User login

Confused, cold, and lethargic

CASE Confused and cold

Ms. K, age 48, is brought to the emergency department (ED) by her husband because she has become increasingly lethargic over the past 2 weeks and cannot attend to activities of daily living. She is incontinent of stool and poorly responsive.

Ms. K’s husband reports that lethargy culminated in his wife sleeping 30 continuous hours. She has a history of a ruptured cerebral arteriovenous malformation (AVM) complicated by a secondary infarct 7 years ago, with residual symptoms of frontal lobe syndrome. Until 2 weeks ago, however, she was in her usual state of health.

Symptoms have included depression, mood lability, impulsivity, disinhibition, poor focus, and apathy. An outpatient psychiatrist has managed these symptoms with antidepressants and atypical antipsychotics.

When Ms. K arrives in the ED, she is taking citalopram, 30 mg/d, and paliperidone,

6 mg/d. Her psychiatrist started paliperidone 2 months ago, increasing the dosage to 6 mg/d 6 weeks before presentation because of worsening mood lability, disinhibition, and paranoia regarding her caregivers. Her husband denies any other medication changes or exposure to environmental toxins.

In the ED, Ms. K is confused and oriented only to person. Vital signs are: pulse 46 bpm; blood pressure, 66/51 mm Hg; respirations, 12/min; and temperature, 29.9ºC (85.8ºF) via bladder probe.

a) major depressive disorder, severe, with catatonic features

b) exposure to cold

c) hypothyroidism

d) drug-induced hypothermia

e) stroke

f) sepsis

g) delirium

The authors’ observations

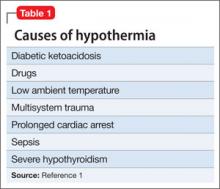

Hypothermia is core body temperature <35ºC (95ºF).1 It often is caused by exposure to low ambient temperature (Table 1),1 but Ms. K’s husband denied that she had been exposed to cold. Because of Ms. K’s neurologic history, stroke was high on the differential diagnosis, but physical examination did not reveal evidence of focal dysfunction and was significant only for altered mental status.

Ms. K had no posturing, rigidity, negativism, or excessive motor activity that would suggest catatonia. Before she became lethargic, her husband had not noted any deterioration of mood, although she did exhibit other behavioral changes that prompted her outpatient psychiatrist to increase the dosage of paliperidone. Although Ms. K began experiencing persecutory delusions—she believed that her caregivers were trying to harm her—she and her family denied perceptual disturbances. On examination, she did not appear responsive to auditory or visual hallucinations.

Frontal lobe syndrome is defined as a set of changes in the cognitive, behavioral, or emotional domains, often leading to disturbed affect, alteration of attention, aphasia, perseveration, disinhibition, and personality changes.2 These symptoms are not specific to lesions in the frontal lobes but can arise from lesions anywhere in the frontal-striatal-thalamic circuit.3 Causes include traumatic brain injury, neurodegenerative disorders, cerebrovascular disease, tumors, and aging.2 Recommended treatment incorporates psychosocial interventions with drug treatment to target specific symptoms. Medications reported to be effective include typical and atypical antipsychotics to target aggression and agitation; benzodiazepines to reduce arousal; antidepressants for mood symptoms, dopamine agonists (eg, bromocriptine) to decrease apathy, and mood stabilizers to target mood lability.4

Before her AVM rupture, review of Ms. K’s psychiatric history revealed no psychiatric symptoms or impaired functioning. When hospitalized for the AVM repair, she was started on sertraline. She began seeing a psychiatrist 2 years later because of increased agitation and behavioral disturbances, and aripiprazole was added. Persistent agitation prompted a trial of divalproex sodium, which was discontinued because of slurred speech and increased distractibility. Aripiprazole was tapered and replaced with paliperidone because of poor response. Citalopram was initiated 1 year before she presented to the ED.

a) brain MRI

b) infectious evaluation (lumbar puncture with analysis of cerebrospinal fluid, complete blood count, blood cultures, chest radiographs)

c) endocrine panel

d) urine toxicology screen

EVALUATION Hypothermia

Laboratory tests reveal multiple abnormalities, including thrombocytopenia (platelet level, 53 ×103/μL), altered coagulation (partial thromboplastin time, 55.6 s), elevated levels of hepatic transaminases (aspartate aminotransferase, 168 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 357 U/L), and increased alkaline phosphatase (206 U/L). Other mild metabolic disturbances include: sodium, 149 mEq/L; CO2, 33 mEq/L; and blood urea nitrogen, 24 mg/dL.

These laboratory values are consistent with complications of hypothermia.1

ECG reveals sinus bradycardia (40 bpm) and Osborn waves (additional deflection at the end of the QRS complex), which are seen often in hypothermia.1 Head CT and brain MRI show chronic changes after Ms. K’s right temporoparietal AVM rupture, but no acute abnormality. Urinalysis, blood cultures, and chest radiographs are negative for infection. Urine toxicology screen is negative. Results of thyroid function tests and pituitary hormones studies are significant only for hyperprolactinemia of 155.7 ng/mL, a known adverse effect of antipsychotics.5

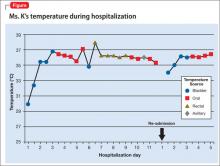

Ms. K is admitted and rewarmed passively and with warm IV fluids; by day 10 of hospitalization, temperature is stable (>35.1ºC [95.2ºF]). Thrombocytopenia, transaminitis, and altered mental status resolve.

Ms. K’s oral medications, including citalopram and paliperidone, have been held since admission because of her altered mental status. The psychiatry service is consulted to evaluate whether her presentation could be related to her change of medication.

A literature search reveals no report of paliperidone-induced hypothermia, but we consider it a possible explanation for Ms. K’s presentation. Lamotrigine (titrated to 50 mg/d), a benzodiazepine (oral lorazepam as needed), and discontinuing antipsychotics are recommended. After she returns to her baseline functioning, Ms. K is discharged to a skilled nursing facility.

Ms. K presents to the ED 2 days after discharge with altered mental status. Vital signs are: blood pressure, 90/55 mm Hg; pulse, 59 bpm; respiratory rate, 14/min; and temperature, 34.4ºC (93.9ºF) via bladder probe (Figure). Laboratory tests were significant for hepatic transaminitis (aspartate aminotransferase, 75 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 122 U/L) and elevated alkaline phosphatase (226 U/L). A review of records from the nursing facility revealed that Ms. K was receiving paliperidone because of an error in the discharge summary, which recommended restarting all prior medications.

The authors’ observations

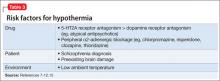

The Naranjo Causality Scale,6 which categorizes the probability that an adverse event is related to a drug (based on several variables, including timing of the drug administration with the onset of event, drug dosage and levels, response relationships to a drug, including re-challenge when possible, and previous patient experience with the medication), often is used to evaluate whether an adverse clinical event has been caused by a drug (Table 2). We applied the Scale to Ms. K’s case, which revealed a score of 7—indicating a probable adverse drug reaction. The sequence of events in Ms. K’s case that led to a paliperidone challenge-dechallenge-rechallenge, and the resulting hypothermia, are, we concluded, evidence of an adverse drug reaction.

Using the World Health Organization database for adverse drug reactions, van Marum et al7 found 480 reports hypothermia with antipsychotics as of 2007 (compared with 524 reports of hyperthermia in the same period); 55% involved atypical antipsychotics, mainly risperidone. There are no case reports of paliperidone-induced hypothermia; however, several reports of hypothermia have been attributed to risperidone, and paliperidone is the primary active metabolite of risperidone.5

To identify risk factors for hypothermia with antipsychotic use, van Marum et al7 performed a literature search for case reports of antipsychotic-induced hypothermia, which revealed no association with age or sex. The most common diagnosis in cases of antipsychotic-induced hypothermia was schizophrenia (51%). In 73% of the cases, hypothermia followed the start or dosage increase of the antipsychotic. These observations have been noted in case reports and case series of hypothermia associated with antipsychotic use.8-12

Mechanism of action

One proposed mechanism for antipsychotic-induced hypothermia includes preferential 5-HT2A receptor antagonism over D2 receptor antagonism.7,12 It has been believed that, under normal conditions, the action of dopamine to reduce body temperature and the action of serotonin to elevate it are in balance.9

Another possible mechanism is peripheral á2-adrenergic blockade, which might increase the hypothermic effect by inhibiting peripheral responses to cooling, such as vasoconstriction and shivering.7,8 Boschi et al13 found that antipsychotics cause hypothermia in rats when the drug is administered intraperitoneally but not when given intrathecally. Perhaps for these reasons, in the early 1950s, before its psychotropic properties were known, chlorpromazine was used during surgery to induce artificial hibernation and suppress the body’s response to cooling.7 The therapeutic activity of paliperidone is mediated though a D2, 5-HT2A, and á2-receptor antagonism5; these mechanisms could, therefore, be contributing to Ms. K’s hypothermia.

