User login

Rheumatic diseases and assisted reproductive technology: Things to consider

The field of “reproductive rheumatology” has received growing attention in recent years as we learn more about how autoimmune rheumatic diseases and their treatment affect women of reproductive age. In 2020, the American College of Rheumatology published a comprehensive guideline that includes recommendations and supporting evidence for managing issues related to reproductive health in patients with rheumatic diseases and has since launched an ongoing Reproductive Health Initiative, with the goal of translating established guidelines into practice through various education and awareness campaigns. One area addressed by the guideline that comes up commonly in practice but receives less attention and research is the use of assisted reproductive technology (ART) in patients with rheumatic diseases.

Literature is conflicting regarding whether patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases are inherently at increased risk for infertility, defined as failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected intercourse, or subfertility, defined as a delay in conception. Regardless, several factors indirectly contribute to a disproportionate risk for infertility or subfertility in this patient population, including active inflammatory disease, reduced ovarian reserve, and medications.

Patients with subfertility or infertility who desire pregnancy may pursue ovulation induction with timed intercourse or intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilization (IVF)/intracytoplasmic sperm injection with either embryo transfer, or gestational surrogacy. Those who require treatment with cyclophosphamide or who plan to defer pregnancy for whatever reason can opt for oocyte cryopreservation (colloquially known as “egg freezing”). For IVF and oocyte cryopreservation, controlled ovarian stimulation is typically the first step (except in unstimulated, or “natural cycle,” IVF).

Various protocols are used for ovarian stimulation and ovulation induction, the nuances of which are beyond the scope of this article. In general, ovarian stimulation involves gonadotropin therapy (follicle-stimulating hormone and/or human menopausal gonadotropin) administered via scheduled subcutaneous injections to stimulate follicular growth, as well as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists or antagonists to suppress luteinizing hormone, preventing ovulation. Adjunctive oral therapy (clomiphene citrate or letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor) may be used as well. The patient has frequent lab monitoring of hormone levels and transvaginal ultrasounds to measure follicle number and size and, when the timing is right, receives an “ovulation trigger” – either human chorionic gonadotropin or GnRH agonist, depending on the protocol. At this point, transvaginal ultrasound–guided egg retrieval is done under sedation. Recovered oocytes are then either frozen for later use or fertilized in the lab for embryo transfer. Lastly, exogenous hormones are often used: estrogen to support frozen embryo transfers and progesterone for so-called luteal phase support.

ART is not contraindicated in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases, but there may be additional factors to consider, particularly for those with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), and antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) without clinical APS.

Ovarian stimulation elevates estrogen levels to varying degrees depending on the patient and the medications used. In all cases, though, peak levels are significantly lower than levels reached during pregnancy. It is well established that elevated estrogen – whether from hormone therapies or pregnancy – significantly increases thrombotic risk, even in healthy people. High-risk patients should receive low-molecular-weight heparin – a prophylactic dose for patients with either positive aPL without clinical APS (including those with SLE) or with obstetric APS, and a therapeutic dose for those with thrombotic APS – during ART procedures.

In patients with SLE, another concern is that increased estrogen will cause disease flare. One case series published in 2017 reported 37 patients with SLE and/or APS who underwent 97 IVF cycles, of which 8% were complicated by flare or thrombotic events. Notably, half of these complications occurred in patients who stopped prescribed therapies (immunomodulatory therapy in two patients with SLE, anticoagulation in two patients with APS) after failure to conceive. In a separate study from 2000 including 19 patients with SLE, APS, or high-titer aPL who underwent 68 IVF cycles, 19% of cycles in patients with SLE were complicated by flare, and no thrombotic events occurred in the cohort. The authors concluded that ovulation induction does not exacerbate SLE or APS. In these studies, the overall pregnancy rates were felt to be consistent with those achieved by the general population through IVF. Although obstetric complications, such as preeclampsia and preterm delivery, were reported in about half of the pregnancies described, these are known to occur more frequently in those with SLE and APS, especially when active disease or other risk factors are present. There are no large-scale, controlled studies evaluating ART outcomes in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases to date.

Finally, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) is an increasingly rare but severe complication of ovarian stimulation. OHSS is characterized by capillary leak, fluid overload, and cytokine release syndrome and can lead to thromboembolic events. Comorbidities like hypertension and renal failure, which can go along with autoimmune rheumatic diseases, are risk factors for OHSS. The use of human chorionic gonadotropin to trigger ovulation is also associated with an increased risk for OHSS, so a GnRH agonist trigger may be preferable.

The ACR guideline recommends that individuals with any of these underlying conditions undergo ART only in expert centers. The ovarian stimulation protocol needs to be tailored to the individual patient to minimize risk and optimize outcomes. The overall goal when managing patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases during ART is to establish and maintain disease control with pregnancy-compatible medications (when pregnancy is the goal). With adequate planning, appropriate treatment, and collaboration between obstetricians and rheumatologists, individuals with autoimmune rheumatic diseases can safely pursue ART and go on to have successful pregnancies.

Dr. Siegel is a 2022-2023 UCB Women’s Health rheumatology fellow in the rheumatology reproductive health program of the Barbara Volcker Center for Women and Rheumatic Diseases at Hospital for Special Surgery/Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. Her clinical and research focus is on reproductive health issues in individuals with rheumatic disease. Dr. Chan is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College and an attending physician at Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a columnist for a monthly rheumatology publication, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice. Follow Dr Chan on Twitter. Dr. Siegel and Dr. Chan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article – an editorial collaboration between Medscape and the Hospital for Special Surgery – first appeared on Medscape.com.

The field of “reproductive rheumatology” has received growing attention in recent years as we learn more about how autoimmune rheumatic diseases and their treatment affect women of reproductive age. In 2020, the American College of Rheumatology published a comprehensive guideline that includes recommendations and supporting evidence for managing issues related to reproductive health in patients with rheumatic diseases and has since launched an ongoing Reproductive Health Initiative, with the goal of translating established guidelines into practice through various education and awareness campaigns. One area addressed by the guideline that comes up commonly in practice but receives less attention and research is the use of assisted reproductive technology (ART) in patients with rheumatic diseases.

