User login

Autism: Is it in the water?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Few diseases have stymied explanation like autism spectrum disorder (ASD). We know that the prevalence has been increasing dramatically, but we aren’t quite sure whether that is because of more screening and awareness or more fundamental changes. We know that much of the risk appears to be genetic, but there may be 1,000 genes involved in the syndrome. We know that certain environmental exposures, like pollution, might increase the risk – perhaps on a susceptible genetic background – but we’re not really sure which exposures are most harmful.

So, the search continues, across all domains of inquiry from cell culture to large epidemiologic analyses. And this week, a new player enters the field, and, as they say, it’s something in the water.

We’re talking about this paper, by Zeyan Liew and colleagues, appearing in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using the incredibly robust health data infrastructure in Denmark, the researchers were able to identify 8,842 children born between 2000 and 2013 with ASD and matched each one to five control kids of the same sex and age without autism.

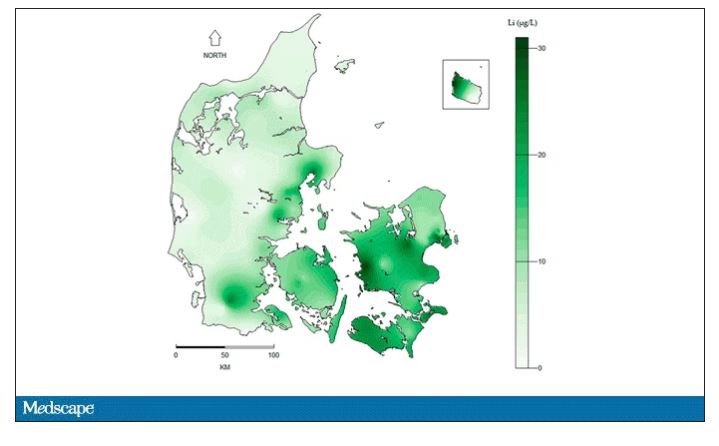

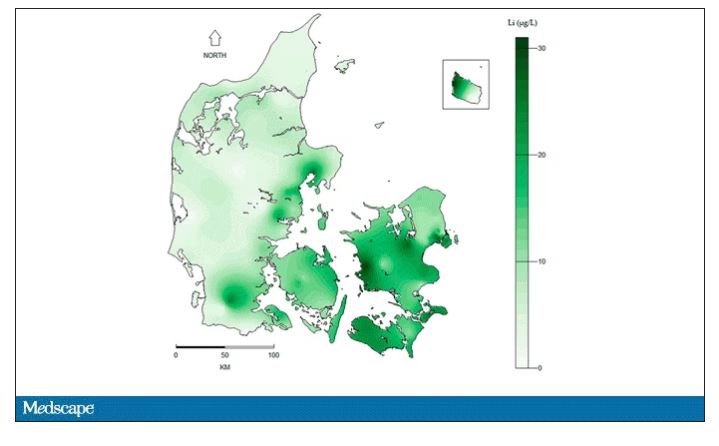

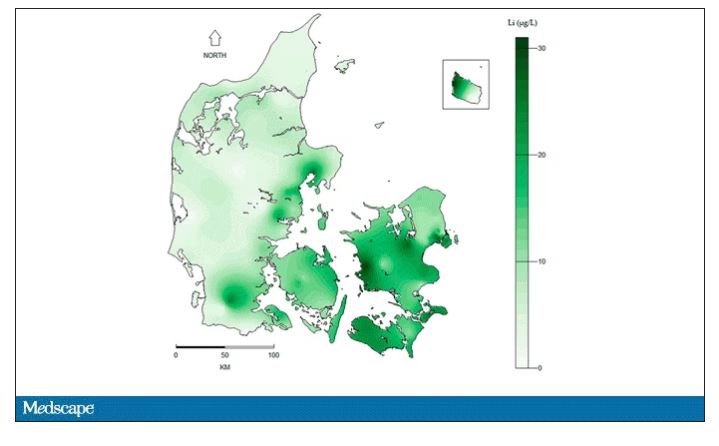

They then mapped the location the mothers of these kids lived while they were pregnant – down to 5 meters resolution, actually – to groundwater lithium levels.

Once that was done, the analysis was straightforward. Would moms who were pregnant in areas with higher groundwater lithium levels be more likely to have kids with ASD?

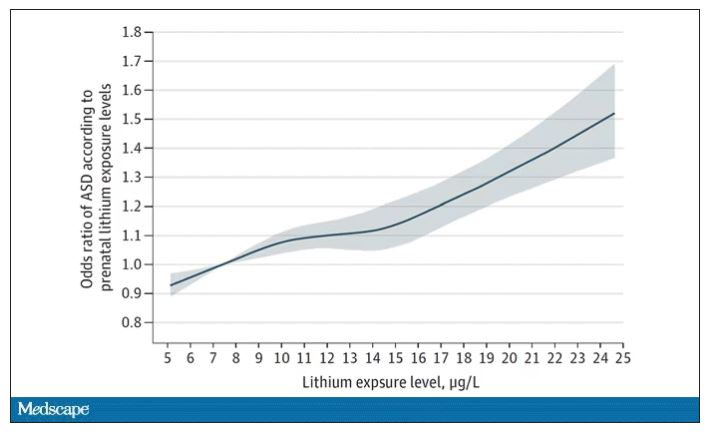

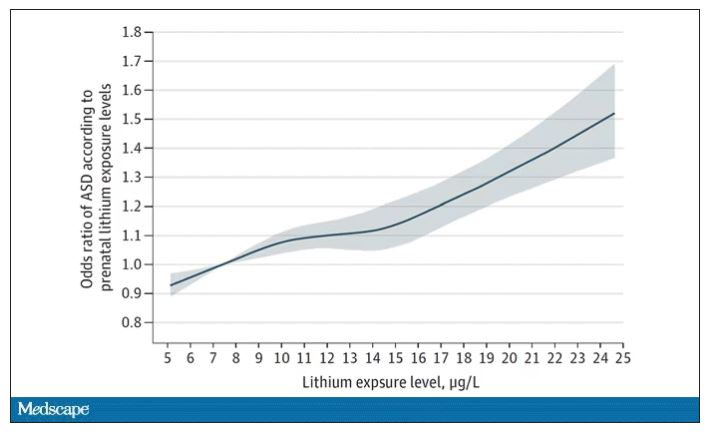

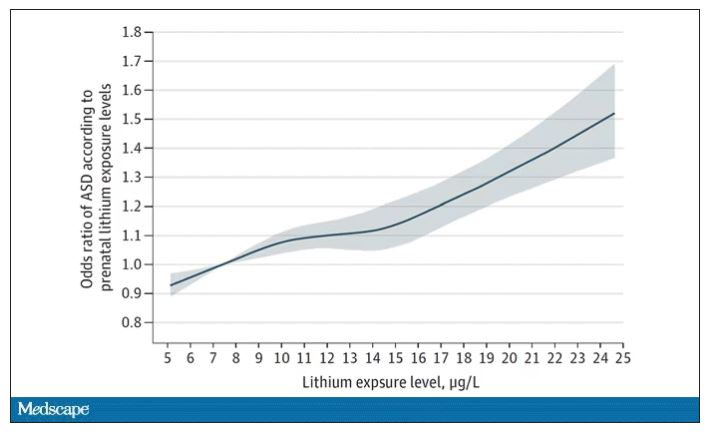

The results show a rather steady and consistent association between higher lithium levels in groundwater and the prevalence of ASD in children.

We’re not talking huge numbers, but moms who lived in the areas of the highest quartile of lithium were about 46% more likely to have a child with ASD. That’s a relative risk, of course – this would be like an increase from 1 in 100 kids to 1.5 in 100 kids. But still, it’s intriguing.

But the case is far from closed here.

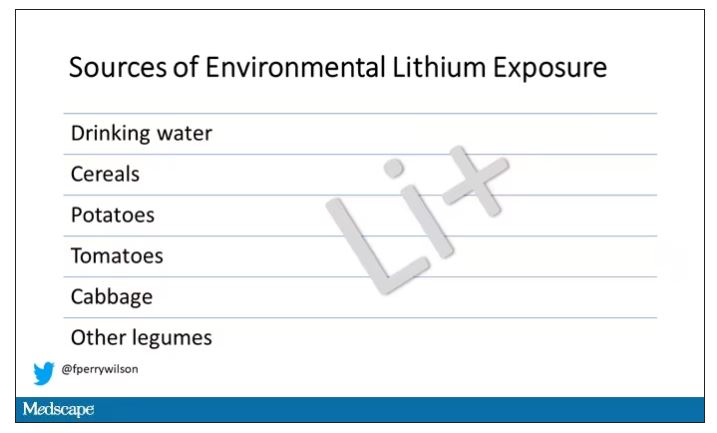

Groundwater concentration of lithium and the amount of lithium a pregnant mother ingests are not the same thing. It does turn out that virtually all drinking water in Denmark comes from groundwater sources – but not all lithium comes from drinking water. There are plenty of dietary sources of lithium as well. And, of course, there is medical lithium, but we’ll get to that in a second.

First, let’s talk about those lithium measurements. They were taken in 2013 – after all these kids were born. The authors acknowledge this limitation but show a high correlation between measured levels in 2013 and earlier measured levels from prior studies, suggesting that lithium levels in a given area are quite constant over time. That’s great – but if lithium levels are constant over time, this study does nothing to shed light on why autism diagnoses seem to be increasing.

Let’s put some numbers to the lithium concentrations the authors examined. The average was about 12 mcg/L.

As a reminder, a standard therapeutic dose of lithium used for bipolar disorder is like 600 mg. That means you’d need to drink more than 2,500 of those 5-gallon jugs that sit on your water cooler, per day, to approximate the dose you’d get from a lithium tablet. Of course, small doses can still cause toxicity – but I wanted to put this in perspective.

Also, we have some data on pregnant women who take medical lithium. An analysis of nine studies showed that first-trimester lithium use may be associated with congenital malformations – particularly some specific heart malformations – and some birth complications. But three of four separate studies looking at longer-term neurodevelopmental outcomes did not find any effect on development, attainment of milestones, or IQ. One study of 15 kids exposed to medical lithium in utero did note minor neurologic dysfunction in one child and a low verbal IQ in another – but that’s a very small study.

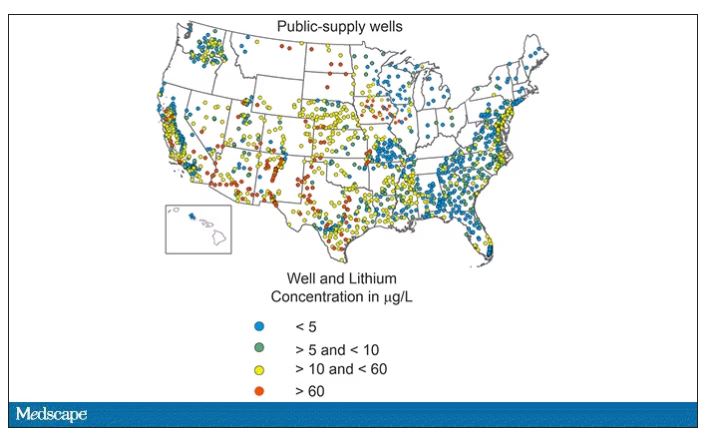

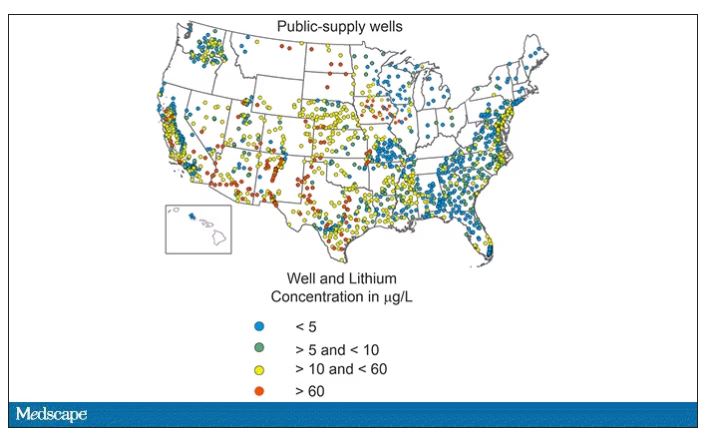

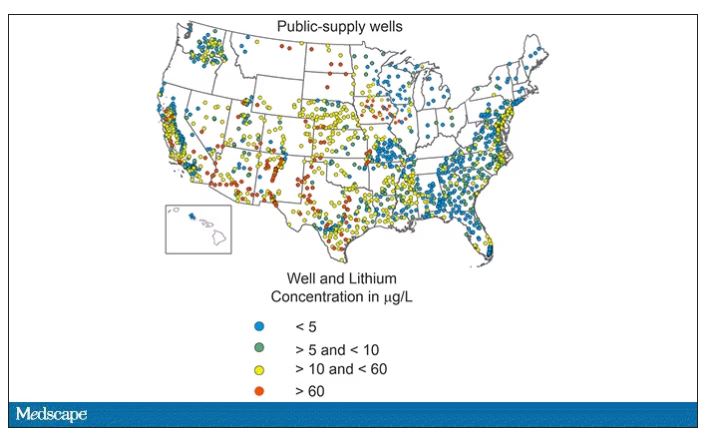

Of course, lithium levels vary around the world as well. The U.S. Geological Survey examined lithium content in groundwater in the United States, as you can see here.

