User login

Product Update: LILETTA, myHDL, KleenSpec, STEPS Forward

NEW, SMALL IUD NOW AVAILABLE

LILETTA™ (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system) 52 mg is now available for use by women to prevent pregnancy for up to 3 years. LILETTA is a small, flexible plastic T-shaped system 32 mm x 32 mm in size. It works to prevent pregnancy by slowly releasing levonorgestrel (LNG), a progestin, at an initial release rate of 18.6 µg/day with an average in vivo release rate of LNG of approximately 15.6 µg/day over a period of 3 years. Generally, LILETTA can be inserted at any time if the provider is reasonably certain that the woman is not pregnant. While LILETTA is intended for use up to 3 years, according to a press release from Actavis, it can be removed by a clinician at any time and can be replaced at the time of removal with a new LILETTA if continued contraceptive protection is desired.

The February 2015 FDA approval of LILETTA was based on the largest hormonal IUD trial conducted in the United States, designed to reflect the US population, says the manufacturer. The IUD was studied in women aged 16 to 45 years who were nulliparous or parous with a BMI of 15.8 kg/m2 to 61.6 kg/m2.

Through a partnership between Actavis and Medicines360 described at www.liletta.com, IUD-appropriate women, regardless of income and insurance coverage, now have access to this IUD at their doctor’s offices and at public health clinics enrolled in the 340B Drug Pricing Program.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.liletta.com

MYHDL APP ON APPLE WATCH, iPAD, iPHONE

The myHDL Physician App from Health Diagnostic Laboratory, Inc. (HDL) is newly available on the Apple Watch, iPhone, and iPad. The app is designed to allow users to view and manage patient cases from their wrist on all models of Apple Watch. HDL says that the myHDL app helps clinicians offer effective, personalized care to their patients, and features include the ability to manage multiple patients’ results, ease of use through color coding and categorized test results, and security and privacy. HDL provides comprehensive biomarker testing and clinical health consulting for earlier disease detection and targeted disease management. The myHDL app is available on iTunes App Store and can be downloaded at www.myhdlapp.com.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.hdlabinc.com

SINGLE-USE LED SPECULA IN 3 SIZES

Welch Allyn, Inc. recently launched the KleenSpec® Single Use LED Vaginal Specula intended for use in hospital emergency departments, labor and delivery units, urgent care centers, ambulatory care surgery centers, clinics, and other women’s health treatment centers.

Welch Allyn says that the KleenSpec Single Use LED Vaginal Specula are 100% acrylic and designed with smooth, molded edges to deliver maximum patient comfort. Wide handles are meant to provide comfortable ergonomics, ease of use, and good balance. According to Welch Allyn, the cordless device’s LED light source provides enhanced visualization of the examination area by supplying uniform white light for more than 30 minutes. The sealed LED light source and Lithium-primary battery are placed in the handle to reduce patient risk. The LED and battery can be removed for disposal or recycling. The device is ready to use out of the package and has a 5-year shelf life. The KleenSpec Single Use LED Vaginal Specula are available in extra small, small, and medium sizes in a distinctive color scheme to help clinicians identify various sizes.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.welchallyn.com

AMA’S PRACTICE TRANSFORMATION SERIES

AMA STEPS Forward™ is an online, interactive practice transformation series offering innovative strategies to help physicians and their staff refocus their practice. The American Medical Association (AMA) developed this initiative after a recent AMA-RAND report found that the satisfaction physicians derive from their work is eroding as they spend more and more time on administrative tasks. The AMA’s goal by offering STEPS Forward is to help clinicians achieve the “Quadruple Aim” to provide better patient experiences, better population health, lower overall costs, and improved professional satisfaction.

Physicians can access a collection of interactive educational modules to help deal with common practice challenges and also earn CME credit. Currently, 16 modules include steps for implementation, case studies, and downloadable videos, tools, and resources that address: practice efficiency and patient care, patient health, physician health, and technology and innovation. Additional modules are planned.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.stepsforward.org

NEW, SMALL IUD NOW AVAILABLE

LILETTA™ (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system) 52 mg is now available for use by women to prevent pregnancy for up to 3 years. LILETTA is a small, flexible plastic T-shaped system 32 mm x 32 mm in size. It works to prevent pregnancy by slowly releasing levonorgestrel (LNG), a progestin, at an initial release rate of 18.6 µg/day with an average in vivo release rate of LNG of approximately 15.6 µg/day over a period of 3 years. Generally, LILETTA can be inserted at any time if the provider is reasonably certain that the woman is not pregnant. While LILETTA is intended for use up to 3 years, according to a press release from Actavis, it can be removed by a clinician at any time and can be replaced at the time of removal with a new LILETTA if continued contraceptive protection is desired.

The February 2015 FDA approval of LILETTA was based on the largest hormonal IUD trial conducted in the United States, designed to reflect the US population, says the manufacturer. The IUD was studied in women aged 16 to 45 years who were nulliparous or parous with a BMI of 15.8 kg/m2 to 61.6 kg/m2.

Through a partnership between Actavis and Medicines360 described at www.liletta.com, IUD-appropriate women, regardless of income and insurance coverage, now have access to this IUD at their doctor’s offices and at public health clinics enrolled in the 340B Drug Pricing Program.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.liletta.com

MYHDL APP ON APPLE WATCH, iPAD, iPHONE

The myHDL Physician App from Health Diagnostic Laboratory, Inc. (HDL) is newly available on the Apple Watch, iPhone, and iPad. The app is designed to allow users to view and manage patient cases from their wrist on all models of Apple Watch. HDL says that the myHDL app helps clinicians offer effective, personalized care to their patients, and features include the ability to manage multiple patients’ results, ease of use through color coding and categorized test results, and security and privacy. HDL provides comprehensive biomarker testing and clinical health consulting for earlier disease detection and targeted disease management. The myHDL app is available on iTunes App Store and can be downloaded at www.myhdlapp.com.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.hdlabinc.com

SINGLE-USE LED SPECULA IN 3 SIZES

Welch Allyn, Inc. recently launched the KleenSpec® Single Use LED Vaginal Specula intended for use in hospital emergency departments, labor and delivery units, urgent care centers, ambulatory care surgery centers, clinics, and other women’s health treatment centers.

Welch Allyn says that the KleenSpec Single Use LED Vaginal Specula are 100% acrylic and designed with smooth, molded edges to deliver maximum patient comfort. Wide handles are meant to provide comfortable ergonomics, ease of use, and good balance. According to Welch Allyn, the cordless device’s LED light source provides enhanced visualization of the examination area by supplying uniform white light for more than 30 minutes. The sealed LED light source and Lithium-primary battery are placed in the handle to reduce patient risk. The LED and battery can be removed for disposal or recycling. The device is ready to use out of the package and has a 5-year shelf life. The KleenSpec Single Use LED Vaginal Specula are available in extra small, small, and medium sizes in a distinctive color scheme to help clinicians identify various sizes.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.welchallyn.com

AMA’S PRACTICE TRANSFORMATION SERIES

AMA STEPS Forward™ is an online, interactive practice transformation series offering innovative strategies to help physicians and their staff refocus their practice. The American Medical Association (AMA) developed this initiative after a recent AMA-RAND report found that the satisfaction physicians derive from their work is eroding as they spend more and more time on administrative tasks. The AMA’s goal by offering STEPS Forward is to help clinicians achieve the “Quadruple Aim” to provide better patient experiences, better population health, lower overall costs, and improved professional satisfaction.

