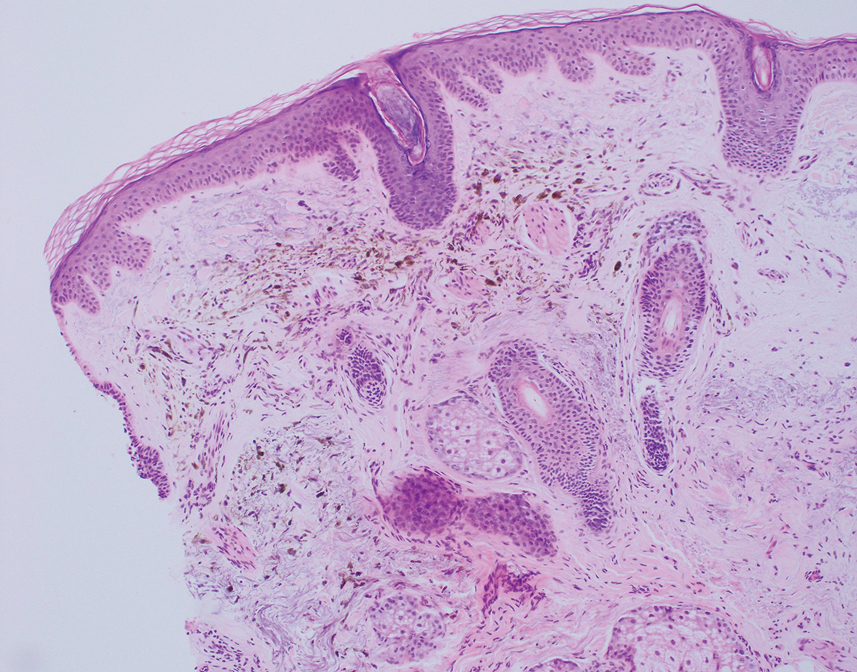

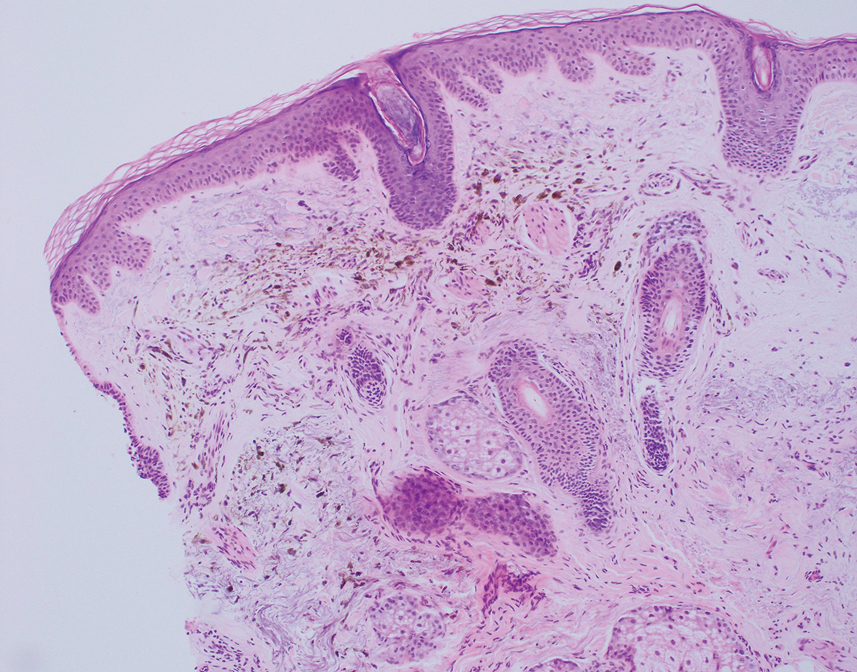

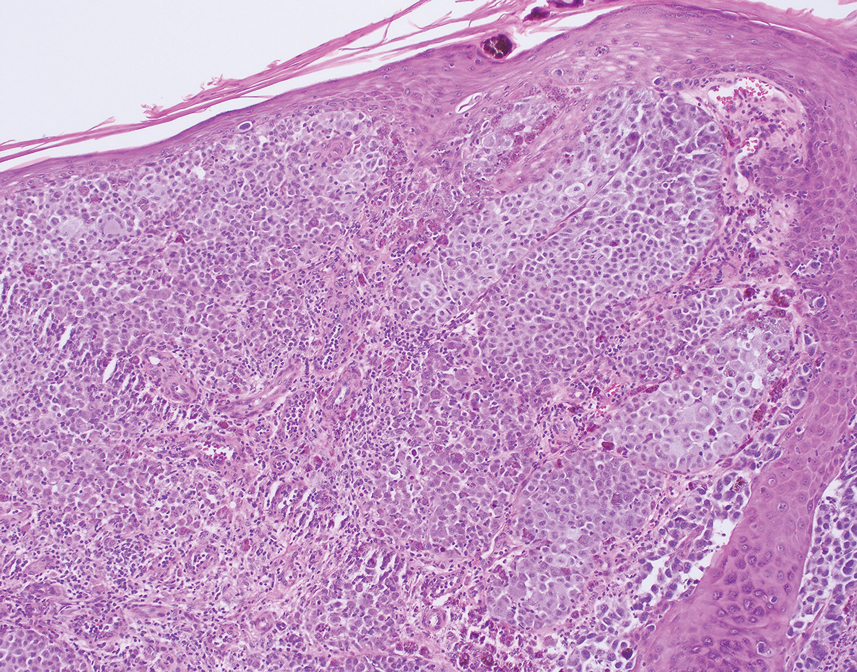

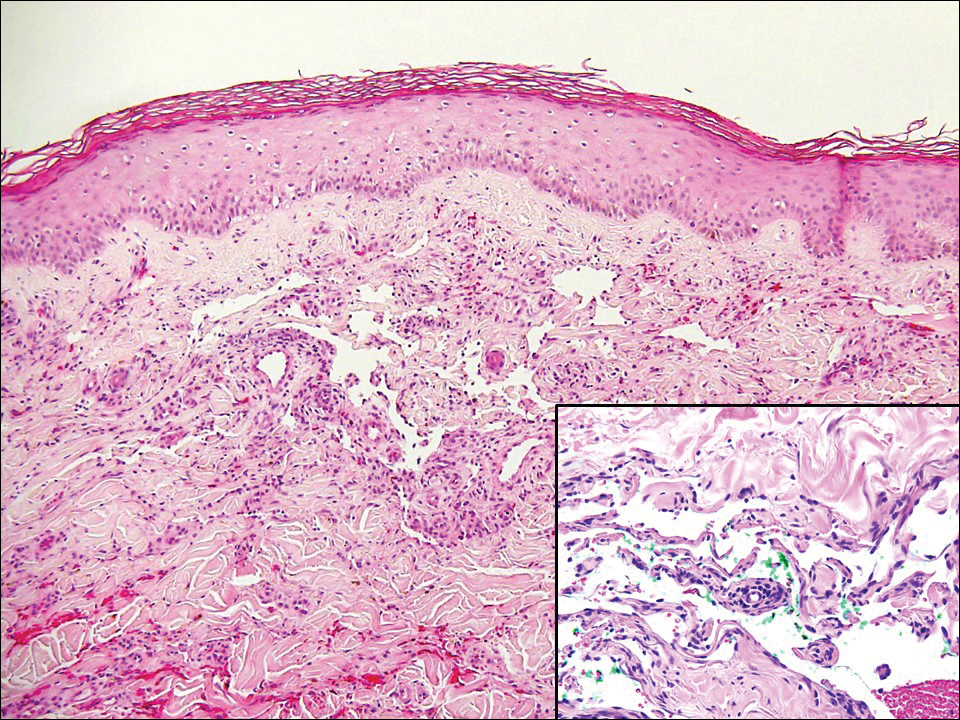

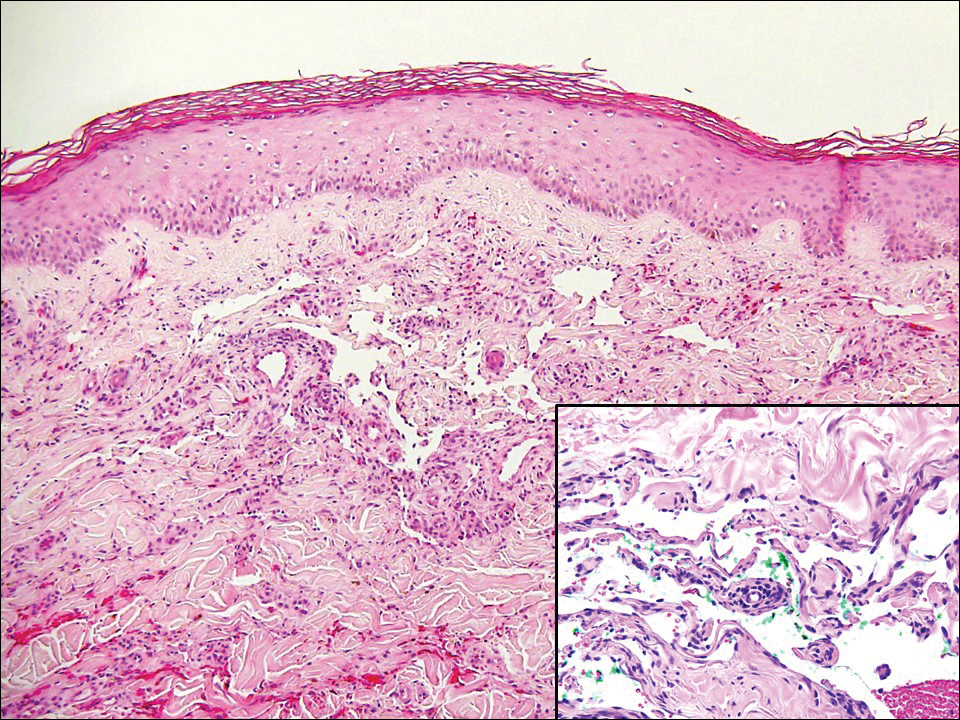

The differential diagnosis for our patient included agminated blue nevi, melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and seborrheic keratosis. A blue nevus is a dermal melanocytic lesion that manifests as a well-demarcated, blue to blue-black papule that typically appears on the face, scalp, arms, legs, lower back, and buttocks. Although there are several histologic subtypes, the common blue nevus usually manifests as a solitary lesion measuring less than 1 cm, often developing during childhood to young adulthood.8 Histologically, common blue nevi are characterized by a dermal proliferation of deeply pigmented bipolar spindled melanocytes embedded in thickened collagen bundles, often with scattered epithelioid melanophages, and no conspicuous mitotic activity (Figure 2).9 There are other types of blue nevi, including cellular blue nevi, which tend to be larger and manifest commonly on the buttocks and sacrococcygeal region in early adulthood.9 Histologically, cellular blue nevi contain oval to spindled melanocytes with scattered melanophages forming a well-demarcated nodule typically in the reticular dermis. There may be bulbous extension into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Occasional mitoses may be seen.9,10 Melanoma can arise from common or cellular blue nevi, though it more frequently occurs with cellular blue nevi. Other subtypes of blue nevi have been described, including the sclerosing, plaque-type, combined, hypomelanotic/amelanotic, and pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma.11 However, they typically have features of the common blue nevus or cellular blue nevus, such as oval/spindle cell morphology, some degree of melanin, and biphasic architecture, but are classified according to their dominant histologic characteristics.

