User login

Group identifies malaria resistance locus

outside of Nairobi, Kenya

Photo by Gabrielle Tenenbaum

Researchers say they have identified genetic variants that protect African children from developing severe malaria, in some cases nearly halving a child’s chance of developing the disease.

The variants are at a locus located next to a cluster of genes that are responsible for creating the receptors the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum uses to infect red blood cells.

The researchers described their findings in a letter to Nature.

“The risk of developing severe malaria turns out to be strongly linked to the process by which the malaria parasite gains entry to the human red blood cell,” said Dr Kevin Marsh, of the Kemri-Wellcome Research Programme in Kilifi, Kenya.

“This study strengthens the argument for focusing on the malaria side of the parasite-human interaction in our search for new vaccine candidates.”

For this study, Dr Marsh and his colleagues analyzed data from 8 different African countries: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, The Gambia, and Tanzania.

They compared the DNA of 5633 children with severe malaria and the DNA of 5919 children without severe malaria. The researchers then replicated their key findings in a further 14,000 children.

The locus the team identified is near a cluster of genes that code for glycophorins, which are involved in P falciparum’s invasion of red blood cells.

The researchers also found an allele that was common among children in Kenya. Having this allele reduced the risk of severe malaria by about 40% in Kenyan children, with a slightly smaller effect across all the other populations studied.

The team said this difference between populations could be due to the genetic features of the local malaria parasite in East Africa.

Balancing selection

The newly identified malaria resistance locus lies within a region of the genome where humans and chimpanzees have been known to share particular combinations of haplotypes.

This indicates that some of the variation seen in contemporary humans has been present for millions of years. The finding also suggests that this region of the genome is the subject of balancing selection.

Balancing selection happens when a particular genetic variant evolves because it confers health benefits, but it is carried by only a proportion of the population because it also has damaging consequences.

“These findings indicate that balancing selection and resistance to malaria are deeply intertwined themes in our ancient evolutionary history,” said Dr Dominic Kwiatkowski, of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, UK.

“This new resistance locus is particularly interesting because it lies so close to genes that are gatekeepers for the malaria parasite’s invasion machinery. We now need to drill down at this locus to characterize these complex patterns of genetic variation more precisely and to understand the molecular mechanisms by which they act.” ![]()

outside of Nairobi, Kenya

Photo by Gabrielle Tenenbaum

Researchers say they have identified genetic variants that protect African children from developing severe malaria, in some cases nearly halving a child’s chance of developing the disease.

The variants are at a locus located next to a cluster of genes that are responsible for creating the receptors the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum uses to infect red blood cells.

The researchers described their findings in a letter to Nature.

“The risk of developing severe malaria turns out to be strongly linked to the process by which the malaria parasite gains entry to the human red blood cell,” said Dr Kevin Marsh, of the Kemri-Wellcome Research Programme in Kilifi, Kenya.

“This study strengthens the argument for focusing on the malaria side of the parasite-human interaction in our search for new vaccine candidates.”

For this study, Dr Marsh and his colleagues analyzed data from 8 different African countries: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, The Gambia, and Tanzania.

They compared the DNA of 5633 children with severe malaria and the DNA of 5919 children without severe malaria. The researchers then replicated their key findings in a further 14,000 children.

The locus the team identified is near a cluster of genes that code for glycophorins, which are involved in P falciparum’s invasion of red blood cells.

The researchers also found an allele that was common among children in Kenya. Having this allele reduced the risk of severe malaria by about 40% in Kenyan children, with a slightly smaller effect across all the other populations studied.

The team said this difference between populations could be due to the genetic features of the local malaria parasite in East Africa.

Balancing selection

The newly identified malaria resistance locus lies within a region of the genome where humans and chimpanzees have been known to share particular combinations of haplotypes.

This indicates that some of the variation seen in contemporary humans has been present for millions of years. The finding also suggests that this region of the genome is the subject of balancing selection.

Balancing selection happens when a particular genetic variant evolves because it confers health benefits, but it is carried by only a proportion of the population because it also has damaging consequences.

“These findings indicate that balancing selection and resistance to malaria are deeply intertwined themes in our ancient evolutionary history,” said Dr Dominic Kwiatkowski, of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, UK.

“This new resistance locus is particularly interesting because it lies so close to genes that are gatekeepers for the malaria parasite’s invasion machinery. We now need to drill down at this locus to characterize these complex patterns of genetic variation more precisely and to understand the molecular mechanisms by which they act.” ![]()

outside of Nairobi, Kenya

Photo by Gabrielle Tenenbaum

Researchers say they have identified genetic variants that protect African children from developing severe malaria, in some cases nearly halving a child’s chance of developing the disease.

The variants are at a locus located next to a cluster of genes that are responsible for creating the receptors the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum uses to infect red blood cells.

The researchers described their findings in a letter to Nature.

“The risk of developing severe malaria turns out to be strongly linked to the process by which the malaria parasite gains entry to the human red blood cell,” said Dr Kevin Marsh, of the Kemri-Wellcome Research Programme in Kilifi, Kenya.

“This study strengthens the argument for focusing on the malaria side of the parasite-human interaction in our search for new vaccine candidates.”

For this study, Dr Marsh and his colleagues analyzed data from 8 different African countries: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, The Gambia, and Tanzania.

They compared the DNA of 5633 children with severe malaria and the DNA of 5919 children without severe malaria. The researchers then replicated their key findings in a further 14,000 children.

The locus the team identified is near a cluster of genes that code for glycophorins, which are involved in P falciparum’s invasion of red blood cells.

The researchers also found an allele that was common among children in Kenya. Having this allele reduced the risk of severe malaria by about 40% in Kenyan children, with a slightly smaller effect across all the other populations studied.

The team said this difference between populations could be due to the genetic features of the local malaria parasite in East Africa.

Balancing selection

The newly identified malaria resistance locus lies within a region of the genome where humans and chimpanzees have been known to share particular combinations of haplotypes.

This indicates that some of the variation seen in contemporary humans has been present for millions of years. The finding also suggests that this region of the genome is the subject of balancing selection.

Balancing selection happens when a particular genetic variant evolves because it confers health benefits, but it is carried by only a proportion of the population because it also has damaging consequences.

“These findings indicate that balancing selection and resistance to malaria are deeply intertwined themes in our ancient evolutionary history,” said Dr Dominic Kwiatkowski, of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, UK.

“This new resistance locus is particularly interesting because it lies so close to genes that are gatekeepers for the malaria parasite’s invasion machinery. We now need to drill down at this locus to characterize these complex patterns of genetic variation more precisely and to understand the molecular mechanisms by which they act.” ![]()

Investigating Unstable Thyroid Function

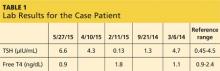

A 43-year-old man presents for his thyroid checkup. He has known hypothyroidism secondary to Hashimoto thyroiditis, also known as chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. He is taking levothyroxine (LT4) 250 μg (two 125-μg tablets once per day). Review of his prior lab results and notes (see Table 1) reveals frequent dose changes (about every three to six months) and a high dosage of LT4, considering his weight (185 lb).

Patients with little or no residual thyroid function require replacement doses of LT4 at approximately 1.6 μg/kg/d, based on lean body weight.1 Since the case patient weighs 84 kg, the expected LT4 dosage would be around 125 to 150 μg/d.

This patient requires a significantly higher dose than expected, and his thyroid levels are fluctuating. These facts should trigger further investigation.

Important historical questions I consider when patients have frequent or significant fluctuations in TSH include

• Are you consistent in taking your medication?

• How do you take your thyroid medication?

• Are you taking any iron supplements, vitamins with iron, or contraceptive pills containing iron?

