User login

Billing audits: The bane of a small practice

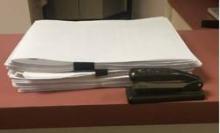

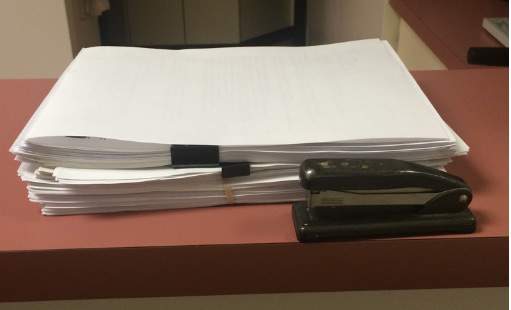

The photo you see below is a reasonably thick pile of paper, roughly 2 inches high. It’s certainly not as bad as some charts I’ve seen, especially at the VA, but still a lot of pages.

What is it?

This is, believe it or not, the stacked copies of charts we had to print in the last 30 days to fax to insurance companies for billing audits. Yeah – just the last 30 days.

Mind you, to date I don’t have any sort of actual complaints or charges against me for fraudulent billing. If anything, I tend to underbill for fear of risking the ire of insurance companies.

On one level, I understand it. The news is replete with stories of physicians who made fraudulent insurance claims, and the insurance companies want to make sure others are playing fair. Just like security cameras and magnetic tags at retailers, they’re doing what they can to avoid losses. I get that.

On the other hand, this irritates me, and it is a pain in the butt. Someone here has to print up the requested notes, organize them, fill out the accompanying forms, and fax them back. I also have to sign each note in the pile. For the number of charts they typically want, this process takes about 30-45 minutes. Then we fax them, and a 100-plus-page document ties up your office fax for a while. Incoming and outgoing faxes, such as medication refills, get put on hold. Overall, it takes maybe an hour of staff time to do this, not to mention the cost of paper and ink used.

About 25% of the time the company calls us after a few days to say they never got them (even though we have a confirmation). For this reason, we always hold onto the print-out for a month so we don’t have to start over again. Then it all has to be shredded.

In a large practice, I’m sure there are dedicated medical records staff members for this. But in my small solo world it means that someone has to let phones go to voicemail, dictations get delayed, and other work piles up, just so the insurance red tape gets done. Then we have to catch up on the more routine issues of patient care.

I can’t really refuse to send them, either. Doing so, in the insurance company’s mind, would be an admission of guilt that I never saw the patient and my claim is bogus. Then they’ll withhold payment, or ask for a refund.

This is, regrettably, a case where a few bad apples – docs filing bogus claims – have spoiled the entire barrel. Now we’re all guilty of fraud until proven innocent by sending these records. Isn’t that the reverse of the American justice system’s ideal?

I also wonder if there’s an intentional drudgery factor here. By making me do something that’s irritatingly time-wasting, is an insurance plan hoping I’ll drop them because I’m sick of this process? Does having fewer contracted neurologists work out to their benefit? It certainly isn’t to the patient’s advantage.

I don’t have an easy answer. I don’t like the wrench these requests throw into the office routine, but I also know that fraud surveillance is a necessary evil. I just wish there was a less time-consuming way of doing it.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The photo you see below is a reasonably thick pile of paper, roughly 2 inches high. It’s certainly not as bad as some charts I’ve seen, especially at the VA, but still a lot of pages.

What is it?

This is, believe it or not, the stacked copies of charts we had to print in the last 30 days to fax to insurance companies for billing audits. Yeah – just the last 30 days.

Mind you, to date I don’t have any sort of actual complaints or charges against me for fraudulent billing. If anything, I tend to underbill for fear of risking the ire of insurance companies.

On one level, I understand it. The news is replete with stories of physicians who made fraudulent insurance claims, and the insurance companies want to make sure others are playing fair. Just like security cameras and magnetic tags at retailers, they’re doing what they can to avoid losses. I get that.

On the other hand, this irritates me, and it is a pain in the butt. Someone here has to print up the requested notes, organize them, fill out the accompanying forms, and fax them back. I also have to sign each note in the pile. For the number of charts they typically want, this process takes about 30-45 minutes. Then we fax them, and a 100-plus-page document ties up your office fax for a while. Incoming and outgoing faxes, such as medication refills, get put on hold. Overall, it takes maybe an hour of staff time to do this, not to mention the cost of paper and ink used.

About 25% of the time the company calls us after a few days to say they never got them (even though we have a confirmation). For this reason, we always hold onto the print-out for a month so we don’t have to start over again. Then it all has to be shredded.

In a large practice, I’m sure there are dedicated medical records staff members for this. But in my small solo world it means that someone has to let phones go to voicemail, dictations get delayed, and other work piles up, just so the insurance red tape gets done. Then we have to catch up on the more routine issues of patient care.

I can’t really refuse to send them, either. Doing so, in the insurance company’s mind, would be an admission of guilt that I never saw the patient and my claim is bogus. Then they’ll withhold payment, or ask for a refund.

This is, regrettably, a case where a few bad apples – docs filing bogus claims – have spoiled the entire barrel. Now we’re all guilty of fraud until proven innocent by sending these records. Isn’t that the reverse of the American justice system’s ideal?

I also wonder if there’s an intentional drudgery factor here. By making me do something that’s irritatingly time-wasting, is an insurance plan hoping I’ll drop them because I’m sick of this process? Does having fewer contracted neurologists work out to their benefit? It certainly isn’t to the patient’s advantage.

I don’t have an easy answer. I don’t like the wrench these requests throw into the office routine, but I also know that fraud surveillance is a necessary evil. I just wish there was a less time-consuming way of doing it.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The photo you see below is a reasonably thick pile of paper, roughly 2 inches high. It’s certainly not as bad as some charts I’ve seen, especially at the VA, but still a lot of pages.

What is it?

This is, believe it or not, the stacked copies of charts we had to print in the last 30 days to fax to insurance companies for billing audits. Yeah – just the last 30 days.

Mind you, to date I don’t have any sort of actual complaints or charges against me for fraudulent billing. If anything, I tend to underbill for fear of risking the ire of insurance companies.

On one level, I understand it. The news is replete with stories of physicians who made fraudulent insurance claims, and the insurance companies want to make sure others are playing fair. Just like security cameras and magnetic tags at retailers, they’re doing what they can to avoid losses. I get that.

On the other hand, this irritates me, and it is a pain in the butt. Someone here has to print up the requested notes, organize them, fill out the accompanying forms, and fax them back. I also have to sign each note in the pile. For the number of charts they typically want, this process takes about 30-45 minutes. Then we fax them, and a 100-plus-page document ties up your office fax for a while. Incoming and outgoing faxes, such as medication refills, get put on hold. Overall, it takes maybe an hour of staff time to do this, not to mention the cost of paper and ink used.

About 25% of the time the company calls us after a few days to say they never got them (even though we have a confirmation). For this reason, we always hold onto the print-out for a month so we don’t have to start over again. Then it all has to be shredded.

In a large practice, I’m sure there are dedicated medical records staff members for this. But in my small solo world it means that someone has to let phones go to voicemail, dictations get delayed, and other work piles up, just so the insurance red tape gets done. Then we have to catch up on the more routine issues of patient care.

I can’t really refuse to send them, either. Doing so, in the insurance company’s mind, would be an admission of guilt that I never saw the patient and my claim is bogus. Then they’ll withhold payment, or ask for a refund.

This is, regrettably, a case where a few bad apples – docs filing bogus claims – have spoiled the entire barrel. Now we’re all guilty of fraud until proven innocent by sending these records. Isn’t that the reverse of the American justice system’s ideal?

I also wonder if there’s an intentional drudgery factor here. By making me do something that’s irritatingly time-wasting, is an insurance plan hoping I’ll drop them because I’m sick of this process? Does having fewer contracted neurologists work out to their benefit? It certainly isn’t to the patient’s advantage.

