User login

Gestational HTN, preeclampsia worsen long-term risk for ischemic, nonischemic heart failure

, an observational study suggests.

The risks were most pronounced, jumping more than sixfold in the case of ischemic HF, during the first 6 years after the pregnancy. They then receded to plateau at a lower, still significantly elevated level of risk that persisted even years later, in the analysis of women in a Swedish medical birth registry.

The case-matching study compared women with no history of cardiovascular (CV) disease and a first successful pregnancy during which they either developed or did not experience gestational hypertension or preeclampsia.

It’s among the first studies to explore the impact of pregnancy-induced hypertensive disease on subsequent HF risk separately for both ischemic and nonischemic HF and to find that the severity of such risk differs for the two HF etiologies, according to a report published in JACC: Heart Failure.

The adjusted risk for any HF during a median of 13 years after the pregnancy rose 70% for those who had developed gestational hypertension or preeclampsia. Their risk of nonischemic HF went up 60%, and their risk of ischemic HF more than doubled.

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy “are so much more than short-term disorders confined to the pregnancy period. They have long-term implications throughout a lifetime,” lead author Ängla Mantel, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Obstetric history doesn’t figure into any formal HF risk scoring systems, observed Dr. Mantel of Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm. Still, women who develop gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, or other pregnancy complications “should be considered a high-risk population even after the pregnancy and monitored for cardiovascular risk factors regularly throughout life.”

In many studies, she said, “knowledge of women-specific risk factors for cardiovascular disease is poor among both clinicians and patients.” The current findings should help raise awareness about such obstetric risk factors for HF, “especially” in patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), which isn’t closely related to a number of traditional CV risk factors.

Even though pregnancy complications such as gestational hypertension and preeclampsia don’t feature in risk calculators, “they are actually risk enhancers per the 2019 primary prevention guidelines,” Natalie A. Bello, MD, MPH, who was not involved in the current study, said in an interview.

“We’re working to educate physicians and cardiovascular team members to take a pregnancy history” for risk stratification of women in primary prevention,” said Dr. Bello, director of hypertension research at the Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

The current study, she said, “is an important step” for its finding that hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are associated separately with both ischemic and nonischemic HF.

She pointed out, however, that because the study excluded women with peripartum cardiomyopathy, a form of nonischemic HF, it may “underestimate the impact of hypertensive disorders on the short-term risk of nonischemic heart failure.” Women who had peripartum cardiomyopathy were excluded to avoid misclassification of other HF outcomes, the authors stated.

Also, Dr. Bello said, the study’s inclusion of patients with either gestational hypertension or preeclampsia may complicate its interpretation. Compared with the former condition, she said, preeclampsia “involves more inflammation and more endothelial dysfunction. It may cause a different impact on the heart and the vasculature.”

In the analysis, about 79,000 women with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia were identified among more than 1.4 million primiparous women who entered the Swedish Medical Birth Register over a period of about 30 years. They were matched with about 396,000 women in the registry who had normotensive pregnancies.

Excluded, besides women with peripartum cardiomyopathy, were women with a prepregnancy history of HF, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, or valvular heart disease.

Hazard ratios (HRs) for HF, ischemic HF, and nonischemic HF were significantly elevated over among the women with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia compared to those with normotensive pregnancies:

- Any HF: HR, 1.70 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.51-1.91)

- Nonischemic HF: HR, 1.60 (95% CI, 1.40-1.83)

- Ischemic HF: HR, 2.28 (95% CI, 1.74-2.98)

The analyses were adjusted for maternal age at delivery, year of delivery, prepregnancy comorbidities, maternal education level, smoking status, and body mass index.

Sharper risk increases were seen among women with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia who delivered prior to gestational week 34:

- Any HF: HR, 2.46 (95% CI, 1.82-3.32)

- Nonischemic HF: HR, 2.33 (95% CI, 1.65-3.31)

- Ischemic HF: HR, 3.64 (95% CI, 1.97-6.74)

Risks for HF developing within 6 years of pregnancy characterized by gestational hypertension or preeclampsia were far more pronounced for ischemic HF than for nonischemic HF:

- Any HF: HR, 2.09 (95% CI, 1.52-2.89)

- Nonischemic HF: HR, 1.86 (95% CI, 1.32-2.61)

- Ischemic HF: HR, 6.52 (95% CI, 2.00-12.34).

The study couldn’t directly explore potential mechanisms for the associations between pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorders and different forms of HF, but it may have provided clues, Dr. Mantel said.

The hypertensive disorders and ischemic HF appear to share risk factors that could lead to both conditions, she noted. Also, hypertension itself is a risk factor for ischemic heart disease.

In contrast, “the risk of nonischemic heart failure might be driven by other factors, such as the inflammatory profile, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiac remodeling induced by preeclampsia or gestational hypertension.”

Those disorders, moreover, are associated with cardiac structural changes that are also seen in HFpEF, Dr. Mantel said. And both HFpEF and preeclampsia are characterized by systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction.

“These pathophysiological similarities,” she proposed, “might explain the link between pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorder and HFpEF.”

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bello has received grants from the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, an observational study suggests.

The risks were most pronounced, jumping more than sixfold in the case of ischemic HF, during the first 6 years after the pregnancy. They then receded to plateau at a lower, still significantly elevated level of risk that persisted even years later, in the analysis of women in a Swedish medical birth registry.

The case-matching study compared women with no history of cardiovascular (CV) disease and a first successful pregnancy during which they either developed or did not experience gestational hypertension or preeclampsia.

It’s among the first studies to explore the impact of pregnancy-induced hypertensive disease on subsequent HF risk separately for both ischemic and nonischemic HF and to find that the severity of such risk differs for the two HF etiologies, according to a report published in JACC: Heart Failure.

The adjusted risk for any HF during a median of 13 years after the pregnancy rose 70% for those who had developed gestational hypertension or preeclampsia. Their risk of nonischemic HF went up 60%, and their risk of ischemic HF more than doubled.

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy “are so much more than short-term disorders confined to the pregnancy period. They have long-term implications throughout a lifetime,” lead author Ängla Mantel, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Obstetric history doesn’t figure into any formal HF risk scoring systems, observed Dr. Mantel of Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm. Still, women who develop gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, or other pregnancy complications “should be considered a high-risk population even after the pregnancy and monitored for cardiovascular risk factors regularly throughout life.”

In many studies, she said, “knowledge of women-specific risk factors for cardiovascular disease is poor among both clinicians and patients.” The current findings should help raise awareness about such obstetric risk factors for HF, “especially” in patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), which isn’t closely related to a number of traditional CV risk factors.

Even though pregnancy complications such as gestational hypertension and preeclampsia don’t feature in risk calculators, “they are actually risk enhancers per the 2019 primary prevention guidelines,” Natalie A. Bello, MD, MPH, who was not involved in the current study, said in an interview.

“We’re working to educate physicians and cardiovascular team members to take a pregnancy history” for risk stratification of women in primary prevention,” said Dr. Bello, director of hypertension research at the Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

The current study, she said, “is an important step” for its finding that hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are associated separately with both ischemic and nonischemic HF.

She pointed out, however, that because the study excluded women with peripartum cardiomyopathy, a form of nonischemic HF, it may “underestimate the impact of hypertensive disorders on the short-term risk of nonischemic heart failure.” Women who had peripartum cardiomyopathy were excluded to avoid misclassification of other HF outcomes, the authors stated.

