User login

Helping patients with cystic fibrosis live longer

› Prescribe inhaled dornase alpha and inhaled tobramycin for maintenance pulmonary treatment of moderate to severe cystic fibrosis (CF). A

› Give aggressive nutritional supplementation to maintain a patient’s body mass index and blood sugar control and to attain maximal forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1). B

› Consider prescribing cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators, which have demonstrated a 5% to 10% improvement in FEV1 for CF patients. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The focus of treatment. CF is not limited to the classic picture of lung and pancreas destruction with subsequent loss of function. The underlying pathology can occur in body epithelial tissues from the intestinal lining to sweat glands. These tissues contain cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a protein that allows for the transport of chloride across epithelial cell membranes.2 In individuals homozygous for mutated CFTR genes, chloride transport can be impaired. In addition to regulating chloride transport, CFTR is part of a larger, complex interaction of ion transport proteins such as the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) and others that regulate bicarbonate secretion.2 Decreased chloride ion transport in mutant CFTR negatively affects the ion transport complex; the result is a higher-than-normal viscosity of secreted body fluids.

Reason for hope. It is this impairment of chloride ion transport that leads to the classic phenotypic features of CF (eg, pulmonary function decline, pancreatic insufficiency, malnutrition, chronic respiratory infection), and is the target of both established and emerging therapies3—both of which I will review here.

When to consider a CF diagnosis

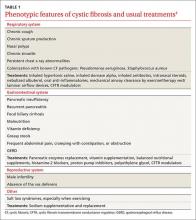

Cystic fibrosis remains a clinical diagnosis when evidence of at least one phenotypic feature of the disease (TABLE 1) exists in the presence of laboratory evidence of a CFTR abnormality.4 Confirmation of CFTR dysfunction is demonstrated by an abnormality on sweat testing or identification of a CF-causing mutation in each copy of CFTR (ie, one on each chromosome).5 All 50 states now have neonatal laboratory screening programs;4 despite this, 30% of cases in 2012 were still diagnosed in those older than 1 year of age, with 3% to 5% diagnosed after age 18.1

A sweat chloride reading in the abnormal range (>60 mmol/L) is present in 90% of patients diagnosed with CF in adulthood; this test remains the gold standard in the diagnosis of CF and the initial test of choice in suspected cases.4 Newborn screening programs identify those at risk by detecting persistent hypertrypsinogenemia and referring those with positive results for definitive testing with sweat chloride evaluation. Keep CF in mind when evaluating adolescents and adults who have chronic sinusitis, chronic/recurrent pulmonary infections, chronic/recurrent pancreatitis, or infertility from absence of the vas deferens.4 When features of the CF phenotype are present, especially if there is a known positive family history of CF or CF carrier status, order sweat chloride testing.

Traditional therapies

Both maintenance and acute therapies are directed throughout the body at decreasing fluid viscosity, clearing fluid with a high viscosity, or treating the tissue destruction that results from highly-viscous fluid.3 The traditional classic picture of CF is one of lung and pancreas destruction with subsequent loss of function. However, CF is, in reality, a full-body disease.

Respiratory system: Lungs

CFTR dysfunction in the lungs results in thick pulmonary secretions as the aqueous surface layer (ASL) lining the alveolar epithelium becomes dehydrated and creates a prime environment for the development of chronic infection. What ensues is a recurrent cycle of chronic infection, inflammation, and tissue destruction with loss of lung volume and function. Current therapies interrupt this cycle at multiple points.6

Airway clearance is one of the hallmarks of CF therapy, using both chemical and mechanical treatments. Daily, most patients will use either a therapy vest that administers sheering forces to the chest cavity or an airflow device that creates positive expiratory pressure and laminar flow to aid in expectorating pulmonary secretions.7 Because exercise has yielded comparable results to mechanical or airflow clearance devices, it is recommended that all CF patients who are not otherwise prohibited engage in regular, vigorous exercise in accordance with standard recommendations for the general public.7

Mechanical therapies are often preceded by airway dilation with short- and long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled steroids that open airways for optimal airway clearance.4 Thick secretions can be treated directly and enzymatically with nebulized dornase alpha,4,8 which is also best administered before mechanical clearance therapy. Finally, viscosity of airway secretions can be decreased by improving the hydration of the ASL with nebulized 7% hypertonic saline.4,8

Infection suppression. Thickened pulmonary secretions create a fertile environment for the development of chronic infection. By the time most CF patients reach adulthood, many are colonized with mucoid producing strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.4,8-10 Many may also have chronic infection with Staphylococcus aureus, some strains of which may be methicillin-resistant. Quarterly culture and sensitivity results can be essential in directing acute antibiotic therapy, both in the hospital and ambulatory settings. In addition, in the case of Pseudomonas, inhaled antibiotics suppress chronic infection, improve lung function, decrease pulmonary secretions, and reduce inflammation.

Formulations are available for tobramycin and aztreonam, both of which are administered every other month to reduce toxicities and to deter antibiotic resistance. Some patients may use a single agent or may alternate agents every month. When acute antibiotic therapy is necessary for a pulmonary exacerbation, the inhaled agent is generally withheld. If outpatient treatment is warranted, the only available oral antibiotics with anti-pseudomonal activity are ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin.4,8-10S aureus can be treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or doxycycline.4,8-10

Inflammation reduction is addressed with high-dose ibuprofen twice daily, azithromycin daily or 3 times weekly, or both. Children up to age 18 benefit from ibuprofen, which also improves forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) to a greater extent than azithromycin.8 Adults, however, face the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and renal dysfunction with ibuprofen, which must be weighed against its potential anti-inflammatory benefit. Both populations, however, benefit from chronic azithromycin, whose mechanism of action in this setting is believed to be more anti-inflammatory than bacterial suppression, since it has no direct bactericidal effect on the primary colonizing microbe, P aeruginosa.4,11

Gastrointestinal system: Pancreas

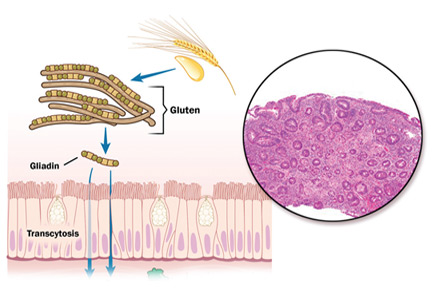

Cystic fibrosis was first comprehensively described in 1938 and was named for the diseased appearance of the pancreas.12 As happens in the lungs, thick pancreatic duct secretions create a cycle of tissue destruction, inflammation, and dysfunction.2 CF patients lack adequate secretion of pancreatic enzymes and bicarbonate into the small bowel, which progressively leads to pancreatic dysfunction in most patients.

As malabsorption of nutrients advances, patients suffer varying degrees of malnutrition and vitamin deficiency, especially of the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K. Over 85% of CF patients have deficient pancreatic function, requiring pancreatic enzyme supplementation with all food intake and daily vitamin supplementation.2

Ensuring adequate nutrition. Most CF patients experience a chronic mismatch of dietary intake against caloric expenditure and benefit from aggressive nutritional management featuring a high-calorie diet with supplementation in the form of nutrition shakes or bars.2 There is a well-documented linear relationship between BMI and FEV1. Lung function declines in CF when a man’s body mass index (BMI) falls below 23 kg/m2 and a woman’s BMI drops below 22 kg/m2.2 For this reason, the goal for caloric intake can be as high as 200% of the customary recommended daily allowance.2

Watch for CF-related diabetes. Since the pancreas is also the major source of endogenous insulin, nearly half of adults with CF will develop cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (CFRD) as pancreatic deficiency progresses.13 Similar to the relationship between BMI and FEV1, there is a relationship between glucose intolerance and FEV1. For this reason, annual diabetes screening is recommended for all CF patients ages 10 years and older.13 Because glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) may not accurately reflect low levels of glucose intolerance, screen for CFRD with a 2-hour 75-g oral glucose tolerance test.13 Early insulin therapy can help maintain BMI and lower average blood sugar in support of FEV1. Once CFRD is diagnosed, the goals and recommendations for control are largely the same as those recommended by the American Diabetes Association for other forms of diabetes.13

Cystic Fibrosis Resources

Cystic Fibrosis Foundation

www.cff.org

Consensus report on cystic fibrosis management

Yankaskas JR, Marchall BC, Sufian B, et al. Cystic fibrosis adult care. Chest. 2004;125:1S-39S.

