User login

Diagnosis and Management of Complex Pelvic Floor Disorders in Women

From Beaumont Health System, Royal Oak, MI.

Abstract

- Objective: To review the evaluation and management of complex pelvic floor disorders in elderly women.

- Methods: Literature review and presentation of a clinical case.

- Results: Pelvic floor disorders are a common problem in elderly women. Pelvic organ prolapse and voiding complaints often coexist and several treatment options are available. A step-wise approach should be used in which management of the most bothersome symptoms occurs first. Conservative, medication, and surgical options should be discussed with each patient depending on treatment goals and health status. Some effects do overlap; however, treatment of one condition may not preclude treatment of other symptoms.

- Conclusion: In women with complex pelvic floor disorders, addressing the most bothersome symptom first will increase patient satisfaction. Patients should be counseled about the potential need for multiple treatments for optimal results.

The female pelvic floor consists of a complex relationship of muscles, connective tissue and fascia, ligaments, and neurovascular support. These structures are responsible for support of the pelvic organs (uterus, bladder, rectum, and vagina), maintain continence, and assist in normal bowel function. Pelvic floor disorders occur when there is a compromise in these structures, resulting in prolapse, urinary incontinence, bowel complaints, or pain. Often several symptoms coexist with overlapping pathophysiology. Examinations and studies should aim to correctly diagnose the disorders and guide treatments toward the most bothersome symptoms.

Pelvic organ prolapse occurs when there is a weakening of the pelvic floor connective tissue, muscles, and nerves, allowing a bulge or protrusion of the vaginal walls and their associated pelvic organs. Between 3% to 50% of women in the United States have some degree of pelvic organ prolapse depending on whether the definition is based on symptoms or anatomic evaluation [1–3]. Risk factors include vaginal delivery, obesity, Caucasian race, and prior prolapse surgery. Despite the non–life-threatening nature of pelvic organ prolapse, the associated social and physical restrictions can significantly impact quality of life [4]. The cost of prolapse surgery has been estimated to be over $1.4 billion per year [3].

The sensation of a vaginal bulge is the only symptom consistently related to pelvic organ prolapse, with patients typically reporting symptoms once the prolapse extends beyond the hymenal ring [5]. The diagnosis of pelvic organ prolapse is made based on symptoms and confirmed by physical exam.

Patients with pelvic organ prolapse may experience obstructive voiding symptoms, such as hesitancy, straining, or incomplete bladder emptying. In some cases, patients may have to manually reduce the bulge to be able to void, a practice known as “splinting.” Overactive bladder (OAB), a syndrome of urinary urgency, frequency, and nocturia with or without urgency incontinence, can also occur. In patients with lower urinary tract complaints, repair of a vaginal bulge, especially a cystocele, can be associated with improved voiding symptoms [6]. Additionally, prolapse treatment can unmask de novo stress urinary incontinence (SUI), leaking with cough, sneeze or other activity that increases abdominal pressure. Urinary tract infections, pelvic pain, dyspareunia and defecatory problems can also be present.

When evaluating a woman with pelvic organ prolapse and voiding complaints, the clinician should strive to illicit which symptoms bother the patient most. A patient with primarily OAB symptoms and minimal prolapse may be treated with physical therapy or medications addressing the OAB rather than reconstructive surgery. In contrast, the patient with OAB symptoms and bothersome prolapse must be counseled on possible need for additional treatment of voiding complaints following surgical repair. This may include management of persistent OAB symptoms or SUI occurring following prolapse repair. Defecatory problems may be independent of a small rectocele present on exam, especially if long-term constipation is present. Choice of treatment depends on the severity of symptoms, the degree of prolapse, and the patient’s health status and activity level.

Case Study

Initial Presentation

A 68-year-old woman with a 15-month history of urinary urgency, frequency, incontinence and vaginal pressure presents to a urologist.

History and Physical Examination

The patient’s symptoms began shortly after the death of her husband. She initially saw her internist who prescribed antibiotics for a suspected urinary tract infection (UTI) based on office urinalysis. The symptoms did not resolve so another course of antibiotics was tried, again without relief. At her 3rd visit, a urine culture was done which was negative and she was referred to a urologist.

The patient reports 3 UTIs in the last 6 months. Following antibiotic treatment, the burning improves but she still complains of urgency and frequency. She also wears 2 to 3 pads per day for leakage that occurs with coughing and also when she feels an urge but cannot make it to the bathroom. She wakes 1 to 3 times at night to void. She feels that she empties her bladder well but often has to strain to void and sometimes feels a “bulge” in her vagina. All of these symptoms increase after being on her feet all day while she works as a grocery store cashier.

Physical exam demonstrates mild suprapubic tenderness and mild atrophic vaginitis. The anterior vaginal wall protrudes to the hymen with straining and her vaginal apex is supported 5 cm above the hymenal ring. With reduction of the cystocele there was urine leakage with cough. The cervix is surgically absent and her posterior vaginal wall is without bulge on valsalva. Her catheterized post-void residual (PVR) was 105 mL. Urine dipstick analysis was negative for infection or blood.

What is the initial evaluation of a woman with pelvic organ prolapse and voiding complaints?

The initial evaluation of a woman with pelvic organ prolapse and voiding complaints consists of a detailed history and physical examination. The nature, duration, and severity of symptoms should be assessed. Complaints of vaginal pressure or bulge are important, as well as exacerbating instances (standing, straining, defecation). Local irritation or vaginal spotting is common if prolapse is beyond the hymen. Splinting or reduction of a bulge to void or defecate are important elements of the history. Sexual history should never be overlooked, including both sexual status (active or not) as well as goals for future sexual activity. Voiding symptoms such as dysuria, frequency, urgency, nocturia and incontinence should be discussed. A 3-day voiding diary that captures number of voids per day, voided volumes, and fluid intake can be obtained. If incontinence is present, the clinician should determine what causes the incontinence. Incontinence that is associated with urgency or no warning (urge incontinence) should be treated differently than incontinence associated with activity (SUI). Mixed urinary incontinence is the presence of both stress and urgency incontinence.

Past medical history should include common medical comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Obstetric history is important due to the increased risk for pelvic floor disorders in women with multiple pregnancies and vaginal deliveries [2]. Prior hysterectomy, colon resection, or other pelvic surgeries may also contribute to symptoms. Smokers have a greater risk of genitourinary malignancy and high caffeine consumption is implicated in urgency-frequency syndromes. Exercise, sleep, and work may also be affected.

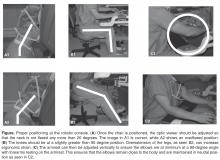

Pelvic examination should evaluate for vaginal atrophy or other vaginal mucosal abnormalities such as tears, ulcerations, lichen sclerosis, or erythema. To evaluate for prolapse, using one-half of a Graves or Pederson speculum, examine the 3 compartments of the vagina: anterior, posterior and apical. To view the anterior wall, the speculum is placed posteriorly to retract the posterior wall downward. Next it is rotated anteriorly to retract the anterior wall up and examine the posterior compartment. The uterus or the apex is evaluated with 2 halves of the speculum, one pushing anteriorly and the other posteriorly. At each point in the evaluation, the patient is told to strain or valsalva. The pelvic organ prolapse quantification system (POP-Q) is a systematic description of site-specific measurements of a woman’s pelvic support [7]. Using this classification system, a standardized and reproducible method of documenting the severity of the prolapse is done based on 6 points of the vaginal wall in relation to the hymen (2 on the anterior wall, 2 in the superior vagina, and 2 on the posterior vaginal wall). A corresponding prolapse stage can then be assigned to the patient based on POP-Q measurements. If unable to reproduce the patient’s symptoms, or exam findings do not correlate with the history, a standing exam can be helpful. Close evaluation of the urethra is also important. In severe prolapse the urethra may become kinked and mask a potential underlying problem (occult SUI). Patients should be asked to valsalva or cough with prolapse reduction and a full bladder to evaluate for this. Lastly, the pelvic floor muscles should be palpated to assess for pain or pelvic floor atrophy, hypertonicity, tenderness, or spasms.