• Has there been any change in your other medication regimen(s) or medical condition(s)?

• Did you change pharmacies, or did the shape or color of your pill change?

• Have you experienced significant weight changes?

• Do you have any gastrointestinal complaints (nausea/vomiting/diarrhea/bloating)?

MEDICATION ADHERENCE

It is well known but still puzzling to hear that, overall, patients’ medication adherence is merely 50%.2 It is very important that you verify whether your patient is taking his/her medication consistently. Rather than asking “Are you taking your medications?” (to which they are more likely to answer “yes”), I ask “How many pills do you miss in a given week or month?”

For those who have a hard time remembering to take their medication on a regular basis, I recommend setting up a routine: Keep the medication at their bedside and take it first thing upon awakening, or place it beside the toothpaste so they see it every time they brush their teeth in the morning. Another option is of course to set up an alarm as a reminder.

Continue for rules for taking hypothyroid >>

RULES FOR TAKING HYPOTHYROID MEDICATIONS

Thyroid hormone replacement has a narrow therapeutic index, and a subtle change in dosage can significantly alter the therapeutic target. Hypothyroid medications are absorbed in the jejunum/ileum, and an acidic pH in the stomach is optimal for thyroid absorption.3 Therefore, taking the medication on an empty stomach (fasting) with a full glass of water and waiting at least one hour before breakfast is recommended, if possible. An alternate option is to take it at bedtime, at least three hours after the last meal. Taking medication along with food, especially high-fiber and soy products, can decrease absorption of thyroid hormone, which may result in an unstable thyroid function test.

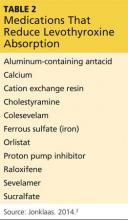

There are supplements and medications that can decrease hypothyroid medication absorption; it is recommended that patients separate these medications by four hours or more in order to minimize this interference. A full list is available in Table 2, but the most commonly encountered are iron supplements, calcium supplements, and proton pump inhibitors.2

In many patients—especially the elderly and those with multiple comorbidities that require polypharmacy—it can be very challenging, if not impossible, to isolate thyroid medication. For these patients, recommend that they be “consistent” with their routine to ensure they achieve a similar absorption rate each time. For example, a patient’s hypothyroid medication absorption might be reduced by 50% by taking it with omeprazole, but as long as the patient consistently takes the medication that way, she can have stable thyroid function.

NEW MEDICATION REGIMEN OR MEDICAL CONDITION

In addition to medications that can interfere with the absorption of thyroid hormone replacement, there are those that affect levels of thyroxine-binding globulin. This affects the bioavailability of thyroid hormones and alters thyroid status.

Thyroid hormones such as thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) are predominantly bound to carrier proteins, and < 1% is unbound (so-called free hormones). Changes in thyroid-binding proteins can alter free hormone levels and thereby change TSH levels. In disease-free euthyroid subjects, the body can compensate by adjusting hormone production for changes in binding proteins to keep the free hormone levels within normal ranges. However, patients who are at or near full replacement doses of hypothyroid medication cannot adjust to the changes.

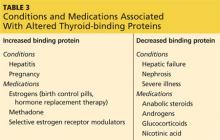

In patients with hypothyroidism who are taking thyroid hormone replacement, medications or conditions that increase binding proteins will decrease free hormones (by increasing bound hormones) and thereby raise TSH (hypothyroid state). Vice versa, medications and conditions that decrease binding protein will increase free hormones (by decreasing bound hormones) and thereby lower TSH (thyrotoxic state). Table 3 lists commonly encountered medications and conditions associated with altered thyroid-binding proteins.1

It is important to consider pregnancy in women of childbearing age whose TSH has risen for no apparent reason, as their thyroid levels should be maintained in a narrow therapeutic range to prevent fetal complications. Details on thyroid disease during pregnancy can be found in the April 2015 Endocrine Consult, “Managing Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy.”

In women treated for hypothyroidism, starting or discontinuing estrogen-containing medications (birth control pills or hormone replacement therapy) often results in changes in thyroid status. It is a good practice to inform the patient about these changes and to recheck her thyroid labs four to eight weeks after she starts or discontinues estrogen, adjusting the dose if needed.

Continue for changes in manufacturer/brand >>

CHANGES IN MANUFACTURER/BRAND

There are currently multiple brands and generic manufacturers supplying hypothyroid medications and reports that absorption rates and bioavailability vary among them.2 Switching products can result in changes in thyroid status and in TSH levels.

Once a patient has reached euthyroid status, it is imperative to stay on the same dose from the same manufacturer. This may be challenging, as it can be affected by the patient’s insurance carrier, policy changes, or even a change in the pharmacy’s medication supplier. Although patients are supposed to be informed by the pharmacy when the manufacturer is being changed, you may want to educate them to check the shape, color, and dose of their pills and also verify that the manufacturer listed on the bottle is consistent each time they refill their hypothyroid medications. This is especially important for those who require a very narrow TSH target, such as young children, thyroid cancer patients, pregnant women, and frail patients.3

WEIGHT CHANGES

As mentioned, thyroid medications are weight-based, and big changes in weight can lead to changes in thyroid function studies. It is the lean body mass, rather than total body weight, that will affect the thyroid requirement.3 A quick review of the patient’s weight history needs to be done when thyroid function test results have changed.

GASTROINTESTINAL DISTURBANCES

Hypothyroid medications are absorbed in the small intestine, and gastric acidity levels have an impact on absorption. Any acute or chronic conditions that affect these areas can alter medication absorption quite significantly. Commonly encountered diseases and conditions are H pylori–related gastritis, atrophic gastritis, celiac disease, and lactose intolerance. Treating these diseases and conditions can improve medication absorption.

I went through the list with the patient, but there was no applicable scenario. I adjusted his medication but went ahead and tested for tissue transglutaminase antibody IgA to rule out celiac disease; results came back mildly positive. The patient was referred to a gastroenterologist, who performed a small intestine biopsy for definitive diagnosis. This revealed “severe” celiac disease. A strict gluten-free diet was started, and the patient’s LT4 dose was adjusted, with regular monitoring, down to 150 μg/d.

Common symptoms of celiac disease include bloating, abdominal pain, and loose stool after consumption of gluten-containing meals. It should be noted that this patient denied all these symptoms, even though he was asked specifically about them. After he started a gluten-free diet, he reported that he actually felt “very calm” in his abdomen and realized he did have symptoms of celiac disease—but he’d had them for so long that he considered it normal. As is often the case, presence of symptoms would raise suspicion ... but lack of symptoms (or report thereof) does not rule out the disease.

CONCLUSION

Most patients with hypothyroidism are fairly well managed with relatively stable medication dosages, but there are subsets of patients who struggle to maintain euthyroid range. The latter require frequent office visits and dosage changes. Carefully reviewing the list of possible reasons for thyroid level changes can improve stability and patient quality of life, prevent complications of fluctuating thyroid levels, and reduce medical costs, such as repeated labs and frequent clinic visits.

REFERENCES

1. Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Thyroid Association Taskforce on Hypothyroidism in Adults. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults [published correction appears in Endocr Pract. 2013;19(1):175]. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(6):988-1028.

2. Sabate E. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003.

3. Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, et al; American Thyroid Association Task Force on Thyroid Hormone Replacement. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism. Thyroid. 2014;24(12):1670-1751.

A 43-year-old man presents for his thyroid checkup. He has known hypothyroidism secondary to Hashimoto thyroiditis, also known as chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. He is taking levothyroxine (LT4) 250 μg (two 125-μg tablets once per day). Review of his prior lab results and notes (see Table 1) reveals frequent dose changes (about every three to six months) and a high dosage of LT4, considering his weight (185 lb).

