User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Biden chooses California Attorney General Xavier Becerra to head HHS

If confirmed by the US Senate, Becerra will face the challenge of overseeing the federal agency charged with protecting the health of all Americans in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. At the time of the announcement, nearly 15 million Americans had tested positive for COVID-19 and more than 280,000 had died.

Becerra served 12 terms in Congress, representing the Los Angeles area. Although his public health experience is limited, he served on the Congressional Ways and Means Committee overseeing health-related issues. Becerra is known as an advocate for the health and well-being of women in particular.

The American College of Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists, American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American Psychiatric Association wrote a letter to Biden on December 3 urging him to select leaders with medical and healthcare expertise, in particular physicians.

“We believe that your administration and the country would be well-served by the appointment of qualified physicians to serve in key positions critical to advancing the health of our nation,” they wrote. “Therefore, our organizations, which represent more than 400,000 front-line physicians practicing in the United States, write to request that you identify and appoint physicians to healthcare leadership positions within your administration.”

Recent advocacy

Becerra has worked with Republican attorneys general to lobby HHS to increase access to remdesivir to treat people with COVID-19.

As attorney general, Becerra filed more than 100 lawsuits against the Trump administration. In November, he also represented more than 20 states in arguments supporting the Affordable Care Act before the Supreme Court.

On December 4, Becerra joined with attorneys general from 23 states and the District of Columbia opposing a proposed rule from the outgoing Trump administration. The rule would deregulate HHS and “sunset”many agency provisions before Trump leaves office next month.

Becerra will be the first Latino appointed as HHS secretary, which furthers Biden’s goal to create a diverse cabinet. Becerra has been attorney general of California since 2017, replacing Vice President-elect Kamala Harris when she became senator.

Biden’s choice of Becerra was unexpected, according to The New York Times, and he was not the only candidate. Speculation was that Biden initially considered Vivek Murthy, MD, later chosen as the next US surgeon general, as well New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham and Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo.

A huge undertaking

As HHS secretary, Becerra would oversee a wide range of federal agencies, including the US Food and Drug Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The fiscal year 2021 budget proposed for HHS includes $94.5 billion in discretionary budget authority and $1.3 trillion in mandatory funding. Overall, HHS controls nearly one quarter of all federal expenditures and provides more grant money than all other federal agencies combined.

Becerra, 62, grew up in Sacramento, California. He was the first in his family to graduate from college. He received his undergraduate and law degrees from Stanford University.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

If confirmed by the US Senate, Becerra will face the challenge of overseeing the federal agency charged with protecting the health of all Americans in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. At the time of the announcement, nearly 15 million Americans had tested positive for COVID-19 and more than 280,000 had died.

Becerra served 12 terms in Congress, representing the Los Angeles area. Although his public health experience is limited, he served on the Congressional Ways and Means Committee overseeing health-related issues. Becerra is known as an advocate for the health and well-being of women in particular.

The American College of Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists, American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American Psychiatric Association wrote a letter to Biden on December 3 urging him to select leaders with medical and healthcare expertise, in particular physicians.

“We believe that your administration and the country would be well-served by the appointment of qualified physicians to serve in key positions critical to advancing the health of our nation,” they wrote. “Therefore, our organizations, which represent more than 400,000 front-line physicians practicing in the United States, write to request that you identify and appoint physicians to healthcare leadership positions within your administration.”

Recent advocacy

Becerra has worked with Republican attorneys general to lobby HHS to increase access to remdesivir to treat people with COVID-19.

As attorney general, Becerra filed more than 100 lawsuits against the Trump administration. In November, he also represented more than 20 states in arguments supporting the Affordable Care Act before the Supreme Court.

On December 4, Becerra joined with attorneys general from 23 states and the District of Columbia opposing a proposed rule from the outgoing Trump administration. The rule would deregulate HHS and “sunset”many agency provisions before Trump leaves office next month.

Becerra will be the first Latino appointed as HHS secretary, which furthers Biden’s goal to create a diverse cabinet. Becerra has been attorney general of California since 2017, replacing Vice President-elect Kamala Harris when she became senator.

Biden’s choice of Becerra was unexpected, according to The New York Times, and he was not the only candidate. Speculation was that Biden initially considered Vivek Murthy, MD, later chosen as the next US surgeon general, as well New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham and Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo.

A huge undertaking

As HHS secretary, Becerra would oversee a wide range of federal agencies, including the US Food and Drug Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The fiscal year 2021 budget proposed for HHS includes $94.5 billion in discretionary budget authority and $1.3 trillion in mandatory funding. Overall, HHS controls nearly one quarter of all federal expenditures and provides more grant money than all other federal agencies combined.

Becerra, 62, grew up in Sacramento, California. He was the first in his family to graduate from college. He received his undergraduate and law degrees from Stanford University.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

If confirmed by the US Senate, Becerra will face the challenge of overseeing the federal agency charged with protecting the health of all Americans in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. At the time of the announcement, nearly 15 million Americans had tested positive for COVID-19 and more than 280,000 had died.

Becerra served 12 terms in Congress, representing the Los Angeles area. Although his public health experience is limited, he served on the Congressional Ways and Means Committee overseeing health-related issues. Becerra is known as an advocate for the health and well-being of women in particular.

The American College of Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists, American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American Psychiatric Association wrote a letter to Biden on December 3 urging him to select leaders with medical and healthcare expertise, in particular physicians.

“We believe that your administration and the country would be well-served by the appointment of qualified physicians to serve in key positions critical to advancing the health of our nation,” they wrote. “Therefore, our organizations, which represent more than 400,000 front-line physicians practicing in the United States, write to request that you identify and appoint physicians to healthcare leadership positions within your administration.”

Recent advocacy

Becerra has worked with Republican attorneys general to lobby HHS to increase access to remdesivir to treat people with COVID-19.

As attorney general, Becerra filed more than 100 lawsuits against the Trump administration. In November, he also represented more than 20 states in arguments supporting the Affordable Care Act before the Supreme Court.

On December 4, Becerra joined with attorneys general from 23 states and the District of Columbia opposing a proposed rule from the outgoing Trump administration. The rule would deregulate HHS and “sunset”many agency provisions before Trump leaves office next month.

Becerra will be the first Latino appointed as HHS secretary, which furthers Biden’s goal to create a diverse cabinet. Becerra has been attorney general of California since 2017, replacing Vice President-elect Kamala Harris when she became senator.

Biden’s choice of Becerra was unexpected, according to The New York Times, and he was not the only candidate. Speculation was that Biden initially considered Vivek Murthy, MD, later chosen as the next US surgeon general, as well New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham and Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo.

A huge undertaking

As HHS secretary, Becerra would oversee a wide range of federal agencies, including the US Food and Drug Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The fiscal year 2021 budget proposed for HHS includes $94.5 billion in discretionary budget authority and $1.3 trillion in mandatory funding. Overall, HHS controls nearly one quarter of all federal expenditures and provides more grant money than all other federal agencies combined.

Becerra, 62, grew up in Sacramento, California. He was the first in his family to graduate from college. He received his undergraduate and law degrees from Stanford University.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19: Hand sanitizer poisonings soar, psych patients at high risk

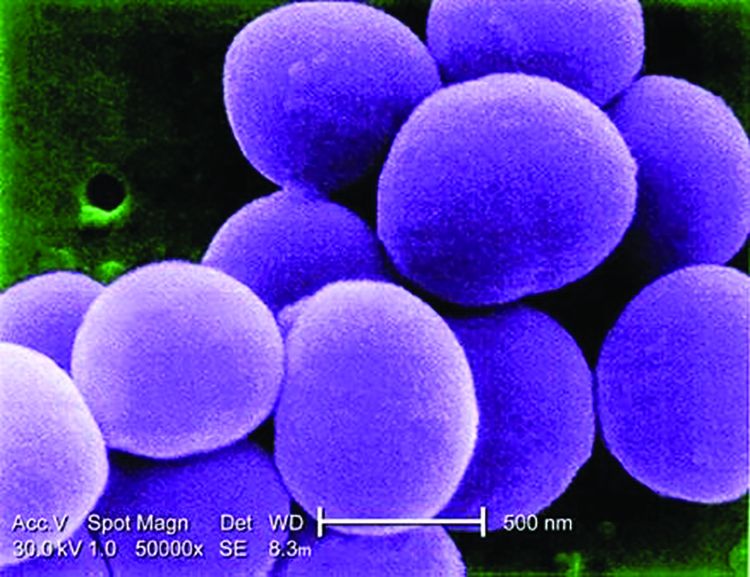

Cases of poisoning – intentional and unintentional – from ingestion of alcohol-based hand sanitizer have soared during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the United Kingdom alone, alcohol-based hand sanitizer poisonings reported to the National Poisons Information Service jumped 157% – from 155 between January 1 and September 16, 2019, to 398 between Jan. 1 and Sept. 14, 2020, new research shows.