Patients with preexisting brain damage— such as Ms. K—might be at increased risk of antipsychotic-induced hypothermia.7,8 This includes focal damage to central thermoregulatory centers, such as the pre-optic anterior hypothalamic region,14 and more diffuse damage seen in patients with cognitive impairment or a seizure disorder.8

Studies of people with schizophrenia show a decrease in core temperature after administration of an antipsychotic,15 raising the possibility of an impairment of baseline thermoregulatory control. Such thermal dysregulation in patients with schizophrenia might be explained by changes in neurotensin levels.7

The neuropeptide neurotensin has been implicated in the regulation of prolactin release and interacts to a significant degree with the dopaminergic system.16 When administered to animals, neurotensin suppresses heat production and increases heat loss.17 The neurotensin level in CSF was found to be lower in non-medicated patients with schizophrenia than in healthy controls, with an inverse correlation between the severity of symptoms and the neurotensin level.18

Additionally, persons with schizophrenia might be at increased risk of developing hypothermia when exposed to a low environmental temperature.7,8 Kudoh et al19 investigated temperature regulation during anesthesia in patients with chronic (≥7 years) schizophrenia receiving antipsychotics, and compared findings against what was seen in controls. The team reported that patients with schizophrenia had significantly lower intraoperative temperatures.

A published analysis of cases and studies of antipsychotic-induced hypothermia describes the combination of drug variables, patient variables, and environmental variables that contribute to thermal dysregulation (Table 3).7-12,15 The recommendation for practitioners is that, when considering an antipsychotic for a patient at high risk of thermal dysregulation, your choice of an agent should take that risk into account, especially when that drug is one that has comparatively stronger serotonergic and peripheral á-adrenergic effects. You should monitor patients closely for hypothermia after starting and when increasing the dosage of the drug. In patients with schizophrenia who might have a problem with baseline thermoregulation, advise them to take measures to counteract their increased susceptibility to low ambient temperatures.

OUTCOME Readmission

Ms. K was readmitted, rewarmed, and discharged to a skilled nursing facility 4 days later, after baseline function returned to normal and temperature stabilized. Paliperidone is now listed in her electronic medical record as “drug intolerance.”

This case also highlights the importance of adequate medication reconciliation at

admission and discharge, especially when using an electronic medical record system, because what might otherwise be considered a minor mistake can have devastating consequences.

Bottom Line

Thermal dysregulation—hyperthermia and hypothermia—can occur secondary to an antipsychotic. Determining whether a patient is at increased risk of either of these adverse effects is important when deciding to use antipsychotics. Recognizing agents that can cause hypothermia is essential, because management requires prompt discontinuation of the offending drug.

Related Resource

- Espay AJ, et al. Frontal lobe syndromes. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1135866-overview. Updated September 17, 2012. Accessed November 3, 2012.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Bromocriptine • Parlodel Lorazepam • Ativan

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine Paliperidone • Invega

Citalopram • Celexa Risperidone • Risperdal

Clozapine • Clozaril Sertraline • Zoloft

Divalproex sodium • Depakote Thioridazine • Mellaril

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Aslam AF, Aslam AK, Vasavada BC, et al. Hypothermia: evaluation, electrocardiographic manifestations, and management. Am J Med. 2006;119(4):297-301.

2. Hanna-Pladdy B. Dysexecutive syndromes in neurologic disease. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31(3):119-127.

3. Salloway SP. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with “frontal lobe” syndromes. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;6(4):388-398.

4. Campbell JJ, Duffy JD, Salloway SP. Treatment strategies for patients with dysexecutive syndromes. In: Salloway SP, Malloy PF, Duffy JD, eds. The frontal lobes and neuropsychiatric illness. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2001:153-163.

5. Stahl SM. Essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000:336.

6. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239-245.

7. van Marum RJ, Wegewijs MA, Loonen AJM, et al. Hypothermia following antipsychotic drug use. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(6):627-631.

8. Kreuzer P, Landgrebe M, Wittmann M, et al. Hypothermia associated with antipsychotic drug use: a clinical case series and review of current literature. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52(7)1090-1097.

9. Hung CF, Huang TY, Lin PY. Hypothermia and rhabdomyolysis following olanzapine injection in an adolescent with schizophreniform disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(4):376-378.

10. Razaq M, Samma M. A case of risperidone-induced hypothermia. Am J Ther. 2004;11(3):229-230.

11. Schwaninger M, Weisbrod M, Schwab S, et al. Hypothermia induced by atypical neuroleptics. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1998;21(6):344-346.

12. Bookstaver PB, Miller AD. Possible long-acting risperidone-induced hypothermia precipitating phenytoin toxicity in an elderly patient. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011; 36(3):426-429.

13. Boschi G, Launay N, Rips R. Neuroleptic-induced hypothermia in mice: lack of evidence for a central mechanism. Br J Pharmacol. 1987;90(4):745-751.

14. Sessler DI. Thermoregulatory defense mechanisms. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(suppl 7):S203-S210.

15. Shiloh R, Weizman A, Epstein Y, et al. Abnormal thermoregulation in drug-free male schizophrenia patients. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001;11(4):285-288.

16. McCann SM, Vijayan E. Control of anterior pituitary hormone secretion by neurotensin. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992; 668:287-297.

17. Chandra A, Chou HC, Chang C, et al. Effecst of intraventricular administration of neurotensin and somatostatin on thermoregulation in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 1981;20(7):715-718.

18. Sharma RP, Janicak PG, Bissette G, et al. CSF neurotensin concentrations and antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1997; 154(7):1019-1021.

19. Kudoh A, Takase H, Takazawa T. Chronic treatment with antipsychotics enhances intraoperative core hypothermia. Anesth Analg. 2004;98(1):111-115.

CASE Confused and cold

Ms. K, age 48, is brought to the emergency department (ED) by her husband because she has become increasingly lethargic over the past 2 weeks and cannot attend to activities of daily living. She is incontinent of stool and poorly responsive.

Ms. K’s husband reports that lethargy culminated in his wife sleeping 30 continuous hours. She has a history of a ruptured cerebral arteriovenous malformation (AVM) complicated by a secondary infarct 7 years ago, with residual symptoms of frontal lobe syndrome. Until 2 weeks ago, however, she was in her usual state of health.

Symptoms have included depression, mood lability, impulsivity, disinhibition, poor focus, and apathy. An outpatient psychiatrist has managed these symptoms with antidepressants and atypical antipsychotics.

When Ms. K arrives in the ED, she is taking citalopram, 30 mg/d, and paliperidone,

6 mg/d. Her psychiatrist started paliperidone 2 months ago, increasing the dosage to 6 mg/d 6 weeks before presentation because of worsening mood lability, disinhibition, and paranoia regarding her caregivers. Her husband denies any other medication changes or exposure to environmental toxins.

In the ED, Ms. K is confused and oriented only to person. Vital signs are: pulse 46 bpm; blood pressure, 66/51 mm Hg; respirations, 12/min; and temperature, 29.9ºC (85.8ºF) via bladder probe.

a) major depressive disorder, severe, with catatonic features

b) exposure to cold

c) hypothyroidism

d) drug-induced hypothermia

e) stroke

f) sepsis

g) delirium

The authors’ observations

Hypothermia is core body temperature <35ºC (95ºF).1 It often is caused by exposure to low ambient temperature (Table 1),1 but Ms. K’s husband denied that she had been exposed to cold. Because of Ms. K’s neurologic history, stroke was high on the differential diagnosis, but physical examination did not reveal evidence of focal dysfunction and was significant only for altered mental status.

