User login

A toxic and fractured political system can breed angst and PTSD

As psychiatrists know, many of our severely traumatized adult patients were victims of abuse during childhood. We routinely ask every new patient about physical, emotional, or sexual abuse when they were growing up because of the well-established, serious neurobiological and mental repercussions.1,2

Perhaps one of the worst experiences for a child is to witness bitterly adversarial parents (their vital role models) who argue viciously, despise each other, and hurl insults (and even punches) at each other. Such a chronically and emotionally traumatic upbringing can haunt kids well into adulthood, disrupting their hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and triggering anxiety, depression, and even psychosis due to epigenetic changes that ultimately lead to abnormal brain development.3

It often feels that the governance of our country, or the national “political family,” is seriously fractured like a hopelessly dysfunctional family. Could that be negatively impacting the mental health of the citizenry? Having 2 antagonistic political parties expressing visceral hatred and undisguised contempt for each other 24/7 (thanks to the enabling era of cable TV, the internet, and social media) has transformed each party’s fanatic followers from fellow citizens to ideological combatants. In this poisonous societal zeitgeist of bidirectional acrimony and mutual detestation, the opposing parties and their “intellectual militias” label each other as “extremists” or “radicals.” They become completely blind to any redeeming social value in the ideas or principles of their political opponents. They spend enormous time and energy on undermining each other instead of attending to the myriad vital issues involved in the governance of a massive and complex country.

Winston Churchill said, “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others that have been tried.”4 The current toxic cloud of intense “hyperpartisanship” is emblematic of the dark Machiavellian side of democracy. But those who lament the current distorted version of democracy should contemplate living in a dictatorship or totalitarian regime, where a despot would execute any dissenter or invade and destroy an adjacent country at a whim.

Churchill made that statement in 1947. The internet, social media, and smartphones were science fiction back then. Those technological advances have added fuel to the political process and significantly stoked the flames of hyperpartisanship. It’s now democracy on steroids, where freedom of expression goes to extremes, highlighting the warts and pitfalls of the democratic system. Political rivals can now communicate their ferocious disagreements to millions of their disciples instantaneously, triggering immediate rebuttals and counterattacks by their adversaries. This “virtual guerilla warfare” is mentally and emotionally exhausting to all involved, especially to the subset of neutral bystanders who are unaffiliated with either political party, which, due to the “religification” of politics, have become like secular religions.5 Chronic, unremitting, inescapable stress is a sure pathway for anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and even brain atrophy.

Optimists may point out that the United States has weathered and emerged stronger from many serious traumas, including the Civil War (with its lethal divisiveness), World War I, the deadly 1918 influenza pandemic, the Great Depression, Pearl Harbor, World War II, the Cold War, the Vietnam War, the Watergate political scandal, the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the banking collapse and recession, and most recently the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought society to a standstill and induced so much anxiety and uncertainty.

On the other hand, pessimists would insist those sequential crises left indelible scars that cumulatively altered the mindset of political rivals, predisposing them to extreme views of each other. Alienation inevitably leads to fanaticism. It’s perplexing but fascinating how the fierce bidirectional missives of weaponized ideas can be as virulent and destructive as a traditional physical war. Perhaps in this era, the pen is mightier than the sword after all.

Continue to: From a psychiatric perspective...

From a psychiatric perspective, the intransigent groupthink of political partisanship eerily resembles folie en masse, a psychiatric syndrome for which there is no established treatment. It has become a serious threat to our modern democracy. So I decided to ask the “know-it-all” artificial intelligence ChatGPT, whom I previously had “invited” to write a “guest editorial” about myths surrounding psychiatry,6 to answer 3 burning questions:

1. Is there toxic hyperpartisanship in the USA today? (Box 1)

Box 1

Yes, there is toxic hyperpartisanship in the United States today. Political polarization has been on the rise for several decades, and in recent years, it has become increasingly toxic and divisive. This toxic hyperpartisanship has contributed to a breakdown in civil discourse and a lack of cooperation and compromise in government.

The toxic hyperpartisanship is evident in many aspects of American society, including politics, media, and social media. Political leaders often engage in divisive rhetoric and focus on winning at all costs, rather than working towards solutions that benefit the country as a whole. Media outlets often present news in a partisan manner, further fueling political polarization. Social media platforms have also played a role in exacerbating toxic hyperpartisanship by allowing the spread of misinformation and creating echo chambers where people are only exposed to like-minded viewpoints.

The consequences of toxic hyperpartisanship are significant, as it can hinder progress on important issues and erode trust in institutions and government. It also makes it difficult for people to engage in productive dialogue and find common ground, leading to a lack of cooperation and compromise.

It is important for individuals to be aware of the impact of toxic hyperpartisanship and work towards finding ways to bridge the political divide and engage in constructive dialogue.

2. How can severe hyperpartisanship be corrected? (Supplemental Box 1)

Supplemental Box 1

Severe hyperpartisanship, characterized by intense and entrenched divisions between political parties, can be a challenging issue to address, but there are several steps that can be taken to work towards correcting it. Here are some potential approaches:

1. Promote civil discourse: Encourage respectful and constructive conversations between individuals with differing political views. This can be achieved through education programs, media campaigns, and initiatives to foster open dialogue.

2. Electoral reforms: Consider implementing electoral reforms that can reduce the influence of extreme partisanship. For example, ranked-choice voting or nonpartisan primaries may encourage candidates to appeal to a broader base of voters rather than just their party’s base.

3. Campaign finance reform: Limit the influence of money in politics, as it can exacerbate hyperpartisanship by allowing wealthy donors to have undue influence over candidates and parties.

4. Independent redistricting: Ensure that electoral district boundaries are drawn in a fair and nonpartisan manner. Gerrymandering, the manipulation of district lines to favor one party, can contribute to hyperpartisanship by creating “safe” districts where extreme candidates are more likely to be elected.

5. Promote media literacy: Encourage media literacy education to help citizens critically evaluate information sources and avoid echo chambers. A well-informed electorate is less susceptible to extreme partisanship.

6. Encourage bipartisan collaboration: Highlight and support instances of successful bipartisan collaboration. Elected officials who work across the aisle can serve as positive examples and encourage others to follow suit.

7. Address economic inequality: Tackling economic disparities can alleviate some of the underlying factors that contribute to polarization. When people feel economically secure, they may be more willing to seek common ground.

8. Civics education: Improve civics education in schools to foster a deeper understanding of democratic values, the political process, and the importance of civic engagement.

9. Leadership example: Encourage political leaders to model cooperation and compromise rather than relying on divisive rhetoric. Voters often take cues from their leaders’ behavior.

10. Promote third parties: Support and encourage the emergence of viable thirdparty candidates. A more diverse political landscape can provide alternatives to extreme partisanship.

11. Focus on common ground: Identify and prioritize issues where there is potential for bipartisan consensus and progress. Building success on these issues can create momentum for further cooperation.

12. Encourage grassroots activism: Support grassroots movements that seek to bridge divides and foster understanding between individuals and communities with different political perspectives.

It’s essential to recognize that addressing severe hyperpartisanship is a complex and long-term process that requires collective effort from citizens, political leaders, educators, and institutions. It won’t be achieved overnight, but through sustained and committed actions, progress can be made toward a more collaborative and less divisive political climate.

3. What can cause the collapse of a democracy? (Supplemental Box 2).

Supplemental Box 2

The collapse of a democracy can be a complex and multifaceted process, influenced by various factors and circumstances. Some of the common causes that can lead to the erosion or breakdown of a democratic system include:

1. Authoritarianism and power concentration: When leaders or institutions become increasingly authoritarian, centralizing power and weakening checks and balances, it can undermine democratic principles.

2. Corruption and lack of accountability: Rampant corruption among political leaders and institutions can erode public trust in the democratic system, leading to disillusionment and disengagement.

3. Economic instability: Prolonged economic crises or severe inequality can lead to social unrest, increasing the appeal of populist or extremist movements that may challenge democratic norms.

4. Weakening of rule of law: If the rule of law is weakened, and there is a lack of respect for judicial independence and constitutional principles, democratic institutions can become vulnerable to manipulation.

5. Erosion of civil liberties: Suppression of freedom of speech, media, assembly, and association can limit citizens’ ability to express their opinions and participate in the democratic process.

6. Polarization and divisive politics: Extreme political polarization and a breakdown of civil discourse can hinder cooperation and compromise essential for a functioning democracy.

7. External interference: Foreign intervention, propaganda, or cyberattacks can influence electoral processes and undermine democratic institutions.

8. Rise of populism and nationalism: Populist movements that challenge democratic norms, demonize minorities, or advocate for a strongman leadership can pose a threat to democracy.

9. Demographic and social shifts: Demographic changes and social tensions can exacerbate political divisions and weaken the fabric of democratic societies.

10. Lack of civic education and participation: A lack of civic education and low voter turnout can lead to reduced civic engagement and undermine the democratic process.

It is crucial to understand that no democracy is immune to these challenges, and the strength of a democratic system depends on the vigilance and engagement of its citizens, the integrity of its institutions, and the commitment to upholding democratic values. Safeguarding and strengthening democracy requires ongoing efforts to address these issues and protect the principles that underpin democratic governance.

Judge for yourself, but I believe the ChatGPT responses were spot-on.

1. Lippard ETC, Nemeroff CB. The devastating clinical consequences of child abuse and neglect: increased disease vulnerability and poor treatment response in mood disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180(8):548-564.

2. Nemeroff CB. Paradise lost: the neurobiological and clinical consequences of child abuse and neglect. Neuron. 2016;89(5):892-909.

3. Zhang ZZ, Moeckel C, Mustafa M, et al. The association of epigenetic age acceleration and depressive and anxiety symptom severity among children recently exposed to substantiated maltreatment. J Psychiatr Res. 2023;165:7-13.

4. International Churchill Society. The worst form of government. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://winstonchurchill.org/resources/quotes/the-worst-form-of-government/

5. Nasrallah HA. From ideology to articles of faith: the ‘religification’ of political beliefs. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(7):4-5,19.

6. Nasrallah HA. A ‘guest editorial’ … generated by ChatGPT? Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(4):22:6-7.

