User login

Zinc oxide

Zinc is a trace element, and it is not synthesized by the human body. The element was identified in the 1960s as being essential for human health and development. Zinc is a cofactor in more than 300 enzymes necessary for cell function. In the dermatologic realm, zinc deficiency has been associated with skin alterations, delayed wound healing, and hair loss.

Zinc oxide (ZnO) is a metal oxide that also has a broad profile in dermatology. It is perhaps best known as a physical sunscreen ingredient. ZnO and titanium dioxide (TiO2) have long been used in this manner. Both ZnO and TiO2 also have been increasingly used to replace large-particle compounds in numerous cosmetics and sunscreens. These two compounds have demonstrated effective protection against UV-induced damage, providing stronger protection against UV radiation while leaving less white residue than previous generations of physical sunscreens.

Particles of ZnO in earlier sunscreens were found to be too large to penetrate the stratum corneum and, thus, were deemed biologically inactive (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1999;40:85-90). However, in novel nanoparticle form, such metal oxides absorb UV radiation, leading to photocatalysis and the release of reactive oxygen species (Australas. J. Dermatol. 2011;52:1-6). Indeed, nanoparticles exhibit new physiochemical properties as a result of increased surface area as compared to large-form products, and the potential adverse effects of the novel nanoparticle formulations in sunscreens cannot be adequately extrapolated from the effects of older-generation larger-particle skin care products (J. Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:475-81; Int. J. Dermatol. 2011;50:247-54. The relative safety of ZnO nanoparticles will be discussed in a future column. The focus in this column will be a brief comparison with TiO2 and other indications for ZnO.

ZnO and TiO2

While numerous studies explore both TiO2 and ZnO, the latter is noted for greater versatility within the dermatologic armamentarium. In addition, ZnO is less photoactive and is associated with a lower refractive index in visible light than TiO2 (1.9 vs. 2.6, respectively) (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1999;40:85-90); therefore, TiO2 appears whiter and is more difficult to incorporate into transparent products.

Another important difference is the spectrum of action. That is, only avobenzone (butyl methoxydibenzoylmethane) and ZnO are approved in the United States for broad-spectrum protection against UVA wavelengths greater than 360 nm, because TiO2 has been shown to be effective only against UV wavelengths less than 360 nm (UVA is 320-400 nm). In a study by Beasley and Meyer, TiO2 delivered neither the same level of UVA attenuation nor protection from UVA to human skin as did photostabilized formulations of avobenzone or ZnO. Therefore, TiO2 is not a suitable substitute for avobenzone and ZnO for strong UVA protection (Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2010;11:413-21).

Indications beyond photoprotection

More than 20 years ago, Hughes and McLean showed that a ZnO tape was effective in dressing fingertip and soft tissue injuries that were resistant to healing (Arch. Emerg. Med. 1988;5:223-7). More recently, Parboteeah and Brown demonstrated the efficacy of treating recalcitrant venous leg ulcers with ZnO paste bandages (Br. J. Nurs. 2008;17:S30, S32, S34-6). In addition, Treadwell has shown that the weekly application of ZnO compression dressings to surgical wounds of the lower leg promotes healing (Dermatol. Surg. 2011;37:166-7).

Micronized zinc oxide is included in a 4% hydroquinone/10% L-ascorbic acid treatment system recently found (in a small study of 34 females) to be effective in alleviating early signs of photodamage in normal to oily skin. Thirty patients, with minimal or mild facial photodamage and hyperpigmentation, completed the 12-week treatment regimen. All the participants were satisfied with the appearance of their skin after the study, with median scores for all assessment parameters significantly improved compared with baseline (J. Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1455-61). ZnO also is an active ingredient in formulations intended to support the healing of perianal eczema (Hautarzt. 2010;61:33-8).

A 2001 report on a series of blinded, randomized clinical trials conducted by Baldwin et al. showed that clinical benefits were derived from the continuous topical administration of a ZnO/petrolatum formulation in a diaper introduced at that time. The first study was undertaken to verify that the ZnO/petrolatum formulation was indeed transferred from the diaper to the child’s skin. Stratum corneum (SC) samples were analyzed from each child after the wearing of a single diaper for 3 hours or multiple diapers for 24 hours. The results indicated effective transfer, with ZnO increasing in the SC from 4.2 mcg/cm2 at 3 hours to more than 8 mcg/cm2 at 24 hours.

The second study of the formulation, in an adult arm model, assessed the prevention of irritation and SC damage induced by sodium laureth sulfate. The investigators found that the ZnO/petrolatum combination yielded significant reductions in SC damage and erythema. The third study, a 4-week trial in which 268 infants were assessed, considered the effects of the formulation on erythema and diaper rash. Half of the infants wore the test diaper and half used a control diaper lacking the ZnO/petrolatum product. Significant reductions in erythema and diaper rash were indeed observed in the test group (J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2001;15 Suppl 1:5-11).

A 2009 study showed that an unmedicated ZnO/petrolatum paste was effective in restoring the properties of the skin, allowing for balanced transepidermal water loss and water retention by SC previously compromised by diaper dermatitis. This skin condition affects approximately 50% of infants and a small percentage of the bedridden elderly (Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2009;31:369-74).

In 2010, a study that assessed the effectiveness of topical ZnO ointment using the rabbit ear hypertrophic scar model showed that the application of 40% ZnO significantly reduced clinical scar hypertrophy scores at 6 weeks compared with placebo. The researchers concluded that these results may suggest clinical applications for ZnO in the treatment of hypertrophic scars in humans (Burns 2010;36:1027-35). In addition, ZnO has demonstrated antibacterial properties, with nanoparticles exhibiting more potent antibacterial activity than bulk ZnO (Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2008;9:1-7).

Products

ZnO is a key ingredient in calamine lotion, an antipruritic compound used to treat various mild conditions such as bites and stings from insects, eczema, poison ivy, rashes, and sunburn. It is also available over the counter in ointment or suppository form for healing hemorrhoids and fissures. In addition, ZnO is used widely in baby powders, barrier creams, moisturizers, antiseptic ointments, antidandruff shampoos, athletic bandage tape, and, of course, sunscreens.

Conclusion

ZnO is a versatile inorganic metal oxide with multiple indications in dermatology. Consequently, it is included in a wide array of skin care products, including shampoos, moisturizers, and sunscreens. Its use in nanoparticle form, along with the similar use of its physical sunscreen counterpart TiO2, represents one of the many subjects debated within the larger context of sunscreen use. The next edition of this column will focus on the relative safety of zinc oxide nanoparticles.

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in Miami Beach. She founded the cosmetic dermatology center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook "Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice" (McGraw-Hill, April 2002), and a book for consumers, "The Skin Type Solution" (Bantam, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2001 and joined the editorial advisory board in 2004. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Galderma, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy, Stiefel, Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

This column, "Cosmeceutical Critique," appears regularly in Skin & Allergy News, a publication of Frontline Medical News.

Zinc is a trace element, and it is not synthesized by the human body. The element was identified in the 1960s as being essential for human health and development. Zinc is a cofactor in more than 300 enzymes necessary for cell function. In the dermatologic realm, zinc deficiency has been associated with skin alterations, delayed wound healing, and hair loss.

Zinc oxide (ZnO) is a metal oxide that also has a broad profile in dermatology. It is perhaps best known as a physical sunscreen ingredient. ZnO and titanium dioxide (TiO2) have long been used in this manner. Both ZnO and TiO2 also have been increasingly used to replace large-particle compounds in numerous cosmetics and sunscreens. These two compounds have demonstrated effective protection against UV-induced damage, providing stronger protection against UV radiation while leaving less white residue than previous generations of physical sunscreens.

Particles of ZnO in earlier sunscreens were found to be too large to penetrate the stratum corneum and, thus, were deemed biologically inactive (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1999;40:85-90). However, in novel nanoparticle form, such metal oxides absorb UV radiation, leading to photocatalysis and the release of reactive oxygen species (Australas. J. Dermatol. 2011;52:1-6). Indeed, nanoparticles exhibit new physiochemical properties as a result of increased surface area as compared to large-form products, and the potential adverse effects of the novel nanoparticle formulations in sunscreens cannot be adequately extrapolated from the effects of older-generation larger-particle skin care products (J. Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:475-81; Int. J. Dermatol. 2011;50:247-54. The relative safety of ZnO nanoparticles will be discussed in a future column. The focus in this column will be a brief comparison with TiO2 and other indications for ZnO.

