User login

The 15-Year Itch

A 58-year-old woman presents to dermatology with a 15-year history of an itchy rash on her left leg. A native of India, she has been in this country for more than 20 years and enjoys generally good health.

But about 15 years ago, she experienced some personal problems that caused great stress. About that same time, she developed a small rash on her left leg, which she began to scratch.

Over time, the lesion has become larger and more pruritic, prompting her to scratch and rub it more. Lately, she has started to use a hairbrush to scratch it. The itching has taken on a whole new level of intensity.

Her primary care provider referred her to a wound care clinic, where her lesion was treated with twice-weekly whirlpool therapy, followed by debridement and dressing with a zinc oxide–based paste. Although this calmed the affected site a bit, when treatment ceased, the rash flared again.

EXAMINATION

The patient has type IV skin, consistent with her origins. The lesion is an impressive, elongated oval plaque measuring about 20 x 10 cm. It covers most of the anterolateral portion of her left leg and calf.

An underlying area of brown macular hyperpigmentation extends an additional 2 to 3 cm around the periphery of the plaque. The central area is slightly edematous, quite pink, and shiny. No focal breaks in the skin are observed. There is no increased warmth or tenderness on palpation.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This complaint and its location are typical of an extremely common dermatologic entity called lichen simplex chronicus (LSC), formerly known as neurodermatitis. All cases of LSC start with a relatively minor, itchy trigger—such as dry skin, eczema, or a bug bite—that the patient begins to scratch or rub. This has the effect of lowering the threshold for itching by making the nerves more numerous and sensitive; the patient then reacts by scratching or rubbing even more. As a result, the epidermal layer thickens and, particularly in patients with darker skin, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation develops.

The patient will persistently respond to the itching by scratching, a reaction that becomes habitual (and in some cases, even pleasurable) and perpetuates the cycle. Although the original insult has long since resolved, the problem has taken on a life of its own.

In the 15-year history of this lesion, the patient had seen a number of clinicians but, incredibly, never a dermatology provider. She had taken several courses of oral antibiotics, used triple-antibiotic ointment, and tried tea tree oil, emu oil, antifungal creams, and most recently, topical triamcinolone cream—the last of which helped a bit.

The actual solution to the problem is utterly simple, at least in concept: Stop scratching. But there’s the rub—the impulse to scratch is quite powerful, and habits are difficult to break.

That’s where we intervened, with the use of a stronger topical steroid ointment (clobetasol 0.05% bid) on an occlusive dressing (eg, an elastic bandage wrap), which potentiates the steroid and serves as a barrier to the patient’s scratching. A soft cast (eg, an Unna boot) would accomplish the same thing but is more troublesome to apply.

Given this patient’s skin type, this area of her leg will always be discolored. She should, however, be able to control the problem from now on. If this treatment attempt were to fail, a biopsy would be needed to rule out other diagnostic possibilities, such as psoriasis or lichen planus.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is quite common, especially on the anterolateral leg.

• LSC is always secondary to an original trigger, such as xerosis, eczema, bug bite, or even psoriasis.

• The chronicity of the problem, sometimes extreme (as in this case), is not only common but often diagnostic.

• Postinflammatory color changes, especially on darker skinned individuals, are common with LSC.

• Other common areas for LSC include the scrotum/vulvae and nuchal scalp.

A 58-year-old woman presents to dermatology with a 15-year history of an itchy rash on her left leg. A native of India, she has been in this country for more than 20 years and enjoys generally good health.

But about 15 years ago, she experienced some personal problems that caused great stress. About that same time, she developed a small rash on her left leg, which she began to scratch.

Over time, the lesion has become larger and more pruritic, prompting her to scratch and rub it more. Lately, she has started to use a hairbrush to scratch it. The itching has taken on a whole new level of intensity.

Her primary care provider referred her to a wound care clinic, where her lesion was treated with twice-weekly whirlpool therapy, followed by debridement and dressing with a zinc oxide–based paste. Although this calmed the affected site a bit, when treatment ceased, the rash flared again.

EXAMINATION

The patient has type IV skin, consistent with her origins. The lesion is an impressive, elongated oval plaque measuring about 20 x 10 cm. It covers most of the anterolateral portion of her left leg and calf.

An underlying area of brown macular hyperpigmentation extends an additional 2 to 3 cm around the periphery of the plaque. The central area is slightly edematous, quite pink, and shiny. No focal breaks in the skin are observed. There is no increased warmth or tenderness on palpation.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This complaint and its location are typical of an extremely common dermatologic entity called lichen simplex chronicus (LSC), formerly known as neurodermatitis. All cases of LSC start with a relatively minor, itchy trigger—such as dry skin, eczema, or a bug bite—that the patient begins to scratch or rub. This has the effect of lowering the threshold for itching by making the nerves more numerous and sensitive; the patient then reacts by scratching or rubbing even more. As a result, the epidermal layer thickens and, particularly in patients with darker skin, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation develops.

The patient will persistently respond to the itching by scratching, a reaction that becomes habitual (and in some cases, even pleasurable) and perpetuates the cycle. Although the original insult has long since resolved, the problem has taken on a life of its own.

In the 15-year history of this lesion, the patient had seen a number of clinicians but, incredibly, never a dermatology provider. She had taken several courses of oral antibiotics, used triple-antibiotic ointment, and tried tea tree oil, emu oil, antifungal creams, and most recently, topical triamcinolone cream—the last of which helped a bit.

The actual solution to the problem is utterly simple, at least in concept: Stop scratching. But there’s the rub—the impulse to scratch is quite powerful, and habits are difficult to break.

That’s where we intervened, with the use of a stronger topical steroid ointment (clobetasol 0.05% bid) on an occlusive dressing (eg, an elastic bandage wrap), which potentiates the steroid and serves as a barrier to the patient’s scratching. A soft cast (eg, an Unna boot) would accomplish the same thing but is more troublesome to apply.

Given this patient’s skin type, this area of her leg will always be discolored. She should, however, be able to control the problem from now on. If this treatment attempt were to fail, a biopsy would be needed to rule out other diagnostic possibilities, such as psoriasis or lichen planus.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is quite common, especially on the anterolateral leg.

• LSC is always secondary to an original trigger, such as xerosis, eczema, bug bite, or even psoriasis.

• The chronicity of the problem, sometimes extreme (as in this case), is not only common but often diagnostic.

• Postinflammatory color changes, especially on darker skinned individuals, are common with LSC.

• Other common areas for LSC include the scrotum/vulvae and nuchal scalp.

A 58-year-old woman presents to dermatology with a 15-year history of an itchy rash on her left leg. A native of India, she has been in this country for more than 20 years and enjoys generally good health.

But about 15 years ago, she experienced some personal problems that caused great stress. About that same time, she developed a small rash on her left leg, which she began to scratch.

Over time, the lesion has become larger and more pruritic, prompting her to scratch and rub it more. Lately, she has started to use a hairbrush to scratch it. The itching has taken on a whole new level of intensity.

Her primary care provider referred her to a wound care clinic, where her lesion was treated with twice-weekly whirlpool therapy, followed by debridement and dressing with a zinc oxide–based paste. Although this calmed the affected site a bit, when treatment ceased, the rash flared again.

EXAMINATION

The patient has type IV skin, consistent with her origins. The lesion is an impressive, elongated oval plaque measuring about 20 x 10 cm. It covers most of the anterolateral portion of her left leg and calf.

An underlying area of brown macular hyperpigmentation extends an additional 2 to 3 cm around the periphery of the plaque. The central area is slightly edematous, quite pink, and shiny. No focal breaks in the skin are observed. There is no increased warmth or tenderness on palpation.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This complaint and its location are typical of an extremely common dermatologic entity called lichen simplex chronicus (LSC), formerly known as neurodermatitis. All cases of LSC start with a relatively minor, itchy trigger—such as dry skin, eczema, or a bug bite—that the patient begins to scratch or rub. This has the effect of lowering the threshold for itching by making the nerves more numerous and sensitive; the patient then reacts by scratching or rubbing even more. As a result, the epidermal layer thickens and, particularly in patients with darker skin, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation develops.

