User login

Digestive Disease Week (DDW 2015)

Colon cancer, colonoscopy, and intestinal issues

Hereditary syndromes in gastroenterology have emerged from being esoteric to being common issues that all of us must deal with, according to Dr. Sapna Syngal of Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center, Boston. Screening, surveillance, and treatment of hereditary cancers are all different, compared with sporadic cancer. For colorectal cancers, an excellent resource is http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_colon.pdf, and there are recent society summaries (Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015;110:223-62). These recommend a family history of cancer be recorded for all patients, including type of cancer, age at diagnosis, and relationship to patient. Lynch syndrome testing should now be done on all newly diagnosed colorectal cancers by testing of mismatch repair proteins or microsatellite instability. Genetic testing should be done when these are detected and on all family members of affected individuals. Familial adenomatous polyposis testing, including the APC and MUTYH genes, should be done for individuals with more than 10 cumulative adenomas, or a family history of any familial adenomatous condition. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome should be tested for in individuals with perioral/buccal pigmentation or those with two or more hamartomatous polyps. Juvenile polyposis syndrome should be tested for in individuals with five or more juvenile polyps in the colorectum or any juvenile polyps in other parts of the GI tract. Simple clinical questions can help identify those who should be tested (Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1508-18).

Modern evidence has refuted several long-held beliefs about diverticulosis and diverticulitis, said Dr. Neil Stollman of the University of California, San Francisco. Evidence now shows that diverticulosis is not associated with a low-fiber diet and that high-fiber diets are associated with higher rates of diverticular complications, although this may be due to confounding. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are associated with increased risk of diverticular bleeding. The risk of diverticulitis is much lower than previously thought. Prior estimates of 10%-25% have now been revised downward to 1%-4%. Nuts and seeds do not cause acute diverticulitis and do not need to be avoided. Diverticulitis is a spectrum of diseases from asymptomatic to symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD) to acute diverticulitis. Mesalamine may be effective in SUDD and acute diverticulitis but evidence is mixed. Cyclic rifaximin and probiotics may also be helpful in SUDD. Antibiotics, previously thought to be mandatory in acute diverticulitis, have not been clearly beneficial in large randomized trials. Surgery, which was also previously recommended after a second attack of acute diverticulitis, is now considered optional and should be individualized.

Dr. Douglas K. Rex of Indiana University Health, Indianapolis, reviewed key measures of quality in colonoscopy and how to achieve these, even under difficult circumstances. Key measures include adenoma detection rate, which can be improved through careful attention to good technique (looking behind folds, adequate distention, and washing) and recognition of flat and sessile polyps. New technologies include high definition, special endoscope caps that flatten folds, and new wide-angle colonoscopes. Water immersion and CO2 insufflation have also improved quality through easier insertion and less gas distention and pain after the procedure. For removal of large, lateral spreading polyps, the technique of endoscopic mucosal resection has been highly effective. Use of a “bulking agent” for submucosal injection such as hydroxyethyl starch, injectable contrast agent, underwater endoscopic mucosal resection, and avulsion (with cold or hot forceps) of fibrotic/scarred polyps have all been demonstrated to be effective in expert hands.

Dr. Charlene M. Prather of Saint Louis University summarized the increasing prevalence of constipation and reviewed risk factors (decreased activity, low fiber consumption, and use of multiple constipating medications). Constipation can be divided into three types: normal transit, slow transit, and pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD). Physical exam, particularly a high-quality rectal exam, can be very effective with high negative predictive value for PFD. Treatment includes fiber supplementation (most effective for mild/moderate constipation, less helpful in slow transit or PFD), laxatives (best data are for osmotic laxatives and bisacodyl), and newer agents that stimulate chloride secretion. Testing is appropriate for refractory constipation and includes transit time studies, balloon expulsion, and anorectal manometry.

Dr. Brennan Spiegel of the Cedars-Sinai Center for Outcomes Research and Education, Los Angeles, provided a summary of current national efforts to measure, report, and improve quality in gastroenterology. He highlighted several reports of high variability in quality such as adenoma detection, testing in patients with uncomplicated inflammatory bowel disease, and approaches to diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. A general approach to achieving quality was outlined, including: 1. standardization, 2. measurement, 3. reporting, 4. incentivizing (getting paid for performance), and 5. improving. U.S. Medicare oversight groups (PQRS) have chosen four general areas of quality (polyp surveillance, gastroesophageal reflux disease, hepatitis C, and IBD) measures. Gastroenterology societies have provided effective tools to measure and report these, including GIQUIC and the AGA Digestive Health Recognition Program.

Dr. Wallace is professor of medicine and director, digestive diseases research program, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla. He has received grants from BSCI and Cosmo and has consulted for Olympus and iLumen. This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the spring postgraduate course sessions held at DDW 2015.

Hereditary syndromes in gastroenterology have emerged from being esoteric to being common issues that all of us must deal with, according to Dr. Sapna Syngal of Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center, Boston. Screening, surveillance, and treatment of hereditary cancers are all different, compared with sporadic cancer. For colorectal cancers, an excellent resource is http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_colon.pdf, and there are recent society summaries (Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015;110:223-62). These recommend a family history of cancer be recorded for all patients, including type of cancer, age at diagnosis, and relationship to patient. Lynch syndrome testing should now be done on all newly diagnosed colorectal cancers by testing of mismatch repair proteins or microsatellite instability. Genetic testing should be done when these are detected and on all family members of affected individuals. Familial adenomatous polyposis testing, including the APC and MUTYH genes, should be done for individuals with more than 10 cumulative adenomas, or a family history of any familial adenomatous condition. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome should be tested for in individuals with perioral/buccal pigmentation or those with two or more hamartomatous polyps. Juvenile polyposis syndrome should be tested for in individuals with five or more juvenile polyps in the colorectum or any juvenile polyps in other parts of the GI tract. Simple clinical questions can help identify those who should be tested (Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1508-18).

Modern evidence has refuted several long-held beliefs about diverticulosis and diverticulitis, said Dr. Neil Stollman of the University of California, San Francisco. Evidence now shows that diverticulosis is not associated with a low-fiber diet and that high-fiber diets are associated with higher rates of diverticular complications, although this may be due to confounding. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are associated with increased risk of diverticular bleeding. The risk of diverticulitis is much lower than previously thought. Prior estimates of 10%-25% have now been revised downward to 1%-4%. Nuts and seeds do not cause acute diverticulitis and do not need to be avoided. Diverticulitis is a spectrum of diseases from asymptomatic to symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD) to acute diverticulitis. Mesalamine may be effective in SUDD and acute diverticulitis but evidence is mixed. Cyclic rifaximin and probiotics may also be helpful in SUDD. Antibiotics, previously thought to be mandatory in acute diverticulitis, have not been clearly beneficial in large randomized trials. Surgery, which was also previously recommended after a second attack of acute diverticulitis, is now considered optional and should be individualized.

Dr. Douglas K. Rex of Indiana University Health, Indianapolis, reviewed key measures of quality in colonoscopy and how to achieve these, even under difficult circumstances. Key measures include adenoma detection rate, which can be improved through careful attention to good technique (looking behind folds, adequate distention, and washing) and recognition of flat and sessile polyps. New technologies include high definition, special endoscope caps that flatten folds, and new wide-angle colonoscopes. Water immersion and CO2 insufflation have also improved quality through easier insertion and less gas distention and pain after the procedure. For removal of large, lateral spreading polyps, the technique of endoscopic mucosal resection has been highly effective. Use of a “bulking agent” for submucosal injection such as hydroxyethyl starch, injectable contrast agent, underwater endoscopic mucosal resection, and avulsion (with cold or hot forceps) of fibrotic/scarred polyps have all been demonstrated to be effective in expert hands.

Dr. Charlene M. Prather of Saint Louis University summarized the increasing prevalence of constipation and reviewed risk factors (decreased activity, low fiber consumption, and use of multiple constipating medications). Constipation can be divided into three types: normal transit, slow transit, and pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD). Physical exam, particularly a high-quality rectal exam, can be very effective with high negative predictive value for PFD. Treatment includes fiber supplementation (most effective for mild/moderate constipation, less helpful in slow transit or PFD), laxatives (best data are for osmotic laxatives and bisacodyl), and newer agents that stimulate chloride secretion. Testing is appropriate for refractory constipation and includes transit time studies, balloon expulsion, and anorectal manometry.