I don’t have an easy answer. I don’t like the wrench these requests throw into the office routine, but I also know that fraud surveillance is a necessary evil. I just wish there was a less time-consuming way of doing it.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Racial, Economic Disparities in Life Expectancy after Heart Attack

After a heart attack, black patients typically don't live as long as whites - a racial difference that is starkest among the affluent - according to a new U.S. study.

Researchers evaluated data on more than 132,000 white heart attack patients and almost 9,000 black patients covered by Medicare, the government health program for the elderly and disabled. They used postal codes to assess income levels in patients' communities.

After 17 years of follow-up, the overall survival rate was 7.4 percent for white patients and 5.7 percent for black patients, according to the results published in Circulation, the journal of the American Heart Association.

On average, across all ages, white patients in low-income areas lived longer after a heart attack - about 5.6 years compared with 5.4 years for black patients. But in high-income communities, the gap widened to a life expectancy of seven years for white people and 6.3 years for black individuals.

"We found that socioeconomic status did not explain the racial disparities in life expectancy after a heart attack," lead study author Dr. Emily Bucholz of Boston Children's Hospital said by email.

"Contrary to common belief, this suggests that improving socioeconomic standing may improve outcomes for black and white patients globally but is unlikely to eliminate racial disparities in health," Bucholz added.

To see how race and class impact heart attack outcomes, Bucholz and colleagues reviewed health records collected from 1994 to 1996 for patients aged 65 to 90 years.

Just 6.3 percent of the patients were black, and only 6.8 percent lived in low-income communities, based on the typical household income in their postal codes.

Among white patients under 80, life expectancy was longest for patients in the most affluent neighborhoods and it got progressively shorter for middle-income and poor communities, the study found.

By contrast, life expectancy was similar for black patients residing in poor and middle-income communities across all ages. Only black patients under age 75 living in affluent areas had a survival advantage compared with their peers in less wealthy neighborhoods.

One shortcoming of the study is that it included a small proportion of black and poor patients, the authors acknowledge. It's also possible that using postal codes to assess income may have led to some instances where income levels were inflated or underestimated, the authors note.

It's possible that black patients living in affluent areas don't fare as well as white patients because they don't have the same amount of social support from their peers, said Dr. Joaquin Cigarroa, a cardiovascular medicine researcher at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

In poor neighborhoods, black patients may face additional challenges to surviving a heart attack, added Cigarroa, who wasn't involved in the study.

"They more often live in low socioeconomic segments of our community that often have less access to health care resources and less access to stores with good nutrition," Cigarroa said by email. "In addition, these segments of our community are often not ideally configured for promoting physical activity with parks, sidewalks, bike lanes, etc."

The study findings highlight a need to improve outcomes among poor and black patients and suggest some differences in heart attack survival may come down to disparities in quality of care, said senior study author Dr. Harlan Krumholz of Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

Because black patients have a greater burden of heart disease than white people, doctors may also need to focus more on prevention in this community, Krumholz said by email.

"Healthy heart habits may be even more important for African-Americans, for whom avoiding a heart attack is even more important given their worse outcomes after the event," Krumholz said.

After a heart attack, black patients typically don't live as long as whites - a racial difference that is starkest among the affluent - according to a new U.S. study.

Researchers evaluated data on more than 132,000 white heart attack patients and almost 9,000 black patients covered by Medicare, the government health program for the elderly and disabled. They used postal codes to assess income levels in patients' communities.

After 17 years of follow-up, the overall survival rate was 7.4 percent for white patients and 5.7 percent for black patients, according to the results published in Circulation, the journal of the American Heart Association.

On average, across all ages, white patients in low-income areas lived longer after a heart attack - about 5.6 years compared with 5.4 years for black patients. But in high-income communities, the gap widened to a life expectancy of seven years for white people and 6.3 years for black individuals.

"We found that socioeconomic status did not explain the racial disparities in life expectancy after a heart attack," lead study author Dr. Emily Bucholz of Boston Children's Hospital said by email.

"Contrary to common belief, this suggests that improving socioeconomic standing may improve outcomes for black and white patients globally but is unlikely to eliminate racial disparities in health," Bucholz added.

To see how race and class impact heart attack outcomes, Bucholz and colleagues reviewed health records collected from 1994 to 1996 for patients aged 65 to 90 years.

Just 6.3 percent of the patients were black, and only 6.8 percent lived in low-income communities, based on the typical household income in their postal codes.

Among white patients under 80, life expectancy was longest for patients in the most affluent neighborhoods and it got progressively shorter for middle-income and poor communities, the study found.

By contrast, life expectancy was similar for black patients residing in poor and middle-income communities across all ages. Only black patients under age 75 living in affluent areas had a survival advantage compared with their peers in less wealthy neighborhoods.

One shortcoming of the study is that it included a small proportion of black and poor patients, the authors acknowledge. It's also possible that using postal codes to assess income may have led to some instances where income levels were inflated or underestimated, the authors note.

It's possible that black patients living in affluent areas don't fare as well as white patients because they don't have the same amount of social support from their peers, said Dr. Joaquin Cigarroa, a cardiovascular medicine researcher at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

In poor neighborhoods, black patients may face additional challenges to surviving a heart attack, added Cigarroa, who wasn't involved in the study.

"They more often live in low socioeconomic segments of our community that often have less access to health care resources and less access to stores with good nutrition," Cigarroa said by email. "In addition, these segments of our community are often not ideally configured for promoting physical activity with parks, sidewalks, bike lanes, etc."

The study findings highlight a need to improve outcomes among poor and black patients and suggest some differences in heart attack survival may come down to disparities in quality of care, said senior study author Dr. Harlan Krumholz of Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

Because black patients have a greater burden of heart disease than white people, doctors may also need to focus more on prevention in this community, Krumholz said by email.

"Healthy heart habits may be even more important for African-Americans, for whom avoiding a heart attack is even more important given their worse outcomes after the event," Krumholz said.

After a heart attack, black patients typically don't live as long as whites - a racial difference that is starkest among the affluent - according to a new U.S. study.

Researchers evaluated data on more than 132,000 white heart attack patients and almost 9,000 black patients covered by Medicare, the government health program for the elderly and disabled. They used postal codes to assess income levels in patients' communities.

After 17 years of follow-up, the overall survival rate was 7.4 percent for white patients and 5.7 percent for black patients, according to the results published in Circulation, the journal of the American Heart Association.

On average, across all ages, white patients in low-income areas lived longer after a heart attack - about 5.6 years compared with 5.4 years for black patients. But in high-income communities, the gap widened to a life expectancy of seven years for white people and 6.3 years for black individuals.

"We found that socioeconomic status did not explain the racial disparities in life expectancy after a heart attack," lead study author Dr. Emily Bucholz of Boston Children's Hospital said by email.

"Contrary to common belief, this suggests that improving socioeconomic standing may improve outcomes for black and white patients globally but is unlikely to eliminate racial disparities in health," Bucholz added.

To see how race and class impact heart attack outcomes, Bucholz and colleagues reviewed health records collected from 1994 to 1996 for patients aged 65 to 90 years.

Just 6.3 percent of the patients were black, and only 6.8 percent lived in low-income communities, based on the typical household income in their postal codes.

Among white patients under 80, life expectancy was longest for patients in the most affluent neighborhoods and it got progressively shorter for middle-income and poor communities, the study found.

By contrast, life expectancy was similar for black patients residing in poor and middle-income communities across all ages. Only black patients under age 75 living in affluent areas had a survival advantage compared with their peers in less wealthy neighborhoods.

One shortcoming of the study is that it included a small proportion of black and poor patients, the authors acknowledge. It's also possible that using postal codes to assess income may have led to some instances where income levels were inflated or underestimated, the authors note.

