User login

‘Decapitated’ boy saved by surgery team

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE: I am joined today by Dr. Ohad Einav. He’s a staff surgeon in orthopedics at Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem. He’s with me to talk about an absolutely incredible surgical case, something that is terrifying to most non–orthopedic surgeons and I imagine is fairly scary for spine surgeons like him as well. But what we don’t have is information about how this works from a medical perspective. So, first of all, Dr. Einav, thank you for taking time to speak with me today.

Ohad Einav, MD: Thank you for having me.

Dr. Wilson: Can you tell us about Suleiman Hassan and what happened to him before he came into your care?

Dr. Einav: Hassan is a 12-year-old child who was riding his bicycle on the West Bank, about 40 minutes from here. Unfortunately, he was involved in a motor vehicle accident and he suffered injuries to his abdomen and cervical spine. He was transported to our service by helicopter from the scene of the accident.

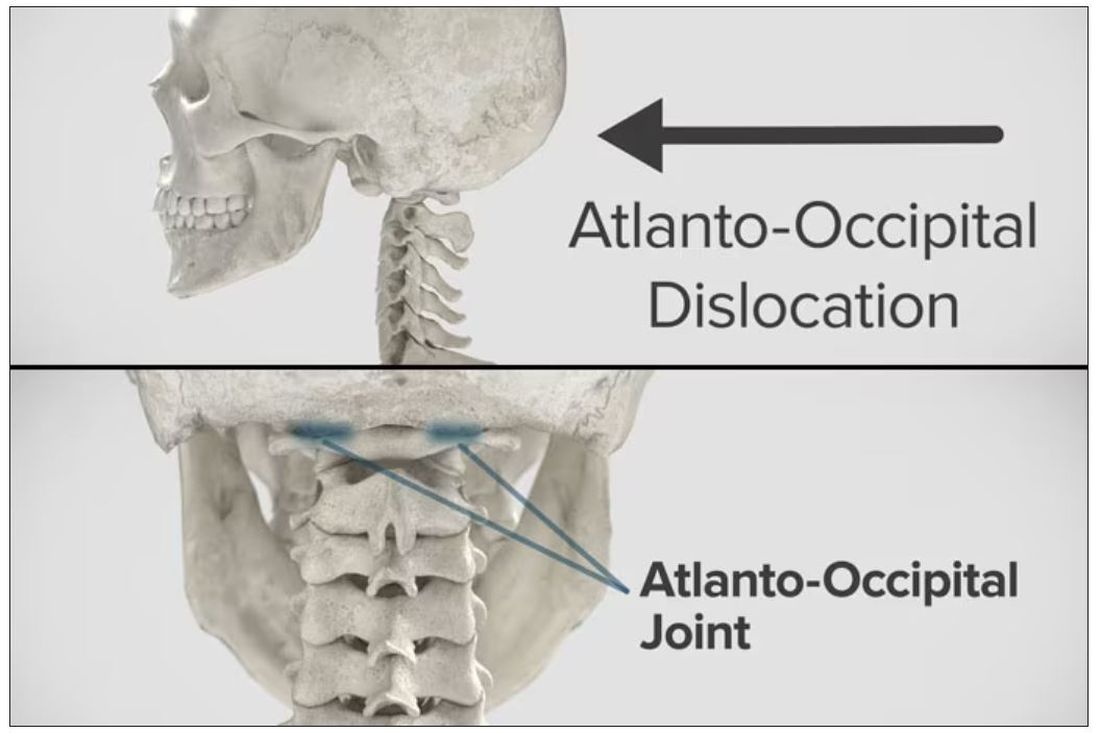

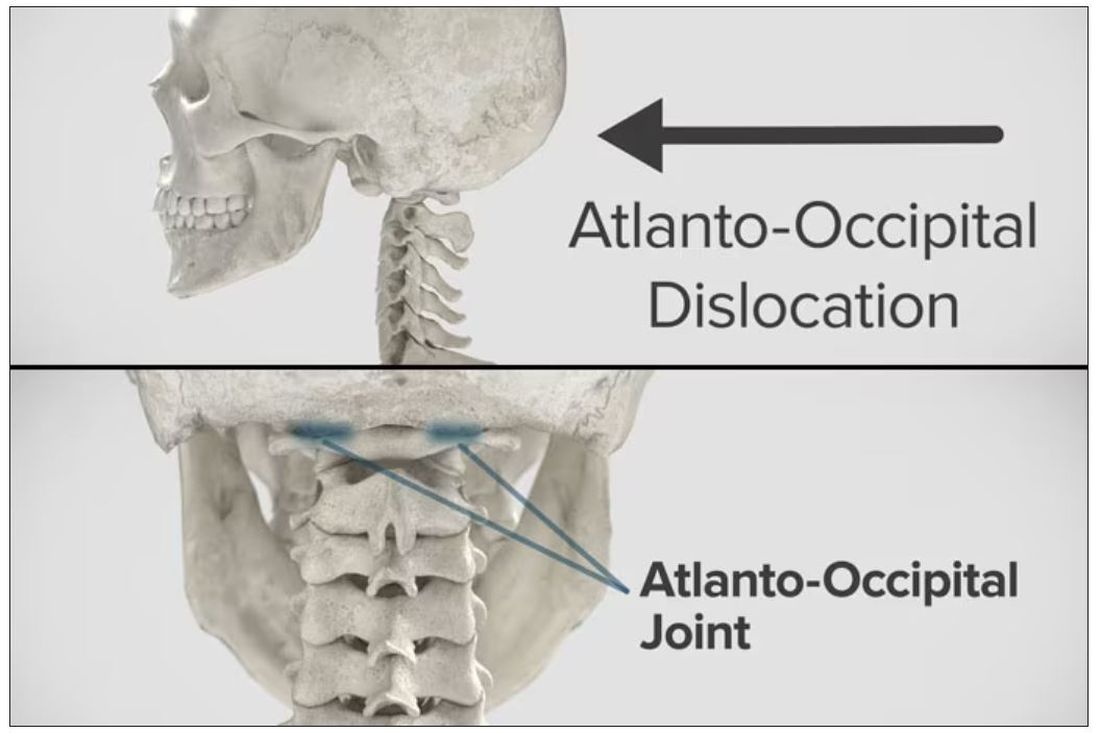

Dr. Wilson: “Injury to the cervical spine” might be something of an understatement. He had what’s called atlanto-occipital dislocation, colloquially often referred to as internal decapitation. Can you tell us what that means? It sounds terrifying.

Dr. Einav: It’s an injury to the ligaments between the occiput and the upper cervical spine, with or without bony fracture. The atlanto-occipital joint is formed by the superior articular facet of the atlas and the occipital condyle, stabilized by an articular capsule between the head and neck, and is supported by various ligaments around it that stabilize the joint and allow joint movements, including flexion, extension, and some rotation in the lower levels.

Dr. Wilson: This joint has several degrees of freedom, which means it needs a lot of support. With this type of injury, where essentially you have severing of the ligaments, is it usually survivable? How dangerous is this?

Dr. Einav: The mortality rate is 50%-60%, depending on the primary impact, the injury, transportation later on, and then the surgery and surgical management.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us a bit about this patient’s status when he came to your medical center. I assume he was in bad shape.

Dr. Einav: Hassan arrived at our medical center with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15. He was fully conscious. He was hemodynamically stable except for a bad laceration on his abdomen. He had a Philadelphia collar around his neck. He was transported by chopper because the paramedics suspected that he had a cervical spine injury and decided to bring him to a Level 1 trauma center.

He was monitored and we treated him according to the ATLS [advanced trauma life support] protocol. He didn’t have any gross sensory deficits, but he was a little confused about the whole situation and the accident. Therefore, we could do a general examination but we couldn’t rely on that regarding any sensory deficit that he may or may not have. We decided as a team that it would be better to slow down and control the situation. We decided not to operate on him immediately. We basically stabilized him and made sure that he didn’t have any traumatic internal organ damage. Later on we took him to the OR and performed surgery.

Dr. Wilson: It’s amazing that he had intact motor function, considering the extent of his injury. The spinal cord was spared somewhat during the injury. There must have been a moment when you realized that this kid, who was conscious and could move all four extremities, had a very severe neck injury. Was that due to a CT scan or physical exam? And what was your feeling when you saw that he had atlanto-occipital dislocation?

Dr. Einav: As a surgeon, you have a gut feeling in regard to the general examination of the patient. But I never rely on gut feelings. On the CT, I understood exactly what he had, what we needed to do, and the time frame.

Dr. Wilson: You’ve done these types of surgeries before, right? Obviously, no one has done a lot of them because this isn’t very common. But you knew what to do. Did you have a plan? Where does your experience come into play in a situation like this?

Dr. Einav: I graduated from the spine program of Toronto University, where I did a fellowship in trauma of the spine and complex spine surgery. I had very good teachers, and during my fellowship I treated a few cases in older patients that were similar but not the same. Therefore, I knew exactly what needed to be done.