If the patient complains of urgency, frequency, and/or dysuria, urine cultures should be performed to exclude infection even if the urinalysis is negative. Antibiotics should be given based on culture results. A postvoid ultrasound or catheterization is used to evaluate for incomplete bladder emptying. Patients with microscopic or gross hematuria should undergo further testing with radiologic and cystoscopic evaluation as indicated, especially with a history of smoking. Women should be questioned regarding their menstrual history and if postmenopausal, about any vaginal bleeding. A pelvic ultrasound should be considered if the patient has a history of endometriosis, gynecological cancers, uterine fibroids, or ovarian cysts or if considering uterine preserving surgery or colpocleisis. Urodynamics are often indicated in complex patients with prolapse and lower urinary tract complaints or prior pelvic surgery.

Diagnosis

The patient was diagnosed with mixed urinary incontinence and a grade 2 cystocele. Treatment options were discussed and she was most interested in conservative management options.

What is first-line treatment for the complaints of urgency, frequency, and incontinence?

In an older patient with complaints of urgency, frequency, and incontinence, dietary and behavioral modifications as well as pelvic floor physical therapy are considered first-line minimally invasive treatments.

Dietary irritants such as coffee, tea, soda, and other caffeinated beverages can contribute to worsening of symptoms [8]. A randomized study measuring the effects of caffeine noted a significant reduction in urgency and frequency of voids and in symptom scores with reduction of caffeine use [9]. Some elderly patients are reluctant to change their lifestyle, but even small changes can significantly improve their urgency symptoms.

Timed voiding is an effective method for bladder retraining, which can be critical for managing symptoms both alone and as an adjunct to other interventions. Studies of behavioral therapy show significant improvement in urgency, frequency, and incontinence episodes. In a study by Wyman and Fanti, patients participating in bladder training and Kegel exercises noted a 57% decrease in incontinence episodes and 54% decrease in urine loss without medications [10]. Burgio et al compared behavioral therapy to anticholinergic medication administration. After 4 sessions over 8 weeks they reported 81% reduction in incontinence episodes compared to 69% in the drug group and 39% in the placebo group [11].

Elderly patients may take several medications, some of which can affect urine volume and timing of urine production. Diuretics given later in the day can increase nighttime urine production and worsen nocturia. Similarly, lower extremity edema can increase nocturnal urine volumes when the patient reclines. Compressive stockings and leg elevation 2-3 hours prior to bedtime will help evenly distribute fluids and decrease reabsorption when supine at night.

Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy

Pelvic floor physical therapy (PFPT) can be an effective treatment for OAB, SUI, and pelvic organ prolapse. PFPT is used as an urge suppression strategy for OAB by teaching patients how to contract their pelvic muscles to occlude the urethra and prevent leakage during a detrusor contraction. Strategies to help suppress urge and manage stress situations can reduce incontinence episodes up to 60% to 80% [12]. Behavioral programs can include bladder diaries, scheduled voiding, delayed voiding, double voiding, fluid management, and caffeine reduction. When combined with PFPT they can be very effective in the management of OAB symptoms and incontinence. The BE-DRI study showed that combined behavioral training and drug therapy yielded better outcomes over time in OAB symptoms, patient distress and treatment satisfaction than drug therapy alone [13]. PFPT is considered a first-line treatment for OAB and is a noninvasive and effective treatment for these symptoms [14].

Pelvic floor programs for SUI aim to teach pelvic floor muscle contraction to help prevent stress leakage and use a variety of methods including biofeedback and personalized training programs. A recent Cochrane review included 18 studies of PFPT for incontinence. They concluded that there was high quality evidence that PFPT was associated with cure and moderate evidence for improvement in SUI [15]. In a study comparing surgery versus PFPT at 1 year, subjective improvement in the surgery group was 91% compared to 64% in the PFPT group. While PFPT was not as effective as surgery, over 50% had improvement. PFPT remains an effective noninvasive option that should be considered, particularly in an older patient [16].

PFPT has also been studied as a treatment option for pelvic organ prolapse. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) that compared PFPT to controls over time, more women in the PFPT group improved 1 POP-Q stage compared to the control group. They also had significantly improved pelvic floor symptom bother [17]. In the POPPY study examining PFPT versus a control condition, researchers were not able to show statistically significant improvement in prolapse stages but did show improvement in secondary outcomes, including symptom bother and the feeling of “bulge.” Fewer women sought further treatment for prolapse after undergoing PFPT [18]. PFPT can be effective in managing prolapse symptoms and may help improve prolapse stage.

Pessary

Pessaries are commonly used for management of pelvic organ prolapse in patients who choose nonoperative management. In a large study of pessary use in the Medicare population, it was noted that of 34,782 women diagnosed with prolapse between 1999 and 2000, 11.6% were treated with a pessary. Complications noted during the 9 years of follow-up included 3% with vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistulas and 5% with a device-associated complication [19]. Use increased with age, with 24% of women over 85 being managed with a pessary. In a review examining quality of life, improvement in bulge, irritative symptoms, and sexual satisfaction occurred with pessary use. In the medium-term, prolapse-related bother symptoms, quality of life, and overall perception of body image improved with the use of a pessary [20]. For SUI, rings with a knob or an incontinence dish can provide support to the urethra and help to pinch it closed with coughing, sneezing, and laughing, preventing leakage. In an RCT comparing women who received behavioral therapy, an incontinence pessary, or both, at 3 months 33% of those assigned to pessary reported improved incontinence symptoms compared to 49% with behavioral therapy, and 63% were satisfied with pessary treatment compared to 75% with behavioral therapy [21,22]. Differences did not persist to 12 months with over one third of all women improved and even more satisfied. A pessary can be safely used in the elderly population but does require office management and regular follow-up to prevent complications.

Initital Treatment

The patient was treated with 3 months of PFPT with biofeedback and pelvic floor muscle strengthening. In addition, she was able to decrease her caffeine use from 4 cups of coffee per day to 1 cup in the morning. At her 3-month follow-up visit, she noticed significant improvement in her voiding symptoms, and her voiding diary showed improved voided volumes and decreased frequency and nocturia. However, she was becoming more active in her community, going to aerobics and dance classes. She was more bothered by the “bulge” feeling in her vagina. She was not interested in a pessary but wanted to hear about surgical options for prolapse treatment.

What is operative management of pelvic organ prolapse?

The goals for surgical pelvic organ prolapse repair are to resolve symptoms, restore normal or near-normal anatomy, preserve sexual, urinary and bowel function, and minimize patient morbidity. The extent of prolapse, patient risk factors for recurrence, patient preference, and overall medical condition all influence the method for surgical repair. Surgeon familiarity and experience is also important when selecting the appropriate repair. Recent concerns regarding the use of synthetic mesh material has become a factor in counseling patients since the 2011 US Food and Drug Administration safety communication on transvaginal mesh [23].

Vaginal Approaches

Numerous techniques for pelvic organ prolapse repair have been described, though most repairs can broadly be divided into vaginal and abdominal procedures. Vaginal surgery is consistently associated with shorter operative times, less postoperative pain, and a shorter length of stay than abdominal approaches. All prolapsing compartments can be addressed vaginally using a patient’s own tissue, often called a “native tissue repair.” The vaginal apex is suspended from either the uterosacral ligament (USL) condensations or to the sacrospinous ligaments (SSL). Sutures are placed through these structures and tied to hold the vaginal vault in place, often at the time of concomitant enterocele, cystocele, or rectocele repairs. A recent randomized trial comparing USL and SSL repair showed composite functional and symptomatic success was 60% at 2 years and did not differ by technique [24]. While overall success may appear low, symptomatic vaginal bulge was present in only 17% to 19% of women at 2 years and only 5% underwent re-treatment with surgery or pessary during follow-up. Similar outcomes have been demonstrated for isolated cystocele repairs plicating the pubo-cervical fascia (anterior colporrhaphy). Cited failure rates have been as high as 70% [25], though this depends on the definition of success. When symptoms of bulge and/or prolapse beyond the hymen are used, success rates are closer to 89% at 2 years [26]. In one study comparing mesh-augmented cystocele repair with native tissue anterior colporrhaphy, 49% of women had a successful composite outcome at 2 years of grade 0 or 1 prolapse and no symptoms of bulge without the use of mesh graft [27]. Despite lower anatomic success rates, anterior colporrhaphy consistently relieves symptoms of bulge with low retreatment rates.