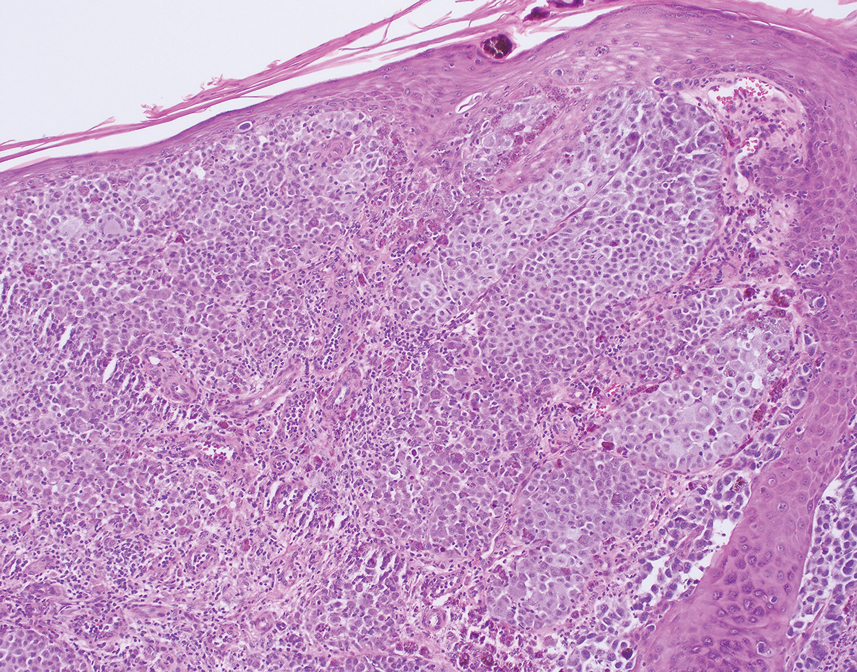

Given the location of our patient’s lesions on the scalp and his extensive history of sun exposure, malignancy was high in the differential. Multiple synchronous primary melanomas including nodular melanoma, blue nevus–like metastatic melanoma, and metastatic melanoma were considered. The leg and the scalp have the highest reported incidence of cutaneous metastases of melanoma, with many cases presenting as dermal or subcutaneous nodules and eruptive blue nevus–like papules, similar to our patient’s clinical presentation.12,13 Nodular melanoma (NM) is one of 4 major types of melanoma, accounting for approximately 15% to 30% of cases in the United States.14 Nodular melanoma typically manifests as a smooth, raised, symmetric, well-circumscribed lesion with variable pigmentation, from very dark to amelanotic. Histologically, NM is defined as a dermal mass, either in isolation or with an epidermal component, not to exceed 3 rete ridges beyond the dermal component.15 Tumor cells have a high cell density with pleomorphism, usually with atypical epithelioid cells with vesicular nuclei and irregular cytoplasm, and occasionally spindle cells (Figure 2).16 Mitoses and necrosis are frequent. Scalp location independently is responsible for worse survival, both overall and melanoma specific.17 Nodular melanoma tends to have greater Breslow thickness at diagnosis than other melanoma subtypes and often carries a worse prognosis.

Malignant melanomas that develop from or in conjunction with or bear histologic resemblance to blue nevi are termed blue nevus–like melanoma or blue nevus–associated melanoma. These malignancies are exceedingly rare, accounting for only 0.3% of melanomas in one Turkey-based multicenter study.18 The histologic criteria for diagnosing blue nevus–like melanoma are poorly defined, and terminology of these lesions has led to some debate in naming conventions.19 Nevertheless, unlike blue nevus, blue nevus–like melanoma demonstrates histologic features of malignancy, including pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, mitotic activity, vascular invasion, and potential necrosis.10 The lack of an inflammatory infiltrate, surrounding fibrosis, junctional activity, and pre-existing nevus can help distinguish cutaneous melanoma metastases from primary nodular melanoma. Immunohistochemical stains such as S100, Melan-A/MART1, or SOX-10 can help confirm melanocytic lineage.12

Pigmented BCC is a clinical and histologic variant of BCC characterized by increased melanin pigmentation due to melanocytes admixed with tumor cells. Dermoscopically, the pigment can have a maple leaf–like appearance with spoke-wheel areas, in-focus dots, and concentric structures at the dermoepidermal junction, which is more characteristic of superficial and infiltrating BCC.20 In nodular BCC, the pigment occurs as blue-gray ovoid nests and globules in deeper layers of the dermis.20

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) can vary widely in clinical appearance, with pigmentation ranging from flesh colored to yellow to brown to black. Melanoacanthomas are acanthotic SKs that are highly pigmented due to intermixed epidermal melanocytes and subepidermal melanophages.21 Dermoscopy can help distinguish cutaneous malignancies from SKs, which often demonstrate fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and milialike cysts. Biopsy sometimes is required to assess for malignancy, as was the case in our patient. The classic histologic features of SKs include acanthosis, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis.22

This case highlights the need to consider apocrine hidrocystoma, along with malignancy, in the differential diagnosis of pigmented cystic masses of the face and scalp. Because apocrine hidrocystomas are benign, they do not need to be treated but often are surgically excised for cosmesis or complete histopathologic examination. Destruction via electrodessication, carbon dioxide ablation, trichloroacetic acid chemical ablation, botulinum toxin injection, and anticholinergic creams sometimes is used, especially for cosmetic treatment of multiple small lesions.5 Our patient was treated with surgical excision with no evidence of recurrence on follow-up 1 year later.

- Ioannidis DG, Drivas EI, Papadakis CE, et al. Hidrocystoma of the external auditory canal: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:79. doi:10.1186/1757- 1626-2-79

- Nguyen HP, Barker HS, Bloomquist L, et al. Giant pigmented apocrine hidrocystoma of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26. doi:10.5070/D3268049895

- Mendoza-Cembranos MD, Haro R, Requena L, et al. Digital apocrine hidrocystoma: the exception confirms the rule. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:79. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001044

- May C, Chang O, Compton N. A giant apocrine hidrocystoma of the trunk. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23. doi:10.5070/D3239036497

- Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Hidrocystomas—a brief review. Medscape Gen Med. 2006;8:57.

- Kruse ALD, Zwahlen R, Bredell MG, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma of the cheek. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:594-596. doi:10.1097 /SCS.0b013e3181d08c77

- Zaballos P, Bañuls J, Medina C, et al. Dermoscopy of apocrine hidrocystomas: a morphological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:378-381. doi:10.1111/jdv.12044

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405. doi:10.1002 /1097-0142(196803)21:3<393::aid-cncr2820210309>3.0.co;2-k

- Murali R, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Blue nevi and related lesions: a review highlighting atypical and newly described variants, distinguishing features and diagnostic pitfalls. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:365. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181bb6b53

- Borgenvik TL, Karlsvik TM, Ray S, et al. Blue nevus-like and blue nevusassociated melanoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:345-349. doi:10.1111/ans.13946

- de la Fouchardiere A. Blue naevi and the blue tumour spectrum. Pathology. 2023;55:187-195. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.12.342

- Lowe L. Metastatic melanoma and rare melanoma variants: a review. Pathology (Phila). 2023;55:236-244. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.11.006

- Plaza JA, Torres-Cabala C, Evans H, et al. Cutaneous metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic study of 192 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:129-136. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181b34a19

- Shaikh WR, Xiong M, Weinstock MA. The contribution of nodular subtype to melanoma mortality in the United States, 1978 to 2007. Archives of Dermatology. 2012;148:30-36. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.264

- Clark WH, From L, Bernardino EA, et al. The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res. 1969;29:705-727.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321. doi:10.23736/S2784-8671.21.06958-3

- Ozao-Choy J, Nelson DW, Hiles J, et al. The prognostic importance of scalp location in primary head and neck melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:337-343. doi:10.1002/jso.24679

- Gamsizkan M, Yilmaz I, Buyukbabani N, et al. A retrospective multicenter evaluation of cutaneous melanomas in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2014;15:10451-10456. doi:10.7314 /apjcp.2014.15.23.10451

- Mones JM, Ackerman AB. “Atypical” blue nevus, “malignant” blue nevus, and “metastasizing” blue nevus: a critique in historical perspective of three concepts flawed fatally. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:407-430. doi:10.1097/00000372-200410000-00012

- Tanese K. Diagnosis and management of basal cell carcinoma Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:13. doi:10.1007/s11864 -019-0610-0

- Barthelmann S, Butsch F, Lang BM, et al. Seborrheic keratosis. JDDG J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023;21:265-277. doi:10.1111/ddg.14984

- Taylor S. Advancing the understanding of seborrheic keratosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:419-424.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

Histology for all 3 lesions demonstrated similar cystic structures lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells, with the outermost layer composed of flattened myoepithelial cells and the inner layer composed of cells with apocrine features (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystoma was made. The patient underwent successful surgical excision shortly thereafter without recurrence at follow-up 1 year later.

