User login

Commentary: Updates in mantle cell lymphoma, September 2023

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is a rare subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that is characterized by t(11;14) and cyclin D1 overexpression. It is also known to be clinically heterogenous, with disease presentations ranging from indolent to aggressive. Baseline risk can be determined on the basis of a combination of clinical and pathologic features. A key prognostic tool, for example, is the Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index-Combined (MIPI-c), which integrates the standard MIPI clinical factors (age, performance status, lactate dehydrogenase, and leukocyte count) with estimates of proliferation (Ki-67).1 Other features, including the presence of TP53 alterations, have also been associated with poor outcomes, even with intensive therapy.2

Recently, a study aimed to further refine prognostication in MCL in order to identify high-risk patients that may be more likely to benefit from novel treatment strategies (Scheubeck et al). This retrospective study included 684 patients with MCL from the MCL-Younger and MCL-Elderly trials with evaluable data for Ki-67 or p53 expression (a surrogate for TP53 alterations). Patients were classified as having high-risk disease on the basis of a high-risk MIPI-c or p53 expression > 50% or as having low-risk disease on the basis of low, low-intermediate, or high-intermediate MIPI-c and p53 expression ≤ 50%. Patients with high-risk disease had significantly shorter median failure-free survival (1.1 vs 5.6 years; P < .0001) and overall survival (2.2 vs 13.2 years; P < .0001) compared with those with low-risk disease. The differences were confirmed in two validation cohorts from the Italian MCL0208 and Nordic-MCL4 trials. These data highlight the poor outcomes of conventional therapy in patients with high-risk MCL. Evaluation of novel approaches should be considered in these patients.

Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors have been promising options for patients with MCL, including those with high-risk features. Acalabrutinib is a second-generation covalent BTK inhibitor that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for patients who have received at least one prior line of therapy. The final results of the single-arm, phase 2 ACE-LY-004 study recently demonstrated long-term safety and efficacy in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL (Le Gouill et al). The overall and complete response rates were 81.5% (95% CI 73.5%-87.9%) and 47.6% (95% CI 38.5%-56.7%), respectively. After a 38.1-month median follow-up, the median duration of response and progression-free survival were 28.6 months (95% CI 17.5-39.1) and 22.0 months (95% CI 16.6-33.3), respectively. Responses were also seen in patients with high-risk features, including blastoid morphology, high-risk MIPI score, and high Ki-67. No new safety signals were observed. This study confirms the role of BTK inhibitors in MCL and providers longer-term estimates of response. Evaluation of BTK inhibitors in earlier lines of therapy and in combination with other agents are ongoing.

Although the majority of patients with MCL will have favorable responses to initial therapy, those with high-risk features, particularly TP53 aberrations, have poor outcomes with standard approaches. Despite a growing number of treatment options in the relapsed setting, such as targeted therapies and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, relapses remain common. Allogenic stem cell transplantation can be associated with prolonged response for patients with relapsed MCL, though it has the potential for significant treatment-associated toxicity.

Recently, prolonged follow-up of a retrospective cohort of patients with MCL, including a subset with TP53 aberrations, was reported (Lew et al). Thirty-six patients with MCL were included, including 13 with TP53-mutated disease. A subset of patients (61%) received an allogeneic transplant in first remission. The estimated overall survival rates after allogenic transplant were 56% (95% CI 36%-72%) at 10 years for the overall cohort and 59% (95% CI 21%-75%) at 4 years for patients with TP53-mutated disease at median follow-ups of 10.8 and 4.2 years, respectively. No relapses were observed in the TP53-mutated subset beyond 6 months after transplantation. These data suggest a potentially curative option for patients with high-risk MCL. Given the availability of CAR T-cell therapy, the optimal timing of allogenic stem cell transplant has become less clear for patients with TP53-mutant disease. Although this study was small and retrospective, these data are encouraging for patients with high-risk disease.

Additional References

1. Hoster E, Rosenwald A, Berger F, et al. Prognostic value of Ki-67 index, cytology, and growth pattern in mantle-cell lymphoma: Results from randomized trials of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1386-1394. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.8387

2. Eskelund CW, Dahl C, Hansen JW, et al. TP53 mutations identify younger mantle cell lymphoma patients who do not benefit from intensive chemoimmunotherapy. Blood. 2017;130:1903-1910. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-04-77973

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is a rare subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that is characterized by t(11;14) and cyclin D1 overexpression. It is also known to be clinically heterogenous, with disease presentations ranging from indolent to aggressive. Baseline risk can be determined on the basis of a combination of clinical and pathologic features. A key prognostic tool, for example, is the Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index-Combined (MIPI-c), which integrates the standard MIPI clinical factors (age, performance status, lactate dehydrogenase, and leukocyte count) with estimates of proliferation (Ki-67).1 Other features, including the presence of TP53 alterations, have also been associated with poor outcomes, even with intensive therapy.2

Recently, a study aimed to further refine prognostication in MCL in order to identify high-risk patients that may be more likely to benefit from novel treatment strategies (Scheubeck et al). This retrospective study included 684 patients with MCL from the MCL-Younger and MCL-Elderly trials with evaluable data for Ki-67 or p53 expression (a surrogate for TP53 alterations). Patients were classified as having high-risk disease on the basis of a high-risk MIPI-c or p53 expression > 50% or as having low-risk disease on the basis of low, low-intermediate, or high-intermediate MIPI-c and p53 expression ≤ 50%. Patients with high-risk disease had significantly shorter median failure-free survival (1.1 vs 5.6 years; P < .0001) and overall survival (2.2 vs 13.2 years; P < .0001) compared with those with low-risk disease. The differences were confirmed in two validation cohorts from the Italian MCL0208 and Nordic-MCL4 trials. These data highlight the poor outcomes of conventional therapy in patients with high-risk MCL. Evaluation of novel approaches should be considered in these patients.

Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors have been promising options for patients with MCL, including those with high-risk features. Acalabrutinib is a second-generation covalent BTK inhibitor that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for patients who have received at least one prior line of therapy. The final results of the single-arm, phase 2 ACE-LY-004 study recently demonstrated long-term safety and efficacy in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL (Le Gouill et al). The overall and complete response rates were 81.5% (95% CI 73.5%-87.9%) and 47.6% (95% CI 38.5%-56.7%), respectively. After a 38.1-month median follow-up, the median duration of response and progression-free survival were 28.6 months (95% CI 17.5-39.1) and 22.0 months (95% CI 16.6-33.3), respectively. Responses were also seen in patients with high-risk features, including blastoid morphology, high-risk MIPI score, and high Ki-67. No new safety signals were observed. This study confirms the role of BTK inhibitors in MCL and providers longer-term estimates of response. Evaluation of BTK inhibitors in earlier lines of therapy and in combination with other agents are ongoing.

Although the majority of patients with MCL will have favorable responses to initial therapy, those with high-risk features, particularly TP53 aberrations, have poor outcomes with standard approaches. Despite a growing number of treatment options in the relapsed setting, such as targeted therapies and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, relapses remain common. Allogenic stem cell transplantation can be associated with prolonged response for patients with relapsed MCL, though it has the potential for significant treatment-associated toxicity.

Recently, prolonged follow-up of a retrospective cohort of patients with MCL, including a subset with TP53 aberrations, was reported (Lew et al). Thirty-six patients with MCL were included, including 13 with TP53-mutated disease. A subset of patients (61%) received an allogeneic transplant in first remission. The estimated overall survival rates after allogenic transplant were 56% (95% CI 36%-72%) at 10 years for the overall cohort and 59% (95% CI 21%-75%) at 4 years for patients with TP53-mutated disease at median follow-ups of 10.8 and 4.2 years, respectively. No relapses were observed in the TP53-mutated subset beyond 6 months after transplantation. These data suggest a potentially curative option for patients with high-risk MCL. Given the availability of CAR T-cell therapy, the optimal timing of allogenic stem cell transplant has become less clear for patients with TP53-mutant disease. Although this study was small and retrospective, these data are encouraging for patients with high-risk disease.

