User login

Palmoplantar Eruption in a Patient With Mercury Poisoning

Mercury poisoning affects multiple body systems, leading to variable clinical presentations. Mercury intoxication at low levels frequently presents with weakness, fatigue, weight loss, and abdominal pain. At higher levels of mercury intoxication, tremors and neurologic dysfunction are more prevalent.1 Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure vary and include pink disease (acrodynia), mercury exanthem, contact dermatitis, and cutaneous granulomas. Untreated mercury poisoning may result in severe complications, including renal tubular necrosis, pneumonitis, persistent neurologic dysfunction, and fatality in some cases.1,2

Pink disease is a rare disease that typically arises in infants and young children from chronic mercury exposure.3 We report a unique presentation of pink disease occurring in an 18-year-old woman following mercury exposure.

Case Report

An 18-year-old woman who was previously healthy presented to the hospital for evaluation of body aches and back pain. She reported a transient rash on the torso 2 weeks prior, but at the current presentation, only the distal upper and lower extremities were involved. A review of systems revealed myalgia, most severe in the lower back; muscle spasms; stiffness in the fingers; abdominal pain; constipation; paresthesia in the hands and feet; hyperhidrosis; and generalized weakness.

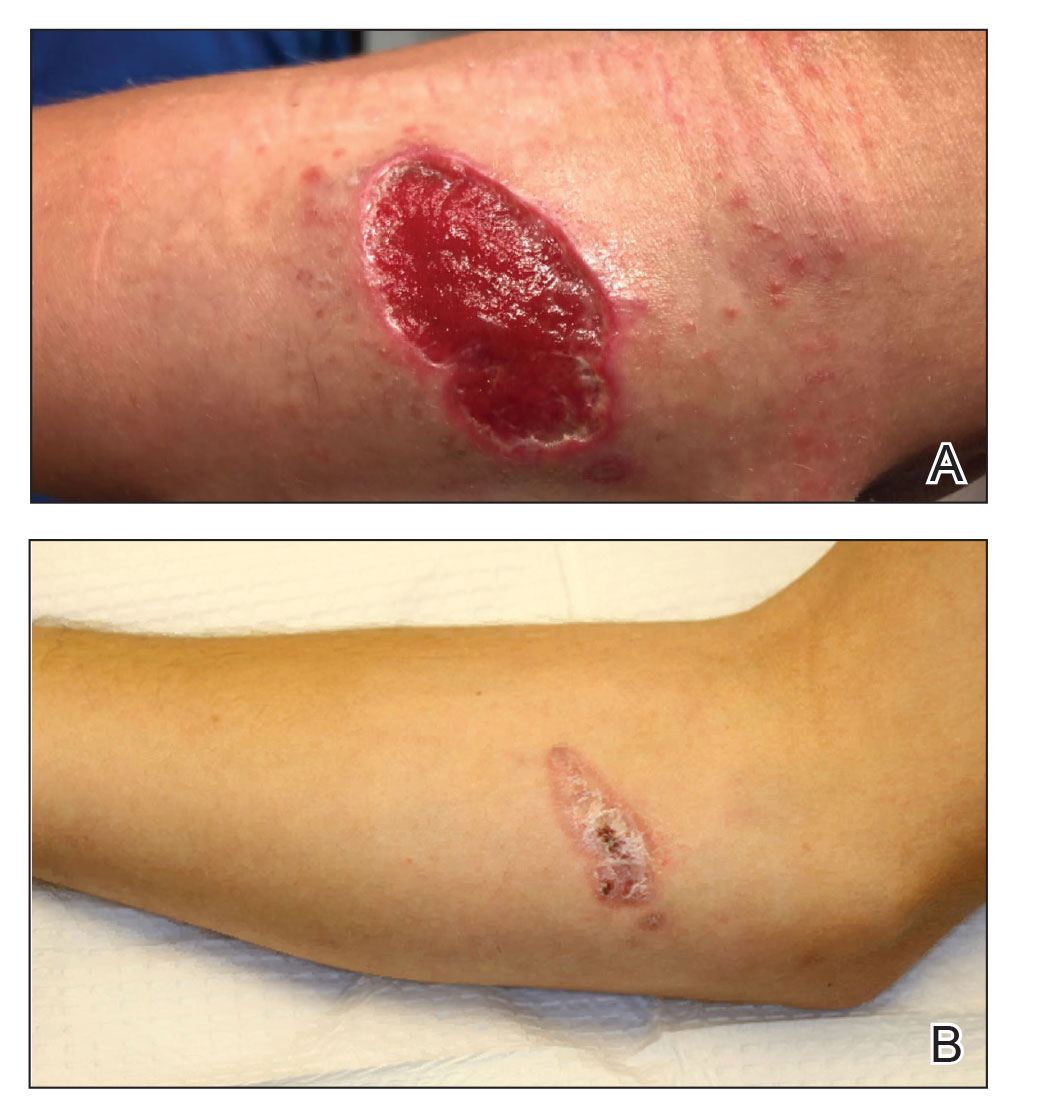

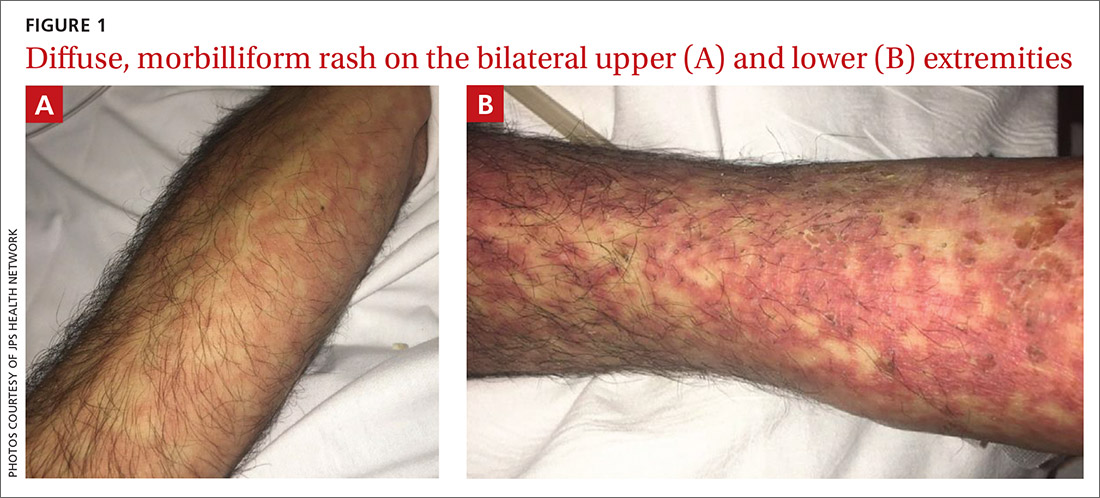

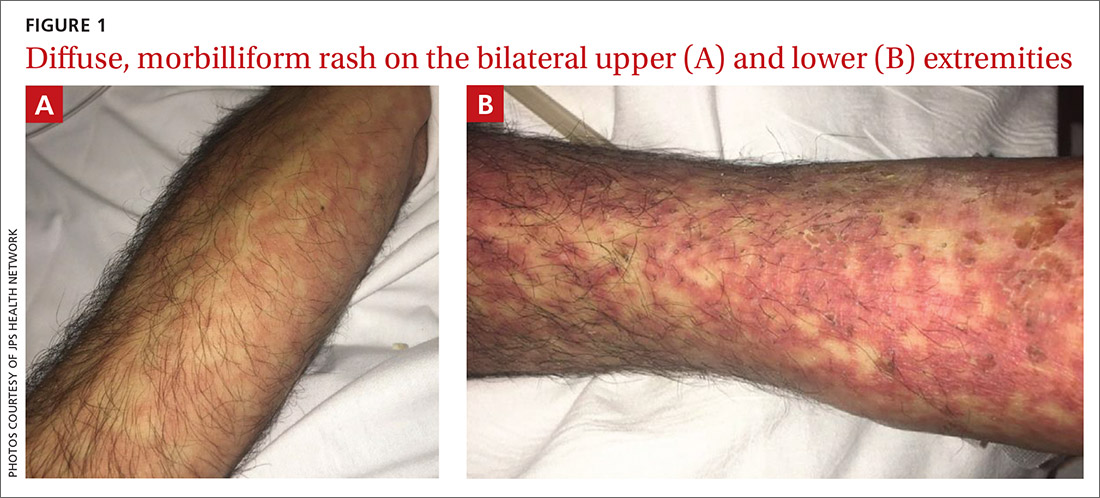

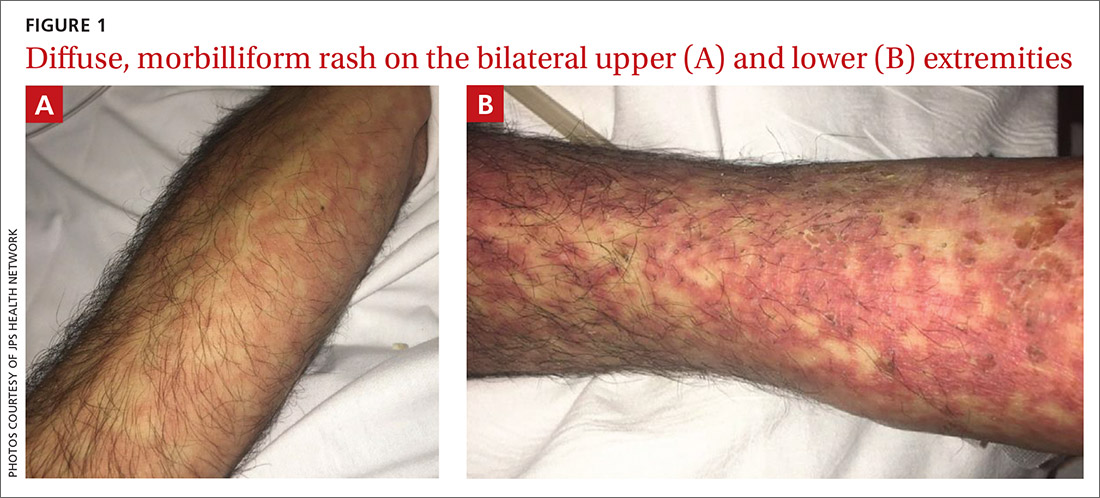

Vitals on admission revealed tachycardia (112 beats per minute). Physical examination revealed the patient was pale and fatigued; she appeared to be in pain, with observable facial grimacing and muscle spasms in the legs. She had poorly demarcated pink macules and papules scattered on the left palm (Figure 1), right forearm, right wrist, and dorsal aspects of the feet including the soles. A few pinpoint pustules were present on the left fifth digit.

