User login

Group ‘rewrites rules’ on pluripotency

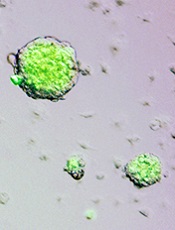

Credit: Haruko Obokata

Researchers say they have developed a novel technique for inducing pluripotency in somatic cells.

Unlike methods for creating induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), the new process—called stimulus-triggered acquisition of pluripotency (STAP)—does not require the introduction of genetic material.

Instead, adult cells must only be injured in order to revert to a pluripotent state.

The investigators tested STAP in preclinical models and reported the results in both a letter and an article published in Nature.

Inspired by plants

Haruko Obokata, PhD, of the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology in Japan, and her colleagues said this research was inspired by the ability of a plant callus—a node of plant cells created by injuring an existing plant—to grow into a new plant.

The researchers thought this phenomenon suggested that any somatic cell could be de-differentiated through injury.

To find out, they tested cells derived from mice. The team chose hematopoietic cells positive for CD45 because these are lineage-committed, somatic cells that do not express pluripotency-related markers unless they are reprogrammed.

The investigators stressed the cells almost to the point of death by exposing them to various stimuli in vitro, including trauma, a low-oxygen environment, and a low-pH environment.

Within a few days, the cells had recovered from the stressful stimuli by naturally reverting to a pluripotent state. These stem cells were then able to re-differentiate and mature into any type of cell and grow into any type of tissue, depending on the environment into which they were placed.

“It was really surprising to see that such a remarkable transformation could be triggered simply by stimuli from outside of the cell,” Dr Obokata said.

She and her colleagues found that the low-pH environment was most effective for inducing pluripotency.

“Once again, Japanese scientists have unexpectedly rewritten the rules on making pluripotent cells from adult cells,” said Chris Mason, MD, PhD, of the University College London in the UK, who was not involved in this research.

“In 2006, [Shinya] Yamanaka used 4 genes [to create iPSCs]. And now, the far simpler and quicker route discovered by Obokata . . . requires only transient exposure of adult cells to an acidic solution.”

Growth in mice

To examine the cells’ growth potential in vivo, Dr Obokata and her colleagues used CD45+ cells from GFP+ mice. The team exposed the cells to a low-pH environment and found that, in the days following the stress, the cells reverted back to a pluripotent state.

These stem cells then began growing in spherical clusters, similar to a plant callus. The researchers introduced the cell clusters into the developing embryo of a non-GFP mouse and found the clusters could create GFP+ tissues in all organs tested, thereby confirming that the cells are pluripotent.

The investigators think these findings raise the possibility that unknown cellular functions activated through external stress may set somatic cells free from their current commitment and permit them to revert to their naïve state.

“Our findings suggest that, somehow, through part of a natural repair process, mature cells turn off some of the epigenetic controls that inhibit expression of certain nuclear genes that result in differentiation,” said study author Charles Vacanti, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

If this process can be replicated in human cells, researchers might one day be able to use a skin biopsy or blood sample to create stem cells specific to each individual. And this could have implications for treating cancers and other diseases.

The investigators are now testing the STAP technique in human cells. ![]()

Credit: Haruko Obokata

Researchers say they have developed a novel technique for inducing pluripotency in somatic cells.

Unlike methods for creating induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), the new process—called stimulus-triggered acquisition of pluripotency (STAP)—does not require the introduction of genetic material.

Instead, adult cells must only be injured in order to revert to a pluripotent state.

The investigators tested STAP in preclinical models and reported the results in both a letter and an article published in Nature.

Inspired by plants

Haruko Obokata, PhD, of the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology in Japan, and her colleagues said this research was inspired by the ability of a plant callus—a node of plant cells created by injuring an existing plant—to grow into a new plant.

The researchers thought this phenomenon suggested that any somatic cell could be de-differentiated through injury.

To find out, they tested cells derived from mice. The team chose hematopoietic cells positive for CD45 because these are lineage-committed, somatic cells that do not express pluripotency-related markers unless they are reprogrammed.

The investigators stressed the cells almost to the point of death by exposing them to various stimuli in vitro, including trauma, a low-oxygen environment, and a low-pH environment.

Within a few days, the cells had recovered from the stressful stimuli by naturally reverting to a pluripotent state. These stem cells were then able to re-differentiate and mature into any type of cell and grow into any type of tissue, depending on the environment into which they were placed.

“It was really surprising to see that such a remarkable transformation could be triggered simply by stimuli from outside of the cell,” Dr Obokata said.

She and her colleagues found that the low-pH environment was most effective for inducing pluripotency.

“Once again, Japanese scientists have unexpectedly rewritten the rules on making pluripotent cells from adult cells,” said Chris Mason, MD, PhD, of the University College London in the UK, who was not involved in this research.

“In 2006, [Shinya] Yamanaka used 4 genes [to create iPSCs]. And now, the far simpler and quicker route discovered by Obokata . . . requires only transient exposure of adult cells to an acidic solution.”

Growth in mice

To examine the cells’ growth potential in vivo, Dr Obokata and her colleagues used CD45+ cells from GFP+ mice. The team exposed the cells to a low-pH environment and found that, in the days following the stress, the cells reverted back to a pluripotent state.

These stem cells then began growing in spherical clusters, similar to a plant callus. The researchers introduced the cell clusters into the developing embryo of a non-GFP mouse and found the clusters could create GFP+ tissues in all organs tested, thereby confirming that the cells are pluripotent.

The investigators think these findings raise the possibility that unknown cellular functions activated through external stress may set somatic cells free from their current commitment and permit them to revert to their naïve state.

“Our findings suggest that, somehow, through part of a natural repair process, mature cells turn off some of the epigenetic controls that inhibit expression of certain nuclear genes that result in differentiation,” said study author Charles Vacanti, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

If this process can be replicated in human cells, researchers might one day be able to use a skin biopsy or blood sample to create stem cells specific to each individual. And this could have implications for treating cancers and other diseases.

The investigators are now testing the STAP technique in human cells. ![]()

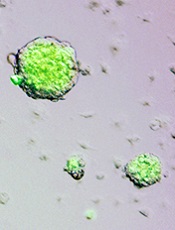

Credit: Haruko Obokata

Researchers say they have developed a novel technique for inducing pluripotency in somatic cells.

Unlike methods for creating induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), the new process—called stimulus-triggered acquisition of pluripotency (STAP)—does not require the introduction of genetic material.

Instead, adult cells must only be injured in order to revert to a pluripotent state.

The investigators tested STAP in preclinical models and reported the results in both a letter and an article published in Nature.

Inspired by plants

Haruko Obokata, PhD, of the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology in Japan, and her colleagues said this research was inspired by the ability of a plant callus—a node of plant cells created by injuring an existing plant—to grow into a new plant.

The researchers thought this phenomenon suggested that any somatic cell could be de-differentiated through injury.

To find out, they tested cells derived from mice. The team chose hematopoietic cells positive for CD45 because these are lineage-committed, somatic cells that do not express pluripotency-related markers unless they are reprogrammed.

The investigators stressed the cells almost to the point of death by exposing them to various stimuli in vitro, including trauma, a low-oxygen environment, and a low-pH environment.

Within a few days, the cells had recovered from the stressful stimuli by naturally reverting to a pluripotent state. These stem cells were then able to re-differentiate and mature into any type of cell and grow into any type of tissue, depending on the environment into which they were placed.

