User login

Community Care Radiation Oncology Cost Calculations for a VA Medical Center

Community Care Radiation Oncology Cost Calculations for a VA Medical Center

William Kissick’s description of health care’s iron triangle in 1994 still resonates. Access, quality, and cost will always come at the expense of the others.1 In 2018, Congress passed the VA MISSION Act, allowing patients to pursue community care options for extended waits (> 28 days) or longer distance drive times of > 60 minutes for specialty care services, such as radiation oncology. According to Albanese et al, the VA MISSION Act sought to address gaps in care for veterans living in rural and underserved areas.2 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) continues to increase community care spending, with a 13.8% increase in fiscal year 2024 and an expected cost of > $40 billion for 2025.3 One could argue this pays for access for remote patients and quality when services are unavailable, making it a direct application of the iron triangle.

The VA MISSION Act also bolstered the expansion of existing community care department staff to expediently facilitate and coordinate care and payments.2 Cost management and monitoring have become critical in predicting future staff requirements, maintaining functionality, and ensuring patients receive optimal care. The VHA purchases care through partner networks and defines these bundled health care services as standard episodes of care (SEOCs), which are “clinically related health care services for a specific unique illness or medical condition… over a defined period of time.”4 Medicare publishes its rates quarterly, and outpatient procedure pricing is readily available online.5 Along these same lines, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) publishes a current list of available procedures and associated Current Procedure Technology (CPT) codes that are covered under its VA fee schedule for community care.

Unique challenges persist when using this system to accurately account for radiation oncology expenditures. This study was based on the current practices at the Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center (RLRVAMC), a large 1a hospital. A detailed analysis reveals the contemporaneous cost of radiation oncology cancer care from October 1, 2021, through February 1, 2024, highlights the challenges in SEOC definition and duration, communication issues between RLRVAMC and purchase partners, inconsistencies in billing, erroneous payments, and difficulty of cost categorization.

METHODS

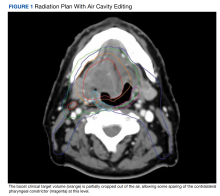

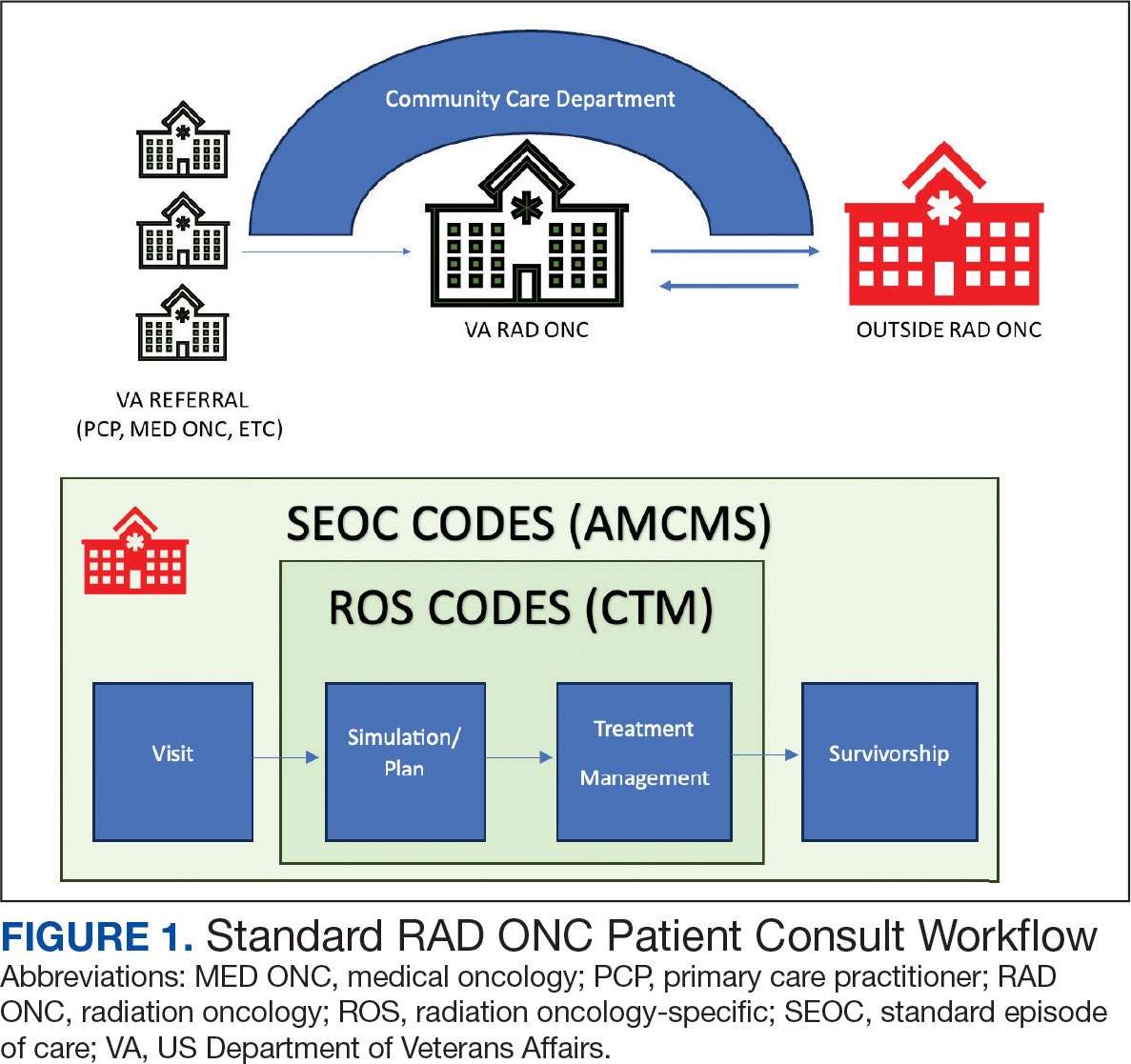

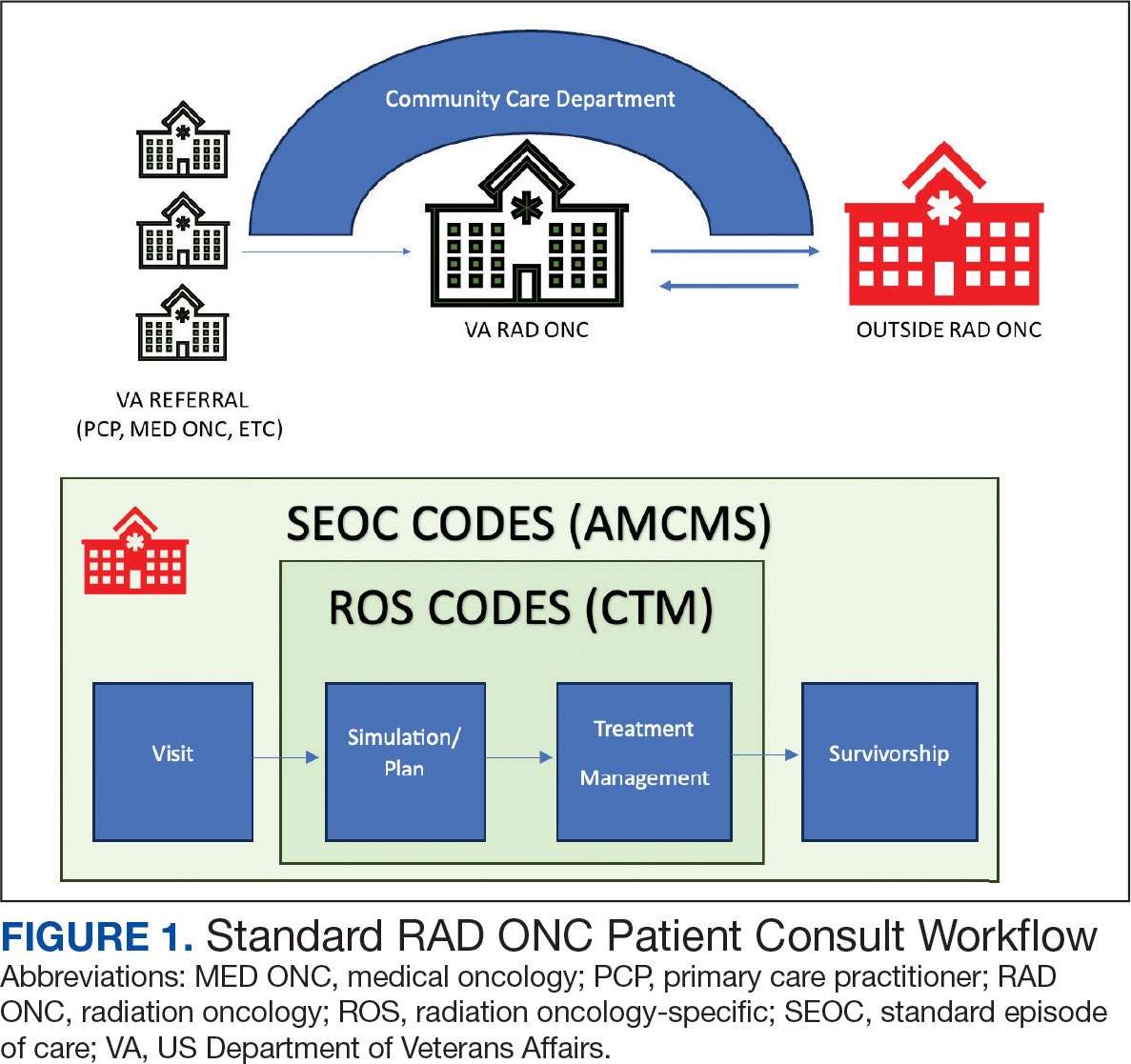

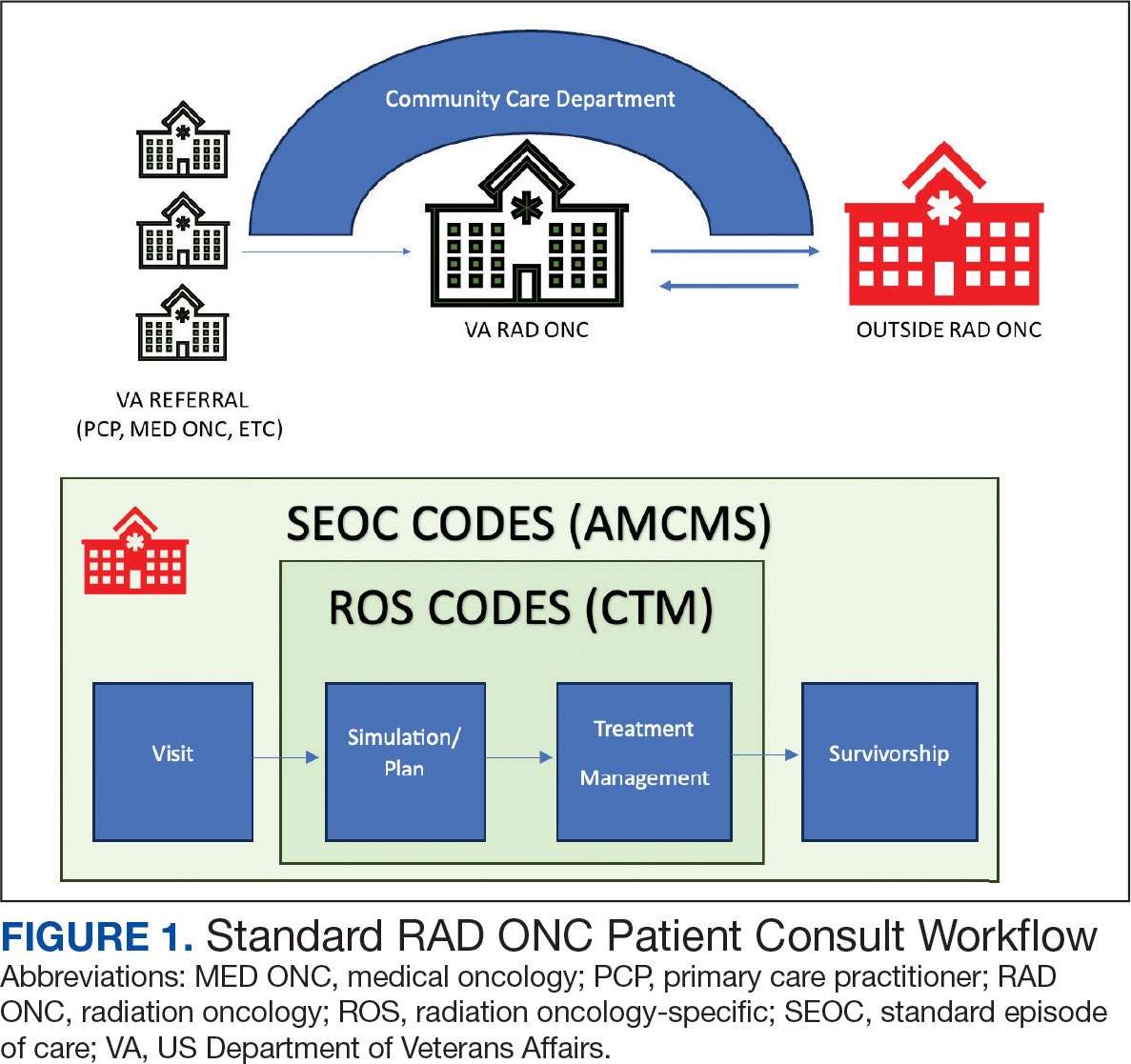

Community care radiation oncology-related costs were examined from October 1, 2021, to February 1, 2024 for RLRVAMC, 6 months prior to billing data extraction. Figure 1 shows a simple radiation oncology patient pathway with consultation or visit, simulation and planning, and treatment, with codes used to check billing. It illustrates the expected relationships between the VHA (radiation oncology, primary, and specialty care) and community care (clinicians and radiation oncology treatment sites).

VHA standard operating procedures for a patient requesting community-based radiation oncology care require a board-certified radiation oncologist at RLRVAMC to review and approve the outside care request. Community care radiation oncology consultation data were accessed from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) using Pyramid Analytics (V25.2). Nurses, physicians, and community care staff can add comments, forward consultations to other services, and mark them as complete or discontinued, when appropriate. Consultations not completed within 91 days are automatically discontinued. All community care requests from 2018 through 2024 were extracted; analysis began April 1, 2021, 6 months prior to the cost evaluation date of October 1, 2021.

An approved consultation is reviewed for eligibility by a nurse in the community care department and assigned an authorization number (a VA prefix followed by 12 digits). Billing codes are approved and organized by the community care networks, and all procedure codes should be captured and labeled under this number. The VAMC Community Care department obtains initial correspondence from the treating clinicians. Subsequent records from the treating radiation oncologist are expected to be scanned into the electronic health record and made accessible via the VA Joint Legacy Viewer (JLV) and Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS).