The high failure rates of native tissue vaginal repairs, especially in women with high-grade or recurrent prolapse, led to an interest in graft-augmented repairs. Furthermore, anatomic studies showed that up to 88% of cystoceles were associated with a lateral defect, or tearing of the pubocervical fascia from the pelvic sidewall (arcus tendineous fascia pelvis) [28]. Plicating the already weak fascia centrally would not repair an underlying lateral defect resulting in treatment failure. Replacing this weak fascia with a graft and anchoring it laterally and proximally should result in better anatomic and functional outcomes. These patches can be made from autologous tissue (rectus fascia), donor allograft material (fascia lata), xenografts (porcine dermis, bovine pericardium), or synthetic mesh. Initial studies using cadaveric dermis grafts for recurrent stage II or stage III/IV pelvic organ prolapse resulted in 50% failure at 4 years, but symptomatic failure was only 11% [29]. Further publications utilizing cadaveric tissue patches showed lower rates of cystocele recurrences of 0 to 17% between 20 and 56 months of follow-up [30].

As interest in patch repairs became popular, the use of synthetic mesh was applied to tension-free mid-urethral tapes for SUI. Studies were also showing rapid cadaveric and xenograft graft metabolism, graft extrusion, and early failure in some women [31]. This led to the use of larger pieces of synthetic mesh for prolapse repair, as it had been for abdominal wall and inguinal hernia repairs. Ultimately large-pore, light-weight polypropylene mesh was seen as the most favorable material and large randomized studies were performed to compare outcomes. Theoretically, a synthetic material would provide a replacement for the weakened and torn pubocervical fascia and not be subjected to enzymatic degradation. Altman et al published a widely cited randomized trial comparing native tissue vs. synthetic mesh showing that improvement in the composite primary outcome (no prolapse on the basis of both objective and subjective assessments) was more common in the mesh group (61% vs. 35%) at 1 year. Mesh placement was associated with longer operative times, higher blood loss, and 3.2% of women underwent secondary procedures for vaginal mesh exposure [27]. While there is still debate on the routine use of transvaginal mesh placement, current recommendations generally limit its use for recurrent or high grade pelvic organ prolapse (> Stage III), and possibly those at higher risks for recurrence. The American Urological Association has supported the FDA recommendation that patients undergo a thorough consent process and that surgeons are properly trained in pelvic reconstruction and mesh placement techniques. Furthermore, surgeons placing transvaginal mesh should be equipped to diagnose and treat any complications that may arise subsequent to its use.

Abdominal Approaches

Pelvic organ prolapse can also be approached through an abdominal technique. The classic description for vaginal vault prolapse repair is the abdominal sacrocolpopexy. This involves fixating the vaginal apex to the anterior longitudinal ligament at the sacral promontory. Hysterectomy is performed at the same setting if still in situ. A strip of lightweight polypropylene mesh is sutured to the anterior and posterior vaginal walls after dissecting the bladder and rectum off, then suspended in a tension-free manner to the sacrum. Large trials with long-term follow-up show durability of this repair. Seven-year follow-up of a large NIH-sponsored trial comparing sacrocolpopexy with and without urethropexy found 31/181 (17%) with anatomic prolapse beyond the hymen [32]. Of these women one-third had involvement of the vaginal apex, though 50% of women were asymptomatic. Overall, 95% of women had no retreatment for pelvic organ prolapse. A surprising finding was a 10.5% mesh exposure rate with a mean follow-up of 6.1 years. Previously, abdominally placed mesh was thought to be much safer than transvaginal mesh, but exposure rates are roughly similar in newer studies at high-volume, fellowship-trained centers [33]. The largest advance in abdominal prolapse surgery has come with the adoption of laparoscopic and robotic-assisted technology. Minimally invasive approaches to abdominal surgery have resulted in less blood loss and shorter length of stay, though longer operative times [34]. Short- and medium-term outcomes have been compared to the open techniques in smaller single-center series. At least 1 randomized trial comparing laparoscopic to robotic sacrocolpopexy showed similar complications and perioperative outcomes, though the robotic technique was more costly [35].

Stress Urinary Incontinence Procedures

When SUI is identified preoperatively, treatment should be considered at the time of prolapse repair [32,36]. The gold standard for treatment of SUI with urethral hypermobility has been placement of a synthetic mid-urethral sling. There are several types of slings available, mainly categorized as retropubic, transobturator, or single-incision “mini-slings.” In a multicenter study by the Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network (UITN), patient satisfaction after retropubic and transobturator sling placement was studied 12 months after surgery. Both groups had a high satisfaction rate (from 85% to 90%) for urine leakage, urgency, and frequency [37]. There was no significant difference in outcomes between the 2 approaches. Several other studies and systematic reviews have also shown excellent long-term results with sling treatment. In the recently published 5-year follow-up of the Trial of Mid-Urethral Slings (TOMUS), researchers demonstrated an 80% to 85% patient satisfaction rate with a 10% adverse event rate. Of these adverse events, only 6 were classified as serious requiring surgical, radiologic, or endoscopic intervention [38].

If the patient has SUI but no urethral hypermobility, consider intrinsic sphincter deficiency as the etiology of her incontinence. In that case, injectable therapy with urethral bulking agents is an effective treatment. Some commonly used injectables include carbon beads (Durasphere), calcium hydroxylapatite (Coaptite), bovine collagen (Contigen), and silicon particles (Macroplastique). In a Cochrane review of injectable therapy, they compared urethral injection to conservative treatment with physical therapy and noted an improvement with injection at 3 months. Surgical treatment was overall more effective; however, 50% of the women that received a collagen injection were satisfied at 12 months after the procedure. They also note lower morbidity for this procedure compared to surgery [39].

Treatment in This Patient

The patient underwent successful robotic sacrocolpopexy with mesh and a transobturator sling. There were no complications during the procedure and she reports no bulge or SUI symptoms. She has not been straining to void and has been emptying her bladder well since the Foley catheter was removed the day after surgery. However, she continues to complain of bothersome urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence. She is wearing 1 to 3 pads daily for leakage. At her 6-week postoperative visit, the exam showed excellent vaginal support, no SUI, low PVR, and her urine culture was negative.

What are the clinical implications of these findings?

At this point it is reasonable to continue treatment of OAB. The patient may continue to see improvement as she gets further out from surgery but especially in a patient that had preoperative OAB symptoms, treatment is indicated and may consist of reminding her of behavioral modifications, returning to pelvic floor physical therapy, or starting her on a medication.

What medications are used to treat OAB?

Anticholinergic Drugs

Anticholinergics are second-line therapy for OAB; these medications prevent the binding of acetylcholine to the M3 muscarinic receptor in the detrusor muscle and inhibit uncontrolled bladder contraction. There are numerous medications and delivery methods (pills, patches, gels) but efficacy is similar among the different drugs and all are limited by side effects such as dry mouth, constipation, and central nervous system side effects. Mirabegron, approved by the FDA in June 2012 and released in October 2012, is an agonist of the β3-adrenoceptor receptor in the detrusor muscle promoting bladder storage. A phase III trial found that mirabegron significantly decreased incontinence episodes and micturition frequency compared to placebo [40]. Dry mouth, common with anticholinergics, was 3 times less likely compared to tolterodine [41]. The most common side effects (headache, urinary tract infection, hypertension, and nasopharyngitis) were similar between treatment and placebo groups.

Long-term compliance, side effects, and decreased efficacy limit the benefits of medication therapy [42]. In one survey, 25% of patients taking OAB medications discontinued them within 12 months with 89% reporting unmet treatment expectations and/or tolerability [43].

6 Months Later

The patient continues to complain of persistent OAB symptoms despite anticholinergic and beta-3 agonist therapy. She reported significant constipation and dry mouth with an anticholinergic and symptoms did not improve with mirebegron. Despite having OAB symptoms prior to her prolapse repair, it is important to evaluate for any other cause of her persistent symptoms. Her surgical repair remains intact and urodynamics and cystoscopy were performed showing no evidence of bladder outlet obstruction and no mesh or suture material in the bladder. There was no leakage with valsalva, though she had some early sensation of fullness (sensory urge). With a negative evaluation, refractory OAB is diagnosed and the patient is a candidate for third-line OAB treatment.

What are third-line OAB treatments?

