User login

Hospitalists Should Make Commitment to Improve Healthcare Safety

Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, FCCM, knows how to deliver a great talk. It is no wonder he is highly sought after and was asked to speak at the plenary for SHM’s annual meeting. Dr. Pronovost, also known as the “Checklist Doctor,” knows how to combine just the right amount of sadness, inspiration, and humor to make his audience feel motivated and compelled to DO something. And, in fact, he implores you—DO something.

Most of us feel excited and inspired during the annual meeting. But those feelings serve little purpose unless we translate them into actions that will make the medical industry a better place for clinicians to work and for patients to receive care. As Dr. Pronovost said, “We are the only hope that the healthcare system has of improving quality and safety.”

He was inspired years ago by the watershed event that will forever be imprinted upon Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, the preventable death of 18-month-old Josie King on Feb. 22, 2001. Years after the event, her mother, Sorrel King, a passionate patient safety advocate, wanted to know if hospitals are any safer than they were the day that Josie died. She wanted to know what patient safety experts at Hopkins had done to ensure there would not be another Josie King story.

Patients and their families consistently voice similar desires after they have suffered preventable harm. They want to know what happened, why it happened, what it means for them, and what will be done to prevent it from happening again.1 The latter question is one I am frequently asked by patients and their families at my hospital. “What are you going to do to make sure this does not happen again?”

I would venture to guess most hospitalists have been responsible for some type of preventable patient harm during their careers. We work in complex, high-volume, unpredictable, and continuously changing environments. Many of the patients and families in our care are new to us and are with us for only short periods of time. Those of us who have been responsible for preventable patient harm know that it is an unforgettable moment in time that can weigh upon your conscious. And, of course, we all want to do something to make sure it does not happen again.

That is exactly what patients and their families expect of all of us—to DO something—and they should.

But this can be an overwhelming responsibility, especially when the root causes of harm are difficult either to identify or to fix—such as a miscommunication, a diagnostic error, or an inadequate handoff.

Which gets me back to Dr. Pronovost giving a great talk. His appeal to our audience of about 3,000 hospitalists was to DO something. To make the healthcare system improve quality and safety for future patients. To not wait until we or our colleagues are involved in a preventable harm event. To do something, anything, now, that contributes to safer care, today and every day going forward.

He ended his talk with “I will….” Dr. Pronovost (and I would venture to guess patients and their families) wants each of us to fill in the blank with a statement of personal accountability for action. Unfortunately, many of us still believe that we are personally unable to make complex systems safer for patients. Many of us still believe that patients and the systems they traverse are too complex, unpredictable, unreliable, or noncompliant.

The truth is, patients and systems are indeed complex, unpredictable, unreliable, and noncompliant. The further truth is, the only way to make care safer is for each of us to start with a collective shared mental model that we can make it better—and for each of us to commit to personal accountability for action.

My “I Will”

So, while I really enjoyed Dr. Pronovost’s talk, what I enjoyed even more was reading the section in last month’s edition of The Hospitalist in which about a half dozen hospitalists interviewed after the plenary accepted the challenge of filling in the blank “I will….” A few excerpts:

- “I will let them know that everything is possible…”

- “I will improve healthcare…”

- “[I will] make sure the patient is heard…”

By a simple proclamation of personal accountability, a mere thousand hospitalists attending an annual meeting can collectively and progressively change the safety of healthcare in thousands of hospitals around the country. It starts with thinking we can do it and publicly committing to the journey. Although we are still a relatively new specialty, we have permeated almost every hospital in the country, and we have outpaced the growth of any specialty in the history of modern medicine. We are perfectly poised to be the safety change agents for every hospital system. As Margaret Meade famously said, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has….”

So don’t delay. Whether or not you had the good fortune of being inspired at the SHM annual meeting, each of us owes it to our patients to commit to improving the safety of healthcare and paving the future of hospital care. Get out your pen, craft a commitment now, follow through with it, and make hospitals safer tomorrow than they were yesterday.

I will…

Reference

- Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Ebers AG, Fraser VJ, Levinson W. Patients’ and physicians’ attitudes regarding the disclosure of medical errors. JAMA. 2003;289(8):1001-1007.

Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, FCCM, knows how to deliver a great talk. It is no wonder he is highly sought after and was asked to speak at the plenary for SHM’s annual meeting. Dr. Pronovost, also known as the “Checklist Doctor,” knows how to combine just the right amount of sadness, inspiration, and humor to make his audience feel motivated and compelled to DO something. And, in fact, he implores you—DO something.

Most of us feel excited and inspired during the annual meeting. But those feelings serve little purpose unless we translate them into actions that will make the medical industry a better place for clinicians to work and for patients to receive care. As Dr. Pronovost said, “We are the only hope that the healthcare system has of improving quality and safety.”

He was inspired years ago by the watershed event that will forever be imprinted upon Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, the preventable death of 18-month-old Josie King on Feb. 22, 2001. Years after the event, her mother, Sorrel King, a passionate patient safety advocate, wanted to know if hospitals are any safer than they were the day that Josie died. She wanted to know what patient safety experts at Hopkins had done to ensure there would not be another Josie King story.

Patients and their families consistently voice similar desires after they have suffered preventable harm. They want to know what happened, why it happened, what it means for them, and what will be done to prevent it from happening again.1 The latter question is one I am frequently asked by patients and their families at my hospital. “What are you going to do to make sure this does not happen again?”

I would venture to guess most hospitalists have been responsible for some type of preventable patient harm during their careers. We work in complex, high-volume, unpredictable, and continuously changing environments. Many of the patients and families in our care are new to us and are with us for only short periods of time. Those of us who have been responsible for preventable patient harm know that it is an unforgettable moment in time that can weigh upon your conscious. And, of course, we all want to do something to make sure it does not happen again.

That is exactly what patients and their families expect of all of us—to DO something—and they should.

But this can be an overwhelming responsibility, especially when the root causes of harm are difficult either to identify or to fix—such as a miscommunication, a diagnostic error, or an inadequate handoff.

Which gets me back to Dr. Pronovost giving a great talk. His appeal to our audience of about 3,000 hospitalists was to DO something. To make the healthcare system improve quality and safety for future patients. To not wait until we or our colleagues are involved in a preventable harm event. To do something, anything, now, that contributes to safer care, today and every day going forward.

He ended his talk with “I will….” Dr. Pronovost (and I would venture to guess patients and their families) wants each of us to fill in the blank with a statement of personal accountability for action. Unfortunately, many of us still believe that we are personally unable to make complex systems safer for patients. Many of us still believe that patients and the systems they traverse are too complex, unpredictable, unreliable, or noncompliant.

The truth is, patients and systems are indeed complex, unpredictable, unreliable, and noncompliant. The further truth is, the only way to make care safer is for each of us to start with a collective shared mental model that we can make it better—and for each of us to commit to personal accountability for action.

My “I Will”

So, while I really enjoyed Dr. Pronovost’s talk, what I enjoyed even more was reading the section in last month’s edition of The Hospitalist in which about a half dozen hospitalists interviewed after the plenary accepted the challenge of filling in the blank “I will….” A few excerpts:

- “I will let them know that everything is possible…”

- “I will improve healthcare…”

- “[I will] make sure the patient is heard…”

By a simple proclamation of personal accountability, a mere thousand hospitalists attending an annual meeting can collectively and progressively change the safety of healthcare in thousands of hospitals around the country. It starts with thinking we can do it and publicly committing to the journey. Although we are still a relatively new specialty, we have permeated almost every hospital in the country, and we have outpaced the growth of any specialty in the history of modern medicine. We are perfectly poised to be the safety change agents for every hospital system. As Margaret Meade famously said, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has….”

So don’t delay. Whether or not you had the good fortune of being inspired at the SHM annual meeting, each of us owes it to our patients to commit to improving the safety of healthcare and paving the future of hospital care. Get out your pen, craft a commitment now, follow through with it, and make hospitals safer tomorrow than they were yesterday.

