User login

New and Noteworthy Information—January 2014

The Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine may benefit patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), according to research published online ahead of print December 4, 2013, in Neurology. A total of 82 participants with CIS were randomized to BCG or placebo and monitored monthly with brain MRI for six months. All patients subsequently received IM interferon β-1a for 12 months. In an open-label extension phase, patients received disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) recommended by their neurologists. During the initial six months, the number of cumulative lesions was significantly lower among vaccinated subjects. The number of total T1-hypointense lesions was lower in the BCG group at months 6, 12, and 18. After 60 months, the probability of clinically definite multiple sclerosis was lower in the BCG plus DMT arm, and more vaccinated people remained DMT-free.

Exercise programs may significantly improve the ability of people with dementia to perform activities of daily living, according to a study published online ahead of print December 4, 2013, in the Cochrane Library. Exercise also may improve cognition in these patients, but may not affect depression. Investigators reviewed randomized controlled trials in which older people diagnosed with dementia were allocated to exercise programs or to control groups, which received standard care or social contact. Sixteen trials with 937 participants met the inclusion criteria. The trials were highly heterogeneous in terms of subtype and severity of participants’ dementia, and type, duration, and frequency of exercise. The researchers found that informal caregivers’ burden may be reduced when the family member with dementia participates in an exercise program.

Thrombin activity may enable neurologists to detect multiple sclerosis (MS) before clinical signs of the disease are present, according to research published online ahead of print November 29, 2013, in Annals of Neurology. Using a novel molecular probe, investigators characterized the activity pattern of thrombin, the central protease of the coagulation cascade, in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Thrombin activity preceded the onset of neurologic signs; increased at disease peak; and correlated with fibrin deposition, microglial activation, demyelination, axonal damage, and clinical severity. Mice with a genetic deficit in prothrombin confirmed the specificity of the thrombin probe. Scientists may be able to use thrombin activity to develop sensitive probes for the preclinical detection and monitoring of neuroinflammation and MS progression, according to the investigators.

An athlete with concussion symptoms should not be allowed to return to play on the same day, according to the latest consensus statement on sports-related concussion, which was summarized in the December 2013 issue of Neurosurgery. The Concussion in Sport Group (CISG 4) based its recommendations on the advice of an expert panel that was sponsored by five international sports governing bodies. Between 80% and 90% of concussions resolve within seven to 10 days, but recovery may take longer in children and adolescents, according to the consensus statement. The updated statement emphasizes the distinction between concussion and mild traumatic brain injury. The CISG 4 suggests that patients with concussion have normal findings on brain neuroimaging studies (eg, CT scan), but those with traumatic brain injury have abnormal imaging findings.

Vitamin D may prevent multiple sclerosis (MS) by blocking T helper (TH) cells from migrating into the CNS, according to research published online ahead of print December 9, 2013, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Investigators administered 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3], the bioactive form of vitamin D, to animals with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a mouse model of MS. Myelin-reactive TH cells were generated in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3, secreted proinflammatory cytokines, and did not preferentially differentiate into suppressor T cells. The cells left the lymph node, entered the peripheral circulation, and migrated to the immunization sites. TH cells from 1,25(OH)2D3-treated mice were unable to enter the CNS parenchyma, however. Instead, the cells were maintained in the periphery. The mice developed experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis when treatment ceased.

Among people with type 2 diabetes, dementia incidence may be highest among Native Americans and African Americans and lowest among Asians, according to a study published online ahead of print November 22, 2013, in Diabetes Care. Scientists identified 22,171 patients age 60 or older with diabetes and without preexisting dementia in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Diabetes Registry. The investigators abstracted prevalent medical history and dementia incidence from medical records and calculated age-adjusted incidence densities. Dementia was diagnosed in 17.1% of patients. Age-adjusted dementia incidence densities were 34/1,000 person-years among Native Americans, 27/1,000 person-years among African Americans, and 19/1,000 person-years among Asians. Hazard ratios (relative to Asians) were 1.64 for Native Americans, 1.44 for African Americans, 1.30 for non-Hispanic whites, and 1.19 for Latinos.

Veterans with blast injuries have changes in brain tissue that may be apparent on imaging years later, according to data presented at the 99th Annual Meeting of the Radiological Society of North America. Researchers compared diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)-derived fractional anisotropy (FA) values in 10 veterans of Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom who had been diagnosed with mild traumatic brain injury with those of 10 healthy controls. The average time elapsed between the blast-induced injury and DTI scan among the patients was 51.3 months. FA values were significantly different between the two groups, and the researchers found significant correlations between FA values and attention, delayed memory, and psychomotor test scores. The results suggest that blast injury may have a long-term impact on the brain.

Among college athletes, head impact exposure may be related to white matter diffusion measures and cognition during the course of one playing season, even in the absence of diagnosed concussion, according to data published online ahead of print December 11, 2013, in Neurology. Researchers prospectively studied 79 noncontact sport athletes and 80 nonconcussed varsity football and ice hockey players who wore helmets that recorded the acceleration-time history of the head following impact. Mean diffusivity (MD) in the corpus callosum was significantly different between groups. Measures of head impact exposure correlated with white matter diffusivity measures in the corpus callosum, amygdala, cerebellar white matter, hippocampus, and thalamus. The magnitude of change in corpus callosum MD postseason was associated with poorer performance on a measure of verbal learning and memory.

Among veterans, traumatic brain injury (TBI) during the most recent deployment is the strongest predictor of postdeployment symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), even when accounting for predeployment symptoms, prior TBI, and combat intensity, according to research published online ahead of print December 11, 2013, in JAMA Psychiatry. A total of 1,648 active-duty Marine and Navy servicemen underwent clinical interviews and completed self-assessments approximately one month before a seven-month deployment and three to six months after deployment. At the predeployment assessment, 56.8% of participants reported prior TBI. At postdeployment assessment, 19.8% reported sustaining TBI between predeployment and postdeployment assessments. Probability of PTSD was highest for participants with severe predeployment symptoms, high combat intensity, and deployment-related TBI. TBI doubled the PTSD rates for participants with less severe predeployment PTSD symptoms.

Fidgetin inhibition could promote tissue regeneration and repair the broken cell connections that occur in spinal cord injury and other conditions, according to research presented at the 2013 Annual Meeting of the American Society for Cell Biology. Fidgetin prunes unstable microtubule scaffolding in cells, as well as unneeded connections in the neuronal network as the latter grows. Researchers used a novel nanoparticle technology to block fidgetin in the injured nerves of adult rats. The nanoparticles were infused with small interfering RNA that bound the messenger RNA (mRNA) transcribed from the fidgetin gene. The mRNA for fidgetin was not translated, and the cell did not produce fidgetin. Blocking fidgetin restarted tissue growth in the animals. The technique could benefit patients with myocardial infarction or chronic cutaneous wounds.

Deep brain stimulation may improve driving ability for people with Parkinson’s disease, according to a study published online ahead of print December 18, 2013, in Neurology. Investigators studied 23 people who had deep brain stimulators, 21 people with Parkinson’s disease without stimulators, and 21 healthy individuals. Participants were tested with a driving simulator. Individuals with stimulators completed the test once with the stimulator on, once with it off, and once with the stimulator off after receiving levodopa. People with Parkinson’s disease without stimulators performed worse than controls in almost every category. People with stimulators did not perform significantly worse than the controls. Participants with stimulators had an average of 3.8 slight driving errors on the test, compared with 7.5 for the controls and 11.4 for people with Parkinson’s disease without stimulators.

Gadolinium-based contrast medium (Gd-CM) may be associated with abnormalities on brain MRI, according to research published online ahead of print December 17, 2013, in Radiology. Researchers compared unenhanced T1-weighted MR images of 19 patients who had undergone six or more contrast-enhanced brain scans with images of 16 people who had received six or fewer unenhanced scans. The hyperintensity of the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus correlated with the number of Gd-CM administrations. Hyperintensity in the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus on unenhanced MRI may be a consequence of the number of previous Gd-CM administrations, according to the researchers. Because gadolinium has a high signal intensity in the body, the data suggest that the toxic gadolinium component remains in the body in patients with normal renal function.

—Erik Greb

The Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine may benefit patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), according to research published online ahead of print December 4, 2013, in Neurology. A total of 82 participants with CIS were randomized to BCG or placebo and monitored monthly with brain MRI for six months. All patients subsequently received IM interferon β-1a for 12 months. In an open-label extension phase, patients received disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) recommended by their neurologists. During the initial six months, the number of cumulative lesions was significantly lower among vaccinated subjects. The number of total T1-hypointense lesions was lower in the BCG group at months 6, 12, and 18. After 60 months, the probability of clinically definite multiple sclerosis was lower in the BCG plus DMT arm, and more vaccinated people remained DMT-free.

Exercise programs may significantly improve the ability of people with dementia to perform activities of daily living, according to a study published online ahead of print December 4, 2013, in the Cochrane Library. Exercise also may improve cognition in these patients, but may not affect depression. Investigators reviewed randomized controlled trials in which older people diagnosed with dementia were allocated to exercise programs or to control groups, which received standard care or social contact. Sixteen trials with 937 participants met the inclusion criteria. The trials were highly heterogeneous in terms of subtype and severity of participants’ dementia, and type, duration, and frequency of exercise. The researchers found that informal caregivers’ burden may be reduced when the family member with dementia participates in an exercise program.

Thrombin activity may enable neurologists to detect multiple sclerosis (MS) before clinical signs of the disease are present, according to research published online ahead of print November 29, 2013, in Annals of Neurology. Using a novel molecular probe, investigators characterized the activity pattern of thrombin, the central protease of the coagulation cascade, in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Thrombin activity preceded the onset of neurologic signs; increased at disease peak; and correlated with fibrin deposition, microglial activation, demyelination, axonal damage, and clinical severity. Mice with a genetic deficit in prothrombin confirmed the specificity of the thrombin probe. Scientists may be able to use thrombin activity to develop sensitive probes for the preclinical detection and monitoring of neuroinflammation and MS progression, according to the investigators.

