User login

Heroin overdoses up dramatically since 2010

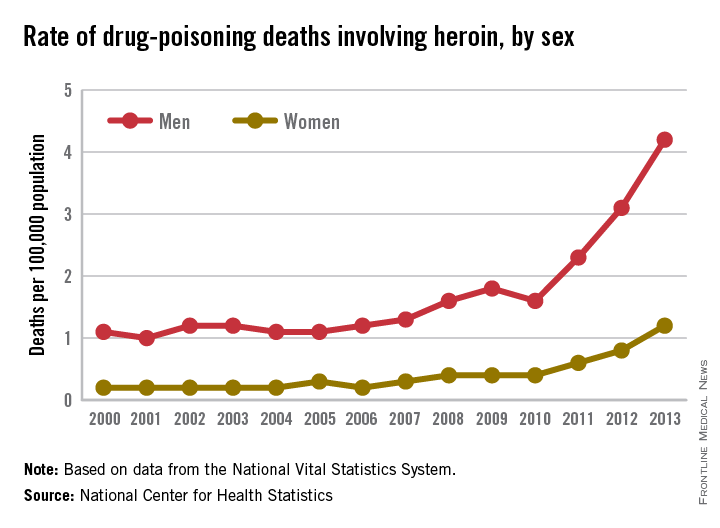

Drug-poisoning deaths involving heroin have soared since 2000, and most of the increase occurred since 2010, according to a report from the National Center for Health Statistics.

From 2010 to 2013, the rate of heroin overdose deaths increased 163% for men, from a rate of 1.6/100,000 population in 2010 to 4.2 in 2013. For women, the death rate increased by 200%, from 0.4/100,000 in 2010 to 1.2/100,000 in 2013. From 2000 to 2010, however, the rate of increase was much slower, with the death rate increasing from 1.1 to 1.6 for men and from 0.2 to 0.4 for women.

The overall rate for heroin overdose from 2000 to 2013 increased from 0.7 to 2.7/100,000. Most of this increase occurred from 2010 to 2013: From 2000 to 2010, the death rate increased to only 1/100,000, a growth rate of 6%, but after 2010, the rate grew by 37% per year, the NCHS reported.

In 2013, non-Hispanic whites aged 18-44 years had the highest heroin poisoning death rate among measured racial/ethnic groups at 7/100,000. In 2000, older, non-Hispanic blacks aged 45-64 years had the highest death rate among the reported racial/ethnic groups at 2/100,000. The death rate for whites aged 18-44 in 2000 was 1.2/100,000, meaning that the death rate increased by 483% from 2000 to 2013. For non-Hispanic blacks aged 45-64, the death rate in 2013 was 4.9, an increase of 145%.

The number of heroin-related overdose deaths climbed in every region of the country from 2000 through 2013. The largest change in heroin overdose by region occurred in the Midwest, where the death rate rose from 0.4/100,000 in 2000 to 4.3 in 2013, an increase of 975%, said the NCHS report, which used data collected by the National Vital Statistics System.

Drug-poisoning deaths involving heroin have soared since 2000, and most of the increase occurred since 2010, according to a report from the National Center for Health Statistics.

From 2010 to 2013, the rate of heroin overdose deaths increased 163% for men, from a rate of 1.6/100,000 population in 2010 to 4.2 in 2013. For women, the death rate increased by 200%, from 0.4/100,000 in 2010 to 1.2/100,000 in 2013. From 2000 to 2010, however, the rate of increase was much slower, with the death rate increasing from 1.1 to 1.6 for men and from 0.2 to 0.4 for women.

The overall rate for heroin overdose from 2000 to 2013 increased from 0.7 to 2.7/100,000. Most of this increase occurred from 2010 to 2013: From 2000 to 2010, the death rate increased to only 1/100,000, a growth rate of 6%, but after 2010, the rate grew by 37% per year, the NCHS reported.

In 2013, non-Hispanic whites aged 18-44 years had the highest heroin poisoning death rate among measured racial/ethnic groups at 7/100,000. In 2000, older, non-Hispanic blacks aged 45-64 years had the highest death rate among the reported racial/ethnic groups at 2/100,000. The death rate for whites aged 18-44 in 2000 was 1.2/100,000, meaning that the death rate increased by 483% from 2000 to 2013. For non-Hispanic blacks aged 45-64, the death rate in 2013 was 4.9, an increase of 145%.

The number of heroin-related overdose deaths climbed in every region of the country from 2000 through 2013. The largest change in heroin overdose by region occurred in the Midwest, where the death rate rose from 0.4/100,000 in 2000 to 4.3 in 2013, an increase of 975%, said the NCHS report, which used data collected by the National Vital Statistics System.

Drug-poisoning deaths involving heroin have soared since 2000, and most of the increase occurred since 2010, according to a report from the National Center for Health Statistics.

From 2010 to 2013, the rate of heroin overdose deaths increased 163% for men, from a rate of 1.6/100,000 population in 2010 to 4.2 in 2013. For women, the death rate increased by 200%, from 0.4/100,000 in 2010 to 1.2/100,000 in 2013. From 2000 to 2010, however, the rate of increase was much slower, with the death rate increasing from 1.1 to 1.6 for men and from 0.2 to 0.4 for women.

The overall rate for heroin overdose from 2000 to 2013 increased from 0.7 to 2.7/100,000. Most of this increase occurred from 2010 to 2013: From 2000 to 2010, the death rate increased to only 1/100,000, a growth rate of 6%, but after 2010, the rate grew by 37% per year, the NCHS reported.

In 2013, non-Hispanic whites aged 18-44 years had the highest heroin poisoning death rate among measured racial/ethnic groups at 7/100,000. In 2000, older, non-Hispanic blacks aged 45-64 years had the highest death rate among the reported racial/ethnic groups at 2/100,000. The death rate for whites aged 18-44 in 2000 was 1.2/100,000, meaning that the death rate increased by 483% from 2000 to 2013. For non-Hispanic blacks aged 45-64, the death rate in 2013 was 4.9, an increase of 145%.

The number of heroin-related overdose deaths climbed in every region of the country from 2000 through 2013. The largest change in heroin overdose by region occurred in the Midwest, where the death rate rose from 0.4/100,000 in 2000 to 4.3 in 2013, an increase of 975%, said the NCHS report, which used data collected by the National Vital Statistics System.

ACOG President John Jennings comments on the risks of home birth

Responses from both sides of the home-birth controversy are parried in an Opinion Page debate titled “Is Home Birth Ever a Safe Choice?” published on February 24, 2015, in the New York Times.

Debaters include John Jennings, MD, President of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG); Tekoa King, a certified nurse midwife (CNM) and Deputy Editor of the Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health; Amos Grunebaum, MD, Director of Obstetrics, and Frank Chervenak, MD, Obstetrician and Gynecologist-in-chief at New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Weill Medical College of Cornell University; Marinah Valenzuela Farrell, a certified professional midwife (CPM) and president of the Midwives Alliance of North America; Aaron Caughey, MD, Chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Associate Dean for Women’s Health Research and Policy at Oregon Health and Science University’s School of Medicine; and Aja Graydon, a musician who experienced home birth.

To read the New York Times article, click here.

Responses from both sides of the home-birth controversy are parried in an Opinion Page debate titled “Is Home Birth Ever a Safe Choice?” published on February 24, 2015, in the New York Times.

Debaters include John Jennings, MD, President of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG); Tekoa King, a certified nurse midwife (CNM) and Deputy Editor of the Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health; Amos Grunebaum, MD, Director of Obstetrics, and Frank Chervenak, MD, Obstetrician and Gynecologist-in-chief at New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Weill Medical College of Cornell University; Marinah Valenzuela Farrell, a certified professional midwife (CPM) and president of the Midwives Alliance of North America; Aaron Caughey, MD, Chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Associate Dean for Women’s Health Research and Policy at Oregon Health and Science University’s School of Medicine; and Aja Graydon, a musician who experienced home birth.

