User login

Smallpox Vaccination-Associated Myopericarditis

A renewed effort to vaccinate service members fighting the global war on terrorism has brought new diagnostic challenges. Vaccinations not generally given to the public are routinely given to service members when they deploy to various parts of the world. Examples include anthrax, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, rabies, polio, and smallpox. Every vaccination has potential for adverse effects (AEs), which can range from mild to severe life-threatening complications. These AEs often go unrecognized and untreated because physicians are not routinely screening for vaccination administration.

Background

Smallpox (Variola major) was successfully eradicated in 1977 due to worldwide vaccination efforts.1 However, the threat of bioterrorism has renewed mandatory smallpox vaccinations for high-risk individuals, such as active-duty military personnel.1,2 A notable increase in myopericarditis has been reported with the new generation of smallpox vaccination, ACAM2000.3 We present a case of a 27-year-old healthy male who presented with chest pain and diffuse ST segment elevations consistent with myopericarditis after vaccination with ACAM2000.

Case Presentation

A healthy 27-year-old soldier presented to the emergency department with sudden, new onset, sharp-stabbing, substernal chest pain, which was made worse with lying flat and better with leaning forward. Vital signs were unremarkable. He recently enlisted in the US Army and received the smallpox vaccination about 11 days before as part of a routine predeployment checklist. The patient reported he did not have any viral symptoms, such as fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, shortness of breath, sore throat, rhinorrhea, or sputum production. He also reported having no prior illness for the past 3 months, sick contacts at home or work, or recent travel outside the US. He reported no tobacco use, alcohol use, or illicit drug use. The patient’s family history was negative for significant cardiac disease.

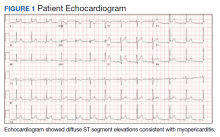

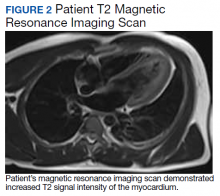

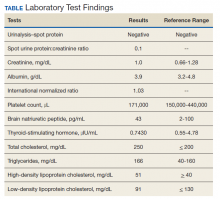

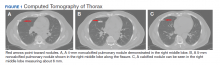

A physical examination was unremarkable. The initial laboratory report showed no leukocytosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, electrolytes derangement, abnormal kidney function, or abnormal liver function tests. Initial troponin was 0.25 ng/mL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 40 mmol/h and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 120.2 mg/L suggestive of acute inflammation. A urine drug screen was negative. D-dimer was < 0.27. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed diffuse ST segment elevation (Figure 1). An echocardiogram showed normal left ventricle size, and function with ejection fraction 55 to 60%, normal diastolic dysfunction, and trivial pericardial effusion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed increased T2 signal intensity of the myocardium suggestive of myopericarditis (Figure 2). A computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the coronary arteries showed no significant stenosis.

The patient was treated with ibuprofen for 2 weeks and colchicine for 3 months, and his symptoms resolved. He followed up with an appointment in the cardiology clinic 1 month later, and his ESR, CRP, and troponin results were negative. A limited echocardiogram showed ejection fraction 60 to 65%, no regional wall motion abnormalities, normal diastolic function, and resolution of the pericardial effusion.

Discussion

Smallpox was a major worldwide cause of mortality; about 30% of those infected died because of smallpox.2,4,5 Due to a worldwide vaccination effort, the World Health Organization declared smallpox was eradicated in 1977.2,4,5 However, despite successful eradication, smallpox is considered a possible bioterrorism target, which prompted a resurgence of mandatory smallpox vaccinations for active-duty personnel.2,5

Dryvax, a freeze-dried calf lymph smallpox vaccine was used extensively from the 1940s to the 1980s but was replaced in 2008 by ACAM2000, a smallpox vaccine cultured in kidney epithelial cells from African green monkeys.3,5 Myopericarditis was rarely associated with the Dryvax, with only 5 cases reported from 1955 to 1986 after millions of doses of vaccines were administered; however, in 230,734 administered ACAM2000 doses, 18 cases of myopericarditis (incidence, 7.8 per 100,000) were reported during a surveillance study in 2002 and 2003.3,5

Myopericarditis presents with a wide variety of symptoms, such as chest pain, palpitations, chills, shortness of breath, and fever.6,7 Mainstay diagnostic criteria include ECG findings consistent with myopericarditis (such as diffuse ST segment elevations) and elevated cardiac biomarkers (elevated troponins).5-7 An echocardiogram can be helpful in diagnosis, as most cases will not have regional wall motion abnormalities (to distinguish against coronary artery disease).5-7 MRI with diffuse enhancement of the myocardium can be helpful in diagnosis.5,6 The gold standard for diagnosis is an endomyocardial biopsy, which carries a significant risk of complications and is not routinely performed to diagnose myopericarditis.5,6 US military smallpox vaccination data showed that the onset of vaccine-associated myopericarditis averaged (SD) 10.4 (3.6) days after vaccination.5

Vaccine-associated myopericarditis treatment is focused on decreasing inflammation.5,6 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are advised for about 2 weeks with cessation of intensive cardiac activities for between 4 and 6 weeks due to risks of congestive heart failure and fatal cardiac arrhythmias.5,6

Conclusions

Since the September 11 attacks, the US needs to be continually prepared for potential terrorism on American soil and abroad. The threat of bioterrorism has renewed efforts to vaccinate or revaccinate American service members deployed to high-risk regions. These vaccinations put them at risk for vaccination-induced complications that can range from mild fever to life-threatening complications.

1. Bruner DI, Butler BS. Smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis is more common with the newest smallpox vaccine. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(3):e85-e87. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.06.001

2. Halsell JS, Riddle JR, Atwood JE, et al. Myopericarditis following smallpox vaccination among vaccinia-naive US military personnel. JAMA. 2003;289(24):3283-3289. doi:10.1001/jama.289.24.3283

3. Nalca A, Zumbrun EE. ACAM2000: the new smallpox vaccine for United States Strategic National Stockpile. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2010;4:71-79. doi:10.2147/dddt.s3687

4. Wollenberg A, Engler R. Smallpox, vaccination and adverse reactions to smallpox vaccine. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4(4):271-275. doi:10.1097/01.all.0000136758.66442.28

5. Cassimatis DC, Atwood JE, Engler RM, Linz PE, Grabenstein JD, Vernalis MN. Smallpox vaccination and myopericarditis: a clinical review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(9):1503-1510. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.053

6. Sharma U, Tak T. A report of 2 cases of myopericarditis after Vaccinia virus (smallpox) immunization. WMJ. 2011;110(6):291-294.

7. Sarkisian SA, Hand G, Rivera VM, Smith M, Miller JA. A case series of smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis: effects on safety and readiness of the active duty soldier. Mil Med. 2019;184(1-2):e280-e283. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy159

A renewed effort to vaccinate service members fighting the global war on terrorism has brought new diagnostic challenges. Vaccinations not generally given to the public are routinely given to service members when they deploy to various parts of the world. Examples include anthrax, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, rabies, polio, and smallpox. Every vaccination has potential for adverse effects (AEs), which can range from mild to severe life-threatening complications. These AEs often go unrecognized and untreated because physicians are not routinely screening for vaccination administration.

Background

Smallpox (Variola major) was successfully eradicated in 1977 due to worldwide vaccination efforts.1 However, the threat of bioterrorism has renewed mandatory smallpox vaccinations for high-risk individuals, such as active-duty military personnel.1,2 A notable increase in myopericarditis has been reported with the new generation of smallpox vaccination, ACAM2000.3 We present a case of a 27-year-old healthy male who presented with chest pain and diffuse ST segment elevations consistent with myopericarditis after vaccination with ACAM2000.

Case Presentation

A healthy 27-year-old soldier presented to the emergency department with sudden, new onset, sharp-stabbing, substernal chest pain, which was made worse with lying flat and better with leaning forward. Vital signs were unremarkable. He recently enlisted in the US Army and received the smallpox vaccination about 11 days before as part of a routine predeployment checklist. The patient reported he did not have any viral symptoms, such as fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, shortness of breath, sore throat, rhinorrhea, or sputum production. He also reported having no prior illness for the past 3 months, sick contacts at home or work, or recent travel outside the US. He reported no tobacco use, alcohol use, or illicit drug use. The patient’s family history was negative for significant cardiac disease.

A physical examination was unremarkable. The initial laboratory report showed no leukocytosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, electrolytes derangement, abnormal kidney function, or abnormal liver function tests. Initial troponin was 0.25 ng/mL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 40 mmol/h and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 120.2 mg/L suggestive of acute inflammation. A urine drug screen was negative. D-dimer was < 0.27. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed diffuse ST segment elevation (Figure 1). An echocardiogram showed normal left ventricle size, and function with ejection fraction 55 to 60%, normal diastolic dysfunction, and trivial pericardial effusion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed increased T2 signal intensity of the myocardium suggestive of myopericarditis (Figure 2). A computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the coronary arteries showed no significant stenosis.

The patient was treated with ibuprofen for 2 weeks and colchicine for 3 months, and his symptoms resolved. He followed up with an appointment in the cardiology clinic 1 month later, and his ESR, CRP, and troponin results were negative. A limited echocardiogram showed ejection fraction 60 to 65%, no regional wall motion abnormalities, normal diastolic function, and resolution of the pericardial effusion.

Discussion

Smallpox was a major worldwide cause of mortality; about 30% of those infected died because of smallpox.2,4,5 Due to a worldwide vaccination effort, the World Health Organization declared smallpox was eradicated in 1977.2,4,5 However, despite successful eradication, smallpox is considered a possible bioterrorism target, which prompted a resurgence of mandatory smallpox vaccinations for active-duty personnel.2,5

Dryvax, a freeze-dried calf lymph smallpox vaccine was used extensively from the 1940s to the 1980s but was replaced in 2008 by ACAM2000, a smallpox vaccine cultured in kidney epithelial cells from African green monkeys.3,5 Myopericarditis was rarely associated with the Dryvax, with only 5 cases reported from 1955 to 1986 after millions of doses of vaccines were administered; however, in 230,734 administered ACAM2000 doses, 18 cases of myopericarditis (incidence, 7.8 per 100,000) were reported during a surveillance study in 2002 and 2003.3,5

Myopericarditis presents with a wide variety of symptoms, such as chest pain, palpitations, chills, shortness of breath, and fever.6,7 Mainstay diagnostic criteria include ECG findings consistent with myopericarditis (such as diffuse ST segment elevations) and elevated cardiac biomarkers (elevated troponins).5-7 An echocardiogram can be helpful in diagnosis, as most cases will not have regional wall motion abnormalities (to distinguish against coronary artery disease).5-7 MRI with diffuse enhancement of the myocardium can be helpful in diagnosis.5,6 The gold standard for diagnosis is an endomyocardial biopsy, which carries a significant risk of complications and is not routinely performed to diagnose myopericarditis.5,6 US military smallpox vaccination data showed that the onset of vaccine-associated myopericarditis averaged (SD) 10.4 (3.6) days after vaccination.5

Vaccine-associated myopericarditis treatment is focused on decreasing inflammation.5,6 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are advised for about 2 weeks with cessation of intensive cardiac activities for between 4 and 6 weeks due to risks of congestive heart failure and fatal cardiac arrhythmias.5,6

Conclusions

Since the September 11 attacks, the US needs to be continually prepared for potential terrorism on American soil and abroad. The threat of bioterrorism has renewed efforts to vaccinate or revaccinate American service members deployed to high-risk regions. These vaccinations put them at risk for vaccination-induced complications that can range from mild fever to life-threatening complications.

A renewed effort to vaccinate service members fighting the global war on terrorism has brought new diagnostic challenges. Vaccinations not generally given to the public are routinely given to service members when they deploy to various parts of the world. Examples include anthrax, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, rabies, polio, and smallpox. Every vaccination has potential for adverse effects (AEs), which can range from mild to severe life-threatening complications. These AEs often go unrecognized and untreated because physicians are not routinely screening for vaccination administration.

Background

Smallpox (Variola major) was successfully eradicated in 1977 due to worldwide vaccination efforts.1 However, the threat of bioterrorism has renewed mandatory smallpox vaccinations for high-risk individuals, such as active-duty military personnel.1,2 A notable increase in myopericarditis has been reported with the new generation of smallpox vaccination, ACAM2000.3 We present a case of a 27-year-old healthy male who presented with chest pain and diffuse ST segment elevations consistent with myopericarditis after vaccination with ACAM2000.

Case Presentation

A healthy 27-year-old soldier presented to the emergency department with sudden, new onset, sharp-stabbing, substernal chest pain, which was made worse with lying flat and better with leaning forward. Vital signs were unremarkable. He recently enlisted in the US Army and received the smallpox vaccination about 11 days before as part of a routine predeployment checklist. The patient reported he did not have any viral symptoms, such as fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, shortness of breath, sore throat, rhinorrhea, or sputum production. He also reported having no prior illness for the past 3 months, sick contacts at home or work, or recent travel outside the US. He reported no tobacco use, alcohol use, or illicit drug use. The patient’s family history was negative for significant cardiac disease.

A physical examination was unremarkable. The initial laboratory report showed no leukocytosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, electrolytes derangement, abnormal kidney function, or abnormal liver function tests. Initial troponin was 0.25 ng/mL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 40 mmol/h and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 120.2 mg/L suggestive of acute inflammation. A urine drug screen was negative. D-dimer was < 0.27. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed diffuse ST segment elevation (Figure 1). An echocardiogram showed normal left ventricle size, and function with ejection fraction 55 to 60%, normal diastolic dysfunction, and trivial pericardial effusion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed increased T2 signal intensity of the myocardium suggestive of myopericarditis (Figure 2). A computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the coronary arteries showed no significant stenosis.

The patient was treated with ibuprofen for 2 weeks and colchicine for 3 months, and his symptoms resolved. He followed up with an appointment in the cardiology clinic 1 month later, and his ESR, CRP, and troponin results were negative. A limited echocardiogram showed ejection fraction 60 to 65%, no regional wall motion abnormalities, normal diastolic function, and resolution of the pericardial effusion.

Discussion

Smallpox was a major worldwide cause of mortality; about 30% of those infected died because of smallpox.2,4,5 Due to a worldwide vaccination effort, the World Health Organization declared smallpox was eradicated in 1977.2,4,5 However, despite successful eradication, smallpox is considered a possible bioterrorism target, which prompted a resurgence of mandatory smallpox vaccinations for active-duty personnel.2,5

Dryvax, a freeze-dried calf lymph smallpox vaccine was used extensively from the 1940s to the 1980s but was replaced in 2008 by ACAM2000, a smallpox vaccine cultured in kidney epithelial cells from African green monkeys.3,5 Myopericarditis was rarely associated with the Dryvax, with only 5 cases reported from 1955 to 1986 after millions of doses of vaccines were administered; however, in 230,734 administered ACAM2000 doses, 18 cases of myopericarditis (incidence, 7.8 per 100,000) were reported during a surveillance study in 2002 and 2003.3,5

Myopericarditis presents with a wide variety of symptoms, such as chest pain, palpitations, chills, shortness of breath, and fever.6,7 Mainstay diagnostic criteria include ECG findings consistent with myopericarditis (such as diffuse ST segment elevations) and elevated cardiac biomarkers (elevated troponins).5-7 An echocardiogram can be helpful in diagnosis, as most cases will not have regional wall motion abnormalities (to distinguish against coronary artery disease).5-7 MRI with diffuse enhancement of the myocardium can be helpful in diagnosis.5,6 The gold standard for diagnosis is an endomyocardial biopsy, which carries a significant risk of complications and is not routinely performed to diagnose myopericarditis.5,6 US military smallpox vaccination data showed that the onset of vaccine-associated myopericarditis averaged (SD) 10.4 (3.6) days after vaccination.5

Vaccine-associated myopericarditis treatment is focused on decreasing inflammation.5,6 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are advised for about 2 weeks with cessation of intensive cardiac activities for between 4 and 6 weeks due to risks of congestive heart failure and fatal cardiac arrhythmias.5,6

Conclusions

Since the September 11 attacks, the US needs to be continually prepared for potential terrorism on American soil and abroad. The threat of bioterrorism has renewed efforts to vaccinate or revaccinate American service members deployed to high-risk regions. These vaccinations put them at risk for vaccination-induced complications that can range from mild fever to life-threatening complications.

