User login

Comorbidities Up Risk for Thyroidectomy Complications, In-Hospital Deaths

MIAMI BEACH – Cardiac and respiratory comorbidities were "common culprits" and present in more than half of thyroidectomy patients who died in the hospital, according to analysis of a large inpatient database.

Although overall mortality is less than 1% for thyroidectomy patients nationwide, researcher Rishi Vashishta said, "Patient comorbidities can often contribute to perioperative death and should really be considered when discussing treatment options with patients."

Mr. Vashishta and his associates identified 11,862 patients who underwent thyroidectomy using ICD-9 codes from the Healthcare Cost Utilization Project Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database for 2009. Two-thirds of patients were white and three-fourths were female A total of 73 of these patients died during their hospitalization that year.

"We calculated the mortality rate during hospitalization to be 0.61%," Mr. Vashishta, a medical student at George Washington University, Washington, said at the Triological Society Combined Sections meeting.

Other aims of the study were to assess thyroid surgery complications, length of stay, and total hospital charges. "There are a large number of institutional studies, but there remains a relative paucity of studies examining this procedure on a more macro and socioeconomic level," said Mr. Vashishta.

Among the nearly 12,000 admissions, mean length of stay was 2.97 days and mean total hospital charges accrued was $39,236.

In contrast, a subgroup analysis revealed mean length of stay was 13.8 days and mean increase in total hospital charges was nearly $218,855 among patients who died during hospitalization. "Interestingly, the respiratory status in these patients was markedly worse, with a tracheostomy required in 28%, prolonged mechanical ventilation required in 43%, and endotracheal intubation in 55%," Mr. Vashishta said at the meeting, which was jointly sponsored by the Triological Society and the American College of Surgeons.

Acute cerebrovascular disease was involved in 62% of deaths, he reported.

The mean age of patients who died was 65 years, compared with a mean of 53 years for all thyroidectomy patients in the study.

Approximately 80% of all surgeries in the study were elective. The majority of patients, 55%, underwent total thyroidectomy, 32% underwent unilateral lobectomy, and the remainder had partial thyroidectomy.

When Mr. Vashishta and his colleagues assessed complications, they found hypocalcemia present in 6%, vocal cord paresis in 1.4%, and hypoparathyroidism in 0.77% of patients using bivariate analyses. The incidence of hematoma and hemorrhage were low at 1.43% and 0.67%, respectively. "Our complication rates were generally consistent with those from institutional studies published in the literature."

"We found strong predictors of [these] complications during hospitalization included female gender; hospital location and teaching status; and type of thyroid diagnosis," he said. "Although the majority of cases were conducted at large teaching hospitals in urban centers, no socioeconomic or regional differences were observed," the investigators noted in their abstract but did not offer further explanation.

Admissions data showed that nontoxic nodular goiter was a diagnosis code for 36% of patients. In addition, malignant neoplasm was a code for 31% and benign neoplasm for 11%, "Graves’ disease, which we classified under acquired hypothyroidism, was much less common, around 8%," Mr. Vashishta said. ICD-9 codes for thyrotoxicosis and thyroiditis each were noted on 8% of records.

Errors in coding and sampling are a potential limitation of this and any study based on a large administrative database, Mr. Vashishta said. For example, use of ICD-9 codes "inevitably included patients in our stratified sample admitted for some other problem who underwent incidental thyroidectomies during their hospitalization." Furthermore, thyroidectomy is increasingly being performed as an outpatient procedure and the NIS is an inpatient database. "This effectively skewed our mean total charges and mean length of stay in the hospital upwards."

The study was not funded by industry. Mr. Vashishta said that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

MIAMI BEACH – Cardiac and respiratory comorbidities were "common culprits" and present in more than half of thyroidectomy patients who died in the hospital, according to analysis of a large inpatient database.

Although overall mortality is less than 1% for thyroidectomy patients nationwide, researcher Rishi Vashishta said, "Patient comorbidities can often contribute to perioperative death and should really be considered when discussing treatment options with patients."

Mr. Vashishta and his associates identified 11,862 patients who underwent thyroidectomy using ICD-9 codes from the Healthcare Cost Utilization Project Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database for 2009. Two-thirds of patients were white and three-fourths were female A total of 73 of these patients died during their hospitalization that year.

"We calculated the mortality rate during hospitalization to be 0.61%," Mr. Vashishta, a medical student at George Washington University, Washington, said at the Triological Society Combined Sections meeting.

Other aims of the study were to assess thyroid surgery complications, length of stay, and total hospital charges. "There are a large number of institutional studies, but there remains a relative paucity of studies examining this procedure on a more macro and socioeconomic level," said Mr. Vashishta.

Among the nearly 12,000 admissions, mean length of stay was 2.97 days and mean total hospital charges accrued was $39,236.

In contrast, a subgroup analysis revealed mean length of stay was 13.8 days and mean increase in total hospital charges was nearly $218,855 among patients who died during hospitalization. "Interestingly, the respiratory status in these patients was markedly worse, with a tracheostomy required in 28%, prolonged mechanical ventilation required in 43%, and endotracheal intubation in 55%," Mr. Vashishta said at the meeting, which was jointly sponsored by the Triological Society and the American College of Surgeons.

Acute cerebrovascular disease was involved in 62% of deaths, he reported.

The mean age of patients who died was 65 years, compared with a mean of 53 years for all thyroidectomy patients in the study.

Approximately 80% of all surgeries in the study were elective. The majority of patients, 55%, underwent total thyroidectomy, 32% underwent unilateral lobectomy, and the remainder had partial thyroidectomy.

When Mr. Vashishta and his colleagues assessed complications, they found hypocalcemia present in 6%, vocal cord paresis in 1.4%, and hypoparathyroidism in 0.77% of patients using bivariate analyses. The incidence of hematoma and hemorrhage were low at 1.43% and 0.67%, respectively. "Our complication rates were generally consistent with those from institutional studies published in the literature."

"We found strong predictors of [these] complications during hospitalization included female gender; hospital location and teaching status; and type of thyroid diagnosis," he said. "Although the majority of cases were conducted at large teaching hospitals in urban centers, no socioeconomic or regional differences were observed," the investigators noted in their abstract but did not offer further explanation.

Admissions data showed that nontoxic nodular goiter was a diagnosis code for 36% of patients. In addition, malignant neoplasm was a code for 31% and benign neoplasm for 11%, "Graves’ disease, which we classified under acquired hypothyroidism, was much less common, around 8%," Mr. Vashishta said. ICD-9 codes for thyrotoxicosis and thyroiditis each were noted on 8% of records.

Errors in coding and sampling are a potential limitation of this and any study based on a large administrative database, Mr. Vashishta said. For example, use of ICD-9 codes "inevitably included patients in our stratified sample admitted for some other problem who underwent incidental thyroidectomies during their hospitalization." Furthermore, thyroidectomy is increasingly being performed as an outpatient procedure and the NIS is an inpatient database. "This effectively skewed our mean total charges and mean length of stay in the hospital upwards."

The study was not funded by industry. Mr. Vashishta said that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

MIAMI BEACH – Cardiac and respiratory comorbidities were "common culprits" and present in more than half of thyroidectomy patients who died in the hospital, according to analysis of a large inpatient database.

Although overall mortality is less than 1% for thyroidectomy patients nationwide, researcher Rishi Vashishta said, "Patient comorbidities can often contribute to perioperative death and should really be considered when discussing treatment options with patients."

Mr. Vashishta and his associates identified 11,862 patients who underwent thyroidectomy using ICD-9 codes from the Healthcare Cost Utilization Project Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database for 2009. Two-thirds of patients were white and three-fourths were female A total of 73 of these patients died during their hospitalization that year.

"We calculated the mortality rate during hospitalization to be 0.61%," Mr. Vashishta, a medical student at George Washington University, Washington, said at the Triological Society Combined Sections meeting.

Other aims of the study were to assess thyroid surgery complications, length of stay, and total hospital charges. "There are a large number of institutional studies, but there remains a relative paucity of studies examining this procedure on a more macro and socioeconomic level," said Mr. Vashishta.

Among the nearly 12,000 admissions, mean length of stay was 2.97 days and mean total hospital charges accrued was $39,236.

