User login

Vulvar syringoma

To the Editor:

Syringomas are common benign tumors of the eccrine sweat glands that usually manifest clinically as multiple flesh-colored papules. They are most commonly seen on the face, neck, and chest of adolescent girls. Syringomas may appear at any site of the body but are rare in the vulva. We present a case of a 51-year-old woman who was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of a tumor carrying a differential diagnosis of vulvar syringoma vs microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC).

A 51-year-old woman presented to dermatology (G.G.) and was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of possible vulvar syringoma vs MAC. The patient previously had been evaluated at an outside community practice due to dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities of 1 month’s duration. At that time, a small biopsy was performed, and the histologic differential diagnosis included syringoma vs an adnexal carcinoma. Consequently, she was referred to gynecologic oncology for further management.

Pelvic examination revealed multilobular nodular areas overlying the clitoral hood that extended down to the labia majora. The nodular processes did not involve the clitoris, labia minora, or perineum. A mobile isolated lymph node measuring 2.0×1.0 cm in the right inguinal area also was noted. The patient’s clinical history was notable for right breast carcinoma treated with a right mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection that showed metastatic disease. She also underwent adjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel and doxorubicin for breast carcinoma.

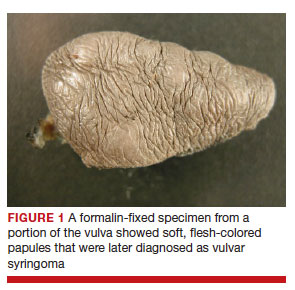

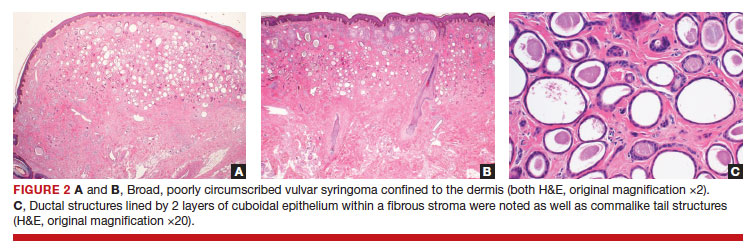

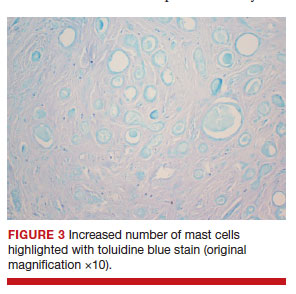

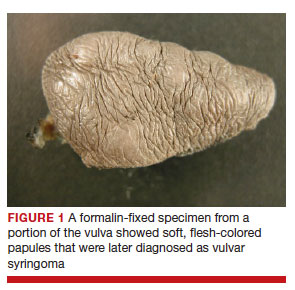

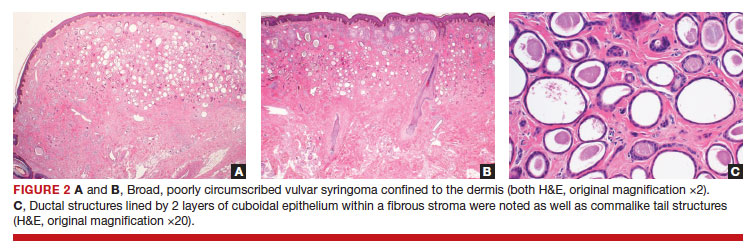

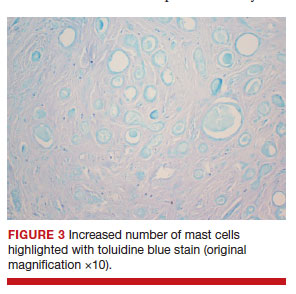

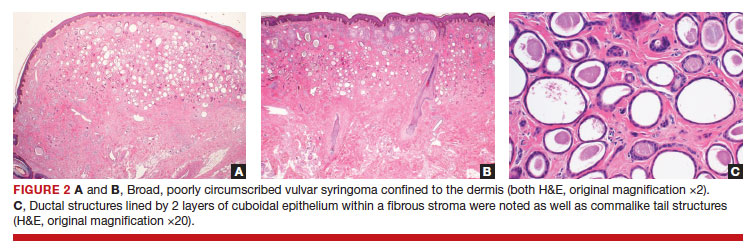

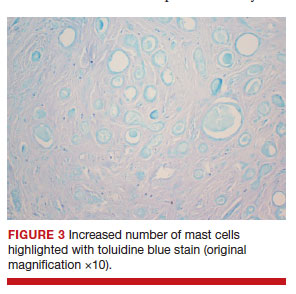

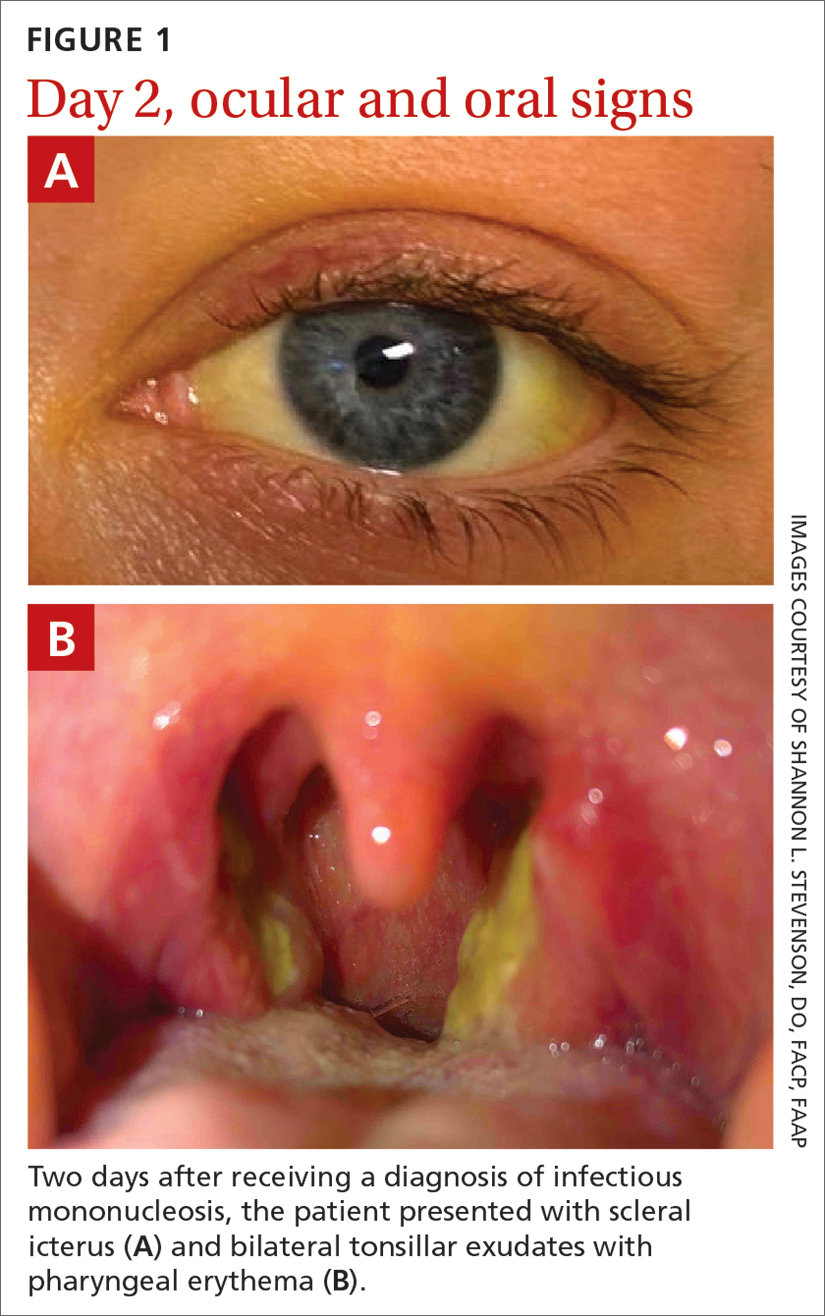

After discussing the diagnostic differential and treatment options, the patient elected to undergo a bilateral partial radical vulvectomy with reconstruction and resection of the right inguinal lymph node. Gross examination of the vulvectomy specimen showed multiple flesh-colored papules (FIGURE 1). Histologic examination revealed a neoplasm with sweat gland differentiation that was broad and poorly circumscribed but confined to the dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The neoplasm was composed of epithelial cells that formed ductlike structures, lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a fibrous stroma (FIGURE 2C). A toluidine blue special stain was performed and demonstrated an increased amount of mast cells in the tissue (FIGURE 3). Immunohistochemical stains for gross cystic disease fluid protein, estrogen receptor (ER), and progesterone receptor (PR) were negative in the tumor cells. The lack of cytologic atypia, perineural invasion, and deep infiltration into the subcutis favored a syringoma. One month later, the case was presented at the Tumor Board Conference at the University of Alabama at Birmingham where a final diagnosis of vulvar syringoma was agreed upon and discussed with the patient. At that time, no recurrence was evident and follow-up was recommended.