I will…

Reference

- Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Ebers AG, Fraser VJ, Levinson W. Patients’ and physicians’ attitudes regarding the disclosure of medical errors. JAMA. 2003;289(8):1001-1007.

Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, FCCM, knows how to deliver a great talk. It is no wonder he is highly sought after and was asked to speak at the plenary for SHM’s annual meeting. Dr. Pronovost, also known as the “Checklist Doctor,” knows how to combine just the right amount of sadness, inspiration, and humor to make his audience feel motivated and compelled to DO something. And, in fact, he implores you—DO something.

Most of us feel excited and inspired during the annual meeting. But those feelings serve little purpose unless we translate them into actions that will make the medical industry a better place for clinicians to work and for patients to receive care. As Dr. Pronovost said, “We are the only hope that the healthcare system has of improving quality and safety.”

He was inspired years ago by the watershed event that will forever be imprinted upon Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, the preventable death of 18-month-old Josie King on Feb. 22, 2001. Years after the event, her mother, Sorrel King, a passionate patient safety advocate, wanted to know if hospitals are any safer than they were the day that Josie died. She wanted to know what patient safety experts at Hopkins had done to ensure there would not be another Josie King story.

Patients and their families consistently voice similar desires after they have suffered preventable harm. They want to know what happened, why it happened, what it means for them, and what will be done to prevent it from happening again.1 The latter question is one I am frequently asked by patients and their families at my hospital. “What are you going to do to make sure this does not happen again?”

I would venture to guess most hospitalists have been responsible for some type of preventable patient harm during their careers. We work in complex, high-volume, unpredictable, and continuously changing environments. Many of the patients and families in our care are new to us and are with us for only short periods of time. Those of us who have been responsible for preventable patient harm know that it is an unforgettable moment in time that can weigh upon your conscious. And, of course, we all want to do something to make sure it does not happen again.

That is exactly what patients and their families expect of all of us—to DO something—and they should.

But this can be an overwhelming responsibility, especially when the root causes of harm are difficult either to identify or to fix—such as a miscommunication, a diagnostic error, or an inadequate handoff.

Which gets me back to Dr. Pronovost giving a great talk. His appeal to our audience of about 3,000 hospitalists was to DO something. To make the healthcare system improve quality and safety for future patients. To not wait until we or our colleagues are involved in a preventable harm event. To do something, anything, now, that contributes to safer care, today and every day going forward.

He ended his talk with “I will….” Dr. Pronovost (and I would venture to guess patients and their families) wants each of us to fill in the blank with a statement of personal accountability for action. Unfortunately, many of us still believe that we are personally unable to make complex systems safer for patients. Many of us still believe that patients and the systems they traverse are too complex, unpredictable, unreliable, or noncompliant.

The truth is, patients and systems are indeed complex, unpredictable, unreliable, and noncompliant. The further truth is, the only way to make care safer is for each of us to start with a collective shared mental model that we can make it better—and for each of us to commit to personal accountability for action.

My “I Will”

So, while I really enjoyed Dr. Pronovost’s talk, what I enjoyed even more was reading the section in last month’s edition of The Hospitalist in which about a half dozen hospitalists interviewed after the plenary accepted the challenge of filling in the blank “I will….” A few excerpts:

- “I will let them know that everything is possible…”

- “I will improve healthcare…”

- “[I will] make sure the patient is heard…”

By a simple proclamation of personal accountability, a mere thousand hospitalists attending an annual meeting can collectively and progressively change the safety of healthcare in thousands of hospitals around the country. It starts with thinking we can do it and publicly committing to the journey. Although we are still a relatively new specialty, we have permeated almost every hospital in the country, and we have outpaced the growth of any specialty in the history of modern medicine. We are perfectly poised to be the safety change agents for every hospital system. As Margaret Meade famously said, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has….”

So don’t delay. Whether or not you had the good fortune of being inspired at the SHM annual meeting, each of us owes it to our patients to commit to improving the safety of healthcare and paving the future of hospital care. Get out your pen, craft a commitment now, follow through with it, and make hospitals safer tomorrow than they were yesterday.

I will…

Reference

- Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Ebers AG, Fraser VJ, Levinson W. Patients’ and physicians’ attitudes regarding the disclosure of medical errors. JAMA. 2003;289(8):1001-1007.

How Should a Patient with Pulmonary Hypertension Be Evaluated, Managed?

Case

A 62-year-old female with no significant past medical history presents with three weeks of progressive dyspnea on exertion and bilateral lower extremity edema. Family members report that the patient often snores and “gasps for air” during sleep. B-type natriuretic peptide is elevated at 2,261 pg/ml. Due to concern for congestive heart failure, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is performed and shows normal left ventricular systolic function, mild left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, severely elevated right ventricular systolic pressure of 74 mm Hg, and right ventricular dilatation and hypokinesis.

How should this patient with newfound pulmonary hypertension (PH) be evaluated and managed?

Background

PH is a progressive disease that presents with nonspecific signs and symptoms and can be fatal if untreated. Ernst von Romberg first identified the disease in 1891, and efforts have been made through the last century to understand its etiology and mechanisms.1

PH is defined as an elevated mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) of ≥25 mmHg at rest; a mPAP of ≤20 mmHg is considered normal, and a mPAP of 21-24 mmHg is borderline.2 This elevation of the mPAP can be due to a primary elevation of pressures in the pulmonary arterial system alone (pulmonary arterial hypertension) or secondary to elevation in pressures in the pulmonary venous and pulmonary capillary systems (pulmonary venous hypertension).

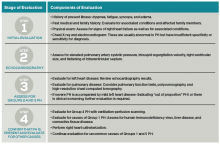

PH classification has endured many modifications through the years with better understanding of its pathophysiology. Currently, the World Health Organization (WHO) classification system includes five groups based on etiology (see Table 1):3,4

- Group 1: Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH);

- Group 2: PH due to left heart disease;

- Group 3: PH due to chronic lung disease and hypoxemia;

- Group 4: Chronic thromboembolic PH (CTEPH); and

- Group 5: PH due to unclear multifactorial mechanisms.

The pathophysiology differs among the groups, and much of what is known has come from studies performed in patients with idiopathic PAH. It is a proliferative vasculopathy characterized by vasoconstriction, cell proliferation, fibrosis, and thrombosis. Both genetic predisposition and modifiers that include drugs and toxins, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), congenital heart disease with left-to-right shunting, and potassium channel dysfunction play a role in the pathogenesis.3,5,6 Although many processes underlying the pathophysiology of PH groups 2, 3, 4, and 5 are not fully understood, vascular remodeling and increased vascular resistance are common to all of them.

PH affects both genders and all age groups and races. Due to its broad classification and multiple etiologies, it is difficult to assess PH prevalence in the general population. There are wide ranges among different populations, with PH prevalence in sickle cell disease ranging from 20% to 40%, in systemic sclerosis from 10% to 15%, and in portal hypertension from 2% to 16%.7,8,9 PH in COPD is usually mild to moderate, with preserved cardiac output, although a minority of patients develop severe PH.10-12 PH is present in approximately 20% of patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea.13 The prevalence of PH in left heart disease is unknown due to variability in populations assessed and methods used in various studies; estimates have ranged from 25-100%.14

Evaluation

Initial evaluation: A thorough history and physical examination can help determine PH etiology, identify associated conditions, and determine the severity of disease. Dyspnea on exertion is the most common presenting complaint; weakness, fatigue, and angina may be present.15 Lower extremity edema and ascites are indicative of more advanced disease.

A patient’s symptoms may suggest the presence of undiagnosed conditions that are associated with PH, and past medical history should evaluate for previous diagnoses of these conditions (see Table 1).