Patients with little or no residual thyroid function require replacement doses of LT4 at approximately 1.6 μg/kg/d, based on lean body weight.1 Since the case patient weighs 84 kg, the expected LT4 dosage would be around 125 to 150 μg/d.

This patient requires a significantly higher dose than expected, and his thyroid levels are fluctuating. These facts should trigger further investigation.

Important historical questions I consider when patients have frequent or significant fluctuations in TSH include

• Are you consistent in taking your medication?

• How do you take your thyroid medication?

• Are you taking any iron supplements, vitamins with iron, or contraceptive pills containing iron?

• Has there been any change in your other medication regimen(s) or medical condition(s)?

• Did you change pharmacies, or did the shape or color of your pill change?

• Have you experienced significant weight changes?

• Do you have any gastrointestinal complaints (nausea/vomiting/diarrhea/bloating)?

MEDICATION ADHERENCE

It is well known but still puzzling to hear that, overall, patients’ medication adherence is merely 50%.2 It is very important that you verify whether your patient is taking his/her medication consistently. Rather than asking “Are you taking your medications?” (to which they are more likely to answer “yes”), I ask “How many pills do you miss in a given week or month?”

For those who have a hard time remembering to take their medication on a regular basis, I recommend setting up a routine: Keep the medication at their bedside and take it first thing upon awakening, or place it beside the toothpaste so they see it every time they brush their teeth in the morning. Another option is of course to set up an alarm as a reminder.

Continue for rules for taking hypothyroid >>

RULES FOR TAKING HYPOTHYROID MEDICATIONS

Thyroid hormone replacement has a narrow therapeutic index, and a subtle change in dosage can significantly alter the therapeutic target. Hypothyroid medications are absorbed in the jejunum/ileum, and an acidic pH in the stomach is optimal for thyroid absorption.3 Therefore, taking the medication on an empty stomach (fasting) with a full glass of water and waiting at least one hour before breakfast is recommended, if possible. An alternate option is to take it at bedtime, at least three hours after the last meal. Taking medication along with food, especially high-fiber and soy products, can decrease absorption of thyroid hormone, which may result in an unstable thyroid function test.

There are supplements and medications that can decrease hypothyroid medication absorption; it is recommended that patients separate these medications by four hours or more in order to minimize this interference. A full list is available in Table 2, but the most commonly encountered are iron supplements, calcium supplements, and proton pump inhibitors.2

In many patients—especially the elderly and those with multiple comorbidities that require polypharmacy—it can be very challenging, if not impossible, to isolate thyroid medication. For these patients, recommend that they be “consistent” with their routine to ensure they achieve a similar absorption rate each time. For example, a patient’s hypothyroid medication absorption might be reduced by 50% by taking it with omeprazole, but as long as the patient consistently takes the medication that way, she can have stable thyroid function.

NEW MEDICATION REGIMEN OR MEDICAL CONDITION

In addition to medications that can interfere with the absorption of thyroid hormone replacement, there are those that affect levels of thyroxine-binding globulin. This affects the bioavailability of thyroid hormones and alters thyroid status.

Thyroid hormones such as thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) are predominantly bound to carrier proteins, and < 1% is unbound (so-called free hormones). Changes in thyroid-binding proteins can alter free hormone levels and thereby change TSH levels. In disease-free euthyroid subjects, the body can compensate by adjusting hormone production for changes in binding proteins to keep the free hormone levels within normal ranges. However, patients who are at or near full replacement doses of hypothyroid medication cannot adjust to the changes.

In patients with hypothyroidism who are taking thyroid hormone replacement, medications or conditions that increase binding proteins will decrease free hormones (by increasing bound hormones) and thereby raise TSH (hypothyroid state). Vice versa, medications and conditions that decrease binding protein will increase free hormones (by decreasing bound hormones) and thereby lower TSH (thyrotoxic state). Table 3 lists commonly encountered medications and conditions associated with altered thyroid-binding proteins.1

It is important to consider pregnancy in women of childbearing age whose TSH has risen for no apparent reason, as their thyroid levels should be maintained in a narrow therapeutic range to prevent fetal complications. Details on thyroid disease during pregnancy can be found in the April 2015 Endocrine Consult, “Managing Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy.”

In women treated for hypothyroidism, starting or discontinuing estrogen-containing medications (birth control pills or hormone replacement therapy) often results in changes in thyroid status. It is a good practice to inform the patient about these changes and to recheck her thyroid labs four to eight weeks after she starts or discontinues estrogen, adjusting the dose if needed.

Continue for changes in manufacturer/brand >>

CHANGES IN MANUFACTURER/BRAND

There are currently multiple brands and generic manufacturers supplying hypothyroid medications and reports that absorption rates and bioavailability vary among them.2 Switching products can result in changes in thyroid status and in TSH levels.

Once a patient has reached euthyroid status, it is imperative to stay on the same dose from the same manufacturer. This may be challenging, as it can be affected by the patient’s insurance carrier, policy changes, or even a change in the pharmacy’s medication supplier. Although patients are supposed to be informed by the pharmacy when the manufacturer is being changed, you may want to educate them to check the shape, color, and dose of their pills and also verify that the manufacturer listed on the bottle is consistent each time they refill their hypothyroid medications. This is especially important for those who require a very narrow TSH target, such as young children, thyroid cancer patients, pregnant women, and frail patients.3

WEIGHT CHANGES

As mentioned, thyroid medications are weight-based, and big changes in weight can lead to changes in thyroid function studies. It is the lean body mass, rather than total body weight, that will affect the thyroid requirement.3 A quick review of the patient’s weight history needs to be done when thyroid function test results have changed.

GASTROINTESTINAL DISTURBANCES

Hypothyroid medications are absorbed in the small intestine, and gastric acidity levels have an impact on absorption. Any acute or chronic conditions that affect these areas can alter medication absorption quite significantly. Commonly encountered diseases and conditions are H pylori–related gastritis, atrophic gastritis, celiac disease, and lactose intolerance. Treating these diseases and conditions can improve medication absorption.

I went through the list with the patient, but there was no applicable scenario. I adjusted his medication but went ahead and tested for tissue transglutaminase antibody IgA to rule out celiac disease; results came back mildly positive. The patient was referred to a gastroenterologist, who performed a small intestine biopsy for definitive diagnosis. This revealed “severe” celiac disease. A strict gluten-free diet was started, and the patient’s LT4 dose was adjusted, with regular monitoring, down to 150 μg/d.

Common symptoms of celiac disease include bloating, abdominal pain, and loose stool after consumption of gluten-containing meals. It should be noted that this patient denied all these symptoms, even though he was asked specifically about them. After he started a gluten-free diet, he reported that he actually felt “very calm” in his abdomen and realized he did have symptoms of celiac disease—but he’d had them for so long that he considered it normal. As is often the case, presence of symptoms would raise suspicion ... but lack of symptoms (or report thereof) does not rule out the disease.

CONCLUSION

Most patients with hypothyroidism are fairly well managed with relatively stable medication dosages, but there are subsets of patients who struggle to maintain euthyroid range. The latter require frequent office visits and dosage changes. Carefully reviewing the list of possible reasons for thyroid level changes can improve stability and patient quality of life, prevent complications of fluctuating thyroid levels, and reduce medical costs, such as repeated labs and frequent clinic visits.

REFERENCES

1. Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Thyroid Association Taskforce on Hypothyroidism in Adults. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults [published correction appears in Endocr Pract. 2013;19(1):175]. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(6):988-1028.

2. Sabate E. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003.

3. Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, et al; American Thyroid Association Task Force on Thyroid Hormone Replacement. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism. Thyroid. 2014;24(12):1670-1751.