More needs to be done to protect those at risk of unintentional and intentional swallowing of alcohol-based hand sanitizer, including children, people with dementia/confusion, and those with mental health issues, according to Georgia Richards, DPhil student, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford (England).

“If providers are supplying alcohol-based hand sanitizers in the community to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2, Ms. Richards said in an interview.

The study was published online Dec. 1 in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine.

European, U.S. poisoning rates soar

In the paper Ms. Richards described two deaths that occurred in hospitals in England.

In one case, a 30-year-old woman, detained in a psychiatric unit who received the antidepressant venlafaxine was found dead in her hospital bed with a container of hand-sanitizing gel beside her.

“The gel was readily accessible to patients on the ward from a communal dispenser, and patients were allowed to fill cups or other containers with it to keep in their rooms,” Ms. Richards reported.

A postmortem analysis found a high level of alcohol in her blood (214 mg of alcohol in 100 mL of blood). The medical cause of death was listed as “ingestion of alcohol and venlafaxine.” The coroner concluded that the combination of these substances suppressed the patient’s breathing, leading to her death.

The other case involved a 76-year-old man who unintentionally swallowed an unknown quantity of alcohol-based hand-sanitizing foam attached to the foot of his hospital bed.

The patient had a history of agitation and depression and was treated with antidepressants. He had become increasingly confused over the preceding 9 months, possibly because of vascular dementia.

His blood ethanol concentration was 463 mg/dL (100 mmol/L) initially and 354 mg/dL (77mmol/L) 10 hours later. He was admitted to the ICU, where he received lorazepam and haloperidol and treated with ventilation, with a plan to allow the alcohol to be naturally metabolized.

The patient developed complications and died 6 days later. The primary causes of death were bronchopneumonia and acute alcohol toxicity, secondary to acute delirium and coronary artery disease.

Since COVID-19 started, alcohol-based hand sanitizers are among the most sought-after commodities around the world. The volume of these products – now found in homes, hospitals, schools, workplaces, and elsewhere – “may be a cause for concern,” Ms. Richards wrote.

Yet, warnings about the toxicity and lethality of intentional or unintentional ingestion of these products have not been widely disseminated, she noted.

To reduce the risk of harm, Ms. Richards suggested educating the public and health care professionals, improving warning labels on products, and increasing the awareness and reporting of such exposures to public health authorities.

“While governments and public health authorities have successfully heightened our awareness of, and need for, better hand hygiene during the COVID-19 outbreak, they must also make the public aware of the potential harms and encourage the reporting of such harms to poisons information centers,” she noted.

Increases in alcohol-based hand sanitizer poisoning during the pandemic have also been reported in the United States.

The American Association of Poison Control Centers reports that data from the National Poison Data System show 32,892 hand sanitizer exposure cases reported to the 55 U.S. poison control centers from Jan. 1 to Nov. 15, 2020 – an increase of 73%, compared with the same time period during the previous year.

An increase in self-harm

Weighing in on this issue, Robert Bassett, DO, associate medical director of the Poison Control Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview that “cleaning agents and disinfectants have been around for eons and their potential for toxicity hasn’t changed.

“Now with COVID, and this hypervigilance when it comes to cleanliness, there is increased access and the exposure risk has gone up,” he said.

“One of the sad casualties of an overstressed health care system and a globally depressed environment is worsening behavioral health emergencies and, as part of that, the risk of self-harm goes up,” Dr. Bassett added.

“The consensus is that there has been an exacerbation of behavioral health emergencies and behavioral health needs since COVID started and hand sanitizers are readily accessible to someone who may be looking to self-harm,” he said.

This research had no specific funding. Ms. Richards is the editorial registrar of BMJ Evidence Based Medicine and is developing a website to track preventable deaths. Dr. Bassett disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Cases of poisoning – intentional and unintentional – from ingestion of alcohol-based hand sanitizer have soared during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the United Kingdom alone, alcohol-based hand sanitizer poisonings reported to the National Poisons Information Service jumped 157% – from 155 between January 1 and September 16, 2019, to 398 between Jan. 1 and Sept. 14, 2020, new research shows.

More needs to be done to protect those at risk of unintentional and intentional swallowing of alcohol-based hand sanitizer, including children, people with dementia/confusion, and those with mental health issues, according to Georgia Richards, DPhil student, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford (England).

“If providers are supplying alcohol-based hand sanitizers in the community to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2, Ms. Richards said in an interview.

The study was published online Dec. 1 in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine.

European, U.S. poisoning rates soar

In the paper Ms. Richards described two deaths that occurred in hospitals in England.

In one case, a 30-year-old woman, detained in a psychiatric unit who received the antidepressant venlafaxine was found dead in her hospital bed with a container of hand-sanitizing gel beside her.

“The gel was readily accessible to patients on the ward from a communal dispenser, and patients were allowed to fill cups or other containers with it to keep in their rooms,” Ms. Richards reported.

A postmortem analysis found a high level of alcohol in her blood (214 mg of alcohol in 100 mL of blood). The medical cause of death was listed as “ingestion of alcohol and venlafaxine.” The coroner concluded that the combination of these substances suppressed the patient’s breathing, leading to her death.

The other case involved a 76-year-old man who unintentionally swallowed an unknown quantity of alcohol-based hand-sanitizing foam attached to the foot of his hospital bed.

The patient had a history of agitation and depression and was treated with antidepressants. He had become increasingly confused over the preceding 9 months, possibly because of vascular dementia.

His blood ethanol concentration was 463 mg/dL (100 mmol/L) initially and 354 mg/dL (77mmol/L) 10 hours later. He was admitted to the ICU, where he received lorazepam and haloperidol and treated with ventilation, with a plan to allow the alcohol to be naturally metabolized.

The patient developed complications and died 6 days later. The primary causes of death were bronchopneumonia and acute alcohol toxicity, secondary to acute delirium and coronary artery disease.

Since COVID-19 started, alcohol-based hand sanitizers are among the most sought-after commodities around the world. The volume of these products – now found in homes, hospitals, schools, workplaces, and elsewhere – “may be a cause for concern,” Ms. Richards wrote.

Yet, warnings about the toxicity and lethality of intentional or unintentional ingestion of these products have not been widely disseminated, she noted.

To reduce the risk of harm, Ms. Richards suggested educating the public and health care professionals, improving warning labels on products, and increasing the awareness and reporting of such exposures to public health authorities.

“While governments and public health authorities have successfully heightened our awareness of, and need for, better hand hygiene during the COVID-19 outbreak, they must also make the public aware of the potential harms and encourage the reporting of such harms to poisons information centers,” she noted.

Increases in alcohol-based hand sanitizer poisoning during the pandemic have also been reported in the United States.

The American Association of Poison Control Centers reports that data from the National Poison Data System show 32,892 hand sanitizer exposure cases reported to the 55 U.S. poison control centers from Jan. 1 to Nov. 15, 2020 – an increase of 73%, compared with the same time period during the previous year.

An increase in self-harm

Weighing in on this issue, Robert Bassett, DO, associate medical director of the Poison Control Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview that “cleaning agents and disinfectants have been around for eons and their potential for toxicity hasn’t changed.

“Now with COVID, and this hypervigilance when it comes to cleanliness, there is increased access and the exposure risk has gone up,” he said.