To read the New York Times article, click here.

Responses from both sides of the home-birth controversy are parried in an Opinion Page debate titled “Is Home Birth Ever a Safe Choice?” published on February 24, 2015, in the New York Times.

Debaters include John Jennings, MD, President of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG); Tekoa King, a certified nurse midwife (CNM) and Deputy Editor of the Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health; Amos Grunebaum, MD, Director of Obstetrics, and Frank Chervenak, MD, Obstetrician and Gynecologist-in-chief at New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Weill Medical College of Cornell University; Marinah Valenzuela Farrell, a certified professional midwife (CPM) and president of the Midwives Alliance of North America; Aaron Caughey, MD, Chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Associate Dean for Women’s Health Research and Policy at Oregon Health and Science University’s School of Medicine; and Aja Graydon, a musician who experienced home birth.

To read the New York Times article, click here.

Addressing the shortage of psychiatrists: What keeps us from seeing more patients?

Recently I was contacted by a reporter who wanted to speak to me about why it’s so difficult for patients to find a psychiatrist. She’d found me by Googling “Why psychiatrists don’t take insurance” and already had read an article I’d written with that title. That day, it had snowed hard enough that most of my patients had canceled; the grocery store had closed; and I had plenty of time to chat with a reporter. The other thing I noted – perhaps because other psychiatrists had unexpected free time because of the snow – was that Maryland Psychiatric Society’s listserv was getting a lot of posts. The posts focused on issues to do with maintenance of certification (MOC) or with the fact that every physician in the state was now going to be required to have a CME credit on opioid prescribing for licensure renewal, and there would be a requirement for physicians to take a course on substance abuse to renew their CDS registration. The hope is that these courses will reduce deaths caused by narcotic overdose, and the courses would be required for all physicians without regard to whether they are relevant to their practice.

The reporter and I started with a discussion of why so many psychiatrists have chosen not to accept health insurance (myself included). She then told me about an insured man who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and substance abuse who was unable to get an appointment with a psychiatrist. She asked me an interesting question: “Don’t psychiatrists want the challenge of treating the difficult cases?” The patient in question never did find a psychiatrist in time and he ended up committing a murder then dying by suicide – an awful tragedy that highlights access to care problems.

In addition to a private practice, I have worked in community mental health centers, and I discussed how that setting is often better suited for patients with serious psychiatric illnesses. More services are offered, and having a variety of mental health professionals in the same facility promotes better coordination of care between psychiatrists, therapists, and case managers, as well as with family, residential care providers, and day programs. The problem is that demand for treatment at outpatient clinics is high, and sometimes the waits for an initial appointment are long, or clinics even may stop accepting new patients at times when they get overloaded.

We talked about the logistics and trade-offs of working in a clinic vs. a private practice, and the reasons why working full time in a high-volume clinic might lead physicians to want a change after a few years. And then the reporter asked me another interesting question – with such long waits, why don’t the clinics hire more doctors? I explained that there was a shortage of psychiatrists and began to talk with her about demands on physician time that take time away from patient care. With the e-mails flying about MOC and new course requirements, it was a place to start, but the snow was still falling, and she heard a lot about the factors that drain physician time and money, both limiting how many patients a psychiatrist can see and driving up the cost of care.

By the time I got off the phone, I decided to tally all of the things that we are required to do to see patients. I was able to get some quick help on the listserv, from friends, and on Twitter.

Every time an agency or insurance company sets up a requirement for a physician, there is a small diversion of time. There is no limit on how many different requirements can be set or whether they need to be relevant to the physician’s work. While I realize there is little sympathy for physicians who, for the most part, are still blessed to earn a good living while doing meaningful work, these diversions add hours to a doctor’s day and cause them to burn out more quickly. So the insurance company that demands that a physician devote 20 minutes to get authorization to prescribe a medication that costs pennies a pill is actually harming society. And no one oversees the big picture.

That said, here was the list we came up with of factors that drain time and money in a clinical practice. Please note that some of these items – for example, uncompensated time returning calls to patients or keeping clinical records – are just part of being a doctor; they’re not something that should be eliminated. Similarly, issues related to having a space to work are part of having a business. I wanted the list to be complete to illustrate the demands on a psychiatrist, not to suggest that none of these things are important. Obviously, some doctors are faster or slower at certain tasks, and people vary greatly in how much time they devote to clinical practice vs. teaching, research, or writing articles for Clinical Psychiatry News. I obtained information in a very quick and casual manner; none of this should be construed as scientific.

Here is the list:

• Maintenance of certification requirements and testing. This is required every 10 years and one estimate was that the cost to register, take the test, and purchase review materials came to $2,800, with a time investment of about 50 hours. Some specialties are pushing back against MOC, and some physicians are forgoing board certification. Psychiatrists who subspecialize usually do MOC for general psychiatry and all their subspecialties.

• CME. Twenty to 50 hours per year depending on your state, and presumably physicians choose courses that enrich their ability to practice medicine. This can be expensive, depending on how the physician decides to get these credits, and many valuable learning events do not qualify for CME.

• Writing clinical notes. Again, this is part of routine medical care. Notes must justify the CPT codes on insurance claims, and very specific areas of inquiry and examination are needed to justify billing specific codes. Agency requirements may be different from what is clinically indicated for the care of the patient, and this uses some of the appointment time in a way that may not be helpful to medical care. Copying, faxing, or sending notes to other clinicians and time spent requesting records all add to the mix. One psychiatrist noted that the overall administrative responsibilities for seeing patients takes half an hour for every hour spent with a patient. Others estimated that anywhere from 30 minutes to 2 hours per day are devoted to writing notes, and some mentioned doing this in the evening at home. One child psychiatrist with a large high-volume practice noted that he is required to keep charts until a patient reaches adulthood, and that storing, locating, and shredding charts was a time drain.

• Billing the patient. One private practice psychiatrist estimated this takes approximately 8 hours a month, include record-keeping and rebilling patients who failed to pay. Some psychiatrists have a secretary or billing staff.

• Patient insurance. Time spent preauthorizing care, including time spent to preauthorize hospitalizations or to justify each day of inpatient treatment. (No time estimates were offered.)

• Filing claims. The psychiatrists I spoke with who participate with insurers all had support staff to do this.

• Preauthorizing medications. This was by far the biggest complaint by psychiatrists. One noted that it had taken her 2 hours the night before to get a medication authorized; another had spent an hour that day on it. Another rough figure I got was 20-60 minutes a week, and it was noted that preauthorization often is required for very inexpensive medications. Another psychiatrist said her office manager spends a couple of hours a week on preauthorizations and that she had to give her a raise to get her to agree to do it. Personally, I feel insurance companies should not be permitted to divert physician time away from care for inexpensive medications. Does it really make sense to have a physician spend 20 minutes of uncompensated time getting authorization for a medication that costs $10 a month?

• Paperwork related to being credentialed with insurance companies. This was estimated at 40 minutes every 3 months.

• Credentialing. Cost and paperwork for malpractice insurance varies by state and, some malpractice agencies require doctors to do specific forms of training. In addition, practicing requires renewal of a DEA number, CDS renewal (in Maryland), and state licensure.

• Electronic medical records (EMR). Medicare has provided financial incentives to doctors for the meaningful use of certified electronic health record (EHR) technology to improve patient care and now penalizes doctors who do not have this technology. One psychiatrist told me that she spent hundreds of hours working on this, but something went wrong so she is still penalized. Another said she spent 3 hours in a 3-month period attesting to her compliance with meaningful use. Everyone I spoke to said using an electronic record – related to Medicare’s meaningful use or not – increased the time it takes them to write notes. One psychiatrist reduced her clinical care to 1 day a week, and I left a community clinic when the effort of learning to use EPIC overwhelmed me.

