User login

CASE Grief and confusion

Mr. P, age 47, is arrested for entering the apartment of a woman he does not know and tossing her belongings out the window. When he is assessed to determine if he can participate in his legal defense, examiners find an attentive, courteous man who is baffled by his own behavior.

Mr. P says that he had been “stressed out” after the recent death of his grandmother, with whom he was close. He says he entered the apartment because voices told him to do so. He has no recent history of substance abuse or psychiatric hospitalizations, but he had a similar episode of “confusion” years before, when another close family member died.

Mr. P is found not fit to stand trial and the charges are dropped. He accepts haloperidol, 10 mg/d, and benztropine, 2 mg/d, and is transferred to a hospital for psychiatric treatment.

On interview, Mr. P is well groomed, soft-spoken, and shy, without formal thought disorder. Physical exam and routine lab tests are within normal limits. He says that 18 months before his arrest, he and his frail grandmother moved to a large city in hopes that he would find a wife. Both depended on the grandmother’s Social Security benefits while he cared for her.

In the 2 months after she died, he reports that he felt sad and alone and slept poorly, but made efforts to find a job and keep his apartment. When his efforts failed and he lost the apartment, he stayed with various friends for a few days at a time, then spent several days in the subway before ending up on the streets.

His arrest on the current charge occurred 4 days after he began walking the streets.

a) continue haloperidol to treat psychotic symptoms

b) discontinue haloperidol and observe him

c) add an antidepressant to haloperidol

HISTORY Imagining nonsense

Mr. P cannot explain why he started “trashing” the woman’s apartment, but says he entered it because he thought it was his apartment. With embarrassment and regret, he admits he has been depressed and confused, “imagining things”—“foolish things,” he admits—such as being in a different “time zone.”

Contradicting his earlier statements, Mr. P now admits that he had “a few beers” and denies that he experienced auditory hallucinations, saying he only talks to himself. He now says that within 2 days after his arrest, he was “all over it.” Mr. P denies current symptoms, including hallucinations, but, when pressed, waffles, then admits to a strange belief: that some people, including him, can move from one “time zone” to another.

Mr. P says he was treated for psychiatric problems 4 years earlier when his parents were killed in a car crash. By his recollection, his reaction to their death was similar to his reaction to his grandmother’s death: He became upset and wandered the streets for a few days, “moving between time zones” and talking to himself but not experiencing hallucinations. After he was taken to a hospital and “given an injection,” he calmed down and was released. Within a few days he recovered and returned to supporting himself and caring for his grandmother. Mr. P says the idea of travelling between “time zones” is embarrassing and nonsensical but adds that he was affected in this way because he “bickered” with his mother.

Mr. P’s grandmother raised him until he was age 15, although he frequently visited his parents, who lived nearby and worked during the day. Mr. P initially denies substance abuse, then admits to smoking marijuana every day for about a year before admission. He also admits to cocaine abuse in his 20s. He denies a history of suicide attempts.

The author’s observations

Mr. P reported only 2 episodes of “confusion” (or psychosis) and strange behavior in his life, both precipitated by the loss of a loved one, and at least 1 while under the influence of alcohol and Cannabis. He gave an inconsistent and ambiguous history of auditory hallucinations associated with episodes of confusion. He believes that time travel is possible, an idea that he acknowledged is nonsense. This alone was not enough to warrant long-term antipsychotic treatment. The most likely diagnosis seemed to be brief psychotic episode induced by Cannabis and the stressors of homelessness and his grandmother’s death.

EVALUATION Changing stories

No longer taking haloperidol, Mr. P continues to deny hallucinations and depressed mood, but keeps to himself. Nine days after admission he becomes tearful after he informs his aunt of his grandmother’s death in a telephone call, then approaches a nurse and complains of sadness and auditory hallucinations.

Mr. P confesses that he denied hallucinations on admission because he feared he would remain in the hospital for years if he revealed the truth that he had been experiencing auditory hallucinations almost continuously from age 10. He reports that the voices distracted him when he worked; seem to be male; often spoke gibberish; and alternate between deprecating and positive and supportive. Mr. P is reluctant to disclose more about what the voices actually say, although he acknowledges that they are not commenting or conversing with him, and that he has never believed the voices were his own thoughts but did believe that they came from inside his brain.

With haloperidol, the voices stopped. They resumed, however, when haloperidol was discontinued.

When we ask what happened to him at age 10, Mr. P shrugs.

a) childhood onset schizophrenia

b) substance abuse

c) posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

d) none

The author’s observations

In community samples of children and adolescents, auditory hallucinations are not rare and usually do not cause distress or dysfunction. In a study of 3,870 children age 7 and 8,1 9% endorsed auditory hallucinations. Most heard 1 voice, once a week or less, at low volume. In 85% of children who experienced hallucinations, they caused minimal or no suffering; 97% reported minimal or no interference with daily functioning. Among children who experienced auditory hallucinations at age 7 or 8, 24% continued to hallucinate 5 years later.2 Persistent hallucinations were associated with more problematic behaviors at baseline and follow up.