“It was really surprising to see that such a remarkable transformation could be triggered simply by stimuli from outside of the cell,” Dr Obokata said.

She and her colleagues found that the low-pH environment was most effective for inducing pluripotency.

“Once again, Japanese scientists have unexpectedly rewritten the rules on making pluripotent cells from adult cells,” said Chris Mason, MD, PhD, of the University College London in the UK, who was not involved in this research.

“In 2006, [Shinya] Yamanaka used 4 genes [to create iPSCs]. And now, the far simpler and quicker route discovered by Obokata . . . requires only transient exposure of adult cells to an acidic solution.”

Growth in mice

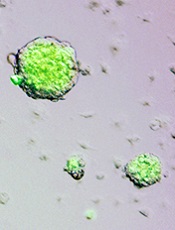

To examine the cells’ growth potential in vivo, Dr Obokata and her colleagues used CD45+ cells from GFP+ mice. The team exposed the cells to a low-pH environment and found that, in the days following the stress, the cells reverted back to a pluripotent state.

These stem cells then began growing in spherical clusters, similar to a plant callus. The researchers introduced the cell clusters into the developing embryo of a non-GFP mouse and found the clusters could create GFP+ tissues in all organs tested, thereby confirming that the cells are pluripotent.

The investigators think these findings raise the possibility that unknown cellular functions activated through external stress may set somatic cells free from their current commitment and permit them to revert to their naïve state.

“Our findings suggest that, somehow, through part of a natural repair process, mature cells turn off some of the epigenetic controls that inhibit expression of certain nuclear genes that result in differentiation,” said study author Charles Vacanti, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

If this process can be replicated in human cells, researchers might one day be able to use a skin biopsy or blood sample to create stem cells specific to each individual. And this could have implications for treating cancers and other diseases.

The investigators are now testing the STAP technique in human cells. ![]()

Listen Now! Dining and Nightlife Recommendations for HM14

Listen Up! What Hospitalists Need to Know About Healthcare Post-Obamacare

Click here to listen to more of our interview with Dr. Morrison

Click here to listen to more of our interview with Dr. Morrison

Click here to listen to more of our interview with Dr. Morrison

Likelihood for Readmission of Hospitalized Medicare Patients with Multiple Chronic Conditions Up 600%

600%

The increased likelihood of 30-day hospital readmission for hospitalized Medicare patients who have 10 or more chronic conditions, compared with those who have only one to four chronic conditions.4 These patients with multiple chronic conditions represent only 8.9% of Medicare beneficiaries but account for 50% of all rehospitalizations. The numbers are drawn from a 5% sample of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries during the first nine months of 2008. Those with five to nine chronic conditions had 2.5 times the odds for being readmitted.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

- Shieh L, Pummer E, Tsui J, et al. Septris: improving sepsis recognition and management through a mobile educational game [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(Suppl 1):1053.

- Mitchell SE, Gardiner PM, Sadikova E, et al. Patient activation and 30-day post-discharge hospital utilization. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):349-355.

- Daniels KR, Lee GC, Frei CR. Trends in catheter-associated urinary tract infections among a national cohort of hospitalized adults, 2001-2010. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(1):17-22.

- Berkowitz SA. Anderson GF. Medicare beneficiaries most likely to be readmitted. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):639-641.

600%

The increased likelihood of 30-day hospital readmission for hospitalized Medicare patients who have 10 or more chronic conditions, compared with those who have only one to four chronic conditions.4 These patients with multiple chronic conditions represent only 8.9% of Medicare beneficiaries but account for 50% of all rehospitalizations. The numbers are drawn from a 5% sample of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries during the first nine months of 2008. Those with five to nine chronic conditions had 2.5 times the odds for being readmitted.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

- Shieh L, Pummer E, Tsui J, et al. Septris: improving sepsis recognition and management through a mobile educational game [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(Suppl 1):1053.

- Mitchell SE, Gardiner PM, Sadikova E, et al. Patient activation and 30-day post-discharge hospital utilization. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):349-355.

- Daniels KR, Lee GC, Frei CR. Trends in catheter-associated urinary tract infections among a national cohort of hospitalized adults, 2001-2010. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(1):17-22.

- Berkowitz SA. Anderson GF. Medicare beneficiaries most likely to be readmitted. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):639-641.

600%

The increased likelihood of 30-day hospital readmission for hospitalized Medicare patients who have 10 or more chronic conditions, compared with those who have only one to four chronic conditions.4 These patients with multiple chronic conditions represent only 8.9% of Medicare beneficiaries but account for 50% of all rehospitalizations. The numbers are drawn from a 5% sample of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries during the first nine months of 2008. Those with five to nine chronic conditions had 2.5 times the odds for being readmitted.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

- Shieh L, Pummer E, Tsui J, et al. Septris: improving sepsis recognition and management through a mobile educational game [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(Suppl 1):1053.

- Mitchell SE, Gardiner PM, Sadikova E, et al. Patient activation and 30-day post-discharge hospital utilization. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):349-355.

- Daniels KR, Lee GC, Frei CR. Trends in catheter-associated urinary tract infections among a national cohort of hospitalized adults, 2001-2010. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(1):17-22.

- Berkowitz SA. Anderson GF. Medicare beneficiaries most likely to be readmitted. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):639-641.

Shift from Productivity to Value-Based Compensation Gains Momentum

At the 2011 SHM annual meeting in Dallas, I served on an expert panel that reviewed the latest hospitalist survey data. Included in this review were the latest compensation and productivity figures. As the session concluded, I was satisfied that the panel had discussed important information in an accessible way; however, the keynote speaker who followed us to address an entirely different topic began his talk by pointing out that the data we had reviewed, including things like wRVUs, would very soon have little to do with compensation for any physician, regardless of specialty. He implied, quite persuasively, that we were pretty old school to be talking about wRVUs and compensation based on productivity; everyone should be prepared for and embrace compensation based on value, not production.

I hear a similar sentiment reasonably often. And I agree, but I think many make the mistake of oversimplifying the issue.

Physician Value-Based Payment

Measurement of physician performance using costs, quality, and outcomes has already begun and will influence Medicare payments to doctors beginning in 2015 for large groups (>100 providers with any mix of specialties billing under the same tax ID number) and in 2017 for smaller groups.

If Medicare is moving away from payment based on wRVUs, likely followed soon by other payors, then hospitalist compensation should do the same. But I don’t think that changes the potential role of compensation based on productivity.

Compensation Should Include Performance and Productivity Metrics

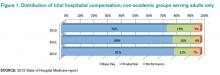

Survey data show a move from an essentially fixed annual compensation early in our field to an inclusion of components tied to performance several years before the introduction of the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier program. Data from SHM’s 2010, 2011, and 2012 State of Hospital Medicine reports (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) show that a small, but probably increasing, part of compensation has been tied to performance on things like patient satisfaction and core measures (see “Distribution of Total Hospitalist Compensation,” below). Note that the percentages in the chart refer to the fraction of total compensation dollars allocated to each domain and not the portion of hospitalists who have compensation tied to each domain.

Over the same three years, the percentage of compensation tied to productivity has been decreasing overall, while “private groups are more likely to pay a higher proportion of compensation based on productivity, and hospital-employed groups are more likely to pay a higher proportion of compensation based on performance.”