1. Bruner DI, Butler BS. Smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis is more common with the newest smallpox vaccine. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(3):e85-e87. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.06.001

2. Halsell JS, Riddle JR, Atwood JE, et al. Myopericarditis following smallpox vaccination among vaccinia-naive US military personnel. JAMA. 2003;289(24):3283-3289. doi:10.1001/jama.289.24.3283

3. Nalca A, Zumbrun EE. ACAM2000: the new smallpox vaccine for United States Strategic National Stockpile. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2010;4:71-79. doi:10.2147/dddt.s3687

4. Wollenberg A, Engler R. Smallpox, vaccination and adverse reactions to smallpox vaccine. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4(4):271-275. doi:10.1097/01.all.0000136758.66442.28

5. Cassimatis DC, Atwood JE, Engler RM, Linz PE, Grabenstein JD, Vernalis MN. Smallpox vaccination and myopericarditis: a clinical review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(9):1503-1510. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.053

6. Sharma U, Tak T. A report of 2 cases of myopericarditis after Vaccinia virus (smallpox) immunization. WMJ. 2011;110(6):291-294.

7. Sarkisian SA, Hand G, Rivera VM, Smith M, Miller JA. A case series of smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis: effects on safety and readiness of the active duty soldier. Mil Med. 2019;184(1-2):e280-e283. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy159

1. Bruner DI, Butler BS. Smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis is more common with the newest smallpox vaccine. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(3):e85-e87. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.06.001

2. Halsell JS, Riddle JR, Atwood JE, et al. Myopericarditis following smallpox vaccination among vaccinia-naive US military personnel. JAMA. 2003;289(24):3283-3289. doi:10.1001/jama.289.24.3283

3. Nalca A, Zumbrun EE. ACAM2000: the new smallpox vaccine for United States Strategic National Stockpile. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2010;4:71-79. doi:10.2147/dddt.s3687

4. Wollenberg A, Engler R. Smallpox, vaccination and adverse reactions to smallpox vaccine. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4(4):271-275. doi:10.1097/01.all.0000136758.66442.28

5. Cassimatis DC, Atwood JE, Engler RM, Linz PE, Grabenstein JD, Vernalis MN. Smallpox vaccination and myopericarditis: a clinical review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(9):1503-1510. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.053

6. Sharma U, Tak T. A report of 2 cases of myopericarditis after Vaccinia virus (smallpox) immunization. WMJ. 2011;110(6):291-294.

7. Sarkisian SA, Hand G, Rivera VM, Smith M, Miller JA. A case series of smallpox vaccination-associated myopericarditis: effects on safety and readiness of the active duty soldier. Mil Med. 2019;184(1-2):e280-e283. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy159

Long-standing Dermatitis Treated With Dupilumab With Subsequent Progression to Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma

Dupilumab is a novel medication that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) in patients 6 years and older. Dupilumab is an injectable fully human monoclonal antibody. It provides a giant leap toward a better quality of life for patients with AD. Dupilumab works by binding to the shared α subunit of the IL-4 receptor (IL-4R), thus inhibiting IL-4 and IL-13 from using that signaling pathway. The documented side-effect profile includes injection-site reaction, keratitis, nasopharyngitis, and headache.1

We initiated off-label treatment with dupilumab in 3 adult patients who had a history of long-standing adult-onset dermatitis confirmed by histopathology. The 3 patients received a loading dose of 600 mg subcutaneously, followed by 300 mg every other week. Following treatment, the patients had expansion of their disease, with features consistent with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) on subsequent biopsies. These 3 cases demonstrate the well-known adage that the diagnosis of CTCL often requires multiple biopsies performed over time. Although dupilumab has proved efficacious and safe for treating AD, dermatologists should be cautious before starting this medication in an adult who has new-onset dermatitis and no history of atopy.