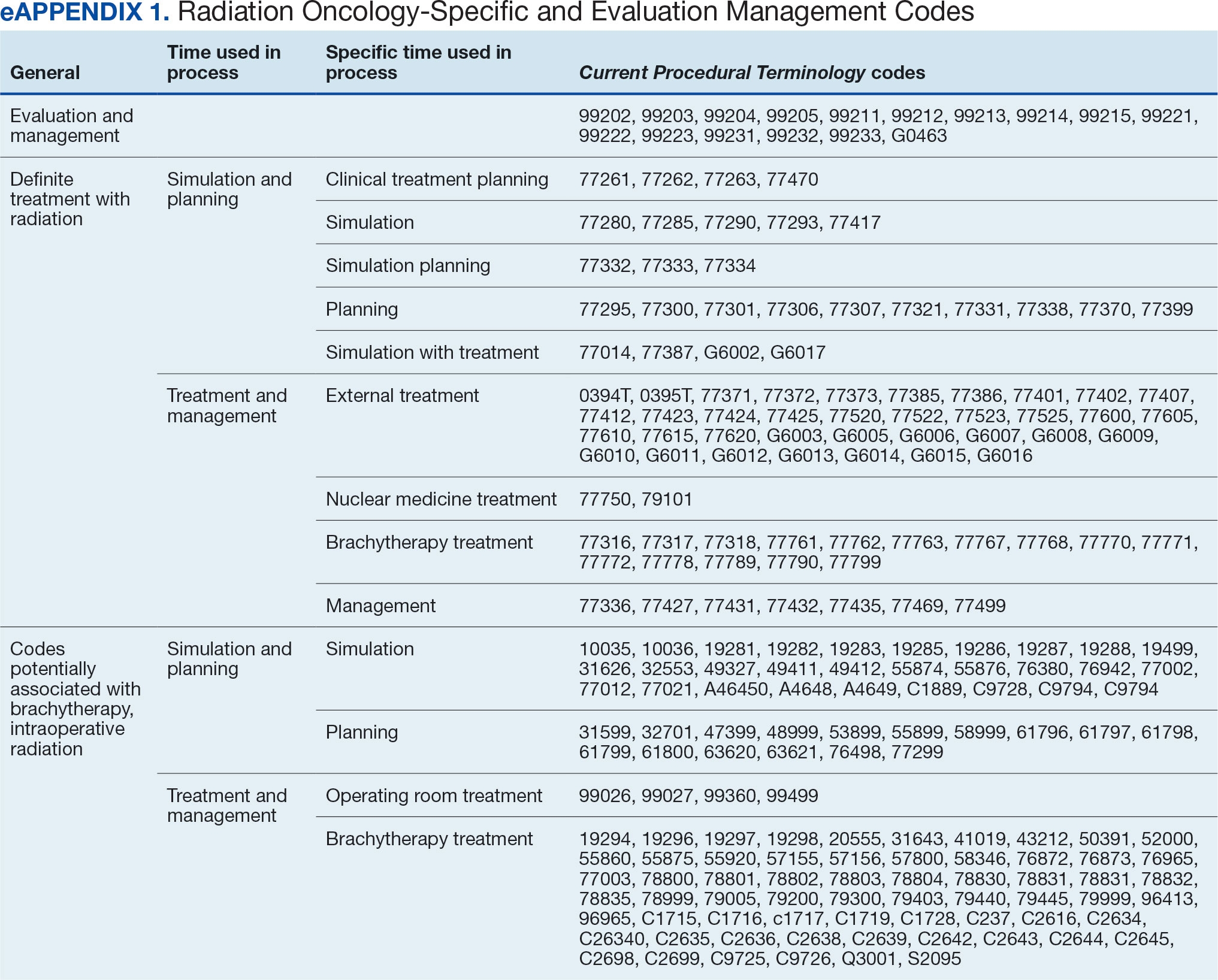

Radiation Oncology SEOC

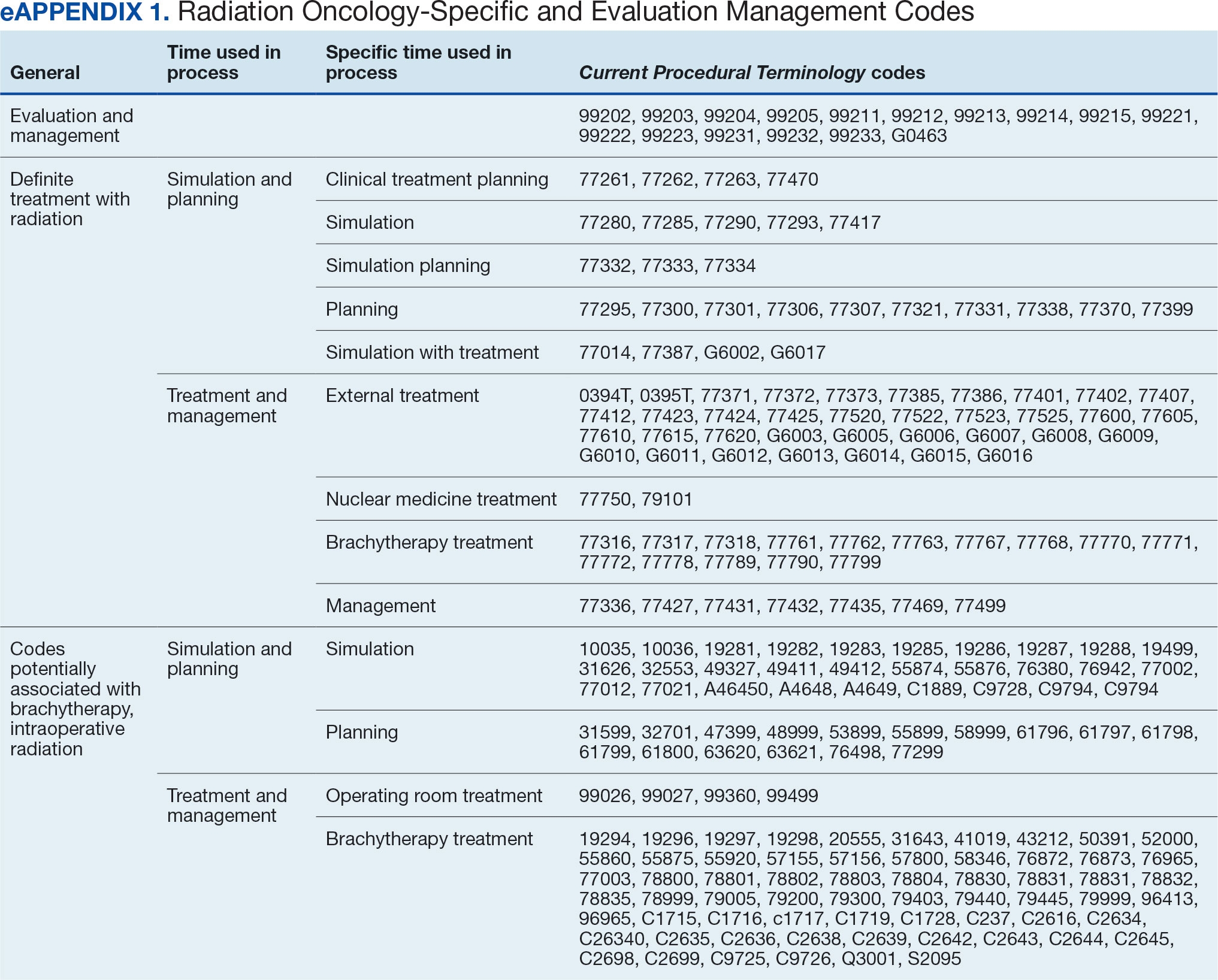

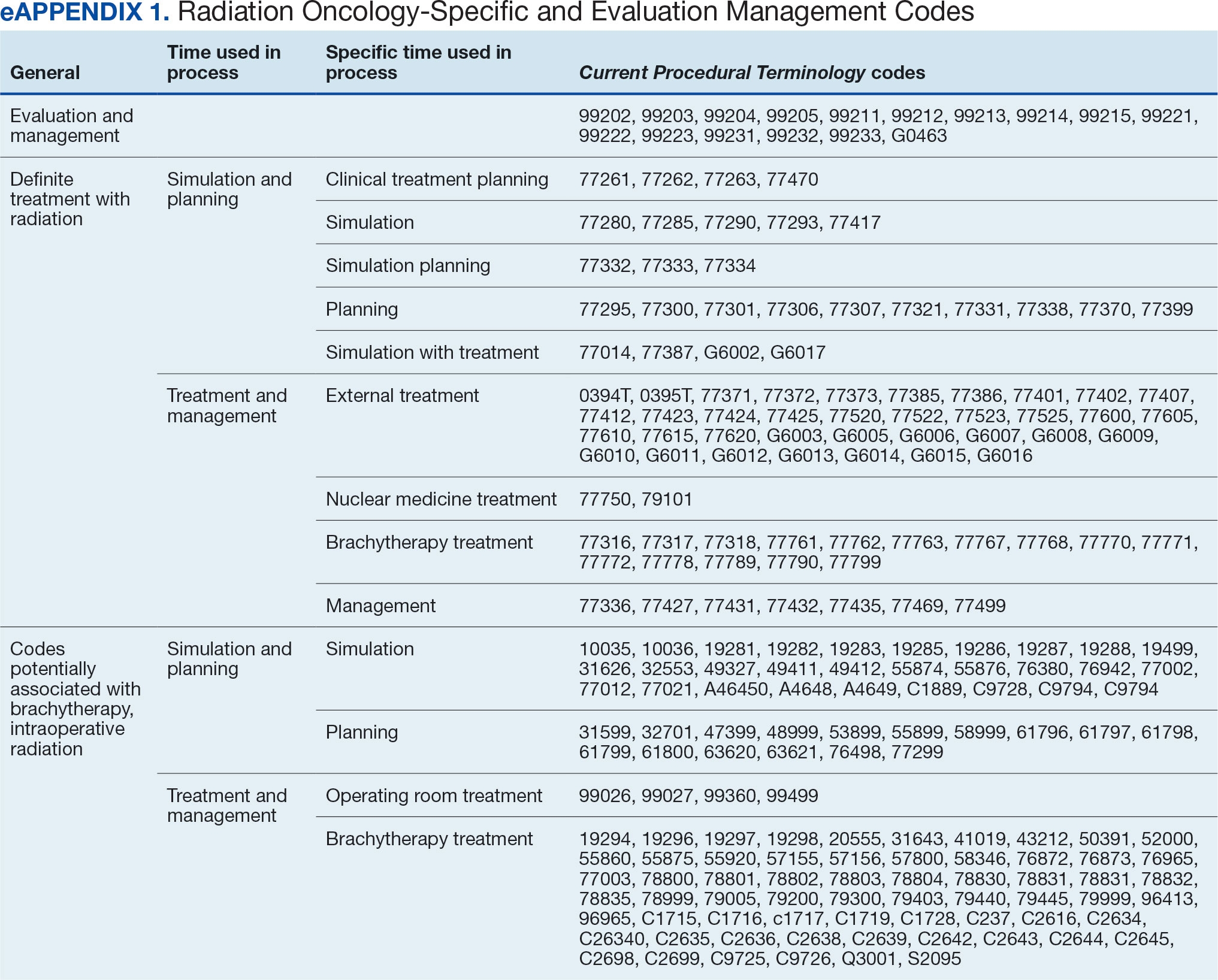

The start date of the radiation oncology SEOC is determined by the community care nurse based on guidance established by the VA. It can be manually backdated or delayed, but current practice is to start at first visit or procedure code entry after approval from the VAMC Radiation Oncology department. Approved CPT codes from SEOC versions between October 1, 2021, and February 1, 2024, are in eAppendix 1 (available at doi:10.12788/fp.0585). These generally include 10 types of encounters, about 115 different laboratory tests, 115 imaging studies, 25 simulation and planning procedures, and 115 radiation treatment codes. The radiation oncology SEOCs during the study period had an approval duration of 180 days. Advanced Medical Cost Management Solutions software (AMCMS) is the VHA data analytics platform for community care medical service costs. AMCMS includes all individual CPT codes billed by specific radiation oncology SEOC versions. Data are refreshed monthly, and all charges were extracted on September 12, 2024, > 6 months after the final evaluated service date to allow for complete billing returns.6

Radiation Oncology-Specific Costs

The VA Close to Me (CTM) program was used to find 84 specific radiation oncology CPT codes, nearly all within the 77.XXX or G6.XXX series, which included all radiation oncology-specific (ROS) codes (except visits accrued during consultation and return appointments). ROS costs are those that could not be performed by any other service and include procedures related to radiation oncology simulation, treatment planning, treatment delivery (with or without image guidance), and physician or physicist management. All ROS costs should be included in a patient’s radiation oncology SEOC. Other costs that may accompany operating room or brachytherapy administration did not follow a 77.XXX or G6.XXX pattern but were included in total radiation therapy operating costs.

Data obtained from AMCMS and CTM included patient name and identifier; CPT billed amount; CPT paid amount; dates of service; number of claims; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD) diagnosis; and VA authorization numbers. Only CTM listed code modifiers. Only items categorized as paid were included in the analysis. Charges associated with discontinued consultations that had accrued costs also were included. Codes that were not directly related to ROS were separately characterized as other and further subcategorized.

Deep Dive Categorization

All scanned documents tagged to the community consultation were accessed and evaluated for completeness by a radiation oncologist (RS). The presence or absence of consultation notes and treatment summaries was evaluated based on necessity (ie, not needed for continuation of care or treatment was not given). In the absence of a specific completion summary or follow-up note detailing the treatment modality, number of fractions, and treatment sites, available documentation, including clinical notes and billing information, was used. Radical or curative therapies were identified as courses expected to eradicate disease, including stereotactic ablative radiotherapy to the brain, lung, liver, and other organs. Palliative therapies included whole-brain radiotherapy or other low-dose treatments. If the patient received the intended course, this was categorized as full. If incomplete, it was considered partial.

Billing Deviations

The complete document review allowed for close evaluation of paid therapy and identification of gaps in billing (eg, charges not found in extracted data that should have occurred) for external beam radiotherapy patients. Conversely, extra charges, such as an additional weekly treatment management charge (CPT code 77427), would be noted. Patients were expected to have the number of treatments specified in the summary, a clinical treatment planning code, and weekly treatment management notes from physicians and physicists every 5 fractions. Consultations and follow-up visits were expected to have 1 visit code; CPT codes 99205 and 99215, respectively, were used to estimate costs in their absence.

Costs were based on Medicare rates as of January 1 of the year in which they were accrued. 7-10 Duplicates were charges with the same code, date, billed quantity, and paid amounts for a given patient. These would always be considered erroneous. Medicare treatment costs for procedures such as intensity modulated radiotherapy (CPT code 77385 or 77386) are available on the Medicare website. When reviewing locality deviations for 77427, there was a maximum of 33% increase in Medicare rates. Therefore, for treatment codes, one would expect the range to be at least the Medicare rate and maximally 33% higher. These rates are negotiated with insurance companies, but this range was used for the purpose of reviewing and adjusting large data sets.