A 43-year-old man presents for his thyroid checkup. He has known hypothyroidism secondary to Hashimoto thyroiditis, also known as chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. He is taking levothyroxine (LT4) 250 μg (two 125-μg tablets once per day). Review of his prior lab results and notes (see Table 1) reveals frequent dose changes (about every three to six months) and a high dosage of LT4, considering his weight (185 lb).

Patients with little or no residual thyroid function require replacement doses of LT4 at approximately 1.6 μg/kg/d, based on lean body weight.1 Since the case patient weighs 84 kg, the expected LT4 dosage would be around 125 to 150 μg/d.

This patient requires a significantly higher dose than expected, and his thyroid levels are fluctuating. These facts should trigger further investigation.

Important historical questions I consider when patients have frequent or significant fluctuations in TSH include

• Are you consistent in taking your medication?

• How do you take your thyroid medication?

• Are you taking any iron supplements, vitamins with iron, or contraceptive pills containing iron?

• Has there been any change in your other medication regimen(s) or medical condition(s)?

• Did you change pharmacies, or did the shape or color of your pill change?

• Have you experienced significant weight changes?

• Do you have any gastrointestinal complaints (nausea/vomiting/diarrhea/bloating)?

MEDICATION ADHERENCE

It is well known but still puzzling to hear that, overall, patients’ medication adherence is merely 50%.2 It is very important that you verify whether your patient is taking his/her medication consistently. Rather than asking “Are you taking your medications?” (to which they are more likely to answer “yes”), I ask “How many pills do you miss in a given week or month?”

For those who have a hard time remembering to take their medication on a regular basis, I recommend setting up a routine: Keep the medication at their bedside and take it first thing upon awakening, or place it beside the toothpaste so they see it every time they brush their teeth in the morning. Another option is of course to set up an alarm as a reminder.

Continue for rules for taking hypothyroid >>

RULES FOR TAKING HYPOTHYROID MEDICATIONS

Thyroid hormone replacement has a narrow therapeutic index, and a subtle change in dosage can significantly alter the therapeutic target. Hypothyroid medications are absorbed in the jejunum/ileum, and an acidic pH in the stomach is optimal for thyroid absorption.3 Therefore, taking the medication on an empty stomach (fasting) with a full glass of water and waiting at least one hour before breakfast is recommended, if possible. An alternate option is to take it at bedtime, at least three hours after the last meal. Taking medication along with food, especially high-fiber and soy products, can decrease absorption of thyroid hormone, which may result in an unstable thyroid function test.

There are supplements and medications that can decrease hypothyroid medication absorption; it is recommended that patients separate these medications by four hours or more in order to minimize this interference. A full list is available in Table 2, but the most commonly encountered are iron supplements, calcium supplements, and proton pump inhibitors.2

In many patients—especially the elderly and those with multiple comorbidities that require polypharmacy—it can be very challenging, if not impossible, to isolate thyroid medication. For these patients, recommend that they be “consistent” with their routine to ensure they achieve a similar absorption rate each time. For example, a patient’s hypothyroid medication absorption might be reduced by 50% by taking it with omeprazole, but as long as the patient consistently takes the medication that way, she can have stable thyroid function.

NEW MEDICATION REGIMEN OR MEDICAL CONDITION

In addition to medications that can interfere with the absorption of thyroid hormone replacement, there are those that affect levels of thyroxine-binding globulin. This affects the bioavailability of thyroid hormones and alters thyroid status.

Thyroid hormones such as thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) are predominantly bound to carrier proteins, and < 1% is unbound (so-called free hormones). Changes in thyroid-binding proteins can alter free hormone levels and thereby change TSH levels. In disease-free euthyroid subjects, the body can compensate by adjusting hormone production for changes in binding proteins to keep the free hormone levels within normal ranges. However, patients who are at or near full replacement doses of hypothyroid medication cannot adjust to the changes.

In patients with hypothyroidism who are taking thyroid hormone replacement, medications or conditions that increase binding proteins will decrease free hormones (by increasing bound hormones) and thereby raise TSH (hypothyroid state). Vice versa, medications and conditions that decrease binding protein will increase free hormones (by decreasing bound hormones) and thereby lower TSH (thyrotoxic state). Table 3 lists commonly encountered medications and conditions associated with altered thyroid-binding proteins.1

It is important to consider pregnancy in women of childbearing age whose TSH has risen for no apparent reason, as their thyroid levels should be maintained in a narrow therapeutic range to prevent fetal complications. Details on thyroid disease during pregnancy can be found in the April 2015 Endocrine Consult, “Managing Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy.”

In women treated for hypothyroidism, starting or discontinuing estrogen-containing medications (birth control pills or hormone replacement therapy) often results in changes in thyroid status. It is a good practice to inform the patient about these changes and to recheck her thyroid labs four to eight weeks after she starts or discontinues estrogen, adjusting the dose if needed.

Continue for changes in manufacturer/brand >>

CHANGES IN MANUFACTURER/BRAND

There are currently multiple brands and generic manufacturers supplying hypothyroid medications and reports that absorption rates and bioavailability vary among them.2 Switching products can result in changes in thyroid status and in TSH levels.

Once a patient has reached euthyroid status, it is imperative to stay on the same dose from the same manufacturer. This may be challenging, as it can be affected by the patient’s insurance carrier, policy changes, or even a change in the pharmacy’s medication supplier. Although patients are supposed to be informed by the pharmacy when the manufacturer is being changed, you may want to educate them to check the shape, color, and dose of their pills and also verify that the manufacturer listed on the bottle is consistent each time they refill their hypothyroid medications. This is especially important for those who require a very narrow TSH target, such as young children, thyroid cancer patients, pregnant women, and frail patients.3

WEIGHT CHANGES

As mentioned, thyroid medications are weight-based, and big changes in weight can lead to changes in thyroid function studies. It is the lean body mass, rather than total body weight, that will affect the thyroid requirement.3 A quick review of the patient’s weight history needs to be done when thyroid function test results have changed.

GASTROINTESTINAL DISTURBANCES

Hypothyroid medications are absorbed in the small intestine, and gastric acidity levels have an impact on absorption. Any acute or chronic conditions that affect these areas can alter medication absorption quite significantly. Commonly encountered diseases and conditions are H pylori–related gastritis, atrophic gastritis, celiac disease, and lactose intolerance. Treating these diseases and conditions can improve medication absorption.

I went through the list with the patient, but there was no applicable scenario. I adjusted his medication but went ahead and tested for tissue transglutaminase antibody IgA to rule out celiac disease; results came back mildly positive. The patient was referred to a gastroenterologist, who performed a small intestine biopsy for definitive diagnosis. This revealed “severe” celiac disease. A strict gluten-free diet was started, and the patient’s LT4 dose was adjusted, with regular monitoring, down to 150 μg/d.

Common symptoms of celiac disease include bloating, abdominal pain, and loose stool after consumption of gluten-containing meals. It should be noted that this patient denied all these symptoms, even though he was asked specifically about them. After he started a gluten-free diet, he reported that he actually felt “very calm” in his abdomen and realized he did have symptoms of celiac disease—but he’d had them for so long that he considered it normal. As is often the case, presence of symptoms would raise suspicion ... but lack of symptoms (or report thereof) does not rule out the disease.

CONCLUSION

Most patients with hypothyroidism are fairly well managed with relatively stable medication dosages, but there are subsets of patients who struggle to maintain euthyroid range. The latter require frequent office visits and dosage changes. Carefully reviewing the list of possible reasons for thyroid level changes can improve stability and patient quality of life, prevent complications of fluctuating thyroid levels, and reduce medical costs, such as repeated labs and frequent clinic visits.

REFERENCES

1. Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Thyroid Association Taskforce on Hypothyroidism in Adults. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults [published correction appears in Endocr Pract. 2013;19(1):175]. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(6):988-1028.