Matching Performance Compensation to Medicare’s Value-Based Modifier

It makes sense for physician compensation to generally mirror Medicare and other payor professional fee reimbursement formulas. But, in that regard, hospitalists are ahead of the market already, because the portion of dollars allocated to performance (value) in hospitalist compensation plans already exceeds the 2% or less portion of Medicare reimbursement that is influenced by performance.

Medicare will steadily increase the portion of reimbursement allocated to performance (value) and decrease the part tied solely to wRVUs. So it makes sense that hospitalist compensation plans should do the same. Who knows, within the next 5-10 years, hospitalists, and potentially doctors in all specialties, might see 20% to 50% of their compensation tied to performance. I think that might be a good thing, as long as we can come up with effective measures of performance and value—not an easy thing to do in any business or industry.

Future Role of Productivity Compensation

I don’t think all the talk about value-based reimbursement means we should abandon the idea of connecting a portion of compensation to productivity. The first two practice management columns I wrote for The Hospitalist appeared in May 2006 (www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/252413/The_Sweet_Spot.html) and June 2006 (www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/246297.html) and recommended tying a meaningful portion of compensation to individual hospitalist productivity, and I think it still makes sense to do so.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report

In any business or industry, financial performance is connected to the amount of product produced and its value. In the future, both metrics will determine reimbursement for even the highest performing healthcare providers. The new emphasis on value won’t ever make it unnecessary to produce at a reasonable level.

Unquestionably, there are many high-performing hospitalist practices with little or no productivity component in the compensation formula. So it isn’t an absolute sine qua non for success. But I think many practices dismiss it as a viable option when it might solve problems and liberate individuals in the group to exercise some autonomy in finding their own sweet spot between workload and compensation.

It will be interesting to see if future surveys show that the portion of dollars tied to hospitalist productivity continues to decrease, despite what I see as its potential benefits.

At the 2011 SHM annual meeting in Dallas, I served on an expert panel that reviewed the latest hospitalist survey data. Included in this review were the latest compensation and productivity figures. As the session concluded, I was satisfied that the panel had discussed important information in an accessible way; however, the keynote speaker who followed us to address an entirely different topic began his talk by pointing out that the data we had reviewed, including things like wRVUs, would very soon have little to do with compensation for any physician, regardless of specialty. He implied, quite persuasively, that we were pretty old school to be talking about wRVUs and compensation based on productivity; everyone should be prepared for and embrace compensation based on value, not production.

I hear a similar sentiment reasonably often. And I agree, but I think many make the mistake of oversimplifying the issue.

Physician Value-Based Payment

Measurement of physician performance using costs, quality, and outcomes has already begun and will influence Medicare payments to doctors beginning in 2015 for large groups (>100 providers with any mix of specialties billing under the same tax ID number) and in 2017 for smaller groups.

If Medicare is moving away from payment based on wRVUs, likely followed soon by other payors, then hospitalist compensation should do the same. But I don’t think that changes the potential role of compensation based on productivity.

Compensation Should Include Performance and Productivity Metrics

Survey data show a move from an essentially fixed annual compensation early in our field to an inclusion of components tied to performance several years before the introduction of the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier program. Data from SHM’s 2010, 2011, and 2012 State of Hospital Medicine reports (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) show that a small, but probably increasing, part of compensation has been tied to performance on things like patient satisfaction and core measures (see “Distribution of Total Hospitalist Compensation,” below). Note that the percentages in the chart refer to the fraction of total compensation dollars allocated to each domain and not the portion of hospitalists who have compensation tied to each domain.

Over the same three years, the percentage of compensation tied to productivity has been decreasing overall, while “private groups are more likely to pay a higher proportion of compensation based on productivity, and hospital-employed groups are more likely to pay a higher proportion of compensation based on performance.”

Matching Performance Compensation to Medicare’s Value-Based Modifier

It makes sense for physician compensation to generally mirror Medicare and other payor professional fee reimbursement formulas. But, in that regard, hospitalists are ahead of the market already, because the portion of dollars allocated to performance (value) in hospitalist compensation plans already exceeds the 2% or less portion of Medicare reimbursement that is influenced by performance.

Medicare will steadily increase the portion of reimbursement allocated to performance (value) and decrease the part tied solely to wRVUs. So it makes sense that hospitalist compensation plans should do the same. Who knows, within the next 5-10 years, hospitalists, and potentially doctors in all specialties, might see 20% to 50% of their compensation tied to performance. I think that might be a good thing, as long as we can come up with effective measures of performance and value—not an easy thing to do in any business or industry.

Future Role of Productivity Compensation

I don’t think all the talk about value-based reimbursement means we should abandon the idea of connecting a portion of compensation to productivity. The first two practice management columns I wrote for The Hospitalist appeared in May 2006 (www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/252413/The_Sweet_Spot.html) and June 2006 (www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/246297.html) and recommended tying a meaningful portion of compensation to individual hospitalist productivity, and I think it still makes sense to do so.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report

In any business or industry, financial performance is connected to the amount of product produced and its value. In the future, both metrics will determine reimbursement for even the highest performing healthcare providers. The new emphasis on value won’t ever make it unnecessary to produce at a reasonable level.

Unquestionably, there are many high-performing hospitalist practices with little or no productivity component in the compensation formula. So it isn’t an absolute sine qua non for success. But I think many practices dismiss it as a viable option when it might solve problems and liberate individuals in the group to exercise some autonomy in finding their own sweet spot between workload and compensation.

It will be interesting to see if future surveys show that the portion of dollars tied to hospitalist productivity continues to decrease, despite what I see as its potential benefits.

At the 2011 SHM annual meeting in Dallas, I served on an expert panel that reviewed the latest hospitalist survey data. Included in this review were the latest compensation and productivity figures. As the session concluded, I was satisfied that the panel had discussed important information in an accessible way; however, the keynote speaker who followed us to address an entirely different topic began his talk by pointing out that the data we had reviewed, including things like wRVUs, would very soon have little to do with compensation for any physician, regardless of specialty. He implied, quite persuasively, that we were pretty old school to be talking about wRVUs and compensation based on productivity; everyone should be prepared for and embrace compensation based on value, not production.

I hear a similar sentiment reasonably often. And I agree, but I think many make the mistake of oversimplifying the issue.

Physician Value-Based Payment

Measurement of physician performance using costs, quality, and outcomes has already begun and will influence Medicare payments to doctors beginning in 2015 for large groups (>100 providers with any mix of specialties billing under the same tax ID number) and in 2017 for smaller groups.

If Medicare is moving away from payment based on wRVUs, likely followed soon by other payors, then hospitalist compensation should do the same. But I don’t think that changes the potential role of compensation based on productivity.

Compensation Should Include Performance and Productivity Metrics

Survey data show a move from an essentially fixed annual compensation early in our field to an inclusion of components tied to performance several years before the introduction of the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier program. Data from SHM’s 2010, 2011, and 2012 State of Hospital Medicine reports (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) show that a small, but probably increasing, part of compensation has been tied to performance on things like patient satisfaction and core measures (see “Distribution of Total Hospitalist Compensation,” below). Note that the percentages in the chart refer to the fraction of total compensation dollars allocated to each domain and not the portion of hospitalists who have compensation tied to each domain.

Over the same three years, the percentage of compensation tied to productivity has been decreasing overall, while “private groups are more likely to pay a higher proportion of compensation based on productivity, and hospital-employed groups are more likely to pay a higher proportion of compensation based on performance.”