“One of the sad casualties of an overstressed health care system and a globally depressed environment is worsening behavioral health emergencies and, as part of that, the risk of self-harm goes up,” Dr. Bassett added.

“The consensus is that there has been an exacerbation of behavioral health emergencies and behavioral health needs since COVID started and hand sanitizers are readily accessible to someone who may be looking to self-harm,” he said.

This research had no specific funding. Ms. Richards is the editorial registrar of BMJ Evidence Based Medicine and is developing a website to track preventable deaths. Dr. Bassett disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Cases of poisoning – intentional and unintentional – from ingestion of alcohol-based hand sanitizer have soared during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the United Kingdom alone, alcohol-based hand sanitizer poisonings reported to the National Poisons Information Service jumped 157% – from 155 between January 1 and September 16, 2019, to 398 between Jan. 1 and Sept. 14, 2020, new research shows.

More needs to be done to protect those at risk of unintentional and intentional swallowing of alcohol-based hand sanitizer, including children, people with dementia/confusion, and those with mental health issues, according to Georgia Richards, DPhil student, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford (England).

“If providers are supplying alcohol-based hand sanitizers in the community to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2, Ms. Richards said in an interview.

The study was published online Dec. 1 in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine.

European, U.S. poisoning rates soar

In the paper Ms. Richards described two deaths that occurred in hospitals in England.

In one case, a 30-year-old woman, detained in a psychiatric unit who received the antidepressant venlafaxine was found dead in her hospital bed with a container of hand-sanitizing gel beside her.

“The gel was readily accessible to patients on the ward from a communal dispenser, and patients were allowed to fill cups or other containers with it to keep in their rooms,” Ms. Richards reported.

A postmortem analysis found a high level of alcohol in her blood (214 mg of alcohol in 100 mL of blood). The medical cause of death was listed as “ingestion of alcohol and venlafaxine.” The coroner concluded that the combination of these substances suppressed the patient’s breathing, leading to her death.

The other case involved a 76-year-old man who unintentionally swallowed an unknown quantity of alcohol-based hand-sanitizing foam attached to the foot of his hospital bed.

The patient had a history of agitation and depression and was treated with antidepressants. He had become increasingly confused over the preceding 9 months, possibly because of vascular dementia.

His blood ethanol concentration was 463 mg/dL (100 mmol/L) initially and 354 mg/dL (77mmol/L) 10 hours later. He was admitted to the ICU, where he received lorazepam and haloperidol and treated with ventilation, with a plan to allow the alcohol to be naturally metabolized.

The patient developed complications and died 6 days later. The primary causes of death were bronchopneumonia and acute alcohol toxicity, secondary to acute delirium and coronary artery disease.

Since COVID-19 started, alcohol-based hand sanitizers are among the most sought-after commodities around the world. The volume of these products – now found in homes, hospitals, schools, workplaces, and elsewhere – “may be a cause for concern,” Ms. Richards wrote.

Yet, warnings about the toxicity and lethality of intentional or unintentional ingestion of these products have not been widely disseminated, she noted.

To reduce the risk of harm, Ms. Richards suggested educating the public and health care professionals, improving warning labels on products, and increasing the awareness and reporting of such exposures to public health authorities.

“While governments and public health authorities have successfully heightened our awareness of, and need for, better hand hygiene during the COVID-19 outbreak, they must also make the public aware of the potential harms and encourage the reporting of such harms to poisons information centers,” she noted.

Increases in alcohol-based hand sanitizer poisoning during the pandemic have also been reported in the United States.

The American Association of Poison Control Centers reports that data from the National Poison Data System show 32,892 hand sanitizer exposure cases reported to the 55 U.S. poison control centers from Jan. 1 to Nov. 15, 2020 – an increase of 73%, compared with the same time period during the previous year.

An increase in self-harm

Weighing in on this issue, Robert Bassett, DO, associate medical director of the Poison Control Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview that “cleaning agents and disinfectants have been around for eons and their potential for toxicity hasn’t changed.

“Now with COVID, and this hypervigilance when it comes to cleanliness, there is increased access and the exposure risk has gone up,” he said.

“One of the sad casualties of an overstressed health care system and a globally depressed environment is worsening behavioral health emergencies and, as part of that, the risk of self-harm goes up,” Dr. Bassett added.

“The consensus is that there has been an exacerbation of behavioral health emergencies and behavioral health needs since COVID started and hand sanitizers are readily accessible to someone who may be looking to self-harm,” he said.

This research had no specific funding. Ms. Richards is the editorial registrar of BMJ Evidence Based Medicine and is developing a website to track preventable deaths. Dr. Bassett disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Infant’s COVID-19–related myocardial injury reversed

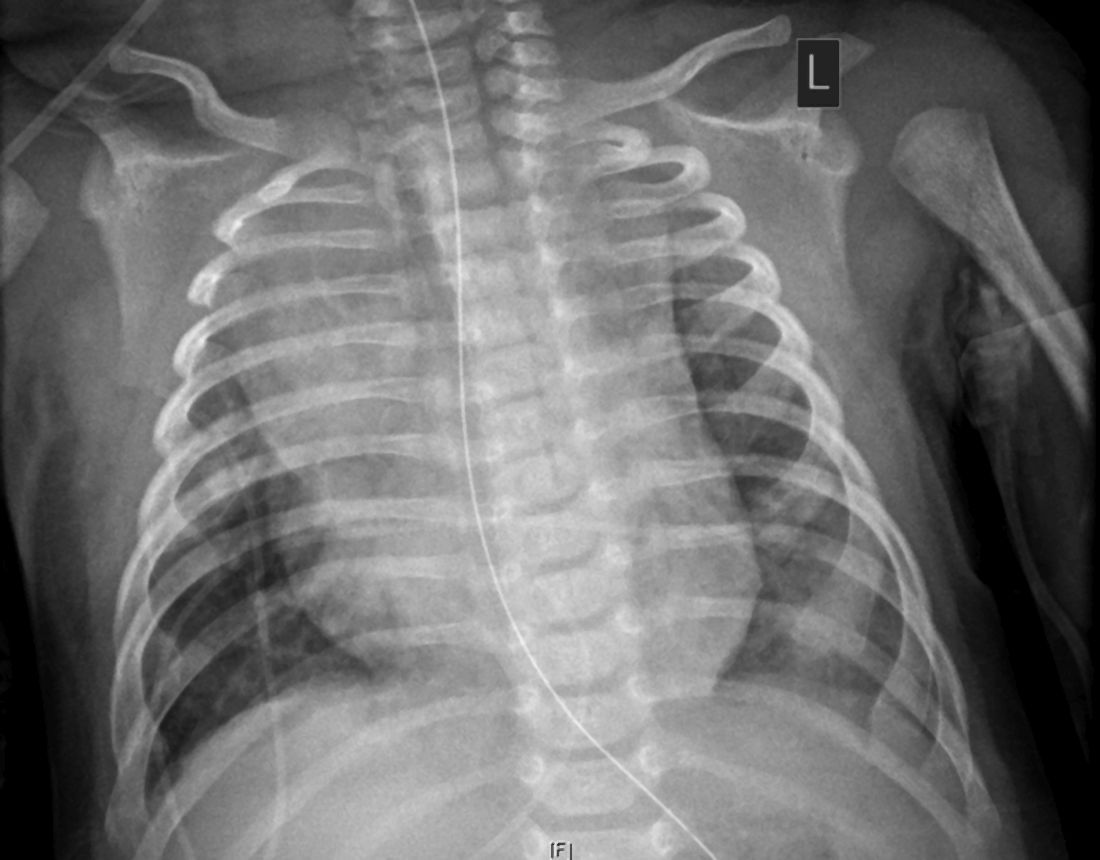

Reports of signs of heart failure in adults with COVID-19 have been rare – just four such cases have been published since the outbreak started in China – and now a team of pediatric cardiologists in New York have reported a case of acute but reversible myocardial injury in an infant with COVID-19.

and right upper lobe atelectasis.