The patient will persistently respond to the itching by scratching, a reaction that becomes habitual (and in some cases, even pleasurable) and perpetuates the cycle. Although the original insult has long since resolved, the problem has taken on a life of its own.

In the 15-year history of this lesion, the patient had seen a number of clinicians but, incredibly, never a dermatology provider. She had taken several courses of oral antibiotics, used triple-antibiotic ointment, and tried tea tree oil, emu oil, antifungal creams, and most recently, topical triamcinolone cream—the last of which helped a bit.

The actual solution to the problem is utterly simple, at least in concept: Stop scratching. But there’s the rub—the impulse to scratch is quite powerful, and habits are difficult to break.

That’s where we intervened, with the use of a stronger topical steroid ointment (clobetasol 0.05% bid) on an occlusive dressing (eg, an elastic bandage wrap), which potentiates the steroid and serves as a barrier to the patient’s scratching. A soft cast (eg, an Unna boot) would accomplish the same thing but is more troublesome to apply.

Given this patient’s skin type, this area of her leg will always be discolored. She should, however, be able to control the problem from now on. If this treatment attempt were to fail, a biopsy would be needed to rule out other diagnostic possibilities, such as psoriasis or lichen planus.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is quite common, especially on the anterolateral leg.

• LSC is always secondary to an original trigger, such as xerosis, eczema, bug bite, or even psoriasis.

• The chronicity of the problem, sometimes extreme (as in this case), is not only common but often diagnostic.

• Postinflammatory color changes, especially on darker skinned individuals, are common with LSC.

• Other common areas for LSC include the scrotum/vulvae and nuchal scalp.

MHM: Novel agents, combos show promise for relapsed/refractory CLL

CHICAGO – Consider using novel agents in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients who are refractory to treatment or who relapse within 2 years of first-line therapy, Dr. John G. Gribben said.

Ibrutinib or idelalisib/rituximab, or other novel agent combinations within clinical trials are his choice in these patients, thus fitness for therapy becomes irrelevant, he said at the American Society of Hematology Meeting on Hematologic Malignancies.

“Of course, I’m particularly excited by the results in CLL of ABT-199. We saw at [the International Workshop on CLL] last week that there are increasing numbers of patients who are on this therapy in combination with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies who are achieving minimal residual disease (MRD) eradication and are able to stop that therapy, unlike what we’ve been seeing,” he said. “I have a patient at my own center now who was treated with ABT-199 plus obinutuzumab within a clinical trial – a 17p deletion patient refractory to seven previous lines of therapy. Had a donor, I was trying to get him to transplant, and now he’s MRD-negative and off therapy, having had 6 months of therapy with ABT-199 and obinutuzumab. [This is] a very exciting combination.”

Other novel-novel agent combinations are also being looked at, he noted.

In CLL patients without 17p deletions who progress later than 2 years after initial chemotherapy, novel agents can be considered, as could alternative approaches with chemotherapy.

“But of course, in the setting of p53 deletions or mutations, then ibrutinib or idelalisib/rituximab, or novel agents like ABT-199 within clinical trials become the treatment approach to be thinking about,” he said.

CHICAGO – Consider using novel agents in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients who are refractory to treatment or who relapse within 2 years of first-line therapy, Dr. John G. Gribben said.

Ibrutinib or idelalisib/rituximab, or other novel agent combinations within clinical trials are his choice in these patients, thus fitness for therapy becomes irrelevant, he said at the American Society of Hematology Meeting on Hematologic Malignancies.

“Of course, I’m particularly excited by the results in CLL of ABT-199. We saw at [the International Workshop on CLL] last week that there are increasing numbers of patients who are on this therapy in combination with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies who are achieving minimal residual disease (MRD) eradication and are able to stop that therapy, unlike what we’ve been seeing,” he said. “I have a patient at my own center now who was treated with ABT-199 plus obinutuzumab within a clinical trial – a 17p deletion patient refractory to seven previous lines of therapy. Had a donor, I was trying to get him to transplant, and now he’s MRD-negative and off therapy, having had 6 months of therapy with ABT-199 and obinutuzumab. [This is] a very exciting combination.”

Other novel-novel agent combinations are also being looked at, he noted.

In CLL patients without 17p deletions who progress later than 2 years after initial chemotherapy, novel agents can be considered, as could alternative approaches with chemotherapy.

“But of course, in the setting of p53 deletions or mutations, then ibrutinib or idelalisib/rituximab, or novel agents like ABT-199 within clinical trials become the treatment approach to be thinking about,” he said.

CHICAGO – Consider using novel agents in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients who are refractory to treatment or who relapse within 2 years of first-line therapy, Dr. John G. Gribben said.

Ibrutinib or idelalisib/rituximab, or other novel agent combinations within clinical trials are his choice in these patients, thus fitness for therapy becomes irrelevant, he said at the American Society of Hematology Meeting on Hematologic Malignancies.

“Of course, I’m particularly excited by the results in CLL of ABT-199. We saw at [the International Workshop on CLL] last week that there are increasing numbers of patients who are on this therapy in combination with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies who are achieving minimal residual disease (MRD) eradication and are able to stop that therapy, unlike what we’ve been seeing,” he said. “I have a patient at my own center now who was treated with ABT-199 plus obinutuzumab within a clinical trial – a 17p deletion patient refractory to seven previous lines of therapy. Had a donor, I was trying to get him to transplant, and now he’s MRD-negative and off therapy, having had 6 months of therapy with ABT-199 and obinutuzumab. [This is] a very exciting combination.”

Other novel-novel agent combinations are also being looked at, he noted.

In CLL patients without 17p deletions who progress later than 2 years after initial chemotherapy, novel agents can be considered, as could alternative approaches with chemotherapy.

“But of course, in the setting of p53 deletions or mutations, then ibrutinib or idelalisib/rituximab, or novel agents like ABT-199 within clinical trials become the treatment approach to be thinking about,” he said.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM MHM 2015

MHM: Novel agents, combos show promise for relapsed/refractory CLL

CHICAGO – Consider using novel agents in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients who are refractory to treatment or who relapse within 2 years of first-line therapy, Dr. John G. Gribben said.

Ibrutinib or idelalisib/rituximab, or other novel agent combinations within clinical trials are his choice in these patients, thus fitness for therapy becomes irrelevant, he said at the American Society of Hematology Meeting on Hematologic Malignancies.

“Of course, I’m particularly excited by the results in CLL of ABT-199. We saw at [the International Workshop on CLL] last week that there are increasing numbers of patients who are on this therapy in combination with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies who are achieving minimal residual disease (MRD) eradication and are able to stop that therapy, unlike what we’ve been seeing,” he said. “I have a patient at my own center now who was treated with ABT-199 plus obinutuzumab within a clinical trial – a 17p deletion patient refractory to seven previous lines of therapy. Had a donor, I was trying to get him to transplant, and now he’s MRD-negative and off therapy, having had 6 months of therapy with ABT-199 and obinutuzumab. [This is] a very exciting combination.”

Other novel-novel agent combinations are also being looked at, he noted.

In CLL patients without 17p deletions who progress later than 2 years after initial chemotherapy, novel agents can be considered, as could alternative approaches with chemotherapy.

“But of course, in the setting of p53 deletions or mutations, then ibrutinib or idelalisib/rituximab, or novel agents like ABT-199 within clinical trials become the treatment approach to be thinking about,” he said.

CHICAGO – Consider using novel agents in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients who are refractory to treatment or who relapse within 2 years of first-line therapy, Dr. John G. Gribben said.

Ibrutinib or idelalisib/rituximab, or other novel agent combinations within clinical trials are his choice in these patients, thus fitness for therapy becomes irrelevant, he said at the American Society of Hematology Meeting on Hematologic Malignancies.