Matching Performance Compensation to Medicare’s Value-Based Modifier

It makes sense for physician compensation to generally mirror Medicare and other payor professional fee reimbursement formulas. But, in that regard, hospitalists are ahead of the market already, because the portion of dollars allocated to performance (value) in hospitalist compensation plans already exceeds the 2% or less portion of Medicare reimbursement that is influenced by performance.

Medicare will steadily increase the portion of reimbursement allocated to performance (value) and decrease the part tied solely to wRVUs. So it makes sense that hospitalist compensation plans should do the same. Who knows, within the next 5-10 years, hospitalists, and potentially doctors in all specialties, might see 20% to 50% of their compensation tied to performance. I think that might be a good thing, as long as we can come up with effective measures of performance and value—not an easy thing to do in any business or industry.

Future Role of Productivity Compensation

I don’t think all the talk about value-based reimbursement means we should abandon the idea of connecting a portion of compensation to productivity. The first two practice management columns I wrote for The Hospitalist appeared in May 2006 (www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/252413/The_Sweet_Spot.html) and June 2006 (www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/246297.html) and recommended tying a meaningful portion of compensation to individual hospitalist productivity, and I think it still makes sense to do so.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report

In any business or industry, financial performance is connected to the amount of product produced and its value. In the future, both metrics will determine reimbursement for even the highest performing healthcare providers. The new emphasis on value won’t ever make it unnecessary to produce at a reasonable level.

Unquestionably, there are many high-performing hospitalist practices with little or no productivity component in the compensation formula. So it isn’t an absolute sine qua non for success. But I think many practices dismiss it as a viable option when it might solve problems and liberate individuals in the group to exercise some autonomy in finding their own sweet spot between workload and compensation.

It will be interesting to see if future surveys show that the portion of dollars tied to hospitalist productivity continues to decrease, despite what I see as its potential benefits.

Mid-Flight Medical Emergencies Benefit from Hospitalist on Board

We were still climbing from the airport tarmac, and the movie on my iPad, “Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan,” was at an exciting point where Klingons are attacking the USS Enterprise when it came: “Is there a doctor on the plane?”

If you talk to your physician and healthcare colleagues who fly, you’ll hear about this scenario enough to know that it is not a rare event. Healthcare providers who fly routinely are more likely to tend to a sick airline passenger than they are to diagnose pheochromocytoma in their day jobs. Pheo is a two-in-a-million disease, but getting ill on a plane happens to one to two people in every 20,000. In fact, the sick airline passenger is relatively common, with an FAA study estimating 13 events per day in the 1990s (Anesthesiology. 2008;108(4):749-755). There have been a number of interesting articles written about the doctor-on-the-plane scenario. Our own Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, blogged about it in his usual humorous and insightful way a few years ago here, (http://community.the-hospitalist.org/2010/08/22/if-there-s-a-doctor-on-board-please-ring-your-call-button), and The New England Journal of Medicine published a perspective on it at www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1006331?query=TOC (NEJM; 2010;363(21):1988-1989).

My most recent experience happened on a flight just before the New Year, and because many of us will be flying to and from the annual meeting in Las Vegas and it seems to fit naturally (in many cases) with what we do as hospitalists, I thought I’d put pen to paper regarding the sick airline passenger in flight.

Fasten Your Seatbelt

As I was walked up to the first row, the flight attendant said a passenger had almost passed out. A doctor was tending to the sick woman already, as were two very concerned flight attendants. I have been through this before, so I knew I couldn’t go back to my seat just yet. I asked the physician if everything was OK and if he needed help. In my previous experiences, the initial doctor was often a specialist, or retired, or both. They often were relieved to see a hospitalist and happily handed over the care of the airline patient once they heard I’m a hospitalist. Sound familiar from your day job?

This episode was no different: Although pleasant and concerned, the initial doctor was retired, and he made it clear this was outside of his area of expertise. He didn’t exactly sprint back to his seat, but you get the picture.

The patient was pale, looked ill, and was semi-conscious. She was about 70 (later confirmed at 73) and was sitting with her son, who worriedly showed me the auto-blood pressure cuff they had brought with her; it read 81/60. She denied chest pain or shortness of breath. Her pulse was 65, and her breathing was not labored.

For a hospitalist, attending to the ill airline passenger can be quite rewarding. Most diagnoses are those we see every day: syncope/pre-syncope, respiratory, and GI complaints make up more than half of the calls. Death is rare (0.3%), and other “big” decisions, like whether to force the plane to land early (landing a plane still full of fuel or at a smaller airport is not to be taken lightly), are uncommon (7.3%). Still, the illnesses can be real, and more than a quarter of aircraft patients are transported to a hospital upon landing (N Engl J Med. 2013;368(22):2075-2083). Our skills at diagnosis are undoubtedly valuable in the air.

Also, as Dr. Wachter said in his blog on the subject, tending to the ill airline passenger is “one of the purest expressions of our Hippocratic oath, and our professionalism. We have no obligation to respond, and no contractual relationship. It’s just you, armed with your wits and experience, a sick and scared patient and family member, and about 200 interested observers.”

We broke open the aircraft medical kit, which was surprisingly well supplied, complete with a manual BP cuff and medications any registered respiratory therapist or code responder would find familiar. Bronchodilators, epinephrine and lidocaine, the usual aspirin, even IV tubing and needles. The one thing I was shocked to find was that there is limited supplemental oxygen: only enough to supply a nasal cannula at 4L max, and that for only a few hours.

As with the vast majority of medical cases, a thorough history of my 73-year-old air traveler proved invaluable. She felt light-headed but never lost consciousness. She had no other symptoms. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension but no heart disease. Was there anything else? She had been discharged from a hospital three days before for severe hypertension. Her ACE inhibitor and beta-blocker doses had been doubled and HCTZ added (her hospitalist had done an excellent job educating her on her disease, her medication changes, and possible side effects).

Anything else? She had been traveling more than 12 hours with little to drink, but she had taken all of her meds just before boarding the flight. After some oral rehydration, leaning back, and elevating her feet, her blood pressure increased to 125/71. I checked on her frequently for the rest of the flight, and she was talking happily to neighbors and her son long before we deplaned. They were en route to Boston, where she was moving and had no doctor, but she had an appointment scheduled with a new one soon. I gave her my card and my cell number and instructed them to call me if there were any problems. She and her son were thankful (and her neighbors were too!), and I was glad to have helped.

The Aftermath

The only thing left was the administrative paperwork for the airline. Would I please sign here? What was my license number (they were confused as to whether to take my NPI, my state license number, or DEA number, so I gave them all three), and where was I employed?

After getting home and recovering from my jet lag, I did some research on this topic. Colleagues of mine expressed concern over the legal liability of providing assistance in flight, but, compared to our day jobs, that concern seems to be unwarranted. The Aviation Medical Assistance Act of 1998 (www.gpo.gov) protects healthcare providers who render care in good faith.

As of the 2008 article by Ruskin, no physician providing care for an airline patient had been successfully sued. I learned that the medical kits are fairly well stocked and are set up for the physician/medical professional. I also learned that supplemental oxygen, so ubiquitous in the hospital, is more limited on an airplane. And, I found out that, while airlines contract with ground-based medical services, half of all emergencies are cared for by Good Samaritan doctors, licensed providers, nurses, and EMTs.

So, before my next flight, in addition to packing my iPad and thumb drive, boarding pass, and ID, I plan to pack those reference articles by Ruskin and Peterson.

We were still climbing from the airport tarmac, and the movie on my iPad, “Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan,” was at an exciting point where Klingons are attacking the USS Enterprise when it came: “Is there a doctor on the plane?”