It's possible that black patients living in affluent areas don't fare as well as white patients because they don't have the same amount of social support from their peers, said Dr. Joaquin Cigarroa, a cardiovascular medicine researcher at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

In poor neighborhoods, black patients may face additional challenges to surviving a heart attack, added Cigarroa, who wasn't involved in the study.

"They more often live in low socioeconomic segments of our community that often have less access to health care resources and less access to stores with good nutrition," Cigarroa said by email. "In addition, these segments of our community are often not ideally configured for promoting physical activity with parks, sidewalks, bike lanes, etc."

The study findings highlight a need to improve outcomes among poor and black patients and suggest some differences in heart attack survival may come down to disparities in quality of care, said senior study author Dr. Harlan Krumholz of Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

Because black patients have a greater burden of heart disease than white people, doctors may also need to focus more on prevention in this community, Krumholz said by email.

"Healthy heart habits may be even more important for African-Americans, for whom avoiding a heart attack is even more important given their worse outcomes after the event," Krumholz said.

Bipolar phenotype affects present, future self-image

Higher positivity ratings for current self-images were associated with lower depression and anxiety scores among young adults with Bipolar Spectrum Disorder (BPSD), suggesting that BPSD phenotype can shape the relationship between affect and current and future self-images.

As reported in the Journal of Affective Disorders, lead author Dr. Martina Di Simplicio of MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, Cambridge, England, and her associates assessed a nonclinical sample of 47 participants (66% female; mean age, 23) for hypomanic experiences and BPSD vulnerability, split into two groups based on their Mood Disorders Questionnaire (MDQ) score. Seventy-five percent of the participants in the high MDQ group generated at least one negative current self-image, compared with 48% of participants in the low MDQ group (P = .055).

The investigators noted that, for those with high MDQ scores, the relationship between affect and perception of the stability of negative self-images is different compared with those with low MDQ scores. And while 75% participants in the BPSD phenotype group were likely to endorse negative images of the current self (compared with less than 50% of the group without hypomanic experiences, almost none of the patients from either group had negative images of the future self).

“BPSD phenotype presents with both alterations and resilience in how self-images and mood shape each other. Further investigations could elucidate how this relationship is affected by illness progression and offer targets for early interventions based on experimental cognitive models,” the investigators wrote.

Read the article in Journal of Affective Disorders (doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.042).

Higher positivity ratings for current self-images were associated with lower depression and anxiety scores among young adults with Bipolar Spectrum Disorder (BPSD), suggesting that BPSD phenotype can shape the relationship between affect and current and future self-images.

As reported in the Journal of Affective Disorders, lead author Dr. Martina Di Simplicio of MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, Cambridge, England, and her associates assessed a nonclinical sample of 47 participants (66% female; mean age, 23) for hypomanic experiences and BPSD vulnerability, split into two groups based on their Mood Disorders Questionnaire (MDQ) score. Seventy-five percent of the participants in the high MDQ group generated at least one negative current self-image, compared with 48% of participants in the low MDQ group (P = .055).

The investigators noted that, for those with high MDQ scores, the relationship between affect and perception of the stability of negative self-images is different compared with those with low MDQ scores. And while 75% participants in the BPSD phenotype group were likely to endorse negative images of the current self (compared with less than 50% of the group without hypomanic experiences, almost none of the patients from either group had negative images of the future self).

“BPSD phenotype presents with both alterations and resilience in how self-images and mood shape each other. Further investigations could elucidate how this relationship is affected by illness progression and offer targets for early interventions based on experimental cognitive models,” the investigators wrote.

Read the article in Journal of Affective Disorders (doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.042).

Higher positivity ratings for current self-images were associated with lower depression and anxiety scores among young adults with Bipolar Spectrum Disorder (BPSD), suggesting that BPSD phenotype can shape the relationship between affect and current and future self-images.

As reported in the Journal of Affective Disorders, lead author Dr. Martina Di Simplicio of MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, Cambridge, England, and her associates assessed a nonclinical sample of 47 participants (66% female; mean age, 23) for hypomanic experiences and BPSD vulnerability, split into two groups based on their Mood Disorders Questionnaire (MDQ) score. Seventy-five percent of the participants in the high MDQ group generated at least one negative current self-image, compared with 48% of participants in the low MDQ group (P = .055).

The investigators noted that, for those with high MDQ scores, the relationship between affect and perception of the stability of negative self-images is different compared with those with low MDQ scores. And while 75% participants in the BPSD phenotype group were likely to endorse negative images of the current self (compared with less than 50% of the group without hypomanic experiences, almost none of the patients from either group had negative images of the future self).

“BPSD phenotype presents with both alterations and resilience in how self-images and mood shape each other. Further investigations could elucidate how this relationship is affected by illness progression and offer targets for early interventions based on experimental cognitive models,” the investigators wrote.

Read the article in Journal of Affective Disorders (doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.042).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

CBT improves depression but not self-care in heart failure patients

Cognitive behavioral therapy significantly improved major depression but did not improve self-care by heart failure patients, investigators reported online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The results suggest that CBT is superior to usual care for depression in patients with heart failure,” said Dr. Kenneth Freedland and his associates at Washington University in St. Louis. They called the findings “especially encouraging” in light of recent negative results from the SADHART-CHF and MOOD-HF trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in this population.Patients in heart failure often have major depression, which increases their chances of poor self-care, hospitalization, and mortality, the researchers noted. Their single-blind, randomized trial included 158 patients who were in New York Heart Association class I, II, or III heart failure and met criteria for major depression. Patients in the intervention group received standard medical care, plus up to 6 months of CBT designed for cardiac patients.Patients received CBT weekly, then biweekly, and then monthly as they reached their treatment goals, but they also received telephone follow-up to help prevent relapse. The control group received standard medical care plus consultation with a cardiac nurse, written materials on heart failure self-care, and three follow-up phone calls with the nurse (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sept. 28. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5220). At 6 months, the CBT group scored significantly lower on the BDI-II than did controls (mean score, 12.8 [standard deviation, 10.6] vs. 17.3 [10.7]; P = .008), the researchers said. Remission rates with CBT were 46% based on the BDI-II and 51% based on the Hamilton Depression Scale, both of which significantly exceeded remission rates of 19-20% for controls. The CBT group also improved significantly more than did controls on standard measures for anxiety, heart failure-related quality of life, mental health–related quality of life, fatigue, and social functioning, but not on measures of physical functioning, the researchers reported.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute partially funded the study. The researchers declared no competing interests.

When depression occurs in patients with heart failure, which is often, the illness burden and management complexity increase multifold. Freedland et al. tested the hypothesis that the effective treatment of comorbid depression with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) would also lead to improvements in heart failure self-care and physical functioning and found that it did not. The good news is that CBT did significantly improve emotional health and overall quality of life, and the improvement in depressive symptoms associated with CBT was larger than observed in pharmacotherapy trials for depression in patients with heart disease. This supports evidence for a shift in practice away from so much pharmacotherapy and more use of psychotherapy to achieve better mental health and overall quality of life outcomes in patients with heart failure. In reframing how we think about the management of depression in patients with heart failure, we should be talking more and prescribing less.

Dr. Patrick G. O’Malley is deputy editor of JAMA Internal Medicine. He declared no competing interests. These comments were taken from his accompanying editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sept. 28).

When depression occurs in patients with heart failure, which is often, the illness burden and management complexity increase multifold. Freedland et al. tested the hypothesis that the effective treatment of comorbid depression with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) would also lead to improvements in heart failure self-care and physical functioning and found that it did not. The good news is that CBT did significantly improve emotional health and overall quality of life, and the improvement in depressive symptoms associated with CBT was larger than observed in pharmacotherapy trials for depression in patients with heart disease. This supports evidence for a shift in practice away from so much pharmacotherapy and more use of psychotherapy to achieve better mental health and overall quality of life outcomes in patients with heart failure. In reframing how we think about the management of depression in patients with heart failure, we should be talking more and prescribing less.