An athlete with concussion symptoms should not be allowed to return to play on the same day, according to the latest consensus statement on sports-related concussion, which was summarized in the December 2013 issue of Neurosurgery. The Concussion in Sport Group (CISG 4) based its recommendations on the advice of an expert panel that was sponsored by five international sports governing bodies. Between 80% and 90% of concussions resolve within seven to 10 days, but recovery may take longer in children and adolescents, according to the consensus statement. The updated statement emphasizes the distinction between concussion and mild traumatic brain injury. The CISG 4 suggests that patients with concussion have normal findings on brain neuroimaging studies (eg, CT scan), but those with traumatic brain injury have abnormal imaging findings.

Vitamin D may prevent multiple sclerosis (MS) by blocking T helper (TH) cells from migrating into the CNS, according to research published online ahead of print December 9, 2013, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Investigators administered 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3], the bioactive form of vitamin D, to animals with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a mouse model of MS. Myelin-reactive TH cells were generated in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3, secreted proinflammatory cytokines, and did not preferentially differentiate into suppressor T cells. The cells left the lymph node, entered the peripheral circulation, and migrated to the immunization sites. TH cells from 1,25(OH)2D3-treated mice were unable to enter the CNS parenchyma, however. Instead, the cells were maintained in the periphery. The mice developed experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis when treatment ceased.

Among people with type 2 diabetes, dementia incidence may be highest among Native Americans and African Americans and lowest among Asians, according to a study published online ahead of print November 22, 2013, in Diabetes Care. Scientists identified 22,171 patients age 60 or older with diabetes and without preexisting dementia in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Diabetes Registry. The investigators abstracted prevalent medical history and dementia incidence from medical records and calculated age-adjusted incidence densities. Dementia was diagnosed in 17.1% of patients. Age-adjusted dementia incidence densities were 34/1,000 person-years among Native Americans, 27/1,000 person-years among African Americans, and 19/1,000 person-years among Asians. Hazard ratios (relative to Asians) were 1.64 for Native Americans, 1.44 for African Americans, 1.30 for non-Hispanic whites, and 1.19 for Latinos.

Veterans with blast injuries have changes in brain tissue that may be apparent on imaging years later, according to data presented at the 99th Annual Meeting of the Radiological Society of North America. Researchers compared diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)-derived fractional anisotropy (FA) values in 10 veterans of Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom who had been diagnosed with mild traumatic brain injury with those of 10 healthy controls. The average time elapsed between the blast-induced injury and DTI scan among the patients was 51.3 months. FA values were significantly different between the two groups, and the researchers found significant correlations between FA values and attention, delayed memory, and psychomotor test scores. The results suggest that blast injury may have a long-term impact on the brain.

Among college athletes, head impact exposure may be related to white matter diffusion measures and cognition during the course of one playing season, even in the absence of diagnosed concussion, according to data published online ahead of print December 11, 2013, in Neurology. Researchers prospectively studied 79 noncontact sport athletes and 80 nonconcussed varsity football and ice hockey players who wore helmets that recorded the acceleration-time history of the head following impact. Mean diffusivity (MD) in the corpus callosum was significantly different between groups. Measures of head impact exposure correlated with white matter diffusivity measures in the corpus callosum, amygdala, cerebellar white matter, hippocampus, and thalamus. The magnitude of change in corpus callosum MD postseason was associated with poorer performance on a measure of verbal learning and memory.

Among veterans, traumatic brain injury (TBI) during the most recent deployment is the strongest predictor of postdeployment symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), even when accounting for predeployment symptoms, prior TBI, and combat intensity, according to research published online ahead of print December 11, 2013, in JAMA Psychiatry. A total of 1,648 active-duty Marine and Navy servicemen underwent clinical interviews and completed self-assessments approximately one month before a seven-month deployment and three to six months after deployment. At the predeployment assessment, 56.8% of participants reported prior TBI. At postdeployment assessment, 19.8% reported sustaining TBI between predeployment and postdeployment assessments. Probability of PTSD was highest for participants with severe predeployment symptoms, high combat intensity, and deployment-related TBI. TBI doubled the PTSD rates for participants with less severe predeployment PTSD symptoms.

Fidgetin inhibition could promote tissue regeneration and repair the broken cell connections that occur in spinal cord injury and other conditions, according to research presented at the 2013 Annual Meeting of the American Society for Cell Biology. Fidgetin prunes unstable microtubule scaffolding in cells, as well as unneeded connections in the neuronal network as the latter grows. Researchers used a novel nanoparticle technology to block fidgetin in the injured nerves of adult rats. The nanoparticles were infused with small interfering RNA that bound the messenger RNA (mRNA) transcribed from the fidgetin gene. The mRNA for fidgetin was not translated, and the cell did not produce fidgetin. Blocking fidgetin restarted tissue growth in the animals. The technique could benefit patients with myocardial infarction or chronic cutaneous wounds.

Deep brain stimulation may improve driving ability for people with Parkinson’s disease, according to a study published online ahead of print December 18, 2013, in Neurology. Investigators studied 23 people who had deep brain stimulators, 21 people with Parkinson’s disease without stimulators, and 21 healthy individuals. Participants were tested with a driving simulator. Individuals with stimulators completed the test once with the stimulator on, once with it off, and once with the stimulator off after receiving levodopa. People with Parkinson’s disease without stimulators performed worse than controls in almost every category. People with stimulators did not perform significantly worse than the controls. Participants with stimulators had an average of 3.8 slight driving errors on the test, compared with 7.5 for the controls and 11.4 for people with Parkinson’s disease without stimulators.

Gadolinium-based contrast medium (Gd-CM) may be associated with abnormalities on brain MRI, according to research published online ahead of print December 17, 2013, in Radiology. Researchers compared unenhanced T1-weighted MR images of 19 patients who had undergone six or more contrast-enhanced brain scans with images of 16 people who had received six or fewer unenhanced scans. The hyperintensity of the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus correlated with the number of Gd-CM administrations. Hyperintensity in the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus on unenhanced MRI may be a consequence of the number of previous Gd-CM administrations, according to the researchers. Because gadolinium has a high signal intensity in the body, the data suggest that the toxic gadolinium component remains in the body in patients with normal renal function.

—Erik Greb

The Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine may benefit patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), according to research published online ahead of print December 4, 2013, in Neurology. A total of 82 participants with CIS were randomized to BCG or placebo and monitored monthly with brain MRI for six months. All patients subsequently received IM interferon β-1a for 12 months. In an open-label extension phase, patients received disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) recommended by their neurologists. During the initial six months, the number of cumulative lesions was significantly lower among vaccinated subjects. The number of total T1-hypointense lesions was lower in the BCG group at months 6, 12, and 18. After 60 months, the probability of clinically definite multiple sclerosis was lower in the BCG plus DMT arm, and more vaccinated people remained DMT-free.

Exercise programs may significantly improve the ability of people with dementia to perform activities of daily living, according to a study published online ahead of print December 4, 2013, in the Cochrane Library. Exercise also may improve cognition in these patients, but may not affect depression. Investigators reviewed randomized controlled trials in which older people diagnosed with dementia were allocated to exercise programs or to control groups, which received standard care or social contact. Sixteen trials with 937 participants met the inclusion criteria. The trials were highly heterogeneous in terms of subtype and severity of participants’ dementia, and type, duration, and frequency of exercise. The researchers found that informal caregivers’ burden may be reduced when the family member with dementia participates in an exercise program.

Thrombin activity may enable neurologists to detect multiple sclerosis (MS) before clinical signs of the disease are present, according to research published online ahead of print November 29, 2013, in Annals of Neurology. Using a novel molecular probe, investigators characterized the activity pattern of thrombin, the central protease of the coagulation cascade, in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Thrombin activity preceded the onset of neurologic signs; increased at disease peak; and correlated with fibrin deposition, microglial activation, demyelination, axonal damage, and clinical severity. Mice with a genetic deficit in prothrombin confirmed the specificity of the thrombin probe. Scientists may be able to use thrombin activity to develop sensitive probes for the preclinical detection and monitoring of neuroinflammation and MS progression, according to the investigators.

An athlete with concussion symptoms should not be allowed to return to play on the same day, according to the latest consensus statement on sports-related concussion, which was summarized in the December 2013 issue of Neurosurgery. The Concussion in Sport Group (CISG 4) based its recommendations on the advice of an expert panel that was sponsored by five international sports governing bodies. Between 80% and 90% of concussions resolve within seven to 10 days, but recovery may take longer in children and adolescents, according to the consensus statement. The updated statement emphasizes the distinction between concussion and mild traumatic brain injury. The CISG 4 suggests that patients with concussion have normal findings on brain neuroimaging studies (eg, CT scan), but those with traumatic brain injury have abnormal imaging findings.

Vitamin D may prevent multiple sclerosis (MS) by blocking T helper (TH) cells from migrating into the CNS, according to research published online ahead of print December 9, 2013, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Investigators administered 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3], the bioactive form of vitamin D, to animals with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a mouse model of MS. Myelin-reactive TH cells were generated in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3, secreted proinflammatory cytokines, and did not preferentially differentiate into suppressor T cells. The cells left the lymph node, entered the peripheral circulation, and migrated to the immunization sites. TH cells from 1,25(OH)2D3-treated mice were unable to enter the CNS parenchyma, however. Instead, the cells were maintained in the periphery. The mice developed experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis when treatment ceased.

Among people with type 2 diabetes, dementia incidence may be highest among Native Americans and African Americans and lowest among Asians, according to a study published online ahead of print November 22, 2013, in Diabetes Care. Scientists identified 22,171 patients age 60 or older with diabetes and without preexisting dementia in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Diabetes Registry. The investigators abstracted prevalent medical history and dementia incidence from medical records and calculated age-adjusted incidence densities. Dementia was diagnosed in 17.1% of patients. Age-adjusted dementia incidence densities were 34/1,000 person-years among Native Americans, 27/1,000 person-years among African Americans, and 19/1,000 person-years among Asians. Hazard ratios (relative to Asians) were 1.64 for Native Americans, 1.44 for African Americans, 1.30 for non-Hispanic whites, and 1.19 for Latinos.