• E-prescribing. One colleague in New York wrote, “E-prescribing takes up a lot of time, especially since I don’t do it during sessions. For a noncontrolled medication, it’s maybe 4-5 minutes per prescription. For controlled, it’s 3-4 minutes more, because I have to check I-STOP and use the token, and then record the I-STOP number. And for all prescriptions, I hand write an entry in the medication record, just for backup.” She noted it took several hours to set up the system. Most psychiatrists still spend significant time calling in prescriptions that patients have forgotten to request during appointments, and pharmacists often call to have refills authorized. This can be quite time consuming, and sometimes refills are requested automatically for medications the patients no longer take, and time spent on hold can be significant. My own experience was that e-prescribing took significantly longer than paper prescribing, and that handing a patient a prescription during a session is simply part of medical care and not a “drain,” per se.

• Secretarial. No one was able to give me an estimate of how many hours per week were spent directing, managing, and training support staff, or of how many hours this freed up to see patients. One psychiatrist in a large practice noted that they have 32 full- and part-time professions, including 3 psychiatrists; they participate with insurance, and this requires 18 full-time support staff.

• Office-related issues. Rent – this is both taste and geographically driven, and there are several ways to come by office space. Other factors are time related to restocking supplies, furnishings, technological hardware, phones, faxes, pagers, mobile lines, postage, technology support, cleaning, and assorted office-related issues. I have no time estimates on this; some people have support staff who do most of it, and again, this is part of the routine practice of having a business. It takes time, but it’s not irrelevant. Also, time is spent keeping an office both OSHA and HIPAA compliant.

• Hospital/agency-related requirements:

– Risk management seminars.

– CPR training.

– Health maintenance (required TB testing and flu shot).

• Required learning modules. When I worked 4 hours a week at a hospital clinic, there were many requirements. I watched modules on how to use elevators in buildings I never entered, how to place a central line, hand-washing and infection control, and how to store chemicals I never used. I believe that Maryland state employees may be required to have training in trauma-informed-care.

• Uncompensated time returning calls/communications to patients, families, other clinicians, and prospective patients who then decide not to come in, as well as filling out paperwork for disability claims, other agencies, and writing letters for patients. While this also is part of routine medical care, several people mentioned that other professionals can bill for this work and that insurers can force unnecessary care because only face-to-face treatment gets reimbursed, so issues that might be resolved on the phone or by telepsychiatry then require an office visit.

One colleague was kind enough to examine her own full-time practice and sum up her activities. She came up with an estimate that she devoted 40 hours per month to administrative issues that divert time from seeing patients. This did not include the time she recently devoted to MOC.

Obviously, I want to make the point that part of the psychiatrist shortage is related to the fact that there are administrative demands – many that don’t improve clinical care – that decrease the number of patients we can see and increase the cost of care. In addition to the weekly toll, many of these time drains are frustrating, and serve as disincentives to seeing patients with what time is available. The statistics prove that psychiatrists are less willing than other specialists to participate with insurance networks, and I suspect the litany of clinically irrelevant requirements may lead to earlier retirement by people who might otherwise be willing to practice for more years.

One might ask, at what point do we fight back against spending our time meeting the agendas of agencies and insurers when they aren’t relevant to the care that is needed to help patients?

With thanks to Dr. Mahmood Jarhomi, Dr. Patricia Sullivan, Dr. Sue Kim, Dr. Laura Gaffney, Dr. Maria Yang, Dr. Marsden McGuire, Dr. Annette Hanson, Dr. Robert Herman, Dr. Kimberly Hogan Pesaniello, Dr. Peter Kahn, Dr. Mark Komrad, Dr. Susan Molchan, Dr. Suzy Nashed, and Dr. Rebecca Twersky-Kengmana.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Recently I was contacted by a reporter who wanted to speak to me about why it’s so difficult for patients to find a psychiatrist. She’d found me by Googling “Why psychiatrists don’t take insurance” and already had read an article I’d written with that title. That day, it had snowed hard enough that most of my patients had canceled; the grocery store had closed; and I had plenty of time to chat with a reporter. The other thing I noted – perhaps because other psychiatrists had unexpected free time because of the snow – was that Maryland Psychiatric Society’s listserv was getting a lot of posts. The posts focused on issues to do with maintenance of certification (MOC) or with the fact that every physician in the state was now going to be required to have a CME credit on opioid prescribing for licensure renewal, and there would be a requirement for physicians to take a course on substance abuse to renew their CDS registration. The hope is that these courses will reduce deaths caused by narcotic overdose, and the courses would be required for all physicians without regard to whether they are relevant to their practice.

The reporter and I started with a discussion of why so many psychiatrists have chosen not to accept health insurance (myself included). She then told me about an insured man who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and substance abuse who was unable to get an appointment with a psychiatrist. She asked me an interesting question: “Don’t psychiatrists want the challenge of treating the difficult cases?” The patient in question never did find a psychiatrist in time and he ended up committing a murder then dying by suicide – an awful tragedy that highlights access to care problems.

In addition to a private practice, I have worked in community mental health centers, and I discussed how that setting is often better suited for patients with serious psychiatric illnesses. More services are offered, and having a variety of mental health professionals in the same facility promotes better coordination of care between psychiatrists, therapists, and case managers, as well as with family, residential care providers, and day programs. The problem is that demand for treatment at outpatient clinics is high, and sometimes the waits for an initial appointment are long, or clinics even may stop accepting new patients at times when they get overloaded.

We talked about the logistics and trade-offs of working in a clinic vs. a private practice, and the reasons why working full time in a high-volume clinic might lead physicians to want a change after a few years. And then the reporter asked me another interesting question – with such long waits, why don’t the clinics hire more doctors? I explained that there was a shortage of psychiatrists and began to talk with her about demands on physician time that take time away from patient care. With the e-mails flying about MOC and new course requirements, it was a place to start, but the snow was still falling, and she heard a lot about the factors that drain physician time and money, both limiting how many patients a psychiatrist can see and driving up the cost of care.

By the time I got off the phone, I decided to tally all of the things that we are required to do to see patients. I was able to get some quick help on the listserv, from friends, and on Twitter.

Every time an agency or insurance company sets up a requirement for a physician, there is a small diversion of time. There is no limit on how many different requirements can be set or whether they need to be relevant to the physician’s work. While I realize there is little sympathy for physicians who, for the most part, are still blessed to earn a good living while doing meaningful work, these diversions add hours to a doctor’s day and cause them to burn out more quickly. So the insurance company that demands that a physician devote 20 minutes to get authorization to prescribe a medication that costs pennies a pill is actually harming society. And no one oversees the big picture.

That said, here was the list we came up with of factors that drain time and money in a clinical practice. Please note that some of these items – for example, uncompensated time returning calls to patients or keeping clinical records – are just part of being a doctor; they’re not something that should be eliminated. Similarly, issues related to having a space to work are part of having a business. I wanted the list to be complete to illustrate the demands on a psychiatrist, not to suggest that none of these things are important. Obviously, some doctors are faster or slower at certain tasks, and people vary greatly in how much time they devote to clinical practice vs. teaching, research, or writing articles for Clinical Psychiatry News. I obtained information in a very quick and casual manner; none of this should be construed as scientific.

Here is the list:

• Maintenance of certification requirements and testing. This is required every 10 years and one estimate was that the cost to register, take the test, and purchase review materials came to $2,800, with a time investment of about 50 hours. Some specialties are pushing back against MOC, and some physicians are forgoing board certification. Psychiatrists who subspecialize usually do MOC for general psychiatry and all their subspecialties.

• CME. Twenty to 50 hours per year depending on your state, and presumably physicians choose courses that enrich their ability to practice medicine. This can be expensive, depending on how the physician decides to get these credits, and many valuable learning events do not qualify for CME.

