User login

Peri-Operative Hyperglycemia and Risk of Adverse Events in Diabetic Patients

Clinical question: How does peri-operative hyperglycemia affect the risk of adverse events in diabetic patients compared to nondiabetic patients?

Background: Peri-operative hyperglycemia is associated with increased rates of infection, myocardial infarction, stroke, and death. Recent studies suggest that nondiabetics are more prone to hyperglycemia-related complications than diabetics. This study sought to analyze the effect and mechanism by which nondiabetics may be at increased risk for such complications.

Study Design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Fifty-three hospitals in Washington.

Synopsis: Among 40,836 patients who underwent surgery, diabetics had a higher rate of peri-operative adverse events overall compared to nondiabetics (12% vs. 9%, P<0.001). Peri-operative hyperglycemia, defined as blood glucose 180 or greater, was also associated with an increased rate of adverse events. Ironically, this association was more significant in nondiabetic patients [OR 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3-2.1] than in diabetic patients (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.6-1.0). Although the exact reason for this is unknown, existing theories include the following:

- Diabetics are more apt to receive insulin for peri-operative hyperglycemia than nondiabetics (P<0.001);

- Hyperglycemia in diabetics may be a less reliable marker of surgical stress than in nondiabetics; and

- Diabetics may be better adapted to hyperglycemia than nondiabetics.

Bottom Line: Peri-operative hyperglycemia leads to an increased risk of adverse events; this relationship is more pronounced in nondiabetic patients than in diabetic patients.

Citation: Kotagal M, Symons RG, Hirsch IB, et al. Perioperative hyperglycemia and risk of adverse events among patients with and without diabetes. Ann Surg. 2015;261(1):97-103.

Clinical question: How does peri-operative hyperglycemia affect the risk of adverse events in diabetic patients compared to nondiabetic patients?

Background: Peri-operative hyperglycemia is associated with increased rates of infection, myocardial infarction, stroke, and death. Recent studies suggest that nondiabetics are more prone to hyperglycemia-related complications than diabetics. This study sought to analyze the effect and mechanism by which nondiabetics may be at increased risk for such complications.

Study Design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Fifty-three hospitals in Washington.

Synopsis: Among 40,836 patients who underwent surgery, diabetics had a higher rate of peri-operative adverse events overall compared to nondiabetics (12% vs. 9%, P<0.001). Peri-operative hyperglycemia, defined as blood glucose 180 or greater, was also associated with an increased rate of adverse events. Ironically, this association was more significant in nondiabetic patients [OR 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3-2.1] than in diabetic patients (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.6-1.0). Although the exact reason for this is unknown, existing theories include the following:

- Diabetics are more apt to receive insulin for peri-operative hyperglycemia than nondiabetics (P<0.001);

- Hyperglycemia in diabetics may be a less reliable marker of surgical stress than in nondiabetics; and

- Diabetics may be better adapted to hyperglycemia than nondiabetics.

Bottom Line: Peri-operative hyperglycemia leads to an increased risk of adverse events; this relationship is more pronounced in nondiabetic patients than in diabetic patients.

Citation: Kotagal M, Symons RG, Hirsch IB, et al. Perioperative hyperglycemia and risk of adverse events among patients with and without diabetes. Ann Surg. 2015;261(1):97-103.

Clinical question: How does peri-operative hyperglycemia affect the risk of adverse events in diabetic patients compared to nondiabetic patients?

Background: Peri-operative hyperglycemia is associated with increased rates of infection, myocardial infarction, stroke, and death. Recent studies suggest that nondiabetics are more prone to hyperglycemia-related complications than diabetics. This study sought to analyze the effect and mechanism by which nondiabetics may be at increased risk for such complications.

Study Design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Fifty-three hospitals in Washington.

Synopsis: Among 40,836 patients who underwent surgery, diabetics had a higher rate of peri-operative adverse events overall compared to nondiabetics (12% vs. 9%, P<0.001). Peri-operative hyperglycemia, defined as blood glucose 180 or greater, was also associated with an increased rate of adverse events. Ironically, this association was more significant in nondiabetic patients [OR 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3-2.1] than in diabetic patients (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.6-1.0). Although the exact reason for this is unknown, existing theories include the following:

- Diabetics are more apt to receive insulin for peri-operative hyperglycemia than nondiabetics (P<0.001);

- Hyperglycemia in diabetics may be a less reliable marker of surgical stress than in nondiabetics; and

- Diabetics may be better adapted to hyperglycemia than nondiabetics.

Bottom Line: Peri-operative hyperglycemia leads to an increased risk of adverse events; this relationship is more pronounced in nondiabetic patients than in diabetic patients.

Citation: Kotagal M, Symons RG, Hirsch IB, et al. Perioperative hyperglycemia and risk of adverse events among patients with and without diabetes. Ann Surg. 2015;261(1):97-103.

Complaints Against Doctors Linked to Depression, Defensive Medicine

Clinical question: What is the impact of complaints on doctors’ psychological welfare and health?

Background: Studies have shown that malpractice litigation is associated with physician depression and suicide. Though complaints and investigations are part of appropriate physician oversight, unintentional consequences, such as defensive medicine and physician burnout, often occur.

Study design: Cross-sectional, anonymous survey study.

Setting: Surveys sent to members of the British Medical Association.

Synopsis: Only 8.3% of 95,636 invited physicians completed the survey. This study demonstrated that 16.9% of doctors with recent or ongoing complaints reported clinically significant symptoms of moderate to severe depression, compared to 9.5% of doctors with no complaints; 15% of doctors in the recent complaints group reported clinically significant levels of anxiety, compared to 7.3% of doctors with no complaints. Overall, 84.7% of doctors with a recent complaint and 79.9% with a past complaint reported changing the way they practiced medicine as a result of the complaint.

Since this study is a cross-sectional survey, it does not prove causation; it is possible that doctors with depression and anxiety are more likely to have complaints filed against them.

Bottom line: Doctors involved with complaints have a high prevalence of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.

Citation: Bourne T, Wynants L, Peters M, et al. The impact of complaints procedures on the welfare, health and clinical practise of 7926 doctors in the UK: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006687.

Clinical question: What is the impact of complaints on doctors’ psychological welfare and health?

Background: Studies have shown that malpractice litigation is associated with physician depression and suicide. Though complaints and investigations are part of appropriate physician oversight, unintentional consequences, such as defensive medicine and physician burnout, often occur.

Study design: Cross-sectional, anonymous survey study.

Setting: Surveys sent to members of the British Medical Association.

Synopsis: Only 8.3% of 95,636 invited physicians completed the survey. This study demonstrated that 16.9% of doctors with recent or ongoing complaints reported clinically significant symptoms of moderate to severe depression, compared to 9.5% of doctors with no complaints; 15% of doctors in the recent complaints group reported clinically significant levels of anxiety, compared to 7.3% of doctors with no complaints. Overall, 84.7% of doctors with a recent complaint and 79.9% with a past complaint reported changing the way they practiced medicine as a result of the complaint.

Since this study is a cross-sectional survey, it does not prove causation; it is possible that doctors with depression and anxiety are more likely to have complaints filed against them.

Bottom line: Doctors involved with complaints have a high prevalence of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.

Citation: Bourne T, Wynants L, Peters M, et al. The impact of complaints procedures on the welfare, health and clinical practise of 7926 doctors in the UK: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006687.

Clinical question: What is the impact of complaints on doctors’ psychological welfare and health?