ZnO and TiO2

While numerous studies explore both TiO2 and ZnO, the latter is noted for greater versatility within the dermatologic armamentarium. In addition, ZnO is less photoactive and is associated with a lower refractive index in visible light than TiO2 (1.9 vs. 2.6, respectively) (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1999;40:85-90); therefore, TiO2 appears whiter and is more difficult to incorporate into transparent products.

Another important difference is the spectrum of action. That is, only avobenzone (butyl methoxydibenzoylmethane) and ZnO are approved in the United States for broad-spectrum protection against UVA wavelengths greater than 360 nm, because TiO2 has been shown to be effective only against UV wavelengths less than 360 nm (UVA is 320-400 nm). In a study by Beasley and Meyer, TiO2 delivered neither the same level of UVA attenuation nor protection from UVA to human skin as did photostabilized formulations of avobenzone or ZnO. Therefore, TiO2 is not a suitable substitute for avobenzone and ZnO for strong UVA protection (Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2010;11:413-21).

Indications beyond photoprotection

More than 20 years ago, Hughes and McLean showed that a ZnO tape was effective in dressing fingertip and soft tissue injuries that were resistant to healing (Arch. Emerg. Med. 1988;5:223-7). More recently, Parboteeah and Brown demonstrated the efficacy of treating recalcitrant venous leg ulcers with ZnO paste bandages (Br. J. Nurs. 2008;17:S30, S32, S34-6). In addition, Treadwell has shown that the weekly application of ZnO compression dressings to surgical wounds of the lower leg promotes healing (Dermatol. Surg. 2011;37:166-7).

Micronized zinc oxide is included in a 4% hydroquinone/10% L-ascorbic acid treatment system recently found (in a small study of 34 females) to be effective in alleviating early signs of photodamage in normal to oily skin. Thirty patients, with minimal or mild facial photodamage and hyperpigmentation, completed the 12-week treatment regimen. All the participants were satisfied with the appearance of their skin after the study, with median scores for all assessment parameters significantly improved compared with baseline (J. Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1455-61). ZnO also is an active ingredient in formulations intended to support the healing of perianal eczema (Hautarzt. 2010;61:33-8).

A 2001 report on a series of blinded, randomized clinical trials conducted by Baldwin et al. showed that clinical benefits were derived from the continuous topical administration of a ZnO/petrolatum formulation in a diaper introduced at that time. The first study was undertaken to verify that the ZnO/petrolatum formulation was indeed transferred from the diaper to the child’s skin. Stratum corneum (SC) samples were analyzed from each child after the wearing of a single diaper for 3 hours or multiple diapers for 24 hours. The results indicated effective transfer, with ZnO increasing in the SC from 4.2 mcg/cm2 at 3 hours to more than 8 mcg/cm2 at 24 hours.

The second study of the formulation, in an adult arm model, assessed the prevention of irritation and SC damage induced by sodium laureth sulfate. The investigators found that the ZnO/petrolatum combination yielded significant reductions in SC damage and erythema. The third study, a 4-week trial in which 268 infants were assessed, considered the effects of the formulation on erythema and diaper rash. Half of the infants wore the test diaper and half used a control diaper lacking the ZnO/petrolatum product. Significant reductions in erythema and diaper rash were indeed observed in the test group (J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2001;15 Suppl 1:5-11).

A 2009 study showed that an unmedicated ZnO/petrolatum paste was effective in restoring the properties of the skin, allowing for balanced transepidermal water loss and water retention by SC previously compromised by diaper dermatitis. This skin condition affects approximately 50% of infants and a small percentage of the bedridden elderly (Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2009;31:369-74).

In 2010, a study that assessed the effectiveness of topical ZnO ointment using the rabbit ear hypertrophic scar model showed that the application of 40% ZnO significantly reduced clinical scar hypertrophy scores at 6 weeks compared with placebo. The researchers concluded that these results may suggest clinical applications for ZnO in the treatment of hypertrophic scars in humans (Burns 2010;36:1027-35). In addition, ZnO has demonstrated antibacterial properties, with nanoparticles exhibiting more potent antibacterial activity than bulk ZnO (Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2008;9:1-7).

Products

ZnO is a key ingredient in calamine lotion, an antipruritic compound used to treat various mild conditions such as bites and stings from insects, eczema, poison ivy, rashes, and sunburn. It is also available over the counter in ointment or suppository form for healing hemorrhoids and fissures. In addition, ZnO is used widely in baby powders, barrier creams, moisturizers, antiseptic ointments, antidandruff shampoos, athletic bandage tape, and, of course, sunscreens.

Conclusion

ZnO is a versatile inorganic metal oxide with multiple indications in dermatology. Consequently, it is included in a wide array of skin care products, including shampoos, moisturizers, and sunscreens. Its use in nanoparticle form, along with the similar use of its physical sunscreen counterpart TiO2, represents one of the many subjects debated within the larger context of sunscreen use. The next edition of this column will focus on the relative safety of zinc oxide nanoparticles.

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in Miami Beach. She founded the cosmetic dermatology center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook "Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice" (McGraw-Hill, April 2002), and a book for consumers, "The Skin Type Solution" (Bantam, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2001 and joined the editorial advisory board in 2004. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Galderma, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy, Stiefel, Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

This column, "Cosmeceutical Critique," appears regularly in Skin & Allergy News, a publication of Frontline Medical News.

Zinc is a trace element, and it is not synthesized by the human body. The element was identified in the 1960s as being essential for human health and development. Zinc is a cofactor in more than 300 enzymes necessary for cell function. In the dermatologic realm, zinc deficiency has been associated with skin alterations, delayed wound healing, and hair loss.

Zinc oxide (ZnO) is a metal oxide that also has a broad profile in dermatology. It is perhaps best known as a physical sunscreen ingredient. ZnO and titanium dioxide (TiO2) have long been used in this manner. Both ZnO and TiO2 also have been increasingly used to replace large-particle compounds in numerous cosmetics and sunscreens. These two compounds have demonstrated effective protection against UV-induced damage, providing stronger protection against UV radiation while leaving less white residue than previous generations of physical sunscreens.

Particles of ZnO in earlier sunscreens were found to be too large to penetrate the stratum corneum and, thus, were deemed biologically inactive (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1999;40:85-90). However, in novel nanoparticle form, such metal oxides absorb UV radiation, leading to photocatalysis and the release of reactive oxygen species (Australas. J. Dermatol. 2011;52:1-6). Indeed, nanoparticles exhibit new physiochemical properties as a result of increased surface area as compared to large-form products, and the potential adverse effects of the novel nanoparticle formulations in sunscreens cannot be adequately extrapolated from the effects of older-generation larger-particle skin care products (J. Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:475-81; Int. J. Dermatol. 2011;50:247-54. The relative safety of ZnO nanoparticles will be discussed in a future column. The focus in this column will be a brief comparison with TiO2 and other indications for ZnO.

ZnO and TiO2

While numerous studies explore both TiO2 and ZnO, the latter is noted for greater versatility within the dermatologic armamentarium. In addition, ZnO is less photoactive and is associated with a lower refractive index in visible light than TiO2 (1.9 vs. 2.6, respectively) (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1999;40:85-90); therefore, TiO2 appears whiter and is more difficult to incorporate into transparent products.

Another important difference is the spectrum of action. That is, only avobenzone (butyl methoxydibenzoylmethane) and ZnO are approved in the United States for broad-spectrum protection against UVA wavelengths greater than 360 nm, because TiO2 has been shown to be effective only against UV wavelengths less than 360 nm (UVA is 320-400 nm). In a study by Beasley and Meyer, TiO2 delivered neither the same level of UVA attenuation nor protection from UVA to human skin as did photostabilized formulations of avobenzone or ZnO. Therefore, TiO2 is not a suitable substitute for avobenzone and ZnO for strong UVA protection (Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2010;11:413-21).