Consensus report on cystic fibrosis diagnostic guidelines

Farrell PM, Rosenstein BJ, White RB. Guidelines for diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in newborns through older adults: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Consensus Report. J Pediatr. 2008;153:S4-S14.

Gastrointestinal system: Alimentary canal

CF is often mistakenly believed to be primarily a pulmonary disease since 85% of the mortality is due to lung dysfunction,7 but intermittent abdominal pain is a common experience for most patients, and disorders can range from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) to small bowel bacterial overgrowth (SBBO) to constipation. Up to 85% of adult patients experience symptoms of reflux, with as many as 40% of cases occurring silently.2 Proton pump inhibitors are a first-line treatment, but they can also contribute to intestinal bacterial overgrowth and pulmonary infections.

In SBBO, gram-negative colonic bacteria colonize the small bowel and can contribute to abdominal pain and malabsorption, weight loss, and malnutrition. Treatment requires antibiotics with activity against gram-negative organisms, or non-absorbable agents such as rifamyxin, sometimes on a chronic, recurrent, or rotating basis.2

Chronic constipation is also quite common among CF patients and many require daily administration of poly-ethylene-glycol. Before newborn screening programs were introduced, infants would on occasion present with complete distal intestinal obstruction. Adults are not immune to obstructive complications and may require hospitalization for bowel cleansing.

Gastrointestinal system: Liver

Liver disease is relatively common in CF, with up to 24% of adults experiencing hepatomegaly or persistently elevated liver function tests (LFT).4 Progressive biliary fibrosis and cirrhosis are encountered more often as the median survival age has increased. There is evidence that ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) can be a useful adjunct in the treatment of cholestasis, but it is not clear if it alters mortality or progression to cirrhosis. Only CF patients with elevated LFTs should be started on UDCA.4

Other areas of concern: Sinuses, serum sodium levels

Chronic, symptomatic sinus disease in CF patients—chiefly polyposis—is common and may require repeat surgery, although most patients with extensive nasal polyps find symptom relief with daily sinus rinses. Intranasal steroids and intranasal antibiotics are also often employed, and many CF patients need to be in regular contact with an otolaryngologist.14 For symptoms of allergic rhinitis, recommend OTC antihistamines in standard dosages.

Exercise is recommended for all CF patients, as noted earlier, and as life expectancy increases, many are engaging in more strenuous and longer duration activities.15 Due to high sweat sodium loss, CF patients are at risk for hyponatremia, especially when exercising on days with high temperatures and humidity. CF patients need to replace sodium losses in these conditions and when exercising for extended periods.

There are no evidence-based guidelines for sodium replacement. The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) recommends that patients increase salt in the diet when under conditions likely to result in increased sodium loss, such as exercise. It has been thought that CF patients can easily dehydrate due to an impaired thirst mechanism and, when exercising, should consume fluids beyond the need to quench thirst.16,17 More recent evidence suggests, however, that the thirst mechanism in those with CF remains normally intact and that overconsumption of fluids beyond the level of thirst may predispose the individual to exercise-associated hyponatremia as serum sodium is diluted.15

New therapies

Small-molecule CFTR-modulating compounds are a promising development in the treatment of CF. The first such available medication was ivacaftor in 2012. Because these molecules are mutation specific, ivacaftor was available at first only for patients with at least one copy of the G551D mutation,18 which means about 5% of patients with CF.3

Ivacaftor increases the likelihood that the CFTR chloride channel will open and patients will exhibit a reduction in sweat chloride levels. In the first reported clinical trial of ivacaftor involving patients with the G551D mutation, FEV1 improvements of 10% occurred by the second week of therapy and persisted for 48 weeks.18 The drug has now been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patients 12 years of age and older with at least one of the following mutations: R117H, G551D, G178R, S549N, S549R, G551S, G1244E, S1251N, S1255P, or G1349D.19

A medication combining ivacaftor with lumacaftor is also now available for patients with a copy of F508del on both chromosomes. F508del is the most common CFTR mutation, with one copy present in almost 87% of people with CF in the United States.1 Since 47% of CF patients have 2 copies of F508del,1 about half of those with CF in the United States are now eligible for small-molecule therapy. Lumacaftor acts by facilitating transport of a misfolded CFTR to the cell membrane where ivacaftor then increases the probability of an open chloride channel. This combination medication has improved lung function by about 5%.

The ivacaftor/lumacaftor combination was approved by the FDA in July 2015. Both ivacaftor and the ivacaftor/lumacaftor combination were deemed by the FDA to demonstrate statistically significant and sustained FEV1 improvements over placebo.

The CFF was instrumental in providing financial support for the development of both ivacaftor and the ivacaftor/lumacaftor combination and continues to provide significant research advancement. According to the CFF (www.cff.org), medications currently in the development pipeline include compounds that provide CFTR modulation, surface airway liquid restoration, anti-inflammation, inhaled anti-infection, and pancreatic enzyme function. For more on CFF, see "The traditional CF care model.”4,20

The traditional CF care model

The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) has been a driving force behind the increased life expectancy CF patients have seen over the last 3 decades. Its contributions include the development of medication through the CFF Therapeutics Development Network (TDN) and disease management through a network of CF Care Centers throughout the United States. The CFF recommends a minimum of quarterly visits to a CF Care Center, and the primary care physician can play a critical role alongside the multidisciplinary CF team.20

At every CF Care Center encounter, the entire team (nurse, physician, dietician, social worker, psychologist) interacts with each patient and their families to maximize overall medical care. Respiratory cultures are generally obtained at each visit. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry is performed biannually. Lab work (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, glycated hemoglobin, vitamins A, D, E, and K, 2-hour glucose tolerance test), and chest x-ray are obtained at least annually (TABLE 2).4

Since CF generally involves both restrictive and obstructive lung components, complete spirometry evaluation is performed annually in the pulmonary function lab, with static lung volumes in addition to airflow measurement. Office spirometry to measure airflow alone is performed at each visit. FEV1 is tracked both as an indicator of disease progression and as a measure of current pulmonary status.

The CFF recommends that each patient receive full genetic testing and encourages patient participation in the CFF Registry, where mutation data are documented among other disease parameters to ensure that patients receive mutation specific therapies as they become available.4 The vaccine schedule recommended for CF patients is the same as for the general population.

CORRESPONDENCE

Douglas Lewis, MD, 1121 S. Clifton, Wichita, KS 67218; [email protected].

1. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Patient registry 2012 annual data report. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Web site. Available at: http://www.cff.org/UploadedFiles/research/ClinicalResearch/PatientRegistryReport/2012-CFF-Patient-Registry.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2014.

2. Haller W, Ledder O, Lewindon PJ, et al. Cystic fibrosis: An update for clinicians. Part 1: Nutrition and gastrointestinal complications. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1344-1355.

3. Hoffman LR, Ramsey BW. Cystic fibrosis therapeutics: the road ahead. Chest. 2013;143:207-213.

4. Yankaskas JR, Marshall BC, Sufian B, et al. Cystic fibrosis adult care: consensus conference report. Chest. 2004;125:1S-39S.

5. Farrell PM, Rosenstein BJ, White TB, et al; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Guidelines for diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in newborns through older adults: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation consensus report. J Pediatr. 2008;153:S4-S14.

6. Donaldson SH, Boucher RC. Sodium channels and cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2007;132:1631-1636.