Dr. Wilson: For those of us who aren’t surgeons, take us into the OR with you. This is obviously an incredibly delicate procedure. You are high up in the spinal cord at the base of the brain. The slightest mistake could have devastating consequences. What are the key elements of this procedure? What can go wrong here? What is the number-one thing you have to look out for when you’re trying to fix an internal decapitation?

Dr. Einav: The key element in surgeries of the cervical spine – trauma and complex spine surgery – is planning. I never go to the OR without knowing what I’m going to do. I have a few plans – plan A, plan B, plan C – in case something fails. So, I definitely know what the next step will be. I always think about the surgery a few hours before, if I have time to prepare.

The second thing that is very important is teamwork. The team needs to be coordinated. Everybody needs to know what their job is. With these types of injuries, it’s not the time for rookies. If you are new, please stand back and let the more experienced people do that job. I’m talking about surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists – everyone.

Another important thing in planning is choosing the right hardware. For example, in this case we had a problem because most of the hardware is designed for adults, and we had to improvise because there isn’t a lot of hardware on the market for the pediatric population. The adult plates and screws are too big, so we had to improvise.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us more about that. How do you improvise spinal hardware for a 12-year-old?

Dr. Einav: In this case, I chose to use hardware from one of the companies that works with us.

You can see in this model the area of the injury, and the area that we worked on. To perform the surgery, I had to use some plates and rods from a different company. This company’s (NuVasive) hardware has a small attachment to the skull, which was helpful for affixing the skull to the cervical spine, instead of using a big plate that would sit at the base of the skull and would not be very good for him. Most of the hardware is made for adults and not for kids.

Dr. Wilson: Will that hardware preserve the motor function of his neck? Will he be able to turn his head and extend and flex it?

Dr. Einav: The injury leads to instability and destruction of both articulations between the head and neck. Therefore, those articulations won’t be able to function the same way in the future. There is a decrease of something like 50% of the flexion and extension of Hassan’s cervical spine. Therefore, I decided that in this case there would be no chance of saving Hassan’s motor function unless we performed a fusion between the head and the neck, and therefore I decided that this would be the best procedure with the best survival rate. So, in the future, he will have some diminished flexion, extension, and rotation of his head.

Dr. Wilson: How long did his surgery take?

Dr. Einav: To be honest, I don’t remember. But I can tell you that it took us time. It was very challenging to coordinate with everyone. The most problematic part of the surgery to perform is what we call “flip-over.”

The anesthesiologist intubated the patient when he was supine, and later on, we flipped him prone to operate on the spine. This maneuver can actually lead to injury by itself, and injury at this level is fatal. So, we took our time and got Hassan into the OR. The anesthesiologist did a great job with the GlideScope – inserting the endotracheal tube. Later on, we neuromonitored him. Basically, we connected Hassan’s peripheral nerves to a computer and monitored his motor function. Gently we flipped him over, and after that we saw a little change in his motor function, so we had to modify his position so we could preserve his motor function. We then started the procedure, which took a few hours. I don’t know exactly how many.

Dr. Wilson: That just speaks to how delicate this is for everything from the intubation, where typically you’re manipulating the head, to the repositioning. Clearly this requires a lot of teamwork.

What happened after the operation? How is he doing?

Dr. Einav: After the operation, Hassan had a great recovery. He’s doing well. He doesn’t have any motor or sensory deficits. He’s able to ambulate without any aid. He had no signs of infection, which can happen after a car accident, neither from his abdominal wound nor from the occipital cervical surgery. He feels well. We saw him in the clinic. We removed his collar. We monitored him at the clinic. He looked amazing.

Dr. Wilson: That’s incredible. Are there long-term risks for him that you need to be looking out for?

Dr. Einav: Yes, and that’s the reason that we are monitoring him post surgery. While he was in the hospital, we monitored his motor and sensory functions, as well as his wound healing. Later on, in the clinic, for a few weeks after surgery we monitored for any failure of the hardware and bone graft. We check for healing of the bone graft and bone substitutes we put in to heal those bones.

Dr. Wilson: He will grow, right? He’s only 12, so he still has some years of growth in him. Is he going to need more surgery or any kind of hardware upgrade?

Dr. Einav: I hope not. In my surgeries, I never rely on the hardware for long durations. If I decide to do, for example, fusion, I rely on the hardware for a certain amount of time. And then I plan that the biology will do the work. If I plan for fusion, I put bone grafts in the preferred area for a fusion. Then if the hardware fails, I wouldn’t need to take out the hardware, and there would be no change in the condition of the patient.

Dr. Wilson: What an incredible story. It’s clear that you and your team kept your cool despite a very high-acuity situation with a ton of risk. What a tremendous outcome that this boy is not only alive but fully functional. So, congratulations to you and your team. That was very strong work.

Dr. Einav: Thank you very much. I would like to thank our team. We have to remember that the surgeon is not standing alone in the war. Hassan’s story is a success story of a very big group of people from various backgrounds and religions. They work day and night to help people and save lives. To the paramedics, the physiologists, the traumatologists, the pediatricians, the nurses, the physiotherapists, and obviously the surgeons, a big thank you. His story is our success story.

Dr. Wilson: It’s inspiring to see so many people come together to do what we all are here for, which is to fight against suffering, disease, and death. Thank you for keeping up that fight. And thank you for joining me here.

Dr. Einav: Thank you very much.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE: I am joined today by Dr. Ohad Einav. He’s a staff surgeon in orthopedics at Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem. He’s with me to talk about an absolutely incredible surgical case, something that is terrifying to most non–orthopedic surgeons and I imagine is fairly scary for spine surgeons like him as well. But what we don’t have is information about how this works from a medical perspective. So, first of all, Dr. Einav, thank you for taking time to speak with me today.

Ohad Einav, MD: Thank you for having me.

Dr. Wilson: Can you tell us about Suleiman Hassan and what happened to him before he came into your care?

Dr. Einav: Hassan is a 12-year-old child who was riding his bicycle on the West Bank, about 40 minutes from here. Unfortunately, he was involved in a motor vehicle accident and he suffered injuries to his abdomen and cervical spine. He was transported to our service by helicopter from the scene of the accident.

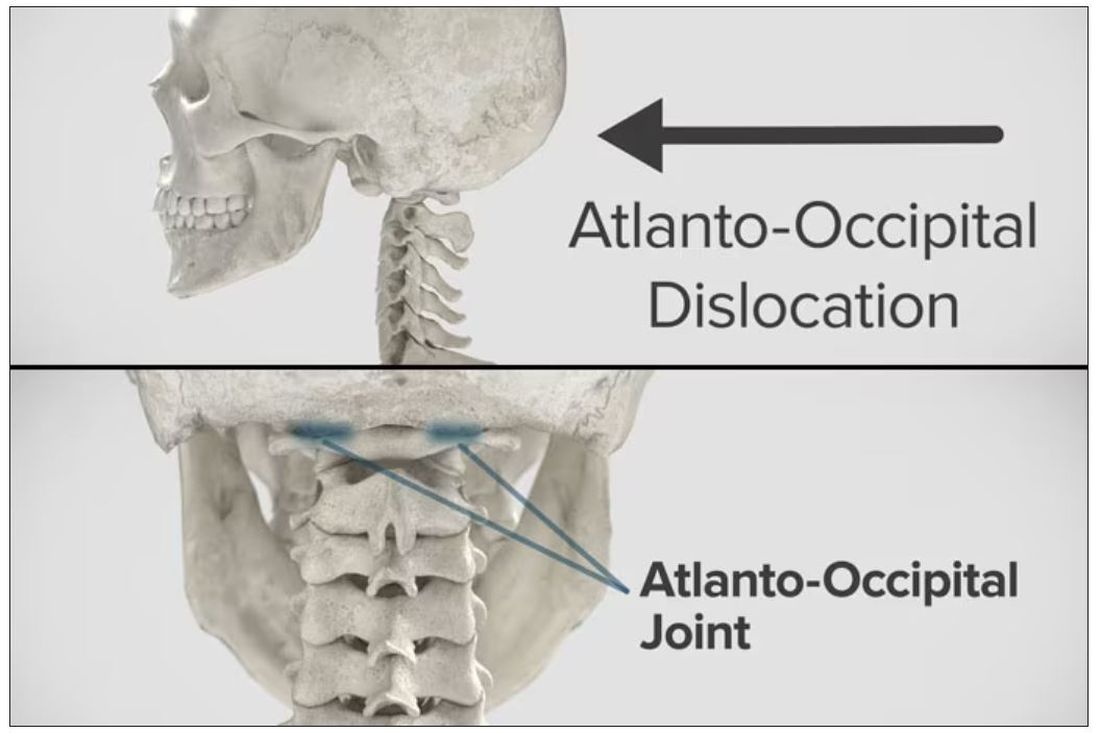

Dr. Wilson: “Injury to the cervical spine” might be something of an understatement. He had what’s called atlanto-occipital dislocation, colloquially often referred to as internal decapitation. Can you tell us what that means? It sounds terrifying.