Indications beyond photoprotection

More than 20 years ago, Hughes and McLean showed that a ZnO tape was effective in dressing fingertip and soft tissue injuries that were resistant to healing (Arch. Emerg. Med. 1988;5:223-7). More recently, Parboteeah and Brown demonstrated the efficacy of treating recalcitrant venous leg ulcers with ZnO paste bandages (Br. J. Nurs. 2008;17:S30, S32, S34-6). In addition, Treadwell has shown that the weekly application of ZnO compression dressings to surgical wounds of the lower leg promotes healing (Dermatol. Surg. 2011;37:166-7).

Micronized zinc oxide is included in a 4% hydroquinone/10% L-ascorbic acid treatment system recently found (in a small study of 34 females) to be effective in alleviating early signs of photodamage in normal to oily skin. Thirty patients, with minimal or mild facial photodamage and hyperpigmentation, completed the 12-week treatment regimen. All the participants were satisfied with the appearance of their skin after the study, with median scores for all assessment parameters significantly improved compared with baseline (J. Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1455-61). ZnO also is an active ingredient in formulations intended to support the healing of perianal eczema (Hautarzt. 2010;61:33-8).

A 2001 report on a series of blinded, randomized clinical trials conducted by Baldwin et al. showed that clinical benefits were derived from the continuous topical administration of a ZnO/petrolatum formulation in a diaper introduced at that time. The first study was undertaken to verify that the ZnO/petrolatum formulation was indeed transferred from the diaper to the child’s skin. Stratum corneum (SC) samples were analyzed from each child after the wearing of a single diaper for 3 hours or multiple diapers for 24 hours. The results indicated effective transfer, with ZnO increasing in the SC from 4.2 mcg/cm2 at 3 hours to more than 8 mcg/cm2 at 24 hours.

The second study of the formulation, in an adult arm model, assessed the prevention of irritation and SC damage induced by sodium laureth sulfate. The investigators found that the ZnO/petrolatum combination yielded significant reductions in SC damage and erythema. The third study, a 4-week trial in which 268 infants were assessed, considered the effects of the formulation on erythema and diaper rash. Half of the infants wore the test diaper and half used a control diaper lacking the ZnO/petrolatum product. Significant reductions in erythema and diaper rash were indeed observed in the test group (J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2001;15 Suppl 1:5-11).

A 2009 study showed that an unmedicated ZnO/petrolatum paste was effective in restoring the properties of the skin, allowing for balanced transepidermal water loss and water retention by SC previously compromised by diaper dermatitis. This skin condition affects approximately 50% of infants and a small percentage of the bedridden elderly (Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2009;31:369-74).

In 2010, a study that assessed the effectiveness of topical ZnO ointment using the rabbit ear hypertrophic scar model showed that the application of 40% ZnO significantly reduced clinical scar hypertrophy scores at 6 weeks compared with placebo. The researchers concluded that these results may suggest clinical applications for ZnO in the treatment of hypertrophic scars in humans (Burns 2010;36:1027-35). In addition, ZnO has demonstrated antibacterial properties, with nanoparticles exhibiting more potent antibacterial activity than bulk ZnO (Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2008;9:1-7).

Products

ZnO is a key ingredient in calamine lotion, an antipruritic compound used to treat various mild conditions such as bites and stings from insects, eczema, poison ivy, rashes, and sunburn. It is also available over the counter in ointment or suppository form for healing hemorrhoids and fissures. In addition, ZnO is used widely in baby powders, barrier creams, moisturizers, antiseptic ointments, antidandruff shampoos, athletic bandage tape, and, of course, sunscreens.

Conclusion

ZnO is a versatile inorganic metal oxide with multiple indications in dermatology. Consequently, it is included in a wide array of skin care products, including shampoos, moisturizers, and sunscreens. Its use in nanoparticle form, along with the similar use of its physical sunscreen counterpart TiO2, represents one of the many subjects debated within the larger context of sunscreen use. The next edition of this column will focus on the relative safety of zinc oxide nanoparticles.

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in Miami Beach. She founded the cosmetic dermatology center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook "Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice" (McGraw-Hill, April 2002), and a book for consumers, "The Skin Type Solution" (Bantam, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2001 and joined the editorial advisory board in 2004. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Galderma, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy, Stiefel, Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

This column, "Cosmeceutical Critique," appears regularly in Skin & Allergy News, a publication of Frontline Medical News.

The personal dimension of informed consent

Recently, a medical student assigned to my service spent a day in the outpatient office seeing patients with me. After seeing two consecutive patients who needed thyroidectomies, this student commented on the differences in how I obtained informed consent for thyroidectomy from the two patients. Why, she asked, had I spent relatively little time emphasizing the risks of the operation with one patient and so much more time discussing risks with the second patient?

In order to understand why there appeared to be such a dramatic difference between the discussions with the two patients, it is helpful to understand the different indications for surgery. The first patient had recently been diagnosed with a 2.3-cm papillary thyroid cancer. I had explained that the first step in the treatment was to remove the thyroid, and I detailed the risks to the recurrent laryngeal nerves and the parathyroid glands.

The second patient had been treated for Graves’ disease for the last 3 years. She had many cycles of hyper- and hypothyroidism and had now decided that she needed definitive treatment. Although she had discussed the option of radioactive iodine with her endocrinologist, she had a significant fear of radiation and also was hoping to become pregnant in the next several months. I had discussed the risks of thyroidectomy with this patient. However, even though the risk I quoted of having a complication from the thyroidectomy was just the same as in the first case, I deliberately spent more time discussing the ramifications of the complications and the alternatives with the second patient.

My student was initially perplexed by this description. As she correctly stated, if the risks are the same for the same operation between the two patients, why emphasize the risks so much more for the second patient, compared with the first?

To most surgeons, the reason for this difference is clear. The first patient needed to know the risks, but there were few options to total thyroidectomy as the initial step in the treatment. The second patient had the clear option of getting radioactive iodine instead of surgery. Although the risks of the surgical procedure are the same with the two operations, I felt that the second patient needed to clearly understand the alternative to surgery and to fully consider the implications of the potential complications should one occur in her case.

As I think back over this interchange with my student, it is clear that the informed consent discussion for any operation cannot be fully standardized for every patient. Even if the risks remain the same, the indications for surgery are different and, of course, the patients are different.

More than 30 years ago, Dr. C. Rollins Hanlon, then executive director of the American College of Surgeons wrote, "Both ethics and surgery are inexact disciplines, in definition, practice, and in relation to one another." The more years I have been in practice, the more I am convinced of the truth of these words. Although my two patients both needed the same operation, it was important for me to emphasize the choices that the second patient had. In so doing, I felt it was essential to ensure that in evaluating the choices, the patient fully understood the implications of the risks. Although the patient with thyroid cancer had the same risks of the procedure, she did not have a good alternative choice to surgery. The difference between these two patients, and in how I altered my discussions of the proposed thyroidectomy, reveal the personal dimension of informed consent that goes beyond a simple statement of risks.

In obtaining informed consent from my patients, I should be providing them with much more than "just the facts." Patients can (and often do) obtain the data about the risks of surgical procedures from the Internet prior to seeing me. I believe that I should be giving them something more than they could obtain from reading about the risks of a procedure. I should provide them with a context in which to consider the risks, relative to their particular condition. Even small risks may be very significant if there are alternatives that have no risks. In contrast, patients often quickly agree to high-risk operations when there is no good nonoperative alternative. As surgeons, we must be cognizant of the critical personal dimension of the informed consent process and thereby be sure to put the discussion of risks in the appropriate context to help our patients make good decisions.

Dr. Angelos is an ACS Fellow; the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics; chief, endocrine surgery; and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

Recently, a medical student assigned to my service spent a day in the outpatient office seeing patients with me. After seeing two consecutive patients who needed thyroidectomies, this student commented on the differences in how I obtained informed consent for thyroidectomy from the two patients. Why, she asked, had I spent relatively little time emphasizing the risks of the operation with one patient and so much more time discussing risks with the second patient?