Veterans with blast injuries have changes in brain tissue that may be apparent on imaging years later, according to data presented at the 99th Annual Meeting of the Radiological Society of North America. Researchers compared diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)-derived fractional anisotropy (FA) values in 10 veterans of Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom who had been diagnosed with mild traumatic brain injury with those of 10 healthy controls. The average time elapsed between the blast-induced injury and DTI scan among the patients was 51.3 months. FA values were significantly different between the two groups, and the researchers found significant correlations between FA values and attention, delayed memory, and psychomotor test scores. The results suggest that blast injury may have a long-term impact on the brain.

Among college athletes, head impact exposure may be related to white matter diffusion measures and cognition during the course of one playing season, even in the absence of diagnosed concussion, according to data published online ahead of print December 11, 2013, in Neurology. Researchers prospectively studied 79 noncontact sport athletes and 80 nonconcussed varsity football and ice hockey players who wore helmets that recorded the acceleration-time history of the head following impact. Mean diffusivity (MD) in the corpus callosum was significantly different between groups. Measures of head impact exposure correlated with white matter diffusivity measures in the corpus callosum, amygdala, cerebellar white matter, hippocampus, and thalamus. The magnitude of change in corpus callosum MD postseason was associated with poorer performance on a measure of verbal learning and memory.

Among veterans, traumatic brain injury (TBI) during the most recent deployment is the strongest predictor of postdeployment symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), even when accounting for predeployment symptoms, prior TBI, and combat intensity, according to research published online ahead of print December 11, 2013, in JAMA Psychiatry. A total of 1,648 active-duty Marine and Navy servicemen underwent clinical interviews and completed self-assessments approximately one month before a seven-month deployment and three to six months after deployment. At the predeployment assessment, 56.8% of participants reported prior TBI. At postdeployment assessment, 19.8% reported sustaining TBI between predeployment and postdeployment assessments. Probability of PTSD was highest for participants with severe predeployment symptoms, high combat intensity, and deployment-related TBI. TBI doubled the PTSD rates for participants with less severe predeployment PTSD symptoms.

Fidgetin inhibition could promote tissue regeneration and repair the broken cell connections that occur in spinal cord injury and other conditions, according to research presented at the 2013 Annual Meeting of the American Society for Cell Biology. Fidgetin prunes unstable microtubule scaffolding in cells, as well as unneeded connections in the neuronal network as the latter grows. Researchers used a novel nanoparticle technology to block fidgetin in the injured nerves of adult rats. The nanoparticles were infused with small interfering RNA that bound the messenger RNA (mRNA) transcribed from the fidgetin gene. The mRNA for fidgetin was not translated, and the cell did not produce fidgetin. Blocking fidgetin restarted tissue growth in the animals. The technique could benefit patients with myocardial infarction or chronic cutaneous wounds.

Deep brain stimulation may improve driving ability for people with Parkinson’s disease, according to a study published online ahead of print December 18, 2013, in Neurology. Investigators studied 23 people who had deep brain stimulators, 21 people with Parkinson’s disease without stimulators, and 21 healthy individuals. Participants were tested with a driving simulator. Individuals with stimulators completed the test once with the stimulator on, once with it off, and once with the stimulator off after receiving levodopa. People with Parkinson’s disease without stimulators performed worse than controls in almost every category. People with stimulators did not perform significantly worse than the controls. Participants with stimulators had an average of 3.8 slight driving errors on the test, compared with 7.5 for the controls and 11.4 for people with Parkinson’s disease without stimulators.

Gadolinium-based contrast medium (Gd-CM) may be associated with abnormalities on brain MRI, according to research published online ahead of print December 17, 2013, in Radiology. Researchers compared unenhanced T1-weighted MR images of 19 patients who had undergone six or more contrast-enhanced brain scans with images of 16 people who had received six or fewer unenhanced scans. The hyperintensity of the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus correlated with the number of Gd-CM administrations. Hyperintensity in the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus on unenhanced MRI may be a consequence of the number of previous Gd-CM administrations, according to the researchers. Because gadolinium has a high signal intensity in the body, the data suggest that the toxic gadolinium component remains in the body in patients with normal renal function.

—Erik Greb

Ponatinib may be returning to market with new safety measures

The leukemia drug ponatinib is expected to return to market once the drug’s manufacturer has implemented measures to address the recently discovered safety risks.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is requiring that a number of safety measures be adopted, including changes to ponatinib’s label to narrow the drug’s indication and the addition of warnings about the increased risk of thrombosis and venous occlusion associated with ponatinib use.

In addition, dosing and administration recommendations must be revised, the patient medication guide must be updated, a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) must be implemented, and postmarket investigations must be conducted to further characterize the drug’s safety and dosing.

Ponatinib was approved by the FDA in December 2012 to treat adults with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) that is resistant to or intolerant of other tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).

But in October 2013, follow-up results of the phase 2 PACE trial suggested ponatinib can increase a patient’s risk of arterial and venous thrombotic events. So all trials of the drug were placed on partial clinical hold, with the exception of the phase 3 EPIC trial, which was discontinued.

Then, the FDA suspended sales and marketing of ponatinib, pending results of a safety evaluation. Now, the agency has decided ponatinib can return to the market if the new safety measures are implemented.

Safety measures in detail

The FDA is requiring that ponatinib use be restricted to:

- Adults with T315I-positive CML (chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase)

- Adults with T315I-positive Ph+ ALL

- Adults with CML (chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase) who cannot receive another TKI

- Adults with Ph+ ALL who cannot receive another TKI.

The Warnings and Precautions section of the drug’s label must be revised to include a description of the arterial and venous thrombosis and occlusions that have occurred in at least 27%—more than 1 in every 4—of patients treated with ponatinib.

The Dosage and Administration recommendations must be revised to state that the optimal dose of ponatinib has not been identified. The recommended starting dose remains 45 mg administered orally once daily, with or without food.

The patient Medication Guide must be revised to include additional safety information consistent with the safety information in the revised drug label.

The ponatinib REMS must inform prescribers about the approved indications for use and the serious risk of vascular occlusion and thromboembolism associated with the drug. The REMS must include the following:

- REMS letter to healthcare professionals who are known or likely to prescribe ponatinib

- REMS letter for professional societies to be distributed to their members

- REMS fact sheet for healthcare professionals

- Public statement to be published quarterly for 1 year in several professional journals

- Information to be prominently displayed at scientific meetings

- Ponatinib REMS website to provide access to all REMS materials for the duration of the REMS.

And postmarket investigations must further evaluate the dose selection, drug exposure, treatment response, and toxicity of ponatinib.

For more information, see the FDA’s safety communication. ![]()

The leukemia drug ponatinib is expected to return to market once the drug’s manufacturer has implemented measures to address the recently discovered safety risks.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is requiring that a number of safety measures be adopted, including changes to ponatinib’s label to narrow the drug’s indication and the addition of warnings about the increased risk of thrombosis and venous occlusion associated with ponatinib use.

In addition, dosing and administration recommendations must be revised, the patient medication guide must be updated, a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) must be implemented, and postmarket investigations must be conducted to further characterize the drug’s safety and dosing.

Ponatinib was approved by the FDA in December 2012 to treat adults with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) that is resistant to or intolerant of other tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).

But in October 2013, follow-up results of the phase 2 PACE trial suggested ponatinib can increase a patient’s risk of arterial and venous thrombotic events. So all trials of the drug were placed on partial clinical hold, with the exception of the phase 3 EPIC trial, which was discontinued.

Then, the FDA suspended sales and marketing of ponatinib, pending results of a safety evaluation. Now, the agency has decided ponatinib can return to the market if the new safety measures are implemented.

Safety measures in detail

The FDA is requiring that ponatinib use be restricted to:

- Adults with T315I-positive CML (chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase)

- Adults with T315I-positive Ph+ ALL

- Adults with CML (chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase) who cannot receive another TKI

- Adults with Ph+ ALL who cannot receive another TKI.

The Warnings and Precautions section of the drug’s label must be revised to include a description of the arterial and venous thrombosis and occlusions that have occurred in at least 27%—more than 1 in every 4—of patients treated with ponatinib.

The Dosage and Administration recommendations must be revised to state that the optimal dose of ponatinib has not been identified. The recommended starting dose remains 45 mg administered orally once daily, with or without food.

The patient Medication Guide must be revised to include additional safety information consistent with the safety information in the revised drug label.

The ponatinib REMS must inform prescribers about the approved indications for use and the serious risk of vascular occlusion and thromboembolism associated with the drug. The REMS must include the following:

- REMS letter to healthcare professionals who are known or likely to prescribe ponatinib

- REMS letter for professional societies to be distributed to their members

- REMS fact sheet for healthcare professionals

- Public statement to be published quarterly for 1 year in several professional journals

- Information to be prominently displayed at scientific meetings

- Ponatinib REMS website to provide access to all REMS materials for the duration of the REMS.

And postmarket investigations must further evaluate the dose selection, drug exposure, treatment response, and toxicity of ponatinib.

For more information, see the FDA’s safety communication. ![]()

The leukemia drug ponatinib is expected to return to market once the drug’s manufacturer has implemented measures to address the recently discovered safety risks.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is requiring that a number of safety measures be adopted, including changes to ponatinib’s label to narrow the drug’s indication and the addition of warnings about the increased risk of thrombosis and venous occlusion associated with ponatinib use.

In addition, dosing and administration recommendations must be revised, the patient medication guide must be updated, a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) must be implemented, and postmarket investigations must be conducted to further characterize the drug’s safety and dosing.

Ponatinib was approved by the FDA in December 2012 to treat adults with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) that is resistant to or intolerant of other tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).

But in October 2013, follow-up results of the phase 2 PACE trial suggested ponatinib can increase a patient’s risk of arterial and venous thrombotic events. So all trials of the drug were placed on partial clinical hold, with the exception of the phase 3 EPIC trial, which was discontinued.

Then, the FDA suspended sales and marketing of ponatinib, pending results of a safety evaluation. Now, the agency has decided ponatinib can return to the market if the new safety measures are implemented.

Safety measures in detail

The FDA is requiring that ponatinib use be restricted to:

- Adults with T315I-positive CML (chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase)

- Adults with T315I-positive Ph+ ALL

- Adults with CML (chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase) who cannot receive another TKI

- Adults with Ph+ ALL who cannot receive another TKI.

The Warnings and Precautions section of the drug’s label must be revised to include a description of the arterial and venous thrombosis and occlusions that have occurred in at least 27%—more than 1 in every 4—of patients treated with ponatinib.

