User login

Albuminuria: When urine predicts kidney and cardiovascular disease

“One can obtain considerable information concerning the general health by examining the urine.”

—Hippocrates (460?–355? BCE)

Chronic kidney disease is a notable public health concern because it is an important risk factor for end-stage renal disease, cardiovascular disease, and death. Its prevalence1 exceeds 10% and is considerably higher in high-risk groups, such as those with diabetes or hypertension, which are growing in the United States.

While high levels of total protein in the urine have always been recognized as pathologic, a growing body of evidence links excretion of the protein albumin to adverse cardiovascular outcomes, and most international guidelines now recommend measuring albumin specifically. Albuminuria is a predictor of declining renal function and is independently associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Thus, clinicians need to detect it early, manage it effectively, and reduce concurrent risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

Therefore, this review will focus on albuminuria. However, because the traditional standard for urinary protein measurement was total protein, and because a few guidelines still recommend measuring total protein rather than albumin, we will also briefly discuss total urinary protein.

MOST URINARY PROTEIN IS ALBUMIN

Most of the protein in the urine is albumin filtered from the plasma. Less than half of the rest is derived from the distal renal tubules (uromodulin or Tamm-Horsfall mucoprotein), 2 and urine also contains a small and varying proportion of immunoglobulins, low-molecular-weight proteins, and light chains.

Normal healthy people lose less than 30 mg of albumin in the urine per day. In greater amounts, albumin is the major urinary protein in most kidney diseases. Other proteins in urine can be specific markers of less-common illnesses such as plasma cell dyscrasia, glomerulopathy, and renal tubular disease.

MEASURING PROTEINURIA AND ALBUMINURIA

Albumin is not a homogeneous molecule in urine. It undergoes changes to its molecular configuration in the presence of certain ions, peptides, hormones, and drugs, and as a result of proteolytic fragmentation both in the plasma and in renal tubules.3 Consequently, measuring urinary albumin involves a trade-off between convenience and accuracy.

A 24-hour timed urine sample has long been the gold standard for measuring albuminuria, but the collection is cumbersome and time-consuming, and the test is prone to laboratory error.

Dipstick measurements are more convenient and are better at detecting albumin than other proteins in urine, but they have low sensitivity and high interobserver variation.3–5

The albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR). As the quantity of protein in the urine changes with time of day, exertion, stress level, and posture, spot-checking of urine samples is not as good as timed collection. However, a simultaneous measurement of creatinine in a spot urine sample adjusts for protein concentration, which can vary with a person’s hydration status. The ACR so obtained is consistent with the 24-hour timed collection (the gold standard) and is the recommended method of assessing albuminuria.3 An early morning urine sample is favored, as it avoids orthostatic variations and varies less in the same individual.

In a study in the general population comparing the ACR in a random sample and in an early morning sample, only 44% of those who had an ACR of 30 mg/g or higher in the random sample had one this high in the early morning sample.6 However, getting an early morning sample is not always feasible in clinical practice. If you are going to measure albuminuria, the Kidney Disease Outcomes and Quality Initiative7 suggests checking the ACR in a random sample and then, if the test is positive, following up and confirming it within 3 months with an early morning sample.

Also, since creatinine excretion differs with race, diet, and muscle mass, if the 24-hour creatinine excretion is not close to 1 g, the ACR will give an erroneous estimate of the 24-hour excretion rate.3

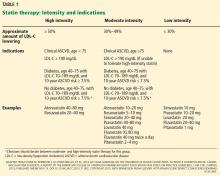

Table 1 compares the various methods of measuring protein in the urine.3,5,8,9 Of note, methods of measuring albumin and total protein vary considerably in their precision and accuracy, making it impossible to reliably translate values from one to the other.5

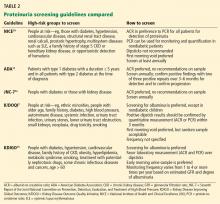

National and international guidelines (Table 2)7,10–13 agree that albuminuria should be tested in diabetic patients, as it is a surrogate marker for early diabetic nephropathy.3,13 Most guidelines also recommend measuring albuminuria by a urine ACR test as the preferred measure, even in people without diabetes.

Also, no single cutoff is universally accepted for distinguishing pathologic albuminuria from physiologic albuminuria, nor is there a universally accepted unit of measure.14 Because approximately 1 g of creatinine is lost in the urine per day, the ACR has the convenient property of numerically matching the albumin excretory rate expressed in milligrams per 24 hours. The other commonly used unit is milligrams of albumin per millimole of creatinine; 30 mg/g is roughly equal to 3 mg/mmol.

The term microalbuminuria was traditionally used to refer to albumin excretion of 30 to 299 mg per 24 hours, and macroalbuminuria to 300 mg or more per 24 hours. However, as there is no pathophysiologic basis to these thresholds (see outcomes data below), the current Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines do not recommend using these terms.13,15

RENAL COMPLICATIONS OF ALBUMINURIA

A failure of the glomerular filtration barrier or of proximal tubular reabsorption accounts for most cases of pathologic albuminuria.16 Processes affecting the glomerular filtration of albumin include endothelial cell dysfunction and abnormalities with the glomerular basement membrane, podocytes, or the slit diaphragms among the podocytic processes.17

Ultrafiltrated albumin has been directly implicated in tubulointerstitial damage and glomerulosclerosis through diverse pathways. In the proximal tubule, albumin up-regulates interleukin 8 (a chemoattractant for lymphocytes and neutrophils), induces synthesis of endothelin 1 (which stimulates renal cell proliferation, extracellular matrix production, and monocyte attraction), and causes apoptosis of tubular cells.18 In response to albumin, proximal tubular cells also stimulate interstitial fibroblasts via paracrine release of transforming growth factor beta, either directly or by activating complement or macrophages.18,19

Studies linking albuminuria to kidney disease

Albuminuria has traditionally been associated with diabetes mellitus as a predictor of overt diabetic nephropathy,20,21 although in type 1 diabetes, established albuminuria can spontaneously regress.22

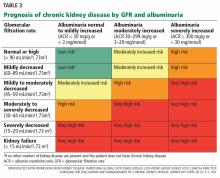

Albuminuria is also a strong predictor of progression in chronic kidney disease.23 In fact, in the last decade, albuminuria has become an independent criterion in the definition of chronic kidney disease; excretion of more than 30 mg of albumin per day, sustained for at least 3 months, qualifies as chronic kidney disease, with independent prognostic implications (Table 3).13

Astor et al,24 in a meta-analysis of 13 studies with more than 21,000 patients with chronic kidney disease, found that the risk of end-stage renal disease was three times higher in those with albuminuria.

Gansevoort et al,23 in a meta-analysis of nine studies with nearly 850,000 participants from the general population, found that the risk of end-stage renal disease increased continuously as albumin excretion increased. They also found that as albuminuria increased, so did the risk of progression of chronic kidney disease and the incidence of acute kidney injury.

Hemmelgarn et al,25 in a large pooled cohort study with more than 1.5 million participants from the general population, showed that increasing albuminuria was associated with a decline in the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and with progression to end-stage renal disease across all strata of baseline renal function. For example, in persons with an estimated GFR of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2

- 1 per 1,000 person-years for those with no proteinuria

- 2.8 per 1,000 person-years for those with mild proteinuria (trace or 1+ by dipstick or ACR 30–300 mg/g)

- 13.4 per 1,000 person-years for those with heavy proteinuria (2+ or ACR > 300 mg/g).

Rates of progression to end-stage renal disease were:

- 0.03 per 1,000 person-years with no proteinuria

- 0.05 per 1,000 person-years with mild proteinuria

- 1 per 1,000 person-years with heavy proteinuria.25

CARDIOVASCULAR CONSEQUENCES OF ALBUMINURIA

The exact pathophysiologic link between albuminuria and cardiovascular disease is unknown, but several mechanisms have been proposed.