In contrast, a subgroup analysis revealed mean length of stay was 13.8 days and mean increase in total hospital charges was nearly $218,855 among patients who died during hospitalization. "Interestingly, the respiratory status in these patients was markedly worse, with a tracheostomy required in 28%, prolonged mechanical ventilation required in 43%, and endotracheal intubation in 55%," Mr. Vashishta said at the meeting, which was jointly sponsored by the Triological Society and the American College of Surgeons.

Acute cerebrovascular disease was involved in 62% of deaths, he reported.

The mean age of patients who died was 65 years, compared with a mean of 53 years for all thyroidectomy patients in the study.

Approximately 80% of all surgeries in the study were elective. The majority of patients, 55%, underwent total thyroidectomy, 32% underwent unilateral lobectomy, and the remainder had partial thyroidectomy.

When Mr. Vashishta and his colleagues assessed complications, they found hypocalcemia present in 6%, vocal cord paresis in 1.4%, and hypoparathyroidism in 0.77% of patients using bivariate analyses. The incidence of hematoma and hemorrhage were low at 1.43% and 0.67%, respectively. "Our complication rates were generally consistent with those from institutional studies published in the literature."

"We found strong predictors of [these] complications during hospitalization included female gender; hospital location and teaching status; and type of thyroid diagnosis," he said. "Although the majority of cases were conducted at large teaching hospitals in urban centers, no socioeconomic or regional differences were observed," the investigators noted in their abstract but did not offer further explanation.

Admissions data showed that nontoxic nodular goiter was a diagnosis code for 36% of patients. In addition, malignant neoplasm was a code for 31% and benign neoplasm for 11%, "Graves’ disease, which we classified under acquired hypothyroidism, was much less common, around 8%," Mr. Vashishta said. ICD-9 codes for thyrotoxicosis and thyroiditis each were noted on 8% of records.

Errors in coding and sampling are a potential limitation of this and any study based on a large administrative database, Mr. Vashishta said. For example, use of ICD-9 codes "inevitably included patients in our stratified sample admitted for some other problem who underwent incidental thyroidectomies during their hospitalization." Furthermore, thyroidectomy is increasingly being performed as an outpatient procedure and the NIS is an inpatient database. "This effectively skewed our mean total charges and mean length of stay in the hospital upwards."

The study was not funded by industry. Mr. Vashishta said that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE TRIOLOGICAL SOCIETY COMBINED SECTIONS MEETING

Major Finding: A total 73 of 11,862 thyroidectomy patients (0.61%) died during hospitalization.

Data Source: Retrospective study of ICD-9 codes for thyroidectomy in 2009 from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database.

Disclosures: The study was not funded by industry. Mr. Vashishta said that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Don't Call That Child 'Fat' or 'Obese'

STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLO. – In discussing a child’s weight problem with the parents, it’s best for physicians to refrain from using the terms "fat," "extremely obese," and even "obese."

"Parents find those terms undesirable. They’re stigmatizing, blaming, nonmotivating, and condescending," Dr. Paul R. Stricker said at a meeting on practical pediatrics sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

And that’s not just his personal opinion, either. He cited a recent groundbreaking study in which investigators at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., conducted a national online survey of the parents of 455 children aged 2-18 years. The purpose was to examine parental perceptions of language related to weight in order to improve the quality of physician-parent discussions about their child’s obesity. The underlying idea is that the likelihood of successful long-term weight loss is enhanced if the parents are committed to the proposed lifestyle modifications.

On a 5-point rating scale, most parents ranked "weight" and "unhealthy weight" as terms they preferred physicians to use in describing their child’s extra pounds. Moreover, the parents indicated they found the terms "unhealthy weight," "overweight," and "weight problem" to be the most motivating to lose weight, noted Dr. Stricker, a youth sports medicine specialist at the Scripps Clinic in San Diego.

On the other hand, parents perceived the terms "chubby," "fat," "obese," and "extremely obese" quite negatively, rating them as the least motivating to encourage weight loss (Pediatrics 2011;128:e786-93).

These data cast doubt on the wisdom of the British public health minister's 2010 declaration that U.K. health providers should call their obese patients "fat" to motivate them to lose weight.

As a pediatric sports medicine specialist, Dr. Stricker’s goal is to help overweight kids have a positive sports and exercise experience. He wants it to be "something they’ll want to pass along to their own children." He combines his exercise guidance with dietary instruction in weight loss, with an emphasis placed on eating multiple small meals to keep the metabolic rate revved so more calories are burned.

But lifestyle interventions don’t always work, and Dr. Stricker highlighted a recent German study that’s eye-opening as to why.

The prospective study included 111 overweight and obese 7- to 15-year-olds and their parents. The youths were referred to a 1-year-long best-practice lifestyle intervention program.

Treatment success was defined as at least a 5% weight reduction at follow-up 1 year after completing the year-long intervention. The investigators found – consistent with their study hypothesis – that psychosocial familial characteristics were significantly predictive of long-term success or failure. This was true even after the researchers controlled for familial obesity in order to cancel out the impact of genetic factors.

The strongest predictor of long-term failure for the lifestyle intervention was maternal depression. Maternal attachment insecurity and family adversity also predicted long-term treatment failure (Pediatrics 2011;128: e779-85).

These findings point to the need for further research aimed at developing lifestyle interventions for pediatric weight loss that are tailored to a family’s psychosocial dynamics, Dr. Stricker observed.

He reported having no financial conflicts.

STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLO. – In discussing a child’s weight problem with the parents, it’s best for physicians to refrain from using the terms "fat," "extremely obese," and even "obese."

"Parents find those terms undesirable. They’re stigmatizing, blaming, nonmotivating, and condescending," Dr. Paul R. Stricker said at a meeting on practical pediatrics sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

And that’s not just his personal opinion, either. He cited a recent groundbreaking study in which investigators at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., conducted a national online survey of the parents of 455 children aged 2-18 years. The purpose was to examine parental perceptions of language related to weight in order to improve the quality of physician-parent discussions about their child’s obesity. The underlying idea is that the likelihood of successful long-term weight loss is enhanced if the parents are committed to the proposed lifestyle modifications.

On a 5-point rating scale, most parents ranked "weight" and "unhealthy weight" as terms they preferred physicians to use in describing their child’s extra pounds. Moreover, the parents indicated they found the terms "unhealthy weight," "overweight," and "weight problem" to be the most motivating to lose weight, noted Dr. Stricker, a youth sports medicine specialist at the Scripps Clinic in San Diego.

On the other hand, parents perceived the terms "chubby," "fat," "obese," and "extremely obese" quite negatively, rating them as the least motivating to encourage weight loss (Pediatrics 2011;128:e786-93).

These data cast doubt on the wisdom of the British public health minister's 2010 declaration that U.K. health providers should call their obese patients "fat" to motivate them to lose weight.

As a pediatric sports medicine specialist, Dr. Stricker’s goal is to help overweight kids have a positive sports and exercise experience. He wants it to be "something they’ll want to pass along to their own children." He combines his exercise guidance with dietary instruction in weight loss, with an emphasis placed on eating multiple small meals to keep the metabolic rate revved so more calories are burned.

But lifestyle interventions don’t always work, and Dr. Stricker highlighted a recent German study that’s eye-opening as to why.

The prospective study included 111 overweight and obese 7- to 15-year-olds and their parents. The youths were referred to a 1-year-long best-practice lifestyle intervention program.

Treatment success was defined as at least a 5% weight reduction at follow-up 1 year after completing the year-long intervention. The investigators found – consistent with their study hypothesis – that psychosocial familial characteristics were significantly predictive of long-term success or failure. This was true even after the researchers controlled for familial obesity in order to cancel out the impact of genetic factors.

The strongest predictor of long-term failure for the lifestyle intervention was maternal depression. Maternal attachment insecurity and family adversity also predicted long-term treatment failure (Pediatrics 2011;128: e779-85).

These findings point to the need for further research aimed at developing lifestyle interventions for pediatric weight loss that are tailored to a family’s psychosocial dynamics, Dr. Stricker observed.

He reported having no financial conflicts.

STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLO. – In discussing a child’s weight problem with the parents, it’s best for physicians to refrain from using the terms "fat," "extremely obese," and even "obese."

