User login

Hearing voices, time traveling, and being hit with a high-heeled shoe

CASE Grief and confusion

Mr. P, age 47, is arrested for entering the apartment of a woman he does not know and tossing her belongings out the window. When he is assessed to determine if he can participate in his legal defense, examiners find an attentive, courteous man who is baffled by his own behavior.

Mr. P says that he had been “stressed out” after the recent death of his grandmother, with whom he was close. He says he entered the apartment because voices told him to do so. He has no recent history of substance abuse or psychiatric hospitalizations, but he had a similar episode of “confusion” years before, when another close family member died.

Mr. P is found not fit to stand trial and the charges are dropped. He accepts haloperidol, 10 mg/d, and benztropine, 2 mg/d, and is transferred to a hospital for psychiatric treatment.

On interview, Mr. P is well groomed, soft-spoken, and shy, without formal thought disorder. Physical exam and routine lab tests are within normal limits. He says that 18 months before his arrest, he and his frail grandmother moved to a large city in hopes that he would find a wife. Both depended on the grandmother’s Social Security benefits while he cared for her.

In the 2 months after she died, he reports that he felt sad and alone and slept poorly, but made efforts to find a job and keep his apartment. When his efforts failed and he lost the apartment, he stayed with various friends for a few days at a time, then spent several days in the subway before ending up on the streets.

His arrest on the current charge occurred 4 days after he began walking the streets.

a) continue haloperidol to treat psychotic symptoms

b) discontinue haloperidol and observe him

c) add an antidepressant to haloperidol

HISTORY Imagining nonsense

Mr. P cannot explain why he started “trashing” the woman’s apartment, but says he entered it because he thought it was his apartment. With embarrassment and regret, he admits he has been depressed and confused, “imagining things”—“foolish things,” he admits—such as being in a different “time zone.”

Contradicting his earlier statements, Mr. P now admits that he had “a few beers” and denies that he experienced auditory hallucinations, saying he only talks to himself. He now says that within 2 days after his arrest, he was “all over it.” Mr. P denies current symptoms, including hallucinations, but, when pressed, waffles, then admits to a strange belief: that some people, including him, can move from one “time zone” to another.

Mr. P says he was treated for psychiatric problems 4 years earlier when his parents were killed in a car crash. By his recollection, his reaction to their death was similar to his reaction to his grandmother’s death: He became upset and wandered the streets for a few days, “moving between time zones” and talking to himself but not experiencing hallucinations. After he was taken to a hospital and “given an injection,” he calmed down and was released. Within a few days he recovered and returned to supporting himself and caring for his grandmother. Mr. P says the idea of travelling between “time zones” is embarrassing and nonsensical but adds that he was affected in this way because he “bickered” with his mother.

Mr. P’s grandmother raised him until he was age 15, although he frequently visited his parents, who lived nearby and worked during the day. Mr. P initially denies substance abuse, then admits to smoking marijuana every day for about a year before admission. He also admits to cocaine abuse in his 20s. He denies a history of suicide attempts.

The author’s observations

Mr. P reported only 2 episodes of “confusion” (or psychosis) and strange behavior in his life, both precipitated by the loss of a loved one, and at least 1 while under the influence of alcohol and Cannabis. He gave an inconsistent and ambiguous history of auditory hallucinations associated with episodes of confusion. He believes that time travel is possible, an idea that he acknowledged is nonsense. This alone was not enough to warrant long-term antipsychotic treatment. The most likely diagnosis seemed to be brief psychotic episode induced by Cannabis and the stressors of homelessness and his grandmother’s death.

EVALUATION Changing stories

No longer taking haloperidol, Mr. P continues to deny hallucinations and depressed mood, but keeps to himself. Nine days after admission he becomes tearful after he informs his aunt of his grandmother’s death in a telephone call, then approaches a nurse and complains of sadness and auditory hallucinations.

Mr. P confesses that he denied hallucinations on admission because he feared he would remain in the hospital for years if he revealed the truth that he had been experiencing auditory hallucinations almost continuously from age 10. He reports that the voices distracted him when he worked; seem to be male; often spoke gibberish; and alternate between deprecating and positive and supportive. Mr. P is reluctant to disclose more about what the voices actually say, although he acknowledges that they are not commenting or conversing with him, and that he has never believed the voices were his own thoughts but did believe that they came from inside his brain.

With haloperidol, the voices stopped. They resumed, however, when haloperidol was discontinued.

When we ask what happened to him at age 10, Mr. P shrugs.

a) childhood onset schizophrenia

b) substance abuse

c) posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

d) none

The author’s observations

In community samples of children and adolescents, auditory hallucinations are not rare and usually do not cause distress or dysfunction. In a study of 3,870 children age 7 and 8,1 9% endorsed auditory hallucinations. Most heard 1 voice, once a week or less, at low volume. In 85% of children who experienced hallucinations, they caused minimal or no suffering; 97% reported minimal or no interference with daily functioning. Among children who experienced auditory hallucinations at age 7 or 8, 24% continued to hallucinate 5 years later.2 Persistent hallucinations were associated with more problematic behaviors at baseline and follow up.

In a group of 12-year-old twins, 4.2% reported auditory hallucinations.3 In that study, hallucinations were not related to Cannabis use; rather, they were heritable and related to risk factors such as cognitive impairment; behavioral, emotional, and educational problems at age 5; and a history of physical abuse and self-harm at age 12. The authors noted that these are risk factors and correlates of schizophrenia, but are not specific to schizophrenia.

Hallucinations and delusions have been found in 4% to 8% of children and adolescents referred for psychiatric treatment,4 far more than the prevalence of childhood-onset schizophrenia (0.01% of children).5 Psychotic symptoms in children have been associated with bipolar disorder, but also with anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD, pervasive developmental disorder, conduct disorder, and substance abuse.4

Childhood-onset schizophrenia is rare and would require that Mr. P have a diagnosis of schizophrenia as an adult. It is possible that Mr. P’s childhood symptoms were related to substance abuse but he was not asked for this history because it seemed unlikely in a 10-year-old boy. A PTSD diagnosis requires a traumatic event, which Mr. P did not reveal. It is possible that at age 10 he did not have a psychiatric disorder.

a) PTSD

b) dissociative disorder

c) borderline personality disorder

d) chronic schizophrenia

e) no psychiatric diagnosis

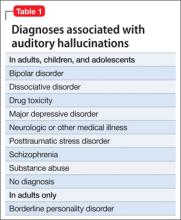

Among adults in the general population, 10% to 15% report auditory hallucinations.6 Hallucinations could be caused by substance abuse or psychiatric conditions other than schizophrenia; however, in adults—as in children—auditory hallucinations can occur in the absence of these conditions (Table 1) and rarely cause distress or dysfunction.6 In Sommer and colleagues’6 study of 103 healthy persons, none who heard voices had disorganization or negative symptoms. Those who heard voices had significantly more schizotypal symptoms and more childhood trauma, including emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, than those who did not hear voices.6

Conditions associated with hallucinations

PTSD is associated with auditory hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms.7 Most studies are of combat veterans with PTSD, in whom auditory hallucinations and delusions were associated with major depressive disorder, not a thought disorder or inappropriate affect.8 In a community sample,9 psychotic symptoms—particularly auditory hallucinations—were associated with PTSD. Subjects with PTSD and psychotic symptoms were more likely to have other psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder and substance use disorder, than patients with PTSD but no psychotic symptoms; however, the relationship between PTSD and psychosis remained after controlling for other psychiatric disorders.

Hallucinations can occur in persons with dissociative disorders in the absence of distinct personality states.10 Hallucinations have been seen transiently and chronically in persons with borderline personality disorder and can be associated with comorbid conditions such as substance abuse disorders, mood disorders, and PTSD.11

Mr. P lacked the reduced capacity for interpersonal relationships required for a schizotypal personality disorder diagnosis. A diagnosis of PTSD or dissociative disorder requires a history of trauma, which Mr. P did not report.