OnabotulinumtoxinA

OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) was approved in 2013 for patients intolerant or unresponsive to behavioral therapy and oral medications. OnabotulinumtoxinA is a chemical neuromodulator that cleaves the SNARE protein SNAP-25, inhibits the fusion of the cytoplasmic vesical to the nerve terminal, and prevents the release of acetylcholine. This causes detrusor muscle relaxation and may also inhibit sensory afferent pathways [44].

Nitti et al compared Botox 100 U to placebo in 557 patients that were refractory to anticholinergics [45]. Botox decreased the frequency of daily urinary incontinence episodes vs placebo (–2.65 vs –0.87, P < 0.001) and 22.9% vs 6.5% of patients became completely continent. A 5.4% rate of urinary retention occurred and UTI was the most common side effect (16%) in those receiving active drug. A dose of 100 U is recommended to limit side effects while maintaining efficacy [46].

Comparision of a daily anticholinergic (solifenacin) versus Botox 100 U for 6 months was done in a randomized double-blind, double-placebo-controlled trial [47]. Patients underwent saline injection or took an oral placebo in the anticholinergic and Botox groups, respectively. Complete resolution of urinary symptoms occurred in 13% of the medication group and 27% of the Botox group (P = 0.003). Dry mouth was more common in the medication group (46% vs. 31%) and the Botox group had a higher rate of catheter use and urinary tract infections (5% vs. 0%; 33% vs. 13%). Quality of life measures have also been shown to improve significantly following Botox injection [45,48].

When considering whether Botox is appropriate for a particular patient, physicians must determine whether the patient is willing and able to perform clean intermittent catheterization. Contraindications include active UTI, urinary retention, unwilling or unable to do clean intermittent catheterization, and known hypersenstivitiy to botulinum toxin type A. Although the definition of urinary retention and the PVR at which clean intermittent catheterization should be initiated varies, one study found a 94% rate of urinary retention with a preoperative PVR > 100 mL [49].

Botox can be administered in the clinic with or without local anesthetic but general anesthetic may be used in patients who might be poorly tolerant of the procedure. Using flexible or rigid cystoscopy, the bladder is filled to 100 to 200 mL. An injection needle is used to inject 0.5 cc aliquots of reconstituted onabotulinumtoxinA in 20 areas spaced 1 cm apart. Periprocedure antibiotics are recommended by the manufacturer but actual usage varies [50]. Patients should understand that the effects of Botox may take up to 4 weeks and an appointment should be scheduled within 2 weeks to evaluate PVR and any other adverse reactions. Repeat injections are needed between 3 to 9 months as symptoms return; however, efficacy is maintained with subsequent treatments [51].

Neuromodulation

Additional third-line treatment options include sacral or posterior tibial nerve neuromodulation. Sacral neuromodulation has been FDA approved for treatment of urgency, frequency and urgency incontinence since 1997. Also known as InterStim (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN), this involves placement of a tined electrode adjacent to the S3 nerve root and is thought to result in modulation of the afferent nerve signals from the bladder to the spinal cord and the pontine micturition center.

Since the FDA approved sacral neuromodulation, long-term results for this therapy have been positive. A multicenter study with a 5-year follow-up showed a statistically significant reduction in daily leakage episodes, number of daily voids, and increase in voided volume, with a 5-year success rate of 68% for urgency incontinence and 56% for urgency/frequency [52]. Al-Zahrani et al followed 96 patients (35% with urgency incontinence) for a mean of 50.7 months and approximately 85% of the incontinent patients remained improved [53]. Conversely, Groen et al observed a gradual decrease in success rate from 1 month to 5 years in 60 women with urge incontinence, with only 15% completely continent at 5 years [54].

Sacral neuromodulation is typically performed in 2 stages. The first stage is electrode placement and trial period. A percutaneous nerve evaluation is a temporary electrode placement in the office or a permanent lead placement can be performed in the operating room. Correct placement stimulating the S3 nerve root is confirmed by motor and/or sensory testing. If there is an appropriate response, the electrode lead is connected to a temporary external pulse generator and is worn by the patient for a 2–14 day test period. If more than a 50% improvement in symptoms occur, a permanent lead and battery is placed in the operating room. If there is inadequate symptom response, the lead is removed. There are several recognized limitations of the office percutaneous nerve evaluation compared to operating room lead placement, including false-negative responses, possibly due to lead migration [55], incorrect lead placement, or an inadequate test period [56]. However, it is relatively noninvasive and potentially avoids 2 operating room procedures. Regardless of the choice of the initial test period, sacral neuromodulation offers a minimally invasive, long-term treatment option for refractory OAB.

Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) is an office procedure that stimulates the posterior tibial nerve. This nerve contains L4–S3 fibers that originate from the same spinal segments that innervate the bladder and pelvic floor. In comparision to sacral neuromodulation, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation is less invasive, less expensive and there is no permanent implant required [57].

Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation is performed by a physician, nurse, or other advanced practice provider. Patients sit with knees abducted and the leg externally rotated. A 34-gauge needle is inserted 3 cm into the skin 3 fingerbreadths above the medial malleolus. The Urgent PC Neuromodulation System (Uroplasty, Minnetonka, MN) is attached and the amplitude of the stimulation is increased until the large toe curls or the toes fan. Each session lasts 30 minutes and 12 weekly treatments provides the best improvement in patient symptoms [58, 59]. There is a strong carry-over effect and patients generally need re-treatments every 4-6 weeks for 30 minutes.

Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation has been compared favorably to both anticholinergic and sham treatments. The Overactive Bladder Innovative Therapy Trial (OrBIT) randomized 100 patients to PTNS or tolterodine for 12 weeks. The global response assessment demonstrated a statistically significant subjective improvement or cure over baseline in OAB symptoms in 79.5% of the PTNS group vs. 54.8% of the tolterodine group (P = 0.01)[60]. The SUmiT trial compared the efficacy of PTNS to sham for 12 weeks of therapy [59]. In this multicenter study, subjects were assessed at 13 weeks using the global response assessment for overall bladder symptoms. 55% of PTNS subjects achieved moderately or marked improvement in bladder symptoms compared to 20.9% of sham subjects (P < 0.001). Voiding diary parameters also improved compared to sham. In an earlier sham controlled trial, 12 patients (71%) in the treatment arm compared to none of the 15 placebo patients, demonstrated more than 50% improvement in diary and quality of life scores [61].

To evaluate long-term efficacy and safety, 36-month results of 29 positive responders of the initial SUmiT trial was reported [59]. In addition, a maintenance regimen was developed so patients received PTNS at tapering intervals over a 3-month period followed by a personalized treatment plan to sustain subjective improvement in their symptoms. With an average of 1 treatment a month, symptom severity scores and health related quality of life scores were statistically significant for improvement at each tested time-point. Yoong et al followed patients for 2 years following initial treatment with PTNS and confirmed a durable improvement in nocturia, frequency, urgency incontinence and symptom scores with a longer median length between treatments of 64 days [62].

PTNS is office-based, has few side effects, and avoids an implantable device. In addition, continuous stimulation is not necessary and a decreased treatment frequency is needed over time. Limitations include the time commitment that is required for both the initial treatment phase and the maintenance phase. Logistical concerns of weekly and monthly office visits or arranging for transportation can limit treatment.

Additional Treatment

The patient received injection of 100 U of Botox in the office. At her 2-week follow up appointment, her PVR was 90 mL and she was already seeing improvement in her incontinence episodes. At 6 weeks she was wearing 1 pad per day but using it mainly for protection. She still notices urgency, particularly if she drinks more than 1 cup of coffee in the morning, but overall she reports significant improvement in her symptoms. She has no complaints of a vaginal bulge and on exam has a grade 1 distal rectocele and no SUI with a full bladder. The physician discussed need for continued yearly examinations and repeat injections due to the duration of action of Botox.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates the complex step-wise management strategy of a patient with pelvic organ prolapse and voiding dysfunction. Interventions directed at patient bother and recognition of the various modalities and timing of treatment are essential to provide the greatest chance of positive treatment outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Corresponding author: Jaimie M Bartley, DO, 3601 W. 13 Mile Rd., Royal Oak, MI 48073.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA 2008;300:1311–6.

2. Hendrix SL, Clark A, Nygaard I, et al. Pelvic organ prolapse in the Women's Health Initiative: gravity and gravidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186:1160–6.

3. Barber MD, Maher C. Epidemiology and outcome assessment of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J 2013;24:1783–90.