Literature is conflicting regarding whether patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases are inherently at increased risk for infertility, defined as failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected intercourse, or subfertility, defined as a delay in conception. Regardless, several factors indirectly contribute to a disproportionate risk for infertility or subfertility in this patient population, including active inflammatory disease, reduced ovarian reserve, and medications.

Patients with subfertility or infertility who desire pregnancy may pursue ovulation induction with timed intercourse or intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilization (IVF)/intracytoplasmic sperm injection with either embryo transfer, or gestational surrogacy. Those who require treatment with cyclophosphamide or who plan to defer pregnancy for whatever reason can opt for oocyte cryopreservation (colloquially known as “egg freezing”). For IVF and oocyte cryopreservation, controlled ovarian stimulation is typically the first step (except in unstimulated, or “natural cycle,” IVF).

Various protocols are used for ovarian stimulation and ovulation induction, the nuances of which are beyond the scope of this article. In general, ovarian stimulation involves gonadotropin therapy (follicle-stimulating hormone and/or human menopausal gonadotropin) administered via scheduled subcutaneous injections to stimulate follicular growth, as well as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists or antagonists to suppress luteinizing hormone, preventing ovulation. Adjunctive oral therapy (clomiphene citrate or letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor) may be used as well. The patient has frequent lab monitoring of hormone levels and transvaginal ultrasounds to measure follicle number and size and, when the timing is right, receives an “ovulation trigger” – either human chorionic gonadotropin or GnRH agonist, depending on the protocol. At this point, transvaginal ultrasound–guided egg retrieval is done under sedation. Recovered oocytes are then either frozen for later use or fertilized in the lab for embryo transfer. Lastly, exogenous hormones are often used: estrogen to support frozen embryo transfers and progesterone for so-called luteal phase support.

ART is not contraindicated in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases, but there may be additional factors to consider, particularly for those with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), and antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) without clinical APS.

Ovarian stimulation elevates estrogen levels to varying degrees depending on the patient and the medications used. In all cases, though, peak levels are significantly lower than levels reached during pregnancy. It is well established that elevated estrogen – whether from hormone therapies or pregnancy – significantly increases thrombotic risk, even in healthy people. High-risk patients should receive low-molecular-weight heparin – a prophylactic dose for patients with either positive aPL without clinical APS (including those with SLE) or with obstetric APS, and a therapeutic dose for those with thrombotic APS – during ART procedures.

In patients with SLE, another concern is that increased estrogen will cause disease flare. One case series published in 2017 reported 37 patients with SLE and/or APS who underwent 97 IVF cycles, of which 8% were complicated by flare or thrombotic events. Notably, half of these complications occurred in patients who stopped prescribed therapies (immunomodulatory therapy in two patients with SLE, anticoagulation in two patients with APS) after failure to conceive. In a separate study from 2000 including 19 patients with SLE, APS, or high-titer aPL who underwent 68 IVF cycles, 19% of cycles in patients with SLE were complicated by flare, and no thrombotic events occurred in the cohort. The authors concluded that ovulation induction does not exacerbate SLE or APS. In these studies, the overall pregnancy rates were felt to be consistent with those achieved by the general population through IVF. Although obstetric complications, such as preeclampsia and preterm delivery, were reported in about half of the pregnancies described, these are known to occur more frequently in those with SLE and APS, especially when active disease or other risk factors are present. There are no large-scale, controlled studies evaluating ART outcomes in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases to date.

Finally, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) is an increasingly rare but severe complication of ovarian stimulation. OHSS is characterized by capillary leak, fluid overload, and cytokine release syndrome and can lead to thromboembolic events. Comorbidities like hypertension and renal failure, which can go along with autoimmune rheumatic diseases, are risk factors for OHSS. The use of human chorionic gonadotropin to trigger ovulation is also associated with an increased risk for OHSS, so a GnRH agonist trigger may be preferable.

The ACR guideline recommends that individuals with any of these underlying conditions undergo ART only in expert centers. The ovarian stimulation protocol needs to be tailored to the individual patient to minimize risk and optimize outcomes. The overall goal when managing patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases during ART is to establish and maintain disease control with pregnancy-compatible medications (when pregnancy is the goal). With adequate planning, appropriate treatment, and collaboration between obstetricians and rheumatologists, individuals with autoimmune rheumatic diseases can safely pursue ART and go on to have successful pregnancies.

Dr. Siegel is a 2022-2023 UCB Women’s Health rheumatology fellow in the rheumatology reproductive health program of the Barbara Volcker Center for Women and Rheumatic Diseases at Hospital for Special Surgery/Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. Her clinical and research focus is on reproductive health issues in individuals with rheumatic disease. Dr. Chan is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College and an attending physician at Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a columnist for a monthly rheumatology publication, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice. Follow Dr Chan on Twitter. Dr. Siegel and Dr. Chan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article – an editorial collaboration between Medscape and the Hospital for Special Surgery – first appeared on Medscape.com.

The field of “reproductive rheumatology” has received growing attention in recent years as we learn more about how autoimmune rheumatic diseases and their treatment affect women of reproductive age. In 2020, the American College of Rheumatology published a comprehensive guideline that includes recommendations and supporting evidence for managing issues related to reproductive health in patients with rheumatic diseases and has since launched an ongoing Reproductive Health Initiative, with the goal of translating established guidelines into practice through various education and awareness campaigns. One area addressed by the guideline that comes up commonly in practice but receives less attention and research is the use of assisted reproductive technology (ART) in patients with rheumatic diseases.

Literature is conflicting regarding whether patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases are inherently at increased risk for infertility, defined as failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected intercourse, or subfertility, defined as a delay in conception. Regardless, several factors indirectly contribute to a disproportionate risk for infertility or subfertility in this patient population, including active inflammatory disease, reduced ovarian reserve, and medications.