One is that generalized endothelial dysfunction causes both albuminuria and cardiovascular disease.26 Endothelium-derived nitric oxide has vasodilator, antiplatelet, antiproliferative, antiadhesive, permeability-decreasing, and anti-inflammatory properties. Impaired endothelial synthesis of nitric oxide has been independently associated with both microalbuminuria and diabetes.27

Low levels of heparan sulfate (which has antithrombogenic effects and decreases vessel permeability) in the glycocalyx lining vessel walls may also account for albuminuria and for the other cardiovascular effects.28–30 These changes may be the consequence of chronic low-grade inflammation, which precedes the occurrence and progression of both albuminuria and atherothrombotic disease. The resulting abnormalities in the endothelial glycocalyx could lead to increased glomerular permeability to albumin and may also be implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.26

In an atherosclerotic aorta and coronary arteries, the endothelial dysfunction may cause increased leakage of cholesterol and glycated end-products into the myocardium, resulting in increasing wall stiffness and left ventricular mass. A similar atherosclerotic process may account for coronary artery microthrombi, resulting in subendocardial ischemia that could lead to systolic and diastolic heart dysfunction.31

Studies linking albuminuria to heart disease

There is convincing evidence that albuminuria is associated with cardiovascular disease. An ACR between 30 and 300 mg/g was independently associated with myocardial infarction and ischemia.32 People with albuminuria have more than twice the risk of severe coronary artery disease, and albuminuria is also associated with increased intimal thickening in the carotid arteries.33,34 An ACR in the same range has been associated with increased incidence and progression of coronary artery calcification.35 Higher brachial-ankle pulse-wave velocity has also been demonstrated with albuminuria in a dose-dependent fashion.36,37

An ACR of 30 to 300 mg/g has been linked to left ventricular hypertrophy independently of other risk factors,38 and functionally with diastolic dysfunction and abnormal midwall shortening.39 In a study of a subgroup of patients with diabetes from a population-based cohort of Native American patients (the Strong Heart Study),39 the prevalence of diastolic dysfunction was:

- 16% in those with no albuminuria

- 26% in those with an ACR of 30 to 300 mg/g

- 31% in those with an ACR greater than 300 mg/g.

The association persisted even after controlling for age, sex, hypertension, and other covariates.

Those pathologic associations have been directly linked to clinical outcomes. For patients with heart failure (New York Heart Association class II–IV), a study found that albuminuria (an ACR > 30 mg/g) conferred a 41% higher risk of admission for heart failure, and an ACR greater than 300 mg/g was associated with an 88% higher risk.40

In an analysis of a prospective cohort from the general population with albuminuria and a low prevalence of renal dysfunction (the Prevention of Renal and Vascular Endstage Disease study),41 albuminuria was associated with a modest increase in the incidence of the composite end point of myocardial infarction, stroke, ischemic heart disease, revascularization procedures, and all-cause mortality per doubling of the urine albumin excretion (hazard ratio 1.08, range 1.04 –1.12).

The relationship to cardiovascular outcomes extends below traditional lower-limit thresholds of albuminuria (corresponding to an ACR > 30 mg/g). A subgroup of patients from the Framingham Offspring Study without prevalent cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, or kidney disease, and thus with a low to intermediate probability of cardiovascular events, were found to have thresholds for albuminuria as low as 5.3 mg/g in men and 10.8 mg/g in women to discriminate between incident coronary artery disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, other peripheral vascular disease, or death.42

In a meta-analysis including more than 1 million patients in the general population, increasing albuminuria was associated with an increase in deaths from all causes in a continuous manner, with no threshold effect.43 In patients with an ACR of 30 mg/g, the hazard ratio for death was 1.63, increasing to 2.22 for those with more than 300 mg/g compared with those with no albuminuria. A similar increase in the risk of myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, or sudden cardiac death was noted with higher ACR.43

Important prospective cohort studies and meta-analyses related to albuminuria and kidney and cardiovascular disease and death are summarized in the eTable.23,39–50

THE CASE FOR TREATING ALBUMINURIA

Reduced progression of renal disease

Treating patients who have proteinuric chronic kidney disease with an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) can reduce the risk of progression of renal failure. However, it is unclear whether this benefit is the result of treating concomitant risk factors independent of the reduction in albuminuria, and there is no consistent treatment effect in improving renal outcomes across studies.

Fink et al,51 in a meta-analysis, found that chronic kidney disease patients with diabetes, hypertension, and macroalbuminuria had a 40% lower risk of progression to end-stage renal disease if they received an ACE inhibitor (relative risk [RR] 0.60, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.43–0.83). In the same meta-analysis, ARBs also reduced the risk of progression to end-stage renal disease (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.66–0.90).

Jafar et al,52 in an analysis of pooled patient-level data including only nondiabetic patients on ACE inhibitor therapy (n = 1,860), found that the risk of progression of renal failure, defined as a doubling of serum creatinine or end-stage renal disease, was reduced (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.55–0.88). Patients with higher levels of albuminuria showed the most benefit, but the effect was not conclusive for albuminuria below 500 mg/day at baseline.

Maione et al,53 in a meta-analysis that included patients with albuminuria who were treated with ACE inhibitors vs placebo (n = 8,231), found a similar reduction in risk of:

- Progression to end-stage renal disease (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.54–0.84)

- Doubling of serum creatinine (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.46–0.84)

- Progression of albuminuria (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.36–0.65)

- Normalization of pathologic albuminuria (as defined by the trialists in the individual studies) (RR 2.99, 95% CI 1.82–4.91).

Similar results were obtained for patients with albuminuria who were treated with ARBs.53

ONTARGET.54 In contrast, in the Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination With Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial, the combination of an ACE inhibitor and an ARB showed no benefit in reducing the progression of renal failure, and in those patients with chronic kidney disease there was a higher risk of a doubling of serum creatinine or of the development of end-stage renal disease and hyperkalemia.

Also, in a pooled analysis of the ONTARGET and Telmisartan Randomized Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects With Cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) trials, a 50% reduction in baseline albuminuria was associated with reduced progression of renal failure in those with a baseline ACR less than 10 mg/g.55

Improved cardiovascular outcomes

There is also evidence of better cardiovascular outcomes with treatment of albuminuria. Again, it is uncertain whether this is a result of treating risk factors other than albuminuria with ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and there is no parallel benefit demonstrated across all studies.

LIFE.47,48 In the Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension trial, survival analyses suggested a decrease in risk of cardiovascular adverse events as the degree of proteinuria improved with ARB therapy.

Maione et al,53 in a meta-analysis including 8,231 patients with albuminuria and at least one other risk factor, found a significant reduction in the rate of nonfatal cardiovascular outcomes (angina, myocardial infarction, revascularization, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or heart failure) with ACE inhibitors vs placebo (RR 0.88, CI 0.82–0.94) and also in 3,888 patients treated with ARBs vs placebo (RR 0.77, CI 0.61–0.98). However, the meta-analysis did not show that ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy reduced rate of cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

Fink et al,51 in their meta-analysis of 18 trials of ACE inhibitors and four trials of ARBs, also found no evidence that ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy reduced cardiovascular mortality rates.38

The ONTARGET trial evaluated the combination of an ACE inhibitor and ARB therapy in patients with diabetes or preexisting peripheral vascular disease. Reductions in the rate of cardiovascular disease or death were not observed, and in those with chronic kidney disease, there was a higher risk of doubling of serum creatinine or development of end-stage renal disease and adverse events of hyperkalemia.56 And although an increase in baseline albuminuria was associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes, its reduction in the ONTARGET and TRANSCEND trials did not demonstrate better outcomes when the baseline ACR was greater than 10 mg/g.55

WHO SHOULD BE TESTED?

The benefit of adding albuminuria to conventional cardiovascular risk stratification such as Framingham risk scoring is not conclusive. However, today’s clinician may view albuminuria as a biomarker for renal and cardiovascular disease, as albuminuria might be a surrogate marker for endothelial dysfunction in the glomerular capillaries or other vital vascular beds.

High-risk populations and chronic kidney disease patients

Nearly all the current guidelines recommend annual screening for albuminuria in patients with diabetes and hypertension (Table 2).7,10–13 Other high-risk populations include people with cardiovascular disease, a family history of end-stage renal disease, and metabolic syndrome. Additionally, chronic kidney disease patients whose estimated GFR defines them as being in stage 3 or higher (ie, GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2), regardless of other comorbidities, should be tested for albuminuria, as it is an important risk predictor.