RESULTS

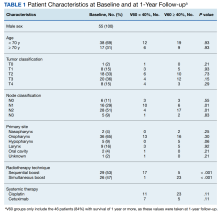

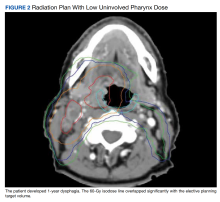

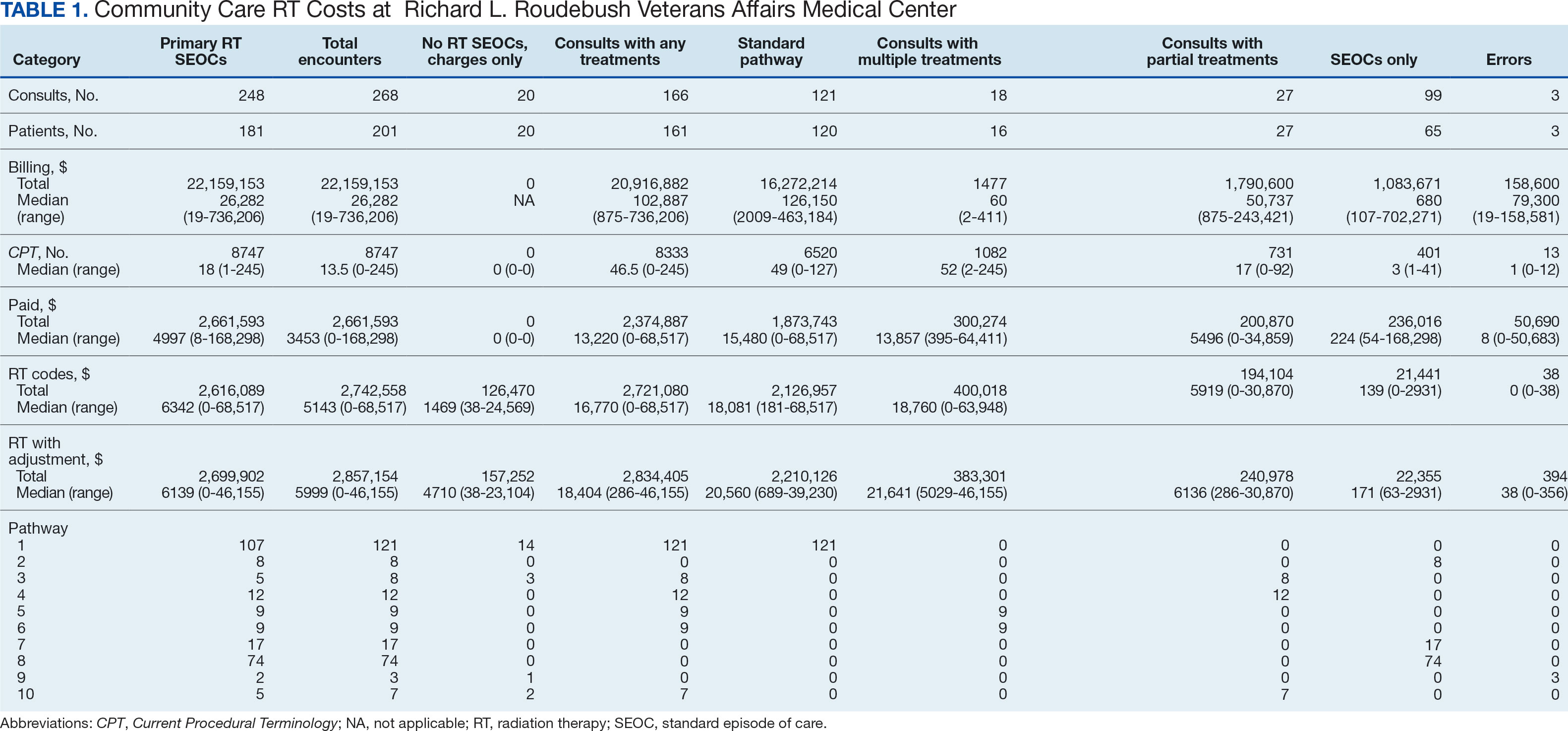

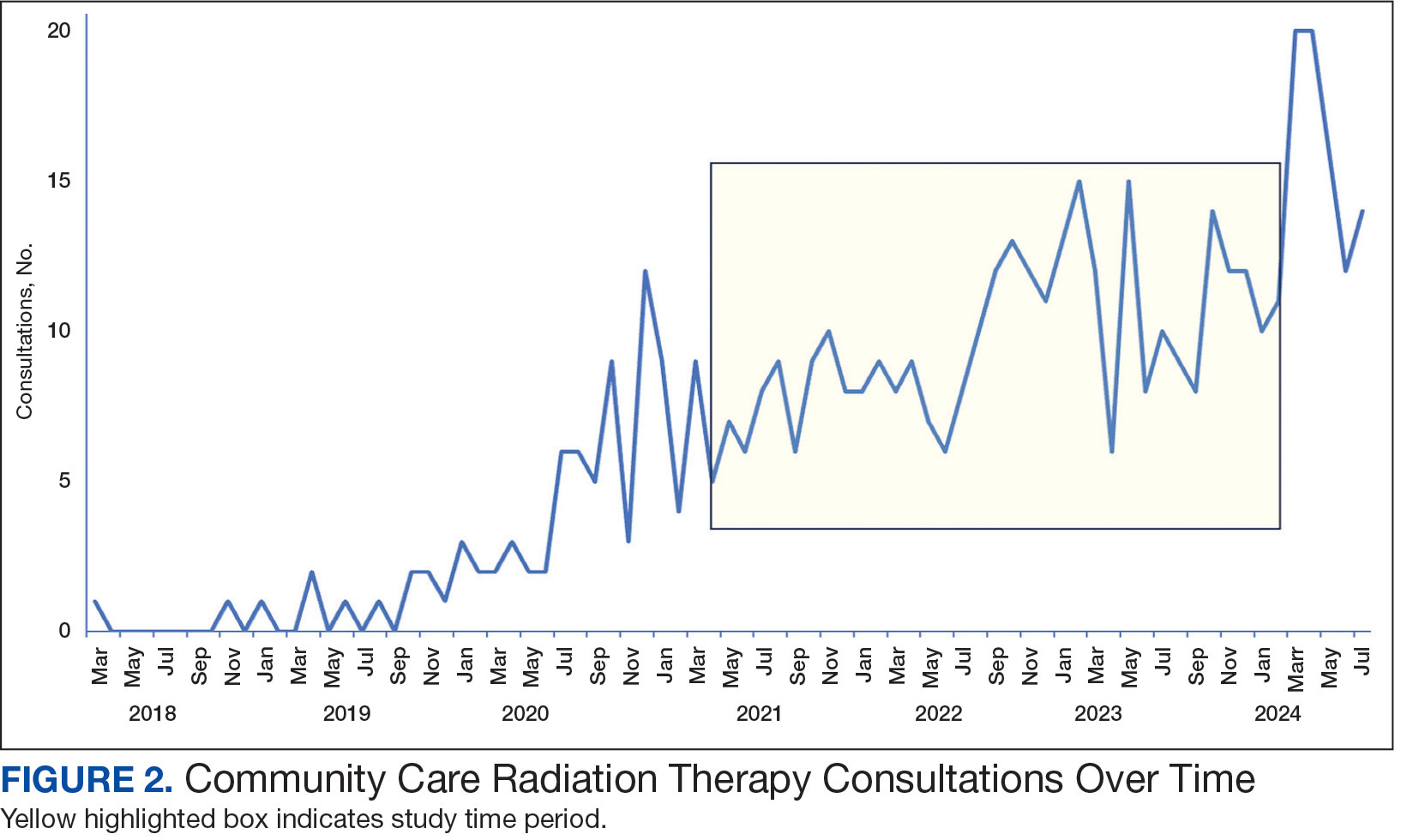

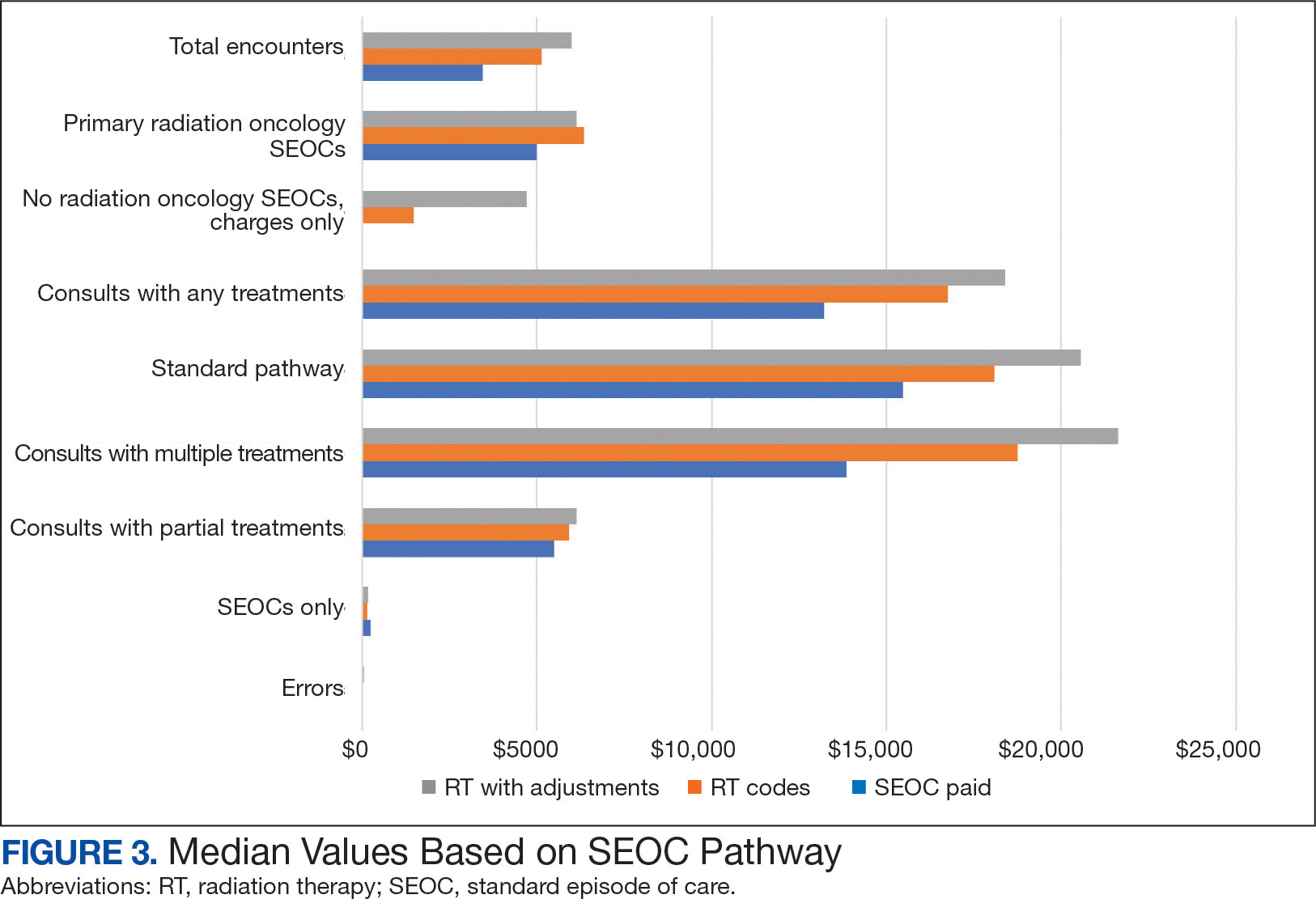

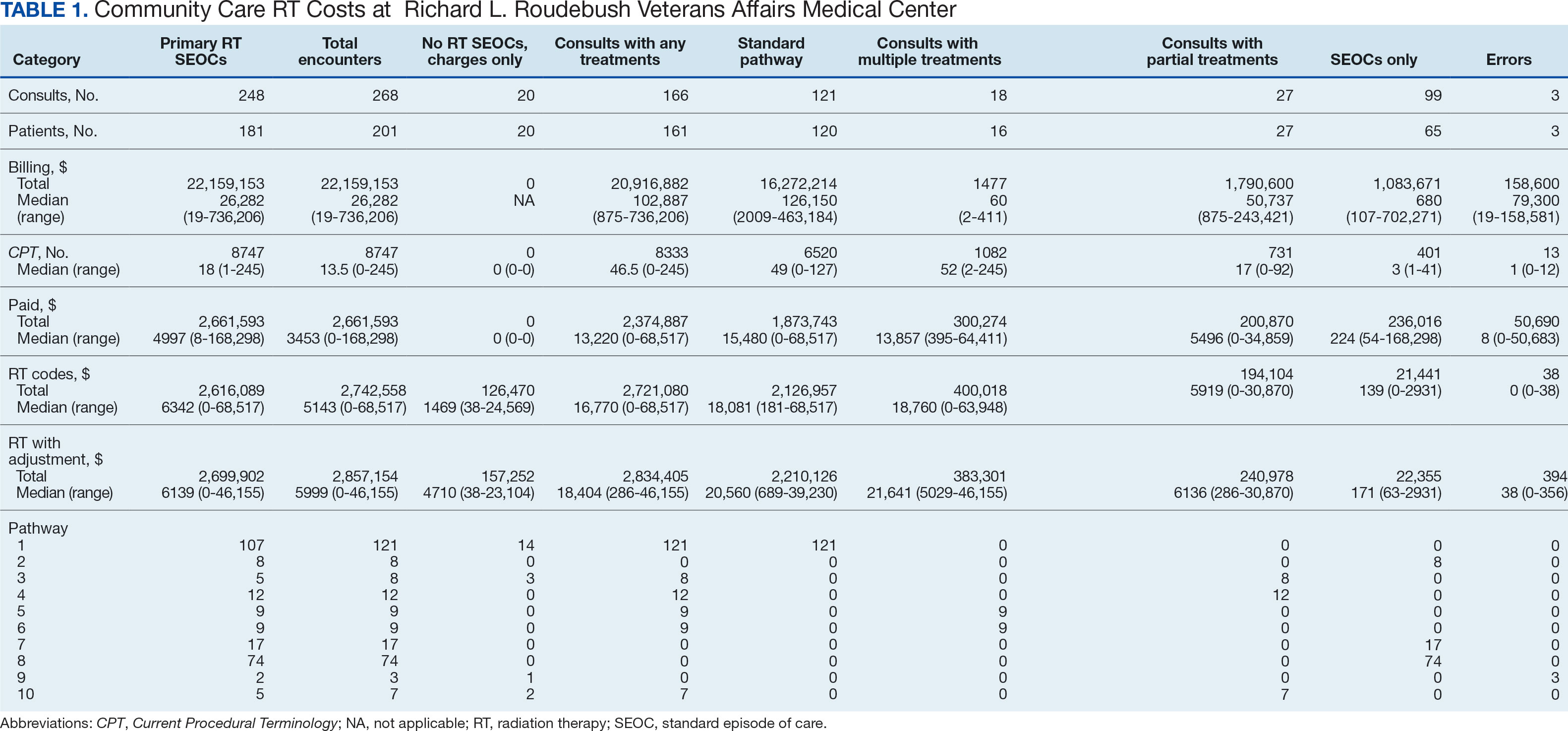

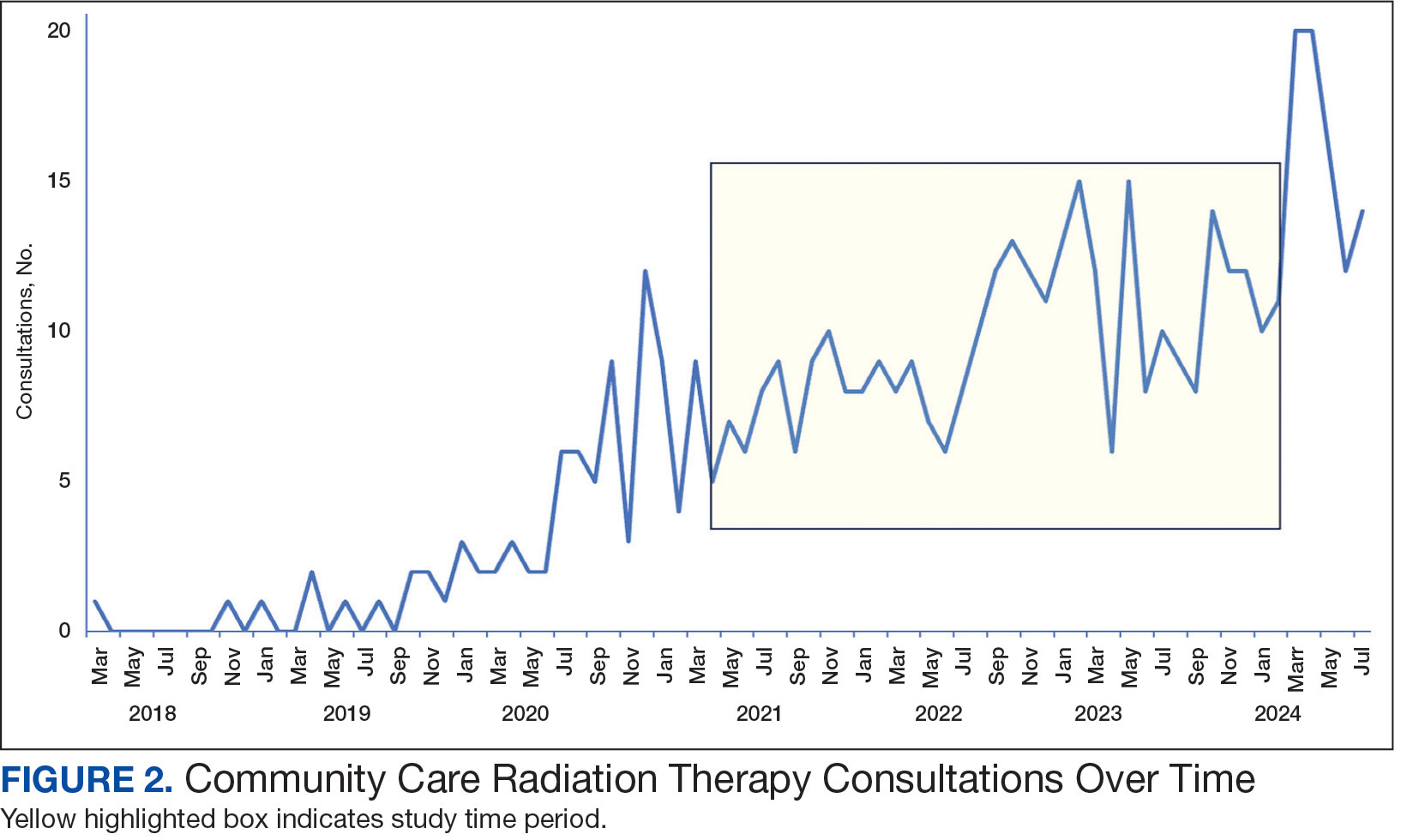

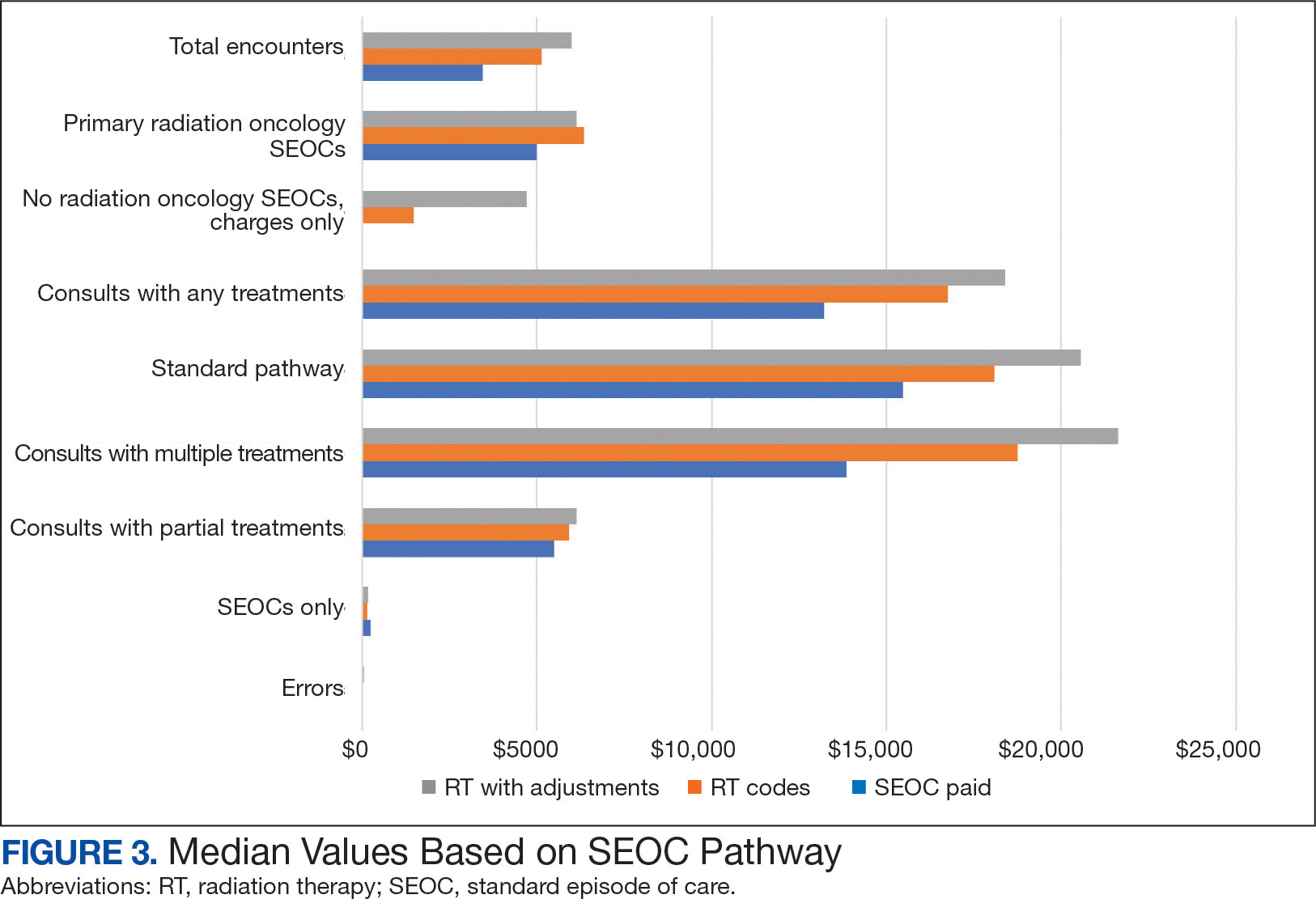

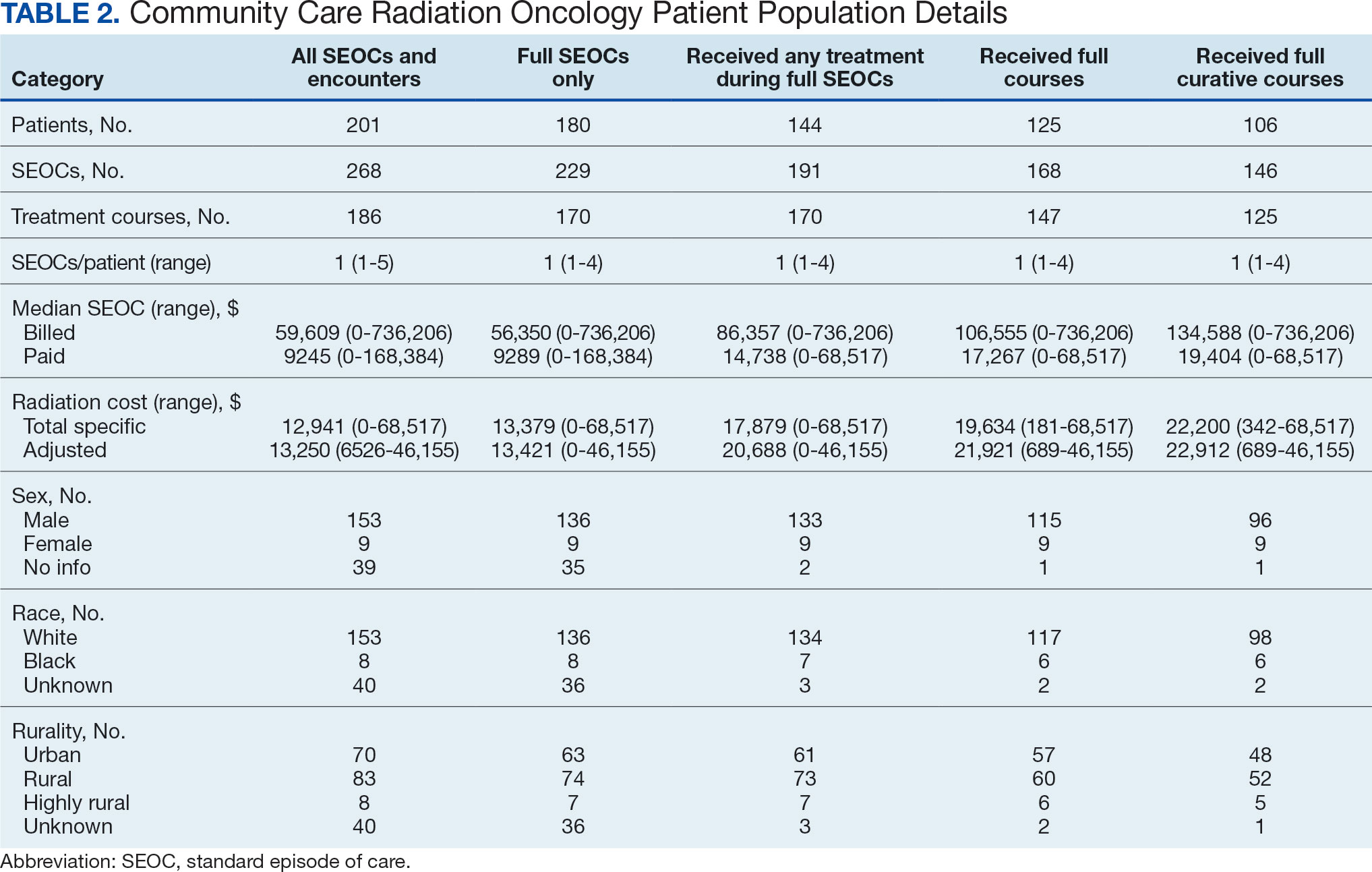

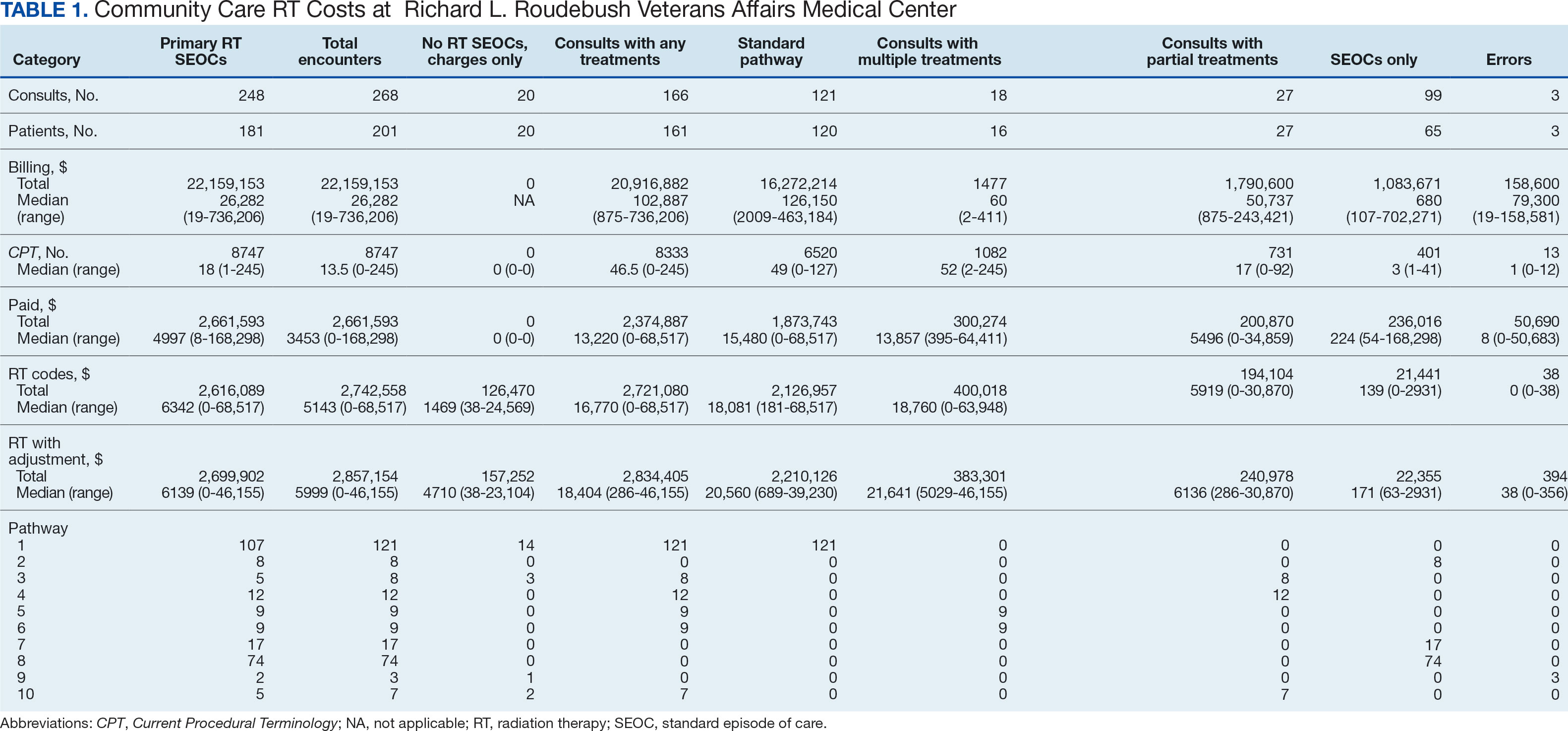

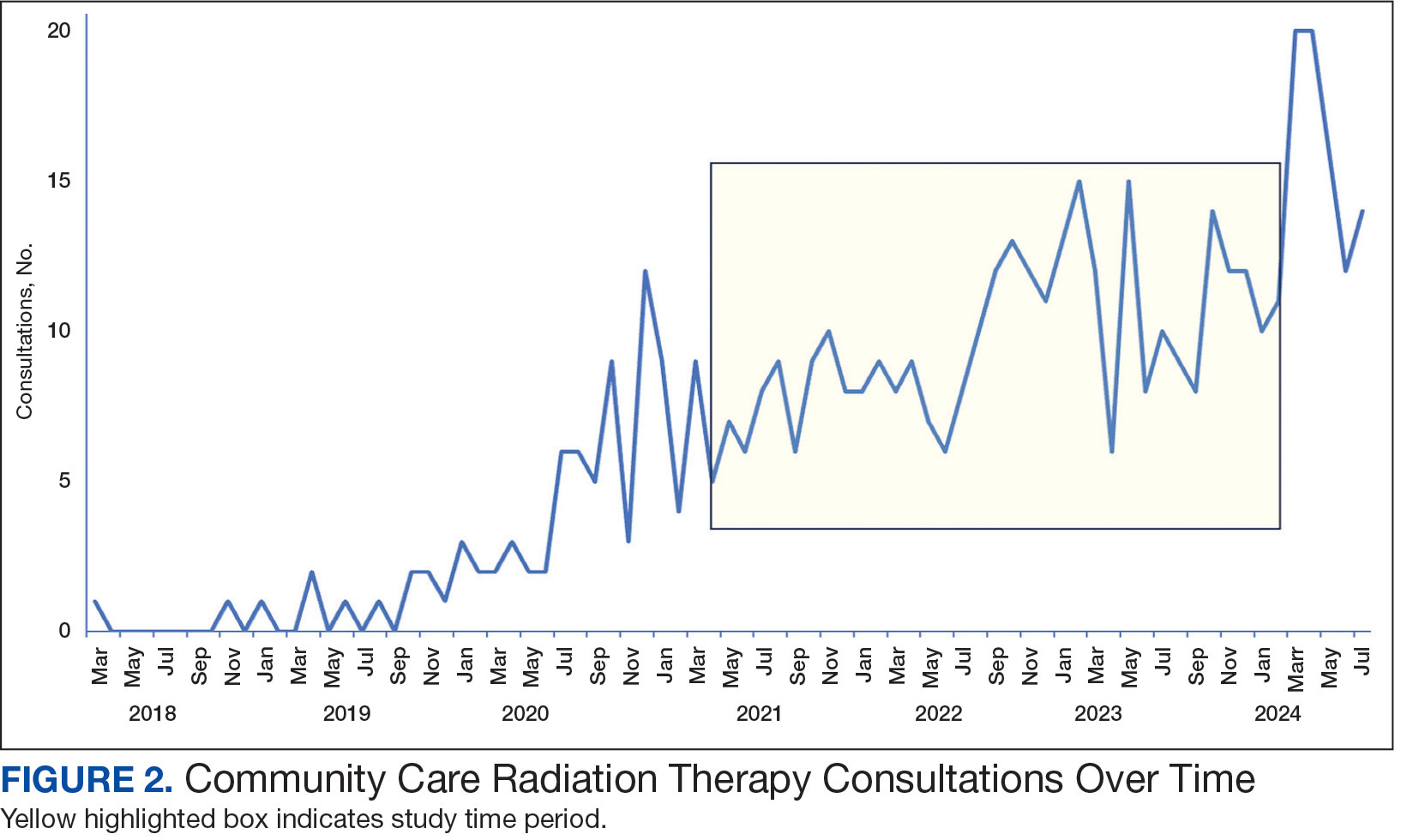

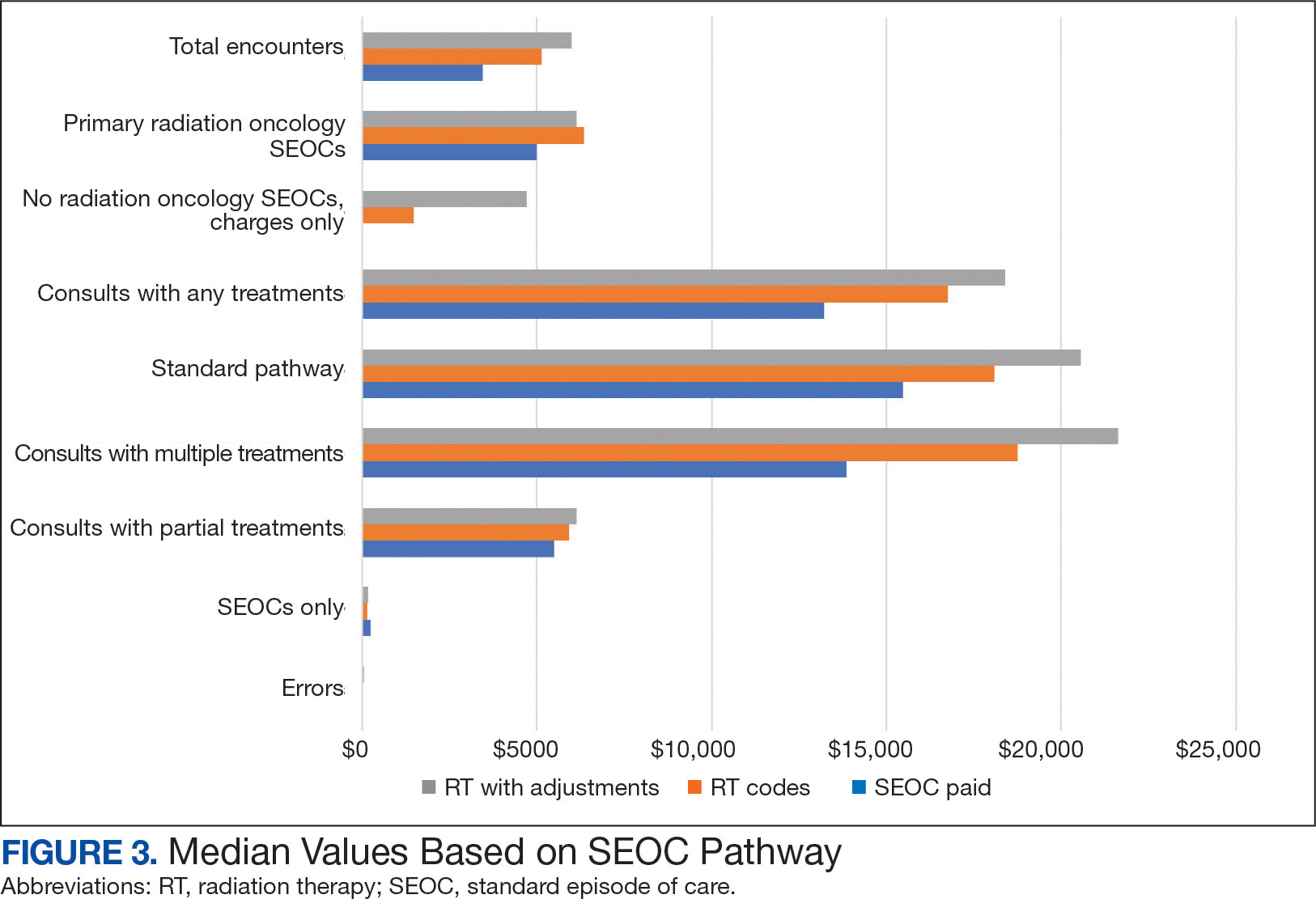

Since 2018, > 500 community care consults have been placed by radiation oncology for treatment in the community, with more following implementation of the VA MISSION Act. Use of radiation oncology community care services annually increased during the study period for this facility (Table 1, Figure 2). Of the 325 community care consults placed from October 1, 2021, to February 1, 2024, 248 radiation oncology SEOCs were recorded with charges for 181 patients (range, 1-5 SEOCs). Long drive time was the rationale for > 97% of patients directed to community care (Supplemental materials, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0585). Based on AMCMS data, $22.2 million was billed and $2.7 million was paid (20%) for 8747 CPT codes. Each community care interval cost the VA a median (range) of $5000 ($8-$168,000 (Figure 3).