“Time travelling” with incomprehensible behavior could be interpreted as dissociation, but dissociative fugue or dissociative disorder not otherwise specified (NOS) cannot be diagnosed if symptoms might be the direct effect of a substance, such as Cannabis. Mr. P admitted to substance abuse. We can rule out borderline personality disorder because he did not display or admit to tempestuous interpersonal relationships.

A schizophrenia diagnosis requires the presence of auditory hallucinations that commented on his behavior or conversed among themselves, a second psychotic symptom for ≥1 month, or negative symptoms, which Mr. P lacked (unless belief in time travel is considered delusional).

Last, a physician might have considered malingering or a factitious disorder when Mr. P was found not able to participate in his own defense, but this seemed less likely after he revealed that he experienced auditory hallucinations since age 10.

HISTORY Bad beatings

With a few days of beginning risperidone, 4 mg/d, Mr. P reports that his hallucinations have stopped and he feels less sad. He reveals that, at age 10, when the hallucinations began, his mother hit him over the head with a high-heeled shoe, causing a scalp laceration that required a visit to the emergency room for suturing. His mother beat Mr. P for as long as he could remember. She beat him “bad” at least twice weekly, and he was taken to the hospital 7 or 8 times for injury, but she also beat him “constantly” with a belt buckle, sometimes striking his head. She instructed him to tell nobody.

The author’s observations

Auditory hallucinations in adults have been associated with childhood abuse, particularly childhood sexual abuse,12 in clinical and non-clinical samples.13 Some argue13 that child abuse itself causes hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms.

OUTCOME Depressed and sleepless

Mr. P admits that he had been smoking marijuana 2 to 3 times daily for a year. He also reports insomnia, sleeping approximately 4 hours a night and spending hours awake in bed thinking of his grandmother, with depressed mood and tearfulness. He denies suicidal ideas and hallucinations. He is treated for depressive disorder NOS first with amitriptyline, 50 mg at bedtime, for sleep, then paroxetine, 20 mg/d, for depressive symptoms, in addition to risperidone, 4 mg/d. Although Mr. P does not describe re-experiencing his childhood trauma, avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma, or symptoms of increased arousal (except for insomnia), the treatment team did not ask, so it remains uncertain if he has PTSD (Table 2).

When Mr. P is discharged to a clinic, he smiles easily and is positive and supportive with other patients. He spruces up his appearance by wearing jewelry and works in the hospital kitchen.

Bottom Line

Chronic auditory hallucinations are associated with psychiatric illnesses other than chronic schizophrenia, particularly those resulting from trauma such as posttraumatic stress disorder. They can also occur in the absence of diagnosable psychiatric illness and rarely cause distress or functional impairment. Auditory hallucinations in adults have been associated with childhood abuse.

Related Resources

- Moskowitz A, Schafer I, Dorahy MJ. Psychosis, trauma and dissociation: emerging perspectives on severe psychopathology. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.; 2008.

- The International Hearing Voices Network. www.intervoiceonline.org.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Paroxetine • Paxil

Benztropine • Cogentin Risperidone • Risperdal

Haloperidol • Haldol

Disclosure

Dr. Crowner reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Barthel-Velthuis AA, Jenner JA, van de Willige G, et al Prevalence and correlates of auditory vocal hallucinations in middle childhood. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(1):41-46.

2. Bartels-Velthuis AA, van de Willige G, Jenner JA, et al. Course of auditory vocal hallucinations in childhood: 5-year follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(4):296-302.

3. Polanczyk G, Moffitt TE, Arsensault L, et al. Etiological and clinical features of childhood psychotic symptoms: results from a birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):328-338.

4. Biederman J, Pety C, Faracone SV, et al. Phenomenology of childhood psychosis: Findings from a large sample of psychiatrically referred youth. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004;192(9):607-614.

5. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(suppl 7):4SS-23S.

6. Sommer IEC, Daalman K, Rietkerk T, et al. Healthy individuals with auditory verbal hallucinations; Who are they? Psychiatric assessments of a selected sample of 103 subjects. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(3):633-641.

7. Butler RW, Mueser KT, Sprock J, et al. Positive symptoms of psychosis in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:839-844.

8. David D, Kutcher GS, Jackson EI, et al Psychotic symptoms in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(1):29-32.

9. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Goodwin RD, et al. Co-occurrence of posttraumatic stress disorder with positive psychotic symptoms in a nationally representative sample. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18(4):313-322.

10. Sar V, Akyuv G, Dogan O. Prevalence of dissociative disorders among women in the general population. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149:169-176.

11. Barnow S, Arens EA, Sieswerda S, et al. Borderline personality disorder and psychosis: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(3):186-195.

12. Bebbington P, Jonas S, Kuipers E, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and psychosis: data from a cross-sectional national psychiatric survey in England. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(1):29-37.

13. Read J, van Os J, Morrison AP, et al. Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: a literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112(5):330-350.

CASE Grief and confusion

Mr. P, age 47, is arrested for entering the apartment of a woman he does not know and tossing her belongings out the window. When he is assessed to determine if he can participate in his legal defense, examiners find an attentive, courteous man who is baffled by his own behavior.

Mr. P says that he had been “stressed out” after the recent death of his grandmother, with whom he was close. He says he entered the apartment because voices told him to do so. He has no recent history of substance abuse or psychiatric hospitalizations, but he had a similar episode of “confusion” years before, when another close family member died.

Mr. P is found not fit to stand trial and the charges are dropped. He accepts haloperidol, 10 mg/d, and benztropine, 2 mg/d, and is transferred to a hospital for psychiatric treatment.

On interview, Mr. P is well groomed, soft-spoken, and shy, without formal thought disorder. Physical exam and routine lab tests are within normal limits. He says that 18 months before his arrest, he and his frail grandmother moved to a large city in hopes that he would find a wife. Both depended on the grandmother’s Social Security benefits while he cared for her.

In the 2 months after she died, he reports that he felt sad and alone and slept poorly, but made efforts to find a job and keep his apartment. When his efforts failed and he lost the apartment, he stayed with various friends for a few days at a time, then spent several days in the subway before ending up on the streets.

His arrest on the current charge occurred 4 days after he began walking the streets.

a) continue haloperidol to treat psychotic symptoms

b) discontinue haloperidol and observe him

c) add an antidepressant to haloperidol

HISTORY Imagining nonsense

Mr. P cannot explain why he started “trashing” the woman’s apartment, but says he entered it because he thought it was his apartment. With embarrassment and regret, he admits he has been depressed and confused, “imagining things”—“foolish things,” he admits—such as being in a different “time zone.”

Contradicting his earlier statements, Mr. P now admits that he had “a few beers” and denies that he experienced auditory hallucinations, saying he only talks to himself. He now says that within 2 days after his arrest, he was “all over it.” Mr. P denies current symptoms, including hallucinations, but, when pressed, waffles, then admits to a strange belief: that some people, including him, can move from one “time zone” to another.

Mr. P says he was treated for psychiatric problems 4 years earlier when his parents were killed in a car crash. By his recollection, his reaction to their death was similar to his reaction to his grandmother’s death: He became upset and wandered the streets for a few days, “moving between time zones” and talking to himself but not experiencing hallucinations. After he was taken to a hospital and “given an injection,” he calmed down and was released. Within a few days he recovered and returned to supporting himself and caring for his grandmother. Mr. P says the idea of travelling between “time zones” is embarrassing and nonsensical but adds that he was affected in this way because he “bickered” with his mother.

Mr. P’s grandmother raised him until he was age 15, although he frequently visited his parents, who lived nearby and worked during the day. Mr. P initially denies substance abuse, then admits to smoking marijuana every day for about a year before admission. He also admits to cocaine abuse in his 20s. He denies a history of suicide attempts.