In a group of 12-year-old twins, 4.2% reported auditory hallucinations.3 In that study, hallucinations were not related to Cannabis use; rather, they were heritable and related to risk factors such as cognitive impairment; behavioral, emotional, and educational problems at age 5; and a history of physical abuse and self-harm at age 12. The authors noted that these are risk factors and correlates of schizophrenia, but are not specific to schizophrenia.

Hallucinations and delusions have been found in 4% to 8% of children and adolescents referred for psychiatric treatment,4 far more than the prevalence of childhood-onset schizophrenia (0.01% of children).5 Psychotic symptoms in children have been associated with bipolar disorder, but also with anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD, pervasive developmental disorder, conduct disorder, and substance abuse.4

Childhood-onset schizophrenia is rare and would require that Mr. P have a diagnosis of schizophrenia as an adult. It is possible that Mr. P’s childhood symptoms were related to substance abuse but he was not asked for this history because it seemed unlikely in a 10-year-old boy. A PTSD diagnosis requires a traumatic event, which Mr. P did not reveal. It is possible that at age 10 he did not have a psychiatric disorder.

a) PTSD

b) dissociative disorder

c) borderline personality disorder

d) chronic schizophrenia

e) no psychiatric diagnosis

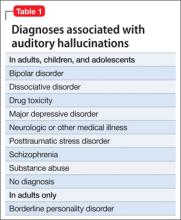

Among adults in the general population, 10% to 15% report auditory hallucinations.6 Hallucinations could be caused by substance abuse or psychiatric conditions other than schizophrenia; however, in adults—as in children—auditory hallucinations can occur in the absence of these conditions (Table 1) and rarely cause distress or dysfunction.6 In Sommer and colleagues’6 study of 103 healthy persons, none who heard voices had disorganization or negative symptoms. Those who heard voices had significantly more schizotypal symptoms and more childhood trauma, including emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, than those who did not hear voices.6

Conditions associated with hallucinations

PTSD is associated with auditory hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms.7 Most studies are of combat veterans with PTSD, in whom auditory hallucinations and delusions were associated with major depressive disorder, not a thought disorder or inappropriate affect.8 In a community sample,9 psychotic symptoms—particularly auditory hallucinations—were associated with PTSD. Subjects with PTSD and psychotic symptoms were more likely to have other psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder and substance use disorder, than patients with PTSD but no psychotic symptoms; however, the relationship between PTSD and psychosis remained after controlling for other psychiatric disorders.

Hallucinations can occur in persons with dissociative disorders in the absence of distinct personality states.10 Hallucinations have been seen transiently and chronically in persons with borderline personality disorder and can be associated with comorbid conditions such as substance abuse disorders, mood disorders, and PTSD.11

Mr. P lacked the reduced capacity for interpersonal relationships required for a schizotypal personality disorder diagnosis. A diagnosis of PTSD or dissociative disorder requires a history of trauma, which Mr. P did not report.

“Time travelling” with incomprehensible behavior could be interpreted as dissociation, but dissociative fugue or dissociative disorder not otherwise specified (NOS) cannot be diagnosed if symptoms might be the direct effect of a substance, such as Cannabis. Mr. P admitted to substance abuse. We can rule out borderline personality disorder because he did not display or admit to tempestuous interpersonal relationships.

A schizophrenia diagnosis requires the presence of auditory hallucinations that commented on his behavior or conversed among themselves, a second psychotic symptom for ≥1 month, or negative symptoms, which Mr. P lacked (unless belief in time travel is considered delusional).

Last, a physician might have considered malingering or a factitious disorder when Mr. P was found not able to participate in his own defense, but this seemed less likely after he revealed that he experienced auditory hallucinations since age 10.

HISTORY Bad beatings

With a few days of beginning risperidone, 4 mg/d, Mr. P reports that his hallucinations have stopped and he feels less sad. He reveals that, at age 10, when the hallucinations began, his mother hit him over the head with a high-heeled shoe, causing a scalp laceration that required a visit to the emergency room for suturing. His mother beat Mr. P for as long as he could remember. She beat him “bad” at least twice weekly, and he was taken to the hospital 7 or 8 times for injury, but she also beat him “constantly” with a belt buckle, sometimes striking his head. She instructed him to tell nobody.

The author’s observations

Auditory hallucinations in adults have been associated with childhood abuse, particularly childhood sexual abuse,12 in clinical and non-clinical samples.13 Some argue13 that child abuse itself causes hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms.