After reviewing ROS charges extracted from CTM, 20 additional patients had radiation oncology charges but did not have a radiation oncology SEOC for 268 episodes of care for 201 unique patients. In addition to the 20 patients who did not have a SEOC, 42 nonradiation oncology SEOCs contained 1148 radiation oncology codes, corresponding to almost $500,000 paid. Additional charges of about $416,000, which included biologic agents (eg, durvalumab, nivolumab), procedures (eg, mastectomies), and ambulance rides were inappropriately added to radiation oncology SEOCs.

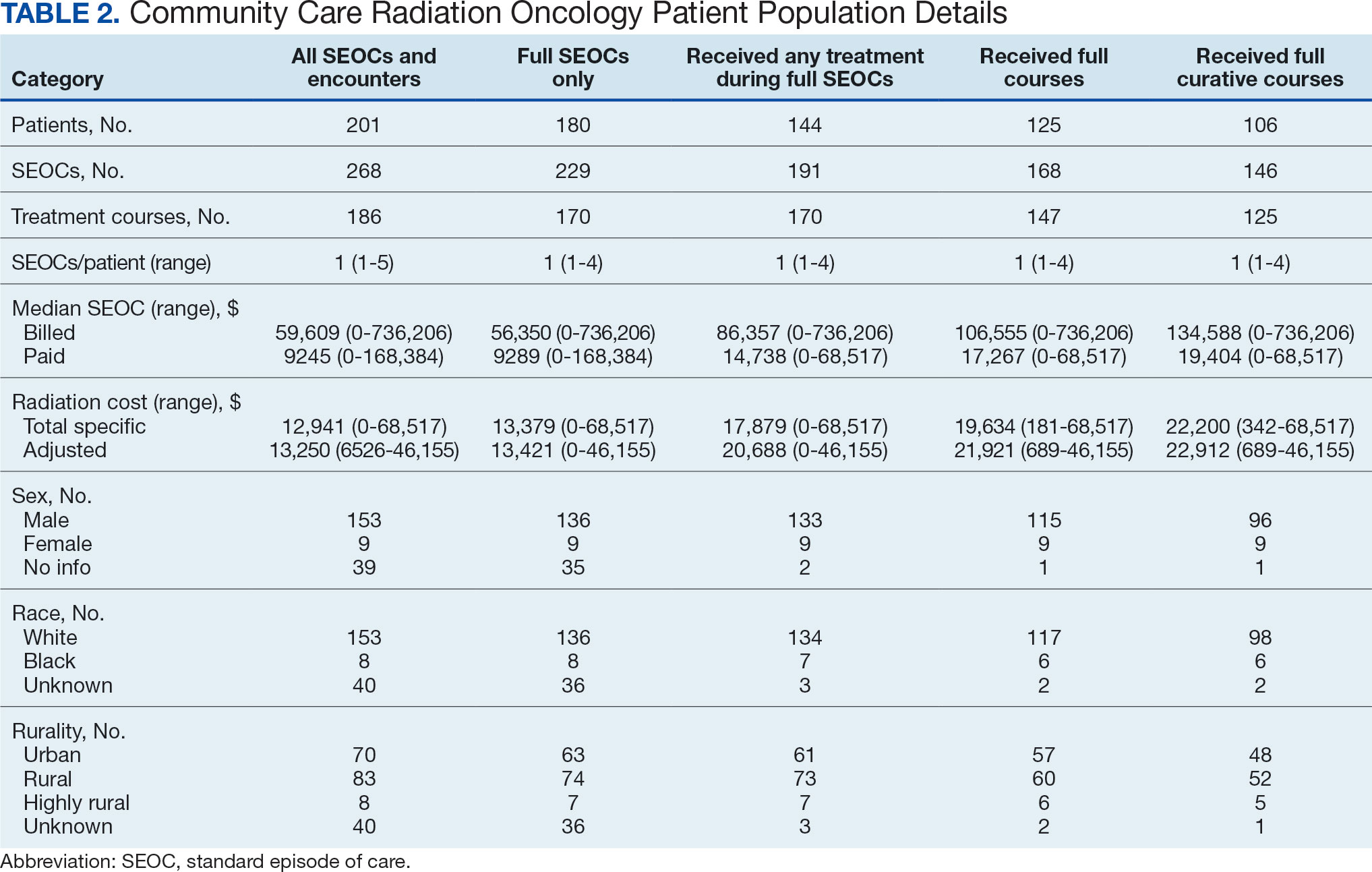

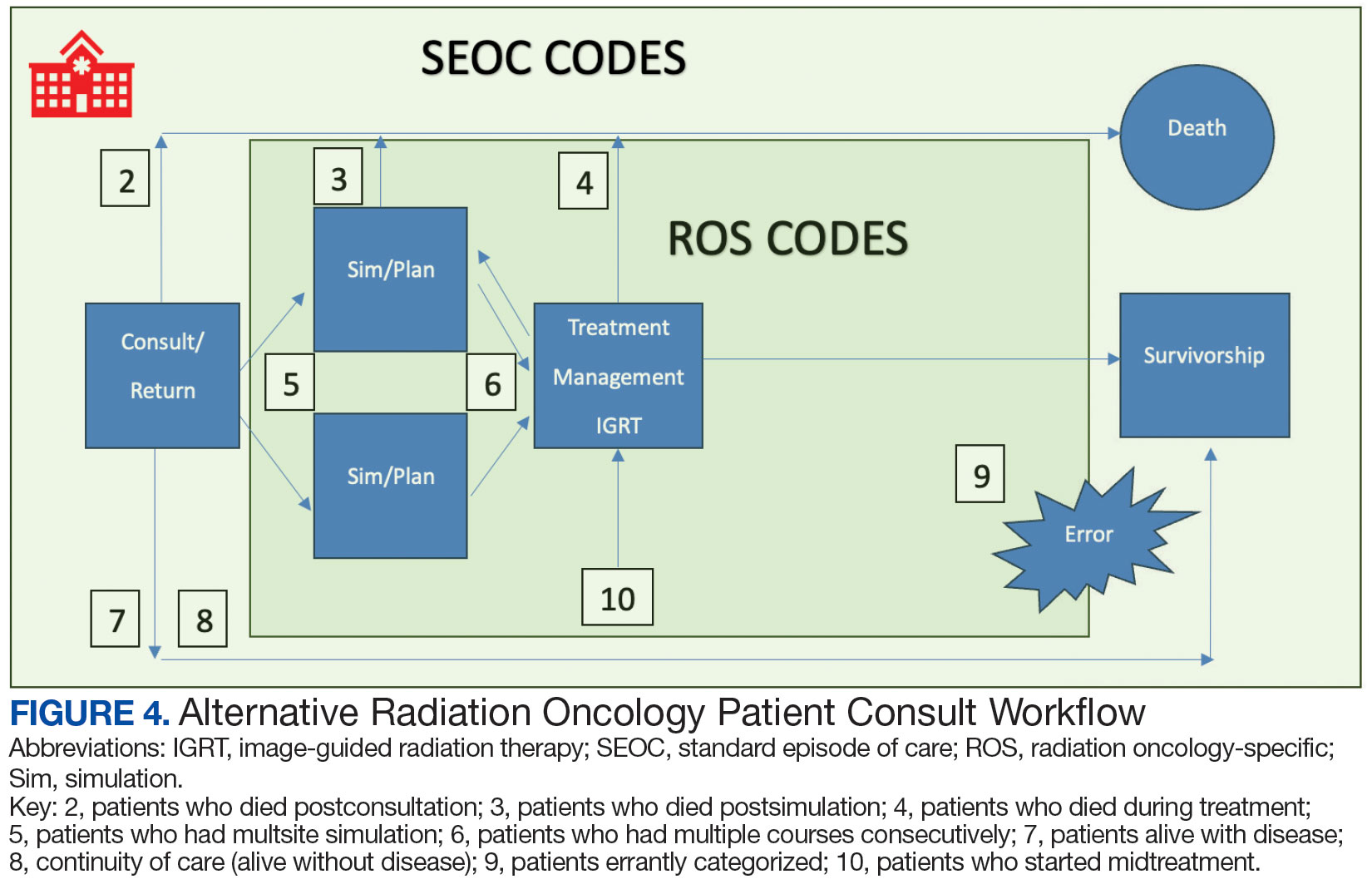

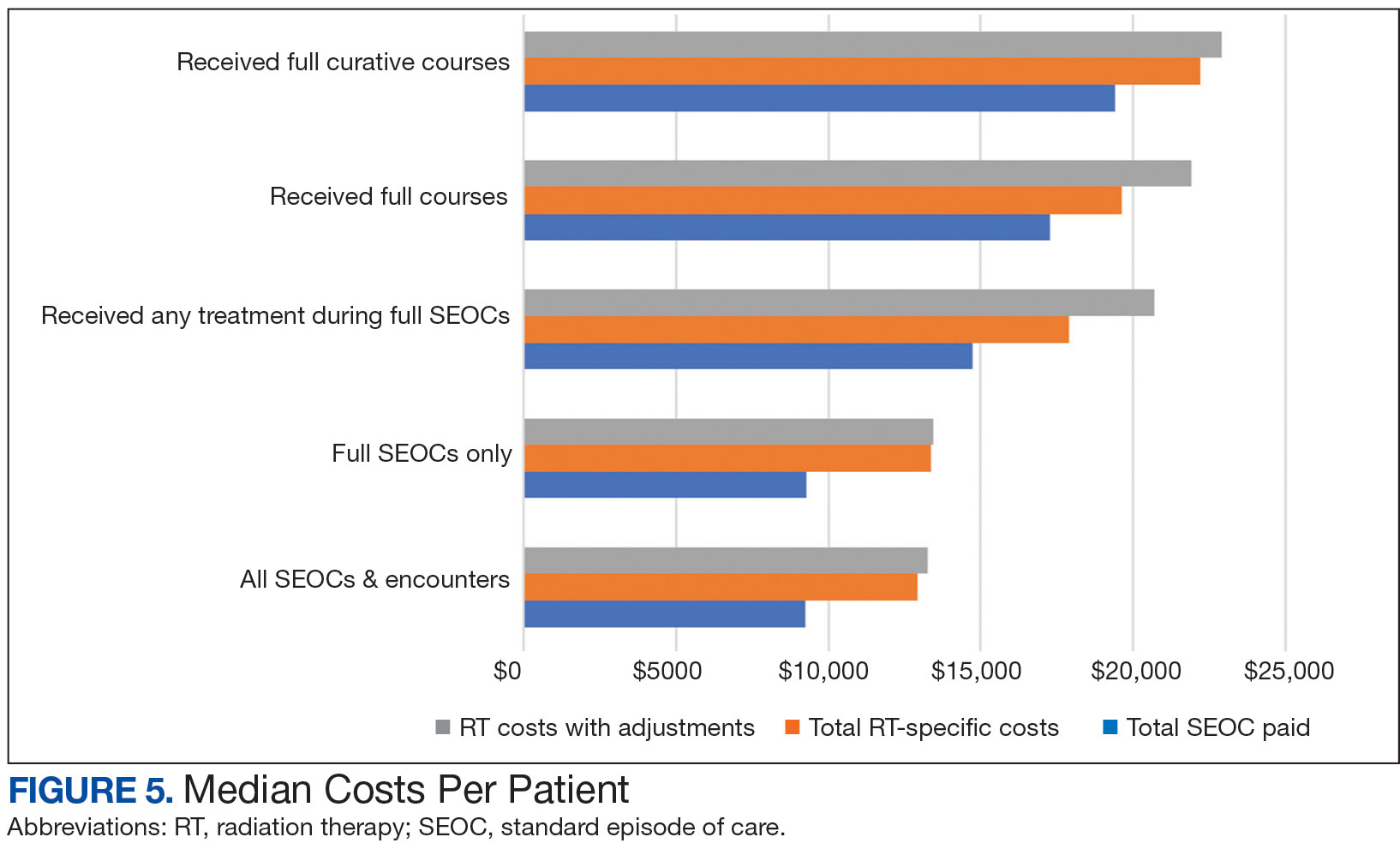

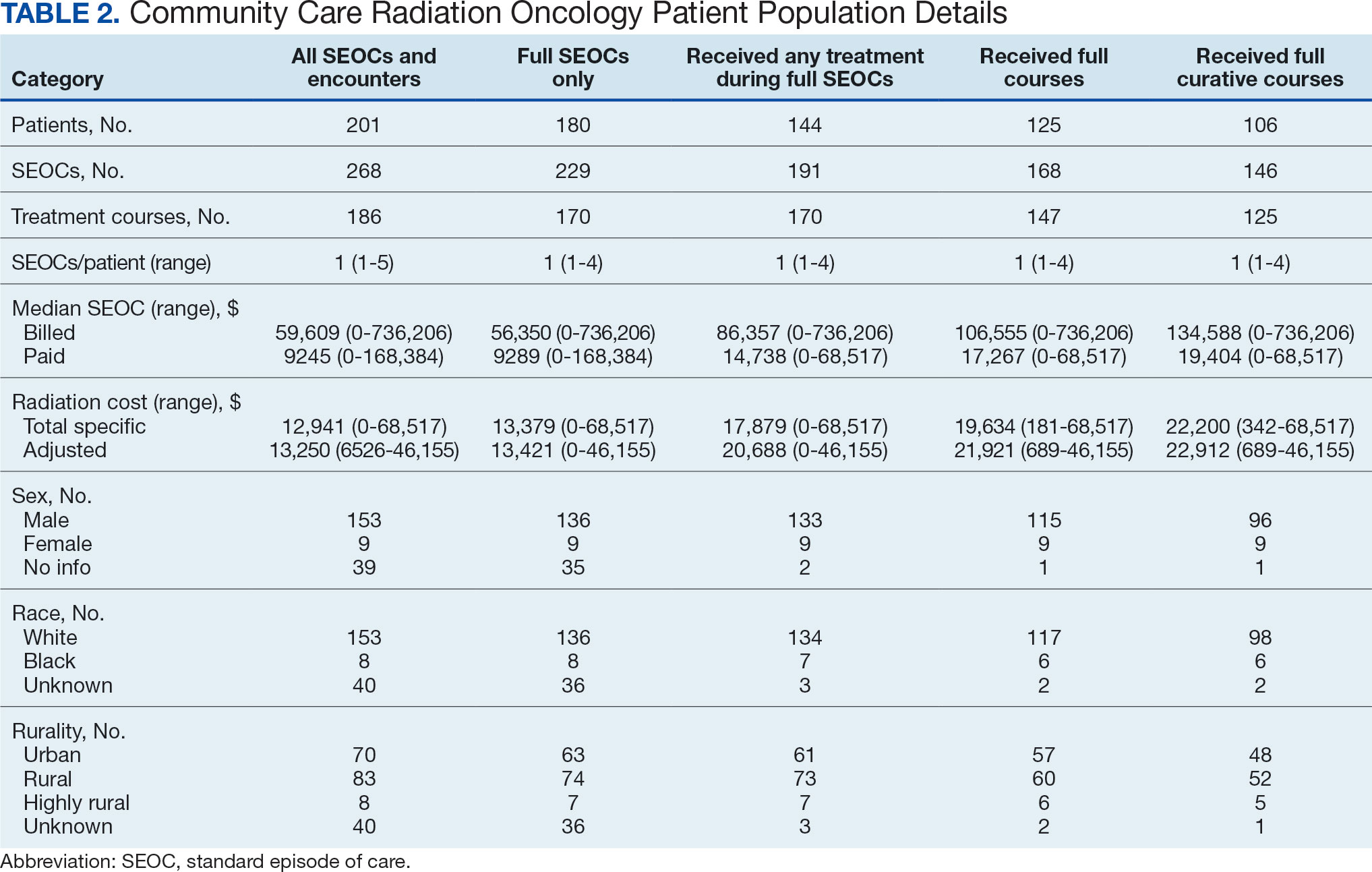

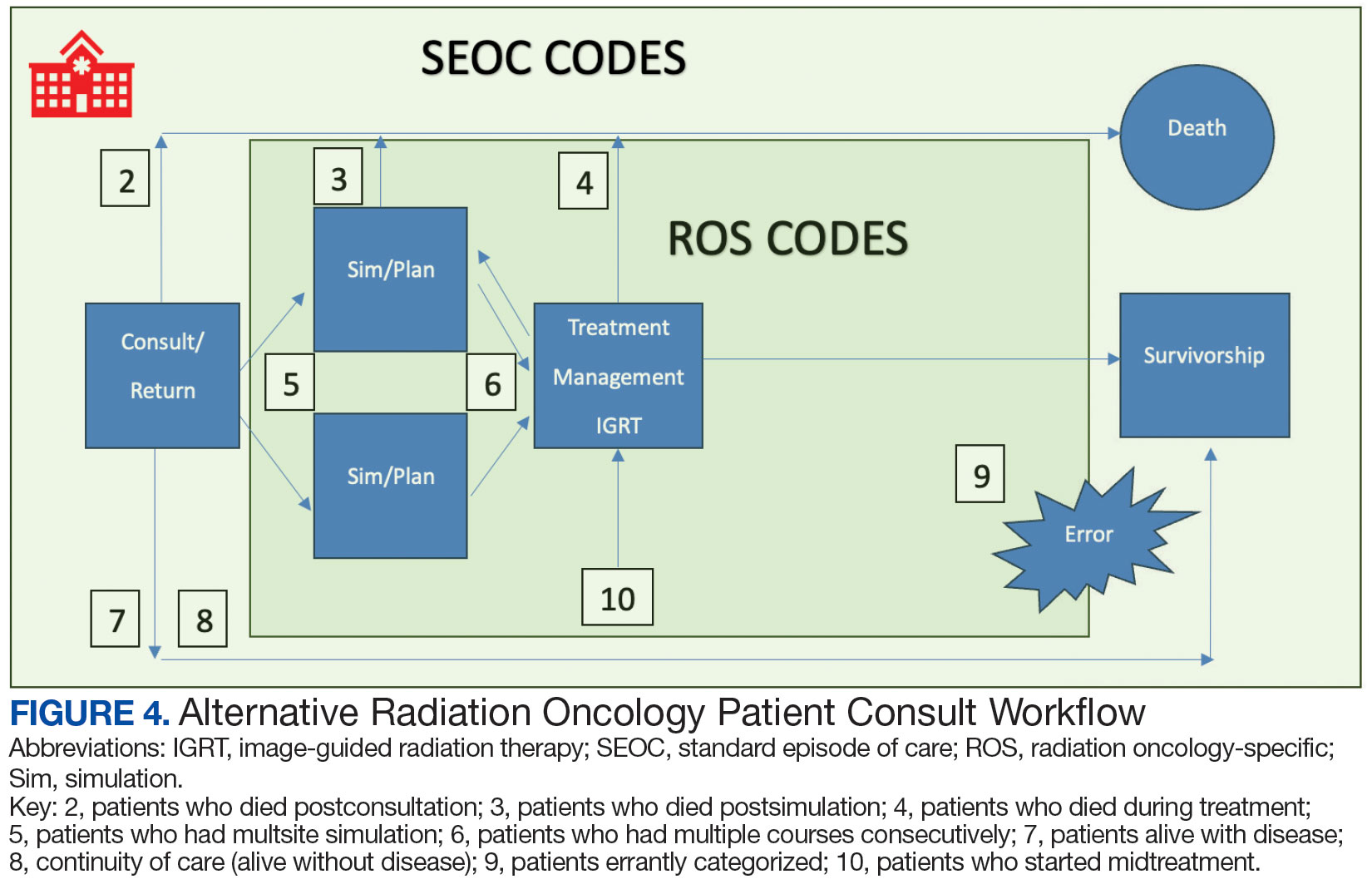

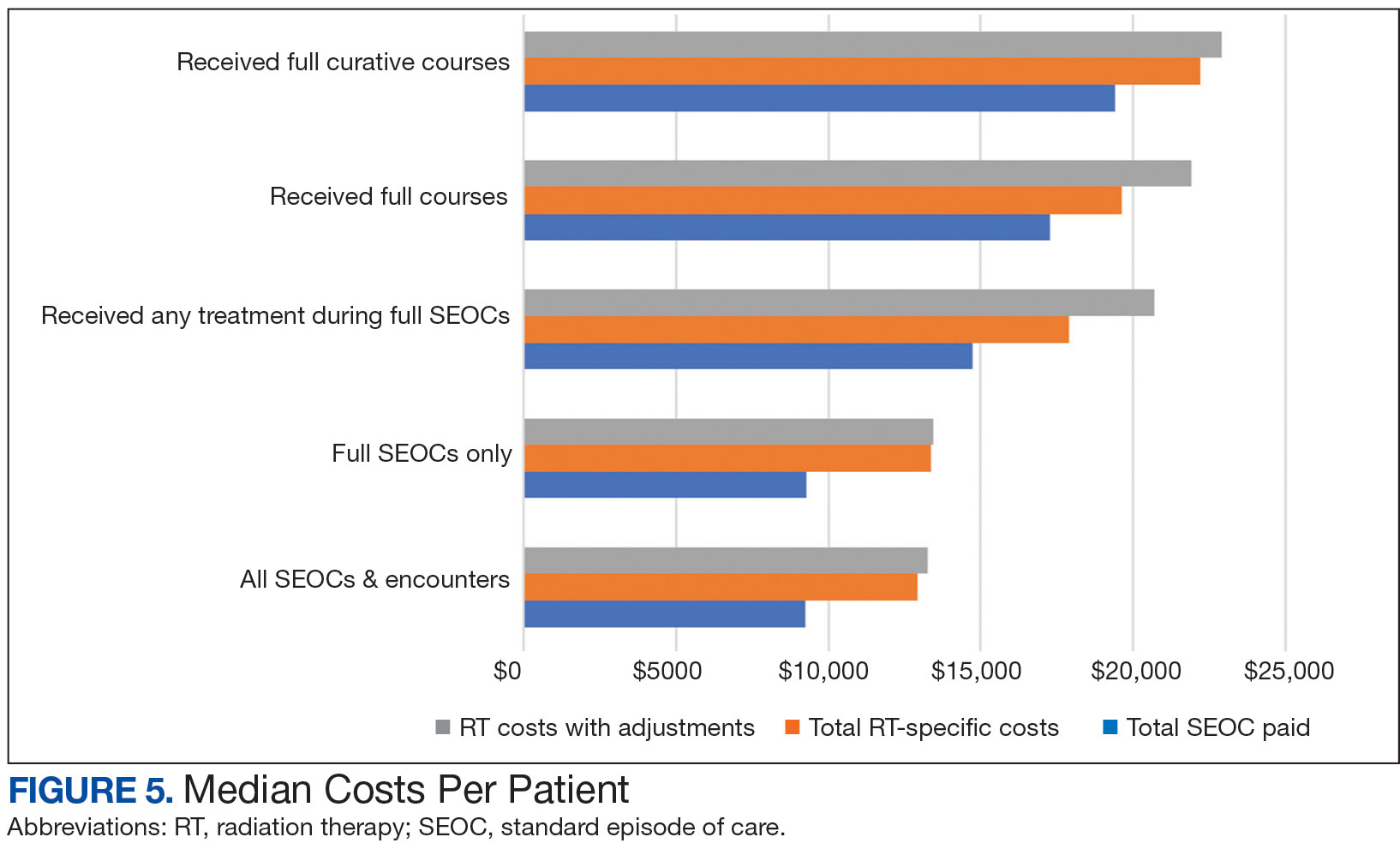

While 77% of consultations were scanned into CPRS and JLV, only 54% of completion summaries were available with an estimated $115,000 in additional costs. The total adjusted costs was about $2.9 million. Almost 37% of SEOCs were for visits only. For the 166 SEOCs where patients received any radiation treatment or planning, the median cost was $18,000. Differences in SEOC pathways are shown in Figure 4. One hundred twenty-one SEOCs (45%) followed the standard pathway, with median SEOC costs of $15,500; when corrected for radiation-specific costs, the median cost increased to $18,000. When adjusted for billing irregularities, the median cost was $20,600. Ninety-nine SEOCs (37%) were for consultation/ follow-up visits only, with a median cost of $220. When omitting shared scans and nonradiation therapy costs and correcting for billing gaps, the median cost decreased to $170. A median of $9200 was paid per patient, with $12,900 for radiation therapy-specific costs and $13,300 adjusted for billing deviations. Narrowing to the 106 patients who received full, radical courses, the median SEOC, ROS, and adjusted radiation therapy costs increased to $19,400, $22,200, and $22,900, respectively (Table 2, Figure 5). Seventy-one SEOCs (26%) had already seen a radiation oncologist before the VA radiation oncology department was aware, and 49 SEOCs (18%) had retroactive approvals (Supplemental materials available at doi:10.12788/fp.0585).