Our numbers are pretty similar to Denmark’s – in the 0-60 range. But an area in the Argentine Andes has levels as high as 1,600 mcg/L. A study of 194 babies from that area found higher lithium exposure was associated with lower fetal size, but I haven’t seen follow-up on neurodevelopmental outcomes.

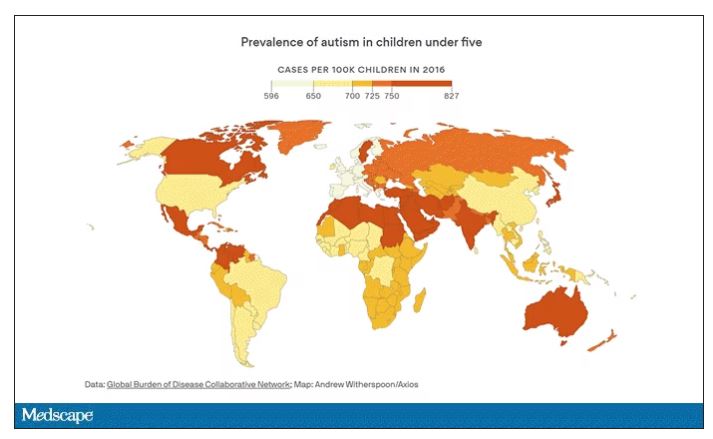

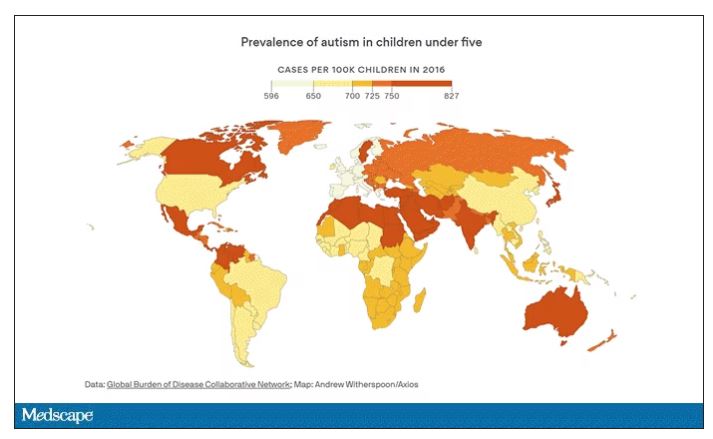

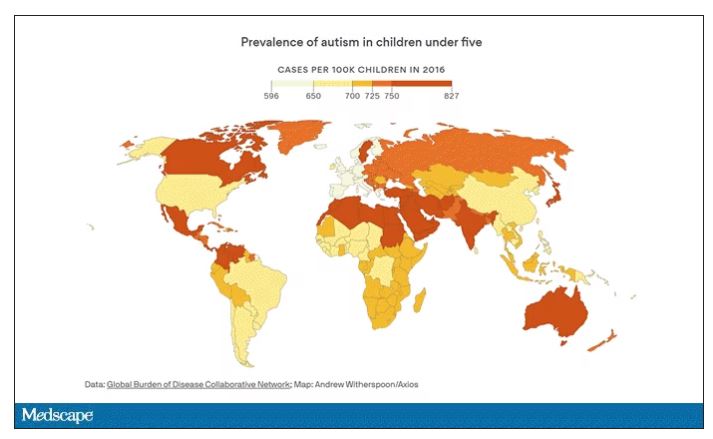

The point is that there is a lot of variability here. It would be really interesting to map groundwater lithium levels to autism rates around the world. As a teaser, I will point out that, if you look at worldwide autism rates, you may be able to convince yourself that they are higher in more arid climates, and arid climates tend to have more groundwater lithium. But I’m really reaching here. More work needs to be done.

And I hope it is done quickly. Lithium is in the midst of becoming a very important commodity thanks to the shift to electric vehicles. While we can hope that recycling will claim most of those batteries at the end of their life, some will escape reclamation and potentially put more lithium into the drinking water. I’d like to know how risky that is before it happens.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t”, is available now.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Few diseases have stymied explanation like autism spectrum disorder (ASD). We know that the prevalence has been increasing dramatically, but we aren’t quite sure whether that is because of more screening and awareness or more fundamental changes. We know that much of the risk appears to be genetic, but there may be 1,000 genes involved in the syndrome. We know that certain environmental exposures, like pollution, might increase the risk – perhaps on a susceptible genetic background – but we’re not really sure which exposures are most harmful.

So, the search continues, across all domains of inquiry from cell culture to large epidemiologic analyses. And this week, a new player enters the field, and, as they say, it’s something in the water.

We’re talking about this paper, by Zeyan Liew and colleagues, appearing in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using the incredibly robust health data infrastructure in Denmark, the researchers were able to identify 8,842 children born between 2000 and 2013 with ASD and matched each one to five control kids of the same sex and age without autism.

They then mapped the location the mothers of these kids lived while they were pregnant – down to 5 meters resolution, actually – to groundwater lithium levels.

Once that was done, the analysis was straightforward. Would moms who were pregnant in areas with higher groundwater lithium levels be more likely to have kids with ASD?

The results show a rather steady and consistent association between higher lithium levels in groundwater and the prevalence of ASD in children.

We’re not talking huge numbers, but moms who lived in the areas of the highest quartile of lithium were about 46% more likely to have a child with ASD. That’s a relative risk, of course – this would be like an increase from 1 in 100 kids to 1.5 in 100 kids. But still, it’s intriguing.

But the case is far from closed here.

Groundwater concentration of lithium and the amount of lithium a pregnant mother ingests are not the same thing. It does turn out that virtually all drinking water in Denmark comes from groundwater sources – but not all lithium comes from drinking water. There are plenty of dietary sources of lithium as well. And, of course, there is medical lithium, but we’ll get to that in a second.

First, let’s talk about those lithium measurements. They were taken in 2013 – after all these kids were born. The authors acknowledge this limitation but show a high correlation between measured levels in 2013 and earlier measured levels from prior studies, suggesting that lithium levels in a given area are quite constant over time. That’s great – but if lithium levels are constant over time, this study does nothing to shed light on why autism diagnoses seem to be increasing.

Let’s put some numbers to the lithium concentrations the authors examined. The average was about 12 mcg/L.

As a reminder, a standard therapeutic dose of lithium used for bipolar disorder is like 600 mg. That means you’d need to drink more than 2,500 of those 5-gallon jugs that sit on your water cooler, per day, to approximate the dose you’d get from a lithium tablet. Of course, small doses can still cause toxicity – but I wanted to put this in perspective.

Also, we have some data on pregnant women who take medical lithium. An analysis of nine studies showed that first-trimester lithium use may be associated with congenital malformations – particularly some specific heart malformations – and some birth complications. But three of four separate studies looking at longer-term neurodevelopmental outcomes did not find any effect on development, attainment of milestones, or IQ. One study of 15 kids exposed to medical lithium in utero did note minor neurologic dysfunction in one child and a low verbal IQ in another – but that’s a very small study.

Of course, lithium levels vary around the world as well. The U.S. Geological Survey examined lithium content in groundwater in the United States, as you can see here.

Our numbers are pretty similar to Denmark’s – in the 0-60 range. But an area in the Argentine Andes has levels as high as 1,600 mcg/L. A study of 194 babies from that area found higher lithium exposure was associated with lower fetal size, but I haven’t seen follow-up on neurodevelopmental outcomes.

The point is that there is a lot of variability here. It would be really interesting to map groundwater lithium levels to autism rates around the world. As a teaser, I will point out that, if you look at worldwide autism rates, you may be able to convince yourself that they are higher in more arid climates, and arid climates tend to have more groundwater lithium. But I’m really reaching here. More work needs to be done.

And I hope it is done quickly. Lithium is in the midst of becoming a very important commodity thanks to the shift to electric vehicles. While we can hope that recycling will claim most of those batteries at the end of their life, some will escape reclamation and potentially put more lithium into the drinking water. I’d like to know how risky that is before it happens.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t”, is available now.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Few diseases have stymied explanation like autism spectrum disorder (ASD). We know that the prevalence has been increasing dramatically, but we aren’t quite sure whether that is because of more screening and awareness or more fundamental changes. We know that much of the risk appears to be genetic, but there may be 1,000 genes involved in the syndrome. We know that certain environmental exposures, like pollution, might increase the risk – perhaps on a susceptible genetic background – but we’re not really sure which exposures are most harmful.

So, the search continues, across all domains of inquiry from cell culture to large epidemiologic analyses. And this week, a new player enters the field, and, as they say, it’s something in the water.

We’re talking about this paper, by Zeyan Liew and colleagues, appearing in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using the incredibly robust health data infrastructure in Denmark, the researchers were able to identify 8,842 children born between 2000 and 2013 with ASD and matched each one to five control kids of the same sex and age without autism.

They then mapped the location the mothers of these kids lived while they were pregnant – down to 5 meters resolution, actually – to groundwater lithium levels.

Once that was done, the analysis was straightforward. Would moms who were pregnant in areas with higher groundwater lithium levels be more likely to have kids with ASD?

The results show a rather steady and consistent association between higher lithium levels in groundwater and the prevalence of ASD in children.

We’re not talking huge numbers, but moms who lived in the areas of the highest quartile of lithium were about 46% more likely to have a child with ASD. That’s a relative risk, of course – this would be like an increase from 1 in 100 kids to 1.5 in 100 kids. But still, it’s intriguing.

But the case is far from closed here.

Groundwater concentration of lithium and the amount of lithium a pregnant mother ingests are not the same thing. It does turn out that virtually all drinking water in Denmark comes from groundwater sources – but not all lithium comes from drinking water. There are plenty of dietary sources of lithium as well. And, of course, there is medical lithium, but we’ll get to that in a second.

First, let’s talk about those lithium measurements. They were taken in 2013 – after all these kids were born. The authors acknowledge this limitation but show a high correlation between measured levels in 2013 and earlier measured levels from prior studies, suggesting that lithium levels in a given area are quite constant over time. That’s great – but if lithium levels are constant over time, this study does nothing to shed light on why autism diagnoses seem to be increasing.

Let’s put some numbers to the lithium concentrations the authors examined. The average was about 12 mcg/L.

As a reminder, a standard therapeutic dose of lithium used for bipolar disorder is like 600 mg. That means you’d need to drink more than 2,500 of those 5-gallon jugs that sit on your water cooler, per day, to approximate the dose you’d get from a lithium tablet. Of course, small doses can still cause toxicity – but I wanted to put this in perspective.

Also, we have some data on pregnant women who take medical lithium. An analysis of nine studies showed that first-trimester lithium use may be associated with congenital malformations – particularly some specific heart malformations – and some birth complications. But three of four separate studies looking at longer-term neurodevelopmental outcomes did not find any effect on development, attainment of milestones, or IQ. One study of 15 kids exposed to medical lithium in utero did note minor neurologic dysfunction in one child and a low verbal IQ in another – but that’s a very small study.

Of course, lithium levels vary around the world as well. The U.S. Geological Survey examined lithium content in groundwater in the United States, as you can see here.

Our numbers are pretty similar to Denmark’s – in the 0-60 range. But an area in the Argentine Andes has levels as high as 1,600 mcg/L. A study of 194 babies from that area found higher lithium exposure was associated with lower fetal size, but I haven’t seen follow-up on neurodevelopmental outcomes.