Ms. K had no posturing, rigidity, negativism, or excessive motor activity that would suggest catatonia. Before she became lethargic, her husband had not noted any deterioration of mood, although she did exhibit other behavioral changes that prompted her outpatient psychiatrist to increase the dosage of paliperidone. Although Ms. K began experiencing persecutory delusions—she believed that her caregivers were trying to harm her—she and her family denied perceptual disturbances. On examination, she did not appear responsive to auditory or visual hallucinations.

Frontal lobe syndrome is defined as a set of changes in the cognitive, behavioral, or emotional domains, often leading to disturbed affect, alteration of attention, aphasia, perseveration, disinhibition, and personality changes.2 These symptoms are not specific to lesions in the frontal lobes but can arise from lesions anywhere in the frontal-striatal-thalamic circuit.3 Causes include traumatic brain injury, neurodegenerative disorders, cerebrovascular disease, tumors, and aging.2 Recommended treatment incorporates psychosocial interventions with drug treatment to target specific symptoms. Medications reported to be effective include typical and atypical antipsychotics to target aggression and agitation; benzodiazepines to reduce arousal; antidepressants for mood symptoms, dopamine agonists (eg, bromocriptine) to decrease apathy, and mood stabilizers to target mood lability.4

Before her AVM rupture, review of Ms. K’s psychiatric history revealed no psychiatric symptoms or impaired functioning. When hospitalized for the AVM repair, she was started on sertraline. She began seeing a psychiatrist 2 years later because of increased agitation and behavioral disturbances, and aripiprazole was added. Persistent agitation prompted a trial of divalproex sodium, which was discontinued because of slurred speech and increased distractibility. Aripiprazole was tapered and replaced with paliperidone because of poor response. Citalopram was initiated 1 year before she presented to the ED.

a) brain MRI

b) infectious evaluation (lumbar puncture with analysis of cerebrospinal fluid, complete blood count, blood cultures, chest radiographs)

c) endocrine panel

d) urine toxicology screen

EVALUATION Hypothermia

Laboratory tests reveal multiple abnormalities, including thrombocytopenia (platelet level, 53 ×103/μL), altered coagulation (partial thromboplastin time, 55.6 s), elevated levels of hepatic transaminases (aspartate aminotransferase, 168 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 357 U/L), and increased alkaline phosphatase (206 U/L). Other mild metabolic disturbances include: sodium, 149 mEq/L; CO2, 33 mEq/L; and blood urea nitrogen, 24 mg/dL.

These laboratory values are consistent with complications of hypothermia.1

ECG reveals sinus bradycardia (40 bpm) and Osborn waves (additional deflection at the end of the QRS complex), which are seen often in hypothermia.1 Head CT and brain MRI show chronic changes after Ms. K’s right temporoparietal AVM rupture, but no acute abnormality. Urinalysis, blood cultures, and chest radiographs are negative for infection. Urine toxicology screen is negative. Results of thyroid function tests and pituitary hormones studies are significant only for hyperprolactinemia of 155.7 ng/mL, a known adverse effect of antipsychotics.5

Ms. K is admitted and rewarmed passively and with warm IV fluids; by day 10 of hospitalization, temperature is stable (>35.1ºC [95.2ºF]). Thrombocytopenia, transaminitis, and altered mental status resolve.

Ms. K’s oral medications, including citalopram and paliperidone, have been held since admission because of her altered mental status. The psychiatry service is consulted to evaluate whether her presentation could be related to her change of medication.

A literature search reveals no report of paliperidone-induced hypothermia, but we consider it a possible explanation for Ms. K’s presentation. Lamotrigine (titrated to 50 mg/d), a benzodiazepine (oral lorazepam as needed), and discontinuing antipsychotics are recommended. After she returns to her baseline functioning, Ms. K is discharged to a skilled nursing facility.

Ms. K presents to the ED 2 days after discharge with altered mental status. Vital signs are: blood pressure, 90/55 mm Hg; pulse, 59 bpm; respiratory rate, 14/min; and temperature, 34.4ºC (93.9ºF) via bladder probe (Figure). Laboratory tests were significant for hepatic transaminitis (aspartate aminotransferase, 75 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 122 U/L) and elevated alkaline phosphatase (226 U/L). A review of records from the nursing facility revealed that Ms. K was receiving paliperidone because of an error in the discharge summary, which recommended restarting all prior medications.

The authors’ observations

The Naranjo Causality Scale,6 which categorizes the probability that an adverse event is related to a drug (based on several variables, including timing of the drug administration with the onset of event, drug dosage and levels, response relationships to a drug, including re-challenge when possible, and previous patient experience with the medication), often is used to evaluate whether an adverse clinical event has been caused by a drug (Table 2). We applied the Scale to Ms. K’s case, which revealed a score of 7—indicating a probable adverse drug reaction. The sequence of events in Ms. K’s case that led to a paliperidone challenge-dechallenge-rechallenge, and the resulting hypothermia, are, we concluded, evidence of an adverse drug reaction.

Using the World Health Organization database for adverse drug reactions, van Marum et al7 found 480 reports hypothermia with antipsychotics as of 2007 (compared with 524 reports of hyperthermia in the same period); 55% involved atypical antipsychotics, mainly risperidone. There are no case reports of paliperidone-induced hypothermia; however, several reports of hypothermia have been attributed to risperidone, and paliperidone is the primary active metabolite of risperidone.5

To identify risk factors for hypothermia with antipsychotic use, van Marum et al7 performed a literature search for case reports of antipsychotic-induced hypothermia, which revealed no association with age or sex. The most common diagnosis in cases of antipsychotic-induced hypothermia was schizophrenia (51%). In 73% of the cases, hypothermia followed the start or dosage increase of the antipsychotic. These observations have been noted in case reports and case series of hypothermia associated with antipsychotic use.8-12

Mechanism of action

One proposed mechanism for antipsychotic-induced hypothermia includes preferential 5-HT2A receptor antagonism over D2 receptor antagonism.7,12 It has been believed that, under normal conditions, the action of dopamine to reduce body temperature and the action of serotonin to elevate it are in balance.9

Another possible mechanism is peripheral á2-adrenergic blockade, which might increase the hypothermic effect by inhibiting peripheral responses to cooling, such as vasoconstriction and shivering.7,8 Boschi et al13 found that antipsychotics cause hypothermia in rats when the drug is administered intraperitoneally but not when given intrathecally. Perhaps for these reasons, in the early 1950s, before its psychotropic properties were known, chlorpromazine was used during surgery to induce artificial hibernation and suppress the body’s response to cooling.7 The therapeutic activity of paliperidone is mediated though a D2, 5-HT2A, and á2-receptor antagonism5; these mechanisms could, therefore, be contributing to Ms. K’s hypothermia.

Patients with preexisting brain damage— such as Ms. K—might be at increased risk of antipsychotic-induced hypothermia.7,8 This includes focal damage to central thermoregulatory centers, such as the pre-optic anterior hypothalamic region,14 and more diffuse damage seen in patients with cognitive impairment or a seizure disorder.8

Studies of people with schizophrenia show a decrease in core temperature after administration of an antipsychotic,15 raising the possibility of an impairment of baseline thermoregulatory control. Such thermal dysregulation in patients with schizophrenia might be explained by changes in neurotensin levels.7

The neuropeptide neurotensin has been implicated in the regulation of prolactin release and interacts to a significant degree with the dopaminergic system.16 When administered to animals, neurotensin suppresses heat production and increases heat loss.17 The neurotensin level in CSF was found to be lower in non-medicated patients with schizophrenia than in healthy controls, with an inverse correlation between the severity of symptoms and the neurotensin level.18

Additionally, persons with schizophrenia might be at increased risk of developing hypothermia when exposed to a low environmental temperature.7,8 Kudoh et al19 investigated temperature regulation during anesthesia in patients with chronic (≥7 years) schizophrenia receiving antipsychotics, and compared findings against what was seen in controls. The team reported that patients with schizophrenia had significantly lower intraoperative temperatures.

A published analysis of cases and studies of antipsychotic-induced hypothermia describes the combination of drug variables, patient variables, and environmental variables that contribute to thermal dysregulation (Table 3).7-12,15 The recommendation for practitioners is that, when considering an antipsychotic for a patient at high risk of thermal dysregulation, your choice of an agent should take that risk into account, especially when that drug is one that has comparatively stronger serotonergic and peripheral á-adrenergic effects. You should monitor patients closely for hypothermia after starting and when increasing the dosage of the drug. In patients with schizophrenia who might have a problem with baseline thermoregulation, advise them to take measures to counteract their increased susceptibility to low ambient temperatures.