Most experts prefer that albuminuria be measured by urine ACR in a first morning voided sample, though this is not the only option.

Screening the general population

Given that albuminuria has been shown to be such an important prognosticator for patients at high risk and those with chronic kidney disease, the question arises whether screening for albuminuria in the asymptomatic low-risk general population would foster earlier detection and therefore enable earlier intervention and result in improved outcomes. However, a systematic review done for the United States Preventive Services Task Force and for an American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline did not find robust evidence to support this.51

OUR RECOMMENDATIONS

Who should be tested?

- Patients with chronic kidney disease stage 3, 4, or 5 (GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2) who are not on dialysis

- Patients who are considered at higher risk of adverse outcomes, such as those with diabetes, hypertension, a family history of end-stage renal disease, or cardiovascular disease. Testing is useful for recognizing increased renal and cardiovascular risk and may lead clinicians to prescribe or titrate a renin-angiotensin system antagonist, a statin, or both, or to modify other cardiovascular risk factors.

- Not recommended: routine screening in the general population who are asymptomatic or are considered at low risk.

Which test should be used?

Based on current evidence and most guidelines, we recommend the urine ACR test as the screening test for people with diabetes and others deemed to be at high risk.

What should be done about albuminuria?

- Controlling blood pressure is important, and though there is debate about the target blood pressure, an individualized plan should be developed with the patient based on age, comorbidities, and goals of care.

- An ACE inhibitor or ARB, if not contraindicated, is recommended for patients with diabetes whose ACR is greater than 30 mg/g and for patients with chronic kidney disease and an ACR greater than 300 mg/g.

- Current evidence does not support the combined use of an ACE inhibitor and an ARB, as proof of benefit is lacking and the risk of adverse events is higher.

- Refer patients with high or unexplained albuminuria to a nephrologist or clinic specializing in chronic kidney disease.

- Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 2007; 298:2038–2047.

- Hoyer JR, Seiler MW. Pathophysiology of Tamm-Horsfall protein. Kidney Int 1979; 16:279–289.

- Viswanathan G, Upadhyay A. Assessment of proteinuria. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2011; 18:243–248.

- Guh JY. Proteinuria versus albuminuria in chronic kidney disease. Nephrology (Carlton) 2010; 15(suppl 2):53–56.

- Lamb EJ, MacKenzie F, Stevens PE. How should proteinuria be detected and measured? Ann Clin Biochem 2009; 46:205–217.

- Saydah SH, Pavkov ME, Zhang C, et al. Albuminuria prevalence in first morning void compared with previous random urine from adults in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009-2010. Clin Chem 2013; 59:675–683.

- National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 2002; 39(suppl 1):S1–S266.

- Younes N, Cleary PA, Steffes MW, et al; DCCT/EDIC Research Group. Comparison of urinary albumin-creatinine ratio and albumin excretion rate in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:1235–1242.

- Brinkman JW, de Zeeuw D, Duker JJ, et al. Falsely low urinary albumin concentrations after prolonged frozen storage of urine samples. Clin Chem 2005; 51:2181–2183.

- National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions (UK). Chronic Kidney Disease: National Clinical Guideline for Early Identification and Management in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care. London: Royal College of Physicians (UK) 2008.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2013. Diabetes Care 2013; 36(suppl 1):S11–S66.

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al; Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2003; 42:1206–1252.

- Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 2013; 3:1–150.

- Johnson DW. Global proteinuria guidelines: are we nearly there yet? Clin Biochem Rev 2011; 32:89–95.

- Ruggenenti P, Remuzzi G. Time to abandon microalbuminuria? Kidney Int 2006; 70:1214–1222.

- Glassock RJ. Is the presence of microalbuminuria a relevant marker of kidney disease? Curr Hypertens Rep 2010; 12:364–368.

- Zhang A, Huang S. Progress in pathogenesis of proteinuria. Int J Nephrol 2012; 2012:314251.

- Abbate M, Zoja C, Remuzzi G. How does proteinuria cause progressive renal damage? J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17:2974–2984.

- Karalliedde J, Viberti G. Proteinuria in diabetes: bystander or pathway to cardiorenal disease? J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 21:2020–2027.

- Svendsen PA, Oxenbøll B, Christiansen JS. Microalbuminuria in diabetic patients—a longitudinal study. Acta Endocrinol Suppl (Copenh) 1981; 242:53–54.

- Viberti GC, Hill RD, Jarrett RJ, Argyropoulos A, Mahmud U, Keen H. Microalbuminuria as a predictor of clinical nephropathy in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Lancet 1982; 1:1430–1432.

- Perkins BA, Ficociello LH, Silva KH, Finkelstein DM, Warram JH, Krolewski AS. Regression of microalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:2285–2293.

- Gansevoort RT, Matsushita K, van der Velde M, et al; Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium. Lower estimated GFR and higher albuminuria are associated with adverse kidney outcomes. A collaborative meta-analysis of general and high-risk population cohorts. Kidney Int 2011; 80:93–104.

- Astor BC, Matsushita K, Gansevoort RT, et al. Lower estimated glomerular filtration rate and higher albuminuria are associated with mortality and end-stage renal disease. A collaborative meta-analysis of kidney disease population cohorts. Kidney Int 2011; 79:1331–1340.

- Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Lloyd A, et al; Alberta Kidney Disease Network. Relation between kidney function, proteinuria, and adverse outcomes. JAMA 2010; 303:423–429.

- Stehouwer CD, Smulders YM. Microalbuminuria and risk for cardiovascular disease: analysis of potential mechanisms. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17:2106–2111.

- Stehouwer CD, Henry RM, Dekker JM, Nijpels G, Heine RJ, Bouter LM. Microalbuminuria is associated with impaired brachial artery, flow-mediated vasodilation in elderly individuals without and with diabetes: further evidence for a link between microalbuminuria and endothelial dysfunction—the Hoorn Study. Kidney Int Suppl 2004; 92:S42–S44.

- Wasty F, Alavi MZ, Moore S. Distribution of glycosaminoglycans in the intima of human aortas: changes in atherosclerosis and diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1993; 36:316–322.

- Ylä-Herttuala S, Sumuvuori H, Karkola K, Möttönen M, Nikkari T. Glycosaminoglycans in normal and atherosclerotic human coronary arteries. Lab Invest 1986; 54:402–407.

- Deckert T, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Borch-Johnsen K, Jensen T, Kofoed-Enevoldsen A. Albuminuria reflects widespread vascular damage. The Steno hypothesis. Diabetologia 1989; 32:219–226.

- van Hoeven KH, Factor SM. A comparison of the pathological spectrum of hypertensive, diabetic, and hypertensive-diabetic heart disease. Circulation 1990; 82:848–855.

- Diercks GF, van Boven AJ, Hillege HL, et al. Microalbuminuria is independently associated with ischaemic electrocardiographic abnormalities in a large non-diabetic population. The PREVEND (Prevention of REnal and Vascular ENdstage Disease) study. Eur Heart J 2000; 21:1922–1927.

- Bigazzi R, Bianchi S, Nenci R, Baldari D, Baldari G, Campese VM. Increased thickness of the carotid artery in patients with essential hypertension and microalbuminuria. J Hum Hypertens 1995; 9:827–833.

- Tuttle KR, Puhlman ME, Cooney SK, Short R. Urinary albumin and insulin as predictors of coronary artery disease: an angiographic study. Am J Kidney Dis 1999; 34:918–925.

- DeFilippis AP, Kramer HJ, Katz R, et al. Association between coronary artery calcification progression and microalbuminuria: the MESA study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2010; 3:595–604.

- Liu CS, Pi-Sunyer FX, Li CI, et al. Albuminuria is strongly associated with arterial stiffness, especially in diabetic or hypertensive subjects—a population-based study (Taichung Community Health Study, TCHS). Atherosclerosis 2010; 211:315–321.

- Upadhyay A, Hwang SJ, Mitchell GF, et al. Arterial stiffness in mild-to-moderate CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 20:2044–2053.

- Pontremoli R, Sofia A, Ravera M, et al. Prevalence and clinical correlates of microalbuminuria in essential hypertension: the MAGIC Study. Microalbuminuria: a Genoa Investigation on Complications. Hypertension 1997; 30:1135–1143.