Physicians can access a collection of interactive educational modules to help deal with common practice challenges and also earn CME credit. Currently, 16 modules include steps for implementation, case studies, and downloadable videos, tools, and resources that address: practice efficiency and patient care, patient health, physician health, and technology and innovation. Additional modules are planned.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.stepsforward.org

NEW, SMALL IUD NOW AVAILABLE

LILETTA™ (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system) 52 mg is now available for use by women to prevent pregnancy for up to 3 years. LILETTA is a small, flexible plastic T-shaped system 32 mm x 32 mm in size. It works to prevent pregnancy by slowly releasing levonorgestrel (LNG), a progestin, at an initial release rate of 18.6 µg/day with an average in vivo release rate of LNG of approximately 15.6 µg/day over a period of 3 years. Generally, LILETTA can be inserted at any time if the provider is reasonably certain that the woman is not pregnant. While LILETTA is intended for use up to 3 years, according to a press release from Actavis, it can be removed by a clinician at any time and can be replaced at the time of removal with a new LILETTA if continued contraceptive protection is desired.

The February 2015 FDA approval of LILETTA was based on the largest hormonal IUD trial conducted in the United States, designed to reflect the US population, says the manufacturer. The IUD was studied in women aged 16 to 45 years who were nulliparous or parous with a BMI of 15.8 kg/m2 to 61.6 kg/m2.

Through a partnership between Actavis and Medicines360 described at www.liletta.com, IUD-appropriate women, regardless of income and insurance coverage, now have access to this IUD at their doctor’s offices and at public health clinics enrolled in the 340B Drug Pricing Program.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.liletta.com

MYHDL APP ON APPLE WATCH, iPAD, iPHONE

The myHDL Physician App from Health Diagnostic Laboratory, Inc. (HDL) is newly available on the Apple Watch, iPhone, and iPad. The app is designed to allow users to view and manage patient cases from their wrist on all models of Apple Watch. HDL says that the myHDL app helps clinicians offer effective, personalized care to their patients, and features include the ability to manage multiple patients’ results, ease of use through color coding and categorized test results, and security and privacy. HDL provides comprehensive biomarker testing and clinical health consulting for earlier disease detection and targeted disease management. The myHDL app is available on iTunes App Store and can be downloaded at www.myhdlapp.com.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.hdlabinc.com

SINGLE-USE LED SPECULA IN 3 SIZES

Welch Allyn, Inc. recently launched the KleenSpec® Single Use LED Vaginal Specula intended for use in hospital emergency departments, labor and delivery units, urgent care centers, ambulatory care surgery centers, clinics, and other women’s health treatment centers.

Welch Allyn says that the KleenSpec Single Use LED Vaginal Specula are 100% acrylic and designed with smooth, molded edges to deliver maximum patient comfort. Wide handles are meant to provide comfortable ergonomics, ease of use, and good balance. According to Welch Allyn, the cordless device’s LED light source provides enhanced visualization of the examination area by supplying uniform white light for more than 30 minutes. The sealed LED light source and Lithium-primary battery are placed in the handle to reduce patient risk. The LED and battery can be removed for disposal or recycling. The device is ready to use out of the package and has a 5-year shelf life. The KleenSpec Single Use LED Vaginal Specula are available in extra small, small, and medium sizes in a distinctive color scheme to help clinicians identify various sizes.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.welchallyn.com

AMA’S PRACTICE TRANSFORMATION SERIES

AMA STEPS Forward™ is an online, interactive practice transformation series offering innovative strategies to help physicians and their staff refocus their practice. The American Medical Association (AMA) developed this initiative after a recent AMA-RAND report found that the satisfaction physicians derive from their work is eroding as they spend more and more time on administrative tasks. The AMA’s goal by offering STEPS Forward is to help clinicians achieve the “Quadruple Aim” to provide better patient experiences, better population health, lower overall costs, and improved professional satisfaction.

Physicians can access a collection of interactive educational modules to help deal with common practice challenges and also earn CME credit. Currently, 16 modules include steps for implementation, case studies, and downloadable videos, tools, and resources that address: practice efficiency and patient care, patient health, physician health, and technology and innovation. Additional modules are planned.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.stepsforward.org

Merck Manuals end print publication, go all digital

Pharmaceutical manufacturer Merck & Co. is ceasing print publication of the Merck Manuals, a popular series of reference books, but the long-running publication will continue on in all-digital format starting this month.

The company first published the original Merck Manual for doctors in 1898 and has updated the manual 18 times, most recently in 2011. The new all-digital edition, which includes separate pages on medical conditions for patients and health care providers, will be available online at no charge, and no registration is required to view the new content.

“Merck will no longer publish the Merck Manuals, at least not on paper,” explained Editor-in-Chief Robert S. Porter. “We are continually updating our content and publishing it online as soon as it is ready, so we make no distinction among ‘editions.’ Our sole distinction is audience.”

Find the newly published reference books here: http://www.merckmanuals.com/.

Pharmaceutical manufacturer Merck & Co. is ceasing print publication of the Merck Manuals, a popular series of reference books, but the long-running publication will continue on in all-digital format starting this month.

The company first published the original Merck Manual for doctors in 1898 and has updated the manual 18 times, most recently in 2011. The new all-digital edition, which includes separate pages on medical conditions for patients and health care providers, will be available online at no charge, and no registration is required to view the new content.

“Merck will no longer publish the Merck Manuals, at least not on paper,” explained Editor-in-Chief Robert S. Porter. “We are continually updating our content and publishing it online as soon as it is ready, so we make no distinction among ‘editions.’ Our sole distinction is audience.”

Find the newly published reference books here: http://www.merckmanuals.com/.

Pharmaceutical manufacturer Merck & Co. is ceasing print publication of the Merck Manuals, a popular series of reference books, but the long-running publication will continue on in all-digital format starting this month.

The company first published the original Merck Manual for doctors in 1898 and has updated the manual 18 times, most recently in 2011. The new all-digital edition, which includes separate pages on medical conditions for patients and health care providers, will be available online at no charge, and no registration is required to view the new content.

“Merck will no longer publish the Merck Manuals, at least not on paper,” explained Editor-in-Chief Robert S. Porter. “We are continually updating our content and publishing it online as soon as it is ready, so we make no distinction among ‘editions.’ Our sole distinction is audience.”

Find the newly published reference books here: http://www.merckmanuals.com/.

Auto accidents in sleepy medical trainees

Question: Driving home after a demanding 24 hours on call, the sleepy and fatigued first-year medical resident momentarily dozed off at the wheel, ran a stop sign, and struck an oncoming car, injuring its driver. In a lawsuit by the injured victim, which of the following answers is best?

A. The residency program is definitely liable, being in violation of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education rules on consecutive work hours.

B. The resident is solely liable, because he’s the one who owed the duty of due care.

C. The hospital may be a named codefendant, because it knew or should have known that sleep deprivation can impair a person’s driving ability.

D. A and C are correct.

E. Only B and C are correct.

Answer: E. Residency training programs face many potential liabilities, such as those arising from disciplinary actions, employer-employee disputes, sexual harassment, and so on. But one issue deserving attention is auto accidents in overfatigued trainees. The incidence of falling asleep at the wheel is very high – in some surveys, close to 50% – and accidents are more likely to occur in the immediate post-call period.

The two main research papers documenting a relationship between extended work duty and auto accidents are from Laura K. Barger, Ph.D., and Dr. Colin P. West.

In the Barger study, the authors conducted a nationwide Web-based survey of 2,737 interns (N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:125-34). They found that an extended work shift (greater than 24 hours) was 2.3 times as likely for a motor vehicle crash, and 5.9 times for a near-miss accident. The researchers calculated that every extended shift in the month increased the crash risk by 9.1% and near-miss risk by 16.2%.

In the West study, the authors performed a prospective, 5-year longitudinal study of a cohort of 340 first-year Mayo Clinic residents in internal medicine (Mayo Clin. Proc. 2012;87:1138-44). In self-generated quarterly filings, 11.3% reported a motor vehicle crash and 43.3% a near-miss accident. Sleepiness (as well as other variables such as depression, burnout, diminished quality of life, and fatigue) significantly increased the odds of a motor vehicle incident in the subsequent 3-month period. Each 1-point increase in fatigue or Epworth Sleepiness Scale score was associated with a 52% and 12% respective increase in a motor vehicle crash.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has formulated rules, which have undergone recent changes, regarding consecutive work-duty hours. Its latest edict in June 2014 can be found on its website and stipulates that “Duty periods of PGY-1 residents must not exceed 16 hours in duration,” and “Duty periods of PGY-2 residents and above may be scheduled to a maximum of 24 hours of continuous duty in the hospital.”