Family history may reveal relatives with PH, given the genetic predisposition to development of Group 1 PH. Physical exam findings include a prominent pulmonic valve closure during the second heart sound, a palpable left parasternal heave, and a tricuspid regurgitation murmur.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) and chest X-ray (CXR) are not sufficiently sensitive or specific to diagnose PH but may provide initial supporting evidence that prompts further testing. Signs of right ventricular hypertrophy and right atrial enlargement may be present on ECG. The CXR may show pruning (prominent hilar vasculature with reduced vasculature peripherally) and right ventricular hypertrophy, as evidenced by shrinking of the retrosternal window on lateral CXR. An unremarkable ECG or normal CXR does not rule out PH.

Echocardiography: TTE allows estimation of pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) via measurement of tricuspid regurgitation jet velocity and estimation of right atrial pressure. Although results of TTE do correlate with measurements from right heart catheterization (RHC), underestimation and overestimation commonly occur. PASP thresholds for diagnosing or ruling out PH cannot thus be defined easily. An elevated PASP less than 36 mmHg, tricuspid regurgitation velocity <2.8 m/s, and no additional echocardiographic variables suggestive of PH may indicate that PH is unlikely, based on arbitrary criteria from one clinical practice guideline.16

The guideline suggested that tricuspid regurgitation velocity >3.4 m/s or estimated PASP >50 mmHg indicated that PH was likely. Other echocardiographic variables that may suggest the presence of PH include right ventricular enlargement or intraventricular septal flattening. Finally, TTE should also be used to assess for possible causes of PH, such as left heart disease or cardiac shunts.

Further evaluation: Following identification of PH via TTE, further testing can confirm the diagnosis, determine the etiology of the PH, and allow appropriate treatment (see Table 2). Much of this evaluation may occur after hospital discharge and, in cases of unexplained PH, referral to a pulmonologist for further evaluation and management is appropriate. Depending on patient stability, test availability, and patient ability to follow up, some testing may be reasonable during the inpatient stay.

Patients should undergo a stepwise series of testing that initially may be guided by clinical suspicion for underlying conditions.15-19 Polysomnography can identify sleep-disordered breathing, and pulmonary function tests and high-resolution chest CT can assess for chronic pulmonary diseases. Patients with groups 2 and 3 PH, whose PH can be explained by left heart disease or lung disease, do not necessarily require RHC or extensive evaluation for other etiologies of PH.2,17 These patients may be monitored while their underlying conditions are managed.

Patients with worsening clinical course or PH that is “out of proportion” to their lung disease or heart disease, however, do require further evaluation, including RHC. “Out of proportion” has not been consistently defined but generally refers to severe PH observed in patients with mild left heart or lung disease.18 More precise terminology and criteria to define patients with out of proportion PH have been proposed.14

Ventilation-perfusion scanning is required in all cases of PH of unknown etiology to evaluate for CTEPH (Group 4 PH). CT angiography, while appropriate to use in testing for acute pulmonary embolism, is not sufficiently sensitive to evaluate for CTEPH. Tests for liver function, HIV, and connective tissue disease may identify conditions associated with Group 1 PH. Ultimately, RHC is required to confirm the diagnosis of PH, given the shortcomings of TTE. A vasodilator study during RHC allows identification of candidates for advanced therapies, such as patients with Group 1 PH.

Management

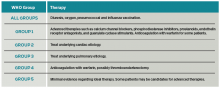

The prognosis and treatment of PH varies by WHO Group. The hospitalist will often undertake initial management of symptomatic patients (see Table 3). Intravenous loop diuretics will successfully treat peripheral edema and hepatic congestion in all PH patients.20 Due to the possibility of decreased cardiac output or worsened hypotension in some PH groups, patients should be monitored closely during initial diuresis.

All patients with PH should be assessed for hypoxia during rest, ambulation, and sleep during their hospitalization. Supplemental oxygen therapy should be initiated in all patients with evidence of persistent hypoxia (arterial oxygen blood pressure <60 mmHg).20 Vaccination against pneumococcus and influenza should also be performed during the initial hospitalization. Pregnant patients diagnosed with PH require urgent maternal-fetal medicine consultation.

Further management should be guided by the underlying etiology of the PH:17,18

- Group 1 PH. These patients should be evaluated by a pulmonology consultant, if one is available, as they require intense outpatient follow-up with a pulmonologist. Specialized treatment regimens include calcium channel blockers, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, prostanoids, endothelin receptor antagonists, or newly approved guanylate cyclase stimulants. In previously diagnosed patients, these medications should be continued during a patient’s admission unless the medication is clearly causing the patient harm (such as worsening hypotension) or preventing improvement. Many of these patients are placed on chronic anticoagulation with warfarin, with a goal international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.5 to 2.5.

- Group 2 PH. Patients with left heart or valvular dysfunction and PH have a worse prognosis than similar patients without PH. Management of these patients should focus on treating the underlying etiology. Use of prostanoids may be harmful in this patient population.18

- Group 3 PH. Patients whose PH is fully explained by pulmonary disease should be started on continuous oxygen therapy to treat persistent hypoxemia, and their underlying disorder should be treated, with pulmonologist consultation and referral if necessary.

- Group 4 PH. Patients with newly diagnosed CTEPH should be initiated on warfarin with a goal INR of 2.0 to 3.0. They should undergo evaluation by a pulmonologist for thromboendarterectomy and possibly advanced medical therapies.

- Group 5 PH. Patients with sarcoidosis as the cause of their PH may benefit from prostanoid or endothelin receptor antagonist therapy and should undergo evaluation by a pulmonologist.21,22

Patients with sickle cell anemia, metabolic disorders, and other causes should undergo further subspecialist evaluation prior to initiating therapy to treat their PH.

Back to the Case

The patient underwent diuresis with intravenous furosemide over several days, with gradual improvement in her lower extremity edema and dyspnea. She was placed on oxygen therapy for persistent hypoxemia. As her highly elevated pulmonary artery pressure appeared to be “out of proportion” to her mild left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, further evaluation was pursued. Ventilation-perfusion scanning was performed and showed no mismatch of perfusion and ventilation, effectively ruling out CTEPH. Liver function, HIV, and connective tissue disease testing yielded unremarkable results.

The patient was euvolemic after one week of diuresis and was discharged home with plans for PH specialist follow-up, polysomnography to evaluate for sleep-disordered breathing, and likely RHC. The etiology of her PH was not clear at discharge.

Bottom Line

Evaluation of PH is a step-wise process that starts with history and physical exam and may require extensive evaluation, including right heart catheterization to confirm the diagnosis and define the etiology. A primary goal of evaluation is to define the appropriate therapy for a given patient, which may include advanced therapies in some cases.

Dr. Griffith is a quality improvement fellow and instructor of medicine in the Hospital Medicine Division at the University of Colorado Denver. Drs. McFarland and Smolkin are hospitalists and instructors of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver.

References

- von Romberg E. Über sklerose der lungenarterie. Dtsch Arch Klin Med. 1891;48:197-206.

- Hoeper MM, Bogaard HJ, Condliffe R, et al. Definitions and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D42-D50.

- Simonneau G, Gatzoulis MA, Adatia I, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D34-D41.

- Rich S, Rubin L, Abenhail L, et al. Executive summary from the World Symposium on primary pulmonary hypertension. Evian, France: The World Health Organization; 1998.

- Newman JH, Wheeler L, Lane KB, et al. Mutation in the gene for bone morphogenetic protein receptor II as a cause of primary pulmonary hypertension in a large kindred. New Engl J Med. 2001;345(5):319-24.'

- Petitpretz P, Brenot F, Azarian R, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Comparison with primary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 1994;89(6):2722-2727.

- Gladwin MT, Vichinsky E. Pulmonary complications of sickle cell disease. New Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2254-2265.