As psychiatrists know, many of our severely traumatized adult patients were victims of abuse during childhood. We routinely ask every new patient about physical, emotional, or sexual abuse when they were growing up because of the well-established, serious neurobiological and mental repercussions.1,2

Perhaps one of the worst experiences for a child is to witness bitterly adversarial parents (their vital role models) who argue viciously, despise each other, and hurl insults (and even punches) at each other. Such a chronically and emotionally traumatic upbringing can haunt kids well into adulthood, disrupting their hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and triggering anxiety, depression, and even psychosis due to epigenetic changes that ultimately lead to abnormal brain development.3

It often feels that the governance of our country, or the national “political family,” is seriously fractured like a hopelessly dysfunctional family. Could that be negatively impacting the mental health of the citizenry? Having 2 antagonistic political parties expressing visceral hatred and undisguised contempt for each other 24/7 (thanks to the enabling era of cable TV, the internet, and social media) has transformed each party’s fanatic followers from fellow citizens to ideological combatants. In this poisonous societal zeitgeist of bidirectional acrimony and mutual detestation, the opposing parties and their “intellectual militias” label each other as “extremists” or “radicals.” They become completely blind to any redeeming social value in the ideas or principles of their political opponents. They spend enormous time and energy on undermining each other instead of attending to the myriad vital issues involved in the governance of a massive and complex country.

Winston Churchill said, “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others that have been tried.”4 The current toxic cloud of intense “hyperpartisanship” is emblematic of the dark Machiavellian side of democracy. But those who lament the current distorted version of democracy should contemplate living in a dictatorship or totalitarian regime, where a despot would execute any dissenter or invade and destroy an adjacent country at a whim.

Churchill made that statement in 1947. The internet, social media, and smartphones were science fiction back then. Those technological advances have added fuel to the political process and significantly stoked the flames of hyperpartisanship. It’s now democracy on steroids, where freedom of expression goes to extremes, highlighting the warts and pitfalls of the democratic system. Political rivals can now communicate their ferocious disagreements to millions of their disciples instantaneously, triggering immediate rebuttals and counterattacks by their adversaries. This “virtual guerilla warfare” is mentally and emotionally exhausting to all involved, especially to the subset of neutral bystanders who are unaffiliated with either political party, which, due to the “religification” of politics, have become like secular religions.5 Chronic, unremitting, inescapable stress is a sure pathway for anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and even brain atrophy.

Optimists may point out that the United States has weathered and emerged stronger from many serious traumas, including the Civil War (with its lethal divisiveness), World War I, the deadly 1918 influenza pandemic, the Great Depression, Pearl Harbor, World War II, the Cold War, the Vietnam War, the Watergate political scandal, the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the banking collapse and recession, and most recently the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought society to a standstill and induced so much anxiety and uncertainty.

On the other hand, pessimists would insist those sequential crises left indelible scars that cumulatively altered the mindset of political rivals, predisposing them to extreme views of each other. Alienation inevitably leads to fanaticism. It’s perplexing but fascinating how the fierce bidirectional missives of weaponized ideas can be as virulent and destructive as a traditional physical war. Perhaps in this era, the pen is mightier than the sword after all.

Continue to: From a psychiatric perspective...

From a psychiatric perspective, the intransigent groupthink of political partisanship eerily resembles folie en masse, a psychiatric syndrome for which there is no established treatment. It has become a serious threat to our modern democracy. So I decided to ask the “know-it-all” artificial intelligence ChatGPT, whom I previously had “invited” to write a “guest editorial” about myths surrounding psychiatry,6 to answer 3 burning questions:

1. Is there toxic hyperpartisanship in the USA today? (Box 1)

Box 1

Yes, there is toxic hyperpartisanship in the United States today. Political polarization has been on the rise for several decades, and in recent years, it has become increasingly toxic and divisive. This toxic hyperpartisanship has contributed to a breakdown in civil discourse and a lack of cooperation and compromise in government.

The toxic hyperpartisanship is evident in many aspects of American society, including politics, media, and social media. Political leaders often engage in divisive rhetoric and focus on winning at all costs, rather than working towards solutions that benefit the country as a whole. Media outlets often present news in a partisan manner, further fueling political polarization. Social media platforms have also played a role in exacerbating toxic hyperpartisanship by allowing the spread of misinformation and creating echo chambers where people are only exposed to like-minded viewpoints.

The consequences of toxic hyperpartisanship are significant, as it can hinder progress on important issues and erode trust in institutions and government. It also makes it difficult for people to engage in productive dialogue and find common ground, leading to a lack of cooperation and compromise.

It is important for individuals to be aware of the impact of toxic hyperpartisanship and work towards finding ways to bridge the political divide and engage in constructive dialogue.

2. How can severe hyperpartisanship be corrected? (Supplemental Box 1)

Supplemental Box 1

Severe hyperpartisanship, characterized by intense and entrenched divisions between political parties, can be a challenging issue to address, but there are several steps that can be taken to work towards correcting it. Here are some potential approaches:

1. Promote civil discourse: Encourage respectful and constructive conversations between individuals with differing political views. This can be achieved through education programs, media campaigns, and initiatives to foster open dialogue.

2. Electoral reforms: Consider implementing electoral reforms that can reduce the influence of extreme partisanship. For example, ranked-choice voting or nonpartisan primaries may encourage candidates to appeal to a broader base of voters rather than just their party’s base.

3. Campaign finance reform: Limit the influence of money in politics, as it can exacerbate hyperpartisanship by allowing wealthy donors to have undue influence over candidates and parties.

4. Independent redistricting: Ensure that electoral district boundaries are drawn in a fair and nonpartisan manner. Gerrymandering, the manipulation of district lines to favor one party, can contribute to hyperpartisanship by creating “safe” districts where extreme candidates are more likely to be elected.

5. Promote media literacy: Encourage media literacy education to help citizens critically evaluate information sources and avoid echo chambers. A well-informed electorate is less susceptible to extreme partisanship.

6. Encourage bipartisan collaboration: Highlight and support instances of successful bipartisan collaboration. Elected officials who work across the aisle can serve as positive examples and encourage others to follow suit.

7. Address economic inequality: Tackling economic disparities can alleviate some of the underlying factors that contribute to polarization. When people feel economically secure, they may be more willing to seek common ground.

8. Civics education: Improve civics education in schools to foster a deeper understanding of democratic values, the political process, and the importance of civic engagement.

9. Leadership example: Encourage political leaders to model cooperation and compromise rather than relying on divisive rhetoric. Voters often take cues from their leaders’ behavior.

10. Promote third parties: Support and encourage the emergence of viable thirdparty candidates. A more diverse political landscape can provide alternatives to extreme partisanship.

11. Focus on common ground: Identify and prioritize issues where there is potential for bipartisan consensus and progress. Building success on these issues can create momentum for further cooperation.

12. Encourage grassroots activism: Support grassroots movements that seek to bridge divides and foster understanding between individuals and communities with different political perspectives.

It’s essential to recognize that addressing severe hyperpartisanship is a complex and long-term process that requires collective effort from citizens, political leaders, educators, and institutions. It won’t be achieved overnight, but through sustained and committed actions, progress can be made toward a more collaborative and less divisive political climate.

3. What can cause the collapse of a democracy? (Supplemental Box 2).

Supplemental Box 2

The collapse of a democracy can be a complex and multifaceted process, influenced by various factors and circumstances. Some of the common causes that can lead to the erosion or breakdown of a democratic system include:

1. Authoritarianism and power concentration: When leaders or institutions become increasingly authoritarian, centralizing power and weakening checks and balances, it can undermine democratic principles.

2. Corruption and lack of accountability: Rampant corruption among political leaders and institutions can erode public trust in the democratic system, leading to disillusionment and disengagement.

3. Economic instability: Prolonged economic crises or severe inequality can lead to social unrest, increasing the appeal of populist or extremist movements that may challenge democratic norms.

4. Weakening of rule of law: If the rule of law is weakened, and there is a lack of respect for judicial independence and constitutional principles, democratic institutions can become vulnerable to manipulation.

5. Erosion of civil liberties: Suppression of freedom of speech, media, assembly, and association can limit citizens’ ability to express their opinions and participate in the democratic process.

6. Polarization and divisive politics: Extreme political polarization and a breakdown of civil discourse can hinder cooperation and compromise essential for a functioning democracy.

7. External interference: Foreign intervention, propaganda, or cyberattacks can influence electoral processes and undermine democratic institutions.

8. Rise of populism and nationalism: Populist movements that challenge democratic norms, demonize minorities, or advocate for a strongman leadership can pose a threat to democracy.

9. Demographic and social shifts: Demographic changes and social tensions can exacerbate political divisions and weaken the fabric of democratic societies.

10. Lack of civic education and participation: A lack of civic education and low voter turnout can lead to reduced civic engagement and undermine the democratic process.

It is crucial to understand that no democracy is immune to these challenges, and the strength of a democratic system depends on the vigilance and engagement of its citizens, the integrity of its institutions, and the commitment to upholding democratic values. Safeguarding and strengthening democracy requires ongoing efforts to address these issues and protect the principles that underpin democratic governance.

Judge for yourself, but I believe the ChatGPT responses were spot-on.

As psychiatrists know, many of our severely traumatized adult patients were victims of abuse during childhood. We routinely ask every new patient about physical, emotional, or sexual abuse when they were growing up because of the well-established, serious neurobiological and mental repercussions.1,2

Perhaps one of the worst experiences for a child is to witness bitterly adversarial parents (their vital role models) who argue viciously, despise each other, and hurl insults (and even punches) at each other. Such a chronically and emotionally traumatic upbringing can haunt kids well into adulthood, disrupting their hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and triggering anxiety, depression, and even psychosis due to epigenetic changes that ultimately lead to abnormal brain development.3

It often feels that the governance of our country, or the national “political family,” is seriously fractured like a hopelessly dysfunctional family. Could that be negatively impacting the mental health of the citizenry? Having 2 antagonistic political parties expressing visceral hatred and undisguised contempt for each other 24/7 (thanks to the enabling era of cable TV, the internet, and social media) has transformed each party’s fanatic followers from fellow citizens to ideological combatants. In this poisonous societal zeitgeist of bidirectional acrimony and mutual detestation, the opposing parties and their “intellectual militias” label each other as “extremists” or “radicals.” They become completely blind to any redeeming social value in the ideas or principles of their political opponents. They spend enormous time and energy on undermining each other instead of attending to the myriad vital issues involved in the governance of a massive and complex country.