OUTCOME Readmission

Ms. K was readmitted, rewarmed, and discharged to a skilled nursing facility 4 days later, after baseline function returned to normal and temperature stabilized. Paliperidone is now listed in her electronic medical record as “drug intolerance.”

This case also highlights the importance of adequate medication reconciliation at

admission and discharge, especially when using an electronic medical record system, because what might otherwise be considered a minor mistake can have devastating consequences.

Bottom Line

Thermal dysregulation—hyperthermia and hypothermia—can occur secondary to an antipsychotic. Determining whether a patient is at increased risk of either of these adverse effects is important when deciding to use antipsychotics. Recognizing agents that can cause hypothermia is essential, because management requires prompt discontinuation of the offending drug.

Related Resource

- Espay AJ, et al. Frontal lobe syndromes. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1135866-overview. Updated September 17, 2012. Accessed November 3, 2012.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Bromocriptine • Parlodel Lorazepam • Ativan

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine Paliperidone • Invega

Citalopram • Celexa Risperidone • Risperdal

Clozapine • Clozaril Sertraline • Zoloft

Divalproex sodium • Depakote Thioridazine • Mellaril

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Confused and cold

Ms. K, age 48, is brought to the emergency department (ED) by her husband because she has become increasingly lethargic over the past 2 weeks and cannot attend to activities of daily living. She is incontinent of stool and poorly responsive.

Ms. K’s husband reports that lethargy culminated in his wife sleeping 30 continuous hours. She has a history of a ruptured cerebral arteriovenous malformation (AVM) complicated by a secondary infarct 7 years ago, with residual symptoms of frontal lobe syndrome. Until 2 weeks ago, however, she was in her usual state of health.

Symptoms have included depression, mood lability, impulsivity, disinhibition, poor focus, and apathy. An outpatient psychiatrist has managed these symptoms with antidepressants and atypical antipsychotics.

When Ms. K arrives in the ED, she is taking citalopram, 30 mg/d, and paliperidone,

6 mg/d. Her psychiatrist started paliperidone 2 months ago, increasing the dosage to 6 mg/d 6 weeks before presentation because of worsening mood lability, disinhibition, and paranoia regarding her caregivers. Her husband denies any other medication changes or exposure to environmental toxins.

In the ED, Ms. K is confused and oriented only to person. Vital signs are: pulse 46 bpm; blood pressure, 66/51 mm Hg; respirations, 12/min; and temperature, 29.9ºC (85.8ºF) via bladder probe.

a) major depressive disorder, severe, with catatonic features

b) exposure to cold

c) hypothyroidism

d) drug-induced hypothermia

e) stroke

f) sepsis

g) delirium

The authors’ observations

Hypothermia is core body temperature <35ºC (95ºF).1 It often is caused by exposure to low ambient temperature (Table 1),1 but Ms. K’s husband denied that she had been exposed to cold. Because of Ms. K’s neurologic history, stroke was high on the differential diagnosis, but physical examination did not reveal evidence of focal dysfunction and was significant only for altered mental status.

Ms. K had no posturing, rigidity, negativism, or excessive motor activity that would suggest catatonia. Before she became lethargic, her husband had not noted any deterioration of mood, although she did exhibit other behavioral changes that prompted her outpatient psychiatrist to increase the dosage of paliperidone. Although Ms. K began experiencing persecutory delusions—she believed that her caregivers were trying to harm her—she and her family denied perceptual disturbances. On examination, she did not appear responsive to auditory or visual hallucinations.

Frontal lobe syndrome is defined as a set of changes in the cognitive, behavioral, or emotional domains, often leading to disturbed affect, alteration of attention, aphasia, perseveration, disinhibition, and personality changes.2 These symptoms are not specific to lesions in the frontal lobes but can arise from lesions anywhere in the frontal-striatal-thalamic circuit.3 Causes include traumatic brain injury, neurodegenerative disorders, cerebrovascular disease, tumors, and aging.2 Recommended treatment incorporates psychosocial interventions with drug treatment to target specific symptoms. Medications reported to be effective include typical and atypical antipsychotics to target aggression and agitation; benzodiazepines to reduce arousal; antidepressants for mood symptoms, dopamine agonists (eg, bromocriptine) to decrease apathy, and mood stabilizers to target mood lability.4

Before her AVM rupture, review of Ms. K’s psychiatric history revealed no psychiatric symptoms or impaired functioning. When hospitalized for the AVM repair, she was started on sertraline. She began seeing a psychiatrist 2 years later because of increased agitation and behavioral disturbances, and aripiprazole was added. Persistent agitation prompted a trial of divalproex sodium, which was discontinued because of slurred speech and increased distractibility. Aripiprazole was tapered and replaced with paliperidone because of poor response. Citalopram was initiated 1 year before she presented to the ED.

a) brain MRI

b) infectious evaluation (lumbar puncture with analysis of cerebrospinal fluid, complete blood count, blood cultures, chest radiographs)

c) endocrine panel

d) urine toxicology screen

EVALUATION Hypothermia

Laboratory tests reveal multiple abnormalities, including thrombocytopenia (platelet level, 53 ×103/μL), altered coagulation (partial thromboplastin time, 55.6 s), elevated levels of hepatic transaminases (aspartate aminotransferase, 168 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 357 U/L), and increased alkaline phosphatase (206 U/L). Other mild metabolic disturbances include: sodium, 149 mEq/L; CO2, 33 mEq/L; and blood urea nitrogen, 24 mg/dL.

These laboratory values are consistent with complications of hypothermia.1

ECG reveals sinus bradycardia (40 bpm) and Osborn waves (additional deflection at the end of the QRS complex), which are seen often in hypothermia.1 Head CT and brain MRI show chronic changes after Ms. K’s right temporoparietal AVM rupture, but no acute abnormality. Urinalysis, blood cultures, and chest radiographs are negative for infection. Urine toxicology screen is negative. Results of thyroid function tests and pituitary hormones studies are significant only for hyperprolactinemia of 155.7 ng/mL, a known adverse effect of antipsychotics.5

Ms. K is admitted and rewarmed passively and with warm IV fluids; by day 10 of hospitalization, temperature is stable (>35.1ºC [95.2ºF]). Thrombocytopenia, transaminitis, and altered mental status resolve.

Ms. K’s oral medications, including citalopram and paliperidone, have been held since admission because of her altered mental status. The psychiatry service is consulted to evaluate whether her presentation could be related to her change of medication.

A literature search reveals no report of paliperidone-induced hypothermia, but we consider it a possible explanation for Ms. K’s presentation. Lamotrigine (titrated to 50 mg/d), a benzodiazepine (oral lorazepam as needed), and discontinuing antipsychotics are recommended. After she returns to her baseline functioning, Ms. K is discharged to a skilled nursing facility.

Ms. K presents to the ED 2 days after discharge with altered mental status. Vital signs are: blood pressure, 90/55 mm Hg; pulse, 59 bpm; respiratory rate, 14/min; and temperature, 34.4ºC (93.9ºF) via bladder probe (Figure). Laboratory tests were significant for hepatic transaminitis (aspartate aminotransferase, 75 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 122 U/L) and elevated alkaline phosphatase (226 U/L). A review of records from the nursing facility revealed that Ms. K was receiving paliperidone because of an error in the discharge summary, which recommended restarting all prior medications.

The authors’ observations

The Naranjo Causality Scale,6 which categorizes the probability that an adverse event is related to a drug (based on several variables, including timing of the drug administration with the onset of event, drug dosage and levels, response relationships to a drug, including re-challenge when possible, and previous patient experience with the medication), often is used to evaluate whether an adverse clinical event has been caused by a drug (Table 2). We applied the Scale to Ms. K’s case, which revealed a score of 7—indicating a probable adverse drug reaction. The sequence of events in Ms. K’s case that led to a paliperidone challenge-dechallenge-rechallenge, and the resulting hypothermia, are, we concluded, evidence of an adverse drug reaction.