Dr. Einav: It’s an injury to the ligaments between the occiput and the upper cervical spine, with or without bony fracture. The atlanto-occipital joint is formed by the superior articular facet of the atlas and the occipital condyle, stabilized by an articular capsule between the head and neck, and is supported by various ligaments around it that stabilize the joint and allow joint movements, including flexion, extension, and some rotation in the lower levels.

Dr. Wilson: This joint has several degrees of freedom, which means it needs a lot of support. With this type of injury, where essentially you have severing of the ligaments, is it usually survivable? How dangerous is this?

Dr. Einav: The mortality rate is 50%-60%, depending on the primary impact, the injury, transportation later on, and then the surgery and surgical management.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us a bit about this patient’s status when he came to your medical center. I assume he was in bad shape.

Dr. Einav: Hassan arrived at our medical center with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15. He was fully conscious. He was hemodynamically stable except for a bad laceration on his abdomen. He had a Philadelphia collar around his neck. He was transported by chopper because the paramedics suspected that he had a cervical spine injury and decided to bring him to a Level 1 trauma center.

He was monitored and we treated him according to the ATLS [advanced trauma life support] protocol. He didn’t have any gross sensory deficits, but he was a little confused about the whole situation and the accident. Therefore, we could do a general examination but we couldn’t rely on that regarding any sensory deficit that he may or may not have. We decided as a team that it would be better to slow down and control the situation. We decided not to operate on him immediately. We basically stabilized him and made sure that he didn’t have any traumatic internal organ damage. Later on we took him to the OR and performed surgery.

Dr. Wilson: It’s amazing that he had intact motor function, considering the extent of his injury. The spinal cord was spared somewhat during the injury. There must have been a moment when you realized that this kid, who was conscious and could move all four extremities, had a very severe neck injury. Was that due to a CT scan or physical exam? And what was your feeling when you saw that he had atlanto-occipital dislocation?

Dr. Einav: As a surgeon, you have a gut feeling in regard to the general examination of the patient. But I never rely on gut feelings. On the CT, I understood exactly what he had, what we needed to do, and the time frame.

Dr. Wilson: You’ve done these types of surgeries before, right? Obviously, no one has done a lot of them because this isn’t very common. But you knew what to do. Did you have a plan? Where does your experience come into play in a situation like this?

Dr. Einav: I graduated from the spine program of Toronto University, where I did a fellowship in trauma of the spine and complex spine surgery. I had very good teachers, and during my fellowship I treated a few cases in older patients that were similar but not the same. Therefore, I knew exactly what needed to be done.

Dr. Wilson: For those of us who aren’t surgeons, take us into the OR with you. This is obviously an incredibly delicate procedure. You are high up in the spinal cord at the base of the brain. The slightest mistake could have devastating consequences. What are the key elements of this procedure? What can go wrong here? What is the number-one thing you have to look out for when you’re trying to fix an internal decapitation?

Dr. Einav: The key element in surgeries of the cervical spine – trauma and complex spine surgery – is planning. I never go to the OR without knowing what I’m going to do. I have a few plans – plan A, plan B, plan C – in case something fails. So, I definitely know what the next step will be. I always think about the surgery a few hours before, if I have time to prepare.

The second thing that is very important is teamwork. The team needs to be coordinated. Everybody needs to know what their job is. With these types of injuries, it’s not the time for rookies. If you are new, please stand back and let the more experienced people do that job. I’m talking about surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists – everyone.

Another important thing in planning is choosing the right hardware. For example, in this case we had a problem because most of the hardware is designed for adults, and we had to improvise because there isn’t a lot of hardware on the market for the pediatric population. The adult plates and screws are too big, so we had to improvise.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us more about that. How do you improvise spinal hardware for a 12-year-old?

Dr. Einav: In this case, I chose to use hardware from one of the companies that works with us.

You can see in this model the area of the injury, and the area that we worked on. To perform the surgery, I had to use some plates and rods from a different company. This company’s (NuVasive) hardware has a small attachment to the skull, which was helpful for affixing the skull to the cervical spine, instead of using a big plate that would sit at the base of the skull and would not be very good for him. Most of the hardware is made for adults and not for kids.

Dr. Wilson: Will that hardware preserve the motor function of his neck? Will he be able to turn his head and extend and flex it?

Dr. Einav: The injury leads to instability and destruction of both articulations between the head and neck. Therefore, those articulations won’t be able to function the same way in the future. There is a decrease of something like 50% of the flexion and extension of Hassan’s cervical spine. Therefore, I decided that in this case there would be no chance of saving Hassan’s motor function unless we performed a fusion between the head and the neck, and therefore I decided that this would be the best procedure with the best survival rate. So, in the future, he will have some diminished flexion, extension, and rotation of his head.

Dr. Wilson: How long did his surgery take?

Dr. Einav: To be honest, I don’t remember. But I can tell you that it took us time. It was very challenging to coordinate with everyone. The most problematic part of the surgery to perform is what we call “flip-over.”

The anesthesiologist intubated the patient when he was supine, and later on, we flipped him prone to operate on the spine. This maneuver can actually lead to injury by itself, and injury at this level is fatal. So, we took our time and got Hassan into the OR. The anesthesiologist did a great job with the GlideScope – inserting the endotracheal tube. Later on, we neuromonitored him. Basically, we connected Hassan’s peripheral nerves to a computer and monitored his motor function. Gently we flipped him over, and after that we saw a little change in his motor function, so we had to modify his position so we could preserve his motor function. We then started the procedure, which took a few hours. I don’t know exactly how many.

Dr. Wilson: That just speaks to how delicate this is for everything from the intubation, where typically you’re manipulating the head, to the repositioning. Clearly this requires a lot of teamwork.

What happened after the operation? How is he doing?

Dr. Einav: After the operation, Hassan had a great recovery. He’s doing well. He doesn’t have any motor or sensory deficits. He’s able to ambulate without any aid. He had no signs of infection, which can happen after a car accident, neither from his abdominal wound nor from the occipital cervical surgery. He feels well. We saw him in the clinic. We removed his collar. We monitored him at the clinic. He looked amazing.

Dr. Wilson: That’s incredible. Are there long-term risks for him that you need to be looking out for?

Dr. Einav: Yes, and that’s the reason that we are monitoring him post surgery. While he was in the hospital, we monitored his motor and sensory functions, as well as his wound healing. Later on, in the clinic, for a few weeks after surgery we monitored for any failure of the hardware and bone graft. We check for healing of the bone graft and bone substitutes we put in to heal those bones.

Dr. Wilson: He will grow, right? He’s only 12, so he still has some years of growth in him. Is he going to need more surgery or any kind of hardware upgrade?

Dr. Einav: I hope not. In my surgeries, I never rely on the hardware for long durations. If I decide to do, for example, fusion, I rely on the hardware for a certain amount of time. And then I plan that the biology will do the work. If I plan for fusion, I put bone grafts in the preferred area for a fusion. Then if the hardware fails, I wouldn’t need to take out the hardware, and there would be no change in the condition of the patient.

Dr. Wilson: What an incredible story. It’s clear that you and your team kept your cool despite a very high-acuity situation with a ton of risk. What a tremendous outcome that this boy is not only alive but fully functional. So, congratulations to you and your team. That was very strong work.

Dr. Einav: Thank you very much. I would like to thank our team. We have to remember that the surgeon is not standing alone in the war. Hassan’s story is a success story of a very big group of people from various backgrounds and religions. They work day and night to help people and save lives. To the paramedics, the physiologists, the traumatologists, the pediatricians, the nurses, the physiotherapists, and obviously the surgeons, a big thank you. His story is our success story.

Dr. Wilson: It’s inspiring to see so many people come together to do what we all are here for, which is to fight against suffering, disease, and death. Thank you for keeping up that fight. And thank you for joining me here.

Dr. Einav: Thank you very much.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE: I am joined today by Dr. Ohad Einav. He’s a staff surgeon in orthopedics at Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem. He’s with me to talk about an absolutely incredible surgical case, something that is terrifying to most non–orthopedic surgeons and I imagine is fairly scary for spine surgeons like him as well. But what we don’t have is information about how this works from a medical perspective. So, first of all, Dr. Einav, thank you for taking time to speak with me today.

Ohad Einav, MD: Thank you for having me.

Dr. Wilson: Can you tell us about Suleiman Hassan and what happened to him before he came into your care?

Dr. Einav: Hassan is a 12-year-old child who was riding his bicycle on the West Bank, about 40 minutes from here. Unfortunately, he was involved in a motor vehicle accident and he suffered injuries to his abdomen and cervical spine. He was transported to our service by helicopter from the scene of the accident.

Dr. Wilson: “Injury to the cervical spine” might be something of an understatement. He had what’s called atlanto-occipital dislocation, colloquially often referred to as internal decapitation. Can you tell us what that means? It sounds terrifying.

Dr. Einav: It’s an injury to the ligaments between the occiput and the upper cervical spine, with or without bony fracture. The atlanto-occipital joint is formed by the superior articular facet of the atlas and the occipital condyle, stabilized by an articular capsule between the head and neck, and is supported by various ligaments around it that stabilize the joint and allow joint movements, including flexion, extension, and some rotation in the lower levels.

