User login

March 2016 Digital Edition

Table of Contents

- Our Sacred Trust

- How to Make Your Patient With Sleep Apnea a Super User of Positive Airway Pressure Therapy

- Complete Atrioventricular Nodal Block Due to Malignancy-Related Hypercalcemia

- Peer Technical Consultant: Veteran Technical Support for VA Home-Based Telehealth Programs

- Polypharmacy Review of Vulnerable Elders: Can We IMPROVE Outcomes?

- Predictors of VA and Non-VA Health Care Service Use by Homeless Veterans Residing in a Low-Demand Emergency Shelter

Table of Contents

- Our Sacred Trust

- How to Make Your Patient With Sleep Apnea a Super User of Positive Airway Pressure Therapy

- Complete Atrioventricular Nodal Block Due to Malignancy-Related Hypercalcemia

- Peer Technical Consultant: Veteran Technical Support for VA Home-Based Telehealth Programs

- Polypharmacy Review of Vulnerable Elders: Can We IMPROVE Outcomes?

- Predictors of VA and Non-VA Health Care Service Use by Homeless Veterans Residing in a Low-Demand Emergency Shelter

Table of Contents

- Our Sacred Trust

- How to Make Your Patient With Sleep Apnea a Super User of Positive Airway Pressure Therapy

- Complete Atrioventricular Nodal Block Due to Malignancy-Related Hypercalcemia

- Peer Technical Consultant: Veteran Technical Support for VA Home-Based Telehealth Programs

- Polypharmacy Review of Vulnerable Elders: Can We IMPROVE Outcomes?

- Predictors of VA and Non-VA Health Care Service Use by Homeless Veterans Residing in a Low-Demand Emergency Shelter

Mirtazapine improves functional dyspepsia in small study

The antidepressant mirtazapine improved weight loss, early satiation, nausea, and other signs and symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia, said the authors of a placebo-controlled pilot study published in the March issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The findings suggest that mirtazapine “has the potential to become the treatment of choice for functional dyspepsia in patients with weight loss, and evaluation in larger multicenter studies is warranted,” said Dr. Jan Tack and his associates at the University of Leuven, Belgium.

Functional dyspepsia, one of the most prevalent gastrointestinal disorders, is characterized by early satiation, postprandial fullness, and epigastric pain and burning in the absence of underlying systemic or metabolic disease. Up to 40% of affected patients lose weight, an “alarm symptom” that until now has lacked effective treatment, the researchers said.

Mirtazapine, an antagonist of the H1, alpha2, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)2c, and 5-HT3 receptors, often causes weight gain when used to treat depression. Therefore, the investigators designed a double-blind single-center pilot trial of 34 patients with functional dyspepsia who had lost more than 10% of their original body weight. After a 2-week run-in period, half the patients were randomized to 15 mg of mirtazapine every evening and the other half to placebo (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Jan 9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.09.043).

The average weight of placebo patients remained almost unchanged throughout the trial, while patients on mirtazapine gained an average of 2.5 + 0.6 kg by week 4 (P = .003 for between-group comparison) and 3.9 + 0.7 kg, or 6.4% of their original body weight, by week 8 (P less than .0001). Mean scores on a validated dyspepsia symptom severity (DSS) questionnaire improved significantly between baseline and weeks 4 (P = .003) and 8 (P = .017) for mirtazapine but not placebo. Directly comparing the two groups in terms of the DSS revealed a large effect size that trended toward significance (P = .06) at week 4 but not at week 8 (P = .55). However, mirtazapine significantly outperformed placebo in measures of early satiety, quality of life, gastrointestinal-specific anxiety, and nutrient tolerance, “mostly with large effect sizes,” the investigators said.

Mirtazapine did not affect epigastric pain or gastric emptying, and had little effect on postprandial fullness. Moreover, 2 of 17 patients in the mirtazapine group dropped out of the study because of unacceptable levels of drowsiness, which is a common side effect of the medication.

Many patients with functional dyspepsia respond inadequately to first-line treatment with acid-suppressive or prokinetic drugs, the investigators noted. While tegaserod, buspirone, and acotiamide can improve gastric accommodation, it is unknown if they promote weight gain. The results for mirtazapine are promising, but the pilot trial included only tertiary care patients, and the small sample size precluded separate analyses of patients with postprandial distress syndrome as opposed to epigastric pain syndrome, the researchers said.

The study was funded by Leuven University, the FWO, and the KU Leuven Special Research Fund. Mirtazapine and placebo were supplied by MSD Belgium. The investigators had no disclosures.

The antidepressant mirtazapine improved weight loss, early satiation, nausea, and other signs and symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia, said the authors of a placebo-controlled pilot study published in the March issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The findings suggest that mirtazapine “has the potential to become the treatment of choice for functional dyspepsia in patients with weight loss, and evaluation in larger multicenter studies is warranted,” said Dr. Jan Tack and his associates at the University of Leuven, Belgium.

Functional dyspepsia, one of the most prevalent gastrointestinal disorders, is characterized by early satiation, postprandial fullness, and epigastric pain and burning in the absence of underlying systemic or metabolic disease. Up to 40% of affected patients lose weight, an “alarm symptom” that until now has lacked effective treatment, the researchers said.

Mirtazapine, an antagonist of the H1, alpha2, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)2c, and 5-HT3 receptors, often causes weight gain when used to treat depression. Therefore, the investigators designed a double-blind single-center pilot trial of 34 patients with functional dyspepsia who had lost more than 10% of their original body weight. After a 2-week run-in period, half the patients were randomized to 15 mg of mirtazapine every evening and the other half to placebo (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Jan 9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.09.043).

The average weight of placebo patients remained almost unchanged throughout the trial, while patients on mirtazapine gained an average of 2.5 + 0.6 kg by week 4 (P = .003 for between-group comparison) and 3.9 + 0.7 kg, or 6.4% of their original body weight, by week 8 (P less than .0001). Mean scores on a validated dyspepsia symptom severity (DSS) questionnaire improved significantly between baseline and weeks 4 (P = .003) and 8 (P = .017) for mirtazapine but not placebo. Directly comparing the two groups in terms of the DSS revealed a large effect size that trended toward significance (P = .06) at week 4 but not at week 8 (P = .55). However, mirtazapine significantly outperformed placebo in measures of early satiety, quality of life, gastrointestinal-specific anxiety, and nutrient tolerance, “mostly with large effect sizes,” the investigators said.

Mirtazapine did not affect epigastric pain or gastric emptying, and had little effect on postprandial fullness. Moreover, 2 of 17 patients in the mirtazapine group dropped out of the study because of unacceptable levels of drowsiness, which is a common side effect of the medication.

Many patients with functional dyspepsia respond inadequately to first-line treatment with acid-suppressive or prokinetic drugs, the investigators noted. While tegaserod, buspirone, and acotiamide can improve gastric accommodation, it is unknown if they promote weight gain. The results for mirtazapine are promising, but the pilot trial included only tertiary care patients, and the small sample size precluded separate analyses of patients with postprandial distress syndrome as opposed to epigastric pain syndrome, the researchers said.

The study was funded by Leuven University, the FWO, and the KU Leuven Special Research Fund. Mirtazapine and placebo were supplied by MSD Belgium. The investigators had no disclosures.

The antidepressant mirtazapine improved weight loss, early satiation, nausea, and other signs and symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia, said the authors of a placebo-controlled pilot study published in the March issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The findings suggest that mirtazapine “has the potential to become the treatment of choice for functional dyspepsia in patients with weight loss, and evaluation in larger multicenter studies is warranted,” said Dr. Jan Tack and his associates at the University of Leuven, Belgium.

Functional dyspepsia, one of the most prevalent gastrointestinal disorders, is characterized by early satiation, postprandial fullness, and epigastric pain and burning in the absence of underlying systemic or metabolic disease. Up to 40% of affected patients lose weight, an “alarm symptom” that until now has lacked effective treatment, the researchers said.