Additional References

1. Hoster E, Rosenwald A, Berger F, et al. Prognostic value of Ki-67 index, cytology, and growth pattern in mantle-cell lymphoma: Results from randomized trials of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1386-1394. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.8387

2. Eskelund CW, Dahl C, Hansen JW, et al. TP53 mutations identify younger mantle cell lymphoma patients who do not benefit from intensive chemoimmunotherapy. Blood. 2017;130:1903-1910. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-04-77973

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is a rare subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that is characterized by t(11;14) and cyclin D1 overexpression. It is also known to be clinically heterogenous, with disease presentations ranging from indolent to aggressive. Baseline risk can be determined on the basis of a combination of clinical and pathologic features. A key prognostic tool, for example, is the Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index-Combined (MIPI-c), which integrates the standard MIPI clinical factors (age, performance status, lactate dehydrogenase, and leukocyte count) with estimates of proliferation (Ki-67).1 Other features, including the presence of TP53 alterations, have also been associated with poor outcomes, even with intensive therapy.2

Recently, a study aimed to further refine prognostication in MCL in order to identify high-risk patients that may be more likely to benefit from novel treatment strategies (Scheubeck et al). This retrospective study included 684 patients with MCL from the MCL-Younger and MCL-Elderly trials with evaluable data for Ki-67 or p53 expression (a surrogate for TP53 alterations). Patients were classified as having high-risk disease on the basis of a high-risk MIPI-c or p53 expression > 50% or as having low-risk disease on the basis of low, low-intermediate, or high-intermediate MIPI-c and p53 expression ≤ 50%. Patients with high-risk disease had significantly shorter median failure-free survival (1.1 vs 5.6 years; P < .0001) and overall survival (2.2 vs 13.2 years; P < .0001) compared with those with low-risk disease. The differences were confirmed in two validation cohorts from the Italian MCL0208 and Nordic-MCL4 trials. These data highlight the poor outcomes of conventional therapy in patients with high-risk MCL. Evaluation of novel approaches should be considered in these patients.

Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors have been promising options for patients with MCL, including those with high-risk features. Acalabrutinib is a second-generation covalent BTK inhibitor that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for patients who have received at least one prior line of therapy. The final results of the single-arm, phase 2 ACE-LY-004 study recently demonstrated long-term safety and efficacy in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL (Le Gouill et al). The overall and complete response rates were 81.5% (95% CI 73.5%-87.9%) and 47.6% (95% CI 38.5%-56.7%), respectively. After a 38.1-month median follow-up, the median duration of response and progression-free survival were 28.6 months (95% CI 17.5-39.1) and 22.0 months (95% CI 16.6-33.3), respectively. Responses were also seen in patients with high-risk features, including blastoid morphology, high-risk MIPI score, and high Ki-67. No new safety signals were observed. This study confirms the role of BTK inhibitors in MCL and providers longer-term estimates of response. Evaluation of BTK inhibitors in earlier lines of therapy and in combination with other agents are ongoing.

Although the majority of patients with MCL will have favorable responses to initial therapy, those with high-risk features, particularly TP53 aberrations, have poor outcomes with standard approaches. Despite a growing number of treatment options in the relapsed setting, such as targeted therapies and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, relapses remain common. Allogenic stem cell transplantation can be associated with prolonged response for patients with relapsed MCL, though it has the potential for significant treatment-associated toxicity.

Recently, prolonged follow-up of a retrospective cohort of patients with MCL, including a subset with TP53 aberrations, was reported (Lew et al). Thirty-six patients with MCL were included, including 13 with TP53-mutated disease. A subset of patients (61%) received an allogeneic transplant in first remission. The estimated overall survival rates after allogenic transplant were 56% (95% CI 36%-72%) at 10 years for the overall cohort and 59% (95% CI 21%-75%) at 4 years for patients with TP53-mutated disease at median follow-ups of 10.8 and 4.2 years, respectively. No relapses were observed in the TP53-mutated subset beyond 6 months after transplantation. These data suggest a potentially curative option for patients with high-risk MCL. Given the availability of CAR T-cell therapy, the optimal timing of allogenic stem cell transplant has become less clear for patients with TP53-mutant disease. Although this study was small and retrospective, these data are encouraging for patients with high-risk disease.

Additional References

1. Hoster E, Rosenwald A, Berger F, et al. Prognostic value of Ki-67 index, cytology, and growth pattern in mantle-cell lymphoma: Results from randomized trials of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1386-1394. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.8387

2. Eskelund CW, Dahl C, Hansen JW, et al. TP53 mutations identify younger mantle cell lymphoma patients who do not benefit from intensive chemoimmunotherapy. Blood. 2017;130:1903-1910. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-04-77973

Commentary: Cardiovascular risk, anti-drug antibodies, and prednisolone in RA, September 2023

Anti-drug antibody (ADA) testing for biologics, particularly anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, has been commercially available for several years, though its clinical use in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is not known owing to lack of prospective data. Bitoun and colleagues analyzed data from the European ABI-RA registry to evaluate the association between ADA and the anti–TNF monoclonal antibodies (mAb) etanercept, tocilizumab, and rituximab, and clinical response (as measured by disease activity scores, inflammatory markers, and European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology [EULAR] response rate). Higher rates of ADA positivity were seen in patients treated with rituximab (50%), anti-TNF mAb (38%), and tocilizumab (20%) compared with etanercept (6%). Patients who had a positive ADA test were less likely to have a EULAR response. In addition, patients treated with methotrexate were less likely to have persistent ADA. Though the study was not powered enough to detect differences between the drug classes, the evidence presented is compelling and suggests a role for measuring ADA in patients with RA who do not respond to treatment.

RA is well-known to be associated with cardiovascular disease, particularly atherosclerotic disease and heart failure, but its association with valvular heart disease and its progression has not been well-explored in the literature. Johnson and colleagues performed a cohort study of over 73,000 patients with RA in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system compared with 640,000 patients without RA to evaluate the incidence of aortic stenosis, need for intervention, and risk for death. Though the overall incidence rate was low (about 3%), patients with RA had a higher risk for aortic stenosis, with a hazard ratio of 1.48 compared with those without RA, as well as a higher risk for aortic valve replacement and aortic stenosis–related death. The risk for aortic stenosis was associated with hypertension, stroke, and other cardiovascular disease, as well as a body mass index > 30 kg/m2, although not with a history of smoking or diabetes. Because the study was performed using data from the VHA — that is, from predominantly male patients — this finding may not be generalizable. In addition, the diagnosis of aortic stenosis is generally reliant on echocardiography and may be detected while searching for other conditions not evaluated here (such as pericarditis). As such, these findings would not support routine screening in patients with RA without other reasons for suspicion of valvular heart disease.

In particular, the increase in cardiovascular risk associated with glucocorticoid therapy in patients with RA has received increased scrutiny, along with other side effects of systemic glucocorticoids. In a recent retrospective study, So and colleagues examined the clinical data of over 12,000 patients with RA treated in public hospitals in Hong Kong with a mean of 9 years of follow-up. Consistent with prior studies, systemic glucocorticoid use (prednisolone equivalent > 5 mg daily) was associated with an increased risk for adverse cardiovascular events, whereas lower doses did not increase cardiovascular risk. Because the data on some disease activity measures and traditional cardiovascular risk factors (such as smoking or obesity) were not available in the database, the study supports, but does not expand on, prior evidence regarding cardiovascular risk.

Almayali and colleagues also looked at glucocorticoid therapy in RA in a follow-up study to the previously published pragmatic randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled GLORIA study, which evaluated the effects of 5 mg/d prednisolone added to standard care for 2 years in patients with active RA who were age 65 years or older. In the current study, 191 patients out of the initial 451 were followed for 3 months and prednisolone tapered off. Patients who tapered off prednisolone had, as expected, an increased risk for flare but no evidence of adrenal insufficiency. Although, again, this is not likely to change practice, it does suggest that glucocorticoid tapering is a reasonable goal in RA therapeutic trials.

Anti-drug antibody (ADA) testing for biologics, particularly anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, has been commercially available for several years, though its clinical use in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is not known owing to lack of prospective data. Bitoun and colleagues analyzed data from the European ABI-RA registry to evaluate the association between ADA and the anti–TNF monoclonal antibodies (mAb) etanercept, tocilizumab, and rituximab, and clinical response (as measured by disease activity scores, inflammatory markers, and European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology [EULAR] response rate). Higher rates of ADA positivity were seen in patients treated with rituximab (50%), anti-TNF mAb (38%), and tocilizumab (20%) compared with etanercept (6%). Patients who had a positive ADA test were less likely to have a EULAR response. In addition, patients treated with methotrexate were less likely to have persistent ADA. Though the study was not powered enough to detect differences between the drug classes, the evidence presented is compelling and suggests a role for measuring ADA in patients with RA who do not respond to treatment.

RA is well-known to be associated with cardiovascular disease, particularly atherosclerotic disease and heart failure, but its association with valvular heart disease and its progression has not been well-explored in the literature. Johnson and colleagues performed a cohort study of over 73,000 patients with RA in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system compared with 640,000 patients without RA to evaluate the incidence of aortic stenosis, need for intervention, and risk for death. Though the overall incidence rate was low (about 3%), patients with RA had a higher risk for aortic stenosis, with a hazard ratio of 1.48 compared with those without RA, as well as a higher risk for aortic valve replacement and aortic stenosis–related death. The risk for aortic stenosis was associated with hypertension, stroke, and other cardiovascular disease, as well as a body mass index > 30 kg/m2, although not with a history of smoking or diabetes. Because the study was performed using data from the VHA — that is, from predominantly male patients — this finding may not be generalizable. In addition, the diagnosis of aortic stenosis is generally reliant on echocardiography and may be detected while searching for other conditions not evaluated here (such as pericarditis). As such, these findings would not support routine screening in patients with RA without other reasons for suspicion of valvular heart disease.

