User login

Three trials cement embolectomy for acute ischemic stroke

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Treatment of selected patients with acute ischemic stroke underwent a dramatic, sudden shift with reports from three randomized, controlled trials that showed substantial added benefit and no incremental risk with the use of catheter-based embolic retrieval to open blocked intracerebral arteries when performed on top of standard thrombolytic therapy.

The three studies, each run independently and based in different countries, supported the results first reported last October and published online in December (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:11-20) from the MR CLEAN (Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial of Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke in the Netherlands) study. These were the first contemporary trial results to show a jump in functional outcomes with use of a stent retriever catheter to pluck out the occluding embolus from an artery in the stroke patient’s brain to restore normal blood flow.

All three of the newly-reported studies stopped before reaching their prespecified enrollment levels because of overwhelming evidence for embolectomy’s incremental efficacy.

With four reports from prospective, randomized trials showing similar benefits and no added harm to patients, experts at the International Stroke Conference uniformly anointed catheter-based embolectomy the new standard of care for the small percentage of acute, ischemic-stroke patients who present with proximal, large-artery obstructions and also match the other strict clinical and imaging inclusion and exclusion criteria used in the studies.

“Starting now, in patients with an acute ischemic stroke due to proximal vessel occlusion, rapid endovascular treatment using a retrieval stent is the standard of care,” Dr. Mayank Goyal declared from the plenary-session podium. He is a professor of diagnostic imaging at the University of Calgary (Canada) and an investigator in two of the three trials presented at the conference, which was sponsored by the American Heart Association.

“Today the world changed. We are now in a new era, the era of highly-effective intravascular recanalization therapy,” said Dr. Jeffrey L. Saver, professor of neurology and director of the Stroke Center at the University of California, Los Angeles, and lead investigator for one of the new studies.

In three of the four studies, the researchers did not report specific numbers on how selective they were in focusing in on the ischemic stroke patients most likely to benefit from this treatment, but the one study that did, EXTEND-IA (Extending the Time for Thrombolysis in Emergency Neurological Deficits – Intra-Arterial), run at nine Australian centers and one in New Zealand, showed the extensive winnowing that occurred. Of 7,796 patients with an acute ischemic stroke who initially presented, 1,044 (13%) were eligible to receive thrombolytic therapy (alteplase in this study). And from among these 1,044 patients, a mere 70 – less than 1% of the initial group – were deemed eligible for randomization into the embolectomy trial. The top three reasons for exclusion of patients who qualified for thrombolytic treatment from the trial was an absence of a major-vessel occlusion (45% of the excluded patients), presentation outside of the times when enrollment personnel were available (22%), and poor premorbid function (16%).

But subgroup analyses in three of the four studies (EXTEND-IA with a total of 70 patients was too small for subgroup analyses) showed no subgroup of patients who failed to benefit from embolectomy, including elderly patients who in some cases were nonagenarians.

The unusual confluence of having four major trials showing remarkably consistent results meant that the stroke experts gathered at the meeting focused their attention not on whether stent retrievers should now be widely and routinely used in appropriate patients but instead on how this technology will roll out worldwide.

“From here on out we are obligated to treat patients with this technology at centers that can do this, and we are obligated to have more centers that can provide it,” said Dr. Kyra J. Becker, professor of neurology and neurological surgery and codirector of the Stroke Center at the University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Becker had no involvement in any of the stent retriever trials. “I had been a doubter of this technology,” primarily because results reported at the International Stroke Conference a couple of years ago failed to prove the efficacy of clot retrieval in ischemic stroke patients, she noted. “Our ability to select appropriate patients and do it in a timely fashion hadn’t gotten to where it had to be until now,” Dr. Becker said in an interview.

“We only enrolled patients with blockages, we treated them quickly, and we used much better devices to open their arteries,” Dr. Saver added, explaining why the new studies succeeded when earlier studies had not.

The trial led by Dr. Saver, SWIFT-PRIME (SOLITAIRE™ FR With the Intention for Thrombectomy as Primary Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke), enrolled 195 patients at 39 sites in the United States and in Europe. At 90 days after treatment, 59 patients (60%) among those treated with thrombolysis plus embolectomy had a modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2, compared with 33 patients (36%) among those treated only with thrombolysis (in this trial intravenous treatment with tissue plasminogen activator), a highly significant difference for the study’s primary endpoint.

“For every two and half patients treated, one more patient had a better disability outcome, and for every four patients treated, one more patient was independent at long-term follow-up,” Dr. Saver said. Safety measures were similar among patients in the study’s two arms.

The EXTEND-IA results showed a 90-day modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2 in 52% of the embolectomy patients, compared with 28% of those treated only with thrombolysis. The study’s co–primary endpoints were median level of reperfusion at 24 hours after treatment, 100% with embolectomy and 37% with thrombolysis only, and early neurologic recovery, defined as at least an 8-point drop from the baseline in the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score or a score of 0 or 1 when assessed 3 days after treatment. Patients met this second endpoint at an 80% rate with embolectomy and a 37% rate with thrombolysis only. Results of EXTEND-IA appeared in an article published online concurrently with the meeting report (N. Engl J. Med. 2015 Feb. 11 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1414792]).

The third, and largest, of the three studies presented at the conference, ESCAPE (Endovascular Treatment for Small Core and Anterior Circulation Proximal Occlusion with Emphasis on Minimizing CT to Recanalization Times), enrolled 316 patients at 11 centers in Canada, 6 in the United States, 3 in South Korea, and 1 in Ireland. After 90 days, 53% of patients in the embolectomy arm had achieved a modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2, this study’s primary endpoint, compared with 29% of patients in the thrombolysis-only arm (treatment with alteplase). These results also appeared in an article published online concurrently with the conference report (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015 Feb. 11 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1414905]).

SWIFT PRIME was sponsored by Covidien, which markets the stent retriever used in the study. Dr. Saver and Dr. Goyal are consultants to Covidien. EXTEND-IA used stent retrievers provided by Covidien. ESCAPE received a grant from Covidien. Dr. Becker had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Many U.S. centers have interventionalists who already perform endovascular treatments within intracerebral arteries, but the issue is can they do this form of embolectomy in the high-quality, highly-reliable, rapid way that it was done in these trials? Stent-retriever catheters are relatively straightforward to use by operators who are experienced doing vascular procedures in the brain, but they don’t deliver this treatment by themselves. You need a team that is focused on doing it quickly, and that will be the kind of training we’ll need to roll out this treatment broadly. We achieved it for stroke thrombolytic treatment through the Target Stroke program (JAMA 2014;311:1632-40), so we know that we can achieve this sort of goal. Delivering embolectomy requires more people and more technology than thrombolysis, but it is not rocket science; it just needs a system.

|

| Dr. Lee H. Schwamm |

Embolectomy will not replace routine thrombolysis treatment; it will piggyback on top of it. The percentage of patients with a proximal occlusion in a large artery is relatively small. The results we have seen suggest that using embolectomy plus thrombolysis has no adverse-effect downside, compared with thrombolysis alone. Once routine use of embolectomy becomes established, we can directly compare catheter treatment only against combined embolectomy and thrombolysis. My impression today is that what we’d compare is transporting stroke patients directly to a center that can perform embolectomy against taking patients to the closest center that can treat them with thrombolysis and then transporting them to the center that performs embolectomy.

The results of these three new studies plus the previously-reported results from MR CLEAN are not exactly a game changer, because many centers were already performing embolectomy but in a limited way. Now we have the data to give us confidence to do it routinely and to know which patients to select for embolectomy. Because many centers are already doing this, it will not take 5 years to diffuse the technology.