4. Zhang C, Hai T, Yu L, et al. Association between occupational stress and risk of overactive bladder and other lower urinary tract symptoms: a cross-sectional study of female nurses in China. Neurourol Urodyn 2013;32:254–60.

5. Swift SE, Tate SB, Nicholas J. Correlation of symptoms with degree of pelvic organ support in a general population of women: what is pelvic organ prolapse? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:372–7.

6. Baessler K, Maher C. Pelvic organ prolapse surgery and bladder function. Int Urogynecol J 2013;24:1843–52.

7. Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;175:10–7.

8. Lohsiriwat S, Hirunsai M, Chaiyaprasithi B. Effect of caffeine on bladder function in patients with overactive bladder symptoms. Urol Ann 2011;3:14–8.

9. Wells MJ, Jamieson K, Markham TC, et al. The effect of caffeinated versus decaffeinated drinks on overactive bladder: a double-blind, randomized, crossover study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2014;41:371–8.

10. Fantl JA, Wyman JF, McClish DK, et al. Efficacy of bladder training in older women with urinary incontinence. JAMA 1991;265:609–13.

11. Burgio KL, Locher JL, Goode PS, et al. Behavioral vs drug treatment for urge urinary incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;280:1995–2000.

12. Burgio KL. Update on behavioral and physical therapies for incontinence and overactive bladder: the role of pelvic floor muscle training. Curr Urol Rep 2013;14:457–64.

13. Burgio KL, Kraus SR, Menefee S, et al; Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Behavioral therapy to enable women with urge incontinence to discontinue drug treatment: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:161–9.

14. Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Faraday M, Vasavada SP. Diagnosis and Treatment of Overactive Bladder (Non-Neurogenic) in Adults: AUA/SUFU Guideline Amendment. J Urol 2015;193:1572–80.

15. Dumoulin C, Hay-Smith J, Habée-Séguin GM, Mercier J. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women: A short version Cochrane systematic review with meta-analysis. Neurourol Urodyn 2015;34:300–8.

16. Labrie J, Berghmans BL, Fischer K, et al. Surgery versus physiotherapy for stress urinary incontinence. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1124–33.

17. Braekken IH, Majida M, Engh ME, Bø K. Can pelvic floor muscle training reverse pelvic organ prolapse and reduce prolapse symptoms? An assessor-blinded, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;203:170.e1–7.

18. Hagen S, Stark D, Glazener C, et al; POPPY Trial Collaborators. Individualised pelvic floor muscle training in women with pelvic organ prolapse (POPPY): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:796–806.

19. Alperin M, Khan A, Dubina E, et al. Patterns of pessary care and outcomes for medicare beneficiaries with pelvic organ prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2013;19:142-7.

20. Lamers BH, Broekman BM, Milani AL. Pessary treatment for pelvic organ prolapse and health-related quality of life: a review. Int Urogynecol J 2011;22:637–44.

21. Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2010;115:609–17.

22. Wood LN, Anger JT. Urinary incontinence in women. BMJ 2014;349:g4531.

23. FDA Safety Communication. Update on serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Available at http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm262435.htm.

24. Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, Meikle SF; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: the OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA 2014;311:1023–34.

25. Weber AM, Walters MD, Piedmonte MR, Ballard LA. Anterior colporrhaphy: a randomized trial of three surgical techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;185:1299–304.

26. Chmielewski L, Walters MD, Weber AM, Barber MD. Reanalysis of a randomized trial of 3 techniques of anterior colporrhaphy using clinically relevan tdefinitions of success. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205:69.e1–8.

27. Altman D, Väyrynen T, Engh ME, et al; Nordic Transvaginal Mesh Group. Anterior colporrhaphy versus transvaginal mesh for pelvic-organ prolapse. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1826–36. Erratum in: N Engl J Med 2013;368:394.

28. Delancey JO. Fascial and muscular abnormalities in women with urethral hypermobility and anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;187:93–8.

29. Clemons JL, Myers DL, Aguilar VC, Arya LA. Vaginal paravaginal repair with an AlloDerm graft. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:1612–8.

30. Gomelsky A, Rudy DC, Dmochowski RR. Porcine dermis interposition graft for repair of high grade anterior compartment defects with or without concomitant pelvic organ prolapse procedures. J Urol 2004;171:1581–4.

31. Handel LN, Frenkl TL, Kim YH. Results of cystocele repair: a comparison of traditional anterior colporrhaphy, polypropylene mesh and porcine dermis. J Urol 2007;178:153–6.

32. Nygaard I, Brubaker L, Zyczynski HM, et al. Long-term outcomes following abdominal sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse. JAMA 2013;309:2016–24.

33. Sirls LT, McLennan GP, Killinger KA, et al. Exploring predictors of mesh exposure after vaginal prolapse repair. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2013;19:206–9.

34. Hsiao KC, Latchamsetty K, Govier FE, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic and abdominal sacrocolpopexy for the treatment of vaginal vault prolapse. J Endourol 2007;21:926–30.

35. Anger JT, Mueller ER, Tarnay C, et al. Robotic compared with laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:5–12.

36. Wei JT, Nygaard I, Richter HE, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. A midurethral sling to reduce incontinence after vaginal prolapse repair. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2358–67.

37. Wai CY, Curto TM, Zyczynski HM, et al; Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Patient satisfaction after midurethral sling surgery for stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:1009–16.

38. Kenton K, Stoddard AM, Zyczynski H, et al. 5-year longitudinal followup after retropubic and transobturator mid urethral slings. J Urol 2015;193:203–10.

39. Kirchin V, Page T, Keegan PE, Atiemo K, Cody JD, McClinton S. Urethral injection therapy for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;2:CD003881.

40. Chapple CR, Kaplan SA, Mitcheson D, et al. Randomized double-blind, active-controlled phase 3 study to assess 12-month safety and efficacy of mirabegron, a β(3)-adrenoceptor agonist, in overactive bladder. Eur Urol 2013;63:296–305.

41. Nitti VW, Auerbach S, Martin N, et al. Results of a randomized phase III trial of mirabegron in patients with overactive bladder. J Urol 2013;189:1388–95.

42. Dmochowski RR, Newman DK. Impact of overactive bladder on women in the United States: results of a national survey. Curr Med Res Opin 2007;23:65–76.

43. Benner JS, Nichol MB, Rovner ES, et al. Patient-reported reasons for discontinuing overactive bladder medication. BJU Int 2010;105:1276–82.

44. Apostolidis A, Dasgupta P, Fowler CJ. Proposed mechanism for the efficacy of injected botulinum toxin in the treatment of human detrusor overactivity. Eur Urol 2006;49:644–50.

45. Nitti VW, Dmochowski R, Herschorn S, et al; EMBARK Study Group. OnabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of patients with overactive bladder and urinary incontinence: results of a phase 3, randomized, placebo controlled trial. J Urol 2013;189:2186–93.

46. Dmochowski R, Chapple C, Nitti VW, et al. Efficacy and safety of onabotulinumtoxinA for idiopathic overactive bladder: a double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized, dose ranging trial. J Urol 2010;184:2416–22.

47. Visco AG, Brubaker L, Richter HE, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Anticholinergic versus botulinum toxin A comparison trial for the treatment of bothersome urge urinary incontinence: ABC trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2012;33:184–96.

48. Chapple C, Sievert KD, MacDiarmid S, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA 100 U significantly improves all idiopathic overactive bladder symptoms and quality of life in patients with overactive bladder and urinary incontinence: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Urol 2013;64:249–56.

49. Osborn DJ, Kaufman MR, Mock S, et al. Urinary retention rates after intravesical onabotulinumtoxinA injection for idiopathic overactive bladder in clinical practice and predictors of this outcome. Neurourol Urodyn 2014 Jun 29.

50. Rovner E. Chapter 6: Practical aspects of administration of onabotulinumtoxinA. Neurourol Urodyn 2014;33 Suppl 3:S32–7.

51. Duthie JB, Vincent M, Herbison GP, et al. Botulinum toxin injections for adults with overactive bladder syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(12):CD005493.

52. van Kerrebroeck PE, van Voskuilen AC, Heesakkers JP, et al. Results of sacral neuromodulation therapy for urinary voiding dysfunction: outcomes of a prospective, worldwide clinical study. J Urol 2007;178:2029–34.