In order to understand why there appeared to be such a dramatic difference between the discussions with the two patients, it is helpful to understand the different indications for surgery. The first patient had recently been diagnosed with a 2.3-cm papillary thyroid cancer. I had explained that the first step in the treatment was to remove the thyroid, and I detailed the risks to the recurrent laryngeal nerves and the parathyroid glands.

The second patient had been treated for Graves’ disease for the last 3 years. She had many cycles of hyper- and hypothyroidism and had now decided that she needed definitive treatment. Although she had discussed the option of radioactive iodine with her endocrinologist, she had a significant fear of radiation and also was hoping to become pregnant in the next several months. I had discussed the risks of thyroidectomy with this patient. However, even though the risk I quoted of having a complication from the thyroidectomy was just the same as in the first case, I deliberately spent more time discussing the ramifications of the complications and the alternatives with the second patient.

My student was initially perplexed by this description. As she correctly stated, if the risks are the same for the same operation between the two patients, why emphasize the risks so much more for the second patient, compared with the first?

To most surgeons, the reason for this difference is clear. The first patient needed to know the risks, but there were few options to total thyroidectomy as the initial step in the treatment. The second patient had the clear option of getting radioactive iodine instead of surgery. Although the risks of the surgical procedure are the same with the two operations, I felt that the second patient needed to clearly understand the alternative to surgery and to fully consider the implications of the potential complications should one occur in her case.

As I think back over this interchange with my student, it is clear that the informed consent discussion for any operation cannot be fully standardized for every patient. Even if the risks remain the same, the indications for surgery are different and, of course, the patients are different.

More than 30 years ago, Dr. C. Rollins Hanlon, then executive director of the American College of Surgeons wrote, "Both ethics and surgery are inexact disciplines, in definition, practice, and in relation to one another." The more years I have been in practice, the more I am convinced of the truth of these words. Although my two patients both needed the same operation, it was important for me to emphasize the choices that the second patient had. In so doing, I felt it was essential to ensure that in evaluating the choices, the patient fully understood the implications of the risks. Although the patient with thyroid cancer had the same risks of the procedure, she did not have a good alternative choice to surgery. The difference between these two patients, and in how I altered my discussions of the proposed thyroidectomy, reveal the personal dimension of informed consent that goes beyond a simple statement of risks.

In obtaining informed consent from my patients, I should be providing them with much more than "just the facts." Patients can (and often do) obtain the data about the risks of surgical procedures from the Internet prior to seeing me. I believe that I should be giving them something more than they could obtain from reading about the risks of a procedure. I should provide them with a context in which to consider the risks, relative to their particular condition. Even small risks may be very significant if there are alternatives that have no risks. In contrast, patients often quickly agree to high-risk operations when there is no good nonoperative alternative. As surgeons, we must be cognizant of the critical personal dimension of the informed consent process and thereby be sure to put the discussion of risks in the appropriate context to help our patients make good decisions.

Dr. Angelos is an ACS Fellow; the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics; chief, endocrine surgery; and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

Recently, a medical student assigned to my service spent a day in the outpatient office seeing patients with me. After seeing two consecutive patients who needed thyroidectomies, this student commented on the differences in how I obtained informed consent for thyroidectomy from the two patients. Why, she asked, had I spent relatively little time emphasizing the risks of the operation with one patient and so much more time discussing risks with the second patient?

In order to understand why there appeared to be such a dramatic difference between the discussions with the two patients, it is helpful to understand the different indications for surgery. The first patient had recently been diagnosed with a 2.3-cm papillary thyroid cancer. I had explained that the first step in the treatment was to remove the thyroid, and I detailed the risks to the recurrent laryngeal nerves and the parathyroid glands.

The second patient had been treated for Graves’ disease for the last 3 years. She had many cycles of hyper- and hypothyroidism and had now decided that she needed definitive treatment. Although she had discussed the option of radioactive iodine with her endocrinologist, she had a significant fear of radiation and also was hoping to become pregnant in the next several months. I had discussed the risks of thyroidectomy with this patient. However, even though the risk I quoted of having a complication from the thyroidectomy was just the same as in the first case, I deliberately spent more time discussing the ramifications of the complications and the alternatives with the second patient.

My student was initially perplexed by this description. As she correctly stated, if the risks are the same for the same operation between the two patients, why emphasize the risks so much more for the second patient, compared with the first?

To most surgeons, the reason for this difference is clear. The first patient needed to know the risks, but there were few options to total thyroidectomy as the initial step in the treatment. The second patient had the clear option of getting radioactive iodine instead of surgery. Although the risks of the surgical procedure are the same with the two operations, I felt that the second patient needed to clearly understand the alternative to surgery and to fully consider the implications of the potential complications should one occur in her case.

As I think back over this interchange with my student, it is clear that the informed consent discussion for any operation cannot be fully standardized for every patient. Even if the risks remain the same, the indications for surgery are different and, of course, the patients are different.

More than 30 years ago, Dr. C. Rollins Hanlon, then executive director of the American College of Surgeons wrote, "Both ethics and surgery are inexact disciplines, in definition, practice, and in relation to one another." The more years I have been in practice, the more I am convinced of the truth of these words. Although my two patients both needed the same operation, it was important for me to emphasize the choices that the second patient had. In so doing, I felt it was essential to ensure that in evaluating the choices, the patient fully understood the implications of the risks. Although the patient with thyroid cancer had the same risks of the procedure, she did not have a good alternative choice to surgery. The difference between these two patients, and in how I altered my discussions of the proposed thyroidectomy, reveal the personal dimension of informed consent that goes beyond a simple statement of risks.

In obtaining informed consent from my patients, I should be providing them with much more than "just the facts." Patients can (and often do) obtain the data about the risks of surgical procedures from the Internet prior to seeing me. I believe that I should be giving them something more than they could obtain from reading about the risks of a procedure. I should provide them with a context in which to consider the risks, relative to their particular condition. Even small risks may be very significant if there are alternatives that have no risks. In contrast, patients often quickly agree to high-risk operations when there is no good nonoperative alternative. As surgeons, we must be cognizant of the critical personal dimension of the informed consent process and thereby be sure to put the discussion of risks in the appropriate context to help our patients make good decisions.

Dr. Angelos is an ACS Fellow; the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics; chief, endocrine surgery; and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

The long view

If you can believe it, I once read a witty article about hair transplants. The authors suggested that the reporting of results should show follow-ups much longer than 6 or 12 months, since hair loss keeps on happening after transplants. What looks fine at 1 year may not look so good 10 years later.

They labeled one figure in their paper as follows: "True long-term follow-up." It was a photo of a tombstone.

Neither medical school nor residency training fosters the long view. You see a patient during a hospitalization for an acute illness. Case presentation focuses on diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment for the few days he or she is on the ward. You may follow the patient for at most a few months, or a year after discharge. Those discussing the case might note a prognosis in passing, but don’t give much sense of what is likely to happen to the patient over the course of years, let alone decades.

What actually happens, long after the patient goes home or the residency ends, varies much more than may seem plausible based on the snapshot you get during an acute episode.

Medical practice in the community, by contrast, is a long-haul affair. What you see when you follow patients for years can be quite unexpected.

I think of John, for instance. As a teenager, he had many bouts of widespread and debilitating atopic dermatitis. Topical therapy often failed to make a dent, leading to courses of prednisone that were followed at once by severe recurrences. Had someone asked me at the time, I would have predicted for John a life of miserable itch, and morbidity from systemic treatment.

We lost touch when John went off to college. He returned 15 years later, now all grown up, with a wife and family. He wanted to show me a mole.

"How’s your eczema been?" I asked.

"It’s hardly bothered me much the last 10 years," John said. "I just use your cream now and then."

Then there was Samantha, who developed extensive acne at age 8. With such an early start, she seemed headed for a rough adolescence. Yet her face cleared and the acne never recurred.