• Writing clinical notes. Again, this is part of routine medical care. Notes must justify the CPT codes on insurance claims, and very specific areas of inquiry and examination are needed to justify billing specific codes. Agency requirements may be different from what is clinically indicated for the care of the patient, and this uses some of the appointment time in a way that may not be helpful to medical care. Copying, faxing, or sending notes to other clinicians and time spent requesting records all add to the mix. One psychiatrist noted that the overall administrative responsibilities for seeing patients takes half an hour for every hour spent with a patient. Others estimated that anywhere from 30 minutes to 2 hours per day are devoted to writing notes, and some mentioned doing this in the evening at home. One child psychiatrist with a large high-volume practice noted that he is required to keep charts until a patient reaches adulthood, and that storing, locating, and shredding charts was a time drain.

• Billing the patient. One private practice psychiatrist estimated this takes approximately 8 hours a month, include record-keeping and rebilling patients who failed to pay. Some psychiatrists have a secretary or billing staff.

• Patient insurance. Time spent preauthorizing care, including time spent to preauthorize hospitalizations or to justify each day of inpatient treatment. (No time estimates were offered.)

• Filing claims. The psychiatrists I spoke with who participate with insurers all had support staff to do this.

• Preauthorizing medications. This was by far the biggest complaint by psychiatrists. One noted that it had taken her 2 hours the night before to get a medication authorized; another had spent an hour that day on it. Another rough figure I got was 20-60 minutes a week, and it was noted that preauthorization often is required for very inexpensive medications. Another psychiatrist said her office manager spends a couple of hours a week on preauthorizations and that she had to give her a raise to get her to agree to do it. Personally, I feel insurance companies should not be permitted to divert physician time away from care for inexpensive medications. Does it really make sense to have a physician spend 20 minutes of uncompensated time getting authorization for a medication that costs $10 a month?

• Paperwork related to being credentialed with insurance companies. This was estimated at 40 minutes every 3 months.

• Credentialing. Cost and paperwork for malpractice insurance varies by state and, some malpractice agencies require doctors to do specific forms of training. In addition, practicing requires renewal of a DEA number, CDS renewal (in Maryland), and state licensure.

• Electronic medical records (EMR). Medicare has provided financial incentives to doctors for the meaningful use of certified electronic health record (EHR) technology to improve patient care and now penalizes doctors who do not have this technology. One psychiatrist told me that she spent hundreds of hours working on this, but something went wrong so she is still penalized. Another said she spent 3 hours in a 3-month period attesting to her compliance with meaningful use. Everyone I spoke to said using an electronic record – related to Medicare’s meaningful use or not – increased the time it takes them to write notes. One psychiatrist reduced her clinical care to 1 day a week, and I left a community clinic when the effort of learning to use EPIC overwhelmed me.

• E-prescribing. One colleague in New York wrote, “E-prescribing takes up a lot of time, especially since I don’t do it during sessions. For a noncontrolled medication, it’s maybe 4-5 minutes per prescription. For controlled, it’s 3-4 minutes more, because I have to check I-STOP and use the token, and then record the I-STOP number. And for all prescriptions, I hand write an entry in the medication record, just for backup.” She noted it took several hours to set up the system. Most psychiatrists still spend significant time calling in prescriptions that patients have forgotten to request during appointments, and pharmacists often call to have refills authorized. This can be quite time consuming, and sometimes refills are requested automatically for medications the patients no longer take, and time spent on hold can be significant. My own experience was that e-prescribing took significantly longer than paper prescribing, and that handing a patient a prescription during a session is simply part of medical care and not a “drain,” per se.

• Secretarial. No one was able to give me an estimate of how many hours per week were spent directing, managing, and training support staff, or of how many hours this freed up to see patients. One psychiatrist in a large practice noted that they have 32 full- and part-time professions, including 3 psychiatrists; they participate with insurance, and this requires 18 full-time support staff.

• Office-related issues. Rent – this is both taste and geographically driven, and there are several ways to come by office space. Other factors are time related to restocking supplies, furnishings, technological hardware, phones, faxes, pagers, mobile lines, postage, technology support, cleaning, and assorted office-related issues. I have no time estimates on this; some people have support staff who do most of it, and again, this is part of the routine practice of having a business. It takes time, but it’s not irrelevant. Also, time is spent keeping an office both OSHA and HIPAA compliant.

• Hospital/agency-related requirements:

– Risk management seminars.

– CPR training.

– Health maintenance (required TB testing and flu shot).

• Required learning modules. When I worked 4 hours a week at a hospital clinic, there were many requirements. I watched modules on how to use elevators in buildings I never entered, how to place a central line, hand-washing and infection control, and how to store chemicals I never used. I believe that Maryland state employees may be required to have training in trauma-informed-care.

• Uncompensated time returning calls/communications to patients, families, other clinicians, and prospective patients who then decide not to come in, as well as filling out paperwork for disability claims, other agencies, and writing letters for patients. While this also is part of routine medical care, several people mentioned that other professionals can bill for this work and that insurers can force unnecessary care because only face-to-face treatment gets reimbursed, so issues that might be resolved on the phone or by telepsychiatry then require an office visit.

One colleague was kind enough to examine her own full-time practice and sum up her activities. She came up with an estimate that she devoted 40 hours per month to administrative issues that divert time from seeing patients. This did not include the time she recently devoted to MOC.

Obviously, I want to make the point that part of the psychiatrist shortage is related to the fact that there are administrative demands – many that don’t improve clinical care – that decrease the number of patients we can see and increase the cost of care. In addition to the weekly toll, many of these time drains are frustrating, and serve as disincentives to seeing patients with what time is available. The statistics prove that psychiatrists are less willing than other specialists to participate with insurance networks, and I suspect the litany of clinically irrelevant requirements may lead to earlier retirement by people who might otherwise be willing to practice for more years.

One might ask, at what point do we fight back against spending our time meeting the agendas of agencies and insurers when they aren’t relevant to the care that is needed to help patients?

With thanks to Dr. Mahmood Jarhomi, Dr. Patricia Sullivan, Dr. Sue Kim, Dr. Laura Gaffney, Dr. Maria Yang, Dr. Marsden McGuire, Dr. Annette Hanson, Dr. Robert Herman, Dr. Kimberly Hogan Pesaniello, Dr. Peter Kahn, Dr. Mark Komrad, Dr. Susan Molchan, Dr. Suzy Nashed, and Dr. Rebecca Twersky-Kengmana.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Recently I was contacted by a reporter who wanted to speak to me about why it’s so difficult for patients to find a psychiatrist. She’d found me by Googling “Why psychiatrists don’t take insurance” and already had read an article I’d written with that title. That day, it had snowed hard enough that most of my patients had canceled; the grocery store had closed; and I had plenty of time to chat with a reporter. The other thing I noted – perhaps because other psychiatrists had unexpected free time because of the snow – was that Maryland Psychiatric Society’s listserv was getting a lot of posts. The posts focused on issues to do with maintenance of certification (MOC) or with the fact that every physician in the state was now going to be required to have a CME credit on opioid prescribing for licensure renewal, and there would be a requirement for physicians to take a course on substance abuse to renew their CDS registration. The hope is that these courses will reduce deaths caused by narcotic overdose, and the courses would be required for all physicians without regard to whether they are relevant to their practice.

The reporter and I started with a discussion of why so many psychiatrists have chosen not to accept health insurance (myself included). She then told me about an insured man who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and substance abuse who was unable to get an appointment with a psychiatrist. She asked me an interesting question: “Don’t psychiatrists want the challenge of treating the difficult cases?” The patient in question never did find a psychiatrist in time and he ended up committing a murder then dying by suicide – an awful tragedy that highlights access to care problems.

In addition to a private practice, I have worked in community mental health centers, and I discussed how that setting is often better suited for patients with serious psychiatric illnesses. More services are offered, and having a variety of mental health professionals in the same facility promotes better coordination of care between psychiatrists, therapists, and case managers, as well as with family, residential care providers, and day programs. The problem is that demand for treatment at outpatient clinics is high, and sometimes the waits for an initial appointment are long, or clinics even may stop accepting new patients at times when they get overloaded.

