User login

Bivalirudin edges unfractionated heparin for PCI in acute coronary syndrome patients

SAN DIEGO– The antithrombin drug bivalirudin received a boost, compared with unfractionated heparin, as the safer drug for preventing ischemic events in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in results from a multicenter, randomized trial with more than 7,000 patients.

Although the two primary endpoints from this head-to-head comparison showed no statistically significant differences between the two agents, prespecified secondary endpoints showed that treatment with bivalirudin (Angiomax) during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) resulted in significantly fewer deaths after 30 days and significantly fewer major bleeding events, compared with unfractionated heparin (UFH), Dr. Marco Valgimigli said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology. Participating physicians administered the UFH with an antiplatelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (at the operator’s discretion) 26% of the time.

In the antithrombin-randomization analysis of the MATRIX (Minimizing Adverse Hemorrhagic Events by Transradial Access Site and Systemic Implementation of Angiox) trial, which included 7,213 of the 8,404 acute coronary syndrome patients enrolled in MATRIX, treatment with bivalirudin or UFH led to similar combined rates of all-cause death, myocardial infarction, or stroke, as well as similar rates of death, MI, stroke, and major bleeds, said Dr. Valgimigli, an interventional cardiologist at Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. A separate analysis of MATRIX focused on PCI outcomes with transradial vs. transfemoral access (Lancet 2015 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60292-6]).

But treatment with bivalirudin cut the 30-day rate of all-cause death by an absolute 0.6%, driven by a concurrent cut in cardiovascular death by 0.7%, which meant that treatment with bivalirudin reduced 30-day cardiovascular deaths by one event for about every 150 patients treated, compared with patients treated with UFH, he reported. Another secondary-endpoint analysis showed that bivalirudin treatment cut the 30-day rate of major bleeding events by an absolute 1.1%, but also increased the rate of definite stent thrombosis by an absolute 0.4%, both statistically significant differences. These important differences got diluted in the primary, combined endpoints by a relatively large number of periprocedural MIs that occurred at an equal rate in both arms of the study, Dr. Valgimigli said.

The antithrombin results from MATRIX followed mixed results in several prior comparisons of bivalirudin and UFH for percutaneous coronary intervention acute coronary syndrome patients (JAMA 2015 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.2345]). A year ago, results from the HEAT-PCI (Unfractionated Heparin Versus Bivalirudin in Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) trial (Lancet 2014;384:1849-58), which enrolled 1,829 ST-elevation MI patients at one U.K. center, showed a significant reduction in ischemic events and no increased bleeding in patients treated with UFH, compared with those who received bivalirudin, a finding that experts now say seemed to lead to increased use of UFH in both U.S. and global practice relative to the more expensive bivalirudin. But the MATRIX results, as well as results published on the same day as the MATRIX report from the Chinese BRIGHT (Bivalirudin vs. Heparin With or Without Tirofiban During Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Acute Myocardial Infarction) study (JAMA 2015 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.232]) that also compared bivalirudin and UFH, seemed to throw the balance of evidence back in bivalirudin’s favor.

MATRIX “was a win for bivalirudin,” commented Dr. Sanjit S. Jolly, an interventional cardiologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont. “Clearly mortality is the most important endpoint, and the totality of data from all the trials suggest that bivalirudin reduced mortality, compared with UFH. I think that physicians who stopped using bivalirudin after HEAT-PCI may go back to bivalirudin,” he said during a press conference at the meeting.

“Following HEAT-PCI there was a shift to greater use of UFH and more selective use of bivalirudin, even in the United States, and especially for patients with ST-elevation MI,” commented Dr. David E. Kandzari , director of interventional cardiology at the Piedmont Heart Institute in Atlanta. The new MATRIX findings “will probably prompt clinicians to revisit this given that MATRIX was the largest study to compare bivalirudin and UFH. That is not to discount the HEAT-PCI findings, but that was a much smaller trial and at a single center.”

Bivalirudin treatment results in additional expense, compared with UFH, and physicians are “under pressure to cut costs, so following the HEAT-PCI results, there was a big reduction in bivalirudin use. But with the subsequent BRIGHT results and now the MATRIX results, I think there will be an uptick again in bivalirudin use,” commented Dr. Cindy L. Grines, an interventional cardiologist at the Detroit Medical Center. The MATRIX results make her “more confident about the benefit from bivalirudin,” she said in an interview.

MATRIX was an investigator-initiated study that received grant support from Terumo and the Medicines Co. Dr. Valgimigli had no disclosures. Dr. Jolly has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, a speaker on behalf of St. Jude, and received research grants from Medtronic. Dr. Kandzari has been a consultant to Medtronic and Boston Scientific and has received research support from Abbott Vascular, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. Dr. Grines has been a consultant to and received honoraria from Abbott Vascular, the Medicines Co., Merck, and the Volcano Group.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SAN DIEGO– The antithrombin drug bivalirudin received a boost, compared with unfractionated heparin, as the safer drug for preventing ischemic events in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in results from a multicenter, randomized trial with more than 7,000 patients.

Although the two primary endpoints from this head-to-head comparison showed no statistically significant differences between the two agents, prespecified secondary endpoints showed that treatment with bivalirudin (Angiomax) during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) resulted in significantly fewer deaths after 30 days and significantly fewer major bleeding events, compared with unfractionated heparin (UFH), Dr. Marco Valgimigli said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology. Participating physicians administered the UFH with an antiplatelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (at the operator’s discretion) 26% of the time.

In the antithrombin-randomization analysis of the MATRIX (Minimizing Adverse Hemorrhagic Events by Transradial Access Site and Systemic Implementation of Angiox) trial, which included 7,213 of the 8,404 acute coronary syndrome patients enrolled in MATRIX, treatment with bivalirudin or UFH led to similar combined rates of all-cause death, myocardial infarction, or stroke, as well as similar rates of death, MI, stroke, and major bleeds, said Dr. Valgimigli, an interventional cardiologist at Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. A separate analysis of MATRIX focused on PCI outcomes with transradial vs. transfemoral access (Lancet 2015 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60292-6]).

But treatment with bivalirudin cut the 30-day rate of all-cause death by an absolute 0.6%, driven by a concurrent cut in cardiovascular death by 0.7%, which meant that treatment with bivalirudin reduced 30-day cardiovascular deaths by one event for about every 150 patients treated, compared with patients treated with UFH, he reported. Another secondary-endpoint analysis showed that bivalirudin treatment cut the 30-day rate of major bleeding events by an absolute 1.1%, but also increased the rate of definite stent thrombosis by an absolute 0.4%, both statistically significant differences. These important differences got diluted in the primary, combined endpoints by a relatively large number of periprocedural MIs that occurred at an equal rate in both arms of the study, Dr. Valgimigli said.

The antithrombin results from MATRIX followed mixed results in several prior comparisons of bivalirudin and UFH for percutaneous coronary intervention acute coronary syndrome patients (JAMA 2015 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.2345]). A year ago, results from the HEAT-PCI (Unfractionated Heparin Versus Bivalirudin in Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) trial (Lancet 2014;384:1849-58), which enrolled 1,829 ST-elevation MI patients at one U.K. center, showed a significant reduction in ischemic events and no increased bleeding in patients treated with UFH, compared with those who received bivalirudin, a finding that experts now say seemed to lead to increased use of UFH in both U.S. and global practice relative to the more expensive bivalirudin. But the MATRIX results, as well as results published on the same day as the MATRIX report from the Chinese BRIGHT (Bivalirudin vs. Heparin With or Without Tirofiban During Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Acute Myocardial Infarction) study (JAMA 2015 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.232]) that also compared bivalirudin and UFH, seemed to throw the balance of evidence back in bivalirudin’s favor.

MATRIX “was a win for bivalirudin,” commented Dr. Sanjit S. Jolly, an interventional cardiologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont. “Clearly mortality is the most important endpoint, and the totality of data from all the trials suggest that bivalirudin reduced mortality, compared with UFH. I think that physicians who stopped using bivalirudin after HEAT-PCI may go back to bivalirudin,” he said during a press conference at the meeting.