The 2-month-old infant went home after more than 2 weeks in the hospital with no apparent lingering cardiac effects of the illness and not needing any oral heart failure medications, Madhu Sharma, MD, of the Children’s Hospital and Montefiore in New York and colleagues reported in JACC Case Reports. With close follow-up, the child’s left ventricle size and systolic function have remained normal and mitral regurgitation resolved. The case report didn’t mention the infant’s gender.

But before the straightforward postdischarge course emerged, the infant was in a precarious state, and Dr. Sharma and her team were challenged to diagnose the underlying causes.

The child, who was born about 7 weeks premature, first came to the hospital having turned blue after choking on food. Nonrebreather mask ventilation was initiated in the ED, and an examination detected a holosystolic murmur. A test for COVID-19 was negative, but a later test was positive, and a chest x-ray exhibited cardiomegaly and signs of fluid and inflammation in the lungs.

An electrocardiogram detected sinus tachycardia, ST-segment depression and other anomalies in cardiac function. Further investigation with a transthoracic ECG showed severely depressed left ventricle systolic function with an ejection fraction of 30%, severe mitral regurgitation, and normal right ventricular systolic function.

Treatment included remdesivir and intravenous antibiotics. Through the hospital course, the patient was extubated to noninvasive ventilation, reintubated, put on intravenous steroid (methylprednisolone) and low-molecular-weight heparin, extubated, and tested throughout for cardiac function.

By day 14, left ventricle size and function normalized, and while the mitral regurgitation remained severe, it improved later without HF therapies. Left ventricle ejection fraction had recovered to 60%, and key cardiac biomarkers had normalized. On day 16, milrinone was discontinued, and the care team determined the patient no longer needed oral heart failure therapies.

“Most children with COVID-19 are either asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, but our case shows the potential for reversible myocardial injury in infants with COVID-19,” said Dr. Sharma. “Testing for COVID-19 in children presenting with signs and symptoms of heart failure is very important as we learn more about the impact of this virus.”

Dr. Sharma and coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Sharma M et al. JACC Case Rep. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.031.

Reports of signs of heart failure in adults with COVID-19 have been rare – just four such cases have been published since the outbreak started in China – and now a team of pediatric cardiologists in New York have reported a case of acute but reversible myocardial injury in an infant with COVID-19.

and right upper lobe atelectasis.

The 2-month-old infant went home after more than 2 weeks in the hospital with no apparent lingering cardiac effects of the illness and not needing any oral heart failure medications, Madhu Sharma, MD, of the Children’s Hospital and Montefiore in New York and colleagues reported in JACC Case Reports. With close follow-up, the child’s left ventricle size and systolic function have remained normal and mitral regurgitation resolved. The case report didn’t mention the infant’s gender.

But before the straightforward postdischarge course emerged, the infant was in a precarious state, and Dr. Sharma and her team were challenged to diagnose the underlying causes.

The child, who was born about 7 weeks premature, first came to the hospital having turned blue after choking on food. Nonrebreather mask ventilation was initiated in the ED, and an examination detected a holosystolic murmur. A test for COVID-19 was negative, but a later test was positive, and a chest x-ray exhibited cardiomegaly and signs of fluid and inflammation in the lungs.

An electrocardiogram detected sinus tachycardia, ST-segment depression and other anomalies in cardiac function. Further investigation with a transthoracic ECG showed severely depressed left ventricle systolic function with an ejection fraction of 30%, severe mitral regurgitation, and normal right ventricular systolic function.

Treatment included remdesivir and intravenous antibiotics. Through the hospital course, the patient was extubated to noninvasive ventilation, reintubated, put on intravenous steroid (methylprednisolone) and low-molecular-weight heparin, extubated, and tested throughout for cardiac function.

By day 14, left ventricle size and function normalized, and while the mitral regurgitation remained severe, it improved later without HF therapies. Left ventricle ejection fraction had recovered to 60%, and key cardiac biomarkers had normalized. On day 16, milrinone was discontinued, and the care team determined the patient no longer needed oral heart failure therapies.

“Most children with COVID-19 are either asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, but our case shows the potential for reversible myocardial injury in infants with COVID-19,” said Dr. Sharma. “Testing for COVID-19 in children presenting with signs and symptoms of heart failure is very important as we learn more about the impact of this virus.”

Dr. Sharma and coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Sharma M et al. JACC Case Rep. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.031.

Reports of signs of heart failure in adults with COVID-19 have been rare – just four such cases have been published since the outbreak started in China – and now a team of pediatric cardiologists in New York have reported a case of acute but reversible myocardial injury in an infant with COVID-19.

and right upper lobe atelectasis.

The 2-month-old infant went home after more than 2 weeks in the hospital with no apparent lingering cardiac effects of the illness and not needing any oral heart failure medications, Madhu Sharma, MD, of the Children’s Hospital and Montefiore in New York and colleagues reported in JACC Case Reports. With close follow-up, the child’s left ventricle size and systolic function have remained normal and mitral regurgitation resolved. The case report didn’t mention the infant’s gender.

But before the straightforward postdischarge course emerged, the infant was in a precarious state, and Dr. Sharma and her team were challenged to diagnose the underlying causes.

The child, who was born about 7 weeks premature, first came to the hospital having turned blue after choking on food. Nonrebreather mask ventilation was initiated in the ED, and an examination detected a holosystolic murmur. A test for COVID-19 was negative, but a later test was positive, and a chest x-ray exhibited cardiomegaly and signs of fluid and inflammation in the lungs.

An electrocardiogram detected sinus tachycardia, ST-segment depression and other anomalies in cardiac function. Further investigation with a transthoracic ECG showed severely depressed left ventricle systolic function with an ejection fraction of 30%, severe mitral regurgitation, and normal right ventricular systolic function.

Treatment included remdesivir and intravenous antibiotics. Through the hospital course, the patient was extubated to noninvasive ventilation, reintubated, put on intravenous steroid (methylprednisolone) and low-molecular-weight heparin, extubated, and tested throughout for cardiac function.

By day 14, left ventricle size and function normalized, and while the mitral regurgitation remained severe, it improved later without HF therapies. Left ventricle ejection fraction had recovered to 60%, and key cardiac biomarkers had normalized. On day 16, milrinone was discontinued, and the care team determined the patient no longer needed oral heart failure therapies.

“Most children with COVID-19 are either asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, but our case shows the potential for reversible myocardial injury in infants with COVID-19,” said Dr. Sharma. “Testing for COVID-19 in children presenting with signs and symptoms of heart failure is very important as we learn more about the impact of this virus.”

Dr. Sharma and coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Sharma M et al. JACC Case Rep. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.031.

FROM JACC CASE REPORTS

Key clinical point: Children presenting with COVID-19 should be tested for heart failure.

Major finding: A 2-month-old infant with COVID-19 had acute but reversible myocardial injury.

Study details: Single case report.

Disclosures: Dr. Sharma, MD, has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Source: Sharma M et al. JACC Case Rep. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.031.

FDA clears first drug for rare genetic causes of severe obesity

The Food and Drug Administration has approved setmelanotide (Imcivree, Rhythm Pharmaceuticals) for weight management in adults and children as young as 6 years with obesity because of proopiomelanocortin (POMC), proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1 (PCSK1), or leptin receptor (LEPR) deficiency confirmed by genetic testing.

Individuals with these rare genetic causes of severe obesity have a normal weight at birth but develop persistent severe obesity within months because of insatiable hunger (hyperphagia).

Setmelanotide, a melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) agonist, is the first FDA-approved therapy for these disorders.

“Many patients and families who live with these diseases face an often-burdensome stigma associated with severe obesity. To manage this obesity and control disruptive food-seeking behavior, caregivers often lock cabinets and refrigerators and significantly limit social activities,” said Jennifer Miller, MD, a pediatric endocrinologist at University of Florida Health, Gainesville, in a press release issued by the company.

“This FDA approval marks an important turning point, providing a much needed therapy and supporting the use of genetic testing to identify and properly diagnose patients with these rare genetic diseases of obesity,” she noted.

David Meeker, MD, chair, president, and CEO of Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, added: “We are advancing a first-in-class, precision medicine that is designed to directly address the underlying cause of obesities driven by genetic deficits in the MC4R pathway.”