“Of course, I’m particularly excited by the results in CLL of ABT-199. We saw at [the International Workshop on CLL] last week that there are increasing numbers of patients who are on this therapy in combination with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies who are achieving minimal residual disease (MRD) eradication and are able to stop that therapy, unlike what we’ve been seeing,” he said. “I have a patient at my own center now who was treated with ABT-199 plus obinutuzumab within a clinical trial – a 17p deletion patient refractory to seven previous lines of therapy. Had a donor, I was trying to get him to transplant, and now he’s MRD-negative and off therapy, having had 6 months of therapy with ABT-199 and obinutuzumab. [This is] a very exciting combination.”

Other novel-novel agent combinations are also being looked at, he noted.

In CLL patients without 17p deletions who progress later than 2 years after initial chemotherapy, novel agents can be considered, as could alternative approaches with chemotherapy.

“But of course, in the setting of p53 deletions or mutations, then ibrutinib or idelalisib/rituximab, or novel agents like ABT-199 within clinical trials become the treatment approach to be thinking about,” he said.

CHICAGO – Consider using novel agents in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients who are refractory to treatment or who relapse within 2 years of first-line therapy, Dr. John G. Gribben said.

Ibrutinib or idelalisib/rituximab, or other novel agent combinations within clinical trials are his choice in these patients, thus fitness for therapy becomes irrelevant, he said at the American Society of Hematology Meeting on Hematologic Malignancies.

“Of course, I’m particularly excited by the results in CLL of ABT-199. We saw at [the International Workshop on CLL] last week that there are increasing numbers of patients who are on this therapy in combination with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies who are achieving minimal residual disease (MRD) eradication and are able to stop that therapy, unlike what we’ve been seeing,” he said. “I have a patient at my own center now who was treated with ABT-199 plus obinutuzumab within a clinical trial – a 17p deletion patient refractory to seven previous lines of therapy. Had a donor, I was trying to get him to transplant, and now he’s MRD-negative and off therapy, having had 6 months of therapy with ABT-199 and obinutuzumab. [This is] a very exciting combination.”

Other novel-novel agent combinations are also being looked at, he noted.

In CLL patients without 17p deletions who progress later than 2 years after initial chemotherapy, novel agents can be considered, as could alternative approaches with chemotherapy.

“But of course, in the setting of p53 deletions or mutations, then ibrutinib or idelalisib/rituximab, or novel agents like ABT-199 within clinical trials become the treatment approach to be thinking about,” he said.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM MHM 2015

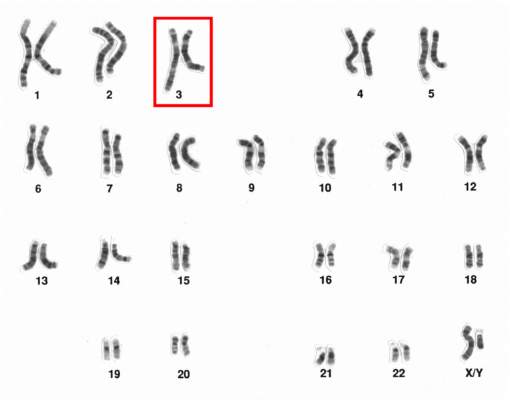

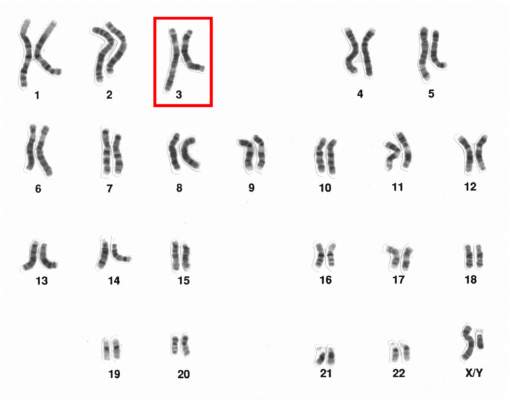

Chromosome 3 abnormalities linked to poor CML outcomes

Chromosome 3 abnormalities, specifically 3q26.2 rearrangements, were associated with treatment resistance and poor prognosis in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), report Dr. Wei Wang and coauthors of the department of hematopathology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

A study of 2,013 CML patients found that just 6% of those with 3q26.2 abnormalities achieved complete cytogenetic response during the course of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment. Patients with other chromosome 3 abnormalities had a significantly better response rate of 42% the investigators found.

Additionally, patients with 3q26.2 chromosome rearrangements had significantly worse survival rates than those with abnormalities involving other chromosomes, with 2-year overall survival rates of 22% and 60%, respectively.

The lack of response to TKI treatment “raises the issue of how to manage these patients,” Dr. Wang and associates said in the report.

“TKIs themselves are not sufficient to control the disease with 3q26.2 abnormalities,” they added. “Intensive therapy, stem cell transplantation, or investigational therapy targeted to EVI1 should be considered,” concluded the authors, who declared that they had no competing financial interests.

Read the full article in Blood.

Chromosome 3 abnormalities, specifically 3q26.2 rearrangements, were associated with treatment resistance and poor prognosis in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), report Dr. Wei Wang and coauthors of the department of hematopathology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

A study of 2,013 CML patients found that just 6% of those with 3q26.2 abnormalities achieved complete cytogenetic response during the course of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment. Patients with other chromosome 3 abnormalities had a significantly better response rate of 42% the investigators found.

Additionally, patients with 3q26.2 chromosome rearrangements had significantly worse survival rates than those with abnormalities involving other chromosomes, with 2-year overall survival rates of 22% and 60%, respectively.

The lack of response to TKI treatment “raises the issue of how to manage these patients,” Dr. Wang and associates said in the report.

“TKIs themselves are not sufficient to control the disease with 3q26.2 abnormalities,” they added. “Intensive therapy, stem cell transplantation, or investigational therapy targeted to EVI1 should be considered,” concluded the authors, who declared that they had no competing financial interests.

Read the full article in Blood.

Chromosome 3 abnormalities, specifically 3q26.2 rearrangements, were associated with treatment resistance and poor prognosis in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), report Dr. Wei Wang and coauthors of the department of hematopathology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

A study of 2,013 CML patients found that just 6% of those with 3q26.2 abnormalities achieved complete cytogenetic response during the course of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment. Patients with other chromosome 3 abnormalities had a significantly better response rate of 42% the investigators found.

Additionally, patients with 3q26.2 chromosome rearrangements had significantly worse survival rates than those with abnormalities involving other chromosomes, with 2-year overall survival rates of 22% and 60%, respectively.

The lack of response to TKI treatment “raises the issue of how to manage these patients,” Dr. Wang and associates said in the report.

“TKIs themselves are not sufficient to control the disease with 3q26.2 abnormalities,” they added. “Intensive therapy, stem cell transplantation, or investigational therapy targeted to EVI1 should be considered,” concluded the authors, who declared that they had no competing financial interests.

Read the full article in Blood.

Chromosome 3 abnormalities linked to poor CML outcomes

Chromosome 3 abnormalities, specifically 3q26.2 rearrangements, were associated with treatment resistance and poor prognosis in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), report Dr. Wei Wang and coauthors of the department of hematopathology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

A study of 2,013 CML patients found that just 6% of those with 3q26.2 abnormalities achieved complete cytogenetic response during the course of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment. Patients with other chromosome 3 abnormalities had a significantly better response rate of 42% the investigators found.

Additionally, patients with 3q26.2 chromosome rearrangements had significantly worse survival rates than those with abnormalities involving other chromosomes, with 2-year overall survival rates of 22% and 60%, respectively.

The lack of response to TKI treatment “raises the issue of how to manage these patients,” Dr. Wang and associates said in the report.

“TKIs themselves are not sufficient to control the disease with 3q26.2 abnormalities,” they added. “Intensive therapy, stem cell transplantation, or investigational therapy targeted to EVI1 should be considered,” concluded the authors, who declared that they had no competing financial interests.