“Following HEAT-PCI there was a shift to greater use of UFH and more selective use of bivalirudin, even in the United States, and especially for patients with ST-elevation MI,” commented Dr. David E. Kandzari , director of interventional cardiology at the Piedmont Heart Institute in Atlanta. The new MATRIX findings “will probably prompt clinicians to revisit this given that MATRIX was the largest study to compare bivalirudin and UFH. That is not to discount the HEAT-PCI findings, but that was a much smaller trial and at a single center.”

Bivalirudin treatment results in additional expense, compared with UFH, and physicians are “under pressure to cut costs, so following the HEAT-PCI results, there was a big reduction in bivalirudin use. But with the subsequent BRIGHT results and now the MATRIX results, I think there will be an uptick again in bivalirudin use,” commented Dr. Cindy L. Grines, an interventional cardiologist at the Detroit Medical Center. The MATRIX results make her “more confident about the benefit from bivalirudin,” she said in an interview.

MATRIX was an investigator-initiated study that received grant support from Terumo and the Medicines Co. Dr. Valgimigli had no disclosures. Dr. Jolly has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, a speaker on behalf of St. Jude, and received research grants from Medtronic. Dr. Kandzari has been a consultant to Medtronic and Boston Scientific and has received research support from Abbott Vascular, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. Dr. Grines has been a consultant to and received honoraria from Abbott Vascular, the Medicines Co., Merck, and the Volcano Group.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SAN DIEGO– The antithrombin drug bivalirudin received a boost, compared with unfractionated heparin, as the safer drug for preventing ischemic events in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in results from a multicenter, randomized trial with more than 7,000 patients.

Although the two primary endpoints from this head-to-head comparison showed no statistically significant differences between the two agents, prespecified secondary endpoints showed that treatment with bivalirudin (Angiomax) during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) resulted in significantly fewer deaths after 30 days and significantly fewer major bleeding events, compared with unfractionated heparin (UFH), Dr. Marco Valgimigli said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology. Participating physicians administered the UFH with an antiplatelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (at the operator’s discretion) 26% of the time.

In the antithrombin-randomization analysis of the MATRIX (Minimizing Adverse Hemorrhagic Events by Transradial Access Site and Systemic Implementation of Angiox) trial, which included 7,213 of the 8,404 acute coronary syndrome patients enrolled in MATRIX, treatment with bivalirudin or UFH led to similar combined rates of all-cause death, myocardial infarction, or stroke, as well as similar rates of death, MI, stroke, and major bleeds, said Dr. Valgimigli, an interventional cardiologist at Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. A separate analysis of MATRIX focused on PCI outcomes with transradial vs. transfemoral access (Lancet 2015 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60292-6]).

But treatment with bivalirudin cut the 30-day rate of all-cause death by an absolute 0.6%, driven by a concurrent cut in cardiovascular death by 0.7%, which meant that treatment with bivalirudin reduced 30-day cardiovascular deaths by one event for about every 150 patients treated, compared with patients treated with UFH, he reported. Another secondary-endpoint analysis showed that bivalirudin treatment cut the 30-day rate of major bleeding events by an absolute 1.1%, but also increased the rate of definite stent thrombosis by an absolute 0.4%, both statistically significant differences. These important differences got diluted in the primary, combined endpoints by a relatively large number of periprocedural MIs that occurred at an equal rate in both arms of the study, Dr. Valgimigli said.

The antithrombin results from MATRIX followed mixed results in several prior comparisons of bivalirudin and UFH for percutaneous coronary intervention acute coronary syndrome patients (JAMA 2015 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.2345]). A year ago, results from the HEAT-PCI (Unfractionated Heparin Versus Bivalirudin in Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) trial (Lancet 2014;384:1849-58), which enrolled 1,829 ST-elevation MI patients at one U.K. center, showed a significant reduction in ischemic events and no increased bleeding in patients treated with UFH, compared with those who received bivalirudin, a finding that experts now say seemed to lead to increased use of UFH in both U.S. and global practice relative to the more expensive bivalirudin. But the MATRIX results, as well as results published on the same day as the MATRIX report from the Chinese BRIGHT (Bivalirudin vs. Heparin With or Without Tirofiban During Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Acute Myocardial Infarction) study (JAMA 2015 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.232]) that also compared bivalirudin and UFH, seemed to throw the balance of evidence back in bivalirudin’s favor.

MATRIX “was a win for bivalirudin,” commented Dr. Sanjit S. Jolly, an interventional cardiologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont. “Clearly mortality is the most important endpoint, and the totality of data from all the trials suggest that bivalirudin reduced mortality, compared with UFH. I think that physicians who stopped using bivalirudin after HEAT-PCI may go back to bivalirudin,” he said during a press conference at the meeting.

“Following HEAT-PCI there was a shift to greater use of UFH and more selective use of bivalirudin, even in the United States, and especially for patients with ST-elevation MI,” commented Dr. David E. Kandzari , director of interventional cardiology at the Piedmont Heart Institute in Atlanta. The new MATRIX findings “will probably prompt clinicians to revisit this given that MATRIX was the largest study to compare bivalirudin and UFH. That is not to discount the HEAT-PCI findings, but that was a much smaller trial and at a single center.”

Bivalirudin treatment results in additional expense, compared with UFH, and physicians are “under pressure to cut costs, so following the HEAT-PCI results, there was a big reduction in bivalirudin use. But with the subsequent BRIGHT results and now the MATRIX results, I think there will be an uptick again in bivalirudin use,” commented Dr. Cindy L. Grines, an interventional cardiologist at the Detroit Medical Center. The MATRIX results make her “more confident about the benefit from bivalirudin,” she said in an interview.

MATRIX was an investigator-initiated study that received grant support from Terumo and the Medicines Co. Dr. Valgimigli had no disclosures. Dr. Jolly has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, a speaker on behalf of St. Jude, and received research grants from Medtronic. Dr. Kandzari has been a consultant to Medtronic and Boston Scientific and has received research support from Abbott Vascular, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. Dr. Grines has been a consultant to and received honoraria from Abbott Vascular, the Medicines Co., Merck, and the Volcano Group.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT ACC 15

Key clinical point: In acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, bivalirudin led to significantly fewer deaths and major bleeds than did unfractionated heparin.

Major finding: Treatment with bivalirudin cut all-cause, 30-day mortality by an absolute 0.6%, compared with unfractionated heparin.

Data source: MATRIX, a multicenter, randomized trial that enrolled 7,213 acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.

Disclosures: MATRIX was an investigator-initiated study that received grant support from Terumo and the Medicines Co. Dr. Valgimigli had no disclosures. Dr. Jolly has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, a speaker on behalf of St. Jude, and received research grants from Medtronic. Dr. Kandzari has been a consultant to Medtronic and Boston Scientific and has received research support from Abbott Vascular, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. Dr. Grines has been a consultant to and received honoraria from Abbott Vascular, the Medicines Co., Merck, and the Volcano Group.

Adult ALL survivors reflect on once-revolutionary treatment

Total Therapy III, a combination treatment regimen of chemotherapy and radiation, is now commonly administered to patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. But this was not always the case.

In an interview with National Public Radio, childhood ALL patients James Eversull and Pat Patchell, now among the oldest of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital’s leukemia survivors, reflect on their experiences with the once-experimental treatment.

Read and listen to the full interview at npr.org.

Total Therapy III, a combination treatment regimen of chemotherapy and radiation, is now commonly administered to patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. But this was not always the case.

In an interview with National Public Radio, childhood ALL patients James Eversull and Pat Patchell, now among the oldest of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital’s leukemia survivors, reflect on their experiences with the once-experimental treatment.

Read and listen to the full interview at npr.org.

Total Therapy III, a combination treatment regimen of chemotherapy and radiation, is now commonly administered to patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. But this was not always the case.