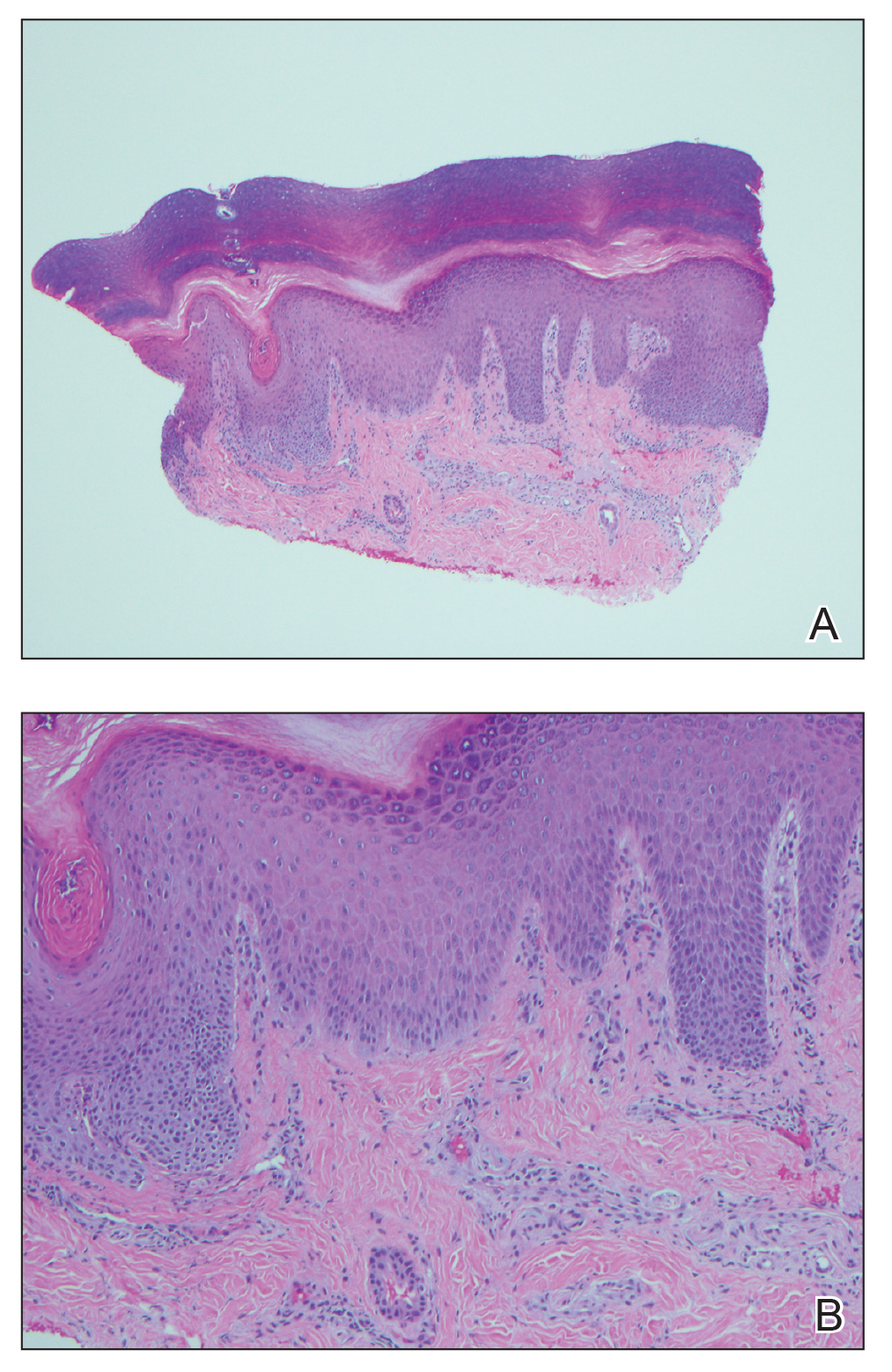

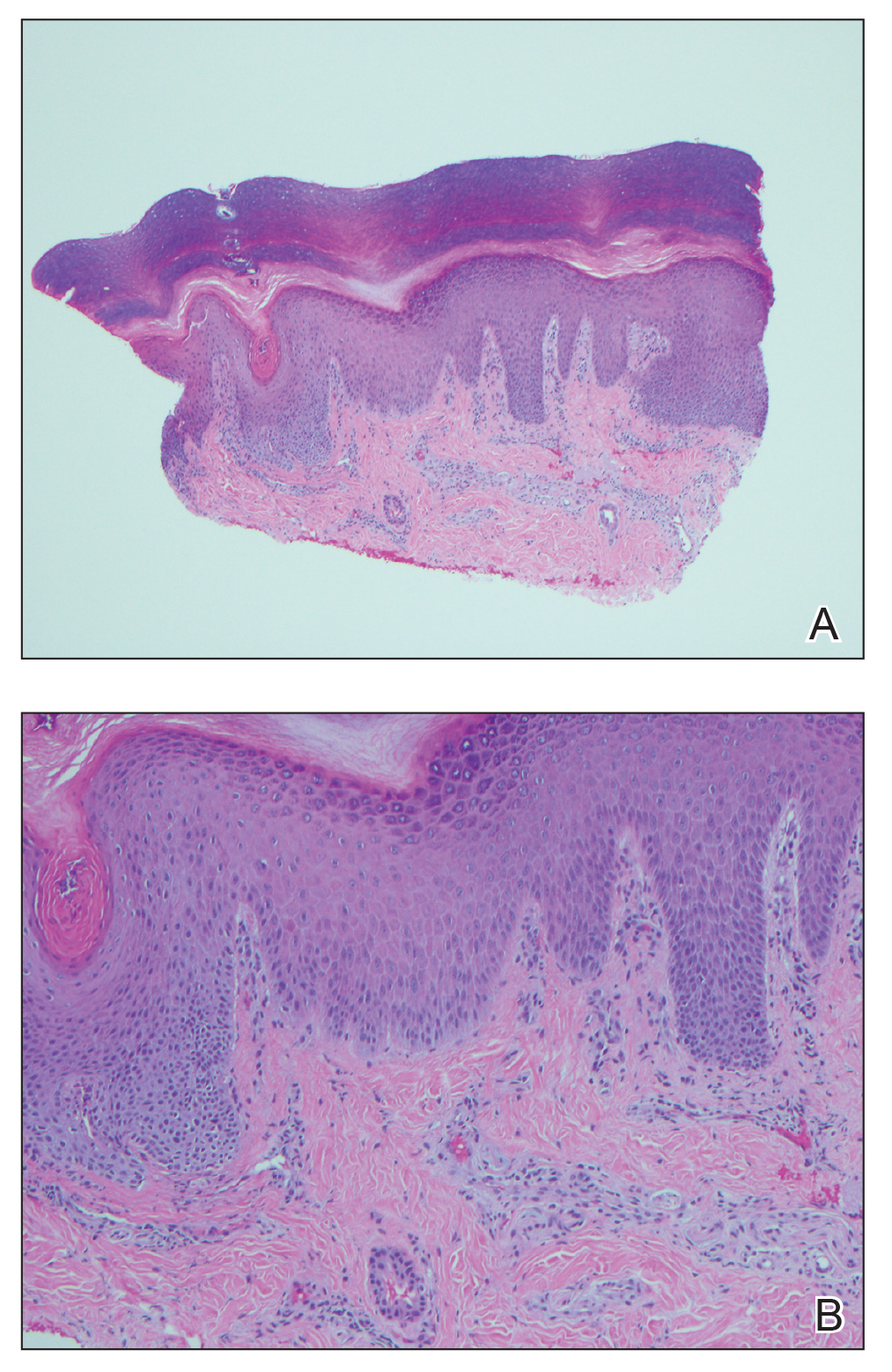

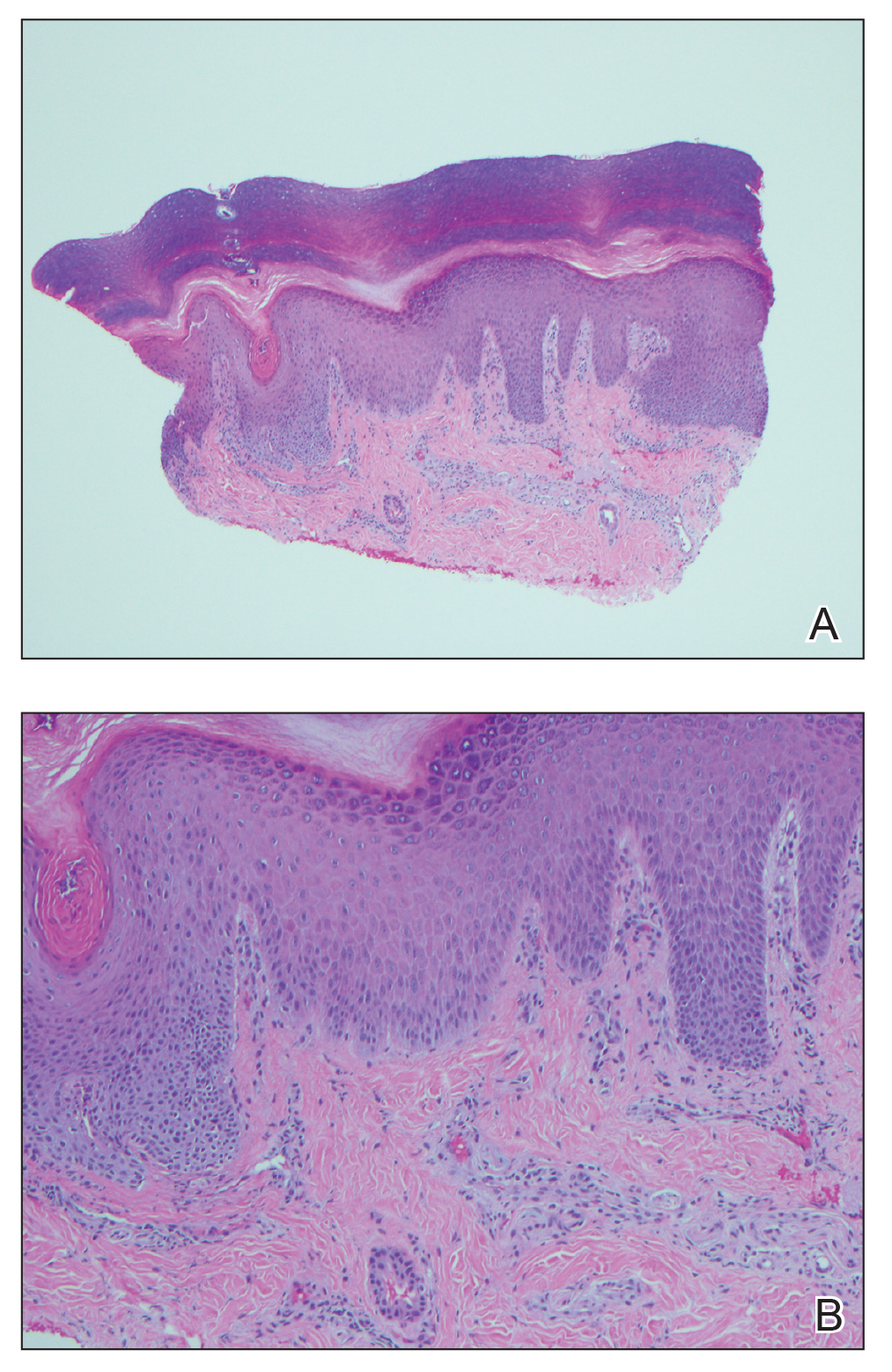

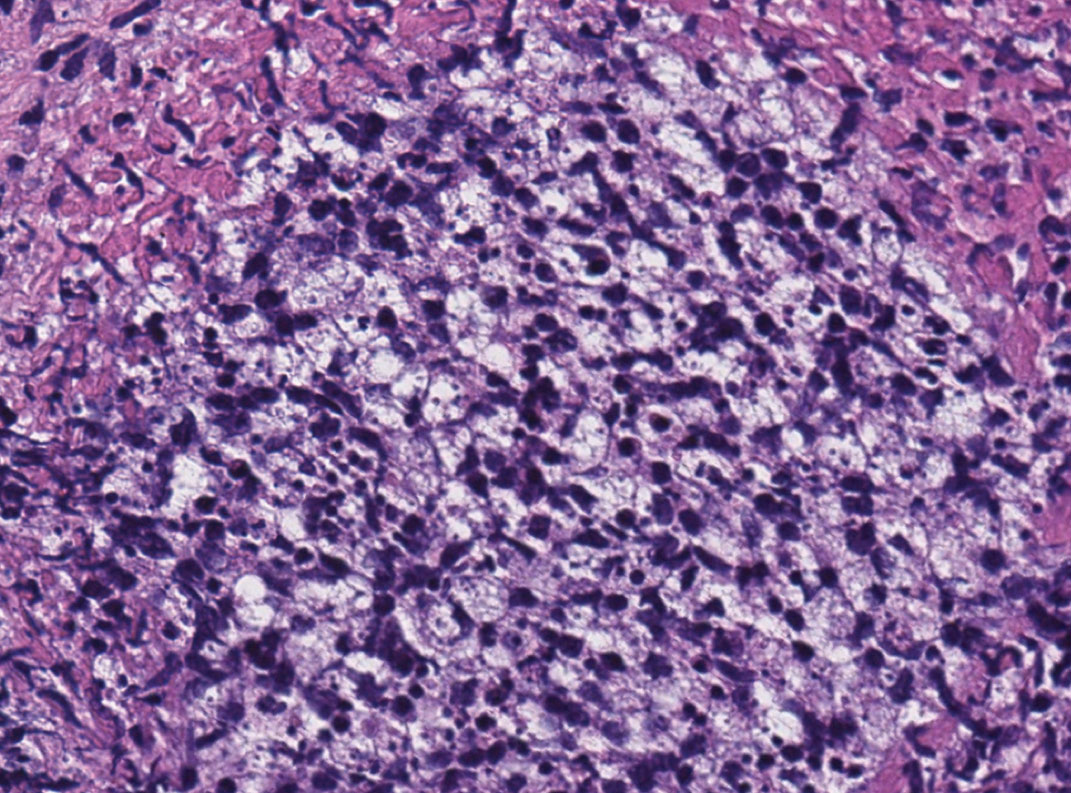

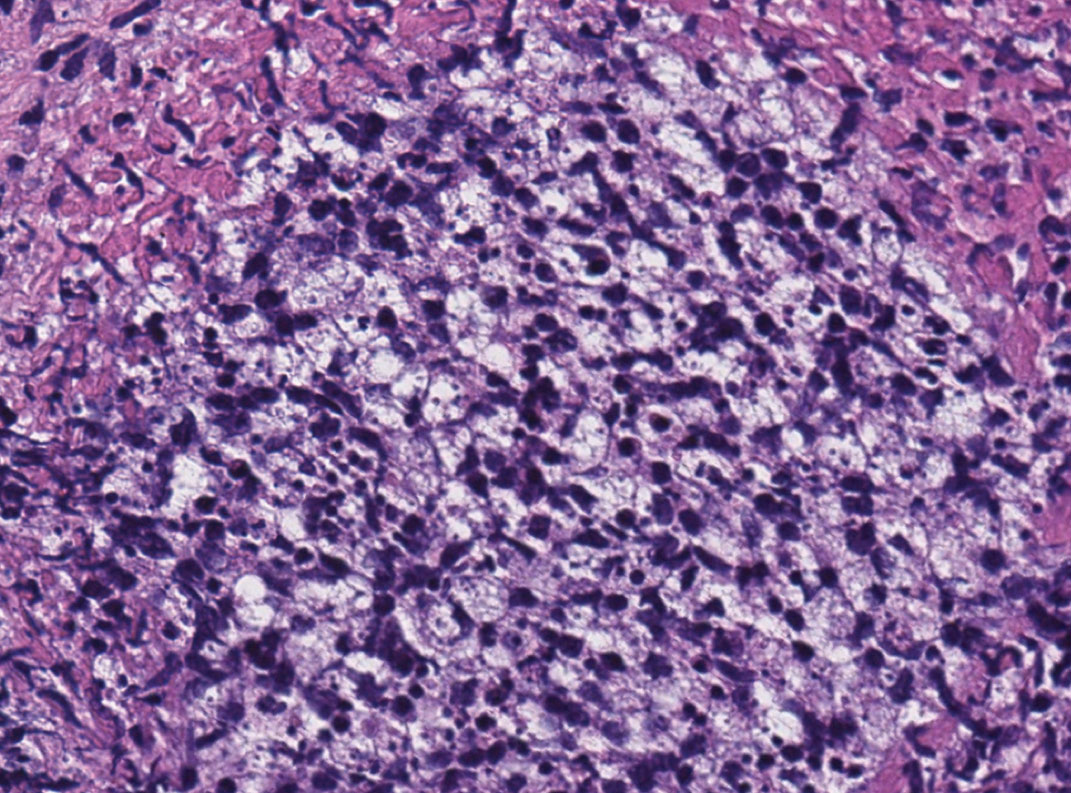

An extensive workup was initiated to rule out infectious, autoimmune, or toxic etiologies. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the left palm were performed for hematoxylin and eosin staining and tissue culture. Findings on hematoxylin and eosin stain were nonspecific, showing acanthosis, orthokeratosis, and a mild interface and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2); superficial bacterial colonization was present, but the tissue culture was negative.

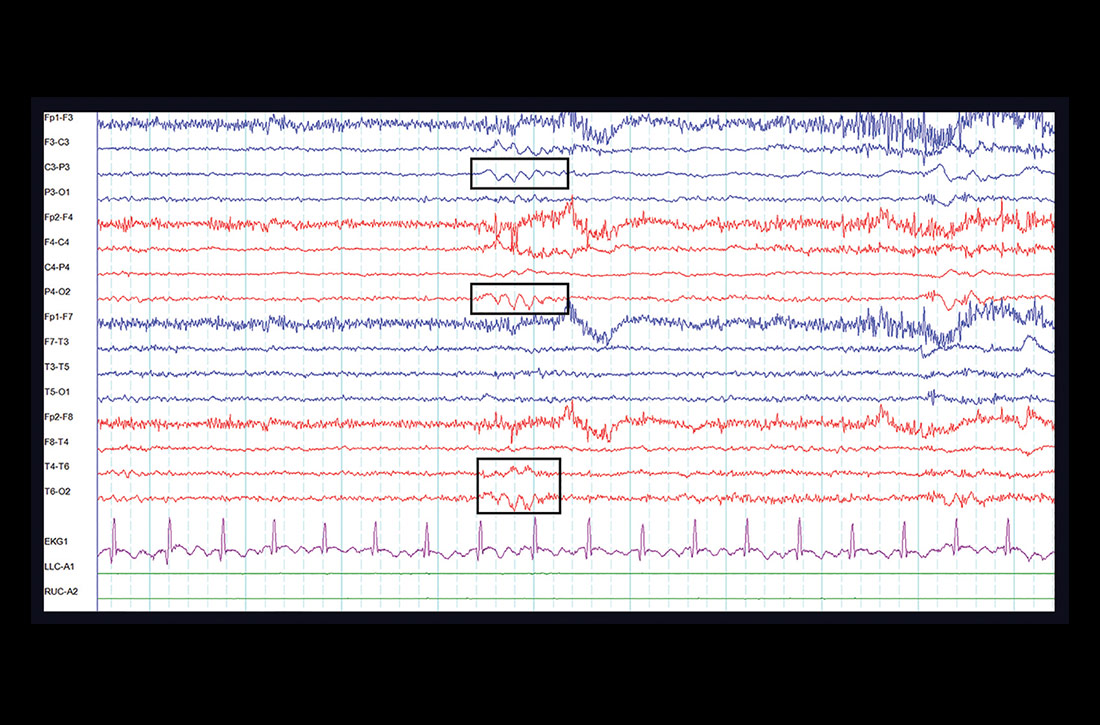

Laboratory studies showed mild transaminitis, and stool was positive for Campylobacter antigen. Electromyography showed myokymia (fascicular muscle contractions). A heavy metal serum panel and urine screen were positive for elevated mercury levels, with a serum mercury level of 23 µg/L (reference range, 0.0–14.9 µg/L) and a urine mercury level of 76 µg/L (reference range, 0–19 µg/L).

Upon further questioning, it was discovered that the patient’s brother and neighbor found a glass bottle containing mercury in their house 10 days prior. They played with the mercury beads with their hands, throwing them around the room and spilling them around the house, which led to mercury exposure in multiple individuals, including our patient. Of note, her brother and neighbor also were hospitalized at the same time as our patient with similar symptoms.

A diagnosis of mercury poisoning was made along with a component of postinfectious reactive arthropathy due to Campylobacter. The myokymia and skin eruption were believed to be secondary to mercury poisoning. The patient was started on ciprofloxacin (750 mg twice daily), intravenous immunoglobulin for Campylobacter, a 2-week treatment regimen with the chelating agent succimer (500 mg twice daily) for mercury poisoning, and a 3-day regimen of pulse intravenous steroids (intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg once daily) to reduce inflammation. Repeat mercury levels showed a downward trend, and the rash improved with time. All family members were advised to undergo testing for mercury exposure.

Comment

Manifestations of Mercury Poisoning

Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure are varied. The most common—allergic contact dermatitis—presents after repeat systemic or topical exposure.4 Mercury exanthem is an acute systemic contact dermatitis most commonly triggered by mercury vapor inhalation. It manifests as an erythematous maculopapular eruption predominantly involving the flexural areas and the anterior thighs in a V-shaped distribution.5 Purpura may be seen in severe cases. Cutaneous granulomas after direct injection of mercury also have been reported as well as cutaneous hyperpigmentation after chronic mercury absorption.6

Presentation of Pink Disease

Pink disease occurs in children after chronic mercury exposure. It was a common pediatric disorder in the 19th century due to the presence of mercury in certain anthelmintics and teething powders.7 However, prevalence drastically decreased after the removal of mercury from these products.3 Although pink disease classically was associated with mercury ingestion, cases also occurred secondary to external application of mercury.7 Additionally, in 1988 a case was reported in a 14-month-old girl after inhalation of mercury vapor from a spilled bottle of mercury.3

Pink disease begins with pink discoloration of the fingertips, nose, and toes, and later progresses to involvement of the hands and feet. Erythema, edema, and desquamation of the hands and feet are seen, along with irritability and autonomic dysfunction that manifests as profuse perspiration, tachycardia, and hypertension.3

Diagnosis of Pink Disease

The differential diagnosis of palmoplantar rash is broad and includes rickettsial disease; syphilis; scabies; toxic shock syndrome; infective endocarditis; meningococcal infection; hand-foot-and-mouth disease; dermatophytosis; and palmoplantar keratodermas. The involvement of the hands and feet in our patient, along with hyperhidrosis, tachycardia, and paresthesia, led us to believe that her condition was a variation of pink disease. The patient’s age at presentation (18 years) was unique, as it is atypical for pink disease. Although the polyarthropathy was attributed to Campylobacter, it is important to note that high levels of mercury exposure also have been associated with polyarthritis,8 polyneuropathy,4 and neuromuscular abnormalities on electromyography.4 Therefore, it is possible that the presence of these symptoms in our patient was either secondary to or compounded by mercury exposure.