In particular, the increase in cardiovascular risk associated with glucocorticoid therapy in patients with RA has received increased scrutiny, along with other side effects of systemic glucocorticoids. In a recent retrospective study, So and colleagues examined the clinical data of over 12,000 patients with RA treated in public hospitals in Hong Kong with a mean of 9 years of follow-up. Consistent with prior studies, systemic glucocorticoid use (prednisolone equivalent > 5 mg daily) was associated with an increased risk for adverse cardiovascular events, whereas lower doses did not increase cardiovascular risk. Because the data on some disease activity measures and traditional cardiovascular risk factors (such as smoking or obesity) were not available in the database, the study supports, but does not expand on, prior evidence regarding cardiovascular risk.

Almayali and colleagues also looked at glucocorticoid therapy in RA in a follow-up study to the previously published pragmatic randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled GLORIA study, which evaluated the effects of 5 mg/d prednisolone added to standard care for 2 years in patients with active RA who were age 65 years or older. In the current study, 191 patients out of the initial 451 were followed for 3 months and prednisolone tapered off. Patients who tapered off prednisolone had, as expected, an increased risk for flare but no evidence of adrenal insufficiency. Although, again, this is not likely to change practice, it does suggest that glucocorticoid tapering is a reasonable goal in RA therapeutic trials.

Anti-drug antibody (ADA) testing for biologics, particularly anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, has been commercially available for several years, though its clinical use in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is not known owing to lack of prospective data. Bitoun and colleagues analyzed data from the European ABI-RA registry to evaluate the association between ADA and the anti–TNF monoclonal antibodies (mAb) etanercept, tocilizumab, and rituximab, and clinical response (as measured by disease activity scores, inflammatory markers, and European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology [EULAR] response rate). Higher rates of ADA positivity were seen in patients treated with rituximab (50%), anti-TNF mAb (38%), and tocilizumab (20%) compared with etanercept (6%). Patients who had a positive ADA test were less likely to have a EULAR response. In addition, patients treated with methotrexate were less likely to have persistent ADA. Though the study was not powered enough to detect differences between the drug classes, the evidence presented is compelling and suggests a role for measuring ADA in patients with RA who do not respond to treatment.

RA is well-known to be associated with cardiovascular disease, particularly atherosclerotic disease and heart failure, but its association with valvular heart disease and its progression has not been well-explored in the literature. Johnson and colleagues performed a cohort study of over 73,000 patients with RA in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system compared with 640,000 patients without RA to evaluate the incidence of aortic stenosis, need for intervention, and risk for death. Though the overall incidence rate was low (about 3%), patients with RA had a higher risk for aortic stenosis, with a hazard ratio of 1.48 compared with those without RA, as well as a higher risk for aortic valve replacement and aortic stenosis–related death. The risk for aortic stenosis was associated with hypertension, stroke, and other cardiovascular disease, as well as a body mass index > 30 kg/m2, although not with a history of smoking or diabetes. Because the study was performed using data from the VHA — that is, from predominantly male patients — this finding may not be generalizable. In addition, the diagnosis of aortic stenosis is generally reliant on echocardiography and may be detected while searching for other conditions not evaluated here (such as pericarditis). As such, these findings would not support routine screening in patients with RA without other reasons for suspicion of valvular heart disease.

In particular, the increase in cardiovascular risk associated with glucocorticoid therapy in patients with RA has received increased scrutiny, along with other side effects of systemic glucocorticoids. In a recent retrospective study, So and colleagues examined the clinical data of over 12,000 patients with RA treated in public hospitals in Hong Kong with a mean of 9 years of follow-up. Consistent with prior studies, systemic glucocorticoid use (prednisolone equivalent > 5 mg daily) was associated with an increased risk for adverse cardiovascular events, whereas lower doses did not increase cardiovascular risk. Because the data on some disease activity measures and traditional cardiovascular risk factors (such as smoking or obesity) were not available in the database, the study supports, but does not expand on, prior evidence regarding cardiovascular risk.

Almayali and colleagues also looked at glucocorticoid therapy in RA in a follow-up study to the previously published pragmatic randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled GLORIA study, which evaluated the effects of 5 mg/d prednisolone added to standard care for 2 years in patients with active RA who were age 65 years or older. In the current study, 191 patients out of the initial 451 were followed for 3 months and prednisolone tapered off. Patients who tapered off prednisolone had, as expected, an increased risk for flare but no evidence of adrenal insufficiency. Although, again, this is not likely to change practice, it does suggest that glucocorticoid tapering is a reasonable goal in RA therapeutic trials.