Patients with subfertility or infertility who desire pregnancy may pursue ovulation induction with timed intercourse or intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilization (IVF)/intracytoplasmic sperm injection with either embryo transfer, or gestational surrogacy. Those who require treatment with cyclophosphamide or who plan to defer pregnancy for whatever reason can opt for oocyte cryopreservation (colloquially known as “egg freezing”). For IVF and oocyte cryopreservation, controlled ovarian stimulation is typically the first step (except in unstimulated, or “natural cycle,” IVF).

Various protocols are used for ovarian stimulation and ovulation induction, the nuances of which are beyond the scope of this article. In general, ovarian stimulation involves gonadotropin therapy (follicle-stimulating hormone and/or human menopausal gonadotropin) administered via scheduled subcutaneous injections to stimulate follicular growth, as well as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists or antagonists to suppress luteinizing hormone, preventing ovulation. Adjunctive oral therapy (clomiphene citrate or letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor) may be used as well. The patient has frequent lab monitoring of hormone levels and transvaginal ultrasounds to measure follicle number and size and, when the timing is right, receives an “ovulation trigger” – either human chorionic gonadotropin or GnRH agonist, depending on the protocol. At this point, transvaginal ultrasound–guided egg retrieval is done under sedation. Recovered oocytes are then either frozen for later use or fertilized in the lab for embryo transfer. Lastly, exogenous hormones are often used: estrogen to support frozen embryo transfers and progesterone for so-called luteal phase support.

ART is not contraindicated in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases, but there may be additional factors to consider, particularly for those with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), and antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) without clinical APS.

Ovarian stimulation elevates estrogen levels to varying degrees depending on the patient and the medications used. In all cases, though, peak levels are significantly lower than levels reached during pregnancy. It is well established that elevated estrogen – whether from hormone therapies or pregnancy – significantly increases thrombotic risk, even in healthy people. High-risk patients should receive low-molecular-weight heparin – a prophylactic dose for patients with either positive aPL without clinical APS (including those with SLE) or with obstetric APS, and a therapeutic dose for those with thrombotic APS – during ART procedures.

In patients with SLE, another concern is that increased estrogen will cause disease flare. One case series published in 2017 reported 37 patients with SLE and/or APS who underwent 97 IVF cycles, of which 8% were complicated by flare or thrombotic events. Notably, half of these complications occurred in patients who stopped prescribed therapies (immunomodulatory therapy in two patients with SLE, anticoagulation in two patients with APS) after failure to conceive. In a separate study from 2000 including 19 patients with SLE, APS, or high-titer aPL who underwent 68 IVF cycles, 19% of cycles in patients with SLE were complicated by flare, and no thrombotic events occurred in the cohort. The authors concluded that ovulation induction does not exacerbate SLE or APS. In these studies, the overall pregnancy rates were felt to be consistent with those achieved by the general population through IVF. Although obstetric complications, such as preeclampsia and preterm delivery, were reported in about half of the pregnancies described, these are known to occur more frequently in those with SLE and APS, especially when active disease or other risk factors are present. There are no large-scale, controlled studies evaluating ART outcomes in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases to date.

Finally, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) is an increasingly rare but severe complication of ovarian stimulation. OHSS is characterized by capillary leak, fluid overload, and cytokine release syndrome and can lead to thromboembolic events. Comorbidities like hypertension and renal failure, which can go along with autoimmune rheumatic diseases, are risk factors for OHSS. The use of human chorionic gonadotropin to trigger ovulation is also associated with an increased risk for OHSS, so a GnRH agonist trigger may be preferable.

The ACR guideline recommends that individuals with any of these underlying conditions undergo ART only in expert centers. The ovarian stimulation protocol needs to be tailored to the individual patient to minimize risk and optimize outcomes. The overall goal when managing patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases during ART is to establish and maintain disease control with pregnancy-compatible medications (when pregnancy is the goal). With adequate planning, appropriate treatment, and collaboration between obstetricians and rheumatologists, individuals with autoimmune rheumatic diseases can safely pursue ART and go on to have successful pregnancies.

Dr. Siegel is a 2022-2023 UCB Women’s Health rheumatology fellow in the rheumatology reproductive health program of the Barbara Volcker Center for Women and Rheumatic Diseases at Hospital for Special Surgery/Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. Her clinical and research focus is on reproductive health issues in individuals with rheumatic disease. Dr. Chan is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College and an attending physician at Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a columnist for a monthly rheumatology publication, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice. Follow Dr Chan on Twitter. Dr. Siegel and Dr. Chan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article – an editorial collaboration between Medscape and the Hospital for Special Surgery – first appeared on Medscape.com.

How Twitter amplifies my doctor and human voice

When I graduated from residency in 2007, Facebook had just become “a thing,” and my cohort decided to use it to keep in touch. These days, Twitter seems to be the social media platform of choice for health care professionals.

When I started on Twitter a few years ago, it was in reaction to the current political climate. I wanted to keep track of what my favorite thinkers were writing. I was anonymous and tweeted about politics mostly. My husband was my only follower for a while.

I deanonymized when, at last year’s American College of Rheumatology meeting, I presented a poster and wanted to reach a wider audience. I could have created two different personas on Twitter, like many doctors apparently do. Initially, I resisted doing that because I am frankly too lazy to keep track of two different social media profiles, but now I resist because I see my profession as an extension of my political self, and have no problem with using my (very low) profile to amplify both my doctor voice and my human voice.

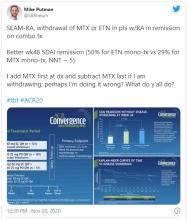

Professionally, Twitter is rewarding. It is a space for networking and for promoting one’s work. It is a fantastic learning format, as evidenced by the popularity of tweetorials. The international consortium that has worked to collect information on rheumatology patients with COVID started as an idea on Twitter. The fact that ACR Convergence 2020 abstracts are now available? I only know because of the #ACRambassadors that I follow.