Mercury Poisoning

Diagnosis of mercury poisoning can be made by assessing blood, urine, hair, or nail concentrations. However, as mercury deposits in multiple organs, individual concentrations do not correlate with total-body mercury levels.1 Currently, no universal diagnostic criteria for mercury toxicity exist, though a provocation test with the chelating agent 2,

Elemental mercury, as found in some thermometers, dental amalgams, and electrical appliances (eg, certain switches, fluorescent light bulbs), can be converted to inorganic mercury in the body.9 Elemental mercury is vaporized at room temperature; the predominant route of exposure is by subsequent inhalation and lung absorbtion.10 Cutaneous absorption of high concentrations of elementary mercury in either liquid or vapor form may occur, though the rate is slow and absorption is poor. In cases of accidental exposure, contaminated clothing should be removed and immediately decontaminated or disposed. Exposed skin should be washed with a mild soap and water and rinsed thoroughly.10

The treatment of inorganic mercury poisoning is accomplished with the chelating agents succimer, dimercaptopropanesulfonate, dimercaprol, or D-penicillamine.1 In symptomatic cases with high clinical suspicion, the first dose of chelation treatment should be initiated early without delay for laboratory confirmation, as treatment efficacy decreases with an increased interim between exposure and onset of chelation.11 Combination chelation therapy also may be used in treatment. Plasma exchange or hemodialysis are treatment options for extreme, life-threatening cases.1

Conclusion

Mercury exposure should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with a rash on the palms and soles, especially in young patients with systemic symptoms. A high level of suspicion and a thorough history can prevent a delay in treatment and an unnecessarily extensive and expensive workup. An emphasis on early diagnosis and treatment is important for optimal outcomes and can prevent the severe and potentially devastating consequences of mercury toxicity.

- Bernhoft RA. Mercury toxicity and treatment: a review of the literature. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:460508.

- Kamensky OL, Horton D, Kingsley DP, et al. A case of accidental mercury intoxication. J Emerg Med. 2019;56:275-278.

- Dinehart SM, Dillard R, Raimer SS, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of acrodynia (pink disease). Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:107-109.

- Malek A, Aouad K, El Khoury R, et al. Chronic mercury intoxication masquerading as systemic disease: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2017;4:000632.

- Nakayama H, Niki F, Shono M, et al. Mercury exanthem. Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9:411-417.

- Boyd AS, Seger D, Vannucci S, et al. Mercury exposure and cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:81-90.

- Warkany J. Acrodynia—postmortem of a disease. Am J Dis Child. 1966;112:147-156.

- Karatas¸ GK, Tosun AK, Karacehennem E, et al. Mercury poisoning: an unusual cause of polyarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21:73-75.

- Mercury Factsheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/Mercury_FactSheet.html. Reviewed April 7, 2017. Accessed October 21, 2020.

- Medical management guidelines for mercury. Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry website. https://www.atsdr.cdc .gov/MMG/MMG.asp?id=106&tid=24. Update October 21, 2014. Accessed September 11, 2020.

- Kosnett MJ. The role of chelation in the treatment of arsenic and mercury poisoning. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9:347-354.

Mercury poisoning affects multiple body systems, leading to variable clinical presentations. Mercury intoxication at low levels frequently presents with weakness, fatigue, weight loss, and abdominal pain. At higher levels of mercury intoxication, tremors and neurologic dysfunction are more prevalent.1 Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure vary and include pink disease (acrodynia), mercury exanthem, contact dermatitis, and cutaneous granulomas. Untreated mercury poisoning may result in severe complications, including renal tubular necrosis, pneumonitis, persistent neurologic dysfunction, and fatality in some cases.1,2

Pink disease is a rare disease that typically arises in infants and young children from chronic mercury exposure.3 We report a unique presentation of pink disease occurring in an 18-year-old woman following mercury exposure.

Case Report

An 18-year-old woman who was previously healthy presented to the hospital for evaluation of body aches and back pain. She reported a transient rash on the torso 2 weeks prior, but at the current presentation, only the distal upper and lower extremities were involved. A review of systems revealed myalgia, most severe in the lower back; muscle spasms; stiffness in the fingers; abdominal pain; constipation; paresthesia in the hands and feet; hyperhidrosis; and generalized weakness.

Vitals on admission revealed tachycardia (112 beats per minute). Physical examination revealed the patient was pale and fatigued; she appeared to be in pain, with observable facial grimacing and muscle spasms in the legs. She had poorly demarcated pink macules and papules scattered on the left palm (Figure 1), right forearm, right wrist, and dorsal aspects of the feet including the soles. A few pinpoint pustules were present on the left fifth digit.

An extensive workup was initiated to rule out infectious, autoimmune, or toxic etiologies. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the left palm were performed for hematoxylin and eosin staining and tissue culture. Findings on hematoxylin and eosin stain were nonspecific, showing acanthosis, orthokeratosis, and a mild interface and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2); superficial bacterial colonization was present, but the tissue culture was negative.

Laboratory studies showed mild transaminitis, and stool was positive for Campylobacter antigen. Electromyography showed myokymia (fascicular muscle contractions). A heavy metal serum panel and urine screen were positive for elevated mercury levels, with a serum mercury level of 23 µg/L (reference range, 0.0–14.9 µg/L) and a urine mercury level of 76 µg/L (reference range, 0–19 µg/L).

Upon further questioning, it was discovered that the patient’s brother and neighbor found a glass bottle containing mercury in their house 10 days prior. They played with the mercury beads with their hands, throwing them around the room and spilling them around the house, which led to mercury exposure in multiple individuals, including our patient. Of note, her brother and neighbor also were hospitalized at the same time as our patient with similar symptoms.

A diagnosis of mercury poisoning was made along with a component of postinfectious reactive arthropathy due to Campylobacter. The myokymia and skin eruption were believed to be secondary to mercury poisoning. The patient was started on ciprofloxacin (750 mg twice daily), intravenous immunoglobulin for Campylobacter, a 2-week treatment regimen with the chelating agent succimer (500 mg twice daily) for mercury poisoning, and a 3-day regimen of pulse intravenous steroids (intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg once daily) to reduce inflammation. Repeat mercury levels showed a downward trend, and the rash improved with time. All family members were advised to undergo testing for mercury exposure.

Comment

Manifestations of Mercury Poisoning

Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure are varied. The most common—allergic contact dermatitis—presents after repeat systemic or topical exposure.4 Mercury exanthem is an acute systemic contact dermatitis most commonly triggered by mercury vapor inhalation. It manifests as an erythematous maculopapular eruption predominantly involving the flexural areas and the anterior thighs in a V-shaped distribution.5 Purpura may be seen in severe cases. Cutaneous granulomas after direct injection of mercury also have been reported as well as cutaneous hyperpigmentation after chronic mercury absorption.6

Presentation of Pink Disease

Pink disease occurs in children after chronic mercury exposure. It was a common pediatric disorder in the 19th century due to the presence of mercury in certain anthelmintics and teething powders.7 However, prevalence drastically decreased after the removal of mercury from these products.3 Although pink disease classically was associated with mercury ingestion, cases also occurred secondary to external application of mercury.7 Additionally, in 1988 a case was reported in a 14-month-old girl after inhalation of mercury vapor from a spilled bottle of mercury.3

Pink disease begins with pink discoloration of the fingertips, nose, and toes, and later progresses to involvement of the hands and feet. Erythema, edema, and desquamation of the hands and feet are seen, along with irritability and autonomic dysfunction that manifests as profuse perspiration, tachycardia, and hypertension.3

Diagnosis of Pink Disease

The differential diagnosis of palmoplantar rash is broad and includes rickettsial disease; syphilis; scabies; toxic shock syndrome; infective endocarditis; meningococcal infection; hand-foot-and-mouth disease; dermatophytosis; and palmoplantar keratodermas. The involvement of the hands and feet in our patient, along with hyperhidrosis, tachycardia, and paresthesia, led us to believe that her condition was a variation of pink disease. The patient’s age at presentation (18 years) was unique, as it is atypical for pink disease. Although the polyarthropathy was attributed to Campylobacter, it is important to note that high levels of mercury exposure also have been associated with polyarthritis,8 polyneuropathy,4 and neuromuscular abnormalities on electromyography.4 Therefore, it is possible that the presence of these symptoms in our patient was either secondary to or compounded by mercury exposure.

Mercury Poisoning

Diagnosis of mercury poisoning can be made by assessing blood, urine, hair, or nail concentrations. However, as mercury deposits in multiple organs, individual concentrations do not correlate with total-body mercury levels.1 Currently, no universal diagnostic criteria for mercury toxicity exist, though a provocation test with the chelating agent 2,

Elemental mercury, as found in some thermometers, dental amalgams, and electrical appliances (eg, certain switches, fluorescent light bulbs), can be converted to inorganic mercury in the body.9 Elemental mercury is vaporized at room temperature; the predominant route of exposure is by subsequent inhalation and lung absorbtion.10 Cutaneous absorption of high concentrations of elementary mercury in either liquid or vapor form may occur, though the rate is slow and absorption is poor. In cases of accidental exposure, contaminated clothing should be removed and immediately decontaminated or disposed. Exposed skin should be washed with a mild soap and water and rinsed thoroughly.10

The treatment of inorganic mercury poisoning is accomplished with the chelating agents succimer, dimercaptopropanesulfonate, dimercaprol, or D-penicillamine.1 In symptomatic cases with high clinical suspicion, the first dose of chelation treatment should be initiated early without delay for laboratory confirmation, as treatment efficacy decreases with an increased interim between exposure and onset of chelation.11 Combination chelation therapy also may be used in treatment. Plasma exchange or hemodialysis are treatment options for extreme, life-threatening cases.1

Conclusion

Mercury exposure should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with a rash on the palms and soles, especially in young patients with systemic symptoms. A high level of suspicion and a thorough history can prevent a delay in treatment and an unnecessarily extensive and expensive workup. An emphasis on early diagnosis and treatment is important for optimal outcomes and can prevent the severe and potentially devastating consequences of mercury toxicity.

Mercury poisoning affects multiple body systems, leading to variable clinical presentations. Mercury intoxication at low levels frequently presents with weakness, fatigue, weight loss, and abdominal pain. At higher levels of mercury intoxication, tremors and neurologic dysfunction are more prevalent.1 Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure vary and include pink disease (acrodynia), mercury exanthem, contact dermatitis, and cutaneous granulomas. Untreated mercury poisoning may result in severe complications, including renal tubular necrosis, pneumonitis, persistent neurologic dysfunction, and fatality in some cases.1,2

Pink disease is a rare disease that typically arises in infants and young children from chronic mercury exposure.3 We report a unique presentation of pink disease occurring in an 18-year-old woman following mercury exposure.

Case Report

An 18-year-old woman who was previously healthy presented to the hospital for evaluation of body aches and back pain. She reported a transient rash on the torso 2 weeks prior, but at the current presentation, only the distal upper and lower extremities were involved. A review of systems revealed myalgia, most severe in the lower back; muscle spasms; stiffness in the fingers; abdominal pain; constipation; paresthesia in the hands and feet; hyperhidrosis; and generalized weakness.

Vitals on admission revealed tachycardia (112 beats per minute). Physical examination revealed the patient was pale and fatigued; she appeared to be in pain, with observable facial grimacing and muscle spasms in the legs. She had poorly demarcated pink macules and papules scattered on the left palm (Figure 1), right forearm, right wrist, and dorsal aspects of the feet including the soles. A few pinpoint pustules were present on the left fifth digit.

An extensive workup was initiated to rule out infectious, autoimmune, or toxic etiologies. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the left palm were performed for hematoxylin and eosin staining and tissue culture. Findings on hematoxylin and eosin stain were nonspecific, showing acanthosis, orthokeratosis, and a mild interface and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2); superficial bacterial colonization was present, but the tissue culture was negative.

Laboratory studies showed mild transaminitis, and stool was positive for Campylobacter antigen. Electromyography showed myokymia (fascicular muscle contractions). A heavy metal serum panel and urine screen were positive for elevated mercury levels, with a serum mercury level of 23 µg/L (reference range, 0.0–14.9 µg/L) and a urine mercury level of 76 µg/L (reference range, 0–19 µg/L).

Upon further questioning, it was discovered that the patient’s brother and neighbor found a glass bottle containing mercury in their house 10 days prior. They played with the mercury beads with their hands, throwing them around the room and spilling them around the house, which led to mercury exposure in multiple individuals, including our patient. Of note, her brother and neighbor also were hospitalized at the same time as our patient with similar symptoms.

A diagnosis of mercury poisoning was made along with a component of postinfectious reactive arthropathy due to Campylobacter. The myokymia and skin eruption were believed to be secondary to mercury poisoning. The patient was started on ciprofloxacin (750 mg twice daily), intravenous immunoglobulin for Campylobacter, a 2-week treatment regimen with the chelating agent succimer (500 mg twice daily) for mercury poisoning, and a 3-day regimen of pulse intravenous steroids (intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg once daily) to reduce inflammation. Repeat mercury levels showed a downward trend, and the rash improved with time. All family members were advised to undergo testing for mercury exposure.

Comment

Manifestations of Mercury Poisoning

Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure are varied. The most common—allergic contact dermatitis—presents after repeat systemic or topical exposure.4 Mercury exanthem is an acute systemic contact dermatitis most commonly triggered by mercury vapor inhalation. It manifests as an erythematous maculopapular eruption predominantly involving the flexural areas and the anterior thighs in a V-shaped distribution.5 Purpura may be seen in severe cases. Cutaneous granulomas after direct injection of mercury also have been reported as well as cutaneous hyperpigmentation after chronic mercury absorption.6

Presentation of Pink Disease

Pink disease occurs in children after chronic mercury exposure. It was a common pediatric disorder in the 19th century due to the presence of mercury in certain anthelmintics and teething powders.7 However, prevalence drastically decreased after the removal of mercury from these products.3 Although pink disease classically was associated with mercury ingestion, cases also occurred secondary to external application of mercury.7 Additionally, in 1988 a case was reported in a 14-month-old girl after inhalation of mercury vapor from a spilled bottle of mercury.3

Pink disease begins with pink discoloration of the fingertips, nose, and toes, and later progresses to involvement of the hands and feet. Erythema, edema, and desquamation of the hands and feet are seen, along with irritability and autonomic dysfunction that manifests as profuse perspiration, tachycardia, and hypertension.3

Diagnosis of Pink Disease

The differential diagnosis of palmoplantar rash is broad and includes rickettsial disease; syphilis; scabies; toxic shock syndrome; infective endocarditis; meningococcal infection; hand-foot-and-mouth disease; dermatophytosis; and palmoplantar keratodermas. The involvement of the hands and feet in our patient, along with hyperhidrosis, tachycardia, and paresthesia, led us to believe that her condition was a variation of pink disease. The patient’s age at presentation (18 years) was unique, as it is atypical for pink disease. Although the polyarthropathy was attributed to Campylobacter, it is important to note that high levels of mercury exposure also have been associated with polyarthritis,8 polyneuropathy,4 and neuromuscular abnormalities on electromyography.4 Therefore, it is possible that the presence of these symptoms in our patient was either secondary to or compounded by mercury exposure.

Mercury Poisoning

Diagnosis of mercury poisoning can be made by assessing blood, urine, hair, or nail concentrations. However, as mercury deposits in multiple organs, individual concentrations do not correlate with total-body mercury levels.1 Currently, no universal diagnostic criteria for mercury toxicity exist, though a provocation test with the chelating agent 2,

Elemental mercury, as found in some thermometers, dental amalgams, and electrical appliances (eg, certain switches, fluorescent light bulbs), can be converted to inorganic mercury in the body.9 Elemental mercury is vaporized at room temperature; the predominant route of exposure is by subsequent inhalation and lung absorbtion.10 Cutaneous absorption of high concentrations of elementary mercury in either liquid or vapor form may occur, though the rate is slow and absorption is poor. In cases of accidental exposure, contaminated clothing should be removed and immediately decontaminated or disposed. Exposed skin should be washed with a mild soap and water and rinsed thoroughly.10

The treatment of inorganic mercury poisoning is accomplished with the chelating agents succimer, dimercaptopropanesulfonate, dimercaprol, or D-penicillamine.1 In symptomatic cases with high clinical suspicion, the first dose of chelation treatment should be initiated early without delay for laboratory confirmation, as treatment efficacy decreases with an increased interim between exposure and onset of chelation.11 Combination chelation therapy also may be used in treatment. Plasma exchange or hemodialysis are treatment options for extreme, life-threatening cases.1

Conclusion

Mercury exposure should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with a rash on the palms and soles, especially in young patients with systemic symptoms. A high level of suspicion and a thorough history can prevent a delay in treatment and an unnecessarily extensive and expensive workup. An emphasis on early diagnosis and treatment is important for optimal outcomes and can prevent the severe and potentially devastating consequences of mercury toxicity.

- Bernhoft RA. Mercury toxicity and treatment: a review of the literature. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:460508.

- Kamensky OL, Horton D, Kingsley DP, et al. A case of accidental mercury intoxication. J Emerg Med. 2019;56:275-278.

- Dinehart SM, Dillard R, Raimer SS, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of acrodynia (pink disease). Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:107-109.

- Malek A, Aouad K, El Khoury R, et al. Chronic mercury intoxication masquerading as systemic disease: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2017;4:000632.