Case Reports

Patient 1

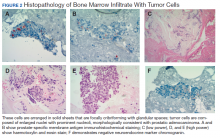

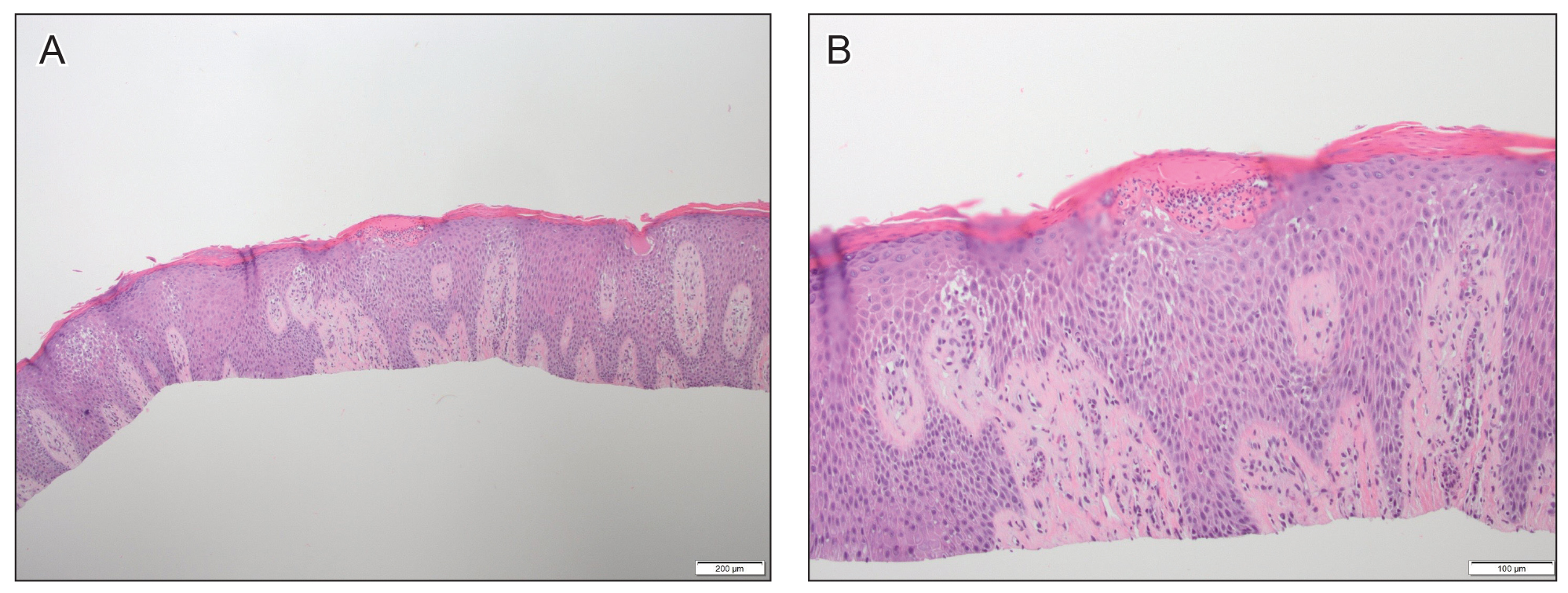

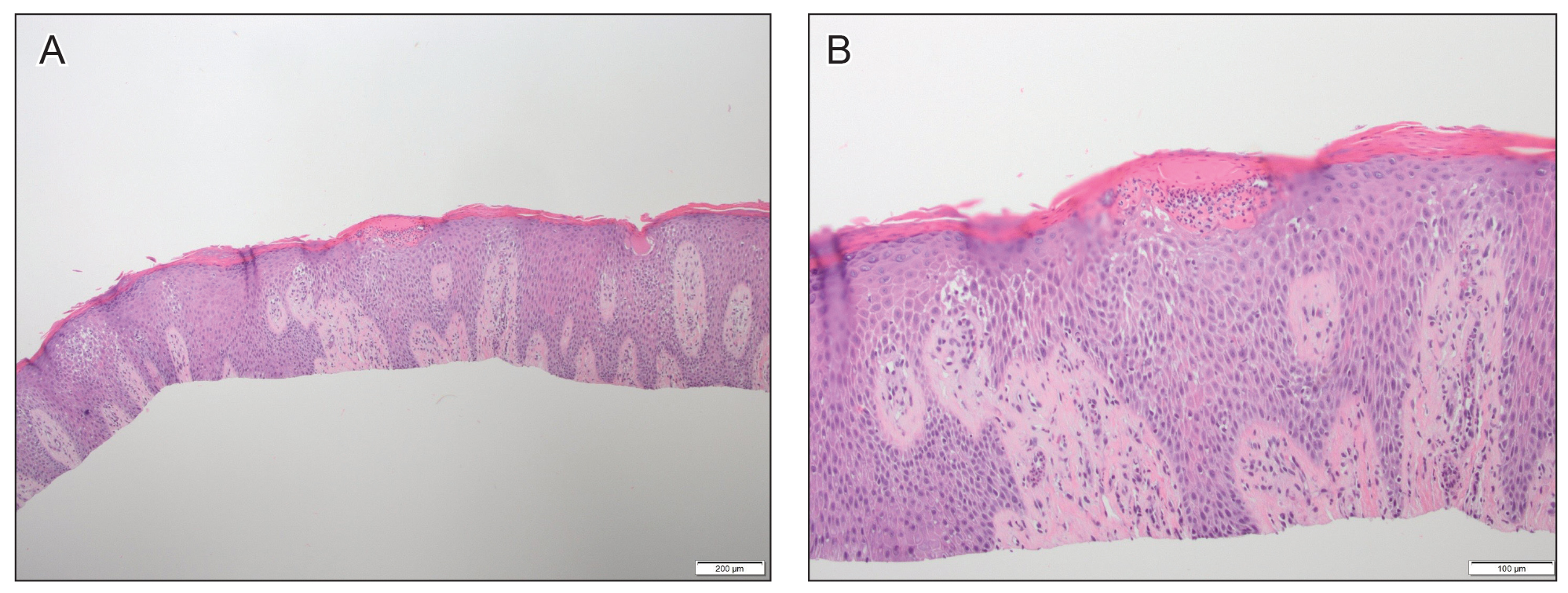

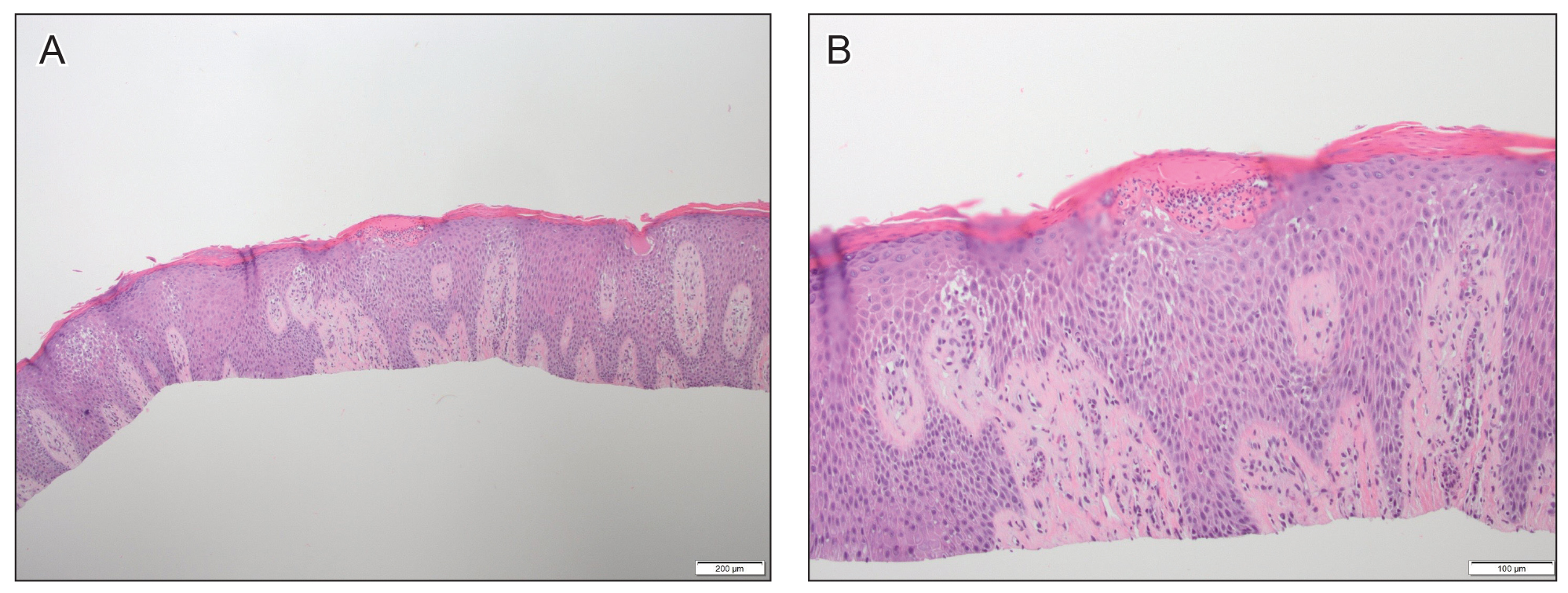

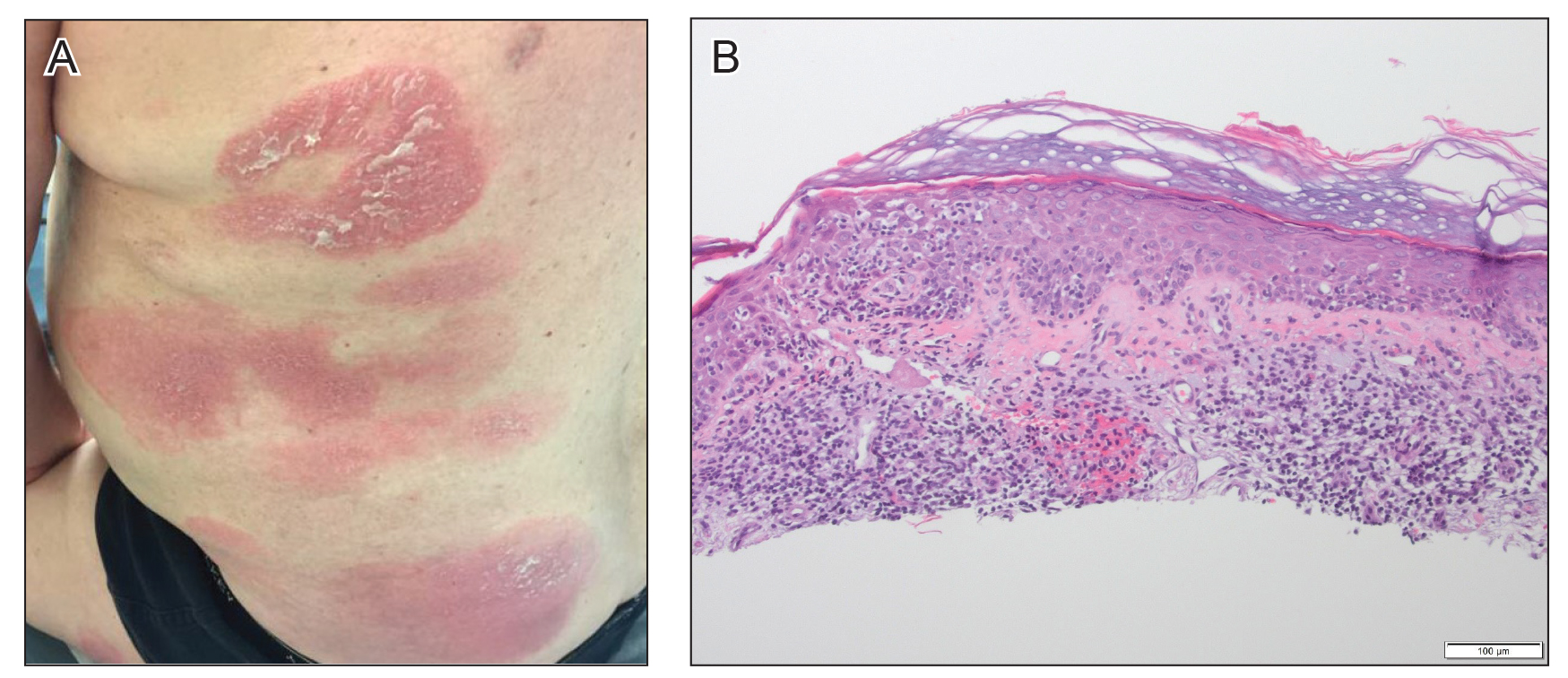

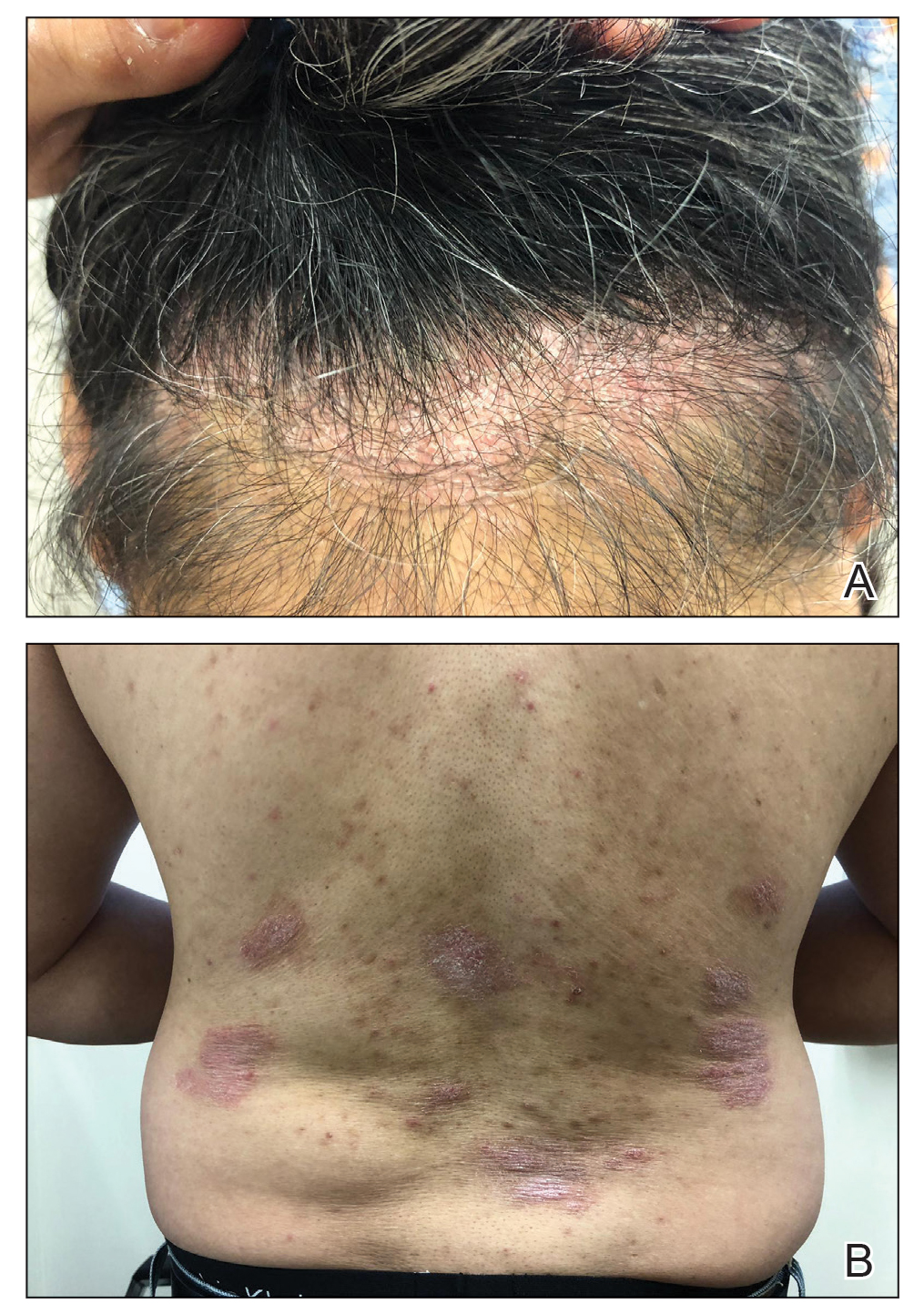

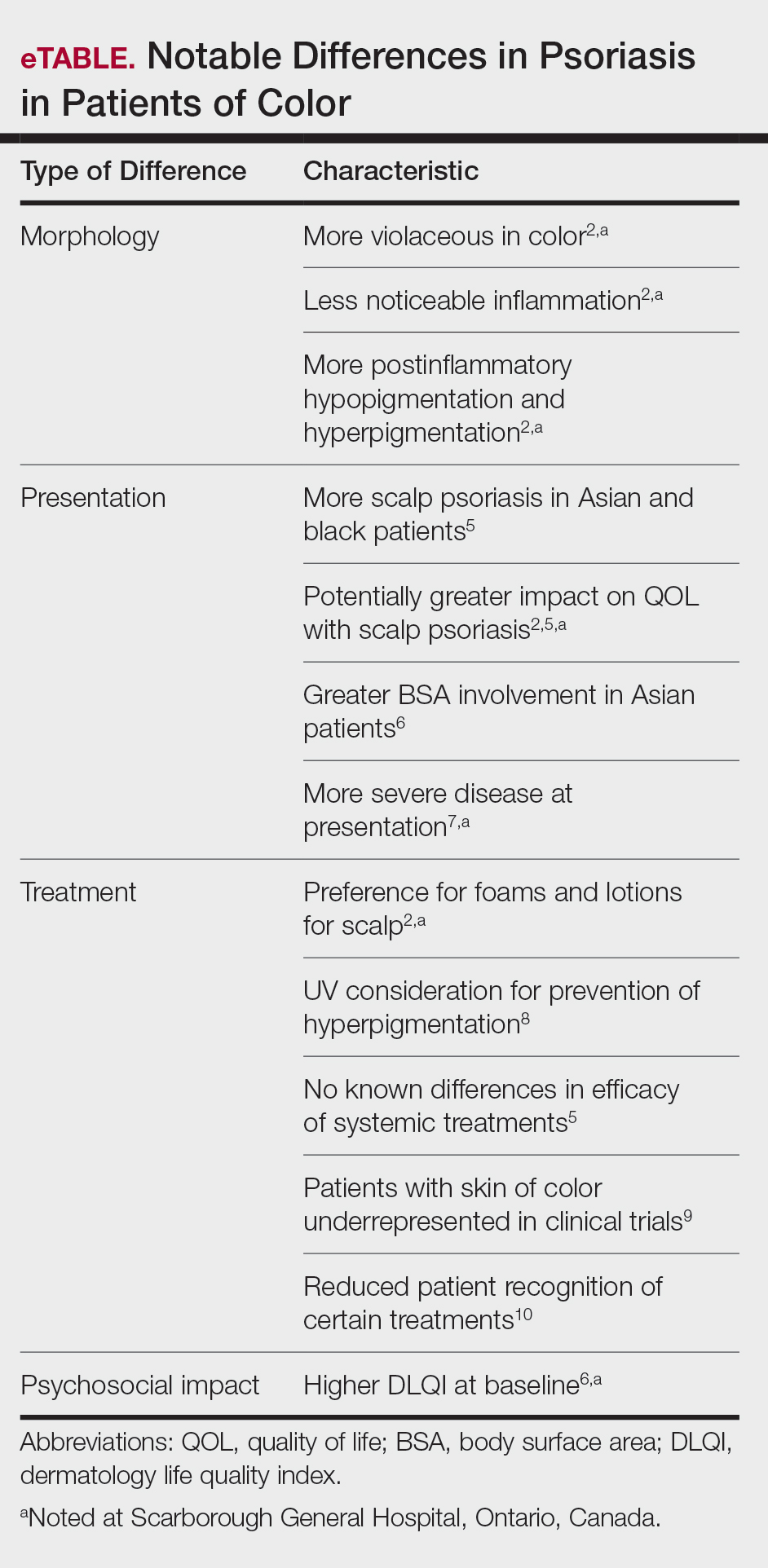

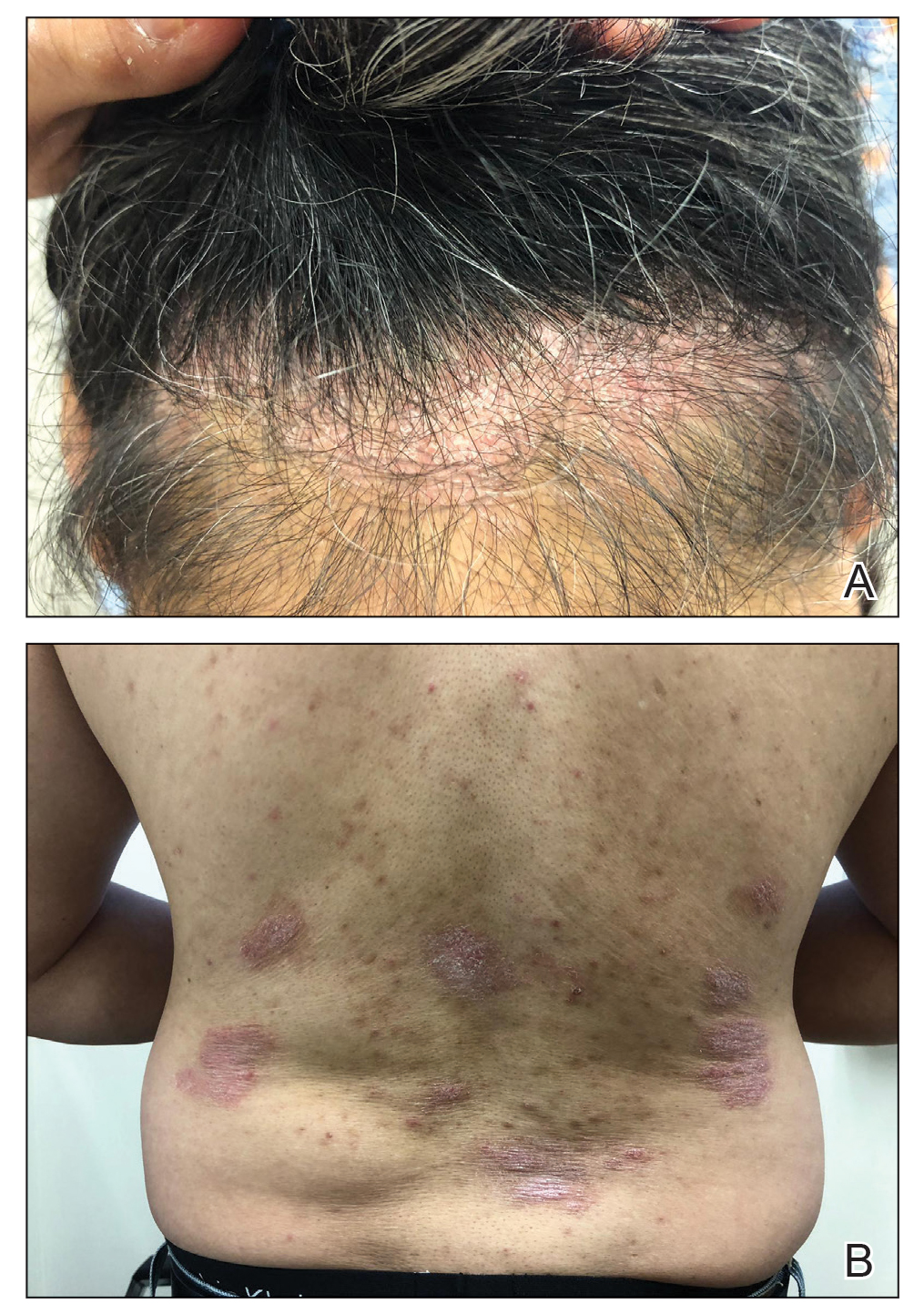

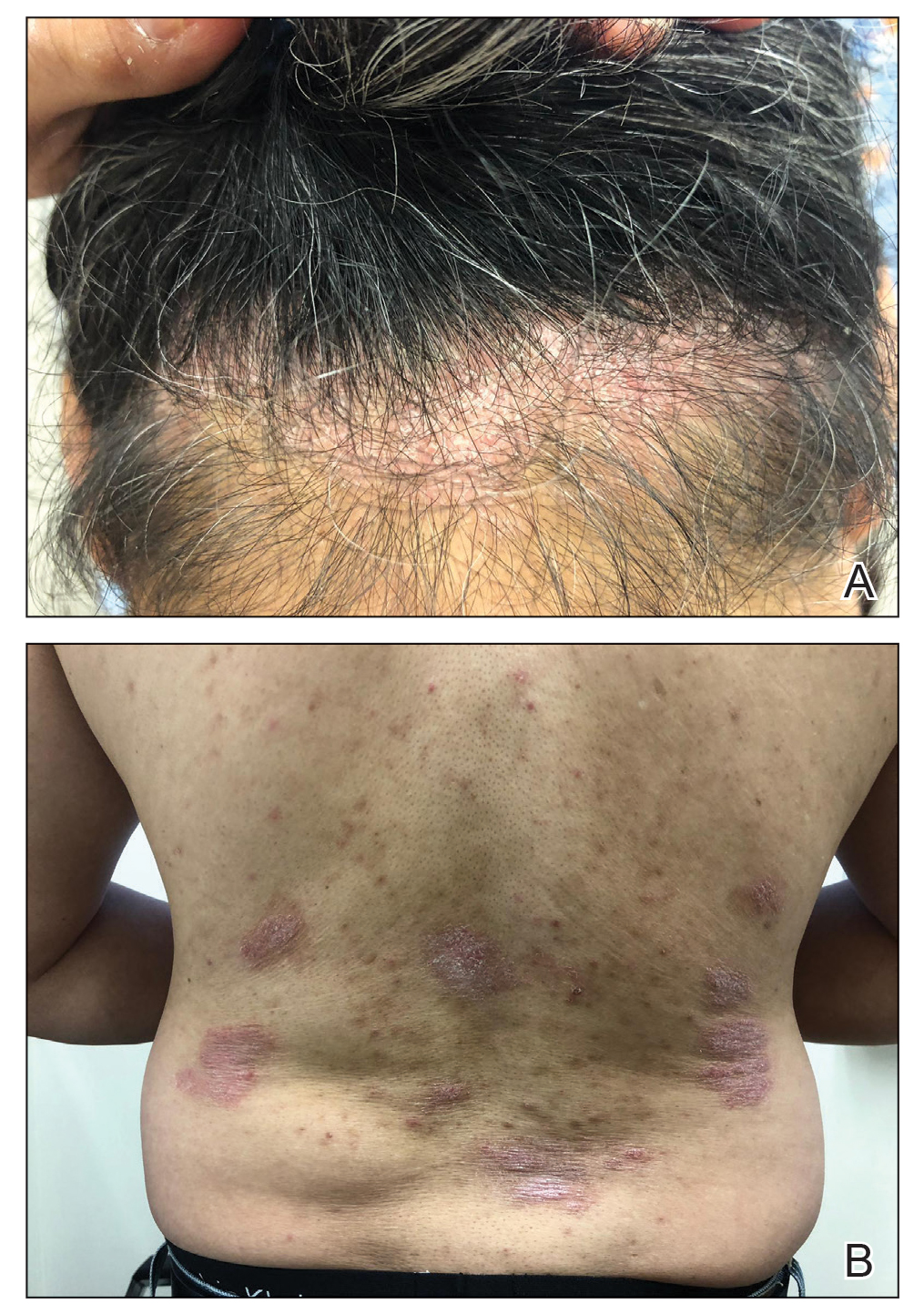

A 61-year-old man presented to dermatology after being lost to follow-up for several years and was started on dupilumab for long-standing nonspecific eczematous dermatitis based on histopathology. He had a pruritic rash of 10 years’ duration that had been biopsied multiple times and was found to be consistent with dermatitis and lichen simplex chronicus (Figure 1). He had been treated with triamcinolone ointment 0.1% and narrowband UVB as often as 3 times weekly over many years. The patient also had a history of idiopathic CD4 lymphopenia with consistently negative tests for human immunodeficiency virus.