Dr. Wilson: This joint has several degrees of freedom, which means it needs a lot of support. With this type of injury, where essentially you have severing of the ligaments, is it usually survivable? How dangerous is this?

Dr. Einav: The mortality rate is 50%-60%, depending on the primary impact, the injury, transportation later on, and then the surgery and surgical management.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us a bit about this patient’s status when he came to your medical center. I assume he was in bad shape.

Dr. Einav: Hassan arrived at our medical center with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15. He was fully conscious. He was hemodynamically stable except for a bad laceration on his abdomen. He had a Philadelphia collar around his neck. He was transported by chopper because the paramedics suspected that he had a cervical spine injury and decided to bring him to a Level 1 trauma center.

He was monitored and we treated him according to the ATLS [advanced trauma life support] protocol. He didn’t have any gross sensory deficits, but he was a little confused about the whole situation and the accident. Therefore, we could do a general examination but we couldn’t rely on that regarding any sensory deficit that he may or may not have. We decided as a team that it would be better to slow down and control the situation. We decided not to operate on him immediately. We basically stabilized him and made sure that he didn’t have any traumatic internal organ damage. Later on we took him to the OR and performed surgery.

Dr. Wilson: It’s amazing that he had intact motor function, considering the extent of his injury. The spinal cord was spared somewhat during the injury. There must have been a moment when you realized that this kid, who was conscious and could move all four extremities, had a very severe neck injury. Was that due to a CT scan or physical exam? And what was your feeling when you saw that he had atlanto-occipital dislocation?

Dr. Einav: As a surgeon, you have a gut feeling in regard to the general examination of the patient. But I never rely on gut feelings. On the CT, I understood exactly what he had, what we needed to do, and the time frame.

Dr. Wilson: You’ve done these types of surgeries before, right? Obviously, no one has done a lot of them because this isn’t very common. But you knew what to do. Did you have a plan? Where does your experience come into play in a situation like this?

Dr. Einav: I graduated from the spine program of Toronto University, where I did a fellowship in trauma of the spine and complex spine surgery. I had very good teachers, and during my fellowship I treated a few cases in older patients that were similar but not the same. Therefore, I knew exactly what needed to be done.

Dr. Wilson: For those of us who aren’t surgeons, take us into the OR with you. This is obviously an incredibly delicate procedure. You are high up in the spinal cord at the base of the brain. The slightest mistake could have devastating consequences. What are the key elements of this procedure? What can go wrong here? What is the number-one thing you have to look out for when you’re trying to fix an internal decapitation?

Dr. Einav: The key element in surgeries of the cervical spine – trauma and complex spine surgery – is planning. I never go to the OR without knowing what I’m going to do. I have a few plans – plan A, plan B, plan C – in case something fails. So, I definitely know what the next step will be. I always think about the surgery a few hours before, if I have time to prepare.

The second thing that is very important is teamwork. The team needs to be coordinated. Everybody needs to know what their job is. With these types of injuries, it’s not the time for rookies. If you are new, please stand back and let the more experienced people do that job. I’m talking about surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists – everyone.

Another important thing in planning is choosing the right hardware. For example, in this case we had a problem because most of the hardware is designed for adults, and we had to improvise because there isn’t a lot of hardware on the market for the pediatric population. The adult plates and screws are too big, so we had to improvise.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us more about that. How do you improvise spinal hardware for a 12-year-old?

Dr. Einav: In this case, I chose to use hardware from one of the companies that works with us.

You can see in this model the area of the injury, and the area that we worked on. To perform the surgery, I had to use some plates and rods from a different company. This company’s (NuVasive) hardware has a small attachment to the skull, which was helpful for affixing the skull to the cervical spine, instead of using a big plate that would sit at the base of the skull and would not be very good for him. Most of the hardware is made for adults and not for kids.

Dr. Wilson: Will that hardware preserve the motor function of his neck? Will he be able to turn his head and extend and flex it?

Dr. Einav: The injury leads to instability and destruction of both articulations between the head and neck. Therefore, those articulations won’t be able to function the same way in the future. There is a decrease of something like 50% of the flexion and extension of Hassan’s cervical spine. Therefore, I decided that in this case there would be no chance of saving Hassan’s motor function unless we performed a fusion between the head and the neck, and therefore I decided that this would be the best procedure with the best survival rate. So, in the future, he will have some diminished flexion, extension, and rotation of his head.

Dr. Wilson: How long did his surgery take?

Dr. Einav: To be honest, I don’t remember. But I can tell you that it took us time. It was very challenging to coordinate with everyone. The most problematic part of the surgery to perform is what we call “flip-over.”

The anesthesiologist intubated the patient when he was supine, and later on, we flipped him prone to operate on the spine. This maneuver can actually lead to injury by itself, and injury at this level is fatal. So, we took our time and got Hassan into the OR. The anesthesiologist did a great job with the GlideScope – inserting the endotracheal tube. Later on, we neuromonitored him. Basically, we connected Hassan’s peripheral nerves to a computer and monitored his motor function. Gently we flipped him over, and after that we saw a little change in his motor function, so we had to modify his position so we could preserve his motor function. We then started the procedure, which took a few hours. I don’t know exactly how many.

Dr. Wilson: That just speaks to how delicate this is for everything from the intubation, where typically you’re manipulating the head, to the repositioning. Clearly this requires a lot of teamwork.

What happened after the operation? How is he doing?

Dr. Einav: After the operation, Hassan had a great recovery. He’s doing well. He doesn’t have any motor or sensory deficits. He’s able to ambulate without any aid. He had no signs of infection, which can happen after a car accident, neither from his abdominal wound nor from the occipital cervical surgery. He feels well. We saw him in the clinic. We removed his collar. We monitored him at the clinic. He looked amazing.

Dr. Wilson: That’s incredible. Are there long-term risks for him that you need to be looking out for?

Dr. Einav: Yes, and that’s the reason that we are monitoring him post surgery. While he was in the hospital, we monitored his motor and sensory functions, as well as his wound healing. Later on, in the clinic, for a few weeks after surgery we monitored for any failure of the hardware and bone graft. We check for healing of the bone graft and bone substitutes we put in to heal those bones.

Dr. Wilson: He will grow, right? He’s only 12, so he still has some years of growth in him. Is he going to need more surgery or any kind of hardware upgrade?

Dr. Einav: I hope not. In my surgeries, I never rely on the hardware for long durations. If I decide to do, for example, fusion, I rely on the hardware for a certain amount of time. And then I plan that the biology will do the work. If I plan for fusion, I put bone grafts in the preferred area for a fusion. Then if the hardware fails, I wouldn’t need to take out the hardware, and there would be no change in the condition of the patient.

Dr. Wilson: What an incredible story. It’s clear that you and your team kept your cool despite a very high-acuity situation with a ton of risk. What a tremendous outcome that this boy is not only alive but fully functional. So, congratulations to you and your team. That was very strong work.

Dr. Einav: Thank you very much. I would like to thank our team. We have to remember that the surgeon is not standing alone in the war. Hassan’s story is a success story of a very big group of people from various backgrounds and religions. They work day and night to help people and save lives. To the paramedics, the physiologists, the traumatologists, the pediatricians, the nurses, the physiotherapists, and obviously the surgeons, a big thank you. His story is our success story.

Dr. Wilson: It’s inspiring to see so many people come together to do what we all are here for, which is to fight against suffering, disease, and death. Thank you for keeping up that fight. And thank you for joining me here.

Dr. Einav: Thank you very much.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Targeted warnings

I was probably about 9 or 10 and I am assuming it was early winter when my mother took me aside and said in her usual quiet tone, “Willy, don’t ever stick your tongue on a metal pipe when it is cold outside.”

Putting my tongue on a frozen pipe was something that had never occurred to me even in my wildest preadolescent dreams. My mother’s caution only served to pique my interest and provide me with one more tempting scenario to consider.

Recently, a prank has gone viral on TikTok that shows an adult, usually the parent, cracking (not smashing) an egg on the child’s head and then emptying the egg contents into a bowl. Unlike the tongue-pipe disaster, it is hard to imagine how this stunt can be dangerous as long as the child is old enough to be walking around. But, at least one pediatrician has warned that there is a risk to the child from contracting salmonella.

There may be a few young children who are frightened by having an egg cracked on their head, but I can’t imagine that it would leave any lasting emotional scars. Given the minuscule theoretical risk of infection and the fact that the videos have accumulated more than 670 million views, this is another example of when we “experts” should keep a low profile and let the virus fade into Internet oblivion.

There is, however, a difference between harmless foolishness and stupidity, and one wonders when and in what manner we pediatricians should become involved. For example, in a recent study published in the journal Pediatrics, the investigators searched through a national emergency department database and found that

There were two peaks of distribution, one at less than 1 year of age and another at age 4. The older children were more often injured playing on furniture, most often bunk beds. The younger children were more likely to have been injured by being lifted or tossed in the air. No deaths were reported.