- Nakayama H, Niki F, Shono M, et al. Mercury exanthem. Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9:411-417.

- Boyd AS, Seger D, Vannucci S, et al. Mercury exposure and cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:81-90.

- Warkany J. Acrodynia—postmortem of a disease. Am J Dis Child. 1966;112:147-156.

- Karatas¸ GK, Tosun AK, Karacehennem E, et al. Mercury poisoning: an unusual cause of polyarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21:73-75.

- Mercury Factsheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/Mercury_FactSheet.html. Reviewed April 7, 2017. Accessed October 21, 2020.

- Medical management guidelines for mercury. Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry website. https://www.atsdr.cdc .gov/MMG/MMG.asp?id=106&tid=24. Update October 21, 2014. Accessed September 11, 2020.

- Kosnett MJ. The role of chelation in the treatment of arsenic and mercury poisoning. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9:347-354.

- Bernhoft RA. Mercury toxicity and treatment: a review of the literature. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:460508.

- Kamensky OL, Horton D, Kingsley DP, et al. A case of accidental mercury intoxication. J Emerg Med. 2019;56:275-278.

- Dinehart SM, Dillard R, Raimer SS, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of acrodynia (pink disease). Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:107-109.

- Malek A, Aouad K, El Khoury R, et al. Chronic mercury intoxication masquerading as systemic disease: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2017;4:000632.

- Nakayama H, Niki F, Shono M, et al. Mercury exanthem. Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9:411-417.

- Boyd AS, Seger D, Vannucci S, et al. Mercury exposure and cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:81-90.

- Warkany J. Acrodynia—postmortem of a disease. Am J Dis Child. 1966;112:147-156.

- Karatas¸ GK, Tosun AK, Karacehennem E, et al. Mercury poisoning: an unusual cause of polyarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21:73-75.

- Mercury Factsheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/Mercury_FactSheet.html. Reviewed April 7, 2017. Accessed October 21, 2020.

- Medical management guidelines for mercury. Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry website. https://www.atsdr.cdc .gov/MMG/MMG.asp?id=106&tid=24. Update October 21, 2014. Accessed September 11, 2020.

- Kosnett MJ. The role of chelation in the treatment of arsenic and mercury poisoning. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9:347-354.

Practice Points

- The dermatologic and histologic presentation of mercury exposure may be nonspecific, requiring a high degree of clinical suspicion to make a diagnosis.

- Mercury exposure should be included in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with a rash of the palms and soles, especially in young patients with systemic symptoms.

An Unusual Skin Infection With Achromobacter xylosoxidans

Case Report

A 50-year-old woman presented with a sore, tender, red lump on the right superior buttock of 5 months’ duration. Five months prior to presentation the patient used this area to attach the infusion set for an insulin pump, which was left in place for 7 days as opposed to the 2 or 3 days recommended by the device manufacturer. A firm, slightly tender lump formed, similar to prior scars that had developed from use of the insulin pump. However, the lump began to grow and get softer. It was intermittently warm and red. Although the area was sore and tender, she never had any major pain. She also denied any fever, malaise, or other systemic symptoms.

The patient indicated a medical history of type 1 diabetes mellitus diagnosed at 9 years of age; hypertension; asthma; gastroesophageal reflux disease; allergic rhinitis; migraine headaches; depression; hidradenitis suppurativa that resolved after surgical excision; and recurrent vaginal yeast infections, especially when taking antibiotics. She had a surgical history of hidradenitis suppurativa excision at the inguinal folds, bilateral carpal tunnel release, tubal ligation, abdominoplasty, and cholecystectomy. The patient’s current medications included insulin aspart, mometasone furoate, inhaled fluticasone, pantoprazole, cetirizine, spironolactone, duloxetine, sumatriptan, fluconazole, topiramate, and enalapril.

Physical examination revealed normal vital signs and the patient was afebrile. She had no swollen or tender lymph nodes. There was a 5.5×7.0-cm, soft, tender, erythematous subcutaneous mass with no visible punctum or overlying epidermal change on the right superior buttock (Figure 1). Based on the history and physical examination, the differential diagnosis included subcutaneous fat necrosis, epidermal inclusion cyst, and an abscess.

The patient was scheduled for excision of the mass the day after presenting to the clinic. During excision, 10 mL of thick purulent liquid was drained. A sample of the liquid was sent for Gram stain, aerobic and anaerobic culture, and antibiotic sensitivities. Necrotic-appearing adipose and fibrotic tissues were dissected and extirpated through an elliptical incision and submitted for pathologic evaluation.