Background: Studies have shown that malpractice litigation is associated with physician depression and suicide. Though complaints and investigations are part of appropriate physician oversight, unintentional consequences, such as defensive medicine and physician burnout, often occur.

Study design: Cross-sectional, anonymous survey study.

Setting: Surveys sent to members of the British Medical Association.

Synopsis: Only 8.3% of 95,636 invited physicians completed the survey. This study demonstrated that 16.9% of doctors with recent or ongoing complaints reported clinically significant symptoms of moderate to severe depression, compared to 9.5% of doctors with no complaints; 15% of doctors in the recent complaints group reported clinically significant levels of anxiety, compared to 7.3% of doctors with no complaints. Overall, 84.7% of doctors with a recent complaint and 79.9% with a past complaint reported changing the way they practiced medicine as a result of the complaint.

Since this study is a cross-sectional survey, it does not prove causation; it is possible that doctors with depression and anxiety are more likely to have complaints filed against them.

Bottom line: Doctors involved with complaints have a high prevalence of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.

Citation: Bourne T, Wynants L, Peters M, et al. The impact of complaints procedures on the welfare, health and clinical practise of 7926 doctors in the UK: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006687.

ICU Delirium: Little Attributable Mortality after Adjustment

Clinical question: Does delirium contribute to chance of death?

Background: Delirium is a well-recognized predictor of mortality. Prior observational studies have estimated a risk of death two to four times higher in ICU patients with delirium compared with those who do not experience delirium. The degree to which this association reflects a causal relationship is debated.

Study design: Prospective cohort study; used logistic regression and competing risks survival analyses along with a marginal structural model analysis to adjust for both baseline characteristics and severity of illness developing during ICU stay.

Setting: Single ICU in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Regression analysis of 1,112 ICU patients confirmed the strong association between delirium and mortality; however, additional analysis, adjusting for the severity of illness as it progressed during the ICU stay, attenuated the relationship to nonsignificance. This suggests that both delirium and mortality were being driven by the common underlying illness.

In post hoc analysis, only persistent delirium was associated with a small increase in mortality. Although this observational study can neither prove nor disprove causation, the adjustment for changing severity of illness during the ICU stay was more sophisticated than prior studies. This study suggests that delirium and mortality are likely companions on the road of critical illness but that one may not directly cause the other.

Bottom line: Delirium in the ICU likely does not cause death, but its presence portends increased risk of mortality.

Citations: Klouwenberg PM, Zaal IJ, Spitoni C, et al. The attributable mortality of delirium in critically ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2014;349:g6652. Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911-922.

Clinical question: Does delirium contribute to chance of death?

Background: Delirium is a well-recognized predictor of mortality. Prior observational studies have estimated a risk of death two to four times higher in ICU patients with delirium compared with those who do not experience delirium. The degree to which this association reflects a causal relationship is debated.

Study design: Prospective cohort study; used logistic regression and competing risks survival analyses along with a marginal structural model analysis to adjust for both baseline characteristics and severity of illness developing during ICU stay.

Setting: Single ICU in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Regression analysis of 1,112 ICU patients confirmed the strong association between delirium and mortality; however, additional analysis, adjusting for the severity of illness as it progressed during the ICU stay, attenuated the relationship to nonsignificance. This suggests that both delirium and mortality were being driven by the common underlying illness.

In post hoc analysis, only persistent delirium was associated with a small increase in mortality. Although this observational study can neither prove nor disprove causation, the adjustment for changing severity of illness during the ICU stay was more sophisticated than prior studies. This study suggests that delirium and mortality are likely companions on the road of critical illness but that one may not directly cause the other.

Bottom line: Delirium in the ICU likely does not cause death, but its presence portends increased risk of mortality.

Citations: Klouwenberg PM, Zaal IJ, Spitoni C, et al. The attributable mortality of delirium in critically ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2014;349:g6652. Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911-922.

Clinical question: Does delirium contribute to chance of death?

Background: Delirium is a well-recognized predictor of mortality. Prior observational studies have estimated a risk of death two to four times higher in ICU patients with delirium compared with those who do not experience delirium. The degree to which this association reflects a causal relationship is debated.

Study design: Prospective cohort study; used logistic regression and competing risks survival analyses along with a marginal structural model analysis to adjust for both baseline characteristics and severity of illness developing during ICU stay.

Setting: Single ICU in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Regression analysis of 1,112 ICU patients confirmed the strong association between delirium and mortality; however, additional analysis, adjusting for the severity of illness as it progressed during the ICU stay, attenuated the relationship to nonsignificance. This suggests that both delirium and mortality were being driven by the common underlying illness.

In post hoc analysis, only persistent delirium was associated with a small increase in mortality. Although this observational study can neither prove nor disprove causation, the adjustment for changing severity of illness during the ICU stay was more sophisticated than prior studies. This study suggests that delirium and mortality are likely companions on the road of critical illness but that one may not directly cause the other.

Bottom line: Delirium in the ICU likely does not cause death, but its presence portends increased risk of mortality.

Citations: Klouwenberg PM, Zaal IJ, Spitoni C, et al. The attributable mortality of delirium in critically ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2014;349:g6652. Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911-922.

Academic Hospitalist Groups Lag Behind in Admissions, Discharges

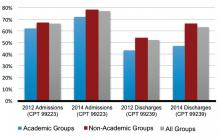

In 2012, SHM reported increasing numbers of hospital encounters coded for high-level evaluation and management services, as reported by the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) survey respondents. The 2014 SOHM report shows a solid continuation of this trend, with high-level CPT codes predominating in admission and discharge services by wider margins than ever before.

The 2014 report provides CPT code data from 173 hospitalist groups, who reported the number of inpatient admissions with CPT codes corresponding to Level 1, Level 2, or Level 3. Inpatient discharges have codes corresponding to either Level 1 or Level 2.

Compared to 2012, Level 3 admissions (CPT 99223) increased by 14% in 2014 and now account for 77% of all admissions (see Figure 1). Level 2 discharges (CPT 99239) have increased by 17% since 2012 and now account for 63% of discharges.

In 2014, SOHM added CPT code distribution data for observation care. Observation admissions and inpatient and observation subsequent care are also reported as Level 1, 2, or 3 by the corresponding CPT codes. Observation discharges, which have only one code level, are also reported, in addition to the three levels of same-day admit/discharge encounters.

The rate of Level 3 CPT codes reported for observation admissions, which was 72%, roughly approximated that of inpatient admissions. For subsequent care, Level 2 accounts for the majority of both observation and inpatient codes.

Despite the general predominance of Level 3 admissions and now Level 2 inpatient discharges, not all hospitalist groups deal equally in these higher billing evaluation and management services. Groups in the West region previously dominated the high-level encounters in both admissions and discharges; in 2014, the South took the lead in high-level admissions.

One factor that has consistently signaled lower rates of high-level coding, however, is academic status. A likely reason, as alluded to in a previous “Survey Insights” column, relates to the fact that residents’ time is not billable. This is particularly important in the discharge coding, in which the higher Level 2 code is strictly based on the statement by an attending that discharge services were personally provided for more than 30 minutes. Understandably, this happens less often when a resident’s education includes providing discharge services.

If attending face-to-face time is a major factor in the discharge coding differential, it does not explain where academic groups are missing the boat on the admission side, where residents’ documentation is incorporated by attendings—and can have a substantial effect on accurate billing. This assumes that academic groups are not treating far fewer sick patients, less comprehensively, across the board.