- Wigley FM, Lima JA, Mayes M, McLain D, Chapin JL, Ward-Able C. The prevalence of undiagnosed pulmonary arterial hypertension in subjects with connective tissue disease at the secondary health care level of community-based rheumatologists (the UNCOVER study). Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(7):2125-2132.

- Ramsay MA, Simpson BR, Nguyen AT, Ramsay KJ, East C, Klintmalm GB. Severe pulmonary hypertension in liver transplant candidates. Liver Transpl Surg. 1997;3(5):494-500.

- Kessler R, Faller M, Weitzenblum E, et al. “Natural history” of pulmonary hypertension in a series of 131 patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(2):219-24.

- Chaouat A, Bugnet AS, Kadaoui N, et al. Severe pulmonary hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(2):189-94.

- Thabut G, Dauriat G, Stern JB, et al. Pulmonary hemodynamics in advanced COPD candidates for lung volume reduction surgery or lung transplantation. Chest. 2005;127(5):1531-1536.

- Yamakawa H, Shiomi T, Sasanabe R, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;56(3):311-312.

- Vachiery JL, Adir Y, Barberà JA, et al. Pulmonary hypertension due to left heart diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D100-D108.

- McGoon M, Gutterman D, Steen V, et al. Screening, early detection, and diagnosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2004;126(1 Suppl):14S-34S.

- Grünig E, Barner A, Bell M, et al. Non-invasive diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension: ESC/ERS Guidelines with Updated Commentary of the Cologne Consensus Conference 2011. Int J Cardiol. 2011;154 Suppl 1:S3-12.

- Galiè N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), endorsed by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J. 2009;30(20):2493-2537.

- McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association: developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, Inc., and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. Circulation. 2009;119(16):2250-2294.

- Brown K, Gutierrez AJ, Mohammed TL, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria(R) pulmonary hypertension. J Thorac Imaging. 2013;28(4):W57-60.

- Galiè N, Corris PA, Frost A, et al. Updated treatment algorithm of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D60-72.

- Fisher KA, Serlin DM, Wilson KC, Walter RE, Berman JS, Farber HW. Sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension: outcome with long-term epoprostenol treatment. Chest. 2006;130(5):1481-1488.

- Steiner MK, Preston IR, Klinger JR, et al. Conversion to bosentan from prostacyclin infusion therapy in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a pilot study. Chest. 2006;130(5):1471-1480.

Case

A 62-year-old female with no significant past medical history presents with three weeks of progressive dyspnea on exertion and bilateral lower extremity edema. Family members report that the patient often snores and “gasps for air” during sleep. B-type natriuretic peptide is elevated at 2,261 pg/ml. Due to concern for congestive heart failure, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is performed and shows normal left ventricular systolic function, mild left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, severely elevated right ventricular systolic pressure of 74 mm Hg, and right ventricular dilatation and hypokinesis.

How should this patient with newfound pulmonary hypertension (PH) be evaluated and managed?

Background

PH is a progressive disease that presents with nonspecific signs and symptoms and can be fatal if untreated. Ernst von Romberg first identified the disease in 1891, and efforts have been made through the last century to understand its etiology and mechanisms.1

PH is defined as an elevated mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) of ≥25 mmHg at rest; a mPAP of ≤20 mmHg is considered normal, and a mPAP of 21-24 mmHg is borderline.2 This elevation of the mPAP can be due to a primary elevation of pressures in the pulmonary arterial system alone (pulmonary arterial hypertension) or secondary to elevation in pressures in the pulmonary venous and pulmonary capillary systems (pulmonary venous hypertension).

PH classification has endured many modifications through the years with better understanding of its pathophysiology. Currently, the World Health Organization (WHO) classification system includes five groups based on etiology (see Table 1):3,4

- Group 1: Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH);

- Group 2: PH due to left heart disease;

- Group 3: PH due to chronic lung disease and hypoxemia;

- Group 4: Chronic thromboembolic PH (CTEPH); and

- Group 5: PH due to unclear multifactorial mechanisms.

The pathophysiology differs among the groups, and much of what is known has come from studies performed in patients with idiopathic PAH. It is a proliferative vasculopathy characterized by vasoconstriction, cell proliferation, fibrosis, and thrombosis. Both genetic predisposition and modifiers that include drugs and toxins, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), congenital heart disease with left-to-right shunting, and potassium channel dysfunction play a role in the pathogenesis.3,5,6 Although many processes underlying the pathophysiology of PH groups 2, 3, 4, and 5 are not fully understood, vascular remodeling and increased vascular resistance are common to all of them.

PH affects both genders and all age groups and races. Due to its broad classification and multiple etiologies, it is difficult to assess PH prevalence in the general population. There are wide ranges among different populations, with PH prevalence in sickle cell disease ranging from 20% to 40%, in systemic sclerosis from 10% to 15%, and in portal hypertension from 2% to 16%.7,8,9 PH in COPD is usually mild to moderate, with preserved cardiac output, although a minority of patients develop severe PH.10-12 PH is present in approximately 20% of patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea.13 The prevalence of PH in left heart disease is unknown due to variability in populations assessed and methods used in various studies; estimates have ranged from 25-100%.14

Evaluation

Initial evaluation: A thorough history and physical examination can help determine PH etiology, identify associated conditions, and determine the severity of disease. Dyspnea on exertion is the most common presenting complaint; weakness, fatigue, and angina may be present.15 Lower extremity edema and ascites are indicative of more advanced disease.

A patient’s symptoms may suggest the presence of undiagnosed conditions that are associated with PH, and past medical history should evaluate for previous diagnoses of these conditions (see Table 1).

Family history may reveal relatives with PH, given the genetic predisposition to development of Group 1 PH. Physical exam findings include a prominent pulmonic valve closure during the second heart sound, a palpable left parasternal heave, and a tricuspid regurgitation murmur.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) and chest X-ray (CXR) are not sufficiently sensitive or specific to diagnose PH but may provide initial supporting evidence that prompts further testing. Signs of right ventricular hypertrophy and right atrial enlargement may be present on ECG. The CXR may show pruning (prominent hilar vasculature with reduced vasculature peripherally) and right ventricular hypertrophy, as evidenced by shrinking of the retrosternal window on lateral CXR. An unremarkable ECG or normal CXR does not rule out PH.

Echocardiography: TTE allows estimation of pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) via measurement of tricuspid regurgitation jet velocity and estimation of right atrial pressure. Although results of TTE do correlate with measurements from right heart catheterization (RHC), underestimation and overestimation commonly occur. PASP thresholds for diagnosing or ruling out PH cannot thus be defined easily. An elevated PASP less than 36 mmHg, tricuspid regurgitation velocity <2.8 m/s, and no additional echocardiographic variables suggestive of PH may indicate that PH is unlikely, based on arbitrary criteria from one clinical practice guideline.16

The guideline suggested that tricuspid regurgitation velocity >3.4 m/s or estimated PASP >50 mmHg indicated that PH was likely. Other echocardiographic variables that may suggest the presence of PH include right ventricular enlargement or intraventricular septal flattening. Finally, TTE should also be used to assess for possible causes of PH, such as left heart disease or cardiac shunts.

Further evaluation: Following identification of PH via TTE, further testing can confirm the diagnosis, determine the etiology of the PH, and allow appropriate treatment (see Table 2). Much of this evaluation may occur after hospital discharge and, in cases of unexplained PH, referral to a pulmonologist for further evaluation and management is appropriate. Depending on patient stability, test availability, and patient ability to follow up, some testing may be reasonable during the inpatient stay.

Patients should undergo a stepwise series of testing that initially may be guided by clinical suspicion for underlying conditions.15-19 Polysomnography can identify sleep-disordered breathing, and pulmonary function tests and high-resolution chest CT can assess for chronic pulmonary diseases. Patients with groups 2 and 3 PH, whose PH can be explained by left heart disease or lung disease, do not necessarily require RHC or extensive evaluation for other etiologies of PH.2,17 These patients may be monitored while their underlying conditions are managed.