OUTCOME Depressed and sleepless

Mr. P admits that he had been smoking marijuana 2 to 3 times daily for a year. He also reports insomnia, sleeping approximately 4 hours a night and spending hours awake in bed thinking of his grandmother, with depressed mood and tearfulness. He denies suicidal ideas and hallucinations. He is treated for depressive disorder NOS first with amitriptyline, 50 mg at bedtime, for sleep, then paroxetine, 20 mg/d, for depressive symptoms, in addition to risperidone, 4 mg/d. Although Mr. P does not describe re-experiencing his childhood trauma, avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma, or symptoms of increased arousal (except for insomnia), the treatment team did not ask, so it remains uncertain if he has PTSD (Table 2).

When Mr. P is discharged to a clinic, he smiles easily and is positive and supportive with other patients. He spruces up his appearance by wearing jewelry and works in the hospital kitchen.

Bottom Line

Chronic auditory hallucinations are associated with psychiatric illnesses other than chronic schizophrenia, particularly those resulting from trauma such as posttraumatic stress disorder. They can also occur in the absence of diagnosable psychiatric illness and rarely cause distress or functional impairment. Auditory hallucinations in adults have been associated with childhood abuse.

Related Resources

- Moskowitz A, Schafer I, Dorahy MJ. Psychosis, trauma and dissociation: emerging perspectives on severe psychopathology. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.; 2008.

- The International Hearing Voices Network. www.intervoiceonline.org.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Paroxetine • Paxil

Benztropine • Cogentin Risperidone • Risperdal

Haloperidol • Haldol

Disclosure

Dr. Crowner reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Barthel-Velthuis AA, Jenner JA, van de Willige G, et al Prevalence and correlates of auditory vocal hallucinations in middle childhood. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(1):41-46.

2. Bartels-Velthuis AA, van de Willige G, Jenner JA, et al. Course of auditory vocal hallucinations in childhood: 5-year follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(4):296-302.

3. Polanczyk G, Moffitt TE, Arsensault L, et al. Etiological and clinical features of childhood psychotic symptoms: results from a birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):328-338.

4. Biederman J, Pety C, Faracone SV, et al. Phenomenology of childhood psychosis: Findings from a large sample of psychiatrically referred youth. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004;192(9):607-614.

5. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(suppl 7):4SS-23S.

6. Sommer IEC, Daalman K, Rietkerk T, et al. Healthy individuals with auditory verbal hallucinations; Who are they? Psychiatric assessments of a selected sample of 103 subjects. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(3):633-641.

7. Butler RW, Mueser KT, Sprock J, et al. Positive symptoms of psychosis in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:839-844.

8. David D, Kutcher GS, Jackson EI, et al Psychotic symptoms in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(1):29-32.

9. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Goodwin RD, et al. Co-occurrence of posttraumatic stress disorder with positive psychotic symptoms in a nationally representative sample. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18(4):313-322.

10. Sar V, Akyuv G, Dogan O. Prevalence of dissociative disorders among women in the general population. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149:169-176.

11. Barnow S, Arens EA, Sieswerda S, et al. Borderline personality disorder and psychosis: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(3):186-195.

12. Bebbington P, Jonas S, Kuipers E, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and psychosis: data from a cross-sectional national psychiatric survey in England. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(1):29-37.

13. Read J, van Os J, Morrison AP, et al. Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: a literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112(5):330-350.

CASE Grief and confusion

Mr. P, age 47, is arrested for entering the apartment of a woman he does not know and tossing her belongings out the window. When he is assessed to determine if he can participate in his legal defense, examiners find an attentive, courteous man who is baffled by his own behavior.

Mr. P says that he had been “stressed out” after the recent death of his grandmother, with whom he was close. He says he entered the apartment because voices told him to do so. He has no recent history of substance abuse or psychiatric hospitalizations, but he had a similar episode of “confusion” years before, when another close family member died.

Mr. P is found not fit to stand trial and the charges are dropped. He accepts haloperidol, 10 mg/d, and benztropine, 2 mg/d, and is transferred to a hospital for psychiatric treatment.

On interview, Mr. P is well groomed, soft-spoken, and shy, without formal thought disorder. Physical exam and routine lab tests are within normal limits. He says that 18 months before his arrest, he and his frail grandmother moved to a large city in hopes that he would find a wife. Both depended on the grandmother’s Social Security benefits while he cared for her.

In the 2 months after she died, he reports that he felt sad and alone and slept poorly, but made efforts to find a job and keep his apartment. When his efforts failed and he lost the apartment, he stayed with various friends for a few days at a time, then spent several days in the subway before ending up on the streets.

His arrest on the current charge occurred 4 days after he began walking the streets.

a) continue haloperidol to treat psychotic symptoms

b) discontinue haloperidol and observe him

c) add an antidepressant to haloperidol

HISTORY Imagining nonsense

Mr. P cannot explain why he started “trashing” the woman’s apartment, but says he entered it because he thought it was his apartment. With embarrassment and regret, he admits he has been depressed and confused, “imagining things”—“foolish things,” he admits—such as being in a different “time zone.”