In an interview with National Public Radio, childhood ALL patients James Eversull and Pat Patchell, now among the oldest of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital’s leukemia survivors, reflect on their experiences with the once-experimental treatment.

Read and listen to the full interview at npr.org.

Society of Hospital Medicine Pediatric Committee Updates at HM15

During a session at the Society of Hospital Medicine's HM15 annual meeting, SHM Pediatric Committee chair Kris Rehm, MD, outlined a number of the committee's current endeavors. They include:

1) American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) Certification for Pediatric Hospitalists.

- Since 2010 a leadership group has worked on certification options.

- In 2013, determination was made that a two-year fellowship would be proposed to the ABP.

- Formal petition for certification was submitted to the ABP in October 2014, with clarification in March 2015.

- ABP is currently reviewing the proposal prior to its presentation to the American Board of Medical Specialties, with an expected minimum five-year horizon before a first exam.

2) SHM has developed multiple online ABP MOC learning platforms for pediatric hospitalists.

3) The SHM Pediatric Committee encourages pediatric hospitalists to seek Hospital Medicine Fellowship status to demonstrate one’s commitment to, and accomplishment in, hospital medicine.

4) A SHM pediatric discussion forum is ongoing.

5) The annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting, jointly sponsored by APA, AAP and SHM will be in San Antonio, July 23-26. TH

During a session at the Society of Hospital Medicine's HM15 annual meeting, SHM Pediatric Committee chair Kris Rehm, MD, outlined a number of the committee's current endeavors. They include:

1) American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) Certification for Pediatric Hospitalists.

- Since 2010 a leadership group has worked on certification options.

- In 2013, determination was made that a two-year fellowship would be proposed to the ABP.

- Formal petition for certification was submitted to the ABP in October 2014, with clarification in March 2015.

- ABP is currently reviewing the proposal prior to its presentation to the American Board of Medical Specialties, with an expected minimum five-year horizon before a first exam.

2) SHM has developed multiple online ABP MOC learning platforms for pediatric hospitalists.

3) The SHM Pediatric Committee encourages pediatric hospitalists to seek Hospital Medicine Fellowship status to demonstrate one’s commitment to, and accomplishment in, hospital medicine.

4) A SHM pediatric discussion forum is ongoing.

5) The annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting, jointly sponsored by APA, AAP and SHM will be in San Antonio, July 23-26. TH

During a session at the Society of Hospital Medicine's HM15 annual meeting, SHM Pediatric Committee chair Kris Rehm, MD, outlined a number of the committee's current endeavors. They include:

1) American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) Certification for Pediatric Hospitalists.

- Since 2010 a leadership group has worked on certification options.

- In 2013, determination was made that a two-year fellowship would be proposed to the ABP.

- Formal petition for certification was submitted to the ABP in October 2014, with clarification in March 2015.

- ABP is currently reviewing the proposal prior to its presentation to the American Board of Medical Specialties, with an expected minimum five-year horizon before a first exam.

2) SHM has developed multiple online ABP MOC learning platforms for pediatric hospitalists.

3) The SHM Pediatric Committee encourages pediatric hospitalists to seek Hospital Medicine Fellowship status to demonstrate one’s commitment to, and accomplishment in, hospital medicine.

4) A SHM pediatric discussion forum is ongoing.

5) The annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting, jointly sponsored by APA, AAP and SHM will be in San Antonio, July 23-26. TH

Gout increases risk of vascular disease, especially for women

Gout’s association with a host of vascular events was confirmed in a new study that explored the links between the inflammatory condition and coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, and cerebrovascular events.

Though both men and women with gout were at increased risk for vascular events overall, the association appeared strongest for women. Dr. Lorna Clarson of Keele (England) University and her associates drew these conclusions from a retrospective cohort study of men and women with an incident diagnosis of gout (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015;74:642-7).

Gout, caused by the deposition of uric acid crystals in joints, is characterized by acute flares of intensely painful and inflamed joints. However, the state of hyperuricemia that predisposes patients to acute attacks of gout may precede the first attack by years, and may persist between flares. The proinflammatory course of the natural history of gout has increasingly been recognized as a potential contributor to vascular disease.

The precise mechanism by which gout may increase vascular risk has not been identified. Dr. Clarson and associates noted that in addition to the acute and chronic inflammation associated with gout and hyperuricemia, serum uric acid may have a more direct effect on vascular health, as urate crystal deposition on vessel walls may promote vascular damage.

To clarify gout’s impact on vascular risk, Dr. Clarson and her associates used the Clinical Practice Datalink, a large United Kingdom health database, to compare 8,366 patients with gout to 39,766 age- and sex-matched controls. None of those studied had a baseline history of vascular disease, and all were aged 50 or older.

Careful accounting for covariates was accomplished by multivariate analysis that took into account sex, age, body mass index, tobacco and alcohol consumption, statin or aspirin use, and any history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, or chronic kidney disease. In addition, the study employed the composite Charlson Comorbidity Index, which weights 19 comorbid conditions – including diabetes – to arrive at a single score that captures many risk factors. Patients in the cohort were tracked until their first vascular event, or until death or loss to follow-up. Patient data collection was censored at 10 years from baseline or at the end of study data collection, whichever came first.

To assess the incidence of vascular events, the study noted the first recording in the medical record of any events signaling vascular disease. These included angina or myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack and stroke, and a range of diagnoses associated with peripheral vascular disease.

Final analysis after accounting for the many covariates tracked in the study showed increased risk for vascular events for those with gout, with a definite difference between the sexes. For men, gout predicted an increased risk of any vascular event (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 1.01–1.12) and of coronary heart disease and peripheral vascular disease. For women, gout predicted an increased risk of all vascular events (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.15-1.35) except myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular disease overall. Further, the degree of increased risk of vascular events was greater for women than for men with gout (P< .001 for intersex difference).

Dr. Clarson and her associates proposed that the higher risk for vascular events among women with gout may arise from the longer exposure to elevated serum uric acid, since women have a longer prodrome before first gout attack, though they recommend further study to elucidate the mechanism.

Noting that “clinical management of gout in primary care is suboptimal,” Dr. Clarson and her colleagues urged greater attention to screening for vascular risk in those diagnosed with gout; these individuals comprise a significant population of over 8 million people in the United States. International guidelines recommend screening for cardiovascular risk when gout is diagnosed, but only one in four gout patients are so evaluated.

Regarding the sex differences unearthed in their study, Dr. Clarson and her associates observed that “both gout and vascular disease have historically been considered diseases of men ... [M]ore attention should be paid to prompt and reliable diagnosis of gout, followed by optimal management in female patients, including serious consideration of vascular risk reduction.”

The United Kingdom’s National School for Primary Research funded the study. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

The significant strengths of Dr. Clarson and colleagues’ study of the association between gout and vascular disease are its large sample size, its accounting for many potentially confounding risk factors, and its exclusion of those with known antecedent heart disease. It is limited by its lack of validation of gout and cardiac diagnoses and the self-selection bias inherent in using primary care registries, rather than a true population-based cohort.

For individuals without gout, women’s overall vascular risk is lower, but the lack of a difference in cardiovascular disease risk in men and women with gout means that we do not yet understand why women’s risk rises more with the disease. It is possible that systemic inflammation induced by gout in women is more atherogenic than that in men, which necessitates studies to determine whether there are sex-based differences in the pathogenesis of gout-associated heart disease.

|

Dr. Jasvinder Singh |

Patients older than 35 or 40 with gout should be screened and followed with lipid profiles, hemoglobin A1c levels, blood pressure levels, and smoking status, and should undergo an assessment of other lifestyle factors that may impact cardiovascular risk.

Recognizing gout’s contribution to cardiac risk, and managing both the disease and associated risk factors, will be a key task for primary care doctors, rheumatologists, and cardiologists going forward.