- Liu JE, Robbins DC, Palmieri V, et al. Association of albuminuria with systolic and diastolic left ventricular dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: the Strong Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 41:2022–2028.

- Jackson CE, Solomon SD, Gerstein HC, et al; CHARM Investigators and Committees. Albuminuria in chronic heart failure: prevalence and prognostic importance. Lancet 2009; 374:543–550.

- Smink PA, Lambers Heerspink HJ, Gansevoort RT, et al. Albuminuria, estimated GFR, traditional risk factors, and incident cardiovascular disease: the PREVEND (Prevention of Renal and Vascular Endstage Disease) study. Am J Kidney Dis 2012; 60:804–811.

- Arnlöv J, Evans JC, Meigs JB, et al. Low-grade albuminuria and incidence of cardiovascular disease events in nonhypertensive and nondiabetic individuals: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2005; 112:969–975.

- Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium; Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet 2010; 375:2073–2081.

- van der Velde M, Matsushita K, Coresh J, et al. Lower estimated glomerular filtration rate and higher albuminuria are associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. A collaborative meta-analysis of high-risk population cohorts. Kidney Int 2011; 79:1341–1352.

- Ruggenenti P, Porrini E, Motterlini N, et al; BENEDICT Study Investigators. Measurable urinary albumin predicts cardiovascular risk among normoalbuminuric patients with type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 23:1717–1724.

- Hallan S, Astor B, Romundstad S, Aasarød K, Kvenild K, Coresh J. Association of kidney function and albuminuria with cardiovascular mortality in older vs younger individuals: the HUNT II Study. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167:2490–2496.

- Ibsen H, Wachtell K, Olsen MH, et al. Albuminuria and cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy: the LIFE Study. Kidney Int Suppl 2004; 92:S56–S58.

- Olsen MH, Wachtell K, Bella JN, et al. Albuminuria predicts cardiovascular events independently of left ventricular mass in hypertension: a LIFE substudy. J Hum Hypertens 2004; 18:453–459.

- Klausen K, Borch-Johnsen K, Feldt-Rasmussen B, et al. Very low levels of microalbuminuria are associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease and death independently of renal function, hypertension, and diabetes. Circulation 2004; 110:32–35.

- Gerstein HC, Mann JF, Yi Q, et al; HOPE Study Investigators. Albuminuria and risk of cardiovascular events, death, and heart failure in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals. JAMA 2001; 286:421–426.

- Fink HA, Ishani A, Taylor BC, et al. Screening for, monitoring, and treatment of chronic kidney disease stages 1 to 3: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force and for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med 2012; 156:570–581.

- Jafar TH, Schmid CH, Landa M, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and progression of nondiabetic renal disease. A meta-analysis of patient-level data. Ann Intern Med 2001; 135:73–87.

- Maione A, Navaneethan SD, Graziano G, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers and combined therapy in patients with micro- and macroalbuminuria and other cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26:2827–2847.

- Mann JF, Schmieder RE, McQueen M, et al; ONTARGET investigators. Renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both, in people at high vascular risk (the ONTARGET study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet 2008; 372:547–553.

- Schmieder RE, Mann JF, Schumacher H, et al; ONTARGET Investigators. Changes in albuminuria predict mortality and morbidity in patients with vascular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 22:1353–1364.

- Tobe SW, Clase CM, Gao P, et al; ONTARGET and TRANSCEND Investigators. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both in people at high renal risk: results from the ONTARGET and TRANSCEND studies. Circulation 2011; 123:1098–1107.

“One can obtain considerable information concerning the general health by examining the urine.”

—Hippocrates (460?–355? BCE)

Chronic kidney disease is a notable public health concern because it is an important risk factor for end-stage renal disease, cardiovascular disease, and death. Its prevalence1 exceeds 10% and is considerably higher in high-risk groups, such as those with diabetes or hypertension, which are growing in the United States.

While high levels of total protein in the urine have always been recognized as pathologic, a growing body of evidence links excretion of the protein albumin to adverse cardiovascular outcomes, and most international guidelines now recommend measuring albumin specifically. Albuminuria is a predictor of declining renal function and is independently associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Thus, clinicians need to detect it early, manage it effectively, and reduce concurrent risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

Therefore, this review will focus on albuminuria. However, because the traditional standard for urinary protein measurement was total protein, and because a few guidelines still recommend measuring total protein rather than albumin, we will also briefly discuss total urinary protein.

MOST URINARY PROTEIN IS ALBUMIN

Most of the protein in the urine is albumin filtered from the plasma. Less than half of the rest is derived from the distal renal tubules (uromodulin or Tamm-Horsfall mucoprotein), 2 and urine also contains a small and varying proportion of immunoglobulins, low-molecular-weight proteins, and light chains.

Normal healthy people lose less than 30 mg of albumin in the urine per day. In greater amounts, albumin is the major urinary protein in most kidney diseases. Other proteins in urine can be specific markers of less-common illnesses such as plasma cell dyscrasia, glomerulopathy, and renal tubular disease.

MEASURING PROTEINURIA AND ALBUMINURIA

Albumin is not a homogeneous molecule in urine. It undergoes changes to its molecular configuration in the presence of certain ions, peptides, hormones, and drugs, and as a result of proteolytic fragmentation both in the plasma and in renal tubules.3 Consequently, measuring urinary albumin involves a trade-off between convenience and accuracy.

A 24-hour timed urine sample has long been the gold standard for measuring albuminuria, but the collection is cumbersome and time-consuming, and the test is prone to laboratory error.

Dipstick measurements are more convenient and are better at detecting albumin than other proteins in urine, but they have low sensitivity and high interobserver variation.3–5

The albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR). As the quantity of protein in the urine changes with time of day, exertion, stress level, and posture, spot-checking of urine samples is not as good as timed collection. However, a simultaneous measurement of creatinine in a spot urine sample adjusts for protein concentration, which can vary with a person’s hydration status. The ACR so obtained is consistent with the 24-hour timed collection (the gold standard) and is the recommended method of assessing albuminuria.3 An early morning urine sample is favored, as it avoids orthostatic variations and varies less in the same individual.

In a study in the general population comparing the ACR in a random sample and in an early morning sample, only 44% of those who had an ACR of 30 mg/g or higher in the random sample had one this high in the early morning sample.6 However, getting an early morning sample is not always feasible in clinical practice. If you are going to measure albuminuria, the Kidney Disease Outcomes and Quality Initiative7 suggests checking the ACR in a random sample and then, if the test is positive, following up and confirming it within 3 months with an early morning sample.

Also, since creatinine excretion differs with race, diet, and muscle mass, if the 24-hour creatinine excretion is not close to 1 g, the ACR will give an erroneous estimate of the 24-hour excretion rate.3

Table 1 compares the various methods of measuring protein in the urine.3,5,8,9 Of note, methods of measuring albumin and total protein vary considerably in their precision and accuracy, making it impossible to reliably translate values from one to the other.5

National and international guidelines (Table 2)7,10–13 agree that albuminuria should be tested in diabetic patients, as it is a surrogate marker for early diabetic nephropathy.3,13 Most guidelines also recommend measuring albuminuria by a urine ACR test as the preferred measure, even in people without diabetes.

Also, no single cutoff is universally accepted for distinguishing pathologic albuminuria from physiologic albuminuria, nor is there a universally accepted unit of measure.14 Because approximately 1 g of creatinine is lost in the urine per day, the ACR has the convenient property of numerically matching the albumin excretory rate expressed in milligrams per 24 hours. The other commonly used unit is milligrams of albumin per millimole of creatinine; 30 mg/g is roughly equal to 3 mg/mmol.