7. Flume PA, Robinson KA, O’Sullivan BP, et al; Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pulmonary Therapies Committee. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: airway clearance therapies. Respir Care. 2009;54:522-537.

8. Flume PA, O’Sullivan BP, Robinson KA, et al; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Pulmonary Therapies Committee. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: chronic medications for maintenance of lung health. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:957-969.

9. Döring G, Flume P, Heijerman H, et al; Consensus Study Group. Treatment of lung infection in patients with cystic fibrosis: current and future strategies. J Cyst Fibros. 2012;11:461-479.

10. Flume PA, Mogayzel PJ Jr, Robinson KA, et al; Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pulmonary Therapies Committee. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: treatment of pulmonary exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:802-808.

11. Southern KW, Barker PM. Azithromycin for cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:834-838.

12. Andersen DH. Cystic fibrosis of the pancreas and its relation to celiac disease: a clinical and pathologic study. Am J Dis Child. 1938;56:344-399.

13. Moran A, Brunzell C, Cohen RC, et al; CFRD Guidelines Committee. Clinical care guidelines for cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and a clinical practice guideline of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, endorsed by the Pediatric Endocrine Society. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2697-2708.

14. Kerem E, Conway S, Elborn S, et al; Consensus Committee. Standards of care for patients with cystic fibrosis: a European consensus. J Cyst Fibros. 2005;4:7-26.

15. Hew-Butler T, Rosner MH, Fowkes-Godek S, et al. Statement of the third international exercise-associated hyponatremia consensus development conference, Carlsbad, California, 2015. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:303-320.

16. Brown MB, McCarty NA, Millard-Stafford M. High-sweat Na+ in cystic fibrosis and healthy individuals does not diminish thirst during exercise in the heat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;301:R1177-R1185.

17. Wheatley CM, Wilkins BW, Snyder EM. Exercise is medicine in cystic fibrosis. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2011;39:155-160.

18. Ramsey BW, Davies J, McElvaney NG, et al; VX08-770-102 Study Group. ACFTR potentiator in patients with cystic fibrosis and the G551D mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1663-1672.

19. Pettit RS, Fellner C. CFTR Modulators for the Treatment of Cystic Fibrosis. P T. 2014;39:500-511.

20. Lewis D. Role of the family physician in the management of cystic fibrosis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:822-824.

› Prescribe inhaled dornase alpha and inhaled tobramycin for maintenance pulmonary treatment of moderate to severe cystic fibrosis (CF). A

› Give aggressive nutritional supplementation to maintain a patient’s body mass index and blood sugar control and to attain maximal forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1). B

› Consider prescribing cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators, which have demonstrated a 5% to 10% improvement in FEV1 for CF patients. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The focus of treatment. CF is not limited to the classic picture of lung and pancreas destruction with subsequent loss of function. The underlying pathology can occur in body epithelial tissues from the intestinal lining to sweat glands. These tissues contain cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a protein that allows for the transport of chloride across epithelial cell membranes.2 In individuals homozygous for mutated CFTR genes, chloride transport can be impaired. In addition to regulating chloride transport, CFTR is part of a larger, complex interaction of ion transport proteins such as the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) and others that regulate bicarbonate secretion.2 Decreased chloride ion transport in mutant CFTR negatively affects the ion transport complex; the result is a higher-than-normal viscosity of secreted body fluids.

Reason for hope. It is this impairment of chloride ion transport that leads to the classic phenotypic features of CF (eg, pulmonary function decline, pancreatic insufficiency, malnutrition, chronic respiratory infection), and is the target of both established and emerging therapies3—both of which I will review here.

When to consider a CF diagnosis

Cystic fibrosis remains a clinical diagnosis when evidence of at least one phenotypic feature of the disease (TABLE 1) exists in the presence of laboratory evidence of a CFTR abnormality.4 Confirmation of CFTR dysfunction is demonstrated by an abnormality on sweat testing or identification of a CF-causing mutation in each copy of CFTR (ie, one on each chromosome).5 All 50 states now have neonatal laboratory screening programs;4 despite this, 30% of cases in 2012 were still diagnosed in those older than 1 year of age, with 3% to 5% diagnosed after age 18.1

A sweat chloride reading in the abnormal range (>60 mmol/L) is present in 90% of patients diagnosed with CF in adulthood; this test remains the gold standard in the diagnosis of CF and the initial test of choice in suspected cases.4 Newborn screening programs identify those at risk by detecting persistent hypertrypsinogenemia and referring those with positive results for definitive testing with sweat chloride evaluation. Keep CF in mind when evaluating adolescents and adults who have chronic sinusitis, chronic/recurrent pulmonary infections, chronic/recurrent pancreatitis, or infertility from absence of the vas deferens.4 When features of the CF phenotype are present, especially if there is a known positive family history of CF or CF carrier status, order sweat chloride testing.

Traditional therapies

Both maintenance and acute therapies are directed throughout the body at decreasing fluid viscosity, clearing fluid with a high viscosity, or treating the tissue destruction that results from highly-viscous fluid.3 The traditional classic picture of CF is one of lung and pancreas destruction with subsequent loss of function. However, CF is, in reality, a full-body disease.

Respiratory system: Lungs

CFTR dysfunction in the lungs results in thick pulmonary secretions as the aqueous surface layer (ASL) lining the alveolar epithelium becomes dehydrated and creates a prime environment for the development of chronic infection. What ensues is a recurrent cycle of chronic infection, inflammation, and tissue destruction with loss of lung volume and function. Current therapies interrupt this cycle at multiple points.6

Airway clearance is one of the hallmarks of CF therapy, using both chemical and mechanical treatments. Daily, most patients will use either a therapy vest that administers sheering forces to the chest cavity or an airflow device that creates positive expiratory pressure and laminar flow to aid in expectorating pulmonary secretions.7 Because exercise has yielded comparable results to mechanical or airflow clearance devices, it is recommended that all CF patients who are not otherwise prohibited engage in regular, vigorous exercise in accordance with standard recommendations for the general public.7

Mechanical therapies are often preceded by airway dilation with short- and long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled steroids that open airways for optimal airway clearance.4 Thick secretions can be treated directly and enzymatically with nebulized dornase alpha,4,8 which is also best administered before mechanical clearance therapy. Finally, viscosity of airway secretions can be decreased by improving the hydration of the ASL with nebulized 7% hypertonic saline.4,8

Infection suppression. Thickened pulmonary secretions create a fertile environment for the development of chronic infection. By the time most CF patients reach adulthood, many are colonized with mucoid producing strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.4,8-10 Many may also have chronic infection with Staphylococcus aureus, some strains of which may be methicillin-resistant. Quarterly culture and sensitivity results can be essential in directing acute antibiotic therapy, both in the hospital and ambulatory settings. In addition, in the case of Pseudomonas, inhaled antibiotics suppress chronic infection, improve lung function, decrease pulmonary secretions, and reduce inflammation.

Formulations are available for tobramycin and aztreonam, both of which are administered every other month to reduce toxicities and to deter antibiotic resistance. Some patients may use a single agent or may alternate agents every month. When acute antibiotic therapy is necessary for a pulmonary exacerbation, the inhaled agent is generally withheld. If outpatient treatment is warranted, the only available oral antibiotics with anti-pseudomonal activity are ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin.4,8-10S aureus can be treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or doxycycline.4,8-10

Inflammation reduction is addressed with high-dose ibuprofen twice daily, azithromycin daily or 3 times weekly, or both. Children up to age 18 benefit from ibuprofen, which also improves forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) to a greater extent than azithromycin.8 Adults, however, face the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and renal dysfunction with ibuprofen, which must be weighed against its potential anti-inflammatory benefit. Both populations, however, benefit from chronic azithromycin, whose mechanism of action in this setting is believed to be more anti-inflammatory than bacterial suppression, since it has no direct bactericidal effect on the primary colonizing microbe, P aeruginosa.4,11

Gastrointestinal system: Pancreas

Cystic fibrosis was first comprehensively described in 1938 and was named for the diseased appearance of the pancreas.12 As happens in the lungs, thick pancreatic duct secretions create a cycle of tissue destruction, inflammation, and dysfunction.2 CF patients lack adequate secretion of pancreatic enzymes and bicarbonate into the small bowel, which progressively leads to pancreatic dysfunction in most patients.