Is this a phenomenon that demands a response by pediatricians? Do we have time to ask every family if they have a ceiling fan? Should we be handing out brochures to every family? To whom should we target our message? This is a situation that seems to sort easily into two categories. One that involves stupidity and a second that is ignorance that may respond to education.

Tossing young children in the air is fun for the tosser and the child. I am sure there are a few children every year who slip out of the grasp of an adult and are injured. I have never seen a child brought in with this history. But it must happen. The result is likely to trigger a very tricky child protective investigation. But tossing a child underneath a ceiling fan is just plain stupid. I’m not sure our intervention is going to prevent it from happening. Bunk beds and ceiling fans are a different story. Posters in our offices and warnings and labels at the point of purchase of both fans and bunk beds makes some sense.

And while we are sticking labels on furniture, we should take a hard look at couches. Researchers have recently found that the accumulation of sedentary time in childhood can lead to early evidence of heart damage, which may portend heart disease in adulthood. Instead of those tags under the cushions, we need a big blaze orange sticker in prominent view that warns of the danger of becoming a couch potato.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

I was probably about 9 or 10 and I am assuming it was early winter when my mother took me aside and said in her usual quiet tone, “Willy, don’t ever stick your tongue on a metal pipe when it is cold outside.”

Putting my tongue on a frozen pipe was something that had never occurred to me even in my wildest preadolescent dreams. My mother’s caution only served to pique my interest and provide me with one more tempting scenario to consider.

Recently, a prank has gone viral on TikTok that shows an adult, usually the parent, cracking (not smashing) an egg on the child’s head and then emptying the egg contents into a bowl. Unlike the tongue-pipe disaster, it is hard to imagine how this stunt can be dangerous as long as the child is old enough to be walking around. But, at least one pediatrician has warned that there is a risk to the child from contracting salmonella.

There may be a few young children who are frightened by having an egg cracked on their head, but I can’t imagine that it would leave any lasting emotional scars. Given the minuscule theoretical risk of infection and the fact that the videos have accumulated more than 670 million views, this is another example of when we “experts” should keep a low profile and let the virus fade into Internet oblivion.

There is, however, a difference between harmless foolishness and stupidity, and one wonders when and in what manner we pediatricians should become involved. For example, in a recent study published in the journal Pediatrics, the investigators searched through a national emergency department database and found that

There were two peaks of distribution, one at less than 1 year of age and another at age 4. The older children were more often injured playing on furniture, most often bunk beds. The younger children were more likely to have been injured by being lifted or tossed in the air. No deaths were reported.

Is this a phenomenon that demands a response by pediatricians? Do we have time to ask every family if they have a ceiling fan? Should we be handing out brochures to every family? To whom should we target our message? This is a situation that seems to sort easily into two categories. One that involves stupidity and a second that is ignorance that may respond to education.

Tossing young children in the air is fun for the tosser and the child. I am sure there are a few children every year who slip out of the grasp of an adult and are injured. I have never seen a child brought in with this history. But it must happen. The result is likely to trigger a very tricky child protective investigation. But tossing a child underneath a ceiling fan is just plain stupid. I’m not sure our intervention is going to prevent it from happening. Bunk beds and ceiling fans are a different story. Posters in our offices and warnings and labels at the point of purchase of both fans and bunk beds makes some sense.

And while we are sticking labels on furniture, we should take a hard look at couches. Researchers have recently found that the accumulation of sedentary time in childhood can lead to early evidence of heart damage, which may portend heart disease in adulthood. Instead of those tags under the cushions, we need a big blaze orange sticker in prominent view that warns of the danger of becoming a couch potato.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

I was probably about 9 or 10 and I am assuming it was early winter when my mother took me aside and said in her usual quiet tone, “Willy, don’t ever stick your tongue on a metal pipe when it is cold outside.”

Putting my tongue on a frozen pipe was something that had never occurred to me even in my wildest preadolescent dreams. My mother’s caution only served to pique my interest and provide me with one more tempting scenario to consider.

Recently, a prank has gone viral on TikTok that shows an adult, usually the parent, cracking (not smashing) an egg on the child’s head and then emptying the egg contents into a bowl. Unlike the tongue-pipe disaster, it is hard to imagine how this stunt can be dangerous as long as the child is old enough to be walking around. But, at least one pediatrician has warned that there is a risk to the child from contracting salmonella.

There may be a few young children who are frightened by having an egg cracked on their head, but I can’t imagine that it would leave any lasting emotional scars. Given the minuscule theoretical risk of infection and the fact that the videos have accumulated more than 670 million views, this is another example of when we “experts” should keep a low profile and let the virus fade into Internet oblivion.

There is, however, a difference between harmless foolishness and stupidity, and one wonders when and in what manner we pediatricians should become involved. For example, in a recent study published in the journal Pediatrics, the investigators searched through a national emergency department database and found that

There were two peaks of distribution, one at less than 1 year of age and another at age 4. The older children were more often injured playing on furniture, most often bunk beds. The younger children were more likely to have been injured by being lifted or tossed in the air. No deaths were reported.

Is this a phenomenon that demands a response by pediatricians? Do we have time to ask every family if they have a ceiling fan? Should we be handing out brochures to every family? To whom should we target our message? This is a situation that seems to sort easily into two categories. One that involves stupidity and a second that is ignorance that may respond to education.

Tossing young children in the air is fun for the tosser and the child. I am sure there are a few children every year who slip out of the grasp of an adult and are injured. I have never seen a child brought in with this history. But it must happen. The result is likely to trigger a very tricky child protective investigation. But tossing a child underneath a ceiling fan is just plain stupid. I’m not sure our intervention is going to prevent it from happening. Bunk beds and ceiling fans are a different story. Posters in our offices and warnings and labels at the point of purchase of both fans and bunk beds makes some sense.

And while we are sticking labels on furniture, we should take a hard look at couches. Researchers have recently found that the accumulation of sedentary time in childhood can lead to early evidence of heart damage, which may portend heart disease in adulthood. Instead of those tags under the cushions, we need a big blaze orange sticker in prominent view that warns of the danger of becoming a couch potato.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Five ways to avert a malpractice lawsuit with better EHR techniques

Although most physicians have gotten used to working with EHRs, despite their irritations, the use of EHRs has contributed to a growing number of malpractice lawsuits. Defense attorneys say that

According to a study in the Journal of Patient Safety, more than 30% of all EHR-related malpractice cases are associated with medication errors; 28% with diagnosis; and 31% with a complication of treatment, such as entering wrong information, entering information in the wrong place, and overlooking EHR flags and warnings for interactions or contraindications.

The study gave these examples of EHR-related errors that led to patient harm and ultimately to malpractice lawsuits:

- A discharge order omitted a patient’s medication that prevented strokes; the patient had a stroke days later.

- An electronic order for morphine failed to state the upper dose limit; the patient died.

- A physician meant to click on “discontinue” for an anticoagulant but mistakenly clicked on “continue” for home use.

Catching potential issues such as drug interactions or critical medical history that should inform treatment is more important than ever. “We know from safety engineering principles that just relying on vigilance is not a long-term safety strategy,” says Aaron Zach Hettinger, MD, chief research information officer at MedStar Health Research Institute, Washington, D.C. “So, it’s critical that we design these safe systems and leverage the data that’s in them.”

Here are five smart EHR practices to help protect your patients’ health and your own liability.

1. Double-check dropdown boxes

When it comes to user error, it’s easy to click the wrong choice from a drop-down menu. Better to take the time to explain your answer in a box, even if it takes a few more minutes. Or if you are choosing from a menu, proofread any information it auto-fills in the chart.

Dr. Hettinger says you can strike a balance between these templated approaches to diagnosis and long-term care by working with third-party systems and your organization or vendor IT department to help with follow-up questions to keep populated data in check.

“Make sure you have a back-end system that can help monitor that structured data,” says Dr. Hettinger. Structured data are the patient’s demographic information, like name, address, age, height, weight, vital signs, and data elements like diagnosis, medications, and lab results. “Wherever you can leverage the underlying tools that are part of the electronic health record to make sure that we’re constantly checking the right results, that helps reduce the workload so that clinicians can focus on taking care of the patients and doing the right thing and not be as focused on entering data into the system.”

2. Supplement EHR notes with direct communication

The failure to diagnose cancer because one physician doesn’t know what another physician saw in an imaging report is one of the most common claims in the cases he tries, says Aaron Boeder, a plaintiff’s medical negligence lawyer in Chicago.

Physicians often assume that if they put a note in the electronic chart, others will look for it, but Mr. Boeder says it’s far more prudent to communicate directly.

“Let’s say a radiologist interprets a scan and sees what might be cancer,” he says. “If the ordering doctor is an orthopedist who’s ordered a CT scan for DVT, there’s going to be a report for that scan. It’s going to get auto-populated back into that physician’s note,” says Mr. Boeder.