Embolectomy is already a treatment cited in the guidelines, but now it will be a level 1A recommendation.

The significance of the new reports is that they will have a dramatic impact on public health systems and in the triage of patients with stroke. It will affect how patients get triaged, and will allow us to identify which patients should go to which centers. I believe we will soon develop clinical examination tools that will allow prehospital providers to discern patients with mild strokes who can go to the nearest center that can administer thrombolysis and which patients need to go to comprehensive centers that can perform embolectomy. We now need to do what we did for thrombolysis, and help centers develop the expertise to do embolectomy as a team and to shave minutes off the delivery at every step of the process. It’s clear that it is the time from stroke onset to getting the artery open that is the key to improved patient outcomes.

If I have my way, we will launch later this year a big effort to focus on improving embolectomy delivery. Now that we know for certain that it works we need to turn the crank and make sure that as many patients as possible who qualify get this treatment.

Dr. Lee H. Schwamm is professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, and director of acute stroke services at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston. He is a consultant to Penumbra and has received research support from Genentech. He made these comments in an interview.

Many U.S. centers have interventionalists who already perform endovascular treatments within intracerebral arteries, but the issue is can they do this form of embolectomy in the high-quality, highly-reliable, rapid way that it was done in these trials? Stent-retriever catheters are relatively straightforward to use by operators who are experienced doing vascular procedures in the brain, but they don’t deliver this treatment by themselves. You need a team that is focused on doing it quickly, and that will be the kind of training we’ll need to roll out this treatment broadly. We achieved it for stroke thrombolytic treatment through the Target Stroke program (JAMA 2014;311:1632-40), so we know that we can achieve this sort of goal. Delivering embolectomy requires more people and more technology than thrombolysis, but it is not rocket science; it just needs a system.

|

| Dr. Lee H. Schwamm |

Embolectomy will not replace routine thrombolysis treatment; it will piggyback on top of it. The percentage of patients with a proximal occlusion in a large artery is relatively small. The results we have seen suggest that using embolectomy plus thrombolysis has no adverse-effect downside, compared with thrombolysis alone. Once routine use of embolectomy becomes established, we can directly compare catheter treatment only against combined embolectomy and thrombolysis. My impression today is that what we’d compare is transporting stroke patients directly to a center that can perform embolectomy against taking patients to the closest center that can treat them with thrombolysis and then transporting them to the center that performs embolectomy.

The results of these three new studies plus the previously-reported results from MR CLEAN are not exactly a game changer, because many centers were already performing embolectomy but in a limited way. Now we have the data to give us confidence to do it routinely and to know which patients to select for embolectomy. Because many centers are already doing this, it will not take 5 years to diffuse the technology.

Embolectomy is already a treatment cited in the guidelines, but now it will be a level 1A recommendation.

The significance of the new reports is that they will have a dramatic impact on public health systems and in the triage of patients with stroke. It will affect how patients get triaged, and will allow us to identify which patients should go to which centers. I believe we will soon develop clinical examination tools that will allow prehospital providers to discern patients with mild strokes who can go to the nearest center that can administer thrombolysis and which patients need to go to comprehensive centers that can perform embolectomy. We now need to do what we did for thrombolysis, and help centers develop the expertise to do embolectomy as a team and to shave minutes off the delivery at every step of the process. It’s clear that it is the time from stroke onset to getting the artery open that is the key to improved patient outcomes.

If I have my way, we will launch later this year a big effort to focus on improving embolectomy delivery. Now that we know for certain that it works we need to turn the crank and make sure that as many patients as possible who qualify get this treatment.

Dr. Lee H. Schwamm is professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, and director of acute stroke services at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston. He is a consultant to Penumbra and has received research support from Genentech. He made these comments in an interview.

Many U.S. centers have interventionalists who already perform endovascular treatments within intracerebral arteries, but the issue is can they do this form of embolectomy in the high-quality, highly-reliable, rapid way that it was done in these trials? Stent-retriever catheters are relatively straightforward to use by operators who are experienced doing vascular procedures in the brain, but they don’t deliver this treatment by themselves. You need a team that is focused on doing it quickly, and that will be the kind of training we’ll need to roll out this treatment broadly. We achieved it for stroke thrombolytic treatment through the Target Stroke program (JAMA 2014;311:1632-40), so we know that we can achieve this sort of goal. Delivering embolectomy requires more people and more technology than thrombolysis, but it is not rocket science; it just needs a system.

|

| Dr. Lee H. Schwamm |

Embolectomy will not replace routine thrombolysis treatment; it will piggyback on top of it. The percentage of patients with a proximal occlusion in a large artery is relatively small. The results we have seen suggest that using embolectomy plus thrombolysis has no adverse-effect downside, compared with thrombolysis alone. Once routine use of embolectomy becomes established, we can directly compare catheter treatment only against combined embolectomy and thrombolysis. My impression today is that what we’d compare is transporting stroke patients directly to a center that can perform embolectomy against taking patients to the closest center that can treat them with thrombolysis and then transporting them to the center that performs embolectomy.

The results of these three new studies plus the previously-reported results from MR CLEAN are not exactly a game changer, because many centers were already performing embolectomy but in a limited way. Now we have the data to give us confidence to do it routinely and to know which patients to select for embolectomy. Because many centers are already doing this, it will not take 5 years to diffuse the technology.

Embolectomy is already a treatment cited in the guidelines, but now it will be a level 1A recommendation.

The significance of the new reports is that they will have a dramatic impact on public health systems and in the triage of patients with stroke. It will affect how patients get triaged, and will allow us to identify which patients should go to which centers. I believe we will soon develop clinical examination tools that will allow prehospital providers to discern patients with mild strokes who can go to the nearest center that can administer thrombolysis and which patients need to go to comprehensive centers that can perform embolectomy. We now need to do what we did for thrombolysis, and help centers develop the expertise to do embolectomy as a team and to shave minutes off the delivery at every step of the process. It’s clear that it is the time from stroke onset to getting the artery open that is the key to improved patient outcomes.

If I have my way, we will launch later this year a big effort to focus on improving embolectomy delivery. Now that we know for certain that it works we need to turn the crank and make sure that as many patients as possible who qualify get this treatment.

Dr. Lee H. Schwamm is professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, and director of acute stroke services at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston. He is a consultant to Penumbra and has received research support from Genentech. He made these comments in an interview.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Treatment of selected patients with acute ischemic stroke underwent a dramatic, sudden shift with reports from three randomized, controlled trials that showed substantial added benefit and no incremental risk with the use of catheter-based embolic retrieval to open blocked intracerebral arteries when performed on top of standard thrombolytic therapy.

The three studies, each run independently and based in different countries, supported the results first reported last October and published online in December (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:11-20) from the MR CLEAN (Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial of Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke in the Netherlands) study. These were the first contemporary trial results to show a jump in functional outcomes with use of a stent retriever catheter to pluck out the occluding embolus from an artery in the stroke patient’s brain to restore normal blood flow.

All three of the newly-reported studies stopped before reaching their prespecified enrollment levels because of overwhelming evidence for embolectomy’s incremental efficacy.

With four reports from prospective, randomized trials showing similar benefits and no added harm to patients, experts at the International Stroke Conference uniformly anointed catheter-based embolectomy the new standard of care for the small percentage of acute, ischemic-stroke patients who present with proximal, large-artery obstructions and also match the other strict clinical and imaging inclusion and exclusion criteria used in the studies.

“Starting now, in patients with an acute ischemic stroke due to proximal vessel occlusion, rapid endovascular treatment using a retrieval stent is the standard of care,” Dr. Mayank Goyal declared from the plenary-session podium. He is a professor of diagnostic imaging at the University of Calgary (Canada) and an investigator in two of the three trials presented at the conference, which was sponsored by the American Heart Association.