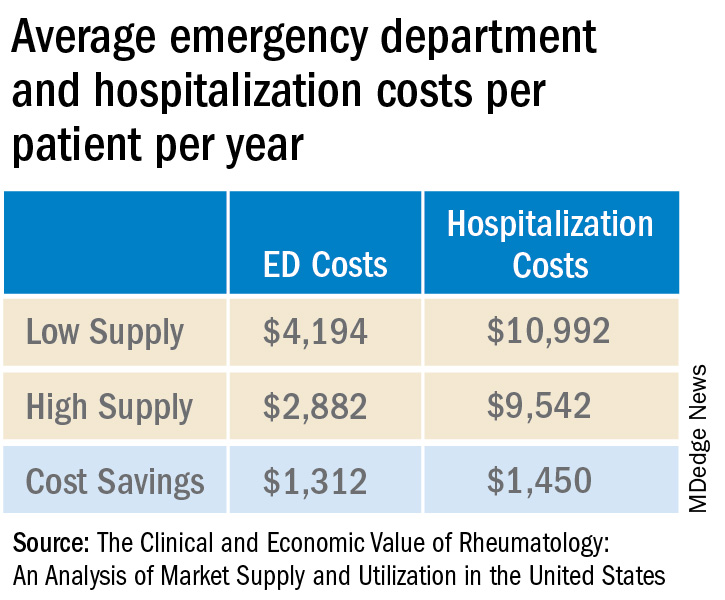

ACR: Rheumatologists help reduce ED, hospitalization costs

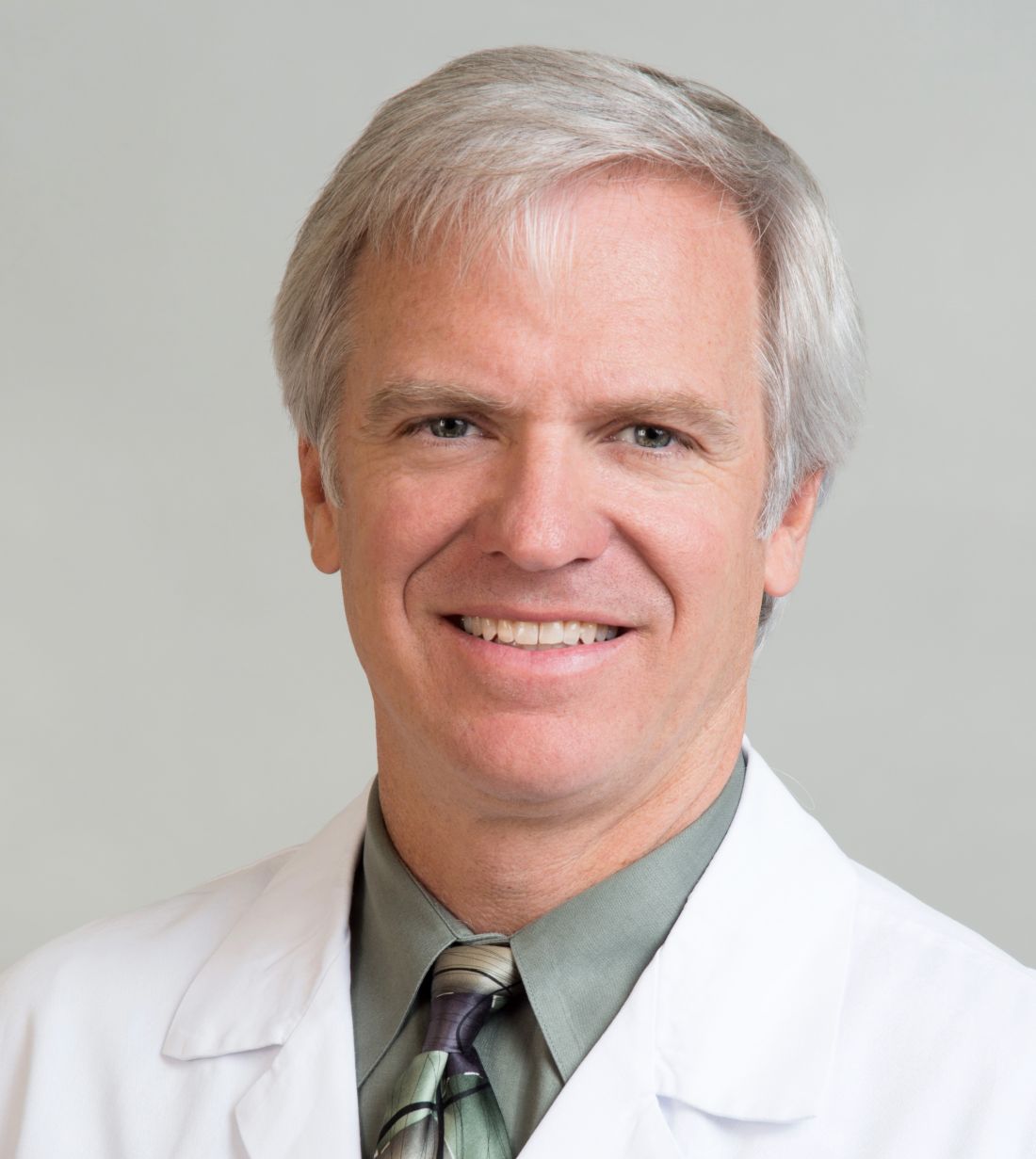

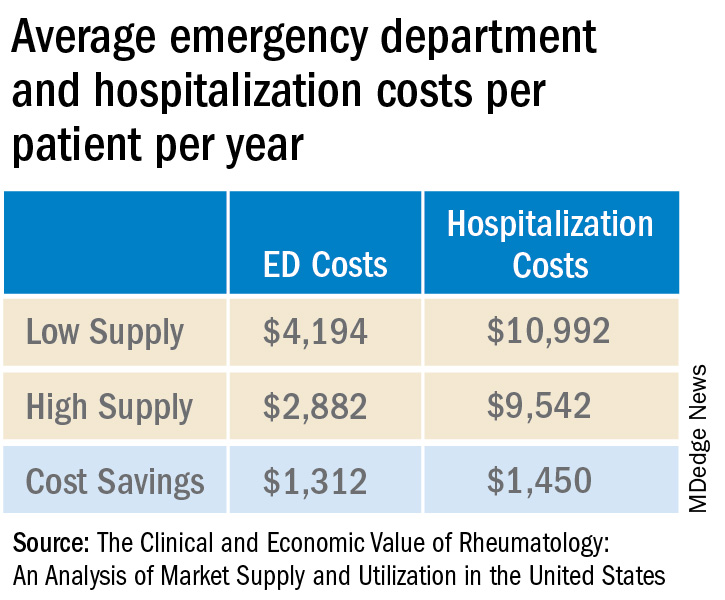

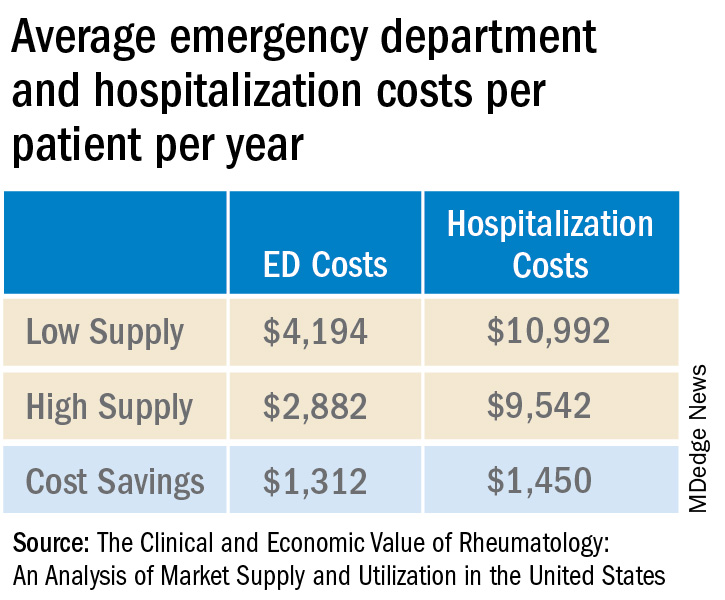

Rheumatology care can save health systems more than $2,700 per patient per year, according to a new report from the American College of Rheumatology.

In a white paper and corresponding position statement, the organization outlined how rheumatology care delivers financial benefits for health systems.

The work also highlighted prior research on the positive outcomes associated with rheumatology care, including a decline in hip and knee replacements for patients with rheumatoid arthritis after the introduction of biologics, while the total number of hip and knee replacements for patients with osteoarthritis increased, as well as lower 30-day readmission rates among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus with access to a rheumatology clinic post discharge.

“Many rheumatologists can attest to the value they bring to the care team at a health care system,” said Christina Downey, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at Loma Linda (Calif.) University, in a press release. She is the lead author of the white paper and chair of the ACR’s Government Affairs Committee. “Our goal with the paper and position statement is to emphasize what that value looks like from a preventive and financial perspective. A rheumatologist on the care team benefits patients, practices, and the economy.”

The analysis used adjusted claims insurance data to compare markets with a high vs. low supply of rheumatologists. A high supply was defined as at least 1.5 rheumatologists per 100,000 population, whereas a low supply was less than this amount. On average, markets with a high supply of rheumatologists had lower emergency department (ED) and hospitalization costs per patient per year.

Added together, high-supply rheumatology markets save on average $2,762 in ED visit and hospitalization costs per patient per year.

Dr. Downey and colleagues also tallied the direct and downstream billings associated with rheumatologists, including office visits, consultations, lab testing, and radiology services. The average revenue generated per rheumatologist was $3.5 million per year.

“Emphasizing the impact rheumatologists have on the entire medical community is more important than ever, especially as we contend with an impending rheumatology workforce shortage coupled with an expected increase in patient demand for rheumatologic care,” Dr. Downey said. “This paper supports our recruitment and sustainability efforts for the specialty by spotlighting the significant contributions we make every day and every year to patient outcomes, hospitals, and other health care practices.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rheumatology care can save health systems more than $2,700 per patient per year, according to a new report from the American College of Rheumatology.

In a white paper and corresponding position statement, the organization outlined how rheumatology care delivers financial benefits for health systems.

The work also highlighted prior research on the positive outcomes associated with rheumatology care, including a decline in hip and knee replacements for patients with rheumatoid arthritis after the introduction of biologics, while the total number of hip and knee replacements for patients with osteoarthritis increased, as well as lower 30-day readmission rates among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus with access to a rheumatology clinic post discharge.

“Many rheumatologists can attest to the value they bring to the care team at a health care system,” said Christina Downey, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at Loma Linda (Calif.) University, in a press release. She is the lead author of the white paper and chair of the ACR’s Government Affairs Committee. “Our goal with the paper and position statement is to emphasize what that value looks like from a preventive and financial perspective. A rheumatologist on the care team benefits patients, practices, and the economy.”

The analysis used adjusted claims insurance data to compare markets with a high vs. low supply of rheumatologists. A high supply was defined as at least 1.5 rheumatologists per 100,000 population, whereas a low supply was less than this amount. On average, markets with a high supply of rheumatologists had lower emergency department (ED) and hospitalization costs per patient per year.

Added together, high-supply rheumatology markets save on average $2,762 in ED visit and hospitalization costs per patient per year.

Dr. Downey and colleagues also tallied the direct and downstream billings associated with rheumatologists, including office visits, consultations, lab testing, and radiology services. The average revenue generated per rheumatologist was $3.5 million per year.

“Emphasizing the impact rheumatologists have on the entire medical community is more important than ever, especially as we contend with an impending rheumatology workforce shortage coupled with an expected increase in patient demand for rheumatologic care,” Dr. Downey said. “This paper supports our recruitment and sustainability efforts for the specialty by spotlighting the significant contributions we make every day and every year to patient outcomes, hospitals, and other health care practices.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rheumatology care can save health systems more than $2,700 per patient per year, according to a new report from the American College of Rheumatology.

In a white paper and corresponding position statement, the organization outlined how rheumatology care delivers financial benefits for health systems.

The work also highlighted prior research on the positive outcomes associated with rheumatology care, including a decline in hip and knee replacements for patients with rheumatoid arthritis after the introduction of biologics, while the total number of hip and knee replacements for patients with osteoarthritis increased, as well as lower 30-day readmission rates among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus with access to a rheumatology clinic post discharge.

“Many rheumatologists can attest to the value they bring to the care team at a health care system,” said Christina Downey, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at Loma Linda (Calif.) University, in a press release. She is the lead author of the white paper and chair of the ACR’s Government Affairs Committee. “Our goal with the paper and position statement is to emphasize what that value looks like from a preventive and financial perspective. A rheumatologist on the care team benefits patients, practices, and the economy.”