Apocrine hidrocystomas are rare benign cystic lesions that are considered to be adenomatous proliferations of apocrine glands. They typically manifest as solitary asymptomatic lesions measuring 3 to 15 mm.1 They tend to appear on the face, usually in the periorbital region, but also have been described on the neck, scalp, trunk, arms, and legs.2-4 Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas can be a marker of 2 rare inherited disorders: Gorlin-Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome.5 Apocrine hidrocystomas may be flesh colored or may have a blue, black, or brown appearance due to the Tyndall effect, in which light with shorter wavelengths is scattered by the contents of the lesions.2 Histologically, apocrine hidrocystomas are cysts lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells. The inner layer is composed of cells with apocrine features, and the outer layer is composed of flattened myoepithelial cells. Due to their range of colors and predilection for sun-exposed surfaces, apocrine hidrocystomas may be mistaken for various malignant neoplasms, including melanoma.6,7

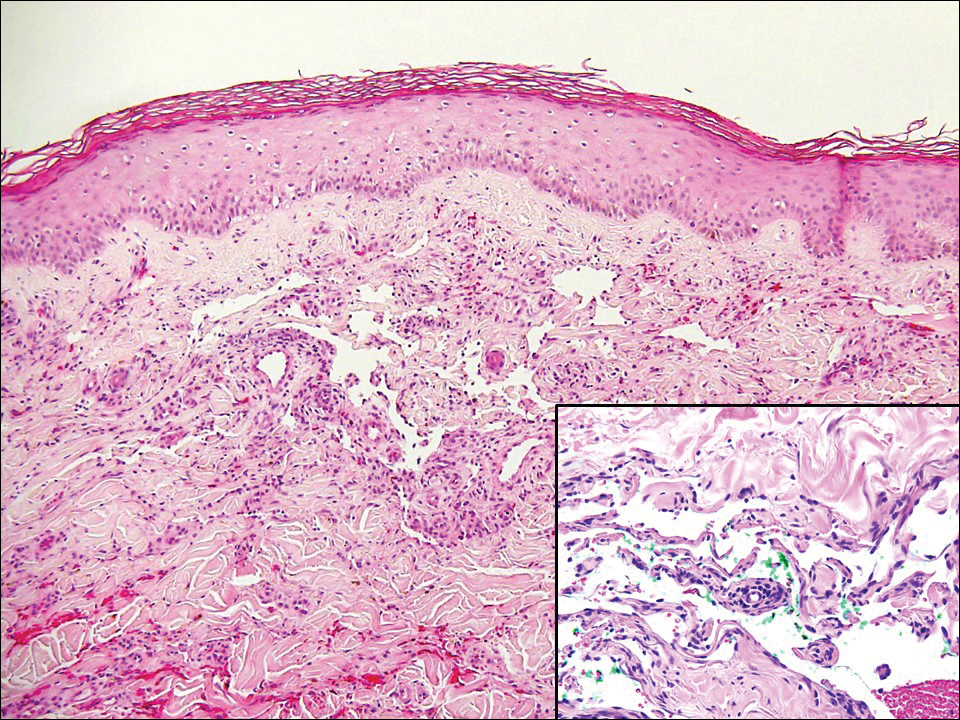

The differential diagnosis for our patient included agminated blue nevi, melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and seborrheic keratosis. A blue nevus is a dermal melanocytic lesion that manifests as a well-demarcated, blue to blue-black papule that typically appears on the face, scalp, arms, legs, lower back, and buttocks. Although there are several histologic subtypes, the common blue nevus usually manifests as a solitary lesion measuring less than 1 cm, often developing during childhood to young adulthood.8 Histologically, common blue nevi are characterized by a dermal proliferation of deeply pigmented bipolar spindled melanocytes embedded in thickened collagen bundles, often with scattered epithelioid melanophages, and no conspicuous mitotic activity (Figure 2).9 There are other types of blue nevi, including cellular blue nevi, which tend to be larger and manifest commonly on the buttocks and sacrococcygeal region in early adulthood.9 Histologically, cellular blue nevi contain oval to spindled melanocytes with scattered melanophages forming a well-demarcated nodule typically in the reticular dermis. There may be bulbous extension into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Occasional mitoses may be seen.9,10 Melanoma can arise from common or cellular blue nevi, though it more frequently occurs with cellular blue nevi. Other subtypes of blue nevi have been described, including the sclerosing, plaque-type, combined, hypomelanotic/amelanotic, and pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma.11 However, they typically have features of the common blue nevus or cellular blue nevus, such as oval/spindle cell morphology, some degree of melanin, and biphasic architecture, but are classified according to their dominant histologic characteristics.

Given the location of our patient’s lesions on the scalp and his extensive history of sun exposure, malignancy was high in the differential. Multiple synchronous primary melanomas including nodular melanoma, blue nevus–like metastatic melanoma, and metastatic melanoma were considered. The leg and the scalp have the highest reported incidence of cutaneous metastases of melanoma, with many cases presenting as dermal or subcutaneous nodules and eruptive blue nevus–like papules, similar to our patient’s clinical presentation.12,13 Nodular melanoma (NM) is one of 4 major types of melanoma, accounting for approximately 15% to 30% of cases in the United States.14 Nodular melanoma typically manifests as a smooth, raised, symmetric, well-circumscribed lesion with variable pigmentation, from very dark to amelanotic. Histologically, NM is defined as a dermal mass, either in isolation or with an epidermal component, not to exceed 3 rete ridges beyond the dermal component.15 Tumor cells have a high cell density with pleomorphism, usually with atypical epithelioid cells with vesicular nuclei and irregular cytoplasm, and occasionally spindle cells (Figure 2).16 Mitoses and necrosis are frequent. Scalp location independently is responsible for worse survival, both overall and melanoma specific.17 Nodular melanoma tends to have greater Breslow thickness at diagnosis than other melanoma subtypes and often carries a worse prognosis.

Malignant melanomas that develop from or in conjunction with or bear histologic resemblance to blue nevi are termed blue nevus–like melanoma or blue nevus–associated melanoma. These malignancies are exceedingly rare, accounting for only 0.3% of melanomas in one Turkey-based multicenter study.18 The histologic criteria for diagnosing blue nevus–like melanoma are poorly defined, and terminology of these lesions has led to some debate in naming conventions.19 Nevertheless, unlike blue nevus, blue nevus–like melanoma demonstrates histologic features of malignancy, including pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, mitotic activity, vascular invasion, and potential necrosis.10 The lack of an inflammatory infiltrate, surrounding fibrosis, junctional activity, and pre-existing nevus can help distinguish cutaneous melanoma metastases from primary nodular melanoma. Immunohistochemical stains such as S100, Melan-A/MART1, or SOX-10 can help confirm melanocytic lineage.12

Pigmented BCC is a clinical and histologic variant of BCC characterized by increased melanin pigmentation due to melanocytes admixed with tumor cells. Dermoscopically, the pigment can have a maple leaf–like appearance with spoke-wheel areas, in-focus dots, and concentric structures at the dermoepidermal junction, which is more characteristic of superficial and infiltrating BCC.20 In nodular BCC, the pigment occurs as blue-gray ovoid nests and globules in deeper layers of the dermis.20

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) can vary widely in clinical appearance, with pigmentation ranging from flesh colored to yellow to brown to black. Melanoacanthomas are acanthotic SKs that are highly pigmented due to intermixed epidermal melanocytes and subepidermal melanophages.21 Dermoscopy can help distinguish cutaneous malignancies from SKs, which often demonstrate fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and milialike cysts. Biopsy sometimes is required to assess for malignancy, as was the case in our patient. The classic histologic features of SKs include acanthosis, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis.22

This case highlights the need to consider apocrine hidrocystoma, along with malignancy, in the differential diagnosis of pigmented cystic masses of the face and scalp. Because apocrine hidrocystomas are benign, they do not need to be treated but often are surgically excised for cosmesis or complete histopathologic examination. Destruction via electrodessication, carbon dioxide ablation, trichloroacetic acid chemical ablation, botulinum toxin injection, and anticholinergic creams sometimes is used, especially for cosmetic treatment of multiple small lesions.5 Our patient was treated with surgical excision with no evidence of recurrence on follow-up 1 year later.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

Histology for all 3 lesions demonstrated similar cystic structures lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells, with the outermost layer composed of flattened myoepithelial cells and the inner layer composed of cells with apocrine features (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystoma was made. The patient underwent successful surgical excision shortly thereafter without recurrence at follow-up 1 year later.

Apocrine hidrocystomas are rare benign cystic lesions that are considered to be adenomatous proliferations of apocrine glands. They typically manifest as solitary asymptomatic lesions measuring 3 to 15 mm.1 They tend to appear on the face, usually in the periorbital region, but also have been described on the neck, scalp, trunk, arms, and legs.2-4 Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas can be a marker of 2 rare inherited disorders: Gorlin-Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome.5 Apocrine hidrocystomas may be flesh colored or may have a blue, black, or brown appearance due to the Tyndall effect, in which light with shorter wavelengths is scattered by the contents of the lesions.2 Histologically, apocrine hidrocystomas are cysts lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells. The inner layer is composed of cells with apocrine features, and the outer layer is composed of flattened myoepithelial cells. Due to their range of colors and predilection for sun-exposed surfaces, apocrine hidrocystomas may be mistaken for various malignant neoplasms, including melanoma.6,7

The differential diagnosis for our patient included agminated blue nevi, melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and seborrheic keratosis. A blue nevus is a dermal melanocytic lesion that manifests as a well-demarcated, blue to blue-black papule that typically appears on the face, scalp, arms, legs, lower back, and buttocks. Although there are several histologic subtypes, the common blue nevus usually manifests as a solitary lesion measuring less than 1 cm, often developing during childhood to young adulthood.8 Histologically, common blue nevi are characterized by a dermal proliferation of deeply pigmented bipolar spindled melanocytes embedded in thickened collagen bundles, often with scattered epithelioid melanophages, and no conspicuous mitotic activity (Figure 2).9 There are other types of blue nevi, including cellular blue nevi, which tend to be larger and manifest commonly on the buttocks and sacrococcygeal region in early adulthood.9 Histologically, cellular blue nevi contain oval to spindled melanocytes with scattered melanophages forming a well-demarcated nodule typically in the reticular dermis. There may be bulbous extension into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Occasional mitoses may be seen.9,10 Melanoma can arise from common or cellular blue nevi, though it more frequently occurs with cellular blue nevi. Other subtypes of blue nevi have been described, including the sclerosing, plaque-type, combined, hypomelanotic/amelanotic, and pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma.11 However, they typically have features of the common blue nevus or cellular blue nevus, such as oval/spindle cell morphology, some degree of melanin, and biphasic architecture, but are classified according to their dominant histologic characteristics.