The author’s observations

Mr. P reported only 2 episodes of “confusion” (or psychosis) and strange behavior in his life, both precipitated by the loss of a loved one, and at least 1 while under the influence of alcohol and Cannabis. He gave an inconsistent and ambiguous history of auditory hallucinations associated with episodes of confusion. He believes that time travel is possible, an idea that he acknowledged is nonsense. This alone was not enough to warrant long-term antipsychotic treatment. The most likely diagnosis seemed to be brief psychotic episode induced by Cannabis and the stressors of homelessness and his grandmother’s death.

EVALUATION Changing stories

No longer taking haloperidol, Mr. P continues to deny hallucinations and depressed mood, but keeps to himself. Nine days after admission he becomes tearful after he informs his aunt of his grandmother’s death in a telephone call, then approaches a nurse and complains of sadness and auditory hallucinations.

Mr. P confesses that he denied hallucinations on admission because he feared he would remain in the hospital for years if he revealed the truth that he had been experiencing auditory hallucinations almost continuously from age 10. He reports that the voices distracted him when he worked; seem to be male; often spoke gibberish; and alternate between deprecating and positive and supportive. Mr. P is reluctant to disclose more about what the voices actually say, although he acknowledges that they are not commenting or conversing with him, and that he has never believed the voices were his own thoughts but did believe that they came from inside his brain.

With haloperidol, the voices stopped. They resumed, however, when haloperidol was discontinued.

When we ask what happened to him at age 10, Mr. P shrugs.

a) childhood onset schizophrenia

b) substance abuse

c) posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

d) none

The author’s observations

In community samples of children and adolescents, auditory hallucinations are not rare and usually do not cause distress or dysfunction. In a study of 3,870 children age 7 and 8,1 9% endorsed auditory hallucinations. Most heard 1 voice, once a week or less, at low volume. In 85% of children who experienced hallucinations, they caused minimal or no suffering; 97% reported minimal or no interference with daily functioning. Among children who experienced auditory hallucinations at age 7 or 8, 24% continued to hallucinate 5 years later.2 Persistent hallucinations were associated with more problematic behaviors at baseline and follow up.

In a group of 12-year-old twins, 4.2% reported auditory hallucinations.3 In that study, hallucinations were not related to Cannabis use; rather, they were heritable and related to risk factors such as cognitive impairment; behavioral, emotional, and educational problems at age 5; and a history of physical abuse and self-harm at age 12. The authors noted that these are risk factors and correlates of schizophrenia, but are not specific to schizophrenia.

Hallucinations and delusions have been found in 4% to 8% of children and adolescents referred for psychiatric treatment,4 far more than the prevalence of childhood-onset schizophrenia (0.01% of children).5 Psychotic symptoms in children have been associated with bipolar disorder, but also with anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD, pervasive developmental disorder, conduct disorder, and substance abuse.4

Childhood-onset schizophrenia is rare and would require that Mr. P have a diagnosis of schizophrenia as an adult. It is possible that Mr. P’s childhood symptoms were related to substance abuse but he was not asked for this history because it seemed unlikely in a 10-year-old boy. A PTSD diagnosis requires a traumatic event, which Mr. P did not reveal. It is possible that at age 10 he did not have a psychiatric disorder.

a) PTSD

b) dissociative disorder

c) borderline personality disorder

d) chronic schizophrenia

e) no psychiatric diagnosis

Among adults in the general population, 10% to 15% report auditory hallucinations.6 Hallucinations could be caused by substance abuse or psychiatric conditions other than schizophrenia; however, in adults—as in children—auditory hallucinations can occur in the absence of these conditions (Table 1) and rarely cause distress or dysfunction.6 In Sommer and colleagues’6 study of 103 healthy persons, none who heard voices had disorganization or negative symptoms. Those who heard voices had significantly more schizotypal symptoms and more childhood trauma, including emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, than those who did not hear voices.6

Conditions associated with hallucinations

PTSD is associated with auditory hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms.7 Most studies are of combat veterans with PTSD, in whom auditory hallucinations and delusions were associated with major depressive disorder, not a thought disorder or inappropriate affect.8 In a community sample,9 psychotic symptoms—particularly auditory hallucinations—were associated with PTSD. Subjects with PTSD and psychotic symptoms were more likely to have other psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder and substance use disorder, than patients with PTSD but no psychotic symptoms; however, the relationship between PTSD and psychosis remained after controlling for other psychiatric disorders.

Hallucinations can occur in persons with dissociative disorders in the absence of distinct personality states.10 Hallucinations have been seen transiently and chronically in persons with borderline personality disorder and can be associated with comorbid conditions such as substance abuse disorders, mood disorders, and PTSD.11

Mr. P lacked the reduced capacity for interpersonal relationships required for a schizotypal personality disorder diagnosis. A diagnosis of PTSD or dissociative disorder requires a history of trauma, which Mr. P did not report.

“Time travelling” with incomprehensible behavior could be interpreted as dissociation, but dissociative fugue or dissociative disorder not otherwise specified (NOS) cannot be diagnosed if symptoms might be the direct effect of a substance, such as Cannabis. Mr. P admitted to substance abuse. We can rule out borderline personality disorder because he did not display or admit to tempestuous interpersonal relationships.

A schizophrenia diagnosis requires the presence of auditory hallucinations that commented on his behavior or conversed among themselves, a second psychotic symptom for ≥1 month, or negative symptoms, which Mr. P lacked (unless belief in time travel is considered delusional).

Last, a physician might have considered malingering or a factitious disorder when Mr. P was found not able to participate in his own defense, but this seemed less likely after he revealed that he experienced auditory hallucinations since age 10.

HISTORY Bad beatings

With a few days of beginning risperidone, 4 mg/d, Mr. P reports that his hallucinations have stopped and he feels less sad. He reveals that, at age 10, when the hallucinations began, his mother hit him over the head with a high-heeled shoe, causing a scalp laceration that required a visit to the emergency room for suturing. His mother beat Mr. P for as long as he could remember. She beat him “bad” at least twice weekly, and he was taken to the hospital 7 or 8 times for injury, but she also beat him “constantly” with a belt buckle, sometimes striking his head. She instructed him to tell nobody.

The author’s observations

Auditory hallucinations in adults have been associated with childhood abuse, particularly childhood sexual abuse,12 in clinical and non-clinical samples.13 Some argue13 that child abuse itself causes hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms.

OUTCOME Depressed and sleepless

Mr. P admits that he had been smoking marijuana 2 to 3 times daily for a year. He also reports insomnia, sleeping approximately 4 hours a night and spending hours awake in bed thinking of his grandmother, with depressed mood and tearfulness. He denies suicidal ideas and hallucinations. He is treated for depressive disorder NOS first with amitriptyline, 50 mg at bedtime, for sleep, then paroxetine, 20 mg/d, for depressive symptoms, in addition to risperidone, 4 mg/d. Although Mr. P does not describe re-experiencing his childhood trauma, avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma, or symptoms of increased arousal (except for insomnia), the treatment team did not ask, so it remains uncertain if he has PTSD (Table 2).

When Mr. P is discharged to a clinic, he smiles easily and is positive and supportive with other patients. He spruces up his appearance by wearing jewelry and works in the hospital kitchen.

Bottom Line

Chronic auditory hallucinations are associated with psychiatric illnesses other than chronic schizophrenia, particularly those resulting from trauma such as posttraumatic stress disorder. They can also occur in the absence of diagnosable psychiatric illness and rarely cause distress or functional impairment. Auditory hallucinations in adults have been associated with childhood abuse.

Related Resources

- Moskowitz A, Schafer I, Dorahy MJ. Psychosis, trauma and dissociation: emerging perspectives on severe psychopathology. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.; 2008.

- The International Hearing Voices Network. www.intervoiceonline.org.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Paroxetine • Paxil

Benztropine • Cogentin Risperidone • Risperdal

Haloperidol • Haldol

Disclosure

Dr. Crowner reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Grief and confusion

Mr. P, age 47, is arrested for entering the apartment of a woman he does not know and tossing her belongings out the window. When he is assessed to determine if he can participate in his legal defense, examiners find an attentive, courteous man who is baffled by his own behavior.