Syringomas are benign tumors of the sweat glands that are fairly common and appear to have a predilection for women. Although most of the literature classifies them as eccrine neoplasms, the term syringoma can be used to describe neoplasms of either apocrine or eccrine lineage.1 To rule out an apocrine lineage of the tumor in our patient, we performed immunohistochemistry for gross cystic disease fluid protein, a marker of apocrine differentiation. This stain highlighted normal apocrine glands that were not involved in the tumor proliferation.

Syringomas may occur at any site on the body but are prone to occur on the periorbital area, especially the eyelids.1 Some of the atypical locations for a syringoma include the anterior neck, chest, abdomen, genitals, axillae, groin, and buttocks.2 Vulvar syringomas were first reported by Carneiro3 in 1971 as usually affecting adolescent girls and middle-aged women. There have been approximately 40 reported cases affecting women aged 8 to 78 years.4,5 Vulvar syringomas classically appear as firm or soft, flesh-colored to transparent, papular lesions. The 2 other clinical variants are miliumlike, whitish, cystic papules as well as lichenoid papules.6 Pérez-Bustillo et al5 reported a case of the lichenoid papule variant on the labia majora of a 78-year-old woman who presented with intermittent vulvar pruritus of 4 years’ duration. Due to this patient’s 9-year history of urinary incontinence, the lesions had been misdiagnosed as irritant dermatitis and associated lichen simplex chronicus (LSC). This case is a reminder to consider vulvar syringoma in patients with LSC who respond poorly to oral antihistamines and topical steroids.5 Rarely, multiple clinical variants may coexist. In a case reported by Dereli et al,7 a 19-year-old woman presented with concurrent classical and miliumlike forms of vulvar syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually present as multiple lesions involving both sides of the labia majora; however, Blasdale and McLelland8 reported a single isolated syringoma of the vulva on the anterior right labia minora that measured 1.0×0.5 cm, leading the lesion to be described as a giant syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually are asymptomatic and noticed during routine gynecologic examination. Therefore, it is believed that they likely are underdiagnosed.5 When symptomatic, they commonly present with constant9 or intermittent5 pruritus, which may intensify during menstruation, pregnancy, and summertime.6,10-12 Gerdsen et al10 documented a 27-year-old woman who presented with a 2-year history of pruritic vulvar skin lesions that became exacerbated during menstruation, which raised the possibility of cyclical hormonal changes being responsible for periodic exacerbation of vulvar pruritus during menstruation. In addition, patients may experience an increase in size and number of the lesions during pregnancy. Bal et al11 reported a 24-year-old primigravida with vulvar papular lesions that intensified during pregnancy. She had experienced intermittent vulvar pruritus for 12 years but had no change in symptoms during menstruation.11 Few studies have attempted to evaluate the presence of ER and PR in the syringomas. A study of 9 nonvulvar syringomas by Wallace and Smoller13 showed ER positivity in 1 case and PR positivity in 8 cases, lending support to the hormonal theory; however, in another case series of 15 vulvar syringomas, Huang et al6 failed to show ER and PR expression by immunohistochemical staining. A case report published 3 years earlier documented the first case of PR positivity on a vulvar syringoma.14 Our patient also was negative for ER and PR, which suggested that hormonal status is important in some but not all syringomas.

Patients with vulvar syringomas also might have coexisting extragenital syringomas in the neck,4 eyelids,6,7,10 and periorbital area,6 and thorough examination of the body is essential. If an extragenital syringoma is diagnosed, a vulvar syringoma should be considered, especially when the patient presents with unexplained genital symptoms. Although no proven hereditary transmission pattern has been established, family history of syringomas has been established in several cases.15 In a case series reported by Huang et al,6 4 of 18 patients reported a family history of periorbital syringomas. In our case, the patient did not report a family history of syringomas.

The differential diagnosis of vulvar lesions with pruritus is broad and includes Fox-Fordyce disease, lichen planus, LSC, epidermal cysts, senile angiomas, dystrophic calcinosis, xanthomas, steatocytomas, soft fibromas, condyloma acuminatum, and candidiasis. Vulvar syringomas might have a nonspecific appearance, and histologic examination is essential to confirm the diagnosis and rule out any malignant process such as MAC, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, extramammary Paget disease, or other glandular neoplasms of the vulva.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma was first reported in 1982 by Goldstein et al16 as a locally aggressive neoplasm that can be confused with benign adnexal neoplasms, particularly desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, trichoadenoma, and syringoma. Microcystic adnexal carcinomas present as slow-growing, flesh-colored papules that may resemble syringomas and appear in similar body sites. Histologic examination is essential to differentiate between these two entities. Syringomas are tumors confined to the dermis and are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a dense fibrous stroma. Unlike syringomas, MACs usually infiltrate diffusely into the dermis and subcutis and may extend into the underlying muscle. Although bland cytologic features predominate, perineural invasion frequently is present in MACs. A potential pitfall of misdiagnosis can be caused by a superficial biopsy that may reveal benign histologic appearance, particularly in the upper level of the tumor where it may be confused with a syringoma or a benign follicular neoplasm.17

The initial biopsy performed on our patient was possibly not deep enough to render an unequivocal diagnosis and therefore bilateral partial radical vulvectomy was considered. After surgery, histologic examination of the resection specimen revealed a poorly circumscribed tumor confined to the dermis. The tumor was broad and the lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis and perineural invasion favored a syringoma (FIGURES 2A and 2B). These findings were consistent with case reports that documented syringomas as being more wide than deep on microscopic examination, whereas the opposite pertained to MAC.18 Cases of plaque-type syringomas that initially were misdiagnosed as MACs also have been reported.19 Because misdiagnosis may affect the treatment plan and potentially result in unnecessary surgery, caution should be taken when differentiating between these two entities. When a definitive diagnosis cannot be rendered on a superficial biopsy, a recommendation should be made for a deeper biopsy sampling the subcutis.

For the majority of the patients with vulvar syringomas, treatment is seldom required due to their asymptomatic nature; however, patients who present with symptoms usually report pruritus of variable intensities and patterns. A standardized treatment does not exist for vulvar syringomas, and oral or topical treatment might be used as an initial approach. Commonly prescribed medications with variable results include topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, and topical retinoids. In a case reported by Iwao et al,20 vulvar syringomas were successfully treated with tranilast, which has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. This medication could have a possible dual action—inhibiting the release of chemical mediators from the mast cells and inhibiting the release of IL-1β from the eccrine duct, which could suppress the proliferation of stromal connective tissue. Our case was stained with toluidine blue and showed an increased number of mast cells in the tissue (FIGURE 3).Patients who are unresponsive to tranilast or have extensive disease resulting in cosmetic disfigurement might benefit from more invasive treatment methods including a variety of lasers, cryotherapy, electrosurgery, and excision. Excisions should include the entire tumor to avoid recurrence. In a case reported by Garman and Metry,21 the lesions were surgically excised using small 2- to 3-mm punches; however, several weeks later the lesions recurred. Our patient presented with a 1-month evolution of dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities that were probably not treated with oral or topical medications before being referred for surgery.

We report a case of a vulvar syringoma that presented diagnostic challenges in the initial biopsy, which prevented the exclusion of an MAC. After partial radical vulvectomy, histologic examination was more definitive, showing lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis or perineural invasion that are commonly seen in MAC. This case is an example of a notable pitfall in the diagnosis of vulvar syringoma on a limited biopsy leading to overtreatment. Raising awareness of this entity is the only modality to prevent misdiagnosis. We encourage reporting of further cases of syringomas, particularly those with atypical locations or patterns that may cause diagnostic problems. ●

- Ensure adequate depth of biopsy to assist in the histologic diagnosis of syringoma vs microcystic adnexal carcinoma.

- Vulvar syringomas also may contribute to notable pruritus and ultimately be the underlying etiology for secondary skin changes leading to a lichen simplex chronicus–like phenotype

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

- Weedon D. Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010.

- Carneiro SJ, Gardner HL, Knox JM. Syringoma of the vulva. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:494-496.

- Trager JD, Silvers J, Reed JA, et al. Neck and vulvar papules in an 8-year-old girl. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:203, 206.

- Pérez-Bustillo A, Ruiz-González I, Delgado S, et al. Vulvar syringoma: a rare cause of vulvar pruritus. Actas DermoSifiliográficas. 2008; 99:580-581.