The physician may or may not look at it, but it will be in their note, and they’re supposed to follow up on it because they ordered the scan. “But they may not follow up on it, and they may not get a call from the radiologist,” he says.

“Next thing you know, 2 or 3 years later, that patient is diagnosed with very advanced cancer.”

3. Tailor auto-fill information to your common practices

Suppose, as a physician, you find that you need to change a default setting time and time again. Dr. Hettinger says it’s worth your time to take an extra couple of minutes to work with your vendor or your health system to try and make changes to auto-population settings that align with your practices.

“Let’s say a default dose of 20 milligrams of a medication is what automatically pops up, but in reality, your practice is to use a smaller dose because it’s safer, even though they’re all within the acceptable realm of what you would order,” he says. “Rather than have the default to the higher dose, see if you can change the default to a lower dose. And that way, you don’t have to catch yourself every time.”

If your auto-fills are amounts that constantly need changing, an interruption could easily knock you off course before you make that correction.

“If there are ways to have the system defaults be safer or more in line with your clinical practice, and especially across a group, then you’re designing a safer system and not relying on vigilance or memory prone to interruptions,” says Dr. Hettinger.

4. Curb the copy and paste

It’s tempting to copy a note from a previous patient visit and make only minimal changes as needed, but you risk including outdated information if you do. Even if you’re repeating questions asked by the intake nurse, it is safer to not to rely on that information, says Beth Kanik, a defense medical malpractice attorney in Atlanta.

“If it later goes into litigation, the argument then becomes that it looks like you didn’t do your job,” says Ms. Kanik. “Instead, try to ask questions in a way that would elicit responses that may be a little different than what the nurse got, so that it’s clear you asked the questions and didn’t just simply rely upon someone else’s information.”

5. Separate typing from listening

While EHR may be an excellent tool for data collection and safety checking, it’s not a stand-in for doctor-patient interaction. As technology practices push medicine toward more and more efficiency, Mr. Boeder says it’s most often listening over all else that makes the difference in the quality of care. And good listening requires full attention.

“A real concern for physicians is the number of visits they’re expected to accomplish in a set amount of time,” says Mr. Boeder. “Often this translates into a doctor talking to a patient while typing notes or while reading a note from the last time the patient was in.”

Taking the time to pause after entering data and briefly reviewing your understanding of what your patient has told you can be invaluable and may save you – and your patient – problems later.

“In so many cases, it comes down to people not being heard,” says Mr. Boeder. “So listen to what your patients are saying.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although most physicians have gotten used to working with EHRs, despite their irritations, the use of EHRs has contributed to a growing number of malpractice lawsuits. Defense attorneys say that

According to a study in the Journal of Patient Safety, more than 30% of all EHR-related malpractice cases are associated with medication errors; 28% with diagnosis; and 31% with a complication of treatment, such as entering wrong information, entering information in the wrong place, and overlooking EHR flags and warnings for interactions or contraindications.

The study gave these examples of EHR-related errors that led to patient harm and ultimately to malpractice lawsuits:

- A discharge order omitted a patient’s medication that prevented strokes; the patient had a stroke days later.

- An electronic order for morphine failed to state the upper dose limit; the patient died.

- A physician meant to click on “discontinue” for an anticoagulant but mistakenly clicked on “continue” for home use.

Catching potential issues such as drug interactions or critical medical history that should inform treatment is more important than ever. “We know from safety engineering principles that just relying on vigilance is not a long-term safety strategy,” says Aaron Zach Hettinger, MD, chief research information officer at MedStar Health Research Institute, Washington, D.C. “So, it’s critical that we design these safe systems and leverage the data that’s in them.”

Here are five smart EHR practices to help protect your patients’ health and your own liability.

1. Double-check dropdown boxes

When it comes to user error, it’s easy to click the wrong choice from a drop-down menu. Better to take the time to explain your answer in a box, even if it takes a few more minutes. Or if you are choosing from a menu, proofread any information it auto-fills in the chart.

Dr. Hettinger says you can strike a balance between these templated approaches to diagnosis and long-term care by working with third-party systems and your organization or vendor IT department to help with follow-up questions to keep populated data in check.

“Make sure you have a back-end system that can help monitor that structured data,” says Dr. Hettinger. Structured data are the patient’s demographic information, like name, address, age, height, weight, vital signs, and data elements like diagnosis, medications, and lab results. “Wherever you can leverage the underlying tools that are part of the electronic health record to make sure that we’re constantly checking the right results, that helps reduce the workload so that clinicians can focus on taking care of the patients and doing the right thing and not be as focused on entering data into the system.”

2. Supplement EHR notes with direct communication

The failure to diagnose cancer because one physician doesn’t know what another physician saw in an imaging report is one of the most common claims in the cases he tries, says Aaron Boeder, a plaintiff’s medical negligence lawyer in Chicago.

Physicians often assume that if they put a note in the electronic chart, others will look for it, but Mr. Boeder says it’s far more prudent to communicate directly.

“Let’s say a radiologist interprets a scan and sees what might be cancer,” he says. “If the ordering doctor is an orthopedist who’s ordered a CT scan for DVT, there’s going to be a report for that scan. It’s going to get auto-populated back into that physician’s note,” says Mr. Boeder.

The physician may or may not look at it, but it will be in their note, and they’re supposed to follow up on it because they ordered the scan. “But they may not follow up on it, and they may not get a call from the radiologist,” he says.

“Next thing you know, 2 or 3 years later, that patient is diagnosed with very advanced cancer.”

3. Tailor auto-fill information to your common practices

Suppose, as a physician, you find that you need to change a default setting time and time again. Dr. Hettinger says it’s worth your time to take an extra couple of minutes to work with your vendor or your health system to try and make changes to auto-population settings that align with your practices.

“Let’s say a default dose of 20 milligrams of a medication is what automatically pops up, but in reality, your practice is to use a smaller dose because it’s safer, even though they’re all within the acceptable realm of what you would order,” he says. “Rather than have the default to the higher dose, see if you can change the default to a lower dose. And that way, you don’t have to catch yourself every time.”

If your auto-fills are amounts that constantly need changing, an interruption could easily knock you off course before you make that correction.

“If there are ways to have the system defaults be safer or more in line with your clinical practice, and especially across a group, then you’re designing a safer system and not relying on vigilance or memory prone to interruptions,” says Dr. Hettinger.

4. Curb the copy and paste

It’s tempting to copy a note from a previous patient visit and make only minimal changes as needed, but you risk including outdated information if you do. Even if you’re repeating questions asked by the intake nurse, it is safer to not to rely on that information, says Beth Kanik, a defense medical malpractice attorney in Atlanta.

“If it later goes into litigation, the argument then becomes that it looks like you didn’t do your job,” says Ms. Kanik. “Instead, try to ask questions in a way that would elicit responses that may be a little different than what the nurse got, so that it’s clear you asked the questions and didn’t just simply rely upon someone else’s information.”

5. Separate typing from listening

While EHR may be an excellent tool for data collection and safety checking, it’s not a stand-in for doctor-patient interaction. As technology practices push medicine toward more and more efficiency, Mr. Boeder says it’s most often listening over all else that makes the difference in the quality of care. And good listening requires full attention.

“A real concern for physicians is the number of visits they’re expected to accomplish in a set amount of time,” says Mr. Boeder. “Often this translates into a doctor talking to a patient while typing notes or while reading a note from the last time the patient was in.”

Taking the time to pause after entering data and briefly reviewing your understanding of what your patient has told you can be invaluable and may save you – and your patient – problems later.

“In so many cases, it comes down to people not being heard,” says Mr. Boeder. “So listen to what your patients are saying.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although most physicians have gotten used to working with EHRs, despite their irritations, the use of EHRs has contributed to a growing number of malpractice lawsuits. Defense attorneys say that

According to a study in the Journal of Patient Safety, more than 30% of all EHR-related malpractice cases are associated with medication errors; 28% with diagnosis; and 31% with a complication of treatment, such as entering wrong information, entering information in the wrong place, and overlooking EHR flags and warnings for interactions or contraindications.

The study gave these examples of EHR-related errors that led to patient harm and ultimately to malpractice lawsuits:

- A discharge order omitted a patient’s medication that prevented strokes; the patient had a stroke days later.

- An electronic order for morphine failed to state the upper dose limit; the patient died.

- A physician meant to click on “discontinue” for an anticoagulant but mistakenly clicked on “continue” for home use.

Catching potential issues such as drug interactions or critical medical history that should inform treatment is more important than ever. “We know from safety engineering principles that just relying on vigilance is not a long-term safety strategy,” says Aaron Zach Hettinger, MD, chief research information officer at MedStar Health Research Institute, Washington, D.C. “So, it’s critical that we design these safe systems and leverage the data that’s in them.”

Here are five smart EHR practices to help protect your patients’ health and your own liability.

1. Double-check dropdown boxes

When it comes to user error, it’s easy to click the wrong choice from a drop-down menu. Better to take the time to explain your answer in a box, even if it takes a few more minutes. Or if you are choosing from a menu, proofread any information it auto-fills in the chart.