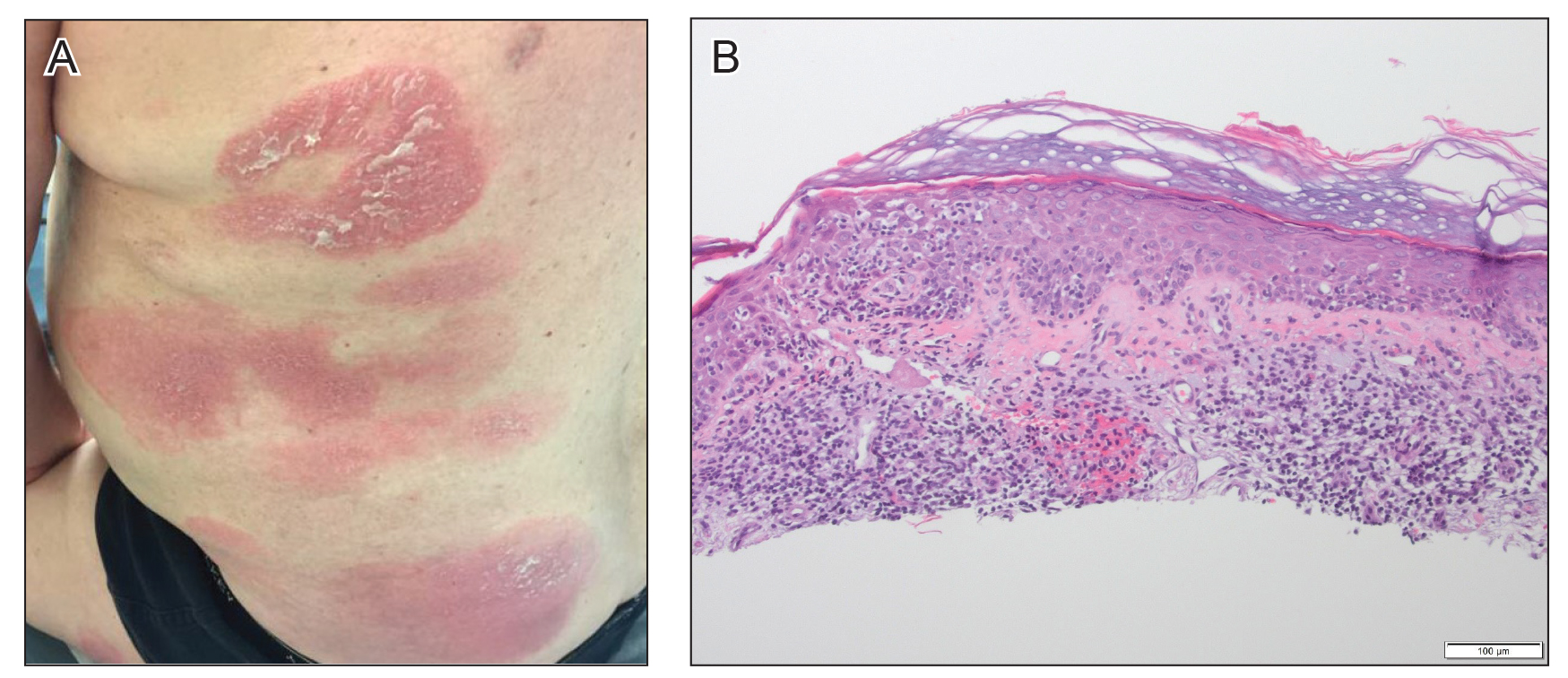

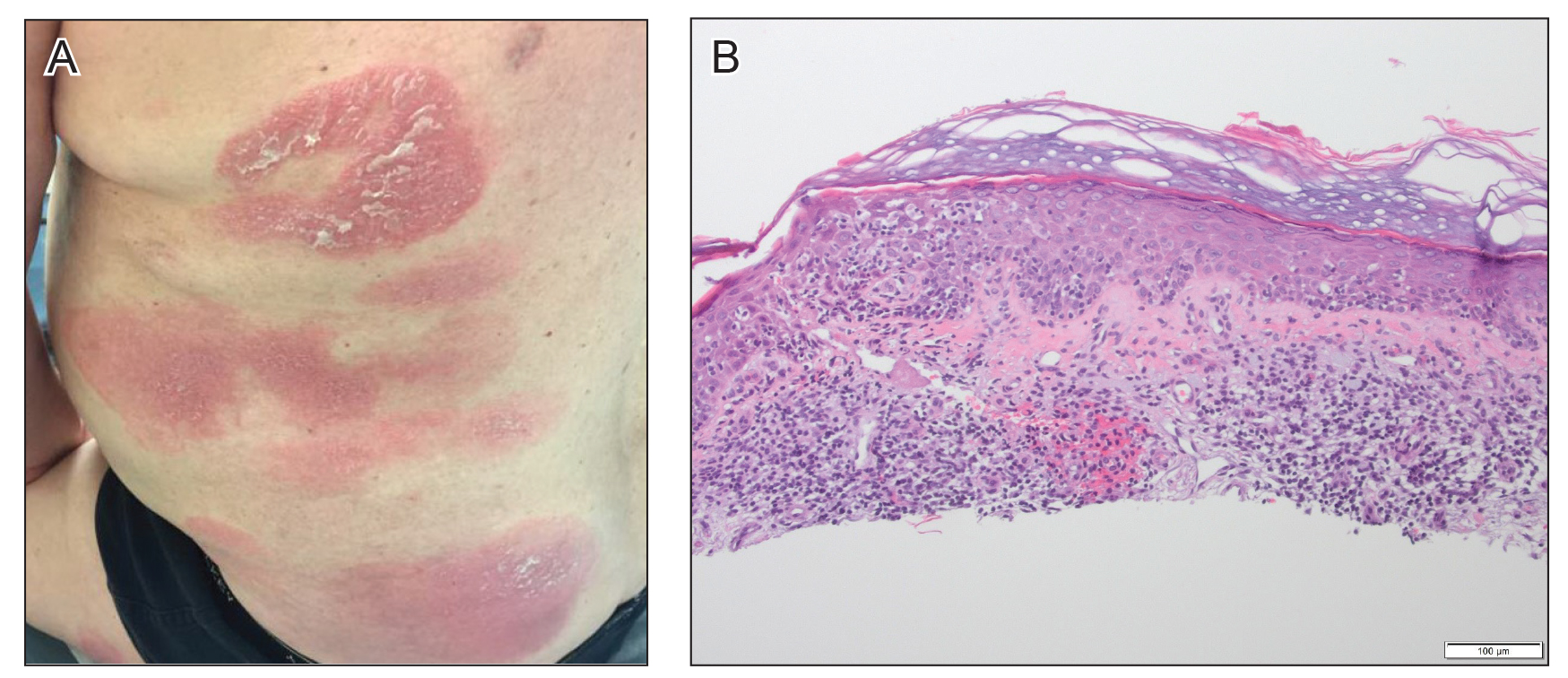

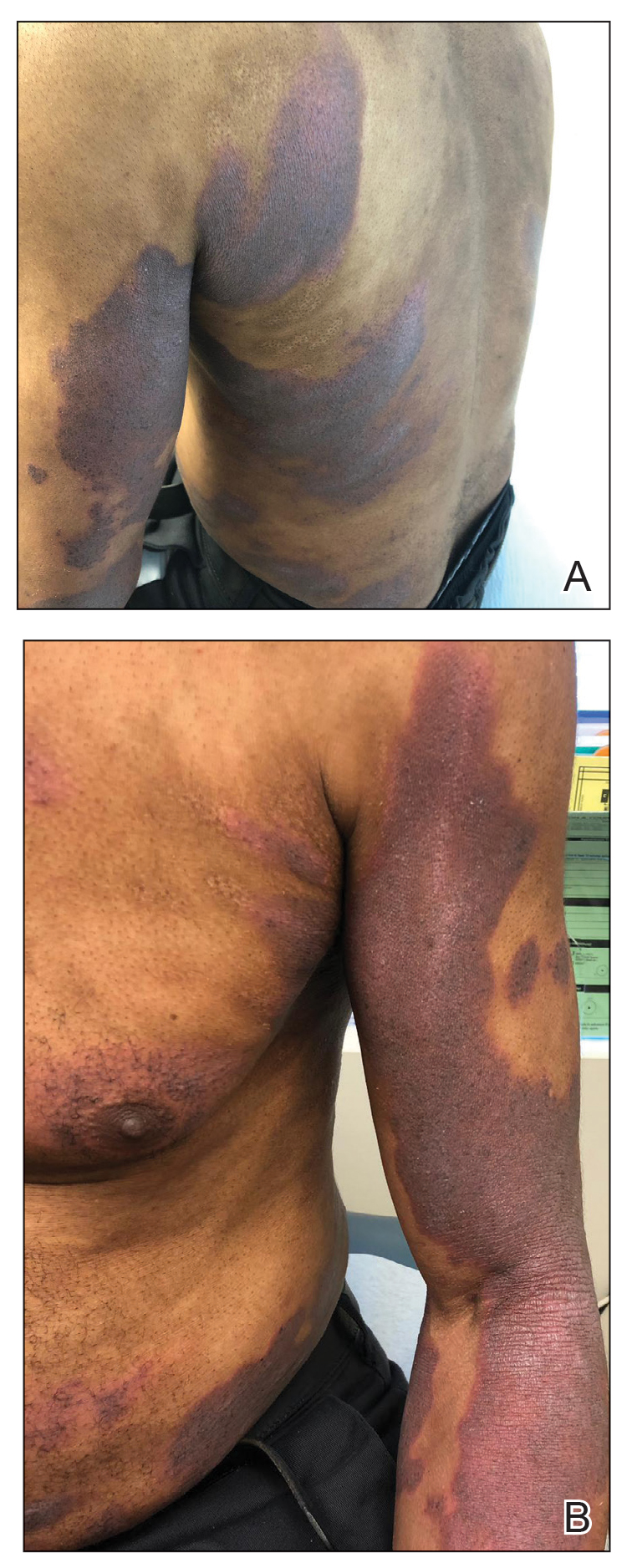

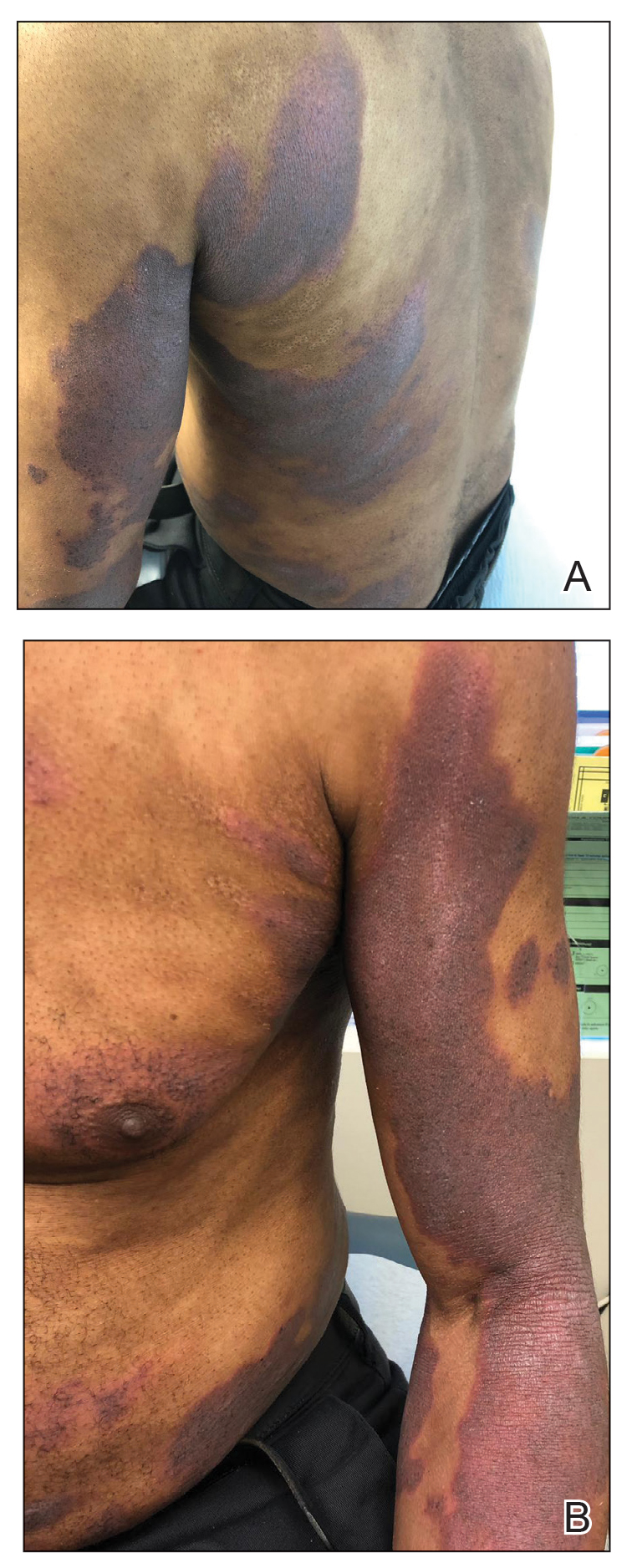

At approximately the same time as dupilumab was initiated, he was started on 60 mg daily of prednisone by his pulmonologist because of a history of restrictive lung disease of unknown cause. While taking prednisone, he experienced notable improvement in his skin condition; however, as he was slowly tapered off prednisone, he noted remarkable worsening of the dermatitis. Dupilumab was discontinued. Two more biopsies were performed; findings on both were consistent with mycosis fungoides (MF)(Figure 2).

