User login

A Joint Effort to Save the Joints: What Dermatologists Need to Know About Psoriatic Arthritis

Nearly all dermatologists are aware that psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is one of the most prevalent comorbidities associated with psoriasis, yet we may lack the insight regarding how to utilize this information. After all, we specialize in the skin, not the joints, right?

When I graduated from residency in 2014, I began staffing our psoriasis clinic, where we care for the toughest, most complicated psoriasis patients, many of them struggling with both severe recalcitrant psoriasis as well as debilitating PsA. In 2016, we partnered with rheumatology to open a multidisciplinary psoriasis and PsA clinic, and I quickly began to appreciate how much PsA was being overlooked simply because patients with psoriasis were not being asked about their joints.

To start, let’s look at several facts:

- One quarter of patients with psoriasis also have PsA.1

- Skin disease most commonly develops before PsA.1

- Fifteen percent of PsA cases go undiagnosed, which dramatically increases the risk for deformed joints, erosions, osteolysis, sacroiliitis, and arthritis mutilans2 and also increases the cost of health care.3

- Everyone is crazy busy—rheumatology wait lists often are months long.

Given that dermatologists are the ones who already are seeing the majority of patients who develop PsA, we play a key role in screening for this debilitating comorbidity and starting therapy for patients with both psoriasis and PsA. We, too, are crazy busy; therefore, we need to make this process quick and efficient but also reliable. Fortunately, the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) is effective, fast, and very easy. With only 5 questions and a sensitivity and specificity of around 70%,4 this short and simple questionnaire can be incorporated into an intake form or rooming note or can just be asked during the visit. The questions include whether the patient currently has or has had a swollen joint, nail pits, heel pain, and/or dactylitis, as well as if they have been told by a physician that they have arthritis. A score of 3 or higher is considered positive and a referral to rheumatology should be considered. At the bare minimum, I highly encourage all dermatologists to incorporate the PEST screening tool into their practice.

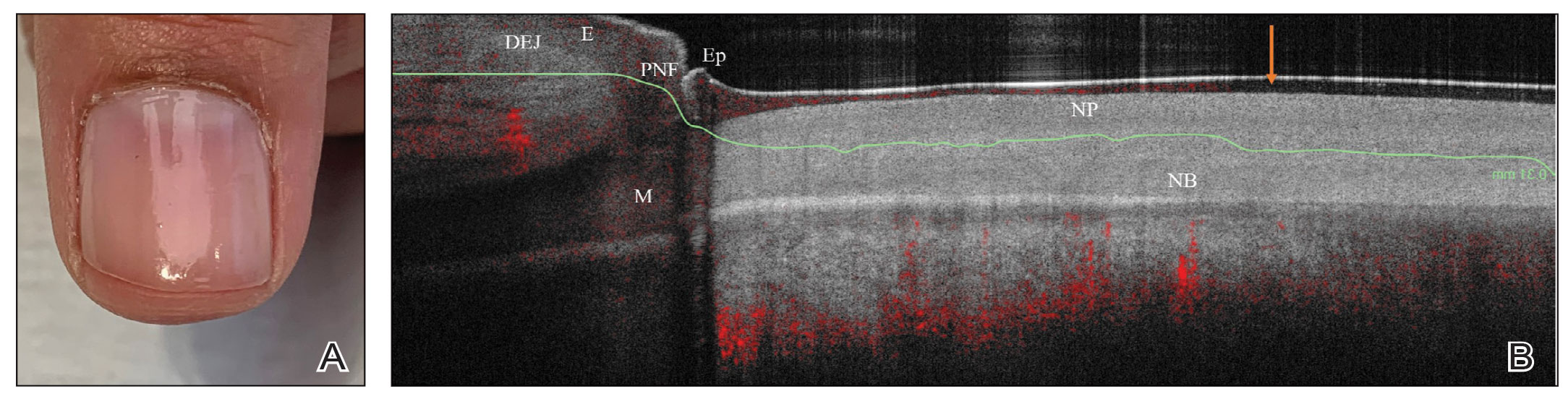

During the physical examination itself, be sure to look at the patient’s nails and also look for joint swelling and redness, especially in the hands. When palpating a swollen joint, the presence of inflammatory arthritis will feel spongy or boggy, while the osteophytes associated with osteoarthritis will feel hard. Radiography of the affected joint may be helpful, but keep in mind that bone changes are latter sequelae of PsA, and negative radiographs do not rule out PsA.

If you highly suspect PsA after using the PEST screening tool and palpating any swollen joints, then a rheumatology referral certainly is warranted. Medication that covers both psoriasis and PsA also can be initiated. Although methotrexate often is used for joints, higher doses (ie, >15 mg/wk) usually are needed. A 2019 Cochrane review found that low-dose methotrexate (ie, ≤15 mg/wk) may be only slightly more effective then placebo5—certainly not a ringing endorsement for its use in PsA. Additionally, quality data demonstrating methotrexate’s efficacy for enthesitis or axial spondyloarthritis is lacking, and methotrexate has not demonstrated an ability to slow the radiographic progression of joints. In contrast, the anti–tumor necrosis factor agents, including adalimumab, infliximab, etanercept, and certolizumab, as well as ustekinumab and the anti–IL-17 biologics secukinumab and ixekizumab have demonstrated efficacy in American College of Rheumatology (ACR) scores, enthesitis, dactylitis, and prevention of radiographic progression of joints.6,7 Although brodalumab, an anti–IL-17 receptor inhibitor, demonstrated improvement in ACR scores, enthesitis, and dactylitis, data on its effects on radiographic progression of joints were inconclusive given the phase III trial’s premature ending due to suicidal ideation and behavior in participants.8 Several of the anti–IL-23 agents also may help PsA, with trials demonstrating improvements in ACR scores, enthesitis, and dactylitis; however, only guselkumab 100 mg every 4 weeks decreased radiographic progression of joints.9 Additionally, with the age of the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor upon us, there are several JAK/TYK2 inhibitors that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for psoriasis (deucravacitinib) as well as for PsA (tofacitinib, upadacitinib), and there are more JAK inhibitors in the pipeline. These medications are effective; however, I do encourage caution and careful consideration in selecting the appropriate patient, as data demonstrated an increased risk for major adverse cardiovascular events and cancer in older (>50 years) rheumatoid arthritis patients who had at least 1 cardiovascular risk factor and were treated with tofacitinib.10 Although several other trials have not demonstrated this increased risk, further data are needed to determine risk for both pan-JAK inhibitors as well as selective JAK inhibitors and TYK2 inhibitors. Additionally, given psoriasis already is closely linked with many cardiovascular risk factors including heart disease, obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus,11 it will be important to have long-term safety information for JAK inhibitors in the psoriasis and PsA population.

Dermatologists are in a pivotal position to identify patients affected by PsA and start an appropriate systemic medication. We can help make an enormous impact on our patients’ lives as well as help decrease the economic impact of untreated disease. Let’s join the effort to save the joints!

- Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen L, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:251-265.

- Villani A, Zouzaud M, Sevrain M, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:242-248.

- Iragorri N, Hazlewood G, Manns B, et al. Model to determine the cost-effectiveness of screening psoriasis patients for psoriatic arthritis. Arth Car Res. 2021;73:266-274.

- Karreman M, Weel A, Van der Ven M, et al. Performance of screening tools for psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional study in primary care. Rheumatology. 2017;56:597-602.

- Wilsdon TD, Whittle SL, Thynne TR, et al. Methotrexate for psoriatic arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:CD012722. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012722.pub2

- Mourad A, Gniadecki R. Treatment of dactylitis and enthesitis in psoriatic arthritis with biologic agents: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheum. 2020;47:59-65.

- Wu D, Li C, Zhang S, et al. Effect of biologics on radiographic progression of peripheral joint in patients with psoriatic arthritis: meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59:3172-3180.

- Mease P, Helliwell P, Fjellhaugen Hjuler K, et al. Brodalumab in psoriatic arthritis: results from the randomised phase III AMVISION-1 and AMVISION-2 trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:185-193.

- McInnes I, Rahman P, Gottlieb A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of guselkumab, a monoclonal antibody specific to the p19 subunit of interleukin-23, through two years: results from a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted in biologic-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis. Arth Rheum. 2022;74:475-485.

- Ytterberg S, Bhatt D, Mikuls T, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:316-326.

- Miller I, Ellervik C, Yazdanyar S, et al. Meta-analysis of psoriasis, cardiovascular disease, and associated risk factors. JAAD. 2013;69:1014-1024.

Nearly all dermatologists are aware that psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is one of the most prevalent comorbidities associated with psoriasis, yet we may lack the insight regarding how to utilize this information. After all, we specialize in the skin, not the joints, right?

When I graduated from residency in 2014, I began staffing our psoriasis clinic, where we care for the toughest, most complicated psoriasis patients, many of them struggling with both severe recalcitrant psoriasis as well as debilitating PsA. In 2016, we partnered with rheumatology to open a multidisciplinary psoriasis and PsA clinic, and I quickly began to appreciate how much PsA was being overlooked simply because patients with psoriasis were not being asked about their joints.

To start, let’s look at several facts:

- One quarter of patients with psoriasis also have PsA.1

- Skin disease most commonly develops before PsA.1

- Fifteen percent of PsA cases go undiagnosed, which dramatically increases the risk for deformed joints, erosions, osteolysis, sacroiliitis, and arthritis mutilans2 and also increases the cost of health care.3

- Everyone is crazy busy—rheumatology wait lists often are months long.

Given that dermatologists are the ones who already are seeing the majority of patients who develop PsA, we play a key role in screening for this debilitating comorbidity and starting therapy for patients with both psoriasis and PsA. We, too, are crazy busy; therefore, we need to make this process quick and efficient but also reliable. Fortunately, the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) is effective, fast, and very easy. With only 5 questions and a sensitivity and specificity of around 70%,4 this short and simple questionnaire can be incorporated into an intake form or rooming note or can just be asked during the visit. The questions include whether the patient currently has or has had a swollen joint, nail pits, heel pain, and/or dactylitis, as well as if they have been told by a physician that they have arthritis. A score of 3 or higher is considered positive and a referral to rheumatology should be considered. At the bare minimum, I highly encourage all dermatologists to incorporate the PEST screening tool into their practice.