Patients with worsening clinical course or PH that is “out of proportion” to their lung disease or heart disease, however, do require further evaluation, including RHC. “Out of proportion” has not been consistently defined but generally refers to severe PH observed in patients with mild left heart or lung disease.18 More precise terminology and criteria to define patients with out of proportion PH have been proposed.14

Ventilation-perfusion scanning is required in all cases of PH of unknown etiology to evaluate for CTEPH (Group 4 PH). CT angiography, while appropriate to use in testing for acute pulmonary embolism, is not sufficiently sensitive to evaluate for CTEPH. Tests for liver function, HIV, and connective tissue disease may identify conditions associated with Group 1 PH. Ultimately, RHC is required to confirm the diagnosis of PH, given the shortcomings of TTE. A vasodilator study during RHC allows identification of candidates for advanced therapies, such as patients with Group 1 PH.

Management

The prognosis and treatment of PH varies by WHO Group. The hospitalist will often undertake initial management of symptomatic patients (see Table 3). Intravenous loop diuretics will successfully treat peripheral edema and hepatic congestion in all PH patients.20 Due to the possibility of decreased cardiac output or worsened hypotension in some PH groups, patients should be monitored closely during initial diuresis.

All patients with PH should be assessed for hypoxia during rest, ambulation, and sleep during their hospitalization. Supplemental oxygen therapy should be initiated in all patients with evidence of persistent hypoxia (arterial oxygen blood pressure <60 mmHg).20 Vaccination against pneumococcus and influenza should also be performed during the initial hospitalization. Pregnant patients diagnosed with PH require urgent maternal-fetal medicine consultation.

Further management should be guided by the underlying etiology of the PH:17,18

- Group 1 PH. These patients should be evaluated by a pulmonology consultant, if one is available, as they require intense outpatient follow-up with a pulmonologist. Specialized treatment regimens include calcium channel blockers, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, prostanoids, endothelin receptor antagonists, or newly approved guanylate cyclase stimulants. In previously diagnosed patients, these medications should be continued during a patient’s admission unless the medication is clearly causing the patient harm (such as worsening hypotension) or preventing improvement. Many of these patients are placed on chronic anticoagulation with warfarin, with a goal international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.5 to 2.5.

- Group 2 PH. Patients with left heart or valvular dysfunction and PH have a worse prognosis than similar patients without PH. Management of these patients should focus on treating the underlying etiology. Use of prostanoids may be harmful in this patient population.18

- Group 3 PH. Patients whose PH is fully explained by pulmonary disease should be started on continuous oxygen therapy to treat persistent hypoxemia, and their underlying disorder should be treated, with pulmonologist consultation and referral if necessary.

- Group 4 PH. Patients with newly diagnosed CTEPH should be initiated on warfarin with a goal INR of 2.0 to 3.0. They should undergo evaluation by a pulmonologist for thromboendarterectomy and possibly advanced medical therapies.

- Group 5 PH. Patients with sarcoidosis as the cause of their PH may benefit from prostanoid or endothelin receptor antagonist therapy and should undergo evaluation by a pulmonologist.21,22

Patients with sickle cell anemia, metabolic disorders, and other causes should undergo further subspecialist evaluation prior to initiating therapy to treat their PH.

Back to the Case

The patient underwent diuresis with intravenous furosemide over several days, with gradual improvement in her lower extremity edema and dyspnea. She was placed on oxygen therapy for persistent hypoxemia. As her highly elevated pulmonary artery pressure appeared to be “out of proportion” to her mild left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, further evaluation was pursued. Ventilation-perfusion scanning was performed and showed no mismatch of perfusion and ventilation, effectively ruling out CTEPH. Liver function, HIV, and connective tissue disease testing yielded unremarkable results.

The patient was euvolemic after one week of diuresis and was discharged home with plans for PH specialist follow-up, polysomnography to evaluate for sleep-disordered breathing, and likely RHC. The etiology of her PH was not clear at discharge.

Bottom Line

Evaluation of PH is a step-wise process that starts with history and physical exam and may require extensive evaluation, including right heart catheterization to confirm the diagnosis and define the etiology. A primary goal of evaluation is to define the appropriate therapy for a given patient, which may include advanced therapies in some cases.

Dr. Griffith is a quality improvement fellow and instructor of medicine in the Hospital Medicine Division at the University of Colorado Denver. Drs. McFarland and Smolkin are hospitalists and instructors of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver.

References

- von Romberg E. Über sklerose der lungenarterie. Dtsch Arch Klin Med. 1891;48:197-206.

- Hoeper MM, Bogaard HJ, Condliffe R, et al. Definitions and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D42-D50.

- Simonneau G, Gatzoulis MA, Adatia I, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D34-D41.

- Rich S, Rubin L, Abenhail L, et al. Executive summary from the World Symposium on primary pulmonary hypertension. Evian, France: The World Health Organization; 1998.

- Newman JH, Wheeler L, Lane KB, et al. Mutation in the gene for bone morphogenetic protein receptor II as a cause of primary pulmonary hypertension in a large kindred. New Engl J Med. 2001;345(5):319-24.'

- Petitpretz P, Brenot F, Azarian R, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Comparison with primary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 1994;89(6):2722-2727.

- Gladwin MT, Vichinsky E. Pulmonary complications of sickle cell disease. New Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2254-2265.

- Wigley FM, Lima JA, Mayes M, McLain D, Chapin JL, Ward-Able C. The prevalence of undiagnosed pulmonary arterial hypertension in subjects with connective tissue disease at the secondary health care level of community-based rheumatologists (the UNCOVER study). Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(7):2125-2132.

- Ramsay MA, Simpson BR, Nguyen AT, Ramsay KJ, East C, Klintmalm GB. Severe pulmonary hypertension in liver transplant candidates. Liver Transpl Surg. 1997;3(5):494-500.

- Kessler R, Faller M, Weitzenblum E, et al. “Natural history” of pulmonary hypertension in a series of 131 patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(2):219-24.

- Chaouat A, Bugnet AS, Kadaoui N, et al. Severe pulmonary hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(2):189-94.

- Thabut G, Dauriat G, Stern JB, et al. Pulmonary hemodynamics in advanced COPD candidates for lung volume reduction surgery or lung transplantation. Chest. 2005;127(5):1531-1536.

- Yamakawa H, Shiomi T, Sasanabe R, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;56(3):311-312.

- Vachiery JL, Adir Y, Barberà JA, et al. Pulmonary hypertension due to left heart diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D100-D108.

- McGoon M, Gutterman D, Steen V, et al. Screening, early detection, and diagnosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2004;126(1 Suppl):14S-34S.

- Grünig E, Barner A, Bell M, et al. Non-invasive diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension: ESC/ERS Guidelines with Updated Commentary of the Cologne Consensus Conference 2011. Int J Cardiol. 2011;154 Suppl 1:S3-12.

- Galiè N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), endorsed by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J. 2009;30(20):2493-2537.

- McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association: developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, Inc., and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. Circulation. 2009;119(16):2250-2294.

- Brown K, Gutierrez AJ, Mohammed TL, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria(R) pulmonary hypertension. J Thorac Imaging. 2013;28(4):W57-60.

- Galiè N, Corris PA, Frost A, et al. Updated treatment algorithm of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D60-72.

- Fisher KA, Serlin DM, Wilson KC, Walter RE, Berman JS, Farber HW. Sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension: outcome with long-term epoprostenol treatment. Chest. 2006;130(5):1481-1488.

- Steiner MK, Preston IR, Klinger JR, et al. Conversion to bosentan from prostacyclin infusion therapy in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a pilot study. Chest. 2006;130(5):1471-1480.