Furthermore, programs must encourage residents to use alertness management strategies in the context of patient care responsibilities. Strategic napping, especially after 16 hours of continuous duty and between the hours of 10:00 p.m. and 8:00 a.m., was a strong suggestion.

In a 2005 lawsuit naming Chicago’s Rush Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center as a defendant, an Illinois court faced the issue of whether a hospital owed a duty to a plaintiff injured by an off-duty resident doctor allegedly suffering from sleep deprivation as a result of a hospital’s policy on working hours (Brewster v. Rush Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center (836 N.E.2d 635 (Il. App. 2005)). The doctor was an intern who had worked 34 hours of a 36-hour work shift, and fell asleep behind the wheel of her car, striking and seriously injuring the driver of an oncoming car.

In its decision, the court noted the plaintiff’s argument that it was reasonably foreseeable and likely that drivers who were sleep deprived would cause traffic accidents resulting in injuries. For public policy reasons, the plaintiff also maintained that such injuries could be prevented if hospitals either changed work schedules of their residents or provided them with additional rest periods.

However, the court held that there was no liability imputed to health care providers for injuries to nonpatient third parties absent the existence of a “special relationship” between the parties.

Thus, training programs or hospitals may or may not be found liable in future such cases or in other jurisdictions – but the new, stricter ACGME rules suggest that they will, at a minimum, be a named defendant.

Note that in some jurisdictions, injured nonpatient third parties have successfully sued doctors for failing to warn their patients that certain medications can adversely affect their driving ability, and for failing to warn about medical conditions, e.g., syncope, that can adversely impact driving.

Court decisions in analogous factual circumstances have sometimes favored the accident victim.

In Robertson v. LeMaster (301 S.E.2d 563 (W. Va. 1983)), the West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals noted that the defendant’s employer, Norfolk & Western Railway Company, “could have reasonably foreseen that its exhausted employee, who had been required to work 27 hours without rest, would pose a risk of harm to other motorists.”

In Faverty v. McDonald’s Restaurants of Oregon (892 P.2d 703 (Ore. Ct. App.1995)), an Oregon appeals court held that the defendant corporation (McDonald’s Restaurants of Oregon) knew or should have known that its employee was a hazard to himself and others when he drove home from the workplace after working multiple shifts in a 24-hour period.

On the other hand, in Barclay v. Briscoe (47 A.3d 560 (Md. 2012)), a longshoreman employed by Ports America Baltimore fell asleep at the wheel while traveling home after working a 22-hour shift and caused a head-on collision resulting in catastrophic injuries. Ports America Baltimore contended that it could not be held primarily liable, because it owed no duty to the public to ensure that an employee was fit to drive his personal vehicle home. The trial court agreed, and the Maryland Court of Appeals affirmed.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, and currently directs the St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, “Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk,” and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, “Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct.” For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: Driving home after a demanding 24 hours on call, the sleepy and fatigued first-year medical resident momentarily dozed off at the wheel, ran a stop sign, and struck an oncoming car, injuring its driver. In a lawsuit by the injured victim, which of the following answers is best?

A. The residency program is definitely liable, being in violation of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education rules on consecutive work hours.

B. The resident is solely liable, because he’s the one who owed the duty of due care.

C. The hospital may be a named codefendant, because it knew or should have known that sleep deprivation can impair a person’s driving ability.

D. A and C are correct.

E. Only B and C are correct.

Answer: E. Residency training programs face many potential liabilities, such as those arising from disciplinary actions, employer-employee disputes, sexual harassment, and so on. But one issue deserving attention is auto accidents in overfatigued trainees. The incidence of falling asleep at the wheel is very high – in some surveys, close to 50% – and accidents are more likely to occur in the immediate post-call period.

The two main research papers documenting a relationship between extended work duty and auto accidents are from Laura K. Barger, Ph.D., and Dr. Colin P. West.

In the Barger study, the authors conducted a nationwide Web-based survey of 2,737 interns (N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:125-34). They found that an extended work shift (greater than 24 hours) was 2.3 times as likely for a motor vehicle crash, and 5.9 times for a near-miss accident. The researchers calculated that every extended shift in the month increased the crash risk by 9.1% and near-miss risk by 16.2%.

In the West study, the authors performed a prospective, 5-year longitudinal study of a cohort of 340 first-year Mayo Clinic residents in internal medicine (Mayo Clin. Proc. 2012;87:1138-44). In self-generated quarterly filings, 11.3% reported a motor vehicle crash and 43.3% a near-miss accident. Sleepiness (as well as other variables such as depression, burnout, diminished quality of life, and fatigue) significantly increased the odds of a motor vehicle incident in the subsequent 3-month period. Each 1-point increase in fatigue or Epworth Sleepiness Scale score was associated with a 52% and 12% respective increase in a motor vehicle crash.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has formulated rules, which have undergone recent changes, regarding consecutive work-duty hours. Its latest edict in June 2014 can be found on its website and stipulates that “Duty periods of PGY-1 residents must not exceed 16 hours in duration,” and “Duty periods of PGY-2 residents and above may be scheduled to a maximum of 24 hours of continuous duty in the hospital.”

Furthermore, programs must encourage residents to use alertness management strategies in the context of patient care responsibilities. Strategic napping, especially after 16 hours of continuous duty and between the hours of 10:00 p.m. and 8:00 a.m., was a strong suggestion.

In a 2005 lawsuit naming Chicago’s Rush Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center as a defendant, an Illinois court faced the issue of whether a hospital owed a duty to a plaintiff injured by an off-duty resident doctor allegedly suffering from sleep deprivation as a result of a hospital’s policy on working hours (Brewster v. Rush Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center (836 N.E.2d 635 (Il. App. 2005)). The doctor was an intern who had worked 34 hours of a 36-hour work shift, and fell asleep behind the wheel of her car, striking and seriously injuring the driver of an oncoming car.

In its decision, the court noted the plaintiff’s argument that it was reasonably foreseeable and likely that drivers who were sleep deprived would cause traffic accidents resulting in injuries. For public policy reasons, the plaintiff also maintained that such injuries could be prevented if hospitals either changed work schedules of their residents or provided them with additional rest periods.

However, the court held that there was no liability imputed to health care providers for injuries to nonpatient third parties absent the existence of a “special relationship” between the parties.

Thus, training programs or hospitals may or may not be found liable in future such cases or in other jurisdictions – but the new, stricter ACGME rules suggest that they will, at a minimum, be a named defendant.

Note that in some jurisdictions, injured nonpatient third parties have successfully sued doctors for failing to warn their patients that certain medications can adversely affect their driving ability, and for failing to warn about medical conditions, e.g., syncope, that can adversely impact driving.

Court decisions in analogous factual circumstances have sometimes favored the accident victim.

In Robertson v. LeMaster (301 S.E.2d 563 (W. Va. 1983)), the West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals noted that the defendant’s employer, Norfolk & Western Railway Company, “could have reasonably foreseen that its exhausted employee, who had been required to work 27 hours without rest, would pose a risk of harm to other motorists.”

In Faverty v. McDonald’s Restaurants of Oregon (892 P.2d 703 (Ore. Ct. App.1995)), an Oregon appeals court held that the defendant corporation (McDonald’s Restaurants of Oregon) knew or should have known that its employee was a hazard to himself and others when he drove home from the workplace after working multiple shifts in a 24-hour period.