Mr. P says that he had been “stressed out” after the recent death of his grandmother, with whom he was close. He says he entered the apartment because voices told him to do so. He has no recent history of substance abuse or psychiatric hospitalizations, but he had a similar episode of “confusion” years before, when another close family member died.

Mr. P is found not fit to stand trial and the charges are dropped. He accepts haloperidol, 10 mg/d, and benztropine, 2 mg/d, and is transferred to a hospital for psychiatric treatment.

On interview, Mr. P is well groomed, soft-spoken, and shy, without formal thought disorder. Physical exam and routine lab tests are within normal limits. He says that 18 months before his arrest, he and his frail grandmother moved to a large city in hopes that he would find a wife. Both depended on the grandmother’s Social Security benefits while he cared for her.

In the 2 months after she died, he reports that he felt sad and alone and slept poorly, but made efforts to find a job and keep his apartment. When his efforts failed and he lost the apartment, he stayed with various friends for a few days at a time, then spent several days in the subway before ending up on the streets.

His arrest on the current charge occurred 4 days after he began walking the streets.

a) continue haloperidol to treat psychotic symptoms

b) discontinue haloperidol and observe him

c) add an antidepressant to haloperidol

HISTORY Imagining nonsense

Mr. P cannot explain why he started “trashing” the woman’s apartment, but says he entered it because he thought it was his apartment. With embarrassment and regret, he admits he has been depressed and confused, “imagining things”—“foolish things,” he admits—such as being in a different “time zone.”

Contradicting his earlier statements, Mr. P now admits that he had “a few beers” and denies that he experienced auditory hallucinations, saying he only talks to himself. He now says that within 2 days after his arrest, he was “all over it.” Mr. P denies current symptoms, including hallucinations, but, when pressed, waffles, then admits to a strange belief: that some people, including him, can move from one “time zone” to another.

Mr. P says he was treated for psychiatric problems 4 years earlier when his parents were killed in a car crash. By his recollection, his reaction to their death was similar to his reaction to his grandmother’s death: He became upset and wandered the streets for a few days, “moving between time zones” and talking to himself but not experiencing hallucinations. After he was taken to a hospital and “given an injection,” he calmed down and was released. Within a few days he recovered and returned to supporting himself and caring for his grandmother. Mr. P says the idea of travelling between “time zones” is embarrassing and nonsensical but adds that he was affected in this way because he “bickered” with his mother.

Mr. P’s grandmother raised him until he was age 15, although he frequently visited his parents, who lived nearby and worked during the day. Mr. P initially denies substance abuse, then admits to smoking marijuana every day for about a year before admission. He also admits to cocaine abuse in his 20s. He denies a history of suicide attempts.

The author’s observations

Mr. P reported only 2 episodes of “confusion” (or psychosis) and strange behavior in his life, both precipitated by the loss of a loved one, and at least 1 while under the influence of alcohol and Cannabis. He gave an inconsistent and ambiguous history of auditory hallucinations associated with episodes of confusion. He believes that time travel is possible, an idea that he acknowledged is nonsense. This alone was not enough to warrant long-term antipsychotic treatment. The most likely diagnosis seemed to be brief psychotic episode induced by Cannabis and the stressors of homelessness and his grandmother’s death.

EVALUATION Changing stories

No longer taking haloperidol, Mr. P continues to deny hallucinations and depressed mood, but keeps to himself. Nine days after admission he becomes tearful after he informs his aunt of his grandmother’s death in a telephone call, then approaches a nurse and complains of sadness and auditory hallucinations.

Mr. P confesses that he denied hallucinations on admission because he feared he would remain in the hospital for years if he revealed the truth that he had been experiencing auditory hallucinations almost continuously from age 10. He reports that the voices distracted him when he worked; seem to be male; often spoke gibberish; and alternate between deprecating and positive and supportive. Mr. P is reluctant to disclose more about what the voices actually say, although he acknowledges that they are not commenting or conversing with him, and that he has never believed the voices were his own thoughts but did believe that they came from inside his brain.

With haloperidol, the voices stopped. They resumed, however, when haloperidol was discontinued.

When we ask what happened to him at age 10, Mr. P shrugs.

a) childhood onset schizophrenia

b) substance abuse

c) posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

d) none

The author’s observations

In community samples of children and adolescents, auditory hallucinations are not rare and usually do not cause distress or dysfunction. In a study of 3,870 children age 7 and 8,1 9% endorsed auditory hallucinations. Most heard 1 voice, once a week or less, at low volume. In 85% of children who experienced hallucinations, they caused minimal or no suffering; 97% reported minimal or no interference with daily functioning. Among children who experienced auditory hallucinations at age 7 or 8, 24% continued to hallucinate 5 years later.2 Persistent hallucinations were associated with more problematic behaviors at baseline and follow up.

In a group of 12-year-old twins, 4.2% reported auditory hallucinations.3 In that study, hallucinations were not related to Cannabis use; rather, they were heritable and related to risk factors such as cognitive impairment; behavioral, emotional, and educational problems at age 5; and a history of physical abuse and self-harm at age 12. The authors noted that these are risk factors and correlates of schizophrenia, but are not specific to schizophrenia.

Hallucinations and delusions have been found in 4% to 8% of children and adolescents referred for psychiatric treatment,4 far more than the prevalence of childhood-onset schizophrenia (0.01% of children).5 Psychotic symptoms in children have been associated with bipolar disorder, but also with anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD, pervasive developmental disorder, conduct disorder, and substance abuse.4

Childhood-onset schizophrenia is rare and would require that Mr. P have a diagnosis of schizophrenia as an adult. It is possible that Mr. P’s childhood symptoms were related to substance abuse but he was not asked for this history because it seemed unlikely in a 10-year-old boy. A PTSD diagnosis requires a traumatic event, which Mr. P did not reveal. It is possible that at age 10 he did not have a psychiatric disorder.

a) PTSD

b) dissociative disorder

c) borderline personality disorder

d) chronic schizophrenia

e) no psychiatric diagnosis

Among adults in the general population, 10% to 15% report auditory hallucinations.6 Hallucinations could be caused by substance abuse or psychiatric conditions other than schizophrenia; however, in adults—as in children—auditory hallucinations can occur in the absence of these conditions (Table 1) and rarely cause distress or dysfunction.6 In Sommer and colleagues’6 study of 103 healthy persons, none who heard voices had disorganization or negative symptoms. Those who heard voices had significantly more schizotypal symptoms and more childhood trauma, including emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, than those who did not hear voices.6

Conditions associated with hallucinations

PTSD is associated with auditory hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms.7 Most studies are of combat veterans with PTSD, in whom auditory hallucinations and delusions were associated with major depressive disorder, not a thought disorder or inappropriate affect.8 In a community sample,9 psychotic symptoms—particularly auditory hallucinations—were associated with PTSD. Subjects with PTSD and psychotic symptoms were more likely to have other psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder and substance use disorder, than patients with PTSD but no psychotic symptoms; however, the relationship between PTSD and psychosis remained after controlling for other psychiatric disorders.

Hallucinations can occur in persons with dissociative disorders in the absence of distinct personality states.10 Hallucinations have been seen transiently and chronically in persons with borderline personality disorder and can be associated with comorbid conditions such as substance abuse disorders, mood disorders, and PTSD.11

Mr. P lacked the reduced capacity for interpersonal relationships required for a schizotypal personality disorder diagnosis. A diagnosis of PTSD or dissociative disorder requires a history of trauma, which Mr. P did not report.

“Time travelling” with incomprehensible behavior could be interpreted as dissociation, but dissociative fugue or dissociative disorder not otherwise specified (NOS) cannot be diagnosed if symptoms might be the direct effect of a substance, such as Cannabis. Mr. P admitted to substance abuse. We can rule out borderline personality disorder because he did not display or admit to tempestuous interpersonal relationships.