Dr. Patrick G. O’Malley is deputy editor of JAMA Internal Medicine. He declared no competing interests. These comments were taken from his accompanying editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sept. 28).

When depression occurs in patients with heart failure, which is often, the illness burden and management complexity increase multifold. Freedland et al. tested the hypothesis that the effective treatment of comorbid depression with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) would also lead to improvements in heart failure self-care and physical functioning and found that it did not. The good news is that CBT did significantly improve emotional health and overall quality of life, and the improvement in depressive symptoms associated with CBT was larger than observed in pharmacotherapy trials for depression in patients with heart disease. This supports evidence for a shift in practice away from so much pharmacotherapy and more use of psychotherapy to achieve better mental health and overall quality of life outcomes in patients with heart failure. In reframing how we think about the management of depression in patients with heart failure, we should be talking more and prescribing less.

Dr. Patrick G. O’Malley is deputy editor of JAMA Internal Medicine. He declared no competing interests. These comments were taken from his accompanying editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sept. 28).

Cognitive behavioral therapy significantly improved major depression but did not improve self-care by heart failure patients, investigators reported online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The results suggest that CBT is superior to usual care for depression in patients with heart failure,” said Dr. Kenneth Freedland and his associates at Washington University in St. Louis. They called the findings “especially encouraging” in light of recent negative results from the SADHART-CHF and MOOD-HF trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in this population.Patients in heart failure often have major depression, which increases their chances of poor self-care, hospitalization, and mortality, the researchers noted. Their single-blind, randomized trial included 158 patients who were in New York Heart Association class I, II, or III heart failure and met criteria for major depression. Patients in the intervention group received standard medical care, plus up to 6 months of CBT designed for cardiac patients.Patients received CBT weekly, then biweekly, and then monthly as they reached their treatment goals, but they also received telephone follow-up to help prevent relapse. The control group received standard medical care plus consultation with a cardiac nurse, written materials on heart failure self-care, and three follow-up phone calls with the nurse (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sept. 28. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5220). At 6 months, the CBT group scored significantly lower on the BDI-II than did controls (mean score, 12.8 [standard deviation, 10.6] vs. 17.3 [10.7]; P = .008), the researchers said. Remission rates with CBT were 46% based on the BDI-II and 51% based on the Hamilton Depression Scale, both of which significantly exceeded remission rates of 19-20% for controls. The CBT group also improved significantly more than did controls on standard measures for anxiety, heart failure-related quality of life, mental health–related quality of life, fatigue, and social functioning, but not on measures of physical functioning, the researchers reported.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute partially funded the study. The researchers declared no competing interests.

Cognitive behavioral therapy significantly improved major depression but did not improve self-care by heart failure patients, investigators reported online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The results suggest that CBT is superior to usual care for depression in patients with heart failure,” said Dr. Kenneth Freedland and his associates at Washington University in St. Louis. They called the findings “especially encouraging” in light of recent negative results from the SADHART-CHF and MOOD-HF trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in this population.Patients in heart failure often have major depression, which increases their chances of poor self-care, hospitalization, and mortality, the researchers noted. Their single-blind, randomized trial included 158 patients who were in New York Heart Association class I, II, or III heart failure and met criteria for major depression. Patients in the intervention group received standard medical care, plus up to 6 months of CBT designed for cardiac patients.Patients received CBT weekly, then biweekly, and then monthly as they reached their treatment goals, but they also received telephone follow-up to help prevent relapse. The control group received standard medical care plus consultation with a cardiac nurse, written materials on heart failure self-care, and three follow-up phone calls with the nurse (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sept. 28. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5220). At 6 months, the CBT group scored significantly lower on the BDI-II than did controls (mean score, 12.8 [standard deviation, 10.6] vs. 17.3 [10.7]; P = .008), the researchers said. Remission rates with CBT were 46% based on the BDI-II and 51% based on the Hamilton Depression Scale, both of which significantly exceeded remission rates of 19-20% for controls. The CBT group also improved significantly more than did controls on standard measures for anxiety, heart failure-related quality of life, mental health–related quality of life, fatigue, and social functioning, but not on measures of physical functioning, the researchers reported.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute partially funded the study. The researchers declared no competing interests.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Cognitive behavior therapy significantly improved major depression but not self-care among patients with heart failure.

Major finding: At 6 months, mean BDI-II scores were 12.8 for CBT vs. 17.3 for enhanced usual care (P = .008).

Data source: Single-blind, randomized trial of 158 patients.

Disclosures: The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute partially funded the study. The researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

Tool helps patients, clinicians choose depression meds

A new tool, the Depression Medication Choice decision aid, helped adults with moderate to severe depression and their primary care physicians choose appropriate medications together, according to a report published online Sept. 28 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Researchers developed the Depression Medication Choice (DMC) tool to enhance patient involvement in the decision-making process, in the hope that taking their preferences and circumstances into account would improve adherence and stave off premature discontinuation of antidepressants. The investigators then performed a cluster-randomized trial to assess the usefulness of the decision aid in real-world practice, said Annie LeBlanc, Ph.D., of the Knowledge and Evaluation Research Unit, Mayo Clinic, Rochester ,Minn.

The study involved 297 adults treated during a 2-year period by 117 clinicians in 10 rural, urban, and suburban private practices across Minnesota and Wisconsin. These demographically diverse patients had moderate to severe depression as measured by scores of 10 or higher on the Patent Health Questionnaire–9 and were considering antidepressant therapy. They were randomly assigned to clinicians who chose antidepressant therapy in the usual manner (139 patients in the control group) or to clinicians who used the DMC to choose antidepressant therapy together (158 patients in the intervention group).

The DMC tool comprised several laminated 10-by-25-cm cards that presented general information about antidepressant efficacy and adverse effects “in terms that matter to patients: weight change, sleep, libido, discontinuation, and cost,” as well as a leaflet for patients to take home, Dr. LeBlanc and her associates wrote.

Participating clinicians received training in using these cards to prompt discussion during a regular office consultation. Use of the decision aid did not add to the duration of office visits, which is key to routine implementation, the investigators said.

At 3- and 6-month follow-up, patients in the intervention group reported significantly greater comfort with the choice of antidepressant, with a mean difference between the two study groups of 5.3 out of a possible 100 points on a “comfort” scale. Patients in the intervention group also were more knowledgeable about antidepressants (OR, 9.5) and satisfied with their health care (RR, 1.25-2.40), compared with the control group.

Clinicians also were more comfortable with treatment decisions, with a mean difference between the two study groups of 11.4 out of 100 possible points. And clinicians who used the DMC tool reported being more satisfied with the decision-making process (RR, 1.64).

However, there were no significant differences between patients in the two groups regarding control of depression symptoms, remission rate, or rate of response to treatment, as measured by mean PHQ-9 scores. There also was no significant difference in medication adherence. Since most of the clinicians in this study used the DMC tool with very few patients, “it is possible that our trial underestimates the efficacy of the decision aid when used repeatedly and expertly,” Dr. LeBlanc and her associates noted (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sep 28. doi:10.10001/jamainternmed.2015.5214).

“Policy makers will have to decide whether the value of decision aids as promoters of patient-centered care and informed patient engagement, as demonstrated in this trial, argue on their own merit for priority,” they noted.

A new tool, the Depression Medication Choice decision aid, helped adults with moderate to severe depression and their primary care physicians choose appropriate medications together, according to a report published online Sept. 28 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Researchers developed the Depression Medication Choice (DMC) tool to enhance patient involvement in the decision-making process, in the hope that taking their preferences and circumstances into account would improve adherence and stave off premature discontinuation of antidepressants. The investigators then performed a cluster-randomized trial to assess the usefulness of the decision aid in real-world practice, said Annie LeBlanc, Ph.D., of the Knowledge and Evaluation Research Unit, Mayo Clinic, Rochester ,Minn.