Dr. Brennan Spiegel of the Cedars-Sinai Center for Outcomes Research and Education, Los Angeles, provided a summary of current national efforts to measure, report, and improve quality in gastroenterology. He highlighted several reports of high variability in quality such as adenoma detection, testing in patients with uncomplicated inflammatory bowel disease, and approaches to diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. A general approach to achieving quality was outlined, including: 1. standardization, 2. measurement, 3. reporting, 4. incentivizing (getting paid for performance), and 5. improving. U.S. Medicare oversight groups (PQRS) have chosen four general areas of quality (polyp surveillance, gastroesophageal reflux disease, hepatitis C, and IBD) measures. Gastroenterology societies have provided effective tools to measure and report these, including GIQUIC and the AGA Digestive Health Recognition Program.

Dr. Wallace is professor of medicine and director, digestive diseases research program, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla. He has received grants from BSCI and Cosmo and has consulted for Olympus and iLumen. This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the spring postgraduate course sessions held at DDW 2015.

Hereditary syndromes in gastroenterology have emerged from being esoteric to being common issues that all of us must deal with, according to Dr. Sapna Syngal of Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center, Boston. Screening, surveillance, and treatment of hereditary cancers are all different, compared with sporadic cancer. For colorectal cancers, an excellent resource is http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_colon.pdf, and there are recent society summaries (Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015;110:223-62). These recommend a family history of cancer be recorded for all patients, including type of cancer, age at diagnosis, and relationship to patient. Lynch syndrome testing should now be done on all newly diagnosed colorectal cancers by testing of mismatch repair proteins or microsatellite instability. Genetic testing should be done when these are detected and on all family members of affected individuals. Familial adenomatous polyposis testing, including the APC and MUTYH genes, should be done for individuals with more than 10 cumulative adenomas, or a family history of any familial adenomatous condition. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome should be tested for in individuals with perioral/buccal pigmentation or those with two or more hamartomatous polyps. Juvenile polyposis syndrome should be tested for in individuals with five or more juvenile polyps in the colorectum or any juvenile polyps in other parts of the GI tract. Simple clinical questions can help identify those who should be tested (Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1508-18).

Modern evidence has refuted several long-held beliefs about diverticulosis and diverticulitis, said Dr. Neil Stollman of the University of California, San Francisco. Evidence now shows that diverticulosis is not associated with a low-fiber diet and that high-fiber diets are associated with higher rates of diverticular complications, although this may be due to confounding. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are associated with increased risk of diverticular bleeding. The risk of diverticulitis is much lower than previously thought. Prior estimates of 10%-25% have now been revised downward to 1%-4%. Nuts and seeds do not cause acute diverticulitis and do not need to be avoided. Diverticulitis is a spectrum of diseases from asymptomatic to symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD) to acute diverticulitis. Mesalamine may be effective in SUDD and acute diverticulitis but evidence is mixed. Cyclic rifaximin and probiotics may also be helpful in SUDD. Antibiotics, previously thought to be mandatory in acute diverticulitis, have not been clearly beneficial in large randomized trials. Surgery, which was also previously recommended after a second attack of acute diverticulitis, is now considered optional and should be individualized.

Dr. Douglas K. Rex of Indiana University Health, Indianapolis, reviewed key measures of quality in colonoscopy and how to achieve these, even under difficult circumstances. Key measures include adenoma detection rate, which can be improved through careful attention to good technique (looking behind folds, adequate distention, and washing) and recognition of flat and sessile polyps. New technologies include high definition, special endoscope caps that flatten folds, and new wide-angle colonoscopes. Water immersion and CO2 insufflation have also improved quality through easier insertion and less gas distention and pain after the procedure. For removal of large, lateral spreading polyps, the technique of endoscopic mucosal resection has been highly effective. Use of a “bulking agent” for submucosal injection such as hydroxyethyl starch, injectable contrast agent, underwater endoscopic mucosal resection, and avulsion (with cold or hot forceps) of fibrotic/scarred polyps have all been demonstrated to be effective in expert hands.

Dr. Charlene M. Prather of Saint Louis University summarized the increasing prevalence of constipation and reviewed risk factors (decreased activity, low fiber consumption, and use of multiple constipating medications). Constipation can be divided into three types: normal transit, slow transit, and pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD). Physical exam, particularly a high-quality rectal exam, can be very effective with high negative predictive value for PFD. Treatment includes fiber supplementation (most effective for mild/moderate constipation, less helpful in slow transit or PFD), laxatives (best data are for osmotic laxatives and bisacodyl), and newer agents that stimulate chloride secretion. Testing is appropriate for refractory constipation and includes transit time studies, balloon expulsion, and anorectal manometry.

Dr. Brennan Spiegel of the Cedars-Sinai Center for Outcomes Research and Education, Los Angeles, provided a summary of current national efforts to measure, report, and improve quality in gastroenterology. He highlighted several reports of high variability in quality such as adenoma detection, testing in patients with uncomplicated inflammatory bowel disease, and approaches to diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. A general approach to achieving quality was outlined, including: 1. standardization, 2. measurement, 3. reporting, 4. incentivizing (getting paid for performance), and 5. improving. U.S. Medicare oversight groups (PQRS) have chosen four general areas of quality (polyp surveillance, gastroesophageal reflux disease, hepatitis C, and IBD) measures. Gastroenterology societies have provided effective tools to measure and report these, including GIQUIC and the AGA Digestive Health Recognition Program.

Dr. Wallace is professor of medicine and director, digestive diseases research program, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla. He has received grants from BSCI and Cosmo and has consulted for Olympus and iLumen. This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the spring postgraduate course sessions held at DDW 2015.

Upper GI tract

This year’s session on esophagus/upper GI at the AGA Spring Postgraduate Course was packed with pragmatic, useful information for the evaluation of patients with upper GI disorders. The session began with a talk on the manifestations of extraesophageal reflux disease. The take-home message of this talk was that putative extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease rarely respond to high-dose therapy with PPIs (proton-pump inhibitors), in the absence of concurrent esophageal symptoms such as heartburn or regurgitation. In such situations, investigation of other etiologies of patients’ symptoms, including occult postnasal drainage or cough-variant asthma, may be more rewarding than escalating anti-acid therapy.

Dr. John E. Pandolfino, AGAF, of Northwestern University, Chicago, discussed the utilization of high-resolution manometry in the evaluation of dysphagia. A central focus of this discussion was the use of the Chicago classification of motility abnormalities in assessing these patients. In the future, it is likely that the care of these patients will be dictated by the type of abnormality the patient has in this classification scheme. Especially in the setting of achalasia, data are emerging that some subtypes of achalasia are less likely to respond to some therapies. For instance, type 3 achalasia is unlikely to respond to pneumatic balloon dilatation.

Dr. Rhonda Souza of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, taught us that a diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis requires an 8-week trial of PPI therapy with no resolution of the eosinophilia. Esophageal dilation is generally safe in the setting of a dominant stricture, but it can be delayed prior to medical therapy if the patient is tolerating oral intake well. Although the most commonly used therapies for EoE now involve either swallowed steroids or dietary elimination therapy, several new agents are on the horizon that may give us new treatment options.

Finally, Dr. Amitabh Chak of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, reviewed the care of patients with Barrett’s esophagus and low-grade dysplasia. This is an especially difficult group of patients to care for, due in part to the low reproducibility in the diagnosis of low-grade dysplasia, as well as the highly variable reported cancer outcomes in this patient population. Level 1 evidence now exists demonstrating that treatment with radiofrequency ablation decreases the incidence of cancer in patients with low-grade dysplasia, but most patients with this finding will not progress. Therefore, the field would benefit from better risk stratification of these patients.

Dr. Shaheen is professor of medicine and epidemiology and chief of the division of gastroenterology & hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the spring postgraduate course sessions held at DDW 2015.

This year’s session on esophagus/upper GI at the AGA Spring Postgraduate Course was packed with pragmatic, useful information for the evaluation of patients with upper GI disorders. The session began with a talk on the manifestations of extraesophageal reflux disease. The take-home message of this talk was that putative extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease rarely respond to high-dose therapy with PPIs (proton-pump inhibitors), in the absence of concurrent esophageal symptoms such as heartburn or regurgitation. In such situations, investigation of other etiologies of patients’ symptoms, including occult postnasal drainage or cough-variant asthma, may be more rewarding than escalating anti-acid therapy.