53. Al-zahrani AA, Elzayat EA, Gajewski JB. Long-term outcome and surgical interventions after sacral neuromodulation implant for lower urinary tract symptoms: 14-year experience at 1 center. J Urol 2011;185:981–6.

54. Groen J, Blok BF, Bosch JL. Sacral neuromodulation as treatment for refractory idiopathic urge urinary incontinence: 5-year results of a longitudinal study in 60 women. J Urol 2011;186:954–9.

55. Carey M, Fynes M, Murray C, Maher C. Sacral nerve root stimulation for lower urinary tract dysfunction: overcoming the problem of lead migration. BJU Int 2001;87:15–8.

56. Everaert K, Kerckhaert W, Caluwaerts H, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing the 1-stage with the 2-stage implantation of a pulse generator in patients with pelvic floor dysfunction selected for sacral nerve stimulation. Eur Urol 2004;45:649–54.

57. Staskin DR, Peters KM, MacDiarmid S, et al. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation: a clinically and cost effective addition to the overactive bladder algorithm of care. Curr Urol Rep 2012;13:327–34.

58. Peters KM, Carrico DJ, Wooldridge LS, et al. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation for the long-term treatment of overactive bladder: 3-year results of the STEP study. J Urol 2013;189:2194–201.

59. Peters KM, Carrico DJ, Perez-Marrero RA, et al. Randomized trial of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation versus Sham efficacy in the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome: results from the SUmiT trial. J Urol 2010;183:1438–43.

60. Peters KM, Macdiarmid SA, Wooldridge LS, et al. Randomized trial of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation versus extended-release tolterodine: results from the overactive bladder innovative therapy trial. J Urol 2009;182:1055–61.

61. Finazzi-Agrò E, Petta F, Sciobica F, et al. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation effects on detrusor overactivity incontinence are not due to a placebo effect: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Urol 2010;184:2001–6.

62. Yoong W, Shah P, Dadswell R, Green L. Sustained effectiveness of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation for overactive bladder syndrome: 2-year follow-up of positive responders. Int Urogynecol J 2013;24:795–9.

From Beaumont Health System, Royal Oak, MI.

Abstract

- Objective: To review the evaluation and management of complex pelvic floor disorders in elderly women.

- Methods: Literature review and presentation of a clinical case.

- Results: Pelvic floor disorders are a common problem in elderly women. Pelvic organ prolapse and voiding complaints often coexist and several treatment options are available. A step-wise approach should be used in which management of the most bothersome symptoms occurs first. Conservative, medication, and surgical options should be discussed with each patient depending on treatment goals and health status. Some effects do overlap; however, treatment of one condition may not preclude treatment of other symptoms.

- Conclusion: In women with complex pelvic floor disorders, addressing the most bothersome symptom first will increase patient satisfaction. Patients should be counseled about the potential need for multiple treatments for optimal results.

The female pelvic floor consists of a complex relationship of muscles, connective tissue and fascia, ligaments, and neurovascular support. These structures are responsible for support of the pelvic organs (uterus, bladder, rectum, and vagina), maintain continence, and assist in normal bowel function. Pelvic floor disorders occur when there is a compromise in these structures, resulting in prolapse, urinary incontinence, bowel complaints, or pain. Often several symptoms coexist with overlapping pathophysiology. Examinations and studies should aim to correctly diagnose the disorders and guide treatments toward the most bothersome symptoms.

Pelvic organ prolapse occurs when there is a weakening of the pelvic floor connective tissue, muscles, and nerves, allowing a bulge or protrusion of the vaginal walls and their associated pelvic organs. Between 3% to 50% of women in the United States have some degree of pelvic organ prolapse depending on whether the definition is based on symptoms or anatomic evaluation [1–3]. Risk factors include vaginal delivery, obesity, Caucasian race, and prior prolapse surgery. Despite the non–life-threatening nature of pelvic organ prolapse, the associated social and physical restrictions can significantly impact quality of life [4]. The cost of prolapse surgery has been estimated to be over $1.4 billion per year [3].

The sensation of a vaginal bulge is the only symptom consistently related to pelvic organ prolapse, with patients typically reporting symptoms once the prolapse extends beyond the hymenal ring [5]. The diagnosis of pelvic organ prolapse is made based on symptoms and confirmed by physical exam.

Patients with pelvic organ prolapse may experience obstructive voiding symptoms, such as hesitancy, straining, or incomplete bladder emptying. In some cases, patients may have to manually reduce the bulge to be able to void, a practice known as “splinting.” Overactive bladder (OAB), a syndrome of urinary urgency, frequency, and nocturia with or without urgency incontinence, can also occur. In patients with lower urinary tract complaints, repair of a vaginal bulge, especially a cystocele, can be associated with improved voiding symptoms [6]. Additionally, prolapse treatment can unmask de novo stress urinary incontinence (SUI), leaking with cough, sneeze or other activity that increases abdominal pressure. Urinary tract infections, pelvic pain, dyspareunia and defecatory problems can also be present.

When evaluating a woman with pelvic organ prolapse and voiding complaints, the clinician should strive to illicit which symptoms bother the patient most. A patient with primarily OAB symptoms and minimal prolapse may be treated with physical therapy or medications addressing the OAB rather than reconstructive surgery. In contrast, the patient with OAB symptoms and bothersome prolapse must be counseled on possible need for additional treatment of voiding complaints following surgical repair. This may include management of persistent OAB symptoms or SUI occurring following prolapse repair. Defecatory problems may be independent of a small rectocele present on exam, especially if long-term constipation is present. Choice of treatment depends on the severity of symptoms, the degree of prolapse, and the patient’s health status and activity level.

Case Study

Initial Presentation

A 68-year-old woman with a 15-month history of urinary urgency, frequency, incontinence and vaginal pressure presents to a urologist.

History and Physical Examination

The patient’s symptoms began shortly after the death of her husband. She initially saw her internist who prescribed antibiotics for a suspected urinary tract infection (UTI) based on office urinalysis. The symptoms did not resolve so another course of antibiotics was tried, again without relief. At her 3rd visit, a urine culture was done which was negative and she was referred to a urologist.

The patient reports 3 UTIs in the last 6 months. Following antibiotic treatment, the burning improves but she still complains of urgency and frequency. She also wears 2 to 3 pads per day for leakage that occurs with coughing and also when she feels an urge but cannot make it to the bathroom. She wakes 1 to 3 times at night to void. She feels that she empties her bladder well but often has to strain to void and sometimes feels a “bulge” in her vagina. All of these symptoms increase after being on her feet all day while she works as a grocery store cashier.

Physical exam demonstrates mild suprapubic tenderness and mild atrophic vaginitis. The anterior vaginal wall protrudes to the hymen with straining and her vaginal apex is supported 5 cm above the hymenal ring. With reduction of the cystocele there was urine leakage with cough. The cervix is surgically absent and her posterior vaginal wall is without bulge on valsalva. Her catheterized post-void residual (PVR) was 105 mL. Urine dipstick analysis was negative for infection or blood.

What is the initial evaluation of a woman with pelvic organ prolapse and voiding complaints?

The initial evaluation of a woman with pelvic organ prolapse and voiding complaints consists of a detailed history and physical examination. The nature, duration, and severity of symptoms should be assessed. Complaints of vaginal pressure or bulge are important, as well as exacerbating instances (standing, straining, defecation). Local irritation or vaginal spotting is common if prolapse is beyond the hymen. Splinting or reduction of a bulge to void or defecate are important elements of the history. Sexual history should never be overlooked, including both sexual status (active or not) as well as goals for future sexual activity. Voiding symptoms such as dysuria, frequency, urgency, nocturia and incontinence should be discussed. A 3-day voiding diary that captures number of voids per day, voided volumes, and fluid intake can be obtained. If incontinence is present, the clinician should determine what causes the incontinence. Incontinence that is associated with urgency or no warning (urge incontinence) should be treated differently than incontinence associated with activity (SUI). Mixed urinary incontinence is the presence of both stress and urgency incontinence.

Past medical history should include common medical comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Obstetric history is important due to the increased risk for pelvic floor disorders in women with multiple pregnancies and vaginal deliveries [2]. Prior hysterectomy, colon resection, or other pelvic surgeries may also contribute to symptoms. Smokers have a greater risk of genitourinary malignancy and high caffeine consumption is implicated in urgency-frequency syndromes. Exercise, sleep, and work may also be affected.