We talked about the logistics and trade-offs of working in a clinic vs. a private practice, and the reasons why working full time in a high-volume clinic might lead physicians to want a change after a few years. And then the reporter asked me another interesting question – with such long waits, why don’t the clinics hire more doctors? I explained that there was a shortage of psychiatrists and began to talk with her about demands on physician time that take time away from patient care. With the e-mails flying about MOC and new course requirements, it was a place to start, but the snow was still falling, and she heard a lot about the factors that drain physician time and money, both limiting how many patients a psychiatrist can see and driving up the cost of care.

By the time I got off the phone, I decided to tally all of the things that we are required to do to see patients. I was able to get some quick help on the listserv, from friends, and on Twitter.

Every time an agency or insurance company sets up a requirement for a physician, there is a small diversion of time. There is no limit on how many different requirements can be set or whether they need to be relevant to the physician’s work. While I realize there is little sympathy for physicians who, for the most part, are still blessed to earn a good living while doing meaningful work, these diversions add hours to a doctor’s day and cause them to burn out more quickly. So the insurance company that demands that a physician devote 20 minutes to get authorization to prescribe a medication that costs pennies a pill is actually harming society. And no one oversees the big picture.

That said, here was the list we came up with of factors that drain time and money in a clinical practice. Please note that some of these items – for example, uncompensated time returning calls to patients or keeping clinical records – are just part of being a doctor; they’re not something that should be eliminated. Similarly, issues related to having a space to work are part of having a business. I wanted the list to be complete to illustrate the demands on a psychiatrist, not to suggest that none of these things are important. Obviously, some doctors are faster or slower at certain tasks, and people vary greatly in how much time they devote to clinical practice vs. teaching, research, or writing articles for Clinical Psychiatry News. I obtained information in a very quick and casual manner; none of this should be construed as scientific.

Here is the list:

• Maintenance of certification requirements and testing. This is required every 10 years and one estimate was that the cost to register, take the test, and purchase review materials came to $2,800, with a time investment of about 50 hours. Some specialties are pushing back against MOC, and some physicians are forgoing board certification. Psychiatrists who subspecialize usually do MOC for general psychiatry and all their subspecialties.

• CME. Twenty to 50 hours per year depending on your state, and presumably physicians choose courses that enrich their ability to practice medicine. This can be expensive, depending on how the physician decides to get these credits, and many valuable learning events do not qualify for CME.

• Writing clinical notes. Again, this is part of routine medical care. Notes must justify the CPT codes on insurance claims, and very specific areas of inquiry and examination are needed to justify billing specific codes. Agency requirements may be different from what is clinically indicated for the care of the patient, and this uses some of the appointment time in a way that may not be helpful to medical care. Copying, faxing, or sending notes to other clinicians and time spent requesting records all add to the mix. One psychiatrist noted that the overall administrative responsibilities for seeing patients takes half an hour for every hour spent with a patient. Others estimated that anywhere from 30 minutes to 2 hours per day are devoted to writing notes, and some mentioned doing this in the evening at home. One child psychiatrist with a large high-volume practice noted that he is required to keep charts until a patient reaches adulthood, and that storing, locating, and shredding charts was a time drain.

• Billing the patient. One private practice psychiatrist estimated this takes approximately 8 hours a month, include record-keeping and rebilling patients who failed to pay. Some psychiatrists have a secretary or billing staff.

• Patient insurance. Time spent preauthorizing care, including time spent to preauthorize hospitalizations or to justify each day of inpatient treatment. (No time estimates were offered.)

• Filing claims. The psychiatrists I spoke with who participate with insurers all had support staff to do this.

• Preauthorizing medications. This was by far the biggest complaint by psychiatrists. One noted that it had taken her 2 hours the night before to get a medication authorized; another had spent an hour that day on it. Another rough figure I got was 20-60 minutes a week, and it was noted that preauthorization often is required for very inexpensive medications. Another psychiatrist said her office manager spends a couple of hours a week on preauthorizations and that she had to give her a raise to get her to agree to do it. Personally, I feel insurance companies should not be permitted to divert physician time away from care for inexpensive medications. Does it really make sense to have a physician spend 20 minutes of uncompensated time getting authorization for a medication that costs $10 a month?

• Paperwork related to being credentialed with insurance companies. This was estimated at 40 minutes every 3 months.

• Credentialing. Cost and paperwork for malpractice insurance varies by state and, some malpractice agencies require doctors to do specific forms of training. In addition, practicing requires renewal of a DEA number, CDS renewal (in Maryland), and state licensure.

• Electronic medical records (EMR). Medicare has provided financial incentives to doctors for the meaningful use of certified electronic health record (EHR) technology to improve patient care and now penalizes doctors who do not have this technology. One psychiatrist told me that she spent hundreds of hours working on this, but something went wrong so she is still penalized. Another said she spent 3 hours in a 3-month period attesting to her compliance with meaningful use. Everyone I spoke to said using an electronic record – related to Medicare’s meaningful use or not – increased the time it takes them to write notes. One psychiatrist reduced her clinical care to 1 day a week, and I left a community clinic when the effort of learning to use EPIC overwhelmed me.

• E-prescribing. One colleague in New York wrote, “E-prescribing takes up a lot of time, especially since I don’t do it during sessions. For a noncontrolled medication, it’s maybe 4-5 minutes per prescription. For controlled, it’s 3-4 minutes more, because I have to check I-STOP and use the token, and then record the I-STOP number. And for all prescriptions, I hand write an entry in the medication record, just for backup.” She noted it took several hours to set up the system. Most psychiatrists still spend significant time calling in prescriptions that patients have forgotten to request during appointments, and pharmacists often call to have refills authorized. This can be quite time consuming, and sometimes refills are requested automatically for medications the patients no longer take, and time spent on hold can be significant. My own experience was that e-prescribing took significantly longer than paper prescribing, and that handing a patient a prescription during a session is simply part of medical care and not a “drain,” per se.

• Secretarial. No one was able to give me an estimate of how many hours per week were spent directing, managing, and training support staff, or of how many hours this freed up to see patients. One psychiatrist in a large practice noted that they have 32 full- and part-time professions, including 3 psychiatrists; they participate with insurance, and this requires 18 full-time support staff.

• Office-related issues. Rent – this is both taste and geographically driven, and there are several ways to come by office space. Other factors are time related to restocking supplies, furnishings, technological hardware, phones, faxes, pagers, mobile lines, postage, technology support, cleaning, and assorted office-related issues. I have no time estimates on this; some people have support staff who do most of it, and again, this is part of the routine practice of having a business. It takes time, but it’s not irrelevant. Also, time is spent keeping an office both OSHA and HIPAA compliant.

• Hospital/agency-related requirements:

– Risk management seminars.

– CPR training.

– Health maintenance (required TB testing and flu shot).

• Required learning modules. When I worked 4 hours a week at a hospital clinic, there were many requirements. I watched modules on how to use elevators in buildings I never entered, how to place a central line, hand-washing and infection control, and how to store chemicals I never used. I believe that Maryland state employees may be required to have training in trauma-informed-care.

• Uncompensated time returning calls/communications to patients, families, other clinicians, and prospective patients who then decide not to come in, as well as filling out paperwork for disability claims, other agencies, and writing letters for patients. While this also is part of routine medical care, several people mentioned that other professionals can bill for this work and that insurers can force unnecessary care because only face-to-face treatment gets reimbursed, so issues that might be resolved on the phone or by telepsychiatry then require an office visit.

One colleague was kind enough to examine her own full-time practice and sum up her activities. She came up with an estimate that she devoted 40 hours per month to administrative issues that divert time from seeing patients. This did not include the time she recently devoted to MOC.