Dr. John E. Pandolfino, AGAF, of Northwestern University, Chicago, discussed the utilization of high-resolution manometry in the evaluation of dysphagia. A central focus of this discussion was the use of the Chicago classification of motility abnormalities in assessing these patients. In the future, it is likely that the care of these patients will be dictated by the type of abnormality the patient has in this classification scheme. Especially in the setting of achalasia, data are emerging that some subtypes of achalasia are less likely to respond to some therapies. For instance, type 3 achalasia is unlikely to respond to pneumatic balloon dilatation.

Dr. Rhonda Souza of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, taught us that a diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis requires an 8-week trial of PPI therapy with no resolution of the eosinophilia. Esophageal dilation is generally safe in the setting of a dominant stricture, but it can be delayed prior to medical therapy if the patient is tolerating oral intake well. Although the most commonly used therapies for EoE now involve either swallowed steroids or dietary elimination therapy, several new agents are on the horizon that may give us new treatment options.

Finally, Dr. Amitabh Chak of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, reviewed the care of patients with Barrett’s esophagus and low-grade dysplasia. This is an especially difficult group of patients to care for, due in part to the low reproducibility in the diagnosis of low-grade dysplasia, as well as the highly variable reported cancer outcomes in this patient population. Level 1 evidence now exists demonstrating that treatment with radiofrequency ablation decreases the incidence of cancer in patients with low-grade dysplasia, but most patients with this finding will not progress. Therefore, the field would benefit from better risk stratification of these patients.

Dr. Shaheen is professor of medicine and epidemiology and chief of the division of gastroenterology & hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the spring postgraduate course sessions held at DDW 2015.

This year’s session on esophagus/upper GI at the AGA Spring Postgraduate Course was packed with pragmatic, useful information for the evaluation of patients with upper GI disorders. The session began with a talk on the manifestations of extraesophageal reflux disease. The take-home message of this talk was that putative extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease rarely respond to high-dose therapy with PPIs (proton-pump inhibitors), in the absence of concurrent esophageal symptoms such as heartburn or regurgitation. In such situations, investigation of other etiologies of patients’ symptoms, including occult postnasal drainage or cough-variant asthma, may be more rewarding than escalating anti-acid therapy.

Dr. John E. Pandolfino, AGAF, of Northwestern University, Chicago, discussed the utilization of high-resolution manometry in the evaluation of dysphagia. A central focus of this discussion was the use of the Chicago classification of motility abnormalities in assessing these patients. In the future, it is likely that the care of these patients will be dictated by the type of abnormality the patient has in this classification scheme. Especially in the setting of achalasia, data are emerging that some subtypes of achalasia are less likely to respond to some therapies. For instance, type 3 achalasia is unlikely to respond to pneumatic balloon dilatation.

Dr. Rhonda Souza of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, taught us that a diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis requires an 8-week trial of PPI therapy with no resolution of the eosinophilia. Esophageal dilation is generally safe in the setting of a dominant stricture, but it can be delayed prior to medical therapy if the patient is tolerating oral intake well. Although the most commonly used therapies for EoE now involve either swallowed steroids or dietary elimination therapy, several new agents are on the horizon that may give us new treatment options.

Finally, Dr. Amitabh Chak of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, reviewed the care of patients with Barrett’s esophagus and low-grade dysplasia. This is an especially difficult group of patients to care for, due in part to the low reproducibility in the diagnosis of low-grade dysplasia, as well as the highly variable reported cancer outcomes in this patient population. Level 1 evidence now exists demonstrating that treatment with radiofrequency ablation decreases the incidence of cancer in patients with low-grade dysplasia, but most patients with this finding will not progress. Therefore, the field would benefit from better risk stratification of these patients.

Dr. Shaheen is professor of medicine and epidemiology and chief of the division of gastroenterology & hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the spring postgraduate course sessions held at DDW 2015.

Liver and functional GI issues

Dr. Lin Chang at the University of California, Los Angeles, discussed how to work-up and manage functional abdominal pain. She reviewed a diagnostic algorithm that is evidence based and uses characteristics of the abdominal pain, coexisting warning signs, and a diagnostic work-up. A patient must be diagnosed with functional abdominal pain only after careful medical history, physical examination, and adequate consideration of competing etiologies.

Physical examination can be helpful in differentiating abdominal wall pain from that of visceral pain (Carnett’s sign) although some patients with functional abdominal pain may exhibit positive Carnett’s sign. Managing a patient with suspected functional abdominal pain includes careful attention to warning signs for organic disease (for example, unintended weight loss, hematochezia, abnormal labs, fever, or family history of serious GI disorders), avoiding unnecessary diagnostic testing, consideration of mental health consultation and pharmacotherapy as appropriate.

Dr. Chang reviewed the role of various pharmacologic agents for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) with diarrhea (alosetron, rifaximin, and loperamide), IBS with constipation (linaclotide, lubiprostone, and polyethylene glycol) and agents such antispasmodics, tricyclic antidepressants, and SSRIs (reviewed extensively in the AGA Technical Review and Guidelines for Pharmacotherapy for IBS published in Gastroenterology. 2014 Nov;147[5]:1149-72.e2). It is important to establish a strong patient-provider relationship and to incorporate behavioral therapies into management of patients with recurrent or chronic functional abdominal pain.

Dr. Peter Gibson at Monash University in Melbourne discussed non–celiac gluten sensitivity and low-FODMAP diet in managing food sensitivity and functional bowel disorders. He pointed out that recent dietary strategies have changed from patient-initiated, whole-food strategies to avoiding specific dietary components such as FODMAPs and gluten and wheat products. FODMAPS (fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols) are foods that are generally high in fructose, lactose, oligosaccharides (e.g., beans, onions, garlic, complex carbohydrates) and polyols (e.g., mushrooms). FODMAPs are generally osmotic and lead to fermentation and diarrhea, bloating, and flatulence. General principles in offering a low-FODMAP diet are the selection of appropriate patients; correct education about FODMAP diets, preferably by a trained dietitian; and a step-down approach in which a strict diet is slowly liberalized. Dr. Gibson pointed out that there are a subset of IBS patients who are gluten sensitive but recent data suggest that wheat protein sensitivity may not be as common as it has been suggested and, in fact, FODMAPs may indeed be the major inducers of symptoms in individuals with supposed wheat intolerance. The potential risks of dietary manipulation such as creation of a dietary cripple or induction of an eating disorder should be kept in mind.

Dr. Anna Mae Diehl at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., spoke about the diagnosis, role of the microbiome, and the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). It was pointed out that most patients with NAFLD have benign progression although individuals with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), especially those with significant fibrosis, are at risk for developing cirrhosis, liver failure, and liver cancer. Therapeutic investigations undertaken to date have not sufficiently focused on improving fibrosis although several ongoing clinical trials are directed at this goal. Gut microbiome might be a new NAFLD diagnostic/therapeutic target because several recent animal studies have shown that gut microbiome may play a role in conferring susceptibility to liver injury, fibrosis, and cancer.

Dr. Lawrence J. Brandt at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, gave an update on fecal microbiota therapy (FMT). He highlighted that FMT has historic roots going back to the 4th century when Ge Hong described use of human fecal suspension to treat food poisoning or severe diarrhea. He made it clear that FMT should be offered only to those with recurrent Clostridium difficile infections (CDI), meeting selected criteria such as severe illness and prior treatment failures. The protocol for FMT in recurrent CDI includes careful selection of donor (may range from any healthy person, universal donor, or stool-bank product) and testing stool and blood of potential donors for any transmittable agents. A recent systematic review showed that the success rate for FMT in individuals with CDI is generally quite high (greater than 80%) but it may depend on the site of FMT – for example, if FMT is administered to duodenum/jejunum, the success rate is 86%, whereas if it is delivered to right colon/cecum, then the success rate can be as high as 93%. He highlighted the efficacy of FMT in severe, complicated CDI, which generally carries high morbidity and mortality. Practitioners offering FMT should carefully review the FDA guidance that was issued in March 2014. He noted that long-term consequences of FMT are not well understood and thus, risks versus benefits of FMT on a patient-by-patient basis must be carefully weighed.