Felicia, on the other hand, showed up at age 32 with severe, cystic acne. She insisted this had started only 6 months before. "I never had it when I was younger," she said.

I was skeptical, and asked her to show me photos from before the outbreak. Sure enough, a picture taken a year earlier showed a completely unblemished complexion.

Then there was Caroline, who at age 9 had severe psoriasis that was hard to control. Because unpleasant scaling affected her forehead and face, classmates often made comments. I’ll never forget her answer when I asked Caroline how she responded to these remarks. She said, "I tell them, ‘At least my face they can fix!’ "

I lost track of Caroline too. (Patients call more when they’re bothered than when they’re doing well.) Her father visited me years later for issues of his own. "How is Caroline’s psoriasis?" I asked him.

"Went away," he said. "No problems anymore." I’d never have guessed.

What about patients with skin cancer? If someone gets a basal cell carcinoma at age 21 years, you would expect him to be at serious risk for getting many more and want to follow him closely.

So would I, and of course I do. But as the years roll by, many of the patients I’ve seen who fall into this category never get another skin cancer, of whatever kind.

There have been plenty of times when my own track record of anticipating the course of disease has been no better than those of the experts on sports talk radio who predict the outcome of professional football games. By the end of the season, they don’t look so expert, but they go on predicting anyway.

Predictions have consequences. Rheumatologists who prescribe biologic agents have been sending patients for skin checks "because I have a high risk of skin cancer," as do surgeons for people from whom they’ve removed a mildly dysplastic nevus. Skin checks are harmless enough, but thinking of yourself as "high risk" is not conducive to equanimity.

Chronic skin issues, like hair loss, go on for a long time. Unexpected things happen, in both directions. When you take the long view, circumspection is best.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass. He is on the clinical faculty at Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Dr. Rockoff has contributed to the Under My Skin column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2002.

If you can believe it, I once read a witty article about hair transplants. The authors suggested that the reporting of results should show follow-ups much longer than 6 or 12 months, since hair loss keeps on happening after transplants. What looks fine at 1 year may not look so good 10 years later.

They labeled one figure in their paper as follows: "True long-term follow-up." It was a photo of a tombstone.

Neither medical school nor residency training fosters the long view. You see a patient during a hospitalization for an acute illness. Case presentation focuses on diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment for the few days he or she is on the ward. You may follow the patient for at most a few months, or a year after discharge. Those discussing the case might note a prognosis in passing, but don’t give much sense of what is likely to happen to the patient over the course of years, let alone decades.

What actually happens, long after the patient goes home or the residency ends, varies much more than may seem plausible based on the snapshot you get during an acute episode.

Medical practice in the community, by contrast, is a long-haul affair. What you see when you follow patients for years can be quite unexpected.

I think of John, for instance. As a teenager, he had many bouts of widespread and debilitating atopic dermatitis. Topical therapy often failed to make a dent, leading to courses of prednisone that were followed at once by severe recurrences. Had someone asked me at the time, I would have predicted for John a life of miserable itch, and morbidity from systemic treatment.

We lost touch when John went off to college. He returned 15 years later, now all grown up, with a wife and family. He wanted to show me a mole.

"How’s your eczema been?" I asked.

"It’s hardly bothered me much the last 10 years," John said. "I just use your cream now and then."

Then there was Samantha, who developed extensive acne at age 8. With such an early start, she seemed headed for a rough adolescence. Yet her face cleared and the acne never recurred.

Felicia, on the other hand, showed up at age 32 with severe, cystic acne. She insisted this had started only 6 months before. "I never had it when I was younger," she said.

I was skeptical, and asked her to show me photos from before the outbreak. Sure enough, a picture taken a year earlier showed a completely unblemished complexion.

Then there was Caroline, who at age 9 had severe psoriasis that was hard to control. Because unpleasant scaling affected her forehead and face, classmates often made comments. I’ll never forget her answer when I asked Caroline how she responded to these remarks. She said, "I tell them, ‘At least my face they can fix!’ "

I lost track of Caroline too. (Patients call more when they’re bothered than when they’re doing well.) Her father visited me years later for issues of his own. "How is Caroline’s psoriasis?" I asked him.

"Went away," he said. "No problems anymore." I’d never have guessed.

What about patients with skin cancer? If someone gets a basal cell carcinoma at age 21 years, you would expect him to be at serious risk for getting many more and want to follow him closely.

So would I, and of course I do. But as the years roll by, many of the patients I’ve seen who fall into this category never get another skin cancer, of whatever kind.

There have been plenty of times when my own track record of anticipating the course of disease has been no better than those of the experts on sports talk radio who predict the outcome of professional football games. By the end of the season, they don’t look so expert, but they go on predicting anyway.

Predictions have consequences. Rheumatologists who prescribe biologic agents have been sending patients for skin checks "because I have a high risk of skin cancer," as do surgeons for people from whom they’ve removed a mildly dysplastic nevus. Skin checks are harmless enough, but thinking of yourself as "high risk" is not conducive to equanimity.

Chronic skin issues, like hair loss, go on for a long time. Unexpected things happen, in both directions. When you take the long view, circumspection is best.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass. He is on the clinical faculty at Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Dr. Rockoff has contributed to the Under My Skin column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2002.

If you can believe it, I once read a witty article about hair transplants. The authors suggested that the reporting of results should show follow-ups much longer than 6 or 12 months, since hair loss keeps on happening after transplants. What looks fine at 1 year may not look so good 10 years later.

They labeled one figure in their paper as follows: "True long-term follow-up." It was a photo of a tombstone.

Neither medical school nor residency training fosters the long view. You see a patient during a hospitalization for an acute illness. Case presentation focuses on diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment for the few days he or she is on the ward. You may follow the patient for at most a few months, or a year after discharge. Those discussing the case might note a prognosis in passing, but don’t give much sense of what is likely to happen to the patient over the course of years, let alone decades.

What actually happens, long after the patient goes home or the residency ends, varies much more than may seem plausible based on the snapshot you get during an acute episode.

Medical practice in the community, by contrast, is a long-haul affair. What you see when you follow patients for years can be quite unexpected.

I think of John, for instance. As a teenager, he had many bouts of widespread and debilitating atopic dermatitis. Topical therapy often failed to make a dent, leading to courses of prednisone that were followed at once by severe recurrences. Had someone asked me at the time, I would have predicted for John a life of miserable itch, and morbidity from systemic treatment.

We lost touch when John went off to college. He returned 15 years later, now all grown up, with a wife and family. He wanted to show me a mole.

"How’s your eczema been?" I asked.

"It’s hardly bothered me much the last 10 years," John said. "I just use your cream now and then."

Then there was Samantha, who developed extensive acne at age 8. With such an early start, she seemed headed for a rough adolescence. Yet her face cleared and the acne never recurred.

Felicia, on the other hand, showed up at age 32 with severe, cystic acne. She insisted this had started only 6 months before. "I never had it when I was younger," she said.

I was skeptical, and asked her to show me photos from before the outbreak. Sure enough, a picture taken a year earlier showed a completely unblemished complexion.

Then there was Caroline, who at age 9 had severe psoriasis that was hard to control. Because unpleasant scaling affected her forehead and face, classmates often made comments. I’ll never forget her answer when I asked Caroline how she responded to these remarks. She said, "I tell them, ‘At least my face they can fix!’ "

I lost track of Caroline too. (Patients call more when they’re bothered than when they’re doing well.) Her father visited me years later for issues of his own. "How is Caroline’s psoriasis?" I asked him.

"Went away," he said. "No problems anymore." I’d never have guessed.

What about patients with skin cancer? If someone gets a basal cell carcinoma at age 21 years, you would expect him to be at serious risk for getting many more and want to follow him closely.

So would I, and of course I do. But as the years roll by, many of the patients I’ve seen who fall into this category never get another skin cancer, of whatever kind.

There have been plenty of times when my own track record of anticipating the course of disease has been no better than those of the experts on sports talk radio who predict the outcome of professional football games. By the end of the season, they don’t look so expert, but they go on predicting anyway.