Contradicting his earlier statements, Mr. P now admits that he had “a few beers” and denies that he experienced auditory hallucinations, saying he only talks to himself. He now says that within 2 days after his arrest, he was “all over it.” Mr. P denies current symptoms, including hallucinations, but, when pressed, waffles, then admits to a strange belief: that some people, including him, can move from one “time zone” to another.

Mr. P says he was treated for psychiatric problems 4 years earlier when his parents were killed in a car crash. By his recollection, his reaction to their death was similar to his reaction to his grandmother’s death: He became upset and wandered the streets for a few days, “moving between time zones” and talking to himself but not experiencing hallucinations. After he was taken to a hospital and “given an injection,” he calmed down and was released. Within a few days he recovered and returned to supporting himself and caring for his grandmother. Mr. P says the idea of travelling between “time zones” is embarrassing and nonsensical but adds that he was affected in this way because he “bickered” with his mother.

Mr. P’s grandmother raised him until he was age 15, although he frequently visited his parents, who lived nearby and worked during the day. Mr. P initially denies substance abuse, then admits to smoking marijuana every day for about a year before admission. He also admits to cocaine abuse in his 20s. He denies a history of suicide attempts.

The author’s observations

Mr. P reported only 2 episodes of “confusion” (or psychosis) and strange behavior in his life, both precipitated by the loss of a loved one, and at least 1 while under the influence of alcohol and Cannabis. He gave an inconsistent and ambiguous history of auditory hallucinations associated with episodes of confusion. He believes that time travel is possible, an idea that he acknowledged is nonsense. This alone was not enough to warrant long-term antipsychotic treatment. The most likely diagnosis seemed to be brief psychotic episode induced by Cannabis and the stressors of homelessness and his grandmother’s death.

EVALUATION Changing stories

No longer taking haloperidol, Mr. P continues to deny hallucinations and depressed mood, but keeps to himself. Nine days after admission he becomes tearful after he informs his aunt of his grandmother’s death in a telephone call, then approaches a nurse and complains of sadness and auditory hallucinations.

Mr. P confesses that he denied hallucinations on admission because he feared he would remain in the hospital for years if he revealed the truth that he had been experiencing auditory hallucinations almost continuously from age 10. He reports that the voices distracted him when he worked; seem to be male; often spoke gibberish; and alternate between deprecating and positive and supportive. Mr. P is reluctant to disclose more about what the voices actually say, although he acknowledges that they are not commenting or conversing with him, and that he has never believed the voices were his own thoughts but did believe that they came from inside his brain.

With haloperidol, the voices stopped. They resumed, however, when haloperidol was discontinued.

When we ask what happened to him at age 10, Mr. P shrugs.

a) childhood onset schizophrenia

b) substance abuse

c) posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

d) none

The author’s observations

In community samples of children and adolescents, auditory hallucinations are not rare and usually do not cause distress or dysfunction. In a study of 3,870 children age 7 and 8,1 9% endorsed auditory hallucinations. Most heard 1 voice, once a week or less, at low volume. In 85% of children who experienced hallucinations, they caused minimal or no suffering; 97% reported minimal or no interference with daily functioning. Among children who experienced auditory hallucinations at age 7 or 8, 24% continued to hallucinate 5 years later.2 Persistent hallucinations were associated with more problematic behaviors at baseline and follow up.

In a group of 12-year-old twins, 4.2% reported auditory hallucinations.3 In that study, hallucinations were not related to Cannabis use; rather, they were heritable and related to risk factors such as cognitive impairment; behavioral, emotional, and educational problems at age 5; and a history of physical abuse and self-harm at age 12. The authors noted that these are risk factors and correlates of schizophrenia, but are not specific to schizophrenia.

Hallucinations and delusions have been found in 4% to 8% of children and adolescents referred for psychiatric treatment,4 far more than the prevalence of childhood-onset schizophrenia (0.01% of children).5 Psychotic symptoms in children have been associated with bipolar disorder, but also with anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD, pervasive developmental disorder, conduct disorder, and substance abuse.4

Childhood-onset schizophrenia is rare and would require that Mr. P have a diagnosis of schizophrenia as an adult. It is possible that Mr. P’s childhood symptoms were related to substance abuse but he was not asked for this history because it seemed unlikely in a 10-year-old boy. A PTSD diagnosis requires a traumatic event, which Mr. P did not reveal. It is possible that at age 10 he did not have a psychiatric disorder.