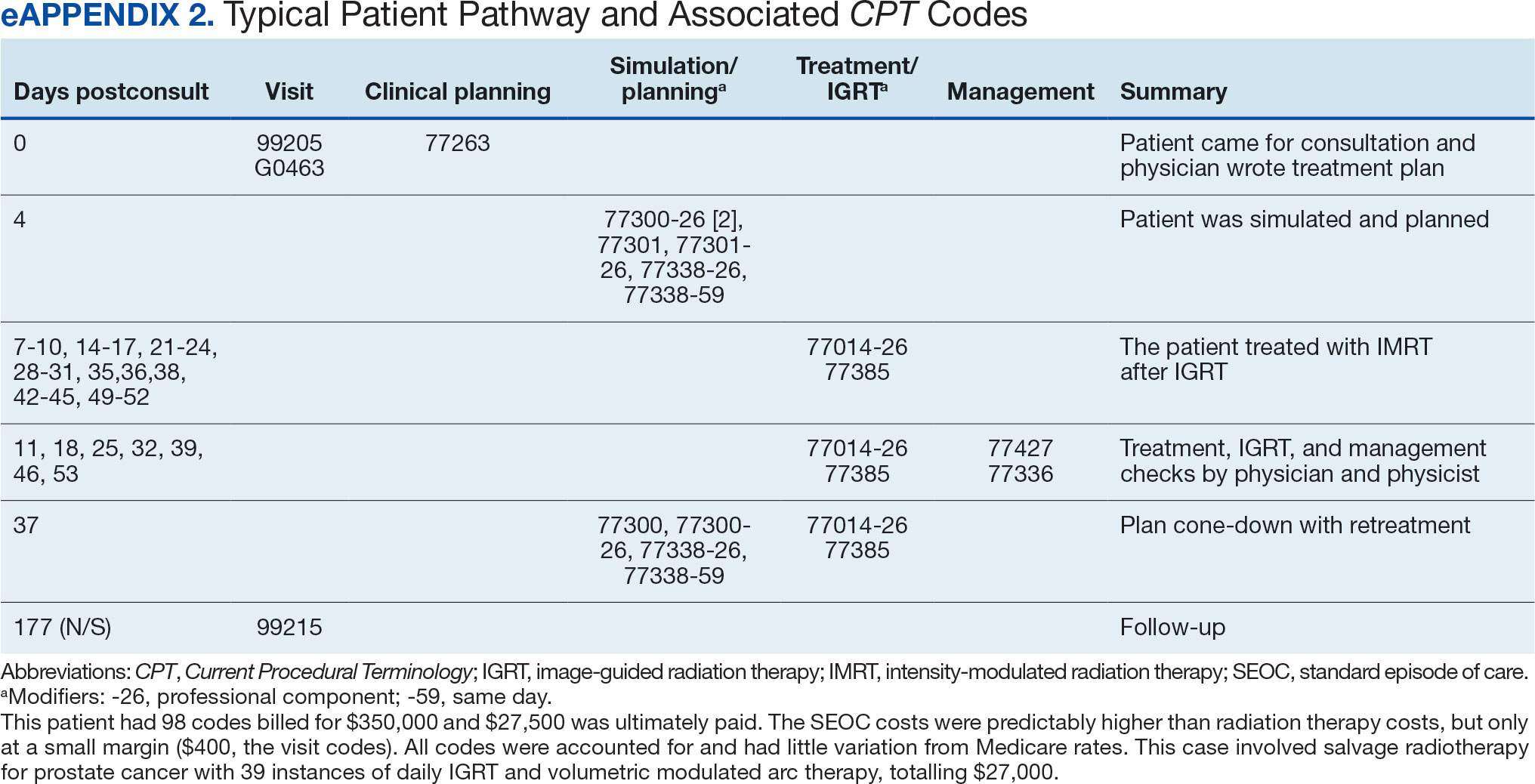

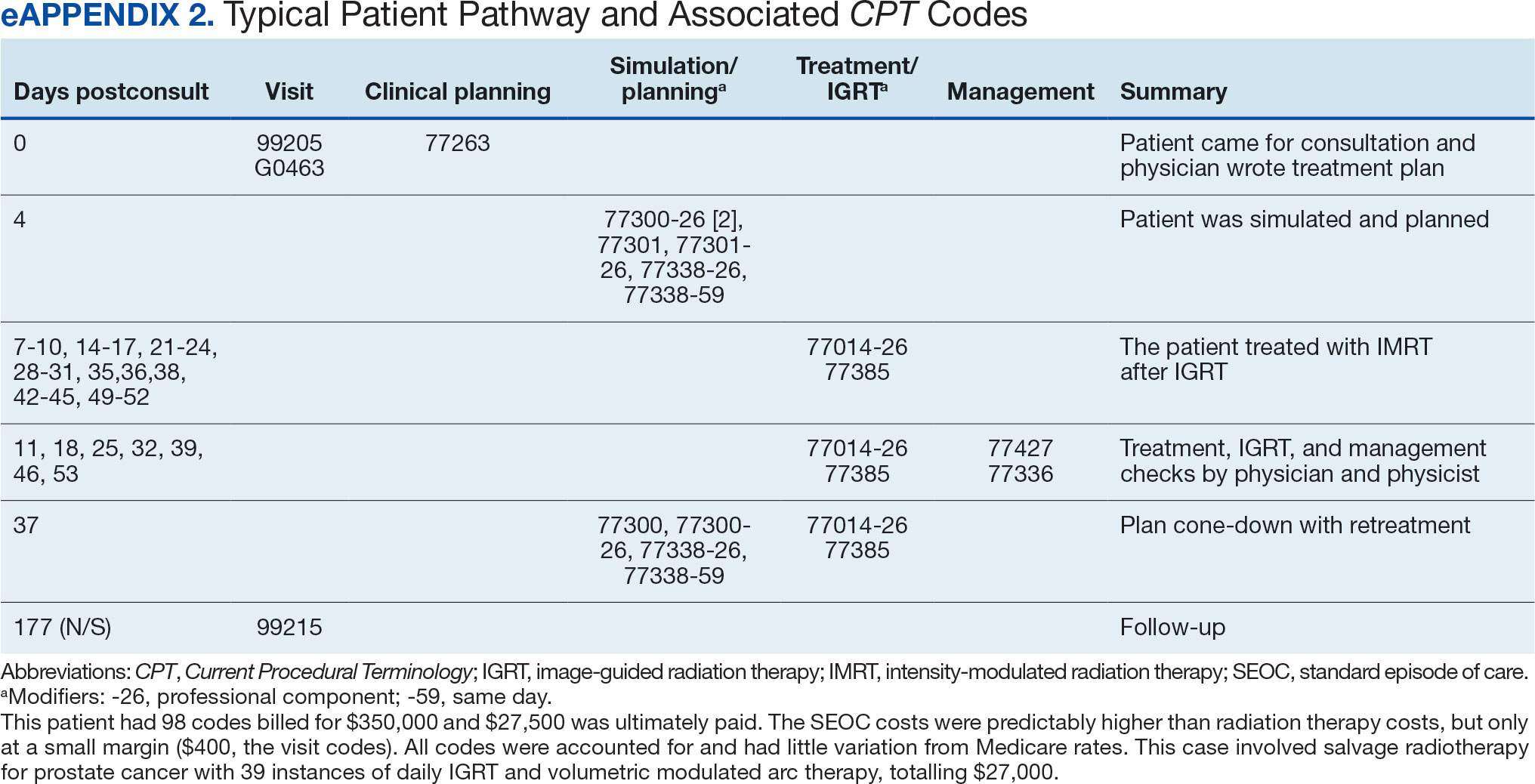

Every consultation charge was reviewed. A typical patient following the standard pathway (eAppendix 2, available at doi:10.12788/ fp.0585) exhibited a predictable pattern of consultation payment, simulation and planning, multiple radiation treatments interspersed with treatment management visits and a cone-down phase, and finishing with a follow-up visit. A less predictable case with excess CPT codes, gaps in charges, and an additional unexpected palliative course is shown in eAppendix 3 (available at doi:10.12788/fp.0585). Gaps occurred in 42% of SEOCs with missed bills costing as much as $12,000. For example, a patient with lung cancer had a treatment summary note for lung cancer after completion that showed the patient received 30 fractions of 2 Gy, a typical course. Only 10 treatment codes and 3 of 6 weekly treatment management codes were available. There was a gap of 20 volumetric modulated arc therapy treatments, 3 physics weekly status checks, 3 physician managements notes, and a computed tomography simulation charge.

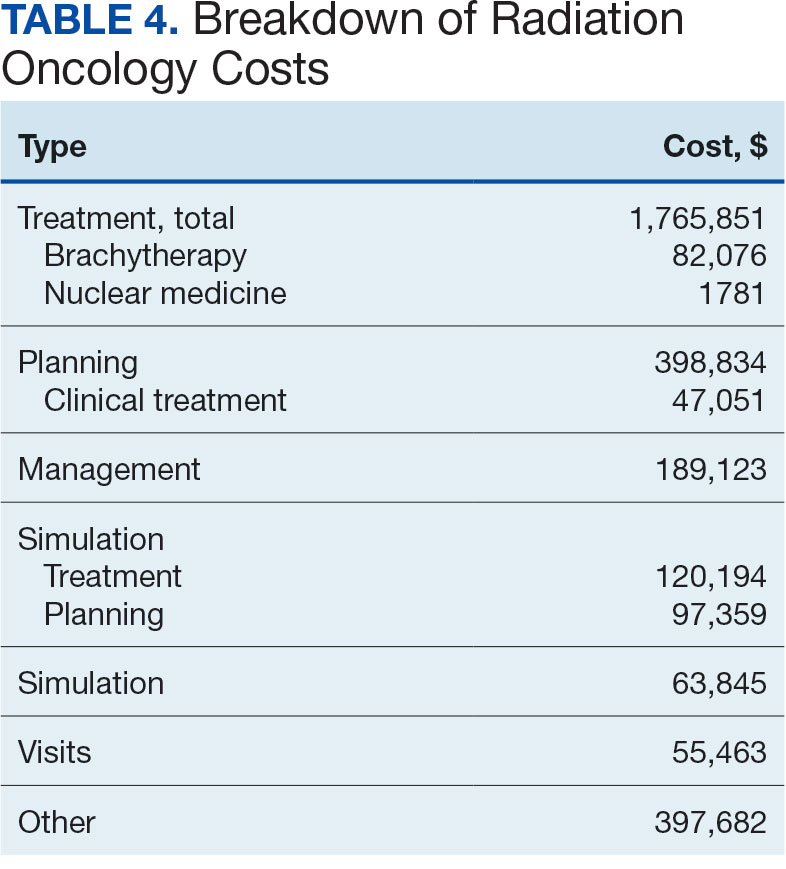

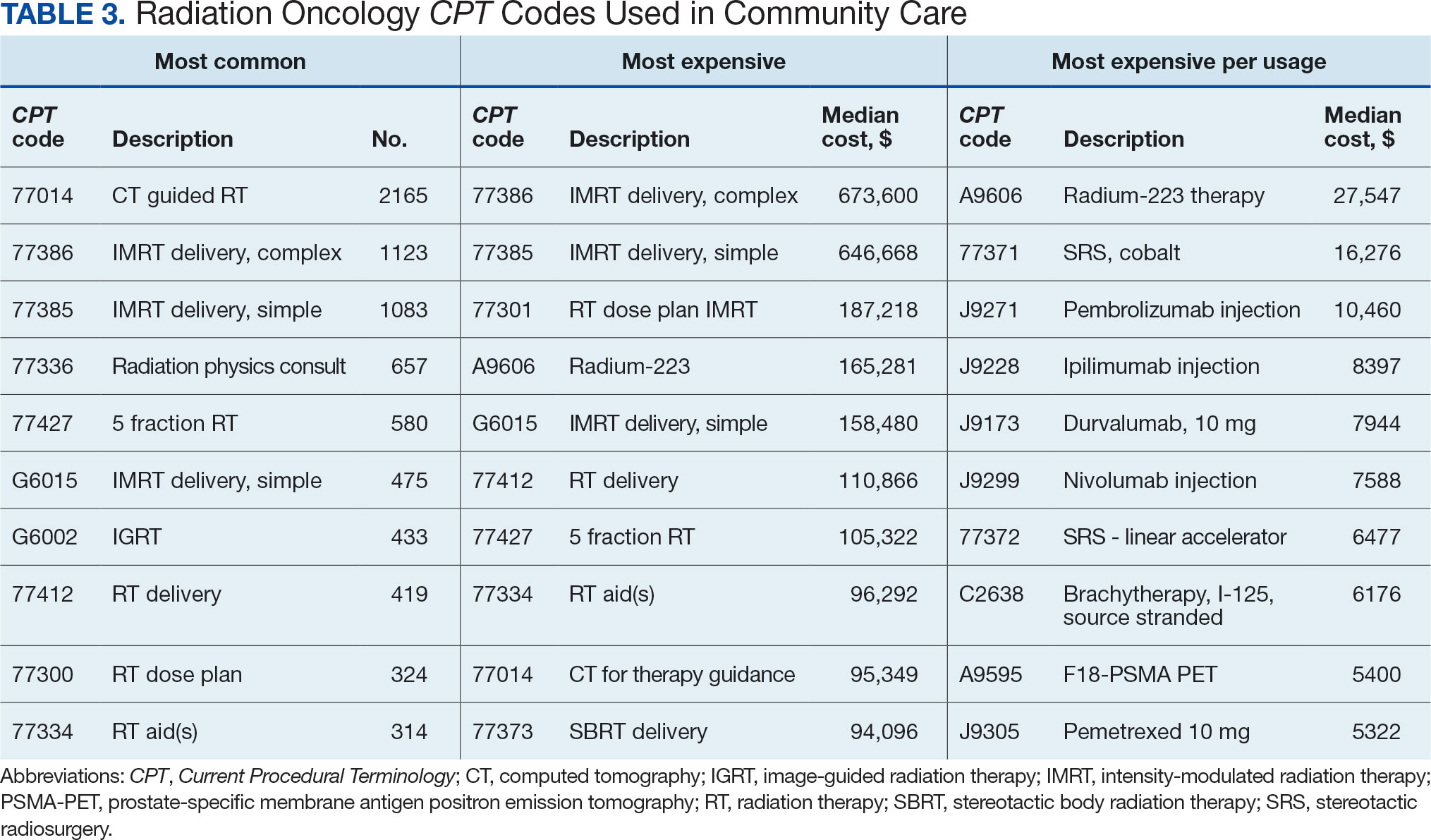

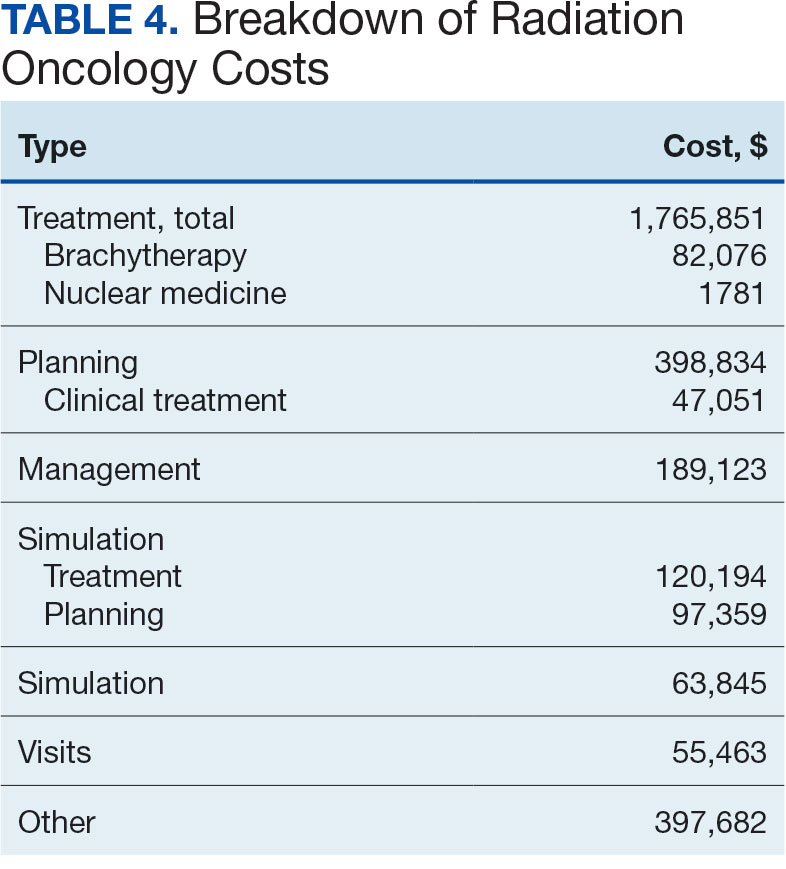

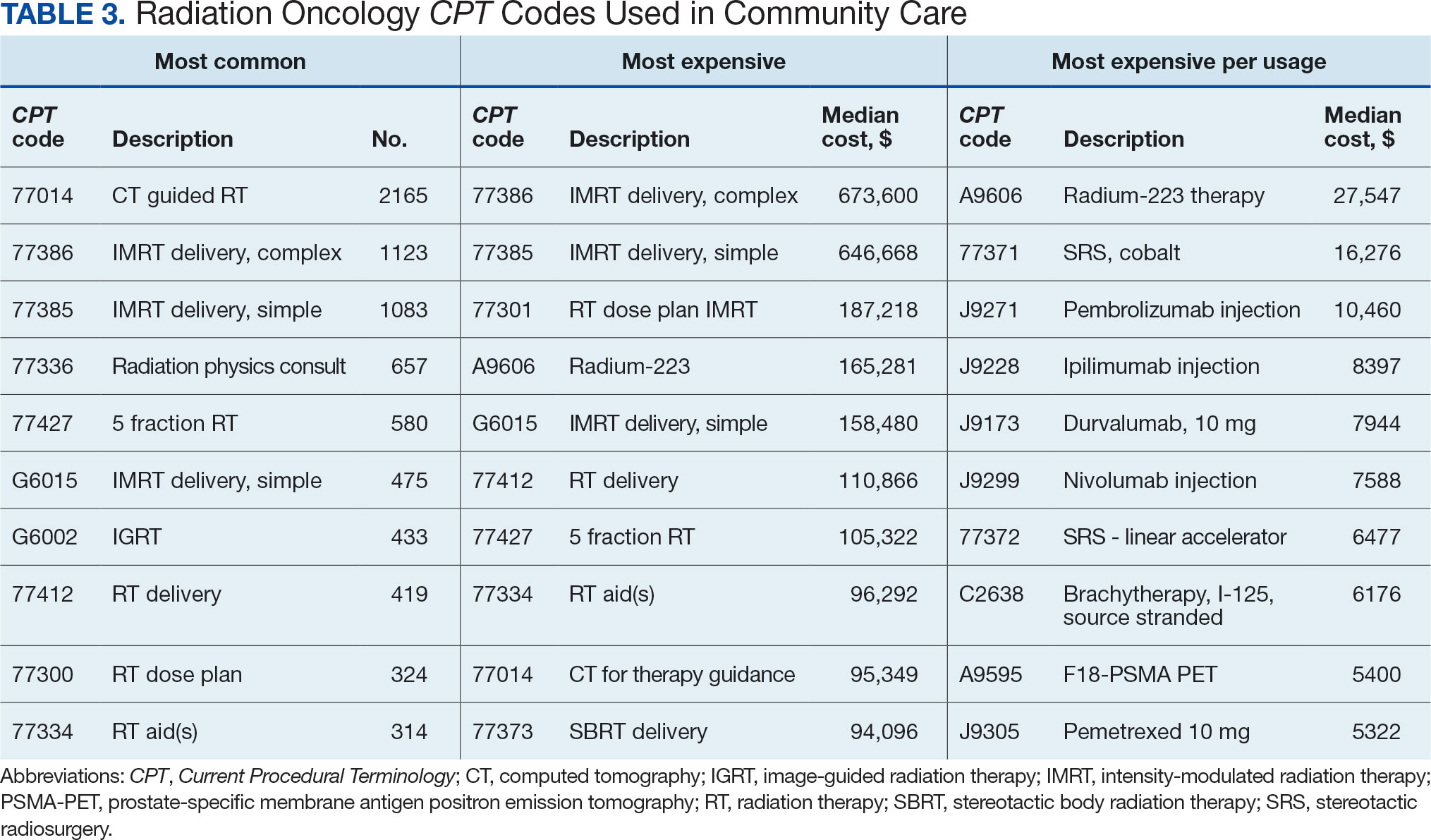

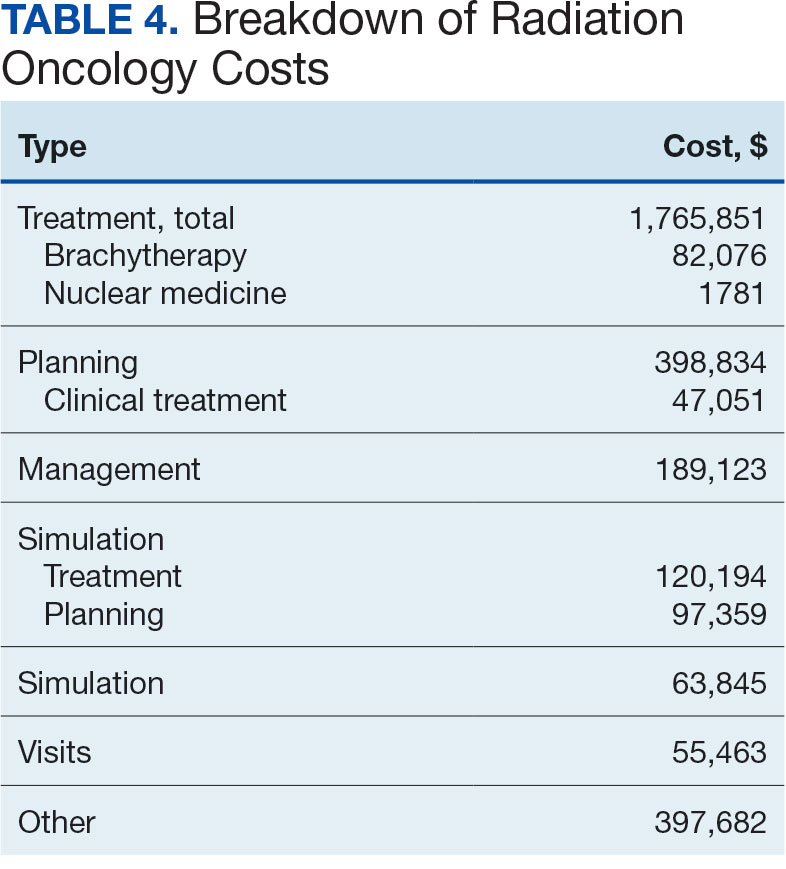

Between AMCMS and CTM, 10,005 CPT codes were evaluated; 1255 (12.5%) were unique to AMCMS (either related to the radiation oncology course, such as Evaluation and Management CPT codes or “other” unrelated codes) while 1158 (11.6%) were unique to CTM. Of the 7592 CPT codes shared between AMCMS and CTM, there was a discrepancy in 135 (1.8%); all were duplicates (CTM showed double payment while AMCMS showed $0 paid). The total CPT code costs came to $3.2 million with $560,000 unique to SEOCs and $500,000 unique to CTM. Treatment codes were the most common (33%) as shown in Table 3 and accounted for 55% of the cost ($1.8 million). About 700 CPT codes were considered “other,” typically for biologic therapeutic agents (Table 4 and eAppendix 4, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0585).