Dr. Naga P. Chalasani is the David W. Crabb Professor and director of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Indiana University, Indianapolis. He has consulting agreements and receives research support from several pharmaceutical companies but none represent a conflict of interest for this activity.

This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the spring postgraduate course sessions held at DDW 2015.

Dr. Lin Chang at the University of California, Los Angeles, discussed how to work-up and manage functional abdominal pain. She reviewed a diagnostic algorithm that is evidence based and uses characteristics of the abdominal pain, coexisting warning signs, and a diagnostic work-up. A patient must be diagnosed with functional abdominal pain only after careful medical history, physical examination, and adequate consideration of competing etiologies.

Physical examination can be helpful in differentiating abdominal wall pain from that of visceral pain (Carnett’s sign) although some patients with functional abdominal pain may exhibit positive Carnett’s sign. Managing a patient with suspected functional abdominal pain includes careful attention to warning signs for organic disease (for example, unintended weight loss, hematochezia, abnormal labs, fever, or family history of serious GI disorders), avoiding unnecessary diagnostic testing, consideration of mental health consultation and pharmacotherapy as appropriate.

Dr. Chang reviewed the role of various pharmacologic agents for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) with diarrhea (alosetron, rifaximin, and loperamide), IBS with constipation (linaclotide, lubiprostone, and polyethylene glycol) and agents such antispasmodics, tricyclic antidepressants, and SSRIs (reviewed extensively in the AGA Technical Review and Guidelines for Pharmacotherapy for IBS published in Gastroenterology. 2014 Nov;147[5]:1149-72.e2). It is important to establish a strong patient-provider relationship and to incorporate behavioral therapies into management of patients with recurrent or chronic functional abdominal pain.

Dr. Peter Gibson at Monash University in Melbourne discussed non–celiac gluten sensitivity and low-FODMAP diet in managing food sensitivity and functional bowel disorders. He pointed out that recent dietary strategies have changed from patient-initiated, whole-food strategies to avoiding specific dietary components such as FODMAPs and gluten and wheat products. FODMAPS (fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols) are foods that are generally high in fructose, lactose, oligosaccharides (e.g., beans, onions, garlic, complex carbohydrates) and polyols (e.g., mushrooms). FODMAPs are generally osmotic and lead to fermentation and diarrhea, bloating, and flatulence. General principles in offering a low-FODMAP diet are the selection of appropriate patients; correct education about FODMAP diets, preferably by a trained dietitian; and a step-down approach in which a strict diet is slowly liberalized. Dr. Gibson pointed out that there are a subset of IBS patients who are gluten sensitive but recent data suggest that wheat protein sensitivity may not be as common as it has been suggested and, in fact, FODMAPs may indeed be the major inducers of symptoms in individuals with supposed wheat intolerance. The potential risks of dietary manipulation such as creation of a dietary cripple or induction of an eating disorder should be kept in mind.

Dr. Anna Mae Diehl at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., spoke about the diagnosis, role of the microbiome, and the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). It was pointed out that most patients with NAFLD have benign progression although individuals with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), especially those with significant fibrosis, are at risk for developing cirrhosis, liver failure, and liver cancer. Therapeutic investigations undertaken to date have not sufficiently focused on improving fibrosis although several ongoing clinical trials are directed at this goal. Gut microbiome might be a new NAFLD diagnostic/therapeutic target because several recent animal studies have shown that gut microbiome may play a role in conferring susceptibility to liver injury, fibrosis, and cancer.

Dr. Lawrence J. Brandt at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, gave an update on fecal microbiota therapy (FMT). He highlighted that FMT has historic roots going back to the 4th century when Ge Hong described use of human fecal suspension to treat food poisoning or severe diarrhea. He made it clear that FMT should be offered only to those with recurrent Clostridium difficile infections (CDI), meeting selected criteria such as severe illness and prior treatment failures. The protocol for FMT in recurrent CDI includes careful selection of donor (may range from any healthy person, universal donor, or stool-bank product) and testing stool and blood of potential donors for any transmittable agents. A recent systematic review showed that the success rate for FMT in individuals with CDI is generally quite high (greater than 80%) but it may depend on the site of FMT – for example, if FMT is administered to duodenum/jejunum, the success rate is 86%, whereas if it is delivered to right colon/cecum, then the success rate can be as high as 93%. He highlighted the efficacy of FMT in severe, complicated CDI, which generally carries high morbidity and mortality. Practitioners offering FMT should carefully review the FDA guidance that was issued in March 2014. He noted that long-term consequences of FMT are not well understood and thus, risks versus benefits of FMT on a patient-by-patient basis must be carefully weighed.

Dr. Naga P. Chalasani is the David W. Crabb Professor and director of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Indiana University, Indianapolis. He has consulting agreements and receives research support from several pharmaceutical companies but none represent a conflict of interest for this activity.

This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the spring postgraduate course sessions held at DDW 2015.

Dr. Lin Chang at the University of California, Los Angeles, discussed how to work-up and manage functional abdominal pain. She reviewed a diagnostic algorithm that is evidence based and uses characteristics of the abdominal pain, coexisting warning signs, and a diagnostic work-up. A patient must be diagnosed with functional abdominal pain only after careful medical history, physical examination, and adequate consideration of competing etiologies.

Physical examination can be helpful in differentiating abdominal wall pain from that of visceral pain (Carnett’s sign) although some patients with functional abdominal pain may exhibit positive Carnett’s sign. Managing a patient with suspected functional abdominal pain includes careful attention to warning signs for organic disease (for example, unintended weight loss, hematochezia, abnormal labs, fever, or family history of serious GI disorders), avoiding unnecessary diagnostic testing, consideration of mental health consultation and pharmacotherapy as appropriate.

Dr. Chang reviewed the role of various pharmacologic agents for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) with diarrhea (alosetron, rifaximin, and loperamide), IBS with constipation (linaclotide, lubiprostone, and polyethylene glycol) and agents such antispasmodics, tricyclic antidepressants, and SSRIs (reviewed extensively in the AGA Technical Review and Guidelines for Pharmacotherapy for IBS published in Gastroenterology. 2014 Nov;147[5]:1149-72.e2). It is important to establish a strong patient-provider relationship and to incorporate behavioral therapies into management of patients with recurrent or chronic functional abdominal pain.

Dr. Peter Gibson at Monash University in Melbourne discussed non–celiac gluten sensitivity and low-FODMAP diet in managing food sensitivity and functional bowel disorders. He pointed out that recent dietary strategies have changed from patient-initiated, whole-food strategies to avoiding specific dietary components such as FODMAPs and gluten and wheat products. FODMAPS (fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols) are foods that are generally high in fructose, lactose, oligosaccharides (e.g., beans, onions, garlic, complex carbohydrates) and polyols (e.g., mushrooms). FODMAPs are generally osmotic and lead to fermentation and diarrhea, bloating, and flatulence. General principles in offering a low-FODMAP diet are the selection of appropriate patients; correct education about FODMAP diets, preferably by a trained dietitian; and a step-down approach in which a strict diet is slowly liberalized. Dr. Gibson pointed out that there are a subset of IBS patients who are gluten sensitive but recent data suggest that wheat protein sensitivity may not be as common as it has been suggested and, in fact, FODMAPs may indeed be the major inducers of symptoms in individuals with supposed wheat intolerance. The potential risks of dietary manipulation such as creation of a dietary cripple or induction of an eating disorder should be kept in mind.

Dr. Anna Mae Diehl at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., spoke about the diagnosis, role of the microbiome, and the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). It was pointed out that most patients with NAFLD have benign progression although individuals with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), especially those with significant fibrosis, are at risk for developing cirrhosis, liver failure, and liver cancer. Therapeutic investigations undertaken to date have not sufficiently focused on improving fibrosis although several ongoing clinical trials are directed at this goal. Gut microbiome might be a new NAFLD diagnostic/therapeutic target because several recent animal studies have shown that gut microbiome may play a role in conferring susceptibility to liver injury, fibrosis, and cancer.