Dr. Jasvinder Singh is a professor of medicine in the division of clinical immunology and rheumatology at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. These comments are summarized from his editorial accompanying Dr. Clarson’s report (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015;74:631-4). He reported receiving research and travel grants from Takeda and Savient, and consultant fees from Takeda, Savient, Regeneron, and Allergan.

The significant strengths of Dr. Clarson and colleagues’ study of the association between gout and vascular disease are its large sample size, its accounting for many potentially confounding risk factors, and its exclusion of those with known antecedent heart disease. It is limited by its lack of validation of gout and cardiac diagnoses and the self-selection bias inherent in using primary care registries, rather than a true population-based cohort.

For individuals without gout, women’s overall vascular risk is lower, but the lack of a difference in cardiovascular disease risk in men and women with gout means that we do not yet understand why women’s risk rises more with the disease. It is possible that systemic inflammation induced by gout in women is more atherogenic than that in men, which necessitates studies to determine whether there are sex-based differences in the pathogenesis of gout-associated heart disease.

|

Dr. Jasvinder Singh |

Patients older than 35 or 40 with gout should be screened and followed with lipid profiles, hemoglobin A1c levels, blood pressure levels, and smoking status, and should undergo an assessment of other lifestyle factors that may impact cardiovascular risk.

Recognizing gout’s contribution to cardiac risk, and managing both the disease and associated risk factors, will be a key task for primary care doctors, rheumatologists, and cardiologists going forward.

Dr. Jasvinder Singh is a professor of medicine in the division of clinical immunology and rheumatology at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. These comments are summarized from his editorial accompanying Dr. Clarson’s report (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015;74:631-4). He reported receiving research and travel grants from Takeda and Savient, and consultant fees from Takeda, Savient, Regeneron, and Allergan.

The significant strengths of Dr. Clarson and colleagues’ study of the association between gout and vascular disease are its large sample size, its accounting for many potentially confounding risk factors, and its exclusion of those with known antecedent heart disease. It is limited by its lack of validation of gout and cardiac diagnoses and the self-selection bias inherent in using primary care registries, rather than a true population-based cohort.

For individuals without gout, women’s overall vascular risk is lower, but the lack of a difference in cardiovascular disease risk in men and women with gout means that we do not yet understand why women’s risk rises more with the disease. It is possible that systemic inflammation induced by gout in women is more atherogenic than that in men, which necessitates studies to determine whether there are sex-based differences in the pathogenesis of gout-associated heart disease.

|

Dr. Jasvinder Singh |

Patients older than 35 or 40 with gout should be screened and followed with lipid profiles, hemoglobin A1c levels, blood pressure levels, and smoking status, and should undergo an assessment of other lifestyle factors that may impact cardiovascular risk.

Recognizing gout’s contribution to cardiac risk, and managing both the disease and associated risk factors, will be a key task for primary care doctors, rheumatologists, and cardiologists going forward.

Dr. Jasvinder Singh is a professor of medicine in the division of clinical immunology and rheumatology at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. These comments are summarized from his editorial accompanying Dr. Clarson’s report (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015;74:631-4). He reported receiving research and travel grants from Takeda and Savient, and consultant fees from Takeda, Savient, Regeneron, and Allergan.

Gout’s association with a host of vascular events was confirmed in a new study that explored the links between the inflammatory condition and coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, and cerebrovascular events.

Though both men and women with gout were at increased risk for vascular events overall, the association appeared strongest for women. Dr. Lorna Clarson of Keele (England) University and her associates drew these conclusions from a retrospective cohort study of men and women with an incident diagnosis of gout (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015;74:642-7).

Gout, caused by the deposition of uric acid crystals in joints, is characterized by acute flares of intensely painful and inflamed joints. However, the state of hyperuricemia that predisposes patients to acute attacks of gout may precede the first attack by years, and may persist between flares. The proinflammatory course of the natural history of gout has increasingly been recognized as a potential contributor to vascular disease.

The precise mechanism by which gout may increase vascular risk has not been identified. Dr. Clarson and associates noted that in addition to the acute and chronic inflammation associated with gout and hyperuricemia, serum uric acid may have a more direct effect on vascular health, as urate crystal deposition on vessel walls may promote vascular damage.

To clarify gout’s impact on vascular risk, Dr. Clarson and her associates used the Clinical Practice Datalink, a large United Kingdom health database, to compare 8,366 patients with gout to 39,766 age- and sex-matched controls. None of those studied had a baseline history of vascular disease, and all were aged 50 or older.

Careful accounting for covariates was accomplished by multivariate analysis that took into account sex, age, body mass index, tobacco and alcohol consumption, statin or aspirin use, and any history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, or chronic kidney disease. In addition, the study employed the composite Charlson Comorbidity Index, which weights 19 comorbid conditions – including diabetes – to arrive at a single score that captures many risk factors. Patients in the cohort were tracked until their first vascular event, or until death or loss to follow-up. Patient data collection was censored at 10 years from baseline or at the end of study data collection, whichever came first.

To assess the incidence of vascular events, the study noted the first recording in the medical record of any events signaling vascular disease. These included angina or myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack and stroke, and a range of diagnoses associated with peripheral vascular disease.

Final analysis after accounting for the many covariates tracked in the study showed increased risk for vascular events for those with gout, with a definite difference between the sexes. For men, gout predicted an increased risk of any vascular event (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 1.01–1.12) and of coronary heart disease and peripheral vascular disease. For women, gout predicted an increased risk of all vascular events (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.15-1.35) except myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular disease overall. Further, the degree of increased risk of vascular events was greater for women than for men with gout (P< .001 for intersex difference).

Dr. Clarson and her associates proposed that the higher risk for vascular events among women with gout may arise from the longer exposure to elevated serum uric acid, since women have a longer prodrome before first gout attack, though they recommend further study to elucidate the mechanism.

Noting that “clinical management of gout in primary care is suboptimal,” Dr. Clarson and her colleagues urged greater attention to screening for vascular risk in those diagnosed with gout; these individuals comprise a significant population of over 8 million people in the United States. International guidelines recommend screening for cardiovascular risk when gout is diagnosed, but only one in four gout patients are so evaluated.

Regarding the sex differences unearthed in their study, Dr. Clarson and her associates observed that “both gout and vascular disease have historically been considered diseases of men ... [M]ore attention should be paid to prompt and reliable diagnosis of gout, followed by optimal management in female patients, including serious consideration of vascular risk reduction.”

The United Kingdom’s National School for Primary Research funded the study. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

Gout’s association with a host of vascular events was confirmed in a new study that explored the links between the inflammatory condition and coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, and cerebrovascular events.

Though both men and women with gout were at increased risk for vascular events overall, the association appeared strongest for women. Dr. Lorna Clarson of Keele (England) University and her associates drew these conclusions from a retrospective cohort study of men and women with an incident diagnosis of gout (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015;74:642-7).

Gout, caused by the deposition of uric acid crystals in joints, is characterized by acute flares of intensely painful and inflamed joints. However, the state of hyperuricemia that predisposes patients to acute attacks of gout may precede the first attack by years, and may persist between flares. The proinflammatory course of the natural history of gout has increasingly been recognized as a potential contributor to vascular disease.

The precise mechanism by which gout may increase vascular risk has not been identified. Dr. Clarson and associates noted that in addition to the acute and chronic inflammation associated with gout and hyperuricemia, serum uric acid may have a more direct effect on vascular health, as urate crystal deposition on vessel walls may promote vascular damage.

To clarify gout’s impact on vascular risk, Dr. Clarson and her associates used the Clinical Practice Datalink, a large United Kingdom health database, to compare 8,366 patients with gout to 39,766 age- and sex-matched controls. None of those studied had a baseline history of vascular disease, and all were aged 50 or older.