Patient 2

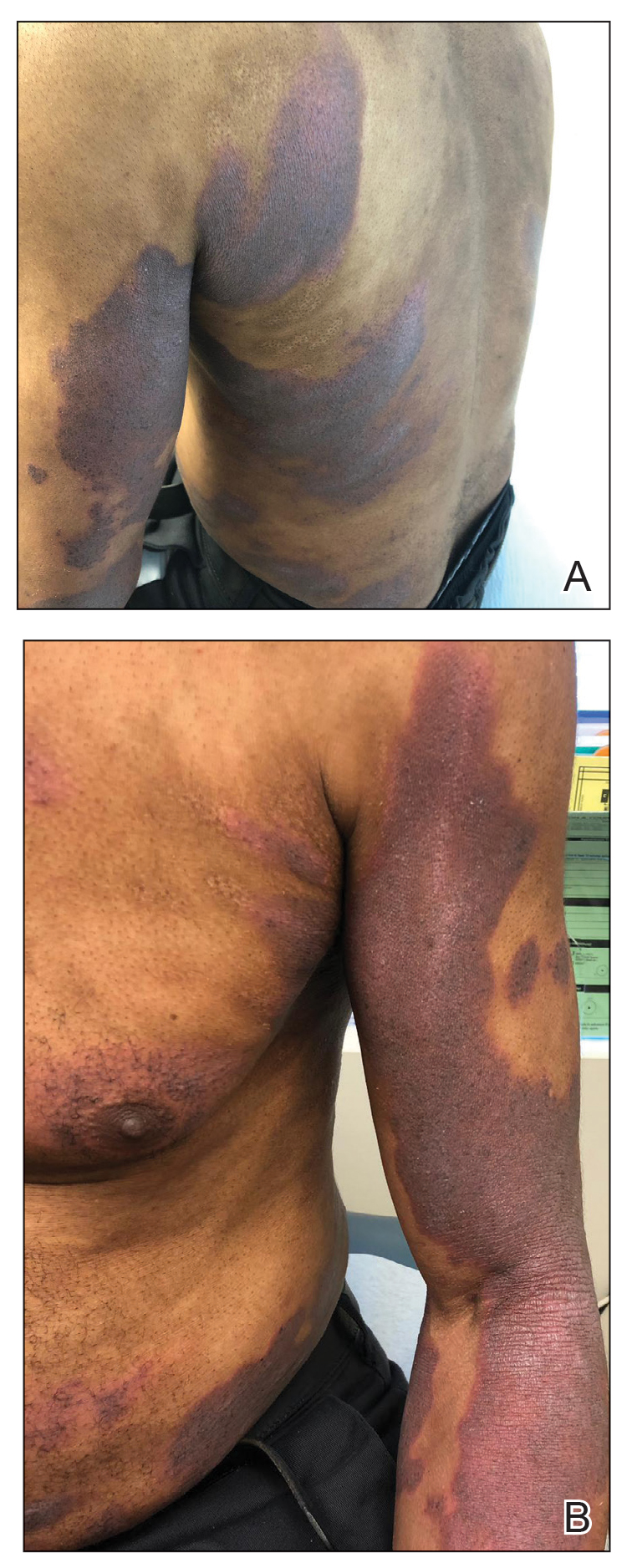

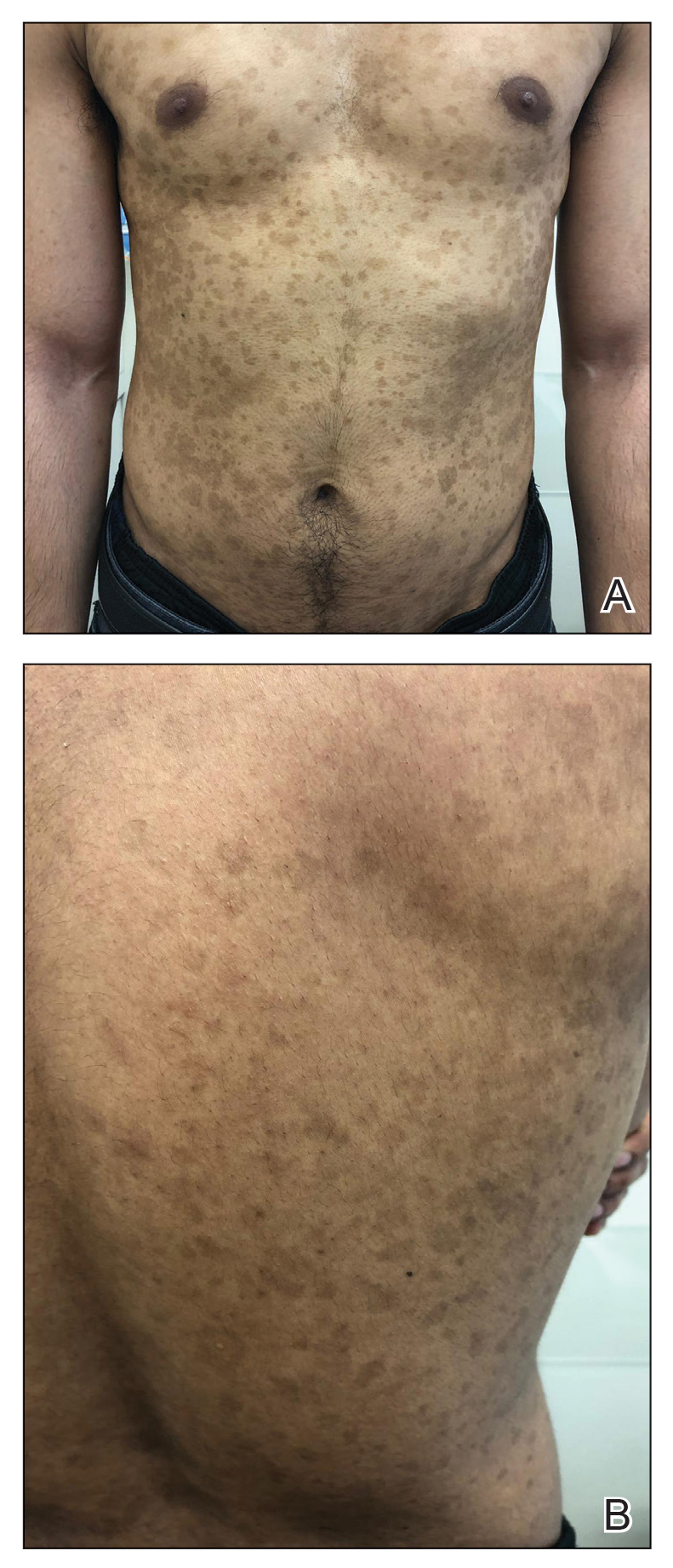

A 52-year-old man presented with indurated, red, scaly plaques on the legs and arms. Initial biopsy was consistent with psoriasiform dermatitis that was thought to be due to a primarily eczematous process. Because of the clinical suspicion of psoriasis, the patient was at first treated with topical betamethasone and eventually was transitioned to multiple injectable biologics without improvement. There was no response to multiple psoriasis treatments, and the original pathology report was re-reviewed. The report noted a substantial eczematous component; therefore, a decision was made to transition him to dupilumab. He also was at first provided with a prednisone taper due to the severity of the cutaneous disease.

Initially, the patient noted 15% to 20% improvement; however, after 6 injections, dupilumab appeared to lose efficacy. Due to a lack of response to multiple biologic medications as well as dupilumab, another biopsy was performed. Findings were consistent with MF.

Patient 3

A 60-year-old woman with diffuse, pruritic, and erythematous dermatitis of 3 years’ duration was referred from an outside dermatology group. Prior biopsies were consistent with eczematous dermatitis. However, because 1 isolated plaque demonstrated findings consistent with psoriasis, she was started on guselkumab, which was discontinued after 12 weeks of therapy for lack of efficacy. The patient also had been treated with a short course of narrowband UVB and topical corticosteroids without benefit.

Upon initial evaluation in our clinic, there was concern for Sézary syndrome; however, peripheral blood studies were normal, and there was no monoclonal spike or irregularity in the patient’s Sézary flow cytometry panel. A biopsy demonstrated lichenoid dermatitis, possibly consistent with drug eruption. All supplements and likely medication culprits were discontinued without improvement.

Prior to follow-up in our clinic, the patient was again evaluated by an outside dermatologist and started on dupilumab. After 3 doses, she discontinued the medication because there was no improvement in the cutaneous symptoms. Findings on repeat biopsy following dupilumab treatment were consistent with MF.

Comment

Mycosis fungoides is a rare chronic T-cell lymphoma that can smolder for decades as nonspecific dermatitis before declaring itself fully on skin biopsy.2 In many cases, MF masquerades as eczema, psoriasis, contact dermatitis, or other dermatitides, and it often responds to the same medications, making diagnosis even more challenging. Treatment options include topical steroids, narrowband UVB, topical nitrogen mustard, topical carmustine, and bexarotene gel for early-stage disease.3 Although it cannot be determined which patients will progress, some do, and therapies must then be upgraded.

We reported 3 patients with adult-onset dermatitis and multiple biopsies demonstrating nondiagnostic findings, which, in retrospect, likely represented early smoldering CTCL. Each of these patients was treated with dupilumab because multiple biopsies demonstrated findings consistent with nondiagnostic dermatitis, along with a lack of response to standard therapies. In all 3 cases, however, the patients had no history of eczema or atopy. After starting dupilumab, each patient had an acute exacerbation of dermatitis; immediately thereafter, biopsies were consistent with CTCL.

These patients most likely had smoldering CTCL that expressed itself fully after dupilumab was started. Biologic medications and their effects on the immune system have been shown to have multiple unanticipated effects on the skin.4-6 We are not insinuating that dupilumab was the cause of our patients having developed CTCL, but we do propose that the underlying interplay of dupilumab with the immune system might have accelerated progression of underlying CTCL, resulting in the lymphoma presenting itself clinically and histopathologically. We also must mention that all 3 cases could represent a “true, true, and unrelated” phenomenon.

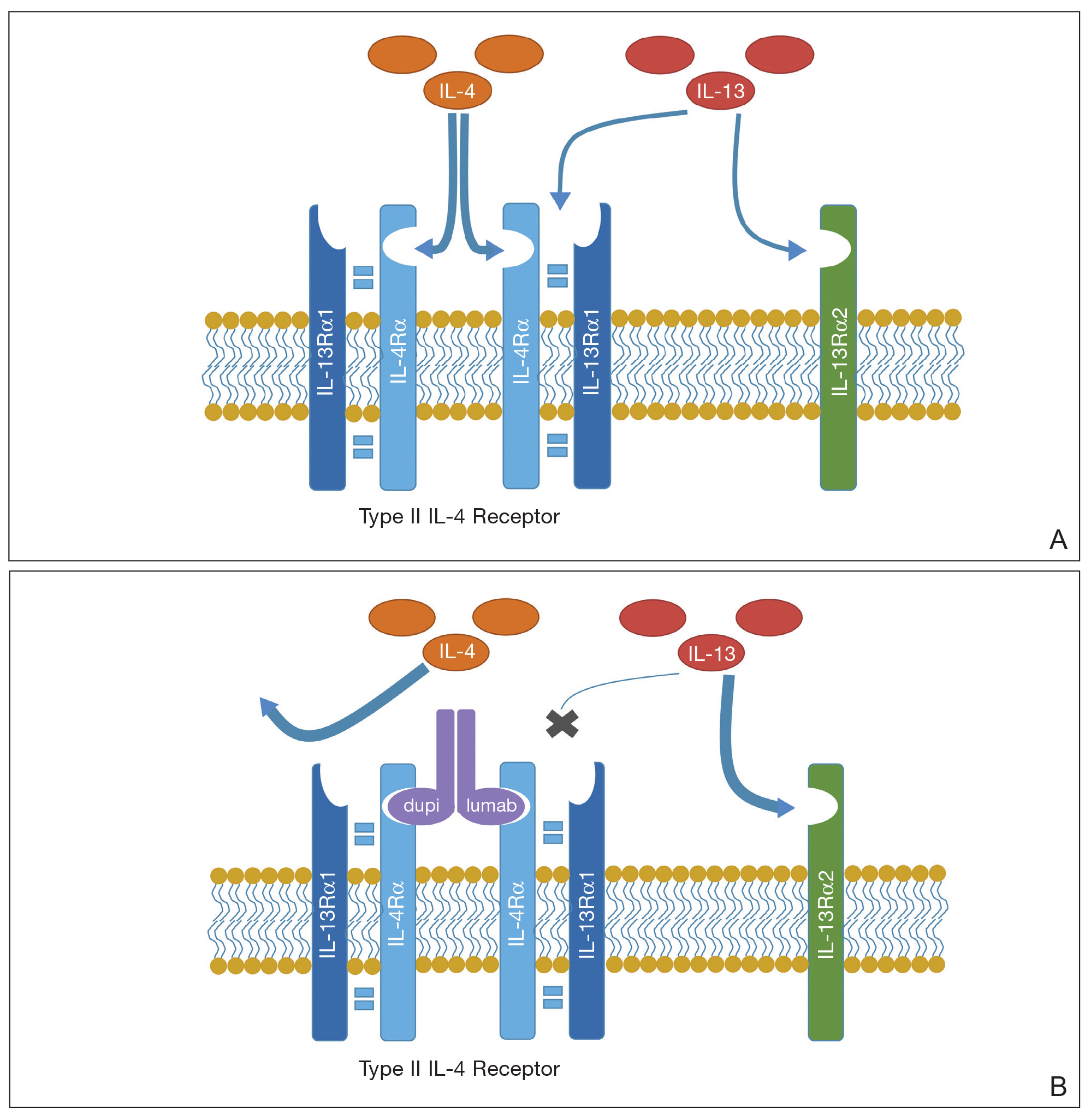

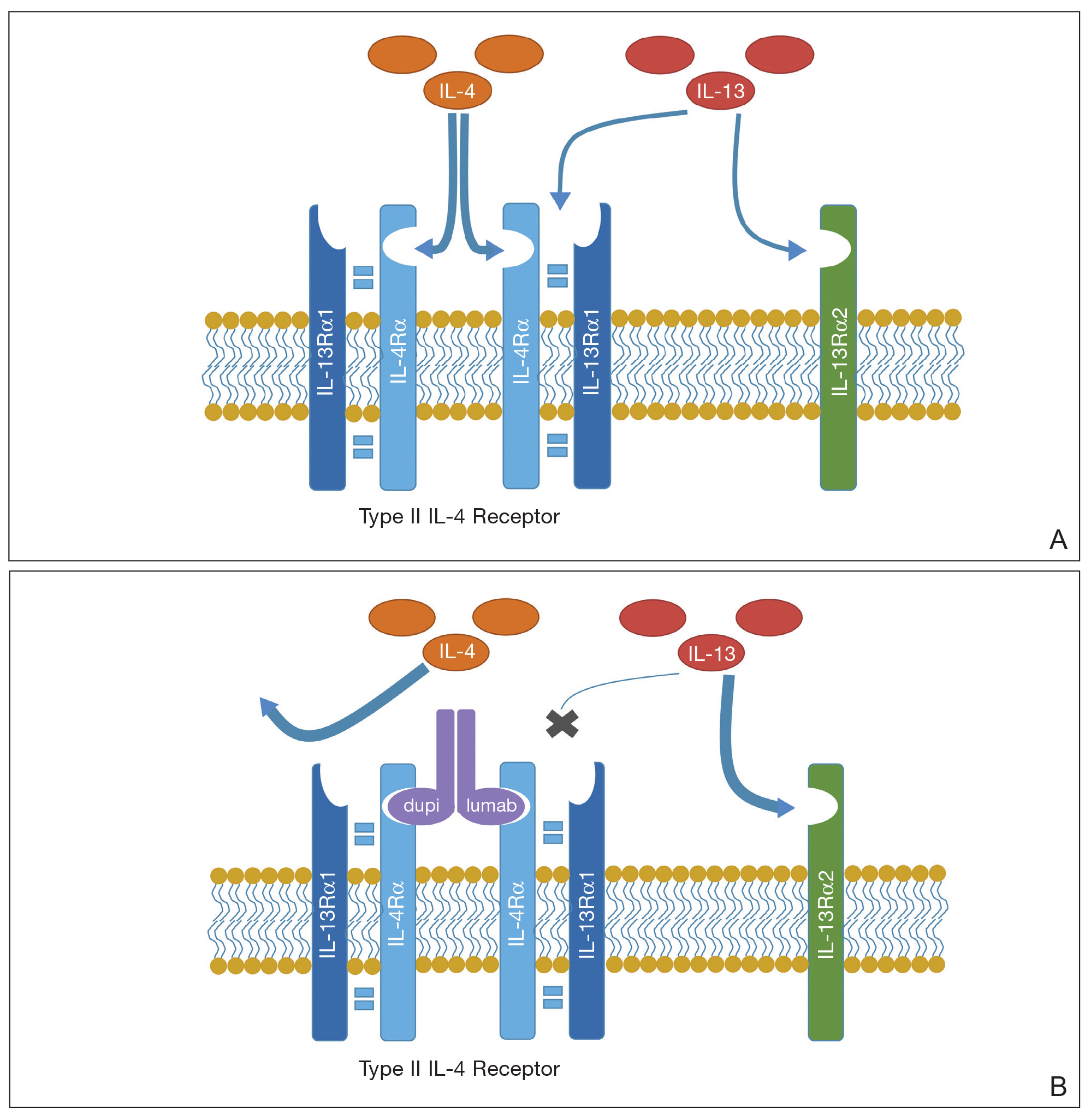

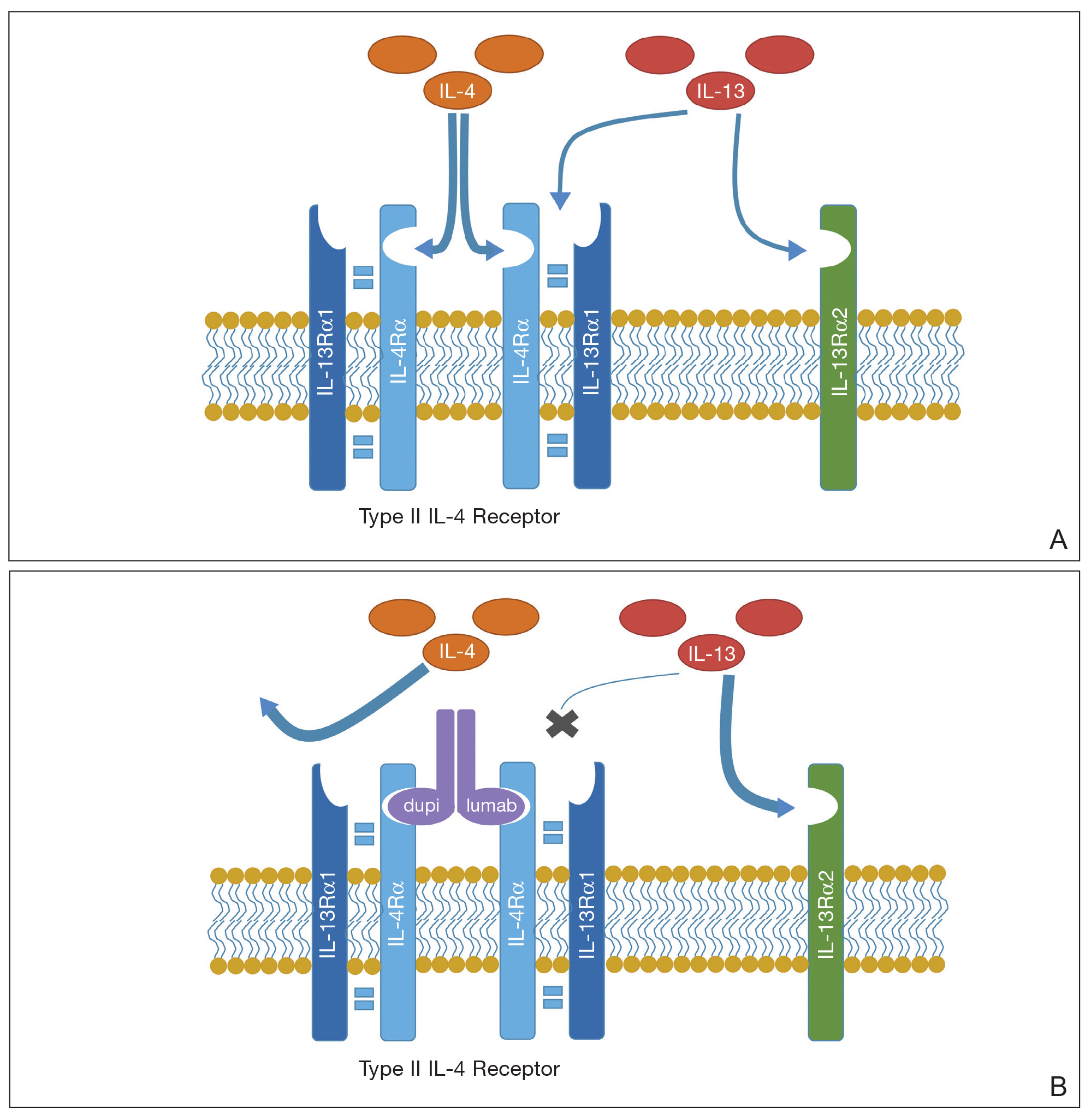

A proposed mechanism for how dupilumab might hasten progression of CTCL is based on a functional increase of IL-13 available for binding at the IL-13 receptor (IL-13R) α2 site following blockade of the IL-13Rα1 site by dupilumab (Figure 3). The pathway that is blocked by dupilumab provides improvement in AD by blocking the α subunit of the IL-4R, making it a receptor antagonist for both IL-4 and IL-13. The IL-4R forms a heterodimer with both γ c and separately with IL-13Rα1. As a result, IL-4 and IL-13 cannot bind to their respective targets; thus, downstream signaling that is required for AD is halted.7 IL-13, in addition to IL-4R, also binds to an IL-13Rα2. IL-13 and both of its receptors are upregulated in CTCL, particularly IL-13Rα2.8

One of the principal ways that CTCL survives is through autocrine signaling, inducing more IL-13 and more IL-13Rα2, which is not seen in normal skin.8 Autocrine signaling plays a critical role in cancer activation and in providing self-sustaining growth signals to tumors.9 In addition, it has been documented that IL-13Rα2 has a higher affinity for IL-13 than the affinity of IL-13Rα1.10 As such, when the dupilumab receptor is blocked, our proposed mechanism of acceleration of CTCL is based on a functional increase in IL-13 available for binding at the IL-13Rα2 site, following indirect blockade of the α1 receptor with dupilumab, which effectively increases available IL-13 to be shunted down the tumorigenic pathway.