On the other hand, in Barclay v. Briscoe (47 A.3d 560 (Md. 2012)), a longshoreman employed by Ports America Baltimore fell asleep at the wheel while traveling home after working a 22-hour shift and caused a head-on collision resulting in catastrophic injuries. Ports America Baltimore contended that it could not be held primarily liable, because it owed no duty to the public to ensure that an employee was fit to drive his personal vehicle home. The trial court agreed, and the Maryland Court of Appeals affirmed.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, and currently directs the St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, “Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk,” and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, “Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct.” For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: Driving home after a demanding 24 hours on call, the sleepy and fatigued first-year medical resident momentarily dozed off at the wheel, ran a stop sign, and struck an oncoming car, injuring its driver. In a lawsuit by the injured victim, which of the following answers is best?

A. The residency program is definitely liable, being in violation of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education rules on consecutive work hours.

B. The resident is solely liable, because he’s the one who owed the duty of due care.

C. The hospital may be a named codefendant, because it knew or should have known that sleep deprivation can impair a person’s driving ability.

D. A and C are correct.

E. Only B and C are correct.

Answer: E. Residency training programs face many potential liabilities, such as those arising from disciplinary actions, employer-employee disputes, sexual harassment, and so on. But one issue deserving attention is auto accidents in overfatigued trainees. The incidence of falling asleep at the wheel is very high – in some surveys, close to 50% – and accidents are more likely to occur in the immediate post-call period.

The two main research papers documenting a relationship between extended work duty and auto accidents are from Laura K. Barger, Ph.D., and Dr. Colin P. West.

In the Barger study, the authors conducted a nationwide Web-based survey of 2,737 interns (N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:125-34). They found that an extended work shift (greater than 24 hours) was 2.3 times as likely for a motor vehicle crash, and 5.9 times for a near-miss accident. The researchers calculated that every extended shift in the month increased the crash risk by 9.1% and near-miss risk by 16.2%.

In the West study, the authors performed a prospective, 5-year longitudinal study of a cohort of 340 first-year Mayo Clinic residents in internal medicine (Mayo Clin. Proc. 2012;87:1138-44). In self-generated quarterly filings, 11.3% reported a motor vehicle crash and 43.3% a near-miss accident. Sleepiness (as well as other variables such as depression, burnout, diminished quality of life, and fatigue) significantly increased the odds of a motor vehicle incident in the subsequent 3-month period. Each 1-point increase in fatigue or Epworth Sleepiness Scale score was associated with a 52% and 12% respective increase in a motor vehicle crash.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has formulated rules, which have undergone recent changes, regarding consecutive work-duty hours. Its latest edict in June 2014 can be found on its website and stipulates that “Duty periods of PGY-1 residents must not exceed 16 hours in duration,” and “Duty periods of PGY-2 residents and above may be scheduled to a maximum of 24 hours of continuous duty in the hospital.”

Furthermore, programs must encourage residents to use alertness management strategies in the context of patient care responsibilities. Strategic napping, especially after 16 hours of continuous duty and between the hours of 10:00 p.m. and 8:00 a.m., was a strong suggestion.

In a 2005 lawsuit naming Chicago’s Rush Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center as a defendant, an Illinois court faced the issue of whether a hospital owed a duty to a plaintiff injured by an off-duty resident doctor allegedly suffering from sleep deprivation as a result of a hospital’s policy on working hours (Brewster v. Rush Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center (836 N.E.2d 635 (Il. App. 2005)). The doctor was an intern who had worked 34 hours of a 36-hour work shift, and fell asleep behind the wheel of her car, striking and seriously injuring the driver of an oncoming car.

In its decision, the court noted the plaintiff’s argument that it was reasonably foreseeable and likely that drivers who were sleep deprived would cause traffic accidents resulting in injuries. For public policy reasons, the plaintiff also maintained that such injuries could be prevented if hospitals either changed work schedules of their residents or provided them with additional rest periods.

However, the court held that there was no liability imputed to health care providers for injuries to nonpatient third parties absent the existence of a “special relationship” between the parties.

Thus, training programs or hospitals may or may not be found liable in future such cases or in other jurisdictions – but the new, stricter ACGME rules suggest that they will, at a minimum, be a named defendant.

Note that in some jurisdictions, injured nonpatient third parties have successfully sued doctors for failing to warn their patients that certain medications can adversely affect their driving ability, and for failing to warn about medical conditions, e.g., syncope, that can adversely impact driving.

Court decisions in analogous factual circumstances have sometimes favored the accident victim.

In Robertson v. LeMaster (301 S.E.2d 563 (W. Va. 1983)), the West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals noted that the defendant’s employer, Norfolk & Western Railway Company, “could have reasonably foreseen that its exhausted employee, who had been required to work 27 hours without rest, would pose a risk of harm to other motorists.”

In Faverty v. McDonald’s Restaurants of Oregon (892 P.2d 703 (Ore. Ct. App.1995)), an Oregon appeals court held that the defendant corporation (McDonald’s Restaurants of Oregon) knew or should have known that its employee was a hazard to himself and others when he drove home from the workplace after working multiple shifts in a 24-hour period.

On the other hand, in Barclay v. Briscoe (47 A.3d 560 (Md. 2012)), a longshoreman employed by Ports America Baltimore fell asleep at the wheel while traveling home after working a 22-hour shift and caused a head-on collision resulting in catastrophic injuries. Ports America Baltimore contended that it could not be held primarily liable, because it owed no duty to the public to ensure that an employee was fit to drive his personal vehicle home. The trial court agreed, and the Maryland Court of Appeals affirmed.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, and currently directs the St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, “Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk,” and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, “Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct.” For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Study establishes protocol for perioperative dabigatran discontinuation

TORONTO – In atrial fibrillation (AF) patients who must discontinue dabigatran for elective surgery, the risk of both stroke and major bleeding can be reduced to low levels using a formalized strategy for stopping and then restarting anticoagulation, according to results of a prospective study presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis Congress.

Among key findings presented at a press conference at the ISTH 2015 Congress, no strokes were recorded in more than 500 patients managed with the protocol, and the major bleeding rate was less than 2%, reported the study’s principal investigator, Dr. Sam Schulman, professor of hematology and thromboembolism, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

Data from this study (Circulation 2015) were reported at the press conference alongside a second study of perioperative warfarin management. Both studies are potentially practice changing, because they supply evidence-based guidance for anticoagulation in patients with AF.

Based on the findings from these two studies, “it is important to get this message out” that there are now data available on which to base clinical decisions, reported Dr. Schulman, who is also president of the ISTH 2015 Congress. His data were presented alongside a study that found no benefit from heparin bridging in AF patients when warfarin was stopped 5 days in advance of surgery.

In the study presented by Dr. Schulman, 542 patients with AF who were on dabigatran and scheduled for elective surgery were managed on a prespecified protocol for risk assessment. The protocol provided a time for stopping dabigatran before surgery based on such factors as renal function and procedure-related bleeding risk. Dabigatran was restarted after surgery on prespecified measures of surgery complexity and severity of consequences if bleeding occurred.

The primary outcome evaluated in the study was major bleeding in the first 30 days. Other outcomes of interest included thromboembolic complications, death and minor bleeding.

Major bleeding was observed in 1.8% of patients, a rate that Dr. Schulman characterized as “low and acceptable” in the context of expected background bleeding rates. There were four deaths, but all were unrelated to either bleeding or arterial thromboembolism. The only thromboembolic complication was a single transient ischemic attack. Minor bleeding occurred in 5.2%.

On the basis of the protocol, about half of the patients discontinued dabigatran 24 hours before surgery. No patient discontinued therapy more than 96 hours prior to surgery. The median time to resumption of dabigatran after surgery was 1 day, but the point at which it was restarted ranged between hours and 2 days. Bridging, which describes the injection of heparin for short-term anticoagulation, was not employed preoperatively but was used in 1.7% of cases postoperatively.

At the press conference, data also were reported from the BRIDGE study. That study, published online in the New England Journal of Medicine (2015 June 22; epub ahead of print ), found that bridging was not an effective strategy in AF patients who discontinue warfarin prior to elective surgery. In the press conference, Dr. Thomas L. Ortel, hematology/oncology division, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., agreed with Dr. Schulman that this is an area where evidence is needed to guide care.