“Today the world changed. We are now in a new era, the era of highly-effective intravascular recanalization therapy,” said Dr. Jeffrey L. Saver, professor of neurology and director of the Stroke Center at the University of California, Los Angeles, and lead investigator for one of the new studies.

In three of the four studies, the researchers did not report specific numbers on how selective they were in focusing in on the ischemic stroke patients most likely to benefit from this treatment, but the one study that did, EXTEND-IA (Extending the Time for Thrombolysis in Emergency Neurological Deficits – Intra-Arterial), run at nine Australian centers and one in New Zealand, showed the extensive winnowing that occurred. Of 7,796 patients with an acute ischemic stroke who initially presented, 1,044 (13%) were eligible to receive thrombolytic therapy (alteplase in this study). And from among these 1,044 patients, a mere 70 – less than 1% of the initial group – were deemed eligible for randomization into the embolectomy trial. The top three reasons for exclusion of patients who qualified for thrombolytic treatment from the trial was an absence of a major-vessel occlusion (45% of the excluded patients), presentation outside of the times when enrollment personnel were available (22%), and poor premorbid function (16%).

But subgroup analyses in three of the four studies (EXTEND-IA with a total of 70 patients was too small for subgroup analyses) showed no subgroup of patients who failed to benefit from embolectomy, including elderly patients who in some cases were nonagenarians.

The unusual confluence of having four major trials showing remarkably consistent results meant that the stroke experts gathered at the meeting focused their attention not on whether stent retrievers should now be widely and routinely used in appropriate patients but instead on how this technology will roll out worldwide.

“From here on out we are obligated to treat patients with this technology at centers that can do this, and we are obligated to have more centers that can provide it,” said Dr. Kyra J. Becker, professor of neurology and neurological surgery and codirector of the Stroke Center at the University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Becker had no involvement in any of the stent retriever trials. “I had been a doubter of this technology,” primarily because results reported at the International Stroke Conference a couple of years ago failed to prove the efficacy of clot retrieval in ischemic stroke patients, she noted. “Our ability to select appropriate patients and do it in a timely fashion hadn’t gotten to where it had to be until now,” Dr. Becker said in an interview.

“We only enrolled patients with blockages, we treated them quickly, and we used much better devices to open their arteries,” Dr. Saver added, explaining why the new studies succeeded when earlier studies had not.

The trial led by Dr. Saver, SWIFT-PRIME (SOLITAIRE™ FR With the Intention for Thrombectomy as Primary Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke), enrolled 195 patients at 39 sites in the United States and in Europe. At 90 days after treatment, 59 patients (60%) among those treated with thrombolysis plus embolectomy had a modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2, compared with 33 patients (36%) among those treated only with thrombolysis (in this trial intravenous treatment with tissue plasminogen activator), a highly significant difference for the study’s primary endpoint.

“For every two and half patients treated, one more patient had a better disability outcome, and for every four patients treated, one more patient was independent at long-term follow-up,” Dr. Saver said. Safety measures were similar among patients in the study’s two arms.

The EXTEND-IA results showed a 90-day modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2 in 52% of the embolectomy patients, compared with 28% of those treated only with thrombolysis. The study’s co–primary endpoints were median level of reperfusion at 24 hours after treatment, 100% with embolectomy and 37% with thrombolysis only, and early neurologic recovery, defined as at least an 8-point drop from the baseline in the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score or a score of 0 or 1 when assessed 3 days after treatment. Patients met this second endpoint at an 80% rate with embolectomy and a 37% rate with thrombolysis only. Results of EXTEND-IA appeared in an article published online concurrently with the meeting report (N. Engl J. Med. 2015 Feb. 11 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1414792]).

The third, and largest, of the three studies presented at the conference, ESCAPE (Endovascular Treatment for Small Core and Anterior Circulation Proximal Occlusion with Emphasis on Minimizing CT to Recanalization Times), enrolled 316 patients at 11 centers in Canada, 6 in the United States, 3 in South Korea, and 1 in Ireland. After 90 days, 53% of patients in the embolectomy arm had achieved a modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2, this study’s primary endpoint, compared with 29% of patients in the thrombolysis-only arm (treatment with alteplase). These results also appeared in an article published online concurrently with the conference report (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015 Feb. 11 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1414905]).

SWIFT PRIME was sponsored by Covidien, which markets the stent retriever used in the study. Dr. Saver and Dr. Goyal are consultants to Covidien. EXTEND-IA used stent retrievers provided by Covidien. ESCAPE received a grant from Covidien. Dr. Becker had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Treatment of selected patients with acute ischemic stroke underwent a dramatic, sudden shift with reports from three randomized, controlled trials that showed substantial added benefit and no incremental risk with the use of catheter-based embolic retrieval to open blocked intracerebral arteries when performed on top of standard thrombolytic therapy.

The three studies, each run independently and based in different countries, supported the results first reported last October and published online in December (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:11-20) from the MR CLEAN (Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial of Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke in the Netherlands) study. These were the first contemporary trial results to show a jump in functional outcomes with use of a stent retriever catheter to pluck out the occluding embolus from an artery in the stroke patient’s brain to restore normal blood flow.

All three of the newly-reported studies stopped before reaching their prespecified enrollment levels because of overwhelming evidence for embolectomy’s incremental efficacy.

With four reports from prospective, randomized trials showing similar benefits and no added harm to patients, experts at the International Stroke Conference uniformly anointed catheter-based embolectomy the new standard of care for the small percentage of acute, ischemic-stroke patients who present with proximal, large-artery obstructions and also match the other strict clinical and imaging inclusion and exclusion criteria used in the studies.

“Starting now, in patients with an acute ischemic stroke due to proximal vessel occlusion, rapid endovascular treatment using a retrieval stent is the standard of care,” Dr. Mayank Goyal declared from the plenary-session podium. He is a professor of diagnostic imaging at the University of Calgary (Canada) and an investigator in two of the three trials presented at the conference, which was sponsored by the American Heart Association.

“Today the world changed. We are now in a new era, the era of highly-effective intravascular recanalization therapy,” said Dr. Jeffrey L. Saver, professor of neurology and director of the Stroke Center at the University of California, Los Angeles, and lead investigator for one of the new studies.

In three of the four studies, the researchers did not report specific numbers on how selective they were in focusing in on the ischemic stroke patients most likely to benefit from this treatment, but the one study that did, EXTEND-IA (Extending the Time for Thrombolysis in Emergency Neurological Deficits – Intra-Arterial), run at nine Australian centers and one in New Zealand, showed the extensive winnowing that occurred. Of 7,796 patients with an acute ischemic stroke who initially presented, 1,044 (13%) were eligible to receive thrombolytic therapy (alteplase in this study). And from among these 1,044 patients, a mere 70 – less than 1% of the initial group – were deemed eligible for randomization into the embolectomy trial. The top three reasons for exclusion of patients who qualified for thrombolytic treatment from the trial was an absence of a major-vessel occlusion (45% of the excluded patients), presentation outside of the times when enrollment personnel were available (22%), and poor premorbid function (16%).

But subgroup analyses in three of the four studies (EXTEND-IA with a total of 70 patients was too small for subgroup analyses) showed no subgroup of patients who failed to benefit from embolectomy, including elderly patients who in some cases were nonagenarians.

The unusual confluence of having four major trials showing remarkably consistent results meant that the stroke experts gathered at the meeting focused their attention not on whether stent retrievers should now be widely and routinely used in appropriate patients but instead on how this technology will roll out worldwide.