The analysis used adjusted claims insurance data to compare markets with a high vs. low supply of rheumatologists. A high supply was defined as at least 1.5 rheumatologists per 100,000 population, whereas a low supply was less than this amount. On average, markets with a high supply of rheumatologists had lower emergency department (ED) and hospitalization costs per patient per year.

Added together, high-supply rheumatology markets save on average $2,762 in ED visit and hospitalization costs per patient per year.

Dr. Downey and colleagues also tallied the direct and downstream billings associated with rheumatologists, including office visits, consultations, lab testing, and radiology services. The average revenue generated per rheumatologist was $3.5 million per year.

“Emphasizing the impact rheumatologists have on the entire medical community is more important than ever, especially as we contend with an impending rheumatology workforce shortage coupled with an expected increase in patient demand for rheumatologic care,” Dr. Downey said. “This paper supports our recruitment and sustainability efforts for the specialty by spotlighting the significant contributions we make every day and every year to patient outcomes, hospitals, and other health care practices.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Commentary: Alcohol, PPI use, BMI, and lymph node dissection in BC, September 2023

The use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) can affect the bioavailability and effectiveness of concomitant medications, including cancer therapies. A retrospective study by Lee and colleagues aimed to identify the clinical outcomes of patients with hormone receptor–positive (HR+) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative advanced or metastatic BC who were concomitantly using PPI and palbociclib. The study included 1310 patients, of which 344 received concomitant PPI plus palbociclib and 966 patients received palbociclib alone. Results showed that patients who received concomitant PPI plus palbociclib had significantly shorter progression-free survival (hazard ratio 1.76; 95% CI 1.46-2.13) and overall survival (hazard ratio 2.72; 95% CI 2.07-3.53) rates compared with those who received palbociclib alone. These results suggest that the concomitant use of PPI with palbociclib may alter the therapeutic efficacy of the drug. More research studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Pfeiler and colleagues examined the association of BMI with side effects, treatment discontinuation, and efficacy of palbociclib. This study looked at 5698 patients with early-stage HR+ BC who received palbociclib plus endocrine therapy as part of a preplanned analysis of the PALLAS trial. Results showed that in women who received adjuvant palbociclib, higher BMI was associated with a significantly lower rate of neutropenia (odds ratio for a 1-unit change in BMI 0.93; 95% CI 0.92-0.95) and a lower rate of treatment discontinuation (adjusted hazard ratio for a 10-unit change in BMI 0.75; 95% CI 0.67-0.83) compared with normal-weight patients. No effect of BMI on palbociclib efficacy was observed at 31 months of follow-up. Further studies are needed to validate these findings in different cohorts.

In cases of early-stage breast cancer (clinical T1, T2) where patients undergo upfront breast-conserving therapy and sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), completion of axillary lymph node dissection (CLND) is often omitted if only one or two positive sentinel lymph nodes are detected. A study by Zaveri and colleagues looked at outcomes among 548 patients with cT1-2 N0 BC who were treated with upfront mastectomy and had one or two positive lymph nodes on SLNB. The 5-year cumulative incidence rate of overall locoregional recurrence was comparable between patients who underwent vs those who did not undergo CLND (1.8% vs 1.3%; P = .93); receipt of post-mastectomy radiation therapy did not affect the locoregional recurrence rate in both categories of patients who underwent SLNB alone and SLNB with CLND (P = .1638). These results suggest that CLND may not necessarily improve outcomes in this patient population. Larger prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings.

The use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) can affect the bioavailability and effectiveness of concomitant medications, including cancer therapies. A retrospective study by Lee and colleagues aimed to identify the clinical outcomes of patients with hormone receptor–positive (HR+) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative advanced or metastatic BC who were concomitantly using PPI and palbociclib. The study included 1310 patients, of which 344 received concomitant PPI plus palbociclib and 966 patients received palbociclib alone. Results showed that patients who received concomitant PPI plus palbociclib had significantly shorter progression-free survival (hazard ratio 1.76; 95% CI 1.46-2.13) and overall survival (hazard ratio 2.72; 95% CI 2.07-3.53) rates compared with those who received palbociclib alone. These results suggest that the concomitant use of PPI with palbociclib may alter the therapeutic efficacy of the drug. More research studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Pfeiler and colleagues examined the association of BMI with side effects, treatment discontinuation, and efficacy of palbociclib. This study looked at 5698 patients with early-stage HR+ BC who received palbociclib plus endocrine therapy as part of a preplanned analysis of the PALLAS trial. Results showed that in women who received adjuvant palbociclib, higher BMI was associated with a significantly lower rate of neutropenia (odds ratio for a 1-unit change in BMI 0.93; 95% CI 0.92-0.95) and a lower rate of treatment discontinuation (adjusted hazard ratio for a 10-unit change in BMI 0.75; 95% CI 0.67-0.83) compared with normal-weight patients. No effect of BMI on palbociclib efficacy was observed at 31 months of follow-up. Further studies are needed to validate these findings in different cohorts.

In cases of early-stage breast cancer (clinical T1, T2) where patients undergo upfront breast-conserving therapy and sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), completion of axillary lymph node dissection (CLND) is often omitted if only one or two positive sentinel lymph nodes are detected. A study by Zaveri and colleagues looked at outcomes among 548 patients with cT1-2 N0 BC who were treated with upfront mastectomy and had one or two positive lymph nodes on SLNB. The 5-year cumulative incidence rate of overall locoregional recurrence was comparable between patients who underwent vs those who did not undergo CLND (1.8% vs 1.3%; P = .93); receipt of post-mastectomy radiation therapy did not affect the locoregional recurrence rate in both categories of patients who underwent SLNB alone and SLNB with CLND (P = .1638). These results suggest that CLND may not necessarily improve outcomes in this patient population. Larger prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings.

The use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) can affect the bioavailability and effectiveness of concomitant medications, including cancer therapies. A retrospective study by Lee and colleagues aimed to identify the clinical outcomes of patients with hormone receptor–positive (HR+) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative advanced or metastatic BC who were concomitantly using PPI and palbociclib. The study included 1310 patients, of which 344 received concomitant PPI plus palbociclib and 966 patients received palbociclib alone. Results showed that patients who received concomitant PPI plus palbociclib had significantly shorter progression-free survival (hazard ratio 1.76; 95% CI 1.46-2.13) and overall survival (hazard ratio 2.72; 95% CI 2.07-3.53) rates compared with those who received palbociclib alone. These results suggest that the concomitant use of PPI with palbociclib may alter the therapeutic efficacy of the drug. More research studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Pfeiler and colleagues examined the association of BMI with side effects, treatment discontinuation, and efficacy of palbociclib. This study looked at 5698 patients with early-stage HR+ BC who received palbociclib plus endocrine therapy as part of a preplanned analysis of the PALLAS trial. Results showed that in women who received adjuvant palbociclib, higher BMI was associated with a significantly lower rate of neutropenia (odds ratio for a 1-unit change in BMI 0.93; 95% CI 0.92-0.95) and a lower rate of treatment discontinuation (adjusted hazard ratio for a 10-unit change in BMI 0.75; 95% CI 0.67-0.83) compared with normal-weight patients. No effect of BMI on palbociclib efficacy was observed at 31 months of follow-up. Further studies are needed to validate these findings in different cohorts.

In cases of early-stage breast cancer (clinical T1, T2) where patients undergo upfront breast-conserving therapy and sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), completion of axillary lymph node dissection (CLND) is often omitted if only one or two positive sentinel lymph nodes are detected. A study by Zaveri and colleagues looked at outcomes among 548 patients with cT1-2 N0 BC who were treated with upfront mastectomy and had one or two positive lymph nodes on SLNB. The 5-year cumulative incidence rate of overall locoregional recurrence was comparable between patients who underwent vs those who did not undergo CLND (1.8% vs 1.3%; P = .93); receipt of post-mastectomy radiation therapy did not affect the locoregional recurrence rate in both categories of patients who underwent SLNB alone and SLNB with CLND (P = .1638). These results suggest that CLND may not necessarily improve outcomes in this patient population. Larger prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Ruxolitinib for vitiligo: Experts share experiences from first year

.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the cream formulation of ruxolitinib (Opzelura), a JAK inhibitor, for repigmentation of nonsegmental vitiligo in July 2022 for people aged 12 years and older.

Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, assistant professor of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said that he likes to use ruxolitinib cream in combination with other treatments.

“In the real world with vitiligo patients, we’re oftentimes doing combinatorial therapy anyway. So phototherapy, specifically, narrow-band UVB, is something that we have a lot of clinical evidence for over the years, and it’s a modality that can combine with topical steroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors.”