Mirtazapine, an antagonist of the H1, alpha2, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)2c, and 5-HT3 receptors, often causes weight gain when used to treat depression. Therefore, the investigators designed a double-blind single-center pilot trial of 34 patients with functional dyspepsia who had lost more than 10% of their original body weight. After a 2-week run-in period, half the patients were randomized to 15 mg of mirtazapine every evening and the other half to placebo (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Jan 9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.09.043).

The average weight of placebo patients remained almost unchanged throughout the trial, while patients on mirtazapine gained an average of 2.5 + 0.6 kg by week 4 (P = .003 for between-group comparison) and 3.9 + 0.7 kg, or 6.4% of their original body weight, by week 8 (P less than .0001). Mean scores on a validated dyspepsia symptom severity (DSS) questionnaire improved significantly between baseline and weeks 4 (P = .003) and 8 (P = .017) for mirtazapine but not placebo. Directly comparing the two groups in terms of the DSS revealed a large effect size that trended toward significance (P = .06) at week 4 but not at week 8 (P = .55). However, mirtazapine significantly outperformed placebo in measures of early satiety, quality of life, gastrointestinal-specific anxiety, and nutrient tolerance, “mostly with large effect sizes,” the investigators said.

Mirtazapine did not affect epigastric pain or gastric emptying, and had little effect on postprandial fullness. Moreover, 2 of 17 patients in the mirtazapine group dropped out of the study because of unacceptable levels of drowsiness, which is a common side effect of the medication.

Many patients with functional dyspepsia respond inadequately to first-line treatment with acid-suppressive or prokinetic drugs, the investigators noted. While tegaserod, buspirone, and acotiamide can improve gastric accommodation, it is unknown if they promote weight gain. The results for mirtazapine are promising, but the pilot trial included only tertiary care patients, and the small sample size precluded separate analyses of patients with postprandial distress syndrome as opposed to epigastric pain syndrome, the researchers said.

The study was funded by Leuven University, the FWO, and the KU Leuven Special Research Fund. Mirtazapine and placebo were supplied by MSD Belgium. The investigators had no disclosures.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Mirtazapine treatment led to weight gain and a number of other improvements among patients with functional dyspepsia and weight loss.

Major finding: Patients regained an average of 6.5% of their original body weight on mirtazapine, and did not regain weight on placebo.

Data source: A single-center randomized double-blind study of 34 patients with functional dyspepsia.

Disclosures: Leuven University, the FWO, and the KU Leuven Special Research Fund helped fund the study. Mirtazapine and placebo were supplied by MSD Belgium. The investigators had no disclosures.

Study backed familial component of advanced adenoma risk

Siblings of patients with advanced adenoma had sixfold higher odds of having the tumors themselves, as compared with controls, said the authors of a blinded cross-sectional study reported in the March issue of Gastroenterology.

The results reinforce the need for early screening of individuals whose siblings have advanced adenoma, said Dr. Siew Ng at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and her associates. The risk of advanced adenoma was even higher when affected probands were younger than average or had multiple adenomas, the researchers added.

Most studies that have purported to study the familial risk of adenoma actually studied the risk of adenoma in persons whose first-degree relatives have colorectal cancer, according to Dr. Ng and her associates. Their study included 200 asymptomatic (“exposed”) siblings of individuals with advanced adenomas as diagnosed on colonoscopy, and 400 controls whose siblings had no family history of colorectal cancer or colonoscopic evidence of neoplasia. The researchers defined advanced adenomas as those measuring at least 10 mm or that had high-grade dysplasia or villous or tubulovillous characteristics. “We focused on advanced lesions, as they have the greatest malignant potential, and removing these lesions can reduce colorectal cancer incidence and mortality,” they said (Gastroenterology. 2015 Nov 14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.003).

Exposed siblings were consistently more likely to have adenomas themselves, compared with the control group, said the investigators. For example, the prevalence of any advanced adenoma was 11.5% among exposed siblings compared with only 2.5% among controls (matched odds ratio, 6.05; 95% confidence interval, 2.7-13.4; P less than .001). Similarly, the prevalence of adenomas measuring at least 10 mm was 10.5% among exposed individuals and 1.8% among controls (mOR, 8.6; 95% CI, 3.4-21.4; P less than .001). The prevalence of villous adenomas was 5.5% among exposed individuals and 1.3% among controls (mOR, 6.3; 95% CI, 2.0-19.5; P = .001) and the prevalence of all colorectal adenomas was 39% among exposed individuals and 19% among controls (mOR, 3.3; 95% CI, 2.2-5.0; P less than .001). Finally, two cases of colorectal cancer were detected among the exposed siblings, while no such cases were detected among the controls.

The exposed siblings and controls resembled each other in terms of aspirin use, smoking, body mass index, and metabolic diseases, the researchers said. However, the probands with adenoma were identified from a consecutive group of patients, while control siblings were enrolled through a screening program, they said. Therefore, the groups might have differed in terms of unmeasured environmental risk factors for cancer, such as physical activity and dietary habits. They also noted the difficulties in obtaining accurate family histories of colonic neoplasia, especially distinguishing adenoma from advanced adenoma. Finally, Hong Kong is ethnically homogenous, and the data might not be generalizable to other populations, although Asia and Western countries do tend to have comparable rates of advanced adenoma in average-risk individuals and in families with histories of colorectal neoplasias.

The Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region funded the study. The investigators had no disclosures.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Current guidelines recommend early screening and shorter surveillance intervals in individuals with a first-degree relative (FDR) with colorectal cancer (CRC) (Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570-950). Existing literature is limited by either lack of an appropriate comparison group or inability to assess adenoma risk in subjects who have an FDR with adenomas.

|

| Dr. Harini S. Naidu |

To date, this is the first prospective study to demonstrate increased prevalence of advanced adenomas in siblings of probands with advanced adenomas detected during colonoscopy. The authors should be congratulated on completing an organized, well-powered study using colonoscopy and histopathology and were careful to limit familial clustering by randomly selecting only one sibling from each family. Although this study has important findings, there are a few points worthy of consideration.

First, it would be helpful to understand whether the siblings shared both parents, one parent, or were adopted, as this would affect the genetic implications of the findings.

Second, the analysis did not stratify probands and siblings based on whether the colonoscopy included in the study was the first or second screening, or surveillance colonoscopy. The risk of advanced adenomas is expected to be different in someone with numerous normal colonoscopies, compared with someone undergoing their initial screening colonoscopy, and this point deserves clarification.

|

| Dr. Audrey H. Calderwood |

Third, it would be helpful to know how many siblings in each group were excluded due to previous adenomas, which bias results towards the null. For example, exclusion of high-risk individuals with previous adenomas in the control group may make the prevalence of adenoma detection appear lower if only lower-risk individuals are included.

Lastly, this study was performed in a uniform Asian patient population, and may not be generalizable to other populations. Validation in a more ethnically heterogeneous setting is warranted. Overall, this is a solid, clinically relevant study that can help inform the impact of family history of advanced adenomas on CRC screening recommendations.

In addition, the study’s findings corroborate the American College of Gastroenterology’s recommendations for earlier CRC screening at shorter surveillance intervals in patients who have FDRs with advanced adenomas detected at age less than 60, or two FDRs diagnosed with advanced adenomas at any age (Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:739–50).

Dr. Harini S. Naidu and Dr. Audrey H. Calderwood are in the section of gastroenterology, Boston University. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Current guidelines recommend early screening and shorter surveillance intervals in individuals with a first-degree relative (FDR) with colorectal cancer (CRC) (Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570-950). Existing literature is limited by either lack of an appropriate comparison group or inability to assess adenoma risk in subjects who have an FDR with adenomas.

|

| Dr. Harini S. Naidu |

To date, this is the first prospective study to demonstrate increased prevalence of advanced adenomas in siblings of probands with advanced adenomas detected during colonoscopy. The authors should be congratulated on completing an organized, well-powered study using colonoscopy and histopathology and were careful to limit familial clustering by randomly selecting only one sibling from each family. Although this study has important findings, there are a few points worthy of consideration.

First, it would be helpful to understand whether the siblings shared both parents, one parent, or were adopted, as this would affect the genetic implications of the findings.