"Parents find those terms undesirable. They’re stigmatizing, blaming, nonmotivating, and condescending," Dr. Paul R. Stricker said at a meeting on practical pediatrics sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

And that’s not just his personal opinion, either. He cited a recent groundbreaking study in which investigators at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., conducted a national online survey of the parents of 455 children aged 2-18 years. The purpose was to examine parental perceptions of language related to weight in order to improve the quality of physician-parent discussions about their child’s obesity. The underlying idea is that the likelihood of successful long-term weight loss is enhanced if the parents are committed to the proposed lifestyle modifications.

On a 5-point rating scale, most parents ranked "weight" and "unhealthy weight" as terms they preferred physicians to use in describing their child’s extra pounds. Moreover, the parents indicated they found the terms "unhealthy weight," "overweight," and "weight problem" to be the most motivating to lose weight, noted Dr. Stricker, a youth sports medicine specialist at the Scripps Clinic in San Diego.

On the other hand, parents perceived the terms "chubby," "fat," "obese," and "extremely obese" quite negatively, rating them as the least motivating to encourage weight loss (Pediatrics 2011;128:e786-93).

These data cast doubt on the wisdom of the British public health minister's 2010 declaration that U.K. health providers should call their obese patients "fat" to motivate them to lose weight.

As a pediatric sports medicine specialist, Dr. Stricker’s goal is to help overweight kids have a positive sports and exercise experience. He wants it to be "something they’ll want to pass along to their own children." He combines his exercise guidance with dietary instruction in weight loss, with an emphasis placed on eating multiple small meals to keep the metabolic rate revved so more calories are burned.

But lifestyle interventions don’t always work, and Dr. Stricker highlighted a recent German study that’s eye-opening as to why.

The prospective study included 111 overweight and obese 7- to 15-year-olds and their parents. The youths were referred to a 1-year-long best-practice lifestyle intervention program.

Treatment success was defined as at least a 5% weight reduction at follow-up 1 year after completing the year-long intervention. The investigators found – consistent with their study hypothesis – that psychosocial familial characteristics were significantly predictive of long-term success or failure. This was true even after the researchers controlled for familial obesity in order to cancel out the impact of genetic factors.

The strongest predictor of long-term failure for the lifestyle intervention was maternal depression. Maternal attachment insecurity and family adversity also predicted long-term treatment failure (Pediatrics 2011;128: e779-85).

These findings point to the need for further research aimed at developing lifestyle interventions for pediatric weight loss that are tailored to a family’s psychosocial dynamics, Dr. Stricker observed.

He reported having no financial conflicts.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING ON PRACTICAL PEDIATRICS SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

Transfusion Medicine

Transfusion therapy is an essential part of hematology practice, allowing for curative therapy of diseases such as leukemia, aplastic anemia, and aggressive lymphomas. Nonetheless, transfusions are associated with significant risks, including transfusion-transmitted infections and transfusion-related reactions, and controversy remains about key issues in transfusion therapy, such as triggers for red cell transfusions. This article reviews the available blood products and indications for transfusion along with the associated risks and also discusses specific clinical situations, such as massive transfusion.

To read the full article in PDF:

Transfusion therapy is an essential part of hematology practice, allowing for curative therapy of diseases such as leukemia, aplastic anemia, and aggressive lymphomas. Nonetheless, transfusions are associated with significant risks, including transfusion-transmitted infections and transfusion-related reactions, and controversy remains about key issues in transfusion therapy, such as triggers for red cell transfusions. This article reviews the available blood products and indications for transfusion along with the associated risks and also discusses specific clinical situations, such as massive transfusion.

To read the full article in PDF:

Transfusion therapy is an essential part of hematology practice, allowing for curative therapy of diseases such as leukemia, aplastic anemia, and aggressive lymphomas. Nonetheless, transfusions are associated with significant risks, including transfusion-transmitted infections and transfusion-related reactions, and controversy remains about key issues in transfusion therapy, such as triggers for red cell transfusions. This article reviews the available blood products and indications for transfusion along with the associated risks and also discusses specific clinical situations, such as massive transfusion.

To read the full article in PDF:

A 37-year-old man with a chronic cough

A 37-year-old man presented to the emergency department with an 8-week history of a mildly productive cough and shortness of breath accompanied by high fevers, chills, and night sweats. He also had some nausea but no vomiting.

Four days earlier, he had been evaluated by his primary care physician, who prescribed a 14-day course of one double-strength trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole tablet (Bactrim DS) every 12 hours for presumed acute bronchitis, but his symptoms did not improve.

He was unemployed, living in Arizona, married with children. He denied any use of tobacco, alcohol, or injection drugs. On further questioning, he disclosed that he had unintentionally lost 30 pounds over the past 2 to 3 months and had been feeling tired.

When asked about his medical history, he revealed that he had been diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in 2008 and that recently he had not been taking his antiretroviral medication, a once-daily combination pill containing efavirenz, emtricitabine, and tenofovir (Atripla). He had no other significant medical history, and the only medication he was currently taking was the trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

On examination, his temperature was 38.7°C (101.7°F), blood pressure 109/68 mm Hg, heart rate 60 beats per minute, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 100% while breathing supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula at 2 L/min. He did not appear seriously ill.

Initial blood tests (Table 1) showed a normal white blood cell count, normal results on a complete metabolic panel, and a lactate dehydrogenase level of 539 IU/L (reference range 313–618). His serum lactate level was within normal limits.

HIV-specific tests performed on the second day of hospitalization showed extreme immunosuppression, with a CD4 count of 5 cells/μL (normal 326–1,404 cells/μL).

WHICH ORGANISM IS CAUSING HIS LUNG INFECTION?

1. Which of the following organisms is the least likely to be associated with this patient’s condition?

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- Pneumocystis jirovecii

- Coccidioides immitis

- Candida albicans

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Cytomegalovirus

Bacterial, fungal, and viral lung infections are common in HIV-infected patients, especially if they are not on antiretroviral therapy and their CD4 lymphocyte counts are low. Clues to the cause can be derived from the history, physical examination, and general laboratory studies. For instance, knowing where the patient lives and where he has travelled recently provides insight into exposure to endemic infectious agents.

The complete blood cell count with differential white blood cell count can help narrow the differential diagnosis but rarely helps exclude a possibility. Neutrophilia is common in bacterial infections. Lymphocytosis can be seen in tuberculosis, in fungal and viral infections, and, rarely, in hematologic malignancies. Eosinophilia can be seen in acute retroviral syndrome, fungal and helminthic infections, adrenal insufficiency, autoimmune disease, and lymphoma.

A caveat to these clues is that in severely immunocompromised hosts, like this man, diagnoses should not be excluded without firm evidence. This patient has severe, active immunosuppression, and only one of the six answer choices above is not a possible causative agent: C albicans rarely causes lung infection, even in immunocompromised people.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Tuberculosis can be the first manifestation of HIV infection. It can occur at any CD4 count, but as the count decreases, the risk of dissemination increases.1 Classic symptoms are fever, night sweats, hemoptysis, and weight loss.

The CD4 count also affects the radiographic presentation. If the count is higher than 350 cells/μL, then infiltration of the upper lobe is likely; if it is lower than 200 cells/μL, then middle, lower, miliary, and extrapulmonary manifestations are likely.1,2 Cavitation is less common in HIV-infected patients, but mediastinal adenopathy is more common.1

Definitive diagnosis is via sputum examination, blood culture, nucleic acid amplification, or microscopic study of biopsy specimens of affected tissues to look for acid-fast bacilli.1

Interferon-gamma-release assays such as the QuantiFERON test (Cellestis, Valencia, CA) or a tuberculin skin test can be used to check for latent tuberculosis infection. These tests can also provide evidence of active infection in the appropriate clinical context.3

Interferon-gamma-release assays have several advantages over skin testing: they are more sensitive (76% to 80%) and specific (97%); they do not give false-positive results in people who previously received bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine; they react only minimally to previous exposure to nontuberculous mycobacteria; and interpretation is not subject to interreader variability.4,5 However, concordance between skin testing and interferon-gamma-release assays is low. Therefore, either or both tests can be used if tuberculosis is strongly suspected, and a positive result on either test should prompt further workup.6,7

Of note, both tests may be affected by immunosuppression, making both susceptible to false-negative results as the CD4 count declines.3

In any case, a positive acid-fast bacillus smear, radiographic evidence of latent infection, or pulmonary symptoms should be presumed to represent active tuberculosis. In such a situation, directly observed treatment with the typical four-drug regimen—rifampin (Rifadin), isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (Myambutol)—is recommended while awaiting definitive results from culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.1

Pneumocystis jirovecii

P jirovecii was previously known as P carinii, and P jirovecii pneumonia is an AIDS-defining illness. Most cases occur when the CD4 count falls below 200 cells/μL.1 Symptoms, including a nonproductive cough, develop insidiously over days to weeks.