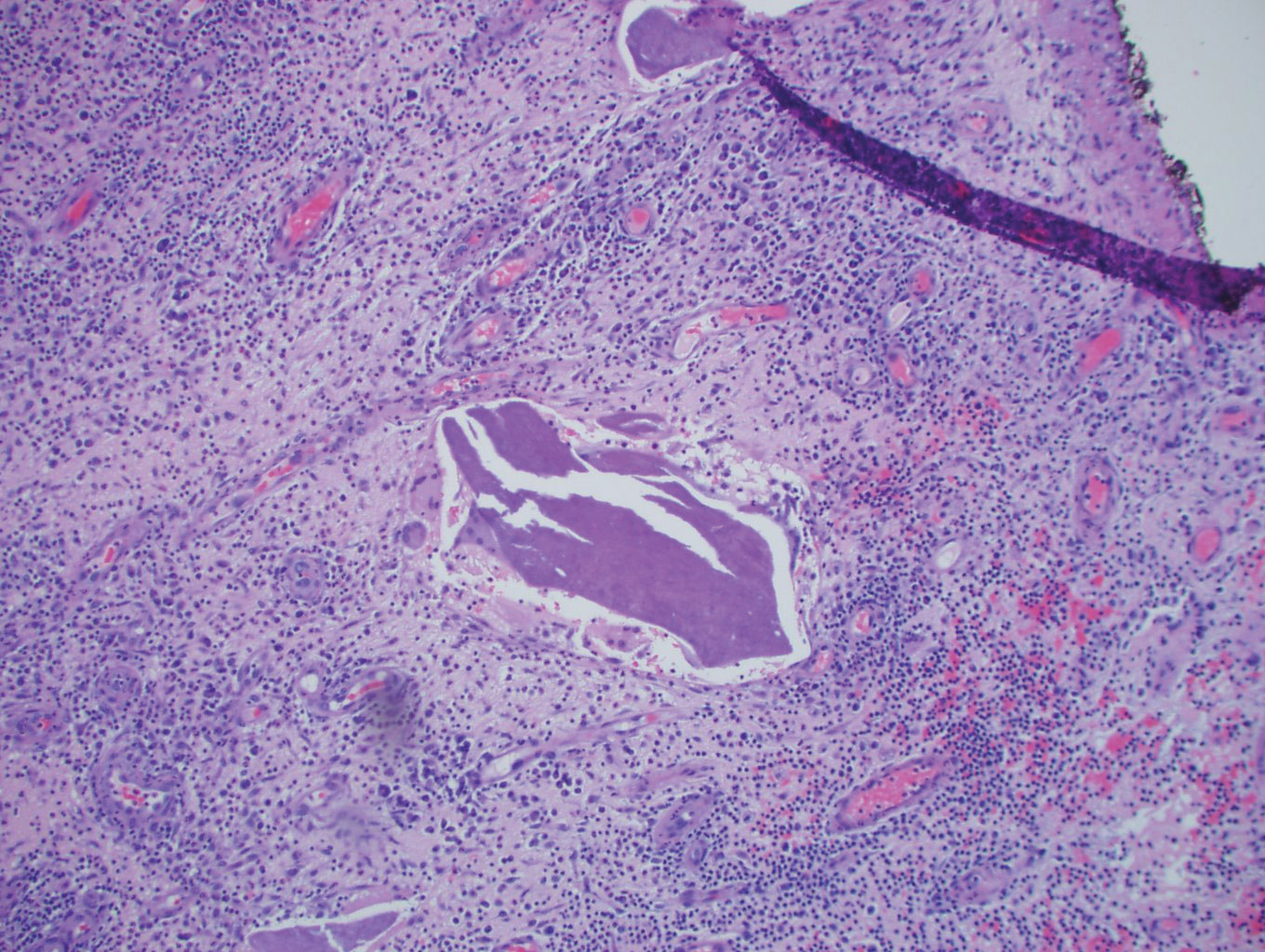

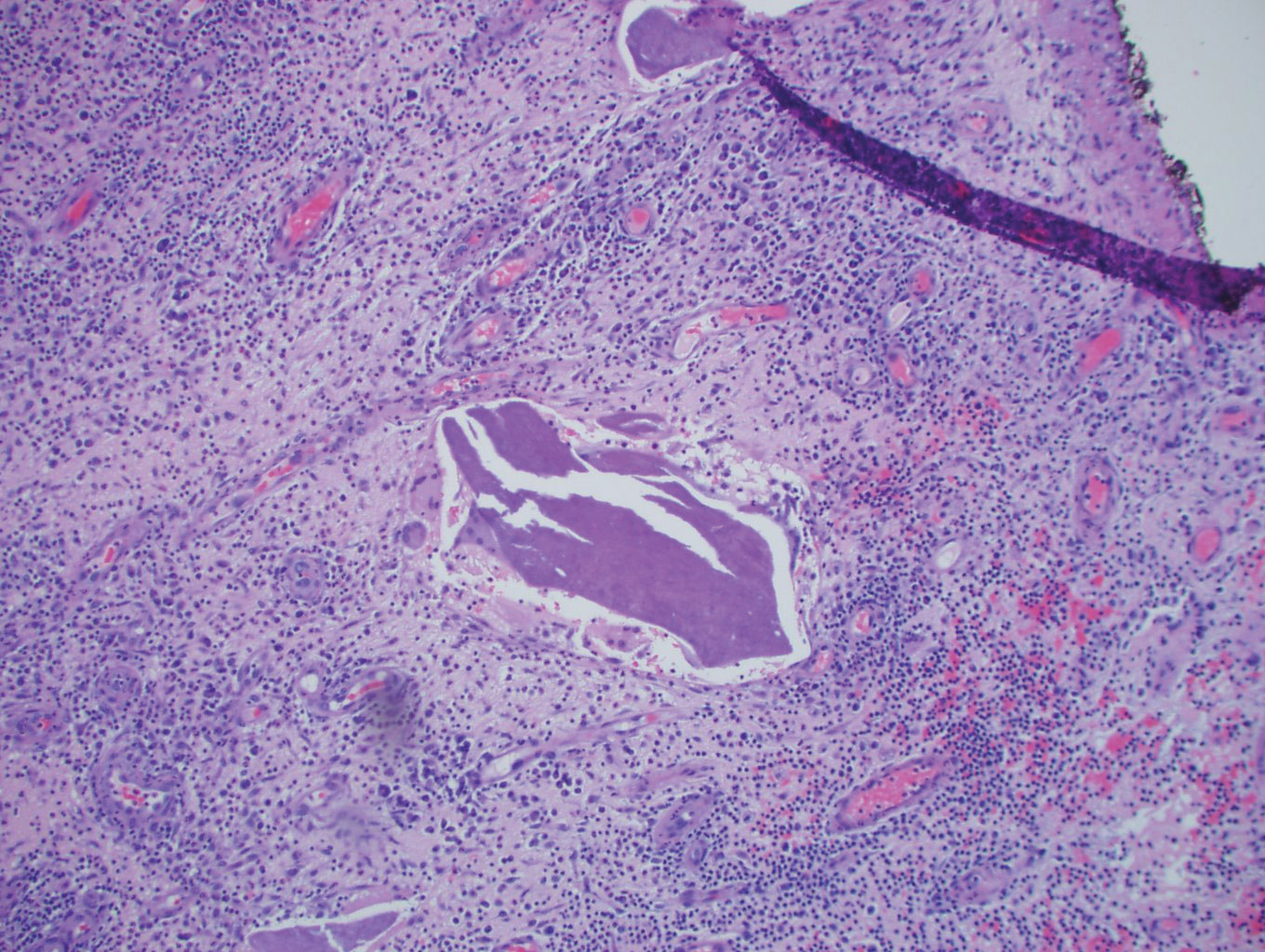

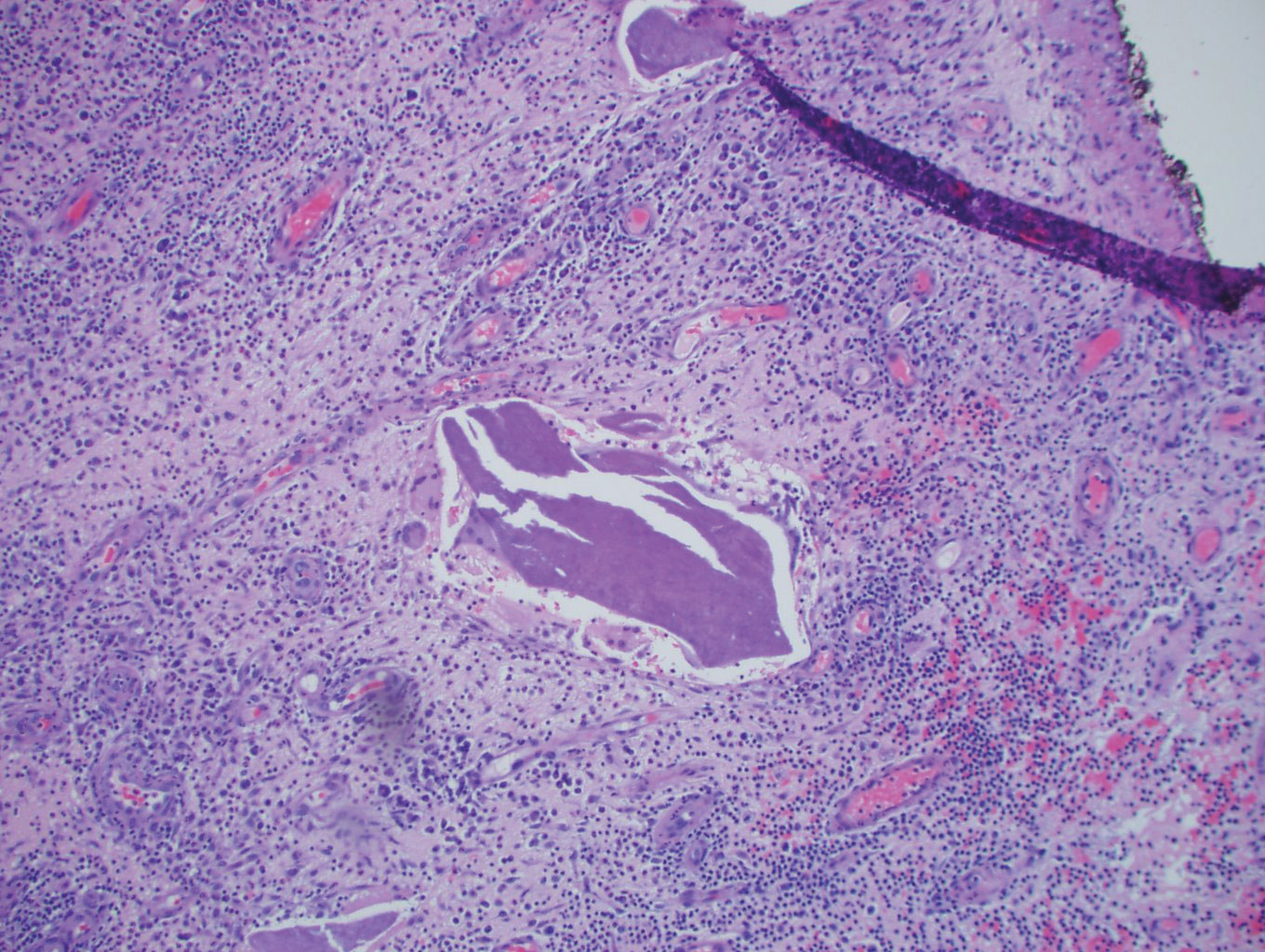

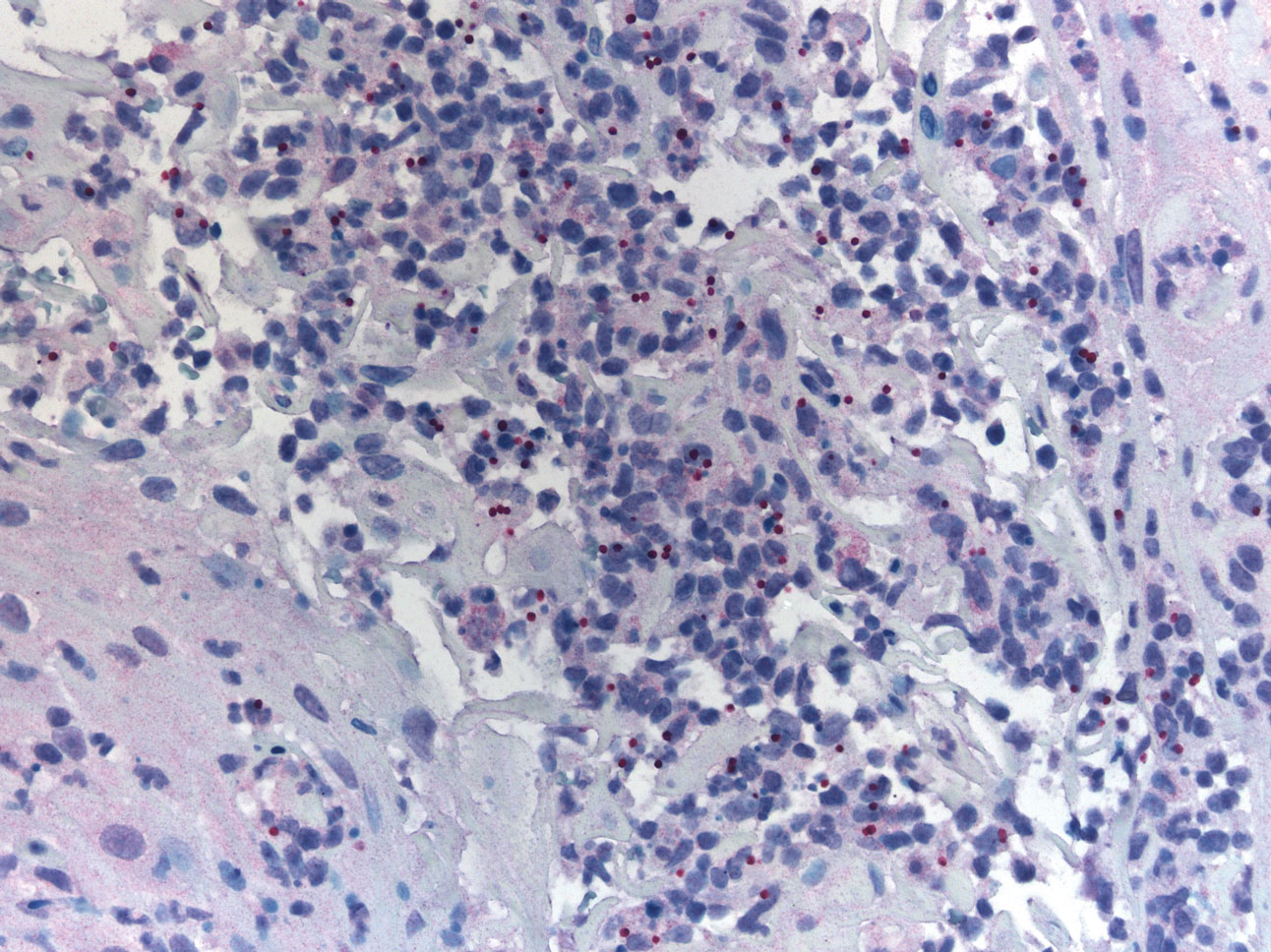

Histopathology showed a subcutaneous defect with palisaded granulomatous inflammation and sclerosis (Figure 2). There was no detection of microorganisms with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, tissue Gram, or acid-fast stains. There was a focus of acellular material embedded within the inflammation (Figure 3). The Gram stain of the purulent material showed few white blood cells and rare gram-negative bacilli. Culture grew moderate Achromobacter xylosoxidans resistant to cefepime, cefotaxime, and gentamicin. The culture was susceptible to ceftazidime, imipenem, levofloxacin, piperacillin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX).

The patient was prescribed oral TMP-SMX (160 mg of TMP and 800 mg of SMX) twice daily for 10 days. The patient tolerated the procedure and the subsequent antibiotics well. The patient had normal levels of IgA, IgG, and IgM, as well as a negative screening test for human immunodeficiency virus. She healed well from the surgical procedure and has had no recurrence of symptoms.

Comment

Achromobacter xylosoxidans is a nonfermentative, non–spore-forming, motile, gram-negative, aerobic, catalase-positive and oxidase-positive flagellate bacterium. It is an emerging pathogen that was first isolated in 1971 from patients with chronic otitis media.1 Since its recognition, it has been documented to cause a variety of infections, including pneumonia, meningitis, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, and bacteremia, as well as abdominal, urinary tract, ocular, and skin and soft tissue infections.2,3 Those affected usually are immunocompromised, have hematologic disorders, or have indwelling catheters.4 Strains of A xylosoxidans have shown resistance to multiple antibiotics including penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, aminoglycosides, macrolides, fluoroquinolones, and TMP-SMX. Achromobacter xylosoxidans has been documented to form biofilms on plastics, including on contact lenses, urinary and intravenous catheters, and reusable tissue dispensers treated with disinfectant solution.4-6 One study demonstrated that A xylosoxidans is even capable of biodegradation of plastic, using the plastic as its sole source of carbon.7

Our case illustrates an indolent infection with A xylosoxidans forming a granulomatous abscess at the site of an insulin pump that was left in place for 7 days in an immunocompetent patient. Although infections with A xylosoxidans in patients with urinary or intravenous catheters have been reported,4 our case is unique, as the insulin pump was the source of such an infection. It is possible that the subcutaneous focus of acellular material described on the pathology report represented a partially biodegraded piece of the insulin pump catheter that broke off and was serving as a nidus of infection for A xylosoxidans. Although multidrug resistance is common, the culture grown from our patient was susceptible to TMP-SMX, among other antibiotics. Our patient was treated successfully with surgical excision, drainage, and a 10-day course of TMP-SMX.

Conclusion

Health care providers should recognize A xylosoxidans as an emerging pathogen that is capable of forming biofilms on “disinfected” surfaces and medical products, especially plastics. Achromobacter xylosoxidans may be resistant to multiple antibiotics and can cause infections with various presentations.

- Yabuuchi E, Oyama A. Achromobacter xylosoxidans n. sp. from human ear discharge. Jpn J Microbiol. 1971;15:477-481.

- Rodrigues CG, Rays J, Kanegae MY. Native-valve endocarditis caused by Achromobacter xylosoxidans: a case report and review of literature. Autops Case Rep. 2017;7:50-55.

- Tena D, Martínez NM, Losa C, et al. Skin and soft tissue infection caused by Achromobacter xylosoxidans: report of 14 cases. Scand J Infect Dis. 2014;46:130-135.

- Pérez Barragán E, Sandino Pérez J, Corbella L, et al. Achromobacter xylosoxidans bacteremia: clinical and microbiological features in a 10-year case series. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2018;31:268-273.

- Konstantinović N, Ćirković I, Đukić S, et al. Biofilm formation of Achromobacter xylosoxidans on contact lens. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2017;64:293-300.

- Günther F, Merle U, Frank U, et al. Pseudobacteremia outbreak of biofilm-forming Achromobacter xylosoxidans—environmental transmission. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:584.

- Kowalczyk A, Chyc M, Ryszka P, et al. Achromobacter xylosoxidans as a new microorganism strain colonizing high-density polyethylene as a key step to its biodegradation. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016;23:11349-11356.

Case Report

A 50-year-old woman presented with a sore, tender, red lump on the right superior buttock of 5 months’ duration. Five months prior to presentation the patient used this area to attach the infusion set for an insulin pump, which was left in place for 7 days as opposed to the 2 or 3 days recommended by the device manufacturer. A firm, slightly tender lump formed, similar to prior scars that had developed from use of the insulin pump. However, the lump began to grow and get softer. It was intermittently warm and red. Although the area was sore and tender, she never had any major pain. She also denied any fever, malaise, or other systemic symptoms.

The patient indicated a medical history of type 1 diabetes mellitus diagnosed at 9 years of age; hypertension; asthma; gastroesophageal reflux disease; allergic rhinitis; migraine headaches; depression; hidradenitis suppurativa that resolved after surgical excision; and recurrent vaginal yeast infections, especially when taking antibiotics. She had a surgical history of hidradenitis suppurativa excision at the inguinal folds, bilateral carpal tunnel release, tubal ligation, abdominoplasty, and cholecystectomy. The patient’s current medications included insulin aspart, mometasone furoate, inhaled fluticasone, pantoprazole, cetirizine, spironolactone, duloxetine, sumatriptan, fluconazole, topiramate, and enalapril.

Physical examination revealed normal vital signs and the patient was afebrile. She had no swollen or tender lymph nodes. There was a 5.5×7.0-cm, soft, tender, erythematous subcutaneous mass with no visible punctum or overlying epidermal change on the right superior buttock (Figure 1). Based on the history and physical examination, the differential diagnosis included subcutaneous fat necrosis, epidermal inclusion cyst, and an abscess.

The patient was scheduled for excision of the mass the day after presenting to the clinic. During excision, 10 mL of thick purulent liquid was drained. A sample of the liquid was sent for Gram stain, aerobic and anaerobic culture, and antibiotic sensitivities. Necrotic-appearing adipose and fibrotic tissues were dissected and extirpated through an elliptical incision and submitted for pathologic evaluation.

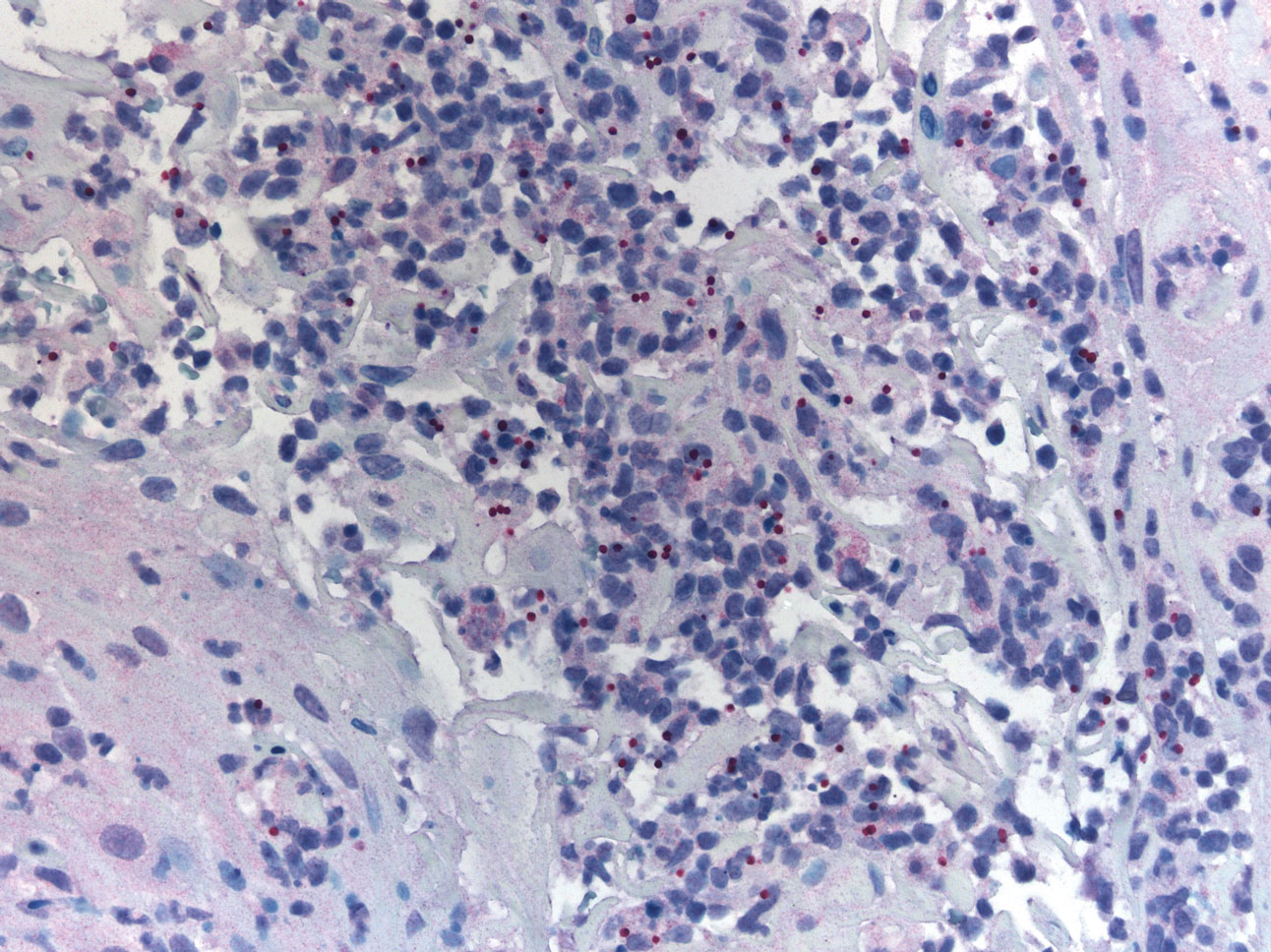

Histopathology showed a subcutaneous defect with palisaded granulomatous inflammation and sclerosis (Figure 2). There was no detection of microorganisms with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, tissue Gram, or acid-fast stains. There was a focus of acellular material embedded within the inflammation (Figure 3). The Gram stain of the purulent material showed few white blood cells and rare gram-negative bacilli. Culture grew moderate Achromobacter xylosoxidans resistant to cefepime, cefotaxime, and gentamicin. The culture was susceptible to ceftazidime, imipenem, levofloxacin, piperacillin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX).

The patient was prescribed oral TMP-SMX (160 mg of TMP and 800 mg of SMX) twice daily for 10 days. The patient tolerated the procedure and the subsequent antibiotics well. The patient had normal levels of IgA, IgG, and IgM, as well as a negative screening test for human immunodeficiency virus. She healed well from the surgical procedure and has had no recurrence of symptoms.

Comment

Achromobacter xylosoxidans is a nonfermentative, non–spore-forming, motile, gram-negative, aerobic, catalase-positive and oxidase-positive flagellate bacterium. It is an emerging pathogen that was first isolated in 1971 from patients with chronic otitis media.1 Since its recognition, it has been documented to cause a variety of infections, including pneumonia, meningitis, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, and bacteremia, as well as abdominal, urinary tract, ocular, and skin and soft tissue infections.2,3 Those affected usually are immunocompromised, have hematologic disorders, or have indwelling catheters.4 Strains of A xylosoxidans have shown resistance to multiple antibiotics including penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, aminoglycosides, macrolides, fluoroquinolones, and TMP-SMX. Achromobacter xylosoxidans has been documented to form biofilms on plastics, including on contact lenses, urinary and intravenous catheters, and reusable tissue dispensers treated with disinfectant solution.4-6 One study demonstrated that A xylosoxidans is even capable of biodegradation of plastic, using the plastic as its sole source of carbon.7

Our case illustrates an indolent infection with A xylosoxidans forming a granulomatous abscess at the site of an insulin pump that was left in place for 7 days in an immunocompetent patient. Although infections with A xylosoxidans in patients with urinary or intravenous catheters have been reported,4 our case is unique, as the insulin pump was the source of such an infection. It is possible that the subcutaneous focus of acellular material described on the pathology report represented a partially biodegraded piece of the insulin pump catheter that broke off and was serving as a nidus of infection for A xylosoxidans. Although multidrug resistance is common, the culture grown from our patient was susceptible to TMP-SMX, among other antibiotics. Our patient was treated successfully with surgical excision, drainage, and a 10-day course of TMP-SMX.

Conclusion

Health care providers should recognize A xylosoxidans as an emerging pathogen that is capable of forming biofilms on “disinfected” surfaces and medical products, especially plastics. Achromobacter xylosoxidans may be resistant to multiple antibiotics and can cause infections with various presentations.

Case Report

A 50-year-old woman presented with a sore, tender, red lump on the right superior buttock of 5 months’ duration. Five months prior to presentation the patient used this area to attach the infusion set for an insulin pump, which was left in place for 7 days as opposed to the 2 or 3 days recommended by the device manufacturer. A firm, slightly tender lump formed, similar to prior scars that had developed from use of the insulin pump. However, the lump began to grow and get softer. It was intermittently warm and red. Although the area was sore and tender, she never had any major pain. She also denied any fever, malaise, or other systemic symptoms.

The patient indicated a medical history of type 1 diabetes mellitus diagnosed at 9 years of age; hypertension; asthma; gastroesophageal reflux disease; allergic rhinitis; migraine headaches; depression; hidradenitis suppurativa that resolved after surgical excision; and recurrent vaginal yeast infections, especially when taking antibiotics. She had a surgical history of hidradenitis suppurativa excision at the inguinal folds, bilateral carpal tunnel release, tubal ligation, abdominoplasty, and cholecystectomy. The patient’s current medications included insulin aspart, mometasone furoate, inhaled fluticasone, pantoprazole, cetirizine, spironolactone, duloxetine, sumatriptan, fluconazole, topiramate, and enalapril.

Physical examination revealed normal vital signs and the patient was afebrile. She had no swollen or tender lymph nodes. There was a 5.5×7.0-cm, soft, tender, erythematous subcutaneous mass with no visible punctum or overlying epidermal change on the right superior buttock (Figure 1). Based on the history and physical examination, the differential diagnosis included subcutaneous fat necrosis, epidermal inclusion cyst, and an abscess.

The patient was scheduled for excision of the mass the day after presenting to the clinic. During excision, 10 mL of thick purulent liquid was drained. A sample of the liquid was sent for Gram stain, aerobic and anaerobic culture, and antibiotic sensitivities. Necrotic-appearing adipose and fibrotic tissues were dissected and extirpated through an elliptical incision and submitted for pathologic evaluation.