a) PTSD

b) dissociative disorder

c) borderline personality disorder

d) chronic schizophrenia

e) no psychiatric diagnosis

Among adults in the general population, 10% to 15% report auditory hallucinations.6 Hallucinations could be caused by substance abuse or psychiatric conditions other than schizophrenia; however, in adults—as in children—auditory hallucinations can occur in the absence of these conditions (Table 1) and rarely cause distress or dysfunction.6 In Sommer and colleagues’6 study of 103 healthy persons, none who heard voices had disorganization or negative symptoms. Those who heard voices had significantly more schizotypal symptoms and more childhood trauma, including emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, than those who did not hear voices.6

Conditions associated with hallucinations

PTSD is associated with auditory hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms.7 Most studies are of combat veterans with PTSD, in whom auditory hallucinations and delusions were associated with major depressive disorder, not a thought disorder or inappropriate affect.8 In a community sample,9 psychotic symptoms—particularly auditory hallucinations—were associated with PTSD. Subjects with PTSD and psychotic symptoms were more likely to have other psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder and substance use disorder, than patients with PTSD but no psychotic symptoms; however, the relationship between PTSD and psychosis remained after controlling for other psychiatric disorders.

Hallucinations can occur in persons with dissociative disorders in the absence of distinct personality states.10 Hallucinations have been seen transiently and chronically in persons with borderline personality disorder and can be associated with comorbid conditions such as substance abuse disorders, mood disorders, and PTSD.11

Mr. P lacked the reduced capacity for interpersonal relationships required for a schizotypal personality disorder diagnosis. A diagnosis of PTSD or dissociative disorder requires a history of trauma, which Mr. P did not report.

“Time travelling” with incomprehensible behavior could be interpreted as dissociation, but dissociative fugue or dissociative disorder not otherwise specified (NOS) cannot be diagnosed if symptoms might be the direct effect of a substance, such as Cannabis. Mr. P admitted to substance abuse. We can rule out borderline personality disorder because he did not display or admit to tempestuous interpersonal relationships.

A schizophrenia diagnosis requires the presence of auditory hallucinations that commented on his behavior or conversed among themselves, a second psychotic symptom for ≥1 month, or negative symptoms, which Mr. P lacked (unless belief in time travel is considered delusional).

Last, a physician might have considered malingering or a factitious disorder when Mr. P was found not able to participate in his own defense, but this seemed less likely after he revealed that he experienced auditory hallucinations since age 10.

HISTORY Bad beatings

With a few days of beginning risperidone, 4 mg/d, Mr. P reports that his hallucinations have stopped and he feels less sad. He reveals that, at age 10, when the hallucinations began, his mother hit him over the head with a high-heeled shoe, causing a scalp laceration that required a visit to the emergency room for suturing. His mother beat Mr. P for as long as he could remember. She beat him “bad” at least twice weekly, and he was taken to the hospital 7 or 8 times for injury, but she also beat him “constantly” with a belt buckle, sometimes striking his head. She instructed him to tell nobody.

The author’s observations

Auditory hallucinations in adults have been associated with childhood abuse, particularly childhood sexual abuse,12 in clinical and non-clinical samples.13 Some argue13 that child abuse itself causes hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms.

OUTCOME Depressed and sleepless

Mr. P admits that he had been smoking marijuana 2 to 3 times daily for a year. He also reports insomnia, sleeping approximately 4 hours a night and spending hours awake in bed thinking of his grandmother, with depressed mood and tearfulness. He denies suicidal ideas and hallucinations. He is treated for depressive disorder NOS first with amitriptyline, 50 mg at bedtime, for sleep, then paroxetine, 20 mg/d, for depressive symptoms, in addition to risperidone, 4 mg/d. Although Mr. P does not describe re-experiencing his childhood trauma, avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma, or symptoms of increased arousal (except for insomnia), the treatment team did not ask, so it remains uncertain if he has PTSD (Table 2).

When Mr. P is discharged to a clinic, he smiles easily and is positive and supportive with other patients. He spruces up his appearance by wearing jewelry and works in the hospital kitchen.

Bottom Line

Chronic auditory hallucinations are associated with psychiatric illnesses other than chronic schizophrenia, particularly those resulting from trauma such as posttraumatic stress disorder. They can also occur in the absence of diagnosable psychiatric illness and rarely cause distress or functional impairment. Auditory hallucinations in adults have been associated with childhood abuse.

Related Resources

- Moskowitz A, Schafer I, Dorahy MJ. Psychosis, trauma and dissociation: emerging perspectives on severe psychopathology. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.; 2008.

- The International Hearing Voices Network. www.intervoiceonline.org.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Paroxetine • Paxil

Benztropine • Cogentin Risperidone • Risperdal

Haloperidol • Haldol

Disclosure

Dr. Crowner reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Grief and confusion

Mr. P, age 47, is arrested for entering the apartment of a woman he does not know and tossing her belongings out the window. When he is assessed to determine if he can participate in his legal defense, examiners find an attentive, courteous man who is baffled by his own behavior.