Predictions have consequences. Rheumatologists who prescribe biologic agents have been sending patients for skin checks "because I have a high risk of skin cancer," as do surgeons for people from whom they’ve removed a mildly dysplastic nevus. Skin checks are harmless enough, but thinking of yourself as "high risk" is not conducive to equanimity.

Chronic skin issues, like hair loss, go on for a long time. Unexpected things happen, in both directions. When you take the long view, circumspection is best.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass. He is on the clinical faculty at Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Dr. Rockoff has contributed to the Under My Skin column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2002.

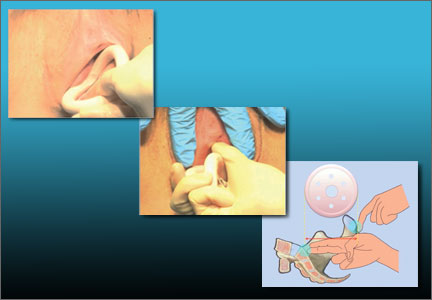

Vaginal pessaries VIDEO: Proper insertion and removal

Written and narrated by Teresa Tam, MD

For the related article, see: Pessaries for vaginal prolapse: Critical factors to successful fit and continued use Teresa Tam, MD, and Matthew Davies, MD (Surgical Techniques, December 2013)

Written and narrated by Teresa Tam, MD

For the related article, see: Pessaries for vaginal prolapse: Critical factors to successful fit and continued use Teresa Tam, MD, and Matthew Davies, MD (Surgical Techniques, December 2013)

Written and narrated by Teresa Tam, MD

For the related article, see: Pessaries for vaginal prolapse: Critical factors to successful fit and continued use Teresa Tam, MD, and Matthew Davies, MD (Surgical Techniques, December 2013)

A Simple Wrist Arthroscopy Tower: The Wrist Triangle

Pessaries for vaginal prolapse: Critical factors to successful fit and continued use

CASE 1. EARLY-STAGE PELVIC ORGAN PROLAPSE

AC is a 64-year-old white woman with early stage III anterior and apical pelvic organ prolapse (POP). The prolapse is now affecting her ability to do some of the things that she enjoys, such as gardening and golfing.

She has hypertension controlled with medication and no other significant medical issues except mild arthritic changes in her hands and hips. She reports being sexually active with her husband on roughly a weekly basis.

On examination, the leading edge of her prolapse is the anterior vaginal wall, protruding 1 cm beyond the introitus, and the cervix is at the hymenal ring. There is no significant posterior wall prolapse.

After she is counseled about all possible treatment approaches for her early-stage POP, the patient elects to try the vaginal pessary. Now, it is your job to determine the optimal pessary based on the extent of her condition and to educate her about the potential side effects and best practices for its ongoing use.

The vaginal pessary is an important component of a gynecologist’s armamentarium. It is a low-risk, cost-effective, nonsurgical treatment option for the management of POP and genuine stress urinary incontinence (SUI).1,2 It is unfortunate that training in North America typically provides clinicians with only a cursory experience with pessary selection and care, minimizing the device’s importance as a viable tool in a practitioner’s ongoing practice. In fact, most clinicians tend to view the pessary with a mixture of reluctance and disregard.

This is regrettable, as a majority (89%) of patients can be successfully fitted with a pessary,3 regardless of their stage or site of prolapse.4 Although high-stage prolapse does not predict failure, ring pessaries are used most successfully with stage II (100%) and stage III (71%) prolapse, while Gellhorn pessaries are most successful with stage IV (64%) prolapse.5

In this article we review the several pessary options available to clinicians, as well as how to insert them and the best scenarios for their use. We also discuss the key requirements for patient assessment and in-office fitting (meant to optimize the fit and, thereby, the success of use), the possible side effects of pessary use that patients need to be aware of, and appropriate follow-up.

WHEN IS A PESSARY YOUR BEST MANAGEMENT APPROACH?

There are several indications for pessary use,6 namely when:

- the patient has significant comorbid risk factors for surgery

- the patient prefers a nonsurgical alternative

- a goal is to avoid reoperation

- POP or cervical insufficiency is present during pregnancy

- the patient desires future fertility

- surgery must be delayed due to treatment of vaginal ulcerations

- the pessary will be used as a postoperative adjunct to mesh-based repair.

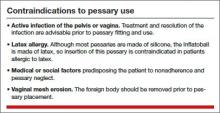

Pessaries have very few contraindications (TABLE). However, factors that do negatively affect successful fitting include:

- prior pelvic surgery

- multiparity

- obesity

- SUI

- short vaginal length (<7 cm)

- wide vaginal introitus (>4 fingerbreadths)

- significant posterior vaginal wall defect.5,7-9

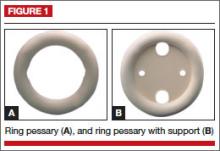

There are two main categories of vaginal pessaries: support and space-filling. All pessaries come in different sizes and shapes. Most are made of medical-grade silicone, rendering them durable and autoclavable as well as resistant to absorption of vaginal discharge and odors. The ring pessary with support is the most commonly used support pessary. The Gellhorn pessary is the most commonly used space-filling pessary. It is used as a second-line treatment for patients unable to retain the ring-with-support pessary.

Related Article: Pessary and pelvic floor exercises for incontinence—are two better than one? G. Willy Davila, MD (Examining the Evidence, May 2010)

SUPPORT PESSARY OPTIONS

The support pessaries are used to treat SUI and POP. These pessaries typically are the easiest types for patients to use because they are more comfortable and simpler to remove and insert than space-filling pessaries. For example, a ring pessary is two-dimensional and lies perpendicular to the long axis of the vagina, allowing patients to have intercourse with it in place. Support-type pessaries include the ring, Gehrung, Shaatz, and lever.

Ring

This is the most commonly used pessary because it fits most women. There are four types of ring pessaries: the ring (FIGURE 1A), ring with support (FIGURE 1B), incontinence ring, and incontinence ring with support. The ring pessary is appropriate for all stages of POP. The ring with support has a diaphragm that is useful in women who have uterine prolapse with or without cystocele. The incontinence ring has a knob that is placed beneath the urethra to increase urethral pressure and is useful in cases of SUI.

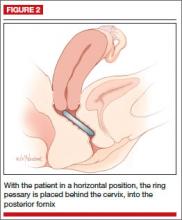

Insertion. Fold the pessary by bringing the two small holes together, and lubricate the leading edge. Insert it past the introitus with the folded edge facing down. Allow the pessary to reopen, and direct it behind the cervix into the posterior fornix (FIGURE 2). Give it a slight twist with your index finger to prevent expulsion.

To see insertion demonstrated, watch Vaginal pessaries: An instructional video

Gehrung

This pessary is designed with an arch-shaped malleable rim with wires incorporated into the arms (FIGURE 3). Use of the Gehrung pessary is rare; it is most often used in women with cystocele or rectocele.

Insertion. Fold the pessary to insert it into the vagina. Upon insertion, keep both heels of the pessary parallel to the posterior vagina with the back arch pushed over the cervix in the anterior fornix and the front arch resting behind the symphysis pubis. The concave surface and diaphragm support the anterior vagina. Place the convex portion of the curve beneath the bulge. The two bases rest on the posterior vagina against the lateral levator muscles.

Shaatz

This support pessary has a circular base similar to the Gellhorn pessary but without the rigid stem (FIGURE 4).

Insertion. Because it is stiff, insert this pessary vertically and then turn it to a horizontal position once it is inside the vagina.

Lever

The Hodge, Smith, and Risser pessaries are collectively called the lever pessaries. They are used to manage uterine retroversion and POP. They are rarely used.

The Hodge pessary is beneficial to patients with a narrow vaginal introitus, mild cystocele, and cervical insufficiency. The anterior portion of a Hodge pessary is rectangular (FIGURE 5A).

The Smith pessary is useful for patients with well-defined pubic notches because the anterior portion is rounded (FIGURE 5B).

For patients with a very shallow pubic notch, the Risser pessary is useful. The Risser’s anterior portion is rectangular with indentation but wider than the Hodge pessary (FIGURE 5C).