Careful accounting for covariates was accomplished by multivariate analysis that took into account sex, age, body mass index, tobacco and alcohol consumption, statin or aspirin use, and any history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, or chronic kidney disease. In addition, the study employed the composite Charlson Comorbidity Index, which weights 19 comorbid conditions – including diabetes – to arrive at a single score that captures many risk factors. Patients in the cohort were tracked until their first vascular event, or until death or loss to follow-up. Patient data collection was censored at 10 years from baseline or at the end of study data collection, whichever came first.

To assess the incidence of vascular events, the study noted the first recording in the medical record of any events signaling vascular disease. These included angina or myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack and stroke, and a range of diagnoses associated with peripheral vascular disease.

Final analysis after accounting for the many covariates tracked in the study showed increased risk for vascular events for those with gout, with a definite difference between the sexes. For men, gout predicted an increased risk of any vascular event (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 1.01–1.12) and of coronary heart disease and peripheral vascular disease. For women, gout predicted an increased risk of all vascular events (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.15-1.35) except myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular disease overall. Further, the degree of increased risk of vascular events was greater for women than for men with gout (P< .001 for intersex difference).

Dr. Clarson and her associates proposed that the higher risk for vascular events among women with gout may arise from the longer exposure to elevated serum uric acid, since women have a longer prodrome before first gout attack, though they recommend further study to elucidate the mechanism.

Noting that “clinical management of gout in primary care is suboptimal,” Dr. Clarson and her colleagues urged greater attention to screening for vascular risk in those diagnosed with gout; these individuals comprise a significant population of over 8 million people in the United States. International guidelines recommend screening for cardiovascular risk when gout is diagnosed, but only one in four gout patients are so evaluated.

Regarding the sex differences unearthed in their study, Dr. Clarson and her associates observed that “both gout and vascular disease have historically been considered diseases of men ... [M]ore attention should be paid to prompt and reliable diagnosis of gout, followed by optimal management in female patients, including serious consideration of vascular risk reduction.”

The United Kingdom’s National School for Primary Research funded the study. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Key clinical point: Gout increased the risk of a variety of vascular events, with women at greatest risk.

Major finding: Men with gout were at increased risk of vascular events with an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of 1.06 overall; women’s risk was greater, with an overall adjusted HR of 1.25.

Data source: Comparison of 8,836 patients with gout to 39,766 matched controls without gout, from the United Kingdom’s Clinical Practice Research Datalink.

Disclosures: The United Kingdom’s National School for Primary Research funded the study. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

Bedside Procedures and Ultrasound: Evidence and Cost of Doing Business

HM15 presenters: Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, FACP, SFHM, and Nilam Soni, MD, FHM

Summary: Drs. Lenchus and Soni focused on the forces that are driving the value and success of established procedure teams in hospital medicine groups (HMGs). These stem from a need to rapidly address the growing shortage of skilled internists who can perform diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, thus leading to a subset of hospitalists who are willing to provide these services, particularly with the assistance of bedside ultrasonography.

They stressed the importance of providing a platform that is preemptive, proprietary, and scalable. With a defined set of value-creating metrics such as faster turn-around times, a reduction in complication rates, and ultimately a reduction in cost, LOS, and utilization, data must be collected to adequately measure the impact of these services on the institution.

They also discussed the key components necessary to create a procedure service, starting with the logistics of adequate training and demonstration of competence, proper staffing, supplies and equipment, ultrasound image archiving, and the use of documentation templates. The process is followed by the development of pre-procedure and post-procedure guidelines, as well as standardized procedural techniques.

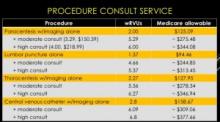

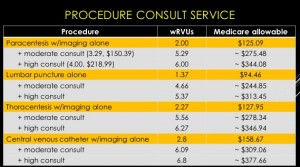

The session also reviewed billing practices and professional fees. An analysis was made comparing Medicare reimbursement and work RVUs for each procedure service with and without a full procedure consultation. A complete consultation significantly increases the allowable fee and associated wRVU. The caveat is that billing for consults is limited to services rendered for patients that are not cared for by the same hospitalist group.

Furthermore, sub-specialists historically perform these procedures. The argument can be made that hospitalists will reduce an unnecessary burden on interventional radiologists, thereby enabling them to focus on more acomplex invasive and highly technical procedures.

The key to success is the ability to find a strategic partner in the C-suite who will directly or indirectly provide the financial and political support. Other sources of funding include private foundations, medical schools, the Department of Veteran Affairs, and such patient safety organizations as AHRQ, IOM, and IHI. HMG leaders also should consider scalability across other hospitalist groups.

“If you build it, they will come."

HM takeaways

- Create a business plan;

- Find institutional financial and political support;

- Start small and selective;

- Plan for standardization and training of colleagues;

- Create a credentialing/privileging process;

- Bill for services and consider billing for full consults; and

- Gather baseline and follow-up data.

HM15 presenters: Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, FACP, SFHM, and Nilam Soni, MD, FHM

Summary: Drs. Lenchus and Soni focused on the forces that are driving the value and success of established procedure teams in hospital medicine groups (HMGs). These stem from a need to rapidly address the growing shortage of skilled internists who can perform diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, thus leading to a subset of hospitalists who are willing to provide these services, particularly with the assistance of bedside ultrasonography.

They stressed the importance of providing a platform that is preemptive, proprietary, and scalable. With a defined set of value-creating metrics such as faster turn-around times, a reduction in complication rates, and ultimately a reduction in cost, LOS, and utilization, data must be collected to adequately measure the impact of these services on the institution.

They also discussed the key components necessary to create a procedure service, starting with the logistics of adequate training and demonstration of competence, proper staffing, supplies and equipment, ultrasound image archiving, and the use of documentation templates. The process is followed by the development of pre-procedure and post-procedure guidelines, as well as standardized procedural techniques.

The session also reviewed billing practices and professional fees. An analysis was made comparing Medicare reimbursement and work RVUs for each procedure service with and without a full procedure consultation. A complete consultation significantly increases the allowable fee and associated wRVU. The caveat is that billing for consults is limited to services rendered for patients that are not cared for by the same hospitalist group.

Furthermore, sub-specialists historically perform these procedures. The argument can be made that hospitalists will reduce an unnecessary burden on interventional radiologists, thereby enabling them to focus on more acomplex invasive and highly technical procedures.

The key to success is the ability to find a strategic partner in the C-suite who will directly or indirectly provide the financial and political support. Other sources of funding include private foundations, medical schools, the Department of Veteran Affairs, and such patient safety organizations as AHRQ, IOM, and IHI. HMG leaders also should consider scalability across other hospitalist groups.

“If you build it, they will come."

HM takeaways

- Create a business plan;

- Find institutional financial and political support;

- Start small and selective;

- Plan for standardization and training of colleagues;

- Create a credentialing/privileging process;

- Bill for services and consider billing for full consults; and

- Gather baseline and follow-up data.

HM15 presenters: Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, FACP, SFHM, and Nilam Soni, MD, FHM

Summary: Drs. Lenchus and Soni focused on the forces that are driving the value and success of established procedure teams in hospital medicine groups (HMGs). These stem from a need to rapidly address the growing shortage of skilled internists who can perform diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, thus leading to a subset of hospitalists who are willing to provide these services, particularly with the assistance of bedside ultrasonography.

They stressed the importance of providing a platform that is preemptive, proprietary, and scalable. With a defined set of value-creating metrics such as faster turn-around times, a reduction in complication rates, and ultimately a reduction in cost, LOS, and utilization, data must be collected to adequately measure the impact of these services on the institution.

They also discussed the key components necessary to create a procedure service, starting with the logistics of adequate training and demonstration of competence, proper staffing, supplies and equipment, ultrasound image archiving, and the use of documentation templates. The process is followed by the development of pre-procedure and post-procedure guidelines, as well as standardized procedural techniques.

The session also reviewed billing practices and professional fees. An analysis was made comparing Medicare reimbursement and work RVUs for each procedure service with and without a full procedure consultation. A complete consultation significantly increases the allowable fee and associated wRVU. The caveat is that billing for consults is limited to services rendered for patients that are not cared for by the same hospitalist group.