DISCUSSION

The current method of reporting radiation oncology costs used by VA is insufficient and misleading. Better data are needed to summarize purchased care costs to guide decisions about community care at the VA. Investigations into whether the extra costs for quality care (ie, expensive capital equipment, specialized staff, mandatory accreditations) are worthwhile if omitted at other facilities patients choose for their health care needs. No study has defined specialty care-specific costs by evaluating billing receipts from the CDW to answer the question. Kenamond et al highlight the need for radiation oncology for rural patients.11 Drive time was cited as the reason for community care referral for 97% of veterans, many of whom lived in rural locations. Of patients with rurality information who enrolled in community care, 57% came from rural or highly rural counties, and this ratio held for those who received full curative therapies. An executive administrator relying on AMCMS reports would see a median SEOC cost of $5000, but without ROS knowledge in coding, the administrator would miss many additional costs. For example, 2 patients who each had 5 SEOCs during the evaluated period, incurred a total cost of only $1800.

Additionally, an administrator could include miscategorized costs with significant ramifications. The 2 most expensive SEOCs were not typical radiation oncology treatments. A patient undergoing radium-223 dichloride therapy incurred charges exceeding $165,000, contributing disproportionately to the overall median cost analysis; this would normally be administered by the nuclear medicine department. Immunotherapy and chemotherapy are uniformly overseen by medical oncology services, but drug administration codes were still found in radiation oncology SEOCs. A patient (whose SEOC was discontinued but accrued charges) had an electrocardiogram interpretation for $8 as the SEOC cost; 3 other SEOCs continued to incur costs after being discontinued. There were 24 empty SEOCs for patients that had consults to the community, and 2 had notes stating treatment had been delivered yet there was no ROS costs or SEOC costs. Of the 268 encounters, 43% had some sort of billing irregularities (ie, missing treatment costs) that would be unlikely for a private practice to omit; it would be much more likely that the CDW miscategorized the payment despite confirmation of the 2 retrieval systems.

It would be inadvisable to make staffing decisions or forecast costs based on current SEOC reports without specialized curation. A simple yet effective improvement to the cost attribution process would be to restrict the analysis to encounters containing primary radiation treatment codes. This targeted approach allows more accurate identification of patients actively receiving radiation oncology treatment, while excluding those seen solely for consultations or follow-up visits. Implementing this refinement leads to a substantial increase in the median payment—from $5000 to $13,000—without requiring additional coding or data processing, thereby enhancing the accuracy of cost estimates with minimal effort.

Clarifying radiation oncology service costs requires addressing the time frame and services included, given laxity and interpretation of the SEOCs. VA community care departments have streamlined the reimbursement process at the expense of medical cost organization and accuracy; 86% of VA practitioners reported that ≥ 1 potential community health care partners had refused to work with the VA because of payment delays.12 Payments are contingent on correspondence from outside practices for community work. For radiation oncology, this includes the consultation but also critical radiation-related details of treatment, which were omitted nearly half the time. SEOC approval forms have many costly laboratory tests, imaging, and procedures that have little to do with radiation oncology cancer treatments but may be used in the workup and staging process; this creates noise when calculating radiation oncology fiscal cost.

The presumption that an episode of care equates to a completed radiation therapy course is incorrect; this occurs less than half of the time. An episode often refers to a return visit, or conversely, multiple treatment courses. As the patients’ medical homes are their VHA primary care practitioners, it would be particularly challenging to care for the patients without full treatment information, especially if adverse effects from therapy were to arise. As a tertiary specialty, radiation oncology does not seek out patients and are sent consultations from medical oncology, surgical, and medical oncologic specialties. Timesensitive processes such as workup, staging, and diagnosis often occur in parallel. This analysis revealed that patients see outside radiation oncologists prior to the VA. There are ≥ 100 patients who had radiation oncology codes without a radiation oncology SEOC or community care consultation, and in many cases, the consultation was placed after the patient was seen.

Given the lack of uniformity and standardization of patient traffic, the typical and expected pathways were insufficient to find the costs. Too many opportunities for errors and incorrect categorization of costs meant a different method would be necessary. Starting at the inception of the community care consult, only 1 diagnosis code can be entered. For patients with multiple diagnoses, one would not be able to tell what was treated without chart access. Radiation oncology consults come from primary and specialty care practitioners and nurses throughout the VA. Oftentimes, the referral would be solicited by the community radiation oncology clinic, diagnosing community specialty (ie, urology for a patient with prostate cancer), or indirectly from the patient through primary care. Many cases were retroactively approved as the veteran had already been consulted by the community care radiation oncologist. If the patient is drive-time eligible, it would be unlikely that they would leave and choose to return to the VA. There is no way for a facility VA service chief or administrator to mitigate VA community costs of care, especially as shown by the miscategorization of several codes. Database challenges exacerbate the issue: 1 patient changed her first and last name during this time frame, and 2 patients had the same name but different social security numbers. In order to strictly find costs between 2 discrete timepoints, 39 (15%) SEOCs were split and incomplete, and 6 SEOCs contained charges for 2 different patients. This was corrected, and all inadvertent charges were cancelled. Only 1 ICD code is allowed per community care consultation, so an investigation is required to find costs for patients with multiple sites of disease. Additionally, 5 of the patients marked for drive time were actually patients who received Gamma Knife and brachytherapy, services not available at the VA.

Hanks et al first attempted to calculate cost of radiation oncology services. External beam prostate cancer radiotherapy at 3 suburban California centers cost $6750 ($20,503 inflation adjusted) per patient before October 1984 and $5600 ($17,010 inflation adjusted) afterwards.13 According to the American Society for Radiation Oncology, Advocacy Radiation Oncology Case Rate Program Curative radiation courses should cost $20,000 to $30,000 and palliative courses should cost $10,000 to $15,000. These costs are consistent with totals demonstrated in this analysis and similar to the inflation-adjusted Hanks et al figures. Preliminary findings suggest that radiation treatment constituted more than half of the total expenditures, with a notable $4 million increase in adjusted cost compared to the Medicare rates, indicating significant variation. Direct comparisons with Medicaid or commercial payer rates remain unexplored.

Future Directions

During the study period, 201 patients received 186 courses of radiation therapy in the community, while 1014 patients were treated in-house for a total of 833 courses. A forthcoming analysis will directly compare the cost of in-house care with that of communitybased treatment, specifically breaking down expenditure differences by diagnosis. Future research should investigate strategies to align reimbursement with quality metrics, including the potential role of tertiary accreditation in incentivizing high-value care. Additional work is also warranted to assess patient out-ofpocket expenses across care settings and to benchmark VA reimbursement against Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance rates. In any case, with the increasing possibility of fewer fractions for treatments such as stereotactic radiotherapy or palliative care therapy, there is a clear financial incentive to treat as frequently as allowed despite equal clinical outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Veterans increasingly choose to receive care closer to home if the option is available. In the VA iron triangle, cost comes at the expense of access but quantifying this has proved elusive in the cost accounting model currently used at the VA.1 The inclusion of all charges loosely associated with SEOCs significantly impairs the ability to conduct meaningful cost analyses. The current VA methodology not only introduces substantial noise into the data but also leads to a marked underestimation of the true cost of care delivered in community settings. Such misrepresentation risks driving policy decisions that could inappropriately reduce or eliminate in-house radiation oncology services. Categorizing costs effectively in the VA could assist in making managerial and administrative decisions and would prevent damaging service lines based on misleading or incorrect data. A system which differentiates between patients who have received any treatment codes vs those who have not would increase accuracy.

- Kissick W. Medicine’s Dilemmas: Infinite Needs Versus Finite Resources. 1st ed. Yale University Press; 1994.

- Albanese AP, Bope ET, Sanders KM, Bowman M. The VA MISSION Act of 2018: a potential game changer for rural GME expansion and veteran health care. J Rural Health. 2020;36(1):133-136. doi:10.1111/jrh.12360

- Office of Management and Budget (US). Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2025. Washington, DC: US Government Publishing Office; 2024. Available from: US Department of Veterans Affairs FY 2025 Budget Submission: Budget in Brief.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran care claims. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/revenue-ops/Veteran-Care-Claims.asp

- US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed April 3, 2025. Procedure price lookup https://www.medicare.gov/procedure-price-lookup

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. WellHive -Enterprise. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://department.va.gov/privacy/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2023/05/FY23WellHiveEnterprisePIA.pdf

- US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. RVU21a physician fee schedule, January 2021 release. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/medicaremedicare-fee-service-paymentphysicianfeeschedpfs-relative-value-files/rvu21a

- US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. RVU22a physician fee schedule, January 2022 release. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/medicaremedicare-fee-service-paymentphysicianfeeschedpfs-relative-value-files/rvu22a

- US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. RVU23a physician fee schedule, January 2023 release. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-service-payment/physicianfeesched/pfs-relative-value-files/rvu23a

- US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. RVU23a Medicare Physician Fee Schedule rates effective January 1, 2024, through March 8, 2024. Accessed on April 3, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/fee-schedules/physician/pfs-relative-value-files/rvu24a

- Kenamond MC, Mourad WF, Randall ME, Kaushal A. No oncology patient left behind: challenges and solutions in rural radiation oncology. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;13:100289. doi:10.1016/j.lana.2022.100289

- Mattocks KM, Kroll-Desrosiers A, Kinney R, Elwy AR, Cunningham KJ, Mengeling MA. Understanding VA’s use of and relationships with community care providers under the MISSION Act. Med Care. 2021;59(Suppl 3):S252-S258. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001545

- Hanks GE, Dunlap K. A comparison of the cost of various treatment methods for early cancer of the prostate. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1986;12(10):1879-1881. doi:10.1016/0360-3016(86)90334-2

- American Society of Radiation Oncology. Radiation oncology case rate program (ROCR). Accessed April 3, 2025. https://www.astro.org/advocacy/key-issues-8f3e5a3b76643265ee93287d79c4fc40/rocr

William Kissick’s description of health care’s iron triangle in 1994 still resonates. Access, quality, and cost will always come at the expense of the others.1 In 2018, Congress passed the VA MISSION Act, allowing patients to pursue community care options for extended waits (> 28 days) or longer distance drive times of > 60 minutes for specialty care services, such as radiation oncology. According to Albanese et al, the VA MISSION Act sought to address gaps in care for veterans living in rural and underserved areas.2 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) continues to increase community care spending, with a 13.8% increase in fiscal year 2024 and an expected cost of > $40 billion for 2025.3 One could argue this pays for access for remote patients and quality when services are unavailable, making it a direct application of the iron triangle.

The VA MISSION Act also bolstered the expansion of existing community care department staff to expediently facilitate and coordinate care and payments.2 Cost management and monitoring have become critical in predicting future staff requirements, maintaining functionality, and ensuring patients receive optimal care. The VHA purchases care through partner networks and defines these bundled health care services as standard episodes of care (SEOCs), which are “clinically related health care services for a specific unique illness or medical condition… over a defined period of time.”4 Medicare publishes its rates quarterly, and outpatient procedure pricing is readily available online.5 Along these same lines, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) publishes a current list of available procedures and associated Current Procedure Technology (CPT) codes that are covered under its VA fee schedule for community care.

Unique challenges persist when using this system to accurately account for radiation oncology expenditures. This study was based on the current practices at the Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center (RLRVAMC), a large 1a hospital. A detailed analysis reveals the contemporaneous cost of radiation oncology cancer care from October 1, 2021, through February 1, 2024, highlights the challenges in SEOC definition and duration, communication issues between RLRVAMC and purchase partners, inconsistencies in billing, erroneous payments, and difficulty of cost categorization.

METHODS

Community care radiation oncology-related costs were examined from October 1, 2021, to February 1, 2024 for RLRVAMC, 6 months prior to billing data extraction. Figure 1 shows a simple radiation oncology patient pathway with consultation or visit, simulation and planning, and treatment, with codes used to check billing. It illustrates the expected relationships between the VHA (radiation oncology, primary, and specialty care) and community care (clinicians and radiation oncology treatment sites).

VHA standard operating procedures for a patient requesting community-based radiation oncology care require a board-certified radiation oncologist at RLRVAMC to review and approve the outside care request. Community care radiation oncology consultation data were accessed from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) using Pyramid Analytics (V25.2). Nurses, physicians, and community care staff can add comments, forward consultations to other services, and mark them as complete or discontinued, when appropriate. Consultations not completed within 91 days are automatically discontinued. All community care requests from 2018 through 2024 were extracted; analysis began April 1, 2021, 6 months prior to the cost evaluation date of October 1, 2021.

An approved consultation is reviewed for eligibility by a nurse in the community care department and assigned an authorization number (a VA prefix followed by 12 digits). Billing codes are approved and organized by the community care networks, and all procedure codes should be captured and labeled under this number. The VAMC Community Care department obtains initial correspondence from the treating clinicians. Subsequent records from the treating radiation oncologist are expected to be scanned into the electronic health record and made accessible via the VA Joint Legacy Viewer (JLV) and Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS).

Radiation Oncology SEOC

The start date of the radiation oncology SEOC is determined by the community care nurse based on guidance established by the VA. It can be manually backdated or delayed, but current practice is to start at first visit or procedure code entry after approval from the VAMC Radiation Oncology department. Approved CPT codes from SEOC versions between October 1, 2021, and February 1, 2024, are in eAppendix 1 (available at doi:10.12788/fp.0585). These generally include 10 types of encounters, about 115 different laboratory tests, 115 imaging studies, 25 simulation and planning procedures, and 115 radiation treatment codes. The radiation oncology SEOCs during the study period had an approval duration of 180 days. Advanced Medical Cost Management Solutions software (AMCMS) is the VHA data analytics platform for community care medical service costs. AMCMS includes all individual CPT codes billed by specific radiation oncology SEOC versions. Data are refreshed monthly, and all charges were extracted on September 12, 2024, > 6 months after the final evaluated service date to allow for complete billing returns.6

Radiation Oncology-Specific Costs

The VA Close to Me (CTM) program was used to find 84 specific radiation oncology CPT codes, nearly all within the 77.XXX or G6.XXX series, which included all radiation oncology-specific (ROS) codes (except visits accrued during consultation and return appointments). ROS costs are those that could not be performed by any other service and include procedures related to radiation oncology simulation, treatment planning, treatment delivery (with or without image guidance), and physician or physicist management. All ROS costs should be included in a patient’s radiation oncology SEOC. Other costs that may accompany operating room or brachytherapy administration did not follow a 77.XXX or G6.XXX pattern but were included in total radiation therapy operating costs.

Data obtained from AMCMS and CTM included patient name and identifier; CPT billed amount; CPT paid amount; dates of service; number of claims; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD) diagnosis; and VA authorization numbers. Only CTM listed code modifiers. Only items categorized as paid were included in the analysis. Charges associated with discontinued consultations that had accrued costs also were included. Codes that were not directly related to ROS were separately characterized as other and further subcategorized.

Deep Dive Categorization

All scanned documents tagged to the community consultation were accessed and evaluated for completeness by a radiation oncologist (RS). The presence or absence of consultation notes and treatment summaries was evaluated based on necessity (ie, not needed for continuation of care or treatment was not given). In the absence of a specific completion summary or follow-up note detailing the treatment modality, number of fractions, and treatment sites, available documentation, including clinical notes and billing information, was used. Radical or curative therapies were identified as courses expected to eradicate disease, including stereotactic ablative radiotherapy to the brain, lung, liver, and other organs. Palliative therapies included whole-brain radiotherapy or other low-dose treatments. If the patient received the intended course, this was categorized as full. If incomplete, it was considered partial.

Billing Deviations

The complete document review allowed for close evaluation of paid therapy and identification of gaps in billing (eg, charges not found in extracted data that should have occurred) for external beam radiotherapy patients. Conversely, extra charges, such as an additional weekly treatment management charge (CPT code 77427), would be noted. Patients were expected to have the number of treatments specified in the summary, a clinical treatment planning code, and weekly treatment management notes from physicians and physicists every 5 fractions. Consultations and follow-up visits were expected to have 1 visit code; CPT codes 99205 and 99215, respectively, were used to estimate costs in their absence.

Costs were based on Medicare rates as of January 1 of the year in which they were accrued. 7-10 Duplicates were charges with the same code, date, billed quantity, and paid amounts for a given patient. These would always be considered erroneous. Medicare treatment costs for procedures such as intensity modulated radiotherapy (CPT code 77385 or 77386) are available on the Medicare website. When reviewing locality deviations for 77427, there was a maximum of 33% increase in Medicare rates. Therefore, for treatment codes, one would expect the range to be at least the Medicare rate and maximally 33% higher. These rates are negotiated with insurance companies, but this range was used for the purpose of reviewing and adjusting large data sets.

RESULTS

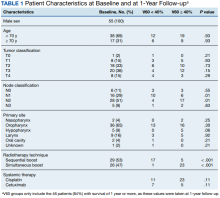

Since 2018, > 500 community care consults have been placed by radiation oncology for treatment in the community, with more following implementation of the VA MISSION Act. Use of radiation oncology community care services annually increased during the study period for this facility (Table 1, Figure 2). Of the 325 community care consults placed from October 1, 2021, to February 1, 2024, 248 radiation oncology SEOCs were recorded with charges for 181 patients (range, 1-5 SEOCs). Long drive time was the rationale for > 97% of patients directed to community care (Supplemental materials, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0585). Based on AMCMS data, $22.2 million was billed and $2.7 million was paid (20%) for 8747 CPT codes. Each community care interval cost the VA a median (range) of $5000 ($8-$168,000 (Figure 3).

After reviewing ROS charges extracted from CTM, 20 additional patients had radiation oncology charges but did not have a radiation oncology SEOC for 268 episodes of care for 201 unique patients. In addition to the 20 patients who did not have a SEOC, 42 nonradiation oncology SEOCs contained 1148 radiation oncology codes, corresponding to almost $500,000 paid. Additional charges of about $416,000, which included biologic agents (eg, durvalumab, nivolumab), procedures (eg, mastectomies), and ambulance rides were inappropriately added to radiation oncology SEOCs.