- Huang YH, Chuang YH, Kuo TT, et al. Vulvar syringoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistologic study of 18 patients and results of treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:735-739.

- Dereli T, Turk BG, Kazandi AC. Syringomas of the vulva. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;99:65-66.

- Blasdale C, McLelland J. Solitary giant vulval syringoma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:374-375.

- Kavala M, Can B, Zindanci I, et al. Vulvar pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:831-832.

- Gerdsen R, Wenzel J, Uerlich M, et al. Periodic genital pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:369-370.

- Bal N, Aslan E, Kayaselcuk F, et al. Vulvar syringoma aggravated by pregnancy. Pathol Oncol Res. 2003;9:196-197.

- Turan C, Ugur M, Kutluay L, et al. Vulvar syringoma exacerbated during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;64:141-142.

- Wallace ML, Smoller BR. Progesterone receptor positivity supports hormonal control of syringomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1995; 22:442-445.

- Yorganci A, Kale A, Dunder I, et al. Vulvar syringoma showing progesterone receptor positivity. BJOG. 2000;107:292-294.

- Draznin M. Hereditary syringomas: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:19.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Hamsch C, Hartschuh W. Microcystic adnexal carcinomaaggressive infiltrative tumor often with innocent clinical appearance. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:275-278.

- Henner MS, Shapiro PE, Ritter JH, et al. Solitary syringoma. report of five cases and clinicopathologic comparison with microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:465-470.

- Suwattee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Iwao F, Onozuka T, Kawashima T. Vulval syringoma successfully treated with tranilast. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1228-1230.

- Garman M, Metry D. Vulvar syringomas in a 9-year-old child with review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:369372.

To the Editor:

Syringomas are common benign tumors of the eccrine sweat glands that usually manifest clinically as multiple flesh-colored papules. They are most commonly seen on the face, neck, and chest of adolescent girls. Syringomas may appear at any site of the body but are rare in the vulva. We present a case of a 51-year-old woman who was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of a tumor carrying a differential diagnosis of vulvar syringoma vs microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC).

A 51-year-old woman presented to dermatology (G.G.) and was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of possible vulvar syringoma vs MAC. The patient previously had been evaluated at an outside community practice due to dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities of 1 month’s duration. At that time, a small biopsy was performed, and the histologic differential diagnosis included syringoma vs an adnexal carcinoma. Consequently, she was referred to gynecologic oncology for further management.

Pelvic examination revealed multilobular nodular areas overlying the clitoral hood that extended down to the labia majora. The nodular processes did not involve the clitoris, labia minora, or perineum. A mobile isolated lymph node measuring 2.0×1.0 cm in the right inguinal area also was noted. The patient’s clinical history was notable for right breast carcinoma treated with a right mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection that showed metastatic disease. She also underwent adjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel and doxorubicin for breast carcinoma.

After discussing the diagnostic differential and treatment options, the patient elected to undergo a bilateral partial radical vulvectomy with reconstruction and resection of the right inguinal lymph node. Gross examination of the vulvectomy specimen showed multiple flesh-colored papules (FIGURE 1). Histologic examination revealed a neoplasm with sweat gland differentiation that was broad and poorly circumscribed but confined to the dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The neoplasm was composed of epithelial cells that formed ductlike structures, lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a fibrous stroma (FIGURE 2C). A toluidine blue special stain was performed and demonstrated an increased amount of mast cells in the tissue (FIGURE 3). Immunohistochemical stains for gross cystic disease fluid protein, estrogen receptor (ER), and progesterone receptor (PR) were negative in the tumor cells. The lack of cytologic atypia, perineural invasion, and deep infiltration into the subcutis favored a syringoma. One month later, the case was presented at the Tumor Board Conference at the University of Alabama at Birmingham where a final diagnosis of vulvar syringoma was agreed upon and discussed with the patient. At that time, no recurrence was evident and follow-up was recommended.

Syringomas are benign tumors of the sweat glands that are fairly common and appear to have a predilection for women. Although most of the literature classifies them as eccrine neoplasms, the term syringoma can be used to describe neoplasms of either apocrine or eccrine lineage.1 To rule out an apocrine lineage of the tumor in our patient, we performed immunohistochemistry for gross cystic disease fluid protein, a marker of apocrine differentiation. This stain highlighted normal apocrine glands that were not involved in the tumor proliferation.

Syringomas may occur at any site on the body but are prone to occur on the periorbital area, especially the eyelids.1 Some of the atypical locations for a syringoma include the anterior neck, chest, abdomen, genitals, axillae, groin, and buttocks.2 Vulvar syringomas were first reported by Carneiro3 in 1971 as usually affecting adolescent girls and middle-aged women. There have been approximately 40 reported cases affecting women aged 8 to 78 years.4,5 Vulvar syringomas classically appear as firm or soft, flesh-colored to transparent, papular lesions. The 2 other clinical variants are miliumlike, whitish, cystic papules as well as lichenoid papules.6 Pérez-Bustillo et al5 reported a case of the lichenoid papule variant on the labia majora of a 78-year-old woman who presented with intermittent vulvar pruritus of 4 years’ duration. Due to this patient’s 9-year history of urinary incontinence, the lesions had been misdiagnosed as irritant dermatitis and associated lichen simplex chronicus (LSC). This case is a reminder to consider vulvar syringoma in patients with LSC who respond poorly to oral antihistamines and topical steroids.5 Rarely, multiple clinical variants may coexist. In a case reported by Dereli et al,7 a 19-year-old woman presented with concurrent classical and miliumlike forms of vulvar syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually present as multiple lesions involving both sides of the labia majora; however, Blasdale and McLelland8 reported a single isolated syringoma of the vulva on the anterior right labia minora that measured 1.0×0.5 cm, leading the lesion to be described as a giant syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually are asymptomatic and noticed during routine gynecologic examination. Therefore, it is believed that they likely are underdiagnosed.5 When symptomatic, they commonly present with constant9 or intermittent5 pruritus, which may intensify during menstruation, pregnancy, and summertime.6,10-12 Gerdsen et al10 documented a 27-year-old woman who presented with a 2-year history of pruritic vulvar skin lesions that became exacerbated during menstruation, which raised the possibility of cyclical hormonal changes being responsible for periodic exacerbation of vulvar pruritus during menstruation. In addition, patients may experience an increase in size and number of the lesions during pregnancy. Bal et al11 reported a 24-year-old primigravida with vulvar papular lesions that intensified during pregnancy. She had experienced intermittent vulvar pruritus for 12 years but had no change in symptoms during menstruation.11 Few studies have attempted to evaluate the presence of ER and PR in the syringomas. A study of 9 nonvulvar syringomas by Wallace and Smoller13 showed ER positivity in 1 case and PR positivity in 8 cases, lending support to the hormonal theory; however, in another case series of 15 vulvar syringomas, Huang et al6 failed to show ER and PR expression by immunohistochemical staining. A case report published 3 years earlier documented the first case of PR positivity on a vulvar syringoma.14 Our patient also was negative for ER and PR, which suggested that hormonal status is important in some but not all syringomas.

Patients with vulvar syringomas also might have coexisting extragenital syringomas in the neck,4 eyelids,6,7,10 and periorbital area,6 and thorough examination of the body is essential. If an extragenital syringoma is diagnosed, a vulvar syringoma should be considered, especially when the patient presents with unexplained genital symptoms. Although no proven hereditary transmission pattern has been established, family history of syringomas has been established in several cases.15 In a case series reported by Huang et al,6 4 of 18 patients reported a family history of periorbital syringomas. In our case, the patient did not report a family history of syringomas.

The differential diagnosis of vulvar lesions with pruritus is broad and includes Fox-Fordyce disease, lichen planus, LSC, epidermal cysts, senile angiomas, dystrophic calcinosis, xanthomas, steatocytomas, soft fibromas, condyloma acuminatum, and candidiasis. Vulvar syringomas might have a nonspecific appearance, and histologic examination is essential to confirm the diagnosis and rule out any malignant process such as MAC, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, extramammary Paget disease, or other glandular neoplasms of the vulva.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma was first reported in 1982 by Goldstein et al16 as a locally aggressive neoplasm that can be confused with benign adnexal neoplasms, particularly desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, trichoadenoma, and syringoma. Microcystic adnexal carcinomas present as slow-growing, flesh-colored papules that may resemble syringomas and appear in similar body sites. Histologic examination is essential to differentiate between these two entities. Syringomas are tumors confined to the dermis and are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a dense fibrous stroma. Unlike syringomas, MACs usually infiltrate diffusely into the dermis and subcutis and may extend into the underlying muscle. Although bland cytologic features predominate, perineural invasion frequently is present in MACs. A potential pitfall of misdiagnosis can be caused by a superficial biopsy that may reveal benign histologic appearance, particularly in the upper level of the tumor where it may be confused with a syringoma or a benign follicular neoplasm.17

The initial biopsy performed on our patient was possibly not deep enough to render an unequivocal diagnosis and therefore bilateral partial radical vulvectomy was considered. After surgery, histologic examination of the resection specimen revealed a poorly circumscribed tumor confined to the dermis. The tumor was broad and the lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis and perineural invasion favored a syringoma (FIGURES 2A and 2B). These findings were consistent with case reports that documented syringomas as being more wide than deep on microscopic examination, whereas the opposite pertained to MAC.18 Cases of plaque-type syringomas that initially were misdiagnosed as MACs also have been reported.19 Because misdiagnosis may affect the treatment plan and potentially result in unnecessary surgery, caution should be taken when differentiating between these two entities. When a definitive diagnosis cannot be rendered on a superficial biopsy, a recommendation should be made for a deeper biopsy sampling the subcutis.