Also, Dr. Bello said, the study’s inclusion of patients with either gestational hypertension or preeclampsia may complicate its interpretation. Compared with the former condition, she said, preeclampsia “involves more inflammation and more endothelial dysfunction. It may cause a different impact on the heart and the vasculature.”

In the analysis, about 79,000 women with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia were identified among more than 1.4 million primiparous women who entered the Swedish Medical Birth Register over a period of about 30 years. They were matched with about 396,000 women in the registry who had normotensive pregnancies.

Excluded, besides women with peripartum cardiomyopathy, were women with a prepregnancy history of HF, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, or valvular heart disease.

Hazard ratios (HRs) for HF, ischemic HF, and nonischemic HF were significantly elevated over among the women with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia compared to those with normotensive pregnancies:

- Any HF: HR, 1.70 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.51-1.91)

- Nonischemic HF: HR, 1.60 (95% CI, 1.40-1.83)

- Ischemic HF: HR, 2.28 (95% CI, 1.74-2.98)

The analyses were adjusted for maternal age at delivery, year of delivery, prepregnancy comorbidities, maternal education level, smoking status, and body mass index.

Sharper risk increases were seen among women with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia who delivered prior to gestational week 34:

- Any HF: HR, 2.46 (95% CI, 1.82-3.32)

- Nonischemic HF: HR, 2.33 (95% CI, 1.65-3.31)

- Ischemic HF: HR, 3.64 (95% CI, 1.97-6.74)

Risks for HF developing within 6 years of pregnancy characterized by gestational hypertension or preeclampsia were far more pronounced for ischemic HF than for nonischemic HF:

- Any HF: HR, 2.09 (95% CI, 1.52-2.89)

- Nonischemic HF: HR, 1.86 (95% CI, 1.32-2.61)

- Ischemic HF: HR, 6.52 (95% CI, 2.00-12.34).

The study couldn’t directly explore potential mechanisms for the associations between pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorders and different forms of HF, but it may have provided clues, Dr. Mantel said.

The hypertensive disorders and ischemic HF appear to share risk factors that could lead to both conditions, she noted. Also, hypertension itself is a risk factor for ischemic heart disease.

In contrast, “the risk of nonischemic heart failure might be driven by other factors, such as the inflammatory profile, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiac remodeling induced by preeclampsia or gestational hypertension.”

Those disorders, moreover, are associated with cardiac structural changes that are also seen in HFpEF, Dr. Mantel said. And both HFpEF and preeclampsia are characterized by systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction.

“These pathophysiological similarities,” she proposed, “might explain the link between pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorder and HFpEF.”

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bello has received grants from the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, an observational study suggests.

The risks were most pronounced, jumping more than sixfold in the case of ischemic HF, during the first 6 years after the pregnancy. They then receded to plateau at a lower, still significantly elevated level of risk that persisted even years later, in the analysis of women in a Swedish medical birth registry.

The case-matching study compared women with no history of cardiovascular (CV) disease and a first successful pregnancy during which they either developed or did not experience gestational hypertension or preeclampsia.

It’s among the first studies to explore the impact of pregnancy-induced hypertensive disease on subsequent HF risk separately for both ischemic and nonischemic HF and to find that the severity of such risk differs for the two HF etiologies, according to a report published in JACC: Heart Failure.

The adjusted risk for any HF during a median of 13 years after the pregnancy rose 70% for those who had developed gestational hypertension or preeclampsia. Their risk of nonischemic HF went up 60%, and their risk of ischemic HF more than doubled.

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy “are so much more than short-term disorders confined to the pregnancy period. They have long-term implications throughout a lifetime,” lead author Ängla Mantel, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Obstetric history doesn’t figure into any formal HF risk scoring systems, observed Dr. Mantel of Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm. Still, women who develop gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, or other pregnancy complications “should be considered a high-risk population even after the pregnancy and monitored for cardiovascular risk factors regularly throughout life.”

In many studies, she said, “knowledge of women-specific risk factors for cardiovascular disease is poor among both clinicians and patients.” The current findings should help raise awareness about such obstetric risk factors for HF, “especially” in patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), which isn’t closely related to a number of traditional CV risk factors.

Even though pregnancy complications such as gestational hypertension and preeclampsia don’t feature in risk calculators, “they are actually risk enhancers per the 2019 primary prevention guidelines,” Natalie A. Bello, MD, MPH, who was not involved in the current study, said in an interview.

“We’re working to educate physicians and cardiovascular team members to take a pregnancy history” for risk stratification of women in primary prevention,” said Dr. Bello, director of hypertension research at the Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

The current study, she said, “is an important step” for its finding that hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are associated separately with both ischemic and nonischemic HF.

She pointed out, however, that because the study excluded women with peripartum cardiomyopathy, a form of nonischemic HF, it may “underestimate the impact of hypertensive disorders on the short-term risk of nonischemic heart failure.” Women who had peripartum cardiomyopathy were excluded to avoid misclassification of other HF outcomes, the authors stated.

Also, Dr. Bello said, the study’s inclusion of patients with either gestational hypertension or preeclampsia may complicate its interpretation. Compared with the former condition, she said, preeclampsia “involves more inflammation and more endothelial dysfunction. It may cause a different impact on the heart and the vasculature.”

In the analysis, about 79,000 women with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia were identified among more than 1.4 million primiparous women who entered the Swedish Medical Birth Register over a period of about 30 years. They were matched with about 396,000 women in the registry who had normotensive pregnancies.

Excluded, besides women with peripartum cardiomyopathy, were women with a prepregnancy history of HF, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, or valvular heart disease.

Hazard ratios (HRs) for HF, ischemic HF, and nonischemic HF were significantly elevated over among the women with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia compared to those with normotensive pregnancies:

- Any HF: HR, 1.70 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.51-1.91)

- Nonischemic HF: HR, 1.60 (95% CI, 1.40-1.83)

- Ischemic HF: HR, 2.28 (95% CI, 1.74-2.98)

The analyses were adjusted for maternal age at delivery, year of delivery, prepregnancy comorbidities, maternal education level, smoking status, and body mass index.

Sharper risk increases were seen among women with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia who delivered prior to gestational week 34:

- Any HF: HR, 2.46 (95% CI, 1.82-3.32)

- Nonischemic HF: HR, 2.33 (95% CI, 1.65-3.31)

- Ischemic HF: HR, 3.64 (95% CI, 1.97-6.74)

Risks for HF developing within 6 years of pregnancy characterized by gestational hypertension or preeclampsia were far more pronounced for ischemic HF than for nonischemic HF:

- Any HF: HR, 2.09 (95% CI, 1.52-2.89)

- Nonischemic HF: HR, 1.86 (95% CI, 1.32-2.61)

- Ischemic HF: HR, 6.52 (95% CI, 2.00-12.34).

The study couldn’t directly explore potential mechanisms for the associations between pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorders and different forms of HF, but it may have provided clues, Dr. Mantel said.

The hypertensive disorders and ischemic HF appear to share risk factors that could lead to both conditions, she noted. Also, hypertension itself is a risk factor for ischemic heart disease.

In contrast, “the risk of nonischemic heart failure might be driven by other factors, such as the inflammatory profile, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiac remodeling induced by preeclampsia or gestational hypertension.”