The term microalbuminuria was traditionally used to refer to albumin excretion of 30 to 299 mg per 24 hours, and macroalbuminuria to 300 mg or more per 24 hours. However, as there is no pathophysiologic basis to these thresholds (see outcomes data below), the current Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines do not recommend using these terms.13,15

RENAL COMPLICATIONS OF ALBUMINURIA

A failure of the glomerular filtration barrier or of proximal tubular reabsorption accounts for most cases of pathologic albuminuria.16 Processes affecting the glomerular filtration of albumin include endothelial cell dysfunction and abnormalities with the glomerular basement membrane, podocytes, or the slit diaphragms among the podocytic processes.17

Ultrafiltrated albumin has been directly implicated in tubulointerstitial damage and glomerulosclerosis through diverse pathways. In the proximal tubule, albumin up-regulates interleukin 8 (a chemoattractant for lymphocytes and neutrophils), induces synthesis of endothelin 1 (which stimulates renal cell proliferation, extracellular matrix production, and monocyte attraction), and causes apoptosis of tubular cells.18 In response to albumin, proximal tubular cells also stimulate interstitial fibroblasts via paracrine release of transforming growth factor beta, either directly or by activating complement or macrophages.18,19

Studies linking albuminuria to kidney disease

Albuminuria has traditionally been associated with diabetes mellitus as a predictor of overt diabetic nephropathy,20,21 although in type 1 diabetes, established albuminuria can spontaneously regress.22

Albuminuria is also a strong predictor of progression in chronic kidney disease.23 In fact, in the last decade, albuminuria has become an independent criterion in the definition of chronic kidney disease; excretion of more than 30 mg of albumin per day, sustained for at least 3 months, qualifies as chronic kidney disease, with independent prognostic implications (Table 3).13

Astor et al,24 in a meta-analysis of 13 studies with more than 21,000 patients with chronic kidney disease, found that the risk of end-stage renal disease was three times higher in those with albuminuria.

Gansevoort et al,23 in a meta-analysis of nine studies with nearly 850,000 participants from the general population, found that the risk of end-stage renal disease increased continuously as albumin excretion increased. They also found that as albuminuria increased, so did the risk of progression of chronic kidney disease and the incidence of acute kidney injury.

Hemmelgarn et al,25 in a large pooled cohort study with more than 1.5 million participants from the general population, showed that increasing albuminuria was associated with a decline in the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and with progression to end-stage renal disease across all strata of baseline renal function. For example, in persons with an estimated GFR of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2

- 1 per 1,000 person-years for those with no proteinuria

- 2.8 per 1,000 person-years for those with mild proteinuria (trace or 1+ by dipstick or ACR 30–300 mg/g)

- 13.4 per 1,000 person-years for those with heavy proteinuria (2+ or ACR > 300 mg/g).

Rates of progression to end-stage renal disease were:

- 0.03 per 1,000 person-years with no proteinuria

- 0.05 per 1,000 person-years with mild proteinuria

- 1 per 1,000 person-years with heavy proteinuria.25

CARDIOVASCULAR CONSEQUENCES OF ALBUMINURIA

The exact pathophysiologic link between albuminuria and cardiovascular disease is unknown, but several mechanisms have been proposed.

One is that generalized endothelial dysfunction causes both albuminuria and cardiovascular disease.26 Endothelium-derived nitric oxide has vasodilator, antiplatelet, antiproliferative, antiadhesive, permeability-decreasing, and anti-inflammatory properties. Impaired endothelial synthesis of nitric oxide has been independently associated with both microalbuminuria and diabetes.27

Low levels of heparan sulfate (which has antithrombogenic effects and decreases vessel permeability) in the glycocalyx lining vessel walls may also account for albuminuria and for the other cardiovascular effects.28–30 These changes may be the consequence of chronic low-grade inflammation, which precedes the occurrence and progression of both albuminuria and atherothrombotic disease. The resulting abnormalities in the endothelial glycocalyx could lead to increased glomerular permeability to albumin and may also be implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.26

In an atherosclerotic aorta and coronary arteries, the endothelial dysfunction may cause increased leakage of cholesterol and glycated end-products into the myocardium, resulting in increasing wall stiffness and left ventricular mass. A similar atherosclerotic process may account for coronary artery microthrombi, resulting in subendocardial ischemia that could lead to systolic and diastolic heart dysfunction.31

Studies linking albuminuria to heart disease

There is convincing evidence that albuminuria is associated with cardiovascular disease. An ACR between 30 and 300 mg/g was independently associated with myocardial infarction and ischemia.32 People with albuminuria have more than twice the risk of severe coronary artery disease, and albuminuria is also associated with increased intimal thickening in the carotid arteries.33,34 An ACR in the same range has been associated with increased incidence and progression of coronary artery calcification.35 Higher brachial-ankle pulse-wave velocity has also been demonstrated with albuminuria in a dose-dependent fashion.36,37

An ACR of 30 to 300 mg/g has been linked to left ventricular hypertrophy independently of other risk factors,38 and functionally with diastolic dysfunction and abnormal midwall shortening.39 In a study of a subgroup of patients with diabetes from a population-based cohort of Native American patients (the Strong Heart Study),39 the prevalence of diastolic dysfunction was:

- 16% in those with no albuminuria

- 26% in those with an ACR of 30 to 300 mg/g

- 31% in those with an ACR greater than 300 mg/g.

The association persisted even after controlling for age, sex, hypertension, and other covariates.

Those pathologic associations have been directly linked to clinical outcomes. For patients with heart failure (New York Heart Association class II–IV), a study found that albuminuria (an ACR > 30 mg/g) conferred a 41% higher risk of admission for heart failure, and an ACR greater than 300 mg/g was associated with an 88% higher risk.40

In an analysis of a prospective cohort from the general population with albuminuria and a low prevalence of renal dysfunction (the Prevention of Renal and Vascular Endstage Disease study),41 albuminuria was associated with a modest increase in the incidence of the composite end point of myocardial infarction, stroke, ischemic heart disease, revascularization procedures, and all-cause mortality per doubling of the urine albumin excretion (hazard ratio 1.08, range 1.04 –1.12).

The relationship to cardiovascular outcomes extends below traditional lower-limit thresholds of albuminuria (corresponding to an ACR > 30 mg/g). A subgroup of patients from the Framingham Offspring Study without prevalent cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, or kidney disease, and thus with a low to intermediate probability of cardiovascular events, were found to have thresholds for albuminuria as low as 5.3 mg/g in men and 10.8 mg/g in women to discriminate between incident coronary artery disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, other peripheral vascular disease, or death.42

In a meta-analysis including more than 1 million patients in the general population, increasing albuminuria was associated with an increase in deaths from all causes in a continuous manner, with no threshold effect.43 In patients with an ACR of 30 mg/g, the hazard ratio for death was 1.63, increasing to 2.22 for those with more than 300 mg/g compared with those with no albuminuria. A similar increase in the risk of myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, or sudden cardiac death was noted with higher ACR.43

Important prospective cohort studies and meta-analyses related to albuminuria and kidney and cardiovascular disease and death are summarized in the eTable.23,39–50

THE CASE FOR TREATING ALBUMINURIA

Reduced progression of renal disease

Treating patients who have proteinuric chronic kidney disease with an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) can reduce the risk of progression of renal failure. However, it is unclear whether this benefit is the result of treating concomitant risk factors independent of the reduction in albuminuria, and there is no consistent treatment effect in improving renal outcomes across studies.

Fink et al,51 in a meta-analysis, found that chronic kidney disease patients with diabetes, hypertension, and macroalbuminuria had a 40% lower risk of progression to end-stage renal disease if they received an ACE inhibitor (relative risk [RR] 0.60, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.43–0.83). In the same meta-analysis, ARBs also reduced the risk of progression to end-stage renal disease (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.66–0.90).

Jafar et al,52 in an analysis of pooled patient-level data including only nondiabetic patients on ACE inhibitor therapy (n = 1,860), found that the risk of progression of renal failure, defined as a doubling of serum creatinine or end-stage renal disease, was reduced (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.55–0.88). Patients with higher levels of albuminuria showed the most benefit, but the effect was not conclusive for albuminuria below 500 mg/day at baseline.

Maione et al,53 in a meta-analysis that included patients with albuminuria who were treated with ACE inhibitors vs placebo (n = 8,231), found a similar reduction in risk of:

- Progression to end-stage renal disease (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.54–0.84)

- Doubling of serum creatinine (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.46–0.84)

- Progression of albuminuria (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.36–0.65)

- Normalization of pathologic albuminuria (as defined by the trialists in the individual studies) (RR 2.99, 95% CI 1.82–4.91).