As malabsorption of nutrients advances, patients suffer varying degrees of malnutrition and vitamin deficiency, especially of the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K. Over 85% of CF patients have deficient pancreatic function, requiring pancreatic enzyme supplementation with all food intake and daily vitamin supplementation.2

Ensuring adequate nutrition. Most CF patients experience a chronic mismatch of dietary intake against caloric expenditure and benefit from aggressive nutritional management featuring a high-calorie diet with supplementation in the form of nutrition shakes or bars.2 There is a well-documented linear relationship between BMI and FEV1. Lung function declines in CF when a man’s body mass index (BMI) falls below 23 kg/m2 and a woman’s BMI drops below 22 kg/m2.2 For this reason, the goal for caloric intake can be as high as 200% of the customary recommended daily allowance.2

Watch for CF-related diabetes. Since the pancreas is also the major source of endogenous insulin, nearly half of adults with CF will develop cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (CFRD) as pancreatic deficiency progresses.13 Similar to the relationship between BMI and FEV1, there is a relationship between glucose intolerance and FEV1. For this reason, annual diabetes screening is recommended for all CF patients ages 10 years and older.13 Because glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) may not accurately reflect low levels of glucose intolerance, screen for CFRD with a 2-hour 75-g oral glucose tolerance test.13 Early insulin therapy can help maintain BMI and lower average blood sugar in support of FEV1. Once CFRD is diagnosed, the goals and recommendations for control are largely the same as those recommended by the American Diabetes Association for other forms of diabetes.13

Cystic Fibrosis Resources

Cystic Fibrosis Foundation

www.cff.org

Consensus report on cystic fibrosis management

Yankaskas JR, Marchall BC, Sufian B, et al. Cystic fibrosis adult care. Chest. 2004;125:1S-39S.

Consensus report on cystic fibrosis diagnostic guidelines

Farrell PM, Rosenstein BJ, White RB. Guidelines for diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in newborns through older adults: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Consensus Report. J Pediatr. 2008;153:S4-S14.

Gastrointestinal system: Alimentary canal

CF is often mistakenly believed to be primarily a pulmonary disease since 85% of the mortality is due to lung dysfunction,7 but intermittent abdominal pain is a common experience for most patients, and disorders can range from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) to small bowel bacterial overgrowth (SBBO) to constipation. Up to 85% of adult patients experience symptoms of reflux, with as many as 40% of cases occurring silently.2 Proton pump inhibitors are a first-line treatment, but they can also contribute to intestinal bacterial overgrowth and pulmonary infections.

In SBBO, gram-negative colonic bacteria colonize the small bowel and can contribute to abdominal pain and malabsorption, weight loss, and malnutrition. Treatment requires antibiotics with activity against gram-negative organisms, or non-absorbable agents such as rifamyxin, sometimes on a chronic, recurrent, or rotating basis.2

Chronic constipation is also quite common among CF patients and many require daily administration of poly-ethylene-glycol. Before newborn screening programs were introduced, infants would on occasion present with complete distal intestinal obstruction. Adults are not immune to obstructive complications and may require hospitalization for bowel cleansing.

Gastrointestinal system: Liver

Liver disease is relatively common in CF, with up to 24% of adults experiencing hepatomegaly or persistently elevated liver function tests (LFT).4 Progressive biliary fibrosis and cirrhosis are encountered more often as the median survival age has increased. There is evidence that ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) can be a useful adjunct in the treatment of cholestasis, but it is not clear if it alters mortality or progression to cirrhosis. Only CF patients with elevated LFTs should be started on UDCA.4

Other areas of concern: Sinuses, serum sodium levels

Chronic, symptomatic sinus disease in CF patients—chiefly polyposis—is common and may require repeat surgery, although most patients with extensive nasal polyps find symptom relief with daily sinus rinses. Intranasal steroids and intranasal antibiotics are also often employed, and many CF patients need to be in regular contact with an otolaryngologist.14 For symptoms of allergic rhinitis, recommend OTC antihistamines in standard dosages.

Exercise is recommended for all CF patients, as noted earlier, and as life expectancy increases, many are engaging in more strenuous and longer duration activities.15 Due to high sweat sodium loss, CF patients are at risk for hyponatremia, especially when exercising on days with high temperatures and humidity. CF patients need to replace sodium losses in these conditions and when exercising for extended periods.

There are no evidence-based guidelines for sodium replacement. The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) recommends that patients increase salt in the diet when under conditions likely to result in increased sodium loss, such as exercise. It has been thought that CF patients can easily dehydrate due to an impaired thirst mechanism and, when exercising, should consume fluids beyond the need to quench thirst.16,17 More recent evidence suggests, however, that the thirst mechanism in those with CF remains normally intact and that overconsumption of fluids beyond the level of thirst may predispose the individual to exercise-associated hyponatremia as serum sodium is diluted.15

New therapies

Small-molecule CFTR-modulating compounds are a promising development in the treatment of CF. The first such available medication was ivacaftor in 2012. Because these molecules are mutation specific, ivacaftor was available at first only for patients with at least one copy of the G551D mutation,18 which means about 5% of patients with CF.3

Ivacaftor increases the likelihood that the CFTR chloride channel will open and patients will exhibit a reduction in sweat chloride levels. In the first reported clinical trial of ivacaftor involving patients with the G551D mutation, FEV1 improvements of 10% occurred by the second week of therapy and persisted for 48 weeks.18 The drug has now been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patients 12 years of age and older with at least one of the following mutations: R117H, G551D, G178R, S549N, S549R, G551S, G1244E, S1251N, S1255P, or G1349D.19

A medication combining ivacaftor with lumacaftor is also now available for patients with a copy of F508del on both chromosomes. F508del is the most common CFTR mutation, with one copy present in almost 87% of people with CF in the United States.1 Since 47% of CF patients have 2 copies of F508del,1 about half of those with CF in the United States are now eligible for small-molecule therapy. Lumacaftor acts by facilitating transport of a misfolded CFTR to the cell membrane where ivacaftor then increases the probability of an open chloride channel. This combination medication has improved lung function by about 5%.

The ivacaftor/lumacaftor combination was approved by the FDA in July 2015. Both ivacaftor and the ivacaftor/lumacaftor combination were deemed by the FDA to demonstrate statistically significant and sustained FEV1 improvements over placebo.

The CFF was instrumental in providing financial support for the development of both ivacaftor and the ivacaftor/lumacaftor combination and continues to provide significant research advancement. According to the CFF (www.cff.org), medications currently in the development pipeline include compounds that provide CFTR modulation, surface airway liquid restoration, anti-inflammation, inhaled anti-infection, and pancreatic enzyme function. For more on CFF, see "The traditional CF care model.”4,20

The traditional CF care model

The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) has been a driving force behind the increased life expectancy CF patients have seen over the last 3 decades. Its contributions include the development of medication through the CFF Therapeutics Development Network (TDN) and disease management through a network of CF Care Centers throughout the United States. The CFF recommends a minimum of quarterly visits to a CF Care Center, and the primary care physician can play a critical role alongside the multidisciplinary CF team.20

At every CF Care Center encounter, the entire team (nurse, physician, dietician, social worker, psychologist) interacts with each patient and their families to maximize overall medical care. Respiratory cultures are generally obtained at each visit. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry is performed biannually. Lab work (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, glycated hemoglobin, vitamins A, D, E, and K, 2-hour glucose tolerance test), and chest x-ray are obtained at least annually (TABLE 2).4

Since CF generally involves both restrictive and obstructive lung components, complete spirometry evaluation is performed annually in the pulmonary function lab, with static lung volumes in addition to airflow measurement. Office spirometry to measure airflow alone is performed at each visit. FEV1 is tracked both as an indicator of disease progression and as a measure of current pulmonary status.