Case

A 62-year-old female with no significant past medical history presents with three weeks of progressive dyspnea on exertion and bilateral lower extremity edema. Family members report that the patient often snores and “gasps for air” during sleep. B-type natriuretic peptide is elevated at 2,261 pg/ml. Due to concern for congestive heart failure, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is performed and shows normal left ventricular systolic function, mild left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, severely elevated right ventricular systolic pressure of 74 mm Hg, and right ventricular dilatation and hypokinesis.

How should this patient with newfound pulmonary hypertension (PH) be evaluated and managed?

Background

PH is a progressive disease that presents with nonspecific signs and symptoms and can be fatal if untreated. Ernst von Romberg first identified the disease in 1891, and efforts have been made through the last century to understand its etiology and mechanisms.1

PH is defined as an elevated mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) of ≥25 mmHg at rest; a mPAP of ≤20 mmHg is considered normal, and a mPAP of 21-24 mmHg is borderline.2 This elevation of the mPAP can be due to a primary elevation of pressures in the pulmonary arterial system alone (pulmonary arterial hypertension) or secondary to elevation in pressures in the pulmonary venous and pulmonary capillary systems (pulmonary venous hypertension).

PH classification has endured many modifications through the years with better understanding of its pathophysiology. Currently, the World Health Organization (WHO) classification system includes five groups based on etiology (see Table 1):3,4

- Group 1: Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH);

- Group 2: PH due to left heart disease;

- Group 3: PH due to chronic lung disease and hypoxemia;

- Group 4: Chronic thromboembolic PH (CTEPH); and

- Group 5: PH due to unclear multifactorial mechanisms.

The pathophysiology differs among the groups, and much of what is known has come from studies performed in patients with idiopathic PAH. It is a proliferative vasculopathy characterized by vasoconstriction, cell proliferation, fibrosis, and thrombosis. Both genetic predisposition and modifiers that include drugs and toxins, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), congenital heart disease with left-to-right shunting, and potassium channel dysfunction play a role in the pathogenesis.3,5,6 Although many processes underlying the pathophysiology of PH groups 2, 3, 4, and 5 are not fully understood, vascular remodeling and increased vascular resistance are common to all of them.

PH affects both genders and all age groups and races. Due to its broad classification and multiple etiologies, it is difficult to assess PH prevalence in the general population. There are wide ranges among different populations, with PH prevalence in sickle cell disease ranging from 20% to 40%, in systemic sclerosis from 10% to 15%, and in portal hypertension from 2% to 16%.7,8,9 PH in COPD is usually mild to moderate, with preserved cardiac output, although a minority of patients develop severe PH.10-12 PH is present in approximately 20% of patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea.13 The prevalence of PH in left heart disease is unknown due to variability in populations assessed and methods used in various studies; estimates have ranged from 25-100%.14

Evaluation

Initial evaluation: A thorough history and physical examination can help determine PH etiology, identify associated conditions, and determine the severity of disease. Dyspnea on exertion is the most common presenting complaint; weakness, fatigue, and angina may be present.15 Lower extremity edema and ascites are indicative of more advanced disease.

A patient’s symptoms may suggest the presence of undiagnosed conditions that are associated with PH, and past medical history should evaluate for previous diagnoses of these conditions (see Table 1).

Family history may reveal relatives with PH, given the genetic predisposition to development of Group 1 PH. Physical exam findings include a prominent pulmonic valve closure during the second heart sound, a palpable left parasternal heave, and a tricuspid regurgitation murmur.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) and chest X-ray (CXR) are not sufficiently sensitive or specific to diagnose PH but may provide initial supporting evidence that prompts further testing. Signs of right ventricular hypertrophy and right atrial enlargement may be present on ECG. The CXR may show pruning (prominent hilar vasculature with reduced vasculature peripherally) and right ventricular hypertrophy, as evidenced by shrinking of the retrosternal window on lateral CXR. An unremarkable ECG or normal CXR does not rule out PH.

Echocardiography: TTE allows estimation of pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) via measurement of tricuspid regurgitation jet velocity and estimation of right atrial pressure. Although results of TTE do correlate with measurements from right heart catheterization (RHC), underestimation and overestimation commonly occur. PASP thresholds for diagnosing or ruling out PH cannot thus be defined easily. An elevated PASP less than 36 mmHg, tricuspid regurgitation velocity <2.8 m/s, and no additional echocardiographic variables suggestive of PH may indicate that PH is unlikely, based on arbitrary criteria from one clinical practice guideline.16

The guideline suggested that tricuspid regurgitation velocity >3.4 m/s or estimated PASP >50 mmHg indicated that PH was likely. Other echocardiographic variables that may suggest the presence of PH include right ventricular enlargement or intraventricular septal flattening. Finally, TTE should also be used to assess for possible causes of PH, such as left heart disease or cardiac shunts.

Further evaluation: Following identification of PH via TTE, further testing can confirm the diagnosis, determine the etiology of the PH, and allow appropriate treatment (see Table 2). Much of this evaluation may occur after hospital discharge and, in cases of unexplained PH, referral to a pulmonologist for further evaluation and management is appropriate. Depending on patient stability, test availability, and patient ability to follow up, some testing may be reasonable during the inpatient stay.

Patients should undergo a stepwise series of testing that initially may be guided by clinical suspicion for underlying conditions.15-19 Polysomnography can identify sleep-disordered breathing, and pulmonary function tests and high-resolution chest CT can assess for chronic pulmonary diseases. Patients with groups 2 and 3 PH, whose PH can be explained by left heart disease or lung disease, do not necessarily require RHC or extensive evaluation for other etiologies of PH.2,17 These patients may be monitored while their underlying conditions are managed.

Patients with worsening clinical course or PH that is “out of proportion” to their lung disease or heart disease, however, do require further evaluation, including RHC. “Out of proportion” has not been consistently defined but generally refers to severe PH observed in patients with mild left heart or lung disease.18 More precise terminology and criteria to define patients with out of proportion PH have been proposed.14

Ventilation-perfusion scanning is required in all cases of PH of unknown etiology to evaluate for CTEPH (Group 4 PH). CT angiography, while appropriate to use in testing for acute pulmonary embolism, is not sufficiently sensitive to evaluate for CTEPH. Tests for liver function, HIV, and connective tissue disease may identify conditions associated with Group 1 PH. Ultimately, RHC is required to confirm the diagnosis of PH, given the shortcomings of TTE. A vasodilator study during RHC allows identification of candidates for advanced therapies, such as patients with Group 1 PH.

Management

The prognosis and treatment of PH varies by WHO Group. The hospitalist will often undertake initial management of symptomatic patients (see Table 3). Intravenous loop diuretics will successfully treat peripheral edema and hepatic congestion in all PH patients.20 Due to the possibility of decreased cardiac output or worsened hypotension in some PH groups, patients should be monitored closely during initial diuresis.

All patients with PH should be assessed for hypoxia during rest, ambulation, and sleep during their hospitalization. Supplemental oxygen therapy should be initiated in all patients with evidence of persistent hypoxia (arterial oxygen blood pressure <60 mmHg).20 Vaccination against pneumococcus and influenza should also be performed during the initial hospitalization. Pregnant patients diagnosed with PH require urgent maternal-fetal medicine consultation.

Further management should be guided by the underlying etiology of the PH:17,18

- Group 1 PH. These patients should be evaluated by a pulmonology consultant, if one is available, as they require intense outpatient follow-up with a pulmonologist. Specialized treatment regimens include calcium channel blockers, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, prostanoids, endothelin receptor antagonists, or newly approved guanylate cyclase stimulants. In previously diagnosed patients, these medications should be continued during a patient’s admission unless the medication is clearly causing the patient harm (such as worsening hypotension) or preventing improvement. Many of these patients are placed on chronic anticoagulation with warfarin, with a goal international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.5 to 2.5.