Mr. P says that he had been “stressed out” after the recent death of his grandmother, with whom he was close. He says he entered the apartment because voices told him to do so. He has no recent history of substance abuse or psychiatric hospitalizations, but he had a similar episode of “confusion” years before, when another close family member died.

Mr. P is found not fit to stand trial and the charges are dropped. He accepts haloperidol, 10 mg/d, and benztropine, 2 mg/d, and is transferred to a hospital for psychiatric treatment.

On interview, Mr. P is well groomed, soft-spoken, and shy, without formal thought disorder. Physical exam and routine lab tests are within normal limits. He says that 18 months before his arrest, he and his frail grandmother moved to a large city in hopes that he would find a wife. Both depended on the grandmother’s Social Security benefits while he cared for her.

In the 2 months after she died, he reports that he felt sad and alone and slept poorly, but made efforts to find a job and keep his apartment. When his efforts failed and he lost the apartment, he stayed with various friends for a few days at a time, then spent several days in the subway before ending up on the streets.

His arrest on the current charge occurred 4 days after he began walking the streets.

a) continue haloperidol to treat psychotic symptoms

b) discontinue haloperidol and observe him

c) add an antidepressant to haloperidol

HISTORY Imagining nonsense

Mr. P cannot explain why he started “trashing” the woman’s apartment, but says he entered it because he thought it was his apartment. With embarrassment and regret, he admits he has been depressed and confused, “imagining things”—“foolish things,” he admits—such as being in a different “time zone.”

Contradicting his earlier statements, Mr. P now admits that he had “a few beers” and denies that he experienced auditory hallucinations, saying he only talks to himself. He now says that within 2 days after his arrest, he was “all over it.” Mr. P denies current symptoms, including hallucinations, but, when pressed, waffles, then admits to a strange belief: that some people, including him, can move from one “time zone” to another.

Mr. P says he was treated for psychiatric problems 4 years earlier when his parents were killed in a car crash. By his recollection, his reaction to their death was similar to his reaction to his grandmother’s death: He became upset and wandered the streets for a few days, “moving between time zones” and talking to himself but not experiencing hallucinations. After he was taken to a hospital and “given an injection,” he calmed down and was released. Within a few days he recovered and returned to supporting himself and caring for his grandmother. Mr. P says the idea of travelling between “time zones” is embarrassing and nonsensical but adds that he was affected in this way because he “bickered” with his mother.

Mr. P’s grandmother raised him until he was age 15, although he frequently visited his parents, who lived nearby and worked during the day. Mr. P initially denies substance abuse, then admits to smoking marijuana every day for about a year before admission. He also admits to cocaine abuse in his 20s. He denies a history of suicide attempts.

The author’s observations

Mr. P reported only 2 episodes of “confusion” (or psychosis) and strange behavior in his life, both precipitated by the loss of a loved one, and at least 1 while under the influence of alcohol and Cannabis. He gave an inconsistent and ambiguous history of auditory hallucinations associated with episodes of confusion. He believes that time travel is possible, an idea that he acknowledged is nonsense. This alone was not enough to warrant long-term antipsychotic treatment. The most likely diagnosis seemed to be brief psychotic episode induced by Cannabis and the stressors of homelessness and his grandmother’s death.

EVALUATION Changing stories

No longer taking haloperidol, Mr. P continues to deny hallucinations and depressed mood, but keeps to himself. Nine days after admission he becomes tearful after he informs his aunt of his grandmother’s death in a telephone call, then approaches a nurse and complains of sadness and auditory hallucinations.

Mr. P confesses that he denied hallucinations on admission because he feared he would remain in the hospital for years if he revealed the truth that he had been experiencing auditory hallucinations almost continuously from age 10. He reports that the voices distracted him when he worked; seem to be male; often spoke gibberish; and alternate between deprecating and positive and supportive. Mr. P is reluctant to disclose more about what the voices actually say, although he acknowledges that they are not commenting or conversing with him, and that he has never believed the voices were his own thoughts but did believe that they came from inside his brain.

With haloperidol, the voices stopped. They resumed, however, when haloperidol was discontinued.

When we ask what happened to him at age 10, Mr. P shrugs.

a) childhood onset schizophrenia

b) substance abuse

c) posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

d) none

The author’s observations

In community samples of children and adolescents, auditory hallucinations are not rare and usually do not cause distress or dysfunction. In a study of 3,870 children age 7 and 8,1 9% endorsed auditory hallucinations. Most heard 1 voice, once a week or less, at low volume. In 85% of children who experienced hallucinations, they caused minimal or no suffering; 97% reported minimal or no interference with daily functioning. Among children who experienced auditory hallucinations at age 7 or 8, 24% continued to hallucinate 5 years later.2 Persistent hallucinations were associated with more problematic behaviors at baseline and follow up.