Histopathology showed a subcutaneous defect with palisaded granulomatous inflammation and sclerosis (Figure 2). There was no detection of microorganisms with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, tissue Gram, or acid-fast stains. There was a focus of acellular material embedded within the inflammation (Figure 3). The Gram stain of the purulent material showed few white blood cells and rare gram-negative bacilli. Culture grew moderate Achromobacter xylosoxidans resistant to cefepime, cefotaxime, and gentamicin. The culture was susceptible to ceftazidime, imipenem, levofloxacin, piperacillin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX).

The patient was prescribed oral TMP-SMX (160 mg of TMP and 800 mg of SMX) twice daily for 10 days. The patient tolerated the procedure and the subsequent antibiotics well. The patient had normal levels of IgA, IgG, and IgM, as well as a negative screening test for human immunodeficiency virus. She healed well from the surgical procedure and has had no recurrence of symptoms.

Comment

Achromobacter xylosoxidans is a nonfermentative, non–spore-forming, motile, gram-negative, aerobic, catalase-positive and oxidase-positive flagellate bacterium. It is an emerging pathogen that was first isolated in 1971 from patients with chronic otitis media.1 Since its recognition, it has been documented to cause a variety of infections, including pneumonia, meningitis, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, and bacteremia, as well as abdominal, urinary tract, ocular, and skin and soft tissue infections.2,3 Those affected usually are immunocompromised, have hematologic disorders, or have indwelling catheters.4 Strains of A xylosoxidans have shown resistance to multiple antibiotics including penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, aminoglycosides, macrolides, fluoroquinolones, and TMP-SMX. Achromobacter xylosoxidans has been documented to form biofilms on plastics, including on contact lenses, urinary and intravenous catheters, and reusable tissue dispensers treated with disinfectant solution.4-6 One study demonstrated that A xylosoxidans is even capable of biodegradation of plastic, using the plastic as its sole source of carbon.7

Our case illustrates an indolent infection with A xylosoxidans forming a granulomatous abscess at the site of an insulin pump that was left in place for 7 days in an immunocompetent patient. Although infections with A xylosoxidans in patients with urinary or intravenous catheters have been reported,4 our case is unique, as the insulin pump was the source of such an infection. It is possible that the subcutaneous focus of acellular material described on the pathology report represented a partially biodegraded piece of the insulin pump catheter that broke off and was serving as a nidus of infection for A xylosoxidans. Although multidrug resistance is common, the culture grown from our patient was susceptible to TMP-SMX, among other antibiotics. Our patient was treated successfully with surgical excision, drainage, and a 10-day course of TMP-SMX.

Conclusion

Health care providers should recognize A xylosoxidans as an emerging pathogen that is capable of forming biofilms on “disinfected” surfaces and medical products, especially plastics. Achromobacter xylosoxidans may be resistant to multiple antibiotics and can cause infections with various presentations.

- Yabuuchi E, Oyama A. Achromobacter xylosoxidans n. sp. from human ear discharge. Jpn J Microbiol. 1971;15:477-481.

- Rodrigues CG, Rays J, Kanegae MY. Native-valve endocarditis caused by Achromobacter xylosoxidans: a case report and review of literature. Autops Case Rep. 2017;7:50-55.

- Tena D, Martínez NM, Losa C, et al. Skin and soft tissue infection caused by Achromobacter xylosoxidans: report of 14 cases. Scand J Infect Dis. 2014;46:130-135.

- Pérez Barragán E, Sandino Pérez J, Corbella L, et al. Achromobacter xylosoxidans bacteremia: clinical and microbiological features in a 10-year case series. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2018;31:268-273.

- Konstantinović N, Ćirković I, Đukić S, et al. Biofilm formation of Achromobacter xylosoxidans on contact lens. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2017;64:293-300.

- Günther F, Merle U, Frank U, et al. Pseudobacteremia outbreak of biofilm-forming Achromobacter xylosoxidans—environmental transmission. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:584.

- Kowalczyk A, Chyc M, Ryszka P, et al. Achromobacter xylosoxidans as a new microorganism strain colonizing high-density polyethylene as a key step to its biodegradation. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016;23:11349-11356.

- Yabuuchi E, Oyama A. Achromobacter xylosoxidans n. sp. from human ear discharge. Jpn J Microbiol. 1971;15:477-481.

- Rodrigues CG, Rays J, Kanegae MY. Native-valve endocarditis caused by Achromobacter xylosoxidans: a case report and review of literature. Autops Case Rep. 2017;7:50-55.

- Tena D, Martínez NM, Losa C, et al. Skin and soft tissue infection caused by Achromobacter xylosoxidans: report of 14 cases. Scand J Infect Dis. 2014;46:130-135.

- Pérez Barragán E, Sandino Pérez J, Corbella L, et al. Achromobacter xylosoxidans bacteremia: clinical and microbiological features in a 10-year case series. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2018;31:268-273.

- Konstantinović N, Ćirković I, Đukić S, et al. Biofilm formation of Achromobacter xylosoxidans on contact lens. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2017;64:293-300.

- Günther F, Merle U, Frank U, et al. Pseudobacteremia outbreak of biofilm-forming Achromobacter xylosoxidans—environmental transmission. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:584.

- Kowalczyk A, Chyc M, Ryszka P, et al. Achromobacter xylosoxidans as a new microorganism strain colonizing high-density polyethylene as a key step to its biodegradation. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016;23:11349-11356.

Practice Points

- Achromobacter xylosoxidans is an emerging pathogen primarily in the immunocompromised patient.

- Achromobacter xylosoxidans can form biofilms on plastics treated with disinfectant solution, including medical products.

- Strains of A xylosoxidans have shown multiantibiotic resistance.

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Successfully Treated With Miltefosine

Leishmaniasis is a neglected parasitic disease with an estimated annual incidence of 1.3 million cases, the majority of which manifest as cutaneous leishmaniasis.1 The cutaneous and mucosal forms demonstrate substantial global burden with morbidity and socioeconomic repercussions, while the visceral form is responsible for up to 30,000 deaths annually.2 Despite increasing prevalence in the United States, awareness and diagnosis remain relatively low.3 We describe 2 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in New England, United States, in travelers returning from Central America, both successfully treated with miltefosine. We also review prevention, diagnosis, and treatment options.