Second, the analysis did not stratify probands and siblings based on whether the colonoscopy included in the study was the first or second screening, or surveillance colonoscopy. The risk of advanced adenomas is expected to be different in someone with numerous normal colonoscopies, compared with someone undergoing their initial screening colonoscopy, and this point deserves clarification.

|

| Dr. Audrey H. Calderwood |

Third, it would be helpful to know how many siblings in each group were excluded due to previous adenomas, which bias results towards the null. For example, exclusion of high-risk individuals with previous adenomas in the control group may make the prevalence of adenoma detection appear lower if only lower-risk individuals are included.

Lastly, this study was performed in a uniform Asian patient population, and may not be generalizable to other populations. Validation in a more ethnically heterogeneous setting is warranted. Overall, this is a solid, clinically relevant study that can help inform the impact of family history of advanced adenomas on CRC screening recommendations.

In addition, the study’s findings corroborate the American College of Gastroenterology’s recommendations for earlier CRC screening at shorter surveillance intervals in patients who have FDRs with advanced adenomas detected at age less than 60, or two FDRs diagnosed with advanced adenomas at any age (Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:739–50).

Dr. Harini S. Naidu and Dr. Audrey H. Calderwood are in the section of gastroenterology, Boston University. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Current guidelines recommend early screening and shorter surveillance intervals in individuals with a first-degree relative (FDR) with colorectal cancer (CRC) (Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570-950). Existing literature is limited by either lack of an appropriate comparison group or inability to assess adenoma risk in subjects who have an FDR with adenomas.

|

| Dr. Harini S. Naidu |

To date, this is the first prospective study to demonstrate increased prevalence of advanced adenomas in siblings of probands with advanced adenomas detected during colonoscopy. The authors should be congratulated on completing an organized, well-powered study using colonoscopy and histopathology and were careful to limit familial clustering by randomly selecting only one sibling from each family. Although this study has important findings, there are a few points worthy of consideration.

First, it would be helpful to understand whether the siblings shared both parents, one parent, or were adopted, as this would affect the genetic implications of the findings.

Second, the analysis did not stratify probands and siblings based on whether the colonoscopy included in the study was the first or second screening, or surveillance colonoscopy. The risk of advanced adenomas is expected to be different in someone with numerous normal colonoscopies, compared with someone undergoing their initial screening colonoscopy, and this point deserves clarification.

|

| Dr. Audrey H. Calderwood |

Third, it would be helpful to know how many siblings in each group were excluded due to previous adenomas, which bias results towards the null. For example, exclusion of high-risk individuals with previous adenomas in the control group may make the prevalence of adenoma detection appear lower if only lower-risk individuals are included.

Lastly, this study was performed in a uniform Asian patient population, and may not be generalizable to other populations. Validation in a more ethnically heterogeneous setting is warranted. Overall, this is a solid, clinically relevant study that can help inform the impact of family history of advanced adenomas on CRC screening recommendations.

In addition, the study’s findings corroborate the American College of Gastroenterology’s recommendations for earlier CRC screening at shorter surveillance intervals in patients who have FDRs with advanced adenomas detected at age less than 60, or two FDRs diagnosed with advanced adenomas at any age (Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:739–50).

Dr. Harini S. Naidu and Dr. Audrey H. Calderwood are in the section of gastroenterology, Boston University. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Siblings of patients with advanced adenoma had sixfold higher odds of having the tumors themselves, as compared with controls, said the authors of a blinded cross-sectional study reported in the March issue of Gastroenterology.

The results reinforce the need for early screening of individuals whose siblings have advanced adenoma, said Dr. Siew Ng at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and her associates. The risk of advanced adenoma was even higher when affected probands were younger than average or had multiple adenomas, the researchers added.

Most studies that have purported to study the familial risk of adenoma actually studied the risk of adenoma in persons whose first-degree relatives have colorectal cancer, according to Dr. Ng and her associates. Their study included 200 asymptomatic (“exposed”) siblings of individuals with advanced adenomas as diagnosed on colonoscopy, and 400 controls whose siblings had no family history of colorectal cancer or colonoscopic evidence of neoplasia. The researchers defined advanced adenomas as those measuring at least 10 mm or that had high-grade dysplasia or villous or tubulovillous characteristics. “We focused on advanced lesions, as they have the greatest malignant potential, and removing these lesions can reduce colorectal cancer incidence and mortality,” they said (Gastroenterology. 2015 Nov 14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.003).

Exposed siblings were consistently more likely to have adenomas themselves, compared with the control group, said the investigators. For example, the prevalence of any advanced adenoma was 11.5% among exposed siblings compared with only 2.5% among controls (matched odds ratio, 6.05; 95% confidence interval, 2.7-13.4; P less than .001). Similarly, the prevalence of adenomas measuring at least 10 mm was 10.5% among exposed individuals and 1.8% among controls (mOR, 8.6; 95% CI, 3.4-21.4; P less than .001). The prevalence of villous adenomas was 5.5% among exposed individuals and 1.3% among controls (mOR, 6.3; 95% CI, 2.0-19.5; P = .001) and the prevalence of all colorectal adenomas was 39% among exposed individuals and 19% among controls (mOR, 3.3; 95% CI, 2.2-5.0; P less than .001). Finally, two cases of colorectal cancer were detected among the exposed siblings, while no such cases were detected among the controls.

The exposed siblings and controls resembled each other in terms of aspirin use, smoking, body mass index, and metabolic diseases, the researchers said. However, the probands with adenoma were identified from a consecutive group of patients, while control siblings were enrolled through a screening program, they said. Therefore, the groups might have differed in terms of unmeasured environmental risk factors for cancer, such as physical activity and dietary habits. They also noted the difficulties in obtaining accurate family histories of colonic neoplasia, especially distinguishing adenoma from advanced adenoma. Finally, Hong Kong is ethnically homogenous, and the data might not be generalizable to other populations, although Asia and Western countries do tend to have comparable rates of advanced adenoma in average-risk individuals and in families with histories of colorectal neoplasias.

The Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region funded the study. The investigators had no disclosures.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Siblings of patients with advanced adenoma had sixfold higher odds of having the tumors themselves, as compared with controls, said the authors of a blinded cross-sectional study reported in the March issue of Gastroenterology.

The results reinforce the need for early screening of individuals whose siblings have advanced adenoma, said Dr. Siew Ng at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and her associates. The risk of advanced adenoma was even higher when affected probands were younger than average or had multiple adenomas, the researchers added.

Most studies that have purported to study the familial risk of adenoma actually studied the risk of adenoma in persons whose first-degree relatives have colorectal cancer, according to Dr. Ng and her associates. Their study included 200 asymptomatic (“exposed”) siblings of individuals with advanced adenomas as diagnosed on colonoscopy, and 400 controls whose siblings had no family history of colorectal cancer or colonoscopic evidence of neoplasia. The researchers defined advanced adenomas as those measuring at least 10 mm or that had high-grade dysplasia or villous or tubulovillous characteristics. “We focused on advanced lesions, as they have the greatest malignant potential, and removing these lesions can reduce colorectal cancer incidence and mortality,” they said (Gastroenterology. 2015 Nov 14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.003).

Exposed siblings were consistently more likely to have adenomas themselves, compared with the control group, said the investigators. For example, the prevalence of any advanced adenoma was 11.5% among exposed siblings compared with only 2.5% among controls (matched odds ratio, 6.05; 95% confidence interval, 2.7-13.4; P less than .001). Similarly, the prevalence of adenomas measuring at least 10 mm was 10.5% among exposed individuals and 1.8% among controls (mOR, 8.6; 95% CI, 3.4-21.4; P less than .001). The prevalence of villous adenomas was 5.5% among exposed individuals and 1.3% among controls (mOR, 6.3; 95% CI, 2.0-19.5; P = .001) and the prevalence of all colorectal adenomas was 39% among exposed individuals and 19% among controls (mOR, 3.3; 95% CI, 2.2-5.0; P less than .001). Finally, two cases of colorectal cancer were detected among the exposed siblings, while no such cases were detected among the controls.