Similar results were obtained for patients with albuminuria who were treated with ARBs.53

ONTARGET.54 In contrast, in the Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination With Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial, the combination of an ACE inhibitor and an ARB showed no benefit in reducing the progression of renal failure, and in those patients with chronic kidney disease there was a higher risk of a doubling of serum creatinine or of the development of end-stage renal disease and hyperkalemia.

Also, in a pooled analysis of the ONTARGET and Telmisartan Randomized Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects With Cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) trials, a 50% reduction in baseline albuminuria was associated with reduced progression of renal failure in those with a baseline ACR less than 10 mg/g.55

Improved cardiovascular outcomes

There is also evidence of better cardiovascular outcomes with treatment of albuminuria. Again, it is uncertain whether this is a result of treating risk factors other than albuminuria with ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and there is no parallel benefit demonstrated across all studies.

LIFE.47,48 In the Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension trial, survival analyses suggested a decrease in risk of cardiovascular adverse events as the degree of proteinuria improved with ARB therapy.

Maione et al,53 in a meta-analysis including 8,231 patients with albuminuria and at least one other risk factor, found a significant reduction in the rate of nonfatal cardiovascular outcomes (angina, myocardial infarction, revascularization, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or heart failure) with ACE inhibitors vs placebo (RR 0.88, CI 0.82–0.94) and also in 3,888 patients treated with ARBs vs placebo (RR 0.77, CI 0.61–0.98). However, the meta-analysis did not show that ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy reduced rate of cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

Fink et al,51 in their meta-analysis of 18 trials of ACE inhibitors and four trials of ARBs, also found no evidence that ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy reduced cardiovascular mortality rates.38

The ONTARGET trial evaluated the combination of an ACE inhibitor and ARB therapy in patients with diabetes or preexisting peripheral vascular disease. Reductions in the rate of cardiovascular disease or death were not observed, and in those with chronic kidney disease, there was a higher risk of doubling of serum creatinine or development of end-stage renal disease and adverse events of hyperkalemia.56 And although an increase in baseline albuminuria was associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes, its reduction in the ONTARGET and TRANSCEND trials did not demonstrate better outcomes when the baseline ACR was greater than 10 mg/g.55

WHO SHOULD BE TESTED?

The benefit of adding albuminuria to conventional cardiovascular risk stratification such as Framingham risk scoring is not conclusive. However, today’s clinician may view albuminuria as a biomarker for renal and cardiovascular disease, as albuminuria might be a surrogate marker for endothelial dysfunction in the glomerular capillaries or other vital vascular beds.

High-risk populations and chronic kidney disease patients

Nearly all the current guidelines recommend annual screening for albuminuria in patients with diabetes and hypertension (Table 2).7,10–13 Other high-risk populations include people with cardiovascular disease, a family history of end-stage renal disease, and metabolic syndrome. Additionally, chronic kidney disease patients whose estimated GFR defines them as being in stage 3 or higher (ie, GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2), regardless of other comorbidities, should be tested for albuminuria, as it is an important risk predictor.

Most experts prefer that albuminuria be measured by urine ACR in a first morning voided sample, though this is not the only option.

Screening the general population

Given that albuminuria has been shown to be such an important prognosticator for patients at high risk and those with chronic kidney disease, the question arises whether screening for albuminuria in the asymptomatic low-risk general population would foster earlier detection and therefore enable earlier intervention and result in improved outcomes. However, a systematic review done for the United States Preventive Services Task Force and for an American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline did not find robust evidence to support this.51

OUR RECOMMENDATIONS

Who should be tested?

- Patients with chronic kidney disease stage 3, 4, or 5 (GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2) who are not on dialysis

- Patients who are considered at higher risk of adverse outcomes, such as those with diabetes, hypertension, a family history of end-stage renal disease, or cardiovascular disease. Testing is useful for recognizing increased renal and cardiovascular risk and may lead clinicians to prescribe or titrate a renin-angiotensin system antagonist, a statin, or both, or to modify other cardiovascular risk factors.

- Not recommended: routine screening in the general population who are asymptomatic or are considered at low risk.

Which test should be used?

Based on current evidence and most guidelines, we recommend the urine ACR test as the screening test for people with diabetes and others deemed to be at high risk.

What should be done about albuminuria?

- Controlling blood pressure is important, and though there is debate about the target blood pressure, an individualized plan should be developed with the patient based on age, comorbidities, and goals of care.

- An ACE inhibitor or ARB, if not contraindicated, is recommended for patients with diabetes whose ACR is greater than 30 mg/g and for patients with chronic kidney disease and an ACR greater than 300 mg/g.

- Current evidence does not support the combined use of an ACE inhibitor and an ARB, as proof of benefit is lacking and the risk of adverse events is higher.

- Refer patients with high or unexplained albuminuria to a nephrologist or clinic specializing in chronic kidney disease.

“One can obtain considerable information concerning the general health by examining the urine.”

—Hippocrates (460?–355? BCE)

Chronic kidney disease is a notable public health concern because it is an important risk factor for end-stage renal disease, cardiovascular disease, and death. Its prevalence1 exceeds 10% and is considerably higher in high-risk groups, such as those with diabetes or hypertension, which are growing in the United States.

While high levels of total protein in the urine have always been recognized as pathologic, a growing body of evidence links excretion of the protein albumin to adverse cardiovascular outcomes, and most international guidelines now recommend measuring albumin specifically. Albuminuria is a predictor of declining renal function and is independently associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Thus, clinicians need to detect it early, manage it effectively, and reduce concurrent risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

Therefore, this review will focus on albuminuria. However, because the traditional standard for urinary protein measurement was total protein, and because a few guidelines still recommend measuring total protein rather than albumin, we will also briefly discuss total urinary protein.

MOST URINARY PROTEIN IS ALBUMIN

Most of the protein in the urine is albumin filtered from the plasma. Less than half of the rest is derived from the distal renal tubules (uromodulin or Tamm-Horsfall mucoprotein), 2 and urine also contains a small and varying proportion of immunoglobulins, low-molecular-weight proteins, and light chains.

Normal healthy people lose less than 30 mg of albumin in the urine per day. In greater amounts, albumin is the major urinary protein in most kidney diseases. Other proteins in urine can be specific markers of less-common illnesses such as plasma cell dyscrasia, glomerulopathy, and renal tubular disease.

MEASURING PROTEINURIA AND ALBUMINURIA

Albumin is not a homogeneous molecule in urine. It undergoes changes to its molecular configuration in the presence of certain ions, peptides, hormones, and drugs, and as a result of proteolytic fragmentation both in the plasma and in renal tubules.3 Consequently, measuring urinary albumin involves a trade-off between convenience and accuracy.

A 24-hour timed urine sample has long been the gold standard for measuring albuminuria, but the collection is cumbersome and time-consuming, and the test is prone to laboratory error.

Dipstick measurements are more convenient and are better at detecting albumin than other proteins in urine, but they have low sensitivity and high interobserver variation.3–5

The albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR). As the quantity of protein in the urine changes with time of day, exertion, stress level, and posture, spot-checking of urine samples is not as good as timed collection. However, a simultaneous measurement of creatinine in a spot urine sample adjusts for protein concentration, which can vary with a person’s hydration status. The ACR so obtained is consistent with the 24-hour timed collection (the gold standard) and is the recommended method of assessing albuminuria.3 An early morning urine sample is favored, as it avoids orthostatic variations and varies less in the same individual.

In a study in the general population comparing the ACR in a random sample and in an early morning sample, only 44% of those who had an ACR of 30 mg/g or higher in the random sample had one this high in the early morning sample.6 However, getting an early morning sample is not always feasible in clinical practice. If you are going to measure albuminuria, the Kidney Disease Outcomes and Quality Initiative7 suggests checking the ACR in a random sample and then, if the test is positive, following up and confirming it within 3 months with an early morning sample.

Also, since creatinine excretion differs with race, diet, and muscle mass, if the 24-hour creatinine excretion is not close to 1 g, the ACR will give an erroneous estimate of the 24-hour excretion rate.3

Table 1 compares the various methods of measuring protein in the urine.3,5,8,9 Of note, methods of measuring albumin and total protein vary considerably in their precision and accuracy, making it impossible to reliably translate values from one to the other.5

National and international guidelines (Table 2)7,10–13 agree that albuminuria should be tested in diabetic patients, as it is a surrogate marker for early diabetic nephropathy.3,13 Most guidelines also recommend measuring albuminuria by a urine ACR test as the preferred measure, even in people without diabetes.