During the physical examination itself, be sure to look at the patient’s nails and also look for joint swelling and redness, especially in the hands. When palpating a swollen joint, the presence of inflammatory arthritis will feel spongy or boggy, while the osteophytes associated with osteoarthritis will feel hard. Radiography of the affected joint may be helpful, but keep in mind that bone changes are latter sequelae of PsA, and negative radiographs do not rule out PsA.

If you highly suspect PsA after using the PEST screening tool and palpating any swollen joints, then a rheumatology referral certainly is warranted. Medication that covers both psoriasis and PsA also can be initiated. Although methotrexate often is used for joints, higher doses (ie, >15 mg/wk) usually are needed. A 2019 Cochrane review found that low-dose methotrexate (ie, ≤15 mg/wk) may be only slightly more effective then placebo5—certainly not a ringing endorsement for its use in PsA. Additionally, quality data demonstrating methotrexate’s efficacy for enthesitis or axial spondyloarthritis is lacking, and methotrexate has not demonstrated an ability to slow the radiographic progression of joints. In contrast, the anti–tumor necrosis factor agents, including adalimumab, infliximab, etanercept, and certolizumab, as well as ustekinumab and the anti–IL-17 biologics secukinumab and ixekizumab have demonstrated efficacy in American College of Rheumatology (ACR) scores, enthesitis, dactylitis, and prevention of radiographic progression of joints.6,7 Although brodalumab, an anti–IL-17 receptor inhibitor, demonstrated improvement in ACR scores, enthesitis, and dactylitis, data on its effects on radiographic progression of joints were inconclusive given the phase III trial’s premature ending due to suicidal ideation and behavior in participants.8 Several of the anti–IL-23 agents also may help PsA, with trials demonstrating improvements in ACR scores, enthesitis, and dactylitis; however, only guselkumab 100 mg every 4 weeks decreased radiographic progression of joints.9 Additionally, with the age of the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor upon us, there are several JAK/TYK2 inhibitors that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for psoriasis (deucravacitinib) as well as for PsA (tofacitinib, upadacitinib), and there are more JAK inhibitors in the pipeline. These medications are effective; however, I do encourage caution and careful consideration in selecting the appropriate patient, as data demonstrated an increased risk for major adverse cardiovascular events and cancer in older (>50 years) rheumatoid arthritis patients who had at least 1 cardiovascular risk factor and were treated with tofacitinib.10 Although several other trials have not demonstrated this increased risk, further data are needed to determine risk for both pan-JAK inhibitors as well as selective JAK inhibitors and TYK2 inhibitors. Additionally, given psoriasis already is closely linked with many cardiovascular risk factors including heart disease, obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus,11 it will be important to have long-term safety information for JAK inhibitors in the psoriasis and PsA population.

Dermatologists are in a pivotal position to identify patients affected by PsA and start an appropriate systemic medication. We can help make an enormous impact on our patients’ lives as well as help decrease the economic impact of untreated disease. Let’s join the effort to save the joints!

Nearly all dermatologists are aware that psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is one of the most prevalent comorbidities associated with psoriasis, yet we may lack the insight regarding how to utilize this information. After all, we specialize in the skin, not the joints, right?

When I graduated from residency in 2014, I began staffing our psoriasis clinic, where we care for the toughest, most complicated psoriasis patients, many of them struggling with both severe recalcitrant psoriasis as well as debilitating PsA. In 2016, we partnered with rheumatology to open a multidisciplinary psoriasis and PsA clinic, and I quickly began to appreciate how much PsA was being overlooked simply because patients with psoriasis were not being asked about their joints.

To start, let’s look at several facts:

- One quarter of patients with psoriasis also have PsA.1

- Skin disease most commonly develops before PsA.1

- Fifteen percent of PsA cases go undiagnosed, which dramatically increases the risk for deformed joints, erosions, osteolysis, sacroiliitis, and arthritis mutilans2 and also increases the cost of health care.3

- Everyone is crazy busy—rheumatology wait lists often are months long.

Given that dermatologists are the ones who already are seeing the majority of patients who develop PsA, we play a key role in screening for this debilitating comorbidity and starting therapy for patients with both psoriasis and PsA. We, too, are crazy busy; therefore, we need to make this process quick and efficient but also reliable. Fortunately, the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) is effective, fast, and very easy. With only 5 questions and a sensitivity and specificity of around 70%,4 this short and simple questionnaire can be incorporated into an intake form or rooming note or can just be asked during the visit. The questions include whether the patient currently has or has had a swollen joint, nail pits, heel pain, and/or dactylitis, as well as if they have been told by a physician that they have arthritis. A score of 3 or higher is considered positive and a referral to rheumatology should be considered. At the bare minimum, I highly encourage all dermatologists to incorporate the PEST screening tool into their practice.

During the physical examination itself, be sure to look at the patient’s nails and also look for joint swelling and redness, especially in the hands. When palpating a swollen joint, the presence of inflammatory arthritis will feel spongy or boggy, while the osteophytes associated with osteoarthritis will feel hard. Radiography of the affected joint may be helpful, but keep in mind that bone changes are latter sequelae of PsA, and negative radiographs do not rule out PsA.

If you highly suspect PsA after using the PEST screening tool and palpating any swollen joints, then a rheumatology referral certainly is warranted. Medication that covers both psoriasis and PsA also can be initiated. Although methotrexate often is used for joints, higher doses (ie, >15 mg/wk) usually are needed. A 2019 Cochrane review found that low-dose methotrexate (ie, ≤15 mg/wk) may be only slightly more effective then placebo5—certainly not a ringing endorsement for its use in PsA. Additionally, quality data demonstrating methotrexate’s efficacy for enthesitis or axial spondyloarthritis is lacking, and methotrexate has not demonstrated an ability to slow the radiographic progression of joints. In contrast, the anti–tumor necrosis factor agents, including adalimumab, infliximab, etanercept, and certolizumab, as well as ustekinumab and the anti–IL-17 biologics secukinumab and ixekizumab have demonstrated efficacy in American College of Rheumatology (ACR) scores, enthesitis, dactylitis, and prevention of radiographic progression of joints.6,7 Although brodalumab, an anti–IL-17 receptor inhibitor, demonstrated improvement in ACR scores, enthesitis, and dactylitis, data on its effects on radiographic progression of joints were inconclusive given the phase III trial’s premature ending due to suicidal ideation and behavior in participants.8 Several of the anti–IL-23 agents also may help PsA, with trials demonstrating improvements in ACR scores, enthesitis, and dactylitis; however, only guselkumab 100 mg every 4 weeks decreased radiographic progression of joints.9 Additionally, with the age of the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor upon us, there are several JAK/TYK2 inhibitors that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for psoriasis (deucravacitinib) as well as for PsA (tofacitinib, upadacitinib), and there are more JAK inhibitors in the pipeline. These medications are effective; however, I do encourage caution and careful consideration in selecting the appropriate patient, as data demonstrated an increased risk for major adverse cardiovascular events and cancer in older (>50 years) rheumatoid arthritis patients who had at least 1 cardiovascular risk factor and were treated with tofacitinib.10 Although several other trials have not demonstrated this increased risk, further data are needed to determine risk for both pan-JAK inhibitors as well as selective JAK inhibitors and TYK2 inhibitors. Additionally, given psoriasis already is closely linked with many cardiovascular risk factors including heart disease, obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus,11 it will be important to have long-term safety information for JAK inhibitors in the psoriasis and PsA population.

Dermatologists are in a pivotal position to identify patients affected by PsA and start an appropriate systemic medication. We can help make an enormous impact on our patients’ lives as well as help decrease the economic impact of untreated disease. Let’s join the effort to save the joints!

- Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen L, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:251-265.

- Villani A, Zouzaud M, Sevrain M, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:242-248.

- Iragorri N, Hazlewood G, Manns B, et al. Model to determine the cost-effectiveness of screening psoriasis patients for psoriatic arthritis. Arth Car Res. 2021;73:266-274.

- Karreman M, Weel A, Van der Ven M, et al. Performance of screening tools for psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional study in primary care. Rheumatology. 2017;56:597-602.

- Wilsdon TD, Whittle SL, Thynne TR, et al. Methotrexate for psoriatic arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:CD012722. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012722.pub2

- Mourad A, Gniadecki R. Treatment of dactylitis and enthesitis in psoriatic arthritis with biologic agents: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheum. 2020;47:59-65.

- Wu D, Li C, Zhang S, et al. Effect of biologics on radiographic progression of peripheral joint in patients with psoriatic arthritis: meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59:3172-3180.

- Mease P, Helliwell P, Fjellhaugen Hjuler K, et al. Brodalumab in psoriatic arthritis: results from the randomised phase III AMVISION-1 and AMVISION-2 trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:185-193.

- McInnes I, Rahman P, Gottlieb A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of guselkumab, a monoclonal antibody specific to the p19 subunit of interleukin-23, through two years: results from a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted in biologic-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis. Arth Rheum. 2022;74:475-485.

- Ytterberg S, Bhatt D, Mikuls T, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:316-326.

- Miller I, Ellervik C, Yazdanyar S, et al. Meta-analysis of psoriasis, cardiovascular disease, and associated risk factors. JAAD. 2013;69:1014-1024.

- Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen L, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:251-265.

- Villani A, Zouzaud M, Sevrain M, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:242-248.

- Iragorri N, Hazlewood G, Manns B, et al. Model to determine the cost-effectiveness of screening psoriasis patients for psoriatic arthritis. Arth Car Res. 2021;73:266-274.

- Karreman M, Weel A, Van der Ven M, et al. Performance of screening tools for psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional study in primary care. Rheumatology. 2017;56:597-602.

- Wilsdon TD, Whittle SL, Thynne TR, et al. Methotrexate for psoriatic arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:CD012722. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012722.pub2

- Mourad A, Gniadecki R. Treatment of dactylitis and enthesitis in psoriatic arthritis with biologic agents: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheum. 2020;47:59-65.

- Wu D, Li C, Zhang S, et al. Effect of biologics on radiographic progression of peripheral joint in patients with psoriatic arthritis: meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59:3172-3180.

- Mease P, Helliwell P, Fjellhaugen Hjuler K, et al. Brodalumab in psoriatic arthritis: results from the randomised phase III AMVISION-1 and AMVISION-2 trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:185-193.