But I find that I cannot separate who I am from what I do. As a rheumatologist, I build long-term relationships with patients. I cannot care for their medical conditions in isolation without also concerning myself with their nonmedical circumstances. For that reason, I have opinions that one might call humanist, and I suspect that I am not alone among rheumatologists.

I can think of three areas, broadly construed but with huge overlaps, that concern me a great deal.

First, there are things that affect all physicians: race and gender discrimination in the workplace; advancement of women in science, technology, engineering, or math; Medicare reimbursement; COVID-19 preparedness; immigration issues (an issue near and dear to me, as I am an immigrant and a foreign medical graduate); and federal funding (including funding for training programs and community health centers, funding for the National Institutes of Health, and funding for stem cell research).

Then there are the things that affect rheumatologists in particular. Access to medications and procedures is one thing. (I did say these categories hugely overlap.) If you›ve ever tried to prescribe even a drug as old as oral cyclophosphamide, you’ll have experienced the difficulty of getting it for Medicare patients. Patients who need biologics are limited by insurance contracts with pharmaceutical companies, but also by requirements such as step therapy. I am all varieties of annoyed, incredulous, and apologetic that when a patient asks me how much a treatment will cost him/her, I do not have an answer.

Speaking of pricing, don’t even get me started on pharmaceutical company price gouging. Yes, the H.P. Acthar gel may be the most egregious offender among rheumatology medications, but it’s easy to not prescribe a drug that costs $80,000 a vial and which does not do much more than prednisone does. On the other hand, I remember a time when colchicine cost $0.10 cents a pill and patients did not have to jump through hoops to get it.

And what of reproductive freedom? Our patients rely on us for advice about their childbearing options, including birth control, in vitro fertilization, and pregnancy termination.

Finally, and most important, the things that affect me most are the issues that affect patients. The lowest-hanging fruit here is the abject incompetence of the federal response to the ongoing pandemic. How many of our patients’ lives have been lost or adversely affected? And what of coverage for preexisting conditions for the vast majority of our patients, whose illnesses are chronic?

While we’re at it, the fact of health insurance being tied to employment, something that seemingly no other country in the developed world does, makes living with chronic conditions outright scary, doesn’t it? It isn’t quite so easy to remain employed when one cannot get the right medications for RA.

I could go on. Gun violence and health care disparities, vaccine denialism, coverage for mental health issues, LGBTQ rights, refugee rights, police brutality … there is a seemingly endless list of things to care about. It’s exhausting.

While I do use my Twitter account to learn from colleagues and to promote work that interests me, my primary aim is to participate in civil society as a person. Critics will use “stay in your lane” as shorthand to say x professionals should stick to x (actors to acting, musicians to music, athletes to sports). If only I could. But my humanity won’t let me. Aristotle said man is a political animal; even the venerable New England Journal of Medicine has found it impossible to keep silent.

Karmela Kim Chan, MD, is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and an attending physician at the Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, both in New York. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a past columnist for MDedge Rheumatology, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

When I graduated from residency in 2007, Facebook had just become “a thing,” and my cohort decided to use it to keep in touch. These days, Twitter seems to be the social media platform of choice for health care professionals.

When I started on Twitter a few years ago, it was in reaction to the current political climate. I wanted to keep track of what my favorite thinkers were writing. I was anonymous and tweeted about politics mostly. My husband was my only follower for a while.

I deanonymized when, at last year’s American College of Rheumatology meeting, I presented a poster and wanted to reach a wider audience. I could have created two different personas on Twitter, like many doctors apparently do. Initially, I resisted doing that because I am frankly too lazy to keep track of two different social media profiles, but now I resist because I see my profession as an extension of my political self, and have no problem with using my (very low) profile to amplify both my doctor voice and my human voice.

Professionally, Twitter is rewarding. It is a space for networking and for promoting one’s work. It is a fantastic learning format, as evidenced by the popularity of tweetorials. The international consortium that has worked to collect information on rheumatology patients with COVID started as an idea on Twitter. The fact that ACR Convergence 2020 abstracts are now available? I only know because of the #ACRambassadors that I follow.

But I find that I cannot separate who I am from what I do. As a rheumatologist, I build long-term relationships with patients. I cannot care for their medical conditions in isolation without also concerning myself with their nonmedical circumstances. For that reason, I have opinions that one might call humanist, and I suspect that I am not alone among rheumatologists.

I can think of three areas, broadly construed but with huge overlaps, that concern me a great deal.

First, there are things that affect all physicians: race and gender discrimination in the workplace; advancement of women in science, technology, engineering, or math; Medicare reimbursement; COVID-19 preparedness; immigration issues (an issue near and dear to me, as I am an immigrant and a foreign medical graduate); and federal funding (including funding for training programs and community health centers, funding for the National Institutes of Health, and funding for stem cell research).

Then there are the things that affect rheumatologists in particular. Access to medications and procedures is one thing. (I did say these categories hugely overlap.) If you›ve ever tried to prescribe even a drug as old as oral cyclophosphamide, you’ll have experienced the difficulty of getting it for Medicare patients. Patients who need biologics are limited by insurance contracts with pharmaceutical companies, but also by requirements such as step therapy. I am all varieties of annoyed, incredulous, and apologetic that when a patient asks me how much a treatment will cost him/her, I do not have an answer.

Speaking of pricing, don’t even get me started on pharmaceutical company price gouging. Yes, the H.P. Acthar gel may be the most egregious offender among rheumatology medications, but it’s easy to not prescribe a drug that costs $80,000 a vial and which does not do much more than prednisone does. On the other hand, I remember a time when colchicine cost $0.10 cents a pill and patients did not have to jump through hoops to get it.

And what of reproductive freedom? Our patients rely on us for advice about their childbearing options, including birth control, in vitro fertilization, and pregnancy termination.