In the absence of data, “physicians do whatever they think is best,” Dr. Schulman noted at the press conference. Referring to strategies for stopping anticoagulants for surgery in patients with AF, Dr. Schulman said, “some of them stop the blood thinner too early because they are afraid that the patient is going to bleed during surgery and instead the patient can have a stroke. Some stop too late, and the patient can have bleeding.”

The data presented at the meeting provide an evidence base for clinical decisions. Dr. Schulman suggested that these data are meaningful for guiding care.

Dr. Ortel disclosed grant/research support from Eisai and Pfizer. Dr. Schulman had no disclosures.

TORONTO – In atrial fibrillation (AF) patients who must discontinue dabigatran for elective surgery, the risk of both stroke and major bleeding can be reduced to low levels using a formalized strategy for stopping and then restarting anticoagulation, according to results of a prospective study presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis Congress.

Among key findings presented at a press conference at the ISTH 2015 Congress, no strokes were recorded in more than 500 patients managed with the protocol, and the major bleeding rate was less than 2%, reported the study’s principal investigator, Dr. Sam Schulman, professor of hematology and thromboembolism, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

Data from this study (Circulation 2015) were reported at the press conference alongside a second study of perioperative warfarin management. Both studies are potentially practice changing, because they supply evidence-based guidance for anticoagulation in patients with AF.

Based on the findings from these two studies, “it is important to get this message out” that there are now data available on which to base clinical decisions, reported Dr. Schulman, who is also president of the ISTH 2015 Congress. His data were presented alongside a study that found no benefit from heparin bridging in AF patients when warfarin was stopped 5 days in advance of surgery.

In the study presented by Dr. Schulman, 542 patients with AF who were on dabigatran and scheduled for elective surgery were managed on a prespecified protocol for risk assessment. The protocol provided a time for stopping dabigatran before surgery based on such factors as renal function and procedure-related bleeding risk. Dabigatran was restarted after surgery on prespecified measures of surgery complexity and severity of consequences if bleeding occurred.

The primary outcome evaluated in the study was major bleeding in the first 30 days. Other outcomes of interest included thromboembolic complications, death and minor bleeding.

Major bleeding was observed in 1.8% of patients, a rate that Dr. Schulman characterized as “low and acceptable” in the context of expected background bleeding rates. There were four deaths, but all were unrelated to either bleeding or arterial thromboembolism. The only thromboembolic complication was a single transient ischemic attack. Minor bleeding occurred in 5.2%.

On the basis of the protocol, about half of the patients discontinued dabigatran 24 hours before surgery. No patient discontinued therapy more than 96 hours prior to surgery. The median time to resumption of dabigatran after surgery was 1 day, but the point at which it was restarted ranged between hours and 2 days. Bridging, which describes the injection of heparin for short-term anticoagulation, was not employed preoperatively but was used in 1.7% of cases postoperatively.

At the press conference, data also were reported from the BRIDGE study. That study, published online in the New England Journal of Medicine (2015 June 22; epub ahead of print ), found that bridging was not an effective strategy in AF patients who discontinue warfarin prior to elective surgery. In the press conference, Dr. Thomas L. Ortel, hematology/oncology division, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., agreed with Dr. Schulman that this is an area where evidence is needed to guide care.

In the absence of data, “physicians do whatever they think is best,” Dr. Schulman noted at the press conference. Referring to strategies for stopping anticoagulants for surgery in patients with AF, Dr. Schulman said, “some of them stop the blood thinner too early because they are afraid that the patient is going to bleed during surgery and instead the patient can have a stroke. Some stop too late, and the patient can have bleeding.”

The data presented at the meeting provide an evidence base for clinical decisions. Dr. Schulman suggested that these data are meaningful for guiding care.

Dr. Ortel disclosed grant/research support from Eisai and Pfizer. Dr. Schulman had no disclosures.

TORONTO – In atrial fibrillation (AF) patients who must discontinue dabigatran for elective surgery, the risk of both stroke and major bleeding can be reduced to low levels using a formalized strategy for stopping and then restarting anticoagulation, according to results of a prospective study presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis Congress.

Among key findings presented at a press conference at the ISTH 2015 Congress, no strokes were recorded in more than 500 patients managed with the protocol, and the major bleeding rate was less than 2%, reported the study’s principal investigator, Dr. Sam Schulman, professor of hematology and thromboembolism, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

Data from this study (Circulation 2015) were reported at the press conference alongside a second study of perioperative warfarin management. Both studies are potentially practice changing, because they supply evidence-based guidance for anticoagulation in patients with AF.

Based on the findings from these two studies, “it is important to get this message out” that there are now data available on which to base clinical decisions, reported Dr. Schulman, who is also president of the ISTH 2015 Congress. His data were presented alongside a study that found no benefit from heparin bridging in AF patients when warfarin was stopped 5 days in advance of surgery.

In the study presented by Dr. Schulman, 542 patients with AF who were on dabigatran and scheduled for elective surgery were managed on a prespecified protocol for risk assessment. The protocol provided a time for stopping dabigatran before surgery based on such factors as renal function and procedure-related bleeding risk. Dabigatran was restarted after surgery on prespecified measures of surgery complexity and severity of consequences if bleeding occurred.

The primary outcome evaluated in the study was major bleeding in the first 30 days. Other outcomes of interest included thromboembolic complications, death and minor bleeding.

Major bleeding was observed in 1.8% of patients, a rate that Dr. Schulman characterized as “low and acceptable” in the context of expected background bleeding rates. There were four deaths, but all were unrelated to either bleeding or arterial thromboembolism. The only thromboembolic complication was a single transient ischemic attack. Minor bleeding occurred in 5.2%.

On the basis of the protocol, about half of the patients discontinued dabigatran 24 hours before surgery. No patient discontinued therapy more than 96 hours prior to surgery. The median time to resumption of dabigatran after surgery was 1 day, but the point at which it was restarted ranged between hours and 2 days. Bridging, which describes the injection of heparin for short-term anticoagulation, was not employed preoperatively but was used in 1.7% of cases postoperatively.

At the press conference, data also were reported from the BRIDGE study. That study, published online in the New England Journal of Medicine (2015 June 22; epub ahead of print ), found that bridging was not an effective strategy in AF patients who discontinue warfarin prior to elective surgery. In the press conference, Dr. Thomas L. Ortel, hematology/oncology division, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., agreed with Dr. Schulman that this is an area where evidence is needed to guide care.

In the absence of data, “physicians do whatever they think is best,” Dr. Schulman noted at the press conference. Referring to strategies for stopping anticoagulants for surgery in patients with AF, Dr. Schulman said, “some of them stop the blood thinner too early because they are afraid that the patient is going to bleed during surgery and instead the patient can have a stroke. Some stop too late, and the patient can have bleeding.”

The data presented at the meeting provide an evidence base for clinical decisions. Dr. Schulman suggested that these data are meaningful for guiding care.

Dr. Ortel disclosed grant/research support from Eisai and Pfizer. Dr. Schulman had no disclosures.

AT 2015 ISTH CONGRESS

Key clinical point: The risk of stroke and major bleeding can be reduced to low levels using a formalized strategy for stopping and then restarting dabigatran.

Major finding: The protocol developed provided a time for stopping dabigatran before surgery based on such factors as renal function and procedure-related bleeding risk. Dabigatran was restarted after surgery on prespecified measures of surgery complexity and severity of consequences if bleeding occurred.

Data source: 542 patients with AF who were on dabigatran and scheduled for elective surgery were managed on a prespecified protocol for risk assessment.

Disclosures: Dr. Ortel disclosed grant/research support from Eisai and Pfizer. Dr. Schulman had no disclosures.

Beware of high blood pressure

High blood pressure may not have any symptoms except in the most extreme cases, but the effect it can have on the human body is real and severe.

The only symptom of high blood pressure is a very serious condition known as hypertensive crisis, which occurs only when blood pressure rises over 180/110 mm Hg. This condition requires immediate medical attention. High blood pressure can cause a series of other serious health issues, such as damage to the heart and arteries, stroke, kidney damage, vision loss, erectile dysfunction, memory loss, angina, and peripheral artery disease.