The Dosage and Administration recommendations must be revised to state that the optimal dose of ponatinib has not been identified. The recommended starting dose remains 45 mg administered orally once daily, with or without food.

The patient Medication Guide must be revised to include additional safety information consistent with the safety information in the revised drug label.

The ponatinib REMS must inform prescribers about the approved indications for use and the serious risk of vascular occlusion and thromboembolism associated with the drug. The REMS must include the following:

- REMS letter to healthcare professionals who are known or likely to prescribe ponatinib

- REMS letter for professional societies to be distributed to their members

- REMS fact sheet for healthcare professionals

- Public statement to be published quarterly for 1 year in several professional journals

- Information to be prominently displayed at scientific meetings

- Ponatinib REMS website to provide access to all REMS materials for the duration of the REMS.

And postmarket investigations must further evaluate the dose selection, drug exposure, treatment response, and toxicity of ponatinib.

For more information, see the FDA’s safety communication. ![]()

Emerging therapies for melanoma

Metastatic melanoma is a highly challenging cancer to treat. Like other solid tumors, it is a very heterogeneous disease both clinically and biologically. Consequently, the first decision point in its management is to assess the severity of an individual patient’s disease. This can be done based on the patient’s symptoms and how they have evolved over the preceding 1-2 months, performance status, the extent of disease as determined by physical examination, and staging workup, which should include either computed tomography scans of the body or a positron emission tomography/CT study as well as a brain magnetic resonance imaging scan. Patients with brain metastases as a subset (which is sizable – 20%-25% have brain metastases) require special attention because they may not respond to systemic therapies and will thus have to be managed with brain-targeted treatment options. Tumor testing for BRAF mutations is necessary in all patients with metastatic melanoma because the BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib or dabrafenib) are a preferred choice of targeted therapy for this subset of patients, which constitutes about 50% of all melanoma patients. Immunotherapy plays an important role in nearly all patients with metastatic melanoma including those who have progressed after anti-BRAF therapy. Chemotherapy still has a significant (yet diminishing) role for patients who are no longer suitable for immunotherapy.

Metastatic melanoma is a highly challenging cancer to treat. Like other solid tumors, it is a very heterogeneous disease both clinically and biologically. Consequently, the first decision point in its management is to assess the severity of an individual patient’s disease. This can be done based on the patient’s symptoms and how they have evolved over the preceding 1-2 months, performance status, the extent of disease as determined by physical examination, and staging workup, which should include either computed tomography scans of the body or a positron emission tomography/CT study as well as a brain magnetic resonance imaging scan. Patients with brain metastases as a subset (which is sizable – 20%-25% have brain metastases) require special attention because they may not respond to systemic therapies and will thus have to be managed with brain-targeted treatment options. Tumor testing for BRAF mutations is necessary in all patients with metastatic melanoma because the BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib or dabrafenib) are a preferred choice of targeted therapy for this subset of patients, which constitutes about 50% of all melanoma patients. Immunotherapy plays an important role in nearly all patients with metastatic melanoma including those who have progressed after anti-BRAF therapy. Chemotherapy still has a significant (yet diminishing) role for patients who are no longer suitable for immunotherapy.

Metastatic melanoma is a highly challenging cancer to treat. Like other solid tumors, it is a very heterogeneous disease both clinically and biologically. Consequently, the first decision point in its management is to assess the severity of an individual patient’s disease. This can be done based on the patient’s symptoms and how they have evolved over the preceding 1-2 months, performance status, the extent of disease as determined by physical examination, and staging workup, which should include either computed tomography scans of the body or a positron emission tomography/CT study as well as a brain magnetic resonance imaging scan. Patients with brain metastases as a subset (which is sizable – 20%-25% have brain metastases) require special attention because they may not respond to systemic therapies and will thus have to be managed with brain-targeted treatment options. Tumor testing for BRAF mutations is necessary in all patients with metastatic melanoma because the BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib or dabrafenib) are a preferred choice of targeted therapy for this subset of patients, which constitutes about 50% of all melanoma patients. Immunotherapy plays an important role in nearly all patients with metastatic melanoma including those who have progressed after anti-BRAF therapy. Chemotherapy still has a significant (yet diminishing) role for patients who are no longer suitable for immunotherapy.

Nilotinib beats imatinib in newly diagnosed CML

Credit: CDC

NEW ORLEANS—New data indicate a trend for longer overall survival and event-free survival in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients on nilotinib versus imatinib.

Five-year data from the phase 3 ENESTnd study demonstrate higher rates of early and deeper molecular response in newly diagnosed CML patients taking nilotinib, as well as a reduced risk of progression compared to imatinib.

These results were presented at the 2013 ASH Annual Meeting as abstract 92.

“These new, updated data reaffirm the superiority of nilotinib over imatinib at achieving deeper molecular responses and provide even more evidence supporting nilotinib as an appropriate treatment of choice in newly diagnosed patients,” said Giuseppe Saglio, MD, of the University of Turin in Italy.

“Now, we are looking at how deeper molecular responses may help guide our approach towards how we treat CML in the future.”

The 5-year ENESTnd data showed that nilotinib can produce superior responses across various Philadelphia chromosome-positive CML patient populations, including newly diagnosed patients. Results showed higher rates of early and deeper sustained molecular response, known as MR4.5.

The difference in the rates of MR4.5 continued to be higher when nilotinib was given at 300 mg or 400 mg twice daily, when compared to imatinib (MR4.5: 6%-10% difference by 1 year, 21%-23% difference by 5 years).

“The most important endpoint is cumulative incidence of MR4.5,” Dr Saglio said. “At 5 years, this is achieved by 54% of those in nilotinib-300-mg group, 52% in the nilotinib-400-mg group, and 31% in the imatinib group. And the curves are still diverging.”

The data also indicate a trend for higher overall survival and event-free survival rates in patients treated with nilotinib.

Fifteen patients treated with imatinib had CML-related deaths, compared to 6 patients in the arm receiving nilotinib at 300 mg twice daily and 4 patients in the arm receiving nilotinib at 400 mg twice daily.

Few new adverse events and laboratory abnormalities were observed between year 4 and year 5. Rates of patients with adverse events leading to discontinuation were 11.1% in the 300-mg nilotinib group, 17.7% in the 400-mg nilotinib group, and 13.2% in the imatinib group.

Dr Saglio noted that select cardiac and vascular events are slightly more frequent on nilotinib versus imatinib. But there has been no increase in the annual incidence of these events over time.

Therefore, Dr Saglio concluded, “Nilotinib, a standard-of-care frontline therapy option for newly diagnosed, chronic-phase CML patients, affords superior efficacy compared with imatinib, including higher rates of early molecular response (which is associated with improved long-term outcomes), higher rates of deep molecular response, and a lower risk of disease progression. Nilotinib continues to show good tolerability with long-term follow-up.” ![]()

Credit: CDC

NEW ORLEANS—New data indicate a trend for longer overall survival and event-free survival in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients on nilotinib versus imatinib.

Five-year data from the phase 3 ENESTnd study demonstrate higher rates of early and deeper molecular response in newly diagnosed CML patients taking nilotinib, as well as a reduced risk of progression compared to imatinib.

These results were presented at the 2013 ASH Annual Meeting as abstract 92.

“These new, updated data reaffirm the superiority of nilotinib over imatinib at achieving deeper molecular responses and provide even more evidence supporting nilotinib as an appropriate treatment of choice in newly diagnosed patients,” said Giuseppe Saglio, MD, of the University of Turin in Italy.

“Now, we are looking at how deeper molecular responses may help guide our approach towards how we treat CML in the future.”

The 5-year ENESTnd data showed that nilotinib can produce superior responses across various Philadelphia chromosome-positive CML patient populations, including newly diagnosed patients. Results showed higher rates of early and deeper sustained molecular response, known as MR4.5.

The difference in the rates of MR4.5 continued to be higher when nilotinib was given at 300 mg or 400 mg twice daily, when compared to imatinib (MR4.5: 6%-10% difference by 1 year, 21%-23% difference by 5 years).

“The most important endpoint is cumulative incidence of MR4.5,” Dr Saglio said. “At 5 years, this is achieved by 54% of those in nilotinib-300-mg group, 52% in the nilotinib-400-mg group, and 31% in the imatinib group. And the curves are still diverging.”

The data also indicate a trend for higher overall survival and event-free survival rates in patients treated with nilotinib.

Fifteen patients treated with imatinib had CML-related deaths, compared to 6 patients in the arm receiving nilotinib at 300 mg twice daily and 4 patients in the arm receiving nilotinib at 400 mg twice daily.

Few new adverse events and laboratory abnormalities were observed between year 4 and year 5. Rates of patients with adverse events leading to discontinuation were 11.1% in the 300-mg nilotinib group, 17.7% in the 400-mg nilotinib group, and 13.2% in the imatinib group.

Dr Saglio noted that select cardiac and vascular events are slightly more frequent on nilotinib versus imatinib. But there has been no increase in the annual incidence of these events over time.

Therefore, Dr Saglio concluded, “Nilotinib, a standard-of-care frontline therapy option for newly diagnosed, chronic-phase CML patients, affords superior efficacy compared with imatinib, including higher rates of early molecular response (which is associated with improved long-term outcomes), higher rates of deep molecular response, and a lower risk of disease progression. Nilotinib continues to show good tolerability with long-term follow-up.” ![]()

Credit: CDC

NEW ORLEANS—New data indicate a trend for longer overall survival and event-free survival in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients on nilotinib versus imatinib.

Five-year data from the phase 3 ENESTnd study demonstrate higher rates of early and deeper molecular response in newly diagnosed CML patients taking nilotinib, as well as a reduced risk of progression compared to imatinib.

These results were presented at the 2013 ASH Annual Meeting as abstract 92.

“These new, updated data reaffirm the superiority of nilotinib over imatinib at achieving deeper molecular responses and provide even more evidence supporting nilotinib as an appropriate treatment of choice in newly diagnosed patients,” said Giuseppe Saglio, MD, of the University of Turin in Italy.

“Now, we are looking at how deeper molecular responses may help guide our approach towards how we treat CML in the future.”