The exposed siblings and controls resembled each other in terms of aspirin use, smoking, body mass index, and metabolic diseases, the researchers said. However, the probands with adenoma were identified from a consecutive group of patients, while control siblings were enrolled through a screening program, they said. Therefore, the groups might have differed in terms of unmeasured environmental risk factors for cancer, such as physical activity and dietary habits. They also noted the difficulties in obtaining accurate family histories of colonic neoplasia, especially distinguishing adenoma from advanced adenoma. Finally, Hong Kong is ethnically homogenous, and the data might not be generalizable to other populations, although Asia and Western countries do tend to have comparable rates of advanced adenoma in average-risk individuals and in families with histories of colorectal neoplasias.

The Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region funded the study. The investigators had no disclosures.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Siblings of patients with advanced adenoma were substantially more likely to also have advanced adenomas as compared with controls.

Major finding: The odds of advanced adenomas among exposed siblings were six times greater than for controls (95% confidence interval, 2.7-13.4; P less than .001).

Data source: A cross-sectional study of 200 asymptomatic siblings of individuals with advanced adenomas and 400 controls whose siblings had no family history of colorectal cancer or colonoscopic evidence of neoplasia.

Disclosures: The Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region funded the study. The investigators had no disclosures.

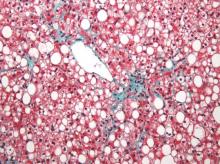

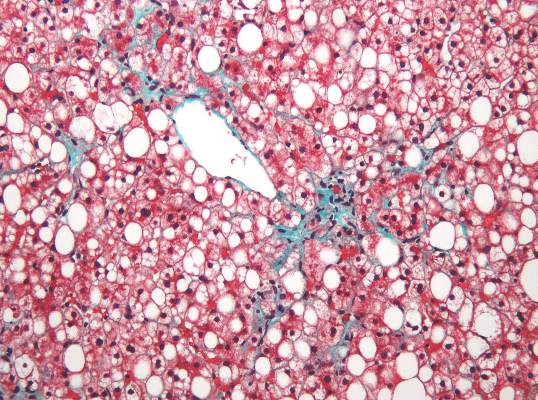

MRI topped transient elastography for staging nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

Two magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques topped transient elastography (TE) for diagnosing hepatic fibrosis and steatosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), according to a first-in-kind study.

Magnetic resonance elastography surpassed all other methods for staging fibrosis, while MRI-based measurement of proton density fat fraction (PDFF) was superior for grading steatosis, with liver biopsy used as the comparative gold standard, said Dr. Kento Imajo at Yokohama (Japan) City University Graduate School of Medicine and his associates. “Magnetic resonance imaging–based noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis and steatosis is a potential alternative to liver biopsy in clinical practice,” the investigators wrote in the March issue of Gastroenterology.

Assessing liver fibrosis and steatosis is important for staging NAFLD. Although “useful” overall, transient elastography can be unreliable in morbidly obese NAFLD patients or those with ascites because of low-frequency vibrations created by the probe, the researchers noted. To compare TE with MRI-based magnetic resonance elastography and PDFF, they evaluated 142 patients with biopsy-confirmed NAFLD and 10 controls, all of whom they also assessed with five clinical scoring systems for fibrosis – the FIB4 index, the NAFLD fibrosis score, the aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to platelet ratio, the AST-to-alanine transaminase (ALT) ratio, and the BARD score (Gastroenterology. 2015 Dec 8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.048).

Magnetic resonance elastography detected stage 2 or higher hepatic fibrosis with an area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve value of 0.91 (95% confidence interval, 0.86-0.96), compared with 0.82 (0.74-0.89) for transient elastography (P = .001), the investigators reported. The AUROC for MRE also significantly exceeded the AUROCs for all five clinical indexes of fibrosis severity. Furthermore, MRI-based measurement of PDFF identified hepatic steatosis of grade 2 or higher with an AUROC curve value of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.82-0.97), which was significantly greater than the AUROC obtained by using TE to measure the controlled attenuation parameter (0.73; 95% CI, 0.64-0.81; P less than .001).

Adding a measure for serum keratin 18 fragments or ALT did not significantly improve the detection of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis or macrovesicular steatosis affecting at least 5% of hepatocytes by either MRI or TE, the researchers noted. While liver biopsy remains the gold standard for assessing NAFLD, it is associated with sampling errors and intra- and interobserver variability, and these errors could have affected their study results, they acknowledged. The study also did not account for hepatic perfusion, which can elevate liver stiffness measurement independently from liver disease.

Both the magnetic resonance elastography and PDFF techniques require specialized hardware and software that are available from several commercial suppliers, the researchers also noted.

The study was partially supported by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, the Japanese Science and Technology Agency, and Kiban-B, Shingakujuturyouiki. The investigators had no disclosures.

Two magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques topped transient elastography (TE) for diagnosing hepatic fibrosis and steatosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), according to a first-in-kind study.

Magnetic resonance elastography surpassed all other methods for staging fibrosis, while MRI-based measurement of proton density fat fraction (PDFF) was superior for grading steatosis, with liver biopsy used as the comparative gold standard, said Dr. Kento Imajo at Yokohama (Japan) City University Graduate School of Medicine and his associates. “Magnetic resonance imaging–based noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis and steatosis is a potential alternative to liver biopsy in clinical practice,” the investigators wrote in the March issue of Gastroenterology.

Assessing liver fibrosis and steatosis is important for staging NAFLD. Although “useful” overall, transient elastography can be unreliable in morbidly obese NAFLD patients or those with ascites because of low-frequency vibrations created by the probe, the researchers noted. To compare TE with MRI-based magnetic resonance elastography and PDFF, they evaluated 142 patients with biopsy-confirmed NAFLD and 10 controls, all of whom they also assessed with five clinical scoring systems for fibrosis – the FIB4 index, the NAFLD fibrosis score, the aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to platelet ratio, the AST-to-alanine transaminase (ALT) ratio, and the BARD score (Gastroenterology. 2015 Dec 8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.048).

Magnetic resonance elastography detected stage 2 or higher hepatic fibrosis with an area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve value of 0.91 (95% confidence interval, 0.86-0.96), compared with 0.82 (0.74-0.89) for transient elastography (P = .001), the investigators reported. The AUROC for MRE also significantly exceeded the AUROCs for all five clinical indexes of fibrosis severity. Furthermore, MRI-based measurement of PDFF identified hepatic steatosis of grade 2 or higher with an AUROC curve value of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.82-0.97), which was significantly greater than the AUROC obtained by using TE to measure the controlled attenuation parameter (0.73; 95% CI, 0.64-0.81; P less than .001).

Adding a measure for serum keratin 18 fragments or ALT did not significantly improve the detection of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis or macrovesicular steatosis affecting at least 5% of hepatocytes by either MRI or TE, the researchers noted. While liver biopsy remains the gold standard for assessing NAFLD, it is associated with sampling errors and intra- and interobserver variability, and these errors could have affected their study results, they acknowledged. The study also did not account for hepatic perfusion, which can elevate liver stiffness measurement independently from liver disease.

Both the magnetic resonance elastography and PDFF techniques require specialized hardware and software that are available from several commercial suppliers, the researchers also noted.

The study was partially supported by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, the Japanese Science and Technology Agency, and Kiban-B, Shingakujuturyouiki. The investigators had no disclosures.

Two magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques topped transient elastography (TE) for diagnosing hepatic fibrosis and steatosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), according to a first-in-kind study.

Magnetic resonance elastography surpassed all other methods for staging fibrosis, while MRI-based measurement of proton density fat fraction (PDFF) was superior for grading steatosis, with liver biopsy used as the comparative gold standard, said Dr. Kento Imajo at Yokohama (Japan) City University Graduate School of Medicine and his associates. “Magnetic resonance imaging–based noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis and steatosis is a potential alternative to liver biopsy in clinical practice,” the investigators wrote in the March issue of Gastroenterology.

Assessing liver fibrosis and steatosis is important for staging NAFLD. Although “useful” overall, transient elastography can be unreliable in morbidly obese NAFLD patients or those with ascites because of low-frequency vibrations created by the probe, the researchers noted. To compare TE with MRI-based magnetic resonance elastography and PDFF, they evaluated 142 patients with biopsy-confirmed NAFLD and 10 controls, all of whom they also assessed with five clinical scoring systems for fibrosis – the FIB4 index, the NAFLD fibrosis score, the aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to platelet ratio, the AST-to-alanine transaminase (ALT) ratio, and the BARD score (Gastroenterology. 2015 Dec 8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.048).