The point is that there is a lot of variability here. It would be really interesting to map groundwater lithium levels to autism rates around the world. As a teaser, I will point out that, if you look at worldwide autism rates, you may be able to convince yourself that they are higher in more arid climates, and arid climates tend to have more groundwater lithium. But I’m really reaching here. More work needs to be done.

And I hope it is done quickly. Lithium is in the midst of becoming a very important commodity thanks to the shift to electric vehicles. While we can hope that recycling will claim most of those batteries at the end of their life, some will escape reclamation and potentially put more lithium into the drinking water. I’d like to know how risky that is before it happens.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t”, is available now.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The sacrifice of orthodoxy: Maintaining collegiality in psychiatry

Psychiatrists practice in a wide array of ways. We approach our work and our patients with beliefs and preconceptions that develop over time. Our training has significant influence, though our own personalities and biases also affect our understanding.

Psychiatrists have philosophical lenses through which they see patients. We can reflect and see some standard archetypes. We are familiar with the reductionistic pharmacologist, the somatic treatment specialist, the psychodynamic ‘guru,’ and the medicolegally paralyzed practitioner. It is without judgment that we lay these out, for our very point is that we have these constituent parts within our own clinical identities. The intensity with which we subscribe to these clinical sensibilities could contribute to a biased orthodoxy.

Orthodoxy can be defined as an accepted theory that stems from an authoritative entity. This is a well-known phenomenon that continues to be visible. For example, one can quickly peruse psychodynamic literature to find one school of thought criticizing another. It is not without some confrontation and even interpersonal rifts that the lineage of psychoanalytic theory has evolved. This has always been of interest to us. A core facet of psychoanalysis is empathy, truly knowing the inner state of a different person. And yet, the very bastions of this clinical sensibility frequently resort to veiled attacks on those in their field who have opposing views. It then begs the question: If even enlightened institutions fail at a nonjudgmental approach toward their colleagues, what hope is there for the rest of us clinicians, mired in the thick of day-to-day clinical practice?

It is our contention that the odds are against us. Even the aforementioned critique of psychoanalytic orthodoxy is just another example of how we humans organize our experience. Even as we write an article in argument against unbridled critique, we find it difficult to do so without engaging in it. For to criticize another is to help shore up our own personal identities. This is especially the case when clinicians deal with issues that we feel strongly about. The human psyche has a need to organize its experience, as “our experience of ourselves is fundamental to how we operate in the world. Our subjective experience is the phenomenology of all that one might be aware of.”1

In this vein, we would like to cite attribution theory. This is a view of human behavior within social psychology. The Austrian psychologist Fritz Heider, PhD, investigated “the domain of social interactions, wondering how people perceive each other in interaction and especially how they make sense of each other’s behavior.”2 Attribution theory suggests that as humans organize our social interactions, we may make two basic assumptions. One is that our own behavior is highly affected by an environment that is beyond our control. The second is that when judging the behavior of others, we are more likely to attribute it to internal traits that they have. A classic example is automobile traffic. When we see someone driving erratically, we are more likely to blame them for being an inherently bad driver. However, if attention is called to our own driving, we are more likely to cite external factors such as rush hour, a bad driver around us, or a faulty vehicle.

We would like to reference one last model of human behavior. It has become customary within the field of neuroscience to view the brain as a predictive organ: “Theories of prediction in perception, action, and learning suggest that the brain serves to reduce the discrepancies between expectation and actual experience, i.e., by reducing the prediction error.”3 Perception itself has recently been described as a controlled hallucination, where the brain makes predictions of what it thinks it is about to see based on past experiences. Visual stimulus ultimately takes time to enter our eyes and be processed in the brain – “predictions would need to preactivate neural representations that would typically be driven by sensory input, before the actual arrival of that input.”4 It thus seems to be an inherent method of the brain to anticipate visual and even social events to help human beings sustain themselves.

Having spoken of a psychoanalytic conceptualization of self-organization, the theory of attribution, and research into social neuroscience, we turn our attention back to the central question that this article would like to address.

When we find ourselves busy in rote clinical practice, we believe the likelihood of intercollegiate mentalization is low; our ability to relate to our peers becomes strained. We ultimately do not practice in a vacuum. Psychiatrists, even those in a solo private practice, are ultimately part of a community of providers who, more or less, follow some emergent ‘standard of care.’ This can be a vague concept; but one that takes on a concrete form in the minds of certain clinicians and certainly in the setting of a medicolegal court. Yet, the psychiatrists that we know all have very stereotyped ways of practice. And at the heart of it, we all think that we are right.

We can use polypharmacy as an example. Imagine that you have a new patient intake, who tells you that they are transferring care from another psychiatrist. They inform you of their medication regimen. This patient presents on eight or more psychotropics. Many of us may have a visceral reaction at this point and, following the aforementioned attribution theory, we may ask ourselves what ‘quack’ of a doctor would do this. Yet some among us would think that a very competent psychopharmacologist was daring enough to use the full armamentarium of psychopharmacology to help this patient, who must be treatment refractory.

When speaking with such a patient, we would be quick to reflect on our own parsimonious use of medications. We would tell ourselves that we are responsible providers and would be quick to recommend discontinuation of medications. This would help us feel better about ourselves, and would of course assuage the ever-present medicolegal ‘big brother’ in our minds. It is through this very process that we affirm our self-identities. For if this patient’s previous physician was a bad psychiatrist, then we are a good psychiatrist. It is through this process that our clinical selves find confirmation.

We do not mean to reduce the complexities of human behavior to quick stereotypes. However, it is our belief that when confronted with clinical or philosophical disputes with our colleagues, the basic rules of human behavior will attempt to dissolve and override efforts at mentalization, collegiality, or interpersonal sensitivity. For to accept a clinical practice view that is different from ours would be akin to giving up the essence of our clinical identities. It could be compared to the fragmentation process of a vulnerable psyche when confronted with a reality that is at odds with preconceived notions and experiences.

While we may be able to appreciate the nuances and sensibilities of another provider, we believe it would be particularly difficult for most of us to actually attempt to practice in a fashion that is not congruent with our own organizers of experience. Whether or not our practice style is ‘perfect,’ it has worked for us. Social neuroscience and our understanding of the organization of the self would predict that we would hold onto our way of practice with all the mind’s defenses. Externalization, denial, and projection could all be called into action in this battle against existential fragmentation.

Do we seek to portray a clinical world where there is no hope for genuine modeling of clinical sensibilities to other psychiatrists? That is not our intention. Yet it seems that many of the theoretical frameworks that we subscribe to argue against this possibility. We would be hypocritical if we did not here state that our own theoretical frameworks are yet other examples of “organizers of experience.” Attribution theory, intersubjectivity, and social neuroscience are simply our ways of organizing the chaos of perceptions, ideas, and intricacies of human behavior.

If we accept that psychiatrists, like all human beings, are trapped in a subjective experience, then we can be more playful and flexible when interacting with our colleagues. We do not have to be as defensive of our practices and accusatory of others. If we practice daily according to some orthodoxy, then we color our experiences of the patient and of our colleagues’ ways of practice. We automatically start off on the wrong foot. And yet, to give up this orthodoxy would, by definition, be disorganizing and fragmenting to us. For as Nietzsche said, “truth is an illusion without which a certain species could not survive.”5

Dr. Khalafian practices full time as a general outpatient psychiatrist. He trained at the University of California, San Diego, for his psychiatric residency and currently works as a telepsychiatrist, serving an outpatient clinic population in northern California. Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com. Dr. Badre and Dr. Khalafian have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Buirski P and Haglund P. Making sense together: The intersubjective approach to psychotherapy. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 2001.

2. Malle BF. Attribution theories: How people make sense of behavior. In Chadee D (ed.), Theories in social psychology. pp. 72-95. Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

3. Brown EC and Brune M. The role of prediction in social neuroscience. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012 May 24;6:147. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00147.

4. Blom T et al. Predictions drive neural representations of visual events ahead of incoming sensory information. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020 Mar 31;117(13):7510-7515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1917777117.

5. Yalom I. The Gift of Therapy. Harper Perennial; 2002.

Psychiatrists practice in a wide array of ways. We approach our work and our patients with beliefs and preconceptions that develop over time. Our training has significant influence, though our own personalities and biases also affect our understanding.

Psychiatrists have philosophical lenses through which they see patients. We can reflect and see some standard archetypes. We are familiar with the reductionistic pharmacologist, the somatic treatment specialist, the psychodynamic ‘guru,’ and the medicolegally paralyzed practitioner. It is without judgment that we lay these out, for our very point is that we have these constituent parts within our own clinical identities. The intensity with which we subscribe to these clinical sensibilities could contribute to a biased orthodoxy.

Orthodoxy can be defined as an accepted theory that stems from an authoritative entity. This is a well-known phenomenon that continues to be visible. For example, one can quickly peruse psychodynamic literature to find one school of thought criticizing another. It is not without some confrontation and even interpersonal rifts that the lineage of psychoanalytic theory has evolved. This has always been of interest to us. A core facet of psychoanalysis is empathy, truly knowing the inner state of a different person. And yet, the very bastions of this clinical sensibility frequently resort to veiled attacks on those in their field who have opposing views. It then begs the question: If even enlightened institutions fail at a nonjudgmental approach toward their colleagues, what hope is there for the rest of us clinicians, mired in the thick of day-to-day clinical practice?

It is our contention that the odds are against us. Even the aforementioned critique of psychoanalytic orthodoxy is just another example of how we humans organize our experience. Even as we write an article in argument against unbridled critique, we find it difficult to do so without engaging in it. For to criticize another is to help shore up our own personal identities. This is especially the case when clinicians deal with issues that we feel strongly about. The human psyche has a need to organize its experience, as “our experience of ourselves is fundamental to how we operate in the world. Our subjective experience is the phenomenology of all that one might be aware of.”1

In this vein, we would like to cite attribution theory. This is a view of human behavior within social psychology. The Austrian psychologist Fritz Heider, PhD, investigated “the domain of social interactions, wondering how people perceive each other in interaction and especially how they make sense of each other’s behavior.”2 Attribution theory suggests that as humans organize our social interactions, we may make two basic assumptions. One is that our own behavior is highly affected by an environment that is beyond our control. The second is that when judging the behavior of others, we are more likely to attribute it to internal traits that they have. A classic example is automobile traffic. When we see someone driving erratically, we are more likely to blame them for being an inherently bad driver. However, if attention is called to our own driving, we are more likely to cite external factors such as rush hour, a bad driver around us, or a faulty vehicle.

We would like to reference one last model of human behavior. It has become customary within the field of neuroscience to view the brain as a predictive organ: “Theories of prediction in perception, action, and learning suggest that the brain serves to reduce the discrepancies between expectation and actual experience, i.e., by reducing the prediction error.”3 Perception itself has recently been described as a controlled hallucination, where the brain makes predictions of what it thinks it is about to see based on past experiences. Visual stimulus ultimately takes time to enter our eyes and be processed in the brain – “predictions would need to preactivate neural representations that would typically be driven by sensory input, before the actual arrival of that input.”4 It thus seems to be an inherent method of the brain to anticipate visual and even social events to help human beings sustain themselves.

Having spoken of a psychoanalytic conceptualization of self-organization, the theory of attribution, and research into social neuroscience, we turn our attention back to the central question that this article would like to address.

When we find ourselves busy in rote clinical practice, we believe the likelihood of intercollegiate mentalization is low; our ability to relate to our peers becomes strained. We ultimately do not practice in a vacuum. Psychiatrists, even those in a solo private practice, are ultimately part of a community of providers who, more or less, follow some emergent ‘standard of care.’ This can be a vague concept; but one that takes on a concrete form in the minds of certain clinicians and certainly in the setting of a medicolegal court. Yet, the psychiatrists that we know all have very stereotyped ways of practice. And at the heart of it, we all think that we are right.

We can use polypharmacy as an example. Imagine that you have a new patient intake, who tells you that they are transferring care from another psychiatrist. They inform you of their medication regimen. This patient presents on eight or more psychotropics. Many of us may have a visceral reaction at this point and, following the aforementioned attribution theory, we may ask ourselves what ‘quack’ of a doctor would do this. Yet some among us would think that a very competent psychopharmacologist was daring enough to use the full armamentarium of psychopharmacology to help this patient, who must be treatment refractory.

When speaking with such a patient, we would be quick to reflect on our own parsimonious use of medications. We would tell ourselves that we are responsible providers and would be quick to recommend discontinuation of medications. This would help us feel better about ourselves, and would of course assuage the ever-present medicolegal ‘big brother’ in our minds. It is through this very process that we affirm our self-identities. For if this patient’s previous physician was a bad psychiatrist, then we are a good psychiatrist. It is through this process that our clinical selves find confirmation.