In my own public academic hospital, I see reviewing the required elements of the history and physical examination (H&P) as survival for our hospital and our mission, as well as an opportunity to educate residents simultaneously in patient interviewing skills and system-based practice.

But before I get too far into waxing altruistic, let me recognize another factor suggested by the SOHM report: I am not 100% salaried. That means thorough documentation and accurate coding directly impact my personal compensation.

The 2014 SOHM report shows, as it did in 2012, an inverse correlation between high-level admissions and percent salaried compensation. Although this relationship remains less clear in follow-ups and discharges, perhaps hospitalists pay more attention to coding criteria when it’s bread on the table…and if time permits.

Dr. Creamer is medical director of the short-stay unit at MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

In 2012, SHM reported increasing numbers of hospital encounters coded for high-level evaluation and management services, as reported by the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) survey respondents. The 2014 SOHM report shows a solid continuation of this trend, with high-level CPT codes predominating in admission and discharge services by wider margins than ever before.

The 2014 report provides CPT code data from 173 hospitalist groups, who reported the number of inpatient admissions with CPT codes corresponding to Level 1, Level 2, or Level 3. Inpatient discharges have codes corresponding to either Level 1 or Level 2.

Compared to 2012, Level 3 admissions (CPT 99223) increased by 14% in 2014 and now account for 77% of all admissions (see Figure 1). Level 2 discharges (CPT 99239) have increased by 17% since 2012 and now account for 63% of discharges.

In 2014, SOHM added CPT code distribution data for observation care. Observation admissions and inpatient and observation subsequent care are also reported as Level 1, 2, or 3 by the corresponding CPT codes. Observation discharges, which have only one code level, are also reported, in addition to the three levels of same-day admit/discharge encounters.

The rate of Level 3 CPT codes reported for observation admissions, which was 72%, roughly approximated that of inpatient admissions. For subsequent care, Level 2 accounts for the majority of both observation and inpatient codes.

Despite the general predominance of Level 3 admissions and now Level 2 inpatient discharges, not all hospitalist groups deal equally in these higher billing evaluation and management services. Groups in the West region previously dominated the high-level encounters in both admissions and discharges; in 2014, the South took the lead in high-level admissions.

One factor that has consistently signaled lower rates of high-level coding, however, is academic status. A likely reason, as alluded to in a previous “Survey Insights” column, relates to the fact that residents’ time is not billable. This is particularly important in the discharge coding, in which the higher Level 2 code is strictly based on the statement by an attending that discharge services were personally provided for more than 30 minutes. Understandably, this happens less often when a resident’s education includes providing discharge services.

If attending face-to-face time is a major factor in the discharge coding differential, it does not explain where academic groups are missing the boat on the admission side, where residents’ documentation is incorporated by attendings—and can have a substantial effect on accurate billing. This assumes that academic groups are not treating far fewer sick patients, less comprehensively, across the board.

In my own public academic hospital, I see reviewing the required elements of the history and physical examination (H&P) as survival for our hospital and our mission, as well as an opportunity to educate residents simultaneously in patient interviewing skills and system-based practice.

But before I get too far into waxing altruistic, let me recognize another factor suggested by the SOHM report: I am not 100% salaried. That means thorough documentation and accurate coding directly impact my personal compensation.

The 2014 SOHM report shows, as it did in 2012, an inverse correlation between high-level admissions and percent salaried compensation. Although this relationship remains less clear in follow-ups and discharges, perhaps hospitalists pay more attention to coding criteria when it’s bread on the table…and if time permits.

Dr. Creamer is medical director of the short-stay unit at MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

In 2012, SHM reported increasing numbers of hospital encounters coded for high-level evaluation and management services, as reported by the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) survey respondents. The 2014 SOHM report shows a solid continuation of this trend, with high-level CPT codes predominating in admission and discharge services by wider margins than ever before.

The 2014 report provides CPT code data from 173 hospitalist groups, who reported the number of inpatient admissions with CPT codes corresponding to Level 1, Level 2, or Level 3. Inpatient discharges have codes corresponding to either Level 1 or Level 2.

Compared to 2012, Level 3 admissions (CPT 99223) increased by 14% in 2014 and now account for 77% of all admissions (see Figure 1). Level 2 discharges (CPT 99239) have increased by 17% since 2012 and now account for 63% of discharges.

In 2014, SOHM added CPT code distribution data for observation care. Observation admissions and inpatient and observation subsequent care are also reported as Level 1, 2, or 3 by the corresponding CPT codes. Observation discharges, which have only one code level, are also reported, in addition to the three levels of same-day admit/discharge encounters.

The rate of Level 3 CPT codes reported for observation admissions, which was 72%, roughly approximated that of inpatient admissions. For subsequent care, Level 2 accounts for the majority of both observation and inpatient codes.

Despite the general predominance of Level 3 admissions and now Level 2 inpatient discharges, not all hospitalist groups deal equally in these higher billing evaluation and management services. Groups in the West region previously dominated the high-level encounters in both admissions and discharges; in 2014, the South took the lead in high-level admissions.

One factor that has consistently signaled lower rates of high-level coding, however, is academic status. A likely reason, as alluded to in a previous “Survey Insights” column, relates to the fact that residents’ time is not billable. This is particularly important in the discharge coding, in which the higher Level 2 code is strictly based on the statement by an attending that discharge services were personally provided for more than 30 minutes. Understandably, this happens less often when a resident’s education includes providing discharge services.

If attending face-to-face time is a major factor in the discharge coding differential, it does not explain where academic groups are missing the boat on the admission side, where residents’ documentation is incorporated by attendings—and can have a substantial effect on accurate billing. This assumes that academic groups are not treating far fewer sick patients, less comprehensively, across the board.

In my own public academic hospital, I see reviewing the required elements of the history and physical examination (H&P) as survival for our hospital and our mission, as well as an opportunity to educate residents simultaneously in patient interviewing skills and system-based practice.

But before I get too far into waxing altruistic, let me recognize another factor suggested by the SOHM report: I am not 100% salaried. That means thorough documentation and accurate coding directly impact my personal compensation.

The 2014 SOHM report shows, as it did in 2012, an inverse correlation between high-level admissions and percent salaried compensation. Although this relationship remains less clear in follow-ups and discharges, perhaps hospitalists pay more attention to coding criteria when it’s bread on the table…and if time permits.

Dr. Creamer is medical director of the short-stay unit at MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Patient, Family-Centered Care at Veterans Affairs Hospitals

The journey toward patient and family centered care (PFCC) has been one of the hallmarks of early twenty-first century healthcare transformation. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA, including all of its VAMC hospitals) understands the critical importance of PFCC and has fully embraced—indeed, extended—its tenets as a core foundational structure going into the future. As full participants in the collaborative VHA care model, hospitalists and collaborating care teams are enhancing best care/best treatment practices with PFCC modalities.

Transformation is not new to VHA. Starting in the late 1990s, the organization expanded from a hospital-based, specialty care-only institution to one that adopted primary care in a wheel-and-spoke design: a centralized medical center with surrounding community-based primary care clinics. This brought about the infrastructure necessary to create the fully integrated national network that is VHA today. The current PFCC transformation aims to grow VHA a step further by restyling the culture of VHA care to a model that completely focuses the system around the needs of the veterans. VHA’s Blueprint for Excellence, a prescient guiding document for VHA transformation today, explains that the direction to Whole Health encompasses “support for both care needs and health into a coherent experience of veteran-centered care that maximizes well-being.”