- Group 2 PH. Patients with left heart or valvular dysfunction and PH have a worse prognosis than similar patients without PH. Management of these patients should focus on treating the underlying etiology. Use of prostanoids may be harmful in this patient population.18

- Group 3 PH. Patients whose PH is fully explained by pulmonary disease should be started on continuous oxygen therapy to treat persistent hypoxemia, and their underlying disorder should be treated, with pulmonologist consultation and referral if necessary.

- Group 4 PH. Patients with newly diagnosed CTEPH should be initiated on warfarin with a goal INR of 2.0 to 3.0. They should undergo evaluation by a pulmonologist for thromboendarterectomy and possibly advanced medical therapies.

- Group 5 PH. Patients with sarcoidosis as the cause of their PH may benefit from prostanoid or endothelin receptor antagonist therapy and should undergo evaluation by a pulmonologist.21,22

Patients with sickle cell anemia, metabolic disorders, and other causes should undergo further subspecialist evaluation prior to initiating therapy to treat their PH.

Back to the Case

The patient underwent diuresis with intravenous furosemide over several days, with gradual improvement in her lower extremity edema and dyspnea. She was placed on oxygen therapy for persistent hypoxemia. As her highly elevated pulmonary artery pressure appeared to be “out of proportion” to her mild left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, further evaluation was pursued. Ventilation-perfusion scanning was performed and showed no mismatch of perfusion and ventilation, effectively ruling out CTEPH. Liver function, HIV, and connective tissue disease testing yielded unremarkable results.

The patient was euvolemic after one week of diuresis and was discharged home with plans for PH specialist follow-up, polysomnography to evaluate for sleep-disordered breathing, and likely RHC. The etiology of her PH was not clear at discharge.

Bottom Line

Evaluation of PH is a step-wise process that starts with history and physical exam and may require extensive evaluation, including right heart catheterization to confirm the diagnosis and define the etiology. A primary goal of evaluation is to define the appropriate therapy for a given patient, which may include advanced therapies in some cases.

Dr. Griffith is a quality improvement fellow and instructor of medicine in the Hospital Medicine Division at the University of Colorado Denver. Drs. McFarland and Smolkin are hospitalists and instructors of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver.

References

- von Romberg E. Über sklerose der lungenarterie. Dtsch Arch Klin Med. 1891;48:197-206.

- Hoeper MM, Bogaard HJ, Condliffe R, et al. Definitions and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D42-D50.

- Simonneau G, Gatzoulis MA, Adatia I, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D34-D41.

- Rich S, Rubin L, Abenhail L, et al. Executive summary from the World Symposium on primary pulmonary hypertension. Evian, France: The World Health Organization; 1998.

- Newman JH, Wheeler L, Lane KB, et al. Mutation in the gene for bone morphogenetic protein receptor II as a cause of primary pulmonary hypertension in a large kindred. New Engl J Med. 2001;345(5):319-24.'

- Petitpretz P, Brenot F, Azarian R, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Comparison with primary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 1994;89(6):2722-2727.

- Gladwin MT, Vichinsky E. Pulmonary complications of sickle cell disease. New Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2254-2265.

- Wigley FM, Lima JA, Mayes M, McLain D, Chapin JL, Ward-Able C. The prevalence of undiagnosed pulmonary arterial hypertension in subjects with connective tissue disease at the secondary health care level of community-based rheumatologists (the UNCOVER study). Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(7):2125-2132.

- Ramsay MA, Simpson BR, Nguyen AT, Ramsay KJ, East C, Klintmalm GB. Severe pulmonary hypertension in liver transplant candidates. Liver Transpl Surg. 1997;3(5):494-500.

- Kessler R, Faller M, Weitzenblum E, et al. “Natural history” of pulmonary hypertension in a series of 131 patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(2):219-24.

- Chaouat A, Bugnet AS, Kadaoui N, et al. Severe pulmonary hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(2):189-94.

- Thabut G, Dauriat G, Stern JB, et al. Pulmonary hemodynamics in advanced COPD candidates for lung volume reduction surgery or lung transplantation. Chest. 2005;127(5):1531-1536.

- Yamakawa H, Shiomi T, Sasanabe R, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;56(3):311-312.

- Vachiery JL, Adir Y, Barberà JA, et al. Pulmonary hypertension due to left heart diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D100-D108.

- McGoon M, Gutterman D, Steen V, et al. Screening, early detection, and diagnosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2004;126(1 Suppl):14S-34S.

- Grünig E, Barner A, Bell M, et al. Non-invasive diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension: ESC/ERS Guidelines with Updated Commentary of the Cologne Consensus Conference 2011. Int J Cardiol. 2011;154 Suppl 1:S3-12.

- Galiè N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), endorsed by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J. 2009;30(20):2493-2537.

- McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association: developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, Inc., and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. Circulation. 2009;119(16):2250-2294.

- Brown K, Gutierrez AJ, Mohammed TL, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria(R) pulmonary hypertension. J Thorac Imaging. 2013;28(4):W57-60.

- Galiè N, Corris PA, Frost A, et al. Updated treatment algorithm of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D60-72.

- Fisher KA, Serlin DM, Wilson KC, Walter RE, Berman JS, Farber HW. Sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension: outcome with long-term epoprostenol treatment. Chest. 2006;130(5):1481-1488.

- Steiner MK, Preston IR, Klinger JR, et al. Conversion to bosentan from prostacyclin infusion therapy in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a pilot study. Chest. 2006;130(5):1471-1480.

Your postop patient is confused and agitated—next steps?

› Conduct a baseline cognitive assessment during your patient’s routine visits and preoperative assessments to gauge his or her risk for delirium. A

› Work with the hospital team to implement nonpharmacologic interventions, such as reorienting the patient to day and time and avoiding sensory deprivation, as an initial treatment for delirium. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Your patient, Mark Q, age 80, is admitted to the hospital to undergo hemicolectomy for colon cancer. His medical history includes hypertension, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and colon cancer. He did well immediately postop, but when you make morning rounds the day after his surgery, you notice that he is confused and agitated. Mr. Q’s chart reveals that earlier that morning, he pulled out his Foley catheter and intravenous (IV) line when his nurse declined his request to walk him to the bathroom.

How would you proceed?

Up to 50% of older adults who undergo surgical procedures develop delirium—a disturbance in attention and awareness accompanied by changes in cognition.1 Older adults are at heightened risk for this postoperative complication for several reasons. For one thing, older patients have a reduced capacity for homeostatic regulation when they undergo anesthesia and surgery.2 For another, age-related changes in brain neurochemistry and drug metabolism increase the likelihood of adverse drug effects, including those that could precipitate delirirum.3

Although postop delirium is a common complication in older patients, it sometimes goes unrecognized. Missed or delayed diagnosis of delirium can result in patients exhibiting behaviors that can compromise their safety, delay recuperation, and result in longer hospital stays, a greater financial burden, and increased morbidity and mortality.4 The American Geriatric Society recently published clinical guidelines and a best practices statement for preventing and treating postop delirium in patients ages >65 years.1,5 This article describes steps family physicians can take to assess their patients’ risk of delirium before they undergo surgery, and to recognize and treat delirium in the postop period.

Defining delirium

According to the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5), the criteria for delirium are:6

A. A disturbance in attention (ie, reduced ability to direct, focus, sustain, and shift attention) and awareness (reduced orientation to the environment).

B. The disturbance develops over a short time (usually hours to a few days), represents a change from baseline attention and awareness, and tends to fluctuate in severity during the course of a day.

C. An additional disturbance in cognition (eg, memory deficits, disorientation, language, visuospatial ability, perception).

D. The disturbances in attention, awareness, and cognition aren’t better explained by another preexisting or evolving neurocognitive disorder and don’t occur in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal.