“From here on out we are obligated to treat patients with this technology at centers that can do this, and we are obligated to have more centers that can provide it,” said Dr. Kyra J. Becker, professor of neurology and neurological surgery and codirector of the Stroke Center at the University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Becker had no involvement in any of the stent retriever trials. “I had been a doubter of this technology,” primarily because results reported at the International Stroke Conference a couple of years ago failed to prove the efficacy of clot retrieval in ischemic stroke patients, she noted. “Our ability to select appropriate patients and do it in a timely fashion hadn’t gotten to where it had to be until now,” Dr. Becker said in an interview.

“We only enrolled patients with blockages, we treated them quickly, and we used much better devices to open their arteries,” Dr. Saver added, explaining why the new studies succeeded when earlier studies had not.

The trial led by Dr. Saver, SWIFT-PRIME (SOLITAIRE™ FR With the Intention for Thrombectomy as Primary Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke), enrolled 195 patients at 39 sites in the United States and in Europe. At 90 days after treatment, 59 patients (60%) among those treated with thrombolysis plus embolectomy had a modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2, compared with 33 patients (36%) among those treated only with thrombolysis (in this trial intravenous treatment with tissue plasminogen activator), a highly significant difference for the study’s primary endpoint.

“For every two and half patients treated, one more patient had a better disability outcome, and for every four patients treated, one more patient was independent at long-term follow-up,” Dr. Saver said. Safety measures were similar among patients in the study’s two arms.

The EXTEND-IA results showed a 90-day modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2 in 52% of the embolectomy patients, compared with 28% of those treated only with thrombolysis. The study’s co–primary endpoints were median level of reperfusion at 24 hours after treatment, 100% with embolectomy and 37% with thrombolysis only, and early neurologic recovery, defined as at least an 8-point drop from the baseline in the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score or a score of 0 or 1 when assessed 3 days after treatment. Patients met this second endpoint at an 80% rate with embolectomy and a 37% rate with thrombolysis only. Results of EXTEND-IA appeared in an article published online concurrently with the meeting report (N. Engl J. Med. 2015 Feb. 11 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1414792]).

The third, and largest, of the three studies presented at the conference, ESCAPE (Endovascular Treatment for Small Core and Anterior Circulation Proximal Occlusion with Emphasis on Minimizing CT to Recanalization Times), enrolled 316 patients at 11 centers in Canada, 6 in the United States, 3 in South Korea, and 1 in Ireland. After 90 days, 53% of patients in the embolectomy arm had achieved a modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2, this study’s primary endpoint, compared with 29% of patients in the thrombolysis-only arm (treatment with alteplase). These results also appeared in an article published online concurrently with the conference report (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015 Feb. 11 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1414905]).

SWIFT PRIME was sponsored by Covidien, which markets the stent retriever used in the study. Dr. Saver and Dr. Goyal are consultants to Covidien. EXTEND-IA used stent retrievers provided by Covidien. ESCAPE received a grant from Covidien. Dr. Becker had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: Results from three randomized, controlled trials confirmed the safety and dramatic efficacy of endovascular embolectomy for selected patients with acute, ischemic stroke.

Major finding: In SWIFT PRIME, a 90-day modified Rankin Scale score of 0-2 occurred in 60% of patients treated with thrombolysis plus embolectomy and 36% of patients treated with thrombolysis only.

Data source: SWIFT PRIME, a prospective, multicenter randomized trial that enrolled 195 patients at 39 centers in the United States and Europe.

Disclosures: SWIFT PRIME was sponsored by Covidien, which markets the stent retriever used in the study. Dr. Saver and Dr. Goyal are consultants to Covidien. EXTEND-IA used stent retrievers provided by Covidien. ESCAPE received a grant from Covidien. Dr. Becker had no relevant disclosures.

The tipping point for value-based pay?

Over the last several years, doctors and other health care professionals – no doubt including many readers of this column – have worked to develop the accountable care organization model from an academic idea into a meaningful presence in the health care marketplace.

In January, the federal government threw its considerable weight squarely behind that effort, for the first time setting clear goals for ramping up the use of ACOs and other alternative payment models in Medicare.

In an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell announced that by the end of 2016, her agency plans to have 30% of all Medicare payments “tied to quality through alternative payment models,” including ACOs, patient-centered medical homes, and bundled payments – and to have 50% of Medicare payments made under alternative payment models by the end of 2018.

Furthermore, even among the payments that remain under the fee-for-service model, the vast majority will be linked to quality and value in some way – 85% by 2016, and 90% by 2018.

Right now, only about 20% of Medicare payments are made through alternative payment models, meaning that HHS’ new goals entail a 50% increase in the quantity of Medicare dollars going to alternative payment models by the end of next year, and a 150% increase by the end of 2018. In 2014, Medicare made $362 billion in fee-for-service payments – a huge number, much of which increasingly will be directed toward ACOs.

“We believe these goals can drive transformative change, help us manage and track progress, and create accountability for measurable improvement,” Secretary Burwell said in a press release accompanying the announcement.

“Ultimately, this is about improving the health of each person by making the best use of our resources for patient good,” Dr. Douglas E. Henley, CEO of the American Academy of Family Physicians, noted in the same press release. “We’re on board, and we’re committed to changing how we pay for and deliver care to achieve better health.”

Of course, setting ambitious goals is not the same thing as meeting them, and many details have yet to be ironed out. Will the administration focus on ACOs or on other alternative payment models such as bundled payments? How will it measure quality? And Medicare, though massive, is only one part of the health industry. To what extent will the rest of the industry join in the federal government’s push toward accountable care?

To help answer these questions, HHS also announced that it is creating the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network, which “will accelerate the transition to more advanced payment models by fostering collaboration between HHS, private payers, large employers, providers, consumers, and state and federal partners.”

January’s announcement is the strongest signal yet that the federal government has bought into the idea of paying for value, not volume, and that it is willing to invest substantially in the emerging accountable care model.

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the health law group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. Mr. Wilson is an associate at Smith Anderson. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the authors at [email protected] or [email protected], or by phone at 919-821-6612.

Over the last several years, doctors and other health care professionals – no doubt including many readers of this column – have worked to develop the accountable care organization model from an academic idea into a meaningful presence in the health care marketplace.

In January, the federal government threw its considerable weight squarely behind that effort, for the first time setting clear goals for ramping up the use of ACOs and other alternative payment models in Medicare.

In an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell announced that by the end of 2016, her agency plans to have 30% of all Medicare payments “tied to quality through alternative payment models,” including ACOs, patient-centered medical homes, and bundled payments – and to have 50% of Medicare payments made under alternative payment models by the end of 2018.

Furthermore, even among the payments that remain under the fee-for-service model, the vast majority will be linked to quality and value in some way – 85% by 2016, and 90% by 2018.

Right now, only about 20% of Medicare payments are made through alternative payment models, meaning that HHS’ new goals entail a 50% increase in the quantity of Medicare dollars going to alternative payment models by the end of next year, and a 150% increase by the end of 2018. In 2014, Medicare made $362 billion in fee-for-service payments – a huge number, much of which increasingly will be directed toward ACOs.

“We believe these goals can drive transformative change, help us manage and track progress, and create accountability for measurable improvement,” Secretary Burwell said in a press release accompanying the announcement.

“Ultimately, this is about improving the health of each person by making the best use of our resources for patient good,” Dr. Douglas E. Henley, CEO of the American Academy of Family Physicians, noted in the same press release. “We’re on board, and we’re committed to changing how we pay for and deliver care to achieve better health.”