The CFF recommends that each patient receive full genetic testing and encourages patient participation in the CFF Registry, where mutation data are documented among other disease parameters to ensure that patients receive mutation specific therapies as they become available.4 The vaccine schedule recommended for CF patients is the same as for the general population.

CORRESPONDENCE

Douglas Lewis, MD, 1121 S. Clifton, Wichita, KS 67218; [email protected].

› Prescribe inhaled dornase alpha and inhaled tobramycin for maintenance pulmonary treatment of moderate to severe cystic fibrosis (CF). A

› Give aggressive nutritional supplementation to maintain a patient’s body mass index and blood sugar control and to attain maximal forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1). B

› Consider prescribing cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators, which have demonstrated a 5% to 10% improvement in FEV1 for CF patients. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The focus of treatment. CF is not limited to the classic picture of lung and pancreas destruction with subsequent loss of function. The underlying pathology can occur in body epithelial tissues from the intestinal lining to sweat glands. These tissues contain cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a protein that allows for the transport of chloride across epithelial cell membranes.2 In individuals homozygous for mutated CFTR genes, chloride transport can be impaired. In addition to regulating chloride transport, CFTR is part of a larger, complex interaction of ion transport proteins such as the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) and others that regulate bicarbonate secretion.2 Decreased chloride ion transport in mutant CFTR negatively affects the ion transport complex; the result is a higher-than-normal viscosity of secreted body fluids.

Reason for hope. It is this impairment of chloride ion transport that leads to the classic phenotypic features of CF (eg, pulmonary function decline, pancreatic insufficiency, malnutrition, chronic respiratory infection), and is the target of both established and emerging therapies3—both of which I will review here.

When to consider a CF diagnosis

Cystic fibrosis remains a clinical diagnosis when evidence of at least one phenotypic feature of the disease (TABLE 1) exists in the presence of laboratory evidence of a CFTR abnormality.4 Confirmation of CFTR dysfunction is demonstrated by an abnormality on sweat testing or identification of a CF-causing mutation in each copy of CFTR (ie, one on each chromosome).5 All 50 states now have neonatal laboratory screening programs;4 despite this, 30% of cases in 2012 were still diagnosed in those older than 1 year of age, with 3% to 5% diagnosed after age 18.1

A sweat chloride reading in the abnormal range (>60 mmol/L) is present in 90% of patients diagnosed with CF in adulthood; this test remains the gold standard in the diagnosis of CF and the initial test of choice in suspected cases.4 Newborn screening programs identify those at risk by detecting persistent hypertrypsinogenemia and referring those with positive results for definitive testing with sweat chloride evaluation. Keep CF in mind when evaluating adolescents and adults who have chronic sinusitis, chronic/recurrent pulmonary infections, chronic/recurrent pancreatitis, or infertility from absence of the vas deferens.4 When features of the CF phenotype are present, especially if there is a known positive family history of CF or CF carrier status, order sweat chloride testing.

Traditional therapies

Both maintenance and acute therapies are directed throughout the body at decreasing fluid viscosity, clearing fluid with a high viscosity, or treating the tissue destruction that results from highly-viscous fluid.3 The traditional classic picture of CF is one of lung and pancreas destruction with subsequent loss of function. However, CF is, in reality, a full-body disease.

Respiratory system: Lungs

CFTR dysfunction in the lungs results in thick pulmonary secretions as the aqueous surface layer (ASL) lining the alveolar epithelium becomes dehydrated and creates a prime environment for the development of chronic infection. What ensues is a recurrent cycle of chronic infection, inflammation, and tissue destruction with loss of lung volume and function. Current therapies interrupt this cycle at multiple points.6

Airway clearance is one of the hallmarks of CF therapy, using both chemical and mechanical treatments. Daily, most patients will use either a therapy vest that administers sheering forces to the chest cavity or an airflow device that creates positive expiratory pressure and laminar flow to aid in expectorating pulmonary secretions.7 Because exercise has yielded comparable results to mechanical or airflow clearance devices, it is recommended that all CF patients who are not otherwise prohibited engage in regular, vigorous exercise in accordance with standard recommendations for the general public.7

Mechanical therapies are often preceded by airway dilation with short- and long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled steroids that open airways for optimal airway clearance.4 Thick secretions can be treated directly and enzymatically with nebulized dornase alpha,4,8 which is also best administered before mechanical clearance therapy. Finally, viscosity of airway secretions can be decreased by improving the hydration of the ASL with nebulized 7% hypertonic saline.4,8

Infection suppression. Thickened pulmonary secretions create a fertile environment for the development of chronic infection. By the time most CF patients reach adulthood, many are colonized with mucoid producing strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.4,8-10 Many may also have chronic infection with Staphylococcus aureus, some strains of which may be methicillin-resistant. Quarterly culture and sensitivity results can be essential in directing acute antibiotic therapy, both in the hospital and ambulatory settings. In addition, in the case of Pseudomonas, inhaled antibiotics suppress chronic infection, improve lung function, decrease pulmonary secretions, and reduce inflammation.

Formulations are available for tobramycin and aztreonam, both of which are administered every other month to reduce toxicities and to deter antibiotic resistance. Some patients may use a single agent or may alternate agents every month. When acute antibiotic therapy is necessary for a pulmonary exacerbation, the inhaled agent is generally withheld. If outpatient treatment is warranted, the only available oral antibiotics with anti-pseudomonal activity are ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin.4,8-10S aureus can be treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or doxycycline.4,8-10

Inflammation reduction is addressed with high-dose ibuprofen twice daily, azithromycin daily or 3 times weekly, or both. Children up to age 18 benefit from ibuprofen, which also improves forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) to a greater extent than azithromycin.8 Adults, however, face the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and renal dysfunction with ibuprofen, which must be weighed against its potential anti-inflammatory benefit. Both populations, however, benefit from chronic azithromycin, whose mechanism of action in this setting is believed to be more anti-inflammatory than bacterial suppression, since it has no direct bactericidal effect on the primary colonizing microbe, P aeruginosa.4,11

Gastrointestinal system: Pancreas

Cystic fibrosis was first comprehensively described in 1938 and was named for the diseased appearance of the pancreas.12 As happens in the lungs, thick pancreatic duct secretions create a cycle of tissue destruction, inflammation, and dysfunction.2 CF patients lack adequate secretion of pancreatic enzymes and bicarbonate into the small bowel, which progressively leads to pancreatic dysfunction in most patients.

As malabsorption of nutrients advances, patients suffer varying degrees of malnutrition and vitamin deficiency, especially of the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K. Over 85% of CF patients have deficient pancreatic function, requiring pancreatic enzyme supplementation with all food intake and daily vitamin supplementation.2

Ensuring adequate nutrition. Most CF patients experience a chronic mismatch of dietary intake against caloric expenditure and benefit from aggressive nutritional management featuring a high-calorie diet with supplementation in the form of nutrition shakes or bars.2 There is a well-documented linear relationship between BMI and FEV1. Lung function declines in CF when a man’s body mass index (BMI) falls below 23 kg/m2 and a woman’s BMI drops below 22 kg/m2.2 For this reason, the goal for caloric intake can be as high as 200% of the customary recommended daily allowance.2

Watch for CF-related diabetes. Since the pancreas is also the major source of endogenous insulin, nearly half of adults with CF will develop cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (CFRD) as pancreatic deficiency progresses.13 Similar to the relationship between BMI and FEV1, there is a relationship between glucose intolerance and FEV1. For this reason, annual diabetes screening is recommended for all CF patients ages 10 years and older.13 Because glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) may not accurately reflect low levels of glucose intolerance, screen for CFRD with a 2-hour 75-g oral glucose tolerance test.13 Early insulin therapy can help maintain BMI and lower average blood sugar in support of FEV1. Once CFRD is diagnosed, the goals and recommendations for control are largely the same as those recommended by the American Diabetes Association for other forms of diabetes.13

Cystic Fibrosis Resources

Cystic Fibrosis Foundation

www.cff.org

Consensus report on cystic fibrosis management

Yankaskas JR, Marchall BC, Sufian B, et al. Cystic fibrosis adult care. Chest. 2004;125:1S-39S.