The 5-year ENESTnd data showed that nilotinib can produce superior responses across various Philadelphia chromosome-positive CML patient populations, including newly diagnosed patients. Results showed higher rates of early and deeper sustained molecular response, known as MR4.5.

The difference in the rates of MR4.5 continued to be higher when nilotinib was given at 300 mg or 400 mg twice daily, when compared to imatinib (MR4.5: 6%-10% difference by 1 year, 21%-23% difference by 5 years).

“The most important endpoint is cumulative incidence of MR4.5,” Dr Saglio said. “At 5 years, this is achieved by 54% of those in nilotinib-300-mg group, 52% in the nilotinib-400-mg group, and 31% in the imatinib group. And the curves are still diverging.”

The data also indicate a trend for higher overall survival and event-free survival rates in patients treated with nilotinib.

Fifteen patients treated with imatinib had CML-related deaths, compared to 6 patients in the arm receiving nilotinib at 300 mg twice daily and 4 patients in the arm receiving nilotinib at 400 mg twice daily.

Few new adverse events and laboratory abnormalities were observed between year 4 and year 5. Rates of patients with adverse events leading to discontinuation were 11.1% in the 300-mg nilotinib group, 17.7% in the 400-mg nilotinib group, and 13.2% in the imatinib group.

Dr Saglio noted that select cardiac and vascular events are slightly more frequent on nilotinib versus imatinib. But there has been no increase in the annual incidence of these events over time.

Therefore, Dr Saglio concluded, “Nilotinib, a standard-of-care frontline therapy option for newly diagnosed, chronic-phase CML patients, affords superior efficacy compared with imatinib, including higher rates of early molecular response (which is associated with improved long-term outcomes), higher rates of deep molecular response, and a lower risk of disease progression. Nilotinib continues to show good tolerability with long-term follow-up.” ![]()

Pediatric Discharge Systematic Review

The process of discharging a pediatric patient from an acute care facility is currently fraught with difficulties. More than 20% of parents report problems in the transition of care from the hospital to the home and ambulatory care setting.[1] Clinical providers likewise note communication challenges around the time of discharge,[2, 3] especially when inpatient and outpatient providers are different, as with the hospitalist model.[4] Poor communication and problems in discharge transition and continuity of care often culminate in adverse events,[5, 6] including return to emergency department (ED) care and hospital readmission.[7]

Thirty‐day readmissions are common for certain pediatric conditions, such as oncologic diseases, transplantation, and sickle cell anemia and vary significantly across children's hospitals.[8] Discharge planning may decrease 30‐day readmissions in hospitalized adults[9]; however, it is not clear that the same is true in children. Both the preventability of pediatric readmissions[10] and the extent to which readmissions reflect suboptimal care[11] are subjects of debate. Despite these uncertainties, collaborative efforts intended to decrease pediatric readmissions[12] and improve discharge transitions[13, 14] are underway.

To inform these debates and efforts, we undertook a systematic review of the evidence of hospital‐initiated interventions to reduce repeat utilization of the ED and hospital. Acknowledging that existing evidence for condition‐specific discharge interventions in pediatrics might be limited, we sought to identify common elements of successful interventions across pediatric conditions.

METHODS

Search Strategy

With the assistance of a research librarian, we searched MEDLINE and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) from the inception of these databases through to March 28, 2012 (for search strategies, see the Supporting Information, Appendix, Part 1, in the online version of this article).

Study Selection

Two authors (K.A. and C.K.) independently reviewed abstracts identified by the initial search, as well as abstracts of references of included articles. Eligibility criteria for inclusion in full review included: (1) discharge‐oriented process or intervention initiated in the inpatient setting, (2) study outcomes related to subsequent utilization including hospital readmission or emergency department visit after hospitalization, (3) child‐ or adolescent‐focused or child‐specific results presented separately, and (4) written or available in English. If abstract review did not sufficiently clarify whether all eligibility criteria were met, the article was included in the full review. Two authors (K.A. and C.K.) independently reviewed articles meeting criteria for full review to determine eligibility. Disagreements regarding inclusion in the final analysis were discussed with all 4 authors. We excluded studies in countries with low or lower‐middle incomes,[15] as discharge interventions in these countries may not be broadly applicable.

Data Abstraction, Quality Assessment, and Data Synthesis

Two authors (K.A. and C.K.) independently abstracted data using a modified Cochrane Collaboration data collection form.[16] We independently scored the included studies using the Downs and Black checklist, which assesses the risk of bias and the quality of both randomized and nonrandomized studies.[17] This checklist yields a composite score of 0 to 28 points, excluding the item assessing power. As many studies either lacked power calculations or included power calculations based on outcomes not included in our review, we performed calculations to determine the sample size needed to detect a decrease in readmission or ED utilization by 20% from baseline or control rates. Due to the heterogeneous nature of included studies in terms of population, interventions, study design, and outcomes, meta‐analysis was not performed.