Of course, setting ambitious goals is not the same thing as meeting them, and many details have yet to be ironed out. Will the administration focus on ACOs or on other alternative payment models such as bundled payments? How will it measure quality? And Medicare, though massive, is only one part of the health industry. To what extent will the rest of the industry join in the federal government’s push toward accountable care?

To help answer these questions, HHS also announced that it is creating the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network, which “will accelerate the transition to more advanced payment models by fostering collaboration between HHS, private payers, large employers, providers, consumers, and state and federal partners.”

January’s announcement is the strongest signal yet that the federal government has bought into the idea of paying for value, not volume, and that it is willing to invest substantially in the emerging accountable care model.

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the health law group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. Mr. Wilson is an associate at Smith Anderson. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the authors at [email protected] or [email protected], or by phone at 919-821-6612.

Over the last several years, doctors and other health care professionals – no doubt including many readers of this column – have worked to develop the accountable care organization model from an academic idea into a meaningful presence in the health care marketplace.

In January, the federal government threw its considerable weight squarely behind that effort, for the first time setting clear goals for ramping up the use of ACOs and other alternative payment models in Medicare.

In an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell announced that by the end of 2016, her agency plans to have 30% of all Medicare payments “tied to quality through alternative payment models,” including ACOs, patient-centered medical homes, and bundled payments – and to have 50% of Medicare payments made under alternative payment models by the end of 2018.

Furthermore, even among the payments that remain under the fee-for-service model, the vast majority will be linked to quality and value in some way – 85% by 2016, and 90% by 2018.

Right now, only about 20% of Medicare payments are made through alternative payment models, meaning that HHS’ new goals entail a 50% increase in the quantity of Medicare dollars going to alternative payment models by the end of next year, and a 150% increase by the end of 2018. In 2014, Medicare made $362 billion in fee-for-service payments – a huge number, much of which increasingly will be directed toward ACOs.

“We believe these goals can drive transformative change, help us manage and track progress, and create accountability for measurable improvement,” Secretary Burwell said in a press release accompanying the announcement.

“Ultimately, this is about improving the health of each person by making the best use of our resources for patient good,” Dr. Douglas E. Henley, CEO of the American Academy of Family Physicians, noted in the same press release. “We’re on board, and we’re committed to changing how we pay for and deliver care to achieve better health.”

Of course, setting ambitious goals is not the same thing as meeting them, and many details have yet to be ironed out. Will the administration focus on ACOs or on other alternative payment models such as bundled payments? How will it measure quality? And Medicare, though massive, is only one part of the health industry. To what extent will the rest of the industry join in the federal government’s push toward accountable care?

To help answer these questions, HHS also announced that it is creating the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network, which “will accelerate the transition to more advanced payment models by fostering collaboration between HHS, private payers, large employers, providers, consumers, and state and federal partners.”

January’s announcement is the strongest signal yet that the federal government has bought into the idea of paying for value, not volume, and that it is willing to invest substantially in the emerging accountable care model.

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the health law group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. Mr. Wilson is an associate at Smith Anderson. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the authors at [email protected] or [email protected], or by phone at 919-821-6612.

Visit your office

Every year around now, as spring begins to revive the landscape, I like to take a tour of my office from the perspective of a patient visiting our facility for the first time, because more often than not, the internal environment could use a bit of a revival as well.

We tend not to notice gradual deterioration in the workplace we inhabit every day: Carpets fade and dull with constant traffic and cleaning; wallpaper and paint accumulate dirt, stains, and damage; furniture gets dirty and dented, fabric rips, hardware goes missing.

When did you last take a good look at your waiting room? Have your patients been snacking and spilling drinks in there, despite the signs begging them not to? Is the wallpaper smudged on the walls behind chairs, where they rest their heads? How are the carpeting and upholstery holding up?

Even if you don’t find anything obvious, it’s wise to check periodically for subtle evidence of age: Find some patches of protected carpeting and flooring – under desks, for example – and compare them with exposed floors.

And look at the decor itself; is it dated or just plain old looking? Any interior designer will tell you he or she can determine quite accurately when a space was last decorated, simply by the color and style of the materials used. If your office is stuck in the ’90s, it’s probably time for a change.

If you’re planning a vacation this summer (and I hope you are), that would be the perfect time for a redo. Your patients will be spared the dust and turmoil, tradespeople won’t have to work around your office hours, and you won’t have to cancel any hours that weren’t already canceled. Best of all, you’ll come back to a clean, fresh environment.

Start by reviewing your color scheme. If it’s hopelessly out of date and style, or if you are just tired of it, change it. Wallpaper and carpeting should be long-wearing industrial quality, paint should be high-quality eggshell finish to facilitate cleaning, and everything should be professionally applied. (This is neither the time nor place for do-it-yourself experiments.) And get your building’s maintenance crew to fix any nagging plumbing, electrical, or heating/air conditioning problems while pipes, ducts, and wires are more readily accessible.

If your wall decorations are dated and unattractive, now would be a good time to replace at least some of them. This need not be an expensive proposition. I recently redecorated my exam room walls with framed photos from my travel adventures, to very positive responses from patients and staff alike. If you’re not an artist or photographer, invite family members, local artists, or talented patients to display some of their creations on your walls.

Plants are great accents and excellent stress reducers for apprehensive patients, yet many offices have little or no plant life. If you are hesitant to take on the extra work of plant upkeep, consider using one of the many corporate plant services that rent you the plants, keep them healthy, and replace them as necessary.

Furniture is another important element in keeping your office environment fresh and inviting. You may be able to resurface and reupholster what you have now, but if not, shop carefully. Beware of nonmedical products promoted specifically to physicians, as they tend to be overpriced. If you shop online, remember to factor in shipping costs, which can be considerable for furniture. Don’t be afraid to ask for discounts; you won’t get them if you don’t ask.

This is also a good time to clear out old textbooks, magazines, and files that you will never open again – not in this digital age.

Finally, spruce-up time is an excellent opportunity to inventory your medical equipment. We’ve all seen vintage offices full of gadgets that were state-of-the-art decades ago. Nostalgia is nice, but would you want to be treated by a physician whose office could be a Smithsonian exhibit titled, “Doctor’s Office Circa 1975?” Neither would your patients, for the most part. In fact, many of them – particularly younger ones – assume that doctors who don’t keep up with technologic innovations don’t keep up with anything else, either.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News.

Every year around now, as spring begins to revive the landscape, I like to take a tour of my office from the perspective of a patient visiting our facility for the first time, because more often than not, the internal environment could use a bit of a revival as well.

We tend not to notice gradual deterioration in the workplace we inhabit every day: Carpets fade and dull with constant traffic and cleaning; wallpaper and paint accumulate dirt, stains, and damage; furniture gets dirty and dented, fabric rips, hardware goes missing.

When did you last take a good look at your waiting room? Have your patients been snacking and spilling drinks in there, despite the signs begging them not to? Is the wallpaper smudged on the walls behind chairs, where they rest their heads? How are the carpeting and upholstery holding up?

Even if you don’t find anything obvious, it’s wise to check periodically for subtle evidence of age: Find some patches of protected carpeting and flooring – under desks, for example – and compare them with exposed floors.

And look at the decor itself; is it dated or just plain old looking? Any interior designer will tell you he or she can determine quite accurately when a space was last decorated, simply by the color and style of the materials used. If your office is stuck in the ’90s, it’s probably time for a change.

If you’re planning a vacation this summer (and I hope you are), that would be the perfect time for a redo. Your patients will be spared the dust and turmoil, tradespeople won’t have to work around your office hours, and you won’t have to cancel any hours that weren’t already canceled. Best of all, you’ll come back to a clean, fresh environment.