For the majority of the patients with vulvar syringomas, treatment is seldom required due to their asymptomatic nature; however, patients who present with symptoms usually report pruritus of variable intensities and patterns. A standardized treatment does not exist for vulvar syringomas, and oral or topical treatment might be used as an initial approach. Commonly prescribed medications with variable results include topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, and topical retinoids. In a case reported by Iwao et al,20 vulvar syringomas were successfully treated with tranilast, which has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. This medication could have a possible dual action—inhibiting the release of chemical mediators from the mast cells and inhibiting the release of IL-1β from the eccrine duct, which could suppress the proliferation of stromal connective tissue. Our case was stained with toluidine blue and showed an increased number of mast cells in the tissue (FIGURE 3).Patients who are unresponsive to tranilast or have extensive disease resulting in cosmetic disfigurement might benefit from more invasive treatment methods including a variety of lasers, cryotherapy, electrosurgery, and excision. Excisions should include the entire tumor to avoid recurrence. In a case reported by Garman and Metry,21 the lesions were surgically excised using small 2- to 3-mm punches; however, several weeks later the lesions recurred. Our patient presented with a 1-month evolution of dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities that were probably not treated with oral or topical medications before being referred for surgery.

We report a case of a vulvar syringoma that presented diagnostic challenges in the initial biopsy, which prevented the exclusion of an MAC. After partial radical vulvectomy, histologic examination was more definitive, showing lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis or perineural invasion that are commonly seen in MAC. This case is an example of a notable pitfall in the diagnosis of vulvar syringoma on a limited biopsy leading to overtreatment. Raising awareness of this entity is the only modality to prevent misdiagnosis. We encourage reporting of further cases of syringomas, particularly those with atypical locations or patterns that may cause diagnostic problems. ●

- Ensure adequate depth of biopsy to assist in the histologic diagnosis of syringoma vs microcystic adnexal carcinoma.

- Vulvar syringomas also may contribute to notable pruritus and ultimately be the underlying etiology for secondary skin changes leading to a lichen simplex chronicus–like phenotype

To the Editor:

Syringomas are common benign tumors of the eccrine sweat glands that usually manifest clinically as multiple flesh-colored papules. They are most commonly seen on the face, neck, and chest of adolescent girls. Syringomas may appear at any site of the body but are rare in the vulva. We present a case of a 51-year-old woman who was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of a tumor carrying a differential diagnosis of vulvar syringoma vs microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC).

A 51-year-old woman presented to dermatology (G.G.) and was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of possible vulvar syringoma vs MAC. The patient previously had been evaluated at an outside community practice due to dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities of 1 month’s duration. At that time, a small biopsy was performed, and the histologic differential diagnosis included syringoma vs an adnexal carcinoma. Consequently, she was referred to gynecologic oncology for further management.

Pelvic examination revealed multilobular nodular areas overlying the clitoral hood that extended down to the labia majora. The nodular processes did not involve the clitoris, labia minora, or perineum. A mobile isolated lymph node measuring 2.0×1.0 cm in the right inguinal area also was noted. The patient’s clinical history was notable for right breast carcinoma treated with a right mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection that showed metastatic disease. She also underwent adjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel and doxorubicin for breast carcinoma.

After discussing the diagnostic differential and treatment options, the patient elected to undergo a bilateral partial radical vulvectomy with reconstruction and resection of the right inguinal lymph node. Gross examination of the vulvectomy specimen showed multiple flesh-colored papules (FIGURE 1). Histologic examination revealed a neoplasm with sweat gland differentiation that was broad and poorly circumscribed but confined to the dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The neoplasm was composed of epithelial cells that formed ductlike structures, lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a fibrous stroma (FIGURE 2C). A toluidine blue special stain was performed and demonstrated an increased amount of mast cells in the tissue (FIGURE 3). Immunohistochemical stains for gross cystic disease fluid protein, estrogen receptor (ER), and progesterone receptor (PR) were negative in the tumor cells. The lack of cytologic atypia, perineural invasion, and deep infiltration into the subcutis favored a syringoma. One month later, the case was presented at the Tumor Board Conference at the University of Alabama at Birmingham where a final diagnosis of vulvar syringoma was agreed upon and discussed with the patient. At that time, no recurrence was evident and follow-up was recommended.

Syringomas are benign tumors of the sweat glands that are fairly common and appear to have a predilection for women. Although most of the literature classifies them as eccrine neoplasms, the term syringoma can be used to describe neoplasms of either apocrine or eccrine lineage.1 To rule out an apocrine lineage of the tumor in our patient, we performed immunohistochemistry for gross cystic disease fluid protein, a marker of apocrine differentiation. This stain highlighted normal apocrine glands that were not involved in the tumor proliferation.

Syringomas may occur at any site on the body but are prone to occur on the periorbital area, especially the eyelids.1 Some of the atypical locations for a syringoma include the anterior neck, chest, abdomen, genitals, axillae, groin, and buttocks.2 Vulvar syringomas were first reported by Carneiro3 in 1971 as usually affecting adolescent girls and middle-aged women. There have been approximately 40 reported cases affecting women aged 8 to 78 years.4,5 Vulvar syringomas classically appear as firm or soft, flesh-colored to transparent, papular lesions. The 2 other clinical variants are miliumlike, whitish, cystic papules as well as lichenoid papules.6 Pérez-Bustillo et al5 reported a case of the lichenoid papule variant on the labia majora of a 78-year-old woman who presented with intermittent vulvar pruritus of 4 years’ duration. Due to this patient’s 9-year history of urinary incontinence, the lesions had been misdiagnosed as irritant dermatitis and associated lichen simplex chronicus (LSC). This case is a reminder to consider vulvar syringoma in patients with LSC who respond poorly to oral antihistamines and topical steroids.5 Rarely, multiple clinical variants may coexist. In a case reported by Dereli et al,7 a 19-year-old woman presented with concurrent classical and miliumlike forms of vulvar syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually present as multiple lesions involving both sides of the labia majora; however, Blasdale and McLelland8 reported a single isolated syringoma of the vulva on the anterior right labia minora that measured 1.0×0.5 cm, leading the lesion to be described as a giant syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually are asymptomatic and noticed during routine gynecologic examination. Therefore, it is believed that they likely are underdiagnosed.5 When symptomatic, they commonly present with constant9 or intermittent5 pruritus, which may intensify during menstruation, pregnancy, and summertime.6,10-12 Gerdsen et al10 documented a 27-year-old woman who presented with a 2-year history of pruritic vulvar skin lesions that became exacerbated during menstruation, which raised the possibility of cyclical hormonal changes being responsible for periodic exacerbation of vulvar pruritus during menstruation. In addition, patients may experience an increase in size and number of the lesions during pregnancy. Bal et al11 reported a 24-year-old primigravida with vulvar papular lesions that intensified during pregnancy. She had experienced intermittent vulvar pruritus for 12 years but had no change in symptoms during menstruation.11 Few studies have attempted to evaluate the presence of ER and PR in the syringomas. A study of 9 nonvulvar syringomas by Wallace and Smoller13 showed ER positivity in 1 case and PR positivity in 8 cases, lending support to the hormonal theory; however, in another case series of 15 vulvar syringomas, Huang et al6 failed to show ER and PR expression by immunohistochemical staining. A case report published 3 years earlier documented the first case of PR positivity on a vulvar syringoma.14 Our patient also was negative for ER and PR, which suggested that hormonal status is important in some but not all syringomas.

Patients with vulvar syringomas also might have coexisting extragenital syringomas in the neck,4 eyelids,6,7,10 and periorbital area,6 and thorough examination of the body is essential. If an extragenital syringoma is diagnosed, a vulvar syringoma should be considered, especially when the patient presents with unexplained genital symptoms. Although no proven hereditary transmission pattern has been established, family history of syringomas has been established in several cases.15 In a case series reported by Huang et al,6 4 of 18 patients reported a family history of periorbital syringomas. In our case, the patient did not report a family history of syringomas.