He said trials to study combinations will yield better guidance on optimal use of ruxolitinib cream. “In general, vitiligo patients can really benefit from phototherapy,” he said in an interview. (Labeling recommends against combination with other JAK inhibitors, biologics, or potent immunosuppressants, such as azathioprine or cyclosporine.)

This first year has shown that ruxolitinib is an effective option, but counseling patients to expect slow improvement is important so that patients stick with it, he noted.

Documenting what treatments patients with vitiligo have used before is important, he said, as is counseling patients that ruxolitinib is approved only for use on up to 10% of a person’s body surface area. (Product labeling recommends that a thin layer be applied twice a day to affected areas up to 10% of body surface area.)

Ruxolitinib has brought a “louder voice” to vitiligo and has opened up options for patients with the disease, Dr. Chovatiya said. “Having the ability to topically treat people who have very extensive disease really gives us a lot more flexibility than we have had before.”

Good experiences with payers at safety-net hospital

Candrice R. Heath, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at Temple University, Philadelphia, said that real-world experience with topical ruxolitinib will be more evident after its been on the market for 18-24 months.

Dr. Heath said she, too, encourages use of narrow-band UVB phototherapy in conjunction with the treatment.

From an insurance reimbursement standpoint, she said that she is glad that there have been fewer hurdles in getting ruxolitinib to patients than she has experienced with other medications.

In her safety-net hospital, she told this news organization, she sees patients with many types of insurance, but most have Medicaid. “So, I’m always expecting the step therapies, denials, pushbacks, etc.,” she said. But the path has been smoother for ruxolitinib coverage, she noted.

Her colleagues are committed to documenting everything the patient has tried, she added, and that helps with prior authorization.

Dr. Heath said that pointing out to insurers that ruxolitinib is the only approved treatment for repigmentation helps facilitate coverage.

“The science is advancing, and I’m happy to be practicing during a time when we actually have something approved for vitiligo,” she said. But she pointed out that phototherapy often is not covered for vitiligo, “which is horrible, when it is readily approved for psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.”

To document progress, Dr. Heath said that she always takes photographs of her patients with vitiligo because “the pictures remind us how far we have come.”

Data spotlight success in adolescents

Data from two trials give a clinical picture of the drug’s safety and efficacy in younger patients.

Adolescents had particularly good results in the first year with ruxolitinib, according to pooled phase 3 data from TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2, this news organization reported.

The findings, presented at the 25th World Congress of Dermatology in Singapore, indicate that more than half of the participants achieved at least a 50% improvement from baseline in the total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (T-VASI50) at 52 weeks.

The percentages of young patients aged 12-17 years taking twice-daily ruxolitinib who achieved T-VASI 50 at weeks 12, 24, and 52 were 11.5%, 26.9%, and 57.7%, respectively. The corresponding percentages for all in the study population were 10.7%, 22.7%, and 44.4%, respectively.

At the meeting, the presenter, Julien Seneschal, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology and head of the vitiligo and pigmentary disorders clinic at the University of Bordeaux, France, said, “This suggests that younger patients can respond better to the treatment.” He noted, however, that there were few adolescents in the studies.

New excitement in the field

Daniel Gutierrez, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at New York University, said the treatment has brought new excitement to the field.

“Patients with vitiligo are very motivated to treat their disease,” he said, because it typically is on the face and other highly visual areas, which can affect their overall perception of self.

Previously, he noted in an interview, the only FDA-approved treatment was monobenzone, but that was for depigmentation rather than repigmentation.

Otherwise, treatments were being used off label, and patients were receiving compounded formulations that often weren’t covered by insurance and often had shorter shelf life.

He said that he still occasionally gets denials from payers who consider vitiligo a cosmetic condition.

“I’ve had more luck with insurance, at least in the New York State area.” He added that sometimes payers require use of a topical calcineurin inhibitor for about 12 weeks before they will cover ruxolitinib.

Dr. Gutierrez also recommends using phototherapy with topical ruxolitinib “because they work on slightly different pathways.”

When he starts patients on a new therapy such as ruxolitinib, he asks them to come back in 3 months, and often by then, progress is evident. Facial areas show the most response, he said, while hands and feet are less likely to show significant improvement.

He said that it’s important for physicians and patients to know that improvements can take weeks or months to be noticeable. “I tell patients not to give up,” he added.

Showing the patients pictures from the current appointment and comparing them with pictures from previous appointments can help them better understand their progress, he said.

Lead investigator adds observations

David Rosmarin, MD, chair of the department of dermatology at Indiana University, Indianapolis, was the lead investigator of the pivotal TruE-V1 and TruE-V2 trials for vitiligo. In that role, he has been treating vitiligo patients with topical ruxolitinib since 2015.

In an interview, he said that many patients “don’t hit their optimal results at 3 months, 6 months, even the year mark. With continued use, many can see continued benefit.”

Other patients, he said, don’t respond within the first 6 months but with continued use may eventually respond, he said.

“Unfortunately, we have no way of knowing, based on clinical characteristics or baseline demographics, whether a patient will be a delayed responder or not or an early responder,” Dr. Rosmarin added.

He provided several observations about people who have stopped taking the medication.

“When people stop,” he said, “some maintain their response, but some start to depigment again. Again, we have no way of predicting who will be in which category.”

He said that once patients have hit their desired response, he usually advises them to taper down to maybe twice a week or to stop treatment, but if they see any recurrence, they should start reusing the medicine.

“We have some patients who have gone 6 or 7 years now before they had a recurrence, but others may start to depigment again in 2 to 3 months,” Dr. Rosmarin said.

As for phototherapy, he said, the combination with topical ruxolitinib is being studied.

“We think the combination is synergistic and better than either alone, but we’re still waiting for data to prove that,” he said.

In his practice, he offers patients the option either to use just ruxolitinib cream or the combination early on. Many patients, because of convenience, say they’ll first try the cream to see if that works.

“The challenge with light [therapy] is that it can be very inconvenient,” he said. Patients have to live close to a phototherapy unit to receive therapy 2-3 times a week or have a phototherapy product in their home.

Next in the pipeline

Experts say the progress doesn’t stop with ruxolitinib cream. Current trials of several medications show there’s more to come for patients with vitiligo.

Dr. Chovatiya said that next up may be oral ritlecitinib (Litfulo), a JAK inhibitor that was approved for severe alopecia areata in June for people aged 12 years and older. Phase 2 results have been published for its use with vitiligo.

“This would be an oral medication that may be able to help people with much more extensive disease as far as vitiligo goes,” he said, adding that he expects approval for a vitiligo indication within a few years.

He pointed out that longer-term safety data will be available because it is already on the market for alopecia.

Upadacitinib (Rinvoq), an oral JAK inhibitor, is approved for atopic dermatitis but is being studied for vitiligo as well, he noted. “I’m very excited to see what that holds for patients as well,” Dr. Chovatiya said.

Dr. Gutierrez said that he is excited about oral JAK inhibitors but sees potential in finding new ways to transplant melanocytes into areas where there are none.

The pigmentation field has seen new energy since last year’s approval, he said, particularly among people of color.

“We have new options for vitiligo that were lacking compared with other conditions, such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis,” he said. “Hopefully, there will be more promising breakthroughs.”

Dr. Rosmarin is the chief investigator for the pivotal trials that led to FDA approval of ruxolitinib. He disclosed ties with AbbVie, Abcuro, AltruBio, Amgen, Arena, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Celgene, Concert, CSL Behring, Dermavant, Dermira, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Revolo Biotherapeutics, Sanofi, Sun Pharmaceuticals, UCB, and Viela Bio. Dr. Chovatiya disclosed ties with AbbVie, Arcutis, Arena, Argenx, Beiersdorf, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, EPI Health, Incyte, LEO Pharma, L’Oréal, National Eczema Association, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, and UCB. Dr. Heath and Dr. Gutierrez report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the cream formulation of ruxolitinib (Opzelura), a JAK inhibitor, for repigmentation of nonsegmental vitiligo in July 2022 for people aged 12 years and older.

Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, assistant professor of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said that he likes to use ruxolitinib cream in combination with other treatments.

“In the real world with vitiligo patients, we’re oftentimes doing combinatorial therapy anyway. So phototherapy, specifically, narrow-band UVB, is something that we have a lot of clinical evidence for over the years, and it’s a modality that can combine with topical steroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors.”

He said trials to study combinations will yield better guidance on optimal use of ruxolitinib cream. “In general, vitiligo patients can really benefit from phototherapy,” he said in an interview. (Labeling recommends against combination with other JAK inhibitors, biologics, or potent immunosuppressants, such as azathioprine or cyclosporine.)

This first year has shown that ruxolitinib is an effective option, but counseling patients to expect slow improvement is important so that patients stick with it, he noted.

Documenting what treatments patients with vitiligo have used before is important, he said, as is counseling patients that ruxolitinib is approved only for use on up to 10% of a person’s body surface area. (Product labeling recommends that a thin layer be applied twice a day to affected areas up to 10% of body surface area.)