We do not mean to reduce the complexities of human behavior to quick stereotypes. However, it is our belief that when confronted with clinical or philosophical disputes with our colleagues, the basic rules of human behavior will attempt to dissolve and override efforts at mentalization, collegiality, or interpersonal sensitivity. For to accept a clinical practice view that is different from ours would be akin to giving up the essence of our clinical identities. It could be compared to the fragmentation process of a vulnerable psyche when confronted with a reality that is at odds with preconceived notions and experiences.

While we may be able to appreciate the nuances and sensibilities of another provider, we believe it would be particularly difficult for most of us to actually attempt to practice in a fashion that is not congruent with our own organizers of experience. Whether or not our practice style is ‘perfect,’ it has worked for us. Social neuroscience and our understanding of the organization of the self would predict that we would hold onto our way of practice with all the mind’s defenses. Externalization, denial, and projection could all be called into action in this battle against existential fragmentation.

Do we seek to portray a clinical world where there is no hope for genuine modeling of clinical sensibilities to other psychiatrists? That is not our intention. Yet it seems that many of the theoretical frameworks that we subscribe to argue against this possibility. We would be hypocritical if we did not here state that our own theoretical frameworks are yet other examples of “organizers of experience.” Attribution theory, intersubjectivity, and social neuroscience are simply our ways of organizing the chaos of perceptions, ideas, and intricacies of human behavior.

If we accept that psychiatrists, like all human beings, are trapped in a subjective experience, then we can be more playful and flexible when interacting with our colleagues. We do not have to be as defensive of our practices and accusatory of others. If we practice daily according to some orthodoxy, then we color our experiences of the patient and of our colleagues’ ways of practice. We automatically start off on the wrong foot. And yet, to give up this orthodoxy would, by definition, be disorganizing and fragmenting to us. For as Nietzsche said, “truth is an illusion without which a certain species could not survive.”5

Dr. Khalafian practices full time as a general outpatient psychiatrist. He trained at the University of California, San Diego, for his psychiatric residency and currently works as a telepsychiatrist, serving an outpatient clinic population in northern California. Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com. Dr. Badre and Dr. Khalafian have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Buirski P and Haglund P. Making sense together: The intersubjective approach to psychotherapy. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 2001.

2. Malle BF. Attribution theories: How people make sense of behavior. In Chadee D (ed.), Theories in social psychology. pp. 72-95. Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

3. Brown EC and Brune M. The role of prediction in social neuroscience. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012 May 24;6:147. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00147.

4. Blom T et al. Predictions drive neural representations of visual events ahead of incoming sensory information. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020 Mar 31;117(13):7510-7515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1917777117.

5. Yalom I. The Gift of Therapy. Harper Perennial; 2002.

Psychiatrists practice in a wide array of ways. We approach our work and our patients with beliefs and preconceptions that develop over time. Our training has significant influence, though our own personalities and biases also affect our understanding.

Psychiatrists have philosophical lenses through which they see patients. We can reflect and see some standard archetypes. We are familiar with the reductionistic pharmacologist, the somatic treatment specialist, the psychodynamic ‘guru,’ and the medicolegally paralyzed practitioner. It is without judgment that we lay these out, for our very point is that we have these constituent parts within our own clinical identities. The intensity with which we subscribe to these clinical sensibilities could contribute to a biased orthodoxy.

Orthodoxy can be defined as an accepted theory that stems from an authoritative entity. This is a well-known phenomenon that continues to be visible. For example, one can quickly peruse psychodynamic literature to find one school of thought criticizing another. It is not without some confrontation and even interpersonal rifts that the lineage of psychoanalytic theory has evolved. This has always been of interest to us. A core facet of psychoanalysis is empathy, truly knowing the inner state of a different person. And yet, the very bastions of this clinical sensibility frequently resort to veiled attacks on those in their field who have opposing views. It then begs the question: If even enlightened institutions fail at a nonjudgmental approach toward their colleagues, what hope is there for the rest of us clinicians, mired in the thick of day-to-day clinical practice?

It is our contention that the odds are against us. Even the aforementioned critique of psychoanalytic orthodoxy is just another example of how we humans organize our experience. Even as we write an article in argument against unbridled critique, we find it difficult to do so without engaging in it. For to criticize another is to help shore up our own personal identities. This is especially the case when clinicians deal with issues that we feel strongly about. The human psyche has a need to organize its experience, as “our experience of ourselves is fundamental to how we operate in the world. Our subjective experience is the phenomenology of all that one might be aware of.”1

In this vein, we would like to cite attribution theory. This is a view of human behavior within social psychology. The Austrian psychologist Fritz Heider, PhD, investigated “the domain of social interactions, wondering how people perceive each other in interaction and especially how they make sense of each other’s behavior.”2 Attribution theory suggests that as humans organize our social interactions, we may make two basic assumptions. One is that our own behavior is highly affected by an environment that is beyond our control. The second is that when judging the behavior of others, we are more likely to attribute it to internal traits that they have. A classic example is automobile traffic. When we see someone driving erratically, we are more likely to blame them for being an inherently bad driver. However, if attention is called to our own driving, we are more likely to cite external factors such as rush hour, a bad driver around us, or a faulty vehicle.

We would like to reference one last model of human behavior. It has become customary within the field of neuroscience to view the brain as a predictive organ: “Theories of prediction in perception, action, and learning suggest that the brain serves to reduce the discrepancies between expectation and actual experience, i.e., by reducing the prediction error.”3 Perception itself has recently been described as a controlled hallucination, where the brain makes predictions of what it thinks it is about to see based on past experiences. Visual stimulus ultimately takes time to enter our eyes and be processed in the brain – “predictions would need to preactivate neural representations that would typically be driven by sensory input, before the actual arrival of that input.”4 It thus seems to be an inherent method of the brain to anticipate visual and even social events to help human beings sustain themselves.

Having spoken of a psychoanalytic conceptualization of self-organization, the theory of attribution, and research into social neuroscience, we turn our attention back to the central question that this article would like to address.

When we find ourselves busy in rote clinical practice, we believe the likelihood of intercollegiate mentalization is low; our ability to relate to our peers becomes strained. We ultimately do not practice in a vacuum. Psychiatrists, even those in a solo private practice, are ultimately part of a community of providers who, more or less, follow some emergent ‘standard of care.’ This can be a vague concept; but one that takes on a concrete form in the minds of certain clinicians and certainly in the setting of a medicolegal court. Yet, the psychiatrists that we know all have very stereotyped ways of practice. And at the heart of it, we all think that we are right.

We can use polypharmacy as an example. Imagine that you have a new patient intake, who tells you that they are transferring care from another psychiatrist. They inform you of their medication regimen. This patient presents on eight or more psychotropics. Many of us may have a visceral reaction at this point and, following the aforementioned attribution theory, we may ask ourselves what ‘quack’ of a doctor would do this. Yet some among us would think that a very competent psychopharmacologist was daring enough to use the full armamentarium of psychopharmacology to help this patient, who must be treatment refractory.

When speaking with such a patient, we would be quick to reflect on our own parsimonious use of medications. We would tell ourselves that we are responsible providers and would be quick to recommend discontinuation of medications. This would help us feel better about ourselves, and would of course assuage the ever-present medicolegal ‘big brother’ in our minds. It is through this very process that we affirm our self-identities. For if this patient’s previous physician was a bad psychiatrist, then we are a good psychiatrist. It is through this process that our clinical selves find confirmation.

We do not mean to reduce the complexities of human behavior to quick stereotypes. However, it is our belief that when confronted with clinical or philosophical disputes with our colleagues, the basic rules of human behavior will attempt to dissolve and override efforts at mentalization, collegiality, or interpersonal sensitivity. For to accept a clinical practice view that is different from ours would be akin to giving up the essence of our clinical identities. It could be compared to the fragmentation process of a vulnerable psyche when confronted with a reality that is at odds with preconceived notions and experiences.

While we may be able to appreciate the nuances and sensibilities of another provider, we believe it would be particularly difficult for most of us to actually attempt to practice in a fashion that is not congruent with our own organizers of experience. Whether or not our practice style is ‘perfect,’ it has worked for us. Social neuroscience and our understanding of the organization of the self would predict that we would hold onto our way of practice with all the mind’s defenses. Externalization, denial, and projection could all be called into action in this battle against existential fragmentation.

Do we seek to portray a clinical world where there is no hope for genuine modeling of clinical sensibilities to other psychiatrists? That is not our intention. Yet it seems that many of the theoretical frameworks that we subscribe to argue against this possibility. We would be hypocritical if we did not here state that our own theoretical frameworks are yet other examples of “organizers of experience.” Attribution theory, intersubjectivity, and social neuroscience are simply our ways of organizing the chaos of perceptions, ideas, and intricacies of human behavior.

If we accept that psychiatrists, like all human beings, are trapped in a subjective experience, then we can be more playful and flexible when interacting with our colleagues. We do not have to be as defensive of our practices and accusatory of others. If we practice daily according to some orthodoxy, then we color our experiences of the patient and of our colleagues’ ways of practice. We automatically start off on the wrong foot. And yet, to give up this orthodoxy would, by definition, be disorganizing and fragmenting to us. For as Nietzsche said, “truth is an illusion without which a certain species could not survive.”5

Dr. Khalafian practices full time as a general outpatient psychiatrist. He trained at the University of California, San Diego, for his psychiatric residency and currently works as a telepsychiatrist, serving an outpatient clinic population in northern California. Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com. Dr. Badre and Dr. Khalafian have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Buirski P and Haglund P. Making sense together: The intersubjective approach to psychotherapy. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 2001.

2. Malle BF. Attribution theories: How people make sense of behavior. In Chadee D (ed.), Theories in social psychology. pp. 72-95. Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

3. Brown EC and Brune M. The role of prediction in social neuroscience. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012 May 24;6:147. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00147.

4. Blom T et al. Predictions drive neural representations of visual events ahead of incoming sensory information. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020 Mar 31;117(13):7510-7515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1917777117.