The Whole Health program is the sum of patient self-care; personalized, proactive, patient-driven care (PPPDC); and environmental (relationship and community-based) care. The VHA is serious about PFCC: In 2010, the organization created a top-ranking office, aptly named the Office of Patient-Centered Care & Cultural Transformation (OPCC&CT); the office reports directly to national leadership and has as its founding objective the support of this latest transformation.

The VHA’s ambitious adoption of PFCC and the Whole Health program involves fully embracing PPPDC. VHA partners work with each veteran to create a personal health plan (PHP), supported by health coaching, motivational interviewing, and other clinical tools, as a living document aimed at optimizing health and well-being; best practice, evidence-based disease intervention and management provide the chronic and acute care needs.

A veteran’s PHP, essentially a mission and goal-planning document, is founded on what matters most to the veteran and on the aspects of the veteran’s health that are keeping him or her from meeting current and future life goals. Hospitalist providers, including those at VHA, academic, and private sector hospitals, can use the essence of the PHP to guide inpatient care. It is powerful to ask each of our patients what matters most to him or her, to understand a patient’s situational life goal. To partner with patients, helping each one to focus on and realize a pressing individual goal, not only centers us but humanizes an often destabilizing and stressful time for our patients.

Hippocrates is quoted as saying that we “cure sometimes, treat often, and comfort always.” This is true today. We rarely cure, but we can offer treatment with maximal comfort during a hospitalization, assisting our patients in returning to the health they had established prior to their admission. Hospital medicine providers and hospital-based teams act as a safety net, caring for our acutely ill patients, working with them to bring them back to their baseline, and getting them back on track to be able to enjoy what really matters to them, their “mission” at the moment. PFCC and PPPDC provide the culture and tools to meet our patients’ goals.

The VHA’s number one strategic goal has been to provide veterans PPPDC. Hospitalists and hospitals have adopted—and will continue to adopt—practices that move toward this goal. PFCC is at its essence patient empowerment, and its primary benefits are enhancement of patient safety, quality of care, and patient satisfaction. PFCC is one innovation necessary to reach the “triple aim” all healthcare systems strive toward: better health, better care, better value.

Dr. Steinbach is chief of hospital medicine at the Atlanta VAMC and assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

The journey toward patient and family centered care (PFCC) has been one of the hallmarks of early twenty-first century healthcare transformation. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA, including all of its VAMC hospitals) understands the critical importance of PFCC and has fully embraced—indeed, extended—its tenets as a core foundational structure going into the future. As full participants in the collaborative VHA care model, hospitalists and collaborating care teams are enhancing best care/best treatment practices with PFCC modalities.

Transformation is not new to VHA. Starting in the late 1990s, the organization expanded from a hospital-based, specialty care-only institution to one that adopted primary care in a wheel-and-spoke design: a centralized medical center with surrounding community-based primary care clinics. This brought about the infrastructure necessary to create the fully integrated national network that is VHA today. The current PFCC transformation aims to grow VHA a step further by restyling the culture of VHA care to a model that completely focuses the system around the needs of the veterans. VHA’s Blueprint for Excellence, a prescient guiding document for VHA transformation today, explains that the direction to Whole Health encompasses “support for both care needs and health into a coherent experience of veteran-centered care that maximizes well-being.”

The Whole Health program is the sum of patient self-care; personalized, proactive, patient-driven care (PPPDC); and environmental (relationship and community-based) care. The VHA is serious about PFCC: In 2010, the organization created a top-ranking office, aptly named the Office of Patient-Centered Care & Cultural Transformation (OPCC&CT); the office reports directly to national leadership and has as its founding objective the support of this latest transformation.

The VHA’s ambitious adoption of PFCC and the Whole Health program involves fully embracing PPPDC. VHA partners work with each veteran to create a personal health plan (PHP), supported by health coaching, motivational interviewing, and other clinical tools, as a living document aimed at optimizing health and well-being; best practice, evidence-based disease intervention and management provide the chronic and acute care needs.

A veteran’s PHP, essentially a mission and goal-planning document, is founded on what matters most to the veteran and on the aspects of the veteran’s health that are keeping him or her from meeting current and future life goals. Hospitalist providers, including those at VHA, academic, and private sector hospitals, can use the essence of the PHP to guide inpatient care. It is powerful to ask each of our patients what matters most to him or her, to understand a patient’s situational life goal. To partner with patients, helping each one to focus on and realize a pressing individual goal, not only centers us but humanizes an often destabilizing and stressful time for our patients.

Hippocrates is quoted as saying that we “cure sometimes, treat often, and comfort always.” This is true today. We rarely cure, but we can offer treatment with maximal comfort during a hospitalization, assisting our patients in returning to the health they had established prior to their admission. Hospital medicine providers and hospital-based teams act as a safety net, caring for our acutely ill patients, working with them to bring them back to their baseline, and getting them back on track to be able to enjoy what really matters to them, their “mission” at the moment. PFCC and PPPDC provide the culture and tools to meet our patients’ goals.

The VHA’s number one strategic goal has been to provide veterans PPPDC. Hospitalists and hospitals have adopted—and will continue to adopt—practices that move toward this goal. PFCC is at its essence patient empowerment, and its primary benefits are enhancement of patient safety, quality of care, and patient satisfaction. PFCC is one innovation necessary to reach the “triple aim” all healthcare systems strive toward: better health, better care, better value.

Dr. Steinbach is chief of hospital medicine at the Atlanta VAMC and assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

The journey toward patient and family centered care (PFCC) has been one of the hallmarks of early twenty-first century healthcare transformation. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA, including all of its VAMC hospitals) understands the critical importance of PFCC and has fully embraced—indeed, extended—its tenets as a core foundational structure going into the future. As full participants in the collaborative VHA care model, hospitalists and collaborating care teams are enhancing best care/best treatment practices with PFCC modalities.

Transformation is not new to VHA. Starting in the late 1990s, the organization expanded from a hospital-based, specialty care-only institution to one that adopted primary care in a wheel-and-spoke design: a centralized medical center with surrounding community-based primary care clinics. This brought about the infrastructure necessary to create the fully integrated national network that is VHA today. The current PFCC transformation aims to grow VHA a step further by restyling the culture of VHA care to a model that completely focuses the system around the needs of the veterans. VHA’s Blueprint for Excellence, a prescient guiding document for VHA transformation today, explains that the direction to Whole Health encompasses “support for both care needs and health into a coherent experience of veteran-centered care that maximizes well-being.”

The Whole Health program is the sum of patient self-care; personalized, proactive, patient-driven care (PPPDC); and environmental (relationship and community-based) care. The VHA is serious about PFCC: In 2010, the organization created a top-ranking office, aptly named the Office of Patient-Centered Care & Cultural Transformation (OPCC&CT); the office reports directly to national leadership and has as its founding objective the support of this latest transformation.

The VHA’s ambitious adoption of PFCC and the Whole Health program involves fully embracing PPPDC. VHA partners work with each veteran to create a personal health plan (PHP), supported by health coaching, motivational interviewing, and other clinical tools, as a living document aimed at optimizing health and well-being; best practice, evidence-based disease intervention and management provide the chronic and acute care needs.