2. Sabate E. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003.

3. Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, et al; American Thyroid Association Task Force on Thyroid Hormone Replacement. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism. Thyroid. 2014;24(12):1670-1751.

COPD: Optimizing treatment

› Individualize treatment regimens based on severity of symptoms and risk for exacerbation, prescribing short-acting beta2-agonists, as needed, for all patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A

› Limit use of inhaled long-acting beta2-agonists to the recommended dosage; higher doses do not lead to better outcomes. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) carries a high disease burden. In 2012, it was the 4th leading cause of death worldwide.1,2 In 2015, the World Health Organization updated its Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines, classifying patients with COPD based on disease burden as determined by symptoms, airflow obstruction, and exacerbation history.3 These revisions, coupled with expanded therapeutic options within established classes of medications and new combination drugs to treat COPD (TABLE 1),3-6 have led to questions about interclass differences and the best treatment regimen for particular patients.

Comparisons of various agents within a therapeutic class and their impact on lung function and rate of exacerbations address many of these concerns. In the text and tables that follow, we present the latest evidence highlighting differences in dosing, safety, and efficacy. We also include the updated GOLD classifications, evidence of efficacy for pulmonary rehabilitation, and practical implications of these findings for the optimal management of patients with COPD.

But first, a word about terminology.

Understanding COPD

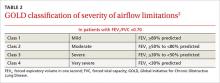

COPD is a chronic lung disease characterized by progressive airflow limitation, usually measured by spirometry (TABLE 2),3 and chronic airway inflammation. Emphysema and chronic bronchitis are often used synonymously with COPD. In fact, there are important differences.

Individuals with chronic bronchitis do not necessarily have the airflow limitations found in those with COPD. And patients with COPD develop pathologic lung changes beyond the alveolar damage characteristic of emphysema, including airway fibrosis and inflammation, luminal plugging, and loss of elastic recoil.3

The medications included in this review aim to reduce both the morbidity and mortality associated with COPD. These drugs can also help relieve the symptoms of patients with chronic bronchitis and emphysema, but have limited effect on patient mortality.

Short- and long-acting beta2-agonists

Bronchodilator therapy with beta2-agonists improves forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) through relaxation of airway smooth muscle. Beta2-agonists have proven to be safe and effective when used as needed or scheduled for patients with COPD.7

Inhaled short-acting beta2-agonists (SABAs) improve FEV1 and symptoms within 10 minutes, with effects lasting up to 4 to 6 hours; long-acting beta2-agonists (LABAs) have a variable onset, with effects lasting 12 to 24 hours.8 Inhaled levalbuterol, the last SABA to receive US Food and Drug Administration approval, has not proven to be superior to conventional bronchodilators in ambulatory patients with stable COPD.3 In clinical trials, however, the slightly longer half-life of the nebulized formulation of levalbuterol was found to reduce both the frequency of administration and the overall cost of therapy in patients hospitalized with acute exacerbations of COPD.9,10

Recently approved LABAs

Clinical trials have studied the safety and efficacy of newer agents vs older LABAs in patients with moderate to severe COPD. Compared with theophylline, for example, formoterol 12 mcg inhaled every 12 hours for a 12-month period provided a clinically significant increase of >120 ml in FEV1 (P=.026).11 Higher doses of formoterol did not provide any additional improvement.

In a trial comparing indacaterol and tiotropium, an inhaled anticholinergic, both treatment groups had a clinically significant increase in FEV1, but patients receiving indacaterol achieved an additional increase of 40 to 50 mL at 12 weeks.12

Exacerbation rates for all LABAs range from 22% to 44%.5,12,13 In a study of patients receiving formoterol 12 mcg compared with 15-mcg and 25-mcg doses of arformoterol, those taking formoterol had a lower exacerbation rate than those on either strength of arformoterol (22% vs 32% and 31%, respectively).10 In various studies, doses greater than the FDA-approved regimens for indacaterol, arformoterol, and olodaterol did not result in a significant improvement in either FEV1 or exacerbation rates compared with placebo.5,12,14

Studies that assessed the use of rescue medication as well as exacerbation rates in patients taking LABAs reported reductions in the use of the rescue drugs ranging from 0.46 to 1.32 actuations per day, but the findings had limited clinical relevance.5,13 With the exception of indacaterol and olodaterol—both of which may be preferable because of their once-daily dosing regimen—no significant differences in safety and efficacy among LABAs have been found.5,12,13

Long-acting inhaled anticholinergics

Inhaled anticholinergic agents (IACs) can be used in place of, or in conjunction with, LABAs to provide bronchodilation for up to 24 hours.3 The introduction of long-acting IACs dosed once or twice daily has the potential to improve medication adherence over traditional short-acting ipratropium, which requires multiple daily doses for symptom control. Over 4 years, tiotropium has been shown to increase time to first exacerbation by approximately 4 months. It did not, however, significantly reduce the number of exacerbations compared with placebo.15

Long-term use of tiotropium appears to have the potential to preserve lung function. In one trial, it slowed the rate of decline in FEV1 by 5 mL per year, but this finding lacked clinical significance.13 In clinical trials of patients with moderate to severe COPD, however, once-daily tiotropium and umeclidinium provided clinically significant improvements in FEV1 (>120 mL; P<.01), regardless of the dose administered.6,16 In another trial, patients taking aclidinium 200 mcg or 400 mcg every 12 hours did not achieve a clinically significant improvement in FEV1 compared with placebo.17

In patients with moderate to severe COPD, the combination of umeclidinium/vilanterol, a LABA, administered once daily resulted in a clinically significant improvement in FEV1 (167 mL; P<.001) vs placebo—but was not significantly better than treatment with either agent alone.18

Few studies have evaluated time to exacerbation in patients receiving aclidinium or umeclidinium. In comparison to salmeterol, tiotropium reduced the time to first exacerbation by 42 days at one year (hazard ratio=0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.77-0.9; P<.001).19 The evidence suggests that when used in combination with LABAs, long-acting IACs have a positive impact on FEV1, but their effect on exacerbation rates has not been established.

Combination therapy with steroids and LABAs

The combination of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and LABAs has been found to improve FEV1 and symptoms in patients with moderate to severe COPD more than monotherapy with either drug class.20,21 In fact, ICS alone have not been proven to slow the progression of the disease or to lower mortality rates in patients with COPD.22

Fluticasone/salmeterol demonstrated a 25% reduction in exacerbation rates compared with placebo (P<.0001), a greater reduction than that of either drug alone.20 A retrospective observational study comparing fixed dose fluticasone/salmeterol with budesonide/formoterol reported a similar reduction in exacerbation rates, but the number of patients requiring the addition of an IAC was 16% lower in the latter group.23

The combination of fluticasone/vilanterol has the potential to improve adherence, given that it is dosed once daily, unlike other COPD combination drugs. Its clinical efficacy is comparable to that of fluticasone/salmeterol after 12 weeks of therapy, with similar improvements in FEV1,24 but fluticasone/vilanterol is associated with an increased risk of pneumonia.3

Chronic use of oral corticosteroids

Oral corticosteroids (OCS) are clinically indicated in individuals whose symptoms continue despite optimal therapy with inhaled agents that have demonstrated efficacy. Such patients are often referred to as “steroid dependent.”