- McInnes I, Rahman P, Gottlieb A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of guselkumab, a monoclonal antibody specific to the p19 subunit of interleukin-23, through two years: results from a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted in biologic-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis. Arth Rheum. 2022;74:475-485.

- Ytterberg S, Bhatt D, Mikuls T, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:316-326.

- Miller I, Ellervik C, Yazdanyar S, et al. Meta-analysis of psoriasis, cardiovascular disease, and associated risk factors. JAAD. 2013;69:1014-1024.

Interacting With Dermatology Patients Online: Private Practice vs Academic Institute Website Content

Patients are finding it easier to use online resources to discover health care providers who fit their personalized needs. In the United States, approximately 70% of individuals use the internet to find health care information, and 80% are influenced by the information presented to them on health care websites.1 Patients utilize the internet to better understand treatments offered by providers and their prices as well as how other patients have rated their experience. Providers in private practice also have noticed that many patients are referring themselves vs obtaining a referral from another provider.2 As a result, it is critical for practice websites to have information that is of value to their patients, including the unique qualities and treatments offered. The purpose of this study was to analyze the differences between the content presented on dermatology private practice websites and academic institutional websites.

Methods

Websites Searched —All 140 academic dermatology programs, including both allopathic and osteopathic programs, were queried from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) database in March 2022. 3 First, the dermatology departmental websites for each program were analyzed to see if they contained information pertinent to patients. Any website that lacked this information or only had information relevant to the dermatology residency program was excluded from the study. After exclusion, a total of 113 websites were used in the academic website cohort. The private practices were found through an incognito Google search with the search term dermatologist and matched to be within 5 miles of each academic institution. The private practices that included at least one board-certified dermatologist and received the highest number of reviews on Google compared to other practices in the same region—a measure of online reputation—were selected to be in the private practice cohort (N = 113). Any duplicate practices, practices belonging to the same conglomerate company, or multispecialty clinics were excluded from the study. Board-certified dermatologists were confirmed using the Find a Dermatologist tool on the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) website. 4