Pelvic examination should evaluate for vaginal atrophy or other vaginal mucosal abnormalities such as tears, ulcerations, lichen sclerosis, or erythema. To evaluate for prolapse, using one-half of a Graves or Pederson speculum, examine the 3 compartments of the vagina: anterior, posterior and apical. To view the anterior wall, the speculum is placed posteriorly to retract the posterior wall downward. Next it is rotated anteriorly to retract the anterior wall up and examine the posterior compartment. The uterus or the apex is evaluated with 2 halves of the speculum, one pushing anteriorly and the other posteriorly. At each point in the evaluation, the patient is told to strain or valsalva. The pelvic organ prolapse quantification system (POP-Q) is a systematic description of site-specific measurements of a woman’s pelvic support [7]. Using this classification system, a standardized and reproducible method of documenting the severity of the prolapse is done based on 6 points of the vaginal wall in relation to the hymen (2 on the anterior wall, 2 in the superior vagina, and 2 on the posterior vaginal wall). A corresponding prolapse stage can then be assigned to the patient based on POP-Q measurements. If unable to reproduce the patient’s symptoms, or exam findings do not correlate with the history, a standing exam can be helpful. Close evaluation of the urethra is also important. In severe prolapse the urethra may become kinked and mask a potential underlying problem (occult SUI). Patients should be asked to valsalva or cough with prolapse reduction and a full bladder to evaluate for this. Lastly, the pelvic floor muscles should be palpated to assess for pain or pelvic floor atrophy, hypertonicity, tenderness, or spasms.

If the patient complains of urgency, frequency, and/or dysuria, urine cultures should be performed to exclude infection even if the urinalysis is negative. Antibiotics should be given based on culture results. A postvoid ultrasound or catheterization is used to evaluate for incomplete bladder emptying. Patients with microscopic or gross hematuria should undergo further testing with radiologic and cystoscopic evaluation as indicated, especially with a history of smoking. Women should be questioned regarding their menstrual history and if postmenopausal, about any vaginal bleeding. A pelvic ultrasound should be considered if the patient has a history of endometriosis, gynecological cancers, uterine fibroids, or ovarian cysts or if considering uterine preserving surgery or colpocleisis. Urodynamics are often indicated in complex patients with prolapse and lower urinary tract complaints or prior pelvic surgery.

Diagnosis

The patient was diagnosed with mixed urinary incontinence and a grade 2 cystocele. Treatment options were discussed and she was most interested in conservative management options.

What is first-line treatment for the complaints of urgency, frequency, and incontinence?

In an older patient with complaints of urgency, frequency, and incontinence, dietary and behavioral modifications as well as pelvic floor physical therapy are considered first-line minimally invasive treatments.

Dietary irritants such as coffee, tea, soda, and other caffeinated beverages can contribute to worsening of symptoms [8]. A randomized study measuring the effects of caffeine noted a significant reduction in urgency and frequency of voids and in symptom scores with reduction of caffeine use [9]. Some elderly patients are reluctant to change their lifestyle, but even small changes can significantly improve their urgency symptoms.

Timed voiding is an effective method for bladder retraining, which can be critical for managing symptoms both alone and as an adjunct to other interventions. Studies of behavioral therapy show significant improvement in urgency, frequency, and incontinence episodes. In a study by Wyman and Fanti, patients participating in bladder training and Kegel exercises noted a 57% decrease in incontinence episodes and 54% decrease in urine loss without medications [10]. Burgio et al compared behavioral therapy to anticholinergic medication administration. After 4 sessions over 8 weeks they reported 81% reduction in incontinence episodes compared to 69% in the drug group and 39% in the placebo group [11].

Elderly patients may take several medications, some of which can affect urine volume and timing of urine production. Diuretics given later in the day can increase nighttime urine production and worsen nocturia. Similarly, lower extremity edema can increase nocturnal urine volumes when the patient reclines. Compressive stockings and leg elevation 2-3 hours prior to bedtime will help evenly distribute fluids and decrease reabsorption when supine at night.

Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy

Pelvic floor physical therapy (PFPT) can be an effective treatment for OAB, SUI, and pelvic organ prolapse. PFPT is used as an urge suppression strategy for OAB by teaching patients how to contract their pelvic muscles to occlude the urethra and prevent leakage during a detrusor contraction. Strategies to help suppress urge and manage stress situations can reduce incontinence episodes up to 60% to 80% [12]. Behavioral programs can include bladder diaries, scheduled voiding, delayed voiding, double voiding, fluid management, and caffeine reduction. When combined with PFPT they can be very effective in the management of OAB symptoms and incontinence. The BE-DRI study showed that combined behavioral training and drug therapy yielded better outcomes over time in OAB symptoms, patient distress and treatment satisfaction than drug therapy alone [13]. PFPT is considered a first-line treatment for OAB and is a noninvasive and effective treatment for these symptoms [14].

Pelvic floor programs for SUI aim to teach pelvic floor muscle contraction to help prevent stress leakage and use a variety of methods including biofeedback and personalized training programs. A recent Cochrane review included 18 studies of PFPT for incontinence. They concluded that there was high quality evidence that PFPT was associated with cure and moderate evidence for improvement in SUI [15]. In a study comparing surgery versus PFPT at 1 year, subjective improvement in the surgery group was 91% compared to 64% in the PFPT group. While PFPT was not as effective as surgery, over 50% had improvement. PFPT remains an effective noninvasive option that should be considered, particularly in an older patient [16].

PFPT has also been studied as a treatment option for pelvic organ prolapse. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) that compared PFPT to controls over time, more women in the PFPT group improved 1 POP-Q stage compared to the control group. They also had significantly improved pelvic floor symptom bother [17]. In the POPPY study examining PFPT versus a control condition, researchers were not able to show statistically significant improvement in prolapse stages but did show improvement in secondary outcomes, including symptom bother and the feeling of “bulge.” Fewer women sought further treatment for prolapse after undergoing PFPT [18]. PFPT can be effective in managing prolapse symptoms and may help improve prolapse stage.

Pessary

Pessaries are commonly used for management of pelvic organ prolapse in patients who choose nonoperative management. In a large study of pessary use in the Medicare population, it was noted that of 34,782 women diagnosed with prolapse between 1999 and 2000, 11.6% were treated with a pessary. Complications noted during the 9 years of follow-up included 3% with vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistulas and 5% with a device-associated complication [19]. Use increased with age, with 24% of women over 85 being managed with a pessary. In a review examining quality of life, improvement in bulge, irritative symptoms, and sexual satisfaction occurred with pessary use. In the medium-term, prolapse-related bother symptoms, quality of life, and overall perception of body image improved with the use of a pessary [20]. For SUI, rings with a knob or an incontinence dish can provide support to the urethra and help to pinch it closed with coughing, sneezing, and laughing, preventing leakage. In an RCT comparing women who received behavioral therapy, an incontinence pessary, or both, at 3 months 33% of those assigned to pessary reported improved incontinence symptoms compared to 49% with behavioral therapy, and 63% were satisfied with pessary treatment compared to 75% with behavioral therapy [21,22]. Differences did not persist to 12 months with over one third of all women improved and even more satisfied. A pessary can be safely used in the elderly population but does require office management and regular follow-up to prevent complications.

Initital Treatment

The patient was treated with 3 months of PFPT with biofeedback and pelvic floor muscle strengthening. In addition, she was able to decrease her caffeine use from 4 cups of coffee per day to 1 cup in the morning. At her 3-month follow-up visit, she noticed significant improvement in her voiding symptoms, and her voiding diary showed improved voided volumes and decreased frequency and nocturia. However, she was becoming more active in her community, going to aerobics and dance classes. She was more bothered by the “bulge” feeling in her vagina. She was not interested in a pessary but wanted to hear about surgical options for prolapse treatment.

What is operative management of pelvic organ prolapse?

The goals for surgical pelvic organ prolapse repair are to resolve symptoms, restore normal or near-normal anatomy, preserve sexual, urinary and bowel function, and minimize patient morbidity. The extent of prolapse, patient risk factors for recurrence, patient preference, and overall medical condition all influence the method for surgical repair. Surgeon familiarity and experience is also important when selecting the appropriate repair. Recent concerns regarding the use of synthetic mesh material has become a factor in counseling patients since the 2011 US Food and Drug Administration safety communication on transvaginal mesh [23].