Those disorders, moreover, are associated with cardiac structural changes that are also seen in HFpEF, Dr. Mantel said. And both HFpEF and preeclampsia are characterized by systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction.

“These pathophysiological similarities,” she proposed, “might explain the link between pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorder and HFpEF.”

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bello has received grants from the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JACC: HEART FAILURE

Could vitamin D supplementation help in long COVID?

, in a retrospective, case-matched study.

The lower levels of vitamin D in patients with long COVID were most notable in those with brain fog.

These findings, by Luigi di Filippo, MD, and colleagues, were recently presented at the European Congress of Endocrinology and published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“Our data suggest that vitamin D levels should be evaluated in COVID-19 patients after hospital discharge,” wrote the researchers, from San Raffaele Hospital, Milan.

“The role of vitamin D supplementation as a preventive strategy of COVID-19 sequelae should be tested in randomized controlled trials,” they urged.

The researchers also stressed that this was a controlled study in a homogeneous population, it included multiple signs and symptoms of long COVID, and it had a longer follow-up than most previous studies (6 vs. 3 months).

“The highly controlled nature of our study helps us better understand the role of vitamin D deficiency in long COVID and establish that there is likely a link between vitamin D deficiency and long COVID,” senior author Andrea Giustina, MD, said in a press release from the ECE.

“Our study shows that COVID-19 patients with low vitamin D levels are more likely to develop long COVID, but it is not yet known whether vitamin D supplements could improve the symptoms or reduce this risk altogether,” he cautioned.

“If confirmed in large, interventional, randomized controlled trials, [our data suggest] that vitamin D supplementation could represent a possible preventive strategy in reducing the burden of COVID-19 sequelae,” Dr. Giustina and colleagues wrote.

Reasonable to test vitamin D levels, consider supplementation

Invited to comment, Amiel Dror, MD, PhD, who led a related study that showed that people with a vitamin D deficiency were more likely to have severe COVID-19, agreed.

“The novelty and significance of this [new] study lie in the fact that it expands on our current understanding of the interplay between vitamin D and COVID-19, taking it beyond the acute phase of the disease,” said Dr. Dror, from Bar-Ilan University, Safed, Israel.

“It’s striking to see how vitamin D levels continue to influence patients’ health even after recovery from the initial infection,” he noted.

“The findings certainly add weight to the argument for conducting a randomized control trial [RCT],” he continued, which “would enable us to conclusively determine whether vitamin D supplementation can effectively reduce the risk or severity of long COVID.”

“In the interim,” Dr. Dror said, “given the safety profile of vitamin D and its broad health benefits, it could be reasonable to test for vitamin D levels in patients admitted with COVID-19. If levels are found to be low, supplementation could be considered.”

“However, it’s important to note that this should be done under medical supervision,” he cautioned, “and further studies are needed to establish the optimal timing and dosage of supplementation.”

“I anticipate that we’ll see more RCTs [of this] in the future,” he speculated.

Low vitamin D and risk of long COVID

Long COVID is an emerging syndrome that affects 50%-70% of COVID-19 survivors.

Low levels of vitamin D have been associated with increased likelihood of needing mechanical ventilation and worse survival in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, but the risk of long COVID associated with vitamin D has not been known.

Researchers analyzed data from adults aged 18 and older hospitalized at San Raffaele Hospital with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 and discharged during the first pandemic wave, from March to May 2020, and then seen 6-months later for follow-up.

Patients were excluded if they had been admitted to the intensive care unit during hospitalization or had missing medical data or blood samples available to determine (OH) vitamin D levels, at admission and the 6-month follow-up.

Long COVID-19 was defined based on the U.K. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines as the concomitant presence of at least two or more of 17 signs and symptoms that were absent prior to the COVID-19 infection and could only be attributed to that acute disease.

Researchers identified 50 patients with long COVID at the 6-month follow-up and matched them with 50 patients without long COVID at that time point, based on age, sex, concomitant comorbidities, need for noninvasive mechanical ventilation, and week of evaluation.

Patients were a mean age of 61 years (range, 51-73) and 56% were men; 28% had been on a ventilator during hospitalization for COVID-19.

The most frequent signs and symptoms at 6 months in the patients with long COVID were asthenia (weakness, 38% of patients), dysgeusia (bad taste in the mouth, 34%), dyspnea (shortness of breath, 34%), and anosmia (loss of sense of smell, 24%).

Most symptoms were related to the cardiorespiratory system (42%), the feeling of well-being (42%), or the senses (36%), and fewer patients had symptoms related to neurocognitive impairment (headache or brain fog, 14%), or ear, nose, and throat (12%), or gastrointestinal system (4%).

Patients with long COVID had lower mean 25(OH) vitamin D levels than patients without long COVID (20.1 vs 23.2 ng/mL; P = .03). However, actual vitamin D deficiency levels were similar in both groups.

Two-thirds of patients with low vitamin D levels at hospital admission still presented with low levels at the 6-month follow-up.

Vitamin D levels were significantly lower in patients with neurocognitive symptoms at follow-up (n = 7) than in those without such symptoms (n = 93) (14.6 vs. 20.6 ng/mL; P = .042).

In patients with vitamin D deficiency (< 20 ng/mL) at admission and at follow-up (n = 42), those with long COVID (n = 22) had lower vitamin D levels at follow-up than those without long COVID (n = 20) (12.7 vs. 15.2 ng/mL; P = .041).

And in multiple regression analyses, a lower 25(OH) vitamin D level at follow-up was the only variable that was significantly associated with long COVID (odds ratio, 1.09; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.16; P = .008).

The findings “strongly reinforce the clinical usefulness of 25(OH) vitamin D evaluation as a possible modifiable pathophysiological factor underlying this emerging worldwide critical health issue,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by Abiogen Pharma. One study author is an employee at Abiogen. Dr. Giustina has reported being a consultant for Abiogen and Takeda and receiving a research grant to his institution from Takeda. Dr. Di Filippo and the other authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, in a retrospective, case-matched study.

The lower levels of vitamin D in patients with long COVID were most notable in those with brain fog.

These findings, by Luigi di Filippo, MD, and colleagues, were recently presented at the European Congress of Endocrinology and published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“Our data suggest that vitamin D levels should be evaluated in COVID-19 patients after hospital discharge,” wrote the researchers, from San Raffaele Hospital, Milan.

“The role of vitamin D supplementation as a preventive strategy of COVID-19 sequelae should be tested in randomized controlled trials,” they urged.

The researchers also stressed that this was a controlled study in a homogeneous population, it included multiple signs and symptoms of long COVID, and it had a longer follow-up than most previous studies (6 vs. 3 months).

“The highly controlled nature of our study helps us better understand the role of vitamin D deficiency in long COVID and establish that there is likely a link between vitamin D deficiency and long COVID,” senior author Andrea Giustina, MD, said in a press release from the ECE.

“Our study shows that COVID-19 patients with low vitamin D levels are more likely to develop long COVID, but it is not yet known whether vitamin D supplements could improve the symptoms or reduce this risk altogether,” he cautioned.

“If confirmed in large, interventional, randomized controlled trials, [our data suggest] that vitamin D supplementation could represent a possible preventive strategy in reducing the burden of COVID-19 sequelae,” Dr. Giustina and colleagues wrote.