Magnetic resonance elastography detected stage 2 or higher hepatic fibrosis with an area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve value of 0.91 (95% confidence interval, 0.86-0.96), compared with 0.82 (0.74-0.89) for transient elastography (P = .001), the investigators reported. The AUROC for MRE also significantly exceeded the AUROCs for all five clinical indexes of fibrosis severity. Furthermore, MRI-based measurement of PDFF identified hepatic steatosis of grade 2 or higher with an AUROC curve value of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.82-0.97), which was significantly greater than the AUROC obtained by using TE to measure the controlled attenuation parameter (0.73; 95% CI, 0.64-0.81; P less than .001).

Adding a measure for serum keratin 18 fragments or ALT did not significantly improve the detection of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis or macrovesicular steatosis affecting at least 5% of hepatocytes by either MRI or TE, the researchers noted. While liver biopsy remains the gold standard for assessing NAFLD, it is associated with sampling errors and intra- and interobserver variability, and these errors could have affected their study results, they acknowledged. The study also did not account for hepatic perfusion, which can elevate liver stiffness measurement independently from liver disease.

Both the magnetic resonance elastography and PDFF techniques require specialized hardware and software that are available from several commercial suppliers, the researchers also noted.

The study was partially supported by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, the Japanese Science and Technology Agency, and Kiban-B, Shingakujuturyouiki. The investigators had no disclosures.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Two specialized MRI techniques surpassed transient elastography for staging fibrosis and steatosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Major finding: The areas under the curve for magnetic resonance elastography and the proton density fat fraction measure were significantly greater than those for transient elastography and the TE-based controlled attenuation parameter (P is less than .001 for both comparisons).

Data source: A cross-sectional study of 142 patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and 10 controls.

Disclosures: The study was partially supported by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, the Japanese Science and Technology Agency, and Kiban-B, Shingakujuturyouiki. The investigators had no disclosures.

Labeled peptide bound the claudin-1 target in colorectal cancer models

An optically labeled peptide rapidly and specifically bound the claudin-1 membrane protein, a “promising” target for early detection of human colonic adenomas, according to a study published online in the March issue of Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

If the peptide holds up in human studies, it might one day be used to screen high-risk patients with multiple polyps, inflammatory bowel disease, Lynch syndrome, or a family history of CRC, said Dr. Emily Rabinsky and her associates at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Peptides can be delivered topically to mucosa in high concentrations to maximize binding and image contrast while minimizing the risk of systemic absorption and toxicity, they added.

Adenomatous polyps express early molecular targets that are candidates for enhanced CRC surveillance. This research area is important because more than 35% of premalignant colonic lesions are flat and therefore difficult to visualize. As a result, up to 25% of adenomas are missed during typical white light colonoscopy. Furthermore, premalignant adenomas cannot be distinguished grossly from noncancerous hyperplastic polyps, the researchers noted (Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 [doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2015.12.001]). Claudin-1 is an integral membrane protein that is known to be overexpressed in human colorectal and squamous cell neoplasias as well as in cancers of the human pancreas, thyroid, cervix, stomach, and nasopharynx. For the study, the investigators used gene expression data to confirm that claudin-1 is an early target in colonic adenomas, and then performed phage display against the extracellular loop of claudin-1 to identify the claudin-1-specific RTSPSSR peptide. After labeling the peptide with Cy5.5, they characterized its binding parameters and confirmed that it also specifically binds to human CRC cells. Next, they performed in vivo fluorescent colonic endoscopy of CPC;Apc mice, which spontaneously develop colonic adenomas. They also used immunofluorescence to confirm that RTSPSSR binds specifically to adenomas from the proximal human colon.

Claudin-1 expression was 2.5 times greater in human colonic adenomas compared with normal colonic mucosa, the researchers found. Furthermore, the RTSPSSR peptide specifically bound claudin-1 in knockdown and competition studies. Binding to CRC cells occurred in 1.2 minutes, with an “adequate” affinity of 42 nmol per liter, the researchers said. Moreover, the peptide specifically bound to both flat and polyploid murine colonic adenomas, with a significantly higher target-to-background ratio compared with normal in vivo images. In addition, immunofluorescence was significantly more intense for peptide that bound to adenomas and sessile serrated adenomas from the proximal human colon compared with normal tissue and hyperplastic polyps.

“Future development of this peptide will require in vivo clinical validation in human studies,” said the investigators. “Although we found promising results with this peptide alone, disease heterogeneity in a broad patient population may require use of additional targets using multiplexed imaging methods.” Nonetheless, this peptide can help detect multiple targets with a single topical application and at relatively low expression levels, they noted.

The study was partially funded by the National Institutes of Health and by Mary L. Petrovich. Dr. Rabinsky and two coinvestigators are co-inventors on a provisional patent on the claudin-1 peptide. The other researchers had no disclosures.

The application of fluorescent affinity probes described in this study is groundbreaking. In the context of advanced imaging techniques, including chromoendoscopy, narrowband imaging, high magnification, and confocal endomicroscopy, this study describes a specific molecular probe. That is a major advance in the area of personalized medicine.

While most would agree that detection of polypoid adenomas does not generally require advanced imaging technologies, the genetically engineered mouse model used in this study is useful for proof of concept. It is, however, important to note that lesions were not detected from a broad area; polyps were labeled during a 5-minute incubation with the fluorescent-tagged peptide and the area was then washed. While the fluorescent intensity of lesions relative to surrounding nondysplastic mucosae were impressively elevated in both polypoid and flat adenomas relative, it is important to note that there was significant overlap between normal mucosae, hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenomas/polyps, and traditional adenomas. While the limited sensitivity and specificity make it unlikely that the probe used here, which targets a surface protein that is only modestly upregulated in dysplasia, will be of great value. However, the idea of specifically detecting lesions using affinity probes does have promise.

On the basis of this study, some might ask whether biopsy and histopathologic examination can be replaced by intravital affinity labeling. At this point, the answer must be no, as the sensitivity and specificity of labeling techniques are far below that of traditional histopathologic examination, even for straightforward lesions such as those studied here. Yet as a means to enhance the sensitivity of sampling when surveying large areas, such as Barrett’s esophagus or long-standing ulcerative colitis, the approaches described in this study point the way to a bright future.

Jerrold R. Turner, M.D., Ph.D., AGAF, is in the departments of pathology and medicine (GI), Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The application of fluorescent affinity probes described in this study is groundbreaking. In the context of advanced imaging techniques, including chromoendoscopy, narrowband imaging, high magnification, and confocal endomicroscopy, this study describes a specific molecular probe. That is a major advance in the area of personalized medicine.

While most would agree that detection of polypoid adenomas does not generally require advanced imaging technologies, the genetically engineered mouse model used in this study is useful for proof of concept. It is, however, important to note that lesions were not detected from a broad area; polyps were labeled during a 5-minute incubation with the fluorescent-tagged peptide and the area was then washed. While the fluorescent intensity of lesions relative to surrounding nondysplastic mucosae were impressively elevated in both polypoid and flat adenomas relative, it is important to note that there was significant overlap between normal mucosae, hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenomas/polyps, and traditional adenomas. While the limited sensitivity and specificity make it unlikely that the probe used here, which targets a surface protein that is only modestly upregulated in dysplasia, will be of great value. However, the idea of specifically detecting lesions using affinity probes does have promise.

On the basis of this study, some might ask whether biopsy and histopathologic examination can be replaced by intravital affinity labeling. At this point, the answer must be no, as the sensitivity and specificity of labeling techniques are far below that of traditional histopathologic examination, even for straightforward lesions such as those studied here. Yet as a means to enhance the sensitivity of sampling when surveying large areas, such as Barrett’s esophagus or long-standing ulcerative colitis, the approaches described in this study point the way to a bright future.