Dr. Hettinger says you can strike a balance between these templated approaches to diagnosis and long-term care by working with third-party systems and your organization or vendor IT department to help with follow-up questions to keep populated data in check.

“Make sure you have a back-end system that can help monitor that structured data,” says Dr. Hettinger. Structured data are the patient’s demographic information, like name, address, age, height, weight, vital signs, and data elements like diagnosis, medications, and lab results. “Wherever you can leverage the underlying tools that are part of the electronic health record to make sure that we’re constantly checking the right results, that helps reduce the workload so that clinicians can focus on taking care of the patients and doing the right thing and not be as focused on entering data into the system.”

2. Supplement EHR notes with direct communication

The failure to diagnose cancer because one physician doesn’t know what another physician saw in an imaging report is one of the most common claims in the cases he tries, says Aaron Boeder, a plaintiff’s medical negligence lawyer in Chicago.

Physicians often assume that if they put a note in the electronic chart, others will look for it, but Mr. Boeder says it’s far more prudent to communicate directly.

“Let’s say a radiologist interprets a scan and sees what might be cancer,” he says. “If the ordering doctor is an orthopedist who’s ordered a CT scan for DVT, there’s going to be a report for that scan. It’s going to get auto-populated back into that physician’s note,” says Mr. Boeder.

The physician may or may not look at it, but it will be in their note, and they’re supposed to follow up on it because they ordered the scan. “But they may not follow up on it, and they may not get a call from the radiologist,” he says.

“Next thing you know, 2 or 3 years later, that patient is diagnosed with very advanced cancer.”

3. Tailor auto-fill information to your common practices

Suppose, as a physician, you find that you need to change a default setting time and time again. Dr. Hettinger says it’s worth your time to take an extra couple of minutes to work with your vendor or your health system to try and make changes to auto-population settings that align with your practices.

“Let’s say a default dose of 20 milligrams of a medication is what automatically pops up, but in reality, your practice is to use a smaller dose because it’s safer, even though they’re all within the acceptable realm of what you would order,” he says. “Rather than have the default to the higher dose, see if you can change the default to a lower dose. And that way, you don’t have to catch yourself every time.”

If your auto-fills are amounts that constantly need changing, an interruption could easily knock you off course before you make that correction.

“If there are ways to have the system defaults be safer or more in line with your clinical practice, and especially across a group, then you’re designing a safer system and not relying on vigilance or memory prone to interruptions,” says Dr. Hettinger.

4. Curb the copy and paste

It’s tempting to copy a note from a previous patient visit and make only minimal changes as needed, but you risk including outdated information if you do. Even if you’re repeating questions asked by the intake nurse, it is safer to not to rely on that information, says Beth Kanik, a defense medical malpractice attorney in Atlanta.

“If it later goes into litigation, the argument then becomes that it looks like you didn’t do your job,” says Ms. Kanik. “Instead, try to ask questions in a way that would elicit responses that may be a little different than what the nurse got, so that it’s clear you asked the questions and didn’t just simply rely upon someone else’s information.”

5. Separate typing from listening

While EHR may be an excellent tool for data collection and safety checking, it’s not a stand-in for doctor-patient interaction. As technology practices push medicine toward more and more efficiency, Mr. Boeder says it’s most often listening over all else that makes the difference in the quality of care. And good listening requires full attention.

“A real concern for physicians is the number of visits they’re expected to accomplish in a set amount of time,” says Mr. Boeder. “Often this translates into a doctor talking to a patient while typing notes or while reading a note from the last time the patient was in.”

Taking the time to pause after entering data and briefly reviewing your understanding of what your patient has told you can be invaluable and may save you – and your patient – problems later.

“In so many cases, it comes down to people not being heard,” says Mr. Boeder. “So listen to what your patients are saying.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Low-dose aspirin cuts type 2 diabetes risk in over-65s

The data come from a secondary analysis of ASPREE, a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of healthy adults aged 65 years or older, showing that 100 mg of aspirin taken daily for about 5 years did not provide a cardiovascular benefit but did significantly raise the risk for bleeding.

This new analysis shows that individuals taking aspirin had a 15% lower risk for developing type 2 diabetes and that the medication slowed the rate of increase in fasting plasma glucose, compared with placebo, during follow-up.

However, lead author Sophia Zoungas, MBBS, PhD, head of the School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, said: “Major prescribing guidelines now recommend older adults take daily aspirin only when there is a medical reason to do so, such as after a heart attack. ... Although these new findings are of interest, they do not change the clinical advice about aspirin use in older people at this time.”

Nonetheless, she said in an interview, “at this time, our findings are exploratory but ignite the debate of the important role that anti-inflammatory approaches may play in preventing diabetes. Further work is currently underway to understand which subpopulations may be better targeted and to understand the balance of risk versus benefit.”

The results are scheduled to be presented at the upcoming meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, taking place Oct. 2-6 in Hamburg, Germany.

New findings not robust enough to change current practice

Asked to comment, Debabrata Mukherjee, MD, said: “Given the post hoc secondary nature of the analysis, the findings should be considered hypothesis generating and not definitive… At this time, based on prospective randomized studies, the risks of aspirin outweigh the benefits for aspirin in older adults.”

Among those studies was an ASPREE substudy showing failure of low-dose aspirin to reduce fracture risk while increasing the risk for serious falls, and two other trials, ARRIVE and ASCEND, also showing that harms of aspirin outweigh the benefits in people with cardiovascular risk but not diabetes, and in those with diabetes, respectively, said Dr. Mukherjee, professor and chair of the department of internal medicine at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center at El Paso.

And, Mukherjee noted, in 2019 the American College of Cardiology updated its practice guidelines to say that low-dose aspirin should not be administered on a routine basis for the primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in adults over age 70. In 2021, the American Diabetes Association seconded that recommendation.

Asked whether these newest findings might change current practice for any higher-risk subgroup, such as people with prediabetes, Dr. Mukherjee replied: “Unless there is a prospective randomized trial that validates these findings in those with prediabetes, the findings should not change practice. There are also no data [showing] that another antiplatelet agent would be indicated or would be beneficial. Instead, I would recommend lifestyle changes including regular exercise and a healthy diet to minimize risk of diabetes.”

The 16,209 ASPREE participants were community dwelling and did not have diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or dementia at baseline. They were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive 100 mg/d of enteric-coated aspirin or placebo. Over a median follow-up of 4.7 years, the proportions developing type 2 diabetes were 5.7% with aspirin versus 6.6% with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.85; P = .01).

The annual rate of increase in fasting plasma glucose over the follow-up period was slowed by 0.006 mmol/L with aspirin, compared with placebo, also a significant difference (P = .004).

According to Dr. Zoungas, “the potential for anti-inflammatory agents like aspirin to prevent type 2 diabetes or improve glucose levels needs further study.”

The ASPREE trial was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Monash University, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Dr. Zoungas and Dr. Mukherjee have no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The data come from a secondary analysis of ASPREE, a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of healthy adults aged 65 years or older, showing that 100 mg of aspirin taken daily for about 5 years did not provide a cardiovascular benefit but did significantly raise the risk for bleeding.

This new analysis shows that individuals taking aspirin had a 15% lower risk for developing type 2 diabetes and that the medication slowed the rate of increase in fasting plasma glucose, compared with placebo, during follow-up.

However, lead author Sophia Zoungas, MBBS, PhD, head of the School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, said: “Major prescribing guidelines now recommend older adults take daily aspirin only when there is a medical reason to do so, such as after a heart attack. ... Although these new findings are of interest, they do not change the clinical advice about aspirin use in older people at this time.”

Nonetheless, she said in an interview, “at this time, our findings are exploratory but ignite the debate of the important role that anti-inflammatory approaches may play in preventing diabetes. Further work is currently underway to understand which subpopulations may be better targeted and to understand the balance of risk versus benefit.”

The results are scheduled to be presented at the upcoming meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, taking place Oct. 2-6 in Hamburg, Germany.

New findings not robust enough to change current practice

Asked to comment, Debabrata Mukherjee, MD, said: “Given the post hoc secondary nature of the analysis, the findings should be considered hypothesis generating and not definitive… At this time, based on prospective randomized studies, the risks of aspirin outweigh the benefits for aspirin in older adults.”

Among those studies was an ASPREE substudy showing failure of low-dose aspirin to reduce fracture risk while increasing the risk for serious falls, and two other trials, ARRIVE and ASCEND, also showing that harms of aspirin outweigh the benefits in people with cardiovascular risk but not diabetes, and in those with diabetes, respectively, said Dr. Mukherjee, professor and chair of the department of internal medicine at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center at El Paso.

And, Mukherjee noted, in 2019 the American College of Cardiology updated its practice guidelines to say that low-dose aspirin should not be administered on a routine basis for the primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in adults over age 70. In 2021, the American Diabetes Association seconded that recommendation.