Start by reviewing your color scheme. If it’s hopelessly out of date and style, or if you are just tired of it, change it. Wallpaper and carpeting should be long-wearing industrial quality, paint should be high-quality eggshell finish to facilitate cleaning, and everything should be professionally applied. (This is neither the time nor place for do-it-yourself experiments.) And get your building’s maintenance crew to fix any nagging plumbing, electrical, or heating/air conditioning problems while pipes, ducts, and wires are more readily accessible.

If your wall decorations are dated and unattractive, now would be a good time to replace at least some of them. This need not be an expensive proposition. I recently redecorated my exam room walls with framed photos from my travel adventures, to very positive responses from patients and staff alike. If you’re not an artist or photographer, invite family members, local artists, or talented patients to display some of their creations on your walls.

Plants are great accents and excellent stress reducers for apprehensive patients, yet many offices have little or no plant life. If you are hesitant to take on the extra work of plant upkeep, consider using one of the many corporate plant services that rent you the plants, keep them healthy, and replace them as necessary.

Furniture is another important element in keeping your office environment fresh and inviting. You may be able to resurface and reupholster what you have now, but if not, shop carefully. Beware of nonmedical products promoted specifically to physicians, as they tend to be overpriced. If you shop online, remember to factor in shipping costs, which can be considerable for furniture. Don’t be afraid to ask for discounts; you won’t get them if you don’t ask.

This is also a good time to clear out old textbooks, magazines, and files that you will never open again – not in this digital age.

Finally, spruce-up time is an excellent opportunity to inventory your medical equipment. We’ve all seen vintage offices full of gadgets that were state-of-the-art decades ago. Nostalgia is nice, but would you want to be treated by a physician whose office could be a Smithsonian exhibit titled, “Doctor’s Office Circa 1975?” Neither would your patients, for the most part. In fact, many of them – particularly younger ones – assume that doctors who don’t keep up with technologic innovations don’t keep up with anything else, either.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News.

Every year around now, as spring begins to revive the landscape, I like to take a tour of my office from the perspective of a patient visiting our facility for the first time, because more often than not, the internal environment could use a bit of a revival as well.

We tend not to notice gradual deterioration in the workplace we inhabit every day: Carpets fade and dull with constant traffic and cleaning; wallpaper and paint accumulate dirt, stains, and damage; furniture gets dirty and dented, fabric rips, hardware goes missing.

When did you last take a good look at your waiting room? Have your patients been snacking and spilling drinks in there, despite the signs begging them not to? Is the wallpaper smudged on the walls behind chairs, where they rest their heads? How are the carpeting and upholstery holding up?

Even if you don’t find anything obvious, it’s wise to check periodically for subtle evidence of age: Find some patches of protected carpeting and flooring – under desks, for example – and compare them with exposed floors.

And look at the decor itself; is it dated or just plain old looking? Any interior designer will tell you he or she can determine quite accurately when a space was last decorated, simply by the color and style of the materials used. If your office is stuck in the ’90s, it’s probably time for a change.

If you’re planning a vacation this summer (and I hope you are), that would be the perfect time for a redo. Your patients will be spared the dust and turmoil, tradespeople won’t have to work around your office hours, and you won’t have to cancel any hours that weren’t already canceled. Best of all, you’ll come back to a clean, fresh environment.

Start by reviewing your color scheme. If it’s hopelessly out of date and style, or if you are just tired of it, change it. Wallpaper and carpeting should be long-wearing industrial quality, paint should be high-quality eggshell finish to facilitate cleaning, and everything should be professionally applied. (This is neither the time nor place for do-it-yourself experiments.) And get your building’s maintenance crew to fix any nagging plumbing, electrical, or heating/air conditioning problems while pipes, ducts, and wires are more readily accessible.

If your wall decorations are dated and unattractive, now would be a good time to replace at least some of them. This need not be an expensive proposition. I recently redecorated my exam room walls with framed photos from my travel adventures, to very positive responses from patients and staff alike. If you’re not an artist or photographer, invite family members, local artists, or talented patients to display some of their creations on your walls.

Plants are great accents and excellent stress reducers for apprehensive patients, yet many offices have little or no plant life. If you are hesitant to take on the extra work of plant upkeep, consider using one of the many corporate plant services that rent you the plants, keep them healthy, and replace them as necessary.

Furniture is another important element in keeping your office environment fresh and inviting. You may be able to resurface and reupholster what you have now, but if not, shop carefully. Beware of nonmedical products promoted specifically to physicians, as they tend to be overpriced. If you shop online, remember to factor in shipping costs, which can be considerable for furniture. Don’t be afraid to ask for discounts; you won’t get them if you don’t ask.

This is also a good time to clear out old textbooks, magazines, and files that you will never open again – not in this digital age.

Finally, spruce-up time is an excellent opportunity to inventory your medical equipment. We’ve all seen vintage offices full of gadgets that were state-of-the-art decades ago. Nostalgia is nice, but would you want to be treated by a physician whose office could be a Smithsonian exhibit titled, “Doctor’s Office Circa 1975?” Neither would your patients, for the most part. In fact, many of them – particularly younger ones – assume that doctors who don’t keep up with technologic innovations don’t keep up with anything else, either.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News.

Dermatologic Emergencies

Dermatologic emergency may sound like an oxymoron, but there are many emergencies that dermatology residents may encounter in their careers. In some instances the skin is the primary organ that is affected, while in others cutaneous symptoms and life-threatening signs are important diagnostic clues for what may lie beneath the skin.

As residents who are occasionally on call or on consultation services, it is important for us to recognize dermatologic emergencies quickly because some of these conditions can acutely evolve and become lethal if a diagnosis is not made early in the disease course with the appropriate treatment administered. Dermatologic emergencies can range from severe drug reactions, infections, autoimmune exacerbations, and inflammatory conditions (eg, erythroderma) to environmental insults such as burns (Figure 1) and child abuse.1

Critical Infections

Some dermatologic emergencies are infectious in origin, and although these infections are most commonly bacterial (eg, necrotizing fasciitis), they also can range from viral to fungal (eg, mucormycosis) in nature. Some areas with large populations of immunocompromised patients (eg, human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients, organ transplant recipients) may warrant a high index of suspicion for possible zebras (rare conditions) and opportunistic infections that may quickly escalate to life-threatening situations.

Although few cutaneous manifestations in emergent infections are pathognomonic, they sometimes can be categorized according to the appearance of the primary lesion: erythrodermic (eg, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome), maculopapular (eg, Lyme disease), purpuric/petechial (eg, Rocky Mountain spotted fever), pustular (eg, disseminated candidiasis), or vesicular (eg, neonatal herpes simplex virus)(Table). On consultations, dermatology residents frequently get called to evaluate hemorrhagic and ischemic lesions in inpatients (Figure 2). Aside from infectious causes, the differential diagnosis may include coagulation abnormalities (eg, concurrent anticoagulant therapies), vasculitides, poisoning, vascular disease, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis, which can occasionally present with hemorrhagic lesions.1,2

Necrotizing Fasciitis

Dermatology residents may frequently encounter necrotizing fasciitis, either in clinic or on the wards (Figure 3). Recognition of the skin signs in this condition is essential to patient survival. As an intern, I once had an attending teach me that patients with necrotizing fasciitis only have a couple of hours to live. The rapid unfolding of this flesh-eating disease and its high morbidity and mortality has led to recent attention in the press and media.