The study involved 297 adults treated during a 2-year period by 117 clinicians in 10 rural, urban, and suburban private practices across Minnesota and Wisconsin. These demographically diverse patients had moderate to severe depression as measured by scores of 10 or higher on the Patent Health Questionnaire–9 and were considering antidepressant therapy. They were randomly assigned to clinicians who chose antidepressant therapy in the usual manner (139 patients in the control group) or to clinicians who used the DMC to choose antidepressant therapy together (158 patients in the intervention group).

The DMC tool comprised several laminated 10-by-25-cm cards that presented general information about antidepressant efficacy and adverse effects “in terms that matter to patients: weight change, sleep, libido, discontinuation, and cost,” as well as a leaflet for patients to take home, Dr. LeBlanc and her associates wrote.

Participating clinicians received training in using these cards to prompt discussion during a regular office consultation. Use of the decision aid did not add to the duration of office visits, which is key to routine implementation, the investigators said.

At 3- and 6-month follow-up, patients in the intervention group reported significantly greater comfort with the choice of antidepressant, with a mean difference between the two study groups of 5.3 out of a possible 100 points on a “comfort” scale. Patients in the intervention group also were more knowledgeable about antidepressants (OR, 9.5) and satisfied with their health care (RR, 1.25-2.40), compared with the control group.

Clinicians also were more comfortable with treatment decisions, with a mean difference between the two study groups of 11.4 out of 100 possible points. And clinicians who used the DMC tool reported being more satisfied with the decision-making process (RR, 1.64).

However, there were no significant differences between patients in the two groups regarding control of depression symptoms, remission rate, or rate of response to treatment, as measured by mean PHQ-9 scores. There also was no significant difference in medication adherence. Since most of the clinicians in this study used the DMC tool with very few patients, “it is possible that our trial underestimates the efficacy of the decision aid when used repeatedly and expertly,” Dr. LeBlanc and her associates noted (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sep 28. doi:10.10001/jamainternmed.2015.5214).

“Policy makers will have to decide whether the value of decision aids as promoters of patient-centered care and informed patient engagement, as demonstrated in this trial, argue on their own merit for priority,” they noted.

A new tool, the Depression Medication Choice decision aid, helped adults with moderate to severe depression and their primary care physicians choose appropriate medications together, according to a report published online Sept. 28 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Researchers developed the Depression Medication Choice (DMC) tool to enhance patient involvement in the decision-making process, in the hope that taking their preferences and circumstances into account would improve adherence and stave off premature discontinuation of antidepressants. The investigators then performed a cluster-randomized trial to assess the usefulness of the decision aid in real-world practice, said Annie LeBlanc, Ph.D., of the Knowledge and Evaluation Research Unit, Mayo Clinic, Rochester ,Minn.

The study involved 297 adults treated during a 2-year period by 117 clinicians in 10 rural, urban, and suburban private practices across Minnesota and Wisconsin. These demographically diverse patients had moderate to severe depression as measured by scores of 10 or higher on the Patent Health Questionnaire–9 and were considering antidepressant therapy. They were randomly assigned to clinicians who chose antidepressant therapy in the usual manner (139 patients in the control group) or to clinicians who used the DMC to choose antidepressant therapy together (158 patients in the intervention group).

The DMC tool comprised several laminated 10-by-25-cm cards that presented general information about antidepressant efficacy and adverse effects “in terms that matter to patients: weight change, sleep, libido, discontinuation, and cost,” as well as a leaflet for patients to take home, Dr. LeBlanc and her associates wrote.

Participating clinicians received training in using these cards to prompt discussion during a regular office consultation. Use of the decision aid did not add to the duration of office visits, which is key to routine implementation, the investigators said.

At 3- and 6-month follow-up, patients in the intervention group reported significantly greater comfort with the choice of antidepressant, with a mean difference between the two study groups of 5.3 out of a possible 100 points on a “comfort” scale. Patients in the intervention group also were more knowledgeable about antidepressants (OR, 9.5) and satisfied with their health care (RR, 1.25-2.40), compared with the control group.

Clinicians also were more comfortable with treatment decisions, with a mean difference between the two study groups of 11.4 out of 100 possible points. And clinicians who used the DMC tool reported being more satisfied with the decision-making process (RR, 1.64).

However, there were no significant differences between patients in the two groups regarding control of depression symptoms, remission rate, or rate of response to treatment, as measured by mean PHQ-9 scores. There also was no significant difference in medication adherence. Since most of the clinicians in this study used the DMC tool with very few patients, “it is possible that our trial underestimates the efficacy of the decision aid when used repeatedly and expertly,” Dr. LeBlanc and her associates noted (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sep 28. doi:10.10001/jamainternmed.2015.5214).

“Policy makers will have to decide whether the value of decision aids as promoters of patient-centered care and informed patient engagement, as demonstrated in this trial, argue on their own merit for priority,” they noted.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: The Depression Medication Choice decision aid helps primary care physicians choose appropriate medication together with patients who have moderate to severe depression.

Major finding: Patients in the intervention group reported significantly greater comfort with the choice of antidepressant, were more knowledgeable about antidepressants (OR, 9.5), and satisfied with their health care (RR, 1.25-2.40), compared with the control group.

Data source: A cluster-randomized trial involving 117 primary care clinicians in 10 private practices who chose antidepressant therapy for and with 297 adult patients.

Disclosures: The Agency for Healthcare and Quality Research funded the study. Dr. LeBlanc and her associates reported having no relevant disclosures.

Is There a Link Between Diabetes and Bone Health?

Diabetes can pose serious complications to bone health. “Clinical trials have revealed a startling elevation in fracture risk in diabetic patients,” says Liyun Wang, PhD, Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Delaware in Newark, Delaware. “Bone fractures can be life threatening — nearly 1 in 6 hip fracture patients dies within a year of injury.”

Because physical exercise is proven to improve bone properties and reduce fracture risk in non-diabetic people, Dr. Wang and colleagues tested its efficacy in type 1 diabetes. Their findings were published online ahead of print July 13 in Bone.

The researchers hypothesized that diabetic bone’s response to anabolic mechanical loading would be attenuated, partially due to impaired mechanosensing of osteocytes under hyperglycemia. For their study, heterozygous male and female diabetic mice and their age- and gender-matched wild-type controls were subjected to unilateral axial ulnar loading with a peak strain of 3500 με at 2 Hz and 3 minutes per day for 5 days.

Overall, the study demonstrated that exercise-induced bone formation was maintained in mildly diabetic mice at a similar level as non-diabetic controls, while the positive effects of exercise were nearly abolished in severely diabetic mice. At the cellular level, the researchers found that hyperglycemia reduced the sensitivity of osteocytes to mechanical stimulation and suppressed osteocytes’ secretion of proteins and signaling molecules that help build stronger bone.

“Our work demonstrates that diabetic bone can respond to exercise when the hyperglycemia is not severe, which suggests that mechanical interventions may be useful to improve bone health and reduce fracture risk in mildly affected diabetic patients,” said Dr. Wang. These results, along with previous findings showing adverse effects of hyperglycemia on osteoblasts and mesenchymal stem cells, suggest that failure to maintain normal glucose levels may impair bone’s responses to mechanical loading in diabetics.

To translate the findings of the study to patient care, Ms. Wang’s team has begun to collaborate with M. James Lenhard, MD, Director of the Center for Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases at Christiana Care Health System in Wilmington, Delaware.

“The plan for collaboration between the University of Delaware and Christiana Care is to evaluate these research findings in humans and expand the research to include other complications of diabetes, such as cardiovascular disease.

Suggested Reading

Parajuli A, Liu C, Wen L, et al. Bone’s responses to mechanical loading are impaired in type 1 diabetes. Bone. 2015 July 13 [Epub ahead of print].