Jerrold R. Turner, M.D., Ph.D., AGAF, is in the departments of pathology and medicine (GI), Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The application of fluorescent affinity probes described in this study is groundbreaking. In the context of advanced imaging techniques, including chromoendoscopy, narrowband imaging, high magnification, and confocal endomicroscopy, this study describes a specific molecular probe. That is a major advance in the area of personalized medicine.

While most would agree that detection of polypoid adenomas does not generally require advanced imaging technologies, the genetically engineered mouse model used in this study is useful for proof of concept. It is, however, important to note that lesions were not detected from a broad area; polyps were labeled during a 5-minute incubation with the fluorescent-tagged peptide and the area was then washed. While the fluorescent intensity of lesions relative to surrounding nondysplastic mucosae were impressively elevated in both polypoid and flat adenomas relative, it is important to note that there was significant overlap between normal mucosae, hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenomas/polyps, and traditional adenomas. While the limited sensitivity and specificity make it unlikely that the probe used here, which targets a surface protein that is only modestly upregulated in dysplasia, will be of great value. However, the idea of specifically detecting lesions using affinity probes does have promise.

On the basis of this study, some might ask whether biopsy and histopathologic examination can be replaced by intravital affinity labeling. At this point, the answer must be no, as the sensitivity and specificity of labeling techniques are far below that of traditional histopathologic examination, even for straightforward lesions such as those studied here. Yet as a means to enhance the sensitivity of sampling when surveying large areas, such as Barrett’s esophagus or long-standing ulcerative colitis, the approaches described in this study point the way to a bright future.

Jerrold R. Turner, M.D., Ph.D., AGAF, is in the departments of pathology and medicine (GI), Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

An optically labeled peptide rapidly and specifically bound the claudin-1 membrane protein, a “promising” target for early detection of human colonic adenomas, according to a study published online in the March issue of Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

If the peptide holds up in human studies, it might one day be used to screen high-risk patients with multiple polyps, inflammatory bowel disease, Lynch syndrome, or a family history of CRC, said Dr. Emily Rabinsky and her associates at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Peptides can be delivered topically to mucosa in high concentrations to maximize binding and image contrast while minimizing the risk of systemic absorption and toxicity, they added.

Adenomatous polyps express early molecular targets that are candidates for enhanced CRC surveillance. This research area is important because more than 35% of premalignant colonic lesions are flat and therefore difficult to visualize. As a result, up to 25% of adenomas are missed during typical white light colonoscopy. Furthermore, premalignant adenomas cannot be distinguished grossly from noncancerous hyperplastic polyps, the researchers noted (Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 [doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2015.12.001]). Claudin-1 is an integral membrane protein that is known to be overexpressed in human colorectal and squamous cell neoplasias as well as in cancers of the human pancreas, thyroid, cervix, stomach, and nasopharynx. For the study, the investigators used gene expression data to confirm that claudin-1 is an early target in colonic adenomas, and then performed phage display against the extracellular loop of claudin-1 to identify the claudin-1-specific RTSPSSR peptide. After labeling the peptide with Cy5.5, they characterized its binding parameters and confirmed that it also specifically binds to human CRC cells. Next, they performed in vivo fluorescent colonic endoscopy of CPC;Apc mice, which spontaneously develop colonic adenomas. They also used immunofluorescence to confirm that RTSPSSR binds specifically to adenomas from the proximal human colon.

Claudin-1 expression was 2.5 times greater in human colonic adenomas compared with normal colonic mucosa, the researchers found. Furthermore, the RTSPSSR peptide specifically bound claudin-1 in knockdown and competition studies. Binding to CRC cells occurred in 1.2 minutes, with an “adequate” affinity of 42 nmol per liter, the researchers said. Moreover, the peptide specifically bound to both flat and polyploid murine colonic adenomas, with a significantly higher target-to-background ratio compared with normal in vivo images. In addition, immunofluorescence was significantly more intense for peptide that bound to adenomas and sessile serrated adenomas from the proximal human colon compared with normal tissue and hyperplastic polyps.

“Future development of this peptide will require in vivo clinical validation in human studies,” said the investigators. “Although we found promising results with this peptide alone, disease heterogeneity in a broad patient population may require use of additional targets using multiplexed imaging methods.” Nonetheless, this peptide can help detect multiple targets with a single topical application and at relatively low expression levels, they noted.

The study was partially funded by the National Institutes of Health and by Mary L. Petrovich. Dr. Rabinsky and two coinvestigators are co-inventors on a provisional patent on the claudin-1 peptide. The other researchers had no disclosures.

An optically labeled peptide rapidly and specifically bound the claudin-1 membrane protein, a “promising” target for early detection of human colonic adenomas, according to a study published online in the March issue of Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

If the peptide holds up in human studies, it might one day be used to screen high-risk patients with multiple polyps, inflammatory bowel disease, Lynch syndrome, or a family history of CRC, said Dr. Emily Rabinsky and her associates at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Peptides can be delivered topically to mucosa in high concentrations to maximize binding and image contrast while minimizing the risk of systemic absorption and toxicity, they added.

Adenomatous polyps express early molecular targets that are candidates for enhanced CRC surveillance. This research area is important because more than 35% of premalignant colonic lesions are flat and therefore difficult to visualize. As a result, up to 25% of adenomas are missed during typical white light colonoscopy. Furthermore, premalignant adenomas cannot be distinguished grossly from noncancerous hyperplastic polyps, the researchers noted (Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 [doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2015.12.001]). Claudin-1 is an integral membrane protein that is known to be overexpressed in human colorectal and squamous cell neoplasias as well as in cancers of the human pancreas, thyroid, cervix, stomach, and nasopharynx. For the study, the investigators used gene expression data to confirm that claudin-1 is an early target in colonic adenomas, and then performed phage display against the extracellular loop of claudin-1 to identify the claudin-1-specific RTSPSSR peptide. After labeling the peptide with Cy5.5, they characterized its binding parameters and confirmed that it also specifically binds to human CRC cells. Next, they performed in vivo fluorescent colonic endoscopy of CPC;Apc mice, which spontaneously develop colonic adenomas. They also used immunofluorescence to confirm that RTSPSSR binds specifically to adenomas from the proximal human colon.

Claudin-1 expression was 2.5 times greater in human colonic adenomas compared with normal colonic mucosa, the researchers found. Furthermore, the RTSPSSR peptide specifically bound claudin-1 in knockdown and competition studies. Binding to CRC cells occurred in 1.2 minutes, with an “adequate” affinity of 42 nmol per liter, the researchers said. Moreover, the peptide specifically bound to both flat and polyploid murine colonic adenomas, with a significantly higher target-to-background ratio compared with normal in vivo images. In addition, immunofluorescence was significantly more intense for peptide that bound to adenomas and sessile serrated adenomas from the proximal human colon compared with normal tissue and hyperplastic polyps.

“Future development of this peptide will require in vivo clinical validation in human studies,” said the investigators. “Although we found promising results with this peptide alone, disease heterogeneity in a broad patient population may require use of additional targets using multiplexed imaging methods.” Nonetheless, this peptide can help detect multiple targets with a single topical application and at relatively low expression levels, they noted.

The study was partially funded by the National Institutes of Health and by Mary L. Petrovich. Dr. Rabinsky and two coinvestigators are co-inventors on a provisional patent on the claudin-1 peptide. The other researchers had no disclosures.

FROM CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: The claudin-1 protein is overexpressed in human colonic adenomas and was bound by the labeled fluorescence RTSPSSR peptide.

Major finding: The peptide bound to claudin-1 in colorectal cancer cells in 1.2 minutes, with an “adequate” affinity of 42 nmol per liter. Immunofluorescence revealed significantly greater binding intensity for human colonic adenomas and sessile serrated adenomas than normal tissue or hyperplastic polyps.

Data source: An analysis of gene expression data, phage display, endoscopy of CPC;Apc mice, and immunofluorescence of normal and cancerous human proximal colon tissue.

Disclosures: The study was partially funded by the National Institutes of Health and by Mary L. Petrovich. Dr. Rabinsky and two coinvestigators are coinventors on a provisional patent on the peptide. The other researchers had no disclosures.