High blood pressure in combination with other risk factors such as age, heredity, gender, obesity, smoking, high cholesterol, diabetes, and physical inactivity can further increase risk of major health issues. Diet and exercise changes, however, can help lessen that risk.

Learn more at the American Heart Association website.

High blood pressure may not have any symptoms except in the most extreme cases, but the effect it can have on the human body is real and severe.

The only symptom of high blood pressure is a very serious condition known as hypertensive crisis, which occurs only when blood pressure rises over 180/110 mm Hg. This condition requires immediate medical attention. High blood pressure can cause a series of other serious health issues, such as damage to the heart and arteries, stroke, kidney damage, vision loss, erectile dysfunction, memory loss, angina, and peripheral artery disease.

High blood pressure in combination with other risk factors such as age, heredity, gender, obesity, smoking, high cholesterol, diabetes, and physical inactivity can further increase risk of major health issues. Diet and exercise changes, however, can help lessen that risk.

Learn more at the American Heart Association website.

High blood pressure may not have any symptoms except in the most extreme cases, but the effect it can have on the human body is real and severe.

The only symptom of high blood pressure is a very serious condition known as hypertensive crisis, which occurs only when blood pressure rises over 180/110 mm Hg. This condition requires immediate medical attention. High blood pressure can cause a series of other serious health issues, such as damage to the heart and arteries, stroke, kidney damage, vision loss, erectile dysfunction, memory loss, angina, and peripheral artery disease.

High blood pressure in combination with other risk factors such as age, heredity, gender, obesity, smoking, high cholesterol, diabetes, and physical inactivity can further increase risk of major health issues. Diet and exercise changes, however, can help lessen that risk.

Learn more at the American Heart Association website.

Lowering Systolic Blood Pressure Tied to Reduced Atrial Fibrillation Risk

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - Lower systolic blood pressure in patients being treated for hypertension is associated with a reduced risk of atrial fibrillation (AF), according to data from the LIFE study.

"Among hypertensive patients at high risk of atrial fibrillation who can tolerate lower systolic blood pressure (SBP) levels, treating to a SBP of 130 or less may be able to reduce or retard the incidence of new AF," Dr. Peter M. Okin from Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, told Reuters Health by email, "but caution should be used when treating to these lower SBP levels to make sure that we are not harming patients in other ways."

Although hypertension clearly increases the risk of AF, studies have not consistently shown that reductions in blood pressure can reduce that risk.

Dr. Okin's team used data from the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint (LIFE) hypertension study to examine whether lower achieved SBP (no greater than 130 mm Hg) is associated with a lower incidence of AF compared with typical SBP control (131-141 mm Hg) and less-adequate SBP control (>=142 mm Hg) in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy on ECG.

The post hoc study included more than 8,800 men and women whose age averaged 67 years.

Compared with the group with less-adequate SBP control, patients with typical SBP control had a 24% lower risk of developing AF. And patients with lower achieved SBP had a 40% lower risk, the researchers report in Hypertension, online June8.

Only at SBP levels <=125 mm Hg was lower SBP no longer associated with a significantly reduced risk of AF.

When SBP was included as a continuous variable in multivariate analyses, every 10-mm Hg decrease in SBP was associated with a 13% lower risk of new-onset AF.

"There are a number of concerns with regards to lowering SBP to these levels in older hypertensives," Dr. Okin cautioned. "First, there are a number of studies (including data from the LIFE study that we have published) that suggests that achieving lower target SBP levels can be associated with an increased mortality risk. Indeed, the most recent US guidelines for treatment of hypertension suggest treating to higher SBP goals in patients 60 years of age and older because of some evidence that treating to lower SBP levels may increase as opposed to decrease risk. However, there is significant disagreement regarding these new recommendations."

"Additional data from the LIFE study, that have been presented but not published in manuscript form, seem to support the notion that achieving SBP levels <140 in this patient population is associated with worse outcomes than a SBP between 140 and 149," he said. "Lastly, lower SBP levels in truly elderly patients can sometimes be associated with light-headedness and an increased risk of falling which can add additional morbidity."

Dr. Okin cautioned, "These findings are based on post-hoc analysis of data from a study that was not specifically designed to address this question. As a consequence, we should use caution when interpreting these findings until there are hopefully more specific studies that address the question of whether treating to a lower SBP goal can reduce the risk of developing new AF."

Dr. Kazem Rahimi from University of Oxford's George Institute for Global Health in the UK showed in a recent meta-analysis that antihypertensive therapy modestly reduced the risk of AF.

"There may be a greater risk of adverse events with very aggressive blood pressure control," Dr. Rahimi, who was not involved in the new study, told Reuters Health by email.

"In a trial (ACCORD), which targeted a blood pressure level of <120 mm Hg, BP reduction increased the risk of serious adverse events, particularly increasing the risk of hypotension and hyperkalemia," he said. "However, at the target blood pressure levels that the authors examined (<130 mm Hg SBP), the benefits of blood pressure lowering in older patients (preventing heart attacks and strokes) are likely to outweigh any risks."

Dr. Rahimi said the new analysis is unlikely to change clinical practice due to its observational nature. "However, in the context of randomized trials showing that blood pressure lowering prevents heart attacks and strokes in elderly hypertensive patients, the suggestive evidence from this and other studies that lowering blood pressure may also lower the risk of AF provides another reason for not withholding blood pressure lowering drugs."

The LIFE trial was sponsored by Merck & Co. The authors of the new report disclosed multiple ties to the company, including employment.

—Reuters Health

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - Lower systolic blood pressure in patients being treated for hypertension is associated with a reduced risk of atrial fibrillation (AF), according to data from the LIFE study.

"Among hypertensive patients at high risk of atrial fibrillation who can tolerate lower systolic blood pressure (SBP) levels, treating to a SBP of 130 or less may be able to reduce or retard the incidence of new AF," Dr. Peter M. Okin from Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, told Reuters Health by email, "but caution should be used when treating to these lower SBP levels to make sure that we are not harming patients in other ways."

Although hypertension clearly increases the risk of AF, studies have not consistently shown that reductions in blood pressure can reduce that risk.

Dr. Okin's team used data from the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint (LIFE) hypertension study to examine whether lower achieved SBP (no greater than 130 mm Hg) is associated with a lower incidence of AF compared with typical SBP control (131-141 mm Hg) and less-adequate SBP control (>=142 mm Hg) in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy on ECG.

The post hoc study included more than 8,800 men and women whose age averaged 67 years.

Compared with the group with less-adequate SBP control, patients with typical SBP control had a 24% lower risk of developing AF. And patients with lower achieved SBP had a 40% lower risk, the researchers report in Hypertension, online June8.

Only at SBP levels <=125 mm Hg was lower SBP no longer associated with a significantly reduced risk of AF.

When SBP was included as a continuous variable in multivariate analyses, every 10-mm Hg decrease in SBP was associated with a 13% lower risk of new-onset AF.

"There are a number of concerns with regards to lowering SBP to these levels in older hypertensives," Dr. Okin cautioned. "First, there are a number of studies (including data from the LIFE study that we have published) that suggests that achieving lower target SBP levels can be associated with an increased mortality risk. Indeed, the most recent US guidelines for treatment of hypertension suggest treating to higher SBP goals in patients 60 years of age and older because of some evidence that treating to lower SBP levels may increase as opposed to decrease risk. However, there is significant disagreement regarding these new recommendations."

"Additional data from the LIFE study, that have been presented but not published in manuscript form, seem to support the notion that achieving SBP levels <140 in this patient population is associated with worse outcomes than a SBP between 140 and 149," he said. "Lastly, lower SBP levels in truly elderly patients can sometimes be associated with light-headedness and an increased risk of falling which can add additional morbidity."