Physical examination may reveal inspiratory crackles; however, half of the time the physical examination is nondiagnostic. Oral candidiasis is a common coinfection. The lactate dehydrogenase level may be elevated.1,8 Radiographs show bilateral interstitial infiltrates, and in 10% to 20% of patients lung cysts develop—hence the name of the organism.1 Pneumothorax in a patient with HIV should prompt a workup for P jirovecii pneumonia.9,10

No consensus exists for the diagnosis. However, if sputum examination is unrevealing but suspicion is high, then bronchoalveolar lavage can help.11–13

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 21 days is the first-line treatment, with glucocorticoids added if the Pao2 is less than 70 mm Hg or if the alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient is greater than 35 mm Hg.1

Coccidioides species

Coccidioides infection is typically due to either C immitis or C posadasii.14 People living in or travelling to areas where it is endemic, such as the southwestern United States, Mexico, and Central and South America, are at higher risk.14

Typical signs and symptoms of this fungal infection include an influenza-like illness with fever, cough, adenopathy, and wasting, and when combined with erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, arthralgia, or ocular involvement, this constellation is colloquially termed “valley fever.”15 Most HIV-infected patients who have CD4 counts higher than 250 cells/μL present with focal pneumonia, while lower counts predispose to disseminated disease.1,2,16

Findings on examination are nonspecific and depend on the various pulmonary manifestations, which include acute, chronic progressive, or diffuse pneumonia, nodules, or cavities.14 Eosinophilia may accompany the infection.15

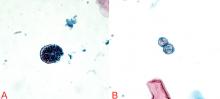

The diagnosis can be made by finding the organisms on direct microscopic examination of involved tissues or secretions or on culture of clinical specimens.1,2,14 Serologic tests, antigen detection tests, or culture can be helpful if positive, but negative results do not rule out the diagnosis.1,2,14

A caveat about testing: if the pretest probability of infection is low, positive tests for immunoglobulin M (IgM) do not necessarily equal infection, and the IgM test should be followed up with confirmatory testing. Along the same lines, a high pretest probability should not be ignored if initial tests are negative, and patients in this situation should also undergo further evaluation.17

Therapy with an azole drug such as fluconazole (Diflucan) or one of the amphotericin B preparations should be started, depending on the severity of the disease.1,2,14,18

Candida albicans

C albicans is a rare cause of lung infection.19,20 It is, however, a common inhabitant of the upper airway tract, and pulmonary infection is usually the result of aspiration or hematogenous spread from either the gastrointestinal tract or an infected central venous catheter.20

The presentation is relatively nonspecific. Fever despite broad-spectrum antibacterial therapy is a major clue. Radiographic abnormalities usually are due to other causes, such as superimposed infections or pulmonary hemorrhage.21 Sputum culture is unreliable because of colonization. The definitive diagnosis is based on lung biopsy demonstrating organisms within the tissue.19,20,22

Therapy with a systemic antifungal agent is recommended.

Streptococcus pneumoniae

S pneumoniae is one of the most common bacterial causes of community-acquired pneumonia in people with or without HIV.23–25 Moreover, two or more episodes of bacterial pneumonia in 12 months can be an AIDS-defining condition in patients with a positive serologic test for HIV.16 Therefore, in patients with fever, cough, and pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiography, S pneumoniae must always be considered.

Urinary antigen testing has a relatively high positive predictive value (> 89%) and specificity (96%) for diagnosing S pneumoniae pneumonia.26 Blood and sputum cultures should be done not only to confirm the diagnosis, but also because the rates of bacteremia and drug resistance are higher with S pneumoniae infection in the HIV-infected.1

A combination of a beta-lactam and a macrolide or respiratory fluoroquinolone is the treatment of choice.1

Cytomegalovirus

Although influenza is the most common cause of viral pneumonia in HIV-infected people, cytomegalovirus is an opportunistic cause.2 This is usually a reactivation of latent infection rather than new infection.27 Typically, infections occur at CD4 counts lower than 50 cells/μL, with cough, dyspnea, and fever that last for 2 to 4 weeks.2

Crackles may be heard on lung examination. The lactate dehydrogenase level can be elevated, as in P jirovecii pneumonia.2 Radiography can show a wide range of nonspecific findings, from reticular and ground-glass opacities to alveolar or interstitial infiltrates to nodules.

The diagnosis of cytomegalovirus pneumonia is not always clear. Since HIV-infected patients typically shed the virus in their airways, bronchoalveolar lavage is not adequate because a positive finding does not necessarily mean the patient has active viral pneumonitis.27 For this reason, infection should be confirmed by biopsy demonstrating characteristic cytomegalovirus inclusions in lung tissue.2

Importantly, once cytomegalovirus pneumonia is confirmed, the patient should be screened for cytomegalovirus retinitis even if he or she has no visual symptoms, as cytomegalovirus pneumonitis is typically a part of a disseminated infection.1

Treatment with intravenous ganciclovir (Cytovene) is required.1

CASE CONTINUED: POSITIVE TESTS FOR COCCIDIOIDES

Our patient began empiric treatment for community-acquired pneumonia with intravenous ceftriaxone (Rocephin) and azithromycin (Zithromax).

On the basis of these findings, the patient was immediately placed in negative pressure respiratory isolation and underwent induced sputum examinations for tuberculosis. Further tests for S pneumoniae, S aureus, Mycoplasma, Legionella, influenza, Pneumocystis, Cryptococcus, Histoplasma, and Coccidioides species were performed.

QuantiFERON testing was negative, and blood cultures were sterile. The first induced sputum examination was negative for acid-fast bacilli. PCR testing for mycobacterial DNA in the sputum was also negative.

Both silver and direct fluorescent antibody staining of the sputum were negative for Pneumocystis. On the basis of these findings and the patient’s lack of clinical improvement with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, Pneumocystis infection was excluded.

THE PATIENT BEGINS TREATMENT

2. Which treatment is most appropriate for this patient?

- Posaconazole (Noxafil)

- Caspofungin (Cancidas) and surgery

- Fluconazole

- Voriconazole (Vfend) and surgery

- Amphotericin B

Solitary pulmonary cavities tend to be asymptomatic and do not require treatment, even if coccidioidal infection is microbiologically confirmed.

However, if there is pain, hemoptysis, or bacterial superinfection, antifungal therapy may result in improvement but not closure of the cavity.18 Therefore, in all cases of symptomatic coccidioidal pulmonary cavities, surgical resection is the only definitive treatment.

Coccidioidal cavities may rupture and cause pyopneumothorax, but this is an infrequent complication, and antifungal therapy combined with surgical decortication is the treatment of choice.18

Commonly prescribed antifungals include fluconazole and amphotericin B, the latter usually reserved for patients with significant hypoxia or rapid clinical deterioration.18 At this time, there are not enough clinical data to show that voriconazole or posaconazole is effective, and thus neither is approved for the treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Likewise, there have been no human trials of the efficacy of caspofungin against Coccidioides infection, although it has been shown to be active in mouse models.18

Our patient was started on oral fluconazole and observed for clinical improvement or, conversely, for signs of dissemination. After 2 days, he had markedly improved, and within 1 week he was almost back to his baseline level of health. Testing for all other infectious etiologies was unrevealing, and he was removed from negative pressure isolation.

However, as we mentioned above, his CD4 count was 5 cells/μL. We discussed the issue with the patient, and he said he was willing to comply with his treatment for both his Coccidioides and his HIV infection. After much deliberation, he said he was also willing to start and comply with prophylactic treatment for opportunistic infections.