Also, no single cutoff is universally accepted for distinguishing pathologic albuminuria from physiologic albuminuria, nor is there a universally accepted unit of measure.14 Because approximately 1 g of creatinine is lost in the urine per day, the ACR has the convenient property of numerically matching the albumin excretory rate expressed in milligrams per 24 hours. The other commonly used unit is milligrams of albumin per millimole of creatinine; 30 mg/g is roughly equal to 3 mg/mmol.

The term microalbuminuria was traditionally used to refer to albumin excretion of 30 to 299 mg per 24 hours, and macroalbuminuria to 300 mg or more per 24 hours. However, as there is no pathophysiologic basis to these thresholds (see outcomes data below), the current Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines do not recommend using these terms.13,15

RENAL COMPLICATIONS OF ALBUMINURIA

A failure of the glomerular filtration barrier or of proximal tubular reabsorption accounts for most cases of pathologic albuminuria.16 Processes affecting the glomerular filtration of albumin include endothelial cell dysfunction and abnormalities with the glomerular basement membrane, podocytes, or the slit diaphragms among the podocytic processes.17

Ultrafiltrated albumin has been directly implicated in tubulointerstitial damage and glomerulosclerosis through diverse pathways. In the proximal tubule, albumin up-regulates interleukin 8 (a chemoattractant for lymphocytes and neutrophils), induces synthesis of endothelin 1 (which stimulates renal cell proliferation, extracellular matrix production, and monocyte attraction), and causes apoptosis of tubular cells.18 In response to albumin, proximal tubular cells also stimulate interstitial fibroblasts via paracrine release of transforming growth factor beta, either directly or by activating complement or macrophages.18,19

Studies linking albuminuria to kidney disease

Albuminuria has traditionally been associated with diabetes mellitus as a predictor of overt diabetic nephropathy,20,21 although in type 1 diabetes, established albuminuria can spontaneously regress.22

Albuminuria is also a strong predictor of progression in chronic kidney disease.23 In fact, in the last decade, albuminuria has become an independent criterion in the definition of chronic kidney disease; excretion of more than 30 mg of albumin per day, sustained for at least 3 months, qualifies as chronic kidney disease, with independent prognostic implications (Table 3).13

Astor et al,24 in a meta-analysis of 13 studies with more than 21,000 patients with chronic kidney disease, found that the risk of end-stage renal disease was three times higher in those with albuminuria.

Gansevoort et al,23 in a meta-analysis of nine studies with nearly 850,000 participants from the general population, found that the risk of end-stage renal disease increased continuously as albumin excretion increased. They also found that as albuminuria increased, so did the risk of progression of chronic kidney disease and the incidence of acute kidney injury.

Hemmelgarn et al,25 in a large pooled cohort study with more than 1.5 million participants from the general population, showed that increasing albuminuria was associated with a decline in the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and with progression to end-stage renal disease across all strata of baseline renal function. For example, in persons with an estimated GFR of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2

- 1 per 1,000 person-years for those with no proteinuria

- 2.8 per 1,000 person-years for those with mild proteinuria (trace or 1+ by dipstick or ACR 30–300 mg/g)

- 13.4 per 1,000 person-years for those with heavy proteinuria (2+ or ACR > 300 mg/g).

Rates of progression to end-stage renal disease were:

- 0.03 per 1,000 person-years with no proteinuria

- 0.05 per 1,000 person-years with mild proteinuria

- 1 per 1,000 person-years with heavy proteinuria.25

CARDIOVASCULAR CONSEQUENCES OF ALBUMINURIA

The exact pathophysiologic link between albuminuria and cardiovascular disease is unknown, but several mechanisms have been proposed.

One is that generalized endothelial dysfunction causes both albuminuria and cardiovascular disease.26 Endothelium-derived nitric oxide has vasodilator, antiplatelet, antiproliferative, antiadhesive, permeability-decreasing, and anti-inflammatory properties. Impaired endothelial synthesis of nitric oxide has been independently associated with both microalbuminuria and diabetes.27

Low levels of heparan sulfate (which has antithrombogenic effects and decreases vessel permeability) in the glycocalyx lining vessel walls may also account for albuminuria and for the other cardiovascular effects.28–30 These changes may be the consequence of chronic low-grade inflammation, which precedes the occurrence and progression of both albuminuria and atherothrombotic disease. The resulting abnormalities in the endothelial glycocalyx could lead to increased glomerular permeability to albumin and may also be implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.26

In an atherosclerotic aorta and coronary arteries, the endothelial dysfunction may cause increased leakage of cholesterol and glycated end-products into the myocardium, resulting in increasing wall stiffness and left ventricular mass. A similar atherosclerotic process may account for coronary artery microthrombi, resulting in subendocardial ischemia that could lead to systolic and diastolic heart dysfunction.31

Studies linking albuminuria to heart disease

There is convincing evidence that albuminuria is associated with cardiovascular disease. An ACR between 30 and 300 mg/g was independently associated with myocardial infarction and ischemia.32 People with albuminuria have more than twice the risk of severe coronary artery disease, and albuminuria is also associated with increased intimal thickening in the carotid arteries.33,34 An ACR in the same range has been associated with increased incidence and progression of coronary artery calcification.35 Higher brachial-ankle pulse-wave velocity has also been demonstrated with albuminuria in a dose-dependent fashion.36,37

An ACR of 30 to 300 mg/g has been linked to left ventricular hypertrophy independently of other risk factors,38 and functionally with diastolic dysfunction and abnormal midwall shortening.39 In a study of a subgroup of patients with diabetes from a population-based cohort of Native American patients (the Strong Heart Study),39 the prevalence of diastolic dysfunction was:

- 16% in those with no albuminuria

- 26% in those with an ACR of 30 to 300 mg/g

- 31% in those with an ACR greater than 300 mg/g.

The association persisted even after controlling for age, sex, hypertension, and other covariates.

Those pathologic associations have been directly linked to clinical outcomes. For patients with heart failure (New York Heart Association class II–IV), a study found that albuminuria (an ACR > 30 mg/g) conferred a 41% higher risk of admission for heart failure, and an ACR greater than 300 mg/g was associated with an 88% higher risk.40

In an analysis of a prospective cohort from the general population with albuminuria and a low prevalence of renal dysfunction (the Prevention of Renal and Vascular Endstage Disease study),41 albuminuria was associated with a modest increase in the incidence of the composite end point of myocardial infarction, stroke, ischemic heart disease, revascularization procedures, and all-cause mortality per doubling of the urine albumin excretion (hazard ratio 1.08, range 1.04 –1.12).

The relationship to cardiovascular outcomes extends below traditional lower-limit thresholds of albuminuria (corresponding to an ACR > 30 mg/g). A subgroup of patients from the Framingham Offspring Study without prevalent cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, or kidney disease, and thus with a low to intermediate probability of cardiovascular events, were found to have thresholds for albuminuria as low as 5.3 mg/g in men and 10.8 mg/g in women to discriminate between incident coronary artery disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, other peripheral vascular disease, or death.42

In a meta-analysis including more than 1 million patients in the general population, increasing albuminuria was associated with an increase in deaths from all causes in a continuous manner, with no threshold effect.43 In patients with an ACR of 30 mg/g, the hazard ratio for death was 1.63, increasing to 2.22 for those with more than 300 mg/g compared with those with no albuminuria. A similar increase in the risk of myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, or sudden cardiac death was noted with higher ACR.43

Important prospective cohort studies and meta-analyses related to albuminuria and kidney and cardiovascular disease and death are summarized in the eTable.23,39–50

THE CASE FOR TREATING ALBUMINURIA

Reduced progression of renal disease

Treating patients who have proteinuric chronic kidney disease with an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) can reduce the risk of progression of renal failure. However, it is unclear whether this benefit is the result of treating concomitant risk factors independent of the reduction in albuminuria, and there is no consistent treatment effect in improving renal outcomes across studies.