Given the location of our patient’s lesions on the scalp and his extensive history of sun exposure, malignancy was high in the differential. Multiple synchronous primary melanomas including nodular melanoma, blue nevus–like metastatic melanoma, and metastatic melanoma were considered. The leg and the scalp have the highest reported incidence of cutaneous metastases of melanoma, with many cases presenting as dermal or subcutaneous nodules and eruptive blue nevus–like papules, similar to our patient’s clinical presentation.12,13 Nodular melanoma (NM) is one of 4 major types of melanoma, accounting for approximately 15% to 30% of cases in the United States.14 Nodular melanoma typically manifests as a smooth, raised, symmetric, well-circumscribed lesion with variable pigmentation, from very dark to amelanotic. Histologically, NM is defined as a dermal mass, either in isolation or with an epidermal component, not to exceed 3 rete ridges beyond the dermal component.15 Tumor cells have a high cell density with pleomorphism, usually with atypical epithelioid cells with vesicular nuclei and irregular cytoplasm, and occasionally spindle cells (Figure 2).16 Mitoses and necrosis are frequent. Scalp location independently is responsible for worse survival, both overall and melanoma specific.17 Nodular melanoma tends to have greater Breslow thickness at diagnosis than other melanoma subtypes and often carries a worse prognosis.

Malignant melanomas that develop from or in conjunction with or bear histologic resemblance to blue nevi are termed blue nevus–like melanoma or blue nevus–associated melanoma. These malignancies are exceedingly rare, accounting for only 0.3% of melanomas in one Turkey-based multicenter study.18 The histologic criteria for diagnosing blue nevus–like melanoma are poorly defined, and terminology of these lesions has led to some debate in naming conventions.19 Nevertheless, unlike blue nevus, blue nevus–like melanoma demonstrates histologic features of malignancy, including pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, mitotic activity, vascular invasion, and potential necrosis.10 The lack of an inflammatory infiltrate, surrounding fibrosis, junctional activity, and pre-existing nevus can help distinguish cutaneous melanoma metastases from primary nodular melanoma. Immunohistochemical stains such as S100, Melan-A/MART1, or SOX-10 can help confirm melanocytic lineage.12

Pigmented BCC is a clinical and histologic variant of BCC characterized by increased melanin pigmentation due to melanocytes admixed with tumor cells. Dermoscopically, the pigment can have a maple leaf–like appearance with spoke-wheel areas, in-focus dots, and concentric structures at the dermoepidermal junction, which is more characteristic of superficial and infiltrating BCC.20 In nodular BCC, the pigment occurs as blue-gray ovoid nests and globules in deeper layers of the dermis.20

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) can vary widely in clinical appearance, with pigmentation ranging from flesh colored to yellow to brown to black. Melanoacanthomas are acanthotic SKs that are highly pigmented due to intermixed epidermal melanocytes and subepidermal melanophages.21 Dermoscopy can help distinguish cutaneous malignancies from SKs, which often demonstrate fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and milialike cysts. Biopsy sometimes is required to assess for malignancy, as was the case in our patient. The classic histologic features of SKs include acanthosis, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis.22

This case highlights the need to consider apocrine hidrocystoma, along with malignancy, in the differential diagnosis of pigmented cystic masses of the face and scalp. Because apocrine hidrocystomas are benign, they do not need to be treated but often are surgically excised for cosmesis or complete histopathologic examination. Destruction via electrodessication, carbon dioxide ablation, trichloroacetic acid chemical ablation, botulinum toxin injection, and anticholinergic creams sometimes is used, especially for cosmetic treatment of multiple small lesions.5 Our patient was treated with surgical excision with no evidence of recurrence on follow-up 1 year later.

- Ioannidis DG, Drivas EI, Papadakis CE, et al. Hidrocystoma of the external auditory canal: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:79. doi:10.1186/1757- 1626-2-79

- Nguyen HP, Barker HS, Bloomquist L, et al. Giant pigmented apocrine hidrocystoma of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26. doi:10.5070/D3268049895

- Mendoza-Cembranos MD, Haro R, Requena L, et al. Digital apocrine hidrocystoma: the exception confirms the rule. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:79. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001044

- May C, Chang O, Compton N. A giant apocrine hidrocystoma of the trunk. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23. doi:10.5070/D3239036497

- Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Hidrocystomas—a brief review. Medscape Gen Med. 2006;8:57.

- Kruse ALD, Zwahlen R, Bredell MG, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma of the cheek. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:594-596. doi:10.1097 /SCS.0b013e3181d08c77

- Zaballos P, Bañuls J, Medina C, et al. Dermoscopy of apocrine hidrocystomas: a morphological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:378-381. doi:10.1111/jdv.12044

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405. doi:10.1002 /1097-0142(196803)21:3<393::aid-cncr2820210309>3.0.co;2-k

- Murali R, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Blue nevi and related lesions: a review highlighting atypical and newly described variants, distinguishing features and diagnostic pitfalls. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:365. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181bb6b53

- Borgenvik TL, Karlsvik TM, Ray S, et al. Blue nevus-like and blue nevusassociated melanoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:345-349. doi:10.1111/ans.13946

- de la Fouchardiere A. Blue naevi and the blue tumour spectrum. Pathology. 2023;55:187-195. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.12.342

- Lowe L. Metastatic melanoma and rare melanoma variants: a review. Pathology (Phila). 2023;55:236-244. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.11.006

- Plaza JA, Torres-Cabala C, Evans H, et al. Cutaneous metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic study of 192 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:129-136. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181b34a19

- Shaikh WR, Xiong M, Weinstock MA. The contribution of nodular subtype to melanoma mortality in the United States, 1978 to 2007. Archives of Dermatology. 2012;148:30-36. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.264

- Clark WH, From L, Bernardino EA, et al. The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res. 1969;29:705-727.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321. doi:10.23736/S2784-8671.21.06958-3

- Ozao-Choy J, Nelson DW, Hiles J, et al. The prognostic importance of scalp location in primary head and neck melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:337-343. doi:10.1002/jso.24679

- Gamsizkan M, Yilmaz I, Buyukbabani N, et al. A retrospective multicenter evaluation of cutaneous melanomas in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2014;15:10451-10456. doi:10.7314 /apjcp.2014.15.23.10451

- Mones JM, Ackerman AB. “Atypical” blue nevus, “malignant” blue nevus, and “metastasizing” blue nevus: a critique in historical perspective of three concepts flawed fatally. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:407-430. doi:10.1097/00000372-200410000-00012

- Tanese K. Diagnosis and management of basal cell carcinoma Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:13. doi:10.1007/s11864 -019-0610-0

- Barthelmann S, Butsch F, Lang BM, et al. Seborrheic keratosis. JDDG J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023;21:265-277. doi:10.1111/ddg.14984

- Taylor S. Advancing the understanding of seborrheic keratosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:419-424.

- Ioannidis DG, Drivas EI, Papadakis CE, et al. Hidrocystoma of the external auditory canal: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:79. doi:10.1186/1757- 1626-2-79

- Nguyen HP, Barker HS, Bloomquist L, et al. Giant pigmented apocrine hidrocystoma of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26. doi:10.5070/D3268049895

- Mendoza-Cembranos MD, Haro R, Requena L, et al. Digital apocrine hidrocystoma: the exception confirms the rule. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:79. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001044

- May C, Chang O, Compton N. A giant apocrine hidrocystoma of the trunk. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23. doi:10.5070/D3239036497

- Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Hidrocystomas—a brief review. Medscape Gen Med. 2006;8:57.

- Kruse ALD, Zwahlen R, Bredell MG, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma of the cheek. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:594-596. doi:10.1097 /SCS.0b013e3181d08c77

- Zaballos P, Bañuls J, Medina C, et al. Dermoscopy of apocrine hidrocystomas: a morphological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:378-381. doi:10.1111/jdv.12044

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405. doi:10.1002 /1097-0142(196803)21:3<393::aid-cncr2820210309>3.0.co;2-k

- Murali R, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Blue nevi and related lesions: a review highlighting atypical and newly described variants, distinguishing features and diagnostic pitfalls. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:365. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181bb6b53

- Borgenvik TL, Karlsvik TM, Ray S, et al. Blue nevus-like and blue nevusassociated melanoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:345-349. doi:10.1111/ans.13946

- de la Fouchardiere A. Blue naevi and the blue tumour spectrum. Pathology. 2023;55:187-195. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.12.342

- Lowe L. Metastatic melanoma and rare melanoma variants: a review. Pathology (Phila). 2023;55:236-244. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.11.006

- Plaza JA, Torres-Cabala C, Evans H, et al. Cutaneous metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic study of 192 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:129-136. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181b34a19

- Shaikh WR, Xiong M, Weinstock MA. The contribution of nodular subtype to melanoma mortality in the United States, 1978 to 2007. Archives of Dermatology. 2012;148:30-36. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.264

- Clark WH, From L, Bernardino EA, et al. The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res. 1969;29:705-727.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321. doi:10.23736/S2784-8671.21.06958-3

- Ozao-Choy J, Nelson DW, Hiles J, et al. The prognostic importance of scalp location in primary head and neck melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:337-343. doi:10.1002/jso.24679

- Gamsizkan M, Yilmaz I, Buyukbabani N, et al. A retrospective multicenter evaluation of cutaneous melanomas in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2014;15:10451-10456. doi:10.7314 /apjcp.2014.15.23.10451

- Mones JM, Ackerman AB. “Atypical” blue nevus, “malignant” blue nevus, and “metastasizing” blue nevus: a critique in historical perspective of three concepts flawed fatally. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:407-430. doi:10.1097/00000372-200410000-00012

- Tanese K. Diagnosis and management of basal cell carcinoma Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:13. doi:10.1007/s11864 -019-0610-0

- Barthelmann S, Butsch F, Lang BM, et al. Seborrheic keratosis. JDDG J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023;21:265-277. doi:10.1111/ddg.14984

- Taylor S. Advancing the understanding of seborrheic keratosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:419-424.