Finally, and most important, the things that affect me most are the issues that affect patients. The lowest-hanging fruit here is the abject incompetence of the federal response to the ongoing pandemic. How many of our patients’ lives have been lost or adversely affected? And what of coverage for preexisting conditions for the vast majority of our patients, whose illnesses are chronic?

While we’re at it, the fact of health insurance being tied to employment, something that seemingly no other country in the developed world does, makes living with chronic conditions outright scary, doesn’t it? It isn’t quite so easy to remain employed when one cannot get the right medications for RA.

I could go on. Gun violence and health care disparities, vaccine denialism, coverage for mental health issues, LGBTQ rights, refugee rights, police brutality … there is a seemingly endless list of things to care about. It’s exhausting.

While I do use my Twitter account to learn from colleagues and to promote work that interests me, my primary aim is to participate in civil society as a person. Critics will use “stay in your lane” as shorthand to say x professionals should stick to x (actors to acting, musicians to music, athletes to sports). If only I could. But my humanity won’t let me. Aristotle said man is a political animal; even the venerable New England Journal of Medicine has found it impossible to keep silent.

Karmela Kim Chan, MD, is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and an attending physician at the Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, both in New York. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a past columnist for MDedge Rheumatology, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

When I graduated from residency in 2007, Facebook had just become “a thing,” and my cohort decided to use it to keep in touch. These days, Twitter seems to be the social media platform of choice for health care professionals.

When I started on Twitter a few years ago, it was in reaction to the current political climate. I wanted to keep track of what my favorite thinkers were writing. I was anonymous and tweeted about politics mostly. My husband was my only follower for a while.

I deanonymized when, at last year’s American College of Rheumatology meeting, I presented a poster and wanted to reach a wider audience. I could have created two different personas on Twitter, like many doctors apparently do. Initially, I resisted doing that because I am frankly too lazy to keep track of two different social media profiles, but now I resist because I see my profession as an extension of my political self, and have no problem with using my (very low) profile to amplify both my doctor voice and my human voice.

Professionally, Twitter is rewarding. It is a space for networking and for promoting one’s work. It is a fantastic learning format, as evidenced by the popularity of tweetorials. The international consortium that has worked to collect information on rheumatology patients with COVID started as an idea on Twitter. The fact that ACR Convergence 2020 abstracts are now available? I only know because of the #ACRambassadors that I follow.

But I find that I cannot separate who I am from what I do. As a rheumatologist, I build long-term relationships with patients. I cannot care for their medical conditions in isolation without also concerning myself with their nonmedical circumstances. For that reason, I have opinions that one might call humanist, and I suspect that I am not alone among rheumatologists.

I can think of three areas, broadly construed but with huge overlaps, that concern me a great deal.

First, there are things that affect all physicians: race and gender discrimination in the workplace; advancement of women in science, technology, engineering, or math; Medicare reimbursement; COVID-19 preparedness; immigration issues (an issue near and dear to me, as I am an immigrant and a foreign medical graduate); and federal funding (including funding for training programs and community health centers, funding for the National Institutes of Health, and funding for stem cell research).

Then there are the things that affect rheumatologists in particular. Access to medications and procedures is one thing. (I did say these categories hugely overlap.) If you›ve ever tried to prescribe even a drug as old as oral cyclophosphamide, you’ll have experienced the difficulty of getting it for Medicare patients. Patients who need biologics are limited by insurance contracts with pharmaceutical companies, but also by requirements such as step therapy. I am all varieties of annoyed, incredulous, and apologetic that when a patient asks me how much a treatment will cost him/her, I do not have an answer.

Speaking of pricing, don’t even get me started on pharmaceutical company price gouging. Yes, the H.P. Acthar gel may be the most egregious offender among rheumatology medications, but it’s easy to not prescribe a drug that costs $80,000 a vial and which does not do much more than prednisone does. On the other hand, I remember a time when colchicine cost $0.10 cents a pill and patients did not have to jump through hoops to get it.

And what of reproductive freedom? Our patients rely on us for advice about their childbearing options, including birth control, in vitro fertilization, and pregnancy termination.

Finally, and most important, the things that affect me most are the issues that affect patients. The lowest-hanging fruit here is the abject incompetence of the federal response to the ongoing pandemic. How many of our patients’ lives have been lost or adversely affected? And what of coverage for preexisting conditions for the vast majority of our patients, whose illnesses are chronic?

While we’re at it, the fact of health insurance being tied to employment, something that seemingly no other country in the developed world does, makes living with chronic conditions outright scary, doesn’t it? It isn’t quite so easy to remain employed when one cannot get the right medications for RA.

I could go on. Gun violence and health care disparities, vaccine denialism, coverage for mental health issues, LGBTQ rights, refugee rights, police brutality … there is a seemingly endless list of things to care about. It’s exhausting.

While I do use my Twitter account to learn from colleagues and to promote work that interests me, my primary aim is to participate in civil society as a person. Critics will use “stay in your lane” as shorthand to say x professionals should stick to x (actors to acting, musicians to music, athletes to sports). If only I could. But my humanity won’t let me. Aristotle said man is a political animal; even the venerable New England Journal of Medicine has found it impossible to keep silent.

Karmela Kim Chan, MD, is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and an attending physician at the Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, both in New York. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a past columnist for MDedge Rheumatology, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Diary of a rheumatologist who briefly became a COVID hospitalist

When the coronavirus pandemic hit New York City in early March, the Hospital for Special Surgery leadership decided that the best way to serve the city was to stop elective orthopedic procedures temporarily and use the facility to take on patients from its sister institution, NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital.

As in other institutions, it was all hands on deck. , other internal medicine subspecialists were asked to volunteer, including rheumatologists and primary care sports medicine doctors.

As a rheumatologist, it had been well over 10 years since I had last done any inpatient work. I was filled with trepidation, but I was also excited to dive in.