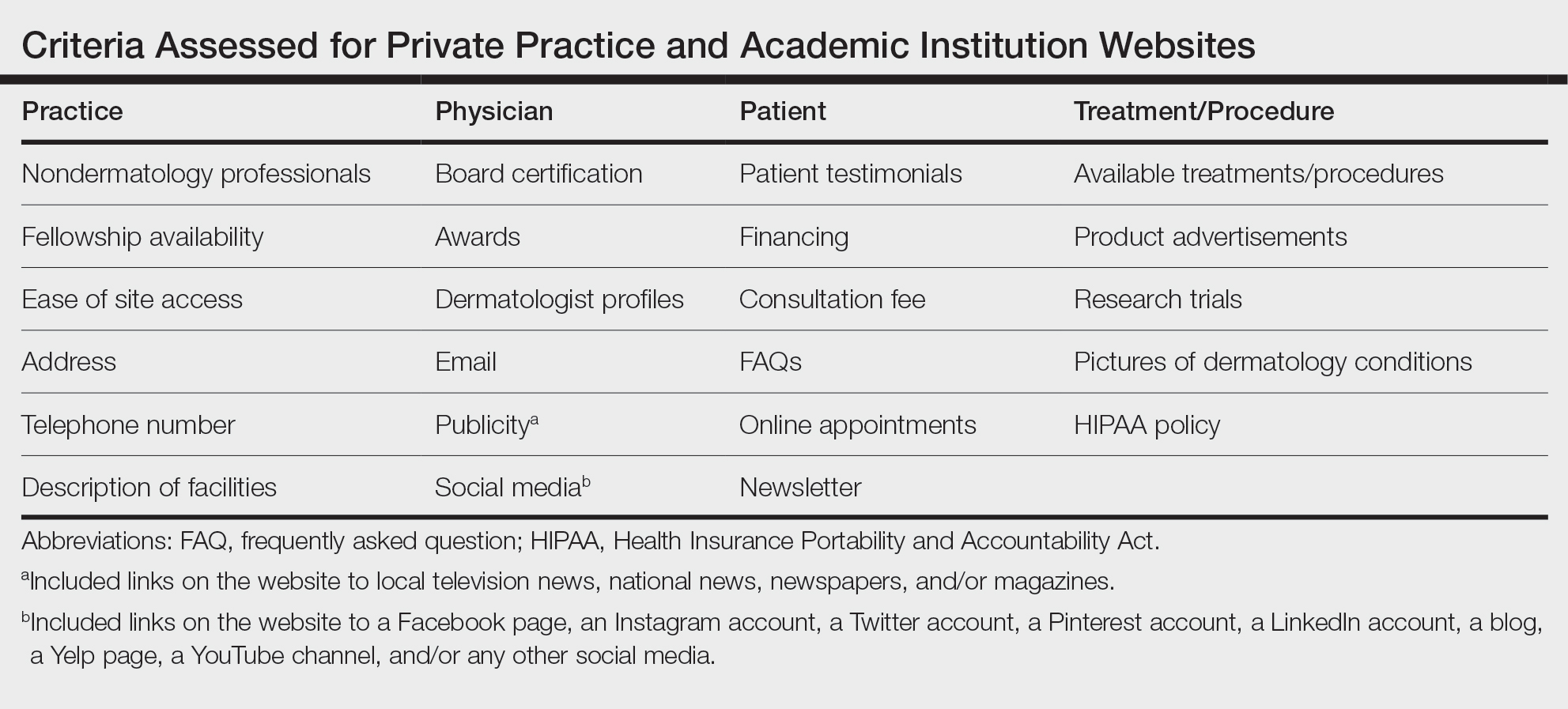

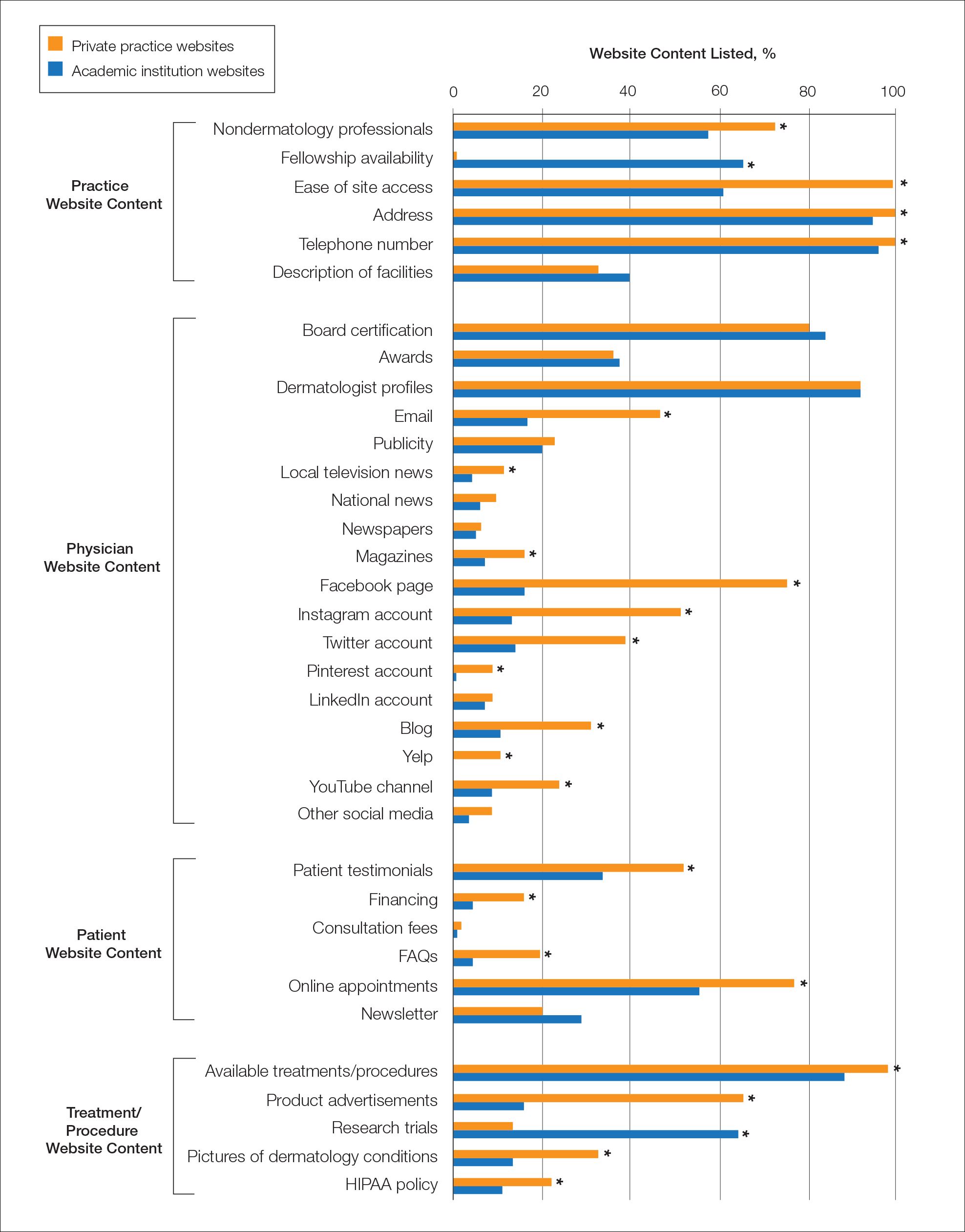

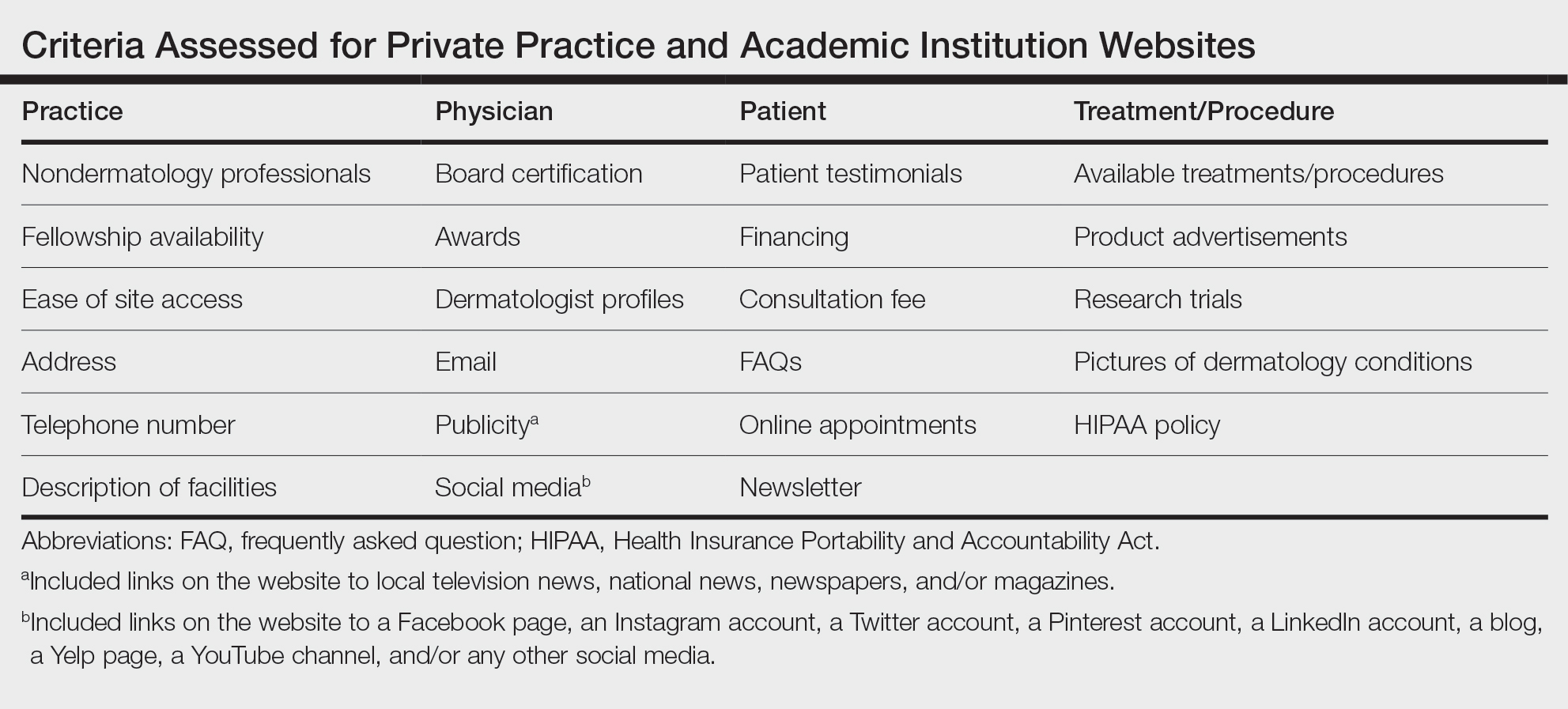

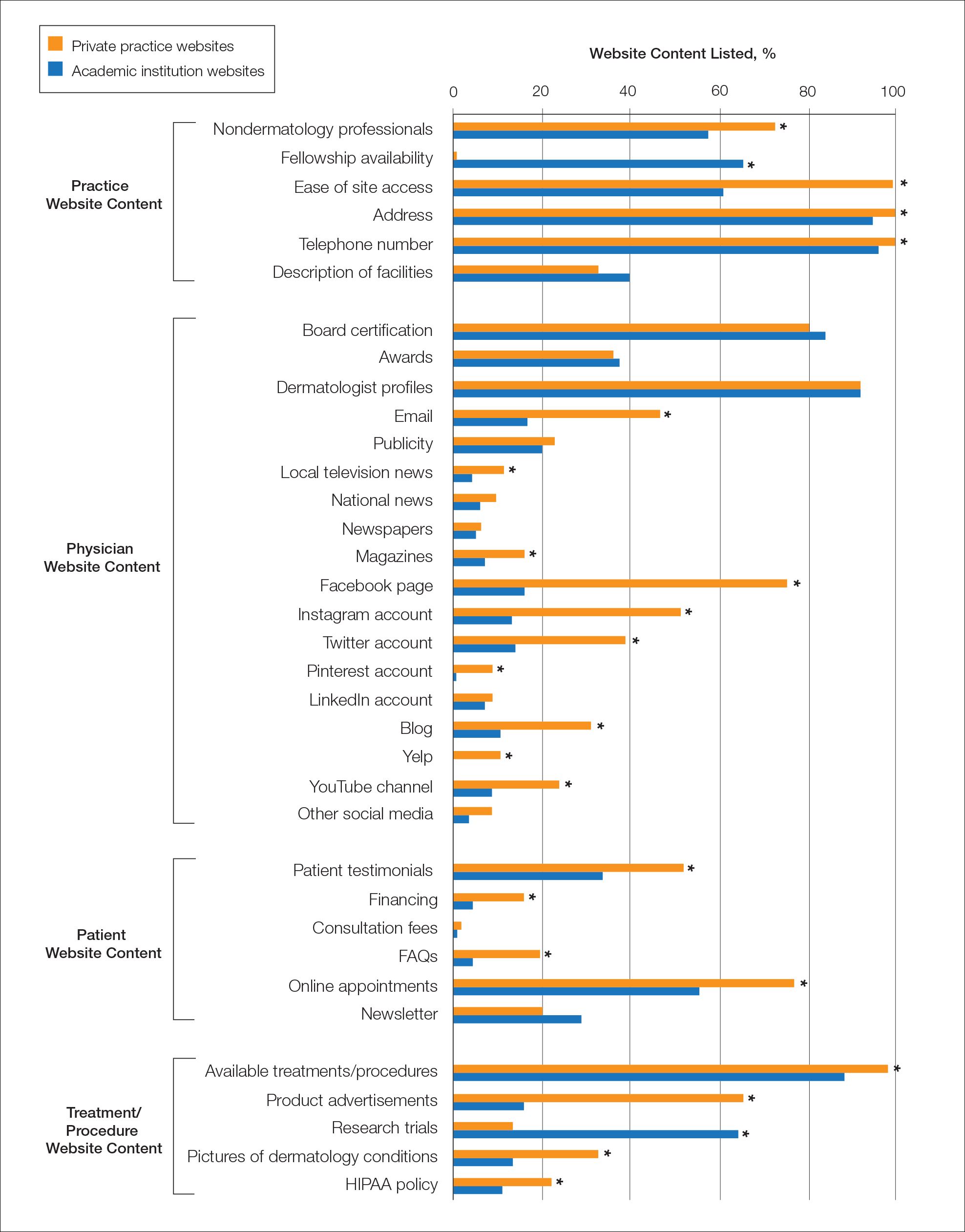

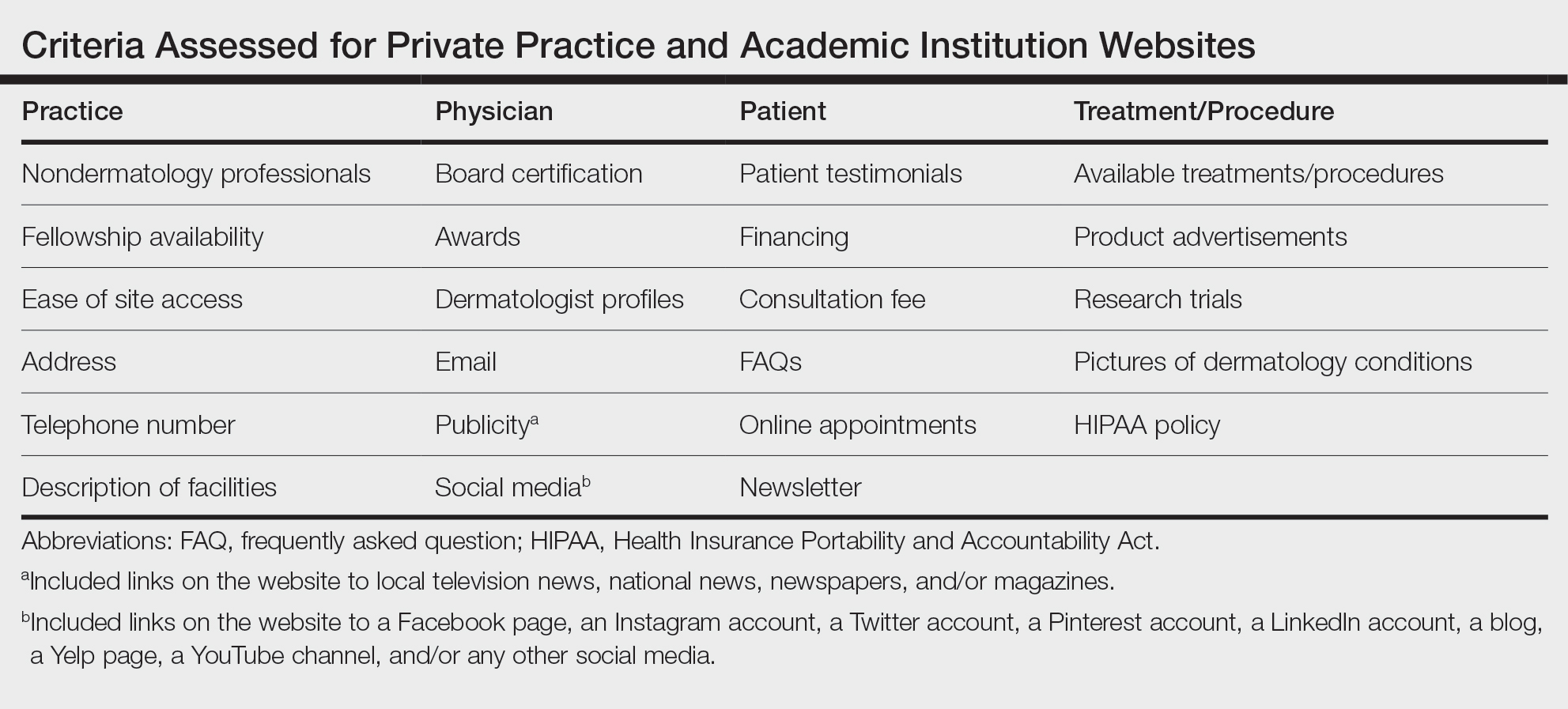

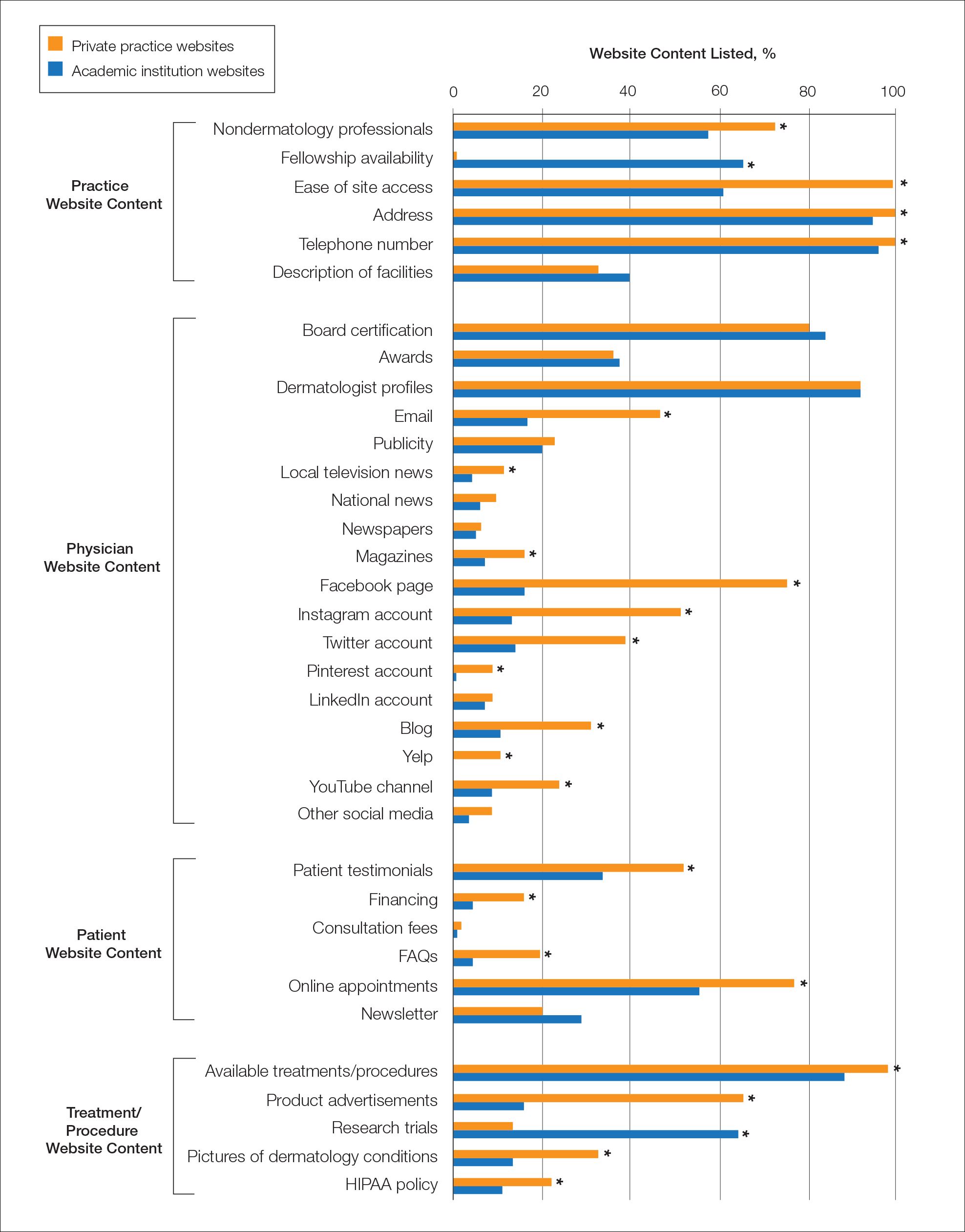

Website Assessments —Each website was assessed using 23 criteria divided into 4 categories: practice, physician(s), patient, and treatment/procedure (Table). Criteria for social media and publicity were further assessed. Criteria for social media included links on the website to a Facebook page, an Instagram account, a Twitter account, a Pinterest account, a LinkedIn account, a blog, a Yelp page, a YouTube channel, and/or any other social media. Criteria for publicity included links on the website to local television news, national news, newspapers, and/or magazines. 5-8 Ease of site access was determined if the website was the first search result found on Google when searching for each website. Nondermatology professionals included listing of mid-level providers or researchers.

Four individuals (V.S.J., A.C.B., M.E.O., and M.B.B.) independently assessed each of the websites using the established criteria. Each criterion was defined and discussed prior to data collection to maintain consistency. The criteria were determined as being present if the website clearly displayed, stated, explained, or linked to the relevant content. If the website did not directly contain the content, it was determined that the criteria were absent. One other individual (J.P.) independently cross-examined the data for consistency and evaluated for any discrepancies. 8

A raw analysis was done between each cohort. Another analysis was done that controlled for population density and the proportionate population age in each city 9 in which an academic institution/private practice was located. We proposed that more densely populated cities naturally may have more competition between practices, which may result in more optimized websites. 10 We also anticipated similar findings in cities with younger populations, as the younger demographic may be more likely to utilize and value online information when compared to older populations. 11 The websites for each cohort were equally divided into 3 tiers of population density (not shown) and population age (not shown).

Statistical Analysis —Statistical analysis was completed using descriptive statistics, χ 2 testing, and Fisher exact tests where appropriate with a predetermined level of significance of P < .05 in Microsoft Excel.

Results

Demographics —A total of 226 websites from both private practices and academic institutions were evaluated. Of them, only 108 private practices and 108 academic institutions listed practicing dermatologists on their site. Of 108 private practices, 76 (70.4%) had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist. Of 108 academic institutions, all 108 (100%) institutions had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist.

Of the dermatologists who practiced at academic institutions (n=2014) and private practices (n=817), 1157 (57.4%) and 419 (51.2%) were females, respectively. The population density of the cities with each of these practices/institutions ranged from 137 individuals per square kilometer to 11,232 individuals per square kilometer (mean [SD] population density, 2579 [2485] individuals per square kilometer). Densely populated, moderately populated, and sparsely populated cities had a median population density of 4618, 1708, and 760 individuals per square kilometer, respectively. The data also were divided into 3 age groups. In the older population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 14.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 63.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 14.9%. In the moderately aged population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 10.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 70.3%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 13.6%. In the younger population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 12%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 66.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 15%.

Practice and Physician Content—In the raw analysis (Figure), the most commonly listed types of content (>90% of websites) in both private practice and academic sites was address (range, 95% to 100%), telephone number (range, 97% to 100%), and dermatologist profiles (both 92%). The least commonly listed types of content in both cohorts was publicity (range, 20% to 23%). Private practices were more likely to list profiles of nondermatology professionals (73% vs 56%; P<.02), email (47% vs 17%; P<.0001), and social media (29% vs 8%; P<.0001) compared with academic institution websites. Although Facebook was the most-linked social media account for both groups, 75% of private practice sites included the link compared with 16% of academic institutions. Academic institutions were more likely to list fellowship availability (66% vs 1%; P<.0001). Accessing each website was significantly easier in the private practice cohort (99% vs 61%; P<.0001).