Setmelanotide was evaluated in two phase 3 clinical trials. In one trial, 80% of patients with obesity caused by POMC or PCSK1 deficiency achieved greater than 10% weight loss after 1 year of treatment.

In the other trial, 45.5% of patients with obesity caused by LEPR deficiency achieved greater than 10% weight loss with 1 year of treatment.

Results for the two trials were recently published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology and discussed at the ObesityWeek Interactive 2020 meeting.

Setmelanotide was generally well tolerated in both trials. The most common adverse events were injection-site reactions, skin hyperpigmentation, and nausea.

The drug label notes that disturbances in sexual arousal, depression, and suicidal ideation; skin pigmentation; and darkening of preexisting nevi may occur with setmelanotide treatment.

The drug label also notes a risk for serious adverse reactions because of benzyl alcohol preservative in neonates and low-birth-weight infants. Setmelanotide is not approved for use in neonates or infants.

The company expects the drug to be commercially available in the United States in the first quarter of 2021.

Setmelanotide for the treatment of obesity associated with rare genetic defects had FDA breakthrough therapy designation as well as orphan drug designation.

The company is also evaluating setmelanotide for reduction in hunger and body weight in a pivotal phase 3 trial in people living with Bardet-Biedl or Alström syndrome, and top-line data are due soon.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved setmelanotide (Imcivree, Rhythm Pharmaceuticals) for weight management in adults and children as young as 6 years with obesity because of proopiomelanocortin (POMC), proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1 (PCSK1), or leptin receptor (LEPR) deficiency confirmed by genetic testing.

Individuals with these rare genetic causes of severe obesity have a normal weight at birth but develop persistent severe obesity within months because of insatiable hunger (hyperphagia).

Setmelanotide, a melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) agonist, is the first FDA-approved therapy for these disorders.

“Many patients and families who live with these diseases face an often-burdensome stigma associated with severe obesity. To manage this obesity and control disruptive food-seeking behavior, caregivers often lock cabinets and refrigerators and significantly limit social activities,” said Jennifer Miller, MD, a pediatric endocrinologist at University of Florida Health, Gainesville, in a press release issued by the company.

“This FDA approval marks an important turning point, providing a much needed therapy and supporting the use of genetic testing to identify and properly diagnose patients with these rare genetic diseases of obesity,” she noted.

David Meeker, MD, chair, president, and CEO of Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, added: “We are advancing a first-in-class, precision medicine that is designed to directly address the underlying cause of obesities driven by genetic deficits in the MC4R pathway.”

Setmelanotide was evaluated in two phase 3 clinical trials. In one trial, 80% of patients with obesity caused by POMC or PCSK1 deficiency achieved greater than 10% weight loss after 1 year of treatment.

In the other trial, 45.5% of patients with obesity caused by LEPR deficiency achieved greater than 10% weight loss with 1 year of treatment.

Results for the two trials were recently published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology and discussed at the ObesityWeek Interactive 2020 meeting.

Setmelanotide was generally well tolerated in both trials. The most common adverse events were injection-site reactions, skin hyperpigmentation, and nausea.

The drug label notes that disturbances in sexual arousal, depression, and suicidal ideation; skin pigmentation; and darkening of preexisting nevi may occur with setmelanotide treatment.

The drug label also notes a risk for serious adverse reactions because of benzyl alcohol preservative in neonates and low-birth-weight infants. Setmelanotide is not approved for use in neonates or infants.

The company expects the drug to be commercially available in the United States in the first quarter of 2021.

Setmelanotide for the treatment of obesity associated with rare genetic defects had FDA breakthrough therapy designation as well as orphan drug designation.

The company is also evaluating setmelanotide for reduction in hunger and body weight in a pivotal phase 3 trial in people living with Bardet-Biedl or Alström syndrome, and top-line data are due soon.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved setmelanotide (Imcivree, Rhythm Pharmaceuticals) for weight management in adults and children as young as 6 years with obesity because of proopiomelanocortin (POMC), proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1 (PCSK1), or leptin receptor (LEPR) deficiency confirmed by genetic testing.

Individuals with these rare genetic causes of severe obesity have a normal weight at birth but develop persistent severe obesity within months because of insatiable hunger (hyperphagia).

Setmelanotide, a melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) agonist, is the first FDA-approved therapy for these disorders.

“Many patients and families who live with these diseases face an often-burdensome stigma associated with severe obesity. To manage this obesity and control disruptive food-seeking behavior, caregivers often lock cabinets and refrigerators and significantly limit social activities,” said Jennifer Miller, MD, a pediatric endocrinologist at University of Florida Health, Gainesville, in a press release issued by the company.

“This FDA approval marks an important turning point, providing a much needed therapy and supporting the use of genetic testing to identify and properly diagnose patients with these rare genetic diseases of obesity,” she noted.

David Meeker, MD, chair, president, and CEO of Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, added: “We are advancing a first-in-class, precision medicine that is designed to directly address the underlying cause of obesities driven by genetic deficits in the MC4R pathway.”

Setmelanotide was evaluated in two phase 3 clinical trials. In one trial, 80% of patients with obesity caused by POMC or PCSK1 deficiency achieved greater than 10% weight loss after 1 year of treatment.

In the other trial, 45.5% of patients with obesity caused by LEPR deficiency achieved greater than 10% weight loss with 1 year of treatment.

Results for the two trials were recently published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology and discussed at the ObesityWeek Interactive 2020 meeting.

Setmelanotide was generally well tolerated in both trials. The most common adverse events were injection-site reactions, skin hyperpigmentation, and nausea.

The drug label notes that disturbances in sexual arousal, depression, and suicidal ideation; skin pigmentation; and darkening of preexisting nevi may occur with setmelanotide treatment.

The drug label also notes a risk for serious adverse reactions because of benzyl alcohol preservative in neonates and low-birth-weight infants. Setmelanotide is not approved for use in neonates or infants.

The company expects the drug to be commercially available in the United States in the first quarter of 2021.

Setmelanotide for the treatment of obesity associated with rare genetic defects had FDA breakthrough therapy designation as well as orphan drug designation.

The company is also evaluating setmelanotide for reduction in hunger and body weight in a pivotal phase 3 trial in people living with Bardet-Biedl or Alström syndrome, and top-line data are due soon.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Understanding and addressing suicide risk in LGBTQ+ youth

Even as dozens of state legislature bills attempt to limit the rights of sexual-diverse and gender-diverse youth, researchers are learning more and more that can help pediatricians better support this population in their practices, according to David Inwards-Breland, MD, MPH, a professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego.

Dr. Inwards-Breland highlighted two key studies in recent years during the LGBTQ+ section at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, held virtually in 2020.

High suicide rates among sexual minority youth

Past research has found that adolescents who identify as sexual minorities have nearly five times the rate of suicide attempts, compared with their heterosexual peers, Dr. Inwards-Breland said as he introduced a recent study on disparities in adolescent suicide.

“This may be from a disproportionate burden of poor mental health that has been linked to stigma,” he said, adding that an estimated 125 state bills have been introduced in the United States that would restrict the rights of sexual minorities.

The study, published in Pediatrics in March 2020, compiled data from 110,243 adolescents in six states on sexual orientation identity; 25,994 adolescents in four states on same-sex sexual contact and sexual assault; and 20,655 adolescents in three states on sexual orientation identity, the sex of sexual contacts, and sexual assault.

The authors found that heterosexual identity dropped from 93% to 86% between 2009 and 2017, but sexual minority youth accounted for an increasing share of suicide attempts over the same period. A quarter of adolescents who attempted suicide in 2009 were sexual minorities, which increased to 36% in 2017. Similarly, among sexually active teens who attempted suicide, the proportion of those who had same-sex contact nearly doubled, from 16% to 30%.

The good news, Dr. Inwards-Breland said, was that overall suicide attempts declined among sexual minorities, but they remain three times as likely to attempt suicide, compared with their heterosexual counterparts.