Fink et al,51 in a meta-analysis, found that chronic kidney disease patients with diabetes, hypertension, and macroalbuminuria had a 40% lower risk of progression to end-stage renal disease if they received an ACE inhibitor (relative risk [RR] 0.60, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.43–0.83). In the same meta-analysis, ARBs also reduced the risk of progression to end-stage renal disease (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.66–0.90).

Jafar et al,52 in an analysis of pooled patient-level data including only nondiabetic patients on ACE inhibitor therapy (n = 1,860), found that the risk of progression of renal failure, defined as a doubling of serum creatinine or end-stage renal disease, was reduced (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.55–0.88). Patients with higher levels of albuminuria showed the most benefit, but the effect was not conclusive for albuminuria below 500 mg/day at baseline.

Maione et al,53 in a meta-analysis that included patients with albuminuria who were treated with ACE inhibitors vs placebo (n = 8,231), found a similar reduction in risk of:

- Progression to end-stage renal disease (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.54–0.84)

- Doubling of serum creatinine (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.46–0.84)

- Progression of albuminuria (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.36–0.65)

- Normalization of pathologic albuminuria (as defined by the trialists in the individual studies) (RR 2.99, 95% CI 1.82–4.91).

Similar results were obtained for patients with albuminuria who were treated with ARBs.53

ONTARGET.54 In contrast, in the Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination With Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial, the combination of an ACE inhibitor and an ARB showed no benefit in reducing the progression of renal failure, and in those patients with chronic kidney disease there was a higher risk of a doubling of serum creatinine or of the development of end-stage renal disease and hyperkalemia.

Also, in a pooled analysis of the ONTARGET and Telmisartan Randomized Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects With Cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) trials, a 50% reduction in baseline albuminuria was associated with reduced progression of renal failure in those with a baseline ACR less than 10 mg/g.55

Improved cardiovascular outcomes

There is also evidence of better cardiovascular outcomes with treatment of albuminuria. Again, it is uncertain whether this is a result of treating risk factors other than albuminuria with ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and there is no parallel benefit demonstrated across all studies.

LIFE.47,48 In the Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension trial, survival analyses suggested a decrease in risk of cardiovascular adverse events as the degree of proteinuria improved with ARB therapy.

Maione et al,53 in a meta-analysis including 8,231 patients with albuminuria and at least one other risk factor, found a significant reduction in the rate of nonfatal cardiovascular outcomes (angina, myocardial infarction, revascularization, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or heart failure) with ACE inhibitors vs placebo (RR 0.88, CI 0.82–0.94) and also in 3,888 patients treated with ARBs vs placebo (RR 0.77, CI 0.61–0.98). However, the meta-analysis did not show that ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy reduced rate of cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

Fink et al,51 in their meta-analysis of 18 trials of ACE inhibitors and four trials of ARBs, also found no evidence that ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy reduced cardiovascular mortality rates.38

The ONTARGET trial evaluated the combination of an ACE inhibitor and ARB therapy in patients with diabetes or preexisting peripheral vascular disease. Reductions in the rate of cardiovascular disease or death were not observed, and in those with chronic kidney disease, there was a higher risk of doubling of serum creatinine or development of end-stage renal disease and adverse events of hyperkalemia.56 And although an increase in baseline albuminuria was associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes, its reduction in the ONTARGET and TRANSCEND trials did not demonstrate better outcomes when the baseline ACR was greater than 10 mg/g.55

WHO SHOULD BE TESTED?

The benefit of adding albuminuria to conventional cardiovascular risk stratification such as Framingham risk scoring is not conclusive. However, today’s clinician may view albuminuria as a biomarker for renal and cardiovascular disease, as albuminuria might be a surrogate marker for endothelial dysfunction in the glomerular capillaries or other vital vascular beds.

High-risk populations and chronic kidney disease patients

Nearly all the current guidelines recommend annual screening for albuminuria in patients with diabetes and hypertension (Table 2).7,10–13 Other high-risk populations include people with cardiovascular disease, a family history of end-stage renal disease, and metabolic syndrome. Additionally, chronic kidney disease patients whose estimated GFR defines them as being in stage 3 or higher (ie, GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2), regardless of other comorbidities, should be tested for albuminuria, as it is an important risk predictor.

Most experts prefer that albuminuria be measured by urine ACR in a first morning voided sample, though this is not the only option.

Screening the general population

Given that albuminuria has been shown to be such an important prognosticator for patients at high risk and those with chronic kidney disease, the question arises whether screening for albuminuria in the asymptomatic low-risk general population would foster earlier detection and therefore enable earlier intervention and result in improved outcomes. However, a systematic review done for the United States Preventive Services Task Force and for an American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline did not find robust evidence to support this.51

OUR RECOMMENDATIONS

Who should be tested?

- Patients with chronic kidney disease stage 3, 4, or 5 (GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2) who are not on dialysis

- Patients who are considered at higher risk of adverse outcomes, such as those with diabetes, hypertension, a family history of end-stage renal disease, or cardiovascular disease. Testing is useful for recognizing increased renal and cardiovascular risk and may lead clinicians to prescribe or titrate a renin-angiotensin system antagonist, a statin, or both, or to modify other cardiovascular risk factors.

- Not recommended: routine screening in the general population who are asymptomatic or are considered at low risk.

Which test should be used?

Based on current evidence and most guidelines, we recommend the urine ACR test as the screening test for people with diabetes and others deemed to be at high risk.

What should be done about albuminuria?

- Controlling blood pressure is important, and though there is debate about the target blood pressure, an individualized plan should be developed with the patient based on age, comorbidities, and goals of care.

- An ACE inhibitor or ARB, if not contraindicated, is recommended for patients with diabetes whose ACR is greater than 30 mg/g and for patients with chronic kidney disease and an ACR greater than 300 mg/g.

- Current evidence does not support the combined use of an ACE inhibitor and an ARB, as proof of benefit is lacking and the risk of adverse events is higher.

- Refer patients with high or unexplained albuminuria to a nephrologist or clinic specializing in chronic kidney disease.

- Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 2007; 298:2038–2047.

- Hoyer JR, Seiler MW. Pathophysiology of Tamm-Horsfall protein. Kidney Int 1979; 16:279–289.

- Viswanathan G, Upadhyay A. Assessment of proteinuria. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2011; 18:243–248.

- Guh JY. Proteinuria versus albuminuria in chronic kidney disease. Nephrology (Carlton) 2010; 15(suppl 2):53–56.

- Lamb EJ, MacKenzie F, Stevens PE. How should proteinuria be detected and measured? Ann Clin Biochem 2009; 46:205–217.

- Saydah SH, Pavkov ME, Zhang C, et al. Albuminuria prevalence in first morning void compared with previous random urine from adults in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009-2010. Clin Chem 2013; 59:675–683.

- National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 2002; 39(suppl 1):S1–S266.

- Younes N, Cleary PA, Steffes MW, et al; DCCT/EDIC Research Group. Comparison of urinary albumin-creatinine ratio and albumin excretion rate in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:1235–1242.

- Brinkman JW, de Zeeuw D, Duker JJ, et al. Falsely low urinary albumin concentrations after prolonged frozen storage of urine samples. Clin Chem 2005; 51:2181–2183.

- National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions (UK). Chronic Kidney Disease: National Clinical Guideline for Early Identification and Management in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care. London: Royal College of Physicians (UK) 2008.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2013. Diabetes Care 2013; 36(suppl 1):S11–S66.

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al; Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2003; 42:1206–1252.

- Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 2013; 3:1–150.

- Johnson DW. Global proteinuria guidelines: are we nearly there yet? Clin Biochem Rev 2011; 32:89–95.

- Ruggenenti P, Remuzzi G. Time to abandon microalbuminuria? Kidney Int 2006; 70:1214–1222.

- Glassock RJ. Is the presence of microalbuminuria a relevant marker of kidney disease? Curr Hypertens Rep 2010; 12:364–368.

- Zhang A, Huang S. Progress in pathogenesis of proteinuria. Int J Nephrol 2012; 2012:314251.

- Abbate M, Zoja C, Remuzzi G. How does proteinuria cause progressive renal damage? J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17:2974–2984.