We recognize that this proposed mechanism is a theory; additionally, it should be noted that dupilumab is approved only for the treatment of AD and asthma. In our 3 cases, we used dupilumab off label in patients who did not have a clear case of AD or a childhood history of the disease.

When screening patients for the use of dupilumab, it is important to treat only those who have a classic history of moderate to severe AD, including itch, family history, and rash in the classic atopic distribution. We propose that these cases represent potential exacerbation of extant CTCL following exposure to dupilumab.

The manufacturer of dupilumab has reported 1 case of stage IV MF in a 57-year-old man 48 days after the first dose of dupilumab, leading to permanent discontinuation. The patient had ongoing disease at the time of the report, and the manufacturer stated that use of dupilumab was unrelated to disease.11 Studies are needed to explore any potential immunologic link between dupilumab and progression of CTCL.

- Raedler LA. Dupixent (dupilumab) first biologic drug approved for patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2018;11:58-60.

- Skov AG, Gniadecki R. Delay in the histopathologic diagnosis of mycosis fungoides. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:472-475.

- Ramsay DL, Meller JA, Zackheim HS. Topical treatment of early cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1995;9:1031-1056.

- Mazloom SE, Yan D, Hu JZ, et al. TNF-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis: a decade of experience at the Cleveland Clinic [published online December 18, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.018.

- Tierney E, Kirthi S, Ramsay B, et al. Ustekinumab-induced subacute cutaneous lupus. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:271-273.

- Orrell KA, Murphrey M, Kelm RC, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease events after exposure to interleukin 17 inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab: postmarketing analysis from the RADAR (“Research on Adverse Drug events And Reports”) program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:777-778.

- Sastre J, Dávila I. Dupilumab: a new paradigm for the treatment of allergic diseases. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2018;28:139-150.

- Geskin LJ, Viragova S, Stolz DB, et al. Interleukin-13 is over-expressed in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cells and regulates their proliferation. Blood. 2015;125:2798-2805.

- Barderas R, Bartolomé RA, Fernandez-Aceñero MJ, et al. High expression of IL-13 receptor α2 in colorectal cancer is associated with invasion, liver metastasis, and poor prognosis. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2780-2790.

- Andrews A-L, Holloway JW, Puddicombe SM, et al. Kinetic analysis of the interleukin-13 receptor complex. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46073-46078.

- Data on file. Tarrytown, NY: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2017.

Dupilumab is a novel medication that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) in patients 6 years and older. Dupilumab is an injectable fully human monoclonal antibody. It provides a giant leap toward a better quality of life for patients with AD. Dupilumab works by binding to the shared α subunit of the IL-4 receptor (IL-4R), thus inhibiting IL-4 and IL-13 from using that signaling pathway. The documented side-effect profile includes injection-site reaction, keratitis, nasopharyngitis, and headache.1

We initiated off-label treatment with dupilumab in 3 adult patients who had a history of long-standing adult-onset dermatitis confirmed by histopathology. The 3 patients received a loading dose of 600 mg subcutaneously, followed by 300 mg every other week. Following treatment, the patients had expansion of their disease, with features consistent with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) on subsequent biopsies. These 3 cases demonstrate the well-known adage that the diagnosis of CTCL often requires multiple biopsies performed over time. Although dupilumab has proved efficacious and safe for treating AD, dermatologists should be cautious before starting this medication in an adult who has new-onset dermatitis and no history of atopy.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 61-year-old man presented to dermatology after being lost to follow-up for several years and was started on dupilumab for long-standing nonspecific eczematous dermatitis based on histopathology. He had a pruritic rash of 10 years’ duration that had been biopsied multiple times and was found to be consistent with dermatitis and lichen simplex chronicus (Figure 1). He had been treated with triamcinolone ointment 0.1% and narrowband UVB as often as 3 times weekly over many years. The patient also had a history of idiopathic CD4 lymphopenia with consistently negative tests for human immunodeficiency virus.

At approximately the same time as dupilumab was initiated, he was started on 60 mg daily of prednisone by his pulmonologist because of a history of restrictive lung disease of unknown cause. While taking prednisone, he experienced notable improvement in his skin condition; however, as he was slowly tapered off prednisone, he noted remarkable worsening of the dermatitis. Dupilumab was discontinued. Two more biopsies were performed; findings on both were consistent with mycosis fungoides (MF)(Figure 2).

Patient 2

A 52-year-old man presented with indurated, red, scaly plaques on the legs and arms. Initial biopsy was consistent with psoriasiform dermatitis that was thought to be due to a primarily eczematous process. Because of the clinical suspicion of psoriasis, the patient was at first treated with topical betamethasone and eventually was transitioned to multiple injectable biologics without improvement. There was no response to multiple psoriasis treatments, and the original pathology report was re-reviewed. The report noted a substantial eczematous component; therefore, a decision was made to transition him to dupilumab. He also was at first provided with a prednisone taper due to the severity of the cutaneous disease.

Initially, the patient noted 15% to 20% improvement; however, after 6 injections, dupilumab appeared to lose efficacy. Due to a lack of response to multiple biologic medications as well as dupilumab, another biopsy was performed. Findings were consistent with MF.

Patient 3

A 60-year-old woman with diffuse, pruritic, and erythematous dermatitis of 3 years’ duration was referred from an outside dermatology group. Prior biopsies were consistent with eczematous dermatitis. However, because 1 isolated plaque demonstrated findings consistent with psoriasis, she was started on guselkumab, which was discontinued after 12 weeks of therapy for lack of efficacy. The patient also had been treated with a short course of narrowband UVB and topical corticosteroids without benefit.

Upon initial evaluation in our clinic, there was concern for Sézary syndrome; however, peripheral blood studies were normal, and there was no monoclonal spike or irregularity in the patient’s Sézary flow cytometry panel. A biopsy demonstrated lichenoid dermatitis, possibly consistent with drug eruption. All supplements and likely medication culprits were discontinued without improvement.

Prior to follow-up in our clinic, the patient was again evaluated by an outside dermatologist and started on dupilumab. After 3 doses, she discontinued the medication because there was no improvement in the cutaneous symptoms. Findings on repeat biopsy following dupilumab treatment were consistent with MF.

Comment

Mycosis fungoides is a rare chronic T-cell lymphoma that can smolder for decades as nonspecific dermatitis before declaring itself fully on skin biopsy.2 In many cases, MF masquerades as eczema, psoriasis, contact dermatitis, or other dermatitides, and it often responds to the same medications, making diagnosis even more challenging. Treatment options include topical steroids, narrowband UVB, topical nitrogen mustard, topical carmustine, and bexarotene gel for early-stage disease.3 Although it cannot be determined which patients will progress, some do, and therapies must then be upgraded.

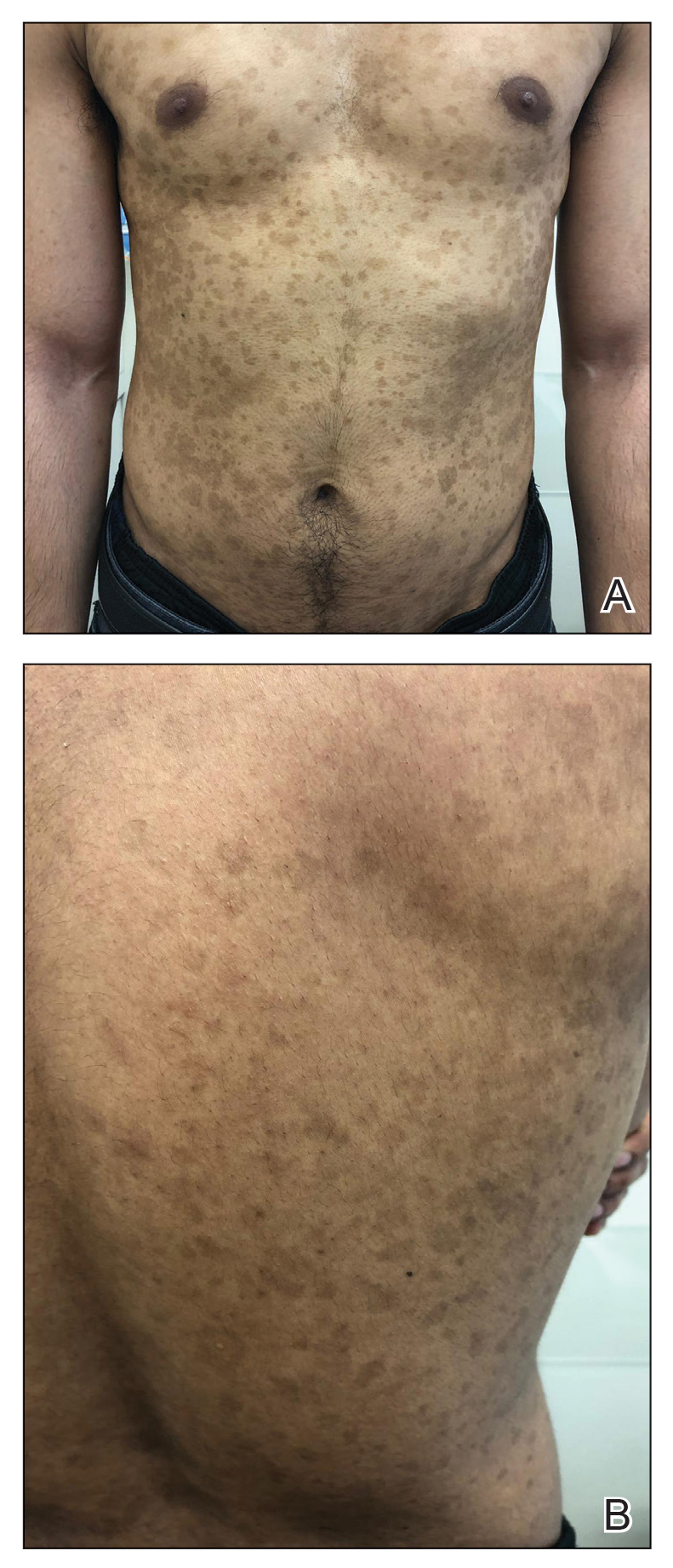

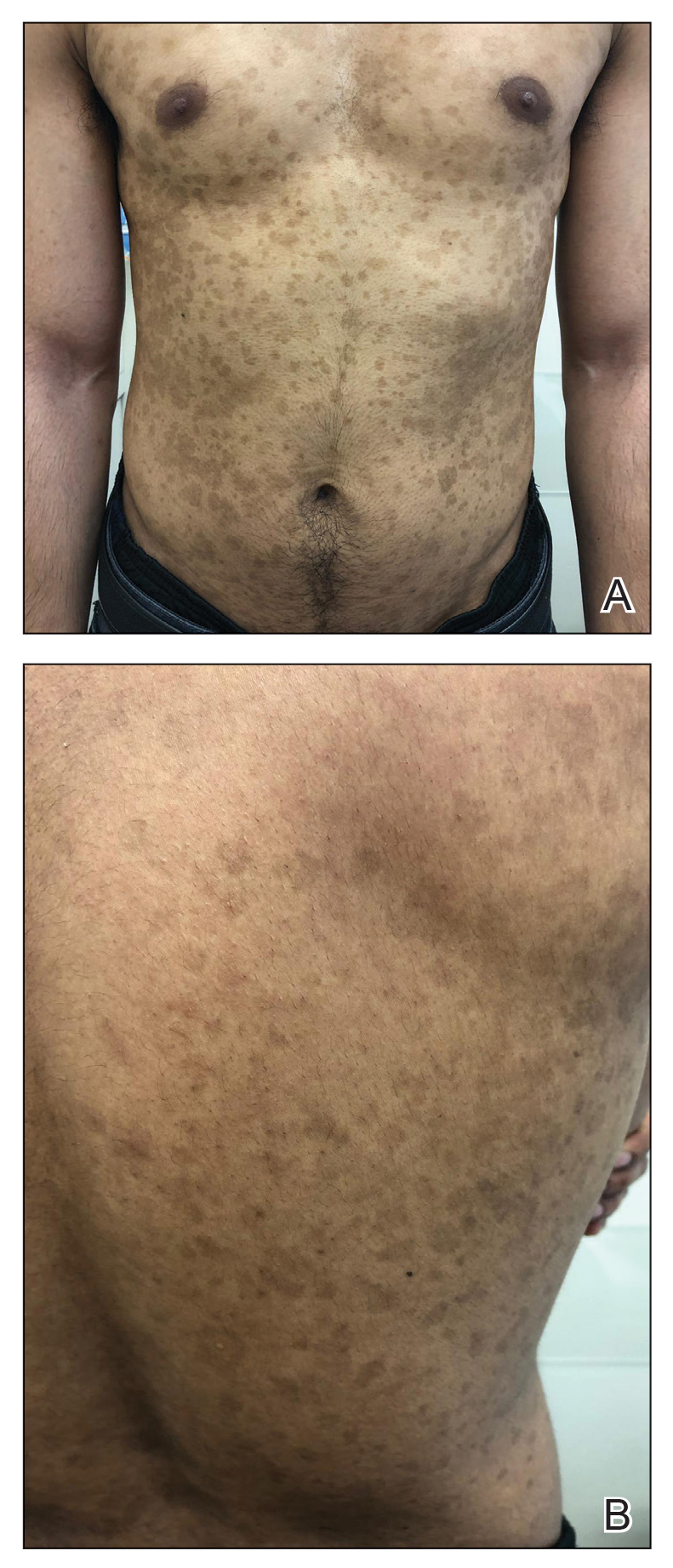

We reported 3 patients with adult-onset dermatitis and multiple biopsies demonstrating nondiagnostic findings, which, in retrospect, likely represented early smoldering CTCL. Each of these patients was treated with dupilumab because multiple biopsies demonstrated findings consistent with nondiagnostic dermatitis, along with a lack of response to standard therapies. In all 3 cases, however, the patients had no history of eczema or atopy. After starting dupilumab, each patient had an acute exacerbation of dermatitis; immediately thereafter, biopsies were consistent with CTCL.

These patients most likely had smoldering CTCL that expressed itself fully after dupilumab was started. Biologic medications and their effects on the immune system have been shown to have multiple unanticipated effects on the skin.4-6 We are not insinuating that dupilumab was the cause of our patients having developed CTCL, but we do propose that the underlying interplay of dupilumab with the immune system might have accelerated progression of underlying CTCL, resulting in the lymphoma presenting itself clinically and histopathologically. We also must mention that all 3 cases could represent a “true, true, and unrelated” phenomenon.