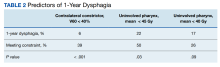

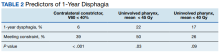

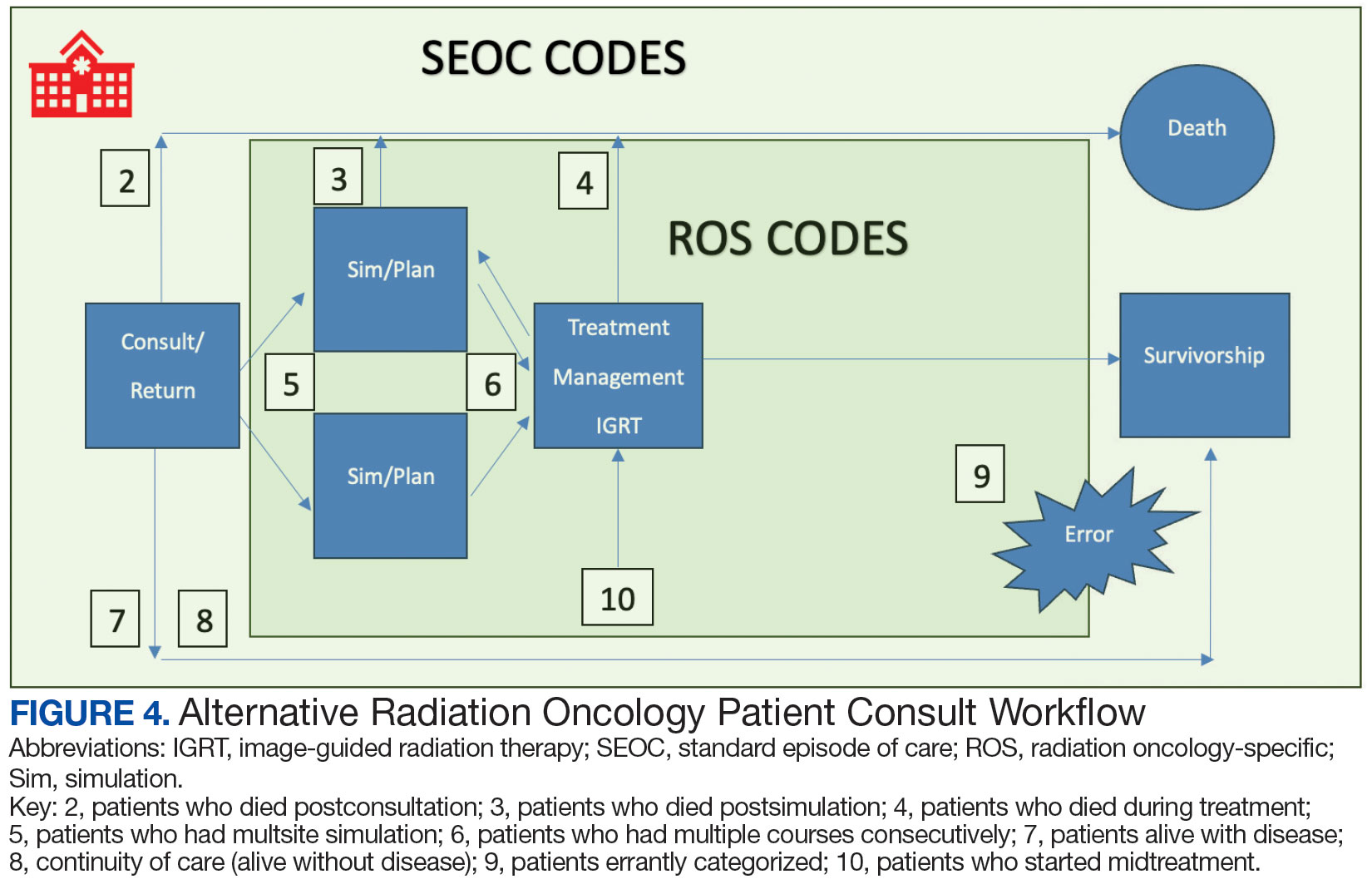

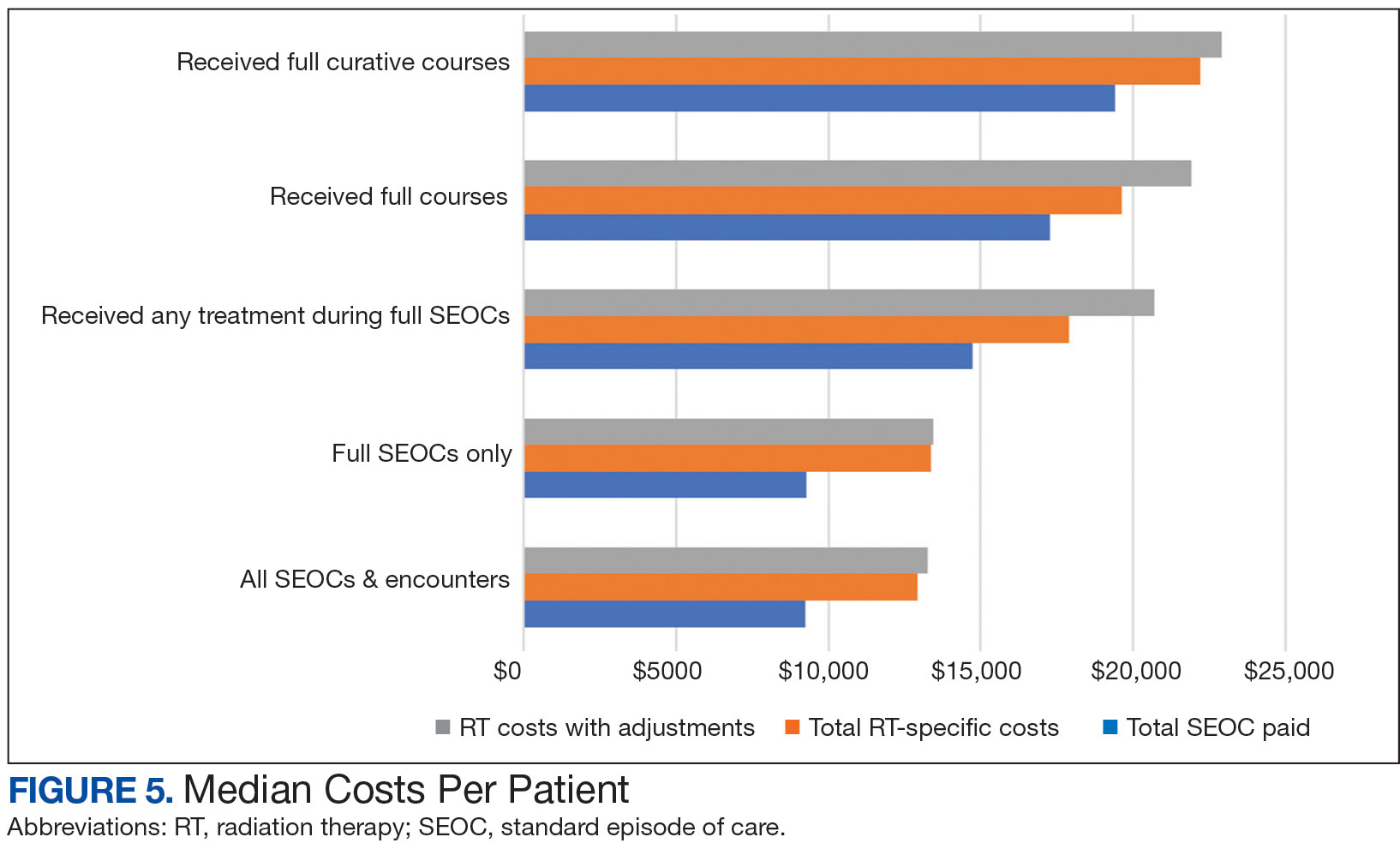

While 77% of consultations were scanned into CPRS and JLV, only 54% of completion summaries were available with an estimated $115,000 in additional costs. The total adjusted costs was about $2.9 million. Almost 37% of SEOCs were for visits only. For the 166 SEOCs where patients received any radiation treatment or planning, the median cost was $18,000. Differences in SEOC pathways are shown in Figure 4. One hundred twenty-one SEOCs (45%) followed the standard pathway, with median SEOC costs of $15,500; when corrected for radiation-specific costs, the median cost increased to $18,000. When adjusted for billing irregularities, the median cost was $20,600. Ninety-nine SEOCs (37%) were for consultation/ follow-up visits only, with a median cost of $220. When omitting shared scans and nonradiation therapy costs and correcting for billing gaps, the median cost decreased to $170. A median of $9200 was paid per patient, with $12,900 for radiation therapy-specific costs and $13,300 adjusted for billing deviations. Narrowing to the 106 patients who received full, radical courses, the median SEOC, ROS, and adjusted radiation therapy costs increased to $19,400, $22,200, and $22,900, respectively (Table 2, Figure 5). Seventy-one SEOCs (26%) had already seen a radiation oncologist before the VA radiation oncology department was aware, and 49 SEOCs (18%) had retroactive approvals (Supplemental materials available at doi:10.12788/fp.0585).

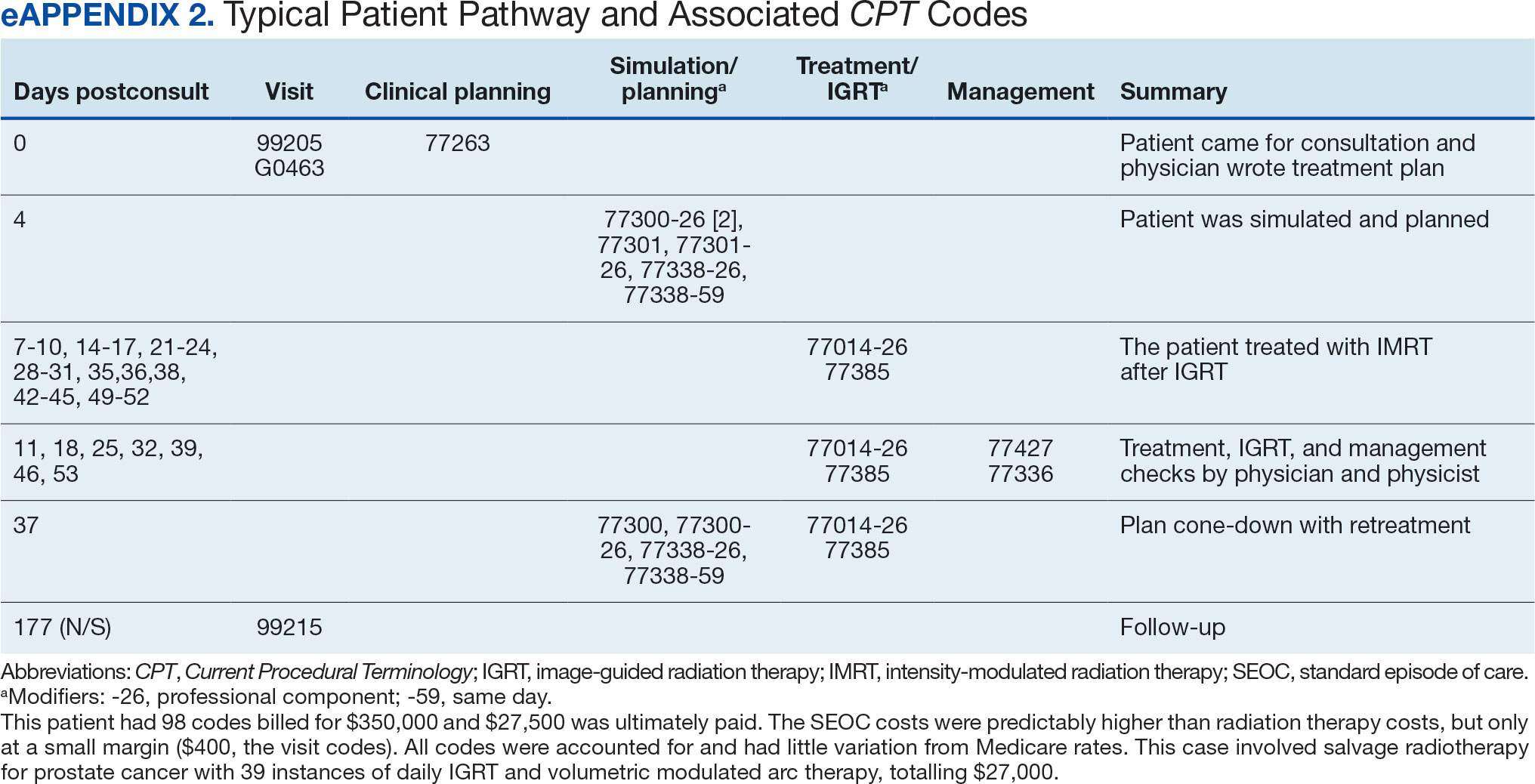

Every consultation charge was reviewed. A typical patient following the standard pathway (eAppendix 2, available at doi:10.12788/ fp.0585) exhibited a predictable pattern of consultation payment, simulation and planning, multiple radiation treatments interspersed with treatment management visits and a cone-down phase, and finishing with a follow-up visit. A less predictable case with excess CPT codes, gaps in charges, and an additional unexpected palliative course is shown in eAppendix 3 (available at doi:10.12788/fp.0585). Gaps occurred in 42% of SEOCs with missed bills costing as much as $12,000. For example, a patient with lung cancer had a treatment summary note for lung cancer after completion that showed the patient received 30 fractions of 2 Gy, a typical course. Only 10 treatment codes and 3 of 6 weekly treatment management codes were available. There was a gap of 20 volumetric modulated arc therapy treatments, 3 physics weekly status checks, 3 physician managements notes, and a computed tomography simulation charge.

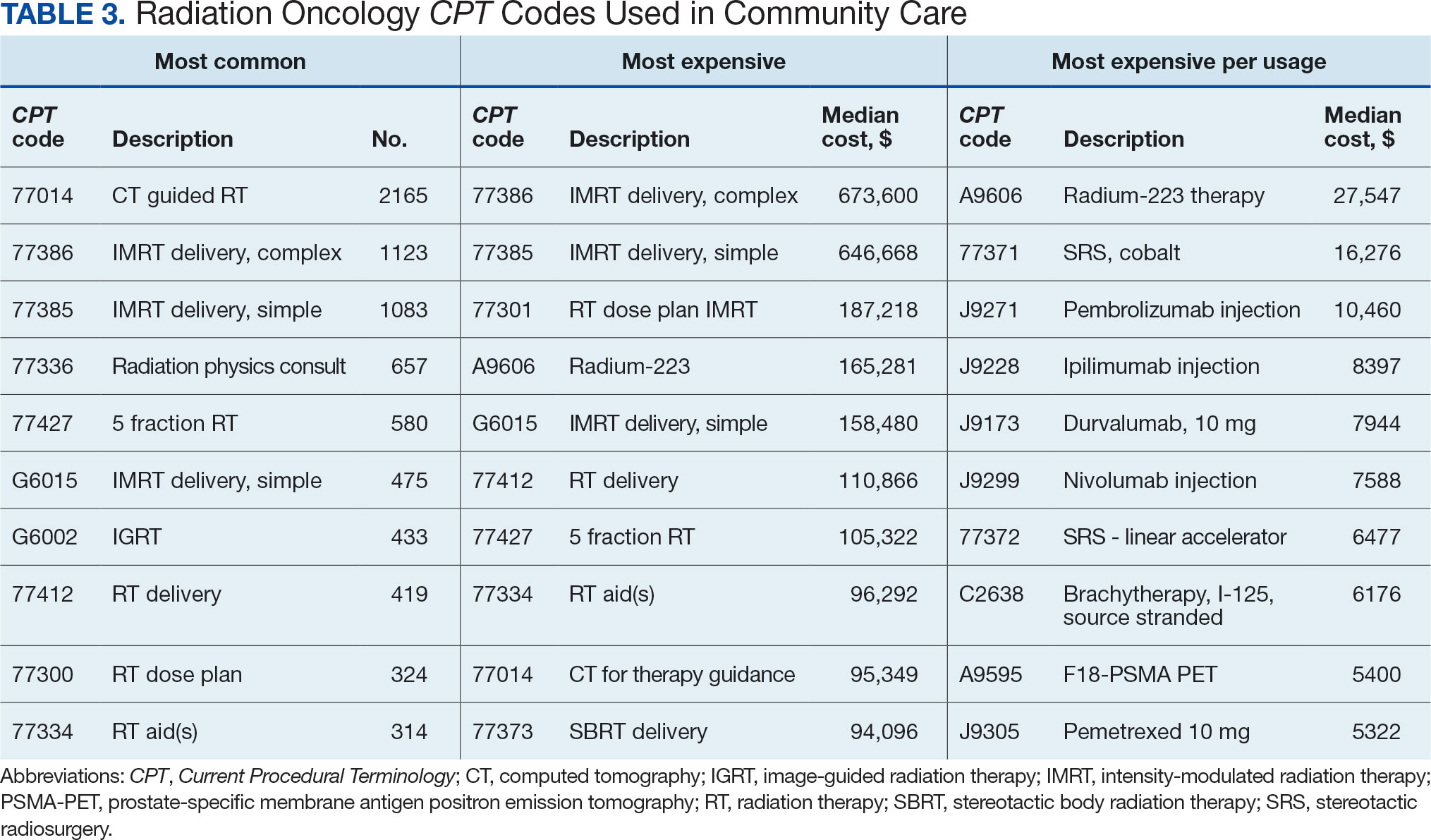

Between AMCMS and CTM, 10,005 CPT codes were evaluated; 1255 (12.5%) were unique to AMCMS (either related to the radiation oncology course, such as Evaluation and Management CPT codes or “other” unrelated codes) while 1158 (11.6%) were unique to CTM. Of the 7592 CPT codes shared between AMCMS and CTM, there was a discrepancy in 135 (1.8%); all were duplicates (CTM showed double payment while AMCMS showed $0 paid). The total CPT code costs came to $3.2 million with $560,000 unique to SEOCs and $500,000 unique to CTM. Treatment codes were the most common (33%) as shown in Table 3 and accounted for 55% of the cost ($1.8 million). About 700 CPT codes were considered “other,” typically for biologic therapeutic agents (Table 4 and eAppendix 4, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0585).

DISCUSSION

The current method of reporting radiation oncology costs used by VA is insufficient and misleading. Better data are needed to summarize purchased care costs to guide decisions about community care at the VA. Investigations into whether the extra costs for quality care (ie, expensive capital equipment, specialized staff, mandatory accreditations) are worthwhile if omitted at other facilities patients choose for their health care needs. No study has defined specialty care-specific costs by evaluating billing receipts from the CDW to answer the question. Kenamond et al highlight the need for radiation oncology for rural patients.11 Drive time was cited as the reason for community care referral for 97% of veterans, many of whom lived in rural locations. Of patients with rurality information who enrolled in community care, 57% came from rural or highly rural counties, and this ratio held for those who received full curative therapies. An executive administrator relying on AMCMS reports would see a median SEOC cost of $5000, but without ROS knowledge in coding, the administrator would miss many additional costs. For example, 2 patients who each had 5 SEOCs during the evaluated period, incurred a total cost of only $1800.

Additionally, an administrator could include miscategorized costs with significant ramifications. The 2 most expensive SEOCs were not typical radiation oncology treatments. A patient undergoing radium-223 dichloride therapy incurred charges exceeding $165,000, contributing disproportionately to the overall median cost analysis; this would normally be administered by the nuclear medicine department. Immunotherapy and chemotherapy are uniformly overseen by medical oncology services, but drug administration codes were still found in radiation oncology SEOCs. A patient (whose SEOC was discontinued but accrued charges) had an electrocardiogram interpretation for $8 as the SEOC cost; 3 other SEOCs continued to incur costs after being discontinued. There were 24 empty SEOCs for patients that had consults to the community, and 2 had notes stating treatment had been delivered yet there was no ROS costs or SEOC costs. Of the 268 encounters, 43% had some sort of billing irregularities (ie, missing treatment costs) that would be unlikely for a private practice to omit; it would be much more likely that the CDW miscategorized the payment despite confirmation of the 2 retrieval systems.

It would be inadvisable to make staffing decisions or forecast costs based on current SEOC reports without specialized curation. A simple yet effective improvement to the cost attribution process would be to restrict the analysis to encounters containing primary radiation treatment codes. This targeted approach allows more accurate identification of patients actively receiving radiation oncology treatment, while excluding those seen solely for consultations or follow-up visits. Implementing this refinement leads to a substantial increase in the median payment—from $5000 to $13,000—without requiring additional coding or data processing, thereby enhancing the accuracy of cost estimates with minimal effort.

Clarifying radiation oncology service costs requires addressing the time frame and services included, given laxity and interpretation of the SEOCs. VA community care departments have streamlined the reimbursement process at the expense of medical cost organization and accuracy; 86% of VA practitioners reported that ≥ 1 potential community health care partners had refused to work with the VA because of payment delays.12 Payments are contingent on correspondence from outside practices for community work. For radiation oncology, this includes the consultation but also critical radiation-related details of treatment, which were omitted nearly half the time. SEOC approval forms have many costly laboratory tests, imaging, and procedures that have little to do with radiation oncology cancer treatments but may be used in the workup and staging process; this creates noise when calculating radiation oncology fiscal cost.

The presumption that an episode of care equates to a completed radiation therapy course is incorrect; this occurs less than half of the time. An episode often refers to a return visit, or conversely, multiple treatment courses. As the patients’ medical homes are their VHA primary care practitioners, it would be particularly challenging to care for the patients without full treatment information, especially if adverse effects from therapy were to arise. As a tertiary specialty, radiation oncology does not seek out patients and are sent consultations from medical oncology, surgical, and medical oncologic specialties. Timesensitive processes such as workup, staging, and diagnosis often occur in parallel. This analysis revealed that patients see outside radiation oncologists prior to the VA. There are ≥ 100 patients who had radiation oncology codes without a radiation oncology SEOC or community care consultation, and in many cases, the consultation was placed after the patient was seen.

Given the lack of uniformity and standardization of patient traffic, the typical and expected pathways were insufficient to find the costs. Too many opportunities for errors and incorrect categorization of costs meant a different method would be necessary. Starting at the inception of the community care consult, only 1 diagnosis code can be entered. For patients with multiple diagnoses, one would not be able to tell what was treated without chart access. Radiation oncology consults come from primary and specialty care practitioners and nurses throughout the VA. Oftentimes, the referral would be solicited by the community radiation oncology clinic, diagnosing community specialty (ie, urology for a patient with prostate cancer), or indirectly from the patient through primary care. Many cases were retroactively approved as the veteran had already been consulted by the community care radiation oncologist. If the patient is drive-time eligible, it would be unlikely that they would leave and choose to return to the VA. There is no way for a facility VA service chief or administrator to mitigate VA community costs of care, especially as shown by the miscategorization of several codes. Database challenges exacerbate the issue: 1 patient changed her first and last name during this time frame, and 2 patients had the same name but different social security numbers. In order to strictly find costs between 2 discrete timepoints, 39 (15%) SEOCs were split and incomplete, and 6 SEOCs contained charges for 2 different patients. This was corrected, and all inadvertent charges were cancelled. Only 1 ICD code is allowed per community care consultation, so an investigation is required to find costs for patients with multiple sites of disease. Additionally, 5 of the patients marked for drive time were actually patients who received Gamma Knife and brachytherapy, services not available at the VA.

Hanks et al first attempted to calculate cost of radiation oncology services. External beam prostate cancer radiotherapy at 3 suburban California centers cost $6750 ($20,503 inflation adjusted) per patient before October 1984 and $5600 ($17,010 inflation adjusted) afterwards.13 According to the American Society for Radiation Oncology, Advocacy Radiation Oncology Case Rate Program Curative radiation courses should cost $20,000 to $30,000 and palliative courses should cost $10,000 to $15,000. These costs are consistent with totals demonstrated in this analysis and similar to the inflation-adjusted Hanks et al figures. Preliminary findings suggest that radiation treatment constituted more than half of the total expenditures, with a notable $4 million increase in adjusted cost compared to the Medicare rates, indicating significant variation. Direct comparisons with Medicaid or commercial payer rates remain unexplored.

Future Directions

During the study period, 201 patients received 186 courses of radiation therapy in the community, while 1014 patients were treated in-house for a total of 833 courses. A forthcoming analysis will directly compare the cost of in-house care with that of communitybased treatment, specifically breaking down expenditure differences by diagnosis. Future research should investigate strategies to align reimbursement with quality metrics, including the potential role of tertiary accreditation in incentivizing high-value care. Additional work is also warranted to assess patient out-ofpocket expenses across care settings and to benchmark VA reimbursement against Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance rates. In any case, with the increasing possibility of fewer fractions for treatments such as stereotactic radiotherapy or palliative care therapy, there is a clear financial incentive to treat as frequently as allowed despite equal clinical outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Veterans increasingly choose to receive care closer to home if the option is available. In the VA iron triangle, cost comes at the expense of access but quantifying this has proved elusive in the cost accounting model currently used at the VA.1 The inclusion of all charges loosely associated with SEOCs significantly impairs the ability to conduct meaningful cost analyses. The current VA methodology not only introduces substantial noise into the data but also leads to a marked underestimation of the true cost of care delivered in community settings. Such misrepresentation risks driving policy decisions that could inappropriately reduce or eliminate in-house radiation oncology services. Categorizing costs effectively in the VA could assist in making managerial and administrative decisions and would prevent damaging service lines based on misleading or incorrect data. A system which differentiates between patients who have received any treatment codes vs those who have not would increase accuracy.