Insertion. Fold the pessary and insert it into the vagina with the index finger on the posterior curved bar until the pessary rests behind the cervix and the anterior horizontal bar rests behind the symphysis pubis.

SPACE-OCCUPYING PESSARIES

The second pessary category is the space-filling pessary. These pessaries are used primarily to support severe POP, especially posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse. They have larger bases to support the vaginal apex or cervix; therefore, they are more difficult to insert and remove. When this pessary type is in place, sexual intercourse is not possible. Examples include the Gellhorn, donut, cube, and inflatable pessaries.

Gellhorn

The Gellhorn pessary is the most commonly used space-filling pessary. It has a broad base with a stem (FIGURE 6). The broad base supports the vaginal apex while the stem keeps the circular base from rotating and prevents pessary expulsion. The stem comes in long or short lengths. The concave base provides vaginal suction and keeps the pessary in place. The holes in the stem and base provide vaginal drainage. The Gellhorn pessary is useful for women with more advanced prolapse and less perineal support.

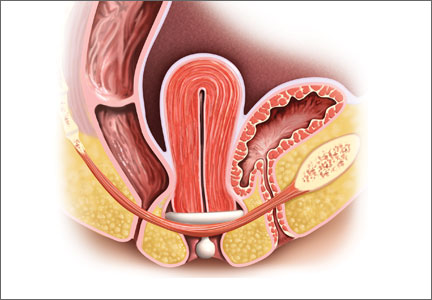

Insertion. Folding one side of the base to the stem, insert the Gellhorn pessary vertically inside the vagina. To facilitate insertion, separate the labia with the nondominant hand or depress the perineum with the index finger. Once the circular base is inside the vagina, push the pessary upward until the tip of the stem is just inside the vaginal introitus (FIGURE 7). Many medical illustrations inaccurately depict the Gellhorn pessary in a final placement that appears too high in the pelvis. This figure, which has the patient in a standing position, shows how low in the pelvis this space-filling pessary can sit in a patient with advanced prolapse.

Remove this pessary by gently pulling the stem while inserting the opposite hand beneath an edge of the pessary base to break the vaginal suction (Watch Vaginal pessaries: An instructional video).

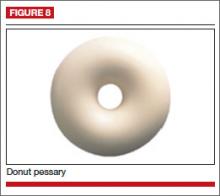

Donut

The donut pessary is used for advanced prolapse because it fills a larger space. It is difficult to insert and remove because it is large, thick, and hollow (FIGURE 8).

Insertion. Insert it vertically and, once it is placed inside the vagina, rotate it to a horizontal position. A Kelly clamp can be used to grasp the pessary and facilitate removal.

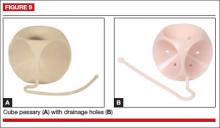

Cube

The cube pessary supports third-degree uterine prolapse by holding the vaginal wall with suction (FIGURE 9). Because of the risk of vaginal erosion and lack of drainage in some designs, the cube pessary requires nightly removal and cleaning.

Insertion. Squeezing the pessary with the thumb, index, and middle fingers, insert the cube pessary at the vaginal apex.

Removal requires breaking the suction by placing a fingertip between the vaginal mucosa and the pessary and compressing the cube between the thumb and forefinger to remove. Gently tugging on the string also helps with removal.

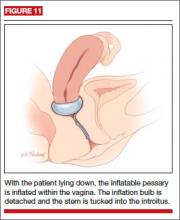

Inflatable

This space-filling pessary is an air-filled ball that is inflated via an attached stem that also enables insertion and removal. The older Inflatoball pessary is made of latex, so its use is contraindicated in patients with latex allergy. Newer inflatable pessaries are silicone-based and consist of an air-filled donut, a stem with a valve, and an air pump (FIGURE 10). Some models also include a deflation key. The inflatable pessary comes in small, medium, large, and extra-large sizes. This pessary type must be removed and cleaned daily.

Insertion. Place the deflated pessary into the vagina. Move the ball-bearing valve within the stem (which controls the air flow) to a lateral projection on the side of the stem. To inflate, attach the inflation bulb. (Inflation typically requires 3 to 5 pumps of the bulb.) Move the ball bearing back into position to maintain the inflation, then detach the bulb. You can leave the stem outside the body or tuck it gently into the introitus (FIGURE 11).

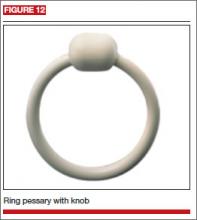

INCONTINENCE PESSARIES

These devices are used specifically for SUI. The incontinence ring (FIGURE 12) and incontinence dish pessaries compress the urethra against the pubic symphysis. The knob is placed beneath the urethra, increasing the urethral closure pressure and thereby preventing urinary incontinence.

Related Article: Update on Urinary Incontinence Karen L. Noblett, MD, MAS, and Stephanie A. Jacobs, MD (December 2011)

CASE 1 CONCLUDED

Given that AC has early-stage POP and is sexually active, a space-occupying pessary is not the optimal choice. Instead, a ring pessary with support is fitted for her trial.

What side effects might a patient anticipate with pessary use?

Vaginal discharge and slight odor are common. Pessary removal and cleaning are usually adequate to eliminate them. Temporary discontinuation of pessary use may be warranted until symptoms subside. If these maneuvers do not resolve the issue, then the patient should be examined to rule out other sources of infection.

Vaginal bleeding. Bleeding from vaginal abrasion and ulceration could be caused by trauma from pessary removal or vaginal impingement. Evaluation is warranted for any vaginal bleeding.

Changes in urinary function. Less commonly, women using a pessary may notice changes in their urinary function. Many women with anterior or apical prolapse will have altered urine streams with slow or trickling flow and possible hesitation upon initiation of voiding.

Alternatively, pessary placement may instigate stress-type incontinence akin to that seen after prolapse surgery. Changing pessary size may alleviate this condition. Otherwise, these side effects may reduce a patient’s willingness to continue pessary use.

How can a patient optimize her use of a pessary?

A patient can remove the pessary on a periodic basis or try to use it continuously. If she cannot or will not remove the pessary, then she will need to come back for scheduled visits, as described in the sidebar, “Essential components of a successfully fitted pessary.” If she is able to remove the pessary on her own, then she can use the device as needed or remove it for intercourse (though it is not necessary). She must remove it weekly, at a minimum, however, to both clean the pessary and give the vaginal walls a “rest,” which can minimize the potential for abrasions or erosions

ESSENTIAL COMPONENTS OF A SUCCESSFULLY FITTED PESSARY

Patient assessment

Accurate selection and placement of a pessary requires appropriate examination and fitting, beginning with determination of the patient’s stage of prolapse and introitus. Key steps include:

– Examine the patient with an empty bladder in the lithotomy position

– Perform bimanual pelvic and speculum examination using a Sims speculum (or bivalve speculum broken in half) with the patient in a supine position

– Administer the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) exam

– Perform digital examination

– Assess vaginal atrophy, vaginal introitus, and vaginal width and length

– Evaluate pelvic floor muscle strength (Kegel squeeze).

Next, gauge the correct pessary size by approximating the number of fingerbreadths accommodated across the vaginal width.

Another method of estimating pessary size is to insert two fingers inside the vagina and estimate the distance between the posterior fornix and the posterior pubic symphysis (Watch Vaginal pessaries: An instructional video). An easy reference is to start with a size 3 or 4 ring pessary if the vaginal introitus is 1 to 2 fingerbreadths in width and the prolapse is stage II to III. If the vagina accommodates 3 to 4 fingerbreadths, or there is stage IV prolapse, use a Gellhorn pessary.

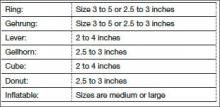

Here are the different types of pessaries and the most common sizes available. (Pessary sizes change in quarter-inch increments.)

In-office trial

Insert the pessary into the vagina using the dominant hand. Using the nondominant hand, separate the introitus and depress the perineal body. Apply a small amount of lubricant to the leading edge of the pessary.