A veteran’s PHP, essentially a mission and goal-planning document, is founded on what matters most to the veteran and on the aspects of the veteran’s health that are keeping him or her from meeting current and future life goals. Hospitalist providers, including those at VHA, academic, and private sector hospitals, can use the essence of the PHP to guide inpatient care. It is powerful to ask each of our patients what matters most to him or her, to understand a patient’s situational life goal. To partner with patients, helping each one to focus on and realize a pressing individual goal, not only centers us but humanizes an often destabilizing and stressful time for our patients.

Hippocrates is quoted as saying that we “cure sometimes, treat often, and comfort always.” This is true today. We rarely cure, but we can offer treatment with maximal comfort during a hospitalization, assisting our patients in returning to the health they had established prior to their admission. Hospital medicine providers and hospital-based teams act as a safety net, caring for our acutely ill patients, working with them to bring them back to their baseline, and getting them back on track to be able to enjoy what really matters to them, their “mission” at the moment. PFCC and PPPDC provide the culture and tools to meet our patients’ goals.

The VHA’s number one strategic goal has been to provide veterans PPPDC. Hospitalists and hospitals have adopted—and will continue to adopt—practices that move toward this goal. PFCC is at its essence patient empowerment, and its primary benefits are enhancement of patient safety, quality of care, and patient satisfaction. PFCC is one innovation necessary to reach the “triple aim” all healthcare systems strive toward: better health, better care, better value.

Dr. Steinbach is chief of hospital medicine at the Atlanta VAMC and assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

Bob Wachter's New Book Examines Healthcare in Digital Age

This month, Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center and well known for his work in patient safety and healthcare quality, debuts his latest book, The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine’s Computer Age. The book explores the realities of U.S. efforts to bring healthcare into the digital age.

Dr. Wachter is especially concerned with the consequences—both intended and unintended—of health information technology. The Hospitalist spoke with Dr. Wachter about why he wrote the book and asked him about some of the burning issues facing hospitalists today.

Question: In the book’s introduction, you state that while computers are preventing medical errors, they are also causing new kinds of mistakes. One was a case at your hospital in which an adolescent was given a 39-fold overdose of a routine antibiotic. What was it about this case that galvanized you to write the book?

Answer: A few weeks after the error, I attended the root cause analysis, and my jaw just fell and fell. I was struck by the disconnect between what we’d been saying for years—‘When we finally get computers, we’re going to fix so many of these problems’—and the reality, that in about as wired an environment as you can imagine, we managed to give a kid 40 pills. [The patient had a seizure but survived.] Clearly, the case was partly about a glitchy computer system. But the larger problems related to the troubling people-computer interfaces. That’s what I wanted to address in the book.

Q: How did you secure buy-in from the hospital, the involved providers, and the family to write about the case?

A: In 2004, I wrote a book, Internal Bleeding, in which we presented many cases of medical mistakes, some of them fatal. We managed to keep the cases anonymous, and from this and similar projects, I developed a reputation for doing this kind of thing diplomatically and carefully. I think that’s why the risk manager didn’t reject the idea out of hand, and, ultimately, my CMO and CEO agreed to it as well. After that, I approached the involved clinicians and the patient and his mother. To everyone’s credit—the providers, the administrators, and the patient and family—they believed that this case was so important that we should be open and honest about it. My experience is that people are sometimes trying to find some meaning in a horrible event, and that meaning can come from helping to prevent a similar case in the future.

Q: What are some of the tensions that affect the interface between frontline providers and healthcare IT?

A: In the book, I contrast the way the healthcare IT companies build their systems—with relatively little input from clinicians—with the philosophy at Boeing, where they bring pilots into the process to develop cockpit computers. There is a powerful concept known as “adaptive change,” as contrasted with technical change. Technical change is like a cookbook: Put in a set of rules, have people follow them, and everything works out fine. Adaptive change is more complex and subtle; it requires the intense involvement of frontline workers.

We made the mistake of treating health IT as technical change, but it is probably the hardest adaptive change we’ve ever tried. My goal was to create a national conversation about this, which is what we need if we’re going to get it right.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

This month, Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center and well known for his work in patient safety and healthcare quality, debuts his latest book, The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine’s Computer Age. The book explores the realities of U.S. efforts to bring healthcare into the digital age.

Dr. Wachter is especially concerned with the consequences—both intended and unintended—of health information technology. The Hospitalist spoke with Dr. Wachter about why he wrote the book and asked him about some of the burning issues facing hospitalists today.

Question: In the book’s introduction, you state that while computers are preventing medical errors, they are also causing new kinds of mistakes. One was a case at your hospital in which an adolescent was given a 39-fold overdose of a routine antibiotic. What was it about this case that galvanized you to write the book?

Answer: A few weeks after the error, I attended the root cause analysis, and my jaw just fell and fell. I was struck by the disconnect between what we’d been saying for years—‘When we finally get computers, we’re going to fix so many of these problems’—and the reality, that in about as wired an environment as you can imagine, we managed to give a kid 40 pills. [The patient had a seizure but survived.] Clearly, the case was partly about a glitchy computer system. But the larger problems related to the troubling people-computer interfaces. That’s what I wanted to address in the book.

Q: How did you secure buy-in from the hospital, the involved providers, and the family to write about the case?

A: In 2004, I wrote a book, Internal Bleeding, in which we presented many cases of medical mistakes, some of them fatal. We managed to keep the cases anonymous, and from this and similar projects, I developed a reputation for doing this kind of thing diplomatically and carefully. I think that’s why the risk manager didn’t reject the idea out of hand, and, ultimately, my CMO and CEO agreed to it as well. After that, I approached the involved clinicians and the patient and his mother. To everyone’s credit—the providers, the administrators, and the patient and family—they believed that this case was so important that we should be open and honest about it. My experience is that people are sometimes trying to find some meaning in a horrible event, and that meaning can come from helping to prevent a similar case in the future.

Q: What are some of the tensions that affect the interface between frontline providers and healthcare IT?

A: In the book, I contrast the way the healthcare IT companies build their systems—with relatively little input from clinicians—with the philosophy at Boeing, where they bring pilots into the process to develop cockpit computers. There is a powerful concept known as “adaptive change,” as contrasted with technical change. Technical change is like a cookbook: Put in a set of rules, have people follow them, and everything works out fine. Adaptive change is more complex and subtle; it requires the intense involvement of frontline workers.

We made the mistake of treating health IT as technical change, but it is probably the hardest adaptive change we’ve ever tried. My goal was to create a national conversation about this, which is what we need if we’re going to get it right.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

This month, Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center and well known for his work in patient safety and healthcare quality, debuts his latest book, The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine’s Computer Age. The book explores the realities of U.S. efforts to bring healthcare into the digital age.

Dr. Wachter is especially concerned with the consequences—both intended and unintended—of health information technology. The Hospitalist spoke with Dr. Wachter about why he wrote the book and asked him about some of the burning issues facing hospitalists today.

Question: In the book’s introduction, you state that while computers are preventing medical errors, they are also causing new kinds of mistakes. One was a case at your hospital in which an adolescent was given a 39-fold overdose of a routine antibiotic. What was it about this case that galvanized you to write the book?

Answer: A few weeks after the error, I attended the root cause analysis, and my jaw just fell and fell. I was struck by the disconnect between what we’d been saying for years—‘When we finally get computers, we’re going to fix so many of these problems’—and the reality, that in about as wired an environment as you can imagine, we managed to give a kid 40 pills. [The patient had a seizure but survived.] Clearly, the case was partly about a glitchy computer system. But the larger problems related to the troubling people-computer interfaces. That’s what I wanted to address in the book.