If you talk to your physician and healthcare colleagues who fly, you’ll hear about this scenario enough to know that it is not a rare event. Healthcare providers who fly routinely are more likely to tend to a sick airline passenger than they are to diagnose pheochromocytoma in their day jobs. Pheo is a two-in-a-million disease, but getting ill on a plane happens to one to two people in every 20,000. In fact, the sick airline passenger is relatively common, with an FAA study estimating 13 events per day in the 1990s (Anesthesiology. 2008;108(4):749-755). There have been a number of interesting articles written about the doctor-on-the-plane scenario. Our own Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, blogged about it in his usual humorous and insightful way a few years ago here, (http://community.the-hospitalist.org/2010/08/22/if-there-s-a-doctor-on-board-please-ring-your-call-button), and The New England Journal of Medicine published a perspective on it at www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1006331?query=TOC (NEJM; 2010;363(21):1988-1989).

My most recent experience happened on a flight just before the New Year, and because many of us will be flying to and from the annual meeting in Las Vegas and it seems to fit naturally (in many cases) with what we do as hospitalists, I thought I’d put pen to paper regarding the sick airline passenger in flight.

Fasten Your Seatbelt

As I was walked up to the first row, the flight attendant said a passenger had almost passed out. A doctor was tending to the sick woman already, as were two very concerned flight attendants. I have been through this before, so I knew I couldn’t go back to my seat just yet. I asked the physician if everything was OK and if he needed help. In my previous experiences, the initial doctor was often a specialist, or retired, or both. They often were relieved to see a hospitalist and happily handed over the care of the airline patient once they heard I’m a hospitalist. Sound familiar from your day job?

This episode was no different: Although pleasant and concerned, the initial doctor was retired, and he made it clear this was outside of his area of expertise. He didn’t exactly sprint back to his seat, but you get the picture.

The patient was pale, looked ill, and was semi-conscious. She was about 70 (later confirmed at 73) and was sitting with her son, who worriedly showed me the auto-blood pressure cuff they had brought with her; it read 81/60. She denied chest pain or shortness of breath. Her pulse was 65, and her breathing was not labored.

For a hospitalist, attending to the ill airline passenger can be quite rewarding. Most diagnoses are those we see every day: syncope/pre-syncope, respiratory, and GI complaints make up more than half of the calls. Death is rare (0.3%), and other “big” decisions, like whether to force the plane to land early (landing a plane still full of fuel or at a smaller airport is not to be taken lightly), are uncommon (7.3%). Still, the illnesses can be real, and more than a quarter of aircraft patients are transported to a hospital upon landing (N Engl J Med. 2013;368(22):2075-2083). Our skills at diagnosis are undoubtedly valuable in the air.

Also, as Dr. Wachter said in his blog on the subject, tending to the ill airline passenger is “one of the purest expressions of our Hippocratic oath, and our professionalism. We have no obligation to respond, and no contractual relationship. It’s just you, armed with your wits and experience, a sick and scared patient and family member, and about 200 interested observers.”

We broke open the aircraft medical kit, which was surprisingly well supplied, complete with a manual BP cuff and medications any registered respiratory therapist or code responder would find familiar. Bronchodilators, epinephrine and lidocaine, the usual aspirin, even IV tubing and needles. The one thing I was shocked to find was that there is limited supplemental oxygen: only enough to supply a nasal cannula at 4L max, and that for only a few hours.

As with the vast majority of medical cases, a thorough history of my 73-year-old air traveler proved invaluable. She felt light-headed but never lost consciousness. She had no other symptoms. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension but no heart disease. Was there anything else? She had been discharged from a hospital three days before for severe hypertension. Her ACE inhibitor and beta-blocker doses had been doubled and HCTZ added (her hospitalist had done an excellent job educating her on her disease, her medication changes, and possible side effects).

Anything else? She had been traveling more than 12 hours with little to drink, but she had taken all of her meds just before boarding the flight. After some oral rehydration, leaning back, and elevating her feet, her blood pressure increased to 125/71. I checked on her frequently for the rest of the flight, and she was talking happily to neighbors and her son long before we deplaned. They were en route to Boston, where she was moving and had no doctor, but she had an appointment scheduled with a new one soon. I gave her my card and my cell number and instructed them to call me if there were any problems. She and her son were thankful (and her neighbors were too!), and I was glad to have helped.

The Aftermath

The only thing left was the administrative paperwork for the airline. Would I please sign here? What was my license number (they were confused as to whether to take my NPI, my state license number, or DEA number, so I gave them all three), and where was I employed?

After getting home and recovering from my jet lag, I did some research on this topic. Colleagues of mine expressed concern over the legal liability of providing assistance in flight, but, compared to our day jobs, that concern seems to be unwarranted. The Aviation Medical Assistance Act of 1998 (www.gpo.gov) protects healthcare providers who render care in good faith.

As of the 2008 article by Ruskin, no physician providing care for an airline patient had been successfully sued. I learned that the medical kits are fairly well stocked and are set up for the physician/medical professional. I also learned that supplemental oxygen, so ubiquitous in the hospital, is more limited on an airplane. And, I found out that, while airlines contract with ground-based medical services, half of all emergencies are cared for by Good Samaritan doctors, licensed providers, nurses, and EMTs.

So, before my next flight, in addition to packing my iPad and thumb drive, boarding pass, and ID, I plan to pack those reference articles by Ruskin and Peterson.

We were still climbing from the airport tarmac, and the movie on my iPad, “Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan,” was at an exciting point where Klingons are attacking the USS Enterprise when it came: “Is there a doctor on the plane?”

If you talk to your physician and healthcare colleagues who fly, you’ll hear about this scenario enough to know that it is not a rare event. Healthcare providers who fly routinely are more likely to tend to a sick airline passenger than they are to diagnose pheochromocytoma in their day jobs. Pheo is a two-in-a-million disease, but getting ill on a plane happens to one to two people in every 20,000. In fact, the sick airline passenger is relatively common, with an FAA study estimating 13 events per day in the 1990s (Anesthesiology. 2008;108(4):749-755). There have been a number of interesting articles written about the doctor-on-the-plane scenario. Our own Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, blogged about it in his usual humorous and insightful way a few years ago here, (http://community.the-hospitalist.org/2010/08/22/if-there-s-a-doctor-on-board-please-ring-your-call-button), and The New England Journal of Medicine published a perspective on it at www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1006331?query=TOC (NEJM; 2010;363(21):1988-1989).

My most recent experience happened on a flight just before the New Year, and because many of us will be flying to and from the annual meeting in Las Vegas and it seems to fit naturally (in many cases) with what we do as hospitalists, I thought I’d put pen to paper regarding the sick airline passenger in flight.

Fasten Your Seatbelt

As I was walked up to the first row, the flight attendant said a passenger had almost passed out. A doctor was tending to the sick woman already, as were two very concerned flight attendants. I have been through this before, so I knew I couldn’t go back to my seat just yet. I asked the physician if everything was OK and if he needed help. In my previous experiences, the initial doctor was often a specialist, or retired, or both. They often were relieved to see a hospitalist and happily handed over the care of the airline patient once they heard I’m a hospitalist. Sound familiar from your day job?

This episode was no different: Although pleasant and concerned, the initial doctor was retired, and he made it clear this was outside of his area of expertise. He didn’t exactly sprint back to his seat, but you get the picture.