Winston Churchill said, “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others that have been tried.”4 The current toxic cloud of intense “hyperpartisanship” is emblematic of the dark Machiavellian side of democracy. But those who lament the current distorted version of democracy should contemplate living in a dictatorship or totalitarian regime, where a despot would execute any dissenter or invade and destroy an adjacent country at a whim.

Churchill made that statement in 1947. The internet, social media, and smartphones were science fiction back then. Those technological advances have added fuel to the political process and significantly stoked the flames of hyperpartisanship. It’s now democracy on steroids, where freedom of expression goes to extremes, highlighting the warts and pitfalls of the democratic system. Political rivals can now communicate their ferocious disagreements to millions of their disciples instantaneously, triggering immediate rebuttals and counterattacks by their adversaries. This “virtual guerilla warfare” is mentally and emotionally exhausting to all involved, especially to the subset of neutral bystanders who are unaffiliated with either political party, which, due to the “religification” of politics, have become like secular religions.5 Chronic, unremitting, inescapable stress is a sure pathway for anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and even brain atrophy.

Optimists may point out that the United States has weathered and emerged stronger from many serious traumas, including the Civil War (with its lethal divisiveness), World War I, the deadly 1918 influenza pandemic, the Great Depression, Pearl Harbor, World War II, the Cold War, the Vietnam War, the Watergate political scandal, the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the banking collapse and recession, and most recently the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought society to a standstill and induced so much anxiety and uncertainty.

On the other hand, pessimists would insist those sequential crises left indelible scars that cumulatively altered the mindset of political rivals, predisposing them to extreme views of each other. Alienation inevitably leads to fanaticism. It’s perplexing but fascinating how the fierce bidirectional missives of weaponized ideas can be as virulent and destructive as a traditional physical war. Perhaps in this era, the pen is mightier than the sword after all.

Continue to: From a psychiatric perspective...

From a psychiatric perspective, the intransigent groupthink of political partisanship eerily resembles folie en masse, a psychiatric syndrome for which there is no established treatment. It has become a serious threat to our modern democracy. So I decided to ask the “know-it-all” artificial intelligence ChatGPT, whom I previously had “invited” to write a “guest editorial” about myths surrounding psychiatry,6 to answer 3 burning questions:

1. Is there toxic hyperpartisanship in the USA today? (Box 1)

Box 1

Yes, there is toxic hyperpartisanship in the United States today. Political polarization has been on the rise for several decades, and in recent years, it has become increasingly toxic and divisive. This toxic hyperpartisanship has contributed to a breakdown in civil discourse and a lack of cooperation and compromise in government.

The toxic hyperpartisanship is evident in many aspects of American society, including politics, media, and social media. Political leaders often engage in divisive rhetoric and focus on winning at all costs, rather than working towards solutions that benefit the country as a whole. Media outlets often present news in a partisan manner, further fueling political polarization. Social media platforms have also played a role in exacerbating toxic hyperpartisanship by allowing the spread of misinformation and creating echo chambers where people are only exposed to like-minded viewpoints.

The consequences of toxic hyperpartisanship are significant, as it can hinder progress on important issues and erode trust in institutions and government. It also makes it difficult for people to engage in productive dialogue and find common ground, leading to a lack of cooperation and compromise.

It is important for individuals to be aware of the impact of toxic hyperpartisanship and work towards finding ways to bridge the political divide and engage in constructive dialogue.

2. How can severe hyperpartisanship be corrected? (Supplemental Box 1)

Supplemental Box 1

Severe hyperpartisanship, characterized by intense and entrenched divisions between political parties, can be a challenging issue to address, but there are several steps that can be taken to work towards correcting it. Here are some potential approaches:

1. Promote civil discourse: Encourage respectful and constructive conversations between individuals with differing political views. This can be achieved through education programs, media campaigns, and initiatives to foster open dialogue.

2. Electoral reforms: Consider implementing electoral reforms that can reduce the influence of extreme partisanship. For example, ranked-choice voting or nonpartisan primaries may encourage candidates to appeal to a broader base of voters rather than just their party’s base.

3. Campaign finance reform: Limit the influence of money in politics, as it can exacerbate hyperpartisanship by allowing wealthy donors to have undue influence over candidates and parties.

4. Independent redistricting: Ensure that electoral district boundaries are drawn in a fair and nonpartisan manner. Gerrymandering, the manipulation of district lines to favor one party, can contribute to hyperpartisanship by creating “safe” districts where extreme candidates are more likely to be elected.

5. Promote media literacy: Encourage media literacy education to help citizens critically evaluate information sources and avoid echo chambers. A well-informed electorate is less susceptible to extreme partisanship.

6. Encourage bipartisan collaboration: Highlight and support instances of successful bipartisan collaboration. Elected officials who work across the aisle can serve as positive examples and encourage others to follow suit.

7. Address economic inequality: Tackling economic disparities can alleviate some of the underlying factors that contribute to polarization. When people feel economically secure, they may be more willing to seek common ground.

8. Civics education: Improve civics education in schools to foster a deeper understanding of democratic values, the political process, and the importance of civic engagement.

9. Leadership example: Encourage political leaders to model cooperation and compromise rather than relying on divisive rhetoric. Voters often take cues from their leaders’ behavior.

10. Promote third parties: Support and encourage the emergence of viable thirdparty candidates. A more diverse political landscape can provide alternatives to extreme partisanship.

11. Focus on common ground: Identify and prioritize issues where there is potential for bipartisan consensus and progress. Building success on these issues can create momentum for further cooperation.

12. Encourage grassroots activism: Support grassroots movements that seek to bridge divides and foster understanding between individuals and communities with different political perspectives.

It’s essential to recognize that addressing severe hyperpartisanship is a complex and long-term process that requires collective effort from citizens, political leaders, educators, and institutions. It won’t be achieved overnight, but through sustained and committed actions, progress can be made toward a more collaborative and less divisive political climate.

3. What can cause the collapse of a democracy? (Supplemental Box 2).

Supplemental Box 2

The collapse of a democracy can be a complex and multifaceted process, influenced by various factors and circumstances. Some of the common causes that can lead to the erosion or breakdown of a democratic system include:

1. Authoritarianism and power concentration: When leaders or institutions become increasingly authoritarian, centralizing power and weakening checks and balances, it can undermine democratic principles.

2. Corruption and lack of accountability: Rampant corruption among political leaders and institutions can erode public trust in the democratic system, leading to disillusionment and disengagement.

3. Economic instability: Prolonged economic crises or severe inequality can lead to social unrest, increasing the appeal of populist or extremist movements that may challenge democratic norms.

4. Weakening of rule of law: If the rule of law is weakened, and there is a lack of respect for judicial independence and constitutional principles, democratic institutions can become vulnerable to manipulation.

5. Erosion of civil liberties: Suppression of freedom of speech, media, assembly, and association can limit citizens’ ability to express their opinions and participate in the democratic process.

6. Polarization and divisive politics: Extreme political polarization and a breakdown of civil discourse can hinder cooperation and compromise essential for a functioning democracy.

7. External interference: Foreign intervention, propaganda, or cyberattacks can influence electoral processes and undermine democratic institutions.

8. Rise of populism and nationalism: Populist movements that challenge democratic norms, demonize minorities, or advocate for a strongman leadership can pose a threat to democracy.

9. Demographic and social shifts: Demographic changes and social tensions can exacerbate political divisions and weaken the fabric of democratic societies.

10. Lack of civic education and participation: A lack of civic education and low voter turnout can lead to reduced civic engagement and undermine the democratic process.

It is crucial to understand that no democracy is immune to these challenges, and the strength of a democratic system depends on the vigilance and engagement of its citizens, the integrity of its institutions, and the commitment to upholding democratic values. Safeguarding and strengthening democracy requires ongoing efforts to address these issues and protect the principles that underpin democratic governance.

Judge for yourself, but I believe the ChatGPT responses were spot-on.

1. Lippard ETC, Nemeroff CB. The devastating clinical consequences of child abuse and neglect: increased disease vulnerability and poor treatment response in mood disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180(8):548-564.

2. Nemeroff CB. Paradise lost: the neurobiological and clinical consequences of child abuse and neglect. Neuron. 2016;89(5):892-909.

3. Zhang ZZ, Moeckel C, Mustafa M, et al. The association of epigenetic age acceleration and depressive and anxiety symptom severity among children recently exposed to substantiated maltreatment. J Psychiatr Res. 2023;165:7-13.

4. International Churchill Society. The worst form of government. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://winstonchurchill.org/resources/quotes/the-worst-form-of-government/

5. Nasrallah HA. From ideology to articles of faith: the ‘religification’ of political beliefs. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(7):4-5,19.

6. Nasrallah HA. A ‘guest editorial’ … generated by ChatGPT? Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(4):22:6-7.

1. Lippard ETC, Nemeroff CB. The devastating clinical consequences of child abuse and neglect: increased disease vulnerability and poor treatment response in mood disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180(8):548-564.

2. Nemeroff CB. Paradise lost: the neurobiological and clinical consequences of child abuse and neglect. Neuron. 2016;89(5):892-909.

3. Zhang ZZ, Moeckel C, Mustafa M, et al. The association of epigenetic age acceleration and depressive and anxiety symptom severity among children recently exposed to substantiated maltreatment. J Psychiatr Res. 2023;165:7-13.

4. International Churchill Society. The worst form of government. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://winstonchurchill.org/resources/quotes/the-worst-form-of-government/

5. Nasrallah HA. From ideology to articles of faith: the ‘religification’ of political beliefs. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(7):4-5,19.

6. Nasrallah HA. A ‘guest editorial’ … generated by ChatGPT? Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(4):22:6-7.

Abnormal sexual behaviors in frontotemporal dementia

Mr. S, age 77, is admitted to a long-term care facility due to progressive cognitive impairment and sexually inappropriate behavior. He has a history of sexual assault of medical staff. His medical history includes significant frontotemporal dementia (FTD) with behavioral disturbances, abnormal sexual behaviors, subclinical hypothyroidism, schizoid personality disorder, Parkinson disease, posttraumatic stress disorder, and hyperammonemia.