PREVENTING OPPORTUNISTIC INFECTIONS IN HIV PATIENTS

3. Which of the following prophylactic regimens is most appropriate for this patient?

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, atovaquone (Mepron), and azithromycin

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and azithromycin

- Pentamidine (Nebupent), dapsone, and clarithromycin (Biaxin)

- Dapsone and clarithromycin

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole by itself

According to guidelines for the prevention of opportunistic diseases in patients with HIV, he needs primary prophylaxis against the following organisms: P jirovecii, Toxoplasma gondii, and Mycobacterium avium complex.1

The CD4 count dictates the appropriate time to start therapy. If the count is lower than 200 cells/μL or if the patient has oropharyngeal candidiasis regardless of the CD4 count, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is indicated to prevent P jirovecii pneumonia. In those who cannot tolerate trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or who are allergic to it, dapsone, pentamidine, or atovaquone can be substituted.1

In patients seropositive for T gondii, a CD4 count lower than 100/μL indicates the need for prophylaxis.1 Prophylactic measures are similar to those for Pneumocystis. However, if the patient cannot tolerate trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, the recommended alternative is dapsone-pyrimethamine with leucovorin, which is also effective against Pneumocystis.1

Finally, if the CD4 count is lower than 50 cells/μL, prophylaxis against M avium complex is mandatory, with either azithromycin weekly or clarithromycin daily.1

Given our patient’s degree of immunosuppression, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole plus azithromycin is his most appropriate option.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and azithromycin were added to his antimicrobial regimen before he was discharged. Two weeks later, he noted no side effects from any of the medications, he had no new symptoms, he was feeling well, and his cough had improved greatly. He did not have any signs of dissemination of his coccidioidal infection, and we concluded that the primary and only infection was located in the lungs.

DISSEMINATED COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS

4. Which of the following extrapulmonary sites is Coccidioides least likely to infect?

- Brain

- Skin

- Meninges

- Lymph nodes

- Bones

- Joints

Extrapulmonary coccidioidomycosis can involve almost any site. However, the most common sites of dissemination are the skin, lymph nodes, bones, and joints.14 The least likely site is the brain.

Central nervous system involvement

In the central nervous system, involvement is typically with the meninges, rather than frank involvement of the brain parenchyma.18,28,29 Although patients with HIV or those who are otherwise severely immunocompromised are at higher risk for coccidioidal meningitis, it is rare even in this population.30,31 Meningitis most commonly presents as headache, vomiting, meningismus, confusion, or diplopia.32,33

If neurologic findings are absent, experts do not generally recommend lumbar puncture because the incidence of meningeal involvement is low. When cerebrospinal fluid is obtained in an active case of coccidioidal meningitis, fluid analysis typically finds elevated protein, low glucose, and lymphocytic pleocytosis.1,32

Meningeal enhancement on CT or magnetic resonance imaging is common.34 The diagnosis is established by culture or serologic testing of cerebrospinal fluid (IgM titer, IgG titer, immunodiffusion, or complement fixation).14

Of note, cerebral infarction and hydrocephalus are feared complications and pose a serious risk of death in any patient.32,35 In these cases, treatment with antifungals is lifelong, regardless of immune system status.18

Skin involvement

Skin involvement is variable, consisting of nodules, verrucae, abscesses, or ulcerations.15,16 Hemorrhage from the skin is relatively common.36 From the skin, the infection can spread to the lymph nodes, leading to regional lymphadenopathy.14,15 Nodes can ulcerate, drain, or even become necrotic.

Bone and joint involvement

Once integrity of the blood vessels is disrupted, Coccidioides can spread via the blood to the bones or joints,14,15 causing osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, or synovitis. Subcutaneous abscesses or sinus tracts may subsequently develop.14,15

HOW LONG MUST HE BE TREATED?

On follow-up, the patient asked how long he needed to continue his antifungal regimen and if any other testing for his coccidioidal infection was necessary, since he was feeling better.

5. Which is the most appropriate response to the patient’s question?

- He can discontinue his antifungal drugs; no further testing is necessary

- He needs 14 more days of antifungal therapy and periodic serologic tests

- He needs 2.5 more months of antifungal therapy and monthly blood cultures

- He needs lifelong antifungal therapy and periodic urinary antigen levels

- He needs 5.5 more months of antifungal therapy; bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage at 1 year

How long to treat and how to monitor for coccidioidomycosis vary by patient.

Duration of therapy depends on symptoms and immune status

The severity of infection (Table 2) and the immune status are important factors that must be considered when tailoring a therapeutic regimen.

Immunocompetent patients without symptoms or with mild symptoms usually do not need therapy and are followed periodically for signs of improvement.14,18,29

Immunocompetent patients with severe symptoms typically receive 3 to 6 months of antifungal therapy.18

Immunocompromised patients (especially HIV-infected patients with CD4 counts < 250 cells/μL) need antifungal treatment, regardless of the severity of infection.14,18,29 In many cases, the type of infection will dictate the duration of therapy.

Diffuse pneumonia or extrapulmonary dissemination typically requires treatment for at least 1 year regardless of immune status.14,18 For those with HIV and diffuse pneumonia, dissemination, or meningitis, guidelines dictate that secondary prophylaxis be started after at least 1 year of therapy and improvement in clinical status; it should be continued indefinitely to prevent reactivation of latent infection.18

The guidelines say that in patients with higher CD4 counts (presumably > 250 cells/μL) and nonmeningeal coccidioidomycosis, providers may consider discontinuing secondary prophylaxis, as long as there is clinical evidence of improvement and control of the primary infection.18 However, many experts advocate continuing secondary prophylaxis regardless of the CD4 count, as the rates of relapse and dissemination are high.1,16,37

Monitoring

Regardless of the therapy chosen, disease monitoring every 2 to 4 months with clinical history and examination, radiography, and coccidioidal-specific testing is recommended for at least 1 year, and perhaps longer, to ensure complete resolution and to monitor for signs of dissemination.14,18

Which test to use is not clear. Serologic testing identifies antibodies (IgM or IgG) to coccidioidal antigens. IgM appears during the acute infection, and tests include immunodiffusion, latex agglutination, and enzymelinked immunoassays. The last two are highly sensitive but have a significant false-positive rate, and should be confirmed with the former if found to be positive.17,18 IgG appears weeks after the acute infection and can be evaluated with immunodiffusion or enzyme-linked immunoassay as well.

Keep in mind that these tests provide only qualitative results on the presence of these antibodies, not quantitative information. Furthermore, enzyme-linked immunoassay is not as accurate as immunodiffusion, which has a sensitivity in immunocompromised patients of only approximately 50%.38,39

For that reason, complement fixation titers are extremely helpful because they reflect the severity of infection, can be used to monitor the response to treatment, and can even provide insight into the prognosis.18 The sensitivity of this test in immunocompromised hosts is 60% to 70%.38 Titers can be checked to confirm the diagnosis and can be periodically monitored throughout the treatment course to ensure efficacy of therapy and to watch for reactivation of the infection.1 In fact, an initial complement fixation titer of 1:2 or 1:4 is associated with favorable outcomes, while a titer greater than 1:16 portends dissemination.18

The caveat to any serologic test (immunodiffusion, enzyme-linked immunoassay, and complement fixation) is that severely immunocompromised patients (as in our case) may not mount an immune response and may have falsely low titers even in the face of a severe infection, and therefore these tests may not be reliable.38 In these situations, urinary coccidioidal antigen detection assay (sensitivity 71%) or nucleic acid amplification of coccidioidal DNA (sensitivity 75%) may be of more help.40,41

Therefore, in the setting of HIV infection, an asymptomatic pulmonary cavity, and diffuse pulmonary involvement secondary to coccidioidal infection, lifelong antibiotics (treatment plus secondary prophylaxis) with periodic testing of urinary coccidioidal antigen levels is the best response to the patient’s question, given that his complement fixation titers were initially negative and antigen levels were positive.

CASE CONCLUDED

The patient continues to be followed for his HIV infection. He is undergoing serologic and urinary antigen testing for Coccidioides infection every 3 months in addition to his maintenance HIV testing. He is on chronic suppressive therapy with fluconazole. He has not had a recurrence of his Coccidioides infection, nor have there been any signs of dissemination.