A schizophrenia diagnosis requires the presence of auditory hallucinations that commented on his behavior or conversed among themselves, a second psychotic symptom for ≥1 month, or negative symptoms, which Mr. P lacked (unless belief in time travel is considered delusional).

Last, a physician might have considered malingering or a factitious disorder when Mr. P was found not able to participate in his own defense, but this seemed less likely after he revealed that he experienced auditory hallucinations since age 10.

HISTORY Bad beatings

With a few days of beginning risperidone, 4 mg/d, Mr. P reports that his hallucinations have stopped and he feels less sad. He reveals that, at age 10, when the hallucinations began, his mother hit him over the head with a high-heeled shoe, causing a scalp laceration that required a visit to the emergency room for suturing. His mother beat Mr. P for as long as he could remember. She beat him “bad” at least twice weekly, and he was taken to the hospital 7 or 8 times for injury, but she also beat him “constantly” with a belt buckle, sometimes striking his head. She instructed him to tell nobody.

The author’s observations

Auditory hallucinations in adults have been associated with childhood abuse, particularly childhood sexual abuse,12 in clinical and non-clinical samples.13 Some argue13 that child abuse itself causes hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms.

OUTCOME Depressed and sleepless

Mr. P admits that he had been smoking marijuana 2 to 3 times daily for a year. He also reports insomnia, sleeping approximately 4 hours a night and spending hours awake in bed thinking of his grandmother, with depressed mood and tearfulness. He denies suicidal ideas and hallucinations. He is treated for depressive disorder NOS first with amitriptyline, 50 mg at bedtime, for sleep, then paroxetine, 20 mg/d, for depressive symptoms, in addition to risperidone, 4 mg/d. Although Mr. P does not describe re-experiencing his childhood trauma, avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma, or symptoms of increased arousal (except for insomnia), the treatment team did not ask, so it remains uncertain if he has PTSD (Table 2).

When Mr. P is discharged to a clinic, he smiles easily and is positive and supportive with other patients. He spruces up his appearance by wearing jewelry and works in the hospital kitchen.

Bottom Line

Chronic auditory hallucinations are associated with psychiatric illnesses other than chronic schizophrenia, particularly those resulting from trauma such as posttraumatic stress disorder. They can also occur in the absence of diagnosable psychiatric illness and rarely cause distress or functional impairment. Auditory hallucinations in adults have been associated with childhood abuse.

Related Resources

- Moskowitz A, Schafer I, Dorahy MJ. Psychosis, trauma and dissociation: emerging perspectives on severe psychopathology. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.; 2008.

- The International Hearing Voices Network. www.intervoiceonline.org.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Paroxetine • Paxil

Benztropine • Cogentin Risperidone • Risperdal

Haloperidol • Haldol

Disclosure

Dr. Crowner reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Barthel-Velthuis AA, Jenner JA, van de Willige G, et al Prevalence and correlates of auditory vocal hallucinations in middle childhood. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(1):41-46.

2. Bartels-Velthuis AA, van de Willige G, Jenner JA, et al. Course of auditory vocal hallucinations in childhood: 5-year follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(4):296-302.

3. Polanczyk G, Moffitt TE, Arsensault L, et al. Etiological and clinical features of childhood psychotic symptoms: results from a birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):328-338.

4. Biederman J, Pety C, Faracone SV, et al. Phenomenology of childhood psychosis: Findings from a large sample of psychiatrically referred youth. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004;192(9):607-614.

5. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(suppl 7):4SS-23S.

6. Sommer IEC, Daalman K, Rietkerk T, et al. Healthy individuals with auditory verbal hallucinations; Who are they? Psychiatric assessments of a selected sample of 103 subjects. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(3):633-641.

7. Butler RW, Mueser KT, Sprock J, et al. Positive symptoms of psychosis in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:839-844.

8. David D, Kutcher GS, Jackson EI, et al Psychotic symptoms in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(1):29-32.

9. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Goodwin RD, et al. Co-occurrence of posttraumatic stress disorder with positive psychotic symptoms in a nationally representative sample. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18(4):313-322.

10. Sar V, Akyuv G, Dogan O. Prevalence of dissociative disorders among women in the general population. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149:169-176.

11. Barnow S, Arens EA, Sieswerda S, et al. Borderline personality disorder and psychosis: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(3):186-195.

12. Bebbington P, Jonas S, Kuipers E, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and psychosis: data from a cross-sectional national psychiatric survey in England. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(1):29-37.

13. Read J, van Os J, Morrison AP, et al. Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: a literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112(5):330-350.

1. Barthel-Velthuis AA, Jenner JA, van de Willige G, et al Prevalence and correlates of auditory vocal hallucinations in middle childhood. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(1):41-46.

2. Bartels-Velthuis AA, van de Willige G, Jenner JA, et al. Course of auditory vocal hallucinations in childhood: 5-year follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(4):296-302.

3. Polanczyk G, Moffitt TE, Arsensault L, et al. Etiological and clinical features of childhood psychotic symptoms: results from a birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):328-338.

4. Biederman J, Pety C, Faracone SV, et al. Phenomenology of childhood psychosis: Findings from a large sample of psychiatrically referred youth. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004;192(9):607-614.

5. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(suppl 7):4SS-23S.

6. Sommer IEC, Daalman K, Rietkerk T, et al. Healthy individuals with auditory verbal hallucinations; Who are they? Psychiatric assessments of a selected sample of 103 subjects. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(3):633-641.

7. Butler RW, Mueser KT, Sprock J, et al. Positive symptoms of psychosis in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:839-844.

8. David D, Kutcher GS, Jackson EI, et al Psychotic symptoms in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(1):29-32.

9. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Goodwin RD, et al. Co-occurrence of posttraumatic stress disorder with positive psychotic symptoms in a nationally representative sample. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18(4):313-322.

10. Sar V, Akyuv G, Dogan O. Prevalence of dissociative disorders among women in the general population. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149:169-176.

11. Barnow S, Arens EA, Sieswerda S, et al. Borderline personality disorder and psychosis: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(3):186-195.

12. Bebbington P, Jonas S, Kuipers E, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and psychosis: data from a cross-sectional national psychiatric survey in England. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(1):29-37.

13. Read J, van Os J, Morrison AP, et al. Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: a literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112(5):330-350.

A questionable diagnosis

CASE: Space traveler

Mr. O, age 69, is a patient at a long-term psychiatric hospital. He has a 56-year psychiatric history, a current diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, and suffered a torn rotator cuff approximately 5 years ago. His medication regimen is haloperidol decanoate, 100 mg IM every month, duloxetine, 60 mg/d, and naproxen, as needed for chronic pain.

He frequently lies on the floor. Attendants urge him to get up and join groups or sit with other patients but he complains of pain and soon finds another spot on the floor to use as a bed.

Eight months earlier, a homeless shelter sent Mr. O to the emergency room (ER) because he tried to eat a dollar bill and a sock. In the ER he was inattentive, with loose associations and bizarre delusions; he believed he was on a spaceship. Mr. O was admitted to the hospital, where clinicians noted that his behavior remained bizarre and he complained of insomnia. They also noted a history of setting fires, which complicated discharge planning and contributed to their decision to transfer him to our psychiatric facility for longer-term care.

During our initial interview, Mr. O readily picks himself off the floor. His responses are logical and direct but abrupt and unelaborated. His first and most vehement complaint is pain. Zolpidem, he says, is the only treatment that helps.

He says he began using zolpidem approximately 5 years ago because pain from a shoulder injury kept him awake at night. When he could not obtain the drug by prescription, he bought it on the street. One day when living in the homeless shelter, he took 30 or 40 mg of zolpidem, then “blacked out” and awoke in the ER.