Consensus report on cystic fibrosis diagnostic guidelines

Farrell PM, Rosenstein BJ, White RB. Guidelines for diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in newborns through older adults: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Consensus Report. J Pediatr. 2008;153:S4-S14.

Gastrointestinal system: Alimentary canal

CF is often mistakenly believed to be primarily a pulmonary disease since 85% of the mortality is due to lung dysfunction,7 but intermittent abdominal pain is a common experience for most patients, and disorders can range from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) to small bowel bacterial overgrowth (SBBO) to constipation. Up to 85% of adult patients experience symptoms of reflux, with as many as 40% of cases occurring silently.2 Proton pump inhibitors are a first-line treatment, but they can also contribute to intestinal bacterial overgrowth and pulmonary infections.

In SBBO, gram-negative colonic bacteria colonize the small bowel and can contribute to abdominal pain and malabsorption, weight loss, and malnutrition. Treatment requires antibiotics with activity against gram-negative organisms, or non-absorbable agents such as rifamyxin, sometimes on a chronic, recurrent, or rotating basis.2

Chronic constipation is also quite common among CF patients and many require daily administration of poly-ethylene-glycol. Before newborn screening programs were introduced, infants would on occasion present with complete distal intestinal obstruction. Adults are not immune to obstructive complications and may require hospitalization for bowel cleansing.

Gastrointestinal system: Liver

Liver disease is relatively common in CF, with up to 24% of adults experiencing hepatomegaly or persistently elevated liver function tests (LFT).4 Progressive biliary fibrosis and cirrhosis are encountered more often as the median survival age has increased. There is evidence that ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) can be a useful adjunct in the treatment of cholestasis, but it is not clear if it alters mortality or progression to cirrhosis. Only CF patients with elevated LFTs should be started on UDCA.4

Other areas of concern: Sinuses, serum sodium levels

Chronic, symptomatic sinus disease in CF patients—chiefly polyposis—is common and may require repeat surgery, although most patients with extensive nasal polyps find symptom relief with daily sinus rinses. Intranasal steroids and intranasal antibiotics are also often employed, and many CF patients need to be in regular contact with an otolaryngologist.14 For symptoms of allergic rhinitis, recommend OTC antihistamines in standard dosages.

Exercise is recommended for all CF patients, as noted earlier, and as life expectancy increases, many are engaging in more strenuous and longer duration activities.15 Due to high sweat sodium loss, CF patients are at risk for hyponatremia, especially when exercising on days with high temperatures and humidity. CF patients need to replace sodium losses in these conditions and when exercising for extended periods.

There are no evidence-based guidelines for sodium replacement. The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) recommends that patients increase salt in the diet when under conditions likely to result in increased sodium loss, such as exercise. It has been thought that CF patients can easily dehydrate due to an impaired thirst mechanism and, when exercising, should consume fluids beyond the need to quench thirst.16,17 More recent evidence suggests, however, that the thirst mechanism in those with CF remains normally intact and that overconsumption of fluids beyond the level of thirst may predispose the individual to exercise-associated hyponatremia as serum sodium is diluted.15

New therapies

Small-molecule CFTR-modulating compounds are a promising development in the treatment of CF. The first such available medication was ivacaftor in 2012. Because these molecules are mutation specific, ivacaftor was available at first only for patients with at least one copy of the G551D mutation,18 which means about 5% of patients with CF.3

Ivacaftor increases the likelihood that the CFTR chloride channel will open and patients will exhibit a reduction in sweat chloride levels. In the first reported clinical trial of ivacaftor involving patients with the G551D mutation, FEV1 improvements of 10% occurred by the second week of therapy and persisted for 48 weeks.18 The drug has now been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patients 12 years of age and older with at least one of the following mutations: R117H, G551D, G178R, S549N, S549R, G551S, G1244E, S1251N, S1255P, or G1349D.19

A medication combining ivacaftor with lumacaftor is also now available for patients with a copy of F508del on both chromosomes. F508del is the most common CFTR mutation, with one copy present in almost 87% of people with CF in the United States.1 Since 47% of CF patients have 2 copies of F508del,1 about half of those with CF in the United States are now eligible for small-molecule therapy. Lumacaftor acts by facilitating transport of a misfolded CFTR to the cell membrane where ivacaftor then increases the probability of an open chloride channel. This combination medication has improved lung function by about 5%.

The ivacaftor/lumacaftor combination was approved by the FDA in July 2015. Both ivacaftor and the ivacaftor/lumacaftor combination were deemed by the FDA to demonstrate statistically significant and sustained FEV1 improvements over placebo.

The CFF was instrumental in providing financial support for the development of both ivacaftor and the ivacaftor/lumacaftor combination and continues to provide significant research advancement. According to the CFF (www.cff.org), medications currently in the development pipeline include compounds that provide CFTR modulation, surface airway liquid restoration, anti-inflammation, inhaled anti-infection, and pancreatic enzyme function. For more on CFF, see "The traditional CF care model.”4,20

The traditional CF care model

The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) has been a driving force behind the increased life expectancy CF patients have seen over the last 3 decades. Its contributions include the development of medication through the CFF Therapeutics Development Network (TDN) and disease management through a network of CF Care Centers throughout the United States. The CFF recommends a minimum of quarterly visits to a CF Care Center, and the primary care physician can play a critical role alongside the multidisciplinary CF team.20

At every CF Care Center encounter, the entire team (nurse, physician, dietician, social worker, psychologist) interacts with each patient and their families to maximize overall medical care. Respiratory cultures are generally obtained at each visit. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry is performed biannually. Lab work (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, glycated hemoglobin, vitamins A, D, E, and K, 2-hour glucose tolerance test), and chest x-ray are obtained at least annually (TABLE 2).4

Since CF generally involves both restrictive and obstructive lung components, complete spirometry evaluation is performed annually in the pulmonary function lab, with static lung volumes in addition to airflow measurement. Office spirometry to measure airflow alone is performed at each visit. FEV1 is tracked both as an indicator of disease progression and as a measure of current pulmonary status.

The CFF recommends that each patient receive full genetic testing and encourages patient participation in the CFF Registry, where mutation data are documented among other disease parameters to ensure that patients receive mutation specific therapies as they become available.4 The vaccine schedule recommended for CF patients is the same as for the general population.

CORRESPONDENCE

Douglas Lewis, MD, 1121 S. Clifton, Wichita, KS 67218; [email protected].

1. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Patient registry 2012 annual data report. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Web site. Available at: http://www.cff.org/UploadedFiles/research/ClinicalResearch/PatientRegistryReport/2012-CFF-Patient-Registry.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2014.

2. Haller W, Ledder O, Lewindon PJ, et al. Cystic fibrosis: An update for clinicians. Part 1: Nutrition and gastrointestinal complications. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1344-1355.

3. Hoffman LR, Ramsey BW. Cystic fibrosis therapeutics: the road ahead. Chest. 2013;143:207-213.

4. Yankaskas JR, Marshall BC, Sufian B, et al. Cystic fibrosis adult care: consensus conference report. Chest. 2004;125:1S-39S.

5. Farrell PM, Rosenstein BJ, White TB, et al; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Guidelines for diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in newborns through older adults: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation consensus report. J Pediatr. 2008;153:S4-S14.

6. Donaldson SH, Boucher RC. Sodium channels and cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2007;132:1631-1636.

7. Flume PA, Robinson KA, O’Sullivan BP, et al; Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pulmonary Therapies Committee. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: airway clearance therapies. Respir Care. 2009;54:522-537.