When controlling for population density, private practices were only more likely to list nondermatology professionals’ profiles in densely populated cities when compared with academic institutions (73% vs 41%; P<.01). Academic institutions continued to list fellowship availability more often than private practices regardless of population density. The same trend was observed for private practices with ease of site access and listing of social media.

When controlling for population age, similar trends were seen as when controlling for population density. However, private practices listing nondermatology professionals’ profiles was only more likely in the cities with a proportionately younger population when compared with academic institutions (74% vs 47%; P<.04).

Patient and Treatment/Procedure—The most commonly listed content types on both private practice websites and academic institution websites were available treatments/procedures (range, 89% to 98%). The least commonly listed content included financing for elective procedures (range, 4% to 16%), consultation fees (range, 1% to 2%), FAQs (frequently asked questions)(range, 4% to 20%), and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) policy (range, 12% to 22%). Private practices were more likely to list patient testimonials (52% vs 35%; P<.005), financing (16% vs 4%; P<.005), FAQs (20% vs 4%; P<.001), online appointments (77% vs 56%; P<.001), available treatments/procedures (98% vs 86%; P<.004), product advertisements (66% vs 16%; P<.0001), pictures of dermatology conditions (33% vs 13%; P<.001), and HIPAA policy (22% vs 12%; P<.04). Academic institutions were more likely to list research trials (65% vs 13%; P<.0001).

When controlling for population density, private practices were only more likely to list patient testimonials in densely populated (P=.035) and moderately populated cities (P=.019). The same trend was observed for online appointments in densely populated (P=.0023) and moderately populated cities (P=.037). Private practices continued to list product availability more often than academic institutions regardless of population density or population age. Academic institutions also continued to list research trials more often than private practices regardless of population density or population age.

Comment

Our study uniquely analyzed the differences in website content between private practices and academic institutions in dermatology. Of the 140 academic institutions accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), only 113 had patient-pertinent websites.

Access to Websites —There was a significant difference in many website content criteria between the 2 groups. Private practice sites were easier to access via a Google search when compared with academic sites, which likely is influenced by the Google search algorithm that ranks websites higher based on several criteria including but not limited to keyword use in the title tag, link popularity of the site, and historic ranking. 12,13 Academic sites often were only accessible through portals found on their main institutional site or institution’s residency site.

Role of Social Media —Social media has been found to assist in educating patients on medical practices as well as selecting a physician. 14,15 Our study found that private practice websites listed links to social media more often than their academic counterparts. Social media consumption is increasing, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and it may be optimal for patients and practices alike to include links on their websites. 16 Facebook and Instagram were listed more often on private practice sites when compared with academic institution sites, which was similar to a recent study analyzing the websites of plastic surgery private practices (N = 310) in which 90% of private practices included some type of social media, with Instagram and Facebook being the most used. 8 Social networking accounts can act as convenient platforms for marketing, providing patient education, and generating referrals, which suggests that the prominence of their usage in private practice poses benefits in patient decision-making when seeking care. 17-19 A study analyzing the impact of Facebook in medicine concluded that a Facebook page can serve as an effective vehicle for medical education, particularly in younger generations that favor technology-oriented teaching methods. 20 A survey on trends in cosmetic facial procedures in plastic surgery found that the most influential online methods patients used for choosing their providers were social media platforms and practice websites. Front-page placement on Google also was commonly associated with the number of social media followers. 21,22 A lack of social media prominence could hinder a website’s potential to reach patients.