April 4:

Feeling very unmoored. I am in unfamiliar territory, and it’s terrifying. There are so many things that I no longer know how to do. Thankfully, the hospitalists are gracious, extremely supportive, and helpful.

My N95 doesn’t fit well. It’s never fit — not during residency or fellowship, not in any job I’ve had, and not today. The lady fit-testing me said she was sorry, but the look on her face said, “I’m sorry, but you’re going to die.”

April 7:

We don’t know how to treat coronavirus. I’ve sent some patients home, others I’ve sent to the ICU. Thank goodness for treatment algorithms from leadership, but we are sorely lacking good-quality data.

Our infectious disease doctor doesn’t think hydroxychloroquine works at all; I suspect he is right. The guidance right now is to give hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin to everyone who is sick enough to be admitted, but there are methodologic flaws in the early enthusiastic preprints, and so far, I’ve not noticed any demonstrable benefit.

The only thing that seems to be happening is that I am seeing more QT prolongation — not something I previously counseled my rheumatology patients on.

April 9:

The patients have been, with a few exceptions, alone in the room. They’re not allowed to have visitors and are required to wear masks all the time. Anyone who enters their rooms is fully covered up so you can barely see them. It’s anonymous and dehumanizing.

We’re instructed to take histories by phone in order to limit the time spent in each room. I buck this instruction; I still take histories in person because human contact seems more important now than ever.

Except maybe I should be smarter about this. One of my patients refuses any treatment, including oxygen support. She firmly believes this is a result of 5G networks — something I later discovered was a common conspiracy theory. She refused to wear a mask despite having a very bad cough. She coughed in my face a lot when we were chatting. My face with my ill-fitting N95 mask. Maybe the fit-testing lady’s eyes weren’t lying and I will die after all.

April 15:

On the days when I’m not working as a hospitalist, I am still doing remote visits with my rheumatology patients. It feels good to be doing something familiar and something I’m actually good at. But it is surreal to be faced with the quotidian on one hand and life and death on the other.

I recently saw a fairly new patient, and I still haven’t figured out if she has a rheumatic condition or if her symptoms all stem from an alcohol use disorder. In our previous visits, she could barely acknowledge that her drinking was an issue. On today’s visit, she told me she was 1½ months sober.

I don’t know her very well, but it was the happiest news I’d heard in a long time. I was so beside myself with joy that I cried, which says more about my current emotional state than anything else, really.

April 21:

On my panel of patients, I have three women with COVID-19 — all of whom lost their husbands to COVID-19, and none of whom were able to say their goodbyes. I cannot even begin to imagine what it must be like to survive this period of illness, isolation, and fear, only to be met on the other side by grief.

Rheumatology doesn’t lend itself too well to such existential concerns; I am not equipped for this. Perhaps my only advantage as a rheumatologist is that I know how to use IVIG, anakinra, and tocilizumab.

Someone on my panel was started on anakinra, and it turned his case around. Would he have gotten better without it anyway? We’ll never know for sure.

April 28:

Patients seem to be requiring prolonged intubation. We have now reached the stage where patients are alive but trached and PEGed. One of my patients had been intubated for close to 3 weeks. She was one of four people in her family who contracted the illness (they had had a dinner party before New York’s state of emergency was declared). We thought she might die once she was extubated, but she is still fighting. Unconscious, unarousable, but breathing on her own.

Will she ever wake up? We don’t know. We put the onus on her family to make decisions about placing a PEG tube in. They can only do so from a distance with imperfect information gleaned from periodic, brief FaceTime interactions — where no interaction happens at all.

May 4:

It’s my last day as a “COVID hospitalist.” When I first started, I felt like I was being helpful. Walking home in the middle of the 7 PM cheers for healthcare workers frequently left me teary eyed. As horrible as the situation was, I was proud of myself for volunteering to help and appreciative of a broken city’s gratitude toward all healthcare workers in general. Maybe I bought into the idea that, like many others around me, I am a hero.

I don’t feel like a hero, though. The stuff I saw was easy compared with the stuff that my colleagues in critical care saw. Our hospital accepted the more stable patient transfers from our sister hospitals. Patients who remained in the NewYork–Presbyterian system were sicker, with encephalitis, thrombotic complications, multiorgan failure, and cytokine release syndrome. It’s the doctors who took care of those patients who deserve to be called heroes.

No, I am no hero. But did my volunteering make a difference? It made a difference to me. The overwhelming feeling I am left with isn’t pride; it’s humility. I feel humbled that I could feel so unexpectedly touched by the lives of people that I had no idea I could feel touched by.

Postscript:

My patient Esther [name changed to hide her identity] died from COVID-19. She was MY patient — not a patient I met as a COVID hospitalist, but a patient with rheumatoid arthritis whom I cared for for years.

She had scleromalacia and multiple failed scleral grafts, which made her profoundly sad. She fought her anxiety fiercely and always with poise and panache. One way she dealt with her anxiety was that she constantly messaged me via our EHR portal. She ran everything by me and trusted me to be her rock.

The past month has been so busy that I just now noticed it had been a month since I last heard from her. I tried to call her but got her voicemail. It wasn’t until I exchanged messages with her ophthalmologist that I found out she had passed away from complications of COVID-19.

She was taking rituximab and mycophenolate. I wonder if these drugs made her sicker than she would have been otherwise; it fills me with sadness. I wonder if she was alone like my other COVID-19 patients. I wonder if she was afraid. I am sorry that I wasn’t able to say goodbye.

Karmela Kim Chan, MD, is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College and an attending physician at Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a columnist for this rheumatology publication, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com. This article is part of a partnership between Medscape and Hospital for Special Surgery.

When the coronavirus pandemic hit New York City in early March, the Hospital for Special Surgery leadership decided that the best way to serve the city was to stop elective orthopedic procedures temporarily and use the facility to take on patients from its sister institution, NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital.

As in other institutions, it was all hands on deck. , other internal medicine subspecialists were asked to volunteer, including rheumatologists and primary care sports medicine doctors.