8. Flume PA, O’Sullivan BP, Robinson KA, et al; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Pulmonary Therapies Committee. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: chronic medications for maintenance of lung health. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:957-969.

9. Döring G, Flume P, Heijerman H, et al; Consensus Study Group. Treatment of lung infection in patients with cystic fibrosis: current and future strategies. J Cyst Fibros. 2012;11:461-479.

10. Flume PA, Mogayzel PJ Jr, Robinson KA, et al; Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pulmonary Therapies Committee. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: treatment of pulmonary exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:802-808.

11. Southern KW, Barker PM. Azithromycin for cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:834-838.

12. Andersen DH. Cystic fibrosis of the pancreas and its relation to celiac disease: a clinical and pathologic study. Am J Dis Child. 1938;56:344-399.

13. Moran A, Brunzell C, Cohen RC, et al; CFRD Guidelines Committee. Clinical care guidelines for cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and a clinical practice guideline of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, endorsed by the Pediatric Endocrine Society. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2697-2708.

14. Kerem E, Conway S, Elborn S, et al; Consensus Committee. Standards of care for patients with cystic fibrosis: a European consensus. J Cyst Fibros. 2005;4:7-26.

15. Hew-Butler T, Rosner MH, Fowkes-Godek S, et al. Statement of the third international exercise-associated hyponatremia consensus development conference, Carlsbad, California, 2015. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:303-320.

16. Brown MB, McCarty NA, Millard-Stafford M. High-sweat Na+ in cystic fibrosis and healthy individuals does not diminish thirst during exercise in the heat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;301:R1177-R1185.

17. Wheatley CM, Wilkins BW, Snyder EM. Exercise is medicine in cystic fibrosis. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2011;39:155-160.

18. Ramsey BW, Davies J, McElvaney NG, et al; VX08-770-102 Study Group. ACFTR potentiator in patients with cystic fibrosis and the G551D mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1663-1672.

19. Pettit RS, Fellner C. CFTR Modulators for the Treatment of Cystic Fibrosis. P T. 2014;39:500-511.

20. Lewis D. Role of the family physician in the management of cystic fibrosis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:822-824.

1. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Patient registry 2012 annual data report. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Web site. Available at: http://www.cff.org/UploadedFiles/research/ClinicalResearch/PatientRegistryReport/2012-CFF-Patient-Registry.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2014.

2. Haller W, Ledder O, Lewindon PJ, et al. Cystic fibrosis: An update for clinicians. Part 1: Nutrition and gastrointestinal complications. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1344-1355.

3. Hoffman LR, Ramsey BW. Cystic fibrosis therapeutics: the road ahead. Chest. 2013;143:207-213.

4. Yankaskas JR, Marshall BC, Sufian B, et al. Cystic fibrosis adult care: consensus conference report. Chest. 2004;125:1S-39S.

5. Farrell PM, Rosenstein BJ, White TB, et al; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Guidelines for diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in newborns through older adults: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation consensus report. J Pediatr. 2008;153:S4-S14.

6. Donaldson SH, Boucher RC. Sodium channels and cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2007;132:1631-1636.

7. Flume PA, Robinson KA, O’Sullivan BP, et al; Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pulmonary Therapies Committee. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: airway clearance therapies. Respir Care. 2009;54:522-537.

8. Flume PA, O’Sullivan BP, Robinson KA, et al; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Pulmonary Therapies Committee. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: chronic medications for maintenance of lung health. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:957-969.

9. Döring G, Flume P, Heijerman H, et al; Consensus Study Group. Treatment of lung infection in patients with cystic fibrosis: current and future strategies. J Cyst Fibros. 2012;11:461-479.

10. Flume PA, Mogayzel PJ Jr, Robinson KA, et al; Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pulmonary Therapies Committee. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: treatment of pulmonary exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:802-808.

11. Southern KW, Barker PM. Azithromycin for cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:834-838.

12. Andersen DH. Cystic fibrosis of the pancreas and its relation to celiac disease: a clinical and pathologic study. Am J Dis Child. 1938;56:344-399.

13. Moran A, Brunzell C, Cohen RC, et al; CFRD Guidelines Committee. Clinical care guidelines for cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and a clinical practice guideline of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, endorsed by the Pediatric Endocrine Society. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2697-2708.

14. Kerem E, Conway S, Elborn S, et al; Consensus Committee. Standards of care for patients with cystic fibrosis: a European consensus. J Cyst Fibros. 2005;4:7-26.

15. Hew-Butler T, Rosner MH, Fowkes-Godek S, et al. Statement of the third international exercise-associated hyponatremia consensus development conference, Carlsbad, California, 2015. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:303-320.

16. Brown MB, McCarty NA, Millard-Stafford M. High-sweat Na+ in cystic fibrosis and healthy individuals does not diminish thirst during exercise in the heat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;301:R1177-R1185.

17. Wheatley CM, Wilkins BW, Snyder EM. Exercise is medicine in cystic fibrosis. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2011;39:155-160.

18. Ramsey BW, Davies J, McElvaney NG, et al; VX08-770-102 Study Group. ACFTR potentiator in patients with cystic fibrosis and the G551D mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1663-1672.

19. Pettit RS, Fellner C. CFTR Modulators for the Treatment of Cystic Fibrosis. P T. 2014;39:500-511.

20. Lewis D. Role of the family physician in the management of cystic fibrosis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:822-824.

The PARADIGM-HF trial

To the Editor: Two considerations concerning the interpretation of the Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure (PARADIGM-HF) trial are not addressed in the article by Sabe et al regarding a new class of drugs for systolic heart failure.1 First of all, the PARADIGM-HF trial compared the maximal dose of sacubitril with a less-than-maximal dose of enalapril. Secondly, sacubitril lowered blood pressure more than enalapril.

The angiotensin receptor blocker dose in sacubitril 200 mg is equivalent to valsartan 160 mg.2 Accordingly, the angiotensin receptor blocker in sacubitril 200 mg twice daily is equivalent to the maximal dosage of valsartan approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The dosage of enalapril in the PARADIGM-HF trial was 10 mg twice daily. While the target enalapril dosage for heart failure is 10 to 20 mg twice daily,3 the dosage of enalapril in PARADIGM-HF was half the maximal approved dosage.

In the PARADIGM-HF trial, sacubitril 200 mg twice daily reduced the incidence of cardiovascular death by 19% compared with enalapril 10 mg twice daily (the rates were 16.5% vs 13.3%, respectively).2 That sacubitril lowered mean systolic blood pressure 3.2 ± 0.4 mm Hg more than enalapril2,4 may account for much of this benefit.

A 2002 study by Lewington et al5 found that a 2-mm Hg decrease in systolic blood pressure reduces the risk of cardiovascular death by 7% in middle-aged adults. Granted, this study did not involve heart failure patients, but if its results are remotely applicable, a 3.2-mm Hg reduction in systolic blood pressure might be expected to reduce the rate of cardiovascular deaths by 10% to 11%.

Would sacubitril be superior to enalapril if the maximal dose of enalapril were compared to the maximal dose of sacubitril? Would sacubitril be superior to enalapril if blood pressure were lowered comparably between the two groups? These are relevant questions that the PARADIGM-HF trial fails to answer.

- Sabe MA, Jacob MS, Taylor DO. A new class of drugs for systolic heart failure: the PARADIGM-HF study. Cleve Clin J Med 2015; 82:693–701.

- McMurray JJV, Packer M, Desai AS, et al; PARADIGM-HF Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:993–1004.

- Hunt SA; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 46:e1–e82.

- Jessup J. Neprilysin inhibition—a novel therapy for heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:1062–1064.

- Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R; Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002; 360:1903–1913.

To the Editor: Two considerations concerning the interpretation of the Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure (PARADIGM-HF) trial are not addressed in the article by Sabe et al regarding a new class of drugs for systolic heart failure.1 First of all, the PARADIGM-HF trial compared the maximal dose of sacubitril with a less-than-maximal dose of enalapril. Secondly, sacubitril lowered blood pressure more than enalapril.