5. Yalom I. The Gift of Therapy. Harper Perennial; 2002.

Melasma

THE COMPARISON

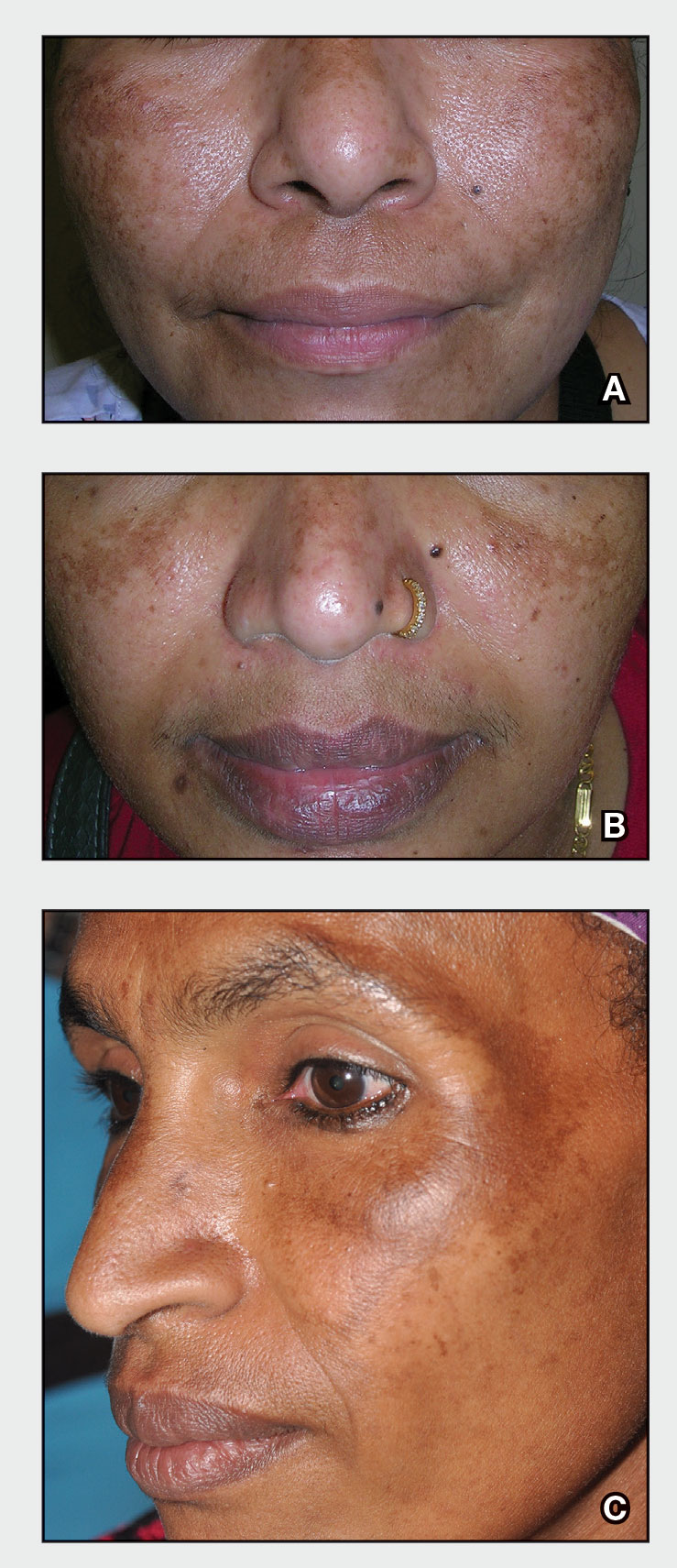

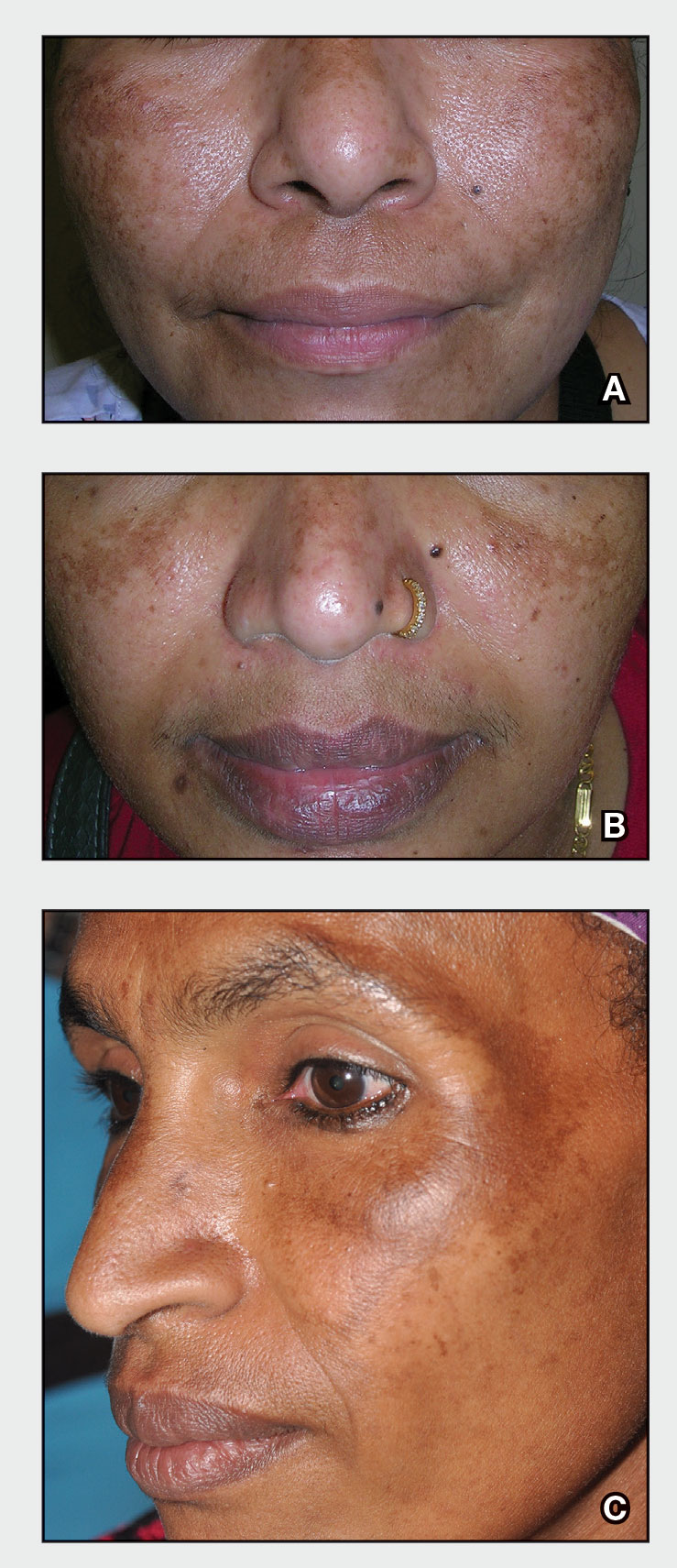

A Melasma on the face of a Hispanic woman, with hyperpigmentation on the cheeks, bridge of the nose, and upper lip.

B Melasma on the face of a Malaysian woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and bridge of the nose.

C Melasma on the face of an African woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and lateral to the eyes.