Dr. Lawrence J. Brandt at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, gave an update on fecal microbiota therapy (FMT). He highlighted that FMT has historic roots going back to the 4th century when Ge Hong described use of human fecal suspension to treat food poisoning or severe diarrhea. He made it clear that FMT should be offered only to those with recurrent Clostridium difficile infections (CDI), meeting selected criteria such as severe illness and prior treatment failures. The protocol for FMT in recurrent CDI includes careful selection of donor (may range from any healthy person, universal donor, or stool-bank product) and testing stool and blood of potential donors for any transmittable agents. A recent systematic review showed that the success rate for FMT in individuals with CDI is generally quite high (greater than 80%) but it may depend on the site of FMT – for example, if FMT is administered to duodenum/jejunum, the success rate is 86%, whereas if it is delivered to right colon/cecum, then the success rate can be as high as 93%. He highlighted the efficacy of FMT in severe, complicated CDI, which generally carries high morbidity and mortality. Practitioners offering FMT should carefully review the FDA guidance that was issued in March 2014. He noted that long-term consequences of FMT are not well understood and thus, risks versus benefits of FMT on a patient-by-patient basis must be carefully weighed.

Dr. Naga P. Chalasani is the David W. Crabb Professor and director of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Indiana University, Indianapolis. He has consulting agreements and receives research support from several pharmaceutical companies but none represent a conflict of interest for this activity.

This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the spring postgraduate course sessions held at DDW 2015.

Genetics and epigenetics in gastroenterology

Genetics in the context of disease causation refers to gene expression altered by DNA mutations. Epigenetics refers to gene expression altered without DNA mutations, but instead by other cellular mechanisms that will be described here. Together, genetic and epigenetic gene expression determine both physiologic and pathologic cellular processes and functions.

Many areas of gastroenterology are now known to involve these mechanisms as part of disease pathophysiology. The area most investigated in gastroenterology is perhaps colon cancer, which will be used as an example in describing clinically pertinent mechanisms and findings in both genetics and epigenetics.

Inherited DNA mutations of certain genes result in colon cancer susceptibility syndromes. Somatic mutations of many of the same genes are part of colon cancer pathogenesis in common or sporadic cases. Pertinent syndromes include familial adenomatous polyposis (APC gene), Lynch syndrome (mismatch repair genes [MMR]), MUTY-associated polyposis (MUTYH gene), Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (STK11 gene), juvenile polyposis (SMAD4 and BMPR1A genes), Cowden syndrome (PTEN gene), and variant polyposis (POLE, POLD1, and Gremm1 genes). For each of these syndromes, genetic testing is now an accepted part of clinical management for diagnosis and guidance as to who should receive more aggressive screening and surveillance for colon cancer prevention.

Acquired or somatic mutations of the same and other genes are involved in the process of benign to malignant transformation in the colon. Involved genes are often divided into three pathways, although there is much overlap between these pathways.

The first pathway is the chromosomal instability pathway that begins with acquired APC gene mutations of a colonocyte. These mutations are followed by the accumulation of additional mutations as normal cells progress to forming adenomatous polyps and then cancer. Such genes include KRAS, SMAD, TP53, PTEN, PI3KCA, and perhaps others. The second pathway involves acquired mutations of the mismatch repair genes early in the benign to malignant process, with mutations occurring especially in the MLH1 gene. It is called the microsatellite instability pathway. Different genes are then involved through mutation in this pathway to cancer. These include TGF beta, BAX, IGF2R, and others. The third pathway is called CIMP for “CpG island methylation phenotype.” It is actually an epigenetic pathway and involves the accumulation of mutations in yet other genes including MLH1, WRN, p16, RARB2, BRAF, and possibly many others, and gives rise to both adenomatous polyps and sessile serrated polyps.

Clinical relevance of somatic mutations of the genes in these three pathways is already informing clinical practice. Cancers with MMR gene mutations, for example, exhibit a better prognosis than other colon cancers but a decreased responsiveness to fluorouracil drugs. Tumors with KRAS or BRAF mutations have little or no response to EGFR-inhibitor drugs. Many of the genes in which acquired mutations occur are now interrogated as part of stool DNA screening tests.

Epigenetic processes change gene expression without DNA mutation and include three primary categories: DNA methylation, histone and chromatin changes, and microRNA changes.

Half of human genes have promotor regions rich in CpG islands. When methylation occurs in these CpG islands, gene expression is usually inhibited. This is the main mechanism of the CIMP pathway and in turn affects numerous cell functions important to cancer pathogenesis. Histones are proteins around which DNA coils. The proteins with coiled DNA are called chromatin units. Histones have protein tails that repress gene transcription when acetylation and specific methylations occur. Some histone proteins have already been observed to be overexpressed in colon cancer. MicroRNAs are short noncoding RNAs that induce gene repression in up to 30% of genes. Altered MicroRNA expression has been observed in many colon cancer–associated genes, and specific microRNA patterns have characterized certain colon cancers.

Epigenetic cancer markers are only beginning to be understood but are being examined for use in early detection and prognosis, tumor subclassifications, following the effectiveness of chemotherapy, and providing targets of intervention.

In summary, colon cancer genetics has provided genetic testing for inherited syndromes and guides to therapy with acquired mutations, while epigenetic mechanisms have the potential of being important to many areas of cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Dr. Burt is professor of medicine and holder of the Barnes Presidential Endowed Chair in Medicine at the Huntsman Cancer Institute and the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. He has consulted for Myriad Genetics. His comments were made during the ASGE and AGA joint Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Genetics in the context of disease causation refers to gene expression altered by DNA mutations. Epigenetics refers to gene expression altered without DNA mutations, but instead by other cellular mechanisms that will be described here. Together, genetic and epigenetic gene expression determine both physiologic and pathologic cellular processes and functions.

Many areas of gastroenterology are now known to involve these mechanisms as part of disease pathophysiology. The area most investigated in gastroenterology is perhaps colon cancer, which will be used as an example in describing clinically pertinent mechanisms and findings in both genetics and epigenetics.

Inherited DNA mutations of certain genes result in colon cancer susceptibility syndromes. Somatic mutations of many of the same genes are part of colon cancer pathogenesis in common or sporadic cases. Pertinent syndromes include familial adenomatous polyposis (APC gene), Lynch syndrome (mismatch repair genes [MMR]), MUTY-associated polyposis (MUTYH gene), Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (STK11 gene), juvenile polyposis (SMAD4 and BMPR1A genes), Cowden syndrome (PTEN gene), and variant polyposis (POLE, POLD1, and Gremm1 genes). For each of these syndromes, genetic testing is now an accepted part of clinical management for diagnosis and guidance as to who should receive more aggressive screening and surveillance for colon cancer prevention.

Acquired or somatic mutations of the same and other genes are involved in the process of benign to malignant transformation in the colon. Involved genes are often divided into three pathways, although there is much overlap between these pathways.

The first pathway is the chromosomal instability pathway that begins with acquired APC gene mutations of a colonocyte. These mutations are followed by the accumulation of additional mutations as normal cells progress to forming adenomatous polyps and then cancer. Such genes include KRAS, SMAD, TP53, PTEN, PI3KCA, and perhaps others. The second pathway involves acquired mutations of the mismatch repair genes early in the benign to malignant process, with mutations occurring especially in the MLH1 gene. It is called the microsatellite instability pathway. Different genes are then involved through mutation in this pathway to cancer. These include TGF beta, BAX, IGF2R, and others. The third pathway is called CIMP for “CpG island methylation phenotype.” It is actually an epigenetic pathway and involves the accumulation of mutations in yet other genes including MLH1, WRN, p16, RARB2, BRAF, and possibly many others, and gives rise to both adenomatous polyps and sessile serrated polyps.

Clinical relevance of somatic mutations of the genes in these three pathways is already informing clinical practice. Cancers with MMR gene mutations, for example, exhibit a better prognosis than other colon cancers but a decreased responsiveness to fluorouracil drugs. Tumors with KRAS or BRAF mutations have little or no response to EGFR-inhibitor drugs. Many of the genes in which acquired mutations occur are now interrogated as part of stool DNA screening tests.

Epigenetic processes change gene expression without DNA mutation and include three primary categories: DNA methylation, histone and chromatin changes, and microRNA changes.