Furthermore, sub-specialists historically perform these procedures. The argument can be made that hospitalists will reduce an unnecessary burden on interventional radiologists, thereby enabling them to focus on more acomplex invasive and highly technical procedures.

The key to success is the ability to find a strategic partner in the C-suite who will directly or indirectly provide the financial and political support. Other sources of funding include private foundations, medical schools, the Department of Veteran Affairs, and such patient safety organizations as AHRQ, IOM, and IHI. HMG leaders also should consider scalability across other hospitalist groups.

“If you build it, they will come."

HM takeaways

- Create a business plan;

- Find institutional financial and political support;

- Start small and selective;

- Plan for standardization and training of colleagues;

- Create a credentialing/privileging process;

- Bill for services and consider billing for full consults; and

- Gather baseline and follow-up data.

Test predicts DLBCL relapse better than CT, team says

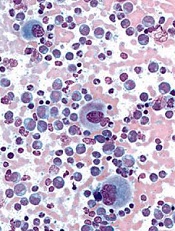

Photo by Larry Young

Surveillance of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) can help predict relapse in most patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma before there is clinical evidence of the disease, according to a study published in The Lancet Oncology.

Investigators analyzed ctDNA using the clonoSEQ minimal residual disease (MRD) test and found they could predict relapse with a positive predictive value (PPV) of 88% and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 98%.

The test detected relapse a median of 3.5 months quicker than computed tomography (CT) scans.

“Patients with DLBCL with low amounts of disease at relapse have better survival than those with more disease, which is the rationale for surveillance CT scans,” said study author Wyndham Wilson, MD, PhD, of the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland.

“Because the ctDNA test detects disease at a molecular level, it detects microscopic disease, which cannot be detected by CT scans, and may improve patient survival. Furthermore, ctDNA is non-invasive and can be employed as frequently needed, unlike surveillance CT scans, which expose patients to radiation and intravenous contrast.”

For this study, Dr Wilson and his colleagues evaluated 126 DLBCL patients who had participated in clinical trials from May 1993 to June 2013 and were followed for a median of 11 years post-treatment.

Surveillance monitoring

To investigate whether ctDNA monitoring could overcome the limitations of standard imaging techniques, the researchers compared serial ctDNA samples to CT scans taken at the same time post-treatment in patients who had achieved complete remission. This was known as “surveillance monitoring.”

The investigators performed surveillance monitoring of ctDNA in 107 patients who achieved complete remission.

The hazard ratio for clinical disease progression was 228 for patients who had detectable ctDNA during surveillance, when compared to patients with undetectable ctDNA (P<0.0001).

Surveillance ctDNA had a PPV of 88.2% and an NPV of 97.8%. And it revealed the risk of recurrence at a median of 3.5 months (range, 0-200 months) before there was evidence of clinical disease.

Interim monitoring

The researchers also analyzed whether the presence of ctDNA at the beginning of the third cycle of treatment predicted relapse, regardless of whether patients achieved complete remission by the end of treatment. This was known as “interim monitoring.”

Of the 108 patients included in the interim monitoring analysis, ctDNA was detected in 24 patients, 15 of whom eventually relapsed. Only 17 of the 84 patients with undetectable interim ctDNA relapsed.

Five years after the interim serum samples were taken, 80.2% of the patients who were negative for ctDNA were relapse-free, as were 41.7% of patients who were positive for ctDNA (P<0.0001).

Detectable interim ctDNA had a PPV of 62.5% and an NPV of 79.8%.

Fourteen of the 15 patients with detectable ctDNA who relapsed did so within 6 months of the end of treatment, as did 7 of the 17 patients without interim ctDNA.

Based on these results, the investigators concluded that surveillance monitoring of ctDNA identifies DLBCL patients at risk of disease recurrence before clinical evidence of disease in most patients, and interim monitoring of ctDNA is a promising biomarker to identify patients at high risk of treatment failure.

This research was funded by Adaptive Biotechnologies, the company developing the clonoSEQ MRD test, as well as the National Cancer Institute. ![]()

Photo by Larry Young

Surveillance of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) can help predict relapse in most patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma before there is clinical evidence of the disease, according to a study published in The Lancet Oncology.

Investigators analyzed ctDNA using the clonoSEQ minimal residual disease (MRD) test and found they could predict relapse with a positive predictive value (PPV) of 88% and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 98%.

The test detected relapse a median of 3.5 months quicker than computed tomography (CT) scans.

“Patients with DLBCL with low amounts of disease at relapse have better survival than those with more disease, which is the rationale for surveillance CT scans,” said study author Wyndham Wilson, MD, PhD, of the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland.

“Because the ctDNA test detects disease at a molecular level, it detects microscopic disease, which cannot be detected by CT scans, and may improve patient survival. Furthermore, ctDNA is non-invasive and can be employed as frequently needed, unlike surveillance CT scans, which expose patients to radiation and intravenous contrast.”

For this study, Dr Wilson and his colleagues evaluated 126 DLBCL patients who had participated in clinical trials from May 1993 to June 2013 and were followed for a median of 11 years post-treatment.

Surveillance monitoring

To investigate whether ctDNA monitoring could overcome the limitations of standard imaging techniques, the researchers compared serial ctDNA samples to CT scans taken at the same time post-treatment in patients who had achieved complete remission. This was known as “surveillance monitoring.”

The investigators performed surveillance monitoring of ctDNA in 107 patients who achieved complete remission.

The hazard ratio for clinical disease progression was 228 for patients who had detectable ctDNA during surveillance, when compared to patients with undetectable ctDNA (P<0.0001).

Surveillance ctDNA had a PPV of 88.2% and an NPV of 97.8%. And it revealed the risk of recurrence at a median of 3.5 months (range, 0-200 months) before there was evidence of clinical disease.

Interim monitoring

The researchers also analyzed whether the presence of ctDNA at the beginning of the third cycle of treatment predicted relapse, regardless of whether patients achieved complete remission by the end of treatment. This was known as “interim monitoring.”

Of the 108 patients included in the interim monitoring analysis, ctDNA was detected in 24 patients, 15 of whom eventually relapsed. Only 17 of the 84 patients with undetectable interim ctDNA relapsed.

Five years after the interim serum samples were taken, 80.2% of the patients who were negative for ctDNA were relapse-free, as were 41.7% of patients who were positive for ctDNA (P<0.0001).

Detectable interim ctDNA had a PPV of 62.5% and an NPV of 79.8%.

Fourteen of the 15 patients with detectable ctDNA who relapsed did so within 6 months of the end of treatment, as did 7 of the 17 patients without interim ctDNA.

Based on these results, the investigators concluded that surveillance monitoring of ctDNA identifies DLBCL patients at risk of disease recurrence before clinical evidence of disease in most patients, and interim monitoring of ctDNA is a promising biomarker to identify patients at high risk of treatment failure.

This research was funded by Adaptive Biotechnologies, the company developing the clonoSEQ MRD test, as well as the National Cancer Institute. ![]()

Photo by Larry Young

Surveillance of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) can help predict relapse in most patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma before there is clinical evidence of the disease, according to a study published in The Lancet Oncology.

Investigators analyzed ctDNA using the clonoSEQ minimal residual disease (MRD) test and found they could predict relapse with a positive predictive value (PPV) of 88% and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 98%.

The test detected relapse a median of 3.5 months quicker than computed tomography (CT) scans.

“Patients with DLBCL with low amounts of disease at relapse have better survival than those with more disease, which is the rationale for surveillance CT scans,” said study author Wyndham Wilson, MD, PhD, of the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland.

“Because the ctDNA test detects disease at a molecular level, it detects microscopic disease, which cannot be detected by CT scans, and may improve patient survival. Furthermore, ctDNA is non-invasive and can be employed as frequently needed, unlike surveillance CT scans, which expose patients to radiation and intravenous contrast.”