Read the full article in Blood.

Chromosome 3 abnormalities, specifically 3q26.2 rearrangements, were associated with treatment resistance and poor prognosis in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), report Dr. Wei Wang and coauthors of the department of hematopathology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

A study of 2,013 CML patients found that just 6% of those with 3q26.2 abnormalities achieved complete cytogenetic response during the course of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment. Patients with other chromosome 3 abnormalities had a significantly better response rate of 42% the investigators found.

Additionally, patients with 3q26.2 chromosome rearrangements had significantly worse survival rates than those with abnormalities involving other chromosomes, with 2-year overall survival rates of 22% and 60%, respectively.

The lack of response to TKI treatment “raises the issue of how to manage these patients,” Dr. Wang and associates said in the report.

“TKIs themselves are not sufficient to control the disease with 3q26.2 abnormalities,” they added. “Intensive therapy, stem cell transplantation, or investigational therapy targeted to EVI1 should be considered,” concluded the authors, who declared that they had no competing financial interests.

Read the full article in Blood.

Chromosome 3 abnormalities, specifically 3q26.2 rearrangements, were associated with treatment resistance and poor prognosis in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), report Dr. Wei Wang and coauthors of the department of hematopathology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

A study of 2,013 CML patients found that just 6% of those with 3q26.2 abnormalities achieved complete cytogenetic response during the course of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment. Patients with other chromosome 3 abnormalities had a significantly better response rate of 42% the investigators found.

Additionally, patients with 3q26.2 chromosome rearrangements had significantly worse survival rates than those with abnormalities involving other chromosomes, with 2-year overall survival rates of 22% and 60%, respectively.

The lack of response to TKI treatment “raises the issue of how to manage these patients,” Dr. Wang and associates said in the report.

“TKIs themselves are not sufficient to control the disease with 3q26.2 abnormalities,” they added. “Intensive therapy, stem cell transplantation, or investigational therapy targeted to EVI1 should be considered,” concluded the authors, who declared that they had no competing financial interests.

Read the full article in Blood.

Dear insurance companies: Stop sending me unnecessary reminder letters

I am, apparently, not a very good doctor. At least, that’s what some mailings I get from insurance companies make me think.

You probably get the same ones. They tell me what guidelines I’m not following or drug interactions I’m not mindful of. I suppose I should be grateful for their efforts to protect patients.

Letters I’ve gotten in the last week have reminded me that:

• Patients with elevated fasting blood sugars should be started on metformin.

• A lady on Eliquis (apixaban) after developing a deep-vein thrombosis should be considered for a less costly alternative, such as warfarin, to help her save money.

• An antihypertensive agent is recommended for a young man with persistently elevated blood pressures.

• An older gentleman’s lipid-lowering agent may interfere with his diabetes medication.

What do these have to do with anything that I, as a neurologist, am doing for the patient? Nothing.

Why are they being sent to me, as opposed to an internist or cardiologist? I have no idea. Of course, for all I know, the other docs might be getting recommendations on how to manage Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis.

The insurance companies pay the bills. They obviously know which doctors are seeing who and prescribing what. Their billing systems track who practices what specialty. If I were to try submitting a claim for pulmonary evaluation, I’m sure they’d immediately notice and deny it.

So why can’t they get this straight? It seems like a big waste of time, paper, and postage all around.

On rare occasions, they actually get it right … sort of. About a month ago, I received a letter about a migraine patient, telling me that, for those with frequent migraines, a preventive medication should be considered. It even listed her current prescriptions to help me understand.

I absolutely agree with the letter, but it completely ignored that her medication list already included topiramate and nortriptyline, both commonly used for migraine prophylaxis. Since she has no other reason to be on either, I have no idea why they thought I’d use them. These kinds of notes all end with some generic comment that these are just suggestions, and only I and my patient can make the correct decisions about treatment, etc. etc.

That letter may be well intentioned, perhaps, but it is also inaccurate, unnecessary, and – to me – even a little demeaning. If you don’t think I know what I’m doing, then why are you sending patients to me? Maybe the software you’re using to screen charts and send these letters should open its own practice instead.

If the real goal of these letters is to save money (and we all know it is), then why is the company wasting it on redundant and inaccurate letters, usually not even sent to the correct doctor?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I am, apparently, not a very good doctor. At least, that’s what some mailings I get from insurance companies make me think.

You probably get the same ones. They tell me what guidelines I’m not following or drug interactions I’m not mindful of. I suppose I should be grateful for their efforts to protect patients.

Letters I’ve gotten in the last week have reminded me that:

• Patients with elevated fasting blood sugars should be started on metformin.

• A lady on Eliquis (apixaban) after developing a deep-vein thrombosis should be considered for a less costly alternative, such as warfarin, to help her save money.

• An antihypertensive agent is recommended for a young man with persistently elevated blood pressures.

• An older gentleman’s lipid-lowering agent may interfere with his diabetes medication.

What do these have to do with anything that I, as a neurologist, am doing for the patient? Nothing.

Why are they being sent to me, as opposed to an internist or cardiologist? I have no idea. Of course, for all I know, the other docs might be getting recommendations on how to manage Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis.

The insurance companies pay the bills. They obviously know which doctors are seeing who and prescribing what. Their billing systems track who practices what specialty. If I were to try submitting a claim for pulmonary evaluation, I’m sure they’d immediately notice and deny it.

So why can’t they get this straight? It seems like a big waste of time, paper, and postage all around.

On rare occasions, they actually get it right … sort of. About a month ago, I received a letter about a migraine patient, telling me that, for those with frequent migraines, a preventive medication should be considered. It even listed her current prescriptions to help me understand.

I absolutely agree with the letter, but it completely ignored that her medication list already included topiramate and nortriptyline, both commonly used for migraine prophylaxis. Since she has no other reason to be on either, I have no idea why they thought I’d use them. These kinds of notes all end with some generic comment that these are just suggestions, and only I and my patient can make the correct decisions about treatment, etc. etc.

That letter may be well intentioned, perhaps, but it is also inaccurate, unnecessary, and – to me – even a little demeaning. If you don’t think I know what I’m doing, then why are you sending patients to me? Maybe the software you’re using to screen charts and send these letters should open its own practice instead.

If the real goal of these letters is to save money (and we all know it is), then why is the company wasting it on redundant and inaccurate letters, usually not even sent to the correct doctor?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I am, apparently, not a very good doctor. At least, that’s what some mailings I get from insurance companies make me think.

You probably get the same ones. They tell me what guidelines I’m not following or drug interactions I’m not mindful of. I suppose I should be grateful for their efforts to protect patients.

Letters I’ve gotten in the last week have reminded me that:

• Patients with elevated fasting blood sugars should be started on metformin.

• A lady on Eliquis (apixaban) after developing a deep-vein thrombosis should be considered for a less costly alternative, such as warfarin, to help her save money.

• An antihypertensive agent is recommended for a young man with persistently elevated blood pressures.

• An older gentleman’s lipid-lowering agent may interfere with his diabetes medication.

What do these have to do with anything that I, as a neurologist, am doing for the patient? Nothing.

Why are they being sent to me, as opposed to an internist or cardiologist? I have no idea. Of course, for all I know, the other docs might be getting recommendations on how to manage Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis.

The insurance companies pay the bills. They obviously know which doctors are seeing who and prescribing what. Their billing systems track who practices what specialty. If I were to try submitting a claim for pulmonary evaluation, I’m sure they’d immediately notice and deny it.

So why can’t they get this straight? It seems like a big waste of time, paper, and postage all around.

On rare occasions, they actually get it right … sort of. About a month ago, I received a letter about a migraine patient, telling me that, for those with frequent migraines, a preventive medication should be considered. It even listed her current prescriptions to help me understand.