Case Reports

Patient 1

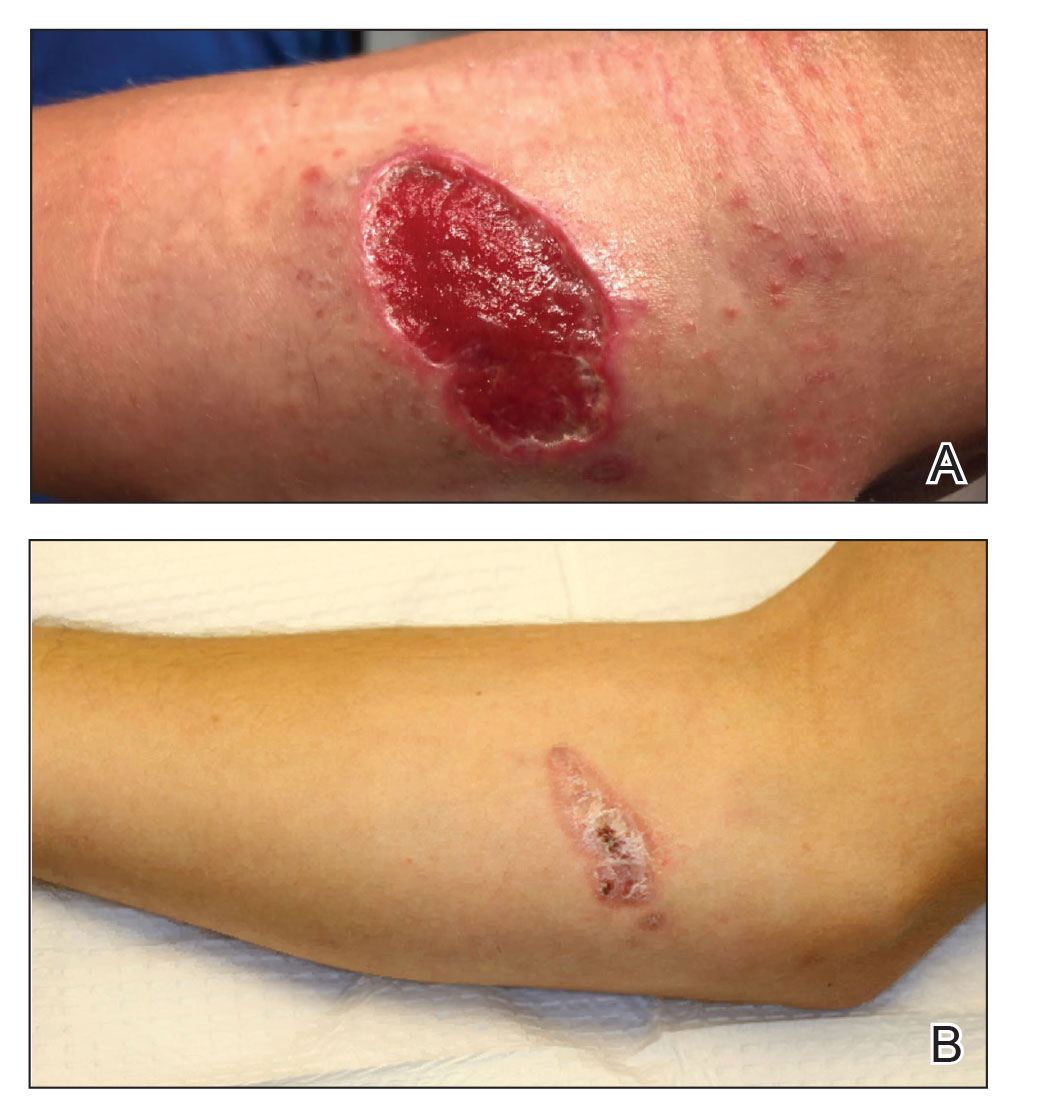

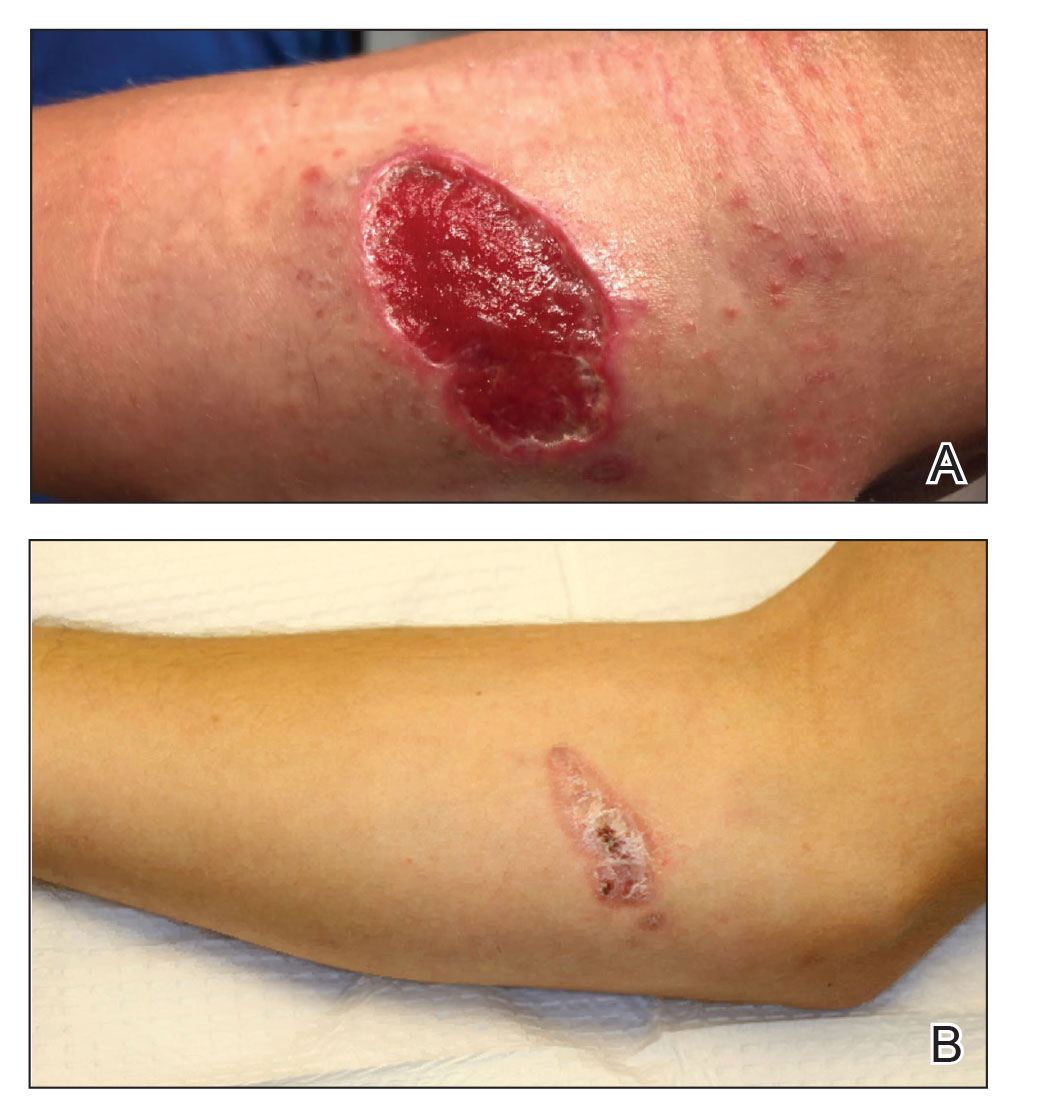

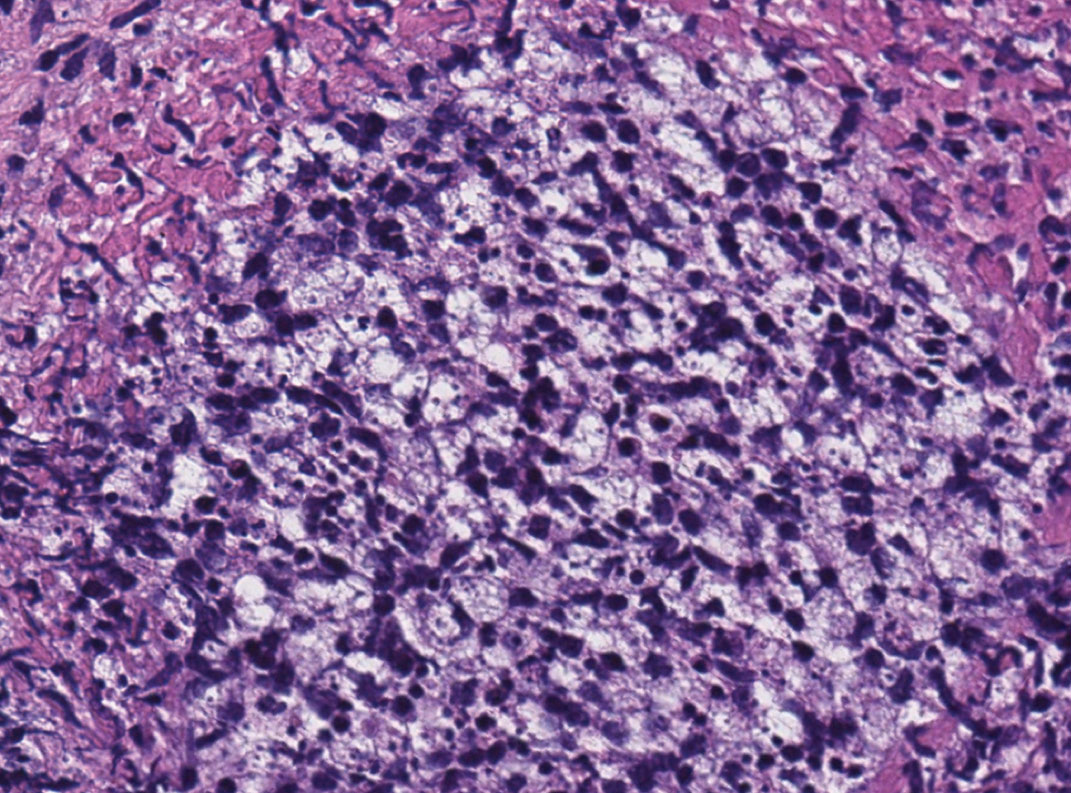

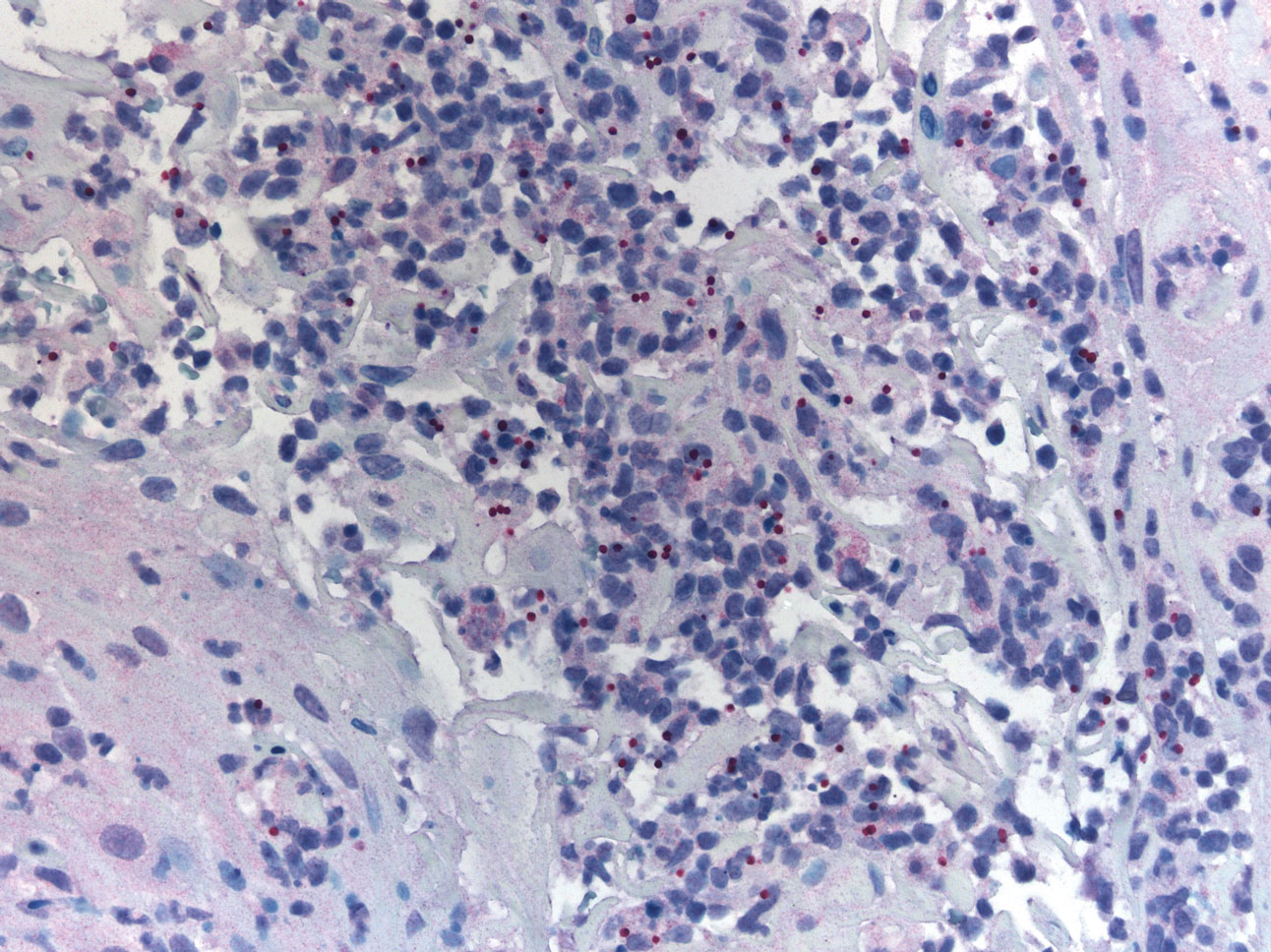

A 47-year-old woman presented with an enlarging, 2-cm, erythematous, ulcerated nodule on the right dorsal hand of 2 weeks’ duration with accompanying right epitrochlear lymphadenopathy (Figure 1A). She noticed the lesion 10 weeks after returning from Panama, where she had been photographing the jungle. Prior to the initial presentation to dermatology, salicylic acid wart remover, intramuscular ceftriaxone, and oral trimethoprim had failed to alleviate the lesion. Her laboratory results were notable for an elevated C-reactive protein level of 5.4 mg/L (reference range, ≤4.9 mg/L). A punch biopsy demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with diffuse dermal lymphohistiocytic inflammation and small intracytoplasmic structures within histiocytes consistent with leishmaniasis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry was consistent with leishmaniasis (Figure 3), and polymerase chain reaction performed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identified the pathogen as Leishmania braziliensis.

Patient 2

An 18-year-old man presented with an enlarging, well-delineated, tender ulcer of 6 weeks’ duration measuring 2.5×2 cm with an erythematous and edematous border on the right medial forearm with associated epitrochlear lymphadenopathy (Figure 4). Nine weeks prior to initial presentation, he had returned from a 3-month outdoor adventure trip to the Florida Keys, Costa Rica, and Panama. He had used bug repellent intermittently, slept under a bug net, and did not recall any trauma or bite at the ulcer site. Biopsy and tissue culture were obtained, and histopathology demonstrated an ulcer with a dense dermal lymphogranulomatous infiltrate and intracytoplasmic organisms consistent with leishmaniasis. Polymerase chain reaction by the CDC identified the pathogen as Leishmania panamensis.

Treatment

Both patients were prescribed oral miltefosine 50 mg twice daily for 28 days. Patient 1 initiated treatment 1 month after lesion onset, and patient 2 initiated treatment 2.5 months after initial presentation. Both patients had noticeable clinical improvement within 21 days of starting treatment, with lesions diminishing in size and lymphadenopathy resolving. Within 2 months of treatment, patient 1’s ulcer completely resolved with only postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (Figure 1B), while patient 2’s ulcer was noticeably smaller and shallower compared with its peak size of 4.2×2.4 cm (Figure 4B). Miltefosine was well tolerated by both patients; emesis resolved with ondansetron in patient 1 and spontaneously in patient 2, who had asymptomatic temporary hyperkalemia of 5.2 mmol/L (reference range, 3.5–5.0 mmol/L).

Comment

Epidemiology and Prevention

Risk factors for leishmaniasis include weak immunity, poverty, poor housing, poor sanitation, malnutrition, urbanization, climate change, and human migration.4 Our patients were most directly affected by travel to locations where leishmaniasis is endemic. Despite an increasing prevalence of endemic leishmaniasis and new animal hosts in the southern United States, most patients diagnosed in the United States are infected abroad by Leishmania mexicana and L braziliensis, both cutaneous New World species.3 Our patients were infected by species within the New World subgenus Viannia that have potential for mucocutaneous spread.4

Because there is no chemoprophylaxis or acquired active immunity such as vaccines that can mitigate the risk for leishmaniasis, public health efforts focus on preventive measures. Although difficult to achieve, avoidance of the phlebotomine sand fly species that transmit the obligate intracellular Leishmania parasite is a most effective measure.4 Travelers entering geographic regions with higher risk for leishmaniasis should be aware of the inherent risk and determine which methods of prevention, such as N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET) insecticides or permethrin-treated protective clothing, are most feasible. Although higher concentrations of DEET provide longer protection, the effectiveness tends to plateau at approximately 50%.5

Presentation and Prognosis

For patients who develop leishmaniasis, the disease course and prognosis depend greatly on the species and manifestation. The most common form of leishmaniasis is localized cutaneous leishmaniasis, which has an annual incidence of up to 1 million cases. It initially presents as macules, usually at the site of inoculation within several months to years of infection.6 The macules expand into papules and plaques that reach maximum size over at least 1 week4 and then progress into crusted ulcers up to 5 cm in diameter with raised edges. Although usually painless and self-limited, these lesions can take years to spontaneously heal, with the risk for atrophic scarring and altered pigmentation. Lymphatic involvement manifests as lymphadenitis or regional lymphadenopathy and is common with lesions caused by the subgenus Viannia.6

Leishmania braziliensis and L panamensis, the species that infected our patients, can uniquely cause cutaneous leishmaniasis that metastasizes into mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, which always affects the nasal mucosa. Risk factors for transformation include a primary lesion site above the waist, multiple or large primary lesions, and delayed healing of primary cutaneous leishmaniasis. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis can result in notable morbidity and even mortality from invasion and destruction of nasal and oropharyngeal mucosa, as well as intercurrent pneumonia, especially if treatment is insufficient or delayed.4

Diagnosis

Prompt treatment relies on accurate and timely diagnosis, which is complicated by the relative unfamiliarity with leishmaniasis in the United States. The differential diagnosis for cutaneous leishmaniasis is broad, including deep fungal infection, Mycobacterium infection, cutaneous granulomatous conditions, nonmelanoma cutaneous neoplasms, and trauma. Taking a thorough patient history, including potential exposures and travels; having high clinical suspicion; and being aware of classic presentation allows for identification of leishmaniasis and subsequent stratification by manifestation.7

Diagnosis is made by detecting Leishmania organisms or DNA using light microscopy and staining to visualize the kinetoplast in an amastigote, molecular methods, or specialized culturing.7 The CDC is a valuable diagnostic partner for confirmation and speciation. Specific instructions for specimen collection and transportation can be found by contacting the CDC or reading their guide.8 To provide prompt care and reassurance to patients, it is important to be aware of the coordination effort that may be needed to send samples, receive results, and otherwise correspond with a separate institution.

Treatment

Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis is indicated to decrease the risk for mucosal dissemination and clinical reactivation of lesions, accelerate healing of lesions, decrease local morbidity caused by large or persistent lesions, and decrease the reservoir of infection in places where infected humans serve as reservoir hosts. Oral treatments include ketoconazole, itraconazole, and fluconazole, recommended at doses ranging from 200 to 600 mg daily for at least 28 days. For severe, refractory, or visceral leishmaniasis, parenteral choices include

Miltefosine is becoming a more common treatment of leishmaniasis because of its oral route, tolerability in nonpregnant patients, and commercial availability. It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2014 for cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L braziliensis, L panamensis, and Leishmania guyanensis; mucosal leishmaniasis due to L braziliensis; and visceral leishmaniasis due to Leishmania donovani in patients at least 12 years of age. For cutaneous leishmaniasis, the standard dosage of 50 mg twice daily (for patients weighing 30–44 kg) or 3 times daily (for patients weighing 45 kg or more) for 28 consecutive days has cure rates of 48% to 85% by 6 months after therapy ends. Cure is defined as epithelialization of lesions, no enlargement greater than 50% in lesions, no appearance of new lesions, and/or negative parasitology. The antileishmanial mechanism of action is unknown and likely involves interaction with lipids, inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase, and apoptosislike cell death. Miltefosine is contraindicated in pregnancy. The most common adverse reactions in patients include nausea (35.9%–41.7%), motion sickness (29.2%), headache (28.1%), and emesis (4.5%–27.5%). With the exception of headache, these adverse reactions can decrease with administration of food, fluids, and antiemetics. Potentially more serious but rarer adverse reactions include elevated serum creatinine (5%–25%) and transaminases (5%). Although our patients had mild hyperkalemia, it is not an established adverse reaction. However, renal injury has been reported.10

Conclusion

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is increasing in prevalence in the United States due to increased foreign travel. Providers should be familiar with the cutaneous presentation of leishmaniasis, even in areas of low prevalence, to limit the risk for mucocutaneous dissemination from infection with the subgenus Viannia. Prompt treatment is vital to ensuring the best prognosis, and first-line treatment with miltefosine should be strongly considered given its efficacy and tolerability.

- Babuadze G, Alvar J, Argaw D, et al. Epidemiology of visceral leishmaniasis in Georgia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2725.

- Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization website. https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/Leishmaniasis. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- McIlwee BE, Weis SE, Hosler GA. Incidence of endemic human cutaneous leishmaniasis in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1032-1039.

- Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis. Update March 2, 2020. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for DEET insect repellent use. https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/toolkit/DEET.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2020.

- Buescher MD, Rutledge LC, Wirtz RA, et al. The dose-persistence relationship of DEET against Aedes aegypti. Mosq News. 1983;43:364-366.

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e202-e264.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Practical guide for specimen collection and reference diagnosis of leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/resources/pdf/cdc_diagnosis_guide_leishmaniasis_2016.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- Visceral leishmaniasis. Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative website. https://www.dndi.org/diseases-projects/leishmaniasis/. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- Impavido Medication Guide. Food and Drug Administration Web site. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/204684s000lbl.pdf. Revised March 2014. Accessed May 18, 2020.

Leishmaniasis is a neglected parasitic disease with an estimated annual incidence of 1.3 million cases, the majority of which manifest as cutaneous leishmaniasis.1 The cutaneous and mucosal forms demonstrate substantial global burden with morbidity and socioeconomic repercussions, while the visceral form is responsible for up to 30,000 deaths annually.2 Despite increasing prevalence in the United States, awareness and diagnosis remain relatively low.3 We describe 2 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in New England, United States, in travelers returning from Central America, both successfully treated with miltefosine. We also review prevention, diagnosis, and treatment options.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 47-year-old woman presented with an enlarging, 2-cm, erythematous, ulcerated nodule on the right dorsal hand of 2 weeks’ duration with accompanying right epitrochlear lymphadenopathy (Figure 1A). She noticed the lesion 10 weeks after returning from Panama, where she had been photographing the jungle. Prior to the initial presentation to dermatology, salicylic acid wart remover, intramuscular ceftriaxone, and oral trimethoprim had failed to alleviate the lesion. Her laboratory results were notable for an elevated C-reactive protein level of 5.4 mg/L (reference range, ≤4.9 mg/L). A punch biopsy demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with diffuse dermal lymphohistiocytic inflammation and small intracytoplasmic structures within histiocytes consistent with leishmaniasis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry was consistent with leishmaniasis (Figure 3), and polymerase chain reaction performed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identified the pathogen as Leishmania braziliensis.