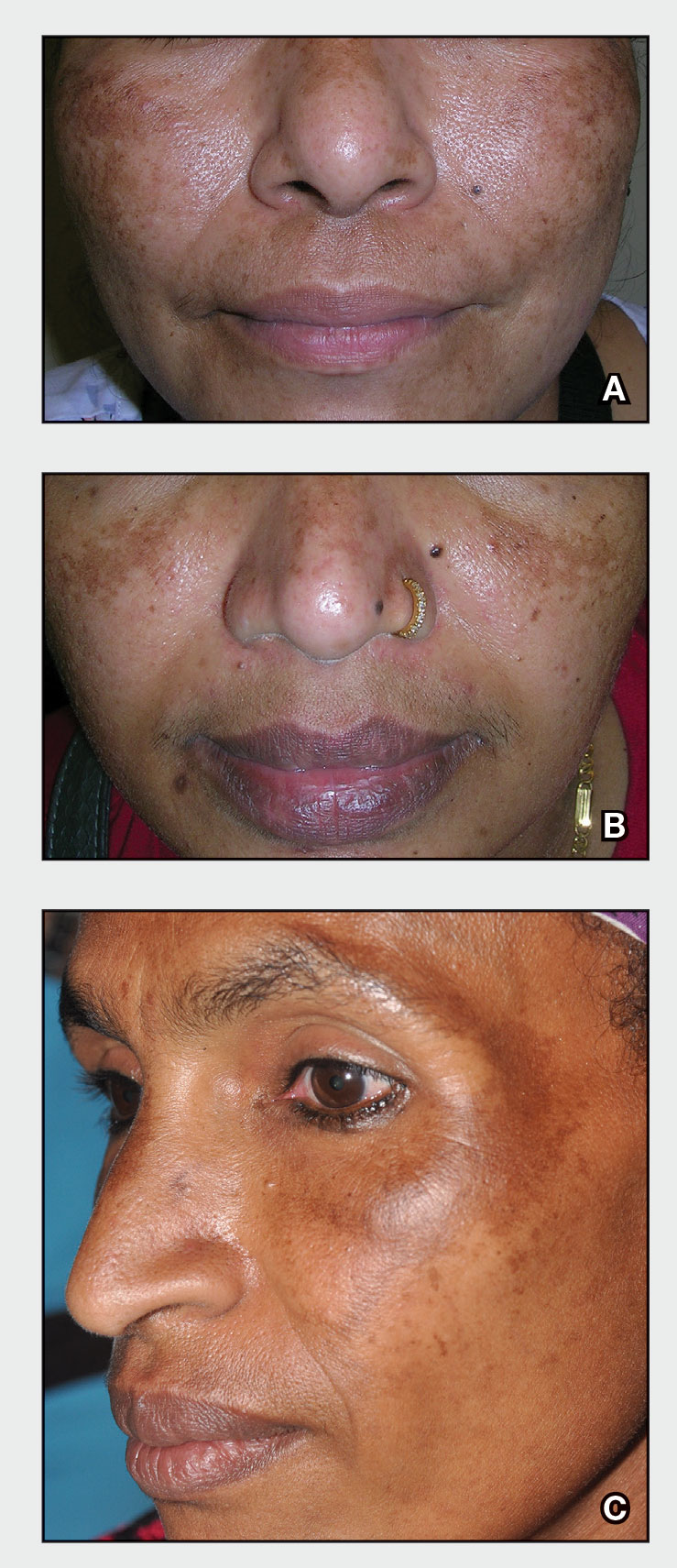

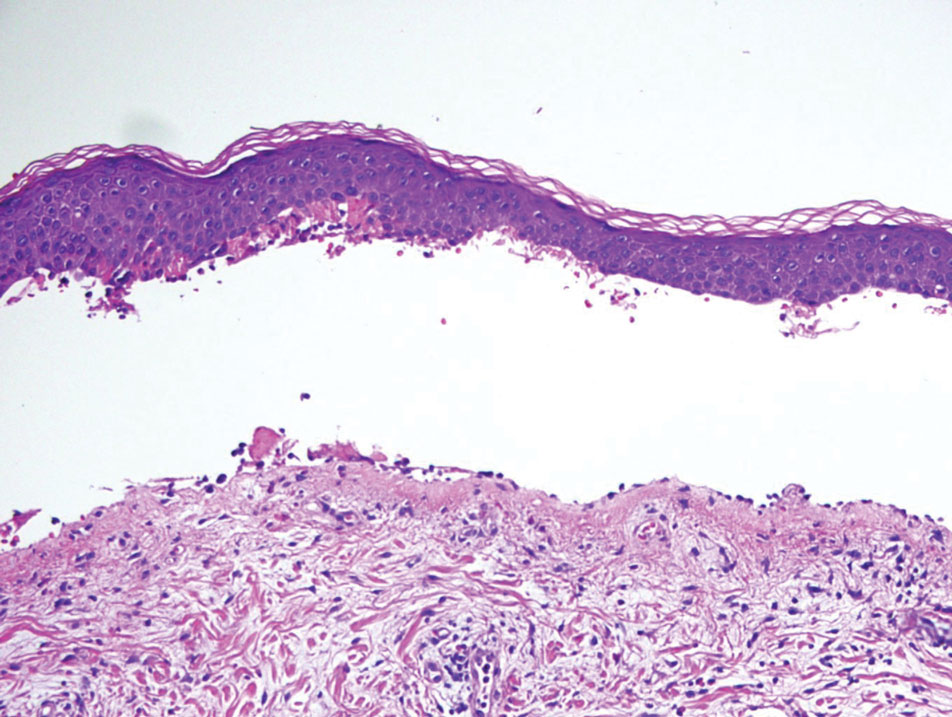

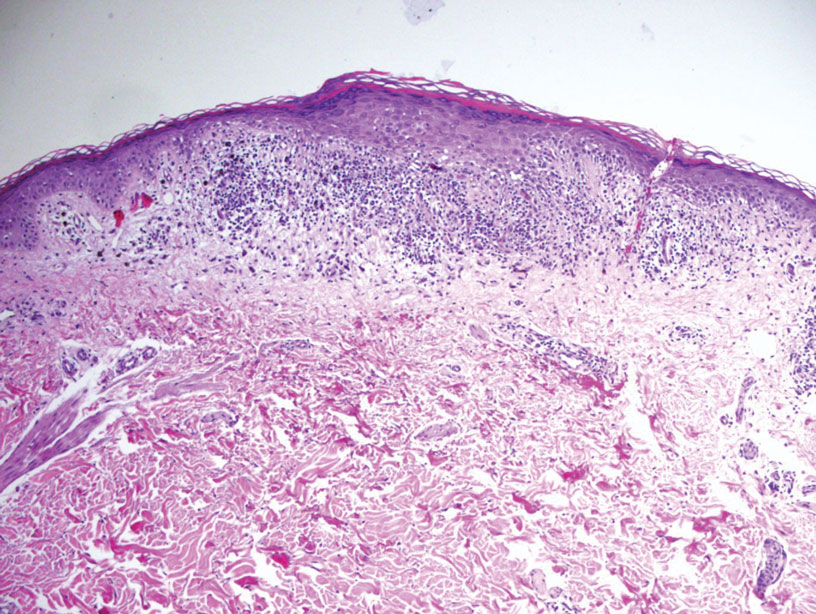

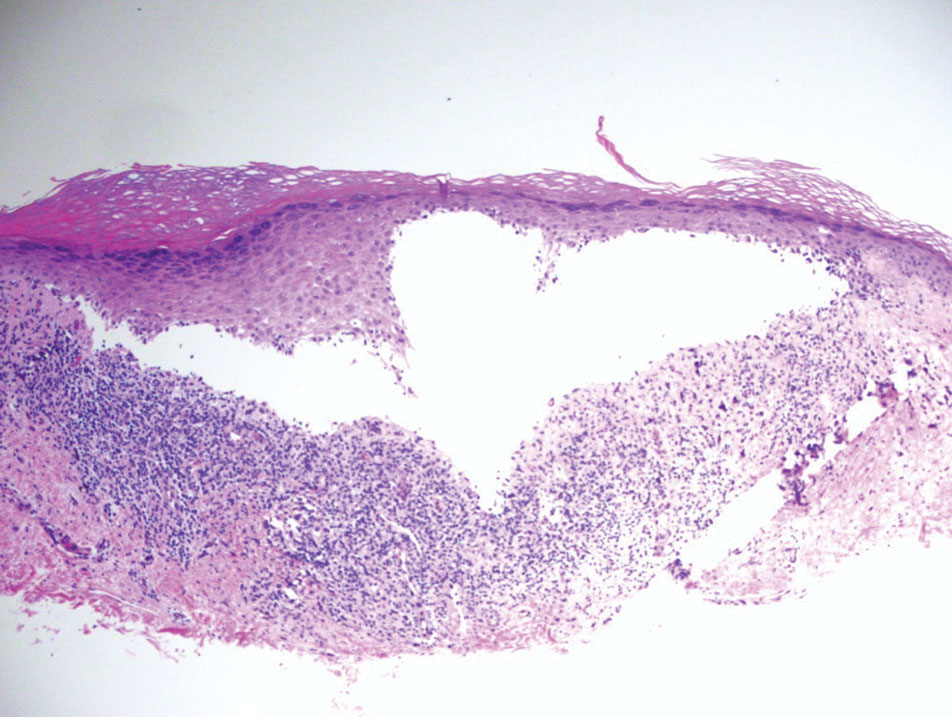

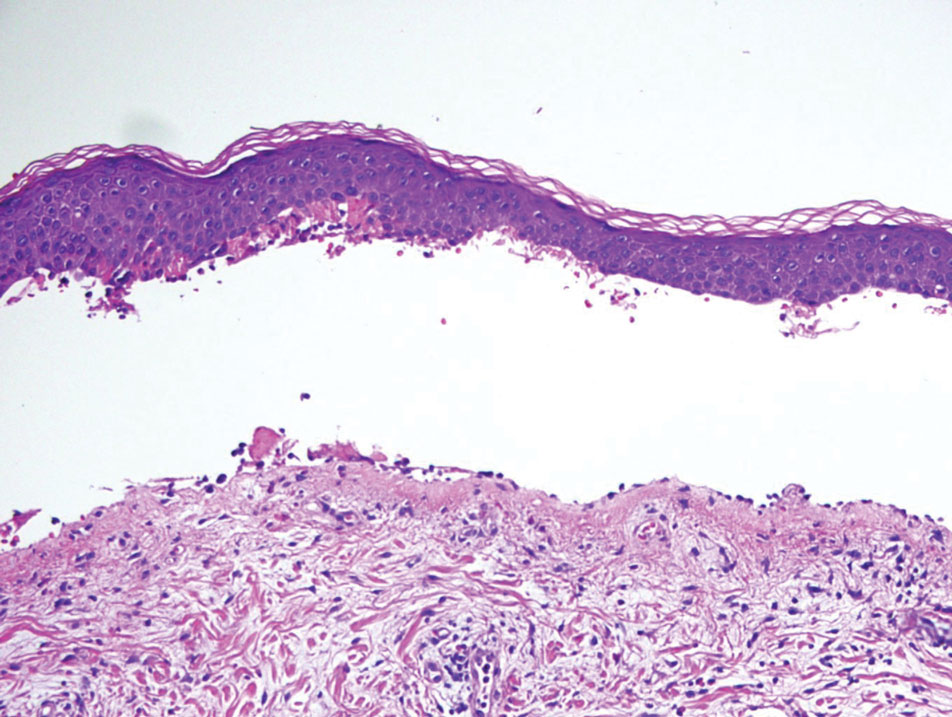

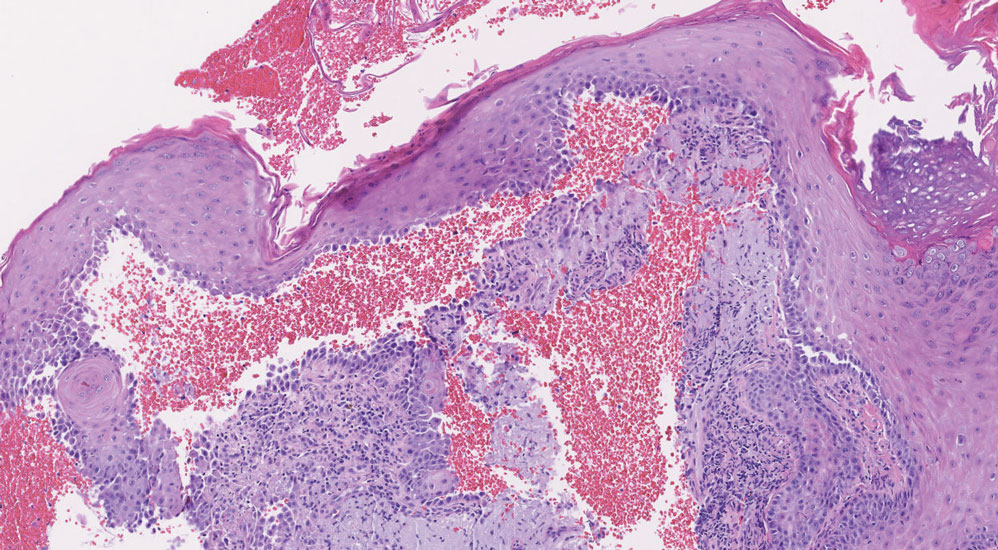

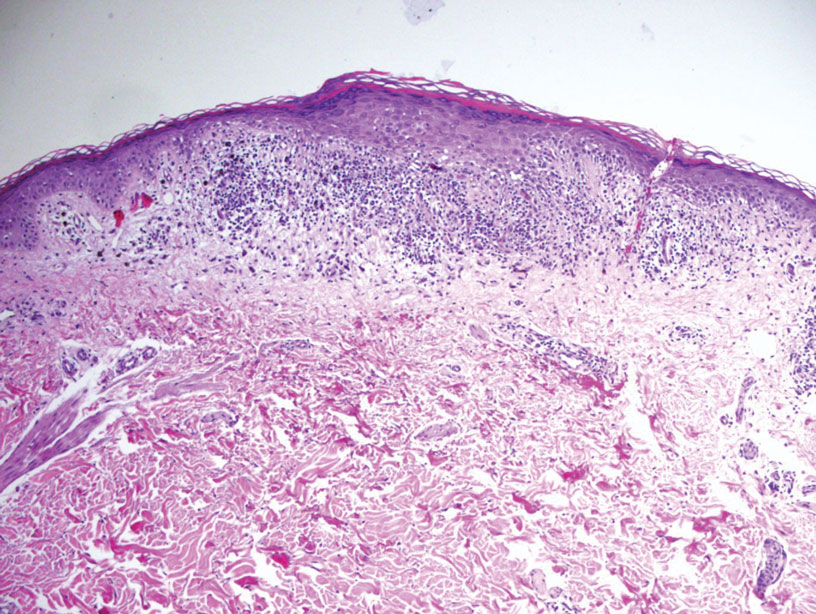

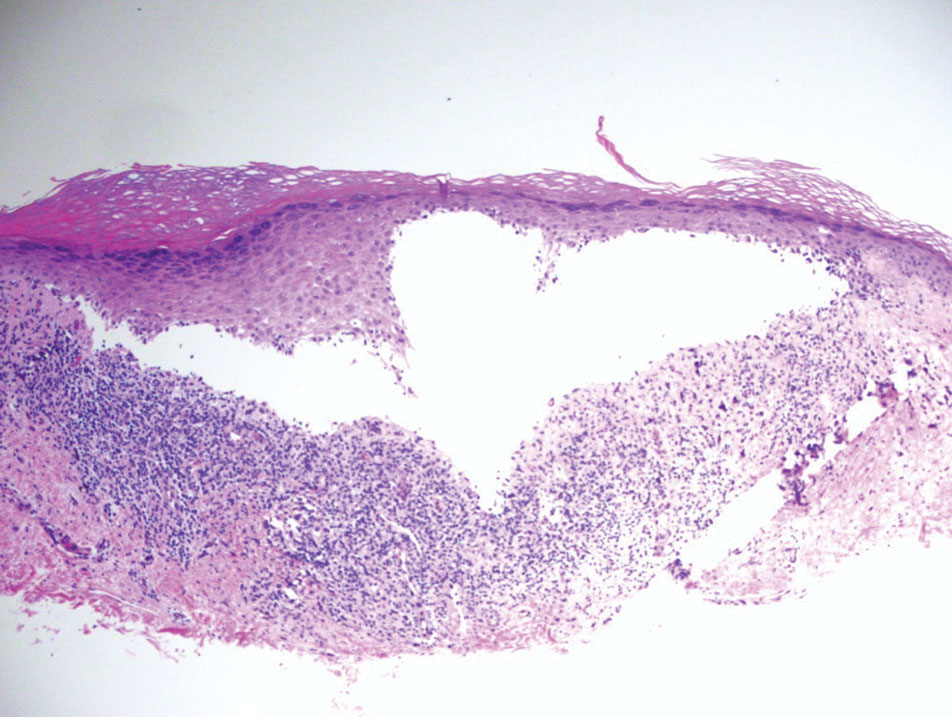

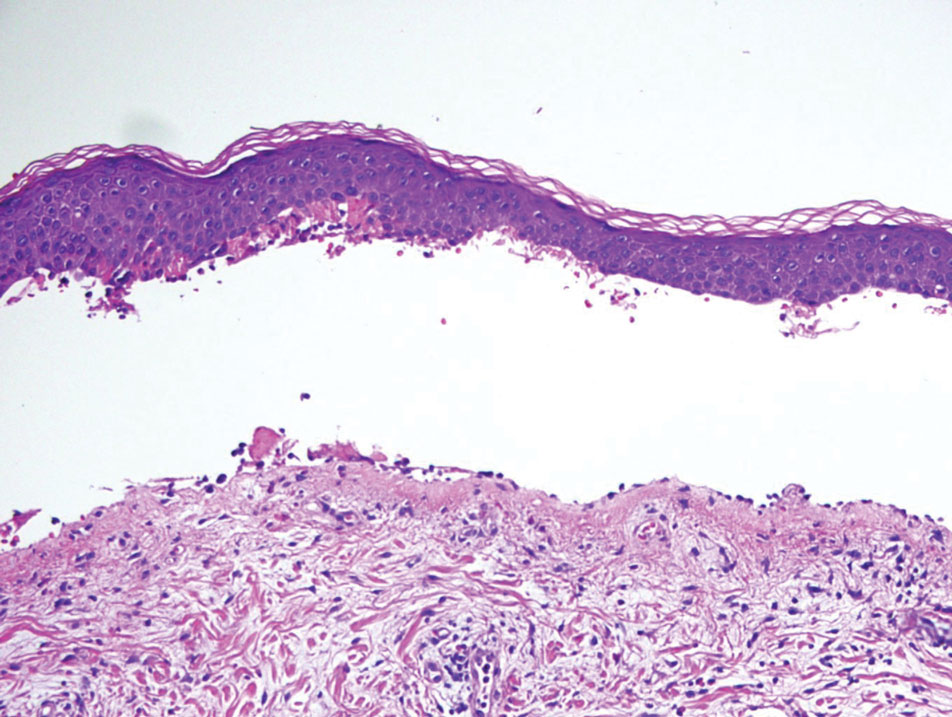

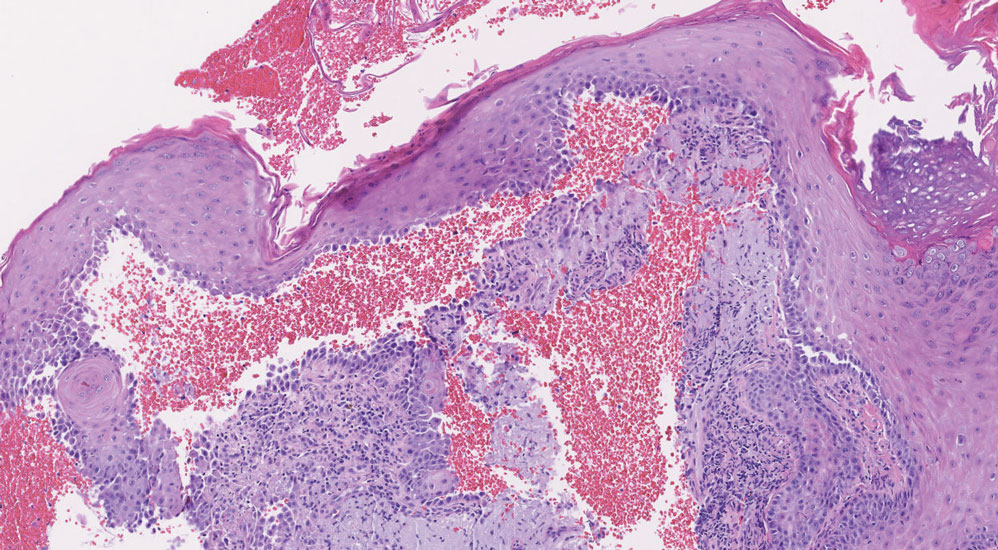

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is a pigmentary disorder that causes chronic symmetric hyperpigmentation on the face. In patients with darker skin tones, centrofacial areas are affected.1 Increased deposition of melanin distributed in the dermis leads to dermal melanosis. Newer research suggests that mast cell and keratinocyte interactions, altered gene regulation, neovascularization, and disruptions in the basement membrane cause melasma.2 Patients present with epidermal or dermal melasma or a combination of both (mixed melasma).3 Wood lamp examination is helpful to distinguish between epidermal and dermal melasma. Dermal and mixed melasma can be difficult to treat and require multimodal treatments.