Reasonable to test vitamin D levels, consider supplementation

Invited to comment, Amiel Dror, MD, PhD, who led a related study that showed that people with a vitamin D deficiency were more likely to have severe COVID-19, agreed.

“The novelty and significance of this [new] study lie in the fact that it expands on our current understanding of the interplay between vitamin D and COVID-19, taking it beyond the acute phase of the disease,” said Dr. Dror, from Bar-Ilan University, Safed, Israel.

“It’s striking to see how vitamin D levels continue to influence patients’ health even after recovery from the initial infection,” he noted.

“The findings certainly add weight to the argument for conducting a randomized control trial [RCT],” he continued, which “would enable us to conclusively determine whether vitamin D supplementation can effectively reduce the risk or severity of long COVID.”

“In the interim,” Dr. Dror said, “given the safety profile of vitamin D and its broad health benefits, it could be reasonable to test for vitamin D levels in patients admitted with COVID-19. If levels are found to be low, supplementation could be considered.”

“However, it’s important to note that this should be done under medical supervision,” he cautioned, “and further studies are needed to establish the optimal timing and dosage of supplementation.”

“I anticipate that we’ll see more RCTs [of this] in the future,” he speculated.

Low vitamin D and risk of long COVID

Long COVID is an emerging syndrome that affects 50%-70% of COVID-19 survivors.

Low levels of vitamin D have been associated with increased likelihood of needing mechanical ventilation and worse survival in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, but the risk of long COVID associated with vitamin D has not been known.

Researchers analyzed data from adults aged 18 and older hospitalized at San Raffaele Hospital with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 and discharged during the first pandemic wave, from March to May 2020, and then seen 6-months later for follow-up.

Patients were excluded if they had been admitted to the intensive care unit during hospitalization or had missing medical data or blood samples available to determine (OH) vitamin D levels, at admission and the 6-month follow-up.

Long COVID-19 was defined based on the U.K. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines as the concomitant presence of at least two or more of 17 signs and symptoms that were absent prior to the COVID-19 infection and could only be attributed to that acute disease.

Researchers identified 50 patients with long COVID at the 6-month follow-up and matched them with 50 patients without long COVID at that time point, based on age, sex, concomitant comorbidities, need for noninvasive mechanical ventilation, and week of evaluation.

Patients were a mean age of 61 years (range, 51-73) and 56% were men; 28% had been on a ventilator during hospitalization for COVID-19.

The most frequent signs and symptoms at 6 months in the patients with long COVID were asthenia (weakness, 38% of patients), dysgeusia (bad taste in the mouth, 34%), dyspnea (shortness of breath, 34%), and anosmia (loss of sense of smell, 24%).

Most symptoms were related to the cardiorespiratory system (42%), the feeling of well-being (42%), or the senses (36%), and fewer patients had symptoms related to neurocognitive impairment (headache or brain fog, 14%), or ear, nose, and throat (12%), or gastrointestinal system (4%).

Patients with long COVID had lower mean 25(OH) vitamin D levels than patients without long COVID (20.1 vs 23.2 ng/mL; P = .03). However, actual vitamin D deficiency levels were similar in both groups.

Two-thirds of patients with low vitamin D levels at hospital admission still presented with low levels at the 6-month follow-up.

Vitamin D levels were significantly lower in patients with neurocognitive symptoms at follow-up (n = 7) than in those without such symptoms (n = 93) (14.6 vs. 20.6 ng/mL; P = .042).

In patients with vitamin D deficiency (< 20 ng/mL) at admission and at follow-up (n = 42), those with long COVID (n = 22) had lower vitamin D levels at follow-up than those without long COVID (n = 20) (12.7 vs. 15.2 ng/mL; P = .041).

And in multiple regression analyses, a lower 25(OH) vitamin D level at follow-up was the only variable that was significantly associated with long COVID (odds ratio, 1.09; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.16; P = .008).

The findings “strongly reinforce the clinical usefulness of 25(OH) vitamin D evaluation as a possible modifiable pathophysiological factor underlying this emerging worldwide critical health issue,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by Abiogen Pharma. One study author is an employee at Abiogen. Dr. Giustina has reported being a consultant for Abiogen and Takeda and receiving a research grant to his institution from Takeda. Dr. Di Filippo and the other authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, in a retrospective, case-matched study.

The lower levels of vitamin D in patients with long COVID were most notable in those with brain fog.

These findings, by Luigi di Filippo, MD, and colleagues, were recently presented at the European Congress of Endocrinology and published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“Our data suggest that vitamin D levels should be evaluated in COVID-19 patients after hospital discharge,” wrote the researchers, from San Raffaele Hospital, Milan.

“The role of vitamin D supplementation as a preventive strategy of COVID-19 sequelae should be tested in randomized controlled trials,” they urged.

The researchers also stressed that this was a controlled study in a homogeneous population, it included multiple signs and symptoms of long COVID, and it had a longer follow-up than most previous studies (6 vs. 3 months).

“The highly controlled nature of our study helps us better understand the role of vitamin D deficiency in long COVID and establish that there is likely a link between vitamin D deficiency and long COVID,” senior author Andrea Giustina, MD, said in a press release from the ECE.

“Our study shows that COVID-19 patients with low vitamin D levels are more likely to develop long COVID, but it is not yet known whether vitamin D supplements could improve the symptoms or reduce this risk altogether,” he cautioned.

“If confirmed in large, interventional, randomized controlled trials, [our data suggest] that vitamin D supplementation could represent a possible preventive strategy in reducing the burden of COVID-19 sequelae,” Dr. Giustina and colleagues wrote.

Reasonable to test vitamin D levels, consider supplementation

Invited to comment, Amiel Dror, MD, PhD, who led a related study that showed that people with a vitamin D deficiency were more likely to have severe COVID-19, agreed.

“The novelty and significance of this [new] study lie in the fact that it expands on our current understanding of the interplay between vitamin D and COVID-19, taking it beyond the acute phase of the disease,” said Dr. Dror, from Bar-Ilan University, Safed, Israel.

“It’s striking to see how vitamin D levels continue to influence patients’ health even after recovery from the initial infection,” he noted.

“The findings certainly add weight to the argument for conducting a randomized control trial [RCT],” he continued, which “would enable us to conclusively determine whether vitamin D supplementation can effectively reduce the risk or severity of long COVID.”

“In the interim,” Dr. Dror said, “given the safety profile of vitamin D and its broad health benefits, it could be reasonable to test for vitamin D levels in patients admitted with COVID-19. If levels are found to be low, supplementation could be considered.”

“However, it’s important to note that this should be done under medical supervision,” he cautioned, “and further studies are needed to establish the optimal timing and dosage of supplementation.”

“I anticipate that we’ll see more RCTs [of this] in the future,” he speculated.

Low vitamin D and risk of long COVID

Long COVID is an emerging syndrome that affects 50%-70% of COVID-19 survivors.

Low levels of vitamin D have been associated with increased likelihood of needing mechanical ventilation and worse survival in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, but the risk of long COVID associated with vitamin D has not been known.

Researchers analyzed data from adults aged 18 and older hospitalized at San Raffaele Hospital with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 and discharged during the first pandemic wave, from March to May 2020, and then seen 6-months later for follow-up.

Patients were excluded if they had been admitted to the intensive care unit during hospitalization or had missing medical data or blood samples available to determine (OH) vitamin D levels, at admission and the 6-month follow-up.