Communication With Practices —Our study also found significant differences in other metrics related to a patient’s ability to directly communicate with a practice, such as physical addresses, telephone numbers, products available for direct purchase, and online appointment booking, all of which were listed more often on private practice websites compared with academic institution websites. Online appointment booking also was found more frequently on private practice websites. Although physical addresses and telephone numbers were listed significantly more often on private practice sites, this information was ubiquitous and easily accessible elsewhere. Academic institution websites listed research trials and fellowship training significantly more often than private practices. These differences imply a divergence in focus between private practices and academic institutions, likely because academic institutions are funded in large part from research grants, begetting a cycle of academic contribution. 23 In contrast, private practices may not rely as heavily on academic revenue and may be more likely to prioritize other revenue streams such as product sales. 24

HIPAA Policy —Surprisingly, HIPAA policy rarely was listed on any private (22%) or academic site (12%). Conversely, in the plastic surgery study, HIPAA policy was listed much more often, with more than half of private practices with board-certified plastic surgeons accredited in the year 2015 including it on their website, 8 which may suggest that surgically oriented specialties, particularly cosmetic subspecialties, aim to more noticeably display their privacy policies for patient reassurance.

Study Limitations —There are several limitations of our study. First, it is common for a conglomerate company to own multiple private practices in different specialties. As with academic sites, private practice sites may be limited by the hosting platforms, which often are tedious to navigate. Also noteworthy is the emergence of designated social media management positions—both by practice employees and by third-party firms 25 —but the impact of these positions in private practices and academic institutions has not been fully explored. Finally, inclusion criteria and standardized criteria definitions were chosen based on the precedent established by the authors of similar analyses in plastic surgery and radiology. 5-8 Further investigation into the most valued aspects of care by patients within the context of the type of practice chosen would be valuable in refining inclusion criteria. Additionally, this study did not stratify the data collected based on factors such as gender, race, and geographical location; studies conducted on website traffic analysis patterns that focus on these aspects likely would further explain the significance of these findings. Differences in the length of time to the next available appointment between private practices and academic institutions also may help support our findings. Finally, there is a need for further investigation into the preferences of patients themselves garnered from website traffic alone.

Conclusion

Our study examined a diverse compilation of private practice and academic institution websites and uncovered numerous differences in content. As technology and health care continuously evolve, it is imperative that both private practices and academic institutions are actively adapting to optimize their online presence. In doing so, patients will be better equipped at accessing provider information, gaining familiarity with the practice, and understanding treatment options.

- Gentry ZL, Ananthasekar S, Yeatts M, et al. Can patients find an endocrine surgeon? how hospital websites hide the expertise of these medical professionals. Am J Surg . 2021;221:101-105.

- Pollack CE, Rastegar A, Keating NL, et al. Is self-referral associated with higher quality care? Health Serv Res . 2015;50:1472-1490.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Residency Explorer TM tool. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/apply-smart-residency/residency-explorer-tool

- Find a dermatologist. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://find-a-derm.aad.org/

- Johnson EJ, Doshi AM, Rosenkrantz AB. Strengths and deficiencies in the content of US radiology private practices’ websites. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:431-435.

- Brunk D. Medical website expert shares design tips. Dermatology News . February 9, 2012. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/article/47413/health-policy/medical-website-expert-shares-design-tips

- Kuhnigk O, Ramuschkat M, Schreiner J, et al. Internet presence of neurologists, psychiatrists and medical psychotherapists in private practice [in German]. Psychiatr Prax . 2013;41:142-147.

- Ananthasekar S, Patel JJ, Patel NJ, et al. The content of US plastic surgery private practices’ websites. Ann Plast Surg . 2021;86(6S suppl 5):S578-S584.

- US Census Bureau. Age and Sex: 2021. Updated December 2, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2023. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/age-and-sex/data/tables.2021.List_897222059.html#list-tab-List_897222059

- Porter ME. The competitive advantage of the inner city. Harvard Business Review . Published August 1, 2014. https://hbr.org/1995/05/the-competitive-advantage-of-the-inner-city

- Clark PG. The social allocation of health care resources: ethical dilemmas in age-group competition. Gerontologist. 1985;25:119-125.

- Su A-J, Hu YC, Kuzmanovic A, et al. How to improve your Google ranking: myths and reality. ACM Transactions on the Web . 2014;8. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/2579990

- McCormick K. 39 ways to increase traffic to your website. WordStream website. Published March 28, 2023. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.wordstream.com/blog/ws/2014/08/14/increase-traffic-to-my-website

- Montemurro P, Porcnik A, Hedén P, et al. The influence of social media and easily accessible online information on the aesthetic plastic surgery practice: literature review and our own experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg . 2015;39:270-277.

- Steehler KR, Steehler MK, Pierce ML, et al. Social media’s role in otolaryngology–head and neck surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg . 2013;149:521-524.

- Tsao S-F, Chen H, Tisseverasinghe T, et al. What social media told us in the time of COVID-19: a scoping review. Lancet Digit Health . 2021;3:E175-E194.

- Geist R, Militello M, Albrecht JM, et al. Social media and clinical research in dermatology. Curr Dermatol Rep . 2021;10:105-111.

- McLawhorn AS, De Martino I, Fehring KA, et al. Social media and your practice: navigating the surgeon-patient relationship. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med . 2016;9:487-495.

- Thomas RB, Johnson PT, Fishman EK. Social media for global education: pearls and pitfalls of using Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. J Am Coll Radiol . 2018;15:1513-1516.

- Lugo-Fagundo C, Johnson MB, Thomas RB, et al. New frontiers in education: Facebook as a vehicle for medical information delivery. J Am Coll Radiol . 2016;13:316-319.

- Ho T-VT, Dayan SH. How to leverage social media in private practice. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am . 2020;28:515-522.

- Fan KL, Graziano F, Economides JM, et al. The public’s preferences on plastic surgery social media engagement and professionalism. Plast Reconstr Surg . 2019;143:619-630.

- Jacob BA, Lefgren L. The impact of research grant funding on scientific productivity. J Public Econ. 2011;95:1168-1177.

- Baumann L. Ethics in cosmetic dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:522-527.

- Miller AR, Tucker C. Active social media management: the case of health care. Info Sys Res . 2013;24:52-70.

Patients are finding it easier to use online resources to discover health care providers who fit their personalized needs. In the United States, approximately 70% of individuals use the internet to find health care information, and 80% are influenced by the information presented to them on health care websites.1 Patients utilize the internet to better understand treatments offered by providers and their prices as well as how other patients have rated their experience. Providers in private practice also have noticed that many patients are referring themselves vs obtaining a referral from another provider.2 As a result, it is critical for practice websites to have information that is of value to their patients, including the unique qualities and treatments offered. The purpose of this study was to analyze the differences between the content presented on dermatology private practice websites and academic institutional websites.

Methods

Websites Searched —All 140 academic dermatology programs, including both allopathic and osteopathic programs, were queried from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) database in March 2022. 3 First, the dermatology departmental websites for each program were analyzed to see if they contained information pertinent to patients. Any website that lacked this information or only had information relevant to the dermatology residency program was excluded from the study. After exclusion, a total of 113 websites were used in the academic website cohort. The private practices were found through an incognito Google search with the search term dermatologist and matched to be within 5 miles of each academic institution. The private practices that included at least one board-certified dermatologist and received the highest number of reviews on Google compared to other practices in the same region—a measure of online reputation—were selected to be in the private practice cohort (N = 113). Any duplicate practices, practices belonging to the same conglomerate company, or multispecialty clinics were excluded from the study. Board-certified dermatologists were confirmed using the Find a Dermatologist tool on the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) website. 4

Website Assessments —Each website was assessed using 23 criteria divided into 4 categories: practice, physician(s), patient, and treatment/procedure (Table). Criteria for social media and publicity were further assessed. Criteria for social media included links on the website to a Facebook page, an Instagram account, a Twitter account, a Pinterest account, a LinkedIn account, a blog, a Yelp page, a YouTube channel, and/or any other social media. Criteria for publicity included links on the website to local television news, national news, newspapers, and/or magazines. 5-8 Ease of site access was determined if the website was the first search result found on Google when searching for each website. Nondermatology professionals included listing of mid-level providers or researchers.

Four individuals (V.S.J., A.C.B., M.E.O., and M.B.B.) independently assessed each of the websites using the established criteria. Each criterion was defined and discussed prior to data collection to maintain consistency. The criteria were determined as being present if the website clearly displayed, stated, explained, or linked to the relevant content. If the website did not directly contain the content, it was determined that the criteria were absent. One other individual (J.P.) independently cross-examined the data for consistency and evaluated for any discrepancies. 8

A raw analysis was done between each cohort. Another analysis was done that controlled for population density and the proportionate population age in each city 9 in which an academic institution/private practice was located. We proposed that more densely populated cities naturally may have more competition between practices, which may result in more optimized websites. 10 We also anticipated similar findings in cities with younger populations, as the younger demographic may be more likely to utilize and value online information when compared to older populations. 11 The websites for each cohort were equally divided into 3 tiers of population density (not shown) and population age (not shown).

Statistical Analysis —Statistical analysis was completed using descriptive statistics, χ 2 testing, and Fisher exact tests where appropriate with a predetermined level of significance of P < .05 in Microsoft Excel.

Results

Demographics —A total of 226 websites from both private practices and academic institutions were evaluated. Of them, only 108 private practices and 108 academic institutions listed practicing dermatologists on their site. Of 108 private practices, 76 (70.4%) had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist. Of 108 academic institutions, all 108 (100%) institutions had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist.

Of the dermatologists who practiced at academic institutions (n=2014) and private practices (n=817), 1157 (57.4%) and 419 (51.2%) were females, respectively. The population density of the cities with each of these practices/institutions ranged from 137 individuals per square kilometer to 11,232 individuals per square kilometer (mean [SD] population density, 2579 [2485] individuals per square kilometer). Densely populated, moderately populated, and sparsely populated cities had a median population density of 4618, 1708, and 760 individuals per square kilometer, respectively. The data also were divided into 3 age groups. In the older population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 14.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 63.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 14.9%. In the moderately aged population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 10.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 70.3%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 13.6%. In the younger population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 12%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 66.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 15%.