A 67-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with 3 asymptomatic pigmented papules on the scalp. The patient reported that he was unaware of the lesions until they were pointed out weeks earlier by his primary care physician during a routine visit. He then was referred to dermatology for follow-up. Physical examination at the current presentation revealed clustered firm, smooth, well-circumscribed, pigmented papules on the scalp measuring 5 to 8 mm. The patient reported no personal or family history of skin cancer but stated that he spent a lot of time outdoors and had a history of 6 blistering sunburns in his life. A punch biopsy of each lesion was performed.

Purpuric Macule of the Right Axilla

The Diagnosis: Atypical Vascular Lesion

Atypical vascular lesion (AVL)(quiz image), named by Fineberg and Rosen,1 is a vascular lesion that arises on mammary skin with a history of radiation exposure. Clinically, AVL can present as a papule or erythematous patch that manifests 3 to 7 years after radiation therapy.2,3 There are 2 histologic subtypes of AVL: lymphatic and vascular.2,4 Lymphatic-type AVL is comprised of a symmetric distribution of thin, dilated, and anastomosing vessels usually found in the superficial and mid dermis. The vessels are lined by flat or hobnail protuberant endothelial cells that lack nuclear irregularity or pleomorphism; however, hyperchromatism of endothelial cell nuclei is a common finding. Vascular-type AVL is morphologically similar to a capillary hemangioma, and histologic features include irregular growth of capillary-sized vessels that extend to the dermis and subcutis.2,4 Atypical vascular lesions are benign lesions but may be a precursor to angiosarcoma. Along with vascular markers, D2-40 typically is positive. Surgical excision with clear margins is recommended when the lesion is small.4,5 Observation is more appropriate for extensive lesions.