I absolutely agree with the letter, but it completely ignored that her medication list already included topiramate and nortriptyline, both commonly used for migraine prophylaxis. Since she has no other reason to be on either, I have no idea why they thought I’d use them. These kinds of notes all end with some generic comment that these are just suggestions, and only I and my patient can make the correct decisions about treatment, etc. etc.

That letter may be well intentioned, perhaps, but it is also inaccurate, unnecessary, and – to me – even a little demeaning. If you don’t think I know what I’m doing, then why are you sending patients to me? Maybe the software you’re using to screen charts and send these letters should open its own practice instead.

If the real goal of these letters is to save money (and we all know it is), then why is the company wasting it on redundant and inaccurate letters, usually not even sent to the correct doctor?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Dear insurance companies: Stop sending me unnecessary reminder letters

I am, apparently, not a very good doctor. At least, that’s what some mailings I get from insurance companies make me think.

You probably get the same ones. They tell me what guidelines I’m not following or drug interactions I’m not mindful of. I suppose I should be grateful for their efforts to protect patients.

Letters I’ve gotten in the last week have reminded me that:

• Patients with elevated fasting blood sugars should be started on metformin.

• A lady on Eliquis (apixaban) after developing a deep-vein thrombosis should be considered for a less costly alternative, such as warfarin, to help her save money.

• An antihypertensive agent is recommended for a young man with persistently elevated blood pressures.

• An older gentleman’s lipid-lowering agent may interfere with his diabetes medication.

What do these have to do with anything that I, as a neurologist, am doing for the patient? Nothing.

Why are they being sent to me, as opposed to an internist or cardiologist? I have no idea. Of course, for all I know, the other docs might be getting recommendations on how to manage Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis.

The insurance companies pay the bills. They obviously know which doctors are seeing who and prescribing what. Their billing systems track who practices what specialty. If I were to try submitting a claim for pulmonary evaluation, I’m sure they’d immediately notice and deny it.

So why can’t they get this straight? It seems like a big waste of time, paper, and postage all around.

On rare occasions, they actually get it right … sort of. About a month ago, I received a letter about a migraine patient, telling me that, for those with frequent migraines, a preventive medication should be considered. It even listed her current prescriptions to help me understand.

I absolutely agree with the letter, but it completely ignored that her medication list already included topiramate and nortriptyline, both commonly used for migraine prophylaxis. Since she has no other reason to be on either, I have no idea why they thought I’d use them. These kinds of notes all end with some generic comment that these are just suggestions, and only I and my patient can make the correct decisions about treatment, etc. etc.

That letter may be well intentioned, perhaps, but it is also inaccurate, unnecessary, and – to me – even a little demeaning. If you don’t think I know what I’m doing, then why are you sending patients to me? Maybe the software you’re using to screen charts and send these letters should open its own practice instead.

If the real goal of these letters is to save money (and we all know it is), then why is the company wasting it on redundant and inaccurate letters, usually not even sent to the correct doctor?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I am, apparently, not a very good doctor. At least, that’s what some mailings I get from insurance companies make me think.

You probably get the same ones. They tell me what guidelines I’m not following or drug interactions I’m not mindful of. I suppose I should be grateful for their efforts to protect patients.

Letters I’ve gotten in the last week have reminded me that:

• Patients with elevated fasting blood sugars should be started on metformin.

• A lady on Eliquis (apixaban) after developing a deep-vein thrombosis should be considered for a less costly alternative, such as warfarin, to help her save money.

• An antihypertensive agent is recommended for a young man with persistently elevated blood pressures.

• An older gentleman’s lipid-lowering agent may interfere with his diabetes medication.

What do these have to do with anything that I, as a neurologist, am doing for the patient? Nothing.

Why are they being sent to me, as opposed to an internist or cardiologist? I have no idea. Of course, for all I know, the other docs might be getting recommendations on how to manage Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis.

The insurance companies pay the bills. They obviously know which doctors are seeing who and prescribing what. Their billing systems track who practices what specialty. If I were to try submitting a claim for pulmonary evaluation, I’m sure they’d immediately notice and deny it.

So why can’t they get this straight? It seems like a big waste of time, paper, and postage all around.

On rare occasions, they actually get it right … sort of. About a month ago, I received a letter about a migraine patient, telling me that, for those with frequent migraines, a preventive medication should be considered. It even listed her current prescriptions to help me understand.

I absolutely agree with the letter, but it completely ignored that her medication list already included topiramate and nortriptyline, both commonly used for migraine prophylaxis. Since she has no other reason to be on either, I have no idea why they thought I’d use them. These kinds of notes all end with some generic comment that these are just suggestions, and only I and my patient can make the correct decisions about treatment, etc. etc.

That letter may be well intentioned, perhaps, but it is also inaccurate, unnecessary, and – to me – even a little demeaning. If you don’t think I know what I’m doing, then why are you sending patients to me? Maybe the software you’re using to screen charts and send these letters should open its own practice instead.

If the real goal of these letters is to save money (and we all know it is), then why is the company wasting it on redundant and inaccurate letters, usually not even sent to the correct doctor?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I am, apparently, not a very good doctor. At least, that’s what some mailings I get from insurance companies make me think.

You probably get the same ones. They tell me what guidelines I’m not following or drug interactions I’m not mindful of. I suppose I should be grateful for their efforts to protect patients.

Letters I’ve gotten in the last week have reminded me that:

• Patients with elevated fasting blood sugars should be started on metformin.

• A lady on Eliquis (apixaban) after developing a deep-vein thrombosis should be considered for a less costly alternative, such as warfarin, to help her save money.

• An antihypertensive agent is recommended for a young man with persistently elevated blood pressures.

• An older gentleman’s lipid-lowering agent may interfere with his diabetes medication.

What do these have to do with anything that I, as a neurologist, am doing for the patient? Nothing.

Why are they being sent to me, as opposed to an internist or cardiologist? I have no idea. Of course, for all I know, the other docs might be getting recommendations on how to manage Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis.

The insurance companies pay the bills. They obviously know which doctors are seeing who and prescribing what. Their billing systems track who practices what specialty. If I were to try submitting a claim for pulmonary evaluation, I’m sure they’d immediately notice and deny it.

So why can’t they get this straight? It seems like a big waste of time, paper, and postage all around.

On rare occasions, they actually get it right … sort of. About a month ago, I received a letter about a migraine patient, telling me that, for those with frequent migraines, a preventive medication should be considered. It even listed her current prescriptions to help me understand.

I absolutely agree with the letter, but it completely ignored that her medication list already included topiramate and nortriptyline, both commonly used for migraine prophylaxis. Since she has no other reason to be on either, I have no idea why they thought I’d use them. These kinds of notes all end with some generic comment that these are just suggestions, and only I and my patient can make the correct decisions about treatment, etc. etc.

That letter may be well intentioned, perhaps, but it is also inaccurate, unnecessary, and – to me – even a little demeaning. If you don’t think I know what I’m doing, then why are you sending patients to me? Maybe the software you’re using to screen charts and send these letters should open its own practice instead.

If the real goal of these letters is to save money (and we all know it is), then why is the company wasting it on redundant and inaccurate letters, usually not even sent to the correct doctor?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Technology Allows Independent Living for Elderly

NEW YORK - Shari Cayle, 75, called "Miracle Mama" by her family ever since she beat back advanced colon cancer seven years ago, is still undergoing treatment and living alone.

"I don't want my grandchildren to remember me as the sick one, I want to be the fun one," said Cayle, who is testing a device that passively monitors her activity. "My family knows what I'm doing and I don't think they should have to change their life around to make sure I'm OK."

Onkol, a product inspired by Cayle that monitors her front door, reminds her when to take her medication and can alert her family if she falls, has allowed her to remain independent at home. Devised by her son Marc, it will hit the U.S. market next year.

As more American seniors plan to remain at home rather than enter a nursing facility, new startups and some well-known technology brands are connecting them to family and healthcare providers.