As a rheumatologist, it had been well over 10 years since I had last done any inpatient work. I was filled with trepidation, but I was also excited to dive in.

April 4:

Feeling very unmoored. I am in unfamiliar territory, and it’s terrifying. There are so many things that I no longer know how to do. Thankfully, the hospitalists are gracious, extremely supportive, and helpful.

My N95 doesn’t fit well. It’s never fit — not during residency or fellowship, not in any job I’ve had, and not today. The lady fit-testing me said she was sorry, but the look on her face said, “I’m sorry, but you’re going to die.”

April 7:

We don’t know how to treat coronavirus. I’ve sent some patients home, others I’ve sent to the ICU. Thank goodness for treatment algorithms from leadership, but we are sorely lacking good-quality data.

Our infectious disease doctor doesn’t think hydroxychloroquine works at all; I suspect he is right. The guidance right now is to give hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin to everyone who is sick enough to be admitted, but there are methodologic flaws in the early enthusiastic preprints, and so far, I’ve not noticed any demonstrable benefit.

The only thing that seems to be happening is that I am seeing more QT prolongation — not something I previously counseled my rheumatology patients on.

April 9:

The patients have been, with a few exceptions, alone in the room. They’re not allowed to have visitors and are required to wear masks all the time. Anyone who enters their rooms is fully covered up so you can barely see them. It’s anonymous and dehumanizing.

We’re instructed to take histories by phone in order to limit the time spent in each room. I buck this instruction; I still take histories in person because human contact seems more important now than ever.

Except maybe I should be smarter about this. One of my patients refuses any treatment, including oxygen support. She firmly believes this is a result of 5G networks — something I later discovered was a common conspiracy theory. She refused to wear a mask despite having a very bad cough. She coughed in my face a lot when we were chatting. My face with my ill-fitting N95 mask. Maybe the fit-testing lady’s eyes weren’t lying and I will die after all.

April 15:

On the days when I’m not working as a hospitalist, I am still doing remote visits with my rheumatology patients. It feels good to be doing something familiar and something I’m actually good at. But it is surreal to be faced with the quotidian on one hand and life and death on the other.

I recently saw a fairly new patient, and I still haven’t figured out if she has a rheumatic condition or if her symptoms all stem from an alcohol use disorder. In our previous visits, she could barely acknowledge that her drinking was an issue. On today’s visit, she told me she was 1½ months sober.

I don’t know her very well, but it was the happiest news I’d heard in a long time. I was so beside myself with joy that I cried, which says more about my current emotional state than anything else, really.

April 21:

On my panel of patients, I have three women with COVID-19 — all of whom lost their husbands to COVID-19, and none of whom were able to say their goodbyes. I cannot even begin to imagine what it must be like to survive this period of illness, isolation, and fear, only to be met on the other side by grief.

Rheumatology doesn’t lend itself too well to such existential concerns; I am not equipped for this. Perhaps my only advantage as a rheumatologist is that I know how to use IVIG, anakinra, and tocilizumab.

Someone on my panel was started on anakinra, and it turned his case around. Would he have gotten better without it anyway? We’ll never know for sure.

April 28:

Patients seem to be requiring prolonged intubation. We have now reached the stage where patients are alive but trached and PEGed. One of my patients had been intubated for close to 3 weeks. She was one of four people in her family who contracted the illness (they had had a dinner party before New York’s state of emergency was declared). We thought she might die once she was extubated, but she is still fighting. Unconscious, unarousable, but breathing on her own.

Will she ever wake up? We don’t know. We put the onus on her family to make decisions about placing a PEG tube in. They can only do so from a distance with imperfect information gleaned from periodic, brief FaceTime interactions — where no interaction happens at all.

May 4:

It’s my last day as a “COVID hospitalist.” When I first started, I felt like I was being helpful. Walking home in the middle of the 7 PM cheers for healthcare workers frequently left me teary eyed. As horrible as the situation was, I was proud of myself for volunteering to help and appreciative of a broken city’s gratitude toward all healthcare workers in general. Maybe I bought into the idea that, like many others around me, I am a hero.

I don’t feel like a hero, though. The stuff I saw was easy compared with the stuff that my colleagues in critical care saw. Our hospital accepted the more stable patient transfers from our sister hospitals. Patients who remained in the NewYork–Presbyterian system were sicker, with encephalitis, thrombotic complications, multiorgan failure, and cytokine release syndrome. It’s the doctors who took care of those patients who deserve to be called heroes.

No, I am no hero. But did my volunteering make a difference? It made a difference to me. The overwhelming feeling I am left with isn’t pride; it’s humility. I feel humbled that I could feel so unexpectedly touched by the lives of people that I had no idea I could feel touched by.

Postscript:

My patient Esther [name changed to hide her identity] died from COVID-19. She was MY patient — not a patient I met as a COVID hospitalist, but a patient with rheumatoid arthritis whom I cared for for years.

She had scleromalacia and multiple failed scleral grafts, which made her profoundly sad. She fought her anxiety fiercely and always with poise and panache. One way she dealt with her anxiety was that she constantly messaged me via our EHR portal. She ran everything by me and trusted me to be her rock.

The past month has been so busy that I just now noticed it had been a month since I last heard from her. I tried to call her but got her voicemail. It wasn’t until I exchanged messages with her ophthalmologist that I found out she had passed away from complications of COVID-19.

She was taking rituximab and mycophenolate. I wonder if these drugs made her sicker than she would have been otherwise; it fills me with sadness. I wonder if she was alone like my other COVID-19 patients. I wonder if she was afraid. I am sorry that I wasn’t able to say goodbye.

Karmela Kim Chan, MD, is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College and an attending physician at Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a columnist for this rheumatology publication, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com. This article is part of a partnership between Medscape and Hospital for Special Surgery.

When the coronavirus pandemic hit New York City in early March, the Hospital for Special Surgery leadership decided that the best way to serve the city was to stop elective orthopedic procedures temporarily and use the facility to take on patients from its sister institution, NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital.