The differential diagnosis of vulvar lesions with pruritus is broad and includes Fox-Fordyce disease, lichen planus, LSC, epidermal cysts, senile angiomas, dystrophic calcinosis, xanthomas, steatocytomas, soft fibromas, condyloma acuminatum, and candidiasis. Vulvar syringomas might have a nonspecific appearance, and histologic examination is essential to confirm the diagnosis and rule out any malignant process such as MAC, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, extramammary Paget disease, or other glandular neoplasms of the vulva.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma was first reported in 1982 by Goldstein et al16 as a locally aggressive neoplasm that can be confused with benign adnexal neoplasms, particularly desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, trichoadenoma, and syringoma. Microcystic adnexal carcinomas present as slow-growing, flesh-colored papules that may resemble syringomas and appear in similar body sites. Histologic examination is essential to differentiate between these two entities. Syringomas are tumors confined to the dermis and are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a dense fibrous stroma. Unlike syringomas, MACs usually infiltrate diffusely into the dermis and subcutis and may extend into the underlying muscle. Although bland cytologic features predominate, perineural invasion frequently is present in MACs. A potential pitfall of misdiagnosis can be caused by a superficial biopsy that may reveal benign histologic appearance, particularly in the upper level of the tumor where it may be confused with a syringoma or a benign follicular neoplasm.17

The initial biopsy performed on our patient was possibly not deep enough to render an unequivocal diagnosis and therefore bilateral partial radical vulvectomy was considered. After surgery, histologic examination of the resection specimen revealed a poorly circumscribed tumor confined to the dermis. The tumor was broad and the lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis and perineural invasion favored a syringoma (FIGURES 2A and 2B). These findings were consistent with case reports that documented syringomas as being more wide than deep on microscopic examination, whereas the opposite pertained to MAC.18 Cases of plaque-type syringomas that initially were misdiagnosed as MACs also have been reported.19 Because misdiagnosis may affect the treatment plan and potentially result in unnecessary surgery, caution should be taken when differentiating between these two entities. When a definitive diagnosis cannot be rendered on a superficial biopsy, a recommendation should be made for a deeper biopsy sampling the subcutis.

For the majority of the patients with vulvar syringomas, treatment is seldom required due to their asymptomatic nature; however, patients who present with symptoms usually report pruritus of variable intensities and patterns. A standardized treatment does not exist for vulvar syringomas, and oral or topical treatment might be used as an initial approach. Commonly prescribed medications with variable results include topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, and topical retinoids. In a case reported by Iwao et al,20 vulvar syringomas were successfully treated with tranilast, which has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. This medication could have a possible dual action—inhibiting the release of chemical mediators from the mast cells and inhibiting the release of IL-1β from the eccrine duct, which could suppress the proliferation of stromal connective tissue. Our case was stained with toluidine blue and showed an increased number of mast cells in the tissue (FIGURE 3).Patients who are unresponsive to tranilast or have extensive disease resulting in cosmetic disfigurement might benefit from more invasive treatment methods including a variety of lasers, cryotherapy, electrosurgery, and excision. Excisions should include the entire tumor to avoid recurrence. In a case reported by Garman and Metry,21 the lesions were surgically excised using small 2- to 3-mm punches; however, several weeks later the lesions recurred. Our patient presented with a 1-month evolution of dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities that were probably not treated with oral or topical medications before being referred for surgery.

We report a case of a vulvar syringoma that presented diagnostic challenges in the initial biopsy, which prevented the exclusion of an MAC. After partial radical vulvectomy, histologic examination was more definitive, showing lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis or perineural invasion that are commonly seen in MAC. This case is an example of a notable pitfall in the diagnosis of vulvar syringoma on a limited biopsy leading to overtreatment. Raising awareness of this entity is the only modality to prevent misdiagnosis. We encourage reporting of further cases of syringomas, particularly those with atypical locations or patterns that may cause diagnostic problems. ●

- Ensure adequate depth of biopsy to assist in the histologic diagnosis of syringoma vs microcystic adnexal carcinoma.

- Vulvar syringomas also may contribute to notable pruritus and ultimately be the underlying etiology for secondary skin changes leading to a lichen simplex chronicus–like phenotype

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

- Weedon D. Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010.

- Carneiro SJ, Gardner HL, Knox JM. Syringoma of the vulva. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:494-496.

- Trager JD, Silvers J, Reed JA, et al. Neck and vulvar papules in an 8-year-old girl. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:203, 206.

- Pérez-Bustillo A, Ruiz-González I, Delgado S, et al. Vulvar syringoma: a rare cause of vulvar pruritus. Actas DermoSifiliográficas. 2008; 99:580-581.

- Huang YH, Chuang YH, Kuo TT, et al. Vulvar syringoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistologic study of 18 patients and results of treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:735-739.

- Dereli T, Turk BG, Kazandi AC. Syringomas of the vulva. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;99:65-66.

- Blasdale C, McLelland J. Solitary giant vulval syringoma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:374-375.

- Kavala M, Can B, Zindanci I, et al. Vulvar pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:831-832.

- Gerdsen R, Wenzel J, Uerlich M, et al. Periodic genital pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:369-370.

- Bal N, Aslan E, Kayaselcuk F, et al. Vulvar syringoma aggravated by pregnancy. Pathol Oncol Res. 2003;9:196-197.

- Turan C, Ugur M, Kutluay L, et al. Vulvar syringoma exacerbated during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;64:141-142.

- Wallace ML, Smoller BR. Progesterone receptor positivity supports hormonal control of syringomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1995; 22:442-445.

- Yorganci A, Kale A, Dunder I, et al. Vulvar syringoma showing progesterone receptor positivity. BJOG. 2000;107:292-294.

- Draznin M. Hereditary syringomas: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:19.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Hamsch C, Hartschuh W. Microcystic adnexal carcinomaaggressive infiltrative tumor often with innocent clinical appearance. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:275-278.

- Henner MS, Shapiro PE, Ritter JH, et al. Solitary syringoma. report of five cases and clinicopathologic comparison with microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:465-470.

- Suwattee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Iwao F, Onozuka T, Kawashima T. Vulval syringoma successfully treated with tranilast. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1228-1230.

- Garman M, Metry D. Vulvar syringomas in a 9-year-old child with review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:369372.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

- Weedon D. Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010.

- Carneiro SJ, Gardner HL, Knox JM. Syringoma of the vulva. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:494-496.

- Trager JD, Silvers J, Reed JA, et al. Neck and vulvar papules in an 8-year-old girl. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:203, 206.

- Pérez-Bustillo A, Ruiz-González I, Delgado S, et al. Vulvar syringoma: a rare cause of vulvar pruritus. Actas DermoSifiliográficas. 2008; 99:580-581.

- Huang YH, Chuang YH, Kuo TT, et al. Vulvar syringoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistologic study of 18 patients and results of treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:735-739.

- Dereli T, Turk BG, Kazandi AC. Syringomas of the vulva. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;99:65-66.

- Blasdale C, McLelland J. Solitary giant vulval syringoma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:374-375.

- Kavala M, Can B, Zindanci I, et al. Vulvar pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:831-832.

- Gerdsen R, Wenzel J, Uerlich M, et al. Periodic genital pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:369-370.

- Bal N, Aslan E, Kayaselcuk F, et al. Vulvar syringoma aggravated by pregnancy. Pathol Oncol Res. 2003;9:196-197.

- Turan C, Ugur M, Kutluay L, et al. Vulvar syringoma exacerbated during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;64:141-142.

- Wallace ML, Smoller BR. Progesterone receptor positivity supports hormonal control of syringomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1995; 22:442-445.

- Yorganci A, Kale A, Dunder I, et al. Vulvar syringoma showing progesterone receptor positivity. BJOG. 2000;107:292-294.

- Draznin M. Hereditary syringomas: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:19.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Hamsch C, Hartschuh W. Microcystic adnexal carcinomaaggressive infiltrative tumor often with innocent clinical appearance. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:275-278.

- Henner MS, Shapiro PE, Ritter JH, et al. Solitary syringoma. report of five cases and clinicopathologic comparison with microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:465-470.

- Suwattee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Iwao F, Onozuka T, Kawashima T. Vulval syringoma successfully treated with tranilast. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1228-1230.

- Garman M, Metry D. Vulvar syringomas in a 9-year-old child with review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:369372.

Risk for breast cancer reduced after bariatric surgery

In a matched cohort study of more than 69,000 Canadian women, risk for incident breast cancer at 1 year was 40% higher among women who had not undergone bariatric surgery, compared with those who had. The risk remained elevated through 5 years of follow-up.