CAVITARY LUNG LESIONS IN HIV PATIENTS

In patients with HIV, cavitary lung lesions on chest radiography can be due to a wide variety of etiologies that range from infection to malignancy. Historical clues, including environmental exposure, occupation, geographic residence, sick contacts, travel, or animal contact can be helpful in ordering subsequent confirmatory testing, especially in the case of infection.

Tuberculosis should be suspected, and appropriate isolation precautions should be taken until it is ruled out.

Laboratory testing, including the complete blood cell count with differential and CD4 count, provide ancillary data to narrow the differential diagnosis. For example, if the CD4 count is greater than 200 cells/μL, mycobacterial infection should be strongly suspected; however, lower CD4 counts should also prompt a search for opportunistic infections. In the appropriate clinical scenario, malignancies including Kaposi sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and bronchogenic carcinoma can be seen and should also be considered.

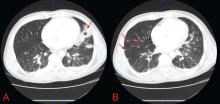

Nevertheless, the evaluation hinges on the sputum examination and CT scan of the chest to further characterize the cavity, surrounding lung parenchyma, lymph nodes, and potential fluid collections. Usually, further serologic tests and even bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage and transbronchial biopsy are required. Treatment should begin once the most likely diagnosis is established.

Coccidioidal pneumonia should be considered in all patients with immunodeficiency, including HIV patients, transplant recipients, those undergoing chemotherapy, and those with intrinsic immune system defects, especially if they have a history of exposure or if they are from an endemic region. Antifungal therapy should be initiated early, and dissemination must be ruled out. Suppressive therapy is mandatory for those with a severely compromised immune system, and serologic testing to ensure remission of the infection is needed. Patients who were previously exposed to Coccidioides or who vacationed or live in the southwestern United States (where it is prevalent) are at risk and may present with any number of symptoms.

- Kaplan JE, Benson C, Holmes KH, Brooks JT, Pau A, Masur H; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep 2009; 58:1–207.

- Huang L, Crothers K. HIV-associated opportunistic pneumonias. Respirology 2009; 14:474–485.

- Mazurek GH, Jereb J, Lobue P, Iademarco MF, Metchock B, Vernon A; Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidelines for using the QuantiFERON-TB Gold test for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, United States. MMWR Recomm Rep 2005; 54:49–55.

- Menzies D, Pai M, Comstock G. Meta-analysis: new tests for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: areas of uncertainty and recommendations for research. Ann Intern Med 2007; 146:340–354.

- Nahid P, Pai M, Hopewell PC. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006; 3:103–110.

- Chapman AL, Munkanta M, Wilkinson KA, et al. Rapid detection of active and latent tuberculosis infection in HIV-positive individuals by enumeration of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific T cells. AIDS 2002; 16:2285–2293.

- Luetkemeyer AF, Charlebois ED, Flores LL, et al. Comparison of an interferon-gamma release assay with tuberculin skin testing in HIV-infected individuals. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175:737–742.

- Zaman MK, White DA. Serum lactate dehydrogenase levels and Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Diagnostic and prognostic significance. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988; 137:796–800.

- Metersky ML, Colt HG, Olson LK, Shanks TG. AIDS-related spontaneous pneumothorax. Risk factors and treatment. Chest 1995; 108:946–951.

- Sepkowitz KA, Telzak EE, Gold JW, et al. Pneumothorax in AIDS. Ann Intern Med 1991; 114:455–459.

- Baughman RP, Dohn MN, Frame PT. The continuing utility of bronchoalveolar lavage to diagnose opportunistic infection in AIDS patients. Am J Med 1994; 97:515–522.

- Kovacs JA, Ng VL, Masur H, et al. Diagnosis of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia: improved detection in sputum with use of monoclonal antibodies. N Engl J Med 1988; 318:589–593.

- Stover DE, Zaman MB, Hajdu SI, Lange M, Gold J, Armstrong D. Bronchoalveolar lavage in the diagnosis of diffuse pulmonary infiltrates in the immunosuppressed host. Ann Intern Med 1984; 101:1–7.

- Parish JM, Blair JE. Coccidioidomycosis. Mayo Clin Proc 2008; 83:343–348.

- Drutz DJ, Catanzaro A. Coccidioidomycosis. Part I. Am Rev Respir Dis 1978; 117:559–585.

- Bartlett JG, Gallant JE, Pham PA. Medical Management of HIV Infection. Durham, NC: Knowledge Source Solutions, LLC; 2009.

- Kuberski T, Herrig J, Pappagianis D. False-positive IgM serology in coccidioidomycosis. J Clin Microbiol 2010; 48:2047–2049.

- Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41:1217–1223.

- Kontoyiannis DP, Reddy BT, Torres HA, et al. Pulmonary candidiasis in patients with cancer: an autopsy study. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 34:400–403.

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 48:503–535.

- Connolly JE, McAdams HP, Erasmus JJ, Rosado-de-Christenson ML. Opportunistic fungal pneumonia. J Thorac Imaging 1999; 14:51–62.

- Meersseman W, Lagrou K, Spriet I, et al. Significance of the isolation of Candida species from airway samples in critically ill patients: a prospective, autopsy study. Intensive Care Med 2009; 35:1526–1531.

- Miller RF, Foley NM, Kessel D, Jeffrey AA. Community acquired lobar pneumonia in patients with HIV infection and AIDS. Thorax 1994; 49:367–368.

- Polsky B, Gold JW, Whimbey E, et al. Bacterial pneumonia in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1986; 104:38–41.

- Rimland D, Navin TR, Lennox JL, et al; Pulmonary Opportunistic Infection Study Group. Prospective study of etiologic agents of community-acquired pneumonia in patients with HIV infection. AIDS 2002; 16:85–95.

- Boulware DR, Daley CL, Merrifield C, Hopewell PC, Janoff EN. Rapid diagnosis of pneumococcal pneumonia among HIV-infected adults with urine antigen detection. J Infect 2007; 55:300–309.

- Salomon N, Perlman DC. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia. Semin Respir Infect 1999; 14:353–358.

- Chiller TM, Galgiani JN, Stevens DA. Coccidioidomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2003; 17:41–57.

- Drutz DJ, Catanzaro A. Coccidioidomycosis. Part II. Am Rev Respir Dis 1978; 117:727–771.

- Fish DG, Ampel NM, Galgiani JN, et al. Coccidioidomycosis during human immunodeficiency virus infection. A review of 77 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1990; 69:384–391.

- Mischel PS, Vinters HV. Coccidioidomycosis of the central nervous system: neuropathological and vasculopathic manifestations and clinical correlates. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 20:400–405.

- Johnson RH, Einstein HE. Coccidioidal meningitis. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42:103–107.

- Vincent T, Galgiani JN, Huppert M, Salkin D. The natural history of coccidioidal meningitis: VA-Armed Forces cooperative studies, 1955–1958. Clin Infect Dis 1993; 16:247–254.

- Erly WK, Bellon RJ, Seeger JF, Carmody RF. MR imaging of acute coccidioidal meningitis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999; 20:509–514.

- Arsura EL, Johnson R, Penrose J, et al. Neuroimaging as a guide to predict outcomes for patients with coccidioidal meningitis. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 40:624–627.

- Tappero JW, Perkins BA, Wenger JD, Berger TG. Cutaneous manifestations of opportunistic infections in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Microbiol Rev 1995; 8:440–450.

- Catanzaro A, Galgiani JN, Levine BE, et al. Fluconazole in the treatment of chronic pulmonary and nonmeningeal disseminated coccidioidomycosis. NIAID Mycoses Study Group. Am J Med 1995; 98:249–256.

- Blair JE, Coakley B, Santelli AC, Hentz JG, Wengenack NL. Serologic testing for symptomatic coccidioidomycosis in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed hosts. Mycopathologia 2006; 162:317–324.

- Martins TB, Jaskowski TD, Mouritsen CL, Hill HR. Comparison of commercially available enzyme immunoassay with traditional serological tests for detection of antibodies to Coccidioides immitis. J Clin Microbiol 1995; 33:940–943.

- Vucicevic D, Blair JE, Binnicker MJ, et al. The utility of Coccidioides polymerase chain reaction testing in the clinical setting. Mycopathologia 2010; 170:345–351.

- Durkin M, Connolly P, Kuberski T, et al. Diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis with use of the Coccidioides antigen enzyme immunoassay. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 47:e69–e73.