After insertion, ask the patient to strain and cough, ambulate in the office, and void. Reexamine the patient to ensure that the pessary is still in the correct position and that placement has not shifted. Perform the cough leak test with the patient in a standing position and the pessary in place. Re-examine the patient while she is in a standing position. Use the largest pessary that is comfortable for her. Advise her to bring the pessary back to the office if it gets expelled.

This is a trial-and-error process; advise the patient of this. It may require a trial of several styles and sizes to find the right pessary fit. Once you find the correct size, document the final pessary size.

Follow-up

Schedule a follow-up appointment 1 to 2 weeks after insertion. Ask the patient whether she has experienced any discomfort, malodorous discharge, or vaginal bleeding. Also inquire about any changes in urinary habits or bowel movements and related complaints.

Remove the pessary and clean it with mild soap and water. Examine the vagina for pressure points, abrasions, ulcerations, and erosions.

Teach the patient how to remove, clean, and reinsert the pessary, and advise her to perform these tasks on a weekly basis.

Schedule a follow-up visit in 1 to 2 months, and another visit 6 to 12 months after that.

CASE 2. ADVANCED-STAGE POP

BD is an 82-year-old widow (G5P4014) with stage IV vaginal prolapse. She has noticed some scant blood staining on her clothing. She frequently voids small amounts of urine but never feels complete relief. She defecates normally.

Her medical history is significant for coronary artery disease with prior myocardial infarction, with multiple stent placements over the years. She has hypertension, reduced ejection fraction, and diabetes. She is morbidly obese and suffers from degenerative joint disease. She had a vaginal hysterectomy several years ago for benign indications.

Upon examination, BD’s prolapse is large, with excoriations and hyperkeratosis of the skin over the prolapse. It is easily reduced in the office.

What is the best pessary for this patient, and how should she be followed and counseled regarding ongoing care?

Since the failure rate for pessary usage increases with advancing prolapse stage, a space-occupying pessary is most appropriate to try initially. A trial with a support pessary could be useful to allow the excoriations to heal and provide a healthier vaginal environment. A Gellhorn pessary is commonly used. An inflatable pessary could be an alternative if the Gellhorn fails to stay in place. The cube pessary, known to cause more abrasions and erosions than other pessaries, is a poor choice given the state of the patient’s vaginal tissues at baseline.

Space-occupying pessaries are more difficult to insert and remove and have a higher risk of pain or trauma. Start with shorter time intervals between visits, eventually spacing them out for the patient’s convenience. The usual interval for follow-up is 3 to 4 months; longer intervals could be offered if the patient is reliable, adherent, and reports no complaints with pessary use.

Related Article: Update on pelvic floor dysfunction: Focus on urinary incontinence Alexis A. Dieter, MD, and Cindy L. Amundsen, MD (November 2013)

OUTCOMES

Only short- and medium-term outcomes for pessary use have been described in the literature. Short-term (2 months) satisfaction and continued use, along with resolution of prolapse, occurred in 92% of patients.7 Previous hysterectomy or prolapse surgery may influence the short-term success of pessary use.10

More than half of sexually active women achieved long-term use (up to 2 years), regardless of prolapse severity. Brincat and colleagues found that long-term pessary use (1 to 2 years) approached 60% in 132 women with both urinary incontinence and prolapse. Women being treated for POP were more likely to continue pessary use than women being treated for SUI.11 Age, parity, estrogen use, and sexual activity were characteristics also studied in pessary fitting. Neither sexual activity nor stage of prolapse was a contraindication to use of a pessary; long-term use was found to be acceptable in sexually active women.11

Successful fitting of a vaginal pessary has been associated with improvement in voiding, urinary and fecal urgency, and incontinence. A vaginal pessary is a viable nonsurgical option for the management of POP and urinary incontinence and remains an optimal minimally invasive approach to such disorders.

CASE 2 CONCLUDED

The patient returns to the clinic 1 month after the original insertion. The pessary is removed, and the vagina is inspected, with no abrasions or ulcerations found. The vaginal cavity and pessary are cleaned with a mild soap-and-water mixture. The pessary is lubricated and reinserted. This process is repeated 2 months later, with subsequent follow-up intervals doubled (up to 6 months between visits) when the patient has no complaints of discharge or odor.

- Colmer, WM Jr. Use of the pessary. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1953;65(1):170–174.

- Culligan PJ. Nonsurgical management to pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(4):852–860.

- Nygaard IE, Heit M. Stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(3):607–620.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 85: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(3):717–729.

- Clemons JL, Aguilar VC, Tillinghast TA, Jackson ND, Myers DL. Risk factors associated with an unsuccessful pessary fitting trial in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(2):345–350.

- Clemons JL, Brubaker L, Falk SJ. Vaginal pessary treatment of prolapse and incontinence. UpToDate. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/vaginal-pessary-treatment-of-prolapse-and-incontinence. Updated February 8, 2013. Accessed November 7, 2013.

- Mutone MF, Terry C, Hale DS, Benson JT. Factors which influence the short-term success of pessary management of pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):89–94.

- Fernando RJ, Thakar R, Sultan AH, Shah SM, Jones PW. Effect of vaginal pessaries on symptoms associated with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(1):93–99.

- Weber AM, Richter HE. Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(3):615–634.

- Donnelly MJ, Powell-Morgan S, Olsen AL, et al. Vaginal pessaries for the management of stress and mixed incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2004;15(5):302–307.

- Brincat C, Kenton K, Fitzgerald MP, et al. Sexual activity predicts continued pessary use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):198–200.

CASE 1. EARLY-STAGE PELVIC ORGAN PROLAPSE

AC is a 64-year-old white woman with early stage III anterior and apical pelvic organ prolapse (POP). The prolapse is now affecting her ability to do some of the things that she enjoys, such as gardening and golfing.

She has hypertension controlled with medication and no other significant medical issues except mild arthritic changes in her hands and hips. She reports being sexually active with her husband on roughly a weekly basis.

On examination, the leading edge of her prolapse is the anterior vaginal wall, protruding 1 cm beyond the introitus, and the cervix is at the hymenal ring. There is no significant posterior wall prolapse.

After she is counseled about all possible treatment approaches for her early-stage POP, the patient elects to try the vaginal pessary. Now, it is your job to determine the optimal pessary based on the extent of her condition and to educate her about the potential side effects and best practices for its ongoing use.

The vaginal pessary is an important component of a gynecologist’s armamentarium. It is a low-risk, cost-effective, nonsurgical treatment option for the management of POP and genuine stress urinary incontinence (SUI).1,2 It is unfortunate that training in North America typically provides clinicians with only a cursory experience with pessary selection and care, minimizing the device’s importance as a viable tool in a practitioner’s ongoing practice. In fact, most clinicians tend to view the pessary with a mixture of reluctance and disregard.

This is regrettable, as a majority (89%) of patients can be successfully fitted with a pessary,3 regardless of their stage or site of prolapse.4 Although high-stage prolapse does not predict failure, ring pessaries are used most successfully with stage II (100%) and stage III (71%) prolapse, while Gellhorn pessaries are most successful with stage IV (64%) prolapse.5

In this article we review the several pessary options available to clinicians, as well as how to insert them and the best scenarios for their use. We also discuss the key requirements for patient assessment and in-office fitting (meant to optimize the fit and, thereby, the success of use), the possible side effects of pessary use that patients need to be aware of, and appropriate follow-up.

WHEN IS A PESSARY YOUR BEST MANAGEMENT APPROACH?

There are several indications for pessary use,6 namely when:

- the patient has significant comorbid risk factors for surgery

- the patient prefers a nonsurgical alternative

- a goal is to avoid reoperation

- POP or cervical insufficiency is present during pregnancy

- the patient desires future fertility

- surgery must be delayed due to treatment of vaginal ulcerations

- the pessary will be used as a postoperative adjunct to mesh-based repair.

Pessaries have very few contraindications (TABLE). However, factors that do negatively affect successful fitting include:

- prior pelvic surgery

- multiparity

- obesity

- SUI

- short vaginal length (<7 cm)

- wide vaginal introitus (>4 fingerbreadths)

- significant posterior vaginal wall defect.5,7-9