The patient was pale, looked ill, and was semi-conscious. She was about 70 (later confirmed at 73) and was sitting with her son, who worriedly showed me the auto-blood pressure cuff they had brought with her; it read 81/60. She denied chest pain or shortness of breath. Her pulse was 65, and her breathing was not labored.

For a hospitalist, attending to the ill airline passenger can be quite rewarding. Most diagnoses are those we see every day: syncope/pre-syncope, respiratory, and GI complaints make up more than half of the calls. Death is rare (0.3%), and other “big” decisions, like whether to force the plane to land early (landing a plane still full of fuel or at a smaller airport is not to be taken lightly), are uncommon (7.3%). Still, the illnesses can be real, and more than a quarter of aircraft patients are transported to a hospital upon landing (N Engl J Med. 2013;368(22):2075-2083). Our skills at diagnosis are undoubtedly valuable in the air.

Also, as Dr. Wachter said in his blog on the subject, tending to the ill airline passenger is “one of the purest expressions of our Hippocratic oath, and our professionalism. We have no obligation to respond, and no contractual relationship. It’s just you, armed with your wits and experience, a sick and scared patient and family member, and about 200 interested observers.”

We broke open the aircraft medical kit, which was surprisingly well supplied, complete with a manual BP cuff and medications any registered respiratory therapist or code responder would find familiar. Bronchodilators, epinephrine and lidocaine, the usual aspirin, even IV tubing and needles. The one thing I was shocked to find was that there is limited supplemental oxygen: only enough to supply a nasal cannula at 4L max, and that for only a few hours.

As with the vast majority of medical cases, a thorough history of my 73-year-old air traveler proved invaluable. She felt light-headed but never lost consciousness. She had no other symptoms. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension but no heart disease. Was there anything else? She had been discharged from a hospital three days before for severe hypertension. Her ACE inhibitor and beta-blocker doses had been doubled and HCTZ added (her hospitalist had done an excellent job educating her on her disease, her medication changes, and possible side effects).

Anything else? She had been traveling more than 12 hours with little to drink, but she had taken all of her meds just before boarding the flight. After some oral rehydration, leaning back, and elevating her feet, her blood pressure increased to 125/71. I checked on her frequently for the rest of the flight, and she was talking happily to neighbors and her son long before we deplaned. They were en route to Boston, where she was moving and had no doctor, but she had an appointment scheduled with a new one soon. I gave her my card and my cell number and instructed them to call me if there were any problems. She and her son were thankful (and her neighbors were too!), and I was glad to have helped.

The Aftermath

The only thing left was the administrative paperwork for the airline. Would I please sign here? What was my license number (they were confused as to whether to take my NPI, my state license number, or DEA number, so I gave them all three), and where was I employed?

After getting home and recovering from my jet lag, I did some research on this topic. Colleagues of mine expressed concern over the legal liability of providing assistance in flight, but, compared to our day jobs, that concern seems to be unwarranted. The Aviation Medical Assistance Act of 1998 (www.gpo.gov) protects healthcare providers who render care in good faith.

As of the 2008 article by Ruskin, no physician providing care for an airline patient had been successfully sued. I learned that the medical kits are fairly well stocked and are set up for the physician/medical professional. I also learned that supplemental oxygen, so ubiquitous in the hospital, is more limited on an airplane. And, I found out that, while airlines contract with ground-based medical services, half of all emergencies are cared for by Good Samaritan doctors, licensed providers, nurses, and EMTs.

So, before my next flight, in addition to packing my iPad and thumb drive, boarding pass, and ID, I plan to pack those reference articles by Ruskin and Peterson.

What Physicians Should Know About Buying into Hospitalist Practice

Physicians who join a hospitalist practice often have the opportunity to purchase an equity interest after some period of employment. The future possibility of the physician-employee becoming an owner of the practice is sometimes addressed in the physician’s employment agreement. The amount of detail in the employment agreement regarding potential ownership will vary depending on the practice and the negotiating power of the individual physician. Clearly, the more specificity found in the contract, the better the hospitalist is served.

Because the circumstances of the individual parties will govern the terms of the buy-in, there is no standard contract language universally used in physician employment agreements. Specific aspects exist in many buy-in provisions contained in physician employment agreements, however. Such issues include: (i) the opportunity to purchase an ownership interest; (ii) performance reviews; (iii) how the interest will be valued; and (iv) payment terms.

Ownership Interest

The employment agreement should specify whether and when the employee-physician will be eligible to acquire an interest in the practice. The idea of remaining an employee may be attractive to some physicians who prefer to have less involvement in the business and financial aspects of the hospitalist practice. Sometimes cost becomes a critical issue.

However, if the parties do intend for the physician to have the right to purchase an ownership interest, the timeframe and conditions for exercising that right should be specified in writing. The following is an example of a provision addressing the opportunity to purchase an equity interest:

“The parties agree that it is their intent that upon X years of continuous employment pursuant to the terms and conditions of this Agreement, Hospitalist shall be given the opportunity to purchase [a partnership interest or stock] in Practice.”

Performance Reviews

One condition precedent to the right to purchase an equity interest may be satisfactory performance reviews by senior physicians. Although these reviews frequently are based on subjective standards, the employee-physician should seek a contractual commitment describing the criteria to be evaluated in order to make the reviews as objective as possible. Standard criteria include statistical analysis (e.g. number of patients seen a day), the quality of patient care rendered, and contributions to the practice’s operations (e.g. marketing, community outreach).

In addition, the physician’s employment agreement should specify the frequency of performance reviews. Physician reviews commonly occur on an annual, and sometimes semi-annual, basis, especially during the initial years of employment. Regardless of how often the reviews are conducted, it is highly beneficial to both the practice and the physician-employee that the time periods for evaluations be strictly enforced. Consistent, formal performance reviews promote improvement and synergy between the physician and the practice.

Equity Interest

Typically, an employment agreement will either provide an exact purchase price or, more often, state the future method to be used for calculating the buy-in price. Ordinarily, the buy-in price will be a function of the valuation of the total equity of the practice and the percentage of that equity, which is represented by the interests to be acquired by the purchasing physician. While there are a few formulas for valuing the equity of a hospitalist practice, the most common method is discounted present value of net revenue stream.

The appropriate valuation method will depend on a number of factors unique to the individual practice. Therefore, the practice should seek the assistance of an accountant or practice valuation specialist when determining the value. Stating an agreed-upon valuation method in the employment agreement will limit surprises and “sticker shock” to the buy-in price when the ownership decision is made down the road.

Payment Terms

In the event that the physician-employee exercises the opportunity to buy in, the employment or purchase agreement should provide terms governing how the purchase price will be paid. Often, the practice will be flexible in negotiating payment terms that meet the physician’s individual financial needs; however, the parties frequently agree that the physician will either pay the owners in full up front or make installment payments over a specified number of years.

If the physician is required to pay the total purchase price up front, he or she will be personally responsible for obtaining the necessary funding through bank loans or other sources. If the purchasing physician is permitted to make installment payments, he or she will be required to sign a promissory note in which the payee is the practice and the note is secured by a security interest in the equity granted to the physician. There are important tax strategies that can be implemented when installment payments are agreed upon. In the event that the physician fails to make the installment payments, the practice may be able to recover the equity interest.

In Sum

Both parties should review and understand the terms and conditions of the buy-in so that all parties enter the employment relationship with the same expectations for future ownership.

Steven Harris is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at [email protected].