The findings were “definitely a bit surprising,” study author Aristithes G. Doumouras, MD, MPH, assistant professor of surgery at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview. “The patients that underwent bariatric surgery had better cancer outcomes than patients who weighed less than they did, so it showed that there was more at play than just weight loss. This effect was durable [and] shows how powerful the surgery is, [as well as] the fact that we haven’t even explored all of its effects.”

The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

Protective association

To determine whether there is a residual risk for breast cancer following bariatric surgery for obesity, the investigators analyzed clinical and administrative data collected between 2010 and 2016 in Ontario. They retrospectively matched women with obesity who underwent bariatric surgery with women without a history of bariatric surgery. Participants were matched by age and breast cancer screening status. Covariates included diabetes status, neighborhood income quintile, and measures of health care use. The population included 69,260 women (mean age, 45 years).

Among participants who underwent bariatric surgery for obesity, baseline body mass index was greater than 35 for those with related comorbid conditions, and BMI was greater than 40 for those without comorbid conditions. The investigators categorized nonsurgical control patients in accordance with the following four BMI categories: less than 25, 25-29, 30-34, and greater than or equal to 35. Each control group, as well as the surgical group, included 13,852 women.

Participants in the surgical group were followed for 5 years after bariatric surgery. Those in the nonsurgical group were followed for 5 years after the index date (that is, the date of BMI measurement).

In the overall population, 659 cases of breast cancer were diagnosed in the overall population (0.95%) during the study period. This total included 103 (0.74%) cancers in the surgical cohort; 128 (0.92%) in the group with BMI less than 25; 143 (1.03%) among those with BMI 25-29; 150 (1.08%) in the group with BMI 30-34; and 135 (0.97%) among those with BMI greater than or equal to 35.

Most cancers were stage I. There were 65 cases among those with BMI less than 25; 76 for those with BMI of 25-29; 65 for BMI of 30-34; 67 for BMI greater than or equal to 35, and 60 for the surgery group.

Most tumors were of medium grade and were estrogen receptor positive, progesterone receptor positive, and ERBB2 negative. No significant differences were observed across the groups for stage, grade, or hormone status.

There was an increased hazard for incident breast cancer in the nonsurgical group, compared with the postsurgical group after washout periods of 1 year (hazard ratio, 1.40), 2 years (HR, 1.31), and 5 years (HR, 1.38).

In a comparison of the postsurgical cohort with the nonsurgical cohort with BMI less than 25, the hazard of incident breast cancer was not significantly different for any of the washout periods, but there was a reduced hazard for incident breast cancer among postsurgical patients than among nonsurgical patients in all high BMI categories (BMI ≥ 25).

“Taken together, these results demonstrate that the protective association between substantial weight loss via bariatric surgery and breast cancer risk is sustained after 5 years following surgery and that it is associated with a baseline risk similar to that of women with BMI less than 25,” the investigators write.

Nevertheless, Dr. Doumouras said “the interaction between the surgery and individuals is poorly studied, and this level of personalized medicine is simply not there yet. We are working on developing a prospective cohort that has genetic, protein, and microbiome [data] to help answer these questions.”

There are not enough women in subpopulations such as BRCA carriers to study at this point, he added. “This is where more patients and time will really help the research process.”

A universal benefit?

“Although these findings are important overall for the general population at risk for breast cancer, we raise an important caveat: The benefit of surgical weight loss may not be universal,” write Justin B. Dimick, MD, MPH, surgical innovation editor for JAMA Surgery, and Melissa L. Pilewskie, MD, both of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, in an accompanying commentary.

“In addition to lifestyle factors, several nonmodifiable risk factors, such as a genetic predisposition, strong family history, personal history of a high-risk breast lesion, or history of chest wall radiation, impart significant elevation in risk, and the data remain mixed on the impact of weight loss for individuals in these high-risk cohorts,” they add.

“Further study to elucidate the underlying mechanism associated with obesity, weight loss, and breast cancer risk should help guide strategies for risk reduction that are specific to unique high-risk cohorts, because modifiable risk factors may not portend the same benefit among all groups.”

Commenting on the findings, Stephen Edge, MD, breast surgeon and vice president for system quality and outcomes at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, N.Y., said, “The importance of this study is that it shows that weight loss in midlife can reduce breast cancer risk back to or even below the risk of similar people who were not obese. This has major implications for counseling women.”

The investigators did not have information on the extent of weight loss with surgery or on which participants maintained the lower weight, Dr. Edge noted; “However, overall, most people who have weight reduction surgery have major weight loss.”

At this point, he said, “we can now tell women with obesity that in addition to the many other advantages of weight loss, their risk of getting breast cancer will also be reduced.”

The study was supported by the Ontario Bariatric Registry and ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ontario Ministry of Long-Term Care. Dr. Doumouras, Dr. Dimick, Dr. Pilewskie, and Dr. Edge reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a matched cohort study of more than 69,000 Canadian women, risk for incident breast cancer at 1 year was 40% higher among women who had not undergone bariatric surgery, compared with those who had. The risk remained elevated through 5 years of follow-up.

The findings were “definitely a bit surprising,” study author Aristithes G. Doumouras, MD, MPH, assistant professor of surgery at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview. “The patients that underwent bariatric surgery had better cancer outcomes than patients who weighed less than they did, so it showed that there was more at play than just weight loss. This effect was durable [and] shows how powerful the surgery is, [as well as] the fact that we haven’t even explored all of its effects.”

The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

Protective association

To determine whether there is a residual risk for breast cancer following bariatric surgery for obesity, the investigators analyzed clinical and administrative data collected between 2010 and 2016 in Ontario. They retrospectively matched women with obesity who underwent bariatric surgery with women without a history of bariatric surgery. Participants were matched by age and breast cancer screening status. Covariates included diabetes status, neighborhood income quintile, and measures of health care use. The population included 69,260 women (mean age, 45 years).

Among participants who underwent bariatric surgery for obesity, baseline body mass index was greater than 35 for those with related comorbid conditions, and BMI was greater than 40 for those without comorbid conditions. The investigators categorized nonsurgical control patients in accordance with the following four BMI categories: less than 25, 25-29, 30-34, and greater than or equal to 35. Each control group, as well as the surgical group, included 13,852 women.

Participants in the surgical group were followed for 5 years after bariatric surgery. Those in the nonsurgical group were followed for 5 years after the index date (that is, the date of BMI measurement).

In the overall population, 659 cases of breast cancer were diagnosed in the overall population (0.95%) during the study period. This total included 103 (0.74%) cancers in the surgical cohort; 128 (0.92%) in the group with BMI less than 25; 143 (1.03%) among those with BMI 25-29; 150 (1.08%) in the group with BMI 30-34; and 135 (0.97%) among those with BMI greater than or equal to 35.

Most cancers were stage I. There were 65 cases among those with BMI less than 25; 76 for those with BMI of 25-29; 65 for BMI of 30-34; 67 for BMI greater than or equal to 35, and 60 for the surgery group.

Most tumors were of medium grade and were estrogen receptor positive, progesterone receptor positive, and ERBB2 negative. No significant differences were observed across the groups for stage, grade, or hormone status.

There was an increased hazard for incident breast cancer in the nonsurgical group, compared with the postsurgical group after washout periods of 1 year (hazard ratio, 1.40), 2 years (HR, 1.31), and 5 years (HR, 1.38).

In a comparison of the postsurgical cohort with the nonsurgical cohort with BMI less than 25, the hazard of incident breast cancer was not significantly different for any of the washout periods, but there was a reduced hazard for incident breast cancer among postsurgical patients than among nonsurgical patients in all high BMI categories (BMI ≥ 25).

“Taken together, these results demonstrate that the protective association between substantial weight loss via bariatric surgery and breast cancer risk is sustained after 5 years following surgery and that it is associated with a baseline risk similar to that of women with BMI less than 25,” the investigators write.

Nevertheless, Dr. Doumouras said “the interaction between the surgery and individuals is poorly studied, and this level of personalized medicine is simply not there yet. We are working on developing a prospective cohort that has genetic, protein, and microbiome [data] to help answer these questions.”

There are not enough women in subpopulations such as BRCA carriers to study at this point, he added. “This is where more patients and time will really help the research process.”

A universal benefit?

“Although these findings are important overall for the general population at risk for breast cancer, we raise an important caveat: The benefit of surgical weight loss may not be universal,” write Justin B. Dimick, MD, MPH, surgical innovation editor for JAMA Surgery, and Melissa L. Pilewskie, MD, both of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, in an accompanying commentary.

“In addition to lifestyle factors, several nonmodifiable risk factors, such as a genetic predisposition, strong family history, personal history of a high-risk breast lesion, or history of chest wall radiation, impart significant elevation in risk, and the data remain mixed on the impact of weight loss for individuals in these high-risk cohorts,” they add.