His first experience with psychiatric treatment was the result of problems getting along with his single mother because of “petty things” such as shooting off a BB gun in their apartment, he says. As a teenager he was sent to a boarding school; as a young adult, to a psychiatric hospital. After his release he returned to his mother’s apartment. He worked steadily for 20 years before he obtained Social Security benefits, and then worked intermittently “off the books” until approximately 15 years ago. Mr. O lived with his mother until her death 17 years earlier, and then in her apartment alone until a fire, which he set accidentally by smoking in bed after taking zolpidem, forced him to leave 3 years ago. He says, “My whole life was in that place.” He was admitted to a psychiatric hospital for an unknown reason, which was his first psychiatric admission in 40 years. After he was released from the hospital, Mr. O lived in various homeless shelters and adult homes until his current hospitalization.

The author’s observations

An effective and well-tolerated drug with a reputation for rarely being abused, zolpidem is widely prescribed as a hypnotic. Zolpidem and benzodiazepines have different chemical structures but both act at the GABAA receptor and have comparable behavioral effects.1 The reported incidence of zolpidem abuse is much lower than the reported rate of benzodiazepine abuse when used for sleep2; however, abuse, dependence, and withdrawal have been reported.2-4 Zolpidem abuse seems to be more common among patients with a history of abusing other substances or a history of psychiatric illness.2 A French study4 found that abusers fell into 2 groups. The younger group (median age 35) used higher doses—a median of 300 mg/d—and took zolpidem in the daytime to achieve euphoria. A second, older group (median age 42) used lower doses—a median of 200 mg/d—at nighttime to sleep.

There are few reports of delirium and symptoms such as visual hallucinations and distortions associated with zolpidem use.5,6 These reactions have occurred in persons without a history of psychosis. They usually are associated with doses ≥10 mg.

In the ER Mr. O showed a disturbance in consciousness with inability to focus attention and a perceptual disturbance (he believed he was in a spaceship) that developed over hours to days. He met criteria for delirium, possibly caused by zolpidem, but his presentation also could have been attributable to an underlying psychiatric disorder.

ER and inpatient psychiatrists noted Mr. O was intoxicated with zolpidem when the shelter brought him to the ER, but both groups diagnosed schizoaffective disorder and treated him with antipsychotics. They saw his >50-year psychiatric history as evidence of an underlying, long-standing condition such as schizoaffective illness.

However, features of Mr. O’s illness are not typical of a chronic psychotic illness. He recalls psychiatric hospitalizations in his youth and recently, but not for the 40 years in between. Mr. O says he has never experienced auditory hallucinations. For these reasons, our treatment team obtains old medical records to investigate his early history (Table).

Table

Mr. O’s clinical course

| Age | Symptoms/behaviors | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| 17 | Temper tantrums and destructive behaviors. No delusions or hallucinations but a flat affect and hostile attitude | Primary behavior disorder, simple adult maladjustment |

| 22 | Returned to the psychiatric hospital when his welfare payments stopped; “psychopathic” symptoms; described as defiant and resented authority and regular work | Primary behavior disorder |

| 24 | His mother complained that he stole from her and carried a weapon; while hospitalized, described as manageable and without overt psychotic symptoms | Primary behavior disorder |

| 26 | Arrested for causing property damage while intoxicated on alcohol; silly laugh, loose associations, irrelevant and incoherent speech, and believed hospital staff were against him | Psychosis with psychopathic personality |

| 66 | A fire that he set accidentally while smoking in bed after taking zolpidem destroyed his home | Diagnosis unknown |

| 68 | Transferred from a homeless shelter to the ER after he took 30 to 40 mg of zolpidem and exhibited bizarre behaviors | Schizoaffective disorder |

| 69 | More spontaneous, remains logical and relevant after haloperidol is discontinued; no delusions or hallucinations, still complains of pain | Substance use disorder and personality disorder |

| ER: emergency room | ||

HISTORY: Destructive and defiant

Mr. O’s mother reported that he had been a nervous, restless child who would scream and yell at the slightest provocation. At age 10 he became wantonly destructive. His mother bought him an expensive toy that he destroyed after a short time; he asked for another toy, which he also destroyed. When such behavior became more frequent, she took him to a city hospital, where he was treated for 6 weeks and released at age 13. He was sent to a boarding school but soon was expelled for drinking and selling beer.

Mr. O was admitted to long-term psychiatric facilities 6 times in the next 10 years, from the late 1950s to the late 1960s. He was first admitted at age 17 for temper tantrums during which he fired an air rifle and smashed windows in the home he shared with his mother. During examination he had no delusions or hallucinations but did have flat affect and a hostile attitude. Doctors documented that almost all his tantrums were as a result of interactions with his mother.

Records from this psychiatric admission state that Mr. O showed no unusual distractibility, “psychotic trends,” or paranoid thinking. After approximately 6 months in the hospital he was discharged home with the diagnosis of primary behavior disorder, simple adult maladjustment. Mr. O, who was age 18 at the time, and his mother were eager for him to complete high school and learn auto mechanics.

Nine months later, he returned to the psychiatric facility because of excessive drinking and inability to secure employment, according to his records. In the hospital, he was productive and reliable. When he was discharged home 3 months later, doctors wrote that his determination to stop drinking was firmly fixed. They encouraged Mr. O to complete high school as a night student and find employment during the day. His mother was delighted with his improvement.

A third admission, less than 2 months later, occurred after he broke a window during an argument with his mother. He had a job but quit. After 5 months he was discharged with the same diagnosis of primary behavior disorder, but his mother would not let him back in her home. He was referred to the social service department to be placed on welfare.

A year later, Mr. O had trouble managing his welfare allotment and moved repeatedly. He said he returned to the psychiatric hospital because his welfare payments had been discontinued. During this admission, doctors noted “psychopathic” symptoms; Mr. O was defiant and resented authority and regular work. Mr. O eloped from the hospital several times and brought beer into the building. After 18 months he was discharged with the same diagnosis, with plans to apply for welfare. He was not prescribed medication.

Mr. O’s fifth admission came nearly 2 years later after his mother complained that he stole from her home and carried a weapon. In the hospital he was described as manageable and without overt psychotic symptoms. When he was discharged a little more than a year after being admitted, doctors wrote that he was a psychopath who had a history of drinking, stealing, and delinquent tendencies as a teenager. His diagnosis remained primary behavior disorder.

A year after this discharge, Mr. O was arrested for causing serious property damage when he was intoxicated on alcohol. Subsequently he was readmitted.

After a few months in the hospital, Mr. O changed. He developed a silly laugh, loose associations, irrelevant and incoherent speech, and a belief that hospital staff were against him. Although Mr. O denied auditory hallucinations, a psychiatrist wrote that he seemed to be experiencing hallucinations and prescribed chlorpromazine. The next day Mr. O slashed his arms and legs in several places, requiring many sutures. His diagnosis was changed to psychosis with psychopathic personality. However, within a few months, psychiatrists determined that Mr. O had recovered, so they stopped chlorpromazine. Months later, clinicians wrote that Mr. O was idle most of the time, neat, clean, and not involved in arguments with other patients. He was discharged after 1 month in the hospital.

Over the years, psychiatrists had differing opinions about Mr. O’s diagnosis. One noted that his mental illness was characterized by emotional instability and poor judgment. He had impulsive reactions without regard for others, rapid mood swings, irritability, and depression with transient paranoia. Another clinician detected evidence of schizoid personality disorder because Mr. O did not experience hallucinations or a gross thought disorder, but did have rambling, circumstantial, autistic (unrealistic), and ambivalent thought content. Another psychiatrist wrote Mr. O best fit in the category of psychosis with psychopathic personality, which was his diagnosis at discharge from his sixth hospitalization.

The author’s observations

Mr. O’s old medical records revealed the diagnostic thinking and treatment practices of a past era. They did not demonstrate that Mr. O met current criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, although he may have had a brief psychotic episode. Because there was little support for a diagnosis of schizoaffective illness and haloperidol use, we stopped the drug but continued duloxetine for chronic pain. It was clear that he has a substance use disorder and perhaps met criteria for antisocial personality disorder.