Asked whether these newest findings might change current practice for any higher-risk subgroup, such as people with prediabetes, Dr. Mukherjee replied: “Unless there is a prospective randomized trial that validates these findings in those with prediabetes, the findings should not change practice. There are also no data [showing] that another antiplatelet agent would be indicated or would be beneficial. Instead, I would recommend lifestyle changes including regular exercise and a healthy diet to minimize risk of diabetes.”

The 16,209 ASPREE participants were community dwelling and did not have diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or dementia at baseline. They were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive 100 mg/d of enteric-coated aspirin or placebo. Over a median follow-up of 4.7 years, the proportions developing type 2 diabetes were 5.7% with aspirin versus 6.6% with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.85; P = .01).

The annual rate of increase in fasting plasma glucose over the follow-up period was slowed by 0.006 mmol/L with aspirin, compared with placebo, also a significant difference (P = .004).

According to Dr. Zoungas, “the potential for anti-inflammatory agents like aspirin to prevent type 2 diabetes or improve glucose levels needs further study.”

The ASPREE trial was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Monash University, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Dr. Zoungas and Dr. Mukherjee have no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The data come from a secondary analysis of ASPREE, a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of healthy adults aged 65 years or older, showing that 100 mg of aspirin taken daily for about 5 years did not provide a cardiovascular benefit but did significantly raise the risk for bleeding.

This new analysis shows that individuals taking aspirin had a 15% lower risk for developing type 2 diabetes and that the medication slowed the rate of increase in fasting plasma glucose, compared with placebo, during follow-up.

However, lead author Sophia Zoungas, MBBS, PhD, head of the School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, said: “Major prescribing guidelines now recommend older adults take daily aspirin only when there is a medical reason to do so, such as after a heart attack. ... Although these new findings are of interest, they do not change the clinical advice about aspirin use in older people at this time.”

Nonetheless, she said in an interview, “at this time, our findings are exploratory but ignite the debate of the important role that anti-inflammatory approaches may play in preventing diabetes. Further work is currently underway to understand which subpopulations may be better targeted and to understand the balance of risk versus benefit.”

The results are scheduled to be presented at the upcoming meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, taking place Oct. 2-6 in Hamburg, Germany.

New findings not robust enough to change current practice

Asked to comment, Debabrata Mukherjee, MD, said: “Given the post hoc secondary nature of the analysis, the findings should be considered hypothesis generating and not definitive… At this time, based on prospective randomized studies, the risks of aspirin outweigh the benefits for aspirin in older adults.”

Among those studies was an ASPREE substudy showing failure of low-dose aspirin to reduce fracture risk while increasing the risk for serious falls, and two other trials, ARRIVE and ASCEND, also showing that harms of aspirin outweigh the benefits in people with cardiovascular risk but not diabetes, and in those with diabetes, respectively, said Dr. Mukherjee, professor and chair of the department of internal medicine at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center at El Paso.

And, Mukherjee noted, in 2019 the American College of Cardiology updated its practice guidelines to say that low-dose aspirin should not be administered on a routine basis for the primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in adults over age 70. In 2021, the American Diabetes Association seconded that recommendation.

Asked whether these newest findings might change current practice for any higher-risk subgroup, such as people with prediabetes, Dr. Mukherjee replied: “Unless there is a prospective randomized trial that validates these findings in those with prediabetes, the findings should not change practice. There are also no data [showing] that another antiplatelet agent would be indicated or would be beneficial. Instead, I would recommend lifestyle changes including regular exercise and a healthy diet to minimize risk of diabetes.”

The 16,209 ASPREE participants were community dwelling and did not have diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or dementia at baseline. They were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive 100 mg/d of enteric-coated aspirin or placebo. Over a median follow-up of 4.7 years, the proportions developing type 2 diabetes were 5.7% with aspirin versus 6.6% with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.85; P = .01).

The annual rate of increase in fasting plasma glucose over the follow-up period was slowed by 0.006 mmol/L with aspirin, compared with placebo, also a significant difference (P = .004).

According to Dr. Zoungas, “the potential for anti-inflammatory agents like aspirin to prevent type 2 diabetes or improve glucose levels needs further study.”

The ASPREE trial was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Monash University, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Dr. Zoungas and Dr. Mukherjee have no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EASD 2023

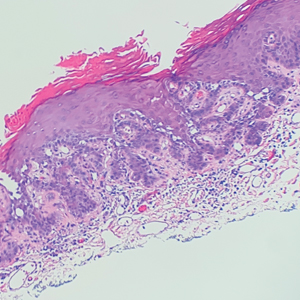

Pruritic Papules in the Perianal and Gluteal Cleft Regions

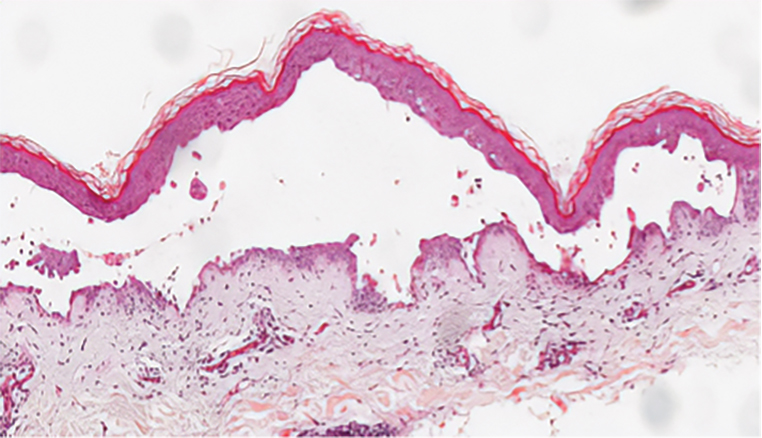

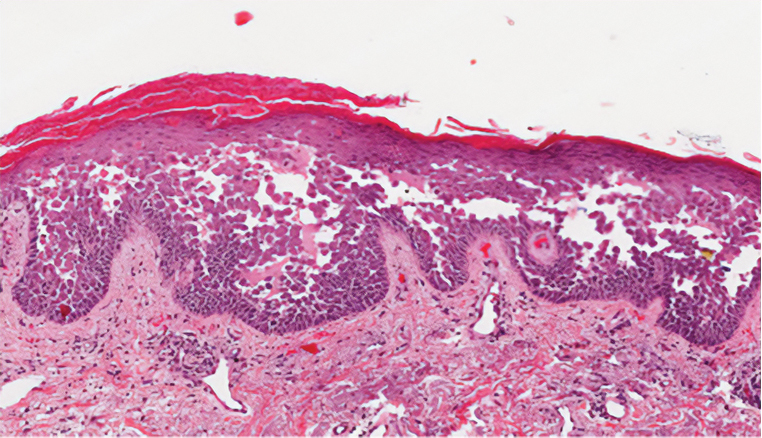

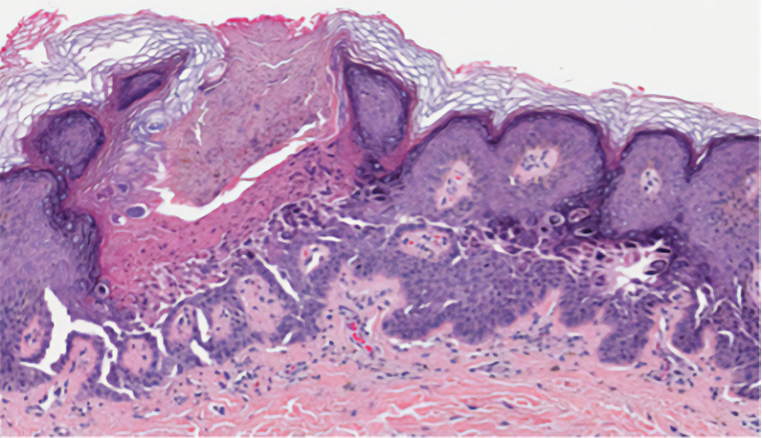

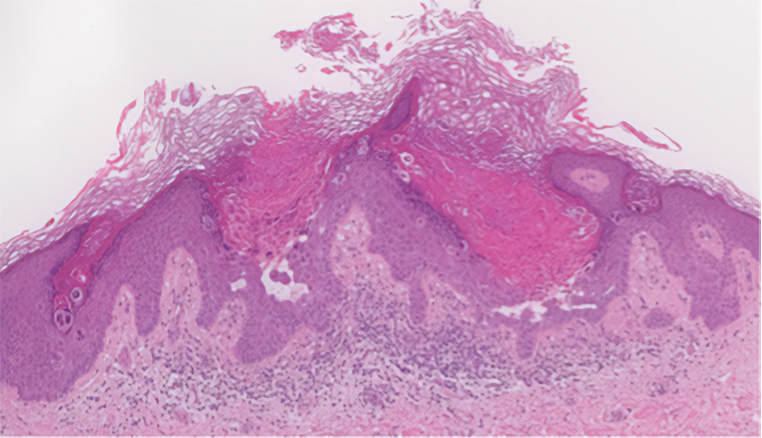

The Diagnosis: Papular Acantholytic Dyskeratosis