Upon admission, Mr. S’s vital signs are within normal limits except for an elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (4.54 mIU/L; reference range 0.40 to 4.50 mIU/L). Prior cognitive testing results and updated ammonia levels are unavailable. Mr. S’s current medications include acetaminophen 650 mg every 4 hours as needed for pain, calcium carbonate/vitamin D twice daily for bone health, carbidopa/levodopa 25/100 mg twice daily for Parkinson disease, melatonin 3 mg/d at bedtime for insomnia, quetiapine 25 mg twice daily for psychosis with disturbance of behavior and 12.5 mg every 4 hours as needed for agitation, and trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime for insomnia. Before Mr. S was admitted, previous therapy with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) had been tapered and discontinued. Mr. S had also started antipsychotic therapy at another facility due to worsening behaviors.

In patients with dementia, the brain is experiencing neurodegeneration. Progressively, neurons may stop functioning, lose connections with other neurons, and ultimately face cell death. The specific dementia diagnosis and its clinical features depend on the type of neurons and region of the brain affected.1,2

FTD occurs in response to damage to the frontal and temporal lobes. The frontal lobe correlates to executive functioning, while the temporal lobe plays a role in speech and comprehension. Damage to these areas may result in loss of movement, trouble speaking, difficulty solving complex problems, and problems with social behavior. Specifically, damage to the orbital frontal cortex may cause disinhibition and abnormal behaviors, including emotional lability, vulgarity, and indifference to social nuances.1 Within an FTD diagnosis, there are 3 disorders: behavioral-variant FTD (bvFTD), semantic dementia, and progressive nonfluent aphasia.1 Specifically, bvFTD can result in abnormal sexual behaviors such as making sexually inappropriate statements, masturbating in public, undressing in public, inappropriately or aggressively touching others, or confusing another individual as an intimate partner. In addition to cognitive impairment, these neurobehavioral symptoms can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life while increasing caregiver burden.2

Occurring at a similar frequency to Alzheimer’s disease in patients age <65, FTD is one of the more common causes of early-onset dementia. The mean age of onset is 58 and onset after age 75 is particularly unusual. Memory may not be affected early in the course of the disease, but social changes are likely. As FTD progresses, symptoms will resemble those of Alzheimer’s disease and patients will require assistance with activities of daily living. In later stages of FTD, patients will exhibit language and behavior symptoms. Due to its unique progression, FTD can be commonly misdiagnosed as other mental illnesses or neurocognitive disorders.1

Approaches to treatment: What to consider

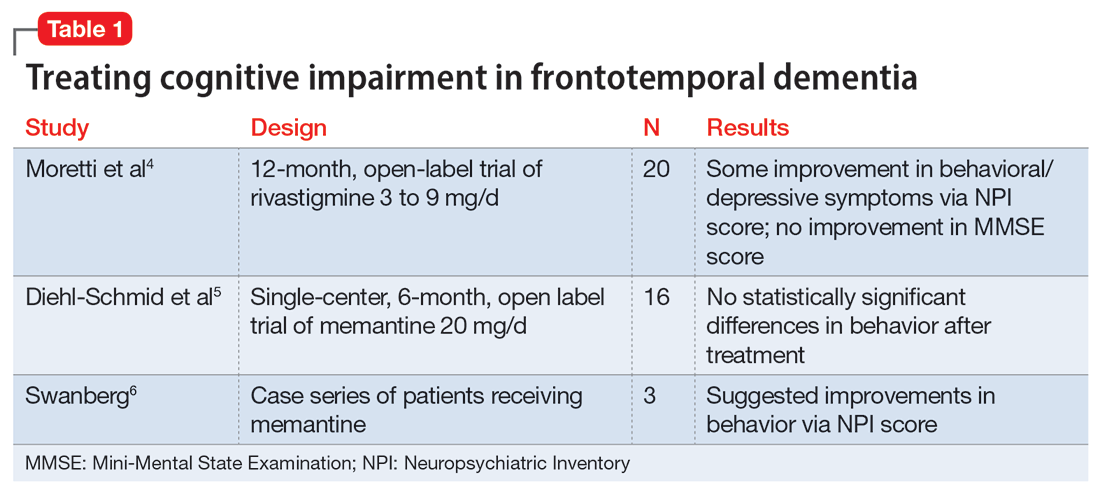

Both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions are appropriate for addressing FTD. Because nonpharmacologic options improve patient safety and overall physical health, they should be used whenever practical. These interventions include safe driving measures, exercise, speech therapy, redirection, offering simple choices when making decisions, and managing environmental cues for behaviors that should be encouraged or discouraged.3

There are no FDA-approved medications to cure or slow the progression of FTD. Therefore, treatment is focused on alleviating neurobehavioral symptoms. The symptoms depend on the type of FTD the patient has; they include cognitive impairment, anxiety, insomnia or sleep disturbances, compulsive behaviors, speech and language problems, and agitation. While many medications have been commonly used for symptomatic relief, evidence for the efficacy of these treatments in FTD is limited.2

Continue to: A review of the literature...