Practice and Physician Content—In the raw analysis (Figure), the most commonly listed types of content (>90% of websites) in both private practice and academic sites was address (range, 95% to 100%), telephone number (range, 97% to 100%), and dermatologist profiles (both 92%). The least commonly listed types of content in both cohorts was publicity (range, 20% to 23%). Private practices were more likely to list profiles of nondermatology professionals (73% vs 56%; P<.02), email (47% vs 17%; P<.0001), and social media (29% vs 8%; P<.0001) compared with academic institution websites. Although Facebook was the most-linked social media account for both groups, 75% of private practice sites included the link compared with 16% of academic institutions. Academic institutions were more likely to list fellowship availability (66% vs 1%; P<.0001). Accessing each website was significantly easier in the private practice cohort (99% vs 61%; P<.0001).

When controlling for population density, private practices were only more likely to list nondermatology professionals’ profiles in densely populated cities when compared with academic institutions (73% vs 41%; P<.01). Academic institutions continued to list fellowship availability more often than private practices regardless of population density. The same trend was observed for private practices with ease of site access and listing of social media.

When controlling for population age, similar trends were seen as when controlling for population density. However, private practices listing nondermatology professionals’ profiles was only more likely in the cities with a proportionately younger population when compared with academic institutions (74% vs 47%; P<.04).

Patient and Treatment/Procedure—The most commonly listed content types on both private practice websites and academic institution websites were available treatments/procedures (range, 89% to 98%). The least commonly listed content included financing for elective procedures (range, 4% to 16%), consultation fees (range, 1% to 2%), FAQs (frequently asked questions)(range, 4% to 20%), and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) policy (range, 12% to 22%). Private practices were more likely to list patient testimonials (52% vs 35%; P<.005), financing (16% vs 4%; P<.005), FAQs (20% vs 4%; P<.001), online appointments (77% vs 56%; P<.001), available treatments/procedures (98% vs 86%; P<.004), product advertisements (66% vs 16%; P<.0001), pictures of dermatology conditions (33% vs 13%; P<.001), and HIPAA policy (22% vs 12%; P<.04). Academic institutions were more likely to list research trials (65% vs 13%; P<.0001).

When controlling for population density, private practices were only more likely to list patient testimonials in densely populated (P=.035) and moderately populated cities (P=.019). The same trend was observed for online appointments in densely populated (P=.0023) and moderately populated cities (P=.037). Private practices continued to list product availability more often than academic institutions regardless of population density or population age. Academic institutions also continued to list research trials more often than private practices regardless of population density or population age.

Comment

Our study uniquely analyzed the differences in website content between private practices and academic institutions in dermatology. Of the 140 academic institutions accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), only 113 had patient-pertinent websites.

Access to Websites —There was a significant difference in many website content criteria between the 2 groups. Private practice sites were easier to access via a Google search when compared with academic sites, which likely is influenced by the Google search algorithm that ranks websites higher based on several criteria including but not limited to keyword use in the title tag, link popularity of the site, and historic ranking. 12,13 Academic sites often were only accessible through portals found on their main institutional site or institution’s residency site.

Role of Social Media —Social media has been found to assist in educating patients on medical practices as well as selecting a physician. 14,15 Our study found that private practice websites listed links to social media more often than their academic counterparts. Social media consumption is increasing, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and it may be optimal for patients and practices alike to include links on their websites. 16 Facebook and Instagram were listed more often on private practice sites when compared with academic institution sites, which was similar to a recent study analyzing the websites of plastic surgery private practices (N = 310) in which 90% of private practices included some type of social media, with Instagram and Facebook being the most used. 8 Social networking accounts can act as convenient platforms for marketing, providing patient education, and generating referrals, which suggests that the prominence of their usage in private practice poses benefits in patient decision-making when seeking care. 17-19 A study analyzing the impact of Facebook in medicine concluded that a Facebook page can serve as an effective vehicle for medical education, particularly in younger generations that favor technology-oriented teaching methods. 20 A survey on trends in cosmetic facial procedures in plastic surgery found that the most influential online methods patients used for choosing their providers were social media platforms and practice websites. Front-page placement on Google also was commonly associated with the number of social media followers. 21,22 A lack of social media prominence could hinder a website’s potential to reach patients.

Communication With Practices —Our study also found significant differences in other metrics related to a patient’s ability to directly communicate with a practice, such as physical addresses, telephone numbers, products available for direct purchase, and online appointment booking, all of which were listed more often on private practice websites compared with academic institution websites. Online appointment booking also was found more frequently on private practice websites. Although physical addresses and telephone numbers were listed significantly more often on private practice sites, this information was ubiquitous and easily accessible elsewhere. Academic institution websites listed research trials and fellowship training significantly more often than private practices. These differences imply a divergence in focus between private practices and academic institutions, likely because academic institutions are funded in large part from research grants, begetting a cycle of academic contribution. 23 In contrast, private practices may not rely as heavily on academic revenue and may be more likely to prioritize other revenue streams such as product sales. 24

HIPAA Policy —Surprisingly, HIPAA policy rarely was listed on any private (22%) or academic site (12%). Conversely, in the plastic surgery study, HIPAA policy was listed much more often, with more than half of private practices with board-certified plastic surgeons accredited in the year 2015 including it on their website, 8 which may suggest that surgically oriented specialties, particularly cosmetic subspecialties, aim to more noticeably display their privacy policies for patient reassurance.

Study Limitations —There are several limitations of our study. First, it is common for a conglomerate company to own multiple private practices in different specialties. As with academic sites, private practice sites may be limited by the hosting platforms, which often are tedious to navigate. Also noteworthy is the emergence of designated social media management positions—both by practice employees and by third-party firms 25 —but the impact of these positions in private practices and academic institutions has not been fully explored. Finally, inclusion criteria and standardized criteria definitions were chosen based on the precedent established by the authors of similar analyses in plastic surgery and radiology. 5-8 Further investigation into the most valued aspects of care by patients within the context of the type of practice chosen would be valuable in refining inclusion criteria. Additionally, this study did not stratify the data collected based on factors such as gender, race, and geographical location; studies conducted on website traffic analysis patterns that focus on these aspects likely would further explain the significance of these findings. Differences in the length of time to the next available appointment between private practices and academic institutions also may help support our findings. Finally, there is a need for further investigation into the preferences of patients themselves garnered from website traffic alone.

Conclusion

Our study examined a diverse compilation of private practice and academic institution websites and uncovered numerous differences in content. As technology and health care continuously evolve, it is imperative that both private practices and academic institutions are actively adapting to optimize their online presence. In doing so, patients will be better equipped at accessing provider information, gaining familiarity with the practice, and understanding treatment options.

Patients are finding it easier to use online resources to discover health care providers who fit their personalized needs. In the United States, approximately 70% of individuals use the internet to find health care information, and 80% are influenced by the information presented to them on health care websites.1 Patients utilize the internet to better understand treatments offered by providers and their prices as well as how other patients have rated their experience. Providers in private practice also have noticed that many patients are referring themselves vs obtaining a referral from another provider.2 As a result, it is critical for practice websites to have information that is of value to their patients, including the unique qualities and treatments offered. The purpose of this study was to analyze the differences between the content presented on dermatology private practice websites and academic institutional websites.

Methods

Websites Searched —All 140 academic dermatology programs, including both allopathic and osteopathic programs, were queried from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) database in March 2022. 3 First, the dermatology departmental websites for each program were analyzed to see if they contained information pertinent to patients. Any website that lacked this information or only had information relevant to the dermatology residency program was excluded from the study. After exclusion, a total of 113 websites were used in the academic website cohort. The private practices were found through an incognito Google search with the search term dermatologist and matched to be within 5 miles of each academic institution. The private practices that included at least one board-certified dermatologist and received the highest number of reviews on Google compared to other practices in the same region—a measure of online reputation—were selected to be in the private practice cohort (N = 113). Any duplicate practices, practices belonging to the same conglomerate company, or multispecialty clinics were excluded from the study. Board-certified dermatologists were confirmed using the Find a Dermatologist tool on the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) website. 4

Website Assessments —Each website was assessed using 23 criteria divided into 4 categories: practice, physician(s), patient, and treatment/procedure (Table). Criteria for social media and publicity were further assessed. Criteria for social media included links on the website to a Facebook page, an Instagram account, a Twitter account, a Pinterest account, a LinkedIn account, a blog, a Yelp page, a YouTube channel, and/or any other social media. Criteria for publicity included links on the website to local television news, national news, newspapers, and/or magazines. 5-8 Ease of site access was determined if the website was the first search result found on Google when searching for each website. Nondermatology professionals included listing of mid-level providers or researchers.

Four individuals (V.S.J., A.C.B., M.E.O., and M.B.B.) independently assessed each of the websites using the established criteria. Each criterion was defined and discussed prior to data collection to maintain consistency. The criteria were determined as being present if the website clearly displayed, stated, explained, or linked to the relevant content. If the website did not directly contain the content, it was determined that the criteria were absent. One other individual (J.P.) independently cross-examined the data for consistency and evaluated for any discrepancies. 8

A raw analysis was done between each cohort. Another analysis was done that controlled for population density and the proportionate population age in each city 9 in which an academic institution/private practice was located. We proposed that more densely populated cities naturally may have more competition between practices, which may result in more optimized websites. 10 We also anticipated similar findings in cities with younger populations, as the younger demographic may be more likely to utilize and value online information when compared to older populations. 11 The websites for each cohort were equally divided into 3 tiers of population density (not shown) and population age (not shown).

Statistical Analysis —Statistical analysis was completed using descriptive statistics, χ 2 testing, and Fisher exact tests where appropriate with a predetermined level of significance of P < .05 in Microsoft Excel.

Results

Demographics —A total of 226 websites from both private practices and academic institutions were evaluated. Of them, only 108 private practices and 108 academic institutions listed practicing dermatologists on their site. Of 108 private practices, 76 (70.4%) had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist. Of 108 academic institutions, all 108 (100%) institutions had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist.

Of the dermatologists who practiced at academic institutions (n=2014) and private practices (n=817), 1157 (57.4%) and 419 (51.2%) were females, respectively. The population density of the cities with each of these practices/institutions ranged from 137 individuals per square kilometer to 11,232 individuals per square kilometer (mean [SD] population density, 2579 [2485] individuals per square kilometer). Densely populated, moderately populated, and sparsely populated cities had a median population density of 4618, 1708, and 760 individuals per square kilometer, respectively. The data also were divided into 3 age groups. In the older population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 14.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 63.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 14.9%. In the moderately aged population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 10.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 70.3%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 13.6%. In the younger population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 12%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 66.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 15%.