Using the World Health Organization database for adverse drug reactions, van Marum et al7 found 480 reports hypothermia with antipsychotics as of 2007 (compared with 524 reports of hyperthermia in the same period); 55% involved atypical antipsychotics, mainly risperidone. There are no case reports of paliperidone-induced hypothermia; however, several reports of hypothermia have been attributed to risperidone, and paliperidone is the primary active metabolite of risperidone.5

To identify risk factors for hypothermia with antipsychotic use, van Marum et al7 performed a literature search for case reports of antipsychotic-induced hypothermia, which revealed no association with age or sex. The most common diagnosis in cases of antipsychotic-induced hypothermia was schizophrenia (51%). In 73% of the cases, hypothermia followed the start or dosage increase of the antipsychotic. These observations have been noted in case reports and case series of hypothermia associated with antipsychotic use.8-12

Mechanism of action

One proposed mechanism for antipsychotic-induced hypothermia includes preferential 5-HT2A receptor antagonism over D2 receptor antagonism.7,12 It has been believed that, under normal conditions, the action of dopamine to reduce body temperature and the action of serotonin to elevate it are in balance.9

Another possible mechanism is peripheral á2-adrenergic blockade, which might increase the hypothermic effect by inhibiting peripheral responses to cooling, such as vasoconstriction and shivering.7,8 Boschi et al13 found that antipsychotics cause hypothermia in rats when the drug is administered intraperitoneally but not when given intrathecally. Perhaps for these reasons, in the early 1950s, before its psychotropic properties were known, chlorpromazine was used during surgery to induce artificial hibernation and suppress the body’s response to cooling.7 The therapeutic activity of paliperidone is mediated though a D2, 5-HT2A, and á2-receptor antagonism5; these mechanisms could, therefore, be contributing to Ms. K’s hypothermia.

Patients with preexisting brain damage— such as Ms. K—might be at increased risk of antipsychotic-induced hypothermia.7,8 This includes focal damage to central thermoregulatory centers, such as the pre-optic anterior hypothalamic region,14 and more diffuse damage seen in patients with cognitive impairment or a seizure disorder.8

Studies of people with schizophrenia show a decrease in core temperature after administration of an antipsychotic,15 raising the possibility of an impairment of baseline thermoregulatory control. Such thermal dysregulation in patients with schizophrenia might be explained by changes in neurotensin levels.7

The neuropeptide neurotensin has been implicated in the regulation of prolactin release and interacts to a significant degree with the dopaminergic system.16 When administered to animals, neurotensin suppresses heat production and increases heat loss.17 The neurotensin level in CSF was found to be lower in non-medicated patients with schizophrenia than in healthy controls, with an inverse correlation between the severity of symptoms and the neurotensin level.18

Additionally, persons with schizophrenia might be at increased risk of developing hypothermia when exposed to a low environmental temperature.7,8 Kudoh et al19 investigated temperature regulation during anesthesia in patients with chronic (≥7 years) schizophrenia receiving antipsychotics, and compared findings against what was seen in controls. The team reported that patients with schizophrenia had significantly lower intraoperative temperatures.

A published analysis of cases and studies of antipsychotic-induced hypothermia describes the combination of drug variables, patient variables, and environmental variables that contribute to thermal dysregulation (Table 3).7-12,15 The recommendation for practitioners is that, when considering an antipsychotic for a patient at high risk of thermal dysregulation, your choice of an agent should take that risk into account, especially when that drug is one that has comparatively stronger serotonergic and peripheral á-adrenergic effects. You should monitor patients closely for hypothermia after starting and when increasing the dosage of the drug. In patients with schizophrenia who might have a problem with baseline thermoregulation, advise them to take measures to counteract their increased susceptibility to low ambient temperatures.

OUTCOME Readmission

Ms. K was readmitted, rewarmed, and discharged to a skilled nursing facility 4 days later, after baseline function returned to normal and temperature stabilized. Paliperidone is now listed in her electronic medical record as “drug intolerance.”

This case also highlights the importance of adequate medication reconciliation at

admission and discharge, especially when using an electronic medical record system, because what might otherwise be considered a minor mistake can have devastating consequences.

Bottom Line

Thermal dysregulation—hyperthermia and hypothermia—can occur secondary to an antipsychotic. Determining whether a patient is at increased risk of either of these adverse effects is important when deciding to use antipsychotics. Recognizing agents that can cause hypothermia is essential, because management requires prompt discontinuation of the offending drug.

Related Resource

- Espay AJ, et al. Frontal lobe syndromes. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1135866-overview. Updated September 17, 2012. Accessed November 3, 2012.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Bromocriptine • Parlodel Lorazepam • Ativan

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine Paliperidone • Invega

Citalopram • Celexa Risperidone • Risperdal

Clozapine • Clozaril Sertraline • Zoloft

Divalproex sodium • Depakote Thioridazine • Mellaril

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Aslam AF, Aslam AK, Vasavada BC, et al. Hypothermia: evaluation, electrocardiographic manifestations, and management. Am J Med. 2006;119(4):297-301.

2. Hanna-Pladdy B. Dysexecutive syndromes in neurologic disease. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31(3):119-127.

3. Salloway SP. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with “frontal lobe” syndromes. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;6(4):388-398.

4. Campbell JJ, Duffy JD, Salloway SP. Treatment strategies for patients with dysexecutive syndromes. In: Salloway SP, Malloy PF, Duffy JD, eds. The frontal lobes and neuropsychiatric illness. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2001:153-163.

5. Stahl SM. Essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000:336.

6. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239-245.

7. van Marum RJ, Wegewijs MA, Loonen AJM, et al. Hypothermia following antipsychotic drug use. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(6):627-631.

8. Kreuzer P, Landgrebe M, Wittmann M, et al. Hypothermia associated with antipsychotic drug use: a clinical case series and review of current literature. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52(7)1090-1097.

9. Hung CF, Huang TY, Lin PY. Hypothermia and rhabdomyolysis following olanzapine injection in an adolescent with schizophreniform disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(4):376-378.

10. Razaq M, Samma M. A case of risperidone-induced hypothermia. Am J Ther. 2004;11(3):229-230.

11. Schwaninger M, Weisbrod M, Schwab S, et al. Hypothermia induced by atypical neuroleptics. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1998;21(6):344-346.

12. Bookstaver PB, Miller AD. Possible long-acting risperidone-induced hypothermia precipitating phenytoin toxicity in an elderly patient. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011; 36(3):426-429.

13. Boschi G, Launay N, Rips R. Neuroleptic-induced hypothermia in mice: lack of evidence for a central mechanism. Br J Pharmacol. 1987;90(4):745-751.

14. Sessler DI. Thermoregulatory defense mechanisms. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(suppl 7):S203-S210.

15. Shiloh R, Weizman A, Epstein Y, et al. Abnormal thermoregulation in drug-free male schizophrenia patients. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001;11(4):285-288.

16. McCann SM, Vijayan E. Control of anterior pituitary hormone secretion by neurotensin. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992; 668:287-297.

17. Chandra A, Chou HC, Chang C, et al. Effecst of intraventricular administration of neurotensin and somatostatin on thermoregulation in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 1981;20(7):715-718.

18. Sharma RP, Janicak PG, Bissette G, et al. CSF neurotensin concentrations and antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1997; 154(7):1019-1021.

19. Kudoh A, Takase H, Takazawa T. Chronic treatment with antipsychotics enhances intraoperative core hypothermia. Anesth Analg. 2004;98(1):111-115.

1. Aslam AF, Aslam AK, Vasavada BC, et al. Hypothermia: evaluation, electrocardiographic manifestations, and management. Am J Med. 2006;119(4):297-301.

2. Hanna-Pladdy B. Dysexecutive syndromes in neurologic disease. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31(3):119-127.

3. Salloway SP. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with “frontal lobe” syndromes. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;6(4):388-398.

4. Campbell JJ, Duffy JD, Salloway SP. Treatment strategies for patients with dysexecutive syndromes. In: Salloway SP, Malloy PF, Duffy JD, eds. The frontal lobes and neuropsychiatric illness. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2001:153-163.

5. Stahl SM. Essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000:336.

6. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239-245.

7. van Marum RJ, Wegewijs MA, Loonen AJM, et al. Hypothermia following antipsychotic drug use. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(6):627-631.

8. Kreuzer P, Landgrebe M, Wittmann M, et al. Hypothermia associated with antipsychotic drug use: a clinical case series and review of current literature. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52(7)1090-1097.