Half of human genes have promotor regions rich in CpG islands. When methylation occurs in these CpG islands, gene expression is usually inhibited. This is the main mechanism of the CIMP pathway and in turn affects numerous cell functions important to cancer pathogenesis. Histones are proteins around which DNA coils. The proteins with coiled DNA are called chromatin units. Histones have protein tails that repress gene transcription when acetylation and specific methylations occur. Some histone proteins have already been observed to be overexpressed in colon cancer. MicroRNAs are short noncoding RNAs that induce gene repression in up to 30% of genes. Altered MicroRNA expression has been observed in many colon cancer–associated genes, and specific microRNA patterns have characterized certain colon cancers.

Epigenetic cancer markers are only beginning to be understood but are being examined for use in early detection and prognosis, tumor subclassifications, following the effectiveness of chemotherapy, and providing targets of intervention.

In summary, colon cancer genetics has provided genetic testing for inherited syndromes and guides to therapy with acquired mutations, while epigenetic mechanisms have the potential of being important to many areas of cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Dr. Burt is professor of medicine and holder of the Barnes Presidential Endowed Chair in Medicine at the Huntsman Cancer Institute and the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. He has consulted for Myriad Genetics. His comments were made during the ASGE and AGA joint Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Genetics in the context of disease causation refers to gene expression altered by DNA mutations. Epigenetics refers to gene expression altered without DNA mutations, but instead by other cellular mechanisms that will be described here. Together, genetic and epigenetic gene expression determine both physiologic and pathologic cellular processes and functions.

Many areas of gastroenterology are now known to involve these mechanisms as part of disease pathophysiology. The area most investigated in gastroenterology is perhaps colon cancer, which will be used as an example in describing clinically pertinent mechanisms and findings in both genetics and epigenetics.

Inherited DNA mutations of certain genes result in colon cancer susceptibility syndromes. Somatic mutations of many of the same genes are part of colon cancer pathogenesis in common or sporadic cases. Pertinent syndromes include familial adenomatous polyposis (APC gene), Lynch syndrome (mismatch repair genes [MMR]), MUTY-associated polyposis (MUTYH gene), Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (STK11 gene), juvenile polyposis (SMAD4 and BMPR1A genes), Cowden syndrome (PTEN gene), and variant polyposis (POLE, POLD1, and Gremm1 genes). For each of these syndromes, genetic testing is now an accepted part of clinical management for diagnosis and guidance as to who should receive more aggressive screening and surveillance for colon cancer prevention.

Acquired or somatic mutations of the same and other genes are involved in the process of benign to malignant transformation in the colon. Involved genes are often divided into three pathways, although there is much overlap between these pathways.

The first pathway is the chromosomal instability pathway that begins with acquired APC gene mutations of a colonocyte. These mutations are followed by the accumulation of additional mutations as normal cells progress to forming adenomatous polyps and then cancer. Such genes include KRAS, SMAD, TP53, PTEN, PI3KCA, and perhaps others. The second pathway involves acquired mutations of the mismatch repair genes early in the benign to malignant process, with mutations occurring especially in the MLH1 gene. It is called the microsatellite instability pathway. Different genes are then involved through mutation in this pathway to cancer. These include TGF beta, BAX, IGF2R, and others. The third pathway is called CIMP for “CpG island methylation phenotype.” It is actually an epigenetic pathway and involves the accumulation of mutations in yet other genes including MLH1, WRN, p16, RARB2, BRAF, and possibly many others, and gives rise to both adenomatous polyps and sessile serrated polyps.

Clinical relevance of somatic mutations of the genes in these three pathways is already informing clinical practice. Cancers with MMR gene mutations, for example, exhibit a better prognosis than other colon cancers but a decreased responsiveness to fluorouracil drugs. Tumors with KRAS or BRAF mutations have little or no response to EGFR-inhibitor drugs. Many of the genes in which acquired mutations occur are now interrogated as part of stool DNA screening tests.

Epigenetic processes change gene expression without DNA mutation and include three primary categories: DNA methylation, histone and chromatin changes, and microRNA changes.

Half of human genes have promotor regions rich in CpG islands. When methylation occurs in these CpG islands, gene expression is usually inhibited. This is the main mechanism of the CIMP pathway and in turn affects numerous cell functions important to cancer pathogenesis. Histones are proteins around which DNA coils. The proteins with coiled DNA are called chromatin units. Histones have protein tails that repress gene transcription when acetylation and specific methylations occur. Some histone proteins have already been observed to be overexpressed in colon cancer. MicroRNAs are short noncoding RNAs that induce gene repression in up to 30% of genes. Altered MicroRNA expression has been observed in many colon cancer–associated genes, and specific microRNA patterns have characterized certain colon cancers.

Epigenetic cancer markers are only beginning to be understood but are being examined for use in early detection and prognosis, tumor subclassifications, following the effectiveness of chemotherapy, and providing targets of intervention.

In summary, colon cancer genetics has provided genetic testing for inherited syndromes and guides to therapy with acquired mutations, while epigenetic mechanisms have the potential of being important to many areas of cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Dr. Burt is professor of medicine and holder of the Barnes Presidential Endowed Chair in Medicine at the Huntsman Cancer Institute and the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. He has consulted for Myriad Genetics. His comments were made during the ASGE and AGA joint Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

IBD surveillance: Quality not quantity

Optimizing colonoscopy quality in patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease involving the colon is important. Their risk for the development of colorectal cancer (CRC) and of interval CRC is significantly higher compared with the non–inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) population.

Most CRC cases in IBD are believed to arise from dysplasia, and thus, surveillance colonoscopy is recommended to detect dysplasia. Key factors that influence the success of surveillance colonoscopy in IBD patients include: 1) endoscopic recognition of dysplasia, 2) adequacy of mucosal sampling, 3) awareness of interfering anatomy, such as strictures and pseudopolyps, 4) appropriate differentiation of dysplastic lesions as endoscopically resectable, 5) complete removal of endoscopically resectable dysplasia, and 6) patient compliance.

Over a decade ago, we learned that most dysplasia discovered in patients with IBD is actually visible. The use of high-definition video-endoscopy and newer methods, such as chromoendoscopy with mucosal dye spraying, enhance the detection of dysplasia. Today, with the widespread use of newer technologies and techniques, the literature indicates that targeted biopsies of visible lesions account for approximately 90% of cases, whereas random biopsy (resulting in detection of an endoscopically invisible lesion) accounts for only 10% of cases of identified dysplasia.

The endoscopic recognition of dysplastic colorectal lesions may have important implications for the surveillance and management of dysplasia, and shift it away from the traditional random biopsy technique, where less than 0.1% of the colonic mucosal surface area is sampled, and from colectomy for any diagnosis of dysplasia.

Enhanced endoscopy techniques such as chromoendoscopy can have a substantial impact upon IBD surveillance, increasing the dysplasia detection rates, as well as informing management decisions. Chromoendoscopy, using a dye solution of either methylene blue or indigo carmine applied onto the colonic mucosa to enhance contrast during surveillance colonoscopy, is performed either in a pancolonic fashion to detect lesions or in a targeted fashion to allow for detailed viewing of an identified lesion (Figure 1).