Q: How did you secure buy-in from the hospital, the involved providers, and the family to write about the case?

A: In 2004, I wrote a book, Internal Bleeding, in which we presented many cases of medical mistakes, some of them fatal. We managed to keep the cases anonymous, and from this and similar projects, I developed a reputation for doing this kind of thing diplomatically and carefully. I think that’s why the risk manager didn’t reject the idea out of hand, and, ultimately, my CMO and CEO agreed to it as well. After that, I approached the involved clinicians and the patient and his mother. To everyone’s credit—the providers, the administrators, and the patient and family—they believed that this case was so important that we should be open and honest about it. My experience is that people are sometimes trying to find some meaning in a horrible event, and that meaning can come from helping to prevent a similar case in the future.

Q: What are some of the tensions that affect the interface between frontline providers and healthcare IT?

A: In the book, I contrast the way the healthcare IT companies build their systems—with relatively little input from clinicians—with the philosophy at Boeing, where they bring pilots into the process to develop cockpit computers. There is a powerful concept known as “adaptive change,” as contrasted with technical change. Technical change is like a cookbook: Put in a set of rules, have people follow them, and everything works out fine. Adaptive change is more complex and subtle; it requires the intense involvement of frontline workers.

We made the mistake of treating health IT as technical change, but it is probably the hardest adaptive change we’ve ever tried. My goal was to create a national conversation about this, which is what we need if we’re going to get it right.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Why Compassion in Patient Care Should Matter to Hospitalists

Hospitalists care for a variety of different types of patients, serving anyone and everyone in need of acute care. Because of the nature of our work, it is difficult to maintain empathy and compassion for all of our patients, especially in light of our unpredictable workload, long hours, and high stress. As such, all hospitalists need to be aware of what exactly compassion is, why it matters, and what we can do to guard against its natural erosion.

What Is Compassion? What Is Empathy?

Wikipedia defines compassion as “the emotion that one feels in response to the suffering of others that motivates a desire to help.” The Latin derivation of compassion is “co-suffering.” Empathy is the ability to see and understand another’s suffering. So compassion is more than just empathy or “co-suffering”; with compassion comes yearning and a motivation to alleviate suffering in others.

Many important pieces within the definition of compassion need more explanation. Notice the three distinct “parts” of the definition: “the emotion that one feels”… “in response to the suffering of others”…“that motivates a desire to help.”

The first part outlines the fact that we have to be willing and able to conjure up an emotion toward and with our patients. Although this may sound basic, some physicians purposefully guard themselves against forming emotional responses toward or with their patients. Some actually think it will make them better—and more “objective”—providers if they guard against the (potentially) painful burden of sharing such empathic emotions.

Social science research has found that providers’ concerns about becoming emotionally exhausted might lead them to reduce their compassion for entire groups of patients, such as mentally ill or drug-addicted patient populations. There is also evidence that your ability to have empathy or compassion for another correlates with the ability to picture yourself with the same issue the patient suffers. This causes a major obstacle for many providers, who find themselves unable to relate to patients with “self-inflicted” issues, such as habits that increase the likelihood of disease (e.g. smoking) or not participating in habits that decrease the likelihood of disease or successful treatments (e.g. not exercising or not taking medications correctly).

Providers are more likely to be compassionate toward patients with whom they can identify; I would have enormous compassion for a 43-year-old female with new-onset ovarian cancer but would have less compassion for a 43-year-old male with new-onset alcohol withdrawal seizures.

The second part of the definition brings up the need to acknowledge suffering, in whatever form it takes. When we think of suffering, we often connect the idea with physical pain. But there are innumerable forms of nonphysical human suffering, including psychological and social trauma; this includes the anxiety that arises from known and unknown diagnoses and treatments and the emotional exhaustion resulting from such diagnoses and treatments. We need to be able to acknowledge all forms of suffering, not just physical suffering.

The last part of the definition shows that after we have allowed ourselves to “feel” the emotion of others and to acknowledge all walks of suffering, we then need to be motivated to help. For a hospitalist, this would mean “going the extra mile” for patients, such as continuously checking and rechecking on how treatments are (or are not) working, keeping the patient and family informed (in their terms) about what is happening, or ensuring that transitions of care (to other services or in/out of the hospital) are done with keen attention to reduce the risk of “voltage drops” in information.

Two videos help illustrate the nature of compassion (see the video sidebar for URLs). Both depict young women who have been called upon to sing the national anthem before a large crowd at an athletic gathering. Both women are clearly excellent singers, and both have a similar outcome in mind: to sing the national anthem in a manner pleasing to everyone in the crowd. In both cases, they forgot the words of the song.

In the first scenario, the woman is heckled, literally “booed,” then quickly shuffled off the ice rink after falling backwards on the ice. In the second scenario, a similarly talented young woman starts out strong, then forgets the words. An unrelated gentleman comes to her aid, puts his arm around her, and sings the words with her. As he continues, he looks to the audience, making hand signals to encourage them to join in supporting her during this presumably highly anxious moment.

The second scenario exemplifies all three components of compassion: The gentleman feels the singer’s anxiety, he acknowledges her “suffering,” and he is motivated to help. What I noticed about his assistance is that he is not even a very good singer! But his kind persuasion and ability to motivate the entire crowd in assisting her remarkably transform the outcome for both the singer and the crowd.

Though both scenarios start quite similarly, they end remarkably differently; the second scenario was completely changed by the compassion of a single person and a simple act of human kindness.

Why It Matters, and How to Build It

As depicted in these short videos, compassion can completely change outcomes. You will not find placebo-controlled randomized trials to support what I just stated. But there are plenty of social science studies to support the notion that compassion is a learned trait that can be improved or eroded over time, depending on the willingness of the person to try.

Compassion is a learned behavior. It is not a personality trait that you either have or you don’t. It is a set of behaviors and actions that can be learned and practiced, and even perfected, for those willing.

The Cleveland Clinic has created several videos (see video info box) that help us consider how to think about the nature of compassion and how to learn and practice it. A hospital is ripe with emotion in all areas, from the elevators to the hallways to the cafeteria. Due to the nature of our work, we are all at risk of compassion erosion toward our patients.

We first have to acknowledge such a risk is present and actively seek out opportunities, as depicted in these videos, to learn and practice compassion. As the Dalai Lama once said, “Compassion is a necessity, not a luxury.” We should all learn, demonstrate, and live compassion as a necessity in our practice.

Hospitalists care for a variety of different types of patients, serving anyone and everyone in need of acute care. Because of the nature of our work, it is difficult to maintain empathy and compassion for all of our patients, especially in light of our unpredictable workload, long hours, and high stress. As such, all hospitalists need to be aware of what exactly compassion is, why it matters, and what we can do to guard against its natural erosion.

What Is Compassion? What Is Empathy?

Wikipedia defines compassion as “the emotion that one feels in response to the suffering of others that motivates a desire to help.” The Latin derivation of compassion is “co-suffering.” Empathy is the ability to see and understand another’s suffering. So compassion is more than just empathy or “co-suffering”; with compassion comes yearning and a motivation to alleviate suffering in others.

Many important pieces within the definition of compassion need more explanation. Notice the three distinct “parts” of the definition: “the emotion that one feels”… “in response to the suffering of others”…“that motivates a desire to help.”

The first part outlines the fact that we have to be willing and able to conjure up an emotion toward and with our patients. Although this may sound basic, some physicians purposefully guard themselves against forming emotional responses toward or with their patients. Some actually think it will make them better—and more “objective”—providers if they guard against the (potentially) painful burden of sharing such empathic emotions.