9. Hung CF, Huang TY, Lin PY. Hypothermia and rhabdomyolysis following olanzapine injection in an adolescent with schizophreniform disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(4):376-378.

10. Razaq M, Samma M. A case of risperidone-induced hypothermia. Am J Ther. 2004;11(3):229-230.

11. Schwaninger M, Weisbrod M, Schwab S, et al. Hypothermia induced by atypical neuroleptics. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1998;21(6):344-346.

12. Bookstaver PB, Miller AD. Possible long-acting risperidone-induced hypothermia precipitating phenytoin toxicity in an elderly patient. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011; 36(3):426-429.

13. Boschi G, Launay N, Rips R. Neuroleptic-induced hypothermia in mice: lack of evidence for a central mechanism. Br J Pharmacol. 1987;90(4):745-751.

14. Sessler DI. Thermoregulatory defense mechanisms. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(suppl 7):S203-S210.

15. Shiloh R, Weizman A, Epstein Y, et al. Abnormal thermoregulation in drug-free male schizophrenia patients. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001;11(4):285-288.

16. McCann SM, Vijayan E. Control of anterior pituitary hormone secretion by neurotensin. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992; 668:287-297.

17. Chandra A, Chou HC, Chang C, et al. Effecst of intraventricular administration of neurotensin and somatostatin on thermoregulation in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 1981;20(7):715-718.

18. Sharma RP, Janicak PG, Bissette G, et al. CSF neurotensin concentrations and antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1997; 154(7):1019-1021.

19. Kudoh A, Takase H, Takazawa T. Chronic treatment with antipsychotics enhances intraoperative core hypothermia. Anesth Analg. 2004;98(1):111-115.

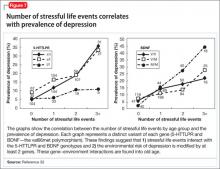

Dissecting melancholia with evidence-based biomarker tools

For more than 50 years, depression has been studied, and understood, as a deficiency of specific neurotransmitters in the brain—namely dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. Treatments for depression have been engineered to increase the release, or block the degradation, of these neurotransmitters within the synaptic cleft. Although a large body of evidence supports involvement of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin in the pathophysiology of depression, the observation that pharmacotherapy is able to induce remission only in <50% of patients1 has prompted researchers to look beyond neurotransmitters for an understanding of depressive disorders (Table 1).

Today, theories of depression focus more on differences in neuron density in various regions of the brain; the effect of stress on neurogenesis and neuronal cell apoptosis; alterations in feedback pathways connecting the pre-frontal cortex to the limbic system; and the role of proinflammatory mediators evoked during the stress response (Box,2,3). These theories should not be viewed as separate entities because they are highly interconnected. Integrating them provides for a more expansive understanding of the pathophysiology of depression and biomarkers that are involved (Table 2).

In this article, we:

- integrate the large body of evidence supporting the contribution of the above variables to the onset and persistence of depression

- propose a possible risk stratification model

- explore possibilities for treatment.

The stress response: How does it affect the brain?

Stress initiates a cascade of events in the brain and peripheral systems that enable an organism to cope with, and adapt to, new and challenging situations. That is why physiologic and behavioral responses to stress generally are considered beneficial to survival.

When stress is maintained for a long period, both brain and body are harmed because target cells undergo prolonged exposure to physiologic stress mediators. For example, Woolley and Gould4 exposed rats to varying durations of glucocorticoids and observed that treating animals with corticosterone injection for 21 days induced neuronal atrophy in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex and increased release of proinflammatory cytokines from astrocytes within the limbic system. Stressful experiences are believed to be closely associated with development of psychological alterations and, thus, neuropsychiatric disorders.5 To go further: Chronic stress is believed to be the leading cause of depression.

When the brain perceives an external threat, the stress response is called into action. The amygdala, part of the primitive limbic system, is the primary area of the brain responsible for triggering the stress response,6 signaling the hypothalamus to release corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) to the anterior pituitary gland, which, in turn releases adrenocorticotropic hormone to the adrenal glands (Figure 1).7 The adrenal glands are responsible for releasing glucocorticoids, which, because of their lipophilic nature, can cross the blood-brain barrier and are found in higher levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of depressed persons.7

Once in the brain, glucocorticoids can be irreversibly degraded in the cytosol by the enzyme 11-β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2, a potential target for treating depression, or can bind to the glucocorticoid receptor (GR). Results of a research study of the role of cortisol in suppression of proinflammatory cytokine signaling activity in rainbow trout hepatocytes suggest a negative feedback loop for GR gene regulation during stress.8

Because this auto-regulation is a crucial step in the physiological stress response, the idea of the GR as an important biomarker in depression has gained popularity. In humans, when the GR binds to glucocorticoids that are released from the adrenal cortex during the stress response, the activated GR-cortisol complex represses expression of proinflammatory proteins in astrocytes and microglial cells and in all cells in the periphery before they are transcribed into proteins.9 The GR also has been shown to modulate neurogenesis.8 Repeated stress that persists over a long period leads to GR resistance, thereby reducing inhibition of production of proinflammatory cytokines.

Exposure to stress for >21 days leads to overactivity of the HPA axis and GR resistance,10 which decreases suppression of proinflammatory cytokines. There is evidence that proinflammatory cytokines, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interleukin-6 further induce GR receptor resistance by preventing the cortisol-GR receptor complex from entering cell nuclei and decreasing binding to DNA within the nuclei.11 Dexamethasone, a GR agonist, has been implicated in research studies for potential re-regulation of the HPA axis in depressed persons.12

Nerve cell death in the hippocampus

Studies showing reduced hippocampal volume in unipolar depression and a correlation between the number of episodes and a consequence of untreated depression and studies suggesting that treatment can stop or reduce shrinkage,13 and recent findings of rapid neurogenesis in hippocampi in response to ketamine, brings our focus to hippocampus in depression.

The greatest density of GRs is found in the hippocampus, which is closely associated with the limbic system.7 Therefore, the hippocampus is sensitive to increases in glucocorticoids in the brain and plays a crucial role in regulation of the HPA axis.

Evidence shows that in chronic stress exposure (≥21 days), nerve cells in the hippocampus begin to atrophy and can no longer provide negative feedback inhibition to the hypothalamus, causing HPA axis dysregulation and uncontrolled release of glucocorticoids into the bloodstream and CSF.2 In patients with Cushing syndrome, who produce abnormally high levels of glucocorticoid, the incidence of depression is as high as 50%.14 Similarly, patients treated with glucocorticoids such as prednisone often experience psychiatric symptoms, the most common being depression. Gould found that partial adrenalectomy increased hippocampal neurogenesis in rat brains, indicating the beneficial effect of stress hormone antagonism.4 CRH antagonists are being looked at as a promising and less invasive treatment option for depression.

Focus has been diverted to the role of the hippocampus in depression because of its ability to regenerate throughout adulthood, leading potentially to a re-regulation of the HPA axis and subsiding of the stress response, which is universally believed to be the primary precipitating factor in depression onset. Rats require 10 to 21 days of rest to recover from the effects of chronic (21 days) administration of glucocorticoids.15 If this proves to be a directly proportional relationship, then rats would need an estimated 120 days to recover from 6 months of constant glucocorticoid exposure. Considering that the same is true for humans, current depression treatment programs, which average 6 weeks, are not long enough for adequate recovery.

Antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and tricyclics stimulate neurogenesis in the hippocampus via increases in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), suggesting that these neurotransmitters play an important role depression.16

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), a noninvasive neuromodulation therapy approved to treat major depression, delivers brief magnetic pulses to the limbic structures. Treatment facilitates focal stimulation, rapidly applying electrical charges to the cortical neurons. TMS targets prefrontal circuits of the brain that are underactive during depressive episodes. Recent animal studies have suggested that bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU)-positive cells (newborn cells) are increased significantly in the dentate gyrus, in turn suggesting that hippocampal neurogenesis might be involved in the antidepressant effects of chronic rTMS.17 Although the underlying therapeutic mechanisms of rTMS treatment of depression remain unclear, it appears that hippocampal neurogenesis might be required to produce the effects of antidepressant treatments, including drugs and electroconvulsive therapy.17

Selective ‘shunting’ of energy occurs during the stress response

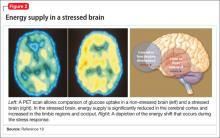

Hormones released from the adrenal glands during stress divert glucose to exercising muscles and the brain’s limbic system, which are involved in the fight-or-flight response.18 However, metabolic functions and areas of the brain that are not involved in the stress response, such as the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, are deprived of energy as a consequence of this innate selective shunting (Figure 2).19

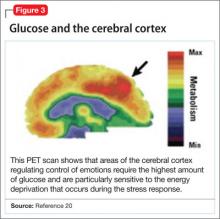

Positron-emission tomography (PET) scanning of the resting brain shows that components of the cerebral cortex (prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, striatum) and areas connecting the cerebral cortex to the limbic system exhibit the most energy consumption in the brain during rest (Figure 3).20 PET studies also show that neuronal connections within these energy-demanding areas atrophy more rapidly than in any other area of the brain when their energy supply is reduced or cut off.6

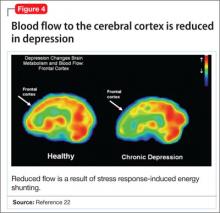

When the supply of oxygen and glucose to certain areas of the brain is reduced—such as in traumatic brain injury or stroke—the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate accumulates in extracellular fluid and causes nerve-cell death.21 When a conditioned stimulus is presented during fear acquisition, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of fear-conditioning have consistently reported, in the prefrontal cortex:

- a decrease in the blood oxygen level-dependent signal, below resting baseline

- a reduction in blood flow (Figure 4).22

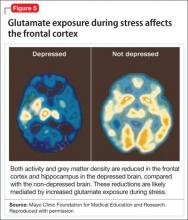

This discovery adds to evidence that demonstrates a decrease in gray-matter density in the frontal lobes as a result of glutaminergic toxicity (Figure 5).

Activation of L-glutamate, believed to play a significant role in depression and other neuropsychiatric disorders, triggers calcium-dependent intracellular responses that “excite cells to death,” so to speak—thereby causing nerve-cell apoptosis and a reduction in synaptic connections between different areas of the brain responsible for learning and memory.23 Malfunction of these synaptic connections is thought to be partially responsible for depression and other psychiatric disorders.

Excessive activation of N-methyl-d-asparate (NMDA) receptors is thought to be the underlying mechanism that leads to neuronal cell death in glutaminergic toxicity. Therefore, NMDA receptor proteins have become a target in treating neurodegenerative psychiatric illnesses. There is more than one type of NMDA receptor; some of them are excitatory, others are inhibitory. Four compounds have presented as therapeutic candidates for inhibition of NMDA receptor functioning and treatment of depression: those that inhibit glutamate binding, those that block the ion channel, and those that inhibit receptor binding to the terminal regulatory domain.24

Regrettably, these chemical compounds are not receptor-selective, but small structural modifications of these NMDA receptors have been found and lead to significant changes in potency and selectivity. This should serve as a unique starting point for developing highly specific NMDA receptor modulator agents for a variety of neuropsychiatric and neurological conditions. GLYX-13, a derivative of ketamine (an NMDA receptor antagonist), has been implicated for use in treating depression. It has been tested on 2 large phase-II study groups.25

Neuronal circuitry of depression is altered by prolonged stress

Symptoms of depression can be explained by the anatomical circuit shown in Figure 6.15,20 Impaired concentration, diminished ability to process new information, and decline in memory function are associated with decreased nerve density in the hippocampus, which plays a key role in learning, memory, and encoding of emotionally relevant data into memory.26 The hippocampus interacts with the amygdala to provide input about the context in which stimuli occur.

Depressed people often demonstrate impulsivity and have difficulty controlling expression of emotions—traits that are attributed to increased neuronal density in the amygdala and insula, which has been illustrated in PET scans and voxel-based morphometry in depressed patients.27 These brain areas are implicated in subjective emotional experience, processing of emotional reactions, and impulsive decision-making. The amygdala is normally highly regulated by the prefrontal cortex, which uses rational judgment to interpret stimuli and regulate the expression of emotion.

A study involving a facial expression processing task demonstrated reduced connectivity between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex and increased functional connectivity among the amygdala, hippocampus, and caudate-putamen in depressed patients.24 And in a study that measured white matter conduction in various brain areas in depressed patients, the greatest reduction was found in areas connecting the limbic system to the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus—believed to be caused by stress response-induced ischemic glutaminergic neuroapoptosis.21 Such neuroapoptosis might lead to irrational interpretation of stimuli, unchecked expression of emotion, and impulsive thoughts and behavior that are often present in depression and other mood disorders.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS), in which electrodes are implanted in the brain, has proved effective at increasing synaptic connections between the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system when electrodes are placed appropriately.28 Patients with refractory depression who are treated with DBS show increased gray-matter density and functional activity in the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and fronto-limbic connections.29 DBS also increases neurotransmission of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine within the fronto-limbic circuitry.30

Identifying risk factors for depression

Genetic risk factors. Forty percent of patients with depression have a first-degree relative with depression, suggesting a strong genetic component.10 Inherited differences in hippocampal volume, synaptic connections between the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)/glutamate balance, BDNF neurotransmitter receptors, and anatomic positioning of the limbic system in relation to other brain structures might account for the heritability of psychiatric disorders such as depression.

Evidence has been consistent that hippocampal volume is diminished in the brain of depressed persons. However, there is no prospective cohort study to determine whether people who have lower gray-matter hippocampal density or volume, or both, before depression onset develop symptoms later in life. There also is no study to determine the percentage of people who have lower-than-average hippocampal gray-matter density or volume and who have a first-degree relative with depression. Such studies would yield valuable information about anatomic variables that increase the risk of depression.

It has been proposed that low GABA function is an inherited biomarker for depression. Bjork and co-workers found a lower plasma level of GABA in depressed subjects and in their first-degree relatives, confirming that GABAergic tone might be under genetic control.11 Genetic loci studies in mice have linked depressive-like behavior to GABAergic loci on chromosomes 8 and 11, encoding alpha 1, alpha 6, and gamma subunits of GABAA receptors.23

A recent study in humans showed that severe, treatment-resistant depression with anxiety was linked to a mutation in the B1 subunit of the GABAA receptor. Positive genetic associations were found between polymorphism in human GABAA receptor subunit genes.11

GABA metabolizing enzymes also can be considered biological modifiers of depression. For example:

- GABA uptake and metabolism is controlled by the enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD); depression has been found to be associated with a polymorphism in the GAD67 gene encoding an isoform of GAD.11

- GABA transaminase (GABA-T) is another key enzyme in GABA turnover.31 It catabolizes GABA.

We can conclude that, to a high degree, depression depends on GABA production and metabolism.

A variant in the human BDNF gene, in which valine is substituted for methionine in position 66 of the pro-domain of the BDNF protein, is associated with

- a decrease in the production of BDNF

- increased susceptibility to neuropsychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety disorder, and bipolar disorder (Figure 7).32

People with the MM allele have been found to have a small hippocampal neuronal density and poor hippocampus-dependent memory function in neuroimaging studies.23 They also displayed diminished ventromedial prefrontal cortex volume and presented with aversive memory extinction deficit (ie, “holding grudges”).

Another neurotrophic factor, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), is a survival factor for endothelial cells and neurons and a modulator of synaptic transmission. Understanding the molecular and cellular specificity of antidepressant-induced VEGF will be critical to determine its potential as a therapeutic target in depression.33 Delineating the relationship between VEGF and depression has, ultimately, the potential to shed light on the still elusive neural mechanisms that underlie the pathophysiology of depression and the mechanisms by which antidepressants exert their effects.34

Genetic polymorphisms in monoamine receptors (5-HT2A), transporters (SERTPR, 5-HTTLPR, STin2, rs25531, SLC6A4), and regulatory enzymes should not be overlooked.35 There is reproducible evidence that variability in these polymorphisms are associated with variability in:

- vulnerability to depression

- the response to treatment with existing antidepressant medications.1

Most studies that look at changes in neuronal circuitry focus on the integrity of synaptic connections between the frontal cortex and limbic system; few of them have closely examined the importance of the anatomic proximity of the 2 regions. It might be that having an amygdala that is relatively closer to the frontal cortex and the hippocampus reduces a person’s risk of depression, and vice versa. This association needs to be investigated further with imaging studies.