Current Management of Nephrolithiasis

Case

A 39-year-old woman presented to the ED with a chief complaint of intermittent right flank pain that radiated into her groin area. She stated the pain had begun suddenly, 4 hours prior to arrival, and was accompanied by nausea and vomiting. The patient said that she had taken acetaminophen for the pain, but had received no relief. Regarding history, according to the patient, her last menstrual period ended 2 days earlier. She denied any urinary symptoms, diarrhea, or constipation. She had no history of abdominal surgery and was currently not on any medications.

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were: temperature 98.7°F; blood pressure, 130/90 mm Hg; heart rate, 110 beats/minute; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths/minute. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. On physical examination, she appeared to be in mild distress, pacing around the room. There was moderate right costovertebral tenderness on percussion; the abdomen was soft and nontender.

Incidence

As ED visits for nephrolithiasis are increasing, so too are the health-care costs associated with this condition. Between 1992 and 2009, emergent-care presentations for nephrolithiasis rose from 178 to 340 visits per 100,000 individuals.1 Approximately 1 in 11 people in the United States will be affected by nephrolithiasis during their lifetime.2 Estimated health-care costs associated with these complaints were roughly $2 billion in 2000—an increase of 50% since 1994.2

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Laboratory Evaluation

Urinalysis is one of the initial studies for patients with suspected nephrolithiasis. Although hematuria is a classic finding associated with renal calculi, its sensitivity on microscopic analysis is around 84%. Therefore, the absence of hematuria does not exclude renal colic in the differential diagnosis.3

In addition to detecting hematuria, urinalysis can also reveal an underlying infection. One study by Abrahamian et al4 found that roughly 8% of patients presenting with acute nephrolithiasis had a urinary tract infection (UTI)—many without any clinical findings of infection. The presence of pyuria, however, has only moderate accuracy in identifying UTIs in patients with kidney stones.4 If an infected stone cannot be excluded clinically, computed tomography (CT) is indicated.

Mild leukocytosis (ie, <15,000 cells/mcL) is another common finding in patients with acute renal colic.5 A leukocyte count >15,000 cells/mcL is suspicious for infection or other pathology. A blood-chemistry panel to evaluate renal function is appropriate as a baseline—particularly for patients in whom treatment with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) drug is anticipated.

With the ability to visualize renal calculi (Figure 1), the use of noncontrast CT has become a standard initial imaging modality in assessing patients with renal colic. Between 1992 and 2009, the use of CT to evaluate patients presenting with flank pain for suspected renal colic more than tripled from 21% to 71%.6 An analysis performed by the American College of National Radiology Data Registry7 shows the mean radiation dose given by institutions for renal colic CT is unnecessarily high, and that few institutions follow CT-stone protocols aimed at minimizing radiation exposure while still maintaining proper diagnostic accuracy. A typical CT of the abdomen and pelvis is equivalent to over 100 two-view chest X-rays.8 Though controversial, data from a white paper by the American College of Radiology suggest that the ionizing radiation exposure from just one CT for renal colic causes an increase in lifetime cancer risk.9

Despite the increase in CT imaging to evaluate patients presenting to the ED with nephrolithiasis/flank pain, the proportion of patients diagnosed with a kidney stone remained the same between 2000 and 2008, with no significant change in outcomes.10-12 Moreover, the use of CT as an initial imaging modality in patients presenting with flank pain—but with no sign of infection—is unlikely to reveal important alternative findings.13

Regarding the sensitivity of CT in detecting nephrolithiasis, one study demonstrates a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 94% for noncontrast CT.14 Controversy, however, still exists regarding the necessity and utility of CT in diagnosing nephrolithiasis,15 and CT is one of the top 10 tests included in the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) 2014 Choosing Wisely campaign. In this campaign, ACEP recommended emergency physicians (EPs) avoid abdominal and pelvic CT in otherwise healthy patients younger than age 50 years who present with symptoms consistent with uncomplicated renal colic and who have a known history of nephrolithiasis or ureterolithiasis.15 The ACEP also noted that CTs in this context do not often change treatment decisions and are associated with unnecessary radiation exposure and cost.15

While keeping the aforementioned recommendations in mind, if an EP intends to refer a renal colic patient to a urologist a CT scan is necessary either in the ED or as an outpatient. In all cases (except perhaps in patients in whom there is a history of renal stones), the urologist will need this study to determine the size and location of the stone in order to provide recommendations for management.

Ultrasound

Clinical Decision Score

Moore et al,17 authors of the Size, Topography, Location, Obstruction, Number of stones, and Evaluation (STONE) scoring system, developed a classification system for patients with suspected nephrolithiasis. This system places patients into low-, moderate-, and high-score groups, with corresponding probabilities of ureteral stone based on symptoms and epidemiological classifications.

The intent of the STONE system is to accurately predict, based on classification, the likelihood of a patient having a simple ureteral stone versus a more significant, complicated stone and to help guide which, if any, imaging studies are indicated. For example, a lower STONE score would help guide the decision to defer advanced imaging studies that would be unlikely to reveal an alternate serious diagnosis. Likewise, an individual with a high STONE score could potentially receive ultrasonography, reduced-dose CT, or no further imaging.

The STONE score performs fairly well and appears to be superior to physician gestalt, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of .78 compared to .68 with physician gestalt. This system, however, is not always accurate in its classification and has been shown to have 87% specificity at the high end to rule in stone and 96% sensitivity rate at the low end to rule out a stone. Of course, when using a clinical decision rule to rule in or rule out a stone, a tool with a very high specificity is preferred. Although the STONE scoring system does show promise, further studies are needed before it can be applied clinically.17

Treatment

Analgesia

By inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis, NSAIDs reduce inflammation and ureteral muscular hyperactivity.18 A recent Cochrane review of over 50 studies concluded that NSAIDs were effective in relieving acute renal colic pain.19 A systematic review by Holdgate and Pollock20 shows that patients treated with NSAIDs achieve greater reductions in pain scores and are less likely to require additional analgesia in the short term compared to patients treated with opioids. Although opioid medications are effective in relieving pain associated with nephrolithiasis, this class of drugs can exacerbate the nausea often associated with this condition. This same study also showed that patients who were prescribed NSAIDs following an ED visit for renal colic required less medication for pain control, experienced less nausea, and had greater improvements in their pain.20

Nevertheless, the utility of opiates as an adjunct therapy should not be overlooked. For example, in patients with renal colic, numerous studies show treatment with a combination of an NSAID and opiate provides superior pain relief compared to either treatment modality in isolation.21 Opioid analgesia may be indicated in patients in whom NSAIDs are not recommended or contraindicated (eg, elderly patients, patients with renal disease). While NSAIDs address the underlying pathophysiology associated with renal colic, they are sometimes not the best treatment option. Depending on the situation, treatment with an opioid should instead be considered.

Intravenous Fluid Therapy

A 2012 Cochrane Review of randomized control trials (RCT) on intravenous (IV) fluid therapy hydration/diuretic use concluded that there was “no reliable evidence in the literature to support the use of diuretics and high-volume fluid therapy for people with acute ureteric colic.” The review, however, did note that further investigation is warranted for a definitive answer.22 Another study by Springhart et al23 showed no difference in pain or stone expulsion between large-volume (2 L IV fluids over 2 hours) and small-volume fluid administration (20 mL/h). Regarding administration, the use of IV fluids in renal colic is no different than the usual indications for fluid therapy in the ED and should be restricted to patients with signs of dehydration or kidney injury.