OUTCOME: Further explanations

Approximately 2 months after stopping haloperidol, Mr. O is more spontaneous, logical, and relevant. He does not have delusions or hallucinations. Despite further attempts at pain management with physical therapy and increased doses of duloxetine, he still complains of pain. We do not prescribe zolpidem.

Mr. O is unwilling to discuss the incident more than 40 years ago when he cut his arms and legs except to say, “That’s the past. My life wasn’t so good at that time.” When we ask why he had been a client of Adult Protective Services 5 years before he was burned out of his apartment, he admitted that he was 21 months in arrears in his rent. “I used to do this thing called crack,” he explains. He was discharged to an adult home with a prescription for duloxetine after he promised to never smoke in his room again.

Related Resource

- Aggarwal A, Sharma DD. Zolpidem withdrawal delirium: a case report. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;22(4):451.

Drug Brand Names

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Haloperidol decanoate • Haloperidol decanoate

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Naproxen • Naproxyn, Aleve, others

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Rush CR. Behavioral pharmacology of zolpidem relative to benzodiazepines: a review. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;61(3):253-269.

2. Hajak G, Müller WE, Wittchen HU, et al. Abuse and dependence potential for the non-benzodiazepine hypnotics zolpidem and zopiclone: a review of case reports and epidemiological data. Addiction. 2003;98(10):1371-1378.

3. Madrak LN, Rosenberg M. Zolpidem abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1330-1331.

4. Victorri-Vigneau C, Dailly E, Veyrac G, et al. Evidence of zolpidem abuse and dependence: results of the French Centre for Evaluation and Information on Pharmacodepencence (CEIP) network survey. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64(2):198-209.

5. Markowitz JS, Brewerton TD. Zolpidem-induced psychosis. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1996;8(2):89-91.

6. Tsai MJ, Huang YB, Wu PC. A novel clinical pattern of visual hallucination after zolpidem use. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41(6):869-872.

CASE: Space traveler

Mr. O, age 69, is a patient at a long-term psychiatric hospital. He has a 56-year psychiatric history, a current diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, and suffered a torn rotator cuff approximately 5 years ago. His medication regimen is haloperidol decanoate, 100 mg IM every month, duloxetine, 60 mg/d, and naproxen, as needed for chronic pain.

He frequently lies on the floor. Attendants urge him to get up and join groups or sit with other patients but he complains of pain and soon finds another spot on the floor to use as a bed.

Eight months earlier, a homeless shelter sent Mr. O to the emergency room (ER) because he tried to eat a dollar bill and a sock. In the ER he was inattentive, with loose associations and bizarre delusions; he believed he was on a spaceship. Mr. O was admitted to the hospital, where clinicians noted that his behavior remained bizarre and he complained of insomnia. They also noted a history of setting fires, which complicated discharge planning and contributed to their decision to transfer him to our psychiatric facility for longer-term care.

During our initial interview, Mr. O readily picks himself off the floor. His responses are logical and direct but abrupt and unelaborated. His first and most vehement complaint is pain. Zolpidem, he says, is the only treatment that helps.

He says he began using zolpidem approximately 5 years ago because pain from a shoulder injury kept him awake at night. When he could not obtain the drug by prescription, he bought it on the street. One day when living in the homeless shelter, he took 30 or 40 mg of zolpidem, then “blacked out” and awoke in the ER.

His first experience with psychiatric treatment was the result of problems getting along with his single mother because of “petty things” such as shooting off a BB gun in their apartment, he says. As a teenager he was sent to a boarding school; as a young adult, to a psychiatric hospital. After his release he returned to his mother’s apartment. He worked steadily for 20 years before he obtained Social Security benefits, and then worked intermittently “off the books” until approximately 15 years ago. Mr. O lived with his mother until her death 17 years earlier, and then in her apartment alone until a fire, which he set accidentally by smoking in bed after taking zolpidem, forced him to leave 3 years ago. He says, “My whole life was in that place.” He was admitted to a psychiatric hospital for an unknown reason, which was his first psychiatric admission in 40 years. After he was released from the hospital, Mr. O lived in various homeless shelters and adult homes until his current hospitalization.

The author’s observations

An effective and well-tolerated drug with a reputation for rarely being abused, zolpidem is widely prescribed as a hypnotic. Zolpidem and benzodiazepines have different chemical structures but both act at the GABAA receptor and have comparable behavioral effects.1 The reported incidence of zolpidem abuse is much lower than the reported rate of benzodiazepine abuse when used for sleep2; however, abuse, dependence, and withdrawal have been reported.2-4 Zolpidem abuse seems to be more common among patients with a history of abusing other substances or a history of psychiatric illness.2 A French study4 found that abusers fell into 2 groups. The younger group (median age 35) used higher doses—a median of 300 mg/d—and took zolpidem in the daytime to achieve euphoria. A second, older group (median age 42) used lower doses—a median of 200 mg/d—at nighttime to sleep.

There are few reports of delirium and symptoms such as visual hallucinations and distortions associated with zolpidem use.5,6 These reactions have occurred in persons without a history of psychosis. They usually are associated with doses ≥10 mg.

In the ER Mr. O showed a disturbance in consciousness with inability to focus attention and a perceptual disturbance (he believed he was in a spaceship) that developed over hours to days. He met criteria for delirium, possibly caused by zolpidem, but his presentation also could have been attributable to an underlying psychiatric disorder.

ER and inpatient psychiatrists noted Mr. O was intoxicated with zolpidem when the shelter brought him to the ER, but both groups diagnosed schizoaffective disorder and treated him with antipsychotics. They saw his >50-year psychiatric history as evidence of an underlying, long-standing condition such as schizoaffective illness.

However, features of Mr. O’s illness are not typical of a chronic psychotic illness. He recalls psychiatric hospitalizations in his youth and recently, but not for the 40 years in between. Mr. O says he has never experienced auditory hallucinations. For these reasons, our treatment team obtains old medical records to investigate his early history (Table).

Table

Mr. O’s clinical course

| Age | Symptoms/behaviors | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| 17 | Temper tantrums and destructive behaviors. No delusions or hallucinations but a flat affect and hostile attitude | Primary behavior disorder, simple adult maladjustment |

| 22 | Returned to the psychiatric hospital when his welfare payments stopped; “psychopathic” symptoms; described as defiant and resented authority and regular work | Primary behavior disorder |

| 24 | His mother complained that he stole from her and carried a weapon; while hospitalized, described as manageable and without overt psychotic symptoms | Primary behavior disorder |

| 26 | Arrested for causing property damage while intoxicated on alcohol; silly laugh, loose associations, irrelevant and incoherent speech, and believed hospital staff were against him | Psychosis with psychopathic personality |

| 66 | A fire that he set accidentally while smoking in bed after taking zolpidem destroyed his home | Diagnosis unknown |

| 68 | Transferred from a homeless shelter to the ER after he took 30 to 40 mg of zolpidem and exhibited bizarre behaviors | Schizoaffective disorder |

| 69 | More spontaneous, remains logical and relevant after haloperidol is discontinued; no delusions or hallucinations, still complains of pain | Substance use disorder and personality disorder |

| ER: emergency room | ||

HISTORY: Destructive and defiant

Mr. O’s mother reported that he had been a nervous, restless child who would scream and yell at the slightest provocation. At age 10 he became wantonly destructive. His mother bought him an expensive toy that he destroyed after a short time; he asked for another toy, which he also destroyed. When such behavior became more frequent, she took him to a city hospital, where he was treated for 6 weeks and released at age 13. He was sent to a boarding school but soon was expelled for drinking and selling beer.

Mr. O was admitted to long-term psychiatric facilities 6 times in the next 10 years, from the late 1950s to the late 1960s. He was first admitted at age 17 for temper tantrums during which he fired an air rifle and smashed windows in the home he shared with his mother. During examination he had no delusions or hallucinations but did have flat affect and a hostile attitude. Doctors documented that almost all his tantrums were as a result of interactions with his mother.