For this study, Dr Wilson and his colleagues evaluated 126 DLBCL patients who had participated in clinical trials from May 1993 to June 2013 and were followed for a median of 11 years post-treatment.

Surveillance monitoring

To investigate whether ctDNA monitoring could overcome the limitations of standard imaging techniques, the researchers compared serial ctDNA samples to CT scans taken at the same time post-treatment in patients who had achieved complete remission. This was known as “surveillance monitoring.”

The investigators performed surveillance monitoring of ctDNA in 107 patients who achieved complete remission.

The hazard ratio for clinical disease progression was 228 for patients who had detectable ctDNA during surveillance, when compared to patients with undetectable ctDNA (P<0.0001).

Surveillance ctDNA had a PPV of 88.2% and an NPV of 97.8%. And it revealed the risk of recurrence at a median of 3.5 months (range, 0-200 months) before there was evidence of clinical disease.

Interim monitoring

The researchers also analyzed whether the presence of ctDNA at the beginning of the third cycle of treatment predicted relapse, regardless of whether patients achieved complete remission by the end of treatment. This was known as “interim monitoring.”

Of the 108 patients included in the interim monitoring analysis, ctDNA was detected in 24 patients, 15 of whom eventually relapsed. Only 17 of the 84 patients with undetectable interim ctDNA relapsed.

Five years after the interim serum samples were taken, 80.2% of the patients who were negative for ctDNA were relapse-free, as were 41.7% of patients who were positive for ctDNA (P<0.0001).

Detectable interim ctDNA had a PPV of 62.5% and an NPV of 79.8%.

Fourteen of the 15 patients with detectable ctDNA who relapsed did so within 6 months of the end of treatment, as did 7 of the 17 patients without interim ctDNA.

Based on these results, the investigators concluded that surveillance monitoring of ctDNA identifies DLBCL patients at risk of disease recurrence before clinical evidence of disease in most patients, and interim monitoring of ctDNA is a promising biomarker to identify patients at high risk of treatment failure.

This research was funded by Adaptive Biotechnologies, the company developing the clonoSEQ MRD test, as well as the National Cancer Institute. ![]()

Study reveals potential strategy for treating CML

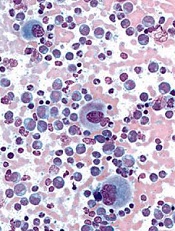

Image courtesy of UCSD

New discoveries concerning a well-known tumor suppressor protein could help advance the diagnosis and treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), according to researchers.

They found that levels of the protein, BRCA1, are significantly decreased in advanced phases of CML, the expression of BCR-ABL1 correlates with decreased levels of BRCA1, and this downregulation of BRCA1 is caused by the inhibition of BRCA1 messenger RNA (mRNA) translation.

These discoveries explain the mechanism that supports CML development and uncover its weakness, the investigators said. They reported their findings in Cell Cycle.

“Our data demonstrated that BRCA1 synthesis is diminished in [the] advanced stage[s] of CML,” said study author Paulina Podszywałow-Bartnicka, PhD, of the Nencki Institute in Warsaw, Poland.

“The gene coding for BRCA1 protein is not mutated. However, BRCA1 mRNA, which is necessary for the protein production, is aggregated and stored in protein complexes [and], thus, not available for the protein synthesis.”

To gain more insight into this phenomenon, the investigators looked at 2 mRNA-binding proteins, HuR and TIAR. They found that BCR-ABL1 promoted cytosolic localization of TIAR and HuR, the proteins’ binding to BRCA1 mRNA, and formation of the TIAR-HuR complex.

The researchers also found that HuR positively regulated BRCA1 mRNA stability and translation, while TIAR negatively regulated BRCA1 translation.

TIAR-dependent downregulation of BRCA1 was a result of endoplasmic reticulum stress, which is activated in BCR-ABL1 expressing cells. And experiments showed that silencing TIAR in CML cells elevated BRCA1 levels.

This suggests that TIAR-mediated repression of BRCA1 mRNA translation is responsible for the downregulation of BRCA1 observed in BCR-ABL1-positive leukemia cells.

The investigators said this research indicates that BRCA1 deficiency, which supports CML, can be also used as a weapon against the disease.

“When a cell has damaged one signaling pathway or one gene, it may function properly due to alternative pathways . . . ,” explained study author Tomasz Skorski, MD, PhD, of Temple University School of Medicine in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

“Only when this alternative pathway is inhibited [do cells] lose the ability to survive. As we know that one of the [DNA double-strand break] repair pathways which depend on BRCA1 is blocked in leukemia cells, we can try to find the alternative, parallel pathway and inhibit it as well.”

This will induce apoptosis via synthetic lethality, but only in leukemia cells, because healthy cells still have functional BRCA1-dependent signaling. Dr Skorski noted that therapies based on BRCA1 deficiency are currently under investigation in clinical trials. ![]()

Image courtesy of UCSD

New discoveries concerning a well-known tumor suppressor protein could help advance the diagnosis and treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), according to researchers.

They found that levels of the protein, BRCA1, are significantly decreased in advanced phases of CML, the expression of BCR-ABL1 correlates with decreased levels of BRCA1, and this downregulation of BRCA1 is caused by the inhibition of BRCA1 messenger RNA (mRNA) translation.

These discoveries explain the mechanism that supports CML development and uncover its weakness, the investigators said. They reported their findings in Cell Cycle.

“Our data demonstrated that BRCA1 synthesis is diminished in [the] advanced stage[s] of CML,” said study author Paulina Podszywałow-Bartnicka, PhD, of the Nencki Institute in Warsaw, Poland.

“The gene coding for BRCA1 protein is not mutated. However, BRCA1 mRNA, which is necessary for the protein production, is aggregated and stored in protein complexes [and], thus, not available for the protein synthesis.”

To gain more insight into this phenomenon, the investigators looked at 2 mRNA-binding proteins, HuR and TIAR. They found that BCR-ABL1 promoted cytosolic localization of TIAR and HuR, the proteins’ binding to BRCA1 mRNA, and formation of the TIAR-HuR complex.

The researchers also found that HuR positively regulated BRCA1 mRNA stability and translation, while TIAR negatively regulated BRCA1 translation.

TIAR-dependent downregulation of BRCA1 was a result of endoplasmic reticulum stress, which is activated in BCR-ABL1 expressing cells. And experiments showed that silencing TIAR in CML cells elevated BRCA1 levels.

This suggests that TIAR-mediated repression of BRCA1 mRNA translation is responsible for the downregulation of BRCA1 observed in BCR-ABL1-positive leukemia cells.

The investigators said this research indicates that BRCA1 deficiency, which supports CML, can be also used as a weapon against the disease.

“When a cell has damaged one signaling pathway or one gene, it may function properly due to alternative pathways . . . ,” explained study author Tomasz Skorski, MD, PhD, of Temple University School of Medicine in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

“Only when this alternative pathway is inhibited [do cells] lose the ability to survive. As we know that one of the [DNA double-strand break] repair pathways which depend on BRCA1 is blocked in leukemia cells, we can try to find the alternative, parallel pathway and inhibit it as well.”

This will induce apoptosis via synthetic lethality, but only in leukemia cells, because healthy cells still have functional BRCA1-dependent signaling. Dr Skorski noted that therapies based on BRCA1 deficiency are currently under investigation in clinical trials. ![]()

Image courtesy of UCSD

New discoveries concerning a well-known tumor suppressor protein could help advance the diagnosis and treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), according to researchers.

They found that levels of the protein, BRCA1, are significantly decreased in advanced phases of CML, the expression of BCR-ABL1 correlates with decreased levels of BRCA1, and this downregulation of BRCA1 is caused by the inhibition of BRCA1 messenger RNA (mRNA) translation.

These discoveries explain the mechanism that supports CML development and uncover its weakness, the investigators said. They reported their findings in Cell Cycle.