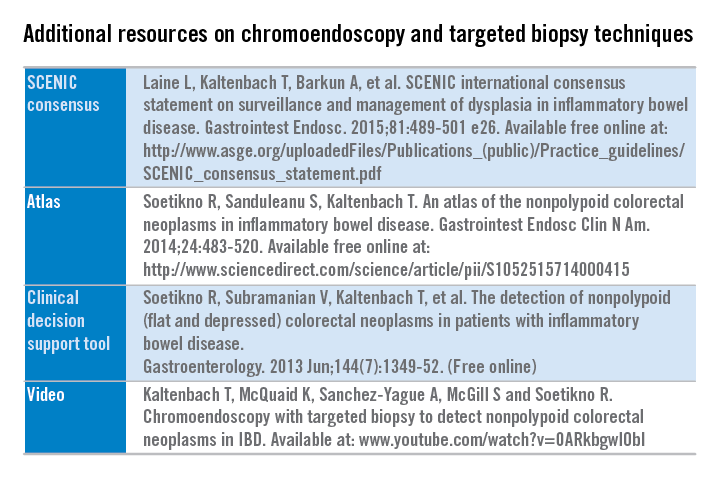

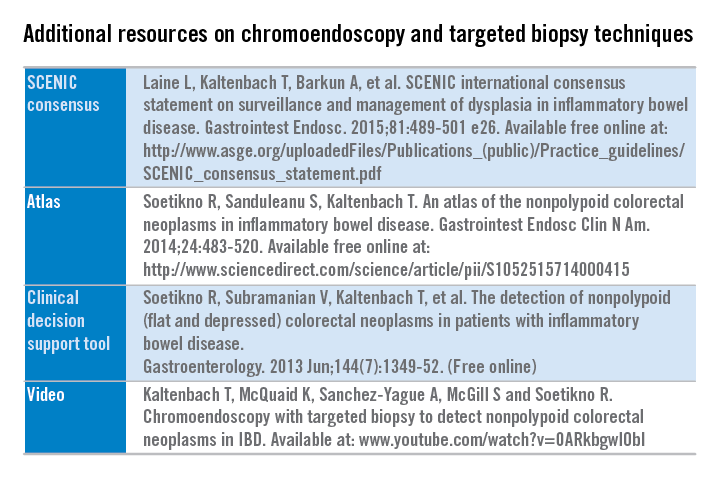

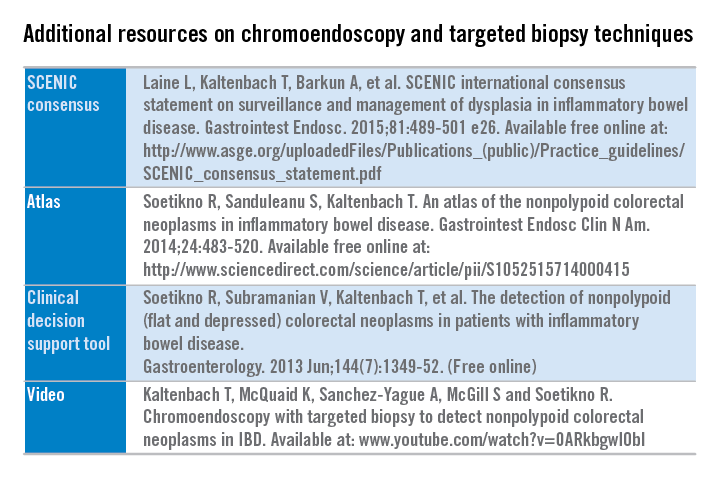

Additional resources are freely available detailing the technique and suggested steps to implement chromoendoscopy into practice. (See additional resources on chromoendoscopy and targeted biopsy techniques.)

An international multidisciplinary group, SCENIC (Surveillance for Colorectal Endoscopic Neoplasia Detection and Management in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: International Consensus), which represents a wide spectrum of stakeholders and attitudes regarding IBD surveillance, sought to develop unifying consensus recommendations addressing two issues: 1) how should surveillance colonoscopy to detect dysplasia be performed, and 2) how should dysplasia identified at colonoscopy be managed. The SCENIC group adhered to suggested standards for guideline development from the Institute of Medicine and others and that incorporated the GRADE methodology. A systematic review was performed for each focused clinical question, followed by a review of a full synthesis of evidence by panelists.

SCENIC key summary recommendations

Detection

• High definition is recommended over standard definition for performance of surveillance colonoscopy.

• Routine performance of chromoendoscopy during IBD surveillance is suggested as an adjunct to high-definition colonoscopy.

• Narrowband imaging is not recommended as an alternative for high-definition, white-light colonoscopy or chromoendoscopy.

• No specific recommendation on performance of random biopsies was made in patients undergoing high-definition, white-light colonoscopy plus chromoendoscopy. The panel did not reach consensus on this topic because 60% of the panel members disagreed with performing random biopsies during chromoendoscopy, and a recommendation required 80% agreement or disagreement.

Management

• When dysplasia is detected, it should be characterized as “endoscopically resectable” or “nonendoscopically resectable” (The terms “dysplasia-associated lesion or mass (DALM),” “adenoma-like,” and “nonadenoma-like” should be abandoned).

• Visible dysplasia should be characterized according to the Paris classification polypoid or nonpolypoid, with modifications including the addition of terms for ulceration and border of the lesion.

• The term endoscopically resectable indicates that 1) distinct margins of the lesion could be identified, 2) the lesion appears to be completely removed on visual inspection after endoscopic resection, 3) histologic examination of the resected specimen is consistent with complete removal, and 4) biopsy specimens taken from mucosa immediately adjacent to the resection site are free of dysplasia on histologic examination.

• After complete removal of endoscopically resectable polypoid or nonpolypoid dysplasia, surveillance colonoscopy is recommended rather than colectomy.

• For patients with endoscopically invisible dysplasia (confirmed by a GI pathologist), referral is suggested to an endoscopist with expertise in IBD surveillance using chromoendoscopy with high-definition colonoscopy.

The SCENIC recommendations aim to optimize the detection and management of dysplasia in IBD patients. Future research in IBD surveillance should assess the potential for chromoendoscopy to improve risk stratification to elucidate optimal surveillance intervals, and the impact on CRC incidence and mortality. In addition, the role of resection of nonpolypoid dysplasia in the reduction in CRC incidence or need for colectomy requires further investigation.

Dr. Kaltenbach is a gastroenterologist at Veterans Affairs, and a clinical assistant professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. She has no conflicts of interest. Her comments were made during the ASGE and AGA joint Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Optimizing colonoscopy quality in patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease involving the colon is important. Their risk for the development of colorectal cancer (CRC) and of interval CRC is significantly higher compared with the non–inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) population.

Most CRC cases in IBD are believed to arise from dysplasia, and thus, surveillance colonoscopy is recommended to detect dysplasia. Key factors that influence the success of surveillance colonoscopy in IBD patients include: 1) endoscopic recognition of dysplasia, 2) adequacy of mucosal sampling, 3) awareness of interfering anatomy, such as strictures and pseudopolyps, 4) appropriate differentiation of dysplastic lesions as endoscopically resectable, 5) complete removal of endoscopically resectable dysplasia, and 6) patient compliance.

Over a decade ago, we learned that most dysplasia discovered in patients with IBD is actually visible. The use of high-definition video-endoscopy and newer methods, such as chromoendoscopy with mucosal dye spraying, enhance the detection of dysplasia. Today, with the widespread use of newer technologies and techniques, the literature indicates that targeted biopsies of visible lesions account for approximately 90% of cases, whereas random biopsy (resulting in detection of an endoscopically invisible lesion) accounts for only 10% of cases of identified dysplasia.

The endoscopic recognition of dysplastic colorectal lesions may have important implications for the surveillance and management of dysplasia, and shift it away from the traditional random biopsy technique, where less than 0.1% of the colonic mucosal surface area is sampled, and from colectomy for any diagnosis of dysplasia.

Enhanced endoscopy techniques such as chromoendoscopy can have a substantial impact upon IBD surveillance, increasing the dysplasia detection rates, as well as informing management decisions. Chromoendoscopy, using a dye solution of either methylene blue or indigo carmine applied onto the colonic mucosa to enhance contrast during surveillance colonoscopy, is performed either in a pancolonic fashion to detect lesions or in a targeted fashion to allow for detailed viewing of an identified lesion (Figure 1).

Additional resources are freely available detailing the technique and suggested steps to implement chromoendoscopy into practice. (See additional resources on chromoendoscopy and targeted biopsy techniques.)

An international multidisciplinary group, SCENIC (Surveillance for Colorectal Endoscopic Neoplasia Detection and Management in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: International Consensus), which represents a wide spectrum of stakeholders and attitudes regarding IBD surveillance, sought to develop unifying consensus recommendations addressing two issues: 1) how should surveillance colonoscopy to detect dysplasia be performed, and 2) how should dysplasia identified at colonoscopy be managed. The SCENIC group adhered to suggested standards for guideline development from the Institute of Medicine and others and that incorporated the GRADE methodology. A systematic review was performed for each focused clinical question, followed by a review of a full synthesis of evidence by panelists.

SCENIC key summary recommendations

Detection

• High definition is recommended over standard definition for performance of surveillance colonoscopy.

• Routine performance of chromoendoscopy during IBD surveillance is suggested as an adjunct to high-definition colonoscopy.

• Narrowband imaging is not recommended as an alternative for high-definition, white-light colonoscopy or chromoendoscopy.