“As the number of adolescents increase in our country, there will be increasing numbers of adolescents identifying as sexual minorities or who have had same-sex sexual contact,” Dr. Inwards-Breland said. “Therefore, providing confidential services is even more important to allow youth to feel comfortable with their health care provider.” He also emphasized the importance of consistent universal depression screening and advocacy to eliminate and prevent policies that harm these youth.

Using youths’ chosen names

Transgender and nonbinary youth – those who do not identify as male or female – have a higher risk of poor mental health and higher levels of suicidal ideation and behaviors, compared with their “cis” peers, those who identify with the gender they were assigned at birth, Dr. Inwards-Breland said. However, using the chosen, or assertive, name of transgender and nonbinary youth predicted fewer depressive symptoms and less suicidal ideation and behavior in a study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health in October 2018.

“Choosing a name is an important part of social transition of transgender individuals, yet they’re unable to use their name because of interpersonal or institutional barriers,” he said. In addition, using a name other than their legally given name can subject them to discrimination and victimization.

The study, drawing from a larger cohort of LGBTQ youth, involved 129 transgender and nonbinary adolescents, aged 15-21, of whom 74 had a chosen name. No other differences in personal characteristics were associated with depressive symptoms or suicidal ideation besides increased use of their assertive name in different life contexts.

An increase in one context where chosen name could be used predicted a 5.37-unit decrease in depressive symptoms, a 29% decrease in suicidal ideation, and a 56% decrease in suicidal behavior, the study found. All three outcomes were at their lowest levels when chosen names were used in all four contexts explored in the study.

“The chosen name affirms their gender identity,” Dr. Inwards-Breland said, but “the legal name change process is very onerous.” He highlighted the need for institutions to adjust regulations and information systems, for policies that promote the transition process, and for youths’ names to be affirmed in multiple contexts.

“We as pediatricians, specialists, and primary care doctors can support families as they adjust the transition process by helping them with assertive names and pronouns and giving them resources,” Dr. Inwards-Breland said. He also called for school policies and teacher/staff training that promote the use of assertive names and pronouns, and ensuring that the assertive name and pronouns are in the medical record and used by office staff and other medical professionals.

‘A light in the dark’ for LGBTQ+ youth

Clair Kronk of the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center attended the LGBTQ+ section at the AAP meeting because of concerns about she and her transgender siblings have been treated by the medical community.

“It has always been important to be ‘on the pulse’ of what is happening in the medical community, especially with new, more discriminatory policies being passed seemingly willy-nilly these days, both in the medical realm and outside of it,” Ms. Kronk said in an interview. “I was overjoyed to see how many people seemed to care so much about the transgender community and LGBTQIA+ people generally.”

As an ontologist and bioinformatician, she did not recall many big clinical takeaways for her particular work, but she appreciated how many areas the session covered, especially given the dearth of instruction about LGBTQ+ care in medical training.

“This session was a bit of a light in the dark given the state of LGBTQIA+ health care rights,” she said. “There is a lot at stake in the next year or so, and providers’ and LGBTQIA+ persons’ voices need to be heard right now more than ever.”

Sonia Khan, MD, a pediatrician and the medical director of the substance use disorder counseling program in the department of health and human services in Fremont, Calif., also attended the session and came away feeling invigorated.

“These data make me feel more optimistic than I have been in ages in terms of increasing the safety of young people being able to come out,” Dr. Khan said in the comments during the session. “These last 4 years felt so regressive. [It’s] good to get the big picture.”

The presenters and commentators had no disclosures.

Even as dozens of state legislature bills attempt to limit the rights of sexual-diverse and gender-diverse youth, researchers are learning more and more that can help pediatricians better support this population in their practices, according to David Inwards-Breland, MD, MPH, a professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego.

Dr. Inwards-Breland highlighted two key studies in recent years during the LGBTQ+ section at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, held virtually in 2020.

High suicide rates among sexual minority youth

Past research has found that adolescents who identify as sexual minorities have nearly five times the rate of suicide attempts, compared with their heterosexual peers, Dr. Inwards-Breland said as he introduced a recent study on disparities in adolescent suicide.

“This may be from a disproportionate burden of poor mental health that has been linked to stigma,” he said, adding that an estimated 125 state bills have been introduced in the United States that would restrict the rights of sexual minorities.

The study, published in Pediatrics in March 2020, compiled data from 110,243 adolescents in six states on sexual orientation identity; 25,994 adolescents in four states on same-sex sexual contact and sexual assault; and 20,655 adolescents in three states on sexual orientation identity, the sex of sexual contacts, and sexual assault.

The authors found that heterosexual identity dropped from 93% to 86% between 2009 and 2017, but sexual minority youth accounted for an increasing share of suicide attempts over the same period. A quarter of adolescents who attempted suicide in 2009 were sexual minorities, which increased to 36% in 2017. Similarly, among sexually active teens who attempted suicide, the proportion of those who had same-sex contact nearly doubled, from 16% to 30%.

The good news, Dr. Inwards-Breland said, was that overall suicide attempts declined among sexual minorities, but they remain three times as likely to attempt suicide, compared with their heterosexual counterparts.

“As the number of adolescents increase in our country, there will be increasing numbers of adolescents identifying as sexual minorities or who have had same-sex sexual contact,” Dr. Inwards-Breland said. “Therefore, providing confidential services is even more important to allow youth to feel comfortable with their health care provider.” He also emphasized the importance of consistent universal depression screening and advocacy to eliminate and prevent policies that harm these youth.

Using youths’ chosen names

Transgender and nonbinary youth – those who do not identify as male or female – have a higher risk of poor mental health and higher levels of suicidal ideation and behaviors, compared with their “cis” peers, those who identify with the gender they were assigned at birth, Dr. Inwards-Breland said. However, using the chosen, or assertive, name of transgender and nonbinary youth predicted fewer depressive symptoms and less suicidal ideation and behavior in a study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health in October 2018.

“Choosing a name is an important part of social transition of transgender individuals, yet they’re unable to use their name because of interpersonal or institutional barriers,” he said. In addition, using a name other than their legally given name can subject them to discrimination and victimization.

The study, drawing from a larger cohort of LGBTQ youth, involved 129 transgender and nonbinary adolescents, aged 15-21, of whom 74 had a chosen name. No other differences in personal characteristics were associated with depressive symptoms or suicidal ideation besides increased use of their assertive name in different life contexts.

An increase in one context where chosen name could be used predicted a 5.37-unit decrease in depressive symptoms, a 29% decrease in suicidal ideation, and a 56% decrease in suicidal behavior, the study found. All three outcomes were at their lowest levels when chosen names were used in all four contexts explored in the study.

“The chosen name affirms their gender identity,” Dr. Inwards-Breland said, but “the legal name change process is very onerous.” He highlighted the need for institutions to adjust regulations and information systems, for policies that promote the transition process, and for youths’ names to be affirmed in multiple contexts.

“We as pediatricians, specialists, and primary care doctors can support families as they adjust the transition process by helping them with assertive names and pronouns and giving them resources,” Dr. Inwards-Breland said. He also called for school policies and teacher/staff training that promote the use of assertive names and pronouns, and ensuring that the assertive name and pronouns are in the medical record and used by office staff and other medical professionals.

‘A light in the dark’ for LGBTQ+ youth

Clair Kronk of the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center attended the LGBTQ+ section at the AAP meeting because of concerns about she and her transgender siblings have been treated by the medical community.

“It has always been important to be ‘on the pulse’ of what is happening in the medical community, especially with new, more discriminatory policies being passed seemingly willy-nilly these days, both in the medical realm and outside of it,” Ms. Kronk said in an interview. “I was overjoyed to see how many people seemed to care so much about the transgender community and LGBTQIA+ people generally.”

As an ontologist and bioinformatician, she did not recall many big clinical takeaways for her particular work, but she appreciated how many areas the session covered, especially given the dearth of instruction about LGBTQ+ care in medical training.

“This session was a bit of a light in the dark given the state of LGBTQIA+ health care rights,” she said. “There is a lot at stake in the next year or so, and providers’ and LGBTQIA+ persons’ voices need to be heard right now more than ever.”