Practice and Physician Content—In the raw analysis (Figure), the most commonly listed types of content (>90% of websites) in both private practice and academic sites was address (range, 95% to 100%), telephone number (range, 97% to 100%), and dermatologist profiles (both 92%). The least commonly listed types of content in both cohorts was publicity (range, 20% to 23%). Private practices were more likely to list profiles of nondermatology professionals (73% vs 56%; P<.02), email (47% vs 17%; P<.0001), and social media (29% vs 8%; P<.0001) compared with academic institution websites. Although Facebook was the most-linked social media account for both groups, 75% of private practice sites included the link compared with 16% of academic institutions. Academic institutions were more likely to list fellowship availability (66% vs 1%; P<.0001). Accessing each website was significantly easier in the private practice cohort (99% vs 61%; P<.0001).

When controlling for population density, private practices were only more likely to list nondermatology professionals’ profiles in densely populated cities when compared with academic institutions (73% vs 41%; P<.01). Academic institutions continued to list fellowship availability more often than private practices regardless of population density. The same trend was observed for private practices with ease of site access and listing of social media.

When controlling for population age, similar trends were seen as when controlling for population density. However, private practices listing nondermatology professionals’ profiles was only more likely in the cities with a proportionately younger population when compared with academic institutions (74% vs 47%; P<.04).

Patient and Treatment/Procedure—The most commonly listed content types on both private practice websites and academic institution websites were available treatments/procedures (range, 89% to 98%). The least commonly listed content included financing for elective procedures (range, 4% to 16%), consultation fees (range, 1% to 2%), FAQs (frequently asked questions)(range, 4% to 20%), and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) policy (range, 12% to 22%). Private practices were more likely to list patient testimonials (52% vs 35%; P<.005), financing (16% vs 4%; P<.005), FAQs (20% vs 4%; P<.001), online appointments (77% vs 56%; P<.001), available treatments/procedures (98% vs 86%; P<.004), product advertisements (66% vs 16%; P<.0001), pictures of dermatology conditions (33% vs 13%; P<.001), and HIPAA policy (22% vs 12%; P<.04). Academic institutions were more likely to list research trials (65% vs 13%; P<.0001).

When controlling for population density, private practices were only more likely to list patient testimonials in densely populated (P=.035) and moderately populated cities (P=.019). The same trend was observed for online appointments in densely populated (P=.0023) and moderately populated cities (P=.037). Private practices continued to list product availability more often than academic institutions regardless of population density or population age. Academic institutions also continued to list research trials more often than private practices regardless of population density or population age.

Comment

Our study uniquely analyzed the differences in website content between private practices and academic institutions in dermatology. Of the 140 academic institutions accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), only 113 had patient-pertinent websites.

Access to Websites —There was a significant difference in many website content criteria between the 2 groups. Private practice sites were easier to access via a Google search when compared with academic sites, which likely is influenced by the Google search algorithm that ranks websites higher based on several criteria including but not limited to keyword use in the title tag, link popularity of the site, and historic ranking. 12,13 Academic sites often were only accessible through portals found on their main institutional site or institution’s residency site.

Role of Social Media —Social media has been found to assist in educating patients on medical practices as well as selecting a physician. 14,15 Our study found that private practice websites listed links to social media more often than their academic counterparts. Social media consumption is increasing, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and it may be optimal for patients and practices alike to include links on their websites. 16 Facebook and Instagram were listed more often on private practice sites when compared with academic institution sites, which was similar to a recent study analyzing the websites of plastic surgery private practices (N = 310) in which 90% of private practices included some type of social media, with Instagram and Facebook being the most used. 8 Social networking accounts can act as convenient platforms for marketing, providing patient education, and generating referrals, which suggests that the prominence of their usage in private practice poses benefits in patient decision-making when seeking care. 17-19 A study analyzing the impact of Facebook in medicine concluded that a Facebook page can serve as an effective vehicle for medical education, particularly in younger generations that favor technology-oriented teaching methods. 20 A survey on trends in cosmetic facial procedures in plastic surgery found that the most influential online methods patients used for choosing their providers were social media platforms and practice websites. Front-page placement on Google also was commonly associated with the number of social media followers. 21,22 A lack of social media prominence could hinder a website’s potential to reach patients.

Communication With Practices —Our study also found significant differences in other metrics related to a patient’s ability to directly communicate with a practice, such as physical addresses, telephone numbers, products available for direct purchase, and online appointment booking, all of which were listed more often on private practice websites compared with academic institution websites. Online appointment booking also was found more frequently on private practice websites. Although physical addresses and telephone numbers were listed significantly more often on private practice sites, this information was ubiquitous and easily accessible elsewhere. Academic institution websites listed research trials and fellowship training significantly more often than private practices. These differences imply a divergence in focus between private practices and academic institutions, likely because academic institutions are funded in large part from research grants, begetting a cycle of academic contribution. 23 In contrast, private practices may not rely as heavily on academic revenue and may be more likely to prioritize other revenue streams such as product sales. 24

HIPAA Policy —Surprisingly, HIPAA policy rarely was listed on any private (22%) or academic site (12%). Conversely, in the plastic surgery study, HIPAA policy was listed much more often, with more than half of private practices with board-certified plastic surgeons accredited in the year 2015 including it on their website, 8 which may suggest that surgically oriented specialties, particularly cosmetic subspecialties, aim to more noticeably display their privacy policies for patient reassurance.

Study Limitations —There are several limitations of our study. First, it is common for a conglomerate company to own multiple private practices in different specialties. As with academic sites, private practice sites may be limited by the hosting platforms, which often are tedious to navigate. Also noteworthy is the emergence of designated social media management positions—both by practice employees and by third-party firms 25 —but the impact of these positions in private practices and academic institutions has not been fully explored. Finally, inclusion criteria and standardized criteria definitions were chosen based on the precedent established by the authors of similar analyses in plastic surgery and radiology. 5-8 Further investigation into the most valued aspects of care by patients within the context of the type of practice chosen would be valuable in refining inclusion criteria. Additionally, this study did not stratify the data collected based on factors such as gender, race, and geographical location; studies conducted on website traffic analysis patterns that focus on these aspects likely would further explain the significance of these findings. Differences in the length of time to the next available appointment between private practices and academic institutions also may help support our findings. Finally, there is a need for further investigation into the preferences of patients themselves garnered from website traffic alone.

Conclusion

Our study examined a diverse compilation of private practice and academic institution websites and uncovered numerous differences in content. As technology and health care continuously evolve, it is imperative that both private practices and academic institutions are actively adapting to optimize their online presence. In doing so, patients will be better equipped at accessing provider information, gaining familiarity with the practice, and understanding treatment options.

- Gentry ZL, Ananthasekar S, Yeatts M, et al. Can patients find an endocrine surgeon? how hospital websites hide the expertise of these medical professionals. Am J Surg . 2021;221:101-105.

- Pollack CE, Rastegar A, Keating NL, et al. Is self-referral associated with higher quality care? Health Serv Res . 2015;50:1472-1490.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Residency Explorer TM tool. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/apply-smart-residency/residency-explorer-tool

- Find a dermatologist. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://find-a-derm.aad.org/

- Johnson EJ, Doshi AM, Rosenkrantz AB. Strengths and deficiencies in the content of US radiology private practices’ websites. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:431-435.

- Brunk D. Medical website expert shares design tips. Dermatology News . February 9, 2012. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/article/47413/health-policy/medical-website-expert-shares-design-tips

- Kuhnigk O, Ramuschkat M, Schreiner J, et al. Internet presence of neurologists, psychiatrists and medical psychotherapists in private practice [in German]. Psychiatr Prax . 2013;41:142-147.

- Ananthasekar S, Patel JJ, Patel NJ, et al. The content of US plastic surgery private practices’ websites. Ann Plast Surg . 2021;86(6S suppl 5):S578-S584.

- US Census Bureau. Age and Sex: 2021. Updated December 2, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2023. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/age-and-sex/data/tables.2021.List_897222059.html#list-tab-List_897222059

- Porter ME. The competitive advantage of the inner city. Harvard Business Review . Published August 1, 2014. https://hbr.org/1995/05/the-competitive-advantage-of-the-inner-city

- Clark PG. The social allocation of health care resources: ethical dilemmas in age-group competition. Gerontologist. 1985;25:119-125.

- Su A-J, Hu YC, Kuzmanovic A, et al. How to improve your Google ranking: myths and reality. ACM Transactions on the Web . 2014;8. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/2579990

- McCormick K. 39 ways to increase traffic to your website. WordStream website. Published March 28, 2023. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.wordstream.com/blog/ws/2014/08/14/increase-traffic-to-my-website

- Montemurro P, Porcnik A, Hedén P, et al. The influence of social media and easily accessible online information on the aesthetic plastic surgery practice: literature review and our own experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg . 2015;39:270-277.

- Steehler KR, Steehler MK, Pierce ML, et al. Social media’s role in otolaryngology–head and neck surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg . 2013;149:521-524.

- Tsao S-F, Chen H, Tisseverasinghe T, et al. What social media told us in the time of COVID-19: a scoping review. Lancet Digit Health . 2021;3:E175-E194.

- Geist R, Militello M, Albrecht JM, et al. Social media and clinical research in dermatology. Curr Dermatol Rep . 2021;10:105-111.

- McLawhorn AS, De Martino I, Fehring KA, et al. Social media and your practice: navigating the surgeon-patient relationship. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med . 2016;9:487-495.

- Thomas RB, Johnson PT, Fishman EK. Social media for global education: pearls and pitfalls of using Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. J Am Coll Radiol . 2018;15:1513-1516.

- Lugo-Fagundo C, Johnson MB, Thomas RB, et al. New frontiers in education: Facebook as a vehicle for medical information delivery. J Am Coll Radiol . 2016;13:316-319.

- Ho T-VT, Dayan SH. How to leverage social media in private practice. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am . 2020;28:515-522.

- Fan KL, Graziano F, Economides JM, et al. The public’s preferences on plastic surgery social media engagement and professionalism. Plast Reconstr Surg . 2019;143:619-630.

- Jacob BA, Lefgren L. The impact of research grant funding on scientific productivity. J Public Econ. 2011;95:1168-1177.