Environmental risk factors. The brain is thought to be plastic until age 30.5 Plasticity diminishes with age after age 7—except for the hippocampus, which can regenerate throughout life.36 Early life experiences play an important role in forming synaptic connections between the frontal cortex and the limbic system, through a process known as fear conditioning.

Children learn early in life which stimuli are to be perceived as threatening or aversive and how to respond to best preserves their safety and internal sense of well-being. Those who grow up in a hostile environment learn to perceive more stimuli as threatening than children who grow up in a nurturing environment.32 It is possible that the amygdala is larger in children who grow up in less-than-ideal circumstances because this region is constantly being recruited—at the expense of the more rational frontal cortex.

Evidence suggests that these conditions reduce hippocampal neurogenesis37:

- increasing age

- substance abuse (opiates and methamphetamines)

- inadequate housing

- minimal physical activity

- little opportunity for social stimulation

- minimal learning experience.

Bottom Line

Depression has been understood as a neurotransmitter deficiency in the brain; treatments were engineered to increase release, or block degradation, of those neurotransmitters. Novel theories—all interconnected—of the neuroanatomical pathophysiology of depression focus more on differences in neuron density in the brain; effects of stress on neurogenesis and neuronal cell apoptosis; alterations in feedback pathways connecting the pre-frontal cortex to the limbic system; and the role of pro-inflammatory mediators evoked during the stress response.

Related Resources

- Fuchs E. Neurogenesis in the adult brain: is there an association with mental disorders? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;257(5):247-249.

- Videbech P, Ravnkilde B. Hippocampal volume and depression: a meta-analysis of MRI studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2004; 161(11):1957-1966.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgement

Anita Rao, second-year medical student, Stritch School of Medicine, Loyola University, Chicago, Illinois, assisted in the preparation of this manuscript.

1. Eley TC, Sugden K, Corsico A, et al. Gene-environment interaction analysis of serotonin system markers with adolescent depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9(10):908-915.

2. Haber SN, Rauch SL. Neurocircuitry: a window into the networks underlying neuropsychiatric disease. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):1-3.

3. Frodl T, Bokde AL, Scheuerecker J, et al. Functional connectivity bias of the orbitofrontal cortex in drug-free patients with major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010; 67(2):161-167.

4. Woolley CS, Gould E, McEwen BS. Exposure to excess glucocorticoids alters dendritic morphology of adult hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Brain Res. 1990;531(1-2): 225-231.

5. Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The impact of early adverse experiences on brain systems involved in the pathophysiology of anxiety and affective disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46(11):1509-1522.

6. Isgor C, Kabbaj M, Akil H, et al. Delayed effects of chronic variable stress during peripubertal-juvenile period on hippocampal morphology and on cognitive and stress axis functions in rats. Hippocampus. 2004;14(5):636-648.

7. De Kloet ER, Vreugdenhil E, Oitzl MS, et al. Brain corticosteroid receptor balance in health and disease. Endocr Rev. 1998;19(3):269-301.

8. Philip AM, Kim SD, Vijayan MM. Cortisol modulates the expression of cytokines and suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) in rainbow trout hepatocytes. Dev Comp Immunol. 2012;38(2):360-367.

9. Coplan JD, Lydiard RB. Brain circuits in panic disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44(12):1264-1276.

10. Anisman H, Merali Z. Cytokines, stress and depressive illness: brain-immune interactions. Ann Med. 2003;35(1):2-11.

11. Crowley JJ, Lucki I. Opportunities to discover genes regulating depression and antidepressant response from rodent behavioral genetics. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11(2):157-169.

12. Covington HE 3rd, Vialou V, Nestler EJ. From synapse to nucleus: novel targets for treating depression. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58(4-5):683-693.

13. Videbech P, Ravnkilde B. Hippocampal volume and depression: a meta-analysis of MRI studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(11):1957-1966.

14. Sandi C. Stress, cognitive impairment and cell adhesion molecules. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(12):917-930.

15. Hartley CA, Phelps EA. Changing fear: the neurocircuitry of emotion regulation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1): 136-146.

16. Kim DK, Lim SW, Lee S, et al. Serotonin transporter gene polymorphism and antidepressant response. Neuroreport. 2000;11(1):215-219.

17. Ueyama E, Ukai S, Ogawa A, et al, Chronic repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation increases hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011; 65(1):77-81.

18. Irwin W, Anderle MJ, Abercrombie HC, et al. Amygdalar interhemispheric functional connectivity differs between the non-depressed and depressed human brain. Neuroimage. 2004;21(2):674-686.

19. McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 2007; 87(3):873-904.

20. Gusnard DA, Raichle ME, Raichle ME. Searching for a baseline: functional imaging and the resting human brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(10):685-694.

21. Hulsebosch CE, Hains BC, Crown ED, et al. Mechanisms of chronic central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60(1):202-213.

22. Gottfried JA, Dolan RJ. Human orbitofrontal cortex mediates extinction learning while accessing conditioned representations of value. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(10):1144-1152.

23 Arnone D, McKie S, Elliott R, et al. State-dependent changes in hippocampal grey matter in depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;1(8):1359-4184.

24. Brunoni AR, Lopes M, Fregni F. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies on major depression and BDNF levels: implications for the role of neuroplasticity in depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11(8):1169-1180.

25. Maeng S, Zarate CA Jr. The role of glutamate in mood disorders: results from the ketamine in major depression study and the presumed cellular mechanism underlying its antidepressant effects. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9(6):467-474.

26. Vaidya VA, Fernandes K, Jha S. Regulation of adult hippocampal neurogenesis: relevance to depression. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7(7):853-864.

27. Lisiecka DM, Carballedo A, Fagan AJ, et al. Altered inhibition of negative emotions in subjects at family risk of major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(2):181-188.

28. Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45(5):651-660.

29. Levkovitz Y, Harel EV, Roth Y, et al. Deep transcranial magnetic stimulation over the prefrontal cortex: evaluation of antidepressant and cognitive effects in depressive patients. Brain Stimul. 2009;2(4):188-200.

30. Schlaepfer TE, Lieb K. Deep brain stimulation for treatment of refractory depression. Lancet. 2005;366(9495):1420-1422.

31. Astrup, J. Energy-requiring cell functions in the ischemic brain. Their critical supply and possible inhibition in protective therapy. J Neurosurg. 1982;56(4):482-497.

32. Fletcher JM. Childhood mistreatment and adolescent and young adult depression. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(5):799-806.

33. Warner-Schmidt JL, Duman R. VEGF as a potential target for therapeutic intervention in depression. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8(1):14-19.

34. Clark-Raymond A, Halaris A. VEGF and depression: a comprehensive assessment of clinical data. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(8):1080-1087.

35. Alonso R, Griebel G, Pavone G, et al. Blockade of CRF(1) or V(1b) receptors reverses stress-induced suppression of neurogenesis in a mouse model of depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9(3):278-286.

36. Thomas RM, Peterson DA. A neurogenic theory of depression gains momentum. Mol Interv. 2003;3(8):441-444.

37. Jacobs BL. Adult brain neurogenesis and depression. Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16(5):602-609.

For more than 50 years, depression has been studied, and understood, as a deficiency of specific neurotransmitters in the brain—namely dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. Treatments for depression have been engineered to increase the release, or block the degradation, of these neurotransmitters within the synaptic cleft. Although a large body of evidence supports involvement of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin in the pathophysiology of depression, the observation that pharmacotherapy is able to induce remission only in <50% of patients1 has prompted researchers to look beyond neurotransmitters for an understanding of depressive disorders (Table 1).

Today, theories of depression focus more on differences in neuron density in various regions of the brain; the effect of stress on neurogenesis and neuronal cell apoptosis; alterations in feedback pathways connecting the pre-frontal cortex to the limbic system; and the role of proinflammatory mediators evoked during the stress response (Box,2,3). These theories should not be viewed as separate entities because they are highly interconnected. Integrating them provides for a more expansive understanding of the pathophysiology of depression and biomarkers that are involved (Table 2).

In this article, we:

- integrate the large body of evidence supporting the contribution of the above variables to the onset and persistence of depression

- propose a possible risk stratification model

- explore possibilities for treatment.

The stress response: How does it affect the brain?

Stress initiates a cascade of events in the brain and peripheral systems that enable an organism to cope with, and adapt to, new and challenging situations. That is why physiologic and behavioral responses to stress generally are considered beneficial to survival.