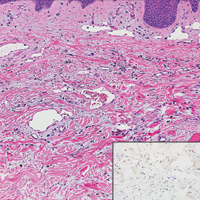

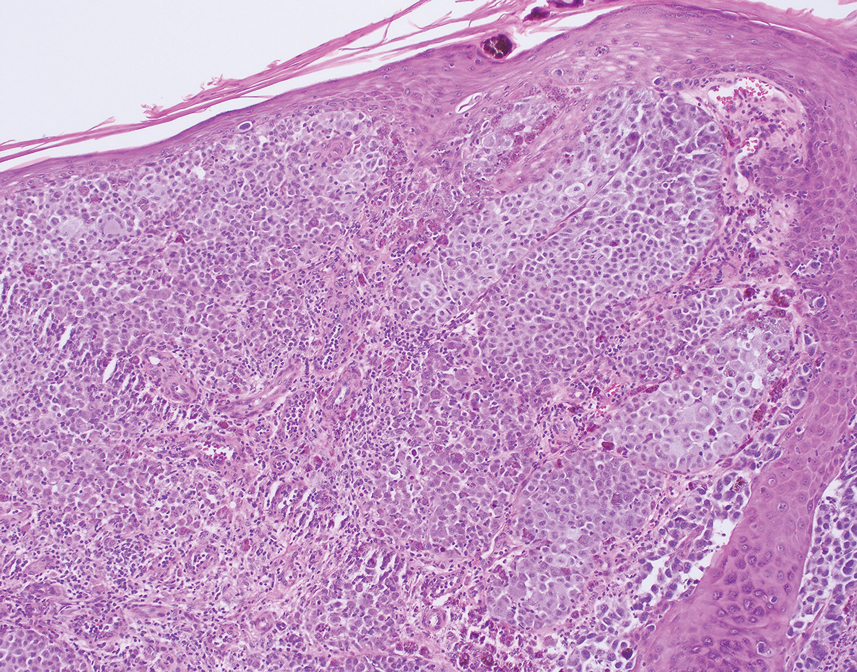

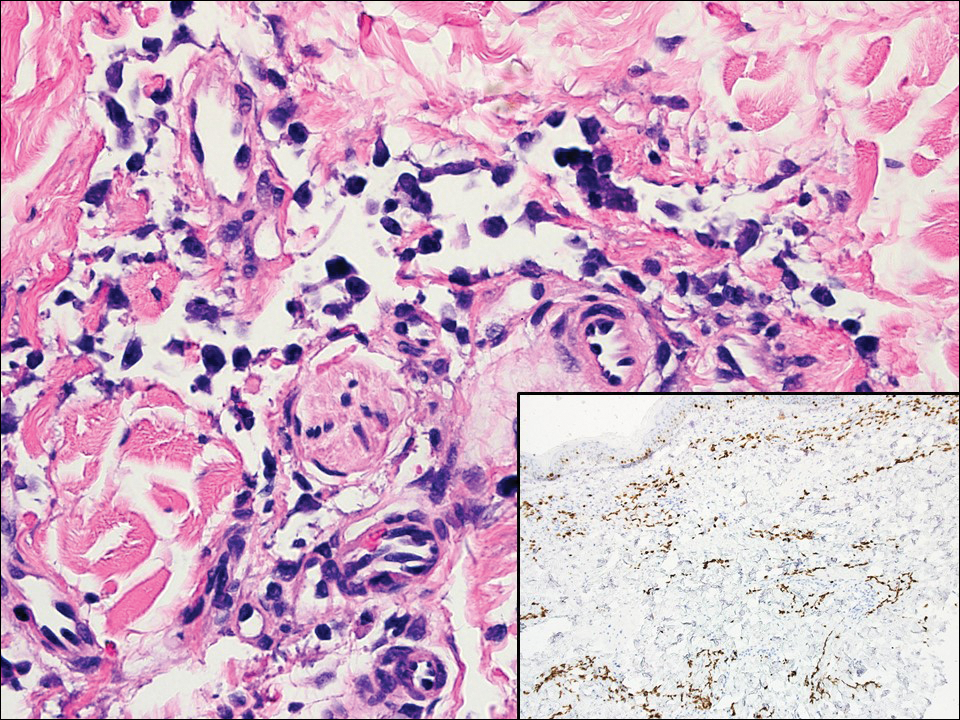

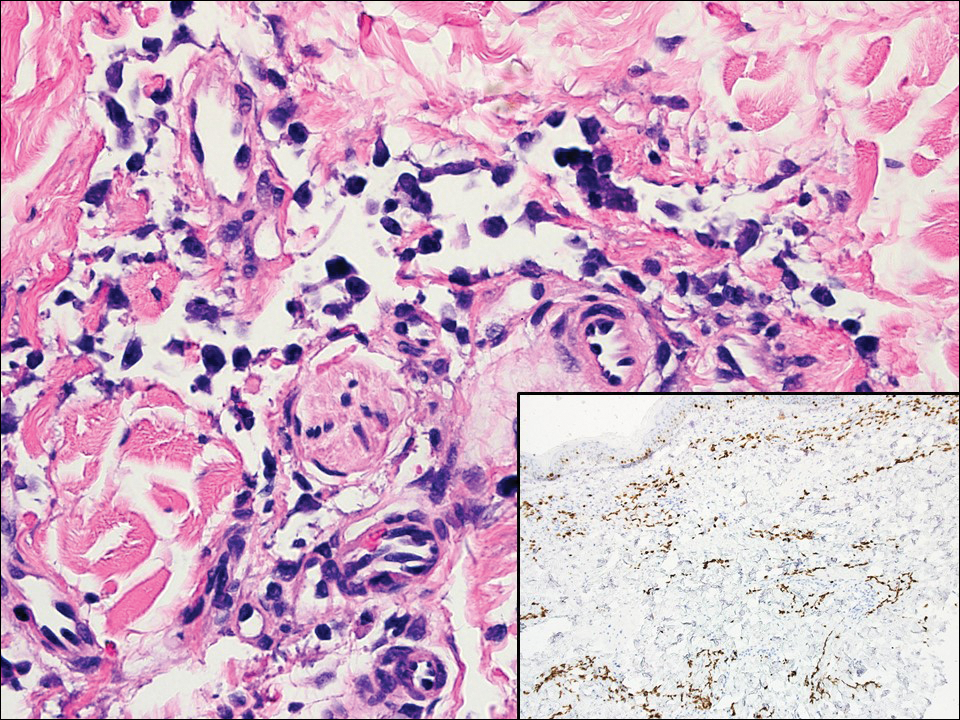

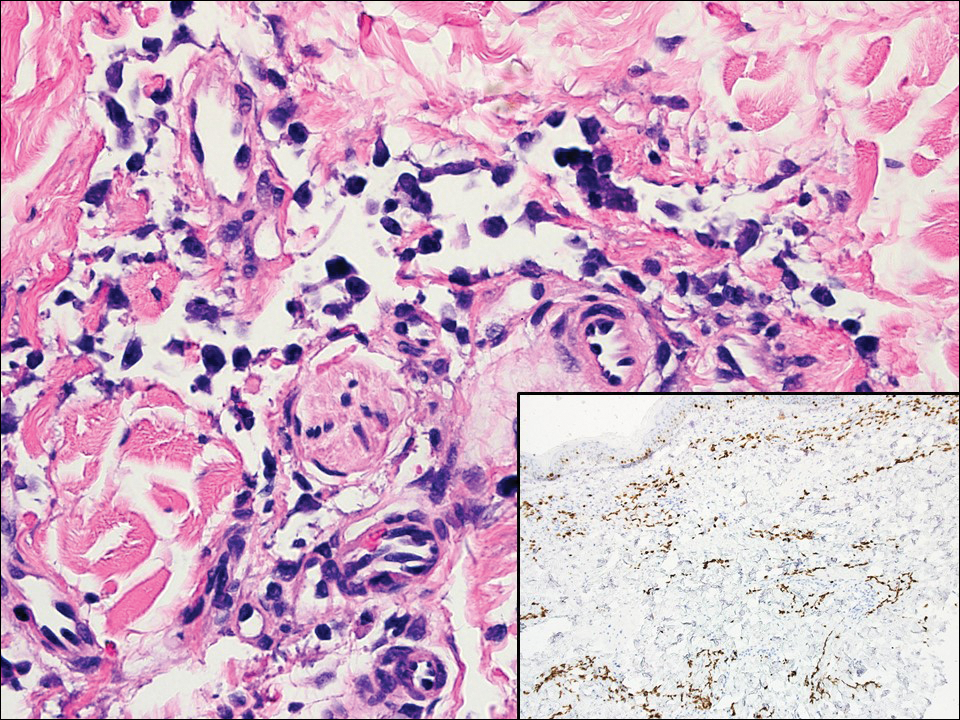

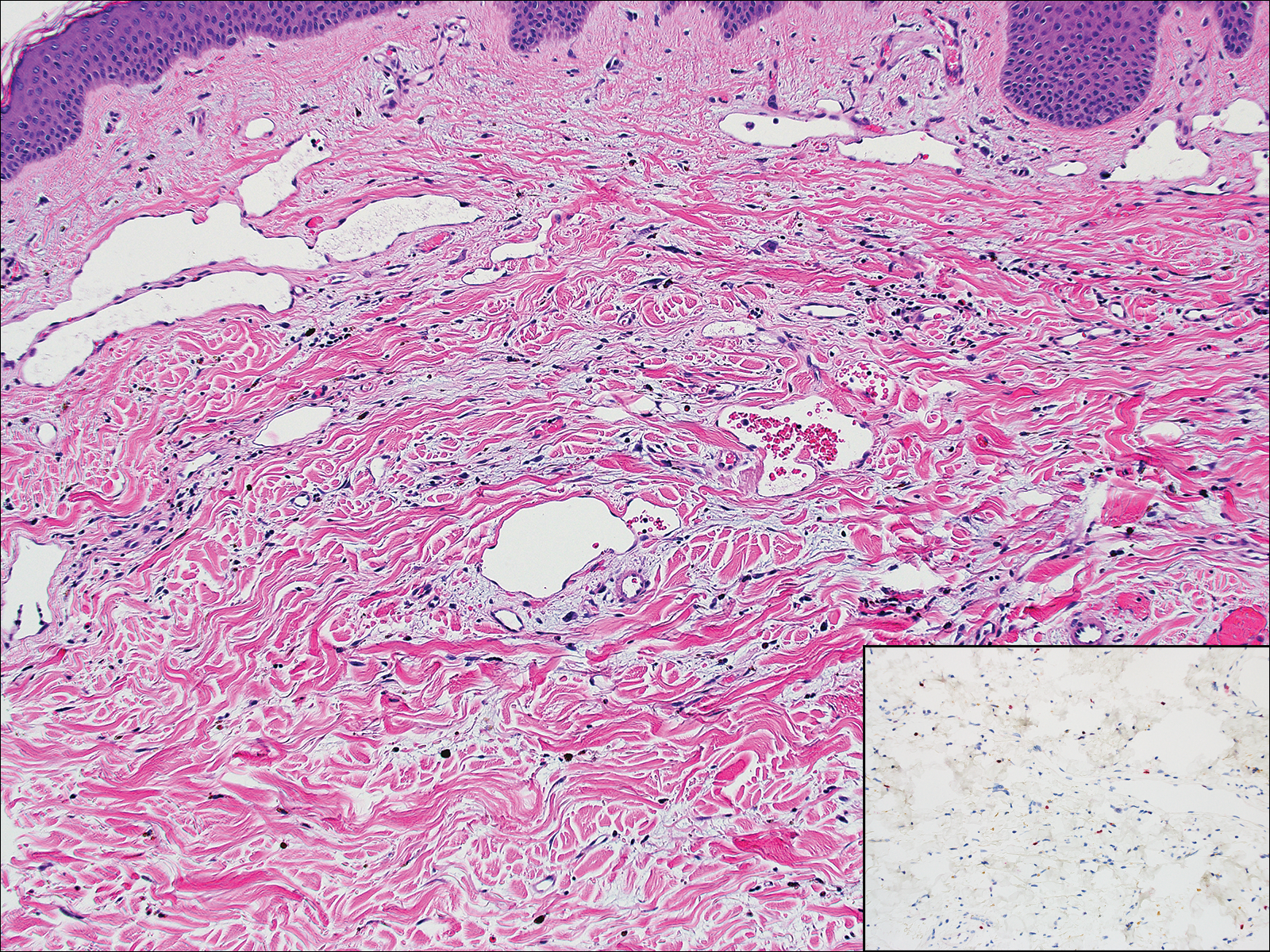

Angiosarcoma can arise spontaneously or in association with radiation or chronic lymphedema. Given the shared risk factors and presentation with AVL, it is essential to differentiate angiosarcoma from AVL. Primary cutaneous angiosarcoma usually presents on the head of elderly patients as an ecchymotic patch or plaque with ulceration.4 Secondary angiosarcoma may arise following radiation or chronic lymphedema (Stewart-Treves syndrome); however, some authors now prefer to consider lymphangiosarcoma arising in chronic lymphedematous limbs a distinct entity.6 Surgical excision with wide margins is the mainstay of therapy, but angiosarcoma has high recurrence rates, and the 5-year survival rate has been reported to be as low as 35%.7 Histologic overlap with AVL includes dissecting anastomosing vessels lined by hyperchromatic nuclei; however, angiosarcoma is distinguished by endothelial cell layering, nuclear pleomorphism, and prominent nucleoli (Figure 1).4,8 Increased positivity for Ki-67 immunostain, which indicates cell proliferation, may be used to distinguish angiosarcoma from an AVL (Figure 1 [inset]).9 Further, in contrast to AVL, radiation-induced angiosarcoma is characterized by amplification of C-MYC, a regulator gene, and FLT4 (FMS-related tyrosine kinase 4), a gene encoding vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3. Gene amplification may be detected through immunohistochemistry or fluorescence in situ hybridization.10 Ki-67 labeling showed less than 10% staining in endothelial cells in our case (quiz image [inset]), and fluorescence in situ hybridization was negative for C-MYC amplification, supporting the diagnosis of AVL.

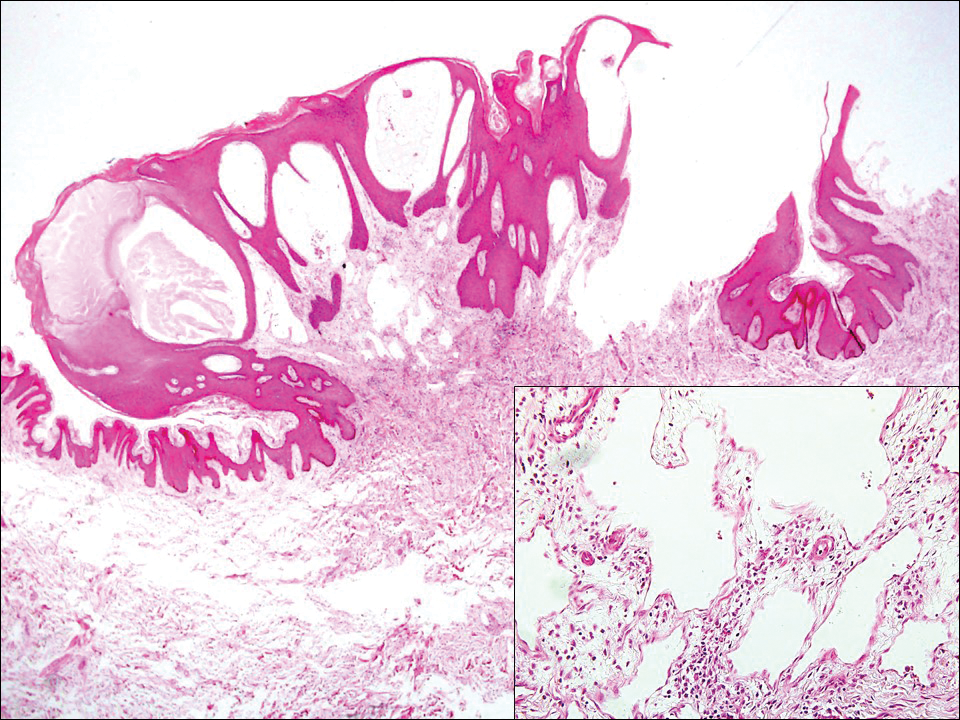

Lymphangioma circumscriptum, the most common superficial lymphangioma, is a hamartomatous malformation that usually occurs at the axillary folds, neck, and trunk. It clinically presents as small agminated vesicles with a characteristic frog spawn appearance.11 Dermoscopic features include yellow lacunae that may alternate with a dark red color secondary to extravasation of erythrocytes.12 These clinical features often lead to a differential diagnosis of verrucae, angiokeratoma, and angiosarcoma. Lymphangioma circumscriptum histologically is characterized by an overgrowth of dilated lymphatic vessels that fill the papillary dermis. The vessels are composed of flat endothelial cells typically filled with acellular proteinaceous debris and occasional erythrocytes (Figure 2). As the lesion traverses deeper into the dermis, the caliber of the lymphatic channel becomes narrower. The presence of deep lymphatic cisterns with surrounding smooth muscle is helpful to differentiate lymphangioma circumscriptum from other lymphatic malformations such as acquired lymphangiectasia. Treatment options include surgical excision, sclerosing agents, and destructive modalities such as cryotherapy.

Hobnail hemangioma, originally termed targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma by Santa Cruz and Aronberg,13 presents as a violaceous papule or nodule surrounded by a characteristic brown halo on the leg. Trauma has been proposed as the inciting factor for the clinical appearance of hobnail hemangioma.14 Microscopically, the lesion shows vessels in a wedge shape. The superficial component has telangiectatic vessels with focal areas of papillary projections lined by endothelial cells. Although the endothelial nuclei typically project into the lumen, the nuclei are small, bland, and without mitotic activity.15 Deeper components show slit-shaped vasculature with dermal collagen dissection. Hemosiderin, extravasated red blood cells, and inflammation are found adjacent to the vessels (Figure 3). Given the benign nature, hobnail hemangiomas may be monitored.