Records from this psychiatric admission state that Mr. O showed no unusual distractibility, “psychotic trends,” or paranoid thinking. After approximately 6 months in the hospital he was discharged home with the diagnosis of primary behavior disorder, simple adult maladjustment. Mr. O, who was age 18 at the time, and his mother were eager for him to complete high school and learn auto mechanics.

Nine months later, he returned to the psychiatric facility because of excessive drinking and inability to secure employment, according to his records. In the hospital, he was productive and reliable. When he was discharged home 3 months later, doctors wrote that his determination to stop drinking was firmly fixed. They encouraged Mr. O to complete high school as a night student and find employment during the day. His mother was delighted with his improvement.

A third admission, less than 2 months later, occurred after he broke a window during an argument with his mother. He had a job but quit. After 5 months he was discharged with the same diagnosis of primary behavior disorder, but his mother would not let him back in her home. He was referred to the social service department to be placed on welfare.

A year later, Mr. O had trouble managing his welfare allotment and moved repeatedly. He said he returned to the psychiatric hospital because his welfare payments had been discontinued. During this admission, doctors noted “psychopathic” symptoms; Mr. O was defiant and resented authority and regular work. Mr. O eloped from the hospital several times and brought beer into the building. After 18 months he was discharged with the same diagnosis, with plans to apply for welfare. He was not prescribed medication.

Mr. O’s fifth admission came nearly 2 years later after his mother complained that he stole from her home and carried a weapon. In the hospital he was described as manageable and without overt psychotic symptoms. When he was discharged a little more than a year after being admitted, doctors wrote that he was a psychopath who had a history of drinking, stealing, and delinquent tendencies as a teenager. His diagnosis remained primary behavior disorder.

A year after this discharge, Mr. O was arrested for causing serious property damage when he was intoxicated on alcohol. Subsequently he was readmitted.

After a few months in the hospital, Mr. O changed. He developed a silly laugh, loose associations, irrelevant and incoherent speech, and a belief that hospital staff were against him. Although Mr. O denied auditory hallucinations, a psychiatrist wrote that he seemed to be experiencing hallucinations and prescribed chlorpromazine. The next day Mr. O slashed his arms and legs in several places, requiring many sutures. His diagnosis was changed to psychosis with psychopathic personality. However, within a few months, psychiatrists determined that Mr. O had recovered, so they stopped chlorpromazine. Months later, clinicians wrote that Mr. O was idle most of the time, neat, clean, and not involved in arguments with other patients. He was discharged after 1 month in the hospital.

Over the years, psychiatrists had differing opinions about Mr. O’s diagnosis. One noted that his mental illness was characterized by emotional instability and poor judgment. He had impulsive reactions without regard for others, rapid mood swings, irritability, and depression with transient paranoia. Another clinician detected evidence of schizoid personality disorder because Mr. O did not experience hallucinations or a gross thought disorder, but did have rambling, circumstantial, autistic (unrealistic), and ambivalent thought content. Another psychiatrist wrote Mr. O best fit in the category of psychosis with psychopathic personality, which was his diagnosis at discharge from his sixth hospitalization.

The author’s observations

Mr. O’s old medical records revealed the diagnostic thinking and treatment practices of a past era. They did not demonstrate that Mr. O met current criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, although he may have had a brief psychotic episode. Because there was little support for a diagnosis of schizoaffective illness and haloperidol use, we stopped the drug but continued duloxetine for chronic pain. It was clear that he has a substance use disorder and perhaps met criteria for antisocial personality disorder.

OUTCOME: Further explanations

Approximately 2 months after stopping haloperidol, Mr. O is more spontaneous, logical, and relevant. He does not have delusions or hallucinations. Despite further attempts at pain management with physical therapy and increased doses of duloxetine, he still complains of pain. We do not prescribe zolpidem.

Mr. O is unwilling to discuss the incident more than 40 years ago when he cut his arms and legs except to say, “That’s the past. My life wasn’t so good at that time.” When we ask why he had been a client of Adult Protective Services 5 years before he was burned out of his apartment, he admitted that he was 21 months in arrears in his rent. “I used to do this thing called crack,” he explains. He was discharged to an adult home with a prescription for duloxetine after he promised to never smoke in his room again.

Related Resource

- Aggarwal A, Sharma DD. Zolpidem withdrawal delirium: a case report. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;22(4):451.

Drug Brand Names

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Haloperidol decanoate • Haloperidol decanoate

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Naproxen • Naproxyn, Aleve, others

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE: Space traveler

Mr. O, age 69, is a patient at a long-term psychiatric hospital. He has a 56-year psychiatric history, a current diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, and suffered a torn rotator cuff approximately 5 years ago. His medication regimen is haloperidol decanoate, 100 mg IM every month, duloxetine, 60 mg/d, and naproxen, as needed for chronic pain.

He frequently lies on the floor. Attendants urge him to get up and join groups or sit with other patients but he complains of pain and soon finds another spot on the floor to use as a bed.

Eight months earlier, a homeless shelter sent Mr. O to the emergency room (ER) because he tried to eat a dollar bill and a sock. In the ER he was inattentive, with loose associations and bizarre delusions; he believed he was on a spaceship. Mr. O was admitted to the hospital, where clinicians noted that his behavior remained bizarre and he complained of insomnia. They also noted a history of setting fires, which complicated discharge planning and contributed to their decision to transfer him to our psychiatric facility for longer-term care.

During our initial interview, Mr. O readily picks himself off the floor. His responses are logical and direct but abrupt and unelaborated. His first and most vehement complaint is pain. Zolpidem, he says, is the only treatment that helps.

He says he began using zolpidem approximately 5 years ago because pain from a shoulder injury kept him awake at night. When he could not obtain the drug by prescription, he bought it on the street. One day when living in the homeless shelter, he took 30 or 40 mg of zolpidem, then “blacked out” and awoke in the ER.

His first experience with psychiatric treatment was the result of problems getting along with his single mother because of “petty things” such as shooting off a BB gun in their apartment, he says. As a teenager he was sent to a boarding school; as a young adult, to a psychiatric hospital. After his release he returned to his mother’s apartment. He worked steadily for 20 years before he obtained Social Security benefits, and then worked intermittently “off the books” until approximately 15 years ago. Mr. O lived with his mother until her death 17 years earlier, and then in her apartment alone until a fire, which he set accidentally by smoking in bed after taking zolpidem, forced him to leave 3 years ago. He says, “My whole life was in that place.” He was admitted to a psychiatric hospital for an unknown reason, which was his first psychiatric admission in 40 years. After he was released from the hospital, Mr. O lived in various homeless shelters and adult homes until his current hospitalization.

The author’s observations

An effective and well-tolerated drug with a reputation for rarely being abused, zolpidem is widely prescribed as a hypnotic. Zolpidem and benzodiazepines have different chemical structures but both act at the GABAA receptor and have comparable behavioral effects.1 The reported incidence of zolpidem abuse is much lower than the reported rate of benzodiazepine abuse when used for sleep2; however, abuse, dependence, and withdrawal have been reported.2-4 Zolpidem abuse seems to be more common among patients with a history of abusing other substances or a history of psychiatric illness.2 A French study4 found that abusers fell into 2 groups. The younger group (median age 35) used higher doses—a median of 300 mg/d—and took zolpidem in the daytime to achieve euphoria. A second, older group (median age 42) used lower doses—a median of 200 mg/d—at nighttime to sleep.

There are few reports of delirium and symptoms such as visual hallucinations and distortions associated with zolpidem use.5,6 These reactions have occurred in persons without a history of psychosis. They usually are associated with doses ≥10 mg.

In the ER Mr. O showed a disturbance in consciousness with inability to focus attention and a perceptual disturbance (he believed he was in a spaceship) that developed over hours to days. He met criteria for delirium, possibly caused by zolpidem, but his presentation also could have been attributable to an underlying psychiatric disorder.