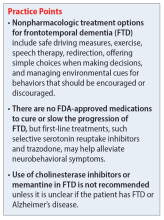

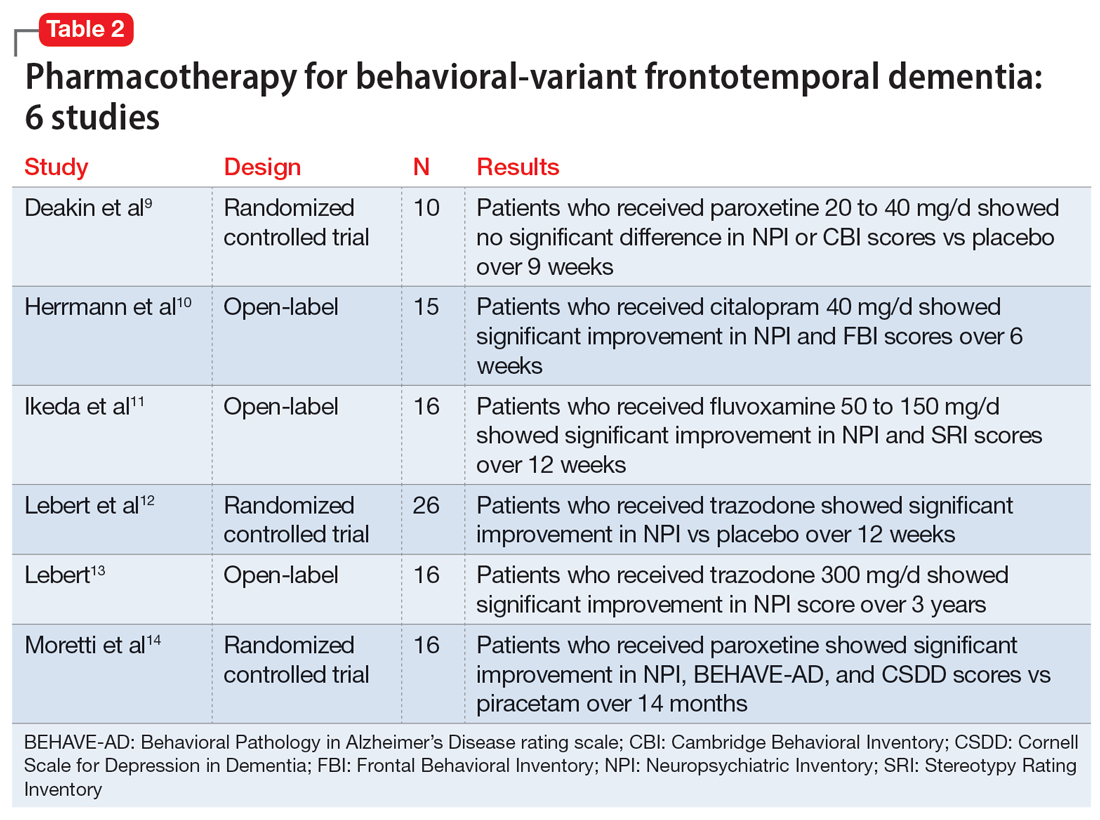

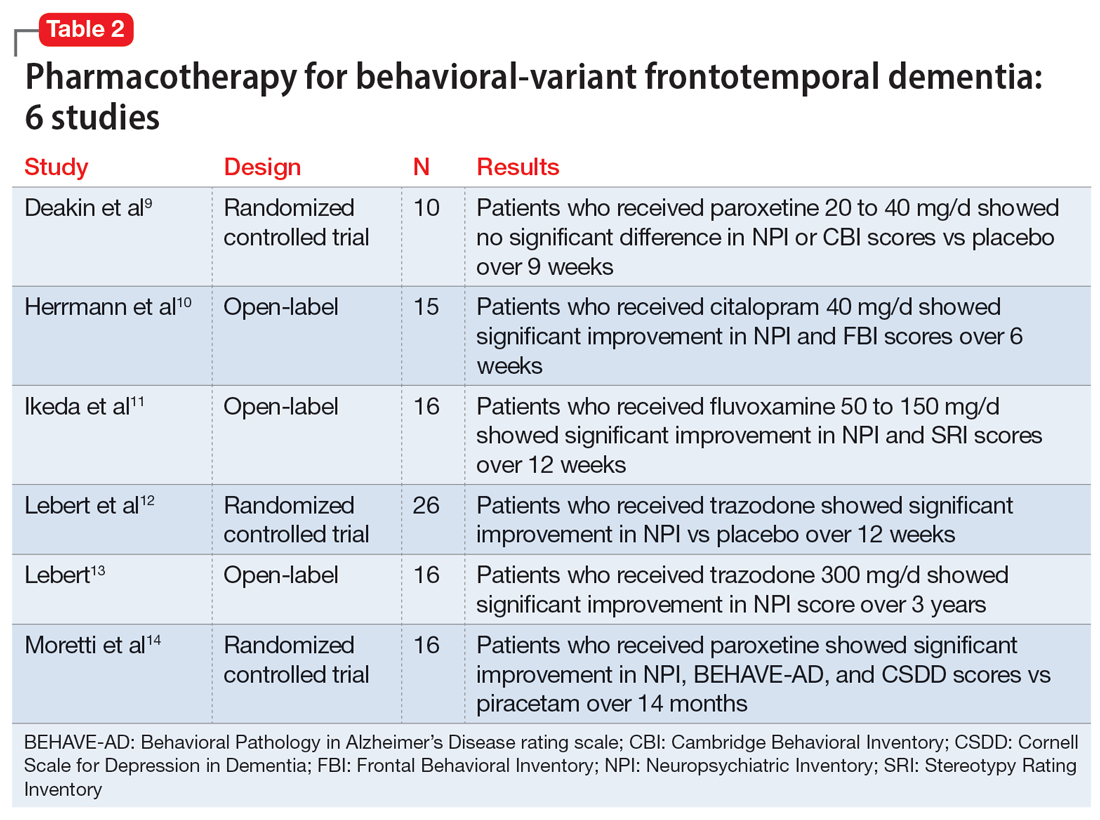

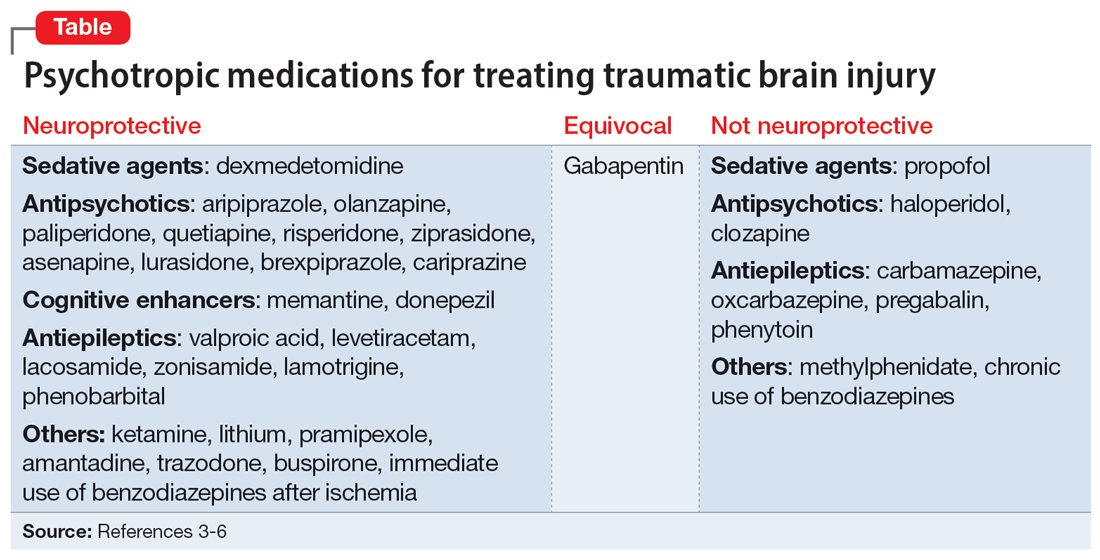

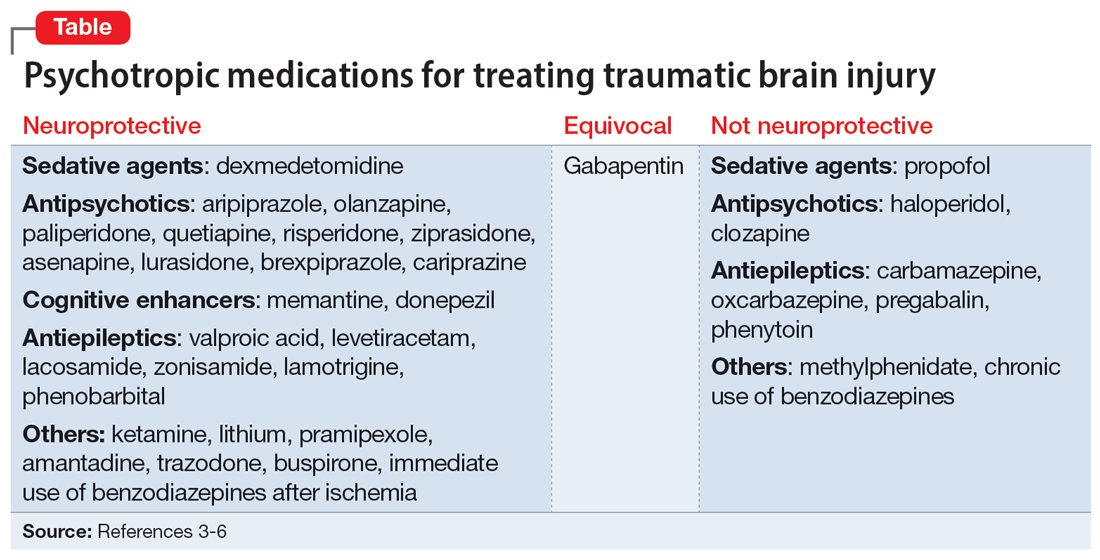

A review of the literature on potential treatments for cognitive impairment and behavioral symptoms of FTD identified 2 trials and 1 case series (Table 14-6) in addition to a 2014 review article7 of current pharmacologic treatments. These trials evaluated cognitive improvement with rivastigmine, memantine, galantamine, and donepezil. None of the trials found a significant benefit from any of these medications for cognitive improvement in FTD. Data were conflicting on whether these medications improved or worsened behavioral symptoms. For example, the case series of 3 patients by Swanberg6 suggested improvement in behavior with memantine, while an open-label study analyzed in a 2014 review article7 found that donepezil may have worsened behaviors. Use of cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine in FTD is not recommended unless it is not certain if the patient has FTD or Alzheimer’s disease.7

Addressing sexual behaviors. Creating a treatment regimen for FTD behavioral symptoms—specifically for abnormal sexual behaviors—can be challenging. Before starting pharmacotherapy directed at behavioral symptoms secondary to FTD, other causes of symptoms such as delirium, pain, or discomfort should be excluded. Nonpharmacologic approaches should be aimed at the type of sexual behavior and likely underlying environmental cause. For example, patients may inappropriately disrobe themselves. To address this behavior, hospital staff or caregivers should first eliminate environmental causes by ensuring the room is at a comfortable temperature, dressing the patient in light, breathable clothing, or checking if the patient needs to use the bathroom. If no environmental causes are found, a one-piece jumpsuit with closures on the back of the garment could be utilized to increase the difficulty of undressing.

Other nonpharmacologic methods include providing private areas for patients who are behaving inappropriately or removing potentially stimulating television or media from the environment. Another option is to increase the use of positive, pleasant stimuli. One approach that has shown benefit is music therapy, utilizing popular music genres from the patient’s youth.3