Ruxolitinib has brought a “louder voice” to vitiligo and has opened up options for patients with the disease, Dr. Chovatiya said. “Having the ability to topically treat people who have very extensive disease really gives us a lot more flexibility than we have had before.”

Good experiences with payers at safety-net hospital

Candrice R. Heath, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at Temple University, Philadelphia, said that real-world experience with topical ruxolitinib will be more evident after its been on the market for 18-24 months.

Dr. Heath said she, too, encourages use of narrow-band UVB phototherapy in conjunction with the treatment.

From an insurance reimbursement standpoint, she said that she is glad that there have been fewer hurdles in getting ruxolitinib to patients than she has experienced with other medications.

In her safety-net hospital, she told this news organization, she sees patients with many types of insurance, but most have Medicaid. “So, I’m always expecting the step therapies, denials, pushbacks, etc.,” she said. But the path has been smoother for ruxolitinib coverage, she noted.

Her colleagues are committed to documenting everything the patient has tried, she added, and that helps with prior authorization.

Dr. Heath said that pointing out to insurers that ruxolitinib is the only approved treatment for repigmentation helps facilitate coverage.

“The science is advancing, and I’m happy to be practicing during a time when we actually have something approved for vitiligo,” she said. But she pointed out that phototherapy often is not covered for vitiligo, “which is horrible, when it is readily approved for psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.”

To document progress, Dr. Heath said that she always takes photographs of her patients with vitiligo because “the pictures remind us how far we have come.”

Data spotlight success in adolescents

Data from two trials give a clinical picture of the drug’s safety and efficacy in younger patients.

Adolescents had particularly good results in the first year with ruxolitinib, according to pooled phase 3 data from TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2, this news organization reported.

The findings, presented at the 25th World Congress of Dermatology in Singapore, indicate that more than half of the participants achieved at least a 50% improvement from baseline in the total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (T-VASI50) at 52 weeks.

The percentages of young patients aged 12-17 years taking twice-daily ruxolitinib who achieved T-VASI 50 at weeks 12, 24, and 52 were 11.5%, 26.9%, and 57.7%, respectively. The corresponding percentages for all in the study population were 10.7%, 22.7%, and 44.4%, respectively.

At the meeting, the presenter, Julien Seneschal, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology and head of the vitiligo and pigmentary disorders clinic at the University of Bordeaux, France, said, “This suggests that younger patients can respond better to the treatment.” He noted, however, that there were few adolescents in the studies.

New excitement in the field

Daniel Gutierrez, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at New York University, said the treatment has brought new excitement to the field.

“Patients with vitiligo are very motivated to treat their disease,” he said, because it typically is on the face and other highly visual areas, which can affect their overall perception of self.

Previously, he noted in an interview, the only FDA-approved treatment was monobenzone, but that was for depigmentation rather than repigmentation.

Otherwise, treatments were being used off label, and patients were receiving compounded formulations that often weren’t covered by insurance and often had shorter shelf life.

He said that he still occasionally gets denials from payers who consider vitiligo a cosmetic condition.

“I’ve had more luck with insurance, at least in the New York State area.” He added that sometimes payers require use of a topical calcineurin inhibitor for about 12 weeks before they will cover ruxolitinib.

Dr. Gutierrez also recommends using phototherapy with topical ruxolitinib “because they work on slightly different pathways.”

When he starts patients on a new therapy such as ruxolitinib, he asks them to come back in 3 months, and often by then, progress is evident. Facial areas show the most response, he said, while hands and feet are less likely to show significant improvement.

He said that it’s important for physicians and patients to know that improvements can take weeks or months to be noticeable. “I tell patients not to give up,” he added.

Showing the patients pictures from the current appointment and comparing them with pictures from previous appointments can help them better understand their progress, he said.

Lead investigator adds observations

David Rosmarin, MD, chair of the department of dermatology at Indiana University, Indianapolis, was the lead investigator of the pivotal TruE-V1 and TruE-V2 trials for vitiligo. In that role, he has been treating vitiligo patients with topical ruxolitinib since 2015.

In an interview, he said that many patients “don’t hit their optimal results at 3 months, 6 months, even the year mark. With continued use, many can see continued benefit.”

Other patients, he said, don’t respond within the first 6 months but with continued use may eventually respond, he said.

“Unfortunately, we have no way of knowing, based on clinical characteristics or baseline demographics, whether a patient will be a delayed responder or not or an early responder,” Dr. Rosmarin added.

He provided several observations about people who have stopped taking the medication.

“When people stop,” he said, “some maintain their response, but some start to depigment again. Again, we have no way of predicting who will be in which category.”

He said that once patients have hit their desired response, he usually advises them to taper down to maybe twice a week or to stop treatment, but if they see any recurrence, they should start reusing the medicine.

“We have some patients who have gone 6 or 7 years now before they had a recurrence, but others may start to depigment again in 2 to 3 months,” Dr. Rosmarin said.

As for phototherapy, he said, the combination with topical ruxolitinib is being studied.

“We think the combination is synergistic and better than either alone, but we’re still waiting for data to prove that,” he said.

In his practice, he offers patients the option either to use just ruxolitinib cream or the combination early on. Many patients, because of convenience, say they’ll first try the cream to see if that works.

“The challenge with light [therapy] is that it can be very inconvenient,” he said. Patients have to live close to a phototherapy unit to receive therapy 2-3 times a week or have a phototherapy product in their home.

Next in the pipeline

Experts say the progress doesn’t stop with ruxolitinib cream. Current trials of several medications show there’s more to come for patients with vitiligo.

Dr. Chovatiya said that next up may be oral ritlecitinib (Litfulo), a JAK inhibitor that was approved for severe alopecia areata in June for people aged 12 years and older. Phase 2 results have been published for its use with vitiligo.

“This would be an oral medication that may be able to help people with much more extensive disease as far as vitiligo goes,” he said, adding that he expects approval for a vitiligo indication within a few years.

He pointed out that longer-term safety data will be available because it is already on the market for alopecia.

Upadacitinib (Rinvoq), an oral JAK inhibitor, is approved for atopic dermatitis but is being studied for vitiligo as well, he noted. “I’m very excited to see what that holds for patients as well,” Dr. Chovatiya said.

Dr. Gutierrez said that he is excited about oral JAK inhibitors but sees potential in finding new ways to transplant melanocytes into areas where there are none.

The pigmentation field has seen new energy since last year’s approval, he said, particularly among people of color.

“We have new options for vitiligo that were lacking compared with other conditions, such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis,” he said. “Hopefully, there will be more promising breakthroughs.”

Dr. Rosmarin is the chief investigator for the pivotal trials that led to FDA approval of ruxolitinib. He disclosed ties with AbbVie, Abcuro, AltruBio, Amgen, Arena, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Celgene, Concert, CSL Behring, Dermavant, Dermira, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Revolo Biotherapeutics, Sanofi, Sun Pharmaceuticals, UCB, and Viela Bio. Dr. Chovatiya disclosed ties with AbbVie, Arcutis, Arena, Argenx, Beiersdorf, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, EPI Health, Incyte, LEO Pharma, L’Oréal, National Eczema Association, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, and UCB. Dr. Heath and Dr. Gutierrez report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the cream formulation of ruxolitinib (Opzelura), a JAK inhibitor, for repigmentation of nonsegmental vitiligo in July 2022 for people aged 12 years and older.

Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, assistant professor of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said that he likes to use ruxolitinib cream in combination with other treatments.

“In the real world with vitiligo patients, we’re oftentimes doing combinatorial therapy anyway. So phototherapy, specifically, narrow-band UVB, is something that we have a lot of clinical evidence for over the years, and it’s a modality that can combine with topical steroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors.”

He said trials to study combinations will yield better guidance on optimal use of ruxolitinib cream. “In general, vitiligo patients can really benefit from phototherapy,” he said in an interview. (Labeling recommends against combination with other JAK inhibitors, biologics, or potent immunosuppressants, such as azathioprine or cyclosporine.)

This first year has shown that ruxolitinib is an effective option, but counseling patients to expect slow improvement is important so that patients stick with it, he noted.

Documenting what treatments patients with vitiligo have used before is important, he said, as is counseling patients that ruxolitinib is approved only for use on up to 10% of a person’s body surface area. (Product labeling recommends that a thin layer be applied twice a day to affected areas up to 10% of body surface area.)

Ruxolitinib has brought a “louder voice” to vitiligo and has opened up options for patients with the disease, Dr. Chovatiya said. “Having the ability to topically treat people who have very extensive disease really gives us a lot more flexibility than we have had before.”

Good experiences with payers at safety-net hospital

Candrice R. Heath, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at Temple University, Philadelphia, said that real-world experience with topical ruxolitinib will be more evident after its been on the market for 18-24 months.