A proposed mechanism for how dupilumab might hasten progression of CTCL is based on a functional increase of IL-13 available for binding at the IL-13 receptor (IL-13R) α2 site following blockade of the IL-13Rα1 site by dupilumab (Figure 3). The pathway that is blocked by dupilumab provides improvement in AD by blocking the α subunit of the IL-4R, making it a receptor antagonist for both IL-4 and IL-13. The IL-4R forms a heterodimer with both γ c and separately with IL-13Rα1. As a result, IL-4 and IL-13 cannot bind to their respective targets; thus, downstream signaling that is required for AD is halted.7 IL-13, in addition to IL-4R, also binds to an IL-13Rα2. IL-13 and both of its receptors are upregulated in CTCL, particularly IL-13Rα2.8

One of the principal ways that CTCL survives is through autocrine signaling, inducing more IL-13 and more IL-13Rα2, which is not seen in normal skin.8 Autocrine signaling plays a critical role in cancer activation and in providing self-sustaining growth signals to tumors.9 In addition, it has been documented that IL-13Rα2 has a higher affinity for IL-13 than the affinity of IL-13Rα1.10 As such, when the dupilumab receptor is blocked, our proposed mechanism of acceleration of CTCL is based on a functional increase in IL-13 available for binding at the IL-13Rα2 site, following indirect blockade of the α1 receptor with dupilumab, which effectively increases available IL-13 to be shunted down the tumorigenic pathway.

We recognize that this proposed mechanism is a theory; additionally, it should be noted that dupilumab is approved only for the treatment of AD and asthma. In our 3 cases, we used dupilumab off label in patients who did not have a clear case of AD or a childhood history of the disease.

When screening patients for the use of dupilumab, it is important to treat only those who have a classic history of moderate to severe AD, including itch, family history, and rash in the classic atopic distribution. We propose that these cases represent potential exacerbation of extant CTCL following exposure to dupilumab.

The manufacturer of dupilumab has reported 1 case of stage IV MF in a 57-year-old man 48 days after the first dose of dupilumab, leading to permanent discontinuation. The patient had ongoing disease at the time of the report, and the manufacturer stated that use of dupilumab was unrelated to disease.11 Studies are needed to explore any potential immunologic link between dupilumab and progression of CTCL.

Dupilumab is a novel medication that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) in patients 6 years and older. Dupilumab is an injectable fully human monoclonal antibody. It provides a giant leap toward a better quality of life for patients with AD. Dupilumab works by binding to the shared α subunit of the IL-4 receptor (IL-4R), thus inhibiting IL-4 and IL-13 from using that signaling pathway. The documented side-effect profile includes injection-site reaction, keratitis, nasopharyngitis, and headache.1

We initiated off-label treatment with dupilumab in 3 adult patients who had a history of long-standing adult-onset dermatitis confirmed by histopathology. The 3 patients received a loading dose of 600 mg subcutaneously, followed by 300 mg every other week. Following treatment, the patients had expansion of their disease, with features consistent with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) on subsequent biopsies. These 3 cases demonstrate the well-known adage that the diagnosis of CTCL often requires multiple biopsies performed over time. Although dupilumab has proved efficacious and safe for treating AD, dermatologists should be cautious before starting this medication in an adult who has new-onset dermatitis and no history of atopy.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 61-year-old man presented to dermatology after being lost to follow-up for several years and was started on dupilumab for long-standing nonspecific eczematous dermatitis based on histopathology. He had a pruritic rash of 10 years’ duration that had been biopsied multiple times and was found to be consistent with dermatitis and lichen simplex chronicus (Figure 1). He had been treated with triamcinolone ointment 0.1% and narrowband UVB as often as 3 times weekly over many years. The patient also had a history of idiopathic CD4 lymphopenia with consistently negative tests for human immunodeficiency virus.

At approximately the same time as dupilumab was initiated, he was started on 60 mg daily of prednisone by his pulmonologist because of a history of restrictive lung disease of unknown cause. While taking prednisone, he experienced notable improvement in his skin condition; however, as he was slowly tapered off prednisone, he noted remarkable worsening of the dermatitis. Dupilumab was discontinued. Two more biopsies were performed; findings on both were consistent with mycosis fungoides (MF)(Figure 2).

Patient 2

A 52-year-old man presented with indurated, red, scaly plaques on the legs and arms. Initial biopsy was consistent with psoriasiform dermatitis that was thought to be due to a primarily eczematous process. Because of the clinical suspicion of psoriasis, the patient was at first treated with topical betamethasone and eventually was transitioned to multiple injectable biologics without improvement. There was no response to multiple psoriasis treatments, and the original pathology report was re-reviewed. The report noted a substantial eczematous component; therefore, a decision was made to transition him to dupilumab. He also was at first provided with a prednisone taper due to the severity of the cutaneous disease.

Initially, the patient noted 15% to 20% improvement; however, after 6 injections, dupilumab appeared to lose efficacy. Due to a lack of response to multiple biologic medications as well as dupilumab, another biopsy was performed. Findings were consistent with MF.

Patient 3

A 60-year-old woman with diffuse, pruritic, and erythematous dermatitis of 3 years’ duration was referred from an outside dermatology group. Prior biopsies were consistent with eczematous dermatitis. However, because 1 isolated plaque demonstrated findings consistent with psoriasis, she was started on guselkumab, which was discontinued after 12 weeks of therapy for lack of efficacy. The patient also had been treated with a short course of narrowband UVB and topical corticosteroids without benefit.

Upon initial evaluation in our clinic, there was concern for Sézary syndrome; however, peripheral blood studies were normal, and there was no monoclonal spike or irregularity in the patient’s Sézary flow cytometry panel. A biopsy demonstrated lichenoid dermatitis, possibly consistent with drug eruption. All supplements and likely medication culprits were discontinued without improvement.

Prior to follow-up in our clinic, the patient was again evaluated by an outside dermatologist and started on dupilumab. After 3 doses, she discontinued the medication because there was no improvement in the cutaneous symptoms. Findings on repeat biopsy following dupilumab treatment were consistent with MF.

Comment

Mycosis fungoides is a rare chronic T-cell lymphoma that can smolder for decades as nonspecific dermatitis before declaring itself fully on skin biopsy.2 In many cases, MF masquerades as eczema, psoriasis, contact dermatitis, or other dermatitides, and it often responds to the same medications, making diagnosis even more challenging. Treatment options include topical steroids, narrowband UVB, topical nitrogen mustard, topical carmustine, and bexarotene gel for early-stage disease.3 Although it cannot be determined which patients will progress, some do, and therapies must then be upgraded.

We reported 3 patients with adult-onset dermatitis and multiple biopsies demonstrating nondiagnostic findings, which, in retrospect, likely represented early smoldering CTCL. Each of these patients was treated with dupilumab because multiple biopsies demonstrated findings consistent with nondiagnostic dermatitis, along with a lack of response to standard therapies. In all 3 cases, however, the patients had no history of eczema or atopy. After starting dupilumab, each patient had an acute exacerbation of dermatitis; immediately thereafter, biopsies were consistent with CTCL.

These patients most likely had smoldering CTCL that expressed itself fully after dupilumab was started. Biologic medications and their effects on the immune system have been shown to have multiple unanticipated effects on the skin.4-6 We are not insinuating that dupilumab was the cause of our patients having developed CTCL, but we do propose that the underlying interplay of dupilumab with the immune system might have accelerated progression of underlying CTCL, resulting in the lymphoma presenting itself clinically and histopathologically. We also must mention that all 3 cases could represent a “true, true, and unrelated” phenomenon.

A proposed mechanism for how dupilumab might hasten progression of CTCL is based on a functional increase of IL-13 available for binding at the IL-13 receptor (IL-13R) α2 site following blockade of the IL-13Rα1 site by dupilumab (Figure 3). The pathway that is blocked by dupilumab provides improvement in AD by blocking the α subunit of the IL-4R, making it a receptor antagonist for both IL-4 and IL-13. The IL-4R forms a heterodimer with both γ c and separately with IL-13Rα1. As a result, IL-4 and IL-13 cannot bind to their respective targets; thus, downstream signaling that is required for AD is halted.7 IL-13, in addition to IL-4R, also binds to an IL-13Rα2. IL-13 and both of its receptors are upregulated in CTCL, particularly IL-13Rα2.8

One of the principal ways that CTCL survives is through autocrine signaling, inducing more IL-13 and more IL-13Rα2, which is not seen in normal skin.8 Autocrine signaling plays a critical role in cancer activation and in providing self-sustaining growth signals to tumors.9 In addition, it has been documented that IL-13Rα2 has a higher affinity for IL-13 than the affinity of IL-13Rα1.10 As such, when the dupilumab receptor is blocked, our proposed mechanism of acceleration of CTCL is based on a functional increase in IL-13 available for binding at the IL-13Rα2 site, following indirect blockade of the α1 receptor with dupilumab, which effectively increases available IL-13 to be shunted down the tumorigenic pathway.

We recognize that this proposed mechanism is a theory; additionally, it should be noted that dupilumab is approved only for the treatment of AD and asthma. In our 3 cases, we used dupilumab off label in patients who did not have a clear case of AD or a childhood history of the disease.

When screening patients for the use of dupilumab, it is important to treat only those who have a classic history of moderate to severe AD, including itch, family history, and rash in the classic atopic distribution. We propose that these cases represent potential exacerbation of extant CTCL following exposure to dupilumab.

The manufacturer of dupilumab has reported 1 case of stage IV MF in a 57-year-old man 48 days after the first dose of dupilumab, leading to permanent discontinuation. The patient had ongoing disease at the time of the report, and the manufacturer stated that use of dupilumab was unrelated to disease.11 Studies are needed to explore any potential immunologic link between dupilumab and progression of CTCL.

- Raedler LA. Dupixent (dupilumab) first biologic drug approved for patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2018;11:58-60.

- Skov AG, Gniadecki R. Delay in the histopathologic diagnosis of mycosis fungoides. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:472-475.

- Ramsay DL, Meller JA, Zackheim HS. Topical treatment of early cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1995;9:1031-1056.

- Mazloom SE, Yan D, Hu JZ, et al. TNF-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis: a decade of experience at the Cleveland Clinic [published online December 18, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.018.

- Tierney E, Kirthi S, Ramsay B, et al. Ustekinumab-induced subacute cutaneous lupus. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:271-273.

- Orrell KA, Murphrey M, Kelm RC, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease events after exposure to interleukin 17 inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab: postmarketing analysis from the RADAR (“Research on Adverse Drug events And Reports”) program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:777-778.

- Sastre J, Dávila I. Dupilumab: a new paradigm for the treatment of allergic diseases. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2018;28:139-150.

- Geskin LJ, Viragova S, Stolz DB, et al. Interleukin-13 is over-expressed in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cells and regulates their proliferation. Blood. 2015;125:2798-2805.

- Barderas R, Bartolomé RA, Fernandez-Aceñero MJ, et al. High expression of IL-13 receptor α2 in colorectal cancer is associated with invasion, liver metastasis, and poor prognosis. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2780-2790.

- Andrews A-L, Holloway JW, Puddicombe SM, et al. Kinetic analysis of the interleukin-13 receptor complex. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46073-46078.

- Data on file. Tarrytown, NY: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2017.

- Raedler LA. Dupixent (dupilumab) first biologic drug approved for patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2018;11:58-60.

- Skov AG, Gniadecki R. Delay in the histopathologic diagnosis of mycosis fungoides. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:472-475.

- Ramsay DL, Meller JA, Zackheim HS. Topical treatment of early cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1995;9:1031-1056.

- Mazloom SE, Yan D, Hu JZ, et al. TNF-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis: a decade of experience at the Cleveland Clinic [published online December 18, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.018.

- Tierney E, Kirthi S, Ramsay B, et al. Ustekinumab-induced subacute cutaneous lupus. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:271-273.

- Orrell KA, Murphrey M, Kelm RC, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease events after exposure to interleukin 17 inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab: postmarketing analysis from the RADAR (“Research on Adverse Drug events And Reports”) program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:777-778.

- Sastre J, Dávila I. Dupilumab: a new paradigm for the treatment of allergic diseases. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2018;28:139-150.

- Geskin LJ, Viragova S, Stolz DB, et al. Interleukin-13 is over-expressed in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cells and regulates their proliferation. Blood. 2015;125:2798-2805.

- Barderas R, Bartolomé RA, Fernandez-Aceñero MJ, et al. High expression of IL-13 receptor α2 in colorectal cancer is associated with invasion, liver metastasis, and poor prognosis. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2780-2790.

- Andrews A-L, Holloway JW, Puddicombe SM, et al. Kinetic analysis of the interleukin-13 receptor complex. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46073-46078.

- Data on file. Tarrytown, NY: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2017.

Practice Points

- Dupilumab is a safe and effective treatment for atopic dermatitis (AD) in both children and adults.

- Prior to starting treatment for presumed adult-onset AD, consider smoldering cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

- Dupilumab may interact with the cutaneous immune system, leading to an expedited presentation of CTCL in patients with chronic adult-onset AD.

Valproate-Induced Lower Extremity Swelling

Bilateral lower extremity edema is a common condition with a broad differential diagnosis. New, severe peripheral edema implies a more nefarious underlying etiology than chronic venous insufficiency and should prompt a thorough evaluation for underlying conditions, such as congestive heart failure (CHF), cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome, hypoalbuminemia, or lymphatic or venous obstruction. We present a case of a patient with sudden onset new bilateral lower extremity edema due to a rare adverse drug reaction (ADR) from valproate.

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old male with a history of seizures, bipolar disorder type I, and memory impairment due to traumatic brain injury (TBI) from a gunshot wound 24 years prior presented to the emergency department for witnessed seizure activity in the community. The patient had been incarcerated for the past 20 years, throughout which he had been taking the antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) phenytoin and divalproex and did not have any seizure activity. No records prior to his incarceration were available for review.

The patient recently had been released from prison and was nonadherent with his AEDs, leading to a witnessed seizure. This episode was described as preceded by an electric sensation, followed by rhythmic shaking of the right upper extremity without loss of consciousness. His regimen prior to admission included divalproex 1,000 mg daily and phenytoin 200 mg daily. His only other medication was folic acid.

Neurology was consulted on admission. An awake and asleep 4-hour electroencephalogram showed intermittent focal slowing of the right frontocentral region and frequent epileptiform discharges in the right prefrontal region during sleep, corresponding to areas of chronic right anterior frontal and temporal encephalomalacia seen on brain imaging. His seizures were thought likely to be secondary to prior head trauma. While the described seizure activity involving the right upper extremity was not consistent with the location of his prior TBI, neurology considered that he might have simple partial seizures with multiple foci or that his seizure event prior to admission was not accurately described. The neurology consult recommended switching from phenytoin 200 mg daily to lacosamide 100 mg twice daily on admission. His prior dose of divalproex 1,000 mg daily also was resumed for its antiepileptic effect and the added benefit of mood stabilization, as the patient reported elevated mood and decreased need for sleep on admission.

Eight days after changing his AED regimen, the patient was found to have new onset bilateral grade 1+ pitting edema to the level of his shins. He had no history of dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, dysuria, or changes in his urination. Although medical records from his incarceration were not available for review, the patient reported that he had never had peripheral edema.

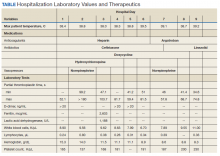

On physical examination, the patient had no periorbital edema, jugular venous pressure of 8 cm H2O, negative hepatojugular reflex, unremarkable cardiac and lung examination, and grade 2+ posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis pulses bilaterally. He underwent extensive laboratory evaluation for potential underlying causes, including nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, hypothyroidism, and CHF (Table). Valproate levels were initially subtherapeutic on admission (< 10 µg/mL, reference range 50-125 µg/mL) then rose to within therapeutic range (54 µg/mL-80 µg/mL throughout admission) after neurology recommended increasing the dose from 1,000 mg daily to 1,500 mg daily. His measured valproate levels were never supratherapeutic.

An electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm unchanged from admission. Transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular (LV) size and estimated LV ejection fraction of 55 to 60%. Abdominal ultrasound showed no evidence of cirrhosis and normal portal vein flow. Ultrasound of the lower extremities showed no deep venous thrombosis or valvular insufficiency. The patient was prescribed compression stockings. However, due to memory impairment, he was relatively nonadherent, and his lower extremity edema worsened to grade 3+ over several days. Due to the progressive swelling with no identified cause, a computed tomographic venogram of the abdomen and pelvis was performed to determine whether an inferior vena cava (IVC) thrombus was present. This study was unremarkable and did not show any external IVC compression.