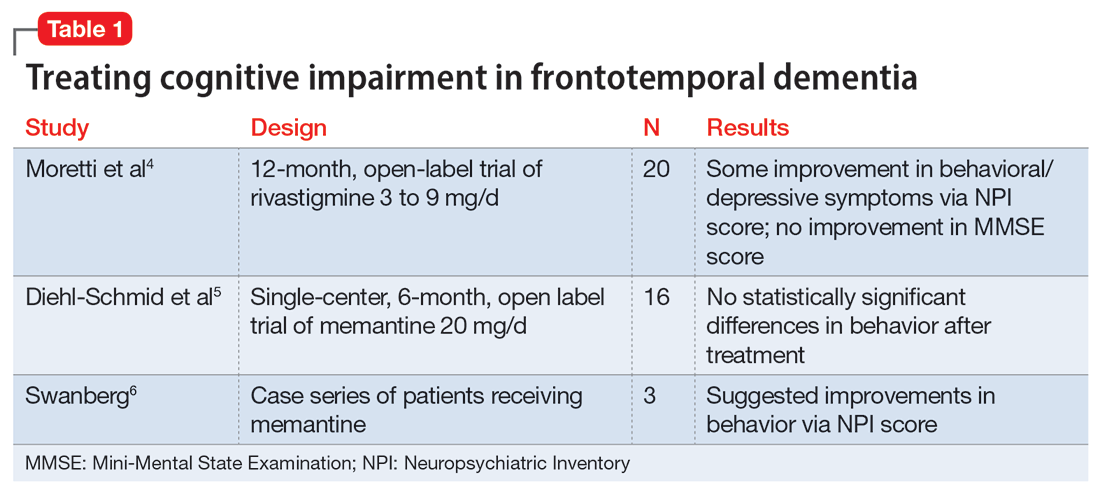

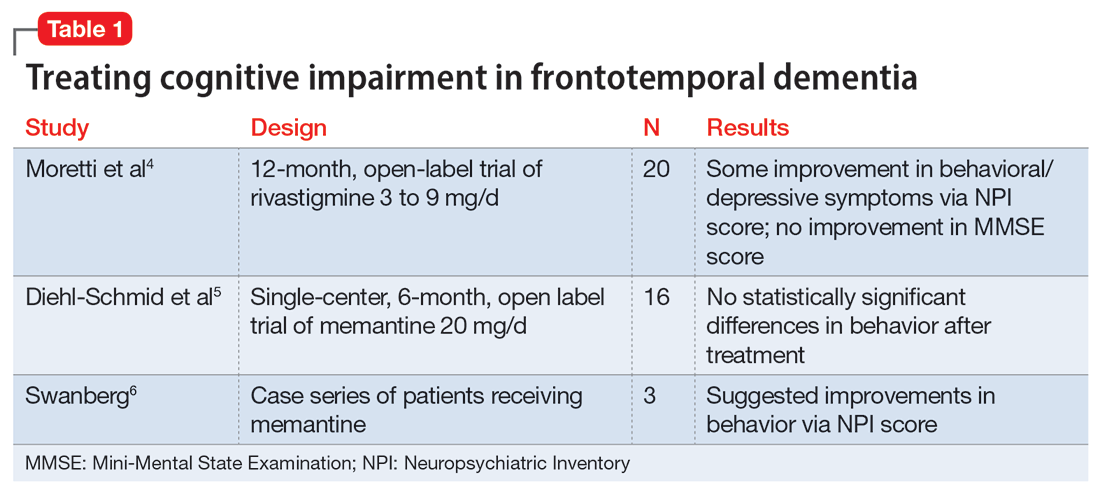

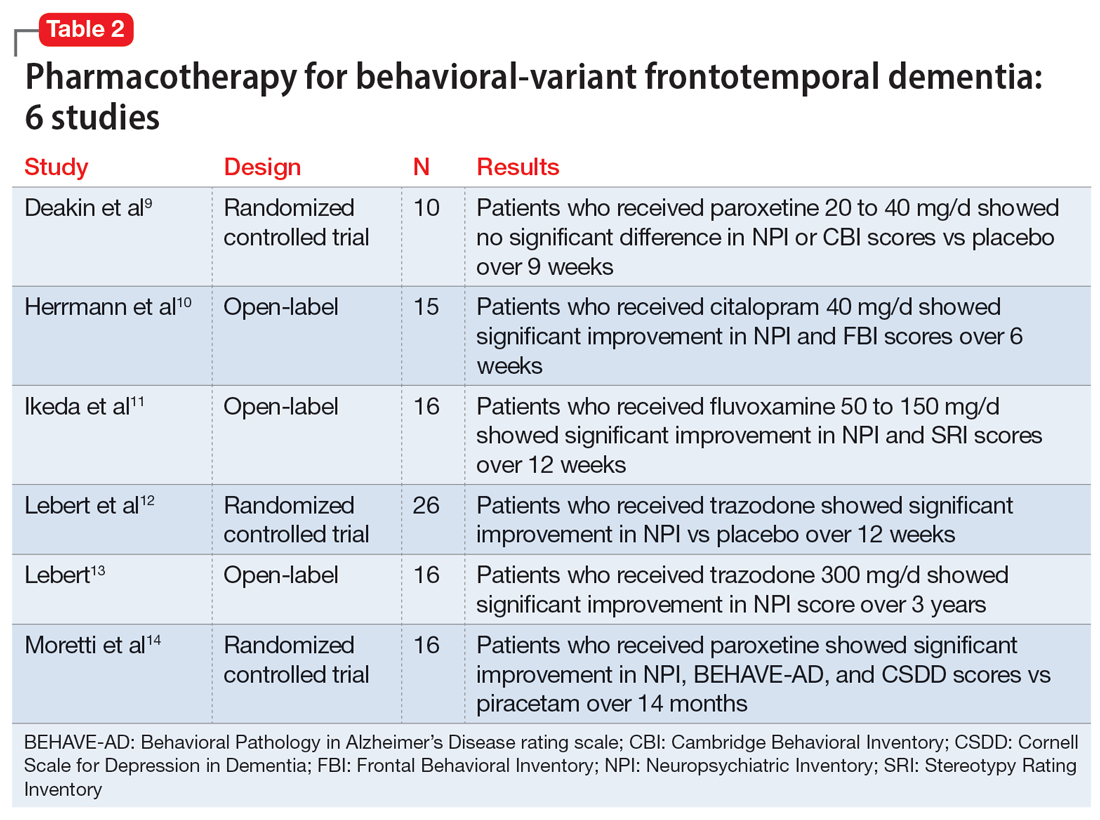

Evidence for pharmacotherapy is limited and largely from case reports and case series. A 2020 meta-analysis by Trieu et al8 reviewed 23 studies to expand on current clinical guidance for patients with bvFTD. These studies showed improvements in behavioral symptoms and reductions in caregiver fatigue with citalopram, trazodone, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine. Six of the trials included in this meta-analysis that evaluated these 4 medications are summarized in Table 2.9-14

Due to the lower risk of adverse effects and favorable safety profiles, SSRIs and trazodone are considered first-line treatment options. Benefit from these medications is theorized to be a result of their serotonergic effects, because serotonin abnormalities and dysfunction have been linked to FTD symptoms. For example, in a patient experiencing hypersexuality, the common adverse effect of low libido associated with SSRIs can be particularly beneficial.8

Continue to: Other medication classes studied in patients...

Other medication classes studied in patients with FTD include antipsychotics, stimulants, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, and hormonal therapies. In addition to a black box warning for increased mortality in older patients with dementia-related psychosis, antipsychotics are associated with other serious adverse effects and should be used with caution.7

FTD is a debilitating disease that has a major impact on quality of life, particularly when behavioral symptoms accompany cognitive decline. Though some therapies may possibly improve behavioral symptoms, their routine use remains controversial due to a lack of clear evidence of benefit. In caring for patients with FTD and behavioral symptoms, a multimodal, team-based approach is vital.1

CASE CONTINUED

The treatment team starts Mr. S on several of the modalities discussed in this article over the span of 2 years, with limited efficacy. Nonpharmacologic methods do not provide much benefit because Mr. S is extremely difficult to redirect. Given Mr. S’s past trials of SSRIs prior to admission, sertraline was retrialed and titrated over 2 years. The highest dose utilized during his admission was 200 mg/d. The team starts estrogen therapy but tapers and discontinues it due to ineffectiveness. Mr. S’s use of carbidopa/levodopa is thought to be contributing to his behavioral abnormalities, so the team tapers it to discontinuation; however, Mr. S’s sexually inappropriate behaviors and agitation continue. The team initiates a plan to reduce the dose of quetiapine and switch to gabapentin, but Mr. S fails gradual dose reduction due to his worsening behaviors. He starts gabapentin. The team gradually increases the dose of gabapentin to decrease libido and agitation, respectively. The increase in sertraline dose and use of nonpharmacologic modalities causes Mr. S’s use of as-needed antipsychotics to decrease.

Related Resources

- Ellison JM. What are the stages of frontotemporal dementia? BrightFocus Foundation. July 5, 2021. Accessed July 7, 2023. https://www.brightfocus.org/alzheimers/article/what-are-stages-frontotemporal-dementia

- Dementia and sexually inappropriate behavior. ReaDementia. January 31, 2022. Accessed July 7, 2023. https://readementia.com/dementia-and-sexually-inappropriate-behavior/

Drug Brand Names

Carbidopa/levodopa • Sinemet

Citalopram • Celexa

Donepezil • Aricept

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Galantamine • Razadyne

Memantine • Namenda

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Rivastigmine • Exelon

Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Desyrel

1. Grossman M. Frontotemporal dementia: a review. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8(4):566-583. doi:10.1017/s1355617702814357

2. The Johns Hopkins University. Frontotemporal dementia. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Accessed September 12, 2021. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/dementia/frontotemporal-dementia

3. Shinagawa S, Nakajima S, Plitman E, et al. Non-pharmacological management for patients with frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45(1):283-293. doi:10.3233/JAD-142109

4. Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello RM, et al. Rivastigmine in frontotemporal dementia: an open-label study. Drugs Aging. 2004;21(14):931-937. doi:10.2165/00002512-200421140-00003

5. Diehl-Schmid J, Förstl H, Perneczky R, et al. A 6-month, open-label study for memantine in patients with frontotemporal dementia. In J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(7):754-759. doi:10.1002/gps.1973

6. Swanberg MM. Memantine for behavioral disturbances in frontotemporal dementia: a case series. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(2):164-166. doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e318047df5d

7. Tsai RM, Boxer AL. Treatment of frontotemporal dementia. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2014;16(11):319. doi:10.1007/s11940-014-0319-0

8. Trieu C, Gossink F, Stek ML, et al. Effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for symptoms of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2020;33(1):1-15. doi:10.1097/WNN.0000000000000217

9. Deakin JB, Rahman S, Nestor PJ, et al. Paroxetine does not improve symptoms and impairs cognition in frontotemporal dementia: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;172(4):400-408. doi:10.1007/s00213-003-1686-5

10. Herrmann N, Black SE, Chow T, et al. Serotonergic function and treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of frontotemporal dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(9):789-797. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e31823033f3

11. Ikeda M, Shigenobu K, Fukuhara R, et al. Efficacy of fluvoxamine as a treatment for behavioral symptoms in frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(3):117-121. doi:10.1159/000076343

12. Lebert F, Stekke W, Hasenbroekx C, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: a randomised, controlled trial with trazodone. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(4):355-359. doi:10.1159/000077171

13. Lebert F. Behavioral benefits of trazodone are sustained for the long term in frontotemporal dementia. Therapy. 2006;3(1):93-96. doi:10.1586/14750708.3.1.93

14. Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello RM, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: paroxetine as a possible treatment of behavior symptoms. A randomized, controlled, open 14-month study. Eur Neurol. 2003;49(1):13-19. doi:10.1159/000067021

Mr. S, age 77, is admitted to a long-term care facility due to progressive cognitive impairment and sexually inappropriate behavior. He has a history of sexual assault of medical staff. His medical history includes significant frontotemporal dementia (FTD) with behavioral disturbances, abnormal sexual behaviors, subclinical hypothyroidism, schizoid personality disorder, Parkinson disease, posttraumatic stress disorder, and hyperammonemia.

Upon admission, Mr. S’s vital signs are within normal limits except for an elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (4.54 mIU/L; reference range 0.40 to 4.50 mIU/L). Prior cognitive testing results and updated ammonia levels are unavailable. Mr. S’s current medications include acetaminophen 650 mg every 4 hours as needed for pain, calcium carbonate/vitamin D twice daily for bone health, carbidopa/levodopa 25/100 mg twice daily for Parkinson disease, melatonin 3 mg/d at bedtime for insomnia, quetiapine 25 mg twice daily for psychosis with disturbance of behavior and 12.5 mg every 4 hours as needed for agitation, and trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime for insomnia. Before Mr. S was admitted, previous therapy with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) had been tapered and discontinued. Mr. S had also started antipsychotic therapy at another facility due to worsening behaviors.

In patients with dementia, the brain is experiencing neurodegeneration. Progressively, neurons may stop functioning, lose connections with other neurons, and ultimately face cell death. The specific dementia diagnosis and its clinical features depend on the type of neurons and region of the brain affected.1,2

FTD occurs in response to damage to the frontal and temporal lobes. The frontal lobe correlates to executive functioning, while the temporal lobe plays a role in speech and comprehension. Damage to these areas may result in loss of movement, trouble speaking, difficulty solving complex problems, and problems with social behavior. Specifically, damage to the orbital frontal cortex may cause disinhibition and abnormal behaviors, including emotional lability, vulgarity, and indifference to social nuances.1 Within an FTD diagnosis, there are 3 disorders: behavioral-variant FTD (bvFTD), semantic dementia, and progressive nonfluent aphasia.1 Specifically, bvFTD can result in abnormal sexual behaviors such as making sexually inappropriate statements, masturbating in public, undressing in public, inappropriately or aggressively touching others, or confusing another individual as an intimate partner. In addition to cognitive impairment, these neurobehavioral symptoms can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life while increasing caregiver burden.2

Occurring at a similar frequency to Alzheimer’s disease in patients age <65, FTD is one of the more common causes of early-onset dementia. The mean age of onset is 58 and onset after age 75 is particularly unusual. Memory may not be affected early in the course of the disease, but social changes are likely. As FTD progresses, symptoms will resemble those of Alzheimer’s disease and patients will require assistance with activities of daily living. In later stages of FTD, patients will exhibit language and behavior symptoms. Due to its unique progression, FTD can be commonly misdiagnosed as other mental illnesses or neurocognitive disorders.1

Approaches to treatment: What to consider

Both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions are appropriate for addressing FTD. Because nonpharmacologic options improve patient safety and overall physical health, they should be used whenever practical. These interventions include safe driving measures, exercise, speech therapy, redirection, offering simple choices when making decisions, and managing environmental cues for behaviors that should be encouraged or discouraged.3

There are no FDA-approved medications to cure or slow the progression of FTD. Therefore, treatment is focused on alleviating neurobehavioral symptoms. The symptoms depend on the type of FTD the patient has; they include cognitive impairment, anxiety, insomnia or sleep disturbances, compulsive behaviors, speech and language problems, and agitation. While many medications have been commonly used for symptomatic relief, evidence for the efficacy of these treatments in FTD is limited.2

Continue to: A review of the literature...