Although necrotizing fasciitis may be caused by several different bacterial organisms (eg, gram positive, gram negative, polymicrobial), it usually is rapidly progressive, destroying muscle and subcutaneous tissues in a matter of hours.3 Bacteria usually enter through a traumatic or present wound and quickly move along fascial planes, destroying blood vessels and whatever subcutaneous tissues happen to be in the way. Within the first few hours, the involved area that was initially erythematous becomes indurated, woody, extremely painful, and dusky, indicating a lack of circulation to the area. Extensive debridement is required until reaching noninfected tissue that is no longer purulent, necrotic, or woody to the touch. If necrotizing fasciitis is not diagnosed and treated early, patients may lose one or several limbs and death may occur.

Key findings of necrotizing fasciitis include systemic toxicity, localized painful induration, well-defined dusky blue discoloration, and a lack of bleeding or purulent discharge on incision and squeezing of the affected tissue. Crepitation or a crackling sensation can occasionally be felt when palpating the area secondary to gas formation in the tissue, though it is not always present. Patients with necrotizing fasciitis often initially present to dermatology clinics because the first manifestation happens to be in the skin. The role of dermatologists in treating this critical condition may prompt recognition and collaboration with other specialists to reach a viable outcome for the patient.3

Drug Reactions

Cutaneous drug eruptions usually are relatively benign, consisting of a morbilliform eruption often without any other accompanying symptoms. However, sometimes these reactions can present as exfoliative dermatitis or red man syndrome in which patients can develop total body erythema with diffuse scaling and pruritus.4 Aside from drug reactions, other causes of exfoliative dermatitis such as psoriasis, atopic and seborrheic dermatitis, mycosis fungoides, and lymphoma should be ruled out. Other drug eruptions that can be classified as dermatologic emergencies include leukocytoclastic vasculitis, severe urticaria or angioedema, erythema multiforme, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Severe Acne

If not treated promptly, serious cases of acne can lead to severe scarring and psychologic problems. Acne fulminans is characterized by a rapid eruption of suppurative and large, highly inflamed nodules, plaques, and cysts that result in ragged ulcerations and cicatrization of the chest, back, and occasionally the face. Systemic symptoms of fever, arthralgia, leukocytosis, and myalgia suggest an upregulation of the immune system in affected patients.

Final Comment

In summary, dermatologic emergencies do exist and some may present with characteristic skin findings. In almost all cases, collaboration with other departments such as trauma, burn, internal medicine, rheumatology, and infectious diseases is extremely helpful in diagnosing and treating these medical emergencies. Collaboration can provide insight into how brainstorming through different approaches can lead to a better outcome whether it be solving the cause of a puzzling rash in a patient with multiple comorbidities or surgically removing a bullet from a trauma patient (Figure 4). Recognition of specific cutaneous manifestations and early diagnosis of dermatologic emergencies can be lifesaving.

1. McQueen A, Martin SA, Lio PA. Derm emergencies: detecting early signs of trouble. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:71-78.

2. Bennion S. Dermatologic emergencies. In: Fitzpatrick J, Morelli J, eds. Dermatology Secrets Plus. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2011:442-452.

3. Sarani B, Strong M, Pascual J, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: current concepts and review of the literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:279-288.

4. Wolf R, Orion E, Marcos B, et al. Life-threatening acute adverse cutaneous drug reactions. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:171-181.

Dermatologic emergency may sound like an oxymoron, but there are many emergencies that dermatology residents may encounter in their careers. In some instances the skin is the primary organ that is affected, while in others cutaneous symptoms and life-threatening signs are important diagnostic clues for what may lie beneath the skin.

As residents who are occasionally on call or on consultation services, it is important for us to recognize dermatologic emergencies quickly because some of these conditions can acutely evolve and become lethal if a diagnosis is not made early in the disease course with the appropriate treatment administered. Dermatologic emergencies can range from severe drug reactions, infections, autoimmune exacerbations, and inflammatory conditions (eg, erythroderma) to environmental insults such as burns (Figure 1) and child abuse.1

Critical Infections

Some dermatologic emergencies are infectious in origin, and although these infections are most commonly bacterial (eg, necrotizing fasciitis), they also can range from viral to fungal (eg, mucormycosis) in nature. Some areas with large populations of immunocompromised patients (eg, human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients, organ transplant recipients) may warrant a high index of suspicion for possible zebras (rare conditions) and opportunistic infections that may quickly escalate to life-threatening situations.

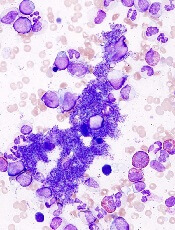

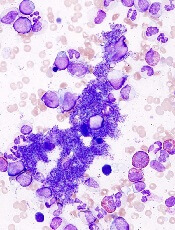

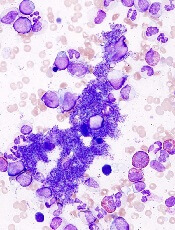

Although few cutaneous manifestations in emergent infections are pathognomonic, they sometimes can be categorized according to the appearance of the primary lesion: erythrodermic (eg, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome), maculopapular (eg, Lyme disease), purpuric/petechial (eg, Rocky Mountain spotted fever), pustular (eg, disseminated candidiasis), or vesicular (eg, neonatal herpes simplex virus)(Table). On consultations, dermatology residents frequently get called to evaluate hemorrhagic and ischemic lesions in inpatients (Figure 2). Aside from infectious causes, the differential diagnosis may include coagulation abnormalities (eg, concurrent anticoagulant therapies), vasculitides, poisoning, vascular disease, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis, which can occasionally present with hemorrhagic lesions.1,2

Necrotizing Fasciitis

Dermatology residents may frequently encounter necrotizing fasciitis, either in clinic or on the wards (Figure 3). Recognition of the skin signs in this condition is essential to patient survival. As an intern, I once had an attending teach me that patients with necrotizing fasciitis only have a couple of hours to live. The rapid unfolding of this flesh-eating disease and its high morbidity and mortality has led to recent attention in the press and media.

Although necrotizing fasciitis may be caused by several different bacterial organisms (eg, gram positive, gram negative, polymicrobial), it usually is rapidly progressive, destroying muscle and subcutaneous tissues in a matter of hours.3 Bacteria usually enter through a traumatic or present wound and quickly move along fascial planes, destroying blood vessels and whatever subcutaneous tissues happen to be in the way. Within the first few hours, the involved area that was initially erythematous becomes indurated, woody, extremely painful, and dusky, indicating a lack of circulation to the area. Extensive debridement is required until reaching noninfected tissue that is no longer purulent, necrotic, or woody to the touch. If necrotizing fasciitis is not diagnosed and treated early, patients may lose one or several limbs and death may occur.

Key findings of necrotizing fasciitis include systemic toxicity, localized painful induration, well-defined dusky blue discoloration, and a lack of bleeding or purulent discharge on incision and squeezing of the affected tissue. Crepitation or a crackling sensation can occasionally be felt when palpating the area secondary to gas formation in the tissue, though it is not always present. Patients with necrotizing fasciitis often initially present to dermatology clinics because the first manifestation happens to be in the skin. The role of dermatologists in treating this critical condition may prompt recognition and collaboration with other specialists to reach a viable outcome for the patient.3

Drug Reactions

Cutaneous drug eruptions usually are relatively benign, consisting of a morbilliform eruption often without any other accompanying symptoms. However, sometimes these reactions can present as exfoliative dermatitis or red man syndrome in which patients can develop total body erythema with diffuse scaling and pruritus.4 Aside from drug reactions, other causes of exfoliative dermatitis such as psoriasis, atopic and seborrheic dermatitis, mycosis fungoides, and lymphoma should be ruled out. Other drug eruptions that can be classified as dermatologic emergencies include leukocytoclastic vasculitis, severe urticaria or angioedema, erythema multiforme, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Severe Acne

If not treated promptly, serious cases of acne can lead to severe scarring and psychologic problems. Acne fulminans is characterized by a rapid eruption of suppurative and large, highly inflamed nodules, plaques, and cysts that result in ragged ulcerations and cicatrization of the chest, back, and occasionally the face. Systemic symptoms of fever, arthralgia, leukocytosis, and myalgia suggest an upregulation of the immune system in affected patients.