Social science research has found that providers’ concerns about becoming emotionally exhausted might lead them to reduce their compassion for entire groups of patients, such as mentally ill or drug-addicted patient populations. There is also evidence that your ability to have empathy or compassion for another correlates with the ability to picture yourself with the same issue the patient suffers. This causes a major obstacle for many providers, who find themselves unable to relate to patients with “self-inflicted” issues, such as habits that increase the likelihood of disease (e.g. smoking) or not participating in habits that decrease the likelihood of disease or successful treatments (e.g. not exercising or not taking medications correctly).

Providers are more likely to be compassionate toward patients with whom they can identify; I would have enormous compassion for a 43-year-old female with new-onset ovarian cancer but would have less compassion for a 43-year-old male with new-onset alcohol withdrawal seizures.

The second part of the definition brings up the need to acknowledge suffering, in whatever form it takes. When we think of suffering, we often connect the idea with physical pain. But there are innumerable forms of nonphysical human suffering, including psychological and social trauma; this includes the anxiety that arises from known and unknown diagnoses and treatments and the emotional exhaustion resulting from such diagnoses and treatments. We need to be able to acknowledge all forms of suffering, not just physical suffering.

The last part of the definition shows that after we have allowed ourselves to “feel” the emotion of others and to acknowledge all walks of suffering, we then need to be motivated to help. For a hospitalist, this would mean “going the extra mile” for patients, such as continuously checking and rechecking on how treatments are (or are not) working, keeping the patient and family informed (in their terms) about what is happening, or ensuring that transitions of care (to other services or in/out of the hospital) are done with keen attention to reduce the risk of “voltage drops” in information.

Two videos help illustrate the nature of compassion (see the video sidebar for URLs). Both depict young women who have been called upon to sing the national anthem before a large crowd at an athletic gathering. Both women are clearly excellent singers, and both have a similar outcome in mind: to sing the national anthem in a manner pleasing to everyone in the crowd. In both cases, they forgot the words of the song.

In the first scenario, the woman is heckled, literally “booed,” then quickly shuffled off the ice rink after falling backwards on the ice. In the second scenario, a similarly talented young woman starts out strong, then forgets the words. An unrelated gentleman comes to her aid, puts his arm around her, and sings the words with her. As he continues, he looks to the audience, making hand signals to encourage them to join in supporting her during this presumably highly anxious moment.

The second scenario exemplifies all three components of compassion: The gentleman feels the singer’s anxiety, he acknowledges her “suffering,” and he is motivated to help. What I noticed about his assistance is that he is not even a very good singer! But his kind persuasion and ability to motivate the entire crowd in assisting her remarkably transform the outcome for both the singer and the crowd.

Though both scenarios start quite similarly, they end remarkably differently; the second scenario was completely changed by the compassion of a single person and a simple act of human kindness.

Why It Matters, and How to Build It

As depicted in these short videos, compassion can completely change outcomes. You will not find placebo-controlled randomized trials to support what I just stated. But there are plenty of social science studies to support the notion that compassion is a learned trait that can be improved or eroded over time, depending on the willingness of the person to try.

Compassion is a learned behavior. It is not a personality trait that you either have or you don’t. It is a set of behaviors and actions that can be learned and practiced, and even perfected, for those willing.

The Cleveland Clinic has created several videos (see video info box) that help us consider how to think about the nature of compassion and how to learn and practice it. A hospital is ripe with emotion in all areas, from the elevators to the hallways to the cafeteria. Due to the nature of our work, we are all at risk of compassion erosion toward our patients.

We first have to acknowledge such a risk is present and actively seek out opportunities, as depicted in these videos, to learn and practice compassion. As the Dalai Lama once said, “Compassion is a necessity, not a luxury.” We should all learn, demonstrate, and live compassion as a necessity in our practice.

Hospitalists care for a variety of different types of patients, serving anyone and everyone in need of acute care. Because of the nature of our work, it is difficult to maintain empathy and compassion for all of our patients, especially in light of our unpredictable workload, long hours, and high stress. As such, all hospitalists need to be aware of what exactly compassion is, why it matters, and what we can do to guard against its natural erosion.

What Is Compassion? What Is Empathy?

Wikipedia defines compassion as “the emotion that one feels in response to the suffering of others that motivates a desire to help.” The Latin derivation of compassion is “co-suffering.” Empathy is the ability to see and understand another’s suffering. So compassion is more than just empathy or “co-suffering”; with compassion comes yearning and a motivation to alleviate suffering in others.

Many important pieces within the definition of compassion need more explanation. Notice the three distinct “parts” of the definition: “the emotion that one feels”… “in response to the suffering of others”…“that motivates a desire to help.”

The first part outlines the fact that we have to be willing and able to conjure up an emotion toward and with our patients. Although this may sound basic, some physicians purposefully guard themselves against forming emotional responses toward or with their patients. Some actually think it will make them better—and more “objective”—providers if they guard against the (potentially) painful burden of sharing such empathic emotions.

Social science research has found that providers’ concerns about becoming emotionally exhausted might lead them to reduce their compassion for entire groups of patients, such as mentally ill or drug-addicted patient populations. There is also evidence that your ability to have empathy or compassion for another correlates with the ability to picture yourself with the same issue the patient suffers. This causes a major obstacle for many providers, who find themselves unable to relate to patients with “self-inflicted” issues, such as habits that increase the likelihood of disease (e.g. smoking) or not participating in habits that decrease the likelihood of disease or successful treatments (e.g. not exercising or not taking medications correctly).

Providers are more likely to be compassionate toward patients with whom they can identify; I would have enormous compassion for a 43-year-old female with new-onset ovarian cancer but would have less compassion for a 43-year-old male with new-onset alcohol withdrawal seizures.

The second part of the definition brings up the need to acknowledge suffering, in whatever form it takes. When we think of suffering, we often connect the idea with physical pain. But there are innumerable forms of nonphysical human suffering, including psychological and social trauma; this includes the anxiety that arises from known and unknown diagnoses and treatments and the emotional exhaustion resulting from such diagnoses and treatments. We need to be able to acknowledge all forms of suffering, not just physical suffering.

The last part of the definition shows that after we have allowed ourselves to “feel” the emotion of others and to acknowledge all walks of suffering, we then need to be motivated to help. For a hospitalist, this would mean “going the extra mile” for patients, such as continuously checking and rechecking on how treatments are (or are not) working, keeping the patient and family informed (in their terms) about what is happening, or ensuring that transitions of care (to other services or in/out of the hospital) are done with keen attention to reduce the risk of “voltage drops” in information.

Two videos help illustrate the nature of compassion (see the video sidebar for URLs). Both depict young women who have been called upon to sing the national anthem before a large crowd at an athletic gathering. Both women are clearly excellent singers, and both have a similar outcome in mind: to sing the national anthem in a manner pleasing to everyone in the crowd. In both cases, they forgot the words of the song.

In the first scenario, the woman is heckled, literally “booed,” then quickly shuffled off the ice rink after falling backwards on the ice. In the second scenario, a similarly talented young woman starts out strong, then forgets the words. An unrelated gentleman comes to her aid, puts his arm around her, and sings the words with her. As he continues, he looks to the audience, making hand signals to encourage them to join in supporting her during this presumably highly anxious moment.