Patient 2

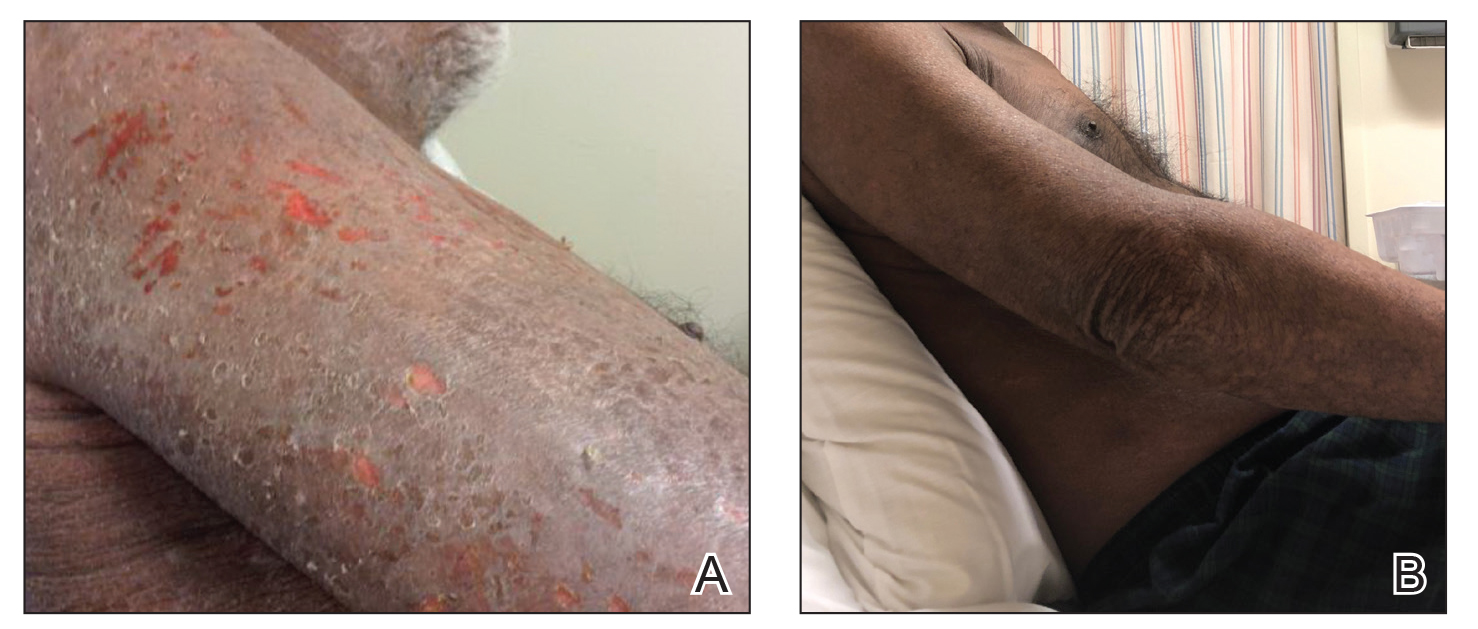

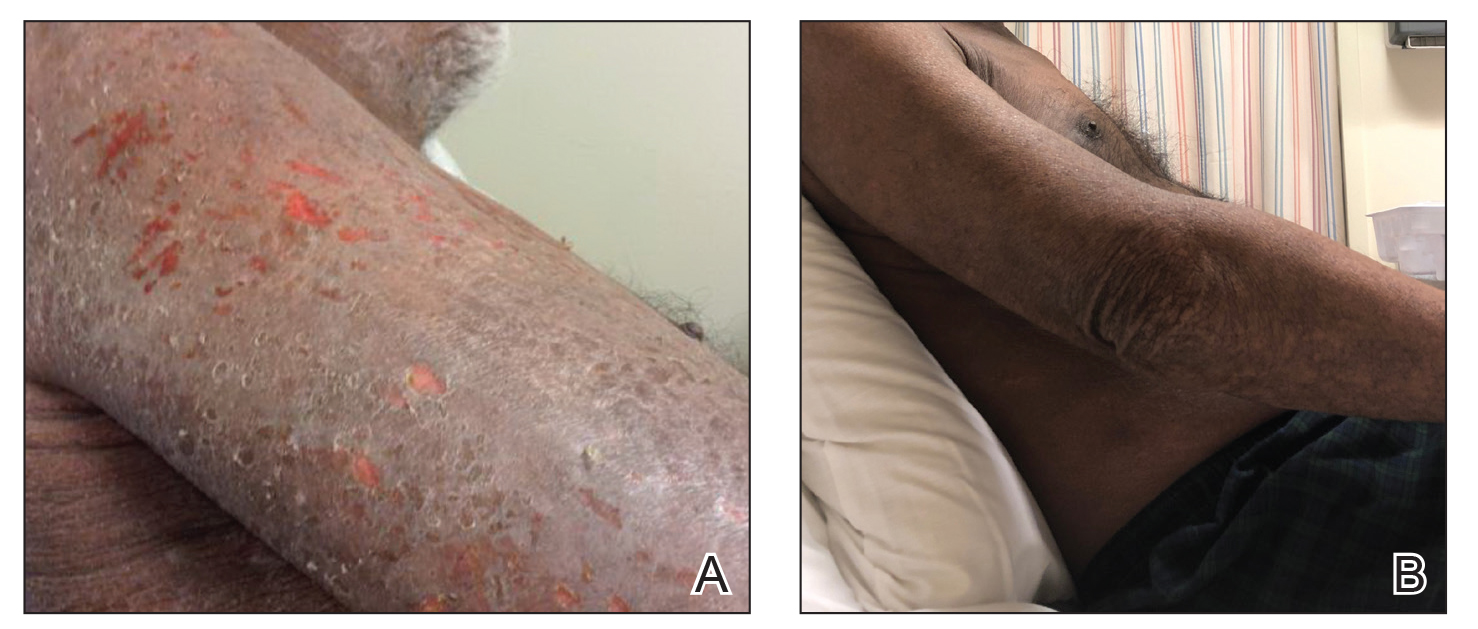

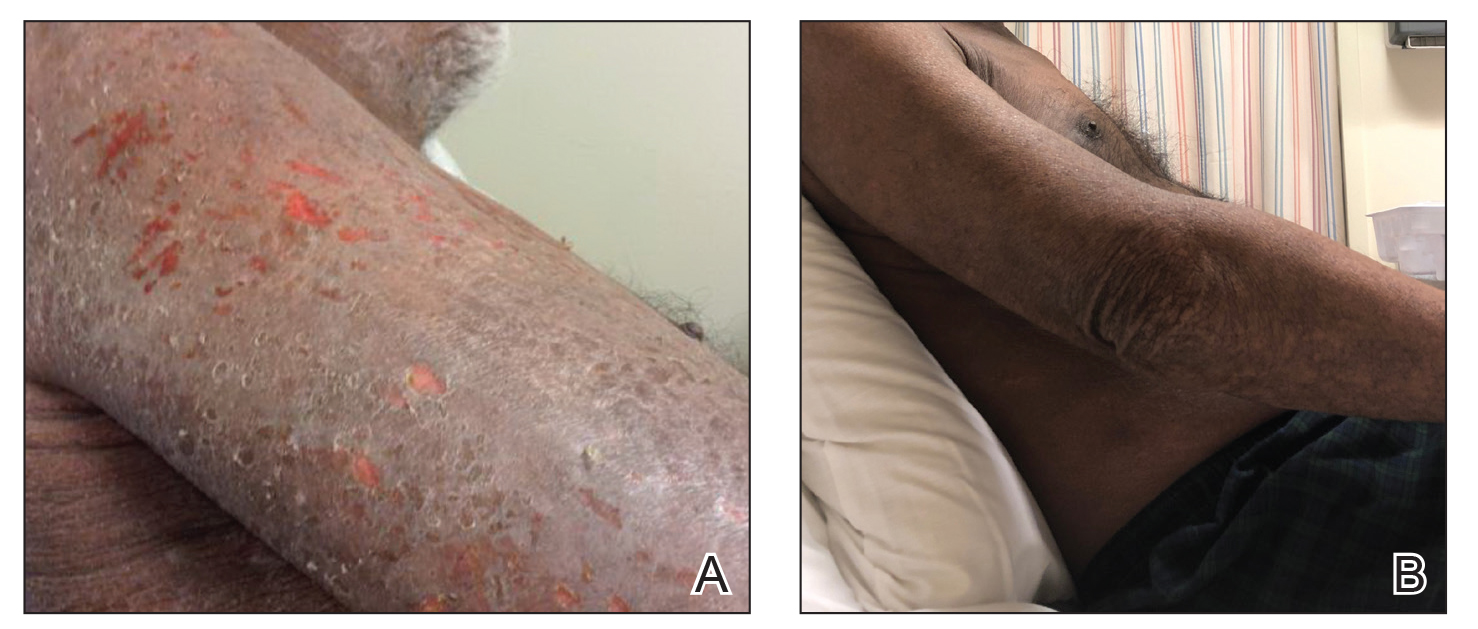

An 18-year-old man presented with an enlarging, well-delineated, tender ulcer of 6 weeks’ duration measuring 2.5×2 cm with an erythematous and edematous border on the right medial forearm with associated epitrochlear lymphadenopathy (Figure 4). Nine weeks prior to initial presentation, he had returned from a 3-month outdoor adventure trip to the Florida Keys, Costa Rica, and Panama. He had used bug repellent intermittently, slept under a bug net, and did not recall any trauma or bite at the ulcer site. Biopsy and tissue culture were obtained, and histopathology demonstrated an ulcer with a dense dermal lymphogranulomatous infiltrate and intracytoplasmic organisms consistent with leishmaniasis. Polymerase chain reaction by the CDC identified the pathogen as Leishmania panamensis.

Treatment

Both patients were prescribed oral miltefosine 50 mg twice daily for 28 days. Patient 1 initiated treatment 1 month after lesion onset, and patient 2 initiated treatment 2.5 months after initial presentation. Both patients had noticeable clinical improvement within 21 days of starting treatment, with lesions diminishing in size and lymphadenopathy resolving. Within 2 months of treatment, patient 1’s ulcer completely resolved with only postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (Figure 1B), while patient 2’s ulcer was noticeably smaller and shallower compared with its peak size of 4.2×2.4 cm (Figure 4B). Miltefosine was well tolerated by both patients; emesis resolved with ondansetron in patient 1 and spontaneously in patient 2, who had asymptomatic temporary hyperkalemia of 5.2 mmol/L (reference range, 3.5–5.0 mmol/L).

Comment

Epidemiology and Prevention

Risk factors for leishmaniasis include weak immunity, poverty, poor housing, poor sanitation, malnutrition, urbanization, climate change, and human migration.4 Our patients were most directly affected by travel to locations where leishmaniasis is endemic. Despite an increasing prevalence of endemic leishmaniasis and new animal hosts in the southern United States, most patients diagnosed in the United States are infected abroad by Leishmania mexicana and L braziliensis, both cutaneous New World species.3 Our patients were infected by species within the New World subgenus Viannia that have potential for mucocutaneous spread.4

Because there is no chemoprophylaxis or acquired active immunity such as vaccines that can mitigate the risk for leishmaniasis, public health efforts focus on preventive measures. Although difficult to achieve, avoidance of the phlebotomine sand fly species that transmit the obligate intracellular Leishmania parasite is a most effective measure.4 Travelers entering geographic regions with higher risk for leishmaniasis should be aware of the inherent risk and determine which methods of prevention, such as N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET) insecticides or permethrin-treated protective clothing, are most feasible. Although higher concentrations of DEET provide longer protection, the effectiveness tends to plateau at approximately 50%.5

Presentation and Prognosis

For patients who develop leishmaniasis, the disease course and prognosis depend greatly on the species and manifestation. The most common form of leishmaniasis is localized cutaneous leishmaniasis, which has an annual incidence of up to 1 million cases. It initially presents as macules, usually at the site of inoculation within several months to years of infection.6 The macules expand into papules and plaques that reach maximum size over at least 1 week4 and then progress into crusted ulcers up to 5 cm in diameter with raised edges. Although usually painless and self-limited, these lesions can take years to spontaneously heal, with the risk for atrophic scarring and altered pigmentation. Lymphatic involvement manifests as lymphadenitis or regional lymphadenopathy and is common with lesions caused by the subgenus Viannia.6

Leishmania braziliensis and L panamensis, the species that infected our patients, can uniquely cause cutaneous leishmaniasis that metastasizes into mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, which always affects the nasal mucosa. Risk factors for transformation include a primary lesion site above the waist, multiple or large primary lesions, and delayed healing of primary cutaneous leishmaniasis. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis can result in notable morbidity and even mortality from invasion and destruction of nasal and oropharyngeal mucosa, as well as intercurrent pneumonia, especially if treatment is insufficient or delayed.4

Diagnosis

Prompt treatment relies on accurate and timely diagnosis, which is complicated by the relative unfamiliarity with leishmaniasis in the United States. The differential diagnosis for cutaneous leishmaniasis is broad, including deep fungal infection, Mycobacterium infection, cutaneous granulomatous conditions, nonmelanoma cutaneous neoplasms, and trauma. Taking a thorough patient history, including potential exposures and travels; having high clinical suspicion; and being aware of classic presentation allows for identification of leishmaniasis and subsequent stratification by manifestation.7

Diagnosis is made by detecting Leishmania organisms or DNA using light microscopy and staining to visualize the kinetoplast in an amastigote, molecular methods, or specialized culturing.7 The CDC is a valuable diagnostic partner for confirmation and speciation. Specific instructions for specimen collection and transportation can be found by contacting the CDC or reading their guide.8 To provide prompt care and reassurance to patients, it is important to be aware of the coordination effort that may be needed to send samples, receive results, and otherwise correspond with a separate institution.

Treatment

Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis is indicated to decrease the risk for mucosal dissemination and clinical reactivation of lesions, accelerate healing of lesions, decrease local morbidity caused by large or persistent lesions, and decrease the reservoir of infection in places where infected humans serve as reservoir hosts. Oral treatments include ketoconazole, itraconazole, and fluconazole, recommended at doses ranging from 200 to 600 mg daily for at least 28 days. For severe, refractory, or visceral leishmaniasis, parenteral choices include

Miltefosine is becoming a more common treatment of leishmaniasis because of its oral route, tolerability in nonpregnant patients, and commercial availability. It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2014 for cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L braziliensis, L panamensis, and Leishmania guyanensis; mucosal leishmaniasis due to L braziliensis; and visceral leishmaniasis due to Leishmania donovani in patients at least 12 years of age. For cutaneous leishmaniasis, the standard dosage of 50 mg twice daily (for patients weighing 30–44 kg) or 3 times daily (for patients weighing 45 kg or more) for 28 consecutive days has cure rates of 48% to 85% by 6 months after therapy ends. Cure is defined as epithelialization of lesions, no enlargement greater than 50% in lesions, no appearance of new lesions, and/or negative parasitology. The antileishmanial mechanism of action is unknown and likely involves interaction with lipids, inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase, and apoptosislike cell death. Miltefosine is contraindicated in pregnancy. The most common adverse reactions in patients include nausea (35.9%–41.7%), motion sickness (29.2%), headache (28.1%), and emesis (4.5%–27.5%). With the exception of headache, these adverse reactions can decrease with administration of food, fluids, and antiemetics. Potentially more serious but rarer adverse reactions include elevated serum creatinine (5%–25%) and transaminases (5%). Although our patients had mild hyperkalemia, it is not an established adverse reaction. However, renal injury has been reported.10

Conclusion

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is increasing in prevalence in the United States due to increased foreign travel. Providers should be familiar with the cutaneous presentation of leishmaniasis, even in areas of low prevalence, to limit the risk for mucocutaneous dissemination from infection with the subgenus Viannia. Prompt treatment is vital to ensuring the best prognosis, and first-line treatment with miltefosine should be strongly considered given its efficacy and tolerability.

Leishmaniasis is a neglected parasitic disease with an estimated annual incidence of 1.3 million cases, the majority of which manifest as cutaneous leishmaniasis.1 The cutaneous and mucosal forms demonstrate substantial global burden with morbidity and socioeconomic repercussions, while the visceral form is responsible for up to 30,000 deaths annually.2 Despite increasing prevalence in the United States, awareness and diagnosis remain relatively low.3 We describe 2 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in New England, United States, in travelers returning from Central America, both successfully treated with miltefosine. We also review prevention, diagnosis, and treatment options.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 47-year-old woman presented with an enlarging, 2-cm, erythematous, ulcerated nodule on the right dorsal hand of 2 weeks’ duration with accompanying right epitrochlear lymphadenopathy (Figure 1A). She noticed the lesion 10 weeks after returning from Panama, where she had been photographing the jungle. Prior to the initial presentation to dermatology, salicylic acid wart remover, intramuscular ceftriaxone, and oral trimethoprim had failed to alleviate the lesion. Her laboratory results were notable for an elevated C-reactive protein level of 5.4 mg/L (reference range, ≤4.9 mg/L). A punch biopsy demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with diffuse dermal lymphohistiocytic inflammation and small intracytoplasmic structures within histiocytes consistent with leishmaniasis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry was consistent with leishmaniasis (Figure 3), and polymerase chain reaction performed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identified the pathogen as Leishmania braziliensis.

Patient 2

An 18-year-old man presented with an enlarging, well-delineated, tender ulcer of 6 weeks’ duration measuring 2.5×2 cm with an erythematous and edematous border on the right medial forearm with associated epitrochlear lymphadenopathy (Figure 4). Nine weeks prior to initial presentation, he had returned from a 3-month outdoor adventure trip to the Florida Keys, Costa Rica, and Panama. He had used bug repellent intermittently, slept under a bug net, and did not recall any trauma or bite at the ulcer site. Biopsy and tissue culture were obtained, and histopathology demonstrated an ulcer with a dense dermal lymphogranulomatous infiltrate and intracytoplasmic organisms consistent with leishmaniasis. Polymerase chain reaction by the CDC identified the pathogen as Leishmania panamensis.

Treatment

Both patients were prescribed oral miltefosine 50 mg twice daily for 28 days. Patient 1 initiated treatment 1 month after lesion onset, and patient 2 initiated treatment 2.5 months after initial presentation. Both patients had noticeable clinical improvement within 21 days of starting treatment, with lesions diminishing in size and lymphadenopathy resolving. Within 2 months of treatment, patient 1’s ulcer completely resolved with only postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (Figure 1B), while patient 2’s ulcer was noticeably smaller and shallower compared with its peak size of 4.2×2.4 cm (Figure 4B). Miltefosine was well tolerated by both patients; emesis resolved with ondansetron in patient 1 and spontaneously in patient 2, who had asymptomatic temporary hyperkalemia of 5.2 mmol/L (reference range, 3.5–5.0 mmol/L).

Comment

Epidemiology and Prevention

Risk factors for leishmaniasis include weak immunity, poverty, poor housing, poor sanitation, malnutrition, urbanization, climate change, and human migration.4 Our patients were most directly affected by travel to locations where leishmaniasis is endemic. Despite an increasing prevalence of endemic leishmaniasis and new animal hosts in the southern United States, most patients diagnosed in the United States are infected abroad by Leishmania mexicana and L braziliensis, both cutaneous New World species.3 Our patients were infected by species within the New World subgenus Viannia that have potential for mucocutaneous spread.4

Because there is no chemoprophylaxis or acquired active immunity such as vaccines that can mitigate the risk for leishmaniasis, public health efforts focus on preventive measures. Although difficult to achieve, avoidance of the phlebotomine sand fly species that transmit the obligate intracellular Leishmania parasite is a most effective measure.4 Travelers entering geographic regions with higher risk for leishmaniasis should be aware of the inherent risk and determine which methods of prevention, such as N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET) insecticides or permethrin-treated protective clothing, are most feasible. Although higher concentrations of DEET provide longer protection, the effectiveness tends to plateau at approximately 50%.5

Presentation and Prognosis

For patients who develop leishmaniasis, the disease course and prognosis depend greatly on the species and manifestation. The most common form of leishmaniasis is localized cutaneous leishmaniasis, which has an annual incidence of up to 1 million cases. It initially presents as macules, usually at the site of inoculation within several months to years of infection.6 The macules expand into papules and plaques that reach maximum size over at least 1 week4 and then progress into crusted ulcers up to 5 cm in diameter with raised edges. Although usually painless and self-limited, these lesions can take years to spontaneously heal, with the risk for atrophic scarring and altered pigmentation. Lymphatic involvement manifests as lymphadenitis or regional lymphadenopathy and is common with lesions caused by the subgenus Viannia.6