Dr. Okin cautioned, "These findings are based on post-hoc analysis of data from a study that was not specifically designed to address this question. As a consequence, we should use caution when interpreting these findings until there are hopefully more specific studies that address the question of whether treating to a lower SBP goal can reduce the risk of developing new AF."

Dr. Kazem Rahimi from University of Oxford's George Institute for Global Health in the UK showed in a recent meta-analysis that antihypertensive therapy modestly reduced the risk of AF.

"There may be a greater risk of adverse events with very aggressive blood pressure control," Dr. Rahimi, who was not involved in the new study, told Reuters Health by email.

"In a trial (ACCORD), which targeted a blood pressure level of <120 mm Hg, BP reduction increased the risk of serious adverse events, particularly increasing the risk of hypotension and hyperkalemia," he said. "However, at the target blood pressure levels that the authors examined (<130 mm Hg SBP), the benefits of blood pressure lowering in older patients (preventing heart attacks and strokes) are likely to outweigh any risks."

Dr. Rahimi said the new analysis is unlikely to change clinical practice due to its observational nature. "However, in the context of randomized trials showing that blood pressure lowering prevents heart attacks and strokes in elderly hypertensive patients, the suggestive evidence from this and other studies that lowering blood pressure may also lower the risk of AF provides another reason for not withholding blood pressure lowering drugs."

The LIFE trial was sponsored by Merck & Co. The authors of the new report disclosed multiple ties to the company, including employment.

—Reuters Health

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - Lower systolic blood pressure in patients being treated for hypertension is associated with a reduced risk of atrial fibrillation (AF), according to data from the LIFE study.

"Among hypertensive patients at high risk of atrial fibrillation who can tolerate lower systolic blood pressure (SBP) levels, treating to a SBP of 130 or less may be able to reduce or retard the incidence of new AF," Dr. Peter M. Okin from Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, told Reuters Health by email, "but caution should be used when treating to these lower SBP levels to make sure that we are not harming patients in other ways."

Although hypertension clearly increases the risk of AF, studies have not consistently shown that reductions in blood pressure can reduce that risk.

Dr. Okin's team used data from the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint (LIFE) hypertension study to examine whether lower achieved SBP (no greater than 130 mm Hg) is associated with a lower incidence of AF compared with typical SBP control (131-141 mm Hg) and less-adequate SBP control (>=142 mm Hg) in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy on ECG.

The post hoc study included more than 8,800 men and women whose age averaged 67 years.

Compared with the group with less-adequate SBP control, patients with typical SBP control had a 24% lower risk of developing AF. And patients with lower achieved SBP had a 40% lower risk, the researchers report in Hypertension, online June8.

Only at SBP levels <=125 mm Hg was lower SBP no longer associated with a significantly reduced risk of AF.

When SBP was included as a continuous variable in multivariate analyses, every 10-mm Hg decrease in SBP was associated with a 13% lower risk of new-onset AF.

"There are a number of concerns with regards to lowering SBP to these levels in older hypertensives," Dr. Okin cautioned. "First, there are a number of studies (including data from the LIFE study that we have published) that suggests that achieving lower target SBP levels can be associated with an increased mortality risk. Indeed, the most recent US guidelines for treatment of hypertension suggest treating to higher SBP goals in patients 60 years of age and older because of some evidence that treating to lower SBP levels may increase as opposed to decrease risk. However, there is significant disagreement regarding these new recommendations."

"Additional data from the LIFE study, that have been presented but not published in manuscript form, seem to support the notion that achieving SBP levels <140 in this patient population is associated with worse outcomes than a SBP between 140 and 149," he said. "Lastly, lower SBP levels in truly elderly patients can sometimes be associated with light-headedness and an increased risk of falling which can add additional morbidity."

Dr. Okin cautioned, "These findings are based on post-hoc analysis of data from a study that was not specifically designed to address this question. As a consequence, we should use caution when interpreting these findings until there are hopefully more specific studies that address the question of whether treating to a lower SBP goal can reduce the risk of developing new AF."

Dr. Kazem Rahimi from University of Oxford's George Institute for Global Health in the UK showed in a recent meta-analysis that antihypertensive therapy modestly reduced the risk of AF.

"There may be a greater risk of adverse events with very aggressive blood pressure control," Dr. Rahimi, who was not involved in the new study, told Reuters Health by email.

"In a trial (ACCORD), which targeted a blood pressure level of <120 mm Hg, BP reduction increased the risk of serious adverse events, particularly increasing the risk of hypotension and hyperkalemia," he said. "However, at the target blood pressure levels that the authors examined (<130 mm Hg SBP), the benefits of blood pressure lowering in older patients (preventing heart attacks and strokes) are likely to outweigh any risks."

Dr. Rahimi said the new analysis is unlikely to change clinical practice due to its observational nature. "However, in the context of randomized trials showing that blood pressure lowering prevents heart attacks and strokes in elderly hypertensive patients, the suggestive evidence from this and other studies that lowering blood pressure may also lower the risk of AF provides another reason for not withholding blood pressure lowering drugs."

The LIFE trial was sponsored by Merck & Co. The authors of the new report disclosed multiple ties to the company, including employment.

—Reuters Health

Nivolumab produces ‘dramatic’ responses in HL

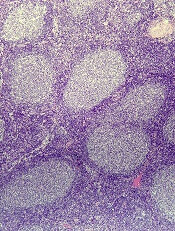

Photo courtesy of UCLA

LUGANO—The PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab produces rapid, durable, and, in some cases, “dramatic” responses in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), according to a speaker at the 13th International Congress on Malignant Lymphoma.

The drug has also produced durable responses in follicular lymphoma (FL), cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), and peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), although patient numbers for these malignancies are small.

John Timmerman, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, presented these results from a phase 1 study of patients with relapsed or refractory lymphoid malignancies and chronic HL (abstract 010).

Bristol-Myers Squibb and Ono Pharmaceutical Company are sponsors of the trial.

Original results of the study, with a data cutoff of June 2014, were reported at ASH 2014, with 40 weeks of median follow-up.

The update presented at 13-ICML, with a data lock in April 2015, includes an additional 10 months of data, for a median follow-up of 76 weeks.

Investigators enrolled 105 patients in this dose-escalation study to receive nivolumab at 1 mg/kg, then 3 mg/kg, every 2 weeks for 2 years.

Twenty-three patients had HL. Thirty-one had B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), including 11 with FL and 10 with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Twenty-three patients had T-cell NHL, including 5 with PTCL and 13 with CTCL/mycosis fungoides (MF). Twenty-seven patients had multiple myeloma (MM), and 1 had chronic myeloid leukemia.

Patients were heavily pretreated. Seventy-eight percent of HL patients and 26% of T-NHL patients had prior brentuximab vedotin. And 78% (HL), 14% (B-NHL), 9% (T-NHL), and 56% (MM) of patients had a prior autologous transplant.

The median number of prior therapies was 5 (range, 2-15) for HL patients and ranged from 1 to 16 for all patients.

The study’s primary endpoint was safety and tolerability, and the secondary endpoint was efficacy.

Safety and tolerability

Ninety-seven percent of patients had an adverse event, 69% of them related to study treatment and 21% of them treatment-related grade 3-4 events.

Fifteen patients (14%) discontinued treatment due to a related adverse event, including 3 with pneumonitis and 1 each with enteritis, stomatitis, pancreatitis, rash, conjunctivitis, sepsis, diplopia, myositis, neutropenia, myelodysplastic syndrome, increased creatinine phosphokinase, and peripheral neuropathy.

“Immune-related adverse events were generally seen early on and generally of low grade,” Dr Timmerman said. “However, it is notable that there were several grade 3 immune-related adverse events that can be seen as far as 6 months out after the start of therapy.”

These included skin, gastrointestinal, and pulmonary events. Most immune-related adverse events (83%) were resolved using protocol-prescribed procedures.

Efficacy

The overall response rate was 87% for HL, 36% for DLBCL, 40% for FL, 15% for CTCL/MF, 40% for PTCL, and 4% for MM.