A review of the literature on potential treatments for cognitive impairment and behavioral symptoms of FTD identified 2 trials and 1 case series (Table 14-6) in addition to a 2014 review article7 of current pharmacologic treatments. These trials evaluated cognitive improvement with rivastigmine, memantine, galantamine, and donepezil. None of the trials found a significant benefit from any of these medications for cognitive improvement in FTD. Data were conflicting on whether these medications improved or worsened behavioral symptoms. For example, the case series of 3 patients by Swanberg6 suggested improvement in behavior with memantine, while an open-label study analyzed in a 2014 review article7 found that donepezil may have worsened behaviors. Use of cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine in FTD is not recommended unless it is not certain if the patient has FTD or Alzheimer’s disease.7

Addressing sexual behaviors. Creating a treatment regimen for FTD behavioral symptoms—specifically for abnormal sexual behaviors—can be challenging. Before starting pharmacotherapy directed at behavioral symptoms secondary to FTD, other causes of symptoms such as delirium, pain, or discomfort should be excluded. Nonpharmacologic approaches should be aimed at the type of sexual behavior and likely underlying environmental cause. For example, patients may inappropriately disrobe themselves. To address this behavior, hospital staff or caregivers should first eliminate environmental causes by ensuring the room is at a comfortable temperature, dressing the patient in light, breathable clothing, or checking if the patient needs to use the bathroom. If no environmental causes are found, a one-piece jumpsuit with closures on the back of the garment could be utilized to increase the difficulty of undressing.

Other nonpharmacologic methods include providing private areas for patients who are behaving inappropriately or removing potentially stimulating television or media from the environment. Another option is to increase the use of positive, pleasant stimuli. One approach that has shown benefit is music therapy, utilizing popular music genres from the patient’s youth.3

Evidence for pharmacotherapy is limited and largely from case reports and case series. A 2020 meta-analysis by Trieu et al8 reviewed 23 studies to expand on current clinical guidance for patients with bvFTD. These studies showed improvements in behavioral symptoms and reductions in caregiver fatigue with citalopram, trazodone, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine. Six of the trials included in this meta-analysis that evaluated these 4 medications are summarized in Table 2.9-14

Due to the lower risk of adverse effects and favorable safety profiles, SSRIs and trazodone are considered first-line treatment options. Benefit from these medications is theorized to be a result of their serotonergic effects, because serotonin abnormalities and dysfunction have been linked to FTD symptoms. For example, in a patient experiencing hypersexuality, the common adverse effect of low libido associated with SSRIs can be particularly beneficial.8

Continue to: Other medication classes studied in patients...

Other medication classes studied in patients with FTD include antipsychotics, stimulants, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, and hormonal therapies. In addition to a black box warning for increased mortality in older patients with dementia-related psychosis, antipsychotics are associated with other serious adverse effects and should be used with caution.7

FTD is a debilitating disease that has a major impact on quality of life, particularly when behavioral symptoms accompany cognitive decline. Though some therapies may possibly improve behavioral symptoms, their routine use remains controversial due to a lack of clear evidence of benefit. In caring for patients with FTD and behavioral symptoms, a multimodal, team-based approach is vital.1

CASE CONTINUED

The treatment team starts Mr. S on several of the modalities discussed in this article over the span of 2 years, with limited efficacy. Nonpharmacologic methods do not provide much benefit because Mr. S is extremely difficult to redirect. Given Mr. S’s past trials of SSRIs prior to admission, sertraline was retrialed and titrated over 2 years. The highest dose utilized during his admission was 200 mg/d. The team starts estrogen therapy but tapers and discontinues it due to ineffectiveness. Mr. S’s use of carbidopa/levodopa is thought to be contributing to his behavioral abnormalities, so the team tapers it to discontinuation; however, Mr. S’s sexually inappropriate behaviors and agitation continue. The team initiates a plan to reduce the dose of quetiapine and switch to gabapentin, but Mr. S fails gradual dose reduction due to his worsening behaviors. He starts gabapentin. The team gradually increases the dose of gabapentin to decrease libido and agitation, respectively. The increase in sertraline dose and use of nonpharmacologic modalities causes Mr. S’s use of as-needed antipsychotics to decrease.

Related Resources

- Ellison JM. What are the stages of frontotemporal dementia? BrightFocus Foundation. July 5, 2021. Accessed July 7, 2023. https://www.brightfocus.org/alzheimers/article/what-are-stages-frontotemporal-dementia

- Dementia and sexually inappropriate behavior. ReaDementia. January 31, 2022. Accessed July 7, 2023. https://readementia.com/dementia-and-sexually-inappropriate-behavior/

Drug Brand Names

Carbidopa/levodopa • Sinemet

Citalopram • Celexa

Donepezil • Aricept

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Galantamine • Razadyne

Memantine • Namenda

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Rivastigmine • Exelon

Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Desyrel

Mr. S, age 77, is admitted to a long-term care facility due to progressive cognitive impairment and sexually inappropriate behavior. He has a history of sexual assault of medical staff. His medical history includes significant frontotemporal dementia (FTD) with behavioral disturbances, abnormal sexual behaviors, subclinical hypothyroidism, schizoid personality disorder, Parkinson disease, posttraumatic stress disorder, and hyperammonemia.

Upon admission, Mr. S’s vital signs are within normal limits except for an elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (4.54 mIU/L; reference range 0.40 to 4.50 mIU/L). Prior cognitive testing results and updated ammonia levels are unavailable. Mr. S’s current medications include acetaminophen 650 mg every 4 hours as needed for pain, calcium carbonate/vitamin D twice daily for bone health, carbidopa/levodopa 25/100 mg twice daily for Parkinson disease, melatonin 3 mg/d at bedtime for insomnia, quetiapine 25 mg twice daily for psychosis with disturbance of behavior and 12.5 mg every 4 hours as needed for agitation, and trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime for insomnia. Before Mr. S was admitted, previous therapy with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) had been tapered and discontinued. Mr. S had also started antipsychotic therapy at another facility due to worsening behaviors.

In patients with dementia, the brain is experiencing neurodegeneration. Progressively, neurons may stop functioning, lose connections with other neurons, and ultimately face cell death. The specific dementia diagnosis and its clinical features depend on the type of neurons and region of the brain affected.1,2

FTD occurs in response to damage to the frontal and temporal lobes. The frontal lobe correlates to executive functioning, while the temporal lobe plays a role in speech and comprehension. Damage to these areas may result in loss of movement, trouble speaking, difficulty solving complex problems, and problems with social behavior. Specifically, damage to the orbital frontal cortex may cause disinhibition and abnormal behaviors, including emotional lability, vulgarity, and indifference to social nuances.1 Within an FTD diagnosis, there are 3 disorders: behavioral-variant FTD (bvFTD), semantic dementia, and progressive nonfluent aphasia.1 Specifically, bvFTD can result in abnormal sexual behaviors such as making sexually inappropriate statements, masturbating in public, undressing in public, inappropriately or aggressively touching others, or confusing another individual as an intimate partner. In addition to cognitive impairment, these neurobehavioral symptoms can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life while increasing caregiver burden.2

Occurring at a similar frequency to Alzheimer’s disease in patients age <65, FTD is one of the more common causes of early-onset dementia. The mean age of onset is 58 and onset after age 75 is particularly unusual. Memory may not be affected early in the course of the disease, but social changes are likely. As FTD progresses, symptoms will resemble those of Alzheimer’s disease and patients will require assistance with activities of daily living. In later stages of FTD, patients will exhibit language and behavior symptoms. Due to its unique progression, FTD can be commonly misdiagnosed as other mental illnesses or neurocognitive disorders.1

Approaches to treatment: What to consider

Both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions are appropriate for addressing FTD. Because nonpharmacologic options improve patient safety and overall physical health, they should be used whenever practical. These interventions include safe driving measures, exercise, speech therapy, redirection, offering simple choices when making decisions, and managing environmental cues for behaviors that should be encouraged or discouraged.3

There are no FDA-approved medications to cure or slow the progression of FTD. Therefore, treatment is focused on alleviating neurobehavioral symptoms. The symptoms depend on the type of FTD the patient has; they include cognitive impairment, anxiety, insomnia or sleep disturbances, compulsive behaviors, speech and language problems, and agitation. While many medications have been commonly used for symptomatic relief, evidence for the efficacy of these treatments in FTD is limited.2

Continue to: A review of the literature...

A review of the literature on potential treatments for cognitive impairment and behavioral symptoms of FTD identified 2 trials and 1 case series (Table 14-6) in addition to a 2014 review article7 of current pharmacologic treatments. These trials evaluated cognitive improvement with rivastigmine, memantine, galantamine, and donepezil. None of the trials found a significant benefit from any of these medications for cognitive improvement in FTD. Data were conflicting on whether these medications improved or worsened behavioral symptoms. For example, the case series of 3 patients by Swanberg6 suggested improvement in behavior with memantine, while an open-label study analyzed in a 2014 review article7 found that donepezil may have worsened behaviors. Use of cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine in FTD is not recommended unless it is not certain if the patient has FTD or Alzheimer’s disease.7

Addressing sexual behaviors. Creating a treatment regimen for FTD behavioral symptoms—specifically for abnormal sexual behaviors—can be challenging. Before starting pharmacotherapy directed at behavioral symptoms secondary to FTD, other causes of symptoms such as delirium, pain, or discomfort should be excluded. Nonpharmacologic approaches should be aimed at the type of sexual behavior and likely underlying environmental cause. For example, patients may inappropriately disrobe themselves. To address this behavior, hospital staff or caregivers should first eliminate environmental causes by ensuring the room is at a comfortable temperature, dressing the patient in light, breathable clothing, or checking if the patient needs to use the bathroom. If no environmental causes are found, a one-piece jumpsuit with closures on the back of the garment could be utilized to increase the difficulty of undressing.