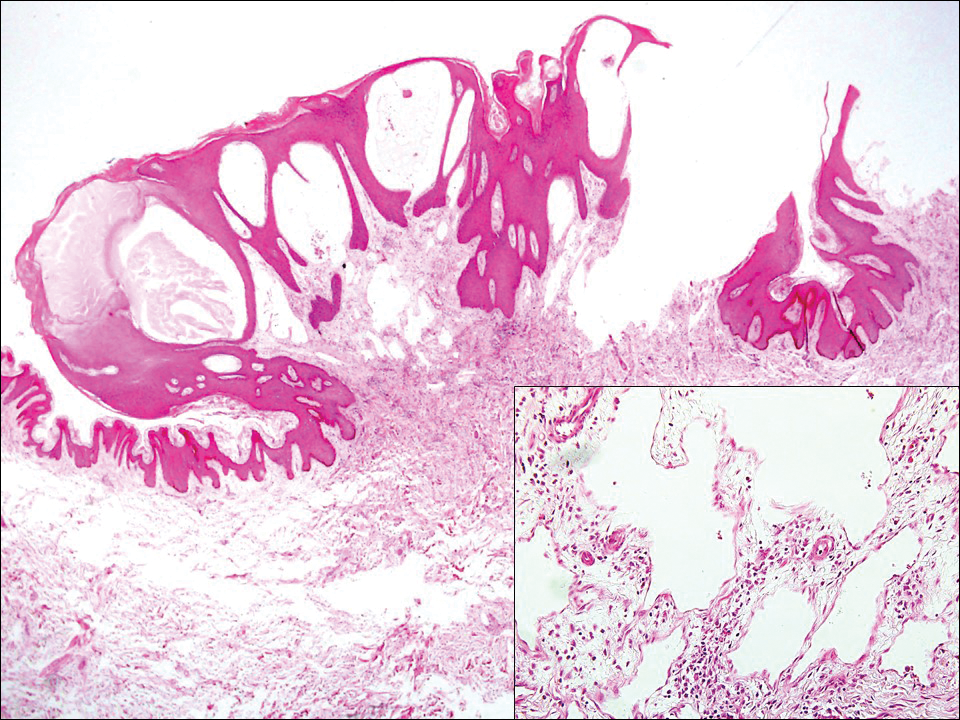

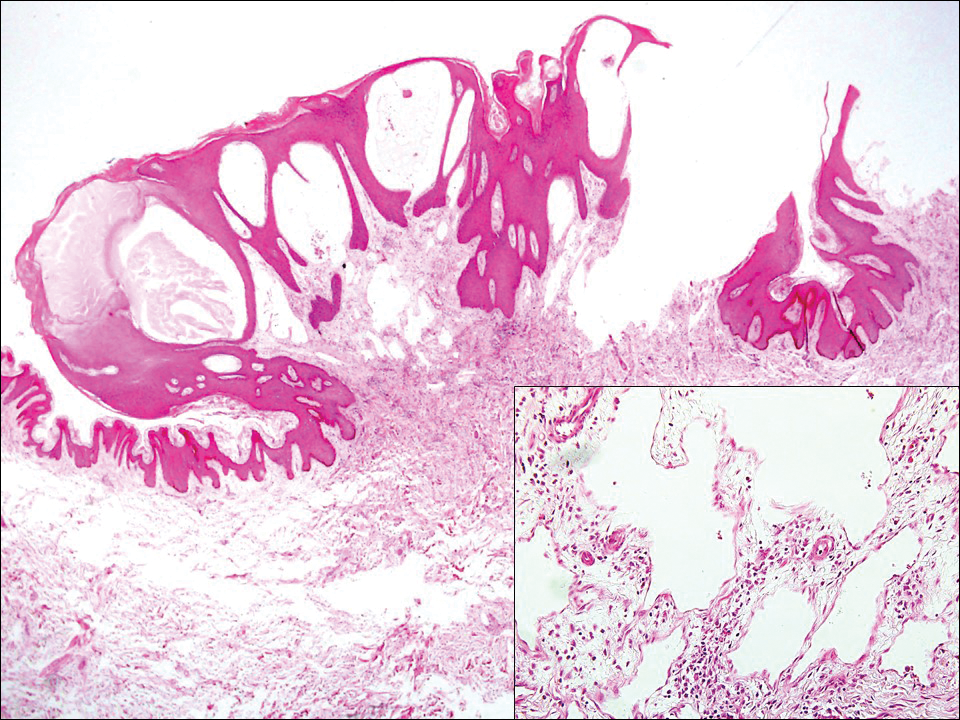

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade vascular neoplasm associated with human herpesvirus 8 that arises in multiple clinical settings, especially in immunosuppression secondary to human immunodeficiency virus. There are 3 distinct clinical stages: patch, plaque, and tumor. The patch stage appears as red macules that blend into larger plaques; the tumor stage is defined as larger nodules developing from plaques. Histologic features differ by stage. Similar to angiosarcoma, KS is comprised of anastomosing vessels that dissect collagen bundles; endothelial cell atypia is minimal. A useful feature of KS is its propensity to involve adnexa and display the promontory sign, which involves the tumor growing into normal vasculature (Figure 4).16 Positive immunohistochemistry for human herpesvirus 8 aids in confirmation of the diagnosis. Treatment options for KS are numerous but include destructive modalities, chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin, or highly active antiretroviral therapy for AIDS-related KS.17

- Fineberg S, Rosen PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions of the skin and breast after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:757-763.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Billings SD, McKenney JK, Folpe AL, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma following breast-conserving surgery and radiation: an analysis of 27 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:781-788.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Udager AM, Ishikawa MK, Lucas DR, et al. MYC immunohistochemistry in angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions: practical considerations based on a single institutional experience. Pathology. 2016;48:697-704.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:1069-1115.

- Shin JY, Roh SG, Lee NH, et al. Predisposing factors for poor prognosis of angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2017;39:380-386.

- Fraga-Guedes C, Gobbi H, Mastropasqua MG, et al. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 30 cases of post-radiation atypical vascular lesion of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146:347-354.

- Shin SJ, Lesser M, Rosen PP. Hemangiomas and angiosarcomas of the breast: diagnostic utility of cell cycle markers with emphasis on Ki-67. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:538-544.

- Cornejo KM, Deng A, Wu H, et al. The utility of MYC and FLT4 in the diagnosis and treatment of postradiation atypical vascular lesion and angiosarcoma of the breast. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:868-875.

- Patel GA, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum: frog spawn on the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1290-1295.

- Massa AF, Menezes N, Baptista A, et al. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum--dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:262-264.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Aronberg J. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:550-558.

- Christenson LJ, Stone MS. Trauma-induced simulator of targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:221-223.

- Trindade F, Kutzner H, Tellechea O, et al. Hobnail hemangioma reclassified as superficial lymphatic malformation: a study of 52 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:112-115.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Di Lorenzo G, Di Trolio R, Montesarchio V, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin as second-line therapy in the treatment of patients with advanced classic Kaposi sarcoma: a retrospective study. Cancer. 2008;112:1147-1152.

The Diagnosis: Atypical Vascular Lesion

Atypical vascular lesion (AVL)(quiz image), named by Fineberg and Rosen,1 is a vascular lesion that arises on mammary skin with a history of radiation exposure. Clinically, AVL can present as a papule or erythematous patch that manifests 3 to 7 years after radiation therapy.2,3 There are 2 histologic subtypes of AVL: lymphatic and vascular.2,4 Lymphatic-type AVL is comprised of a symmetric distribution of thin, dilated, and anastomosing vessels usually found in the superficial and mid dermis. The vessels are lined by flat or hobnail protuberant endothelial cells that lack nuclear irregularity or pleomorphism; however, hyperchromatism of endothelial cell nuclei is a common finding. Vascular-type AVL is morphologically similar to a capillary hemangioma, and histologic features include irregular growth of capillary-sized vessels that extend to the dermis and subcutis.2,4 Atypical vascular lesions are benign lesions but may be a precursor to angiosarcoma. Along with vascular markers, D2-40 typically is positive. Surgical excision with clear margins is recommended when the lesion is small.4,5 Observation is more appropriate for extensive lesions.

Angiosarcoma can arise spontaneously or in association with radiation or chronic lymphedema. Given the shared risk factors and presentation with AVL, it is essential to differentiate angiosarcoma from AVL. Primary cutaneous angiosarcoma usually presents on the head of elderly patients as an ecchymotic patch or plaque with ulceration.4 Secondary angiosarcoma may arise following radiation or chronic lymphedema (Stewart-Treves syndrome); however, some authors now prefer to consider lymphangiosarcoma arising in chronic lymphedematous limbs a distinct entity.6 Surgical excision with wide margins is the mainstay of therapy, but angiosarcoma has high recurrence rates, and the 5-year survival rate has been reported to be as low as 35%.7 Histologic overlap with AVL includes dissecting anastomosing vessels lined by hyperchromatic nuclei; however, angiosarcoma is distinguished by endothelial cell layering, nuclear pleomorphism, and prominent nucleoli (Figure 1).4,8 Increased positivity for Ki-67 immunostain, which indicates cell proliferation, may be used to distinguish angiosarcoma from an AVL (Figure 1 [inset]).9 Further, in contrast to AVL, radiation-induced angiosarcoma is characterized by amplification of C-MYC, a regulator gene, and FLT4 (FMS-related tyrosine kinase 4), a gene encoding vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3. Gene amplification may be detected through immunohistochemistry or fluorescence in situ hybridization.10 Ki-67 labeling showed less than 10% staining in endothelial cells in our case (quiz image [inset]), and fluorescence in situ hybridization was negative for C-MYC amplification, supporting the diagnosis of AVL.

Lymphangioma circumscriptum, the most common superficial lymphangioma, is a hamartomatous malformation that usually occurs at the axillary folds, neck, and trunk. It clinically presents as small agminated vesicles with a characteristic frog spawn appearance.11 Dermoscopic features include yellow lacunae that may alternate with a dark red color secondary to extravasation of erythrocytes.12 These clinical features often lead to a differential diagnosis of verrucae, angiokeratoma, and angiosarcoma. Lymphangioma circumscriptum histologically is characterized by an overgrowth of dilated lymphatic vessels that fill the papillary dermis. The vessels are composed of flat endothelial cells typically filled with acellular proteinaceous debris and occasional erythrocytes (Figure 2). As the lesion traverses deeper into the dermis, the caliber of the lymphatic channel becomes narrower. The presence of deep lymphatic cisterns with surrounding smooth muscle is helpful to differentiate lymphangioma circumscriptum from other lymphatic malformations such as acquired lymphangiectasia. Treatment options include surgical excision, sclerosing agents, and destructive modalities such as cryotherapy.

Hobnail hemangioma, originally termed targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma by Santa Cruz and Aronberg,13 presents as a violaceous papule or nodule surrounded by a characteristic brown halo on the leg. Trauma has been proposed as the inciting factor for the clinical appearance of hobnail hemangioma.14 Microscopically, the lesion shows vessels in a wedge shape. The superficial component has telangiectatic vessels with focal areas of papillary projections lined by endothelial cells. Although the endothelial nuclei typically project into the lumen, the nuclei are small, bland, and without mitotic activity.15 Deeper components show slit-shaped vasculature with dermal collagen dissection. Hemosiderin, extravasated red blood cells, and inflammation are found adjacent to the vessels (Figure 3). Given the benign nature, hobnail hemangiomas may be monitored.