Diabetes can pose serious complications to bone health. “Clinical trials have revealed a startling elevation in fracture risk in diabetic patients,” says Liyun Wang, PhD, Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Delaware in Newark, Delaware. “Bone fractures can be life threatening — nearly 1 in 6 hip fracture patients dies within a year of injury.”

Because physical exercise is proven to improve bone properties and reduce fracture risk in non-diabetic people, Dr. Wang and colleagues tested its efficacy in type 1 diabetes. Their findings were published online ahead of print July 13 in Bone.

The researchers hypothesized that diabetic bone’s response to anabolic mechanical loading would be attenuated, partially due to impaired mechanosensing of osteocytes under hyperglycemia. For their study, heterozygous male and female diabetic mice and their age- and gender-matched wild-type controls were subjected to unilateral axial ulnar loading with a peak strain of 3500 με at 2 Hz and 3 minutes per day for 5 days.

Overall, the study demonstrated that exercise-induced bone formation was maintained in mildly diabetic mice at a similar level as non-diabetic controls, while the positive effects of exercise were nearly abolished in severely diabetic mice. At the cellular level, the researchers found that hyperglycemia reduced the sensitivity of osteocytes to mechanical stimulation and suppressed osteocytes’ secretion of proteins and signaling molecules that help build stronger bone.

“Our work demonstrates that diabetic bone can respond to exercise when the hyperglycemia is not severe, which suggests that mechanical interventions may be useful to improve bone health and reduce fracture risk in mildly affected diabetic patients,” said Dr. Wang. These results, along with previous findings showing adverse effects of hyperglycemia on osteoblasts and mesenchymal stem cells, suggest that failure to maintain normal glucose levels may impair bone’s responses to mechanical loading in diabetics.

To translate the findings of the study to patient care, Ms. Wang’s team has begun to collaborate with M. James Lenhard, MD, Director of the Center for Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases at Christiana Care Health System in Wilmington, Delaware.

“The plan for collaboration between the University of Delaware and Christiana Care is to evaluate these research findings in humans and expand the research to include other complications of diabetes, such as cardiovascular disease.

Diabetes can pose serious complications to bone health. “Clinical trials have revealed a startling elevation in fracture risk in diabetic patients,” says Liyun Wang, PhD, Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Delaware in Newark, Delaware. “Bone fractures can be life threatening — nearly 1 in 6 hip fracture patients dies within a year of injury.”

Because physical exercise is proven to improve bone properties and reduce fracture risk in non-diabetic people, Dr. Wang and colleagues tested its efficacy in type 1 diabetes. Their findings were published online ahead of print July 13 in Bone.

The researchers hypothesized that diabetic bone’s response to anabolic mechanical loading would be attenuated, partially due to impaired mechanosensing of osteocytes under hyperglycemia. For their study, heterozygous male and female diabetic mice and their age- and gender-matched wild-type controls were subjected to unilateral axial ulnar loading with a peak strain of 3500 με at 2 Hz and 3 minutes per day for 5 days.

Overall, the study demonstrated that exercise-induced bone formation was maintained in mildly diabetic mice at a similar level as non-diabetic controls, while the positive effects of exercise were nearly abolished in severely diabetic mice. At the cellular level, the researchers found that hyperglycemia reduced the sensitivity of osteocytes to mechanical stimulation and suppressed osteocytes’ secretion of proteins and signaling molecules that help build stronger bone.

“Our work demonstrates that diabetic bone can respond to exercise when the hyperglycemia is not severe, which suggests that mechanical interventions may be useful to improve bone health and reduce fracture risk in mildly affected diabetic patients,” said Dr. Wang. These results, along with previous findings showing adverse effects of hyperglycemia on osteoblasts and mesenchymal stem cells, suggest that failure to maintain normal glucose levels may impair bone’s responses to mechanical loading in diabetics.

To translate the findings of the study to patient care, Ms. Wang’s team has begun to collaborate with M. James Lenhard, MD, Director of the Center for Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases at Christiana Care Health System in Wilmington, Delaware.

“The plan for collaboration between the University of Delaware and Christiana Care is to evaluate these research findings in humans and expand the research to include other complications of diabetes, such as cardiovascular disease.

Suggested Reading

Parajuli A, Liu C, Wen L, et al. Bone’s responses to mechanical loading are impaired in type 1 diabetes. Bone. 2015 July 13 [Epub ahead of print].

Suggested Reading

Parajuli A, Liu C, Wen L, et al. Bone’s responses to mechanical loading are impaired in type 1 diabetes. Bone. 2015 July 13 [Epub ahead of print].

Generalized, well-dispersed rash • wheal development after tactile irritation • normal vital signs • Dx?

THE CASE

A 3-year-old girl was brought to our clinic with a generalized rash over her scalp, face, neck, chest, abdomen, back, perianal area, extremities, and the plantar surface of her right foot. On physical examination, we noted many round, hyperpigmented, brown and reddish pink, well-circumscribed macules on her body (FIGURE). Only a few of these macules had appeared on the girl’s trunk within the first 3 months of her life, but since then they’d increased in number and spread to other parts of her body as she’d aged. The lesions became edematous and erythematous with tactile irritation. Darier’s sign (the development of a hive or wheal when a lesion is stroked) was present.

The patient’s vitals at the time of examination included a temperature of 98.2°F, respiratory rate of 17 breaths/min, heart rate of 92 beats/min, blood pressure of 100/66 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation level of 100% on room air. The girl’s parents said they hadn’t traveled. There was no mucosal involvement and no systemic involvement. The patient had no past surgical or medical history, was not taking any medications, and had no significant birth history. A skin biopsy was performed.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the presence of a positive Darier’s sign and the results of the skin biopsy (which showed increased mast cells), we diagnosed urticaria pigmentosa (UP), which is the most common form of cutaneous mastocytosis.1

The diagnosis had been delayed for almost 3 years because of several factors. For one thing, there had been few lesions present early in the child’s life, and as a result, the parents chalked them up to “beauty marks.” Then, as the lesions started to increase in number, the parents thought bed bugs were to blame.

As time went on, the parents attempted to treat their daughter’s hives with homeopathic remedies suggested by family members. When the lesions didn’t resolve with homeopathic remedies, the parents tried over-the-counter H1 and H2 antihistamines such as diphenhydramine, loratadine, and ranitidine. When these treatments failed, the parents brought their child to our office for medical evaluation.

DISCUSSION

UP is a chronic skin disorder in which there is an abnormal proliferation of mast cells in the dermis of the skin. It is considered an orphan disease.1 UP that presents in children is most often benign. Approximately 50% of cases occur before 6 months of age and 25% occur before puberty.2 The lesions are often self-limited and completely resolve in approximately 50% of patients by puberty.3 By adulthood, the lesions either resolve or some lightly colored non-urticating macules remain; however, some patients will continue to have a positive Darier’s sign.4

Dermatologic symptoms. A patient with UP may present with brown or reddish maculopapules, papules, nodules, pruritus, and flushing of the face. Darier’s sign is usually seen in cases of UP; in a study of mastocytosis in children, Darier’s sign was present in 94% of cases.5 Lesions are more prominent in areas where clothes can rub the skin, and they often vary in size and appearance. The presence of lesions can vary from localized and scant to hundreds located over the entire body. UP can be difficult to identify when the lesions are limited, which can lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment.6

Systemic involvement. UP also can affect the skeleton, bone marrow, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, cardiovascular system, and/or central nervous system. Skeletal involvement may manifest as osteoporosis or bone pain in 10% to 20% of patients with UP.7 Bone marrow involvement may progress to anemia or mast cell leukemia. UP can result in hepatomegaly or enlarged lymph nodes. Patients may experience nausea, diarrhea, or abdominal pain if the gastrointestinal tract is affected. Cardiovascular involvement may manifest as tachycardia and shock.8

Diagnosis of UP is made based on the physical exam findings noted earlier, as well as skin biopsy laboratory results. Skin biopsy will reveal increased mast cells. In up to two-thirds of patients who have systemic involvement, laboratory testing will show elevated urine histamine levels, as well as elevated serum concentrations of tryptase.9

UP can appear similar to many other skin conditions

The differential diagnosis of UP can include urticaria, atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, an allergic reaction/drug eruption, Henoch-Schonlein purpura, erythema multiforme, fifth disease, folliculitis, guttate psoriasis, miliaria rubra, insect bites, viral exanthem, lichen planus, and scabies.10,11 In addition to the clinical appearance of the rash, these conditions can be distinguished from UP by skin biopsy and other relevant tests, as well as a thorough history.