While OCS are prescribed for both their anti-inflammatory activity and their ability to slow the progression of COPD,25,26 no well-designed studies have investigated their benefits for this patient population. One study concluded that patients who were slowly withdrawn from their OCS regimen had no more frequent exacerbations than those who maintained chronic usage. The withdrawal group did, however, lose weight.27

GOLD guidelines do not recommend OCS for chronic management of COPD due to the risk of toxicity.3 The well-established adverse effects of chronic OCS include hyperglycemia, hypertension, osteoporosis, and myopathy.28,29 A study of muscle function in 21 COPD patients receiving corticosteroids revealed decreases in quadriceps muscle strength and pulmonary function.30 Daily use of OCS will likely result in additional therapies to control drug-induced conditions, as well—another antihypertensive secondary to fluid retention caused by chronic use of OCS in patients with high blood pressure, for example, or additional medication to control elevated blood glucose levels in patients with diabetes.

Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors

The recommendation for roflumilast in patients with GOLD Class 2 to 4 symptoms remains unchanged since the introduction of this agent as a treatment option for COPD.3 Phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibitors such as roflumilast reduce inflammation in the lungs and have no activity as a bronchodilator.31,32

Roflumilast has been shown to improve FEV1 in patients concurrently receiving a long-acting bronchodilator and to reduce exacerbations in steroid-dependent patients, a recent systematic review of 29 PDE-4 trials found.33 Patients taking roflumilast, however, suffered from more adverse events (nausea, appetite reduction, diarrhea, weight loss, sleep disturbances, and headache) than those on placebo.33

Antibiotics

GOLD guidelines do not recommend the use of antibiotics for patients with COPD, except to treat acute exacerbations.1 However, recent studies suggest that routine or pulsed dosing of prophylactic antibiotics can reduce the number of exacerbations.34-36 A 2013 review of 7 studies determined that continuous antibiotics, particularly macrolides, reduced the number of COPD exacerbations in patients with a mean age of 66 years (odds ratio [OR]=0.55; 95% CI, 0.39-0.77).37

A more recent trial randomized 92 patients with a history of ≥3 exacerbations in the previous year to receive either prophylactic azithromycin or placebo daily for 12 months. The treatment group experienced a significant decrease in the number of exacerbations (OR=0.58; 95% CI, 0.42-0.79; P=.001).38 This benefit must be weighed against the potential development of antibiotic resistance and adverse effects, so careful patient selection is important.

Pulmonary rehabilitation has proven benefits

GOLD, the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Thoracic Society, and the European Respiratory Society all recommend pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with COPD.39-41 In addition to reducing morbidity and mortality rates—including a reduction in number of hospitalizations and length of stay and improved post-discharge recovery—pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to have other physical and psychological benefits.42 Specific benefits include improved exercise capacity, greater arm strength and endurance, reduced perception of intensity of breathlessness, and improved overall health-related quality of life.

Key features of rehab programs

Important components of pulmonary rehabilitation include counseling on tobacco cessation, nutrition, education—including correct inhalation technique—and exercise training. There are few contraindications to participation, and patients can derive benefit from both its non-exercise components and upper extremity training regardless of their mobility level.

A 2006 Cochrane review concluded that an effective pulmonary rehabilitation program should be at least 4 weeks in duration,43 and longer programs have been shown to produce greater benefits.44 However, there is no agreement on an optimal time frame. Studies are inconclusive on other specific aspects of pulmonary rehab programs, as well, such as the number of sessions per week, number of hours per session, duration and intensity of exercise regimens, and staff-to-patient ratios.

Home-based exercise training may produce many of the same benefits as a formal pulmonary rehabilitation program. A systematic review found improved quality of life and exercise capacity associated with patient care that lacked formal pulmonary rehabilitation, with no differences between results from home-based training and hospital-based outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation programs.45

Given the lack of availability of formal rehab programs in many communities, homebased training for patients with COPD is important to consider.

Implications for practice

What is the takeaway from this evidence-based review? Overall, it is clear that, with the possible exception of the effect of once-daily dosing on adherence, there is little difference among the therapeutic agents within a particular class of medications—and that more is not necessarily better. Indeed, evidence suggests that higher doses of LABAs may reduce their effectiveness, rendering them no better than placebo. In addition, there is no significant difference in the rate of exacerbations in patients taking ICS/LABA combinations and those receiving IACs alone.

Pulmonary rehabilitation should be recommended for all newly diagnosed patients, while appropriate drug therapies should be individualized based on the GOLD symptoms/risk evaluation categories (TABLE 3).3 While daily OCS and daily antibiotics have the potential to reduce exacerbation rates, for example, the risks of adverse effects and toxicities outweigh the benefits for patients whose condition is stable.

Determining the optimal treatment for a particular patient also requires an assessment of comorbidities, including potential adverse drug effects (TABLE 4).3,27-29,33,46-52 Selection of medication should be driven by patient and physician preference to optimize adherence and clinical outcomes, although cost and accessibility often play a significant role, as well.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nabila Ahmed-Sarwar, PharmD, BCPS, CDE, St. John Fisher College, Wegmans School of Pharmacy, 3690 East Avenue, Rochester, NY 14618; [email protected]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the following people for their assistance in the preparation of this manuscript: Matthew Stryker, PharmD, Timothy Adler, PharmD, and Angela K. Nagel, PharmD, BCPS.

1. World Health Organization. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Fact Sheet No. 315. World Health Organization Web site. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs315/en/. Accessed January 29, 2015.

2. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Morbidity and mortality: 2012 chart book on cardiovascular, lung, and blood diseases. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Web site. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/research/2012_Chart-Book_508.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2015.

3. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Updated 2015. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Available at: http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report_2015_Sept2.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2015.

4. Hanrahan JP, Hanania NA, Calhoun WJ, et al. Effect of nebulized arformoterol on airway function in COPD: results from two randomized trials. COPD. 2008;5:25-34.

5. Hanania NA, Donohue JF, Nelson H, et al. The safety and efficacy of arformoterol and formoterol in COPD. COPD. 2010;7:17-31.

6. Trivedi R, Richard N, Mehta R, et al. Umeclidinium in patients with COPD: a randomised, placebo-controlled study. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:72-81.

7. Vathenen AS, Britton JR, Ebden P, et al. High-dose inhaled albuterol in severe chronic airflow limitation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138:850-855.

8. Cazzola M, Matera MG, Santangelo G, et al. Salmeterol and formoterol in partially reversible severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a dose-response study. Respir Med. 1995;89:357-362.

9. Donohue JF, Hanania NA, Ciubotaru RL, et al. Comparison of levalbuterol and racemic albuterol in hospitalized patients with acute asthma or COPD: a 2-week, multicenter, randomized, open-label study. Clin Ther. 2008;30:989-1002.

10. Truitt T, Witko J, Halpern M. Levalbuterol compared to racemic albuterol: efficacy and outcomes in patients hospitalized with COPD or asthma. Chest. 2003;123:128-135.

11. Rossi A, Kristufek P, Levine BE, et al; Formoterol in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (FICOPD) II Study Group. Comparison of the efficacy, tolerability, and safety of formoterol dry powder and oral, slow-release theophylline in the treatment of COPD. Chest. 2002;121:1058-1069.

12. Donohue JF, Fogarty C, Lötvall J, et al; INHANCE Study Investigators. Once-daily bronchodilators for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: indacaterol versus tiotropium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:155-162.

13. Ferguson GT, Feldman GJ, Hofbauer P, et al. Efficacy and safety of olodaterol once daily delivered via Respimat® in patients with GOLD 2-4 COPD: results from two replicate 48-week studies. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:629-645.

14. Boyd G, Morice AH, Pounsford JC, et al. An evaluation of salmeterol in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Eur Respir J. 1997;10:815-821.

15. Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, et al; UPLIFT Study Investigators. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1543-1554.

16. Casaburi R, Mahler DA, Jones PW, et al. A long-term evaluation of once-daily inhaled tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:217-224.