Epidemiology

Melasma commonly affects women aged 20 to 40 years,4 with a female to male ratio of 9:1.5 Potential triggers of melasma include hormones (eg, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy) and exposure to UV light.2,5 Melasma occurs in patients of all racial and ethnic backgrounds; however, the prevalence is higher in patients with darker skin tones.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melasma commonly manifests as symmetrically distributed, reticulated (lacy), dark brown to grayish brown patches on the cheeks, nose, forehead, upper lip, and chin in patients with darker skin tones.5 The pigment can be tan brown in patients with lighter skin tones. Given that postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and other pigmentary disorders can cause a similar appearance, a biopsy sometimes is needed to confirm the diagnosis, but melasma is diagnosed via physical examination in most patients. Melasma can be misdiagnosed as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, solar lentigines, exogenous ochronosis, and Hori nevus.5

Worth noting

Prevention

• Daily sunscreen use is critical to prevent worsening of melasma. Sunscreen may not appear cosmetically elegant on darker skin tones, which creates a barrier to its use.6 Protection from both sunlight and visible light is necessary. Visible light, including light from light bulbs and device-emitted blue light, can worsen melasma. Iron oxides in tinted sunscreen offer protection from visible light.

• Physicians can recommend sunscreens that are more transparent or tinted for a better cosmetic match.

• Severe flares of melasma can occur with sun exposure despite good control with medications and laser modalities.

Treatment

• First-line therapies include topical hydroquinone 2% to 4%, tretinoin, azelaic acid, kojic acid, or ascorbic acid (vitamin C). A popular topical compound is a steroid, tretinoin, and hydroquinone.1,5 Over-the-counter hydroquinone has been removed from the market due to safety concerns; however, it is still first line in the treatment of melasma. If hydroquinone is prescribed, treatment intervals of 6 to 8 weeks followed by a hydroquinone-free period is advised to reduce the risk for exogenous ochronosis (a paradoxical darkening of the skin).

• Chemical peels are second-line treatments that are effective for melasma. Improvement in epidermal melasma has been shown with chemical peels containing Jessner solution, salicylic acid, or α-hydroxy acid. Patients with dermal and mixed melasma have seen improvement with trichloroacetic acid 25% to 35% with or without Jessner solution.1

• Cysteamine is a topical treatment created from the degradation of coenzyme A. It disrupts the synthesis of melanin to create a more even skin tone. It may be recommended in combination with sunscreen as a first-line or second-line topical therapy.

• Oral tranexamic acid is a third-line treatment that is an analogue for lysine. It decreases prostaglandin production, which leads to a lower number of tyrosine precursors available for the creation of melanin. Tranexamic acid has been shown to lighten the appearance of melasma.7 The most common and dangerous adverse effect of tranexamic acid is blood clots and this treatment should be avoided in those on combination (estrogen and progestin) contraceptives or those with a personal or family history of clotting disorders.8

• Fourth-line treatments such as lasers (performed by dermatologists) can destroy the deposition of pigment while avoiding destruction of epidermal keratinocytes.1,9,10 They also are commonly employed in refractive melasma. The most common lasers are nonablative fractionated lasers and low-fluence Q-switched lasers. The Q-switched Nd:YAG and picosecond lasers are safe for treating melasma in darker skin tones. Ablative fractionated lasers such as CO2 lasers and erbium:YAG lasers also have been used in the treatment of melasma; however, there is still an extremely high risk for postinflammatory dyspigmentation 1 to 2 months after the procedure.10

• Although there is still a risk for rebound hyperpigmentation after laser treatment, use of topical hydroquinone pretreatment may help decrease postoperative hyperpigmentation.1,5 Patients who are treated with the incorrect laser or overtreated may develop postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, rebound hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation.

Health disparity highlight

Melasma, most common in patients with skin of color, is a common chronic pigmentation disorder that is cosmetically and psychologically burdensome,11 leading to decreased quality of life, emotional functioning, and selfesteem.12 Clinicians should counsel patients and work closely on long-term management. The treatment options for melasma are considered cosmetic and may be cost prohibitive for many to cover out-of-pocket. Topical treatments have been found to be the most cost-effective.13 Some compounding pharmacies and drug discount programs provide more affordable treatment pricing; however, some patients are still unable to afford these options.

- Cunha PR, Kroumpouzos G. Melasma and vitiligo: novel and experimental therapies. J Clin Exp Derm Res. 2016;7:2. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000e106

- Rajanala S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Melasma pathogenesis: a review of the latest research, pathological findings, and investigational therapies. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt47b7r28c.

- Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

- Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: a clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380-382.

- Ogbechie-Godec OA, Elbuluk N. Melasma: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:305-318.

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1337-1338.

- Taraz M, Nikham S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: a comprehensive review of clinical studies [published online January 30, 2017]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.12465

- Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-825.

- Castanedo-Cazares JP, Hernandez-Blanco D, Carlos-Ortega B, et al. Near-visible light and UV photoprotection in the treatment of melasma: a double-blind randomized trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:35-42.

- Trivedi MK, Yang FC, Cho BK. A review of laser and light therapy in melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:11-20.

- Dodmani PN, Deshmukh AR. Assessment of quality of life of melasma patients as per melasma quality of life scale (MELASQoL). Pigment Int. 2020;7:75-79.

- Balkrishnan R, McMichael A, Camacho FT, et al. Development and validation of a health‐related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:572-577.

- Alikhan A, Daly M, Wu J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a hydroquinone /tretinoin/fluocinolone acetonide cream combination in treating melasma in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:276-281.

THE COMPARISON

A Melasma on the face of a Hispanic woman, with hyperpigmentation on the cheeks, bridge of the nose, and upper lip.

B Melasma on the face of a Malaysian woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and bridge of the nose.

C Melasma on the face of an African woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and lateral to the eyes.

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is a pigmentary disorder that causes chronic symmetric hyperpigmentation on the face. In patients with darker skin tones, centrofacial areas are affected.1 Increased deposition of melanin distributed in the dermis leads to dermal melanosis. Newer research suggests that mast cell and keratinocyte interactions, altered gene regulation, neovascularization, and disruptions in the basement membrane cause melasma.2 Patients present with epidermal or dermal melasma or a combination of both (mixed melasma).3 Wood lamp examination is helpful to distinguish between epidermal and dermal melasma. Dermal and mixed melasma can be difficult to treat and require multimodal treatments.

Epidemiology

Melasma commonly affects women aged 20 to 40 years,4 with a female to male ratio of 9:1.5 Potential triggers of melasma include hormones (eg, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy) and exposure to UV light.2,5 Melasma occurs in patients of all racial and ethnic backgrounds; however, the prevalence is higher in patients with darker skin tones.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melasma commonly manifests as symmetrically distributed, reticulated (lacy), dark brown to grayish brown patches on the cheeks, nose, forehead, upper lip, and chin in patients with darker skin tones.5 The pigment can be tan brown in patients with lighter skin tones. Given that postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and other pigmentary disorders can cause a similar appearance, a biopsy sometimes is needed to confirm the diagnosis, but melasma is diagnosed via physical examination in most patients. Melasma can be misdiagnosed as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, solar lentigines, exogenous ochronosis, and Hori nevus.5

Worth noting

Prevention

• Daily sunscreen use is critical to prevent worsening of melasma. Sunscreen may not appear cosmetically elegant on darker skin tones, which creates a barrier to its use.6 Protection from both sunlight and visible light is necessary. Visible light, including light from light bulbs and device-emitted blue light, can worsen melasma. Iron oxides in tinted sunscreen offer protection from visible light.

• Physicians can recommend sunscreens that are more transparent or tinted for a better cosmetic match.

• Severe flares of melasma can occur with sun exposure despite good control with medications and laser modalities.

Treatment

• First-line therapies include topical hydroquinone 2% to 4%, tretinoin, azelaic acid, kojic acid, or ascorbic acid (vitamin C). A popular topical compound is a steroid, tretinoin, and hydroquinone.1,5 Over-the-counter hydroquinone has been removed from the market due to safety concerns; however, it is still first line in the treatment of melasma. If hydroquinone is prescribed, treatment intervals of 6 to 8 weeks followed by a hydroquinone-free period is advised to reduce the risk for exogenous ochronosis (a paradoxical darkening of the skin).

• Chemical peels are second-line treatments that are effective for melasma. Improvement in epidermal melasma has been shown with chemical peels containing Jessner solution, salicylic acid, or α-hydroxy acid. Patients with dermal and mixed melasma have seen improvement with trichloroacetic acid 25% to 35% with or without Jessner solution.1

• Cysteamine is a topical treatment created from the degradation of coenzyme A. It disrupts the synthesis of melanin to create a more even skin tone. It may be recommended in combination with sunscreen as a first-line or second-line topical therapy.

• Oral tranexamic acid is a third-line treatment that is an analogue for lysine. It decreases prostaglandin production, which leads to a lower number of tyrosine precursors available for the creation of melanin. Tranexamic acid has been shown to lighten the appearance of melasma.7 The most common and dangerous adverse effect of tranexamic acid is blood clots and this treatment should be avoided in those on combination (estrogen and progestin) contraceptives or those with a personal or family history of clotting disorders.8

• Fourth-line treatments such as lasers (performed by dermatologists) can destroy the deposition of pigment while avoiding destruction of epidermal keratinocytes.1,9,10 They also are commonly employed in refractive melasma. The most common lasers are nonablative fractionated lasers and low-fluence Q-switched lasers. The Q-switched Nd:YAG and picosecond lasers are safe for treating melasma in darker skin tones. Ablative fractionated lasers such as CO2 lasers and erbium:YAG lasers also have been used in the treatment of melasma; however, there is still an extremely high risk for postinflammatory dyspigmentation 1 to 2 months after the procedure.10

• Although there is still a risk for rebound hyperpigmentation after laser treatment, use of topical hydroquinone pretreatment may help decrease postoperative hyperpigmentation.1,5 Patients who are treated with the incorrect laser or overtreated may develop postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, rebound hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation.

Health disparity highlight

Melasma, most common in patients with skin of color, is a common chronic pigmentation disorder that is cosmetically and psychologically burdensome,11 leading to decreased quality of life, emotional functioning, and selfesteem.12 Clinicians should counsel patients and work closely on long-term management. The treatment options for melasma are considered cosmetic and may be cost prohibitive for many to cover out-of-pocket. Topical treatments have been found to be the most cost-effective.13 Some compounding pharmacies and drug discount programs provide more affordable treatment pricing; however, some patients are still unable to afford these options.

THE COMPARISON

A Melasma on the face of a Hispanic woman, with hyperpigmentation on the cheeks, bridge of the nose, and upper lip.