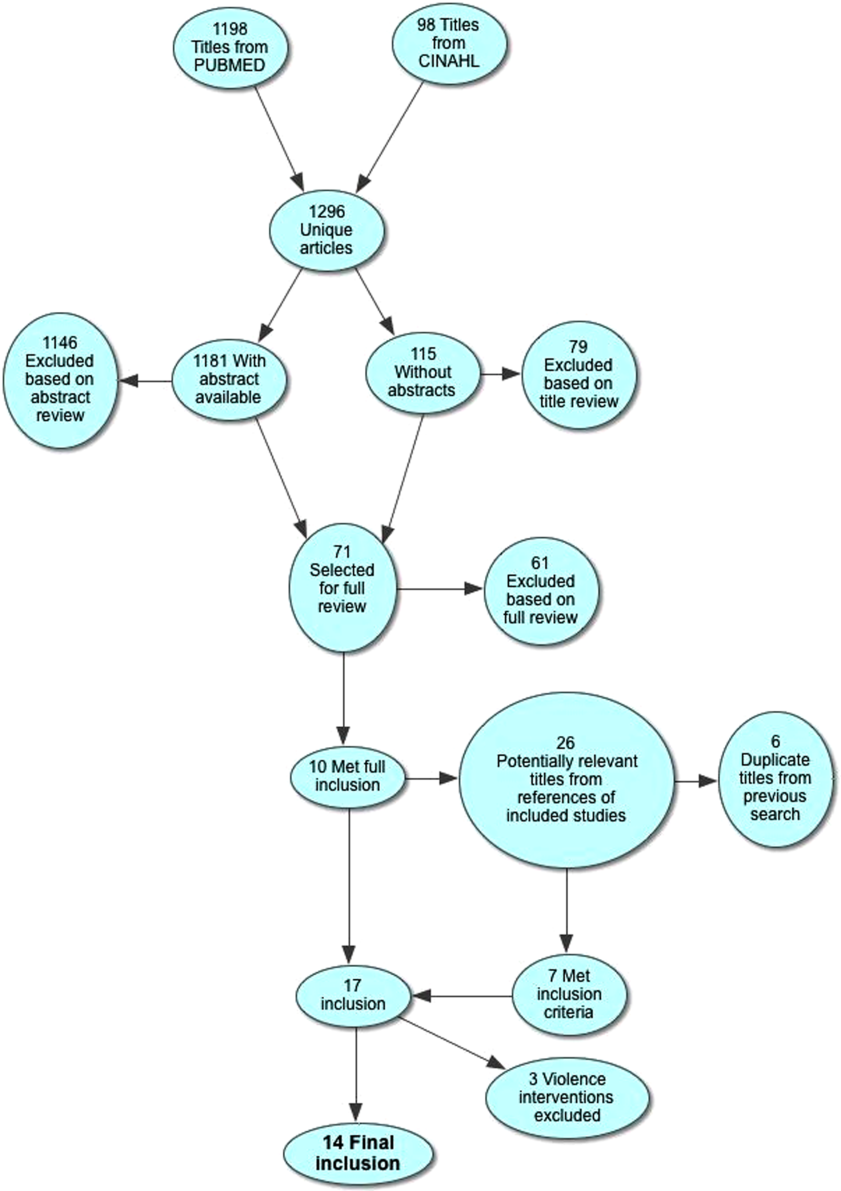

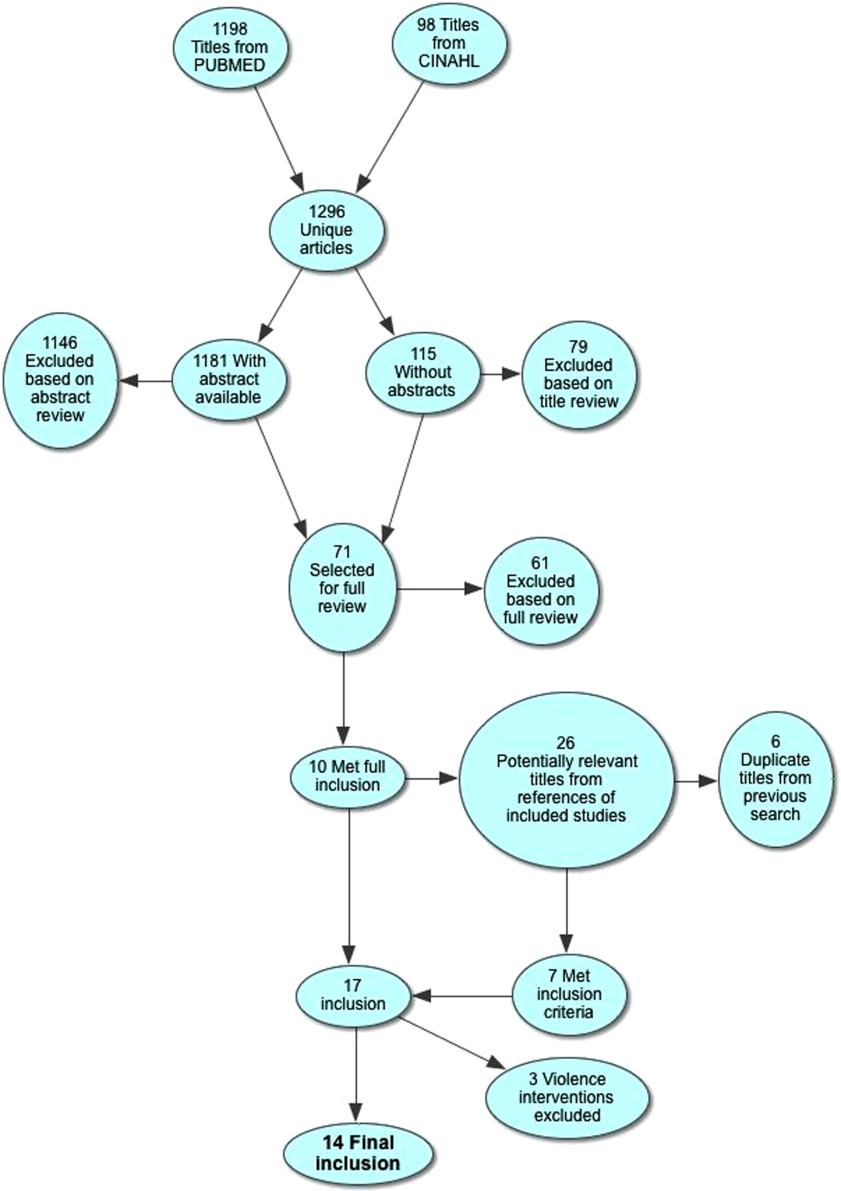

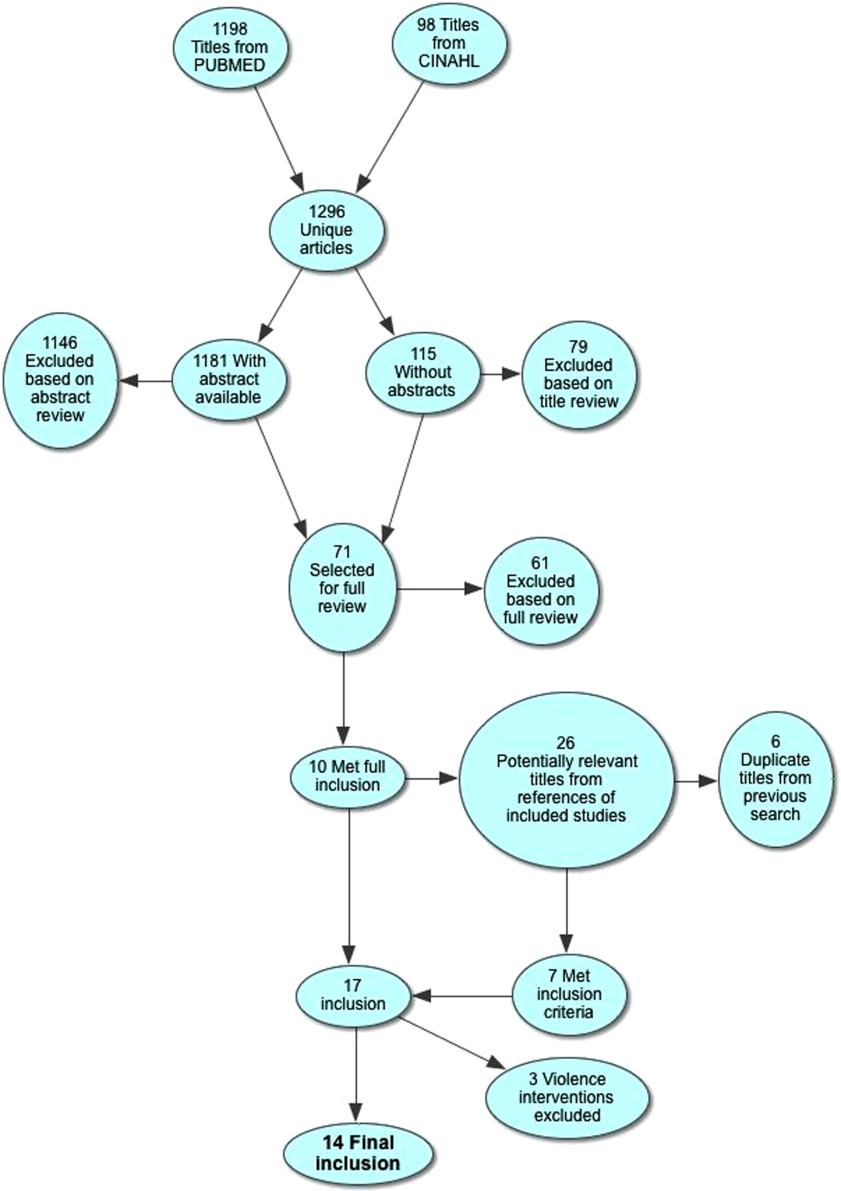

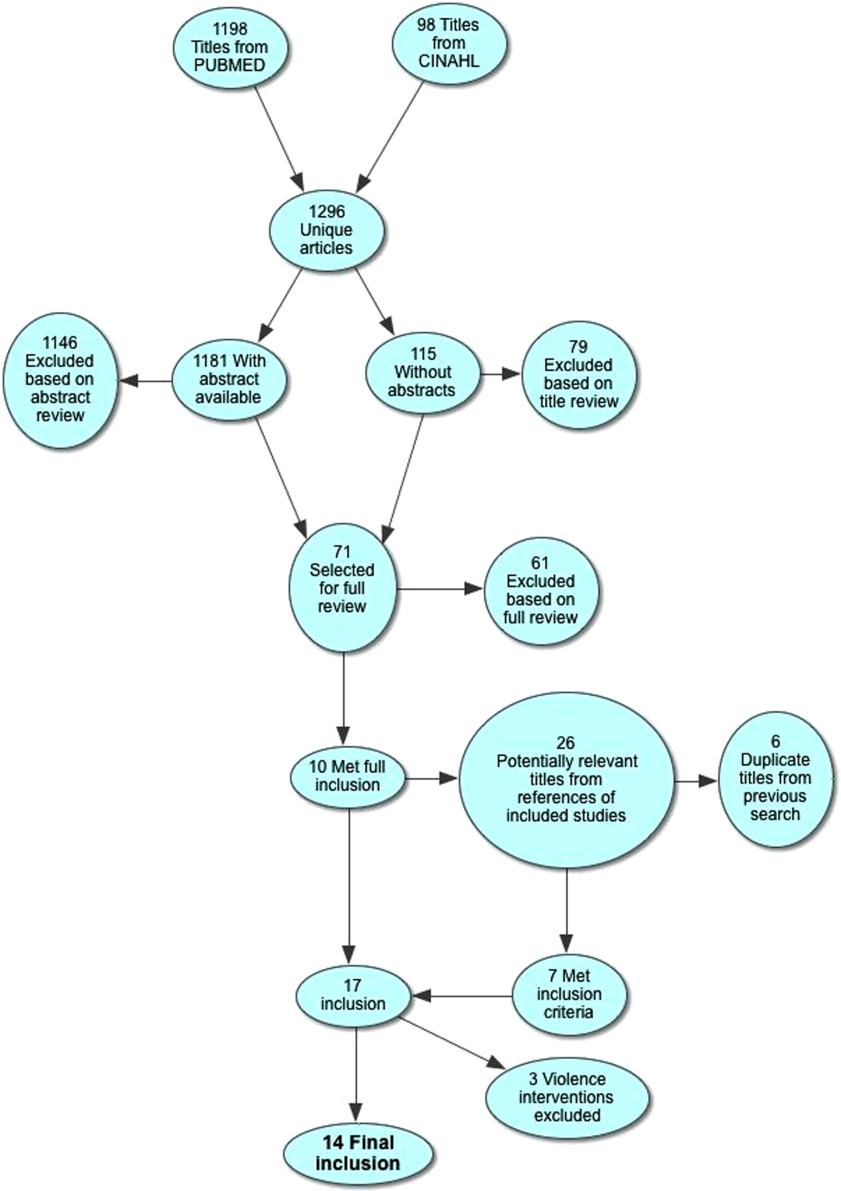

RESULTS

Electronic search yielded a total of 1296 unique citations. Review of abstracts identified 40 studies for full article review. We identified 10 articles that met all inclusion criteria. Subsequent review of references of included articles identified 20 additional articles for full review, 7 of which met all inclusion criteria. However, 3 articles[18, 19, 20] assessed the impact of violence interventions primarily on preventing reinjury and recidivism and thus were excluded (see Supporting Information, Appendix, Part 2, in the online version of this article for findings of the 3 articles). In total, we included 14 articles in our review[21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34] (Figure 1).

Patient Populations and Intervention Timing and Components

Studies varied regarding the specific medical conditions they evaluated. Eight of the papers reported discharge interventions for children with asthma, 5 papers focused on discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and a final study discussed a discharge intervention for children with cancer (Table 1). Although our primary goal was to synthesize discharge interventions across pediatric conditions, we provide a summary of discharge interventions by condition (see Supporting Information, Appendix, Part 3, in the online version of this article).