The noninvasive devices sit in the background as users go about their normal routine. Through Bluetooth technology they are able to gather information and send it to family or doctors when, for example, a sensor reads that a pill box was opened or a wireless medical device such as a glucose monitor is used.

According to PricewaterhouseCoopers' Health Research Institute, at-home options like these will disrupt roughly $64 billion of traditional U.S. provider revenue in the next 20 years.

Monitoring devices for the elderly started with products like privately-held Life Alert, which leapt into public awareness nearly 30 years ago with TV ads showing the elderly "Mrs. Fletcher" reaching for her Life Alert pendant and telling an operator, "I've fallen and I can't get up!"

Now companies like Nortek Security & Control and small startups are taking that much further.

The challenge though is that older consumers may not be ready to use the technology and their medical, security and wellness needs may differ significantly. There are also safety and privacy risks.

"There's a lot of potential, but a big gap between what seniors want and what the market can provide," said Harry Wang, director of health and mobile product research at Parks Associates.

NURSE MOLLY

Milwaukee-based Onkol developed a rectangular hub, roughly the size of a tissue box, that passively monitors things like what their blood glucose reading is and when they open their refrigerator. There is also a wristband that can be pressed for help in an emergency.

"The advantage of it is that the person, the patient, doesn't have to worry about hooking it up and doing stuff with the computer, their kids do that," said Cayle, whose son co-founded Onkol.

Sensely is another device used by providers like Kaiser Permanente, based in California, and the National Health Service in the United Kingdom. Since 2013, its virtual nurse Molly has connected patients with doctors from a mobile device. She asks how they are feeling and lets them know when it is time to take a health reading.

Another startup, San Francisco-based Lively began selling its product to consumers in 2012. Similarly, it collects information from sensors and connects to a smart watch that tracks customers' footsteps, routine and can even call emergency services. Next year it will connect with medical devices, send data to physicians and enable video consultations that can replace some doctor's appointments.

Venture firms including Fenox Venture Capital, Maveron, Capital Midwest Fund and LaunchPad Digital Health have contributed millions of dollars to these startups.

Ideal Life, founded in 2002, which sells it own devices to providers, plans to release its own consumer version next year.

"The clinical community is more open than they've even been before in piloting and testing new technology," said founder Jason Goldberg.

Just this summer, Nortek bought a personal emergency response system called Libris and a healthcare platform from Numera, a health technology company, for $12 million. At the same time, Nortek said some of its smart home customers like ADT Corp want to expand into health and wellness offerings. The goal is to offer software that connects with customers' current systems as well as medical, fitness, emergency and security devices.

"In the smart home and health space today you see a lot of single purpose solutions that don't offer a full connectivity platform, like a smart watch or pressure sensor in a bed," said Mike O'Neal, Nortek Security & Control president. "We're creating that connectivity."

A July study from AARP showed Americans 50 years and older want activity monitors like Fitbit and Jawbone to have more relevant sensors to monitor health conditions and 89% cited difficulties with set up.

"They (companies) have great technology, but when you can't open the package or you can't find directions that's a problem," said Jody Holtzman, senior vice president of thought leadership at AARP.

Such products may help doctors keep up with a growing elderly population. Research firm Gartner estimates that in the next 40 years, one-third of the population in developed countries will be 65 years or older, thus making it impossible to keep everyone who needs care in the hospital.

NEW YORK - Shari Cayle, 75, called "Miracle Mama" by her family ever since she beat back advanced colon cancer seven years ago, is still undergoing treatment and living alone.

"I don't want my grandchildren to remember me as the sick one, I want to be the fun one," said Cayle, who is testing a device that passively monitors her activity. "My family knows what I'm doing and I don't think they should have to change their life around to make sure I'm OK."

Onkol, a product inspired by Cayle that monitors her front door, reminds her when to take her medication and can alert her family if she falls, has allowed her to remain independent at home. Devised by her son Marc, it will hit the U.S. market next year.

As more American seniors plan to remain at home rather than enter a nursing facility, new startups and some well-known technology brands are connecting them to family and healthcare providers.

The noninvasive devices sit in the background as users go about their normal routine. Through Bluetooth technology they are able to gather information and send it to family or doctors when, for example, a sensor reads that a pill box was opened or a wireless medical device such as a glucose monitor is used.

According to PricewaterhouseCoopers' Health Research Institute, at-home options like these will disrupt roughly $64 billion of traditional U.S. provider revenue in the next 20 years.

Monitoring devices for the elderly started with products like privately-held Life Alert, which leapt into public awareness nearly 30 years ago with TV ads showing the elderly "Mrs. Fletcher" reaching for her Life Alert pendant and telling an operator, "I've fallen and I can't get up!"

Now companies like Nortek Security & Control and small startups are taking that much further.

The challenge though is that older consumers may not be ready to use the technology and their medical, security and wellness needs may differ significantly. There are also safety and privacy risks.

"There's a lot of potential, but a big gap between what seniors want and what the market can provide," said Harry Wang, director of health and mobile product research at Parks Associates.

NURSE MOLLY

Milwaukee-based Onkol developed a rectangular hub, roughly the size of a tissue box, that passively monitors things like what their blood glucose reading is and when they open their refrigerator. There is also a wristband that can be pressed for help in an emergency.

"The advantage of it is that the person, the patient, doesn't have to worry about hooking it up and doing stuff with the computer, their kids do that," said Cayle, whose son co-founded Onkol.

Sensely is another device used by providers like Kaiser Permanente, based in California, and the National Health Service in the United Kingdom. Since 2013, its virtual nurse Molly has connected patients with doctors from a mobile device. She asks how they are feeling and lets them know when it is time to take a health reading.

Another startup, San Francisco-based Lively began selling its product to consumers in 2012. Similarly, it collects information from sensors and connects to a smart watch that tracks customers' footsteps, routine and can even call emergency services. Next year it will connect with medical devices, send data to physicians and enable video consultations that can replace some doctor's appointments.

Venture firms including Fenox Venture Capital, Maveron, Capital Midwest Fund and LaunchPad Digital Health have contributed millions of dollars to these startups.

Ideal Life, founded in 2002, which sells it own devices to providers, plans to release its own consumer version next year.

"The clinical community is more open than they've even been before in piloting and testing new technology," said founder Jason Goldberg.

Just this summer, Nortek bought a personal emergency response system called Libris and a healthcare platform from Numera, a health technology company, for $12 million. At the same time, Nortek said some of its smart home customers like ADT Corp want to expand into health and wellness offerings. The goal is to offer software that connects with customers' current systems as well as medical, fitness, emergency and security devices.

"In the smart home and health space today you see a lot of single purpose solutions that don't offer a full connectivity platform, like a smart watch or pressure sensor in a bed," said Mike O'Neal, Nortek Security & Control president. "We're creating that connectivity."

A July study from AARP showed Americans 50 years and older want activity monitors like Fitbit and Jawbone to have more relevant sensors to monitor health conditions and 89% cited difficulties with set up.

"They (companies) have great technology, but when you can't open the package or you can't find directions that's a problem," said Jody Holtzman, senior vice president of thought leadership at AARP.

Such products may help doctors keep up with a growing elderly population. Research firm Gartner estimates that in the next 40 years, one-third of the population in developed countries will be 65 years or older, thus making it impossible to keep everyone who needs care in the hospital.

NEW YORK - Shari Cayle, 75, called "Miracle Mama" by her family ever since she beat back advanced colon cancer seven years ago, is still undergoing treatment and living alone.

"I don't want my grandchildren to remember me as the sick one, I want to be the fun one," said Cayle, who is testing a device that passively monitors her activity. "My family knows what I'm doing and I don't think they should have to change their life around to make sure I'm OK."

Onkol, a product inspired by Cayle that monitors her front door, reminds her when to take her medication and can alert her family if she falls, has allowed her to remain independent at home. Devised by her son Marc, it will hit the U.S. market next year.