Sonia Khan, MD, a pediatrician and the medical director of the substance use disorder counseling program in the department of health and human services in Fremont, Calif., also attended the session and came away feeling invigorated.

“These data make me feel more optimistic than I have been in ages in terms of increasing the safety of young people being able to come out,” Dr. Khan said in the comments during the session. “These last 4 years felt so regressive. [It’s] good to get the big picture.”

The presenters and commentators had no disclosures.

Even as dozens of state legislature bills attempt to limit the rights of sexual-diverse and gender-diverse youth, researchers are learning more and more that can help pediatricians better support this population in their practices, according to David Inwards-Breland, MD, MPH, a professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego.

Dr. Inwards-Breland highlighted two key studies in recent years during the LGBTQ+ section at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, held virtually in 2020.

High suicide rates among sexual minority youth

Past research has found that adolescents who identify as sexual minorities have nearly five times the rate of suicide attempts, compared with their heterosexual peers, Dr. Inwards-Breland said as he introduced a recent study on disparities in adolescent suicide.

“This may be from a disproportionate burden of poor mental health that has been linked to stigma,” he said, adding that an estimated 125 state bills have been introduced in the United States that would restrict the rights of sexual minorities.

The study, published in Pediatrics in March 2020, compiled data from 110,243 adolescents in six states on sexual orientation identity; 25,994 adolescents in four states on same-sex sexual contact and sexual assault; and 20,655 adolescents in three states on sexual orientation identity, the sex of sexual contacts, and sexual assault.

The authors found that heterosexual identity dropped from 93% to 86% between 2009 and 2017, but sexual minority youth accounted for an increasing share of suicide attempts over the same period. A quarter of adolescents who attempted suicide in 2009 were sexual minorities, which increased to 36% in 2017. Similarly, among sexually active teens who attempted suicide, the proportion of those who had same-sex contact nearly doubled, from 16% to 30%.

The good news, Dr. Inwards-Breland said, was that overall suicide attempts declined among sexual minorities, but they remain three times as likely to attempt suicide, compared with their heterosexual counterparts.

“As the number of adolescents increase in our country, there will be increasing numbers of adolescents identifying as sexual minorities or who have had same-sex sexual contact,” Dr. Inwards-Breland said. “Therefore, providing confidential services is even more important to allow youth to feel comfortable with their health care provider.” He also emphasized the importance of consistent universal depression screening and advocacy to eliminate and prevent policies that harm these youth.

Using youths’ chosen names

Transgender and nonbinary youth – those who do not identify as male or female – have a higher risk of poor mental health and higher levels of suicidal ideation and behaviors, compared with their “cis” peers, those who identify with the gender they were assigned at birth, Dr. Inwards-Breland said. However, using the chosen, or assertive, name of transgender and nonbinary youth predicted fewer depressive symptoms and less suicidal ideation and behavior in a study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health in October 2018.

“Choosing a name is an important part of social transition of transgender individuals, yet they’re unable to use their name because of interpersonal or institutional barriers,” he said. In addition, using a name other than their legally given name can subject them to discrimination and victimization.

The study, drawing from a larger cohort of LGBTQ youth, involved 129 transgender and nonbinary adolescents, aged 15-21, of whom 74 had a chosen name. No other differences in personal characteristics were associated with depressive symptoms or suicidal ideation besides increased use of their assertive name in different life contexts.

An increase in one context where chosen name could be used predicted a 5.37-unit decrease in depressive symptoms, a 29% decrease in suicidal ideation, and a 56% decrease in suicidal behavior, the study found. All three outcomes were at their lowest levels when chosen names were used in all four contexts explored in the study.

“The chosen name affirms their gender identity,” Dr. Inwards-Breland said, but “the legal name change process is very onerous.” He highlighted the need for institutions to adjust regulations and information systems, for policies that promote the transition process, and for youths’ names to be affirmed in multiple contexts.

“We as pediatricians, specialists, and primary care doctors can support families as they adjust the transition process by helping them with assertive names and pronouns and giving them resources,” Dr. Inwards-Breland said. He also called for school policies and teacher/staff training that promote the use of assertive names and pronouns, and ensuring that the assertive name and pronouns are in the medical record and used by office staff and other medical professionals.

‘A light in the dark’ for LGBTQ+ youth

Clair Kronk of the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center attended the LGBTQ+ section at the AAP meeting because of concerns about she and her transgender siblings have been treated by the medical community.

“It has always been important to be ‘on the pulse’ of what is happening in the medical community, especially with new, more discriminatory policies being passed seemingly willy-nilly these days, both in the medical realm and outside of it,” Ms. Kronk said in an interview. “I was overjoyed to see how many people seemed to care so much about the transgender community and LGBTQIA+ people generally.”

As an ontologist and bioinformatician, she did not recall many big clinical takeaways for her particular work, but she appreciated how many areas the session covered, especially given the dearth of instruction about LGBTQ+ care in medical training.

“This session was a bit of a light in the dark given the state of LGBTQIA+ health care rights,” she said. “There is a lot at stake in the next year or so, and providers’ and LGBTQIA+ persons’ voices need to be heard right now more than ever.”

Sonia Khan, MD, a pediatrician and the medical director of the substance use disorder counseling program in the department of health and human services in Fremont, Calif., also attended the session and came away feeling invigorated.

“These data make me feel more optimistic than I have been in ages in terms of increasing the safety of young people being able to come out,” Dr. Khan said in the comments during the session. “These last 4 years felt so regressive. [It’s] good to get the big picture.”

The presenters and commentators had no disclosures.

FROM AAP 2020

Watch for cognitive traps that lead diagnostics astray

While it’s important not to think immediately of zebras when hearing hoofbeats, it’s just as important not to assume it’s always a horse. The delicate balance between not jumping to the seemingly obvious diagnosis without overanalyzing and overtesting is familiar to all physicians, and

“When these errors are made, it’s not because physicians lack knowledge, but they go down a wrong path in their thinking process,” Richard Scarfone, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine physician at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told attendees at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, held virtually this year. “An important point to be made here is that how physicians think seems to be much more important than what physicians know.”

Dr. Scarfone and Joshua Nagler, MD, MHPEd, director, pediatric emergency medicine fellowship program at Children’s Hospital Boston, presented a session on the cognitive biases that can trip up clinicians when making diagnoses and how to avoid them. Research shows that the rate of diagnostic error is approximately 15%. Although those findings come from studies in adults, the rates are likely similar in pediatrics, Dr. Scarfone said.

A wide range of clinical factors contribute to diagnostic errors: limited information, vague or undifferentiated symptoms, incomplete history, multiple transitions of care, diagnostic uncertainty, daily decision density, and reliance on pattern recognition, among others. Personal contributing factors can play a role as well, such as atypical work hours, fatigue, one’s emotional or affective state, a high cognitive load, and others. On top of all that, medical decision-making can be really complex on its own, Dr. Scarfone said. He compared differential diagnosis with a tree where a single leaf is the correct diagnosis.

System 1 thinking: Pros and cons

Dr. Scarfone and Dr. Nagler explained system 1 and system 2 thinking, two different ways of thinking that can influence decision-making that Daniel Kahneman explained in his book “Thinking, Fast and Slow.” System 1 refers to the snap judgments that rely on heuristics while system 2 refers to a more analytic, slower process.

Neither system 1 nor 2 is inherently “right or wrong,” Dr. Scarfone said. “The diagnostic sweet spot is to try to apply the correct system to the correct patient.”

Heuristics are the mental shortcuts people use to make decisions based on past experience. They exist because they’re useful, enabling people to focus only on what they need to accomplish everyday tasks, such as driving or brushing teeth. But heuristics can also lead to predictable cognitive errors.

“The good news about heuristics and system 1 thinking is that it’s efficient and simple, and we desire that in a busy practice or ED setting, but we should recognize that the trade-off is that it may be at the expense of accuracy,” Dr. Scarfone said.

The advantage to system 1 thinking is easy, simple, rapid, and efficient decision-making that rejects ambiguity. It’s also usually accurate, which rewards the approach, and accuracy increases with time based on memory, experience, and pattern recognition. Doctors develop “illness scripts” that help in identifying diagnoses.