| Author, Year | Study Design | Age | Inclusion | Exclusion | Intervention | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Asthma | ||||||

| Davis, 2011[21] | Retrospective matched case control | 12 months18 years | Admitted for asthma at a single hospital in California. | 45 minutes of enhanced asthma education and phone call 3 weeks after discharge (n=698) | Patients were matched on age and past utilization who received standard education/care (n=698) | |

| Espinoza‐Palma, 2009[22] | RCT | 515 years | Admitted for asthma at a single hospital in Chile. | Chronic lung disease or neurologic alteration. | Self‐management education program with a postdischarge game to reinforce educational concepts (n=42) | Standard education (n=46) |

| Ng, 2006[23] | RCT | 215 years | Admitted for asthma in a pediatric ward at a single hospital in China. | Admitted to PICU or non‐Chinese speaking. | Evaluation by asthma nurse, animated asthma education booklet, 50‐minute discharge teaching session, follow‐up by phone at 1 week (n=55) | Evaluation by asthma nurse by physician referral, a written asthma education booklet, 30‐minute discharge teaching session (n=45) |

| Stevens, 2002[24] | RCT | 18 months5 years | In ED or admitted with primary diagnosis of asthma/wheezing at 2 hospitals in the United Kingdom. | Admitted when no researcher available. | Enhanced asthma education and follow‐up in a clinic 1 month after encounter (n=101) | Usual care (n=99) |

| Wesseldine, 1999[25] | RCT | 216 years | Admitted for asthma at a single hospital in the United Kingdom. | Admitted when no researcher available. | 20 minutes of enhanced asthma education including: guided self‐management plan, booklet, asthma hotline contact, and sometimes oral steroids (n=80) | Standard discharge that varied by provider (n=80) |

| Madge, 1997[26] | RCT | 214 years | Admitted for asthma at a single hospital in the United Kingdom. | Admitted on weekend. | 45 minutes of enhanced asthma education with written asthma plan, a nurse follow‐up visit 23 weeks postdischarge, telephone support, and a course of oral steroids (n=96) | Standard education (did not include written asthma plan) (n=105) |

| Taggart, 1991[27] | Pre‐post | 612 years | Admitted for asthma at single institution in Washington, DC with history of at least one ED visit in prior 6 months. | If resided outside of metro area. | Received written educational materials, adherence assistance, discussed emotions of asthma, video education provided, and tailored nursing interactions (n=40) | Enrolled patient's prior utilization |

| Mitchell, 1986[28] | RCT | >2 years | Admitted for asthma at single institution in New Zealand. | Having a previous life‐threatening attack. | 6 monthly postdischarge education sessions on lung anatomy/physiology, triggers and avoidance, asthma medication, advice on when and where to seek care (n=94 children of European descent, n=84 children of Polynesian descent) | Standard discharge (n=106 children of European descent; n=84 children of Polynesian descent) |

| Cancer | ||||||

| Caliskan Yilmaz, 2009[29] | Quasiexperimental | 18 years | New oncologic diagnoses in hospital in Turkey. | Children who died during follow‐up. | Frequent needs assessment, education, home visits, fever guidance, telephone consultation, and manual for home care; patients lived in Izmir (n=25) | Routine hospital services without formal education; patients lived outside of Izmir (n=24) |

| NICU | ||||||

| Broyles, 2000[30] | RCT | Neonate | Infants with birth weight 1500 g with mechanical vent use in 48 hours of life, born at single NICU in Texas. | Infant death, infant adopted or moved out of enrollment county. | Specialized follow‐up available 5 days a week for well or sick visits; access to medical advice via phone 24 hours a day, transportation to ED provided when needed; home visitation, parent education, and "foster grandmother" offered (n=446) | Specialized follow‐up available 2 mornings a week for well or sick visits; all other sick visits to be made through acute care clinic or ED (n=441) |

| Finello, 1998[31] | RCT | Neonate | Infants with birth weight between 750 and1750 g; discharged from 2 NICUs in California. | Infants with gross abnormalities. | Three separate intervention groups (n=20 in each): (1) home healthhome visits during the first 4 weeks after discharge, with physician consultation available at all times; (2) home visitinghealth and development support, parental support, support with referral services for 2 years after discharge; (3) home health and home visiting arms combined | Standard discharge (n=20). |

| Kotagal, 1995[32] | Pre‐post | Neonate | Infants discharged from a single NICU in Ohio. | Patients (n=257) discharged after restructuring of discharge practices including: removal of discharge weight criteria, engagement of family prior to discharge, evaluation of home environment prior to discharge, and arrangement of home health visits and follow‐up | Patients discharged before discharge restructuring (n=483) | |

| Casiro, 1993[33] | RCT | Neonate | Infants meeting discharge criteria from 1 of 2 NICUs in Canada. | Congenital anomalies, chronic neonatal illness, parent refusal, family complications, and death. | Early discharge based on prespecified criteria with 8 weeks of services including: assistance with infant care, sibling care and housekeeping; nurse availability via phone; follow‐up phone calls and home visitation tailored to family need (n=50) | Discharged at the discretion of their attending physicians; standard newborn public health referral for routine follow‐up (n=50) |

| Brooten, 1986[34] | RCT | Neonate | Infants born 1500 g at a single NICU in Pennsylvania. | Death, life‐threatening congenital anomalies, grade 4 IVH, surgical history, O2 requirement >10 weeks, family complications. | Early discharge based on prespecified criteria with weekly education prior to discharge, postdischarge follow‐up phone call, and home nurse visitation; consistent nurse availability via phone (n=39) | Standard discharge practices with a discharge weight minimum of 2.2 kg (n=40) |

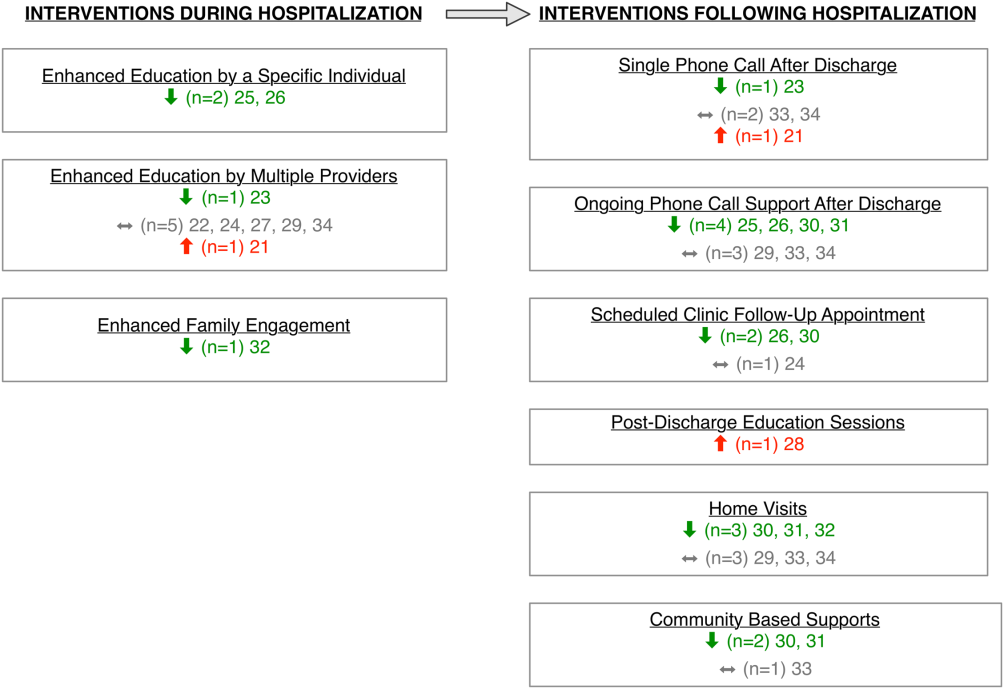

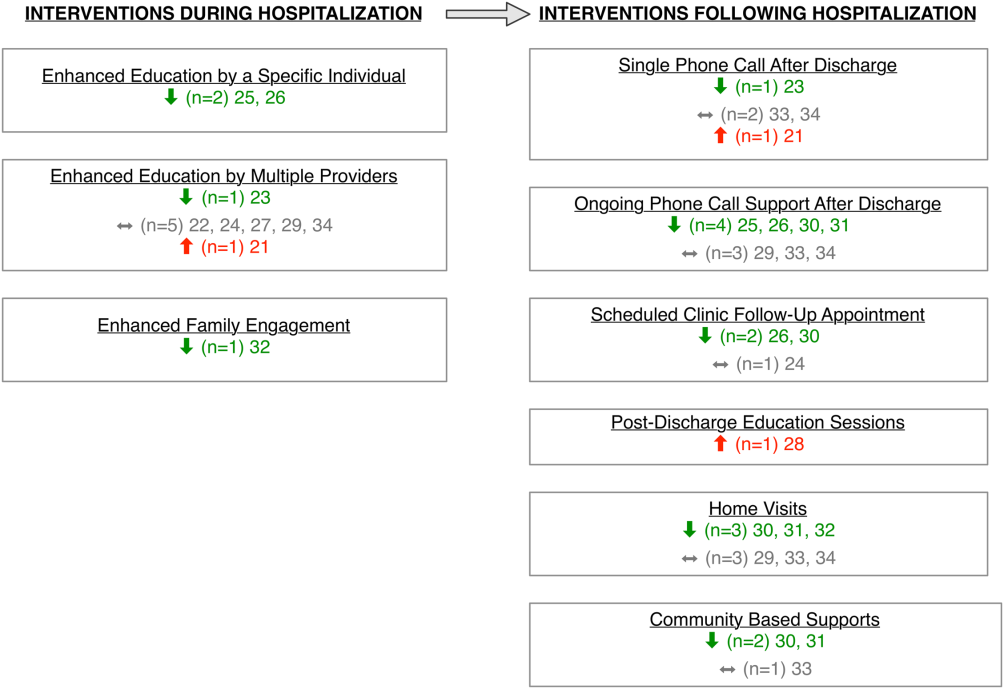

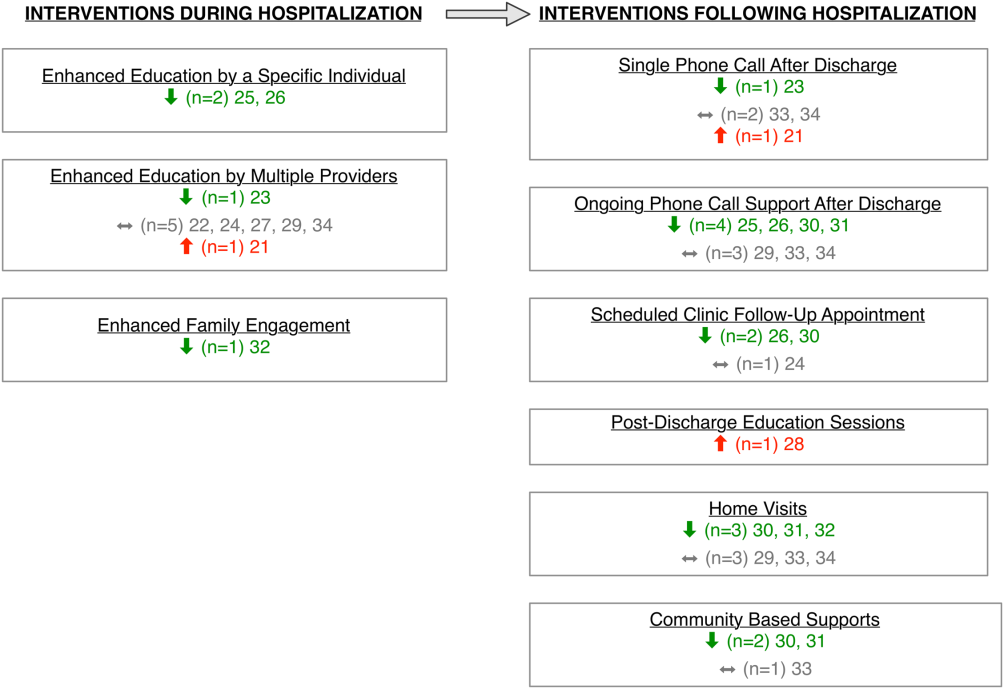

Studies varied regarding the timing and nature of the intervention components. Eight discharge interventions included a major inpatient component, in addition to outpatient support or follow‐up.[21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 29, 32, 34] Two studies included an inpatient education component only.[22, 27] The remainder were initiated during index hospitalization but focused primarily on home visitation, enhanced follow‐up, and support after discharge (Figure 2).[28, 30, 31, 33]