As more American seniors plan to remain at home rather than enter a nursing facility, new startups and some well-known technology brands are connecting them to family and healthcare providers.

The noninvasive devices sit in the background as users go about their normal routine. Through Bluetooth technology they are able to gather information and send it to family or doctors when, for example, a sensor reads that a pill box was opened or a wireless medical device such as a glucose monitor is used.

According to PricewaterhouseCoopers' Health Research Institute, at-home options like these will disrupt roughly $64 billion of traditional U.S. provider revenue in the next 20 years.

Monitoring devices for the elderly started with products like privately-held Life Alert, which leapt into public awareness nearly 30 years ago with TV ads showing the elderly "Mrs. Fletcher" reaching for her Life Alert pendant and telling an operator, "I've fallen and I can't get up!"

Now companies like Nortek Security & Control and small startups are taking that much further.

The challenge though is that older consumers may not be ready to use the technology and their medical, security and wellness needs may differ significantly. There are also safety and privacy risks.

"There's a lot of potential, but a big gap between what seniors want and what the market can provide," said Harry Wang, director of health and mobile product research at Parks Associates.

NURSE MOLLY

Milwaukee-based Onkol developed a rectangular hub, roughly the size of a tissue box, that passively monitors things like what their blood glucose reading is and when they open their refrigerator. There is also a wristband that can be pressed for help in an emergency.

"The advantage of it is that the person, the patient, doesn't have to worry about hooking it up and doing stuff with the computer, their kids do that," said Cayle, whose son co-founded Onkol.

Sensely is another device used by providers like Kaiser Permanente, based in California, and the National Health Service in the United Kingdom. Since 2013, its virtual nurse Molly has connected patients with doctors from a mobile device. She asks how they are feeling and lets them know when it is time to take a health reading.

Another startup, San Francisco-based Lively began selling its product to consumers in 2012. Similarly, it collects information from sensors and connects to a smart watch that tracks customers' footsteps, routine and can even call emergency services. Next year it will connect with medical devices, send data to physicians and enable video consultations that can replace some doctor's appointments.

Venture firms including Fenox Venture Capital, Maveron, Capital Midwest Fund and LaunchPad Digital Health have contributed millions of dollars to these startups.

Ideal Life, founded in 2002, which sells it own devices to providers, plans to release its own consumer version next year.

"The clinical community is more open than they've even been before in piloting and testing new technology," said founder Jason Goldberg.

Just this summer, Nortek bought a personal emergency response system called Libris and a healthcare platform from Numera, a health technology company, for $12 million. At the same time, Nortek said some of its smart home customers like ADT Corp want to expand into health and wellness offerings. The goal is to offer software that connects with customers' current systems as well as medical, fitness, emergency and security devices.

"In the smart home and health space today you see a lot of single purpose solutions that don't offer a full connectivity platform, like a smart watch or pressure sensor in a bed," said Mike O'Neal, Nortek Security & Control president. "We're creating that connectivity."

A July study from AARP showed Americans 50 years and older want activity monitors like Fitbit and Jawbone to have more relevant sensors to monitor health conditions and 89% cited difficulties with set up.

"They (companies) have great technology, but when you can't open the package or you can't find directions that's a problem," said Jody Holtzman, senior vice president of thought leadership at AARP.

Such products may help doctors keep up with a growing elderly population. Research firm Gartner estimates that in the next 40 years, one-third of the population in developed countries will be 65 years or older, thus making it impossible to keep everyone who needs care in the hospital.

Living conditions linked to risk of Hodgkin lymphoma

Photo by Pavel Novak

VIENNA—Living in overcrowded conditions may affect a young person’s risk of developing certain subtypes of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), according to researchers.

They studied more than 600 children and young adults with HL in England and found that patients who lived in areas with more overcrowded households had a lower incidence of nodular sclerosis (NS) HL but a higher incidence of the not-otherwise-specified (NOS) subtype of HL.

“Our findings related to the NS subtype may suggest that the recurrent infections to which children living in overcrowded conditions are likely to have been exposed stimulate their immune systems and, hence, protect them against developing this type of cancer later in their childhood and early adult life,” said Richard McNally, PhD, of Newcastle University in the UK.

“Those who have a genetic susceptibility to HL and have been less exposed to infection through not living in such overcrowded conditions may have less developed immune systems as a result and are therefore at greater risk of developing this subtype.”

Dr McNally and his colleagues added that it’s more difficult to interpret the findings in the NOS group because this subtype of HL is very heterogeneous. The team said the role of chance cannot be ruled out.

They presented this research at the 2015 European Cancer Congress (abstract 1414).

Dr McNally and his colleagues wanted to gain a better understanding of factors that cause HL, so they analyzed a cohort of young HL patients in Northern England, looking at factors such as sex, age, and socio-economic deprivation.

The researchers evaluated 621 cases of HL recorded in the Northern Region Young Persons’ Malignant Disease Registry. Patients were ages 0 to 24 at diagnosis and were diagnosed between 1968 and 2003.

There were 5 different subtypes of HL in this group:

- 247 cases of the NS type

- 143 NOS

- 105 of mixed cellularity

- 58 lymphocyte-rich cases

- 68 “others.”

Age and sex

Overall, more males than females had HL, but the male-female ratio varied by both age group and subtype. The age-standardized rate (ASR) of HL for males was 18.15 per million persons per year, and the ASR for females was 10.52 per million persons per year.

For the NS subtype, there were 130 males and 117 females, but this was reversed at ages 20 to 24, with 72 females and 55 males. The ASR for NS HL at 20 to 24 was 14.26 for males and 18.79 for females.

“That this change takes place after puberty seems to suggest that estrogens may be responsible in some way,” Dr McNally said. “There are a lot of genes directly regulated by sex hormones, and they are obvious suspects. Alternatively, epigenetic changes . . . influencing key genes, induced by sex hormones, may be responsible.”

Overcrowding

The researchers calculated socio-economic deprivation using the 4 components of the Townsend deprivation score: household overcrowding, non-home ownership, unemployment, and households with no car.

They observed a lower incidence of NS HL among those patients living in areas with more overcrowded households. The relative risk of NS HL was 0.88 for a 1% increase in household overcrowding (P<0.001).

For the NOS subtype, the reverse was seen. A 1% increase in household overcrowding was associated with an increased incidence of NOS HL—a relative risk of 1.17.

Overcrowding seemed to have no effect on the incidence of mixed-cellularity HL or lymphocyte-rich HL.

“We knew already that recurrent infections may protect against childhood leukemia, and now it looks as we can add Hodgkin lymphoma and, particularly its NS subtype, to the list,” Dr McNally said. “In order to further investigate the factors involved, prospective studies should investigate the hormonal changes and recurrent infections and their direct link to the risk of lymphoma, but such studies are difficult to do in rare diseases.”

“A practical follow-up would be case-control studies examining biological markers related to exposure to a multitude of infectious agents, and indeed to hormonal status itself, while genetic studies are another possibility.” ![]()

Photo by Pavel Novak

VIENNA—Living in overcrowded conditions may affect a young person’s risk of developing certain subtypes of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), according to researchers.

They studied more than 600 children and young adults with HL in England and found that patients who lived in areas with more overcrowded households had a lower incidence of nodular sclerosis (NS) HL but a higher incidence of the not-otherwise-specified (NOS) subtype of HL.

“Our findings related to the NS subtype may suggest that the recurrent infections to which children living in overcrowded conditions are likely to have been exposed stimulate their immune systems and, hence, protect them against developing this type of cancer later in their childhood and early adult life,” said Richard McNally, PhD, of Newcastle University in the UK.

“Those who have a genetic susceptibility to HL and have been less exposed to infection through not living in such overcrowded conditions may have less developed immune systems as a result and are therefore at greater risk of developing this subtype.”

Dr McNally and his colleagues added that it’s more difficult to interpret the findings in the NOS group because this subtype of HL is very heterogeneous. The team said the role of chance cannot be ruled out.