A 37-year-old man presented to the emergency department with an 8-week history of a mildly productive cough and shortness of breath accompanied by high fevers, chills, and night sweats. He also had some nausea but no vomiting.

Four days earlier, he had been evaluated by his primary care physician, who prescribed a 14-day course of one double-strength trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole tablet (Bactrim DS) every 12 hours for presumed acute bronchitis, but his symptoms did not improve.

He was unemployed, living in Arizona, married with children. He denied any use of tobacco, alcohol, or injection drugs. On further questioning, he disclosed that he had unintentionally lost 30 pounds over the past 2 to 3 months and had been feeling tired.

When asked about his medical history, he revealed that he had been diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in 2008 and that recently he had not been taking his antiretroviral medication, a once-daily combination pill containing efavirenz, emtricitabine, and tenofovir (Atripla). He had no other significant medical history, and the only medication he was currently taking was the trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

On examination, his temperature was 38.7°C (101.7°F), blood pressure 109/68 mm Hg, heart rate 60 beats per minute, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 100% while breathing supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula at 2 L/min. He did not appear seriously ill.

Initial blood tests (Table 1) showed a normal white blood cell count, normal results on a complete metabolic panel, and a lactate dehydrogenase level of 539 IU/L (reference range 313–618). His serum lactate level was within normal limits.

HIV-specific tests performed on the second day of hospitalization showed extreme immunosuppression, with a CD4 count of 5 cells/μL (normal 326–1,404 cells/μL).

WHICH ORGANISM IS CAUSING HIS LUNG INFECTION?

1. Which of the following organisms is the least likely to be associated with this patient’s condition?

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- Pneumocystis jirovecii

- Coccidioides immitis

- Candida albicans

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Cytomegalovirus

Bacterial, fungal, and viral lung infections are common in HIV-infected patients, especially if they are not on antiretroviral therapy and their CD4 lymphocyte counts are low. Clues to the cause can be derived from the history, physical examination, and general laboratory studies. For instance, knowing where the patient lives and where he has travelled recently provides insight into exposure to endemic infectious agents.

The complete blood cell count with differential white blood cell count can help narrow the differential diagnosis but rarely helps exclude a possibility. Neutrophilia is common in bacterial infections. Lymphocytosis can be seen in tuberculosis, in fungal and viral infections, and, rarely, in hematologic malignancies. Eosinophilia can be seen in acute retroviral syndrome, fungal and helminthic infections, adrenal insufficiency, autoimmune disease, and lymphoma.

A caveat to these clues is that in severely immunocompromised hosts, like this man, diagnoses should not be excluded without firm evidence. This patient has severe, active immunosuppression, and only one of the six answer choices above is not a possible causative agent: C albicans rarely causes lung infection, even in immunocompromised people.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Tuberculosis can be the first manifestation of HIV infection. It can occur at any CD4 count, but as the count decreases, the risk of dissemination increases.1 Classic symptoms are fever, night sweats, hemoptysis, and weight loss.

The CD4 count also affects the radiographic presentation. If the count is higher than 350 cells/μL, then infiltration of the upper lobe is likely; if it is lower than 200 cells/μL, then middle, lower, miliary, and extrapulmonary manifestations are likely.1,2 Cavitation is less common in HIV-infected patients, but mediastinal adenopathy is more common.1

Definitive diagnosis is via sputum examination, blood culture, nucleic acid amplification, or microscopic study of biopsy specimens of affected tissues to look for acid-fast bacilli.1

Interferon-gamma-release assays such as the QuantiFERON test (Cellestis, Valencia, CA) or a tuberculin skin test can be used to check for latent tuberculosis infection. These tests can also provide evidence of active infection in the appropriate clinical context.3

Interferon-gamma-release assays have several advantages over skin testing: they are more sensitive (76% to 80%) and specific (97%); they do not give false-positive results in people who previously received bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine; they react only minimally to previous exposure to nontuberculous mycobacteria; and interpretation is not subject to interreader variability.4,5 However, concordance between skin testing and interferon-gamma-release assays is low. Therefore, either or both tests can be used if tuberculosis is strongly suspected, and a positive result on either test should prompt further workup.6,7

Of note, both tests may be affected by immunosuppression, making both susceptible to false-negative results as the CD4 count declines.3

In any case, a positive acid-fast bacillus smear, radiographic evidence of latent infection, or pulmonary symptoms should be presumed to represent active tuberculosis. In such a situation, directly observed treatment with the typical four-drug regimen—rifampin (Rifadin), isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (Myambutol)—is recommended while awaiting definitive results from culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.1

Pneumocystis jirovecii

P jirovecii was previously known as P carinii, and P jirovecii pneumonia is an AIDS-defining illness. Most cases occur when the CD4 count falls below 200 cells/μL.1 Symptoms, including a nonproductive cough, develop insidiously over days to weeks.

Physical examination may reveal inspiratory crackles; however, half of the time the physical examination is nondiagnostic. Oral candidiasis is a common coinfection. The lactate dehydrogenase level may be elevated.1,8 Radiographs show bilateral interstitial infiltrates, and in 10% to 20% of patients lung cysts develop—hence the name of the organism.1 Pneumothorax in a patient with HIV should prompt a workup for P jirovecii pneumonia.9,10

No consensus exists for the diagnosis. However, if sputum examination is unrevealing but suspicion is high, then bronchoalveolar lavage can help.11–13

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 21 days is the first-line treatment, with glucocorticoids added if the Pao2 is less than 70 mm Hg or if the alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient is greater than 35 mm Hg.1

Coccidioides species

Coccidioides infection is typically due to either C immitis or C posadasii.14 People living in or travelling to areas where it is endemic, such as the southwestern United States, Mexico, and Central and South America, are at higher risk.14

Typical signs and symptoms of this fungal infection include an influenza-like illness with fever, cough, adenopathy, and wasting, and when combined with erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, arthralgia, or ocular involvement, this constellation is colloquially termed “valley fever.”15 Most HIV-infected patients who have CD4 counts higher than 250 cells/μL present with focal pneumonia, while lower counts predispose to disseminated disease.1,2,16

Findings on examination are nonspecific and depend on the various pulmonary manifestations, which include acute, chronic progressive, or diffuse pneumonia, nodules, or cavities.14 Eosinophilia may accompany the infection.15

The diagnosis can be made by finding the organisms on direct microscopic examination of involved tissues or secretions or on culture of clinical specimens.1,2,14 Serologic tests, antigen detection tests, or culture can be helpful if positive, but negative results do not rule out the diagnosis.1,2,14

A caveat about testing: if the pretest probability of infection is low, positive tests for immunoglobulin M (IgM) do not necessarily equal infection, and the IgM test should be followed up with confirmatory testing. Along the same lines, a high pretest probability should not be ignored if initial tests are negative, and patients in this situation should also undergo further evaluation.17

Therapy with an azole drug such as fluconazole (Diflucan) or one of the amphotericin B preparations should be started, depending on the severity of the disease.1,2,14,18

Candida albicans

C albicans is a rare cause of lung infection.19,20 It is, however, a common inhabitant of the upper airway tract, and pulmonary infection is usually the result of aspiration or hematogenous spread from either the gastrointestinal tract or an infected central venous catheter.20

The presentation is relatively nonspecific. Fever despite broad-spectrum antibacterial therapy is a major clue. Radiographic abnormalities usually are due to other causes, such as superimposed infections or pulmonary hemorrhage.21 Sputum culture is unreliable because of colonization. The definitive diagnosis is based on lung biopsy demonstrating organisms within the tissue.19,20,22

Therapy with a systemic antifungal agent is recommended.

Streptococcus pneumoniae

S pneumoniae is one of the most common bacterial causes of community-acquired pneumonia in people with or without HIV.23–25 Moreover, two or more episodes of bacterial pneumonia in 12 months can be an AIDS-defining condition in patients with a positive serologic test for HIV.16 Therefore, in patients with fever, cough, and pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiography, S pneumoniae must always be considered.