Obviously, I want to make the point that part of the psychiatrist shortage is related to the fact that there are administrative demands – many that don’t improve clinical care – that decrease the number of patients we can see and increase the cost of care. In addition to the weekly toll, many of these time drains are frustrating, and serve as disincentives to seeing patients with what time is available. The statistics prove that psychiatrists are less willing than other specialists to participate with insurance networks, and I suspect the litany of clinically irrelevant requirements may lead to earlier retirement by people who might otherwise be willing to practice for more years.

One might ask, at what point do we fight back against spending our time meeting the agendas of agencies and insurers when they aren’t relevant to the care that is needed to help patients?

With thanks to Dr. Mahmood Jarhomi, Dr. Patricia Sullivan, Dr. Sue Kim, Dr. Laura Gaffney, Dr. Maria Yang, Dr. Marsden McGuire, Dr. Annette Hanson, Dr. Robert Herman, Dr. Kimberly Hogan Pesaniello, Dr. Peter Kahn, Dr. Mark Komrad, Dr. Susan Molchan, Dr. Suzy Nashed, and Dr. Rebecca Twersky-Kengmana.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Hormone therapy 10 years post menopause increases risks

Hormone therapy in postmenopausal women does not prevent heart disease but does increase the risk of stroke and blood clots, according to a recently updated Cochrane review.

“Our review findings provide strong evidence that treatment with hormone therapy in postmenopausal women for either primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease events has little if any benefit overall, and causes an increase in the risk of stroke, or venous thromboembolic events,” reported Dr. Henry Boardman of the University of Oxford John Radcliffe Hospital, and his associates.

The researchers updated a review published in 2013 with data from an additional six randomized controlled trials. The total of 19 trials, involving 40,410 postmenopausal women, all compared orally-administered estrogen, with or without progestogen, to a placebo or no treatment for a minimum of 6 months (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015 March 10 [doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002229.pub4]).

The average age of the women in the studies, mostly from the United States, was older than 60 years, and the women received hormone therapy anywhere from 7 months to 10 years across the studies. The overall quality of the studies was “good” with a low risk of bias.

The sharp rise in cardiovascular disease rates in women after menopause had been hypothesized to be related to a decline in hormone levels that causes a higher androgen-to-estradiol ratio, and observational studies starting in the 1980s showed lower mortality rates and cardiovascular events in women receiving hormone therapy – previously called hormone replacement therapy – compared to those not receiving hormone therapy.

Two subsequent randomized controlled trials contradicted these observational findings, though, leading to further study. In this review, hormone therapy showed no risk reduction for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, angina, or revascularization.

However, the overall risk of stroke for those receiving hormone therapy for both primary and secondary prevention was 24% higher than that of women receiving placebo treatment (relative risk 1.24), with an absolute risk of 6 additional strokes per 1,000 women.

Venous thromboembolic events occurred 92% more and pulmonary emboli occurred 81% more in the hormone treatment groups (RR 1.92 and 1.81, respectively), with increased absolute risks of 8 per 1,000 women and 4 per 1,000 women, respectively.

The researchers calculated the number needed to treat for an additional harm (NNTH) at 165 women for stroke, 118 for venous thromboembolism, and 242 for pulmonary embolism.

Further analysis revealed that the relative risks or protection hormone therapy conferred depended on how long after menopause women started treatment.

Mortality was reduced 30% and coronary heart disease was reduced 48% in women who began hormone therapy less than 10 years after menopause (RR 0.70 and RR 0.52, respectively); these women still faced a 74% increased risk of venous thromboembolism, but no increased risk of stroke.

Meanwhile, women who started hormone therapy more than 10 years after menopause had a 21% increased risk of stroke and a 96% increased risk of venous thromboembolism, but no reduced risk on overall death or coronary heart disease.

“It is worth noting that the benefit seen in survival and coronary heart disease for the group starting treatment less than 10 years after the menopause is from combining five trials all performed in primary prevention populations and all with quite long follow-up, ranging from 3.4 to 10.1 years,” the authors wrote.

These results may reflect the possibility of a time interaction, with coronary heart disease events occurring earlier in predisposed women, making it impossible to say whether short duration therapy is beneficial in this population or not, the researchers wrote .

Eighteen of the 19 trials included in the analysis reported the funding source. One study was exclusively funded by Wyeth-Ayerst. Two studies received partial funding from Novo-Nordisk Pharmaceutical, and one study was funded by the National Institutes of Health with support from Wyeth-Ayerst, Hoffman-LaRoche, Pharmacia, and Upjohn. Eight other studies used medication provided by various pharmaceutical companies.

Hormone therapy in postmenopausal women does not prevent heart disease but does increase the risk of stroke and blood clots, according to a recently updated Cochrane review.

“Our review findings provide strong evidence that treatment with hormone therapy in postmenopausal women for either primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease events has little if any benefit overall, and causes an increase in the risk of stroke, or venous thromboembolic events,” reported Dr. Henry Boardman of the University of Oxford John Radcliffe Hospital, and his associates.

The researchers updated a review published in 2013 with data from an additional six randomized controlled trials. The total of 19 trials, involving 40,410 postmenopausal women, all compared orally-administered estrogen, with or without progestogen, to a placebo or no treatment for a minimum of 6 months (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015 March 10 [doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002229.pub4]).

The average age of the women in the studies, mostly from the United States, was older than 60 years, and the women received hormone therapy anywhere from 7 months to 10 years across the studies. The overall quality of the studies was “good” with a low risk of bias.

The sharp rise in cardiovascular disease rates in women after menopause had been hypothesized to be related to a decline in hormone levels that causes a higher androgen-to-estradiol ratio, and observational studies starting in the 1980s showed lower mortality rates and cardiovascular events in women receiving hormone therapy – previously called hormone replacement therapy – compared to those not receiving hormone therapy.

Two subsequent randomized controlled trials contradicted these observational findings, though, leading to further study. In this review, hormone therapy showed no risk reduction for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, angina, or revascularization.

However, the overall risk of stroke for those receiving hormone therapy for both primary and secondary prevention was 24% higher than that of women receiving placebo treatment (relative risk 1.24), with an absolute risk of 6 additional strokes per 1,000 women.

Venous thromboembolic events occurred 92% more and pulmonary emboli occurred 81% more in the hormone treatment groups (RR 1.92 and 1.81, respectively), with increased absolute risks of 8 per 1,000 women and 4 per 1,000 women, respectively.

The researchers calculated the number needed to treat for an additional harm (NNTH) at 165 women for stroke, 118 for venous thromboembolism, and 242 for pulmonary embolism.

Further analysis revealed that the relative risks or protection hormone therapy conferred depended on how long after menopause women started treatment.

Mortality was reduced 30% and coronary heart disease was reduced 48% in women who began hormone therapy less than 10 years after menopause (RR 0.70 and RR 0.52, respectively); these women still faced a 74% increased risk of venous thromboembolism, but no increased risk of stroke.

Meanwhile, women who started hormone therapy more than 10 years after menopause had a 21% increased risk of stroke and a 96% increased risk of venous thromboembolism, but no reduced risk on overall death or coronary heart disease.

“It is worth noting that the benefit seen in survival and coronary heart disease for the group starting treatment less than 10 years after the menopause is from combining five trials all performed in primary prevention populations and all with quite long follow-up, ranging from 3.4 to 10.1 years,” the authors wrote.

These results may reflect the possibility of a time interaction, with coronary heart disease events occurring earlier in predisposed women, making it impossible to say whether short duration therapy is beneficial in this population or not, the researchers wrote .

Eighteen of the 19 trials included in the analysis reported the funding source. One study was exclusively funded by Wyeth-Ayerst. Two studies received partial funding from Novo-Nordisk Pharmaceutical, and one study was funded by the National Institutes of Health with support from Wyeth-Ayerst, Hoffman-LaRoche, Pharmacia, and Upjohn. Eight other studies used medication provided by various pharmaceutical companies.