After extensive evaluation did not reveal any other cause, the temporal course of events suggested an association between the patient’s peripheral edema and resumption of divalproex. His swelling remained stable. Discontinuation of divalproex was considered, but the patient’s mood remained euthymic, and he had no further seizure activity while on this medication, so the benefit of continuation was felt to outweigh any risks of switching to another agent.

Discussion

Valproate and its related forms, such as divalproex, often are used in the treatment of generalized or partial seizures, psychiatric disorders, and the prophylaxis of migraine headaches. Common ADRs include gastrointestinal symptoms, sedation, and dose-related thrombocytopenia, among many others. Rare ADRs include fulminant hepatitis, pancreatitis, hyperammonemia, and peripheral edema.1 There have been case reports of valproate-induced peripheral edema, which seems to be an idiosyncratic ADR that occurs after long-term administration of the medication.2,3 Early studies reported valproate-related edema in the context of valproate-induced hepatic injury.4 However, in more recent case reports, valproate-related edema has been found in patients without hepatotoxicity or supratherapeutic drug levels.1,2

The exact mechanism by which valproate causes peripheral edema is unknown. It has been reported that medications affecting the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) system such as benzodiazepines, for example, can cause this rare ADR.5 Unlike benzodiazepines, valproate has an indirect effect on the GABA system, through increasing availability of GABA.6 GABA receptors have been identified on peripheral tissues, suggesting that GABAergic medications also may have an effect on regional vascular resistance.7 This mechanism was proposed by prior case reports but has yet to be proven in studies.2

In this case, initiation of lacosamide temporally coinciding with development of the patient’s edema leads one to question whether lacosamide may have caused this ADR. Other medications commonly used in seizure management (such as benzodiazepines and gabapentin) have been reported to cause new onset peripheral edema.5,8 To date, however, there are no reported cases of peripheral edema due to lacosamide. While there are known interactions between various AEDs that may impact drug levels of valproate, there are no reported drug-drug interactions between lacosamide and valproate.9

Conclusions

Our case adds to the small but growing body of literature that suggests peripheral edema is a rare but clinically significant ADR of valproate. With its broad differential diagnosis, new onset peripheral edema is a concern that often warrants an extensive evaluation for underlying causes. Clinicians should be aware of this ADR as use of valproate becomes increasingly common so that an extensive workup is not always performed on patients with peripheral edema.

1. Prajapati H, Kansal D, Negi R. Magnesium valproate-induced pedal edema on chronic therapy: a rare adverse drug reaction. Indian J Pharmacol. 2017;49(5):399. doi:10.4103/ijp.IJP_239_17

2. Lin ST, Chen CS, Yen CF, Tsei JH, Wang SY. Valproate-related peripheral oedema: a manageable but probably neglected condition. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12(7):991-993. doi:10.1017/S1461145709000509

3. Ettinger A, Moshe S, Shinnar S. Edema associated with long‐term valproate therapy. Epilepsia. 1990;31(2):211-213. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.1990.tb06308.x

4. Zimmerman HJ, Ishak KG. Valproate‐induced hepatic injury: analyses of 23 fatal cases. Hepatology. 1982;2(5):591S-597S. doi:10.1002/hep.1840020513

5. Mathew T, D’Souza D, Nadimpally US, Nadig R. Clobazam‐induced pedal edema: “an unrecognized side effect of a common antiepileptic drug.” Epilepsia. 2016;57(3): 524-525. doi:10.1111/epi.13316

6. Bourin M, Chenu F, Hascoët M. The role of sodium channels in the mechanism of action of antidepressants and mood stabilizers. Curr Drug Targets. 2009;10(11):1052-1060. doi:10.2174/138945009789735138

7. Takemoto Y. Effects of gamma‐aminobutyric acid on regional vascular resistances of conscious spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1995;22(suppl):S102-Sl04. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.1995.tb02839.x

8. Bidaki R, Sadeghi Z, Shafizadegan S, et al. Gabapentin induces edema, hyperesthesia and scaling in a depressed patient; a diagnostic challenge. Adv Biomed Res. 2016;5:1. doi:10.4103/2277-9175.174955

9. Cawello W, Nickel B, Eggert‐Formella A. No pharmacokinetic interaction between lacosamide and carbamazepine in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;50(4):459-471. doi:10.1177/0091270009347675

Bilateral lower extremity edema is a common condition with a broad differential diagnosis. New, severe peripheral edema implies a more nefarious underlying etiology than chronic venous insufficiency and should prompt a thorough evaluation for underlying conditions, such as congestive heart failure (CHF), cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome, hypoalbuminemia, or lymphatic or venous obstruction. We present a case of a patient with sudden onset new bilateral lower extremity edema due to a rare adverse drug reaction (ADR) from valproate.

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old male with a history of seizures, bipolar disorder type I, and memory impairment due to traumatic brain injury (TBI) from a gunshot wound 24 years prior presented to the emergency department for witnessed seizure activity in the community. The patient had been incarcerated for the past 20 years, throughout which he had been taking the antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) phenytoin and divalproex and did not have any seizure activity. No records prior to his incarceration were available for review.

The patient recently had been released from prison and was nonadherent with his AEDs, leading to a witnessed seizure. This episode was described as preceded by an electric sensation, followed by rhythmic shaking of the right upper extremity without loss of consciousness. His regimen prior to admission included divalproex 1,000 mg daily and phenytoin 200 mg daily. His only other medication was folic acid.

Neurology was consulted on admission. An awake and asleep 4-hour electroencephalogram showed intermittent focal slowing of the right frontocentral region and frequent epileptiform discharges in the right prefrontal region during sleep, corresponding to areas of chronic right anterior frontal and temporal encephalomalacia seen on brain imaging. His seizures were thought likely to be secondary to prior head trauma. While the described seizure activity involving the right upper extremity was not consistent with the location of his prior TBI, neurology considered that he might have simple partial seizures with multiple foci or that his seizure event prior to admission was not accurately described. The neurology consult recommended switching from phenytoin 200 mg daily to lacosamide 100 mg twice daily on admission. His prior dose of divalproex 1,000 mg daily also was resumed for its antiepileptic effect and the added benefit of mood stabilization, as the patient reported elevated mood and decreased need for sleep on admission.

Eight days after changing his AED regimen, the patient was found to have new onset bilateral grade 1+ pitting edema to the level of his shins. He had no history of dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, dysuria, or changes in his urination. Although medical records from his incarceration were not available for review, the patient reported that he had never had peripheral edema.

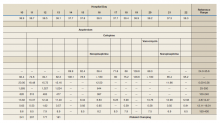

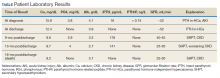

On physical examination, the patient had no periorbital edema, jugular venous pressure of 8 cm H2O, negative hepatojugular reflex, unremarkable cardiac and lung examination, and grade 2+ posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis pulses bilaterally. He underwent extensive laboratory evaluation for potential underlying causes, including nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, hypothyroidism, and CHF (Table). Valproate levels were initially subtherapeutic on admission (< 10 µg/mL, reference range 50-125 µg/mL) then rose to within therapeutic range (54 µg/mL-80 µg/mL throughout admission) after neurology recommended increasing the dose from 1,000 mg daily to 1,500 mg daily. His measured valproate levels were never supratherapeutic.

An electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm unchanged from admission. Transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular (LV) size and estimated LV ejection fraction of 55 to 60%. Abdominal ultrasound showed no evidence of cirrhosis and normal portal vein flow. Ultrasound of the lower extremities showed no deep venous thrombosis or valvular insufficiency. The patient was prescribed compression stockings. However, due to memory impairment, he was relatively nonadherent, and his lower extremity edema worsened to grade 3+ over several days. Due to the progressive swelling with no identified cause, a computed tomographic venogram of the abdomen and pelvis was performed to determine whether an inferior vena cava (IVC) thrombus was present. This study was unremarkable and did not show any external IVC compression.

After extensive evaluation did not reveal any other cause, the temporal course of events suggested an association between the patient’s peripheral edema and resumption of divalproex. His swelling remained stable. Discontinuation of divalproex was considered, but the patient’s mood remained euthymic, and he had no further seizure activity while on this medication, so the benefit of continuation was felt to outweigh any risks of switching to another agent.

Discussion

Valproate and its related forms, such as divalproex, often are used in the treatment of generalized or partial seizures, psychiatric disorders, and the prophylaxis of migraine headaches. Common ADRs include gastrointestinal symptoms, sedation, and dose-related thrombocytopenia, among many others. Rare ADRs include fulminant hepatitis, pancreatitis, hyperammonemia, and peripheral edema.1 There have been case reports of valproate-induced peripheral edema, which seems to be an idiosyncratic ADR that occurs after long-term administration of the medication.2,3 Early studies reported valproate-related edema in the context of valproate-induced hepatic injury.4 However, in more recent case reports, valproate-related edema has been found in patients without hepatotoxicity or supratherapeutic drug levels.1,2

The exact mechanism by which valproate causes peripheral edema is unknown. It has been reported that medications affecting the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) system such as benzodiazepines, for example, can cause this rare ADR.5 Unlike benzodiazepines, valproate has an indirect effect on the GABA system, through increasing availability of GABA.6 GABA receptors have been identified on peripheral tissues, suggesting that GABAergic medications also may have an effect on regional vascular resistance.7 This mechanism was proposed by prior case reports but has yet to be proven in studies.2

In this case, initiation of lacosamide temporally coinciding with development of the patient’s edema leads one to question whether lacosamide may have caused this ADR. Other medications commonly used in seizure management (such as benzodiazepines and gabapentin) have been reported to cause new onset peripheral edema.5,8 To date, however, there are no reported cases of peripheral edema due to lacosamide. While there are known interactions between various AEDs that may impact drug levels of valproate, there are no reported drug-drug interactions between lacosamide and valproate.9

Conclusions

Our case adds to the small but growing body of literature that suggests peripheral edema is a rare but clinically significant ADR of valproate. With its broad differential diagnosis, new onset peripheral edema is a concern that often warrants an extensive evaluation for underlying causes. Clinicians should be aware of this ADR as use of valproate becomes increasingly common so that an extensive workup is not always performed on patients with peripheral edema.

Bilateral lower extremity edema is a common condition with a broad differential diagnosis. New, severe peripheral edema implies a more nefarious underlying etiology than chronic venous insufficiency and should prompt a thorough evaluation for underlying conditions, such as congestive heart failure (CHF), cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome, hypoalbuminemia, or lymphatic or venous obstruction. We present a case of a patient with sudden onset new bilateral lower extremity edema due to a rare adverse drug reaction (ADR) from valproate.

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old male with a history of seizures, bipolar disorder type I, and memory impairment due to traumatic brain injury (TBI) from a gunshot wound 24 years prior presented to the emergency department for witnessed seizure activity in the community. The patient had been incarcerated for the past 20 years, throughout which he had been taking the antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) phenytoin and divalproex and did not have any seizure activity. No records prior to his incarceration were available for review.

The patient recently had been released from prison and was nonadherent with his AEDs, leading to a witnessed seizure. This episode was described as preceded by an electric sensation, followed by rhythmic shaking of the right upper extremity without loss of consciousness. His regimen prior to admission included divalproex 1,000 mg daily and phenytoin 200 mg daily. His only other medication was folic acid.

Neurology was consulted on admission. An awake and asleep 4-hour electroencephalogram showed intermittent focal slowing of the right frontocentral region and frequent epileptiform discharges in the right prefrontal region during sleep, corresponding to areas of chronic right anterior frontal and temporal encephalomalacia seen on brain imaging. His seizures were thought likely to be secondary to prior head trauma. While the described seizure activity involving the right upper extremity was not consistent with the location of his prior TBI, neurology considered that he might have simple partial seizures with multiple foci or that his seizure event prior to admission was not accurately described. The neurology consult recommended switching from phenytoin 200 mg daily to lacosamide 100 mg twice daily on admission. His prior dose of divalproex 1,000 mg daily also was resumed for its antiepileptic effect and the added benefit of mood stabilization, as the patient reported elevated mood and decreased need for sleep on admission.

Eight days after changing his AED regimen, the patient was found to have new onset bilateral grade 1+ pitting edema to the level of his shins. He had no history of dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, dysuria, or changes in his urination. Although medical records from his incarceration were not available for review, the patient reported that he had never had peripheral edema.

On physical examination, the patient had no periorbital edema, jugular venous pressure of 8 cm H2O, negative hepatojugular reflex, unremarkable cardiac and lung examination, and grade 2+ posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis pulses bilaterally. He underwent extensive laboratory evaluation for potential underlying causes, including nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, hypothyroidism, and CHF (Table). Valproate levels were initially subtherapeutic on admission (< 10 µg/mL, reference range 50-125 µg/mL) then rose to within therapeutic range (54 µg/mL-80 µg/mL throughout admission) after neurology recommended increasing the dose from 1,000 mg daily to 1,500 mg daily. His measured valproate levels were never supratherapeutic.

An electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm unchanged from admission. Transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular (LV) size and estimated LV ejection fraction of 55 to 60%. Abdominal ultrasound showed no evidence of cirrhosis and normal portal vein flow. Ultrasound of the lower extremities showed no deep venous thrombosis or valvular insufficiency. The patient was prescribed compression stockings. However, due to memory impairment, he was relatively nonadherent, and his lower extremity edema worsened to grade 3+ over several days. Due to the progressive swelling with no identified cause, a computed tomographic venogram of the abdomen and pelvis was performed to determine whether an inferior vena cava (IVC) thrombus was present. This study was unremarkable and did not show any external IVC compression.

After extensive evaluation did not reveal any other cause, the temporal course of events suggested an association between the patient’s peripheral edema and resumption of divalproex. His swelling remained stable. Discontinuation of divalproex was considered, but the patient’s mood remained euthymic, and he had no further seizure activity while on this medication, so the benefit of continuation was felt to outweigh any risks of switching to another agent.

Discussion

Valproate and its related forms, such as divalproex, often are used in the treatment of generalized or partial seizures, psychiatric disorders, and the prophylaxis of migraine headaches. Common ADRs include gastrointestinal symptoms, sedation, and dose-related thrombocytopenia, among many others. Rare ADRs include fulminant hepatitis, pancreatitis, hyperammonemia, and peripheral edema.1 There have been case reports of valproate-induced peripheral edema, which seems to be an idiosyncratic ADR that occurs after long-term administration of the medication.2,3 Early studies reported valproate-related edema in the context of valproate-induced hepatic injury.4 However, in more recent case reports, valproate-related edema has been found in patients without hepatotoxicity or supratherapeutic drug levels.1,2

The exact mechanism by which valproate causes peripheral edema is unknown. It has been reported that medications affecting the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) system such as benzodiazepines, for example, can cause this rare ADR.5 Unlike benzodiazepines, valproate has an indirect effect on the GABA system, through increasing availability of GABA.6 GABA receptors have been identified on peripheral tissues, suggesting that GABAergic medications also may have an effect on regional vascular resistance.7 This mechanism was proposed by prior case reports but has yet to be proven in studies.2

In this case, initiation of lacosamide temporally coinciding with development of the patient’s edema leads one to question whether lacosamide may have caused this ADR. Other medications commonly used in seizure management (such as benzodiazepines and gabapentin) have been reported to cause new onset peripheral edema.5,8 To date, however, there are no reported cases of peripheral edema due to lacosamide. While there are known interactions between various AEDs that may impact drug levels of valproate, there are no reported drug-drug interactions between lacosamide and valproate.9

Conclusions

Our case adds to the small but growing body of literature that suggests peripheral edema is a rare but clinically significant ADR of valproate. With its broad differential diagnosis, new onset peripheral edema is a concern that often warrants an extensive evaluation for underlying causes. Clinicians should be aware of this ADR as use of valproate becomes increasingly common so that an extensive workup is not always performed on patients with peripheral edema.

1. Prajapati H, Kansal D, Negi R. Magnesium valproate-induced pedal edema on chronic therapy: a rare adverse drug reaction. Indian J Pharmacol. 2017;49(5):399. doi:10.4103/ijp.IJP_239_17

2. Lin ST, Chen CS, Yen CF, Tsei JH, Wang SY. Valproate-related peripheral oedema: a manageable but probably neglected condition. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12(7):991-993. doi:10.1017/S1461145709000509

3. Ettinger A, Moshe S, Shinnar S. Edema associated with long‐term valproate therapy. Epilepsia. 1990;31(2):211-213. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.1990.tb06308.x