“Further study to elucidate the underlying mechanism associated with obesity, weight loss, and breast cancer risk should help guide strategies for risk reduction that are specific to unique high-risk cohorts, because modifiable risk factors may not portend the same benefit among all groups.”

Commenting on the findings, Stephen Edge, MD, breast surgeon and vice president for system quality and outcomes at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, N.Y., said, “The importance of this study is that it shows that weight loss in midlife can reduce breast cancer risk back to or even below the risk of similar people who were not obese. This has major implications for counseling women.”

The investigators did not have information on the extent of weight loss with surgery or on which participants maintained the lower weight, Dr. Edge noted; “However, overall, most people who have weight reduction surgery have major weight loss.”

At this point, he said, “we can now tell women with obesity that in addition to the many other advantages of weight loss, their risk of getting breast cancer will also be reduced.”

The study was supported by the Ontario Bariatric Registry and ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ontario Ministry of Long-Term Care. Dr. Doumouras, Dr. Dimick, Dr. Pilewskie, and Dr. Edge reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a matched cohort study of more than 69,000 Canadian women, risk for incident breast cancer at 1 year was 40% higher among women who had not undergone bariatric surgery, compared with those who had. The risk remained elevated through 5 years of follow-up.

The findings were “definitely a bit surprising,” study author Aristithes G. Doumouras, MD, MPH, assistant professor of surgery at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview. “The patients that underwent bariatric surgery had better cancer outcomes than patients who weighed less than they did, so it showed that there was more at play than just weight loss. This effect was durable [and] shows how powerful the surgery is, [as well as] the fact that we haven’t even explored all of its effects.”

The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

Protective association

To determine whether there is a residual risk for breast cancer following bariatric surgery for obesity, the investigators analyzed clinical and administrative data collected between 2010 and 2016 in Ontario. They retrospectively matched women with obesity who underwent bariatric surgery with women without a history of bariatric surgery. Participants were matched by age and breast cancer screening status. Covariates included diabetes status, neighborhood income quintile, and measures of health care use. The population included 69,260 women (mean age, 45 years).

Among participants who underwent bariatric surgery for obesity, baseline body mass index was greater than 35 for those with related comorbid conditions, and BMI was greater than 40 for those without comorbid conditions. The investigators categorized nonsurgical control patients in accordance with the following four BMI categories: less than 25, 25-29, 30-34, and greater than or equal to 35. Each control group, as well as the surgical group, included 13,852 women.

Participants in the surgical group were followed for 5 years after bariatric surgery. Those in the nonsurgical group were followed for 5 years after the index date (that is, the date of BMI measurement).

In the overall population, 659 cases of breast cancer were diagnosed in the overall population (0.95%) during the study period. This total included 103 (0.74%) cancers in the surgical cohort; 128 (0.92%) in the group with BMI less than 25; 143 (1.03%) among those with BMI 25-29; 150 (1.08%) in the group with BMI 30-34; and 135 (0.97%) among those with BMI greater than or equal to 35.

Most cancers were stage I. There were 65 cases among those with BMI less than 25; 76 for those with BMI of 25-29; 65 for BMI of 30-34; 67 for BMI greater than or equal to 35, and 60 for the surgery group.

Most tumors were of medium grade and were estrogen receptor positive, progesterone receptor positive, and ERBB2 negative. No significant differences were observed across the groups for stage, grade, or hormone status.

There was an increased hazard for incident breast cancer in the nonsurgical group, compared with the postsurgical group after washout periods of 1 year (hazard ratio, 1.40), 2 years (HR, 1.31), and 5 years (HR, 1.38).

In a comparison of the postsurgical cohort with the nonsurgical cohort with BMI less than 25, the hazard of incident breast cancer was not significantly different for any of the washout periods, but there was a reduced hazard for incident breast cancer among postsurgical patients than among nonsurgical patients in all high BMI categories (BMI ≥ 25).

“Taken together, these results demonstrate that the protective association between substantial weight loss via bariatric surgery and breast cancer risk is sustained after 5 years following surgery and that it is associated with a baseline risk similar to that of women with BMI less than 25,” the investigators write.

Nevertheless, Dr. Doumouras said “the interaction between the surgery and individuals is poorly studied, and this level of personalized medicine is simply not there yet. We are working on developing a prospective cohort that has genetic, protein, and microbiome [data] to help answer these questions.”

There are not enough women in subpopulations such as BRCA carriers to study at this point, he added. “This is where more patients and time will really help the research process.”

A universal benefit?

“Although these findings are important overall for the general population at risk for breast cancer, we raise an important caveat: The benefit of surgical weight loss may not be universal,” write Justin B. Dimick, MD, MPH, surgical innovation editor for JAMA Surgery, and Melissa L. Pilewskie, MD, both of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, in an accompanying commentary.

“In addition to lifestyle factors, several nonmodifiable risk factors, such as a genetic predisposition, strong family history, personal history of a high-risk breast lesion, or history of chest wall radiation, impart significant elevation in risk, and the data remain mixed on the impact of weight loss for individuals in these high-risk cohorts,” they add.

“Further study to elucidate the underlying mechanism associated with obesity, weight loss, and breast cancer risk should help guide strategies for risk reduction that are specific to unique high-risk cohorts, because modifiable risk factors may not portend the same benefit among all groups.”

Commenting on the findings, Stephen Edge, MD, breast surgeon and vice president for system quality and outcomes at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, N.Y., said, “The importance of this study is that it shows that weight loss in midlife can reduce breast cancer risk back to or even below the risk of similar people who were not obese. This has major implications for counseling women.”

The investigators did not have information on the extent of weight loss with surgery or on which participants maintained the lower weight, Dr. Edge noted; “However, overall, most people who have weight reduction surgery have major weight loss.”

At this point, he said, “we can now tell women with obesity that in addition to the many other advantages of weight loss, their risk of getting breast cancer will also be reduced.”

The study was supported by the Ontario Bariatric Registry and ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ontario Ministry of Long-Term Care. Dr. Doumouras, Dr. Dimick, Dr. Pilewskie, and Dr. Edge reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Patritumab deruxtecan shows promise for breast cancer patients

according to data presented from Abstract 1240 at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Breast Cancer annual congress.

Patritumab deruxtecan (HER3-DXd) has previously demonstrated an acceptable safety profile and antitumor activity in phase I studies involving heavily pretreated patients with metastatic breast cancer and various levels of HER3 protein expression, said Mafalda Oliveira, MD, of the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital and Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology in Barcelona.

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) are a combination of a monoclonal antibody chemically linked to a drug, as defined by the National Cancer Institute. ADCs work by binding to receptors or proteins and selectively delivering cytotoxic drugs to the site of a tumor.

Dr. Oliveira presented results from part B the of SOLTI TOT-HER3 trial, a window-of-opportunity trial that evaluated the effect of a single dose of HER3-Dxd in patients with treatment-naive HR+/HER2– early breast cancer.

In such trials, patients receive one or more new compounds between the time of cancer diagnosis and standard treatment. Biological and clinical activity from part A of the SOLTI TOT-HER3 trial were presented at last year’s ESMO Breast Cancer Congress, Dr. Oliveira said.

In the current study, Dr. Oliveira and colleagues recruited 37 women with HR+/HER2– early breast cancer, including 20 who were hormone receptor–positive and 17 who had triple negative breast cancer (TNBC). The age of the participants ranged from 30 to 81 years, with a median age of 51 years; 54% were premenopausal. The mean tumor size was 21 mm, with a range of 10-81 mm.

Distinct from part A of the SOLTI TOT-HER3 trial, part B included a subset of patients with TNBC to assess preliminary efficacy in this subtype, Dr. Oliveira noted.

All patients in part B received a single dose of 5.6 mg/kg of HER3-DXd. The primary outcome was the variation in the tumor cellularity and tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (CelTIL) score at baseline and after 21 days via breast ultrasound.

At day 21, the total CelTIL score increased by a significant mean difference of 9.4 points after a single dose; the mean differences for TNBC and HR+/HER2– patients, were 17.9 points and 2.2 points, respectively, Dr. Oliveira said. The overall response rate was 32% (35% in TNBC patients and 30% in HR+/HER2– patients) and was significantly associated with the absolute change in CelTIL (area under the curve = 0.693; P = .049).

In a subtype analysis, a statistically significant change in CelTIL was observed between paired samples overall (P = .046) and in TNBC (P = .016), but not in HR+ (P = .793).

Baseline levels of ERBB3 (also known as human epidermal growth factor receptor type 3, or HER3) were not associated with changes in CelTIL or in overall response rate.