Many patients with renal colic will have decreased oral intake from the pain and nausea associated with the stone and may be vomiting. Under these circumstances, it is reasonable to rehydrate the patients, even though large-volume hydration with the intent of aiding stone expulsion or improving pain has not been shown efficacious. Conversely, in addition to the perceived benefit of rehydrating patients, a small amount of fluid hydration may improve the visualization of hydronephrosis on ultrasound.24

Medical Expulsive Therapy

For many years, clinicians have considered the use of tamsulosin, an α1-receptor blocker, as well as nifedipine, a calcium channel blocker, in treating renal colic due to the theoretical benefit of reducing ureteral smooth muscle spasm/constriction thus expediting stone passage. Over the years, dozens of studies showed positive benefit in the use of medical expulsive therapy (MET). A 2014 Cochrane Review demonstrated that patients treated with α1-blockers experienced a higher stone-free rate and shorter time to stone expulsion, and concluded that α1-blockers should be offered as one of the primary treatment modalities in MET.25 This review, however, has been criticized for using a number of studies with very small patient samples, non-peer-reviewed abstracts, and low-quality study designs.26

More recently, in April 2015, Lancet published a large RCT from 24 hospitals in the United Kingdom, comparing placebo versus 400 mcg tamsulosin and 30 mg nifedipine. The authors concluded that “tamsulosin 400 mcg and nifedipine 30 mg are not effective at decreasing the need for further treatment to achieve stone clearance in 4 weeks for patients with expectantly managed ureteric colic.”27 Another large double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, multicenter trial by Furyk et al28 in July 2015 went a step further and evaluated distal stones, which have historically caused complications requiring intervention. They concluded that there was “no benefit overall of 0.4 mg of tamsulosin daily for patients with distal ureteric calculi less than or equal to 10 mm in terms of spontaneous passage, time to stone passage, pain, or analgesia requirements. In the subgroup with large stones (5 to 10 mm), tamsulosin did increase passage and should be considered.”28 Based on these recent studies, the use of tamsulosin in patients with stones larger than 5 mm—but not those with smaller stones—appears to be an appropriate treatment option.

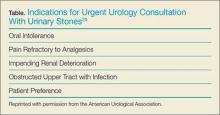

Patient Disposition

The American Urological Association cited indications for urgent/emergent urological interventions necessitating the need for inpatient admission and further workup.29 Patients who do not fall into any of the categories outlined in the Table may be seen on an outpatient basis. These patients may be treated symptomatically until they can follow up with a urologist, who will determine expectant management versus intervention.

Prognosis

The majority of stones <5mm will pass spontaneously.30 Larger stones may still pass spontaneously but are more likely to require lithotripsy or other urologic intervention; therefore, patients with stones >5 mm should be referred to urology services.30

Recurrence

Patients with a first-time kidney stone have a 30% to 50% chance of disease recurrence within 5 years,31 and a 60% to 80% chance of recurrence during their lifetime.32 Those with a family history of nephrolithiasis are likely to develop an earlier onset of stones as well as experience more frequent recurrent episodes.33 Patients with recurrent disease should undergo outpatient risk stratification, including stone-composition analysis and assessment for modifiable risk factors.

Case Conclusion

The patient’s urinalysis demonstrated microscopic hematuria; blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels were within normal limits. As the patient was tachycardic and appeared mildly dehydrated, an IV infusion of 1 L normal saline was initiated, along with ketorolac and ondansetron for symptomatic relief. A POC ultrasound of the right kidney revealed mild-to-moderate hydronephrosis; the left kidney appeared sonographically normal. Since this patient had no history of nephrolithiasis, a nonenhanced CT of the abdomen was obtained, which revealed moderate, right-sided hydronephrosis and a 3-mm distal ureteral stone. Once the patient’s symptoms were controlled, she was discharged home with a prescription for ibuprofen for symptomatic relief and instructions to follow up with her PCP.

Conclusion

The evaluation and treatment of nephrolithiasis is important due to its increasing prevalence, as well as implications on costs to the health-care system and to patients themselves. The workup and treatment of nephrolithiasis has been and continues to be the subject of much controversy. Until very recently, treatment recommendations were founded on physiological theories more so than robust research. In an era where improved imaging technology is becoming more readily available in the ED, EPs should weigh the pros and cons of its utilization for common ED complaints such as nephrolithiasis.

Dr Parsa is an assistant professor in the department of emergency medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso. Dr Khafi is a resident in the department of emergency medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso.

- Scales CD Jr, Smith AC, Hanley JM, Saigal CS; Urologic Diseases in America Project. Prevalence of kidney stones in the United States. Eur Urol. 2012;62(1):160-165.

- Pearle MS, Calhoun EA, Curhan GC; Urologic Diseases of America Project: urolithiasis. J Urol. 2005;173(3):848-857.

- Luchs JS, Katz DS, Lane MJ et al. Utility of hematuria testing in patients with suspected renal colic: correlation with unenhanced helical CT results. Urology. 2002;59(6):839-842.

- Abrahamian FM, Krishnadasan A, Mower WR, Moran GJ, Talan DA. Association of pyuria and clinical characteristics with the presence of urinary tract infection among patients with acute nephrolithiasis. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(5):526-533.

- Yilmaz S, Pekdemir M, Aksu NM, Koyuncu N, Cinar O, Akpinar E. A multicenter case–control study of diagnostic tests for urinary tract infection in the presence of urolithiasis. Urol Res. 2011;40(1):61-65. doi:10.1007/s00240-011-0402-x.

- Fwu CW, Eggers PW, Kimmel PL, Kusek JW, Kirkali Z. Emergency department visits, use of imaging, and drugs for urolithiasis have increased in the United States. Kidney Int. 2013;83(3):479-486. doi:10.1038/ki.2012.419.

- Lukasiewicz A, Bhargavan-Chatfield M, Coombs L, et al. Radiation dose index of renal colic protocol CT studies in the United States: a report from the American College of Radiology National Radiology Data Registry. Radiology. 2014;271(2):445-451. doi:10.1148/radiol.14131601.

- Mettler FA Jr, Huda W, Yoshizumi TT, Mahesh M. Effective doses in radiology and diagnostic nuclear medicine: a catalog. Radiology. 248(1):254-263.

- Amis ES Jr, Butler PF, Applegate KE, et al; American College of Radiology. American College of Radiology white paper on radiation dose in medicine. J Am Coll Radiol. 2007;4(5):272-284.

- Hyams ES, Korley FK, Pham JC, Matlaga BR. Trends in imaging use during the emergency department evaluation of flank pain. J Urol. 2011;186(6):2270-2274. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.079.

- Ripollés T, Agramunt M, Errando J, Martínez MJ, Coronel B, Morales M. Suspected ureteral colic: plain film and sonography vs unenhanced helical CT. A prospective study in 66 patients. Eur Radiol. 2004;14(1):129-36. doi:10.1007/s00330-003-1924-1926.

- Westphalen AC, Hsia RY, Maselli JH, Wang R, Gonzales R. Radiological imaging of patients with suspected urinary tract stones: national trends, diagnoses, and predictors. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(7):699-707. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01103.x.

- Moore CL, Daniels B, Singh D, Luty S, Molinaro A. Prevalence and clinical importance of alternative causes of symptoms using a renal colic computed tomography protocol in patients with flank or back pain and absence of pyuria. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(5):470-478. doi:10.1111/acem.12127.

- Chen MY, Zagoria RJ. Can noncontrast helical computed tomography replace intravenous urography for evaluation of patients with acute urinary tract colic? J Emerg Med. 1999;17(2):299-303.

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Five things physicians and patients should question. Choosing Wisely Web site. 2013;10:1-5. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-college-of-emergency-physicians/. Accessed February 10, 2016.

- Smith-Bindman R, Aubin C, Bailitz J, et al. Ultrasonography versus computed tomography for suspected nephrolithiasis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(12):1100-1110. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1404446.

- Moore CL, Bomann S, Daniels B, et al. Derivation and validation of a clinical prediction rule for uncomplicated ureteral stone—the STONE score: retrospective and prospective observational cohort studies. BMJ. 2014;348:g2191. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2191.

- Cole RS, Fry CH, Shuttleworth KE. The action of the prostaglandins on isolated human ureteric smooth muscle. Br J Urol. 1988;61(1):19-26.

- Afshar K, Jafari S, Marks AJ, Eftekhari R, McNeily AE. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and non-opioids for acute renal colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;6:CD006027. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006027.pub2.

- Holdgate A, Pollock T. Systematic review of the relative efficacy of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids in the treatment of acute renal colic. BMJ. 2004;328(7453):1401. doi:10.1136/bmj.38119.581991.55.

- Safdar B, Degutis LC, Landry K, Vedere SR, Moscovitz HC, D’Onofrio G. Intravenous morphine plus ketorolac is superior to either drug alone for treatment of acute renal colic. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(2):173-181, 181.e1. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.03.013.