Dr. Heath said she, too, encourages use of narrow-band UVB phototherapy in conjunction with the treatment.

From an insurance reimbursement standpoint, she said that she is glad that there have been fewer hurdles in getting ruxolitinib to patients than she has experienced with other medications.

In her safety-net hospital, she told this news organization, she sees patients with many types of insurance, but most have Medicaid. “So, I’m always expecting the step therapies, denials, pushbacks, etc.,” she said. But the path has been smoother for ruxolitinib coverage, she noted.

Her colleagues are committed to documenting everything the patient has tried, she added, and that helps with prior authorization.

Dr. Heath said that pointing out to insurers that ruxolitinib is the only approved treatment for repigmentation helps facilitate coverage.

“The science is advancing, and I’m happy to be practicing during a time when we actually have something approved for vitiligo,” she said. But she pointed out that phototherapy often is not covered for vitiligo, “which is horrible, when it is readily approved for psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.”

To document progress, Dr. Heath said that she always takes photographs of her patients with vitiligo because “the pictures remind us how far we have come.”

Data spotlight success in adolescents

Data from two trials give a clinical picture of the drug’s safety and efficacy in younger patients.

Adolescents had particularly good results in the first year with ruxolitinib, according to pooled phase 3 data from TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2, this news organization reported.

The findings, presented at the 25th World Congress of Dermatology in Singapore, indicate that more than half of the participants achieved at least a 50% improvement from baseline in the total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (T-VASI50) at 52 weeks.

The percentages of young patients aged 12-17 years taking twice-daily ruxolitinib who achieved T-VASI 50 at weeks 12, 24, and 52 were 11.5%, 26.9%, and 57.7%, respectively. The corresponding percentages for all in the study population were 10.7%, 22.7%, and 44.4%, respectively.

At the meeting, the presenter, Julien Seneschal, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology and head of the vitiligo and pigmentary disorders clinic at the University of Bordeaux, France, said, “This suggests that younger patients can respond better to the treatment.” He noted, however, that there were few adolescents in the studies.

New excitement in the field

Daniel Gutierrez, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at New York University, said the treatment has brought new excitement to the field.

“Patients with vitiligo are very motivated to treat their disease,” he said, because it typically is on the face and other highly visual areas, which can affect their overall perception of self.

Previously, he noted in an interview, the only FDA-approved treatment was monobenzone, but that was for depigmentation rather than repigmentation.

Otherwise, treatments were being used off label, and patients were receiving compounded formulations that often weren’t covered by insurance and often had shorter shelf life.

He said that he still occasionally gets denials from payers who consider vitiligo a cosmetic condition.

“I’ve had more luck with insurance, at least in the New York State area.” He added that sometimes payers require use of a topical calcineurin inhibitor for about 12 weeks before they will cover ruxolitinib.

Dr. Gutierrez also recommends using phototherapy with topical ruxolitinib “because they work on slightly different pathways.”

When he starts patients on a new therapy such as ruxolitinib, he asks them to come back in 3 months, and often by then, progress is evident. Facial areas show the most response, he said, while hands and feet are less likely to show significant improvement.

He said that it’s important for physicians and patients to know that improvements can take weeks or months to be noticeable. “I tell patients not to give up,” he added.

Showing the patients pictures from the current appointment and comparing them with pictures from previous appointments can help them better understand their progress, he said.

Lead investigator adds observations

David Rosmarin, MD, chair of the department of dermatology at Indiana University, Indianapolis, was the lead investigator of the pivotal TruE-V1 and TruE-V2 trials for vitiligo. In that role, he has been treating vitiligo patients with topical ruxolitinib since 2015.

In an interview, he said that many patients “don’t hit their optimal results at 3 months, 6 months, even the year mark. With continued use, many can see continued benefit.”

Other patients, he said, don’t respond within the first 6 months but with continued use may eventually respond, he said.

“Unfortunately, we have no way of knowing, based on clinical characteristics or baseline demographics, whether a patient will be a delayed responder or not or an early responder,” Dr. Rosmarin added.

He provided several observations about people who have stopped taking the medication.

“When people stop,” he said, “some maintain their response, but some start to depigment again. Again, we have no way of predicting who will be in which category.”

He said that once patients have hit their desired response, he usually advises them to taper down to maybe twice a week or to stop treatment, but if they see any recurrence, they should start reusing the medicine.

“We have some patients who have gone 6 or 7 years now before they had a recurrence, but others may start to depigment again in 2 to 3 months,” Dr. Rosmarin said.

As for phototherapy, he said, the combination with topical ruxolitinib is being studied.

“We think the combination is synergistic and better than either alone, but we’re still waiting for data to prove that,” he said.

In his practice, he offers patients the option either to use just ruxolitinib cream or the combination early on. Many patients, because of convenience, say they’ll first try the cream to see if that works.

“The challenge with light [therapy] is that it can be very inconvenient,” he said. Patients have to live close to a phototherapy unit to receive therapy 2-3 times a week or have a phototherapy product in their home.

Next in the pipeline

Experts say the progress doesn’t stop with ruxolitinib cream. Current trials of several medications show there’s more to come for patients with vitiligo.

Dr. Chovatiya said that next up may be oral ritlecitinib (Litfulo), a JAK inhibitor that was approved for severe alopecia areata in June for people aged 12 years and older. Phase 2 results have been published for its use with vitiligo.

“This would be an oral medication that may be able to help people with much more extensive disease as far as vitiligo goes,” he said, adding that he expects approval for a vitiligo indication within a few years.

He pointed out that longer-term safety data will be available because it is already on the market for alopecia.

Upadacitinib (Rinvoq), an oral JAK inhibitor, is approved for atopic dermatitis but is being studied for vitiligo as well, he noted. “I’m very excited to see what that holds for patients as well,” Dr. Chovatiya said.

Dr. Gutierrez said that he is excited about oral JAK inhibitors but sees potential in finding new ways to transplant melanocytes into areas where there are none.

The pigmentation field has seen new energy since last year’s approval, he said, particularly among people of color.

“We have new options for vitiligo that were lacking compared with other conditions, such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis,” he said. “Hopefully, there will be more promising breakthroughs.”

Dr. Rosmarin is the chief investigator for the pivotal trials that led to FDA approval of ruxolitinib. He disclosed ties with AbbVie, Abcuro, AltruBio, Amgen, Arena, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Celgene, Concert, CSL Behring, Dermavant, Dermira, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Revolo Biotherapeutics, Sanofi, Sun Pharmaceuticals, UCB, and Viela Bio. Dr. Chovatiya disclosed ties with AbbVie, Arcutis, Arena, Argenx, Beiersdorf, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, EPI Health, Incyte, LEO Pharma, L’Oréal, National Eczema Association, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, and UCB. Dr. Heath and Dr. Gutierrez report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Experts debate low-carb diets for people with diabetes

It’s an ongoing debate in the diabetes world: Is it ideal to consume a very-low-carbohydrate diet, or is it better to go with moderate amounts of healthful carbs?

At the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association, Carol F. Kirkpatrick, PhD, RDN, spoke first, arguing in favor of diets consisting of moderate, high-quality carbohydrates.

Dina Hafez Griauzde, MD, countered that very-low-carbohydrate diets are more beneficial for people with diabetes, primarily type 2 diabetes.

Both speakers based their arguments on published evidence but agreed in the end that discussion with patients about individual dietary preferences should play a major role in the ultimate decision.

Moderate-carbohydrate eating is best

Dr. Kirkpatrick began by explaining that definitions of “low carb” vary in the literature, which makes comparisons between studies difficult. On the basis of a 2019 review that she coauthored, “moderate” carbohydrate consumption was defined as a diet in which 26%-44% of total daily calories are from carbohydrates. “Low” carbohydrate consumption was defined as a diet in which 10%-25% of calories were from carbohydrates. Consuming less than 10% was defined as a very-low-carbohydrate diet (i.e., a ketogenic diet).

Across studies, she noted, the literature shows that within the first 6 months weight loss is typically greater with carbohydrate-restricted diets than with higher-carbohydrate diets, but that by 1 year and beyond weight loss is similar.

“That can be partly due to the difficulty in people maintaining that very severe dietary restriction, although ... we can all acknowledge that it’s difficult for patients to adhere to any dietary pattern, so for sure by 12 months, the difference in the weight loss is gone between the two,” said Dr. Kirkpatrick, of Midwest Biomedical Research, Pocatello, Idaho.

In a recent meta-analysis of 35 trials that examined the dose-dependent effects of carbohydrate restriction for patients with type 2 diabetes, there was a significant decrease in weight as carbohydrates were reduced. But by 12 months (17 trials), the greatest weight reduction was seen at 35% carbohydrate intake.

“It may just be that people were able to adhere to that moderate intake better,” she explained.