• No specific recommendation on performance of random biopsies was made in patients undergoing high-definition, white-light colonoscopy plus chromoendoscopy. The panel did not reach consensus on this topic because 60% of the panel members disagreed with performing random biopsies during chromoendoscopy, and a recommendation required 80% agreement or disagreement.

Management

• When dysplasia is detected, it should be characterized as “endoscopically resectable” or “nonendoscopically resectable” (The terms “dysplasia-associated lesion or mass (DALM),” “adenoma-like,” and “nonadenoma-like” should be abandoned).

• Visible dysplasia should be characterized according to the Paris classification polypoid or nonpolypoid, with modifications including the addition of terms for ulceration and border of the lesion.

• The term endoscopically resectable indicates that 1) distinct margins of the lesion could be identified, 2) the lesion appears to be completely removed on visual inspection after endoscopic resection, 3) histologic examination of the resected specimen is consistent with complete removal, and 4) biopsy specimens taken from mucosa immediately adjacent to the resection site are free of dysplasia on histologic examination.

• After complete removal of endoscopically resectable polypoid or nonpolypoid dysplasia, surveillance colonoscopy is recommended rather than colectomy.

• For patients with endoscopically invisible dysplasia (confirmed by a GI pathologist), referral is suggested to an endoscopist with expertise in IBD surveillance using chromoendoscopy with high-definition colonoscopy.

The SCENIC recommendations aim to optimize the detection and management of dysplasia in IBD patients. Future research in IBD surveillance should assess the potential for chromoendoscopy to improve risk stratification to elucidate optimal surveillance intervals, and the impact on CRC incidence and mortality. In addition, the role of resection of nonpolypoid dysplasia in the reduction in CRC incidence or need for colectomy requires further investigation.

Dr. Kaltenbach is a gastroenterologist at Veterans Affairs, and a clinical assistant professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. She has no conflicts of interest. Her comments were made during the ASGE and AGA joint Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Optimizing colonoscopy quality in patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease involving the colon is important. Their risk for the development of colorectal cancer (CRC) and of interval CRC is significantly higher compared with the non–inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) population.

Most CRC cases in IBD are believed to arise from dysplasia, and thus, surveillance colonoscopy is recommended to detect dysplasia. Key factors that influence the success of surveillance colonoscopy in IBD patients include: 1) endoscopic recognition of dysplasia, 2) adequacy of mucosal sampling, 3) awareness of interfering anatomy, such as strictures and pseudopolyps, 4) appropriate differentiation of dysplastic lesions as endoscopically resectable, 5) complete removal of endoscopically resectable dysplasia, and 6) patient compliance.

Over a decade ago, we learned that most dysplasia discovered in patients with IBD is actually visible. The use of high-definition video-endoscopy and newer methods, such as chromoendoscopy with mucosal dye spraying, enhance the detection of dysplasia. Today, with the widespread use of newer technologies and techniques, the literature indicates that targeted biopsies of visible lesions account for approximately 90% of cases, whereas random biopsy (resulting in detection of an endoscopically invisible lesion) accounts for only 10% of cases of identified dysplasia.

The endoscopic recognition of dysplastic colorectal lesions may have important implications for the surveillance and management of dysplasia, and shift it away from the traditional random biopsy technique, where less than 0.1% of the colonic mucosal surface area is sampled, and from colectomy for any diagnosis of dysplasia.

Enhanced endoscopy techniques such as chromoendoscopy can have a substantial impact upon IBD surveillance, increasing the dysplasia detection rates, as well as informing management decisions. Chromoendoscopy, using a dye solution of either methylene blue or indigo carmine applied onto the colonic mucosa to enhance contrast during surveillance colonoscopy, is performed either in a pancolonic fashion to detect lesions or in a targeted fashion to allow for detailed viewing of an identified lesion (Figure 1).

Additional resources are freely available detailing the technique and suggested steps to implement chromoendoscopy into practice. (See additional resources on chromoendoscopy and targeted biopsy techniques.)

An international multidisciplinary group, SCENIC (Surveillance for Colorectal Endoscopic Neoplasia Detection and Management in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: International Consensus), which represents a wide spectrum of stakeholders and attitudes regarding IBD surveillance, sought to develop unifying consensus recommendations addressing two issues: 1) how should surveillance colonoscopy to detect dysplasia be performed, and 2) how should dysplasia identified at colonoscopy be managed. The SCENIC group adhered to suggested standards for guideline development from the Institute of Medicine and others and that incorporated the GRADE methodology. A systematic review was performed for each focused clinical question, followed by a review of a full synthesis of evidence by panelists.

SCENIC key summary recommendations

Detection

• High definition is recommended over standard definition for performance of surveillance colonoscopy.

• Routine performance of chromoendoscopy during IBD surveillance is suggested as an adjunct to high-definition colonoscopy.

• Narrowband imaging is not recommended as an alternative for high-definition, white-light colonoscopy or chromoendoscopy.

• No specific recommendation on performance of random biopsies was made in patients undergoing high-definition, white-light colonoscopy plus chromoendoscopy. The panel did not reach consensus on this topic because 60% of the panel members disagreed with performing random biopsies during chromoendoscopy, and a recommendation required 80% agreement or disagreement.

Management

• When dysplasia is detected, it should be characterized as “endoscopically resectable” or “nonendoscopically resectable” (The terms “dysplasia-associated lesion or mass (DALM),” “adenoma-like,” and “nonadenoma-like” should be abandoned).

• Visible dysplasia should be characterized according to the Paris classification polypoid or nonpolypoid, with modifications including the addition of terms for ulceration and border of the lesion.

• The term endoscopically resectable indicates that 1) distinct margins of the lesion could be identified, 2) the lesion appears to be completely removed on visual inspection after endoscopic resection, 3) histologic examination of the resected specimen is consistent with complete removal, and 4) biopsy specimens taken from mucosa immediately adjacent to the resection site are free of dysplasia on histologic examination.

• After complete removal of endoscopically resectable polypoid or nonpolypoid dysplasia, surveillance colonoscopy is recommended rather than colectomy.

• For patients with endoscopically invisible dysplasia (confirmed by a GI pathologist), referral is suggested to an endoscopist with expertise in IBD surveillance using chromoendoscopy with high-definition colonoscopy.

The SCENIC recommendations aim to optimize the detection and management of dysplasia in IBD patients. Future research in IBD surveillance should assess the potential for chromoendoscopy to improve risk stratification to elucidate optimal surveillance intervals, and the impact on CRC incidence and mortality. In addition, the role of resection of nonpolypoid dysplasia in the reduction in CRC incidence or need for colectomy requires further investigation.

Dr. Kaltenbach is a gastroenterologist at Veterans Affairs, and a clinical assistant professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. She has no conflicts of interest. Her comments were made during the ASGE and AGA joint Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Bugs and drugs in inflammatory bowel disease

Important new themes are whether we can actually find a cure for inflammatory bowel disease and, in particular, whether there are common pathogenetic mechanisms leading to Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Are Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis infectious diseases? If the answer to that question is ‘yes,’ then eliminating that “pathogen” would turn off the immune response. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis share common genetic origins with the majority of genes shared between both disorders. Indeed, 110 of the 163 confirmed loci in IBD are common between the two disorders (Nature 2012;491:119–24).

In addition to there being many genes contributing even a small amount to the development of IBD, there are also some genetic pathways that have a far more impactful role in IBD. By studying very-early-onset IBD, we have discovered that the IL-10 receptor pathway is very important in controlling intestinal inflammation, such that if you have a mutation in the receptor for IL-10 it can lead to very-early-onset IBD. Children who are born with these disorders can be treated with a hematopoietic bone marrow transplant. At this year’s Digestive Disease Week (DDW) in fact, there was the presentation of the ASTIC trial; it described patients having a prolonged remission after an autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

One of the big advances that has been made in terms of the treatment of IBD is based on an understanding of the pathogenetic pathways; in particular, there has been an increase in the number of medications that are currently available to treat IBD from a variety of different avenues. There was a recent publication describing an anti-sense treatment against SMAD7 in restoring TGF-beta signaling that produced a very rapid and profound improvement in the clinical symptoms of Crohn’s disease. We await more data on that particular compound.