B Melasma on the face of a Malaysian woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and bridge of the nose.

C Melasma on the face of an African woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and lateral to the eyes.

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is a pigmentary disorder that causes chronic symmetric hyperpigmentation on the face. In patients with darker skin tones, centrofacial areas are affected.1 Increased deposition of melanin distributed in the dermis leads to dermal melanosis. Newer research suggests that mast cell and keratinocyte interactions, altered gene regulation, neovascularization, and disruptions in the basement membrane cause melasma.2 Patients present with epidermal or dermal melasma or a combination of both (mixed melasma).3 Wood lamp examination is helpful to distinguish between epidermal and dermal melasma. Dermal and mixed melasma can be difficult to treat and require multimodal treatments.

Epidemiology

Melasma commonly affects women aged 20 to 40 years,4 with a female to male ratio of 9:1.5 Potential triggers of melasma include hormones (eg, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy) and exposure to UV light.2,5 Melasma occurs in patients of all racial and ethnic backgrounds; however, the prevalence is higher in patients with darker skin tones.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melasma commonly manifests as symmetrically distributed, reticulated (lacy), dark brown to grayish brown patches on the cheeks, nose, forehead, upper lip, and chin in patients with darker skin tones.5 The pigment can be tan brown in patients with lighter skin tones. Given that postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and other pigmentary disorders can cause a similar appearance, a biopsy sometimes is needed to confirm the diagnosis, but melasma is diagnosed via physical examination in most patients. Melasma can be misdiagnosed as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, solar lentigines, exogenous ochronosis, and Hori nevus.5

Worth noting

Prevention

• Daily sunscreen use is critical to prevent worsening of melasma. Sunscreen may not appear cosmetically elegant on darker skin tones, which creates a barrier to its use.6 Protection from both sunlight and visible light is necessary. Visible light, including light from light bulbs and device-emitted blue light, can worsen melasma. Iron oxides in tinted sunscreen offer protection from visible light.

• Physicians can recommend sunscreens that are more transparent or tinted for a better cosmetic match.

• Severe flares of melasma can occur with sun exposure despite good control with medications and laser modalities.

Treatment

• First-line therapies include topical hydroquinone 2% to 4%, tretinoin, azelaic acid, kojic acid, or ascorbic acid (vitamin C). A popular topical compound is a steroid, tretinoin, and hydroquinone.1,5 Over-the-counter hydroquinone has been removed from the market due to safety concerns; however, it is still first line in the treatment of melasma. If hydroquinone is prescribed, treatment intervals of 6 to 8 weeks followed by a hydroquinone-free period is advised to reduce the risk for exogenous ochronosis (a paradoxical darkening of the skin).

• Chemical peels are second-line treatments that are effective for melasma. Improvement in epidermal melasma has been shown with chemical peels containing Jessner solution, salicylic acid, or α-hydroxy acid. Patients with dermal and mixed melasma have seen improvement with trichloroacetic acid 25% to 35% with or without Jessner solution.1

• Cysteamine is a topical treatment created from the degradation of coenzyme A. It disrupts the synthesis of melanin to create a more even skin tone. It may be recommended in combination with sunscreen as a first-line or second-line topical therapy.

• Oral tranexamic acid is a third-line treatment that is an analogue for lysine. It decreases prostaglandin production, which leads to a lower number of tyrosine precursors available for the creation of melanin. Tranexamic acid has been shown to lighten the appearance of melasma.7 The most common and dangerous adverse effect of tranexamic acid is blood clots and this treatment should be avoided in those on combination (estrogen and progestin) contraceptives or those with a personal or family history of clotting disorders.8

• Fourth-line treatments such as lasers (performed by dermatologists) can destroy the deposition of pigment while avoiding destruction of epidermal keratinocytes.1,9,10 They also are commonly employed in refractive melasma. The most common lasers are nonablative fractionated lasers and low-fluence Q-switched lasers. The Q-switched Nd:YAG and picosecond lasers are safe for treating melasma in darker skin tones. Ablative fractionated lasers such as CO2 lasers and erbium:YAG lasers also have been used in the treatment of melasma; however, there is still an extremely high risk for postinflammatory dyspigmentation 1 to 2 months after the procedure.10

• Although there is still a risk for rebound hyperpigmentation after laser treatment, use of topical hydroquinone pretreatment may help decrease postoperative hyperpigmentation.1,5 Patients who are treated with the incorrect laser or overtreated may develop postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, rebound hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation.

Health disparity highlight

Melasma, most common in patients with skin of color, is a common chronic pigmentation disorder that is cosmetically and psychologically burdensome,11 leading to decreased quality of life, emotional functioning, and selfesteem.12 Clinicians should counsel patients and work closely on long-term management. The treatment options for melasma are considered cosmetic and may be cost prohibitive for many to cover out-of-pocket. Topical treatments have been found to be the most cost-effective.13 Some compounding pharmacies and drug discount programs provide more affordable treatment pricing; however, some patients are still unable to afford these options.

- Cunha PR, Kroumpouzos G. Melasma and vitiligo: novel and experimental therapies. J Clin Exp Derm Res. 2016;7:2. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000e106

- Rajanala S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Melasma pathogenesis: a review of the latest research, pathological findings, and investigational therapies. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt47b7r28c.

- Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

- Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: a clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380-382.

- Ogbechie-Godec OA, Elbuluk N. Melasma: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:305-318.

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1337-1338.

- Taraz M, Nikham S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: a comprehensive review of clinical studies [published online January 30, 2017]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.12465

- Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-825.

- Castanedo-Cazares JP, Hernandez-Blanco D, Carlos-Ortega B, et al. Near-visible light and UV photoprotection in the treatment of melasma: a double-blind randomized trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:35-42.

- Trivedi MK, Yang FC, Cho BK. A review of laser and light therapy in melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:11-20.

- Dodmani PN, Deshmukh AR. Assessment of quality of life of melasma patients as per melasma quality of life scale (MELASQoL). Pigment Int. 2020;7:75-79.

- Balkrishnan R, McMichael A, Camacho FT, et al. Development and validation of a health‐related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:572-577.

- Alikhan A, Daly M, Wu J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a hydroquinone /tretinoin/fluocinolone acetonide cream combination in treating melasma in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:276-281.

- Cunha PR, Kroumpouzos G. Melasma and vitiligo: novel and experimental therapies. J Clin Exp Derm Res. 2016;7:2. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000e106

- Rajanala S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Melasma pathogenesis: a review of the latest research, pathological findings, and investigational therapies. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt47b7r28c.

- Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

- Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: a clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380-382.

- Ogbechie-Godec OA, Elbuluk N. Melasma: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:305-318.

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1337-1338.

- Taraz M, Nikham S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: a comprehensive review of clinical studies [published online January 30, 2017]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.12465

- Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-825.

- Castanedo-Cazares JP, Hernandez-Blanco D, Carlos-Ortega B, et al. Near-visible light and UV photoprotection in the treatment of melasma: a double-blind randomized trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:35-42.

- Trivedi MK, Yang FC, Cho BK. A review of laser and light therapy in melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:11-20.

- Dodmani PN, Deshmukh AR. Assessment of quality of life of melasma patients as per melasma quality of life scale (MELASQoL). Pigment Int. 2020;7:75-79.

- Balkrishnan R, McMichael A, Camacho FT, et al. Development and validation of a health‐related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:572-577.

- Alikhan A, Daly M, Wu J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a hydroquinone /tretinoin/fluocinolone acetonide cream combination in treating melasma in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:276-281.

Children ate more fruits and vegetables during longer meals: Study

Adding 10 minutes to family mealtimes increased children’s consumption of fruits and vegetables by approximately one portion, based on data from 50 parent-child dyads.

Family meals are known to affect children’s food choices and preferences and can be an effective setting for improving children’s nutrition, wrote Mattea Dallacker, PhD, of the University of Mannheim, Germany, and colleagues.

However, the effect of extending meal duration on increasing fruit and vegetable intake in particular has not been examined, they said.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers provided two free evening meals to 50 parent-child dyads under each of two different conditions. The control condition was defined by the families as a regular family mealtime duration (an average meal was 20.83 minutes), while the intervention was an average meal time 10 minutes (50%) longer. The age of the parents ranged from 22 to 55 years, with a mean of 43 years; 72% of the parent participants were mothers. The children’s ages ranged from 6 to 11 years, with a mean of 8 years, with approximately equal numbers of boys and girls.

The study was conducted in a family meal laboratory setting in Berlin, and groups were randomized to the longer or shorter meal setting first. The primary outcome was the total number of pieces of fruit and vegetables eaten by the child as part of each of the two meals.

Both meals were the “typical German evening meal of sliced bread, cold cuts of cheese and meat, and bite-sized pieces of fruits and vegetables,” followed by a dessert course of chocolate pudding or fruit yogurt and cookies, the researchers wrote. Beverages were water and one sugar-sweetened beverage; the specific foods and beverages were based on the child’s preferences, reported in an online preassessment, and the foods were consistent for the longer and shorter meals. All participants were asked not to eat for 2 hours prior to arriving for their meals at the laboratory.

During longer meals, children ate an average of seven additional bite-sized pieces of fruits and vegetables, which translates to approximately a full portion (defined as 100 g, such as a medium apple), the researchers wrote. The difference was significant compared with the shorter meals for fruits (P = .01) and vegetables (P < .001).

A piece of fruit was approximately 10 grams (6-10 g for grapes and tangerine segments; 10-14 g for cherry tomatoes; and 9-11 g for apple, banana, carrot, or cucumber). Other foods served with the meals included cheese, meats, butter, and sweet spreads.

Children also ate more slowly (defined as fewer bites per minute) during the longer meals, and they reported significantly greater satiety after the longer meals (P < .001 for both). The consumption of bread and cold cuts was similar for the two meal settings.

“Higher intake of fruits and vegetables during longer meals cannot be explained by longer exposure to food alone; otherwise, an increased intake of bread and cold cuts would have occurred,” the researchers wrote in their discussion. “One possible explanation is that the fruits and vegetables were cut into bite-sized pieces, making them convenient to eat.”

Further analysis showed that during the longer meals, more fruits and vegetables were consumed overall, but more vegetables were eaten from the start of the meal, while the additional fruit was eaten during the additional time at the end.

The findings were limited by several factors, primarily use of a laboratory setting that does not generalize to natural eating environments, the researchers noted. Other potential limitations included the effect of a video cameras on desirable behaviors and the limited ethnic and socioeconomic diversity of the study population, they said. The results were strengthened by the within-dyad study design that allowed for control of factors such as video observation, but more research is needed with more diverse groups and across longer time frames, the researchers said.

However, the results suggest that adding 10 minutes to a family mealtime can yield significant improvements in children’s diets, they said. They suggested strategies including playing music chosen by the child/children and setting rules that everyone must remain at the table for a certain length of time, with fruits and vegetables available on the table.

“If the effects of this simple, inexpensive, and low-threshold intervention prove stable over time, it could contribute to addressing a major public health problem,” the researchers concluded.

Findings intriguing, more data needed

The current study is important because food and vegetable intake in the majority of children falls below the recommended daily allowance, Karalyn Kinsella, MD, a pediatrician in private practice in Cheshire, Conn., said in an interview.

The key take-home message for clinicians is the continued need to stress the importance of family meals, said Dr. Kinsella. “Many children continue to be overbooked with activities, and it may be rare for many families to sit down together for a meal for any length of time.”

Don’t discount the potential effect of a longer school lunch on children’s fruit and vegetable consumption as well, she added. “Advocating for longer lunch time is important, as many kids report not being able to finish their lunch at school.”

The current study was limited by being conducted in a lab setting, which may have influenced children’s desire for different foods, “also they had fewer distractions, and were being offered favorite foods,” said Dr. Kinsella.

Looking ahead, “it would be interesting to see if this result carried over to nonpreferred fruits and veggies and made any difference for picky eaters,” she said.

The study received no outside funding. The open-access publication of the study (but not the study itself) was supported by the Max Planck Institute for Human Development Library Open Access Fund. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Kinsella had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

Adding 10 minutes to family mealtimes increased children’s consumption of fruits and vegetables by approximately one portion, based on data from 50 parent-child dyads.

Family meals are known to affect children’s food choices and preferences and can be an effective setting for improving children’s nutrition, wrote Mattea Dallacker, PhD, of the University of Mannheim, Germany, and colleagues.

However, the effect of extending meal duration on increasing fruit and vegetable intake in particular has not been examined, they said.