Hormone therapy in postmenopausal women does not prevent heart disease but does increase the risk of stroke and blood clots, according to a recently updated Cochrane review.

“Our review findings provide strong evidence that treatment with hormone therapy in postmenopausal women for either primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease events has little if any benefit overall, and causes an increase in the risk of stroke, or venous thromboembolic events,” reported Dr. Henry Boardman of the University of Oxford John Radcliffe Hospital, and his associates.

The researchers updated a review published in 2013 with data from an additional six randomized controlled trials. The total of 19 trials, involving 40,410 postmenopausal women, all compared orally-administered estrogen, with or without progestogen, to a placebo or no treatment for a minimum of 6 months (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015 March 10 [doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002229.pub4]).

The average age of the women in the studies, mostly from the United States, was older than 60 years, and the women received hormone therapy anywhere from 7 months to 10 years across the studies. The overall quality of the studies was “good” with a low risk of bias.

The sharp rise in cardiovascular disease rates in women after menopause had been hypothesized to be related to a decline in hormone levels that causes a higher androgen-to-estradiol ratio, and observational studies starting in the 1980s showed lower mortality rates and cardiovascular events in women receiving hormone therapy – previously called hormone replacement therapy – compared to those not receiving hormone therapy.

Two subsequent randomized controlled trials contradicted these observational findings, though, leading to further study. In this review, hormone therapy showed no risk reduction for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, angina, or revascularization.

However, the overall risk of stroke for those receiving hormone therapy for both primary and secondary prevention was 24% higher than that of women receiving placebo treatment (relative risk 1.24), with an absolute risk of 6 additional strokes per 1,000 women.

Venous thromboembolic events occurred 92% more and pulmonary emboli occurred 81% more in the hormone treatment groups (RR 1.92 and 1.81, respectively), with increased absolute risks of 8 per 1,000 women and 4 per 1,000 women, respectively.

The researchers calculated the number needed to treat for an additional harm (NNTH) at 165 women for stroke, 118 for venous thromboembolism, and 242 for pulmonary embolism.

Further analysis revealed that the relative risks or protection hormone therapy conferred depended on how long after menopause women started treatment.

Mortality was reduced 30% and coronary heart disease was reduced 48% in women who began hormone therapy less than 10 years after menopause (RR 0.70 and RR 0.52, respectively); these women still faced a 74% increased risk of venous thromboembolism, but no increased risk of stroke.

Meanwhile, women who started hormone therapy more than 10 years after menopause had a 21% increased risk of stroke and a 96% increased risk of venous thromboembolism, but no reduced risk on overall death or coronary heart disease.

“It is worth noting that the benefit seen in survival and coronary heart disease for the group starting treatment less than 10 years after the menopause is from combining five trials all performed in primary prevention populations and all with quite long follow-up, ranging from 3.4 to 10.1 years,” the authors wrote.

These results may reflect the possibility of a time interaction, with coronary heart disease events occurring earlier in predisposed women, making it impossible to say whether short duration therapy is beneficial in this population or not, the researchers wrote .

Eighteen of the 19 trials included in the analysis reported the funding source. One study was exclusively funded by Wyeth-Ayerst. Two studies received partial funding from Novo-Nordisk Pharmaceutical, and one study was funded by the National Institutes of Health with support from Wyeth-Ayerst, Hoffman-LaRoche, Pharmacia, and Upjohn. Eight other studies used medication provided by various pharmaceutical companies.

FROM COCHRANE DATABASE OF SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

Key clinical point: Hormone therapy in postmenopausal women increases stroke risk.

Major finding: Stroke increased by 24%, venous thromboembolism by 92%, and pulmonary embolism by 81% in postmenopausal women receiving hormone therapy.

Data source: A review and meta-analysis of 19 randomized controlled trials involving 40,140 postmenopausal women who received orally-administered hormone therapy, placebo, or no treatment for prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Disclosures: One study was funded by Wyeth-Ayerst. Two studies received partial funding from Novo-Nordisk Pharmaceutical, and one study was funded by the National Institutes of Health with support from Wyeth-Ayerst, Hoffman-LaRoche, Pharmacia, and Upjohn. Eight other studies used medication provided by various pharmaceutical companies.

VIDEO: Meet Frankie and Sophie, the thyroid cancer–sniffing dogs

SAN DIEGO – Researchers at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock are teaching dogs to detect thyroid cancer from urine samples.

The dogs become alert on samples if they detect cancer, but remain passive if they don’t. The first graduate of the program, a German shepherd mix named Frankie, got it right in 30 of 34 cases, matching final surgical pathology results with a sensitivity of 86.6% and a specificity of 89.5%.

With results like those, it might not be too long before Frankie and his colleagues are providing inexpensive adjunct diagnostic services when test results are uncertain, and helping underserved areas with limited diagnostic capacity, the researchers noted.

At the Endocrine Society meeting, investigator Dr. Andrew Hinson shared clips of Frankie and another recent graduate, a border collie mix named Sophie, and explained the project’s next steps.

Frankie was rescued by principal investigator Dr. Arny Ferrando. Sophie and other dogs in the program were also rescued from local animal shelters.

More information is available at www.thefrankiefoundation.org.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN DIEGO – Researchers at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock are teaching dogs to detect thyroid cancer from urine samples.

The dogs become alert on samples if they detect cancer, but remain passive if they don’t. The first graduate of the program, a German shepherd mix named Frankie, got it right in 30 of 34 cases, matching final surgical pathology results with a sensitivity of 86.6% and a specificity of 89.5%.

With results like those, it might not be too long before Frankie and his colleagues are providing inexpensive adjunct diagnostic services when test results are uncertain, and helping underserved areas with limited diagnostic capacity, the researchers noted.

At the Endocrine Society meeting, investigator Dr. Andrew Hinson shared clips of Frankie and another recent graduate, a border collie mix named Sophie, and explained the project’s next steps.

Frankie was rescued by principal investigator Dr. Arny Ferrando. Sophie and other dogs in the program were also rescued from local animal shelters.

More information is available at www.thefrankiefoundation.org.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN DIEGO – Researchers at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock are teaching dogs to detect thyroid cancer from urine samples.

The dogs become alert on samples if they detect cancer, but remain passive if they don’t. The first graduate of the program, a German shepherd mix named Frankie, got it right in 30 of 34 cases, matching final surgical pathology results with a sensitivity of 86.6% and a specificity of 89.5%.

With results like those, it might not be too long before Frankie and his colleagues are providing inexpensive adjunct diagnostic services when test results are uncertain, and helping underserved areas with limited diagnostic capacity, the researchers noted.

At the Endocrine Society meeting, investigator Dr. Andrew Hinson shared clips of Frankie and another recent graduate, a border collie mix named Sophie, and explained the project’s next steps.

Frankie was rescued by principal investigator Dr. Arny Ferrando. Sophie and other dogs in the program were also rescued from local animal shelters.

More information is available at www.thefrankiefoundation.org.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT ENDO 2015

Heparin, warfarin tied to similar VTE rates after radical cystectomy

Venous thromboembolisms affected 6.4% of patients who underwent radical cystectomy, even though all patients received heparin in the hospital as recommended by the American Urological Association, researchers reported.

“Using an in-house, heparin-based anticoagulation protocol consistent with current AUA guidelines has not decreased the rate of venous thromboembolism compared to historical warfarin use,” wrote Dr. Andrew Sun and his colleagues at the University of Southern California Institute of Urology in Los Angeles. Most episodes of VTE occurred after patients were discharged home, and “future studies are needed to establish the benefits of extended-duration [VTE] prophylaxis regimens that cover the critical posthospitalization period,” the researchers added (J. UroL 2015;193:565-9).