The second scenario exemplifies all three components of compassion: The gentleman feels the singer’s anxiety, he acknowledges her “suffering,” and he is motivated to help. What I noticed about his assistance is that he is not even a very good singer! But his kind persuasion and ability to motivate the entire crowd in assisting her remarkably transform the outcome for both the singer and the crowd.

Though both scenarios start quite similarly, they end remarkably differently; the second scenario was completely changed by the compassion of a single person and a simple act of human kindness.

Why It Matters, and How to Build It

As depicted in these short videos, compassion can completely change outcomes. You will not find placebo-controlled randomized trials to support what I just stated. But there are plenty of social science studies to support the notion that compassion is a learned trait that can be improved or eroded over time, depending on the willingness of the person to try.

Compassion is a learned behavior. It is not a personality trait that you either have or you don’t. It is a set of behaviors and actions that can be learned and practiced, and even perfected, for those willing.

The Cleveland Clinic has created several videos (see video info box) that help us consider how to think about the nature of compassion and how to learn and practice it. A hospital is ripe with emotion in all areas, from the elevators to the hallways to the cafeteria. Due to the nature of our work, we are all at risk of compassion erosion toward our patients.

We first have to acknowledge such a risk is present and actively seek out opportunities, as depicted in these videos, to learn and practice compassion. As the Dalai Lama once said, “Compassion is a necessity, not a luxury.” We should all learn, demonstrate, and live compassion as a necessity in our practice.

What Is the Appropriate Medical and Interventional Treatment for Hyperacute Ischemic Stroke?

Case

A 70-year-old woman was brought to the ED by ambulance with slurred speech after a fall. She arrived in the ED three hours and 29 minutes after the last time she was known to be normal. On initial examination, she had a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 13, with a left facial droop, left hemiplegia, and right gaze deviation. Her acute noncontrast head computed tomography (CT), CT angiogram, and CT perfusion scans are shown in Figure 1.

How should this patient’s acute stroke be managed at this time?

Overview

Pathophysiology/Epidemiology: Stroke is the fourth most common cause of death in the United States and the main cause of disability, resulting in substantial healthcare expenditures.1 Ischemic stroke accounts for about 85% of all stroke cases and has several subtypes. The most common causes of ischemic stroke are small vessel thrombosis, large vessel thromboembolism, and cardioembolism. Both small vessel thrombosis and large vessel thromboembolism often are related to typical atherosclerotic risk factors, and cardioembolism is most often related to atrial fibrillation/flutter.

Minimizing death and disability from stroke is dependent on prevention measures, as well as early response to the onset of symptoms. The typical patient loses 1.9 million neurons for every minute a stroke is untreated—hence the popular adage “Time is Brain.”2 Although the appropriate management and time window of stroke treatment have been somewhat controversial, the acuity of treatment is now undisputed. Intravenous thrombolysis with tPA, also known as alteplase, has been an FDA-approved treatment for stroke since 1996, yet, as of 2006, only 2.4% of patients hospitalized for ischemic stroke were treated with IV tPA.3

The etiology of stroke, in most cases, does not change management in the hyperacute period, when thrombolysis is appropriate regardless of etiology.

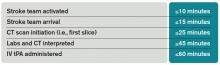

Timely evaluation: Although recognition of stroke symptoms by the public and pre-hospital management is a barrier in the treatment of acute stroke, this article will focus on appropriate ED and in-hospital treatment of stroke. Given the urgent need for management of acute ischemic stroke, it is critical that hospitals have an efficient process for identifying possible strokes and beginning treatment early. In order to accomplish these objectives, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) has established goals for time frames of evaluation and management of patients with stroke in the ED (see Table 1).4

The role of the hospitalist: Hospitalists can play critical roles both as part of a primary stroke team and in identifying missed strokes. Some acute stroke teams have included hospitalists due to their ability to help with medical management, identify mimics, and assess medical contraindications to thrombolytic therapy. In addition, hospitalists may be the first to recognize a stroke in the ED when evaluating a patient with symptoms confused with a medical condition, or when a stroke occurs in an inpatient. In both of these situations, as first responders, hospitalists have knowledge of stroke evaluation and treatment that is crucial in beginning the evaluation and triggering a stroke alert.

Diagnostic tools: The initial evaluation of a patient with a possible stroke includes a brief but thorough history of current symptoms, as well as past medical and medication histories. The most critical piece of information to obtain from patients, family members, or bystanders is the time of symptom onset, or the time the patient was last known normal, so that the options for treatment can be evaluated early.

After basic stabilization of ABCs—airway maintenance, breathing and ventilation, and circulation— a brief but thorough neurologic examination is critical to define severity of neurologic injury and to help localize injury. Some standardized tools help with rapid assessment, including the NIHSS. The NIHSS is a standardized and reproducible evaluation that can be performed by many different specialties and levels of healthcare providers and provides information about stroke severity, localization, and prognosis.5 NIHSS offers free online certification.

Imaging: Early brain imaging and interpretation is another important piece of the acute evaluation of stroke. The most commonly used first-line imaging is noncontrast head CT, which is widely available and quickly performed. This type of imaging is sensitive for intracranial hemorrhage and can help distinguish nonvascular causes of symptoms such as tumor. CT is not sensitive for early signs of infarct, and, most often, initial CT findings are normal in early ischemic stroke. In patients who are candidates for intravenous fibrinolysis, ruling out hemorrhage is the main priority. Noncontrast head CT is the only imaging necessary to make decisions regarding IV thrombolytic treatment.

For further treatment decisions beyond IV tPA, intracranial and extracranial vascular imaging can help with decision making. All patients with stroke should have extracranial vascular imaging to help determine the etiology of stroke and evaluate the need for carotid endarterectomy or stenting for symptomatic stenosis in the days to weeks after stroke. More acutely, vascular imaging can be used to identify large vessel occlusions, in consideration of endovascular intervention (discussed in further detail below). CT angiography, magnetic resonance (MR) angiography, and conventional angiography are all options for evaluating the vasculature, though the first two are generally used as a noninvasive first step. Carotid ultrasound is often considered but only evaluates the extracranial anterior circulation; posterior circulation vessel abnormalities (like dissection) and intracranial abnormalities (like stenosis) may be missed. Although tPA decisions are not based upon these imaging modalities, secondary stroke prevention decisions may be altered by the findings.4

Perfusion imaging is the newest addition to acute stroke imaging, but its utility in guiding decision making remains unclear. Perfusion imaging provides hemodynamic information, ideally to identify areas of infarct versus ischemic penumbra, an area at risk of becoming ischemic. The use of perfusion imaging to identify good candidates for reperfusion (with IV tPA or with interventional techniques) is controversial.9 It is clear that perfusion imaging should not delay the time to treatment for IV tPA within the 4.5-hour window.

Windows: Current guidelines for administration of IV tPA for acute stroke are based in large part on two pivotal studies—the NINDS tPA Stroke Trial and the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study III (ECASS III).6,7 IV alteplase for the treatment of acute stroke was approved by the FDA in 1996 following publication of the NINDS tPA Stroke Trial. This placebo-controlled randomized trial of 624 patients within three hours of ischemic stroke onset found that treatment with IV alteplase improved the odds of minimal or no disability at three months by approximately 30%. The rate of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage was higher in the tPA group (6.4%) compared to the placebo group (0.6%), but mortality was not significantly different at three months. Though the benefit of IV tPA was clear in the three-hour window, subgroup analyses and further studies have clarified that treatment earlier in the window provides further benefit.