The angiotensin receptor blocker dose in sacubitril 200 mg is equivalent to valsartan 160 mg.2 Accordingly, the angiotensin receptor blocker in sacubitril 200 mg twice daily is equivalent to the maximal dosage of valsartan approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The dosage of enalapril in the PARADIGM-HF trial was 10 mg twice daily. While the target enalapril dosage for heart failure is 10 to 20 mg twice daily,3 the dosage of enalapril in PARADIGM-HF was half the maximal approved dosage.

In the PARADIGM-HF trial, sacubitril 200 mg twice daily reduced the incidence of cardiovascular death by 19% compared with enalapril 10 mg twice daily (the rates were 16.5% vs 13.3%, respectively).2 That sacubitril lowered mean systolic blood pressure 3.2 ± 0.4 mm Hg more than enalapril2,4 may account for much of this benefit.

A 2002 study by Lewington et al5 found that a 2-mm Hg decrease in systolic blood pressure reduces the risk of cardiovascular death by 7% in middle-aged adults. Granted, this study did not involve heart failure patients, but if its results are remotely applicable, a 3.2-mm Hg reduction in systolic blood pressure might be expected to reduce the rate of cardiovascular deaths by 10% to 11%.

Would sacubitril be superior to enalapril if the maximal dose of enalapril were compared to the maximal dose of sacubitril? Would sacubitril be superior to enalapril if blood pressure were lowered comparably between the two groups? These are relevant questions that the PARADIGM-HF trial fails to answer.

To the Editor: Two considerations concerning the interpretation of the Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure (PARADIGM-HF) trial are not addressed in the article by Sabe et al regarding a new class of drugs for systolic heart failure.1 First of all, the PARADIGM-HF trial compared the maximal dose of sacubitril with a less-than-maximal dose of enalapril. Secondly, sacubitril lowered blood pressure more than enalapril.

The angiotensin receptor blocker dose in sacubitril 200 mg is equivalent to valsartan 160 mg.2 Accordingly, the angiotensin receptor blocker in sacubitril 200 mg twice daily is equivalent to the maximal dosage of valsartan approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The dosage of enalapril in the PARADIGM-HF trial was 10 mg twice daily. While the target enalapril dosage for heart failure is 10 to 20 mg twice daily,3 the dosage of enalapril in PARADIGM-HF was half the maximal approved dosage.

In the PARADIGM-HF trial, sacubitril 200 mg twice daily reduced the incidence of cardiovascular death by 19% compared with enalapril 10 mg twice daily (the rates were 16.5% vs 13.3%, respectively).2 That sacubitril lowered mean systolic blood pressure 3.2 ± 0.4 mm Hg more than enalapril2,4 may account for much of this benefit.

A 2002 study by Lewington et al5 found that a 2-mm Hg decrease in systolic blood pressure reduces the risk of cardiovascular death by 7% in middle-aged adults. Granted, this study did not involve heart failure patients, but if its results are remotely applicable, a 3.2-mm Hg reduction in systolic blood pressure might be expected to reduce the rate of cardiovascular deaths by 10% to 11%.

Would sacubitril be superior to enalapril if the maximal dose of enalapril were compared to the maximal dose of sacubitril? Would sacubitril be superior to enalapril if blood pressure were lowered comparably between the two groups? These are relevant questions that the PARADIGM-HF trial fails to answer.

- Sabe MA, Jacob MS, Taylor DO. A new class of drugs for systolic heart failure: the PARADIGM-HF study. Cleve Clin J Med 2015; 82:693–701.

- McMurray JJV, Packer M, Desai AS, et al; PARADIGM-HF Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:993–1004.

- Hunt SA; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 46:e1–e82.

- Jessup J. Neprilysin inhibition—a novel therapy for heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:1062–1064.

- Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R; Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002; 360:1903–1913.

- Sabe MA, Jacob MS, Taylor DO. A new class of drugs for systolic heart failure: the PARADIGM-HF study. Cleve Clin J Med 2015; 82:693–701.

- McMurray JJV, Packer M, Desai AS, et al; PARADIGM-HF Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:993–1004.

- Hunt SA; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 46:e1–e82.

- Jessup J. Neprilysin inhibition—a novel therapy for heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:1062–1064.

- Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R; Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002; 360:1903–1913.

In reply: The PARADIGM-HF trial

In Reply: We thank Dr. Blankfield for raising these two important points. Although the findings of the PARADIGM-HF study are compelling, the design and results of this trial have incited many questions.

To address his first point, about the differential dosages of the two drugs, we agree, and we did mention in our review that one concern about the results of PARADIGM-HF is the unequal dosages of valsartan and enalapril in the two different arms. We mentioned that this dosage of enalapril was chosen based on its survival benefit in previous trials. However, this still raises the question of whether the benefit seen in the sacubitril-valsartan group was due to greater inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system rather than to the new drug.

To address his second point, the decrease in blood pressure in the sacubitril-valsartan arm was significant, and the patients taking this drug were more likely to have symptomatic hypotension, which may contribute to patient intolerance and difficulty initiating treatment with this drug. Dr. Blankfield brings up an interesting point regarding reduction of blood pressure driving the decrease of events in the sacubitril-valsartan group. In the original trial results section, the authors mentioned that when the difference in blood pressure between the two groups was examined as a time-dependent covariate, it was not a significant predictor of the benefit of sacubitril-valsartan.1

Furthermore, although higher blood pressure is associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes in the general population, higher blood pressure has been shown to be protective in heart failure patients.2 Several studies have shown that the relationship between blood pressure and the mortality rate in patients with heart failure is paradoxical and complex.2–4 Lee et al3 found that this relationship was U-shaped, with increased mortality risk in those with high and low blood pressures (< 120 mm Hg). Ather et al4 also showed that the relationship was U-shaped in patients with a mild to moderate reduction in left ventricular ejection fraction, but linear in those with severely reduced ejection fraction. This study also found that a decrease in systolic blood pressure below 110 mm Hg was associated with increased mortality risk.

The findings of PARADIGM-HF have sparked much conversation and implementation of practice change in the treatment of heart failure patients, and we await additional data on the use and limitations of sacubitril-valsartan in this group of patients.

- McMurray JJV, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:993–1004.

- Raphael CE, Whinnett ZI, Davies JE, et al. Quantifying the paradoxical effect of higher systolic blood pressure on mortality in chronic heart failure. Heart 2009; 95:56–62.

- Lee DS, Ghosh N, Floras JS, et al. Association of blood pressure at hospital discharge with mortality in patients diagnosed with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2009; 2:616-623.

- Ather S, Chan W, Chillar A, et al. Association of systolic blood pressure with mortality in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a complex relationship. Am Heart J 2011; 161:567–573.

In Reply: We thank Dr. Blankfield for raising these two important points. Although the findings of the PARADIGM-HF study are compelling, the design and results of this trial have incited many questions.

To address his first point, about the differential dosages of the two drugs, we agree, and we did mention in our review that one concern about the results of PARADIGM-HF is the unequal dosages of valsartan and enalapril in the two different arms. We mentioned that this dosage of enalapril was chosen based on its survival benefit in previous trials. However, this still raises the question of whether the benefit seen in the sacubitril-valsartan group was due to greater inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system rather than to the new drug.

To address his second point, the decrease in blood pressure in the sacubitril-valsartan arm was significant, and the patients taking this drug were more likely to have symptomatic hypotension, which may contribute to patient intolerance and difficulty initiating treatment with this drug. Dr. Blankfield brings up an interesting point regarding reduction of blood pressure driving the decrease of events in the sacubitril-valsartan group. In the original trial results section, the authors mentioned that when the difference in blood pressure between the two groups was examined as a time-dependent covariate, it was not a significant predictor of the benefit of sacubitril-valsartan.1