“Illness scripts are common patterns of clinical presentations that usually lead us to a diagnostic possibility,” Dr. Scarfone said. “A classic illness script might be a 4-week-old firstborn male with forceful vomiting, and immediately your mind may go to pyloric stenosis as a likely diagnosis.” But the patient may have a different diagnosis than the initial impression your system 1 thinking leads you to believe.

“Generally, the more experience a clinician has, the more accurate they’ll be in using system 1,” he said. “Seasoned physicians are much more likely to employ system 1 than a newer physician or trainee,” which is why heuristics shouldn’t be thought of as hindrances. Dr. Scarfone quoted Kevin Eva in a 2005 review on clinical reasoning: “Successful heuristics should be embraced rather than overcome.”

A drawback to system 1 thinking, however, is thinking that “what you see is all there is,” which can lead to cognitive errors. Feeling wrong feels the same as feeling right, so you may not realize when you’re off target and therefore neglect to consider alternatives.

“When we learn a little about our patient’s complaint, it’s easier to fit everything into a coherent explanation,” Dr. Scarfone said, but “don’t ask, don’t tell doesn’t work in medicine.”

Another challenge with system 1 thinking is that pattern recognition can be unreliable because it’s dependent on context. For example, consider the difference in assessing a patient’s sore throat in a primary care office versus a resuscitation bay. “Clearly our consideration of what may be going on with the patient and what the diagnosis may be is likely to vary in those two settings,” he said.

System 2 thinking: Of zebras and horses

System 2 is the analytic thinking that involves pondering and seek out the optimal answer rather than the “good-enough” answer.

“The good news about system 2 is that it really can monitor system 1,” said Dr. Nagler, who has a master’s degree in health professions education. “If you spend the time to do analytic reasoning, you can actually mitigate some of those errors that may occur from intuitive judgments from system 1 thinking. System 2 spends the time to say ‘let’s make sure we’re doing this right.’ ” In multiple-choice tests, for example, people are twice as likely to change a wrong answer to a right one than a right one to a wrong one.

System 2 thinking allows for the reasoning to assess questions in the gray zone. It’s vigilant, it’s reliable, it’s effective, it acknowledges uncertainty and doubt, it can be safe in terms of providing care, and it has high scientific rigor. But it also has disadvantages, starting with the fact that it’s slower and more time-consuming. System 2 thinking is resource intensive, requiring a higher cognitive demand and more time and effort.

“Sometimes the quick judgment is the best judgment,” Dr. Nagler said. System 2 thinking also is sometimes unnecessary and counter to value-based care. “If you start to think about all the possibilities of what a presentation may be, all of a sudden you might find yourself wanting to do all kinds of tests and all kinds of referrals and other things, which is not necessarily value-based care.” When system 2 thinking goes astray, it makes us think everything we see is a zebra rather than a horse.

Sonia Khan, MD, a pediatrician in Fremont, Calif., found this session particularly worthwhile.

“It really tries to explain the difference between leaping to conclusions and learning how to hold your horses and do a bit more, to double check that you’re not locking everything into a horse stall and missing a zebra, and avoiding go too far with system 2 and thinking that everything’s a zebra,” Dr. Khan said. “It’s a difficult talk to have because you’re asking pediatricians to look in the mirror and own up, to learn to step back and reconsider the picture, and consider the biases that may come into your decision-making; then learn to extrude them, and rethink the case to be sure your knee-jerk diagnostic response is correct.”

Types of cognitive errors

The presenters listed some of the most common cognitive errors, although their list is far from exhaustive.

- Affective error. Avoiding unpleasant but necessary tests or examinations because of sympathy for the patient, such as avoiding blood work to spare a needle stick in a cancer patient with abdominal pain because the mother is convinced it’s constipation from opioids. This is similar to omission bias, which places excessive concern on avoiding a therapy’s adverse effects when the therapy could be highly effective.

- Anchoring. Clinging to an initial impression or salient features of initial presentation, even as conflicting and contradictory data accumulate, such as diagnosing a patient with fever and vomiting with gastroenteritis even when the patient has an oxygen saturation of 94% and tachypnea.

- Attribution errors. Negative stereotypes lead clinicians to ignore or minimize the possibility of serious disease, such as evaluating a confused teen covered in piercings and tattoos for drug ingestion when the actual diagnosis is new-onset diabetic ketoacidosis.

- Availability bias. Overestimating or underestimating the probability of disease because of recent experience, what was most recently “available” to your brain cognitively, such as getting head imaging on several vomiting patients in a row because you recently had one with a new brain tumor diagnosis.

- Bandwagon effect. Accepting the group’s opinion without assessing a clinical situation yourself, such as sending home a crying, vomiting infant with a presumed viral infection only to see the infant return later with intussusception.

- Base rate neglect. Ignoring the true prevalence of disease by either inflating it or reducing it, such as searching for cardiac disease in all pediatric patients with chest pain.

- Commission. A tendency toward action with the belief that harm may only be prevented by action, such as ordering every possible test for a patient with fever to “rule everything out.”

- Confirmation bias. Subconscious cherry-picking: A tendency to look for, notice, and remember information that fits with preexisting expectations while disregarding information that contradicts those expectations.

- Diagnostic momentum. Clinging to that initial diagnostic impression that may have been generated by others, which is particularly common during transitions of care.

- Premature closure. Narrowing down to a diagnosis without thinking about other diagnoses or asking enough questions about other symptoms that may have opened up other diagnostic possibilities.

- Representation bias. Making a decision in the absence of appropriate context by incorrectly comparing two situations because of a perceived similarity between them, or on the flip side, evaluating a situation without comparing it with other situations.

- Overconfidence. Making a decision without enough supportive evidence yet feeling confident about the diagnosis.

- Search satisfying. Stopping the search for additional diagnoses after the anticipated diagnosis has been made.

Cognitive pills for cognitive ills

Being aware of the pitfalls of cognitive errors is the first step to avoiding and mitigating them. “It really does start with preparation and awareness,” Dr. Scarfone said before presenting strategies to build a cognitive “firewall” that can help physicians practice reflectively instead of reflexively.

First, be aware of your cognitive style. People usually have the same thinking pattern in everyday life as in the clinical setting, so determine whether you’re more of a system 1 or system 2 thinker. System 1 thinkers need to watch out for framing (relying too heavily on context), premature closure, diagnostic momentum, anchoring, and confirmation bias. System 2 thinkers need to watch out for commission, availability bias, and base rate neglect.

“Neither system is inherently right or wrong,” Dr. Scarfone reiterated. “In the perfect world, you may use system 1 to form an initial impression, but then system 2 should really act as a check and balance system to cause you to reflect on your initial diagnostic impressions.”

Additional strategies include being a good history taker and performing a meticulous physical exam: be a good listener, clarify unclear aspects of the history, and identify and address the main concern.

“Remember children and families have a story to tell, and if we listen carefully enough, the diagnostic clues are there,” Dr. Scarfone said. “Sometimes they may be quite subtle.” He recommended doctors perform each part of the physical exam as if expecting an abnormality.

Another strategy is using meta-cognition, a forced analysis of the thinking that led to a diagnosis. It involves asking: “If I had to explain my medical decision-making to others, would this make inherent sense?” Dr. Scarfone said. “If you’re testing, try to avoid anchoring and confirmation biases.”

Finally, take a diagnostic time-out with a checklist that asks these questions:

- Does my presumptive diagnosis make sense?

- What evidence supports or refutes it?

- Did I arrive at it via cognitive biases?

- Are there other diagnostic possibilities that should be considered?

One way to do this is creating a table listing the complaint/finding, diagnostic possibilities with system 1 thinking, diagnostic possibilities with system 2 thinking, and then going beyond system 2 – the potential zebras – when even system 2 diagnostic possibilities don’t account for what the patient is saying or what the exam shows.

Enough overlap exists between these cognitive biases and the intrinsic bias related to individual characteristics that Dr. Khan appreciated the talk on another level as well.