Other nonpharmacologic methods include providing private areas for patients who are behaving inappropriately or removing potentially stimulating television or media from the environment. Another option is to increase the use of positive, pleasant stimuli. One approach that has shown benefit is music therapy, utilizing popular music genres from the patient’s youth.3

Evidence for pharmacotherapy is limited and largely from case reports and case series. A 2020 meta-analysis by Trieu et al8 reviewed 23 studies to expand on current clinical guidance for patients with bvFTD. These studies showed improvements in behavioral symptoms and reductions in caregiver fatigue with citalopram, trazodone, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine. Six of the trials included in this meta-analysis that evaluated these 4 medications are summarized in Table 2.9-14

Due to the lower risk of adverse effects and favorable safety profiles, SSRIs and trazodone are considered first-line treatment options. Benefit from these medications is theorized to be a result of their serotonergic effects, because serotonin abnormalities and dysfunction have been linked to FTD symptoms. For example, in a patient experiencing hypersexuality, the common adverse effect of low libido associated with SSRIs can be particularly beneficial.8

Continue to: Other medication classes studied in patients...

Other medication classes studied in patients with FTD include antipsychotics, stimulants, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, and hormonal therapies. In addition to a black box warning for increased mortality in older patients with dementia-related psychosis, antipsychotics are associated with other serious adverse effects and should be used with caution.7

FTD is a debilitating disease that has a major impact on quality of life, particularly when behavioral symptoms accompany cognitive decline. Though some therapies may possibly improve behavioral symptoms, their routine use remains controversial due to a lack of clear evidence of benefit. In caring for patients with FTD and behavioral symptoms, a multimodal, team-based approach is vital.1

CASE CONTINUED

The treatment team starts Mr. S on several of the modalities discussed in this article over the span of 2 years, with limited efficacy. Nonpharmacologic methods do not provide much benefit because Mr. S is extremely difficult to redirect. Given Mr. S’s past trials of SSRIs prior to admission, sertraline was retrialed and titrated over 2 years. The highest dose utilized during his admission was 200 mg/d. The team starts estrogen therapy but tapers and discontinues it due to ineffectiveness. Mr. S’s use of carbidopa/levodopa is thought to be contributing to his behavioral abnormalities, so the team tapers it to discontinuation; however, Mr. S’s sexually inappropriate behaviors and agitation continue. The team initiates a plan to reduce the dose of quetiapine and switch to gabapentin, but Mr. S fails gradual dose reduction due to his worsening behaviors. He starts gabapentin. The team gradually increases the dose of gabapentin to decrease libido and agitation, respectively. The increase in sertraline dose and use of nonpharmacologic modalities causes Mr. S’s use of as-needed antipsychotics to decrease.

Related Resources

- Ellison JM. What are the stages of frontotemporal dementia? BrightFocus Foundation. July 5, 2021. Accessed July 7, 2023. https://www.brightfocus.org/alzheimers/article/what-are-stages-frontotemporal-dementia

- Dementia and sexually inappropriate behavior. ReaDementia. January 31, 2022. Accessed July 7, 2023. https://readementia.com/dementia-and-sexually-inappropriate-behavior/

Drug Brand Names

Carbidopa/levodopa • Sinemet

Citalopram • Celexa

Donepezil • Aricept

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Galantamine • Razadyne

Memantine • Namenda

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Rivastigmine • Exelon

Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Desyrel

1. Grossman M. Frontotemporal dementia: a review. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8(4):566-583. doi:10.1017/s1355617702814357

2. The Johns Hopkins University. Frontotemporal dementia. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Accessed September 12, 2021. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/dementia/frontotemporal-dementia

3. Shinagawa S, Nakajima S, Plitman E, et al. Non-pharmacological management for patients with frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45(1):283-293. doi:10.3233/JAD-142109

4. Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello RM, et al. Rivastigmine in frontotemporal dementia: an open-label study. Drugs Aging. 2004;21(14):931-937. doi:10.2165/00002512-200421140-00003

5. Diehl-Schmid J, Förstl H, Perneczky R, et al. A 6-month, open-label study for memantine in patients with frontotemporal dementia. In J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(7):754-759. doi:10.1002/gps.1973

6. Swanberg MM. Memantine for behavioral disturbances in frontotemporal dementia: a case series. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(2):164-166. doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e318047df5d

7. Tsai RM, Boxer AL. Treatment of frontotemporal dementia. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2014;16(11):319. doi:10.1007/s11940-014-0319-0

8. Trieu C, Gossink F, Stek ML, et al. Effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for symptoms of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2020;33(1):1-15. doi:10.1097/WNN.0000000000000217

9. Deakin JB, Rahman S, Nestor PJ, et al. Paroxetine does not improve symptoms and impairs cognition in frontotemporal dementia: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;172(4):400-408. doi:10.1007/s00213-003-1686-5

10. Herrmann N, Black SE, Chow T, et al. Serotonergic function and treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of frontotemporal dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(9):789-797. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e31823033f3

11. Ikeda M, Shigenobu K, Fukuhara R, et al. Efficacy of fluvoxamine as a treatment for behavioral symptoms in frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(3):117-121. doi:10.1159/000076343

12. Lebert F, Stekke W, Hasenbroekx C, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: a randomised, controlled trial with trazodone. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(4):355-359. doi:10.1159/000077171

13. Lebert F. Behavioral benefits of trazodone are sustained for the long term in frontotemporal dementia. Therapy. 2006;3(1):93-96. doi:10.1586/14750708.3.1.93

14. Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello RM, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: paroxetine as a possible treatment of behavior symptoms. A randomized, controlled, open 14-month study. Eur Neurol. 2003;49(1):13-19. doi:10.1159/000067021

1. Grossman M. Frontotemporal dementia: a review. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8(4):566-583. doi:10.1017/s1355617702814357

2. The Johns Hopkins University. Frontotemporal dementia. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Accessed September 12, 2021. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/dementia/frontotemporal-dementia

3. Shinagawa S, Nakajima S, Plitman E, et al. Non-pharmacological management for patients with frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45(1):283-293. doi:10.3233/JAD-142109

4. Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello RM, et al. Rivastigmine in frontotemporal dementia: an open-label study. Drugs Aging. 2004;21(14):931-937. doi:10.2165/00002512-200421140-00003

5. Diehl-Schmid J, Förstl H, Perneczky R, et al. A 6-month, open-label study for memantine in patients with frontotemporal dementia. In J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(7):754-759. doi:10.1002/gps.1973

6. Swanberg MM. Memantine for behavioral disturbances in frontotemporal dementia: a case series. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(2):164-166. doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e318047df5d

7. Tsai RM, Boxer AL. Treatment of frontotemporal dementia. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2014;16(11):319. doi:10.1007/s11940-014-0319-0

8. Trieu C, Gossink F, Stek ML, et al. Effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for symptoms of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2020;33(1):1-15. doi:10.1097/WNN.0000000000000217

9. Deakin JB, Rahman S, Nestor PJ, et al. Paroxetine does not improve symptoms and impairs cognition in frontotemporal dementia: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;172(4):400-408. doi:10.1007/s00213-003-1686-5

10. Herrmann N, Black SE, Chow T, et al. Serotonergic function and treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of frontotemporal dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(9):789-797. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e31823033f3

11. Ikeda M, Shigenobu K, Fukuhara R, et al. Efficacy of fluvoxamine as a treatment for behavioral symptoms in frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(3):117-121. doi:10.1159/000076343

12. Lebert F, Stekke W, Hasenbroekx C, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: a randomised, controlled trial with trazodone. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(4):355-359. doi:10.1159/000077171

13. Lebert F. Behavioral benefits of trazodone are sustained for the long term in frontotemporal dementia. Therapy. 2006;3(1):93-96. doi:10.1586/14750708.3.1.93

14. Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello RM, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: paroxetine as a possible treatment of behavior symptoms. A randomized, controlled, open 14-month study. Eur Neurol. 2003;49(1):13-19. doi:10.1159/000067021

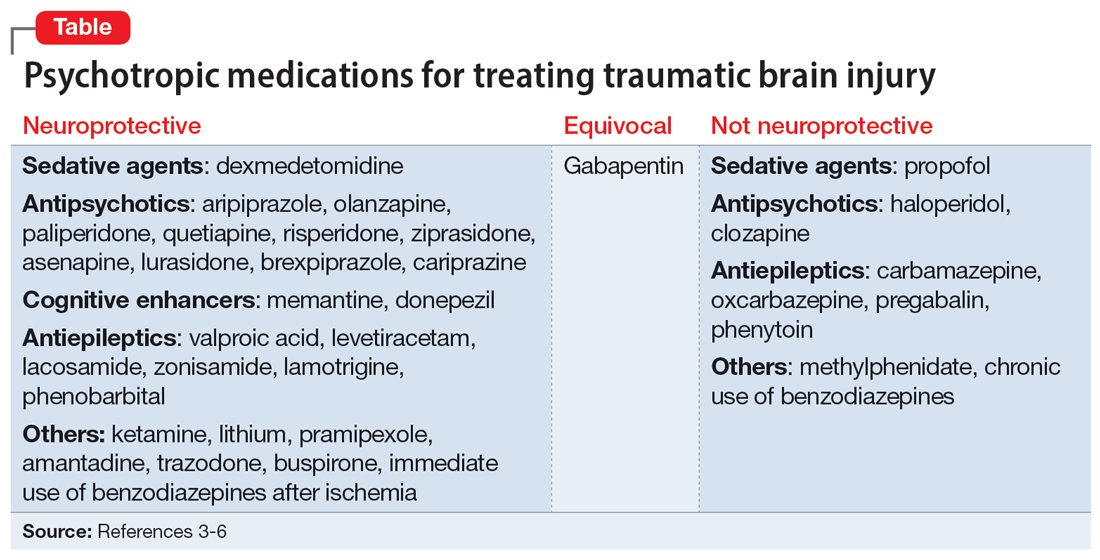

Agitated and depressed with a traumatic brain injury

CASE TBI as a result of self-harm