Long COVID-19 was defined based on the U.K. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines as the concomitant presence of at least two or more of 17 signs and symptoms that were absent prior to the COVID-19 infection and could only be attributed to that acute disease.

Researchers identified 50 patients with long COVID at the 6-month follow-up and matched them with 50 patients without long COVID at that time point, based on age, sex, concomitant comorbidities, need for noninvasive mechanical ventilation, and week of evaluation.

Patients were a mean age of 61 years (range, 51-73) and 56% were men; 28% had been on a ventilator during hospitalization for COVID-19.

The most frequent signs and symptoms at 6 months in the patients with long COVID were asthenia (weakness, 38% of patients), dysgeusia (bad taste in the mouth, 34%), dyspnea (shortness of breath, 34%), and anosmia (loss of sense of smell, 24%).

Most symptoms were related to the cardiorespiratory system (42%), the feeling of well-being (42%), or the senses (36%), and fewer patients had symptoms related to neurocognitive impairment (headache or brain fog, 14%), or ear, nose, and throat (12%), or gastrointestinal system (4%).

Patients with long COVID had lower mean 25(OH) vitamin D levels than patients without long COVID (20.1 vs 23.2 ng/mL; P = .03). However, actual vitamin D deficiency levels were similar in both groups.

Two-thirds of patients with low vitamin D levels at hospital admission still presented with low levels at the 6-month follow-up.

Vitamin D levels were significantly lower in patients with neurocognitive symptoms at follow-up (n = 7) than in those without such symptoms (n = 93) (14.6 vs. 20.6 ng/mL; P = .042).

In patients with vitamin D deficiency (< 20 ng/mL) at admission and at follow-up (n = 42), those with long COVID (n = 22) had lower vitamin D levels at follow-up than those without long COVID (n = 20) (12.7 vs. 15.2 ng/mL; P = .041).

And in multiple regression analyses, a lower 25(OH) vitamin D level at follow-up was the only variable that was significantly associated with long COVID (odds ratio, 1.09; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.16; P = .008).

The findings “strongly reinforce the clinical usefulness of 25(OH) vitamin D evaluation as a possible modifiable pathophysiological factor underlying this emerging worldwide critical health issue,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by Abiogen Pharma. One study author is an employee at Abiogen. Dr. Giustina has reported being a consultant for Abiogen and Takeda and receiving a research grant to his institution from Takeda. Dr. Di Filippo and the other authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ECE 2023

Worsening cognitive impairments

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

AD is the most common type of dementia. It is characterized by cognitive and behavioral impairment that significantly impairs a patient's social and occupational functioning. The predominant AD pathogenesis hypothesis suggests that AD is largely caused by the accumulation of insoluble amyloid beta deposits and neurofibrillary tangles induced by highly phosphorylated tau proteins in the neocortex, hippocampus, and amygdala, as well as significant loss of neurons and synapses, which leads to brain atrophy. Estimates suggest that approximately 6.2 million people ≥ 65 years of age have AD and that by 2060, the number of Americans with AD may increase to 13.8 million, the result of an aging population and the lack of effective prevention and treatment strategies. AD is a chronic disease that confers tremendous emotional and economic burdens to individuals, families, and society.

Insidiously progressive memory loss is commonly seen in patients presenting with AD. As the disease progresses over the course of several years, other areas of cognition are impaired. Patients may develop language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes are also observed in many individuals with AD.

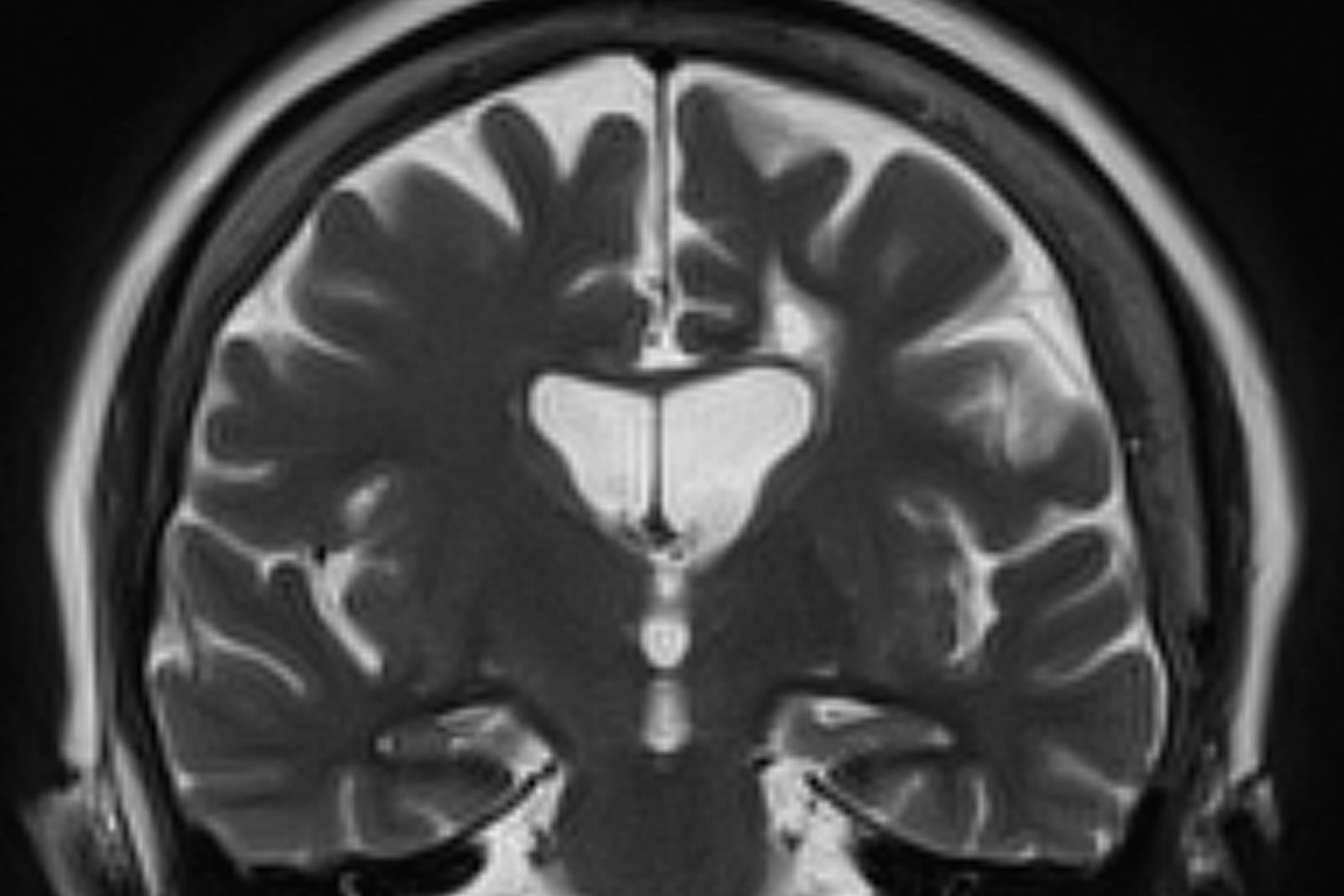

Criteria for the clinical diagnosis of AD (eg, insidious onset of cognitive impairment, clear history of worsening symptoms) have been developed and are frequently employed. Among individuals who meet the core clinical criteria for probable AD dementia, biomarker evidence may help to increase the certainty that AD is the basis of the clinical dementia syndrome. Several cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers have shown excellent diagnostic ability by identifying tau pathology and cerebral amyloid beta for AD. Neuroimaging is becoming increasingly important for identifying the underlying causes of cognitive impairment. Currently, MRI is considered the preferred neuroimaging modality for AD as it enables accurate measurement of the three-dimensional volume of brain structures, particularly the size of the hippocampus and related regions. CT may be used when MRI is not possible, such as in a patient with a pacemaker.