Urinary antigen testing has a relatively high positive predictive value (> 89%) and specificity (96%) for diagnosing S pneumoniae pneumonia.26 Blood and sputum cultures should be done not only to confirm the diagnosis, but also because the rates of bacteremia and drug resistance are higher with S pneumoniae infection in the HIV-infected.1

A combination of a beta-lactam and a macrolide or respiratory fluoroquinolone is the treatment of choice.1

Cytomegalovirus

Although influenza is the most common cause of viral pneumonia in HIV-infected people, cytomegalovirus is an opportunistic cause.2 This is usually a reactivation of latent infection rather than new infection.27 Typically, infections occur at CD4 counts lower than 50 cells/μL, with cough, dyspnea, and fever that last for 2 to 4 weeks.2

Crackles may be heard on lung examination. The lactate dehydrogenase level can be elevated, as in P jirovecii pneumonia.2 Radiography can show a wide range of nonspecific findings, from reticular and ground-glass opacities to alveolar or interstitial infiltrates to nodules.

The diagnosis of cytomegalovirus pneumonia is not always clear. Since HIV-infected patients typically shed the virus in their airways, bronchoalveolar lavage is not adequate because a positive finding does not necessarily mean the patient has active viral pneumonitis.27 For this reason, infection should be confirmed by biopsy demonstrating characteristic cytomegalovirus inclusions in lung tissue.2

Importantly, once cytomegalovirus pneumonia is confirmed, the patient should be screened for cytomegalovirus retinitis even if he or she has no visual symptoms, as cytomegalovirus pneumonitis is typically a part of a disseminated infection.1

Treatment with intravenous ganciclovir (Cytovene) is required.1

CASE CONTINUED: POSITIVE TESTS FOR COCCIDIOIDES

Our patient began empiric treatment for community-acquired pneumonia with intravenous ceftriaxone (Rocephin) and azithromycin (Zithromax).

On the basis of these findings, the patient was immediately placed in negative pressure respiratory isolation and underwent induced sputum examinations for tuberculosis. Further tests for S pneumoniae, S aureus, Mycoplasma, Legionella, influenza, Pneumocystis, Cryptococcus, Histoplasma, and Coccidioides species were performed.

QuantiFERON testing was negative, and blood cultures were sterile. The first induced sputum examination was negative for acid-fast bacilli. PCR testing for mycobacterial DNA in the sputum was also negative.

Both silver and direct fluorescent antibody staining of the sputum were negative for Pneumocystis. On the basis of these findings and the patient’s lack of clinical improvement with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, Pneumocystis infection was excluded.

THE PATIENT BEGINS TREATMENT

2. Which treatment is most appropriate for this patient?

- Posaconazole (Noxafil)

- Caspofungin (Cancidas) and surgery

- Fluconazole

- Voriconazole (Vfend) and surgery

- Amphotericin B

Solitary pulmonary cavities tend to be asymptomatic and do not require treatment, even if coccidioidal infection is microbiologically confirmed.

However, if there is pain, hemoptysis, or bacterial superinfection, antifungal therapy may result in improvement but not closure of the cavity.18 Therefore, in all cases of symptomatic coccidioidal pulmonary cavities, surgical resection is the only definitive treatment.

Coccidioidal cavities may rupture and cause pyopneumothorax, but this is an infrequent complication, and antifungal therapy combined with surgical decortication is the treatment of choice.18

Commonly prescribed antifungals include fluconazole and amphotericin B, the latter usually reserved for patients with significant hypoxia or rapid clinical deterioration.18 At this time, there are not enough clinical data to show that voriconazole or posaconazole is effective, and thus neither is approved for the treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Likewise, there have been no human trials of the efficacy of caspofungin against Coccidioides infection, although it has been shown to be active in mouse models.18

Our patient was started on oral fluconazole and observed for clinical improvement or, conversely, for signs of dissemination. After 2 days, he had markedly improved, and within 1 week he was almost back to his baseline level of health. Testing for all other infectious etiologies was unrevealing, and he was removed from negative pressure isolation.

However, as we mentioned above, his CD4 count was 5 cells/μL. We discussed the issue with the patient, and he said he was willing to comply with his treatment for both his Coccidioides and his HIV infection. After much deliberation, he said he was also willing to start and comply with prophylactic treatment for opportunistic infections.

PREVENTING OPPORTUNISTIC INFECTIONS IN HIV PATIENTS

3. Which of the following prophylactic regimens is most appropriate for this patient?

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, atovaquone (Mepron), and azithromycin

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and azithromycin

- Pentamidine (Nebupent), dapsone, and clarithromycin (Biaxin)

- Dapsone and clarithromycin

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole by itself

According to guidelines for the prevention of opportunistic diseases in patients with HIV, he needs primary prophylaxis against the following organisms: P jirovecii, Toxoplasma gondii, and Mycobacterium avium complex.1

The CD4 count dictates the appropriate time to start therapy. If the count is lower than 200 cells/μL or if the patient has oropharyngeal candidiasis regardless of the CD4 count, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is indicated to prevent P jirovecii pneumonia. In those who cannot tolerate trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or who are allergic to it, dapsone, pentamidine, or atovaquone can be substituted.1

In patients seropositive for T gondii, a CD4 count lower than 100/μL indicates the need for prophylaxis.1 Prophylactic measures are similar to those for Pneumocystis. However, if the patient cannot tolerate trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, the recommended alternative is dapsone-pyrimethamine with leucovorin, which is also effective against Pneumocystis.1

Finally, if the CD4 count is lower than 50 cells/μL, prophylaxis against M avium complex is mandatory, with either azithromycin weekly or clarithromycin daily.1

Given our patient’s degree of immunosuppression, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole plus azithromycin is his most appropriate option.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and azithromycin were added to his antimicrobial regimen before he was discharged. Two weeks later, he noted no side effects from any of the medications, he had no new symptoms, he was feeling well, and his cough had improved greatly. He did not have any signs of dissemination of his coccidioidal infection, and we concluded that the primary and only infection was located in the lungs.

DISSEMINATED COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS

4. Which of the following extrapulmonary sites is Coccidioides least likely to infect?

- Brain

- Skin

- Meninges

- Lymph nodes

- Bones

- Joints

Extrapulmonary coccidioidomycosis can involve almost any site. However, the most common sites of dissemination are the skin, lymph nodes, bones, and joints.14 The least likely site is the brain.

Central nervous system involvement

In the central nervous system, involvement is typically with the meninges, rather than frank involvement of the brain parenchyma.18,28,29 Although patients with HIV or those who are otherwise severely immunocompromised are at higher risk for coccidioidal meningitis, it is rare even in this population.30,31 Meningitis most commonly presents as headache, vomiting, meningismus, confusion, or diplopia.32,33

If neurologic findings are absent, experts do not generally recommend lumbar puncture because the incidence of meningeal involvement is low. When cerebrospinal fluid is obtained in an active case of coccidioidal meningitis, fluid analysis typically finds elevated protein, low glucose, and lymphocytic pleocytosis.1,32

Meningeal enhancement on CT or magnetic resonance imaging is common.34 The diagnosis is established by culture or serologic testing of cerebrospinal fluid (IgM titer, IgG titer, immunodiffusion, or complement fixation).14

Of note, cerebral infarction and hydrocephalus are feared complications and pose a serious risk of death in any patient.32,35 In these cases, treatment with antifungals is lifelong, regardless of immune system status.18

Skin involvement

Skin involvement is variable, consisting of nodules, verrucae, abscesses, or ulcerations.15,16 Hemorrhage from the skin is relatively common.36 From the skin, the infection can spread to the lymph nodes, leading to regional lymphadenopathy.14,15 Nodes can ulcerate, drain, or even become necrotic.

Bone and joint involvement

Once integrity of the blood vessels is disrupted, Coccidioides can spread via the blood to the bones or joints,14,15 causing osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, or synovitis. Subcutaneous abscesses or sinus tracts may subsequently develop.14,15

HOW LONG MUST HE BE TREATED?

On follow-up, the patient asked how long he needed to continue his antifungal regimen and if any other testing for his coccidioidal infection was necessary, since he was feeling better.

5. Which is the most appropriate response to the patient’s question?

- He can discontinue his antifungal drugs; no further testing is necessary

- He needs 14 more days of antifungal therapy and periodic serologic tests

- He needs 2.5 more months of antifungal therapy and monthly blood cultures

- He needs lifelong antifungal therapy and periodic urinary antigen levels