Physicians who join a hospitalist practice often have the opportunity to purchase an equity interest after some period of employment. The future possibility of the physician-employee becoming an owner of the practice is sometimes addressed in the physician’s employment agreement. The amount of detail in the employment agreement regarding potential ownership will vary depending on the practice and the negotiating power of the individual physician. Clearly, the more specificity found in the contract, the better the hospitalist is served.

Because the circumstances of the individual parties will govern the terms of the buy-in, there is no standard contract language universally used in physician employment agreements. Specific aspects exist in many buy-in provisions contained in physician employment agreements, however. Such issues include: (i) the opportunity to purchase an ownership interest; (ii) performance reviews; (iii) how the interest will be valued; and (iv) payment terms.

Ownership Interest

The employment agreement should specify whether and when the employee-physician will be eligible to acquire an interest in the practice. The idea of remaining an employee may be attractive to some physicians who prefer to have less involvement in the business and financial aspects of the hospitalist practice. Sometimes cost becomes a critical issue.

However, if the parties do intend for the physician to have the right to purchase an ownership interest, the timeframe and conditions for exercising that right should be specified in writing. The following is an example of a provision addressing the opportunity to purchase an equity interest:

“The parties agree that it is their intent that upon X years of continuous employment pursuant to the terms and conditions of this Agreement, Hospitalist shall be given the opportunity to purchase [a partnership interest or stock] in Practice.”

Performance Reviews

One condition precedent to the right to purchase an equity interest may be satisfactory performance reviews by senior physicians. Although these reviews frequently are based on subjective standards, the employee-physician should seek a contractual commitment describing the criteria to be evaluated in order to make the reviews as objective as possible. Standard criteria include statistical analysis (e.g. number of patients seen a day), the quality of patient care rendered, and contributions to the practice’s operations (e.g. marketing, community outreach).

In addition, the physician’s employment agreement should specify the frequency of performance reviews. Physician reviews commonly occur on an annual, and sometimes semi-annual, basis, especially during the initial years of employment. Regardless of how often the reviews are conducted, it is highly beneficial to both the practice and the physician-employee that the time periods for evaluations be strictly enforced. Consistent, formal performance reviews promote improvement and synergy between the physician and the practice.

Equity Interest

Typically, an employment agreement will either provide an exact purchase price or, more often, state the future method to be used for calculating the buy-in price. Ordinarily, the buy-in price will be a function of the valuation of the total equity of the practice and the percentage of that equity, which is represented by the interests to be acquired by the purchasing physician. While there are a few formulas for valuing the equity of a hospitalist practice, the most common method is discounted present value of net revenue stream.

The appropriate valuation method will depend on a number of factors unique to the individual practice. Therefore, the practice should seek the assistance of an accountant or practice valuation specialist when determining the value. Stating an agreed-upon valuation method in the employment agreement will limit surprises and “sticker shock” to the buy-in price when the ownership decision is made down the road.

Payment Terms

In the event that the physician-employee exercises the opportunity to buy in, the employment or purchase agreement should provide terms governing how the purchase price will be paid. Often, the practice will be flexible in negotiating payment terms that meet the physician’s individual financial needs; however, the parties frequently agree that the physician will either pay the owners in full up front or make installment payments over a specified number of years.

If the physician is required to pay the total purchase price up front, he or she will be personally responsible for obtaining the necessary funding through bank loans or other sources. If the purchasing physician is permitted to make installment payments, he or she will be required to sign a promissory note in which the payee is the practice and the note is secured by a security interest in the equity granted to the physician. There are important tax strategies that can be implemented when installment payments are agreed upon. In the event that the physician fails to make the installment payments, the practice may be able to recover the equity interest.

In Sum

Both parties should review and understand the terms and conditions of the buy-in so that all parties enter the employment relationship with the same expectations for future ownership.

Steven Harris is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at [email protected].

Physicians who join a hospitalist practice often have the opportunity to purchase an equity interest after some period of employment. The future possibility of the physician-employee becoming an owner of the practice is sometimes addressed in the physician’s employment agreement. The amount of detail in the employment agreement regarding potential ownership will vary depending on the practice and the negotiating power of the individual physician. Clearly, the more specificity found in the contract, the better the hospitalist is served.

Because the circumstances of the individual parties will govern the terms of the buy-in, there is no standard contract language universally used in physician employment agreements. Specific aspects exist in many buy-in provisions contained in physician employment agreements, however. Such issues include: (i) the opportunity to purchase an ownership interest; (ii) performance reviews; (iii) how the interest will be valued; and (iv) payment terms.

Ownership Interest

The employment agreement should specify whether and when the employee-physician will be eligible to acquire an interest in the practice. The idea of remaining an employee may be attractive to some physicians who prefer to have less involvement in the business and financial aspects of the hospitalist practice. Sometimes cost becomes a critical issue.

However, if the parties do intend for the physician to have the right to purchase an ownership interest, the timeframe and conditions for exercising that right should be specified in writing. The following is an example of a provision addressing the opportunity to purchase an equity interest:

“The parties agree that it is their intent that upon X years of continuous employment pursuant to the terms and conditions of this Agreement, Hospitalist shall be given the opportunity to purchase [a partnership interest or stock] in Practice.”

Performance Reviews

One condition precedent to the right to purchase an equity interest may be satisfactory performance reviews by senior physicians. Although these reviews frequently are based on subjective standards, the employee-physician should seek a contractual commitment describing the criteria to be evaluated in order to make the reviews as objective as possible. Standard criteria include statistical analysis (e.g. number of patients seen a day), the quality of patient care rendered, and contributions to the practice’s operations (e.g. marketing, community outreach).

In addition, the physician’s employment agreement should specify the frequency of performance reviews. Physician reviews commonly occur on an annual, and sometimes semi-annual, basis, especially during the initial years of employment. Regardless of how often the reviews are conducted, it is highly beneficial to both the practice and the physician-employee that the time periods for evaluations be strictly enforced. Consistent, formal performance reviews promote improvement and synergy between the physician and the practice.

Equity Interest

Typically, an employment agreement will either provide an exact purchase price or, more often, state the future method to be used for calculating the buy-in price. Ordinarily, the buy-in price will be a function of the valuation of the total equity of the practice and the percentage of that equity, which is represented by the interests to be acquired by the purchasing physician. While there are a few formulas for valuing the equity of a hospitalist practice, the most common method is discounted present value of net revenue stream.

The appropriate valuation method will depend on a number of factors unique to the individual practice. Therefore, the practice should seek the assistance of an accountant or practice valuation specialist when determining the value. Stating an agreed-upon valuation method in the employment agreement will limit surprises and “sticker shock” to the buy-in price when the ownership decision is made down the road.

Payment Terms

In the event that the physician-employee exercises the opportunity to buy in, the employment or purchase agreement should provide terms governing how the purchase price will be paid. Often, the practice will be flexible in negotiating payment terms that meet the physician’s individual financial needs; however, the parties frequently agree that the physician will either pay the owners in full up front or make installment payments over a specified number of years.

If the physician is required to pay the total purchase price up front, he or she will be personally responsible for obtaining the necessary funding through bank loans or other sources. If the purchasing physician is permitted to make installment payments, he or she will be required to sign a promissory note in which the payee is the practice and the note is secured by a security interest in the equity granted to the physician. There are important tax strategies that can be implemented when installment payments are agreed upon. In the event that the physician fails to make the installment payments, the practice may be able to recover the equity interest.

In Sum

Both parties should review and understand the terms and conditions of the buy-in so that all parties enter the employment relationship with the same expectations for future ownership.