Vaginal Approaches

Numerous techniques for pelvic organ prolapse repair have been described, though most repairs can broadly be divided into vaginal and abdominal procedures. Vaginal surgery is consistently associated with shorter operative times, less postoperative pain, and a shorter length of stay than abdominal approaches. All prolapsing compartments can be addressed vaginally using a patient’s own tissue, often called a “native tissue repair.” The vaginal apex is suspended from either the uterosacral ligament (USL) condensations or to the sacrospinous ligaments (SSL). Sutures are placed through these structures and tied to hold the vaginal vault in place, often at the time of concomitant enterocele, cystocele, or rectocele repairs. A recent randomized trial comparing USL and SSL repair showed composite functional and symptomatic success was 60% at 2 years and did not differ by technique [24]. While overall success may appear low, symptomatic vaginal bulge was present in only 17% to 19% of women at 2 years and only 5% underwent re-treatment with surgery or pessary during follow-up. Similar outcomes have been demonstrated for isolated cystocele repairs plicating the pubo-cervical fascia (anterior colporrhaphy). Cited failure rates have been as high as 70% [25], though this depends on the definition of success. When symptoms of bulge and/or prolapse beyond the hymen are used, success rates are closer to 89% at 2 years [26]. In one study comparing mesh-augmented cystocele repair with native tissue anterior colporrhaphy, 49% of women had a successful composite outcome at 2 years of grade 0 or 1 prolapse and no symptoms of bulge without the use of mesh graft [27]. Despite lower anatomic success rates, anterior colporrhaphy consistently relieves symptoms of bulge with low retreatment rates.

The high failure rates of native tissue vaginal repairs, especially in women with high-grade or recurrent prolapse, led to an interest in graft-augmented repairs. Furthermore, anatomic studies showed that up to 88% of cystoceles were associated with a lateral defect, or tearing of the pubocervical fascia from the pelvic sidewall (arcus tendineous fascia pelvis) [28]. Plicating the already weak fascia centrally would not repair an underlying lateral defect resulting in treatment failure. Replacing this weak fascia with a graft and anchoring it laterally and proximally should result in better anatomic and functional outcomes. These patches can be made from autologous tissue (rectus fascia), donor allograft material (fascia lata), xenografts (porcine dermis, bovine pericardium), or synthetic mesh. Initial studies using cadaveric dermis grafts for recurrent stage II or stage III/IV pelvic organ prolapse resulted in 50% failure at 4 years, but symptomatic failure was only 11% [29]. Further publications utilizing cadaveric tissue patches showed lower rates of cystocele recurrences of 0 to 17% between 20 and 56 months of follow-up [30].

As interest in patch repairs became popular, the use of synthetic mesh was applied to tension-free mid-urethral tapes for SUI. Studies were also showing rapid cadaveric and xenograft graft metabolism, graft extrusion, and early failure in some women [31]. This led to the use of larger pieces of synthetic mesh for prolapse repair, as it had been for abdominal wall and inguinal hernia repairs. Ultimately large-pore, light-weight polypropylene mesh was seen as the most favorable material and large randomized studies were performed to compare outcomes. Theoretically, a synthetic material would provide a replacement for the weakened and torn pubocervical fascia and not be subjected to enzymatic degradation. Altman et al published a widely cited randomized trial comparing native tissue vs. synthetic mesh showing that improvement in the composite primary outcome (no prolapse on the basis of both objective and subjective assessments) was more common in the mesh group (61% vs. 35%) at 1 year. Mesh placement was associated with longer operative times, higher blood loss, and 3.2% of women underwent secondary procedures for vaginal mesh exposure [27]. While there is still debate on the routine use of transvaginal mesh placement, current recommendations generally limit its use for recurrent or high grade pelvic organ prolapse (> Stage III), and possibly those at higher risks for recurrence. The American Urological Association has supported the FDA recommendation that patients undergo a thorough consent process and that surgeons are properly trained in pelvic reconstruction and mesh placement techniques. Furthermore, surgeons placing transvaginal mesh should be equipped to diagnose and treat any complications that may arise subsequent to its use.

Abdominal Approaches

Pelvic organ prolapse can also be approached through an abdominal technique. The classic description for vaginal vault prolapse repair is the abdominal sacrocolpopexy. This involves fixating the vaginal apex to the anterior longitudinal ligament at the sacral promontory. Hysterectomy is performed at the same setting if still in situ. A strip of lightweight polypropylene mesh is sutured to the anterior and posterior vaginal walls after dissecting the bladder and rectum off, then suspended in a tension-free manner to the sacrum. Large trials with long-term follow-up show durability of this repair. Seven-year follow-up of a large NIH-sponsored trial comparing sacrocolpopexy with and without urethropexy found 31/181 (17%) with anatomic prolapse beyond the hymen [32]. Of these women one-third had involvement of the vaginal apex, though 50% of women were asymptomatic. Overall, 95% of women had no retreatment for pelvic organ prolapse. A surprising finding was a 10.5% mesh exposure rate with a mean follow-up of 6.1 years. Previously, abdominally placed mesh was thought to be much safer than transvaginal mesh, but exposure rates are roughly similar in newer studies at high-volume, fellowship-trained centers [33]. The largest advance in abdominal prolapse surgery has come with the adoption of laparoscopic and robotic-assisted technology. Minimally invasive approaches to abdominal surgery have resulted in less blood loss and shorter length of stay, though longer operative times [34]. Short- and medium-term outcomes have been compared to the open techniques in smaller single-center series. At least 1 randomized trial comparing laparoscopic to robotic sacrocolpopexy showed similar complications and perioperative outcomes, though the robotic technique was more costly [35].

Stress Urinary Incontinence Procedures

When SUI is identified preoperatively, treatment should be considered at the time of prolapse repair [32,36]. The gold standard for treatment of SUI with urethral hypermobility has been placement of a synthetic mid-urethral sling. There are several types of slings available, mainly categorized as retropubic, transobturator, or single-incision “mini-slings.” In a multicenter study by the Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network (UITN), patient satisfaction after retropubic and transobturator sling placement was studied 12 months after surgery. Both groups had a high satisfaction rate (from 85% to 90%) for urine leakage, urgency, and frequency [37]. There was no significant difference in outcomes between the 2 approaches. Several other studies and systematic reviews have also shown excellent long-term results with sling treatment. In the recently published 5-year follow-up of the Trial of Mid-Urethral Slings (TOMUS), researchers demonstrated an 80% to 85% patient satisfaction rate with a 10% adverse event rate. Of these adverse events, only 6 were classified as serious requiring surgical, radiologic, or endoscopic intervention [38].

If the patient has SUI but no urethral hypermobility, consider intrinsic sphincter deficiency as the etiology of her incontinence. In that case, injectable therapy with urethral bulking agents is an effective treatment. Some commonly used injectables include carbon beads (Durasphere), calcium hydroxylapatite (Coaptite), bovine collagen (Contigen), and silicon particles (Macroplastique). In a Cochrane review of injectable therapy, they compared urethral injection to conservative treatment with physical therapy and noted an improvement with injection at 3 months. Surgical treatment was overall more effective; however, 50% of the women that received a collagen injection were satisfied at 12 months after the procedure. They also note lower morbidity for this procedure compared to surgery [39].

Treatment in This Patient

The patient underwent successful robotic sacrocolpopexy with mesh and a transobturator sling. There were no complications during the procedure and she reports no bulge or SUI symptoms. She has not been straining to void and has been emptying her bladder well since the Foley catheter was removed the day after surgery. However, she continues to complain of bothersome urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence. She is wearing 1 to 3 pads daily for leakage. At her 6-week postoperative visit, the exam showed excellent vaginal support, no SUI, low PVR, and her urine culture was negative.

What are the clinical implications of these findings?

At this point it is reasonable to continue treatment of OAB. The patient may continue to see improvement as she gets further out from surgery but especially in a patient that had preoperative OAB symptoms, treatment is indicated and may consist of reminding her of behavioral modifications, returning to pelvic floor physical therapy, or starting her on a medication.

What medications are used to treat OAB?