Final Comment

In summary, dermatologic emergencies do exist and some may present with characteristic skin findings. In almost all cases, collaboration with other departments such as trauma, burn, internal medicine, rheumatology, and infectious diseases is extremely helpful in diagnosing and treating these medical emergencies. Collaboration can provide insight into how brainstorming through different approaches can lead to a better outcome whether it be solving the cause of a puzzling rash in a patient with multiple comorbidities or surgically removing a bullet from a trauma patient (Figure 4). Recognition of specific cutaneous manifestations and early diagnosis of dermatologic emergencies can be lifesaving.

Dermatologic emergency may sound like an oxymoron, but there are many emergencies that dermatology residents may encounter in their careers. In some instances the skin is the primary organ that is affected, while in others cutaneous symptoms and life-threatening signs are important diagnostic clues for what may lie beneath the skin.

As residents who are occasionally on call or on consultation services, it is important for us to recognize dermatologic emergencies quickly because some of these conditions can acutely evolve and become lethal if a diagnosis is not made early in the disease course with the appropriate treatment administered. Dermatologic emergencies can range from severe drug reactions, infections, autoimmune exacerbations, and inflammatory conditions (eg, erythroderma) to environmental insults such as burns (Figure 1) and child abuse.1

Critical Infections

Some dermatologic emergencies are infectious in origin, and although these infections are most commonly bacterial (eg, necrotizing fasciitis), they also can range from viral to fungal (eg, mucormycosis) in nature. Some areas with large populations of immunocompromised patients (eg, human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients, organ transplant recipients) may warrant a high index of suspicion for possible zebras (rare conditions) and opportunistic infections that may quickly escalate to life-threatening situations.

Although few cutaneous manifestations in emergent infections are pathognomonic, they sometimes can be categorized according to the appearance of the primary lesion: erythrodermic (eg, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome), maculopapular (eg, Lyme disease), purpuric/petechial (eg, Rocky Mountain spotted fever), pustular (eg, disseminated candidiasis), or vesicular (eg, neonatal herpes simplex virus)(Table). On consultations, dermatology residents frequently get called to evaluate hemorrhagic and ischemic lesions in inpatients (Figure 2). Aside from infectious causes, the differential diagnosis may include coagulation abnormalities (eg, concurrent anticoagulant therapies), vasculitides, poisoning, vascular disease, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis, which can occasionally present with hemorrhagic lesions.1,2

Necrotizing Fasciitis

Dermatology residents may frequently encounter necrotizing fasciitis, either in clinic or on the wards (Figure 3). Recognition of the skin signs in this condition is essential to patient survival. As an intern, I once had an attending teach me that patients with necrotizing fasciitis only have a couple of hours to live. The rapid unfolding of this flesh-eating disease and its high morbidity and mortality has led to recent attention in the press and media.

Although necrotizing fasciitis may be caused by several different bacterial organisms (eg, gram positive, gram negative, polymicrobial), it usually is rapidly progressive, destroying muscle and subcutaneous tissues in a matter of hours.3 Bacteria usually enter through a traumatic or present wound and quickly move along fascial planes, destroying blood vessels and whatever subcutaneous tissues happen to be in the way. Within the first few hours, the involved area that was initially erythematous becomes indurated, woody, extremely painful, and dusky, indicating a lack of circulation to the area. Extensive debridement is required until reaching noninfected tissue that is no longer purulent, necrotic, or woody to the touch. If necrotizing fasciitis is not diagnosed and treated early, patients may lose one or several limbs and death may occur.

Key findings of necrotizing fasciitis include systemic toxicity, localized painful induration, well-defined dusky blue discoloration, and a lack of bleeding or purulent discharge on incision and squeezing of the affected tissue. Crepitation or a crackling sensation can occasionally be felt when palpating the area secondary to gas formation in the tissue, though it is not always present. Patients with necrotizing fasciitis often initially present to dermatology clinics because the first manifestation happens to be in the skin. The role of dermatologists in treating this critical condition may prompt recognition and collaboration with other specialists to reach a viable outcome for the patient.3

Drug Reactions

Cutaneous drug eruptions usually are relatively benign, consisting of a morbilliform eruption often without any other accompanying symptoms. However, sometimes these reactions can present as exfoliative dermatitis or red man syndrome in which patients can develop total body erythema with diffuse scaling and pruritus.4 Aside from drug reactions, other causes of exfoliative dermatitis such as psoriasis, atopic and seborrheic dermatitis, mycosis fungoides, and lymphoma should be ruled out. Other drug eruptions that can be classified as dermatologic emergencies include leukocytoclastic vasculitis, severe urticaria or angioedema, erythema multiforme, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Severe Acne

If not treated promptly, serious cases of acne can lead to severe scarring and psychologic problems. Acne fulminans is characterized by a rapid eruption of suppurative and large, highly inflamed nodules, plaques, and cysts that result in ragged ulcerations and cicatrization of the chest, back, and occasionally the face. Systemic symptoms of fever, arthralgia, leukocytosis, and myalgia suggest an upregulation of the immune system in affected patients.

Final Comment

In summary, dermatologic emergencies do exist and some may present with characteristic skin findings. In almost all cases, collaboration with other departments such as trauma, burn, internal medicine, rheumatology, and infectious diseases is extremely helpful in diagnosing and treating these medical emergencies. Collaboration can provide insight into how brainstorming through different approaches can lead to a better outcome whether it be solving the cause of a puzzling rash in a patient with multiple comorbidities or surgically removing a bullet from a trauma patient (Figure 4). Recognition of specific cutaneous manifestations and early diagnosis of dermatologic emergencies can be lifesaving.

1. McQueen A, Martin SA, Lio PA. Derm emergencies: detecting early signs of trouble. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:71-78.

2. Bennion S. Dermatologic emergencies. In: Fitzpatrick J, Morelli J, eds. Dermatology Secrets Plus. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2011:442-452.

3. Sarani B, Strong M, Pascual J, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: current concepts and review of the literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:279-288.

4. Wolf R, Orion E, Marcos B, et al. Life-threatening acute adverse cutaneous drug reactions. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:171-181.

1. McQueen A, Martin SA, Lio PA. Derm emergencies: detecting early signs of trouble. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:71-78.

2. Bennion S. Dermatologic emergencies. In: Fitzpatrick J, Morelli J, eds. Dermatology Secrets Plus. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2011:442-452.

3. Sarani B, Strong M, Pascual J, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: current concepts and review of the literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:279-288.

4. Wolf R, Orion E, Marcos B, et al. Life-threatening acute adverse cutaneous drug reactions. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:171-181.

Order of mutations impacts MPN behavior

essential thrombocythemia

The order in which genetic mutations are acquired determines how myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) behave, according to research published in NEJM.

Investigators found that mutation order impacts everything from the type of MPN a patient develops to how the disease responds to treatment.

“This surprising finding could help us offer more accurate prognoses to MPN patients based on their mutation order and tailor potential therapies towards them,” said study author David Kent, PhD, of the University of Cambridge in the UK.

“For example, our results predict that targeted JAK2 therapy would be more effective in patients with one mutation order but not the other.”