PET is increasingly being used as a noninvasive method for depicting tau pathology deposition and distribution in patients with cognitive impairment. In 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first tau PET tracer, 18F-flortaucipir, a significant achievement in improving AD diagnosis.

Currently, the only therapies available for AD are symptomatic therapies. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical treatment for AD. Recently approved antiamyloid therapies are also available for patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021; and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents are often used to treat the secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and/or sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

AD is the most common type of dementia. It is characterized by cognitive and behavioral impairment that significantly impairs a patient's social and occupational functioning. The predominant AD pathogenesis hypothesis suggests that AD is largely caused by the accumulation of insoluble amyloid beta deposits and neurofibrillary tangles induced by highly phosphorylated tau proteins in the neocortex, hippocampus, and amygdala, as well as significant loss of neurons and synapses, which leads to brain atrophy. Estimates suggest that approximately 6.2 million people ≥ 65 years of age have AD and that by 2060, the number of Americans with AD may increase to 13.8 million, the result of an aging population and the lack of effective prevention and treatment strategies. AD is a chronic disease that confers tremendous emotional and economic burdens to individuals, families, and society.

Insidiously progressive memory loss is commonly seen in patients presenting with AD. As the disease progresses over the course of several years, other areas of cognition are impaired. Patients may develop language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes are also observed in many individuals with AD.

Criteria for the clinical diagnosis of AD (eg, insidious onset of cognitive impairment, clear history of worsening symptoms) have been developed and are frequently employed. Among individuals who meet the core clinical criteria for probable AD dementia, biomarker evidence may help to increase the certainty that AD is the basis of the clinical dementia syndrome. Several cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers have shown excellent diagnostic ability by identifying tau pathology and cerebral amyloid beta for AD. Neuroimaging is becoming increasingly important for identifying the underlying causes of cognitive impairment. Currently, MRI is considered the preferred neuroimaging modality for AD as it enables accurate measurement of the three-dimensional volume of brain structures, particularly the size of the hippocampus and related regions. CT may be used when MRI is not possible, such as in a patient with a pacemaker.

PET is increasingly being used as a noninvasive method for depicting tau pathology deposition and distribution in patients with cognitive impairment. In 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first tau PET tracer, 18F-flortaucipir, a significant achievement in improving AD diagnosis.

Currently, the only therapies available for AD are symptomatic therapies. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical treatment for AD. Recently approved antiamyloid therapies are also available for patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021; and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents are often used to treat the secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and/or sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

AD is the most common type of dementia. It is characterized by cognitive and behavioral impairment that significantly impairs a patient's social and occupational functioning. The predominant AD pathogenesis hypothesis suggests that AD is largely caused by the accumulation of insoluble amyloid beta deposits and neurofibrillary tangles induced by highly phosphorylated tau proteins in the neocortex, hippocampus, and amygdala, as well as significant loss of neurons and synapses, which leads to brain atrophy. Estimates suggest that approximately 6.2 million people ≥ 65 years of age have AD and that by 2060, the number of Americans with AD may increase to 13.8 million, the result of an aging population and the lack of effective prevention and treatment strategies. AD is a chronic disease that confers tremendous emotional and economic burdens to individuals, families, and society.

Insidiously progressive memory loss is commonly seen in patients presenting with AD. As the disease progresses over the course of several years, other areas of cognition are impaired. Patients may develop language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes are also observed in many individuals with AD.

Criteria for the clinical diagnosis of AD (eg, insidious onset of cognitive impairment, clear history of worsening symptoms) have been developed and are frequently employed. Among individuals who meet the core clinical criteria for probable AD dementia, biomarker evidence may help to increase the certainty that AD is the basis of the clinical dementia syndrome. Several cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers have shown excellent diagnostic ability by identifying tau pathology and cerebral amyloid beta for AD. Neuroimaging is becoming increasingly important for identifying the underlying causes of cognitive impairment. Currently, MRI is considered the preferred neuroimaging modality for AD as it enables accurate measurement of the three-dimensional volume of brain structures, particularly the size of the hippocampus and related regions. CT may be used when MRI is not possible, such as in a patient with a pacemaker.

PET is increasingly being used as a noninvasive method for depicting tau pathology deposition and distribution in patients with cognitive impairment. In 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first tau PET tracer, 18F-flortaucipir, a significant achievement in improving AD diagnosis.

Currently, the only therapies available for AD are symptomatic therapies. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical treatment for AD. Recently approved antiamyloid therapies are also available for patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021; and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents are often used to treat the secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and/or sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 73-year-old male restaurant manager presents with concerns of progressively worsening cognitive impairment. The patient's symptoms began approximately 2 years ago. At that time, he attributed them to normal aging. Recently, however, he has begun to have increasing difficulties at work. On several occasions, he has forgotten to place important supply orders and has made errors with staff scheduling. His wife reports that he frequently misplaces items at home, such as his cell phone and car keys, and has been experiencing noticeable deficits with his short-term memory. In addition, he has been "unlike himself" for quite some time, with uncharacteristic episodes of depression, anxiety, and emotional lability. The patient's past medical history is significant for mild obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. There is no history of neurotoxic exposure, head injuries, strokes, or seizures. His family history is negative for dementia. Current medications include rosuvastatin 40 mg/d and metoprolol 100 mg/d. His current height and weight are 5 ft 11 in and 223 lb (BMI 31.1).

No abnormalities are noted on physical exam; the patient's blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and heart rate are within normal ranges. Laboratory tests are within normal ranges, except for elevated levels of fasting blood glucose level (119 mg/dL) and A1c (6.3%). The patient scores 19 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment test. His clinician orders MRI scanning, which reveals generalized atrophy of brain tissue and an accentuated loss of tissue involving the temporal lobes.

Nonpharmacologic therapies for T2D: Five things to know

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Diabetes Statistic Report, there are more than 37 million adults aged 18 years or older with diabetes in the United States, representing 14.7% of the adult population. Approximately 90%-95% of people diagnosed with diabetes have type 2 diabetes (T2D). An increasing aging population with T2D and a disparate incidence and burden of disease in African American and Hispanic populations raise important care considerations in effective disease assessment and management, especially in primary care, where the majority of diabetes management occurs.

This extends to the need for quality patient education in an effort to give persons with diabetes a better understanding of what it’s like to live with the disease.

Here are five things to know about nonpharmacologic therapies for effective T2D management.