William Kissick’s description of health care’s iron triangle in 1994 still resonates. Access, quality, and cost will always come at the expense of the others.1 In 2018, Congress passed the VA MISSION Act, allowing patients to pursue community care options for extended waits (> 28 days) or longer distance drive times of > 60 minutes for specialty care services, such as radiation oncology. According to Albanese et al, the VA MISSION Act sought to address gaps in care for veterans living in rural and underserved areas.2 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) continues to increase community care spending, with a 13.8% increase in fiscal year 2024 and an expected cost of > $40 billion for 2025.3 One could argue this pays for access for remote patients and quality when services are unavailable, making it a direct application of the iron triangle.

The VA MISSION Act also bolstered the expansion of existing community care department staff to expediently facilitate and coordinate care and payments.2 Cost management and monitoring have become critical in predicting future staff requirements, maintaining functionality, and ensuring patients receive optimal care. The VHA purchases care through partner networks and defines these bundled health care services as standard episodes of care (SEOCs), which are “clinically related health care services for a specific unique illness or medical condition… over a defined period of time.”4 Medicare publishes its rates quarterly, and outpatient procedure pricing is readily available online.5 Along these same lines, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) publishes a current list of available procedures and associated Current Procedure Technology (CPT) codes that are covered under its VA fee schedule for community care.

Unique challenges persist when using this system to accurately account for radiation oncology expenditures. This study was based on the current practices at the Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center (RLRVAMC), a large 1a hospital. A detailed analysis reveals the contemporaneous cost of radiation oncology cancer care from October 1, 2021, through February 1, 2024, highlights the challenges in SEOC definition and duration, communication issues between RLRVAMC and purchase partners, inconsistencies in billing, erroneous payments, and difficulty of cost categorization.

METHODS

Community care radiation oncology-related costs were examined from October 1, 2021, to February 1, 2024 for RLRVAMC, 6 months prior to billing data extraction. Figure 1 shows a simple radiation oncology patient pathway with consultation or visit, simulation and planning, and treatment, with codes used to check billing. It illustrates the expected relationships between the VHA (radiation oncology, primary, and specialty care) and community care (clinicians and radiation oncology treatment sites).

VHA standard operating procedures for a patient requesting community-based radiation oncology care require a board-certified radiation oncologist at RLRVAMC to review and approve the outside care request. Community care radiation oncology consultation data were accessed from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) using Pyramid Analytics (V25.2). Nurses, physicians, and community care staff can add comments, forward consultations to other services, and mark them as complete or discontinued, when appropriate. Consultations not completed within 91 days are automatically discontinued. All community care requests from 2018 through 2024 were extracted; analysis began April 1, 2021, 6 months prior to the cost evaluation date of October 1, 2021.

An approved consultation is reviewed for eligibility by a nurse in the community care department and assigned an authorization number (a VA prefix followed by 12 digits). Billing codes are approved and organized by the community care networks, and all procedure codes should be captured and labeled under this number. The VAMC Community Care department obtains initial correspondence from the treating clinicians. Subsequent records from the treating radiation oncologist are expected to be scanned into the electronic health record and made accessible via the VA Joint Legacy Viewer (JLV) and Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS).

Radiation Oncology SEOC

The start date of the radiation oncology SEOC is determined by the community care nurse based on guidance established by the VA. It can be manually backdated or delayed, but current practice is to start at first visit or procedure code entry after approval from the VAMC Radiation Oncology department. Approved CPT codes from SEOC versions between October 1, 2021, and February 1, 2024, are in eAppendix 1 (available at doi:10.12788/fp.0585). These generally include 10 types of encounters, about 115 different laboratory tests, 115 imaging studies, 25 simulation and planning procedures, and 115 radiation treatment codes. The radiation oncology SEOCs during the study period had an approval duration of 180 days. Advanced Medical Cost Management Solutions software (AMCMS) is the VHA data analytics platform for community care medical service costs. AMCMS includes all individual CPT codes billed by specific radiation oncology SEOC versions. Data are refreshed monthly, and all charges were extracted on September 12, 2024, > 6 months after the final evaluated service date to allow for complete billing returns.6

Radiation Oncology-Specific Costs

The VA Close to Me (CTM) program was used to find 84 specific radiation oncology CPT codes, nearly all within the 77.XXX or G6.XXX series, which included all radiation oncology-specific (ROS) codes (except visits accrued during consultation and return appointments). ROS costs are those that could not be performed by any other service and include procedures related to radiation oncology simulation, treatment planning, treatment delivery (with or without image guidance), and physician or physicist management. All ROS costs should be included in a patient’s radiation oncology SEOC. Other costs that may accompany operating room or brachytherapy administration did not follow a 77.XXX or G6.XXX pattern but were included in total radiation therapy operating costs.

Data obtained from AMCMS and CTM included patient name and identifier; CPT billed amount; CPT paid amount; dates of service; number of claims; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD) diagnosis; and VA authorization numbers. Only CTM listed code modifiers. Only items categorized as paid were included in the analysis. Charges associated with discontinued consultations that had accrued costs also were included. Codes that were not directly related to ROS were separately characterized as other and further subcategorized.

Deep Dive Categorization

All scanned documents tagged to the community consultation were accessed and evaluated for completeness by a radiation oncologist (RS). The presence or absence of consultation notes and treatment summaries was evaluated based on necessity (ie, not needed for continuation of care or treatment was not given). In the absence of a specific completion summary or follow-up note detailing the treatment modality, number of fractions, and treatment sites, available documentation, including clinical notes and billing information, was used. Radical or curative therapies were identified as courses expected to eradicate disease, including stereotactic ablative radiotherapy to the brain, lung, liver, and other organs. Palliative therapies included whole-brain radiotherapy or other low-dose treatments. If the patient received the intended course, this was categorized as full. If incomplete, it was considered partial.

Billing Deviations

The complete document review allowed for close evaluation of paid therapy and identification of gaps in billing (eg, charges not found in extracted data that should have occurred) for external beam radiotherapy patients. Conversely, extra charges, such as an additional weekly treatment management charge (CPT code 77427), would be noted. Patients were expected to have the number of treatments specified in the summary, a clinical treatment planning code, and weekly treatment management notes from physicians and physicists every 5 fractions. Consultations and follow-up visits were expected to have 1 visit code; CPT codes 99205 and 99215, respectively, were used to estimate costs in their absence.

Costs were based on Medicare rates as of January 1 of the year in which they were accrued. 7-10 Duplicates were charges with the same code, date, billed quantity, and paid amounts for a given patient. These would always be considered erroneous. Medicare treatment costs for procedures such as intensity modulated radiotherapy (CPT code 77385 or 77386) are available on the Medicare website. When reviewing locality deviations for 77427, there was a maximum of 33% increase in Medicare rates. Therefore, for treatment codes, one would expect the range to be at least the Medicare rate and maximally 33% higher. These rates are negotiated with insurance companies, but this range was used for the purpose of reviewing and adjusting large data sets.

RESULTS

Since 2018, > 500 community care consults have been placed by radiation oncology for treatment in the community, with more following implementation of the VA MISSION Act. Use of radiation oncology community care services annually increased during the study period for this facility (Table 1, Figure 2). Of the 325 community care consults placed from October 1, 2021, to February 1, 2024, 248 radiation oncology SEOCs were recorded with charges for 181 patients (range, 1-5 SEOCs). Long drive time was the rationale for > 97% of patients directed to community care (Supplemental materials, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0585). Based on AMCMS data, $22.2 million was billed and $2.7 million was paid (20%) for 8747 CPT codes. Each community care interval cost the VA a median (range) of $5000 ($8-$168,000 (Figure 3).

After reviewing ROS charges extracted from CTM, 20 additional patients had radiation oncology charges but did not have a radiation oncology SEOC for 268 episodes of care for 201 unique patients. In addition to the 20 patients who did not have a SEOC, 42 nonradiation oncology SEOCs contained 1148 radiation oncology codes, corresponding to almost $500,000 paid. Additional charges of about $416,000, which included biologic agents (eg, durvalumab, nivolumab), procedures (eg, mastectomies), and ambulance rides were inappropriately added to radiation oncology SEOCs.

While 77% of consultations were scanned into CPRS and JLV, only 54% of completion summaries were available with an estimated $115,000 in additional costs. The total adjusted costs was about $2.9 million. Almost 37% of SEOCs were for visits only. For the 166 SEOCs where patients received any radiation treatment or planning, the median cost was $18,000. Differences in SEOC pathways are shown in Figure 4. One hundred twenty-one SEOCs (45%) followed the standard pathway, with median SEOC costs of $15,500; when corrected for radiation-specific costs, the median cost increased to $18,000. When adjusted for billing irregularities, the median cost was $20,600. Ninety-nine SEOCs (37%) were for consultation/ follow-up visits only, with a median cost of $220. When omitting shared scans and nonradiation therapy costs and correcting for billing gaps, the median cost decreased to $170. A median of $9200 was paid per patient, with $12,900 for radiation therapy-specific costs and $13,300 adjusted for billing deviations. Narrowing to the 106 patients who received full, radical courses, the median SEOC, ROS, and adjusted radiation therapy costs increased to $19,400, $22,200, and $22,900, respectively (Table 2, Figure 5). Seventy-one SEOCs (26%) had already seen a radiation oncologist before the VA radiation oncology department was aware, and 49 SEOCs (18%) had retroactive approvals (Supplemental materials available at doi:10.12788/fp.0585).

Every consultation charge was reviewed. A typical patient following the standard pathway (eAppendix 2, available at doi:10.12788/ fp.0585) exhibited a predictable pattern of consultation payment, simulation and planning, multiple radiation treatments interspersed with treatment management visits and a cone-down phase, and finishing with a follow-up visit. A less predictable case with excess CPT codes, gaps in charges, and an additional unexpected palliative course is shown in eAppendix 3 (available at doi:10.12788/fp.0585). Gaps occurred in 42% of SEOCs with missed bills costing as much as $12,000. For example, a patient with lung cancer had a treatment summary note for lung cancer after completion that showed the patient received 30 fractions of 2 Gy, a typical course. Only 10 treatment codes and 3 of 6 weekly treatment management codes were available. There was a gap of 20 volumetric modulated arc therapy treatments, 3 physics weekly status checks, 3 physician managements notes, and a computed tomography simulation charge.

Between AMCMS and CTM, 10,005 CPT codes were evaluated; 1255 (12.5%) were unique to AMCMS (either related to the radiation oncology course, such as Evaluation and Management CPT codes or “other” unrelated codes) while 1158 (11.6%) were unique to CTM. Of the 7592 CPT codes shared between AMCMS and CTM, there was a discrepancy in 135 (1.8%); all were duplicates (CTM showed double payment while AMCMS showed $0 paid). The total CPT code costs came to $3.2 million with $560,000 unique to SEOCs and $500,000 unique to CTM. Treatment codes were the most common (33%) as shown in Table 3 and accounted for 55% of the cost ($1.8 million). About 700 CPT codes were considered “other,” typically for biologic therapeutic agents (Table 4 and eAppendix 4, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0585).

DISCUSSION

The current method of reporting radiation oncology costs used by VA is insufficient and misleading. Better data are needed to summarize purchased care costs to guide decisions about community care at the VA. Investigations into whether the extra costs for quality care (ie, expensive capital equipment, specialized staff, mandatory accreditations) are worthwhile if omitted at other facilities patients choose for their health care needs. No study has defined specialty care-specific costs by evaluating billing receipts from the CDW to answer the question. Kenamond et al highlight the need for radiation oncology for rural patients.11 Drive time was cited as the reason for community care referral for 97% of veterans, many of whom lived in rural locations. Of patients with rurality information who enrolled in community care, 57% came from rural or highly rural counties, and this ratio held for those who received full curative therapies. An executive administrator relying on AMCMS reports would see a median SEOC cost of $5000, but without ROS knowledge in coding, the administrator would miss many additional costs. For example, 2 patients who each had 5 SEOCs during the evaluated period, incurred a total cost of only $1800.

Additionally, an administrator could include miscategorized costs with significant ramifications. The 2 most expensive SEOCs were not typical radiation oncology treatments. A patient undergoing radium-223 dichloride therapy incurred charges exceeding $165,000, contributing disproportionately to the overall median cost analysis; this would normally be administered by the nuclear medicine department. Immunotherapy and chemotherapy are uniformly overseen by medical oncology services, but drug administration codes were still found in radiation oncology SEOCs. A patient (whose SEOC was discontinued but accrued charges) had an electrocardiogram interpretation for $8 as the SEOC cost; 3 other SEOCs continued to incur costs after being discontinued. There were 24 empty SEOCs for patients that had consults to the community, and 2 had notes stating treatment had been delivered yet there was no ROS costs or SEOC costs. Of the 268 encounters, 43% had some sort of billing irregularities (ie, missing treatment costs) that would be unlikely for a private practice to omit; it would be much more likely that the CDW miscategorized the payment despite confirmation of the 2 retrieval systems.

It would be inadvisable to make staffing decisions or forecast costs based on current SEOC reports without specialized curation. A simple yet effective improvement to the cost attribution process would be to restrict the analysis to encounters containing primary radiation treatment codes. This targeted approach allows more accurate identification of patients actively receiving radiation oncology treatment, while excluding those seen solely for consultations or follow-up visits. Implementing this refinement leads to a substantial increase in the median payment—from $5000 to $13,000—without requiring additional coding or data processing, thereby enhancing the accuracy of cost estimates with minimal effort.

Clarifying radiation oncology service costs requires addressing the time frame and services included, given laxity and interpretation of the SEOCs. VA community care departments have streamlined the reimbursement process at the expense of medical cost organization and accuracy; 86% of VA practitioners reported that ≥ 1 potential community health care partners had refused to work with the VA because of payment delays.12 Payments are contingent on correspondence from outside practices for community work. For radiation oncology, this includes the consultation but also critical radiation-related details of treatment, which were omitted nearly half the time. SEOC approval forms have many costly laboratory tests, imaging, and procedures that have little to do with radiation oncology cancer treatments but may be used in the workup and staging process; this creates noise when calculating radiation oncology fiscal cost.

The presumption that an episode of care equates to a completed radiation therapy course is incorrect; this occurs less than half of the time. An episode often refers to a return visit, or conversely, multiple treatment courses. As the patients’ medical homes are their VHA primary care practitioners, it would be particularly challenging to care for the patients without full treatment information, especially if adverse effects from therapy were to arise. As a tertiary specialty, radiation oncology does not seek out patients and are sent consultations from medical oncology, surgical, and medical oncologic specialties. Timesensitive processes such as workup, staging, and diagnosis often occur in parallel. This analysis revealed that patients see outside radiation oncologists prior to the VA. There are ≥ 100 patients who had radiation oncology codes without a radiation oncology SEOC or community care consultation, and in many cases, the consultation was placed after the patient was seen.

Given the lack of uniformity and standardization of patient traffic, the typical and expected pathways were insufficient to find the costs. Too many opportunities for errors and incorrect categorization of costs meant a different method would be necessary. Starting at the inception of the community care consult, only 1 diagnosis code can be entered. For patients with multiple diagnoses, one would not be able to tell what was treated without chart access. Radiation oncology consults come from primary and specialty care practitioners and nurses throughout the VA. Oftentimes, the referral would be solicited by the community radiation oncology clinic, diagnosing community specialty (ie, urology for a patient with prostate cancer), or indirectly from the patient through primary care. Many cases were retroactively approved as the veteran had already been consulted by the community care radiation oncologist. If the patient is drive-time eligible, it would be unlikely that they would leave and choose to return to the VA. There is no way for a facility VA service chief or administrator to mitigate VA community costs of care, especially as shown by the miscategorization of several codes. Database challenges exacerbate the issue: 1 patient changed her first and last name during this time frame, and 2 patients had the same name but different social security numbers. In order to strictly find costs between 2 discrete timepoints, 39 (15%) SEOCs were split and incomplete, and 6 SEOCs contained charges for 2 different patients. This was corrected, and all inadvertent charges were cancelled. Only 1 ICD code is allowed per community care consultation, so an investigation is required to find costs for patients with multiple sites of disease. Additionally, 5 of the patients marked for drive time were actually patients who received Gamma Knife and brachytherapy, services not available at the VA.

Hanks et al first attempted to calculate cost of radiation oncology services. External beam prostate cancer radiotherapy at 3 suburban California centers cost $6750 ($20,503 inflation adjusted) per patient before October 1984 and $5600 ($17,010 inflation adjusted) afterwards.13 According to the American Society for Radiation Oncology, Advocacy Radiation Oncology Case Rate Program Curative radiation courses should cost $20,000 to $30,000 and palliative courses should cost $10,000 to $15,000. These costs are consistent with totals demonstrated in this analysis and similar to the inflation-adjusted Hanks et al figures. Preliminary findings suggest that radiation treatment constituted more than half of the total expenditures, with a notable $4 million increase in adjusted cost compared to the Medicare rates, indicating significant variation. Direct comparisons with Medicaid or commercial payer rates remain unexplored.

Future Directions

During the study period, 201 patients received 186 courses of radiation therapy in the community, while 1014 patients were treated in-house for a total of 833 courses. A forthcoming analysis will directly compare the cost of in-house care with that of communitybased treatment, specifically breaking down expenditure differences by diagnosis. Future research should investigate strategies to align reimbursement with quality metrics, including the potential role of tertiary accreditation in incentivizing high-value care. Additional work is also warranted to assess patient out-ofpocket expenses across care settings and to benchmark VA reimbursement against Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance rates. In any case, with the increasing possibility of fewer fractions for treatments such as stereotactic radiotherapy or palliative care therapy, there is a clear financial incentive to treat as frequently as allowed despite equal clinical outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Veterans increasingly choose to receive care closer to home if the option is available. In the VA iron triangle, cost comes at the expense of access but quantifying this has proved elusive in the cost accounting model currently used at the VA.1 The inclusion of all charges loosely associated with SEOCs significantly impairs the ability to conduct meaningful cost analyses. The current VA methodology not only introduces substantial noise into the data but also leads to a marked underestimation of the true cost of care delivered in community settings. Such misrepresentation risks driving policy decisions that could inappropriately reduce or eliminate in-house radiation oncology services. Categorizing costs effectively in the VA could assist in making managerial and administrative decisions and would prevent damaging service lines based on misleading or incorrect data. A system which differentiates between patients who have received any treatment codes vs those who have not would increase accuracy.

- Kissick W. Medicine’s Dilemmas: Infinite Needs Versus Finite Resources. 1st ed. Yale University Press; 1994.

- Albanese AP, Bope ET, Sanders KM, Bowman M. The VA MISSION Act of 2018: a potential game changer for rural GME expansion and veteran health care. J Rural Health. 2020;36(1):133-136. doi:10.1111/jrh.12360

- Office of Management and Budget (US). Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2025. Washington, DC: US Government Publishing Office; 2024. Available from: US Department of Veterans Affairs FY 2025 Budget Submission: Budget in Brief.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran care claims. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/revenue-ops/Veteran-Care-Claims.asp

- US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed April 3, 2025. Procedure price lookup https://www.medicare.gov/procedure-price-lookup

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. WellHive -Enterprise. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://department.va.gov/privacy/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2023/05/FY23WellHiveEnterprisePIA.pdf

- US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. RVU21a physician fee schedule, January 2021 release. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/medicaremedicare-fee-service-paymentphysicianfeeschedpfs-relative-value-files/rvu21a

- US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. RVU22a physician fee schedule, January 2022 release. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/medicaremedicare-fee-service-paymentphysicianfeeschedpfs-relative-value-files/rvu22a

- US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. RVU23a physician fee schedule, January 2023 release. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-service-payment/physicianfeesched/pfs-relative-value-files/rvu23a

- US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. RVU23a Medicare Physician Fee Schedule rates effective January 1, 2024, through March 8, 2024. Accessed on April 3, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/fee-schedules/physician/pfs-relative-value-files/rvu24a

- Kenamond MC, Mourad WF, Randall ME, Kaushal A. No oncology patient left behind: challenges and solutions in rural radiation oncology. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;13:100289. doi:10.1016/j.lana.2022.100289

- Mattocks KM, Kroll-Desrosiers A, Kinney R, Elwy AR, Cunningham KJ, Mengeling MA. Understanding VA’s use of and relationships with community care providers under the MISSION Act. Med Care. 2021;59(Suppl 3):S252-S258. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001545

- Hanks GE, Dunlap K. A comparison of the cost of various treatment methods for early cancer of the prostate. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1986;12(10):1879-1881. doi:10.1016/0360-3016(86)90334-2

- American Society of Radiation Oncology. Radiation oncology case rate program (ROCR). Accessed April 3, 2025. https://www.astro.org/advocacy/key-issues-8f3e5a3b76643265ee93287d79c4fc40/rocr

- Kissick W. Medicine’s Dilemmas: Infinite Needs Versus Finite Resources. 1st ed. Yale University Press; 1994.

- Albanese AP, Bope ET, Sanders KM, Bowman M. The VA MISSION Act of 2018: a potential game changer for rural GME expansion and veteran health care. J Rural Health. 2020;36(1):133-136. doi:10.1111/jrh.12360

- Office of Management and Budget (US). Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2025. Washington, DC: US Government Publishing Office; 2024. Available from: US Department of Veterans Affairs FY 2025 Budget Submission: Budget in Brief.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran care claims. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/revenue-ops/Veteran-Care-Claims.asp

- US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed April 3, 2025. Procedure price lookup https://www.medicare.gov/procedure-price-lookup

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. WellHive -Enterprise. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://department.va.gov/privacy/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2023/05/FY23WellHiveEnterprisePIA.pdf

- US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. RVU21a physician fee schedule, January 2021 release. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/medicaremedicare-fee-service-paymentphysicianfeeschedpfs-relative-value-files/rvu21a

- US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. RVU22a physician fee schedule, January 2022 release. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/medicaremedicare-fee-service-paymentphysicianfeeschedpfs-relative-value-files/rvu22a

- US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. RVU23a physician fee schedule, January 2023 release. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-service-payment/physicianfeesched/pfs-relative-value-files/rvu23a

- US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. RVU23a Medicare Physician Fee Schedule rates effective January 1, 2024, through March 8, 2024. Accessed on April 3, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/fee-schedules/physician/pfs-relative-value-files/rvu24a

- Kenamond MC, Mourad WF, Randall ME, Kaushal A. No oncology patient left behind: challenges and solutions in rural radiation oncology. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;13:100289. doi:10.1016/j.lana.2022.100289