Treatment options include antihistamines, corticosteroids, PUVA

Patients with UP should be instructed to avoid precipitating factors such as temperature changes, friction, alcohol ingestion, aspirin, physical exertion, or opiates. Treatment options include H1 and H2 antihistamines, cromolyn sodium, topical corticosteroids, and PUVA (psoralen plus ultraviolet A photochemotherapy).3 PUVA is normally avoided in pediatric patients because it is associated with an increased risk of skin cancer later in life.12

Our patient. We prescribed a topical corticosteroid, 0.05% betamethasone dipropionate cream, and oral cromolyn sodium 100 mg qid for our patient, but this failed to significantly improve the macules. The patient and parents grew increasingly anxious. Ultimately, the parents decided to have their daughter treated with PUVA in limited amounts. Topical psoralen was also used. After 2 months of treatment, the patient’s lesions substantially improved and many of them disappeared. In addition, the parents were educated on the importance of sunscreen and limiting their daughter’s exposure to the sun, when possible.

THE TAKEAWAY

UP can be diagnosed by taking a thorough history and conducting a physical examination; a skin biopsy that reveals increased mast cells will confirm the diagnosis. UP is usually self-limited and resolves in about one-half of patients by puberty. Treatment options include H1 and H2 antihistamines, cromolyn sodium, topical corticosteroids, and PUVA. Patients should be referred to a specialist if their symptoms become severe, systemic UP is suspected, or they do not respond to therapy.

1. Lain EL, Hsu S. Photo quiz. Chronic, papular rash that develops a wheal when rubbed. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1493-1494.

2. Jain S. Dermatology: Illustrated Study Guide and Comprehensive Board Review. New York: Springer. 2012;47.

3. Soter NA. The skin in mastocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:32S-38S; discussion 38S-39S.

4. Caplan RM. Urticaria pigmentosa and systemic mastocytosis. JAMA. 1965;194:1077-1080.

5. Kiszewski AE, Durán-Mckinster C, Orozco-Covarrubias L, et al. Cutaneous mastocytosis in children: a clinical analysis of 71 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:285-290.

6. Alto WA, Clarcq L. Cutaneous and systemic manifestations of mastocytosis. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:3047-3054, 3059-3060.

7. Borenstein DG, Wiesel SW, Boden SD, eds. Low Back and Neck Pain: Comprehensive Diagnosis and Management. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2004.

8. Vigorita VJ. Metabolic bone disease: Part II. In: Vigorita VJ, Ghelman B, Mintz D, eds. Orthopaedic Pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Walter Kluwer Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008;197.

9. Rosenbaum RC, Frieri M, Metcalfe DD. Patterns of skeletal scintigraphy and their relationship to plasma and urinary histamine levels in systemic mastocytosis. J Nucl Med. 1984;25:859-864.

10. Islas AA, Penaranda E. Generalized brownish macules in infancy. Urticaria pigmentosa. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:987.

11. Ely JW, Seabury Stone M. The generalized rash: part I. Differential diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:726-734.

12. Archier E, Devaux S, Castela E, et al. Carcinogenic risks of psoralen UV-A therapy and narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26 Suppl 3:22-31.

THE CASE

A 3-year-old girl was brought to our clinic with a generalized rash over her scalp, face, neck, chest, abdomen, back, perianal area, extremities, and the plantar surface of her right foot. On physical examination, we noted many round, hyperpigmented, brown and reddish pink, well-circumscribed macules on her body (FIGURE). Only a few of these macules had appeared on the girl’s trunk within the first 3 months of her life, but since then they’d increased in number and spread to other parts of her body as she’d aged. The lesions became edematous and erythematous with tactile irritation. Darier’s sign (the development of a hive or wheal when a lesion is stroked) was present.

The patient’s vitals at the time of examination included a temperature of 98.2°F, respiratory rate of 17 breaths/min, heart rate of 92 beats/min, blood pressure of 100/66 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation level of 100% on room air. The girl’s parents said they hadn’t traveled. There was no mucosal involvement and no systemic involvement. The patient had no past surgical or medical history, was not taking any medications, and had no significant birth history. A skin biopsy was performed.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the presence of a positive Darier’s sign and the results of the skin biopsy (which showed increased mast cells), we diagnosed urticaria pigmentosa (UP), which is the most common form of cutaneous mastocytosis.1

The diagnosis had been delayed for almost 3 years because of several factors. For one thing, there had been few lesions present early in the child’s life, and as a result, the parents chalked them up to “beauty marks.” Then, as the lesions started to increase in number, the parents thought bed bugs were to blame.

As time went on, the parents attempted to treat their daughter’s hives with homeopathic remedies suggested by family members. When the lesions didn’t resolve with homeopathic remedies, the parents tried over-the-counter H1 and H2 antihistamines such as diphenhydramine, loratadine, and ranitidine. When these treatments failed, the parents brought their child to our office for medical evaluation.

DISCUSSION

UP is a chronic skin disorder in which there is an abnormal proliferation of mast cells in the dermis of the skin. It is considered an orphan disease.1 UP that presents in children is most often benign. Approximately 50% of cases occur before 6 months of age and 25% occur before puberty.2 The lesions are often self-limited and completely resolve in approximately 50% of patients by puberty.3 By adulthood, the lesions either resolve or some lightly colored non-urticating macules remain; however, some patients will continue to have a positive Darier’s sign.4

Dermatologic symptoms. A patient with UP may present with brown or reddish maculopapules, papules, nodules, pruritus, and flushing of the face. Darier’s sign is usually seen in cases of UP; in a study of mastocytosis in children, Darier’s sign was present in 94% of cases.5 Lesions are more prominent in areas where clothes can rub the skin, and they often vary in size and appearance. The presence of lesions can vary from localized and scant to hundreds located over the entire body. UP can be difficult to identify when the lesions are limited, which can lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment.6

Systemic involvement. UP also can affect the skeleton, bone marrow, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, cardiovascular system, and/or central nervous system. Skeletal involvement may manifest as osteoporosis or bone pain in 10% to 20% of patients with UP.7 Bone marrow involvement may progress to anemia or mast cell leukemia. UP can result in hepatomegaly or enlarged lymph nodes. Patients may experience nausea, diarrhea, or abdominal pain if the gastrointestinal tract is affected. Cardiovascular involvement may manifest as tachycardia and shock.8

Diagnosis of UP is made based on the physical exam findings noted earlier, as well as skin biopsy laboratory results. Skin biopsy will reveal increased mast cells. In up to two-thirds of patients who have systemic involvement, laboratory testing will show elevated urine histamine levels, as well as elevated serum concentrations of tryptase.9

UP can appear similar to many other skin conditions

The differential diagnosis of UP can include urticaria, atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, an allergic reaction/drug eruption, Henoch-Schonlein purpura, erythema multiforme, fifth disease, folliculitis, guttate psoriasis, miliaria rubra, insect bites, viral exanthem, lichen planus, and scabies.10,11 In addition to the clinical appearance of the rash, these conditions can be distinguished from UP by skin biopsy and other relevant tests, as well as a thorough history.