Previous studies have reported venous thromboembolism rates of 3%-6% in cystectomy patients, a rate that is more than double that reported for nephrectomy or prostatectomy patients. For their study, the investigators retrospectively assessed 2,316 patients who underwent open radical cystectomy and extended pelvic lymph node dissection for urothelial bladder cancer between 1971 and 2012. Symptomatic VTE developed among 109 patients overall (4.7%), compared with 6.4% of those who received the modern, heparin-based protocol implemented in 2009 (P = .089).

Furthermore, 58% of all cases occurred after patients stopped anticoagulation therapy and were discharged home. The median time of onset was 20 days after surgery (range, 2-91 days), and VTE was significantly more common among patients with a higher body mass index, prolonged hospital stays, positive surgical margins and orthotopic diversion procedures, compared with other patients. Surgical techniques remained consistent throughout the study.

The study was retrospective, and thus “could not prove any cause and effect relationships. This underscores the need for additional prospective data in this area of research,” said the investigators. “We focused only on open radical cystectomy, and thus, findings may not be generalizable to minimally invasive modalities, on which there is even a greater paucity of data.”

Senior author Dr. Siamak Daneshmand reported financial or other relationships with Endo and Cubist. The authors reported no funding sources or other relevant conflicts of interest.

Venous thromboembolisms affected 6.4% of patients who underwent radical cystectomy, even though all patients received heparin in the hospital as recommended by the American Urological Association, researchers reported.

“Using an in-house, heparin-based anticoagulation protocol consistent with current AUA guidelines has not decreased the rate of venous thromboembolism compared to historical warfarin use,” wrote Dr. Andrew Sun and his colleagues at the University of Southern California Institute of Urology in Los Angeles. Most episodes of VTE occurred after patients were discharged home, and “future studies are needed to establish the benefits of extended-duration [VTE] prophylaxis regimens that cover the critical posthospitalization period,” the researchers added (J. UroL 2015;193:565-9).

Previous studies have reported venous thromboembolism rates of 3%-6% in cystectomy patients, a rate that is more than double that reported for nephrectomy or prostatectomy patients. For their study, the investigators retrospectively assessed 2,316 patients who underwent open radical cystectomy and extended pelvic lymph node dissection for urothelial bladder cancer between 1971 and 2012. Symptomatic VTE developed among 109 patients overall (4.7%), compared with 6.4% of those who received the modern, heparin-based protocol implemented in 2009 (P = .089).

Furthermore, 58% of all cases occurred after patients stopped anticoagulation therapy and were discharged home. The median time of onset was 20 days after surgery (range, 2-91 days), and VTE was significantly more common among patients with a higher body mass index, prolonged hospital stays, positive surgical margins and orthotopic diversion procedures, compared with other patients. Surgical techniques remained consistent throughout the study.

The study was retrospective, and thus “could not prove any cause and effect relationships. This underscores the need for additional prospective data in this area of research,” said the investigators. “We focused only on open radical cystectomy, and thus, findings may not be generalizable to minimally invasive modalities, on which there is even a greater paucity of data.”

Senior author Dr. Siamak Daneshmand reported financial or other relationships with Endo and Cubist. The authors reported no funding sources or other relevant conflicts of interest.

Venous thromboembolisms affected 6.4% of patients who underwent radical cystectomy, even though all patients received heparin in the hospital as recommended by the American Urological Association, researchers reported.

“Using an in-house, heparin-based anticoagulation protocol consistent with current AUA guidelines has not decreased the rate of venous thromboembolism compared to historical warfarin use,” wrote Dr. Andrew Sun and his colleagues at the University of Southern California Institute of Urology in Los Angeles. Most episodes of VTE occurred after patients were discharged home, and “future studies are needed to establish the benefits of extended-duration [VTE] prophylaxis regimens that cover the critical posthospitalization period,” the researchers added (J. UroL 2015;193:565-9).

Previous studies have reported venous thromboembolism rates of 3%-6% in cystectomy patients, a rate that is more than double that reported for nephrectomy or prostatectomy patients. For their study, the investigators retrospectively assessed 2,316 patients who underwent open radical cystectomy and extended pelvic lymph node dissection for urothelial bladder cancer between 1971 and 2012. Symptomatic VTE developed among 109 patients overall (4.7%), compared with 6.4% of those who received the modern, heparin-based protocol implemented in 2009 (P = .089).

Furthermore, 58% of all cases occurred after patients stopped anticoagulation therapy and were discharged home. The median time of onset was 20 days after surgery (range, 2-91 days), and VTE was significantly more common among patients with a higher body mass index, prolonged hospital stays, positive surgical margins and orthotopic diversion procedures, compared with other patients. Surgical techniques remained consistent throughout the study.

The study was retrospective, and thus “could not prove any cause and effect relationships. This underscores the need for additional prospective data in this area of research,” said the investigators. “We focused only on open radical cystectomy, and thus, findings may not be generalizable to minimally invasive modalities, on which there is even a greater paucity of data.”

Senior author Dr. Siamak Daneshmand reported financial or other relationships with Endo and Cubist. The authors reported no funding sources or other relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF UROLOGY

Key clinical point: Heparin and warfarin were linked to similar rates of postcystectomy venous thromboembolism.

Major finding: Symptomatic VTE affected 4.7% of patients in the overall cohort, compared with 6.4% of those treated with the modern, heparin-based protocol (P = .089).

Data source: A single-center retrospective cohort study of 2,316 patients who underwent open radical cystectomy and extended pelvic lymph node dissection.

Disclosures: Senior author Dr. Siamak Daneshmand reported financial or other relationships with Endo and Cubist. The authors reported no funding sources or other relevant conflicts of interest.

Questions on stroke ambulance feasibility

The TPA ambulance, armed with its own CT scanner, has arrived in the United States after several successful years in Germany.

Now what?

Like all new advances, it’s a difficult balance between costs and benefits. The money, in the end, is what it really comes down to. Will the cost of a CT ambulance, the equipment needed to send images to a radiologist, the extra training for EMTs, the price of stocking TPA on board, and maybe even having a neurologist on the ride (or telemedicine for one to see the patient) be offset by money saved on rehabilitation costs, better recoveries, fewer complications, even returning a patient to work?

I have no idea. I’m not sure anyone else does, either.

Certainly, I support the idea of improved stroke care. Although far from ideal, TPA is the only thing we have right now, and the sooner it’s given, the better. Most neurologists will agree. But who’s going to pay for this?

The insurance companies, obviously. But money is finite. What if we upgrade all these ambulances, only to find that there’s no significant cost savings on rehab and recovery when TPA is used in the field? Then the money comes out of doctors’ and nurses’ salaries, higher premiums for everyone, and a cutback in treatment for some other disorder. I’m pretty sure it won’t be taken out of an insurance executive’s year-end bonus.

And just try explaining that to the family of a stroke victim.

It’s not practical to put a CT scanner in every ambulance, so where do we put those so equipped? Again, there’s no easy answer. In areas with large retirement communities? Seems like a safe bet, but young people have strokes, too. Only in cities? More people live in cities, but those in rural areas may be too far from a hospital to receive TPA early. Shouldn’t they have one, too?

Who’s going to make the decision to send the TPA ambulance vs. the regular ambulance? That’s another tough question. The layman who calls in usually isn’t sure what’s going on, only that an ambulance is needed. The dispatcher often can’t tell over the phone if the patient has had a stroke, seizure, or psychogenic event. Should a neurologist or emergency medicine physician make the decision? Maybe, but how much extra time will it take to get one on the line? And, even then, they’ll be making a critical decision with sparse, secondhand information. What if the special ambulance is mistakenly sent to deal with a conversion disorder, only to have a legitimate stroke occur elsewhere when it’s no longer immediately available? That, inevitably, will lead to a lawsuit because the wrong ambulance was sent.

I’m not against the stroke ambulance – far from it – but there are still a lot questions to be answered. Putting a CT scanner and TPA in an ambulance is, comparatively, the easiest part.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The TPA ambulance, armed with its own CT scanner, has arrived in the United States after several successful years in Germany.

Now what?