E. History, physical, or laboratory findings show that the disturbance is caused by the direct physiologic consequences of a general medical condition, substance intoxication/withdrawal, exposure to a toxin, or multiple etiologies.

The 3 subtypes of delirium are based on patients’ psychomotor activity.7 In hyperactive delirium, patients exhibit heightened arousal, restlessness, agitation, hallucinations, and inappropriate behavior. Hypoactive delirium is characterized by lethargy, reduced motor activity, incoherent speech, and lack of interest. Mixed delirium consists of a combination of hyperactive and hypoactive signs and symptoms.

Gauge risk before patients undergo surgery

Family physicians can assess their patients’ risk for developing delirium by conducting baseline screening during routine office visits as well as during preoperative evaluations. Factors that increase postop delirium risk include:1

• age >65 years

• dementia

• poor vision

• decreased hearing

• severe illness

• infection.

Routine cognitive screening can be done easily and efficiently using readily available tools such as the Alzheimer Association’s Cognitive Assessment Toolkit.8 This toolkit includes 3 brief, validated screening tools to identify patients with probable cognitive impairment: the General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition, the Memory Impairment Screen, and the Mini-Cog.

If preop screening indicates that the patient is at increased risk for delirium, the family physician should work with hospital’s interdisciplinary teams to institute prevention measures, such as the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP).9 This program offers a structured curriculum for instructing volunteers to deliver daily orientation, early mobilization, feeding assistance, therapeutic activities, and other measures to help prevent delirium.

Prompt screening after surgery is essential, too

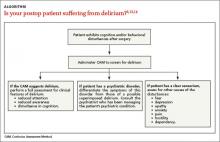

In addition to preop delirium risk assessment, all patients who undergo surgery should receive daily delirium screening during the first postoperative week. The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) is a quick screening tool for assessing a patient’s level of arousal and consciousness.10 Based on the results of 7 high-quality studies (N=1071), CAM has a sensitivity of 94% (95% confidence interval [CI], 91%-97%) and specificity of 89% (95% CI, 85%-94%).11,12

Feature 1 of CAM, “Acute onset and fluctuating course,” requires that you compare the patient’s current mental status to his or her pre-hospital baseline mental status; the baseline status should be obtained from a family member, caretaker, or clinician who has observed the patient over time.10 This is intended to determine if the patient has experienced an acute change in mental status (eg, attention, orientation, cognition), usually over the course of hours to days.10 Feature 2, “Inattention,” is used to determine if the patient has a reduced ability to maintain attention to external stimuli and to appropriately shift attention to new external stimuli, and if the patient is unaware or out of touch with the environment.10 Feature 3, “Disorganized thinking,” is used to assess the patient’s organization of thought as expressed by speech or writing. Disorganized thinking typically manifests as rambling and irrelevant or incoherent speech.10 Feature 4, “Altered level of consciousness,” is used to rate the patient’s alertness level.10

A positive screen for delirium requires the presence of Feature 1 (acute onset and/or fluctuation) and Feature 2, plus either Feature 3 or Feature 4.

Is delirium—or something else—at work?

If an older adult is exhibiting cognitive and/or behavioral disturbances after undergoing surgery, it’s important to discern if these manifestations are the result of delirium, a preexisting psychiatric disorder, or some other cause if the patient has a clear sensorium (ALGORITHM).6,13,14

Delirium. If a patient’s CAM screen suggests delirium, conduct a thorough assessment for the signs and symptoms of delirium to determine if the patient meets DSM-5 criteria for the diagnosis.1 In order to avoid missing hypoactive, subtle, or atypical cases of delirium, conduct a thorough medical record and medications review, and gather assessments from the nursing staff and other team members regarding the patient’s behavior.

Preexisting psychiatric disorder. It’s important to differentiate psychiatric symptoms from those of a superimposed delirium.13 Because patients with preoperative depressive symptoms may be at increased risk for postop delirium, pre-surgical psychiatric evaluations are important for identifying even subtle psychopathological symptoms.15 (The psychiatric interview is the gold standard for diagnosis.16) For patients who have an established psychiatric diagnosis, consider consulting with the psychiatrist who is managing the patient’s psychiatric care.13

Other causes. If a patient who is exhibiting postop cognitive and/or behavioral disturbances has a reasonably accurate memory and a correct orientation for time, place, and person, interviews with the patient and caregivers (along with the psychiatric interview) will likely reveal potential causes for the behavioral problems.13

Is the patient suffering from dehydration? Drug withdrawal?

Assessment for an underlying organic cause must be performed because specific treatment for the underlying diagnosis may improve delirium.17 Common causes include hypoxia, infection, dehydration, acute metabolic disturbance, endocrinopathies, cardiac or vascular disorders, and drug withdrawal.13 An appropriate diagnostic work-up might consist of serum urea, glucose, electrolytes, liver function tests, arterial blood gas analyses, urinalysis, nutritional evaluation, electrocardiogram, and a complete blood count.

Ask patients about their use of alcohol and benzodiazepines, and consider alcohol or drug withdrawal as potential etiologies.18 Patients with delirium should also be assessed for iatrogenic hospital-related factors that could be causing or contributing to the condition, such as immobilization or malnutrition.13

Medications are a common culprit: Approximately 40% of cases of delirium are related to medication use.18 Commonly used postop medications such as analgesics, sedatives, proton pump inhibitors, and others can cause delirium.19 Carefully review the patient’s medication list.13 Medication-induced delirium is influenced by the number of medications taken (generally >3),20 the use of psychoactive medications,21 and the specific agent's anticholinergic potential.22 The 2012 updated Beers Criteria (American Geriatrics Society) is a useful resource for determining if “inappropriate polypharmacy” is the cause of postop delirium.23

Inadequate pain control. In a multisite trial,24 patients who received <10 mg/d of parenteral morphine sulfate equivalents were more likely to develop delirium than patients who received more analgesia. In cognitively intact patients, severe pain significantly increased the risk of delirium. With the exception of meperidine, opioids do not precipitate delirium in patients with acute pain.24 Not treating pain or administering very low—or excessively high—doses of opioids is associated with an increased risk of delirium for both cognitively intact and impaired patients.24

Constipation can contribute to the development of delirium.25 After surgery, patients tend to be less mobile and may be receiving medications that can cause constipation, such as opioids, iron, calcium, and channel blockers. Preventing and treating constipation in postop patients can reduce delirium risk.25

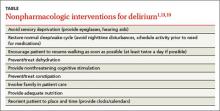

Begin treatment with nonpharmacologic measures

Regardless of whether a patient suffers from hyperactive, hypoactive, or mixed delirium, nonpharmacologic interventions are firstline treatment.19 Such interventions can help patients develop a sense of control over their environment, which can help relieve agitation.13 Because environmental shifts contribute to the development of delirium, avoiding transfers and securing a single room can be helpful.19 Patients with delirium have altered perceptions, and may view normal objects and routine clinician actions as harmful and threatening. Therefore, it is helpful to avoid sensory deprivation by making sure patients have access to their eyeglasses and hearing aids, and to provide nonthreatening cognitive/environmental stimulation.1,13,19 Patients should be encouraged to resume walking as soon as possible.1,19 Other nonpharmacologic interventions are listed in the TABLE.1,13,19

Safety issues must also be addressed.17 Patients with mixed or hyperactive delirium may become agitated, which can lead them to pull tubes, drains, or lines, as occurred with Mr. Q. Patients with hypoactive delirium may be prone to wandering, or receive less attention due to their hypoactive state.17 All patients with delirium are at risk of falls.

Patients should be evaluated for these risks to determine whether assigning a "sitter" or transfer to a stepdown unit or intensive care unit is warranted.17 Restraints are not recommended because they can exacerbate delirium and lead to injuries.26