Steven Harris is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at [email protected].

Tips for Landing Your First Job in Hospital Medicine

Finding the right hospitalist position can help make the transition from resident to attending enjoyable as you adjust to a new level of responsibility. But the wrong job can leave you feeling overwhelmed and unsupported. So what is a busy senior resident to do? Here we offer selected pearls and pitfalls to help you find a great position.

Initial Steps and Things to Consider

Start applying in the fall of your PGY-3 year. The process of interviewing applicants, finalizing contracts, arranging for hospital privileges, and enrolling a new hire in insurance plans can take many months. Many employers start looking early.

Meet with your residency program director and your hospitalist group director to discuss your plans. They can help you clarify your goals, serving as coaches throughout the process, and they may know people at the places you are interested in. Recruiters can be helpful, but remember—many are incentivized to find you a position. Advertisements in the back of journals and professional society publications are useful resources.

Obtain your medical license as early as possible. Getting licensed in the state you will be working in can be much faster if you already have a license from another state. Applicants have lost positions because they didn’t have their medical license in time.

Don’t shop for a job based on schedule and salary alone. There are reasons some jobs pay better than most, and they aren’t always good (home call, for example). A seven-on, seven-off schedule affords a lot of free time, but while you are on service, family life often takes a back seat. Conversely, working every Monday to Friday offers less free time for travel or moonlighting.

Think about the care model you prefer. Do you want to work with residents, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, or in a “direct care” model where it’s just you and the nurses caring for patients? Salaries often are inversely related to the number of providers between you and the patients. Positions without resident support might require procedural competence. Demonstrating academic productivity, especially in the area of quality improvement or patient safety, can help you secure a position working with residents. Some programs first place new hires on the non-teaching service to earn the chance to work with residents and medical students.

Think about what type of career you want. Do you only want to see patients, or do you want a career that includes a non-clinical role for which you will be paid? Some hospitalists find that becoming a patient safety officer or residency program director, trying out a medical student clerkship, or growing into another administrative role is a great complement to their clinical time and prevents burnout.

How to Stand Out

Start off by getting the basics right. Make sure your e-mail address sounds professional. A well-formatted CV, with no spelling errors or unexplained time gaps, is a must. A cover letter that succinctly describes the type of position you are looking for, highlights your strengths, and does not wax on about why you wanted to become a doctor—that was your personal statement for med school—is helpful. Don’t correspond with employers using your smartphone if you’re prone to autocorrect or spelling errors, or if you tend to write too casually from a mobile device. Before you shoot off that immediate e-mail response, make sure you’re addressing people properly and not mixing up employers.

Join SHM (they have trainee rates!), and attend an SHM conference or local chapter meeting if you can (www.hospitalmedicine.org/events). SHM membership reflects your commitment to the specialty. Membership in other professional societies is a plus as well.

Quality improvement (QI), patient safety, and patient satisfaction are central to hospital medicine. Medication reconciliation, infection control, handoff, transitions of care, listening carefully to patients, and explaining things to them are likely things you’ve done throughout residency. Communicate to employers your experience in and appreciation of these areas. Completing a QI or patient safety project and participating on a hospital committee will help make you a competitive applicant.

Interview Do’s and Don’ts

The advice most were given when applying to residency still holds. Be on time, dress professionally, research the program, and be prepared to speak about why you want to work at a particular place. Speak to hospitalists in the group, and be very courteous to everyone.

Don’t start off by asking about salary—if you move along in the process, compensation will be discussed. Get a clear picture of the schedule and how time off/non-clinical time occurs, but don’t come off as inflexible or too needy.

Ask why hospitalists have left a group. Frequent turnover without good reason could be a red flag. If the hospitalist director and/or department chair are new or will be leaving, you should ask how that might affect the group. If the current leadership has been stable, ask what growth has occurred for the group overall and among individuals during their tenure.

Find out whether hospitalists have been promoted academically and if there are career growth opportunities in areas you are interested in. Try to determine if the group has a “voice” with administration by asking for examples of how hospitalist concerns have been positively addressed.

Having a clear picture of how much nursing, social work, case management, subspecialist, and intensivist support is available is critical. Whether billing is done electronically or on paper is important, as is the degree of instruction and support for billing.

Take the opportunity to meet the current hospitalists—and note that their input often is solicited as to whether or not to hire a candidate—and ask them questions away from the ears of the program leadership; most hospitalists like to meet potential colleagues.

Closing the Deal

If you make it past the interview stage, be sure additional deliverables, such as letters of recommendation, are on time. Now is the time to ask about salary. Don’t be afraid to inquire about relocation or sign-on bonuses. At this point, the employer likes you and has invested time in recruiting you. You can gently leverage this in your negotiations. Consult your program director or other mentors at this point—they can provide guidance.

If you are uncertain about accepting an offer, be open about this with the employer. Your honesty in the process is essential, will be viewed positively, and can trigger additional dialogue that may help you decide. Juggling multiple offers dishonestly is not ethical and can backfire, as many hospitalist directors know each other.

Have an attorney familiar with physician contracts review yours. Look at whether “tail coverage,” which insures legal actions brought against you after you have left, is provided. Take note of “non-compete” clauses; they may limit your ability to practice in the area if you leave a practice. Find out if moonlighting is allowed and if the hospital requires you to give them a percentage of your outside earnings.

If you secure a position, whether as a career hospitalist or just for a year or two before fellowship, you should be excited. HM is a wonderful field with tremendous and varied opportunities. Dive in, enjoy, and explore everything it has to offer!

Dr. Bryson is medical director of teaching services, associate program director of internal medicine residency, and assistant professor at Tufts University, and a hospitalist at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. Dr. Steinberg is residency program director in the Department of Medicine at Beth Israel Medical Center, and associate professor of medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. Both are members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee.

Finding the right hospitalist position can help make the transition from resident to attending enjoyable as you adjust to a new level of responsibility. But the wrong job can leave you feeling overwhelmed and unsupported. So what is a busy senior resident to do? Here we offer selected pearls and pitfalls to help you find a great position.

Initial Steps and Things to Consider

Start applying in the fall of your PGY-3 year. The process of interviewing applicants, finalizing contracts, arranging for hospital privileges, and enrolling a new hire in insurance plans can take many months. Many employers start looking early.

Meet with your residency program director and your hospitalist group director to discuss your plans. They can help you clarify your goals, serving as coaches throughout the process, and they may know people at the places you are interested in. Recruiters can be helpful, but remember—many are incentivized to find you a position. Advertisements in the back of journals and professional society publications are useful resources.

Obtain your medical license as early as possible. Getting licensed in the state you will be working in can be much faster if you already have a license from another state. Applicants have lost positions because they didn’t have their medical license in time.

Don’t shop for a job based on schedule and salary alone. There are reasons some jobs pay better than most, and they aren’t always good (home call, for example). A seven-on, seven-off schedule affords a lot of free time, but while you are on service, family life often takes a back seat. Conversely, working every Monday to Friday offers less free time for travel or moonlighting.

Think about the care model you prefer. Do you want to work with residents, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, or in a “direct care” model where it’s just you and the nurses caring for patients? Salaries often are inversely related to the number of providers between you and the patients. Positions without resident support might require procedural competence. Demonstrating academic productivity, especially in the area of quality improvement or patient safety, can help you secure a position working with residents. Some programs first place new hires on the non-teaching service to earn the chance to work with residents and medical students.