1. Understand and treat the person before the disease.

Diabetes is a complex and unrelenting disease of self-management, requiring an individualized care approach to achieve optimal health outcomes and quality of life for persons living with this condition. Over 90% of care is provided by the person with diabetes, therefore understanding the lived world of the person with diabetes and its connected impact on self-care is critical to establishing effective treatment recommendations, especially for people from racial and ethnic minority groups and lower socioeconomic status where diabetes disparities are highest. Disease prevalence, cost of care, and disease burden are driven by social determinants of health (SDOH) factors that need to be assessed, and strategies addressing causative factors need to be implemented. SDOH factors, including the built environment, safety, financial status, education, food access, health care access, and social support, directly affect the ability of a person with diabetes to effectively implement treatment recommendations, including access to new medications. The adoption of a shared decision-making approach is key to person-centered care. Shared decision-making promotes a positive communication feedback loop, therapeutic patient-care team relationship, and collaborative plan of care between the person with diabetes and the care team. It also supports the establishment of mutual respect between the person with diabetes and the care team members. This cultivates the strong, open, and authentic partnership needed for effective chronic disease management.

2. Quality diabetes education is the foundation for effective self-care.

Diabetes self-management education and support (DSMES) is a fundamental component of diabetes care and ensures patients have the knowledge, skills, motivation, and resources necessary for effectively managing this condition. Despite treatment advances and the evidence base for DSMES, less than 5% of Medicare beneficiaries and 6.8% of privately insured beneficiaries have utilized its services, and this is a likely contributor to the lack of improvement for achieving national diabetes clinical targets. The Association of Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (ADCES7) Self-Care Behaviors provides an evidence-based framework for an optimal DSMES curriculum, incorporating the self-care behaviors of healthy coping (e.g., having a positive attitude toward diabetes self-management), nutritious eating, being active, taking medication, monitoring, reducing risk, and problem-solving.

There are four core times to implement and adapt referral for DSMES: (1) at diagnosis, (2) annually or when not meeting targets, (3) when complications arise, and (4) with transitions in life and care. DSMES referrals should be made for programs accredited by the ADCES or American Diabetes Association (ADA) and led by expert Certified Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (CDCES). The multidisciplinary composition and clinical skill level of CDCES make them a highly valued member of the diabetes care team. CDCES have demonstrated not only diabetes education expertise but are involved in broader health care roles to include population health management, technology integration, mitigation of therapeutic inertia, quality improvement activity, and delivery of cost-effective care.

3. Establish a strong foundation in lifestyle medicine.

Lifestyle medicine encompasses healthy eating, physical activity, restorative sleep, stress management, avoidance of risky behaviors, and positive social connections. It has also been strongly connected as a primary modality to prevent and treat chronic conditions like T2D. Lifestyle modifications have been noted in reducing the incidence of developing diabetes, reversing disease, improving clinical markers such as A1c and lipids, weight reduction, reducing use of medications, and improving quality of life. The multidisciplinary care team and CDCES can support the empowerment of individuals with T2D to develop the life skills and knowledge needed to establish positive self-care behaviors and successfully achieve health goals. Lifestyle medicine is not a replacement for pharmacologic interventions but rather serves as an adjunct when medication management is required.

4. Harness technology in diabetes treatment and care delivery.

Diabetes technology is advancing swiftly and includes glucose monitors, medication delivery devices, data-sharing platforms, and disease self-management applications. Combined with education and support, diabetes technology has been shown to have a positive clinical and personal impact on disease outcomes and quality of life. Regardless of its benefits, at times technology can seem overwhelming for the person with diabetes and the care team. Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (DCES) can support the care team and people living with diabetes to effectively identify, implement, and evaluate patient-centered diabetes technologies, as well as implement processes to drive clinical efficiencies and sustainability. Patient-generated health data reports can provide the care team with effective and proficient evaluation of diabetes care and needed treatment changes.

The expansion of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic, including real-time and asynchronous approaches, coupled with in-person care team visits, has resulted in improved access to diabetes care and education. Moreover, there continues to be an expanding health system focus on improving access to care beyond traditional brick and mortar solutions. Telehealth poses one possible access solution for people living with diabetes for whom factors such as transportation, remote geographies, and physical limitations affect their ability to attend in-person care visits.

5. Assess and address diabetes-related distress.

The persistent nature of diabetes self-care expectations and the impact on lifestyle behaviors, medication adherence, and glycemic control demands the need for assessment and treatment of diabetes-related distress (DRD). DRD can be expressed as shame, guilt, anger, fear, and frustration in combination with the everyday context of life priorities and stressors. An assessment of diabetes distress, utilizing a simple scale, should be included as part of an annual therapeutic diabetes care plan. The ADA Standards of Care in Diabetes recommends assessing patients’ psychological and social situations as an ongoing part of medical management, including an annual screening for depression and other psychological problems. The prevalence of depression is nearly twice as high in people with T2D than in the general population and can significantly influence patients’ ability to self-manage their diabetes and achieve healthy outcomes. Assessment and treatment of psychosocial components of care can result in significant improvements in A1c and other positive outcomes, including quality of life.

Kellie M. Rodriguez, director of the global diabetes program at Parkland Health, Dallas, Tex., disclosed ties with the Association of Diabetes Care and Education Specialists.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Diabetes Statistic Report, there are more than 37 million adults aged 18 years or older with diabetes in the United States, representing 14.7% of the adult population. Approximately 90%-95% of people diagnosed with diabetes have type 2 diabetes (T2D). An increasing aging population with T2D and a disparate incidence and burden of disease in African American and Hispanic populations raise important care considerations in effective disease assessment and management, especially in primary care, where the majority of diabetes management occurs.

This extends to the need for quality patient education in an effort to give persons with diabetes a better understanding of what it’s like to live with the disease.

Here are five things to know about nonpharmacologic therapies for effective T2D management.

1. Understand and treat the person before the disease.

Diabetes is a complex and unrelenting disease of self-management, requiring an individualized care approach to achieve optimal health outcomes and quality of life for persons living with this condition. Over 90% of care is provided by the person with diabetes, therefore understanding the lived world of the person with diabetes and its connected impact on self-care is critical to establishing effective treatment recommendations, especially for people from racial and ethnic minority groups and lower socioeconomic status where diabetes disparities are highest. Disease prevalence, cost of care, and disease burden are driven by social determinants of health (SDOH) factors that need to be assessed, and strategies addressing causative factors need to be implemented. SDOH factors, including the built environment, safety, financial status, education, food access, health care access, and social support, directly affect the ability of a person with diabetes to effectively implement treatment recommendations, including access to new medications. The adoption of a shared decision-making approach is key to person-centered care. Shared decision-making promotes a positive communication feedback loop, therapeutic patient-care team relationship, and collaborative plan of care between the person with diabetes and the care team. It also supports the establishment of mutual respect between the person with diabetes and the care team members. This cultivates the strong, open, and authentic partnership needed for effective chronic disease management.

2. Quality diabetes education is the foundation for effective self-care.

Diabetes self-management education and support (DSMES) is a fundamental component of diabetes care and ensures patients have the knowledge, skills, motivation, and resources necessary for effectively managing this condition. Despite treatment advances and the evidence base for DSMES, less than 5% of Medicare beneficiaries and 6.8% of privately insured beneficiaries have utilized its services, and this is a likely contributor to the lack of improvement for achieving national diabetes clinical targets. The Association of Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (ADCES7) Self-Care Behaviors provides an evidence-based framework for an optimal DSMES curriculum, incorporating the self-care behaviors of healthy coping (e.g., having a positive attitude toward diabetes self-management), nutritious eating, being active, taking medication, monitoring, reducing risk, and problem-solving.