In a group of 12-year-old twins, 4.2% reported auditory hallucinations.3 In that study, hallucinations were not related to Cannabis use; rather, they were heritable and related to risk factors such as cognitive impairment; behavioral, emotional, and educational problems at age 5; and a history of physical abuse and self-harm at age 12. The authors noted that these are risk factors and correlates of schizophrenia, but are not specific to schizophrenia.

Hallucinations and delusions have been found in 4% to 8% of children and adolescents referred for psychiatric treatment,4 far more than the prevalence of childhood-onset schizophrenia (0.01% of children).5 Psychotic symptoms in children have been associated with bipolar disorder, but also with anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD, pervasive developmental disorder, conduct disorder, and substance abuse.4

Childhood-onset schizophrenia is rare and would require that Mr. P have a diagnosis of schizophrenia as an adult. It is possible that Mr. P’s childhood symptoms were related to substance abuse but he was not asked for this history because it seemed unlikely in a 10-year-old boy. A PTSD diagnosis requires a traumatic event, which Mr. P did not reveal. It is possible that at age 10 he did not have a psychiatric disorder.

a) PTSD

b) dissociative disorder

c) borderline personality disorder

d) chronic schizophrenia

e) no psychiatric diagnosis

Among adults in the general population, 10% to 15% report auditory hallucinations.6 Hallucinations could be caused by substance abuse or psychiatric conditions other than schizophrenia; however, in adults—as in children—auditory hallucinations can occur in the absence of these conditions (Table 1) and rarely cause distress or dysfunction.6 In Sommer and colleagues’6 study of 103 healthy persons, none who heard voices had disorganization or negative symptoms. Those who heard voices had significantly more schizotypal symptoms and more childhood trauma, including emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, than those who did not hear voices.6

Conditions associated with hallucinations

PTSD is associated with auditory hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms.7 Most studies are of combat veterans with PTSD, in whom auditory hallucinations and delusions were associated with major depressive disorder, not a thought disorder or inappropriate affect.8 In a community sample,9 psychotic symptoms—particularly auditory hallucinations—were associated with PTSD. Subjects with PTSD and psychotic symptoms were more likely to have other psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder and substance use disorder, than patients with PTSD but no psychotic symptoms; however, the relationship between PTSD and psychosis remained after controlling for other psychiatric disorders.

Hallucinations can occur in persons with dissociative disorders in the absence of distinct personality states.10 Hallucinations have been seen transiently and chronically in persons with borderline personality disorder and can be associated with comorbid conditions such as substance abuse disorders, mood disorders, and PTSD.11

Mr. P lacked the reduced capacity for interpersonal relationships required for a schizotypal personality disorder diagnosis. A diagnosis of PTSD or dissociative disorder requires a history of trauma, which Mr. P did not report.

“Time travelling” with incomprehensible behavior could be interpreted as dissociation, but dissociative fugue or dissociative disorder not otherwise specified (NOS) cannot be diagnosed if symptoms might be the direct effect of a substance, such as Cannabis. Mr. P admitted to substance abuse. We can rule out borderline personality disorder because he did not display or admit to tempestuous interpersonal relationships.

A schizophrenia diagnosis requires the presence of auditory hallucinations that commented on his behavior or conversed among themselves, a second psychotic symptom for ≥1 month, or negative symptoms, which Mr. P lacked (unless belief in time travel is considered delusional).

Last, a physician might have considered malingering or a factitious disorder when Mr. P was found not able to participate in his own defense, but this seemed less likely after he revealed that he experienced auditory hallucinations since age 10.

HISTORY Bad beatings

With a few days of beginning risperidone, 4 mg/d, Mr. P reports that his hallucinations have stopped and he feels less sad. He reveals that, at age 10, when the hallucinations began, his mother hit him over the head with a high-heeled shoe, causing a scalp laceration that required a visit to the emergency room for suturing. His mother beat Mr. P for as long as he could remember. She beat him “bad” at least twice weekly, and he was taken to the hospital 7 or 8 times for injury, but she also beat him “constantly” with a belt buckle, sometimes striking his head. She instructed him to tell nobody.

The author’s observations

Auditory hallucinations in adults have been associated with childhood abuse, particularly childhood sexual abuse,12 in clinical and non-clinical samples.13 Some argue13 that child abuse itself causes hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms.

OUTCOME Depressed and sleepless

Mr. P admits that he had been smoking marijuana 2 to 3 times daily for a year. He also reports insomnia, sleeping approximately 4 hours a night and spending hours awake in bed thinking of his grandmother, with depressed mood and tearfulness. He denies suicidal ideas and hallucinations. He is treated for depressive disorder NOS first with amitriptyline, 50 mg at bedtime, for sleep, then paroxetine, 20 mg/d, for depressive symptoms, in addition to risperidone, 4 mg/d. Although Mr. P does not describe re-experiencing his childhood trauma, avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma, or symptoms of increased arousal (except for insomnia), the treatment team did not ask, so it remains uncertain if he has PTSD (Table 2).