17. Jones PW, Singh D, Bateman ED, et al. Efficacy and safety of twice-daily aclidinium bromide in COPD patients: the ATTAIN study. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:830-836.

18. Donohue JF, Maleki-Yazdi MR, Kilbride S, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily umeclidinium/vilanterol 62.5/25 mcg in COPD. Respir Med. 2013;107:1538-1546.

19. Vogelmeier C, Hederer B, Glaab T, et al; POET-COPD Investigators. Tiotropium versus salmeterol for the prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1093-1103.

20. Calverley P, Pauwels R, Vestbo J, et al; Trial of inhaled steroids and long-acting beta2 agonists study group. Combined salmeterol and fluticasone in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:449-456.

21. Szafranski W, Cukier A, Ramirez A, et al. Efficacy and safety of budesonide/formoterol in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:74-81.

22. Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, et al; TORCH investigators. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:775-789.

23. Larsson K, Janson C, Lisspers K, et al. Combination of budesonide/formoterol more effective than fluticasone/salmeterol in preventing exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the PATHOS study. J Intern Med. 2013;273:584-594.

24. Dransfield MT, Feldman G, Korenblat P, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol (100/25 mcg) versus twice-daily fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (250/50 mcg) in COPD patients. Respir Med. 2014;108:1171-1179.

25. Davies L, Nisar M, Pearson MG, et al. Oral corticosteroid trials in the management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. QJM. 1999;92:395-400.

26. Walters JA, Walters EH, Wood-Baker R. Oral corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;CD005374.

27. Rice KL, Rubins JB, Lebahn F, et al. Withdrawal of chronic systemic corticosteroids in patients with COPD: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:174-178.

28. Clore JN, Thurby-Hay L. Glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycemia. Endocr Pract. 2009;15:469-474.

29. McEvoy CE, Ensrud KE, Bender E, et al. Association between corticosteroid use and vertebral fractures in older men with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:704-709.

30. Decramer M, Lacquet LM, Fagard R, et al. Corticosteroids contribute to muscle weakness in chronic airflow obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:11-16.

31. Fabbri LM, Calverley PM, Izquierdo-Alonso JL, et al; M2-127 and M2-128 study groups. Roflumilast in moderate-to-severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treated with longacting bronchodilators: two randomised clinical trials. Lancet. 2009;374:695-703.

32. Calverley PM, Rabe KF, Goehring UM, et al; M2-124 and M2-125 study groups. Roflumilast in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: two randomised clinical trials. Lancet. 2009;374:685-694.

33. Chong J, Leung B, Poole P. Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD002309.

34. Seemungal TA, Wilkinson TM, Hurst JR, et al. Long-term erythromycin therapy is associated with decreased chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:1139-1147.

35. Sethi S, Jones PW, Theron MS, et al; PULSE study group. Pulsed moxifloxacin for the prevention of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. Respir Res. 2010;11:10.

36. Albert RK, Connett J, Bailey WC, et al; COPD Clinical Research Network. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:689-698.

37. Herath SC, Poole P. Prophylactic antibiotic therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD009764.

38. Uzun S, Djamin RS, Kluytmans JA, et al. Azithromycin maintenance treatment in patients with frequent exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COLUMBUS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:361-368.

39. Ries AL, Bauldoff GS, Carlin BW, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation: joint ACCP/AACVPR evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2007;131:S4-S42.

40. Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, et al; ATS/ERS Task Force on Pulmonary Rehabilitation. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:e13-e64.

41. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

42. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Updated 2013. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Available at: http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report_2013_Feb20.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2015.

43. Lacasse Y, Goldstein R, Lasserson TJ, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD003793.

44. Beauchamp MK, Janaudis-Ferreira T, Goldstein RS, et al. Optimal duration of pulmonary rehabilitation for individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease - a systematic review. Chron Respir Dis. 2011;8:129-140.

45. Vieira DS, Maltais F, Bourbeau J. Home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010;16:134-143.

46. Proair HFM (albuterol sulfate) [package insert]. Miami, FL: IVAX Laboratories; 2005.

47. Foradil (formoterol fumarate) [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co; 2012.

48. Spiriva (tiotropium bromide) [package insert]. Ridgefield, Conn: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals; 2014.

49. Fried TR, Vaz Fragoso CA, Rabow MW. Caring for the older person with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2012;308:1254-1263.

50. Flovent HFA (fluticasone propionate) [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2014.

51. Zithromax (azithromycin) [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Labs; 2013.

52. Daliresp (roflumilast) [package insert]. St. Louis, Mo: Forest Pharmaceuticals; 2013.

› Individualize treatment regimens based on severity of symptoms and risk for exacerbation, prescribing short-acting beta2-agonists, as needed, for all patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A

› Limit use of inhaled long-acting beta2-agonists to the recommended dosage; higher doses do not lead to better outcomes. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) carries a high disease burden. In 2012, it was the 4th leading cause of death worldwide.1,2 In 2015, the World Health Organization updated its Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines, classifying patients with COPD based on disease burden as determined by symptoms, airflow obstruction, and exacerbation history.3 These revisions, coupled with expanded therapeutic options within established classes of medications and new combination drugs to treat COPD (TABLE 1),3-6 have led to questions about interclass differences and the best treatment regimen for particular patients.

Comparisons of various agents within a therapeutic class and their impact on lung function and rate of exacerbations address many of these concerns. In the text and tables that follow, we present the latest evidence highlighting differences in dosing, safety, and efficacy. We also include the updated GOLD classifications, evidence of efficacy for pulmonary rehabilitation, and practical implications of these findings for the optimal management of patients with COPD.

But first, a word about terminology.

Understanding COPD

COPD is a chronic lung disease characterized by progressive airflow limitation, usually measured by spirometry (TABLE 2),3 and chronic airway inflammation. Emphysema and chronic bronchitis are often used synonymously with COPD. In fact, there are important differences.

Individuals with chronic bronchitis do not necessarily have the airflow limitations found in those with COPD. And patients with COPD develop pathologic lung changes beyond the alveolar damage characteristic of emphysema, including airway fibrosis and inflammation, luminal plugging, and loss of elastic recoil.3

The medications included in this review aim to reduce both the morbidity and mortality associated with COPD. These drugs can also help relieve the symptoms of patients with chronic bronchitis and emphysema, but have limited effect on patient mortality.

Short- and long-acting beta2-agonists

Bronchodilator therapy with beta2-agonists improves forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) through relaxation of airway smooth muscle. Beta2-agonists have proven to be safe and effective when used as needed or scheduled for patients with COPD.7

Inhaled short-acting beta2-agonists (SABAs) improve FEV1 and symptoms within 10 minutes, with effects lasting up to 4 to 6 hours; long-acting beta2-agonists (LABAs) have a variable onset, with effects lasting 12 to 24 hours.8 Inhaled levalbuterol, the last SABA to receive US Food and Drug Administration approval, has not proven to be superior to conventional bronchodilators in ambulatory patients with stable COPD.3 In clinical trials, however, the slightly longer half-life of the nebulized formulation of levalbuterol was found to reduce both the frequency of administration and the overall cost of therapy in patients hospitalized with acute exacerbations of COPD.9,10

Recently approved LABAs

Clinical trials have studied the safety and efficacy of newer agents vs older LABAs in patients with moderate to severe COPD. Compared with theophylline, for example, formoterol 12 mcg inhaled every 12 hours for a 12-month period provided a clinically significant increase of >120 ml in FEV1 (P=.026).11 Higher doses of formoterol did not provide any additional improvement.