As in other institutions, it was all hands on deck. , other internal medicine subspecialists were asked to volunteer, including rheumatologists and primary care sports medicine doctors.

As a rheumatologist, it had been well over 10 years since I had last done any inpatient work. I was filled with trepidation, but I was also excited to dive in.

April 4:

Feeling very unmoored. I am in unfamiliar territory, and it’s terrifying. There are so many things that I no longer know how to do. Thankfully, the hospitalists are gracious, extremely supportive, and helpful.

My N95 doesn’t fit well. It’s never fit — not during residency or fellowship, not in any job I’ve had, and not today. The lady fit-testing me said she was sorry, but the look on her face said, “I’m sorry, but you’re going to die.”

April 7:

We don’t know how to treat coronavirus. I’ve sent some patients home, others I’ve sent to the ICU. Thank goodness for treatment algorithms from leadership, but we are sorely lacking good-quality data.

Our infectious disease doctor doesn’t think hydroxychloroquine works at all; I suspect he is right. The guidance right now is to give hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin to everyone who is sick enough to be admitted, but there are methodologic flaws in the early enthusiastic preprints, and so far, I’ve not noticed any demonstrable benefit.

The only thing that seems to be happening is that I am seeing more QT prolongation — not something I previously counseled my rheumatology patients on.

April 9:

The patients have been, with a few exceptions, alone in the room. They’re not allowed to have visitors and are required to wear masks all the time. Anyone who enters their rooms is fully covered up so you can barely see them. It’s anonymous and dehumanizing.

We’re instructed to take histories by phone in order to limit the time spent in each room. I buck this instruction; I still take histories in person because human contact seems more important now than ever.

Except maybe I should be smarter about this. One of my patients refuses any treatment, including oxygen support. She firmly believes this is a result of 5G networks — something I later discovered was a common conspiracy theory. She refused to wear a mask despite having a very bad cough. She coughed in my face a lot when we were chatting. My face with my ill-fitting N95 mask. Maybe the fit-testing lady’s eyes weren’t lying and I will die after all.

April 15:

On the days when I’m not working as a hospitalist, I am still doing remote visits with my rheumatology patients. It feels good to be doing something familiar and something I’m actually good at. But it is surreal to be faced with the quotidian on one hand and life and death on the other.

I recently saw a fairly new patient, and I still haven’t figured out if she has a rheumatic condition or if her symptoms all stem from an alcohol use disorder. In our previous visits, she could barely acknowledge that her drinking was an issue. On today’s visit, she told me she was 1½ months sober.

I don’t know her very well, but it was the happiest news I’d heard in a long time. I was so beside myself with joy that I cried, which says more about my current emotional state than anything else, really.

April 21:

On my panel of patients, I have three women with COVID-19 — all of whom lost their husbands to COVID-19, and none of whom were able to say their goodbyes. I cannot even begin to imagine what it must be like to survive this period of illness, isolation, and fear, only to be met on the other side by grief.

Rheumatology doesn’t lend itself too well to such existential concerns; I am not equipped for this. Perhaps my only advantage as a rheumatologist is that I know how to use IVIG, anakinra, and tocilizumab.

Someone on my panel was started on anakinra, and it turned his case around. Would he have gotten better without it anyway? We’ll never know for sure.

April 28:

Patients seem to be requiring prolonged intubation. We have now reached the stage where patients are alive but trached and PEGed. One of my patients had been intubated for close to 3 weeks. She was one of four people in her family who contracted the illness (they had had a dinner party before New York’s state of emergency was declared). We thought she might die once she was extubated, but she is still fighting. Unconscious, unarousable, but breathing on her own.

Will she ever wake up? We don’t know. We put the onus on her family to make decisions about placing a PEG tube in. They can only do so from a distance with imperfect information gleaned from periodic, brief FaceTime interactions — where no interaction happens at all.

May 4:

It’s my last day as a “COVID hospitalist.” When I first started, I felt like I was being helpful. Walking home in the middle of the 7 PM cheers for healthcare workers frequently left me teary eyed. As horrible as the situation was, I was proud of myself for volunteering to help and appreciative of a broken city’s gratitude toward all healthcare workers in general. Maybe I bought into the idea that, like many others around me, I am a hero.

I don’t feel like a hero, though. The stuff I saw was easy compared with the stuff that my colleagues in critical care saw. Our hospital accepted the more stable patient transfers from our sister hospitals. Patients who remained in the NewYork–Presbyterian system were sicker, with encephalitis, thrombotic complications, multiorgan failure, and cytokine release syndrome. It’s the doctors who took care of those patients who deserve to be called heroes.

No, I am no hero. But did my volunteering make a difference? It made a difference to me. The overwhelming feeling I am left with isn’t pride; it’s humility. I feel humbled that I could feel so unexpectedly touched by the lives of people that I had no idea I could feel touched by.

Postscript:

My patient Esther [name changed to hide her identity] died from COVID-19. She was MY patient — not a patient I met as a COVID hospitalist, but a patient with rheumatoid arthritis whom I cared for for years.

She had scleromalacia and multiple failed scleral grafts, which made her profoundly sad. She fought her anxiety fiercely and always with poise and panache. One way she dealt with her anxiety was that she constantly messaged me via our EHR portal. She ran everything by me and trusted me to be her rock.

The past month has been so busy that I just now noticed it had been a month since I last heard from her. I tried to call her but got her voicemail. It wasn’t until I exchanged messages with her ophthalmologist that I found out she had passed away from complications of COVID-19.

She was taking rituximab and mycophenolate. I wonder if these drugs made her sicker than she would have been otherwise; it fills me with sadness. I wonder if she was alone like my other COVID-19 patients. I wonder if she was afraid. I am sorry that I wasn’t able to say goodbye.

Karmela Kim Chan, MD, is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College and an attending physician at Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a columnist for this rheumatology publication, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com. This article is part of a partnership between Medscape and Hospital for Special Surgery.