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade vascular neoplasm associated with human herpesvirus 8 that arises in multiple clinical settings, especially in immunosuppression secondary to human immunodeficiency virus. There are 3 distinct clinical stages: patch, plaque, and tumor. The patch stage appears as red macules that blend into larger plaques; the tumor stage is defined as larger nodules developing from plaques. Histologic features differ by stage. Similar to angiosarcoma, KS is comprised of anastomosing vessels that dissect collagen bundles; endothelial cell atypia is minimal. A useful feature of KS is its propensity to involve adnexa and display the promontory sign, which involves the tumor growing into normal vasculature (Figure 4).16 Positive immunohistochemistry for human herpesvirus 8 aids in confirmation of the diagnosis. Treatment options for KS are numerous but include destructive modalities, chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin, or highly active antiretroviral therapy for AIDS-related KS.17

The Diagnosis: Atypical Vascular Lesion

Atypical vascular lesion (AVL)(quiz image), named by Fineberg and Rosen,1 is a vascular lesion that arises on mammary skin with a history of radiation exposure. Clinically, AVL can present as a papule or erythematous patch that manifests 3 to 7 years after radiation therapy.2,3 There are 2 histologic subtypes of AVL: lymphatic and vascular.2,4 Lymphatic-type AVL is comprised of a symmetric distribution of thin, dilated, and anastomosing vessels usually found in the superficial and mid dermis. The vessels are lined by flat or hobnail protuberant endothelial cells that lack nuclear irregularity or pleomorphism; however, hyperchromatism of endothelial cell nuclei is a common finding. Vascular-type AVL is morphologically similar to a capillary hemangioma, and histologic features include irregular growth of capillary-sized vessels that extend to the dermis and subcutis.2,4 Atypical vascular lesions are benign lesions but may be a precursor to angiosarcoma. Along with vascular markers, D2-40 typically is positive. Surgical excision with clear margins is recommended when the lesion is small.4,5 Observation is more appropriate for extensive lesions.

Angiosarcoma can arise spontaneously or in association with radiation or chronic lymphedema. Given the shared risk factors and presentation with AVL, it is essential to differentiate angiosarcoma from AVL. Primary cutaneous angiosarcoma usually presents on the head of elderly patients as an ecchymotic patch or plaque with ulceration.4 Secondary angiosarcoma may arise following radiation or chronic lymphedema (Stewart-Treves syndrome); however, some authors now prefer to consider lymphangiosarcoma arising in chronic lymphedematous limbs a distinct entity.6 Surgical excision with wide margins is the mainstay of therapy, but angiosarcoma has high recurrence rates, and the 5-year survival rate has been reported to be as low as 35%.7 Histologic overlap with AVL includes dissecting anastomosing vessels lined by hyperchromatic nuclei; however, angiosarcoma is distinguished by endothelial cell layering, nuclear pleomorphism, and prominent nucleoli (Figure 1).4,8 Increased positivity for Ki-67 immunostain, which indicates cell proliferation, may be used to distinguish angiosarcoma from an AVL (Figure 1 [inset]).9 Further, in contrast to AVL, radiation-induced angiosarcoma is characterized by amplification of C-MYC, a regulator gene, and FLT4 (FMS-related tyrosine kinase 4), a gene encoding vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3. Gene amplification may be detected through immunohistochemistry or fluorescence in situ hybridization.10 Ki-67 labeling showed less than 10% staining in endothelial cells in our case (quiz image [inset]), and fluorescence in situ hybridization was negative for C-MYC amplification, supporting the diagnosis of AVL.

Lymphangioma circumscriptum, the most common superficial lymphangioma, is a hamartomatous malformation that usually occurs at the axillary folds, neck, and trunk. It clinically presents as small agminated vesicles with a characteristic frog spawn appearance.11 Dermoscopic features include yellow lacunae that may alternate with a dark red color secondary to extravasation of erythrocytes.12 These clinical features often lead to a differential diagnosis of verrucae, angiokeratoma, and angiosarcoma. Lymphangioma circumscriptum histologically is characterized by an overgrowth of dilated lymphatic vessels that fill the papillary dermis. The vessels are composed of flat endothelial cells typically filled with acellular proteinaceous debris and occasional erythrocytes (Figure 2). As the lesion traverses deeper into the dermis, the caliber of the lymphatic channel becomes narrower. The presence of deep lymphatic cisterns with surrounding smooth muscle is helpful to differentiate lymphangioma circumscriptum from other lymphatic malformations such as acquired lymphangiectasia. Treatment options include surgical excision, sclerosing agents, and destructive modalities such as cryotherapy.

Hobnail hemangioma, originally termed targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma by Santa Cruz and Aronberg,13 presents as a violaceous papule or nodule surrounded by a characteristic brown halo on the leg. Trauma has been proposed as the inciting factor for the clinical appearance of hobnail hemangioma.14 Microscopically, the lesion shows vessels in a wedge shape. The superficial component has telangiectatic vessels with focal areas of papillary projections lined by endothelial cells. Although the endothelial nuclei typically project into the lumen, the nuclei are small, bland, and without mitotic activity.15 Deeper components show slit-shaped vasculature with dermal collagen dissection. Hemosiderin, extravasated red blood cells, and inflammation are found adjacent to the vessels (Figure 3). Given the benign nature, hobnail hemangiomas may be monitored.

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade vascular neoplasm associated with human herpesvirus 8 that arises in multiple clinical settings, especially in immunosuppression secondary to human immunodeficiency virus. There are 3 distinct clinical stages: patch, plaque, and tumor. The patch stage appears as red macules that blend into larger plaques; the tumor stage is defined as larger nodules developing from plaques. Histologic features differ by stage. Similar to angiosarcoma, KS is comprised of anastomosing vessels that dissect collagen bundles; endothelial cell atypia is minimal. A useful feature of KS is its propensity to involve adnexa and display the promontory sign, which involves the tumor growing into normal vasculature (Figure 4).16 Positive immunohistochemistry for human herpesvirus 8 aids in confirmation of the diagnosis. Treatment options for KS are numerous but include destructive modalities, chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin, or highly active antiretroviral therapy for AIDS-related KS.17

- Fineberg S, Rosen PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions of the skin and breast after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:757-763.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Billings SD, McKenney JK, Folpe AL, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma following breast-conserving surgery and radiation: an analysis of 27 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:781-788.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Udager AM, Ishikawa MK, Lucas DR, et al. MYC immunohistochemistry in angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions: practical considerations based on a single institutional experience. Pathology. 2016;48:697-704.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:1069-1115.

- Shin JY, Roh SG, Lee NH, et al. Predisposing factors for poor prognosis of angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2017;39:380-386.

- Fraga-Guedes C, Gobbi H, Mastropasqua MG, et al. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 30 cases of post-radiation atypical vascular lesion of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146:347-354.

- Shin SJ, Lesser M, Rosen PP. Hemangiomas and angiosarcomas of the breast: diagnostic utility of cell cycle markers with emphasis on Ki-67. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:538-544.

- Cornejo KM, Deng A, Wu H, et al. The utility of MYC and FLT4 in the diagnosis and treatment of postradiation atypical vascular lesion and angiosarcoma of the breast. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:868-875.

- Patel GA, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum: frog spawn on the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1290-1295.

- Massa AF, Menezes N, Baptista A, et al. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum--dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:262-264.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Aronberg J. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:550-558.

- Christenson LJ, Stone MS. Trauma-induced simulator of targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:221-223.

- Trindade F, Kutzner H, Tellechea O, et al. Hobnail hemangioma reclassified as superficial lymphatic malformation: a study of 52 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:112-115.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Di Lorenzo G, Di Trolio R, Montesarchio V, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin as second-line therapy in the treatment of patients with advanced classic Kaposi sarcoma: a retrospective study. Cancer. 2008;112:1147-1152.

- Fineberg S, Rosen PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions of the skin and breast after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:757-763.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Billings SD, McKenney JK, Folpe AL, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma following breast-conserving surgery and radiation: an analysis of 27 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:781-788.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Udager AM, Ishikawa MK, Lucas DR, et al. MYC immunohistochemistry in angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions: practical considerations based on a single institutional experience. Pathology. 2016;48:697-704.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:1069-1115.

- Shin JY, Roh SG, Lee NH, et al. Predisposing factors for poor prognosis of angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2017;39:380-386.

- Fraga-Guedes C, Gobbi H, Mastropasqua MG, et al. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 30 cases of post-radiation atypical vascular lesion of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146:347-354.

- Shin SJ, Lesser M, Rosen PP. Hemangiomas and angiosarcomas of the breast: diagnostic utility of cell cycle markers with emphasis on Ki-67. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:538-544.

- Cornejo KM, Deng A, Wu H, et al. The utility of MYC and FLT4 in the diagnosis and treatment of postradiation atypical vascular lesion and angiosarcoma of the breast. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:868-875.

- Patel GA, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum: frog spawn on the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1290-1295.

- Massa AF, Menezes N, Baptista A, et al. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum--dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:262-264.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Aronberg J. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:550-558.

- Christenson LJ, Stone MS. Trauma-induced simulator of targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:221-223.

- Trindade F, Kutzner H, Tellechea O, et al. Hobnail hemangioma reclassified as superficial lymphatic malformation: a study of 52 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:112-115.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Di Lorenzo G, Di Trolio R, Montesarchio V, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin as second-line therapy in the treatment of patients with advanced classic Kaposi sarcoma: a retrospective study. Cancer. 2008;112:1147-1152.

A 67-year-old woman presented with a lesion on the medial aspect of the right axilla of 2 weeks' duration. The patient had a history of cancer of the right breast treated with a mastectomy and adjuvant radiation. She denied pain, bleeding, pruritus, or rapid growth, as well as any changes in medication or recent trauma. Physical examination revealed a 5-mm purpuric macule of the right axilla. A punch biopsy was performed. Amplification for the C-MYC gene was negative by fluorescence in situ hybridization.