Treatment options include antihistamines, corticosteroids, PUVA

Patients with UP should be instructed to avoid precipitating factors such as temperature changes, friction, alcohol ingestion, aspirin, physical exertion, or opiates. Treatment options include H1 and H2 antihistamines, cromolyn sodium, topical corticosteroids, and PUVA (psoralen plus ultraviolet A photochemotherapy).3 PUVA is normally avoided in pediatric patients because it is associated with an increased risk of skin cancer later in life.12

Our patient. We prescribed a topical corticosteroid, 0.05% betamethasone dipropionate cream, and oral cromolyn sodium 100 mg qid for our patient, but this failed to significantly improve the macules. The patient and parents grew increasingly anxious. Ultimately, the parents decided to have their daughter treated with PUVA in limited amounts. Topical psoralen was also used. After 2 months of treatment, the patient’s lesions substantially improved and many of them disappeared. In addition, the parents were educated on the importance of sunscreen and limiting their daughter’s exposure to the sun, when possible.

THE TAKEAWAY

UP can be diagnosed by taking a thorough history and conducting a physical examination; a skin biopsy that reveals increased mast cells will confirm the diagnosis. UP is usually self-limited and resolves in about one-half of patients by puberty. Treatment options include H1 and H2 antihistamines, cromolyn sodium, topical corticosteroids, and PUVA. Patients should be referred to a specialist if their symptoms become severe, systemic UP is suspected, or they do not respond to therapy.

THE CASE

A 3-year-old girl was brought to our clinic with a generalized rash over her scalp, face, neck, chest, abdomen, back, perianal area, extremities, and the plantar surface of her right foot. On physical examination, we noted many round, hyperpigmented, brown and reddish pink, well-circumscribed macules on her body (FIGURE). Only a few of these macules had appeared on the girl’s trunk within the first 3 months of her life, but since then they’d increased in number and spread to other parts of her body as she’d aged. The lesions became edematous and erythematous with tactile irritation. Darier’s sign (the development of a hive or wheal when a lesion is stroked) was present.

The patient’s vitals at the time of examination included a temperature of 98.2°F, respiratory rate of 17 breaths/min, heart rate of 92 beats/min, blood pressure of 100/66 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation level of 100% on room air. The girl’s parents said they hadn’t traveled. There was no mucosal involvement and no systemic involvement. The patient had no past surgical or medical history, was not taking any medications, and had no significant birth history. A skin biopsy was performed.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the presence of a positive Darier’s sign and the results of the skin biopsy (which showed increased mast cells), we diagnosed urticaria pigmentosa (UP), which is the most common form of cutaneous mastocytosis.1

The diagnosis had been delayed for almost 3 years because of several factors. For one thing, there had been few lesions present early in the child’s life, and as a result, the parents chalked them up to “beauty marks.” Then, as the lesions started to increase in number, the parents thought bed bugs were to blame.

As time went on, the parents attempted to treat their daughter’s hives with homeopathic remedies suggested by family members. When the lesions didn’t resolve with homeopathic remedies, the parents tried over-the-counter H1 and H2 antihistamines such as diphenhydramine, loratadine, and ranitidine. When these treatments failed, the parents brought their child to our office for medical evaluation.

DISCUSSION

UP is a chronic skin disorder in which there is an abnormal proliferation of mast cells in the dermis of the skin. It is considered an orphan disease.1 UP that presents in children is most often benign. Approximately 50% of cases occur before 6 months of age and 25% occur before puberty.2 The lesions are often self-limited and completely resolve in approximately 50% of patients by puberty.3 By adulthood, the lesions either resolve or some lightly colored non-urticating macules remain; however, some patients will continue to have a positive Darier’s sign.4

Dermatologic symptoms. A patient with UP may present with brown or reddish maculopapules, papules, nodules, pruritus, and flushing of the face. Darier’s sign is usually seen in cases of UP; in a study of mastocytosis in children, Darier’s sign was present in 94% of cases.5 Lesions are more prominent in areas where clothes can rub the skin, and they often vary in size and appearance. The presence of lesions can vary from localized and scant to hundreds located over the entire body. UP can be difficult to identify when the lesions are limited, which can lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment.6

Systemic involvement. UP also can affect the skeleton, bone marrow, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, cardiovascular system, and/or central nervous system. Skeletal involvement may manifest as osteoporosis or bone pain in 10% to 20% of patients with UP.7 Bone marrow involvement may progress to anemia or mast cell leukemia. UP can result in hepatomegaly or enlarged lymph nodes. Patients may experience nausea, diarrhea, or abdominal pain if the gastrointestinal tract is affected. Cardiovascular involvement may manifest as tachycardia and shock.8

Diagnosis of UP is made based on the physical exam findings noted earlier, as well as skin biopsy laboratory results. Skin biopsy will reveal increased mast cells. In up to two-thirds of patients who have systemic involvement, laboratory testing will show elevated urine histamine levels, as well as elevated serum concentrations of tryptase.9

UP can appear similar to many other skin conditions

The differential diagnosis of UP can include urticaria, atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, an allergic reaction/drug eruption, Henoch-Schonlein purpura, erythema multiforme, fifth disease, folliculitis, guttate psoriasis, miliaria rubra, insect bites, viral exanthem, lichen planus, and scabies.10,11 In addition to the clinical appearance of the rash, these conditions can be distinguished from UP by skin biopsy and other relevant tests, as well as a thorough history.

Treatment options include antihistamines, corticosteroids, PUVA

Patients with UP should be instructed to avoid precipitating factors such as temperature changes, friction, alcohol ingestion, aspirin, physical exertion, or opiates. Treatment options include H1 and H2 antihistamines, cromolyn sodium, topical corticosteroids, and PUVA (psoralen plus ultraviolet A photochemotherapy).3 PUVA is normally avoided in pediatric patients because it is associated with an increased risk of skin cancer later in life.12

Our patient. We prescribed a topical corticosteroid, 0.05% betamethasone dipropionate cream, and oral cromolyn sodium 100 mg qid for our patient, but this failed to significantly improve the macules. The patient and parents grew increasingly anxious. Ultimately, the parents decided to have their daughter treated with PUVA in limited amounts. Topical psoralen was also used. After 2 months of treatment, the patient’s lesions substantially improved and many of them disappeared. In addition, the parents were educated on the importance of sunscreen and limiting their daughter’s exposure to the sun, when possible.

THE TAKEAWAY

UP can be diagnosed by taking a thorough history and conducting a physical examination; a skin biopsy that reveals increased mast cells will confirm the diagnosis. UP is usually self-limited and resolves in about one-half of patients by puberty. Treatment options include H1 and H2 antihistamines, cromolyn sodium, topical corticosteroids, and PUVA. Patients should be referred to a specialist if their symptoms become severe, systemic UP is suspected, or they do not respond to therapy.

1. Lain EL, Hsu S. Photo quiz. Chronic, papular rash that develops a wheal when rubbed. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1493-1494.

2. Jain S. Dermatology: Illustrated Study Guide and Comprehensive Board Review. New York: Springer. 2012;47.

3. Soter NA. The skin in mastocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:32S-38S; discussion 38S-39S.

4. Caplan RM. Urticaria pigmentosa and systemic mastocytosis. JAMA. 1965;194:1077-1080.

5. Kiszewski AE, Durán-Mckinster C, Orozco-Covarrubias L, et al. Cutaneous mastocytosis in children: a clinical analysis of 71 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:285-290.

6. Alto WA, Clarcq L. Cutaneous and systemic manifestations of mastocytosis. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:3047-3054, 3059-3060.

7. Borenstein DG, Wiesel SW, Boden SD, eds. Low Back and Neck Pain: Comprehensive Diagnosis and Management. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2004.

8. Vigorita VJ. Metabolic bone disease: Part II. In: Vigorita VJ, Ghelman B, Mintz D, eds. Orthopaedic Pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Walter Kluwer Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008;197.