When Mr. P is discharged to a clinic, he smiles easily and is positive and supportive with other patients. He spruces up his appearance by wearing jewelry and works in the hospital kitchen.

Bottom Line

Chronic auditory hallucinations are associated with psychiatric illnesses other than chronic schizophrenia, particularly those resulting from trauma such as posttraumatic stress disorder. They can also occur in the absence of diagnosable psychiatric illness and rarely cause distress or functional impairment. Auditory hallucinations in adults have been associated with childhood abuse.

Related Resources

- Moskowitz A, Schafer I, Dorahy MJ. Psychosis, trauma and dissociation: emerging perspectives on severe psychopathology. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.; 2008.

- The International Hearing Voices Network. www.intervoiceonline.org.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Paroxetine • Paxil

Benztropine • Cogentin Risperidone • Risperdal

Haloperidol • Haldol

Disclosure

Dr. Crowner reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Barthel-Velthuis AA, Jenner JA, van de Willige G, et al Prevalence and correlates of auditory vocal hallucinations in middle childhood. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(1):41-46.

2. Bartels-Velthuis AA, van de Willige G, Jenner JA, et al. Course of auditory vocal hallucinations in childhood: 5-year follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(4):296-302.

3. Polanczyk G, Moffitt TE, Arsensault L, et al. Etiological and clinical features of childhood psychotic symptoms: results from a birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):328-338.

4. Biederman J, Pety C, Faracone SV, et al. Phenomenology of childhood psychosis: Findings from a large sample of psychiatrically referred youth. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004;192(9):607-614.

5. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(suppl 7):4SS-23S.

6. Sommer IEC, Daalman K, Rietkerk T, et al. Healthy individuals with auditory verbal hallucinations; Who are they? Psychiatric assessments of a selected sample of 103 subjects. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(3):633-641.

7. Butler RW, Mueser KT, Sprock J, et al. Positive symptoms of psychosis in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:839-844.

8. David D, Kutcher GS, Jackson EI, et al Psychotic symptoms in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(1):29-32.

9. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Goodwin RD, et al. Co-occurrence of posttraumatic stress disorder with positive psychotic symptoms in a nationally representative sample. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18(4):313-322.

10. Sar V, Akyuv G, Dogan O. Prevalence of dissociative disorders among women in the general population. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149:169-176.

11. Barnow S, Arens EA, Sieswerda S, et al. Borderline personality disorder and psychosis: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(3):186-195.

12. Bebbington P, Jonas S, Kuipers E, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and psychosis: data from a cross-sectional national psychiatric survey in England. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(1):29-37.

13. Read J, van Os J, Morrison AP, et al. Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: a literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112(5):330-350.

1. Barthel-Velthuis AA, Jenner JA, van de Willige G, et al Prevalence and correlates of auditory vocal hallucinations in middle childhood. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(1):41-46.

2. Bartels-Velthuis AA, van de Willige G, Jenner JA, et al. Course of auditory vocal hallucinations in childhood: 5-year follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(4):296-302.

3. Polanczyk G, Moffitt TE, Arsensault L, et al. Etiological and clinical features of childhood psychotic symptoms: results from a birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):328-338.

4. Biederman J, Pety C, Faracone SV, et al. Phenomenology of childhood psychosis: Findings from a large sample of psychiatrically referred youth. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004;192(9):607-614.

5. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(suppl 7):4SS-23S.

6. Sommer IEC, Daalman K, Rietkerk T, et al. Healthy individuals with auditory verbal hallucinations; Who are they? Psychiatric assessments of a selected sample of 103 subjects. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(3):633-641.

7. Butler RW, Mueser KT, Sprock J, et al. Positive symptoms of psychosis in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:839-844.

8. David D, Kutcher GS, Jackson EI, et al Psychotic symptoms in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(1):29-32.

9. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Goodwin RD, et al. Co-occurrence of posttraumatic stress disorder with positive psychotic symptoms in a nationally representative sample. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18(4):313-322.

10. Sar V, Akyuv G, Dogan O. Prevalence of dissociative disorders among women in the general population. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149:169-176.

11. Barnow S, Arens EA, Sieswerda S, et al. Borderline personality disorder and psychosis: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(3):186-195.

12. Bebbington P, Jonas S, Kuipers E, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and psychosis: data from a cross-sectional national psychiatric survey in England. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(1):29-37.

13. Read J, van Os J, Morrison AP, et al. Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: a literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112(5):330-350.