There are four core times to implement and adapt referral for DSMES: (1) at diagnosis, (2) annually or when not meeting targets, (3) when complications arise, and (4) with transitions in life and care. DSMES referrals should be made for programs accredited by the ADCES or American Diabetes Association (ADA) and led by expert Certified Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (CDCES). The multidisciplinary composition and clinical skill level of CDCES make them a highly valued member of the diabetes care team. CDCES have demonstrated not only diabetes education expertise but are involved in broader health care roles to include population health management, technology integration, mitigation of therapeutic inertia, quality improvement activity, and delivery of cost-effective care.

3. Establish a strong foundation in lifestyle medicine.

Lifestyle medicine encompasses healthy eating, physical activity, restorative sleep, stress management, avoidance of risky behaviors, and positive social connections. It has also been strongly connected as a primary modality to prevent and treat chronic conditions like T2D. Lifestyle modifications have been noted in reducing the incidence of developing diabetes, reversing disease, improving clinical markers such as A1c and lipids, weight reduction, reducing use of medications, and improving quality of life. The multidisciplinary care team and CDCES can support the empowerment of individuals with T2D to develop the life skills and knowledge needed to establish positive self-care behaviors and successfully achieve health goals. Lifestyle medicine is not a replacement for pharmacologic interventions but rather serves as an adjunct when medication management is required.

4. Harness technology in diabetes treatment and care delivery.

Diabetes technology is advancing swiftly and includes glucose monitors, medication delivery devices, data-sharing platforms, and disease self-management applications. Combined with education and support, diabetes technology has been shown to have a positive clinical and personal impact on disease outcomes and quality of life. Regardless of its benefits, at times technology can seem overwhelming for the person with diabetes and the care team. Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (DCES) can support the care team and people living with diabetes to effectively identify, implement, and evaluate patient-centered diabetes technologies, as well as implement processes to drive clinical efficiencies and sustainability. Patient-generated health data reports can provide the care team with effective and proficient evaluation of diabetes care and needed treatment changes.

The expansion of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic, including real-time and asynchronous approaches, coupled with in-person care team visits, has resulted in improved access to diabetes care and education. Moreover, there continues to be an expanding health system focus on improving access to care beyond traditional brick and mortar solutions. Telehealth poses one possible access solution for people living with diabetes for whom factors such as transportation, remote geographies, and physical limitations affect their ability to attend in-person care visits.

5. Assess and address diabetes-related distress.

The persistent nature of diabetes self-care expectations and the impact on lifestyle behaviors, medication adherence, and glycemic control demands the need for assessment and treatment of diabetes-related distress (DRD). DRD can be expressed as shame, guilt, anger, fear, and frustration in combination with the everyday context of life priorities and stressors. An assessment of diabetes distress, utilizing a simple scale, should be included as part of an annual therapeutic diabetes care plan. The ADA Standards of Care in Diabetes recommends assessing patients’ psychological and social situations as an ongoing part of medical management, including an annual screening for depression and other psychological problems. The prevalence of depression is nearly twice as high in people with T2D than in the general population and can significantly influence patients’ ability to self-manage their diabetes and achieve healthy outcomes. Assessment and treatment of psychosocial components of care can result in significant improvements in A1c and other positive outcomes, including quality of life.

Kellie M. Rodriguez, director of the global diabetes program at Parkland Health, Dallas, Tex., disclosed ties with the Association of Diabetes Care and Education Specialists.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Diabetes Statistic Report, there are more than 37 million adults aged 18 years or older with diabetes in the United States, representing 14.7% of the adult population. Approximately 90%-95% of people diagnosed with diabetes have type 2 diabetes (T2D). An increasing aging population with T2D and a disparate incidence and burden of disease in African American and Hispanic populations raise important care considerations in effective disease assessment and management, especially in primary care, where the majority of diabetes management occurs.

This extends to the need for quality patient education in an effort to give persons with diabetes a better understanding of what it’s like to live with the disease.

Here are five things to know about nonpharmacologic therapies for effective T2D management.

1. Understand and treat the person before the disease.

Diabetes is a complex and unrelenting disease of self-management, requiring an individualized care approach to achieve optimal health outcomes and quality of life for persons living with this condition. Over 90% of care is provided by the person with diabetes, therefore understanding the lived world of the person with diabetes and its connected impact on self-care is critical to establishing effective treatment recommendations, especially for people from racial and ethnic minority groups and lower socioeconomic status where diabetes disparities are highest. Disease prevalence, cost of care, and disease burden are driven by social determinants of health (SDOH) factors that need to be assessed, and strategies addressing causative factors need to be implemented. SDOH factors, including the built environment, safety, financial status, education, food access, health care access, and social support, directly affect the ability of a person with diabetes to effectively implement treatment recommendations, including access to new medications. The adoption of a shared decision-making approach is key to person-centered care. Shared decision-making promotes a positive communication feedback loop, therapeutic patient-care team relationship, and collaborative plan of care between the person with diabetes and the care team. It also supports the establishment of mutual respect between the person with diabetes and the care team members. This cultivates the strong, open, and authentic partnership needed for effective chronic disease management.

2. Quality diabetes education is the foundation for effective self-care.

Diabetes self-management education and support (DSMES) is a fundamental component of diabetes care and ensures patients have the knowledge, skills, motivation, and resources necessary for effectively managing this condition. Despite treatment advances and the evidence base for DSMES, less than 5% of Medicare beneficiaries and 6.8% of privately insured beneficiaries have utilized its services, and this is a likely contributor to the lack of improvement for achieving national diabetes clinical targets. The Association of Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (ADCES7) Self-Care Behaviors provides an evidence-based framework for an optimal DSMES curriculum, incorporating the self-care behaviors of healthy coping (e.g., having a positive attitude toward diabetes self-management), nutritious eating, being active, taking medication, monitoring, reducing risk, and problem-solving.

There are four core times to implement and adapt referral for DSMES: (1) at diagnosis, (2) annually or when not meeting targets, (3) when complications arise, and (4) with transitions in life and care. DSMES referrals should be made for programs accredited by the ADCES or American Diabetes Association (ADA) and led by expert Certified Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (CDCES). The multidisciplinary composition and clinical skill level of CDCES make them a highly valued member of the diabetes care team. CDCES have demonstrated not only diabetes education expertise but are involved in broader health care roles to include population health management, technology integration, mitigation of therapeutic inertia, quality improvement activity, and delivery of cost-effective care.

3. Establish a strong foundation in lifestyle medicine.

Lifestyle medicine encompasses healthy eating, physical activity, restorative sleep, stress management, avoidance of risky behaviors, and positive social connections. It has also been strongly connected as a primary modality to prevent and treat chronic conditions like T2D. Lifestyle modifications have been noted in reducing the incidence of developing diabetes, reversing disease, improving clinical markers such as A1c and lipids, weight reduction, reducing use of medications, and improving quality of life. The multidisciplinary care team and CDCES can support the empowerment of individuals with T2D to develop the life skills and knowledge needed to establish positive self-care behaviors and successfully achieve health goals. Lifestyle medicine is not a replacement for pharmacologic interventions but rather serves as an adjunct when medication management is required.

4. Harness technology in diabetes treatment and care delivery.