They presented this research at the 2015 European Cancer Congress (abstract 1414).

Dr McNally and his colleagues wanted to gain a better understanding of factors that cause HL, so they analyzed a cohort of young HL patients in Northern England, looking at factors such as sex, age, and socio-economic deprivation.

The researchers evaluated 621 cases of HL recorded in the Northern Region Young Persons’ Malignant Disease Registry. Patients were ages 0 to 24 at diagnosis and were diagnosed between 1968 and 2003.

There were 5 different subtypes of HL in this group:

- 247 cases of the NS type

- 143 NOS

- 105 of mixed cellularity

- 58 lymphocyte-rich cases

- 68 “others.”

Age and sex

Overall, more males than females had HL, but the male-female ratio varied by both age group and subtype. The age-standardized rate (ASR) of HL for males was 18.15 per million persons per year, and the ASR for females was 10.52 per million persons per year.

For the NS subtype, there were 130 males and 117 females, but this was reversed at ages 20 to 24, with 72 females and 55 males. The ASR for NS HL at 20 to 24 was 14.26 for males and 18.79 for females.

“That this change takes place after puberty seems to suggest that estrogens may be responsible in some way,” Dr McNally said. “There are a lot of genes directly regulated by sex hormones, and they are obvious suspects. Alternatively, epigenetic changes . . . influencing key genes, induced by sex hormones, may be responsible.”

Overcrowding

The researchers calculated socio-economic deprivation using the 4 components of the Townsend deprivation score: household overcrowding, non-home ownership, unemployment, and households with no car.

They observed a lower incidence of NS HL among those patients living in areas with more overcrowded households. The relative risk of NS HL was 0.88 for a 1% increase in household overcrowding (P<0.001).

For the NOS subtype, the reverse was seen. A 1% increase in household overcrowding was associated with an increased incidence of NOS HL—a relative risk of 1.17.

Overcrowding seemed to have no effect on the incidence of mixed-cellularity HL or lymphocyte-rich HL.

“We knew already that recurrent infections may protect against childhood leukemia, and now it looks as we can add Hodgkin lymphoma and, particularly its NS subtype, to the list,” Dr McNally said. “In order to further investigate the factors involved, prospective studies should investigate the hormonal changes and recurrent infections and their direct link to the risk of lymphoma, but such studies are difficult to do in rare diseases.”

“A practical follow-up would be case-control studies examining biological markers related to exposure to a multitude of infectious agents, and indeed to hormonal status itself, while genetic studies are another possibility.” ![]()

Photo by Pavel Novak

VIENNA—Living in overcrowded conditions may affect a young person’s risk of developing certain subtypes of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), according to researchers.

They studied more than 600 children and young adults with HL in England and found that patients who lived in areas with more overcrowded households had a lower incidence of nodular sclerosis (NS) HL but a higher incidence of the not-otherwise-specified (NOS) subtype of HL.

“Our findings related to the NS subtype may suggest that the recurrent infections to which children living in overcrowded conditions are likely to have been exposed stimulate their immune systems and, hence, protect them against developing this type of cancer later in their childhood and early adult life,” said Richard McNally, PhD, of Newcastle University in the UK.

“Those who have a genetic susceptibility to HL and have been less exposed to infection through not living in such overcrowded conditions may have less developed immune systems as a result and are therefore at greater risk of developing this subtype.”

Dr McNally and his colleagues added that it’s more difficult to interpret the findings in the NOS group because this subtype of HL is very heterogeneous. The team said the role of chance cannot be ruled out.

They presented this research at the 2015 European Cancer Congress (abstract 1414).

Dr McNally and his colleagues wanted to gain a better understanding of factors that cause HL, so they analyzed a cohort of young HL patients in Northern England, looking at factors such as sex, age, and socio-economic deprivation.

The researchers evaluated 621 cases of HL recorded in the Northern Region Young Persons’ Malignant Disease Registry. Patients were ages 0 to 24 at diagnosis and were diagnosed between 1968 and 2003.

There were 5 different subtypes of HL in this group:

- 247 cases of the NS type

- 143 NOS

- 105 of mixed cellularity

- 58 lymphocyte-rich cases

- 68 “others.”

Age and sex

Overall, more males than females had HL, but the male-female ratio varied by both age group and subtype. The age-standardized rate (ASR) of HL for males was 18.15 per million persons per year, and the ASR for females was 10.52 per million persons per year.

For the NS subtype, there were 130 males and 117 females, but this was reversed at ages 20 to 24, with 72 females and 55 males. The ASR for NS HL at 20 to 24 was 14.26 for males and 18.79 for females.

“That this change takes place after puberty seems to suggest that estrogens may be responsible in some way,” Dr McNally said. “There are a lot of genes directly regulated by sex hormones, and they are obvious suspects. Alternatively, epigenetic changes . . . influencing key genes, induced by sex hormones, may be responsible.”

Overcrowding

The researchers calculated socio-economic deprivation using the 4 components of the Townsend deprivation score: household overcrowding, non-home ownership, unemployment, and households with no car.

They observed a lower incidence of NS HL among those patients living in areas with more overcrowded households. The relative risk of NS HL was 0.88 for a 1% increase in household overcrowding (P<0.001).

For the NOS subtype, the reverse was seen. A 1% increase in household overcrowding was associated with an increased incidence of NOS HL—a relative risk of 1.17.

Overcrowding seemed to have no effect on the incidence of mixed-cellularity HL or lymphocyte-rich HL.

“We knew already that recurrent infections may protect against childhood leukemia, and now it looks as we can add Hodgkin lymphoma and, particularly its NS subtype, to the list,” Dr McNally said. “In order to further investigate the factors involved, prospective studies should investigate the hormonal changes and recurrent infections and their direct link to the risk of lymphoma, but such studies are difficult to do in rare diseases.”

“A practical follow-up would be case-control studies examining biological markers related to exposure to a multitude of infectious agents, and indeed to hormonal status itself, while genetic studies are another possibility.” ![]()

CHMP grants accelerated assessment for MM drug

Photo by Linda Bartlett

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has agreed to provide accelerated assessment for daratumumab.

The drug is under review as monotherapy for patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The CHMP grants accelerated assessment when a product is expected to be of major public health interest, particularly from the point of view of therapeutic innovation.

Accelerated assessment shortens the review period from 210 days to 150 days.

About daratumumab

Daratumumab is an investigational monoclonal antibody that works by binding to CD38 on the surface of MM cells. In doing so, daratumumab triggers the patient’s own immune system to attack MM cells, resulting in cell death through multiple mechanisms of action.

In July 2013, daratumumab was granted orphan drug status by the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of plasma cell myeloma.

The drug has been accepted for priority review in the US as monotherapy for MM patients who are refractory to both a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent or who have received 3 or more prior lines of therapy, including a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent.

In August 2012, Janssen Biotech, Inc. and Genmab entered an agreement that granted Janssen an exclusive worldwide license to develop, manufacture, and commercialize daratumumab.

Daratumumab trials

The marketing authorization application for daratumumab includes data from the phase 2 MMY2002 (SIRIUS) study, the phase 1/2 GEN501 study, and 3 additional supportive studies.

The GEN501 study enrolled 102 patients with relapsed MM or relapsed MM that was refractory to 2 or more prior lines of therapy. The patients received daratumumab at a range of doses and on a number of different schedules.

The results suggested that daratumumab is most effective at a dose of 16 mg/kg. At this dose, the overall response rate was 36%.

Most adverse events in this study were grade 1 or 2, although serious events did occur.

The SIRIUS study enrolled 124 MM patients who had received 3 or more prior lines of therapy. They received daratumumab at different doses and on different schedules, but 106 of the patients received the drug at 16 mg/kg.

Twenty-nine percent of the 106 patients responded to treatment, and the median duration of response was 7 months. Thirty percent of patients experienced serious adverse events. ![]()

Photo by Linda Bartlett