Dr Timmerman pointed out that, since ASH, 2 additional conversions from partial response (PR) to complete response (CR) occurred in patients with HL. To date, 6 of 23 HL patients have achieved a CR and 14 a PR.

In B-cell NHL, there were additional conversions from PR to CR in DLBCL, while responses remained the same in FL and in the 4 responders with T-cell lymphomas.

“Intriguingly, there has been 1 late CR in the multiple myeloma cohort, which previously had shown no responses,” Dr Timmerman said.

Durability of response

This study suggests PD-1 blockade can produce durable responses in hematologic malignancies, as it does in melanoma and renal cell carcinoma.

In HL, the median response duration at a median follow-up of 86 weeks has not yet been reached, and half (n=10) of the responses are still ongoing.

In FL, CTCL, and PTCL, the median response duration has not been reached at a median follow-up of 81, 43, and 31 weeks, respectively. Of note, there are ongoing responses in at least half of patients in these tumor types.

In HL, none of the 6 patients in CR has progressed, although there have been some progressions in the PR group.

The rapidity of responses is also notable, Dr Timmerman said.

“[I]t’s very interesting that some patients have resolution of symptoms and improvement of symptoms within even 1 day of starting nivolumab therapy,” he said.

And responses to nivolumab in HL “can be very dramatic,” he added, as illustrated in the following case from the Mayo Clinic.

A patient with multiple sites of bulky FDG-avid tumors was scheduled to enter hospice. But first, he entered the nivolumab trial. Within 6 weeks of initiating treatment, he had achieved a near-CR. This response has been maintained for 2 years.

“The occurrence of very durable responses in the PR and CR groups has led us to question whether patients should go on to allogeneic stem cell transplantation after achieving responses with nivolumab or, rather, continue on nivolumab as long as their response remains,” Dr Timmerman said.

He added that an international, phase 2 trial in HL is underway and is accruing briskly.

Nivolumab was awarded breakthrough designation by the US Food and Drug Administration last year. Breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of drugs for serious or life-threatening conditions. ![]()

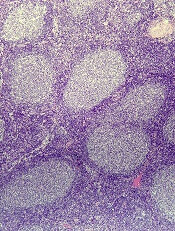

Photo courtesy of UCLA

LUGANO—The PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab produces rapid, durable, and, in some cases, “dramatic” responses in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), according to a speaker at the 13th International Congress on Malignant Lymphoma.

The drug has also produced durable responses in follicular lymphoma (FL), cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), and peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), although patient numbers for these malignancies are small.

John Timmerman, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, presented these results from a phase 1 study of patients with relapsed or refractory lymphoid malignancies and chronic HL (abstract 010).

Bristol-Myers Squibb and Ono Pharmaceutical Company are sponsors of the trial.

Original results of the study, with a data cutoff of June 2014, were reported at ASH 2014, with 40 weeks of median follow-up.

The update presented at 13-ICML, with a data lock in April 2015, includes an additional 10 months of data, for a median follow-up of 76 weeks.

Investigators enrolled 105 patients in this dose-escalation study to receive nivolumab at 1 mg/kg, then 3 mg/kg, every 2 weeks for 2 years.

Twenty-three patients had HL. Thirty-one had B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), including 11 with FL and 10 with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Twenty-three patients had T-cell NHL, including 5 with PTCL and 13 with CTCL/mycosis fungoides (MF). Twenty-seven patients had multiple myeloma (MM), and 1 had chronic myeloid leukemia.

Patients were heavily pretreated. Seventy-eight percent of HL patients and 26% of T-NHL patients had prior brentuximab vedotin. And 78% (HL), 14% (B-NHL), 9% (T-NHL), and 56% (MM) of patients had a prior autologous transplant.

The median number of prior therapies was 5 (range, 2-15) for HL patients and ranged from 1 to 16 for all patients.

The study’s primary endpoint was safety and tolerability, and the secondary endpoint was efficacy.

Safety and tolerability

Ninety-seven percent of patients had an adverse event, 69% of them related to study treatment and 21% of them treatment-related grade 3-4 events.

Fifteen patients (14%) discontinued treatment due to a related adverse event, including 3 with pneumonitis and 1 each with enteritis, stomatitis, pancreatitis, rash, conjunctivitis, sepsis, diplopia, myositis, neutropenia, myelodysplastic syndrome, increased creatinine phosphokinase, and peripheral neuropathy.

“Immune-related adverse events were generally seen early on and generally of low grade,” Dr Timmerman said. “However, it is notable that there were several grade 3 immune-related adverse events that can be seen as far as 6 months out after the start of therapy.”

These included skin, gastrointestinal, and pulmonary events. Most immune-related adverse events (83%) were resolved using protocol-prescribed procedures.

Efficacy

The overall response rate was 87% for HL, 36% for DLBCL, 40% for FL, 15% for CTCL/MF, 40% for PTCL, and 4% for MM.

Dr Timmerman pointed out that, since ASH, 2 additional conversions from partial response (PR) to complete response (CR) occurred in patients with HL. To date, 6 of 23 HL patients have achieved a CR and 14 a PR.

In B-cell NHL, there were additional conversions from PR to CR in DLBCL, while responses remained the same in FL and in the 4 responders with T-cell lymphomas.

“Intriguingly, there has been 1 late CR in the multiple myeloma cohort, which previously had shown no responses,” Dr Timmerman said.

Durability of response

This study suggests PD-1 blockade can produce durable responses in hematologic malignancies, as it does in melanoma and renal cell carcinoma.

In HL, the median response duration at a median follow-up of 86 weeks has not yet been reached, and half (n=10) of the responses are still ongoing.

In FL, CTCL, and PTCL, the median response duration has not been reached at a median follow-up of 81, 43, and 31 weeks, respectively. Of note, there are ongoing responses in at least half of patients in these tumor types.

In HL, none of the 6 patients in CR has progressed, although there have been some progressions in the PR group.

The rapidity of responses is also notable, Dr Timmerman said.

“[I]t’s very interesting that some patients have resolution of symptoms and improvement of symptoms within even 1 day of starting nivolumab therapy,” he said.

And responses to nivolumab in HL “can be very dramatic,” he added, as illustrated in the following case from the Mayo Clinic.

A patient with multiple sites of bulky FDG-avid tumors was scheduled to enter hospice. But first, he entered the nivolumab trial. Within 6 weeks of initiating treatment, he had achieved a near-CR. This response has been maintained for 2 years.

“The occurrence of very durable responses in the PR and CR groups has led us to question whether patients should go on to allogeneic stem cell transplantation after achieving responses with nivolumab or, rather, continue on nivolumab as long as their response remains,” Dr Timmerman said.

He added that an international, phase 2 trial in HL is underway and is accruing briskly.

Nivolumab was awarded breakthrough designation by the US Food and Drug Administration last year. Breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of drugs for serious or life-threatening conditions. ![]()

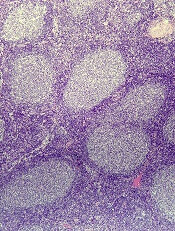

Photo courtesy of UCLA

LUGANO—The PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab produces rapid, durable, and, in some cases, “dramatic” responses in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), according to a speaker at the 13th International Congress on Malignant Lymphoma.

The drug has also produced durable responses in follicular lymphoma (FL), cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), and peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), although patient numbers for these malignancies are small.

John Timmerman, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, presented these results from a phase 1 study of patients with relapsed or refractory lymphoid malignancies and chronic HL (abstract 010).

Bristol-Myers Squibb and Ono Pharmaceutical Company are sponsors of the trial.

Original results of the study, with a data cutoff of June 2014, were reported at ASH 2014, with 40 weeks of median follow-up.

The update presented at 13-ICML, with a data lock in April 2015, includes an additional 10 months of data, for a median follow-up of 76 weeks.

Investigators enrolled 105 patients in this dose-escalation study to receive nivolumab at 1 mg/kg, then 3 mg/kg, every 2 weeks for 2 years.