In a trial comparing indacaterol and tiotropium, an inhaled anticholinergic, both treatment groups had a clinically significant increase in FEV1, but patients receiving indacaterol achieved an additional increase of 40 to 50 mL at 12 weeks.12

Exacerbation rates for all LABAs range from 22% to 44%.5,12,13 In a study of patients receiving formoterol 12 mcg compared with 15-mcg and 25-mcg doses of arformoterol, those taking formoterol had a lower exacerbation rate than those on either strength of arformoterol (22% vs 32% and 31%, respectively).10 In various studies, doses greater than the FDA-approved regimens for indacaterol, arformoterol, and olodaterol did not result in a significant improvement in either FEV1 or exacerbation rates compared with placebo.5,12,14

Studies that assessed the use of rescue medication as well as exacerbation rates in patients taking LABAs reported reductions in the use of the rescue drugs ranging from 0.46 to 1.32 actuations per day, but the findings had limited clinical relevance.5,13 With the exception of indacaterol and olodaterol—both of which may be preferable because of their once-daily dosing regimen—no significant differences in safety and efficacy among LABAs have been found.5,12,13

Long-acting inhaled anticholinergics

Inhaled anticholinergic agents (IACs) can be used in place of, or in conjunction with, LABAs to provide bronchodilation for up to 24 hours.3 The introduction of long-acting IACs dosed once or twice daily has the potential to improve medication adherence over traditional short-acting ipratropium, which requires multiple daily doses for symptom control. Over 4 years, tiotropium has been shown to increase time to first exacerbation by approximately 4 months. It did not, however, significantly reduce the number of exacerbations compared with placebo.15

Long-term use of tiotropium appears to have the potential to preserve lung function. In one trial, it slowed the rate of decline in FEV1 by 5 mL per year, but this finding lacked clinical significance.13 In clinical trials of patients with moderate to severe COPD, however, once-daily tiotropium and umeclidinium provided clinically significant improvements in FEV1 (>120 mL; P<.01), regardless of the dose administered.6,16 In another trial, patients taking aclidinium 200 mcg or 400 mcg every 12 hours did not achieve a clinically significant improvement in FEV1 compared with placebo.17

In patients with moderate to severe COPD, the combination of umeclidinium/vilanterol, a LABA, administered once daily resulted in a clinically significant improvement in FEV1 (167 mL; P<.001) vs placebo—but was not significantly better than treatment with either agent alone.18

Few studies have evaluated time to exacerbation in patients receiving aclidinium or umeclidinium. In comparison to salmeterol, tiotropium reduced the time to first exacerbation by 42 days at one year (hazard ratio=0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.77-0.9; P<.001).19 The evidence suggests that when used in combination with LABAs, long-acting IACs have a positive impact on FEV1, but their effect on exacerbation rates has not been established.

Combination therapy with steroids and LABAs

The combination of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and LABAs has been found to improve FEV1 and symptoms in patients with moderate to severe COPD more than monotherapy with either drug class.20,21 In fact, ICS alone have not been proven to slow the progression of the disease or to lower mortality rates in patients with COPD.22

Fluticasone/salmeterol demonstrated a 25% reduction in exacerbation rates compared with placebo (P<.0001), a greater reduction than that of either drug alone.20 A retrospective observational study comparing fixed dose fluticasone/salmeterol with budesonide/formoterol reported a similar reduction in exacerbation rates, but the number of patients requiring the addition of an IAC was 16% lower in the latter group.23

The combination of fluticasone/vilanterol has the potential to improve adherence, given that it is dosed once daily, unlike other COPD combination drugs. Its clinical efficacy is comparable to that of fluticasone/salmeterol after 12 weeks of therapy, with similar improvements in FEV1,24 but fluticasone/vilanterol is associated with an increased risk of pneumonia.3

Chronic use of oral corticosteroids

Oral corticosteroids (OCS) are clinically indicated in individuals whose symptoms continue despite optimal therapy with inhaled agents that have demonstrated efficacy. Such patients are often referred to as “steroid dependent.”

While OCS are prescribed for both their anti-inflammatory activity and their ability to slow the progression of COPD,25,26 no well-designed studies have investigated their benefits for this patient population. One study concluded that patients who were slowly withdrawn from their OCS regimen had no more frequent exacerbations than those who maintained chronic usage. The withdrawal group did, however, lose weight.27

GOLD guidelines do not recommend OCS for chronic management of COPD due to the risk of toxicity.3 The well-established adverse effects of chronic OCS include hyperglycemia, hypertension, osteoporosis, and myopathy.28,29 A study of muscle function in 21 COPD patients receiving corticosteroids revealed decreases in quadriceps muscle strength and pulmonary function.30 Daily use of OCS will likely result in additional therapies to control drug-induced conditions, as well—another antihypertensive secondary to fluid retention caused by chronic use of OCS in patients with high blood pressure, for example, or additional medication to control elevated blood glucose levels in patients with diabetes.

Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors

The recommendation for roflumilast in patients with GOLD Class 2 to 4 symptoms remains unchanged since the introduction of this agent as a treatment option for COPD.3 Phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibitors such as roflumilast reduce inflammation in the lungs and have no activity as a bronchodilator.31,32

Roflumilast has been shown to improve FEV1 in patients concurrently receiving a long-acting bronchodilator and to reduce exacerbations in steroid-dependent patients, a recent systematic review of 29 PDE-4 trials found.33 Patients taking roflumilast, however, suffered from more adverse events (nausea, appetite reduction, diarrhea, weight loss, sleep disturbances, and headache) than those on placebo.33

Antibiotics

GOLD guidelines do not recommend the use of antibiotics for patients with COPD, except to treat acute exacerbations.1 However, recent studies suggest that routine or pulsed dosing of prophylactic antibiotics can reduce the number of exacerbations.34-36 A 2013 review of 7 studies determined that continuous antibiotics, particularly macrolides, reduced the number of COPD exacerbations in patients with a mean age of 66 years (odds ratio [OR]=0.55; 95% CI, 0.39-0.77).37

A more recent trial randomized 92 patients with a history of ≥3 exacerbations in the previous year to receive either prophylactic azithromycin or placebo daily for 12 months. The treatment group experienced a significant decrease in the number of exacerbations (OR=0.58; 95% CI, 0.42-0.79; P=.001).38 This benefit must be weighed against the potential development of antibiotic resistance and adverse effects, so careful patient selection is important.

Pulmonary rehabilitation has proven benefits

GOLD, the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Thoracic Society, and the European Respiratory Society all recommend pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with COPD.39-41 In addition to reducing morbidity and mortality rates—including a reduction in number of hospitalizations and length of stay and improved post-discharge recovery—pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to have other physical and psychological benefits.42 Specific benefits include improved exercise capacity, greater arm strength and endurance, reduced perception of intensity of breathlessness, and improved overall health-related quality of life.

Key features of rehab programs

Important components of pulmonary rehabilitation include counseling on tobacco cessation, nutrition, education—including correct inhalation technique—and exercise training. There are few contraindications to participation, and patients can derive benefit from both its non-exercise components and upper extremity training regardless of their mobility level.

A 2006 Cochrane review concluded that an effective pulmonary rehabilitation program should be at least 4 weeks in duration,43 and longer programs have been shown to produce greater benefits.44 However, there is no agreement on an optimal time frame. Studies are inconclusive on other specific aspects of pulmonary rehab programs, as well, such as the number of sessions per week, number of hours per session, duration and intensity of exercise regimens, and staff-to-patient ratios.

Home-based exercise training may produce many of the same benefits as a formal pulmonary rehabilitation program. A systematic review found improved quality of life and exercise capacity associated with patient care that lacked formal pulmonary rehabilitation, with no differences between results from home-based training and hospital-based outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation programs.45

Given the lack of availability of formal rehab programs in many communities, homebased training for patients with COPD is important to consider.

Implications for practice