Outcome Assessment Methods

Readmission and subsequent ED utilization events were identified using multiple techniques. Some authors accessed claims records to capture all outcomes.[30, 33] Others relied on chart review.[21, 25, 26, 27, 28, 31, 32] One study supplemented hospital records with outpatient records.[24] Some investigators used parental reports.[22, 23, 31] Two studies did not describe methods for identifying postdischarge events.[29, 34]

Study Quality

The quality of the included studies varied (Table 2). Many of the studies had inadequate sample size to detect a difference in either readmission or ED visit subsequent to discharge. Eight studies found differences in either subsequent ED utilization, hospitalization, or both and were considered adequately powered for these specific outcomes.[21, 23, 25, 26, 28, 30, 31, 32] In contrast, among studies with readmission as an outcome, 6 were not adequately powered to detect a difference in this particular outcome.[24, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34] In these 6 studies, all except 1 study30 had 10% of the sample size required to detect differences in readmission. Further, 2 studies that examined ED utilization were underpowered to detect differences between intervention and control groups.[24, 26] We were unable to perform power calculations for 3 studies,[22, 27, 29] as the authors presented the number of events without clear denominators.

| Author, Year | Study Design | D&B Score* | Adequately Powered (Yes/No)** | Timing of Outcome | Major Findings | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Asthma | ||||||

| Davis, 2011[21] | Retrospective matched case control | 14 | Readmission: N/A; ED: yes | 1 year | Patients with enhanced education had higher hazards of return to ED visit. | Intervention not randomized; only 29% of eligible children enrolled with unclear selection decisions due to lack of study personnel or caregiver presence in hospital; only 67% completed the intervention; 50% of patients were not local; follow‐up was not well described. |

| Espinoza‐Palma, 2009[22] | RCT | 19 | Readmission: b; ED:b | 1 year | No difference between the intervention and control in hospitalizations or ED visits. ED visits and hospitalizations decreased in year after compared to the year prior for both intervention and control. | Pre‐post analysis with similar effects in cases and controls, results may reflect regression to mean; follow‐up was not well described, and 12.5% who were lost to follow‐up were excluded from analysis; study was in Chile with different demographics than in the United States. |

| Ng, 2006[23] | RCT | 20 | Readmission: yes; ED: yes | 3 months | Patients in the intervention group were less likely to be readmitted or visit the ED. | Recruitment/refusal was not well described; number lost to follow‐up was not reported; study was in China with different demographics than the United States. |

| Stevens, 2002[24] | RCT | 20 | Readmission: no ED: no | 1 year | No differences between intervention and control for any outcomes. | 11% were lost to follow‐up; number of patients who refused was not reported; analysis did not adjust for site of recruitment (ED vs inpatient); 30% of children did not have a prior diagnosis of asthma; study was in England with different demographics than in the United States. |

| Wesseldine, 1999[25] | RCT | 20 | Readmission: yes; ED: yes | 6 months | Patients in intervention group less likely to be readmitted or visit ED. | Unclear if intervention group received oral steroids that might drive effect; number lost to follow‐up was not reported; high miss rate for recruitment; study was in England with different demographics than the United States. |

| Madge, 1997 [26] | RCT | 22 | Readmission: yes; ED: no | 214 months | Patients in intervention group were less likely to be readmitted compared to controls. No differences in repeat ED visits. | Unclear if education or oral steroids drove effect; number of patients who refused or were lost to follow‐not reported; time to outcome (214 months) varied for different patients, which may introduce bias given the seasonality of asthma; study was in Scotland with different demographics than the United States. |

| Taggart, 1991[27] | Pre‐post | 12 | Readmission:b; ED:b | 15 months | Overall there was no change in ED or hospitalization utilization from pre to post. When limited to children with severe asthma, there was a decrease in ED utilization after the intervention compared to prior ED use. | Use of historical utilization as a comparison does not account for potential effects of regression to mean or improvement with age; over one‐half of eligible patients were excluded due to lack of consent or inability to collect baseline data; inclusion criterion did not specify that prior utilization was necessarily for asthma exacerbation; number lost to follow‐up was not reported. |

| Mitchell, 1986[28] | RCT | 14 | Readmission: yesc; ED: N/A | 6 months and 618 months | Increase in percentage of readmission between 6 and 18 months for children of European descent. | Unclear exclusion criterion; full compliance with intervention only 52%; number of patients lost to follow‐up (outcome) was not reported; statistical analysis was not clearly described. |

| Cancer | ||||||

| Caliskan Yilmaz, 2009[29] | Quasiexperimental | 10 | Readmission:b; ED: N/A | Not specified | For the first readmission to the hospital, more of the readmissions were planned in the intervention group compared to the control group. Number of readmissions was not assessed. | Intervention was not randomized; children who died were excluded (4%); planned vs unplanned distinction not validated; unclear cointerventions regarding chemotherapy administration; recruitment and follow‐up was not well described; not all comparisons were described in methods. |

| NICU | ||||||

| Broyles, 2000[30] | RCT | 23 | Readmission: no; ED: yes | At 1 year adjusted age | Overall hospitalization rates were similar but there were fewer admissions to the ICU. Intervention group had fewer ED visits. Total costs were less in intervention group. | 10% refused to participate or consent was not sought, and 12% were excluded after randomization; different periods of follow‐up (outcomes observed at 1 year of life regardless of discharge timing); analysis did not adjust for site of recruitment (1 of 2 nurseries). |

| Finello, 1998[31] | RCT | 11 | Readmission: nod; ED: yes | At 6 months adjusted age and between 6 and 12 months adjusted age | No changes in hospitalization rates.d The home health+home visit arm had fewer ED visits between 6 and 12 months of life. Intervention was reported as saving money by decreasing initial length of stay. | Inclusion and exclusion criteria, recruitment/refusal, outcomes, and analysis plan were not clearly described; sample size was too small for effective randomization; different periods of follow‐up (outcomes observed at 1 year of life regardless of discharge timing); analysis did not adjust for site of recruitment; 15% of outcomes were missing. |

| Kotagal, 1995[32] | Pre‐post | 15 | Readmission: no; ED: yes | 14 days | Decreased number of ED visits in patients in intervention. No difference in readmission. Costs and length of stay were less in intervention. | Designed to decrease length of stay; pre‐post nature of study allows for possibility of other changes to practices other than the intervention. |

| Casiro, 1993[33] | RCT | 18 | Readmission: no; ED: N/A | 1 year of life | There were no differences in the readmissions or number of ambulatory care visits after discharge. Infants were discharged earlier in the intervention group, which resulted in cost savings. | Designed to decrease length of stay; 13% refused or were excluded due to family complications; and 8% were lost to follow‐up; different periods of follow‐up (outcomes observed at 1 year of life regardless of discharge timing); analysis did not adjust for site of recruitment (1 of 2 nurseries); 81% of infants were born to Caucasian women, which may limit generalizability. |

| Brooten, 1986[34] | RCT | 15 | Readmission: no; ED: N/A | 14 days and 18 months | No difference in readmission. Significantly lower charges during initial hospitalization for intervention group. | Designed to decrease length of stay; unclear when randomization occurred and exclusions unclear; 12.5% were excluded due to refusal or family issues; follow‐up not well described, and loss to follow‐up was unknown. |

Excluding the assessment of statistical power, Downs and Black scores ranged from 10 to 23 (maximum 28 possible points) indicating varying quality. As would be expected with discharge interventions, studies did not blind participants; 2 studies did, however, appropriately blind the outcome evaluators to intervention assignment.[22, 30] Even though 10 out of the 14 studies were randomized controlled trials, randomization may not have been completely effective due to sample size being too small for effective randomization,[31] large numbers of excluded subjects after randomization,[30] and unclear randomization process.[34] Several studies had varying follow‐up periods for patients within a given study. For example, 3 NICU studies assessed readmission at 1‐year corrected age,[30, 31, 33] creating the analytic difficulty that the amount of time a given patient was at risk for readmission was dependent on when the patient was discharged, yet this was not accounted for in the analyses. Only 2 studies demonstrated low rates of loss to follow‐up (10%).[30, 33] The remainder of the studies either had high incompletion/loss to follow‐up rates (>10%)[22, 24, 31] or did not report rates.[21, 23, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 32, 34] Finally, 3 studies recruited patients from multiple sites,[24, 31, 33] and none adjusted for potential differences in effect based on enrollment site.

Findings Across Patient Populations Regarding Readmission

Of the 4 studies that demonstrated change in overall readmission,[23, 25, 26, 28] all were asthma focused; 3 demonstrated a decrease in readmissions,[23, 25, 26] and 1 an increase in readmissions.[28] The 3 effective interventions included 1‐on‐1 inpatient education delivered by an asthma nurse, in addition to postdischarge follow‐up support, either by telephone or clinic visit. Two of these interventions provided rescue oral steroids to some patients on discharge.[25, 26] In contrast, a study from New Zealand evaluated a series of postdischarge visits using an existing public health nurse infrastructure and demonstrated an increase in readmission between 6 to 18 months after admission in European children.[28] An additional study focused on outpatient support after discharge from the NICU, and demonstrated a lower frequency of readmission to the intensive care unit without overall reduction of hospital readmission (Tables 1 and 2).[30]

Findings Across Patient Populations Regarding Subsequent ED Visits