“Our data demonstrated that BRCA1 synthesis is diminished in [the] advanced stage[s] of CML,” said study author Paulina Podszywałow-Bartnicka, PhD, of the Nencki Institute in Warsaw, Poland.

“The gene coding for BRCA1 protein is not mutated. However, BRCA1 mRNA, which is necessary for the protein production, is aggregated and stored in protein complexes [and], thus, not available for the protein synthesis.”

To gain more insight into this phenomenon, the investigators looked at 2 mRNA-binding proteins, HuR and TIAR. They found that BCR-ABL1 promoted cytosolic localization of TIAR and HuR, the proteins’ binding to BRCA1 mRNA, and formation of the TIAR-HuR complex.

The researchers also found that HuR positively regulated BRCA1 mRNA stability and translation, while TIAR negatively regulated BRCA1 translation.

TIAR-dependent downregulation of BRCA1 was a result of endoplasmic reticulum stress, which is activated in BCR-ABL1 expressing cells. And experiments showed that silencing TIAR in CML cells elevated BRCA1 levels.

This suggests that TIAR-mediated repression of BRCA1 mRNA translation is responsible for the downregulation of BRCA1 observed in BCR-ABL1-positive leukemia cells.

The investigators said this research indicates that BRCA1 deficiency, which supports CML, can be also used as a weapon against the disease.

“When a cell has damaged one signaling pathway or one gene, it may function properly due to alternative pathways . . . ,” explained study author Tomasz Skorski, MD, PhD, of Temple University School of Medicine in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

“Only when this alternative pathway is inhibited [do cells] lose the ability to survive. As we know that one of the [DNA double-strand break] repair pathways which depend on BRCA1 is blocked in leukemia cells, we can try to find the alternative, parallel pathway and inhibit it as well.”

This will induce apoptosis via synthetic lethality, but only in leukemia cells, because healthy cells still have functional BRCA1-dependent signaling. Dr Skorski noted that therapies based on BRCA1 deficiency are currently under investigation in clinical trials. ![]()

FDA grants drug orphan designation for DLBCL

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation for IMO-8400, an antagonist of the endosomal toll-like receptors (TLRs) 7, 8, and 9, for the treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs intended to treat conditions that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation will provide Idera Pharmaceuticals, the company developing IMO-8400, with certain incentives. These include eligibility for federal grants, research and development tax credits, and a 7-year period of marketing exclusivity if the product is approved.

Relevant research

Preclinical research published in Leukemia showed that the MYD88 L265P oncogenic mutation is an independent prognostic factor in DLBCL. In DLBCL patients with this mutation, TLR signaling is over-activated, which enables tumor cell survival and proliferation.

Data presented at the 2014 AACR Annual Meeting showed that IMO-8400 inhibited the survival and proliferation of DLBCL cells and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia (WM) cells harboring the MYD88 L265P mutation.

A phase 1 trial of IMO-8400 presented at the 2013 FOCIS Annual Meeting showed the drug was active and well-tolerated in 42 healthy subjects. IMO-8400 was given at single and multiple escalating doses up to 0.6 mg/kg for 4 weeks. The drug inhibited immune responses mediated by TLRs 7, 8, and 9.

Idera Pharmaceuticals is currently conducting a phase 1/2 trial of IMO-8400 in patients with relapsed or refractory DLBCL who harbor the MYD88 L265P mutation. The protocol includes 3 dose-escalation cohorts in which IMO-8400 is administered subcutaneously.

Idera is also pursuing clinical development of IMO-8400 in WM. The FDA recently granted the drug orphan designation to treat WM. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation for IMO-8400, an antagonist of the endosomal toll-like receptors (TLRs) 7, 8, and 9, for the treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs intended to treat conditions that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation will provide Idera Pharmaceuticals, the company developing IMO-8400, with certain incentives. These include eligibility for federal grants, research and development tax credits, and a 7-year period of marketing exclusivity if the product is approved.

Relevant research

Preclinical research published in Leukemia showed that the MYD88 L265P oncogenic mutation is an independent prognostic factor in DLBCL. In DLBCL patients with this mutation, TLR signaling is over-activated, which enables tumor cell survival and proliferation.

Data presented at the 2014 AACR Annual Meeting showed that IMO-8400 inhibited the survival and proliferation of DLBCL cells and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia (WM) cells harboring the MYD88 L265P mutation.

A phase 1 trial of IMO-8400 presented at the 2013 FOCIS Annual Meeting showed the drug was active and well-tolerated in 42 healthy subjects. IMO-8400 was given at single and multiple escalating doses up to 0.6 mg/kg for 4 weeks. The drug inhibited immune responses mediated by TLRs 7, 8, and 9.

Idera Pharmaceuticals is currently conducting a phase 1/2 trial of IMO-8400 in patients with relapsed or refractory DLBCL who harbor the MYD88 L265P mutation. The protocol includes 3 dose-escalation cohorts in which IMO-8400 is administered subcutaneously.

Idera is also pursuing clinical development of IMO-8400 in WM. The FDA recently granted the drug orphan designation to treat WM. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation for IMO-8400, an antagonist of the endosomal toll-like receptors (TLRs) 7, 8, and 9, for the treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs intended to treat conditions that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation will provide Idera Pharmaceuticals, the company developing IMO-8400, with certain incentives. These include eligibility for federal grants, research and development tax credits, and a 7-year period of marketing exclusivity if the product is approved.

Relevant research

Preclinical research published in Leukemia showed that the MYD88 L265P oncogenic mutation is an independent prognostic factor in DLBCL. In DLBCL patients with this mutation, TLR signaling is over-activated, which enables tumor cell survival and proliferation.

Data presented at the 2014 AACR Annual Meeting showed that IMO-8400 inhibited the survival and proliferation of DLBCL cells and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia (WM) cells harboring the MYD88 L265P mutation.

A phase 1 trial of IMO-8400 presented at the 2013 FOCIS Annual Meeting showed the drug was active and well-tolerated in 42 healthy subjects. IMO-8400 was given at single and multiple escalating doses up to 0.6 mg/kg for 4 weeks. The drug inhibited immune responses mediated by TLRs 7, 8, and 9.

Idera Pharmaceuticals is currently conducting a phase 1/2 trial of IMO-8400 in patients with relapsed or refractory DLBCL who harbor the MYD88 L265P mutation. The protocol includes 3 dose-escalation cohorts in which IMO-8400 is administered subcutaneously.

Idera is also pursuing clinical development of IMO-8400 in WM. The FDA recently granted the drug orphan designation to treat WM. ![]()

Most childhood cancer survivors have morbidities

Photo by Logan Tuttle

New research suggests the prevalence of childhood cancer survivors in the US has increased, and the majority of pediatric patients who have survived 5

or more years beyond cancer diagnosis may have at least one chronic health condition.

About 70% of the childhood cancer survivors studied were estimated to have a mild or moderate chronic condition, and nearly a third were estimated to have a severe, disabling, or life-threatening chronic condition.

“Our study findings highlight that a singular focus on curing cancer yields an incomplete picture of childhood cancer survivorship,” said study author Siobhan M. Phillips, PhD, of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, Illinois.

“The burden of chronic conditions in this population is profound, both in occurrence and severity. Efforts to understand how to effectively decrease morbidity burden and incorporate effective care coordination and rehabilitation models to optimize longevity and well-being in this population should be a priority.”

Dr Phillips and her colleagues reported their findings in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.

The researchers analyzed data on cancer incidence and survival for children who were diagnosed with cancer between 0 and 19 years of age. The data had been recorded between 1975 and 2011 in 9 different US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries.

The team also used data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) cohort, which had information on a range of potential adverse and late effects of cancer treatment from more than 14,000 long-term survivors of childhood cancers who were treated at 26 cancer centers across the US and Canada.

The investigators first obtained estimates of the probability of each measure of morbidity from CCSS and then multiplied these estimates by the relevant number of survivors in the US estimated from the SEER data.