HER3-DXd induced high expression of immune-related genes (such as PD1, CD8, and CD19), and suppressed proliferation-related genes, she said.

A total of 31 patients (84%) reported any adverse events. Of these, the most common were nausea, fatigue, alopecia, diarrhea, constipation, and vomiting, and one patient experienced grade 3 treatment-related nausea. No interstitial lung disease events were reported during the study, and the incidence of hematological and hepatic toxicity was lower with the lower dose in part B, compared with the 6.5 mg/kg dose used in part A, Dr. Oliveira noted.

To further validate the findings of the current study and assess the activity of HER3-DXd in early breast cancer, Dr. Oliveira and colleagues are conducting a neoadjuvant phase II trial known as SOLTI-2103 VALENTINE. In this study, they are testing six cycles of HER3-DXd at a 5.6 mg/kg dose in HR+/HER2– breast cancer patients, she said.

During a question-and-answer session, Dr. Oliveira was asked whether CelTIL is the best endpoint for assessing HER3-DXd. Finding the best endpoint is always a challenge when conducting window-of-opportunity trials, she said. The CelTIL score has been correlated with pathologic complete response (pCR), as well as with disease-free survival and overall survival, she added.

ICARUS-BREAST01

In a presentation of Abstract 1890 during the same session, Barbari Pistilli, MD, of Gustave Roussy Cancer Center, Villejuif, France, shared data from a phase II study known as ICARUS-BREAST.

The study population included women with unresectable locally advanced breast cancer (ABC) who had undergone a median of two previous systemic therapies. In the current study, the patients underwent a median of eight cycles of HER3-DXd. The dosage was 5.6 mg/kg every 3 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The primary outcome was overall response and disease progression after 3 months. Dr. Pistilli, who is also a coauthor of the research, provided data from 56 evaluable patients.

After 3 months, 16 patients (28.6%) showed a partial response, 30 patients showed stable disease (54%), and 10 (18%) showed disease progression. “No patients had a complete response,” Dr. Pistilli noted.

As for the safety profile, all patients reported at least one treatment-emergent event of any grade, but less than half (48.2%) were grade 3 or higher, and 12.5% led to treatment discontinuation. Fatigue and nausea were the most frequently reported adverse events overall, and occurred in 89.3% and 76.8% of patients, respectively. All grade and grade 3 or higher neutropenia occurred in four patients and six patients, respectively; all grade and grade 3 or higher thrombocytopenia occurred in four patients and two patients, respectively, Dr. Pistilli said.

Data on circulating tumor cells (CTCs) were available for 31 patients, and the researchers reviewed CTC counts after the first HER3-DXd cycle.

“We found that the median number of CTCs decreased by one to two cell cycles of HER3-DXd,” said Dr. Pistilli. She and her coauthors found no substantial impact of the treatment on HER3 negative CTC counts, and “more importantly, no increase of HER3 negative CTC counts at disease progression,” Dr. Pistilli continued.

In addition, patients with higher HER+ CTC counts at baseline or a greater decrease in HER3+ CTC counts after one cycle of HER3-DXd were more likely to have an early treatment response, but this association was not statistically significant.

Looking ahead, further analysis will be performed to evaluate the association between HER3+ CTC counts and dynamics and the main outcomes of overall response rate and progression-free survival to determine the potential of HER3+ CTC counts to identify patients who can benefit from HER3-DXd, said Dr. Pistilli. The ICARUS-BREAST01 study is ongoing, and further efficacy and biomarker analysis will be presented, she added.

In the question-and-answer session, Dr. Pistilli was asked why she chose CTC as a measure.

Dr. Pistilli responded that she and her coauthors wanted to understand whether CTC could serve as a biomarker to help in patient selection.

Also, when asked about which genes might be upregulated and downregulated in responders vs. nonresponders, she noted that some genes related to DNA repair were involved in patients who were responders, but more research is needed.

Early results merit further exploration

Although patritumab deruxtecan is early in development, “there is a clear signal to expand,” based on preliminary research, said Rebecca A. Dent, MD, who served as discussant for the two studies.

“There is no clear role for a specific subtype in both protein and gene expression,” noted Dr. Dent, who is a professor at Duke NUS Medical School, a collaboration between Duke University, Durham, N.C., and the National University of Singapore.

In the SOLTI TOT-HER3 trial, the small numbers make teasing out correlations a challenge, said Dr. Dent. However, changes were observed after just one cycle of the drug, and the upregulation of immune signature genes was reassuring, she said.

“A single dose of HER3-DXd induced an overall response of approximately 30% independently of hormone receptor status,” she emphasized, and the lower incidence of hematological and hepatic toxicity with the lower dose is good news as well. The findings were limited by the small sample size, but the results support moving forward with clinical development of HER3-DXd, she said.

The ICARUS-BREAST01 study researchers tried to show whether they could identify potential markers of early treatment response, and they examined CTCs and gene alterations, said Dr. Dent. “I think it is reassuring that despite these patients being heavily pretreated, HER-DXd seems to be active regardless of most frequent breast cancer genomic alterations,” she noted. Remaining questions include the need for more data on primary resistance.

“We are able to get these patients to respond, but what makes patients resistant to ADCs is just as important,” she said. “We see exciting data across all these subtypes,”

In Dr. Dent’s opinion, future research should focus on triple negative breast cancer, an opinion supported by the stronger response in this subset of patients in the SOLTI TOT-HER3 trial. “I think you need to bring triple negative to the table,” she said.

The SOLTI TOT-HER3 study was funded by Daiichi Sankyo. Dr. Oliveira disclosed relationships with companies including AstraZeneca, Ayala Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Genentech, Gilead, GSK, Novartis, Roche, Seagen, Zenith Epigenetics, Daiichi Sankyo, iTEOS, MSD, Pierre-Fabre, Relay Therapeutics, and Eisai. ICARUS-BREAST01 was sponsored by the Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and supported by Daiichi Sankyo. Dr. Pistilli disclosed relationships with multiple companies including Daiichi-Sankyo, AstraZeneca, Gilead, Seagen, MSD, Novartis, Lilly, and Pierre Fabre. Dr. Dent disclosed financial relationships with companies including AstraZeneca, Roche, Eisai, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, and Pfizer.

according to data presented from Abstract 1240 at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Breast Cancer annual congress.

Patritumab deruxtecan (HER3-DXd) has previously demonstrated an acceptable safety profile and antitumor activity in phase I studies involving heavily pretreated patients with metastatic breast cancer and various levels of HER3 protein expression, said Mafalda Oliveira, MD, of the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital and Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology in Barcelona.

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) are a combination of a monoclonal antibody chemically linked to a drug, as defined by the National Cancer Institute. ADCs work by binding to receptors or proteins and selectively delivering cytotoxic drugs to the site of a tumor.

Dr. Oliveira presented results from part B the of SOLTI TOT-HER3 trial, a window-of-opportunity trial that evaluated the effect of a single dose of HER3-Dxd in patients with treatment-naive HR+/HER2– early breast cancer.

In such trials, patients receive one or more new compounds between the time of cancer diagnosis and standard treatment. Biological and clinical activity from part A of the SOLTI TOT-HER3 trial were presented at last year’s ESMO Breast Cancer Congress, Dr. Oliveira said.

In the current study, Dr. Oliveira and colleagues recruited 37 women with HR+/HER2– early breast cancer, including 20 who were hormone receptor–positive and 17 who had triple negative breast cancer (TNBC). The age of the participants ranged from 30 to 81 years, with a median age of 51 years; 54% were premenopausal. The mean tumor size was 21 mm, with a range of 10-81 mm.

Distinct from part A of the SOLTI TOT-HER3 trial, part B included a subset of patients with TNBC to assess preliminary efficacy in this subtype, Dr. Oliveira noted.

All patients in part B received a single dose of 5.6 mg/kg of HER3-DXd. The primary outcome was the variation in the tumor cellularity and tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (CelTIL) score at baseline and after 21 days via breast ultrasound.

At day 21, the total CelTIL score increased by a significant mean difference of 9.4 points after a single dose; the mean differences for TNBC and HR+/HER2– patients, were 17.9 points and 2.2 points, respectively, Dr. Oliveira said. The overall response rate was 32% (35% in TNBC patients and 30% in HR+/HER2– patients) and was significantly associated with the absolute change in CelTIL (area under the curve = 0.693; P = .049).

In a subtype analysis, a statistically significant change in CelTIL was observed between paired samples overall (P = .046) and in TNBC (P = .016), but not in HR+ (P = .793).

Baseline levels of ERBB3 (also known as human epidermal growth factor receptor type 3, or HER3) were not associated with changes in CelTIL or in overall response rate.

HER3-DXd induced high expression of immune-related genes (such as PD1, CD8, and CD19), and suppressed proliferation-related genes, she said.